Greenland ice sheet

| Greenland ice sheet | |

|---|---|

| Grønlands indlandsis Sermersuaq | |

| |

| Type | Ice sheet |

| Coordinates | 76°42′N 41°12′W / 76.7°N 41.2°W[1] |

| Area | 1,710,000 km2 (660,000 sq mi)[2] |

| Length | 2,400 km (1,500 mi)[1] |

| Width | 1,100 km (680 mi)[1] |

| Thickness | 1.67 km (1.0 mi) (average), ~3.5 km (2.2 mi) (maximum)[2] |

The Greenland ice sheet is an ice sheet which forms the second largest body of ice in the world. It is an average of 1.67 km (1.0 mi) thick, and over 3 km (1.9 mi) thick at its maximum.[2] It is almost 2,900 kilometres (1,800 mi) long in a north–south direction, with a maximum width of 1,100 kilometres (680 mi) at a latitude of 77°N, near its northern edge.[1] The ice sheet covers 1,710,000 square kilometres (660,000 sq mi), around 80% of the surface of Greenland, or about 12% of the area of the Antarctic ice sheet.[2] The term 'Greenland ice sheet' is often shortened to GIS or GrIS in scientific literature.[3][4][5][6]

Greenland has had major glaciers and ice caps for at least 18 million years,[7] but a single ice sheet first covered most of the island some 2.6 million years ago.[8] Since then, it has both grown[9][10] and contracted significantly.[11][12][13] The oldest known ice on Greenland is about 1 million years old.[14] Due to anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions, the ice sheet is now the warmest it has been in the past 1000 years,[15] and is losing ice at the fastest rate in at least the past 12,000 years.[16]

Every summer, parts of the surface melt and ice cliffs calve into the sea. Normally the ice sheet would be replenished by winter snowfall,[4] but due to global warming the ice sheet is melting two to five times faster than before 1850,[17] and snowfall has not kept up since 1996.[18] If the Paris Agreement goal of staying below 2 °C (3.6 °F) is achieved, melting of Greenland ice alone would still add around 6 cm (2+1⁄2 in) to global sea level rise by the end of the century. If there are no reductions in emissions, melting would add around 13 cm (5 in) by 2100,[19]: 1302 with a worst-case of about 33 cm (13 in).[20] For comparison, melting has so far contributed 1.4 cm (1⁄2 in) since 1972,[21] while sea level rise from all sources was 15–25 cm (6–10 in)) between 1901 and 2018.[22]: 5

If all 2,900,000 cubic kilometres (696,000 cu mi) of the ice sheet were to melt, it would increase global sea levels by ~7.4 m (24 ft).[2] Global warming between 1.7 °C (3.1 °F) and 2.3 °C (4.1 °F) would likely make this melting inevitable.[6] However, 1.5 °C (2.7 °F) would still cause ice loss equivalent to 1.4 m (4+1⁄2 ft) of sea level rise,[23] and more ice will be lost if the temperatures exceed that level before declining.[6] If global temperatures continue to rise, the ice sheet will likely disappear within 10,000 years.[24][25] At very high warming, its future lifetime goes down to around 1,000 years.[20]

Description

[edit]

Ice sheets form through a process of glaciation, when the local climate is sufficiently cold that snow is able to accumulate from year to year. As the annual snow layers pile up, their weight gradually compresses the deeper levels of snow to firn and then to solid glacier ice over hundreds of years.[13] Once the ice sheet formed in Greenland, its size remained similar to its current state.[26] However, there have been 11 periods in Greenland's history when the ice sheet extended up to 120 km (75 mi) beyond its current boundaries; with the last one around 1 million years ago.[9][10]

The weight of the ice causes it to slowly "flow", unless it is stopped by a sufficiently large obstacle, such as a mountain.[13] Greenland has many mountains near its coastline, which normally prevent the ice sheet from flowing further into the Arctic Ocean. The 11 previous episodes of glaciation are notable because the ice sheet grew large enough to flow over those mountains.[9][10] Nowadays, the northwest and southeast margins of the ice sheet are the main areas where there are sufficient gaps in the mountains to enable the ice sheet to flow out to the ocean through outlet glaciers. These glaciers regularly shed ice in what is known as ice calving.[28] Sediment released from calved and melting ice sinks accumulates on the seafloor, and sediment cores from places such as the Fram Strait provide long records of glaciation at Greenland.[7]

Geological history

[edit]

While there is evidence of large glaciers in Greenland for most of the past 18 million years,[7] these ice bodies were probably similar to various smaller modern examples, such as Maniitsoq and Flade Isblink, which cover 76,000 and 100,000 square kilometres (29,000 and 39,000 sq mi) around the periphery. Conditions in Greenland were not initially suitable for a single coherent ice sheet to develop, but this began to change around 10 million years ago, during the middle Miocene, when the two passive continental margins which now form the uplands of West and East Greenland experienced uplift, and ultimately formed the upper planation surface at a height of 2000 to 3000 meter above sea level.[29][30]

Later uplift, during the Pliocene, formed a lower planation surface at 500 to 1000 meters above sea level. A third stage of uplift created multiple valleys and fjords below the planation surfaces. This uplift intensified glaciation due to increased orographic precipitation and cooler surface temperatures, allowing ice to accumulate and persist.[29][30] As recently as 3 million years ago, during the Pliocene warm period, Greenland's ice was limited to the highest peaks in the east and the south.[31] Ice cover gradually expanded since then,[8] until the atmospheric CO2 levels dropped to between 280 and 320 ppm 2.7–2.6 million years ago, by which time temperatures had dropped sufficiently for the disparate ice caps to connect and cover most of the island.[3]

Ice cores and sediment samples

[edit]

The base of the ice sheet may be warm enough due to geothermal activity to have liquid water beneath it.[33] This liquid water, under pressure from the weight of ice above it, may cause erosion, eventually leaving nothing but bedrock below the ice sheet. However, there are parts of the Greenland ice sheet, near the summit, where the ice sheet slides over a basal layer of ice which had frozen solid to the ground, preserving ancient soil, which can then be recovered by drilling. The oldest such soil was continuously covered by ice for around 2.7 million years,[13] while another, 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) deep ice core from the summit has revealed ice that is around ~1,000,000 years old.[14]

Sediment samples from the Labrador Sea provide evidence that nearly all of the south Greenland ice had melted around 400,000 years ago, during Marine Isotope Stage 11.[11][34] Other ice core samples from Camp Century in northwestern Greenland, show that the ice there melted at least once during the past 1.4 million years, during the Pleistocene, and did not return for at least 280,000 years.[12] These findings suggest that less than 10% of the current ice sheet volume was left during those geologically recent periods, when the temperatures were less than 2.5 °C (4.5 °F) warmer than preindustrial conditions. This contradicts how climate models typically simulate the continuous presence of solid ice under those conditions.[35][13] Analysis of the ~100,000-year records obtained from 3 km (1.9 mi) long ice cores drilled between 1989 and 1993 into the summit of Greenland's ice sheet, had provided evidence for geologically rapid changes in climate, and informed research on tipping points such as in the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC).[36]

Ice cores provide valuable information about the past states of the ice sheet, and other kinds of paleoclimate data. Subtle differences in the oxygen isotope composition of the water molecules in ice cores can reveal important information about the water cycle at the time,[37] while air bubbles frozen within the ice core provide a snapshot of the gas and particulate composition of the atmosphere through time.[38][39]When properly analyzed, ice cores provide a wealth of proxies suitable for reconstructing the past temperature record,[37] precipitation patterns,[40] volcanic eruptions,[41] solar variation,[38] ocean primary production,[39] and even changes in soil vegetation cover and the associated wildfire frequency.[42] The ice cores from Greenland also record human impact, such as lead production during the time of Ancient Greece[43] and the Roman Empire.[44]

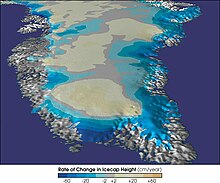

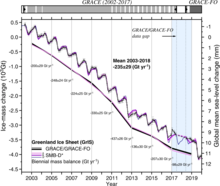

Recent melting

[edit]

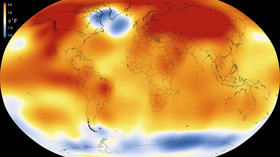

From the 1960s to the 1980s an area in the North Atlantic which included southern Greenland was one of the few locations in the world which showed cooling rather than warming.[45][46] This location was relatively warmer in the 1930s and 1940s than in the decades immediately before or after.[47] More complete data sets have established trends of warming and ice loss starting from 1900[48](well after the start of the Industrial Revolution and its impact on global carbon dioxide levels[49]) and a trend of strong warming starting around 1979, in line with concurrent observed Arctic sea ice decline.[50] In 1995– 1999, central Greenland was already 2 °C (3.6 °F) warmer than it was in the 1950s. Between 1991 and 2004, average winter temperature at one location, Swiss Camp, rose almost 6 °C (11 °F).[51]

Consistent with this warming, the 1970s were the last decade when the Greenland ice sheet grew, gaining about 47 gigatonnes per year. From 1980–1990 there was an average annual mass loss of ~51 Gt/y.[21] The period 1990–2000 showed an average annual loss of 41 Gt/y,[21] with 1996 being the last year the Greenland ice sheet saw net mass gain. As of 2022, the Greenland ice sheet had been losing ice for 26 years in a row,[18] and temperatures there had been the highest in the entire past last millennium – about 1.5 °C (2.7 °F) warmer than the 20th century average.[15]

Several factors determine the net rate of ice sheet growth or decline. These are:

- Accumulation and melting rates of snow in and around the centre

- Melting of ice along the sheet's margins

- Ice calving into the sea from outlet glaciers also along the sheet's edges

When the IPCC Third Assessment Report was published in 2001, the analysis of observations to date had shown that the ice accumulation of 520 ± 26 gigatonnes per year was offset by runoff and bottom melting equivalent to ice losses of 297±32 Gt/yr and 32±3 Gt/yr, and iceberg production of 235±33 Gt/yr, with a net loss of −44 ± 53 gigatonnes per year.[52]

Annual ice losses from the Greenland ice sheet accelerated in the 2000s, reaching ~187 Gt/yr in 2000–2010, and an average mass loss during 2010–2018 of 286 Gt per year. Half of the ice sheet's observed net loss (3,902 gigatons (Gt) of ice between 1992 and 2018, or approximately 0.13% of its total mass[53]) happened during those 8 years. When converted to sea level rise equivalent, the Greenland ice sheet contributed about 13.7 mm since 1972.[21]

Between 2012 and 2017, it contributed 0.68 mm per year, compared to 0.07 mm per year between 1992 and 1997.[53] Greenland's net contribution for the 2012–2016 period was equivalent to 37% of sea level rise from land ice sources (excluding thermal expansion).[55] These melt rates are comparable to the largest experienced by the ice sheet over the past 12,000 years.[16]

Currently, the Greenland ice sheet loses more mass every year than the Antarctic ice sheet, because of its position in the Arctic, where it is subject to intense regional amplification of warming.[45][56][57] Ice losses from the West Antarctic Ice Sheet have been accelerating due to its vulnerable Thwaites and Pine Island Glaciers, and the Antarctic contribution to sea level rise is expected to overtake that of Greenland later this century.[17][19]

Observed glacier retreat

[edit]

Retreat of outlet glaciers as they shed ice into the Arctic is a large factor in the decline of Greenland's ice sheet. Estimates suggest that losses from glaciers explain between 49% and 66.8% of observed ice loss since the 1980s.[21][53] Net loss of ice was already observed across 70% of the ice sheet margins by the 1990s, with thinning detected as the glaciers started to lose height.[59] Between 1998 and 2006, thinning occurred four times faster for coastal glaciers compared to the early 1990s,[60] falling at rates between 1 m (3+1⁄2 ft) and 10 m (33 ft) per year,[61] while the landlocked glaciers experienced almost no such acceleration.[60]

One of the most dramatic examples of thinning was in the southeast, at Kangerlussuaq Glacier. It is over 20 mi (32 km) long, 4.5 mi (7 km) wide and around 1 km (1⁄2 mi) thick, which makes it the third largest glacier in Greenland.[62] Between 1993 and 1998, parts of the glacier within 5 km (3 mi) of the coast lost 50 m (164 ft) in height.[63] Its observed ice flow speed went from 3.1–3.7 mi (5–6 km) per year in 1988–1995 to 8.7 mi (14 km) per year in 2005, which was then the fastest known flow of any glacier.[62] The retreat of Kangerlussuaq slowed down by 2008,[64] and showed some recovery until 2016–2018, when more rapid ice loss occurred.[65]

Greenland's other major outlet glaciers have also experienced rapid change in recent decades. Its single largest outlet glacier is Jakobshavn Isbræ (Greenlandic: Sermeq Kujalleq) in west Greenland, which has been observed by glaciologists for many decades.[66] It historically sheds ice from 6.5% of the ice sheet[67] (compared to 4% for Kangerlussuaq[62]), at speeds of ~20 metres (66 ft) per day.[68] While it lost enough ice to retreat around 30 km (19 mi) between 1850 and 1964, its mass gain increased sufficiently to keep it in balance for the next 35 years,[68] only to switch to rapid mass loss after 1997.[69][67] By 2003, the average annual ice flow speed had almost doubled since 1997, as the ice tongue in front of the glacier disintegrated,[69] and the glacier shed 94 square kilometres (36 sq mi) of ice between 2001 and 2005.[70] The ice flow reached 45 metres (148 ft) per day in 2012,[71] but slowed down substantially afterwards, and showed mass gain between 2016 and 2019.[72][73]

Northern Greenland's Petermann Glacier is smaller in absolute terms, but experienced some of the most rapid degradation in recent decades. It lost 85 square kilometres (33 sq mi) of floating ice in 2000–2001, followed by a 28-square-kilometre (11 sq mi) iceberg breaking off in 2008, and then a 260 square kilometres (100 sq mi) iceberg calving from ice shelf in August 2010. This became the largest Arctic iceberg since 1962, and amounted to a quarter of the shelf's size.[74] In July 2012, Petermann glacier lost another major iceberg, measuring 120 square kilometres (46 sq mi), or twice the area of Manhattan.[75] As of 2023, the glacier's ice shelf had lost around 40% of its pre-2010 state, and it is considered unlikely to recover from further ice loss.[76]

In the early 2010s, some estimates suggested that tracking the largest glaciers would be sufficient to account for most of the ice loss.[77] However, glacier dynamics can be hard to predict, as shown by the ice sheet's second largest glacier, Helheim Glacier. Its ice loss culminated in rapid retreat in 2005,[78] associated with a marked increase in glacial earthquakes between 1993 and 2005.[79] Since then, it has remained comparatively stable near its 2005 position, losing relatively little mass in comparison to Jakobshavn and Kangerlussuaq,[80] although it may have eroded sufficiently to experience another rapid retreat in the near future.[81] Meanwhile, smaller glaciers have been consistently losing mass at an accelerating rate,[82] and later research has concluded that total glacier retreat is underestimated unless the smaller glaciers are accounted for.[21] By 2023, the rate of ice loss across Greenland's coasts had doubled in the two decades since 2000, in large part due to the accelerated losses from smaller glaciers.[83][84]

Processes accelerating glacier retreat

[edit]

Since the early 2000s, glaciologists have concluded that glacier retreat in Greenland is accelerating too quickly to be explained by a linear increase in melting in response to greater surface temperatures alone, and that additional mechanisms must also be at work.[86][87][88] Rapid calving events at the largest glaciers match what was first described as the "Jakobshavn effect" in 1986:[89] thinning causes the glacier to be more buoyant, reducing friction that would otherwise impede its retreat, and resulting in a force imbalance at the calving front, with an increase in velocity spread across the mass of the glacier.[90][91][67] The overall acceleration of Jakobshavn Isbrae and other glaciers from 1997 onwards had been attributed to the warming of North Atlantic waters which melt the glacier fronts from underneath. While this warming had been going on since the 1950s,[92] 1997 also saw a shift in circulation which brought relatively warmer currents from the Irminger Sea into closer contact with the glaciers of West Greenland.[93] By 2016, waters across much of West Greenland's coastline had warmed by 1.6 °C (2.9 °F) relative to 1990s, and some of the smaller glaciers were losing more ice to such melting than normal calving processes, leading to rapid retreat.[94]

Conversely, Jakobshavn Isbrae is sensitive to changes in ocean temperature as it experiences elevated exposure through a deep subglacial trench.[95][96] This sensitivity meant that an influx of cooler ocean water to its location was responsible for its slowdown after 2015,[73] in large part because the sea ice and icebergs immediately off-shore were able to survive for longer, and thus helped to stabilize the glacier.[97] Likewise, the rapid retreat and then slowdown of Helheim and Kangerdlugssuaq has also been connected to the respective warming and cooling of nearby currents.[98] At Petermann Glacier, the rapid rate of retreat has been linked to the topography of its grounding line, which appears to shift back and forth by around a kilometer with the tide. It has been suggested that if similar processes can occur at the other glaciers, then their eventual rate of mass loss could be doubled.[99][85]

There are several ways in which increased melting at the surface of the ice sheet can accelerate lateral retreat of outlet glaciers. Firstly, the increase in meltwater at the surface causes larger amounts to flow through the ice sheet down to bedrock via moulins. There, it lubricates the base of the glaciers and generates higher basal pressure, which collectively reduces friction and accelerates glacial motion, including the rate of ice calving. This mechanism was observed at Sermeq Kujalleq in 1998 and 1999, where flow increased by up to 20% for two to three months.[100][101] However, some research suggests that this mechanism only applies to certain small glaciers, rather than to the largest outlet glaciers,[102] and may have only a marginal impact on ice loss trends.[103]

Secondly, once meltwater flows into the ocean, it can still impact the glaciers by interacting with ocean water and altering its local circulation - even in the absence of any ocean warming.[104] In certain fjords, large meltwater flows from beneath the ice may mix with ocean water to create turbulent plumes that can be damaging to the calving front.[105] While the models generally consider the impact from meltwater run-off as secondary to ocean warming,[106] observations of 13 glaciers found that meltwater plumes play a greater role for glaciers with shallow grounding lines.[107] Further, 2022 research suggests that the warming from plumes had a greater impact on underwater melting across northwest Greenland.[104]

Finally, it has been shown that meltwater can also flow through cracks that are too small to be picked up by most research tools - only 2 cm (1 in) wide. Such cracks do not connect to bedrock through the entire ice sheet but may still reach several hundred meters down from the surface.[108] Their presence is important, as it weakens the ice sheet, conducts more heat directly through the ice, and allows it to flow faster.[109] This recent research is not currently captured in models. One of the scientists behind these findings, Alun Hubbard, described finding moulins where "current scientific understanding doesn’t accommodate" their presence, because it disregards how they may develop from hairline cracks in the absence of existing large crevasses that are normally thought to be necessary for their formation.[110]

Observed surface melting

[edit]Currently, the total accumulation of ice on the surface of Greenland ice sheet is larger than either outlet glacier losses individually or surface melting during the summer, and it is the combination of both which causes net annual loss.[4] For instance, the ice sheet's interior thickened by an average of 6 cm (2.4 in) each year between 1994 and 2005, in part due to a phase of [[North Atlantic oscillation]] increasing snowfall.[111] Every summer, a so-called snow line separates the ice sheet's surface into areas above it, where snow continues to accumulate even then, with the areas below the line where summer melting occurs.[112] The exact position of the snow line moves around every summer, and if it moves away from some areas it covered the previous year, then those tend to experience substantially greater melt as their darker ice is exposed. Uncertainty about the snow line is one of the factors making it hard to predict each melting season in advance.[113]

A notable example of ice accumulation rates above the snow line is provided by Glacier Girl, a Lockheed P-38 Lightning fighter plane which had crashed early in World War II and was recovered in 1992, by which point it had been buried under 268 ft (81+1⁄2 m) of ice.[114] Another example occurred in 2017, when an Airbus A380 had to make an emergency landing in Canada after one of its jet engines exploded while it was above Greenland; the engine's massive air intake fan was recovered from the ice sheet two years later, when it was already buried beneath 4 ft (1 m)of ice and snow.[115]

While summer surface melting has been increasing, it is still expected that it will be decades before melting will consistently exceed snow accumulation on its own.[4] It is also hypothesized that the increase in global precipitation associated with the effects of climate change on the water cycle could increase snowfall over Greenland, and thus further delay this transition.[116] This hypothesis was difficult to test in the 2000s due to the poor state of long-term precipitation records over the ice sheet.[117] By 2019, it was found that while there was an increase in snowfall over southwest Greenland,[118] there had been a substantial decrease in precipitation over western Greenland as a whole.[116] Further, more precipitation in the northwest had been falling as rain instead of snow, with a fourfold increase in rain since 1980.[119] Rain is warmer than snow and forms darker and less thermally insulating ice layer once it does freeze on the ice sheet. It is particularly damaging when it falls due to late-summer cyclones, whose increasing occurrence has been overlooked by the earlier models.[120] There has also been an increase in water vapor, which paradoxically increases melting by making it easier for heat to radiate downwards through moist, as opposed to dry, air.[121]

Altogether, the melt zone below the snow line, where summer warmth turns snow and ice into slush and melt ponds, has been expanding at an accelerating rate since the beginning of detailed measurements in 1979. By 2002, its area was found to have increased by 16% since 1979, and the annual melting season broke all previous records.[45] Another record was set in July 2012, when the melt zone extended to 97% of the ice sheet's cover,[122] and the ice sheet lost approximately 0.1% of its total mass (2900 Gt) during that year's melting season, with the net loss (464 Gt) setting another record.[123] It became the first directly observed example of a "massive melting event", when the melting took place across practically the entire ice sheet surface, rather than specific areas.[124] That event led to the counterintuitive discovery that cloud cover, which normally results in cooler temperature due to their albedo, actually interferes with meltwater refreezing in the firn layer at night, which can increase total meltwater runoff by over 30%.[125][126] Thin, water-rich clouds have the worst impact, and they were the most prominent in July 2012.[127]

Ice cores had shown that the last time a melting event of the same magnitude as in 2012 took place was in 1889, and some glaciologists had expressed hope that 2012 was part of a 150-year cycle.[128][129] This was disproven in summer 2019, when a combination of high temperatures and unsuitable cloud cover led to an even larger mass melting event, which ultimately covered over 300,000 sq mi (776,996.4 km2) at its greatest extent. Predictably, 2019 set a new record of 586 Gt net mass loss.[54][130] In July 2021, another record mass melting event occurred. At its peak, it covered 340,000 sq mi (880,596.0 km2), and led to daily ice losses of 88 Gt across several days.[131][132] High temperatures continued in August 2021, with the melt extent staying at 337,000 sq mi (872,826.0 km2). At that time, rain fell for 13 hours at Greenland's Summit Station, located at 10,551 ft (3,215.9 m) elevation.[133] Researchers had no rain gauges to measure the rainfall, because temperatures at the summit have risen above freezing only three times since 1989 and it had never rained there before.[134]

Due to the enormous thickness of the central Greenland ice sheet, even the most extensive melting event can only affect a small fraction of it before the start of the freezing season, and so they are considered "short-term variability" in the scientific literature. Nevertheless, their existence is important: the fact that the current models underestimate the extent and frequency of such events is considered to be one of the main reasons why the observed ice sheet decline in Greenland and Antarctica tracks the worst-case rather than the moderate scenarios of the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report's sea-level rise projections.[135][136][137] Some of the most recent scientific projections of Greenland melt now include an extreme scenario where a massive melting event occurs every year across the studied period (i.e. every year between now and 2100 or between now and 2300), to illustrate that such a hypothetical future would greatly increase ice loss, but still wouldn't melt the entire ice sheet within the study period.[138][139]

Changes in albedo

[edit]

On the ice sheet, annual temperatures are generally substantially lower than elsewhere in Greenland: about −20 °C (−4 °F) at the south dome (latitudes 63°–65°N) and −31 °C (−24 °F) near the center of the north dome (latitude 72°N (the fourth highest "summit" of Greenland).[1] On 22 December 1991, a temperature of −69.6 °C (−93.3 °F) was recorded at an automatic weather station near the topographic summit of the Greenland Ice Sheet, making it the lowest temperature ever recorded in the Northern Hemisphere. The record went unnoticed for more than 28 years and was finally recognized in 2020.[140] These low temperatures are in part caused by the high albedo of the ice sheet, as its bright white surface is very effective at reflecting sunlight. Ice-albedo feedback means that as the temperatures increase, this causes more ice to melt and either reveal bare ground or even just to form darker melt ponds, both of which act to reduce albedo, which accelerates the warming and contributes to further melting. This is taken into account by the climate models, which estimate that a total loss of the ice sheet would increase global temperature by 0.13 °C (0.23 °F), while Greenland's local temperatures would increase by between 0.5 °C (0.90 °F) and 3 °C (5.4 °F).[141][24][25]

Even incomplete melting already has some impact on the ice-albedo feedback. Besides the formation of darker melt ponds, warmer temperatures enable increasing growth of algae on the ice sheet's surface. Mats of algae are darker in colour than the surface of the ice, so they absorb more thermal radiation and increase the rate of ice melt.[142] In 2018, it was found that the regions covered in dust, soot, and living microbes and algae altogether grew by 12% between 2000 and 2012.[143] In 2020, it was demonstrated that the presence of algae, which is not accounted for by ice sheet models unlike soot and dust, had already been increasing annual melting by 10–13%.[144] Additionally, as the ice sheet slowly gets lower due to melting, surface temperatures begin to increase and it becomes harder for snow to accumulate and turn to ice, in what is known as surface-elevation feedback.[145][146]

Geophysical and biochemical role of Greenland's meltwater

[edit]Even in 1993, Greenland's melt resulted in 300 cubic kilometers of fresh meltwater entering the seas annually, which was substantially larger than the liquid meltwater input from the Antarctic ice sheet, and equivalent to 0.7% of freshwater entering the oceans from all of the world's rivers.[148] This meltwater is not pure, and contains a range of elements - most notably iron, about half of which (around 0.3 million tons every year) is bioavailable as a nutrient for phytoplankton.[149] Thus, meltwater from Greenland enhances ocean primary production, both in the local fjords,[150] and further out in the Labrador Sea, where 40% of the total primary production had been attributed to nutrients from meltwater.[151]

Since the 1950s, the acceleration of Greenland melt caused by climate change has already been increasing productivity in waters off the North Icelandic Shelf,[152] while productivity in Greenland's fjords is also higher than it had been at any point in the historical record, which spans from late 19th century to present.[153] Some research suggests that Greenland's meltwater mainly benefits marine productivity not by adding carbon and iron, but through stirring up lower water layers that are rich in nitrates and thus bringing more of those nutrients to phytoplankton on the surface. As the outlet glaciers retreat inland, the meltwater will be less able to impact the lower layers, which implies that benefit from the meltwater will diminish even as its volume grows.[147]

The impact of meltwater from Greenland goes beyond nutrient transport. For instance, meltwater also contains dissolved organic carbon, which comes from the microbial activity on the ice sheet's surface, and, to a lesser extent, from the remnants of ancient soil and vegetation beneath the ice.[155] There is about 0.5-27 billion tonnes of pure carbon underneath the entire ice sheet, and much less within it.[156] This is much less than the 1400–1650 billion tonnes contained within the Arctic permafrost,[157] or the annual anthropogenic emissions of around 40 billion tonnes of CO2.[19]: 1237 ) Yet, the release of this carbon through meltwater can still act as a climate change feedback if it increases overall carbon dioxide emissions.[158]

There is one known area, at Russell Glacier, where meltwater carbon is released into the atmosphere in the form of methane (see arctic methane emissions), which has a much larger global warming potential than carbon dioxide.[154] However, the area also harbours large numbers of methanotrophic bacteria, which limit those methane emissions.[159][160]

In 2021, research claimed that there must be mineral deposits of mercury (a highly toxic heavy metal) beneath the southwestern ice sheet, because of the exceptional concentrations in meltwater entering the local fjords. If confirmed, these concentrations would have equalled up to 10% of mercury in all of the world's rivers.[161][162] In 2024, a follow-up study found only "very low" concentrations in meltwater from 21 locations. It concluded that the 2021 findings were best explained by accidental sample contamination with mercury(II) chloride, used by the first team of researchers as a reagent.[163] However, there is still a risk of toxic waste being released from Camp Century, formerly a United States military site built to carry nuclear weapons for the Project Iceworm. The project was cancelled, but the site was never cleaned up, and it now threatens to pollute the meltwater with nuclear waste, 20,000 liters of chemical waste and 24 million liters of untreated sewage as the melt progresses.[164][165]

Finally, increased quantities of fresh meltwater can affect ocean circulation.[45] Some scientists have connected this increased discharge from Greenland with the so-called cold blob in the North Atlantic, which is in turn connected to Atlantic meridional overturning circulation, or AMOC, and its apparent slowdown.[167][168][169][170] In 2016, a study attempted to improve forecasts of future AMOC changes by incorporating better simulation of Greenland trends into projections from eight state-of-the-art climate models. That research found that by 2090–2100, the AMOC would weaken by around 18% (with a range of potential weakening between 3% and 34%) under Representative Concentration Pathway 4.5, which is most akin to the current trajectory,[171][172] while it would weaken by 37% (with a range between 15% and 65%) under Representative Concentration Pathway 8.5, which assumes continually increasing emissions. If the two scenarios are extended past 2100, then the AMOC ultimately stabilizes under RCP 4.5, but it continues to decline under RCP 8.5: the average decline by 2290–2300 is 74%, and there is 44% likelihood of an outright collapse in that scenario, with a wide range of adverse effects.[173]

Future ice loss

[edit]Near-term

[edit]In 2021, the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report estimated that under SSP5-8.5, the scenario associated with the highest global warming, Greenland ice sheet melt would add around 13 cm (5 in) to the global sea levels (with a likely (17%–83%) range of 9–18 cm (3+1⁄2–7 in) and a very likely range (5–95% confidence level) of 5–23 cm (2–9 in)), while the "moderate" SSP2-4.5 scenario adds 8 cm (3 in) with a likely and very likely range of 4–13 cm (1+1⁄2–5 in) and 1–18 cm (1⁄2–7 in), respectively. The optimistic scenario which assumes that the Paris Agreement goals are largely fulfilled, SSP1-2.6, adds around 6 cm (2+1⁄2 in) and no more than 15 cm (6 in), with a small chance of the ice sheet gaining mass and thus reducing the sea levels by around 2 cm (1 in).[19]: 1260

Some scientists, led by James Hansen, have claimed that the ice sheets can disintegrate substantially faster than estimated by the ice sheet models,[176] but even their projections also have much of Greenland, whose total size amounts to 7.4 m (24 ft) of sea level rise,[2] survive the 21st century. A 2016 paper from Hansen claimed that Greenland ice loss could add around 33 cm (13 in) by 2060, in addition to double that figure from the Antarctic ice sheet, if the CO2 concentration exceeded 600 parts per million,[177] which was immediately controversial amongst the scientific community,[178] while 2019 research from different scientists claimed a maximum of 33 cm (13 in) by 2100 under the worst-case climate change scenario.[20]

As with the present losses, not all parts of the ice sheet would contribute to them equally. For instance, it is estimated that on its own, the Northeast Greenland ice stream would contribute 1.3–1.5 cm by 2100 under RCP 4.5 and RCP 8.5, respectively.[179] On the other hand, the three largest glaciers - Jakobshavn, Helheim, and Kangerlussuaq - are all located in the southern half of the ice sheet, and just the three of them are expected to add 9.1–14.9 mm under RCP 8.5.[28] Similarly, 2013 estimates suggested that by 2200, they and another large glacier would add 29 to 49 millimetres by 2200 under RCP 8.5, or 19 to 30 millimetres under RCP 4.5.[180] Altogether, the single largest contribution to 21st century ice loss in Greenland is expected to be from the northwest and central west streams (the latter including Jakobshavn), and glacier retreat will be responsible for at least half of the total ice loss, as opposed to earlier studies which suggested that surface melting would become dominant later this century.[58] If Greenland were to lose all of its coastal glaciers, though, then whether or not it will continue to shrink will be entirely determined by whether its surface melting in the summer consistently outweighs ice accumulation during winter. Under the highest-emission scenario, this could happen around 2055, well before the coastal glaciers are lost.[4]

Sea level rise from Greenland does not affect every coast equally. The south of the ice sheet is much more vulnerable than the other parts, and the quantities of ice involved mean that there is an impact on the deformation of Earth's crust and on Earth's rotation. While this effect is subtle, it already causes East Coast of the United States to experience faster sea level rise than the global average.[181] At the same time, Greenland itself would experience isostatic rebound as its ice sheet shrinks and its ground pressure becomes lighter. Similarly, a reduced mass of ice would exert a lower gravitational pull on the coastal waters relative to the other land masses. These two processes would cause sea level around Greenland's own coasts to fall, even as it rises elsewhere.[182] The opposite of this phenomenon happened when the ice sheet gained mass during the Little Ice Age: increased weight attracted more water and flooded certain Viking settlements, likely playing a large role in the Viking abandonment soon afterwards.[183][184]

Long-term

[edit]

Notably, the ice sheet's massive size simultaneously makes it insensitive to temperature changes in the short run, yet also commits it to enormous changes down the line, as demonstrated by paleoclimate evidence.[11][35][34] Polar amplification causes the Arctic, including Greenland, to warm three to four times more than the global average:[186][187][188] thus, while a period like the Eemian interglacial 130,000–115,000 years ago was not much warmer than today globally, the ice sheet was 8 °C (14 °F) warmer, and its northwest part was 130 ± 300 meters lower than it is at present.[189][190] Some estimates suggest that the most vulnerable and fastest-receding parts of the ice sheet have already passed "a point of no return" around 1997, and will be committed to disappearance even if the temperature stops rising.[191][185][192]

A 2022 paper found that the 2000–2019 climate would already result in the loss of ~3.3% volume of the entire ice sheet in the future, committing it to an eventual 27 cm (10+1⁄2 in) of SLR, independent of any future temperature change. They have additionally estimated that if the then-record melting seen on the ice sheet in 2012 were to become its new normal, then the ice sheet would be committed to around 78 cm (30+1⁄2 in) SLR.[138] Another paper suggested that paleoclimate evidence from 400,000 years ago is consistent with ice losses from Greenland equivalent to at least 1.4 m (4+1⁄2 ft) of sea level rise in a climate with temperatures close to 1.5 °C (2.7 °F), which are now inevitable at least in the near future.[23]

It is also known that at a certain level of global warming, effectively the entirety of the Greenland Ice Sheet will eventually melt. Its volume was initially estimated to amount to ~2,850,000 km3 (684,000 cu mi), which would increase the global sea levels by 7.2 m (24 ft),[52] but later estimates increased its size to ~2,900,000 km3 (696,000 cu mi), leading to ~7.4 m (24 ft) of sea level rise.[2]

Thresholds for total ice sheet loss

[edit]In 2006, it was estimated that the ice sheet is most likely to be committed to disappearance at 3.1 °C (5.6 °F), with a plausible range between 1.9 °C (3.4 °F) and 5.1 °C (9.2 °F).[193] However, these estimates were drastically reduced in 2012, with the suggestion that the threshold may lie anywhere between 0.8 °C (1.4 °F) and 3.2 °C (5.8 °F), with 1.6 °C (2.9 °F) the most plausible global temperature for the ice sheet's disappearance.[194] That lowered temperature range had been widely used in the subsequent literature,[34][195] and in the year 2015, prominent NASA glaciologist Eric Rignot claimed that "even the most conservative people in our community" will agree that "Greenland’s ice is gone" after 2 °C (3.6 °F) or 3 °C (5.4 °F) of global warming.[145]

In 2022, a major review of scientific literature on tipping points in the climate system barely modified these values: it suggested that the threshold would be most likely be at 1.5 °C (2.7 °F), with the upper level at 3 °C (5.4 °F) and the worst-case threshold of 0.8 °C (1.4 °F) remained unchanged.[24][25] At the same time, it noted that the fastest plausible timeline for the ice sheet disintegration is 1000 years, which is based on research assuming the worst-case scenario of global temperatures exceeding 10 °C (18 °F) by 2500,[20] while its ice loss otherwise takes place over around 10,000 years after the threshold is crossed; the longest possible estimate is 15,000 years.[24][25]

Model-based projections published in the year 2023 had indicated that the Greenland ice sheet could be a little more stable than suggested by the earlier estimates. One paper found that the threshold for ice sheet disintegration is more likely to lie between 1.7 °C (3.1 °F) and 2.3 °C (4.1 °F). It also indicated that the ice sheet could still be saved, and its sustained collapse averted, if the warming were reduced to below 1.5 °C (2.7 °F), up to a few centuries after the threshold was first breached. However, while that would avert the loss of the entire ice sheet, it would increase the overall sea level rise by up to several meters, as opposed to a scenario where the warming threshold was not breached in the first place.[6]

Another paper using a more complex ice sheet model has found that since the warming passed 0.6 °C (1.1 °F) degrees, ~26 cm (10 in) of sea level rise became inevitable,[5] closely matching the estimate derived from direct observation in 2022.[138] However, it had also found that 1.6 °C (2.9 °F) would likely only commit the ice sheet to 2.4 m (8 ft) of long-term sea level rise, while near-complete melting of 6.9 m (23 ft) worth of sea level rise would occur if the temperatures consistently stay above 2 °C (3.6 °F). The paper also suggested that ice losses from Greenland may be reversed by reducing temperature to 0.6 °C (1.1 °F) or lower, up until the entirety of South Greenland ice melts, which would cause 1.8 m (6 ft) of sea level rise and prevent any regrowth unless CO2 concentrations is reduced to 300 ppm. If the entire ice sheet were to melt, it would not begin to regrow until temperatures fall to below the preindustrial levels.[5]

See also

[edit]- List of glaciers in Greenland

- Glaciation

- Climate change in the Arctic

- Sea level rise

- Arctic sea ice decline

- Isostatic depression – induced by Greenland ice sheet

References

[edit]- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Greenland Ice Sheet. 24 October 2023. Archived from the original on 30 October 2017. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g "How Greenland would look without its ice sheet". BBC News. 14 December 2017. Archived from the original on 7 December 2023. Retrieved 7 December 2023.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Tan, Ning; Ladant, Jean-Baptiste; Ramstein, Gilles; Dumas, Christophe; Bachem, Paul; Jansen, Eystein (12 November 2018). "Dynamic Greenland ice sheet driven by pCO2 variations across the Pliocene Pleistocene transition". Nature Communications. 9 (1): 4755. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-07206-w. PMC 6232173. PMID 30420596.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Noël, B.; van Kampenhout, L.; Lenaerts, J. T. M.; van de Berg, W. J.; van den Broeke, M. R. (19 January 2021). "A 21st Century Warming Threshold for Sustained Greenland Ice Sheet Mass Loss". Geophysical Research Letters. 48 (5): e2020GL090471. Bibcode:2021GeoRL..4890471N. doi:10.1029/2020GL090471. hdl:2268/301943. S2CID 233632072.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Höning, Dennis; Willeit, Matteo; Calov, Reinhard; Klemann, Volker; Bagge, Meike; Ganopolski, Andrey (27 March 2023). "Multistability and Transient Response of the Greenland Ice Sheet to Anthropogenic CO2 Emissions". Geophysical Research Letters. 50 (6): e2022GL101827. doi:10.1029/2022GL101827. S2CID 257774870.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Bochow, Nils; Poltronieri, Anna; Robinson, Alexander; Montoya, Marisa; Rypdal, Martin; Boers, Niklas (18 October 2023). "Overshooting the critical threshold for the Greenland ice sheet". Nature. 622 (7983): 528–536. Bibcode:2023Natur.622..528B. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06503-9. PMC 10584691. PMID 37853149.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Thiede, Jörn; Jessen, Catherine; Knutz, Paul; Kuijpers, Antoon; Mikkelsen, Naja; Nørgaard-Pedersen, Niels; Spielhagen, Robert F (2011). "Millions of Years of Greenland Ice Sheet History Recorded in Ocean Sediments". Polarforschung. 80 (3): 141–159. hdl:10013/epic.38391.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Contoux, C.; Dumas, C.; Ramstein, G.; Jost, A.; Dolan, A.M. (15 August 2015). "Modelling Greenland ice sheet inception and sustainability during the Late Pliocene" (PDF). Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 424: 295–305. Bibcode:2015E&PSL.424..295C. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2015.05.018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 7 December 2023.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Knutz, Paul C.; Newton, Andrew M. W.; Hopper, John R.; Huuse, Mads; Gregersen, Ulrik; Sheldon, Emma; Dybkjær, Karen (15 April 2019). "Eleven phases of Greenland Ice Sheet shelf-edge advance over the past 2.7 million years" (PDF). Nature Geoscience. 12 (5): 361–368. Bibcode:2019NatGe..12..361K. doi:10.1038/s41561-019-0340-8. S2CID 146504179. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 December 2023. Retrieved 7 December 2023.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Робинсон, Бен (15 апреля 2019 г.). «Ученые в первое время состоит в том, чтобы в первый раз» . Университет Манчестера . Архивировано из оригинала 7 декабря 2023 года . Получено 7 декабря 2023 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Рейес, Альберто В.; Carlson, Anders E.; Борода, Брайан Л.; Хэтфилд, Роберт Дж.; Стоунер, Джозеф С.; Уинзор, Келси; Уэлке, Бетани; Уллман, Дэвид Дж. (25 июня 2014 г.). «Область ледяных листов в Южной Гренландии во время этапа морской изотопной стадии 11». Природа . 510 (7506): 525–528. Bibcode : 2014natur.510..525r . doi : 10.1038/nature13456 . PMID 24965655 . S2CID 4468457 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Христос, Эндрю Дж.; Bierman, Paul R.; Schaefer, Joerg M.; Даль-Дженсен, Дорт; Steffensen, Jørgen P.; Корбетт, Ли Б.; Питом, Дороти М.; Томас, Элизабет К.; Стейг, Эрик Дж.; Rittenour, Tammy M.; Тисон, Жан-Луи; Блард, Пьер-Хенри; Perdrial, Николас; Dethier, David P.; Лини, Андреа; Хиди, Алан Дж.; Caffee, Marc W.; Саутон, Джон (30 марта 2021 года). «Мультимиллионная запись о растительности Гренландии и ледниковой истории сохранилась в отложениях под 1,4 км льда в лагере» . Труды Национальной академии наук . 118 (13): E2021442118. Bibcode : 2021pnas..11821442C . doi : 10.1073/pnas.2021442118 . ISSN 0027-8424 . PMC 8020747 . PMID 33723012 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и Gautier, Agnieszka (29 марта 2023 г.). "Как и когда образовался ледяной покров Гренландии?" Полем Национальный центр данных снега и льда . Архивировано из оригинала 28 мая 2023 года . Получено 5 декабря 2023 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Яу, Одри М.; Бендер, Майкл Л.; Чертче, Томас; Жузель, Джин (15 июля 2016 г.). «Установка хронологии для базального льда в Dye-3 и Grip: последствия для долгосрочной стабильности ледяного шпата Гренландии» . Земля и планетарные научные письма . 451 : 1–9. BIBCODE : 2016E & PSL.451 .... 1y . doi : 10.1016/j.epsl.2016.06.053 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Hörhold, M.; Münch, T.; Weißbach, S.; Kipfstuhl, S.; Freitag, J.; Сасген, я.; Lohmann, G.; Винтер, Б.; Laepple, T. (18 января 2023 г.). «Современные температуры в центральной части Гренландии в прошлом тысячелетие». Природа . 613 (7506): 525–528. Bibcode : 2014natur.510..525r . doi : 10.1038/nature13456 . PMID 24965655 . S2CID 4468457 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Бринер, Джейсон П.; Куззоне, Джошуа К.; Бэджли, Джессика А.; Янг, Николас Э.; Стейг, Эрик Дж.; Morlighem, Mathieu; Шлегель, Николь-Жанна; Хаким, Грегори Дж.; Schaefer, Joerg M.; Джонсон, Джесси В.; Lesnek, Alia J.; Томас, Элизабет К.; Аллан, Эстель; Беннике, Оле; Cluett, Allison A.; Csatho, Beata; де Вернал, Энн; Даунс, Джейкоб; Ларур, Эрик; Новицки, Софи (30 сентября 2020 года). «Скорость потери массы от ледяного покрова Гренландии превысит значения голоцена в этом столетии». Природа . 586 (7827): 70–74. Bibcode : 2020nater.586 ... 70b . doi : 10.1038/s41586-020-2742-6 . PMID 32999481 . S2CID 222147426 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный «Специальный отчет о океане и криосфере в изменяющемся климате: резюме исполнительной власти» . МГЭИК . Архивировано из оригинала 8 ноября 2023 года . Получено 5 декабря 2023 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Stendel, Martin; Mottram, Ruth (22 сентября 2022 г.). «Гостевой пост: как ледяной щит Гренландии в 2022 году» . Углеродная бригада . Архивировано из оригинала 22 октября 2022 года . Получено 22 октября 2022 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Fox-Kemper, B.; Хьюитт, HT ; Xiao, C.; Adalgeirsdóttir, G.; Drijfhout, ss; Эдвардс, TL; Голледж, NR; Hemer, M.; Kopp, re; Krinner, G.; Микс, А. (2021). Masson-Delmotte, V.; Zhai, P.; Pirani, A.; Коннорс, SL; Péan, C.; Berger, S.; Caud, N.; Chen, Y.; Goldfarb, L. (Eds.). «Глава 9: Изменения в океане, криосфере и уровне моря» (PDF) . Изменение климата 2021: Основа физической науки. Вклад рабочей группы I в шестой отчет об оценке межправительственной группы по изменению климата . Издательство Кембриджского университета, Кембридж, Великобритания и Нью -Йорк, Нью -Йорк, США. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 24 октября 2022 года . Получено 22 октября 2022 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Ашванден, Энди; Fahnestock, Mark A.; Трюффер, Мартин; Бринкерхофф, Дуглас Дж.; Хок, Регин; Хроулев, Константин; Mottram, Ruth; Хан, С. Аббас (19 июня 2019 г.). «Вклад ледяного покрова Гренландии на уровень моря в течение следующего тысячелетия» . Наука достижения . 5 (6): 218–222. Bibcode : 2019scia .... 5.9396a . doi : 10.1126/sciadv.aav9396 . PMC 6584365 . PMID 31223652 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон Mouginot, Jérémie; Риньот, Эрик; Bjørk, Anders A.; Ван Ден Броке, Михиэль; Миллан, Роман; Morlighem, Mathieu; Ноэль, Брайс; Scheuchl, Bernd; Вуд, Майкл (20 марта 2019 г.). «Сорок шесть лет баланса на льду Гренландии с 1972 по 2018 год» . Труды Национальной академии наук . 116 (19): 9239–9244. Bibcode : 2019pnas..116.9239m . doi : 10.1073/pnas.1904242116 . PMC 6511040 . PMID 31010924 .

- ^ IPCC, 2021: Резюме для политиков архивировали 11 августа 2021 года на машине Wayback . В кн.: Изменение климата 2021: Физическая научная основа. Вклад рабочей группы I в шестой отчет об оценке межправительственной панели по изменению климата архивировал 26 мая 2023 года на машине Wayback [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, SL Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, Mi Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, JBR Мэтьюз, Т.К. Мейкок, Т. Уотерфилд, О. Йелекчи, Р. Ю и Б. Чжоу (ред.)]. Издательство Кембриджского университета, Кембридж, Великобритания и Нью -Йорк, Нью -Йорк, США, с. 3–32, doi: 10.1017/9781009157896.001.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Христос, Эндрю Дж.; Rittenour, Tammy M.; Bierman, Paul R.; Кейслинг, Бенджамин А.; Кнуц, Пол С.; Томсен, Тонни Б.; Кейлен, Нинке; Фосдик, Джули С.; Хемминг, Сидни Р.; Тисон, Жан-Луи; Блард, Пьер-Хенри; Steffensen, Jørgen P.; Caffee, Marc W.; Корбетт, Ли Б.; Даль-Дженсен, Дорт; Dethier, David P.; Хиди, Алан Дж.; Perdrial, Николас; Питом, Дороти М.; Стейг, Эрик Дж.; Томас, Элизабет К. (20 июля 2023 г.). «Деглакация Северо -Западной Гренландии во время морской изотопной стадии 11». Наука . 381 (6655): 330–335. Bibcode : 2023sci ... 381..330C . doi : 10.1126/science.ade4248 . PMID 37471537 . S2CID 259985096 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Армстронг Маккей, Дэвид; Абрамс, Джесси; Винкельманн, Рикарда; Sakschewski, Boris; Лориани, Сина; Fetzer, Ingo; Корнелл, Сара; Рокстрем, Йохан; Стаал, Ари; Лентон, Тимоти (9 сентября 2022 г.). «Превышение 1,5 ° C Глобальное потепление может вызвать несколько моментов климата» . Наука . 377 (6611): EABN7950. doi : 10.1126/science.abn7950 . HDL : 10871/131584 . ISSN 0036-8075 . PMID 36074831 . S2CID 252161375 . Архивировано из оригинала 14 ноября 2022 года . Получено 22 октября 2022 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Армстронг Маккей, Дэвид (9 сентября 2022 г.). «Превышение 1,5 ° C глобальное потепление может вызвать несколько климатических точек переплета - бумажный объяснитель» . Климат Архивировано из оригинала 18 июля 2023 года . Получено 2 октября 2022 года .

- ^ Струнк, Астрид; Кнудсен, Мэдс Фауршоу; Эгольм, Дэвид Л. Э; Янсен, Джон д .; Леви, Лора Б.; Jacobsen, bo h .; Ларсен, Николай К. (18 января 2017 г.). «Один миллион лет истории оледенения и денуда в Западной Гренландии» . Природная связь . 8 : 14199. Bibcode : 2017natco ... 814199s . doi : 10.1038/ncomms14199 . PMC 5253681 . PMID 28098141 .

- ^ Ашванден, Энди; Fahnestock, Mark A.; Труффер, Мартин (1 февраля 2016 г.). «Сложный поток ледника Гренландии захвачен» . Природная связь . 7 : 10524. Bibcode : 2016natco ... 710524a . doi : 10.1038/ncomms10524 . PMC 4740423 . PMID 26830316 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Хан, Шфакат а.; Bjørk, Anders a.; Бамбер, Джонатан Л.; Morlight, Mathieu; Доказательство, Майкл; Kjær, Kurt H.; Mouginot, Jérémie; Løkkegaard, Anja; Голландия, Дэвид М.; Ашванден, Энди; Чжан, Бао; Хелм, Вейт; Korsgaard, Niels J.; Колган, Уильям; Ларсен, Николай К.; Лю, Лин; Хансен, Карина; Барлетта, Валентина; Дал-Дженсен, Трин с.; Сёндергаард, Энн Софи; Като, Бейта м.; Сасген, Инго; Коробка, Джейсон; Шенк, Тони (17 ноября 2020 г.). «Столетний ответ трех крупнейших ведущих ледников Гренландии» . Природная связь . 11 (1): 5718. Бибкод : 2020natco..11.5718k . Doi : 10.1038/s41467-020-19580-5 . PMC 7672108 . PMID 33203883 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Джапсен, Питер; Зеленый, Пол Ф.; Боноу, Йохан М.; Нильсен, Troels FD; Чалмерс, Джеймс А. (5 февраля 2014 г.). «От вулканических равнин до ледяных пиков: история захоронения, подъема и эксгумации Южной Восточной Гренландии после открытия NE Atlantic». Глобальные и планетарные изменения . 116 : 91–114. Bibcode : 2014GPC ... 116 ... 91J . doi : 10.1016/j.gloplacha.2014.01.012 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Solgaard, Anne M.; Боноу, Йохан М.; Ланген, Питер Л.; Джапсен, Питер; Хвидберг, Кристина (27 сентября 2013 г.). «Горное здание и посвящение Ледяного покрова Гренландии». Палеогеография, палеоклиматология, палеоэкология . 392 : 161–176. Bibcode : 2013ppp ... 392..161s . doi : 10.1016/j.palaeo.2013.09.019 .

- ^ Koenig, SJ; Долан, Ам; de Boer, B.; Камень, EJ; Хилл, диджей; Deconto, RM; Abe-ouchi, A.; Lunt, DJ; Поллард, Д.; Quiquet, A.; Сайто, Ф.; Savage, J.; Ван де Валь, Р. (5 марта 2015 г.). «Зависимость от ледяного покрова моделируемого ледяного щита Гренландии в среднем плиоцене» . Климат прошлого . 11 (3): 369–381. Bibcode : 2015clipa..11..369k . doi : 10.5194/cp-11-369-2015 .

- ^ Ян, Ху; Кребс-Канзов, штат Юта; Кляйнер, Томас; Sidorenko, Dmitry; Родехак, Кристиан Бернд; Ши, Сяосу; Герц, Пол; Niu, Lu J.; Гован, Эван Дж.; Хинк, Себастьян; Лю, Синсинг; Stap, Lennert B.; Ломанн, Геррит (20 января 2022 года). «Влияние палеоклимата на нынешнюю и будущую эволюцию Ледяного покрова Гренландии» . Plos один . 17 (1): E0259816. Bibcode : 2022ploso..1759816Y . doi : 10.1371/journal.pone.0259816 . PMC 8776332 . PMID 35051173 .

- ^ Винас, Мария-Джозе (3 августа 2016 г.). «Карты НАСА оттаили районы под ледяным покровом Гренландии» . НАСА. Архивировано из оригинала 12 декабря 2023 года . Получено 12 декабря 2023 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Irvalı, ноль; Galaasen, Eirik v.; Ninnemann, Ulysses S.; Розенталь, Яир; Родился, Андреас; Кляйвен, Хельга (Кикки) Ф. (18 декабря 2019 г.). «Низкий климат порог для кончины Ледяного поленового поема Южного Гренландии во время позднего плейстоцена» . Труды Национальной академии наук . 117 (1): 190–195. doi : 10.1073/pnas.1911902116 . ISSN 0027-8424 . PMC 6955352 . PMID 31871153 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Schaefer, Joerg M.; Финкель, Роберт С.; Балко, Грег; Alley, Richard B.; Caffee, Marc W.; Бринер, Джейсон П.; Молодой, Николас Э.; Гоу, Энтони Дж.; Шварц, Розанна (7 декабря 2016 года). «Гренландия была почти без льда в течение длительных периодов во время плейстоцена». Природа . 540 (7632): 252–255. Bibcode : 2016natur.540..252s . doi : 10.1038/nature20146 . PMID 27929018 . S2CID 4471742 .

- ^ Alley, Richard B (2000). Двухмильная машина времени: ледяные ядра, резкое изменение климата и наше будущее . ПРИЗНАЯ УНИВЕРСИТЕТА ПРИСЕТА . ISBN 0-691-00493-5 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Gkinis, v.; Симонсен, SB; Бухардт, SL; Белый, jwc; Винтер, Б.М. (1 ноября 2014 г.). «Скорость диффузии изотопов воды от ледяного ядра Northgrip за последние 16 000 лет - гляциологические и палеоклиматические последствия». Земля и планетарные научные письма . 405 : 132–141. Arxiv : 1404.4201 . BIBCODE : 2014E & PSL.405..132G . doi : 10.1016/j.epsl.2014.08.022 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Адольфи, Флориан; Мушцы, Roommund; Свенссон ис; Алдахан, Ала; Возможно, Питтон; Пиво, жонгг; Шолт, Джеспер; Бьёрак, Сванте; Матнс, Катжа; Thiabblemnt, Romia (17 августа 2014 г.). «Постоянная связь между активностью Соллара и Климатом Гренландии во время последнего позднего обхода». Природа Геонаука . 7 (9): 662-666. Код BIB : 2014Natg ... 7..662a . Doi : 10.1038 / ngeo2225 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Куросаки, Ютака; Матоба, Смито; Изука, Йошорри; Фудзита, Коджи; Шимада, Риген (26 декабря 2022 г.). «Повышенные выбросы диметилсульфида океана в районах морского ледяного отступления выведены из ледяного ядра Гренландии » Коммуникации Земля и окружающая среда 3 (1): Bibcode : 2022comee.3..327k 327. Doi : 10.1038/s43247-022-00661- w ISSN 2662-4

Текст и изображения доступны в рамках Attribution Creative Commons 4.0 Международная лицензия, архивная 16 октября 2017 года на машине Wayback .

Текст и изображения доступны в рамках Attribution Creative Commons 4.0 Международная лицензия, архивная 16 октября 2017 года на машине Wayback .

- ^ Masson-Delmotte, V.; Jouzel, J.; Landais, A.; Stievenard, M.; Джонсен, SJ; Белый, jwc; Werner, M.; Sveinbjornsdottir, A.; Фурер, К. (1 июля 2005 г.). «Избыток дейтерия сцепления выявляет быстрые и орбитальные изменения в влажности Гренландии» (PDF) . Наука . 309 (5731): 118–121. Bibcode : 2005sci ... 309..118m . doi : 10.1126/science.1108575 . PMID 15994553 . S2CID 10566001 . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 19 мая 2022 года . Получено 13 декабря 2023 года .

- ^ Zielinski, GA; Мэйвски, Пенсильвания; Meeker, Ld; Whitlow, S.; Twickler, MS; Моррисон, М.; Миз, да; Gow, AJ; Alley, RB (13 мая 1994 г.). «Запись вулканизма с 7000 г. до н.э. из ледяного ядра GISP2 и последствий для системы вулканового климата». Наука . 264 (5161): 948–952. Bibcode : 1994sci ... 264..948Z . doi : 10.1126/science.264.5161.948 . PMID 17830082 . S2CID 21695750 .

- ^ Фишер, Хубертус; Шюпбах, Саймон; Gfeller, Gideon; Биглер, Матиас; Röthlisberger, Regine; Эрхардт, Тобиас; Стокер, Томас Ф.; Малвани, Роберт; Вольф, Эрик У. (10 августа 2015 г.). «Миллениальные изменения в североамериканской дикой природе и почвенной активности в течение последнего ледникового цикла» (PDF) . Природа Геонаука . 8 (9): 723–727. Bibcode : 2015natge ... 8..723f . doi : 10.1038/ngeo2495 . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 3 декабря 2023 года . Получено 13 декабря 2023 года .

- ^ Вуд, младший (21 октября 2022 г.). «Другие способы изучения финансов, стоящих за рождением классической Греции» . Археометрия . 65 (3): 570–586. doi : 10.1111/arcm.12839 .

- ^ Макконнелл, Джозеф Р.; Уилсон, Эндрю I.; Стол, Андреас; Arienzo, Monica M.; Челлман, Натан Дж.; Экхардт, Сабина; Томпсон, Элизабет М.; Поллард, А. Марк; Стеффенсен, Джёрген Педер (29 мая 2018 г.). «Ведущее загрязнение, зарегистрированное в Гренландском льду, указывает на то, что европейские выбросы отслеживали лихие, войны и имперскую экспансию во время древности» . Труды Национальной академии наук . 115 (22): 5726–5731. Bibcode : 2018pnas..115.5726m . doi : 10.1073/pnas.1721818115 . PMC 5984509 . PMID 29760088 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый «Арктическая оценка воздействия климата» . Архивировано из оригинала 14 декабря 2010 года . Получено 23 февраля 2006 года .

- ^ «Арктическая оценка воздействия климата» . Союз заинтересованных ученых . 16 июля 2008 года. Архивировано с оригинала 5 декабря 2023 года . Получено 5 декабря 2023 года .

- ^ Винтер, Б.М.; Андерсен, KK; Джонс, П.Д.; Бриффа, Кр; Cappelen, J. (6 июня 2006 г.). «Расширение температурных записей Гренландии в конце восемнадцатого века» (PDF) . Журнал геофизических исследований . 111 (D11): D11105. Bibcode : 2006jgrd..11111105V . doi : 10.1029/2005jd006810 . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 23 февраля 2011 года . Получено 10 июля 2007 года .

- ^ Кьелдсен, Кристиан К.; Korsgaard, Niels J.; Bjørk, Anders a.; Хан, Шфакат а.; Коробка, Джейсон е.; Спешник, Svend; Ларсен, Николай К.; Бамбер, Джонатан Л.; Колган, Уильям; Ван Ден Борк, Михиэль; Siggaard-Andersen, Marie-Louise; Нут, Кристофер; Schomacker, Anders; Андресен, Камилла с.; Уиллерслев, Эске; Kjær, Kurt H. (16 декабря 2015 г.). «Пространственное и временное распределение потери массы от ледяного покрова Гренландии с 1900 г. н.». Природа . 528 (7582): 396–400. Bibcode : 2015nature.528..396K . Doi : 10.1038/nature16183 . HDL : 1874/329934 . PMID 26672555 . S2CID 4468824 .

- ^ Фредериксе, Томас; Ландерер, Феликс; Карон, Ламберт; Адхикари, Сурендра; Паркс, Дэвид; Хамфри, Винсент В.; Дандрендорф, Сенке; Хогарт, Питер; Занна, Лоре; Ченг, Лиджин; Ву, Юн-Хао (19 августа 2020 г.). «Причины повышения уровня моря с 1900 года». Природа . 584 (7821): 393–397. doi : 10.1038/s41586-020-2591-3 . PMID 32814886 . S2CID 221182575 .

- ^ IPCC, 2007. Trenberth, Ke, Pd Jones, P. Ambenje, R. Bojariu, D. Easterling, A. Klein Tank, D. Parker, F. Rahimzadeh, Ja Renwick, M. rusticucci, B. Соден и P. Zhai, 2007: Наблюдения: поверхностное и атмосферное изменение климата. В кн.: Изменение климата 2007: Наука физическая наука. Вклад рабочей группы I в четвертый отчет об оценке межправительственной группы по изменению климата [Соломон С., Д. Цин .)]. Издательство Кембриджского университета, Кембридж, Великобритания и Нью -Йорк, Нью -Йорк, США. [1] Архивировано 23 октября 2017 года на машине Wayback

- ^ Штеффен, Конрад; Каллен, Никлоас; Хафф, Рассел (13 января 2005 г.). Изменчивость климата и тенденции вдоль западного склона ледяного покрова Гренландии в 1991-2004 годах (PDF) . 85th American Meteorogical Union Ежегодное собрание. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 14 июня 2007 года.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Изменение климата 2001: Научная основа. Вклад рабочей группы I в третий отчет об оценке межправительственной панели по изменению климата (МГЭИК) [Houghton, JT, Y. Ding, DJ Griggs, M. Noguer, PJ Van Der Linden, X. Dai, K. Maskell, и и CA Johnson (Eds.)] Издательство Кембриджского университета , Кембридж, Великобритания и Нью -Йорк, Нью -Йорк, США, 881pp. [2] Архивировано 16 декабря 2007 года на машине Wayback , «Изменение климата 2001: научная основа» . Архивировано из оригинала 10 февраля 2006 года . Получено 10 февраля 2006 года . и [3] архивировали 19 января 2017 года на машине Wayback .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Шепард, Эндрю; Айвин, Эрик; Риньот, Эрик; Смит, Бен; Ван Ден Броке, Михиэль; Velicogna, Изабелла ; Уайтхаус, Пиппа; Бриггс, Кейт; Йоуин, Ян; Криннер, Герхард; Новицки, Софи (12 марта 2020 года). «Массовый баланс Ледяного покрова Гренландии с 1992 по 2018 год» . Природа . 579 (7798): 233–239. doi : 10.1038/s41586-019-1855-2 . HDL : 2268/242139 . ISSN 1476-4687 . PMID 31822019 . S2CID 219146922 . Архивировано из оригинала 23 октября 2022 года . Получено 23 октября 2022 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный «Расплавался: Гренландия потеряла 586 миллиардов тонн льда в 2019 году» . Phys.org . Архивировано из оригинала 13 сентября 2020 года . Получено 6 сентября 2020 года .

- ^ Бамбер, Джонатан Л; Вестей, Ричард М; Marzeion, Ben; Вутерс, Берт (1 июня 2018 года). «Вклад земельного льда в уровень моря во время спутниковой эры» . Экологические исследования . 13 (6): 063008. BIBCODE : 2018ERL .... 13F3008B . doi : 10.1088/1748-9326/AAC2F0 .

- ^ Се, Айхонг; Чжу, Цзянпинг; Кан, Шичанг; Цинь, Сян; Сюй, Бинг; Ван, Йихенг (3 октября 2022 г.). «Сравнение полярного усиления между тремя полюсами Земли при различных социально -экономических сценариях от температуры поверхностного воздуха CMIP6» . Научные отчеты . 12 (1): 16548. Bibcode : 2022natsr..1216548x . doi : 10.1038/s41598-022-21060-3 . PMC 9529914 . PMID 36192431 .

- ^ Луна, Твила ; Ahlstrøm, Andreas; Гелцер, Хейко; Липскомб, Уильям; Новицки, Софи (2018). «Растущие океаны гарантированы: потерь льда в арктических землях и повышение уровня моря» . Текущие отчеты об изменении климата . 4 (3): 211–222. Bibcode : 2018cccr .... 4..211m . doi : 10.1007/s40641-018-0107-0 . ISSN 2198-6061 . PMC 6428231 . PMID 30956936 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Choi, Youngmin; Morlighem, Mathieu; Риньот, Эрик; Вуд, Майкл (4 февраля 2021 года). «Ледяная динамика останется основным фактором потери массовой массы ледяного облига Гренландии в течение следующего столетия» . Коммуникации Земля и окружающая среда . 2 (1): 26. Bibcode : 2021come ... 2 ... 26с . doi : 10.1038/s43247-021-00092-z .

Текст и изображения доступны в рамках Attribution Creative Commons 4.0 Международная лицензия, архивная 16 октября 2017 года на машине Wayback .

Текст и изображения доступны в рамках Attribution Creative Commons 4.0 Международная лицензия, архивная 16 октября 2017 года на машине Wayback .

- ^ Луна, Твила; Йоуин, Ян (7 июня 2008 г.). «Изменения в положении Ледяного фронта в« Гренландских ледниках »с 1992 по 2007 год». Журнал геофизических исследований: Земля поверхность . 113 (F2). Bibcode : 2008jgrf..113.2022m . doi : 10.1029/2007jf000927 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Sole, A.; Payne, T.; Bamber, J.; Nienow, P.; Krabill, W. (16 декабря 2008 г.). «Проверка гипотез причины периферического прореживания ледяного покрова Гренландии: Является ли загромождающее ледоволое с аномально высокими показателями?» Полем Криосфера . 2 (2): 205–218. Bibcode : 2008tcry .... 2..205s . doi : 10.5194/TC-2-205-2008 . ISSN 1994-0424 . S2CID 16539240 .

- ^ Шукман, Дэвид (28 июля 2004 г.). "Гренландия" Расплавляется ", ускоряясь » . BBC. Архивировано из оригинала 22 декабря 2023 года . Получено 22 декабря 2023 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Коннор, Стив (25 июля 2005 г.). «Таящий ледник Гренландии может ускорить повышение уровня моря» . Независимый . Архивировано из оригинала 27 июля 2005 года . Получено 30 апреля 2010 года .

- ^ Томас, Роберт Х.; Абдалати, Уалид; Акинс, Торри Л.; Csatho, Beata M.; Фредерик, граф Б.; Гогинени, Шива П.; Крабилл, Уильям Б.; Manizade, Serdar S.; Риньот, Эрик Дж. (1 мая 2000 г.). «Существенное истончение крупного ледника Восточной Гренландии». Геофизические исследования . 27 (9): 1291–1294. Bibcode : 2000georl..27.1291t . doi : 10.1029/1999gl008473 .

- ^ Ховат, Ян М.; Ан, Юшин; Йоуин, Ян; Ван Ден Броке, Михиэль Р.; Ленертс, Ян Т.М.; Смит, Бен (18 июня 2011 г.). «Массовый баланс трех крупнейших ледников Гренландии, 2000–2010». Геофизические исследования . 27 (9). Bibcode : 2000georl..27.1291t . doi : 10.1029/1999gl008473 .

- ^ Барнетт, Джейми; Холмс, Фелисити А.; Киршнер, Нина (23 августа 2022 г.). «Моделированное динамическое отступление ледника Кангерлусуака, Восточная Гренландия, сильно под влиянием последовательного отсутствия ледяного меланжа в Кангерлусуаке фьорд». Журнал гляциологии . 59 (275): 433–444. doi : 10.1017/jog.2022.70 .

- ^ "Ilulissat Icefjord" . Центр Всемирного наследия ЮНЕСКО . Организационная, научная и культурная организация Организации Объединенных Наций. Архивировано с оригинала 24 декабря 2018 года . Получено 19 июня 2021 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Йоуин, Ян; Абдалати, Уалид; Fahnestock, Mark (декабрь 2004 г.). «Большие колебания скорости на леднике Джакобшавна в Джакобшавне Гренландии». Природа . 432 (7017): 608–610. Bibcode : 2004natur.432..608j . doi : 10.1038/nature03130 . PMID 15577906 . S2CID 4406447 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Pelto.M, Hughes, T, Fastook J., Brecher, H. (1989). «Равновесное состояние Jakobshavns Isbræ, Западная Гренландия» . Анналы гляциологии . 12 : 781–783. Bibcode : 1989angla..12..127p . doi : 10.3189/s0260305500007084 .

{{cite journal}}: Cs1 maint: несколько имен: список авторов ( ссылка ) - ^ Jump up to: а беременный «Самый быстрый ледник удваивается в скорости» . НАСА. Архивировано из оригинала 19 июня 2006 года . Получено 2 февраля 2009 года .

- ^ «Изображения показывают разрыв двух крупнейших ледников Гренландии, предсказывают распад в ближайшем будущем» . НАСА Земля Обсерватория. 20 августа 2008 года. Архивировано из оригинала 31 августа 2008 года . Получено 31 августа 2008 года .

- ^ Хикки, Ханна; Феррейра, Барбара (3 февраля 2014 г.). «Самый быстрый ледник Гренландии устанавливает новую скоростную запись» . Университет Вашингтона . Архивировано из оригинала 23 декабря 2023 года . Получено 23 декабря 2023 года .

- ^ Расмуссен, Кэрол (25 марта 2019 г.). «Холодная вода в настоящее время замедляет самый быстрый ледник Гренландии» . НАСА/JPL . Архивировано из оригинала 22 марта 2022 года . Получено 23 декабря 2023 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Хазендар, Ала; Fenty, Ian G.; Кэрролл, Дастин; Гарднер, Алекс; Ли, Крейг М.; Фукумори, Ичиро; Ван, Оу; Чжан, Хонг; Серусси, Элен; Моллер, Делвин; Ноэль, Брайс Пи; Ван Ден Броке, Михиэль Р.; Динардо, Стивен; Уиллис, Джош (25 марта 2019 г.). «Прерывание двух десятилетий ускорения и прореживания джакобшавн и истончения, когда региональное океан охлаждается». Природа Геонаука . 12 (4): 277–283. Bibcode : 2019natge..12..277k . doi : 10.1038/s41561-019-0329-3 . HDL : 1874/379731 . S2CID 135428855 .

- ^ «Огромный ледяной остров отрывается от ледника Гренландии» . BBC News . 7 августа 2010 года. Архивировано с оригинала 8 апреля 2018 года . Получено 21 июля 2018 года .

- ^ «Айсберг вдвое больше, чем Манхэттен отрывается от ледника Гренландии» . Канадская вещательная корпорация . Ассошиэйтед Пресс. 18 июля 2012 года. Архивировано с оригинала 31 июля 2013 года . Получено 22 декабря 2023 года .

- ^ Окссон, Хеннинг; Morlighem, Mathieu; Нильссон, Йохан; Странн, Кристиан; Якобссон, Мартин (9 мая 2022 г.). «Ice Shelf Petermann не может восстановиться после будущего распада». Природная связь . 13 : 2519. Bibcode : 2022natco..13.2519a . doi : 10.1038/s41467-022-29529-5 .

- ^ Эндерлин, Эллин М.; Ховат, Ян М.; Чон, Сонсу; Noh, myoung-jong; Ван Анджелен, январь Х.; Ван Ден Броке, Михиэль (16 января 2014 г.). «Улучшенный массовый бюджет на ледяной щите Гренландии». Геофизические исследования . 41 (3): 866–872. Bibcode : 2014georl..41..866e . doi : 10.1002/2013GL059010 .

- ^ Хова, я; Joughin, я.; Tulaczyk, S.; Gogineni, S. (22 ноября 2005 г.). «Быстрое отступление и ускорение ледника Хелхейма, Восточная Гренландия». Геофизические исследования . 32 (22). Bibcode : 2005georl..3222202H . doi : 10.1029/2005gl024737 .

- ^ Крпита, Мередит; Ekström, Göran (1 апреля 2010 г.). «Ледяные землетрясения в Гренландии и Антарктиде». Ежегодный обзор земли и планетарных наук . 38 (1): 467–491. Bibcode : 2010areps..38..467n . doi : 10.1146/annurev-arth-040809-152414 . ISSN 0084-6597 .

- ^ Kehrl, LM; Joughin, я.; Шин, де; Floricioiu, D.; Кригер Л. (17 августа 2017 г.). «Сезонные и межгодовые переменные в положении термина, скорости ледника и возвышении на ледниках Хелхейма и Кангерлусуака с 2008 по 2016 год» (PDF) . Журнал геофизических исследований: Земля поверхность . 122 (9): 1635–1652. Bibcode : 2017jgrf..122.1635K . doi : 10.1002/2016JF004133 . S2CID 52086165 . Архивировано (PDF) от оригинала 17 ноября 2023 года . Получено 22 декабря 2023 года .

- ^ Уильямс, Джошуа Дж.; Гурмелен, Ноэль; Ниеноу, Петр; Бунс, Чарли; Слейтер, Дональд (24 ноября 2021 г.). «Ледник Хелхейма, готовясь к драматическому отступлению». Геофизические исследования . 35 (17). Bibcode : 2021georl..4894546W . doi : 10.1029/2021GL094546 .

- ^ Ховат, Ян М.; Смит, Бен Э.; Йоуин, Ян; Скамбос, Тед А. (9 сентября 2008 г.). «Скорость потери объема льда Юго -Восточной Гренландии от комбинированных наблюдений Icesat и Aster» . Геофизические исследования . 35 (17). Bibcode : 2008georl..3517505H . doi : 10.1029/2008gl034496 . ISSN 0094-8276 . S2CID 3468378 .

- ^ Larocca, LJ; Twining - Ward, M.; AXFORD, Y.; Schweinsberg, AD; Ларсен, Ш; Вестергаард -Нильсен, а.; Luetzenburg, G.; Бринер, JP; Кьелдсен, KK; Бьёрк, А.А. (9 ноября 2023 г.). «Ускоренное ускоренное отступление периферийных ледников в двадцать первом веке». Изменение климата природы . 13 (12): 1324–1328. Bibcode : 2023natcc..13.1324L . doi : 10.1038/s41558-023-01855-6 .

- ^ Моррис, Аманда (9 ноября 2023 г.). «За последние два десятилетия уровень отступления Гренландии удвоился» . Северо -западный университет . Архивировано из оригинала 22 декабря 2023 года . Получено 22 декабря 2023 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Ciracì, Enrico; Риньот, Эрик; Scheuchl, Bernd (8 мая 2023 г.). «Стоимость расплава в зоне заземления размером с километр в Гренландии Петерманна, Гренландии, до и во время отступления» . ПНА . 120 (20): E2220924120. Bibcode : 2023pnas..12020924C . doi : 10.1073/pnas.2220924120 . PMC 10193949 . PMID 37155853 .

- ^ Риньот, Эрик; Сухой, Свапрасад; Йоуин, Ян; Крабилл, Уильям (1 декабря 2001 г.). «Вклад в гляциологию Северной Гренландии из спутниковой радиолокационной интернетрии» Журнал геофизических исследований: атмосферы 106 (D24): 34007–34 Bibcode : 2001jgr ... 10634007R Doi : 10.1029/ 2001jd900071

- ^ Rignot, E.; Braaten, D.; Gogineni, S.; Krabill, W.; McConnell, Jr (25 мая 2004 г.). «Быстрые льды из юго -восточных ледников Гренландии». Геофизические исследования . 31 (10). Bibcode : 2004georl..3110401r . doi : 10.1029/2004gl019474 .

- ^ Лакман, Адриан; Мюррей, Тави; де Ланге, Ремко; Ханна, Эдвард (3 февраля 2006 г.). «Быстрые и синхронные изменения ледоладах в Восточной Гренландии» . Геофизические исследования . 33 (3). Bibcode : 2006georl..33.3503L . doi : 10.1029/2005gl025428 . ISSN 0094-8276 . S2CID 55517773 .

- ^ Хьюз, Т. (1986). «Эффект Jakobshavn». Геофизические исследования . 13 (1): 46–48. Bibcode : 1986georl..13 ... 46h . doi : 10.1029/gl013i001p00046 .

- ^ Томас, Роберт Х. (2004). «Анализ силовой переносчики недавнего истончения и ускорения Jakobshavn Isbræ, Гренландия» . Журнал гляциологии . 50 (168): 57–66. Bibcode : 2004jglac..50 ... 57t . doi : 10.3189/172756504781830321 . ISSN 0022-1430 . S2CID 128911716 .

- ^ Томас, Роберт Х.; Абдалати, Уалид; Фредерик, граф; Крабилл, Уильям; Манизаде, Сердар; Штеффен, Конрад (2003). «Исследование поверхностного плавления и динамического истончения на Джакобшавн -Исбраре, Гренландия» . Журнал гляциологии . 49 (165): 231–239. Bibcode : 2003jglac..49..231t . doi : 10.3189/172756503781830764 .

- ^ Странео, Фиамметта; Хеймбах, Патрик (4 декабря 2013 г.). «Северная атлантическая потепление и отступление в розетках Гренландии». Природа . 504 (7478): 36–43. Bibcode : 2013natur.504 ... 36S . doi : 10.1038/nature12854 . PMID 24305146 . S2CID 205236826 .

- ^ Голландия, D M.; Younn, BD; Ribergaard, MH; Лайберт, Б. (28 сентября 2008 г.). «Ускорение Jakobshavn Isbrae, вызванное теплыми водами океана». Природа Геонаука . 1 (10): 659–664. Bibcode : 2008natge ... 1..659h . doi : 10.1038/ngeo316 . S2CID 131559096 .

- ^ Rignot, E.; Сюй, у.; Menemenlis, D.; Mouginot, J.; Scheuchl, B.; Li, x.; Morlighem, M.; Seroussi, H.; Ван ден Броке, м.; Fenty, я.; Cai, C.; An, L.; Де Флууриан, Б. (30 мая 2016 г.). «Моделирование океана, индуцированного океаном, показателя таяния льда в пяти ледниках Западной Гренландии за последние два десятилетия». Геофизические исследования . 43 (12): 6374–6382. Bibcode : 2016georl..43.6374r . doi : 10.1002/2016gl068784 . HDL : 1874/350987 . S2CID 102341541 .

- ^ Кларк, Тед С.; Echelmeyer, Keith (1996). «Сейсмическое повторное свидетельство о глубоком субджизическом впадине под Jakobshavns Isbræ, Западная Гренландия». Журнал гляциологии . 43 (141): 219–232. doi : 10.3189/s0022143000004081 .

- ^ van der Veen, CJ; Leftwich, T.; von Frese, R.; Csatho, BM; Li, J. (21 июня 2007 г.). «Подледниковая топография и геотермальный тепловой поток: потенциальные взаимодействия с дренажом ледяного покрова Гренландии» . Геофизические исследования . L12501. 34 (12): 5 стр. Bibcode : 2007georl..3412501V . doi : 10.1029/2007gl030046 . HDL : 1808/17298 . S2CID 54213033 . Архивировано из оригинала 8 сентября 2011 года . Получено 16 января 2011 года .

- ^ Йоуин, Ян; Шин, Дэвид Э.; Смит, Бенджамин Е.; Floricioiu, Дана (24 января 2020 года). «Десятилетие изменчивости на Jakobshavn Isbræ: скорость температуры океана скорость за счет влияния на жесткость Mélange» . Криосфера . 14 (1): 211–227. Bibcode : 2020tcry ... 14..211j . doi : 10.5194/TC-14-211-2020 . PMID 32355554 .

- ^ Йоуин, Ян; Ховат, Ян; Alley, Richard B.; Экстрем, Горан; Фансток, Марк; Луна, Твила; Крпита, Мередит; Трюффер, Мартин; Цай, Виктор С. (26 января 2008 г.). «Изменение льда и поведение приливной воды на ледниках Хельхейма и Кангердлугссуака, Гренландия». Журнал геофизических исследований: Земля поверхность . 113 (F1). Bibcode : 2008jgrf..113.1004j . doi : 10.1029/2007jf000837 .

- ^ Miller, Brandon (8 May 2023). "A major Greenland glacier is melting away with the tide, which could signal faster sea level rise, study finds". CNN. Archived from the original on 16 June 2023. Retrieved 16 June 2023.

- ^ Zwally, H. Jay; Abdalati, Waleed; Herring, Tom; Larson, Kristine; Saba, Jack; Steffen, Konrad (12 July 2002). "Surface Melt-Induced Acceleration of Greenland Ice-Sheet Flow". Science. 297 (5579): 218–222. Bibcode:2002Sci...297..218Z. doi:10.1126/science.1072708. PMID 12052902. S2CID 37381126.

- ^ Pelto, M. (2008). "Moulins, Calving Fronts and Greenland Outlet Glacier Acceleration". RealClimate. Archived from the original on 27 July 2009. Retrieved 27 September 2008.

- ^ Das, Sarah B.; Joughin, Ian; Behn, Mark D.; Howat, Ian M.; King, Matt A.; Lizarralde, Dan; Bhatia, Maya P. (9 May 2008). "Fracture Propagation to the Base of the Greenland Ice Sheet During Supraglacial Lake Drainage". Science. 320 (5877): 778–781. Bibcode:2008Sci...320..778D. doi:10.1126/science.1153360. hdl:1912/2506. PMID 18420900. S2CID 41582882. Archived from the original on 7 March 2022. Retrieved 7 March 2022.