Кларенс Томас

Кларенс Томас | |

|---|---|

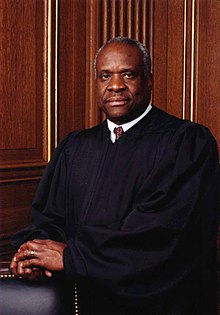

Официальный портрет, 2007 г. | |

| Помощник судьи Верховного суда США | |

| Assumed office 23 октября 1991 г. | |

| Appointed by | George H. W. Bush |

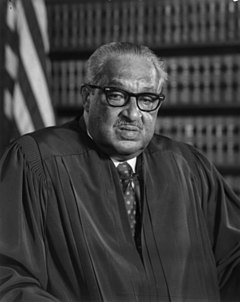

| Preceded by | Thurgood Marshall |

| Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit | |

| In office March 12, 1990 – October 23, 1991 | |

| Appointed by | George H. W. Bush |

| Preceded by | Robert Bork |

| Succeeded by | Judith W. Rogers |

| Chair of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission | |

| In office May 6, 1982 – March 8, 1990 | |

| President | Ronald Reagan George H. W. Bush |

| Preceded by | Eleanor Holmes Norton[1] |

| Succeeded by | Evan Kemp[2] |

| Assistant Secretary of Education for the Office for Civil Rights | |

| In office June 26, 1981 – May 6, 1982 | |

| President | Ronald Reagan |

| Preceded by | Cynthia Brown[3] |

| Succeeded by | Harry Singleton[4] |

| Personal details | |

| Born | June 23, 1948 Pin Point, Georgia, U.S. |

| Spouses | |

| Children | 1 |

| Education | |

| Signature | |

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in the United States |

|---|

|

Кларенс Томас (родился 23 июня 1948 года) — американский юрист и юрист, член Верховного суда США . Он был назначен президентом Джорджем Бушем- старшим на смену Тергуду Маршаллу и занимал эту должность с 1991 года. После Маршалла Томас является вторым афроамериканцем , работающим в Верховном суде, и был его членом дольше всех после выхода на пенсию Энтони Кеннеди в 2018 году. После выхода на пенсию Стивена Брейера в 2022 году он также является старейшим членом Суда.

Томас родился в Пин-Пойнте, штат Джорджия . После того, как его отец бросил семью, его воспитывал дедушка в бедной общине Галла недалеко от Саванны . Выросший как набожный католик, Томас изначально намеревался стать священником в католической церкви , но был разочарован недостаточными попытками церкви бороться с расизмом. Он отказался от своего стремления стать священнослужителем и поступил в Колледж Святого Креста и Йельскую юридическую школу , где на него повлиял ряд консервативных авторов, в частности Томас Соуэлл . После окончания учебы он был назначен помощником генерального прокурора в штате Миссури , а затем занялся там частной практикой. Он стал помощником по законодательным вопросам сенатора США Джона Дэнфорта в 1979 году и был назначен помощником министра по гражданским правам в Министерстве образования США президент Рональд Рейган назначил Томаса председателем Комиссии по равным возможностям в сфере занятости в 1981 году . В следующем году (EEOC).

President George H. W. Bush nominated Thomas to the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit in 1990. He served in that role for 19 months before filling Marshall's seat on the Supreme Court. Thomas's confirmation hearings were bitter and intensely fought, centering on an accusation that he had sexually harassed Anita Hill, a subordinate at the Department of Education and the EEOC.[5] Hill alleged that Thomas made multiple inappropriate sexual and romantic overtures to her; Thomas and his supporters alleged that Hill and her political supporters had fabricated the accusation to prevent the appointment of a black conservative. The Senate confirmed Thomas by a vote of 52–48, the narrowest margin in a century.[6]

Since the death of Antonin Scalia, Thomas has been the Court's foremost originalist, stressing the original meaning in interpreting the Constitution.[7] In contrast to Scalia—who had been the only other consistent originalist—he pursues a more classically liberal variety of originalism.[8] Thomas was known for his silence during most oral arguments,[9] though has since begun asking more questions to counsel.[10] He is notable for his majority opinions in Good News Club v. Milford Central School (determining the freedom of religious speech in relation to the First Amendment) and New York State Rifle & Pistol Association, Inc. v. Bruen (affirming the individual right to bear arms outside the home), as well as his dissent in Gonzales v. Raich (arguing that Congress may not criminalize the private cultivation of medical marijuana). He is widely considered to be the Court's most conservative member.

Early life

Thomas was born on June 23, 1948, in his parents' wooden shack in Pin Point, Georgia.[11][12] Pin Point was a small community near Savannah founded by freedmen in the 1880s.[13] He was the second of three children of M.C. Thomas, a farm worker, and Leola Williams.[11] Williams had been born out of wedlock; after her mother's death, she was sent from Liberty County, Georgia, to live with an aunt in Pin Point.[14][15][16] The family were descendants of enslaved people and spoke Gullah as a first language.[17] Thomas's earliest known ancestors were slaves named Sandy and Peggy, who were born in the late 18th century and owned by wealthy planter Josiah Wilson of Liberty County.[18] Thomas's older sister, Emma, was born in 1946, and his younger brother, Myers, in 1949.[19]

Upon becoming pregnant with Thomas's older sister, Leola was expelled from her Baptist church and dropped out of high school after the 10th grade; her father ordered her to marry M.C. in January 1947. After three years of marriage, M.C. sued for divorce, claiming that Leola neglected the children, and a judge granted the request in March 1951.[19] After the divorce, M.C. moved to Savannah and later Pennsylvania, visiting his children only once. Leola went to work as a maid in Savannah during the week and returned to Pin Point on the weekends. Custody of the children was awarded to Leola's aunt.[20][21] When her aunt's house burned down in 1955, Leola took her children to live with her in the room she rented in a tenement with an outdoor toilet in Savannah, leaving her daughter with the aunt in Pin Point. She asked her father, Myers Anderson, for help. He initially refused but agreed after his wife threatened to throw him out.[22][23]

Thomas and his brother went to live with Anderson, his maternal grandfather, in 1955 and experienced amenities such as indoor plumbing and regular meals for the first time.[24] Despite having little formal education, Anderson had built a successful business delivering coal, oil, and ice.[22] When racial unrest led to widespread protest and marches in Savannah from 1960 to 1963, Anderson used his wealth to bail out demonstrators and took his grandchildren to meetings promoted by the NAACP.[25] Thomas has described his grandfather as the person who has influenced his life the most.[26]

Anderson converted to Catholicism and sent Thomas to be educated at a series of Catholic schools. Thomas attended the predominantly black St. Pius X High School in Chatham County[27] for two years before transferring to St. John Vianney's Minor Seminary on the Isle of Hope, where he was the segregated boarding school's first black student.[28][29] Though he experienced hazing, he performed well academically.[15] He spent many hours at the Carnegie Library, the only library for Blacks in Savannah before libraries were desegregated in 1961.[30][31][a]

When Thomas was ten years old, Anderson began putting his grandsons to work during the summers, helping him build a house on a plot of farmland he owned, building fences, and doing farm work.[33] He believed in hard work and self-reliance,[34] never showed his grandsons affection,[33] beat them frequently according to Leola, and impressed the importance of a good education on them.[35] Anderson taught Thomas that "all of our rights as human beings came from God, not man", and that racial segregation was a violation of divine law.[36]

Education

During his freshman year from 1967 to 1968, Thomas attended Conception Seminary College, a Benedictine seminary in Missouri, with the intent to become a priest; no one in Thomas's family had attended college before.[37][28] After Martin Luther King Jr.'s assassination, he overheard a fellow student say, "Good. I hope the son of a bitch dies" and "[t]hat's what they should do to all the niggers".[38][39][40] The display of racism moved Thomas to leave the seminary.[41] He thought the church did not do enough to combat racism and resolved to abandon the priesthood.[42][38] He left at the end of the semester.[38]

At a nun's suggestion, Thomas enrolled at the College of the Holy Cross, an elite Catholic college in Massachusetts, as a sophomore transfer student on a full academic scholarship.[43][44] He was one of the college's first black students, being one of twenty recruited by President John E. Brooks in 1968 in a group that also included future attorney Ted Wells, running back Eddie Jenkins Jr., and novelist Edward P. Jones.[45] In the fall of that year, Thomas and other black students founded the college's Black Student Union (BSU), which became an important part of their campus identity.[46] Without financial support from his grandfather, he defrayed his expenses by working as a waiter and dishwasher in the college's dining hall.[47] Thomas later recalled, "I was 19. My only hope was Holy Cross College".[48]

Professors at Holy Cross remembered Thomas as a determined, diligent student.[49] He kept to a strict routine of studying alone and stayed back during holidays to continue working.[50] Thomas C. Lawler, an English professor at Holy Cross,[51] recalled him as having "never talked very much in class. He was the kind of person you really might not notice".[49] By contrast, he was outspoken at BSU meetings, distinguishing himself as a contrarian who often feuded with Ted Wells. Future NFL running back Ed Jenkins, a BSU member, said Thomas "could turn on a dime and reduce you to intellectual rubble".[52][53] Edward P. Jones, who lived across from Thomas as a sophomore, reflected that "there was a fierce determination I sensed from him [Thomas], that he was going to get as much as he could and get as far, ultimately, as he could".[54]

Thomas became a vocal student activist as an undergraduate. He became acquainted with Black separatism, the Black Muslim Movement, the Black power movement, and displayed a poster of Malcolm X in his dormitory room.[56] When some black students were disproportionately punished in comparison with white students for the same violation, he suggested a walkout in protest. The BSU adopted his idea, and Thomas, along with sixty other black students, departed campus.[57][58] Some of the priests negotiated with the protesting black students to reenter the school.[28] When administrators granted amnesty to all protesters, Thomas returned to the college, later also to attend anti-war marches. In April 1970, he participated in the violent 1970 Harvard Square riots.[59] He has credited his protests for his turn toward conservatism and subsequent disillusionment with leftist movements.[60][61][54]

Having struggled with English as a native speaker of Gullah, Thomas chose to major in English literature.[62][63] He became a member of Alpha Sigma Nu, the Jesuit honor society, and the Purple Key Society, of which he was the only black member.[64] The college's focus on a liberal arts education introduced him to the writings of black intellectuals such as Richard Wright, whose literary works Thomas sympathized with.[56] He also admired Malcolm X and recalled reading The Autobiography of Malcolm X to the point of wearing down the pages of his copy.[65]

Thomas graduated on June 4, 1971, with a Bachelor of Arts, cum laude, ranked ninth in his class.[66] He applied to and was accepted by Yale Law School, Harvard Law School, and the University of Pennsylvania Law School.[67][68] That same year, Thomas matriculated at Yale Law School as one of twelve black students.[69] Yale offered him the best financial aid package, and he was attracted to the civil rights activism of some of its faculty members.[70][71] Finding it difficult to keep up with the school's expectations, he struggled to connect with other students who came from upper-class backgrounds. He enrolled in the most difficult courses and became a student of property law scholar Quintin Johnstone, who became his favorite professor.[72][73] Johnstone remembered Thomas as having "performed very well".[74] Guido Calabresi, the dean of Yale Law School, described Thomas and fellow student Hillary Clinton as "both excellent students [who] had the same kind of reputation".[74]

Thomas obtained his Juris Doctor on May 20, 1974.[75] After graduation, he sought to enter private practice as a corporate lawyer in Atlanta, Georgia.[76] He saw his experience in law school as disappointing, as law firms assumed he was accepted because of affirmative action.[77] According to Thomas, the law firms also "asked pointed questions, unsubtly suggesting that they doubted I was as smart as my grades indicated".[78] In his 2007 memoir, he wrote: "I peeled a fifteen-cent sticker off a package of cigars and stuck it on the frame of my law degree to remind myself of the mistake I'd made by going to Yale. I never did change my mind about its value."[79] Hill, Jones, and Farrington, the Savannah law firm where Thomas had interned the previous summer, offered him a job upon graduation, but he declined.[80][81]

Early legal career

With no job offers from major law firms, Thomas took a position as an associate with Missouri attorney general John Danforth, who offered him the prospect of practicing what he liked.[82] Thomas moved to Saint Louis to study for the Missouri bar, and was admitted on September 13, 1974.[83] He remained financially destitute even after leaving Yale, trying unsuccessfully on one occasion to make money by selling his blood at a blood bank, and hoped that by working for Danforth he might later acquire a job in private practice.[84][85]

From 1974 to 1977, Thomas was an assistant attorney general of Missouri—the only African-American member of Danforth's staff. He worked first in the office's criminal appeals division and later in the revenue and taxation division. Thomas conducted lawsuits independently, gaining a reputation as a fair but controversial prosecutor.[86] Years later, after he joined the Supreme Court, Thomas recalled his position in Missouri as "the best job I've ever had".[87]

When Danforth was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1976, Thomas left to become an attorney in Monsanto's legal department in Saint Louis.[88] He found the job unsatisfying, so left to rejoin Danforth in Washington, D.C., as a legislative assistant.[89] From 1979 to 1981, he handled energy issues for the Senate Commerce Committee. Thomas, who had switched his party affiliation from Democratic to Republican while working for Danforth in Missouri,[90] soon drew the attention of officials in the newly elected Reagan Administration as a Black conservative.[90][91] Pendleton James, Reagan's personnel director, offered Thomas the position of assistant secretary for civil rights at the U.S. Department of Education. Initially reluctant, Thomas agreed after Danforth and others pressed him to take the post.[92]

President Ronald Reagan nominated Thomas as assistant secretary of education for the Office for Civil Rights (OCR) on May 1, 1981.[93][94] The Senate received the nomination on May 28, 1981, and Thomas was quickly confirmed before the Senate Labor and Human Resources Committee on June 19, succeeding Cynthia Brown at the age of 32.[95][96] He held the position for a brief period before James offered him a new position as chairman of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), a promotion that Thomas believed, as with his position in the OCR, was because of his race.[97] After James consulted the President, Thomas hesitantly took up the chair with Reagan's approval.[98]

Thomas chaired the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) from 1982 to 1990. As chairman, he was tasked with enforcing the Civil Rights Act of 1964 in an agency that had been mutually resented by both Democrats and Republicans. He announced a reorganization of the EEOC and upgraded its record-keeping under an uncompromising leadership that eschewed racial quotas.[97][99] Concerned by the EEOC's limited statutory authority, Thomas sought to impose criminal penalties for employers who practiced employment discrimination, moving to shift funding towards agency investigators. Though he had been critical of affirmative action, Thomas also opposed the Reagan Administration's agenda to remove affirmative action policies, believing it to be a detraction from socioeconomic issues.[100][90]

During Thomas's tenure, he was credited with improving the efficiency of the EEOC.[101] Settlement award amounts to victims of discrimination tripled, while the number of suits filed decreased. The EEOC's lack of the use of goals and timetables drew criticism from civil rights advocates, who lobbied representatives to review the EEOC's practices; Thomas testified before Congress more than 50 times. Near the end of his final term, the EEOC came under congressional scrutiny for the mishandling of age-discrimination cases.[102][103]

District of Columbia Court of Appeals

In early 1989, President George H. W. Bush expressed interest in nominating Thomas to a federal judgeship. Thomas, now at age 41, initially rejected the position, believing himself unready to make a lifetime commitment to being a judge. White House Counsel C. Boyden Gray and White House Chief of Staff John H. Sununu advocated for his nomination, and Judge Laurence Silberman advised Thomas to accept an appointment.[104] Anticipating Thomas's nomination, a liberal coalition—including the Alliance for Justice and the National Organization for Women (NOW)—emerged to oppose his candidacy.[105]

On October 30, 1989, President George H. W. Bush nominated Thomas to the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit to fill the seat vacated by Robert Bork.[106][107] Thomas gained the support of other African American officials, including former transportation secretary William Coleman, and said that when meeting white Democratic staffers in the United States Senate, he was "struck by how easy it had become for sanctimonious whites to accuse a black man of not caring about civil rights".[65]

In February 1990, the Senate Judiciary Committee recommended Thomas by a vote of 12 to 1. On March 6, 1990, the Senate confirmed him to the Court of Appeals by a vote of 98 to 2.[105] He developed cordial relationships during his 19 months on the federal court, including with Judge Ruth Bader Ginsburg.[65] During his judgeship, Thomas authored 19 opinions.[108]

Nomination to the Supreme Court

When Justice William Brennan retired from the Supreme Court in July 1990, Thomas was Bush's favorite among the five candidates on his shortlist for the position. However, Bush's advisors, including Attorney General Dick Thornburgh, considered Thomas inexperienced,[111] and he instead nominated David Souter of the First Circuit Court of Appeals.[65] A year later, Justice Thurgood Marshall announced his retirement on June 27, 1991, and Bush nominated Thomas to replace him.[112][113] Bush announced his selection on July 1, calling Thomas the "best qualified at this time".[65] Thornburgh cautioned Bush that replacing Marshall with any candidate who was not perceived to share Marshall's views would make confirmation difficult.[114]

Liberal interest groups sought to challenge Thomas's nomination by paralleling the same strategy used against Robert Bork's confirmation.[115] Abortion-rights groups, including the National Abortion Rights Action League and the NOW, were concerned that Thomas would be among those to overrule Roe v. Wade.[116] Republican officials in turn emphasized his personal history and gathered support from African American interest groups, including the NAACP.[117] Other civil rights organizations, such as the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and the National Urban League, were convinced not to oppose Thomas, believing that he was Bush's last black nominee. On July 31, 1991, the board of directors of the NAACP voted against endorsing Thomas, announcing their opposition to his confirmation the same day.[118]

The American Bar Association (ABA) appraised Thomas as "qualified" for the Supreme Court.[119][b] The result came in contrast to the "well qualified" rating some nominees had received previously.[121][122] The Bush Administration anticipated that the organization would rate Thomas more poorly than it thought he deserved, so pressured the ABA for at least the mid-level qualified rating while simultaneously discrediting it as partisan.[123] Opponents of Thomas's nomination saw the assessment as indicating that he was unfit for the Court.[124] The ABA gave Thomas its highest rankings in integrity and judicial temperament and a middle-grade in professional competence.[125]

On September 10, 1991, formal confirmation hearings began before the Senate Judiciary Committee.[126][127] Thomas testified for 25 hours, the second-longest of any Supreme Court nominee.[128] He was reticent when answering senators' questions, recalling what had happened to Robert Bork when Bork expounded on his judicial philosophy during his confirmation hearings four years earlier.[129] As many of his earlier writings frequently referenced natural law, his views on the legal theory became a focus of the hearings. Thomas said he regarded natural law as a "philosophical background" to the Constitution.[130][131][132]

Ninety witnesses testified in favor of or against Thomas.[133][citation needed] A motion on September 27, 1991, to give the nomination a favorable recommendation failed 7–7, and the Judiciary Committee voted 13–1 to send it to the full Senate without recommendation.[134][135][136]

Anita Hill accusations

At the conclusion of the committee's confirmation hearings, the Senate was debating whether to give final approval to Thomas's nomination. An FBI interview with Anita Hill, a former colleague of Thomas at the EEOC, was soon leaked to the press and allegations of sexual harassment followed.[137][138] As a result, on October 8, the final vote was postponed, and the confirmation hearings were reopened. It was only the third time in the Senate's history that such an action was taken and the first since 1925, when Justice Harlan F. Stone's nomination was recommitted to the Judiciary Committee.[136]

Hill was raised in Oklahoma and, like Thomas, graduated from Yale Law School.[139] She told James Brudney, a fellow Yale alumnus, about alleged sexual advances Thomas had made, telling him that she also did not wish to testify or make the allegations public to the Senate Judiciary Committee. Hill requested to the staff of Senator Joe Biden, the chair of the committee, that her allegations be made anonymously if she chose to testify and that Thomas not be informed of them, which Biden declined. Hill then notified Democratic staffers the day after the hearings had ended that she wished to make her allegations known to the committee.[140]

Hill's allegations were corroborated by Susan Hoerchner, a judge in California, who also wished to remain anonymous.[141][142] Hoerchner called Harriet Grant, a chief counsel to Biden, to inform him of her allegations. She recalled that Thomas told Hill in an elevator at the EEOC that he would ruin her career if she spoke about his behavior.[143] When Grant told Hill and Hoerchner that the FBI would be involved, they were reluctant to be investigated. Hill declined to speak with the FBI, as she feared it would misconstrue her words, so instead arranged to deliver a written statement. The statement described how Thomas pressured her to date him, and included descriptions of him speaking about sexual interests involving pornographic films.[144] Hill also alleged that Thomas spoke of sex at work despite her being uncomfortable with the subject, adding, "I sensed that my discomfort with his discussions only urged him on, as though my reaction of feeling ill at ease and vulnerable was what he wanted".[145] The FBI report of its investigation was not made public. The White House announced that the FBI had found the allegations "without foundation". Congressional officials who had seen the report told the New York Times that "the bureau could not draw any conclusion because of the 'he said, she said' nature of the subject".[146][147] The use of the FBI was contentious in the Judiciary Committee because it answers to the president, who was sponsoring Thomas. Biden used the FBI instead of the committee's investigators to avoid the appearance of partisanship.[148]

Second hearing

The hearings reconvened on October 11, 1991, with Thomas going first. In his opening statement, he denied that he had said or done anything to Hill "that could have been mistaken for sexual harassment". He told the Committee that he would not allow any questions about "what goes on in the most intimate parts of my private life or the sanctity of my bedroom" so as not to "provide the rope for my own lynching".[149]

The committee then questioned Hill for seven hours. She testified that ten years earlier Thomas had subjected her to comments of a sexual nature, calling it "behavior that is unbefitting an individual who will be a member of the Court".[150][151][152] Her testimony included graphic details, and some senators questioned her aggressively.[153][154] Hill accused Thomas of making two sexually offensive remarks to her: comparing his penis to that of Long Dong Silver, a black porn star, and saying he had discovered a pubic hair on his Coca-Cola can.[155][156]

And from my standpoint as a black American, as far as I'm concerned, [this proceeding] is a high-tech lynching for uppity blacks that in any way deign to think for themselves, to do for themselves, to have different ideas, and it is a message that unless you kowtow to the old order, this is what will happen to you. You will be lynched, destroyed, caricatured by a committee of the United States Senate rather than hung from a tree.

Thomas, testifying as part of his opening statement before the Senate Judiciary Committee[157]

In the evening, Thomas was recalled before the committee. He again denied the allegations and was prompted by Senator Orrin Hatch's questioning to launch a speech that criticized the proceeding as a "high-tech lynching for uppity blacks".[158] The speech resonated with Southern blacks and stimulated Thomas's supporters,[159] with public opinion shifting in his favor afterward.[160][161]

Hill was the only person to publicly testify that Thomas had sexually harassed her.[162] Angela Wright, who worked under Thomas at the EEOC and had alleged that "Thomas had continually pressured her to date him and made sexual comments about women's bodies",[163][164] and a corroborating witness she had named were not called to testify.[163] Their written depositions were entered into the congressional records unrebutted.[165][166][167] Sukari Hardnett, a former Thomas assistant, wrote to the Senate committee that although Thomas had not harassed her, "If you were young, black, female and reasonably attractive, you knew full well you were being inspected and auditioned as a female."[168][169]

In addition to Hill and Thomas, the committee heard other witnesses.[136] A former colleague, Nancy Altman, testified that for two years she had shared an office with Thomas at the Department of Education and "heard virtually every conversation" Thomas had and never heard him make a sexist or offensive comment.[170][non-primary sources needed]

On October 13, Hill voluntarily took and passed a polygraph test, which her lawyer took as proof that she had been truthful about the harassment claims, even if the test was not admissible as evidence in court. Danforth's office then issued a statement saying that persons suffering from a delusional disorder might pass a lie detector test.[171][172][173][174] After the confirmation hearings ended, they became a focus of divided scholarship, with authors who revisited them reaching varying conclusions in favor of either Thomas or Hill.[161]

Senate votes

On October 15, 1991, the Senate voted to confirm Thomas as an associate justice, 52–48.[136] Thomas received the votes of 41 Republicans and 11 Democrats, while 46 Democrats and two Republicans voted to reject his nomination.[175]

The 99 days during which Thomas's nomination was pending in the Senate was the second-longest of the 16 nominees receiving a final vote since 1975, second only to Bork's 108 days.[136] The vote to confirm Thomas was the narrowest margin for approval in more than 100 years.[176]

Thomas received his commission on October 23 and took the prescribed constitutional and judicial oaths of office, becoming the Court's 106th justice.[177][c] He was sworn in by Justice Byron White in a ceremony initially scheduled for October 21, which was postponed because of the death of Chief Justice William Rehnquist's wife, Natalie.[179][180][181] His first set of law clerks included future judges Gregory Katsas and Gregory Maggs and U.S. Ambassador Christopher Landau.[182][183]

| Vote to confirm the Thomas nomination | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| October 15, 1991 | Party | Total votes | |

| Democratic | Republican | ||

| Yea | 11 | 41 | 52 |

| Nay | 46 | 2 | 48 |

| Result: Confirmed | |||

Supreme Court of the United States

After joining the Supreme Court, Thomas emerged as a member of the Court's conservative wing.[184] He aligned himself with Justice Antonin Scalia, with whom he shared an originalist approach to constitutional interpretation, and sided with him in 92 percent of cases during his first 13 years on the bench.[d] Over time, Thomas and Scalia's jurisprudence separated,[e] with Thomas favoring stronger emphasis on the Constitution's original understanding and demonstrating greater willingness to overrule precedent.[192] His appointment represented a decline in the Court's liberal wing, which then comprised only Justices John Paul Stevens and Harry Blackmun.[193][194]

In his early days on the Court, Thomas adopted a bold style of legal jurisprudence that alienated him from Justices Blackmun and Sandra Day O'Connor. He became the subject of intense media criticism for his decisions, including from figures that supported his appointment. Having previously experienced scrutiny during his confirmation hearings, Thomas believed in producing results without regard for his public image, a characteristic embodied in his lack of questions during oral arguments. His conservative approach moved O'Connor to take liberal positions but attracted Scalia. He formed a friendship with Justice Byron White, with whom he shared multiple interests, and found support from Justice David Souter.[195][196]

Thomas is a proponent of original meaning, incorporating what had been Scalia's narrower approach to the doctrine and the original intent of the Framers of the Constitution, including those espoused in the Declaration of Independence. As a means to impartiality, he is an advocate of judicial restraint to limit judicial discretion.[197][f] Thomas has been the most-willing of all justices on the Court to overrule precedent; according to Scalia, "he does not believe in stare decisis, period".[200][201][g] By October 1, 2012, he had written 475 opinions, including 171 majority opinions, 138 concurrences, and 166 dissenting opinions—approximately 10 percent of the 1,772 cases the Court had decided since he was elevated.[203] In 2016, Thomas wrote nearly twice as many opinions as any other justice.[9]

Thomas has been called the most conservative member of the Supreme Court,[196][204][205] though others gave Scalia that designation while they served on the Court together.[206][207] Thomas's influence, particularly among conservatives, was perceived to have significantly increased during Donald Trump's presidency,[208][209] and Trump appointed many of his former clerks to political positions and judgeships.[210][211][212] As the Supreme Court became more conservative, Thomas and his legal views became more influential on the Court.[213][214][215] This influence increased further by 2022, with Thomas authoring an opinion expanding Second Amendment rights and contributing to the Court's overruling of Roe v. Wade. He was also the most senior associate justice by that time.[216][217][218]

Government powers and legal structure

Court precedent

Thomas believes the Court should not follow erroneous precedent, a view not currently held by other justices.[219] He has called to reconsider New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964), and criticized Roe v. Wade (1973) and Gideon v. Wainwright (1963). At a 2013 Federalist Society dinner, Judge Diane S. Sykes asked Thomas whether "stare decisis doesn't hold much force for you?" He responded, "Oh, it sure does, but not enough to keep me from going to the Constitution".[220][221] In 2019, The New York Times reported that data gathered by political scientist Stephen L. Wasby of the University at Albany found that Thomas wrote "more than 250 concurring or dissenting opinions seriously questioning precedents, calling for their reconsideration or suggesting that they be overruled".[220]

In the 2010 gun regulation case McDonald v. City of Chicago, Thomas sought to repeal past precedents and insisted that "stare decisis is only an 'adjunct' of our duty as judges to decide by our best lights what the Constitution means".[222] In Gamble v. United States (2019), he joined the majority opinion, which revisited an exception to the Double Jeopardy Clause, writing separately to state his position against the Court's prevailing view of multi-factor analysis regarding whether to follow precedent:[223]

In my view, if the Court encounters a decision that is demonstrably erroneous—i.e., one that is not a permissible interpretation of the text—the Court should correct the error, regardless of whether other factors support overruling the precedent. Federal courts may (but need not) adhere to an incorrect decision as precedent, but only when traditional tools of legal interpretation show that the earlier decision adopted a textually permissible interpretation of the law. A demonstrably incorrect judicial decision, by contrast, is tantamount to making law, and adhering to it both disregards the supremacy of the Constitution and perpetuates a usurpation of the legislative power.[224]

In Franchise Tax Board of California v. Hyatt (2019),[h] Thomas wrote the 5–4 decision overruling Nevada v. Hall (1979), which said states could be sued in courts of other states. In his majority opinion, he noted that stare decisis "is not an inexorable command". Thomas explicitly disavowed the concept of reliance interests as justification for adhering to precedent. In dissent from Hyatt III, Justice Breyer asked what other decisions might eventually be overruled, and suggested Roe v. Wade might be among them. Breyer stated that it is best to leave precedents alone unless they are widely seen as erroneous or become impractical.[225]

Executive power

Thomas has supported a broad interpretation of executive power and has theorized about its constitutional aspects.[9] In Hamdi v. Rumsfeld (2004),[i] he dissented from the majority opinion, arguing that courts should have had complete deference to the executive decision to determine that Yaser Esam Hamdi was an enemy combatant.[226] He wrote in Hamdi that the president does not have the singular authority to detain a citizen who was captured while in enemy service.[227] In addition, Thomas noted that "structural advantages [of the Presidency] are most important in the national-security and foreign-affairs contexts" and thus "the Founders intended that the President have primary responsibility—along with the necessary power—to protect the national security and to conduct the nation's foreign relations".[228]

Thomas was one of three justices to dissent in Hamdan v. Rumsfeld (2006),[j] which concerned whether the president can establish military tribunals to try detained enemy combatants for war crimes conspiracy. As in Hamdi, he relied on The Federalist Papers in proposing that the president is responsible for protecting national security.[229][230]

In Zivotofsky v. Kerry (2015), Thomas relied on the Articles of Confederation for his opinion. He wrote, "the President is not confined to those powers expressly identified in [the Constitution]", concluding that residual foreign affairs were vested in the president, not Congress.[231] Rather than finding the original intent or original understanding, Thomas wrote in the case that he sought the "understanding of executive power [that] prevailed in America" at the time of the founding.[232]

In the Ninth Circuit case East Bay Sanctuary Covenant v. Trump (2018), which placed an injunction on the Trump administration's asylum policy, Thomas dissented from a denial of stay application. The Ninth Circuit imposed an injunction on the Trump administration's policy granting asylum only to refugees entering from a designated port of entry, ruling that it violated the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952. Ninth Circuit Judge Jay Bybee's majority opinion concluded that denial of the ability to apply for asylum regardless of entry point is "the hollowest of rights that an alien must be allowed to apply for asylum regardless of whether she arrived through a port of entry if another rule makes her categorically ineligible for asylum based on precisely that fact." Gorsuch, Alito, Kavanaugh also dissented in the decision to deny a stay to the Ninth Circuit's injunction.[233][234][non-primary sources needed]

Federalism

Thomas views federalism as a foundational limit on federal power.[235] In interpreting congressional powers, he has defended strict constructionism—an approach Scalia rejected.[236] On September 24, 1999, Thomas delivered the Dwight D. Opperman Lecture at Drake University Law School on "Why Federalism Matters", saying that it was an essential safeguard to protect "individual liberty and the private ordering of our lives". He also asserted that federalism enhances self-government, protects individual liberty by separating political power, and checks federal authority.[237] According to law professor Ann Althouse, the Court has yet to move toward "the broader, more principled version of federalism propounded by Justice Thomas".[238]

Nothing in the Constitution deprives the people of each State of the power to prescribe eligibility requirements for the candidates who seek to represent them in Congress. The Constitution is simply silent on this question. And where the Constitution is silent, it raises no bar to action by the States or the people.

— Thomas, dissenting in U.S. Term Limits, Inc. v. Thornton (1995)[239][235]

In the 1995 case U.S. Term Limits, Inc. v. Thornton,[k] parties challenged the constitutionality of an amendment to the Arkansas Constitution that added age, citizenship, and residency requirements for congressional service. In a 5-4 decision, the Supreme Court ruled the amendment unconstitutional, also affirming the previous rulings of both the state's trial court and the Arkansas Supreme Court; Justice Stevens wrote for the majority. Thomas—joined by Justices Rehnquist, O'Connor, and Scalia—dissented in what is to date his lengthiest opinion.[240] He argued that states could impose term limits on members of Congress, as state citizens are "the ultimate source of the Constitution's authority".[241] That same year, Thomas concurred in United States v. Lopez, which invalidated the Gun-Free School Zones Act of 1990 for going beyond the Commerce Clause. He opined that the Court had deviated "from the original understanding of the Commerce Clause" and that the substantial effects test, "if taken to its logical extreme, would give Congress a 'police power' over all aspects of American life".[242]

Thomas dissented in Gonzales v. Raich (2005), which held that the Controlled Substances Act applies to homegrown marijuana, on the grounds of original meaning.[243] His interpretation of the interstate commerce clause differed from Scalia's, and they also held conflicting beliefs about the general welfare clause, the Indian commerce clause, and the necessary and proper clause. Scalia joined the majority opinion, but Thomas disputed the relevance of homegrown marijuana to interstate commerce, writing that if Congress can regulate it, "it can regulate virtually anything—and the Federal Government is no longer one of limited and enumerated powers".[244][245]

In United States v. Comstock (2010),[l] the Supreme Court, in a majority opinion by Justice Stephen Breyer, held that the Necessary and Proper Clause allows Congress to enact a law that authorized the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) to detain a mentally ill and dangerous federal prisoner beyond the DOJ's original lawful date. Thomas's dissent, joined by Scalia, argued that the clause allows Congress only to execute enumerated powers.[246] When the Court upheld the Affordable Care Act in National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius (2012), he authored a short dissent and joined the joint dissent finding the act completely unconstitutional.[247]

Federal statutes

As of 2007, Thomas was the justice most willing to exercise judicial review of federal statutes but among the least likely to overturn state statutes.[248] According to a New York Times editorial, "from 1994 to 2005 ... Justice Thomas voted to overturn federal laws in 34 cases and Justice Scalia in 31, compared with just 15 for Justice Stephen Breyer".[249]

In Northwest Austin Municipal Utility District No. 1 v. Holder, Thomas was the sole dissenter, voting to throw out Section Five of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. Section Five requires states with a history of racial voter discrimination—mostly states from the old South—to gain Justice Department clearance when revising election procedures. Congress had reauthorized Section Five in 2006 for another 25 years, but Thomas said the law was no longer necessary, stating that the rate of black voting in seven Section Five states was higher than the national average. He wrote, "the violence, intimidation and subterfuge that led Congress to pass Section 5 and this court to uphold it no longer remains."[250] He took this position again in Shelby County v. Holder, voting with the majority and concurring with the reasoning that struck down Section Five.[251][non-primary source needed]

Individual rights

Free speech and expression

Thomas has generally written opinions in favor of protections for free speech.[252][253] He has voted in favor of First Amendment claims in cases involving issues including campaign contributions and commercial speech.[254] A 2002 study by Eugene Volokh found Thomas to be the justice second-most likely to uphold free speech claims (tied with Souter).[255] He has ruled against laws regulating hate speech, as in R.A.V. v. City of St. Paul (1992), United States v. Stevens (2010), and Snyder v. Phelps (2011).[256] Conversely, he has been reluctant to uphold speech deemed intimidating, as in Virginia v. Black (2003).[257][258]

Thomas's first opinion on free speech was the 1995 case McIntyre v. Ohio Elections Commission,[m] finding that the Founding Era contained the expansive use of anonymous pamphlets and columns. Although he agreed with the result of Justice John Paul Stevens's majority opinion, he disagreed with its methodology and did not join it.[259] With the announcement of McIntyre, the Court also decided Rubin v. Coors Brewing Company, in which Thomas wrote his first majority opinion concerning free speech. In Rubin, Thomas was joined unanimously in ruling unconstitutional a 1935 federal law that prohibited beer labels from disclosing alcohol content. He similarly concurred the next year in 44 Liquormart v. Rhode Island, which struck down a state law that banned the advertisement of prices of alcoholic beverages.[260]

In Colorado Republican Federal Campaign Committee v. FEC (1996), the Supreme Court ruled against the decision of the Federal Election Commission (FEC) to fine the Colorado Republican Federal Campaign Committee for running a political advertisement targeting Senator Tim Wirth. Thomas joined Justice Stephen Breyer's majority opinion in the case, but wrote separately to call against the framework established in the previous campaign finance case of Buckley v Valeo (1976):

I believe that contribution limits infringe as directly and as seriously upon freedom of political expression and association as do expenditure limits. The protections of the First Amendment do not depend upon so fine a line as that between spending money to support a candidate or group and giving money to the candidate or group to spend for the same purpose. In principle, people and groups give money to candidates and other groups for the same reason that they spend money in support of those candidates and groups: because they share social, economic, and political beliefs and seek to have those beliefs affect governmental policy.[261]

Thomas has made public his belief that all limits on federal campaign contributions are unconstitutional and should be struck down.[262] In Citizens United v. FEC (2010), Thomas joined the majority but dissented in part, arguing that the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act's disclaimer and disclosure requirements were unconstitutional. He reinforced his defense of anonymous speech in Doe v. Reed (2010), writing that the First Amendment protects "political association" by means of signing a petition.[263]

In Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District (1969), Justice Hugo Black dissented from the Court's opinion invalidating a school's policy to forbid students from wearing armbands in protest of the Vietnam War. Thomas endorsed Black's dissent in Morse v. Frederick (2007), concurring with narrowing the rationale of Tinker and arguing that Tinker be overruled as it was a constitutionally unsupported "sea change in students’ speech rights".[264] In his view, the Constitution does not govern whether public school students may be disciplined for expressive behavior.[265]

In Mahanoy Area School District v. B.L.—in which a high school punished a student for sending a profane message on social media about her school, softball team, and cheer team—Thomas was the lone dissenter, siding with the school. He criticized the majority for relying on "vague considerations" and wrote that historically schools could discipline students in similar situations.[266] In Walker v. Texas Division, Sons of Confederate Veterans, he joined the majority opinion that Texas's decision to deny a request for a Confederate Battle Flag specialty license plate was constitutional.[267]

Second Amendment

Thomas agreed with the judgment in McDonald v. Chicago (2010) that the right to keep and bear arms is applicable to state and local governments, but he wrote a separate concurrence finding that an individual's right to bear arms is fundamental as a privilege of American citizenship under the Privileges or Immunities Clause rather than as a fundamental right under the due process clause.[268] The four justices in the plurality opinion specifically rejected incorporation under the privileges or immunities clause, "declin[ing] to disturb" the holding in the Slaughter-House Cases, which, according to the plurality, had held that the clause applied only to federal matters.[269][270]

Since 2010, Thomas has dissented from denial of certiorari in several Second Amendment cases. He voted to grant certiorari in Friedman v. City of Highland Park (2015), which upheld bans on certain semi-automatic rifles; Jackson v. San Francisco (2014), which upheld trigger lock ordinances similar to those struck down in Heller; Peruta v. San Diego County (2016), which upheld restrictive concealed carry licensing in California; and Silvester v. Becerra (2017), which upheld waiting periods for firearm purchasers who have already passed background checks and already own firearms. He was joined by Scalia in the first two cases, and by Gorsuch in Peruta.[271][272][273][274][non-primary sources needed]

Thomas dissented from the denial of an application for a stay presented to Chief Justice Roberts in the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit case Guedes v. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (2019), a case challenging the Trump administration's ban on bump stocks. Only Thomas and Gorsuch publicly dissented.[275][non-primary source needed]

Thomas authored the majority opinion in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association, Inc. v. Bruen (2022), guaranteeing the right of law-abiding citizens to carry firearms in public. The case held: "When the Second Amendment's plain text covers an individual's conduct, the Constitution presumptively protects that conduct. The government must then justify its regulation by demonstrating that it is consistent with the Nation's historical tradition of firearm regulation. Only then may a court conclude that the individual's conduct falls outside the Second Amendment's 'unqualified command.'" Justice Stephen Breyer, dissenting, wrote, "when courts interpret the Second Amendment, it is constitutionally proper, indeed often necessary, for them to consider the serious dangers and consequences of gun violence that lead States to regulate firearms."[276]

Thomas was the sole dissenter in United States v. Rahimi, 602 U.S. --- (2024). In Rahimi, the Court was tasked with deciding whether or not 18 U.S.C. § 922(g)(8) (a federal statute which prohibits individuals who are subject to a domestic restraining order from possessing guns during the time they are subject to the order and can be punished by up to 15 years imprisonment for each conviction under said statute) is unconstitutional on its face. While the other eight sitting members of the Court ultimately voted that the statute could be applied constitutionally, Thomas disagreed and argued that the surety, affray, and "going armed" laws proffered by the Government were not sufficient analogies to §922(g)(8) for many reasons, including the fact that historical surety laws did not actually disarm individuals but only required them to post a bond that would be forfeited if they breached the peace, and that affray laws targeted violence that occurred in public, not private interpersonal domestic violence within the home. [277]

Fourth Amendment

In cases regarding the Fourth Amendment, which prohibits unreasonable searches and seizures, Thomas often favors police over defendants. For example, his opinion for the Court in Board of Education v. Earls upheld drug testing for students involved in extracurricular activities, and he wrote again for the Court in Samson v. California, permitting random searches on parolees. He dissented in Georgia v. Randolph, which prohibited warrantless searches that one resident approves and the other opposes, arguing that the Court's decision in Coolidge v. New Hampshire controlled the case. In Indianapolis v. Edmond, Thomas described the Court's extant case law as having held that "suspicionless roadblock seizures are constitutionally permissible if conducted according to a plan that limits the discretion of the officers conducting the stops." He expressed doubt that those cases were decided correctly but concluded that since the litigants in the case at bar had not briefed or argued that the earlier cases be overruled, he believed that the Court should assume their validity and rule accordingly.[278] Thomas was in the majority in Kyllo v. United States, which held that the use of thermal imaging technology to probe a suspect's home without a warrant violated the Fourth Amendment.[non-primary sources needed]

In cases involving schools, Thomas has advocated greater respect for the doctrine of in loco parentis,[279] which he defines as "parents delegat[ing] to teachers their authority to discipline and maintain order".[280] His dissent in Safford Unified School District v. Redding illustrates his application of this postulate in the Fourth Amendment context. School officials in the Safford case had a reasonable suspicion that 13-year-old Savana Redding was illegally distributing prescription-only drugs. All the justices concurred that it was therefore reasonable for the school officials to search Redding, and the main issue before the Court was only whether the search went too far by becoming a strip search or the like.[280] All the justices except Thomas concluded that the search violated the Fourth Amendment. The majority required a finding of danger or reason to believe drugs were hidden in a student's underwear in order to justify a strip search. Thomas wrote, "It is a mistake for judges to assume the responsibility for deciding which school rules are important enough to allow for invasive searches and which rules are not"[281] and "reasonable suspicion that Redding was in possession of drugs in violation of these policies, therefore, justified a search extending to any area where small pills could be concealed". He added, "[t]here can be no doubt that a parent would have had the authority to conduct the search."[280][non-primary source needed]

Sixth Amendment

In Doggett v. United States, the defendant had technically been a fugitive from the time he was indicted in 1980 until his arrest in 1988. The Court held that the delay between indictment and arrest violated Doggett's Sixth Amendment right to a speedy trial, finding that the government had been negligent in pursuing him and that he was unaware of the indictment.[282][non-primary source needed] Thomas dissented, arguing that the Speedy Trial Clause's purpose was to prevent "'undue and oppressive incarceration' and the 'anxiety and concern accompanying public accusation'" and that the case implicated neither.[282][non-primary source needed] He cast the case instead as "present[ing] the question [of] whether, independent of these core concerns, the Speedy Trial Clause protects an accused from two additional harms: (1) prejudice to his ability to defend himself caused by the passage of time; and (2) disruption of his life years after the alleged commission of his crime". Thomas dissented from the court's decision to, as he saw it, answer the former in the affirmative.[282][non-primary source needed] He wrote that dismissing the conviction "invites the Nation's judges to indulge in ad hoc and result-driven second guessing of the government's investigatory efforts. Our Constitution neither contemplates nor tolerates such a role".[283]

In Garza v. Idaho, Thomas and Gorsuch, in dissent, suggested that Gideon v. Wainwright (1963), which required that indigent criminal defendants be provided counsel, was wrongly decided and should be overruled.[220]

Eighth Amendment

Thomas was among the dissenters in Atkins v. Virginia and Roper v. Simmons, which held that the Eighth Amendment prohibits the application of the death penalty to certain classes of persons. In Kansas v. Marsh, his majority opinion indicated a belief that the Constitution affords states broad procedural latitude in imposing the death penalty, provided they remain within the limits of Furman v. Georgia and Gregg v. Georgia, the 1976 case in which the Court reversed its 1972 ban on death sentences if states followed procedural guidelines.[citation needed]

In Hudson v. McMillian, a prisoner had been beaten by respondent prison guards, sustaining a cracked lip, broken dental plate, loosened teeth, cuts, and bruises. Although these were not "serious injuries", the Court believed, it held that "the use of excessive physical force against a prisoner may constitute cruel and unusual punishment even though the inmate does not suffer serious injury."[284] Dissenting, Thomas wrote, "a use of force that causes only insignificant harm to a prisoner may be immoral, it may be tortious, it may be criminal, and it may even be remediable under other provisions of the Federal Constitution, but it is not 'cruel and unusual punishment'. In concluding to the contrary, the Court today goes far beyond our precedents."[284] Thomas's vote—in one of his first cases after joining the Court—was an early example of his willingness to be the sole dissenter (Scalia later joined the opinion).[285] His opinion was criticized by the seven-member majority, which wrote that, by comparing physical assault to other prison conditions such as poor prison food, it ignored "the concepts of dignity, civilized standards, humanity, and decency that animate the Eighth Amendment".[284] According to historian David Garrow, Thomas's dissent in Hudson was a "classic call for federal judicial restraint, reminiscent of views that were held by Felix Frankfurter and John M. Harlan II a generation earlier, but editorial criticism rained down on him".[286][non-primary sources needed] Thomas later responded to the accusation "that I supported the beating of prisoners in that case. Well, one must either be illiterate or fraught with malice to reach that conclusion ... no honest reading can reach such a conclusion."[286]

In United States v. Bajakajian, Thomas joined with the Court's liberal justices to write the majority opinion declaring a fine unconstitutional under the Eighth Amendment. The fine was for failing to declare more than $300,000 in a suitcase on an international flight. Under a federal statute, 18 U.S.C. § 982(a)(1), the passenger would have had to forfeit the entire amount. Thomas noted that the case required a distinction to be made between civil forfeiture and a fine exacted with the intention of punishing the respondent. He found that the forfeiture in this case was clearly intended as a punishment at least in part, was "grossly disproportional" and violated the Excessive Fines Clause.[287][non-primary source needed]

Thomas has written that the "Cruel and Unusual Punishment" clause "contains no proportionality principle", meaning that the question whether a sentence should be rejected as "cruel and unusual" depends only on the sentence itself, not on what crime is being punished.[288] He was concurring with the Court's decision to reject a request for review from a petitioner who had been sentenced to 25 years to life in prison under California's "Three-Strikes" law for stealing some golf clubs because the combined value of the clubs made the theft a felony and he had two previous felonies in his criminal record.[non-primary source needed]

Race, equal protection, and affirmative action

Thomas believes the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment forbids consideration of race, such as race-based affirmative action or preferential treatment. In Adarand Constructors v. Peña, he wrote, "there is a 'moral [and] constitutional equivalence' between laws designed to subjugate a race and those that distribute benefits on the basis of race in order to foster some current notion of equality. Government cannot make us equal; it can only recognize, respect, and protect us as equal before the law. That [affirmative action] programs may have been motivated, in part, by good intentions cannot provide refuge from the principle that under our Constitution, the government may not make distinctions on the basis of race."[289][non-primary source needed]

In Gratz v. Bollinger, Thomas wrote, "a State's use of racial discrimination in higher education admissions is categorically prohibited by the Equal Protection Clause."[290] In Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No. 1, Thomas joined the opinion of Chief Justice Roberts, who wrote that "[t]he way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race."[291] Concurring, Thomas wrote, "if our history has taught us anything, it has taught us to beware of elites bearing racial theories", and charged that the dissent carried "similarities" to the arguments of the segregationist litigants in Brown v. Board of Education.[291][non-primary sources needed]

Thomas joined the majority in Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard, which struck down affirmative action in college admissions. He filed a concurring opinion, which he read from the bench, a rare practice for Supreme Court justices.[292]

Abortion and family planning

Thomas has contended that the Constitution does not address abortion.[293] In Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992), the Court reaffirmed Roe v. Wade. Thomas and Justice Byron White joined the dissenting opinions of Rehnquist and Scalia. Rehnquist wrote, "[w]e believe Roe was wrongly decided, and that it can and should be overruled consistently with our traditional approach to stare decisis in constitutional cases."[294] Scalia's opinion concluded that the right to obtain an abortion is not "a liberty protected by the Constitution of the United States".[294] "[T]he Constitution says absolutely nothing about it," Scalia wrote, "and [ ] the longstanding traditions of American society have permitted it to be legally proscribed".[294][non-primary source needed]

In Stenberg v. Carhart (2000), the Court struck down a state ban on partial-birth abortion, concluding that it failed Casey's "undue burden" test. Thomas dissented, writing, "Although a State may permit abortion, nothing in the Constitution dictates that a State must do so."[295][citation needed] He went on to criticize the reasoning of the Casey and Stenberg majorities: "The majority's insistence on a health exception is a fig leaf barely covering its hostility to any abortion regulation by the States—a hostility that Casey purported to reject."[non-primary source needed]

In Gonzales v. Carhart (2007), the Court rejected a facial challenge to a federal ban on partial-birth abortion.[296][citation needed] Concurring, Thomas asserted that the court's abortion jurisprudence had no basis in the Constitution but that the court had accurately applied that jurisprudence in rejecting the challenge.[296][citation needed] He added that the Court was not deciding the question of whether Congress had the power to outlaw partial-birth abortions: "[W]hether the Act constitutes a permissible exercise of Congress's power under the Commerce Clause is not before the Court [in this case] ... the parties did not raise or brief that issue; it is outside the question presented; and the lower courts did not address it."[296][non-primary source needed]

In December 2018, Thomas dissented when the Court voted not to hear cases brought by Louisiana and Kansas to deny Medicaid funding to Planned Parenthood.[297] Alito and Gorsuch joined Thomas's dissent, arguing that the Court was "abdicating its judicial duty".[298]

In February 2019, Thomas joined three of the Court's other conservative justices in voting to reject a stay to temporarily block a law restricting abortion in Louisiana.[299] The law that the court temporarily stayed, in a 5–4 decision, would have required that doctors performing abortions have admitting privileges in a hospital.[300]

In Box v. Planned Parenthood of Indiana and Kentucky, Inc. (2019), a per curiam decision upholding the provision of Indiana's abortion restriction regarding fetal remains disposal on rational basis scrutiny and upholding the lower court rulings striking down the provision banning race, sex, and disability, Thomas wrote a concurring opinion comparing abortion and birth control to eugenics, which was practiced in the U.S. in the early 20th century and by the Nazi government in Germany in the 1930s and 1940s, and comparing Box to Buck v. Bell (1927), which upheld a forced sterilization law regarding people with mental disabilities. In his opinion, Thomas quoted Margaret Sanger's support for contraception as a form of personal reproductive control that she considered superior to "the horrors of abortion and infanticide" (Sanger's words).[301][non-primary source needed] His opinion referred several times to historian/journalist Adam Cohen's book Imbeciles: The Supreme Court, American Eugenics, and the Sterilization of Carrie Buck; shortly afterward, Cohen published a sharply worded criticism saying that Thomas had misinterpreted his book and misunderstood the history of the eugenics movement.[302] In Box, only Thomas, Sonia Sotomayor, and Ginsburg publicly registered their votes. Ginsburg and Sotomayor concurred in part and dissented in part, stating they would have upheld the lower court decision on striking down the race, sex, and disability ban as well as the lower court decision striking down the fetal remains disposal provision.[301][non-primary source needed]

In a concurring opinion in Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization (2022), Thomas wrote that "any substantive due process decision is 'demonstrably erroneous'",[citation needed] and argued that the Supreme Court should go beyond Roe vs. Wade and reconsider other substantive due process precedents, including those established in Griswold v. Connecticut (1965), Lawrence v. Texas (2003) and Obergefell v. Hodges (2015). The overturning of these previous decisions would enable states to limit access to contraception, criminalize sodomy, and criminalize same-sex marriage, respectively.[303][304][305]

LGBTQ rights

In Romer v. Evans (1996), Thomas joined Scalia's dissenting opinion arguing that Amendment Two to the Colorado State Constitution did not violate the Equal Protection Clause. The Colorado amendment forbade any judicial, legislative, or executive action designed to protect persons from discrimination based on "homosexual, lesbian, or bisexual orientation, conduct, practices or relationships".[306][non-primary source needed]

In Lawrence v. Texas (2003), Thomas issued a one-page dissent in which he called the Texas statute prohibiting sodomy "uncommonly silly", a phrase originally used by Justice Potter Stewart. He then said that if he were a member of the Texas legislature he would vote to repeal the law, as it was not a worthwhile use of "law enforcement resources" to police private sexual behavior. But Thomas opined that the Constitution does not contain a right to privacy and therefore did not vote to strike the statute down. He saw the issue as a matter for states to decide for themselves.[307][non-primary source needed]

In Bostock v. Clayton County, Georgia (2020), Thomas joined Alito and Kavanaugh in dissenting from the decision that Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 protects employees against discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity. (Alito wrote a dissent that Thomas joined, and Kavanaugh dissented separately.) The 6–3 ruling's majority consisted of two Republican-appointed justices, Roberts and Gorsuch, along with four Democratic-appointed justices: Ginsburg, Breyer, Sotomayor, and Kagan.[308]

In October 2020, Thomas joined the other justices in denying an appeal from Kim Davis, a county clerk who refused to give marriage licenses to same-sex couples, but wrote a separate opinion reiterating his dissent from Obergefell v. Hodges and expressing his belief that it was wrongly decided.[309][310][311] In July 2021, he was one of three justices, with Gorsuch and Alito, who voted to hear an appeal from a Washington florist who had refused service to a same-sex couple based on her religious beliefs against same-sex marriage.[312][313][314] In November 2021, Thomas dissented from the majority of justices in a 6–3 vote to reject an appeal from Mercy San Juan Medical Center, a hospital affiliated with the Roman Catholic Church, which had sought to deny a hysterectomy to a transgender patient on religious grounds.[315] Alito and Gorsuch also dissented, and the vote to reject the appeal left in place a lower court ruling in the patient's favor.[316][317]

Oral arguments

During a 10-year period from February 2006 to February 2016, Thomas read his opinions from the bench but asked no questions during oral arguments.[318][319] By May 2020, he had asked questions in two oral arguments since 2006 and had spoken during 32 of the roughly 2,400 arguments since 1991.[320][321] Thomas has given many reasons for his silence, including self-consciousness about how he speaks, a preference for listening to those arguing the case, and difficulty getting in a word.[322] He said in 2013 that it was "unnecessary in deciding cases to ask that many questions ... we should listen to lawyers who are arguing their cases, and I think we should allow the advocates to advocate."[322] His speaking and listening habits may have been influenced by his Gullah upbringing, during which his English was relatively unpolished.[17][63][323] In a 2017 paper in Northwestern University Law Review, RonNell Andersen Jones and Aaron L. Nielson wrote that while asking few questions, "in many ways, [Thomas] is a model questioner."[324][325]

Thomas took a more active role in questioning when the Supreme Court shifted to holding teleconferenced arguments in May 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic, in which the justices took turns asking questions in order of seniority.[326][327][328][321] Since the court resumed in-person oral arguments at the beginning of the 2021 term, the justices agreed to allow Thomas to ask the first question of each lawyer following their opening statements.[329]

Personal life

Family

In 1971, Thomas married Kathy Grace Ambush. The couple had one child, Jamal Adeen, born in 1973, who is Thomas's sole child. Thomas and his first wife separated in 1981 and divorced in 1984.[330][331] In 1987, Thomas married Virginia Lamp, a lobbyist and aide to U.S. Representative Dick Armey.[332] In 1997, they took in Thomas's six-year-old great-nephew, Mark Martin Jr.,[333] who had lived with his mother in Savannah public housing.[334] Since 1999, Thomas and his wife have traveled across the U.S. in a motorcoach between Court terms.[335][336]

Virginia "Ginni" Thomas has remained active in conservative politics, serving as a consultant to The Heritage Foundation and as founder and president of Liberty Central.[337] In 2011, she stepped down from Liberty Central to open a conservative lobbying firm, touting her "experience and connections", meeting with newly elected Republican representatives and calling herself an "ambassador to the Tea Party".[338][339] Also in 2011, 74 Democratic members of the House of Representatives wrote that Justice Thomas should recuse himself on cases regarding the Affordable Care Act because of "appearance of a conflict of interest" based on his wife's work.[340]

The Washington Post reported in February 2021 that Ginni Thomas apologized to a group of Thomas's former clerks on the email listserv "Thomas Clerk World" for her role in contributing to a rift relating to "pro-Trump postings and former Thomas clerk John Eastman, who spoke at the rally and represented Trump in some of his failed lawsuits filed to overturn the election results".[341] In March 2022, texts between Ginni Thomas and Trump's chief of staff Mark Meadows from 2020 were turned over to the Select Committee on the January 6 Attack.[342] The texts show Ginni Thomas repeatedly urging Meadows to overturn the election results and repeating conspiracy theories about ballot fraud.[343] In response, 24 Democratic members of the House of Representatives and the Senate demanded that Thomas recuse himself from cases related to efforts to overturn the results of the 2020 presidential election and the January 6 attack at the U.S. Capitol on the grounds that Ginni Thomas's involvement in such efforts raised questions about his impartiality.[344] An April 2022 Quinnipiac poll found that 52% of Americans agreed that, in light of Ginni Thomas's texts about overturning the results of the 2020 presidential election, Thomas should have recused himself from related cases.[345]

Religion

Thomas was reconciled to the Catholic Church in the mid-1990s.[346] In his autobiography, he criticized the church for failing to grapple with racism in the 1960s during the civil rights movement, saying it was not so "adamant about ending racism then as it is about ending abortion now".[347] As of 2021, Thomas is one of 14 practicing Catholic justices in the Court's history and one of six currently serving (along with Alito, Kavanaugh, Roberts, Sotomayor and Barrett).[348]

Literary influences

In 1975, when Thomas read economist Thomas Sowell's Race and Economics, he found an intellectual foundation for his philosophy.[349][350] The book criticizes social reform by government and argues for individual action to overcome circumstances and adversity. Ayn Rand's works also influenced him, particularly The Fountainhead, and he later required his staffers to watch the 1949 film version of the novel.[351][352] Thomas acknowledges "some very strong libertarian leanings", though he does not consider himself a libertarian.[353]

Thomas has said novelist Richard Wright is the most influential writer in his life; Wright's books Native Son and Black Boy "capture[d] a lot of the feelings that I had inside that you learn how to repress".[330] Native Son and Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man are Thomas's two favorite novels.[191]

Moira Smith allegations

In 2016, Moira Smith, vice-president and general counsel of a natural gas distributor in Alaska, said that Thomas groped her buttocks at a dinner party in 1999. She was a Truman Foundation scholar helping the director of the foundation set up for a dinner party honoring Thomas and David Adkins. Smith's roommates at the time confirmed that she had told them about the incident. Thomas denied the allegation.[354][355]

Louis Blair, who was the head of the Truman Foundation and hosted the dinner at his home, said he had "no recollection of the incident" and that he had neither seen nor heard of Smith's allegation. Blair acknowledged that he was in the kitchen most of the time so, if the incident happened, he wouldn't have seen it, but was also "skeptical that the justice and Moira would have been alone", given that there were approximately 16 people in three rooms.[356][357] Norma Stevens, who attended the event, said that the incident "couldn't have happened" because Thomas was never alone, as he was the guest of honor.[358]

Nondisclosure of finances

In 2004, the Los Angeles Times reported that Thomas had accepted gifts from Harlan Crow, a wealthy Dallas-based real estate investor and prominent Republican donor—notably a Bible, valued at $19,000, that once belonged to abolitionist Frederick Douglass, and a bust of Abraham Lincoln valued at $15,000.[359][360] Crow also gave Thomas a portrait of the justice and his wife, according to the painter, Sharif Tarabay. Crow's foundation gave $105,000 to Yale Law School, Thomas's alma mater, for the "Justice Thomas Portrait Fund", tax filings show.[361]

In 2011, Politico reported that Crow gave $500,000 to a Tea Party group founded by Thomas's wife and that Thomas had failed to report her income on his disclosure for more than a decade.[362][363] Also that year, the advocacy group Common Cause reported that between 2003 and 2007, Thomas failed to disclose $686,589 in income his wife earned from The Heritage Foundation, instead reporting "none" where "spousal noninvestment income" would be reported on his Supreme Court financial disclosure forms.[364] The next week, Thomas said the disclosure of his wife's income had been "inadvertently omitted due to a misunderstanding of the filing instructions".[365] He amended reports going back to 1989.[366]

In April 2023, ProPublica reported that Thomas had "accepted luxury trips virtually every year" from Crow for two decades and failed to report them. They included flights on Crow's private jet, cruises on Crow's superyacht at locations around the globe, and stays at Crow's private resort in the Adirondacks and the private club Bohemian Grove.[361][367][363] The Ethics in Government Act requires justices, judges, members of Congress and federal officials to annually disclose gifts they receive.[368] Many elected officials criticized the appearance of impropriety, given Crow's donations to conservative causes and Republican candidates, and his service on the Board of Trustees for the American Enterprise Institute and the Hoover Institution, which have filed amicus briefs before the Supreme Court.[369][361]

In May 2023, ProPublica reported that Crow had paid for private school tuition for Thomas's grandnephew, Mark Martin, of whom Thomas had legal custody. Thomas did not report the payments on his financial disclosure forms, while ethics law experts said that they were required to be disclosed as gifts. Mark Paoletta, a longtime friend of Thomas, said that Crow paid for one year each at Hidden Lake and Randolph-Macon Academy, which ProPublica estimated to total around $100,000.[370][363]

On the same day, The Washington Post reported that in January 2012 conservative judicial activist Leonard Leo had Republican pollster Kellyanne Conway's polling firm bill the Judicial Education Project $25,000, which her firm then paid to Ginni Thomas's firm, Liberty Consulting, for a total of $80,000 between June 2011 and June 2012. Leo instructed Conway not to mention Thomas's name on the paperwork. The documents the newspaper reviewed did not indicate the nature of the work Thomas did for the Judicial Education Project or Conway's company. In 2012 the Judicial Education Project filed a brief to the Supreme Court in a landmark voting rights case.[371][363]

In 2023, The New York Times reported that a friend had paid for Thomas's Prevost Le Mirage XL Marathon RV, purchased for $267,230 in 1999 (roughly equivalent to $489,000 in 2023). Anthony Welters, a former UnitedHealthcare executive and a close friend, lent Thomas the purchase price. In response to a Senate inquiry, Welters revealed that the loan was discharged in 2008, forgiving much of the original balance. A bank would have been unlikely to offer such a loan, given the Marathon's high capacity for customization, which can make used models difficult to appraise. Thomas had previously said that he "had scrimped and saved to afford the motor coach", according to the Times, and a friend, Armstrong Williams, said that Thomas had told him that "he saved up all his money to buy it". When the loan was forgiven, Thomas was required to disclose the money as a gift.[372][373][374][363][375]

In June 2024, Fix the Court released an analysis showing that, between 2004 and 2023, Thomas had accepted at least 103 gifts worth more than $2.4 million. Fix the Court also identified an additional 101 "likely gifts" Thomas received worth an additional $1.7 million, based on reporting by ProPublica and others.[376][377]