Фтор

Жидкий фтор (F 2 при экстремально низкой температуре ) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Фтор | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Произношение | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Аллотропы | альфа, бета (см. Аллотропы фтора ) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Появление | газ: очень бледно-желтый жидкость: ярко-желтый сплошной: альфа непрозрачен, бета прозрачен | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar°(F) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Fluorine in the periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 9 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 17 (halogens) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | p-block | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [He] 2s2 2p5[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 7 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | gas | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | (F2) 53.48 K (−219.67 °C, −363.41 °F)[4] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | (F2) 85.03 K (−188.11 °C, −306.60 °F)[4] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (at STP) | 1.696 g/L[5] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| when liquid (at b.p.) | 1.505 g/cm3[6] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Triple point | 53.48 K, .252 kPa[7] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Critical point | 144.41 K, 5.1724 MPa[4] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 6.51 kJ/mol[5] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | Cp: 31 J/(mol·K)[6] (at 21.1 °C) Cv: 23 J/(mol·K)[6] (at 21.1 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||

Vapor pressure

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | −1, 0[8] (oxidizes oxygen) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 3.98[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 64 pm[10] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Van der Waals radius | 135 pm[11] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | ||||||||||||||||||||

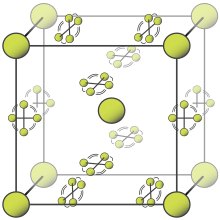

| Crystal structure | cubic | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 0.02591 W/(m⋅K)[12] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | diamagnetic (−1.2×10−4)[13][14] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7782-41-4[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Naming | after the mineral fluorite, itself named after Latin fluo (to flow, in smelting) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery | André-Marie Ampère (1810) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| First isolation | Henri Moissan[3] (June 26, 1886) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Named by | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Isotopes of fluorine | |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Фтор — химический элемент ; имеет символ F и атомный номер 9. Это самый легкий галоген. [примечание 1] и существует при стандартных условиях в виде бледно-желтого двухатомного газа. Фтор чрезвычайно реакционноспособен , так как реагирует со всеми другими элементами, за исключением легких инертных газов . Он очень токсичен .

Среди элементов фтор занимает 24-е место по всеобщему распространению и 13-е место по земному распространению . Флюорит , основной минеральный источник фтора, давший этому элементу название, был впервые описан в 1529 году; Поскольку его добавляли в металлические руды для снижения их температуры плавления при плавке , латинский глагол fluo, означающий « течь », дал минералу свое название. Фтор, предложенный в качестве элемента в 1810 году, оказался трудным и опасным для отделения от его соединений, и несколько первых экспериментаторов погибли или получили травмы в результате своих попыток. Только в 1886 году французский химик Анри Муассан выделил элементарный фтор с помощью низкотемпературного электролиза — процесса, который до сих пор используется в современном производстве. Промышленное производство газообразного фтора для обогащения урана , его крупнейшее применение, началось во время Манхэттенского проекта во время Второй мировой войны .

Owing to the expense of refining pure fluorine, most commercial applications use fluorine compounds, with about half of mined fluorite used in steelmaking. The rest of the fluorite is converted into hydrogen fluoride en route to various organic fluorides, or into cryolite, which plays a key role in aluminium refining. The carbon–fluorine bond is usually very stable. Organofluorine compounds are widely used as refrigerants, electrical insulation, and PTFE (Teflon). Pharmaceuticals such as atorvastatin and fluoxetine contain C−F bonds. The fluoride ion from dissolved fluoride salts inhibits dental cavities and so finds use in toothpaste and water fluoridation. Global fluorochemical sales amount to more than US$15 billion a year.

Fluorocarbon gases are generally greenhouse gases with global-warming potentials 100 to 23,500 times that of carbon dioxide, and SF6 has the highest global warming potential of any known substance. Organofluorine compounds often persist in the environment due to the strength of the carbon–fluorine bond. Fluorine has no known metabolic role in mammals; a few plants and marine sponges synthesize organofluorine poisons (most often monofluoroacetates) that help deter predation.[16]

Characteristics[edit]

Electron configuration[edit]

Fluorine atoms have nine electrons, one fewer than neon, and electron configuration 1s22s22p5: two electrons in a filled inner shell and seven in an outer shell requiring one more to be filled. The outer electrons are ineffective at nuclear shielding, and experience a high effective nuclear charge of 9 − 2 = 7; this affects the atom's physical properties.[3]

Fluorine's first ionization energy is third-highest among all elements, behind helium and neon,[17] which complicates the removal of electrons from neutral fluorine atoms. It also has a high electron affinity, second only to chlorine,[18] and tends to capture an electron to become isoelectronic with the noble gas neon;[3] it has the highest electronegativity of any reactive element.[19] Fluorine atoms have a small covalent radius of around 60 picometers, similar to those of its period neighbors oxygen and neon.[20][21][note 2]

Reactivity[edit]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

The bond energy of difluorine is much lower than that of either Cl

2 or Br

2 and similar to the easily cleaved peroxide bond; this, along with high electronegativity, accounts for fluorine's easy dissociation, high reactivity, and strong bonds to non-fluorine atoms.[22][23] Conversely, bonds to other atoms are very strong because of fluorine's high electronegativity. Unreactive substances like powdered steel, glass fragments, and asbestos fibers react quickly with cold fluorine gas; wood and water spontaneously combust under a fluorine jet.[5][24]

Reactions of elemental fluorine with metals require varying conditions. Alkali metals cause explosions and alkaline earth metals display vigorous activity in bulk; to prevent passivation from the formation of metal fluoride layers, most other metals such as aluminium and iron must be powdered,[22] and noble metals require pure fluorine gas at 300–450 °C (575–850 °F).[25] Some solid nonmetals (sulfur, phosphorus) react vigorously in liquid fluorine.[26] Hydrogen sulfide[26] and sulfur dioxide[27] combine readily with fluorine, the latter sometimes explosively; sulfuric acid exhibits much less activity, requiring elevated temperatures.[28]

Hydrogen, like some of the alkali metals, reacts explosively with fluorine.[29] Carbon, as lamp black, reacts at room temperature to yield tetrafluoromethane. Graphite combines with fluorine above 400 °C (750 °F) to produce non-stoichiometric carbon monofluoride; higher temperatures generate gaseous fluorocarbons, sometimes with explosions.[30] Carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide react at or just above room temperature,[31] whereas paraffins and other organic chemicals generate strong reactions:[32] even completely substituted haloalkanes such as carbon tetrachloride, normally incombustible, may explode.[33] Although nitrogen trifluoride is stable, nitrogen requires an electric discharge at elevated temperatures for reaction with fluorine to occur, due to the very strong triple bond in elemental nitrogen;[34] ammonia may react explosively.[35][36] Oxygen does not combine with fluorine under ambient conditions, but can be made to react using electric discharge at low temperatures and pressures; the products tend to disintegrate into their constituent elements when heated.[37][38][39] Heavier halogens[40] react readily with fluorine as does the noble gas radon;[41] of the other noble gases, only xenon and krypton react, and only under special conditions.[42] Argon does not react with fluorine gas; however, it does form a compound with fluorine, argon fluorohydride.

Phases[edit]

2 molecules that may assume any angle. Other molecules are constrained to planes.

At room temperature, fluorine is a gas of diatomic molecules,[5] pale yellow when pure (sometimes described as yellow-green).[43] It has a characteristic halogen-like pungent and biting odor detectable at 20 ppb.[44] Fluorine condenses into a bright yellow liquid at −188 °C (−306 °F), a transition temperature similar to those of oxygen and nitrogen.[45]

Fluorine has two solid forms, α- and β-fluorine. The latter crystallizes at −220 °C (−364 °F) and is transparent and soft, with the same disordered cubic structure of freshly crystallized solid oxygen,[45][note 3] unlike the orthorhombic systems of other solid halogens.[47][48] Further cooling to −228 °C (−378 °F) induces a phase transition into opaque and hard α-fluorine, which has a monoclinic structure with dense, angled layers of molecules. The transition from β- to α-fluorine is more exothermic than the condensation of fluorine, and can be violent.[47][48]

Isotopes[edit]

Only one isotope of fluorine occurs naturally in abundance, the stable isotope 19

F.[49] It has a high magnetogyric ratio[note 4] and exceptional sensitivity to magnetic fields; because it is also the only stable isotope, it is used in magnetic resonance imaging.[51] Eighteen radioisotopes with mass numbers from 13 to 31 have been synthesized, of which 18

F is the most stable with a half-life of 109.77 minutes. 18

F is a natural trace radioisotope produced by cosmic ray spallation of atmospheric argon as well as by reaction of protons with natural oxygen: 18O + p → 18F + n.[52] Other radioisotopes have half-lives less than 70 seconds; most decay in less than half a second.[53] The isotopes 17

F and 18

F undergo β+ decay and electron capture, lighter isotopes decay by proton emission, and those heavier than 19

F undergo β− decay (the heaviest ones with delayed neutron emission).[53][54] Two metastable isomers of fluorine are known, 18m

F, with a half-life of 162(7) nanoseconds, and 26m

F, with a half-life of 2.2(1) milliseconds.[55]

Occurrence[edit]

Universe[edit]

| Atomic number | Element | Relative amount |

|---|---|---|

| 6 | Carbon | 4,800 |

| 7 | Nitrogen | 1,500 |

| 8 | Oxygen | 8,800 |

| 9 | Fluorine | 1 |

| 10 | Neon | 1,400 |

| 11 | Sodium | 24 |

| 12 | Magnesium | 430 |

Among the lighter elements, fluorine's abundance value of 400 ppb (parts per billion) – 24th among elements in the universe – is exceptionally low: other elements from carbon to magnesium are twenty or more times as common.[57] This is because stellar nucleosynthesis processes bypass fluorine, and any fluorine atoms otherwise created have high nuclear cross sections, allowing collisions with hydrogen or helium to generate oxygen or neon respectively.[57][58]

Beyond this transient existence, three explanations have been proposed for the presence of fluorine:[57][59]

- during type II supernovae, bombardment of neon atoms by neutrinos could transmute them to fluorine;

- the solar wind of Wolf–Rayet stars could blow fluorine away from any hydrogen or helium atoms; or

- fluorine is borne out on convection currents arising from fusion in asymptotic giant branch stars.

Earth[edit]

Fluorine is the thirteenth most common element in Earth's crust at 600–700 ppm (parts per million) by mass.[60] Though believed not to occur naturally, elemental fluorine has been shown to be present as an occlusion in antozonite, a variant of fluorite.[61] Most fluorine exists as fluoride-containing minerals. Fluorite, fluorapatite and cryolite are the most industrially significant.[60][62] Fluorite (CaF

2), also known as fluorspar, abundant worldwide, is the main source of fluoride, and hence fluorine. China and Mexico are the major suppliers.[62][63][64][65][66] Fluorapatite (Ca5(PO4)3F), which contains most of the world's fluoride, is an inadvertent source of fluoride as a byproduct of fertilizer production.[62] Cryolite (Na

3AlF

6), used in the production of aluminium, is the most fluorine-rich mineral. Economically viable natural sources of cryolite have been exhausted, and most is now synthesised commercially.[62]

- Fluorite: Pink globular mass with crystal facets

- Cryolite: A parallelogram-shaped outline with diatomic molecules arranged in two layers

Other minerals such as topaz contain fluorine. Fluorides, unlike other halides, are insoluble and do not occur in commercially favorable concentrations in saline waters.[62] Trace quantities of organofluorines of uncertain origin have been detected in volcanic eruptions and geothermal springs.[67] The existence of gaseous fluorine in crystals, suggested by the smell of crushed antozonite, is contentious;[68][61] a 2012 study reported the presence of 0.04% F

2 by weight in antozonite, attributing these inclusions to radiation from the presence of tiny amounts of uranium.[61]

History[edit]

Early discoveries[edit]

In 1529, Georgius Agricola described fluorite as an additive used to lower the melting point of metals during smelting.[69][70][note 5] He penned the Latin word fluorēs (fluor, flow) for fluorite rocks. The name later evolved into fluorspar (still commonly used) and then fluorite.[63][74][75] The composition of fluorite was later determined to be calcium difluoride.[76]

Hydrofluoric acid was used in glass etching from 1720 onward.[note 6] Andreas Sigismund Marggraf first characterized it in 1764 when he heated fluorite with sulfuric acid, and the resulting solution corroded its glass container.[78][79] Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele repeated the experiment in 1771, and named the acidic product fluss-spats-syran (fluorspar acid).[79][80] In 1810, the French physicist André-Marie Ampère suggested that hydrogen and an element analogous to chlorine constituted hydrofluoric acid.[81] He also proposed in a letter to Sir Humphry Davy dated August 26, 1812 that this then-unknown substance may be named fluorine from fluoric acid and the -ine suffix of other halogens.[82][83] This word, often with modifications, is used in most European languages; however, Greek, Russian, and some others, following Ampère's later suggestion, use the name ftor or derivatives, from the Greek φθόριος (phthorios, destructive).[84] The New Latin name fluorum gave the element its current symbol F; Fl was used in early papers.[85][note 7]

Isolation[edit]

Initial studies on fluorine were so dangerous that several 19th-century experimenters were deemed "fluorine martyrs" after misfortunes with hydrofluoric acid.[note 8] Isolation of elemental fluorine was hindered by the extreme corrosiveness of both elemental fluorine itself and hydrogen fluoride, as well as the lack of a simple and suitable electrolyte.[76][86] Edmond Frémy postulated that electrolysis of pure hydrogen fluoride to generate fluorine was feasible and devised a method to produce anhydrous samples from acidified potassium bifluoride; instead, he discovered that the resulting (dry) hydrogen fluoride did not conduct electricity.[76][86][87] Frémy's former student Henri Moissan persevered, and after much trial and error found that a mixture of potassium bifluoride and dry hydrogen fluoride was a conductor, enabling electrolysis. To prevent rapid corrosion of the platinum in his electrochemical cells, he cooled the reaction to extremely low temperatures in a special bath and forged cells from a more resistant mixture of platinum and iridium, and used fluorite stoppers.[86][88] In 1886, after 74 years of effort by many chemists, Moissan isolated elemental fluorine.[87][89]

In 1906, two months before his death, Moissan received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry,[90] with the following citation:[86]

[I]n recognition of the great services rendered by him in his investigation and isolation of the element fluorine ... The whole world has admired the great experimental skill with which you have studied that savage beast among the elements.[note 9]

Later uses[edit]

The Frigidaire division of General Motors (GM) experimented with chlorofluorocarbon refrigerants in the late 1920s, and Kinetic Chemicals was formed as a joint venture between GM and DuPont in 1930 hoping to market Freon-12 (CCl

2F

2) as one such refrigerant. It replaced earlier and more toxic compounds, increased demand for kitchen refrigerators, and became profitable; by 1949 DuPont had bought out Kinetic and marketed several other Freon compounds.[79][91][92][93] Polytetrafluoroethylene (Teflon) was serendipitously discovered in 1938 by Roy J. Plunkett while working on refrigerants at Kinetic, and its superlative chemical and thermal resistance lent it to accelerated commercialization and mass production by 1941.[79][91][92]

Large-scale production of elemental fluorine began during World War II. Germany used high-temperature electrolysis to make tons of the planned incendiary chlorine trifluoride[94] and the Manhattan Project used huge quantities to produce uranium hexafluoride for uranium enrichment. Since UF

6 is as corrosive as fluorine, gaseous diffusion plants required special materials: nickel for membranes, fluoropolymers for seals, and liquid fluorocarbons as coolants and lubricants. This burgeoning nuclear industry later drove post-war fluorochemical development.[95]

Compounds[edit]

Fluorine has a rich chemistry, encompassing organic and inorganic domains. It combines with metals, nonmetals, metalloids, and most noble gases,[96] and almost exclusively assumes an oxidation state of −1.[note 10] Fluorine's high electron affinity results in a preference for ionic bonding; when it forms covalent bonds, these are polar, and almost always single.[99][100][note 11]

Metals[edit]

Alkali metals form ionic and highly soluble monofluorides; these have the cubic arrangement of sodium chloride and analogous chlorides.[101][102] Alkaline earth difluorides possess strong ionic bonds but are insoluble in water,[85] with the exception of beryllium difluoride, which also exhibits some covalent character and has a quartz-like structure.[103] Rare earth elements and many other metals form mostly ionic trifluorides.[104][105][106]

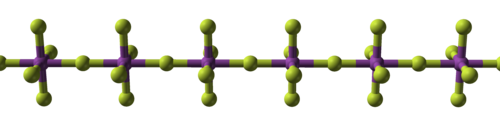

Covalent bonding first comes to prominence in the tetrafluorides: those of zirconium, hafnium[107][108] and several actinides[109] are ionic with high melting points,[110][note 12] while those of titanium,[113] vanadium,[114] and niobium are polymeric,[115] melting or decomposing at no more than 350 °C (660 °F).[116] Pentafluorides continue this trend with their linear polymers and oligomeric complexes.[117][118][119] Thirteen metal hexafluorides are known,[note 13] all octahedral, and are mostly volatile solids but for liquid MoF

6 and ReF

6, and gaseous WF

6.[120][121][122] Rhenium heptafluoride, the only characterized metal heptafluoride, is a low-melting molecular solid with pentagonal bipyramidal molecular geometry.[123] Metal fluorides with more fluorine atoms are particularly reactive.[124]

| Structural progression of metal fluorides | ||

|  |  |

| Sodium fluoride, ionic | Bismuth pentafluoride, polymeric | Rhenium heptafluoride, molecular |

Hydrogen[edit]

Hydrogen and fluorine combine to yield hydrogen fluoride, in which discrete molecules form clusters by hydrogen bonding, resembling water more than hydrogen chloride.[125][126][127] It boils at a much higher temperature than heavier hydrogen halides and unlike them is miscible with water.[128] Hydrogen fluoride readily hydrates on contact with water to form aqueous hydrogen fluoride, also known as hydrofluoric acid. Unlike the other hydrohalic acids, which are strong, hydrofluoric acid is a weak acid at low concentrations.[129][130] However, it can attack glass, something the other acids cannot do.[131]

Other reactive nonmetals[edit]

Binary fluorides of metalloids and p-block nonmetals are generally covalent and volatile, with varying reactivities. Period 3 and heavier nonmetals can form hypervalent fluorides.[133]

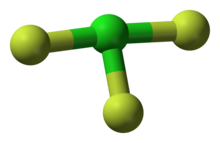

Boron trifluoride is planar and possesses an incomplete octet. It functions as a Lewis acid and combines with Lewis bases like ammonia to form adducts.[134] Carbon tetrafluoride is tetrahedral and inert;[note 14] its group analogues, silicon and germanium tetrafluoride, are also tetrahedral[135] but behave as Lewis acids.[136][137] The pnictogens form trifluorides that increase in reactivity and basicity with higher molecular weight, although nitrogen trifluoride resists hydrolysis and is not basic.[138] The pentafluorides of phosphorus, arsenic, and antimony are more reactive than their respective trifluorides, with antimony pentafluoride the strongest neutral Lewis acid known, only behind gold pentafluoride.[117][139][140]

Chalcogens have diverse fluorides: unstable difluorides have been reported for oxygen (the only known compound with oxygen in an oxidation state of +2), sulfur, and selenium; tetrafluorides and hexafluorides exist for sulfur, selenium, and tellurium. The latter are stabilized by more fluorine atoms and lighter central atoms, so sulfur hexafluoride is especially inert. [141][142] Chlorine, bromine, and iodine can each form mono-, tri-, and pentafluorides, but only iodine heptafluoride has been characterized among possible interhalogen heptafluorides.[143] Many of them are powerful sources of fluorine atoms, and industrial applications using chlorine trifluoride require precautions similar to those using fluorine.[144][145]

Noble gases[edit]

Noble gases, having complete electron shells, defied reaction with other elements until 1962 when Neil Bartlett reported synthesis of xenon hexafluoroplatinate;[147] xenon difluoride, tetrafluoride, hexafluoride, and multiple oxyfluorides have been isolated since then.[148] Among other noble gases, krypton forms a difluoride,[149] and radon and fluorine generate a solid suspected to be radon difluoride.[150][151] Binary fluorides of lighter noble gases are exceptionally unstable: argon and hydrogen fluoride combine under extreme conditions to give argon fluorohydride.[42] Helium has no long-lived fluorides,[152] and no neon fluoride has ever been observed;[153] helium fluorohydride has been detected for milliseconds at high pressures and low temperatures.[152]

Organic compounds[edit]

The carbon–fluorine bond is organic chemistry's strongest,[155] and gives stability to organofluorines.[156] It is almost non-existent in nature, but is used in artificial compounds. Research in this area is usually driven by commercial applications;[157] the compounds involved are diverse and reflect the complexity inherent in organic chemistry.[91]

Discrete molecules[edit]

The substitution of hydrogen atoms in an alkane by progressively more fluorine atoms gradually alters several properties: melting and boiling points are lowered, density increases, solubility in hydrocarbons decreases and overall stability increases. Perfluorocarbons,[note 15] in which all hydrogen atoms are substituted, are insoluble in most organic solvents, reacting at ambient conditions only with sodium in liquid ammonia.[158]

The term perfluorinated compound is used for what would otherwise be a perfluorocarbon if not for the presence of a functional group,[159][note 16] often a carboxylic acid. These compounds share many properties with perfluorocarbons such as stability and hydrophobicity,[161] while the functional group augments their reactivity, enabling them to adhere to surfaces or act as surfactants.[162] Fluorosurfactants, in particular, can lower the surface tension of water more than their hydrocarbon-based analogues. Fluorotelomers, which have some unfluorinated carbon atoms near the functional group, are also regarded as perfluorinated.[161]

Polymers[edit]

Polymers exhibit the same stability increases afforded by fluorine substitution (for hydrogen) in discrete molecules; their melting points generally increase too.[163] Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), the simplest fluoropolymer and perfluoro analogue of polyethylene with structural unit –CF

2–, demonstrates this change as expected, but its very high melting point makes it difficult to mold.[164] Various PTFE derivatives are less temperature-tolerant but easier to mold: fluorinated ethylene propylene replaces some fluorine atoms with trifluoromethyl groups, perfluoroalkoxy alkanes do the same with trifluoromethoxy groups,[164] and Nafion contains perfluoroether side chains capped with sulfonic acid groups.[165][166] Other fluoropolymers retain some hydrogen atoms; polyvinylidene fluoride has half the fluorine atoms of PTFE and polyvinyl fluoride has a quarter, but both behave much like perfluorinated polymers.[167]

Production[edit]

Elemental fluorine and virtually all fluorine compounds are produced from hydrogen fluoride or its aqueous solution, hydrofluoric acid. Hydrogen fluoride is produced in kilns by the endothermic reaction of fluorite (CaF2) with sulfuric acid:[168]

- CaF2 + H2SO4 → 2 HF(g) + CaSO4

The gaseous HF can then be absorbed in water or liquefied.[169]

About 20% of manufactured HF is a byproduct of fertilizer production, which produces hexafluorosilicic acid (H2SiF6), which can be degraded to release HF thermally and by hydrolysis:

- H2SiF6 → 2 HF + SiF4

- SiF4 + 2 H2O → 4 HF + SiO2

Industrial routes to F2[edit]

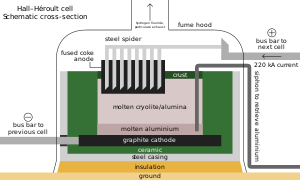

Moissan's method is used to produce industrial quantities of fluorine, via the electrolysis of a potassium bifluoride/hydrogen fluoride mixture: hydrogen ions are reduced at a steel container cathode and fluoride ions are oxidized at a carbon block anode, under 8–12 volts, to generate hydrogen and fluorine gas respectively.[64][170] Temperatures are elevated, KF•2HF melting at 70 °C (158 °F) and being electrolyzed at 70–130 °C (158–266 °F). KF, which acts to provide electrical conductivity, is essential since pure HF cannot be electrolyzed because it is virtually non-conductive.[79][171][172] Fluorine can be stored in steel cylinders that have passivated interiors, at temperatures below 200 °C (392 °F); otherwise nickel can be used.[79][173] Regulator valves and pipework are made of nickel, the latter possibly using Monel instead.[174] Frequent passivation, along with the strict exclusion of water and greases, must be undertaken. In the laboratory, glassware may carry fluorine gas under low pressure and anhydrous conditions;[174] some sources instead recommend nickel-Monel-PTFE systems.[175]

Laboratory routes[edit]

While preparing for a 1986 conference to celebrate the centennial of Moissan's achievement, Karl O. Christe reasoned that chemical fluorine generation should be feasible since some metal fluoride anions have no stable neutral counterparts; their acidification potentially triggers oxidation instead. He devised a method which evolves fluorine at high yield and atmospheric pressure:[176]

- 2 KMnO4 + 2 KF + 10 HF + 3 H2O2 → 2 K2MnF6 + 8 H2O + 3 O2↑

- 2 K2MnF6 + 4 SbF5 → 4 KSbF6 + 2 MnF3 + F2↑

Christe later commented that the reactants "had been known for more than 100 years and even Moissan could have come up with this scheme."[177] As late as 2008, some references still asserted that fluorine was too reactive for any chemical isolation.[178]

Industrial applications[edit]

Fluorite mining, which supplies most global fluorine, peaked in 1989 when 5.6 million metric tons of ore were extracted. Chlorofluorocarbon restrictions lowered this to 3.6 million tons in 1994; production has since been increasing. Around 4.5 million tons of ore and revenue of US$550 million were generated in 2003; later reports estimated 2011 global fluorochemical sales at $15 billion and predicted 2016–18 production figures of 3.5 to 5.9 million tons, and revenue of at least $20 billion.[79][179][180][181][182] Froth flotation separates mined fluorite into two main metallurgical grades of equal proportion: 60–85% pure metspar is almost all used in iron smelting whereas 97%+ pure acidspar is mainly converted to the key industrial intermediate hydrogen fluoride.[64][79][183]

6 current transformers at a Russian railway

At least 17,000 metric tons of fluorine are produced each year. It costs only $5–8 per kilogram as uranium or sulfur hexafluoride, but many times more as an element because of handling challenges. Most processes using free fluorine in large amounts employ in situ generation under vertical integration.[184]

The largest application of fluorine gas, consuming up to 7,000 metric tons annually, is in the preparation of UF

6 for the nuclear fuel cycle. Fluorine is used to fluorinate uranium tetrafluoride, itself formed from uranium dioxide and hydrofluoric acid.[184] Fluorine is monoisotopic, so any mass differences between UF

6 molecules are due to the presence of 235

U or 238

U, enabling uranium enrichment via gaseous diffusion or gas centrifuge.[5][64] About 6,000 metric tons per year go into producing the inert dielectric SF

6 for high-voltage transformers and circuit breakers, eliminating the need for hazardous polychlorinated biphenyls associated with oil-filled devices.[185] Several fluorine compounds are used in electronics: rhenium and tungsten hexafluoride in chemical vapor deposition, tetrafluoromethane in plasma etching[186][187][188] and nitrogen trifluoride in cleaning equipment.[64] Fluorine is also used in the synthesis of organic fluorides, but its reactivity often necessitates conversion first to the gentler ClF

3, BrF

3, or IF

5, which together allow calibrated fluorination. Fluorinated pharmaceuticals use sulfur tetrafluoride instead.[64]

Inorganic fluorides[edit]

As with other iron alloys, around 3 kg (6.5 lb) metspar is added to each metric ton of steel; the fluoride ions lower its melting point and viscosity.[64][189] Alongside its role as an additive in materials like enamels and welding rod coats, most acidspar is reacted with sulfuric acid to form hydrofluoric acid, which is used in steel pickling, glass etching and alkane cracking.[64] One-third of HF goes into synthesizing cryolite and aluminium trifluoride, both fluxes in the Hall–Héroult process for aluminium extraction; replenishment is necessitated by their occasional reactions with the smelting apparatus. Each metric ton of aluminium requires about 23 kg (51 lb) of flux.[64][190] Fluorosilicates consume the second largest portion, with sodium fluorosilicate used in water fluoridation and laundry effluent treatment, and as an intermediate en route to cryolite and silicon tetrafluoride.[191] Other important inorganic fluorides include those of cobalt, nickel, and ammonium.[64][102][192]

Organic fluorides[edit]

Organofluorides consume over 20% of mined fluorite and over 40% of hydrofluoric acid, with refrigerant gases dominating and fluoropolymers increasing their market share.[64][193] Surfactants are a minor application but generate over $1 billion in annual revenue.[194] Due to the danger from direct hydrocarbon–fluorine reactions above −150 °C (−240 °F), industrial fluorocarbon production is indirect, mostly through halogen exchange reactions such as Swarts fluorination, in which chlorocarbon chlorines are substituted for fluorines by hydrogen fluoride under catalysts. Electrochemical fluorination subjects hydrocarbons to electrolysis in hydrogen fluoride, and the Fowler process treats them with solid fluorine carriers like cobalt trifluoride.[91][195]

Refrigerant gases[edit]

Halogenated refrigerants, termed Freons in informal contexts,[note 17] are identified by R-numbers that denote the amount of fluorine, chlorine, carbon, and hydrogen present.[64][196] Chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) like R-11, R-12, and R-114 once dominated organofluorines, peaking in production in the 1980s. Used for air conditioning systems, propellants and solvents, their production was below one-tenth of this peak by the early 2000s, after widespread international prohibition.[64] Hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs) and hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) were designed as replacements; their synthesis consumes more than 90% of the fluorine in the organic industry. Important HCFCs include R-22, chlorodifluoromethane, and R-141b. The main HFC is R-134a[64] with a new type of molecule HFO-1234yf, a Hydrofluoroolefin (HFO) coming to prominence owing to its global warming potential of less than 1% that of HFC-134a.[197]

Polymers[edit]

About 180,000 metric tons of fluoropolymers were produced in 2006 and 2007, generating over $3.5 billion revenue per year.[198] The global market was estimated at just under $6 billion in 2011.[199] Fluoropolymers can only be formed by polymerizing free radicals.[163]

Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), sometimes called by its DuPont name Teflon,[200] represents 60–80% by mass of the world's fluoropolymer production.[198] The largest application is in electrical insulation since PTFE is an excellent dielectric. It is also used in the chemical industry where corrosion resistance is needed, in coating pipes, tubing, and gaskets. Another major use is in PFTE-coated fiberglass cloth for stadium roofs. The major consumer application is for non-stick cookware.[200] Jerked PTFE film becomes expanded PTFE (ePTFE), a fine-pored membrane sometimes referred to by the brand name Gore-Tex and used for rainwear, protective apparel, and filters; ePTFE fibers may be made into seals and dust filters.[200] Other fluoropolymers, including fluorinated ethylene propylene, mimic PTFE's properties and can substitute for it; they are more moldable, but also more costly and have lower thermal stability. Films from two different fluoropolymers replace glass in solar cells.[200][201]

The chemically resistant (but expensive) fluorinated ionomers are used as electrochemical cell membranes, of which the first and most prominent example is Nafion. Developed in the 1960s, it was initially deployed as fuel cell material in spacecraft and then replaced mercury-based chloralkali process cells. Recently, the fuel cell application has reemerged with efforts to install proton exchange membrane fuel cells into automobiles.[202][203][204] Fluoroelastomers such as Viton are crosslinked fluoropolymer mixtures mainly used in O-rings;[200] perfluorobutane (C4F10) is used as a fire-extinguishing agent.[205]

Surfactants[edit]

Fluorosurfactants are small organofluorine molecules used for repelling water and stains. Although expensive (comparable to pharmaceuticals at $200–2000 per kilogram), they yielded over $1 billion in annual revenues by 2006; Scotchgard alone generated over $300 million in 2000.[194][206][207] Fluorosurfactants are a minority in the overall surfactant market, most of which is taken up by much cheaper hydrocarbon-based products. Applications in paints are burdened by compounding costs; this use was valued at only $100 million in 2006.[194]

Agrichemicals[edit]

About 30% of agrichemicals contain fluorine,[208] most of them herbicides and fungicides with a few crop regulators. Fluorine substitution, usually of a single atom or at most a trifluoromethyl group, is a robust modification with effects analogous to fluorinated pharmaceuticals: increased biological stay time, membrane crossing, and altering of molecular recognition.[209] Trifluralin is a prominent example, with large-scale use in the U.S. as a weedkiller,[209][210] but it is a suspected carcinogen and has been banned in many European countries.[211] Sodium monofluoroacetate (1080) is a mammalian poison in which one sodium acetate hydrogen is replaced with fluorine; it disrupts cell metabolism by replacing acetate in the citric acid cycle. First synthesized in the late 19th century, it was recognized as an insecticide in the early 20th century, and was later deployed in its current use. New Zealand, the largest consumer of 1080, uses it to protect kiwis from the invasive Australian common brushtail possum.[212] Europe and the U.S. have banned 1080.[213][214][note 18]

Medicinal applications[edit]

Dental care[edit]

Population studies from the mid-20th century onwards show topical fluoride reduces dental caries. This was first attributed to the conversion of tooth enamel hydroxyapatite into the more durable fluorapatite, but studies on pre-fluoridated teeth refuted this hypothesis, and current theories involve fluoride aiding enamel growth in small caries.[215] After studies of children in areas where fluoride was naturally present in drinking water, controlled public water supply fluoridation to fight tooth decay[216] began in the 1940s and is now applied to water supplying 6 percent of the global population, including two-thirds of Americans.[217][218] Reviews of the scholarly literature in 2000 and 2007 associated water fluoridation with a significant reduction of tooth decay in children.[219] Despite such endorsements and evidence of no adverse effects other than mostly benign dental fluorosis,[220] opposition still exists on ethical and safety grounds.[218][221] The benefits of fluoridation have lessened, possibly due to other fluoride sources, but are still measurable in low-income groups.[222] Sodium monofluorophosphate and sometimes sodium or tin(II) fluoride are often found in fluoride toothpastes, first introduced in the U.S. in 1955 and now ubiquitous in developed countries, alongside fluoridated mouthwashes, gels, foams, and varnishes.[222][223]

Pharmaceuticals[edit]

Twenty percent of modern pharmaceuticals contain fluorine.[224] One of these, the cholesterol-reducer atorvastatin (Lipitor), made more revenue than any other drug until it became generic in 2011.[225] The combination asthma prescription Seretide, a top-ten revenue drug in the mid-2000s, contains two active ingredients, one of which – fluticasone – is fluorinated.[226] Many drugs are fluorinated to delay inactivation and lengthen dosage periods because the carbon–fluorine bond is very stable.[227] Fluorination also increases lipophilicity because the bond is more hydrophobic than the carbon–hydrogen bond, and this often helps in cell membrane penetration and hence bioavailability.[226]

Tricyclics and other pre-1980s antidepressants had several side effects due to their non-selective interference with neurotransmitters other than the serotonin target; the fluorinated fluoxetine was selective and one of the first to avoid this problem. Many current antidepressants receive this same treatment, including the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: citalopram, its enantiomer escitalopram, and fluvoxamine and paroxetine.[228][229] Quinolones are artificial broad-spectrum antibiotics that are often fluorinated to enhance their effects. These include ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin.[230][231][232][233] Fluorine also finds use in steroids:[234] fludrocortisone is a blood pressure-raising mineralocorticoid, and triamcinolone and dexamethasone are strong glucocorticoids.[235] The majority of inhaled anesthetics are heavily fluorinated; the prototype halothane is much more inert and potent than its contemporaries. Later compounds such as the fluorinated ethers sevoflurane and desflurane are better than halothane and are almost insoluble in blood, allowing faster waking times.[236][237]

PET scanning[edit]

F PET scan with glucose tagged with radioactive fluorine-18. The normal brain and kidneys take up enough glucose to be imaged. A malignant tumor is seen in the upper abdomen. Radioactive fluorine is seen in urine in the bladder.

Fluorine-18 is often found in radioactive tracers for positron emission tomography, as its half-life of almost two hours is long enough to allow for its transport from production facilities to imaging centers.[238] The most common tracer is fluorodeoxyglucose[238] which, after intravenous injection, is taken up by glucose-requiring tissues such as the brain and most malignant tumors;[239] computer-assisted tomography can then be used for detailed imaging.[240]

Oxygen carriers[edit]

Liquid fluorocarbons can hold large volumes of oxygen or carbon dioxide, more so than blood, and have attracted attention for their possible uses in artificial blood and in liquid breathing.[241] Because fluorocarbons do not normally mix with water, they must be mixed into emulsions (small droplets of perfluorocarbon suspended in water) to be used as blood.[242][243] One such product, Oxycyte, has been through initial clinical trials.[244] These substances can aid endurance athletes and are banned from sports; one cyclist's near death in 1998 prompted an investigation into their abuse.[245][246] Applications of pure perfluorocarbon liquid breathing (which uses pure perfluorocarbon liquid, not a water emulsion) include assisting burn victims and premature babies with deficient lungs. Partial and complete lung filling have been considered, though only the former has had any significant tests in humans.[247] An Alliance Pharmaceuticals effort reached clinical trials but was abandoned because the results were not better than normal therapies.[248]

Biological role[edit]

Fluorine is not essential for humans and other mammals, but small amounts are known to be beneficial for the strengthening of dental enamel (where the formation of fluorapatite makes the enamel more resistant to attack, from acids produced by bacterial fermentation of sugars). Small amounts of fluorine may be beneficial for bone strength, but the latter has not been definitively established.[249] Both the WHO and the Institute of Medicine of the US National Academies publish recommended daily allowance (RDA) and upper tolerated intake of fluorine, which varies with age and gender.[250][251]

Natural organofluorines have been found in microorganisms, plants[67] and, recently, animals.[252] The most common is fluoroacetate, which is used as a defense against herbivores by at least 40 plants in Africa, Australia and Brazil.[213] Other examples include terminally fluorinated fatty acids, fluoroacetone, and 2-fluorocitrate.[253] An enzyme that binds fluorine to carbon – adenosyl-fluoride synthase – was discovered in bacteria in 2002.[254]

Toxicity[edit]

Elemental fluorine is highly toxic to living organisms. Its effects in humans start at concentrations lower than hydrogen cyanide's 50 ppm[255] and are similar to those of chlorine:[256] significant irritation of the eyes and respiratory system as well as liver and kidney damage occur above 25 ppm, which is the immediately dangerous to life and health value for fluorine.[257] The eyes and nose are seriously damaged at 100 ppm,[257] and inhalation of 1,000 ppm fluorine will cause death in minutes,[258] compared to 270 ppm for hydrogen cyanide.[259]

Hydrofluoric acid[edit]

| Hazards | |

|---|---|

| GHS labelling: | |

| |

| Danger | |

| H270, H314, H330[260] | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

Hydrofluoric acid is the weakest of the hydrohalic acids, having a pKa of 3.2 at 25 °C.[262] Pure hydrogen fluoride is a volatile liquid due to the presence of hydrogen bonding, while the other hydrogen halides are gases. It is able to attack glass, concrete, metals, and organic matter.[263]

Hydrofluoric acid is a contact poison with greater hazards than many strong acids like sulfuric acid even though it is weak: it remains neutral in aqueous solution and thus penetrates tissue faster, whether through inhalation, ingestion or the skin, and at least nine U.S. workers died in such accidents from 1984 to 1994. It reacts with calcium and magnesium in the blood leading to hypocalcemia and possible death through cardiac arrhythmia.[264] Insoluble calcium fluoride formation triggers strong pain[265] and burns larger than 160 cm2 (25 in2) can cause serious systemic toxicity.[266]

Exposure may not be evident for eight hours for 50% HF, rising to 24 hours for lower concentrations, and a burn may initially be painless as hydrogen fluoride affects nerve function. If skin has been exposed to HF, damage can be reduced by rinsing it under a jet of water for 10–15 minutes and removing contaminated clothing.[267] Calcium gluconate is often applied next, providing calcium ions to bind with fluoride; skin burns can be treated with 2.5% calcium gluconate gel or special rinsing solutions.[268][269][270] Hydrofluoric acid absorption requires further medical treatment; calcium gluconate may be injected or administered intravenously. Using calcium chloride – a common laboratory reagent – in lieu of calcium gluconate is contraindicated, and may lead to severe complications. Excision or amputation of affected parts may be required.[266][271]

Fluoride ion[edit]

Soluble fluorides are moderately toxic: 5–10 g sodium fluoride, or 32–64 mg fluoride ions per kilogram of body mass, represents a lethal dose for adults.[272] One-fifth of the lethal dose can cause adverse health effects,[273] and chronic excess consumption may lead to skeletal fluorosis, which affects millions in Asia and Africa, and, in children, to reduced intelligence.[273][274] Ingested fluoride forms hydrofluoric acid in the stomach which is easily absorbed by the intestines, where it crosses cell membranes, binds with calcium and interferes with various enzymes, before urinary excretion. Exposure limits are determined by urine testing of the body's ability to clear fluoride ions.[273][275]

Historically, most cases of fluoride poisoning have been caused by accidental ingestion of insecticides containing inorganic fluorides.[276] Most current calls to poison control centers for possible fluoride poisoning come from the ingestion of fluoride-containing toothpaste.[273] Malfunctioning water fluoridation equipment is another cause: one incident in Alaska affected almost 300 people and killed one person.[277] Dangers from toothpaste are aggravated for small children, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends supervising children below six brushing their teeth so that they do not swallow toothpaste.[278] One regional study examined a year of pre-teen fluoride poisoning reports totaling 87 cases, including one death from ingesting insecticide. Most had no symptoms, but about 30% had stomach pains.[276] A larger study across the U.S. had similar findings: 80% of cases involved children under six, and there were few serious cases.[279]

Environmental concerns[edit]

Atmosphere[edit]

The Montreal Protocol, signed in 1987, set strict regulations on chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and bromofluorocarbons due to their ozone damaging potential (ODP). The high stability which suited them to their original applications also meant that they were not decomposing until they reached higher altitudes, where liberated chlorine and bromine atoms attacked ozone molecules.[281] Even with the ban, and early indications of its efficacy, predictions warned that several generations would pass before full recovery.[282][283] With one-tenth the ODP of CFCs, hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs) are the current replacements,[284] and are themselves scheduled for substitution by 2030–2040 by hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) with no chlorine and zero ODP.[285] In 2007 this date was brought forward to 2020 for developed countries;[286] the Environmental Protection Agency had already prohibited one HCFC's production and capped those of two others in 2003.[285] Fluorocarbon gases are generally greenhouse gases with global-warming potentials (GWPs) of about 100 to 10,000; sulfur hexafluoride has a value of around 20,000.[287] An outlier is HFO-1234yf which is a new type of refrigerant called a Hydrofluoroolefin (HFO) and has attracted global demand due to its GWP of less than 1 compared to 1,430 for the current refrigerant standard HFC-134a.[197]

Biopersistence[edit]

Organofluorines exhibit biopersistence due to the strength of the carbon–fluorine bond. Perfluoroalkyl acids (PFAAs), which are sparingly water-soluble owing to their acidic functional groups, are noted persistent organic pollutants;[289] perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) are most often researched.[290][291][292] PFAAs have been found in trace quantities worldwide from polar bears to humans, with PFOS and PFOA known to reside in breast milk and the blood of newborn babies. A 2013 review showed a slight correlation between groundwater and soil PFAA levels and human activity; there was no clear pattern of one chemical dominating, and higher amounts of PFOS were correlated to higher amounts of PFOA.[290][291][293] In the body, PFAAs bind to proteins such as serum albumin; they tend to concentrate within humans in the liver and blood before excretion through the kidneys. Dwell time in the body varies greatly by species, with half-lives of days in rodents, and years in humans.[290][291][294] High doses of PFOS and PFOA cause cancer and death in newborn rodents but human studies have not established an effect at current exposure levels.[290][291][294]

See also[edit]

- Argon fluoride laser

- Electrophilic fluorination

- Fluoride selective electrode, which measures fluoride concentration

- Fluorine absorption dating

- Fluorous chemistry, a process used to separate reagents from organic solvents

- Krypton fluoride laser

- Radical fluorination

Notes[edit]

- ^ Assuming that hydrogen is not considered a halogen.

- ^ Sources disagree on the radii of oxygen, fluorine, and neon atoms. Precise comparison is thus impossible.

- ^ α-Fluorine has a regular pattern of molecules and is a crystalline solid, but its molecules do not have a specific orientation. β-Fluorine's molecules have fixed locations and minimal rotational uncertainty.[46]

- ^ The ratio of the angular momentum to magnetic moment is called the gyromagnetic ratio. "Certain nuclei can for many purposes be thought of as spinning round an axis like the Earth or like a top. In general the spin endows them with angular momentum and with a magnetic moment; the first because of their mass, the second because all or part of their electric charge may be rotating with the mass."[50]

- ^ Basilius Valentinus supposedly described fluorite in the late 15th century, but because his writings were uncovered 200 years later, this work's veracity is doubtful.[71][72][73]

- ^ Or perhaps from as early as 1670 onwards; Partington[77] and Weeks[76] give differing accounts.

- ^ Fl, since 2012, is used for flerovium.

- ^ Davy, Gay-Lussac, Thénard, and the Irish chemists Thomas and George Knox were injured. Belgian chemist Paulin Louyet and French chemist Jérôme Nicklès died. Moissan also experienced serious hydrogen fluoride poisoning.[76][86]

- ^ Also honored was his invention of the electric arc furnace.

- ^ Fluorine in F

2 is defined to have oxidation state 0. The unstable species F−

2 and F−

3, which decompose at around 40 K, have intermediate oxidation states;[97] F+

4 and a few related species are predicted to be stable.[98] - ^ The metastable boron and nitrogen monofluoride have higher-order fluorine bonds, and some metal complexes use it as a bridging ligand. Hydrogen bonding is another possibility.

- ^ ZrF

4 melts at 932 °C (1710 °F),[111] HfF

4 sublimes at 968 °C (1774 °F),[108] and UF

4 melts at 1036 °C (1897 °F).[112] - ^ These thirteen are those of molybdenum, technetium, ruthenium, rhodium, tungsten, rhenium, osmium, iridium, platinum, polonium, uranium, neptunium, and plutonium.

- ^ Carbon tetrafluoride is formally organic, but is included here rather than in the organofluorine chemistry section – where more complex carbon-fluorine compounds are discussed – for comparison with SiF

4 and GeF

4. - ^ Perfluorocarbon and fluorocarbon are IUPAC synonyms for molecules containing carbon and fluorine only, but in colloquial and commercial contexts the latter term may refer to any carbon- and fluorine-containing molecule, possibly with other elements.

- ^ This terminology is imprecise, and perfluorinated substance is also used.[160]

- ^ This DuPont trademark is sometimes further misused for CFCs, HFCs, or HCFCs.

- ^ American sheep and cattle collars may use 1080 against predators like coyotes.

Sources[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ «Стандартные атомные массы: фтор» . ЦИАВ . 2021.

- ^ Прохаска, Томас; Ирргехер, Йоханна; Бенефилд, Жаклин; Бёлке, Джон К.; Чессон, Лесли А.; Коплен, Тайлер Б.; Дин, Типинг; Данн, Филип Дж. Х.; Грёнинг, Манфред; Холден, Норман Э.; Мейер, Харро Эй Джей (4 мая 2022 г.). «Стандартные атомные веса элементов 2021 (Технический отчет ИЮПАК)» . Чистая и прикладная химия . дои : 10.1515/pac-2019-0603 . ISSN 1365-3075 .

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж Жакко и др. 2000 , с. 381

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б с Хейнс 2011 , с. 4.121.

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б с д и Жакко и др. 2000 , с. 382.

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б с Ассоциация по сжатому газу 1999 , с. 365.

- ^ «Тройная точка | Справочник элементов на сайте KnowledgeDoor» . Дверь Знаний .

- ^ Химмель, Д.; Ридель, С. (2007). «Спустя 20 лет теоретические доказательства того, что AuF 7 на самом деле является AuF 5 ·F 2 ». Неорганическая химия . 46 (13). 5338–5342. дои : 10.1021/ic700431s .

- ^ Дин 1999 , с. 4.6.

- ^ Дин 1999 , с. 4.35.

- ^ Мацуи 2006 , с. 257.

- ^ Yaws & Braker 2001 , с. 385.

- ^ Маккей, Маккей и Хендерсон 2002 , с. 72.

- ^ Ченг и др. 1999 .

- ^ Чисте и Бе 2011 .

- ^ Ли и др. 2014 .

- ^ Дин 1999 , с. 564.

- ^ Лиде 2004 , стр. 10.137–10.138.

- ^ Мур, Станицки и Юрс 2010 , с. 156 .

- ^ Кордеро и др. 2008

- ^ Пююкко и Ацуми 2009 .

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Гринвуд и Эрншоу 1998 , с. 804.

- ^ Макомбер 1996 , с. 230

- ^ Нельсон 1947 .

- ^ Лидин, Молочко и Андреева 2000 , стр. 442–455.

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Виберг, Виберг и Холлеман 2001 , с. 404.

- ^ Патнаик 2007 , с. 472.

- ^ Эгеперс и др. 2000 , с. 400.

- ^ Гринвуд и Эрншоу 1998 , стр. 76, 804.

- ^ Куриакосе и Маркграф 1965 .

- ^ Хасегава и др. 2007 .

- ^ Лагов 1970 , стр. 64–78.

- ^ Lidin, Molochko & Andreeva 2000 , p. 252.

- ^ Таннер Индастриз 2011 .

- ^ Морроу, Перри и Коэн 1959 .

- ^ Эмелеус и Шарп 1974 , с. 111 .

- ^ Wiberg, Wiberg & Holleman 2001 , с. 457.

- ^ Брантли 1949 , с. 26 .

- ^ Жакко и др. 2000 , с. 383.

- ^ Питцер 1975 .

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Хрящев и др. 2000 .

- ^ Бердон, Эмсон и Эдвардс 1987 .

- ^ Как и 2004 г. , стр. 4.12.

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Дин 1999 , с. 523.

- ^ Полинг, Кивени и Робинсон 1970 .

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Янг 1975 , с. 10.

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Барретт, Мейер и Вассерман, 1967 .

- ^ Национальный центр ядерных данных и NuDat 2.1 , Фтор-19 .

- ^ Энергичный 1961 .

- ^ Мейзингер, Чиппендейл и Фэйрхерст, 2012 , стр. 752, 754.

- ^ SCOPE 50 - Радиоэкология после Чернобыля. Архивировано 13 мая 2014 г. в Wayback Machine , Научный комитет по проблемам окружающей среды (SCOPE), 1993. См. таблицу 1.9 в разделе 1.4.5.2.

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Национальный центр ядерных данных и NuDat 2.1 .

- ^ NUBASE 2016 , стр. 030001-23–030001-27.

- ^ NUBASE 2016 , стр. 030001–24.

- ^ Кэмерон 1973 .

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б с Кросвелл 2003 .

- ^ Клейтон 2003 , стр. 101–104 .

- ^ Рент и др. 2004 .

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Жакко и др. 2000 , с. 384

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б с Шмедт, Мангстль и Краус 2012 .

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б с д и Гринвуд и Эрншоу 1998 , с. 795.

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Норвуд и Фос 1907 , с. 52 .

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я дж к л м н Вильяльба, Эйрес и Шредер, 2008 г.

- ^ Келли и Миллер 2005 .

- ^ Ласти и др. 2008 год .

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Гриббл 2002 .

- ^ Рихтер, Хан и Фукс 2001 , стр. 3.

- ^ Гринвуд и Эрншоу 1998 , стр. 790.

- ^ Сеннинг 2007 , с. 149 .

- ^ Стиллман 1912 .

- ^ Принсипи 2012 , стр. 140, 145.

- ^ Agricola, Hoover & Hoover 1912 , сноски и комментарии, стр. xxx, 38, 409, 430, 461, 608.

- ^ Гринвуд и Эрншоу 1998 , стр. 109.

- ^ Агрикола, Гувер и Гувер 1912 , предисловие, стр. 380–381 .

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б с д и Уикс 1932 года .

- ^ Партингтон 1923 .

- ^ Маргграф 1770 .

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час Кирш 2004 , стр. 3–10.

- ^ Шееле 1771 .

- ^ Ампер 1816 .

- ^ Трессо, Ален (6 октября 2018 г.). Фтор: парадоксальный элемент . Академическая пресса. ISBN 9780128129913 .

- ^ Дэви 1813 , с. 278 .

- ^ Бэнкс 1986 , с. 11.

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Сторер 1864 , стр. 278–280 .

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б с д и Шоу 2011 года .

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Азимов 1966 , с. 162.

- ^ Гринвуд и Эрншоу 1998 , стр. 789–791.

- ^ Муассан 1886 .

- ^ Виэль и Голдвайт 1993 , с. 35 .

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б с д Оказоэ 2009 .

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Хауншелл и Смит 1988 , стр. 156–157.

- ^ Дюпон 2013а .

- ^ Мейер 1977 , с. 111.

- ^ Кирш 2004 , стр. 60–66 .

- ^ Ридель и Каупп 2009 .

- ^ Wiberg, Wiberg & Holleman 2001 , с. 422.

- ^ Шлёдер и Ридель 2012 .

- ^ Харбисон 2002 .

- ^ Эдвардс 1994 , с. 515 .

- ^ Катакусе и др. 1999 , с. 267 .

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Эгеперс и др. 2000 , стр. 420–422.

- ^ Уолш 2009 , стр. 99–102 , 118–119 .

- ^ Эмелеус и Шарп 1983 , стр. 89–97.

- ^ Бабель и Трессо 1985 , стр. 91–96 .

- ^ Эйнштейн и др. 1967 год .

- ^ Браун и др. 2005 , с. 144 .

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Перри 2011 , с. 193 .

- ^ Керн и др. 1994 .

- ^ Как и 2004 г. , стр. 4.60, 4.76, 4.92, 4.96.

- ^ Как и 2004 г. , стр. 4.96.

- ^ Как и 2004 г. , стр. 4.92.

- ^ Гринвуд и Эрншоу 1998 , стр. 964.

- ^ Беккер и Мюллер 1990 .

- ^ Гринвуд и Эрншоу 1998 , стр. 990.

- ^ Как и 2004 г. , стр. 4.72, 4.91, 4.93.

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Гринвуд и Эрншоу, 1998 , стр. 561–563.

- ^ Эмелеус и Шарп 1983 , стр. 256–277.

- ^ Маккей, Маккей и Хендерсон 2002 , стр. 355–356.

- ^ Greenwood & Earnshaw 1998 (разные страницы по металлам в соответствующих главах).

- ^ Как и 2004 г. , стр. 4.71, 4.78, 4.92.

- ^ Дрюс и др. 2006 год .

- ^ Гринвуд и Эрншоу 1998 , стр. 819.

- ^ Бартлетт 1962 .

- ^ Полинг 1960 , стр. 454–464 .

- ^ Аткинс и Джонс 2007 , стр. 184–185.

- ^ Эмсли 1981 .

- ^ Гринвуд и Эрншоу 1998 , стр. 812–816.

- ^ Wiberg, Wiberg & Holleman 2001 , с. 425.

- ^ Кларк 2002 .

- ^ Чемберс и Холлидей 1975 , стр. 328–329.

- ^ Air Products and Chemicals 2004 , с. 1.

- ^ Нури, Сильви и Гиллеспи 2002 .

- ^ Чанг и Голдсби, 2013 , с. 706.

- ^ Эллис 2001 , с. 69.

- ^ Эгеперс и др. 2000 , с. 423.

- ^ Wiberg, Wiberg & Holleman 2001 , с. 897.

- ^ Рагхаван 1998 , стр. 164–165 .

- ^ Годфри и др. 1998 , с. 98 .

- ^ Эгеперс и др. 2000 , с. 432.

- ^ Мурти, Мехди Али и Ашок 1995 , стр. 180–182 , 206–208 .

- ^ Greenwood & Earnshaw 1998 , стр. 638–640, 683–689, 767–778.

- ^ Wiberg, Wiberg & Holleman 2001 , стр. 435–436.

- ^ Гринвуд и Эрншоу 1998 , стр. 828–830.

- ^ Патнаик 2007 , стр. 478–479 .

- ^ Мёллер, Байлар и Кляйнберг 1980 , с. 236.

- ^ Wiberg, Wiberg & Holleman 2001 , стр. 392–393.

- ^ Wiberg, Wiberg & Holleman 2001 , с. 395–397, 400.

- ^ Льюарс 2008 , с. 68.

- ^ Питцер 1993 , с. 111 .

- ^ Льюарс 2008 , с. 67.

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Бихари, Чабан и Гербер 2002 .

- ^ Льюарс 2008 , с. 71.

- ^ Хугерс 2002 , стр. 4–12.

- ^ О'Хаган 2008 .

- ^ Зигемунд и др. 2005 , с. 444.

- ^ Сэндфорд 2000 , с. 455.

- ^ Зигемунд и др. 2005 , стр. 451–452.

- ^ Барби, МакКормак и Вартанян 2000 , с. 116 .

- ^ Познер и др. 2013 , стр. +углеводороды+которые+полностью+фторированы+за исключением+одной+функциональной+группы%22&pg=PA187 187–190 .

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Познер 2011 , с. 27.

- ^ Салагер 2002 , с. 45.

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Карлсон и Шмигель 2000 , с. 3.

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Карлсон и Шмигель 2000 , стр. 3–4.

- ^ Роудс 2008 , с. 2 .

- ^ Окада и др. 1998 год .

- ^ Карлсон и Шмигель 2000 , с. 4.

- ^ Эгеперс и др. 2000 .

- ^ Норрис Шрив; Джозеф Бринк-младший (1977). Химическая перерабатывающая промышленность (4-е изд.). МакГроу-Хилл. п. 321. ИСБН 0070571457 .

- ^ Жакко и др. 2000 , с. 386

- ^ Жакко и др. 2000 , стр. 384–285.

- ^ Гринвуд и Эрншоу 1998 , стр. 796–797.

- ^ Жакко и др. 2000 , стр. 384–385.

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Жакко и др. 2000 , стр. 390–391.

- ^ Шрайвер и Аткинс 2010 , с. 427.

- ^ Кристе 1986 .

- ^ Исследовательская группа Christe nd

- ^ Кэри 2008 , с. 173.

- ^ Миллер 2003b .

- ^ ПРВеб 2012 .

- ^ Бомбург 2012 .

- ^ ПМР 2013 .

- ^ Фултон и Миллер 2006 , с. 471 .

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Жакко и др. 2000 , с. 392.

- ^ Эгеперс и др. 2000 , с. 430.

- ^ Жакко и др. 2000 , стр. 391–392.

- ^ Эль-Каре 1994 , с. 317 .

- ^ Арана и др. 2007

- ^ Миллер 2003a .

- ^ Energetics, Inc. 1997 , стр. 41, 50.

- ^ Эгеперс и др. 2000 , с. 428.

- ^ Уилли 2007 , с. 113 .

- ^ ПРВеб 2010 .

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б с Реннер 2006 .

- ^ Грин и др. 1994 , стр. 91–93 .

- ^ Дюпон 2013b .

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Уолтер 2013 .

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Бузник 2009 .

- ^ ПРВеб 2013 .

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б с д и Мартин 2007 , стр. 187–194 .

- ^ ДеБергалис 2004 .

- ^ Грот 2011 , стр. 1-10 .

- ^ Рамкумар 2012 , с. 567 .

- ^ Берни 1999 , с. 111 .

- ^ Слай 2012 , с. 10.

- ^ Кот 2001 , стр. 516–551 .

- ^ Ульманн 2008 , стр. 538, 543–547.

- ^ ICIS 2006 .

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Теодоридис 2006 .

- ^ Агентство по охране окружающей среды, 1996 г.

- ^ Генеральный директор по окружающей среде 2007 .

- ^ Бисли 2002 .

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Праудфут, Брэдберри и Вейл, 2006 г.

- ^ Эйслер 1995 .

- ^ Пиццо и др. 2007 .

- ^ CDC 2001 .

- ^ Рипа 1993 .

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Ченг, Чалмерс и Шелдон 2007 .

- ^ НХМРК 2007 ; см. в Yeung 2008 . резюме

- ^ Марья 2011 , с. 343 .

- ^ Армфилд 2007 .

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Бэлум, Шейхам и Берт 2008 , с. 518 .

- ^ Коса 2012 , с. 12.

- ^ Эмсли 2011 , с. 178.

- ^ Джонсон 2011 .

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Суинсон 2005 .

- ^ Хагманн 2008 .

- ^ Митчелл 2004 , стр. 37–39 .

- ^ Прескорн 1996 , гл. 2 .

- ^ Вернер и др. 2011

- ^ Броуди 2012 .

- ^ Нельсон и др. 2007

- ^ Кинг, Мэлоун и Лилли 2000 .

- ^ Паренте 2001 , с. 40 .

- ^ Радж и Эрдин 2012 , с. 58 .

- ^ Филлер и Саха 2009 .

- ^ Беге и Бонне-Дельпон 2008 , стр. 335–336 .

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Шмитц и др. 2000 .

- ^ Бустаманте и Педерсен 1977 .

- ^ Алави и Хуанг 2007 , с. 41.

- ^ Габриэль и др. 1996 год .

- ^ Саркар 2008 .

- ^ Шиммейер 2002 .

- ^ Дэвис 2006 .

- ^ Доходы 1998 года .

- ^ Табер 1999 .

- ^ Шаффер, Вольфсон и Кларк 1992 , с. 102.

- ^ Качмарек и др. 2006 год .

- ^ Нильсен 2009 .

- ^ Оливарес и Уауи 2004 .

- ^ Совет по продовольствию и питанию .

- ^ Сяо-Хуа, Сюй; Ян-Мин, Ли; Чанг-Цзян, Линь; Чуй-Хуа, Конг (4 января 2003 г.). из губки Phakellia fusca». J. Nat. Prod . 2 (66): 285–288. doi : 10.1021/np020034f . PMID 12608868 .

- ^ Мерфи, Шаффрат и О'Хаган, 2003 г.

- ^ О'Хаган и др. 2002

- ^ Национальный институт безопасности и гигиены труда, 1994a .

- ^ Национальный институт безопасности и гигиены труда, 1994b .

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Кеплингер и Суисса, 1968 .

- ^ Эмсли 2011 , с. 179.

- ^ Биллер 2007 , с. 939.

- ^ «Фтор. Паспорт безопасности» (PDF) . Аэрогаз. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 19 апреля 2015 года.

- ^ Итон 1997 .

- ^ «Неорганическая химия» Гэри Л. Мисслера и Дональда А. Тарра, 4-е издание, Пирсон

- ^ «Неорганическая химия» Шрайвер, Веллер, Овертон, Рурк и Армстронг, 6-е издание, Фриман

- ^ Блоджетт, Суруда и Крауч 2001 .

- ^ Хоффман и др. 2007 , с. 1333.

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б ХСМ 2006 .

- ^ Фишман 2001 , стр. 458–459 .

- ^ Эль Саади и др. 1989 год .

- ^ Роблин и др. 2006

- ^ Хультен и др. 2004 .

- ^ Зорич 1991 , стр. 182–183 .

- ^ Литепло и др. 2002 , с. 100.

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б с д Шин и Сильверберг 2013 .

- ^ Редди 2009 .

- ^ Баэз, Баэз и Марталер 2000 .

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Огенштейн и др. 1991 год .

- ^ Гесснер и др. 1994 .

- ^ CDC 2013 .

- ^ Шульман и Уэллс 1997 .

- ^ Бек и др. 2011 .

- ^ Аукамп и Бьорн 2010 , стр. 4–6, 41, 46–47.

- ^ Митчелл Кроу 2011 .

- ^ Барри и Филлипс 2006 .

- ^ Агентство по охране окружающей среды 2013а .

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Агентство по охране окружающей среды, 2013б .

- ^ Маккой 2007 .

- ^ Форстер и др. 2007 , стр. 212–213.

- ^ Шварц 2004 , с. 37.

- ^ Гизи и Каннан 2002 .

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б с д Стинланд, Флетчер и Савиц 2010 .

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б с д Беттс 2007 .

- ^ Агентство по охране окружающей среды 2012 .

- ^ Зарейиталабад и др. 2013 .

- ^ Jump up to: Перейти обратно: а б Lau et al. 2007Лау и др. 2007

Индексированные ссылки [ править ]

- Агрикола, Георгиус ; Гувер, Герберт Кларк; Гувер, Лу Генри (1912). Де Ре Металлика . Лондон: Горный журнал.

- Эгеперс, Ж.; Моллард, П.; Девильерс, Д.; Чемла, М.; Фарон, Р.; Романо, RE; Кью, JP (2000). «Соединения фтора неорганические». Энциклопедия промышленной химии Ульмана . Вайнхайм: Wiley-VCH. стр. 397–441. дои : 10.1002/14356007 . ISBN 3527306730 .

- Воздушные продукты и химикаты (2004). «Безопасность № 39 трифторида хлора» (PDF) . Воздушные продукты и химикаты. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 18 марта 2006 года . Проверено 16 февраля 2014 г.

- Алави, Аббас; Хуанг, Стив С. (2007). «Позитронно-эмиссионная томография в медицине: обзор». В Хаяте, Массачусетс (ред.). Визуализация рака, Том 1: Карциномы легких и молочной железы . Берлингтон: Академическая пресса. стр. 39–44. ISBN 978-0-12-370468-9 .

- Ампер, Андре-Мари (1816). «Продолжение естественной классификации простых тел» . Анналы химии и физики (на французском языке). 2 :1–5.

- Арана, ЛР; Мас, Н.; Шмидт, Р.; Франц, Эй Джей; Шмидт, Массачусетс; Дженсен, К.Ф. (2007). «Изотропное травление кремния в газообразном фторе для микромеханической обработки МЭМС». Журнал микромеханики и микроинженерии . 17 (2): 384–392. Бибкод : 2007JMiMi..17..384A . дои : 10.1088/0960-1317/17/2/026 . S2CID 135708022 .

- Армфилд, Дж. М. (2007). «Когда общественные действия подрывают общественное здравоохранение: критическое исследование антифторидационной литературы» . Политика здравоохранения Австралии и Новой Зеландии . 4:25 . дои : 10.1186/1743-8462-4-25 . ПМЦ 2222595 . ПМИД 18067684 .

- Азимов, Исаак (1966). Благородные газы . Нью-Йорк: Основные книги. ISBN 978-0-465-05129-8 .

- Аткинс, Питер ; Джонс, Лоретта (2007). Химические принципы: В поисках понимания (4-е изд.). Нью-Йорк: WH Freeman. ISBN 978-1-4292-0965-6 .

- Окамп, Питер Дж.; Бьорн, Ларс Олоф (2010). «Вопросы и ответы о воздействии разрушения озонового слоя и изменения климата на окружающую среду: обновление 2010 г.» (PDF) . Экологическая программа ООН. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 3 сентября 2013 года . Проверено 14 октября 2013 г.

- Ауди, Г.; Кондев, ФГ; Ван, М.; Хуанг, WJ; Наими, С. (2017). «Оценка ядерных свойств NUBASE2016» (PDF) . Китайская физика C . 41 (3): 030001. Бибкод : 2017ChPhC..41c0001A . дои : 10.1088/1674-1137/41/3/030001 . .

- Огенштейн, WL; и др. (1991). «Прием фтора детьми: обзор 87 случаев» . Педиатрия . 88 (5): 907–912. дои : 10.1542/педс.88.5.907 . ПМИД 1945630 . S2CID 22106466 .

- Бабель, Дитрих; Трессо, Ален (1985). «Кристаллохимия фторидов». В Хагенмюллере, Поле (ред.). Неорганические твердые фториды: химия и физика . Орландо: Академическая пресса. стр. 78–203. ISBN 978-0-12-412490-5 .

- Баэлум, Вибеке; Шейхэм, Обри; Берт, Брайан (2008). «Контроль кариеса среди населения». В Фейерскове, Оле; Кидд, Эдвина (ред.). Кариес зубов: болезнь и ее клиническое лечение (2-е изд.). Оксфорд: Блэквелл Манксгаард. стр. 505–526. ISBN 978-1-4051-3889-5 .

- Баэз, Рамон Дж.; Баэз, Марта X.; Марталер, Томас М. (2000). «Выделение фтора с мочой детьми 4–6 лет в сообществе Южного Техаса» . Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública . 7 (4): 242–248. дои : 10.1590/S1020-49892000000400005 . ПМИД 10846927 .

- Бэнкс, RE (1986). «Выделение фтора Муассаном: подготовка сцены». Журнал химии фтора . 33 (1–4): 3–26. Бибкод : 1986JFluC..33....3B . дои : 10.1016/S0022-1139(00)85269-0 .

- Барби, К.; МакКормак, К.; Вартанян, В. (2000). «Проблемы EHS, связанные с обработкой распылением озонированной воды». В Мендичино, Л. (ред.). Экологические проблемы в электронной и полупроводниковой промышленности . Пеннингтон, Нью-Джерси: Электрохимическое общество. стр. 108–121. ISBN 978-1-56677-230-3 .

- Барретт, CS; Мейер, Л.; Вассерман, Дж. (1967). «Фазовая диаграмма аргон-фтор». Журнал химической физики . 47 (2): 740–743. Бибкод : 1967ЖЧФ..47..740Б . дои : 10.1063/1.1711946 .

- Барри, Патрик Л.; Филлипс, Тони (26 мая 2006 г.). «Хорошие новости и загадка» . Национальное управление по аэронавтике и исследованию космического пространства. Архивировано из оригинала 27 мая 2010 года . Проверено 6 января 2012 года .

- Бартлетт, Н. (1962). «Ксенон Гексафторплатинат (V) Xe + [ПтФ 6 ] − «. Труды Химического общества (6): 218. doi : 10.1039/PS9620000197 .

- Бизли, Майкл (август 2002 г.). Рекомендации по безопасному использованию фторацетата натрия (1080) (PDF) . Веллингтон: Служба безопасности и гигиены труда, Министерство труда (Новая Зеландия). ISBN 0-477-03664-3 . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 11 ноября 2013 года . Проверено 11 ноября 2013 г.

- Бек, Джефферсон; Ньюман, Пол; Шиндлер, Трент Л.; Перкинс, Лори (2011). «Что случилось бы с озоновым слоем, если бы хлорфторуглероды (ХФУ) не регулировались?» . Национальное управление по аэронавтике и исследованию космического пространства. Архивировано из оригинала 4 августа 2020 года . Проверено 15 октября 2013 г.

- Беккер, С.; Мюллер, Б.Г. (1990). «Тетрафториды ванадия». Международное издание «Прикладная химия» на английском языке . 29 (4): 406–407. дои : 10.1002/anie.199004061 .

- Беге, Жан-Пьер; Бонне-Дельпон, Даниэль (2008). Биоорганическая и медицинская химия фтора . Хобокен: Джон Уайли и сыновья. ISBN 978-0-470-27830-7 .

- Беттс, Канзас (2007). «Перфторалкиловые кислоты: о чем нам говорят данные?» . Перспективы гигиены окружающей среды . 115 (5): А250–А256. дои : 10.1289/ehp.115-a250 . ПМЦ 1867999 . ПМИД 17520044 .

- Бихари, З.; Чабан, генеральный менеджер; Гербер, РБ (2002). «Стабильность химически связанного соединения гелия в твердом гелии под высоким давлением». Журнал химической физики . 117 (11): 5105–5108. Бибкод : 2002JChPh.117.5105B . дои : 10.1063/1.1506150 .

- Биллер, Хосе (2007). Интерфейс неврологии и внутренней медицины (иллюстрированное издание). Филадельфия: Липпинкотт Уильямс и Уилкинс. ISBN 978-0-7817-7906-7 .

- Блоджетт, Д.В.; Суруда, AJ; Крауч, Б.И. (2001). «Смертельные непреднамеренные профессиональные отравления плавиковой кислотой в США» (PDF) . Американский журнал промышленной медицины . 40 (2): 215–220. дои : 10.1002/аджим.1090 . ПМИД 11494350 . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 17 июля 2012 года.

- Бомбург, Николя (4 июля 2012 г.). «Мировой рынок фторхимии, Фридония» . Репортерлинкер . Проверено 20 октября 2013 г.

- Брантли, Л.Р. (1949). Сквайрс, Рой; Кларк, Артур К. (ред.). "Фтор". Pacific Rockets: Журнал Тихоокеанского ракетного общества . 3 (1). Южная Пасадена: Sawyer Publishing/Историческая библиотека Тихоокеанского ракетного общества: 11–18. ISBN 978-0-9794418-5-1 .

- Броуди, Джейн Э. (10 сентября 2012 г.). «Популярные антибиотики могут иметь серьезные побочные эффекты» . Блог The New York Times Well . Проверено 18 октября 2013 г.

- Браун, Пол Л.; Момпеан, Федерико Дж.; Перроне, Джейн; Ильмассен, Мириам (2005). Химическая термодинамика циркония . Амстердам: ISBN Elsevier BV 978-0-444-51803-3 .

- Бердон, Дж.; Эмсон, Б.; Эдвардс, Эй Джей (1987). «Действительно ли фтор желтый?». Журнал химии фтора . 34 (3–4): 471–474. Бибкод : 1987JFluC..34..471B . дои : 10.1016/S0022-1139(00)85188-X .

- Берни, Х. (1999). «Прошлое, настоящее и будущее хлорщелочной промышленности». В Берни, HS; Фуруя, Н.; Хайн, Ф.; Ота, К.-И. (ред.). Хлор-щелочь и хлоратная технология: Мемориальный симпозиум Р.Б. Макмаллина . Пеннингтон: Электрохимическое общество. стр. 105–126. ISBN 1-56677-244-3 .

- Бустаманте, Э.; Педерсен, PL (1977). «Высокий аэробный гликолиз клеток гепатомы крысы в культуре: роль митохондриальной гексокиназы» . Труды Национальной академии наук . 74 (9): 3735–3739. Бибкод : 1977PNAS...74.3735B . дои : 10.1073/pnas.74.9.3735 . ПМК 431708 . ПМИД 198801 .

- Бузник, В.М. (2009). «Химия фторполимеров в России: современное состояние и перспективы». Российский журнал общей химии . 79 (3): 520–526. дои : 10.1134/S1070363209030335 . S2CID 97518401 .

- Кэмерон, AGW (1973). «Изобилие элементов в Солнечной системе» (PDF) . Обзоры космической науки . 15 (1): 121–146. Бибкод : 1973ССРв...15..121С . дои : 10.1007/BF00172440 . S2CID 120201972 . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 21 октября 2011 года.

- Кэри, Чарльз В. (2008). Афроамериканцы в науке . Санта-Барбара: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-998-6 .

- Карлсон, Д.П.; Шмигель, В. (2000). «Фторполимеры органические». Энциклопедия промышленной химии Ульмана . Вайнхайм: Wiley-VCH. стр. 495–533. дои : 10.1002/14356007.a11_393 . ISBN 3527306730 .

- Центры по контролю и профилактике заболеваний (2001). «Рекомендации по использованию фтора для предотвращения и контроля кариеса зубов в Соединенных Штатах» . Рекомендации и отчеты MMWR . 50 (РР–14): 1–42. ПМИД 11521913 . Проверено 14 октября 2013 г.

- Центры болезней по контролю и профилактике (10 июля 2013 г.). «Фторирование воды в общинах» . Проверено 25 октября 2013 г.

- Чемберс, К.; Холлидей, АК (1975). Современная неорганическая химия: текст для среднего уровня (PDF) . Лондон: ISBN Баттерворта и Ко. 978-0-408-70663-6 . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 23 марта 2013 года.

- Чанг, Раймонд ; Голдсби, Кеннет А. (2013). Химия (11-е изд.). Нью-Йорк: МакГроу-Хилл. ISBN 978-0-07-131787-0 .

- Ченг, Х.; Фаулер, Делавэр; Хендерсон, ПБ; Хоббс, JP; Пасколини, MR (1999). «О магнитной восприимчивости фтора». Журнал физической химии А. 103 (15): 2861–2866. Бибкод : 1999JPCA..103.2861C . дои : 10.1021/jp9844720 .

- Ченг, К.К.; Чалмерс, И.; Шелдон, Т.А. (2007). «Добавление фтора в воду» (PDF) . БМЖ . 335 (7622): 699–702. doi : 10.1136/bmj.39318.562951.BE . ПМК 2001050 . ПМИД 17916854 . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 3 марта 2016 года . Проверено 26 марта 2012 г.

- Чисте, В.; Бе, ММ (2011). «Ф-18» (PDF) . В Бе, ММ; Курсоль, Н.; Дюшемен, Б.; Лагутин, Ф.; и др. (ред.). Таблица радионуклидов (Отчет). CEA (Комиссия по атомной энергии и альтернативным источникам энергии), LIST, LNE-LNHB (Национальная лаборатория Анри Беккереля/Комиссия по атомной энергии). Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 11 августа 2020 г. Проверено 15 июня 2011 г.

- Кристе, Карл О. (1986). «Химический синтез элементарного фтора». Неорганическая химия . 25 (21): 3721–3722. дои : 10.1021/ic00241a001 .

- Исследовательская группа Кристе (nd). «Химический синтез элементарного фтора» . Архивировано из оригинала 4 марта 2016 года . Проверено 12 января 2013 г.

- Кларк, Джим (2002). «Кислотность галогеноводородов» . chemguide.co.uk . Проверено 15 октября 2013 г.

- Клейтон, Дональд (2003). Справочник по изотопам в космосе: от водорода до галлия . Нью-Йорк: Издательство Кембриджского университета. ISBN 978-0-521-82381-4 .

- Ассоциация по сжатому газу (1999). Справочник по сжатым газам (4-е изд.). Бостон: Академическое издательство Kluwer. ISBN 978-0-412-78230-5 .

- Кордеро, Б.; Гомес, В.; Платеро-Прац, А.Е.; Ревес, М.; Эчеверрия, Дж.; Кремадес, Э.; Барраган, Ф.; Альварес, С. (2008). «Возвращение к ковалентным радиусам». Далтон Транзакции (21): 2832–2838. дои : 10.1039/b801115j . ПМИД 18478144 .

- Крейчер, Конни М. (2012). «Современные концепции профилактической стоматологии» (PDF) . DentalCare.com. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 14 октября 2013 года . Проверено 14 октября 2013 г.

- Кросвелл, Кен (сентябрь 2003 г.). «Фтор: элементарная загадка» . Небо и телескоп . Проверено 17 октября 2013 г.

- Митчелл Кроу, Джеймс (2011). «Обнаружены первые признаки восстановления озоновых дыр». Природа . дои : 10.1038/news.2011.293 .

- Дэвис, Николь (ноябрь 2006 г.). «Лучше крови» . Популярная наука . Архивировано из оригинала 4 июня 2011 года . Проверено 20 октября 2013 г.