Кантон Женева

Кантон Женева Кантон Женева ( французский ) | |

|---|---|

| Республика и кантон Женева Республика и кантон Женева ( французский ) | |

| Девиз(ы): | |

| Anthem: Cé qu'è lainô ("The one who is up there") | |

Location in Switzerland Map of Geneva | |

| Coordinates: 46°2′N 6°7′E / 46.033°N 6.117°E | |

| Country | Switzerland |

| Capital | Geneva |

| Subdivisions | 45 municipalities |

| Government | |

| • President | Serge Dal Busco |

| • Executive | Conseil d'État (7) |

| • Legislative | Grand Council (100) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 282.49 km2 (109.07 sq mi) |

| Population (December 2020)[2] | |

| • Total | 506,343 |

| • Density | 1,800/km2 (4,600/sq mi) |

| GDP | |

| • Total | CHF 51.967 billion (2020) |

| • Per capita | CHF 102,876 (2020) |

| ISO 3166 code | CH-GE |

| Highest point | 516 m (1,693 ft): Les Arales |

| Lowest point | 332 m (1,089 ft): Rhône at Chancy |

| Joined | 1815 |

| Languages | French |

| Website | www |

Кантон Женева , официально Республика и кантон Женева , [4] [5] — один из 26 кантонов Швейцарской Конфедерации . В его состав входят сорок пять муниципалитетов , а резиденция правительства и парламента находится в городе Женева .

Женева — самый западный франкоязычный кантон Швейцарии . Он расположен на западной оконечности Женевского озера и по обе стороны Роны , его главной реки. Внутри страны кантон граничит на востоке с единственным прилегающим кантоном Во. Однако большая часть границы Женевы проходит с Францией, особенно по региону Овернь-Рона-Альпы . Как и в некоторых других швейцарских кантонах ( Тичино , Невшатель и Юра ), Женева считается республикой в составе Швейцарской Конфедерации.

Женева, один из самых густонаселенных кантонов, считается одним из самых космополитичных регионов страны. Будучи центром кальвинистской Реформации , город Женева оказал большое влияние на кантон, который по существу состоит из города и его пригородов. Известными учреждениями международного значения, базирующимися в кантоне, являются Организация Объединенных Наций , Международный комитет Красного Креста и ЦЕРН .

History

[edit]The Canton of Geneva, whose official name is the Republic and Canton of Geneva, is the successor of the Republic of Geneva.[6]

This article focuses on the history of the canton, which begins in 1815, and some of the context leading to modern borders and events after that date. For more detail on the history of Geneva prior to that year, refer to the history of the city of Geneva.

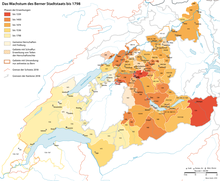

Context

[edit]Compared to other urban cantons of Switzerland (Zürich, Bern, Basel before it split, Fribourg, Lucerne), Geneva's geographical size is relatively small. This article explains the political context that led to the present-day borders.

Early history

[edit]Geneva was controlled by the Allobroges, a rich and powerful Celtic tribe until 121 BC, when they were defeated by the Roman Empire. The city was then annexed to the Roman Empire in 121 BC and attached to Gallia Narbonensis province. Its political importance in the region was low, but it soon developed an important economy owing to the city's port that facilitated trade over Lake Geneva from the routes joining from Seyssel and Annecy towards the Roman colonies of Nyon and Avenches.[7] The city remained part of the Empire until 443 when, welcomed by the Romans, the Burgundians settled in an ill-defined region named Sapaudia and Geneva was chosen as the capital of the newly formed kingdom for its first 20 years due to the city's economic importance as well as the prestige of its Bishop. As the kingdom began expanding towards Lyon and Grenoble, Geneva lost its central geographical location of the kingdom and for a time became a secondary capital until the kingdom was divided between Godegisel and Gundobad, sons of Gondioc. Godegisel settled in Geneva from which he controlled the northern bishoprics. The nature of the political relationship between both brothers is not well known, but in the year 500 the kingdoms went to war, during which Godegisel was defeated and Geneva pillaged and destroyed.

In 532, the Burgundians were conquered by the Francs, who administratively divide the area in three parts: one centred on the city of Besançon, one around Dijon, and the last one, the Pagus Ultraioranus ("Transjurane") includes the cities of Geneva, Nyon, Sion, and Avenches. Given the peripheral location of Geneva within this region, it lost its status of capital, although it kept a certain religious prestige.[7] In 864, Conrad II acquired the title of Duke of Transjurane and in 888 his son Rudolph I becomes king of the second kingdom of Burgundy after seizing the opportunity of death of Charles the Fat. At its maximum extent around the year 1000, the new kingdom extends from Provence to Basel and controls the main alpine passes of the region. In this context, Geneva regains its importance as the city was located in the intersection between several important roads connecting Italy to Northern Europe via the western Alps mountain passes of Mont Cenis and Great St Bernard Pass.

Counts of Geneva (11th–15th centuries)

[edit]However, by the end of the 10th century the kingdom was engulfed in several conflicts between the king's power and the aristocracy. Notably for Geneva, some of the most important nobles began to offer some lands to the Church, such as in 912 when Eldegarde (probably a Countess in an area near Nyon) gave up her lands in the area of Satigny which eventually became the Mandement, or in 962 when Queen Berthe offered lands in Saint-Genis.[8] The income of the Kingdom suffered from these transfers of lands and, in an attempt to stop the process, in 995 King Rudolph III tried to withdraw the hereditary rights away from some of his nobles. However, the King was defeated in this power struggle, and this led to a weakening of the central power. As the King weakened, some of his local officers such as the Counts rejected his authority and even opposed him. Several independent fiefdoms emerge from this time, including the County of Geneva.[9]

In 1032 Rudolph III died without an heir. The Kingdom of Burgundy then reverted to HRE Conrad II, who tried to re-assert control of the lands by rallying the nobles who opposed Rodolph III. In exchange for his loyalty, Gerold, count of Geneva, obtained full powers over his County, becoming a direct vassal of the Emperor and so his lands became part of the Holy Roman Empire.[10]

However, it is not clear how the power over the city proper was shared between the Prince-Bishopric of Geneva and the counts.[7] Thus, a power struggle between both ensued in which the counts received the support from the canons of the chapter, a large majority of whom were members of vassal families of the count. The apex of the count's power took place from 1078 to 1129, when Count Aymon I managed to get his brother Guy de Faucigny appointed as bishop of Geneva. Aymon took advantage of this situation by transferring the administration of some of the lands away from the Diocese of Geneva to the priory of Saint-Victor of which he became protector at the request of the Bishop, and siphoned the resources of the priory to himself.[8]

The successor of Guy de Faucigny, Bishop Humbert de Grammont, was outraged by this situation, and requested the restitution of the churches transferred to the administration of the Count. The outcome of the Gregorian Reform materialised in the council of Vienne of 1124 which legislated on securing the ecclesiastical rights and possessions of the church.[11] Pope Callixtus II then pressured Aymon to return the Church's estates, going as far as excommunicating him. The Count repented, and greeted the Bishop on the border of his County in Seyssel[12] as the Bishop was on his way back to Geneva from Vienne, whose Bishop had been tasked by the Pope to mediate in the conflict.[13] There, they concluded a treaty (the Traité de Seyssel [fr]), whereby the Count restored to the Bishop of Geneva some of the churches whose rights and revenues he had acquired.

Although this treaty did not fully solve the conflict, which only got fully resolved by the treaty of Saint-Sigismond in 1156 which confirmed all the provisions, it marked an important step for Geneva as the count also gave up his temporal rights over the City of Geneva to the Bishop, except for the right to execute criminal sentences. The following bishops, Arducius de Faucigny (1135-1185) and Nantelme (1185-1205) kept eroding the counts' power. The touchstone of this erosion of power was the acquisition of the Imperial immediacy by the Prince-Bishopric in 1154, which designated the Bishop of Geneva as a Prince of the Empire and, by right, the only lord of the city after the Emperor,[7] a status employed several times by the Bishops in the defence of their independence from local rulers. As a result, some time around 1219 the Counts of Geneva completely quit the city and moved their capital to Annecy,[14] which marked an important step for the future evolution of the canton of Geneva, as for the first time there was a complete separation of the ruling of the city of Geneva, by the Bishops, from the ruling of its hinterlands, the Counts.

At the same time, the county was in a continuous power struggle with the House of Savoy, which by the middle of the 12th century governed a vast principality centred on the control of the main mountain passes of the western Alps. By the beginning of the 13th century, the Counts of Geneva were facing an alliance of the Maison de Faucigny, de Gex, as well as the counts of Savoy. After several decades of wars of the gebenno-faucigneran conflict of 1205–1250, the counts of Geneva lost all their main lands and fortresses. In the Treaty of Paris (1355), Savoy was awarded the Faucigny and Gex, leaving the counts of Geneva as secondary regional actors. After the death of antipope count Robert in 1394, the county passed to the house of Thoire-Villars, who were related to the house of Geneva. However, some of the local nobility was displeased with the outcome and, profiting from the situation, the County of Geneva finally disappeared when it was sold to Amadeus VIII of Savoy for 45,000 gold francs on 5 August 1401.[15]

House of Savoy (15th century – 1534)

[edit]The economic rise of cities and international commerce from the 11th century onwards also affected Geneva. Medieval fairs appeared in Northern Europe, often driven by a political will to promote a city. In contrast, the origins of the trade fairs in the city, active from at least by the middle of the 13th century, remain unknown. However, these expanded greatly during the 14th century and their apogee took place in the middle of the 15th century, when the city counted seven yearly trade fairs, four of which had large international significance: the Epiphany, Easter, August, and October/November.[7] Geneva benefited from several external factors at this time to explain this economic expansion: the crisis of trade fairs in Chalon-sur-Saône, and the Hundred Years' War, partially removed France from international routes linking Northern Europe to Mediterranean ports such as Montpellier and Marseille, which shifted eastwards, crossing Geneva and the Rhone valley; the city reaped the benefits from the pax sabauda, a long-period of peace during which it was spared from the effects of wars; and in addition, the House of Savoy spent long periods of time in the city, adding to the demand for luxury goods. The trade fairs required credit to function through letters of credit, the development of which adds to the economic expansion of the city.[16] The fairs were also the spark that began the approachment of Geneva with the cities of Fribourg and Bern, both of which partly depended upon the fairs for their extensive textiles manufacturing.[7]

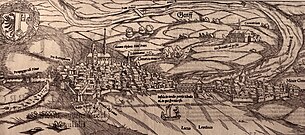

This economic development and the centuries-long peace enjoyed by the city is reflected on its demographic expansion. The city grew from about 2,000 inhabitants by the end of the Black Death, to 11,000 by the middle of the 15th century, making it the largest city in the region as Chambéry and Lausanne counted 5,000 inhabitants at the time and in modern Switzerland only Basel with its 8,000-to- 10,000 came close to Geneva's size.[7]

This explains the interest that the Dukes of Savoy took again to gain control of the city over the Bishops of Geneva upon their acquisition of the title of Counts of Geneva. On two occasions, in 1407 and again in 1420, Amadeus VIII, attempted to gain control of the city from the Bishops by pleading to the Pope. However, both times his requests were rejected.[8] Possibly from the lack of interest by the local population who saw no benefit in replacing the Bishop's control with the Duke, since the Bishop shared his ruling of the city with local civilian authorities.[7] In 1434, however, the Duke abdicated and retreated to a chapel. This added to his prestige as a wise ruler, and he managed to get elected as antipope Felix V in 1439. When Bishop François de Metz died in 1444, Amadeus, now anti-pope, became the administrator of the bishopric and became de facto, but not de jure, ruler of the city.[8] When he finally renounced his position as Pope, he kept a degree of control over the city, and succeeded in agreeing with Pope Nicholas V that the future Bishops of Geneva must be designated by the house of Savoy, but without gaining full control over the city.[7]

Nevertheless, larger events began to catch up with the city. In 1462, Louis XI, king of France, decided to forbid Frenchmen and foreigners in his kingdom from attending Geneva's trade fairs, and promoted its most direct competition in Lyon, whose trade fairs began in 1420. This led to an economic decline of the city, which received support from its trade partners, Bern and Fribourg, in view of defending the city's interests in the French court.[17] Trade with the central cities of the Swiss confederation sparked an economy recovery from 1480 to 1520, but it also showed the decline of Savoy as the protector of Geneva.[18] In addition, in the Battle of Nancy during the Burgundian Wars, the Old Swiss Confederacy achieved a decisive military victory against Charles the Bold who died in the battle. Geneva was on the losing side since its Bishop, Jean-Louis de Savoie, had sided with Burgundy following directions from Yolande of Valois, regent of Savoy. Immediately, the confederate troops invaded Vaud, and Bernese troops threatened to conquer Geneva, which, owing to its status as a protected enclave within Savoy, had no standing army of its own. The treaty of Morges in 1477 put a stop to the troops advance in exchange for a ransom of 28,000 écus of Savoy.[19]

The Duchy recovered most of its possessions lost to Bern in exchange for payments, but this period marked the beginning of the end of its hegemony over the Genevan region and the start of an unstable time for the city. The right to appoint the Bishop of Geneva granted to Amadeus III was eroded and it became a political and diplomatic negotiation, between Savoy, the Swiss, the chapel of the cathedral, and the civil authorities of the city.[7] The decline of the Duchy was exacerbated by the internal rebellions and the series of weak and physically ill Dukes. Sensing this weakness, the Duchy's neighbours made it into a prey, incapable as well of defending Geneva's economic interests against French interference as well as incapable of physically protecting the city against foreign invasions. With this loss of reputation, new factions emerge in the city seeking to distance the city from the Duchy.[20]

The degradation of the political relations between Savoy and the civil authorities of Geneva rose to prominence in 1513, when upon the death of Bishop Charles de Seyssel, Charles III maneuvred to get Jean de Savoie appointed by the Pope. Several Genevan citizens who disapproved the influence of the Duke, led by Besançon Hugues and Philibert Berthelier, form the faction of the Eidguenots (named after the German Eidgenossen, "confederates"), and sought the rapprochement of the city with the Swiss confederation.[7] However, part of the Genevan political elite maintained their preference for the precarious political equilibrium with the House of Savoy, partly to stay in good terms with the rulers of all of Geneva's surroundings. As a sign of contempt, the Eidguenots named this faction the Mammelus, after the Mamluks, the slave-soldiers of the sultan in Cairo.[7]

In 1519, the Eidguenots attempted to conclude a treaty of alliance (combourgeoisie) with the Swiss confederation, but this was rejected by all the cantons except for Fribourg.[21] Bern in particular was an ally of Savoy at this time, and central Swiss cantons viewed with suspicion an eventual expansion to the west. Upon their return to Geneva, Charles II, supported by the Bishop, attempts to destroy this faction and executed several Eidguenots, including Philibert Berthelier in 1519 and Amé Lévrier in 1524, accused of plotting against the Bishop.

The Eidguenots took refuge in Fribourg after the death of Amé Lévrier and, in 1525, successfully negotiated an alliance with the confederates that this time included Bern in addition to Fribourg.[21] The changing attitude of Bern was explained by the decision of the successor of Charles II, Charles III, to side with HRE Charles V in his conflict with Francis I of France, with whom the Swiss had allied themselves and signed the Perpetual Peace after the Battle of Marignano.[7] Upon the return to Geneva of the Eidguenots, the government ratified the treaty of alliance on 25 February 1526, despite the protestations of the Mammelus and Bishop Pierre de la Baume. When the Eidguenots took over the control of the city, they executed the leaders of the opposing faction in retaliation for the previous ruthless behaviour of the Duke. In an attempt to regain his influence, Bishop Pierre de la Baume requested to join the alliance with Bern and Fribourg, which refused.[7] Afraid for his safety, he quit the city on 1 August 1527 and he would only go back for two weeks before permanently leaving Geneva in 1533.

Despite its newly regained independence from the influence of Savoy, Geneva had no real army of its own and remained a city largely dependent on the diplomatic circumstances of the large European powers.

However, the supporters of Charles III did not give up in their quest to seize Geneva. They withdrew to the Pays de Vaud from where they plotted against Geneva under the banner of "Gentilshommes de la Cuiller". Discreetly supported by the Duke, they harassed the city by confiscating food products in its borders, attacking men and ravaging the countryside. After an attempt to assault the city in March 1529 and again in October 1530, Geneva requested the aid of its allies from Bern and Fribourg. Several thousand soldiers, accompanied by negotiators from eight Swiss cantons, entered the city on the 10th of October and stayed for ten days within its walls until the signature of a treaty with Savoy, whereby the Duke abandoned his attacks on the city and re-established the right to trade. Apart from the financial consequences on Geneva, which had to pay for the Swiss soldiers, this intervention left deep marks in the city with consequences for its future.[22]

Republic of Geneva (1534/1541–1798, 1813–1815)

[edit]At the time of the alliance with the confederates in 1525, few Protestants were in Geneva. Bern, however, had converted to Protestantism two years before its intervention in 1530. Bernese troops displayed a brutal conviction in their new faith by destroying images, statues, and other objects of worship. The troops quickly spread Protestant ideas, and in 1532, supported by Bern, Guillaume Farel arrived at the city to preach the new faith.[23]

Meanwhile, the authorities had been reforming the governing bodies of the city. In 1526 they set up a Council of Two Hundred, emulating the Swiss model. In 1528 the right to appoint the 4 mayors ("syndics") was granted to the Council of Two Hundred, which also received, from 1530, the task to appoint the members of the Little Council (between 12 and 20 magistrates led by the 4 mayors), which itself appoints the members of the Council of Two Hundred. This circular election system characterised the government system of Geneva until 1792. So it is that when in 1533 the Bishop Pierre de la Baume arrived to Geneva to exercise his right of justice on the murder of a canon, he expressed his opposition to the new Councils by leaving the city forever.[22] He then sides with Charles III, and in August 1534, he excommunicates the city. In response, the city authorities declare in October of the same year the vacancy of the Bishopric and attribute for themselves all seigniorial rights (to make laws, to declare war and peace, to mint coin etc.). This act of independence marks the birth of the Republic of Geneva,[24] then still mostly confined to the city and the few medieval territories gifted to the Bishops, the largest of which were Satigny, Peney, and an area around modern-day Jussy.

In addition, owing to the increased rate of conversions to Protestantism, on the 21 May 1536, the General Council of Geneva fully adopted the reformation and confiscated all the assets of the Catholic Church. With this decision, the commune of Geneva, the civil authority of the city, merged with new institutions, including the territories that depended on the Bishop, the mandements. As a response, the catholic canton of Fribourg breaks its alliance with the city.

Charles III took advantage of the tumultuous situation in Geneva to attempt to conquer the city in 1535–36,[25] but coming to the aid of Geneva, a new army of Bernese in alliance with France defeated Savoy. It occupied the lands of Savoy in the Genevan basin (including all the Pays de Gex),[26] marking the end of the Duchy as a threat to Geneva and the recognition of Geneva's sovereignty. This was not without risk to Geneva, given how Bernese troops conquered Lausanne despite the cities' alliance.

In 1536, John Calvin, a then 26-year old French theologist, spent some time in summer in Geneva and was convinced by William Farel to stay and establish together a new Church. In January 1537 they presented their project to the mayors. They were initially reluctant to adopt Farel and Calvin's ideas of a Church that would take again control over the city, and were also displeased by both men's refusal to adopt some of the Lutheran liturgy. In April 1538, as the government is torn between supporters of a state religion following the Bernese model and supporters of French reformation, the authorities ask both men to leave the city. However, soon after in September 1541, Calvin is asked by Geneva to return. Upon his arrival he begins to leave his mark on Church with the Ecclesiastical Ordinances[27] and, although he had no official role other than Head of the Ministers, administrative matters as well as he outmanoeuvres political opponents to redact part of the Civil Edicts (Édits Civils) in 1543, a sort of constitution, which fix the form of government, the election rules and powers of the members of the Councils. These two texts, revised over time, would govern the Republic until the end of the 18th century.

If the political Edicts brought only minor changes to prior dispositions adopted over the previous decades, the Ecclesiastical Ordinances would revolutionise the organisation of religious institutions. Thus, the creation of the Consistory launches the period that some historians call the "regime of moral terror"[22] with numerous prohibitions that were severely applied, such as in the sentencing to the pyre of theologian and doctor Michael Servetus in 1553 for heresy, or the marginalisation of ancient, pro-Bernese and anti-French bourgeois families in 1555. The removal of this last opposition, marked the end of Geneva's distinctive identity founded on the memory of the fights for independence and conviviality practices that Calvin could not tolerate.[28]

Internationally, thanks to Calvin's religious reforms, Geneva becomes a beacon for the reformation, attracting thousands of Protestant refugees from all over Europe, but especially from France and to a lesser extent Italy and Spain. With the influx of refugees, the population grew from 10,000 residents in 1550 to 25,000 in 1560. However, many of the new arrivals did not want or could not relocate permanently, and the population stabilised around 14,000 by 1572.[22] Like in other cities in the Swiss landscape, the rights to live in the city was highly organised as follows:[29]

- Habitant (resident): those with the right to live in the Geneva, to acquire goods and to practice all trades except liberal professions;

- The children of habitants were natifs (natives), with limited economic and political rights;

- Bourgeois, the sole status that conferred the political rights to participate in the conseil général, and be eligible for the Council of Two-Hundred. The right to become bourgeois had to be granted by the council, in addition to having to buy the letter of Bourgeoisie, which would fetch for 50 to 100 florins in the second half of the 16th century and jump to over 8,000 florins by the mid-18th century;[22]

- Citoyens (citizens), the children of bourgeois if they were born in the city.

In an effort to attract talent, from 1537 the Republic granted the status of bourgeois cheaply to teachers, doctors, musicians, to the stonemasons who contributed to the construction of the new fortifications, and even for free to jurists, priests, professors, and schoolmasters. The main impacts on the city from the refugees that were therefore attracted would be cultural with the influence of the French language that would gradually replace the local Franco-Provençal language, and economic. Initially this opening to foreigners would attract professions that served the local economy such as stonemasons, tailors, shoemakers, or carpenters. But from the 1550s, thanks to the skills brought for the refugees the economy developed export industries such as fabrics and printing.[30] Printing in particular grew very fast, with the arrival of famous printers such as Jean Crespin or Robert Estienne, employing over 200 workers during Calvin's time before many of the printers moved to Lyon when that city also became for a time Protestant.[22] In the second half of the century, other industries develop, notably gilding and watchmaking.

After the defeat of Charles III by French and Bernese forces, Savoy had temporarily given up on its efforts to take Geneva. However, in the second half of the 16th century the Dukedom allies with Spain and regains some of its power. The son of Charles III, Emmanuel Philibert, defeated the army of French king Henri II in the battle of Saint-Quentin in 1557 and recovered the lands conquered by the French in 1535. In 1559, in the Treaty of Cateau-Cambrésis, France restores an independent Savoy. However, Bern did not participate in the initial negotiations, and only in the Treaty of Lausanne of 1564 did Savoy recover the lands around Geneva, while losing forever the Pays de Vaud to Bern. Until his death, Emmanuel-Philibert practiced tolerance with his non-Catholic subjects and largely respected the "cujus regio, ejus religio" principle for Geneva. However, the Genevan authorities were highly suspicious and worked towards obtaining the support of catholic Solothurn and France, who agree to protect the city against potential attacks from Savoy.

In effect, the threats to the city materialise with Emmanuel-Philibert's son, Charles Emmanuel I, who dreams of conquering the city and he begins plotting against Protestants, employing mercenaries to intimidate those converted by Bernese preachers. Intensifying its diplomatic efforts, Geneva obtains the alliance with Zürich in 1584.

Between 1586 and 1587 large outbreaks of the plague affects Geneva and Savoy, which came coupled with bad harvests and famines affecting the continent. In these conditions, it was difficult to supply with food the 15,000 inhabitants of the city, despite diplomatic efforts to seek help from its allies. The Council forbids the production of white bread and pastries and bans some residents from the city. The catastrophe affected Savoy equally, and in response Charles Emmanuel I forbids the export of grains from his lands, which in essence means blockading Geneva from any supplies since the city was surrounded by the Duchy except for what goods could be imported by the lake.[22]

In response, Geneva, supported by France and a contingent of 12,000 Swiss soldiers, intermittently occupied the Pays de Gex from 1589, but the city was finally forced to abandon it when France defeated Savoy and annexed the Pays de Gex for itself in the Treaty of Lyon of 1601. This marked the point where most of Geneva's hinterland was divided between two different strong states along the Rhone banks: the Kingdom of France on the right, and the Duchy of Savoy on the left.

This event and the prior domination of the area by Savoy and the Counts of Geneva, largely explains why, unlike other Swiss urban cantons, Geneva was unable to expand geographically, as its borders were dominated by those two powerful states.

Unwilling to give up on the city, Savoy launched one last attempt to conquer the city during the events of the Escalade in 1602. This incursion against the “Protestant Rome” would paradoxically lead to the recognition of the city's independence.[31] The negotiations between Savoy and Geneva from spring 1603 were successfully completed in July the same year with the treaty of Saint-Julien.[32] Thanks to the arbitration provided by several Swiss cantons as well as France, the Republic obtained a very advantageous deal that politically placed the city in equal terms with Savoy. In addition, it obtained economic (free commerce and exemption from taxes on real estate located in Savoy owned by Genevan residents) and military rights (prohibition from building any military facilities and from keeping any garrison on a 15-km radius around the city), that would guarantee the city's independence and prosperity. In addition, Geneva also obtained an annual subsidy from France, and a permanent garrison funded by the Kingdom.[22]

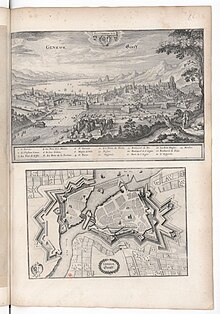

Since then, both Savoy and France largely respected Geneva's independence, protected by its strong fortresses, and guaranteed by its alliance with the Protestant cantons of the Old Swiss Confederacy of Zürich and Bern. Nevertheless, the threats to the Republic's existence did not disappear, particularly as France switched its European alliances and the Kings became less tolerant of Protestants. Threatened by these changing winds and traumatised by the events of the Escalade, Geneva enlarged and professionalised its permanent garrison (from 300 soldiers in 1603 to over 700 a century later) and fortified itself behind mighty walls that become increasingly claustrophobic as the lands in Chablais and the Pays de Gex were progressively converted back to Catholicism by the future Bishop St François de Sales from 1594, who even entered the city de incognito in an attempt to convince Theodore de Beze to hold a public debate on religion.[33] The authorities found themselves unable to respond to the Catholic threat, as they could not afford to irritate the French king, and at the same time the local economy increasingly depended on the use of Catholics as domestic labour and in the textile industry.

Playing now on the defensive, the Republic multiplied the number of population surveys to track poor Catholics and beggars, while it was forced to accept in 1679 by king Louis XIV the presence of a permanent representative who demanded to be allowed to celebrate the Catholic mass in his home for his workers and neighbours, dealing a blow to the city's religious purity,[22] particularly because the first representative, Laurent de Chavingy was very provocative.

In 1681, as France annexed Strasbourg, Geneva fears for the worst and the councils must skilfully navigate the diplomatic situation to safeguard the Republic's independence. The major advantages that the councillors had for this task were on the one hand the strategic position of the city, as France was interested in keeping the status quo with Savoy as well as in respecting Geneva's alliance with the Swiss cantons in order to maintain the supply of Swiss mercenaries,[33] and on the other hand economic interests given that the city was centrally located in the trade routes linking north and south, and that it provided a significant amount of capital to finance France's debt.[16] Tensions were highest during the 1685 second wave of Huguenot refugees forced into exile after the revocation of the Nantes edict since Geneva was a favored passage for the refugees heading to Switzerland and historians estimate that between 100,000 and 120,000 huguenots transited through the city.[34] Buoyed by the economic prosperity and relative peace between 1654 and 1688, when France went to war against the league of Augsburg and blockaded its enemies, Geneva provided much aid to the refugees, some of whom permanently moved to the city and helped to develop new industries such as indiennes and contributed to the watchmaking industry, displeasing France in the process.

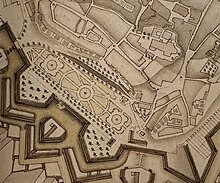

No major changes occurred in Geneva's borders until 1749. In an effort to rationalise the borders marked by the medieval territories gifted to the Bishops in the Middle Ages, the Republic and France exchanged territories in that year: Geneva swapped its rights over Challex, Thoiry, Fenières, and some enclaves it possed in the Pays de Gex, for Chancy, Avully, and Russin. In a similar treaty with Savoy in 1754, Geneva received from Savoy Cartigny, Jussy, Vandoeuvres, Gy, and some other smaller territories, in exchange for its rights on Carouge, Veyrier, Onex, Lancy, Bossey, Presinge, and others. During the baroque and classical periods, Europe saw the emergence of several planned towns. Save for the reconstruction of towns destroyed by fires (such as Schwyz in 1642, Sion in 1788, or La Chaux-de-Fonds in 1794), Switzerland did not jump on this trend mostly circumscribed to the large monarchies and princely states. However, the desire to possess or weaken Geneva by France and Savoy provides two good examples of this urban planning, both of which are now Genevan towns. In the 18th century under Louis XV, France intended to build a large port city in Versoix to deviate the traffic en route to Lake Geneva and from there to the Swiss confederation. The city, intended for around 30,000 inhabitants, would have been bigger than Geneva (by then the largest Swiss city) and included large squares and ports. Voltaire, who had settled in Ferney, was particularly rejoiced about the idea of ruining Geneva. However, opposition from Bern to a new fortified town in its border in Pays de Gex, and budgetary problems in France, finally stopped the project of which few items finally were built and survive. A more lasting project was launched by Savoy in 1777, which transformed Carouge into the gateway to the northern provinces and conferred the village the status of city in 1786. The planned city was particularly innovative in the way that streets were symmetrically laid and by the total absence of fortifications.[35]

After the aura of a highly fortified "Protestant Rome",[36] came an image during the 18th century of a very wealthy, elegant city behind its walls. Except for the periods of crises from the Great Plague of Marseille and the crash of the John Law monetary system in France, the century was prosperous until the year 1785, driven by the production and exports of luxury goods, most notably watches. Between 1760 and 1790, the watchmaking industry employs around 4,000 workers, a third of the men residents. During the century, the government also invests in public parks, most notably the Bastions park in 1720,[37] one of the earliest examples of a public park in Europe created from the start for the public and by the public authorities; in beautifying the city, improving the public lighting amongst others. In a latter in 1775 the writer and philosopher Georges Sulzer wrote "Mr Bonnet was kind enough to accompany me to Geneva. It is well known that this city is, in proportion to its size, one of the richest in Europe. Its avenues already announce its opulence; everything indicates a people who live in the midst of abundance. Nowhere have I seen so many country houses as in the territory of this little Republic: the banks of the lake are entirely covered with them. These buildings all have a pleasant exterior which announces, if not magnificence, at least the last degree of cleanliness. Each house has its own well-tended gardens, often even vineyards, meadows and ploughed land. The main road was swarming with pedestrians, horses and carriages, and the surroundings were as busy as they are elsewhere on days of great solemnity."[22]

At the same time, political troubles were brewing. In 1526 as the Republic institutions were created, most of the power was given to the Council of Two Hundred. However, the Little Council had little by little nibbled its power, the Republic having effectively surrendered the power to the small number of bourgeois who controlled the Little Council. In 1707 the lawyer and member of the Council of Two Hundred Pierre Fatio was executed for his attempt to cut back on the powers of the Little Council, by leading a new faction called the representatives that called for a greater share of powers between the two councils. In addition, owing to increased demographic growth and an increase in the price of bourgeoisie, the proportion of eligible men eligible to the governing councils fell from 28% in 1730 to 18% in 1772, as the majority of the population were then natives and residents, many of whom were educated traders or craftsmen who increasingly rejected being excluded from politics. Increased realisation of their weight, and supported by Voltaire, the natives joined forces with the faction of representatives to overthrow the councils in April 1782 and start a revolution that would facilitate the acquisition of bourgeois rights by the natives. However, only three months later, Bernese, French, and Savoy troops entered the city to re-appoint the ancient government and undo the reforms.[38]

In 1785, economic crisis hits Geneva, driven first by the protectionist policies and financial crisis of France and Germany, which reduce the demand for the luxurious Genevan timepieces. After a difficult winter in 1788–89, riots over the increasing price of bread break in Saint-Gervais and spread to the rest of the city. Concerned by an escalation of the revolts, the government implemented several reforms to appease the population, including the grant of citizenship to natives and residents of the countryside villages.[39]

However, in 1792 the French Revolution reached Geneva when the revolutionaries take over Savoy in September of that year. The genevan government received military support from its Swiss allies, but they quickly withdrew from the city in exchange for an assurance of the respect of their neutrality by France. On the 19 November 1792 the National Convention declared the Edict of Fraternity which called on European peoples to rise against their rulers, both secular and spiritual, and overthrow them; in response, the Genevan government decided to grant on the day of the Escalade, the 12th of December, full rights to all the inhabitants of the city and its towns.[40] However, this was too late and on the 28th of the same month, a new revolt spreads in the city and the old patrician government falls, replaced by a new regime that on the day after adopts the motto of "Liberté, Égalité, Indépendence" French for "Liberty, Equality, Independence", stressing the fact that despite its revolutionary principles, the citizens of Geneva opposed any measure that would surrender the city's independence in a period when the threat of France was not subsiding.[22] A period of political and economic crisis and instability followed, with a new constitution adopted in 1794 and several government changes that adopt increasingly radical and controversial ideas such as vastly higher wealth tax rates for citizens of opposing factions, and death and imprisonment sentences for hundreds of adversaries.

Meanwhile, in France, Robespierre fell the 27 July 1794 and with him the Reign of Terror. Slowly, stability regains Geneva and in September 1795 with the 'act of forgetfulness' all the trials in the revolutionary courts were annulled. Old symbols of the Republic of Geneva make a comeback, and in October 1796 a new, more conservative constitution, is adopted.[40]

Things would quickly evolve when France officially annexes Savoy in the spring 1796 and Geneva is increasingly denounced by Paris as a "den of contrabandists, aristocrats, and emigrants". In January 1798, the French army invades the Swiss confederation and begins a trade embargo on Geneva, but the Directory wishes to annex the city on demand by its citizens and not by force. The wish would be granted on 15 April 1798 when the Genevan government is coerced by economic and political pressure to request the annexation by France.[22] The treaty was relatively favourable to Geneva, whose citizens preserved the assets of the Republic, are left alone in regards to education and the economy, and granted a 5-year exemption from conscription.[41] The city's fortifications are also kept intact and preserved, and the Protestant religion is largely tolerated, although with strict conditions such as the demotion of its status to a simple association.

After long debates in Paris, Geneva is then made capital of a new département du Léman, which resembled the old catholic diocese of Geneva prior to the Protestant reformation.

The Napoleonic army left Geneva on 30 December 1813, and on the next day the return of the Republic (Restauration de la République) was proclaimed.

Modern history

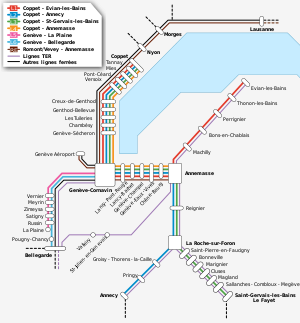

[edit]Geographically, the city and canton had been advantaged in the Middle Ages by its position as a crossroads between France, Savoy and Italy with Northern Europe, via the mountain passes and Lake Geneva (see previous section). However, this advantage evaporated with the construction of the railways. The first railway to link the city, built by the Paris-Lyon-Méditerranée (PLM) linked Geneva to Lyon in 1858, followed soon after during the same year by the Geneva to Lausanne railway line operated by the West Switzerland Company. This provided a basic link between France (Lyon) and Switzerland (Lausanne), but in order to complete the role of a crossroad the network required a north-south connection, linking Annecy to Geneva.

The Victor Emmanuel Railway showed interest in this link. Camillo Benso, prime minister of the Sardinian government, claimed that if the railways did not penetrate the Faucigny and Chablais, those territories "will be more detached from the rest of Savoy than Sardinia is from the rest of the continental provinces [of Italy]. Allowing this separation would be equivalent to abandoning those two good provinces to Switzerland".[42] However only a few kilometres of the line from Annecy would ever be built before the project was abandoned due to Savoy's annexation by France in 1860.[43] After the annexation, France prioritised the connection of its new provinces to the rest of the country with rail and quickly granted a concession to PLM to build a link between Fort l'Écluse on the Lyon-Geneva line to Annemasse and from there to Thonon-les-Bains and Faucigny.[44] This project was opposed by Geneva since the link would avoid crossing the canton. The Swiss government elaborated an alternative treaty in 1869 giving France five years to build the Annecy-Annemasse-Eaux-Vives-Geneva line, and tasking Switzerland with completing the Annemasse-Geneva section.[44] This would give Geneva a pivotal role in becoming the crossroads between Lyon, the Chablais, and Faucigny. Although initially the French government showed willingness to allow the construction of both options, the Franco-Prussian War put a stop to many projects, and only the Fort l'Écluse to Annemasse section would finally be completed.[42]

Another missed opportunity for Geneva to keep its central position came with the Simplon tunnel. Geneva had entertained the idea to build a tunnel through the Col de la Faucille in Gex, linking the canton to Saint-Jean-de-Losne in Burgundy on the Paris-Lyon axis, avoiding Lyon. In 1874 Geneva's government submitted a proposal for this project, complemented in 1886 by the project to link the canton to Gex and Morez and Saint-Julien-en-Genevois and Annecy, which would have transformed the city into a real railway hub.[45] The start of the construction of the Simplon tunnel in 1896 encouraged Geneva to push for this project, and suggested again the construction of a tunnel under the Col de la Faucille to provide a shorter connection between France and Italy than the existing links via the Fréjus tunnel and the Gotthard tunnel. Both France and other western cantons showed great interest in the idea. Alas, the PLM chose instead a route via the tunnel of Mont d'Or to link France to the Simplon tunnel via Lausanne and the Rhône valley in Valais, inaugurated in 1915.[43] The hopes for a railway tunnel under Mont Blanc, which would have led to an increase in rail traffic through Geneva, were also stopped by the commencement of World War I, and by the time that this tunnel was finally completed after the second world war, it had turned into a road tunnel instead.[43]

A small stretch of railway was built between Annemasse and Eaux-Vives, but this station would be left unconnected to the rest of the Swiss network despite the agreement by the Swiss confederation to complete the missing link between that station and Geneva's central station in Cornavin in 1912.[46] Although the link between Cornavin and Eaux-Vives was finally completed in 2019, leading to the creation of the Léman Express suburban rail network, it is not intended for freight transport. Additionally, the south line between Annemasse and Valais that provided a shorter path to the Simplon tunnel from Geneva (the ‘Tonkin line’), was eventually closed between Evian-les-Bains and Saint-Gingolph to passenger traffic in 1937 and to all traffic in 1988.

As a consequence of all these decisions, although freight traffic exists towards the industrial areas of La Praille, Vernier, and Meyrin, the main marshalling yard serving the city, Lausanne-Triage is located near Morges, 50 km away from Geneva and the city never redeveloped its importance as a traffic gateway to central Europe from the Mediterranean.

Financially, the city bankers had long developed their connections and networks across Europe. In the advent of the industrial revolution the main industry of the city was watchmaking, and it had long prided itself on the craftmanship of its workers. The surplus of the abundant capital was therefore channeled by the local bankers to investments in other cities.[47] Some industries managed to develop on the back of the highly skilled workforce, for example the Société Genevoise d’Instruments de Physique (SIP) established in 1860, which produced electrical equipment, and would eventually merge in 1891 with Cuenod Sautter & Cie in 1891 to form Ateliers Sécheron, which produced electrical equipment and train locomotives. It was acquired by Brown Boveri Company in 1919, and today, as Sécheron Hasler, it still produces complex electrical transformers and other electrical equipment in its factory in Satigny. Chemical companies, namely Firmenich and Givaudan were established in 1895 and 1898.

Despite all these examples, due to the relative isolation of the canton, surrounded by France from 1860 and linked with a small railway network to the rest of the continent, the canton did not manage to industrially develop as quickly as better connected cities such as Zürich, which overtook Geneva as the largest city in Switzerland by population in the late 1860s.[48]

The canton's fortunes would improve from 1919 when Geneva was chosen as the headquarters of the League of Nations. This led to large construction works to host the organization, including the Palace of Nations completed in 1938. After the dissolution of the organization, the new United Nations headquarters could not be located in Geneva since the new organization was to be designed with a security council capable of leading military operations, which was incompatible with the principle of Swiss neutrality.[43] Instead, in 1946 an agreement was reached to locate the second headquarters of the organization in Geneva, including the headquarters for its largest organisations such as the International Labour Organization (established in Geneva in 1919), the World Health Organization, the International Telecommunication Union, and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (precursor to the World Trade Organization) (1948), or the World Meteorological Organization (1955) and the World Intellectual Property Organization (1967). The decision was aided by the good condition of the infrastructure left by the League of Nations, and Geneva's airport paved and intact runway (the only one in Switzerland at the time) in a European continent ravaged by the second world war.[49]

This had a profound impact on the local economy, as the connectivity of its airport was boosted by the UN since the organization holds the majority of its conferences in the city.[50] At a time when cross-continental communication was more difficult than today, Geneva became a world center for negotiations and dealmaking thanks to its international status, its resilient telephone network, its international airport, and the convertibility of the Swiss franc.[51] This led to the birth of the large commodity trading sector, starting with the arrival of Cargill's European headquarters in 1956, and the rapid expansion of its already existing large private banking sector,[47] amongst other service-based industries which now power the majority of the local economy alongside the traditional watchmaking industry.[52]

Cross border cooperation began only a century after the creation of the canton. In 1913, an agreement was sealed between Switzerland and France to build the Chancy-Pougny electric dam. Completed in 1925 to supply energy to the steel mills in Creusot, it began to supply electricity to the Services Industriels de Genève by 1958.

Cross-border working movements had existed in Geneva since the Middle Ages and the city was traditionally more open to immigration than others. Around the year 1700, Swiss cities and their allies such as Geneva, had two types of residents: the bourgeois, who held political rights (and a minority of whom formed the patrician class), and the inhabitants, who had no say in the ruling of the city. Amongst the latter, there were the 'established', who had full residence permits, and the 'tolerated' with time-limited permits. The proportion of bourgeois over the total residents in Basle was 70% in 1795; 61% in Zürich in 1780, and 26% in Geneva in 1781. The proportion of 'inhabitants' in Zürich in 1795 was of 8%, whereas in Geneva, a more liberal city, it was 46% in 1764.[53] Note that the remaining residents were 'foreigners', people from other villages and cities.

Building on the liberal roots, in 1882 a convention allowed French citizens a certain degree of freedom to work in Switzerland and vice versa.[54] However, the 1950s and 1960s were years of very high economic growth in Geneva. This led to an increasing need to employ workers from across the border, from Pays de Gex and the Haute-Savoie - from 6,750 workers in 1966 to 22,500 in 1972.[55] Since Geneva refused to participate in the Franco-Swiss agreements for the distribution of income taxes levied on cross border workers of 1935 and 1966 that covered all the other cantons, the municipalities from the neighbouring French regions were increasingly suffocated by the need to finance public equipment for a population that did not financially contribute to the budgets. This situation led to a first grouping of municipalities to defend their interests, the “Association de Communes Frontalières”. Acknowledging the problem, Geneva agreed in 1973 to transfer 3.5% of the gross income of those workers directly to the French municipalities, equivalent to around CHF330 million/year nowadays.[56]

Сотрудничество расширилось после подписания в 1980 году Мадридских соглашений по Рамочной конвенции о приграничном сотрудничестве . Однако это было соглашение 2002 года о свободном передвижении людей между Европейским Союзом и Швейцарией. [57] that had a bigger impact on Geneva's economy and society. The number of cross-border workers increased from 35,000 in 2002 to 92,000 in 2020.[58] Это значительно увеличило потребность в сотрудничестве, особенно в сфере транспорта. Это привело к созданию «Агломерации Франко-Вальдо-Женевуаза», позже переименованной в « Большую Женеву » в 2012 году, которая по географическому охвату примерно соответствует агломерации Женевы с населением в 1 миллион жителей, простирающейся за пределы кантональных границ через Во , Эн и Верхняя Савойя . Его основные достижения включают в себя продвижение к строительству и эксплуатации железнодорожной сети Léman Express и прогнозируемое расширение трамвайной сети tpg до Аннемасса , Сен-Жюльена-ан-Женевуа и Ферни-Вольтера . [59]

Герб

[ редактировать ]

Элементами герба являются:

- Щит: изображен Императорский орел и Ключ Святого Петра (символизирующие статус Женевы как Рейхсштадта и епископской резиденции соответственно), используются с 15 века.

- Герб в виде половины солнца с надписью ΙΗΣ (в честь Иисуса Человека Сальватора)

- Девиз: Свет после тьмы.

Нынешний герб, заимствованный у города Женевы, представляет собой союз полуорла, происходящего от двуглавого орла Священной Римской империи , частью которой Женева была в средние века, и золотого ключа от герб женевского епископства, символизирующий Ключ Святого Петра, покровителя собора. Епископ был прямым вассалом императора и от его имени осуществлял светскую власть над городом. Символизируя союз духовных и смертных сил, герб был принят жителями Женевы в 1387 году. Старые цвета Женевы были серым и черным, а в 17 веке изменились на черный и фиолетовый. Золото и красный стали использовать с 18 века.

Герб с солнцем и надписью ΙΗΣ , обозначающий первые три буквы греческого имени Иисуса, существует с 15 века, но использовался на гербе до 16 века.

Девиз Женевы Post Tenebras Lux , что на латыни означает «свет после тьмы», появляется в версии Вульгаты Иова 17:12. Позднее эта фраза была принята в качестве девиза кальвинистов всей протестантской Реформацией и Женевой.

География

[ редактировать ]Политическая география: определение сегодняшних границ кантонов

[ редактировать ]

После событий, которые превратили Швейцарию в Гельветическую Республику , Женева присоединилась к Швейцарской Конфедерации в 1815 году как 22-й кантон. Территория нынешнего кантона Женева была в основном создана в результате Венского конгресса , чтобы обеспечить непрерывность между городом Женевой и его сателлитными территориями, установленными в ходе предыдущих переговоров с Францией и Савойей, таких как Мандемент, и физически присоединить кантон к остальной части Швейцарии.

В ходе переговоров власти разделились на тех, кто стремился максимизировать прирост территории для нового кантона за счет Франции и Сардинии, и консерваторов, которые хотели минимизировать прирост территории, чтобы избежать включения большого числа католиков в кантон. новый кантон. Первым руководил Шарль Пикте де Рошмон , женевский государственный деятель и дипломат. Консерваторов, состоявших в основном из старой женевской аристократии, возглавлял Жозеф де Ар, который, кроме того, предпочитал сохранять независимость Женевы. Однако в конце концов ни одна из сторон не получила того, чего хотела, поскольку в ситуации доминировали более крупные события.

Шарлю Пикте де Рошмону было поручено вести переговоры с державами в Париже, а затем в Вене. В своих первоначальных планах, представленных императору Александру I , он предложил новый кантон, простирающийся от вершин Юры, окружающей город ( Кре-де-ла-Неж ), до гор Салев и Ле-Вуарон. Таким образом, сюда входили Pays de Gex и все земли женевского бассейна. В рамках этих переговоров даже предлагалось передать территорию Поррантруи Франции в обмен на Пэи-де-Жекс. Однако Людовик XVIII был категорически против передачи католических подданных «протестантскому Риму», поэтому Франции не пришлось уступать какую-либо территорию Женеве по Парижскому миру в мае 1814 года. Только после возвращения Наполеона и второго Парижского договора Женева могла бы добиться ограниченных территориальных выгод, чтобы соединиться с кантоном Во и сломать изоляцию анклавов в Мандементе. В частности, один город, Ферни , продолжает выступать сегодня в качестве узкого места в связи с остальной частью страны, поскольку Франция была эмоционально привязана к выбранному домом. Вольтер и отказался его уступить. Переговоры с Францией были завершены Парижским договором 1815 года , согласно которому к кантону присоединились нынешние муниципалитеты Версуа (который обеспечивал географическую связь с соседним Во), Коллекс-Босси, Преньи-Шамбези, Вернье, Мейрен и Гран-Саконнекс. [60]

В аналогичных переговорах с Королевством Сардиния Шарль Пикте де Рошмон добивался приобретения земель, прилегающих к Женеве, включая склоны горы Салев. Однако Турин выступил против этого требования, поскольку в этом районе проходила важная дорога, соединяющая Тонон-ле-Бен и Фосиньи с Анси . В конце концов, дипломату удалось обменять это требование, как и требование на более длинную часть береговой линии озера, на большой прирост территории от Шанси до Женевы (ныне Кампань), а также земель вокруг повеления Джусси. Эти переговоры завершились Туринским договором 1816 года с Сардинией, по которому новый кантон получил нынешние муниципалитеты Лаконне, Сораль, Перли-Серту, План-ле-Уат, Бернекс, Эйр-ла-Виль, Онекс, Конфигнон, Ланси, Бардоннекс, Труанекс, Вейрье, Шен-Тонекс, Пюплинг, Пресинж, Шулекс, Мейнье, Коллонж-Бельрив, Корсье, Эрманс, Аньер и Каруж. [61]

В общей сложности кантон добавил 159 квадратных километров территории, на которой проживает более 16 000 жителей, в основном католиков и сельских жителей. В то время в городе и его владениях проживало 29 000 жителей. [62]

Первоначально многие из новых деревень были сгруппированы правительством Женевы. Например, деревни Авуси, Сораль и Лаконне образовывали один муниципалитет. То же самое произошло с Бернексом, Онексом и Конфигноном или с План-ле-Уатсом, Бардоннексом, Перли и Серту (четыре деревни образовали « Компезьер »). Однако Парижский и Туринский договоры не касались вопроса общей земли в этих деревнях (как и проблемы общей земли, которая теперь была разделена международными границами). Это привело к напряженности, поскольку жители деревни не хотели делиться своей местной общей землей с жителями того же муниципалитета, что и распределение земли, и в результате доходы были крайне неравномерными. Кантональный закон от 5 февраля 1849 года требовал, чтобы муниципальные акты голосовались советниками, а в протоколах определялась позиция каждого советника и причина их голосования. Это увеличило прозрачность, но привело к напряженности, связанной с размещением школ, ратуш и других общественных зданий и услуг в дополнение к вопросу об общинных землях. В конце концов, эта напряженность привела к разделению этих деревень во второй половине XIX века, что привело к образованию нынешних муниципальных границ для этих недавно приобретенных земель. [63]

Последнее изменение муниципальных границ произошло в 1931 году. В результате стремления к рационализации ресурсов после экономического кризиса 1920-х годов муниципалитеты, образовавшие древнюю городскую часть Женевской Республики (О-Вив, Ле-Пти-Саконне, Пленпале и Женева) объединились и образовали современный город Женева. [64]

В 1956 году в результате запланированного расширения аэропорта Женевы обе страны согласились обменять часть территории, чтобы разместить новую взлетно-посадочную полосу, что затронуло французский муниципалитет Ферни-Вольтер . [65]

Последнее изменение границ кантона произошло в 2003 году, когда строительство погранперехода на новом участке шоссе, соединяющего швейцарскую А1 с французской А41, потребовало обмена территориями. Земля была передана из муниципалитета Бардоннекс в Сен-Жюльен-ан-Женевуа . Чтобы компенсировать потерю женевской земли, муниципалитет Сораль получил территории от Вири и Сен-Жюльена. [66]

Физическая география

[ редактировать ]Женева — кантон с наименьшей разницей между самой низкой и самой высокой точкой — всего 184 метра. Тем не менее, он окружен через свои границы многочисленными горами Юры и предгорьями Альп , в частности, Крет-де-ла-Неж и его соседом Ле-Рекуле (самая высокая и вторая по высоте вершина Юры соответственно), Салевом , Вуарон и Ла-Доль (на территории Во). Площадь кантона Женева составляет 282 квадратных километра (108,9 квадратных миль).

Кантон расположен на крайнем западе Швейцарии. За исключением эксклава муниципалитета Селиньи , кантон делит 95% своей границы с Францией: 103 км из общей сложности 107,5 км, оставшиеся 4,5 км разделены с Во.

Женева окружена французскими департаментами Эн на западе, Верхней Савойей на востоке и юге и кантоном Во на севере.

Кантон расположен в Женевском бассейне. Регион граничит с Женевским озером и пересекается крупными реками Роны, вытекающими из озера, и Арве , исток которого находится в регионе Монблан. На северо-западе он окружен рекой Джура; у реки Вуаше на западе, отделенной от Юры долиной Роны и защищенной фортом Л'Эклюз ; у Мон-де-Сиона на юге; у Салева на юго-востоке гора, которую местные жители называют «горой женевцев», несмотря на то, что она расположена во Франции из-за легкого доступа и близости; а на востоке находятся Альпы, самая высокая вершина которых, Монблан, часто видна из многих частей кантона.

К северо-востоку от Салева, в Монниазе (муниципалитет Жюсси), находится самая высокая точка кантона на высоте 516 метров над уровнем моря. Самая низкая точка кантона находится вдоль реки Роны к югу от Шанси на высоте 332 метра .

В кантоне есть как городской пейзаж Женевы и окрестных городов, так и хорошо сохранившийся сельский пейзаж. Мандеман, расположенный на северо-западе кантона, представляет собой частичную долину, вырытую рекой Аллондон , притоком Роны, и объединяющую основные винодельческие города Сатиньи, Руссен и Дарданьи. Плотина Вербуа, построенная на реке Рона в этом районе, обеспечивает около 15% потребностей кантона в электроэнергии и связывает Мандеман с Шампани, на противоположном берегу реки, между городами Руссен и Эйр-ла-Виль.

Шанси , самый западный муниципалитет Швейцарии, расположен в Шампани. Склон плавно поднимается от Роны к главному городу региона Бернексу , достигая кульминации у Сигнала на высоте 509,9 метра, второй по высоте точки кантона. В этом регионе находится несколько исторических деревень, таких как Сезеннен, Атеназ, Авюси, Лаконнекс, Сораль, Картиньи и Авюлли, переданных Женеве из герцогства Савойского в 1815 году.

В самом узком месте кантон имеет длину 2,1 км между озером Вегнерон и французской границей в Ферни-Вольтер. Поскольку это единственная территория, соединяющая кантон с остальной частью Швейцарии, этот небольшой участок земли пересекает главная железная дорога, ведущая в Лозанну и Невшатель; автодорога А1 и ее развязка; несколько дорог; международный аэропорт; две высоковольтные линии электропередачи; газопровод; нефтепровод; и велосипедная дорожка. [67]

Политика

[ редактировать ]Муниципалитеты

[ редактировать ]

45 В кантоне муниципалитетов . [68]

Кантон Женева не разделен на административные округа. По состоянию на 2020 год было 13 городов с населением более 10 000 человек: [2]

- Женева , 203 856

- Вернье , 34 898

- Лэнси , 33 989

- Мейрин , 26 129 лет.

- Каруж , 22 536

- Онекс , 18 933

- Тонекс , 14 573

- Версуа , 13 281

- Ле Гран-Саконне , 12 378

- Шен-Бужери , 12 621

- Вейрье , 11 861

- План-ле-Уат , 10 601

- Бернекс , 10 258

Правительство

[ редактировать ]Конституция кантона была принята в 1847 году и с тех пор в нее несколько раз вносились поправки. Кантональное исполнительное правительство ( Conseil d'Etat ) состоит из семи членов, которые избираются сроком на пять лет.

Последние очередные выборы по законодательству на 2018-2023 годы состоялись 15 апреля 2018 года и 6 мая 2018 года. [69]

| советник ( Г-н Государственный советник/Г-жа Государственный советник ) | Вечеринка | Руководитель офиса ( Département , с тех пор) | избран с |

|---|---|---|---|

| Антонио Ходжерс [CE 1] | Зеленые (PES) | Территориальный отдел (ДТ) , 2018 г. | 2013 |

| Серж Даль Буско [CE 2] | ПДК | Департамент инфраструктуры (ДИ) , 2018 г. | 2013 |

| Энн Эмери-Торрасинта | ПС | Департамент народного образования, обучения и молодежи (ДИП) , 2013 г. | 2013 |

| Тьерри Апотелоз | ПС | Департамент социальной сплоченности (DCS) , 2018 г. | 2018 |

| Натали Фонтане | ЛНР | Департамент финансов и человеческих ресурсов (DF) , 2018 г. | 2018 |

| Пьер Моде | ЛНР | Департамент экономического развития (ДЭР) , 2019 г. | 2012 |

| Мауро Поджиа | МКГ | Департамент безопасности, занятости и здравоохранения (DSES) , 2019 г. | 2013 |

Мишель Ригетти — канцлер кантона ( Chancilière d’Etat ) с 2018 года.

Парламент

[ редактировать ]Великий совет кантона Женева на мандатный период 2018-2023 гг. [71]

Законодательный орган, Большой совет ( Grand Conseil ), имеет 100 мест, депутаты избираются сроком на четыре года. [72]

Последние выборы состоялись 15 апреля 2018 года. [73]

Подобно тому, что происходит на федеральном уровне, любое изменение Конституции подлежит обязательному референдуму. Кроме того, любой закон может быть вынесен на референдум, если его требуют 7000 человек, имеющих право голоса. [74] и 10 000 человек также могут предложить новый закон. [75]

Федеральные выборы

[ редактировать ]Этот раздел необходимо обновить . ( декабрь 2019 г. ) |

Национальный совет

[ редактировать ]В 2019 году Республика и кантон Женева получили место и направили в Национальный совет в общей сложности 12 представителей . Федеральные выборы, состоявшиеся 20 октября 2019 года, действительно привели к электоральному прорыву Партии зеленых (PES/GPS), которая впервые стала самой популярной партией с долей голосов 24,6%. Либералы (ПЛР/СвДП) отошли на второе место, потеряв 2,6% голосов и место в Национальном совете. Два мандата также получили Социал-демократическая партия (ПС/СП) и УДК/СВП, получившие 14,7% и 13,7% соответственно. Христианско -демократической народной партии (ХДП/ХВП) удалось сохранить свое место с 7,7% голосов, в то время как ЕАГ [ фр ] коалиция получила 7,4% голосов и место. Выборы также привели к тому, что Женевское гражданское движение (MCG) потеряло свое единственное место с уменьшенной долей голосов на 5,4% по сравнению с 7,9% в 2015 году . Явка избирателей снизилась до 38,2%, что стало самым низким показателем среди всех кантонов в 2019 году. [76]

Совет Штатов

[ редактировать ]Последние выборы в Совет кантонов (Швейцария) прошли в два тура – 20 октября 2019 г. и 10 ноября 2019 г. в рамках федеральных выборов. В результате выборов после второго тура голосования были назначены два новых члена. Член совета Лиза Маццоне от Партии зеленых (PES/GPS) была избрана 45 998 голосами, а советник Карло Соммаруга , член Социал-демократической партии (PS/SP) был избран 41 839 голосами. Покидающими свой пост советниками были Лилиан Мори Паскье от Социал-демократической партии и Роберт Крамер от Партии зеленых, которые оба были впервые избраны в 2007 году . Таким образом, обе стороны сохранили свое представительство в совете. [77]

Результаты федеральных выборов

[ редактировать ]| Процент от общего числа голосов от каждой партии в кантоне на в Национальный совет 1971–2019 гг. выборах [78] | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Вечеринка | Идеология | 1971 | 1975 | 1979 | 1983 | 1987 | 1991 | 1995 | 1999 | 2003 | 2007 | 2011 | 2015 | 2019 | ||

| СвДП. Либералы а | Классический либерализм | 19.2 | 16.6 | 14.7 | 16.2 | 18.0 | 12.8 | 13.5 | 12.7 | 7.3 | 7.7 | 18.6 | 20.5 | 17.9 | ||

| ЦВП/ПДК/ППД/ПКД | Христианская демократия | 13.8 | 14.7 | 14.0 | 12.3 | 14.6 | 14.5 | 13.4 | 14.1 | 11.8 | 9.7 | 9.8 | 12.1 | 7.7 | ||

| СП/ПС | Социал-демократия | 19.1 | 22.6 | 21.5 | 19.2 | 18.6 | 26.4 | 30.0 | 20.0 | 24.8 | 19.1 | 19.1 | 19.9 | 14.7 | ||

| Старший вице-президент/УДК | Швейцарский национализм | * б | * | * | * | * | 1.1 | * | 7.5 | 18.3 | 21.1 | 16.0 | 17.6 | 13.7 | ||

| ЛПС/ПЛС | Швейцарский либерал | 14.1 | 16.0 | 21.3 | 19.1 | 18.1 | 22.1 | 17.7 | 18.5 | 16.8 | 14.8 | с | с | с | ||

| Кольцо независимых | Социальный либерализм | 6.2 | 2.4 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||

| EVP/ПЭВ | Христианская демократия | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 1.2 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 0.7 | ||

| ГЛП/ПВЛ | Зеленый либерализм | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 3.2 | 2.3 | 5.4 | ||

| БПР/ПБД | Консерватизм | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| PdA/PST-POP/ПК/PSL | Социализм | 20.8 | 18.0 | 19.9 | 9.5 | 8.7 | 7.8 | 9.4 | 8.7 | 2.7 | 1.9 | 1.3 | * | и | ||

| GPS/ПЭС | Зеленая политика | * | * | * | 7.6 | 11.5 | 6.7 | 5.6 | 8.2 | 11.2 | 16.4 | 14.0 | 11.5 | 24.6 | ||

| Солидарность | Антикапитализм | * | * | * | * | * | * | 3.8 | 8.0 | 5.4 | 4.9 | 5.2 | 6.1 | и | ||

| СД/ДС | Национальный консерватизм | 1.4 | 1.7 | 0.6 | 2.1 | 1.1 | 2.0 | 2.4 | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||

| Представитель | Правый популизм | 5.4 | 6.9 | 6.5 | 12.2 | 6.9 | д | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||

| ЭДУ/ОДФ | Христианское право | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 0.2 | ж | ||

| ФПС/ПСЛ | Правый популизм | * | * | * | * | * | 3.0 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||

| МКР/МКГ | Правый популизм | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 9.8 | 7.9 | 5.4 | ||

| ЕАГ [ фр ] | Эко-социализм | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 7.4 | ||

| Другой | * | 1.1 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 2.5 | 3.4 | 4.2 | 2.3 | 1.7 | 3.2 | 1.9 | 0.3 | 2.0 | |||

| Участие избирателей % | 47.0 | 45.4 | 37.6 | 44.5 | 38.6 | 39.6 | 35.6 | 36.3 | 45.9 | 46.7 | 42.4 | 42.9 | 38.2 | |||

- ^ a СвДП до 2009 г., СвДП. Либералы после 2009 г.

- ^b «*» означает, что партия не была в бюллетенях для голосования в этом кантоне.

- ^ c Часть СвДП на этих выборах.

- ^ d В сочетании с SD на этих выборах

- ^ e Входит в коалицию ЕАГ на этих выборах.

- ^ f Часть коалиции MCR на этих выборах.

Демография

[ редактировать ]Население по месту рождения

[ редактировать ]Этот раздел необходимо обновить . ( апрель 2024 г. ) |

| Национальность | Число | % общий (иностранцы) |

|---|---|---|

| 36,518 | 7.7 (18.8) | |

| 27,231 | 5.7 (14.0) | |

| 20,591 | 4.3 (10.6) | |

| 14,346 | 3.0 (7.4) | |

| 7,440 | 1.6 (3.8) | |

| 4,981 | 1.0 (2.6) | |

| 4,690 | 1.0 (2.4) | |

| 4,637 | 1.0 (2.4) | |

| 3,870 | 0.8 (2.0) | |

| 3,517 | 0.7 (1.8) | |

| 2,263 | 0.5 (1.2) |

Население кантона (по состоянию на 31 декабря 2020 г.) составляло 506 343 человека. [2] В 2013 году в состав населения входило 194 623 жителя иностранного происхождения из 187 разных стран, что составляло 40,1% от общей численности населения. [2]

Население кантона по состоянию на декабрь 2013 г. [update]В нем проживало 168 505 человек родом из Женевы (35,4%) и 112 878 швейцарцев из других кантонов (23,7%). Около 73% жителей иностранного происхождения были выходцами из Европы (ЕС-28: 64,4%), 9,1% из Африки, 9,0% из Америки и 8,5% из Азии. [2] С учетом лиц, имеющих множественное гражданство , 54,4% жителей Женевы имели заграничный паспорт. [79]

Языки

[ редактировать ]В 2014 году преобладающим языком Женевы был французский , на котором говорили 81,04% населения дома; Следующими по величине домашними языками были английский (10,84%), португальский (9,89%), испанский (7,82%) и немецкий (5,32%); респондентам было разрешено указывать более чем один язык. [80]

Религия

[ редактировать ]

родина Жана Кальвина , Реформации Кантон Женева, традиционно был оплотом протестантских христиан. Однако в течение 19 и 20 веков римско-католическое население кантона резко увеличилось, во многом из-за расширения границы в 1815 году в сторону католических территорий и иммиграции из католических европейских стран; их сообщество насчитывало 220 139 человек или 44,5% по состоянию на 2017 год. [update]. Roman Catholics now outnumber members of the Swiss Reformed Church (65,629 people or 13.3% as of 2017[update]) в кантоне, безусловно. [81] Окружающие регионы Франции в основном католические.

В 2012 году 5,4% населения Женевы (в возрасте 15 лет и старше) принадлежали к другим христианским группам, 5,5% были мусульманами и 5,9% принадлежали к другим религиозным группам. [82] [83] Остальная часть населения была религиозно беспристрастной или не ответила на вопрос переписи.

Историческое население

[ редактировать ]Историческое население представлено в следующей таблице:

| Исторические данные о населении [84] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Год | Общая численность населения | швейцарский | Нешвейцарский | Доля населения всей страны |

| 1850 | 64 146 | 49 004 | 15 142 | 2.7% |

| 1880 | 99 712 | 63 688 | 36 024 | 3.5% |

| 1900 | 132 609 | 79 965 | 52 644 | 4.0% |

| 1950 | 202 918 | 167 726 | 35 192 | 4.3% |

| 1970 | 331 599 | 219 780 | 111 819 | 5.3% |

| 2000 | 413 673 | 256 179 | 157 494 | 5.7% |

| 2020 | 506 343 | 5.9% | ||

Экономика

[ редактировать ]Несмотря на относительно небольшой размер по сравнению с другими кантонами Швейцарии, кантон Женева производит четвертый по величине ВВП страны (50 млрд швейцарских франков) после кантонов Цюрих (143 млрд швейцарских франков), Берн (78 млрд швейцарских франков) и Во (54 млрд швейцарских франков). , [85] и имеет третий по величине ВВП на душу населения в стране после Базеля и Цуга. [86]

Экономика Женевы в основном ориентирована на сферу услуг. Кантон неизменно входит в число сильнейших мировых финансовых центров. [87] [88] В финансовом секторе доминируют три основных сектора: торговля сырьевыми товарами; торговое финансирование и управление активами.

Около трети мирового объема свободной торговли маслом, сахаром, зерном и семенами масличных культур продается в Женеве. Примерно 22% мирового хлопка продается в районе Женевского озера. Другие основные товары, торгуемые в кантоне, включают сталь, электричество и кофе. [89] Крупные торговые компании имеют свои региональные или глобальные штаб-квартиры в кантоне, такие как Trafigura , Cargill , Vitol , Gunvor , BNP Paribas или Mercuria Energy Group , а также здесь находится крупнейшая в мире судоходная компания Mediterranean Shipping Company . Торговля сырьевыми товарами поддерживается сильным сектором торгового финансирования, в котором крупные банки, такие как BCGE , Banque de Commerce et de Placements, BCV , Crédit Agricole , ING , Société Générale , BIC-BRED , Bank of China и UBS , имеют свои штаб-квартиры. в регионе для этого бизнеса.

В управлении активами доминируют банки, не котирующиеся на бирже, в частности Pictet , Lombard Odier , Union Bancaire Privée , Edmond de Rothschild Group , Mirabaud Group , Dukascopy Bank , Bordier & Cie , Banque SYZ или REYL & Cie . Кроме того, в кантоне находится самая большая концентрация банков с иностранным участием в Швейцарии, таких как HSBC Private Bank , JPMorgan Chase , Bank of China , Barclays или Arab Bank .

Следующим по величине сектором экономики после финансового сектора является производство часов, в котором доминируют роскошные фирмы Rolex , Richemont , Patek Philippe и другие, чьи фабрики в основном сосредоточены в муниципалитетах План-ле-Уат и Мейрен .

На торговое финансирование, управление активами и производство часов приходится примерно две трети корпоративного налога, уплачиваемого в кантоне. [90]

В кантоне также расположены штаб-квартиры других крупных транснациональных корпораций, таких как Firmenich (в Сатиньи) и Givaudan (в Вернье), два крупнейших в мире производителя ароматизаторов, ароматизаторов и активных косметических ингредиентов; SGS , крупнейшая в мире компания, предоставляющая услуги по инспекции, проверке, испытаниям и сертификации; Alcon (в Вернье), компания, специализирующаяся на средствах по уходу за глазами; Temenos , крупный поставщик банковского программного обеспечения; или местную штаб-квартиру Procter & Gamble , Japan Tobacco International или L'Oréal .

Хотя они не вносят прямого вклада в местную экономику, в кантоне Женева также находится крупнейшая в мире концентрация международных организаций и агентств ООН, таких как Красный Крест , Всемирная организация здравоохранения , Всемирная торговая организация , Международный союз электросвязи. Всемирная организация интеллектуальной собственности , Всемирная метеорологическая организация и Международная организация труда , а также европейская штаб-квартира Организации Объединенных Наций .

Ее международный подход, хорошее транспортное сообщение с аэропортом и центральное положение на континенте также делают Женеву хорошим местом для проведения конгрессов и торговых ярмарок, две из которых — Женевский автосалон и «Часы и чудеса» , которые проводятся в Палэкспо .

Сельское хозяйство является обычным явлением во внутренних районах Женевы, особенно пшеница и вино. Несмотря на относительно небольшой размер, кантон производит около 10% швейцарского вина и имеет самую высокую плотность виноградников в стране. [91] Крупнейшие сорта, выращиваемые в Женеве, — это гаме, шасла, пино нуар, гамаре и шардоне.

Транспорт

[ редактировать ]

Женева связана с остальной частью Швейцарии поездами, обслуживаемыми Швейцарскими федеральными железными дорогами , с основными линиями в направлении Брига в кантоне Вале через Лозанну , в Санкт-Галлен через Лозанну , Фрибур , Берн и Цюрих или, альтернативно, через Невшатель на подножии Юры. железной дороги и в Люцерн .

С 1984 года французские высокоскоростные поезда (TGV) обслуживают Женеву с сообщением с Парижем и Марселем , которыми управляет TGV Lyria , совместная компания, принадлежащая SNCF и Швейцарским федеральным железным дорогам. SNCF также управляет региональными поездами до Лиона .