Genghis Khan

| Genghis Khan | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Reproduction of a 1278 portrait taken from a Yuan-era album – National Palace Museum, Taipei | |||||||||||||||||

| Khan of the Mongol Empire | |||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 1206 – August 1227 | ||||||||||||||||

| Successor | |||||||||||||||||

| Born | Temüjin c. 1162 Khentii Mountains | ||||||||||||||||

| Died | August 1227 Xingqing, Western Xia | ||||||||||||||||

| Burial | |||||||||||||||||

| Spouse | |||||||||||||||||

| Issue | |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| House | Borjigin | ||||||||||||||||

| Father | Yesugei | ||||||||||||||||

| Mother | Hö'elün | ||||||||||||||||

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Tribal campaigns

Legacy

|

||

Genghis Khan[a] (born Temüjin; c. 1162 – August 1227), also known as Chinggis Khan,[b] was the founder and first khan of the Mongol Empire. After spending most of his life uniting the Mongol tribes, he launched a series of military campaigns, conquering large parts of China and Central Asia.

Born between 1155 and 1167 and given the name Temüjin, he was the eldest child of Yesugei, a Mongol chieftain of the Borjigin clan, and his wife Hö'elün. When Temüjin was eight, his father died and his family was abandoned by its tribe. Reduced to near-poverty, Temüjin killed his older half-brother to secure his familial position. His charismatic personality helped to attract his first followers and to form alliances with two prominent steppe leaders named Jamukha and Toghrul; they worked together to retrieve Temüjin's newlywed wife Börte, who had been kidnapped by raiders. As his reputation grew, his relationship with Jamukha deteriorated into open warfare. Temüjin was badly defeated in c. 1187, and may have spent the following years as a subject of the Jin dynasty; upon reemerging in 1196, he swiftly began gaining power. Toghrul came to view Temüjin as a threat and launched a surprise attack on him in 1203. Temüjin retreated, then regrouped and overpowered Toghrul; after defeating the Naiman tribe and executing Jamukha, he was left as the sole ruler on the Mongolian steppe.

Temüjin formally adopted the title "Genghis Khan", the meaning of which is uncertain, at an assembly in 1206. Carrying out reforms designed to ensure long-term stability, he transformed the Mongols' tribal structure into an integrated meritocracy dedicated to the service of the ruling family. After thwarting a coup attempt from a powerful shaman, Genghis began to consolidate his power. In 1209, he led a large-scale raid into the neighbouring Western Xia, who agreed to Mongol terms the following year. He then launched a campaign against the Jin dynasty, which lasted for four years and ended in 1215 with the capture of the Jin capital Zhongdu. His general Jebe annexed the Central Asian state of Qara Khitai in 1218. Genghis was provoked to invade the Khwarazmian Empire the following year by the execution of his envoys; the campaign toppled the Khwarazmian state and devastated the regions of Transoxiana and Khorasan, while Jebe and his colleague Subutai led an expedition that reached Georgia and Kievan Rus'. In 1227, Genghis died while subduing the rebellious Western Xia; following a two-year interregnum, his third son and heir Ögedei acceded to the throne in 1229.

Genghis Khan remains a controversial figure. He was generous and intensely loyal to his followers, but ruthless towards his enemies. He welcomed advice from diverse sources in his quest for world domination, for which he believed the shamanic supreme deity Tengri had destined him. The Mongol army under Genghis killed millions of people, yet his conquests also facilitated unprecedented commercial and cultural exchange over a vast geographical area. He is remembered as a backwards, savage tyrant in Russia and the Arab world, while recent Western scholarship has begun to reassess its previous view of him as a barbarian warlord. He was posthumously deified in Mongolia; modern Mongolians recognise him as the founding father of their nation.

Name and title

There is no universal romanisation system used for Mongolian; as a result, modern spellings of Mongolian names vary greatly and may result in considerably different pronunciations from the original.[1] The honorific most commonly rendered as "Genghis" ultimately derives from the Mongolian ᠴᠢᠩᠭᠢᠰ, which may be romanised as Činggis. This was adapted into Chinese as 成吉思 Chéngjísī, and into Persian as چنگیز Čəngīz. As Arabic lacks a sound similar to [tʃ], represented in the Mongolian and Persian romanisations by ⟨č⟩, writers transcribed the name as J̌ingiz, while Syriac authors used Šīngīz.[2]

In addition to "Genghis", introduced into English during the 18th century based on a misreading of Persian sources, modern English spellings include "Chinggis", "Chingis", "Jinghis", and "Jengiz".[3] His birth name "Temüjin" (ᠲᠡᠮᠦᠵᠢᠨ; 鐵木真 Tiěmùzhēn) is sometimes also spelled "Temuchin" in English.[4]

When Genghis's grandson Kublai Khan established the Yuan dynasty in 1271, he bestowed the temple name Taizu (太祖, meaning 'Supreme Progenitor') and the posthumous name Shengwu Huangdi (聖武皇帝, meaning 'Holy-Martial Emperor') upon his grandfather. Kublai's great-grandson Külüg Khan later expanded this title into Fatian Qiyun Shengwu Huangdi (法天啟運聖武皇帝, meaning 'Interpreter of the Heavenly Law, Initiator of the Good Fortune, Holy-Martial Emperor').[5]

Sources

As the sources are written in more than a dozen languages from across Eurasia, modern historians have found it difficult to compile information on the life of Genghis Khan.[6] All accounts of his adolescence and rise to power derive from two Mongolian-language sources—the Secret History of the Mongols, and the Altan Debter (Golden Book). The latter, now lost, served as inspiration for two Chinese chronicles—the 14th-century History of Yuan and the Shengwu qinzheng lu (Campaigns of Genghis Khan).[7] The History of Yuan, while poorly edited, provides a large amount of detail on individual campaigns and people; the Shengwu is more disciplined in its chronology, but does not criticise Genghis and occasionally contains errors.[8]

The Secret History survived through being transliterated into Chinese characters during the 14th and 15th centuries.[9] Its historicity has been disputed: the 20th-century sinologist Arthur Waley considered it a literary work with no historiographical value, but more recent historians have given the work much more credence.[10] Although it is clear that the work's chronology is suspect and that some passages were removed or modified for better narration, the Secret History is valued highly because the anonymous author is often critical of Genghis Khan: in addition to presenting him as indecisive and as having a phobia of dogs, the Secret History also recounts taboo events such as his fratricide and the possibility of his son Jochi's illegitimacy.[11]

Multiple chronicles in Persian have also survived, which display a mix of positive and negative attitudes towards Genghis Khan and the Mongols. Both Minhaj-i Siraj Juzjani and Ata-Malik Juvayni completed their respective histories in 1260.[12] Juzjani was an eyewitness to the brutality of the Mongol conquests, and the hostility of his chronicle reflects his experiences.[13] His contemporary Juvayni, who had travelled twice to Mongolia and attained a high position in the administration of a Mongol successor state, was more sympathetic; his account is the most reliable for Genghis Khan's western campaigns.[14] The most important Persian source is the Jami' al-tawarikh (Compendium of Chronicles) compiled by Rashid al-Din on the order of Genghis's descendant Ghazan in the early 14th century. Ghazan allowed Rashid privileged access to both confidential Mongol sources such as the Altan Debter and to experts on the Mongol oral tradition, including Kublai Khan's ambassador Bolad Chingsang. As he was writing an official chronicle, Rashid censored inconvenient or taboo details.[15]

There are many other contemporary histories which include additional information on Genghis Khan and the Mongols, although their neutrality and reliability are often suspect. Additional Chinese sources include the chronicles of the dynasties conquered by the Mongols, and the Song diplomat Zhao Hong, who visited the Mongols in 1221.[c] Arabic sources include a contemporary biography of the Khwarazmian prince Jalal al-Din by his companion al-Nasawi. There are also several later Christian chronicles, including the Georgian Chronicles, and works by European travellers such as Carpini and Marco Polo.[17]

Early life

Birth and childhood

The year of Temüjin's birth is disputed, as historians favour different dates: 1155, 1162 or 1167. Some traditions place his birth in the Year of the Pig, which was either 1155 or 1167.[18] While a dating to 1155 is supported by the writings of both Zhao Hong and Rashid al-Din, other major sources such as the History of Yuan and the Shengwu favour the year 1162.[19][d] The 1167 dating, favoured by the sinologist Paul Pelliot, is derived from a minor source—a text of the Yuan artist Yang Weizhen—but is more compatible with the events of Genghis Khan's life than a 1155 placement, which implies that he did not have children until after the age of thirty and continued actively campaigning into his seventh decade.[20] 1162 is the date accepted by most historians;[21] the historian Paul Ratchnevsky noted that Temüjin himself may not have known the truth.[22] The location of Temüjin's birth, which the Secret History records as Delüün Boldog on the Onon River, is similarly debated: it has been placed at either Dadal in Khentii Province or in southern Agin-Buryat Okrug, Russia.[23]

Temüjin was born into the Borjigin clan of the Mongol tribe[e] to Yesügei, a chieftain who claimed descent from the legendary warlord Bodonchar Munkhag, and his principal wife Hö'elün, originally of the Olkhonud clan, whom Yesügei had abducted from her Merkit bridegroom Chiledu.[25] The origin of his birth name is contested: the earliest traditions hold that his father had just returned from a successful campaign against the Tatars with a captive named Temüchin-uge, after whom he named the newborn in celebration of his victory, while later traditions highlight the root temür (meaning 'iron') and connect to theories that "Temüjin" means 'blacksmith'.[26]

Several legends surround Temüjin's birth. The most prominent is that he was born clutching a blood clot in his hand, a motif in Asian folklore indicating the child would be a warrior.[27] Others claimed that Hö'elün was impregnated by a ray of light which announced the child's destiny, a legend which echoed that of the mythical Borjigin ancestor Alan Gua.[28] Yesügei and Hö'elün had three younger sons after Temüjin: Qasar, Hachiun, and Temüge, as well as one daughter, Temülün. Temüjin also had two half-brothers, Behter and Belgutei, from Yesügei's secondary wife Sochigel, whose identity is uncertain. The siblings grew up at Yesugei's main camp on the banks of the Onon, where they learned how to ride a horse and shoot a bow.[29]

When Temüjin was eight years old, his father decided to betroth him to a suitable girl. Yesügei took his heir to the pastures of Hö'elün's prestigious Onggirat tribe, which had intermarried with the Mongols on many previous occasions. There, he arranged a betrothal between Temüjin and Börte, the daughter of an Onggirat chieftain named Dei Sechen. As the betrothal meant Yesügei would gain a powerful ally and as Börte commanded a high bride price, Dei Sechen held the stronger negotiating position, and demanded that Temüjin remain in his household to work off his future debt.[30] Accepting this condition, Yesügei requested a meal from a band of Tatars he encountered while riding homewards alone, relying on the steppe tradition of hospitality to strangers. However, the Tatars recognised their old enemy and slipped poison into his food. Yesügei gradually sickened but managed to return home; close to death, he requested a trusted retainer called Münglig to retrieve Temüjin from the Onggirat. He died soon after.[31]

Adolescence

Yesügei's death shattered the unity of his people, which included members of the Borjigin, Tayichiud, and other clans. As Temüjin was not yet ten and Behter around two years older, neither was considered experienced enough to rule. The Tayichiud faction excluded Hö'elün from the ancestor worship ceremonies which followed a ruler's death and soon abandoned her camp. The Secret History relates that the entire Borjigin clan followed, despite Hö'elün's attempts to shame them into staying by appealing to their honour.[32] Rashid al-Din and the Shengwu however imply that Yesügei's brothers stood by the widow. It is possible that Hö'elün may have refused to join in levirate marriage with one, resulting in later tensions, or that the author of the Secret History dramatised the situation.[33] All the sources agree that most of Yesügei's people renounced his family in favour of the Tayichiuds and that Hö'elün's family were reduced to a much harsher life.[34] Taking up a hunter-gatherer lifestyle, they collected roots and nuts, hunted for small animals, and caught fish.[35]

Tensions developed as the children grew older. Both Temüjin and Behter had claims to be their father's heir: although Temüjin was the child of Yesügei's chief wife, Behter was at least two years his senior. There was even the possibility that, as permitted under levirate law, Behter could marry Hö'elün upon attaining his majority and become Temüjin's stepfather.[36] As the friction, exacerbated by frequent disputes over the division of hunting spoils, intensified, Temüjin and his younger brother Qasar ambushed and killed Behter. This taboo act was omitted from the official chronicles but not from the Secret History, which recounts that Hö'elün angrily reprimanded her sons. Behter's younger full-brother Belgutei did not seek vengeance, and became one of Temüjin's highest-ranking followers alongside Qasar.[37] Around this time, Temüjin developed a close friendship with Jamukha, another boy of aristocratic descent; the Secret History notes that they exchanged knucklebones and arrows as gifts and swore the anda pact—the traditional oath of Mongol blood brothers–at eleven.[38]

As the family lacked allies, Temüjin was taken prisoner on multiple occasions.[39] Captured by the Tayichiuds, he escaped during a feast and hid first in the Onon and then in the tent of Sorkan-Shira, a man who had seen him in the river and not raised the alarm. Sorkan-Shira sheltered Temüjin for three days at great personal risk before helping him to escape.[40] Temüjin was assisted on another occasion by Bo'orchu, an adolescent who aided him in retrieving stolen horses. Soon afterwards, Bo'orchu joined Temüjin's camp as his first nökor ('personal companion'; pl. nökod).[41] These incidents, related by the Secret History, are indicative of the emphasis its author put on Genghis' personal charisma.[42]

Rise to power

Early campaigns

Temüjin returned to Dei Sechen to marry Börte when he reached the age of majority at fifteen. Delighted to see the son-in-law he feared had died, Dei Sechen consented to the marriage and accompanied the newlyweds back to Temüjin's camp; his wife Čotan presented Hö'elün with an expensive sable cloak.[43] Seeking a patron, Temüjin chose to regift the cloak to Toghrul, khan (ruler) of the Kerait tribe, who had fought alongside Yesügei and sworn the anda pact with him. Toghrul ruled a vast territory in central Mongolia but distrusted many of his followers. In need of loyal replacements, he was delighted with the valuable gift and welcomed Temüjin into his protection. The two grew close, and Temüjin began to build a following, as nökod such as Jelme entered into his service.[44] Temüjin and Börte had their first child, a daughter named Qojin, around this time.[45]

Soon afterwards, seeking revenge for Yesügei's abduction of Hö'elün, around 300 Merkits raided Temüjin's camp. While Temüjin and his brothers were able to hide on Burkhan Khaldun mountain, Börte and Sochigel were abducted. In accordance with levirate law, Börte was given in marriage to the younger brother of the now-deceased Chiledu.[46] Temüjin appealed for aid from Toghrul and his childhood anda Jamukha, who had risen to become chief of the Jadaran tribe. Both chiefs were willing to field armies of 20,000 warriors, and with Jamukha in command, the campaign was soon won. A now-pregnant Börte was recovered successfully and soon gave birth to a son, Jochi; although Temüjin raised him as his own, questions over his true paternity followed Jochi throughout his life.[47] This is narrated in the Secret History and contrasts with Rashid al-Din's account, which protects the family's reputation by removing any hint of illegitimacy.[48] Over the next decade and a half, Temüjin and Börte had three more sons (Chagatai, Ögedei, and Tolui) and four more daughters (Checheyigen, Alaqa, Tümelün, and Al Altan).[49]

The followers of Temüjin and Jamukha camped together for a year and a half, during which their leaders reforged their anda pact and slept together under one blanket, according to the Secret History. The source presents this period as close friends bonding, but Ratchnevsky questioned if Temüjin actually entered into Jamukha's service in return for the assistance with the Merkits.[50] Tensions arose and the two leaders parted, ostensibly on account of a cryptic remark made by Jamukha on the subject of camping;[f] in any case, Temüjin followed the advice of Hö'elün and Börte and began to build an independent following. The major tribal rulers remained with Jamukha, but forty-one leaders gave their support to Temüjin along with many commoners: these included Subutai and others of the Uriankhai, the Barulas, the Olkhonuds, and many more.[52] Many were attracted by Temüjin's reputation as a fair and generous lord who could offer better lives, while his shamans prophesied that heaven had allocated him a great destiny.[53]

Temüjin was soon acclaimed by his close followers as khan of the Mongols.[54] Toghrul was pleased at his vassal's elevation but Jamukha was resentful. Tensions escalated into open hostility, and in around 1187 the two leaders clashed in battle at Dalan Baljut: the two forces were evenly matched but Temüjin suffered a clear defeat. Later chroniclers including Rashid al-Din instead state that he was victorious but their accounts contradict themselves and each other.[55]

Modern historians such as Ratchnevsky and Timothy May consider it very likely that Temüjin spent a large portion of the decade following the clash at Dalan Baljut as a servant of the Jurchen Jin dynasty in North China.[56] Zhao Hong recorded that the future Genghis Khan spent several years as a slave of the Jin. Formerly seen as an expression of nationalistic arrogance, the statement is now thought to be based in fact, especially as no other source convincingly explains Temüjin's activities between Dalan Baljut and c. 1195.[57] Taking refuge across the border was a common practice both for disaffected steppe leaders and disgraced Chinese officials. Temüjin's reemergence having retained significant power indicates that he probably profited in the service of the Jin. As he later overthrew that state, such an episode, detrimental to Mongol prestige, was omitted from all their sources. Zhao Hong was bound by no such taboos.[58]

Defeating rivals

The sources do not agree on the events of Temüjin's return to the steppe. In early summer 1196, he participated in a joint campaign with the Jin against the Tatars, who had begun to act contrary to Jin interests. As a reward, the Jin awarded him the honorific cha-ut kuri, the meaning of which probably approximated "commander of hundreds" in Jurchen. At around the same time, he assisted Toghrul with reclaiming the lordship of the Kereit, which had been usurped by one of Toghrul's relatives with the support of the powerful Naiman tribe.[59] The actions of 1196 fundamentally changed Temüjin's position in the steppe—although nominally still Toghrul's vassal, he was de facto an equal ally.[60]

Jamukha behaved cruelly following his victory at Dalan Baljut—he allegedly boiled seventy prisoners alive and humiliated the corpses of leaders who had opposed him. A number of disaffected followers, including Yesügei's follower Münglig and his sons, defected to Temüjin as a consequence; they were also probably attracted by his newfound wealth.[61] Temüjin subdued the disobedient Jurkin tribe that had previously offended him at a feast and refused to participate in the Tatar campaign. After executing their leaders, he had Belgutei symbolically break a leading Jurkin's back in a staged wrestling match in retribution. This latter incident, which contravened Mongol customs of justice, was only noted by the author of the Secret History, who openly disapproved. These events occurred c. 1197.[62]

During the following years, Temüjin and Toghrul campaigned against the Merkits, the Naimans, and the Tatars; sometimes separately and sometimes together. In around 1201, a collection of dissatisfied tribes including the Onggirat, the Tayichiud, and the Tatars swore to break the domination of the Borjigin-Kereit alliance, electing Jamukha as their leader and gurkhan (lit. '"khan of the tribes"'). After some initial successes, Temüjin and Toghrul routed this loose confederation at Yedi Qunan, and Jamukha was forced to beg for Toghrul's clemency.[63] Desiring complete supremacy in eastern Mongolia, Temüjin defeated first the Tayichiud and then, in 1202, the Tatars; after both campaigns, he executed the clan leaders and took the remaining warriors into his service. These included Sorkan-Shira, who had come to his aid previously, and a young warrior named Jebe, who, by killing Temüjin's horse and refusing to hide that fact, had displayed martial ability and personal courage.[64]

The absorption of the Tatars left three military powers in the steppe: the Naimans in the west, the Mongols in the east, and the Kereit in between.[65] Seeking to cement his position, Temüjin proposed that his son Jochi marry one of Toghrul's daughters. Led by Toghrul's son Senggum, the Kereit elite believed the proposal to be an attempt to gain control over their tribe, while the doubts over Jochi's parentage would have offended them further. In addition, Jamukha drew attention to the threat Temüjin posed to the traditional steppe aristocracy by his habit of promoting commoners to high positions, which subverted social norms. Yielding eventually to these demands, Toghrul attempted to lure his vassal into an ambush, but his plans were overheard by two herdsmen. Temüjin was able to gather some of his forces, but was soundly defeated at the Battle of Qalaqaljid Sands.[66]

"[Temüjin] raised his hands and looking up at Heaven swore, saying "If I am able to achieve my 'Great Work', I shall [always] share with you men the sweet and the bitter. If I break this word, may I be like the water of the River, drunk up by others."

Among officers and men there was none who was not moved to tears.

The History of Yuan, vol 120 (1370)[67]

Retreating southeast to Baljuna, an unidentified lake or river, Temüjin waited for his scattered forces to regroup: Bo'orchu had lost his horse and was forced to flee on foot, while Temüjin's badly wounded son Ögedei had been transported and tended to by Borokhula, a leading warrior. Temüjin called in every possible ally and swore a famous oath of loyalty, later known as the Baljuna Covenant, to his faithful followers, which subsequently granted them great prestige.[68] The oath-takers of Baljuna were a very heterogeneous group—men from nine different tribes who included Christians, Muslims, and Buddhists, united only by loyalty to Temüjin and to each other. This group became a model for the later empire, termed a "proto-government of a proto-nation" by historian John Man.[69] The Baljuna Covenant was omitted from the Secret History—as the group was predominantly non-Mongol, the author presumably wished to downplay the role of other tribes.[70]

A ruse de guerre involving Qasar allowed the Mongols to ambush the Kereit at the Jej'er Heights, but though the ensuing battle still lasted three days, it ended in a decisive victory for Temüjin. Toghrul and Senggum were both forced to flee, and while the latter escaped to Tibet, Toghrul was killed by a Naiman who did not recognise him. Temüjin sealed his victory by absorbing the Kereit elite into his own tribe: he took the princess Ibaqa as a wife, and married her sister Sorghaghtani and niece Doquz to his youngest son Tolui.[71] The ranks of the Naimans had swelled due to the arrival of Jamukha and others defeated by the Mongols, and they prepared for war. Temüjin was informed of these events by Alaqush, the sympathetic ruler of the Ongud tribe. In May 1204, at the Battle of Chakirmaut in the Altai Mountains, the Naimans were decisively defeated: their leader Tayang Khan was killed, and his son Kuchlug was forced to flee west.[72] The Merkits were decimated later that year, while Jamukha, who had abandoned the Naimans at Chakirmaut, was betrayed to Temüjin by companions who were executed for their lack of loyalty. According to the Secret History, Jamukha convinced his childhood anda to execute him honourably; other accounts state that he was killed by dismemberment.[73]

Early reign: reforms and Chinese campaigns (1206–1215)

Kurultai of 1206 and reforms

Now sole ruler of the steppe, Temüjin held a large assembly called a kurultai at the source of the Onon River in 1206.[75] Here, he formally adopted the title Genghis Khan, the etymology and meaning of which have been much debated. Some commentators hold that the title had no meaning, simply representing Temüjin's eschewal of the traditional gurkhan title, which had been accorded to Jamukha and was thus of lesser worth.[76] Another theory suggests that the word "Genghis" bears connotations of strength, firmness, hardness, or righteousness.[77] A third hypothesis proposes that the title is related to the Turkic tängiz ('ocean'), the title "Genghis Khan" would mean "master of the ocean", and as the ocean was believed to surround the earth, the title thus ultimately implied "Universal Ruler".[78]

Having attained control over one million people,[79] Genghis Khan began a "social revolution", in May's words.[80] As traditional tribal systems had primarily evolved to benefit small clans and families, they were unsuitable as the foundations for larger states and had been the downfall of previous steppe confederations. Genghis thus began a series of administrative reforms designed to suppress the power of tribal affiliations and to replace them with unconditional loyalty to the khan and the ruling family.[81] As most of the traditional tribal leaders had been killed during his rise to power, Genghis was able to reconstruct the Mongol social hierarchy in his favour. The highest tier was occupied solely by his and his brothers' families, who became known as the altan uruq (lit. 'Golden Family') or chaghan yasun (lit. 'white bone'); underneath them came the qara yasun (lit. 'black bone'; sometimes qarachu), composed of the surviving pre-empire aristocracy and the most important of the new families.[82]

To break any concept of tribal loyalty, Mongol society was reorganised into a military decimal system. Every man between the age of fifteen and seventy was conscripted into a minqan (pl. minkad), a unit of a thousand soldiers, which was further subdivided into units of hundreds (jaghun, pl. jaghat) and tens (arban, pl. arbat).[83] The units also encompassed each man's household, meaning that each military minqan was supported by a minqan of households in what May has termed "a military–industrial complex". Each minqan operated as both a political and social unit, while the warriors of defeated tribes were dispersed to different minqad to make it difficult for them to rebel as a single body. This was intended to ensure the disappearance of old tribal identities, replacing them with loyalty to the "Great Mongol State", and to commanders who had gained their rank through merit and loyalty to the khan.[84] This particular reform proved extremely effective—even after the division of the Mongol Empire, fragmentation never happened along tribal lines. Instead, the descendants of Genghis continued to reign unchallenged, in some cases until as late as the 1700s, and even powerful non-imperial dynasts such as Timur and Edigu were compelled to rule from behind a puppet ruler of his lineage.[85]

Genghis's senior nökod were appointed to the highest ranks and received the greatest honours. Bo'orchu and Muqali were each given ten thousand men to lead as commanders of the right and left wings of the army respectively.[86] The other nökod were each given commands of one of the ninety-five minkad. In a display of Genghis' meritocratic ideals, many of these men were born to low social status: Ratchnevsky cited Jelme and Subutai, the sons of blacksmiths, in addition to a carpenter, a shepherd, and even the two herdsmen who had warned Temüjin of Toghrul's plans in 1203.[87] As a special privilege, Genghis allowed certain loyal commanders to retain the tribal identities of their units. Alaqush of the Ongud was allowed to retain five thousand warriors of his tribe because his son had entered into an alliance pact with Genghis, marrying his daughter Alaqa.[88]

A key tool which underpinned these reforms was the expansion of the keshig ('bodyguard'). After Temüjin defeated Toghrul in 1203, he had appropriated this Kereit institution in a minor form, but at the 1206 kurultai its numbers were greatly expanded, from 1,150 to 10,000 men. The keshig was not only the khan's bodyguard, but his household staff, a military academy, and the centre of governmental administration.[89] All the warriors in this elite corps were brothers or sons of military commanders and were essentially hostages. The members of the keshig nevertheless received special privileges and direct access to the khan, whom they served and who in return evaluated their capabilities and their potential to govern or command.[90] Commanders such as Subutai, Chormaqan, and Baiju all started out in the keshig, before being given command of their own force.[91]

Consolidation of power (1206–1210)

From 1204 to 1209, Genghis Khan was predominantly focused on consolidating and maintaining his new nation.[92] He faced a challenge from the shaman Kokechu, whose father Münglig had been allowed to marry Hö'elün after he defected to Temüjin. Kokechu, who had proclaimed Temüjin as Genghis Khan and taken the Tengrist title "Teb Tenggeri" (lit. "Wholly Heavenly") on account of his sorcery, was very influential among the Mongol commoners and sought to divide the imperial family.[93] Genghis's brother Qasar was the first of Kokechu's targets—always distrusted by his brother, Qasar was humiliated and almost imprisoned on false charges before Hö'elün intervened by publicly reprimanding Genghis. Nevertheless, Kokechu's power steadily increased, and he publicly shamed Temüge, Genghis's youngest brother, when he attempted to intervene.[94] Börte saw that Kokechu was a threat to Genghis's power and warned her husband, who still superstitiously revered the shaman but now recognised the political threat he posed. Genghis allowed Temüge to arrange Kokechu's death, and then usurped the shaman's position as the Mongols' highest spiritual authority.[95]

During these years, the Mongols imposed their control on surrounding areas. Genghis dispatched Jochi northwards in 1207 to subjugate the Hoi-yin Irgen, a collection of tribes on the edge of the Siberian taiga. Having secured a marriage alliance with the Oirats and defeated the Yenisei Kyrgyz, he took control of the region's trade in grain and furs, as well as its gold mines.[96] Mongol armies also rode westwards, defeating the Naiman-Merkit alliance on the River Irtysh in late 1208. Their khan was killed and Kuchlug fled into Central Asia.[97] Led by Barchuk, the Uyghurs freed themselves from the suzerainty of the Qara Khitai and pledged themselves to Genghis in 1211 as the first sedentary society to submit to the Mongols.[98]

The Mongols had started raiding the border settlements of the Tangut-led Western Xia kingdom in 1205, ostensibly in retaliation for allowing Senggum, Toghrul's son, refuge.[99] More prosaic explanations include rejuvenating the depleted Mongol economy with an influx of fresh goods and livestock,[100] or simply subjugating a semi-hostile state to protect the nascent Mongol nation.[101] Most Xia troops were stationed along the southern and eastern borders of the kingdom to guard against attacks from the Song and Jin dynasties respectively, while its northern border relied only on the Gobi desert for protection.[102] After a raid in 1207 sacked the Xia fortress of Wulahai, Genghis decided to personally lead a full-scale invasion in 1209.[103]

Wulahai was captured again in May and the Mongols advanced on the capital Zhongxing (modern-day Yinchuan) but suffered a reverse against a Xia army. After a two-month stalemate, Genghis broke the deadlock with a feigned retreat; the Xia forces were deceived out of their defensive positions and overpowered.[104] Although Zhongxing was now mostly undefended, the Mongols lacked any siege equipment better than crude battering rams and were unable to progress the siege.[105] The Xia requested aid from the Jin, but Emperor Zhangzong rejected the plea. Genghis's attempt to redirect the Yellow River into the city with a dam initially worked, but the poorly-constructed earthworks broke—possibly breached by the Xia—in January 1210 and the Mongol camp was flooded, forcing them to retreat. A peace treaty was soon formalised: the Xia emperor Xiangzong submitted and handed over tribute, including his daughter Chaka, in exchange for the Mongol withdrawal.[106]

Campaign against the Jin (1211–1215)

Wanyan Yongji usurped the Jin throne in 1209. He had previously served on the steppe frontier and Genghis greatly disliked him.[107] When asked to submit and pay the annual tribute to Yongji in 1210, Genghis instead mocked the emperor, spat, and rode away from the Jin envoy—a challenge that meant war.[108] Despite the possibility of being outnumbered eight-to-one by 600,000 Jin soldiers, Genghis had prepared to invade the Jin since learning in 1206 that the state was wracked by internal instabilities.[109] Genghis had two aims: to take vengeance for past wrongs committed by the Jin, foremost among which was the death of Ambaghai Khan in the mid-12th century, and to win the vast amounts of plunder his troops and vassals expected.[110]

After calling for a kurultai in March 1211, Genghis launched his invasion of Jin China in May, reaching the outer ring of Jin defences the following month. These border fortifications were guarded by Alaqush's Ongud, who allowed the Mongols to pass without difficulty.[111] The three-pronged chevauchée aimed both to plunder and burn a vast area of Jin territory to deprive them of supplies and popular legitimacy, and to secure the mountain passes which allowed access to the North China Plain.[112] The Jin lost numerous towns and were hindered by a series of defections, the most prominent of which led directly to Muqali's victory at the Battle of Huan'erzhui in autumn 1211.[113] The campaign was halted in 1212 when Genghis was wounded by an arrow during the unsuccessful siege of Xijing (modern Datong).[114] Following this failure, Genghis set up a corps of siege engineers, which recruited 500 Jin experts over the next two years.[115]

The defences of Juyong Pass had been strongly reinforced by the time the conflict resumed in 1213, but a Mongol detachment led by Jebe managed to infiltrate the pass and surprise the elite Jin defenders, opening the road to the Jin capital Zhongdu (modern-day Beijing).[116] The Jin administration began to disintegrate: after the Khitans, a tribe subject to the Jin, entered open rebellion, Hushahu, the commander of the forces at Xijing, abandoned his post and staged a coup in Zhongdu, killing Yongji and installing his own puppet ruler, Xuanzong.[117] This governmental breakdown was fortunate for Genghis's forces; emboldened by their victories, they had seriously overreached and lost the initiative. Unable to do more than camp before Zhongdu's fortifications while his army suffered from an epidemic and famine—they resorted to cannibalism according to Carpini, who may have been exaggerating—Genghis opened peace negotiations despite his commanders' militance.[118] He secured tribute, including 3,000 horses, 500 slaves, a Jin princess, and massive amounts of gold and silk, before lifting the siege and setting off homewards in May 1214.[119]

As the northern Jin lands had been ravaged by plague and war, Xuanzong moved the capital and imperial court 600 kilometres (370 mi) southwards to Kaifeng.[120] Interpreting this as an attempt to regroup in the south and then restart the war, Genghis concluded the terms of the peace treaty had been broken. He immediately prepared to return and capture Zhongdu.[121] According to Christopher Atwood, it was only at this juncture that Genghis decided to fully conquer northern China.[122] Muqali captured numerous towns in Liaodong during winter 1214–15, and although the inhabitants of Zhongdu surrendered to Genghis on 31 May 1215, the city was sacked.[123] When Genghis returned to Mongolia in early 1216, Muqali was left in command in China.[124] He waged a brutal but effective campaign against the unstable Jin regime until his death in 1223.[125]

Later reign: western expansion and return to China (1216–1227)

Defeating rebellions and Qara Khitai (1216–1218)

In 1207, Genghis had appointed a man named Qorchi as governor of the subdued Hoi-yin Irgen tribes in Siberia. Appointed not for his talents but for prior services rendered, Qorchi's tendency to abduct women as concubines for his harem caused the tribes to rebel and take him prisoner in early 1216. The following year, they ambushed and killed Boroqul, one of Genghis's highest-ranking nökod.[126] The khan was livid at the loss of his close friend and prepared to lead a retaliatory campaign; eventually dissuaded from this course, he dispatched his eldest son Jochi and a Dörbet commander. They managed to surprise and defeat the rebels, securing control over this economically important region.[127]

Kuchlug, the Naiman prince who had been defeated in 1204, had usurped the throne of the Central Asian Qara Khitai dynasty between 1211 and 1213. He was a greedy and arbitrary ruler who probably earned the enmity of the native Islamic populace whom he attempted to forcibly convert to Buddhism.[128] Genghis reckoned that Kuchlug could be a threat to his empire, and Jebe was sent with an army of 20,000 cavalry to the city of Kashgar; he undermined Kuchlug's rule by emphasising the Mongol policies of religious tolerance and gained the loyalty of the local elite.[129] Kuchlug was forced to flee southwards to the Pamir Mountains, but was captured by local hunters. Jebe had him beheaded and paraded his corpse through Qara Khitai, proclaiming the end of religious persecution in the region.[130]

Invasion of the Khwarazmian Empire (1219–1221)

Genghis had now attained complete control of the eastern portion of the Silk Road, and his territory bordered that of the Khwarazmian Empire, which ruled over much of Central Asia, Persia and Afghanistan.[131] Merchants from both sides were eager to restart trading, which had halted during Kuchlug's rule; the Khwarazmian ruler Muhammad II dispatched an envoy shortly after the Mongol capture of Zhongdu, while Genghis instructed his merchants to obtain the high-quality textiles and steel of Central and Western Asia.[132] Many members of the altan uruq invested in one particular caravan of 450 merchants which set off to Khwarazmia in 1218 with a large quantity of wares. Inalchuq, the governor of the Khwarazmian border town of Otrar, decided to massacre the merchants on grounds of espionage and seize the goods; Muhammad had grown suspicious of Genghis's intentions and either supported Inalchuq or turned a blind eye.[133] A Mongol ambassador was sent with two companions to avert war, but Muhammad killed him and humiliated his companions. The killing of an envoy infuriated Genghis, who resolved to leave Muqali with a small force in North China and invade Khwarazmia with most of his army.[134]

Muhammad's empire was large but disunited: he ruled alongside his mother Terken Khatun in what the historian Peter Golden terms "an uneasy diarchy", while the Khwarazmian nobility and populace were discontented with his warring and the centralisation of government. For these reasons and others he declined to meet the Mongols in the field, instead garrisoning his unruly troops in his major cities.[135] This allowed the lightly armoured, highly mobile Mongol armies uncontested superiority outside city walls.[136] Otrar was besieged in autumn 1219—the siege dragged on for five months, but in February 1220 the city fell and Inalchuq was executed.[137] Genghis had meanwhile divided his forces. Leaving his sons Chagatai and Ögedei to besiege the city, he had sent Jochi northwards down the Syr Darya river and another force southwards into central Transoxiana, while he and Tolui took the main Mongol army across the Kyzylkum Desert, surprising the garrison of Bukhara in a pincer movement.[138]

Bukhara's citadel was captured in February 1220 and Genghis moved against Muhammad's residence Samarkand, which fell the following month.[139] Bewildered by the speed of the Mongol conquests, Muhammad fled from Balkh, closely followed by Jebe and Subutai; the two generals pursued the Khwarazmshah until he died from dysentry on a Caspian Sea island in winter 1220–21, having nominated his eldest son Jalal al-Din as his successor.[140] Jebe and Subutai then set out on a 7,500-kilometre (4,700 mi)-expedition around the Caspian Sea. Later called the Great Raid, this lasted four years and saw the Mongols come into contact with Europe for the first time.[141] Meanwhile, the Khwarazmian capital of Gurganj was being besieged by Genghis's three eldest sons. The long siege ended in spring 1221 amid brutal urban conflict.[142] Jalal al-Din moved southwards to Afghanistan, gathering forces on the way and defeating a Mongol unit under the command of Shigi Qutuqu, Genghis's adopted son, in the Battle of Parwan.[ 143 ] Джалал был ослаблен аргументами среди его командиров, и, решительно проиграв в битве при Инду в ноябре 1221 года, он был вынужден сбежать через реку Инд в Индию. [ 144 ]

Младший сын Чингиса Толуи одновременно проводил жестокую кампанию в регионах Хорасана . Каждый город, который сопротивлялся, был уничтожен - Нишапур , Мерв и Герат , три из самых крупных и богатых городов мира, были уничтожены. [ H ] [ 146 ] Эта кампания установила длительный образ Чингиса как безжалостный, бесчеловечный завоеватель. Современные персидские историки поставили число погибших только из трех осадков более 5,7 миллиона человек - число, которое считается крайне преувеличенным современными учеными. [ 147 ] Тем не менее, даже общее количество погибших в 1,25 миллиона за всю кампанию, по оценкам Джона Мана, была бы демографической катастрофой. [ 148 ]

Возвращение в Китай и окончательную кампанию (1222–1227)

Дингис внезапно остановил свои кампании в Центральной Азии в 1221 году. [ 149 ] Первоначально стремясь вернуться через Индию , Чингис понял, что жара и влажность южноазиатского климата препятствовали навыкам его армии, в то время как предзнаменования были дополнительно неблагоприятными. [ 150 ] Хотя монголы проводили большую часть 1222 года, неоднократно преодолевая восстания в Хорасане, они полностью вышли из региона, чтобы избежать переизбытков, установив свою новую границу на реке Аму Дарья . [ 151 ] время своего длительного обратного путешествия Чингис подготовил новое административное подразделение, которое будет регулировать завоеванные территории, назначив ( комиссары, горит . Во Даругхачи [ 152 ] Он также вызвал и поговорил с даосским патриархом Чанчуном в индуистском куше . Хан внимательно слушал учения Чанчуна и предоставил своим последователям многочисленные привилегии, в том числе налоговые льготы и полномочия над всеми монахами по всей Империи - грант, который даоисты позже использовали, чтобы попытаться получить превосходство над буддизмом. [ 153 ]

Обычная причина, приведенная для остановки кампании, заключается в том, что западная XIA , отказавшись предоставлять вспомогательные услуги для вторжения 1219, дополнительно не подчинился Мукали в его кампании против оставшегося Джина в Шэньси . [ 149 ] Мэй оспорил это, утверждая, что СИА боролась с Мукали до его смерти в 1223 году, когда, когда, разочарованная монгольским контролем и ощущая возможность с кампании Чингиса в Центральной Азии, они прекратили борьбу. [ 154 ] В любом случае, Гингис первоначально пытался разрешить ситуацию дипломатически, но когда Элита Ся не смогла прийти к соглашению о заложниках, которые они должны были отправить на монголы, он потерял терпение. [ 155 ]

Вернувшись в Монголию в начале 1225 года, Чингис провел год, готовясь к кампании против них. Это началось в первые месяцы 1226 года с захвата Хара-Кото на западной границе Ся. [ 156 ] Вторжение продолжалось в любом случае. Чингис приказал, чтобы города коридора Гансу были уволены один за другим, предоставив помилования лишь некоторые из них. [ 157 ] Пройдя желтую реку осенью, монголы осадили современный лингву , расположенный всего в 30 километрах (19 миль) к югу от столицы Ся Чжунсинг в ноябре. 4 декабря Чингис решительно победил армию помощи СИА ; Хан оставил осаду столицы своим генералам и переехал на юг с субитай, чтобы разграбить и защитить территории Джин. [ 158 ]

Смерть и последствия

Чингис упал с лошади во время охоты зимой 1226–27 лет и становился все более больным в течение следующих месяцев. Это замедлило осаду прогресса Чжунсинга, так как его сыновья и командиры призвали его прекратить кампанию и вернуться в Монголию, чтобы выздороветь, утверждая, что СИА будет еще один год. [ 160 ] Дингис настаивал на том, чтобы осада была продолжена. Он умер 18 или 25 августа 1227 года, но его смерть оставалась тщательно охраняемым секретом, и в следующем месяце Чжунсинг не знал. Город был поставлен на меч, и его население относилось к чрезвычайной дикости - цивилизация XIA была по существу погашена в том, что человек назвал «очень успешным этноцидом ». [ 161 ] Точная природа смерти Хана была предметом интенсивных спекуляций. Рашид Аль-Дин и история Юаня упомянули, что он страдал от болезни-предположительно малярии , тифа или бубонной чумы . [ 162 ] Марко Поло утверждал, что его застрелила стрела во время осады, в то время как Карпини сообщил, что Чингис был поражен молнией . Вокруг этого события появились легенды - самые известные рассказы о том, как прекрасная Гурбельчин, бывшая жена Императора СИА, повредила гениталии Чингиса с кинжалом во время секса. [ 163 ]

После его смерти Чингис был доставлен обратно в Монголию и похоронен на пике Священного Бурхана Халдуна в горах или рядом с ним, на месте, которое он выбрал годы назад. [ 164 ] Конкретные детали похоронной процессии и погребения не были сделаны общественными знаниями; Гора, объявленная Их Хоригом ( Lit. «Great Taboo»; т.е. запрещенная зона), была вне границ со всем, кроме его охранника Уурианкхай . Когда в 1229 году Эгедей вступил на престол, могила была удостоена трехдневных предложений и жертвы тридцати девиц. [ 165 ] Ратчневский предположил, что монголы, которые не знали о методах бальзамирования , могли бы похоронить хана в Ордос, чтобы избежать разложения его тела в летнем жаре во время пути в Монголию; Этвуд отвергает эту гипотезу. [ 166 ]

Последовательность

У племен монгольского степи не было фиксированной системы преемственности, но часто не дефолтали на какую -то форму ультрагенерации - концентрацию младшего сына - потому что у него было бы наименьшее время, чтобы получить последовательно для себя и нуждался в помощи наследства своего отца. [ 167 ] Однако этот тип наследования применяется только к собственности, а не к названиям. [ 168 ]

Секретная история записывает, что Чингис выбрал своего преемника во время подготовки к хварзмианским кампаниям в 1219 году; Рашид Аль-Дин, с другой стороны, заявляет, что решение было принято перед финальной кампанией Чингиса против СИА. [ 169 ] Независимо от даты, было пять возможных кандидатов: четверо сыновей Чингиса и его младший брат Темуж, у которых самые слабые требования и которые никогда не рассматривались серьезно. [ 170 ] Несмотря на то, что была сильная вероятность, что Джочи был незаконным, Чингис не был особенно обеспокоен этим; [ 171 ] Тем не менее, он и Джочи со временем все больше отчуждены из -за озабоченности Джочи своим собственным Апнаж. После осады Гургана, где он только неохотно участвовал в осаждении богатого города, который станет частью его территории, он не смог дать Дингису нормальную долю добычи, которая усугубила напряженность. [ 172 ] Чингис был возмущен отказом Джочи вернуться к нему в 1223 году и рассматривал вопрос о отправке Огедей и Чагатая, чтобы доставить его на пятку, когда появились новости, что Джочи умер от болезни. [ 173 ]

Отношение Чагатая к возможной преемственности Джочи-он назвал своего старшего брата «Меркит-ублюдок» и сразился с ним перед своим отцом-возглавлял Чингиса, чтобы рассматривать его как бескомпромиссное, высокомерное и узкое, несмотря на его великое знание Монгола юридические обычаи . [ 174 ] Его устранение оставило Огедей и Толуи в качестве двух основных кандидатов. Толуи, несомненно, был превосходен в военном терминах - его кампания в Хорасане сломала Хваразминскую империю, в то время как его старший брат был гораздо менее способным в качестве командира. [ 175 ] Также известно, что Огедэй чрезмерно пил даже по монгольским стандартам - это в конечном итоге вызвало его смерть в 1241 году. [ 176 ] Тем не менее, он обладал талантами, которых не хватало его братьев-он был щедрым и в целом любимым. Зная о своем собственном отсутствии военных навыков, он смог доверять своим способным подчиненным, и, в отличие от своих старших братьев, идти на компромисс по вопросам; Он также с большей вероятностью сохранил монгольские традиции, чем Толуи, чья жена Соргагтани, сама несторианская христианин , была покровителем многих религий, включая ислам. Таким образом, Огедей был признан наследником монгольского престола. [ 177 ]

Служив в качестве регента после смерти Чингиса, Толуи установил прецедент для обычных традиций после смерти Хана. Они включали в себя остановку всех военных наступлений с участием монгольских войск, создание длительного траурного периода, контролируемого регентом, и удержания Курултая, который выдвигал бы преемников и выберет их. [ 178 ] Для Толуи это дало возможность. Он все еще был жизнеспособным кандидатом на преемственность и получил поддержку семьи Джочи. Любой генерал Курульты , в котором приняли участие командиры, пропагандировавшие и почитание, посоветовавшись и почитал, без вопросов будет соблюдать желания своего бывшего правителя и назначить Огедей правителем. Было высказано предположение, что нежелание Толуи удерживать Курультаи было обусловлено знанием угрозы, которую она представляла для его амбиций. [ 179 ] В конце концов, толуи должен был быть убежден советником Йелу Чукаем, чтобы удержать Курултай ; В 1229 году он короновал Огедей как Хан, с присутствованием Толуи. [ 180 ]

Семья

Борте, на котором Темуджин женился в. 1178 , остался его старшей женой. [ 181 ] Она родила четырех сыновей и пять дочерей, которые все стали влиятельными фигурами в империи. [ 182 ] Дингис предоставил сыновьям Бёрте земли и имущество через систему Монголь Апнаж , [ 183 ] в то время как он обеспечил брачные альянсы, женившись на ее дочерях с важными семьями. [ 182 ] Ее дети были:

- Коджин, дочь, родившаяся в. 1179 , который позже женился на Буту из Икире, одного из самых ранних и ближайших сторонников Темуджина и вдовца Тюмолин . [ 184 ]

- Джочи , сын, родившийся в. 1182 после похищения Борте, чье отцовство было подозреваемым, хотя Темюдзин принял его легитимность. [ 185 ] Jochi предопределил Чингис; Его Апнаж, вдоль реки Иртиш и простирающийся в Сибири , превратилось в золотую орду . [ 186 ]

- Чагатай , родился в. 1184 ; [ 187 ] Его Апканаж был бывшим острым хитайским террориями, окружающими Альмалика в Туркестане , который стал Чагатай -ханатом [ 188 ]

- Огедей , сын, родившийся в. 1186 , который получил земли в Дзангарии и сменил своего отца в качестве правителя империи. [ 189 ]

- Чечиген , дочь, родившаяся в. 1188 , чей брак с Тёрельчи обеспечил верность Оирата на севере. [ 190 ]

- Алака , дочь, родившаяся в. 1190 , который женился на нескольких членах племени Онгуд в период с 1207 по 1225. [ 191 ]

- Тюмелин, дочь, родившаяся в. 1192 , который женился на Чигу из племени Онгирата . [ 192 ]

- Толуи , сын, родившийся в. 1193 , который получил земли возле Альтайских гор в качестве Апнаж; Двое из его сыновей, Мёнгке и Кубли , позже управляли империей, в то время как другой, Хулагу , основал Ильханат . [ 193 ]

- Аль Алтан, дочь, родившаяся в. 1196 , женился на могущественном Угурского правителе Барчука . [ 194 ] Вскоре после вступления Гююк -хана в 1240 -х годах ее судили и выполнили по обвинениям, которые были позже подавлены. [ 195 ]

После последнего родов Бёрте Темюдзин начал приобретать ряд младших жен в завоевании. Все эти жены ранее были принцессами или королевами, и Темюдзин женился на них, чтобы продемонстрировать его политическое господство. Они включали принцессу Керет Ибака ; Татарские сестры Осуген и Есуи ; Кулан , Меркит; Гюрбесу, королева Наймана Тайанга Хана ; и две китайские принцессы, Чака и Цигуо, из династий Западного Ся и Джин соответственно. [ 196 ] Дети этих младших жен всегда подчинялись детям Бёрте, когда дочери вышли замуж, чтобы запечатать меньшие альянсы и сыновья, такие как ребенок Кулана Кёльген , никогда не кандидат на преемственность. [ 197 ]

Характер и достижения

Никакого описания очевидцев или одновременного изображения Чингисхана выживает. [ 198 ] Персидский хрониклер Джузджани и песня дипломат Чжао Хонг предоставляют два самых ранних описания. [ я ] Оба записали, что он был высоким и сильным с мощным ростом. Чжао писал, что у Дингиса была широкая бровь и длинная борода, в то время как Джузджани прокомментировал глаза своей кошки и отсутствие седых волос. Секретная история записывает, что отец Берте заметил его «мигающими глазами и живым лицом», когда встречается с ним. [ 200 ]

Этвуд предположил, что многие из ценностей Чингисхана, особенно акцент, который он выделил на упорядоченное общество, происходящие из его бурной молодежи. [ 201 ] Он ценил лояльность, и взаимная верность стала краеугольным камнем его новой нации. [ 202 ] Гингису не было трудно получить верность других: он был великолепно харизматичным, даже в молодости, как показано количество людей, которые оставили существующие социальные роли, чтобы присоединиться к нему. [ 203 ] Хотя его доверие было трудно заработать, если он почувствовал, что лояльность была уверена, он надел свою полную уверенность в ответ. [ 204 ] Признанный за его щедрость по отношению к своим последователям, Чингис без колебаний вознаградил предыдущую помощь. Нёкод , наиболее почитаемый в 1206 Курультаи, были теми, кто сопровождал его с самого начала, и те, кто поклялся с ним в Бальджуна завет в его самой низкой точке. [ 205 ] Он взял на себя ответственность за семьи Нёкода , убитых в бою или которые в противном случае ушли в трудные времена, подняв налог, чтобы обеспечить им одежду и поддержку. [ 206 ]

Небеса устали от чрезмерной гордости и роскоши в Китае ... Я с варварского севера ... Я ношу ту же одежду и ем ту же еду, что и пахеры и закуски лошадей. Мы приносим те же жертвы и делимся нашим богатством. Я рассматриваю нацию как новорожденного ребенка, и я забочусь о своих солдатах, как будто они были моими братьями.

Основным источником степи богатства была грабежа после битвы, из которого лидер обычно претендует на большую долю; Чингис избежал этого обычая, решив вместо этого разделить добычу в равной степени между собой и всеми своими людьми. [ 208 ] Не любив любую форму роскоши, он превозносил простую жизнь кочевника в письме в Чанчун и возражал против того, чтобы быть обращенным с непристойной лести. Он призвал своих спутников обращаться к нему неофициально, дать ему совет и критиковать его ошибки. [ 209 ] Открытость Чингиса к критике и готовности учиться увидел, как он ищет знание членов семьи, компаньонов, соседних государств и врагов. [ 210 ] Он искал и получил знания о изысканном оружии из Китая и мусульманского мира, присвоил Уйгурский алфавит с помощью захваченного писца Тата-Тонга и нанял многочисленных специалистов в юридических, коммерческих и административных областях. [ 211 ] Он также понял необходимость в плавной преемственности, и современные историки согласны с тем, что он проявил здравое решение в выборе своего наследника. [ 212 ]

Хотя он сегодня известен своими военными завоеваниями, очень мало известно о личном оборудовании Чингиса. Его навыки были более подходящими для выявления потенциальных командиров. [ 213 ] Его институт структуры Meritocratic Command дал военному превосходству в армии монголь, хотя оно не было технологически или тактически инновационно. [ 214 ] Армия, которую создала Чингис, была характеризована его драконовской дисциплиной , ее способностью эффективно собирать и использовать военную разведку , мастерство психологической войны и готовность быть совершенно безжалостной. [ 215 ] требовательной местью от своих врагов - концепция лежала в основе Кари'льку ( Lit. » . Гингис полностью наслаждался Ачи В исключительных обстоятельствах, например, когда Мухаммед из Хваразма выполнил своих посланников, необходимость мести отверг все другие соображения. [ 216 ]

Дингис пришел к выводу, что Верховное Божество Тенгри назначило для него большую судьбу. Первоначально границы этой амбиции были ограничены только Монголией, но, поскольку успех последовал за успехом и охват монгольской нации расширился, он и его последователи пришли к выводу, что он был воплощен в Суу ( Lit. '' «Божественная благодать» ) . [ 217 ] Полагая, что у него была интимная связь с небесами, любой, кто не узнал его право на мировую власть, рассматривался как враг. Эта точка зрения позволила Чингисам рационализировать любые лицемерные или двуличные моменты с его собственной стороны, такие как убийство его Анда Джамуха или убийство Нёкода, который колебался в своей верности. [ 218 ]

Наследие и историческая оценка

Чингис Хан оставил обширное и противоречивое наследие. По словам Этвуда , его объединение монгольских племен и основание крупнейшего смежного государства в мировой истории «постоянно изменяют мировоззрение европейских, исламских, [и] восточноазиатских цивилизаций». [ 220 ] Его завоевания позволили создать евразийские торговые системы, беспрецедентные в их масштабе, что принесло богатство и безопасность для племен. [ 221 ] Хотя он, скорее всего, не кодифицировал письменный состав законов, известных как Великий Яса , [ 222 ] Он реорганизовал правовую систему и установил мощную судебную власть при Шиги Кутукку . [ 223 ]

С другой стороны, его завоевания были безжалостными и жестокими. Процветающие цивилизации Китая, Центральной Азии и Персии были опустошены монгольскими нападениями и в результате перенесли травму и страдания с несколькими поколениями. [ 224 ] Возможно, самым большим неудачей Чингиса была его неспособность создать рабочую систему преемственности-его разделение его империи на Апнажи , предназначенные для обеспечения стабильности, фактически делали обратное, поскольку местные и общегосударственные интересы расходились, и Империя начала расколоться на золотую орду , Чагатай -ханат , Ильханат и династия Юань в конце 1200 -х годов. [ 225 ] В середине 1990-х годов « Вашингтон пост» признал Дженгисхан как «Человек тысячелетия», который «воплотил в себе наполовинуцивилизованную двойственность человеческой расы наполовину квалификации». [ 226 ] Этот сложный образ оставался распространенным в современной стипендии, когда историки подчеркивают позитивный и негативный вклад Чингисхана. [ 227 ]

Монголия

На протяжении многих веков в Монголии запомнились Чингис как религиозную фигуру, а не политическую. После того, как Алтан Хан превратился в тибетский буддизм в конце 1500 -х годов, Чингис был обожжен и дал центральную роль в монгольской религиозной традиции. [ 228 ] Как божество, Чингис опирался на буддийские, шаманистические и народные традиции : например, он был определен как новое воплощение чакравартина ( идеализированного правителя), такого как Ашока , или Ваджрапани , боджаттвы ; Он был генеалогически связан с Буддой и древними буддийскими королями; Его вызывали во время свадеб и фестивалей; и он играл большую роль в почитания предков . ритуалах [ 229 ] Он также стал в центре внимания легенды спящего героя , которая говорит, что он вернется, чтобы помочь людям -монголе во время большей нужды. [ 230 ] Его культ был сосредоточен в Наймане Чаган Ордоне ( Lit. « Восемь белых юртов» ) , сегодня мавзолей во Внутренней Монголии , Китай. [ 231 ]

В 19 -м и начале 20 -го века Чингис начал рассматриваться как национальный герой монгольского народа. Иностранные державы признали это: во время своей оккупации внутренней Монголии Имперская Япония финансировала строительство храма в Чингисе, в то время как Куминтанг и Коммунистическая партия Китая использовали память о Джингисе, чтобы ухаживать за потенциальными союзниками в гражданской войне Китая . [ 232 ] Такое отношение поддерживалось во время Второй мировой войны , когда выравниваемая Советом, Монгольская народная Республика, способствовала Джингисам построить патриотическое рвение против захватчиков; Однако, поскольку он был неруссийским героем, который мог бы служить антикоммунистом , это отношение быстро изменилось после конца войны. Согласно маю, Чингис «был осужден как феодальный и реакционный лорд [который] эксплуатировал народ». [ 233 ] Его культ был подавлен, алфавит, который он выбрал, был заменен кириллическим сценарием , а празднование, запланированные на 800 -летие его рождения в 1962 году, были отменены и угрожали после громких советских жалоб. Поскольку китайские историки были в значительной степени более благоприятны для него, чем их советские обстоятельства, Чингис сыграл незначительную роль в китайско-советском расколе . [ 234 ]

Прибытие политики гласности и перестройки в 1980 -х годах проложило путь для официальной реабилитации. Менее чем через два года после революции 1990 года Ленин -авеню в столице Улаанбаатара была переименована в Чинггис -Хан -авеню. [ 235 ] С тех пор Монголия назвала Чинггис Хаанский международный аэропорт и построил большую статую на площади Сукбаатара (которая была переименована в Чингис в период с 2013 по 2016 год). Его облик появляется на предметах, начиная от почтовых маркеров и высоких банкнот до брендов алкоголя и туалетной бумаги. В 2006 году Монгольский парламент официально обсудил тривиализацию своего имени посредством чрезмерной рекламы. [ 236 ]

Современные монголы, как правило, преуменьшают военные завоевания Дингиса в пользу его политического и гражданского наследия - они рассматривают разрушительные кампании как «продукт своего времени», по словам историка Михала Бирана и вторично по отношению к его другим вкладам в Монгольский и мир история [ 237 ] Его политика - такая как его использование Курультая , его установление верховенства закона через независимую судебную власть и права человека - рассматриваются как основы, которые позволяют создавать современное демократическое монгольское государство. Считаемый как человека, который принес мир и знания, а не войну и разрушение, Чингисхан идеализирован для того, чтобы сделать Монголию в центр международной культуры на период. [ 238 ] Он, как правило, признан отцом -основателем Монголии. [ 239 ]

В другом месте

Исторический и современный мусульманский мир связал Чингисхана с множеством идеологий и убеждений. [ 240 ] Его первый инстинкт, поскольку исламская мысль ранее никогда не предполагала, что им не мусульманская власть, заключалась в том, чтобы рассматривать Чингиса как вестник приближающегося Судного дня . Со временем, когда мир не закончился, и когда его потомки начали обращаться в ислам, мусульмане начали рассматривать Гингиса как инструмент Божьей воли, которому суждено было укрепить мусульманский мир, очищая свою врожденную коррупцию. [ 241 ]

В пост-Монгольской Азии Чингис также был источником политической легитимности, потому что его потомки были признаны единственными, кто имел право на правление. В результате, начинающие потенциалы, не произошедшие от него, должны были оправдать их правление, либо путем назначения марионеточных правителей династии Чингиса, либо подчеркивая свои собственные связи с ним. [ 242 ] В частности, великий завоеватель Тимор , который основал свою собственную империю в Центральной Азии, сделал и то, и другое: он был вынужден отдать дань уважения потомкам Дингиса Союргатматмиша и султана Махмуда , а его пропагандистские кампании сильно преувеличивали известность своего предка Карачар , один из Меньшие командиры Чингиса, изображающие его как родственника Дингиса и второго в команде. Он также женился по крайней мере двух из потомков Чингиса. [ 243 ] Бабур , основатель империи Моголов в Индии, [ k ] В свою очередь получил свой авторитет через его спуск как от Тимора, так и от Чингиса. [ 245 ] До восемнадцатого века в Центральной Азии Чингис считался прародителем социального порядка и был вторым только пророком Мухаммедом в юридической власти. [ 246 ]

С ростом арабского национализма в девятнадцатом веке арабский мир начал рассматривать Чингиса все больше негативно. Сегодня он воспринимается как окончательный «проклятый враг», «варварский дикарь, который начал снос цивилизации, которая завершилась [осадой Багдада в 1258 году» его внуком Хулегу . [ 247 ] Точно так же Чингис чрезвычайно негативно рассматривается в России, где историки постоянно изображают правило Золотой Орды - «татарского ига» - как отсталый, разрушительный, враждебный для всех прогрессов и причины всех недостатков России. [ 248 ] Его обращение в современной Центральной Азии и Турции более амбивалентно: его позиция в качестве немусульманского означает другие национальные традиции и герои, такие как Тимор и Сельджуки , рассматриваются более высоко. [ 249 ]

Под династией Юаней в Китае Чингис почитался как создатель страны, и он оставался в этом положении даже после основания династии Мин Хотя покойный Минг несколько дезавуировал его память, позитивная точка зрения была восстановлена под манчжу в 1368 году . Династия (1644–1911), который позиционировал себя как своих наследников. Рост китайского национализма 20-го века изначально вызвал клевету на Джингис как травмирующего оккупанта, но позже он был воскрес как полезный политический символ по различным вопросам. Современная китайская историография, как правило, рассматривает Джингис положительно, и его изображали как китайский герой. [ 250 ] В современной Японии он наиболее известен за легенду о том, что изначально был Минамото но Йошитсун , самурай и трагический герой, который был вынужден совершить Сеппуку в 1189 году. [ 251 ]

Западный мир, никогда непосредственно затронутым Чингисом, рассматривал его сдвигающими и контрастными способами. В течение 14 -го века, как показали работы Марко Поло и Джеффри Чосера , его считали справедливым и мудрым правителем, но в восемнадцатом веке он пришел, чтобы воплотить стереотип просвещения тиранического восточного деспота, и к двадцатому веку. Он представлял прототип варварского военачальника. В последние десятилетия западная стипендия становится все более детальной, рассматривая Гингиса как более сложного человека. [ 252 ]

Ссылки

Примечания

- ^ / Ds ŋ ŋ ŋ ŋ ŋ ˈ n n/

- ^ См. § Имя и заголовок

- ^ Также транслитерированный как Чжао Гонг, его Meng Da Beilu (полная запись монгольских татаров) является единственным выжившим источником монголов, написанных в течение жизни Чингиса. [ 16 ]

- ^ Монгольская народная Республика решила ознаменовать 800 -летие родов Темюджина в 1962 году. [ 18 ]

- ^ На данный момент слово «монголы» относилось только к членам одного племени в северо -восточной Монголии; Поскольку это племя сыграло центральную роль в формировании монгольской империи , их имя позже использовалось для всех племен. [ 24 ]

- ^ Согласно секретной истории , Джамуха сказал: «Если мы разбиваем лагерь недалеко от холма, те, кто ставит у наших лошадей, будут свои палатки. Если мы разбиваем лагерь рядом с горным потоком тех, кто ставит наши овцы и ягнят, будут пищу для их чайков». [ 51 ]

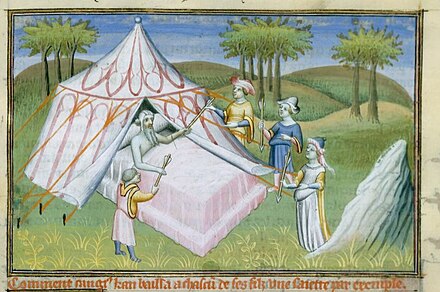

- ^ Тук , баннер , созданный из хвостов як или лошадей, находится справа; Белый Тук, изображенный здесь, представляет мир, в то время как черный Тук будет представлять войну. [ 74 ]

- ^ Герат изначально сдался Толуи, но позже восстал и был уничтожен в 1222 году; Его население было убито. [ 145 ]

- ^ Чжао Хонг посетил Монголию в 1221 году, в то время как Гингис проводил кампанию в Хорасане. [ 199 ] Джузджани, написав тридцать лет после смерти Чингиса, полагался на очевидцы из той же кампании. [ 200 ]

- ^ Субъекты включают (сверху вниз, слева направо): Ginghis, ögedei, Kublai, Temür, Külüg, Buyantu и Rinchinbal. [ 219 ]

- ^ Слово «Моголь» происходит от «монгола», которое использовалось в Индии для любых северных захватчиков. [ 244 ]

Цитаты

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , pp. X - Xi.

- ^ Pelliot 1959 , p. 281.

- ^ Bawden 2022 , § "Введение"; Уилкинсон 2012 , с. 776; Морган 1990 .

- ^ Bawden 2022 , § "Введение".

- ^ Der's 2016 , с. 24; Фуссии 2014 , стр. . 77-82.

- ^ Morgan 1986 , с. 4–5.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , p. xii.

- ^ Sverdrup 2017 , с.

- ^ Повешен 1951 , с. 481.

- ^ Waley 2002 , с. 7–8; Morgan 1986 , p. 11

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , с. XIV - XV.

- ^ Morgan 1986 , с. 16–17.

- ^ Sverdrup 2017 , с.

- ^ Морган 1986 , с. 18; Ratchnevsky 1991 , pp. XV - XVI.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , p. XV; Этвуд 2004 , с. 117; Morgan 1986 , с. 18–21.

- ^ Этвуд 2004 , с. 154

- ^ Sverdrup 2017 , с. XIV - XVI; Райт 2017 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Morgan 1986 , p. 55

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , с. 17–18.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , pp. 17–18; Pelliot 1959 , с. 284–287.

- ^ Человек 2004 , с. 70; Biran 2012 , p. 33; Этвуд 2004 , с. 97; Май 2018 , с. 22; Джексон 2017 , с. 63.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , p. 19

- ^ Этвуд 2004 , с. 97

- ^ Atwood 2004 , с. 389–391.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , pp. 14–15; Май 2018 , с. 20–21.

- ^ Pelliot 1959 , с. 289–291; Человек 2004 , с. 67–68; Ratchnevsky 1991 , p. 17

- ^ Brose 2014 , § «Молодой температура»; Пеллиот 1959 , с. 288

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , p. 17

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , pp. 15–19.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , pp. 20–21; Fitzhugh, Rossabi & Honeychurch 2009 , с. 100

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , pp. 21–22; Broadbridge 2018 , с. 50–51.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , p. 22; Май 2018 , с. 25; De Rachewiltz 2015 , § 71–73.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , с. 22–23; Atwood 2004 , с. 97–98.

- ^ Brose 2014 , § «Молодой температура»; Этвуд 2004 , с. 98

- ^ Май 2018 , с. 25

- ^ Май 2018 , с. 25–26.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , pp. 23–24; De Rachewiltz 2015 , §76–78.

- ^ Человек 2004 , с. 74; De Rachewiltz 2015 , §116; Fitzhugh, Rossabi & Honeychurch 2009 , с. 101.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , pp. 25–26; Fitzhugh, Rossabi & Honeychurch 2009 , стр. 100–101.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , pp. 26–27; Май 2018 , с. 26–27.

- ^ Май 2018 , с. 28

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , p. 27

- ^ Май 2018 , с. 28; Ratchnevsky 1991 , p. 31

- ^ Atwood 2004 , с. 295–296, 390; Ratchnevsky 1991 , pp. 32–33; Май 2018 , с. 28–29.

- ^ Broadbridge 2018 , с. 58

- ^ Ratnevsky 1991 , pp. 34–35; Brose 2014 , § «Появление Чинггис -хана»

- ^ Май 2018 , с. 30; Bawden 2022 , § «Ранняя борьба».

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , pp. 34–35; Май 2018 , с. 30–31.

- ^ Broadbridge 2018 , с. 66–68.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , pp. 37–38.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , p. 37

- ^ Май 2018 , с. 31; Ratchnevsky 1991 , pp. 37–41; Broadbridge 2018 , p. 64

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , pp. 39–41.

- ^ Этвуд 2004 , с. 98; Brose 2014 , § «Создание монгольской конфедерации».

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , pp. 44–47.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , с. 49–50; Май 2018 , с. 32

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , pp. 49–50.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , с. 49–50; Май 2018 , с. 32; Fitzhugh, Rossabi & Honeychurch 2009 , с. 101.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , pp. 52–53; Pelliot 1959 , с. 291–295.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , pp. 52–53; Sverdrup 2017 , с. 56

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , pp. 46–47; Май 2018 , с. 32

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , pp. 54–56.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , pp. 61–62; Май 2018 , с. 34–35.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , pp. 63–67; De Hartog 1999 , с. 21–22; Fitzhugh, Rossabi & Honeychurch 2009 , с.

- ^ Май 2018 , с. 36

- ^ Этвуд 2004 , с. 98; Ratchnevsky 1991 , pp. 67–70; Май 2018 , с. 36–37.

- ^ Cleaves 1955 , p. 397.

- ^ Brose 2014 , § «Построение монгольской конфедерации»; Ratchnevsky 1991 , pp. 70–73; Человек 2004 , с. 96–98.

- ^ Человек 2014 , с. 40; Weatherford 2004 , p. 58; Biran 2012 , p. 38

- ^ Человек 2014 , с. 40

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , с. 78–80; Этвуд 2004 , с. 98; Lane 2004 , с. 26–27.

- ^ Sverdrup 2017 , с. 81–83; Ratchnevsky 1991 , pp. 83–86.

- ^ Brose 2014 , § «Построение монгольской конфедерации»; Fitzhugh, Rossabi & Honeychurch 2009 , с. 103; Ratchnevsky 1991 , pp. 86–88; McLynn 2015 , с. 90–91.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Май 2012 , с. 36

- ^ Fitzhugh, Rossabi & Honeychurch 2009 , p. 103

- ^ Pelliot 1959 , p. 296; Figereau 2021 , с. 37

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , p. 89; Пеллиот 1959 , с. 297

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , pp. 89–90; Pelliot 1959 , с. 298–301.

- ^ Weatherford 2004 , p. 65

- ^ Май 2018 , с. 39

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , p. 90; Fitzhugh, Rossabi & Honeychurch 2009 , с. 104; McLynn 2015 , с. 97

- ^ Atwood 2004 , с. 505–506; Май 2018 , с. 39

- ^ Май 2007 , с. 30–31; McLynn 2015 , с. 99

- ^ Май 2018 , с. 39–40; Fitzhugh, Rossabi & Honeychurch 2009 , с. 104

- ^ Джексон 2017 , с. 65

- ^ Этвуд 2004 , с. 393; Weatherford 2004 , p. 67

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , p. 92; Май 2018 , с. 77; Человек 2004 , с. 104–105.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , pp. 92–93; Май 2018 , с. 77; Atwood 2004 , с. 460–462.

- ^ Этвуд 2004 , с. 297; Weatherford 2004 , с. 71–72; Май 2018 года .

- ^ Май 2018 , с. 78; Этвуд 2004 , с. 297; Ratchnevsky 1991 , p. 94; Человек 2004 , с. 106

- ^ Этвуд 2004 , с. 297

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , p. 101.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , pp. 97–98; Этвуд 2004 , с. 531; Weatherford 2004 , p. 73.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , pp. 98–100.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , pp. 100–101; Этвуд 2004 , с. 100

- ^ Май 2018 , с. 44–45; Этвуд 2004 , с. 502

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , p. 102; Май 2018 , с. 45

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , pp. 102–103; Этвуд 2004 , с. 563.

- ^ Этвуд 2004 , с. 590; Человек 2004 .

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , p. 103; Fitzhugh, Rossabi & Honeychurch 2009 , с. 104

- ^ Май 2012 , с. 38; Waterson 2013 , p. 37

- ^ Sverdrup 2017 , с. Человек 2004 , с.

- ^ Atwood 2004 , с. 590–591; Ratchnevsky 1991 , p. 104

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , p. 104; Sverdrup 2017 , с. 97–98.

- ^ Май 2018 , с. 48; Человек 2014 , с. 55

- ^ Человек 2004 , с. 132–133; Этвуд 2004 , с. 591; Май 2018 , с. 48; Ratchnevsky 1991 , pp. 104–105; Waterson 2013 , p. 38

- ^ Этвуд 2004 , с. 275

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , p. 108; Человек 2004 , с. 134.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , pp. 106–108.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , pp. 109–109; Atwood 2004 , с. 275–276; Май 2012 , с. 39

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , pp. 109–109; Sverdrup 2017 , с. 104; Этвуд 2004 , с. 424.

- ^ Waterson 2013 , p. 39; Май 2018 , с. 50; Atwood 2004 , с. 275–277.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , pp. 109–110; Этвуд 2004 , с. 501; Человек 2004 , с. 135–136; Sverdrup 2017 , с. 105–106.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , p. 110; Человек 2004 , с. 137.

- ^ Sverdrup 2017 , с. 111–112; Waterson 2013 , p.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , pp. 110–111; Sverdrup 2017 , с. 114–115; Человек 2004 , с. 137.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , pp. 111–112; Человек 2004 , с. 137–138; Waterson 2013 , с. 42–43.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , pp. 112–113; Этвуд 2004 , с. 620; Человек 2004 , с. 139–140.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , pp. 113–114; Май 2018 , с. 52–54; Человек 2004 , с. 140; Sverdrup 2017 , с. 114–116.

- ^ Человек 2004 , с. 140–141; Ratchnevsky 1991 , p. 114

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , p. 114; Weatherford 2004 , p. 97; Май 2018 , с. 54

- ^ Этвуд 2004 , с. 277

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , pp. 114–115; Этвуд 2004 , с. 277

- ^ Май 2018 , с. 55

- ^ Этвуд 2004 , с. 393.

- ^ Май 2018 , с. 57; Этвуд 2004 , с. 502; Ratchnevsky 1991 , pp. 116–117.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , pp. 117–118; Май 2018 , с. 57–58; Этвуд 2004 , с. 502

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , pp. 118–119; Atwood 2004 , с. 445–446; Май 2018 , с. 60; Favereau 2021 , с. 45–46.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , pp. 118–119; Этвуд 2004 , с. 446; Человек 2004 , с. 150

- ^ Fittingu 2021 , с. 46; Этвуд 2004 , с. 446; Человек 2004 , с. 151; POW 2017 , с. 35

- ^ Weatherford 2004 , p. 105; Этвуд 2004 , с. 100

- ^ Джексон 2017 , с. 71–73; Ratchnevsky 1991 , pp. 119–120.

- ^ Atwood 2004 , с. 429, 431; Ratchnevsky 1991 , pp. 120–123; Май 2012 , с. 42; Favereau 2021 , с. 54

- ^ Favereau 2021 , с. 55; Ratchnevsky 1991 , p. 123; Этвуд 2004 , с. 431; Fitzhugh, Rossabi & Honeychurch 2009 , с. 104

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , pp. 123–125; Golden 2009 , pp. 14–15; Джексон 2017 , с. 76–77.

- ^ Этвуд 2004 , с. 307

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , p. 130; Этвуд 2004 , с. 307

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , p. 130; Май 2018 , с. 62; Джексон 2017 , с. 77–78; Человек 2004 , с. 163–164.

- ^ Ratchnevsky 1991 , pp. 130–133; Человек 2004 , с. 164, 172; Этвуд 2004 , с. 307

- ^ Этвуд 2004 , с. 307; Май 2018 , с. 62–63; Ratchnevsky 1991 , p. 133; POW 2017 , с. 36

- ^ Человек 2004 , с. 184–191; Этвуд 2004 , с. 521; Май 2012 , с. 43

- ^ Человек 2004 , с. 173–174; Sverdrup 2017 , с.

- ^ Atwood 2004 , с. 307, 436; Ratchnevsky 1991 , p. 133.

- ^ Май 2018 , с. 63; Sverdrup 2017 , с. 162–163; Ratchnevsky 1991 , pp. 133–134.

- ^ Sverdrup 2017 , с. 160–167.

- ^ Этвуд 2004 , с. 307; Май 2018 , с. 63; Человек 2004 , с. 174–175; Sverdrup 2017 , с. 160–161, 164.

- ^ Человек 2004 , с. 177–181; Weatherford 2004 , с. 118–119; Atwood 2004 , с. 308, 344.

- ^ Человек 2004 , с. 180–181; Этвуд 2004 , с. 244