Римско-персидские войны

| Римско-персидские войны | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Воюющие стороны | |||||||

| 54–27 до н.э. Римская республика | 54–27 до н.э. Парфянская империя | ||||||

| 27 г. до н. э. – 224 г. Римская империя | 27 г. до н. э. – 224 г. Парфянская империя | ||||||

| 224–395 Римская империя | 224–395 Сасанидская империя | ||||||

| 395–628 Восточная Римская империя | 395–628 Сасанидская империя | ||||||

Клиенты/союзники | Клиенты/союзники | ||||||

| Командиры и лидеры | |||||||

Clients/allies | Clients/allies | ||||||

Римско -персидские войны , также известные как Римско-иранские войны , представляли собой серию конфликтов между государствами греко -римского мира и двумя последовательными иранскими империями : Парфянской и Сасанидской. Сражения между Парфянской империей и Римской республикой начались в 54 г. до н. э.; [1] войны начались при поздней республике и продолжались в Римской (позже Восточной Римской (Византийской) ) и Сасанидской империях. множество вассальных королевств и союзных кочевых наций в форме буферных государств и доверенных лиц Свою роль также сыграло . Войны завершились ранними мусульманскими завоеваниями , которые привели к падению Сасанидской империи и огромным территориальным потерям Византийской империи вскоре после окончания последней войны между ними.

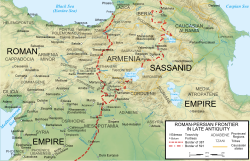

Although warfare between the Romans and Persians continued over seven centuries, the frontier, aside from shifts in the north, remained largely stable. A game of tug of war ensued: towns, fortifications, and provinces were continually sacked, captured, destroyed, and traded. Neither side had the logistical strength or manpower to maintain such lengthy campaigns far from their borders, and thus neither could advance too far without risking stretching its frontiers too thin. Both sides did make conquests beyond the border, but in time the balance was almost always restored. Although initially different in military tactics, the armies of both sides gradually adopted from each other and by the second half of the 6th century, they were similar and evenly matched.[2]

The expense of resources during the Roman–Persian Wars ultimately proved catastrophic for both empires. The prolonged and escalating warfare of the 6th and 7th centuries left them exhausted and vulnerable in the face of the sudden emergence and expansion of the Rashidun Caliphate, whose forces invaded both empires only a few years after the end of the last Roman–Persian war. Benefiting from their weakened condition, the Rashidun armies swiftly conquered the entire Sasanian Empire, and deprived the Eastern Roman Empire of its territories in the Levant, the Caucasus, Egypt, and the rest of North Africa. Over the following centuries, more of the Eastern Roman Empire came under Muslim rule.

Historical background

[edit]

According to James Howard-Johnston, "from the third century BC to the early seventh century AD, the rival players [in the East] were grand polities with imperial pretensions, which had been able to establish and secure stable territories transcending regional divides".[3] The Romans and Parthians came into contact through their respective conquests of parts of the Seleucid Empire. During the 3rd century BC, the Parthians migrated from the Central Asian steppe into northern Iran. Although subdued for a time by the Seleucids, in the 2nd century BC they broke away, and established an independent state that steadily expanded at the expense of their former rulers, and through the course of the 3rd and early 1st century BC, they had conquered Persia, Mesopotamia, and Armenia.[4][5][6] Ruled by the Arsacid dynasty, the Parthians fended off several Seleucid attempts to regain their lost territories, and established several eponymous branches in the Caucasus, namely the Arsacid dynasty of Armenia, the Arsacid dynasty of Iberia, and the Arsacid dynasty of Caucasian Albania. Meanwhile, the Romans expelled the Seleucids from their territories in Anatolia in the early 2nd century BC, after defeating Antiochus III the Great at Thermopylae and Magnesia. Finally, in 64 BC Pompey conquered the remaining Seleucid territories in Syria, extinguishing their state and advancing the Roman eastern frontier to the Euphrates, where it met the territory of the Parthians.[6]

Roman–Parthian wars

[edit]Roman Republic vs. Parthia

[edit]

Parthian enterprise in the West began in the time of Mithridates I and was revived by Mithridates II, who negotiated unsuccessfully with Lucius Cornelius Sulla for a Roman–Parthian alliance (c. 105 BC).[7] When Lucullus invaded Southern Armenia and led an attack against Tigranes in 69 BC, he corresponded with Phraates III to dissuade him from intervening. Although the Parthians remained neutral, Lucullus considered attacking them.[8] In 66–65 BC, Pompey reached agreement with Phraates, and Roman–Parthian troops invaded Armenia, but a dispute soon arose over the Euphrates boundary. Finally, Phraates asserted his control over Mesopotamia, except for the western district of Osroene, which became a Roman dependency.[9]

The Roman general Marcus Licinius Crassus led an invasion of Mesopotamia in 53 BC with catastrophic results; he and his son Publius were killed at the Battle of Carrhae by the Parthians under General Surena;[10] this was the worst Roman defeat since the battle of Arausio. The Parthians raided Syria the following year, and mounted a major invasion in 51 BC, but their army was caught in an ambush near Antigonea by the Romans, and they were driven back.[11]

The Parthians largely remained neutral during Caesar's Civil War, fought between forces supporting Julius Caesar and forces supporting Pompey and the traditional faction of the Roman Senate. However, they maintained relations with Pompey, and after his defeat and death, a force under Pacorus I assisted the Pompeian general Q. Caecilius Bassus, who was besieged at Apamea Valley by Caesarian forces. With the civil war over, Julius Caesar prepared a campaign against Parthia, but his assassination averted the war. The Parthians supported Brutus and Cassius during the ensuing Liberators' civil war and sent a contingent to fight on their side at the Battle of Philippi in 42 BC.[12] After the Liberators' defeat, the Parthians invaded Roman territory in 40 BC in conjunction with the Roman Quintus Labienus, a former supporter of Brutus and Cassius. They swiftly overran the Roman province of Syria and advanced into Judea, overthrowing the Roman client Hyrcanus II and installing his nephew Antigonus. For a moment, the whole of the Roman East seemed lost to the Parthians or about to fall into their hands. However, the conclusion of the second Roman civil war soon revived Roman strength in Asia.[13] Mark Antony had sent Ventidius to oppose Labienus, who had invaded Anatolia. Soon Labienus was driven back to Syria by Roman forces, and, although reinforced by the Parthians, was defeated, taken prisoner, and killed. After suffering a further defeat near the Syrian Gates, the Parthians withdrew from Syria. They returned in 38 BC but were decisively defeated by Ventidius, and Pacorus was killed. In Judaea, Antigonus was ousted with Roman help by Herod in 37 BC.[14] With Roman control of Syria and Judaea restored, Mark Antony led a huge army into Atropatene, but his siege train and its escort were isolated and wiped out, while his Armenian allies deserted. Failing to make progress against Parthian positions, the Romans withdrew with heavy casualties. Antony was again in Armenia in 33 BC to join with the Median king against Octavian and the Parthians. Other preoccupations obliged him to withdraw, and the whole region came under Parthian control.[15]

Roman Empire vs. Parthia

[edit]

With tensions between the two powers threatening renewed war, Octavian and Phraataces worked out a compromise in 1 AD. According to the agreement, Parthia undertook to withdraw its forces from Armenia and to recognize a de facto Roman protectorate there. Nonetheless, Roman–Persian rivalry over control and influence in Armenia continued unabated for the next several decades.[16] The decision of the Parthian King Artabanus III to place his son on the vacant Armenian throne triggered a war with Rome in 36 AD, which ended when Artabanus III abandoned claims to a Parthian sphere of influence in Armenia.[17] War erupted in 58 AD, after the Parthian King Vologases I forcibly installed his brother Tiridates on the Armenian throne.[18] Roman forces overthrew Tiridates and replaced him with a Cappadocian prince, triggering an inconclusive war. This came to an end in 63 AD after the Romans agreed to allow Tiridates and his descendants to rule Armenia on condition that they receive the kingship from the Roman emperor.[19]

A fresh series of conflicts began in the 2nd century AD, during which the Romans consistently held the upper hand over Parthia. The Emperor Trajan invaded Armenia and Mesopotamia during 114 and 115 and annexed them as Roman provinces. He captured the Parthian capital, Ctesiphon, before sailing downriver to the Persian Gulf.[20] However, uprisings erupted in 115 AD in the occupied Parthian territories, while a major Jewish revolt broke out in Roman territory, severely stretching Roman military resources. Parthian forces attacked key Roman positions, and the Roman garrisons at Seleucia, Nisibis and Edessa were expelled by the local inhabitants. Trajan subdued the rebels in Mesopotamia, but having installed the Parthian prince Parthamaspates on the throne as a client ruler, he withdrew his armies and returned to Syria. Trajan died in 117, before he was able to reorganize and consolidate Roman control over the Parthian provinces.[21]

Trajan's Parthian War initiated a "shift of emphasis in the 'grand strategy of the Roman empire' ", but his successor, Hadrian, decided that it was in Rome's interest to re-establish the Euphrates as the limit of its direct control. Hadrian returned to the status quo ante, and surrendered the territories of Armenia, Mesopotamia, and Adiabene to their previous rulers and client-kings.[22]

War over Armenia broke out again in 161, when Vologases IV defeated the Romans there, captured Edessa and ravaged Syria. In 163 a Roman counter-attack under Statius Priscus defeated the Parthians in Armenia and installed a favored candidate on the Armenian throne. The following year Avidius Cassius invaded Mesopotamia, winning battles at Dura-Europos and Seleucia and sacking Ctesiphon in 165. An epidemic which was sweeping Parthia at the time, possibly of smallpox, spread to the Roman army and forced its withdrawal;[23] this was the origin of the Antonine Plague that raged for a generation throughout the Roman Empire. In 195–197, a Roman offensive under the Emperor Septimius Severus led to Rome's acquisition of northern Mesopotamia as far as the areas around Nisibis, Singara and the third sacking of Ctesiphon.[24] A final war against the Parthians was launched by the Emperor Caracalla, who sacked Arbela in 216. After his assassination, his successor, Macrinus, was defeated by the Parthians near Nisibis. In exchange for peace, he was obliged to pay for the damage caused by Caracalla.[25]

Roman–Sasanian wars

[edit]Early Roman–Sasanian conflicts

[edit]Conflict resumed shortly after the overthrow of Parthian rule and Ardashir I's foundation of the Sasanian Empire. Ardashir (r. 226–241) raided Mesopotamia and Syria in 230 and demanded the cession of all the former territories of the Achaemenid Empire.[26] After fruitless negotiations, Alexander Severus set out against Ardashir in 232. One column of his army marched into Armenia, while two other columns operated to the south and failed.[27] In 238–240, towards the end of his reign, Ardashir attacked again, taking several cities in Syria and Mesopotamia, including Carrhae, Nisibis and Hatra.[28]

The struggle resumed and intensified under Ardashir's successor Shapur I; he invaded Mesopotamia and captured Hatra, a buffer state which had recently shifted its loyalty but his forces were defeated at a battle near Resaena in 243; Carrhae and Nisibis were retaken by the Romans.[31] Encouraged by this success, the emperor Gordian III advanced down the Euphrates but was defeated near Ctesiphon in the Battle of Misiche in 244. Gordian either died in the battle or was murdered by his own men; Philip became emperor, and paid 500,000 denarii to the Persians in a hastily negotiated peace settlement.[32]

With the Roman Empire debilitated by Germanic invasions and a series of short-term emperors, Shapur I soon resumed his attacks. In the early 250s, Philip was involved in a struggle over the control of Armenia; Shapur conquered Armenia and killed its king, defeated the Romans at the Battle of Barbalissos in 253, then probably took and plundered Antioch.[33] Between 258 and 260, Shapur captured Emperor Valerian after defeating his army at the Battle of Edessa. He advanced into Anatolia but was defeated by Roman forces there; attacks from Odaenathus of Palmyra forced the Persians to withdraw from Roman territory, surrendering Cappadocia and Antioch.[34]

In 275 and 282 Aurelian and Probus respectively planned to invade Persia, but they were both murdered before they were able to fulfil their plans.[35] In 283 the emperor Carus launched a successful invasion of Persia, sacking its capital, Ctesiphon; they would probably have extended their conquests if Carus had not died in December of the same year.[36] His successor Numerian was forced by his own army to retreat, being frightened by the belief that Carus had died of a strike of lightning.[37]

After a brief period of peace during Diocletian's early reign, Narseh renewed hostilities with the Romans invading Armenia, and defeated Galerius not far from Carrhae in 296 or 297.[38] However, in 298 Galerius defeated Narseh at the Battle of Satala, sacked the capital Ctesiphon and captured the Persian treasury and royal harem. The resulting peace settlement gave the Romans control of the area between the Tigris and the Greater Zab. The Roman victory was the most decisive for many decades: all the territories that had been lost, all the debatable lands, and control of Armenia lay in Roman hands.[39] Many cities east of the Tigris were given to the Romans including Tigranokert, Saird, Martyropolis, Balalesa, Moxos, Daudia, and Arzan. Also, control of Armenia was given to the Romans.[40]

The arrangements of 299 lasted until the mid-330s, when Shapur II began a series of offensives against the Romans. Despite a string of victories in battle, culminating in the overthrow of a Roman army led by Constantius II at Singara (348), his campaigns achieved little lasting effect: three Persian sieges of Nisibis, in that age known as the key to Mesopotamia,[41] were repulsed, and while Shapur succeeded in 359 in successfully laying siege to Amida and taking Singara, both cities were soon regained by the Romans.[42] Following a lull during the 350s while Shapur fought off nomad attacks on Persia's eastern and then northern frontiers, he launched a new campaign in 359 with the aid of the eastern tribes which he had meanwhile defeated, and after a difficult siege again captured Amida (359). In the following year he captured Bezabde and Singara, and repelled the counter-attack of Constantius II.[43] But the enormous cost of these victories weakened him, and he was soon deserted by his barbarian allies, leaving him vulnerable to the major offensive in 363 by the Roman Emperor Julian, who advanced down the Euphrates to Ctesiphon[44] with a major army. Despite a tactical victory[45][46] at the Battle of Ctesiphon before the walls Julian was unable to take the Persian capital or advance any farther and retreated along the Tigris. Harried by the Persians, Julian was killed in the Battle of Samarra, during a difficult retreat along the Tigris. With the Roman army stuck on the eastern bank of the Euphrates, Julian's successor Jovian made peace, agreeing to major concessions in exchange for safe passage out of Sasanian territory. The Romans surrendered their former possessions east of the Tigris, as well as Nisibis and Singara, and Shapur soon conquered Armenia, abandoned by the Romans.[47]

In 383 or 384 Armenia again became a bone of contention between the Roman and the Sasanian empires, but hostilities did not occur.[48] With both empires preoccupied by barbarian threats from the north, in 384 or 387, a definitive peace treaty was signed by Shapur III and Theodosius I dividing Armenia between the two states. Meanwhile, the northern territories of the Roman Empire were invaded by Germanic, Alanic, and Hunnic peoples, while Persia's northern borders were threatened first by a number of Hunnic peoples and then by the Hephthalites. With both empires preoccupied by these threats, a largely peaceful period followed, interrupted only by two brief wars, the first in 421–422 after Bahram V persecuted high-ranking Persian officials who had converted to Christianity, and the second in 440, when Yazdegerd II raided Roman Armenia.[49]

Byzantine–Sasanian wars

[edit]Anastasian War

[edit]

The Anastasian War ended the longest period of peace the two powers ever enjoyed. War broke out when the Persian King Kavadh I attempted to gain financial support by force from the Byzantine Emperor Anastasius I; the emperor refused to provide it and the Persian king tried to take it by force.[50] In 502 AD, he quickly captured the unprepared city of Theodosiopolis[51] and besieged the fortress-city of Amida through the autumn and winter (502–503). The siege of the fortress-city proved to be far more difficult than Kavadh expected; the defenders repelled the Persian assaults for three months before they were beaten.[52] In 503, the Romans attempted an ultimately unsuccessful siege of the Persian-held Amida while Kavadh invaded Osroene and laid siege to Edessa with the same results.[53] Finally in 504, the Romans gained control through the renewed investment of Amida, which led to the fall of the city. That year an armistice was reached as a result of an invasion of Armenia by the Huns from the Caucasus. Although the two powers negotiated, it was not until November 506 that a treaty was agreed to.[54] In 505, Anastasius ordered the building of a great fortified city at Dara. At the same time, the dilapidated fortifications were also upgraded at Edessa, Batnae and Amida.[55] Although no further large-scale conflict took place during Anastasius' reign, tensions continued, especially while work proceeded at Dara. This was because the construction of new fortifications in the border zone by either empire had been prohibited by a treaty concluded some decades earlier. Anastasius pursued the project despite Persian objections, and the walls were completed by 507–508.[56]

Finally in 504, the Romans gained the upper hand with the renewed investment of Amida, leading to the hand-over of the city. That year an armistice was agreed to as a result of an invasion of Armenia by the Huns from the Caucasus. Negotiations between the two powers took place, but such was their distrust that in 506 the Romans, suspecting treachery, seized the Persian officials. Once released, the Persians preferred to stay in Nisibis.[57] In November 506, a treaty was finally agreed upon, but little is known of what the terms of the treaty were. Procopius states that peace was agreed for seven years,[58] and it is likely that some payments were made to the Persians.[59]

In 505 Anastasius ordered the building of a great fortified city at Dara. The dilapidated fortifications were also upgraded at Edessa, Batnac and Amida.[60] Although no further large-scale conflict took place during Anastasius' reign, tensions continued, especially while work continued at Dara. This construction project was to become a key component of the Roman defenses, and also a lasting source of controversy with the Persians, who complained that it violated the treaty of 422, by which both empires had agreed not to establish new fortifications in the frontier zone. Anastasius, however, pursued the project, and the walls were completed by 507/508.[57]

Iberian War

[edit]

In 524–525 AD, Kavadh proposed that Justin I adopt his son, Khosrau, but the negotiations soon broke down. The proposal was initially greeted with enthusiasm by the Roman emperor and his nephew, Justinian, but Justin's quaestor, Proculus, opposed the move.[61] Tensions between the two powers were further heightened by the defection of the Iberian king Gourgen to the Romans: in 524/525 the Iberians rose in revolt against Persia, following the example of the neighboring Christian kingdom of Lazica, and the Romans recruited Huns from the north of the Caucasus to assist them.[62] To start with, the two sides preferred to wage war by proxy, through Arab allies in the south and Huns in the north.[63] Overt Roman–Persian fighting had broken out in the Transcaucasus region and upper Mesopotamia by 526–527.[64] The early years of war favored the Persians: by 527, the Iberian revolt had been crushed, a Roman offensive against Nisibis and Thebetha in that year was unsuccessful, and forces trying to fortify Thannuris and Melabasa were prevented from doing so by Persian attacks.[65] Attempting to remedy the deficiencies revealed by these Persian successes, the new Roman emperor, Justinian I, reorganized the eastern armies.[66] In 528 Belisarius tried unsuccessfully to protect Roman workers in Thannuris, undertaking the construction of a fort right on the frontier.[67] Damaging raids on Syria by the Lakhmids in 529 encouraged Justinian to strengthen his own Arab allies, helping the Ghassanid leader Al-Harith ibn Jabalah turn a loose coalition into a coherent kingdom.[citation needed]

In 530 a major Persian offensive in Mesopotamia was defeated by Roman forces under Belisarius at Dara, while a second Persian thrust in the Caucasus was defeated by Sittas at Satala. Belisarius was defeated by Persian and Lakhmid forces at the Battle of Callinicum in 531, which resulted in his dismissal. In the same year the Romans gained some forts in Armenia, while the Persians had captured two forts in eastern Lazica.[68] Immediately after the Battle of Callinicum, unsuccessful negotiations between Justinian's envoy, Hermogenes, and Kavadh took place.[69] A Persian siege of Martyropolis was interrupted by Kavadh I's death and the new Persian king, Khosrau I, re-opened talks in spring 532 and finally signed the Perpetual Peace in September 532, which lasted less than eight years. Both powers agreed to return all occupied territories, and the Romans agreed to make a one-time payment of 110 centenaria (11,000 lb of gold). The Romans recovered the Lazic forts, Iberia remained in Persian hands, and the Iberians who had left their country were given the choice of remaining in Roman territory or returning to their native land.[70]

Lazic War

[edit]

| Roman (Byzantine) Empire Acquisitions by Justinian | Sasanian Empire Sasanian vassals |

The Persians broke the "Treaty of Eternal Peace" in 540 AD, probably in response to the Roman reconquest of much of the former western empire, which had been facilitated by the cessation of war in the East. Khosrau I invaded and devastated Syria, extorting large sums of money from the cities of Syria and Mesopotamia, and systematically looting other cities including Antioch, whose population was deported to Persian territory.[71] The successful campaigns of Belisarius in the west encouraged the Persians to return to war, both taking advantage of Roman preoccupation elsewhere and seeking to check the expansion of Roman territory and resources.[72] In 539 the resumption of hostilities was foreshadowed by a Lakhmid raid led by al-Mundhir IV, which was defeated by the Ghassanids under al-Harith ibn Jabalah. In 540, the Persians broke the "Treaty of Eternal Peace" and Khosrau I invaded Syria, destroying the city of Antioch and deporting its population to Weh Antiok Khosrow in Persia; as he withdrew, he extorted large sums of money from the cities of Syria and Mesopotamia and systematically looted the key cities. In 541 he invaded Lazica in the north.[73] Belisarius was quickly recalled by Justinian to the East to deal with the Persian threat, while the Ostrogoths in Italy, who were in touch with the Persian King, launched a counter-attack under Totila. Belisarius took the field and waged an inconclusive campaign against Nisibis in 541. In the same year, Lazica switched its allegiance to Persia and Khosrau led an army to secure the kingdom. In 542 Khosrau launched another offensive in Mesopotamia and unsuccessfully attempted to capture Sergiopolis.[74] He soon withdrew in the face of an army under Belisarius, en route sacking the city of Callinicum.[75] Attacks on a number of Roman cities were repulsed and the Persian general Mihr-Mihroe was defeated and captured at Dara by John Troglita.[76] An invasion of Armenia in 543 by the Roman forces in the East, numbering 30,000, against the capital of Persian Armenia, Dvin, was defeated by a meticulous ambush by a small Persian force at Anglon. Khosrau besieged Edessa in 544 without success and was eventually bought off by the defenders.[77] The Edessenes paid five centenaria to Khosrau, and the Persians departed after nearly two months.[77] In the wake of the Persian retreat, two Roman envoys, the newly appointed magister militum, Constantinus, and Sergius proceeded to Ctesiphon to arrange a truce with Khosrau.[78][79] (The war dragged on under other generals and was to some extent hindered by the Plague of Justinian, because of which Khosrau temporarily withdrew from Roman territory)[80] A five-year truce was agreed to in 545, secured by Roman payments to the Persians.[81]

Early in 548, King Gubazes of Lazica, having found Persian protection oppressive, asked Justinian to restore the Roman protectorate. The emperor seized the chance, and in 548–549 combined Roman and Lazic forces with the magister militum of Armenia Dagistheus won a series of victories against Persian armies, although they failed to take the key garrison of Petra (present-day Tsikhisdziri).[82] In 551 AD, general Bessas who replaced Dagistheus put Abasgia and the rest of Lazica under control, and finally subjected Petra after fierce fighting, demolishing its fortifications.[83] In the same year a Persian offensive led by Mihr-Mihroe occupied eastern Lazica.[84] The truce that had been established in 545 was renewed outside Lazica for a further five years on condition that the Romans pay 2,000 lb of gold each year.[85] The Romans failed to completely expel the Sasanians from Lazica, and in 554 AD Mihr-Mihroe launched a new attack, dislodging a newly arrived Byzantine army from Telephis.[86] In Lazica the war dragged on inconclusively for several years, with neither side able to make any major gains. Khosrau, who now had to deal with the White Huns, renewed the truce in 557, this time without excluding Lazica; negotiations continued for a definite peace treaty.[87] Finally, in 562, the envoys of Justinian and Khosrau – Peter the Patrician and Izedh Gushnap – put together the Fifty-Year Peace Treaty. The Persians agreed to evacuate Lazica and received an annual subsidy of 30,000 nomismata (solidi).[88] Both sides agreed not to build new fortifications near the frontier and to ease restrictions on diplomacy and trade.[89]

War for the Caucasus

[edit]War broke again shortly after Armenia and Iberia revolted against Sasanian rule in 571 AD, following clashes involving Roman and Persian proxies in Yemen (between the Axumites and the Himyarites) and the Syrian desert, and after Roman negotiations for an alliance with the Western Turkic Khaganate against Persia.[90] Justin II brought Armenia under his protection, while Roman troops under Justin's cousin Marcian raided Arzanene and invaded Persian Mesopotamia, where they defeated local forces.[91] Marcian's sudden dismissal and the arrival of troops under Khosrau resulted in a ravaging of Syria, the failure of the Roman siege of Nisibis and the fall of Dara.[92] At a cost of 45,000 solidi, a one-year truce in Mesopotamia (eventually extended to five years)[93] was arranged, but in the Caucasus and on the desert frontiers the war continued.[94] In 575, Khosrau I attempted to combine aggression in Armenia with discussion of a permanent peace. He invaded Anatolia and sacked Sebasteia, but to take Theodosiopolis, and after a clash near Melitene the army suffered heavy losses while fleeing across the Euphrates under Roman attack and the Persian royal baggage was captured.[95]

The Romans exploited Persian disarray as general Justinian invaded deep into Persian territory and raided Atropatene.[95] Khosrau sought peace but abandoned this initiative when Persian confidence revived after Tamkhusro won a victory in Armenia, where Roman actions had alienated local inhabitants.[96] In the spring of 578 the war in Mesopotamia resumed with Persian raids on Roman territory. The Roman general Maurice retaliated by raiding Persian Mesopotamia, capturing the stronghold of Aphumon, and sacking Singara. Khosrau again opened peace negotiations but he died early in 579 and his successor Hormizd IV (r. 578–590) preferred to continue the war.[97]

In 580, Hormizd IV abolished the Caucasian Iberian monarchy, and turned Iberia into a Persian province ruled by a marzpan (governor).[98][99] During the 580s, the war continued inconclusively with victories on both sides. In 582, Maurice won a battle at Constantia over Adarmahan and Tamkhusro, who was killed, but the Roman general did not follow up his victory; he had to hurry to Constantinople to pursue his imperial ambitions.[100] Another Roman victory at Solachon in 586 likewise failed to break the stalemate.[101]

The Persians captured Martyropolis through treachery in 589, but that year the stalemate was shattered when the Persian general Bahram Chobin, having been dismissed and humiliated by Hormizd IV, raised a rebellion. Hormizd was overthrown in a palace coup in 590 and replaced by his son Khosrau II, but Bahram pressed on with his revolt regardless and the defeated Khosrau was soon forced to flee for safety to Roman territory, while Bahram took the throne as Bahram VI. With support from Maurice, Khosrau raised a rebellion against Bahram, and in 591 the combined forces of his supporters and the Romans defeated Bahram at the Battle of Blarathon and restored Khosrau II to power. In exchange for their help, Khosrau not only returned Dara and Martyropolis but also agreed to cede the western half of Iberia and more than half of Persian Armenia to the Romans.[102]

Climax

[edit]In 602 the Roman army campaigning in the Balkans mutinied under the leadership of Phocas, who succeeded in seizing the throne and then killed Maurice and his family. Khosrau II used the murder of his benefactor as a pretext for war and reconquer the Roman province of Mesopotamia.[103] In the early years of the war the Persians enjoyed overwhelming and unprecedented success. They were aided by Khosrau's use of a pretender claiming to be Maurice's son, and by the revolt against Phocas led by the Roman general Narses.[104] In 603 Khosrau defeated and killed the Roman general Germanus in Mesopotamia and laid siege to Dara. Despite the arrival of Roman reinforcements from Europe, he won another victory in 604, while Dara fell after a nine-month siege. Over the following years the Persians gradually overcame the fortress cities of Mesopotamia by siege, one after another.[105] At the same time they won a string of victories in Armenia and systematically subdued the Roman garrisons in the Caucasus.[106]

Phocas' brutal repression sparked a succession crisis that ensued as the general Heraclius sent his nephew Nicetas to attack Egypt, enabling his son Heraclius the younger to claim the throne in 610. Phocas, an unpopular ruler who is invariably described in Byzantine sources as a "tyrant", was eventually deposed by Heraclius, having sailed from Carthage.[107] Around the same time, the Persians completed their conquest of Mesopotamia and the Caucasus, and in 611 they overran Syria and entered Anatolia, occupying Caesarea.[108] Having expelled the Persians from Anatolia in 612, Heraclius launched a major counter-offensive in Syria in 613. He was decisively defeated outside Antioch by Shahrbaraz and Shahin, and the Roman position collapsed.[109]

Over the following decade the Persians were able to conquer Palestine, Egypt,[110] Rhodes and several other islands in the eastern Aegean, as well as to devastate Anatolia.[111][112][113][114] Meanwhile, the Avars and Slavs took advantage of the situation to overrun the Balkans, bringing the Roman Empire to the brink of destruction.[115]

During these years, Heraclius strove to rebuild his army, slashing non-military expenditures, devaluing the currency and melting down Church plate, with the backing of Patriarch Sergius, to raise the necessary funds to continue the war.[116] In 622, Heraclius left Constantinople, entrusting the city to Sergius and general Bonus as regents of his son. He assembled his forces in Asia Minor and, after conducting exercises to revive their morale, he launched a new counter-offensive, which took on the character of a holy war.[117] In the Caucasus he inflicted a defeat on an army led by a Persian-allied Arab chief and then won a victory over the Persians under Shahrbaraz.[118] Following a lull in 623, while he negotiated a truce with the Avars, Heraclius resumed his campaigns in the East in 624 and routed an army led by Khosrau at Ganzak in Atropatene.[119] In 625 he defeated the generals Shahrbaraz, Shahin and Shahraplakan in Armenia, and in a surprise attack that winter he stormed Shahrbaraz's headquarters and attacked his troops in their winter billets.[120] Supported by a Persian army commanded by Shahrbaraz, together with the Avars and Slavs, the three unsuccessfully besieged Constantinople in 626,[121] while a second Persian army under Shahin suffered another crushing defeat at the hands of Heraclius' brother Theodore.[122]

Meanwhile, Heraclius formed an alliance with the Western Turkic Khaganate, who took advantage of the dwindling strength of the Persians to ravage their territories in the Caucasus.[123] Late in 627, Heraclius launched a winter offensive into Mesopotamia, where, despite the desertion of the Turkish contingent that had accompanied him, he defeated the Persians at the Battle of Nineveh. Continuing south along the Tigris, he sacked Khosrau's great palace at Dastagird and was prevented from attacking Ctesiphon only by the destruction of the bridges on the Nahrawan Canal. Khosrau was overthrown and killed in a coup led by his son Kavadh II, who at once sued for peace, agreeing to withdraw from all occupied territories.[124] Heraclius restored the True Cross to Jerusalem with a majestic ceremony in 629.[125]

Aftermath

[edit]Разрушительное воздействие этой последней войны в сочетании с совокупным эффектом столетия почти непрерывного конфликта нанесло ущерб обеим империям. Когда Кавад II умер всего через несколько месяцев после вступления на престол, Персия погрузилась в несколько лет династических беспорядков и гражданской войны. Сасаниды были еще более ослаблены экономическим спадом, высокими налогами в результате кампаний Хосрова II, религиозными волнениями и растущей властью провинциальных землевладельцев . [126] The Byzantine Empire was also severely affected, with its financial reserves exhausted by the war and the Balkans now largely in the hands of the Slavs.[127] Кроме того, Анатолия была опустошена неоднократными персидскими вторжениями; Власть Империи над недавно восстановленными территориями на Кавказе, в Сирии, Месопотамии, Палестине и Египте была ослаблена многолетней персидской оккупацией. [128]

Ни одной из империй не было предоставлено никакого шанса на восстановление, поскольку через несколько лет они подверглись нападению арабов ( недавно объединенных исламом), которое, по мнению Говарда-Джонстона, «можно сравнить только с человеческим цунами». [129] По словам Джорджа Лиски, «ненужно затянувшийся византийско-персидский конфликт открыл путь исламу». [130] Сасанидская империя быстро поддалась этим атакам и была полностью завоевана. истощенной Римской империей Во время византийско-арабских войн недавно восстановленные восточные и южные провинции Сирии , Армении , Египта и Северной Африки также были потеряны, в результате чего Империя превратилась в территориальный осколок, состоящий из Анатолии и разбросанных островов и плацдармов на Балканах. и Италия. [131] Эти оставшиеся земли были полностью обеднены частыми нападениями, что ознаменовало переход от классической городской цивилизации к более сельской, средневековой форме общества. Однако, в отличие от Персии, Римская империя в конечном итоге пережила арабское нападение, удержав оставшиеся территории и решительно отбив две арабские осады своей столицы в 674–678 и 717–718 годах . [132] Римская империя также потеряла свои территории на Крите и в южной Италии из-за арабов в ходе более поздних конфликтов, хотя в конечном итоге и они были возвращены . [ нужна ссылка ]

Стратегии и военная тактика

[ редактировать ]| Хронология Римско-персидские войны |

|---|

Когда Римская и Парфянская империи впервые столкнулись в I веке до нашей эры, казалось, что Парфия имеет потенциал расширить свои границы до Эгейского и Средиземноморья. Однако римляне отразили великое вторжение Пакора и Лабиена в Сирию и Анатолию и постепенно смогли воспользоваться слабостями парфянской военной системы, которая, по мнению Джорджа Роулинсона , была приспособлена для национальной обороны, но малопригодна для завоевание. С другой стороны, римляне, , постоянно изменяли и развивали свою « большую стратегию » начиная со времен Траяна и ко времени Пакора были в состоянии перейти в наступление против парфян. [133] Как и сасаниды конца III и IV веков, парфяне обычно избегали какой-либо устойчивой защиты Месопотамии от римлян. Однако иранское плато так и не пало, поскольку римские экспедиции всегда исчерпали свой наступательный импульс к тому времени, когда достигли нижней Месопотамии, а их протяженная линия коммуникаций через недостаточно умиротворенную территорию подвергала их восстаниям и контратакам. [134]

Начиная с 4 века нашей эры, сасаниды набрали силу и взяли на себя роль агрессора. Они считали, что большая часть земель, присоединенных к Римской империи в парфянские и ранние сасанидские времена, по праву принадлежит персидской сфере. [135] Эверетт Уилер утверждает, что «Сасаниды, более централизованные в административном отношении, чем парфяне, формально организовали защиту своей территории, хотя у них не было постоянной армии до Хосрова I ». [134] В целом римляне считали сасанидов более серьезной угрозой, чем парфяне, а сасаниды считали Римскую империю врагом по преимуществу. [136] Война по доверенности использовалась как византийцами, так и сасанидами как альтернатива прямой конфронтации, особенно через арабские королевства на юге и кочевые народы на севере.

В военном отношении сасаниды продолжали сильную зависимость парфян от кавалерийских войск: комбинации конных лучников и катафрактов ; последние представляли собой тяжелую бронированную кавалерию, предоставленную аристократией. Они добавили отряд боевых слонов, добытых из долины Инда , но качество их пехоты уступало римлянам. [137] Объединенные силы конных лучников и тяжелой кавалерии нанесли несколько поражений римским пехотинцам, в том числе под предводительством Красса в 53 г. до н.э. [138] Марк Антоний в 36 г. до н.э. и Валериан в 260 г. н.э. Парфянская тактика постепенно стала стандартным методом ведения войны в Римской империи. [139] катафрактариев в и клибанариев ; состав римской армии были введены отряды [140] в результате значение тяжеловооруженной кавалерии возросло как в римской, так и в персидской армиях после III века нашей эры и до конца войн. [135] Римская армия также постепенно включала в себя конных лучников ( Equites Sagittarii ), и к 5 веку нашей эры они уже не были наемным подразделением и немного превосходили персидских в индивидуальном порядке, как утверждает Прокопий; однако персидские конные лучники в целом всегда оставались проблемой для римлян, что говорит о том, что римских конных лучников было меньше по численности. [141] Ко времени Хосрова I появились составные кавалеристы ( асвараны ), владевшие как стрельбой из лука, так и владением копьем. [142]

С другой стороны, персы переняли боевые машины у римлян. [2] Римляне достигли и сохранили высокий уровень сложности в осадной войне и разработали целый ряд осадных машин . С другой стороны, парфяне не умели вести осаду; их кавалерийские армии больше подходили для тактики «нападай и беги» , которая уничтожила осадный обоз Антония в 36 г. до н. э. Ситуация изменилась с приходом к власти Сасанидов, когда Рим столкнулся с врагом, столь же способным вести осадную войну. Сасаниды в основном использовали насыпи, тараны, мины и в меньшей степени осадные башни, артиллерию, [143] [144] а также химическое оружие , например в Дура-Европос (256) [145] [146] [147] и Петра (550–551) . [144] Использование сложного торсионного снаряжения было редким, поскольку традиционные персидские навыки стрельбы из лука сводили на нет их очевидные преимущества. [148] Слонов использовали (например, в качестве осадных башен) там, где местность была неблагоприятна для машин. [149] Недавние оценки, сравнивающие сасанидов и парфян, подтвердили превосходство сасанидской осадной техники, военной инженерии и организации. [150] а также умение строить оборонительные сооружения. [151]

К началу правления Сасанидов между империями существовал ряд буферных государств. Со временем они были поглощены центральным государством, и к 7 веку последнее буферное государство, арабские Лахмиды , было присоединено к Сасанидской империи. Фрай отмечает, что в III веке нашей эры такие государства-клиенты играли важную роль в римско-сасанидских отношениях, но обе империи постепенно заменили их организованной системой обороны, управляемой центральным правительством и основанной на линии укреплений (липы ) и укрепленные приграничные города, такие как Дара . [152] К концу I века нашей эры Рим организовал защиту своих восточных границ с помощью системы лип , которая продолжалась до мусульманских завоеваний VII века после улучшений Диоклетиана . [153] Как и римляне, сасаниды строили оборонительные стены напротив территории своих противников. По мнению Р. Н. Фрая, именно при Шапуре II персидская система была расширена, вероятно, в подражание построению Диоклетианом лип сирийских и месопотамских границ Римской империи. [154] Римские и персидские пограничные отряды были известны как лимитаны и марзобаны соответственно. [ нужна ссылка ]

Сасаниды и, в меньшей степени, парфяне в качестве инструмента политики практиковали массовые депортации в новые города не только военнопленных (например, в битве при Эдессе ), но и захваченных ими городов, таких как как депортация жителей Антиохии в Ве Антиок Хосров , что привело к упадку первого. Эти депортации также положили начало распространению христианства в Персии . [155]

Персы, похоже, не хотели прибегать к военно-морским действиям. [156] . произошли небольшие сасанидские военно-морские действия В 620–623 гг , а единственная крупная византийского флота операция произошла во время осады Константинополя (626 г.) . [ нужна ссылка ]

Оценки

[ редактировать ]Римско-персидские войны были охарактеризованы как «бесполезные» и слишком «удручающие и утомительные, чтобы обдумывать их». [157] пророчески Кассий Дион отметил их «бесконечный цикл вооруженных столкновений» и заметил, что «сами факты показывают, что завоевание [Северуса] было для нас источником постоянных войн и больших затрат. Ибо оно дает очень мало и тратит огромные суммы; и теперь, когда мы обратились к народам, которые являются соседями мидян и парфян, а не к нам самим, мы всегда, можно сказать, сражаемся в битвах с этими народами». [158] В ходе длинной серии войн между двумя державами граница в верхней Месопотамии оставалась более или менее постоянной. Историки отмечают, что стабильность границы на протяжении веков поразительна, хотя Нисибис, Сингара, Дара и другие города верхней Месопотамии время от времени переходили из рук в руки, и обладание этими приграничными городами давало одной империи торговое преимущество перед другой. . Как утверждает Фрай: [152]

Складывается впечатление, что кровь, пролитая в войне между двумя государствами, принесла той или иной стороне столь же мало реальной выгоды, как и несколько метров земли, завоеванные ужасной ценой в позиционной войне Первой мировой войны.

| «Как может быть хорошо отдавать самое дорогое свое имущество чужеземцу, варвару, правителю злейшего врага своего, тому, чья добросовестность и чувство справедливости не были испытаны, и, более того, тому, кто принадлежал к чужая и языческая вера?» |

| Агафий ( «Истории» , 4.26.6, перевод Аверила Кэмерона) о персах, суждение, типичное для римского взгляда. [159] |

Обе стороны пытались оправдать свои военные цели как активными, так и ответными способами. Согласно письму Тансара и мусульманского писателя Аль-Таалиби , вторжения Ардашира I и Пакора I на римские территории, соответственно, должны были отомстить за завоевание Александром Македонским Персии , которое, как считалось, было причиной последовавшего за этим беспорядка в Иране; [160] [161] этому соответствует понятие imitatio Alexandri, которое лелеяли римские императоры Каракалла, Александр Север, [162] и Джулиан. [163] Римские источники раскрывают давние предрассудки в отношении обычаев, религиозных структур, языков и форм правления восточных держав. Джон Ф. Халдон подчеркивает, что «хотя конфликты между Персией и Восточным Римом вращались вокруг вопросов стратегического контроля над восточной границей, тем не менее, всегда присутствовал религиозно-идеологический элемент». Со времен Константина римские императоры считали себя защитниками христиан Персии. [164] Такое отношение вызывало сильные подозрения в лояльности христиан, живущих в Сасанидском Иране, и часто приводило к римско-персидской напряженности или даже военной конфронтации. [165] (например, в 421–422 гг .). Характерной чертой заключительной фазы конфликта, когда то, что началось в 611–612 годах как набег, вскоре превратилось в завоевательную войну, было преобладание Креста как символа имперской победы и сильного религиозного элемента. в римской имперской пропаганде; Сам Ираклий считал Хосрова врагом Бога, а авторы VI и VII веков были яростно враждебны Персии. [166] [167]

Историография

[ редактировать ]

Источники по истории Парфии и войн с Римом скудны и разбросаны. Парфяне следовали традиции Ахеменидов и предпочитали устную историографию , которая гарантировала искажение их истории после их поражения. Таким образом, основными источниками этого периода являются римские ( Тацит , Марий Максим и Юстин ) и греческие историки ( Иродиан , Кассий Дион и Плутарх ). 13-я книга « Сивиллинских оракулов» повествует о последствиях римско-персидских войн в Сирии, начиная с правления Гордиана III и заканчивая господством в провинции Одената Пальмирского. С окончанием записей Иродиана все современные хронологические повествования римской истории утеряны, вплоть до повествований Лактанция и Евсевия в начале IV века, оба с христианской точки зрения. [168]

Основные источники раннего сасанидского периода не являются современными. них наиболее важными являются греки Агафий и Малалас , персидские мусульмане ат-Табари и Фирдоуси , армянский Агафангелос и сирийские Хроники Эдессы Среди и Арбелы , большинство из которых зависели от позднесасанидских источников, особенно Хвадай-Намага . « История Августа» не является ни современной, ни достоверной, но она является основным повествовательным источником Севера и Каруса. Трехъязычные (среднеперсидские, парфянские, греческие) надписи Шапура являются первоисточниками. [169] Однако это были отдельные попытки приблизиться к письменной историографии, и к концу IV века нашей эры сасаниды отказались даже от практики вырезания наскальных рельефов и оставления коротких надписей. [170]

Для периода между 353 и 378 годами имеется источник очевидца основных событий на восточной границе в Res Gestae Аммиана Марцеллина . Для событий, охватывающих период между IV и VI веками, особую ценность представляют сочинения Созомена , Зосима , Приска и Зонары . [171] Единственным наиболее важным источником информации о персидских войнах Юстиниана до 553 года является Прокопий . Его продолжатели Агафий и Менандр Протектор также сообщают немало важных подробностей. Теофилакт Симокатта является основным источником о правлении Мориса. [172] в то время как Феофан , Chronicon Paschale и стихи Георгия Писидийского являются полезными источниками о последней римско-персидской войне. Помимо византийских источников, два армянских историка, Себеос и Мовсес , вносят свой вклад в связное повествование о войне Ираклия и рассматриваются Говардом-Джонстоном как «наиболее важные из сохранившихся немусульманских источников». [173]

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]Первоисточники

[ редактировать ]- Агафий , Истории . Книга 4.

- Аврелий Виктор , Liber de Caesaribus . Оригинальный текст см. в Латинской библиотеке. [174]

- Кассий Дион , Римская история . Книга LXXX. Перевод Эрнеста Кэри. [175]

- Пасхальный хроникон . Посмотреть оригинальный текст в Google Книгах. [176]

- Корипп , Йоханнис [177] Книга И.

- Евтропий , Сокращение римской истории . Книга IX. Перевод преподобного Джона Селби Уотсона. [178]

- Иродиан , История Римской империи . Книга VI. Перевод Эдварда К. Эколса. [179]

- Иоанн Епифания. История [180]

- Иисус Столпник , Летопись . Перевод Уильяма Райта. [181]

- Джастин , Historiarum Philippicarum . Книга XLI. Оригинальный текст см. в Латинской библиотеке. [182]

- Лактанций , О смерти гонимых . Оригинальный текст см. в Латинской библиотеке. [183]

Плутарх , Антоний . Перевод Джона Драйдена .

Плутарх , Антоний . Перевод Джона Драйдена .  Плутарх , Красс . Перевод Джона Драйдена .

Плутарх , Красс . Перевод Джона Драйдена .  Плутарх , Силла . Перевод Джона Драйдена .

Плутарх , Силла . Перевод Джона Драйдена . - Прокопий , История войн , Книга II. Перевод Х.Б. Дьюинга .

- Сивиллинские оракулы . Книга XIII. Перевод Милтона С. Терри .

- Созомен , Церковная история , книга II. Перевод Честера Д. Хартранфта , Филипа Шаффа и Генри Уэйса. [184]

Тацит , Анналы . Перевод по мотивам Альфреда Джона Черча и Уильяма Джексона Бродрибба.

Тацит , Анналы . Перевод по мотивам Альфреда Джона Черча и Уильяма Джексона Бродрибба. - Феофан Исповедник Хроника Omnia См. исходный текст в католическом документе . (PDF) [185]

- Феофилакт Симокатта . История . Книги I и V. Перевод Майкла и Мэри Уитби. (PDF) [186]

- Вегетиус . Эпитома Рей Милитарис . Книга III. Оригинальный текст см. в Латинской библиотеке. [187]

- Захария Ритор история Церковная

Вторичные источники

[ редактировать ]- Болл, Уорик (2000). Рим на Востоке: трансформация империи . Рутледж. ISBN 0-415-24357-2 .

- Барнс, Т.Д. (1985). «Константин и христиане Персии». Журнал римских исследований . 75 . Журнал римских исследований, Vol. 75: 126–136. дои : 10.2307/300656 . ISSN 0013-8266 . JSTOR 300656 . S2CID 162744718 .

- Барнетт, Гленн (2017). Подражание Александру: как наследие Александра Великого подпитывало войны Рима с Персией (Первое изд.). Великобритания: Военные с пером и мечом. п. 232. ИСБН 978-1526703002 .

- Бэйнс, Норман Х. (1912). «Восстановление Креста в Иерусалиме» . Английский исторический обзор . 27 (106): 287–299. doi : 10.1093/ehr/XXVII.CVI.287 . ISSN 0013-8266 .

- Бивар, ADH (1983). «Политическая история Ирана при Аршакидах» . В Яршатере, Эхсан (ред.). Кембриджская история Ирана, том 3 (1): Селевкидский, парфянский и сасанидский периоды . Кембридж: Издательство Кембриджского университета. стр. 21–99. ISBN 0-521-20092-Х .

- Блокли, Р.К. (1997). «Война и дипломатия». В Кэмероне, Аверил ; Гарнси, Питер (ред.). Кембриджская древняя история, том XIII: Поздняя империя, 337–425 гг . Кембридж: Издательство Кембриджского университета. стр. 411–436. ISBN 978-0-5213-0200-5 .

- Бойд, Келли (2004). «Византия». Энциклопедия историков и исторической письменности . Тейлор и Фрэнсис. ISBN 1-884964-33-8 .

- Бёрм, Хеннинг (2016). « Угроза или благословение? Сасаниды и Римская империя ». В Биндере, Карстен; Бёрм, Хеннинг; Лютер, Андреас (ред.): Диван. Исследования по истории и культуре Древнего Ближнего Востока и Восточного Средиземноморья . Веллем, 615–646.

- Бери, Джон Бэгналл (1923). История Поздней Римской империи . Макмиллан и Ко, ООО

- Кэмерон, Аверил (1979). «Образы власти: элиты и иконы в Византии конца шестого века». Прошлое и настоящее (84): 3–35. дои : 10.1093/прошлое/84.1.3 .

- Кэмпбелл, Брайан (2005). «Династия Северов». В Боумене, Алан К .; Кэмерон, Аверил ; Гарнси, Питер (ред.). Кембриджская древняя история, том XII: Кризис империи, 193–337 годы нашей эры . Кембридж: Издательство Кембриджского университета. ISBN 978-0-5213-0199-2 .

- Корнюэль, Крис. «Обзор сасанидско-персидской армии» . Томас Харлан . Проверено 23 сентября 2013 г.

- Де Блуа, Люк; ван дер Спек, Р.Дж. (2008). Знакомство с Древним миром . Рутледж. ISBN 978-1134047925 .

- Дигнас, Беате; Зима, Энгельберт (2007). Рим и Персия в поздней античности. Соседи и соперники . Издательство Кембриджского университета. ISBN 978-3-515-09052-0 .

- Доджон, Майкл Х.; Грейтрекс, Джеффри; Лью, Сэмюэл, Северная Каролина (2002). Римская восточная граница и персидские войны (Часть I, 226–363 гг. н.э.) . Рутледж. ISBN 0-415-00342-3 .

- Эванс, Джеймс Аллан. «Юстиниан (527–565 гг. н. э.)» . Интернет-энциклопедия римских императоров . Проверено 19 мая 2007 г.

- «Раскопки в Иране раскрывают тайну «Красной змеи» » . Наука Дейли . 26 февраля 2008 г. Новости науки . Проверено 3 июня 2008 г.

- Фосс, Клайв (1975). «Персы в Малой Азии и конец античности». Английский исторический обзор . 90 : 721–747. doi : 10.1093/ehr/XC.CCCLVII.721 .

- Фрай, Р.Н. (1993). «Политическая история Ирана при Сасанидах» . В Бейн Фишер, Уильям; Гершевич, Илья; Яршатер, Эхсан; Фрай, Р.Н.; Бойл, Дж.А.; Джексон, Питер; Локхарт, Лоуренс; Эйвери, Питер; Хэмбли, Гэвин; Мелвилл, Чарльз (ред.). Кембриджская история Ирана . Издательство Кембриджского университета. ISBN 0-521-20092-Х .

- Фрай, Р.Н. (2005). «Сасаниды». В Боумене, Алан К .; Кэмерон, Аверил ; Гарнси, Питер (ред.). Кембриджская древняя история, том XII: Кризис империи, 193–337 годы нашей эры . Кембридж: Издательство Кембриджского университета. ISBN 978-0-5213-0199-2 .

- Габба, Рено Э. (1965). «О взаимном влиянии парфянского и римского орденов». Материалы конференции по Терме: Персия и греко-римский мир . Национальная академия Линчеи.

- Гарнси, Питер; Саллер, Ричард П. (1987). «Римская империя». Римская империя: экономика, общество и культура . Издательство Калифорнийского университета. ISBN 0-520-06067-9 .

- Грабарь, Андре (1984). Византийское иконоборчество: археологические данные . Фламмарион. ISBN 2-08-081634-9 .

- Грейтрекс, Джеффри; Лью, Сэмюэл, Северная Каролина (2002). Римская восточная граница и персидские войны (часть II, 363–630 гг. н.э.) . Рутледж. ISBN 0-415-14687-9 .

- Халдон, Джон (1997). Византия в седьмом веке: трансформация культуры . Кембридж. ISBN 0-521-31917-Х .

- Хэлдон, Джон (1999). «Борьба за мир: отношение к войне в Византии». Война, государство и общество в византийском мире, 565–1204 гг . Лондон: UCL Press. ISBN 1-85728-495-Х .

- Ховард-Джонстон, Джеймс (2006). Восточный Рим, Сасанидская Персия и конец античности: историографические и исторические исследования . Издательство Эшгейт. ISBN 0-86078-992-6 .

- Исаак, Бенджамин Х. (1998). «Армия на позднеримском Востоке: Персидские войны и защита византийских провинций» . Ближний Восток под римским правлением: избранные статьи . Брилл. ISBN 90-04-10736-3 .

- Киа, Мехрдад (2016). Персидская империя: Историческая энциклопедия [2 тома]: Историческая энциклопедия . АВС-КЛИО. ISBN 978-1610693912 .

- Ленски, Ноэль (2002). Крах империи: Валент и Римское государство в четвертом веке нашей эры . Издательство Калифорнийского университета.

- Леви, AHT (1994). «Ктесифон». В Ринге, Труди; Салкин, Роберт М.; Ла Бода, Шэрон (ред.). Международный словарь исторических мест . Тейлор и Фрэнсис. ISBN 1-884964-03-6 .

- Лайтфут, CS (1990). «Парфянская война Траяна и перспектива четвертого века». Журнал римских исследований . 80 . Журнал римских исследований, Vol. 80: 115–116. дои : 10.2307/300283 . JSTOR 300283 . S2CID 162863957 .

- Лиска, Джордж (1998). «Проекция против прогноза: альтернативные варианты будущего и варианты». Расширяющийся реализм: историческое измерение мировой политики . Роуман и Литтлфилд. ISBN 0-8476-8680-9 .

- Лаут, Эндрю (2005). «Восточная империя в шестом веке». В Фуракре, Поль (ред.). Новая Кембриджская средневековая история, Том 1, около 500–700 гг . Кембридж: Издательство Кембриджского университета. ISBN 978-1-13905393-8 .

- Грейтрекс, Джеффри Б. (2005). «Византия и Восток в шестом веке». В Маасе, Майкл (ред.). Кембриджский спутник эпохи Юстиниана . Издательство Кембриджского университета. ISBN 0-521-81746-3 .

- Маккей, Кристофер С. (2004). «Цезарь и конец республиканского правительства». Древний Рим: Военная и политическая история . Издательство Кембриджского университета. ISBN 0-521-80918-5 .

- Макдонаф, SJ (2006). «Гонения в Сасанидской империи». В Дрейке, Гарольд Аллен (ред.). Насилие в поздней античности: представления и практики . Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 0-7546-5498-2 .

- Микаберидзе, Александр (2015). Исторический словарь Грузии (2-е изд.). Роуман и Литтлфилд. ISBN 978-1442241466 .

- Поттер, Дэвид Стоун (2004). «Крах Северанской империи». Римская империя в страхе: 180–395 гг . н.э. Рутледж. ISBN 0-415-10057-7 .

- Роулинсон, Джордж (2007) [1893]. Парфия . Козимо, Инк. ISBN 978-1-60206-136-1 .

- Рекаванди, Хамрид Омрани; Зауэр, Эберхард; Уилкинсон, Тони ; Ноканде, Джебраил. «Загадка Красной Змеи» . Мировая археология . текущий сайт Archaeology.co.uk . Проверено 27 мая 2008 г.

- Шахбази, А.Ш. (1996–2007). «Историография – доисламский период» . В Яршатере, Эхсан (ред.). Энциклопедия Ираника . Архивировано из оригинала 29 января 2009 г.

- Шахид, Ирфан (1984). «Арабо-римские отношения». Рим и арабы . Думбартон Оукс . ISBN 0-88402-115-7 .

- Шервин-Уайт, АН (1994). «Лукулл, Помпей и Восток». Ин- Крук, штат Джорджия ; Линтотт, Эндрю ; Роусон, Элизабет (ред.). Древняя история Кембриджа, том IX: Последняя эпоха Римской республики, 146–43 гг. До н.э. Кембридж: Издательство Кембриджского университета. ISBN 978-0-5212-5603-2 .

- Сикер, Мартин (2000). «Борьба за Евфратскую границу». Доисламский Ближний Восток . Издательская группа Гринвуд. ISBN 0-275-96890-1 .

- Сиднелл, Филип (2006). «Императорский Рим». Боевой конь, кавалерия в древнем мире . Международная издательская группа «Континуум». ISBN 1-85285-374-3 .

- Саузерн, Пэт (2001). «За восточными границами». Римская империя от Севера до Константина . Рутледж. ISBN 0-415-23943-5 .

- Совард, Уоррен; Уитби, Майкл; Уитби, Мэри. «Феофилакт Симокатта и персы» (PDF) . Сасаника. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 10 июня 2011 г. Проверено 27 апреля 2008 г.

- Бэкон, Пол (1984). «Иконоборчество и начало македонского Возрождения». Вария 1 (Пойкила Византина 4) . Рудольф Хальбельт. стр. 175–210.

- Суни, Рональд Григор (1994). Создание грузинской нации (второе изд.). Издательство Университета Индианы. ISBN 0-253-20915-3 .

- Тредголд, Уоррен (1997). История византийского государства и общества . Стэнфорд, Калифорния: Издательство Стэнфордского университета . ISBN 0-8047-2630-2 .

- Вербрюгген, Дж. Ф.; Уиллард, Самнер; Южный, RW (1997). «Историографические проблемы». Военное искусство в Западной Европе в средние века . Бойделл и Брюэр. ISBN 0-85115-570-7 .

- Вагстафф, Джон (1985). «Эллинистический Запад и Персидский Восток». Эволюция ландшафтов Ближнего Востока: очерк до 1840 года нашей эры . Роуман и Литтлфилд. ISBN 0-389-20577-Х .

- Уиллер, Эверетт (2007). «Армия и липы на Востоке». В Эрдкампе, Пол (ред.). Товарищ римской армии . Издательство Блэквелл. ISBN 978-1-4051-2153-8 .

- Уитби, Майкл (2000). «Армия, ок. 420–602». В Кэмероне, Аверил ; Уорд-Перкинс, Брайан ; Уитби, Майкл (ред.). Кембриджская древняя история, том XIV: Поздняя античность: империя и ее преемники, 425–600 гг. н.э. Кембридж: Издательство Кембриджского университета. ISBN 978-0-5213-2591-2 .

- Уитби, Майкл (2000). «Наследники Юстиниана». В Кэмероне, Аверил ; Уорд-Перкинс, Брайан ; Уитби, Майкл (ред.). Кембриджская древняя история, том XIV: Поздняя античность: империя и ее преемники, 425–600 гг. н.э. Кембридж: Издательство Кембриджского университета. ISBN 978-0-5213-2591-2 .

- Уильямс, Стивен; Фрилл, Джеральд (1999). «Императорское богатство и расходы». Рим, который не пал: выживание Востока в пятом веке . Рутледж. ISBN 0-415-15403-0 .

Цитаты

[ редактировать ]- ^ Кертис, Веста Сархош; Стюарт, Сара (24 марта 2010 г.). Эпоха парфян — Google Knihy . ИБТаурис. ISBN 978-18-4511-406-0 . Проверено 9 июня 2019 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б electricpulp.com. «Византийско-иранские отношения - Иранская энциклопедия» . www.iranicaonline.org . Проверено 31 марта 2018 г.

- ^ Ховард-Джонстон (2006), 1

- ^ Киа 2016 , с. маленький

- ^ Де Блуа и ван дер Спек 2008 , с. 137.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Болл (2000), 12–13; Дигнас – Зима (2007), 9 (PDF)

- ^ Плутарх, On , 5. 3–6.

* Маккей (2004), 149; Шервин-Уайт (1994), 262 - ^ Бивар (1993), 46

* Шервин-Уайт (1994), 262–263. - ^ Шервин-Уайт (1994), 264

- ^ Плутарх, Красс , 23–32.

* Маккей (2004), 150 - ^ Бивар (1993), 56

- ^ Юстин, «Истории Филиппов» , стр. 42. 4. Архивировано 11 мая 2008 г. в Wayback Machine.

* Бивар (1993), 56–57. - ^ Бивар (1993), 57

- ^ Юстин, «Истории Филиппов» , стр. 42. 4. Архивировано 11 мая 2008 г. в Wayback Machine ; Плутарх, Антоний , 33–34.

* Бивар (1993), 57–58. - ^ Кассий Дион, Римская история , XLIX, 27–33.

* Бивар (1993), 58–65. - ^ Сикер (2000), 162

- ^ Больной (2000), 162–163

- ^ Тацит, Анналы , XII. 50–51

* Сикер (2000), 163 - ^ Тацит, Анналы , XV. 27–29

* Роулинсон (2007), 286–287. - ^ Сикер (2000), 167

- ^ Кассий Дион, Римская история , 68, 33.

* Сикер (2000), 167–168. - ^ Лайтфут (1990), 115: «Траяну удалось приобрести территорию на этих землях с целью аннексии, чего раньше серьезно не предпринималось ... Хотя Адриан отказался от всех завоеваний Траяна ... эта тенденция не должна была быть реализована. отменил дальнейшие аннексические войны при Луции Вере и Септимии Севере."; Сикер (2000), 167–168.

- ^ Сикер (2000), 169

- ^ Иродиан, Римская история, III, 9.1–12. Архивировано 7 ноября 2014 г. в Wayback Machine.

Кэмпбелл (2005), 6–7; Роулинсон (2007), 337–338. - ↑ Иродиан, Римская история, IV, 10.1–15.9. Архивировано 4 мая 2015 г. в Wayback Machine.

Кэмпбелл (2005), 20 лет - ^ Иродиан, Римская история , VI, 2.1–6. Архивировано 5 ноября 2014 г. в Wayback Machine ; Кассий Дион, Римская история , LXXX, 4.1–2.

* Доджон-Гретрекс-Лью (2002), I, 16 - ^ Иродиан, Римская история , VI, 5.1–6. Архивировано 3 апреля 2015 г. в Wayback Machine.

* Доджон-Грейтрекс-Лью (2002), I, 24–28; Фрай (1993), 124 - ^ Фрай (1993), 124–125; Южный (2001), 234–235.

- ^ Оверлает, Бруно (30 июня 2009 г.). «Римский император в Бишапуре и Дарабгирде». Ираника Антиква . 44 : 461–530. дои : 10.2143/IA.44.0.2034386 .

- ^ Оверлает, Бруно (3 ноября 2017 г.). «Шапур I: Скальные рельефы» . Энциклопедия Ираника . Проверено 25 февраля 2020 г.

- ^ Фрай (1968), 125

- ^ Аврелий Виктор, Книга Цезарей , 27. 7–8 ; Сивиллинские оракулы, XIII, 13–20.

- Фрай (1968), 125; Южный (2001), 235

- ^ Фрай (1993), 125; Южный (2001), 235–236.

- ^ Лактанций, О смерти преследователей , 5 ; Сивиллинские оракулы, XIII, 155–171 гг.

* Фрай (1993), 126; Южный (2001), 238 - ^ Доджон-Гретрекс-Лье (2002), I, 108–109, 112; Южный (2001), 241

- ^ Аврелий Виктор, Книга Цезарей , 38. 2–4 ; Евтропий, Сокращение римской истории , IX, 18.1. [узурпировал]

- Фрай (1968), 128; Южный (2001), 241

- ^ Доджон – Грейтрекс – Лью (2002), 114

- ^ Фрай (1968), 130; Южный (2001), 242

- ^ Аврелий Виктор, Книга Цезарей , 39. 33–36 ; Евтропий, «Краткое изложение римской истории» , IX, 24–25.1. [узурпировал]

* Фрай (1993), 130–131; Южный (2001), 243 - ^ Аврелий Виктор, Книга Цезарей , 39. 33–36 ; Евтропий, «Краткое изложение римской истории» , IX, 24–25.1. [узурпировал]

- Фрай (1968), 130–131; Южный (2001), 243

- ^ Ленски 2002 , с. 162.

- ^ Фрай (1993), 130; Южный (2001), 242

- ^ Блокли 1997 , с. 423.

- ^ Фрай (1993), 137

- ^ Браунинг, Роберт Император Джулиан Калифорнийский университет Press (1978) ISBN 978-0-520-03731-1 стр. 243

- ^ Вахер, Дж. С. Римский мир, Том 1 Routledge; 2 издание (2001 г.) ISBN 978-0-415-26315-3 стр. 143

- ^ Фрай (1993), 138

- ^ Фрай (1968), 141

- ^ Бери (1923), XIV.1 ; Фрай (1968), 145; Грейтрекс-Лье (2002), II, 37–51

- ^ Прокопий, Войны , I.7.1–2.

* Грейтрекс-Лью (2002), II, 62 - ↑ Иисус Навин Столпник, Хроники , XLIII.

* Грейтрекс-Лью (2002), II, 62 - ↑ Захария Ритор, Церковная история , VII, 3–4.

* Грейтрекс-Лье (2002), II, 63 - ^ Грейтрекс – Лью (2002), II, 69–71

- ^ Прокопий, Войны , I.9.24.

* Грейтрекс-Лью (2002), II, 77 - ^ Иисус Навин Столпник, Хроники , XC

* Грейтрекс-Лье (2002), II, 74 - ↑ Иисус Навин Столпник, Хроника , XCIII–XCIV.

* Грейтрекс-Лью (2002), II, 77 - ^ Перейти обратно: а б Грейтрекс-Лье (2002), II, 77

- ^ О Прокопии см. Хеннинг Бёрм: Прокопий и Восток . В: Миша Мейер , Федерико Монтинаро: спутник Прокопия Кесарийского . Брилл, Бостон, 2022 г., стр. 310 и далее.

- ^ Прокопий, Войны , I.9.24.

- Грейтрекс-Лье (2002), II, 77

- ^ Джошуа Столпник, XC

- Грейтрекс-Лье (2002), II, 74

- ^ Прокопий, Войны , I.11.23–30.

* Грейтрекс (2005), 487; Грейтрекс – Лью (2002), II, 81–82. - ^ Грейтрекс-Лье (2002), II, 82

- ^ Грейтрекс-Лье (2002), II, 81–82

- ^ Грейтрекс – Лью (2002), II, 84

- ↑ Захария Ритор, Церковная история , 9, 2.

* Грейтрекс-Лью (2002), II, 83, 86. - ^ Грейтрекс – Лью (2002), II, 85

- ^ Грейтрекс-Лье (2002), II, 86

- ^ Грейтрекс – Лью (2002), II, 92–96

- ^ Грейтрекс – Лью (2002), II, 93

- ^ Эванс (2000), 118; Грейтрекс – Лью (2002), II, 96–97.

- ^ Грейтрекс-Лье (2002), II, 102; см. Х. Бёрм, «Персидский царь в Римской империи», Хирон 36 (2006), 299 и далее.

- ^ Грейтрекс-Лье (2002), II, 102

- ^ « Юстиниан I – Внешняя политика и войны » Британская энциклопедия. 2008. Британская энциклопедия Интернет.

- ^ Прокопий, Войны , II.20.17–19.

- Грейтрекс-Лье (2002), II, 109–110.

- ^ Прокопий, Войны , II.21.30–32.

- Грейтрекс-Лье (2002), II, 110

- ^ Коррипус, Иоаннид , I.68–98.

- Грейтрекс-Лье (2002), II, 111

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Грейтрекс-Лье (2002), II, 113

- ^ Прокопий, Войны , 28.7–11.

- Грейтрекс-Лье (2002), II, 113

- ^ Прокопий, Войны , 28.7–11.

* Грейтрекс (2005), 489; Грейтрекс – Лью (2002), II, 113 - ^ Грейтрекс-Лье (2002), II, 110; « Юстиниан I – Внешняя политика и войны » Британская энциклопедия. 2008. Британская энциклопедия Интернет.

- ^ Прокопий, Войны , 28.7–11.

* Эванс, Юстиниан (527–565 гг. н. э.) ; Грейтрекс – Лью (2002), II, 113 - ^ Тредголд (1997), 204–205

- ^ Тредголд (1997), 205–207

- ^ Тредголд (1997), 204–207

- ^ Тредголд (1997), 209

- ^ Фаррох (2007), 236.

- ^ Грейтрекс (2005), 489; Тредголд (1997), 211

- ^ Менандр Защитник, История , фраг. 6.1. По словам Грейтрекса (2005), 489, многим римлянам такое расположение «казалось опасным и свидетельствовало о слабости».

- ^ Эванс, Юстиниан (527–565 гг. Н.э.)

- ↑ Иоанн из Епифании , История , 2 AncientSites.com. Архивировано 21 июня 2011 г. в Wayback Machine, что дает дополнительную причину начала войны: «Спорливость [мидийцев] возросла еще больше ... когда Джастин не счел платить мидянам пятьсот фунтов золота каждый год, как было согласовано ранее в соответствии с мирными договорами, и позволить Римскому государству навсегда остаться данником персов». См. также Greatrex (2005), 503–504.

- ^ Тредголд (1997), 222

- ↑ Великий бастион римской границы впервые оказался в руках персов (Whitby [2000], 92–94).

- ^ Грейтрекс-Лье (2002), II, 152; Лаут (2005), 113

- ↑ Феофан, Хроника , 246.11–27.

* Уитби (2000), 92–94. - ^ Перейти обратно: а б Феофилакт, История , I, 9.4. Архивировано 10 июня 2011 г. в Wayback Machine (PDF)

Тредголд (1997), 224; Уитби (2000), 95 лет - ^ Тредголд (1997), 224; Уитби (2000), 95–96

- ^ Совард, Теофилакт Симокатта и персы. Архивировано 10 июня 2011 г. в Wayback Machine (PDF); Тредголд (1997), 225; Уитби (2000), 96 лет

- ^ Солнечный 1994 , с. 25.

- ^ Микаберидзе 2015 , с. 529.

- ^ Совард, Теофилакт Симокатта и персы. Архивировано 10 июня 2011 г. в Wayback Machine (PDF); Тредголд (1997), 226; Уитби (2000), 96 лет

- ^ Грейтрекс-Лье (2002), II, 168-169

- ^ Теофилакт, V, История , I, 3.11. Архивировано 10 июня 2011 г. в Wayback Machine и 15.1 (PDF)

* Лаут (2005), 115; Тредголд (1997), 231–232. - ^ Фосс (1975), 722

- ↑ Феофан, Летопись , 290–293.

* Грейтрекс-Лье (2002), II, 183–184. - ↑ Феофан, Летопись , 292–293.

* Грейтрекс-Лье (2002), II, 185–186. - ^ Грейтрекс-Лье (2002), II, 186–187

- ^ Халдон (1997), 41; Спек (1984), 178.

- ^ Грейтрекс-Лье (2002), II, 188–189

- ^ Грейтрекс – Лью (2002), II, 189–190

- ^ Грейтрекс – Лью (2002), II, 190–193, 196.

- ^ Монетный двор Никомедии прекратил работу в 613 году, а Родос пал перед захватчиками в 622–623 годах (Greatrex-Lieu (2002), II, 193–197).

- ^ Киа 2016 , с. 223.

- ^ Ховард-Джонстон 2006 , с. 33.

- ^ Фосс 1975 , с. 725

- ^ Ховард-Джонстон (2006), 85

- ^ Грейтрекс – Лью (2002), II, 196

- ↑ Феофан, Летопись , 303–304, 307.

*Кэмерон (1979), 23 года; Рекорд (1984), 37 лет - ↑ Феофан, Летопись , 304.25–306.7.

* Грейтрекс-Лье (2002), II, 199. - ↑ Феофан, Летопись , 306–308.

* Грейтрекс-Лье (2002), II, 199–202. - ↑ Феофан, Летопись , 308–312.

* Грейтрекс-Лье (2002), II, 202–205. - ↑ Феофан, Летопись , 316.

* Кэмерон (1979), 5–6, 20–22. - ↑ Феофан, Летопись , 315–316.

Макбрайд (2005), 56 лет - ^ Грейтрекс – Лье (2002), II, 209–212.

- ↑ Феофан, Летопись , 317–327.

* Грейтрекс-Лье (2002), II, 217–227. - ^ Халдон (1997), 46; Бэйнс (1912), пассим ; Спек (1984), 178

- ^ Ховард-Джонстон (2006), 9: «Победы [Ираклия] на поле боя в последующие годы и их политические последствия ... спасли главный бастион христианства на Ближнем Востоке и серьезно ослабили его старого зороастрийского соперника».

- ^ Халдон (1997), 43–45, 66, 71, 114–15.

- ^ Двойственное отношение к византийскому правлению со стороны миафизитов, возможно, уменьшило местное сопротивление арабской экспансии (Haldon [1997], 49–50).

- ^ Фосс (1975), 746–47; Ховард-Джонстон (2006), xv

- ^ Liska (1998), 170

- ^ Халдон (1997), 49–50

- ^ Халдон (1997), 61–62; Ховард-Джонстон (2006), 9

- ^ Роулинсон (2007), 199: «Парфянская военная система не обладала гибкостью римлян ... Какой бы свободной и, казалось бы, гибкой, она была жесткой в своем единообразии; она никогда не менялась; она оставалась под властью тридцатого Арсака такой, какой была находился под первой, возможно, улучшенной в деталях, но по сути той же системой». По словам Майкла Уитби (2000), 310, «восточные армии сохраняли римскую военную репутацию до конца VI века, извлекая выгоду из имеющихся ресурсов и демонстрируя способность адаптироваться к различным вызовам».

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Уиллер (2007), 259

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Фрай (2005), 473

- ^ Грейтрекс (2005), 478; Фрай (2005), 472

- ^ Корнюэль, Обзор сасанидско-персидской армии ; Сиднелл (2006), 273

- ^ По словам Рено Э. Габбы, римская армия со временем была реорганизована после битвы при Каррах (Габба [1966], 51–73).

- ^ Кембриджская история Ирана : «Парфянская тактика постепенно стала стандартным методом ведения войны в Римской империи. Таким образом, древняя персидская традиция крупномасштабного гидротехнического строительства была объединена с уникальным римским опытом каменной кладки. Греко-римская картина Персы как нация свирепых и неукротимых воинов странным образом контрастируют с другим стереотипом: персы как прошлые мастера искусства изысканной жизни, роскошной жизни. Персидское влияние на римскую религию было бы огромным, если бы людям было позволено называть митраизм персом. религия».

- ^ Вегетиус, III, Epitoma Rei Militaris , 26

* Вербрюгген – Уиллард – Южный (1997), 4–5. - ^ Хэлдон, Джон Ф. (31 марта 1999 г.). Война, государство и общество в византийском мире, 565–1204 гг . Психология Пресс. ISBN 9781857284959 . Проверено 31 марта 2018 г. - через Google Книги.

- ^ Фаррох, Каве (2012). Сасанидская элитная кавалерия 224–642 гг. н. э . Издательство Блумсбери. п. 42. ИСБН 978-1-78200-848-4 .

- ^ Кэмпбелл-Хук (2005), 57–59; Габба (1966), 51–73.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Элтон, Хью (2018). Римская империя в поздней античности: политическая и военная история . Издательство Кембриджского университета. п. 326. ИСБН 9780521899314 .

- ^ «Подземелье смерти: Газовая война в Дура-Европос» , Текущая археология , 26 ноября 2009 г. (онлайн-функция), по состоянию на 3 октября 2014 г.

- ^ Самир С. Патель, «Ранняя химическая война - Дура-Европос, Сирия» , Археология , Том. 63, № 1, январь/февраль 2010 г. (по состоянию на 3 октября 2014 г.)

- ↑ Стефани Паппас, «Похороненные солдаты могут быть жертвами древнего химического оружия» , LiveScience , 8 марта 2011 г., по состоянию на 3 октября 2014 г.

- ^ Уитби, Майкл (1 января 2013 г.). Осадная война и контросадная тактика в поздней античности (ок. 250–640) . Брилл. п. 446. ИСБН 978-90-04-25258-5 .

- ^ Рэнс, Филип (декабрь 2003 г.). «Слоны на войне в поздней античности» (PDF) . Журнал Древневенгерской академии наук . 43 (3–4): 369–370. дои : 10.1556/aant.43.2003.3-4.10 . ISSN 1588-2543 .

- ↑ Раскопки в Иране раскрывают тайну «Красной змеи» , Science Daily Levi (1994), 192.

- ^ Рекаванди-Зауэр-Уилкинсон-Ноканде, «Загадка Красной Змеи»

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Фрай (1993), 139

- ^ Шахид (1984), 24–25; Вагстафф (1985), 123–125.

- ^ Фрай (1993), 139; Леви (1994), 192

- ^ А. Шапур Шахбази , Эрих Кеттенхофен, Джон Р. Перри, «ДЕПОРТАЦИИ», Энциклопедия Ираника , VII/3, стр. 297–312, доступно в Интернете по адресу http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/deportations (доступен на сайте http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/deportations). 30 декабря 2012 г.).

- ^ Ховард-Джонстон, доктор юридических наук (31 марта 2018 г.). Восточный Рим, Сасанидская Персия и конец античности: историографические и исторические исследования . Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 9780860789925 . Проверено 31 марта 2018 г. - через Google Книги.

- ^ Брейзер, Крис (2001). Серьезный путеводитель по всемирной истории . Версо. п. 42. ИСБН 978-1-8598-4355-0 .

- ^ Кассий Дион, Римская история , LXXV, 3. 2–3.

* Гарнси-Саллер (1987), 8 - ^ Грейтрекс (2005), 477–478

- ^ Спутник Брилла на приеме у Александра Македонского . БРИЛЛ. 2018. с. 214. ИСБН 9789004359932 .

- ^ Яршатер, Эхсан (1983). Кембриджская история Ирана . Издательство Кембриджского университета. п. 475. ИСБН 9780521200929 .

- ^ Визехёфер, Йозеф (11 августа 2011 г.). «АРДАШИР I и. История» . Энциклопедия Ираника .

- ^ Атанассиади, Полимния (2014). Джулиан (Routledge Revivals): интеллектуальная биография . Рутледж. п. 192. ИСБН 978-1-317-69652-0 .

- ^ Барнс (1985), 126

- ^ Созомен, Церковная история , II, 15. Архивировано 22 мая 2011 г. в Wayback Machine.

* Макдонаф (2006), 73 года. - ^ Халдон (1999), 20; Исаак (1998), 441

- ^ Дигнас – Зима (2007), 1–3 (PDF)

- ^ Доджон-Грейтрекс-Лье (2002), I, 5; Поттер (2004), 232–233.

- ^ Фрай (2005), 461–463; Шахбази, Историография. Архивировано 29 января 2009 г. в Wayback Machine.

- ^ Шахбази, Историография. Архивировано 29 января 2009 г. в Wayback Machine.

- ^ Доджон – Грейтрекс – Лью (2002), I, 7

- ^ Бойд (1999), 160

- ^ Ховард-Джонстон (2006), 42–43

- ^ «КНИГА ЦЕЗАРИСА» . www.thelatinlibrary.com Проверено 31 марта 2018 г.

- ^ «LacusCurtius • Римская история Кассия Диона» . penelope.uchicago.edu . Проверено 31 марта 2018 г.

- ^ (сьер), Шарль Дю Френ Дю Канж (31 марта 2018 г.). «Пасхальный хроникон» . Импенсис Эд. Вебери . Проверено 31 марта 2018 г. - через Google Книги.

- ^ Корипп, Флавий Кресконий (1836). Иоаннид: О восхвалениях Юстина Августа Младшего, книга четвертая . Проверено 31 марта 2018 г. - из Интернет-архива.

Тело Джон

- ^ «Евтропий: сокращение римской истории» . www.forumromanum.org . Архивировано из оригинала 3 октября 2003 года . Проверено 31 марта 2018 г.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: неподходящий URL ( ссылка ) - ^ Ливиус. «Римская история Иродиана» . www.livius.org . Архивировано из оригинала 4 мая 2015 года . Проверено 31 марта 2018 г.

- ^ «AncientSites.com» . Архивировано из оригинала 21 июня 2011 г. Проверено 8 июня 2008 г.

- ^ Столпник, Джошуа. «Иисус Навин Столпник, Хроника, составленная на сирийском языке в 507 г. (1882 г.), стр. 1–76» . www.tertullian.org . Проверено 31 марта 2018 г.

- ^ «Джастин XLI» . www.thelatinlibrary.com . Проверено 31 марта 2018 г.

- ^ «Лактантий: о смертях преследуемых» . www.thelatinlibrary.com Проверено 31 марта 2018 г.

- ^ «Freewebs.com» . Архивировано из оригинала 22 мая 2011 года.

- ^ DocumentaCatholicaOmnia.eu

- ^ «Humanities.uci.edu» (PDF) . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 10 июня 2011 г. Проверено 27 апреля 2008 г.

- ^ «Книга Вегетиуса III » www.thelatinlibrary.com Проверено 31 марта 2018 г.

Дальнейшее чтение

[ редактировать ]- Андрес, Хансйоахим (2022). Братская борьба. Структуры и методы дипломатии между Римом и Ираном от раздела Армении до Пятидесятилетнего мира . Штутгарт: Франц Штайнер. ISBN 978-3-515-13363-0 .

- Блокли, Роджер К. (1992). Внешняя политика Восточной Римской империи. Формирование и поведение от Диоклетиана до Анастасия (ARCA 30) . Лидс: Фрэнсис Кэрнс. ISBN 0-905205-83-9 .

- Бёрм, Хеннинг (2007). Прокопий и персы. Исследования римско-сасанидских контактов в поздней поздней античности . Штутгарт: Франц Штайнер. ISBN 978-3-515-09052-0 .