Лувр

Лувр | |

| |

| Учредил | 10 августа 1793 г |

|---|---|

| Location | Musée du Louvre, 75001, Paris, France |

| Type | Art museum and historic site |

| Collection size | 615,797 in 2019[1] (35,000 on display)[2] |

| Visitors | 8.9 million (2023)[3]

|

| Director | Laurence des Cars |

| Curator | Marie-Laure de Rochebrune |

| Public transit access | |

| Website | louvre.fr |

Лувр ( Английский: / ˈ l uː v ( r ə )/ LOOV( -rə) ), [4] или Лувр (французский: Musée du Louvre [myze dy luvʁ] ), — национальный художественный музей в Париже , Франция. Он расположен на правом берегу Сены и (районе или округе) города в 1-м округе для некоторых из самых канонических произведений западного искусства , в том числе Моны Лизы , Венеры Милосской и является домом Крылатой Победы . Музей расположен во дворце Лувр , первоначально построенном в конце 12-13 веков при Филиппе II . остатки средневековой крепости Лувр В подвале музея видны . Из-за расширения городов крепость со временем утратила свою оборонительную функцию, и в 1546 году Франциск I превратил ее в главную резиденцию французских королей . [5]

Здание много раз расширялось, чтобы сформировать нынешний Лувр. В 1682 году Людовик XIV выбрал Версальский дворец для своего двора, оставив Лувр главным образом местом для демонстрации королевской коллекции, в том числе с 1692 года коллекции древнегреческой и римской скульптуры. [6] In 1692, the building was occupied by the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres and the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture, which in 1699 held the first of a series of salons. The Académie remained at the Louvre for 100 years.[7] Во время Французской революции Национальное собрание постановило использовать Лувр как музей для демонстрации национальных шедевров.

The museum opened on 10 August 1793 with an exhibition of 537 paintings, the majority of the works being royal and confiscated church property. Because of structural problems with the building, the museum was closed from 1796 until 1801. The collection was increased under Napoleon and the museum was renamed Musée Napoléon, but after Napoleon's abdication, many works seized by his armies were returned to their original owners. The collection was further increased during the reigns of Louis XVIII and Charles X, and during the Second French Empire the museum gained 20,000 pieces. Holdings have grown steadily through donations and bequests since the Third Republic. The collection is divided among eight curatorial departments: Egyptian Antiquities; Near Eastern Antiquities; Greek, Etruscan, and Roman Antiquities; Islamic Art; Sculpture; Decorative Arts; Paintings; Prints and Drawings.

The Musée du Louvre contains approximately 500,000 objects[8] and displays 35,000 works of art in eight curatorial departments with more than 60,600 m2 (652,000 sq ft) dedicated to the permanent collection.[2] The Louvre exhibits sculptures, objets d'art, paintings, drawings, and archaeological finds. At any given point in time, approximately 38,000 objects from prehistory to the 21st century are being exhibited over an area of 72,735 m2 (782,910 sq ft), making it the largest museum in the world. It received 8.9 million visitors in 2023, 14 percent more than in 2022, but still below the 10.1 million visitors in 2018. The Louvre is the most-visited museum in the world, ahead of the second-place Vatican Museums.[9][10]

Location and visiting[edit]

The Louvre museum is located inside the Louvre Palace, in the center of Paris, adjacent to the Tuileries Gardens. The two nearest Métro stations are Louvre-Rivoli and Palais Royal-Musée du Louvre, the latter having a direct underground access to the Carrousel du Louvre commercial mall.[11]

Before the Grand Louvre overhaul of the late 1980s and 1990s, the Louvre had several street-level entrances, most of which are now permanently closed. Since 1993, the museum's main entrance has been the underground space under the Louvre Pyramid, or Hall Napoléon, which can be accessed from the Pyramid itself, from the underground Carrousel du Louvre, or (for authorized visitors) from the passage Richelieu connecting to the nearby rue de Rivoli. A secondary entrance at the Porte des Lions, near the western end of the Denon Wing, was created in 1999 but is not permanently open.[12]

The museum's entrance conditions have varied over time. Prior to the 1850s, artists and foreign visitors had privileged access. At the time of initial opening in 1793, the French Republican calendar had imposed ten-day "weeks" (French: décades), the first six days of which were reserved for visits by artists and foreigners and the last three for visits by the general public.[13]: 37 In the early 1800s, after the seven-day week had been reinstated, the general public had only four hours of museum access per weeks, between 2pm and 4pm on Saturdays and Sundays.[14]: 8 In 1824, a new regulation allowed public access only on Sundays and holidays; the other days the museum was open only to artists and foreigners, except for closure on Mondays.[13]: 39 That changed in 1855 when the museum became open to the public all days except Mondays.[13]: 40 It was free until 1922, when an entrance fee was introduced except on Sundays.[13]: 42 Since its post-World War II reopening in 1946,[13]: 43 the Louvre has been closed on Tuesdays, and habitually open to the public the rest of the week except for some holidays.

The use of cameras and video recorders is permitted inside, but flash photography is forbidden.[15]

Beginning in 2012, Nintendo 3DS portable video game systems were used as the official museum audio guides. The following year, the museum contracted Nintendo to create a 3DS-based audiovisual visitor guide.[16] Entitled Nintendo 3DS Guide: Louvre, it contains over 30 hours of audio and over 1,000 photographs of artwork and the museum itself, including 3D views,[17] and also provides navigation thanks to differential GPS transmitters installed within the museum.[18]

The upgraded 2013 Louvre guide was also announced in a special Nintendo Direct featuring Satoru Iwata and Shigeru Miyamoto demonstrating it at the museum,[19] and 3DS XLs pre-loaded with the guide are available to rent at the museum.[20] As of August 2023, there are virtual tours through rooms and galleries accessible online.

History[edit]

Before the museum[edit]

The Louvre Palace, which houses the museum, was begun by King Philip II in the late 12th century to protect the city from the attack from the West, as the Kingdom of England still held Normandy at the time. Remnants of the Medieval Louvre are still visible in the crypt.[21]: 32 Whether this was the first building on that spot is not known, and it is possible that Philip modified an existing tower.[22]

The origins of the name "Louvre" are somewhat disputed. According to the authoritative Grand Larousse encyclopédique, the name derives from an association with a wolf hunting den (via Latin: lupus, lower Empire: lupara).[22][23] In the 7th century, Burgundofara (also known as Saint Fare), abbess in Meaux, is said to have gifted part of her "Villa called Luvra situated in the region of Paris" to a monastery,[24] even though it is doubtful that this land corresponded exactly to the present site of the Louvre.

The Louvre Palace has been subject to numerous renovations since its construction. In the 14th century, Charles V converted the building from its military role into a residence. In 1546, Francis I started its rebuilding in French Renaissance style.[25] After Louis XIV chose Versailles as his residence in 1682, construction works slowed to a halt. The royal move away from Paris resulted in the Louvre being used as a residence for artists, under Royal patronage.[25][21]: 42 [26] For example, four generations of craftsmen-artists from the Boulle family were granted Royal patronage and resided in the Louvre.[27][28][29]

Meanwhile, the collections of the Louvre originated in the acquisitions of paintings and other artworks by the monarchs of the House of France. At the Palace of Fontainebleau, Francis collected art that would later be part of the Louvre's art collections, including Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa.[30]

The Cabinet du Roi consisted of seven rooms west of the Galerie d'Apollon on the upper floor of the remodeled Petite Galerie. Many of the king's paintings were placed in these rooms in 1673, when it became an art gallery, accessible to certain art lovers as a kind of museum. In 1681, after the court moved to Versailles, 26 of the paintings were transferred there, somewhat diminishing the collection, but it is mentioned in Paris guide books from 1684 on, and was shown to ambassadors from Siam in 1686.[31]

By the mid-18th century there were an increasing number of proposals to create a public gallery in the Louvre. Art critic Étienne La Font de Saint-Yenne in 1747 published a call for a display of the royal collection. On 14 October 1750, Louis XV decided on a display of 96 pieces from the royal collection, mounted in the Galerie royale de peinture of the Luxembourg Palace. A hall was opened by Le Normant de Tournehem and the Marquis de Marigny for public viewing of the "king's paintings" (Tableaux du Roy) on Wednesdays and Saturdays. The Luxembourg gallery included Andrea del Sarto's Charity and works by Raphael; Titian; Veronese; Rembrandt; Poussin or Van Dyck. It closed in 1780 as a result of the royal gift of the Luxembourg palace to the Count of Provence (the future king, Louis XVIII) by the king in 1778.[32] Under Louis XVI, the idea of a royal museum in the Louvre came closer to fruition.[33] The comte d'Angiviller broadened the collection and in 1776 proposed to convert the Grande Galerie of the Louvre – which at that time contained the plans-reliefs or 3D models of key fortified sites in and around France – into the "French Museum". Many design proposals were offered for the Louvre's renovation into a museum, without a final decision being made on them. Hence the museum remained incomplete until the French Revolution.[32]

Revolutionary opening[edit]

The Louvre finally became a public museum during the French Revolution. In May 1791, the National Constituent Assembly declared that the Louvre would be "a place for bringing together monuments of all the sciences and arts".[32] On 10 August 1792, Louis XVI was imprisoned and the royal collection in the Louvre became national property. Because of fear of vandalism or theft, on 19 August, the National Assembly pronounced the museum's preparation urgent. In October, a committee to "preserve the national memory" began assembling the collection for display.[34]

The museum opened on 10 August 1793, the first anniversary of the monarchy's demise, as Muséum central des Arts de la République. The public was given free accessibility on three days per week, which was "perceived as a major accomplishment and was generally appreciated".[36] The collection showcased 537 paintings and 184 objects of art. Three-quarters were derived from the royal collections, the remainder from confiscated émigrés and Church property (biens nationaux).[37][21]: 68-69 To expand and organize the collection, the Republic dedicated 100,000 livres per year.[32] In 1794, France's revolutionary armies began bringing pieces from Northern Europe, augmented after the Treaty of Tolentino (1797) by works from the Vatican, such as the Laocoön and Apollo Belvedere, to establish the Louvre as a museum and as a "sign of popular sovereignty".[37][38]

The early days were hectic. Privileged artists continued to live in residence, and the unlabeled paintings hung "frame to frame from floor to ceiling".[37] The structure itself closed in May 1796 due to structural deficiencies. It reopened on 14 July 1801, arranged chronologically and with new lighting and columns.[37] On 15 August 1797, the Galerie d'Apollon was opened with an exhibition of drawings. Meanwhile, the Louvre's Gallery of Antiquity sculpture (musée des Antiques), with artefacts brought from Florence and the Vatican, had opened in November 1800 in Anne of Austria's former summer apartment, located on the ground floor just below the Galerie d'Apollon.

Napoleonic era[edit]

On 19 November 1802, Napoleon appointed Dominique Vivant Denon, a scholar and polymath who had participated in the Egyptian campaign of 1798–1801, as the museum's first director, in preference to alternative contenders such as antiquarian Ennio Quirino Visconti, painter Jacques-Louis David, sculptor Antonio Canova and architects Léon Dufourny or Pierre Fontaine.[39] On Denon's suggestion in July 1803, the museum itself was renamed Musée Napoléon.[40]: 79

The collection grew through successful military campaigns.[21]: 52 Acquisitions were made of Spanish, Austrian, Dutch, and Italian works, either as the result of war looting or formalized by treaties such as the Treaty of Tolentino.[41] At the end of Napoleon's First Italian Campaign in 1797, the Treaty of Campo Formio was signed with Count Philipp von Cobenzl of the Austrian Monarchy. This treaty marked the completion of Napoleon's conquest of Italy and the end of the first phase of the French Revolutionary Wars. It compelled Italian cities to contribute pieces of art and heritage to Napoleon's "parades of spoils" through Paris before being put into the Louvre Museum.[42] The Horses of Saint Mark, which had adorned the basilica of San Marco in Venice after the sack of Constantinople in 1204, were brought to Paris where they were placed atop Napoleon's Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel in 1797.[42] Under the Treaty of Tolentino, the two statues of the Nile and Tiber were taken to Paris from the Vatican in 1797, and were both kept in the Louvre until 1815. (The Nile was later returned to Rome,[43] whereas the Tiber has remained in the Louvre to this day.) The despoilment of Italian churches and palaces outraged the Italians and their artistic and cultural sensibilities.[44]

After the French defeat at Waterloo, the looted works' former owners sought their return. The Louvre's administrator, Denon, was loath to comply in absence of a treaty of restitution. In response, foreign states sent emissaries to London to seek help, and many pieces were returned, though far from all.[41][21]: 69 [45] In 1815 Louis XVIII finally concluded agreements with the Austrian government[46][47] for the keeping of works such as Veronese's Wedding at Cana which was exchanged for a large Le Brun or the repurchase of the Albani collection.

From 1815 to 1852[edit]

For most of the 19th century, from Napoleon's time to the Second Empire, the Louvre and other national museums were managed under the monarch's civil list and thus depended much on the ruler's personal involvement. Whereas the most iconic collection remained that of paintings in the Grande Galerie, a number of other initiatives mushroomed in the vast building, named as if they were separate museums even though they were generally managed under the same administrative umbrella. Correspondingly, the museum complex was often referred to in the plural ("les musées du Louvre") rather than singular.[48]

During the Bourbon Restoration (1814–1830), Louis XVIII and Charles X added to the collections. The Greek and Roman sculpture gallery on the ground floor of the southwestern side of the Cour Carrée was completed on designs by Percier and Fontaine. In 1819 an exhibition of manufactured products was opened in the first floor of the Cour Carrée's southern wing and would stay there until the mid-1820s.[40]: 87 Charles X in 1826 created the Musée Égyptien and in 1827 included it in his broader Musée Charles X, a new section of the museum complex located in a suite of lavishly decorated rooms on the first floor of the South Wing of the Cour Carrée. The Egyptian collection, initially curated by Jean-François Champollion, formed the basis for what is now the Louvre's Department of Egyptian Antiquities. It was formed from the purchased collections of Edmé-Antoine Durand, Henry Salt and the second collection of Bernardino Drovetti (the first one having been purchased by Victor Emmanuel I of Sardinia to form the core of the present Museo Egizio in Turin). The Restoration period also saw the opening in 1824 of the Galerie d'Angoulême, a section of largely French sculptures on the ground floor of the Northwestern side of the Cour Carrée, many of whose artefacts came from the Palace of Versailles and from Alexandre Lenoir's Musée des Monuments Français following its closure in 1816. Meanwhile, the French Navy created an exhibition of ship models in the Louvre in December 1827, initially named musée dauphin in honor of Dauphin Louis Antoine,[49] building on an 18th-century initiative of Henri-Louis Duhamel du Monceau. This collection, renamed musée naval in 1833 and later to develop into the Musée national de la Marine, was initially located on the first floor of the Cour Carrée's North Wing, and in 1838 moved up one level to the 2nd-floor attic, where it remained for more than a century.[50]

- Rooms of the Musée Charles X

- First room

- Room 27

- Room 29

- Salle des Colonnes

- Room 35

- Room 36

- Room 38

Following the July Revolution, King Louis Philippe focused his interest on the repurposing of the Palace of Versailles into a Museum of French History conceived as a project of national reconciliation, and the Louvre was kept in comparative neglect. Louis-Philippe did, however, sponsor the creation of the musée assyrien to host the monumental Assyrian sculpture works brought to Paris by Paul-Émile Botta, in the ground-floor gallery north of the eastern entrance of the Cour Carrée. The Assyrian Museum opened on 1 May 1847.[51] Separately, Louis-Philippe had his Spanish gallery displayed in the Louvre from 7 January 1838, in five rooms on the first floor of the Cour Carrée's East (Colonnade) Wing,[52] but the collection remained his personal property. As a consequence, the works were removed after Louis-Philippe was deposed in 1848, and were eventually auctioned away in 1853.

The short-lived Second Republic had more ambitions for the Louvre. It initiated repair work, the completion of the Galerie d'Apollon and of the salle des sept-cheminées, and the overhaul of the Salon Carré (former site of the iconic yearly Salon) and of the Grande Galerie.[21]: 52 In 1848, the Naval Museum in the Cour Carrée's attic was brought under the common Louvre Museum management,[50] a change which was again reversed in 1920. In 1850 under the leadership of curator Adrien de Longpérier, the musée mexicain opened within the Louvre as the first European museum dedicated to pre-Columbian art [53].

Second Empire[edit]

The rule of Napoleon III was transformational for the Louvre, both the building and the museum. In 1852, he created the Musée des Souverains in the Colonnade Wing, an ideological project aimed at buttressing his personal legitimacy. In 1861, he bought 11,835 artworks including 641 paintings, Greek gold and other antiquities of the Campana collection. For its display, he created another new section within the Louvre named Musée Napoléon III, occupying a number of rooms in various parts of the building. Between 1852 and 1870, the museum added 20,000 new artefacts to its collections.[54]

The main change of that period was to the building itself. In the 1850s architects Louis Visconti and Hector Lefuel created massive new spaces around what is now called the Cour Napoléon, some of which (in the South Wing, now Aile Denon) went to the museum.[21]: 52-54 In the 1860s, Lefuel also led the creation of the pavillon des Sessions with a new Salle des Etats closer to Napoleon III's residence in the Tuileries Palace, with the effect of shortening the Grande Galerie by about a third of its previous length. A smaller but significant Second Empire project was the decoration of the salle des Empereurs below the Salon carré.[citation needed]

- Entrance to a section of the Musée Napoléon III from the salle des séances, then a double-height space

- Galerie Daru, part of the New Louvre building program under Napoleon III

- Salle Daru above the galerie Daru, also created under Napoleon III

- Escalier Mollien in the New Louvre

- Salle des Empereurs

From 1870 to 1981[edit]

The Louvre narrowly escaped serious damage during the suppression of the Paris Commune. On 23 May 1871, as the French Army advanced into Paris, a force of Communards led by Jules Bergeret set fire to the adjoining Tuileries Palace. The fire burned for forty-eight hours, entirely destroying the interior of the Tuileries and spreading to the north west wing of the museum next to it. The emperor's Louvre library (Bibliothèque du Louvre) and some of the adjoining halls, in what is now the Richelieu Wing, were separately destroyed. But the museum was saved by the efforts of Paris firemen and museum employees led by curator Henry Barbet de Jouy.[55]

Following the end of the monarchy, several spaces in the Louvre's South Wing went to the museum. The Salle du Manège was transferred to the museum in 1879, and in 1928 became its main entrance lobby.[56] The large Salle des Etats that had been created by Lefuel between the Grande Galerie and Pavillon Denon was redecorated in 1886 by Edmond Guillaume, Lefuel's successor as architect of the Louvre, and opened as a spacious exhibition room.[57][58] Edomond Guillaume also decorated the first-floor room at the northwest corner of the Cour Carrée, on the ceiling of which he placed in 1890 a monumental painting by Carolus-Duran, The Triumph of Marie de' Medici originally created in 1879 for the Luxembourg Palace.[58]

Meanwhile, during the Third Republic (1870–1940) the Louvre acquired new artefacts mainly via donations, gifts, and sharing arrangements on excavations abroad. The 583-item Collection La Caze, donated in 1869 by Louis La Caze, included works by Chardin; Fragonard, Rembrandt and Watteau.[21]: 70-71 In 1883, the Winged Victory of Samothrace, which had been found in the Aegean Sea in 1863, was prominently displayed as the focal point of the Escalier Daru.[21]: 70-71 Major artifacts excavated at Susa in Iran, including the massive Apadana capital and glazed brick decoration from the Palace of Darius there, accrued to the Oriental (Near Eastern) Antiquities Department in the 1880s. The Société des amis du Louvre was established in 1897 and donated prominent works, such as the Pietà of Villeneuve-lès-Avignon. The expansion of the museum and its collections slowed after World War I, however, despite some prominent acquisitions such as Georges de La Tour's Saint Thomas and Baron Edmond de Rothschild's 1935 donation of 4,000 prints, 3,000 drawings, and 500 illustrated books.

From the late 19th century, the Louvre gradually veered away from its mid-century ambition of universality to become a more focused museum of French, Western and Near Eastern art, covering a space ranging from Iran to the Atlantic. The collections of the Louvre's musée mexicain were transferred to the Musée d'Ethnographie du Trocadéro in 1887. As the Musée de Marine was increasingly constrained to display its core naval-themed collections in the limited space it had in the second-floor attic of the northern half of the Cour Carrée, many of its significant holdings of non-Western artefacts were transferred in 1905 to the Trocadéro ethnography museum, the National Antiquities Museum in Saint-Germain-en-Laye, and the Chinese Museum in the Palace of Fontainebleau.[59] The Musée de Marine itself was relocated to the Palais de Chaillot in 1943. The Louvre's extensive collections of Asian art were moved to the Guimet Museum in 1945. Nevertheless, the Louvre's first gallery of Islamic art opened in 1893.[60]

In the late 1920s, Louvre Director Henri Verne devised a master plan for the rationalization of the museum's exhibitions, which was partly implemented in the following decade. In 1932–1934, Louvre architects Camille Lefèvre and Albert Ferran redesigned the Escalier Daru to its current appearance. The Cour du Sphinx in the South Wing was covered by a glass roof in 1934. Decorative arts exhibits were expanded in the first floor of the North Wing of the Cour Carrée, including some of France's first period room displays. In the late 1930s, The La Caze donation was moved to a remodeled Salle La Caze above the salle des Caryatides, with reduced height to create more rooms on the second floor and a sober interior design by Albert Ferran.[citation needed]

During World War II, the Louvre conducted an elaborate plan of evacuation of its art collection. When Germany occupied the Sudetenland, many important artworks such as the Mona Lisa were temporarily moved to the Château de Chambord. When war was formally declared a year later, most of the museum's paintings were sent there as well. Select sculptures such as Winged Victory of Samothrace and the Venus de Milo were sent to the Château de Valençay.[62] On 27 August 1939, after two days of packing, truck convoys began to leave Paris. By 28 December, the museum was cleared of most works, except those that were too heavy and "unimportant paintings [that] were left in the basement".[63] In early 1945, after the liberation of France, art began returning to the Louvre.[64]

New arrangements after the war revealed the further evolution of taste away from the lavish decorative practices of the late 19th century. In 1947, Edmond Guillaume's ceiling ornaments were removed from the Salle des Etats,[58] where the Mona Lisa was first displayed in 1966.[65] Around 1950, Louvre architect Jean-Jacques Haffner streamlined the interior decoration of the Grande Galerie.[58] In 1953, a new ceiling by Georges Braque was inaugurated in the Salle Henri II, next to the Salle La Caze.[66] In the late 1960s, seats designed by Pierre Paulin were installed in the Grande Galerie.[67] In 1972, the Salon Carré's museography was remade with lighting from a hung tubular case, designed by Louvre architect Marc Saltet with assistance from designers André Monpoix, Joseph-André Motte and Paulin.[68]

In 1961, the Finance Ministry accepted to leave the Pavillon de Flore at the southwestern end of the Louvre building, as Verne had recommended in his 1920s plan. New exhibition spaces of sculptures (ground floor) and paintings (first floor) opened there later in the 1960s, on a design by government architect Olivier Lahalle.[69]

Grand Louvre[edit]

In 1981, French President François Mitterrand proposed, as one of his Grands Projets, the Grand Louvre plan to relocate the Finance Ministry, until then housed in the North Wing of the Louvre, and thus devote almost the entire Louvre building (except its northwestern tip, which houses the separate Musée des Arts Décoratifs) to the museum which would be correspondingly restructured. In 1984 I. M. Pei, the architect personally selected by Mitterrand, proposed a master plan including an underground entrance space accessed through a glass pyramid in the Louvre's central Cour Napoléon.[21]: 66

The open spaces surrounding the pyramid were inaugurated on 15 October 1988, and its underground lobby was opened on 30 March 1989. New galleries of early modern French paintings on the 2nd floor of the Cour Carrée, for which the planning had started before the Grand Louvre, also opened in 1989. Further rooms in the same sequence, designed by Italo Rota, opened on 15 December 1992.[citation needed]

On 18 November 1993, Mitterrand inaugurated the next major phase of the Grand Louvre plan: the renovated North (Richelieu) Wing in the former Finance Ministry site, the museum's largest single expansion in its entire history, designed by Pei, his French associate Michel Macary, and Jean-Michel Wilmotte. Further underground spaces known as the Carrousel du Louvre, centered on the Inverted Pyramid and designed by Pei and Macary, had opened in October 1993. Other refurbished galleries, of Italian sculptures and Egyptian antiquities, opened in 1994. The third and last main phase of the plan unfolded mainly in 1997, with new renovated rooms in the Sully and Denon wings. A new entrance at the porte des Lions opened in 1998, leading on the first floor to new rooms of Spanish paintings.[citation needed]

As of 2002, the Louvre's visitor count had doubled from its pre-Grand-Louvre levels.[70]

21st century[edit]

President Jacques Chirac, who had succeeded Mitterrand in 1995, insisted on the return of non-Western art to the Louvre, upon a recommendation from his friend the art collector and dealer Jacques Kerchache. On his initiative, a selection of highlights from the collections of what would become the Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac was installed on the ground floor of the Pavillon des Sessions and opened in 2000, six years ahead of the Musée du Quai Branly itself.

The main other initiative in the aftermath of the Grand Louvre project was Chirac's decision to create a new department of Islamic Art, by executive order of 1 August 2003, and to move the corresponding collections from their prior underground location in the Richelieu Wing to a more prominent site in the Denon Wing. That new section opened on 22 September 2012, together with collections from the Roman-era Eastern Mediterranean, with financial support from the Al Waleed bin Talal Foundation and on a design by Mario Bellini and Rudy Ricciotti.[71][72][73]

In 2007, German painter Anselm Kiefer was invited to create a work for the North stairs of the Perrault Colonnade, Athanor. This decision announces the museum's reengagement with contemporary art under the direction of Henri Loyrette, fifty years after the institution's last order to a contemporary artists, George Braque.[74]

In 2010, American painter Cy Twombly completed a new ceiling for the Salle des Bronzes (the former Salle La Caze), a counterpoint to that of Braque installed in 1953 in the adjacent Salle Henri II. The room's floor and walls were redesigned in 2021 by Louvre architect Michel Goutal to revert the changes made by his predecessor Albert Ferran in the late 1930s, triggering protests from the Cy Twombly Foundation on grounds that the then-deceased painter's work had been created to fit with the room's prior decoration.[75]

That same year, the Louvre commissioned French artist François Morellet to create a work for the Lefuel stairs, on the first floor. For L'esprit d'escalier Morellet redesigned the stairscase's windows, echoing their original structures but distorting them to create a disturbing optical effect.[76]

On 6 June 2014, the Decorative Arts section on the first floor of the Cour Carrée's northern wing opened after comprehensive refurbishment.[77]

In January 2020, under the direction of Jean-Luc Martinez, the museum inaugurated a new contemporary art commission, L'Onde du Midi by Venezuelan kinetic artist Elias Crespin. The sculpture hovers under the Escalier du Midi, the staircase on the South of the Perrault Colonnade.[78]

The Louvre, like many other museums and galleries, felt the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the arts and cultural heritage. It was closed for six months during French coronavirus lockdowns and saw visitor numbers plunge to 2.7 million in 2020, from 9.6 million in 2019 and 10.2 million in 2018, which was a record year.[79][80]

In preparation for the 2024 Olympics, the Louvre staged an exhibit about the Games' history that links their ancient beginnings to the modern era. [81]

Attendance rose to 8.9 million in 2023, 14 percent above 2022, but still short of the record of 10.2 million in 2018.[10]

- The Pavillon des Sessions's display of non-Western art from the Musée du Quai Branly, opened in 2000

- The Cour Visconti's ground floor covered to host the new Islamic Art Department in 2012

- Islamic art display in the covered Cour Visconti, 2012

- Underground display of the Islamic Art Department, 2012

Collections[edit]

The Musée du Louvre owns 615,797 objects[1] of which 482,943 are accessible online since 24 March 2021[82] and displays 35,000 works of art in eight curatorial departments.[2]

The Louvre is home to one of the world's most extensive collections of art, including works from diverse cultures and time periods. Visitors can view iconic works like the Mona Lisa and the Winged Victory of Samothrace, as well as pieces from ancient civilizations such as Egypt, Greece, and Rome. The museum also features collections of decorative arts, Islamic art, and sculptures.[83]

Egyptian antiquities[edit]

The department, comprising over 50,000 pieces,[21]: 74 includes artifacts from the Nile civilizations which date from 4,000 BC to the 4th century AD.[84] The collection, among the world's largest, overviews Egyptian life spanning Ancient Egypt, the Middle Kingdom, the New Kingdom, Coptic art, and the Roman, Ptolemaic, and Byzantine periods.[84]

The department's origins lie in the royal collection, but it was augmented by Napoleon's 1798 expeditionary trip with Dominique Vivant, the future director of the Louvre.[21]: 76-77 After Jean-François Champollion translated the Rosetta Stone, Charles X decreed that an Egyptian Antiquities department be created. Champollion advised the purchase of three collections, formed by Edmé-Antoine Durand, Henry Salt, and Bernardino Drovetti; these additions added 7,000 works. Growth continued via acquisitions by Auguste Mariette, founder of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. Mariette, after excavations at Memphis, sent back crates of archaeological finds including The Seated Scribe.[21]: 76-77 [85]

Guarded by the Great Sphinx of Tanis, the collection is housed in more than 20 rooms. Holdings include art, papyrus scrolls, mummies, tools, clothing, jewelry, games, musical instruments, and weapons.[21]: 76-77 [84] Pieces from the ancient period include the Gebel el-Arak Knife from 3400 BC, The Seated Scribe, and the Head of King Djedefre. Middle Kingdom art, "known for its gold work and statues", moved from realism to idealization; this is exemplified by the schist statue of Amenemhatankh and the wooden Offering Bearer. The New Kingdom and Coptic Egyptian sections are deep, but the statue of the goddess Nephthys and the limestone depiction of the goddess Hathor demonstrate New Kingdom sentiment and wealth.[84][85]

- The Gebel el-Arak Knife; 3300-3200 BC; handle: elephant ivory, blade: flint; length: 25.8 cm

- The Seated Scribe; 2613–2494 BC; painted limestone and inlaid quartz; height: 53.7 cm

- The Great Sphinx of Tanis; circa 2600 BC; rose granite; height: 183 cm, width: 154 cm, thickness: 480 cm

Near Eastern antiquities[edit]

Near Eastern antiquities, the second newest department, dates from 1881 and presents an overview of early Near Eastern civilization and "first settlements", before the arrival of Islam. The department is divided into three geographic areas: the Levant, Mesopotamia (Iraq), and Persia (Iran). The collection's development corresponds to archaeological work such as Paul-Émile Botta's 1843 expedition to Khorsabad and the discovery of Sargon II's palace.[84][21]: 119 These finds formed the basis of the Assyrian museum, the precursor to today's department.[84]

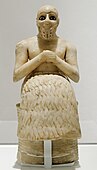

The museum contains exhibits from Sumer and the city of Akkad, with monuments such as the Prince of Lagash's Stele of the Vultures from 2450 BC and the stele erected by Naram-Sin, King of Akkad, to celebrate a victory over barbarians in the Zagros Mountains. The 2.25-metre (7.38 ft) Code of Hammurabi, discovered in 1901, displays Babylonian Laws prominently, so that no man could plead their ignorance. The 18th-century BC mural of the Investiture of Zimrilim and the 25th-century BC Statue of Ebih-Il found in the ancient city-state of Mari are also on display at the museum.[86]

A significant portion of the department covers the ancient Levant, including the Sarcophagus of Eshmunazar II discovered in 1855, which catalyzed Ernest Renan's 1860 Mission de Phénicie. It contains one of the world's largest and most comprehensive collections of Canaanite and Aramaic inscriptions. The section also covers North African Punic antiquities (Punic = Western Phoenician), given the significant French presence in the region in the 19th century, with early finds including the 1843 discovery of the Ain Nechma inscriptions.

The Persian portion of Louvre contains work from the archaic period, like the Funerary Head and the Persian Archers of Darius I,[84][87] and rare objects from Persepolis.[88]

- Sarcophagus of Eshmunazar II, one of only three Ancient Egyptian sarcophagi found outside Egypt, and the first Phoenician inscription discovered in Phoenicia

- Phoenician metal bowls from Cyprus

- The Code of Hammurabi; 1755–1750 BC; basalt; height: 225 cm, width: 79 cm, thickness: 47 cm

- Frieze of archers, from the Palace of Darius at Susa; circa 510 BC; bricks

- Statues from the Sidon Mithraeum

Greek, Etruscan, and Roman[edit]

The Greek, Etruscan, and Roman department displays pieces from the Mediterranean Basin dating from the Neolithic to the 6th century.[89] The collection spans from the Cycladic period to the decline of the Roman Empire. This department is one of the museum's oldest, and contains works acquired by Francis I.[84][21]: 155-58 Initially, the collection focused on marble sculptures, such as the Venus de Milo. Works such as the Apollo Belvedere arrived during the Napoleonic Wars, of which some were returned after Napoleon I's fall in 1815. Other works, such as the Borghese Vase, were bought by Napoleon. Later in the 19th century, the Louvre acquired works including vases from the Durand collection and bronzes.[21]: 92 [89]

The archaic is demonstrated by jewellery and pieces such as the limestone Lady of Auxerre, from 640 BC; and the cylindrical Hera of Samos, c. 570–560 BC.[84][90] After the 4th century BC, focus on the human form increased, exemplified by the Borghese Gladiator. The Louvre holds masterpieces from the Hellenistic era, including The Winged Victory of Samothrace (190 BC) and the Venus de Milo, symbolic of classical art.[21]: 155 The long Galerie Campana displays an outstanding collection of more than one thousand Greek potteries. In the galleries paralleling the Seine, much of the museum's Roman sculpture is displayed.[89] The Roman portraiture is representative of that genre; examples include the portraits of Agrippa and Annius Verus; among the bronzes is the Greek Apollo of Piombino.

- Cycladic head of a woman; 27th century BC; marble; height: 27 cm

- The Winged Victory of Samothrace; 200–190 BC; Parian marble; 244 cm

- Venus de Milo; 130–100 BC; marble; height: 203 cm

- Las Incantadas, sculptures from a portico that adorned the Roman Forum of Thessalonica, 150-230 AD[91]

Islamic art[edit]

The Islamic art collection, the museum's newest, spans "thirteen centuries and three continents".[92] These exhibits, of ceramics, glass, metalware, wood, ivory, carpet, textiles, and miniatures, include more than 5,000 works and 1,000 shards.[93] Originally part of the decorative arts department, the holdings became separate in 2003. Among the works are the Pyxide d'al-Mughira, a 10th century ivory box from Andalusia; the Baptistery of Saint-Louis, an engraved brass basin from the 13th or 14th century Mamluk period; and the 10th century Shroud of Saint-Josse from Iran.[21]: 119-121 [92] The collection contains three pages of the Shahnameh, an epic book of poems by Ferdowsi in Persian, and a Syrian metalwork named the Barberini Vase.[93] In September 2019, a new and improved Islamic art department was opened by Princess Lamia bint Majed Al Saud. The new department exhibits 3,000 pieces were collected from Spain to India via the Arabian peninsula dating from the 7th to the 19th centuries.[94]

- The Pyxis of al-Mughira; 10th century (maybe 968); ivory; 15 x 8 cm

- Iranian tile with bismillah; turn of the 13th-14th century; molded ceramic, luster glaze and glaze

- The Baptistère de Saint Louis; by Muhammad ibn al-Zayn; 1320–1340; hammering, engraving, inlay in brass, gold, and silver; 50.2 x 22.2 cm

- Door; 15th-16th century; sculpted, painted and gilded walnut wood

Sculptures[edit]

The sculpture department consists of works created before 1850 not belonging in the Etruscan, Greek, and Roman department.[95] The Louvre has been a repository of sculpted material since its time as a palace; however, only ancient architecture was displayed until 1824, except for Michelangelo's Dying Slave and Rebellious Slave.[21]: 397-401 Initially the collection included only 100 pieces, the rest of the royal sculpture collection being at Versailles. It remained small until 1847, when Léon Laborde was given control of the department. Laborde developed the medieval section and purchased the first such statues and sculptures in the collection, King Childebert and stanga door, respectively.[21]: 397-401 The collection was part of the Department of Antiquities but was given autonomy in 1871 under Louis Courajod, a director who organized a wider representation of French works.[95][21]: 397-401 In 1986, all post-1850 works were relocated to the new Musée d'Orsay. The Grand Louvre project separated the department into two exhibition spaces; the French collection is displayed in the Richelieu Wing, and foreign works in the Denon Wing.[95]

The collection's overview of French sculpture contains Romanesque works such as the 11th-century Daniel in the Lions' Den and the 12th-century Virgin of Auvergne. In the 16th century, Renaissance influence caused French sculpture to become more restrained, as seen in Jean Goujon's bas-reliefs, and Germain Pilon's Descent from the Cross and Resurrection of Christ. The 17th and 18th centuries are represented by Gian Lorenzo Bernini's 1640–1 Bust of Cardinal Richelieu, Étienne Maurice Falconet's Woman Bathing and Amour menaçant, and François Anguier's obelisks. Neoclassical works includes Antonio Canova's Psyche Revived by Cupid's Kiss (1787).[21]: 397-401 The 18th and 19th centuries are represented by the French sculptors like Alfred Barye and Émile Guillemin.

- The Tomb of Philippe Pot; 1477 and 1483; limestone, paint, gold and lead; height: 181 cm, width: 260 cm, depth: 167 cm

- The King's Fame Riding Pegasus; by Antoine Coysevox; 1701–1702; Carrara marble; height: 3.15 m, width: 2.91 m, depth: 1.28 m

- Group sculpture; by Nicolas Coustou; 1701–1712; marble; height: 2.44 m

Decorative arts[edit]

The Objets d'art collection spans the time from the Middle Ages to the mid-19th century. The department began as a subset of the sculpture department, based on royal property and the transfer of work from the Basilique Saint-Denis, the burial ground of French monarchs that held the Coronation Sword of the Kings of France.[96][21]: 451-454 Among the budding collection's most prized works were pietre dure vases and bronzes. The Durand collection's 1825 acquisition added "ceramics, enamels, and stained glass", and 800 pieces were given by Pierre Révoil. The onset of Romanticism rekindled interest in Renaissance and Medieval artwork, and the Sauvageot donation expanded the department with 1,500 middle-age and faïence works. In 1862, the Campana collection added gold jewelry and maiolicas, mainly from the 15th and 16th centuries.[21]: 451-454 [97]

The works are displayed on the Richelieu Wing's first floor and in the Apollo Gallery, named by the painter Charles Le Brun, who was commissioned by Louis XIV (the Sun King) to decorate the space in a solar theme. The medieval collection contains the coronation crown of Louis XIV, Charles V's sceptre, and the 12th century porphyry vase.[98] The Renaissance art holdings include Giambologna's bronze Nessus and Deianira and the tapestry Maximillian's Hunt.[96] From later periods, highlights include Madame de Pompadour's Sèvres vase collection and Napoleon III's apartments.[96]

In September 2000, the Louvre Museum dedicated the Gilbert Chagoury and Rose-Marie Chagoury Gallery to display tapestries donated by the Chagourys, including a 16th-century six-part tapestry suite, sewn with gold and silver threads representing sea divinities, which was commissioned in Paris for Colbert de Seignelay, Secretary of State for the Navy.

- Henry II style wardrobe; c. 1580; walnut and oak, partially gilded and painted; height: 2.06 m, width: 1.50 m, depth: 0.60 m[99]

- Louis XIV style cabinet on stand; by André Charles Boulle; c. 1690–1710; oak frame, resinous wood and walnut, ebony veneer, tortoiseshell, brass and pewter marquetry, and ormolu

- Louis XVI style commode of Madame du Barry; 1772; oak frame, veneer of pearwood, rosewood and kingwood, soft-paste Sèvres porcelain, gilded bronze, white marble, and glass; height: 0.87 m, width: 1.19 m, depth: 0.48 m[100]

- Louis XVI style barometer-thermometer; c. 1776; soft-paste Sèvres porcelain, enamel, and ormolu; height: 1 m, width: 0.27 m[101]

Painting[edit]

The painting collection has more than 7,500 works[13]: 229 from the 13th century to 1848 and is managed by 12 curators who oversee the collection's display. Nearly two-thirds are by French artists, and more than 1,200 are Northern European. The Italian paintings compose most of the remnants of Francis I and Louis XIV's collections, others are unreturned artwork from the Napoleon era, and some were bought.[102][21]: 199-201, 272–273, 333–335 The collection began with Francis, who acquired works from Italian masters such as Raphael and Michelangelo[103] and brought Leonardo da Vinci to his court.[104][105] After the French Revolution, the Royal Collection formed the nucleus of the Louvre. When the d'Orsay train station was converted into the Musée d'Orsay in 1986, the collection was split, and pieces completed after the 1848 Revolution were moved to the new museum. French and Northern European works are in the Richelieu Wing and Cour Carrée; Spanish and Italian paintings are on the first floor of the Denon Wing.[21]: 199

Exemplifying the French School are the early Avignon Pietà of Enguerrand Quarton; the anonymous painting of King Jean le Bon (c. 1360), possibly the oldest independent portrait in Western painting to survive from the postclassical era;[21]: 201 Hyacinthe Rigaud's Louis XIV; Jacques-Louis David's The Coronation of Napoleon; Théodore Géricault's The Raft of the Medusa; and Eugène Delacroix's Liberty Leading the People. Nicolas Poussin, the Le Nain brothers, Philippe de Champaigne, Le Brun, La Tour, Watteau, Fragonard, Ingres, Corot, and Delacroix are well represented.[106]

Northern European works include Johannes Vermeer's The Lacemaker and The Astronomer; Caspar David Friedrich's The Tree of Crows; Rembrandt's The Supper at Emmaus, Bathsheba at Her Bath, and The Slaughtered Ox.

The Italian holdings are notable, particularly the Renaissance collection.[107] The works include Andrea Mantegna and Giovanni Bellini's Calvarys, which reflect realism and detail "meant to depict the significant events of a greater spiritual world".[108] The High Renaissance collection includes Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa, Virgin and Child with St. Anne, St. John the Baptist, and Madonna of the Rocks. The Baroque collection includes Giambattista Pittoni's The Continence of Scipio, Susanna and the Elders, Bacchus and Ariadne, Mars and Venus, and others Caravaggio is represented by The Fortune Teller and Death of the Virgin. From 16th century Venice, the Louvre displays Titian's Le Concert Champetre, The Entombment, and The Crowning with Thorns.[21]: 378 [109]

The La Caze Collection, a bequest to the Musée du Louvre in 1869 by Louis La Caze, was the largest contribution of a person in the history of the Louvre. La Caze gave 584 paintings of his personal collection to the museum. The bequest included Antoine Watteau's Commedia dell'arte player of Pierrot ("Gilles"). In 2007, this bequest was the topic of the exhibition "1869: Watteau, Chardin... entrent au Louvre. La collection La Caze".[110]

Some of the best known paintings of the museum have been digitized by the French Center for Research and Restoration of the Museums of France.[111]

- The Money Changer and His Wife; by Quentin Massys; 1514; oil on panel; 70.5 × 67 cm

- Spring; by Giuseppe Arcimboldo; 1573; oil on canvas; 76 × 64 cm

- Susanna and the Elders; by Giambattista Pittoni; 1720; oil on panel; 37 × 46 cm

- The Continence of Scipio; by Giambattista Pittoni; 1733; oil on panel; 96 × 56 cm

- Diana after the Bath; by François Boucher; 1742; oil on canvas; 73 × 56 cm

- Oath of the Horatii; by Jacques-Louis David; 1784; oil on canvas; height: 330 cm, width: 425 cm

- Paintings by Leonardo da Vinci purchased by François I

Prints and drawings[edit]

The prints and drawings department encompasses works on paper.[21]: 496 The origins of the collection were the 8,600 works in the Royal Collection (Cabinet du Roi), which were increased via state appropriation, purchases such as the 1,200 works from Fillipo Baldinucci's collection in 1806, and donations.[21]: 92 [112] The department opened on 5 August 1797, with 415 pieces displayed in the Galerie d'Apollon. The collection is organized into three sections: the core Cabinet du Roi, 14,000 royal copper printing-plates, and the donations of Edmond de Rothschild,[113] which include 40,000 prints, 3,000 drawings, and 5,000 illustrated books. The holdings are displayed in the Pavillon de Flore; due to the fragility of the paper medium, only a portion are displayed at one time.[21]: 496

- Three lion-like heads; by Charles Le Brun; c. 1671; black chalk, pen and ink, brush and gray wash, white gouache on paper; 21.7 × 32.7 cm

- Studies of Women's Heads and a Man's Head; by Antoine Watteau; first half of the 18th century; sanguine, black chalk and white chalk on gray paper; 28 × 38.1 cm

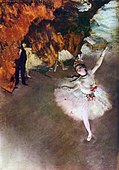

- Danseuse sur la scène; by Edgar Degas; pastel; 58 × 42 cm

- Портрет пожилой женщины работы Матиаса Грюневальда.

- Портрет молодой женщины, Ганс Гольбейн.

- Голова мужчины, Андреа дель Сарто

- Мадонна с Младенцем, Бьяджо Пупини

Менеджмент, администрация, партнёрство [ править ]

Лувр принадлежит французскому правительству. С 1990-х годов его менеджмент и управление стали более независимыми. [114] [115] [116] [117] С 2003 года музей обязан собирать средства для проектов. [116] К 2006 году доля государственных средств упала с 75 процентов от общего бюджета до 62 процентов. Ежегодно Лувр теперь собирает столько, сколько получает от государства, — около 122 миллионов евро. Правительство оплачивает эксплуатационные расходы (заработная плата, безопасность и техническое обслуживание), а остальное – новые крылья, ремонт, приобретения – должен финансировать музей. [118] Еще от 3 до 5 миллионов евро в год Лувр получает от выставок, которые он курирует для других музеев, а деньги за билеты остаются у принимающего музея. [118] Когда Лувр стал центром внимания благодаря книге «Код да Винчи» и фильму 2006 года по этой книге, музей заработал 2,5 миллиона долларов, разрешив съемку в своих галереях. [119] [120] В 2008 году французское правительство выделило 180 миллионов долларов из годового бюджета Лувра в 350 миллионов долларов; остальная часть поступила от частных пожертвований и продажи билетов. [115]

В Лувре работает 2000 сотрудников во главе с директором Жаном-Люком Мартинесом . [121] который подчиняется Министерству культуры и коммуникаций Франции. Мартинес сменил Анри Луаретта в апреле 2013 года. При Лойретте, который сменил Пьера Розенберга в 2001 году, Лувр претерпел изменения в политике, которые позволяют ему давать взаймы и брать больше произведений, чем раньше. [114] [116] В 2006 году он предоставил взаймы 1300 произведений, что позволило ему заимствовать больше зарубежных произведений. С 2006 по 2009 год Лувр одалживал произведения искусства Высшему художественному музею в Атланте, штат Джорджия, и получил выплату в размере 6,9 миллиона долларов для использования на реконструкцию. [116]

В 2009 году министр культуры Фредерик Миттеран утвердил план, согласно которому в 30 км (19 миль) к северо-западу от Парижа будет создано хранилище для предметов из Лувра и двух других национальных музеев в зоне затопления Парижа: Музея на набережной Бранли и Музея на набережной Бранли. Музей Орсе ; Позже план был отменен. В 2013 году его преемница Орели Филиппетти объявила, что Лувр перевезет более 250 000 произведений искусства. [122] хранится в подвале площадью 20 000 квадратных метров (220 000 квадратных футов) в Лиевене ; Стоимость проекта, оцениваемая в 60 миллионов евро, будет разделена между регионом (49%) и Лувром (51%). [123] Лувр станет единственным владельцем и управляющим магазина. [122] В июле 2015 года команда под руководством британской фирмы Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners была выбрана для проектирования комплекса, в котором будут светлые рабочие места под одной огромной зеленой крышей. [122] [124]

В 2012 году Лувр и Музеи изящных искусств Сан-Франциско объявили о пятилетнем сотрудничестве в области выставок, публикаций, консервации произведений искусства и образовательных программ. [125] [126] Расширение галерей исламского искусства стоимостью 98,5 млн евро в 2012 году получило государственное финансирование в размере 31 млн евро, а также 17 млн евро от Фонда Аль-Валида бин Талала, основанного одноименным саудовским принцем. Азербайджанская Республика, Эмир Кувейта, Султан Омана и король Марокко Мохаммед VI пожертвовали в общей сложности 26 миллионов евро. Кроме того, открытие Лувра Абу-Даби предполагает выделение 400 миллионов евро в течение 30 лет за использование бренда музея. [71] Лойретт пытался улучшить слабые части коллекции за счет доходов, полученных от ссуды произведений искусства, и гарантируя, что «20% поступлений от поступления будут ежегодно использоваться для приобретений». [116] Он получил большую административную независимость музея и добился того, что 90 процентов галерей открываются ежедневно, а не 80 процентов раньше. Он курировал введение продленного рабочего дня и бесплатного входа по вечерам в пятницу, а также увеличение бюджета приобретения с 4,5 миллионов долларов до 36 миллионов долларов. [115] [116]

в Тегеране открылась выставка десятков произведений искусства и реликвий, принадлежащих французскому Лувру . В марте 2018 года в Тегеране в результате соглашения между президентами Ирана и Франции, заключенного в 2016 году, [127] В Лувре древностям иранской цивилизации были выделены два отдела, и руководители двух отделов посетили Тегеран. На тегеранской выставке были представлены реликвии, принадлежащие Древнему Египту, Риму и Месопотамии, а также предметы французской королевской семьи. [128] [129] [130]

Ирана Здание Национального музея было спроектировано и построено французским архитектором Андре Годаром . [131] После выставки в Тегеране выставка должна пройти в Большом музее Хорасан в Мешхеде на северо-востоке Ирана в июне 2018 года. [132]

К 500-летию со дня смерти Леонардо да Винчи с 24 октября 2019 года по 24 февраля 2020 года в Лувре прошла крупнейшая в истории выставка его работ. [133] [134] На мероприятии было представлено более ста экспонатов: картины, рисунки и блокноты. Были выставлены полные 11 из менее чем 20 картин, которые да Винчи написал за свою жизнь. [135] Пять из них принадлежат Лувру, но « Мона Лиза» в список не попала, поскольку она пользуется таким большим спросом у посетителей Лувра; работа осталась выставленной в галерее. «Сальватор Мунди» также не был включен в список, поскольку саудовский владелец не согласился вынести произведение из тайника. Однако «Витрувианский человек» был выставлен на обозрение после успешной судебной тяжбы с его владельцем, Галереей Академии в Венеции. [136] [137]

В 2021 году были обнаружены церемониальный шлем и нагрудник эпохи Возрождения, украденные из музея в 1983 году. В музее отметили, что кража 1983 года «глубоко обеспокоила тогда весь персонал». Подробностей о самой краже в открытом доступе мало. [138] [139]

Нынешним директором Лувра является Лоуренс де Карс , выбранный президентом Франции Эммануэлем Макроном в 2021 году. [140] [141] Она первая женщина, занявшая эту должность. [142] Во время пандемии COVID-19 Лувр запустил цифровую платформу, на которой можно увидеть большинство его работ, в том числе тех, которые не выставлены напоказ. База данных включает более 482 000 иллюстрированных пластинок, что составляет 75% коллекций Лувра. [143] В 2022 году музей посетили более 7,6 миллиона посетителей, что на 170 процентов больше, чем в 2021 году, но все же ниже 10,8 миллиона посетителей в 2018 году до пандемии COVID-19. [144]

В 2023 году Лувр в Париже внес существенные изменения в свою ценовую политику, ознаменовав первое повышение цен с 2017 года. [145] Решение поднять цены на билеты на 30% является частью более широкой стратегии, направленной на поддержку свободного входа во время Олимпийских игр и эффективное управление ожидаемым количеством зрителей. Директор Лоуренс де Карс ввел меры по регулированию посещаемости, в том числе ограничил количество ежедневных посетителей до 30 000 и запланировал новый вход, чтобы уменьшить заторы. Эти усилия направлены на обеспечение первоклассных впечатлений для любителей искусства во время Олимпийских игр, поскольку в этом году музей планирует принять около 8,7 миллионов посетителей, причем 80% из них стремятся увидеть знаменитую Мону Лизу.

Археологические исследования [ править ]

Коллекции древнего искусства Лувра в значительной степени являются результатом раскопок, некоторые из которых музей спонсировал в течение долгого времени в соответствии с различными правовыми режимами, часто в качестве дополнения к французской дипломатии и/или колониальным предприятиям. В Ротонде д'Аполлона на резной мраморной панели перечислен ряд таких кампаний, возглавляемых:

- Луи-Франсуа-Себастьян Фовель в Греции (1818 г.)

- Жан-Франсуа Шампольон в Египте (1828–1829)

- Гийом-Абель Блуэ и Леон-Жан-Жозеф Дюбуа с экспедицией Мореи в Греции (1829 г.)

- Адольф Деламар в Алжире (1842–1845)

- Поль-Эмиль Ботта на Ниневийских равнинах (1845 г.)

- Жозеф Ваттье де Бурвиль в Киренаике (1850 г.)

- Огюст Мариетт в Египте (1850–1854)

- Виктор Ланглуа в Киликии (1852 г.)

- Эрнест Ренан с миссией Фениции после гражданского конфликта 1860 года в Горном Ливане и Дамаске (1860–1861)

- Леон Хьюзи и Оноре Доме в Македонии (1861 г.)

- Эжен-Мельхиор де Воге и Эдмон Дютуа на Кипре (1863–1866)

- Шарль Шампуазо в Самофракии (1863 г.)

- Эммануэль Миллер в Салониках и Тасосе (1864–1865)

- Оливье Райе и Альбер-Феликс-Теофиль Тома в Ионии (1872–1873)

- Шарль Симон Клермон-Ганно в Палестине (1873 г.)

- Антуан Эрон де Вильфосс в Алжире и Тунисе (1874 г.)

- Эрнест де Сарцек в Телло / древнем Гирсу , Месопотамия (1877–1900)

- Поль Жирар в Греции (1881)

- Эдмон Потье , Саломон Рейнах и Альфонс Вейрис в «Мирине (Эолиде)» (1872–1873)

- Марсель-Огюст Дьелафуа и Джейн Дьелафуа в Сузах , Персия (1884–1886)

- Чарльз Хубер в Тайме , Аравия (1885 г.)

- Альфред Шарль Огюст Фуше в Индии и современном Пакистане (1895–1897)

- Артур Энгель и Пьер Парис в Испании (1897 г.)

- Жак де Морган в Сузах (1897 г.)

- Гастон Крос в Телло / древнем Гирсу (1902)

- Поль Пеллио в Китайском Туркестане (1907–1909)

- Морис Пезар в Северной Палестине (1923)

- Жорж Аарон Бенедит в Египте (1926)

- Франсуа Тюро-Данжен в Северной Сирии (1929)

- Анри де Женуйяк в Месопотамии (1912, 1929)

- Французский институт восточной археологии в Каире, созданный в 1880 году.

Остальная часть мемориальной доски объединяет доноров археологических предметов, многие из которых сами были археологами, и других археологов, чьи раскопки внесли свой вклад в коллекции Лувра:

- Фредерик Моро во Франции (1899)

- Эдуард Пиетт во Франции (1902)

- Жозеф де Бай во Франции (1899–1906)

- Анри и Жак де Морган в Сузах (1909–1910)

- Леон Анри-Мартен (1906–1920) и его дочь Жермен во Франции (1976)

- Луи Капитан во Франции (1929)

- Рене де Сен-Перье и его жена Сюзанна во Франции (1935)

- Фернан Биссон де ла Рок в Египте (1922–1950)

- Бернар Брюйер в Египте (1920–1951)

- Раймонд Вейль в Египте (1952)

- Пьер Монте в Египте (1921–1956)

- Жан Мари Казаль в долине Инда и Афганистане (1950–1973)

- Сюзанна де Сен-Матюрен во Франции (1973)

- Андре Парро в Мари, Сирия (1931–1974).

- Клод Фредерик-Арман Шеффер в Угарите , Сирия (1929–1970)

- Роман Гиршман в Ираке и Иране (1931–1972)

Спутники и ответвления [ править ]

Несколько музеев во Франции и за ее пределами находились или находятся под административной властью Лувра или связаны с ним эксклюзивными партнерскими отношениями, но не расположены в Луврском дворце . С 2019 года Лувр также поддерживает большое хранилище произведений искусства и исследовательский центр в северном французском городе Льевен , Центр консервации Лувра , который закрыт для публики. [146]

Музей Клюни 1926–1977 ) (

В феврале 1926 года Музей Клюни , создание которого относится к XIX веку, был передан под эгиду отдела декоративного искусства Лувра ( Objets d'Art ). [147] Это членство было прекращено в 1977 году. [148]

Музей Же де Поме 1947–1986 ( )

Здание Же-де-Пом в саду Тюильри , первоначально предназначавшееся как спортивный комплекс, с 1909 года было перепрофилировано под художественную галерею. В 1947 году он стал выставочным пространством для коллекций Лувра картин конца 19-го и начала 20-го века, в первую очередь импрессионизма Лувра , поскольку в Луврском дворце не хватало места для их демонстрации, и, следовательно, он был передан под прямое управление Департаменту живописи . В 1986 году эти коллекции были переданы вновь созданному Музею Орсе . [149]

Музей Пти-Пале, Авиньон (с 1976 г. )

Musée du Petit Palais открылся в 1976 году в бывшем городском особняке архиепископов Авиньона , недалеко от Папского дворца в Авиньоне . По инициативе мэра Авиньона Анри Дюффо и президента-директора Лувра Мишеля Лаклотта часть его постоянной коллекции состоит из произведений искусства из коллекции Кампана переданных на хранение Лувром. 2 апреля 2024 года новое соглашение между городом Авиньон и Лувром позволило провести его ребрендинг в Musée du Petit Palais - Louvre en Avignon . [150]

Лувр Гипсотека (с 2001 г.) [ править ]

Гипсотека , которая была сформирована в 1970 году в результате (галерея гипсовых слепков) Лувра представляет собой коллекцию гипсовых слепков воссоединения соответствующих инвентарей Лувра, Парижского изящных искусств и Института искусств и археологии Сорбоннского университета , последние два произошли после грабежей во время студенческих волнений 68 мая . Первоначально с 1970 по 1978 год проект назывался « Музей антикварных памятников» , но впоследствии проект остался незавершенным и был реализован только после того, как в 2001 году решением министерства он был передан под управление Лувра. [151] Он расположен в Petite Écurie , пристройке Версальского дворца , и открыт для публики с 2012 года. [152]

Музей Делакруа (с 2004 г.) [ править ]

Небольшой музей, расположенный в бывшей мастерской Эжена Делакруа в центре Парижа, созданной в 1930-х годах, с 2004 года находится под управлением Лувра. [153]

Лувр-Ланс (с 2012 г.) [ править ]

Лувр-Ланс следует за инициативой тогдашнего министра культуры Жан-Жака Айягона, выдвинутой в мае 2003 года , по продвижению культурных проектов за пределами Парижа, которые сделают богатства основных парижских учреждений доступными для более широкой французской общественности, включая спутник ( антенну ) Лувра. [154] После нескольких туров конкурса бывший горнодобывающий объект в городе Ланс в качестве места расположения был выбран , о чем объявил премьер-министр Жан-Пьер Раффарен 29 ноября 2004 г. Японские архитекторы SANAA и ландшафтный архитектор Кэтрин Мосбах были выбраны в сентябре 2005 года для проектирования здания музея и сада соответственно. Открытый президентом Франсуа Олландом 4 декабря 2012 г., Лувр-Ланс находится в ведении региона Верхняя-де-Франс в соответствии с контрактом ( научная и культурная конвенция ) с Лувром о кредитовании произведений искусства и использовании брендов. Его главная достопримечательность — это поочередная выставка примерно 200 произведений искусства из Лувра, представленных в хронологическом порядке в одном большом зале (Galerie du Temps или «галерея времени»), который выходит за рамки географических и предметных разделений, по которым парижский музей Организованы выставки Лувра. До пандемии COVID-19 Лувр-Ланс успешно привлекал около 500 000 посетителей в год. [155]

Лувр Абу-Даби (с 2017 г.) [ править ]

Лувр Абу-Даби является отдельным от Лувра юридическим лицом, но между этими двумя организациями существуют многогранные договорные отношения, которые позволяют эмиратскому музею использовать название Лувра до 2037 года и выставлять произведения искусства из Лувра до 2027 года. [156] Он был открыт 8 ноября 2017 года и открыт для публики через три дня. Соглашение сроком на 30 лет, подписанное в начале 2007 года министром культуры Франции Рено Доннедье де Вабром и шейхом Султаном бен Тахнуном Аль Нахайяном, устанавливает, что Абу-Даби должен заплатить 832 миллиона евро (1,3 миллиарда долларов США) в обмен на использование названия Лувра, управленческие консультации, художественные кредиты и специальные выставки. [157] Лувр Абу-Даби расположен на острове Саадият и был спроектирован французским архитектором Жаном Нувелем и инженерной фирмой Buro Happold . [158] Он занимает площадь 24 000 квадратных метров (260 000 квадратных футов) и покрыт культовым металлическим куполом, предназначенным для того, чтобы лучи света, имитирующие солнечный свет, проходили сквозь финиковых пальм листья в оазисе . Французские художественные кредиты, которые, как ожидается, составят от 200 до 300 произведений искусства в течение 10-летнего периода, поступают из нескольких музеев, включая Лувр, Центр Жоржа Помпиду , Музей Орсе , Версаль , Музей Гиме , Музей Родена , и Музей на набережной Бранли . [159]

Споры [ править ]

Лувр участвует в спорах вокруг культурных ценностей, захваченных при Наполеоне I, а также во время Второй мировой войны нацистами . [160] [161] В начале 2010-х годов права рабочих при строительстве Лувра Абу-Даби также были предметом споров для музея. [162]

Наполеоновские грабежи [ править ]

В ходе кампаний Наполеона были приобретены итальянские предметы по договорам в качестве военных репараций и предметы из Северной Европы в качестве трофеев, а также некоторые предметы старины, раскопанные в Египте, хотя подавляющее большинство последних было конфисковано британской армией в качестве военных репараций и теперь является частью коллекций Британский музей . С другой стороны, на Дендерский зодиак , как и на Розеттский камень , претендует Египет, хотя он был приобретен в 1821 году, до принятия египетского законодательства о запрете экспорта 1835 года. Таким образом, администрация Лувра выступала за сохранение этого предмета, несмотря на просьбы. Египтом для его возвращения. Музей также участвует в арбитражных сессиях, проводимых через Комитет ЮНЕСКО по содействию возвращению культурных ценностей в страны их происхождения. [163] В результате в 2009 году музей вернул пять египетских фрагментов фресок (30 х 15 см каждый), о существовании гробницы которых было доведено до сведения властей только в 2008 году, через восемь-пять лет после их добросовестного приобретения музеем. из двух частных коллекций и после необходимого соблюдения процедуры изъятия из французских государственных коллекций перед Национальной научной комиссией по коллекциям музеев Франции. [164]

Нацистские грабежи [ править ]

Во время нацистской оккупации были украдены тысячи произведений искусства. [165] Но после войны 61 233 статьи о более чем 150 000 конфискованных произведениях искусства вернулись во Францию и были переданы в Office des Biens Privés. [166] В 1949 году оно передало 2130 невостребованных экспонатов (в том числе 1001 картину) Дирекции музеев Франции, чтобы держать их в соответствующих условиях консервации до их реституции, а тем временем классифицировало их как MNR (Musées Nationaux Recuperation или, по-английски, Национальный музей восстановления). Музеи восстановленных произведений искусства). Считается, что от 10% до 35% произведений искусства являются результатом грабежа евреев. [167] и до установления их законных владельцев, которое в конце 1960-х годов сократилось, они числятся на неопределенный срок в отдельных описях музейных коллекций. [168]

Они были выставлены в 1946 году и все вместе демонстрировались публике в течение четырех лет (1950–1954), чтобы позволить законным заявителям идентифицировать свою собственность, а затем хранились или выставлялись, в зависимости от их интересов, в нескольких французских музеях, включая Лувр. С 1951 по 1965 год было возвращено около 37 штук. С ноября 1996 г. частично иллюстрированный каталог 1947–1949 гг. доступен в Интернете и дополнен. В 1997 году премьер-министр Ален Жюппе инициировал создание комиссии Маттеоли во главе с Жаном Маттеоли для расследования этого дела. По данным правительства, Лувр отвечает за 678 произведений искусства, до сих пор не востребованных их законными владельцами. [169] В конце 1990-х годов не проводившееся ранее сравнение американских военных архивов с французскими и немецкими, а также два судебных дела, окончательно урегулировавшие некоторые права наследников ( семей Джентили ди Джузеппе и Розенбергов), позволили более точные исследования. С 1996 года реституция, иногда по менее формальным критериям, касалась еще 47 произведений (26 картин, в том числе 6 из Лувра, включая выставленный тогда Тьеполо), пока последние претензии французских владельцев и их наследников снова не прекратились в 2006 году. [ нужна ссылка ]

По словам Сержа Кларсфельда , после полной и постоянной огласки, которую произведения искусства получили в 1996 году, большинство французской еврейской общины, тем не менее, выступает за возвращение к нормальному французскому гражданскому правилу давности, позволяющему приобретать любое невостребованное добро после еще одного длительного периода. времени и, следовательно, к их окончательной интеграции в общее французское наследие, а не передаче их иностранным учреждениям, как во время Второй мировой войны. [ нужна ссылка ]

Строительство Лувра Абу-Даби [ править ]

В 2011 году более 130 художников со всего мира призвали бойкотировать новый музей Гуггенхайма, а также Лувр Абу-Даби, ссылаясь на сообщения, начиная с 2009 года, о злоупотреблениях в отношении иностранных строителей на острове Саадият, включая произвольное удержание заработной платы, небезопасные условия труда и неспособность компаний платить или возмещать высокие сборы за найм, взимаемые с рабочих. [170] [171] По данным Architectural Record , в Абу-Даби действуют всеобъемлющие трудовые законы, защищающие рабочих, но они не соблюдаются добросовестно. [172] В 2010 году Фонд Гуггенхайма разместил на своем веб-сайте совместное заявление с Компанией по развитию туризма и инвестиций Абу-Даби (TDIC), в котором признаются, среди прочего, следующие проблемы прав трудящихся: здоровье и безопасность работников; их доступ к своим паспортам и другим документам, которые работодатели сохраняют, чтобы гарантировать, что они останутся на работе; использование генерального подрядчика, который согласен соблюдать трудовое законодательство; поддержание независимого монитора сайта; и прекращение системы, которая обычно использовалась в регионе Персидского залива и требовала от работников возмещать плату за прием на работу. [173]

В 2013 году газета The Observer сообщила, что условия содержания рабочих на стройках Лувра и Нью-Йоркского университета на Саадияте приравниваются к «современному рабству». [174] [175] В 2014 году директор Гуггенхайма Ричард Армстронг заявил, что, по его мнению, условия жизни для работников проекта Лувра теперь хорошие и что у «гораздо меньшего числа» из них конфисковали паспорта. Он заявил, что основным вопросом, который тогда оставался, были сборы за найм, взимаемые с работников агентами, которые их нанимают. [176] [177] Позже в 2014 году архитектор Гуггенхайма Гери отметил, что работать с властями Абу-Даби над выполнением закона об улучшении условий труда на территории музея является «моральной ответственностью». [172] Он призвал TDIC построить дополнительное жилье для рабочих и предложил, чтобы подрядчик покрыл расходы на оплату труда. В 2012 году TDIC привлекла PricewaterhouseCoopers в качестве независимого наблюдателя, обязанного предоставлять отчеты каждый квартал. Юрист по трудовым вопросам Скотт Хортон рассказал Architectural Record , что он надеется, что проект Гуггенхайма повлияет на отношение к работникам на других объектах Саадията и «послужит моделью для того, чтобы все делать правильно». [172] [178]

См. также [ править ]

- Центр исследований и реставрации музеев Франции

- Лувр Отель

- Список музеев Парижа

- Музей моды и текстиля

- Список туристических достопримечательностей Парижа

- Список крупнейших художественных музеев

Ссылки [ править ]

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Отчет о деятельности Лувра за 2019 год , с. 29, сайт www.louvre.fr.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с «Музей Лувр» . www.museums.eu .

- ^ [1] Franceinfo Culture, 4 января 2024 г.

- ^ Новый Оксфордский американский словарь дает изменение «/'l oo v(rə)/», которое было преобразовано в его IPA эквивалент . Часть в скобках указывает на вариант произношения.

- ^ «Музей Лувр» . Неэкспонат . Проверено 15 октября 2016 г.

- ^ «Сайт Лувра – Замок-музей, 1672 и 1692 годы» . Лувр.фр. Архивировано из оригинала 15 июня 2011 года . Проверено 21 августа 2011 г.

- ^ «Сайт Лувра – Замок-музей, 1692 год» . Лувр.фр. Архивировано из оригинала 15 июня 2011 года . Проверено 21 августа 2011 г.

- ^ «Доклад о деятельности на 2022 год» (PDF) . Лувр . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 15 декабря 2023 года.

- ^ «Лувр сохраняет свое место самого посещаемого художественного музея в мире» . The Art Newspaper - Международные новости и события в сфере искусства . 27 марта 2023 г. Проверено 17 мая 2024 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б «В 2023 году Лувр вернулся к уровню посещаемости, существовавшему до Covid, с почти 9 миллионами посетителей» . 3 января 2024 г.

- ^ «Как сюда добраться» . Музей Лувр . Архивировано из оригинала 21 сентября 2008 года . Проверено 28 сентября 2008 г.

- ^ Менон, Лакшми (22 июля 2019 г.). «Какой вход в Лувр подойдет вам лучше всего | Все о четырех входах в Лувр» . Головной блог . Проверено 6 июля 2023 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж Пьер Розенберг (2007). Словарь любителей Лувра . Пэрис: Плон.

- ^ Филипп Малгуир (1999). Музей Наполеона . Встреча национальных музеев.

- ^ «Правила музея» . Ле Лувр . Проверено 7 декабря 2022 г.

- ^ Филлипс, Том (27 ноября 2013 г.). «Руководство Nintendo по 3DS Louvre выпущено в интернет-магазине» . Еврогеймер . Архивировано из оригинала 7 сентября 2015 года . Проверено 30 июня 2023 г.

- ^ «Путеводитель по Лувру для Nintendo 3DS» . Нинтендо . Архивировано из оригинала 20 февраля 2016 года.

- ^ Нетберн, Дебора (16 апреля 2012 г.). «Как Лувр и Nintendo заново изобретают аудиотур по музею» . Лос-Анджелес Таймс . Архивировано из оригинала 30 июня 2023 года . Проверено 30 июня 2023 г.

- ^ Nintendo (27 ноября 2013 г.). «Nintendo Direct – Руководство по Nintendo 3DS: Лувр» . Ютуб . Нинтендо Америки . Проверено 9 июля 2023 г.

- ^ Уорр, Филиппа (2 декабря 2013 г.). «Руководство Nintendo 3DS Louvre не блокирует регион» . Проводной . Архивировано из оригинала 25 апреля 2016 года.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я дж к л м н тот п д р с т в v В х и С аа аб и объявление но из в Клод Миньо (1999). Карманный Лувр: Путеводитель по 500 произведениям . Нью-Йорк: Абвиль Пресс. ISBN 0-7892-0578-5 . OCLC 40762767 .

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Эдвардс, стр. 193–94.

- ^ Ларусса В Новом этимологическом и историческом словаре , Librairie Larousse, Париж, 1971, с. 430: *** волк 1080, Роланд ( leu , форма сохранена в виде очереди leu leu , Saint Leu и т. д.); от лат. волчанка; волк переделан на фем. louve, где *v* препятствовал переходу от *ou* к *eu* (ср. Louvre, от лат. поп. lupara)*** этимология слова louvre — от lupara , женской (поп. лат.) формы волчанки .

- ^ В Лебефе (аббате), Фернан Бурнон, История города и всей Парижской епархии аббата Лебефа , Том. 2, Париж: Féchoz et Letouzey, 1883, с. 296: «Лувр».

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Эдвардс, с. 198

- ^ Нор, с. 274

- ^ «Жан-Филипп Буль, сын Андре-Шарля Буля» . ИДТИ. 21 июля 2019 г.

- ^ «Смерть Андре-Шарля Буля» . Меркюр де Франс. Март 1732 года.

- ^ «Мастера маркетри в 17 веке: Буль» . Ханакадемия. Архивировано из оригинала 8 марта 2020 года . Проверено 30 ноября 2017 г.

- ^ Чаунди, Боб (29 сентября 2006 г.). «Лица недели» . Би-би-си . Проверено 5 октября 2007 г.

- ^ Роберт В. Бергер (1999). Публичный доступ к искусству в Париже: документальная история от средневековья до 1800 года . Университетский парк: Издательство Пенсильванского государственного университета. стр. 83–86.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с д Нора, с. 278

- ^ Карбонелл, с. 56

- ^ Оливер, стр. 21–22.

- ^ Монаган, Шон М.; Роджерс, Майкл (2000). «Французская скульптура 1800–1825, Канова» . Проект Парижа XIX века . Школа искусств и дизайна Государственного университета Сан-Хосе. Архивировано из оригинала 20 апреля 2008 года . Проверено 24 апреля 2008 г.

- ^ Оливер, с. 35

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с д Олдерсон, стр. 24, 25.

- ^ Макклеллан, с. 7

- ^ Вивьен Ришар (лето 2021 г.), «Когда Бонапарт назначает Денона», Galerie – le Journal du Louvre , 55:74 Grande

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Женевьева Бреск (1989). Мемуары Лувра . Париж: Галлимар.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Олдерсон, с. 25

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Завод, с. 36

- ^ Светнам-Берланд, Молли (2009). «Воплощение Египта: Ватиканский Нил». Американский журнал археологии . 113 (3): 440. дои : 10.3764/aja.113.3.439 . JSTOR 20627596 . S2CID 191377908 .

- ^ Попкин, с. 88

- ^ Например, , » Мантеньи «Голгофа « Веронезе Свадьба в Кане|Брак Каны» Рогира ван дер Вейдена и «Благовещение» не были возвращены.

- ^ «Паоло Веронезе» . Журнал Джентльмена . № Декабрь 1867 г. А. Додд и А. Смит. 1867. с. 741.

- ^ Джонс, Кристофер М.С. (1998). Антонио Канова и политика патронажа в революционной и наполеоновской Европе . Издательство Калифорнийского университета. п. 190. ИСБН 978-0520212015 .

- ^ Марси, Пьер (1867). Популярный путеводитель по Лувру . Париж: Librairie du Petit Journal . Проверено 14 июня 2024 г.