Критическая расовая теория

Примеры и перспективы в этой статье касаются главным образом Соединенных Штатов и не отражают мировую точку зрения на этот вопрос . ( Ноябрь 2023 г. ) |

Критическая расовая теория ( CRT ) — это междисциплинарная академическая область, сосредоточенная на отношениях между социальными концепциями расы и этнической принадлежности , социальными и политическими законами и средствами массовой информации. CRT также считает, что расизм носит системный характер в различных законах и правилах, а не основан только на индивидуальных предрассудках. [1] [2] Слово «критический» в названии является академической ссылкой на критическую теорию, а не на критику или обвинение отдельных лиц. [3] [4]

ЭЛТ также используется в социологии для объяснения социальных, политических и правовых структур и распределения власти через «линзу», фокусирующуюся на концепции расы и опыте расизма . [5] [6] Например, концептуальная основа CRT исследует расовую предвзятость в законах и правовых институтах, например, крайне разный уровень тюремного заключения среди расовых групп в Соединенных Штатах. [7] Ключевой концепцией CRT является интерсекциональность – то, как на различные формы неравенства и идентичности влияют взаимосвязи расы, класса, пола и инвалидности. [8] Ученые CRT рассматривают расу как социальную конструкцию, не имеющую биологической основы. [9] [10] Один из принципов CRT заключается в том, что расизм и несопоставимые расовые последствия, нарушающие фактическое равенство, являются результатом сложной, меняющейся и часто тонкой социальной и институциональной динамики, а не явных и преднамеренных предрассудков отдельных лиц. [10] [3] [11] CRT scholars argue that the social and legal construction of race advances the interests of white people[9][12] at the expense of people of color,[13][14] and that the liberal notion of U.S. law as "neutral" plays a significant role in maintaining a racially unjust social order,[15] where formally color-blind laws continue to have racially discriminatory outcomes.[16]

CRT began in the United States in the post–civil rights era, as 1960s landmark civil rights laws were being eroded and schools were being re-segregated.[17][18] With racial inequalities persisting even after civil rights legislation and color-blind laws were enacted, CRT scholars in the 1970s and 1980s began reworking and expanding critical legal studies (CLS) theories on class, economic structure, and the law[19] to examine the role of US law in perpetuating racism.[20] CRT, a framework of analysis grounded in critical theory,[21] originated in the mid-1970s in the writings of several American legal scholars, including Derrick Bell, Alan Freeman, Kimberlé Crenshaw, Richard Delgado, Cheryl Harris, Charles R. Lawrence III, Mari Matsuda, and Patricia J. Williams.[22] CRT draws from the work of thinkers such as Antonio Gramsci, Sojourner Truth, Frederick Douglass, and W. E. B. Du Bois, as well as the Black Power, Chicano, and radical feminist movements from the 1960s and 1970s.[22]

Academic critics of CRT argue it is based on storytelling instead of evidence and reason, rejects truth and merit, and undervalues liberalism.[17][23] Since 2020, conservative US lawmakers have sought to ban or restrict the teaching of CRT in primary and secondary schools,[3][24] as well as relevant training inside federal agencies.[25] Advocates of such bans argue that CRT is false, anti-American, villainizes white people, promotes radical leftism, and indoctrinates children.[17][26] Advocates of bans on CRT have been accused of misrepresenting its tenets, and of having the goal to broadly silence discussions of racism, equality, social justice, and the history of race.[27][28]

Definitions

This section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

In his introduction to the comprehensive 1995 publication of critical race theory's key writings, Cornel West described CRT as "an intellectual movement that is both particular to our postmodern (and conservative) times and part of a long tradition of human resistance and liberation."[29] Law professor Roy L. Brooks defined critical race theory in 1994 as "a collection of critical stances against the existing legal order from a race-based point of view".[30]

Gloria Ladson-Billings, who—along with co-author William Tate—had introduced CRT to the field of education in 1995,[31] described it in 2015 as an "interdisciplinary approach that seeks to understand and combat race inequity in society."[32] Ladson-Billings wrote in 1998 that CRT "first emerged as a counterlegal scholarship to the positivist and liberal legal discourse of civil rights."[33]

In 2017, University of Alabama School of Law professor Richard Delgado, a co-founder of critical race theory,[citation needed] and legal writer Jean Stefancic define CRT as "a collection of activists and scholars interested in studying and transforming the relationship among race, racism, and power".[34] In 2021, Khiara Bridges, a law professor and author of the textbook Critical Race Theory: A Primer,[11] defined critical race theory as an "intellectual movement", a "body of scholarship", and an "analytical toolset for interrogating the relationship between law and racial inequality."[20]

The 2021 Encyclopaedia Britannica described CRT as an "intellectual and social movement and loosely organized framework of legal analysis based on the premise that race is not a natural, biologically grounded feature of physically distinct subgroups of human beings but a socially constructed (culturally invented) category that is used to oppress and exploit people of colour."[17][35]

Tenets

Scholars of CRT say that race is not "biologically grounded and natural";[9][10] rather, it is a socially constructed category used to oppress and exploit people of color;[35] and that racism is not an aberration,[36] but a normalized feature of American society.[35] According to CRT, negative stereotypes assigned to members of minority groups benefit white people[35] and increase racial oppression.[37]Individuals can belong to a number of different identity groups.[35] The concept of intersectionality—one of CRT's main concepts—was introduced by legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw.[38]

Derrick Albert Bell Jr. (1930 – 2011), an American lawyer, professor, and civil rights activist, wrote that racial equality is "impossible and illusory" and that racism in the US is permanent.[36]According to Bell, civil-rights legislation will not on its own bring about progress in race relations;[36] alleged improvements or advantages to people of color "tend to serve the interests of dominant white groups", in what Bell called "interest convergence".[35] These changes do not typically affect—and at times even reinforce—racial hierarchies.[35] This is representative of the shift in the 1970s, in Bell's re-assessment of his earlier desegregation work as a civil rights lawyer. He was responding to the Supreme Court's decisions that had resulted in the re-segregation of schools.[39]

The concept of standpoint theory became particularly relevant to CRT when it was expanded to include a black feminist standpoint by Patricia Hill Collins. First introduced by feminist sociologists in the 1980s, standpoint theory holds that people in marginalized groups, who share similar experiences, can bring a collective wisdom and a unique voice to discussions on decreasing oppression.[40] In this view, insights into racism can be uncovered by examining the nature of the US legal system through the perspective of the everyday lived experiences of people of color.[35]

According to Encyclopedia Britannica, tenets of CRT have spread beyond academia, and are used to deepen understanding of socio-economic issues such as "poverty, police brutality, and voting rights violations", that are affected by the ways in which race and racism are "understood and misunderstood" in the United States.[35]

Common themes

This section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

Richard Delgado and Jean Stefancic published an annotated bibliography of CRT references in 1993, listing works of legal scholarship that addressed one or more of the following themes: "critique of liberalism"; "storytelling/counterstorytelling and 'naming one's own reality'"; "revisionist interpretations of American civil rights law and progress"; "a greater understanding of the underpinnings of race and racism"; "structural determinism"; "race, sex, class, and their intersections"; "essentialism and anti-essentialism"; "cultural nationalism/separatism"; "legal institutions, critical pedagogy, and minorities in the bar"; and "criticism and self-criticism".[41] When Gloria Ladson-Billings introduced CRT into education in 1995, she cautioned that its application required a "thorough analysis of the legal literature upon which it is based".[33]

Critique of liberalism

First and foremost to CRT legal scholars in 1993 was their "discontent" with the way in which liberalism addressed race issues in the US. They critiqued "liberal jurisprudence", including affirmative action,[42] color-blindness, role modeling, and the merit principle.[43] Specifically, they claimed that the liberal concept of value-neutral law contributed to maintenance of the US's racially unjust social order.[15]

An example questioning foundational liberal conceptions of Enlightenment values, such as rationalism and progress, is Rennard Strickland's 1986 Kansas Law Review article, "Genocide-at-Law: An Historic and Contemporary View of the Native American Experience". In it, he "introduced Native American traditions and world-views" into law school curriculum, challenging the entrenchment at that time of the "contemporary ideas of progress and enlightenment". He wrote that US laws that "permeate" the everyday lives of Native Americans were in "most cases carried out with scrupulous legality" but still resulted in what he called "cultural genocide".[44]

In 1993, David Theo Goldberg described how countries that adopt classical liberalism's concepts of "individualism, equality, and freedom"—such as the United States and European countries—conceal structural racism in their cultures and languages, citing terms such as "Third World" and "primitive".[45]: 6–7

In 1988, Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw traced the origins of the New Right's use of the concept of color-blindness from 1970s neoconservative think tanks to the Ronald Reagan administration in the 1980s.[46] She described how prominent figures such as neoconservative scholars Thomas Sowell[47] and William Bradford Reynolds,[48] who served as Assistant Attorney General for the Civil Rights Division from 1981 to 1988,[48] called for "strictly color-blind policies".[47] Sowell and Reynolds, like many conservatives at that time, believed that the goal of equality of the races had already been achieved, and therefore the race-specific civil rights movement was a "threat to democracy".[47] The color-blindness logic used in "reverse discrimination" arguments in the post-civil rights period is informed by a particular viewpoint on "equality of opportunity", as adopted by Sowell,[49] in which the state's role is limited to providing a "level playing field", not to promoting equal distribution of resources.

Crenshaw claimed that "equality of opportunity" in antidiscrimination law can have both an expansive and a restrictive aspect.[49] Crenshaw wrote that formally color-blind laws continue to have racially discriminatory outcomes.[16] According to her, this use of formal color-blindness rhetoric in claims of reverse discrimination, as in the 1978 Supreme Court ruling on Bakke, was a response to the way in which the courts had aggressively imposed affirmative action and busing during the Civil Rights era, even on those who were hostile to those issues.[46] In 1990, legal scholar Duncan Kennedy described the dominant approach to affirmative action in legal academia as "colorblind meritocratic fundamentalism". He called for a postmodern "race consciousness" approach that included "political and cultural relations" while avoiding "racialism" and "essentialism".[50]

Sociologist Eduardo Bonilla-Silva describes this newer, subtle form of racism as "color-blind racism", which uses frameworks of abstract liberalism to decontextualize race, naturalize outcomes such as segregation in neighborhoods, attribute certain cultural practices to race, and cause "minimization of racism".[51]

In his influential 1984 article, Delgado challenged the liberal concept of meritocracy in civil rights scholarship.[52] He questioned how the top articles in most well-established journals were all written by white men.[53]

Storytelling/counterstorytelling and "naming one's own reality"

This refers to the use of narrative (storytelling) to illuminate and explore lived experiences of racial oppression.[41]

One of the prime tenets of liberal jurisprudence is that people can create appealing narratives to think and talk about greater levels of justice.[54] Delgado and Stefancic call this the empathic fallacy—the belief that it is possible to "control our consciousness" by using language alone to overcome bigotry and narrow-mindedness.[55] They examine how people of color, considered outsiders in mainstream US culture, are portrayed in media and law through stereotypes and stock characters that have been adapted over time to shield the dominant culture from discomfort and guilt. For example, slaves in the 18th-century Southern States were depicted as childlike and docile; Harriet Beecher Stowe adapted this stereotype through her character Uncle Tom, depicting him as a "gentle, long-suffering", pious Christian.[56]

Following the American Civil War, the African-American woman was depicted as a wise, care-giving "Mammy" figure.[57] During the Reconstruction period, African-American men were stereotyped as "brutish and bestial", a danger to white women and children. This was exemplified in Thomas Dixon Jr.'s novels, used as the basis for the epic film The Birth of a Nation, which celebrated the Ku Klux Klan and lynching.[58] During the Harlem Renaissance, African-Americans were depicted as "musically talented" and "entertaining".[59] Following World War II, when many Black veterans joined the nascent civil rights movement, African Americans were portrayed as "cocky [and] street-smart", the "unreasonable, opportunistic" militant, the "safe, comforting, cardigan-wearing" TV sitcom character, and the "super-stud" of blaxploitation films.[60]

The empathic fallacy informs the "time-warp aspect of racism", where the dominant culture can see racism only through the hindsight of a past era or distant land, such as South Africa.[61] Through centuries of stereotypes, racism has become normalized; it is a "part of the dominant narrative we use to interpret experience".[62] Delgado and Stefancic argue that speech alone is an ineffective tool to counter racism,[61] since the system of free expression tends to favor the interests of powerful elites[63] and to assign responsibility for racist stereotypes to the "marketplace of ideas".[64] In the decades following the passage of civil rights laws, acts of racism had become less overt and more covert—invisible to, and underestimated by, most of the dominant culture.[65]

Since racism makes people feel uncomfortable, the empathic fallacy helps the dominant culture to mistakenly believe that it no longer exists, and that dominant images, portrayals, stock characters, and stereotypes—which usually portray minorities in a negative light—provide them with a true image of race in America.[citation needed] Based on these narratives, the dominant group has no need to feel guilty or to make an effort to overcome racism, as it feels "right, customary, and inoffensive to those engaged in it", while self-described liberals who uphold freedom of expression can feel virtuous while maintaining their own superior position.[66]

Standpoint epistemology

This is the view that members of racial minority groups have a unique authority and ability to speak about racism. This is seen as undermining dominant narratives relating to racial inequality, such as legal neutrality and personal responsibility or bootstrapping, through valuable first-hand accounts of the experience of racism.[67]

Revisionist interpretations of American civil rights law and progress

Interest convergence is a concept introduced by Derrick Bell in his 1980 Harvard Law Review article, "Brown v. Board of Education and the Interest-Convergence Dilemma".[68] In this article, Bell described how he re-assessed the impact of the hundreds of NAACP LDF de-segregation cases he won from 1960 to 1966, and how he began to believe that in spite of his sincerity at the time, anti-discrimination law had not resulted in improving Black children's access to quality education.[69] He listed and described how Supreme Court cases had gutted civil rights legislation, which had resulted in African-American students continuing to attend all-black schools that lacked adequate funding and resources.[68] In examining these Supreme Court cases, Bell concluded that the only civil-rights legislation that was passed coincided with the self-interest of white people, which Bell termed interest convergence.[68][70][71]

One of the best-known examples of interest convergence is the way in which American geopolitics during the Cold War in the aftermath of World War II was a critical factor in the passage of civil rights legislation by both Republicans and Democrats. Bell described this in numerous articles, including the aforementioned, and it was supported by the research and publications of legal scholar Mary L. Dudziak. In her journal articles and her 2000 book Cold War Civil Rights—based on newly released documents—Dudziak provided detailed evidence that it was in the interest of the United States to quell the negative international press about treatment of African-Americans when the majority of the populations of newly decolonized countries which the US was trying to attract to Western-style democracy, were not white. The US sought to promote liberal values throughout Africa, Asia, and Latin America to prevent the Soviet Union from spreading communism.[72] Dudziak described how the international press widely circulated stories of segregation and violence against African-Americans.

The Moore's Ford lynchings, where a World War II veteran was lynched, were particularly widespread in the news.[73] American allies followed stories of American racism through the international press, and the Soviets used stories of racism against Black Americans as a vital part of their propaganda.[74] Dudziak performed extensive archival research in the US Department of State and Department of Justice and concluded that US government support for civil-rights legislation "was motivated in part by the concern that racial discrimination harmed the United States' foreign relations".[41][75] When the National Guard was called in to prevent nine African-American students from integrating the Little Rock Central High School, the international press covered the story extensively.[74] The then-Secretary of State told President Dwight Eisenhower that the Little Rock situation was "ruining" American foreign policy, particularly in Asia and Africa.[76] The US's ambassador to the United Nations told President Eisenhower that as two-thirds of the world's population was not white, he was witnessing their negative reactions to American racial discrimination. He suspected that the US "lost several votes on the Chinese communist item because of Little Rock."[77]

Intersectional theory

This refers to the examination of race, sex, class, national origin, and sexual orientation, and how their intersections play out in various settings, such as how the needs of a Latina are different from those of a Black male, and whose needs are promoted.[41][78][further explanation needed] These intersections provide a more holistic picture for evaluating different groups of people. Intersectionality is a response to identity politics insofar as identity politics does not take into account the different intersections of people's identities.[79]

Essentialism vs. anti-essentialism

Delgado and Stefancic write, "Scholars who write about these issues are concerned with the appropriate unit for analysis: Is the black community one, or many, communities? Do middle- and working-class African-Americans have different interests and needs? Do all oppressed peoples have something in common?" This is a look at the ways that oppressed groups may share in their oppression but also have different needs and values that need to be analyzed differently. It is a question of how groups can be essentialized or are unable to be essentialized.[41][80][further explanation needed]

From an essentialist perspective, one's identity consists of an internal "essence" that is static and unchanging from birth, whereas a non-essentialist position holds that "the subject has no fixed or permanent identity."[81] Racial essentialism diverges into biological and cultural essentialism, where subordinated groups may endorse one over the other. "Cultural and biological forms of racial essentialism share the idea that differences between racial groups are determined by a fixed and uniform essence that resides within and defines all members of each racial group. However, they differ in their understanding of the nature of this essence."[82] Subordinated communities may be more likely to endorse cultural essentialism as it provides a basis of positive distinction for establishing a cumulative resistance as a means to assert their identities and advocacy of rights, whereas biological essentialism may be unlikely to resonate with marginalized groups as historically, dominant groups have used genetics and biology in justifying racism and oppression.

Essentialism is the idea of a singular, shared experience between a specific group of people. Anti-essentialism, on the other hand, believes that there are other various factors that can affect a person's being and their overall life experience. The race of an individual is viewed more as a social construct that does not necessarily dictate the outcome of their life circumstances. Race is viewed as "a social and historical construction, rather than an inherent, fixed, essential biological characteristic."[83][84] Anti-essentialism "forces a destabilization in the very concept of race itself…"[83] The results of this destabilization vary on the analytic focus falling into two general categories, "... consequences for the analytic concepts of racial identity or racial subjectivity."[83]

Structural determinism, and race, sex, class, and their intersections

This refers to the exploration of how "the structure of legal thought or culture influences its content" in a way that determines social outcomes.[41][85] Delgado and Stefancic cited "empathic fallacy" as one example of structural determinism—the "idea that our system, by reason of its structure and vocabulary, cannot redress certain types of wrong."[86] They interrogate the absence of terms such as intersectionality, anti-essentialism, and jury nullification in standard legal reference research tools in law libraries.[87]

Cultural nationalism/separatism

This refers to the exploration of more radical views that argue for separation and reparations as a form of foreign aid (including black nationalism).[41][example needed]

Legal institutions, critical pedagogy, and minorities in the bar

Camara Phyllis Jones defines institutionalized racism as "differential access to the goods, services, and opportunities of society by race. Institutionalized racism is normative, sometimes legalized and often manifests as inherited disadvantage. It is structural, having been absorbed into our institutions of custom, practice, and law, so there need not be an identifiable offender. Indeed, institutionalized racism is often evident as inaction in the face of need, manifesting itself both in material conditions and in access to power. With regard to the former, examples include differential access to quality education, sound housing, gainful employment, appropriate medical facilities, and a clean environment."[88]

Black–white binary

The black–white binary is a paradigm identified by legal scholars through which racial issues and histories are typically articulated within a racial binary between black and white Americans. The binary largely governs how race has been portrayed and addressed throughout US history.[89] Critical race theorists Richard Delgado and Jean Stefancic argue that anti-discrimination law has blindspots for non-black minorities due to its language being confined within the black–white binary.[90]

Applications and adaptations

Scholars of critical race theory have focused, with some particularity, on the issues of hate crime and hate speech. In response to the opinion of the US Supreme Court in the hate speech case of R.A.V. v. City of St. Paul (1992), in which the Court struck down an anti-bias ordinance as applied to a teenager who had burned a cross, Mari Matsuda and Charles Lawrence argued that the Court had paid insufficient attention to the history of racist speech and the actual injury produced by such speech.[91]

Critical race theorists have also argued in favor of affirmative action. They propose that so-called merit standards for hiring and educational admissions are not race-neutral and that such standards are part of the rhetoric of neutrality through which whites justify their disproportionate share of resources and social benefits.[92][93][94]

In his 2009 article "Will the Real CRT Please Stand Up: The Dangers of Philosophical Contributions to CRT", Curry distinguished between the original CRT key writings and what is being done in the name of CRT by a "growing number of white feminists".[95] The new CRT movement "favors narratives that inculcate the ideals of a post-racial humanity and racial amelioration between compassionate (Black and White) philosophical thinkers dedicated to solving America's race problem."[96] They are interested in discourse (i.e., how individuals speak about race) and the theories of white Continental philosophers, over and against the structural and institutional accounts of white supremacy which were at the heart of the realist analysis of racism introduced in Derrick Bell's early works,[97] and articulated through such African-American thinkers as W. E. B. Du Bois, Paul Robeson, and Judge Robert L. Carter.[98]

History

Early years

Although the terminology critical race theory began in its application to laws, the subject emerges from the broader frame of critical theory in how it analyzes power structures in society despite whatever laws may be in effect.[29] In the 1998 article, "Critical Race Theory: Past, Present, and Future", Delgado and Stefancic trace the origins of CRT to the early writings of Derrick Albert Bell Jr. including his 1976 Yale Law Journal article, "Serving Two Masters"[99] and his 1980 Harvard Law Review article entitled "Brown v. Board of Education and the Interest-Convergence Dilemma".[100][101]

In the 1970s, as a professor at Harvard Law School Bell began to critique, question and re-assess the civil rights cases he had litigated in the 1960s to desegregate schools following the passage of Brown v. Board of Education.[68] This re-assessment became the "cornerstone of critical race theory".[69] Delgado and Stefancic, who together wrote Critical Race Theory: a Introduction in 2001,[102] described Bell's "interest convergence" as a "means of understanding Western racial history".[103] The focus on desegregation after the 1954 Supreme Court decision in Brown—declaring school segregation unconstitutional—left "civil-rights lawyers compromised between their clients' interests and the law". The concern of many Black parents—for their children's access to better education—was being eclipsed by the interests of litigators who wanted a "breakthrough"[103] in their "pursuit of racial balance in schools".[104] In 1995, Cornel West said that Bell was "virtually the lone dissenter" writing in leading law reviews who challenged basic assumptions about how the law treated people of color.[29]

In his Harvard Law Review articles, Bell cites the 1964 Hudson v. Leake County School Board case which the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund (NAACP LDF) won, mandating that the all-white school board comply with desegregation. At that time it was seen as a success. By the 1970s, White parents were removing their children from the desegregated schools and enrolling them in segregation academies.[105] Bell came to believe that he had been mistaken in 1964 when, as a young lawyer working for the LDF, he had convinced Winson Hudson, who was the head of the newly formed local NAACP chapter in Harmony, Mississippi, to fight the all-White Leake County School Board to desegregate schools.[106] She and the other Black parents had initially sought LDF assistance to fight the board's closure of their school—one of the historic Rosenwald Schools for Black children.[106][69] Bell explained to Hudson, that—following Brown—the LDF could not fight to keep a segregated Black school open; they would have to fight for desegregation.[107] In 1964, Bell and the NAACP had believed that resources for desegregated schools would be increased and Black children would access higher quality education, since White parents would insist on better quality schools; by the 1970s, Black children were again attending segregated schools and the quality of education had deteriorated.[107]

Bell began to work for the NAACP LDF shortly after the Montgomery bus boycott and the ensuing 1956 Supreme Court ruling following Browder v. Gayle that the Alabama and Montgomery bus segregation laws were unconstitutional.[108] From 1960 to 1966 Bell successfully litigated 300 civil rights cases in Mississippi. Bell was inspired by Thurgood Marshall, who had been one of the two leaders of a decades-long legal campaign starting in the 1930s, in which they filed hundreds of lawsuits to reverse the "separate but equal" doctrine announced by the Supreme Court's decision in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896). The Court ruled that racial segregation laws enacted by the states were not in violation of the United States Constitution as long as the facilities for each race were equal in quality.[109] The Plessy decision provided the legal mandate at the federal level to enforce Jim Crow laws that had been introduced by white Southern Democrats starting in the 1870s for racial segregation in all public facilities, including public schools. The Court's 1954 Brown decision—which held that the "separate but equal" doctrine is unconstitutional in the context of public schools and educational facilities—severely weakened Plessy.[110] The Supreme Court concept of constitutional colorblindness in regards to case evaluation began with Plessy. Before Plessy, the Court considered color as a determining factor in many landmark cases, which reinforced Jim Crow laws.[111] Bell's 1960s civil rights work built on Justice Marshall's groundwork begun in the 1930s. It was a time when the legal branch of the civil rights movement was launching thousands of civil rights cases. It was a period of idealism for the civil rights movement.[69]

At Harvard, Bell developed new courses that studied American law through a racial lens. He compiled his own course materials which were published in 1970 under the title Race, Racism, and American Law.[112] He became Harvard Law School's first Black tenured professor in 1971.[104]

During the 1970s, the courts were using legislation to enforce affirmative action programs and busing—where the courts mandated busing to achieve racial integration in school districts that rejected desegregation. In response, in the 1970s, neoconservative think tanks—hostile to these two issues in particular—developed a color-blind rhetoric to oppose them,[46] claiming they represented reverse discrimination. In 1978, Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, when Bakke won this landmark Supreme Court case by using the argument of reverse racism, Bell's skepticism that racism would end increased. Justice Lewis F. Powell Jr. held that the "guarantee of equal protection cannot mean one thing when applied to one individual and something else when applied to a person of another color." In a 1979 article, Bell asked if there were any groups of the White population that would be willing to suffer any disadvantage that might result from the implementation of a policy to rectify harms to Black people resulting from slavery, segregation, or discrimination.[113]

Bell resigned in 1980 because of what he viewed as the university's discriminatory practices,[28] became the dean at University of Oregon School of Law and later returned to Harvard as a visiting professor.

While he was absent from Harvard, his supporters organized protests against Harvard's lack of racial diversity in the curriculum, in the student body and in the faculty.[114][115] The university had rejected student requests, saying no sufficiently qualified black instructor existed.[116] Legal scholar Randall Kennedy writes that some students had "felt affronted" by Harvard's choice to employ an "archetypal white liberal... in a way that precludes the development of black leadership".[117]

One of these students was Kimberlé Crenshaw, who had chosen Harvard in order to study under Bell; she was introduced to his work at Cornell.[118] Crenshaw organized the student-led initiative to offer an alternative course on race and law in 1981—based on Bell's course and textbook—where students brought in visiting professors, such as Charles Lawrence, Linda Greene, Neil Gotanda, and Richard Delgado,[104] to teach chapter-by-chapter from Race, Racism, and American Law.[119][120][114][115]

Critical race theory emerged as an intellectual movement with the organization of this boycott; CRT scholars included graduate law students and professors.[22]

Alan Freeman was a founding member of the Critical Legal Studies (CLS) movement that hosted forums in the 1980s. CLS legal scholars challenged claims to the alleged value-neutral position of the law. They criticized the legal system's role in generating and legitimizing oppressive social structures which contributed to maintaining an unjust and oppressive class system.[22] Delgado and Stefancic cite the work of Alan Freeman in the 1970s as formative to critical race theory.[121] In his 1978 Minnesota Law Review article Freeman reinterpreted, through a critical legal studies perspective, how the Supreme Court oversaw civil rights legislation from 1953 to 1969 under the Warren Court. He criticized the narrow interpretation of the law which denied relief for victims of racial discrimination.[122] In his article, Freeman describes two perspectives on the concept of racial discrimination: that of victim or perpetrator. Racial discrimination to the victim includes both objective conditions and the "consciousness associated with those objective conditions". To the perpetrator, racial discrimination consists only of actions without consideration of the objective conditions experienced by the victims, such as the "lack of jobs, lack of money, lack of housing".[122] Only those individuals who could prove they were victims of discrimination were deserving of remedies.[47] By the late 1980s, Freeman, Bell, and other CRT scholars left the CLS movement claiming it was too narrowly focused on class and economic structures while neglecting the role of race and race relations in American law.[123]

Emergence as a movement

This section may rely excessively on sources too closely associated with the subject, potentially preventing the article from being verifiable and neutral. (November 2021) |

In 1989, Kimberlé Crenshaw, Neil Gotanda, and Stephanie Phillips organized a workshop at the University of Wisconsin-Madison entitled "New Developments in Critical Race Theory". The organizers coined the term "Critical Race Theory" to signify an "intersection of critical theory and race, racism and the law."[21]

Afterward, legal scholars began publishing a higher volume of works employing critical race theory, including more than "300 leading law review articles" and books.[124]: 108 In 1990, Duncan Kennedy published his article on affirmative action in legal academia in the Duke Law Journal,[125] and Anthony E. Cook published his article "Beyond Critical Legal Studies" in the Harvard Law Review.[126] In 1991, Patricia Williams published The Alchemy of Race and Rights, while Derrick Bell published Faces at the Bottom of the Well in 1992.[120]: 124 Cheryl I. Harris published her 1993 Harvard Law Review article "Whiteness as Property" in which she described how passing led to benefits akin to owning property.[127][128] In 1995, two dozen legal scholars contributed to a major compilation of key writings on CRT.[129]

By the early 1990s, key concepts and features of CRT had emerged. Bell had introduced his concept of "interest convergence" in his 1973 article.[100] He developed the concept of racial realism in a 1992 series of essays and book, Faces at the bottom of the well: the permanence of racism.[36] He said that Black people needed to accept that the civil rights era legislation would not on its own bring about progress in race relations; anti-Black racism in the US was a "permanent fixture" of American society; and equality was "impossible and illusory" in the US. Crenshaw introduced the term intersectionality in the 1990s.[130]

In 1995, pedagogical theorists Gloria Ladson-Billings and William F. Tate began applying the critical race theory framework in the field of education.[131] In their 1995 article Ladson-Billings and Tate described the role of the social construction of white norms and interests in education. They sought to better understand inequities in schooling. Scholars have since expanded work to explore issues including school segregation in the US; relations between race, gender, and academic achievement; pedagogy; and research methodologies.[132]

As of 2002[update], over 20 American law schools and at least three non-American law schools offered critical race theory courses or classes.[133] Critical race theory is also applied in the fields of education, political science, women's studies, ethnic studies, communication, sociology, and American studies. Other movements developed that apply critical race theory to specific groups. These include the Latino-critical (LatCrit), queer-critical, and Asian-critical movements. These continued to engage with the main body of critical theory research, over time developing independent priorities and research methods.[134]

CRT has also been taught internationally, including in the United Kingdom (UK) and Australia.[135][failed verification][136] According to educational researcher Mike Cole, the main proponents of CRT in the UK include David Gillborn, John Preston, and Namita Chakrabarty.[137]

Philosophical foundations

CRT scholars draw on the work of Antonio Gramsci, Sojourner Truth, Frederick Douglass, and W. E. B. DuBois. Bell shared Paul Robeson's belief that "Black self-reliance and African cultural continuity should form the epistemic basis of Blacks' worldview."[138]Their writing is also informed by the 1960s and 1970s movements such as Black Power, Chicano, and radical feminism.[22] Critical race theory shares many intellectual commitments with critical theory, critical legal studies, feminist jurisprudence, and postcolonial theory. University of Connecticut philosopher, Lewis Gordon, who has focused on postcolonial phenomenology, and race and racism, wrote that CRT is notable for its use of postmodern poststructural scholarship, including an emphasis on "subaltern" or "marginalized" communities and the "use of alternative methodology in the expression of theoretical work, most notably their use of "narratives" and other literary techniques".[139]

Standpoint theory, which has been adopted by some CRT scholars, emerged from the first wave of the women's movement in the 1970s. The main focus of feminist standpoint theory is epistemology—the study of how knowledge is produced. The term was coined by Sandra Harding, an American feminist theorist, and developed by Dorothy Smith in her 1989 publication, The Everyday World as Problematic: A Feminist Sociology.[140] Smith wrote that by studying how women socially construct their own everyday life experiences, sociologists could ask new questions.[141] Patricia Hill Collins introduced black feminist standpoint—a collective wisdom of those who have similar perspectives in society which sought to heighten awareness to these marginalized groups and provide ways to improve their position in society.[40]

Критическая расовая теория опирается на приоритеты и перспективы как критических юридических исследований (CLS), так и традиционных исследований гражданских прав, одновременно резко оспаривая обе эти области. Школы права Калифорнийского университета в Дэвисе Ученый-юрист Анджела П. Харрис описывает критическую расовую теорию как разделяющую «приверженность видению освобождения от расизма посредством разумного разума» с традицией гражданских прав. [142] Он деконструирует некоторые предпосылки и аргументы теории права и одновременно утверждает, что юридически созданные права невероятно важны. [143] Ученые CRT не согласились с позицией CLS, направленной против юридических прав, и не хотели «полностью отказываться от понятий права»; Ученые-правоведы CRT признали, что некоторые законы и реформы помогли цветным людям. [17] По описанию Деррика Белла, критическая расовая теория, по мнению Харриса, направлена на «радикальную критику закона ( нормативно деконструктивистскую ) и… радикальную эмансипацию с помощью закона (нормативно реконструктивистскую)». [144]

Эдинбургского университета Профессор философии Томми Дж. Карри говорит, что к 2009 году взгляд CRT на расу как социальную конструкцию был принят «многими исследователями расы» как «здравый взгляд», согласно которому раса не является «биологически обоснованной и естественной». [9] [10] Социальный конструкт — это термин из социального конструктивизма, корни которого можно проследить до ранних научных войн, частично спровоцированных книгой Томаса Куна 1962 года «Структура научных революций» . [145] Ян Хакинг , канадский философ , специализирующийся на философии науки , описывает, как социальное строительство распространилось через социальные науки. В качестве примера он приводит социальное конструирование расы, задаваясь вопросом, как можно лучше «сконструировать» расу. [146]

Критика

Академическая критика

Согласно Британской энциклопедии , аспекты CRT подвергались критике со стороны «ученых-правоведов и юристов всего политического спектра». [17] Критика ЭЛТ сосредоточена на акценте на повествовании, критике принципа достоинств и объективной истины, а также на тезисе о голосе цвета . [147] Критики говорят, что он содержит « вдохновленный постмодернизмом скептицизм в отношении объективности и истины» и имеет тенденцию интерпретировать «любое расовое неравенство или дисбаланс [...] как доказательство институционального расизма и как основание для прямого навязывания расово справедливых результатов в этих сферах». ", сообщает Britannica . Сторонников ЭЛТ также обвиняют в том, что они рассматривают даже благонамеренную критику ЭЛТ как свидетельство скрытого расизма. [17]

В книге 1997 года профессора права Дэниел А. Фарбер и Сюзанна Шерри раскритиковали CRT за то, что она основывает свои утверждения на личных рассказах и за отсутствие проверяемых гипотез и измеримых данных. [148] Ученые CRT, в том числе Креншоу, Дельгадо и Стефанчич, ответили, что такая критика представляет собой доминирующие методы в социальных науках, которые имеют тенденцию исключать цветных людей. [149] Дельгадо и Стефанчич писали: «В этих сферах [социальных наук и политики] истина — это социальная конструкция, созданная для удовлетворения целей доминирующей группы». [149] Фарбер и Шерри также утверждали, что антимеритократические принципы критической расовой теории, критического феминизма и критических юридических исследований могут непреднамеренно привести к антисемитским и антиазиатским последствиям. [150] [151] Они пишут, что успех евреев и азиатов в системе, которую критически настроенные расовые теоретики называют структурно несправедливой, может привести к обвинениям в мошенничестве и извлечении выгоды. [152] В ответ Дельгадо и Стефанчич пишут, что есть разница между критикой несправедливой системы и критикой людей, которые хорошо работают внутри этой системы. [153]

Общественные споры

Критическая расовая теория вызвала споры в Соединенных Штатах из-за пропаганды использования нарратива в юридических исследованиях , защиты «правового инструментализма » в отличие от идеального использования закона и поощрения ученых-юристов продвигать расовое равенство. [154]

До 1993 года термин «критическая расовая теория» не был частью общественного дискурса. [28] Весной того же года консерваторы начали кампанию под руководством Клинта Болика. [155] изобразить Лани Гинье тогдашнего президента Билла Клинтона — кандидатуру на пост помощника генерального прокурора по гражданским правам — как радикалку из-за ее связи с CRT. Через несколько месяцев Клинтон отозвала свою кандидатуру. [156] охарактеризовав попытку остановить назначение Гинье как «кампанию правого искажения и очернения». [157] Это было частью более широкой консервативной стратегии, направленной на то, чтобы склонить Верховный суд в свою пользу. [158] [159] [160] [161]

Эми Э. Анселл пишет, что логика правового инструментализма получила широкий общественный отклик в деле об убийстве О. Дж. Симпсона , когда адвокат Джонни Кокран «применил своего рода прикладной CRT», выбрав афроамериканских присяжных и призвав их оправдать Симпсона, несмотря на доказательства против него — форма аннулирования присяжных . [162] Ученый-юрист Джеффри Розен называет это «наиболее ярким примером» влияния CRT на правовую систему США. [163] Профессор права Маргарет М. Рассел ответила на утверждение Розена в Michigan Law Review , заявив, что «драматичный» и «спорный» стиль зала суда и стратегический смысл Кокрана в деле Симпсонов стали результатом его многолетнего опыта работы адвокатом; на него не оказали существенного влияния сочинения ЭЛТ. [164]

В 2010 году программа мексикано-американских исследований в Тусоне, штат Аризона , была остановлена из-за закона штата, запрещающего государственным школам предлагать расово-ориентированное образование в форме «пропаганды этнической солидарности вместо обращения с учениками как с личностями». . [165] Некоторые книги, в том числе учебник по ЭЛТ, были исключены из учебной программы. [165] Мэтта де ла Пенья « юношеский роман Мексиканский белый мальчик» был запрещен за «содержание «критической расовой теории » ». По словам государственных чиновников, [166] Запрет на программы этнических исследований позже был признан неконституционным на том основании, что штат продемонстрировал дискриминационные намерения: «Как принятие закона, так и его исполнение были мотивированы расовой враждебностью», - федеральный судья А. Уоллес Ташима . постановил [167]

вызовы 2020-х годов

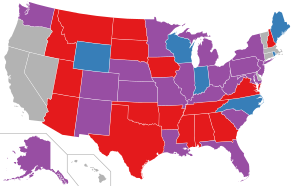

и другие предпринимают усилия, С 2020 года консерваторы чтобы бросить вызов критической теории расы (CRT), преподаваемой в школах США .

После протестов 2020 года, вызванных убийствами Ахмауда Арбери и Джорджа Флойда , а также убийства Бреонны Тейлор , школьные округа начали вводить дополнительные учебные программы и создавать позиции разнообразия, равенства и инклюзивности (DEI) для устранения «диспропорций, вызванных расой, экономика, инвалидность и другие факторы». [168] Эти меры были встречены критикой со стороны консерваторов, особенно членов Республиканской партии . Критики охарактеризовали эту критику как часть цикла негативной реакции на то, что они считают прогрессом на пути к расовому равенству и справедливости. [169]

Ярыми критиками критической расовой теории являются бывший президент США Дональд Трамп , консервативный активист Кристофер Руфо , различные республиканские чиновники и консервативные комментаторы на Fox News и правых ток-радиошоу. [170] В результате разногласий возникли движения; в частности, движение «Нет повороту налево в образовании», которое описывается как одна из крупнейших групп, выступающих против школьных советов в отношении критической расовой теории. В ответ на необоснованное утверждение о том, что CRT преподается в государственных школах, десятки штатов внесли законопроекты, ограничивающие преподавание в школах вопросов расы, американской истории , политики и пола. [171]Подполя

В рамках критической расовой теории различные подгруппы сосредотачивают внимание на проблемах и нюансах, уникальных для конкретных этнорасовых и/или маргинализированных сообществ. Это включает в себя пересечение расы с инвалидностью, этнической принадлежностью, полом, сексуальностью, классом или религией. Например, критические расовые исследования инвалидности (DisCrit), критический расовый феминизм (CRF), еврейская теория критической расы (HebCrit, [172] произносится как «Хиб»), Теория критической расы черных (Black Crit), латиноамериканские критические расовые исследования (LatCrit [173] ), критические расовые исследования американцев азиатского происхождения (AsianCrit [174] ), критические расовые исследования американцев Южной Азии (DesiCrit [175] ), Количественная критическая расовая теория (QuantCrit [176] ), Странная критическая расовая теория (QueerCrit [177] ), а также исследования критической расы американских индейцев или теорию критической расы племен (иногда называемую TribalCrit [174] ). Методологии ЭЛТ также применялись для изучения групп белых иммигрантов. [178] ЭЛТ побудила некоторых учёных призвать ко второй волне исследований белизны , которая теперь является небольшим ответвлением, известным как Вторая волна белизны (SWW). [179] Критическая расовая теория также начала порождать исследования, изучающие понимание расы за пределами Соединенных Штатов. [180] [181]

Теория критической расы инвалидности

Еще одной ответвленной областью являются исследования расы, критической для инвалидов (DisCrit), которая сочетает в себе исследования инвалидности и ЭЛТ, чтобы сосредоточиться на пересечении инвалидности и расы. [182]

Латиноамериканская критическая расовая теория

Латиноамериканская критическая расовая теория (LatCRT или LatCrit) — это исследовательская основа, в которой социальная конструкция расы рассматривается как центральная часть того, как цветные люди ограничиваются и угнетаются в обществе. Ученые-расисты разработали LatCRT как критический ответ на «проблему цветовой линии », впервые объясненную У.Б. Дюбуа . [183] В то время как CRT фокусируется на черно-белой парадигме, LatCRT перешел к рассмотрению других расовых групп, в основном чикана/чикано , а также латиноамериканцев/ас , азиатов , коренных американцев / первых наций и цветных женщин.

В книге «Контристории критических рас в образовательном трубопроводе чикана/чикано» Тара Дж. Йоссо обсуждает, как можно определить ограничение POC. Глядя на различия между студентами чикана/о , можно выделить следующие принципы, которые разделяют таких людей: межцентричность расы и расизма, вызов доминирующей идеологии , приверженность социальной справедливости , центральное место практического знания и междисциплинарная перспектива. [184]

Основная цель LatCRT — отстаивать социальную справедливость для тех, кто живет в маргинализированных сообществах (в частности, чикана/ос), которые руководствуются структурными механизмами, которые ставят в невыгодное положение цветных людей. Механизмы, в которых социальные институты действуют как лишение собственности , лишение избирательных прав и дискриминация групп меньшинств. В попытке дать голос тем, кто стал жертвой , [183] LatCRT создал две общие темы:

Во-первых, CRT предлагает, чтобы превосходство белых и расовая власть сохранялись с течением времени, и в этом процессе закон играет центральную роль. Разным расовым группам не хватает голоса, чтобы говорить в этом гражданском обществе , и, таким образом, CRT ввел новый критический подход. форма выражения, называемая голосом цвета . [183] Голос цвета — это повествования и повествовательные монологи, используемые как средства передачи личного расового опыта. Они также используются для противодействия метанарративам , которые продолжают поддерживать расовое неравенство . Таким образом, опыт угнетенных является важным аспектом для разработки аналитического подхода LatCRT, и со времен возникновения рабства институт так фундаментально формировал жизненные возможности тех, кто носит ярлык преступника.

Во-вторых, работа LatCRT исследовала возможность трансформации отношений между правоохранительными органами и расовой властью, а также реализацию проекта достижения расовой эмансипации и борьбы с подчинением в более широком смысле. [185] Его объем исследований отличается от общей критической расовой теории тем, что он уделяет особое внимание теории и политике иммиграции, языковым правам, а также формам дискриминации по акценту и национальному происхождению. [186] ЭЛТ находит экспериментальные знания цветных людей и явно черпает из этого жизненного опыта в виде данных, представляя результаты исследований через рассказывание историй, хроник, сценариев, повествований и притч. [187]

Азиатская теория критической расы

Азиатская критическая расовая теория рассматривает влияние расы и расизма на американцев азиатского происхождения и их опыт обучения в системе образования США. [188] Как и латиноамериканская критическая расовая теория, азиатская критическая расовая теория отличается от основной части CRT своим акцентом на теории и политике иммиграции. [186]

Племенная критическая расовая теория

Теория критической расы возникла в 1970-х годах в ответ на критические юридические исследования. [189] Tribal Critical Theory (TribalCrit) фокусируется на историях и ценит устные данные как основной источник информации. [189] TribalCrit основывается на идее о том, что превосходство белых и империализм лежат в основе политики США в отношении коренных народов. [189] В отличие от CRT, он утверждает, что колонизация, а не расизм, присуща обществу. [189] Ключевой принцип TribalCrit заключается в том, что коренные народы существуют в обществе США, которое одновременно политизирует их и расово пропагандирует, помещая их в «пограничное пространство», где самопредставление коренных народов противоречит тому, как их воспринимают другие. [189] TribalCrit утверждает, что идеи культуры, информации и власти приобретают новое значение, если рассматривать их через призму коренных народов. [189] TribalCrit отвергает цели ассимиляции в образовательных учреждениях США и утверждает, что понимание реалий жизни коренных народов зависит от понимания племенной философии, верований, традиций и видений будущего. [189]

Критическая философия расы

Критическая философия расы (CPR) основана на использовании междисциплинарных исследований как в критических юридических исследованиях, так и в критической теории расы. И CLS, и CRT исследуют скрытую природу массового использования «очевидно нейтральных понятий, таких как заслуги или свобода». [52]

См. также

- Учебная программа по борьбе с предвзятостью

- Теория заговора культурного марксизма

- Культурная гегемония

- Институциональный или системный расизм

- Судебные аспекты расы в Соединенных Штатах

- Расизм в Соединенных Штатах

- Рабство в Соединенных Штатах

- Белая привилегия

Примечания

- ^ Уоллес-Уэллс, Бенджамин (18 июня 2021 г.). «Как консервативный активист изобрел конфликт вокруг критической расовой теории» . Житель Нью-Йорка . Проверено 19 июня 2021 г.

- ^ Меклер, Лаура; Доуси, Джош (21 июня 2021 г.). «Республиканцы, вдохновленные маловероятной фигурой, видят политические перспективы в критической расовой теории» . Вашингтон Пост . Том. 144. ISSN 0190-8286 . Проверено 19 июня 2021 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Иати, Мариса (29 мая 2021 г.). «Что такое критическая расовая теория и почему республиканцы хотят запретить ее в школах?» . Вашингтон Пост .

вместо того, чтобы поощрять белых людей чувствовать себя виноватыми, По словам Томаса, критически настроенные расовые теоретики стремятся сместить акцент с плохих действий отдельных людей на то, как системы поддерживают расовое неравенство.

- ^ Кан, Крис (15 июля 2021 г.). «Многие американцы придерживаются ложных взглядов на критическую расовую теорию» . Рейтер . Проверено 22 января 2022 г.

- ^ Кристиан, Мишель; Симстер, Луиза; Рэй, Виктор (ноябрь 2019 г.). «Новые направления в критической расовой теории и социологии: расизм, превосходство белой расы и сопротивление». Американский учёный-бихевиорист . 63 (13): 1731–1740. дои : 10.1177/0002764219842623 . S2CID 151160318 .

- ^ Йоссо, Тара; Солорсано, Дэниел Дж. (2005). «Концептуализация критической расовой теории в социологии». В Ромеро, Мэри (ред.). Блэквеллский компаньон по социальному неравенству .

- ^ Бортер, Габриэлла (22 сентября 2021 г.). «Объяснитель: что означает «критическая расовая теория» и почему она вызывает споры» . Рейтер . Проверено 22 января 2022 г.

- ^ Гиллборн 2015 , с. 278.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Карри 2009а , с. 166.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Гиллборн, Дэвид; Ладсон-Биллингс, Глория (2020). «Критическая расовая теория». У Пола Аткинсона; и др. (ред.). Фонды методов исследования SAGE . Теоретические основы качественных исследований. Публикации SAGE. дои : 10.4135/9781526421036764633 . ISBN 978-1-5264-2103-6 . S2CID 240846071 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Мосты 2019 .

- ^ Рупарелия 2019 , стр. 77–89.

- ^ Милнер, Ричард (март 2013 г.). «Анализ бедности, обучения и преподавания через призму критической расовой теории». Обзор исследований в области образования . 37 (1): 1–53. дои : 10.3102/0091732X12459720 . JSTOR 24641956 . S2CID 146634183 .

- ^ Креншоу 1991 ; Креншоу 1989 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Ansell 2008 , стр. 344–345.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Креншоу, 2019 , стр. 52–84.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г «Критическая расовая теория» . Британская энциклопедия . 21 сентября 2021 г. Архивировано из оригинала 22 ноября 2021 г.

- ^ Анселл 2008 , стр. 344–345; Мосты 2019 , с. 7; Креншоу и др. 1995 , с. xiii.

- ^ Анселл 2008 , стр. 344; Cole 2007 , стр. 112–113: «CRT была реакцией на критические правовые исследования (CLS) ... CRT была ответом на CLS, критикуя последнюю за неправомерный акцент на классовой и экономической структуре и настаивая на том, что «раса» это более критическая личность».

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Мосты 2021 , 2:06.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Креншоу и др. 1995 , с. xxvii. «Действительно, организаторы придумали термин «критическая расовая теория», чтобы прояснить, что наша работа находится на пересечении критической теории и расы, расизма и закона».

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и Анселл 2008 , с. 344.

- ^ Кабрера 2018 , с. 213.

- ^ Уоллес-Уэллс, Бенджамин (18 июня 2021 г.). «Как консервативный активист изобрел конфликт вокруг критической расовой теории» . Житель Нью-Йорка . OCLC 909782404 . Архивировано из оригинала 18 июня 2021 года.

- ^ Кэролайн Келли (5 сентября 2020 г.). «Трамп запрещает «пропагандистские» тренировки по вопросам предвыборной гонки в рамках последнего визита к своей базе» . CNN .

- ^ Духани, Патрина (8 марта 2022 г.). «Почему критическая расовая теория заставляет людей чувствовать себя так некомфортно?» . Разговор . Проверено 15 марта 2022 г.

- ^ Бамп, Филип (15 июня 2021 г.). «Анализ | Стратегия ученых: как тревоги «критической расовой теории» могут превратить расовую тревогу в политическую энергию» . Вашингтон Пост . Архивировано из оригинала 22 июня 2021 года.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Харрис 2021 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Вест 1995 , с. xi.

- ^ Брукс 1994 , с. 85.

- ^ Ладсон-Биллингс и Тейт 1995 .

- ^ Гиллборн, 2015 ; Ладсон-Биллингс 1998 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Ладсон-Биллингс 1998 , с. 7.

- ^ Кабрера 2018 , с. 211; Дельгадо и Стефанчич 2017 , с. 3.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я «Изучите критическую расовую теорию (CRT)» . Британская энциклопедия . Видео с транскриптом. Архивировано из оригинала 24 ноября 2021 года.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Белл 1992 .

- ^ МакКристал-Калп 1992 , с. 1149.

- ^ Хэнкок 2016 , с. 192; Креншоу 1989 .

- ^ Цезарио 2008 , стр. 201–212; Белл 1980 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Арнуа 2010 ; Коллинз 2009 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г Дельгадо и Стефанчич 1993 .

- ^ Кеннеди 1995 ; Кеннеди 1990 .

- ^ Дельгадо и Стефанчич 1993 , с. 462.

- ^ Дельгадо и Стефанчич 1993 ; Стрикленд 1997 .

- ^ Голдберг, Дэвид Тео (1993). Расистская культура: философия и политика смысла . Блэквелл. ISBN 978-0-631-18078-4 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Креншоу 1988 , с. 103.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Креншоу 1988 , с. 104–105.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Креншоу 1988 , с. 104.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Креншоу 1988 , с. 106.

- ^ Кеннеди 1990 , с. 705.

- ^ Бонилья-Сильва 2020 ; Бонилья-Сильва 2010 , с. 26.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Алькофф 2021 .

- ^ Алькофф 2021 ; Дельгадо 1984 .

- ^ Дельгадо и Стефанчич 1992 , с. 1276.

- ^ Дельгадо и Стефанчич 1992 , с. 1261.

- ^ Дельгадо и Стефанчич 1992 , стр. 1262–1263.

- ^ Дельгадо и Стефанчич 1992 , с. 1263–1264.

- ^ Дельгадо и Стефанчич 1992 , стр. 1264–1265.

- ^ Дельгадо и Стефанчич 1992 , с. 1266.

- ^ Дельгадо и Стефанчич 1992 , стр. 1266–1267.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Дельгадо и Стефанчич 1992 , с. 1278.

- ^ Дельгадо и Стефанчич 1992 , с. 1279.

- ^ Дельгадо и Стефанчич 1992 , стр. 1284–1285.

- ^ Дельгадо и Стефанчич 1992 , стр. 1286–1287.

- ^ Дельгадо и Стефанчич 1992 , с. 1282.

- ^ Дельгадо и Стефанчич 1992 , с. 1288.

- ^ Леонардо 2013 , стр. 603–604; Анселл 2008 , с. 345.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Белл 1980 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Райт и Кобб 2021 .

- ^ Ши, Дэвид (19 апреля 2017 г.). «Теория, позволяющая лучше понять разнообразие и понять, кому оно действительно выгодно» . Кодовый переключатель . ЭНЕРГЕТИЧЕСКИЙ ЯДЕРНЫЙ РЕАКТОР . Проверено 20 октября 2021 г.

- ^ Огбонная-Огбуру, Ихудия Финда; Смит, Анджела Д.Р.; Александре; Тояма, Кентаро (2020). «Теория критической расы для HCI». Материалы конференции CHI 2020 года по человеческому фактору в вычислительных системах . стр. 1–16. дои : 10.1145/3313831.3376392 . ISBN 978-1-4503-6708-0 . S2CID 218483077 .

Те, кто обладает властью, редко признают это без совпадения интересов . Расизм приносит пользу некоторым группам, и эти группы не хотят выступать против него. Они будут предпринимать или разрешать антирасистские действия чаще всего тогда, когда это также приносит им выгоду. В контексте США движение вперед за гражданские права обычно происходит только тогда, когда оно материально отвечает интересам Белого большинства.

- ^ Белл 1989 , с. [ нужна страница ] ; Дудзяк 2000 , с. [ нужна страница ] .

- ^ Дудзяк 2000 ; Иоффе 2017 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Дудзяк 2000 .

- ^ Дельгадо и Стефанчич 2017 , стр. 25–26; Дудзяк 1988 .

- ^ Дудзяк 1997 .

- ^ Ioffe 2017 .

- ^ Дельгадо и Стефанчич 2012 , стр. 51–55.

- ^ Креншоу 1991 .

- ^ Дельгадо и Стефанчич 2017 , стр. 63–66.

- ^ Зиллиакус, Харриет; Паулсруд, БетАнн; Холм, Гунилла (3 апреля 2017 г.). «Эссенциализация и неэссенциализация культурной идентичности студентов: учебные дискурсы в Финляндии и Швеции» . Журнал мультикультурных дискурсов . 12 (2): 166–180. дои : 10.1080/17447143.2017.1311335 . S2CID 49215486 .

- ^ Сойлу Ялчинкая, Нур; Эстрада-Вильялта, Сара; Адамс, Гленн (2017). «(Биологическая или культурная) Сущность эссенциализма: последствия для политической поддержки среди доминирующих и подчиненных групп» . Границы в психологии . 8 : 900. doi : 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00900 . ПМЦ 5447748 . ПМИД 28611723 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Ван Вагенен, Эйми (2007). «Обещание и невозможность представления антиэссенциализма: чтение Булворта через критическую расовую теорию». Раса, пол и класс . 14 (1/2): 157–177. JSTOR 41675202 . ПроКвест 218827114 .

- ^ «Раса и расовая идентичность» . Национальный музей афроамериканской истории и культуры . Проверено 1 декабря 2022 г.

- ^ Дельгадо и Стефанчич 2012 , стр. 26, 155.

- ^ Дельгадо и Стефанчич 2001 , с. 26.

- ^ Дельгадо и Стефанчич 2001 , с. 27.

- ^ Джонс 2002 , стр. 9–10.

- ^ Переа, Хуан (1997). «Черно-белая бинарная парадигма расы:« нормальная наука »американской расовой мысли» . California Law Review, журнал La Raza Journal . 85 (5): 1213–1258. дои : 10.2307/3481059 . JSTOR 3481059 .

- ^ Дельгадо и Стефанчич 2017 , с. 76.

- ^ Мацуда, Мари Дж.; Лоуренс, Чарльз Р. (1993). «Эпилог: Сожжение крестов и дело РАВ». Слова, которые ранили: критическая расовая теория, оскорбительные высказывания и первая поправка (1-е изд.). Вествью Пресс. стр. 133–136. ISBN 978-0-429-50294-1 .

- ^ Дельгадо 1995 .

- ^ Кеннеди 1990 .

- ^ Уильямс 1991 .

- ^ Карри 2009b , с. 1.

- ^ Карри 2009b , с. 2.

- ^ Карри 2011 , с. [ нужна страница ] .

- ^ Карри 2009b , с. [ нужна страница ] .

- ^ Дельгадо и Стефанчич 1998a , с. 467; Дельгадо и Стефанчич 2001 , с. 30; Белл 1976 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Дельгадо и Стефанчич 1998a ; Белл 1980 .

- ^ Фридман, Джонатан (8 ноября 2021 г.). Приказы об образовательном запрете: законодательные ограничения свободы читать, учиться и преподавать (отчет). Нью-Йорк: ПЕН-Америка. Архивировано из оригинала 9 ноября 2021 года.

- ^ Дельгадо и Стефанчич 2001 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Дельгадо и Стефанчич 1998a , с. 467.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Джексон, Лорен Мишель (7 июля 2021 г.). «Пустота, которую была создана критическая расовая теория» . Житель Нью-Йорка . Проверено 8 ноября 2021 г.

- ^ Белл 1976 ; Белл 1980 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Кобб, Джелани (13 сентября 2021 г.). «Человек, стоящий за критической расовой теорией» . Житель Нью-Йорка . Проверено 14 ноября 2021 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Райт и Кобб 2021 ; Белл 1976 ; Белл 1980 .

- ^ «Бойкот автобусов в Монтгомери» . Архив движения за гражданские права .

- ^ Гроувс, Гарри Э. (1951). «Отдельные, но равные — доктрина Плесси против Фергюсона». Филон . 12 (1): 66–72. дои : 10.2307/272323 . JSTOR 272323 .

- ^ Шауэр, Фредерик (1997). «Общность и равенство». Право и философия . 16 (3): 279–97. дои : 10.2307/3504874 . JSTOR 3504874 .

- ^ Готанда 1991 .

- ^ Белл 1970 .

- ^ Белл 1979a .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Креншоу и др. 1995 , стр. XIX–XX.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Бурас, Кристен Л. (2014). «От Картера Г. Вудсона к изучению учебной программы по критическим расам». В Диксоне, Адриенн Д. (ред.). Исследование расы в образовании: политика, практика и качественные исследования . Шарлотта, Северная Каролина: Издательство Information Age. стр. 49–50. ISBN 978-1-6239-6678-2 .

Когда Белл ушел из Гарварда, чтобы возглавить юридический факультет Университета Орегона, цветные студенты-юристы Гарварда потребовали, чтобы на его место был нанят еще один цветной преподаватель.

- ^ Креншоу и др. 1995 , с. xx: «Либеральная белая администрация Гарварда отреагировала на студенческие протесты, демонстрации, митинги и сидячие забастовки, включая захват офиса декана, заявив, что не существует квалифицированных чернокожих ученых, заслуживающих интереса Гарварда».

- ^ Кеннеди, Рэндалл Л. (июнь 1989 г.). «Расовая критика юридических академий» . Гарвардский обзор права . 102 (8): 1745–1819. дои : 10.2307/1341357 . JSTOR 1341357 .

- ^ Кук и др. 2021 г. , около 14:36.

- ^ Кук и др. 2021 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Готтесман, Исаак (2016). «Критическая расовая теория и юридические исследования». Критический поворот в образовании: от марксистской критики к постструктуралистскому феминизму и критическим теориям расы . Лондон: Тейлор и Фрэнсис. п. 123. ИСБН 978-1-3176-7095-7 .

- ^ Дельгадо и Стефанчич 2001 , с. 30.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Фриман, Алан Дэвид (1 января 1978 г.). «Легитимизация расовой дискриминации посредством закона о борьбе с дискриминацией: критический обзор доктрины Верховного суда». Обзор права Миннесоты . 62 (73).

- ^ Йоссо 2005 , с. 71.

- ^ Ладсон-Биллингс, Глория (2021). Критическая расовая теория в образовании: путешествие ученого . Издательство педагогического колледжа. ISBN 978-0-8077-6583-8 .

- ^ Кеннеди 1990 ; Кеннеди 1995 .

- ^ Кук, Энтони Э. (1990). «Помимо критических юридических исследований: реконструктивная теология доктора Мартина Лютера Кинга-младшего». Гарвардский обзор права . 103 (5): 985–1044. дои : 10.2307/1341453 . JSTOR 1341453 .

- ^ Харрис 1993 .

- ^ Уоррен, Джеймс (5 сентября 1993 г.). « Белизна как собственность » . Чикаго Трибьюн .

- ^ Креншоу и др. 1995 , с. xiii.

- ^ Гиллборн, 2015 ; Креншоу 1991 .

- ^ Карри 2008 , стр. 35–36; Ладсон-Биллингс 1998 , стр. 7–24; Ладсон-Биллингс и Тейт, 1995 .

- ^ Доннор, Джамель; Ладсон-Биллингс, Глория (2017). «Критическая расовая теория и пострасовое воображение». В Дензине, Норман; Линкольн, Ивонна (ред.). Справочник SAGE по качественным исследованиям (5-е изд.). Таузенд-Оукс, Калифорния: Публикации Sage. п. 366. ИСБН 978-1-4833-4980-0 .

- ^ Харрис 2002 , с. 1216: «Более двадцати американских юридических школ предлагают курсы теории критической расы или включают теорию критической расы в качестве центральной части других курсов. Теория критической расы является формальным курсом в ряде университетов Соединенных Штатов и как минимум в трех иностранных юридических факультетах. школы».

- ^ Дельгадо и Стефанчич 2017 , стр. 7–8.

- ^ «Критическая расовая теория» . Центр исследований в области расы и образования; Университет Бирмингема . Проверено 25 июня 2021 г.

- ^ Куинн, Карл (6 ноября 2020 г.). «Все ли белые люди расисты? Почему нас встревожила критическая расовая теория» . Сидней Морнинг Геральд . Проверено 26 июня 2021 г.

- ^ Коул, Майк (2009). «Критическая расовая теория приходит в Великобританию: марксистский ответ». Этносы . 9 (2): 246–269. дои : 10.1177/1468796809103462 . S2CID 144325161 .

- ^ Карри 2011 , с. 4.

- ^ Гордон 1999 .

- ^ Борланд, Элизабет. «Теория точки зрения» . Британская энциклопедия . Проверено 22 ноября 2021 г.

- ^ Масьонис, Джон Дж.; Гербер, Линда М. (2011). Социология (7-е канадское изд.). Торонто: Пирсон Прентис Холл. п. 12. ISBN 978-0-13-800270-1 .

- ^ Харрис 1994 , стр. 741–743.

- ^ Креншоу и др. 1995 , с. xxiv: «Для появляющихся расовых критиков дискурс о правах имел социальную и преобразующую ценность в контексте расового подчинения, выходившего за рамки более узкого вопроса о том, может ли опора на одни только права привести к каким-либо определенным результатам»; Харрис 1994 , с. [ нужна страница ] .

- ^ Белл 1995 , с. 899.

- ^ Мэллон 2007 .

- ^ Взлом 2003 .

- ^ Дельгадо и Стефанчич 2017 , с. 102.

- ^ Кабрера 2018 , с. 213; Фарбер и Шерри 1997а .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Кабрера 2018 , с. 213.

- ^ Эрнандес-Труйоль, Берта Э.; Харрис, Анджела П.; Вальдес, Франциско (2006). «За пределами первого десятилетия: перспективная история теории, сообщества и практики LatCrit». Юридический журнал Беркли ла Раза . ССНН 2666047 .

- ^ Фарбер, Дэниел А.; Шерри, Сюзанна (май 1995 г.). «Является ли радикальная критика заслуг антисемитской?». Обзор законодательства Калифорнии . 83 (3): 853. дои : 10.2307/3480866 . hdl : 1803/6607 . JSTOR 3480866 .

Таким образом, предполагают авторы, радикальная критика заслуг имеет совершенно непреднамеренные последствия, становясь антисемитской и, возможно, расистской.

- ^ Фарбер и Шерри 1997a .

- ^ Дельгадо и Стефанчич 2017 , стр. 103–104.

- ^ Ansell 2008 , стр. 345–346.

- ^ Холмс 1997 .

- ^ Харрис 2021 ; Лочин и Тэкетт, 1993 .

- ^ Apple, RW (5 июня 1993 г.). «БИТВА ГИНЬЕРА; Президент винит себя в негодовании по поводу кандидата» . Нью-Йорк Таймс .

- ^ Тотенберг, Нина (5 июля 2022 г.). «Верховный суд является самым консервативным за 90 лет» . ЭНЕРГЕТИЧЕСКИЙ ЯДЕРНЫЙ РЕАКТОР . Проверено 11 июня 2023 г.

- ^ Крузель, Джон (4 мая 2022 г.). «Консервативная судебная стратегия приносит свои плоды, поскольку Роу грозит опасность» . Холм . Проверено 11 июня 2023 г.

- ^ Херли, Лоуренс; Чанг, Эндрю; Херли, Лоуренс (1 июля 2022 г.). «Объяснитель: как консервативный Верховный суд меняет законодательство США» . Рейтер . Проверено 11 июня 2023 г.

- ^ Роудс, Кристофер. «Общество федералистов: архитекторы американской антиутопии» . www.aljazeera.com . Проверено 11 июня 2023 г.

- ^ Анселл 2008 , стр. 346.

- ^ Розен 1996 .

- ^ Рассел 1997 , примечание 67, стр. 791.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Гиллборн, Дэвид (2014). «Расизм как политика: критический расовый анализ реформ образования в Соединенных Штатах и Англии». Образовательный форум . 78 (1): 30–31. дои : 10.1080/00131725.2014.850982 . S2CID 144670114 .

- ^ Вайнрип, Майкл (19 марта 2012 г.). «Расовая линза, использованная для отбора учебных программ в Аризоне» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . Архивировано из оригинала 8 июля 2017 года.

- ^ Депенброк, Джули (22 августа 2017 г.). «Федеральный судья находит расизм в законе Аризоны, запрещающем этнические исследования» . Все учтено . ЭНЕРГЕТИЧЕСКИЙ ЯДЕРНЫЙ РЕАКТОР. Архивировано из оригинала 6 июля 2019 года.

- ^ Карр (2022) .

- ^ Уилсон (2021) .

- ^ Доуси и Штейн (2020) ; Ланг (2020) ; Ваксман (2021) ; Неделя образования (2021) .

- ^ Гросс (2022) .

- ^ Рубин, Дэниел Ян (3 июля 2020 г.). «Еврокрит: новое измерение критической теории расы». Социальные идентичности . 26 (4): 499–514. дои : 10.1080/13504630.2020.1773778 . S2CID 219923352 .

- ^ Йоссо 2005 , с. 72; Дельгадо и Стефанчич 1998b .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Йоссо 2005 , с. 72.

- ^ Харпалани 2013 .

- ^ Кастильо, Венди; Гиллборн, Дэвид (9 марта 2022 г.). «Как использовать «QuantCrit:» Практика и вопросы для исследователей и пользователей образовательных данных» .

- ^ Хиль Де Ламадрид, Дэниел (2023). «QueerCrit: пересечение странности и черно-белой бинарности» . Академия .

- ^ Мыслинская 2014a , стр. 559–660.

- ^ Джапп, Берри и Ленсмир, 2016 .

- ^ Мыслинская 2014б .

- ^ См., например, Левин 2008 .

- ^ Аннамма, Коннор и Ферри 2012 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Тревино, Харрис и Уоллес 2008 .

- ^ Йоссо 2006 , с. 7.

- ^ Йоссо 2005 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Дельгадо и Стефанчич 2001 , с. 6.

- ^ Йоссо 2006 .

- ^ Ифтикар, Джон С.; Museus, Сэмюэл Д. (26 ноября 2018 г.). «О полезности азиатской критической (AsianCrit) теории в области образования». Международный журнал качественных исследований в образовании . 31 (10): 935–949. дои : 10.1080/09518398.2018.1522008 . S2CID 149949621 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г Брейбой, Брайан МакКинли Джонс (декабрь 2005 г.). «К теории племенной критической расы в образовании». Городское обозрение . 37 (5): 425–446. дои : 10.1007/s11256-005-0018-y . S2CID 145515195 .

Ссылки

- Алькофф, Линда (2021). «Критическая философия расы» . В Залте, Эдвард Н. (ред.). Стэнфордская энциклопедия философии (изд. осени 2021 г.).

- Анселл, Эми (2008). «Критическая расовая теория» . В Шефере, Ричард Т. (ред.). Энциклопедия расы, этнической принадлежности и общества, том 1 . Публикации SAGE. стр. 344–346. дои : 10.4135/9781412963879.n138 . ISBN 978-1-4129-2694-2 .

- Аннамма, Субини Анси; Коннор, Дэвид; Ферри, Бет (2012). «Критические расовые исследования инвалидности / способностей (DisCrit): теоретизирование на стыке расы и инвалидности / способностей». Раса Этническая принадлежность и образование . 16 (1): 1–31. дои : 10.1080/13613324.2012.730511 . S2CID 145739550 .

- Белл, Деррик А. (1970). Раса, расизм и американское право . Кембридж, Массачусетс: Гарвардская школа права. ОСЛК 22681096 .

- Белл, Деррик А. (март 1976 г.). «Служение двум господам: идеалы интеграции и интересы клиентов в судебном процессе по поводу десегрегации школ» . Йельский юридический журнал . 85 (4): 470–516. дои : 10.2307/795339 . JSTOR 795339 . Перепечатано в Crenshaw et al. (1995) .

- Белл, Деррик А. (1979a). «Бакке, прием меньшинств и обычная цена расовых средств защиты» . Обзор законодательства Калифорнии . 67 (1): 3–19. дои : 10.2307/3480087 . JSTOR 3480087 .

- Белл, Деррик А. младший (1980). « Браун против Совета по образованию и дилемма сближения интересов». Гарвардский обзор права . 93 (3): 518–533. дои : 10.2307/1340546 . JSTOR 1340546 . Перепечатано в Crenshaw et al. (1995) .

- Белл, Деррик (1989) [впервые опубликовано в 1973 году]. Раса, расизм и американское право (2-е изд.). Издательство Аспен. ISBN 978-0-7355-7574-5 .

- Белл, Деррик (1992). Лица на дне колодца: постоянство расизма . Нью-Йорк: Основные книги. ISBN 978-0-465-06817-3 . ОСЛК 25410809 .

- Белл, Деррик А. (1995). «Кто боится критической расовой теории?» . Обзор права Университета Иллинойса . 1995 (4): 893–.

- Бонилья-Сильва, Эдуардо (2010). Расизм без расистов: дальтоник по расизму и сохранение расового неравенства в Соединенных Штатах (3-е изд.). Лэнхэм, Мэриленд: Роуман и Литтлфилд. ISBN 978-1-44-220218-4 .

- Бонилья-Сильва, Эдуардо (31 июля 2020 г.). «Расизм с цветовой слепотой во времена пандемии» . Социология расы и этнической принадлежности . 8 (3): 343–354. дои : 10.1177/2332649220941024 .

- Бриджес, Хиара М. (2019). Критическая расовая теория: учебник для начинающих . Сент-Пол, Миннесота: Foundation Press. ISBN 978-1-6832-8443-7 . OCLC 1054004570 .

- Бриджес, Хиара М. (2 сентября 2021 г.). Хиара М. Бриджес объясняет критическую расовую теорию (видео). Международная ассоциация студентов-политологов. Событие происходит в 15:43. Архивировано из оригинала 13 декабря 2021 года . Проверено 27 ноября 2021 г. - через YouTube.

- Брукс, Рой (1994). «Теория критической расы: предлагаемая структура и применение к федеральным заявлениям» . Гарвардский юридический журнал BlackLetter . 11 :85–.

- Кабрера, Нолан Л. (2018). «Где расовая теория в критической теории расы?: Конструктивная критика критиков». Обзор высшего образования . 42 (1): 209–233. дои : 10.1353/rhe.2018.0038 . S2CID 149791522 .