Университет Бирмингема

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Девиз | Латынь : Per Ardua ad Alta. | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Девиз на английском языке | Через усилия к высотам [1] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Тип | Общественный | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Учредил |

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Endowment | £142.5 million (2023)[4] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Budget | £909.1 million (2022/23)[4] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Chancellor | Lord Bilimoria[5] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Vice-Chancellor | Adam Tickell | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Visitor | The Rt Hon Lucy Powell MP (as Lord President of the Council ex officio) | ||||||||||||||||||||

Academic staff | 4,100 (2021/22)[6] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Students | 37,990 (2021/22)[7] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Undergraduates | 25,150 (2021/22)[7] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Postgraduates | 12,840 (2021/22)[7] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Location | , England 52°27′2″N 1°55′50″W / 52.45056°N 1.93056°W | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Campus | Urban, suburban | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Colours | The University College scarves | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Affiliations | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Website | birmingham | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

( Бирмингемский университет неофициально Бирмингемский университет ) [8] [9] — государственный исследовательский университет в Бирмингеме , Англия. Он получил свою королевскую хартию в 1900 году как преемник Королевского колледжа Бирмингема (основанного в 1825 году как Бирмингемская школа медицины и хирургии ) и Научного колледжа Мейсона (основанного в 1875 году сэром Джозайей Мэйсоном ), что сделало его первым английским гражданским или университет из «красного кирпича», получивший собственную королевскую хартию, и первый английский унитарный университет . [2] [10] [11] Он является одним из основателей Расселской группы британских исследовательских университетов и международной сети исследовательских университетов Universitas 21 .

В 2019–2020 годах студенческое население включает 23 155 студентов и 12 605 аспирантов, что является 7-м по величине в Великобритании (из 169). Годовой доход университета на 2022–2023 годы составил 909,1 миллиона фунтов стерлингов, из которых 196,7 миллиона фунтов стерлингов были получены от исследовательских грантов и контрактов, а расходы составили 884,7 миллиона фунтов стерлингов. [4] В рейтинге научных достижений 2021 года Бирмингемский университет занял 13-е место из 129 учебных заведений по среднему баллу по сравнению с 31-м местом в предыдущем REF в 2014 году. [12]

The university is home to the Barber Institute of Fine Arts, housing works by Van Gogh, Picasso and Monet; the Shakespeare Institute; the Cadbury Research Library, the Mingana Collection of Middle Eastern manuscripts; the Lapworth Museum of Geology; and the 100-metre Joseph Chamberlain Memorial Clock Tower, which is a prominent landmark visible from many parts of the city.[13] Academics and alumni of the university include former British Prime Ministers Neville Chamberlain and Stanley Baldwin,[14] the British composer Sir Edward Elgar and eleven Nobel laureates.[15]

History

[edit]Queen's College

[edit]

The earliest beginnings of the university were originally traced back to the Queen's College, which is linked to William Sands Cox in his aim of creating a medical school along strictly Christian lines, unlike the contemporary London medical schools.[citation needed] Further research[by whom?] revealed the roots of the Birmingham Medical School in the medical education seminars of John Tomlinson, the first surgeon to the Birmingham Workhouse Infirmary, and later to the Birmingham General Hospital. These classes, held in the winter of 1767–68, were the first such lectures ever held in England or Wales. The first clinical teaching was undertaken by medical apprentices at the General Hospital, founded in 1779. The medical school which grew out of the Birmingham Workhouse Infirmary was founded in 1828, but Cox began teaching in December 1825. Queen Victoria granted her patronage to the Clinical Hospital in Birmingham and allowed it to be styled "The Queen's Hospital". It was the first provincial teaching hospital in England. In 1843, the medical college became known as Queen's College.[16]

Mason Science College

[edit]

In 1870, Sir Josiah Mason, the Birmingham industrialist and philanthropist, who made his fortune in making key rings, pens, pen nibs and electroplating, drew up the Foundation Deed for Mason Science College.[3] The college was founded in 1875.[2] It was this institution that would eventually form the nucleus of the University of Birmingham. In 1882, the Departments of Chemistry, Botany and Physiology were transferred to Mason Science College, soon followed by the Departments of Physics and Comparative Anatomy. The transfer of the Medical School to Mason Science College gave considerable impetus to the growing importance of that college and in 1896 a move to incorporate it as a university college was made. As the result of the Mason University College Act 1897 (60 & 61 Vict. c. xx) it became incorporated as Mason University College on 1 January 1898, with Joseph Chamberlain becoming the President of its Court of Governors.

Royal charter

[edit]| Birmingham University Act 1900 |

|---|

It was largely due to Chamberlain's enthusiasm that the university was granted a royal charter by Queen Victoria on 24 March 1900.[17] The Calthorpe family offered twenty-five acres (10 hectares) of land on the Bournbrook side of their estate in July. The Court of Governors received the Birmingham University Act 1900 (63 & 64 Vict. c. xix), which put the royal charter into effect on 31 May.

The transfer of Mason University College to the new University of Birmingham, with Chamberlain as its first chancellor and Sir Oliver Lodge as the first principal, was complete. A remnant of Josiah Mason's legacy is the Mermaid from his coat-of-arms, which appears in the sinister chief of the university shield and of his college, the double-headed lion in the dexter.[18]

The commerce faculty was founded by Sir William Ashley in 1901, who from 1902 until 1923 served as first Professor of Commerce and Dean of the Faculty. From 1905 to 1908, Edward Elgar held the position of Peyton Professor of Music at the university. He was succeeded by his friend Granville Bantock.[19]

The university's own heritage archives are accessible for research through the university's Cadbury Research Library which is open to all interested researchers.[20]

During the First World War, the Great Hall in the Aston Webb Building was requisitioned by the War Office to create the 1st Southern General Hospital, a facility for the Royal Army Medical Corps to treat military casualties; it was equipped with 520 beds and treated 125,000 injured servicemen.[21]

In June 1921, the university appointed Linetta de Castelvecchio as Serena Professor of Italian: she was the first woman to hold a chair at the university and one of the first women professors in Great Britain.[22][23]

Expansion

[edit]

In 1939, the Barber Institute of Fine Arts, designed by Robert Atkinson, was opened. In 1956, the first MSc programme in Geotechnical Engineering commenced under the title of "Foundation Engineering", and has been run annually at the university since.

The UK's longest-running MSc programme in Physics and Technology of Nuclear Reactors also started at the university in 1956, the same year that the world's first commercial nuclear power station was opened at Calder Hall in Cumbria.

In 1957, Sir Hugh Casson and Neville Conder were asked by the university to prepare a masterplan on the site of the original 1900 buildings which were incomplete. The university drafted in other architects to amend the masterplan produced by the group. During the 1960s, the university constructed numerous large buildings, expanding the campus.[24] In 1963, the university helped in the establishment of the faculty of medicine at the University of Rhodesia, now the University of Zimbabwe (UZ). UZ is now independent but both institutions maintain relations through student exchange programmes.

Birmingham also supported the creation of Keele University (formerly University College of North Staffordshire) and the University of Warwick under the Vice-Chancellorship of Sir Robert Aitken who acted as 'godfather' to the University of Warwick.[25] The initial plan was to establish a satellite university college in Coventry but Aitken advised an independent initiative to the University Grants Committee.[26]

Malcolm X, the Afro-American human rights activist, addressed the University Debating Society in 1965.[21]

Scientific discoveries and inventions

[edit]

The university has been involved in many scientific breakthroughs and inventions. From 1925 until 1948, Sir Norman Haworth was Professor and Director of the Department of Chemistry. He was appointed Dean of the Faculty of Science and acted as Vice-Principal from 1947 until 1948. His research focused predominantly on carbohydrate chemistry in which he confirmed a number of structures of optically active sugars. By 1928, he had deduced and confirmed the structures of maltose, cellobiose, lactose, gentiobiose, melibiose, gentianose, raffinose, as well as the glucoside ring tautomeric structure of aldose sugars. His research helped to define the basic features of the starch, cellulose, glycogen, inulin and xylan molecules. He also contributed towards solving the problems with bacterial polysaccharides. He was a recipient of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1937.[27]

The cavity magnetron was developed in the Department of Physics by Sir John Randall, Harry Boot and James Sayers. This was vital to the Allied victory in World War II. In 1940, the Frisch–Peierls memorandum, a document which demonstrated that the atomic bomb was more than simply theoretically possible, was written in the Physics Department by Sir Rudolf Peierls and Otto Frisch. The university also hosted early work on gaseous diffusion in the Chemistry department when it was located in the Hills building.

Physicist Sir Mark Oliphant made a proposal for the construction of a proton-synchrotron in 1943; however, he made no assertion that the machine would work. In 1945, phase stability was discovered; consequently, the proposal was revived, and construction of a machine that could surpass proton energies of 1 GeV began at the university. However, because of lack of funds, the machine did not start until 1953. The Brookhaven National Laboratory managed to beat them; they started their Cosmotron in 1952, and had it entirely working in 1953, before the University of Birmingham.[28]

In 1947, Sir Peter Medawar was appointed Mason Professor of Zoology at the university. His work involved investigating the phenomenon of tolerance and transplantation immunity. He collaborated with Rupert E. Billingham and they did research on problems of pigmentation and skin grafting in cattle. They used skin grafting to differentiate between monozygotic and dizygotic twins in cattle. Taking the earlier research of R. D. Owen into consideration, they concluded that actively acquired tolerance of homografts could be artificially reproduced. For this research, Medawar was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. He left Birmingham in 1951 and joined the faculty at University College London, where he continued his research on transplantation immunity. He was a recipient of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1960.[29]

Recent history

[edit]

In 1999 talks commenced on the possibility of Aston University integrating itself into the University of Birmingham as the University of Birmingham, Aston Campus. This would have resulted in the University of Birmingham expanding to become one of the largest universities in the UK, with a student body of 30,000. Talks were halted in 2001 after Aston University determined the timing to be inopportune. While Aston University management was in favour of the integration, and reception among staff was generally positive, the Aston student union voted two-to-one against the integration. Despite this set back, the Vice Chancellor of the University of Birmingham said the door remained open to recommence talks when Aston University is ready.[30]

The final round of the first ever televised leaders' debates, hosted by the BBC, was held at the university during the 2010 British general election campaign on 29 April 2010.[31][32]

On 9 August 2010 the university announced that for the first time it would not enter the UCAS clearing process for 2010 admission, which matches under-subscribed courses to students who did not meet their firm or insurance choices, due to all places being taken. Largely a result of the financial crisis of 2007–2010, Birmingham joined fellow Russell Group universities including Oxford, Cambridge, Edinburgh and Bristol in not offering any clearing places.[33]

The university acted as a training camp for the Jamaican athletics team prior to the 2012 London Olympics.[34]

A new library was opened for the 2016/17 academic year, and a new sports centre opened in May 2017.[35] The previous Main Library and the old Munrow Sports Centre, including the athletics track, have both since been demolished, with the demolition of the old library being completed in November 2017.[36]

Controversies

[edit]This article's "criticism" or "controversy" section may compromise the article's neutrality. (May 2021) |

The discipline of cultural studies was founded at the university and between 1964 and 2002 the campus was home to the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies, a research centre whose members' work came to be known as the Birmingham School of Cultural Studies. Despite being established by one of the key figures in the field, Richard Hoggart, and being later directed by the theorist Stuart Hall, the department was controversially closed down.[37]

Analysis showed that the university was fourth in a list of British universities that faced the most employment tribunal claims between 2008 and 2011. They were the second most likely to settle these before the hearing date.[38]

In 2011 a parliamentary early day motion was proposed, arguing against the Guild suspending the elected Sabbatical Vice President (Education), who was arrested while taking part in protest activity.[39]

In December 2011 it was announced that the university had obtained a 12-month-long injunction[40] against a group of around 25 students, who occupied a residential building on campus from 23 to 26 November 2011, preventing them from engaging in further "occupational protest action" on the university's grounds without prior permission. It was misreported in the press that this injunction applied to all students; however, the court order defines the defendants as:

Persons unknown (including students of the University of Birmingham) entering or remaining upon the buildings known as No. 2 Lodge Pritchatts Road, Birmingham at the University of Birmingham for the purpose of protest action (without the consent of the University of Birmingham).[41]

The university and the Guild of Students also clarified the scope of the injunction in an e-mail sent to all students on 11 January 2012, stating: "The injunction applies only to those individuals who occupied the lodge".[42] The university said that it sought this injunction as a safety precaution based on a previous occupation.[43] Three separate human rights groups, including Amnesty International, condemned the move as restrictive on human rights.[44]

In 2019, several women said the university refused to investigate allegations of campus rape. One student who complained of rape in university accommodation was told by employees of the university that there were no specific procedures for handling rape complaints. In other cases students were told they would have to prove the alleged rapes occurred on university property. The university has been criticized by legal professionals for not adequately assessing the risk to students by refusing to investigate complaints of criminal conduct.[45]

In June 2022 the University published a report into, and apologised for, its involvement in developing, promoting and administering electric-shock conversion therapy to gay men, during the period 1966-1983.[46][47]

Campuses

[edit]Edgbaston campus

[edit]Original buildings

[edit]

The main campus of the university occupies a site some 3 miles (4.8 km) south-west of Birmingham city centre, in Edgbaston. It is arranged around Joseph Chamberlain Memorial Clock Tower (affectionately known as 'Old Joe' or 'Big Joe'), a grand campanile which commemorates the university's first chancellor, Joseph Chamberlain.[48] Chamberlain may be considered the founder of Birmingham University, and was largely responsible for the university gaining its Royal Charter in 1900 and for the development of the Edgbaston campus. The university's Great Hall is located in the domed Aston Webb Building, which is named after one of the architects – the other was Ingress Bell. The initial 25-acre (100,000 m2) site was given to the university in 1900 by Lord Calthorpe. The grand buildings were an outcome of the £50,000 given by steel magnate and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie to establish a "first class modern scientific college"[49] on the model of Cornell University in the United States.[50] Funding was also provided by Sir Charles Holcroft.[51]

The original domed buildings, built in Accrington red brick, semicircle to form Chancellor's Court. This sits on a 30 feet (9.1 m) drop, so the architects placed their buildings on two tiers with a 16 feet (4.9 m) drop between them. The clock tower stands in the centre of the Court.

The campanile itself draws its inspiration from the Torre del Mangia, a medieval clock tower that forms part of the Town Hall in Siena, Italy.[52] When it was built, it was described as 'the intellectual beacon of the Midlands' by the Birmingham Post. The clock tower was Birmingham's tallest building from the date of its construction in 1908 until 1969; it is now the third highest in the city. It is one of the top 50 tallest buildings in the UK,[53] and the tallest free-standing clock tower in the world,[13] although there is some confusion about its actual height, with the university listing it both as 110 metres (361 ft)[54] and 325 feet (99 m) tall in different sources.[55]

The campus has a wide diversity in architectural types and architects. "What makes Birmingham so exceptional among the Red Brick universities is the deployment of so many other major Modernist practices: only Oxford and Cambridge boast greater selections".[56] The Guild of Students original section was designed by Birmingham inter-war architect Holland Hobbiss who also designed the King Edward's School opposite. It was described as "Redbrick Tudorish" by Nikolaus Pevsner.[57]

The statue on horseback fronting the entrance to the university and Barber Institute of Fine Arts is a 1722 statue of George I rescued from Dublin in 1937. This was saved by Bodkin, a director of the National Gallery of Ireland and first director of the Barber Institute. The statue was commissioned by the Dublin Corporation from the Flemish sculptor John van Nost.[58]

Final negotiations for part of what is now the Vale were only completed in March 1947. By then, properties which would have their names used for halls of residences such as Wyddrington and Maple Bank were under discussion and more land was obtained from the Calthorpe estate in 1948 and 1949 providing the setting for the Vale.[59] Landscape architect Mary Mitchell designed the layout of the campus and she included mature trees that were retained from the former gardens.[60] Construction on the Vale started in 1962 with the creation of a 3-acre (12,000 m2) artificial lake and the building of Ridge, High, Wyddrington and Lake Halls. The first, Ridge Hall, opened for 139 women in January 1964, with its counterpart High Hall admitting its first male residents the following October.[61]

1960s and modern expansion

[edit]

The university underwent a major expansion in the 1960s due to the production of a masterplan by Casson, Conder and Partners. The first of the major buildings to be constructed to a design by the firm was the Refectory and Staff House which was built in 1961 and 1962. The two buildings are connected by a bridge. The next major buildings to be constructed were the Wyddrington and Lake Halls and the Faculty of Commerce and Social Science, all completed in 1965. The Wyddrington and Lake Halls, on Edgbaston Park Road, were designed by H. T. Cadbury-Brown and contained three floors of student dwellings above a single floor of communal facilities.[citation needed]

The Faculty of Commerce and Social Science, now known as the Ashley Building, was designed by Howell, Killick, Partridge and Amis and is a long, curving two-storey block linked to a five-storey whorl. The two-storey block follows the curve of the road, and has load-bearing brick cross walls. It is faced in specially-made concrete blocks. The spiral is faced with faceted pre-cast concrete cladding panels.[24] It was statutorily listed in 1993[62] and a refurbishment by Berman Guedes Stretton was completed in 2006.[63]

Chamberlain, Powell and Bon were commissioned to design the Physical Education Centre which was built in 1966. The main characteristic of the building is the roof of the changing rooms and small gymnasium which has hyperbolic paraboloid roof light shells and is completely paved in quarry tiles. The roof of the sports hall consists of eight conoidal 2½-inch thick sprayed concrete shells springing from 80-foot (24 m) long pre-stressed valley beams. On the south elevation, the roof is supported on raking pre-cast columns and reversed shells form a cantilevered canopy.[citation needed]

Also completed in 1966 was the Mining and Minerals Engineering and Physical Metallurgy Departments, which was designed by Philip Dowson of Arup Associates. This complex consisted of four similar three-storey blocks linked at the corners. The frame is of pre-cast reinforced concrete with columns in groups of four and the whole is planned as a tartan grid, allowing services to be carried vertically and horizontally so that at no point in a room are services more than ten feet away. The building received the 1966 RIBA Architecture Award for the West Midlands.[24] It was statutorily listed in 1993.[62] Taking the full five years from 1962 to 1967, Birmingham erected twelve buildings which each cost in excess of a quarter of a million pounds.[64]

In 1967, Lucas House, a new hall of residence designed by The John Madin Design Group, was completed, providing 150 study bedrooms. It was constructed in the garden of a large house. The Medical School was extended in 1967 to a design by Leonard J. Multon and Partners. The two-storey building was part of a complex which covers the southside of Metchley Fort, a Roman fort. In 1968, the Institute for Education in the Department for Education was opened. This was another Casson, Conder and Partners-designed building. The complex consisted of a group of buildings centred around an eight-storey block, containing study offices, laboratories and teaching rooms. The building has a reinforced concrete frame which is exposed internally and the external walls are of silver-grey rustic bricks. The roofs of the lecture halls, penthouse and Child Study wing are covered in copper.[24]

Arup Associates returned in the 1960s to design the Arts and Commerce Building, better known as Muirhead Tower and houses the Institute of Local Government Studies. This was completed in 1969.[24] A£42 million refurbishment of the 16-storey tower was completed in 2009 and it now houses the Colleges of Social Sciences and the Cadbury Research Library, the new home for the university's Special Collections. The podium was remodeled around the existing Allardyce Nicol studio theatre, providing additional rehearsal spaces and changing and technical facilities. The ground floor lobby now incorporates a Starbucks coffee shop.[65] The name, Muirhead Tower, came from that of the first philosophy professor of the university John Henry Muirhead.[65][66][67]

Recently[when?] completed is a 450-seat concert hall, called the Bramall Music Building, which completes the redbrick semicircle of the Aston Webb building designed by Glenn Howells Architects with venue design by Acoustic Dimensions. This auditorium, with its associated research, teaching and rehearsal facilities, houses the Department of Music.[68] In August 2011 the university announced that architects Lifschutz Davidson Sandilands and S&P were appointed to develop a new Indoor Sports Centre as part of a £175 million investment in the campus.[needs update][69]

Other features

[edit]

In 1978, University station, on the Cross-City Line, was opened to serve the university and its hospital. It is the only university campus in mainland Britain with its own railway station.[citation needed] In 2021, construction began on a redeveloped facility adjacent to the existing structure as part of the West Midlands Rail Programme (WMRP).[70] The rebuilt station was completed and opened to the public in January 2024.[71] Nearby, the Steampipe Bridge, which was constructed in 2011, transports steam across the Cross-City Railway Line and Worcester & Birmingham Canal from the energy generation plant to the medical school as part of the university's sustainable energy strategy. Its laser-cut exterior is also a public art feature.[72]

Located within the Edgbaston site of the university is the Winterbourne Botanic Garden, a 24,000 square metre (258,000 square foot) Edwardian Arts and Crafts style garden. The large statue in the foreground was a gift to the university by its sculptor Sir Edward Paolozzi – the sculpture is named 'Faraday', and has an excerpt from the poem 'The Dry Salvages' by T. S. Eliot around its base.

The University of Birmingham operates the Lapworth Museum of Geology in the Aston Webb Building in Edgbaston. It is named after Charles Lapworth, a geologist who worked at Mason Science College.

Since November 2007, the university has been holding a farmers' market on the campus.[73] Birmingham is the first university in the country to have an accredited farmers' market.[74]

The considerable extent of the estate meant that by the end of the 1990s it was valued at £536 million.[75]

University of Birmingham marked its grand ending of Green Heart Project at the start of 2019.[76][77]

In 2021, the University opened a central-city meeting and conference site called The Exchange in the former Birmingham Municipal Bank in Centenary Square.[78]

Selly Oak campus

[edit]The university's Selly Oak campus is a short distance to the south of the main campus. It was the home of a federation of nine colleges, known as Selly Oak Colleges, mainly focused on theology, social work, and teacher training.[79] The Federation was for many years associated with the University of Birmingham. A new library, the Orchard Learning Resource Centre, was opened in 2001, shortly before the Federation ceased to exist. The OLRC is now one of Birmingham University's site libraries.[80] Among the Selly Oak Colleges was Westhill College, (later the University of Birmingham, Westhill), which merged with the university's School of Education in 2001.[81] In the following years most of the remaining colleges closed, leaving two colleges which continue today, Woodbrooke College, a study and conference centre for the Society of Friends, and Fircroft College, a small adult education college with residential provision. Woodbrooke College's Centre for Postgraduate Quaker Studies, established in 1998, works with the University of Birmingham to deliver research supervision for the degrees of MA by research and PhD.[82]

The Selly Oak campus is now home to the Department of Drama and Theatre Arts in the newly refurbished Selly Oak Colleges Old Library and George Cadbury Hall 200-seat theatre.[83] The UK daytime television show Doctors is filmed on this campus.[84] The University of Birmingham School occupies a brand new, purpose-built building located on the university's Selly Oak campus.[85] The University of Birmingham School is sponsored by the University of Birmingham and managed by an Academy Trust. The University of Birmingham School opened in September 2015.[86]

Mason College and Queen's College campus

[edit]

The Victorian neo-gothic Mason College Building in Birmingham city centre housed Birmingham University's Faculties of Arts and Law for over 50 years after the founding of the university in 1900. The Faculty of Arts building on the Edgbaston campus was not constructed until 1959–61. The Faculties of Arts and Law then moved to the Edgbaston campus.[87] The original Mason College Building was demolished in 1962 as part of the redevelopment within the inner ring road.

The 1843 Gothic Revival building constructed opposite the Town Hall between Paradise Street (the main entrance) and Swallow Street served as Queen's College, one of the founder colleges of the university. In 1904 the building was given a new buff-coloured terracotta and brick front. The medical and scientific departments merged with Mason College in 1900 to form the University of Birmingham and sought new premises in Edgbaston. The theological department of Queen's College did not merge with Mason College, but later moved in 1923 to Somerset Road in Edgbaston, next to the University of Birmingham as the Queen's Foundation, maintaining a relationship with the University of Birmingham until a 2010 review. In the mid 1970s, the original Queen's College building was demolished, with the exception of the grade II listed façade.

Dubai Campus

[edit]The university also has an affiliated Dubai campus established in 2017 at Dubai International Academic City (DIAC). They have since moved from the DIAC headquarters with the construction of a new campus in 2022 in the same area, inaugurated by the Dubai crown prince Hamdan Bin Mohammed Al Maktoum. The campus boasts of having all faculty flown in or permanently staffed from the UK campus.[88]

Organisation and administration

[edit]Academic departments

[edit]

Birmingham has departments covering a wide range of subjects. On 1 August 2008, the university's system was restructured into five 'colleges', which are composed of numerous 'schools':

- Arts and Law (English, Drama and Creative Studies; History and Cultures; Languages, Cultures, Art History and Music; Birmingham Law School; Philosophy, Theology and Religion)

- Engineering and Physical Sciences (Chemistry; Chemical Engineering; Computer Science; Engineering (comprising the Departments of civil, Mechanical and Electrical, Electronic & Systems Engineering); Mathematics; Metallurgy and Materials; Physics and Astronomy)

- Life and Environmental Sciences (Biosciences; Geography, Earth and Environmental Sciences; Psychology; Sport and Exercise Sciences)

- Medical and Dental Sciences (Institute of Cancer and Genomic Sciences; Institute of Clinical Sciences; Institute of Inflammation and Ageing; Institute of Applied Health Research; Institute of Cardiovascular Science; Institute of Immunology and Immunotherapy; Institute of Metabolism and Systems Research; Institute of Microbiology and Infection).

- Social Sciences (Birmingham Business School; Education; Government and Society; Social Policy)

- Liberal Arts and Sciences

The university is home to a number of research centres and schools, including the Birmingham Business School, the oldest business school in England, the University of Birmingham Medical School, the International Development Department, the Institute of Local Government Studies, the Centre of West African Studies, the Centre for Russian and East European Studies, the Centre of Excellence for Research in Computational Intelligence and Applications and the Shakespeare Institute. The Third Sector Research Centre was established in 2008,[89] and the Institute for Research into Superdiversity was established in 2013.[90] Apart from traditional research and PhDs, under the department of Engineering and Physical Sciences, the university offers split-site PhD in Computer Science.[91] The university is also home to the Birmingham Solar Oscillations Network (BiSON) which consists of a network of six remote solar observatories monitoring low-degree solar oscillation modes. It is operated by the High Resolution Optical Spectroscopy group of the School of Physics and Astronomy, funded by the Science and Technology Facilities Council (STFC).[92]

International Development Department

[edit]The International Development Department (IDD) is a multi-disciplinary academic department focused on poverty reduction through developing effective governance systems. The department is one of the leading UK centres for the postgraduate study of international development.[93] The department has been described as being a "highly regarded, long-established specialist unit" with a "global reputation" by The Independent.[94]

Off-campus establishments

[edit]

A number of the university's centres, schools and institutes are located away from its two campuses in Edgbaston and Selly Oak:

- The Shakespeare Institute, in Stratford-upon-Avon, which is a centre for postgraduate study dedicated to the study of William Shakespeare and the literature of the English Renaissance.

- The Ironbridge Institute, in Ironbridge, which offers postgraduate and professional development courses in heritage.

- The School of Dentistry (the UK's oldest dental school), in Birmingham City Centre.

- The Raymond Priestley Centre, near Coniston in the Lake District, which is used for outdoor pursuits and field work.[95]

There is also a Masonic Lodge that has been associated with the university since 1938.[96]

University of Birmingham Observatory

[edit]

In the early 1980s, the University of Birmingham constructed an observatory next to the university playing fields, approximately 5 miles (8.0 km) south of the Edgbaston campus. The site was chosen because the night sky was ~100 times darker than the skies above campus. First light was on 8 December 1982, and the Observatory was officially opened by the Astronomer Royal, Francis Graham-Smith, on 13 June 1984.[97] The observatory was upgraded in 2013.

The Observatory is used primarily for undergraduate teaching.[98] It has two main instruments, a 16" Cassegrain (working at f/19) and a 14" Meade LX200R (working at f/6.35). A third telescope is also present and is used exclusively for visual observations.

Members of the public are given chance to visit the Observatory at regular Astronomy in the City events during the winter months.[99] These events include a talk on the night sky from a member of the university's student Astronomical Society; a talk on current astrophysics research, such as exoplanets, galaxy clusters or gravitational-wave astronomy,[100] a question-and-answer session, and the chance to observing using telescopes both on campus and at the Observatory.

Branding

[edit]The original coat of arms was designed in 1900. It features a double headed lion (on the left) and a mermaid holding a mirror and comb (to the right). These symbols owe to the coat of arms of the institution's predecessor, Mason College.

In 2005 the university began rebranding itself. A simplified edition of the shield which had been introduced in the 1980s reverted to a detailed version based on how it appears on the university's original Royal Charter.

Academic profile

[edit]Libraries and collections

[edit]

Library Services operates six libraries. They are the Barber Fine Art Library, Barnes Library, Main Library, Orchard Learning Resource Centre, Dental Library, and the Shakespeare Institute Library. Library Services also operates the Cadbury Research Library.[101]

The Shakespeare Institute's library is a major United Kingdom resource for the study of English Renaissance literature.[102]

The Cadbury Research Library is home to the University of Birmingham's historic collections of rare books, manuscripts, archives, photographs and associated artefacts. The collections, which have been built up over a period of 120 years consist of over 200,000 rare printed books including significant incunabula, as well as over 4 million unique archive and manuscript collections.[103] The Cadbury Research Library is responsible for directly supporting the university's research, learning and teaching agenda, along with supporting the national and international research community.

The Cadbury Research Library contains the Chamberlain collection of papers from Neville Chamberlain, Joseph Chamberlain and Austen Chamberlain, the Avon Papers belonging to Anthony Eden with material on the Suez Crisis, the Cadbury Papers relating to the Cadbury firm from 1900 to 1960, the Mingana Collection of Middle Eastern Manuscripts of Alphonse Mingana, the Noël Coward Collection, the papers of Edward Elgar, Oswald Mosley, and David Lodge, and the records of the English YMCA and of the Church Missionary Society. The Cadbury Research Library has recently taken in the complete archive of UK Save the Children. The Library holds important first editions such as De Humani Corporis (1543) by Versalius, the Complete Works (1616) of Ben Jonson, two copies of The Temple of Flora (1799-1807) by Robert Thornton and comprehensive collections of the works of Joseph Priestley and D H Lawrence as well as many other significant works.

In 2015, a Quranic manuscript in the Mingana Collection was identified as one of the oldest to have survived, having been written between 568 and 645.[104][105]

At the beginning of the 2016/17 academic year, a new main library opened on the Edgbaston campus and the old library has now been demolished as part of the plans to create a 'Green Heart' as per the original plans for the university whereby the clock tower would be visible from the North Gate.[106][107] The Harding Law Library was closed and renovated to become the university's Translation and Interpreting Suite.

Medicine

[edit]

The University of Birmingham's medical school is one of the largest in Europe with well over 450 medical students being trained in each of the clinical years and over 1,000 teaching, research, technical and administrative staff [citation needed]. The school has centres of excellence in cancer, pharmacy, immunology, cardiovascular disease, neuroscience and endocrinology, and is renowned nationally and internationally for its research and developments in these fields.[108][better source needed] The medical school has close links with the NHS and works closely with 15 teaching hospitals and 50 primary care training practices in the West Midlands.

The University Hospital Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust is the main teaching hospital in the West Midlands. It has been given three stars for the past four consecutive years.[109]

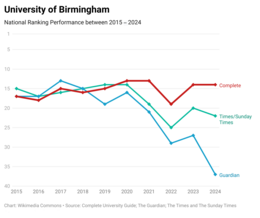

Rankings and reputation

[edit]| National rankings | |

|---|---|

| Complete (2025)[110] | 12= |

| Guardian (2024)[111] | 37 |

| Times / Sunday Times (2024)[112] | 22 |

| Global rankings | |

| ARWU (2023)[113] | 151–200 |

| QS (2025)[114] | 80= |

| THE (2024)[115] | 101 |

The 2022 U.S. News & World Report ranks Birmingham 91st in the world.[116] In 2019, it is ranked 137th among the universities around the world by SCImago Institutions Rankings.[117]

In 2021 the Times Higher Education placed Birmingham 12th in the UK.[118]

In 2013, Birmingham was named 'Sunday Times University of the Year 2014'.[119] The 2013 QS World University Rankings placed Birmingham University at 10th in the UK and 62nd internationally. Birmingham was ranked 12th in the UK in the 2008 Research Assessment Exercise with 16 per cent of the university's research regarded as world-leading and 41 per cent as internationally excellent, with particular strengths in the fields of music, physics, biosciences, computer science, mechanical engineering, political science, international relations and law.[120][121][122] Course satisfaction was at 85% in 2011 which grew to 88% in 2012.[123]

In 2015 the Complete University Guide placed Birmingham 5th in the UK for graduate prospects.[124]

Data from the Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE) placed the university amongst the twelve elite institutions who among them take more than half of the students with the highest A-level grades.[125]

Birmingham traditionally had a focus on science, engineering, commerce and coal mining, but has now expanded its provision. It hosted the first Cancer Research UK Centre,[126] and making notable contributions to gravitational-wave astronomy, hosting the Institute of Gravitational Wave Astronomy.[127]

The School of Computer Science ranked 1st in the 2014 Guardian University Guide,[128] 4th in the 2013 Sunday Times League Table and 6th in the 2014 Sunday Times League Table.[129]

The Department of Philosophy ranked 3rd in the 2017 Guardian University League Tables,[130] below the University of Oxford and above the University of Cambridge, with the first being the University of St Andrews.

The combined course of Computer Science and Information Systems, titled Computer Systems Engineering was ranked 4th in the 2016 Guardian University guide.[131]

The Department of Political Science and International Studies (POLSIS) ranked 4th in the UK and 22nd in the world in the Hix rankings of political science departments.[132] The sociology department also ranked 4th by The Guardian University guide. The Research Fortnight's University Power Ranking, based on quality and quantity of research activity, put the University of Birmingham 12th in the UK, leading the way across a broad range of disciplines including Primary Care, Cancer Studies, Psychology and Sport and Exercise Sciences.[133] The School of Physics and Astronomy also performed well in the rankings, being ranked 3rd in the 2012 Guardian University Guide[134] and 7th in The Complete University Guide 2012.[135] The School of Chemical Engineering is ranked second in the UK by the 2014 Guardian University Guide.[136]

Admissions

[edit]

|

In terms of the average UCAS points of entrants, Birmingham ranked 26th in Britain in 2021.[139] According to the 2017 Times and Sunday Times Good University Guide, approximately 20% of Birmingham's undergraduates come from independent schools.[144] In 2016, the university gave offers of admission to 79.2% of applicants, the 8th highest amongst the Russell Group.[145] In 2022, offers were given to 61.3% of undergraduate applicants, the 30th lowest offer rate across the country.[146]

In the 2016–17 academic year, the university had a domicile breakdown of 76:5:18 of UK:EU:non-EU students respectively, with a female to male ratio of 56:44.[147] 50.3% of international students enrolled at the institution are from China, the fourth highest proportion out of all mainstream universities in the UK.[148]

Birmingham Heroes

[edit]To highlight leading areas of research, the university has launched the Birmingham Heroes scheme. Academics who lead research that impacts on the lives of people regionally, nationally and globally can be nominated for selection.[149] Heroes include:

- Alberto Vecchio and Andreas Freise for their work as part of the LIGO Scientific Collaboration towards the first observation of gravitational waves[150]

- Martin Freer, Toby Peters and Yulong Ding for their work on energy efficient cooling[151]

- Philip Newsome, Thomas Solomon and Patricia Lalor for tackling the silent killers, liver disease and diabetes[152]

- James Arthur, Kristján Kristjánsson, Sandra Cooke and Tom Harrison for promoting character in education[153]

- Lisa Bortolotti, Ema Sullivan-Bissett and Michael Larkin for their work on how to break down the stigma associated with mental illness[154]

- Kate Thomas, Joe Alderman, Rima Dhillon and Shayan Ahmed for their research in and teaching of life sciences[155]

- Pam Kearns, Charlie Craddock and Paul Moss for cancer research[156]

- Anna Phillips, Glyn Humphreys and Janet Lord who research healthy ageing[157]

- Pierre Purseigle, Peter Gray and Bob Stone for using their historical knowledge to advise government organisations[158]

- Paul Bowen and Nick Green for research into new materials to improve energy generation[159]

- Lynne Macaskie, William Bloss and Jamie Lead for their study of pollutants, particularly nanoscale pollutants[160]

- Paul Jackson, Scott Lucas and Stefan Wolff for their work helping with post-conflict and advice on the application of aid[161]

- Hongming Xu, Clive Roberts and Roger Reed for work on sustainable transport[162]

- Moataz Attallah, Kiran Trehan and Tim Daffron for driving economic growth through improving aerospace engineering, developing enterprise and pioneering industrial applications of synthetic biology[163]

Birmingham Fellows

[edit]

The Birmingham Fellowship scheme was launched in 2011. The scheme encourages high potential early career researchers to establish themselves as rounded academics and continue pursuing their research interests. This scheme was the first of its kind, and has since been emulated in several other Russell Group universities across the UK.[164] Since 2014, the scheme has been divided into Birmingham Research Fellowships and Birmingham Teaching Fellowships. Birmingham Fellows are appointed to permanent academic posts (with two or three year probation periods), with five years protected time to develop their research.[165]

Birmingham Fellows are usually recruited at a lecturer or senior lecturer level. In the first period of the fellowship, emphasis is placed on the research aspect, publishing high quality academic outputs, developing a trajectory for their work and gaining external funding. However, development of teaching skills is encouraged.[165] Teaching and supervisory responsibilities, as well as administrative duties, then steadily increase to a normal lecturer's load in the Fellow's respective discipline by the fifth year of the fellowship. Birmingham Fellows are not expected to carry out academic administration during their term as Fellows, but will do once their posts turn into lectureships ('three-legged contract'). When accepted into the Birmingham Research Fellowship, Fellows receive a start-up package to develop or continue their research projects, an academic mentor and support for both research and teaching. All fellows are said to become part of the Birmingham Fellows Cohort, which provides them a university-wide network and an additional source of support and mentoring.[165]

International cooperation

[edit]In Germany the University of Birmingham cooperates with the Goethe University Frankfurt. Both cities are linked by a long-lasting partnership agreement.

Student life

[edit]Guild of Students

[edit]

The University of Birmingham Guild of Students is the university's student union. Originally the Guild of Undergraduates, the institution had its first foundations in the Mason Science College in the centre of Birmingham around 1876. The University of Birmingham itself formally received its Royal Charter in 1900 with the Guild of Students being provided for as a Student Representative Council.[166] It is not known for certain why the name 'Guild of Students' was chosen as opposed to 'Union of Students'; however, the Guild shares its name with Liverpool Guild of Students, another 'redbrick university'; both organisations subsequently founded the National Union of Students. The Union Building, the Guild's bricks and mortar presence, was designed by the architect Holland W. Hobbiss.

The Guild's official purposes are to represent its members and provide a means of socialising, though societies and general amenities. The university provides the Guild with the Union Building effectively rent free as well as a block grant to support student services. The Guild also runs several bars, eateries, social spaces and social events.

The Guild supports a variety of student societies and volunteering projects, roughly around 220 at any one time. The Guild complements these societies and volunteering projects with professional staffed services, including its walk-in Advice and Representation Centre (ARC), Student Activities, Jobs/Skills/Volunteering, Student Mentors in halls, and Community Wardens around Bournbrook.[167] The Guild of Students was where the student volunteering charity InterVol was conceived and developed as a student-led volunteering project in the early 2000s; the project links students will local volunteering opportunities as well as placements with charitable partners overseas.[168][169] Another two of the Guild's long-standing societies are Student Advice and Nightline (previously Niteline), which both provide peer-to-peer welfare support. The Guild was one of the first universities in the United Kingdom to publish a campus newspaper, Redbrick, supported financially by the Guild of Students and advertising revenue.[170]

The Guild undertakes its representative function through its officer group, seven of whom are full-time, on sabbatical from their studies, and ten of whom are part-time and hold their positions whilst still studying. Elections are held yearly, conventionally February, for the following academic year. These officers have regular contact with the university's officer-holders and managers. In theory, the Guild's officers are directed and kept to account over their year in office by Guild Council, an 80-seat decision-making body. The Guild also supports the university "student reps" scheme, which aims to provide an effective channel of feedback from students on more of a departmental level.

Sport

[edit]This section's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. (March 2021) |

This section contains content that is written like an advertisement. (March 2021) |

В мае 2017 года Бирмингемский университет открыл спортивно-фитнес-центр, включающий тренажерный зал, корты для сквоша, 50- метровый бассейн и стену для скалолазания. Университет располагает двумя хоккейными полями международного стандарта, построенными в 2017 году. [171] гибкие поля 3G, которые можно использовать для игры в футбол с участием 5 и 11 игроков, а также корты для нетбола и тенниса, а также 400-метровую легкоатлетическую дорожку на Эджбастон-Парк-роуд. [172]

По состоянию на 2019 год университет занимает седьмое место в британских университетов и колледжей . спортивной лиге [173]

Университет Бирмингема Спорт предлагает широкий спектр соревновательных и коллективных видов спорта как для студентов, так и для местного сообщества. Услуги включают 180 занятий фитнесом в неделю, 56 различных спортивных клубов, включая греблю, баскетбол, крикет, футбол, регби, нетбол, хоккей на траве, хоккей с шайбой, американский футбол и триатлон. Благодаря широкому выбору в университете ежегодно занимаются спортом более 4000 студентов. В 1981 году университет также открыл Центр Раймонда Пристли на берегу Конистон-Уотер в Озерном крае, предлагая студентам, сотрудникам и сообществу исследовать возможности активного отдыха и обучения в этом районе.

Сэр Рэймонд Пристли, вице-канцлер университета в 1938 году, и его директор по спорту А.Д. Манроу помогли открыть первые курсы физического воспитания для студентов в 1946 году, развили их спортивные сооружения, начиная с гимназии в 1939 году, и приняли участие в развлекательных мероприятиях. спорт был обязательным для всех новых студентов с 1940 по 1968 год. Бирмингем стал первым британским университетом, предлагающим спортивную степень.

Студенты и выпускники Бирмингемского университета участвовали в Олимпийских, Паралимпийских играх и Играх Содружества. В 2004 году шесть выпускников и один студент участвовали в летних Олимпийских играх 2004 года в Афинах , а четыре выпускника участвовали в Олимпийских играх 2008 года в Пекине , включая велосипедиста Пола Мэннинга, выигравшего олимпийское золото. [174] В 2012 году Памела Релф, MBE, входила в состав смешанной четверки с рулевым, выигравшей паралимпийское золото, и успешно защитила свой титул в Рио: единственная действующая международная пара-гребец, двукратная чемпионка Паралимпийских игр.

В Играх Содружества 2018 года в Голд-Косте, Австралия, приняли участие шесть студентов и восемнадцать выпускников, которые представляли Англию, Шотландию, Уэльс и Гернси и соревновались в таких видах спорта, как хоккей, бег на 1500 метров, бадминтон и велоспорт. [175]

университет принимал сборную Ямайки по легкой атлетике Перед Олимпийскими играми в Лондоне в 2012 году . Команда, в которую входит самый быстрый человек в мире Усэйн Болт, который стал первым человеком в истории, защитившим свои титулы на дистанциях 100 и 200 метров на Олимпийских играх, выиграла командное золото в беге 4х400 м вместе с Нестой Картер, Йоханом Блейком и Майклом. Брат. Шелли-Энн Фрейзер-Прайс выиграла золото на дистанции 100 метров среди женщин. Команда вернулась в университет в 2017 году, чтобы подготовиться к чемпионату Лондона в закрытых помещениях, остановившись в Чемберлен-холле в Вейл-Виллидж и используя недавно созданные спортивные и фитнес-центры и легкоатлетическую дорожку.

С тех пор Университет Бирмингема Спорт принимал ряд международных команд; команды Австралии и Южной Африки перед мужским чемпионатом мира по регби в 2015 году, команды Ямайки, Англии и Новой Зеландии по нетболу перед Кубком Vitality Nations в январе 2020 года и 19 стран в индивидуальных соревнованиях на чемпионате мира по сквошу среди университетов в 2018 году.

Бирмингем был выбран местом проведения Игр Содружества 2022 года, а университет был выбран местом проведения игр по хоккею и сквошу из-за способности существующих объектов проводить игры, при этом необходимо построить только временные конструкции для сидения, освещения и трансляции. . Университет был крупнейшей спортивной деревней во время игр, принимая 3500 спортсменов на теннисных кортах и в долине, а университет был официальным местом тренировок как по плаванию, так и по легкой атлетике. [176]

Университет Бирмингема Спорт также предлагает около 30 стипендий и стипендий национальным и иностранным студентам с исключительными спортивными способностями. [177]

Жилье

[ редактировать ]Университет предоставляет жилье большинству студентов-первокурсников, используя схему гарантий для всех тех абитуриентов из Великобритании, которые выбирают Бирмингем в качестве своего твердого выбора UCAS. 90 процентов жилья, предоставляемого университетом, проживают студенты-первокурсники. [178]

В университете существовали залы, разделенные по признаку пола, до начала 1998-99 учебного года, когда «залы» Лейк и Уиддрингтон (рассматриваемые как два разных зала, несмотря на то, что физически это одно здание) были переименованы в Шеклтон-холл. Чемберлен-холл (Иденская башня), семнадцатиэтажный многоэтажный дом, первоначально был известен как Высокий зал для студентов-мужчин и соединенный с ним Ридж-холл (позже переименованный в Хэмптонское крыло) для студенток. Университетский дом был выведен из эксплуатации как помещение для размещения расширяющейся бизнес-школы, а Мейсон-холл был снесен и перестроен и открылся в 2008 году. [ нужна ссылка ] Летом 2006 года университет продал три своих самых отдаленных зала (Хантер Корт, Бичес и Квинс Больница Клоуз) частным операторам, а позже в том же году и во время семестра университет был вынужден срочно вывести из эксплуатации оба старых здания Чемберлена. Башня (Высокий зал), а также Усадьба из-за сбоев проверки пожарной безопасности. [ нужна ссылка ] Университет переименовал свои залы в три деревни. [ нужна ссылка ]

Вейл-Виллидж

[ редактировать ]

Деревня Вейл включает в себя Чемберлен-холл, Шеклтон, Мэйпл-Бэнк, Теннисный корт, Элгар-Корт и резиденции Эйткен. Шестой общежитие, Мейсон-Холл, вновь открылось в сентябре 2008 года после полной реконструкции. В селе проживает около 2700 студентов. [179]

Шеклтон-холл (первоначально Лейк-холл для студентов-мужчин и Уиддрингтон-холл для студенток) подвергся ремонту стоимостью 11 миллионов фунтов стерлингов и был вновь открыт осенью 2004 года. Всего в нем проживают 72 квартиры, в которых проживают 350 студентов. Большинство квартир состоят из шести-восьми спален, а также небольшого количества студий/квартир с одной, двумя, тремя или пятью спальнями. [180] Реконструкция была спроектирована архитектором из Бирмингема Патриком Николлсом, когда он работал в Aedas, а сейчас является директором Glancy Nicholls Architects. [181]

Maple Bank был отремонтирован и открыт летом 2005 года. Он состоит из 87 квартир с пятью спальнями, в которых проживают 435 студентов. [182]

Резиденция Elgar Court состоит из 40 квартир с шестью спальнями, в которых проживают в общей сложности 236 студентов. [183] Он открылся в сентябре 2003 года.

Теннисный корт состоит из 138 квартир с тремя, четырьмя, пятью и шестью спальнями и вмещает 697 студентов. [184]

Крыло Эйткен представляет собой небольшой комплекс, состоящий из 23 квартир с шестью и восемью спальнями. Здесь обучаются 147 студентов. [185]

Строительство нового Мейсон-холла началось в июне 2006 года после полного сноса первоначальных построек 1960-х годов. Его спроектировала компания Aedas Architects. Предполагается, что весь проект обошелся в 36,75 миллиона фунтов стерлингов. [186] С тех пор он был завершен, и в сентябре 2008 года студенты первого курса переехали.

Новая Башня Чемберлена и соседние малоэтажные кварталы открылись в сентябре 2015 года. В Чемберлене учатся более 700 студентов-первокурсников. Он заменил старый, построенный в 1964 году 18-этажный (над уровнем земли) Высокий зал (позже переименованный в Eden Tower) для студентов-мужчин и невысокий Ridge Hall (позже переименованный в Hampton Wing) для студенток, который закрылся в 2006 году. летняя башня Eden Tower была снесена в начале 2014 года. Ранее известная как High Hall, башня и связанные с ней малоэтажные блоки были снесены после того, как исследования показали, что их ремонт будет неэкономичен и не обеспечит качество проживания, которое обеспечивает университет. желаний Бирмингема для студентов.

крупнейшее студенческое мероприятие, фестиваль Вейл Ежегодно в Долине проводится или «ВалеФест». В 2014 году фестиваль отпраздновал свое 10-е мероприятие, собрав 25 000 фунтов стерлингов на благотворительность. Хедлайнерами мероприятия 2019 года выступили The Hunna и Saint Raymond.

Притчаттс Парк Виллидж

[ редактировать ]

В деревне Притчаттс-Парк обучается более 700 студентов и аспирантов. Залы включают «Эшкрофт», «Спинни» и «Оукли Корт», а также «Дом Притчаттс» и «Дома Притчаттс Роуд». [187]

Спинни представляет собой небольшой комплекс из шести домов и двенадцати небольших квартир, в котором в общей сложности проживают 104 студента. [188] Эшкрофт состоит из четырех специально построенных многоквартирных домов, в которых проживают 198 студентов. [189] Четырехэтажный Дом Притчаттса состоит из 24 двухуровневых квартир и вмещает 159 студентов. [190] Oakley Court состоит из 21 индивидуально построенной квартиры размером от пяти до тринадцати спален. Также включены 36 дуплексных квартир. Всего в Окли-Корт проживают 213 студентов, состоящих из студентов. [191] Окли-Корт был построен в 1993 году и обошелся в 2,9 миллиона фунтов стерлингов. Его спроектировала компания Associated Architects из Бирмингема . [192] Притчаттс-роуд представляет собой группу из четырех частных домов, переоборудованных в студенческие общежития. В доме максимум 16 спален. [193]

Селли-Оук-Виллидж

[ редактировать ]

Селли-Оук-Виллидж состоит из трех резиденций в районах Селли-Оук и Борнбрук : Джаррат-Холл, который принадлежит университету, Дупер-Холл и Металлургический завод. По состоянию на 2008 год в селе было 637 коек для студентов. [194]

Джарратт Холл — это большой комплекс, спроектированный вокруг центрального двора и трех ландшафтных зон. По состоянию на 2012 год здесь обучалось 587 студентов бакалавриата. [195] Джарратт-холл не принимал аспирантов до сентября 2013 года из-за продолжающегося ремонта кухонь и системы отопления. [196]

Усадебный дом, Нортфилд

[ редактировать ]

Университету Бирмингема также принадлежит особняк Нортфилд , который приобрел его у семьи Кэдбери в 1953 году. Это здание использовалось в качестве студенческого общежития до 2007 года, когда выяснилось, что залы нуждаются в реставрации и ремонте. Однако в 2014 году поджигатели устроили пожар, в результате которого была уничтожена большая часть имущества. С тех пор Бирмингемский университет перестроил и отреставрировал это здание, а также превратил большую часть территории в квартиры. [197]

Жилье студенческого жилищного кооператива

[ редактировать ]Студенческий жилищный кооператив Бирмингема был открыт в 2014 году студентами университета для обеспечения своих членов доступным самоуправляемым жильем. Кооператив управляет недвижимостью на Першор-роуд в Селли-Оук. [ нужна ссылка ]

Известные люди

[ редактировать ]академики

[ редактировать ]

В число преподавателей и сотрудников, связанных с университетом, входят лауреаты Нобелевской премии сэр Норман Хаворт (профессор химии, 1925–1948 гг.), [198] Сэр Питер Медавар (мейсонский профессор зоологии, 1947–1951), [29] Джон Роберт Шриффер (сотрудник Национального научного фонда в Бирмингеме, 1957 г.), [199] Дэвид Таулесс , Майкл Костерлиц , [200] и сэр Фрейзер Стоддарт . [201]

В число физиков входят Джон Генри Пойнтинг , Фримен Дайсон , сэр Отто Фриш , сэр Рудольф Пайерлс , сэр Маркус Олифант , сэр Леонард Хаксли , Гарри Бут , сэр Джон Рэндалл и Эдвин Эрнест Солпитер . В число химиков входит сэр Уильям А. Тилден . Математики включают Джонатан Беннетт , Генри Дэниелс , Даниэла Кюн , Дерик Остус , Дэниел Педо и Дж. Н. Уотсон . Среди преподавателей музыки — композиторы сэр Эдвард Элгар и сэр Грэнвилл Банток . В число геологов входят Чарльз Лэпворт , Фредерик Шоттон и сэр Алвин Уильямс . Среди преподавателей медицины — сэр Мелвилл Арнотт и сэр Бертрам Виндл . В число биологов входят Уильям Хиллхаус и Джордж Стивен Уэст , оба профессора ботаники Мейсона.

Писатель и литературный критик Дэвид Лодж преподавал английский язык с 1960 по 1987 год. Поэт и драматург Луи Макнис читал лекции по классической литературе в 1930–1936 годах. Английский писатель, критик и литератор Энтони Берджесс преподавал на заочном отделении (1946–50). [202] Ричард Хоггарт основал Центр исследований современной культуры . Сэр Алан Уолтерс был профессором эконометрики и статистики (1951–68), а затем стал главным экономическим советником премьер-министра Маргарет Тэтчер. Лорд Цукерман был профессором анатомии в 1946–1968 годах, а также занимал пост главного научного советника британского правительства с 1964 по 1971 год. Лорд Кинг Лотбери был профессором коммерческого факультета, а затем стал управляющим Банка Англии . Сэр Уильям Джеймс Эшли был первым деканом и основателем Бирмингемской школы бизнеса.

Сэр Натан Бодингтон был профессором классической литературы. Сэр Майкл Лайонс был профессором государственной политики с 2001 по 2006 год. Сэр Кеннет Мэзер был профессором генетики (1948 г.) и лауреатом Дарвина медали 1964 г. Сэр Ричард Редмэйн был профессором горного дела, а позже стал первым главным инспектором горной промышленности. Историк искусства сэр Николаус Певснер занимал исследовательскую должность в университете. Сэр Эллис Уотерхаус был профессором изящных искусств Барбера (1952–1970). Лорд Кэдман преподавал нефтяную инженерию, и ему приписывают создание курса «Нефтяная инженерия». Философ сэр Майкл Даммит работал ассистентом лектора в университете. Лорд Борри был профессором права и деканом юридического факультета. Сэр Чарльз Рэймонд Бизли был профессором истории. Тюремная реформаторка Марджери Фрай была первым надзирателем Университетского дома . [203]

В число вице-канцлеров и директоров входят сэр Оливер Лодж , лорд Хантер Ньюингтонский , сэр Чарльз Грант Робертсон , сэр Рэймонд Пристли и сэр Майкл Стерлинг .

Выпускники

[ редактировать ]

Четыре лауреата Нобелевской премии — выпускники Бирмингемского университета: Фрэнсис Астон , Морис Уилкинс , сэр Джон Вейн и сэр Пол Нерс . [198] Кроме того, почвовед Питер Буллок внес свой вклад в доклады МГЭИК , которая была удостоена Нобелевской премии мира в 2007 году . [204]

Среди выпускников университета, работающих в сфере британского правительства и политики: премьер-министры Великобритании Стэнли Болдуин и Невилл Чемберлен ; [14] главный министр Гибралтара Джо Боссано ; член кабинета министров Великобритании и заместитель генерального секретаря ООН баронесса Амос ; министры кабинета министров Джулиан Смит и Хилари Армстронг ; британские государственные министры Энн Уиддекомб , Ричард Трейси , Дерек Фатчетт и Анна Субри ; Верховный комиссар Великобритании в Новой Зеландии и посол в Южной Африке сэр Дэвид Обри Скотт ; губернатор островов Тёркс и Кайкос Найджел Дакин ; министр правительства Ассамблеи Уэльса Джейн Дэвидсон ; и инспектор ООН по вооружениям Дэвид Келли .

Среди выпускников Бирмингема, работающих в области государственного управления и политики в других странах, - премьер-министр Сент-Люсии Кенни Энтони ; премьер-министр Багамских островов Перри Кристи ; министр финансов Сингапура Ху Цу Тау Ричард ; старший государственный министр Сингапура Маттиас Яо ; министр обороны Кении Мохамед Юсуф Хаджи ; министр Танзании Марк Мвандося ; министр Тонги Ана Тауфеулунгаки ; министр кабинета министров Эфиопии Джундин Садо ; заместитель премьер-министра Маврикия Рашид Бибиджаун ; Саудовский министр Абдулазиз бин Мохиеддин Ходжа ; министр иностранных дел Гамбии Бала Гарба Джахумпа ; министр Ганы Джулиана Азумах-Менса ; министр Египта Уильям Селим Ханна ; Нигерийский министр Эммануэль Чука Осаммор ; министр Сент-Люсии Альвина Рейнольдс ; министр иностранных дел Ливана Люсьен Дахда ; Президент Замбии Хакаинде Хичилема и министры Зимбабве Давид Кариманзира и Дидимус Мутаса .

Среди выпускников в мире бизнеса: директор Банка Англии лорд Ролл из Ипсдена ; генеральный директор J Sainsbury plc Майк Куп ; председатель Shell Transport and Trading Company plc сэр Джон Дженнингс ; руководитель автомобильной компании сэр Джордж Тернбулл ; президент Конфедерации британской промышленности сэр Клайв Томпсон ; генеральный директор и председатель BP сэр Питер Уолтерс ; председатель British Aerospace сэр Остин Пирс ; предприниматель мобильной связи Мо Ибрагим ; модельер и продавец Джордж Дэвис ; основатель Osborne Computer Corporation Адам Осборн ; и председатель и главный исполнительный директор Bass plc сэр Ян Проссер .

Среди выпускников, работающих в юридической сфере, - главный судья Апелляционного суда последней инстанции Гонконга Джеффри Ма Тао-ли ; судья Апелляционного суда последней инстанции Гонконга Роберт Тан ; судья апелляционного суда Танзании Роберт Кисанга ; судья Верховного суда Белиза Мишель Арана ; Апелляционный лорд-судья сэр Филип Оттон ; и судьи Высокого суда дама Никола Дэвис , сэр Майкл Дэвис , сэр Генри Глоуб и дама Люси Тайс .

Среди выпускников вооруженных сил - начальник Генерального штаба генерал сэр Майк Джексон ; и генеральный директор медицинской службы армии Алан Хоули .

В число выпускников в сфере религии входят митрополит архиепископ и предстоятель Англиканской церкви в Юго-Восточной Азии Болли Лапок ; англиканские епископы Пол Байес , Алан Смит , Стивен Веннер , Майкл Лэнгриш и Эбер Пристли ; Англиканские епископы-суфражисты Брайан Касл и Колин Докер ; Католический архиепископ Кевин Макдональд ; и католический епископ Филип Иган .

Среди выпускников в области здравоохранения: председатель Национального института клинического мастерства Дэвид Хаслам ; Дама Хильда Ллойд , первая женщина, избранная президентом Королевского колледжа акушеров и гинекологов; главный научный сотрудник Национальной службы здравоохранения Сью Хилл ; главный стоматолог в Англии Барри Кокрофт ; и главный медицинский директор Англии сэр Лиам Дональдсон .

Среди выпускников в области инженерии: председатель Управления по атомной энергии Соединенного Королевства и Центрального совета по производству электроэнергии лорд Маршалл Геринг ; председатель British Aerospace сэр Остин Пирс ; Главный инженер PWD Shaef во время Второй мировой войны сэр Фрэнсис Маклин ; и директор по производству Министерства боеприпасов во время Первой мировой войны сэр Генри Фаулер .

Среди выпускников творческих индустрий актеры Мадлен Кэрролл , Тим Карри , Тэмсин Грейг , Мэтью Гуд , Найджел Линдси , Эллиот Коуэн , Джеффри Хатчингс , Джуди Ло , Джейн Ваймарк , Мэрайя Гейл , Хэдли Фрейзер , Элизабет Хенстридж и Норман Пейнтинг ; актеры и комики Виктория Вуд и Крис Аддисон ; танцовщица/хореограф и соавтор «Riverdance» Джин Батлер , влиятельная личность в социальных сетях и ютубер Ханна Уиттон , детский писатель и ученый Фавзия Гилани-Уильямс , автор Полли Хо-Йен , музыканты Саймон Ле Бон из Duran Duran и Кристин МакВи из Fleetwood Mac и писатель-путешественник Алан Бут .

Среди выпускников академических кругов: проректоры университета Фрэнк Хортон , сэр Роберт Хаусон Пикард , сэр Луи Мэтисон , Дерек Берк , сэр Алекс Джарратт , сэр Филип Бакстер , Винсент Уоттс , П. Б. Шарма , Беррик Сол и Вахид Омар ; нейробиолог и почетный профессор Кембриджского университета сэр Габриэль Хорн , врачи сэр Александр Маркхэм , сэр Гилберт Барлинг , Брайан МакМахон , Аарон Валеро и сэр Артур Томсон ; невролог сэр Майкл Оуэн ; физики Джон Стюарт Белл , сэр Алан Коттрелл , Лорд Флауэрс , Гарри Бут , Эллиот Х. Либ (лауреат премии Анри Пуанкаре 2003 года ), Стэнли Мандельштам , Эдвин Эрнест Солпитер (лауреат премии Крафорда в области астрономии 1997 года), сэр Эрнест Уильям Титтертон и Раймонд Уилсон (лауреат премии Кавли в области астрофизики 2010 г.); статистик Питер МакКаллах ; химик сэр Роберт Хаусон Пикард ; биологи сэр Кеннет Мюррей и леди Норин Мюррей ; зоологи Десмонд Моррис и Карл Шукер ; поведенческий нейробиолог Барри Эверитт ; палеонтолог Гарри Б. Уиттингтон ; учёный-компьютерщик Майк Коулишоу ; Академик женского письма Лорна Сейдж ; философ Джон Льюис ; экономист и историк Хома Катузян ; теолог и биохимик Артур Пикок ; экономист по вопросам труда Дэвид Бланчфлауэр ; профессор социальной политики Лондонской школы экономики сэр Джон Хиллс ; географ Джеффри Дж. Д. Хьюингс ; профессор геологии и девятый президент Корнелльского университета Фрэнк Х.Т. Роудс ; главный научный советник правительства сэр Алан Коттрелл ; и бывший астронавт Родольфо Нери Вела .

Выпускников в мире спорта много. Среди них Лиза Клейтон , первая женщина, совершившая кругосветное путешествие в одиночку; бегунья на 400 метров Эллисон Кербишли , завоевавшая серебро на Играх Содружества 1998 года ; командного преследования велосипедист Пол Мэннинг , завоевавший бронзу, серебро и золото на Олимпийских играх 2004, 2008 и 2012 годов; спортивный ученый Иззи Кристиансен , которая играла в футбол за «Бирмингем Сити», «Эвертон» и «Манчестер Сити» до того, как ее призвали в высшую сборную Англии; игрок в крикет из Уорикшира и Англии Джим Тротон ; и Адам Пенджилли , который выступал в качестве скелетониста на 2006 и зимних Олимпийских играх 2010 годов и был избран в Комиссию спортсменов Международного олимпийского комитета в 2010 году. [205]

Триатлонистки Крисси Веллингтон и Рэйчел Джойс выиграли чемпионат мира ITU на длинные дистанции в 2008 и 2011 годах, а Крисси показывает четыре лучших результата в мировых соревнованиях Ironman. В 2009 году она получила Орден Британской империи, а нынешний тренажерный зал мирового класса в спортивном и фитнес-клубе на территории кампуса назван в ее честь.

Еще учась в университете, студентка Лили Оусли забила гол, завоевавший золотую медаль по хоккею на траве на Олимпийских играх в Рио в 2016 году с помощью своей товарища по команде и выпускницы UoB Софи Брэй .

Спортсменка на средней дистанции Ханна Ингланд выиграла серебро чемпионата мира на дистанции 1500 метров в 2011 году. [206] и после официального ухода из легкой атлетики в 2019 году работал вместе со своим коллегой-спортсменом и мужем Люком Ганном на спортивном факультете университета. [207]

В последние годы в Бирмингеме видели таких ученых, как спортсмены Джонни Дэвис , чемпион Великобритании 2020 года в закрытых помещениях на дистанции 3000 метров; Сара Макдональд, бывшая чемпионка Великобритании в беге на 1500 метров, и Мари Смит, действующая серебряная медалистка Великобритании в закрытых помещениях на дистанции 800 метров, проходят через двери. Фрэн Уильямс, старший игрок сборной Англии по нетболу, выиграла бронзу с командой England Roses на чемпионате мира по нетболу Vitality в Ливерпуле в 2019 году, будучи самым молодым игроком в команде в возрасте 22 лет, и Лора Китс, игрок сборной Англии по регби, которая была частью сборной Англии. Команда-победитель чемпионата мира 2014 года. [ нужна ссылка ]

Барбара Слейтер, дочь легенды «Вулверхэмптона Уондерер» и спортивного директора UoB в 1972 году Билла Слейтера, стала директором BBC Sport с 2009 года и была первой женщиной, удостоившейся этого титула. Она вела трансляцию Олимпийских игр 2012 года в Лондоне – крупнейшего телевизионного события в истории британского телевещания. Бывший исполнительный директор «Манчестер Юнайтед» Дэвид Гилл изучил основы финансирования в Бирмингеме, изучая промышленные, экономические и бизнес-исследования в 1978 году; спортивный комментатор Саймон Бразертон сделал свою карьеру во время учебы в UoB, а сэр Патрик Хед, основатель команды Williams, которая доминировала в Формуле-1 в 1990-х годах, изучал машиностроение. [ нужна ссылка ]

По всем дисциплинам Джон Крэбтри , получивший юридический факультет в 1972 году, добился успеха как юрист и бизнесмен, был награжден Орденом Британской империи за свою благотворительную деятельность, занимал должности верховного шерифа Уэст-Мидлендса и лорда-лейтенанта Уэст-Мидлендса , а также председателя член организационного комитета Игр Содружества в Бирмингеме 2022 года . [208]

См. также

[ редактировать ]- Гербовник университетов Великобритании

- Список современных университетов Европы (1801–1945 гг.)

- Список университетов Соединенного Королевства

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- Примечания

- ^ Включает тех, кто указывает, что они идентифицируют себя как азиаты , чернокожие , смешанного происхождения , арабы или представители любой другой этнической принадлежности, кроме белых.

- ^ Рассчитано на основе измерения Polar4 с использованием Quintile1 в Англии и Уэльсе. Рассчитано на основе Шотландского индекса множественной депривации (SIMD) с использованием SIMD20 в Шотландии.

- ^ Айвс и др. 2000, с. 238.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с «Мейсон Колледж» . Бирмингемский университет. Архивировано из оригинала 25 декабря 2018 года . Проверено 9 октября 2014 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Айвс и др. 2000, с. 12.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с «Финансовая отчетность за год до 31 июля 2023 г.» (PDF) . Университет Бирмингема. п. 55 . Проверено 15 декабря 2023 г.

- ^ «Лорд Билимория назначен ректором Бирмингемского университета» . Университет Бирмингема. 18 июля 2014 года . Проверено 8 августа 2014 г.

- ^ «Кто работает в HE?» . www.hesa.ac.uk.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с «Где учатся студенты ВО? | HESA» . www.hesa.ac.uk.

- ^ Кертис, Полли (29 июля 2005 г.). «В Бирмингемском университете размещаются жертвы торнадо» . Хранитель . Лондон . Проверено 28 марта 2010 г.

- ^ Боуден, Анна (11 февраля 2005 г.). «Студенты-мусульмане угрожают подать в суд на Бирмингемский университет» . Хранитель . Лондон . Проверено 28 марта 2010 г.

- ^ Уайт, Уильям (16 января 2015 г.). Redbrick: Социальная и архитектурная история британских гражданских университетов . ISBN 978-0-19-102522-8 .

- ↑ Путеводитель по университету 2014: Бирмингемский университет , The Guardian , 8 июня 2008 г. Проверено 11 июня 2010 г.

- ^ «REF 2021: Золотой треугольник, похоже, потеряет долю финансирования» . Высшее образование Таймс . 12 мая 2022 г. Проверено 15 мая 2022 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «25 самых высоких башен с часами/правительственных сооружений/дворцов» (PDF) . Совет по высотным зданиям и городской среде обитания. Январь 2008 г. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 30 октября 2008 г. . Проверено 9 августа 2008 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б К. Фейлинг, Жизнь Невилла Чемберлена (Лондон, 1970), 11–12.

- ^ «Наши нобелевские лауреаты» . Университет Бирмингема. Архивировано из оригинала 9 августа 2018 года . Проверено 5 октября 2016 г.

- ^ «История медицинской школы Бирмингемского университета, 1825–2001 гг.» . Университет Бирмингема .

- ^ Госден, Питер. «От окружного колледжа до гражданского университета, Лидс, 1904 год», Northern History 42.2 (2005): 317–328. Академический поиск Премьер , Интернет. 12 ноября 2014 г.

- ^ «Сказка русалки: истоки университетского герба» . Научно-исследовательские и культурные коллекции . Университет Бирмингема . Проверено 28 апреля 2021 г.

- ^ Кейт Андертон, slevenotes, Банток: Гебридская симфония , Наксос 8.555473, 1989.

- ^ «Исследовательская библиотека Кэдбери – специальные коллекции» . Университет Бирмингема.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Наше влияние» (PDF) . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 11 сентября 2014 года . Проверено 18 октября 2014 г.

- ^ Макнейр, Филип (январь 1977 г.). «Линетта де Кастельвеккьо Ричардсон». Итальянские исследования . 32 (1). Общество итальянских исследований: 1–3. дои : 10.1179/its.1977.32.1.1 .

- ^ Тейлор, Сара. «Линетта Ричардсон (1880–1975)» . Думбартон Оукс . Проверено 4 февраля 2022 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и Хикман, Дуглас (1970). Бирмингем . Студия Виста Лимитед.

- ^ Айвс и др. 2000, с. 342.

- ^ Айвс и др. 2000, с. 343.

- ^ «Норман Хаворт - Биографический» . Нобелевская премия . Проверено 15 августа 2014 г.

- ^ Браун, Лори М.; Дрезден, Макс; Ходдесон, Лилиан (1989). От пионов к кваркам: физика элементарных частиц в 1950-е годы: на основе симпозиума Фермилаб . Издательство Кембриджского университета. стр. 167–9. ISBN 0-521-30984-0 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Питер Медавар - Биографический» . Нобелевская премия . Проверено 15 июля 2014 г.

- ^ Харрис, Тилли (22 марта 2001 г.). «Aston выходит из переговоров о слиянии с Бирмингемом» . Хранитель .

- ^ «Университет Бирмингема проведет заключительные дебаты премьер-министра» . Университет Бирмингема. 29 апреля 2010 г. Проверено 29 апреля 2010 г.

- ^ «Поле битвы готово к финальным дебатам премьер-министра» . Новости Би-би-си. 29 апреля 2010 г. Проверено 29 апреля 2010 г.