Антикоммунизм

| Часть серии о |

| Коммунизм |

|---|

|

Антикоммунизм — это политическая и идеологическая оппозиция коммунистическим убеждениям, группам и отдельным лицам. Организованный антикоммунизм развился после Октябрьской революции 1917 года в Российской империи и достиг глобальных масштабов во время холодной войны , когда Соединенные Штаты и Советский Союз вступили в ожесточенное соперничество. Антикоммунизм был элементом многих движений и различных политических позиций по всему политическому спектру , включая анархизм , центризм , консерватизм , фашизм , либерализм , национализм , социал-демократию , социализм , левые взгляды и либертарианство , а также широкие движения, сопротивляющиеся коммунистическому управлению. . Антикоммунизм также выражался несколькими религиозными группами , а также в искусстве и литературе .

Первой организацией, которая специально занималась противодействием коммунизму, было Русское белое движение , которое участвовало в Гражданской войне в России , начавшейся в 1918 году, против недавно созданного большевистского правительства . Белое движение получило военную поддержку со стороны нескольких союзных иностранных правительств , что представляло собой первый пример антикоммунизма как государственной политики. Тем не менее, Красная Армия победила Белое движение, и в 1922 году был создан Советский Союз. За время существования Советского Союза антикоммунизм стал важной чертой многих различных политических движений и правительств по всему миру.

In the United States, anti-communism came to prominence during the First Red Scare of 1919–1920. During the 1920s and 1930s, opposition to communism in America and in Europe was promoted by conservatives, monarchists, fascists, liberals, and social democrats. Fascist governments rose to prominence as major opponents of communism in the 1930s. Liberal and social democrats in Germany formed the Iron Front to oppose communists, Nazi fascists, and revanchist conservative monarchists alike. In 1936, the Anti-Comintern Pact, initially between Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan, was formed as an anti-communist alliance.[1] In Asia, Imperial Japan and the Kuomintang (Chinese Nationalist Party) were the leading anti-communist forces in this period.

By 1945, the communist Soviet Union was among major Allied nations fighting against the Axis powers in World War II (WII.)[2] Shortly after the end of the war, rivalry between the Marxist–Leninist Soviet Union and liberal capitalist United States resulted in the Cold War. During this period, the United States government played a leading role in supporting global anti-communism as part of its containment policy. Military conflicts between communists and anti-communists occurred in various parts of the world, including during the Chinese Civil War, the Korean War, the Malayan Emergency, the Vietnam War, the Soviet–Afghan War, and Operation Condor. NATO was founded as an anti-communist military alliance in 1949, and continued throughout the Cold War.

After the Revolutions of 1989 and the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, most of the world's communist governments were overthrown, and the Cold War ended. Nevertheless, anti-communism remains an important intellectual element of many contemporary political movements. Organized anti-communist movements remain in opposition to the People's Republic of China and other communist states.

Anti-communist movements

[edit]Left-wing anti-communism

[edit]

Since the split of the communist parties from the socialist Second International to form the Marxist–Leninist Third International, social democrats have been critical of communism for its anti-liberal nature. Examples of left-wing critics of Marxist–Leninist states and parties are Friedrich Ebert, Boris Souvarine, George Orwell, Bayard Rustin, Irving Howe, and Max Shachtman. The American Federation of Labor was always strongly anti-communist. The more leftist Congress of Industrial Organizations purged its communists in 1947 and was staunchly anti-communist afterwards.[3][4] In Britain, the Labour Party strenuously resisted Communist efforts to infiltrate its ranks and take control of locals in the 1930s. The Labour Party became anti-communist and Labour Prime Minister Clement Attlee was a staunch supporter of NATO.[5]

Despite anarcho-communism being a well known anarchist school of thought, there are also anarchists who oppose communism. Anti-communist anarchists include anarcho-primitivists and other green anarchists, who critique communism for its need of industrialisation and its perceived authoritarianism.[6]

Liberalism

[edit]In The Communist Manifesto, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels outlined some provisional short-term measures that could be steps towards communism. They noted that "these measures will, of course, be different in different countries. Nevertheless, in most advanced countries, the following will be pretty generally applicable."[7] Ludwig von Mises described this as a "10-point plan" for the redistribution of land and production and argued that the initial and ongoing forms of redistribution constitute direct coercion.[8] Neither Marx's 10-point plan nor the rest of the manifesto say anything about who has the right to carry out the plan.[9] Milton Friedman argued that the absence of voluntary economic activity makes it too easy for repressive political leaders to grant themselves coercive powers. Friedman's view was also shared by Friedrich Hayek and John Maynard Keynes, both of whom believed that capitalism is vital for freedom to survive and thrive.[10][11] Ayn Rand was strongly anti-communist.[12] She argued that Communist leaders typically claim to work for the common good, but many or all of them were corrupt and totalitarian.[13]

At the end of World War I, liberal internationalists developed an early opposition to the Bolshevik regime, which they saw as betraying the war effort with peace with Germany, followed by annexed portions of the Soviet Union losing their self-determination.[14]: 12–17 Later, knowledge of Stalinist show trials and other repressions in the USSR, from 1922 onward, led to a liberal anti-communist consensus by the start of WWII, which temporarily gave way during the WWII alliance with the Soviet Union.[14]: 141–142 Historian Richard Powers distinguishes two main forms of anti-communism during the period, liberal anti-communism and countersubversive anti-communism. The countersubversives, he argues, derived from a pre-WWII isolationist tradition on the right. Liberal anti-communists believed that political debate was enough to show Communists as disloyal and irrelevant, while countersubversive anticommunists believed that Communists had to be exposed and punished.[14]: 214

Cold War liberals supported the growth of labor unions, the Civil Rights Movement, and the War on Poverty and simultaneously opposed what they saw as Communist totalitarianism abroad. As such, they supported efforts to contain Soviet communism and other forms of communism.[15]

President Harry Truman formulated the Truman Doctrine to stop Soviet expansionism. Truman also called Joseph McCarthy "the greatest asset the Kremlin has," for dividing the bipartisan foreign policy of the United States.[16] Liberal anti-communists like Edward Shils and Daniel Moynihan had a contempt for McCarthyism. As Moynihan put it, "reaction to McCarthy took the form of a modish anti anti-communism that considered impolite any discussion of the very real threat Communism posed to Western values and security." After revelations of Soviet spy networks from the declassified Venona project, Moynihan wondered: "Might less secrecy have prevented the liberal overreaction to McCarthyism as well as McCarthyism itself?"[17]

Chancellor Konrad Adenauer, who presided over postwar West Germany as a market liberal democracy, signaled that the Soviet Union was the "greatest threat to liberty", an idea that exerted major domestic and international influence.[18]

After the fall of Gorbachev and the Soviet Union in 1991, the anti-communist movement grew rapidly.

In the early 1990s, many new anti-communist movements emerged in the former Soviet bloc as a result of failed elections and Boris Yeltsin's Palace Coup. When this seizure of power occurred, more than thirty electoral blocs set out to contest the election.[19] Some of these anti-Stalinist groups were: Choice of Russia, the Civic Union for Stability, Justice & Progress, Constructive Ecological Movement, Russian Democratic Reform Movement, Dignity and Mercy, and Women of Russia.[19] Even though these movements were not successful in contesting the election, they displayed how there was still a strong support of anti-communism after the collapse of the Soviet Union. All of these movements were all critical of the Stalinist policy of the USSR, and some leftist parties and organizations within the movements called it an "unmitigated disaster for socialists"[20]

Former communists

[edit]Milovan Djilas was a former Yugoslav communist official who became a prominent dissident and critic of communism.[21] Leszek Kołakowski was a Polish communist who became a famous anti-communist. He was best known for his critical analyses of Marxist thought, especially his acclaimed three-volume history, Main Currents of Marxism, which is "considered by some[22] to be one of the most important books on political theory of the 20th century".[23] The God That Failed is a 1949 book which collects together six essays with the testimonies of a number of famous former communists who were writers and journalists. The common theme of the essays is the authors' disillusionment with and abandonment of communism. The promotional byline to the book is "Six famous men tell how they changed their minds about communism." Anatoliy Golitsyn and Oleg Kalugin were both former KGB officers, the latter being a general. Dmitri Volkogonov was a Soviet general who got access to soviet archives following glasnost, and wrote a critical biography dismantling the cult of Lenin by refuting Leninist ideology.

Whittaker Chambers was a former spy for the Soviet Union who testified against his fellow spies before the House Un-American Activities Committee;[24] Bella Dodd was another American anticommunist.

Other anti-communists who were once Marxists include the writers Max Eastman, John Dos Passos, James Burnham, Morrie Ryskind, Frank Meyer, Will Herberg, Sidney Hook,[25] the contributors to the book The God That Failed: Louis Fischer, André Gide, Arthur Koestler, Ignazio Silone, Stephen Spender Tajar Zavalani and Richard Wright.[26] Anti-communists who were once socialists, liberals or social democrats include John Chamberlain,[27] Friedrich Hayek,[28] Raymond Moley,[29] Norman Podhoretz, David Horowitz, and Irving Kristol.[30]

Counter-revolutionary movements

[edit]

A wave of revolutionary impulses since the French Revolution that had swept over Europe and other parts of the world and thus also created as a counter-revolutionary reaction. Historian James H. Billington describes, in the book Fire in the Minds of Men, the historical frame of revolutions that extended from the waning of the French Revolution in the late eighteenth century and that culminated in the Russian Revolution. Most exiled Russian White émigré that included exiled Russian liberals were actively anti-communist in the 1920s and 1930s.[32] Many of them had been active in the White movements that functioned as a big tent movement representing an array of political opinions in Russia united in their opposition to the Bolsheviks.

In Britain, anti-communism was widespread among the British foreign policy elite in the 1930s with its strong upperclass connections.[33] The upper-class Cliveden set was strongly anti-communist in Britain.[34] In the United States, anti-communist fervor was at its highest during the late 1940s and early 1950s, when a Hollywood blacklist was established, the House Un-American Activities Committee held the televised Army–McCarthy hearings, led by Senator Joseph McCarthy, and the John Birch Society was formed.

White movement

[edit]The White movement was a loose confederation of anti-communist forces that fought against the communist Bolsheviks, also known as the Reds, in the Russian Civil War. After the civil war, the movement continued operating to a lesser extent as militarized associations of insurrectionists both outside and within Russian borders in Siberia until roughly World War II.

During the Russian Civil War, the White movement functioned as a big-tent political movement representing an array of political opinions in Russia united in their opposition to the communist Bolsheviks. They ranged from the republican-minded liberals and Kerenskyite social-democrats on the left through monarchists and supporters of a united multinational Russia to the ultra-nationalist Black Hundreds on the right.

Following the military defeat of the Whites, remnants and continuations of the movement remained in several organizations, some of which only had narrow support, enduring within the wider White émigré overseas community until after the fall of the European communist states in the Revolutions of 1989 and the subsequent dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1990–1991. This community-in-exile of anti-communists often divided into liberal-leaning and conservative-leaning segments, with some still hoping for the restoration of the Romanov dynasty. Two claimants to the empty throne emerged during the Civil War, Grand Duke Kirill Vladimirovich of Russia and Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevich of Russia.

Fascism

[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Integralism |

|---|

|

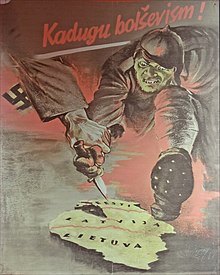

Fascism is often considered to be a reaction to communist and socialist uprisings in Europe.[35] Italian Fascism, founded and led by Benito Mussolini, took power after years of leftist unrest led many disgruntled conservatives to fear that a communist revolution was inevitable. Nazi Germany's massacres and killings included the persecution of communists[36][37] and among the first to be sent to concentration camps.[38]

In Europe, numerous right and far-right activists including conservative intellectuals, capitalists and industrialists were vocal opponents of communism. During the late 1930s and the 1940s, several other anti-communist regimes and groups supported fascism. These included the Falange Española Tradicionalista y de las JONS in Spain; the Vichy regime and the Legion of French Volunteers against Bolshevism (Wehrmacht Infantry Regiment 638) in France; and in South America movements such as the Argentine Anticommunist Alliance and Brazilian Integralism.

Nazism

[edit]Historians Ian Kershaw and Joachim Fest argue that in the early 1920s the Nazis were only one of many nationalist and fascist political parties contending for the leadership of Germany's anti-communist movement. The Nazis only came to dominance during the Great Depression, when they organized street battles against German Communist formations. When Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933, his propaganda chief Joseph Goebbels set up the "Anti-Komintern". It published massive amounts of anti-Bolshevik propaganda, with the goal of demonizing Bolshevism and the Soviet Union before a worldwide audience.[39]

In 1936, Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan signed the Anti-Comintern Pact. Italy joined as a signatory in 1937 and other countries in or affiliated with the Axis Powers such as Finland and Spain joined in 1941. In the first article of the treaty, Germany and Japan agreed to share information about Comintern activities and to plan their operations against such activities jointly. In the second article, the two parties opened the possibility of extending the pact to other countries "whose domestic peace is endangered by the disruptive activities of the Communist Internationale". Such invitations to third parties would be undertaken jointly and after the expressed consent by both parties.[40]

Communists were among the first people targeted by the Nazis, with Dachau concentration camp when it first opened being for the holding of communists, leading socialists and other "enemies of the state" in 1933.[41]

Religions

[edit]Buddhism

[edit]Thích Huyền Quang was a prominent Vietnamese Buddhist monk and anti-communist dissident. In 1977, Quang wrote a letter to Prime Minister Phạm Văn Đồng detailing accounts of oppression by the Marxist–Leninist regime.[42] For this, he and five other senior monks were arrested and detained.[42] In 1982, Quang was arrested and subsequently placed under permanent house arrest for opposition to government policy after publicly denouncing the establishment of the state-controlled Vietnam Buddhist Sangha.[43] Thích Quảng Độ was a Vietnamese Buddhist monk and an anti-communist dissident. In January 2008, the Europe-based magazine A Different View chose Thích Quảng Độ as one of the 15 Champions of World Democracy.

Christianity

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Integralism |

|---|

|

The Catholic Church has a long history of anti-communism. The most recent Catechism of the Catholic Church states: "The Catholic Church has rejected the totalitarian and atheistic ideologies that have been associated with 'communism' in modern times. ... Regulating the economy solely by centralized planning perverts the basis of social bonds ... [Still,] reasonable regulation of the marketplace and economic initiatives, in keeping with a just hierarchy of values and a view to the common good, is to be commended".[44]

Pope John Paul II, was a harsh critic of communism[45] as was Pope Pius IX, who issued a Papal encyclical, entitled Quanta cura, in which he called "communism and Socialism" the most fatal error.[46] Popes' anti-communist stances were carried on in Italy by the Christian Democracy (DC), the centrist party founded by Alcide De Gasperi in 1943, which dominated Italian politics for almost fifty years, until its dissolution in 1993,[47] preventing the Italian Communist Party (PCI) from reaching power.[48][49]

From 1945 onward, the Australian Labor Party (ALP) leadership accepted the assistance of an anti-communist Roman Catholic movement, led by B. A. Santamaria to oppose alleged communist subversion of Australian trade unions, of which Catholics were an important traditional support base. Bert Cremean, Deputy Leader of State Parliamentary Labor Party and Santamaria, met with ALP's political and industrial leaders to discuss the movements assisting their opposition to what they alleged was Communist subversion of Australian trade unionism.[50] To oppose Communist infiltration of unions, Industrial Groups were formed. The groups were active from 1945 to 1954, with the knowledge and support of the ALP leadership,[51] until after Labor's loss of the 1954 election, when federal leader H. V. Evatt in the context of his response to the Petrov affair blamed "subversive" activities of the "Groupers" for the defeat. After bitter public dispute, many Groupers (including most members of the New South Wales and Victorian state executives and most Victorian Labor branches) were expelled from the ALP and formed the historical Democratic Labor Party (DLP). In an attempt to force the ALP reform and remove alleged Communist influence, with a view to then rejoining the "purged" ALP, the DLP preferenced the Liberal Party of Australia (LPA), enabling them to remain in power for over two decades. The strategy was unsuccessful and after the Whitlam government during the 1970s the majority of the DLP decided to wind up the party in 1978, although the small federal and state-based Democratic Labour Party continued based in Victoria, with state parties reformed in New South Wales and Queensland in 2008.

After the Soviet occupation of Hungary during the final stages of the Second World War, many clerics were arrested. The case of the Archbishop József Mindszenty of Esztergom, head of the Catholic Church in Hungary, was the most known. He was accused of treason to the Communist ideas and was sent to trials and tortured during several years between 1949 and 1956. During the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 against Marxism–Leninism and Soviet control, Mindszenty was set free and after the failure of the movement he was forced to move to the United States' embassy in Budapest, where he lived until 1971 when the Vatican and the Marxist–Leninist government of Hungary arranged his way out to Austria. In the following years, Mindszenty travelled all over the world visiting the Hungarian colonies in Canada, United States, Germany, Austria, South Africa and Venezuela. He led a high critical campaign against the Leninist regime denouncing the atrocities committed by them against him and the Hungarian people. The Leninist government accused him and demanded that the Vatican remove him the title of Archbishop of Esztergom and forbid him to make public speeches against communism. The Vatican eventually annulled the excommunication imposed on his political opponents and stripped him of his titles. Pope Paul VI, who declared the Archdiocese of Esztergom officially vacated, refused to fill the seat while Mindszenty was still alive.[52]

According to the Christian Science Monitor, Gao Zhisheng, a Christian lawyer in China, is "one of the most persistent and courageous thorns" against China under communist rule.[53] Gao gained acclaim for challenging the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) by defending coal miners, migrant workers, political activists, and people persecuted for their religious beliefs, including Christians and Falun Gong adherents.[54][55][56] According to ChinaAid, a U.S.-based Christian rights group, in 2006, Gao was sentenced to a suspended three-year sentence for "incitement to subversion"[53] against the communist state, and ultimately was imprisoned in Xinjiang in December 2011.[55][57] Released from prison in August 2014, he was placed under house arrest. In a memoir published in 2016, Gao recounted the torture sessions and three years of solitary confinement, during which he said he was sustained by his Christian faith and his hopes for China.[58][53] Gao predicted that the communist rule of China would end in 2017, a revelation he reportedly received from God.[59][60] Gao was "disappeared" in August 2017. As of April 2024, his family has not heard from him or about his whereabouts since his disappearance.[57]

Sikhism

[edit]In the Indian state of Punjab, communism was opposed by the Damdami Taksal order of Sikhs. Communism was weakened after Sikh youth who had become communists were reinitiated into Sikhism and initiated into the Khalsa by the influence of Damdami Taksal Jathedar Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale. Many communist party members and supporters were assassinated by Taksalis and other Sikh militants.[61]

Falun Gong

[edit]

Falun Gong practitioners are against the Chinese Communist Party's persecution of Falun Gong. In April 1999, over ten thousand Falun Gong practitioners gathered at the Communist Party headquarters (Zhongnanhai) in a silent protest following an incident in Tianjin.[62][63][64] Two months later, the Communist Party banned the practice, initiated a security crackdown and launched a propaganda campaign against it.[65][66][67] Since 1999, Falun Gong practitioners in China have reportedly been subjected to torture,[65] arbitrary imprisonment,[68] beatings, forced labor, organ harvesting[69] and psychiatric abuses.[70][71] Falun Gong responded with their own media campaign and have emerged as a notable voice of dissent against the Communist Party by founding organizations such as the far-right Epoch Times, New Tang Dynasty Television and others that criticize the Communist Party.[72]

Falun Gong activists repeatedly alleged that they were tortured while they were in custody. The Chinese government rejects the allegations, stating that deaths which occurred in custody occurred due to factors such as natural causes and the refusal to accept medical treatment.[73] According to David Ownby, "[t]he Chinese government has suppressed movements like the Falun Gong hundreds of times over the course of Chinese history", adding that the Chinese Communist government did "the same thing the imperial state had always done, which was to arrest and generally, not always, execute the leaders and pretend to reeducate the others and send them back home and hope that they would be good people from there on".[73]

Most of the information which the Western media obtains about Falun Gong is distributed by the Rachlin media group which is described as a public relations firm for Falun Gong.[73] According to reports which were released by the Vienna Radio Network on July 12, Gunther von Hagens, a famous German anatomist, recently held an exhibition of human bodies which provoked Falun Gong's allegations of live organ harvesting. Hagens held a news conference at which he confirmed that none of the human bodies exhibited had come from China. The statement made by Hagens refuted the Falun Gong's rumors.[74][75]

According to Chinese government officials, "[t]he allegations that Falun Gong members are being murdered in China for organ harvesting, as well as the Kilgour-Matas report, have long before been found false and proved to be nothing but a lie fabricated by a handful of anti-China people to tarnish China's reputation. The virulent accusations made during the hearing had already been robustly refuted seven years before, not only by Chinese authorities but also by diplomats and journalists of several other countries who conducted their own conscientious investigations in China, including officers and staff of the U.S. Embassy in Beijing and the U.S. Consulate-General in Shenyang".[76]

In 2006, allegations emerged that a large number of Falun Gong practitioners had been killed to supply China's organ transplant industry.[69][77] The Kilgour-Matas report found that "the source of 41,500 transplants for the six-year period 2000 to 2005 is unexplained" and concluded that "there has been and continues today to be large scale organ seizures from unwilling Falun Gong practitioners".[69] Ethan Gutmann estimated that 65,000 Falun Gong practitioners were killed for their organs from 2000 to 2008.[78][79][80]

In 2009, courts in Spain and Argentina indicted senior Chinese officials for genocide and crimes against humanity for their role in orchestrating the suppression of Falun Gong.[81][82][83]

Unification Church

[edit]In the 1940s, Unification Church founder Sun Myung Moon cooperated with Communist Party of Korea members in support of the Korean independence movement against Imperial Japan. After the Korean War (1950–1953), he became an outspoken anti-communist.[84] Moon viewed the Cold War between liberal democracy and communism as the final conflict between God and Satan, with divided Korea as its primary front line.[85]

Soon after its founding, the Unification Church began supporting anti-communist organizations, including the World League for Freedom and Democracy founded in 1966 in Taipei, Republic of China (Taiwan), by Chiang Kai-shek,[86] and the Korean Culture and Freedom Foundation, an international public diplomacy organization which also sponsored Radio Free Asia.[87] The Unification movement was criticized for its anti-communist activism by the mainstream media and the alternative press, and many members of them said that it could lead to World War Three and a nuclear holocaust. The movement's anti-communist activities received financial support from Japanese millionaire and activist Ryōichi Sasakawa.[88][89][90]

In 1972, Moon predicted the decline of communism, based on the teachings of his book, the Divine Principle: "After 7,000 biblical years—6,000 years of restoration history plus the millennium, the time of completion—communism will fall in its 70th year. Here is the meaning of the year 1978. Communism, begun in 1917, could maintain itself approximately 60 years and reach its peak. So 1978 is the border line and afterward communism will decline; in the 70th year it will be altogether ruined. This is true. Therefore, now is the time for people who are studying communism to abandon it."[91] In 1973, he called for an "automatic theocracy" to replace communism and solve "every political and economic situation in every field".[92] In 1975, Moon spoke at a government sponsored rally against potential North Korean military aggression on Yeouido Island in Seoul to an audience of around 1 million.[93]

In 1976, Moon established News World Communications, an international news media conglomerate which publishes The Washington Times newspaper in Washington, D.C., and newspapers in South Korea, Japan, and South America, partly to promote political conservatism. According to The Washington Post, "the Times was established by Moon to combat communism and be a conservative alternative to what he perceived as the liberal bias of The Washington Post."[94] Bo Hi Pak, called Moon's "right-hand man", was the founding president and the founding chairman of the board.[95] Moon asked Richard L. Rubenstein, a rabbi and college professor, to join its board of directors.[96] The Washington Times has often been noted for its generally pro-Israel editorial policies.[97] In 2002, during the 20th anniversary party for the Times, Moon said: "The Washington Times will become the instrument in spreading the truth about God to the world."[94]

In 1980, members founded CAUSA International, an anti-communist educational organization based in New York City.[98] In the 1980s, it was active in 21 countries. In the United States, it sponsored educational conferences for evangelical and fundamentalist Christian leaders[99] as well as seminars and conferences for Senate staffers, Hispanic Americans and conservative activists.[100] In 1986, CAUSA International sponsored the documentary film Nicaragua Was Our Home, about the Miskito Indians of Nicaragua and their persecution at the hands of the Nicaraguan government. It was filmed and produced by USA-UWC member Lee Shapiro, who later died while filming with anti-Soviet forces during the Soviet–Afghan War.[101][102][103][104] At this time CAUSA international also directly assisted the United States Central Intelligence Agency in supplying the Contras, in addition to paying for flights by rebel leaders. CAUSA's aid to the Contras escalated after Congress cut off CIA funding for them. According to contemporary CIA reports, supplies for the anti-Sandinista forces and their families came from a variety of sources in the US ranging from Moon's Unification Church to U.S. politicians, evangelical groups and former military officers.[105][106][107][108]

In 1983, some American members joined a public protest against the Soviet Union in response to its shooting down of Korean Airlines Flight 007.[109] In 1984, the HSA–UWC founded the Washington Institute for Values in Public Policy, a Washington, D.C. think tank that underwrites conservative-oriented research and seminars at Stanford University, the University of Chicago, and other institutions.[110] In the same year, member Dan Fefferman founded the International Coalition for Religious Freedom in Virginia, which is active in protesting what it considers to be threats to religious freedom by governmental agencies.[111] In August 1985, the Professors World Peace Academy, an organization founded by Moon, sponsored a conference in Geneva to debate the theme "The situation in the world after the fall of the communist empire."[112] After the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 the Unification movement promoted extensive missionary work in Russia and other former Soviet nations.[113]

Islam

[edit]In the Muslim parts of the Soviet Union (Caucasus and Central Asia), the party-state suppressed Islamic worship, education, association, and pilgrimage institutions that were seen as obstacles to ideological and social change along communist lines. Where the Islamic state was established, left-wing politics were often associated with profanity and outlawed. In countries such as Sudan, Yemen, Syria, Iraq and Iran, communists and other leftist parties find themselves in a bitter competition for power with Islamists.[114]

Paganism

[edit]This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (July 2022) |

Literature

[edit]

George Orwell, a democratic socialist, wrote two of the most widely read and influential anti-totalitarian novels, namely Nineteen Eighty-Four and Animal Farm, both of which featured allusions to the Soviet Union under the rule of Joseph Stalin.[115]

Also on the left-wing, Arthur Koestler—a former member of the Communist Party of Germany—explored the ethics of revolution from an anti-communist perspective in a variety of works. His trilogy of early novels testified to Koestler's growing conviction that utopian ends do not justify the means often used by revolutionary governments. These novels are The Gladiators (which explores the slave uprising led by Spartacus in the Roman Empire as an allegory for the Russian Revolution), Darkness at Noon (based on the Moscow Trials, this was a very widely read novel that made Koestler one of the most prominent anti-communist intellectuals of the period), The Yogi and the Commissar and Arrival and Departure.[116]

Whittaker Chambers—an American ex-Communist who became famous for his cooperation with the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), where he implicated Alger Hiss—published an anti-communist memoir, Witness, in 1952. It became "the principal rallying cry of anti-Communist conservatives".[117]

Boris Pasternak, a Russian writer, rose to international fame after his anti-communist novel Doctor Zhivago was smuggled out of the Soviet Union (where it was banned) and published in the West in 1957. He received the Nobel Prize for Literature, much to the chagrin of the Soviet authorities.[118]

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn was a Russian novelist, dramatist and historian. Through his writings—particularly The Gulag Archipelago and One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, his two best-known works—he made the world aware of the Gulag, the Soviet Union's forced labor camp system. For these efforts, Solzhenitsyn was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1970 and was exiled from the Soviet Union in 1974.

Herta Müller is a Romanian-born German novelist, poet and essayist noted for her works depicting the harsh conditions of life in Communist Romania under the repressive Nicolae Ceauşescu regime, the history of the Germans in the Banat (and more broadly, Transylvania) and the persecution of Romanian ethnic Germans by Stalinist Soviet occupying forces in Romania and the Soviet-imposed Communist regime of Romania. Müller has been an internationally known author since the early 1990s and her works have been translated into more than 20 languages.[119][120] She has received over 20 awards, including the 1994 Kleist Prize, the 1995 Aristeion Prize, the 1998 International Dublin Literary Award, the 2009 Franz Werfel Human Rights Award and the 2009 Nobel Prize in Literature.[121]

Ayn Rand was a Russian–American 20th-century writer who was an enthusiastic supporter of laissez-faire capitalism. She wrote We the Living about the effects of communism in Russia.[122]

Richard Wurmbrand wrote about his experiences being tortured for his faith in Communist Romania. He ascribed communism to a demonic conspiracy and alluded to Karl Marx being demon-possessed.[123]

Evasion of censorship

[edit]Samizdat was a key form of dissident activity across the Soviet bloc. Individuals reproduced censored publications by hand and passed the documents from reader to reader, thus building a foundation for the successful resistance of the 1980s. This grassroots practice to evade officially imposed censorship was fraught with danger as harsh punishments were meted out to people caught possessing or copying censored materials. Vladimir Bukovsky defined it as follows: "I myself create it, edit it, censor it, publish it, distribute it, and get imprisoned for it."

During the Cold War, Western countries invested heavily in powerful transmitters which enabled broadcasters to be heard in the Eastern Bloc, despite attempts by authorities to jam such signals. In 1947, Voice of America (VOA) started broadcasting in Russian with the intent to counter Soviet propaganda directed against American leaders and policies.[124] These included Radio Free Europe (RFE), RIAS, Deutsche Welle (DW), Radio France International (RFI), the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), ABS-CBN and the Japan Broadcasting Corporation (NHK).[125] The Soviet Union responded by attempting aggressive, electronic jamming of VOA (and some other Western) broadcasts in 1949.[124] The BBC World Service similarly broadcast language-specific programming to countries behind the Iron Curtain.

In the People's Republic of China, people have to bypass the Chinese Internet censorship and other forms of censorship.

Anti-communism in different countries and regions

[edit]

Europe

[edit]Council of Europe and European Union

[edit]Resolution 1481/2006 of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE), issued on 25 January 2006 during its winter session, "strongly condemns crimes of totalitarian communist regimes".

The European Parliament has designated August 23 as the Black Ribbon Day, a Europe-wide day of remembrance for victims of the 20th-century totalitarian and authoritarian regimes.[126]

Albania

[edit]In the early years of the Cold War, Midhat Frashëri tried to patch together a coalition of anti-communist opposition forces in Britain and the United States.[127] The "Free Albania" National Committee was officially formed on 26 August 1949 in Paris, France. Frashëri was its chairman, with other members of the Directing Board: Nuçi Kotta, Albaz Kupi, Said Kryeziu and Zef Pali.[128] It was supported by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and placed as member of National Committee for a Free Europe.[129][130]

Albania has enacted the Law on Communist Genocide with the purpose[131] of expediting the prosecution of the violations of the basic human rights and freedoms by the former Hoxhaist and Maoist governments of the Socialist People's Republic of Albania. The law has also been referred to in English as the "Genocide Law"[132][133][134] and the "Law on Communist Genocide".[135][136]

Armenia

[edit]In February 1921 the left-wing nationalist Armenian Revolutionary Federation (Dashnaktsutyun) staged an uprising against the Bolshevik authorities of Armenia just three months after the disestablishment of the First Republic of Armenia and its Sovietization. The nationalists temporarily took power. Subsequently, the anti-communist rebels, led by the prominent nationalist leader Garegin Nzhdeh, retreated to the mountainous region of Zangezur (Syunik) and established the Republic of Mountainous Armenia, which lasted until mid-1921.

Belgium

[edit]Since before World War II, there were some anti-communist organizations such as the Union Civique Belge and the Société d'Etudes Politiques, Economiques et Sociales (SEPES).[137] Catholic anti-communism was especially prominent; members of clergy supported anti-communist literature ventures, including Belina-Podgaetsky's first novel, L'Ouragan rouge, in the 1930s.[138]

Czechoslovakia

[edit]

Interwar Czechoslovakia contained fascist movements that had anti-communist ideas. Czechoslovak Fascists of Moravia had powerful patrons. One patron was the Union of Industrialists (Svaz průmyslníků), which helped them financially. The Union of Industrialists acted as an in-between through which Frantisek Zavfel, a National Democratic member of Czechoslovakian legislature, supported the movement. The Moravian wing of fascism also enjoyed the support of the anti-Bolshevik Russians centered around Hetman Ostranic. The fascists of Moravia shared many of the same ideas as fascists in Bohemia such as hostility to the Soviet Union and anti-communism. The Moravians also campaigned against what they perceived to be the divisive idea of class struggle.[139]

The view of fascism as a barrier against communism was widespread in Czechoslovakia, where during the 1920s propaganda was conducted against establishing diplomatic relations with the Soviet government in Russia. In 1922, after Czechoslovakia and Russia concluded a trade agreement, the extreme right fascist-inclined elements of the National Democratic Party increased their opposition to the government. The country's foremost fascist, Radola Gajda, founded the National Fascist Camp. The National Fascist Camp condemned communism, Jews and anti-Nazi refugees from Germany. There was a strong anti-communist campaign in January 1923 following the attempted assassination of the country's Finance Minister, which they linked to the beginning of a communist-led takeover.[139]

The uprising in Plzeň was an anti-communist revolt by Czechoslovak workers in 1953. The Velvet Revolution or Gentle Revolution was a non-violent revolution in Czechoslovakia that saw the overthrow of the Soviet-backed Marxist–Leninist government.[140] It is seen as one of the most important of the Revolutions of 1989. On 17 November 1989, riot police suppressed a peaceful student demonstration in Prague. That event sparked a series of popular demonstrations from 19 November to late December. By 20 November, the number of peaceful protesters assembled in Prague had swollen from 200,000 the previous day to an estimated half-million. A two-hour general strike, involving all citizens of Czechoslovakia, was held on 27 November. In June 1990, Czechoslovakia held its first democratic elections since 1946.

Finland

[edit]

Anti-communism in the Nordic countries was at its highest extent in Finland between the world wars. In Finland, nationalistic anti-communism existed before the Cold War in the forms of the Lapua Movement and the Patriotic People's Movement, which was outlawed after the Continuation War. During the Cold War, the Constitutional Right Party was opposed to communism. Anti-communist Finnish White Guards were engaged in armed hostilities against the Russian Soviet Government in Russia's civil war across the border in the Russian province of East Karelia. These armed hostilities preceded the overthrow of Finland's revolutionary government in 1918 and after the 1920 peace agreement with Russia that established Russian-Finnish borders.[144]

Following Finland's independence in 1917–1918, the Finnish White Guard forces had negotiated and acquired help from Germany. Germany landed close 10,000 men in the city of Hanko on 3 April 1918. Finland's civil war was short and bloody. A recorded 5,717 pro-Communist forces were killed in battle. Communists and their supporters fell victim to an anti-communist campaign of White Terror in which an estimated 7,300 people were killed. Following the end of the conflict, estimates of 13,000 to 75,000 pro-communist prisoners perished in prison camps due to factors such as malnutrition.[145]

Finnish anti-communism persisted during the 1920s. White Guard militias formed during the civil war in 1918 were retained as an armed 100,000 strong 'civil guard'. The Finnish used these militias as a permanent anti-communist auxiliary to the military. In Finland, anti-communism had an official character and was prolific in institutions.[144] After the Finnish increased its support and received nearly 14 per cent of the vote in the 1929 elections, civil guards and local farmers violently suppressed up a communist party meeting in Lapua. This place gave its name to a direct-action movement, the sole purpose of which was to fight against communism.[144]

France

[edit]International anti-communism played a major role in Franco-German-Soviet relations in the 1920s. Pragmatic realists and anti-Communist ideologues confronted each other over trade, security, electoral politics, and the danger of socialist revolution.[146]

At the end of 1932, François de Boisjolin organized the Ligue Internationale Anti-Communiste.[147][148] The organization members came mainly from the wine region of South West France.[147] In 1939, the Law on the Freedom of the Press of 29 July 1881 was amended and François de Boisjolin and others were arrested.[149]

French communists played a major role in the wartime Resistance but were distrusted by the key leader Charles de Gaulle. By 1947, Raymond Aron (1905–83) was the leading intellectual challenging the far-left that permeated much of the French intellectual community. He became a combative Cold Warrior quick to challenge anyone, including Jean-Paul Sartre, who embraced communism and defended Stalin. Aron praised American capitalism, supported NATO, and denounced Marxist Leninism as a totalitarian movement opposed to the values of Western liberal democracy.[150]

Germany

[edit]

In Nazi Germany, the Nazi Party (NSDAP) banned Communist parties and targeted communists. After the Reichstag Fire, violent suppression of Communists by the Sturmabteilung was undertaken nationwide and 4,000 members of the Communist Party of Germany were arrested.[151] The Nazi Party also established concentration camps for their political opponents, such as communists.[152] Nazi propaganda dismissed the communists as "Red subhumans".[153]

Nazi German leader Adolf Hitler focused on the threat of communism. He described communists as "a mob storming about in some of our streets in Germany, it a conception of the world which is in the act of subjecting to itself the entire Asiatic continent". Hitler believed that about communism, "unless it were halted it would 'gradually shatter the whole world ... and transform it as completely as did Christianity".[154] Anti-communism was a significant part of Hitler's propaganda throughout his career. Hitler's foreign relations focused around the Anti-Comintern Pact and always looked towards Russia as the point of Germany's expansion. Surpassed only by antisemitism, Anti-communism was the most continuous and persistent theme of Hitler's political life and that of the Nazi Party.[154]

According to Hitler "[t]he Jewish doctrine of Marxism repudiates the aristocratic principle of nature and substitutes for it and the eternal privilege of force and energy, numerical mass and its dead weight. Thus it denies the individual worth of the human personality, impugns the teaching that nationhood and race have a primary significance, and by doing this takes away the very foundations of human existence and human civilization."[154] Shortly after the Nazis in Germany seized power, they repressed communists. Beginning in 1933, the Nazis perpetrated repressions against communists, including detainment in concentration camps and torture. The first prisoners in the first Nazi concentration camp of Dachau were communists. Whereas communism prioritised social class, Nazism emphasized the nation and race above all else. Nazi propaganda recast communism as "Judeo-Bolshevism", with Nazi leaders characterizing communism as a Jewish plot seeking to harm Germany. The Nazis view of "Judeo-Bolshevism" as a threat was influenced by Germany's proximity to the Soviet Union. For Nazis, Jews and communists became interchangeable. Hitler's speech to a Nuremberg Rally in September 1937 had forceful attacks on communism. He identified communism with a Jewish world conspiracy from Moscow as "a fact proved by irrefutable evidence". He believed that Jews had established a cruel rule over Russians and other nationalities and sought to expand their rule to the rest of Europe and the world.[154]

During the invasion and occupation of the Soviet Union, the Nazis and their military leaders targeted Soviet commissars for persecution. Nazis leaders saw commissars as embodiment of "Jewish Bolshevism" that would force their military to fight to the end and commit cruelties against Germans. On 6 June 1941, German Army High Command ordered the execution of all "political commissars" who acted against German troops. The order had the widespread support among the strongly anti-communist German officers and was applied widely. The order was applied against combatants and prisoners as well as on battlefields and occupied territories.[38]

Following their placement in concentration camps, most Soviet "commissars" were executed within days. The systematic mass extermination of Soviet "commissars" had exceeded all previous campaigns of murder by the Nazis. For the first time and towards Soviet "commissars", Nazi concentration camps executed people on a large scale. During the two-month period spanning September to October 1941, German SS men put to death around 9,000 Soviet POWs in Sachsenhausen.[38]

Following the fall of Nazi Germany and emergence of two rival states, East and West Germany, the larger, democratic and significantly wealthier Western country positioned itself as an antithesis to the Soviet-dominated East. As such, the Communist Party of Germany was banned in 1956, and all major political parties, including the Christian Democratic Union of Germany and Social Democratic Party of Germany became staunchly anti-communist. The first post-WW2 German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer became an anti-communist icon who placed his opposition to the totalitarian USSR even higher than his dislike of Nazism. Adenauer prioritized the struggle against the USSR over denazification policies, and put an end to the persecution of former Nazis, granting clemency to those who were not involved in abhorrent human rights abuses and even allowed some to hold governmental positions.[155][156][157] Officials were allowed to retake jobs in civil service, with the exception of people assigned to Group I (Major Offenders) and II (Offenders) during the denazification review process.[158][159]

Hungary

[edit]

In Hungary, a Soviet Republic was formed in March 1919. It was led by communists and socialists. Acting with support of the French government, the Romanian army, along with Czech and Yugoslav forces (the future Little Entente) already occupying parts of Hungary, invaded and overthrew the communist government in the capital, Budapest, in late 1919. Local Hungarian counter-revolutionary militias, rallying around Nicholas Horthy, ex-admiral of the Austro-Hungarian fleet, attacked and killed socialists, communists and Jews in a counter-revolutionary terror, lasting into 1920.[144] The Hungarian regime subsequently established had refused to establish diplomatic relations with Soviet Russia.[160]

An estimated 5,000 people were put to death during the Hungarian White Terror of 1919–1920, and tens of thousands were imprisoned without trial. Alleged Communists were sought and jailed by the Hungarian regime and murdered by right-wing vigilante groups. The Jewish population that Hungarian regime elements accused of being connected with communism was also persecuted.[161]

Anti-communist Hungarian military officers linked Jews with communism. Following the overthrow of the Soviet government in Hungary, the lawyer Oscar Szollosy published a widely circulated newspaper article on "The Criminals of the Dictatorship of the Proletariat" in which he identified Jewish "red, blood-stained knights of hate" as the main perpetrators as the driving force behind communism.[162]

German leader Adolf Hitler wrote a letter to Hungarian leader Horthy in which Germany's attack on the Soviet Union was justified because Germany felt that it was upholding European culture and civilization. According to the German ambassador in Budapest, who delivered Hitler's letter, Horthy declared: "For 22 years he had longed for this day, and was now delighted. Centuries later humanity would be thanking the Fuhrer for his deed. One hundred and eighty million Russians would now be liberated from the yoke forced upon them by 2 million Bolshevists".[163]

At the end of November 1941 Hungarian brigades began to arrive in Ukraine to perform exclusively police functions in the occupied territories. For 1941–1943 only in Chernigov region and the surrounding villages, Hungarian troops took part in the extermination of an estimated 60,000 Soviet citizens. Hungarian troops were characterized by ill-treatment of Soviet partisans and also Soviet prisoners of war. When retreating from the Chernyansky district of the Kursk region, it was testified that "the Hungarian military units kidnapped 200 prisoners of war of the Red Army and 160 Soviet patriots from the concentration camp. On the way, the fascists blocked all of these 360 people in the school building, doused with gasoline and lit them. Those who tried to escape were shot".[164]

The Hungarian Revolution of 1956 was a revolt against the government of the Hungarian People's Republic and its Stalinist policies, lasting from 23 October until 10 November 1956. The revolt began as a student demonstration which attracted thousands as it marched through central Budapest to the Parliament building. A student delegation entering the radio building in an attempt to broadcast its demands was detained. When the delegation's release was demanded by the demonstrators outside, they were fired upon by the State Security Police (ÁVH) from within the building. As the news spread quickly, disorder and violence erupted throughout the capital. The revolt moved quickly across Hungary and the government fell. After announcing a willingness to negotiate a withdrawal of Soviet forces, the Politburo of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union changed its mind and moved to crush the revolution.

Moldova

[edit]

The Moldovan anti-communist social movement emerged on 7 April 2009 in major cities of Moldova after the Party of Communists of the Republic of Moldova (PCRM) had allegedly rigged elections.

The anti-communists organized themselves using an online social network service, Twitter, hence its moniker used by the media, the Twitter Revolution[165][166] or Grape revolution.

Poland

[edit]

Vladimir Lenin saw Poland as the bridge which the Red Army would have to cross to assist the other Communist movements and help bring about other European revolutions. Poland was the first country which successfully stopped a Communist military advance. Between February 1919 and March 1921, Poland's successful defence of its independence was known as the Polish–Soviet War. According to American sociologist Alexander Gella, "the Polish victory had gained twenty years of independence not only for Poland, but at least for an entire central part of Europe".[167]

After the German and Soviet invasion of Poland in 1939, the first Polish uprising during World War II was against the Soviets. The Czortków Uprising occurred during 21–22 January 1940 in the Soviet-occupied Podolia. Teenagers from local high schools stormed the local Red Army barracks and a prison to release Polish soldiers who had been imprisoned there.[168]

In the latter years of the war, there were increasing conflicts between Polish and Soviet partisans and some groups continued to oppose the Soviets long after the war.[169] Between 1944 and 1946, soldiers of the anti-communist armed groups, known as the cursed soldiers, made a series of attacks on communist prisons immediately following the end of World War II in Poland.[170] The last of the cursed soldiers, members of the militant anti-communist resistance in Poland, was Józef Franczak, who was killed with a pistol in his hand by ZOMO in 1963.[171]

Poznań 1956 protests were massive anti-communist protests in the People's Republic of Poland. Protesters were repressed by the regime.

The Polish 1970 protests (Polish: Grudzień 1970) were anti-Comintern protests which occurred in northern Poland in December 1970. The protests were sparked by a sudden increase in the prices of food and other everyday items. As a result of the riots, brutally put down by the Polish People's Army and the Citizen's Militia, at least 42 people were killed and more than 1,000 were wounded. Solidarity was an anti-communist trade union in a Warsaw Pact country. In the 1980s, it constituted a broad anti-communist movement. The government attempted to destroy the union during the period of martial law in the early 1980s and several years of repression, but in the end, it had to start negotiating with the union. The Round Table Talks between the government and the Solidarity-led opposition led to semi-free elections in 1989. By the end of August, a Solidarity-led coalition government was formed and in December 1990 Wałęsa was elected President of Poland. Since then, it has become a more traditional trade union.

Romania

[edit]The Romanian anti-communist resistance movement lasted between 1948 and the early 1960s. Armed resistance was the first and most structured form of resistance against the Communist regime. It was not until the overthrow of Nicolae Ceauşescu in late 1989 that details about what was called "anti-communist armed resistance" were made public. It was only then that the public learned about the numerous small groups of "haiducs" who had taken refuge in the Carpathian Mountains, where some resisted for ten years against the troops of the Securitate. The last "haiduc" was killed in the mountains of Banat in 1962. The Romanian resistance was one of the longest lasting armed movements in the former Soviet bloc.[172]

The Romanian Revolution of 1989 was a week-long series of increasingly violent riots and fighting in late December 1989 that overthrew the government of Ceauşescu. After a show trial, Ceauşescu and his wife Elena were executed.[173] Romania was the only Eastern Bloc country to overthrow its government violently or to execute its leaders.

Serbia

[edit]During the occupation of Yugoslavia between 1941 to 1945, two distinct resistance movements formed, the royalist and anti-communist Chetniks and the communist Yugoslav partisans. Although initially allied, animosity between the two grew due to ideological differences [174] and Chetnik actions against Axis being mistakenly credited to Tito and his Communist forces by Allied liaison officers.[175] Gradually, the Chetniks ended up primarily fighting the Partisans instead of the occupation forces, and started cooperating with the Axis in a struggle to destroy the Partisans, receiving increasing amounts of logistical assistance. General Draža Mihailović, leader of the Chetnik detachment in occupied Serbia admitted to a British colonel that the Chetniks' principal enemies were "the partisans, the Ustasha, the Muslims, the Croats and last the Germans and Italians" [in that order].[176] By the end of the war, the partisans achieved total victory and enacted widespread purges throughout Serbia from 1944 to 1945. By 1946, anti-communist Chetniks were largely defeated by communist authorities.[177]

Spain

[edit]Pre-Francoist Spain

[edit]In Spain, anti-communism has been present in both the political left and right.

In the decade preceding the Spanish Civil War, the Communist Party of Spain (PCE) was overshadowed by and competed with Spain's anarcho-syndicalist and Socialist counterparts.[178] Under the dictatorship of Miguel Primo de Rivera, "most prominent party members were jailed", and the party headquarters were moved to Paris.[179] Furthermore, the party was weakened by factionalism in the Comintern and the poor representatives it was sent from Moscow.[179] Until 1934, when the PCE joined Manuel Azaña's government, the PCE opposed the Republic.[179] Left consolidation under Prime Minister Azaña corresponded with the Comintern directive[180] to form broad coalitions opposing fascism.[179] Upon their 1934 merger with the PSOE under the Alianza Obrera,[180] the communists reversed their view on the Republic and their influence expanded.[179] Between 1934 and 1936, the PCE's membership grew from approximately one thousand to thirty thousand.[181]

During the Spanish Civil War the PCE was uncharacteristically moderate, prioritized garnering middle-class support and the war effort over revolutionary policy.[179]

Communists lost favor after the Republicans lost the war, and anti-communism spread to the remainder of the Spanish left. This shift was, in part, at reaction to the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, which was seen as a Soviet concession to Nazi fascism, and the PCE's refusal to share the aid it received from the Soviet Union with other leftists. Some leftists blamed the PCE for the Republicans' defeat.[179]

In Spain and internationally, the Catholic Church was a critical anti-communist influence.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries the Catholic Church retained a great deal of Spain's wealth but were losing social influence.[183][184] The Second Republic's new constitution "withdrew education ... from the clergy, dissolved the Jesuit order, banned monks and nuns from trading, and secularized marriage." This marked a sharp contrast from the Restoration period, during which the Church retained a religious monopoly.[154][144] The Church reacted to this change and anti-clerical destruction of Church property by funding the Spanish Confederation of Autonomous Rights (CEDA) and denouncing the 'red' Republican government.[184]

In 1937 Pope Pius XI released Divini Redemptoris, an anti-communist encyclical.[154] The document reflected the attitudes of Spanish bishops, claiming that communists were slaughtering clerics and all opposed to atheism.[182]

Anti-communism was a shared ideological feature among Spain's various right-wing groups in the lead-up to the Spanish Civil War. Within the right-wing, the Catholic Church's anti-communism pulled together the political interests of the lower, agrarian classes, the landed aristocracy, and industrialists.[185] Despite these groups' political differences, The Popular Front's electoral victory in 1936 spurred Catholic authoritarians, Carlists, monarchists, some military officers, and fascists to consolidate under the Falange Española Tradicionalista y de las JONS headed by the general and future dictator, Francisco Franco.[185]

Francoist Spain

[edit]Shortly after the end of the Spanish Civil War, Spain entered the Anti-Comintern Pact and a Treaty of Friendship with Nazi Germany.[186][187] The Franco regime continued to retaliate and discriminate against the "Jewish-Masonic-Communist" Republicans. The divide between Republicans and Francoists was maintained until the regime ended in 1975.[188]

Francoist retaliation was multifaceted. No political organization outside of the Franco regime was permitted,[189] and the Law of Repression of Freemasonry and communism was enacted in 1940.[190] Under this law, the term "communism" was applied to all revolutionary leftists, many of whom did not actually identify as Communists.[189] Political approval from the Franco regime was required "in order to obtain such vital things as a ration card or a job."[190]

Military courts were ordered to eliminate all political opposition to the Franco regime,[189] and hundreds of thousands were executed and imprisoned under political pretenses.[191] Among these were those in the "defeated republican constituencies", including "urban workers, the rural landless, regional nationalists, liberal professionals, and 'new' women." The Francoist prison system comprised two hundred camps, which separated Republican prisoners deemed recoverable, who were used for forced labor, from the rest, who were immediately killed.[188] Some in these camps were subjected to unethical human experimentation that sought to find "the bio-psychic roots of Marxism."[188] Additionally, thousands of exiled Republicans were forced "to work for the German war effort" or imprisoned in Nazi concentration camps. Franco "actively encouraged Germans to detain and deport exiled Republicans."[188]

Anti-communism was also perpetuated in the education system. "A quarter of all teachers" were purged from school and university education, and Spain's history, including that of the recent war,[190] was taught from an extremely conservative, pro-Franco perspective.[191]

Turkey

[edit]Anti-communist opinions in Anatolia started in the early 20th century, and first anti-communist incident occurred in the 1920s. On 28 January 1920, Mustafa Subhi, founder of the Communist Party of Turkey, was assassinated together with his wife and his 21 communist comrades traveling while to Batumi in the Black Sea.[192] In the following years, more pressure was put on communist activities. In 1925, the Turkish government shut down several communist newspapers, such as Aydınlık and Yeni Dünya.[193] Many members and symphatisers of the Communist Party of Turkey including Hikmet Kıvılcımlı, Nâzım Hikmet and Şefik Hüsnü were mass arrested on 25 October 1927.[194][195][196] Later, in 1937, a committee with the leadership of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk decided that works of Hikmet Kıvılcımlı are detrimental communist propaganda, and that they should be censored.[197]

During the 1960s the Turkish state used nationalist and Islamist youth groups to establish "Associations of the Struggle Against Communism."[198] These associations, in conjunction with the Turkish police, were responsible for the Kanlı Pazar, or "Bloody Sunday" incident in Istanbul on February 16, 1969.[198] Leftist student protestors clashed with police and members of the "Associations of the Struggle Against Communism", causing many injuries and two deaths.[198] Islamist writers frequently invoked the idea that religion and communism were incompatible, and this was one of the main causes of the fighting.[198] The Azeri immigrant community in Turkey was important in cultivating anti-communist thought, as they had experiences with Marxism.[193] Odlu Yurt and Azerbaycan, popular Azeri newspapers, frequently criticized the Soviet Union and outwardly professed their anti-communist perspective, drawing in a wide range of intellectuals from the surrounding area.[193] The Azeri population of Turkey opposed communism primarily in the intellectual sphere, using journals and publications to criticize the Soviet Union.[193]

World War II caused a rapid increase in anti-communism in Turkey. Then the Prime Minister of Turkey Şükrü Saracoğlu said that "as a Turk, he passionately wants Russia to be eliminated" and then the Turkish embassy to Germany Hüseyin Numan Menemencioğlu stated that "Turkey certainly will benefit from a complete as possible defeat of Bolshevik Russia" in a speech he made in Berlin.[199] On 4 December 1945, main printing press of the Tan newspaper, which had communist opinions and defended normalization of the relations between Turkey and Soviet Union, was raided and looted by Turanist and Islamist mobs, leaving several journalists wounded.[200][201]

After the 1971 Turkish military memorandum the new administration started a purge campaign against communist institutions and persons both in military and public, resulting in arrestings and in some cases, torture of many communist intellectuals, soldiers and students. Leaders of the Workers' Party of Turkey, Behice Boran and Sadun Aren were arrested and many communist intellectuals such as Hikmet Kıvılcımlı, Mihri Belli and Doğan Avcıoğlu had to flee the country for their life safety. In 1971, Deniz Gezmiş, Hüseyin İnan and Yusuf Aslan were executed.[202][203]

In March 1973 Turkish Armed Forces published a book named How Communists Deceive Our Workers and Our Youth. The book consisted of 32 pages and included many anti-communist phrases in it.[204]

Bülent Ecevit, who served as the Prime Minister of Turkey four times between 1974 and 2002, openly expressed anti-communist opinions. Most famously, in 1975, Ecevit said "Republican People's Party is the most powerful party of Turkey. It will block communism, as long as it stays strong, there will not be communism in Turkey."[205]

Ukraine

[edit]During and after Euromaidan, starting with the fall of the monument to Lenin in Kyiv on 8 December 2013, several Lenin monuments and statues were removed/destroyed by protesters. The ban on communist symbols did result in the removement of hundreds of statues, the replacement of millions of street signs and the renaming of populated places including some of Ukraine's biggest cities like Dnipro, Horishni Plavni and Kropyvnytskyi.[206]

Asia

[edit]China

[edit]Singapore

[edit]South Korea

[edit]

Choi ji-ryong is an outspoken anti-communist cartoonist in South Korea. His editorial cartoons have been critical of Korean presidents Kim Dae-jung and Roh Moo Hyun.

India

[edit]During the Cold War, while the Indian National Congress pursued a pro-Soviet policy, parties committed to Hindu nationalism continued to oppose communism.[207]

India is involved in law-and-order operations against a long-standing Naxalite–Maoist insurgency. Along with this, there are many state-sponsored anti-Maoist militias.[208] In the 2011 West Bengal Legislative Assembly elections, Mamata Banerjee led her party AITC to a landslide victory over the ruling Left Front that had become the world's longest-ruling democratically elected communist government. Since Bharatiya Janata Party's rise under Narendra Modi's premiership, the influence of communists and left-wing movements overall in India continue to decline.[209][210]

Indonesia

[edit]Because of suspicions regarding Communist involvement in the September 30 incident, an estimated 500,000–1,000,000 people were killed by the Indonesian military and allied militia in anti-communist purges which targeted members of the Communist Party of Indonesia and alleged sympathizers from October 1965 to the early months of 1966.[211][212][213] Western governments colluded in the massacres, in particular the United States, which provided the Indonesian military weapons, money, equipment and lists containing the names of thousands of suspected communists.[214][215][216][217] A tribunal in late 2016 declared the massacres a crime against humanity and also named the United States, the United Kingdom and Australia as accomplices to those crimes.[218]

Also stemming from the incident, Indonesia banned the spread of Communist/Marxist–Leninist thought since 1966. This is achieved through the passing of Article 2 of the Temporary People's Consultative Assembly Resolution no. 25, 1966 (Indonesian: TAP MPRS no. 25 tahun 1966)[219] and letters (a), (c), (d), and (e) section (b) of Article 107 of Law no. 27, 1999 (Indonesian: UU no. 27 tahun 1999).[220] Violators are subject to a 12-year, 15-year, or 20-year prison sentence for violating letter (a) (spreading the Communist thought in public), (c) (spreading the Communist thought in public and causing disorder afterwards), (e) (forming Communist organizations or aiding Marxist–Leninist organizations, be it explicit or suspected, foreign or domestic, with the intention of changing the state ideology of Pancasila with Marxism–Leninism), and (d) (spreading Communist thought with the intention of replacing the state ideology Pancasila with Marxism–Leninism), respectively.

Vietnam

[edit]Anti-communist organizations that are located outside Vietnam but also hold demonstrations in Vietnam are Provisional National Government of Vietnam, Khmers Kampuchea-Krom Federation, Viet Tan, People's Action Party of Vietnam, Government of Free Vietnam, Montagnard Foundation, Inc., Vietnamese Constitutional Monarchist League and Nationalist Party of Greater Vietnam.

Japan and Manchukuo

[edit]During the Nikolayevsk incident starting in March 1920, Russian Jewish journalist Gutman Anatoly Yakovlevich began to issue the Delo Rossii in Tokyo, an anti-Bolshevistic Russian language newspaper.[221][222][223] In June, Romanovsky Georgy Dmitrievich, who had been the chief authorized officer and military representative at the Allied command in the Far East,[224] discussed with a delegate of Semyonov's army, Syro-Boyarsky Alexander Vladimirovich and thereafter acquired the Delo Rossii gazette.[223] In July, he began to distribute the translated version of the Delo Rossii gazette to noted Japanese officials and socialites.[222][223]

In 1933 Japan participated in the ninth conference of the International Entente Against the Third International and founded the Association for the Study of International Socialistic Ideas and Movements (Japanese: 国際思想研究会).[225] In the summer of 1935, the Comintern held the Seventh World Congress of the Comintern in which they set Japan and Germany as the communizing targets[226][227] and the Chinese Communist Party declared the August 1 Declaration. After that, Japan defined their anti-communistic "Three Principles of HIROTA" for relations with China and also Japan concluded the Anti-Comintern Pact with Germany.

In November 1938 Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe declared the anti-communistic New Order in East Asia. In 1940, Japan, Manchukuo and the Reorganized National Government of the Republic of China declared the which is based on the New Order in East Asia.

During the period of American occupation between 1948 and 1951, a "Red Purge" occurred in Japan in which over 20,000 people accused of being Communists were purged from their places of employment.[228]

Philippines

[edit]Middle East

[edit]The "materialism" advocated by Marxism–Leninism had a serious conflict with the strong religious atmosphere of the traditional Muslim society,[229] especially the rise of Islamism after the 1970s, the Iranian Revolution and Soviet invade Afghanistan intensifies Muslim world's conflict with communism. Eventually, there were mass executions of members of the Tudeh Party of Iran, and after the defeat of the pro-Soviet Afghan regime the Taliban tortured the former communist leader Najibullah to death.[230]

Saudi Arabia

[edit]In 1953 Saudi oil field workers petitioned the oil company Aramco for "better working conditions, higher pay, and an end to the company's discriminatory hiring practices." In response, the Saudi Arabian government arrested the workers' leaders, at which point a pre-planned strike by the oil field workers occurred.[231] Though these leaders were later pardoned, the Saudi Arabian government, in conjunction with Aramco, implemented violent measures to discipline the workers. Over 200 workers suspected of having links to communism were arrested and expelled. In 1956, after sustained protests by the leftist group NRF (National Reform Front), the government decided to suppress the protests by promoting anti-communist propaganda, canceling the municipal elections, outlawing protests and arresting the NRF leaders. Governmental opposition to communist elements within Saudi Arabia came to a head with the ascension of King Faisal to the Saudi throne, saying he would "not be lenient with any communist principle which seeps into Saudi Arabia, or with any slogans that contradict Islamic shari'a ... Communism has not entered any land or country without inflicting destruction upon it." Faisal employed three strategies to weaken and discredit the growing communist influences in Saudi Arabia, namely, economic development, creating a Saudi identity, and repression of the NLF (National Liberation Front), the leading communist group in Saudi Arabia and successor to the NRF.

Islam was important in legitimizing his actions and garnering wider opposition to communism.For example, Mufti 'Abd al-'Aziz Bin Baz said communists were, "more disbelieving than the Jews and the Christians, for they were atheists that do not believe in God or the Last Day." Newspapers drew anti-semitic connections from Communism to Judaism, on account of Marx's Jewish heritage. Faisal also employed surveillance, including coordination with the US government, for the identification of communists or communist sympathizers.This led to mass arrests of communist sympathizers and their political repression.[231]

The Saudi Arabian government was vehemently opposed to communism for its atheistic principles, its expansionism, and its persecution of Muslims. The country consistently provided billions of dollars of foreign aid to promote anti-communism.The Saudi government also sent Moroccan troops to fight Angola's communist insurgents in Zaire.[232] In 1955, King Saud wrote to the United States:

"Our very special attitude towards communism is well known to [the] US government and to [the] world. It is our interest that communism not infiltrate into any area of the Middle East. In opposing communism, we do so on basic religious belief and Islamic principle, in which we believe with all of our heart, and not to please America or western states. My position, in particular, of Moslem Arab King, servant to Holy Shrines, looked up to by 400 million Moslems in East and West, is extremely delicate and serious before God, my nation, and history."

Lebanon

[edit]Islamic clergy were influential in the formation of Lebanese political thought, especially as it relates to the policies of Hizbullah.[233] For example, Iraqi cleric Muhammed Baqir Al-Sadr, wrote two books to counter Marxist narratives.[233] One aimed to discredit Marxist philosophy, and the other aimed to discredit Marxist economic thought, while both reached the conclusion of Islam being a more suitable ideology for the world.[233] Thus, it can be understood that the Islamic fundamentalist elements of the Hizbullah party in Lebanon clearly stem from an Islamic ideological opposition to Marxism.[233]

Libya

[edit]The 1969 coup that overthrew King Idris in Libya was received well in Italy due in part to the religion-based anti-communist ideology of Muammar Gaddafi.[234] Libya, being a former colony of Italy, maintained good relations with the Italians under the reign of King Idris, and this good relationship continued despite the regime change as the Italians viewed the revolution as nationalist, rather than communist, in nature.[234] Quranic justifications of the revolution by the new regime further assured Italians that Libya would not align with the communist world.[234]

Jordan

[edit]Jordanian King Hussein ibn Talal, maintained good relations with the U.S. on the basis of his anti-communism.[235]

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (June 2020) |

South America

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2019) |

During the 1970s, the right-wing military juntas of South America implemented Operation Condor, a campaign of political repression involving tens of thousands of political assassinations, illegal detentions and tortures of communist sympathizers. The campaign was aimed at eradicating alleged communist and socialist influences in their respective countries and control opposition against the government, which resulted in a large number of deaths.[236] Participatory governments include Argentina, Bolivia, Paraguay, Brazil, Chile and Uruguay, with limited support from the United States.[237][238]

Brazil