Взлет и падение Зигги Стардаста и пауков с Марса

| Взлет и падение Зигги Стардаста и пауков с Марса | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Студийный альбом | ||||

| Выпущенный | 16 июня 1972 г. [а] | |||

| Записано |

| |||

| Studio | Trident, London | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 38:29 | |||

| Label | RCA | |||

| Producer |

| |||

| David Bowie chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars | ||||

| ||||

Взлет и падение Зигги Стардаста и пауков с Марса (часто сокращается до Зигги Стардаста) [1] — пятый студийный альбом английского музыканта Дэвида Боуи , выпущенный 16 июня 1972 года в Великобритании на лейбле RCA Records . Он был сопродюсирован Боуи и Кеном Скоттом , и в нем участвует группа Боуи Spiders from Mars — гитарист Мик Ронсон , басист Тревор Болдер и барабанщик Мик Вудмэнси . Он был записан с ноября 1971 года по февраль 1972 года в студии Trident Studios в Лондоне .

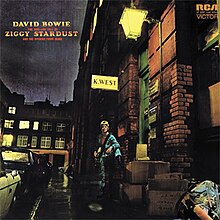

Описанный как свободный концептуальный альбом и рок-опера , Ziggy Stardust Боуи фокусируется на титульном альтер-эго Зигги Стардасте , вымышленной андрогинной и бисексуальной рок-звезде, которую отправляют на Землю как спасителя перед надвигающейся апокалиптической катастрофой. По сюжету Зигги покоряет сердца фанатов, но терпит впадение в немилость после того, как поддался собственному эго. Персонаж был вдохновлен многочисленными музыкантами, в том числе Винсом Тейлором . Большая часть концепции альбома была разработана уже после записи песен. На музыкальные стили глэм -рок и прото-панк повлияли Игги Поп , The Velvet Underground и Марк Болан . В текстах обсуждаются искусственность рок-музыки, политические проблемы, употребление наркотиков, сексуальность и слава. Обложка альбома, сфотографированная в монохромном режиме и перекрашенная, была сделана в Лондоне возле дома скорняков «К. Уэст».

Preceded by the single "Starman", Ziggy Stardust reached top five of the UK Albums Chart. Critics responded favourably; some praised the musicality and concept while others struggled to comprehend it. Shortly after its release, Bowie performed "Starman" on Britain's Top of the Pops in early July 1972, which propelled him to stardom. The Ziggy character was retained for the subsequent Ziggy Stardust Tour, performances from which have appeared on live albums and a concert film. Bowie described the follow-up album, Aladdin Sane, as "Ziggy goes to America".

In later decades, Ziggy Stardust has been considered one of Bowie's best works, appearing on numerous professional lists of the greatest albums of all time. Bowie had ideas for a musical based on the album, although this project never came to fruition; ideas were later used for Diamond Dogs (1974). Ziggy Stardust has been reissued several times and was remastered in 2012 for its 40th anniversary. In 2017, it was selected for preservation in the National Recording Registry by the Library of Congress, being deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".

Background

[edit]After his promotional tour of America in February 1971,[2] David Bowie returned to Haddon Hall in England and began writing songs,[3] many of which were inspired by the diverse musical genres that were present in America.[4] He wrote over three dozen songs, many of which would appear on his fourth studio album Hunky Dory and Ziggy Stardust;[5] among these were "Moonage Daydream" and "Hang On to Yourself", which he recorded with his short-lived band Arnold Corns in February 1971,[6] and subsequently reworked for Ziggy Stardust.[3][5] Work officially began on Hunky Dory in June 1971 at Trident Studios in London.[7] The sessions featured the musicians who would later become known as the Spiders from Mars – the guitarist Mick Ronson, the bassist Trevor Bolder, and the drummer Mick Woodmansey.[8] Ken Scott, who previously worked as an engineer for Bowie's two previous albums and the Beatles, was chosen to be the producer.[3] The sessions also featured Rick Wakeman on piano who[9] after completing work on the album, declined Bowie's offer to join the Spiders to instead join the English progressive rock band Yes.[10] According to Woodmansey, Hunky Dory and Ziggy Stardust were almost recorded back-to-back, but the Spiders realised that most of the songs on Hunky Dory were not suitable live material, so they needed a follow-up album with material they could use on tour.[11]

After Bowie's manager Tony Defries ended his contract with Mercury Records, Defries presented the album to multiple labels in the US, including New York City's RCA Records. The head of the label, Dennis Katz, heard the tapes and saw the potential of the piano-based songs, signing Bowie to a three-album deal on 9 September 1971; RCA became Bowie's label for the rest of the decade.[12][13] Hunky Dory was released on 17 December to very positive reviews from critics but sold poorly and failed to break the UK Albums Chart,[14] partly due to poor marketing from RCA; the label had heard from Scott that Bowie was going to be changing his image for his next record so they did not know how to promote it.[3][15]

Recording and production

[edit]

The first song to be properly recorded for Ziggy Stardust was the Ron Davies cover "It Ain't Easy", on 9 July 1971. Originally slated for release on Hunky Dory, the song was passed for inclusion on that album and subsequently placed on Ziggy Stardust. With Hunky Dory being readied for release, the sessions for Ziggy Stardust officially began at Trident on 8 November 1971,[16] using the same personnel as Hunky Dory minus Wakeman. In 2012, Scott said that "95 percent of the vocals on the four albums I did with him as producer, they were first takes."[17] According to the biographer Nicholas Pegg, Bowie's "sense of purpose" during the sessions was "decisive and absolute"; he knew exactly what he wanted for each individual track. Since most of the tracks were recorded almost entirely live, Bowie recalled that at some points, he had to hum Ronson's solos to him.[18] Due to Bowie's generally dismissive attitude during the sessions for The Man Who Sold the World (1970),[19][3] Ronson had to craft his solos individually and had very little guidance.[18] Bowie had a much better attitude when recording Hunky Dory[3][19] and Ziggy Stardust, and gave Ronson guidance on what he was looking for.[18] For the album, Ronson used an electric guitar plugged to a 100-watt Marshall amplifier and a wah-wah pedal;[17] Bowie played acoustic rhythm guitar.[20]

On 8 November 1971, the band recorded initial versions of "Star" (then titled "Rock 'n' Roll Star") and "Hang On to Yourself", both of which were deemed unsuccessful. Both songs were rerecorded three days later on 11 November, along with "Ziggy Stardust", "Looking For a Friend", "Velvet Goldmine", and "Sweet Head".[21][18] The next day the band recorded two takes of "Moonage Daydream", one of "Soul Love", two of "Lady Stardust", and two of a new version of The Man Who Sold the World track "The Supermen". Three days later on 15 November, the band recorded "Five Years" as well as unfinished versions of "It's Gonna Rain Again" and "Shadow Man".[21][22] Woodmansey described the recording process as very fast-paced. He said they would record the songs, listen to them, and if they did not capture the sound they were looking for, record them again.[18] On that day a running order was created, which included the Chuck Berry cover "Around and Around" (titled "Round and Round"), the Jacques Brel cover "Amsterdam", a new recording of "Holy Holy", and "Velvet Goldmine". "It Ain't Easy" was absent from the list.[21] According to Pegg, the album was to be titled Round and Round as late as 15 December.[18]

After the 15 November session the group took a break for the holiday season.[18] Reconvening on 4 January 1972, the band held rehearsals for three days at Will Palin's Underhill Studios in Blackheath, London, in preparation for the final recording sessions.[23] After recording some of the new songs for radio presenter Bob Harris's Sounds of the 70s as the newly dubbed Spiders from Mars in January 1972,[23] the band returned to Trident that month to begin work on "Suffragette City" and "Rock 'n' Roll Suicide".[18] After receiving a complaint from the RCA executive Dennis Katz that the album did not contain a single, Bowie wrote "Starman", which replaced "Round and Round" on the track listing at the last minute.[24] According to biographer Kevin Cann, the replacement occurred on 2 February. Two days later, the band recorded "Starman",[b] "Suffragette City", and "Rock 'n' Roll Suicide"[26] bringing the sessions to a close.[17]

Concept and themes

[edit]Overview

[edit][Ziggy Stardust] was never discussed as a concept album from the start ... We were recording a bunch of songs—some of them happened to fit together, some didn't work.[27]

—Ken Scott on the Ziggy Stardust concept

The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and The Spiders from Mars is about a bisexual alien rock superstar named Ziggy Stardust.[28][29] It was not initially conceived as a concept album; much of the story was written after the album was recorded.[30][31] Tracks rewritten for the narrative included "Star" (originally titled "Rock 'n' Roll Star"),[31] "Moonage Daydream",[32] and "Hang On to Yourself".[33] Some reviewers have categorised the record as being a rock opera,[34][35][36] although Paul Trynka argues that it is less an opera and more a "collection of snapshots thrown together and later edited into a sequence that makes sense."[37] The characters were androgynous. Mick Woodmansey said the clothes they had worn had "femininity and sheer outrageousness". He also said that the characters' looks "definitely appealed to our rebellious artistic instincts".[38] Nenad Georgievski of All About Jazz said the record was presented with "high-heeled boots, multicolored dresses, extravagant makeup and outrageous sexuality".[39] Bowie had already developed an androgynous appearance, which was approved by critics, but received mixed reactions from audiences.[40]

The album's lyrics discuss the artificiality of rock music in general, political issues, drug use, sexual orientation, and stardom.[41][20] Stephen Thomas Erlewine described the lyrics as "fractured, paranoid" and "evocative of a decadent, decaying future".[29] Apart from the narrative, "Star" reflects Bowie's idealisations of becoming a star himself and shows his frustrations at not having fulfilled his potential.[42] On the other hand, "It Ain't Easy" has nothing to do with the overarching narrative.[31][43] The outtakes "Velvet Goldmine" and "Sweet Head" did fit the narrative, but both contained provocative lyrics, which likely contributed to their exclusions.[44][45] Meanwhile "Suffragette City" contains a false ending, followed by the phrase "wham bam, thank you, ma'am!"[46][47] Bowie uses American slang and pronunciations throughout, such as "news guy", "cop" and "TV" (instead of "newsreader", "policeman", and "telly" respectively).[48][49] Richard Cromelin of Rolling Stone called Bowie's imagery and storytelling in the track some of his most "adventuresome" up to that point,[47] while James Parker of The Atlantic wrote that Bowie is "one of the most potent lyricists in rock history".[35]

Inspirations

[edit]

One of the main inspirations for Ziggy Stardust was the English singer Vince Taylor, whom Bowie met after Taylor had a mental breakdown and believed himself to be a cross between a god and an alien.[50] Iggy Pop, the singer of the proto-punk band the Stooges,[51] provided another main inspiration. Bowie had recently become infatuated with the singer and took influence from him for his next record, both musically and lyrically.[52] Other influences for the character included Bowie's earlier album The Man Who Sold the World,[51] Lou Reed, the singer and guitarist of the Velvet Underground;[51] Marc Bolan, the singer and guitarist of the glam rock band T. Rex;[18][29] and the cult musician Legendary Stardust Cowboy.[53] An alternative theory is that during a tour, Bowie developed the concept of Ziggy as a melding of the persona of Iggy Pop with the music of Reed, producing "the ultimate pop idol".[40][18] Woodmansey also cited the guitarist and singer Jimi Hendrix and the progressive rock band King Crimson as being influences.[54]

Sources for the Ziggy Stardust name included the Legendary Stardust Cowboy, the song "Stardust" by Hoagy Carmichael, and Bowie's fascination with glitter.[37] A girlfriend recalled Bowie "scrawling notes on a cocktail napkin about a crazy rock star named Iggy or Ziggy", and on his return to England he declared his intention to create a character "who looks like he's landed from Mars".[40] In 1990, Bowie explained that the "Ziggy" part came from a tailor's shop called Ziggy's that he passed on a train. He liked it because it had "that Iggy [Pop] connotation but it was a tailor's shop, and I thought, Well, this whole thing is gonna be about clothes, so it was my own little joke calling him Ziggy. So Ziggy Stardust was a real compilation of things."[55][56] He later asserted that Ziggy Stardust was born out of a desire to move away from the denim and hippies of the 1960s.[57]

In 2015, Tanja Stark proposed that due to Bowie's well-known fascination with esoterica and his self-identification as 'Jungian', the Ziggy character may be a neologism influenced by Carl Jung, Greek and Gnostic concepts of Syzygy with their connotations of androgyny, the conjunction of male and female, and union of celestial bodies "hinting perhaps, at 'Syzygy' Stardust as futuristic alchemical theatre... foreshadow[ing] the double-headed mannequin of 'Where Are We Now?' (2013)".[58]

Story

[edit]The album begins with "Five Years"; a news broadcast reveals that the Earth only has five years left before it gets destroyed by an impending apocalyptic disaster.[48][59] The first two verses are from the point of view of a child hearing this news for the first time and going numb as it sinks in. The listener is addressed directly by the third verse, while the character of Ziggy Stardust is introduced indirectly.[60] Afterwards the listener hears the point of view of numerous characters dealing with love before the impending disaster ("Soul Love").[61] Biographer Marc Spitz called attention to the sense of "pre-apocalypse frustration" in the track.[60] Doggett said that following the "panoramic vision" of "Five Years", "Soul Love" offers a more "optimistic" landscape, with bongos and acoustic guitar indicating "mellow fruitfulness."[62] Ziggy directly introduces himself in "Moonage Daydream", where he proclaims himself "an alligator" (strong and remorseless), "a mama-papa" (non-gender specific), "the space invader" (alien and phallic), "a rock 'n' rollin' bitch", and a "pink-monkey-bird" (gay slang for a recipient of anal sex).[63][64]

"Starman" sees Ziggy bringing a message of hope to Earth's youth through the radio, salvation by an alien 'Starman', told from the point of view of one of the youths who hears Ziggy.[31] "Lady Stardust" presents an unfinished tale with what Doggett states as "no hint at a denouement beyond a vague air of melancholy".[65] Ziggy is recalled by the audience using both 'he' and 'she' pronouns, showing a lack of gender distinction.[31][65] Ziggy then looks at himself through a mirror, pondering what it would be like to make it "as a rock 'n' roll star" and if it would all be "worthwhile" ("Star").[31][42] In "Hang On to Yourself", Ziggy is put in front of the crowd. The track emphasises the metaphor that rock music goes from sex to fulfilment and back to sex again; Ziggy plans to abandon the sexual climax for a chance at stardom, which ultimately leads to his downfall.[31][33]

"Ziggy Stardust" is the central piece of the narrative, presenting a complete "birth-to-death chronology" of Ziggy.[65] He is described as a "well-hung, snow white-tanned, left-hand guitar-playing man" who rises to fame with his backing band the Spiders from Mars, but he lets his ego take control of him, effectively alienating his fans and losing his bandmates.[66] Unlike "Lady Stardust", "Ziggy Stardust" shows the character's rise and fall in a very human manner.[67] O'Leary notes that the song's narrator is not definitive: it could be an audience member retrospectively discussing Ziggy, it could be one of the Spiders or even the "dissociated memories" of Ziggy himself.[31] After his fall from grace, Ziggy is described by Pegg as "a hollow figure caught in the headlights of braking cars as he stumbles across the road."[68] Rather than dying in blood, Ziggy cries to the audience ("Rock 'n' Roll Suicide"), requesting they "give him their hands" because they are "wonderful" before perishing on stage.[66][68]

Musical styles

[edit]

The music on Ziggy Stardust has been retrospectively described as glam rock and proto-punk.[20][69][70] Georgievski felt the record represents Bowie's interests in "theater, dance, pantomime, kabuki, cabaret, and science fiction".[39] The Library of Congress also notes the presence of blues, garage rock, soul, and stadium rock.[71] Some of the tracks also feature elements of 1950s rock and pop ("Rock 'n' Roll Suicide" and "Sweet Head"),[31][72] pop and jazz ("Soul Love"),[60] heavy metal ("Moonage Daydream") and late-1970s punk rock ("Hang On to Yourself").[20] Bowie himself compared the record's sound to the music of Iggy Pop.[21] Author James Perone opined that the music is "more focused" than Bowie's previous works, being full of melodic and harmonic hooks.[20]

After the departure of Rick Wakeman on keyboards, the songs on Ziggy Stardust are considerably less piano-led than the songs on Hunky Dory and are more guitar-led, primarily due to the influence of Ronson's guitar and string arrangements.[18] Nevertheless, biographers have noted stylistic similarities to Hunky Dory in "Velvet Goldmine" and the string arrangement for "Starman".[31][73] Ronson played piano on the album as well as guitar and strings; according to Pegg, his playing on tracks like "Five Years" and "Lady Stardust" foreshadows the skills he showcases on Lou Reed's Transformer (1972).[18] Meanwhile his electric guitar playing dominates tracks including "Moonage Daydream",[31][63] "It Ain't Easy",[74] "Ziggy Stardust",[60] and "Suffragette City".[70] Additionally Bowie's acoustic guitar playing is prominent on some tracks, notably "Rock 'n' Roll Suicide". Perone argues that although listeners tend to pay closer attention to Ronson's electric, Ziggy Stardust is "one of the better albums" in Bowie's catalogue to highlight his rhythm guitar playing.[20]

The songwriting includes a wide variety of influences, from singer Elton John and poet Lord Alfred Douglas ("Lady Stardust"),[31][65][75] Little Richard ("Suffragette City"),[76][77][78] "Over the Rainbow" from the 1939 film The Wizard of Oz ("Starman"),[79] and the Velvet Underground ("Suffragette City" and "Velvet Goldmine").[76][80] As well as covering Chuck Berry's "Around and Around" during the sessions, Berry and Eddie Cochran influence the straightforward rock songs "Hang On to Yourself" and "Suffragette City".[81][20]

As well as including faster-paced numbers ("Star"),[42] the album contains the minimalist tracks "Five Years" and "Rock 'n' Roll Suicide". Both tracks are mostly led by Bowie's voice,[81] building intensity throughout their runtimes.[82][83] While "Five Years" contains what author David Buckley calls a "heartbeat-like" drum beat,[84] "Rock 'n' Roll Suicide" starts acoustic and builds to a lush arrangement, backed by an orchestra.[83] Pegg describes "Rock 'n' Roll Suicide" as Bowie's own "A Day in the Life".[68] The album also features some experimentation. "Soul Love" contains bongos, a hand-clap rhythm, and a saxophone solo from Bowie which Doggett calls "relaxing".[20][85] "It Ain't Easy" features a harpsichord contribution from Rick Wakeman and backing vocals from Dana Gillespie, both of which were uncredited.[c][44] Additionally "Suffragette City" features one of Bowie's earliest uses of the ARP synthesiser, which later became the backbone of his late-1970s Berlin Trilogy.[78][77]

Artwork and packaging

[edit]The idea was to hit a look somewhere between the Malcolm McDowell thing with the one mascaraed eyelash and insects. It was the era of Wild Boys, by William S. Burroughs ... [It] was a cross between that and Clockwork Orange that really started to put together the shape and the look of what Ziggy and the Spiders were going to become ... Everything had to be infinitely symbolic.[87]

—Bowie discussing the album's packaging, 1993

The album cover photograph was taken by photographer Brian Ward in monochrome;[88] it was recoloured by illustrator Terry Pastor, a partner at the Main Artery design studio in Covent Garden with Bowie's longtime friend George Underwood. Both Ward and Underwood had done the artwork and sleeve for Hunky Dory.[18][89] The typography, initially pressed onto the original image using Letraset, was airbrushed by Pastor in red and yellow, and inset with white stars.[89] Pegg said that unlike many of Bowie's album sleeves, which feature close-ups of Bowie in a studio, the Ziggy image has Bowie almost in the foreground. Pegg describes the shot as: "Bowie (or Ziggy) [stands] as a diminutive figure dwarfed by the shabby urban landscape, picked out in the light of a street lamp, framed by cardboard boxes and parked cars".[18] Bowie is also holding a Gibson Les Paul guitar, which was owned by Arnold Corns guitarist Mark Pritchett and was the same guitar Pritchett used on Corns' recordings of "Moonage Daydream" and "Hang On to Yourself". Similar to Hunky Dory's cover, Bowie's jumpsuit and hair, which was still his natural brown at the time,[89] were artificially retinted. Pegg believes it gives the impression that the "guitar-clutching visitor" is from another dimension or world.[18]

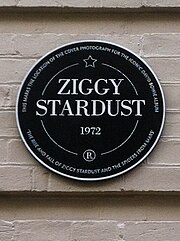

The photograph was taken during a photoshoot on 13 January 1972 at Ward's Heddon Street studio in London, just off Regent Street. Suggesting they take photos outside before natural light was lost, the Spiders chose to stay inside while Bowie, who was ill with flu[90] went outside just as it started to rain. Not willing to go very far, he stood outside the home of furriers "K. West" at 23 Heddon Street.[91][92] According to Cann, the "K" stands for Konn, the surname of the company's founder Henry Konn, and the "West" indicated it was on the west end of London.[89] Soon after Ziggy Stardust became a massive success, the directors of K. West were displeased with their company's name appearing on a pop album. A solicitor for K. West wrote a letter to RCA saying: "Our clients are Furriers of high repute who deal with a clientele generally far removed from the pop music world. Our clients certainly have no wish to be associated with Mr. Bowie or this record as it might be assumed that there was some connection between our client's firm and Mr. Bowie, which is certainly not the case". However tensions eased and the company soon became accustomed to tourists photographing themselves on the doorstep.[89] K. West moved out of the Heddon Street location in 1991 and the sign was taken down; according to Pegg, the site remains a popular "place of pilgrimage" for Bowie fans.[18] Bowie said of the sign, "It's such a shame that sign [was removed]. People read so much into it. They thought 'K. West' must be some sort of code for 'quest.' It took on all these sort of mystical overtones".[87]

The rear cover of the original vinyl LP contained the instruction "To be played at maximum volume" (stylised in all caps). The cover was among the ten chosen by the Royal Mail for a set of "Classic Album Cover" postage stamps issued in January 2010.[18][93] In March 2012, The Crown Estate, which owns Regent Street and Heddon Street, installed a commemorative brown plaque at No. 23 in the same place as the "K. West" sign on the cover photo. The unveiling ceremony was attended by Woodmansey and Bolder; it was unveiled by Gary Kemp.[94] The plaque was the first to be installed by The Crown Estate and is one of few plaques in the country devoted to fictional characters.[95]

Release and promotion

[edit]Before Bowie changed his appearance to his Ziggy persona, he conducted an interview with journalist Michael Watts of Melody Maker where he came out as gay.[96] Published on 22 January 1972 with the headline "Oh You Pretty Thing",[97] the announcement garnered publicity in both Britain and America,[98] although according to Pegg the declaration was not as monumental as latter-day accounts perceive. Nevertheless Bowie was adopted as a gay icon in both countries, with Gay News describing him as "probably the best rock musician in Britain" and "a potent spokesman" for "gay rock". Although Defries was reportedly "shocked" by the announcement, Scott believed Defries was behind it from the start, wanting to use it for publicity.[18] According to Cann, the ambiguity surrounding Bowie's sexuality drew press attention for his tour dates, the upcoming album and the subsequent "John, I'm Only Dancing" non-album single.[98]

RCA released the lead single, "Starman", on 28 April 1972, backed by "Suffragette City".[31] The single sold steadily rather than spectacularly but earned many positive reviews. Promoting the upcoming album, Bowie, the Spiders, and keyboardist Nicky Graham performed the song on the Granada children's music programme Lift Off with Ayshea on 15 June; it was presented by Ayshea Brough.[73] Ziggy Stardust was released a day later in the United Kingdom on 16 June,[99][100][d][a] with the catalogue number SF 8287. It sold 8,000 copies in Britain in its first week and entered the top 10 in its second week on the UK Albums Chart.[18] The Lift Off performance was broadcast on 21 June in a "post-school" time slot, where it was witnessed by thousands of British children.[105] By 1 July, "Starman" rose to number 41 on the UK Singles Chart, earning Bowie an invitation to perform on the BBC television programme Top of the Pops.[106]

Bowie, the Spiders, and Graham performed "Starman" on Top of the Pops on 5 July 1972.[73] Bowie appeared in a brightly coloured rainbow jumpsuit, astronaut boots, and with "shocking" red hair while the Spiders wore blue, pink, scarlet, and gold velvet attire. During the performance, Bowie was relaxed and confident and wrapped his arm around Ronson's shoulder.[106] Shown the following day,[107] the performance brought public attention to the album[108] and helped solidify Bowie as a controversial pop icon. Buckley writes: "Many fans date their conversion to all things Bowie to this Top of the Pops appearance."[109] The performance was a defining moment for many British children.[110] U2 singer Bono said in 2010, "The first time I saw [Bowie] was singing 'Starman' on television. It was like a creature falling from the sky. Americans put a man on the moon. We had our own British guy from space–with an Irish mother."[111] After the performance,[110] "Starman" charted at number 10 in the UK while peaking at number 65 in the US.[112] On 11 April 1974,[113] impatient for a follow-up to "Rebel Rebel", RCA belatedly released "Rock 'n' Roll Suicide" as a single. Buckley calls this move a "dosh-catching exercise".[114][115]

After dropping down the chart in late 1972, the album began climbing the chart again; by the end of 1972, the album had sold 95,968 units in Britain. It peaked at number five on the chart in February 1973.[116] In Canada, the album reached number 59 and was on the charts for 27 weeks.[117] In the US, the album peaked at number 75 on the Billboard Top LPs & Tape chart in April 1973.[118] The album returned to the UK chart on 31 January 1981, peaking at No. 73,[119] amid the New Romantic era that Bowie had helped inspire.[120] After Bowie's death in 2016, the album reached a new peak of No. 21 in the US Billboard 200.[121] It has sold an estimated 7.5 million copies worldwide, making it Bowie's second-best-selling album after Let’s Dance (1983).[122]

Critical reception

[edit]After its release, The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars received generally lukewarm reviews from contemporaneous critics.[123] James Johnson of New Musical Express (NME) said the album has "a bit more pessimism" than on previous releases and called the songs "fine".[124] Watts said in Melody Maker that while Ziggy Stardust had "no well-defined story line", it had "odd songs and references to the business of being a pop star that overall add up to a strong sense of biographical drama."[125] In Rolling Stone, writer Richard Cromelin thought the album was good, but he felt that it and its style might not be of lasting interest: "We should all say a brief prayer that his fortunes are not made to rise and fall with the fate of the 'drag-rock' syndrome."[47]

Some reviewers gave overwhelming praise to the album. A writer for Circus magazine wrote that the album is "from start to finish... of dazzling intensity and mad design", and called it a "stunning work of genius".[126] Referencing the album, Jack Lloyd of The Philadelphia Inquirer declared that "David Bowie is one of the most creative, compelling writers around today".[127] The Evening Standard's Andrew Bailey agreed, praising the songwriting, performances, production, and "operatic" music.[128] Robert Hilburn positively compared Ziggy to the Who's Tommy (1969) in the Los Angeles Times, describing the music as "exciting, literate and imaginative".[129]

Jon Tiven of Phonograph Record praised the album, calling it "the Aftermath of the Seventies", where there are no filler tracks. He further called Bowie "one of the most distinctive personalities in rock" believing that should Bowie ever become a star "of the Ziggy Stardust magnitude", he deserves it.[130] In Creem, Dave Marsh considered Ziggy Stardust Bowie's best record up to that point, stating "I can't see him stopping here for long".[131] Creem later placed the album at the top of their end of year list.[132] Meanwhile Lillian Roxon of New York Sunday News chose Ziggy Stardust over the Rolling Stones' Exile on Main St. as the best album of the year up to that point, even considering Bowie "the Elvis of the Seventies".[133]

Nevertheless the album did receive some negative reviews. A writer for Sounds magazine, who praised Hunky Dory, opined: "It would be a pity if this album was the one to make it... much of it sounds the work of a competent plagiarist."[134] Writing for The Times, Richard Williams felt that the persona was just for show and Bowie "doesn't mean it".[135] Although Nick Kent of Oz magazine enjoyed the album as a whole, he felt the character of Ziggy Stardust did not quite come together as well, stating that Bowie was "over-reaching himself".[136] Doggett said that this was the general verdict for reviewers who had enjoyed the "dense, philosophical songs" of Bowie's previous releases, as they could not relate to the "mythology" of Ziggy Stardust.[123]

Tour

[edit]

Bowie began touring as a promotion of Ziggy Stardust. The first part began in the United Kingdom and ran from 29 January to 7 September 1972.[137] A show at the Toby Jug pub in Tolworth on 10 February of the same year was hugely popular, catapulting him to stardom and creating, as described by Buckley, a "cult of Bowie".[138] Bowie retained the Ziggy character for the tour. His love of acting led to his total immersion in the characters he created for his music. After acting the same role over an extended period, it became impossible for him to separate Ziggy from his own offstage character. Bowie said that Ziggy "wouldn't leave me alone for years. That was when it all started to go sour... My whole personality was affected. It became very dangerous. I really did have doubts about my sanity."[139]

After arriving in America in September 1972, he told Newsweek magazine that he began having trouble differentiating between himself and Ziggy.[140] Fearing that Ziggy would define his career, Bowie quickly developed a new persona for his follow-up album, Aladdin Sane (1973), which was mostly recorded from December 1972 to January 1973 between legs of the tour.[141] Described by Bowie as "Ziggy goes to America", Aladdin Sane contained songs he wrote while travelling to and across America during the earlier part of the Ziggy tour. The character of Aladdin Sane was far less optimistic, rather engaging in aggressive sexual activities and heavy drugs. Aladdin Sane became Bowie's first number-one album in the UK.[142][143][144]

The tour lasted 18 months and passed through North America; it then went to Japan to promote Aladdin Sane.[143] The final date of the tour was 3 July 1973, which was performed at the Hammersmith Odeon in London. At this show, Bowie made the sudden surprise announcement that the show would be "the last show that we'll ever do", later understood to mean that he was retiring his Ziggy Stardust persona.[145][146] The performance was documented by filmmaker D. A. Pennebaker in a documentary and concert film, which premiered in 1979 and commercially released in 1983 as Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, with an accompanying soundtrack album titled Ziggy Stardust: The Motion Picture.[147][148][149] After being widely bootlegged, a show performed in Santa Monica, California, on 20 October 1972 was officially issued in 2008 as Live Santa Monica '72.[150][151]

Other projects

[edit]While recording Ziggy Stardust, Bowie offered "Suffragette City" to the band Mott the Hoople, who were on the verge of breaking up, but they declined. So Bowie wrote a new song for them, "All the Young Dudes".[26][77] With Bowie producing, the band recorded the track in May 1972.[152] Bowie would also produce the band's fifth album named after the song. Bowie would perform the song on the Ziggy Stardust Tour and record his own version during the Aladdin Sane sessions.[153] The tour took a toll on Bowie's mental health; it marked the beginning of his longtime cocaine addiction.[154] During this time, he underwent other projects that contributed to growing exhaustion. In August 1972, he co-produced Lou Reed's Transformer with Ronson in London in between tour commitments. Two months later, he mixed the Stooges' 1973 album Raw Power in Hollywood during the first US tour; Bowie had become friends with the band's frontman Iggy Pop.[155]

In November 1973, Bowie conducted an interview with the writer William S. Burroughs for Rolling Stone. He spoke of a musical based on Ziggy Stardust, saying: "Forty scenes are in it and it would be nice if the characters and actors learned the scenes and we all shuffled them around in a hat the afternoon of the performance and just performed it as the scenes come out." The musical, considered by Pegg a "retrograde step", fell through, but Bowie salvaged two songs for he had written for it—"Rebel Rebel" and "Rock 'n' Roll with Me"—for his 1974 album Diamond Dogs.[156]

Influence and legacy

[edit]The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars made [Bowie] a household name and left a milestone on the highway of popular music, rewriting the terms of the performer's contract with his audience and ushering in a new approach to rock's relationship with artifice and theatre that permanently altered the cultural aesthetic of the twentieth century.[18]

—Nicholas Pegg, 2016

Ziggy Stardust is widely considered to be Bowie's breakthrough album.[157][158][159] Although Pegg believes Ziggy Stardust was not Bowie's greatest work, he said that it had the biggest cultural impact of all his records.[18] Trynka stated that besides the music itself, the album "works overall as a drama that demands suspension of disbelief", making each listener a member of Ziggy's audience. He believes that decades later, "it's a thrill to be a part of the action."[160]

В ретроспективах The Independent и Record Collector Барни Хоскинс и Марк Пэйтресс соответственно заявили, что в отличие от Болана, который стал звездой за год до Боуи и повлиял на его гламурный образ Зигги Стардаста, не смог долго оставаться на позиции звезды. бегут из-за отсутствия адаптивности. Боуи, с другой стороны, сделал перемены темой всей своей карьеры, развиваясь на протяжении 1970-х годов в разных музыкальных жанрах, от глэм-рока Зигги Стардаста до Thin White Duke of Station to Station (1976). [161] [162] Хоскинс утверждал, что через образ Зигги Боуи «перенес глэм-рок в места, о которых Sweet снились только в кошмарах». [161] Дэйв Свенсон из Ultimate Classic Rock заявил , что, поскольку публика адаптировалась к глэму, Боуи решил двигаться дальше, отказавшись от этого образа в течение двух лет. [110] Говоря о влиянии Боуи на жанр глэм-рока в целом, Джо Линч из Billboard назвал записи Зигги Стардаста и Аладдина Сане , которые «обеспечили его долгосрочную карьеру и позорную славу». Он утверждает, что оба альбома «вышли за рамки» жанра, являются «произведениями искусства» и являются не просто «глэм-классикой», а «рок-классикой». [163] В 2002 году Крис Джонс из BBC Music утверждал, что с помощью альбома Боуи создал образец «по-настоящему современной поп-звезды», которому еще предстоит соответствовать. [164]

Перед своим формированием участники английской готик-рок -группы Bauhaus смотрели выступление Боуи «Starman» на Top of the Pops , вспоминая, что это был «значительный и глубокий поворотный момент в их жизни». После этого группа боготворила Боуи и впоследствии сделала кавер на "Ziggy Stardust" в 1982 году. [165] В 2004 году бразильский певец Сеу Хорхе внес пять кавер-версий песен Боуи, три из них с Ziggy Stardust , в саундтрек к фильму The Life Aquatic со Стивом Зиссу . [166] Позже Хорхе перезаписал песни в виде сольного альбома под названием The Life Aquatic Studio Sessions . В примечаниях к этому альбому Боуи написал: «Если бы Сеу Хорхе не записал мои песни на португальском, я бы никогда не услышал этот новый уровень красоты, которым он их наполнил». [167] В 2016 году Хорхе гастролировал, исполняя свои португальские каверы на песни Боуи перед экранами в форме парусника. [168] Музыкант Сол Уильямс назвал свой альбом 2007 года The Inevitable Rise and Liberation of NiggyTardust! после альбома. [169] В июне 2017 года вымерший вид ос был назван Archaeoteleia astropulvis в честь Зигги Стардаста (« astropulvis » в переводе с латыни означает «звездная пыль»). [170] [171]

Переоценка

[ редактировать ]| Оценки по отзывам | |

|---|---|

| Источник | Рейтинг |

| Вся музыка | |

| Блендер | |

| Чикаго Трибьюн | |

| Путеводитель по рекордам Кристгау | B+ [174] |

| Энциклопедия популярной музыки | |

| Вилы | 10/10 [150] |

| вопрос | |

| Путеводитель по альбомам Rolling Stone | |

| Наклонный журнал | |

| Вращаться | |

| Руководство по альтернативной записи Spin | 8/10 [179] |

| Необрезанный | |

Ретроспективно, Ziggy Stardust получил признание критиков и признан одним из самых важных рок-альбомов. [70] [181] [182] Рецензируя издание Ziggy Stardust, посвященное 30-летию группы в 2002 году, Дэрил Исли из Record Collector назвал альбом «монументальным произведением», высоко оценив аккомпанирующую группу The Spiders и отметив его культурное влияние. [183] Джонс отметил важность альбома в рок-музыке 30 лет спустя и назвал Скотта и Пауков элементами, которые подняли альбом до полученного статуса, посчитав его «пиком» творчества и достижений этой группы. [164] Billboard написал, что пластинка служит напоминанием звукозаписывающим компаниям о том, что «безнадежно своеобразная и чрезмерно провокационная» музыка может сначала не нравиться, но позже отмечаться как «вневременная». [182] В статье для журнала Slant Magazine в 2004 году Барри Уолш сказал, что, помимо «феномена поп-культуры», альбом стал, песни Боуи являются одними из лучших и самых запоминающихся, и в конечном итоге назвал альбом «поистине вечным». [159] Эрлевин написал для AllMusic: «Боуи добивается успеха не вопреки своим притязаниям, а благодаря им, и Зигги Стардаст – знакомый по структуре, но чуждый по исполнению – впервые встречается в таком грандиозном и размашистом виде, когда его видение и исполнение встречаются». [29] Грег Кот, писавший для Chicago Tribune , описал альбом как «цикл песен, наполненный гитарой», заявив, что он «разыгрывает смерть Джоплина , Моррисона, Хендрикса и 60-е годы» и что он «предвещает страх, упадок и эротизм новая эра». [173]

Многие рецензенты сочли альбом шедевром. [110] [159] [184] Говоря о 40-летнем юбилее, Джордан Блюм из PopMatters пишет: «Легко понять, что Ziggy Stardust стал революционной пластинкой в 1972 году, и сегодня она остается такой же яркой, значимой и приятной». [70] По результатам опроса читателей журнала Rolling Stone , проведенного в 2013 году , Ziggy Stardust был признан лучшим альбомом Боуи. Журнал утверждает, что «это альбом Боуи, который будет в учебниках по истории». [185] В обзоре 2015 года Дуглас Волк из Pitchfork отметил, что, хотя в целом у него бессвязная концепция, он по-прежнему остается великолепной коллекцией треков, «переполненной огромными риффами и огромными персонажами». [150] Ян Фортнэм написал для Classic Rock в 2016 году, что « Ziggy Stardust — главное достижение Дэвида Боуи. Очевидно, противники будут настаивать на том, что другие альбомы имеют больший культурный вес или лучше определяют его творческое наследие, но стоит вернуться к Зигги сегодня, и его интуитивное и эмоциональное воздействие останется». неоспоримо, особенно если играть, как советуют, «на максимальной громкости»… Зигги отразил и сформировал свое время и свою аудиторию, как никакой другой альбом». [66]

Рейтинги

[ редактировать ]The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars часто появлялся в многочисленных списках величайших альбомов всех времен по версии многих изданий. В 1987 году, в рамках своего 20-летия, журнал Rolling Stone поставил его на шестое место в списке «100 лучших альбомов за последние двадцать лет». [186] В 1997 году Ziggy Stardust был назван 20-м величайшим альбомом всех времен по результатам опроса Music of the Millennium , проведенного в Великобритании. [187] Он занял 11-е и 27-е места во втором и третьем изданиях английского писателя Колина Ларкина книги «1000 лучших альбомов за все время» соответственно. Во втором издании он сказал: «Смесь образа рок-звезды и инопланетного существа, характеризующая Зигги Стардаста, была, вероятно, лучшим творением [Боуи]». [188] В 2003 году журнал Rolling Stone поставил его на 35-е место в списке 500 величайших альбомов всех времён . [189] Он сохранил ту же позицию в обновленном списке 2012 года. [190] и снова занял 40-е место в 2020 году. [191] В 2004 году он занял 81-е место в Pitchfork . версии списке 100 лучших альбомов 1970-х годов по [192] в то время как Ultimate Classic Rock включил его в аналогичный список 100 лучших рок-альбомов 1970-х годов в 2015 году, назвав его «мастерским ходом гениального мифотворчества». [193] В 2006 году читатели журнала Q поставили его на 41-е место среди лучших альбомов всех времен. [194] а журнал Time назвал его одним из 100 лучших альбомов всех времен. [195] В 2013 году журнал NME поставил альбом на 23-е место в своем списке 500 величайших альбомов всех времен , написав: « Ziggy Stardust... требует, чтобы с ним работали от начала до конца». [196] В Apple Music списке 100 лучших альбомов за 2024 год альбом занял 24-е место. [197]

Альбом также был включен в издание 2018 года книги Роберта Димери « 1001 альбом, который вы должны услышать, прежде чем умереть» . [198] В марте 2017 года альбом был выбран для сохранения в Национальном реестре записей США Национальным советом по сохранению записей , который определяет его как звукозапись, оказавшую значительное культурное, историческое или эстетическое влияние на американскую жизнь. [71]

Переиздания

[ редактировать ]Ziggy Stardust был впервые выпущен на компакт-диске в ноябре 1984 года компанией RCA. [199] Доктор Тоби Маунтин позже обновил альбом в студии Northeastern Digital Recording в Саутборо, Массачусетс. [200] из оригинальных мастер-лент для Rykodisc . Переиздание вышло 6 июня 1990 года с пятью бонус-треками. [201] Он четыре недели находился в чарте альбомов Великобритании, достигнув 25-го места. [202] Альбом был снова ремастирован Питером Мью и выпущен 28 сентября 1999 года компанией Virgin. [203]

16 июля 2002 года EMI/Virgin выпустила двухдисковую версию. Этот выпуск , первый из серии 30th Anniversary 2CD Editions , включал в себя обновленную версию в качестве первого компакт-диска. Второй диск содержал двенадцать треков, большинство из которых ранее были выпущены на компакт-диске в качестве бонус-треков к переизданиям 1990–1992 годов. Новый микс "Moonage Daydream" изначально был сделан для телевизионной рекламы Dunlop 1998 года . [204]

4 июня 2012 года EMI/Virgin выпустила «40-летие издания». Это издание было обновлено инженером оригинальной Trident Studios Рэем Стаффом . [205] Ремастер 2012 года был доступен на компакт-диске, а также в специальном ограниченном выпуске на виниле и DVD, включающем новый ремастер на LP, а также ремиксы на альбом Скотта 2003 года ( 5.1 и стереомиксы) на DVD-Audio . Последний включал бонусные миксы Скотта 2003 года на песни "Moonage Daydream" (инструментальная), "The Supermen", "Velvet Goldmine" и "Sweet Head". [199] [206]

Ремастер альбома 2012 года и ремикс 2003 года (только стереомикс) были включены в Parlophone бокс-сет Five Years (1969–1973) , выпущенный 25 сентября 2015 года. [207] [208] Альбом с ремастерингом 2012 года также был переиздан отдельно в 2015–2016 годах на компакт-дисках, виниле и в цифровом формате. [209] Parlophone выпустил отдельный LP 26 февраля 2016 года на виниле плотностью 180 г. [210] 16 июня 2017 года Parlophone переиздал альбом ограниченным тиражом на золотом виниле. [211]

17 июня 2022 года Parlophone переиздал альбом в честь своего 50-летия на виниловом диске с картинками и в версиях с половинной скоростью. [212] [213] Два года спустя лейбл объявил о выпуске Waiting in the Sky , альтернативной версии альбома, основанной на трек-листе, составленном до записи "Starman", ко Дню музыкального магазина 2024 года. [214] В том же году Parlophone выпустит бокс-сет из пяти дисков, посвященный периоду Боуи Зигги Стардаста, в который войдут различные неизданные треки, включая демо, отрывки и живые выступления. Бокс-сет « Звезда рок-н-ролла!» , планируется выпустить 14 июня. [215]

Список треков

[ редактировать ]Все треки написаны Дэвидом Боуи , кроме «It Ain't Easy», написанной Роном Дэвисом . [216]

Сторона первая

- « Пять лет » — 4:42

- « Любовь души » - 3:34

- « Лунная мечта » - 4:40

- « Звездный человек » – 4:10

- «Это непросто» - 2:58

Вторая сторона

- « Леди Звездная пыль » — 3:22

- «Звезда» – 2:47

- « Держись себя » - 2:40

- « Зигги Стардаст » — 3:13

- « Город суфражисток » — 3:25

- « Рок-н-ролльное самоубийство » - 2:58

Персонал

[ редактировать ]Источники: [216] [217] [218] [219] [220]

- Дэвид Боуи — вокал, акустическая гитара, саксофон, струнные аранжировки; Пеннивистл о " Moonage Daydream "

- Мик Ронсон — электрогитара, клавишные, бэк-вокал, струнные аранжировки; автоарфа на тему " Пятилетие "

- Тревор Болдер — бас-гитара

- Вуди Вудмэнси — ударные; конги на тему " Любовь души "

- Рик Уэйкман — клавесин в песне «It Ain’t Easy» (в титрах не указан)

- Дана Гиллеспи — бэк-вокал в «It Ain’t Easy» (в титрах не указан)

Технический

- Дэвид Боуи — производство

- Кен Скотт — продюсирование, аудиотехника , инженерия микширования

Диаграммы и сертификаты

[ редактировать ]Недельные графики[ редактировать ]

| Графики на конец года[ редактировать ]

Продажи и сертификаты[ редактировать ]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Примечания

[ редактировать ]- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Несколько источников указывают дату выпуска 6 июня 1972 года. [104] В 2015 году на официальном сайте Боуи было обнаружено письмо от менеджера RCA того же времени, в котором указывалось, что дата выпуска — 16 июня. [99]

- ^ Существуют различные смеси «Звездного человека». Оригинальный британский альбом Ziggy Stardust представлял собой «громкую смесь» фортепианно-гитарной части «азбуки Морзе» между куплетом и припевом. В выпуске альбома в США раздел «Азбука Морзе» был в миксе ниже. [25]

- ↑ Вклад Гиллеспи в "It Ain't Easy" был зачислен в переиздание альбома в 1999 году. [86]

- ^ Дата выхода в США неясна. от 27 В выпуске Record World мая 1972 года упоминается, что альбом «доступен», и он появился в чарте Billboard Bubbling Under the Top LP под номером 207 за неделю, закончившуюся 10 июня, что предполагает дату выпуска в конце мая. [101] [102] Клерк называет это 6 июня. [103]

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ Пероне 2007 , с. 162.

- ^ Сэндфорд 1997 , стр. 72–74.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж Пегг 2016 , стр. 340–350.

- ^ Грин, Энди (16 декабря 2019 г.). «Hunky Dory» Дэвида Боуи: Как Америка вдохновила шедевр 1971 года» . Роллинг Стоун . Архивировано из оригинала 10 марта 2020 года . Проверено 28 апреля 2020 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Шпиц 2009 , с. 156.

- ^ Канн 2010 , стр. 206–207.

- ^ Канн 2010 , с. 219.

- ^ Галлуччи, Майкл (17 декабря 2016 г.). «Возвращаясь к первому шедевру Дэвида Боуи «Hunky Dory» » . Абсолютный классический рок . Архивировано из оригинала 20 сентября 2019 года . Проверено 23 апреля 2020 г.

- ^ Бакли 2005 , с. 93.

- ^ Канн 2010 , с. 224.

- ^ Вудмэнси 2017 , стр. 107, 117.

- ^ Канн 2010 , стр. 195, 227.

- ^ Сэндфорд 1997 , с. 81.

- ^ Бакли 2005 , с. 104.

- ^ Канн 2010 , с. 234.

- ^ Канн 2010 , стр. 223, 230.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Фанелли, Дамиан (23 апреля 2012 г.). «В свой 40-летний юбилей сопродюсер «Зигги Стардаст» Кен Скотт обсуждает работу с Дэвидом Боуи» . Гитарный мир . Архивировано из оригинала 17 сентября 2017 года . Проверено 16 сентября 2017 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я дж к л м н тот п д р с т в Пегг 2016 , стр. 351–360.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Канн 2010 , с. 197.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час Пероне 2007 , стр. 26–34.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Канн 2010 , стр. 230–231.

- ^ Вудмэнси 2017 , стр. 88, 114.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Канн 2010 , стр. 238–239.

- ^ Пегг 2016 , с. 262.

- ^ Пегг 2016 , с. 263.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Канн 2010 , с. 242.

- ↑ Trynka 2011 , pp. 182-183.

- ^ Ауслендер 2006 , с. 120.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и Эрлевайн, Стивен Томас . « Взлет и падение Зигги Стардаста и пауков с Марса — Дэвид Боуи» . Вся музыка . Архивировано из оригинала 18 ноября 2015 года . Проверено 21 ноября 2015 г.

- ^ Вудмэнси 2017 , с. 112.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я дж к л м О'Лири 2015 , гл. 5.

- ^ Канн 2010 , с. 253.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Пегг 2016 , стр. 104–105.

- ^ Нельсон, Майкл (5 ноября 2012 г.). «10 лучших рок-опер, заслуживающих сценической адаптации» . Стереогум . Архивировано из оригинала 25 апреля 2019 года . Проверено 25 апреля 2019 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Паркер, Джеймс (апрель 2016 г.). «Блестящие тексты Дэвида Боуи» . Атлантика . Архивировано из оригинала 25 апреля 2019 года . Проверено 25 апреля 2019 г.

- ^ Ауслендер 2006 , с. 138.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Трынка 2011 , стр. 182.

- ^ Вудмэнси 2017 , с. 123.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Георгиевский, Ненад (21 июля 2012 г.). «Дэвид Боуи: Взлет и падение Зигги Стардаста и пауков с Марса (ремастер, посвященный 40-летию)» . Все о джазе . Архивировано из оригинала 1 октября 2017 года . Проверено 1 октября 2017 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Сэндфорд 1997 , стр. 73–74.

- ^ Маклеод, Кен. «Космические странности: инопланетяне, футуризм и смысл в популярной музыке». Популярная музыка . Том. 22. JSTOR 3877579 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Пегг 2016 , стр. 260–261.

- ^ Доггетт 2012 , с. 132.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Пегг 2016 , стр. 133–134.

- ^ Пегг 2016 , с. 298.

- ^ Доггетт 2012 , с. 168.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Кромелин, Ричард (20 июля 1972 г.). «Взлет и падение Зигги Стардаста и пауков с Марса» . Роллинг Стоун . Архивировано из оригинала 21 ноября 2015 года . Проверено 21 ноября 2015 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Пегг 2016 , стр. 92–93.

- ^ Бакли 2005 , с. 130.

- ^ «BBC – Программы BBC Radio 4 – Зигги Стардаст пришел из Айлворта» . Би-би-си . Архивировано из оригинала 30 сентября 2010 года . Проверено 5 ноября 2010 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Людвиг, Джейми (13 января 2016 г.). «Дух трансгрессии Дэвида Боуи сделал его металлическим еще до того, как металл появился» . Шумный . Вице Медиа . Архивировано из оригинала 2 октября 2017 года . Проверено 2 октября 2017 г.

- ↑ Trynka 2011 , pp. 175-182.

- ^ Шиндер и Шварц 2008 , с. 448.

- ^ Вудмэнси 2017 , с. 114.

- ^ Кэмпбелл 2005 .

- ^ Боуи, Дэвид (25 августа 2009 г.). «Дэвид Боуи: Интервью 1990 года» . Поль Дю Нуайе (интервью). Беседовал Поль Дю Нойе . Архивировано из оригинала 15 июля 2011 года . Проверено 26 апреля 2011 г. В: «Дэвид Боуи». Вопрос . № 43. Апрель 1990 г.

- ^ «Дэвид Боуи о годах Зигги Стардаста: «Мы создавали XXI век в 1971 году » . ЭНЕРГЕТИЧЕСКИЙ ЯДЕРНЫЙ РЕАКТОР . 19 сентября 2003 г. Архивировано из оригинала 20 июля 2017 г. Проверено 21 мая 2018 г.

- ^ Старк, Таня (22 июня 2015 г.). «Старк, Т., Сбой с Сильвианом: Дэвид Боуи, Карл Юнг и бессознательное, в Деверо, Э., М.Пауэр и А. Диллейн (ред.) Дэвид Боуи: Критические перспективы: Серия современной музыки Routledge Press. (глава) 5) Рутледж Академик, 2015» . www.tanjastark.com . Проверено 24 марта 2022 г.

- ^ Бут, Сьюзен (2016). « «Взлет и падение Зигги Стардаста и пауков с Марса» — Дэвид Боуи (1972)» (PDF) . Национальный реестр . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 23 мая 2018 года . Проверено 22 мая 2018 г. - через www.loc.gov.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Шпиц 2009 , стр. 187–188.

- ^ Пегг 2016 , с. 253.

- ^ Доггетт 2012 , с. 162.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Пегг 2016 , стр. 186–187.

- ^ Доггетт 2012 , с. 118.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Доггетт 2012 , стр. 120–121.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Фортнэм, Ян (11 ноября 2016 г.). «Каждая песня на альбоме Дэвида Боуи Ziggy Stardust ранжирована от худшей к лучшей» . Громче . Архивировано из оригинала 26 августа 2019 года . Проверено 26 августа 2019 г.

- ^ Пегг 2016 , стр. 325–326.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Пегг 2016 , стр. 227–228.

- ^ Инглис 2013 , с. 71.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Блюм, Иордания (12 июля 2012 г.). «Дэвид Боуи – Взлет и падение Зигги Стардаста и пауков с Марса » . ПопМатерс . Архивировано из оригинала 1 января 2017 года . Проверено 8 января 2017 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Выборы в Национальном реестре звукозаписи «за радугой» » . Библиотека Конгресса . 29 марта 2016 г. Архивировано из оригинала 29 марта 2017 г. . Проверено 29 марта 2016 г.

- ^ Доггетт 2012 , с. 160.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Пегг 2016 , стр. 261–263.

- ^ Рэггетт, Нед. « Это непросто» — Дэвид Боуи» . Вся музыка. Архивировано из оригинала 29 октября 2017 года . Проверено 29 октября 2017 г.

- ^ Пегг 2016 , стр. 148–149.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Рэггетт, Нед. « Город суфражисток» – Дэвид Боуи» . Вся музыка. Архивировано из оригинала 4 июля 2019 года . Проверено 15 марта 2020 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Пегг 2016 , стр. 271–272.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Овсински, Бобби (11 января 2016 г.). «Создание альбома Дэвида Боуи Зигги Стардаста» . Форбс . Архивировано из оригинала 16 сентября 2017 года . Проверено 16 сентября 2017 г.

- ^ Доггетт 2012 , с. 169.

- ^ Доггетт 2012 , с. 158.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Трынка 2011 , стр. 183.

- ^ Пегг 2016 , стр. 92–93, 227–228.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Доггетт 2012 , стр. 161, 171.

- ^ Бакли 2005 , с. 118.

- ^ Доггетт 2012 , стр. 162–163.

- ^ Канн 2010 , с. 223.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Синклер, Дэвид (1993). «От станции к станции» . Роллинг Стоун . Архивировано из оригинала 19 января 2016 года . Проверено 24 мая 2013 г.

- ^ «Альтернативные фотографии со съемок обложки Дэвида Боуи «Ziggy Stardust»» . Ароматная проволока . 23 мая 2012 г. Архивировано из оригинала 22 января 2019 г. . Проверено 22 января 2019 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и Канн 2010 , с. 254.

- ^ Шпиц 2009 , с. 175.

- ^ Канн 2010 , стр. 238–239, 254.

- ^ Кемп, Гэри (27 марта 2012 г.). «Как Зигги Звездная пыль упала на Землю» . Лондонский вечерний стандарт . Архивировано из оригинала 29 июня 2015 года . Проверено 15 июня 2019 г.

- ^ «Обложки классических альбомов: дата выпуска — 7 января 2010 г.» . Королевская почта . Архивировано из оригинала 2 марта 2012 года . Проверено 8 января 2010 г.

- ^ Ассоциация прессы (27 марта 2012 г.). «Альбом Зигги Стардаста Дэвида Боуи отмечен синей табличкой» . Хранитель . Архивировано из оригинала 22 сентября 2017 года . Проверено 18 сентября 2017 г.

- ^ «Место съемки обложки альбома Зигги Стардаста отмечено мемориальной доской» . Новости Би-би-си . 27 марта 2012 года. Архивировано из оригинала 28 марта 2012 года . Проверено 27 марта 2012 г.

- ^ Уоттс, Майкл (22 января 2006 г.). «Дэвид Боуи говорит Melody Maker, что он гей» . Хранитель . Архивировано из оригинала 7 июля 2017 года . Проверено 17 сентября 2017 г.

- ^ Уоттс, Майкл (22 января 1972 г.). «Ох ты, красотка» . Создатель мелодий . стр. 13–15 - через The History of Rock 1972.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Канн 2010 , стр. 239–240.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Поздравляем Зигги Стардаста с 43-м днем рождения» . Официальный сайт Дэвида Боуи . 16 июня 2015 года. Архивировано из оригинала 4 июля 2017 года . Проверено 4 декабря 2017 г.

- ^ Джонс 2017 , с. С12.

- ^ Росс, Рон (27 мая 1972 г.). «Боуи соблазняет подростков: новый альбом, сингл». «Кто в мире» (PDF) . Рекордный мир . п. 23 . Проверено 5 октября 2017 г. - через americanradiohistory.com.

- ^ «Билборд» (PDF) . Рекламный щит . 10 июня 1972 г. с. 43 . Проверено 5 октября 2017 г. - через americanradiohistory.com.

- ^ Клерк 2021 , с. 137.

- ^

- Эрлевайн, Стивен Томас . « Взлет и падение Зигги Стардаста и пауков с Марса — Дэвид Боуи» . Вся музыка . Архивировано из оригинала 18 ноября 2015 года . Проверено 21 ноября 2015 г.

- Суонсон, Дэйв (6 июня 2017 г.). «Как Дэвид Боуи создал шедевр с «Ziggy Stardust» » . Абсолютный классический рок . Архивировано из оригинала 6 октября 2021 года . Проверено 12 октября 2021 г.

- О'Лири 2015 , гл. 5.

- Канн 2010 , с. 252.

- Шпиц 2009 , с. 186.

- Пегг 2016 , с. 360.

- Клерк 2021 , с. 137.

- ^ Канн 2010 , с. 256.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Канн 2010 , с. 258.

- ^ «Боуи исполняет «Starman» на «Top of the Pops» » . 7 веков рока . Би-би-си . 5 июля 1972 года. Архивировано из оригинала 21 марта 2013 года.

- ^ Инглис 2013 , с. 73.

- ^ Бакли 2005 , стр. 125–127.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Суонсон, Дэйв (6 июня 2017 г.). «Как Дэвид Боуи создал шедевр с «Ziggy Stardust» » . Абсолютный классический рок . Архивировано из оригинала 6 октября 2021 года . Проверено 12 октября 2021 г.

- ^ Шеффилд 2016 , с. 70.

- ^ Колфилд, Кейт (1 ноября 2016 г.). «20 самых больших хитов Дэвида Боуи на рекламных щитах» . Рекламный щит . Архивировано из оригинала 22 сентября 2017 года . Проверено 3 октября 2017 г.

- ^ Клерк 2021 , с. 153.

- ^ Пегг 2016 , стр. 228, 780.

- ^ Бакли 2005 , с. 213.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Дэвид Боуи» . Официальная чартерная компания . Архивировано из оригинала 1 июля 2017 года . Проверено 12 июня 2017 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «100 лучших альбомов RPM — 28 апреля 1973 г.» (PDF) .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Уитберн, Джоэл (2001). Лучшие поп-альбомы 1955–2001 годов . Меномони-Фолс: Record Research Inc., с. 94 . ISBN 978-0-89820-147-5 .

- ^ «Топ-75 официальных альбомов - Дэвид Боуи» . Официальная чартерная компания. Архивировано из оригинала 3 октября 2017 года . Проверено 2 октября 2017 г.

- ^ Бакли 2005 , с. 318.

- ^ «Дэвид Боуи» . Рекламный щит . Архивировано из оригинала 26 июня 2017 года . Проверено 12 июня 2017 г.

- ^ Ди, Джонни (7 января 2012 г.). «Дэвид Боуи: Инфомания» . Хранитель . Архивировано из оригинала 8 января 2014 года . Проверено 14 июня 2013 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Доггетт 2012 , с. 173.

- ^ Джонсон, Джеймс (3 июня 1972 г.). «Зигги Стардаст». Новый Музыкальный Экспресс . В: «Дэвид Боуи» . История рока 1972 . стр. 12–15. Архивировано из оригинала 6 октября 2017 года . Проверено 5 октября 2017 г.

- ^ Уоттс, Майкл (7 июня 1972 г.). «Зигги Стардаст». Создатель мелодий . В: «Дэвид Боуи» . История рока 1972 . стр. 12–15. Архивировано из оригинала 6 октября 2017 года . Проверено 1 октября 2017 г.

- ^ «Зигги Стардаст». Цирк . Июнь 1972 года.

- ^ Ллойд, Джек (16 июля 1972 г.). «Музыка Дэвида Боуи тревожит холод» . Филадельфийский исследователь . п. 101 . Проверено 21 ноября 2021 г. - через Newspapers.com (требуется подписка) .

- ^ Бейли, Эндрю (1 июля 1972 г.). «Рекордные обзоры – Из космоса приходит Зигги: суперзвезда» . Вечерний стандарт . п. 14 . Проверено 29 декабря 2021 г. - через Newspapers.com (требуется подписка) .

- ^ Хилберн, Роберт (17 сентября 1972 г.). «Музыка для поступления в колледж» . Лос-Анджелес Таймс . п. 540 . Проверено 29 декабря 2021 г. - через Newspapers.com (требуется подписка) .

- ^ Тивен, Джон (июль 1972 г.). «Дэвид Боуи: Взлет и падение Зигги Стардаста и пауков с Марса (RCA)» . Фонографическая запись . Проверено 10 октября 2021 г. - через Rock's Backpages (требуется подписка) .

- ^ Марш, Дэйв (сентябрь 1972 г.). «Дэвид Боуи: Взлет и падение Зигги Стардаста и пауков с Марса (RCA)» . Крим . Проверено 9 мая 2021 г. на Rock's Backpages (требуется подписка) .

- ^ «Альбомы года» . Крим . Архивировано из оригинала 24 февраля 2006 года . Проверено 1 октября 2017 г.

- ^ Роксон, Лилиан (18 июня 1972 г.). «Дэвид Боуи: Элвис семидесятых» . Нью-Йоркские воскресные новости . Проверено 10 октября 2021 г. - через Rock's Backpages (требуется подписка) .

- ^ Трынка 2011 , стр. 193.

- ^ Уильямс, Ричард (2 сентября 1972 г.). «Альбомы Дэвида Боуи, Ти Рекса, Рода Стюарта и Roxy Music» . Таймс . Проверено 10 октября 2021 г. - через Rock's Backpages (требуется подписка) .

- ^ Кент, Ник (июль 1972 г.). «Дэвид Боуи: Взлет и падение Зигги Стардаста и пауков с Марса (RCA)» . Оз . Проверено 9 мая 2021 г. на Rock's Backpages (требуется подписка) .

- ^ Пегг 2016 , с. 539.

- ^ Бакли 2005 , стр. 135–136.

- ^ Сэндфорд 1997 , стр. 106–107.

- ^ Доггетт 2012 , с. 175.

- ^ Пегг 2016 , стр. 361–363.

- ^ Шеффилд, 2016 , стр. 81–86.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Сэндфорд 1997 , стр. 108.

- ^ Бакли 2005 , с. 157.

- ^ Пегг 2016 , стр. 552–555.

- ^ Бакли 2005 , стр. 165–167.

- ^ «Зигги Стардаст и пауки с Марса» . phfilms.com . Pennebaker Hegedus Films. Архивировано из оригинала 4 октября 2017 года . Проверено 3 октября 2017 г.

- ^ Гибсон, Джон (август 1979 г.). «Дэвид Боуи приглашен на премьеру кинофестиваля». Эдинбургские вечерние новости .

- ^ «Театральный гид» . Нью-Йорк . 30 января 1984 г. с. 63 . Проверено 3 октября 2017 г. - через Google Книги .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Волк, Дуглас (1 октября 2015 г.). «Дэвид Боуи: пять лет 1969–1973 » . Вилы . Архивировано из оригинала 14 ноября 2015 года . Проверено 21 ноября 2015 г.

- ^ Торнтон, Энтони (1 июля 2008 г.). «Дэвид Боуи – обзор «Live: Santa Monica '72»» . НМЕ . Архивировано из оригинала 4 октября 2012 года . Проверено 10 марта 2020 г.

- ^ Трынка 2011 , стр. 195.

- ^ Пегг 2016 , с. 20.

- ^ Доггетт 2012 , с. 186.

- ^ Пегг 2016 , стр. 482–485.

- ^ Пегг 2016 , с. 368.

- ^ Карр и Мюррей 1981 , стр. 52–56.

- ^ Бернар, Зуэль (19 мая 2012 г.). «Взлёт и восхождение Зигги» . Сидней Морнинг Геральд . Архивировано из оригинала 19 сентября 2017 года . Проверено 17 сентября 2017 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Уолш, Барри (3 сентября 2004 г.). «МУЗЫКАЛЬНЫЙ ОБЗОР: Дэвид Боуи, Взлет и падение Зигги Стардаста » . Журнал «Слант» . Архивировано из оригинала 1 октября 2021 года . Проверено 12 октября 2021 г.

- ^ Трынка 2011 , стр. 483.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Хоскинс, Барни (15 июня 2002 г.). «Дэвид Боуи: Зигги Стардаст, теперь человек богатый и со вкусом» . Независимый . Проверено 10 октября 2021 г. - через Rock's Backpages (требуется подписка) .

- ^ Пэйтресс, Марк (июнь 1998 г.). « Зигги Стардаст : Альбом, который убил шестидесятые» . Коллекционер пластинок . Проверено 10 октября 2021 г. - через Rock's Backpages (требуется подписка) .

- ^ Линч, Джо (14 января 2016 г.). «Дэвид Боуи повлиял на большее количество музыкальных жанров, чем любая другая рок-звезда» . Рекламный щит . Архивировано из оригинала 18 апреля 2021 года . Проверено 3 сентября 2021 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Джонс, Крис (2002). «Дэвид Боуи. Взлет и падение Зигги Стардаста и обзора пауков с Марса» . Музыка Би-би-си . Архивировано из оригинала 10 октября 2021 года . Проверено 12 октября 2021 г.

- ^ Петтигрю, Джейсон (23 января 2018 г.). «Изобретатели-готы Баухауза вспоминают ночь, когда они встретили Дэвида Боуи» . АльтПресс . Архивировано из оригинала 29 марта 2020 года . Проверено 12 октября 2021 г.

- ^ Пегг 2016 , с. 497.

- ^ Кобо, Лейла (12 января 2016 г.). «Дэвид Боуи похвалил Сеу Хорхе за то, что он вывел его песни на «новый уровень красоты» с помощью португальских каверов: слушайте» . Рекламный щит . Архивировано из оригинала 28 июня 2017 года . Проверено 21 сентября 2017 г.

- ^ « Актер «The Life Aquatic» Сеу Хорхе планирует тур для каверов Дэвида Боуи» . Роллинг Стоун . Архивировано из оригинала 18 мая 2018 года . Проверено 17 мая 2018 г.

- ^ «Сол Уильямс рассказывает о U2 и рассказывает о NiggyTardust » . Стереогум . 5 ноября 2007 г. Архивировано из оригинала 18 сентября 2017 г. . Проверено 17 сентября 2017 г.

- ^ Феррейра, Бекки (23 июня 2017 г.). «Эта причудливая оса возрастом 100 миллионов лет была названа в честь Дэвида Боуи» . Порок . Архивировано из оригинала 23 сентября 2017 года . Проверено 22 сентября 2017 г.

- ^ « Оса «Звездная пыль» — это новый вымерший вид, названный в честь альтер-эго Дэвида Боуи» . Наука Дейли . 22 июня 2017 года. Архивировано из оригинала 23 сентября 2017 года . Проверено 22 сентября 2017 г.

- ^ «Дэвид Боуи: Взлет и падение Зигги Стардаста и пауков с Марса » . Блендер . № 48. Июнь 2006. Архивировано из оригинала 23 августа 2007 года . Проверено 14 июля 2016 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Кот, Грег (10 июня 1990 г.). «Многие лица Боуи запечатлены на компакт-диске» . Чикаго Трибьюн . Архивировано из оригинала 16 апреля 2016 года . Проверено 11 ноября 2020 г.

- ^ Кристгау 1981 .

- ^ Ларкин 2011 .

- ^ «Дэвид Боуи: Взлет и падение Зигги Стардаста и пауков с Марса ». Вопрос . № 128. Май 1997. С. 135–136.

- ^ Шеффилд 2004 , стр. 97–99 .

- ^ Долан, Джон (июль 2006 г.). «Как купить: Дэвид Боуи» . Вращаться . Том. 22, нет. 7. с. 84. Архивировано из оригинала 2 октября 2017 года . Проверено 14 июля 2016 г.

- ^ Шеффилд 1995 , с. 55.

- ^ «Дэвид Боуи: Взлет и падение Зигги Стардаста и пауков с Марса ». Необрезанный . № 63. Август 2002. с. 98.

- ^ «Дэвид Боуи о годах Зигги Стардаста: «Мы создавали XXI век в 1971 году» » . ЭНЕРГЕТИЧЕСКИЙ ЯДЕРНЫЙ РЕАКТОР . 19 сентября 2003 г. Архивировано из оригинала 20 июля 2017 г. Проверено 1 октября 2017 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Взлет и падение Зигги Стардаста и пауков с Марса (издание к 30-летнему юбилею)» . Рекламный щит . 20 июля 2002 г. Архивировано из оригинала 20 сентября 2017 г. Проверено 1 октября 2017 г.

- ^ Исли, Дэрил (июль 2002 г.). «Дэвид Боуи: Взлет и падение Зигги Стардаста и пауков с Марса : издание, посвященное 30-летию» . Коллекционер пластинок . Проверено 9 мая 2021 г. на Rock's Backpages (требуется подписка) .

- ^ Джарруш, Сами (8 июля 2014 г.). «Рецензии на шедевр: «Дэвид Боуи - Взлет и падение Зигги Стардаста и пауков с Марса »» . Последствие звука . Архивировано из оригинала 18 сентября 2017 года . Проверено 17 сентября 2017 г.

- ^ «Опрос читателей: Лучшие альбомы Дэвида Боуи» . Роллинг Стоун . 16 января 2013 г. Архивировано из оригинала 29 мая 2021 г. Проверено 5 октября 2021 г.

- ^ «100 лучших альбомов за последние двадцать лет» . Роллинг Стоун . № 507. Август 1987. Архивировано из оригинала 23 октября 2019 года . Проверено 19 сентября 2017 г.

- ^ «Музыка тысячелетия» . Би-би-си . 24 января 1998 года. Архивировано из оригинала 17 июня 2012 года . Проверено 19 сентября 2017 г.

- ^ Ларкин 1998 , с. 19; Ларкин 2000 , с. 47

- ^ «500 величайших альбомов: Взлет и падение Зигги Стардаста и пауков с Марса – Дэвид Боуи» . Роллинг Стоун . 2003. Архивировано из оригинала 2 сентября 2011 года . Проверено 13 июня 2020 г.

- ^ «500 величайших альбомов: Взлет и падение Зигги Стардаста и пауков с Марса – Дэвид Боуи» . Роллинг Стоун . 2012. Архивировано из оригинала 5 марта 2013 года . Проверено 1 марта 2013 г.

- ^ «500 величайших альбомов: Взлет и падение Зигги Стардаста и пауков с Марса – Дэвид Боуи» . Роллинг Стоун . 22 сентября 2020 года. Архивировано из оригинала 16 июля 2021 года . Проверено 3 апреля 2021 г.

- ^ Пикко, Джадсон (23 июня 2004 г.). «100 лучших альбомов 1970-х» . Вилы . Архивировано из оригинала 28 августа 2017 года . Проверено 19 сентября 2017 г.

- ^ «100 лучших рок-альбомов 70-х» . Абсолютный классический рок . 5 марта 2015 г. Архивировано из оригинала 27 августа 2021 г. Проверено 10 сентября 2021 г.

- ^ «100 величайших альбомов всех времен». Вопрос . № 137. Февраль 1998. С. 37–79.

- ^ «100 альбомов всех времен» . Время . 2 ноября 2006 г. Архивировано из оригинала 24 апреля 2011 г. Проверено 16 января 2008 г.

- ^ Баркер, Эмили (25 октября 2013 г.). «500 величайших альбомов всех времен: 100–1» . НМЕ . Архивировано из оригинала 28 апреля 2020 года . Проверено 30 апреля 2020 г.

- ^ «100 лучших альбомов Apple Music» . Яблоко . Архивировано из оригинала 14 мая 2024 года . Проверено 15 мая 2024 г.

- ^ Димери, Роберт; Лайдон, Майкл (2018). 1001 альбом, который вы должны услышать перед смертью: переработанное и обновленное издание . Лондон: Касселл . стр. 280–281 . ISBN 978-1-78840-080-0 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Гриффин 2016

- ^ «Домашняя страница Northeastern Digital» . Архивировано из оригинала 8 декабря 2007 года . Проверено 26 мая 2008 г.

- ^ « Взлет и падение Зигги Стардаста и пауков с Марса [бонус-треки] – Дэвид Боуи» . Вся музыка. Архивировано из оригинала 2 октября 2017 года . Проверено 2 октября 2017 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Взлет и падение Зигги Стардаста и пауков с Марса (версия 1990 года)» . Официальная чартерная компания . Проверено 24 августа 2021 г.

- ^ « Взлет и падение Зигги Стардаста и пауков с Марса – Дэвид Боуи (титры, 1999 г.)» . Вся музыка. Архивировано из оригинала 3 октября 2017 года . Проверено 2 октября 2017 г.

- ^ Дрейк, Росситер (4 сентября 2002 г.). «Взлет и падение Зигги Стардаста и пауков с Марса: издание, посвященное 30-летию» . Метро Таймс . Архивировано из оригинала 2 октября 2017 года . Проверено 2 октября 2017 г.

- ^ «Премьера альбома: «Ziggy Stardust» Дэвида Боуи (юбилейный ремастер)» . Роллинг Стоун . 30 мая 2012 года. Архивировано из оригинала 9 июня 2016 года . Проверено 2 октября 2017 г.

- ^ «Обновленный винил/CD/DVD Ziggy 40 выйдет в июне» . Официальный сайт Дэвида Боуи . 21 марта 2012 года. Архивировано из оригинала 16 февраля 2013 года . Проверено 2 октября 2017 г.

- ^ Бокс-сет «Пять лет 1969–1973» выйдет в сентябре» . Официальный сайт Дэвида Боуи . 22 июня 2015 г. Архивировано из оригинала 18 февраля 2016 г. Проверено 13 октября 2017 г.

- ^ Спанос, Бретань (23 июня 2015 г.). «Дэвид Боуи выпустит массивный бокс-сет «Пять лет 1969–1973» » . Роллинг Стоун . Архивировано из оригинала 16 августа 2020 года . Проверено 16 августа 2020 г. .

- ^ Синклер, Пол (15 января 2016 г.). «Винил Дэвида Боуи/Five Years будет доступен отдельно в следующем месяце» . Супер Делюкс издание . Архивировано из оригинала 16 февраля 2016 года.

- ^ «180-граммовые виниловые альбомы Боуи выйдут в феврале» . Официальный сайт Дэвида Боуи . 27 января 2016 г. Архивировано из оригинала 1 марта 2016 г.

- ^ "Золотой винил Ханки Дори и Зигги Стардаста" . Официальный сайт Дэвида Боуи . 11 мая 2017 г. Архивировано из оригинала 1 июня 2017 г.

- ^ Синклер, Пол (28 апреля 2022 г.). "Половинная скорость Дэвида Боуи / Зигги Стардаста и диск с картинками" . Супер Делюкс издание . Проверено 8 января 2023 г.

- ^ «Виниловые релизы к 50-летию Зигги Стардаста» . Официальный сайт Дэвида Боуи . 28 апреля 2022 г.

- ^ "Waiting in the Sky Vinyl LP для RSD 2024" . Официальный сайт Дэвида Боуи . 7 января 2024 г. Проверено 8 января 2024 г.

- ^ Марточчио, Энджи (22 марта 2024 г.). «Этим летом вы сможете вернуться в эпоху Зигги Стардаста Дэвида Боуи с масштабным переизданием» . Роллинг Стоун . Архивировано из оригинала 21 марта 2024 года . Проверено 21 марта 2024 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Взлет и падение Зигги Стардаста и пауков с Марса (примечания). Дэвид Боуи. Отчеты РКА. 1972. СФ 8287.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: другие цитируют AV Media (примечания) ( ссылка ) - ^ « Взлет и падение Зигги Стардаста и пауков с Марса – Кредиты» . Вся музыка. Архивировано из оригинала 26 марта 2017 года . Проверено 19 сентября 2017 г.

- ^ Канн 2010 .

- ^ О'Лири 2015 .

- ^ Пегг 2016 .

- ^ Пеннанен, Тимо (2021). «Дэвид Боуи». Включает хит - 2-е издание. Записи и исполнители в финских музыкальных чартах 1.1.1960–30.6.2021 (PDF) (на финском языке). Хельсинки: Издательство «Отава». п.п. 36–37.

- ^ "Австралийские чарты Go-Set - 25 ноября 1972 года" . www.poparchives.com.au .

- ^ Ракка, Гвидо (2019). Альбом M&D Borsa 1964–2019 (на итальянском языке). Amazon Digital Services LLC — Kdp Print Us. ISBN 978-1-0947-0500-2 .

- ^ «Хиты мира – Испания» . Рекламный щит . Nielsen Business Media, Inc., 7 апреля 1973 г., с. 66 . Проверено 22 октября 2020 г.

- ^ "Dutchcharts.nl - Дэвид Боуи - Взлет и падение Зигги Стардаста и пауков с Марса" (на голландском языке). Хунг Медиен. Проверено 14 мая 2020 г.

- ^ "Lescharts.com - Дэвид Боуи - Взлет и падение Зигги Стардаста и пауков с Марса" . Хунг Медиен. Проверено 14 мая 2020 г.

- ^ "Australiancharts.com - Дэвид Боуи - Взлет и падение Зигги Стардаста и пауков с Марса" . Хунг Медиен. Проверено 14 мая 2020 г.

- ^ "Austriancharts.at - Дэвид Боуи - Взлет и падение Зигги Стардаста и пауков с Марса" (на немецком языке). Хунг Медиен. Проверено 14 мая 2020 г.

- ^ "История чарта Дэвида Боуи (канадские альбомы)" . Рекламный щит . Проверено 21 июля 2020 г.

- ^ "Danishcharts.dk - Дэвид Боуи - Взлет и падение Зигги Стардаста и пауков с Марса" . Хунг Медиен. Проверено 14 мая 2020 г.

- ^ « Дэвид Боуи: Взлет и падение Зигги Стардаста и пауков с Марса» (на финском языке). Musiikkituottajat – IFPI Финляндия . Проверено 14 мая 2020 г.

- ^ "Offiziellecharts.de - Дэвид Боуи - Взлет и падение Зигги Звездной пыли и пауков с Марса" (на немецком языке). Чарты GfK Entertainment . Проверено 14 мая 2020 г.

- ^ «Чарт 40 лучших альбомов – 8-я неделя, 2016 г.» . slagerlistak.hu (на венгерском языке) . Проверено 29 ноября 2021 г.

- ^ «Лучший альбом Classifica settimanale WK 9» . ФИМИ . 26 февраля 2016 года . Проверено 24 июля 2020 г.

- ^ "Charts.nz - Дэвид Боуи - Взлет и падение Зигги Стардаста и пауков с Марса" . Хунг Медиен. Проверено 14 мая 2020 г.

- ^ «Альбом Топп 40 2016-03» . ВГ-листа . Проверено 15 мая 2020 г.

- ^ "Portuguesecharts.com - Дэвид Боуи - Взлет и падение Зигги Стардаста и пауков с Марса" . Хунг Медиен. Проверено 14 мая 2020 г.

- ^ "Swedishcharts.com - Дэвид Боуи - Взлет и падение Зигги Стардаста и пауков с Марса" . Хунг Медиен. Проверено 14 мая 2020 г.

- ^ "Swisscharts.com - Дэвид Боуи - Взлет и падение Зигги Стардаста и пауков с Марса" . Хунг Медиен. Проверено 14 мая 2020 г.

- ^ «Билборд 200 30.01.2016» . Рекламный щит . Архивировано из оригинала 28 января 2016 года . Проверено 20 января 2016 г.

- ^ "История чарта Дэвида Боуи (лучшие альбомы каталога)" . Рекламный щит . Проверено 30 января 2016 г.

- ^ «Диаграммы IFPI» . www.ifpi.gr. Архивировано из оригинала 5 ноября 2018 года . Проверено 29 апреля 2018 г.

- ^ «Портал португальских графиков (24/2021)» . www.portuguesecharts.com . Проверено 28 июня 2021 г.

- ^ "Offiziellecharts.de - Дэвид Боуи - Взлет и падение Зигги Звездной пыли и пауков с Марса" (на немецком языке). Чарты GfK Entertainment . Проверено 24 июня 2022 г.

- ^ «Хит-лист альбома Top 40 – 25 неделя, 2022 г.» (на венгерском языке). МАШИНЫ . Проверено 1 июля 2022 г.

- ^ "Ultratop.be - Дэвид Боуи - Взлет и падение Зигги Стардаста и пауков с Марса" (на французском языке). Хунг Медиен. Проверено 26 июня 2022 г.

- ^ "Offiziellecharts.de - Дэвид Боуи - Взлет и падение Зигги Звездной пыли и пауков с Марса" (на немецком языке). Чарты GfK Entertainment . Проверено 18 августа 2023 г.

- ^ «100 лучших альбомов на конец года – 2016» . Официальная чартерная компания . Проверено 25 марта 2021 г.

- ^ «Сертификаты датских альбомов – Дэвид Боуи – Зигги Стардаст» . IFPI Дания . Проверено 23 мая 2023 г.

- ^ «Сертификаты итальянских альбомов – Дэвид Боуи – Зигги Стардаст» (на итальянском языке). Федерация итальянской музыкальной индустрии . Проверено 14 декабря 2022 г.

- ^ Лейн, Дэниел (9 марта 2013 г.). «Обнародован официальный топ-40 самых продаваемых загрузок Дэвида Боуи!» . Официальная чартерная компания . Архивировано из оригинала 27 марта 2013 года . Проверено 6 апреля 2013 г.

- ^ «Сертификаты британских альбомов – Дэвид Боуи – Взлет и падение Зигги Стардаста» . Британская фонографическая индустрия .

- ^ «Американские сертификаты альбомов – Дэвид Боуи – Зигги Стардаст» . Ассоциация звукозаписывающей индустрии Америки . Проверено 10 октября 2021 г.

- ^ Ди, Джонни (7 января 2012 г.). «Дэвид Боуи: Инфомания» . Хранитель . Архивировано из оригинала 8 января 2014 года . Проверено 12 января 2016 г. }

Источники

[ редактировать ]- Ауслендер, Филип (2006). Исполнение глэм-рока: гендер и театральность в популярной музыке . Анн-Арбор, Мичиган: Издательство Мичиганского университета. ISBN 978-0-47-206868-5 .

- Бакли, Дэвид (2005) [Впервые опубликовано в 1999 году]. Странное обаяние – Дэвид Боуи: Полная история . Лондон: Virgin Books . ISBN 978-0-7535-1002-5 .

- Кэмпбелл, Майкл (2005). Популярная музыка в Америке: ритм продолжается . Уодсворт/Томсон Обучение. ISBN 978-0-534-55534-4 .