Фекальная трансплантация микробиоты

| Фекальная трансплантация микробиоты | |

|---|---|

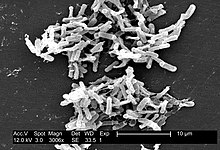

Escherichia coli при увеличении 10000 × | |

| Другие имена | Фекальная бактериотерапия, фекальная трансфузия, трансплантация фекалий, трансплантация стула |

| Специальность | Гастроэнтерология |

| Клинические данные | |

|---|---|

| Код ATC |

|

| Юридический статус | |

| Юридический статус |

|

Фекальная трансплантация микробиоты ( FMT ), также известная как трансплантация стула , [ 2 ] является процессом переноса фекальных бактерий и других микробов от здорового человека в другого человека. FMT является эффективным лечением для Clostridioides Difficile инфекции (CDI). [ 3 ] [ 4 ] [ 5 ] Для повторяющегося CDI FMT является более эффективной, чем только ванкомицин , и может улучшить результат после первой инфекции индекса. [ 3 ] [ 5 ] [ 6 ]

Побочные эффекты могут включать риск инфекций , поэтому донор должен быть проверен на патогены . [ 7 ]

Поскольку CDI становится все более распространенным, FMT приобретает растущую известность, причем некоторые эксперты призывают его стать терапией первой линии для CDI. [ 8 ] FMT использовался экспериментально для лечения других желудочно -кишечных заболеваний , включая колит , запоры , синдром раздраженного кишечника и неврологические состояния, такие как рассеянный склероз и паркинсон . [ 9 ] [ 10 ] В Соединенных Штатах человеческие фекалии регулируются в качестве экспериментального препарата с 2013 года. В Соединенном Королевстве регулирование FMT находится под действием регулирующего органа по лекарствам и здравоохранению . [ 11 ]

Медицинское использование

[ редактировать ]Clostridioides Difficile Infection

[ редактировать ]

Пересадка фекальной микробиоты примерно на 85–90% эффективна у людей с CDI, для которых антибиотики не работали или при которых заболевание повторяется после антибиотиков. [ 12 ] [ 13 ] Большинство людей с CDI восстанавливаются с одним лечением FMT. [ 8 ] [ 14 ] [ 15 ]

Исследование 2009 года показало, что трансплантация фекальной микробиоты была эффективной и простой процедурой, которая была более рентабельной, чем продолжающееся введение антибиотиков, и снижала частоту устойчивости к антибиотикам . [ 16 ]

После того, как некоторые медицинские работники считали «последней курортной терапией» из -за его необычной природы и инвазивности по сравнению с антибиотиками, воспринимаемым потенциальным риском передачи инфекции и отсутствием охвата Medicare для донорского стула, позиционные заявления специалистов по инфекционным заболеваниям и Другие общества [ 14 ] продвигались к принятию FMT в качестве стандартной терапии для рецидивирования CDI, а также покрытия Medicare в Соединенных Штатах. [ 17 ]

Было рекомендовано, чтобы эндоскопический FMT был повышен до первой линии лечения для людей с ухудшением и тяжелой рецидивом C. difficile Infection. [ 8 ]

В ноябре 2022 года трансплантация фекальной микробиоты (Biomictra) была одобрена для медицинского использования в Австралии, [ 1 ] [ 18 ] и фекальная микробиота, Live (Rebyota) была одобрена для медицинского использования в Соединенных Штатах. [ 19 ]

Споры фекальной микробиоты, Live (Vowst) были одобрены для медицинского использования в Соединенных Штатах в апреле 2023 года. [ 20 ] [ 21 ] Это первый продукт фекальной микробиоты, который принимается в рот . [ 20 ]

Другие условия

[ редактировать ]Язвенный колит

[ редактировать ]В мае 1988 года австралийский профессор Томас Бороди лечился первым пациентом с язвенным колитом , используя FMT, что привело к давнему разрешению симптомов. [ 22 ] После этого Джастин Д. Беннет опубликовал первый отчет о случаях, документирующий изменение собственного колита Беннета с использованием FMT. [ 23 ] В то время как C. difficile легко уничтожается одним инфузией FMT, это обычно, по -видимому, не так с язвенным колитом. Опубликованный опыт лечения язвенного колита с помощью FMT в значительной степени показывает, что для достижения длительной ремиссии или лечения требуются множественные и рецидивирующие инфузии. [ 22 ] [ 24 ]

Рак

[ редактировать ]Ведутся клинические испытания, чтобы оценить, может ли FMT от доноров иммунотерапии против PD-1 способствовать терапевтическому ответу у пациентов с иммунотерапией-резистенцией. [ 25 ] [ 26 ]

Аутизм

[ редактировать ]Однажды связанный с натуропатией , [ 27 ] Были проведены серьезные исследования по лечению расстройства аутистического спектра с помощью трансплантации фекальной микробиоты. Одно из таких исследований было проведено в Шанхае , Китай, [ 28 ] и более раннее исследование во главе с Университетом штата Аризона . [ 29 ] Лечение в Аризоне получило патент США (#11,202,808) [ 30 ] И исследователи надеются на одобрение FDA. [ 31 ]

Неблагоприятные эффекты

[ редактировать ]Побочные эффекты были плохо изучены с 2016 года. [ 32 ] Они включали бактериальные инфекции в крови , лихорадку, синдром подобного SIRS , обострение воспалительного заболевания кишечника у людей, у которых также было такое состояние, и легкое расстройство желудочно -кишечного тракта, которое обычно разрешается вскоре после процедуры, включая метеоризм, диарею, нерегулярные движения кишечника, живот Растяжение/вздутие живота, боль в животе/нежность, запор, спазмы и тошнота. [ 32 ] [ 33 ] Есть также опасения, что он может распространять Covid-19 . [ 34 ]

Человек погиб в Соединенных Штатах в 2019 году, после получения FMT, в котором содержались устойчивые к лекарствам бактерии, и другой человек, получивший такую же трансплантацию, также был заражен. [ 35 ] [ 36 ] США Управление по санитарному надзору за продуктами и лекарствами (FDA) выпустило предупреждение против потенциально опасных для жизни последствий пересадки материала из неправильно проверенных доноров. [ 35 ]

Техника

[ редактировать ]Существуют основанные на фактических данных рекомендации по консенсусу для оптимального введения FMT. Такие документы описывают процедуру FMT, включая подготовку материала, выбор доноров и скрининг, а также администрирование FMT. [ 11 ] [ 14 ] [ 37 ] [ 38 ]

Микробиота кишечника включает в себя все микроорганизмы, которые находятся вдоль желудочно -кишечного тракта, включая комменсальные, симбиотические и патогенные организмы. FMT - это перенос фекального материала, содержащего бактерии, и природных антибактерий от здорового человека в больного получателя. [ 14 ]

Выбор донора

[ редактировать ]Подготовка к процедуре требует тщательного отбора и проверки потенциального донора. Близкие родственники часто выбираются из -за простоты проверки; [ 14 ] [ 37 ] [ 39 ] Однако в случае лечения активного C. diff. Члены семьи и интимные контакты могут быть более склонными к самим перевозчикам. [ 14 ] Этот скрининг включает в себя вопросники истории болезни, скрининг на различные хронические медицинские заболевания (например, раздраженные заболевания кишечника , болезнь Крона , желудочно -кишечный рак и т. Д.), [ 37 ] [ 40 ] [ 41 ] [ 42 ] и лабораторные испытания на патогенные желудочно -кишечные инфекции (например, CMV , C. Diff. , Salmonella , Giardia , GI паразиты и т. Д.). [ 14 ] [ 37 ] [ 41 ]

Подготовка образца

[ редактировать ]No laboratory standards have been agreed upon,[41] so recommendations vary for size of sample to be prepared, ranging from 30 to 100 grams (1.1 to 3.5 ounces) of fecal material for effective treatment.[13][37][39][42] Fresh stool is used to increase viability of bacteria within the stool[41][42] and samples are prepared within 6–8 hours.[37][41][42] The sample is then diluted with 2.5–5 times the volume of the sample with either normal saline,[37][41] sterile water,[37][41] or 4% milk.[14] Some locations mix the sample and the solvent with a mortar and pestle,[42] and others use a blender.[37][41][42] There is concern with blender use on account of the introduction of air which may decrease efficacy[9] as well as aerosolization of the feces contaminating the preparation area.[37][42] The suspension is then strained through a filter and transferred to an administration container.[37][41][42] If the suspension is to be used later, it can be frozen after being diluted with 10% glycerol,[37][41][42] and used without loss of efficacy compared to the fresh sample.[37][39] The fecal transplant material is then prepared and administered in a clinical environment to ensure that precautions are taken.[9]

Administration

[edit]After being made into suspensions, the fecal material can be given through nasogastric and nasoduodenal tubes, or through a colonoscope or as a retention enema.[14]

Mechanism of action

[edit]One hypothesis behind fecal microbiota transplant rests on the concept of bacterial interference, i.e., using harmless bacteria to displace pathogenic organisms, such as by competitive niche exclusion.[43] In the case of CDI, the C. difficile pathogen is identifiable.[44] Recently, in a pilot study of five patients, sterile fecal filtrate was demonstrated to be of comparable efficacy to conventional FMT in the treatment of recurrent CDI.[45] The conclusion from this study was that soluble filtrate components (such as bacteriophages, metabolites, and/or bacterial components, such as enzymes) may be the key mediators of FMT's efficacy, rather than intact bacteria. It has now been demonstrated that the short-chain fatty acid valerate is restored in human fecal samples from CDI patients and a bioreactor model of recurrent CDI by FMT, but not by antibiotic cessation alone;[46] as such, this may be a key mediator of FMT's efficacy. Other studies have identified rapid-onset but well-maintained changes in the gut bacteriophage profile after successful FMT (with colonisation of the recipient with donor bacteriophages),[47][48] and this is therefore another key area of interest.

In contrast, in the case of other conditions such as ulcerative colitis, no single culprit has yet been identified.[49] However, analysis of gut microbiome and metabolome changes after FMT as treatment for ulcerative colitis has identified some possible candidates of interest.[50]

History

[edit]The first use of donor feces as a therapeutic agent for food poisoning and diarrhea was recorded in the Handbook of Emergency Medicine by a Chinese man, Hong Ge, in the 4th century. Twelve hundred years later Ming dynasty physician Li Shizhen used "yellow soup" (aka "golden syrup") which contained fresh, dry or fermented stool to treat abdominal diseases.[51] "Yellow soup" was made of fecal matter and water, which was drunk by the person.[52]

The consumption of "fresh, warm camel feces" has also been recommended by Bedouins as a remedy for bacterial dysentery; its efficacy, probably attributable to the antimicrobial subtilisin produced by Bacillus subtilis, was anecdotally confirmed by German soldiers of the Afrika Korps during World War II.[53] However, this story is likely a myth; independent research was not able to verify any of these claims.[54]

The first use of FMT in western medicine was published in 1958 by Ben Eiseman and colleagues, a team of surgeons from Colorado, who treated four critically ill people with fulminant pseudomembranous colitis (before C. difficile was the known cause) using fecal enemas, which resulted in a rapid return to health.[55] For over two decades, FMT has been provided as a treatment option at the Centre for Digestive Diseases in Five Dock, by Thomas Borody, the modern-day proponent of FMT. In May 1988 their group treated the first ulcerative colitis patient using FMT, which resulted in complete resolution of all signs and symptoms long term.[22] In 1989 they treated a total of 55 patients with constipation, diarrhea, abdominal pain, ulcerative colitis, and Crohn's disease with FMT. After FMT, 20 patients were considered "cured" and a further 9 patients had a reduction in symptoms.[56] Stool transplants are considered about 90 percent effective in those with severe cases of C. difficile colonization, in whom antibiotics have not worked.[12]

The first randomized controlled trial in C. difficile infection was published in January 2013.[3] The study was stopped early due to the effectiveness of FMT, with 81% of patients achieving cure after a single infusion and over 90% achieving a cure after a second infusion.

Since that time various institutions have offered FMT as a therapeutic option for a variety of conditions.[22]

Society and culture

[edit]Regulation

[edit]Interest in FMT grew in 2012 and 2013, as measured by the number of clinical trials and scientific publications.[57]

In the United States, the FDA announced in February 2013 that it would hold a public meeting entitled "Fecal Microbiota for Transplantation" which was held on May 2–3, 2013.[58][59] In May 2013 the FDA also announced that it had been regulating human fecal material as a drug.[60] The American Gastroenterological Association (AGA), the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG), the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE), and the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (NASPGHAN) sought clarification, and the FDA Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) stated that FMT falls within the definition of a biological product as defined in the Public Health Service Act and the definition of a drug within the meaning of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act.[61] It argued since FMT is used to prevent, treat, or cure a disease or condition, and intended to affect the structure or any function of the body, "a product for such use" would require an Investigational New Drug (IND) application.[61]

In July 2013, the FDA issued an enforcement policy ("guidance") regarding the IND requirement for using FMT to treat C. difficile infection unresponsive to standard therapies (78 FR 42965, July 18, 2013).[62]

In March 2014, the FDA issued a proposed update (called "draft guidance") that, when finalized, is intended to supersede the July 2013 enforcement policy for FMT to treat C. difficile infections unresponsive to standard therapies. It proposed an interim discretionary enforcement period, if 1) informed consent is used, mentioning investigational aspect and risks, 2) stool donor is known to either the person with the condition or physician, and 3) stool donor and stool are screened and tested under the direction of the physician (79 FR 10814, February 26, 2014).[63] Some doctors and people who want to use FMT have been worried that the proposal, if finalized, would shutter the handful of stool banks which have sprung up, using anonymous donors and ship to providers hundreds of miles away.[57][64][65]

As of 2015[update], FMT for recurrent C. difficile infections can be done without mandatory donor and stool screening, whereas FMT for other indications cannot be performed without an IND.[60]

The FDA has issued three safety alerts regarding the transmission of pathogens. The first safety alert, issued in June 2019, described the transmission of a multidrug resistant organism from a donor stool that resulted in the death of one person.[66] The second safety alert, issued in March 2020, was regarding FMT produced from improperly tested donor stools from a stool bank which resulted in several hospitalizations and two deaths.[67] A safety alert in late March 2020, was due to concerns of transmission of COVID-19 in donor stool.[68]

In November 2022, the AU Therapeutic Goods Administration approved faecal microbiota under the brand name Biomictra,[1][18] and the US FDA approved a specific C. difficile fecal microbiota treatment under the brand name Rebyota,[19] administered rectally. In April 2023, the FDA approved a live spore capsule that can be taken by mouth, under the brand name Vowst.[20][69]

Stool banks

[edit]In 2012, a team of researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology founded OpenBiome, the first public stool bank in the United States.[70]

Across Europe, numerous stool banks have emerged to serve the increasing demand. While consensus rapports exists,[37] standard operation procedures still differ. Institutions in the Netherlands have published their protocols for managing FMT,[42] and in Denmark institutions manages FMT according to the European Tissue and Cell directive.[41]

Names

[edit]Previous terms for the procedure include fecal bacteriotherapy, fecal transfusion, fecal transplant, stool transplant, fecal enema, and human probiotic infusion (HPI). Because the procedure involves the complete restoration of the entire fecal microbiota, not just a single agent or combination of agents, these terms have been replaced by the term fecal microbiota transplantation.[14]

Research

[edit]Cultured intestinal bacteria are being studied as an alternative to fecal microbiota transplant.[71] One example is the rectal bacteriotherapy (RBT), developed by Tvede and Helms, containing 12 individually cultured strains of anaerobic and aerobic bacteria originating from healthy human faeces.[72] Research has also been done to identify the most relevant microbes within fecal transplants, which could then be isolated and manufactured via industrial fermentation; such standardized products would be more scalable, would reduce the risk of infections from unwanted microbes, and would improve the scientific study of the approach, since the same substance would be administered each time.[73]

Veterinary use

[edit]Elephants, hippos, koalas, and pandas are born with sterile intestines, and to digest vegetation need bacteria which they obtain by eating their mothers' feces, a practice termed coprophagia. Other animals eat dung.[74]

In veterinary medicine fecal microbiota transplant has been known as "transfaunation" and is used to treat ruminating animals, like cows and sheep, by feeding rumen contents of a healthy animal to another individual of the same species in order to colonize its gastrointestinal tract with normal bacteria.[75]

References

[edit]- ^ Jump up to: a b c "FAECAL MICROBIOTA TRANSPLANT (FMT) (BiomeBank)". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). May 2, 2024. Archived from the original on January 2, 2024. Retrieved July 4, 2024.

- ^ Rowan K (October 20, 2012). "'Poop Transplants' May Combat Bacterial Infections". LiveScience. Archived from the original on November 11, 2020. Retrieved October 20, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c van Nood E, Vrieze A, Nieuwdorp M, Fuentes S, Zoetendal EG, de Vos WM, et al. (January 2013). "Duodenal infusion of donor feces for recurrent Clostridium difficile". The New England Journal of Medicine. 368 (5): 407–415. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1205037. PMID 23323867. S2CID 25879411.

- ^ Moayyedi P, Yuan Y, Baharith H, Ford AC (August 2017). "Faecal microbiota transplantation for Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhoea: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials". The Medical Journal of Australia. 207 (4): 166–172. doi:10.5694/mja17.00295. PMID 28814204. S2CID 24780848.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Baunwall SM, Andreasen SE, Hansen MM, Kelsen J, Høyer KL, Rågård N, et al. (December 2022). "Faecal microbiota transplantation for first or second Clostridioides difficile infection (EarlyFMT): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial". The Lancet. Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 7 (12): 1083–1091. doi:10.1016/S2468-1253(22)00276-X. PMID 36152636. S2CID 252483680.

- ^ Baunwall SM, Lee MM, Eriksen MK, Mullish BH, Marchesi JR, Dahlerup JF, et al. (December 2020). "Faecal microbiota transplantation for recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis". eClinicalMedicine. 29–30: 100642. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100642. PMC 7788438. PMID 33437951.

- ^ "Fecal Microbiota for Transplantation: Safety Alert - Risk of Serious Adverse Events Likely Due to Transmission of Pathogenic Organisms". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). March 12, 2020. Archived from the original on October 21, 2020. Retrieved March 21, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Brandt LJ, Borody TJ, Campbell J (September 2011). "Endoscopic fecal microbiota transplantation: "first-line" treatment for severe clostridium difficile infection?". Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. 45 (8): 655–657. doi:10.1097/MCG.0b013e3182257d4f. PMID 21716124. S2CID 2508836.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Borody TJ, Khoruts A (December 2011). "Fecal microbiota transplantation and emerging applications". Nature Reviews. Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 9 (2): 88–96. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2011.244. PMID 22183182. S2CID 16747221.

- ^ Borody TJ, Paramsothy S, Agrawal G (August 2013). "Fecal microbiota transplantation: indications, methods, evidence, and future directions". Current Gastroenterology Reports. 15 (8): 337. doi:10.1007/s11894-013-0337-1. PMC 3742951. PMID 23852569.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Mullish BH, Quraishi MN, Segal JP, McCune VL, Baxter M, Marsden GL, et al. (November 2018). "The use of faecal microbiota transplant as treatment for recurrent or refractory Clostridium difficile infection and other potential indications: joint British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) and Healthcare Infection Society (HIS) guidelines". Gut. 67 (11): 1920–1941. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2018-316818. hdl:10044/1/61310. PMID 30154172.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Burke KE, Lamont JT (August 2013). "Fecal transplantation for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection in older adults: a review". Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 61 (8): 1394–1398. doi:10.1111/jgs.12378. PMID 23869970. S2CID 34998497.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Drekonja D, Reich J, Gezahegn S, Greer N, Shaukat A, MacDonald R, et al. (May 2015). "Fecal Microbiota Transplantation for Clostridium difficile Infection: A Systematic Review". Annals of Internal Medicine. 162 (9): 630–638. doi:10.7326/m14-2693. PMID 25938992. S2CID 1307726.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j Bakken JS, Borody T, Brandt LJ, Brill JV, Demarco DC, Franzos MA, et al. (December 2011). "Treating Clostridium difficile infection with fecal microbiota transplantation". Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 9 (12): 1044–1049. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2011.08.014. PMC 3223289. PMID 21871249.

- ^ Kelly CR, de Leon L, Jasutkar N (February 2012). "Fecal microbiota transplantation for relapsing Clostridium difficile infection in 26 patients: methodology and results". Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. 46 (2): 145–149. doi:10.1097/MCG.0b013e318234570b. PMID 22157239. S2CID 30849491.

- ^ Bakken JS (December 2009). "Fecal bacteriotherapy for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection". Anaerobe. 15 (6): 285–289. doi:10.1016/j.anaerobe.2009.09.007. PMID 19778623.

- ^ Floch MH (September 2010). "Fecal bacteriotherapy, fecal transplant, and the microbiome". Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. 44 (8): 529–530. doi:10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181e1d6e2. PMID 20601895. S2CID 32439751.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "BiomeBank announces world first regulatory approval for donor derived microbiome drug". Biome Bank (Press release). November 9, 2022. Archived from the original on January 2, 2024. Retrieved January 2, 2024.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Ferring Receives U.S. FDA Approval for Rebyota (fecal microbiota, live-jslm) – A Novel First-in-Class Microbiota-Based Live Biotherapeutic". Ferring Pharmaceuticals USA (Press release). December 1, 2022. Archived from the original on December 1, 2022. Retrieved December 1, 2022.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "FDA Approves First Orally Administered Fecal Microbiota Product for the Prevention of Recurrence of Clostridioides difficile Infection". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). April 26, 2023. Archived from the original on April 26, 2023. Retrieved April 27, 2023.

- ^ "Seres Therapeutics and Nestlé Health Science Announce FDA Approval of Vowst (fecal microbiota spores, live-brpk) for Prevention of Recurrence of C. difficile Infection in Adults Following Antibacterial Treatment for Recurrent CDI" (Press release). Seres Therapeutics. April 26, 2023. Retrieved April 27, 2023 – via Business Wire.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Borody TJ, Campbell J (December 2011). "Fecal microbiota transplantation: current status and future directions". Expert Review of Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 5 (6): 653–655. doi:10.1586/egh.11.71. PMID 22017691. S2CID 8968197.

- ^ Bennet JD, Brinkman M (January 1989). "Treatment of ulcerative colitis by implantation of normal colonic flora". Lancet. 1 (8630): 164. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(89)91183-5. PMID 2563083. S2CID 33842920.

- ^ Sunkara T, Rawla P, Ofosu A, Gaduputi V (2018). "Fecal microbiota transplant - a new frontier in inflammatory bowel disease". Journal of Inflammation Research. 11: 321–328. doi:10.2147/JIR.S176190. PMC 6124474. PMID 30214266.

- ^ Davar D, Dzutsev AK, McCulloch JA, Rodrigues RR, Chauvin JM, Morrison RM, et al. (February 2021). "Fecal microbiota transplant overcomes resistance to anti-PD-1 therapy in melanoma patients". Science. 371 (6529): 595–602. Bibcode:2021Sci...371..595D. doi:10.1126/science.abf3363. PMC 8097968. PMID 33542131. S2CID 231808119.

- ^ Baruch EN, Youngster I, Ben-Betzalel G, Ortenberg R, Lahat A, Katz L, et al. (February 2021). "Fecal microbiota transplant promotes response in immunotherapy-refractory melanoma patients". Science. 371 (6529): 602–609. Bibcode:2021Sci...371..602B. doi:10.1126/science.abb5920. PMID 33303685. S2CID 228101416.

- ^ Lindsay B (January 10, 2020). "B.C. naturopath's pricey fecal transplants for autism are experimental and risky, scientists say". CBC News. British Columbia. Retrieved August 31, 2023.

- ^ Li Y, Wang Y, Zhang T (December 15, 2022). "Fecal Microbiota Transplantation in Autism Spectrum Disorder". Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 18: 2905–2915. doi:10.2147/NDT.S382571. PMC 9762410. PMID 36544550.

- ^ Kang DW, Adams JB, Gregory AC, Borody T, Chittick L, Fasano A, et al. (January 2017). "Microbiota Transfer Therapy alters gut ecosystem and improves gastrointestinal and autism symptoms: an open-label study". Microbiome. 5 (1): 10. doi:10.1186/s40168-016-0225-7. PMC 5264285. PMID 28122648.

- ^ Leander S (February 1, 2022). "Treatment for autism symptoms earns ASU researchers patent: Microbiota Transplant Therapy offering hope to those with autism spectrum disorder". ASU News. Archived from the original on August 31, 2023. Retrieved August 31, 2023.

- ^ Innes S (April 11, 2019). "ASU researchers see hope for autism symptoms with fecal transplants". The Arizona Republic. Archived from the original on August 31, 2023. Retrieved August 31, 2023.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Baxter M, Colville A (February 2016). "Adverse events in faecal microbiota transplant: a review of the literature". The Journal of Hospital Infection (Submitted manuscript). 92 (2): 117–127. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2015.10.024. hdl:11287/595264. PMID 26803556. Archived from the original on April 28, 2023. Retrieved November 7, 2018.

- ^ Goloshchapov OV, Olekhnovich EI, Sidorenko SV, Moiseev IS, Kucher MA, Fedorov DE, et al. (December 2019). "Long-term impact of fecal transplantation in healthy volunteers". BMC Microbiology. 19 (1): 312. doi:10.1186/s12866-019-1689-y. PMC 6938016. PMID 31888470.

- ^ Office of the Commissioner (March 24, 2020). "Fecal Microbiota for Transplantation: Safety Alert - Regarding Additional Safety Protections Pertaining to SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on April 14, 2020. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Fecal Microbiota for Transplantation: Safety Communication- Risk of Serious Adverse Reactions Due to Transmission of Multi-Drug Resistant Organisms". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). June 14, 2019. Archived from the original on September 4, 2019. Retrieved June 18, 2019.

- ^ Grady D (June 13, 2019). "Fecal Transplant Is Linked to a Patient's Death, the F.D.A. Warns". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 14, 2019. Retrieved June 14, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Cammarota G, Ianiro G, Tilg H, Rajilić-Stojanović M, Kump P, Satokari R, et al. (April 2017). "European consensus conference on faecal microbiota transplantation in clinical practice". Gut. 66 (4): 569–580. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2016-313017. PMC 5529972. PMID 28087657.

- ^ Mullish BH, Quraishi MN, Segal JP, McCune VL, Baxter M, Marsden GL, et al. (September 2018). "The use of faecal microbiota transplant as treatment for recurrent or refractory Clostridium difficile infection and other potential indications: joint British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) and Healthcare Infection Society (HIS) guidelines". The Journal of Hospital Infection. 100 (Suppl 1): S1–S31. doi:10.1016/j.jhin.2018.07.037. hdl:10044/1/61310. PMID 30173851.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Merenstein D, El-Nachef N, Lynch SV (August 2014). "Fecal microbial therapy: promises and pitfalls". Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 59 (2): 157–161. doi:10.1097/mpg.0000000000000415. PMC 4669049. PMID 24796803.

- ^ Woodworth MH, Carpentieri C, Sitchenko KL, Kraft CS (May 2017). "Challenges in fecal donor selection and screening for fecal microbiota transplantation: A review". Gut Microbes. 8 (3): 225–237. doi:10.1080/19490976.2017.1286006. PMC 5479407. PMID 28129018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k Jørgensen SM, Hansen MM, Erikstrup C, Dahlerup JF, Hvas CL (November 2017). "Faecal microbiota transplantation: establishment of a clinical application framework". European Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 29 (11): e36–e45. doi:10.1097/meg.0000000000000958. PMID 28863010. S2CID 25600294.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j Terveer EM, van Beurden YH, Goorhuis A, Seegers JF, Bauer MP, van Nood E, et al. (December 2017). "How to: Establish and run a stool bank". Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 23 (12): 924–930. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2017.05.015. hdl:1887/117537. PMID 28529025.

- ^ Хорутс А, Садоуский М.Дж. (сентябрь 2016 г.). «Понимание механизмов трансплантации фекальной микробиоты» . Природные обзоры. Гастроэнтерология и гепатология . 13 (9): 508–516. doi : 10.1038/nrgastro.2016.98 . PMC 5909819 . PMID 27329806 .

- ^ Келли К.Р., Кан С., Кашьяп П., Лейн Л., Рубин Д., Атрея А. и др. (Июль 2015). «Обновление о трансплантации фекальной микробиоты 2015: показания, методологии, механизмы и перспективы» . Гастроэнтерология . 149 (1): 223–237. doi : 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.05.008 . PMC 4755303 . PMID 25982290 .

- ^ Ott SJ, Waetzig GH, Rehman A, Moltzau-Anderson J, Bharti R, Grasis JA, et al. (Март 2017). «Эффективность стерильного переноса фекального фильтрата для лечения пациентов с инфекцией Clostridium difficile» . Гастроэнтерология . 152 (4): 799–811.e7. doi : 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.11.010 . HDL : 21.11116/0000-0002-F84B-3 . PMID 27866880 .

- ^ McDonald JA, Mullish BH, Pechlivanis A, Liu Z, Brignardello J, Kao D, et al. (Ноябрь 2018). «Ингибирование роста Clostridioides difficile путем восстановления Valerate, продуцируемого кишечной микробиотой» . Гастроэнтерология . 155 (5): 1495–1507.e15. doi : 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.07.014 . PMC 6347096 . PMID 30025704 .

- ^ Zuo T, Wong Sh, Lam K, Lui R, Cheung K, Tang W, et al. (Апрель 2018). «Передача бактериофагов во время трансплантации фекальной микробиоты при инфекции Clostridium difficile связана с исходом лечения» . Кишечник 67 (4): 634–643. doi : 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-313952 . PMC 5868238 . PMID 28539351 .

- ^ Draper LA, Ryan FJ, Smith MK, Jalanka J, Mattila E, Arkkila PA, et al. (Декабрь 2018). «Долгосрочная колонизация с донорскими бактериофагами после успешной трансплантации микробных фекалий» . Микробиом . 6 (1): 220. DOI : 10.1186/S40168-018-0598-X . PMC 6288847 . PMID 30526683 .

- ^ Zhang YJ, Li S, Gan Ry, Zhou T, Xu DP, Li HB (апрель 2015 г.). «Влияние кишечных бактерий на здоровье человека и заболевания» . Международный журнал молекулярных наук . 16 (4): 7493–7519. doi : 10.3390/ijms16047493 . PMC 4425030 . PMID 25849657 .

- ^ Paramsothy S, Nielsen S, Kamm Ma, Deshpande NP, Faith JJ, Clemente JC, et al. (Апрель 2019). «Специфические бактерии и метаболиты, связанные с реакцией на трансплантацию фекальной микробиоты у пациентов с язвенным колитом» . Гастроэнтерология . 156 (5): 1440–1454.e2. doi : 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.12.001 . PMID 30529583 .

- ^ Герке Х (декабрь 2014 г.). "Какое низкое значение на« фекальной трансплантации »?» Полем Здоровье в Айове . У Айовы. Архивировано из оригинала 14 марта 2017 года . Получено 14 января 2015 года .

- ^ «Терапевтическая какашка: надежда на лечение детской диареи приходит прямо из кишки» . Детский центр Джона Хопкинса . Университет Джона Хопкинса. 29 июля 2013 года. Архивировано с оригинала 31 марта 2019 года . Получено 31 марта 2019 года .

- ^ Левин Р.А. (2001). «Подробнее о Мерде». Перспективы биологии и медицины . 44 (4): 594–607. doi : 10.1353/pbm.2001.0067 . PMID 11600805 . S2CID 201764383 .

- ^ Koopman N, Van Leeuwen P, Brul S, Seppen J (10 августа 2022 г.). «История фекальной трансплантации; камеры -камеры содержит ограниченные количества споров Bacillus subtilis и, вероятно, не играют традиционной роли в лечении дизентерии» . Plos один . 17 (8): E0272607. Bibcode : 2022ploso..1772607K . doi : 10.1371/journal.pone.0272607 . PMC 9365175 . PMID 35947590 .

- ^ Eiseman B, Silen W, Bascom GS, Kauvar AJ (ноябрь 1958 г.). «Фекальная клинема как дополнение при лечении псевдомембранового энтероколита». Операция . 44 (5): 854–859. PMID 13592638 .

- ^ Бороди Т.Дж., Джордж Л., Эндрюс П., Брандл С., Нунан С., Коул П. и др. (Май 1989). «Изменение кишечника-флора: потенциальное лекарство от воспалительного заболевания кишечника и синдрома раздраженного кишечника?». Медицинский журнал Австралии . 150 (10): 604. doi : 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1989.tb136704.x . PMID 2783214 . S2CID 1290460 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный «FDA изо всех сил пытается регулировать фекальные пересадки» . CBS News . Ассошиэйтед Пресс . 26 июня 2014 года. Архивировано с оригинала 19 октября 2014 года . Получено 12 октября 2014 года .

- ^ «Публичный семинар: фекальная микробиота для трансплантации» . Управление по контролю за продуктами и лекарствами . 10 марта 2014 года. Архивировано с оригинала 6 апреля 2017 года . Получено 16 декабря 2019 года .

- ^ 78 FR 12763 , 25 февраля 2013 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Смит М.Б., Келли С, ALM EJ (19 февраля 2014 г.). «Политика: как регулировать трансплантацию фекалий» . Природа . Архивировано с оригинала 4 ноября 2014 года . Получено 12 октября 2014 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный AGA подтверждает, что Ind необходима для трансплантации фекальной микробиоты , Американская гастроэнтерологическая ассоциация , 6 мая 2013 года, архивирована с оригинала 10 мая 2013 года.

- ^ «Руководство для промышленности: правоприменение, касающаяся новых требований к лекарствам для использования фекальной микробиоты для трансплантации для лечения инфекции Clostridium difficile, не реагирующей на стандартную терапию» . Управление по контролю за продуктами и лекарствами . Июль 2013 года. Архивировано с оригинала 3 декабря 2017 года . Получено 16 декабря 2019 года .

- ^ «Проект Руководства для промышленности: правоприменительная политика в отношении расследования новых требований к лекарствам для использования фекальной микробиоты для трансплантации для лечения инфекции Clostridium difficile, не реагирующей на стандартную терапию» . Управление по контролю за продуктами и лекарствами. Март 2014 года. Архивировано с оригинала 5 июня 2018 года . Получено 16 декабря 2019 года .

- ^ Emanuel G (7 марта 2014 г.). "MIT Lab проводит первый банк табуреток в стране, но выживет ли он?" Полем Wbur-fm . Архивировано из оригинала 17 октября 2014 года . Получено 13 октября 2014 года .

- ^ Ратнер М (май 2014). «Фекальная трансплантация создает дилемму для FDA». Nature Biotechnology . 32 (5): 401–402. doi : 10.1038/nbt0514-401 . PMID 24811495 . S2CID 205268072 .

- ^ «Важное предупреждение о безопасности в отношении использования фекальной микробиоты для трансплантации и риска серьезных побочных реакций из-за передачи организмов с несколькими лекарствами» . США Управление по контролю за продуктами и лекарствами (FDA) . 20 декабря 2019 года. Архивировано с оригинала 6 мая 2020 года . Получено 13 апреля 2020 года .

- ^ Центр оценки и исследований биологических данных (12 марта 2020 г.). «Предупреждение о безопасности в отношении использования фекальной микробиоты для трансплантации и риска серьезных побочных эффектов, вероятно, из -за передачи патогенных организмов» . США Управление по контролю за продуктами и лекарствами (FDA) . Архивировано из оригинала 30 мая 2020 года . Получено 13 апреля 2020 года - через www.fda.gov.

- ^ «Предупреждение о безопасности в отношении использования фекальной микробиоты для трансплантации и дополнительной защиты безопасности, относящихся к SARS-COV-2 и COVID-19» . США Управление по контролю за продуктами и лекарствами (FDA) . 9 апреля 2020 года. Архивировано с оригинала 14 апреля 2020 года . Получено 13 апреля 2020 года .

- ^ «Проверка кишечника: FDA утверждает терапию на основе микробиомов, и ожидаются будущие разрешения» . Nixon Peabody LLP . 15 мая 2023 года. Архивировано с оригинала 2 января 2024 года . Получено 2 января 2024 года .

- ^ Смит Па (17 февраля 2014 г.). «Новый вид банка трансплантации» . New York Times . Архивировано из оригинала 14 октября 2014 года . Получено 10 июля 2014 года .

- ^ Dupont HL (октябрь 2013 г.). «Диагностика и лечение инфекции Clostridium difficile» . Клиническая гастроэнтерология и гепатология . 11 (10): 1216–23, тест E73. doi : 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.03.016 . PMID 23542332 .

- ^ Тведе М., Тинггаард М., Хелмс М (январь 2015 г.). «Ректальная бактериотерапия для рецидивирующей диареи, ассоциированной с Clostridium difficile: результаты серии случаев из 55 пациентов в Дании 2000-2012» . Клиническая микробиология и инфекция . 21 (1): 48–53. doi : 10.1016/j.cmi.2014.07.003 . PMID 25636927 .

- ^ Allen-Vercoe E , Petrof EO (май 2013). «Трансплантация искусственного стула: прогресс в направлении более безопасной, более эффективной и приемлемой альтернативы» . Экспертный обзор гастроэнтерологии и гепатологии . 7 (4): 291–293. doi : 10.1586/egh.13.16 . PMID 23639085 . S2CID 46550706 .

- ^ «BBC Nature - видео, новости и факты на Dung Eater» . Bbc.co.uk. и архивировал из оригинала 29 декабря 2011 года . Получено 27 ноября 2011 года .

- ^ Depeters EJ, George LW (декабрь 2014 г.). «Трансфунирование рубца». Иммунологические письма . 162 (2 пт а): 69–76. doi : 10.1016/j.imlet.2014.05.009 . PMID 25262872 .

Дальнейшее чтение

[ редактировать ]- Bibbò S, Ianiro G, Gasbarrini A, Cammarota G (декабрь 2017 г.). «Фекальная трансплантация микробиоты: прошлые, настоящие и будущие перспективы». Minerva Gastroenterologica E Dietologica . 63 (4): 420–430. doi : 10.23736/s1121-421x.17.02374-1 . PMID 28927251 .

- El-Salhy M, Patcharatrakul T, Gonlachanvit S (июнь 2021 г.). «Фекальная трансплантация микробиоты для синдрома раздраженного кишечника: вмешательство для 21 -го века» . Всемирный журнал гастроэнтерологии . 27 (22): 2921–2943. doi : 10.3748/wjg.v27.i22.2921 . PMC 8192290 . PMID 34168399 .