Сталинградская битва

| Сталинградская битва | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Часть Восточного фронта . Второй мировой войны | |||||||||

Clockwise from top-left:

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Units involved | |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

During the Axis offensive:

During the Soviet counter-offensive: |

During the Axis offensive:

During the Soviet counter-offensive: | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

See casualties section. | ||||||||

| Total dead: 1,100,000–3,000,000+[23][24][25][20][26] | |||||||||

битва Сталинградская [ Примечание 8 ] (17 июля 1942 г. - 2 февраля 1943 г.) [ 27 ] [ 28 ] [ 29 ] [ 30 ] Это было крупное сражение на Восточном фронте , Второй мировой войны начавшееся с нападения нацистской Германии и ее союзников по Оси и втянутых в длительную борьбу с Советским Союзом за контроль над советским городом Сталинградом на юге России . Битва характеризовалась ожесточенным ближним боем и прямыми нападениями на мирное население в результате воздушных налетов; битва олицетворяла городскую войну , [ 31 ] [ 32 ] [ 33 ] [ 34 ] Это крупнейшее и самое дорогостоящее городское сражение в военной истории . [ 35 ] [ 36 ] Это была самая кровавая и жестокая битва за всю Вторую мировую войну – и, возможно, за всю историю человечества – поскольку обе стороны понесли огромные потери в ходе ожесточенных боев в городе и вокруг него. [ 37 ] [ 38 ] [ 39 ] [ 40 ] [ 41 ] Сегодня Сталинградскую битву принято считать поворотным моментом на европейском театре Второй мировой войны . [42] поскольку немецкое верховное командование вермахта было вынуждено вывести значительное количество вооруженных сил из других регионов, чтобы восполнить потери на Восточном фронте. К моменту окончания боевых действий немецкие 6-я и 4-я танковая армии были уничтожены, а группа армий «Б» разгромлена. Победа Советов под Сталинградом изменила баланс сил на Восточном фронте в их пользу, а также повысила моральный дух Красной Армии .

Both sides placed great strategic importance on Stalingrad, for it was the largest industrial centre of the Soviet Union and an important transport hub on the Volga River:[43] controlling Stalingrad meant gaining access to the oil fields of the Caucasus and having supreme authority over the Volga River.[44] The city also held significant symbolic importance because it bore the name of Joseph Stalin, the incumbent leader of the Soviet Union. As the conflict progressed, Germany's fuel supplies dwindled and thus drove it to focus on moving deeper into Soviet territory and taking the country's oil fields at any cost. The German military first clashed with the Red Army's Stalingrad Front on the distant approaches to Stalingrad on 17 July. On 23 August, the 6th Army and elements of the 4th Panzer Army launched their offensive with support from intensive bombing raids by the Luftwaffe, which reduced much of the city to rubble. The battle soon degenerated into house-to-house fighting, which escalated drastically as both sides continued pouring reinforcements into the city. By mid-November, the Germans, at great cost, had pushed the Soviet defenders back into narrow zones along the Volga's west bank. However, winter set in within a few months and conditions became particularly brutal, with temperatures often dropping tens of degrees below freezing. In addition to fierce urban combat, brutal trench warfare was prevalent at Stalingrad as well.

On 19 November, the Red Army launched Operation Uranus, a two-pronged attack targeting the Romanian armies protecting the 6th Army's flanks.[45] The Axis flanks were overrun and the 6th Army was encircled. Adolf Hitler was determined to hold the city for Germany at all costs and forbade the 6th Army from trying a breakout; instead, attempts were made to supply it by air and to break the encirclement from the outside. Though the Soviets were successful in preventing the Germans from making enough airdrops to the trapped Axis armies at Stalingrad, heavy fighting continued for another two months. On 2 February 1943, the 6th Army, having exhausted their ammunition and food, finally capitulated after several months of battle, making it the first of Hitler's field armies to have surrendered.[46]

In modern-day Russia, the legacy of the Red Army's victory at Stalingrad is commemorated among the Days of Military Honour. It is also well known in many other countries that belonged to the Allied powers, and has thus become ingrained in popular culture. Likewise, in a number of the post-Soviet states, the Battle of Stalingrad is recognized as an important aspect of what is known as the Great Patriotic War.

Background

By the spring of 1942, despite the failure of Operation Barbarossa to defeat the Soviet Union in a single campaign, the Wehrmacht had captured vast territories, including Ukraine, Belarus, and the Baltic republics. On the Western Front, Germany held most of Europe, the U-boat offensive was curbing American support, and in North Africa, Erwin Rommel had just captured Tobruk.[47]: 522 In the east, the Germans had stabilized a front running from Leningrad to Rostov, with several minor salients. Hitler remained confident of breaking the Red Army, despite heavy losses west of Moscow in the winter of 1941–42, because large parts of Army Group Centre had been rested and re-equipped.[48] Hitler decided that the 1942 summer campaign would target the southern Soviet Union. The initial objectives around Stalingrad were to destroy the city's industrial capacity and block the Volga River traffic, crucial for connecting the Caucasus and Caspian Sea to central Russia. The capture of Stalingrad would also disrupt Lend-Lease supplies via the Persian Corridor.[49][50]

On 23 July 1942, Hitler expanded the campaign's objectives to include occupying Stalingrad, a city with immense propaganda value due to its name, which bore that of the Soviet leader.[51] Hitler ordered the annihilation of Stalingrad's population, declaring that after its capture, all male citizens would be killed and women and children deported due to their "thoroughly communistic" nature.[52] The city's fall was intended to secure the northern and western flanks of the German advance on Baku to capture its petroleum resources.[47]: 528 This expansion of objectives stemmed from German overconfidence and an underestimation of Soviet reserves.[53]

Meanwhile, Stalin, convinced that the main German attack would target Moscow,[54] prioritized defending the Soviet capital. As the Soviet winter counteroffensive of 1941–1942 culminated in March, the Soviet high command began planning for the summer campaign. Although Stalin desired a general offensive, he was dissuaded by Chief of the General Staff Boris Shaposhnikov, Deputy Chief of the General Staff Aleksandr Vasilevsky, and Western Main Direction commander Georgy Zhukov. Ultimately, Stalin instructed that the summer campaign be based on "active strategic defense," while also ordering local offensives across the Eastern Front.[55] Southwestern Main Direction commander Semyon Timoshenko proposed an attack from the Izyum salient south of Kharkov to encircle and destroy the German 6th Army. Despite opposition from Shaposhnikov and Vasilevsky, Stalin approved the plan.[56]

After delays in troop movements and logistical challenges, the Kharkov operation began on 12 May. The Soviets achieved initial success, prompting 6th Army commander Friedrich Paulus to request reinforcements. However, a German counterattack on 13 May halted the Soviet advance. On 17 May, Ewald von Kleist's forces launched Operation Fridericus I, encircling and destroying much of the Soviet forces in the ensuing Second Battle of Kharkov. The defeat at Kharkov left the Soviets vulnerable to the German summer offensive. Despite the setback, Stalin continued to prioritize defending Moscow, allocating only limited reinforcements to the Southwestern Front.[57]

The commitment of panzer divisions needed for Case Blue to the Second Battle of Kharkov further delayed the offensive's start. On 1 June, Hitler modified the summer plans, delaying Case Blue to 20 June after preliminary operations in Ukraine.[58]

Prelude

If I do not get the oil of Maikop and Grozny then I must finish [liquidieren; "kill off", "liquidate"] this war.

— Adolf Hitler[47]: 514

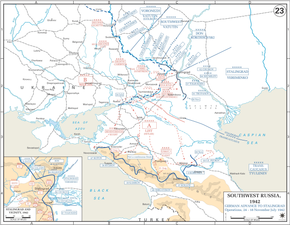

Army Group South was selected for a sprint forward through the southern Russian steppes into the Caucasus to capture the vital Soviet oil fields there. The planned summer offensive, code-named Fall Blau (Case Blue), was to include the German 6th, 17th, 4th Panzer and 1st Panzer Armies.[59]

Hitler intervened, however, ordering the Army Group to split in two. Army Group South (A), under the command of Wilhelm List, was to continue advancing south towards the Caucasus as planned with the 17th Army and First Panzer Army. Army Group South (B), including Paulus's 6th Army and Hermann Hoth's 4th Panzer Army, was to move east towards the Volga and Stalingrad. Army Group B was commanded by General Maximilian von Weichs.[60]

The start of Case Blue had been planned for late May 1942. However, a number of German and Romanian units that were to take part in Blau were besieging Sevastopol on the Crimean Peninsula. Delays in ending the siege pushed back the start date for Blau several times, and the city did not fall until early July.

Operation Fridericus I by the Germans against the "Izyum bulge", pinched off the Soviet salient in the Second Battle of Kharkov, and resulted in the envelopment of a large Soviet force between 17 May and 29 May. Similarly, Operation Wilhelm attacked Voltshansk on 13 June, and Operation Fridericus attacked Kupiansk on 22 June.[61]

Blau finally opened as Army Group South began its attack into southern Russia on 28 June 1942. The German offensive achieved rapid success, as Soviet forces offered little resistance in the vast empty steppes and started streaming eastward. Several attempts to re-establish a defensive line failed when German units outflanked them. Two major pockets were formed and destroyed: the first, northeast of Kharkov, on 2 July, and a second, around Millerovo, Rostov Oblast, a week later. Meanwhile, the Hungarian 2nd Army and the German 4th Panzer Army had launched an assault on Voronezh, capturing the city on 5 July.

The initial advance of the 6th Army was so successful that Hitler intervened and ordered the 4th Panzer Army to join Army Group South (A) to the south. A massive road block resulted when the 4th Panzer and the 1st Panzer choked the roads, stopping both in their tracks while they cleared the mess of thousands of vehicles. The traffic jam is thought to have delayed the advance by at least one week. With the advance now slowed, Hitler changed his mind and reassigned the 4th Panzer Army back to the attack on Stalingrad.

By the end of July, Soviet forces were pushed back across the Don River. At this point, the Don and Volga Rivers are only 65 km (40 mi) apart, and the Germans left their main supply depots west of the Don. The Germans began using the armies of their Italian, Hungarian and Romanian allies to guard their left (northern) flank. Italian actions were also mentioned in official German communiques.[62][63][64][65] Italian forces were generally held in little regard by the Germans, and were accused of low morale: in reality, the Italian divisions fought comparatively well, with the 3rd Infantry Division "Ravenna" and 5th Infantry Division "Cosseria" showing spirit, according to a German liaison officer.[66] Italian forces were forced to retreat only after a massive armoured attack in which German reinforcements failed to arrive in time.[67]

To the south, Army Group A was pushing far into the Caucasus, but the advance slowed as supply lines grew overextended. The two German army groups were too far apart to support one another.

After German intentions became clear in July, Stalin appointed General Andrey Yeryomenko commander of the Southeastern Front on 1 August 1942. Yeryomenko and Commissar Nikita Khrushchev were tasked with planning the defence of Stalingrad.[68] Beyond the Volga River on the eastern boundary of Stalingrad, additional Soviet units were formed into the 62nd Army under Lieutenant General Vasiliy Chuikov on 11 September 1942. Tasked with holding the city at all costs,[69] Chuikov proclaimed, "We will defend the city or die in the attempt."[70] The battle earned him one of his two Hero of the Soviet Union awards.

Orders of battle

Red Army

During the defence of Stalingrad, the Red Army deployed five armies in and around the city (28th, 51st, 57th, 62nd and 64th Armies); and an additional nine armies in the encirclement counteroffensive[71] (24th, 65th, 66th Armies and 16th Air Army from the north as part of the Don Front offensive, and 1st Guards Army, 5th Tank, 21st Army, 2nd Air Army and 17th Air Army from the south as part of the Southwestern Front).

Axis

Attack on Stalingrad

Initial attack

German forces first clashed with the Stalingrad Front on 17 July on the distant approaches to Stalingrad, in the bend of the Don.[72][73] A significant clash in the early stages of the battle was fought at Kalach, in which "We had had to pay a high cost in men and material ... left on the Kalach battlefield were numerous burnt-out or shot-up German tanks."[74] Military historian David Glantz indicated that four hard-fought battles – collectively known as the Kotluban Operations – north of Stalingrad, where the Soviets made their greatest stand, decided Germany's fate before the Nazis ever set foot in the city itself, and were a turning point in the war.[75] Beginning in late August and lasting into October, the Soviets committed between two and four armies in hastily coordinated and poorly controlled attacks against the Germans' northern flank. The actions resulted in over 200,000 Soviet Army casualties but did slow the German assault.[75]

The Germans formed bridgeheads across the Don on 20 August, with the 295th and 76th Infantry Divisions enabling the XIVth Panzer Corps "to thrust to the Volga north of Stalingrad." The German 6th Army was only a few dozen kilometres from Stalingrad. The 4th Panzer Army, ordered south on 13 July to block the Soviet retreat "weakened by the 17th Army and the 1st Panzer Army", had turned northwards to help take the city from the south.[76] On 19 August, German forces were in position to launch an attack on the city.[77][78]

On 23 August, the 6th Army reached the outskirts of Stalingrad in pursuit of the 62nd and 64th Armies, which had fallen back into the city. Kleist said after the war:

The capture of Stalingrad was subsidiary to the main aim. It was only of importance as a convenient place, in the bottleneck between Don and the Volga, where we could block an attack on our flank by Russian forces coming from the east. At the start, Stalingrad was no more than a name on the map to us.[79]

The Soviets had enough warning of the German advance to ship grain, cattle, and railway cars across the Volga out of harm's way. This "harvest victory" left the city short of food even before the German attack began. Before the Heer reached the city itself, the Luftwaffe had cut off shipping on the Volga. In the days between 25 and 31 July, 32 Soviet ships were sunk, with another nine crippled.[80]

Generaloberst Wolfram von Richthofen's Luftflotte 4 dropped some 1,000 tons of bombs on 23 August, with the aerial attack on Stalingrad being the most single intense aerial bombardment at that point on the Eastern Front,[81] and the heaviest bombing raid that had ever taken place on the Eastern Front.[82] At least 90% of the city's housing stock was obliterated as a result.[83] The Stalingrad Tractor Factory continued to turn out T-34 tanks up until German troops burst into the plant. The 369th (Croatian) Reinforced Infantry Regiment was the only non-German unit selected by the Wehrmacht to enter Stalingrad city during assault operations, with it fighting as part of the 100th Jäger Division.

Georgy Zhukov, who was deputy commander-in-chief and commander of Stalingrad's defence during the battle, noted the importance of the battle, stating that:[84]

It was clear to me that the battle for Stalingrad was of the greatest military and political significance. If Stalingrad fell, the enemy command would be able to cut off the south of the country from the center. We could lose the Volga – the important water artery, along which a large amount of goods flowed from the Caucasus.

Stalin rushed all available troops to the east bank of the Volga, some from as far away as Siberia. Regular river ferries were quickly destroyed by the Luftwaffe, which then targeted troop barges being towed slowly across by tugs.[68] It has been said that Stalin prevented civilians from leaving the city in the belief that their presence would encourage greater resistance from the city's defenders.[85] Civilians, including women and children, were put to work building trenchworks and protective fortifications. Casualties due to the air raid on 23 August and beyond are debated, as between 23 and 26 August, Soviet reports indicate 955 people were killed and another 1,181 wounded as a result of the bombing.[86] However, death toll of civilians due to the bombing has been estimated to have been 40,000,[87][82] or as many as 70,000,[83] though these estimates may be exaggerated.[88] Also estimated are 150,000 wounded.[89]

The Soviet Air Force, the Voyenno-Vozdushnye Sily (VVS), was swept aside by the Luftwaffe. The VVS bases in the immediate area lost 201 aircraft between 23 and 31 August, and despite meagre reinforcements of some 100 aircraft in August, it was left with just 192 serviceable aircraft, 57 of which were fighters.[90]

Early on 23 August, the German 16th Panzer and 3rd Motorized Divisions attacked out of the Vertyachy bridgehead with a force 120 tanks and over 200 armored personnel carriers strong. The German attack broke through the 1382nd Rifle Regiment of the 87th Rifle Division and the 137th Tank Brigade, which were forced to retreat towards Dmitryevka. The 16th Panzer Division drove east towards the Volga, supported by the strikes of Henschel Hs 129 ground attack aircraft.[91] Crossing the railway line to Stalingrad at 564 km Station around midday, both divisions continued their rush towards the river. Around 15:00, Hyacinth Graf Strachwitz's Panzer Detachment and the kampfgruppe of the 2nd Battalion, 64th Panzer Grenadier Regiment from the 16th Panzer reached the area of Latashanka, Rynok, and Spartanovka, northern suburbs of Stalingrad, and the Stalingrad Tractor Factory.[92]

A Soviet female soldier stated about the battle that:[93]

I had been imagining what war was like – everything on fire, children crying, cats running about, and when we got to Stalingrad it turned out to be really like that, only more terrible.

One of the first units to offer resistance in this area was the 1077th Anti-Aircraft Regiment,[85] covering the Stalingrad Tractor Factory and the Volga ferry near Latashanka. The majority of the regiment was composed of men, but its directing and rangefinding crews and unit headquarters were made up of women. Several women also crewed anti-aircraft guns. The 1077th was notified of the German tanks' approach at 14:30 and its 6th Battery, dominating the Sukhaya Mechatka ravine, claimed the destruction of 28 German tanks. Later that day, its 3rd Battery on the road between Yerzovka and Stalingrad, saw particularly intense fighting against the 16th Panzer, reportedly fighting "shot for shot."[94] Two women were decorated for their actions that day, and the regiment's report praised the "exceptional steadfastness and heroism" of the women soldiers. The regiment lost 35 guns, eighteen killed, 46 wounded, and 74 missing on 23 and 24 August. The 16th Panzer Division's history mentioned its encounter with the regiment, claiming the destruction of 37 guns, and the unit's surprise that its opponents had in part included women.[95][94]

In the early stages of the battle, the NKVD organised poorly armed "Workers' militias" similar to those that had defended the city twenty-four years earlier, composed of civilians not directly involved in war production for immediate use in the battle. The civilians were often sent into battle without rifles.[96] Staff and students from the local technical university formed a "tank destroyer" unit. They assembled tanks from leftover parts at the tractor factory. These tanks, unpainted and lacking gun-sights, were driven directly from the factory floor to the front line. They could only be aimed at point-blank range through the bore of their gun barrels.[97] Chuikov later remarked that soldiers approaching the battle would say "We are entering hell", but after one or two days, they said "No, this isn't hell, this is ten times worse than hell".[93]

By the end of August, Army Group South (B) had finally reached the Volga, north of Stalingrad. Another advance to the river south of the city followed, while the Soviets abandoned their Rossoshka position for the inner defensive ring west of Stalingrad. The wings of the 6th Army and the 4th Panzer Army met near Jablotchni along the Zaritza on 2 Sept.[98]

September city battles

A letter found on the body of a German officer described the insanity of the battle and brutal nature of the urban combat:[36]

We must reach the Volga. We can see it – less than a kilometer away. We have the constant support of our aircraft and artillery. We are fighting like madmen but cannot reach the river. The whole war for France was shorter than the fight for one Volga factory. We must be up against suicide squads. They have simply decided to fight to the last soldier. And how many soldiers are left over there? When will this hell come to an end?

Historian David Glantz stated that the grinding and brutal battle resembled "the fighting on the Somme and at Verdun in 1916 more than it did the familiar blitzkrieg war of the previous three summers".[99]

On 5 September, the Soviet 24th and 66th Armies organized a massive attack against XIV Panzer Corps. The Luftwaffe helped repel the offensive by heavily attacking Soviet artillery positions and defensive lines. The Soviets were forced to withdraw at midday after only a few hours. Of the 120 tanks the Soviets had committed, 30 were lost to air attack.[100]

On 13 September, the battle for the city itself began. With German forces launching an attack which overran the small hill where the 62nd Soviet Army headquarters was established, in addition, the railway station was captured, and German forces advanced far enough to threaten the Volga landing stage.[101]

Soviet operations were constantly hampered by the Luftwaffe. On 18 September, the Soviet 1st Guards and 24th Army launched an offensive against VIII Army Corps at Kotluban. VIII. Fliegerkorps dispatched multiple waves of Stuka dive-bombers to prevent a breakthrough. The offensive was repelled. The Stukas claimed 41 of the 106 Soviet tanks knocked out that morning, while escorting Bf 109s destroyed 77 Soviet aircraft.[102]

Lieutenant General Alexander Rodimtsev was in charge of the 13th Guards Rifle Division, and received one of two Hero of the Soviet Union awards issued during the battle for his actions. Stalin's Order No. 227 of 27 July 1942 decreed that all commanders who ordered unauthorised retreats would be subject to a military tribunal.[103] Blocking detachments composed of NKVD or regular troops were positioned behind Red Army units to prevent desertion and straggling, sometimes executing deserters and perceived malingerers.[104] During the battle, the 62nd Army had the most arrests and executions: 203 in all, of which 49 were executed, while 139 were sent to penal companies and battalions.[105][106][107] Blocking detachments of the Stalingrad and Don Fronts detained 51,758 men from the beginning of the battle to 15 October, with the majority returned to their units. Of those detained, the vast majority of which were from the Don Front, 980 were executed and 1,349 sent to penal companies.[108][109][110] In the two-day period between 13 and 15 September, the 62nd Army blocking detachment detained 1,218 men, returning most to their units while shooting 21 men and arresting ten.[111] Beevor claims that 13,500 Soviet soldiers were executed by Soviet authorities during the battle,[112] however, this claim has been disputed.[113]

By 12 September, at the time of their retreat into the city, the Soviet 62nd Army had been reduced to 90 tanks, 700 mortars and just 20,000 personnel.[114] The remaining tanks were used as immobile strong-points within the city. The initial German attack on 14 September attempted to take the city in a rush. The 51st Army Corps' 295th Infantry Division went after the Mamayev Kurgan hill, the 71st attacked the central rail station and toward the central landing stage on the Volga, while 48th Panzer Corps attacked south of the Tsaritsa River. Though initially successful, the German attacks stalled in the face of Soviet reinforcements brought in from across the Volga. Rodimtsev's 13th Guards Rifle Division had been hurried up to cross the river and join the defenders inside the city.[115] Assigned to counterattack at the Mamayev Kurgan and at Railway Station No. 1, it suffered particularly heavy losses. Despite their losses, Rodimtsev's troops were able to inflict similar damage on their opponents. By 26 September, the opposing 71st Infantry Division had half of its battalions considered exhausted, reduced from all of them being considered average in combat capability when the attack began twelve days earlier.[116]

The brutality of the battle was noted in a journal found on German lieutenant Weiner of the 24th Panzer Division:[117]

The street is no longer measured by meters but by corpses... Stalingrad is no longer a town. By day it is an enormous cloud of burning, blinding smoke; it is a vast furnace lit by the reflection of the flames. And when night arrives, one of those scorching howling bleeding nights, the dogs plunge into the Volga and swim desperately to gain the other bank. The nights of Stalingrad are a terror for them. Animals flee this hell; the hardest stones cannot bear it for long; only men endure.

A ferocious battle raged for several days at the giant grain elevator in the south of the city.[118] About fifty Red Army defenders, cut off from resupply, held the position for five days and fought off ten different assaults before running out of ammunition and water.[119] Only forty dead Soviet fighters were found, though the Germans had thought there were many more due to the intensity of resistance. The Soviets burned large amounts of grain during their retreat in order to deny the enemy food. The grain elevator and silos were decided upon by Paulus to be the symbol of Stalingrad for a patch he was having designed to commemorate the battle after victory.[119]

Mamayev Kurgan changed hands multiple times over the course of days, with fighting over the hill, rail station and Red Square being so intense that it was difficult to determine who was attacking and who was defending.[120]

In another part of the city, a Soviet platoon under the command of Sergeant Yakov Pavlov fortified a four-story building that oversaw a square 300 meters from the river bank, which was later called Pavlov's House. The soldiers surrounded it with minefields, set up machine-gun positions at the windows and breached the walls in the basement for better communications.[114] The soldiers found about ten Soviet civilians hiding in the basement. They were not relieved, and not significantly reinforced, for two months, with the defense lasting around 60 days. The building was labelled Festung ("Fortress") on German maps. Pavlov was awarded the Hero of the Soviet Union title for his actions. General Chuikov took note of the brutal efficiency of the defense of Pavlov's House, stating that "Pavlov's small group of men, defending one house, killed more enemy soldiers than the Germans lost in taking Paris".[121]

Generalmajor Hans Doerr stated about the conditions of the battle that;[122]

A bitter battle for every house, workshop, water tower, railway embankment, wall, cellar and every pile of rubble was waged, without equal even in the First World War... The distance between the enemy's arms and ours was as small as could possibly be. Despite the concentrated air and artillery power, it was impossible to break out of the area of close fighting. The Russians surpassed the Germans in their use of the terrain and in camouflage, and were more experienced in barricade warfare for individual buildings.

Stubborn defenses of semi-fortified buildings in the center of the city cost the Germans countless soldiers. A violent battle occurred for the Univermag department store on Red Square, which served as the headquarters of the 1st Battalion of the 13th Guards Rifle Division's 42nd Guards Rifle Regiment. Another battle occurred for a nearby warehouse dubbed the "nail factory". In a three-story building close by, guardsmen fought on for five days, their noses and throats filled with brick dust from pulverized walls, with only six out of close to half a battalion escaping alive.[123]

The Germans made slow but steady progress through the city. Positions were taken individually, but the Germans were never able to capture the key crossing points along the river bank. By 27 September, the Germans occupied the southern portion of the city, but the Soviets held the centre and northern part. Most importantly, the Soviets controlled the ferries to their supplies on the east bank of the Volga.[124]

Fighting in the industrial district

After 27 September, much of the fighting in the city shifted north to the industrial district. Having slowly advanced over 10 days against strong Soviet resistance, the 51st Army Corps was finally in front of the three giant factories of Stalingrad: the Red October Steel Factory, the Barrikady Arms Factory and Stalingrad Tractor Factory. It took a few more days for them to prepare for the most savage offensive of all, which was unleashed on 14 October,[125] which Chuikov considered to be the worst day of the battle.[126] Exceptionally intense shelling and bombing paved the way for the first German assault groups. The main attack (led by the 14th Panzer and 305th Infantry Divisions) attacked towards the tractor factory, while another assault led by the 24th Panzer Division hit to the south of the giant plant.[127]

Werth points out the difficulties the Siberian Division faced, as throughout the course of an entire month, German forces launched 117 assaults at the division's regiments, and on one day they launched 23 attacks.[128] Every trench, pillbox, rifle-pit and ruin in the area was turned into a strongpoint with its own direction and system of communications.[129]

According to Beevor, "The Red October complex and Barrikady gun factory had been turned into fortresses as lethal as those of Verdun. If anything, they were more dangerous because the Soviet regiments were so well hidden."[130] The danger of the Barrikady Arms Factory was made apparent firsthand by German sergeant Ernst Wohlfahrt, who witnessed 18 German pioneers get killed by a Russian booby trap.[131] The fighting for the Barrikady has been described as some of the most brutal and ferocious fighting ever, with it being stated that the "battlefield east of the Barrikady blazed with the most violent and profligate clash the world would ever see" and that in regard to hand-to-hand fighting, "nowhere was it more brutal, more savage, more relentless, than in the Barrikady".[132]

The German onslaught crushed the 37th Guards Rifle Division of Major General Viktor Zholudev and in the afternoon the forward assault group reached the tractor factory before arriving at the Volga River, splitting the 62nd Army into two.[133] In response to the German breakthrough to the Volga, the front headquarters committed three battalions from the 300th Rifle Division and the 45th Rifle Division of Colonel Vasily Sokolov, a substantial force of over 2,000 men, to the fighting at the Red October Factory.[134]

According to Werth:[135]

Here, in and around the main building of the October Plant, the fighting had gone on for weeks. It had been a hell of shell-fire and mortarfire, and tank and air attacks, and hand-to-hand fighting; they had fought for a workshop or half a workshop, or for the end of a drainpipe.

Fighting raged inside the Barrikady Factory until the end of October.[136] The Soviet-controlled area shrank down to a few strips of land along the western bank of the Volga, and in November the fighting concentrated around what Soviet newspapers referred to as "Lyudnikov's Island", a small patch of ground behind the Barrikady Factory where the remnants of Colonel Ivan Lyudnikov's 138th Rifle Division resisted all ferocious assaults thrown by the Germans and became a symbol of the stout Soviet defence of Stalingrad.[137]

In the north of Stalingrad, by early November, the 16th Panzer Division referred to the Rynok-Spartanovka region as "little Verdun" because "there was hardly a square meter that had not been churned up by bombs and shells."[138]

Air attacks

From 5 to 12 September, Luftflotte 4 conducted 7,507 sorties (938 per day). From 16 to 25 September, it carried out 9,746 missions (975 per day).[139] Determined to crush Soviet resistance, Luftflotte 4's Stukawaffe flew 900 individual sorties against Soviet positions at the Stalingrad Tractor Factory on 5 October. Several Soviet regiments were wiped out; the entire staff of the Soviet 339th Infantry Regiment was killed the following morning during an air raid.[140]

The Luftwaffe retained air superiority into November, and Soviet daytime aerial resistance was nonexistent. However, the combination of constant air support operations on the German side and the Soviet surrender of the daytime skies began to affect the strategic balance in the air. From 28 June to 20 September, Luftflotte 4's original strength of 1,600 aircraft, of which 1,155 were operational, fell to 950, of which only 550 were operational. The fleet's total strength decreased by 40 percent. Daily sorties decreased from 1,343 per day to 975 per day. Soviet offensives in the central and northern portions of the Eastern Front tied down Luftwaffe reserves and newly built aircraft, reducing Luftflotte 4's percentage of Eastern Front aircraft from 60 percent on 28 June to 38 percent by 20 September. The Kampfwaffe (bomber force) was the hardest hit, having only 232 out of an original force of 480 left.[139]

In mid-October, after receiving reinforcements from the Caucasus theatre, the Luftwaffe intensified its efforts against the remaining Red Army positions holding the west bank. Luftflotte 4 flew 1,250 sorties on 14 October and its Stukas dropped 550 tonnes of bombs, while German infantry surrounded the three factories.[141] Stukageschwader 1, 2, and 77 had largely silenced Soviet artillery on the eastern bank of the Volga before turning their attention to the shipping that was once again trying to reinforce the narrowing Soviet pockets of resistance. The 62nd Army had been cut in two and, due to intensive air attack on its supply ferries, was receiving much less material support. With the Soviets forced into a 1-kilometre (1,000-yard) strip of land on the western bank of the Volga, over 1,208 Stuka missions were flown in an effort to eliminate them.[142]

The Soviet bomber force, the Aviatsiya Dal'nego Deystviya (Long Range Aviation; ADD), having taken crippling losses over the past 18 months, was restricted to flying at night. The Soviets flew 11,317 night sorties over Stalingrad and the Don-bend sector between 17 July and 19 November. These raids caused little damage and were of nuisance value only.[143][144]: 265

As historian Chris Bellamy notes, the Germans paid a high strategic price for the aircraft sent into Stalingrad: the Luftwaffe was forced to divert much of its air strength away from the oil-rich Caucasus, which had been Hitler's original grand-strategic objective.[145]

The Royal Romanian Air Force was also involved in the Axis air operations at Stalingrad. Starting 23 October 1942, Romanian pilots flew a total of 4,000 sorties, during which they destroyed 61 Soviet aircraft. The Romanian Air Force lost 79 aircraft, most of them captured on the ground along with their airfields.[146]

Germans reach the Volga

In August 1942 after three months of slow advance, the Germans finally reached the river banks, capturing 90% of the ruined city and splitting the remaining Soviet forces into two narrow pockets. Ice floes on the Volga now prevented boats and tugs from supplying the Soviet defenders. Nevertheless, the fighting continued, especially on the slopes of Mamayev Kurgan and inside the factory area in the northern part of the city.[147] From 21 August to 20 November, the German 6th Army lost 60,548 men, including 12,782 killed, 45,545 wounded and 2,221 missing.[148] Fighting for the Volga banks has been noted as the "most concentrated and ferocious fighting in perhaps the whole war".[149]

Soviet counter-offensives

Recognising that German troops were ill-prepared for offensive operations during the winter of 1942 and that most of them were deployed elsewhere on the southern sector of the Eastern Front, the Stavka decided to conduct a number of offensive operations between 19 November 1942 and 2 February 1943. These operations opened the Winter Campaign of 1942–1943 (19 November 1942 – 3 March 1943), which involved some fifteen Armies operating on several fronts. As per Zhukov, "German operational blunders were aggravated by poor intelligence: they failed to spot preparations for the major counter-offensive near Stalingrad where there were 10 field, 1 tank and 4 air armies."[150]

Weakness on the Axis flanks

During the siege, the German and allied Italian, Hungarian, and Romanian armies protecting Army Group B's north and south flanks had pressed their headquarters for support. The Hungarian 2nd Army was given the task of defending a 200 km (120 mi) section of the front north of Stalingrad between the Italian Army and Voronezh. This resulted in a very thin line, with some sectors where 1–2 km (0.62–1.24 mi) stretches were being defended by a single platoon (platoons typically have around 20 to 50 men). These forces were also lacking in effective anti-tank weapons. Zhukov states, "Compared with the Germans, the troops of the satellites were not so well armed, less experienced and less efficient, even in defence."[151]

Because of the total focus on the city, the Axis forces had neglected for months to consolidate their positions along the natural defensive line of the Don River. The Soviet forces were allowed to retain bridgeheads on the right bank from which offensive operations could be quickly launched. These bridgeheads in retrospect presented a serious threat to Army Group B.[60]

Similarly, on the southern flank of the Stalingrad sector, the front southwest of Kotelnikovo was held only by the Romanian 4th Army. Beyond that army, a single German division, the 16th Motorised Infantry, covered 400 km. Paulus had requested permission on 10 November to "withdraw the 6th Army behind the Don," but was rejected.[152] According to Paulus's comments to his adjutant Wilhelm Adam, "There is still the order whereby no commander of an army group or an army has the right to relinquish a village, even a trench, without Hitler's consent."[153]

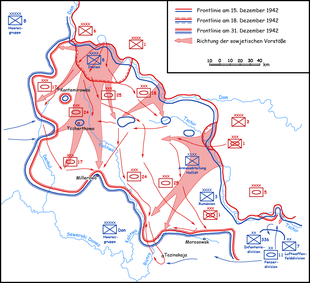

Operation Uranus

In autumn, Zhukov and Vasilevsky, responsible for strategic planning in the Stalingrad area, concentrated forces in the steppes to the north and south of the city. The northern flank was defended by Romanian units, often in open positions on the steppes. The natural line of defence, the Don River, had never been properly established by the German side. The armies in the area were also poorly equipped in terms of anti-tank weapons. The plan was to punch through the overstretched and weakly defended flanks and surround the German forces in the Stalingrad region.

During the preparations for the attack, Marshal Zhukov personally visited the front and noticing the poor organisation, insisted on a one-week delay in the start date of the planned attack.[154] The operation was code-named "Uranus" and launched in conjunction with Operation Mars, which was directed at Army Group Center about 1,000 kilometres (620 mi) to the northwest. The plan was similar to that used by Zhukov to achieve victory at Khalkhin Gol in 1939, where he had sprung a double envelopment and destroyed the 23rd Division of the Japanese army.[155]

On 19 November 1942, Operation Uranus was launched. The attacking Soviet units under the command of Gen. Nikolay Vatutin consisted of three complete armies, the 1st Guards Army, 5th Tank Army and 21st Army, including a total of 18 infantry divisions, eight tank brigades, two motorised brigades, six cavalry divisions and one anti-tank brigade. The preparations for the attack were heard by the Romanians, who pushed for reinforcements, only to be refused. Romania's 3rd Army, which protected the northern flank of the German 6th Army, was overrun, due to thin lines, and being outnumbered and poorly equipped.

On 20 November, a second Soviet offensive (two armies) was launched to the south of Stalingrad against points held by the Romanian 4th Army Corps. The Romanian forces, made up primarily of infantry, were overrun by large numbers of tanks. The Soviet forces raced west and met on 23 November at the town of Kalach, sealing the ring around Stalingrad.[156]

Sixth Army surrounded

By the time of the encirclement, approximately 330,000 Axis personnel, including Germans, Romanians, Italians, and Croatians, were trapped.[157][158] Among them were between 40,000 and 65,000 Hilfswillige (Hiwi), or "volunteer auxiliaries," recruited from Soviet POWs and civilians. These Hiwi often served in supporting roles but were also deployed in frontline units due to their growing numbers.[159][160]

The conditions within the German 6th Army deteriorated to those reminiscent of World War I trench warfare. Troops were forced to take up positions in the open steppe, lacking basic sanitation, which led to rapid spread of infections and dysentery, further debilitating the soldiers.[161] By 19 November 1942, the German forces in the pocket numbered about 210,000, with 50,000 soldiers outside the encirclement. Of those trapped, 10,000 continued to fight, 105,000 eventually surrendered, 35,000 were evacuated by air, and 60,000 died.

Despite the 6th Army's dire situation, no reinforcements were pulled from Army Group A in the Caucasus to aid in the relief of Stalingrad. It was only after Soviet forces broke through in Operation Little Saturn, threatening to encircle Army Group A, that a withdrawal was ordered on December 31 to avoid complete entrapment.[162]

Army Group Don was established under Field Marshal von Manstein, tasked with leading the 20 German and two Romanian divisions encircled at Stalingrad. Despite Manstein's recommendation for a breakout, Hitler insisted on holding the city, relying on an ill-fated airlift to supply the 6th Army, which failed to deliver the necessary supplies.[163][164] The airlift fell drastically short, delivering only 105 tons per day, far below the required 750 tons.[165] The situation worsened after the Soviets captured Tatsinskaya Airfield on 24 December, forcing the Germans to relocate their air operations to more distant and less effective bases. As supplies dwindled, starvation and disease ravaged the 6th Army. By the time the airlift was terminated, the Luftwaffe had lost nearly 500 aircraft, including 266 Ju 52s, and failed to maintain adequate supply levels. Ultimately, the failure to relieve Stalingrad sealed the fate of the 6th Army, leading to one of the most catastrophic defeats in military history.[166]

End of the battle

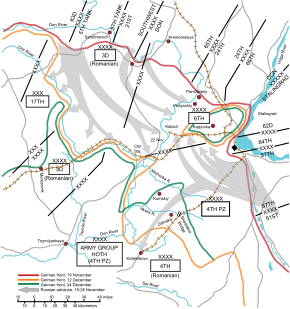

Operation Winter Storm

Manstein's plan to rescue the Sixth Army – Operation Winter Storm – was developed in full consultation with Führer headquarters. It aimed to break through to the Sixth Army and establish a corridor to keep it supplied and reinforced, so that, according to Hitler's order, it could maintain its "cornerstone" position on the Volga, "with regard to operations in 1943". Manstein, however, who knew that Sixth Army could not survive the winter there, instructed his headquarters to draw up a further plan in the event of Hitler's seeing sense.

This would include the subsequent breakout of Sixth Army, in the event of a successful first phase, and its physical reincorporation in Army Group Don. This second plan was given the name Operation Thunderclap. Winter Storm, as Zhukov had predicted, was originally planned as a two-pronged attack. One thrust would come from the area of Kotelnikovo, well to the south, and around 160 kilometres (100 mi) from the Sixth Army. The other would start from the Chir front west of the Don, which was little more than 60 kilometres (40 mi) from the edge of the Kessel, but the continuing attacks of Romanenko's 5th Tank Army against the German detachments along the river Chir ruled out that start-line.

This left only the LVII Panzer Corps around Kotelnikovo, supported by the rest of Hoth's very mixed Fourth Panzer Army, to relieve Paulus's trapped divisions. The LVII Panzer Corps, commanded by General Friedrich Kirchner, had been weak at first. It consisted of two Romanian cavalry divisions and the 23rd Panzer Division, which mustered no more than thirty serviceable tanks. The 6th Panzer Division, arriving from France, was a vastly more powerful formation, but its members hardly received an encouraging impression. The Austrian divisional commander, General Erhard Raus, was summoned to Manstein's royal carriage in Kharkov station on 24 November, where the field marshal briefed him. "He described the situation in very sombre terms", recorded Raus.

Three days later, when the first trainload of Raus's division steamed into Kotelnikovo station to unload, his troops were greeted by "a hail of shells" from Soviet batteries. "As quick as lightning, the Panzergrenadiers jumped from their wagons. But already the enemy was attacking the station with their battle-cries of 'Urrah!'"

By 18 December, the German Army had pushed to within 48 km (30 mi) of Sixth Army's positions. However, the predictable nature of the relief operation brought significant risk for all German forces in the area. The starving encircled forces at Stalingrad made no attempt to break out or link up with Manstein's advance. Some German officers requested that Paulus defy Hitler's orders to stand fast and instead attempt to break out of the Stalingrad pocket. Paulus refused, concerned about the Red Army attacks on the flank of Army Group Don and Army Group B in their advance on Rostov-on-Don, "an early abandonment" of Stalingrad "would result in the destruction of Army Group A in the Caucasus", and the fact that his 6th Army tanks only had fuel for a 30 km advance towards Hoth's spearhead, a futile effort if they did not receive assurance of resupply by air. Of his questions to Army Group Don, Paulus was told, "Wait, implement Operation 'Thunderclap' only on explicit orders!" – Operation Thunderclap being the code word initiating the breakout.[167]

Operation Little Saturn

On 16 December, the Soviets launched Operation Little Saturn, which attempted to punch through the Axis army (mainly Italians) on the Don. The Germans set up a "mobile defence" of small units that were to hold towns until supporting armour arrived. From the Soviet bridgehead at Mamon, 15 divisions – supported by at least 100 tanks – attacked the Italian Cosseria and Ravenna Divisions, and although outnumbered 9 to 1, the Italians initially fought well, with the Germans praising the quality of the Italian defenders,[168] but on 19 December, with the Italian lines disintegrating, ARMIR headquarters ordered the battered divisions to withdraw to new lines.[169]

The fighting forced a total revaluation of the German situation. Sensing that this was the last chance for a breakout, Manstein pleaded with Hitler on 18 December, but Hitler refused. Paulus himself also doubted the feasibility of such a breakout. The attempt to break through to Stalingrad was abandoned and Army Group A was ordered to pull back from the Caucasus. The 6th Army now was beyond all hope of German relief. While a motorised breakout might have been possible in the first few weeks, the 6th Army now had insufficient fuel and the German soldiers would have faced great difficulty breaking through the Soviet lines on foot in harsh winter conditions. But in its defensive position on the Volga, the 6th Army continued to tie down a significant number of Soviet Armies.[170]

On 23 December, the attempt to relieve Stalingrad was abandoned and Manstein's forces switched over to the defensive to deal with new Soviet offensives.[171] As Zhukov states,

The military and political leadership of Nazi Germany sought not to relieve them, but to get them to fight on for as long possible so as to tie up the Soviet forces. The aim was to win as much time as possible to withdraw forces from the Caucasus (Army Group A) and to rush troops from other Fronts to form a new front that would be able in some measure to check our counter-offensive.[172]

Soviet victory

The Red Army High Command sent three envoys while, simultaneously, aircraft and loudspeakers announced the terms of capitulation on 7 January 1943. The letter was signed by Colonel-General of Artillery Voronov and the commander-in-chief of the Don Front, Lieutenant-General Rokossovsky. A low-level Soviet envoy party (comprising Major Aleksandr Smyslov, Captain Nikolay Dyatlenko and a trumpeter) carried generous surrender terms to Paulus: if he surrendered within 24 hours, he would receive a guarantee of safety for all prisoners, medical care for the sick and wounded, prisoners being allowed to keep their personal belongings, "normal" food rations, and repatriation to any country they wished after the war. Rokossovsky's letter also stressed that Paulus' men were in an untenable situation. Paulus requested permission to surrender, but Hitler rejected Paulus' request out of hand. Accordingly, Paulus did not respond.[173][174] The German High Command informed Paulus, "Every day that the army holds out longer helps the whole front and draws away the Russian divisions from it."[175]

The operation launched on 10 January 1943 with what was the single largest bombardment of the war at that point, with nearly 7,000 field guns, launchers and mortars firing against German positions.[176] The operation was likely the largest scale economy-of-force offensive conducted in military history.[177] The Germans retreated from the suburbs of Stalingrad to the city. The loss of the two airfields, Pitomnik on 16 January 1943 and Gumrak on the night of 21/22 January,[178] meant an end to air supplies and the evacuation of the wounded.[179] The third and last serviceable runway was at the Stalingradskaya flight school, which had its last landings and takeoffs on 23 January.[180] After 23 January, there were no more reported landings, just intermittent air drops of ammunition and food until the end.[181]

Despite the horrendous situation that German forces faced, both starving and running out of ammunition, they continued to resist, with transcripts showing that despite many German soldiers yelling "Hitler kaput" to avoid being shot while surrendering, the level of armed resistance remained extraordinarily high till the end of the battle.[182] In particular, the so-called HiWis, Soviet citizens fighting for the Germans, had no illusions about their fate if captured. Bloody urban warfare began again in Stalingrad, but this time it was the Germans who were pushed back to the banks of the Volga. The Germans adopted a simple defence of fixing wire nets over all windows to protect themselves from grenades. The Soviets responded by fixing fish hooks to the grenades so they stuck to the nets when thrown.

On 22 January, Rokossovsky once again offered Paulus a chance to surrender. Paulus requested that he be granted permission to accept the terms. He told Hitler that he was no longer able to command his men, who were without ammunition or food.[183] Hitler rejected it on a point of honour. He telegraphed the 6th Army later that day, claiming that it had made a historic contribution to the greatest struggle in German history and that it should stand fast "to the last soldier and the last bullet". Hitler told Goebbels that the plight of the 6th Army was a "heroic drama of German history".[184] On 24 January, in his radio report to Hitler, Paulus reported: "18,000 wounded without the slightest aid of bandages and medicines."[185]

On 26 January 1943, the German forces inside Stalingrad were split into two pockets north and south of Mamayev-Kurgan. The northern pocket consisting of the VIIIth Corps, under General Walter Heitz, and the XIth Corps, was now cut off from telephone communication with Paulus in the southern pocket. Now "each part of the cauldron came personally under Hitler".[186] On 28 January, the cauldron was split into three parts. The northern cauldron consisted of the XIth Corps, the central with the VIIIth and LIst Corps, and the southern with the XIVth Panzer Corps and IVth Corps "without units". The sick and wounded reached 40,000 to 50,000.[187]

On 30 January 1943, the 10th anniversary of Hitler's coming to power, Goebbels read out a proclamation that included the sentence: "The heroic struggle of our soldiers on the Volga should be a warning for everybody to do the utmost for the struggle for Germany's freedom and the future of our people, and thus in a wider sense for the maintenance of our entire continent."[188] The same day, Hermann Göring broadcast from the air ministry, comparing the situation of the surrounded German 6th Army to that of the Spartans at the Battle of Thermopylae, the speech was not well received by soldiers however.[189] Paulus notified Hitler that his men would likely collapse before the day was out. In response, Hitler then issued a tranche of field promotions to the Sixth Army's officers, with Paulus made a Generalfeldmarschall. In deciding to promote Paulus, Hitler noted that there was no record of a German or Prussian field marshal having ever surrendered. The implication was clear: if Paulus surrendered, he would shame himself and would become the highest-ranking German officer ever to be captured. As a result, Hitler believed that Paulus would either fight to the last man or commit suicide.[190]

On the next day, the southern pocket in Stalingrad collapsed. Soviet forces reached the entrance to the German headquarters in the ruined GUM department store.[191] Major Anatoly Soldatov described the conditions of the department store basement as such, "it was unbelievably filthy, you couldn't get through the front or back doors, the filth came up to your chest, along with human waste and who knows what else. The stench was unbelievable."[192] When interrogated by the Soviets, Paulus claimed that he had not surrendered. He said that he had been taken by surprise. He denied that he was the commander of the remaining northern pocket in Stalingrad and refused to issue an order in his name for them to surrender.[193]

The central pocket, under the command of Heitz, surrendered the same day, while the northern pocket, under the command of General Karl Strecker, held out for two more days.[194] Four Soviet armies were deployed against the northern pocket. At four in the morning on 2 February, Strecker was informed that one of his own officers had gone to the Soviets to negotiate surrender terms. Seeing no point in continuing, he sent a radio message saying that his command had done its duty and fought to the last man. When Strecker finally surrendered, he and his chief of staff, Helmuth Groscurth, drafted the final signal sent from Stalingrad, purposely omitting the customary exclamation to Hitler, replacing it with "Long live Germany!"[195]

Around 91,000 exhausted, ill, wounded, and starving prisoners were taken. The prisoners included 22 generals. Hitler was furious and confided that Paulus "could have freed himself from all sorrow and ascended into eternity and national immortality, but he prefers to go to Moscow".[196]

Tactics and battle conditions

German military doctrine was based on the principle of combined-arms teams and close cooperation between tanks, infantry, engineers, artillery and ground-attack aircraft. To negate the German usage of tanks and artillery in the ruins of the city, Soviet commander Chuikov introduced a tactic he described as "hugging" the enemy: keeping Soviet front-line positions as close as possible to those of the Germans, so German artillery and aircraft could not attack without risking friendly fire.[197][198] After mid-September, to reduce casualties, he ceased launching organized daylight counterattacks, instead emphasizing small unit tactics in which infantry moved through the city's sewers to strike into the rear of attacking German units.[199] The Soviets preferred night attacks, which disrupted German morale by depriving them of sleep. Soviet reconnaissance patrols were used to find German positions and take prisoners for interrogation, enabling them to anticipate attacks. When Soviet troops detected a coming attack, they launched their own counterattacks at dawn before German air support could arrive. Soviet troops blunted the German attacks themselves through ambushes that separated tanks from their supporting infantry, as well as the employment of booby traps and mines. These tactical innovations became widespread.[200]

The Soviets used the great amount of destruction to their advantage, by adding man-made defenses such as barbed wire, minefields, trenches, and bunkers to the rubble, while large factories even housed tanks and large-caliber guns within.[32] "Red Army soldiers enjoyed inventing gadgets to kill Germans. New booby traps were dreamed up, each seemingly more ingenious and unpredictable in its results than the last."[201] The battle saw many types of MOUT combat techniques.[120]

The forces involved in the battle were composed of well-trained, and in some cases, very-experienced troops,[202] "Stalingrad was fought and lost by the finest collection of divisions in an army that had not known strategic defeat for a quarter of a century" in reference to German forces.[203]

Stalingrad was the supreme example of "total war",[204] described as "approaching Clausewitz's theoretical description of absolute war".[36] The Soviets persisted against German forces by using all available means, with the commitment being reflected in their planning, orders and actions. Stalin’s commitment to Stalingrad became total, using every available resource to hold it, and ordering the city be held at all costs. Evidence of commitment was the vast casualties the Soviets were willing to sustain. Collateral damage was not a major concern, the first priority was victory and all weapons would be used to that end with little regard for collateral damage.[205] This is also reflected by a common saying among the Soviet defenders, who often exclaimed that "for us, there is no land beyond the Volga".[206] Total war was reflected by Axis forces, as they attacked without concern and committed to a bombing campaign which utterly destroyed the city and killed thousands of civilians, and Hitler would not allow for German forces to retreat, even with the threat of encirclement.[83] On 14 October, Hitler suspended all operations along the entire Eastern Front except for Stalingrad, and continued pushing even harder for Army Group B to capture the city, showing his willingness to capture it at all costs.[207]

An important weapon was the flamethrower, which was "effectively terrifying" in its use of clearing sewer tunnels, cellars, and inaccessible hiding places.[201] Operators were immediately targeted as soon as they were spotted.[201] The Katyusha rocket launcher, known to the Germans as "Stalin's organ", was used with devastating effect.[208] In hand-to-hand fighting, spades were used as axes.[209] Equipment used during the battle represented a full spectrum of World War II equipment, encompassing manufactured and field-improvised systems,[204] as both sides fielded and used their complete arsenals.[35]

The battle consumed a tremendous amount of ammunition and resources, in September fighting alone, the 6th Army expended 25 million rounds of small arms, 500,000 anti-tank rounds, 752,000 artillery shells and 178,000 hand grenades, with German forces expending 300 to 500 tons of artillery ammunition each day.[210] The Red Army fired more ammunition in this battle than any other operation of the war.[211]

The Soviet urban warfare tactics relied on 20-to-50-man-assault groups, armed with machine guns, grenades and satchel charges, with buildings fortified as strongpoints with clear fields of fire. Strongpoints were defended by guns or tanks on the ground floor, while machine gunners and artillery observers operated from the upper floors. Assault groups used sewers or broke through walls into adjoining buildings, to maintain concealment while moving into the rear of German attacks. Soviet tactical innovations were a "combination of intelligence, discipline, and determination" enabling the Soviet defenders to keep fighting when the Germans had achieved victory by "all conventional measures."[200]

The battle was notable for hand-to-hand combat,[132] the "most savage hand-to-hand battle in human memory".[212] Ferocious fighting raged for ruins, streets, factories, houses, basements, and staircases.[132][32] Blocks and buildings would change hands numerous times through intense hand-to-hand fighting.[213] Combat was so close at times that soldiers preferred using melee weapons, such as knives, and grenades being tossed in such short distances they could be thrown back before they exploded.[214] "Every building had to be fought for; single buildings and single blocks became major military objectives. Often both German and Russian troops occupied parts of the same building."[209] Even the sewers saw firefights. The Germans called this unseen urban warfare "Rat War".[215] Buildings had to be cleared room by room through the bombed-out debris of residential areas, office blocks, basements and apartment high-rises. Antony Beevor describes how this process was particularly brutal, "In its way, the fighting in Stalingrad was even more terrifying than the impersonal slaughter at Verdun...It possessed a savage intimacy which appalled their generals, who felt that they were rapidly losing control over events."[216] According to Peter Calvocoressi and Guy Wint, "The closest and bloodiest battle of the war was fought among the stumps of buildings burnt or burning".[217] Buildings saw floor-by-floor, close combat, with the Germans and Soviets on alternate levels, firing at each other through holes in the floors.[218] Fighting on and around Mamayev Kurgan, a prominent hill above the city, was particularly merciless; indeed, the position changed hands many times.[219][220] A notable building brutally fought for was Gerhardt's Mill, still kept as a memorial. It was eventually cleared by the 39th Guards Regiment in close-quarters combat.[221] Another example was on 14 September, the main railway station changed hands five times, and over the course of the next three days, another thirteen times.[218]

The brutality was shown by the military casualties taken by units.[222] The 13th Guards Rifle Division suffered 30% casualties in the first twenty-four hours, with only 320 men out of 10,000 remaining at the battle's conclusion.[221] With buildings and floors changing hands dozens of times and taking up days to win, platoons and companies took up to 90% and even 100% casualties to win a building or floor within it.[32] Chuikov estimated that about three thousand Germans had been killed during the fighting for the tractor factory on 14 October alone.[223]

The Germans used aircraft, tanks and heavy artillery to clear the city with varying success. Towards the end of August, the gigantic railroad gun nicknamed Dora was brought in, being withdrawn soon after due to Soviet threats to the gun.[224] Germans would shell Soviet reinforcements coming across the Volga without pause, with the Soviets firing back.[225] Despite the notion of the vulnerability of tanks in urban settings, tank warfare was important, and the basis of every Soviet position was anti-tank warfare, with significant efforts made to resist German tank assaults.[226] The Luftwaffe conducted 100,000 sorties and dropped 100,000 tons of bombs on the city and river crossings.[227]

The battle epitomized the use of snipers in urban warfare.[228] Snipers on both sides used the ruins to inflict casualties, with Soviet command heavily emphasizing sniper tactics to wear down the Germans. The most famous Soviet sniper was Vasily Zaytsev, who became a propaganda hero,[200] credited with 225 kills. Targets were often soldiers bringing up food or water to forward positions. Artillery spotters were an especially prized target for snipers.[229]

The ferocious and intense fighting was not only within the city itself. Most brutal fighting that consumed both forces occurred outside and west of the city, in the snow-covered steppes.[37] The battle turned from the mobile warfare during the German push towards the city into positional warfare,[230] with trench warfare becoming common inside and outside the city, as both sides entrenched themselves and built up positions, with trenches being turned into strongpoints and brutally fought for.[231][232][117][233]

A historical debate concerns the degree of terror in the Red Army. Beevor noted the "sinister" message from the Stalingrad Front's Political Department on 8 October 1942 that: "The defeatist mood is almost eliminated and the number of treasonous incidents is getting lower" as an example of the coercion Red Army soldiers experienced under the Special Detachments (renamed SMERSH).[234] On the other hand, Beevor noted the often extraordinary bravery of the Soviet soldiers, and argued terror alone cannot explain such self-sacrifice.[235] A Soviet officer interviewed, explained the feeling, "There was this sense that every soldier and officer in Stalingrad was itching to kill as many Germans as possible. In Stalingrad people felt a particularly intense hatred for the Germans."[236] German observers were perplexed by the relentlessness of the Soviets, with a 29 October 1942 article in the SS newspaper, Das Schwarze Korps, stating "The Bolshevists attack until total exhaustion, and defend themselves until the physical extermination of the last man and weapon . . . Sometimes the individual will fight beyond the point considered humanly possible".[237] One example of the heroism seen in Soviet troops was Soviet marine Mikhail Panikakha, who was covered in flames after his Molotov cocktail was shot while attempting to throw it, however he continued with another Molotov and destroyed a tank.[238]

Richard Overy addresses the question of how important the Red Army's coercive methods were to the war effort compared with other factors such as hatred for the enemy, stating that while it is "easy to argue that from the summer of 1942 the Soviet army fought because it was forced to fight," to concentrate solely on coercion is nonetheless to "distort our view of the Soviet war effort."[239] After conducting interviews with Soviet veterans on the terror on the Eastern Front – and specifically Order No. 227 ("Not a step back!") – Catherine Merridale notes, seemingly paradoxically, "their response was frequently relief."[240] Infantryman Lev Lvovich's explanation is typical, "[i]t was a necessary and important step. We all knew where we stood after we had heard it. And we all – it's true – felt better. Yes, we felt better."[240]

Many women fought on the Soviet side or were under fire. As General Chuikov acknowledged, "Remembering the defence of Stalingrad, I can't overlook the very important question … about the role of women in war, in the rear, but also at the front. Equally with men they bore all the burdens of combat life and together with us men, they went all the way to Berlin."[241] At the beginning of the battle there were 75,000 women and girls from the Stalingrad area who had finished military or medical training, and they were to serve in the battle.[242] Women staffed many anti-aircraft batteries that fought the Luftwaffe and German tanks.[243] Soviet nurses not only treated wounded personnel under fire but were involved in the dangerous work of bringing wounded soldiers back to hospitals under fire.[244] Many Soviet wireless and telephone operators were women who often suffered heavy casualties when their command posts came under fire.[245] Though women were not usually trained as infantry, many Soviet women fought as machine gunners, mortar operators, scouts,[246] and as snipers.[247] Three air regiments at Stalingrad were entirely female.[246] At least three women won the Hero of the Soviet Union while driving tanks.[248]

For Stalin and Hitler, Stalingrad became a matter of prestige beyond its strategic significance.[249] A book analyzing urban warfare remarked that "Among the cases collected here, the most extreme example of politics and sentiment investing a city with importance is that of Stalingrad".[250] Another paper notes "the battle between German and Soviet forces at Stalingrad was representative of the battle of wills between Hitler and Stalin".[251] The strain on military commanders was immense: Paulus developed an uncontrollable tic in his eye, which eventually affected the left side of his face, while Chuikov experienced an outbreak of eczema that required him to have his hands completely bandaged. Troops on both sides faced the constant strain of close-range combat.[130]

The Soviets used psychological warfare tactics to intimidate and demoralize. On loudspeakers throughout the ruined city, it was continuously announced that "Every seven seconds a German soldier dies in Russia. Stalingrad. . .mass grave".[252][253] The sound was interspersed with the monotonous sound of a ticking clock, and an orchestral melody dubbed the "Tango of Death".[253]

Medical and food conditions

The conditions of both armies were atrocious. Disease ran rampant, with many deaths due to dysentery, typhus, diphtheria, tuberculosis and jaundice, causing medical staff to fear a possible epidemic.[254] Rats and mice were plentiful, serving as one reason Germans could not counterattack in time, due to mice having chewed their tank wiring.[254] Lice were heavily prevalent, and plagues of flies would gather around kitchens, adding to the possibility of wound infections. Brutal winter conditions affected soldiers tremendously,[32] with temperatures at times reaching as low as −40 °C in the second half of November,[255] and −30 °C in late January.[254] The weather conditions were considered to be extreme and the worst possible.[256][32] The weather conditions caused rapid frostbite, with many cases of gangrene and amputation. The conditions saw soldiers dying en masse due to frostbite and hypothermia.[254] Both armies suffered food shortages, with mass starvation on both sides. Stress, tiredness and the cold upset the metabolism of soldiers, receiving a reduced amount of calories from food.[254] German forces eventually ran out of medical supplies such as ether, antiseptics and bandages. Surgery had to be done without anaesthesia.[254]

Biologist Kenneth Alibek suggested the Red Army used tularemia as a biological weapon during the battle, though this is thought to have resulted from natural causes.[257]

Casualties

The Axis suffered 800,000–1,500,000 casualties (killed, wounded or captured) among all branches of the German armed forces and their allies:

- 282,606 in the 6th Army from 21 August to the end of the battle; 17,293 in the 4th Panzer Army from 21 August to 31 January; 55,260 in the Army Group Don from 1 December 1942 to the end of the battle (12,727 killed, 37,627 wounded and 4,906 missing)[148][258] Walsh estimates the losses to 6th Army and 4th Panzer division were over 300,000;[259] while Louis A. DiMarco estimated the Germans suffered 400,000 total casualties during the battle.[13] Soviet officials recovered 250,000 German and Romanian corpses in and around Stalingrad.[260]

- According to Peter H. Wilson: German forces suffered 800,000 casualties, including the Romanians.[261]

- According to the multivolume “The Great Patriotic War 1941-1945”: Germany and its allies suffered up up to 1.5 million casualties for the entire battle, in the Don, Volga and Stalingrad areas.[262] The figure of 1.5 million total Axis casualties was also stated by Geoffrey Jukes in 1968.[263] This has been cited as an overestimate however.[40]

- According to G. G. Matishov, et al.: Germany and its allies suffered more than 880,000 casualties from November 1942 to early February 1943 between Stalingrad and the "great bend of the Don".[264]

- According to Frieser, et al.: 109,000 Romanians casualties (from November 1942 to December 1942), included 70,000 captured or missing. 114,000 Italians and 105,000 Hungarians were killed, wounded or captured (from December 1942 to February 1943).[14]

- According to Stephen Walsh: Romanian casualties were 158,854; 114,520 Italians (84,830 killed, missing and 29,690 wounded); and 143,000 Hungarian (80,000 killed, missing and 63,000 wounded),[265] with total losses of Germany's allies at 494,374. Losses among Soviet POW turncoats Hiwis range between 19,300 and 52,000.[16]

235,000 German and allied troops in total, from all units, including Manstein's ill-fated relief force, were captured during the battle.[266]

It is estimated that as many as over one million soldiers and civilians combined were killed during the battle.[267][268][269][39][41] Historian William Craig, while researching for his book, stressed the incredible death toll of the battle, stating that "Most appalling was the growing realization, formed by statistics I uncovered, that the battle was the greatest military bloodbath in recorded history. Well over a million men and women died because of Stalingrad, a number far surpassing the previous records of dead at the first battle of the Somme and Verdun in 1916."[267] Historian Edwin P. Hoyt states that "In less than seven months the Stalingrad dead numbered over three million".[268] Historian Jochen Hellbeck described the lethality of the battle as such, "The battle of Stalingrad—the most ferocious and lethal battle in human history—ended on February 2. With an estimated death toll in an excess of a million, the bloodletting at Stalingrad far exceeded that of Verdun, one of the costliest battles of World War I."[39] According to military historian Louis A. DiMarco, "In terms of raw casualty numbers, the battle for Stalingrad was the single most brutal battle in history."[270] Military historian Victor Davis Hanson affirmed that "The costliest land battle in history took place at Stalingrad"[271] and that the "fighting inside a besieged Stalingrad proved to be the most costly single battle of World War II. At least 1.5 million Russians and Germans died over the months of contesting the city's rubble, comparably only to the World War I German attack on the fortress complex at Verdun."[272] British historian Andrew Roberts stated that "Superlatives are unavoidable when describing the battle of Stalingrad; it was the struggle of Gog and Magog, the merciless clash where the rules of war were discarded . . . Around 1.1 million died in the battle on both sides".[273]

The Germans lost 900 aircraft (including 274 transports and 165 bombers used as transports), 500 tanks and 6,000 artillery pieces.[274] A recent Soviet report states that 5,762 guns, 1,312 mortars, 12,701 heavy machine guns, 156,987 rifles, 80,438 sub-machine guns, 10,722 trucks, 744 aircraft; 1,666 tanks, 261 other armoured vehicles, 571 half-tracks and 10,679 motorcycles were captured by the Soviets.[275]

The USSR, according to archival figures, suffered 1,129,619 total casualties; 478,741 personnel killed or missing, termed to be "irrevocable", and 650,878 wounded or sick. The USSR lost 4,341 tanks destroyed or damaged, 15,728 artillery pieces and 2,769 combat aircraft.[276] Though the losses given by Soviet officials have been met with criticism, for accuracy of Soviet losses and underreporting.[277][278][279] Recent clarifications of data and estimates of losses state that the USSR suffered 1,347,214 total casualties, with 674,990 irrevocable losses, and 672,224 being wounded or sick,[280][278] with an extension of this data to include NKVD troops and volunteer formations, the total casualties could extend to 1.36 to 1.37 million.[40] However, the data is still questioned as being underestimated.[281][282] The British historian Laurence Rees gives a figure of one million Soviet soldiers dead on the Stalingrad front.[283]

Russian historian Boris Vadimovich Sokolov cites the memoirs of a former director of the Tsaritsyn-Stalingrad Defense Museum, who noted that over two million Soviets dead were counted before being ordered to stop, with "still many months of work left". Sokolov states it as being closer to the true death toll than official statistics due to severe underreporting.[278]

According to incomplete data from the Volgograd party archive, 42,754 people died during the course of the battle.[284] However, research by Russian historian Tatyana Pavlova calculated there to be 710,000 inhabitants in the city on 23 August, and of that amount, 185,232 people had died by the battle's conclusion, and including about 50,000 in the rural areas of Stalingrad, for a total of 235,232 civilians dead.[285] Also from her research, Pavlova states that "The losses of the civilian population of Stalingrad are 32.3% higher than the losses of the population of Hiroshima from the atomic bombing" and that "In Stalingrad, an absolute world record was set for the mass destruction of the civilian population during World War II."[286] A 2018 study concluded that the demographic losses due to the battle ranged from 2.5 to 3 million, thereby describing it as a "real demographic catastrophe".[287]

Luftwaffe losses

| Losses | Aircraft type |

|---|---|

| 269 | Junkers Ju 52 |

| 169 | Heinkel He 111 |

| 42 | Junkers Ju 86 |

| 9 | Focke-Wulf Fw 200 |

| 5 | Heinkel He 177 |

| 1 | Junkers Ju 290 |