Федеративная Республика Центральная Америка

Федеративная Республика Центральная Америка Федеративная Республика Центральная Америка | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1823–1839/1841 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Девиз: « Бог, Союз, Свобода ». «Бог, Союз, Свобода» | |||||||||||||||||||

| Гимн: « Ла Гранадера ». "Гренадер" | |||||||||||||||||||

An orthographic projection of the world with the Federal Republic of Central America in green and its uncontrolled territorial claims in light green | |||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Guatemala City (until 1834) Sonsonate (1834) San Salvador (from 1834) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Spanish and various indigenous languages | ||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Catholicism | ||||||||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Central American | ||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Federal presidential republic | ||||||||||||||||||

| President | |||||||||||||||||||

• 1825–1828 | Manuel José Arce (first) | ||||||||||||||||||

• 1829, 1830–1834, 1835–1839 | Francisco Morazán (last) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Federal Congress[a] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Senate | |||||||||||||||||||

| Chamber of Deputies | |||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Spanish American wars of independence | ||||||||||||||||||

• Independence from the Spanish Empire | 15 September 1821 | ||||||||||||||||||

• Independence from the First Mexican Empire | 1 July 1823 | ||||||||||||||||||

• Constitution adopted | 22 November 1824 | ||||||||||||||||||

• Dissolution | 17 April 1839 | ||||||||||||||||||

• El Salvador declares its independence | 30 January 1841 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||||

• Total | 200,000 sq mi (520,000 km2) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||||||

• 1824 | 1,287,491 | ||||||||||||||||||

• 1836 | 1,900,000 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Central American real | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Central America |

|---|

|

Федеративная Республика Центральной Америки ( испанский : República Federal de Centro América ), первоначально известная как Соединенные Провинции Центральной Америки ( Provincias Unidas del Centro de América ), была суверенным государством в Центральной Америке , существовавшим с 1823 по 1839/1841 годы. Федеративная Республика Центральной Америки состояла из пяти штатов: Коста-Рики , Сальвадора , Гватемалы , Гондураса и Никарагуа , а также федерального округа с 1835 по 1839 год. Город Гватемала был столицей федеративной республики до 1834 года, когда резиденция федеральное правительство было переведено в Сан-Сальвадор . Федеративная Республика Центральная Америка граничила на севере с Мексикой , на юге с Великой Колумбией , а на восточном побережье с Берегом Москитов и Британским Гондурасом (оба из которых федеративная республика претендовала как свою суверенную территорию).

Shortly after Central America, then known as the Captaincy General of Guatemala, declared its independence from the Spanish Empire in September 1821, it was annexed by the First Mexican Empire in January 1822 before regaining its independence and forming a federal republic in 1823. The Federal Republic of Central America adopted its constitution, which was based on the federal government of the United States, in November 1824. It held its first presidential election in April 1825, during which, liberal politician Manuel José Arce was elected as the country's first president. Arce subsequently aligned himself with the country's conservatives as the liberals opposed the concessions he granted to conservatives to secure his election as president. From 1827 to 1829, the country fell into civil war between conservatives who supported Arce and liberals who opposed him. Liberal politician Francisco Morazán ultimately led the liberals to victory and was elected president in 1830. The federal republic descended into a вторая гражданская война с 1838 по 1840 год, по итогам которой государства Центральной Америки провозгласили свою независимость и федеративная республика прекратила свое существование.

The Federal Republic of Central America was very politically unstable as it suffered several civil wars, rebellions, and insurrections primarily fought between liberals and conservatives. Historians have attributed the country's political instability to its federal system of government and its economic struggles. Agricultural exports were unable to raise sufficient funds and the federal government was also unable to repay its foreign loans despite favorable terms. Central America's economic troubles were caused in part due to the federal government being unable to collect taxes and a lack of sufficient interstate infrastructure.

Central American politicians, writers, and intellectuals have called for the reunification of Central America since the dissolution of the Federal Republic of Central America. There have been several attempts by the federal republic's successor states during the 19th and 20th centuries to reunify Central America through both diplomatic and military means. None of these attempts succeeded in uniting all five former members under a united Central American state for more than one year. All five former members of the Federal Republic of Central America are members of the Central American Integration System (SICA), an economic and political organization which promotes regional development.

Name

[edit]The country's initial name, adopted upon independence from the First Mexican Empire on 1 July 1823, was the United Provinces of Central America (Spanish: Provincias Unidas del Centro de América).[b][3][4] Upon the adoption of the country's constitution on 22 November 1824, the United Provinces of Central America changed its name to the Federal Republic of Central America (República Federal de Centro América).[5] In the years shortly after independence, some official government documents referred to the country as the Federated States of Central America (Estados Federados del Centro de América).[6][7] Additionally, the federal republic has alternatively been referred to as the Federation of Central America (Federación de Centro América).[8][9]

Background

[edit]Colonial Central America

[edit]The Spanish conquered Central America in the 16th century. In 1542, Central America was organized into an audiencia, prior to which, the region was divided into numerous audiencias.[10] The Central American audiencia initially extended north to the Isthmus of Tehuantepec and south to the Isthmus of Panama,[11] but in 1560, Spain transferred control of the Yucatán Peninsula to New Spain (modern-day Mexico), and in 1567, Spain transferred control of Panama to Peru.[10] In 1568, the Central American audiencia was reorganized as the Captaincy General of Guatemala.[11] The captaincy general was internally subdivided into corregimientos, gobiernos, greater mayorships, and intendancies.[12]

Residents of Central America were divided into a caste system with Spaniards at the top, mixed race individuals in the middle, and Africans and indigenous Central Americans at the bottom. Spaniards owned most of Central America's land and wealth, while indigenous Central Americas composed most of the region's labor force.[13] The Catholic Church also dominated all aspects of Central American society during Spanish colonial rule of the region. Central America's indigenous inhabitants were gradually forced by colonial officials to convert to Catholicism, but they also retained many of their cultural traditions.[14]

Central American independence

[edit]In 1808, Spanish King Ferdinand VII was overthrown by French Emperor Napoleon who installed his brother, Joseph, as the king of Spain. Spain's colonies in the Americas, including the Captaincy General of Guatemala, did not recognize Joseph as the legitimate king and established various provisional governments known as juntas which continued to recognize Ferdinand as king.[15][16] Although the Central American colonial government remained loyal to Ferdinand VII, some criollo leaders in Central America wanted greater autonomy.[17] In November 1811, José Matías Delgado and Manuel José Arce launched a rebellion in San Salvador against Spanish rule, however, this rebellion was defeated by loyalist forces. Further independence rebellions occurred in December 1811 in Nicaragua; in 1813 in Guatemala; and in 1814, again in San Salvador; all these rebellions were defeated by loyalist forces. Although none of these rebellions succeeded, they each led to pro-independence sentiments spreading among Central American leaders.[18]

In 1812, the Cortes of Cádiz, a Spanish constitutional congress located in Cádiz, drafted the Spanish Constitution of 1812 which turned Spain into a constitutional monarchy,[18] however, Ferdinand repealed this liberal constitution in 1814 once he returned to power in 1814 as he wanted to rule as an absolute monarch.[19] Ferdinand's refusal to rule as a constitutional monarchy together with colonial leaders wanting greater local autonomy led to independence rebellions erupting across all of Spain's American colonies.[20] These rebellions were primarily led by liberals who supported Enlightenment ideals of the 1812 constitution. Conservatives eventually joined these independence movements in 1820 once Ferdinand was forced by Colonel Rafael del Riego to restore the 1812 constitution.[21] On 15 September 1821, leading Central American colonial administrators declared independence from Spain and signed the Act of Independence of Central America. Independence leaders established the Consultive Junta to temporarily govern the newly-independent Central America until a permanent government could be established. Most government administrators, including Brigadier General Gabino Gaínza (the final captain general of Guatemala), retained their positions.[22]

After independence, Central American leaders were divided on whether to remain independent or to join the First Mexican Empire;[23] monarchists supported annexation while republicans and nationalists opposed it, both due to ideological similarities or differences.[24] In November 1821, Mexican Regent (and later Mexican Emperor) Agustín de Iturbide formally asked the Consultive Junta to join the First Mexican Empire,[25] and on 5 January 1822, the junta voted in favor of annexation.[26] The Mexicans sent Brigadier General Vicente Filísola to enforce the annexation of Central America.[27] Liberals in Costa Rica, El Salvador, and Nicaragua resisted Mexican attempts to annex the region. In Costa Rica, liberals and conservatives fought each other in the Ochomogo War which ended in the liberals gaining control of Costa Rica.[28] In El Salvador, liberal rebels led by Delgado and Arce resisted two invasions by Filísola in 1822 and 1823; the former resulted in an armistice and a Mexican withdrawal,[29] and the second resulted in Filísola overthrowing Delgado as the political leader of El Salvador, forcing Arce to flee Central America to the United States, and capturing the city of San Salvador.[30][31][32] In Nicaragua, General José Anacleto Ordóñez launched a rebellion against Miguel González Saravia y Colarte, the conservative political leader of Nicaragua, capturing several cities in the process. Ordóñez's rebellion continued even after Central America declared its independence from Mexico.[33]

On 19 March 1823, Iturbide abdicated the Mexican throne.[34] Once news of Iturbide's abdication reached Filísola on 29 March, he called for Central American political leaders to establish a congress to determine the future of the region, and on 1 April, the Mexican Constituent Congress ordered Mexican forces in Central America to cease all hostilities.[35] The Central American congress convened on 24 June.[1] It declared Central American independence from Mexico on 1 July, however, Chiapas chose to remain a part of Mexico.[36]

History

[edit]National Constituent Assembly

[edit]Drafting the constitution

[edit]

Upon Central America's independence from Mexico, the Central American congress proclaimed the establishment of the United Provinces of Central America.[36][37] The following day, the congress reorganized itself into the National Constituent Assembly and tasked itself with drafting a constitution for the newly-independent Central America.[1][38] Delgado initially served as Central America's provisional president until 10 July 1823 when the National Constituent Assembly appointed a triumvirate consisting of Arce, Juan Vicente Villacorta, Pedro Molina Mazariegos. As Arce was in the United States at the time of the triumvirate's establishment, Antonio Rivera Cabezas was appointed as his substitute.[39] The three triumvirs would rotate executive power among themselves on a monthly basis.[40]

Initially, the National Constituent Assembly was composed of delegates from only El Salvador and Guatemala;[41] Costa Rica, Honduras, and Nicaragua did not send their delegates until October 1823[1] as they were refusing to send delegates until Mexican soldiers had withdrawn from Central America.[42] The National Constituent Assembly consisted of 64 delegates distributed across Central America.[c] The National Constituent Assembly served as the de facto government of Central America until the constitution could be adopted.[1] The two political factions which composed the National Constituent Assembly were the liberals and the conservatives; the liberals supported a federalism while the conservatives supported centralism.[39]

The National Constituent Assembly drafted the constitution on 12 June 1824 and published it on 4 July.[43] The constitution was inspired by the federal government of the United States, the United States Declaration of Independence, and the Spanish Constitution of 1812.[25][44][45] On 22 November, the constitution was formally adopted once all 64 members of the assembly signed it. The National Constituent Assembly dissolved itself on 23 January 1825. It was succeeded by the Federal Congress (the country's legislature) on 6 February.[46]

Guatemalan military mutiny

[edit]

On 14 September 1823, Captain Rafael Ariza y Torres launched an insurrection in Guatemala City (the capital city) as the Central American government was unable to pay its debts to the military.[47] Although Ariza pledged his loyalty to the National Constituent Assembly, many assemblymen fled the city and called for soldiers from Chiquimula, Quetzaltenango, and San Salvador to suppress the insurrection.[48] Neither Ariza's rebels nor Colonel José Rivas and his 750 soldiers from San Salvador wanted to engage in battle.[49] Conservatives took advantage of the situation and forced the triumvirate to resign on 6 October.[50] They installed a second, less liberal triumvirate consisting of Arce, José Cecilio del Valle, and Tomás O'Horan. As both Arce and Valle were outside of the country at the time of the second triumvirate's formation, they were substituted by José Santiago Milla and Villacorta, respectively.[51] Valle and Arce did not assume their positions on the triumvirate until February 1824 and March 1824, respectively.[52]

The second triumvirate ordered Rivas to march 150 soldiers into Guatemala City, and soon after, Ariza fled the country for exile in Mexico. The National Constituent Assembly subsequently returned to Guatemala City.[51] The Salvadoran government ordered Rivas to remain near Guatemala City and verify that the National Constituent Assembly was functioning. On 12 October 1823, Rivas determined that the assembly was suppressing civil liberties and marched back into the city. On 17 October, 200 soldiers from Quetzaltenango arrived in Guatemala City and skirmished with Rivas' forces as the soldiers from Quetzaltenango believed that Rivas was acting as an agent on behalf of El Salvador.[53] After a few days, the assembly drafted an agreement to appease both armies. Rivas' forces withdrew back to El Salvador and the soldiers from Quetzaltenango returned home.[54]

Internal conflict in Nicaragua

[edit]Liberals and conservatives had been fighting for control of Nicaragua ever since Ordóñez launched his rebellion against the pro-Mexico Nicaraguan government in 1823.[33] The liberals had control of León (the liberal capital) and Granada while the conservatives had control of Managua (the conservative capital), Rivas, and Chinandega. Both sides clashed with each other resulting in hundreds of deaths. In October 1824, the second triumvirate sent Colonel Manuel Arzú to attempt to mediate a peace between the liberals and conservatives, but the mediation failed,[55] and Arce led a federal invasion of Nicaragua on 22 January 1825 to end the civil conflict.[56] His invading force managed to get both the liberals and conservatives to sign an armistice without engaging in combat. Arce dissolved both rival governments and their leaders were exiled from Nicaragua.[57]

Presidency of Manuel José Arce

[edit]1825 presidential election

[edit]

The federal republic's first presidential election occurred on 21 April 1825.[58][59] Arce was the liberals' candidate while Valle was the conservatives' candidate.[60] During the election, 41 of the 82 electors voted for Valle, 34 voted for Arce, 4 voted for other candidates,[d] and 3 did not vote due to complications in receiving votes from those three electoral districts; no candidate won an absolute majority of all 82 electors. As the constitution required the president to win an absolute majority of all electors, the Federal Congress was tasked with electing the president instead.[62][63] The Federal Congress voted 22–5 in favor of electing Arce as president.[64] Although Valle was entitled to become vice president as he was the election's runner up, he refused to accept the position, as did liberal José Francisco Barrundia. Ultimately, conservative Mariano Beltranena became Arce's vice president.[60] Arce and Beltranena assumed office on 29 April.[58]

Although Arce's electoral victory angered conservatives as he defeated Valle, it also alienated liberals (particularly Guatemalan liberals) as Arce had won over the votes of conservative senators by promising to allow the Federal Congress determine whether a new Catholic archdiocese would or would not be created in El Salvador; the conservatives opposed the archdiocese's creation as Delgado, a liberal symbol of Salvadoran independence, would have become archbishop. The liberals considered Arce's compromise with the conservatives to win the presidential election as Arce betraying his liberal positions.[60][65][66] Due to this perceived betrayal, liberals Molina Mazariegos and Mariano Gálvez refused to accept appointments to the cabinet positions of secretary of relations and secretary of finance, respectively.[67] As a result, Arce appointed conservatives to his cabinet which led to liberals further accusing him of betraying the liberal cause.[68]

Path to civil war

[edit]Juan Barrundia, José Francisco Barrundia's brother, opposed the supremacy of the federal government and was one of Arce's frontmost critics as a result. In mid 1825, Juan Barrundia moved Guatemala's state capital back to Guatemala City from Antigua Guatemala (as it had been temporarily moved in 1823), during which, he seized private property to establish new state government offices as the federal government still occupied the state's government buildings.[68][69] After Juan Barrundia threatened to raise an army to "contain the despotism of a tyrant", in reference to Arce, the Federal Congress agreed to vacate the building used by the federal treasury and gave it to the Guatemalan state government.[70]

In August 1825, Arce called for the army to raise 10,000 soldiers to defend their country against a potential European invasion of the country around the time 28 French warships had arrived in the Caribbean Sea. The Congress of Deputies approves Arce's plan, but the Senate vetoed it citing a lack of funding. In mid 1826, Arce reduced the number of soldiers he called for down to 4,000.[71][72] Guatemalan liberals in the Federal Congress contracted French military officer Nicolás Raoul to help draft a new military code to prevent Arce from exercising control of the military, and in response, Arce exiled Raoul from the country.[73] Eventually, Arce and the Federal Congress compromised; congress approved raising 4,000 soldiers and Raoul was placed in charge of overseeing recruitment.[74] No such European invasion ever manifested other than a minor rebellion in Costa Rica led by José Zamora who claimed that he was a "vassal of the king of Spain".[71] As the liberals attempted to circumvent Arce's role as commander-in-chief, Arce refused to implement some laws passed by the Federal Congress which led to the liberals beginning impeachment proceedings against Arce on 2 June 1826. Salvadoran liberals, who were still loyal to Arce, did not attend the impeachment proceedings and prevent congress from reaching the quorum necessary to impeach Arce. Ten days later, the Guatemalan liberals abandoned their attempt to impeach Arce.[74]

In July 1826, Arce sent federal soldiers to arrest Raoul, accusing him of insubordination by sending letters to Arce calling for his resignation. Juan Barrundia sought to defend Raoul and sent 300 Guatemalan soldiers to arrest the federal soldiers' commander, arguing that the federal government needed a state governor's permission to move soldiers within a state.[72][74] When Arce sought to condemn Juan Barrundia, Guatemalan liberal senators boycotted the meeting and the Senate failed to reach the quorum necessary to condemn Juan Barrundia.[74] Despite inaction by the Senate, Arce had Juan Barrundia arrested and removed from office on 6 September on charges of attempting to conspire against the federal republic. In response to Juan Barrundia's arrest, Lieutenant Governor Cirilo Flores moved the Guatemalan state government to Quetzaltenango where he passed several anti-clerical laws.[75] An indigenous mob subsequently attacked and killed Cirilo on 13 October for passing those anti-clerical laws, and the killing was instigated by conservatives and the Church.[72][76][77] Arce subsequently invaded Quetzaltenango and defeated those who continued to support what remained of Cirilo's government on 28 October.[78][79]

First civil war

[edit]In October 1826, Arce called for a special election to install a new Guatemalan government;[80] the conservatives won the election and Mariano Aycinena became the governor of Guatemala on 1 March 1827.[78] The election led to many liberals fleeing Guatemala to El Salvador seeking assistance from the liberals there in regaining power. They also spread rumors that Arce was controlled by the Guatemalan conservatives and that he would establish a centralized government.[81] On 10 October, Arce called for an extraordinary congress to convene in Cojutepeque to reestablish constitutional order, due the Federal Congress consistently failing to reach quorum following Juan Barrundia's arrest.[82] However, this call for an extraordinary congress was unconstitutional as it exceeded his presidential duties.[75] On 6 December, in response to Arce's call for an extraordinary congress to convene, Mariano Prado (the liberal acting governor of El Salvador) called for delegates from all the states except for Guatemala to convene their own extraordinary congress in Ahuachapán. Ultimately, neither congress convened.[81]

In late December 1826, Prado ordered stationed Salvadoran soldiers on the El Salvador–Guatemala border in preparation to overthrow Arce.[81] In early March 1827, Aycinena declared various leading Guatemalan liberals, including Molina Mazariegos and Rivera Cabezas, as outlaws within Guatemala. In response, Prado ordered his soldiers to invade Guatemala, beginning the First Central American Civil War.[78] There was no formal declaration of war.[83] Honduras supported El Salvador's invasion, but Arce's federal soldiers managed to defeat the invasion in battle on 23 March at Arrazola near Guatemala City.[78] Arce proceeded to launch a counter-invasion into El Salvador, however, his invasion was itself defeated on 18 May at Milingo on near San Salvador.[84][85]

While Arce was campaigning in El Salvador, he sent a division of soldiers under the command of Colonel José Justo Milla into Honduras to arrest Honduran Governor Dionisio de Herrera, a liberal who opposed Arce's government.[86] Milla's forces captured the Honduran capital of Comayagua on 10 May 1827 after a 36-day siege and captured Herrera.[87] Francisco Morazán—the secretary general of Honduras in 1824, a Honduran state senator, and a military officer—was captured shortly afterwards in Tegucigalpa, however, he managed to escape custody and fled to Nicaragua where he rallied an army of Honduran exiles to oppose Arce.[88][89] Morazán's forces were supported by Nicaraguan rebels led by Ordóñez who launched an anti-Arce rebellion in León.[85] On 10 November 1827, Morazán's army defeated Milla's army at the Battle of La Trinidad leading to his forces recapturing both Comayagua and Tegucigalpa.[89]

In early 1828, Arce offered to hold new a presidential election in an attempt to appease the liberals, however, they denied Arce's offer. On 14 February, Arce resigned from the presidency and fled for exile in Mexico; Beltranena succeeded Arce as interim president.[89] In June 1828, Morazán invaded El Salvador in command of an army of Honduran and Nicaraguan soldiers,[90] and on 23 October, he captured San Salvador.[91] In late 1828, Morazán raised 4,000 soldiers for an invasion of Guatemala.[92] Beltranena's government warned its citizens that Morazán's primary objective was to destroy the Catholic Church; Morazán refuted the Guatemalan government's warning, stating that his "Protector Allied Army of the Law" ("Ejército Aliado Protector de la Ley")[93] did not seek to destroy the Church as it was composed of Christians, and that it instead only sought to liberate Guatemala from "the wrongs [they had] suffered" (los males que habéis sufrido").[94] Morazán invaded in January 1829 and began besieging Guatemala City on 5 February.[95] Guatemala City surrendered on 12 April and Morazán's soldiers entered the city the following day, ending the civil war.[89][96]

Presidency of Francisco Morazán

[edit]Consolidating power

[edit]

After capturing Guatemala City in April 1828, Beltranena was removed from the presidency and Morazán became the de facto president of Central America, however, he did not officially assume the office.[97] On 22 June 1829, Morazán appointed a new Federal Congress which proceeded to elected José Francisco Barrundia as Central America's interim president on 25 June as he was the Senate's most senior member.[98][99] At Morazán's instruction, the Federal Congress also declared all legislation passed after September 1826 to be null and void. Many leading conservatives were imprisoned or exiled under threat of death following the civil war, and many also had their properties confiscated.[100][101] Morazán also cracked down on the Church. He expelled many members of the clergy from the country for supporting the conservatives, confiscated Church properties, and forced the Church to reduce the number of priests and nuns in the country.[102]

Morazán ran for president in the 1830 federal election.[103] Although Morazán came in first place with 202 electoral votes, he did not win an absolute majority of the electoral votes.[e] Similar to what happened in the 1825 presidential election, the Federal Congress given the authority to elect the president. The liberal-dominated Federal Congress voted for Morazán,[104] and he assumed office on 16 September.[106] The Federal Congress elected liberal Mariano Prado as Morazán's vice president.[103]

Conservative invasion of 1831–1832

[edit]In May 1829, Morazán sent a letter to the Mexican minister of external relations falsely claiming that Central American refugees fleeing to Mexico were actually enemy forces which sought to "chain and submit their towns to the Spanish yoke" ("encadenar y someter sus pueblos al yugo español"). Morazán asked the Mexican government to extradite these refugees to Central American custody.[107] After not receiving a response, José Francisco Barrundia sent a letter to Mexican President Vicente Guerrero himself in November 1829 making the same request; Guerrero did not respond.[108] In December 1829, Central American Minister of Relations Manuel Julián Ibarra sent a third request to the Mexican government to extradite the refugees, to which the Mexican government stated that it could meet the Central American request.[109]

In late 1831, Arce threatened to invade the Federal Republic of Central America from Soconusco (a territory along the Pacific coast claimed by both Central America and Mexico but which neither asserted full control over)[110][111] with the goal of reclaiming the presidency.[112] In November 1831, General Ramón Guzmán, the mayor of the Honduran city of Omoa, declared a state of rebellion, raised a Spanish flag in the city, sent ships to Cuba to ask for support from conservative archbishop Ramón Casaus y Torres, whom Morazán exiled in 1829.[113] This was followed by a second conservative invasion force led by Colonel Vicente Domínguez which entered Central America from British Honduras and supported Guzmán's rebellion and invaded inland Honduras. The Honduran cities of Opoteca and Trujillo also declared themselves to be in a state of rebellion.[114] José María Cornejo, the conservative governor of El Salvador, politically supported Arce's invasion[115] and declared El Salvador's secession from the federal republic on 7 January 1832.[116]

On 24 February 1832, Raoul led federal soldiers into Soconusco and battled Arce's rebel army in the town of Escuintla. Raoul defeated Arce's outnumbered army and the victorious soldiers proceeded to loot the town.[117][118] After this defeat, Arce was forced to flee back to Mexico.[119] In mid March, Morazán invaded El Salvador and captured San Salvador on 28 March, proclaiming himself as the provisional governor of El Salvador on 3 April.[120] Cornejo and 38 other Salvadoran political leaders were arrested and imprisoned in Guatemala for their involvement in the rebellion.[121] Honduran soldiers under Colonel Francisco Ferrera began a siege of Omoa in March,[122] recaptured Trujillo in April,[123] and recaptured Opoteca in May.[124] The Spanish reinforcements which Guzmán called for were arrested by Honduran soldiers upon reaching the Central American coast.[119] Guzmán continued to resist federal forces in Omoa until 12 September when his soldiers mutinied against him and turned him over to federal custody, ending the rebellion. Guzmán was executed the following day;[125] Domínguez, who was captured by federal forces during the fall of Opoteca, was executed on 14 September.[126]

Rebellions during Morazán's presidency

[edit]On 1 April 1829, Costa Rica declared its secession from the Federal Republic of Central America while at the same time "without separating itself" ("sin separarse") from the federal republic.[127] The Costa Rican government justified its secession by arguing that the federal government had ceased to exist.[128] Costa Rica rejoined the federal republic in February 1831 after recognizing Morazán as Central America's president and renouncing its declaration of secession.[129] In July 1829, Morazán defeated rebellions in Honduras and Nicaragua.[130] In January 1830, he defeated another rebellion in Honduras.[131]

In May 1832, Prado resigned as the vice president of Central America to become the governor of El Salvador, however, he was not popular among El Salvador's residents for helping Morazán overthrow both Arce in the civil war and Cornejo earlier in 1832. Prado established a new tax to help raise funds for the state government.[132] This tax was unpopular among Salvadoran residents, particularly among indigenous Salvadorans who saw it as a restoration of tributes to the white population which had been abolished in 1811.[133][134] On 24 October, San Salvador rebelled against Prado, forcing his government to temporarily relocate to Cojutepeque. Similar rebellions against Prado arose in Ahuachapán, Chalatenango, Izalco, San Miguel, Tejutla, and Zacatecoluca,[135] but these rebellions were quickly suppressed by Salvadoran soldiers.[136]

On 14 February 1833, indigenous laborer Anastasio Aquino launched a rebellion in San Juan Nonualco and Santiago Nonualco in response to indigenous killings by Ladinos (mixed race) the month prior. He and 2,000 supporters (known as the Liberation Army) marched on San Vicente, capturing it the following day. The Liberation Army proclaimed him as the political chief of San Vicente.[137][138] Indigenous Salvadorans in Cojutepeque, Ilopango, San Martín, San Pedro Perulapán, and Soyapango supported Aquino's rebellion.[136] Initial efforts by Salvadoran soldiers to suppress the rebellion were defeated by the Liberation Army in San Vicente and Zacatecoluca, but Aquino's army was defeated in battle by Morazán in San Vicente on 28 February, ending the rebellion. Aquino was captured in April[134][139] and he was executed on 24 July with his corpse being publicly displayed in San Vicente afterwards.[135]

1830s constitutional reforms

[edit]In 1831, Salvadoran conservatives called for political reforms to be implemented in the federal government, including allowing the president to veto laws passed by the Federal Congress, abolishing the electoral college and implementing direct elections, and restricting the eligibility to be elected to office to only landowners.[140] The arrest of these conservatives after Morazán's military victory in El Salvador in 1832 led to political leaders across the federal republic to call for the implementation of such political reforms.[141] On 3 December 1832, Nicaragua declared its independence citing fears of federal authoritarianism over Morazán's invasion of El Salvador and stated that it would not rejoin the federal republic until the federal constitution was reformed.[142] That same month, Costa Rica proposed establishing a new National Constituent Assembly to work on passing a constitutional reform; this assembly assumed office on 20 April 1833.[143] On 13 February 1835, the Federal Congress approved the constitutional reforms drafted by the National Constituent Assembly. The reforms were very minor, and only Nicaragua (which renounced its secession after the reforms were completed) and Costa Rica ever ratified the reforms.[129][144]

Moving the federal capital to San Salvador

[edit]Beginning in 1830, both Morazán and the Federal Congress wanted to move the national capital away from Guatemala City as they wanted the capital to be located in a more defensive position and as the federal government felt as if it was hated by the city's residents due to the civil war.[145] Morazán wanted to move the capital to San Salvador, but conservative Salvadoran political leaders resisted Morazán's proposal and even declared El Salvador's secession from the federal republic in January 1832 in part to prevent San Salvador from becoming the national capital.[146] On 5 February 1834, the federal government officially moved the national capital from Guatemala City to the Salvadoran city of Sonsonate,[147] but Salvadoran politicians in San Salvador did not want the federal government to move its capital to the city.[148]

Salvadoran Governor Joaquín de San Martín believed that Morazán moving the federal capital to San Salvador was an attempt to remove him as governor and saw the capital's temporary relocation to Sonsonate as a threat. After almost the entire Salvadoran state assembly resigned on 15 May 1834 due to rising tensions between San Martín and Morazán, San Martín announced his intention to resign but retained his gubernatorial powers.[149] In late May, Morazán invaded El Salvador to force San Martín out of office. Morazán captured San Salvador on 6 June and San Martín resigned on 12 June. San Martín was succeeded as provisional governor by Carlos Salazar, José Gregorio Salazar's brother, and then later by José Gregorio Salazar himself on 13 July. As provisional governor, José Gregorio Salazar defeated a rebellion launched by San Martín which sought to restore him to power.[150]

San Salvador became the federal capital in June 1834 and it was meant to symbolize the liberal's victory over the conservatives in the civil war of 1827 to 1829.[151][105] The federal government established the Federal District around San Salvador on 7 February 1835 in accordance with article 65 of the federal constitution which called for such a federal district to be created for the country's capital when "circumstances permitted".[152] The Federal District covered a 20 miles (32 km) radius around San Salvador and extended 10 miles (16 km) south to border the Pacific Ocean.[153] All federal government offices subsequently relocated to the Federal District.[154] El Salvador temporarily moved its state government from San Salvador to Cojutepeque[155] before permanently relocating to San Vicente on 21 September.[156]

1833 and 1835 presidential elections

[edit]During the late 1833 presidential election, the electoral college elected Valle as Central America's next president. Valle defeated Morazán as many voters and politicians opposed Morazán's use of military force to settle disputes between liberals and conservatives, and saw Valle as a moderate who could offer peace.[157] Valle died of illness on 2 March 1834 while he was traveling to Guatemala to assume the presidency,[158][159][160] As Morazán came in second in the election, he retained the presidency,[161] but on 2 June, the federal government called for a new presidential election to be held the following year nonetheless.[162] On 2 February 1835, the electoral college re-elected Morazán as Central America's president and José Gregorio Salazar as Morazán's vice president. Both men were sworn in on 14 February.[158]

Second civil war and dissolution

[edit]

On 30 May 1838, the Federal Congress convened and declared that each of the federal republic's five states were free to established whatever form of republican government they wished. Nicaragua declared is secession from the Federal Republic of Central America on 30 April 1838. Honduras declared its secession on 26 October, and Costa Rica did the same on 15 November. On 2 February 1839, all of Central America's federally elected government officials, including Morazán himself, left office. They did not have any successors as no federal election was held.[163] On 17 April, Guatemalan President Rafael Carrera issued a decree declaring the dissolution the Federal Republic of Central America; the Federal Congress accepted Carrera's decree on 14 July.[164] On 30 January 1841, El Salvador declared its independence from the Federal Republic of Central America.[165] Upon the fall of the federal republic, four of its five successor states were led by opponents of federal rule and proponents of their respective states' secession: Braulio Carrillo (Costa Rica), Francisco Malespín (El Salvador), Carrera (Guatemala), and Francisco Ferrera (Honduras).[166]

Government and politics

[edit]Federal government

[edit]

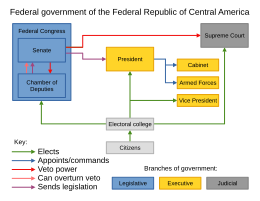

According to the federal constitution, the government of the Federal Republic of Central America was "popular, representative, and federal".[167] All elected officials in the federal republic were elected through indirect elections; voters voted for electors who would vote on behalf their behalf, rather than voting directly for candidates who were seeking public office. In presidential, vice presidential, and legislative elections, there were three rounds of voting; voters elected electors in the first round, electors voted for a further set of electors in the second round, and those electors voted for the actual candidates seeking public office in the third round.[168] Voting was compulsory.[169]

The federal republic's government was also divided into legislative, executive, and judicial branches.[167][170] Term limits were not in place for any office in the federal government.[169] The Federal Congress was the bicameral legislative branch of the Federal Republic of Central America.[171][172] The Chamber of Deputies was the lower house and consisted of 41 deputies allocated across the states[f] on a basis of one deputy per 30,000 people.[59] Each deputy was accompanied by a supplement deputy.[169] Half of the Chamber of Deputies' members are elected annually.[153] The Senate was the upper house and consisted of two senators from each state for a total of ten senators.[36][38] The Senate, which first assumed office on 24 April 1825,[173] acted as a de facto executive council which approved legislation passed by the Council of Deputies.[174] The Senate also served as an advisory body to the president and was able to review Supreme Court rulings.[175] One-third of the Senate's members are elected every year.[153] The Council of Deputies, meanwhile, was able to override a Senate legislative veto with a two-thirds majority, or with a three-fourths majority for legislation regarding taxation.[174] From 1824 to 1838, there were a total of 11 congressional terms.[176]

The president led the executive branch of the federal republic. The president was elected to a four-year term and served as the commander-in-chief of the Federal Army.[174] The president had a cabinet of three secretaries (ministers): the secretary of relations, the secretary of war, and the secretary of the treasury.[177] Article 111 of the federal constitution allowed the president to seek consecutive re-election one time, after which, the president had to leave office for at least one term before being eligible for re-election a second time.[178] The president of the Federal Republic of Central America was relatively weak compared to other contemporary Latin American presidents, particularly because the president could not veto or pocket veto legislation, could not send legislation back to the Federal Congress for reconsiderations, and was required to enact all laws passed by the Federal Congress within fifteen days.[174][179] The presidency was relatively weak as the writers of the federal constitution sought to oppose the rise of a caudillo-like president with dictatorial powers by implementing several checks on presidential power to ensure legislative supremacy. Rodrigo Facio Brenes, a 20th century Costa Rican lawyer and rector of the University of Costa Rica, described the presidency of the Federal Republic of Central America as "merely decorative".[179]

The Supreme Court of Justice was established on 2 August 1824 as the federal republic's judicial branch.[180] The court consisted of six justices. Two justices were elected every two years.[153] The first justices assumed office on 29 April 1825.[181] The Supreme Court was unable to enforce its rulings on unconstitutional laws passed by the Federal Congress as its rulings were subject to a Federal Congress review.[175][182]

Armed forces

[edit]The Federal Republic of Central America found it difficult to maintain its federal army throughout its existence. Prior to Central American independence, few Central Americans pursued a military career. Guatemalan historian Manuel Montúfar y Coronado wrote that "military influence was unknown in Central America; before Independence, there was no military career" ("el influjo militar fue desconocido en Centro América; antes de la Independencia, no había carrera militar").[183] The Central American federal army originated as the various rebel groups which resisted annexation to Mexico in 1822 and 1823, but it was not formally established as a political entity until 1829.[184]

Although the president served as the commander-in-chief of the federal army,[174] only the Federal Congress had the authority to raise and maintain armies, as well as to declare war and peace.[169] In July 1823, the Central American federal army totaled 10,000 soldiers.[185] The legislature increased the size of the federal army to 11,800 soldiers in December 1823 organized into two light battalions, two squadrons, and one artillery brigade.[186] The federal army established defensive garrisons along the Caribbean coast in the event that Spain attempted to reassert its control over the region. George Alexander Thompson, a British diplomat who visited Central America in 1825, assessed that the federal army would only have been able to resist any Spanish invasion through guerrilla warfare.[187]

By the end of 1829, the Central American federal army, now officially established and named the Protector Allied Army of the Law, totaled 4,000 soldiers. That same year, however, the Federal Congress reduced the maximum size of the federal army to only 2,000 soldiers due to general distrust among the states regarding the power and influence of the federal army. Each of the states were instructed to provide soldiers to the federal army.[g] The federal army during peacetime, as established by the Federal Congress in 1829, consisted of three infantry brigades, one artillery brigade, and one cavalry regiment.[188] By 1831, only 800 federal soldiers remained in comparison to the state militias which had more soldiers, were better funded, and were better equipped. During the 1830s, the federal army's military supremacy over the state militias relied solely on the discipline of federal soldiers and public perception that a caudillo-like figure led the federal army. In 1836, Morazán remarked that the federal army had been reduced to "a handful of ancient veterans that have survived the greatest dangers" ("un puñado de antiguos veteranos que han sobrevivido a los mayores peligros").[189]

Administrative divisions

[edit]

The federal republic consisted of five states: Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua.[190] These states were further subdivided into 45 partidos (districts) each.[191] Additionally, from 7 February 1835 to 3 May 1839, the Federal District existed centered around San Salvador to serve as the national capital.[152] Briefly, from 1838 to 1839, the federal government considered separating Los Altos from Guatemala and elevating it to the status of a state.[192] Guatemala claimed Belize as part of its territorial extent, however, the coastal parts of Belize were occupied by the British.[36] Guatemala also claimed sovereignty over Soconusco, as did Mexico, but neither held full control over the region. Additionally, parts of Soconusco were effectively independent, but its leaders did prefer union with Central America.[110] Central America also bordered the Mosquito Coast on its Caribbean coast,[193] which Central America also claimed as part of its sovereign territory.[194] In total, the Federal Republic of Central America covered approximately 200,000 square miles (520,000 km2) and spanned around 900 miles (1,400 km) north-to-south between the 8th and 18th northern parallels.[195]

On 5 May 1824, the National Constituent Assembly ordered each of the federal republic's five states to draft a constitution and install state-level legislative, executive, and judicial branches which resemble those of the federal government.[170][190] Each state was able to elect legislators, a governor, and judicial officials in indirect elections. Like the Senate at the federal level, each state's Senate functioned as an executive council and offered advice to the state governor.[174] All of the states drafted and ratified their constitutions by April 1826.[171] The federal constitution recognized each state government as being "free and independent" ("libre e independiente") and that the state governments could administer some internal affairs duties not offered to the federal government by the federal constitution.[196]

| State | Location (borders c. 1835–1838) | Capital city | State constitution adopted[171] | Population (1824)[197] | Population (1836)[195] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Costa Rica |  | Cartago | 25 January 1825 | 70,000 | 150,000 |

| El Salvador |  | San Salvador (until 1834) Cojutepeque (1834) San Vicente (1834–1839) San Salvador (from 1839) | 12 June 1824 | 212,573 | 350,000 |

| Federal District |  | San Salvador (1835–1839) | Not applicable | 50,000 | |

| Guatemala |  | Antigua Guatemala (until 1825) Guatemala City (from 1825) | 11 October 1825 | 660,580 | 700,000 |

| Honduras |  | Comayagua | 11 December 1825 | 137,069 | 300,000 |

| Nicaragua |  | León | 8 April 1826 | 207,269 | 350,000 |

Political factions

[edit]The two major political factions of the Federal Republic of Central America were the liberals (also referred to as fiebres) and the conservatives[h] (also referred to as serviles). These factions were not proper, organized political parties.[198][199] Liberals and conservatives saw each other as enemies and often accused each other of "demagoguery, disorganization, and anarchism" ("demagogia, desorganización y anarquismo").[200]

The liberals supported implementing a federal government and granting various devolved powers to the country's states[39] as they believed that the centralized colonial government to be inherently defective and that radical change was necessary.[200] The liberals attempted to implement freedom of religion in 1823,[201] however, resistance from the predominantly Catholic population led to the liberals failing to implement the reform; instead, Catholicism was established as the country's official religion.[39][174] In 1825, an executive decree required all Catholic clergymen in the country to swear an oath of allegiance to the federal republic. The clergy opposed this decree as they perceived it as diminishing the power and authority of the Catholic Church.[202] Liberals also supported laissez-faire economic policies, free trade, and foreign immigration in an effort to improve the economy.[161][203] The liberals primarily received support from the upper-middle class and intellectuals.[202]

The conservatives supported centralizing power around the national government[39] as they believed that the colonial centralized government structure in place prior to independence was a preferable alternative to introducing a new system of government (federalism) which they perceived as potentially being a burden on society.[200] The conservatives also supported implementing protectionist economic policies. They defended the role of the Catholic Church in Central American society as an arbiter of morality and a maintainer of the status quo.[203] In contrast, the conservatives viewed Protestantism as inferior to Catholicism.[138] The conservatives also believed that the country's indigenous population should be subservient to the ruling white and mestizo population.[204] The conservatives primarily received support from wealthy landowners, established colonial-era families, and the clergy.[202]

Foreign relations

[edit]

Throughout the Federal Republic of Central America's existence, it sent diplomats to Gran Colombia, France, the Holy See, Mexico, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom and the United States.[205] The federal republic itself received diplomats from Chile, France, Gran Colombia, Hanover, Mexico, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and the United States.[206] Mexico recognized Central American independence in August 1823.[2] On 15 March 1825, a federal diplomats signed a treaty with Gran Colombia ensuring the existence of a "perpetual confederation" ("confederación perpetua") between the two countries. The federal government ratified the treaty on 12 September.[176] Although France, the Holy See, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom sent diplomats to the Federal Republic of Central America, they only recognized Central America's independence until after the federal government had already collapsed in the late 1830s.[207]

Соединенные Штаты признали независимость Федеративной Республики Центральной Америки от Испании 4 августа 1824 года, когда президент США Джеймс Монро принял Каньяса в качестве посланника Центральной Америки в Соединенных Штатах. Обе страны подписали Договор о мире, дружбе, торговле и мореплавании 5 декабря 1825 года. 3 мая 1826 года Центральная Америка приняла временного поверенного в делах США Джона Уильямса в Гватемале. Уильям С. Мерфи был последним американским дипломатом, назначенным в Центральную Америку; он покинул свой пост в марте 1842 года после распада федеративной республики. [208]

16 июня 1825 года Федеральный конгресс принял закон, который одобрил строительство канала в Никарагуа , который соединит Тихий океан и Карибское море . [181] В октябре 1830 года Федеральный конгресс одобрил контракт с правительством Нидерландов на разработку проекта канала, но в следующем году голландское правительство аннулировало контракт в результате Бельгийской революции . [209] Правительство Никарагуа и в 1833, и в 1838 году обращалось к федеральному правительству с просьбой осуществить строительство канала, но федеральное правительство не предприняло никаких действий ни по одному запросу. [181]

Национальные символы

[ редактировать ]Сопротивляясь попытке мексиканцев аннексировать Центральную Америку в 1822 году, силы Арсе размахивали горизонтальным трибандом сине-бело-голубых цветов, вдохновленным флагом Аргентины . [210] Флаг Федеративной Республики Центральной Америки, принятый 21 августа 1823 года. [211] был основан на дизайне Арсе 1822 года. [210] сохранил Принятый флаг сине-бело-голубой горизонтальный трехполосный рисунок с гербом страны в центре. [211] Герб федеративной республики представлял собой равносторонний треугольник. Внутри треугольника находилась радуга наверху, фригийская шапка с исходящими от нее лучами света в центре и ряд из пяти округлых вулканов, окруженных двумя океанами, представляющими Тихий и Атлантический океаны, внизу. Треугольник окружал овал с названием страны внутри него. [211] [212]

Государственным гимном федеральной республики была «Гранадера» , написанная Ромуло Э. Дюроном. [213] Национальным девизом федеративной республики было « Бог, Союз, Свобода » («Dios, Unión, Libertad »). [9] Этот девиз был принят 4 августа 1823 года и заменил предыдущий девиз «Боже, храни вас долгие годы» (« Dios Guarde a Ud. Muchos años »), использовавшийся еще до обретения независимости. [202]

Демография

[ редактировать ]Население

[ редактировать ]В 1824 году численность населения Центральной Америки составляла 1 287 491 человек. [36] [197] К 1836 году численность населения Центральной Америки составляла 1 900 000 человек. [195] однако эта оценка федерального администратора Хуана Галиндо «значительно переоценила» количество белых и полностью исключила коренное население Гондураса. [214] Тем не менее, Центральная Америка была самой густонаселенной страной в Америке . [195] Население страны было неравномерно распределено по штатам: в 1824 году более половины населения проживало только в Гватемале. Конституция предоставила политическое представительство в Федеральном конгрессе, пропорциональное численности населения, поэтому этот дисбаланс населения предоставил Гватемале большую долю представительства в Федеральном конгрессе. законодательный орган, чем в других штатах. [215]

Этнический состав

[ редактировать ]

Центральная Америка не была этнически однородной. [172] В 1824 году 65 процентов населения составляло коренное население, 31 процент — смешанное (ладино или метисы ), а 4 процента — белое (испанцы или криолло ). [36] Чернокожее население было небольшим, однако Галиндо описал чернокожее население в 1836 году как «слишком незначительное, чтобы его можно было принимать во внимание». [153] Этнический состав варьировался во всех государствах Центральной Америки. В 1824 году до 70 процентов населения Гватемалы составляли коренные жители; Сальвадор, Гондурас и Никарагуа почти полностью состояли из метисов ; а Коста-Рика сообщила, что на 80 процентов она белая. [216]

В следующей таблице показано население Центральной Америки в 1836 году, разделенное по этническим группам.

| Состояние | Этническая группа | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Местный | Смешанный | Белый | Общий | |

| Коста-Рика | 25,000 | — | 125,000 | 150,000 |

| Сальвадор | 70,000 | 210,000 | 70,000 | 350,000 |

| Федеральный округ | 20,000 | 20,000 | 10,000 | 50,000 |

| Гватемала | 450,000 | 150,000 | 100,000 | 700,000 |

| Гондурас | — | 240,000 | 60,000 | 300,000 |

| Никарагуа | 120,000 | 120,000 | 110,000 | 350,000 |

| Общий | 685,000 | 740,000 | 475,000 | 1,900,000 |

Белое и смешанное население Центральной Америки преимущественно говорило по-испански, в то время как большинство коренного населения говорило на своих различных родных языках коренных народов . [216] Большинство жителей Центральной Америки в федеративной республике были неграмотными, и как федеральному правительству, так и правительству штатов не хватало средств для инвестиций в строительство школ, чтобы предоставить своим гражданам достаточное образование. [217] Морасан основал университеты в Сан-Сальвадоре и Леоне в начале 1830-х годов, однако им не хватало финансирования и профессоров, чтобы они могли функционировать. [103]

Религия

[ редактировать ]Католицизм был крупнейшей и официальной религией Федеративной Республики Центральной Америки. [218] Первоначально католицизм был единственной религией, которой можно было поклоняться публично. Публичное поклонение любой другой религии было запрещено до мая 1832 года, когда Федеральный конгресс издал указ, разрешающий публичное поклонение любой другой религии, и в 1835 году в конституцию были внесены поправки, чтобы закрепить это. [219] Хотя католическая церковь имела большое влияние в политике Центральной Америки, [218] ни президенту, ни кому-либо из судей Верховного суда не разрешалось быть членами духовенства, и только один из двух сенаторов от каждого штата мог быть священнослужителем. Кроме того, любые папские буллы, издаваемые Папой Центральной Америке, должны были быть одобрены Федеральным конгрессом, прежде чем они могли вступить в силу. [220]

Города

[ редактировать ]В 1836 году в Центральной Америке насчитывалось двадцать девять поселений, официально признанных городами. [153] На следующей карте показано расположение этих городов.

Экономика

[ редактировать ]Валюта

[ редактировать ]

19 марта 1824 года Национальное Учредительное собрание приняло закон, запрещавший чеканку монет с «бюстом, гербом или какими-либо другими эмблемами, типичными и отличительными для испанской монархии » (« el busto, escudo de Armas o cualesquiera otros Emblemas que sean propios y distintivos de la monarquía española »). Закон также предписывал создание новой валюты. На аверсе будет изображен герб страны, а на реверсе — дерево и фраза «Free Grow Fertile» (« Libre Crezca Fecundo »). [222] [223]

Центральноамериканская валюта , называемая «национальной валютой». [224] была разделена на эскудо , песо и реалы . [225] Один щит равнялся двум песо , [226] в то время как одно песо равнялось восьми реалам . [227] Эскудо чеканились из золота номиналом в 1 ⁄ 2 , 1, 2, 4 и 8; песо чеканились из золота номиналом 1 и 2; Реалы были отчеканены из серебра номиналом 1 ⁄ 4 , 1 ⁄ 2 , 1, 2 и 8. [225] Эти монеты были отчеканены в Гватемале, Сан-Хосе и Тегусигальпе. [228]

Экономические проблемы

[ редактировать ]«К сожалению, ни в республике, ни в государстве [Гватемала] не был представлен по-настоящему творческий план казначейства. Рутинный дух, малодушный, без координации и системы, преобладал при установлении налогов, доказывая тем самым, что мы унаследовали от Испании финансовая некомпетентность».

Мариано Гальвес , казначей Гватемалы [229]

Томас Л. Карнес, профессор истории в Университете штата Аризона , охарактеризовал экономику Федеративной Республики Центральной Америки как «хаотическую». [207] Федеративная республика постоянно боролась за то, чтобы иметь достаточно денег для финансирования своих государственных обязанностей. В 1826 году Уильямс написал госсекретарю США Генри Клею , что экономическая ситуация в Центральной Америке «самая бесперспективная». Роберт С. Смит, профессор экономики в Университете Дьюка , охарактеризовал федеральную казну как «хронически пустую». [229] Когда Арсе вступил на пост президента в 1825 году, в казне находилось всего 600 песо. [230]

Под испанским колониальным правлением экономика Центральной Америки в основном зависела от сельского хозяйства, поскольку в регионе не было изобилия природных ресурсов. [231] [232] а Федеративная Республика Центральной Америки продолжала полагаться на экономику, основанную на сельском хозяйстве. Крупнейшим источником дохода федеративной республики был экспорт лесоматериалов , индиго , кошенили , бананов , кофе , какао и особенно табака . [84] [233] Только экспорт табака приносил от 200 000 до 300 000 песо дохода в год. [234] Хотя экспорт сельскохозяйственной продукции обеспечивал федеральной республике большую часть ее доходов, она по-прежнему сильно зависела от иностранных кредитов для финансирования повседневного управления. Многие из этих иностранных кредитов были предоставлены по значительно сниженным ставкам, но зачастую по ним не выполнялся дефолт. [84] В 1828 году федеральное правительство объявило дефолт по внешнему долгу, который на тот момент составлял 163 300 фунтов стерлингов (что эквивалентно 17 666 289 долларам США в 2023 году). [235] В октябре 1823 года Национальное Учредительное собрание обязалось погасить внутренний долг страны на общую сумму 3 583 576 песо, но к февралю 1831 года долг увеличился до 4 768 966 песо. [236]

Инфраструктура как между штатами федеративной республики, так и внутри них была плохой из-за больших территорий густого леса и гористой местности по всей Центральной Америке. [182] Первоначально рабы из числа коренных народов строили и обслуживали дорожную сеть Центральной Америки, но после того, как рабство было отменено 17 апреля 1824 года федеральным указом, [237] строительство этих дорог в основном закончилось, и многие из них стали непригодными для использования из-за отсутствия технического обслуживания. [174] [238] Эта деградация инфраструктуры страны, по сути, привела к сокращению межгосударственной торговли и промышленности. [84] [239] Вспышки проказы , оспы и брюшного тифа также снижали производительность труда. [217]

Экономика Гватемалы была самой сильной из пяти штатов, и она финансировала большую часть гражданских и военных расходов федерального правительства, в то время как некоторые штаты вообще не вносили вклад в финансирование федерального правительства в некоторые моменты из-за своих напряженных экономических условий. [240] Аналогичным образом, Гватемала была ответственна за выплату почти половины внешнего долга федеративной республики до дефолта 1828 года. [241]

Наследие

[ редактировать ]Историческая оценка

[ редактировать ]«Государства перешейка от Панамы до Гватемалы, возможно, образуют конфедерацию. Это великолепное место между двумя великими океанами могло бы со временем стать мировым торговым центром. Его каналы сократят расстояния по всему миру, укрепят торговые связи с Европой, Америки и Азии, и принесите этому счастливому региону дань со всех четырех сторон земного шара. Возможно, когда-нибудь столица мира там окажется , подобно тому, как Константин утверждал, что Византия была столицей древнего мира».

Симон Боливар о потенциале независимой центральноамериканской нации, Письмо Ямайки (1815 г.) [242] [243]

Ричард А. Хаггерти, редактор Федерального исследовательского отдела Библиотеки Конгресса , охарактеризовал Федеративную Республику Центральной Америки как «неработоспособный», но «единственный успешный политический союз центральноамериканских государств» после окончания испанского колониального правления. [242] Министерство образования Сальвадора описало федеративную республику как «политическую лабораторию» (« labatorio político ») для таких политических идей, как республиканизм и конституционализм . [244]

Некоторые эксперты раскритиковали федеральную конституцию как «слишком идеалистическую» как основной компонент, способствовавший распаду федеративной республики. [220] Либеральный гватемальский политик Лоренцо Монтуфар заявил, что, «приняв федеральную систему, [федеративная республика] добилась результатов, войн и катастроф». [245] Никарагуанский журналист Педро Хоакин Чаморро написал, что попытка подражать федеральной системе Соединенных Штатов привела к разногласиям между штатами Центральной Америки, где в противном случае централизованное правительство добилось бы успеха. [246] Министерство образования Сальвадора заявило, что федеральная конституция стала « фатальным выводом, приведшим к анархии и дезорганизации ». [170] Исследователь из Массачусетского университета Линн В. Фостер описала федеративную республику 1820-х годов как «больше похожую на свободную конфедерацию небольших независимых государств, чем на единую республику» из-за большого количества власти и влияния, которыми обладали местные чиновники в своем собственном штате. по сравнению с федеральным правительством. [76] Гильермо Васкес Висенте, профессор экономики Университета короля Хуана Карлоса , писал, что достижение конституционных идеалов федеративной республики было «невозможно» (« невозможно ») без последовательного политического, экономического и социального плана. Он также назвал отсутствие достижения республиканских идеалов конституции вместе с сепаратистскими настроениями внутри пяти штатов «непреодолимым препятствием» (« impedimento insalvable ») на пути к достижению консенсуса национального единства. [247]

Другие эксперты не согласны с тем, что конституция или федерализм были основной причиной распада Федеративной Республики Центральной Америки. Франклин Д. Паркер, профессор истории Университета Северной Каролины в Гринсборо , заявил, что неспособность политических лидеров федеративной республики адекватно соблюдать и обеспечивать соблюдение положений конституции в конечном итоге привела к краху федеративной республики. [248] Либеральный историк из Центральной Америки Алехандро Маруре объяснил «все несчастья, которые пережила нация» попытками Арсе умиротворить как либералов, так и консерваторов в 1820-х годах. [249] Гондурасский юрист и политик Рамон Роза написал в своей биографии Валле, что переизбрание Морасана в 1835 году привело к «разрушению Центральноамериканской Республики» (« la Ruina de la República centroamericana »), утверждая, что использование Морасаном военной силы для разрешения споров, а не чем компромисс подорвал федеральное правительство. [250] Никарагуанский писатель Сальвадор Мендьета заявил, что одной из основных причин распада федеративной республики было отсутствие эффективной коммуникационной инфраструктуры как между штатом, так и внутри самих штатов. [182] Точно так же Филип Ф. Флемион, профессор истории в Государственном университете Сан-Диего , объяснил крах федеративной республики «региональной ревностью, социальными и культурными различиями, неадекватными системами связи и транспорта, ограниченностью финансовых ресурсов и несопоставимыми политическими взглядами». [251] Смит объяснил, что «неэффективное финансовое управление» и «неудачное экономическое развитие» федеративной республики сыграли хотя бы небольшую роль в крахе федеративной республики. [252]

Попытки воссоединения

[ редактировать ]

Еще в 1842 году некоторые жители Центральной Америки пытались воссоединить регион. В течение 19 и 20 веков было предпринято несколько попыток воссоединения либо посредством дипломатии, либо с помощью силы, но ни одна из них не длилась дольше нескольких месяцев и не затрагивала все пять бывших членов Федеративной Республики Центральная Америка. [253] [254] [255] По словам гватемальского историка Хулио Сесара Пинто Сориа, Центральной Америке не удалось добиться воссоединения, прежде всего из-за того, что олигархи в каждом из бывших штатов федеративной республики стремились продвигать свои собственные интересы, для которых воссоединение рассматривалось как препятствие. [166]

17 марта 1842 года делегации Сальвадора, Гондураса и Никарагуа провозгласили Антонио Хосе Каньяса президентом нового федерального правительства, но ни правительства Коста-Рики, ни Гватемалы не признали это провозглашение. [255] Правительство Каньяса прекратило свое существование в 1844 году, когда Сальвадор и Гондурас вторглись в Никарагуа для предоставления убежища сальвадорским и гондурасским политическим изгнанникам. [256] Морасан также пытался воссоединить Центральную Америку силой в 1842 году, когда он стал политическим лидером Коста-Рики. Морасан возглавил вторжение в Никарагуа, однако был разбит, свергнут, а затем расстрелян 15 сентября 1842 года. [257] [258]

В 1848 году делегаты тех же трех стран встретились в Тегусигальпе, чтобы разработать новую конституцию Центральной Америки. [255] Дальнейшие встречи произошли в 1849 году в Леоне, во время которых делегации подписали договор об избрании президента, вице-президента и национального законодательного органа Центральной Америки. Законодательный орган Центральной Америки объявил о создании Центральноамериканского союза 9 октября 1852 года, но сопротивление со стороны Легитимистской партии Никарагуа и начало гражданской войны в Никарагуа привели к краху союза к 1854 году. [259] [260] Кроме того, ни Сальвадор, ни Никарагуа так и не ратифицировали конституцию союза. [256]

В 1876 году президент Гватемалы Хусто Руфино Барриос призвал все пять бывших членов Федеративной Республики Центральной Америки направить делегации в Гватемалу для переговоров о восстановлении единой центральноамериканской страны, но вторжение Барриоса в Сальвадор позже в том же году отменило запланированные переговоры. [261] [262] 28 февраля 1885 года Барриос объявил о создании Федерации Центральной Америки и провозгласил себя ее президентом. Гондурас принял декларацию Барриоса, но Коста-Рика, Сальвадор и Никарагуа отвергли ее. 29 марта 1885 года Барриос вторгся в Сальвадор, чтобы заставить его вступить в Центральноамериканский союз, однако он был убит во время битвы при Чалчуапе 2 апреля. Впоследствии гватемальские войска покинули Сальвадор, положив конец попытке Барриоса воссоединить Центральную Америку. [263] [261]

20 июня 1895 года делегации Сальвадора, Гондураса и Никарагуа подписали Амапальский договор и провозгласили образование Великой Республики Центральной Америки . [264] Договор позволил Коста-Рике и Гватемале присоединиться к нему, если их правительства того пожелают. [265] Соединенные Штаты установили дипломатические отношения с великой республикой в декабре 1896 года. [266] Первая сессия Исполнительного федерального совета (законодательного органа страны) состоялась 1 ноября 1898 года, когда была принята конституция страны и ее название было изменено на Соединенные Штаты Центральной Америки. [265] 13 ноября сальвадорский генерал Томас Регаладо Ромеро сверг президента Рафаэля Антонио Гутьерреса и провозгласил уход Сальвадора из Соединенных Штатов Центральной Америки. 29 ноября Исполнительный федеральный совет официально распустил союз после того, как не смог остановить отделение Сальвадора. [267]

В 21 веке президент Сальвадора Наиб Букеле неоднократно выражал свое желание воссоединить Центральную Америку. В некоторых своих выступлениях после вступления в должность в 2019 году он отмечал, что Центральная Америка должна быть «одной нацией». [268] [269] В 2024 году он подтвердил, что продолжает верить в то, что Центральная Америка должна воссоединиться, и заявил, что регион станет сильнее, если объединится. ему нужна «воля народов» (« la voluntad de los pueblos »). Он добавил, что для достижения воссоединения [270]

См. также

[ редактировать ]Примечания

[ редактировать ]- ↑ С 1823 по 1825 год Национальное Учредительное собрание служило де-факто законодательным органом Центральной Америки. [1]

- ^ « Provincias Unidas del Centro de América » переводится на английский буквально как «Соединенные провинции Центра Америки». [2]

- ^ 64 делегата Национального учредительного собрания были распределены по Центральной Америке следующим образом: 28 делегатов от Гватемалы, 13 от Сальвадора, 11 от Гондураса, 8 от Никарагуа и 4 от Коста-Рики. [1]

- ↑ Другими кандидатами на президентских выборах 1825 года были Алехандро Диас Кабеса де Вака (2 голоса), Хосе Мария Кастилья (1 голос) и Хосе Сантьяго Милья (1 голос). [61]

- ↑ Общее количество голосов выборщиков, поданных на президентских выборах 1830 года, составило 202 голоса за Франсиско Морасану, 103 голоса за Хосе Сесилио дель Валье и неизвестное количество голосов за Хосе Франсиско Баррундиа, Антонио Ривера Кабесас и Педро Молина Масариегос. [104] [105]

- ^ Распределение депутатов нижней палаты Федерального конгресса следующее: 18 депутатов от Гватемалы, 9 от Сальвадора, 6 от Гондураса, 6 от Никарагуа и 2 от Коста-Рики. [170]

- ^ Вклад в лимит численности федеральной армии в 2000 солдат на 1829 год был разделен между штатами федеративной республики следующим образом: 829 солдат из Гватемалы, 439 из Сальвадора, по 316 из Гондураса и Никарагуа каждый и 100 из Коста-Рики. [188]

- ^ Во время существования Федеративной Республики Центральной Америки консерваторы не называли себя «консерваторами», вместо этого они называли себя «умеренными» (« moderados »). [198]

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]Цитаты

[ редактировать ]- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж Карнес 1961 , с. 35.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Пелосо и Тененбаум 1996 , с. 65.

- ^ Слэйд 1917 , с. 88.

- ^ Маруре 1895 , с. 10.

- ^ Пинто Сориа 1987 , стр. 3 и 7.

- ^ Пинто Сориа 1987 , с. 3.

- ^ Маруре 1895 , с. 17.

- ^ Карнес 1961 , с. 49.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Перес Бриньоли 2018 , с. 107.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Карнес 1961 , с. 9.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Стангер 1932 , с. 21.

- ^ Стангер 1932 , с. 22.

- ^ Линдо Фуэнтес, Чинг и Лара Мартинес 2007 , стр. 72–74.

- ^ Линдо Фуэнтес, Чинг и Лара Мартинес 2007 , с. 73.

- ^ Берналь Рамирес и Кихано де Батрес 2009 , с. 138.

- ^ Фостер 2007 , с. 130.

- ^ Берналь Рамирес и Кихано де Батрес 2009 , с. 139.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Берналь Рамирес и Кихано де Батрес 2009 , с. 141.

- ^ Берналь Рамирес и Кихано де Батрес 2009 , с. 143.

- ^ Фостер 2007 , с. 131.

- ^ Фостер 2007 , с. 132–133.

- ^ Манро 1918 , с. 24.

- ^ Кеньон 1961 , с. 176.

- ^ Стангер 1932 , с. 34.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Фостер 2007 , с. 135.

- ^ Кеньон 1961 , стр. 183–184.

- ^ Кеньон 1961 , стр. 182–183.

- ^ Обрегон Кесада 2002 , стр. 25–34.

- ^ Мелендес Чаверри 2000 , стр. 263–264.

- ^ Стангер 1932 , стр. 39–40.

- ^ Кеньон 1961 , с. 193.

- ^ Флемион 1973 , с. 602.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Боланьос Гейер 2018 .

- ^ Кеньон 1961 , с. 196.

- ^ Кеньон 1961 , с. 197–198.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж Фостер 2007 , с. 136.

- ^ Васкес Оливера 2012 , с. 24.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Слэйд 1917 , с. 89.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и Карнес 1961 , с. 37.

- ^ Карнес 1961 , стр. 36–37.

- ^ Кеньон 1961 , с. 200.

- ^ Стангер 1932 , с. 40.

- ^ Мелендес Чаверри 2000 , с. 286.

- ^ Карнес 1961 , стр. 45–46 и 49.

- ^ Перес Бриньоли 1989 , с. 67.

- ^ Лухан Муньос 1982 , с. 83.

- ^ Маруре 1895 , с. 13–14.

- ^ Карнес 1961 , с. 40.

- ^ Карнес 1961 , стр. 40–41.

- ^ Маруре 1895 , с. 135.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Карнес 1961 , с. 41.

- ^ Сото 1991 , с. 27.

- ^ Карнес 1961 , стр. 41–42.

- ^ Карнес 1961 , стр. 42–43.

- ^ Карнес 1961 , с. 47.

- ^ Маруре 1895 , с. 23.

- ^ Карнес 1961 , с. 48.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Маруре 1895 , с. 27.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Уллоа 2014 , стр. 171.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Пелосо и Тененбаум 1996 , с. 69.

- ^ Чаморро Карденаль 1951 , с. 105.

- ^ Флемион 1973 , стр. 604–605.

- ^ Карнес 1961 , с. 56.

- ^ Флемион 1973 , с. 606.

- ^ Филлипс и Аксельрод 2005 , с. 297.

- ^ Флемион 1973 , стр. 607–608 и 611–612.

- ^ Карнес 1961 , с. 57.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Флемион 1973 , с. 612.

- ^ Карнес 1961 , с. 64.

- ^ Флемион 1973 , стр. 612–613.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Флемион 1973 , с. 614.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Карнес 1961 , с. 65.

- ^ Флемион 1973 , стр. 614–615.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Флемион 1973 , с. 615.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Флемион 1973 , с. 616.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Фостер 2007 , с. 142.

- ^ Маруре 1895 , с. 36–37.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Пелосо и Тененбаум 1996 , с. 70.

- ^ Маруре 1895 , с. 38.

- ^ Флемион 1973 , стр. 616–617.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Флемион 1973 , с. 617.

- ^ Маруре 1895 , с. 36 .

- ^ Филлипс и Аксельрод 2005 , с. 296.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Карнес 1961 , с. 66.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Маруре 1895 , с. 42.

- ^ Фостер 2007 , с. 143.

- ^ Маруре 1895 , с. 41.

- ^ Карнес 1961 , с. 70.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Пелосо и Тененбаум 1996 , с. 71.

- ^ Кардинал Чаморро 1951 , с. 236 &

- ^ Чаморро Карденаль 1951 , с. 246.

- ^ Чаморро Карденаль 1951 , с. 248.

- ^ Маруре 1895 , с. 50.

- ^ Чаморро Карденаль 1951 , с. 250.

- ^ Чаморро Карденаль 1951 , с. 251.

- ^ Чаморро Карденаль 1951 , стр. 256–257.

- ^ Чаморро Карденаль 1951 , с. 258.

- ^ Чаморро Карденаль 1951 , стр. 265–266.

- ^ Сото 1991 , стр. 26–27.

- ^ Карнес 1961 , с. 71.

- ^ Молина Морейра 1979 , стр. 61–62.

- ^ Карнес 1961 , стр. 71–72.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Карнес 1961 , с. 74.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Уллоа 2014 , стр. 172.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Пелосо и Тененбаум 1996 , с. 72.

- ^ Чаморро Карденаль 1951 , с. 304.

- ^ Чаморро Карденаль 1951 , стр. 277–278.

- ^ Чаморро Карденаль 1951 , с. 279.

- ^ Чаморро Карденаль 1951 , с. 280.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Чаморро Карденаль 1951 , с. 318.

- ^ Перри 1922 , стр. 30–31.

- ^ Чаморро Карденаль 1951 , стр. 318–320.

- ^ Карнес 1961 , с. 76.

- ^ Чаморро Карденаль 1951 , с. 320.

- ^ Карнес 1961 , стр. 76–77.

- ^ Маруре 1895 , с. 66–67.

- ^ Маруре 1895 , с. 67 .

- ^ Чаморро Карденаль 1951 , с. 321.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Карнес 1961 , с. 77.

- ^ Маруре 1895 , с. 68–69.

- ^ Чаморро Карденаль 1951 , с. 335.

- ^ Маруре 1895 , с. 67–68.

- ^ Маруре 1895 , с. 70.

- ^ Маруре 1895 , с. 70–71.

- ^ Чаморро Карденаль 1951 , стр. 332–333.

- ^ Маруре 1895 , с. 71.

- ^ Сото 1991 , с. 21.

- ^ Карнес 1961 , стр. 73–74.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Сото 1991 , с. 22.

- ^ Берналь Рамирес и Кихано де Батрес 2009 , с. 159.