Ресничный

| Ресничный Временный диапазон:

| |

|---|---|

| |

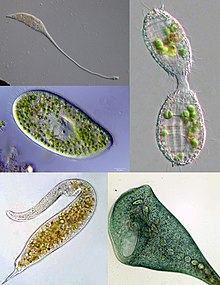

| Some examples of ciliate diversity. Clockwise from top left: Lacrymaria, Coleps, Stentor, Dileptus, Paramecium | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Clade: | Diaphoretickes |

| Clade: | TSAR |

| Clade: | SAR |

| Clade: | Alveolata |

| Phylum: | Ciliophora Doflein, 1901 emend. |

| Subphyla and classes[1] | |

|

See text for subclasses. | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Ресинкологические реснички представляют собой группу альвеолатов , характеризующихся присутствием волос, называемых ресничками , которые идентичны по структуре для эукариотической жгутики , но в целом короче и присутствуют в гораздо большем количестве, с другим волнистым рисунком, чем жгутиков. Реснички встречаются во всех членах группы (хотя специфическая Suctoria имеет их только для части своего жизненного цикла ) и по -разному используются в плавании, ползании, прикреплении, кормлении и ощущениях.

Ресинкости являются важной группой протистов , распространенной почти везде есть вода-в озерах, прудах, океанах, реках и почвах, включая аноксические и истощенные кислородом среды обитания. [ 2 ] Было описано около 4500 уникальных свободных видов, и потенциальное количество существующих видов оценивается в 27 000–40 000. [ 3 ] В это число включены много эктосимбиотических и эндосимбиотических видов, а также некоторые облигатные и оппортунистические паразиты . Ориентировочные виды варьируются размером от 10 мкм у некоторых Кольподеев до 4 мм в некоторых гелеиидах и включают некоторые из наиболее морфологически сложных простейших. [4][5]

In most systems of taxonomy, "Ciliophora" is ranked as a phylum[6] under any of several kingdoms, including Chromista,[7] Protista[8] or Protozoa.[9] In some older systems of classification, such as the influential taxonomic works of Alfred Kahl, ciliated protozoa are placed within the class "Ciliata"[10][11] (a term which can also refer to a genus of fish). In the taxonomic scheme endorsed by the International Society of Protistologists, which eliminates formal rank designations such as "phylum" and "class", "Ciliophora" is an unranked taxon within Alveolata.[12][13]

Cell structure

[edit]

Nuclei

[edit]Unlike most other eukaryotes, ciliates have two different sorts of nuclei: a tiny, diploid micronucleus (the "generative nucleus", which carries the germline of the cell), and a large, ampliploid macronucleus (the "vegetative nucleus", which takes care of general cell regulation, expressing the phenotype of the organism).[14][15] The latter is generated from the micronucleus by amplification of the genome and heavy editing. The micronucleus passes its genetic material to offspring, but does not express its genes. The macronucleus provides the small nuclear RNA for vegetative growth.[16][15]

Division of the macronucleus occurs in most ciliate species, apart from those in class Karyorelictea, whose macronuclei are replaced every time the cell divides.[17] Macronuclear division is accomplished by amitosis, and the segregation of the chromosomes occurs by a process whose mechanism is unknown.[15] After a certain number of generations (200–350, in Paramecium aurelia, and as many as 1,500 in Tetrahymena[17]) the cell shows signs of aging, and the macronuclei must be regenerated from the micronuclei. Usually, this occurs following conjugation, after which a new macronucleus is generated from the post-conjugal micronucleus.[15]

Cytoplasm

[edit]Food vacuoles are formed through phagocytosis and typically follow a particular path through the cell as their contents are digested and broken down by lysosomes so the substances the vacuole contains are then small enough to diffuse through the membrane of the food vacuole into the cell. Anything left in the food vacuole by the time it reaches the cytoproct (anal pore) is discharged by exocytosis. Most ciliates also have one or more prominent contractile vacuoles, which collect water and expel it from the cell to maintain osmotic pressure, or in some function to maintain ionic balance. In some genera, such as Paramecium, these have a distinctive star shape, with each point being a collecting tube.

Specialized structures in ciliates

[edit]

Mostly, body cilia are arranged in mono- and dikinetids, which respectively include one and two kinetosomes (basal bodies), each of which may support a cilium. These are arranged into rows called kineties, which run from the anterior to posterior of the cell. The body and oral kinetids make up the infraciliature, an organization unique to the ciliates and important in their classification, and include various fibrils and microtubules involved in coordinating the cilia. In some forms there are also body polykinetids, for instance, among the spirotrichs where they generally form bristles called cirri.

The infraciliature is one of the main components of the cell cortex. Others are the alveoli, small vesicles under the cell membrane that are packed against it to form a pellicle maintaining the cell's shape, which varies from flexible and contractile to rigid. Numerous mitochondria and extrusomes are also generally present. The presence of alveoli, the structure of the cilia, the form of mitosis and various other details indicate a close relationship between the ciliates, Apicomplexa, and dinoflagellates. These superficially dissimilar groups make up the alveolates.

Feeding

[edit]Most ciliates are heterotrophs, feeding on smaller organisms, such as bacteria and algae, and detritus swept into the oral groove (mouth) by modified oral cilia. This usually includes a series of membranelles to the left of the mouth and a paroral membrane to its right, both of which arise from polykinetids, groups of many cilia together with associated structures. The food is moved by the cilia through the mouth pore into the gullet, which forms food vacuoles.

Many species are also mixotrophic, combining phagotrophy and phototrophy through kleptoplasty or symbiosis with photosynthetic microbes.[18][19]

The ciliate Halteria has been observed to feed on chloroviruses.[20]

Feeding techniques vary considerably, however. Some ciliates are mouthless and feed by absorption (osmotrophy), while others are predatory and feed on other protozoa and in particular on other ciliates. Some ciliates parasitize animals, although only one species, Balantidium coli, is known to cause disease in humans.[21]

Reproduction and sexual phenomena

[edit]

Reproduction

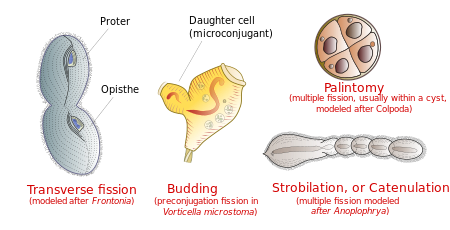

[edit]Ciliates reproduce asexually, by various kinds of fission.[17] During fission, the micronucleus undergoes mitosis and the macronucleus elongates and undergoes amitosis (except among the Karyorelictean ciliates, whose macronuclei do not divide). The cell then divides in two, and each new cell obtains a copy of the micronucleus and the macronucleus.

Typically, the cell is divided transversally, with the anterior half of the ciliate (the proter) forming one new organism, and the posterior half (the opisthe) forming another. However, other types of fission occur in some ciliate groups. These include budding (the emergence of small ciliated offspring, or "swarmers", from the body of a mature parent); strobilation (multiple divisions along the cell body, producing a chain of new organisms); and palintomy (multiple fissions, usually within a cyst).[22]

Fission may occur spontaneously, as part of the vegetative cell cycle. Alternatively, it may proceed as a result of self-fertilization (autogamy),[23] or it may follow conjugation, a sexual phenomenon in which ciliates of compatible mating types exchange genetic material. While conjugation is sometimes described as a form of reproduction, it is not directly connected with reproductive processes, and does not directly result in an increase in the number of individual ciliates or their progeny.[24]

Conjugation

[edit]- Overview

Ciliate conjugation is a sexual phenomenon that results in genetic recombination and nuclear reorganization within the cell.[24][22] During conjugation, two ciliates of a compatible mating type form a bridge between their cytoplasms. The micronuclei undergo meiosis, the macronuclei disappear, and haploid micronuclei are exchanged over the bridge. In some ciliates (peritrichs, chonotrichs and some suctorians), conjugating cells become permanently fused, and one conjugant is absorbed by the other.[21][25] In most ciliate groups, however, the cells separate after conjugation, and both form new macronuclei from their micronuclei.[26] Conjugation and autogamy are always followed by fission.[22]

In many ciliates, such as Paramecium, conjugating partners (gamonts) are similar or indistinguishable in size and shape. This is referred to as "isogamontic" conjugation. In some groups, partners are different in size and shape. This is referred to as "anisogamontic" conjugation. In sessile peritrichs, for instance, one sexual partner (the microconjugant) is small and mobile, while the other (macroconjugant) is large and sessile.[24]

In Paramecium caudatum, the stages of conjugation are as follows (see diagram at right):

- Compatible mating strains meet and partly fuse

- The micronuclei undergo meiosis, producing four haploid micronuclei per cell.

- Three of these micronuclei disintegrate. The fourth undergoes mitosis.

- The two cells exchange a micronucleus.

- The cells then separate.

- The micronuclei in each cell fuse, forming a diploid micronucleus.

- Mitosis occurs three times, giving rise to eight micronuclei.

- Four of the new micronuclei transform into macronuclei, and the old macronucleus disintegrates.

- Binary fission occurs twice, yielding four identical daughter cells.

DNA rearrangements (gene scrambling)

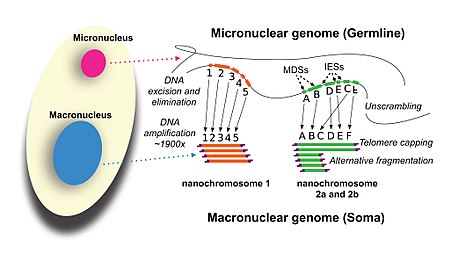

[edit]Ciliates contain two types of nuclei: somatic "macronucleus" and the germline "micronucleus". Only the DNA in the micronucleus is passed on during sexual reproduction (conjugation). On the other hand, only the DNA in the macronucleus is actively expressed and results in the phenotype of the organism. Macronuclear DNA is derived from micronuclear DNA by amazingly extensive DNA rearrangement and amplification.

The macronucleus begins as a copy of the micronucleus. The micronuclear chromosomes are fragmented into many smaller pieces and amplified to give many copies. The resulting macronuclear chromosomes often contain only a single gene. In Tetrahymena, the micronucleus has 10 chromosomes (five per haploid genome), while the macronucleus has over 20,000 chromosomes.[27]

In addition, the micronuclear genes are interrupted by numerous "internal eliminated sequences" (IESs). During development of the macronucleus, IESs are deleted and the remaining gene segments, macronuclear destined sequences (MDSs), are spliced together to give the operational gene. Tetrahymena has about 6,000 IESs and about 15% of micronuclear DNA is eliminated during this process. The process is guided by small RNAs and epigenetic chromatin marks.[27]

In spirotrich ciliates (such as Oxytricha), the process is even more complex due to "gene scrambling": the MDSs in the micronucleus are often in different order and orientation from that in the macronuclear gene, and so in addition to deletion, DNA inversion and translocation are required for "unscrambling". This process is guided by long RNAs derived from the parental macronucleus. More than 95% of micronuclear DNA is eliminated during spirotrich macronuclear development.[27]

Aging

[edit]ln clonal populations of Paramecium, aging occurs over successive generations leading to a gradual loss of vitality, unless the cell line is revitalized by conjugation or autogamy. In Paramecium tetraurelia, the clonally aging line loses vitality and expires after about 200 fissions, if the cell line is not rejuvenated by conjugation or self-fertilization. The basis for clonal aging was clarified by the transplantation experiments of Aufderheide in 1986[28] who demonstrated that the macronucleus, rather than the cytoplasm, is responsible for clonal aging. Additional experiments by Smith-Sonneborn,[29] Holmes and Holmes,[30] and Gilley and Blackburn[31] demonstrated that, during clonal aging, DNA damage increases dramatically. Thus, DNA damage appears to be the cause of aging in P. tetraurelia.

Fossil record

[edit]Until recently, the oldest ciliate fossils known were tintinnids from the Ordovician period. In 2007, Li et al. published a description of fossil ciliates from the Doushantuo Formation, about 580 million years ago, in the Ediacaran period. These included two types of tintinnids and a possible ancestral suctorian.[32] A fossil Vorticella has been discovered inside a leech cocoon from the Triassic period, about 200 million years ago.[33]

Phylogeny

[edit]According to the 2016 phylogenetic analysis,[1] Mesodiniea is consistently found as the sister group to all other ciliates. Additionally, two big sub-groups are distinguished inside subphylum Intramacronucleata: SAL (Spirotrichea+Armophorea+Litostomatea) and CONthreeP or Ventrata (Colpodea+Oligohymenophorea+Nassophorea+Phyllopharyngea+Plagiopylea+Prostomatea).[1] The class Protocruziea is found as the sister group to Ventrata/CONthreeP. The class Cariacotrichea was excluded from the analysis, but it was originally established as part of Intramacronucleata[1].

The odontostomatids were identified in 2018[34] as its own class Odontostomatea, related to Armophorea.

| Ciliophora | |

Classification

[edit]

Several different classification schemes have been proposed for the ciliates. The following scheme is based on a molecular phylogenetic analysis of up to four genes from 152 species representing 110 families:[1]

- Class Mesodiniea (e.g. Mesodinium)

Subphylum Postciliodesmatophora

[edit]- Class Heterotrichea (e.g. Stentor)

- Class Karyorelictea

Subphylum Intramacronucleata

[edit]

- Class Armophorea

- Class Odontostomatea[34] (e.g. Discomorphella, Saprodinium)

- Class Cariacotrichea (only one species, Cariacothrix caudata)

- Class Muranotrichea

- Class Parablepharismea

- Class Colpodea (e.g. Colpoda)

- Class Litostomatea

- Subclass Haptoria (e.g. Didinium)

- Subclass Rhynchostomatia

- Subclass Trichostomatia (e.g. Balantidium)

- Class Nassophorea

- Class Phyllopharyngea

- Subclass Chonotrichia

- Subclass Cyrtophoria

- Subclass Rhynchodia

- Subclass Suctoria (e.g. Podophyra)

- Subclass Synhymenia

- Class Oligohymenophorea

- Subclass Apostomatia

- Subclass Astomatia

- Subclass Hymenostomatia (e.g. Tetrahymena)

- Subclass Peniculia (e.g. Paramecium)

- Subclass Peritrichia (e.g. Vorticella)

- Subclass Scuticociliatia

- Class Plagiopylea

- Class Prostomatea (e.g. Coleps)

- Class Protocruziea

- Class Spirotrichea

- Subclass Choreotrichia

- Subclass Euplotia

- Subclass Hypotrichia

- Subclass Licnophoria

- Subclass Oligotrichia

- Subclass Phacodiniidea

- Subclass Protohypotrichia

Other

[edit]Some old classifications included Opalinidae in the ciliates. The fundamental difference between multiciliate flagellates (e.g., hemimastigids, Stephanopogon, Multicilia, opalines) and ciliates is the presence of macronuclei in ciliates alone.[35]

Pathogenicity

[edit]The only member of the ciliate phylum known to be pathogenic to humans is Balantidium coli,[36][37] which causes the disease balantidiasis. It is not pathogenic to the domestic pig, the primary reservoir of this pathogen.[38]

References

[edit]- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Gao, Feng; Warren, Alan; Zhang, Qianqian; Gong, Jun; Miao, Miao; Sun, Ping; Xu, Dapeng; Huang, Jie; Yi, Zhenzhen (2016-04-29). "The All-Data-Based Evolutionary Hypothesis of Ciliated Protists with a Revised Classification of the Phylum Ciliophora (Eukaryota, Alveolata)". Scientific Reports. 6: 24874. Bibcode:2016NatSR...624874G. doi:10.1038/srep24874. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 4850378. PMID 27126745.

- ^ Rotterová, J.; Edgcomb, V. P.; Čepička, I.; Beinart, R. (2022). "Anaerobic ciliates as a model group for studying symbioses in oxygen-depleted environments". The Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 69 (5): e12912. doi:10.1111/jeu.12912. PMID 35325496. S2CID 247677842.

- ^ Foissner, W.; Hawksworth, David, eds. (2009). Protist Diversity and Geographical Distribution. Topics in Biodiversity and Conservation. Vol. 8. Springer Netherlands. p. 111. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-2801-3. ISBN 9789048128006.

- ^ Nielsen, Torkel Gissel; Kiørboe, Thomas (1994). "Regulation of zooplankton biomass and production in a temperate, coastal ecosystem. 2. Ciliates". Limnology and Oceanography. 39 (3): 508–519. Bibcode:1994LimOc..39..508N. doi:10.4319/lo.1994.39.3.0508.

- ^ Lynn, Denis (2008). The Ciliated Protozoa 3rd Edition. Springer. pp. 129. ISBN 978-1-4020-8238-2.

- ^ "ITIS Report". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 11 December 2014.

- ^ Cavalier-Smith, Thomas (2018-01-01). "Kingdom Chromista and its eight phyla: a new synthesis emphasising periplastid protein targeting, cytoskeletal and periplastid evolution, and ancient divergences". Protoplasma. 255 (1): 297–357. doi:10.1007/s00709-017-1147-3. ISSN 1615-6102. PMC 5756292. PMID 28875267.

- ^ Yi Z, Song W, Clamp JC, Chen Z, Gao S, Zhang Q (December 2008). "Reconsideration of systematic relationships within the order Euplotida (Protista, Ciliophora) using new sequences of the gene coding for small-subunit rRNA and testing the use of combined data sets to construct phylogenies of the Diophrys-complex". Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 50 (3): 599–607. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2008.12.006. PMID 19121402.

- ^ Miao M, Song W, Chen Z, et al. (2007). "A unique euplotid ciliate, Gastrocirrhus (Protozoa, Ciliophora): assessment of its phylogenetic position inferred from the small subunit rRNA gene sequence". J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 54 (4): 371–8. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.2007.00271.x. PMID 17669163. S2CID 25977768.

- ^ Alfred Kahl (1930). Urtiere oder Protozoa I: Wimpertiere oder Ciliata -- Volume I General Section And Prostomata.

- ^ "Medical Definition of CILIATA". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2017-12-22.

- ^ Adl, Sina M.; Bass, David; Lane, Christopher E.; Lukeš, Julius; Schoch, Conrad L.; Smirnov, Alexey; Agatha, Sabine; Berney, Cedric; Brown, Matthew W.; Burki, Fabien; Cárdenas, Paco (2019). "Revisions to the Classification, Nomenclature, and Diversity of Eukaryotes". Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 66 (1): 4–119. doi:10.1111/jeu.12691. ISSN 1550-7408. PMC 6492006. PMID 30257078.

- ^ Adl, Sina M.; et al. (2005). "The new higher level classification of eukaryotes with emphasis on the taxonomy of protists". Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 52 (5): 399–451. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.2005.00053.x. PMID 16248873.

- ^ Raikov, I.B. (1969). "The Macronucleus of Ciliates". Research in Protozoology. 3: 4–115. ISBN 9781483186146.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Archibald, John M.; Simpson, Alastair G. B.; Slamovits, Claudio H., eds. (2017). Handbook of the Protists (2 ed.). Springer International Publishing. p. 691. ISBN 978-3-319-28147-6.

- ^ Prescott, D M (June 1994). "The DNA of ciliated protozoa". Microbiological Reviews. 58 (2): 233–267. doi:10.1128/mr.58.2.233-267.1994. ISSN 0146-0749. PMC 372963. PMID 8078435.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c H., Lynn, Denis (2008). The ciliated protozoa: characterization, classification, and guide to the literature. New York: Springer. p. 324. ISBN 9781402082382. OCLC 272311632.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Esteban, G. F.; Fenchel, T.; Finlay, B. J. (2010). "Mixotrophy in ciliates". Protist. 161 (5): 621–641. doi:10.1016/j.protis.2010.08.002. PMID 20970377.

- ^ Altenburger, A.; Blossom, H. E.; Garcia-Cuetos, L.; Jakobsen, H. H.; Carstensen, J.; Lundholm, N.; Hansen, P. J.; Haraguchi, L.; Haraguchi, L. (2020). "Dimorphism in cryptophytes-The case of Teleaulax amphioxeia/Plagioselmis prolonga and its ecological implications". Science Advances. 6 (37). Bibcode:2020SciA....6.1611A. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abb1611. PMC 7486100. PMID 32917704.

- ^ DeLong, John P.; Van Etten, James L.; Al-Ameeli, Zeina; Agarkova, Irina V.; Dunigan, David D. (2023-01-03). "The consumption of viruses returns energy to food chains". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 120 (1): e2215000120. Bibcode:2023PNAS..12015000D. doi:10.1073/pnas.2215000120. PMC 9910503. PMID 36574690.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lynn, Denis (2008). The Ciliated Protozoa: Characterization, Classification, and Guide to the Literature (3 ed.). Springer. pp. 58. ISBN 978-1-4020-8238-2.

1007/978-1-4020-8239-9

- ^ Jump up to: a b c H., Lynn, Denis (2008). The ciliated protozoa: characterization, classification, and guide to the literature. New York: Springer. p. 23. ISBN 9781402082382. OCLC 272311632.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Berger JD (October 1986). "Autogamy in Paramecium. Cell cycle stage-specific commitment to meiosis". Exp. Cell Res. 166 (2): 475–85. doi:10.1016/0014-4827(86)90492-1. PMID 3743667.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Raikov, I.B (1972). "Nuclear phenomena during conjugation and autogamy in ciliates". Research in Protozoology. 4: 149.

- ^ Finley, Harold E. "The conjugation of Vorticella microstoma." Transactions of the American Microscopical Society (1943): 97-121.

- ^ "Introduction to the Ciliata". Retrieved 2009-01-16.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Mochizuki, Kazufumi (2010). "DNA rearrangements directed by non-coding RNAs in ciliates". Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: RNA. 1 (3): 376–387. doi:10.1002/wrna.34. PMC 3746294. PMID 21956937.

- ^ Aufderheide, Karl J. (1986). «Клональное старение в Paramecium tetraurelia . II. Свидетельство функциональных изменений в Macrinucleus с возрастом». Механизмы старения и развития . 37 (3): 265–279. doi : 10.1016/0047-6374 (86) 90044-8 . PMID 3553762 . S2CID 28320562 .

- ^ Смит-Соннборн, Дж. (1979). «Репарация ДНК и обеспечение долговечности в Paramecium tetraurelia». Наука . 203 (4385): 1115–1117. Bibcode : 1979sci ... 203.1115s . doi : 10.1126/science.424739 . PMID 424739 .

- ^ Холмс, Джордж Э.; Холмс, Норрин Р. (июль 1986 г.). «Накопление повреждений ДНК в стареющем парамеции тетраурелия ». Молекулярная и общая генетика . 204 (1): 108–114. doi : 10.1007/bf00330196 . PMID 3091993 . S2CID 11992591 .

- ^ Гилли, Дэвид; Блэкберн, Элизабет Х. (1994). «Отсутствие укорочения теломер во время старения в Paramecium » (PDF) . Труды Национальной академии наук Соединенных Штатов Америки . 91 (5): 1955–1958. Bibcode : 1994pnas ... 91.1955g . doi : 10.1073/pnas.91.5.1955 . PMC 43283 . PMID 8127914 .

- ^ Li, C.W.; и др. (2007). «Прирученные простейшие из докембрийской формирования Душантуо, Венган, Южный Китай». Геологическое общество, Лондон, Специальные публикации . 286 (1): 151–156. BIBCODE : 2007GSLSP.286..151L . doi : 10.1144/sp286.11 . S2CID 129584945 .

- ^ Bomfleur, Benjamin; Керп, Ганс; Тейлор, Томас Н.; Моэстру, Эйвинд; Тейлор, Эдит Л. (2012-12-18). «Триасский кокон пиявки из Антарктиды содержит ископаемое колокол животное» . Труды Национальной академии наук Соединенных Штатов Америки . 109 (51): 20971–20974. BIBCODE : 2012PNAS..10920971B . doi : 10.1073/pnas.1218879109 . ISSN 1091-6490 . PMC 3529092 . PMID 23213234 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Фернандес, Наоми М.; Vizzoni, Vinicius F.; Борхес, Барбара из N.; Soares, Carlos AG; Da Silva-Neto, Ignatius D.; Paiva, Thiago Da S. (2018), «Молекулярная филогения и сравнительная морфология указывает на то, что одонтоматиды (альвеолата, килиофора) образуют отдельный таксон классового уровня, связанный с Armophora» , Молекулярная филогения и эволюция , 126 : 382–389, doi : 10.1016. /J.ympev.2018.04.026 , ISSN 1055-7903 , PMID 29679715 , S2CID 5032558

- ^ Cavalier-Smith, T. (2000). Плаговая мегаэволюция: основа для диверсификации эукариотов. В: Leadbeater, BSC, Green, JC (ред.). Жгутики. Единство, разнообразие и эволюция . Лондон: Тейлор и Фрэнсис, с. 361-390, с. 362, [1] .

- ^ «Балантидиаз» . DPDX - Лабораторная идентификация паразитических заболеваний заботы о здравоохранении . Центры для контроля и профилактики заболеваний. 2013.

- ^ Рамачандран, Амбили (23 мая 2003 г.). "Введение" . Паразит: Balantidium coli болезнь: балантидиаз . Стэнфордский университет. Архивировано из оригинала 14 апреля 2013 года . Получено 3 сентября 2018 года .

{{cite book}}:|work=игнорируется ( помощь ) - ^ Шистер, Фредерик Л. и Линн Рамирес-Авила (октябрь 2008 г.). «Современный статус мирового статуса Balantidium coli » . Клинические обзоры микробиологии . 21 (4): 626–638. doi : 10.1128/cmr.00021-08 . PMC 2570149 . PMID 18854484 .

Дальнейшее чтение

[ редактировать ]- Линн, Денис Х. (2008). Ресничные простейшие: характеристика, классификация и руководство к литературе . Нью -Йорк: Спрингер. ISBN 9781402082382 Полем OCLC 272311632 .

- Хаусманн, Клаус; Брэдбери, Филлис С., ред. (1996). Реснички: клетки как организм . Штутгарт: Густав Фишер Верлаг. ISBN 978-3437250361 Полем OCLC 34782787 .

- Ли, Джон Дж.; Leedale, Gordon F.; Брэдбери, Филлис С., ред. (2000). Иллюстрированное руководство по простейшим: организмы, традиционно называемые простейшими, или недавно обнаруженными группами (2 -е изд.). Лоуренс, KS: Общество простейших. ISBN 9781891276224 Полем OCLC 49191284 .

Внешние ссылки

[ редактировать ] СМИ, связанные с Ciliophora в Wikimedia Commons

СМИ, связанные с Ciliophora в Wikimedia Commons