Марс

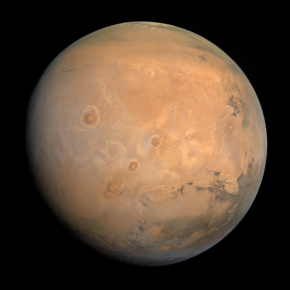

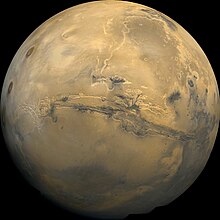

Марс в истинном цвете, [ а ] как было заснято орбитальным аппаратом «Надежда» . гору Олимп В центре можно увидеть гору Тарсис, слева и долину Маринерис справа. | |||||||||

| Designations | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjectives | Martian | ||||||||

| Symbol | |||||||||

| Orbital characteristics[1] | |||||||||

| Epoch J2000 | |||||||||

| Aphelion | 249261000 km (1.66621 AU)[2] | ||||||||

| Perihelion | 206650000 km (1.3814 AU)[2] | ||||||||

| 227939366 km (1.52368055 AU)[3] | |||||||||

| Eccentricity | 0.0934[2] | ||||||||

| 686.980 d (1.88085 yr; 668.5991 sols)[2] | |||||||||

| 779.94 d (2.1354 yr)[3] | |||||||||

Average orbital speed | 24.07 km/s[2] | ||||||||

| 19.412°[2] | |||||||||

| Inclination |

| ||||||||

| 49.57854°[2] | |||||||||

| 2022-Jun-21[5] | |||||||||

| 286.5°[3] | |||||||||

| Satellites | 2 (Phobos and Deimos) | ||||||||

| Physical characteristics | |||||||||

| 3389.5±0.2 km[b][6] | |||||||||

Equatorial radius | 3396.2±0.1 km[b][6] (0.533 Earths) | ||||||||

Polar radius | 3376.2±0.1 km[b][6] (0.531 Earths) | ||||||||

| Flattening | 0.00589±0.00015[5][6] | ||||||||

| 1.4437×108 km2[7] (0.284 Earths) | |||||||||

| Volume | 1.63118×1011 km3[8] (0.151 Earths) | ||||||||

| Mass | 6.4171×1023 kg[9] (0.107 Earths) | ||||||||

Mean density | 3.9335 g/cm3[8] | ||||||||

| 3.72076 m/s2 (0.3794 g0)[10] | |||||||||

| 0.3644±0.0005[9] | |||||||||

| 5.027 km/s (18100 km/h)[11] | |||||||||

| 1.02749125 d[12] 24h 39m 36s | |||||||||

| 1.025957 d 24h 37m 22.7s[8] | |||||||||

Equatorial rotation velocity | 241 m/s (870 km/h)[2] | ||||||||

| 25.19° to its orbital plane[2] | |||||||||

North pole right ascension | 317.269°[13] | ||||||||

North pole declination | 54.432°[13] | ||||||||

| Albedo | |||||||||

| Temperature | 209 K (−64 °C) (blackbody temperature)[15] | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Surface absorbed dose rate | 8.8 μGy/h[18] | ||||||||

| Surface equivalent dose rate | 27 μSv/h[18] | ||||||||

| −2.94 to +1.86[19] | |||||||||

| −1.5[20] | |||||||||

| 3.5–25.1″[2] | |||||||||

| Atmosphere[2][21] | |||||||||

Surface pressure | 0.636 (0.4–0.87) kPa 0.00628 atm | ||||||||

| Composition by volume |

| ||||||||

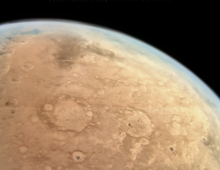

Марс — четвертая планета от Солнца . Поверхность Марса оранжево-красная, потому что она покрыта пылью оксида железа (III) , что дало ей прозвище « Красная планета ». [ 22 ] [ 23 ] Марс является одним из самых ярких объектов на земном небе , а его высококонтрастные характеристики альбедо сделали его частым объектом для наблюдения в телескопы . Она классифицируется как планета земной группы и является второй по величине планетой Солнечной системы с диаметром 6779 км (4212 миль). С точки зрения орбитального движения марсианский солнечный день ( сол ) равен 24,5 часам, а марсианский солнечный год равен 1,88 земных лет (687 земных дней). У Марса есть два естественных спутника , небольших размеров и неправильной формы: Фобос и Деймос .

The relatively flat plains in northern parts of Mars strongly contrast with the cratered terrain in southern highlands – this terrain observation is known as the Martian dichotomy. Mars hosts many enormous extinct volcanoes (the tallest is Olympus Mons, 21.9 km or 13.6 mi tall) and one of the largest canyons in the Solar System (Valles Marineris, 4,000 km or 2,500 mi long). Geologically, the planet is fairly active with marsquakes trembling underneath the ground, dust devils sweeping across the landscape, and cirrus clouds. Carbon dioxide is substantially present in Mars's polar ice caps and thin atmosphere. During a year, there are large surface temperature swings on the surface between −78.5 °C (−109.3 °F) to 5.7 °C (42.3 °F)[c] аналогично временам года на Земле , поскольку обе планеты имеют значительный наклон оси .

Mars was formed approximately 4.5 billion years ago. During the Noachian period (4.5 to 3.5 billion years ago), Mars's surface was marked by meteor impacts, valley formation, erosion, and the possible presence of water oceans. The Hesperian period (3.5 to 3.3–2.9 billion years ago) was dominated by widespread volcanic activity and flooding that carved immense outflow channels. The Amazonian period, which continues to the present, has been marked by the wind as a dominant influence on geological processes. Due to Mars's geological history, the possibility of past or present life on Mars remains of great scientific interest.

Since the late 20th century, Mars has been explored by uncrewed spacecraft and rovers, with the first flyby by the Mariner 4 probe in 1965, the first orbit by the Mars 2 probe in 1971, and the first landing by the Viking 1 probe in 1976. As of 2023, there are at least 11 active probes orbiting Mars or on the Martian surface. Mars is an attractive target for future human exploration missions, though in the 2020s no such mission is planned.

Natural history

Scientists have theorized that during the Solar System's formation, Mars was created as the result of a random process of run-away accretion of material from the protoplanetary disk that orbited the Sun. Mars has many distinctive chemical features caused by its position in the Solar System. Elements with comparatively low boiling points, such as chlorine, phosphorus, and sulfur, are much more common on Mars than on Earth; these elements were probably pushed outward by the young Sun's energetic solar wind.[24]

After the formation of the planets, the inner Solar System may have been subjected to the so-called Late Heavy Bombardment. About 60% of the surface of Mars shows a record of impacts from that era,[25][26][27] whereas much of the remaining surface is probably underlain by immense impact basins caused by those events. However, more recent modeling has disputed the existence of the Late Heavy Bombardment.[28] There is evidence of an enormous impact basin in the Northern Hemisphere of Mars, spanning 10,600 by 8,500 kilometres (6,600 by 5,300 mi), or roughly four times the size of the Moon's South Pole–Aitken basin, which would be the largest impact basin yet discovered if confirmed.[29] It has been hypothesized that the basin was formed when Mars was struck by a Pluto-sized body about four billion years ago. The event, thought to be the cause of the Martian hemispheric dichotomy, created the smooth Borealis basin that covers 40% of the planet.[30][31]

A 2023 study shows evidence, based on the orbital inclination of Deimos (a small moon of Mars), that Mars may once have had a ring system 3.5 billion years to 4 billion years ago.[32] This ring system may have been formed from a moon, 20 times more massive than Phobos, orbiting Mars billions of years ago; and Phobos would be a remnant of that ring.[33][34]

The geological history of Mars can be split into many periods, but the following are the three primary periods:[35][36]

- Noachian period: Formation of the oldest extant surfaces of Mars, 4.5 to 3.5 billion years ago. Noachian age surfaces are scarred by many large impact craters. The Tharsis bulge, a volcanic upland, is thought to have formed during this period, with extensive flooding by liquid water late in the period. Named after Noachis Terra.[37]

- Hesperian period: 3.5 to between 3.3 and 2.9 billion years ago. The Hesperian period is marked by the formation of extensive lava plains. Named after Hesperia Planum.[37]

- Amazonian period: between 3.3 and 2.9 billion years ago to the present. Amazonian regions have few meteorite impact craters but are otherwise quite varied. Olympus Mons formed during this period, with lava flows elsewhere on Mars. Named after Amazonis Planitia.[37]

Geological activity is still taking place on Mars. The Athabasca Valles is home to sheet-like lava flows created about 200 million years ago. Water flows in the grabens called the Cerberus Fossae occurred less than 20 million years ago, indicating equally recent volcanic intrusions.[38] The Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter has captured images of avalanches.[39][40]

Physical characteristics

Mars is approximately half the diameter of Earth, with a surface area only slightly less than the total area of Earth's dry land.[2] Mars is less dense than Earth, having about 15% of Earth's volume and 11% of Earth's mass, resulting in about 38% of Earth's surface gravity. Mars is the only presently known example of a desert planet, a rocky planet with a surface akin to that of Earth's hot deserts. The red-orange appearance of the Martian surface is caused by ferric oxide, or rust.[41] It can look like butterscotch;[42] other common surface colors include golden, brown, tan, and greenish, depending on the minerals present.[42]

Internal structure

Like Earth, Mars is differentiated into a dense metallic core overlaid by less dense rocky layers.[45][46] The outermost layer is the crust, which is on average about 42–56 kilometres (26–35 mi) thick,[47] with a minimum thickness of 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) in Isidis Planitia, and a maximum thickness of 117 kilometres (73 mi) in the southern Tharsis plateau.[48] For comparison, Earth's crust averages 27.3 ± 4.8 km in thickness.[49] The most abundant elements in the Martian crust are silicon, oxygen, iron, magnesium, aluminium, calcium, and potassium. Mars is confirmed to be seismically active;[50] in 2019 it was reported that InSight had detected and recorded over 450 marsquakes and related events.[51][52]

Beneath the crust is a silicate mantle responsible for many of the tectonic and volcanic features on the planet's surface. The upper Martian mantle is a low-velocity zone, where the velocity of seismic waves is lower than surrounding depth intervals. The mantle appears to be rigid down to the depth of about 250 km,[44] giving Mars a very thick lithosphere compared to Earth. Below this the mantle gradually becomes more ductile, and the seismic wave velocity starts to grow again.[53] The Martian mantle does not appear to have a thermally insulating layer analogous to Earth's lower mantle; instead, below 1050 km in depth, it becomes mineralogically similar to Earth's transition zone.[43] At the bottom of the mantle lies a basal liquid silicate layer approximately 150–180 km thick.[44][54]

Mars's iron and nickel core is completely molten, with no solid inner core.[55][56] It is around half of Mars's radius, approximately 1650–1675 km, and is enriched in light elements such as sulfur, oxygen, carbon, and hydrogen.[57][58]

Surface geology

Mars is a terrestrial planet with a surface that consists of minerals containing silicon and oxygen, metals, and other elements that typically make up rock. The Martian surface is primarily composed of tholeiitic basalt,[59] although parts are more silica-rich than typical basalt and may be similar to andesitic rocks on Earth, or silica glass. Regions of low albedo suggest concentrations of plagioclase feldspar, with northern low albedo regions displaying higher than normal concentrations of sheet silicates and high-silicon glass. Parts of the southern highlands include detectable amounts of high-calcium pyroxenes. Localized concentrations of hematite and olivine have been found.[60] Much of the surface is deeply covered by finely grained iron(III) oxide dust.[61]

Although Mars has no evidence of a structured global magnetic field,[62] observations show that parts of the planet's crust have been magnetized, suggesting that alternating polarity reversals of its dipole field have occurred in the past. This paleomagnetism of magnetically susceptible minerals is similar to the alternating bands found on Earth's ocean floors. One hypothesis, published in 1999 and re-examined in October 2005 (with the help of the Mars Global Surveyor), is that these bands suggest plate tectonic activity on Mars four billion years ago, before the planetary dynamo ceased to function and the planet's magnetic field faded.[63]

The Phoenix lander returned data showing Martian soil to be slightly alkaline and containing elements such as magnesium, sodium, potassium and chlorine. These nutrients are found in soils on Earth. They are necessary for growth of plants.[64] Experiments performed by the lander showed that the Martian soil has a basic pH of 7.7, and contains 0.6% perchlorate by weight,[65][66] concentrations that are toxic to humans.[67][68]

Streaks are common across Mars and new ones appear frequently on steep slopes of craters, troughs, and valleys. The streaks are dark at first and get lighter with age. The streaks can start in a tiny area, then spread out for hundreds of metres. They have been seen to follow the edges of boulders and other obstacles in their path. The commonly accepted hypotheses include that they are dark underlying layers of soil revealed after avalanches of bright dust or dust devils.[69] Several other explanations have been put forward, including those that involve water or even the growth of organisms.[70][71]

Environmental radiation levels on the surface are on average 0.64 millisieverts of radiation per day, and significantly less than the radiation of 1.84 millisieverts per day or 22 millirads per day during the flight to and from Mars.[72][73] For comparison the radiation levels in low Earth orbit, where Earth's space stations orbit, are around 0.5 millisieverts of radiation per day.[74] Hellas Planitia has the lowest surface radiation at about 0.342 millisieverts per day, featuring lava tubes southwest of Hadriacus Mons with potentially levels as low as 0.064 millisieverts per day,[75] comparable to radiation levels during flights on Earth.

Geography and features

Although better remembered for mapping the Moon, Johann Heinrich Mädler and Wilhelm Beer were the first areographers. They began by establishing that most of Mars's surface features were permanent and by more precisely determining the planet's rotation period. In 1840, Mädler combined ten years of observations and drew the first map of Mars.[76]

Features on Mars are named from a variety of sources. Albedo features are named for classical mythology. Craters larger than roughly 50 km are named for deceased scientists and writers and others who have contributed to the study of Mars. Smaller craters are named for towns and villages of the world with populations of less than 100,000. Large valleys are named for the word "Mars" or "star" in various languages; smaller valleys are named for rivers.[77]

Large albedo features retain many of the older names but are often updated to reflect new knowledge of the nature of the features. For example, Nix Olympica (the snows of Olympus) has become Olympus Mons (Mount Olympus).[78] The surface of Mars as seen from Earth is divided into two kinds of areas, with differing albedo. The paler plains covered with dust and sand rich in reddish iron oxides were once thought of as Martian "continents" and given names like Arabia Terra (land of Arabia) or Amazonis Planitia (Amazonian plain). The dark features were thought to be seas, hence their names Mare Erythraeum, Mare Sirenum and Aurorae Sinus. The largest dark feature seen from Earth is Syrtis Major Planum.[79] The permanent northern polar ice cap is named Planum Boreum. The southern cap is called Planum Australe.[80]

Mars's equator is defined by its rotation, but the location of its Prime Meridian was specified, as was Earth's (at Greenwich), by choice of an arbitrary point; Mädler and Beer selected a line for their first maps of Mars in 1830. After the spacecraft Mariner 9 provided extensive imagery of Mars in 1972, a small crater (later called Airy-0), located in the Sinus Meridiani ("Middle Bay" or "Meridian Bay"), was chosen by Merton Davies, Harold Masursky, and Gérard de Vaucouleurs for the definition of 0.0° longitude to coincide with the original selection.[81][82][83]

Because Mars has no oceans, and hence no "sea level", a zero-elevation surface had to be selected as a reference level; this is called the areoid[84] of Mars, analogous to the terrestrial geoid.[85] Zero altitude was defined by the height at which there is 610.5 Pa (6.105 mbar) of atmospheric pressure.[86] This pressure corresponds to the triple point of water, and it is about 0.6% of the sea level surface pressure on Earth (0.006 atm).[87]

For mapping purposes, the United States Geological Survey divides the surface of Mars into thirty cartographic quadrangles, each named for a classical albedo feature it contains.[88] In April 2023, The New York Times reported an updated global map of Mars based on images from the Hope spacecraft.[89] A related, but much more detailed, global Mars map was released by NASA on 16 April 2023.[90]

Volcanoes

The vast upland region Tharsis contains several massive volcanoes, which include the shield volcano Olympus Mons. The edifice is over 600 km (370 mi) wide.[91][92] Because the mountain is so large, with complex structure at its edges, giving a definite height to it is difficult. Its local relief, from the foot of the cliffs which form its northwest margin to its peak, is over 21 km (13 mi),[92] a little over twice the height of Mauna Kea as measured from its base on the ocean floor. The total elevation change from the plains of Amazonis Planitia, over 1,000 km (620 mi) to the northwest, to the summit approaches 26 km (16 mi),[93] roughly three times the height of Mount Everest, which in comparison stands at just over 8.8 kilometres (5.5 mi). Consequently, Olympus Mons is either the tallest or second-tallest mountain in the Solar System; the only known mountain which might be taller is the Rheasilvia peak on the asteroid Vesta, at 20–25 km (12–16 mi).[94]

Impact topography

The dichotomy of Martian topography is striking: northern plains flattened by lava flows contrast with the southern highlands, pitted and cratered by ancient impacts. It is possible that, four billion years ago, the Northern Hemisphere of Mars was struck by an object one-tenth to two-thirds the size of Earth's Moon. If this is the case, the Northern Hemisphere of Mars would be the site of an impact crater 10,600 by 8,500 kilometres (6,600 by 5,300 mi) in size, or roughly the area of Europe, Asia, and Australia combined, surpassing Utopia Planitia and the Moon's South Pole–Aitken basin as the largest impact crater in the Solar System.[95][96][97]

Mars is scarred by a number of impact craters: a total of 43,000 observed craters with a diameter of 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) or greater have been found.[98] The largest exposed crater is Hellas, which is 2,300 kilometres (1,400 mi) wide and 7,000 metres (23,000 ft) deep, and is a light albedo feature clearly visible from Earth.[99][100] There are other notable impact features, such as Argyre, which is around 1,800 kilometres (1,100 mi) in diameter,[101] and Isidis, which is around 1,500 kilometres (930 mi) in diameter.[102] Due to the smaller mass and size of Mars, the probability of an object colliding with the planet is about half that of Earth. Mars is located closer to the asteroid belt, so it has an increased chance of being struck by materials from that source. Mars is more likely to be struck by short-period comets, i.e., those that lie within the orbit of Jupiter.[103]

Martian craters can[discuss] have a morphology that suggests the ground became wet after the meteor impact.[104]

Tectonic sites

The large canyon, Valles Marineris (Latin for "Mariner Valleys", also known as Agathodaemon in the old canal maps[105]), has a length of 4,000 kilometres (2,500 mi) and a depth of up to 7 kilometres (4.3 mi). The length of Valles Marineris is equivalent to the length of Europe and extends across one-fifth the circumference of Mars. By comparison, the Grand Canyon on Earth is only 446 kilometres (277 mi) long and nearly 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) deep. Valles Marineris was formed due to the swelling of the Tharsis area, which caused the crust in the area of Valles Marineris to collapse. In 2012, it was proposed that Valles Marineris is not just a graben, but a plate boundary where 150 kilometres (93 mi) of transverse motion has occurred, making Mars a planet with possibly a two-tectonic plate arrangement.[106][107]

Holes and caves

Images from the Thermal Emission Imaging System (THEMIS) aboard NASA's Mars Odyssey orbiter have revealed seven possible cave entrances on the flanks of the volcano Arsia Mons.[108] The caves, named after loved ones of their discoverers, are collectively known as the "seven sisters".[109] Cave entrances measure from 100 to 252 metres (328 to 827 ft) wide and they are estimated to be at least 73 to 96 metres (240 to 315 ft) deep. Because light does not reach the floor of most of the caves, they may extend much deeper than these lower estimates and widen below the surface. "Dena" is the only exception; its floor is visible and was measured to be 130 metres (430 ft) deep. The interiors of these caverns may be protected from micrometeoroids, UV radiation, solar flares and high energy particles that bombard the planet's surface.[110][111]

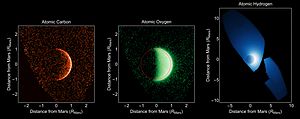

Atmosphere

Mars lost its magnetosphere 4 billion years ago,[112] possibly because of numerous asteroid strikes,[113] so the solar wind interacts directly with the Martian ionosphere, lowering the atmospheric density by stripping away atoms from the outer layer.[114] Both Mars Global Surveyor and Mars Express have detected ionized atmospheric particles trailing off into space behind Mars,[112][115] and this atmospheric loss is being studied by the MAVEN orbiter. Compared to Earth, the atmosphere of Mars is quite rarefied. Atmospheric pressure on the surface today ranges from a low of 30 Pa (0.0044 psi) on Olympus Mons to over 1,155 Pa (0.1675 psi) in Hellas Planitia, with a mean pressure at the surface level of 600 Pa (0.087 psi).[116] The highest atmospheric density on Mars is equal to that found 35 kilometres (22 mi)[117] above Earth's surface. The resulting mean surface pressure is only 0.6% of Earth's 101.3 kPa (14.69 psi). The scale height of the atmosphere is about 10.8 kilometres (6.7 mi),[118] which is higher than Earth's 6 kilometres (3.7 mi), because the surface gravity of Mars is only about 38% of Earth's.[119]

The atmosphere of Mars consists of about 96% carbon dioxide, 1.93% argon and 1.89% nitrogen along with traces of oxygen and water.[2][120][114] The atmosphere is quite dusty, containing particulates about 1.5 μm in diameter which give the Martian sky a tawny color when seen from the surface.[121] It may take on a pink hue due to iron oxide particles suspended in it.[22] The concentration of methane in the Martian atmosphere fluctuates from about 0.24 ppb during the northern winter to about 0.65 ppb during the summer.[122] Estimates of its lifetime range from 0.6 to 4 years,[123][124] so its presence indicates that an active source of the gas must be present. Methane could be produced by non-biological process such as serpentinization involving water, carbon dioxide, and the mineral olivine, which is known to be common on Mars,[125] or by Martian life.[126]

Compared to Earth, its higher concentration of atmospheric CO2 and lower surface pressure may be why sound is attenuated more on Mars, where natural sources are rare apart from the wind. Using acoustic recordings collected by the Perseverance rover, researchers concluded that the speed of sound there is approximately 240 m/s for frequencies below 240 Hz, and 250 m/s for those above.[128][129]

Auroras have been detected on Mars.[130][131][132] Because Mars lacks a global magnetic field, the types and distribution of auroras there differ from those on Earth;[133] rather than being mostly restricted to polar regions as is the case on Earth, a Martian aurora can encompass the planet.[134] In September 2017, NASA reported radiation levels on the surface of the planet Mars were temporarily doubled, and were associated with an aurora 25 times brighter than any observed earlier, due to a massive, and unexpected, solar storm in the middle of the month.[134][135]

Climate

Mars has seasons, alternating between its northern and southern hemispheres, similar to on Earth. Additionally the orbit of Mars has, compared to Earth's, a large eccentricity and approaches perihelion when it is summer in its southern hemisphere and winter in its northern, and aphelion when it is winter in its southern hemisphere and summer in its northern. As a result, the seasons in its southern hemisphere are more extreme and the seasons in its northern are milder than would otherwise be the case. The summer temperatures in the south can be warmer than the equivalent summer temperatures in the north by up to 30 °C (54 °F).[136]

Martian surface temperatures vary from lows of about −110 °C (−166 °F) to highs of up to 35 °C (95 °F) in equatorial summer.[16] The wide range in temperatures is due to the thin atmosphere which cannot store much solar heat, the low atmospheric pressure (about 1% that of the atmosphere of Earth), and the low thermal inertia of Martian soil.[137] The planet is 1.52 times as far from the Sun as Earth, resulting in just 43% of the amount of sunlight.[138][139]

Mars has the largest dust storms in the Solar System, reaching speeds of over 160 km/h (100 mph). These can vary from a storm over a small area, to gigantic storms that cover the entire planet. They tend to occur when Mars is closest to the Sun, and have been shown to increase global temperature.[140]

Seasons also produce dry ice covering polar ice caps. Large areas of the polar regions of Mars

Hydrology

While Mars contains water in larger amounts, most of it is dust covered water ice at the Martian polar ice caps.[141][142][143][144][145] The volume of water ice in the south polar ice cap, if melted, would be enough to cover most of the surface of the planet with a depth of 11 metres (36 ft).[146]

Water in its liquid form cannot prevail on the surface of Mars due to the low atmospheric pressure on Mars, which is less than 1% that of Earth,[147] only at the lowest of elevations pressure and temperature is high enough for water being able to be liquid for short periods.[46][148]

Water in the atmosphere is small, but enough to produce larger clouds of water ice and different cases of snow and frost, often mixed with snow of carbon dioxide dry ice.

Past hydrosphere

Landforms visible on Mars strongly suggest that liquid water has existed on the planet's surface. Huge linear swathes of scoured ground, known as outflow channels, cut across the surface in about 25 places. These are thought to be a record of erosion caused by the catastrophic release of water from subsurface aquifers, though some of these structures have been hypothesized to result from the action of glaciers or lava.[149][150] One of the larger examples, Ma'adim Vallis, is 700 kilometres (430 mi) long, much greater than the Grand Canyon, with a width of 20 kilometres (12 mi) and a depth of 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) in places. It is thought to have been carved by flowing water early in Mars's history.[151] The youngest of these channels is thought to have formed only a few million years ago.[152]

Elsewhere, particularly on the oldest areas of the Martian surface, finer-scale, dendritic networks of valleys are spread across significant proportions of the landscape. Features of these valleys and their distribution strongly imply that they were carved by runoff resulting from precipitation in early Mars history. Subsurface water flow and groundwater sapping may play important subsidiary roles in some networks, but precipitation was probably the root cause of the incision in almost all cases.[153]

Along craters and canyon walls, there are thousands of features that appear similar to terrestrial gullies. The gullies tend to be in the highlands of the Southern Hemisphere and face the Equator; all are poleward of 30° latitude. A number of authors have suggested that their formation process involves liquid water, probably from melting ice,[154][155] although others have argued for formation mechanisms involving carbon dioxide frost or the movement of dry dust.[156][157] No partially degraded gullies have formed by weathering and no superimposed impact craters have been observed, indicating that these are young features, possibly still active.[155] Other geological features, such as deltas and alluvial fans preserved in craters, are further evidence for warmer, wetter conditions at an interval or intervals in earlier Mars history.[158] Such conditions necessarily require the widespread presence of crater lakes across a large proportion of the surface, for which there is independent mineralogical, sedimentological and geomorphological evidence.[159] Further evidence that liquid water once existed on the surface of Mars comes from the detection of specific minerals such as hematite and goethite, both of which sometimes form in the presence of water.[160]

History of observations and findings of water evidence

In 2004, Opportunity detected the mineral jarosite. This forms only in the presence of acidic water, showing that water once existed on Mars.[161][162] The Spirit rover found concentrated deposits of silica in 2007 that indicated wet conditions in the past, and in December 2011, the mineral gypsum, which also forms in the presence of water, was found on the surface by NASA's Mars rover Opportunity.[163][164][165] It is estimated that the amount of water in the upper mantle of Mars, represented by hydroxyl ions contained within Martian minerals, is equal to or greater than that of Earth at 50–300 parts per million of water, which is enough to cover the entire planet to a depth of 200–1,000 metres (660–3,280 ft).[166][167]

On 18 March 2013, NASA reported evidence from instruments on the Curiosity rover of mineral hydration, likely hydrated calcium sulfate, in several rock samples including the broken fragments of "Tintina" rock and "Sutton Inlier" rock as well as in veins and nodules in other rocks like "Knorr" rock and "Wernicke" rock.[168][169] Analysis using the rover's DAN instrument provided evidence of subsurface water, amounting to as much as 4% water content, down to a depth of 60 centimetres (24 in), during the rover's traverse from the Bradbury Landing site to the Yellowknife Bay area in the Glenelg terrain.[168] In September 2015, NASA announced that they had found strong evidence of hydrated brine flows in recurring slope lineae, based on spectrometer readings of the darkened areas of slopes.[170][171][172] These streaks flow downhill in Martian summer, when the temperature is above −23 °C, and freeze at lower temperatures.[173] These observations supported earlier hypotheses, based on timing of formation and their rate of growth, that these dark streaks resulted from water flowing just below the surface.[174] However, later work suggested that the lineae may be dry, granular flows instead, with at most a limited role for water in initiating the process.[175] A definitive conclusion about the presence, extent, and role of liquid water on the Martian surface remains elusive.[176][177]

Researchers suspect much of the low northern plains of the planet were covered with an ocean hundreds of meters deep, though this theory remains controversial.[178] In March 2015, scientists stated that such an ocean might have been the size of Earth's Arctic Ocean. This finding was derived from the ratio of protium to deuterium in the modern Martian atmosphere compared to that ratio on Earth. The amount of Martian deuterium (D/H = 9.3 ± 1.7 10-4) is five to seven times the amount on Earth (D/H = 1.56 10-4), suggesting that ancient Mars had significantly higher levels of water. Results from the Curiosity rover had previously found a high ratio of deuterium in Gale Crater, though not significantly high enough to suggest the former presence of an ocean. Other scientists caution that these results have not been confirmed, and point out that Martian climate models have not yet shown that the planet was warm enough in the past to support bodies of liquid water.[179] Near the northern polar cap is the 81.4 kilometres (50.6 mi) wide Korolev Crater, which the Mars Express orbiter found to be filled with approximately 2,200 cubic kilometres (530 cu mi) of water ice.[180]

In November 2016, NASA reported finding a large amount of underground ice in the Utopia Planitia region. The volume of water detected has been estimated to be equivalent to the volume of water in Lake Superior (which is 12,100 cubic kilometers[181]).[182][183] During observations from 2018 through 2021, the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter spotted indications of water, probably subsurface ice, in the Valles Marineris canyon system.[184]

Orbital motion

Mars's average distance from the Sun is roughly 230 million km (143 million mi), and its orbital period is 687 (Earth) days. The solar day (or sol) on Mars is only slightly longer than an Earth day: 24 hours, 39 minutes, and 35.244 seconds.[185] A Martian year is equal to 1.8809 Earth years, or 1 year, 320 days, and 18.2 hours.[2] The gravitational potential difference and thus the delta-v needed to transfer between Mars and Earth is the second lowest for Earth.[186][187]

The axial tilt of Mars is 25.19° relative to its orbital plane, which is similar to the axial tilt of Earth.[2] As a result, Mars has seasons like Earth, though on Mars they are nearly twice as long because its orbital period is that much longer. In the present day, the orientation of the north pole of Mars is close to the star Deneb.[21]

Mars has a relatively pronounced orbital eccentricity of about 0.09; of the seven other planets in the Solar System, only Mercury has a larger orbital eccentricity. It is known that in the past, Mars has had a much more circular orbit. At one point, 1.35 million Earth years ago, Mars had an eccentricity of roughly 0.002, much less than that of Earth today.[188] Mars's cycle of eccentricity is 96,000 Earth years compared to Earth's cycle of 100,000 years.[189]

Mars has its closest approach to Earth (opposition) in a synodic period of 779.94 days. It should not be confused with Mars conjunction, where the Earth and Mars are at opposite sides of the Solar System and form a straight line crossing the Sun. The average time between the successive oppositions of Mars, its synodic period, is 780 days; but the number of days between successive oppositions can range from 764 to 812.[189] The distance at close approach varies between about 54 and 103 million km (34 and 64 million mi) due to the planets' elliptical orbits, which causes comparable variation in angular size.[190] Mars comes into opposition from Earth every 2.1 years. The planets come into opposition near Mars's perihelion in 2003, 2018 and 2035, with the 2020 and 2033 events being particularly close to perihelic opposition.[191][192][193]

The mean apparent magnitude of Mars is +0.71 with a standard deviation of 1.05.[19] Because the orbit of Mars is eccentric, the magnitude at opposition from the Sun can range from about −3.0 to −1.4.[194] The minimum brightness is magnitude +1.86 when the planet is near aphelion and in conjunction with the Sun.[19] At its brightest, Mars (along with Jupiter) is second only to Venus in apparent brightness.[19] Mars usually appears distinctly yellow, orange, or red. When farthest away from Earth, it is more than seven times farther away than when it is closest. Mars is usually close enough for particularly good viewing once or twice at 15-year or 17-year intervals.[195] Optical ground-based telescopes are typically limited to resolving features about 300 kilometres (190 mi) across when Earth and Mars are closest because of Earth's atmosphere.[196]

As Mars approaches opposition, it begins a period of retrograde motion, which means it will appear to move backwards in a looping curve with respect to the background stars. This retrograde motion lasts for about 72 days, and Mars reaches its peak apparent brightness in the middle of this interval.[197]

Moons

Mars has two relatively small (compared to Earth's) natural moons, Phobos (about 22 kilometres (14 mi) in diameter) and Deimos (about 12 kilometres (7.5 mi) in diameter), which orbit close to the planet. The origin of both moons is unclear, although a popular theory states that they were asteroids captured into Martian orbit.[198]

Both satellites were discovered in 1877 by Asaph Hall and were named after the characters Phobos (the deity of panic and fear) and Deimos (the deity of terror and dread), twins from Greek mythology who accompanied their father Ares, god of war, into battle.[199] Mars was the Roman equivalent to Ares. In modern Greek, the planet retains its ancient name Ares (Aris: Άρης).[96]

From the surface of Mars, the motions of Phobos and Deimos appear different from that of the Earth's satellite, the Moon. Phobos rises in the west, sets in the east, and rises again in just 11 hours. Deimos, being only just outside synchronous orbit – where the orbital period would match the planet's period of rotation – rises as expected in the east, but slowly. Because the orbit of Phobos is below a synchronous altitude, tidal forces from Mars are gradually lowering its orbit. In about 50 million years, it could either crash into Mars's surface or break up into a ring structure around the planet.[200]

The origin of the two satellites is not well understood. Their low albedo and carbonaceous chondrite composition have been regarded as similar to asteroids, supporting a capture theory. The unstable orbit of Phobos would seem to point toward a relatively recent capture. But both have circular orbits near the equator, which is unusual for captured objects, and the required capture dynamics are complex. Accretion early in the history of Mars is plausible, but would not account for a composition resembling asteroids rather than Mars itself, if that is confirmed.[201] Mars may have yet-undiscovered moons, smaller than 50 to 100 metres (160 to 330 ft) in diameter, and a dust ring is predicted to exist between Phobos and Deimos.[202]

A third possibility for their origin as satellites of Mars is the involvement of a third body or a type of impact disruption. More-recent lines of evidence for Phobos having a highly porous interior,[203] and suggesting a composition containing mainly phyllosilicates and other minerals known from Mars,[204] point toward an origin of Phobos from material ejected by an impact on Mars that reaccreted in Martian orbit, similar to the prevailing theory for the origin of Earth's satellite. Although the visible and near-infrared (VNIR) spectra of the moons of Mars resemble those of outer-belt asteroids, the thermal infrared spectra of Phobos are reported to be inconsistent with chondrites of any class.[204] It is also possible that Phobos and Deimos were fragments of an older moon, formed by debris from a large impact on Mars, and then destroyed by a more recent impact upon the satellite.[205]

Human observations and exploration

The history of observations of Mars is marked by oppositions of Mars when the planet is closest to Earth and hence is most easily visible, which occur every couple of years. Even more notable are the perihelic oppositions of Mars, which are distinguished because Mars is close to perihelion, making it even closer to Earth.[191]

Ancient and medieval observations

The ancient Sumerians named Mars Nergal, the god of war and plague. During Sumerian times, Nergal was a minor deity of little significance, but, during later times, his main cult center was the city of Nineveh.[206] In Mesopotamian texts, Mars is referred to as the "star of judgement of the fate of the dead".[207] The existence of Mars as a wandering object in the night sky was also recorded by the ancient Egyptian astronomers and, by 1534 BCE, they were familiar with the retrograde motion of the planet.[208] By the period of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, the Babylonian astronomers were making regular records of the positions of the planets and systematic observations of their behavior. For Mars, they knew that the planet made 37 synodic periods, or 42 circuits of the zodiac, every 79 years. They invented arithmetic methods for making minor corrections to the predicted positions of the planets.[209][210] In Ancient Greece, the planet was known as Πυρόεις.[211] Commonly, the Greek name for the planet now referred to as Mars, was Ares. It was the Romans who named the planet Mars, for their god of war, often represented by the sword and shield of the planet's namesake.[212]

In the fourth century BCE, Aristotle noted that Mars disappeared behind the Moon during an occultation, indicating that the planet was farther away.[213] Ptolemy, a Greek living in Alexandria,[214] attempted to address the problem of the orbital motion of Mars. Ptolemy's model and his collective work on astronomy was presented in the multi-volume collection later called the Almagest (from the Arabic for "greatest"), which became the authoritative treatise on Western astronomy for the next fourteen centuries.[215] Literature from ancient China confirms that Mars was known by Chinese astronomers by no later than the fourth century BCE.[216] In the East Asian cultures, Mars is traditionally referred to as the "fire star" based on the Wuxing system.[217][218][219]

During the seventeenth century A.D., Tycho Brahe measured the diurnal parallax of Mars that Johannes Kepler used to make a preliminary calculation of the relative distance to the planet.[220] From Brahe's observations of Mars, Kepler deduced that the planet orbited the Sun not in a circle, but in an ellipse. Moreover, Kepler showed that Mars sped up as it approached the Sun and slowed down as it moved farther away, in a manner that later physicists would explain as a consequence of the conservation of angular momentum.[221]: 433–437 When the telescope became available, the diurnal parallax of Mars was again measured in an effort to determine the Sun-Earth distance. This was first performed by Giovanni Domenico Cassini in 1672. The early parallax measurements were hampered by the quality of the instruments.[222] The only occultation of Mars by Venus observed was that of 13 October 1590, seen by Michael Maestlin at Heidelberg.[223] In 1610, Mars was viewed by Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei, who was first to see it via telescope.[224] The first person to draw a map of Mars that displayed any terrain features was the Dutch astronomer Christiaan Huygens.[225]

Martian "canals"

By the 19th century, the resolution of telescopes reached a level sufficient for surface features to be identified. On 5 September 1877, a perihelic opposition to Mars occurred. The Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli used a 22-centimetre (8.7 in) telescope in Milan to help produce the first detailed map of Mars. These maps notably contained features he called canali, which were later shown to be an optical illusion. These canali were supposedly long, straight lines on the surface of Mars, to which he gave names of famous rivers on Earth. His term, which means "channels" or "grooves", was popularly mistranslated in English as "canals".[226][227]

Influenced by the observations, the orientalist Percival Lowell founded an observatory which had 30- and 45-centimetre (12- and 18-in) telescopes. The observatory was used for the exploration of Mars during the last good opportunity in 1894, and the following less favorable oppositions. He published several books on Mars and life on the planet, which had a great influence on the public.[228][229] The canali were independently observed by other astronomers, like Henri Joseph Perrotin and Louis Thollon in Nice, using one of the largest telescopes of that time.[230][231]

The seasonal changes (consisting of the diminishing of the polar caps and the dark areas formed during Martian summers) in combination with the canals led to speculation about life on Mars, and it was a long-held belief that Mars contained vast seas and vegetation. As bigger telescopes were used, fewer long, straight canali were observed. During observations in 1909 by Antoniadi with an 84-centimetre (33 in) telescope, irregular patterns were observed, but no canali were seen.[232]

Robotic exploration

Dozens of crewless spacecraft, including orbiters, landers, and rovers, have been sent to Mars by the Soviet Union, the United States, Europe, India, the United Arab Emirates, and China to study the planet's surface, climate, and geology.[233] NASA's Mariner 4 was the first spacecraft to visit Mars; launched on 28 November 1964, it made its closest approach to the planet on 15 July 1965. Mariner 4 detected the weak Martian radiation belt, measured at about 0.1% that of Earth, and captured the first images of another planet from deep space.[234]

Once spacecraft visited the planet during NASA's Mariner missions in the 1960s and 1970s, many previous concepts of Mars were radically broken. After the results of the Viking life-detection experiments, the hypothesis of a dead planet was generally accepted.[235] The data from Mariner 9 and Viking allowed better maps of Mars to be made, and the Mars Global Surveyor mission, which launched in 1996 and operated until late 2006, produced complete, extremely detailed maps of the Martian topography, magnetic field and surface minerals.[236] These maps are available online at websites including Google Mars. Both the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and Mars Express continued exploring with new instruments and supporting lander missions. NASA provides two online tools: Mars Trek, which provides visualizations of the planet using data from 50 years of exploration, and Experience Curiosity, which simulates traveling on Mars in 3-D with Curiosity.[237][238]

As of 2023[update], Mars is host to ten functioning spacecraft. Eight are in orbit: 2001 Mars Odyssey, Mars Express, Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, MAVEN, ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter, the Hope orbiter, and the Tianwen-1 orbiter.[239][240] Another two are on the surface: the Mars Science Laboratory Curiosity rover and the Perseverance rover.[241]

Planned missions to Mars include:

- NASA's EscaPADE spacecraft, planned to launch in late 2024.[242]

- The Rosalind Franklin rover mission, designed to search for evidence of past life, which was intended to be launched in 2018 but has been repeatedly delayed, with a launch date pushed to 2028 at the earliest.[243][244][245] The project was restarted in 2024 with additional funding.[246]

- A current concept for a joint NASA-ESA mission to return samples from Mars would launch in 2026.[247][248]

- China's Tianwen-3, a sample return mission, scheduled to launch in 2030.

As of February 2024[update], debris from these types of missions has reached over seven tons. Most of it consists of crashed and inactive spacecraft as well as discarded components.[249][250]

In April 2024, NASA selected several companies to begin studies on providing commercial services to further enable robotic science on Mars. Key areas include establishing telecommunications, payload delivery and surface imaging.[251]

Habitability and the search for life

During the late 19th century, it was widely accepted in the astronomical community that Mars had life-supporting qualities, including the presence of oxygen and water.[252] However, in 1894 W. W. Campbell at Lick Observatory observed the planet and found that "if water vapor or oxygen occur in the atmosphere of Mars it is in quantities too small to be detected by spectroscopes then available".[252] That observation contradicted many of the measurements of the time and was not widely accepted.[252] Campbell and V. M. Slipher repeated the study in 1909 using better instruments, but with the same results. It was not until the findings were confirmed by W. S. Adams in 1925 that the myth of the Earth-like habitability of Mars was finally broken.[252] However, even in the 1960s, articles were published on Martian biology, putting aside explanations other than life for the seasonal changes on Mars.[253]

The current understanding of planetary habitability – the ability of a world to develop environmental conditions favorable to the emergence of life – favors planets that have liquid water on their surface. Most often this requires the orbit of a planet to lie within the habitable zone, which for the Sun is estimated to extend from within the orbit of Earth to about that of Mars.[254] During perihelion, Mars dips inside this region, but Mars's thin (low-pressure) atmosphere prevents liquid water from existing over large regions for extended periods. The past flow of liquid water demonstrates the planet's potential for habitability. Recent evidence has suggested that any water on the Martian surface may have been too salty and acidic to support regular terrestrial life.[255]

The environmental conditions on Mars are a challenge to sustaining organic life: the planet has little heat transfer across its surface, it has poor insulation against bombardment by the solar wind due to the absence of a magnetosphere and has insufficient atmospheric pressure to retain water in a liquid form (water instead sublimes to a gaseous state). Mars is nearly, or perhaps totally, geologically dead; the end of volcanic activity has apparently stopped the recycling of chemicals and minerals between the surface and interior of the planet.[256]

Evidence suggests that the planet was once significantly more habitable than it is today, but whether living organisms ever existed there remains unknown. The Viking probes of the mid-1970s carried experiments designed to detect microorganisms in Martian soil at their respective landing sites and had positive results, including a temporary increase in CO2 production on exposure to water and nutrients. This sign of life was later disputed by scientists, resulting in a continuing debate, with NASA scientist Gilbert Levin asserting that Viking may have found life.[257] A 2014 analysis of Martian meteorite EETA79001 found chlorate, perchlorate, and nitrate ions in sufficiently high concentrations to suggest that they are widespread on Mars. UV and X-ray radiation would turn chlorate and perchlorate ions into other, highly reactive oxychlorines, indicating that any organic molecules would have to be buried under the surface to survive.[258]

Small quantities of methane and formaldehyde detected by Mars orbiters are both claimed to be possible evidence for life, as these chemical compounds would quickly break down in the Martian atmosphere.[259][260] Alternatively, these compounds may instead be replenished by volcanic or other geological means, such as serpentinite.[125] Impact glass, formed by the impact of meteors, which on Earth can preserve signs of life, has also been found on the surface of the impact craters on Mars.[261][262] Likewise, the glass in impact craters on Mars could have preserved signs of life, if life existed at the site.[263][264][265]

The Cheyava Falls rock discovered on Mars in June 2024 has been designated by NASA as a "potential biosignature" and was core sampled by the Perseverance rover for possible return to Earth and further examination. Although highly intriguing, no definitive final determination on a biological or abiotic origin of this rock can be made with the data currently available.

Human mission proposals

Several plans for a human mission to Mars have been proposed throughout the 20th and 21st centuries, but none have come to fruition. The NASA Authorization Act of 2017 directed NASA to study the feasibility of a crewed Mars mission in the early 2030s; the resulting report eventually concluded that this would be unfeasible.[266][267] In addition, in 2021, China was planning to send a crewed Mars mission in 2033.[268] Privately held companies such as SpaceX have also proposed plans to send humans to Mars, with the eventual goal to settle on the planet.[269]As of 2024, SpaceX has proceeded with the development of the Starship launch vehicle with the goal of Mars colonization. In plans shared with the company in April 2024, Elon Musk envisions the beginning of a Mars colony within the next twenty years. This enabled by the planned mass manufacturing of Starship and initially sustained by resupply from Earth, and in situ resource utilization on Mars, until the Mars colony reaches full self sustainability.[270]Any future human mission to Mars will likely take place within the optimal Mars launch window, which occurs every 26 months. The moon Phobos has been proposed as an anchor point for a space elevator.[271] Besides national space agencies and space companies, there are groups such as the Mars Society[272] and The Planetary Society[273] that advocates for human missions to Mars.

In culture

Mars is named after the Roman god of war. This association between Mars and war dates back at least to Babylonian astronomy, in which the planet was named for the god Nergal, deity of war and destruction.[274][275] It persisted into modern times, as exemplified by Gustav Holst's orchestral suite The Planets, whose famous first movement labels Mars "the bringer of war".[276] The planet's symbol, a circle with a spear pointing out to the upper right, is also used as a symbol for the male gender.[277] The symbol dates from at least the 11th century, though a possible predecessor has been found in the Greek Oxyrhynchus Papyri.[278]

The idea that Mars was populated by intelligent Martians became widespread in the late 19th century. Schiaparelli's "canali" observations combined with Percival Lowell's books on the subject put forward the standard notion of a planet that was a drying, cooling, dying world with ancient civilizations constructing irrigation works.[279] Many other observations and proclamations by notable personalities added to what has been termed "Mars Fever".[280] High-resolution mapping of the surface of Mars revealed no artifacts of habitation, but pseudoscientific speculation about intelligent life on Mars still continues. Reminiscent of the canali observations, these speculations are based on small scale features perceived in the spacecraft images, such as "pyramids" and the "Face on Mars".[281] In his book Cosmos, planetary astronomer Carl Sagan wrote: "Mars has become a kind of mythic arena onto which we have projected our Earthly hopes and fears."[227]

The depiction of Mars in fiction has been stimulated by its dramatic red color and by nineteenth-century scientific speculations that its surface conditions might support not just life but intelligent life.[282] This gave way to many science fiction stories involving these concepts, such as H. G. Wells's The War of the Worlds, in which Martians seek to escape their dying planet by invading Earth; Ray Bradbury's The Martian Chronicles, in which human explorers accidentally destroy a Martian civilization; as well as Edgar Rice Burroughs's series Barsoom, C. S. Lewis's novel Out of the Silent Planet (1938),[283] and a number of Robert A. Heinlein stories before the mid-sixties.[284] Since then, depictions of Martians have also extended to animation. A comic figure of an intelligent Martian, Marvin the Martian, appeared in Haredevil Hare (1948) as a character in the Looney Tunes animated cartoons of Warner Brothers, and has continued as part of popular culture to the present.[285] After the Mariner and Viking spacecraft had returned pictures of Mars as a lifeless and canal-less world, these ideas about Mars were abandoned; for many science-fiction authors, the new discoveries initially seemed like a constraint, but eventually the post-Viking knowledge of Mars became itself a source of inspiration for works like Kim Stanley Robinson's Mars trilogy.[286]

See also

- Astronomy on Mars

- Outline of Mars – Overview of and topical guide to Mars

- List of missions to Mars

- Magnetic field of Mars – Past magnetic field of the planet Mars

- Mineralogy of Mars – Overview of the mineralogy of Mars

Notes

- ^ The light filters are 635 nm, 546 nm, and 437 nm, roughly corresponding to red, green and blue respectively

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Best-fit ellipsoid

- ^ Temperatures taken are the average mean daily minimum and maximum on per year basis, data taken from Climate of Mars#Temperature

References

- ^ Simon J, Bretagnon P, Chapront J, et al. (February 1994). "Numerical expressions for precession formulae and mean elements for the Moon and planets". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 282 (2): 663–683. Bibcode:1994A&A...282..663S.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Williams D (2018). "Mars Fact Sheet". NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. Archived from the original on 17 March 2020. Retrieved 22 March 2020.; Mean Anomaly (deg) 19.412 = (Mean Longitude (deg) 355.45332) – (Longitude of perihelion (deg) 336.04084)

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Allen CW, Cox AN (2000). Allen's Astrophysical Quantities. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 294. ISBN 978-0-387-95189-8. Archived from the original on 1 March 2024. Retrieved 18 May 2022.

- ^ Souami D, Souchay J (July 2012). "The solar system's invariable plane". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 543: 11. Bibcode:2012A&A...543A.133S. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201219011. A133.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "HORIZONS Batch call for 2022 perihelion" (Perihelion occurs when rdot flips from negative to positive). Solar System Dynamics Group, Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Archived from the original on 8 September 2021. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Seidelmann PK, Archinal BA, A'Hearn MF, et al. (2007). "Report of the IAU/IAG Working Group on cartographic coordinates and rotational elements: 2006". Celestial Mechanics and Dynamical Astronomy. 98 (3): 155–180. Bibcode:2007CeMDA..98..155S. doi:10.1007/s10569-007-9072-y.

- ^ Grego P (6 June 2012). Mars and How to Observe It. Springer Science+Business Media. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-4614-2302-7 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Lodders K, Fegley B (1998). The Planetary Scientist's Companion. Oxford University Press. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-19-511694-6.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Коноплив А.С., Асмар С.В., Фолкнер В.М. и др. (январь 2011 г.). «Гравитационные поля Марса с высоким разрешением на основе MRO, сезонная гравитация Марса и другие динамические параметры». Икар . 211 (1): 401–428. Бибкод : 2011Icar..211..401K . дои : 10.1016/j.icarus.2010.10.004 .

- ^ Хирт С., Классенс С.Дж., Кун М. и др. (июль 2012 г.). «Гравитационное поле Марса с километровым разрешением: MGM2011» (PDF) . Планетарная и космическая наука . 67 (1): 147–154. Бибкод : 2012P&SS...67..147H . дои : 10.1016/j.pss.2012.02.006 . hdl : 20.500.11937/32270 . ISSN 0032-0633 . Архивировано из оригинала 1 марта 2024 года . Проверено 25 августа 2019 г.

- ^ Джексон А.П., Габриэль Т.С., Асфауг Э.И. (1 марта 2018 г.). «Ограничения на предударные орбиты гигантских ударников Солнечной системы» . Ежемесячные уведомления Королевского астрономического общества . 474 (3): 2924–2936. arXiv : 1711.05285 . дои : 10.1093/mnras/stx2901 . ISSN 0035-8711 . Архивировано из оригинала 23 апреля 2022 года . Проверено 23 апреля 2022 г.

- ^ Эллисон М., Шмунк Р. «Солнечные часы Mars24 — Время на Марсе» . НАСА ГИСС . Архивировано из оригинала 24 января 2017 года . Проверено 19 августа 2021 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Аршинал Б.А., Актон Ч.Х., А'Хирн М.Ф. и др. (2018). «Отчет Рабочей группы МАС по картографическим координатам и элементам вращения: 2015» . Небесная механика и динамическая астрономия . 130 (3): 22. Бибкод : 2018CeMDA.130...22A . дои : 10.1007/s10569-017-9805-5 . ISSN 0923-2958 .

- ^ Маллама, А. (2007). «Величина и альбедо Марса». Икар . 192 (2): 404–416. Бибкод : 2007Icar..192..404M . дои : 10.1016/j.icarus.2007.07.011 .

- ^ «Атмосферы и планетарные температуры» . Американское химическое общество . 18 июля 2013 г. Архивировано из оригинала 27 января 2023 г. Проверено 3 января 2023 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с «Миссия марсохода по исследованию Марса: В центре внимания» . Marsrover.nasa.gov . 12 июня 2007 г. Архивировано из оригинала 2 ноября 2013 г. Проверено 14 августа 2012 г.

В данной статье использован текст из этого источника, находящегося в свободном доступе .

В данной статье использован текст из этого источника, находящегося в свободном доступе .

- ^ Шарп Т., Гордон Дж., Тиллман Н. (31 января 2022 г.). «Какова температура Марса?» . Space.com . Архивировано из оригинала 22 апреля 2020 года . Проверено 14 марта 2022 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Хасслер Д.М., Цейтлин С., Виммер-Швайнгрубер Р.Ф. и др. (24 января 2014 г.). «Радиационная обстановка на поверхности Марса, измеренная с помощью марсохода Curiosity Марсианской научной лаборатории» . Наука . 343 (6169). Таблицы 1 и 2. Бибкод : 2014Sci...343D.386H . дои : 10.1126/science.1244797 . hdl : 1874/309142 . ПМИД 24324275 . S2CID 33661472 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Маллама А., Хилтон Дж.Л. (октябрь 2018 г.). «Вычисление видимых звездных величин планет для Астрономического альманаха». Астрономия и вычислительная техника . 25 : 10–24. arXiv : 1808.01973 . Бибкод : 2018A&C....25...10M . дои : 10.1016/j.ascom.2018.08.002 . S2CID 69912809 .

- ^ "Энциклопедия - самые яркие тела" . ИМЦСЕ . Архивировано из оригинала 24 июля 2023 года . Проверено 29 мая 2023 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Барлоу Н.Г. (2008). Марс: знакомство с его интерьером, поверхностью и атмосферой . Кембриджская планетология. Том. 8. Издательство Кембриджского университета. п. 21. ISBN 978-0-521-85226-5 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Рис М.Дж., изд. (октябрь 2012 г.). Вселенная: Полное визуальное руководство . Нью-Йорк: Дорлинг Киндерсли. стр. 160–161. ISBN 978-0-7566-9841-6 .

- ^ «Приманка гематита» . Наука@НАСА . НАСА. 28 марта 2001 г. Архивировано из оригинала 14 января 2010 г. Проверено 24 декабря 2009 г.

- ^ Холлидей А.Н., Ванке Х., Бирк Ж.-Л. и др. (2001). «Акреция, состав и ранняя дифференциация Марса». Обзоры космической науки . 96 (1/4): 197–230. Бибкод : 2001ССРв...96..197Х . дои : 10.1023/А:1011997206080 . S2CID 55559040 .

- ^ Жарков В.Н. (1993). «Роль Юпитера в образовании планет». Эволюция Земли и планет . Вашингтон, округ Колумбия. Серия геофизических монографий Американского геофизического союза. Том. 74. стр. 7–17. Бибкод : 1993GMS....74....7Z . дои : 10.1029/GM074p0007 . ISBN 978-1-118-66669-2 .

- ^ Лунин Дж. , Чемберс Дж., Морбиделли А. и др. (2003). «Происхождение воды на Марсе». Икар . 165 (1): 1–8. Бибкод : 2003Icar..165....1L . дои : 10.1016/S0019-1035(03)00172-6 .

- ^ Барлоу Н.Г. (5–7 октября 1988 г.). Х. Фрей (ред.). Условия на раннем Марсе: ограничения, связанные с записью кратеров . Семинар MEVTV по ранней тектонической и вулканической эволюции Марса. Технический отчет LPI 89-04 . Истон, Мэриленд: Институт Луны и планет. п. 15. Бибкод : 1989eamd.work...15B .

- ^ Несворный Д (июнь 2018 г.). «Динамическая эволюция ранней Солнечной системы». Ежегодный обзор астрономии и астрофизики . 56 : 137–174. arXiv : 1807.06647 . Бибкод : 2018ARA&A..56..137N . doi : 10.1146/annurev-astro-081817-052028 .

- ^ Йегер А. (19 июля 2008 г.). «Удар мог изменить Марс» . ScienceNews.org. Архивировано из оригинала 14 сентября 2012 года . Проверено 12 августа 2008 г.

- ^ Минкель-младший (26 июня 2008 г.). «Гигантский астероид сплющил половину Марса, как показывают исследования» . Научный американец . Архивировано из оригинала 4 сентября 2014 года . Проверено 1 апреля 2022 г.

- ^ Чанг К. (26 июня 2008 г.). «Сообщения говорят, что огромный метеоритный удар объясняет форму Марса» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . Архивировано из оригинала 1 июля 2017 года . Проверено 27 июня 2008 г.

- ^ Чук М., Минтон Д.А., Пуплин Дж.Л. и др. (16 июня 2020 г.). «Доказательства существования марсианского кольца в прошлом по наклону орбиты Деймоса» . Астрофизический журнал . 896 (2): Л28. arXiv : 2006.00645 . Бибкод : 2020ApJ...896L..28C . дои : 10.3847/2041-8213/ab974f . ISSN 2041-8213 .

- ^ Сотрудники новостей (4 июня 2020 г.). «Исследователи нашли новые доказательства того, что Марс когда-то имел массивное кольцо | Sci.News» . Sci.News: Последние новости науки . Архивировано из оригинала 7 ноября 2023 года . Проверено 7 ноября 2023 г.

- ^ «Были ли на древнем Марсе кольца?» . Земное небо | Обновления вашего космоса и мира . 5 июня 2020 года. Архивировано из оригинала 7 ноября 2023 года . Проверено 7 ноября 2023 г.

- ^ Танака К.Л. (1986). «Стратиграфия Марса» . Журнал геофизических исследований . 91 (Б13): Е139–Е158. Бибкод : 1986JGR....91E.139T . дои : 10.1029/JB091iB13p0E139 . Архивировано из оригинала 16 декабря 2021 года . Проверено 17 июля 2019 г.

- ^ Хартманн, Уильям К., Нойкум, Герхард (2001). «Хронология кратеров и эволюция Марса». Обзоры космической науки . 96 (1/4): 165–194. Бибкод : 2001ССРв...96..165Х . дои : 10.1023/А:1011945222010 . S2CID 7216371 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с «Наука и технологии ЕКА – Эпоха Марса» . sci.esa.int . Архивировано из оригинала 29 августа 2023 года . Проверено 7 декабря 2021 г.

- ^ Митчелл, Карл Л., Уилсон, Лайонел (2003). «Марс: недавняя геологическая активность: Марс: геологически активная планета» . Астрономия и геофизика . 44 (4): 4.16–4.20. Бибкод : 2003A&G....44d..16M . дои : 10.1046/j.1468-4004.2003.44416.x .

- ^ Рассел П. (3 марта 2008 г.). «В действии: лавины на северных полярных уступах» . Операционный центр HiRISE . Архивировано из оригинала 7 апреля 2022 года . Проверено 28 марта 2022 г.

- ^ «HiRISE ловит лавину на Марсе» . Лаборатория реактивного движения НАСА (JPL) . 12 августа 2020 года. Архивировано из оригинала 1 марта 2022 года . Проверено 28 марта 2022 г.

- ^ Пеплоу М. (6 мая 2004 г.). «Как Марс заржавел» . Природа : news040503–6. дои : 10.1038/news040503-6 . Архивировано из оригинала 28 ноября 2022 года . Проверено 10 марта 2007 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б НАСА – Марс за минуту: действительно ли Марс красный? Архивировано 20 июля 2014 года в Wayback Machine ( расшифровка архивирована 6 ноября 2015 года в Wayback Machine ).

В данной статье использован текст из этого источника, находящегося в свободном доступе .

В данной статье использован текст из этого источника, находящегося в свободном доступе .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Stähler SC, Хан А., Банердт В.Б. и др. (23 июля 2021 г.). «Сейсмическое обнаружение ядра Марса» . Наука . 373 (6553): 443–448. Бибкод : 2021Sci...373..443S . дои : 10.1126/science.abi7730 . hdl : 20.500.11850/498074 . ПМИД 34437118 . S2CID 236179579 . Архивировано из оригинала 1 марта 2024 года . Проверено 17 октября 2021 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Сэмюэл Х, Дрилло, Мелани, Риволдини, Аттилио и др. (октябрь 2023 г.). «Геофизические доказательства существования обогащенного слоя расплавленного силиката над ядром Марса» . Природа . 622 (7984): 712–717. Бибкод : 2023Natur.622..712S . дои : 10.1038/s41586-023-06601-8 . hdl : 20.500.11850/639623 . ISSN 1476-4687 . ПМК 10600000 . ПМИД 37880437 .

- ^ Ниммо Ф, Танака К (2005). «Ранняя эволюция земной коры Марса». Ежегодный обзор наук о Земле и планетах . 33 (1): 133–161. Бибкод : 2005AREPS..33..133N . doi : 10.1146/annurev.earth.33.092203.122637 . S2CID 45843366 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «В глубине | Марс» . Исследование Солнечной системы НАСА . Архивировано из оригинала 21 декабря 2021 года . Проверено 15 января 2022 г.

- ^ Ким Д., Дюран С., Джардини Д. и др. (июнь 2023 г.). «Глобальная толщина земной коры, выявленная поверхностными волнами, вращающимися вокруг Марса». Письма о геофизических исследованиях . 50 (12). Бибкод : 2023GeoRL..5003482K . дои : 10.1029/2023GL103482 . hdl : 20.500.11850/621318 .

- ^ Вечорек М.А., Броке А., МакЛеннан С.М. и др. (май 2022 г.). «Ограничения InSight на глобальный характер марсианской коры». Журнал геофизических исследований: Планеты . 127 (5). Бибкод : 2022JGRE..12707298W . дои : 10.1029/2022JE007298 . hdl : 10919/110830 .

- ^ Хуанг Ю, Чубаков В, Мантовани Ф и др. (июнь 2013 г.). «Эталонная модель Земли для тепловыделяющих элементов и связанного с ними потока геонейтрино». Геохимия, геофизика, геосистемы . 14 (6): 2003–2029. arXiv : 1301.0365 . Бибкод : 2013GGG....14.2003H . дои : 10.1002/ggge.20129 .

- ^ Фернандо Б., Даубар И.Дж., Хараламбус С. и др. (октябрь 2023 г.). «Тектоническое происхождение крупнейшего марсотрясения, наблюдавшегося InSight». Письма о геофизических исследованиях . 50 (20). Бибкод : 2023GeoRL..5003619F . дои : 10.1029/2023GL103619 . hdl : 20.500.11850/639018 .

- ^ Голомбек М., Уорнер Н.Х., Грант Дж.А. и др. (24 февраля 2020 г.). «Геология места посадки InSight на Марсе» . Природа Геонауки . 11 (1014): 1014. Бибкод : 2020NatCo..11.1014G . дои : 10.1038/s41467-020-14679-1 . ПМК 7039939 . ПМИД 32094337 .

- ^ Банердт В.Б., Смрекар С.Е., Банфилд Д. и др. (2020). «Первоначальные результаты миссии InSight на Марсе» . Природа Геонауки . 13 (3): 183–189. Бибкод : 2020NatGe..13..183B . дои : 10.1038/s41561-020-0544-y .

- ^ Хан А., Джейлан С., ван Дрил М. и др. (23 июля 2021 г.). «Строение верхней мантии Марса по сейсмическим данным InSight» (PDF) . Наука . 373 (6553): 434–438. Бибкод : 2021Sci...373..434K . дои : 10.1126/science.abf2966 . ПМИД 34437116 . S2CID 236179554 . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 20 января 2022 года . Проверено 27 ноября 2021 г.

- ^ Хан А., Хуанг Д., Дуран К. и др. (октябрь 2023 г.). «Доказательства наличия жидкого силикатного слоя на поверхности марсианского ядра» . Природа . 622 (7984): 718–723. Бибкод : 2023Natur.622..718K . дои : 10.1038/s41586-023-06586-4 . hdl : 20.500.11850/639367 . ПМК 10600012 . ПМИД 37880439 .

- ^ Ле Местр С., Риволдини А., Кальдьеро А. и др. (14 июня 2023 г.). «Спиновое состояние и глубокая внутренняя структура Марса по данным радиослежения InSight» . Природа . 619 (7971): 733–737. Бибкод : 2023Natur.619..733L . дои : 10.1038/s41586-023-06150-0 . ISSN 1476-4687 . ПМИД 37316663 . S2CID 259162975 . Архивировано из оригинала 12 октября 2023 года . Проверено 3 июля 2023 г.

- ^ Рейн Э. (2 июля 2023 г.). «У Марса жидкие внутренности и странные внутренности, предполагает InSight» . Арс Техника . Архивировано из оригинала 3 июля 2023 года . Проверено 3 июля 2023 г.

- ^ ван дер Ли С. (25 октября 2023 г.). «Глубокий Марс удивительно мягок» . Природа . 622 (7984): 699–700. Бибкод : 2023Natur.622..699V . дои : 10.1038/d41586-023-03151-x . ПМИД 37880433 . Архивировано из оригинала 6 декабря 2023 года . Проверено 12 марта 2024 г.

- ^ Витце А (25 октября 2023 г.). «Внутри Марса находится неожиданный слой расплавленной породы» . Природа . 623 (7985): 20. Бибкод : 2023Natur.623...20W . дои : 10.1038/d41586-023-03271-4 . ПМИД 37880531 . Архивировано из оригинала 9 января 2024 года . Проверено 12 марта 2024 г.

- ^ Максуин Х.И., Тейлор Г.Дж., Вятт М.Б. (май 2009 г.). «Элементарный состав марсианской коры». Наука . 324 (5928): 736–739. Бибкод : 2009Sci...324..736M . CiteSeerX 10.1.1.654.4713 . дои : 10.1126/science.1165871 . ПМИД 19423810 . S2CID 12443584 .

- ^ Бэндфилд Дж.Л. (июнь 2002 г.). «Глобальное распределение полезных ископаемых на Марсе». Журнал геофизических исследований: Планеты . 107 (Е6): 9–1–9–20. Бибкод : 2002JGRE..107.5042B . CiteSeerX 10.1.1.456.2934 . дои : 10.1029/2001JE001510 .

- ^ Кристенсен PR (27 июня 2003 г.). «Морфология и состав поверхности Марса: результаты Mars Odyssey THEMIS» (PDF) . Наука . 300 (5628): 2056–2061. Бибкод : 2003Sci...300.2056C . дои : 10.1126/science.1080885 . ПМИД 12791998 . S2CID 25091239 . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 23 июля 2018 года . Проверено 17 декабря 2018 г.

- ^ Валентин, Тереза, Амде, Лишан (9 ноября 2006 г.). «Магнитные поля и Марс» . Марсианский глобальный исследователь @ НАСА. Архивировано из оригинала 14 сентября 2012 года . Проверено 17 июля 2009 г.

В данной статье использован текст из этого источника, находящегося в свободном доступе .

В данной статье использован текст из этого источника, находящегося в свободном доступе .

- ^ Нил-Джонс Н., О'Кэрролл К. «Новая карта дает больше доказательств того, что Марс когда-то был похож на Землю» . НАСА/Центр космических полетов Годдарда. Архивировано из оригинала 14 сентября 2012 года . Проверено 4 декабря 2011 г.

В данной статье использован текст из этого источника, находящегося в свободном доступе .

В данной статье использован текст из этого источника, находящегося в свободном доступе .

- ^ «Марсианская почва «может поддерживать жизнь» » . Новости Би-би-си. 27 июня 2008 г. Архивировано из оригинала 13 августа 2011 г. . Проверено 7 августа 2008 г.

- ^ Кунавес СП (2010). «Эксперименты по влажной химии на посадочном модуле Phoenix Mars Scout 2007 года: анализ данных и результаты» . Дж. Геофиз. Рез . 115 (Е3): Е00–Е10. Бибкод : 2009JGRE..114.0A19K . дои : 10.1029/2008JE003084 . S2CID 39418301 .

- ^ Кунавес СП (2010). «Растворимый сульфат в марсианском грунте на месте посадки Феникса». Письма о геофизических исследованиях . 37 (9): L09201. Бибкод : 2010GeoRL..37.9201K . дои : 10.1029/2010GL042613 . S2CID 12914422 .

- ^ Дэвид Л. (13 июня 2013 г.). «Токсичный Марс: астронавтам придется иметь дело с перхлоратом на Красной планете» . Space.com . Архивировано из оригинала 20 ноября 2020 года . Проверено 26 ноября 2018 г.

- ^ Образец I (6 июля 2017 г.). «Марс покрыт токсичными химическими веществами, которые могут уничтожить живые организмы, как показали тесты» . Хранитель . Архивировано из оригинала 18 февраля 2021 года . Проверено 26 ноября 2018 г.

- ^ Верба С (2 июля 2009 г.). «Пыльный дьявол Etch-A-Sketch (ESP_013751_1115)» . Операционный центр HiRISE . Университет Аризоны. Архивировано из оригинала 1 февраля 2012 года . Проверено 30 марта 2022 г.

- ^ Шоргофер, Норберт, Ааронсон, Одед, Хативала, Самар (2002). «Наклонные полосы на Марсе: корреляция со свойствами поверхности и потенциальной ролью воды» (PDF) . Письма о геофизических исследованиях . 29 (23): 41–1. Бибкод : 2002GeoRL..29.2126S . дои : 10.1029/2002GL015889 . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 3 августа 2020 г. Проверено 25 августа 2019 г.

- ^ Ганти, Тибор (2003). «Пятна темных дюн: возможные биомаркеры на Марсе?». Происхождение жизни и эволюция биосферы . 33 (4): 515–557. Бибкод : 2003ОЛЕВ...33..515Г . дои : 10.1023/А:1025705828948 . ПМИД 14604189 . S2CID 23727267 .

- ^ Уильямс М. (21 ноября 2016 г.). «Насколько плоха радиация на Марсе?» . Физика.орг . Архивировано из оригинала 4 апреля 2023 года . Проверено 9 апреля 2023 г.

- ^ Стена М (9 декабря 2013 г.). «Радиация на Марсе «управляема» для пилотируемой миссии, сообщает марсоход Curiosity» . Space.com . Архивировано из оригинала 15 декабря 2020 года . Проверено 9 апреля 2023 г.

- ^ «Сравнение радиационной обстановки Марса с Международной космической станцией» . Лаборатория реактивного движения НАСА (JPL) . 13 марта 2003 г. Архивировано из оригинала 9 апреля 2023 г. Проверено 9 апреля 2023 г.

- ^ Пэрис А., Дэвис Э., Тогнетти Л. и др. (27 апреля 2020 г.). «Перспективные лавовые трубы на Планиции Эллады». arXiv : 2004.13156v1 [ astro-ph.EP ].

- ^ «Что на картах Марса было правильным (и неправильным) во времени» . Нэшнл Географик . 19 октября 2016 г. Архивировано из оригинала 21 февраля 2021 г. Проверено 15 января 2022 г.

- ^ «Названия планет: категории для обозначения объектов на планетах и спутниках» . Рабочая группа Международного астрономического союза (МАС) по номенклатуре планетных систем (WGPSN) . Научный центр астрогеологии Геологической службы США. Архивировано из оригинала 5 декабря 2017 года . Проверено 18 апреля 2022 г.

- ^ «Викинг и ресурсы Марса» (PDF) . Люди на Марс: пятьдесят лет планирования миссии, 1950–2000 гг . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 14 июля 2019 года . Проверено 10 марта 2007 г.

В данной статье использован текст из этого источника, находящегося в свободном доступе .

В данной статье использован текст из этого источника, находящегося в свободном доступе .

- ^ Танака К.Л., Коулз К.С., Кристенсен П.Р., ред. (2019), «Большой Сиртис (MC-13)» , Атлас Марса: картирование его географии и геологии , Кембридж: Издательство Кембриджского университета, стр. 136–139, doi : 10.1017/9781139567428.018 , ISBN 978-1-139-56742-8 , S2CID 240843698 , заархивировано из оригинала 1 марта 2024 г. , получено 18 января 2022 г.

- ^ «Полярные шапки» . Марсианское образование в Университете штата Аризона . Архивировано из оригинала 28 мая 2021 года . Проверено 7 декабря 2021 г.

- ^ Дэвис М.Э., Берг Р.А. (10 января 1971 г.). «Предварительная сеть управления Марсом» . Журнал геофизических исследований . 76 (2): 373–393. Бибкод : 1971JGR....76..373D . дои : 10.1029/JB076i002p00373 . Архивировано из оригинала 1 марта 2024 года . Проверено 22 марта 2022 г.

- ^ Аринал, Б.А., Каплингер, М. (осень 2002 г.). «Марс, Меридиан и Мерт: В поисках марсианской долготы». Американский геофизический союз, осеннее собрание 2002 г. 22 : P22D–06. Бибкод : 2002AGUFM.P22D..06A .

- ^ де Вокулер Г. , Дэвис М.Э. , Штурмс Ф.М. младший (1973), «Ареографическая система координат Маринера 9», Журнал геофизических исследований , 78 (20): 4395–4404, Бибкод : 1973JGR....78.4395D , doi : 10.1029/ JB078i020p04395

- ^ НАСА (19 апреля 2007 г.). «Mars Global Surveyor: MOLA MEGDR» . geo.pds.nasa.gov. Архивировано из оригинала 13 ноября 2011 года . Проверено 24 июня 2011 г.

- ^ Ардалан А.А., Карими Р., Графаренд Э.В. (2009). «Новая эталонная эквипотенциальная поверхность и эталонный эллипсоид для планеты Марс». Земля, Луна и планеты . 106 (1): 1–13. дои : 10.1007/s11038-009-9342-7 . ISSN 0167-9295 . S2CID 119952798 .

- ^ Цейтлер В., Ольхоф Т., Эбнер Х. (2000). «Перерасчет глобальной сети контрольных точек Марса». Фотограмметрическая инженерия и дистанционное зондирование . 66 (2): 155–161. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.372.5691 .

- ^ Лунин CJ (1999). Земля: эволюция обитаемого мира . Издательство Кембриджского университета. п. 183 . ISBN 978-0-521-64423-5 .

- ^ «Наука и технологии ЕКА - Использование iMars: просмотр данных Mars Express о четырехугольнике MC11» . sci.esa.int . Архивировано из оригинала 29 декабря 2021 года . Проверено 29 декабря 2021 г.

- ^ Чанг К. (15 апреля 2023 г.). «Новая карта Марса позволяет увидеть всю планету сразу» — ученые собрали 3000 изображений с орбитального аппарата Эмиратов, чтобы создать самый красивый атлас Красной планеты» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . Архивировано из оригинала 16 мая 2023 года . Проверено 15 апреля 2023 г.

- ^ Персонал (16 апреля 2023 г.). «Добро пожаловать на Марс! Потрясающая виртуальная экспедиция Калифорнийского технологического института по Красной планете с разрешением 5,7 терапикселя» . Научные технологии . Архивировано из оригинала 16 апреля 2023 года . Проверено 6 апреля 2023 г.