Карл Саган

Карл Саган | |

|---|---|

Саган в 1980 году | |

| Рожденный | Карл Эдвард Саган 9 ноября 1934 г. Нью-Йорк, США |

| Умер | December 20, 1996 (aged 62) Seattle, Washington, U.S. |

| Resting place | Lake View Cemetery |

| Education | University of Chicago (BA, BS, MS, PhD) |

| Known for | |

| Spouses | |

| Children | 5, including Dorion, Nick, and Sasha |

| Awards | |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | |

| Institutions | |

| Thesis | Physical studies of planets (1960) |

| Doctoral advisor | Gerard Kuiper |

| Doctoral students |

|

| Signature | |

Карл Эдвард Саган ( / ˈ s eɪ ɡ ən / ; SAY -gən ; 9 ноября 1934 — 20 декабря 1996) — американский астроном , планетолог и научный популяризатор . Его самый известный научный вклад — это исследования возможности внеземной жизни , включая экспериментальную демонстрацию производства аминокислот из основных химических веществ под воздействием света. Он собрал первые физические сообщения, отправленные в космос, мемориальную доску «Пионер» и «Золотую пластинку «Вояджера»» , которые были универсальными сообщениями, которые потенциально могли быть поняты любым внеземным разумом, который мог их найти. Он приводил доводы в пользу гипотезы, которая с тех пор была принята, о том, что высокие температуры поверхности Венеры являются результатом парникового эффекта . [ 4 ]

Первоначально Саган работал доцентом в Гарварде , но позже перешёл в Корнеллский университет , где и провёл большую часть своей карьеры. Он опубликовал более 600 научных работ и статей, был автором, соавтором и редактором более 20 книг. [ 5 ] He wrote many popular science books, such as The Dragons of Eden, Broca's Brain, Pale Blue Dot and The Demon-Haunted World. He also co-wrote and narrated the award-winning 1980 television series Cosmos: A Personal Voyage, which became the most widely watched series in the history of American public television: Cosmos has been seen by at least 500 million people in 60 countries.[6] A book, also called Cosmos, was published to accompany the series. Sagan also wrote a science-fiction novel, published in 1985, called Contact, which became the basis for the 1997 film Contact. His papers, comprising 595,000 items,[7] are archived in the Library of Congress.[8]

Sagan was a popular public advocate of skeptical scientific inquiry and the scientific method; he pioneered the field of exobiology and promoted the search for extraterrestrial intelligent life (SETI). He spent most of his career as a professor of astronomy at Cornell University, where he directed the Laboratory for Planetary Studies. Sagan and his works received numerous awards and honors, including the NASA Distinguished Public Service Medal, the National Academy of Sciences Public Welfare Medal, the Pulitzer Prize for General Non-Fiction (for his book The Dragons of Eden), and (for Cosmos: A Personal Voyage) two Emmy Awards, the Peabody Award, and the Hugo Award. He married three times and had five children. After developing myelodysplasia, Sagan died of pneumonia at the age of 62 on December 20, 1996.

Early life

[edit]Childhood

[edit]

Carl Edward Sagan was born in the Bensonhurst neighborhood of New York City's Brooklyn borough on November 9, 1934.[9][10] His mother, Rachel Molly Gruber, was a housewife from New York City; his father, Samuel Sagan, was a Ukrainian-born garment worker who had emigrated from Kamianets-Podilskyi (then in the Russian Empire).[11] Sagan was named in honor of his maternal grandmother, Chaiya Clara, who had died while giving birth to her second child; she was, in Sagan's words, "the mother she [Rachel] never knew."[12] Sagan's maternal grandfather later married a woman named Rose, who Sagan's sister, Carol, would later say, was "never accepted" as Rachel's mother because Rachel "knew she [Rose] wasn't her birth mother."[13] Sagan's family lived in a modest apartment in Bensonhurst. He later described his family as Reform Jews, the most liberal of Judaism's four main branches. He and his sister agreed that their father was not especially religious, but that their mother "definitely believed in God, and was active in the temple [...] and served only kosher meat."[14] During the worst years of the Depression, his father worked as a movie theater usher.[14]

According to biographer Keay Davidson, Sagan experienced a kind of "inner war" as a result of his close relationship with both his parents, who were in many ways "opposites." He traced his analytical inclinations to his mother, who had been extremely poor as a child in New York City during World War I and the 1920s,[15] and whose later intellectual ambitions were sabotaged by her poverty, status as a woman and wife, and Jewish ethnicity. Davidson suggested she "worshipped her only son, Carl" because "he would fulfill her unfulfilled dreams."[15] Sagan believed that he had inherited his sense of wonder from his father, who spent his free time giving apples to the poor or helping soothe tensions between workers and management within New York City's garment industry.[15] Although awed by his son's intellectual abilities, Sagan's father also took his inquisitiveness in stride, viewing it as part of growing up.[15] Later, during his career, Sagan would draw on his childhood memories to illustrate scientific points, as he did in his book Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors.[16]

Describing his parents' influence on his later thinking, Sagan said: "My parents were not scientists. They knew almost nothing about science. But in introducing me simultaneously to skepticism and to wonder, they taught me the two uneasily cohabiting modes of thought that are central to the scientific method."[17] He recalled that a defining moment in his development came when his parents took him, at age four, to the 1939 New York World's Fair. He later described his vivid memories of several exhibits there. One, titled America of Tomorrow, included a moving map, which, as he recalled, "showed beautiful highways and cloverleaves and little General Motors cars all carrying people to skyscrapers, buildings with lovely spires, flying buttresses—and it looked great!"[18] Another involved a flashlight shining on a photoelectric cell, which created a crackling sound, and another showed how the sound from a tuning fork became a wave on an oscilloscope. He also saw an exhibit of the then-nascent medium known as television. Remembering it, he later wrote: "Plainly, the world held wonders of a kind I had never guessed. How could a tone become a picture and light become a noise?"[18]

Sagan also saw one of the fair's most publicized events: the burial at Flushing Meadows of a time capsule, which contained mementos from the 1930s to be recovered by Earth's descendants in a future millennium. Davidson wrote that this "thrilled Carl." As an adult, inspired by his memories of the World's Fair, Sagan and his colleagues would create similar time capsules to be sent out into the galaxy: the Pioneer plaque and the Voyager Golden Record précis.[19]

During World War II, Sagan's parents worried about the fate of their European relatives, but he was generally unaware of the details of the ongoing war. He wrote, "Sure, we had relatives who were caught up in the Holocaust. Hitler was not a popular fellow in our household... but on the other hand, I was fairly insulated from the horrors of the war." His sister, Carol, said that their mother "above all wanted to protect Carl... she had an extraordinarily difficult time dealing with World War II and the Holocaust."[19] Sagan's book The Demon-Haunted World (1996) included his memories of this conflicted period, when his family dealt with the realities of the war in Europe, but tried to prevent it from undermining his optimistic spirit.[17]

Soon after entering elementary school, Sagan began to express his strong inquisitiveness about nature. He recalled taking his first trips to the public library alone, at age five, when his mother got him a library card. He wanted to learn what stars were, since none of his friends or their parents could give him a clear answer: "I went to the librarian and asked for a book about stars [...] and the answer was stunning. It was that the Sun was a star, but really close. The stars were suns, but so far away they were just little points of light. The scale of the universe suddenly opened up to me. It was a kind of religious experience. There was a magnificence to it, a grandeur, a scale which has never left me. Never ever left me."[20] When he was about six or seven, he and a close friend took trips to the American Museum of Natural History, in Manhattan. While there, they visited the Hayden Planetarium and walked around exhibits of space objects, such as meteorites, as well as displays of dinosaur skeletons and naturalistic scenes with animals. As Sagan later wrote, "I was transfixed by the dioramas—lifelike representations of animals and their habitats all over the world. Penguins on the dimly lit Antarctic ice [...] a family of gorillas, the male beating his chest [...] an American grizzly bear standing on his hind legs, ten or twelve feet tall, and staring me right in the eye."[20]

Sagan's parents nurtured his growing interest in science, buying him chemistry sets and reading matter. But his fascination with outer space emerged as his primary focus, especially after he had read science fiction by such writers as H. G. Wells and Edgar Rice Burroughs, stirring his curiosity about the possibility of life on Mars and other planets.[21] According to biographer Ray Spangenburg, Sagan's efforts in his early years to understand the mysteries of the planets became a "driving force in his life, a continual spark to his intellect, and a quest that would never be forgotten."[17] In 1947, Sagan discovered the magazine Astounding Science Fiction, which introduced him to more hard science fiction speculations than those in the Burroughs novels.[21] That same year, mass hysteria developed about the possibility that extraterrestrial visitors had arrived in flying saucers, and the young Sagan joined in the speculation that the flying "discs" people reported seeing in the sky might be alien spaceships.[22]

Education

[edit]

Sagan attended David A. Boody Junior High School in his native Bensonhurst and had his bar mitzvah when he turned 13.[23] In 1948, when he was 14, his father's work took the family to the older semi-industrial town of Rahway, New Jersey, where he attended Rahway High School.[23] He was a straight-A student but was bored because his classes did not challenge him and his teachers did not inspire him.[23] His teachers realized this and tried to convince his parents to send him to a private school, with an administrator telling them, "This kid ought to go to a school for gifted children, he has something really remarkable."[24] However, his parents could not afford to do so. Sagan became president of the school's chemistry club, and set up his own laboratory at home. He taught himself about molecules by making cardboard cutouts to help him visualize how they were formed: "I found that about as interesting as doing [chemical] experiments."[24] He was mostly interested in astronomy, learning about it in his spare time. In his junior year of high school, he discovered that professional astronomers were paid for doing something he always enjoyed, and decided on astronomy as a career goal: "That was a splendid day—when I began to suspect that if I tried hard I could do astronomy full-time, not just part-time."[25] Sagan graduated from Rahway High School in 1951.[23]

Before the end of high school, Sagan entered an essay writing contest in which he explored the idea that human contact with advanced life forms from another planet might be as disastrous for people on Earth as Native Americans' first contact with Europeans had been for Native Americans.[26] The subject was considered controversial, but his rhetorical skill won over the judges and they awarded him first prize.[26] When he was about to graduate from high school, his classmates voted him "most likely to succeed" and put him in line to be valedictorian.[26] He attended the University of Chicago because, despite his excellent high school grades, it was one of the very few colleges he had applied to that would consider accepting a 16-year-old. Its chancellor, Robert Maynard Hutchins, had recently retooled the undergraduate College of the University of Chicago into an "ideal meritocracy" built on Great Books, Socratic dialogue, comprehensive examinations, and early entrance to college with no age requirement.[27]

As an honors-program undergraduate, Sagan worked in the laboratory of geneticist H. J. Muller and wrote a thesis on the origins of life with physical chemist Harold Urey. He also joined the Ryerson Astronomical Society.[28] In 1954, he was awarded a Bachelor of Arts with general and special honors[29] in what he quipped was "nothing."[30] In 1955, he earned a Bachelor of Science in physics. He went on to do graduate work at the University of Chicago, earning a Master of Science in physics in 1956 and a Doctor of Philosophy in astronomy and astrophysics in 1960. His doctoral thesis, submitted to the Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics, was entitled Physical Studies of the Planets.[31][32][33][34] During his graduate studies, he used the summer months to work with planetary scientist Gerard Kuiper, who was his dissertation director,[3] as well as physicist George Gamow and chemist Melvin Calvin. The title of Sagan's dissertation reflected interests he had in common with Kuiper, who had been president of the International Astronomical Union's commission on "Physical Studies of Planets and Satellites" throughout the 1950s.[35]

In 1958, Sagan and Kuiper worked on the classified military Project A119, a secret U.S. Air Force plan to detonate a nuclear warhead on the Moon and document its effects.[36] Sagan had a Top Secret clearance at the Air Force and a Secret clearance with NASA.[37] In 1999, an article published in the journal Nature revealed that Sagan had included the classified titles of two Project A119 papers in his 1959 application for a scholarship to University of California, Berkeley. A follow-up letter to the journal by project leader Leonard Reiffel confirmed Sagan's security leak.[38]

Career and research

[edit]From 1960 to 1962 Sagan was a Miller Fellow at the University of California, Berkeley.[40] Meanwhile, he published an article in 1961 in the journal Science on the atmosphere of Venus, while also working with NASA's Mariner 2 team, and served as a "Planetary Sciences Consultant" to the RAND Corporation.[41]

After the publication of Sagan's Science article, in 1961 Harvard University astronomers Fred Whipple and Donald Menzel offered Sagan the opportunity to give a colloquium at Harvard and subsequently offered him a lecturer position at the institution. Sagan instead asked to be made an assistant professor, and eventually Whipple and Menzel were able to convince Harvard to offer Sagan the assistant professor position he requested.[41] Sagan lectured, performed research, and advised graduate students at the institution from 1963 until 1968, as well as working at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, also located in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

In 1968, Sagan was denied academic tenure at Harvard. He later indicated that the decision was very unexpected.[42] The denial has been blamed on several factors, including that he focused his interests too broadly across a number of areas (while the norm in academia is to become a renowned expert in a narrow specialty), and perhaps because of his well-publicized scientific advocacy, which some scientists perceived as borrowing the ideas of others for little more than self-promotion.[37] An advisor from his years as an undergraduate student, Harold Urey, wrote a letter to the tenure committee recommending strongly against tenure for Sagan.[22]

Science is more than a body of knowledge; it is a way of thinking. I have a foreboding of an America in my children's or grandchildren's time – when the United States is a service and information economy; when nearly all the key manufacturing industries have slipped away to other countries; when awesome technological powers are in the hands of a very few, and no one representing the public interest can even grasp the issues; when the people have lost the ability to set their own agendas or knowledgeably question those in authority; when, clutching our crystals and nervously consulting our horoscopes, our critical faculties in decline, unable to distinguish between what feels good and what's true, we slide, almost without noticing, back into superstition and darkness... The dumbing down of America is most evident in the slow decay of substantive content in the enormously influential media, the 30 second sound bites (now down to 10 seconds or less), lowest common denominator programming, credulous presentations on pseudoscience and superstition, but especially a kind of celebration of ignorance.

Carl Sagan, from Demon-Haunted World (1995)[43]

Long before the ill-fated tenure process, Cornell University astronomer Thomas Gold had courted Sagan to move to Ithaca, New York, and join the recently-hired astronomer Frank Drake amongst the faculty at Cornell. Following the denial of tenure from Harvard, Sagan accepted Gold's offer and remained a faculty member at Cornell for nearly 30 years until his death in 1996. Unlike Harvard, the smaller and more laid-back astronomy department at Cornell welcomed Sagan's growing celebrity status.[44] Following two years as an associate professor, Sagan became a full professor at Cornell in 1970 and directed the Laboratory for Planetary Studies there. From 1972 to 1981, he was associate director of the Center for Radiophysics and Space Research (CRSR) at Cornell. In 1976, he became the David Duncan Professor of Astronomy and Space Sciences, a position he held for the remainder of his life.[45]

Sagan was associated with the U.S. space program from its inception.[citation needed] From the 1950s onward, he worked as an advisor to NASA, where one of his duties included briefing the Apollo astronauts before their flights to the Moon. Sagan contributed to many of the robotic spacecraft missions that explored the Solar System, arranging experiments on many of the expeditions. Sagan assembled the first physical message that was sent into space: a gold-plated plaque, attached to the space probe Pioneer 10, launched in 1972. Pioneer 11, also carrying another copy of the plaque, was launched the following year. He continued to refine his designs; the most elaborate message he helped to develop and assemble was the Voyager Golden Record, which was sent out with the Voyager space probes in 1977. Sagan often challenged the decisions to fund the Space Shuttle and the International Space Station at the expense of further robotic missions.[46]

Scientific achievements

[edit]

Former student David Morrison described Sagan as "an 'idea person' and a master of intuitive physical arguments and 'back of the envelope' calculations",[37] and Gerard Kuiper said that "Some persons work best in specializing on a major program in the laboratory; others are best in liaison between sciences. Dr. Sagan belongs in the latter group."[37]

Sagan's contributions were central to the discovery of the high surface temperatures of the planet Venus.[4][47] In the early 1960s no one knew for certain the basic conditions of Venus' surface, and Sagan listed the possibilities in a report later depicted for popularization in a Time Life book Planets. His own view was that Venus was dry and very hot as opposed to the balmy paradise others had imagined. He had investigated radio waves from Venus and concluded that there was a surface temperature of 500 °C (900 °F). As a visiting scientist to NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, he contributed to the first Mariner missions to Venus, working on the design and management of the project. Mariner 2 confirmed his conclusions on the surface conditions of Venus in 1962.

Sagan was among[clarification needed] the first to hypothesize that Saturn's moon Titan might possess oceans of liquid compounds on its surface and that Jupiter's moon Europa might possess subsurface oceans of water. This would make Europa potentially habitable.[48] Europa's subsurface ocean of water was later indirectly confirmed by the spacecraft Galileo. The mystery of Titan's reddish haze was also solved with Sagan's help. The reddish haze was revealed to be due to complex organic molecules constantly raining down onto Titan's surface.[49]

Sagan further contributed insights regarding the atmospheres of Venus and Jupiter, as well as seasonal changes on Mars. He also perceived global warming as a growing, man-made danger and likened it to the natural development of Venus into a hot, life-hostile planet through a kind of runaway greenhouse effect.[50] He testified to the US Congress in 1985 that the greenhouse effect would change the Earth's climate system.[51] Sagan and his Cornell colleague Edwin Ernest Salpeter speculated about life in Jupiter's clouds, given the planet's dense atmospheric composition rich in organic molecules. He studied the observed color variations on Mars' surface and concluded that they were not seasonal or vegetational changes as most believed,[clarification needed] but shifts in surface dust caused by windstorms.

Sagan is also known for his research on the possibilities of extraterrestrial life, including experimental demonstration of the production of amino acids from basic chemicals by radiation.[52][53]

He is also the 1994 recipient of the Public Welfare Medal, the highest award of the National Academy of Sciences for "distinguished contributions in the application of science to the public welfare."[54] He was denied membership in the academy, reportedly because his media activities made him unpopular with many other scientists.[55][56][57]

As of 2017[update], Sagan is the most cited SETI scientist and one of the most cited planetary scientists.[5]

Cosmos: popularizing science on TV

[edit]

In 1980 Sagan co-wrote and narrated the award-winning 13-part PBS television series Cosmos: A Personal Voyage, which became the most widely watched series in the history of American public television until 1990. The show has been seen by at least 500 million people across 60 countries.[6][58][59] The book, Cosmos, written by Sagan, was published to accompany the series.[60]

Because of his earlier popularity as a science writer from his best-selling books, including The Dragons of Eden, which won him a Pulitzer Prize in 1977, he was asked to write and narrate the show. It was targeted to a general audience of viewers, whom Sagan felt had lost interest in science, partly due to a stifled educational system.[61]

Each of the 13 episodes was created to focus on a particular subject or person, thereby demonstrating the synergy of the universe.[61] They covered a wide range of scientific subjects including the origin of life and a perspective of humans' place on Earth.

The show won an Emmy,[62] along with a Peabody Award, and transformed Sagan from an obscure astronomer into a pop-culture icon.[63] Time magazine ran a cover story about Sagan soon after the show broadcast, referring to him as "creator, chief writer and host-narrator of the show."[64] In 2000, "Cosmos" was released on a remastered set of DVDs.

"Billions and billions"

[edit]After Cosmos aired, Sagan became associated with the catchphrase "billions and billions", although he never actually used the phrase in the Cosmos series.[65] He rather used the term "billions upon billions."[66]

Richard Feynman, a precursor to Sagan, used the phrase "billions and billions" many times in his "red books." However, Sagan's frequent use of the word billions and distinctive delivery emphasizing the "b" (which he did intentionally, in place of more cumbersome alternatives such as "billions with a 'b'", in order to distinguish the word from "millions")[65] made him a favorite target of comic performers, including Johnny Carson,[67][68] Gary Kroeger, Mike Myers, Bronson Pinchot, Penn Jillette, Harry Shearer, and others. Frank Zappa satirized the line in the song "Be in My Video", noting as well "atomic light." Sagan took this all in good humor, and his final book was titled Billions and Billions, which opened with a tongue-in-cheek discussion of this catchphrase, observing that Carson was an amateur astronomer and that Carson's comic caricature often included real science.[65]

As a humorous tribute to Sagan and his association with the catchphrase "billions and billions", a sagan has been defined as a unit of measurement equivalent to a very large number of anything.[69][70]

Sagan's number

[edit]Sagan's number is the number of stars in the observable universe.[71] This number is reasonably well defined, because it is known what stars are and what the observable universe is, but its value is highly uncertain.

- In 1980, Sagan estimated it to be 10 sextillion in short scale (1022).[72]

- In 2003, it was estimated to be 70 sextillion (7 × 1022).[73][74]

- In 2010, it was estimated to be 300 sextillion (3 × 1023).[75]

Scientific and critical thinking advocacy

[edit]

Sagan's ability to convey his ideas allowed many people to understand the cosmos better—simultaneously emphasizing the value and worthiness of the human race, and the relative insignificance of the Earth in comparison to the Universe. He delivered the 1977 series of Royal Institution Christmas Lectures in London.[76]

Sagan was a proponent of the search for extraterrestrial life. He urged the scientific community to listen with radio telescopes for signals from potential intelligent extraterrestrial life-forms. Sagan was so persuasive that by 1982 he was able to get a petition advocating SETI published in the journal Science, signed by 70 scientists, including seven Nobel Prize winners. This signaled a tremendous increase in the respectability of a then-controversial field. Sagan also helped Frank Drake write the Arecibo message, a radio message beamed into space from the Arecibo radio telescope on November 16, 1974, aimed at informing potential extraterrestrials about Earth.

Sagan was chief technology officer of the professional planetary research journal Icarus for 12 years. He co-founded The Planetary Society and was a member of the SETI Institute Board of Trustees. Sagan served as Chairman of the Division for Planetary Science of the American Astronomical Society, as President of the Planetology Section of the American Geophysical Union, and as Chairman of the Astronomy Section of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS).

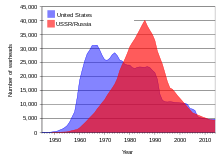

At the height of the Cold War, Sagan became involved in nuclear disarmament efforts by promoting hypotheses on the effects of nuclear war, when Paul Crutzen's "Twilight at Noon" concept suggested that a substantial nuclear exchange could trigger a nuclear twilight and upset the delicate balance of life on Earth by cooling the surface. In 1983 he was one of five authors—the "S"—in the follow-up "TTAPS" model (as the research article came to be known), which contained the first use of the term "nuclear winter", which his colleague Richard P. Turco had coined.[77] In 1984 he co-authored the book The Cold and the Dark: The World after Nuclear War and in 1990 the book A Path Where No Man Thought: Nuclear Winter and the End of the Arms Race, which explains the nuclear-winter hypothesis and advocates nuclear disarmament. Sagan received a great deal of skepticism and disdain for the use of media to disseminate a very uncertain hypothesis. A personal correspondence with nuclear physicist Edward Teller around 1983 began amicably, with Teller expressing support for continued research to ascertain the credibility of the winter hypothesis. However, Sagan and Teller's correspondence would ultimately result in Teller writing: "A propagandist is one who uses incomplete information to produce maximum persuasion. I can compliment you on being, indeed, an excellent propagandist, remembering that a propagandist is the better the less he appears to be one."[78] Biographers of Sagan would also comment that from a scientific viewpoint, nuclear winter was a low point for Sagan, although, politically speaking, it popularized his image amongst the public.[78]

The adult Sagan remained a fan of science fiction, although disliking stories that were not realistic (such as ignoring the inverse-square law) or, he said, did not include "thoughtful pursuit of alternative futures."[21] He wrote books to popularize science, such as Cosmos, which reflected and expanded upon some of the themes of A Personal Voyage and became the best-selling science book ever published in English;[79] The Dragons of Eden: Speculations on the Evolution of Human Intelligence, which won a Pulitzer Prize; and Broca's Brain: Reflections on the Romance of Science. Sagan also wrote the best-selling science fiction novel Contact in 1985, based on a film treatment he wrote with his wife, Ann Druyan, in 1979, but he did not live to see the book's 1997 motion-picture adaptation, which starred Jodie Foster and won the 1998 Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation.

On it, everyone you ever heard of... The aggregate of all our joys and sufferings, thousands of confident religions, ideologies and economic doctrines, every hunter and forager, every hero and coward, every creator and destroyer of civilizations, every king and peasant, every young couple in love, every hopeful child, every mother and father, every inventor and explorer, every teacher of morals, every corrupt politician, every superstar, every supreme leader, every saint and sinner in the history of our species, lived there on a mote of dust, suspended in a sunbeam. ...

Think of the rivers of blood spilled by all those generals and emperors so that in glory and triumph they could become the momentary masters of a fraction of a dot.

Carl Sagan, Cornell lecture in 1994

Sagan wrote a sequel to Cosmos, Pale Blue Dot: A Vision of the Human Future in Space, which was selected as a notable book of 1995 by The New York Times. He appeared on PBS's Charlie Rose program in January 1995.[46] Sagan also wrote the introduction for Stephen Hawking's bestseller A Brief History of Time. Sagan was also known for his popularization of science, his efforts to increase scientific understanding among the general public, and his positions in favor of scientific skepticism and against pseudoscience, such as his debunking of the Betty and Barney Hill abduction. To mark the tenth anniversary of Sagan's death, David Morrison, a former student of Sagan, recalled "Sagan's immense contributions to planetary research, the public understanding of science, and the skeptical movement" in Skeptical Inquirer.[37]

Following Saddam Hussein's threats to light Kuwait's oil wells on fire in response to any physical challenge to Iraqi control of the oil assets, Sagan together with his "TTAPS" colleagues and Paul Crutzen, warned in January 1991 in The Baltimore Sun and Wilmington Morning Star newspapers that if the fires were left to burn over a period of several months, enough smoke from the 600 or so 1991 Kuwaiti oil fires "might get so high as to disrupt agriculture in much of South Asia ..." and that this possibility should "affect the war plans";[82][83] these claims were also the subject of a televised debate between Sagan and physicist Fred Singer on January 22, aired on the ABC News program Nightline.[84][85]

In the televised debate, Sagan argued that the effects of the smoke would be similar to the effects of a nuclear winter, with Singer arguing to the contrary. After the debate, the fires burnt for many months before extinguishing efforts were complete. The results of the smoke did not produce continental-sized cooling. Sagan later conceded in The Demon-Haunted World that the prediction did not turn out to be correct: "it was pitch black at noon and temperatures dropped 4–6 °C over the Persian Gulf, but not much smoke reached stratospheric altitudes and Asia was spared."[86]

In his later years, Sagan advocated the creation of an organized search for asteroids/near-Earth objects (NEOs) that might impact the Earth but to forestall or postpone developing the technological methods that would be needed to defend against them.[87] He argued that all of the numerous methods proposed to alter the orbit of an asteroid, including the employment of nuclear detonations, created a deflection dilemma: if the ability to deflect an asteroid away from the Earth exists, then one would also have the ability to divert a non-threatening object towards Earth, creating an immensely destructive weapon.[88][89] In a 1994 paper he co-authored, he ridiculed a three-day-long "Near-Earth Object Interception Workshop" held by Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) in 1993 that did not, "even in passing" state that such interception and deflection technologies could have these "ancillary dangers."[88]

Sagan remained hopeful that the natural NEO impact threat and the intrinsically double-edged essence of the methods to prevent these threats would serve as a "new and potent motivation to maturing international relations."[88][90] Later acknowledging that, with sufficient international oversight, in the future a "work our way up" approach to implementing nuclear explosive deflection methods could be fielded, and when sufficient knowledge was gained, to use them to aid in mining asteroids.[89] His interest in the use of nuclear detonations in space grew out of his work in 1958 for the Armour Research Foundation's Project A119, concerning the possibility of detonating a nuclear device on the lunar surface.[91]

Sagan was a critic of Plato, having said of the ancient Greek philosopher: "Science and mathematics were to be removed from the hands of the merchants and the artisans. This tendency found its most effective advocate in a follower of Pythagoras named Plato" and[92]

He (Plato) believed that ideas were far more real than the natural world. He advised the astronomers not to waste their time observing the stars and planets. It was better, he believed, just to think about them. Plato expressed hostility to observation and experiment. He taught contempt for the real world and disdain for the practical application of scientific knowledge. Plato's followers succeeded in extinguishing the light of science and experiment that had been kindled by Democritus and the other Ionians.

In 1995 (as part of his book The Demon-Haunted World), Sagan popularized a set of tools for skeptical thinking called the "baloney detection kit", a phrase first coined by Arthur Felberbaum, a friend of his wife Ann Druyan.[93]

Popularizing science

[edit]Speaking about his activities in popularizing science, Sagan said that there were at least two reasons for scientists to share the purposes of science and its contemporary state. Simple self-interest was one: much of the funding for science came from the public, and the public therefore had the right to know how the money was being spent. If scientists increased public admiration for science, there was a good chance of having more public supporters.[94] The other reason was the excitement of communicating one's own excitement about science to others.[10]

Following the success of Cosmos, Sagan set up his own publishing firm, Cosmos Store, to publish science books for the general public. It was not successful.[95]

Criticisms

[edit]While Sagan was widely adored by the general public, his reputation in the scientific community was more polarized.[96] Critics sometimes characterized his work as fanciful, non-rigorous, and self-aggrandizing,[97] and others complained in his later years that he neglected his role as a faculty member to foster his celebrity status.[98]

One of Sagan's harshest critics, Harold Urey, felt that Sagan was getting too much publicity for a scientist and was treating some scientific theories too casually.[99] Urey and Sagan were said to have different philosophies of science, according to Davidson. While Urey was an "old-time empiricist" who avoided theorizing about the unknown, Sagan was by contrast willing to speculate openly about such matters.[42] Fred Whipple wanted Harvard to keep Sagan there, but learned that because Urey was a Nobel laureate, his opinion was an important factor in Harvard denying Sagan tenure.[99]

Sagan's Harvard friend Lester Grinspoon also stated: "I know Harvard well enough to know there are people there who certainly do not like people who are outspoken."[99] Grinspoon added:[99]

Wherever you turned, there was one astronomer being quoted on everything, one astronomer whose face you were seeing on TV, and one astronomer whose books had the preferred display slot at the local bookstore.

Some, like Urey, later believed that Sagan's popular brand of scientific advocacy was beneficial to the science as a whole.[100] Urey especially liked Sagan's 1977 book The Dragons of Eden and wrote Sagan with his opinion: "I like it very much and am amazed that someone like you has such an intimate knowledge of the various features of the problem... I congratulate you... You are a man of many talents."[100]

Sagan was accused of borrowing some ideas of others for his own benefit and countered these claims by explaining that the misappropriation was an unfortunate side effect of his role as a science communicator and explainer, and that he attempted to give proper credit whenever possible.[99]

Social concerns

[edit]Sagan believed that the Drake equation, on substitution of reasonable estimates, suggested that a large number of extraterrestrial civilizations would form, but that the lack of evidence of such civilizations highlighted by the Fermi paradox suggests technological civilizations tend to self-destruct. This stimulated his interest in identifying and publicizing ways that humanity could destroy itself, with the hope of avoiding such a cataclysm and eventually becoming a spacefaring species. Sagan's deep concern regarding the potential destruction of human civilization in a nuclear holocaust was conveyed in a memorable cinematic sequence in the final episode of Cosmos, called "Who Speaks for Earth?" Sagan had already resigned[date missing] from the Air Force Scientific Advisory Board's UFO-investigating Condon Committee and voluntarily surrendered his top-secret clearance in protest over the Vietnam War.[101] Following his marriage to his third wife (novelist Ann Druyan) in June 1981, Sagan became more politically active—particularly in opposing escalation of the nuclear arms race under President Ronald Reagan.

In March 1983, Reagan announced the Strategic Defense Initiative—a multibillion-dollar project to develop a comprehensive defense against attack by nuclear missiles, which was quickly dubbed the "Star Wars" program. Sagan spoke out against the project, arguing that it was technically impossible to develop a system with the level of perfection required, and far more expensive to build such a system than it would be for an enemy to defeat it through decoys and other means—and that its construction would seriously destabilize the "nuclear balance" between the United States and the Soviet Union, making further progress toward nuclear disarmament impossible.[102]

When Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev declared a unilateral moratorium on the testing of nuclear weapons, which would begin on August 6, 1985—the 40th anniversary of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima—the Reagan administration dismissed the dramatic move as nothing more than propaganda and refused to follow suit. In response, US anti-nuclear and peace activists staged a series of protest actions at the Nevada Test Site, beginning on Easter Sunday in 1986 and continuing through 1987. Hundreds of people in the "Nevada Desert Experience" group were arrested, including Sagan, who was arrested on two separate occasions as he climbed over a chain-link fence at the test site during the underground Operation Charioteer and United States's Musketeer nuclear test series of detonations.[103]

Sagan was also a vocal advocate of the controversial notion of testosterone poisoning, arguing in 1992 that human males could become gripped by an "unusually severe [case of] testosterone poisoning" and this could compel them to become genocidal.[104] In his review of Moondance magazine writer Daniela Gioseffi's 1990 book Women on War, he argues that females are the only half of humanity "untainted by testosterone poisoning."[105] One chapter of his 1993 book Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors is dedicated to testosterone and its alleged poisonous effects.[106]

In 1989, Carl Sagan was interviewed by Ted Turner whether he believed in socialism and responded that: "I'm not sure what a socialist is. But I believe the government has a responsibility to care for the people... I'm talking about making the people self-reliant."[107]

Personal life and beliefs

[edit]Sagan was married three times. In 1957, he married biologist Lynn Margulis. The couple had two children, Jeremy and Dorion Sagan; their marriage ended in 1964. Sagan married artist Linda Salzman in 1968 and they had a child together, Nick Sagan, and divorced in 1981. During these marriages, Carl Sagan focused heavily on his career, a factor which may have contributed to Sagan's first divorce.[37] In 1981, Sagan married author Ann Druyan and they later had two children, Alexandra (known as Sasha) and Samuel Sagan. Carl Sagan and Druyan remained married until his death in 1996.

While teaching at Cornell, he lived in an Egyptian revival house in Ithaca perched on the edge of a cliff that had formerly been the headquarters of a Cornell University secret society.[108] While there he drove a red Porsche 911 Targa and an orange 1970 Porsche 914[109] with the license plate PHOBOS.

In 1994, engineers at Apple Computer code-named the Power Macintosh 7100 "Carl Sagan" in the hope that Apple would make "billions and billions" with the sale of the PowerMac 7100.[9] The name was only used internally, but Sagan was concerned that it would become a product endorsement and sent Apple a cease-and-desist letter. Apple complied, but engineers retaliated by changing the internal codename to "BHA" for "Butt-Head Astronomer."[110][111] In November 1995, after further legal battle, an out-of-court settlement was reached and Apple's office of trademarks and patents released a conciliatory statement that "Apple has always had great respect for Dr. Sagan. It was never Apple's intention to cause Dr. Sagan or his family any embarrassment or concern."[112]

In 2019, Carl Sagan's daughter Sasha Sagan released For Small Creatures Such as We: Rituals for Finding Meaning in our Unlikely World, which depicts life with her parents and her father's death when she was fourteen.[113] Building on a theme in her father's work, Sasha Sagan argues in For Small Creatures Such as We that skepticism does not imply pessimism.[114]

I have just finished The Cosmic Connection and loved every word of it. You are my idea of a good writer because you have an unmannered style, and when I read what you write, I hear you talking. One thing about the book made me nervous. It was entirely too obvious that you are smarter than I am. I hate that.

Isaac Asimov, in a letter to Sagan, 1973[115]

Sagan was acquainted with science fiction fandom through his friendship with Isaac Asimov, and he spoke at the Nebula Awards ceremony in 1969.[116][117] Asimov described Sagan as one of only two people he ever met whose intellect surpassed his own, the other being computer scientist and artificial intelligence expert Marvin Minsky.[118]

Naturalism

[edit]Sagan wrote frequently about religion and the relationship between religion and science, expressing his skepticism about the conventional conceptualization of God as a sapient being. For example:

Some people think God is an outsized, light-skinned male with a long white beard, sitting on a throne somewhere up there in the sky, busily tallying the fall of every sparrow. Others—for example Baruch Spinoza and Albert Einstein—considered God to be essentially the sum total of the physical laws which describe the universe. I do not know of any compelling evidence for anthropomorphic patriarchs controlling human destiny from some hidden celestial vantage point, but it would be madness to deny the existence of physical laws.[119]

In another description of his view on the concept of God, Sagan wrote:

The idea that God is an oversized white male with a flowing beard who sits in the sky and tallies the fall of every sparrow is ludicrous. But if by God one means the set of physical laws that govern the universe, then clearly there is such a God. This God is emotionally unsatisfying ... it does not make much sense to pray to the law of gravity.[120]

On atheism, Sagan commented in 1981:

An atheist is someone who is certain that God does not exist, someone who has compelling evidence against the existence of God. I know of no such compelling evidence. Because God can be relegated to remote times and places and to ultimate causes, we would have to know a great deal more about the universe than we do now to be sure that no such God exists. To be certain of the existence of God and to be certain of the nonexistence of God seem to me to be the confident extremes in a subject so riddled with doubt and uncertainty as to inspire very little confidence indeed.[121]

Sagan also commented on Christianity and the Jefferson Bible, stating "My long-time view about Christianity is that it represents an amalgam of two seemingly immiscible parts, the religion of Jesus and the religion of Paul. Thomas Jefferson attempted to excise the Pauline parts of the New Testament. There wasn't much left when he was done, but it was an inspiring document."[122]

Sagan thought that spirituality should be scientifically informed and that traditional religions should be abandoned and replaced with belief systems that revolve around the scientific method,[123] but also the mystery and incompleteness of scientific fields. Regarding spirituality and its relationship with science, Sagan stated:

'Spirit' comes from the Latin word 'to breathe'. What we breathe is air, which is certainly matter, however thin. Despite usage to the contrary, there is no necessary implication in the word 'spiritual' that we are talking of anything other than matter (including the matter of which the brain is made), or anything outside the realm of science. On occasion, I will feel free to use the word. Science is not only compatible with spirituality; it is a profound source of spirituality. When we recognize our place in an immensity of light-years and in the passage of ages, when we grasp the intricacy, beauty, and subtlety of life, then that soaring feeling, that sense of elation and humility combined, is surely spiritual.[124]

An environmental appeal, "Preserving and Cherishing the Earth", primarily written by Sagan and signed by him and other noted scientists as well as religious leaders, and published in January 1990, stated that "The historical record makes clear that religious teaching, example, and leadership are powerfully able to influence personal conduct and commitment... Thus, there is a vital role for religion and science."[125]

In reply to a question in 1996 about his religious beliefs, Sagan answered, "I'm agnostic."[126] Sagan maintained that the idea of a creator God of the Universe was difficult to prove or disprove and that the only conceivable scientific discovery that could challenge it would be an infinitely old universe.[127] His son, Dorion Sagan said, "My father believed in the God of Spinoza and Einstein, God not behind nature but as nature, equivalent to it."[128] His last wife, Ann Druyan, stated:

When my husband died, because he was so famous and known for not being a believer, many people would come up to me—it still sometimes happens—and ask me if Carl changed at the end and converted to a belief in an afterlife. They also frequently ask me if I think I will see him again. Carl faced his death with unflagging courage and never sought refuge in illusions. The tragedy was that we knew we would never see each other again. I don't ever expect to be reunited with Carl.[129]

In 2006, Ann Druyan edited Sagan's 1985 Glasgow Gifford Lectures in Natural Theology into a book, The Varieties of Scientific Experience: A Personal View of the Search for God, in which he elaborates on his views of divinity in the natural world.

Sagan is also widely regarded as a freethinker or skeptic; one of his most famous quotations, in Cosmos, was, "Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence"[130] (called the "Sagan standard" by some[131]). This was based on a nearly identical statement by fellow founder of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal, Marcello Truzzi, "An extraordinary claim requires extraordinary proof."[132][133] This idea had been earlier aphorized in Théodore Flournoy's work From India to the Planet Mars (1899) from a longer quote by Pierre-Simon Laplace (1749–1827), a French mathematician and astronomer, as the Principle of Laplace: "The weight of the evidence should be proportioned to the strangeness of the facts."[134]

Late in his life, Sagan's books elaborated on his naturalistic view of the world. In The Demon-Haunted World, he presented tools for testing arguments and detecting fallacious or fraudulent ones, essentially advocating the wide use of critical thinking and of the scientific method. The compilation Billions and Billions: Thoughts on Life and Death at the Brink of the Millennium, published in 1997 after Sagan's death, contains essays written by him, on topics such as his views on abortion, and also an essay by his widow, Ann Druyan, about the relationship between his agnostic and freethinking beliefs and his death.

Sagan warned against humans' tendency towards anthropocentrism. He was the faculty adviser for the Cornell Students for the Ethical Treatment of Animals. In the Cosmos chapter "Blues For a Red Planet", Sagan wrote, "If there is life on Mars, I believe we should do nothing with Mars. Mars then belongs to the Martians, even if the Martians are only microbes."[135]

Marijuana advocacy

[edit]Sagan was a user and advocate of marijuana. Under the pseudonym "Mr. X", he contributed an essay about smoking cannabis to the 1971 book Marihuana Reconsidered.[136][137] The essay explained that marijuana use had helped to inspire some of Sagan's works and enhance sensual and intellectual experiences. After Sagan's death, his friend Lester Grinspoon disclosed this information to Sagan's biographer, Keay Davidson. The publishing of the biography Carl Sagan: A Life, in 1999 brought media attention to this aspect of Sagan's life.[138][139][140] Not long after his death, his widow Ann Druyan went on to preside over the board of directors of the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML), a non-profit organization dedicated to reforming cannabis laws.[141][142]

UFOs

[edit]In 1947, the year that inaugurated the "flying saucer" craze, the young Sagan suspected the "discs" might be alien spaceships.[22]

Sagan's interest in UFO reports prompted him on August 3, 1952, to write a letter to U.S. Secretary of State Dean Acheson to ask how the United States would respond if flying saucers turned out to be extraterrestrial.[143] He later had several conversations on the subject in 1964 with Jacques Vallée.[144] Though quite skeptical of any extraordinary answer to the UFO question, Sagan thought scientists should study the phenomenon, at least because there was widespread public interest in UFO reports.

Стюарт Аппель отмечает, что Саган «часто писал о том, что он считал логическими и эмпирическими заблуждениями относительно НЛО и опыта похищения . Саган отверг внеземное объяснение этого явления, но чувствовал, что изучение сообщений об НЛО имеет как эмпирическую, так и педагогическую пользу, и что субъект поэтому была законной темой исследования». [ 145 ]

В 1966 году Саган был членом Специального комитета по рассмотрению проекта «Синяя книга» — ВВС США проекта по расследованию НЛО. Комитет пришел к выводу, что «Синей книге» не хватает научного исследования, и рекомендовал университетскому проекту дать феномену НЛО более пристальное научное изучение. Результатом стал Комитет Кондона (1966–68), возглавляемый физиком Эдвардом Кондоном , и в своем заключительном отчете они официально пришли к выводу, что НЛО, независимо от того, чем они на самом деле были, не вели себя так, чтобы представлять угрозу национальной безопасности. безопасность.

Социолог Рон Веструм пишет, что «кульминацией подхода Сагана к вопросу НЛО стал симпозиум AAAS в 1969 году. Участники предложили широкий спектр образованных мнений по этому вопросу, включая не только таких сторонников, как Джеймс Макдональд и Дж. Аллен. Хайнека , а также скептиков, таких как астрономы Уильям Хартманн и Дональд Мензель . Список выступающих был сбалансированным, и в этом следует отдать должное Сагану. это мероприятие было проведено, несмотря на давление со стороны Эдварда Кондона». [ 144 ] Вместе с физиком Торнтоном Пейджем Саган редактировал лекции и дискуссии, проведённые на симпозиуме; они были опубликованы в 1972 году под названием «НЛО: научные дебаты» . В некоторых из многих книг Сагана рассматриваются НЛО (как и в одном из эпизодов «Космоса» ), и он утверждал, что у этого явления есть религиозная подоплека.

Саган снова изложил свои взгляды на межзвездные путешествия в своей серии «Космос» 1980 года . В одной из своих последних письменных работ Саган утверждал, что шансы посещения Земли внеземными космическими кораблями исчезающе малы. Тем не менее, Саган считал правдоподобным, что опасения времен холодной войны способствовали тому, что правительства вводили своих граждан в заблуждение относительно НЛО, и писал, что «некоторые отчеты и анализы НЛО, а также, возможно, объемные файлы, были сделаны недоступными для общественности, которая платит по счетам... Это пришло время рассекретить файлы и сделать их общедоступными». Он предостерег от поспешных выводов о сокрытых данных об НЛО и подчеркнул, что не существует убедительных доказательств того, что инопланетяне посещали Землю ни в прошлом, ни в настоящем. [ 146 ]

Саган некоторое время работал консультантом в Стэнли Кубрика фильме « 2001: Космическая одиссея» . [ 147 ] Саган предложил, чтобы фильм намекал, а не изображал внеземной сверхразум. [ 148 ]

Парадокс Сагана

[ редактировать ]Вклад Сагана на симпозиуме AAAS 1969 года представлял собой атаку на веру в то, что НЛО пилотируются инопланетными существами. Используя уравнение Дрейка и применив несколько логических предположений, Саган подсчитал, что возможное количество развитых цивилизаций, способных к межзвездным путешествиям, составляет около одного миллиона. Он предположил, что любая цивилизация, желающая проверять все остальные на регулярной основе, скажем, раз в год, должна будет запускать 10 000 космических кораблей ежегодно. Мало того, что это кажется необоснованным количеством запусков, но для производства всех космических кораблей, необходимых всем цивилизациям для поиска друг друга, потребуется весь материал, содержащийся в одном проценте звезд Вселенной.

Чтобы утверждать, что Земля выбиралась для регулярных посещений, сказал Саган, нужно было бы предположить, что планета в некотором роде уникальна, и это предположение «прямо противоречит идее о том, что вокруг существует множество цивилизаций. такая цивилизация должна быть довольно распространенной, а если мы не достаточно распространены, то не будет многих цивилизаций, достаточно развитых, чтобы отправлять посетителей».

Этот аргумент, который некоторые назвали парадоксом Сагана, помог создать новую школу мысли, а именно веру в то, что внеземная жизнь существует, но не имеет ничего общего с НЛО. Новое убеждение оказало благотворное влияние на исследования НЛО. Это дало ученым возможность искать во Вселенной разумную жизнь, не отягощенную стигмой, связанной с НЛО. [ 149 ]

Смерть

[ редактировать ]

Страдая от миелодисплазии в течение двух лет и получив три трансплантации костного мозга от своей сестры, Саган умер от пневмонии в возрасте 62 лет в Онкологическом исследовательском центре Фреда Хатчинсона в Сиэтле 20 декабря 1996 года. [ 10 ] [ 150 ] Он был похоронен на кладбище Лейк-Вью в Итаке, Нью-Йорк .

Награды и почести

[ редактировать ]

- Ежегодная премия за выдающиеся достижения на телевидении — 1981 — Университет штата Огайо — сериал PBS «Космос: личное путешествие».

- Премия «Аполлон» за достижения — Национальное управление по аэронавтике и исследованию космического пространства

- Медаль НАСА за выдающиеся заслуги перед обществом - Национальное управление по аэронавтике и исследованию космического пространства (1977 г.)

- Эмми — Выдающиеся индивидуальные достижения — 1981 — сериал PBS «Космос: личное путешествие» [ 62 ]

- Эмми - Выдающийся информационный сериал - 1981 - сериал PBS «Космос: личное путешествие». [ 62 ]

- Член Американского физического общества – 1989 г. [ 151 ]

- Медаль за выдающиеся научные достижения — Национальное управление по аэронавтике и исследованию космического пространства.

- Премия Хелен Калдикотт за лидерство - присуждена Женским движением за ядерное разоружение

- Премия Хьюго — 1981 — Лучшее драматическое представление — «Космос: личное путешествие»

- Премия Хьюго — 1981 — Лучшая научно-популярная книга по теме — «Космос»

- Премия Хьюго — 1998 — Лучшее драматическое представление — Контакты

- Гуманист года — 1981 — награжден Американской гуманистической ассоциацией. [ 152 ]

- Американское философское общество — 1995 г. — Избран в члены. [ 153 ]

- Премия «Похвала разума» — 1987 — Комитет скептических расследований. [ 154 ]

- Премия Исаака Азимова — 1994 — Комитет скептических расследований. [ 155 ]

- Премия Джона Ф. Кеннеди в области астронавтики — 1982 — Американское астронавтическое общество. [ 156 ]

- за научно-популярную литературу Специальная премия Мемориала Кэмпбелла , 1974 г. , «Космическая связь: внеземная перспектива». [ 157 ]

- Премия Джозефа Пристли — «За выдающийся вклад в благосостояние человечества». [ 158 ]

- Премия Клампке-Робертса — Тихоокеанского астрономического общества 1974 г.

- Премия "Золотая тарелка" Американской академии достижений - 1975 г. [ 159 ]

- Медаль Константина Циолковского — вручена Федерацией космонавтов СССР.

- Премия Locus 1986 — Контакты

- Лоуэлла Томаса — Премия Клубу исследователей — 75 лет.

- Премия Масурского — Американское астрономическое общество

- Исследовательская стипендия Миллера - Институт Миллера (1960–1962)

- Медаль Эрстеда — 1990 г. — Американская ассоциация учителей физики.

- Премия Пибоди — 1980 — сериал PBS «Космос: личное путешествие».

- Премия Галаберта в области космонавтики - Международная астронавтическая федерация (IAF) [ 160 ]

- Медаль общественного благосостояния — 1994 г. — Национальная академия наук. [ 161 ]

- Пулитцеровская премия в области научной литературы — 1978 — Драконы Эдема.

- Премия Science Fiction Chronicle — 1998 — Драматическая презентация — Контакты

- Калифорнийского университета в Лос-Анджелесе – 1991 г. Медаль [ 162 ]

- Призывник Международного зала космической славы в 2004 г. [ 163 ]

- Назван « 99-м величайшим американцем » 5 июня 2005 года Величайший американский в телесериале « телесериал» на канале Discovery. [ 164 ]

- Назван почетным членом Демосфенского литературного общества 10 ноября 2011 г.

- Зал славы Нью-Джерси — 2009 г. — призывник. [ 165 ]

- Комитет скептических расследований (CSI) Пантеон скептиков - апрель 2011 г. - призывник. [ а ] [ 167 ]

- Большой крест ордена Святого Иакова Меча , Португалия (23 ноября 1998 г.) [ 168 ]

- Степень почетного доктора наук (Sc.D.) Колледжа Уиттьер в 1978 году. [ 169 ]

Посмертное признание

[ редактировать ]Фильм 1997 года «Контакт» был основан на единственном романе, написанном Саганом. [ 170 ] и завершилось после его смерти. Заканчивается оно посвящением «Карлу». Его фото также можно увидеть в фильме.

В 1997 году прогулка по планете Саган в Итаке, штат Нью-Йорк, была открыта . Это модель Солнечной системы в масштабе пешехода, простирающаяся на 1,2 км от центра Коммонс в центре Итаки до Научного центра , практического музея. Выставка была создана в память о Карле Сагане, жителе Итаки и профессоре Корнеллского университета. Профессор Саган был одним из основателей консультативного совета музея. [ 171 ]

место посадки беспилотного космического корабля Mars Pathfinder было переименовано в Мемориальную станцию Карла Сагана 5 июля 1997 года .

астероид 2709 Саган . В его честь назван [ 93 ] как и Институт Карла Сагана по поиску обитаемых планет.

Сын Сагана, Ник Саган, написал несколько эпизодов франшизы «Звездный путь» . В эпизоде сериала «Звездный путь: Энтерпрайз », озаглавленном « Терра Прайм », показан быстрый снимок реликтового вездехода « Соджорнер» , входящего в состав миссии «Марсианский следопыт» , установленного у исторического маркера на Мемориальной станции Карла Сагана на поверхности Марса. Маркер отображает цитату Сагана: «Какова бы ни была причина вашего пребывания на Марсе, я рад, что вы там, и мне хотелось бы быть с вами». Ученик Сагана Стив Сквайрс возглавил команду, которая марсоходы Spirit и Opportunity успешно доставила на Марс в 2004 году.

9 ноября 2001 года, в день, когда Сагану исполнилось бы 67 лет, Исследовательский центр Эймса посвятил это место Центру Карла Сагана по изучению жизни в космосе. «Карл был невероятным провидцем, и теперь его наследие может быть сохранено и развито исследовательской и образовательной лабораторией XXI века, призванной улучшить наше понимание жизни во Вселенной и способствовать исследованию космоса на все времена», — сказал администратор НАСА Дэниел . Голдин . Энн Друян была в центре, когда он открыл свои двери 22 октября 2006 года.

Саган имеет как минимум три награды, названные в его честь:

- Премия Мемориала Карла Сагана, вручаемая с 1997 года совместно Американским астрономическим обществом и Планетарным обществом,

- Медаль Карла Сагана за выдающиеся достижения в области связей с общественностью в области планетологии, вручаемая с 1998 года Отделом планетарных наук Американского астрономического общества (AAS/DPS) за выдающееся общение активного планетолога с широкой публикой. Карл Саган был одним из первых организаторов. члены комитета ДПС и

- Премия Карла Сагана за общественное понимание науки, врученная президентами Совета научных обществ (CSSP). Саган был первым лауреатом премии CSSP в 1993 году. [ 172 ]

В августе 2007 года Независимая группа расследований (IIG) посмертно наградила Сагана Премией за выдающиеся достижения. Этой чести также удостоились Гарри Гудини и Джеймс Рэнди . [ 173 ]

В сентябре 2008 года музыкальный композитор Бенн Джордан выпустил свой альбом Pale Blue Dot как дань уважения жизни Карла Сагана. [ 174 ] [ 175 ]

Начиная с 2009 года музыкальный проект, известный как Symphony of Science, взял сэмплы из нескольких отрывков Сагана из его сериала «Космос» и сделал их ремиксы на электронную музыку . На сегодняшний день видеоролики получили более 21 миллиона просмотров по всему миру на YouTube. [ 176 ]

В шведском научно-фантастическом короткометражном фильме « Странники» 2014 года используются отрывки из повествования Сагана в 1994 году из его книги « Бледно-голубая точка» , обыгранные поверх созданных в цифровом формате визуальных эффектов возможной будущей экспансии человечества в космическое пространство. [ 177 ] [ 178 ]

В феврале 2015 года финская симфо-метал группа Nightwish выпустила песню «Sagan» в качестве неальбомного бонус-трека к своему синглу « Élan ». [ 179 ] Песня, написанная автором песен, композитором и клавишником группы Туомасом Холопайненом , является данью уважения жизни и творчеству покойного Карла Сагана.

планирует снять биографический фильм о жизни Сагана. В августе 2015 года было объявлено, что Warner Bros. [ 180 ]

Запада в Лос-Анджелесе открылся Театр Карла Сагана и Энн Друян 21 октября 2019 года в Центре исследований . [ 181 ]

В 2022 году Саган был посмертно награжден премией «Будущее жизни» «за снижение риска ядерной войны за счет развития и популяризации науки о ядерной зиме». Эту честь, которую разделили еще семь лауреатов, участвовавших в исследованиях ядерной зимы, приняла его вдова Энн Друян. [ 182 ]

В 2022 году запись аудиокниги книги Сагана « Бледная голубая точка» 1994 года была выбрана Библиотекой Конгресса США для включения в Национальный реестр звукозаписей как «культурно, исторически или эстетически значимая». [ 183 ] [ 184 ]

В 2023 году был анонсирован фильм «Путешественники» Себастьяна Лелио , в котором Саган играет Эндрю Гарфилд , а Дейзи Эдгар-Джонс играет третью жену Сагана, Энн Друян . [ 185 ]

Книги

[ редактировать ]- Саган, Карл (1961). Органическое вещество и Луна . Группа по внеземной жизни для вооруженных сил - Комитет СРН по биоастронавтике, публикация 757. Вашингтон, округ Колумбия: Национальная академия наук - Национальный исследовательский совет. LCCN 61-60064 .

- Саган, Карл; Леонард, Джонатан Нортон (1966). Планеты . Библиотека наук о жизни . Редакция журнала «Жизнь» . Нью-Йорк: Time Inc. LCCN 66022436 . OCLC 346361 .

- ——; Шкловский, И.С. (1966) [Первоначально опубликовано в 1962 году под названием « Вселенная, Жизнь, Разум» ; Москва: Издательство АН СССР . Разумная жизнь во Вселенной . Авторизованный перевод Паулы Ферн. Сан-Франциско: Holden-Day, Inc. LCCN 64018404 . ОСЛК 317314 .

- ——; Пейдж, Торнтон, ред. (1972). НЛО: научные дебаты . Итака, Нью-Йорк: Издательство Корнельского университета . ISBN 978-0-801-40740-6 . LCCN 72004572 . OCLC 415373 .

- ——, изд. (1973). Связь с внеземным разумом (CETI) . Кембридж, Массачусетс: MIT Press . ISBN 978-0-262-19106-7 . LCCN 73013999 . OCLC 700752 .

- ——; Брэдбери, Рэй ; Кларк, Артур С .; и др. (1973). Марс и разум человека (1-е изд.). Нью-Йорк: Харпер и Роу . ISBN 978-0-060-10443-6 . LCCN 72009746 . OCLC 613541 .

- —— (1973). Космическая связь: внеземная перспектива . Продюсер Джером Агель (1-е изд.). Гарден-Сити, Нью-Йорк: Anchor Press . ISBN 978-0-385-00457-2 . LCCN 73081117 . OCLC 756158 .

- —— (1975). Другие миры . Продюсер: Джером Ажель. Торонто, Нью-Йорк: Bantam Books . ISBN 978-0-552-66439-4 . ОСЛК 3029556 .

- —— (1977). Драконы Эдема: размышления об эволюции человеческого интеллекта (1-е изд.). Нью-Йорк: Рэндом Хаус . ISBN 978-0-394-41045-6 . LCCN 76053472 . OCLC 2922889 .

- ——; Дрейк, Флорида ; Ломберг, Джон ; и др. (1978). Шумы Земли: Межзвездные записи "Вояджера" (1-е изд.). Нью-Йорк: Рэндом Хаус. Бибкод : 1978mevi.book.....S . ISBN 978-0-394-41047-0 . LCCN 77005991 . OCLC 4037611 .

- —— (1979). Мозг Брока: размышления о романтике науки (1-е изд.). Нью-Йорк: Рэндом Хаус. ISBN 978-0-394-50169-7 . LCCN 78021810 . OCLC 4493944 .

- —— (1980). Космос (1-е изд.). Нью-Йорк: Рэндом Хаус. ISBN 978-0-394-50294-6 . LCCN 80005286 . OCLC 6280573 .

- ——; Эрлих, Пол Р .; Кеннеди, Дональд ; и др. (1984). Холод и тьма: мир после ядерной войны: Конференция по долгосрочным глобальным биологическим последствиям ядерной войны . Предисловие Льюиса Томаса (1-е изд.). Нью-Йорк: WW Norton & Company . ISBN 978-0-393-01870-7 . LCCN 84006070 . ОСЛК 10697281 .

- ——; Друян, Энн (1985). Комета (1-е изд.). Нью-Йорк: Рэндом Хаус. ISBN 978-0-394-54908-8 . LCCN 85008308 . OCLC 811602694 .

- —— (1985). Контакт: Роман . Нью-Йорк: Саймон и Шустер . ISBN 978-0-671-43400-7 . LCCN 85014645 . OCLC 12344811 .

- ——; Турко, Ричард (1990). Путь, о котором никто не думал: ядерная зима и конец гонки вооружений (1-е изд.). Нью-Йорк: Рэндом Хаус. ISBN 978-0-394-58307-5 . LCCN 89043155 . OCLC 20217496 .

- ——; Друян, Энн (1992). Тени забытых предков: В поисках того, кто мы (1-е изд.). Нью-Йорк: Рэндом Хаус. ISBN 978-0-394-53481-7 . LCCN 92050155 . OCLC 25675747 .

- Саган, Карл; Томпсон, В. Рид; Карлсон, Роберт; Гернетт, Дональд; Хорд, Чарльз (23 октября 1993 г.). «Поиски жизни на Земле с космического корабля Галилео» (PDF) . Природа . 365 (6448): 715–721. Бибкод : 1993Natur.365..715S . дои : 10.1038/365715a0 . ПМИД 11536539 . S2CID 4269717 .

- Саган, Карл; Турко, Ричард П. (ноябрь 1993 г.). «Ядерная зима в эпоху после холодной войны» (PDF) . Журнал исследований мира . 30 (4): 369–373. дои : 10.1177/0022343393030004001 . JSTOR 424481 . S2CID 109843259 . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 15 февраля 2020 г.

- —— (1994). Бледно-голубая точка: видение будущего человечества в космосе (1-е изд.). Нью-Йорк: Рэндом Хаус. ISBN 978-0-679-43841-0 . LCCN 94018121 . OCLC 30736355 .

- —— (1995). Мир, населенный демонами: наука как свеча в темноте (1-е изд.). Нью-Йорк: Рэндом Хаус. ISBN 978-0-394-53512-8 . LCCN 95034076 . OCLC 779687822 . (Примечание: вставлен листок с опечатками.)

- ——; Друян, Энн (1997). Миллиарды и миллиарды: мысли о жизни и смерти на пороге тысячелетия (1-е изд.). Нью-Йорк: Рэндом Хаус. ISBN 978-0-679-41160-4 . LCCN 96052730 . ОСЛК 36066119 .

- —— (2006) [Отредактировано по материалам Гиффордских лекций 1985 года , Университет Глазго ]. Друян, Энн (ред.). Разнообразие научного опыта: личный взгляд на поиски Бога . Нью-Йорк: Penguin Press . ISBN 978-1-59420-107-3 . LCCN 2006044827 . ОСЛК 69021064 .

См. также

[ редактировать ]Пояснительные примечания

[ редактировать ]Ссылки

[ редактировать ]Цитаты

[ редактировать ]- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж Терзян и Тримбл 1997 , Bull AAS 29(4).

- ^ Дэвидсон 1999 , Книга посвящена Поллаку.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Карл Саган в проекте «Математическая генеалогия»

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Саган, Карл; Хед, Том (2006). Беседы с Карлом Саганом (иллюстрированное ред.). Университетское издательство Миссисипи. п. 14 . ISBN 978-1-57806-736-7 . Отрывок со страницы 14. Архивировано 3 декабря 2016 г. в Wayback Machine.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Карл Саган» . ученый.google.com . Архивировано из оригинала 23 декабря 2019 года . Проверено 20 ноября 2018 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «StarChild: Доктор Карл Саган» . СтарЧилд . НАСА . Архивировано из оригинала 7 февраля 2012 года . Проверено 8 октября 2009 г.

- ^ Коллекция Сета Макфарлейна из архива Карла Сагана и Энн Друян: помощь коллекции в Библиотеке Конгресса (PDF) . Отдел рукописей Библиотеки Конгресса. 2013. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 8 марта 2016 года . Проверено 17 января 2016 г.

- ^ Ловенсон, Джош (4 февраля 2014 г.). «Огромный архив Карла Сагана, размещенный Библиотекой Конгресса» . Грань . Архивировано из оригинала 12 января 2020 года . Проверено 16 января 2016 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Паундстоун 1999 , стр. 363–364, 374–375.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Дике, Уильям (21 декабря 1996 г.). «Карл Саган, астроном, добившийся успеха в популяризации науки, умер в возрасте 62 лет» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . Архивировано из оригинала 19 августа 2017 года . Проверено 31 августа 2013 г.

- ^ «Карл Саган» . Проект точности Интернета . Гранвиль, Мичиган. Архивировано из оригинала 8 марта 2012 года . Проверено 22 августа 2012 г.

- ^ Дэвидсон 1999 .

- ^ «Карл Саган» . archive.nytimes.com . Архивировано из оригинала 14 июля 2021 года . Проверено 7 мая 2021 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Дэвидсон 1999 , с. 12.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Дэвидсон 1999 , с. 2.

- ^ Дэвидсон 1999 , с. 9.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Спангенбург и Мозер 2004 , стр. 2–5.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Дэвидсон 1999 , с. 14.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Дэвидсон 1999 , с. 15.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Дэвидсон 1999 , с. 18.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Саган, Карл (28 мая 1978 г.). «Растем с научной фантастикой» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . п. СМ7. ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 11 декабря 2018 года . Проверено 12 декабря 2018 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Дэвидсон, Кей (2000). «Саган, Карл (1934–1996), ученый-космонавт, писатель, популяризатор науки, телеведущий и активист движения против ядерного оружия» . Американская национальная биография . Издательство Оксфордского университета. дои : 10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.1302612 . ISBN 978-0-19-860669-7 . Архивировано из оригинала 14 мая 2021 года . Проверено 23 июня 2021 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Дэвидсон 1999 , с. 23.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Дэвидсон 1999 , с. 24.

- ^ Дэвидсон 1999 , с. 25.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Паундстоун 1999 , с. 15.

- ^ Паундстоун 1999 , с. 14.

- ^ «Астрономическое общество Райерсона» . Астрономическое общество Райерсона (РАН) . Чикагского университета Кафедра астрономии и астрофизики . Архивировано из оригинала 19 сентября 2012 года . Проверено 22 августа 2012 г.

- ^ Карл Саган - веб-сайт Массачусетского технологического института

- ^ Сик. Видеть Спангенбург, Рэй; Мозер, Кит; Мозер, Дайан (2004). Карл Саган: Биография (иллюстрированное издание). Издательская группа Гринвуд. п. 28. ISBN 978-0-313-32265-5 . Архивировано из оригинала 6 декабря 2021 года . Проверено 31 августа 2018 г. Отрывок страницы 28. Архивировано 25 декабря 2019 г. в Wayback Machine.

- ^ Саган, Карл (1960). Физические исследования планет (кандидатская диссертация). Чикагский университет. п. ii. OCLC 20678107 . ПроКвест 301918122 .

Диссертация в четырех частях, представленная в рамках частичного выполнения требований для получения степени доктора философии на факультете астрономии Чикагского университета, июнь 1960 г.

- ^ «Аспиранты получают первые педагогические награды Сагана» . Хроники Чикагского университета . 13 (6). 11 ноября 1993 года. Архивировано из оригинала 10 марта 2012 года . Проверено 30 августа 2013 г.

- ^ Глава 2006 , с. XXI.

- ^ Спангенбург и Мозер 2004 , с. 28.

- ^ Татаревич, Джозеф Н. (1990), Космические технологии и планетарная астрономия , Наука, технологии и общество, Блумингтон, Индиана: Издательство Индианского университета, стр. 22, ISBN 978-0-253-35655-0

- ^ Уливи, Паоло (6 апреля 2004 г.). Исследование Луны: люди-пионеры и роботы-геодезисты . Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-85233-746-9 . Архивировано из оригинала 1 января 2014 года . Проверено 15 апреля 2016 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж Моррисон, Дэвид (январь – февраль 2007 г.). «Жизнь и наследие Карла Сагана как ученого, учителя и скептика» . Скептический исследователь . 31 (1): 29–38. ISSN 0194-6730 . Архивировано из оригинала 1 февраля 2016 года . Проверено 31 августа 2013 г.

- ^ Райффель, Леонард (4 мая 2000 г.). «Саган нарушил правила безопасности, раскрыв информацию о работе США над проектом лунной бомбы» . Природа . 405 (13): Переписка. дои : 10.1038/35011148 . ISSN 0028-0836 . ПМИД 10811192 .

- ^ «Кто там? — Фильмы — Drew Associates» . Дрю Ассошиэйтс . Архивировано из оригинала 14 марта 2024 года . Проверено 14 марта 2024 г.

- ^ «С (запоздалым) днем рождения, Карл!» . Калифорнийский университет в Беркли . Обзор науки Беркли. 11 ноября 2013. Архивировано из оригинала 3 декабря 2013 года . Проверено 1 декабря 2013 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Дэвидсон 1999 , с. 138.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Дэвидсон 1999 , с. 204.

- ^ Саган, Карл. Мир, преследуемый демонами: Наука как свеча в темноте ( в Google Книгах , архивировано 3 октября 2022 г. в Wayback Machine ), Ballantine Books (1996), стр. 25.

- ^ Дэвидсон 1999 , с. 213.

- ^ Саган, Карл; Хед, Том (2006). Беседы с Карлом Саганом (иллюстрированное ред.). унив. Пресса Миссисипи. п. XXI. ISBN 978-1-57806-736-7 . Отрывок страницы xxi. Архивировано 23 декабря 2019 г. в Wayback Machine .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Саган, Карл (5 января 1995 г.). «Интервью с Карлом Саганом» . Чарли Роуз (Интервью). ПБС . Архивировано из оригинала 14 июля 2015 года . Проверено 30 августа 2013 г.

- ^ Пьеррембер, Раймонд Т. (2010). Принципы планетарного климата . Издательство Кембриджского университета. п. 202. ИСБН 978-1-139-49506-6 . Архивировано из оригинала 30 июля 2019 года . Проверено 20 марта 2016 г. Отрывок страницы 202. Архивировано 19 декабря 2019 года в Wayback Machine .

- ^ Большая часть исследований Сагана в области планетологии изложена Уильямом Паундстоуном . Биография Сагана, составленная Паундстоуном, включает 8-страничный список научных статей Сагана, опубликованных с 1957 по 1998 год. Подробная информация о научной работе Сагана взята из основных исследовательских статей. Пример: Саган, К.; Томпсон, WR; Харе, Б.Н. (1992). «Титан: лаборатория добиологической органической химии». Отчеты о химических исследованиях . 25 (7): 286–292. дои : 10.1021/ar00019a003 . ПМИД 11537156 . Комментарий к этой исследовательской статье о Титане есть в Дэвида Дж. Дарлинга, » «Энциклопедии науки заархивированной 10 марта 2005 года, в Wayback Machine .

- ^ Чессон, Эрик ; Макмиллан, Стивен (1997). Астрономия сегодня (иллюстрированное ред.). Прентис Холл. п. 266. ИСБН 978-0-13-712382-7 . Архивировано из оригинала 15 марта 2021 года . Проверено 20 июня 2020 г.

- ^ Саган, Карл (1985) [первоначально опубликовано в 1980 году]. Космос (1-е изд. Ballantine Books). Нью-Йорк: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-33135-9 . LCCN 80005286 . OCLC 12814276 .

- ↑ Карл Саган дает показания Конгрессу, 10 декабря 1985 г., C-SPAN , https://www.c-span.org/video/?125856-1/greenhouse-effect . Архивировано 25 декабря 2021 г., в Wayback Machine.

- ^ «Саган, Карл Эдвард» . Колумбийская энциклопедия (Шестое изд.). Нью-Йорк: Издательство Колумбийского университета . Май 2001. Архивировано из оригинала 11 октября 2007 года . Проверено 30 августа 2013 г.

- ^ Автор не указан (21 августа 1963 г.). «Саган синтезирует АТФ в лаборатории» . Гарвардский малиновый . Архивировано из оригинала 22 декабря 2015 года . Проверено 12 сентября 2015 г.

- ^ «Карл Саган» . Пасадена, Калифорния: Планетарное общество . Архивировано из оригинала 21 февраля 2015 года . Проверено 30 августа 2013 г.

- ^ Бенфорд, Грегори (1997). «Дань Карлу Сагану: популярно и приставлено к позорному столбу» . Скептик . 13 (1). Архивировано из оригинала 16 апреля 2011 года . Проверено 18 февраля 2011 г.

- ^ Шермер, Майкл (2 ноября 2003 г.). «Свеча в темноте» . Работы Майкла Шермера . Майкл Шермер. Архивировано из оригинала 27 сентября 2009 года . Проверено 10 марта 2013 г. Статья первоначально опубликована в ноябрьском номере журнала Scientific American за 2003 год .