Lead

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lead | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˈlɛd/ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | metallic gray | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar°(Pb) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lead in the periodic table | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 82 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 14 (carbon group) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 6 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | p-block | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Xe] 4f14 5d10 6s2 6p2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 18, 32, 18, 4 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | solid | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 600.61 K (327.46 °C, 621.43 °F) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 2022 K (1749 °C, 3180 °F) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (at 20° C) | 11.348 g/cm3 [3] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| when liquid (at m.p.) | 10.66 g/cm3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | 4.77 kJ/mol | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 179.5 kJ/mol | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | 26.650 J/(mol·K) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapor pressure

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | −4, −2, −1, 0,[4] +1, +2, +3, +4 (an amphoteric oxide) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 2.33 (in +4), 1.87 (in +2) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 175 pm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 146±5 pm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Van der Waals radius | 202 pm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | face-centered cubic (fcc) (cF4) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lattice constant | a = 494.99 pm (at 20 °C)[3] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal expansion | 28.73×10−6/K (at 20 °C)[3] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 35.3 W/(m⋅K) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | 208 nΩ⋅m (at 20 °C) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | diamagnetic | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar magnetic susceptibility | −23.0×10−6 cm3/mol (at 298 K)[5] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Young's modulus | 16 GPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shear modulus | 5.6 GPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bulk modulus | 46 GPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound thin rod | 1190 m/s (at r.t.) (annealed) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Poisson ratio | 0.44 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mohs hardness | 1.5 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Brinell hardness | 38–50 MPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7439-92-1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery | Middle East (7000 BCE) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Symbol | "Pb": from Latin plumbum | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Isotopes of lead | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Isotopic abundances vary greatly by sample[7] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Lead is a chemical element; it has symbol Pb (from Latin plumbum) and atomic number 82. It is a heavy metal that is denser than most common materials. Lead is soft and malleable, and also has a relatively low melting point. When freshly cut, lead is a shiny gray with a hint of blue. It tarnishes to a dull gray color when exposed to air. Lead has the highest atomic number of any stable element and three of its isotopes are endpoints of major nuclear decay chains of heavier elements.

Lead is a relatively unreactive post-transition metal. Its weak metallic character is illustrated by its amphoteric nature; lead and lead oxides react with acids and bases, and it tends to form covalent bonds. Compounds of lead are usually found in the +2 oxidation state rather than the +4 state common with lighter members of the carbon group. Exceptions are mostly limited to organolead compounds. Like the lighter members of the group, lead tends to bond with itself; it can form chains and polyhedral structures.

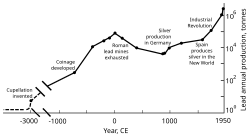

Since lead is easily extracted from its ores, prehistoric people in the Near East were aware of it. Galena is a principal ore of lead which often bears silver. Interest in silver helped initiate widespread extraction and use of lead in ancient Rome. Lead production declined after the fall of Rome and did not reach comparable levels until the Industrial Revolution. Lead played a crucial role in the development of the printing press, as movable type could be relatively easily cast from lead alloys.[8] In 2014, the annual global production of lead was about ten million tonnes, over half of which was from recycling. Lead's high density, low melting point, ductility and relative inertness to oxidation make it useful. These properties, combined with its relative abundance and low cost, resulted in its extensive use in construction, plumbing, batteries, bullets and shot, weights, solders, pewters, fusible alloys, white paints, leaded gasoline, and radiation shielding.

Lead is a neurotoxin that accumulates in soft tissues and bones. It damages the nervous system and interferes with the function of biological enzymes, causing neurological disorders ranging from behavioral problems to brain damage, and also affects general health, cardiovascular, and renal systems. Lead's toxicity was first documented by ancient Greek and Roman writers, who noted some of the symptoms of lead poisoning, but became widely recognized in Europe in the late 19th century.

Physical properties

[edit]Atomic

[edit]A lead atom has 82 electrons, arranged in an electron configuration of [Xe]4f145d106s26p2. The sum of lead's first and second ionization energies—the total energy required to remove the two 6p electrons—is close to that of tin, lead's upper neighbor in the carbon group. This is unusual; ionization energies generally fall going down a group, as an element's outer electrons become more distant from the nucleus, and more shielded by smaller orbitals.

The sum of the first four ionization energies of lead exceeds that of tin,[9] contrary to what periodic trends would predict. This is explained by relativistic effects, which become significant in heavier atoms,[10] which contract s and p orbitals such that lead's 6s electrons have larger binding energies than its 5s electrons.[11] A consequence is the so-called inert pair effect: the 6s electrons of lead become reluctant to participate in bonding, stabilising the +2 oxidation state and making the distance between nearest atoms in crystalline lead unusually long.[12]

Lead's lighter carbon group congeners form stable or metastable allotropes with the tetrahedrally coordinated and covalently bonded diamond cubic structure. The energy levels of their outer s- and p-orbitals are close enough to allow mixing into four hybrid sp3 orbitals. In lead, the inert pair effect increases the separation between its s- and p-orbitals, and the gap cannot be overcome by the energy that would be released by extra bonds following hybridization.[13] Rather than having a diamond cubic structure, lead forms metallic bonds in which only the p-electrons are delocalized and shared between the Pb2+ ions. Lead consequently has a face-centered cubic structure[14] like the similarly sized[15] divalent metals calcium and strontium.[16][a][b][c]

Bulk

[edit]Pure lead has a bright, shiny gray appearance with a hint of blue.[21] It tarnishes on contact with moist air and takes on a dull appearance, the hue of which depends on the prevailing conditions. Characteristic properties of lead include high density, malleability, ductility, and high resistance to corrosion due to passivation.[22]

Lead's close-packed face-centered cubic structure and high atomic weight result in a density[23] of 11.34 g/cm3, which is greater than that of common metals such as iron (7.87 g/cm3), copper (8.93 g/cm3), and zinc (7.14 g/cm3).[24] This density is the origin of the idiom to go over like a lead balloon.[25][26][d] Some rarer metals are denser: tungsten and gold are both at 19.3 g/cm3, and osmium—the densest metal known—has a density of 22.59 g/cm3, almost twice that of lead.[27]

Lead is a very soft metal with a Mohs hardness of 1.5; it can be scratched with a fingernail.[28] It is quite malleable and somewhat ductile.[29][e] The bulk modulus of lead—a measure of its ease of compressibility—is 45.8 GPa. In comparison, that of aluminium is 75.2 GPa; copper 137.8 GPa; and mild steel 160–169 GPa.[30] Lead's tensile strength, at 12–17 MPa, is low (that of aluminium is 6 times higher, copper 10 times, and mild steel 15 times higher); it can be strengthened by adding small amounts of copper or antimony.[31]

The melting point of lead—at 327.5 °C (621.5 °F)[32]—is very low compared to most metals.[23][f] Its boiling point of 1749 °C (3180 °F)[32] is the lowest among the carbon-group elements. The electrical resistivity of lead at 20 °C is 192 nanoohm-meters, almost an order of magnitude higher than those of other industrial metals (copper at 15.43 nΩ·m; gold 20.51 nΩ·m; and aluminium at 24.15 nΩ·m).[34] Lead is a superconductor at temperatures lower than 7.19 K;[35] this is the highest critical temperature of all type-I superconductors and the third highest of the elemental superconductors.[36]

Isotopes

[edit]Natural lead consists of four stable isotopes with mass numbers of 204, 206, 207, and 208,[37] and traces of six short-lived radioisotopes with mass numbers 209–214 inclusive. The high number of isotopes is consistent with lead's atomic number being even.[g] Lead has a magic number of protons (82), for which the nuclear shell model accurately predicts an especially stable nucleus.[38] Lead-208 has 126 neutrons, another magic number, which may explain why lead-208 is extraordinarily stable.[38]

With its high atomic number, lead is the heaviest element whose natural isotopes are regarded as stable; lead-208 is the heaviest stable nucleus. (This distinction formerly fell to bismuth, with an atomic number of 83, until its only primordial isotope, bismuth-209, was found in 2003 to decay very slowly.)[h] The four stable isotopes of lead could theoretically undergo alpha decay to isotopes of mercury with a release of energy, but this has not been observed for any of them; their predicted half-lives range from 1035 to 10189 years[41] (at least 1025 times the current age of the universe).

Three of the stable isotopes are found in three of the four major decay chains: lead-206, lead-207, and lead-208 are the final decay products of uranium-238, uranium-235, and thorium-232, respectively.[42] These decay chains are called the uranium chain, the actinium chain, and the thorium chain.[43] Their isotopic concentrations in a natural rock sample depends greatly on the presence of these three parent uranium and thorium isotopes. For example, the relative abundance of lead-208 can range from 52% in normal samples to 90% in thorium ores;[44] for this reason, the standard atomic weight of lead is given to only one decimal place.[45] As time passes, the ratio of lead-206 and lead-207 to lead-204 increases, since the former two are supplemented by radioactive decay of heavier elements while the latter is not; this allows for lead–lead dating. As uranium decays into lead, their relative amounts change; this is the basis for uranium–lead dating.[46] Lead-207 exhibits nuclear magnetic resonance, a property that has been used to study its compounds in solution and solid state,[47][48] including in the human body.[49]

Apart from the stable isotopes, which make up almost all lead that exists naturally, there are trace quantities of a few radioactive isotopes. One of them is lead-210; although it has a half-life of only 22.2 years,[37] small quantities occur in nature because lead-210 is produced by a long decay series that starts with uranium-238 (that has been present for billions of years on Earth). Lead-211, -212, and -214 are present in the decay chains of uranium-235, thorium-232, and uranium-238, respectively, so traces of all three of these lead isotopes are found naturally. Minute traces of lead-209 arise from the very rare cluster decay of radium-223, one of the daughter products of natural uranium-235, and the decay chain of neptunium-237, traces of which are produced by neutron capture in uranium ores. Lead-213 also occurs in the decay chain of neptunium-237. Lead-210 is particularly useful for helping to identify the ages of samples by measuring its ratio to lead-206 (both isotopes are present in a single decay chain).[50]

In total, 43 lead isotopes have been synthesized, with mass numbers 178–220.[37] Lead-205 is the most stable radioisotope, with a half-life of around 1.70×107 years.[6][i] The second-most stable is lead-202, which has a half-life of about 52,500 years, longer than any of the natural trace radioisotopes.[37]

Chemistry

[edit]

Bulk lead exposed to moist air forms a protective layer of varying composition. Lead(II) carbonate is a common constituent;[52][53][54] the sulfate or chloride may also be present in urban or maritime settings.[55] This layer makes bulk lead effectively chemically inert in the air.[55] Finely powdered lead, as with many metals, is pyrophoric,[56] and burns with a bluish-white flame.[57]

Fluorine reacts with lead at room temperature, forming lead(II) fluoride. The reaction with chlorine is similar but requires heating, as the resulting chloride layer diminishes the reactivity of the elements.[55] Molten lead reacts with the chalcogens to give lead(II) chalcogenides.[58]

Lead metal resists sulfuric and phosphoric acid but not hydrochloric or nitric acid; the outcome depends on insolubility and subsequent passivation of the product salt.[59] Organic acids, such as acetic acid, dissolve lead in the presence of oxygen.[55] Concentrated alkalis will dissolve lead and form plumbites.[60]

Inorganic compounds

[edit]Lead shows two main oxidation states: +4 and +2. The tetravalent state is common for the carbon group. The divalent state is rare for carbon and silicon, minor for germanium, important (but not prevailing) for tin, and is the more important of the two oxidation states for lead.[55] This is attributable to relativistic effects, specifically the inert pair effect, which manifests itself when there is a large difference in electronegativity between lead and oxide, halide, or nitride anions, leading to a significant partial positive charge on lead. The result is a stronger contraction of the lead 6s orbital than is the case for the 6p orbital, making it rather inert in ionic compounds. The inert pair effect is less applicable to compounds in which lead forms covalent bonds with elements of similar electronegativity, such as carbon in organolead compounds. In these, the 6s and 6p orbitals remain similarly sized and sp3 hybridization is still energetically favorable. Lead, like carbon, is predominantly tetravalent in such compounds.[61]

There is a relatively large difference in the electronegativity of lead(II) at 1.87 and lead(IV) at 2.33. This difference marks the reversal in the trend of increasing stability of the +4 oxidation state going down the carbon group; tin, by comparison, has values of 1.80 in the +2 oxidation state and 1.96 in the +4 state.[62]

Lead(II)

[edit]

Lead(II) compounds are characteristic of the inorganic chemistry of lead. Even strong oxidizing agents like fluorine and chlorine react with lead to give only PbF2 and PbCl2.[55] Lead(II) ions are usually colorless in solution,[63] and partially hydrolyze to form Pb(OH)+ and finally [Pb4(OH)4]4+ (in which the hydroxyl ions act as bridging ligands),[64][65] but are not reducing agents as tin(II) ions are. Techniques for identifying the presence of the Pb2+ ion in water generally rely on the precipitation of lead(II) chloride using dilute hydrochloric acid. As the chloride salt is sparingly soluble in water, in very dilute solutions the precipitation of lead(II) sulfide is instead achieved by bubbling hydrogen sulfide through the solution.[66]

Lead monoxide exists in two polymorphs, litharge α-PbO (red) and massicot β-PbO (yellow), the latter being stable only above around 488 °C. Litharge is the most commonly used inorganic compound of lead.[67] There is no lead(II) hydroxide; increasing the pH of solutions of lead(II) salts leads to hydrolysis and condensation.[68]Lead commonly reacts with heavier chalcogens. Lead sulfide is a semiconductor, a photoconductor, and an extremely sensitive infrared radiation detector. The other two chalcogenides, lead selenide and lead telluride, are likewise photoconducting. They are unusual in that their color becomes lighter going down the group.[69]

Lead dihalides are well-characterized; this includes the diastatide[70] and mixed halides, such as PbFCl. The relative insolubility of the latter forms a useful basis for the gravimetric determination of fluorine. The difluoride was the first solid ionically conducting compound to be discovered (in 1834, by Michael Faraday).[71] The other dihalides decompose on exposure to ultraviolet or visible light, especially the diiodide.[72] Many lead(II) pseudohalides are known, such as the cyanide, cyanate, and thiocyanate.[69][73] Lead(II) forms an extensive variety of halide coordination complexes, such as [PbCl4]2−, [PbCl6]4−, and the [Pb2Cl9]n5n− chain anion.[72]

Lead(II) sulfate is insoluble in water, like the sulfates of other heavy divalent cations. Lead(II) nitrate and lead(II) acetate are very soluble, and this is exploited in the synthesis of other lead compounds.[74]

Lead(IV)

[edit]Few inorganic lead(IV) compounds are known. They are only formed in highly oxidizing solutions and do not normally exist under standard conditions.[75] Lead(II) oxide gives a mixed oxide on further oxidation, Pb3O4. It is described as lead(II,IV) oxide, or structurally 2PbO·PbO2, and is the best-known mixed valence lead compound. Lead dioxide is a strong oxidizing agent, capable of oxidizing hydrochloric acid to chlorine gas.[76] This is because the expected PbCl4 that would be produced is unstable and spontaneously decomposes to PbCl2 and Cl2.[77] Analogously to lead monoxide, lead dioxide is capable of forming plumbate anions. Lead disulfide[78] and lead diselenide[79] are only stable at high pressures. Lead tetrafluoride, a yellow crystalline powder, is stable, but less so than the difluoride. Lead tetrachloride (a yellow oil) decomposes at room temperature, lead tetrabromide is less stable still, and the existence of lead tetraiodide is questionable.[80]

Other oxidation states

[edit]

Some lead compounds exist in formal oxidation states other than +4 or +2. Lead(III) may be obtained, as an intermediate between lead(II) and lead(IV), in larger organolead complexes; this oxidation state is not stable, as both the lead(III) ion and the larger complexes containing it are radicals.[82][83][84] The same applies for lead(I), which can be found in such radical species.[85]

Numerous mixed lead(II,IV) oxides are known. When PbO2 is heated in air, it becomes Pb12O19 at 293 °C, Pb12O17 at 351 °C, Pb3O4 at 374 °C, and finally PbO at 605 °C. A further sesquioxide, Pb2O3, can be obtained at high pressure, along with several non-stoichiometric phases. Many of them show defective fluorite structures in which some oxygen atoms are replaced by vacancies: PbO can be considered as having such a structure, with every alternate layer of oxygen atoms absent.[86]

Negative oxidation states can occur as Zintl phases, as either free lead anions, as in Ba2Pb, with lead formally being lead(−IV),[87] or in oxygen-sensitive ring-shaped or polyhedral cluster ions such as the trigonal bipyramidal Pb52− ion, where two lead atoms are lead(−I) and three are lead(0).[88] In such anions, each atom is at a polyhedral vertex and contributes two electrons to each covalent bond along an edge from their sp3 hybrid orbitals, the other two being an external lone pair.[64] They may be made in liquid ammonia via the reduction of lead by sodium.[89]

Organolead

[edit]

Carbon

Hydrogen

Lead

Lead can form multiply-bonded chains, a property it shares with its lighter homologs in the carbon group. Its capacity to do so is much less because the Pb–Pb bond energy is over three and a half times lower than that of the C–C bond.[58] With itself, lead can build metal–metal bonds of an order up to three.[90] With carbon, lead forms organolead compounds similar to, but generally less stable than, typical organic compounds[91] (due to the Pb–C bond being rather weak).[64] This makes the organometallic chemistry of lead far less wide-ranging than that of tin.[92] Lead predominantly forms organolead(IV) compounds, even when starting with inorganic lead(II) reactants; very few organolead(II) compounds are known. The most well-characterized exceptions are Pb[CH(SiMe3)2]2 and Pb(η5-C5H5)2.[92]

The lead analog of the simplest organic compound, methane, is plumbane. Plumbane may be obtained in a reaction between metallic lead and atomic hydrogen.[93] Two simple derivatives, tetramethyllead and tetraethyllead, are the best-known organolead compounds. These compounds are relatively stable: tetraethyllead only starts to decompose if heated[94] or if exposed to sunlight or ultraviolet light.[95][j] With sodium metal, lead readily forms an equimolar alloy that reacts with alkyl halides to form organometallic compounds such as tetraethyllead.[96] The oxidizing nature of many organolead compounds is usefully exploited: lead tetraacetate is an important laboratory reagent for oxidation in organic synthesis.[97] Tetraethyllead, once added to automotive gasoline, was produced in larger quantities than any other organometallic compound,[92] and is still widely used in fuel for small aircraft.[98]Other organolead compounds are less chemically stable.[91] For many organic compounds, a lead analog does not exist.[93]

Origin and occurrence

[edit]| Atomic number | Element | Relative amount |

|---|---|---|

| 42 | Molybdenum | 0.798 |

| 46 | Palladium | 0.440 |

| 50 | Tin | 1.146 |

| 78 | Platinum | 0.417 |

| 80 | Mercury | 0.127 |

| 82 | Lead | 1 |

| 90 | Thorium | 0.011 |

| 92 | Uranium | 0.003 |

In space

[edit]Lead's per-particle abundance in the Solar System is 0.121 ppb (parts per billion).[99][k] This figure is two and a half times higher than that of platinum, eight times more than mercury, and seventeen times more than gold.[99] The amount of lead in the universe is slowly increasing[100] as most heavier atoms (all of which are unstable) gradually decay to lead.[101] The abundance of lead in the Solar System since its formation 4.5 billion years ago has increased by about 0.75%.[102] The solar system abundances table shows that lead, despite its relatively high atomic number, is more prevalent than most other elements with atomic numbers greater than 40.[99]

Primordial lead—which comprises the isotopes lead-204, lead-206, lead-207, and lead-208—was mostly created as a result of repetitive neutron capture processes occurring in stars. The two main modes of capture are the s- and r-processes.[103]

In the s-process (s is for "slow"), captures are separated by years or decades, allowing less stable nuclei to undergo beta decay.[104] A stable thallium-203 nucleus can capture a neutron and become thallium-204; this undergoes beta decay to give stable lead-204; on capturing another neutron, it becomes lead-205, which has a half-life of around 17 million years. Further captures result in lead-206, lead-207, and lead-208. On capturing another neutron, lead-208 becomes lead-209, which quickly decays into bismuth-209. On capturing another neutron, bismuth-209 becomes bismuth-210, and this beta decays to polonium-210, which alpha decays to lead-206. The cycle hence ends at lead-206, lead-207, lead-208, and bismuth-209.[105]

In the r-process (r is for "rapid"), captures happen faster than nuclei can decay.[106] This occurs in environments with a high neutron density, such as a supernova or the merger of two neutron stars. The neutron flux involved may be on the order of 1022 neutrons per square centimeter per second.[107] The r-process does not form as much lead as the s-process.[108] It tends to stop once neutron-rich nuclei reach 126 neutrons.[109] At this point, the neutrons are arranged in complete shells in the atomic nucleus, and it becomes harder to energetically accommodate more of them.[110] When the neutron flux subsides, these nuclei beta decay into stable isotopes of osmium, iridium, and platinum.[111]

On Earth

[edit]Lead is classified as a chalcophile under the Goldschmidt classification, meaning it is generally found combined with sulfur.[112] It rarely occurs in its native, metallic form.[113] Many lead minerals are relatively light and, over the course of the Earth's history, have remained in the crust instead of sinking deeper into the Earth's interior. This accounts for lead's relatively high crustal abundance of 14 ppm; it is the 36th most abundant element in the crust.[114][l]

The main lead-bearing mineral is galena (PbS), which is mostly found with zinc ores.[116] Most other lead minerals are related to galena in some way; boulangerite, Pb5Sb4S11, is a mixed sulfide derived from galena; anglesite, PbSO4, is a product of galena oxidation; and cerussite or white lead ore, PbCO3, is a decomposition product of galena. Arsenic, tin, antimony, silver, gold, copper, and bismuth are common impurities in lead minerals.[116]

World lead resources exceed two billion tons. Significant deposits are located in Australia, China, Ireland, Mexico, Peru, Portugal, Russia, and the United States. Global reserves—resources that are economically feasible to extract—totaled 88 million tons in 2016, of which Australia had 35 million, China 17 million, and Russia 6.4 million.[117]

Typical background concentrations of lead do not exceed 0.1 μg/m3 in the atmosphere; 100 mg/kg in soil; 4 mg/kg in vegetation and 5 μg/L in freshwater and seawater.[118]

Etymology

[edit]The modern English word lead is of Germanic origin; it comes from the Middle English leed and Old English lēad (with the macron above the "e" signifying that the vowel sound of that letter is long).[119] The Old English word is derived from the hypothetical reconstructed Proto-Germanic *lauda- ('lead').[120] According to linguistic theory, this word bore descendants in multiple Germanic languages of exactly the same meaning.[120]

There is no consensus on the origin of the Proto-Germanic *lauda-. One hypothesis suggests it is derived from Proto-Indo-European *lAudh- ('lead'; capitalization of the vowel is equivalent to the macron).[121] Another hypothesis suggests it is borrowed from Proto-Celtic *ɸloud-io- ('lead'). This word is related to the Latin plumbum, which gave the element its chemical symbol Pb. The word *ɸloud-io- is thought to be the origin of Proto-Germanic *bliwa- (which also means 'lead'), from which stemmed the German Blei.[122]

The name of the chemical element is not related to the verb of the same spelling, which is derived from Proto-Germanic *laidijan- ('to lead').[123]

History

[edit]Prehistory and early history

[edit]

Metallic lead beads dating back to 7000–6500 BC have been found in Asia Minor and may represent the first example of metal smelting.[125] At that time lead had few (if any) applications due to its softness and dull appearance.[125] The major reason for the spread of lead production was its association with silver, which may be obtained by burning galena (a common lead mineral).[126] The Ancient Egyptians were the first to use lead minerals in cosmetics, an application that spread to Ancient Greece and beyond;[127] the Egyptians may have used lead for sinkers in fishing nets, glazes, glasses, enamels, and for ornaments.[126] Various civilizations of the Fertile Crescent used lead as a writing material, as coins,[128] and as a construction material.[126] Lead was used in the Ancient Chinese royal court as a stimulant,[126] as currency,[129] and as a contraceptive;[130] the Indus Valley civilization and the Mesoamericans used it for making amulets;[126] and the eastern and southern African peoples used lead in wire drawing.[131]

Classical era

[edit]Because silver was extensively used as a decorative material and an exchange medium, lead deposits came to be worked in Asia Minor from 3000 BC; later, lead deposits were developed in the Aegean and Laurion.[132] These three regions collectively dominated production of mined lead until c. 1200 BC.[133] Beginning c. 2000 BC, the Phoenicians worked deposits in the Iberian peninsula; by 1600 BC, lead mining existed in Cyprus, Greece, and Sardinia.[134]

Rome's territorial expansion in Europe and across the Mediterranean, and its development of mining, led to it becoming the greatest producer of lead during the classical era, with an estimated annual output peaking at 80,000 tonnes. Like their predecessors, the Romans obtained lead mostly as a by-product of silver smelting.[124][136] Lead mining occurred in Central Europe, Britain, the Balkans, Greece, Anatolia, and Hispania, the latter accounting for 40% of world production.[124]

Lead tablets were commonly used as a material for letters.[137] Lead coffins, cast in flat sand forms and with interchangeable motifs to suit the faith of the deceased, were used in ancient Judea.[138] Lead was used to make sling bullets from the 5th century BC. In Roman times, lead sling bullets were amply used, and were effective at a distance of between 100 and 150 meters. The Balearic slingers, used as mercenaries in Carthaginian and Roman armies, were famous for their shooting distance and accuracy.[139]

Lead was used for making water pipes in the Roman Empire; the Latin word for the metal, plumbum, is the origin of the English word "plumbing". Its ease of working, its low melting point enabling the easy fabrication of completely waterproof welded joints, and its resistance to corrosion[140] ensured its widespread use in other applications, including pharmaceuticals, roofing, currency, and warfare.[141][142][143] Writers of the time, such as Cato the Elder, Columella, and Pliny the Elder, recommended lead (or lead-coated) vessels for the preparation of sweeteners and preservatives added to wine and food. The lead conferred an agreeable taste due to the formation of "sugar of lead" (lead(II) acetate), whereas copper or bronze vessels could impart a bitter flavor through verdigris formation.[144]

This metal was by far the most used material in classical antiquity, and it is appropriate to refer to the (Roman) Lead Age. Lead was to the Romans what plastic is to us.

Heinz Eschnauer and Markus Stoeppler

"Wine—An enological specimen bank", 1992[145]

The Roman author Vitruvius reported the health dangers of lead[146][147] and modern writers have suggested that lead poisoning played a major role in the decline of the Roman Empire.[148][149][n] Other researchers have criticized such claims, pointing out, for instance, that not all abdominal pain is caused by lead poisoning.[151][152] According to archaeological research, Roman lead pipes increased lead levels in tap water but such an effect was "unlikely to have been truly harmful".[153][154] When lead poisoning did occur, victims were called "saturnine", dark and cynical, after the ghoulish father of the gods, Saturn. By association, lead was considered the father of all metals.[155] Its status in Roman society was low as it was readily available[156] and cheap.[157]

Confusion with tin and antimony

[edit]Since the Bronze Age, metallurgists and engineers have understood the difference between rare and valuable tin, essential for alloying with copper to produce tough and corrosion resistant bronze, and 'cheap and cheerful' lead. However, the nomenclature in some languages is similar. Romans called lead plumbum nigrum ("black lead"), and tin plumbum candidum ("bright lead"). The association of lead and tin can be seen in other languages: the word olovo in Czech translates to "lead", but in Russian, its cognate олово (olovo) means "tin".[158] To add to the confusion, lead bore a close relation to antimony: both elements commonly occur as sulfides (galena and stibnite), often together. Pliny incorrectly wrote that stibnite would give lead on heating, instead of antimony.[159] In countries such as Turkey and India, the originally Persian name surma came to refer to either antimony sulfide or lead sulfide,[160] and in some languages, such as Russian, gave its name to antimony (сурьма).[161]

Middle Ages and the Renaissance

[edit]

Lead mining in Western Europe declined after the fall of the Western Roman Empire, with Arabian Iberia being the only region having a significant output.[163][164] The largest production of lead occurred in South and East Asia, especially China and India, where lead mining grew rapidly.[164]

In Europe, lead production began to increase in the 11th and 12th centuries, when it was again used for roofing and piping. Starting in the 13th century, lead was used to create stained glass.[165] In the European and Arabian traditions of alchemy, lead (symbol ♄ in the European tradition)[166] was considered an impure base metal which, by the separation, purification and balancing of its constituent essences, could be transformed to pure and incorruptible gold.[167] During the period, lead was used increasingly for adulterating wine. The use of such wine was forbidden for use in Christian rites by a papal bull in 1498, but it continued to be imbibed and resulted in mass poisonings up to the late 18th century.[163][168] Lead was a key material in parts of the printing press, and lead dust was commonly inhaled by print workers, causing lead poisoning.[169] Lead also became the chief material for making bullets for firearms: it was cheap, less damaging to iron gun barrels, had a higher density (which allowed for better retention of velocity), and its lower melting point made the production of bullets easier as they could be made using a wood fire.[170] Lead, in the form of Venetian ceruse, was extensively used in cosmetics by Western European aristocracy as whitened faces were regarded as a sign of modesty.[171][172] This practice later expanded to white wigs and eyeliners, and only faded out with the French Revolution in the late 18th century. A similar fashion appeared in Japan in the 18th century with the emergence of the geishas, a practice that continued long into the 20th century. The white faces of women "came to represent their feminine virtue as Japanese women",[173] with lead commonly used in the whitener.[174]

Outside Europe and Asia

[edit]In the New World, lead production was recorded soon after the arrival of European settlers. The earliest record dates to 1621 in the English Colony of Virginia, fourteen years after its foundation.[175] In Australia, the first mine opened by colonists on the continent was a lead mine, in 1841.[176] In Africa, lead mining and smelting were known in the Benue Trough[177] and the lower Congo Basin, where lead was used for trade with Europeans, and as a currency by the 17th century,[178] well before the scramble for Africa.

Industrial Revolution

[edit]

In the second half of the 18th century, Britain, and later continental Europe and the United States, experienced the Industrial Revolution. This was the first time during which lead production rates exceeded those of Rome.[179] Britain was the leading producer, losing this status by the mid-19th century with the depletion of its mines and the development of lead mining in Germany, Spain, and the United States.[180] By 1900, the United States was the leader in global lead production, and other non-European nations—Canada, Mexico, and Australia—had begun significant production; production outside Europe exceeded that within.[181] A great share of the demand for lead came from plumbing and painting—lead paints were in regular use.[182] At this time, more (working class) people were exposed to the metal and lead poisoning cases escalated. This led to research into the effects of lead intake. Lead was proven to be more dangerous in its fume form than as a solid metal. Lead poisoning and gout were linked; British physician Alfred Baring Garrod noted a third of his gout patients were plumbers and painters. The effects of chronic ingestion of lead, including mental disorders, were also studied in the 19th century. The first laws aimed at decreasing lead poisoning in factories were enacted during the 1870s and 1880s in the United Kingdom.[182]

Modern era

[edit]

Further evidence of the threat that lead posed to humans was discovered in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Mechanisms of harm were better understood, lead blindness was documented, and the element was phased out of public use in the United States and Europe. The United Kingdom introduced mandatory factory inspections in 1878 and appointed the first Medical Inspector of Factories in 1898; as a result, a 25-fold decrease in lead poisoning incidents from 1900 to 1944 was reported.[183] Most European countries banned lead paint—commonly used because of its opacity and water resistance[184]—for interiors by 1930.[185]

The last major human exposure to lead was the addition of tetraethyllead to gasoline as an antiknock agent, a practice that originated in the United States in 1921. It was phased out in the United States and the European Union by 2000.[182]

In the 1970s, the United States and Western European countries introduced legislation to reduce lead air pollution.[186][187] The impact was significant: while a study conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States in 1976–1980 showed that 77.8% of the population had elevated blood lead levels, in 1991–1994, a study by the same institute showed the share of people with such high levels dropped to 2.2%.[188] The main product made of lead by the end of the 20th century was the lead–acid battery.[189]

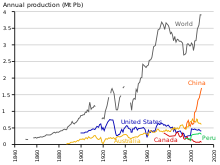

From 1960 to 1990, lead output in the Western Bloc grew by about 31%.[190] The share of the world's lead production by the Eastern Bloc increased from 10% to 30%, from 1950 to 1990, with the Soviet Union being the world's largest producer during the mid-1970s and the 1980s, and China starting major lead production in the late 20th century.[191] Unlike the European communist countries, China was largely unindustrialized by the mid-20th century; in 2004, China surpassed Australia as the largest producer of lead.[192] As was the case during European industrialization, lead has had a negative effect on health in China.[193]

Production

[edit]

As of 2014, production of lead is increasing worldwide due to its use in lead–acid batteries.[194] There are two major categories of production: primary from mined ores, and secondary from scrap. In 2014, 4.58 million metric tons came from primary production and 5.64 million from secondary production. The top three producers of mined lead concentrate in that year were China, Australia, and the United States.[117] The top three producers of refined lead were China, the United States, and India.[195] According to the International Resource Panel's Metal Stocks in Society report of 2010, the total amount of lead in use, stockpiled, discarded, or dissipated into the environment, on a global basis, is 8 kg per capita. Much of this is in more developed countries (20–150 kg per capita) rather than less developed ones (1–4 kg per capita).[196]

The primary and secondary lead production processes are similar. Some primary production plants now supplement their operations with scrap lead, and this trend is likely to increase in the future. Given adequate techniques, lead obtained via secondary processes is indistinguishable from lead obtained via primary processes. Scrap lead from the building trade is usually fairly clean and is re-melted without the need for smelting, though refining is sometimes needed. Secondary lead production is therefore cheaper, in terms of energy requirements, than is primary production, often by 50% or more.[197]

Primary

[edit]Most lead ores contain a low percentage of lead (rich ores have a typical content of 3–8%) which must be concentrated for extraction.[198] During initial processing, ores typically undergo crushing, dense-medium separation, grinding, froth flotation, and drying. The resulting concentrate, which has a lead content of 30–80% by mass (regularly 50–60%),[198] is then turned into (impure) lead metal.

There are two main ways of doing this: a two-stage process involving roasting followed by blast furnace extraction, carried out in separate vessels; or a direct process in which the extraction of the concentrate occurs in a single vessel. The latter has become the most common route, though the former is still significant.[199]

| Country | Output (thousand tons) |

|---|---|

| 2,400 | |

| 500 | |

| 335 | |

| 310 | |

| 250 | |

| 225 | |

| 135 | |

| 80 | |

| 76 | |

| 75 | |

| 41 | |

| 41 | |

| 40 | |

| 40 | |

| 35 | |

| 33 | |

| 33 | |

| Other countries | 170 |

Two-stage process

[edit]First, the sulfide concentrate is roasted in air to oxidize the lead sulfide:[200]

- 2 PbS(s) + 3 O2(g) → 2 PbO(s) + 2 SO2(g)↑

As the original concentrate was not pure lead sulfide, roasting yields not only the desired lead(II) oxide, but a mixture of oxides, sulfates, and silicates of lead and of the other metals contained in the ore.[201] This impure lead oxide is reduced in a coke-fired blast furnace to the (again, impure) metal:[202]

- 2 PbO(s) + C(s) → 2 Pb(s) + CO2(g)↑

Impurities are mostly arsenic, antimony, bismuth, zinc, copper, silver, and gold. Typically they are removed in a series of pyrometallurgical processes. The melt is treated in a reverberatory furnace with air, steam, and sulfur, which oxidizes the impurities except for silver, gold, and bismuth. Oxidized contaminants float to the top of the melt and are skimmed off.[203][204] Metallic silver and gold are removed and recovered economically by means of the Parkes process, in which zinc is added to lead. Zinc, which is immiscible in lead, dissolves the silver and gold. The zinc solution can be separated from the lead, and the silver and gold retrieved.[204][205] De-silvered lead is freed of bismuth by the Betterton–Kroll process, treating it with metallic calcium and magnesium. The resulting bismuth dross can be skimmed off.[204]

Alternatively to the pyrometallurgical processes, very pure lead can be obtained by processing smelted lead electrolytically using the Betts process. Anodes of impure lead and cathodes of pure lead are placed in an electrolyte of lead fluorosilicate (PbSiF6). Once electrical potential is applied, impure lead at the anode dissolves and plates onto the cathode, leaving the majority of the impurities in solution.[204][206] This is a high-cost process and thus mostly reserved for refining bullion containing high percentages of impurities.[207]

Direct process

[edit]In this process, lead bullion and slag is obtained directly from lead concentrates. The lead sulfide concentrate is melted in a furnace and oxidized, forming lead monoxide. Carbon (as coke or coal gas[o]) is added to the molten charge along with fluxing agents. The lead monoxide is thereby reduced to metallic lead, in the midst of a slag rich in lead monoxide.[199]

If the input is rich in lead, as much as 80% of the original lead can be obtained as bullion; the remaining 20% forms a slag rich in lead monoxide. For a low-grade feed, all of the lead can be oxidized to a high-lead slag.[199] Metallic lead is further obtained from the high-lead (25–40%) slags via submerged fuel combustion or injection, reduction assisted by an electric furnace, or a combination of both.[199]

Alternatives

[edit]Research on a cleaner, less energy-intensive lead extraction process continues; a major drawback is that either too much lead is lost as waste, or the alternatives result in a high sulfur content in the resulting lead metal. Hydrometallurgical extraction, in which anodes of impure lead are immersed into an electrolyte and pure lead is deposited (electrowound) onto a cathode, is a technique that may have potential, but is not currently economical except in cases where electricity is very cheap.[208]

Secondary

[edit]Smelting, which is an essential part of the primary production, is often skipped during secondary production. It is only performed when metallic lead has undergone significant oxidation.[197] The process is similar to that of primary production in either a blast furnace or a rotary furnace, with the essential difference being the greater variability of yields: blast furnaces produce hard lead (10% antimony) while reverberatory and rotary kiln furnaces produce semisoft lead (3–4% antimony).[209]

The ISASMELT process is a more recent smelting method that may act as an extension to primary production; battery paste from spent lead–acid batteries (containing lead sulfate and lead oxides) has its sulfate removed by treating it with alkali, and is then treated in a coal-fueled furnace in the presence of oxygen, which yields impure lead, with antimony the most common impurity.[210] Refining of secondary lead is similar to that of primary lead; some refining processes may be skipped depending on the material recycled and its potential contamination.[210]

Of the sources of lead for recycling, lead–acid batteries are the most important; lead pipe, sheet, and cable sheathing are also significant.[197]

Applications

[edit]

Contrary to popular belief, pencil leads in wooden pencils have never been made from lead. When the pencil originated as a wrapped graphite writing tool, the particular type of graphite used was named plumbago (literally, act for lead or lead mockup).[212]

Elemental form

[edit]Lead metal has several useful mechanical properties, including high density, low melting point, ductility, and relative inertness. Many metals are superior to lead in some of these aspects but are generally less common and more difficult to extract from parent ores. Lead's toxicity has led to its phasing out for some uses.[213]

Lead has been used for bullets since their invention in the Middle Ages. It is inexpensive; its low melting point means small arms ammunition and shotgun pellets can be cast with minimal technical equipment; and it is denser than other common metals, which allows for better retention of velocity. It remains the main material for bullets, alloyed with other metals as hardeners.[170] Concerns have been raised that lead bullets used for hunting can damage the environment.[p]

Lead's high density and resistance to corrosion have been exploited in a number of related applications. It is used as ballast in sailboat keels; its density allows it to take up a small volume and minimize water resistance, thus counterbalancing the heeling effect of wind on the sails.[215] It is used in scuba diving weight belts to counteract the diver's buoyancy.[216] In 1993, the base of the Leaning Tower of Pisa was stabilized with 600 tonnes of lead.[217] Because of its corrosion resistance, lead is used as a protective sheath for underwater cables.[218]

Lead has many uses in the construction industry; lead sheets are used as architectural metals in roofing material, cladding, flashing, gutters and gutter joints, and on roof parapets.[219][220] Lead is still used in statues and sculptures,[q] including for armatures.[222] In the past it was often used to balance the wheels of cars; for environmental reasons this use is being phased out in favor of other materials.[117]

Lead is added to copper alloys, such as brass and bronze, to improve machinability and for its lubricating qualities. Being practically insoluble in copper the lead forms solid globules in imperfections throughout the alloy, such as grain boundaries. In low concentrations, as well as acting as a lubricant, the globules hinder the formation of swarf as the alloy is worked, thereby improving machinability. Copper alloys with larger concentrations of lead are used in bearings. The lead provides lubrication, and the copper provides the load-bearing support.[223]

Lead's high density, atomic number, and formability form the basis for use of lead as a barrier that absorbs sound, vibration, and radiation.[224] Lead has no natural resonance frequencies;[224] as a result, sheet-lead is used as a sound deadening layer in the walls, floors, and ceilings of sound studios.[225] Organ pipes are often made from a lead alloy, mixed with various amounts of tin to control the tone of each pipe.[226][227] Lead is an established shielding material from radiation in nuclear science and in X-ray rooms[228] due to its denseness and high attenuation coefficient.[229] Molten lead has been used as a coolant for lead-cooled fast reactors.[230]

Batteries

[edit]The largest use of lead in the early 21st century is in lead–acid batteries. The lead in batteries undergoes no direct contact with humans, so there are fewer toxicity concerns.[r] People who work in lead battery production or recycling plants may be exposed to lead dust and inhale it.[232] The reactions in the battery between lead, lead dioxide, and sulfuric acid provide a reliable source of voltage.[s] Supercapacitors incorporating lead–acid batteries have been installed in kilowatt and megawatt scale applications in Australia, Japan, and the United States in frequency regulation, solar smoothing and shifting, wind smoothing, and other applications.[234] These batteries have lower energy density and charge-discharge efficiency than lithium-ion batteries, but are significantly cheaper.[235]

Coating for cables

[edit]Lead is used in high voltage power cables as shell material to prevent water diffusion into insulation; this use is decreasing as lead is being phased out.[236] Its use in solder for electronics is also being phased out by some countries to reduce the amount of environmentally hazardous waste.[237] Lead is one of three metals used in the Oddy test for museum materials, helping detect organic acids, aldehydes, and acidic gases.[238][239]

Compounds

[edit]

In addition to being the main application for lead metal, lead–acid batteries are also the main consumer of lead compounds. The energy storage/release reaction used in these devices involves lead sulfate and lead dioxide:

- Pb(s) + PbO

2(s) + 2H

2SO

4(aq) → 2PbSO

4(s) + 2H

2O(l)

Other applications of lead compounds are very specialized and often fading. Lead-based coloring agents are used in ceramic glazes and glass, especially for red and yellow shades.[240] While lead paints are phased out in Europe and North America, they remain in use in less developed countries such as China,[241] India,[242] or Indonesia.[243] Lead tetraacetate and lead dioxide are used as oxidizing agents in organic chemistry. Lead is frequently used in the polyvinyl chloride coating of electrical cords.[244][245] It can be used to treat candle wicks to ensure a longer, more even burn. Because of its toxicity, European and North American manufacturers use alternatives such as zinc.[246][247] Lead glass is composed of 12–28% lead oxide, changing its optical characteristics and reducing the transmission of ionizing radiation,[248] a property used in old TVs and computer monitors with cathode-ray tubes. Lead-based semiconductors such as lead telluride and lead selenide are used in photovoltaic cells and infrared detectors.[249]

Biological effects

[edit]| Hazards | |

|---|---|

| GHS labelling: | |

| |

| Danger | |

| H302, H332, H351, H360Df, H373, H410 | |

| P201, P261, P273, P304, P308, P312, P313, P340, P391[250] | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

Lead has no confirmed biological role, and there is no confirmed safe level of lead exposure.[251] A 2009 Canadian–American study concluded that even at levels that are considered to pose little to no risk, lead may cause "adverse mental health outcomes".[252] Its prevalence in the human body—at an adult average of 120 mg[t]—is nevertheless exceeded only by zinc (2500 mg) and iron (4000 mg) among the heavy metals.[254] Lead salts are very efficiently absorbed by the body.[255] A small amount of lead (1%) is stored in bones; the rest is excreted in urine and feces within a few weeks of exposure. Only about a third of lead is excreted by a child. Continual exposure may result in the bioaccumulation of lead.[256]

Toxicity

[edit]Lead is a highly poisonous metal (whether inhaled or swallowed), affecting almost every organ and system in the human body.[257] At airborne levels of 100 mg/m3, it is immediately dangerous to life and health.[258] Most ingested lead is absorbed into the bloodstream.[259] The primary cause of its toxicity is its predilection for interfering with the proper functioning of enzymes. It does so by binding to the sulfhydryl groups found on many enzymes,[260] or mimicking and displacing other metals which act as cofactors in many enzymatic reactions.[261] The essential metals that lead interacts with include calcium, iron, and zinc.[262] High levels of calcium and iron tend to provide some protection from lead poisoning; low levels cause increased susceptibility.[255]

Effects

[edit]Lead can cause severe damage to the brain and kidneys and, ultimately, death. By mimicking calcium, lead can cross the blood–brain barrier. It degrades the myelin sheaths of neurons, reduces their numbers, interferes with neurotransmission routes, and decreases neuronal growth.[260] In the human body, lead inhibits porphobilinogen synthase and ferrochelatase, preventing both porphobilinogen formation and the incorporation of iron into protoporphyrin IX, the final step in heme synthesis. This causes ineffective heme synthesis and microcytic anemia.[263]

Symptoms of lead poisoning include nephropathy, colic-like abdominal pains, and possibly weakness in the fingers, wrists, or ankles. Small blood pressure increases, particularly in middle-aged and older people, may be apparent and can cause anemia.[citation needed] Several studies, mostly cross-sectional, found an association between increased lead exposure and decreased heart rate variability.[264] In pregnant women, high levels of exposure to lead may cause miscarriage. Chronic, high-level exposure has been shown to reduce fertility in males.[265]

In a child's developing brain, lead interferes with synapse formation in the cerebral cortex, neurochemical development (including that of neurotransmitters), and the organization of ion channels.[266] Early childhood exposure has been linked with an increased risk of sleep disturbances and excessive daytime drowsiness in later childhood.[267] High blood levels are associated with delayed puberty in girls.[268] The rise and fall in exposure to airborne lead from the combustion of tetraethyl lead in gasoline during the 20th century has been linked with historical increases and decreases in crime levels.

Exposure sources

[edit]Lead exposure is a global issue since lead mining and smelting, and battery manufacturing, disposal, and recycling, are common in many countries. Lead enters the body via inhalation, ingestion, or skin absorption. Almost all inhaled lead is absorbed into the body; for ingestion, the rate is 20–70%, with children absorbing a higher percentage than adults.[269]

Poisoning typically results from ingestion of food or water contaminated with lead, and less commonly after accidental ingestion of contaminated soil, dust, or lead-based paint.[270] Seawater products can contain lead if affected by nearby industrial waters.[271] Fruit and vegetables can be contaminated by high levels of lead in the soils they were grown in. Soil can be contaminated through particulate accumulation from lead in pipes, lead paint, and residual emissions from leaded gasoline.[272]

The use of lead for water pipes is a problem in areas with soft or acidic water.[273] Hard water forms insoluble protective layers on the inner surface of the pipes, whereas soft and acidic water dissolves the lead pipes.[274] Dissolved carbon dioxide in the carried water may result in the formation of soluble lead bicarbonate; oxygenated water may similarly dissolve lead as lead(II) hydroxide. Drinking such water, over time, can cause health problems due to the toxicity of the dissolved lead. The harder the water the more calcium bicarbonate and sulfate it will contain, and the more the inside of the pipes will be coated with a protective layer of lead carbonate or lead sulfate.[275]

Ingestion of applied lead-based paint is the major source of exposure for children:a direct source is chewing on old painted window sills. Additionally, as lead paint on a surface deteriorates, it peels and is pulverized into dust. The dust then enters the body through hand-to-mouth contact or contaminated food or drink. Ingesting certain home remedies may result in exposure to lead or its compounds.[276]

Inhalation is the second major exposure pathway, affecting smokers and especially workers in lead-related occupations.[259] Cigarette smoke contains, among other toxic substances, radioactive lead-210.[277] "As a result of EPA's regulatory efforts, levels of lead in the air [in the United States] decreased by 86 percent between 2010 and 2020."[278] The concentration of lead in the air in the United States fell below the national standard of 0.15 μg/m3[279] in 2014.[280]

Skin exposure may be significant for people working with organic lead compounds. The rate of skin absorption is lower for inorganic lead.[281]

Lead in foods

[edit]Lead may be found in food when food is grown in soil that is high in lead, airborne lead contaminates the crops, animals eat lead in their diet, or lead enters the food either from what it was stored or cooked in.[282] Ingestion of lead paint and batteries is also a route of exposure for livestock, which can subsequently affect humans.[283] Milk produced by contaminated cattle can be diluted to a lower lead concentration and sold for consumption.[284]

In Bangladesh, lead compounds have been added to turmeric to make it more yellow.[285] This is believed to have started in the 1980s and continues as of 2019[update].[285] It is believed to be one of the main sources of high lead levels in the country.[286] In Hong Kong the maximum allowed lead level in food is 6 parts per million in solids and 1 part per million in liquids.[287]

Lead-containing dust can settle on drying cocoa beans when they are set outside near polluting industrial plants.[288] In December 2022, Consumer Reports tested 28 dark chocolate brands and found that 23 of them contained potentially harmful levels of lead, cadmium or both. They have urged the chocolate makers to reduce the level of lead which could be harmful, especially to a developing fetus.[289]

Lead in plastic toys

[edit]According to the United States Center for Disease Control, the use of lead in plastics has not been banned as of 2024. Lead softens the plastic and makes it more flexible so that it can go back to its original shape. Habitual chewing on colored plastic insulation from stripped electrical wires was found to cause elevated lead levels in a 46-year-old man.[290] Lead may be used in plastic toys to stabilize molecules from heat. Lead dust can be formed when plastic is exposed to sunlight, air, and detergents that break down the chemical bond between the lead and plastics.[291]

Treatment

[edit]Treatment for lead poisoning normally involves the administration of dimercaprol and succimer.[292] Acute cases may require the use of disodium calcium edetate, the calcium chelate, and the disodium salt of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA). It has a greater affinity for lead than calcium, with the result that lead chelate is formed by exchange and excreted in the urine, leaving behind harmless calcium.[293]

Environmental effects

[edit]

The extraction, production, use, and disposal of lead and its products have caused significant contamination of the Earth's soils and waters. Atmospheric emissions of lead were at their peak during the Industrial Revolution, and the leaded gasoline period in the second half of the twentieth century. [294]

Lead releases originate from natural sources (i.e., concentration of the naturally occurring lead), industrial production, incineration and recycling, and mobilization of previously buried lead.[294] In particular, as lead has been phased out from other uses, in the Global South, lead recycling operations designed to extract cheap lead used for global manufacturing have become a well documented source of exposure.[295] Elevated concentrations of lead persist in soils and sediments in post-industrial and urban areas; industrial emissions, including those arising from coal burning,[296] continue in many parts of the world, particularly in the developing countries.[297]

Lead can accumulate in soils, especially those with a high organic content, where it remains for hundreds to thousands of years. Environmental lead can compete with other metals found in and on plant surfaces potentially inhibiting photosynthesis and at high enough concentrations, negatively affecting plant growth and survival. Contamination of soils and plants can allow lead to ascend the food chain affecting microorganisms and animals. In animals, lead exhibits toxicity in many organs, damaging the nervous, renal, reproductive, hematopoietic, and cardiovascular systems after ingestion, inhalation, or skin absorption.[298] Fish uptake lead from both water and sediment;[299] bioaccumulation in the food chain poses a hazard to fish, birds, and sea mammals.[300]

Anthropogenic lead includes lead from shot and sinkers. These are among the most potent sources of lead contamination along with lead production sites.[301] Lead was banned for shot and sinkers in the United States in 2017,[302] although that ban was only effective for a month,[303] and a similar ban is being considered in the European Union.[304]

Analytical methods for the determination of lead in the environment include spectrophotometry, X-ray fluorescence, atomic spectroscopy and electrochemical methods. A specific ion-selective electrode has been developed based on the ionophore S,S'-methylenebis (N,N-diisobutyldithiocarbamate).[305] An important biomarker assay for lead poisoning is δ-aminolevulinic acid levels in plasma, serum, and urine.[306]

Restriction and remediation

[edit]

By the mid-1980s, there was significant decline in the use of lead in industry.[307] In the United States, environmental regulations reduced or eliminated the use of lead in non-battery products, including gasoline, paints, solders, and water systems. Particulate control devices were installed in coal-fired power plants to capture lead emissions.[296] In 1992, U.S. Congress required the Environmental Protection Agency to reduce the blood lead levels of the country's children.[308] Lead use was further curtailed by the European Union's 2003 Restriction of Hazardous Substances Directive.[309] A large drop in lead deposition occurred in the Netherlands after the 1993 national ban on use of lead shot for hunting and sport shooting: from 230 tonnes in 1990 to 47.5 tonnes in 1995.[310] The usage of lead in Avgas 100LL for general aviation is allowed in the EU as of 2022.[311]

In the United States, the permissible exposure limit for lead in the workplace, comprising metallic lead, inorganic lead compounds, and lead soaps, was set at 50 μg/m3 over an 8-hour workday, and the blood lead level limit at 5 μg per 100 g of blood in 2012.[312] Lead may still be found in harmful quantities in stoneware,[313] vinyl[314] (such as that used for tubing and the insulation of electrical cords), and Chinese brass.[u] Old houses may still contain lead paint.[314] White lead paint has been withdrawn from sale in industrialized countries, but specialized uses of other pigments such as yellow lead chromate remain,[184] especially in road pavement marking paint.[316] Stripping old paint by sanding produces dust which can be inhaled.[317] Lead abatement programs have been mandated by some authorities in properties where young children live.[318] The usage of lead in Avgas 100LL for general aviation is generally allowed in United States as of 2023.[319]

Lead waste, depending on the jurisdiction and the nature of the waste, may be treated as household waste (to facilitate lead abatement activities),[320] or potentially hazardous waste requiring specialized treatment or storage.[321] Lead is released into the environment in shooting places and a number of lead management practices have been developed to counter the lead contamination.[322] Lead migration can be enhanced in acidic soils; to counter that, it is advised soils be treated with lime to neutralize the soils and prevent leaching of lead.[323]

Research has been conducted on how to remove lead from biosystems by biological means: Fish bones are being researched for their ability to bioremediate lead in contaminated soil.[324][325] The fungus Aspergillus versicolor is effective at absorbing lead ions from industrial waste before being released to water bodies.[326] Several bacteria have been researched for their ability to remove lead from the environment, including the sulfate-reducing bacteria Desulfovibrio and Desulfotomaculum, both of which are highly effective in aqueous solutions.[327] Millet grass Urochloa ramosa has the ability to accumulate significant amounts of metals such as lead and zinc in its shoot and root tissues making it an important plant for remediation of contaminated soils (Lakshmi et al., 2013).[328]

See also

[edit]- Derek Bryce-Smith – one of the earliest campaigners against lead in petrol in the UK

- Thomas Midgley Jr. – discovered that the addition of tetraethyllead to gasoline prevented "knocking" in internal combustion engines

- Clair Patterson – instrumental in the banning of tetraethyllead in gasoline in the US and lead solder in food cans.

- Robert A. Kehoe – foremost medical advocate for the use of tetraethyllead as an additive in gasoline.

Notes

[edit]- ^ The tetrahedral allotrope of tin is called α- or gray tin and is stable only at or below 13.2 °C (55.8 °F). The stable form of tin above this temperature is called β- or white tin and has a distorted face centered cubic (tetragonal) structure which can be derived by compressing the tetrahedra of gray tin along their cubic axes. White tin effectively has a structure intermediate between the regular tetrahedral structure of gray tin, and the regular face centered cubic structure of lead, consistent with the general trend of increasing metallic character going down any representative group.[17]

- ^ A quasicrystalline thin-film allotrope of lead, with pentagonal symmetry, was reported in 2013. The allotrope was obtained by depositing lead atoms on the surface of an icosahedral silver-indium-ytterbium quasicrystal. Its conductivity was not recorded.[18][19]

- ^ Diamond cubic structures with lattice parameters around the lattice parameter of silicon exists both in thin lead and tin films, and in massive lead and tin, freshly solidified in vacuum of ~5 x 10−6 Torr. Experimental evidence for almost identical structures of at least three oxide types is presented, demonstrating that lead and tin behave like silicon not only in the initial stages of crystallization, but also in the initial stages of oxidation.[20]

- ^ British English: to go down like a lead balloon.

- ^ Malleability describes how easily it deforms under compression, whereas ductility means its ability to stretch.

- ^ A (wet) finger can be dipped into molten lead without risk of a burning injury.[33]

- ^ An even number of either protons or neutrons generally increases the nuclear stability of isotopes, compared to isotopes with odd numbers. No elements with odd atomic numbers have more than two stable isotopes; even-numbered elements have multiple stable isotopes, with tin (element 50) having the highest number of isotopes of all elements, ten.[37] See Even and odd atomic nuclei for more details.

- ^ The half-life found in the experiment was 1.9×1019 years.[39] A kilogram of natural bismuth would have an activity value of approximately 0.003 becquerels (decays per second). For comparison, the activity value of natural radiation in the human body is around 65 becquerels per kilogram of body weight (4500 becquerels on average).[40]

- ^ Lead-205 decays solely via electron capture, which means when there are no electrons available and lead is fully ionized with all 82 electrons removed it cannot decay. Fully ionized thallium-205, the isotope lead-205 would decay to, becomes unstable and can decay into a bound state of lead-205.[51]

- ^ Tetraphenyllead is even more thermally stable, decomposing at 270 °C.[92]

- ^ Abundances in the source are listed relative to silicon rather than in per-particle notation. The sum of all elements per 106 parts of silicon is 2.6682×1010 parts; lead comprises 3.258 parts.

- ^ Elemental abundance figures are estimates and their details may vary from source to source.[115]

- ^ The inscription reads: "Made when the Emperor Vespasian was consul for the ninth term and the Emperor Titus was consul for the seventh term, when Gnaeus Iulius Agricola was imperial governor (of Britain)."

- ^ The fact that Julius Caesar fathered only one child, as well as the alleged sterility of his successor, Caesar Augustus, have been attributed to lead poisoning.[150]

- ^ Gaseous by-product of the coking process, containing carbon monoxide, hydrogen and methane; used as a fuel.

- ^ California began banning lead bullets for hunting on that basis in July 2015.[214]

- ^ For example, a firm "...producing quality [lead] garden ornament from our studio in West London for over a century".[221]

- ^ Potential injuries to regular users of such batteries are not related to lead's toxicity.[231]

- ^ See[233] for details on how a lead–acid battery works.

- ^ Rates vary greatly by country.[253]

- ^ An alloy of brass (copper and zinc) with lead, iron, tin, and sometimes antimony.[315]

References

[edit]- ^ "Standard Atomic Weights: Lead". CIAAW. 2020.

- ^ Prohaska, Thomas; Irrgeher, Johanna; Benefield, Jacqueline; Böhlke, John K.; Chesson, Lesley A.; Coplen, Tyler B.; Ding, Tiping; Dunn, Philip J. H.; Gröning, Manfred; Holden, Norman E.; Meijer, Harro A. J. (4 May 2022). "Standard atomic weights of the elements 2021 (IUPAC Technical Report)". Pure and Applied Chemistry. doi:10.1515/pac-2019-0603. ISSN 1365-3075.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Arblaster, John W. (2018). Selected Values of the Crystallographic Properties of Elements. Materials Park, Ohio: ASM International. ISBN 978-1-62708-155-9.

- ^ Pb(0) carbonyls have been observered in reaction between lead atoms and carbon monoxide; see Лин, Цзян; Цян, Сюй (2005). «Наблюдение карбонилов свинца Pb n CO (n = 1–4): Реакции атомов и небольших кластеров свинца с окисью углерода в твердом аргоне» . Журнал химической физики. 122 (3): 034505 . 122 (3): 34505. Бибкод : 2005JChPh.122c4505J . дои : 10.1063/1.1834915 . ISSN 0021-9606 . ПМИД 15740207 .

- ^ Вест, Астл и Бейер 1983 , с. Е110.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Кондев, ФГ; Ван, М.; Хуанг, WJ; Наими, С.; Ауди, Г. (2021). «Оценка ядерных свойств NUBASE2020» (PDF) . Китайская физика C . 45 (3): 030001. doi : 10.1088/1674-1137/abddae .

- ^ Мэй и др. 2016 .

- ^ Теодор Лоу Де Винн 1899 , стр. 9–36.

- ^ Как и 2005 г. , стр. 10–179.

- ^ Пюиккё 1988 , стр. 563–594.

- ^ Клаудио, Годвин и Мадьяр 2002 , стр. 1–144.

- ^ Норман 1996 , с. 36.

- ^ Гринвуд и Эрншоу 1998 , стр. 226–227, 374.

- ^ Кристенсен 2002 , стр. 867.

- ^ Слейтер 1964 .

- ^ Консидайн и Консидайн 2013 , стр. 501, 2970.

- ^ Парте 1964 , с. 13.

- ^ Шарма и др. 2013 .

- ^ Шарма и др. 2014 , с. 174710.

- ^ Пенева, Джунева и Цукева 1981 .

- ^ Гринвуд и Эрншоу 1998 , стр. 372.

- ^ Гринвуд и Эрншоу 1998 , стр. 372–373.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Торнтон, Раутиу и Браш 2001 , с. 6.

- ^ Лиде 2005 , стр. 12–35, 12–40.

- ^ Бреннер 2003 , с. 396.

- ^ Джонс 2014 , с. 42.

- ^ Лиде 2005 , стр. 4–13, 4–21, 4–33.

- ^ Фогель и Ахиллес 2013 , с. 8.

- ^ Андерсон 1869 , стр. 341–343.

- ^ Гейл и Тотемейер 2003 , стр. 15–2–15–3.

- ^ Торнтон, Раутиу и Браш 2001 , стр. 8.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Как и 2005 , стр. 12-219.

- ^ Уилли 1999 .

- ^ Как и 2005 г. , стр. 12–45.

- ^ Блейкмор 1985 , с. 272.

- ^ Уэбб, Марсильо и Хирш, 2015 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и МАГАТЭ — Секция ядерных данных, 2017 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Стоун 1997 .

- ^ из Марсиллака и др. 2003 , стр. 876–78.

- ^ Всемирная ядерная ассоциация 2015 .

- ^ Биман и др. 2013 .

- ^ Серия «Радиоактивный распад», 2012 г.

- ^ Комитет по оценке руководящих принципов Агентства по охране окружающей среды по воздействию радиоактивных материалов природного происхождения и др. 1999 .

- ^ Смирнов, Борисевич и Сулаберидзе 2012 .

- ^ Гринвуд и Эрншоу 1998 , стр. 368.

- ^ Левин 2009 , стр. 40–41.

- ^ Уэбб 2000 , с. 115.

- ^ Рэкмейер и Хорхлер 1990 .

- ^ Кангелози и Пекораро 2015 .

- ^ Фиорини 2010 , стр. 7–8.

- ^ Такахаши и др. 1987 год .

- ^ Тюрмер, Уильямс и Ройт-Роби 2002 , стр. 2033–2035.

- ^ Тетро, Сируа и Стаматопулу 1998 , стр. 17–32.

- ^ Торнтон, Раутиу и Браш 2001 , стр. 10–11.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж Гринвуд и Эрншоу 1998 , с. 373.

- ^ Бретерик 2016 , с. 1442.

- ^ Харбисон, Буржуа и Джонсон 2015 , с. 132.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Гринвуд и Эрншоу 1998 , с. 374.

- ^ Торнтон, Раутиу и Браш 2001 , стр. 11–12.

- ^ Polyanskiy 1986 , p. 20.

- ^ Каупп 2014 , стр. 9–10 утра.

- ^ Дитер и Уотсон 2009 , с. 509.

- ^ Хант 2014 , с. 215.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Кинг 1995 , стр. 43–63.

- ^ Банкер и Кейси, 2016 , с. 89.

- ^ Уиттен, Гейли и Дэвид 1996 , стр. 904–905.

- ^ Гринвуд и Эрншоу 1998 , стр. 384.

- ^ Гринвуд и Эрншоу 1998 , стр. 387.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Гринвуд и Эрншоу 1998 , с. 389.

- ^ Цукерман и Хаген 1989 , с. 426.

- ^ Функе 2013 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Гринвуд и Эрншоу 1998 , с. 382.

- ^ Бхарара и Этвуд 2006 , с. 4.

- ^ Гринвуд и Эрншоу 1998 , стр. 388.

- ^ Токсикологический профиль свинца, 2007 г. , с. 277.

- ^ Даунс и Адамс 2017 , с. 1128.

- ^ Брешия 2012 , с. 234.

- ^ Макинтайр 1992 , с. 3775.

- ^ Сильверман 1966 , стр. 2067–2069.

- ^ Гринвуд и Эрншоу 1998 , стр. 381.

- ^ Йонг, Хоффманн и Фесслер 2006 , стр. 4774–4778.

- ^ Беккер и др. 2008 , стр. 9965–9978.

- ^ Моссери, Хенглейн и Джаната 1990 , стр. 2722–2726.

- ^ Кон и Чиверс 2011 , стр. 100–100. 391–392.

- ^ Хэдлингтон 2017 , с. 59.

- ^ Гринвуд и Эрншоу 1998 , стр. 384–386.

- ^ Рёр 2017 .

- ^ Альсфассер 2007 , стр. 261–263.

- ^ Гринвуд и Эрншоу 1998 , стр. 393.

- ^ Стабенов, Саак и Вайденбрух 2003 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Polyanskiy 1986 , p. 43.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Гринвуд и Эрншоу 1998 , с. 404.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Виберг, Виберг и Холлеман 2001 , с. 918.

- ^ Токсикологический профиль свинца, 2007 г. , с. 287.

- ^ Polyanskiy 1986 , p. 44.

- ^ Виндхольц 1976 .

- ^ Зыка 1966 , с.

- ^ «Когда мы увидим неэтилированный бензин AvGas?» . 5 августа 2019 года . Проверено 26 мая 2024 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Лоддерс 2003 , стр. 1222–1223.

- ^ Рёдерер и др. 2009 , стр. 1963–1980.