Joseph McCarthy

Joseph McCarthy | |

|---|---|

McCarthy in 1954 | |

| United States Senator from Wisconsin | |

| In office January 3, 1947 – May 2, 1957 | |

| Preceded by | Robert M. La Follette Jr. |

| Succeeded by | William Proxmire |

| Chair of the Senate Government Operations Committee | |

| In office January 3, 1953 – January 3, 1955 | |

| Preceded by | John L. McClellan |

| Succeeded by | John L. McClellan |

| Judge of the Wisconsin Circuit Court for the 10th Circuit | |

| In office January 1, 1940 – January 3, 1947 | |

| Preceded by | Edgar Werner |

| Succeeded by | Michael Eberlein |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Joseph Raymond McCarthy November 14, 1908 Grand Chute, Wisconsin, U.S. |

| Died | May 2, 1957 (aged 48) Bethesda, Maryland, U.S. |

| Resting place | Saint Mary's Cemetery |

| Political party |

|

| Spouse | Jean Kerr (m. 1953) |

| Children | 1 (adopted) |

| Education | Marquette University (LLB) |

| Signature |  |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Branch/service | United States Marine Corps |

| Years of service | 1942–1945 (Marine Corps) 1946–1957 (Reserve) |

| Rank | Lieutenant Colonel |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

| Awards | Distinguished Flying Cross Air Medal (5) |

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in the United States |

|---|

|

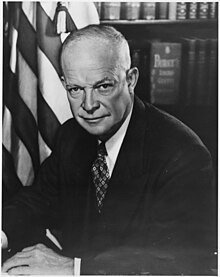

Joseph Raymond McCarthy (November 14, 1908 – May 2, 1957) was an American politician who served as a Republican U.S. Senator from the state of Wisconsin from 1947 until his death at age 48 in 1957. Beginning in 1950, McCarthy became the most visible public face of a period in the United States in which Cold War tensions fueled fears of widespread communist subversion.[1] He alleged that numerous communists and Soviet spies and sympathizers had infiltrated the United States federal government, universities, film industry,[2][3] and elsewhere. Ultimately, he was censured by the Senate in 1954 for refusing to cooperate with, and abusing members of, the committee established to investigate whether or not he should be censured. The term "McCarthyism", coined in 1950 in reference to McCarthy's practices, was soon applied to similar anti-communist activities. Today, the term is used more broadly to mean demagogic, reckless, and unsubstantiated accusations, as well as public attacks on the character or patriotism of political opponents.[4][5]

Born in Grand Chute, Wisconsin, McCarthy commissioned into the Marine Corps in 1942, where he served as an intelligence briefing officer for a dive bomber squadron. Following the end of World War II, he attained the rank of major. He volunteered to fly twelve combat missions as a gunner-observer. These missions were generally safe, and after one where he was allowed to shoot as much ammunition as he wanted to, mainly at coconut trees, he acquired the nickname "Tail-Gunner Joe". Some of his claims of heroism were later shown to be exaggerated or falsified, leading many of his critics to use "Tail-Gunner Joe" as a term of mockery.[6][7][8]

A Democrat until 1944, McCarthy successfully ran for the U.S. Senate in 1946 as a Republican, narrowly defeating incumbent Robert M. La Follette Jr. in the Wisconsin Republican primary, then Democratic challenger Howard McMurray by a 61% - 37% margin. After three largely undistinguished years in the Senate, McCarthy rose suddenly to national fame in February 1950, when he asserted in a speech that he had a list of "members of the Communist Party and members of a spy ring" who were employed in the State Department.[9] In succeeding years after his 1950 speech, McCarthy made additional accusations of Communist infiltration into the State Department, the administration of President Harry S. Truman, the Voice of America, and the U.S. Army. He also used various charges of communism, communist sympathies, disloyalty, or sex crimes to attack a number of politicians and other individuals inside and outside of government.[10] This included a concurrent "Lavender Scare" against suspected homosexuals; as homosexuality was prohibited by law at the time, it was also perceived to increase a person's risk for blackmail.[11]

With the highly publicized Army–McCarthy hearings of 1954, and following the suicide of Wyoming Senator Lester C. Hunt that same year,[12] McCarthy's support and popularity faded. On December 2, 1954, the Senate voted to censure McCarthy by a vote of 67–22, making him one of the few senators ever to be disciplined in this fashion. He continued to rally against communism and socialism until his death at the age of 48 at Bethesda Naval Hospital in Bethesda, Maryland, on May 2, 1957. His death certificate listed the cause of death as "Hepatitis, acute, cause unknown".[13] Doctors had not previously reported him to be in critical condition.[14] Some biographers say this was caused or exacerbated by alcoholism.[15]

Early life and education

[edit]McCarthy was born in 1908 on a farm in Grand Chute, Wisconsin, the fifth of nine children.[16][17] His mother, Bridget McCarthy (nee Tierney), was from County Tipperary, Ireland. His father, Timothy McCarthy, was born in the United States, the son of an Irish father and a German mother. McCarthy dropped out of junior high school at age 14 to help his parents manage their farm. He entered Little Wolf High School, in Manawa, Wisconsin, when he was 20 and graduated in one year.[18]

He attended Marquette University from 1930 to 1935. McCarthy worked his way through college by coaching, boxing etc.[clarification needed] He first studied electrical engineering for two years, then law, and received a Bachelor of Laws degree in 1935 from Marquette University Law School in Milwaukee.[19]

Career

[edit]McCarthy was admitted to the bar in 1935. While working at a law firm in Shawano, Wisconsin, he launched an unsuccessful campaign for district attorney as a Democrat in 1936. During his years as an attorney, McCarthy made money on the side by gambling.[20]

In 1939, McCarthy had better success when he ran for the nonpartisan elected post of 10th District circuit judge.[21][22] McCarthy became the youngest circuit judge in the state's history by defeating incumbent Edgar V. Werner, who had been a judge for 24 years.[23] In the campaign, McCarthy lied about Werner's age of 66, claiming that he was 73, and so allegedly too old and infirm to handle the duties of his office.[24] Writing of Werner in Reds: McCarthyism In Twentieth-Century America, Ted Morgan wrote: "Pompous and condescending, he (Werner) was disliked by lawyers. His judgements had often been reversed by the Wisconsin Supreme Court, and he was so inefficient that he had piled up a huge backlog of cases."[25]

McCarthy's judicial career attracted some controversy because of the speed with which he dispatched many of his cases as he worked to clear the heavily backlogged docket he had inherited from Werner.[26] Wisconsin had strict divorce laws, but when McCarthy heard divorce cases, he expedited them whenever possible, and he made the needs of children involved in contested divorces a priority.[27] When it came to other cases argued before him, McCarthy compensated for his lack of experience as a jurist by demanding and relying heavily upon precise briefs from the contesting attorneys. The Wisconsin Supreme Court reversed a low percentage of the cases he heard,[28] but he was also censured in 1941 for having lost evidence in a price fixing case.[29]

Military service

[edit]

In 1942, shortly after the U.S. entered World War II, McCarthy joined the United States Marine Corps, despite the fact that his judicial office exempted him from military service.[30] His college education qualified him for a direct commission, and he entered the Marines as a first lieutenant.[31]

According to Morgan, writing in Reds, McCarthy's friend and campaign manager, attorney and judge Urban P. Van Susteren, had applied for active duty in the U.S. Army Air Forces in early 1942, and advised McCarthy: "Be a hero—join the Marines."[32][33] When McCarthy seemed hesitant, Van Susteren asked, "You got shit in your blood?"[34]

He served as an intelligence briefing officer for a dive bomber squadron VMSB-235 in the Solomon Islands and Bougainville for 30 months (August 1942 – February 1945), and held the rank of captain at the time he resigned his commission in April 1945.[35] He volunteered to fly twelve combat missions as a gunner-observer. These missions were generally safe, and after one where he was allowed to shoot as much ammunition as he wanted to, mainly at coconut trees, he acquired the nickname "Tail-Gunner Joe".[36] McCarthy remained in the Marine Corps Reserve after the war, attaining the rank of lieutenant colonel.[37][38]

He later falsely claimed participation in 32 aerial missions in order to qualify for a Distinguished Flying Cross and multiple awards of the Air Medal, which the Marine Corps chain of command decided to approve in 1952 because of his political influence.[39][40] McCarthy also publicized a letter of commendation which he claimed had been signed by his commanding officer and Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, then Chief of Naval Operations.[41][42] However, his commander revealed that McCarthy had written this letter himself, probably while preparing award citations and commendation letters as an additional duty, and that he had signed his commander's name, after which Nimitz signed it during the process of just signing numerous other such letters.[43][42] A "war wound"—a badly broken leg—that McCarthy made the subject of varying stories involving airplane crashes or anti-aircraft fire had in fact happened aboard ship during a raucous celebration for sailors crossing the equator for the first time.[44][45][46] Because of McCarthy's various lies about his military heroism, his "Tail-Gunner Joe" nickname was sarcastically used as a term of mockery by his critics.[6][7][8]

McCarthy campaigned for the Republican Senate nomination in Wisconsin while still on active duty in 1944 but was defeated by Alexander Wiley, the incumbent. After he left the Marines in April 1945, five months before the end of the Pacific war in September 1945, McCarthy was reelected unopposed to his circuit court position. He then began a much more systematic campaign for the 1946 Republican Senate primary nomination, with support from Thomas Coleman, the Republican Party's political boss in Wisconsin. In this race, he was challenging three-term senator Robert M. La Follette Jr., founder of the Wisconsin Progressive Party and son of the celebrated Wisconsin governor and senator Robert M. La Follette Sr.

Senate campaign

[edit]In his campaign, McCarthy attacked La Follette for not enlisting during the war, although La Follette had been 46 when Pearl Harbor was bombed. He also claimed La Follette had made huge profits from his investments while he, McCarthy, had been away fighting for his country. In fact, McCarthy had invested in the stock market himself during the war, netting a profit of $42,000 in 1943 (equal to $739,523 today). Where McCarthy got the money to invest in the first place remains a mystery. La Follette's investments consisted of partial interest in a radio station, which earned him a profit of $47,000 over two years.[47]

According to Jack Anderson and Ronald W. May,[48] McCarthy's campaign funds, much of them from out of state, were ten times more than La Follette's and McCarthy's vote benefited from a Communist Party vendetta against La Follette. The suggestion that La Follette had been guilty of war profiteering was deeply damaging, and McCarthy won the primary nomination 207,935 votes to 202,557. It was during this campaign that McCarthy started publicizing his war-time nickname "Tail-Gunner Joe," using the slogan, "Congress needs a tail-gunner." Journalist Arnold Beichman later stated that McCarthy "was elected to his first term in the Senate with support from the Communist-controlled United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers, CIO", which preferred McCarthy to the anti-communist Robert M. La Follette.[49]In the general election against Democratic opponent Howard J. McMurray, McCarthy won 61.2% to McMurray's 37.3%, and thus joined Alexander Wiley, whom he had challenged unsuccessfully two years earlier, in the Senate.

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Joseph McCarthy | 620,430 | 61.2 | |

| Democratic | Howard McMurray | 378,772 | 37.3 | |

| Total votes | 999,202 | 98.5 | ||

| Republican hold | ||||

Personal life

[edit]In 1950, McCarthy assaulted journalist Drew Pearson in the cloakroom at the Sulgrave Club, reportedly kneeing him in the groin. McCarthy, who admitted the assault, claimed he merely "slapped" Pearson.[50] In 1952, using rumors collected by Pearson as well as other sources, Nevada publisher Hank Greenspun wrote that McCarthy was a frequent patron at the White Horse Inn, a Milwaukee gay bar, and cited his involvement with young men. Greenspun named some of McCarthy's alleged lovers, including Charles E. Davis, an ex-Communist and "confessed homosexual" who claimed that he had been hired by McCarthy to spy on U.S. diplomats in Switzerland.[51][52]

McCarthy's FBI file also contains numerous allegations, including a 1952 letter from an Army lieutenant who said, "When I was in Washington some time ago, [McCarthy] picked me up at the bar in the Wardman [Hotel] and took me home, and while I was half-drunk he committed sodomy on me." J. Edgar Hoover conducted a perfunctory investigation of the Senator's alleged sexual assault; Hoover's take was that "homosexuals are very bitter against Senator McCarthy for his attack upon those who are supposed to be in the Government."[53][54]

Although some notable McCarthy biographers have rejected these rumors,[55] others have suggested that he may have been blackmailed. During the early 1950s, McCarthy launched a series of attacks on the CIA, claiming it had been infiltrated by communist agents. Allen Dulles, who suspected McCarthy was using information supplied by Hoover, refused to cooperate. According to the historian David Talbot, Dulles also compiled a "scandalous" intimate dossier on the Senator's personal life and used the homosexual stories to take him down.[56]

In any event, McCarthy did not sue Greenspun for libel. (He was told that if the case went ahead he would be compelled to take the witness stand and to refute the charges made in the affidavit of the young man, which was the basis for Greenspun's story.)In 1953, he married Jean Fraser Kerr, a researcher in his office. In January 1957, McCarthy and his wife adopted an infant with the help of Roy Cohn's close friend Cardinal Francis Spellman. They named the baby girl Tierney Elizabeth McCarthy.[57]

United States Senate

[edit]Senator McCarthy's first three years in the Senate were unremarkable.[58] McCarthy was a popular speaker, invited by many different organizations, covering a wide range of topics. His aides and many in the Washington social circle described him as charming and friendly, and he was a popular guest at cocktail parties. He was far less well liked among fellow senators, however, who found him quick-tempered and prone to impatience and even rage. Outside of a small circle of colleagues, he was soon an isolated figure in the Senate,[59] who was often widely criticized.[60]

McCarthy was active in labor-management issues, with a reputation as a moderate Republican. He fought against continuation of wartime price controls, especially on sugar. His advocacy in this area was associated by critics with a $20,000 personal loan McCarthy received from a Pepsi bottling executive, earning the Senator the derisive nickname "The Pepsi-Cola Kid".[61]McCarthy supported the Taft–Hartley Act over Truman's veto, angering labor unions in Wisconsin but solidifying his business base.[62]

Malmedy massacre trial

[edit]In an incident for which he would be widely criticized, McCarthy lobbied for the commutation of death sentences given to a group of Waffen-SS soldiers convicted of war crimes for carrying out the 1944 Malmedy massacre of American prisoners of war. McCarthy was critical of the convictions because the German soldiers' confessions were allegedly obtained through torture during the interrogations. He argued that the U.S. Army was engaged in a coverup of judicial misconduct, but never presented any evidence to support the accusation.[63]Shortly after this, a 1950 poll of the Senate press corps voted McCarthy "the worst U.S. senator" currently in office.[64]McCarthy biographer Larry Tye has written that antisemitism may have factored into McCarthy's outspoken views on Malmedy. Although he had substantial Jewish support, notably Lewis Rosenstiel of Schenley Industries, Rabbi Benjamin Schultz of the American Jewish League Against Communism, and the columnist George Sokolsky, who convinced him to hire Roy Cohn and G. David Schine,[65][failed verification] McCarthy frequently used anti-Jewish slurs. In this and McCarthy's other characteristics, such as the enthusiastic support he received from antisemitic politicians like Ku Klux Klansman Wesley Swift and his tendency, according to friends, to refer to his copy of Mein Kampf, stating, "That's the way to do it," McCarthy's critics characterize him as driven by antisemitism. However, historian Larry Tye says that this is not the case. Based on accounts of his opposition to Soviet antisemitism, friendship with and employment of Jews, pro-Israel outlook, and testimony of colleagues to his lack of antisemitism, Tye suggests that those aspects his critics denote as antisemitic are rather byproducts of McCarthy's absolute lack of a filter and his inability to avoid colleagues colored by hatred. Tye says, "He certainly knew how to hate, but he wasn't that [antisemitic] kindof bigot."[66] This perspective that McCarthy was not an antisemite is supported by other historians.[67][68]

Tye cites three quotes from European historian Steven Remy, chief Malmedy prosecutor COL Burton Ellis JAG USA, and massacre victim and survivor Virgil P. Lary, Jr:

Both willfully clueless and supremely self-confident, McCarthy impeded but did not derail a truly fair and balanced investigation of the Malmedy affair, — Steven Remy[66]

It beats the hell out of me why everyone tries so hard to show that the prosecution [team] were insidious, underhanded, unethical, immoral and God knows what monsters, that unfairly convicted a group of whiskerless Sunday school boys. — Burton Ellis[66]

I have seen persons bent on murdering me, persons who murdered my companions, defended by a United States senator. … I charge that this action of Senator McCarthy’s became the basis for the Communist propaganda in western Germany, designed to discredit the American armed forces and American justice. — Virgil P. Lary, Jr.[66]

It was later found that McCarthy had received "evidence" of the false torture claims from Rudolf Aschenauer, a prominent Neo-Nazi agitator who often served as a defense attorney for Nazi war criminals, such as Einsatzgruppen commander Otto Ohlendorf.[69]

"Enemies within"

[edit]McCarthy experienced a meteoric rise in national profile beginning on February 9, 1950, when he gave a Lincoln Day speech to the Republican Women's Club of Wheeling, West Virginia. His words in the speech are a matter of some debate, as no audio recording was saved. However, it is generally agreed that he produced a piece of paper that he claimed contained a list of known Communists working for the State Department. McCarthy is usually quoted to have said: "The State Department is infested with communists. I have here in my hand a list of 205—a list of names that were made known to the Secretary of State as being members of the Communist Party and who nevertheless are still working and shaping policy in the State Department."[70][71]

There is some dispute with whether or not McCarthy actually gave the number of people on the list as being "205" or "57". In a later telegram to President Truman, and when entering the speech into the Congressional Record, he used the number 57.[72]The origin of the number 205 can be traced: in later debates on the Senate floor, McCarthy referred to a 1946 letter that then–Secretary of State James Byrnes sent to Congressman Adolph J. Sabath. In that letter, Byrnes said State Department security investigations had resulted in "recommendation against permanent employment" for 284 persons, and that 79 of these had been removed from their jobs; this left 205 still on the State Department's payroll. In fact, by the time of McCarthy's speech only about 65 of the employees mentioned in the Byrnes letter were still with the State Department, and all of these had undergone further security checks.[73]

At the time of McCarthy's speech, communism was a significant concern in the United States. This concern was exacerbated by the actions of the Soviet Union in Eastern Europe, the victory of the communists in the Chinese Civil War, the Soviets' development of a nuclear weapon the year before, and by the contemporary controversy surrounding Alger Hiss and the confession of Soviet spy Klaus Fuchs. With this background and due to the sensational nature of McCarthy's charge against the State Department, the Wheeling speech soon attracted a flood of press interest in McCarthy's claim.[74][75]

Tydings Committee

[edit]McCarthy himself was taken aback by the massive media response to the Wheeling speech, and he was accused of continually revising both his charges and figures. In Salt Lake City, Utah, a few days later, he cited a figure of 57, and in the Senate on February 20, 1950, he claimed 81.[76] During a five-hour speech,[77] McCarthy presented a case-by-case analysis of his 81 "loyalty risks" employed at the State Department. It is widely accepted that most of McCarthy's cases were selected from the so-called "Lee list", a report that had been compiled three years earlier for the House Appropriations Committee. Led by a former Federal Bureau of Investigation agent named Robert E. Lee, the House investigators had reviewed security clearance documents on State Department employees, and had determined that there were "incidents of inefficiencies"[78]in the security reviews of 108 employees. McCarthy hid the source of his list, stating that he had penetrated the "iron curtain" of State Department secrecy with the aid of "some good, loyal Americans in the State Department".[79] In reciting the information from the Lee list cases, McCarthy consistently exaggerated, representing the hearsay of witnesses as facts and converting phrases such as "inclined towards Communism" to "a Communist".[80]

In response to McCarthy's charges, the Senate voted unanimously to investigate, and the Tydings Committee hearings were called.[81] This was a subcommittee of the United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations set up in February 1950 to conduct "a full and complete study and investigation as to whether persons who are disloyal to the United States are, or have been, employed by the Department of State".[82]Many Democrats were incensed at McCarthy's attack on the State Department of a Democratic administration, and had hoped to use the hearings to discredit him. The Democratic chairman of the subcommittee, Senator Millard Tydings, was reported to have said, "Let me have him [McCarthy] for three days in public hearings, and he'll never show his face in the Senate again."[83]

During the hearings, McCarthy made charges against nine specific people: Dorothy Kenyon, Esther Brunauer, Haldore Hanson, Gustavo Durán, Owen Lattimore, Harlow Shapley, Frederick Schuman, John S. Service, and Philip Jessup. They all had previously been the subject of charges of varying worth and validity. Owen Lattimore became a particular focus of McCarthy's, who at one point described him as a "top Russian spy".

From its beginning, the Tydings Committee was marked by intense partisan infighting. Its final report, written by the Democratic majority, concluded that the individuals on McCarthy's list were neither Communists nor pro-communist, and said the State Department had an effective security program. The Tydings Report labeled McCarthy's charges a "fraud and a hoax," and described them as using incensing rhetoric—saying that the result of McCarthy's actions was to "confuse and divide the American people ... to a degree far beyond the hopes of the Communists themselves". Republicans were outraged by the Democratic response. They responded to the report's rhetoric in kind, with William E. Jenner stating that Tydings was guilty of "the most brazen whitewash of treasonable conspiracy in our history".[84]The full Senate voted three times on whether to accept the report, and each time the voting was precisely divided along party lines.[85]

Fame and notoriety

[edit]

From 1950 onward, McCarthy continued to exploit the fear of Communism and to press his accusations that the government was failing to deal with Communism within its ranks. McCarthy also began investigations into homosexuals working in the foreign policy bureaucracy, who were considered prime candidates for blackmail by the Soviets.[86] These accusations received wide publicity, increased his approval rating, and gained him a powerful national following.

In Congress, there was little doubt that homosexuals did not belong in sensitive government positions.[86] Since the late 1940s, the government had been dismissing about five homosexuals a month from civilian posts; by 1954, the number had grown twelve-fold.[87] As historian David M. Barrett would write, "Mixed in with the hysterics were some logic, though: homosexuals faced condemnation and discrimination, and most of them—wishing to conceal their orientation—were vulnerable to blackmail."[88] Director of Central Intelligence Roscoe Hillenkoetter was called to Congress to testify on homosexuals being employed at the CIA. He said, "The use of homosexuals as a control mechanism over individuals recruited for espionage is a generally accepted technique which has been used at least on a limited basis for many years." As soon as the DCI said these words, his aide signaled to take the remainder of the DCI's testimony off the record. Political historian David Barrett uncovered Hillenkoetter's notes, which reveal the remainder of the statement: "While this agency will never employ homosexuals on its rolls, it might conceivably be necessary, and in the past has actually been valuable, to use known homosexuals as agents in the field. I am certain that if Joseph Stalin or a member of the Politburo or a high satellite official were known to be a homosexual, no member of this committee or of the Congress would balk against our use of any technique to penetrate their operations ... after all, intelligence and espionage is, at best, an extremely dirty business."[89] The senators reluctantly agreed the CIA had to be flexible.[90]

McCarthy's methods also brought on the disapproval and opposition of many. Barely a month after McCarthy's Wheeling speech, the term "McCarthyism" was coined by Washington Post cartoonist Herbert Block. Block and others used the word as a synonym for demagoguery, baseless defamation, and mudslinging. Later, it would be embraced by McCarthy and some of his supporters. "McCarthyism is Americanism with its sleeves rolled," McCarthy said in a 1952 speech, and later that year, he published a book titled McCarthyism: The Fight For America.

McCarthy sought to discredit his critics and political opponents by accusing them of being Communists or communist sympathizers. In the 1950 Maryland Senate election, McCarthy campaigned for John Marshall Butler in his race against four-term incumbent Millard Tydings, with whom McCarthy had been in conflict during the Tydings Committee hearings. In speeches supporting Butler, McCarthy accused Tydings of "protecting Communists" and "shielding traitors". McCarthy's staff was heavily involved in the campaign and collaborated in the production of a campaign tabloid that contained a composite photograph doctored to make it appear that Tydings was in intimate conversation with Communist leader Earl Russell Browder.[91][92][93] A Senate subcommittee later investigated this election and referred to it as "a despicable, back-street type of campaign", as well as recommending that the use of defamatory literature in a campaign be made grounds for expulsion from the Senate.[94] The pamphlet was clearly labeled a composite. McCarthy said it was "wrong" to distribute it; though staffer Jean Kerr thought it was fine. After he lost the election by almost 40,000 votes, Tydings claimed foul play.

In addition to the Tydings–Butler race, McCarthy campaigned for several other Republicans in the 1950 elections, including Everett Dirksen against Democratic incumbent and Senate Majority Leader Scott W. Lucas. Dirksen, and indeed all the candidates McCarthy supported, won their elections, and those he opposed lost. The elections, including many that McCarthy was not involved in, were an overall Republican sweep. Although his impact on the elections was unclear, McCarthy was credited as a key Republican campaigner. He was now regarded as one of the most powerful men in the Senate and was treated with new-found deference by his colleagues.[95] In the 1952 Senate elections McCarthy was returned to his Senate seat with 54.2% of the vote, compared to Democrat Thomas Fairchild's 45.6%. As of 2020, McCarthy is the last Republican to win Wisconsin's Class 1 Senate seat.

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Joseph McCarthy | 870,444 | 54.2 | |

| Democratic | Thomas E. Fairchild | 731,402 | 45.6 | |

| Total votes | 1,601,846 | 99.8 | ||

| Republican hold | ||||

McCarthy and the Truman administration

[edit]McCarthy and President Truman clashed often during the years both held office. McCarthy characterized Truman and the Democratic Party as soft on, or even in league with, Communists, and spoke of the Democrats' "twenty years of treason". Truman, in turn, once referred to McCarthy as "the best asset the Kremlin has", calling McCarthy's actions an attempt to "sabotage the foreign policy of the United States" in a cold war and comparing it to shooting American soldiers in the back in a hot war.[96]It was the Truman Administration's State Department that McCarthy accused of harboring 205 (or 57 or 81) "known Communists". Truman's Secretary of Defense, George Marshall, was the target of some of McCarthy's most vitriolic rhetoric. Marshall had been Army Chief of Staff during World War II and was also Truman's former Secretary of State. Marshall was a highly respected general and statesman, remembered today as the architect of victory and peace, the latter based on the Marshall Plan for post-war reconstruction of Europe, for which he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1953. McCarthy made a lengthy speech on Marshall, later published in 1951 as a book titled America's Retreat From Victory: The Story of George Catlett Marshall. Marshall had been involved in American foreign policy with China, and McCarthy charged that Marshall was directly responsible for the loss of China to Communism. In the speech McCarthy also implied that Marshall was guilty of treason;[97]declared that "if Marshall were merely stupid, the laws of probability would dictate that part of his decisions would serve this country's interest";[97] and most famously, accused him of being part of "a conspiracy so immense and an infamy so black as to dwarf any previous venture in the history of man".[97]

In December 1950, McCarthy teamed with right-wing radio star Fulton Lewis Jr. to smear Truman's nominee for Assistant Secretary of Defense, Anna M. Rosenberg. Their smear campaign attracted allies in anti-Semites and extremists like Gerald L. K. Smith, who falsely claimed Rosenberg, who was Jewish, was a communist.[98] Unlike other women targets of McCarthyism, Rosenberg emerged with her career and integrity intact. When the smear campaign fizzled out, journalist Edward R. Murrow said "the character assassin has missed."[98]

During the Korean War, when Truman dismissed General Douglas MacArthur, McCarthy charged that Truman and his advisors must have planned the dismissal during late-night sessions when "they've had time to get the President cheerful" on bourbon and Bénédictine. McCarthy declared, "The son of a bitch should be impeached."[99]

Support from Roman Catholics and the Kennedy family

[edit]One of the strongest bases of anti-Communist sentiment in the United States was the Catholic community, which constituted over 20% of the national vote. McCarthy identified himself as Catholic, and although the great majority of Catholics were Democrats, as his fame as a leading anti-Communist grew, he became popular in Catholic communities across the country, with strong support from many leading Catholics, diocesan newspapers, and Catholic journals. At the same time, some Catholics opposed McCarthy, notably the anti-Communist author Father John Francis Cronin and the influential journal Commonweal.[100]

McCarthy established a bond with the powerful Kennedy family, which had high visibility among Catholics. McCarthy became a close friend of Joseph P. Kennedy Sr., himself a fervent anti-Communist, and he was also a frequent guest at the Kennedy compound in Hyannis Port, Massachusetts. He dated two of Kennedy's daughters, Patricia and Eunice.[101][102] It has been stated that McCarthy was godfather to Robert F. Kennedy's first child, Kathleen Kennedy. This claim has been acknowledged by Robert's wife and Kathleen's mother Ethel,[103] though Kathleen later claimed that she looked at her baptismal certificate and that her actual godfather was Manhattanville College of the Sacred Heart professor Daniel Walsh.[103]

Robert Kennedy was unusual among his Harvard friends for defending McCarthy when they discussed politics after graduation.[104] He was chosen by McCarthy to be a counsel for his investigatory committee, but resigned after six months due to disagreements with McCarthy and Committee Counsel Roy Cohn. Joseph Kennedy had a national network of contacts and became a vocal supporter, building McCarthy's popularity among Catholics and making sizable contributions to McCarthy's campaigns.[105] The Kennedy patriarch hoped that one of his sons would be president. Mindful of the anti-Catholic prejudice which Al Smith faced during his 1928 campaign for that office, Joseph Kennedy supported McCarthy as a national Catholic politician who might pave the way for a younger Kennedy's presidential candidacy.

Unlike many Democrats, John F. Kennedy, who served in the Senate with McCarthy from 1953 until the latter's death in 1957, never attacked McCarthy. McCarthy did not campaign for Kennedy's 1952 opponent, Republican incumbent Henry Cabot Lodge Jr., due to his friendship with the Kennedys[106] and, reportedly, a $50,000 donation from Joseph Kennedy. Lodge lost despite Eisenhower winning the state in the presidential election.[107] When a speaker at a February 1952 final club dinner stated that he was glad that McCarthy had not attended Harvard College, an angry Kennedy jumped up, denounced the speaker, and left the event.[104] When Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. asked John Kennedy why he avoided criticizing McCarthy, Kennedy responded by saying, "Hell, half my voters in Massachusetts look on McCarthy as a hero".[107]

McCarthy and Eisenhower

[edit]

During the 1952 presidential election, the Eisenhower campaign toured Wisconsin with McCarthy. In a speech delivered in Green Bay, Eisenhower declared that while he agreed with McCarthy's goals, he disagreed with his methods. In draft versions of his speech, Eisenhower had also included a strong defense of his mentor, George Marshall, which was a direct rebuke of McCarthy's frequent attacks. However, under the advice of conservative colleagues who were afraid that Eisenhower could lose Wisconsin if he alienated McCarthy supporters, he deleted this defense from later versions of his speech.[108][109] The deletion was discovered by William H. Laurence, a reporter for The New York Times, and featured on its front page the next day. Eisenhower was widely criticized for giving up his personal convictions, and the incident became the low point of his campaign.[108]

With his victory in the 1952 presidential race, Eisenhower became the first Republican president in 20 years. The Republican Party also held a majority in the House of Representatives and the Senate. After being elected president, Eisenhower made it clear to those close to him that he did not approve of McCarthy and he worked actively to diminish his power and influence. Still, he never directly confronted McCarthy or criticized him by name in any speech, thus perhaps prolonging McCarthy's power by giving the impression that even the President was afraid to criticize him directly. Oshinsky disputes this, stating that "Eisenhower was known as a harmonizer, a man who could get diverse factions to work toward a common goal. ... Leadership, he explained, meant patience and conciliation, not 'hitting people over the head.'"[110]

McCarthy won reelection in 1952 with 54% of the vote, defeating former Wisconsin State Attorney General Thomas E. Fairchild but, as stated above, badly trailing a Republican ticket which otherwise swept the state of Wisconsin; all the other Republican winners, including Eisenhower himself, received at least 60% of the Wisconsin vote.[111]Those who expected that party loyalty would cause McCarthy to tone down his accusations of Communists being harbored within the government were soon disappointed. Eisenhower had never been an admirer of McCarthy, and their relationship became more hostile once Eisenhower was in office. In a November 1953 speech that was carried on national television, McCarthy began by praising the Eisenhower Administration for removing "1,456 Truman holdovers who were ... gotten rid of because of Communist connections and activities or perversion." He then went on to complain that John Paton Davies Jr. was still "on the payroll after eleven months of the Eisenhower administration," even though Davies had actually been dismissed three weeks earlier, and repeated an unsubstantiated accusation that Davies had tried to "put Communists and espionage agents in key spots in the Central Intelligence Agency." In the same speech, he criticized Eisenhower for not doing enough to secure the release of missing American pilots shot down over China during the Korean War.[112] By the end of 1953, McCarthy had altered the "twenty years of treason" catchphrase he had coined for the preceding Democratic administrations and began referring to "twenty-one years of treason" to include Eisenhower's first year in office.[113]

As McCarthy became increasingly combative towards the Eisenhower Administration, Eisenhower faced repeated calls that he confront McCarthy directly. Eisenhower refused, saying privately "nothing would please him [McCarthy] more than to get the publicity that would be generated by a public repudiation by the President."[114] On several occasions Eisenhower is reported to have said of McCarthy that he did not want to "get down in the gutter with that guy."[115]

Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations

[edit]With the beginning of his second term as senator in January 1953, McCarthy was made chairman of the Senate Committee on Government Operations. According to some reports, Republican leaders were growing wary of McCarthy's methods and gave him this relatively mundane panel rather than the Internal Security Subcommittee—the committee normally involved with investigating Communists—thus putting McCarthy "where he can't do any harm", in the words of Senate Majority Leader Robert A. Taft.[116] However, the Committee on Government Operations included the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, and the mandate of this subcommittee was sufficiently flexible to allow McCarthy to use it for his own investigations of Communists in the government. McCarthy appointed Roy Cohn as chief counsel and 27-year-old Robert F. Kennedy as an assistant counsel to the subcommittee. Later, McCarthy also hired Gerard David Schine, heir to a hotel-chain fortune, on the recommendation of George Sokolsky.[65]

This subcommittee would be the scene of some of McCarthy's most publicized exploits. When the records of the closed executive sessions of the subcommittee under McCarthy's chairmanship were made public in 2003–04,[117] Senators Susan Collins and Carl Levin wrote the following in their preface to the documents:

Senator McCarthy's zeal to uncover subversion and espionage led to disturbing excesses. His browbeating tactics destroyed careers of people who were not involved in the infiltration of our government. His freewheeling style caused both the Senate and the Subcommittee to revise the rules governing future investigations, and prompted the courts to act to protect the Constitutional rights of witnesses at Congressional hearings. ... These hearings are a part of our national past that we can neither afford to forget nor permit to re-occur.[118]

The subcommittee first investigated allegations of Communist influence in the Voice of America, at that time administered by the State Department's United States Information Agency. Many VOA personnel were questioned in front of television cameras and a packed press gallery, with McCarthy lacing his questions with hostile innuendo and false accusations.[119] A few VOA employees alleged Communist influence on the content of broadcasts, but none of the charges were substantiated. Morale at VOA was badly damaged, and one of its engineers committed suicide during McCarthy's investigation. Ed Kretzman, a policy advisor for the service, would later comment that it was VOA's "darkest hour when Senator McCarthy and his chief hatchet man, Roy Cohn, almost succeeded in muffling it."[119]

The subcommittee then turned to the overseas library program of the International Information Agency. Cohn toured Europe examining the card catalogs of the State Department libraries looking for works by authors he deemed inappropriate. McCarthy then recited the list of supposedly pro-communist authors before his subcommittee and the press. The State Department bowed to McCarthy and ordered its overseas librarians to remove from their shelves "material by any controversial persons, Communists, fellow travelers, etc." Some libraries went as far as burning the newly-forbidden books.[120] Shortly after this, in one of his public criticisms of McCarthy, President Eisenhower urged Americans: "Don't join the book burners. ... Don't be afraid to go in your library and read every book."[121]

Soon after receiving the chair to the Subcommittee on Investigations, McCarthy appointed J. B. Matthews as staff director of the subcommittee. One of the nation's foremost anti-communists, Matthews had formerly been staff director for the House Un-American Activities Committee. The appointment became controversial when it was learned that Matthews had recently written an article titled "Reds and Our Churches",[122][123] which opened with the sentence, "The largest single group supporting the Communist apparatus in the United States is composed of Protestant Clergymen." A group of senators denounced this "shocking and unwarranted attack against the American clergy" and demanded that McCarthy dismiss Matthews. McCarthy initially refused to do this. As the controversy mounted, however, and the majority of his own subcommittee joined the call for Matthews's ouster, McCarthy finally yielded and accepted his resignation. For some McCarthy opponents, this was a signal defeat of the senator, showing he was not as invincible as he had formerly seemed.[124]

Investigating the Army

[edit]In autumn 1953, McCarthy's committee began its ill-fated inquiry into the United States Army. This began with McCarthy opening an investigation into the Army Signal Corps laboratory at Fort Monmouth. McCarthy, newly married to Jean Kerr, cut short his honeymoon to open the investigation. He garnered some headlines with stories of a dangerous spy ring among the army researchers, but after weeks of hearings, nothing came of his investigations.[125] Unable to expose any signs of subversion, McCarthy focused instead on the case of Irving Peress, a New York dentist who had been drafted into the army in 1952 and promoted to major in November 1953. Shortly thereafter it came to the attention of the military bureaucracy that Peress, who was a member of the left-wing American Labor Party, had declined to answer questions about his political affiliations on a loyalty-review form. Peress's superiors were therefore ordered to discharge him from the army within 90 days. McCarthy subpoenaed Peress to appear before his subcommittee on January 30, 1954. Peress refused to answer McCarthy's questions, citing his rights under the Fifth Amendment. McCarthy responded by sending a message to Secretary of the Army Robert T. Stevens, demanding that Peress be court-martialed. On that same day, Peress asked for his pending discharge from the army to be effected immediately, and the next day Brigadier General Ralph W. Zwicker, his commanding officer at Camp Kilmer in New Jersey, gave him an honorable separation from the army. At McCarthy's encouragement, "Who promoted Peress?" became a rallying cry among many anti-communists and McCarthy supporters. In fact, and as McCarthy knew, Peress had been promoted automatically through the provisions of the Doctor Draft Law, for which McCarthy had voted.[126]

Army–McCarthy hearings

[edit]Early in 1954, the U.S. Army accused McCarthy and his chief counsel, Roy Cohn, of improperly pressuring the army to give favorable treatment to G. David Schine, a former aide to McCarthy and a friend of Cohn's, who was then serving in the army as a private.[127] McCarthy claimed that the accusation was made in bad faith, in retaliation for his questioning of Zwicker the previous year. The Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, usually chaired by McCarthy himself, was given the task of adjudicating these conflicting charges. Republican senator Karl Mundt was appointed to chair the committee, and the Army–McCarthy hearings convened on April 22, 1954.[128]

The army consulted with an attorney familiar with McCarthy to determine the best approach to attacking him. Based on his recommendation, it decided not to pursue McCarthy on the issue of communists in government: "The attorney feels it is almost impossible to counter McCarthy effectively on the issue of kicking Communists out of Government, because he generally has some basis, no matter how slight, for his claim of Communist connection."[44]

The hearings lasted for 36 days and were broadcast on live television by ABC and DuMont, with an estimated 20 million viewers. After hearing 32 witnesses and two million words of testimony, the committee concluded that McCarthy himself had not exercised any improper influence on Schine's behalf, but that Cohn had engaged in "unduly persistent or aggressive efforts". The committee also concluded that Army Secretary Robert Stevens and Army Counsel John Adams "made efforts to terminate or influence the investigation and hearings at Fort Monmouth", and that Adams "made vigorous and diligent efforts" to block subpoenas for members of the Army Loyalty and Screening Board "by means of personal appeal to certain members of the [McCarthy] committee".[129]

Of far greater importance to McCarthy than the committee's inconclusive final report was the negative effect that the extensive exposure had on his popularity. Many in the audience saw him as bullying, reckless, and dishonest, and the daily newspaper summaries of the hearings were also frequently unfavorable.[130][131]Late in the hearings, Senator Stuart Symington made an angry and prophetic remark to McCarthy. Upon being told by McCarthy that "You're not fooling anyone", Symington replied: "Senator, the American people have had a look at you now for six weeks; you're not fooling anyone, either."[132]In Gallup polls of January 1954, 50% of those polled had a positive opinion of McCarthy. In June, that number had fallen to 34%. In the same polls, those with a negative opinion of McCarthy increased from 29% to 45%.[133]

An increasing number of Republicans and conservatives were coming to see McCarthy as a liability to the party and to anti-communism. Representative George H. Bender noted, "There is a growing impatience with the Republican Party. McCarthyism has become a synonym for witch-hunting, Star Chamber methods, and the denial of ... civil liberties."[134] Frederick Woltman, a reporter with a long-standing reputation as a staunch anti-communist, wrote a five-part series of articles criticizing McCarthy in the New York World-Telegram. He stated that McCarthy "has become a major liability to the cause of anti-communism", and accused him of "wild twisting of facts and near-facts [that] repels authorities in the field".[135][136]

The most famous incident in the hearings was an exchange between McCarthy and the army's chief legal representative, Joseph Nye Welch. On June 9, 1954,[137] the 30th day of the hearings, Welch challenged Roy Cohn to provide U.S. Attorney General Herbert Brownell Jr. with McCarthy's list of 130 Communists or subversives in defense plants "before the sun goes down". McCarthy stepped in and said that if Welch was so concerned about persons aiding the Communist Party, he should check on a man in his Boston law office named Fred Fisher, who had once belonged to the National Lawyers Guild, a progressive lawyers' association.[138]In an impassioned defense of Fisher, Welch responded, "Until this moment, Senator, I think I never really gauged your cruelty or your recklessness ..." When McCarthy resumed his attack, Welch interrupted him: "Let us not assassinate this lad further, Senator. You've done enough. Have you no sense of decency, Sir, at long last? Have you left no sense of decency?" When McCarthy once again persisted, Welch cut him off and demanded the chairman "call the next witness". At that point, the gallery erupted in applause and a recess was called.[139]

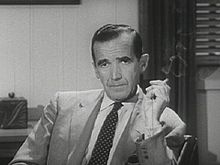

Edward R. Murrow, See It Now

[edit]

Even before McCarthy's clash with Welch in the hearings, one of the most prominent attacks on McCarthy's methods was an episode of the television documentary series See It Now, hosted by journalist Edward R. Murrow, which was broadcast on March 9, 1954. Titled "A Report on Senator Joseph R. McCarthy", the episode consisted largely of clips of McCarthy speaking. In these clips, McCarthy accuses the Democratic party of "twenty years of treason", describes the American Civil Liberties Union as "listed as 'a front for, and doing the work of', the Communist Party",[140] and berates and harangues various witnesses, including General Zwicker.[141]

In his conclusion, Murrow said of McCarthy:

No one familiar with the history of this country can deny that congressional committees are useful. It is necessary to investigate before legislating, but the line between investigating and persecuting is a very fine one, and the junior Senator from Wisconsin has stepped over it repeatedly. His primary achievement has been in confusing the public mind, as between the internal and the external threats of Communism. We must not confuse dissent with disloyalty. We must remember always that accusation is not proof and that conviction depends upon evidence and due process of law. We will not walk in fear, one of another. We will not be driven by fear into an age of unreason, if we dig deep in our history and our doctrine, and remember that we are not descended from fearful men—not from men who feared to write, to speak, to associate and to defend causes that were, for the moment, unpopular.

This is no time for men who oppose Senator McCarthy's methods to keep silent, or for those who approve. We can deny our heritage and our history, but we cannot escape responsibility for the result. There is no way for a citizen of a republic to abdicate his responsibilities. As a nation we have come into our full inheritance at a tender age. We proclaim ourselves, as indeed we are, the defenders of freedom, wherever it continues to exist in the world, but we cannot defend freedom abroad by deserting it at home.

The actions of the junior Senator from Wisconsin have caused alarm and dismay amongst our allies abroad, and given considerable comfort to our enemies. And whose fault is that? Not really his. He didn't create this situation of fear; he merely exploited it—and rather successfully. Cassius was right: "The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, but in ourselves."[142]

The following week, See It Now ran another episode critical of McCarthy, this one focusing on the case of Annie Lee Moss, an African-American army clerk who was the target of one of McCarthy's investigations. The Murrow shows, together with the televised Army–McCarthy hearings of the same year, were the major causes of a nationwide popular opinion backlash against McCarthy,[143] in part because for the first time his statements were being publicly challenged by noteworthy figures. To counter the negative publicity, McCarthy appeared on See It Now on April 6, 1954, and made a number of charges against the popular Murrow, including the accusation that he colluded with VOKS, the "Russian espionage and propaganda organization".[144] This response did not go over well with viewers, and the result was a further decline in McCarthy's popularity.[citation needed]

"Joe Must Go" recall attempt

[edit]On March 18, 1954, Sauk-Prairie Star editor Leroy Gore of Sauk City, Wisconsin urged the recall of McCarthy in a front-page editorial that ran alongside a sample petition that readers could fill out and mail to the newspaper. A Republican and former McCarthy supporter, Gore cited the senator with subverting President Eisenhower's authority, disrespecting Wisconsin's own Gen. Ralph Wise Zwicker and ignoring the plight of Wisconsin dairy farmers faced with price-slashing surpluses.[145]

Despite critics' claims that a recall attempt was foolhardy, the "Joe Must Go" movement caught fire and was backed by a diverse coalition including other Republican leaders, Democrats, businessmen, farmers and students. Wisconsin's constitution stipulates the number of signatures needed to force a recall election must exceed one-quarter the number of voters in the most recent gubernatorial election, requiring the anti-McCarthy movement to gather some 404,000 signatures in sixty days. With little support from organized labor or the state Democratic Party, the roughly organized recall effort attracted national attention, particularly during the concurrent Army-McCarthy hearings.[citation needed]

Following the deadline of June 5, the final number of signatures was never determined because the petitions were sent out of state to avoid a subpoena from Sauk County district attorney Harlan Kelley, an ardent McCarthy supporter who was investigating the leaders of the recall campaign on the grounds that they had violated Wisconsin's Corrupt Practices Act. Chicago newspapermen later tallied 335,000 names while another 50,000 were said to be hidden in Minneapolis, with other lists buried on Sauk County farms.[145]

Public opinion

[edit]| Date | Favorable | No Opinion | Unfavorable | Net Favorable |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1952 August | 15 | 63 | 22 | −7 |

| 1953 April | 19 | 59 | 22 | −3 |

| 1953 June | 35 | 35 | 30 | +5 |

| 1953 August | 34 | 24 | 42 | −8 |

| 1954 January | 50 | 21 | 29 | +21 |

| 1954 March | 46 | 18 | 36 | +10 |

| 1954 April | 38 | 16 | 46 | −8 |

| 1954 May | 35 | 16 | 49 | −14 |

| 1954 June | 34 | 21 | 45 | −11 |

| 1954 August | 36 | 13 | 51 | −15 |

| 1954 November | 35 | 19 | 46 | −11 |

Censure and the Watkins Committee

[edit]

Several members of the U.S. Senate had opposed McCarthy well before 1953. Senator Margaret Chase Smith, a Maine Republican, was the first. She delivered her "Declaration of Conscience" speech on June 1, 1950, calling for an end to the use of smear tactics, without mentioning McCarthy or anyone else by name. Only six other Republican senators—Wayne Morse, Irving Ives, Charles W. Tobey, Edward John Thye, George Aiken, and Robert C. Hendrickson—agreed to join her in condemning McCarthy's tactics. McCarthy referred to Smith and her fellow senators as "Snow White and the six dwarfs".[147]

On March 9, 1954, Vermont Republican senator Ralph E. Flanders gave a humor-laced speech on the Senate floor, questioning McCarthy's tactics in fighting communism, likening McCarthyism to "house-cleaning" with "much clatter and hullabaloo". He recommended that McCarthy turn his attention to the worldwide encroachment of Communism outside North America.[148][149]In a June 1 speech, Flanders compared McCarthy to Adolf Hitler, accusing him of spreading "division and confusion" and saying, "Were the Junior Senator from Wisconsin in the pay of the Communists he could not have done a better job for them."[150]On June 11, Flanders introduced a resolution to have McCarthy removed as chair of his committees. Although there were many in the Senate who believed that some sort of disciplinary action against McCarthy was warranted, there was no clear majority supporting this resolution. Some of the resistance was due to concern about usurping the Senate's rules regarding committee chairs and seniority. Flanders next introduced a resolution to censure McCarthy. The resolution was initially written without any reference to particular actions or misdeeds on McCarthy's part. As Flanders put it, "It was not his breaches of etiquette, or of rules or sometimes even of laws which is so disturbing," but rather his overall pattern of behavior. Ultimately a "bill of particulars" listing 46 charges was added to the censure resolution. A special committee, chaired by Senator Arthur Vivian Watkins, was appointed to study and evaluate the resolution. This committee opened hearings on August 31.[151]

After two months of hearings and deliberations, the Watkins Committee recommended that McCarthy be censured on two of the 46 counts: his contempt of the Subcommittee on Rules and Administration, which had called him to testify in 1951 and 1952, and his abuse of General Zwicker in 1954. The Zwicker count was dropped by the full Senate on the grounds that McCarthy's conduct was arguably "induced" by Zwicker's own behavior. In place of this count, a new one was drafted regarding McCarthy's statements about the Watkins Committee itself.[152]

The two counts on which the Senate ultimately voted were:

- That McCarthy had "failed to co-operate with the Sub-committee on Rules and Administration", and "repeatedly abused the members who were trying to carry out assigned duties ..."

- That McCarthy had charged "three members of the [Watkins] Select Committee with 'deliberate deception' and 'fraud' ... that the special Senate session ... was a 'lynch party'", and had characterized the committee "as the 'unwitting handmaiden', 'involuntary agent' and 'attorneys in fact' of the Communist Party", and had "acted contrary to senatorial ethics and tended to bring the Senate into dishonor and disrepute, to obstruct the constitutional processes of the Senate, and to impair its dignity".[153]

On December 2, 1954, the Senate voted to "condemn" McCarthy on both counts by a vote of 67 to 22.[154] The Democrats present unanimously favored condemnation and the Republicans were split evenly. The only senator not on record was John F. Kennedy, who was hospitalized for back surgery; Kennedy never indicated how he would have voted.[155] Immediately after the vote, Senator H. Styles Bridges, a McCarthy supporter, argued that the resolution was "not a censure resolution" because the word "condemn" rather than "censure" was used in the final draft. The word "censure" was then removed from the title of the resolution, though it is generally regarded and referred to as a censure of McCarthy, both by historians[156]and in Senate documents.[157] McCarthy himself said, "I wouldn't exactly call it a vote of confidence." He added, "I don't feel I've been lynched."[158]Indiana Senator William E. Jenner, one of McCarthy's friends and fellow Republicans likened McCarthy's conduct, however, to that of "the kid who came to the party and peed in the lemonade."[159]

Final years

[edit]

After his condemnation and censure, McCarthy continued to perform his senatorial duties for another two and a half years. His career as a major public figure, however, had been ruined. His colleagues in the Senate avoided him; his speeches on the Senate floor were delivered to a near-empty chamber or received with intentional and conspicuous displays of inattention.[160]The press that had once recorded his every public statement now ignored him, and outside speaking engagements dwindled almost to nothing. Eisenhower, finally freed of McCarthy's political intimidation, quipped to his Cabinet that McCarthyism was now "McCarthywasm".[161]

Still, McCarthy continued to rail against Communism and Socialism. He warned against attendance at summit conferences with "the Reds", saying that "you cannot offer friendship to tyrants and murderers ... without advancing the cause of tyranny and murder."[162]He declared that "co-existence with Communists is neither possible nor honorable nor desirable. Our long-term objective must be the eradication of Communism from the face of the earth." In one of his final acts in the Senate, McCarthy opposed President Eisenhower's nomination to the Supreme Court of William J. Brennan, after reading a speech Brennan had given shortly beforehand in which he characterized McCarthy's anti-Communist investigations as "witch hunts". McCarthy's opposition failed to gain any traction, however, and he was the only senator to vote against Brennan's confirmation.[163]

McCarthy's biographers agree that he was a changed man, for the worse, after the censure; declining both physically and emotionally, he became a "pale ghost of his former self", in the words of Fred J. Cook.[164]It was reported that McCarthy suffered from cirrhosis of the liver and was frequently hospitalized for alcohol abuse.Numerous eyewitnesses, including Senate aide George Reedy and journalist Tom Wicker, reported finding him drunk in the Senate.Journalist Richard Rovere (1959) wrote:

He had always been a heavy drinker, and there were times in those seasons of discontent when he drank more than ever. But he was not always drunk. He went on the wagon (for him this meant beer instead of whiskey) for days and weeks at a time. The difficulty toward the end was that he couldn't hold the stuff. He went to pieces on his second or third drink, and he did not snap back quickly.[165]

McCarthy had also become addicted to morphine. Harry J. Anslinger, head of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, became aware of McCarthy's addiction in the 1950s, and demanded he stop using the drug. McCarthy refused.[166] In Anslinger's memoir, The Murderers, McCarthy is anonymously quoted as saying:

I wouldn't try to do anything about it, Commissioner ... It will be the worse for you ... and if it winds up in a public scandal and that should hurt this country, I wouldn't care […] The choice is yours.[166]

Anslinger decided to give McCarthy access to morphine in secret from a pharmacy in Washington, DC. The morphine was paid for by the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, right up to McCarthy's death. Anslinger never publicly named McCarthy, and he threatened, with prison, a journalist who had uncovered the story.[166] However, McCarthy's identity was known to Anslinger's agents, and journalist Maxine Cheshire confirmed his identity with Will Oursler, co-author of The Murderers, in 1978.[166][167]

Death

[edit]

Маккарти умер в военно-морском госпитале Бетесда 2 мая 1957 года в возрасте 48 лет. В его свидетельстве о смерти указана причина смерти: « Острый гепатит , причина неизвестна»; Ранее врачи не сообщали о его критическом состоянии. В прессе намекали, что он умер от алкоголизма (цирроза печени), и эта оценка принимается теперь современными биографами. [15] Томас С. Ривз утверждает, что он фактически покончил жизнь самоубийством. [168] Ему устроили государственные похороны, на которых присутствовали 70 сенаторов, а торжественная папская заупокойная месса была отслужена перед более чем 100 священниками и 2000 другими людьми в соборе Святого Матфея в Вашингтоне . Тысячи людей осмотрели его тело в Вашингтоне. Он был похоронен на Святой Марии приходском кладбище в Эпплтоне, штат Висконсин , куда более 17 000 человек прошли через церковь Святой Марии, чтобы отдать ему последнее почтение. [169] Трое сенаторов — Джордж Мэлоун , Уильям Э. Дженнер и Герман Уэлкер — прилетели из Вашингтона в Эпплтон на самолете, на котором находился гроб Маккарти. Роберт Ф. Кеннеди присутствовал на похоронах в Висконсине. У Маккарти остались жена Джин и дочь Тирни.

Летом 1957 года были проведены внеочередные выборы, чтобы занять место Маккарти. На праймериз избиратели обеих партий отвернулись от наследия Маккарти. Республиканские праймериз выиграл губернатор Уолтер Дж. Колер-младший , который призвал к полному отказу от подхода Маккарти; он победил бывшего представителя Гленна Роберта Дэвиса , который обвинил президента Эйзенхауэра в мягкости по отношению к коммунизму. [170]

Колер потерпел поражение на внеочередных всеобщих выборах от демократа Уильяма Проксмайра . [171] Заняв свое место, Проксмайр не отдал обычную дань уважения своему предшественнику и вместо этого заявил, что Маккарти является «позором для Висконсина, Сената и Америки». [172] По состоянию на 2024 год Маккарти является последним республиканцем, который занимал или выиграл выборы на место в Сенате штата Висконсин 1 класса.

Наследие

[ редактировать ]Уильям Беннетт , бывший администрации Рейгана министр образования , подытожил свою точку зрения в своей книге 2007 года «Америка: последняя лучшая надежда» :

Дело антикоммунизма, объединившее миллионы американцев и получившее поддержку демократов, республиканцев и независимых, было подорвано сенатором Джо Маккарти... Маккарти обратился к реальной проблеме: нелояльным элементам внутри правительства США. Но его подход к этой реальной проблеме заключался в том, чтобы причинить невыразимое горе стране, которую он, как он утверждал, любил... Хуже всего то, что Маккарти запятнал благородное дело антикоммунизма. Он дискредитировал законные усилия по противодействию советской подрывной деятельности американских институтов. [173]

Комитет Палаты представителей по антиамериканской деятельности

[ редактировать ]Слушания Маккарти часто ошибочно путают со слушаниями Комитета Палаты представителей по расследованию антиамериканской деятельности (HUAC). HUAC наиболее известен своими расследованиями в отношении Алджера Хисса и голливудской киноиндустрии , которые привели к внесению в черный список сотен актеров, писателей и режиссеров. HUAC был комитетом Палаты представителей и, как таковой, не имел формальной связи с Маккарти, который работал в Сенате, хотя существование Комитета Палаты представителей по антиамериканской деятельности процветало отчасти благодаря деятельности Маккарти. HUAC действовал 37 лет (1938–1975). [174]

В популярной культуре

[ редактировать ]С самого начала своей известности Маккарти был любимым персонажем политических карикатуристов. Его традиционно изображали в негативном свете, обычно относящемся к маккартизму и его обвинениям. Карикатура Херблока , которая ввела термин «маккартизм», появилась менее чем через два месяца после теперь знаменитой речи сенатора в феврале 1950 года в Уилинге, Западная Вирджиния .

В 1951 году Рэй Брэдбери опубликовал «Пожарного», аллегорию подавления идей. Это послужило основой для книги «451 градус по Фаренгейту», опубликованной в 1953 году. [175] [176] Брэдбери сказал, что он написал «451 градус по Фаренгейту» из-за своих опасений в то время (в эпоху Маккарти ) по поводу угрозы сожжения книг в Соединенных Штатах. [177] Боб Хоуп был одним из первых комиков, шутивших о Маккарти. Во время своего рождественского шоу 1952 года Хоуп пошутил о том, что Санта-Клаус написал, чтобы сообщить Джо Маккарти, что он собирается носить свой красный костюм, несмотря на красную панику. Хоуп продолжал шутить над Маккарти, поскольку они были хорошо приняты большинством людей, хотя он и получал письма с ненавистью.

В 1953 году популярный ежедневный комикс «Пого» представил персонажа Простого Дж. Маларки , драчливого и коварного дикого кота с безошибочным физическим сходством с Маккарти. После того, как обеспокоенный редактор газеты Род-Айленда выразил протест синдикату, предоставившему полосу, создатель Уолт Келли начал изображать персонажа Маларки с сумкой на голове, скрывающей его черты лица. Объяснение заключалось в том, что Маларки прятался от красной курицы из Род-Айленда , что явно указывает на разногласия по поводу персонажа Маларки. [178] В 1953 году драматург Артур Миллер опубликовал «Горнило» , предположив, что процессы над салемскими ведьмами были аналогом маккартизма. [179]

По мере того как его слава росла, Маккарти все чаще становился объектом насмешек и пародий. Его выдавали за импрессионистов в ночных клубах и на радио , и его высмеивали в журнале Mad , на шоу Рэда Скелтона и в других местах. В 1954 году было выпущено несколько комедийных песен, высмеивающих сенатора, в том числе «Point of Order» Стэна Фреберга и Доуса Батлера , «Senator McCarthy Blues» Хэла Блока и «Joe McCarthy's Band» профсоюзного певца Джо Глейзера , исполненная под музыку мелодия " Группы Макнамары ". Также в 1954 году радиокомедийная группа Боб и Рэй пародировали Маккарти с персонажем «Комиссар Карстерс» в своей пародии на мыльную оперу «Мэри Бэкстейдж, благородная жена». В том же году радиосеть Канадской радиовещательной корпорации транслировала сатиру «Следователь» , главный герой которой был явной имитацией Маккарти. Запись шоу стала популярной в Соединенных Штатах, и, как сообщается, президент Эйзенхауэр проигрывал ее на заседаниях кабинета министров. [180] Рассказ «Мистер Костелло, герой» 1953 Теодора Стерджена года был описан известным журналистом и писателем Полом Уильямсом как «величайшая история всех времен о сенаторе Джозефе Маккарти, о том, кем он был и как он делал то, что делал». [181]

Реакция после порицания

[ редактировать ]«Мистер Костелло, Герой» был адаптирован в 1958 году компанией X Minus One в радиотелеспектакль и транслировался 3 июля 1956 года. [182] Хотя радиоадаптация сохраняет большую часть истории, она полностью переделывает рассказчика и фактически дает ему фразу, произнесенную в оригинале самим г-ном Костелло, тем самым значительно меняя тон истории. В интервью 1977 года Стерджен отметил, что именно его опасения по поводу продолжающихся слушаний Маккарти побудили его написать эту историю. [183]

Более серьёзное художественное изображение Маккарти сыграло центральную роль в романе Маньчжурский кандидат» « Ричарда Кондона 1959 года . [184] Характер сенатора Джона Айзелина, демагогического антикоммуниста, во многом скопирован с Маккарти, даже несмотря на то, что, по его утверждению, в федеральном правительстве работает разное количество коммунистов. [185] Он остается главным персонажем киноверсии 1962 года . [186]

В романе Совет и согласие» « Аллена Друри 1962 года рассказывается о чрезмерно рьяном демагоге, сенаторе Фреде Ван Акермане, основанном на Маккарти. Хотя вымышленный сенатор является ультралибералом, предлагающим капитуляцию перед Советским Союзом, его образ сильно напоминает популярное восприятие характера и методов Маккарти.

Маккарти сыграл Питер Бойл в получившем в 1977 году телефильме « Хвостовой стрелок Джо» , получившем премию «Эмми», инсценировке жизни Маккарти. [187] Его сыграл Джо Дон Бейкер в фильме канала HBO 1992 года «Гражданин Кон» . [188] Архивные кадры самого Маккарти были использованы в фильме 2005 года « Спокойной ночи и удачи» об Эдварде Р. Мерроу и эпизоде «Смотри сейчас», бросившем вызов Маккарти. [189] В немецко-французской документальной драме «Настоящий американец — Джо Маккарти » (2012) режиссёра Лутца Хахмейстера Маккарти сыграл британский актёр и комик Джон Сешнс . [190] В Ли Дэниэлса фильме 2020 года «Соединенные Штаты против Билли Холидей » Маккарти играет актер Рэнди Дэвисон .

Document Песня REM "Exhuming McCarthy" из их альбома 1987 года в основном посвящена Маккарти и содержит аудиоклипы с слушаний Army-McCarthy Hearings .

«Джо» Маккарти также упоминается в песне Билли Джоэла 1989 года « We Didn't Start the Fire ».

Маккартизм – одна из тем Барбары Кингсолвер романа «Лакуна» . [191]

Маккарти — второстепенный персонаж телевизионной драмы Showtime «Попутчики». [192]

пересмотр

[ редактировать ]Маккарти остается противоречивой фигурой. Артур Херман , популярный историк и старший научный сотрудник Гудзоновского института , говорит, что новые доказательства — в виде расшифрованных Веноной советских сообщений, данных о советском шпионаже, теперь открытых Западу, и недавно опубликованных стенограмм закрытых слушаний в подкомитете Маккарти — частично оправдал Маккарти, показав, что некоторые из его определений коммунистов были верны, а масштабы советской шпионской деятельности в Соединенных Штатах в 1940-х и 1950-х годах были больше, чем подозревали многие ученые. [193] В книге «Внесенный в черный список истории: нерассказанная история сенатора Джо Маккарти и его борьбы с врагами Америки » журналист М. Стэнтон Эванс аналогичным образом утверждал, что данные из документов Веноны свидетельствуют о значительном проникновении советских агентов. [194]

Историк Джон Эрл Хейнс , который тщательно изучал расшифровки Веноны, бросил вызов попыткам Германа реабилитировать Маккарти, утверждая, что попытки Маккарти «сделать антикоммунизм партийным оружием» на самом деле «угрожали [послевоенному] антикоммунистическому консенсусу», тем самым в конечном итоге больше вредит антикоммунистическим усилиям, чем помогает им. [195] Хейнс пришел к выводу, что из 159 человек, которые были идентифицированы в списках, использованных или на которые ссылался Маккарти, доказательства лишь существенно доказывают, что девять из них помогали советским шпионским усилиям - хотя на основании Веноны и других доказательств было действительно известно несколько сотен советских шпионов, большинство из них были Маккарти никогда не называл его. По мнению Хейнса, некоторые из обвиняемых в приведенных выше списках Маккарти, возможно, большинство, вероятно, представляли некоторую форму возможной угрозы безопасности, но значительное меньшинство других, вероятно, этого не делало, а некоторые, бесспорно, вообще не представляли никакой угрозы. [196] [197]

См. также

[ редактировать ]- Список смертей от алкоголя

- Список членов Конгресса США, умерших при исполнении служебных обязанностей (1950–99)

- Список сенаторов США, изгнанных или осужденных

- Маккартизм

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]Цитаты

[ редактировать ]- ^ Историю этого периода см., например:

Коут, Дэвид (1978). Великий страх: антикоммунистическая чистка при Трумэне и Эйзенхауэре . Нью-Йорк: Саймон и Шустер . ISBN 0-671-22682-7 . ; Фрид, Ричард М. (1990). Кошмар в красном: Эра Маккарти в перспективе | . Нью-Йорк: Издательство Оксфордского университета. ISBN 0-19-504361-8 .

Шрекер, Эллен (1998). Преступлений много: маккартизм в Америке . Бостон: Литтл, Браун. ISBN 0-316-77470-7 . - ^ Янгблад, Дениз Дж.; Шоу, Тони (2014). Кинематографическая холодная война: борьба американцев за сердца и умы . Соединенные Штаты Америки: Университетское издательство Канзаса. ISBN 978-0700620203 .

- ^ Фейерхерд, Питер (2 декабря 2017 г.). «Как Голливуд процветал, несмотря на красную панику» . JSTOR Daily . Архивировано из оригинала 2 августа 2020 года . Проверено 29 июля 2020 г.

- ^ Издательство ХарперКоллинз. «Запись в словаре американского наследия: Маккартизм» . www.ahdictionary.com . Архивировано из оригинала 23 декабря 2023 года . Проверено 23 декабря 2023 г.

- ^ Лук, Ребекка, мы никогда не получим нашего «У вас нет чувства порядочности, сэр?» Момент. Архивировано 1 августа 2018 г., в Wayback Machine , Slate, 26 июля 2018 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Гаррати, Джон (1989). 1001 вещь, которую каждый должен знать об американской истории. Нью-Йорк: Даблдей. п. 24

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б О'Брайен, Стивен (1991). Санта-Барбара, ABC-CLIO, с. 265

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Карикатуристы Коннектикута № 5: Философ болота Окефеноки» . Журнал комиксов. 22 июня 2016. Архивировано из оригинала 23 июня 2016 года . Проверено 23 июня 2016 г.

- ^ «Коммунисты на государственной службе, говорит Маккарти» . Веб-сайт истории Сената США. Архивировано из оригинала 8 июля 2023 года . Проверено 8 июля 2023 г.

- ^ Макдэниел, Роджер Э. (2013). Умереть за грехи Джо Маккарти: Самоубийство сенатора от Вайоминга Лестера Ханта . Коди, Вайоминг: WordsWorth Press. ISBN 978-0983027591 .

- ^ Симпсон, Алан К.; Макдэниел, Роджер (2013). «Пролог». Умереть за грехи Джо Маккарти: Самоубийство сенатора от Вайоминга Лестера Ханта . WordsWorth Press. п. х. ISBN 978-0983027591 .

- ^ Макдэниел, Роджер. Умереть за грехи Джо Маккарти

- ^ «Свидетельство о смерти Маккарти» . Архивировано из оригинала 7 декабря 2022 года . Проверено 19 августа 2017 г.

- ^ Тед Льюис (3 мая 1957 г.). «Джозеф Маккарти, скандальный сенатор, умирает в 1957 году в возрасте 48 лет» . Нью-Йорк Дейли Ньюс . Архивировано из оригинала 24 февраля 2017 года . Проверено 19 августа 2017 г. Перепечатано 1 мая 2016 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б См., например: Ошинский, Дэвид М. (2005) [1983]. Огромный заговор: мир Джо Маккарти . Нью-Йорк: Свободная пресса. стр. 503–504. ISBN 0-19-515424-Х . ; Ривз, Томас К. (1982). Жизнь и времена Джо Маккарти: Биография . Нью-Йорк: Штейн и Дэй. стр. 669–671 . ISBN 1-56833-101-0 . ; Герман, Артур (2000). Джозеф Маккарти: Переосмысление жизни и наследия самого ненавистного сенатора Америки . Нью-Йорк: Свободная пресса. стр. 302–303 . ISBN 0-684-83625-4 .

- ^ Ровер, Ричард Х. (1959). Сенатор Джо Маккарти . Нью-Йорк: Харкорт, Брейс. п. 79. ИСБН 0-520-20472-7 .

- ^ «Джозеф Маккарти: Биография» . Публичная библиотека Эпплтона. 2003. Архивировано из оригинала 1 декабря 2017 года . Проверено 30 ноября 2017 г.

- ^ «Маккарти как студент» . Архивировано из оригинала 28 февраля 2013 года . Проверено 7 сентября 2015 г.