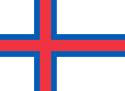

Фарерские острова

В этой статье должен быть указан язык содержания, отличного от английского, с использованием {{ lang }} , {{ транслитерации }} для языков с транслитерацией и {{ IPA }} для фонетической транскрипции с соответствующим кодом ISO 639 . Википедии шаблоны многоязычной поддержки Также можно использовать ( июль 2023 г. ) |

Фарерские острова | |

|---|---|

| Гимн : « Tú alfagraland mítt » ( фарерский язык ). (Английский: «Ты, прекраснейшая моя земля» ) | |

Location of the Faroe Islands (green) in Europe (green and dark grey) | |

Location of the Faroe Islands (red; circled) in the Kingdom of Denmark (yellow) | |

| Sovereign state | Kingdom of Denmark |

| Settlement | early 9th century |

| Union with Norway | c. 1035 |

| Kalmar Union | 1397–1523 |

| Denmark-Norway | 1523–1814 |

| Cession to Denmark | 14 January 1814 |

| Independence referendum | 14 September 1946 |

| Home rule | 30 March 1948 |

| Further autonomy | 29 July 2005[1] |

| Capital and largest city | Tórshavn 62°00′N 06°47′W / 62.000°N 6.783°W |

| Official languages | |

| Ethnic groups | Faroe Islanders |

| Religion | Christianity (Church of the Faroe Islands) |

| Demonym(s) |

|

| Government | Devolved government within a parliamentary constitutional monarchy |

• Monarch | Frederik X |

| Mette Frederiksen | |

| Lene Moyell Johansen | |

| Aksel V. Johannesen | |

| Legislature | Folketinget (Realm legislature) Løgting (Local legislature) |

| National representation | |

| 2 members | |

| Area | |

• Total | 1,393[4] km2 (538 sq mi) (not ranked) |

• Water (%) | 0.5 |

| Highest elevation | 882 m (2,894 ft) |

| Population | |

• April 2024 estimate | 54,642[5] (214th) |

• 2011 census | 48,346 |

• Density | 38.6/km2 (100.0/sq mi) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2019 estimate |

• Total | US$3.126 billion[6] (not ranked) |

• Per capita | US$58,585 (not ranked) |

| Gini (2018) | low · 1st place |

| HDI (2008) | 0.950[8] very high |

| Currency | (DKK) |

| Time zone | UTC±00:00 (WET) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+01:00 (WEST) |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +298 |

| Postal code | FO-xxx |

| ISO 3166 code | FO |

| Internet TLD | .fo |

Фарерские / , или просто острова ( / ˈ f ɛər oʊ ) FAIR -oh Фарерские острова ( фарерский : Føroyar , произносится [ˈfœɹjaɹ] ; Датский : Færøerne [ˈfeɐ̯ˌøˀɐnə] ) — архипелаг в северной части Атлантического океана и автономная территория Королевства Дания . Официальным языком страны является фарерский язык и частично взаимопонятен с ним , который тесно связан с исландским языком .

Расположенные на таком же расстоянии от Исландии , Норвегии и Великобритании , острова имеют общую площадь около 1400 квадратных километров (540 квадратных миль) с населением 54 676 человек по состоянию на август 2023 года. [10] Местность пересеченная, а субполярный океанический климат (Cfc) ветреный, влажный, облачный и прохладный. Несмотря на северный климат, температура смягчается Гольфстримом и в среднем выше нуля в течение года, колеблясь около 12 ° C (54 ° F) летом и 5 ° C (41 ° F) зимой. [11] As a result of its northerly latitude and proximity to the Arctic Circle, the islands experience perpetual civil twilight during summer nights and very short winter days. The capital and largest city, Tórshavn, receives the fewest recorded hours of sunshine of any city in the world at only 840 per year.[12]

While archaeological evidence placing the first known habitation as early as the 4th century, Færeyinga Saga and the writings of Dicuil place initial Norse settlement in the early 9th century.[13][14] As with the subsequent Settlement of Iceland, the islands were mainly settled by Norwegians and Norse-Gaels, who additionally brought thralls (i.e. slaves or serfs) of Gaelic origin. Following the introduction of Christianity by Sigmundur Brestisson, the islands came under Norwegian rule in the early 11th century. The Faroe Islands followed Norway's integration into the Kalmar Union in 1397, and came under de facto Danish rule following that union's dissolution in 1523. Following the introduction of Lutheranism in 1538, the usage of Faroese was banned in churches, schools and state institutions, and disappeared from writing for more than three centuries. The islands were formally ceded to Denmark in 1814 by the Treaty of Kiel along with Greenland and Iceland, and the Løgting was subsequently replaced by a Danish judiciary.

Following the re-establishment of an official Faroese orthography by Venceslaus Ulricus Hammershaimb, the Faroese language conflict saw Danish being gradually displaced by Faroese as the language of the church, public education and law in the first half of the 20th century. The islands were occupied by the British during the Second World War, who refrained from governing Faroese internal affairs: inspired by this period of relative self-government and the declaration of Iceland as a republic in 1944, the islands held a referendum in 1946 that resulted in a narrow majority for independence. The results were annulled by Christian X, and subsequent negotiations led to the Faroe Islands being granted home rule in 1948.[15]

While remaining part of the Kingdom of Denmark to this day, the Faroe Islands have extensive autonomy and control most areas apart from military defence, policing, justice and currency, with partial control over its foreign affairs.[16] Because the Faroe Islands are not part of the same customs area as Denmark, they have an independent trade policy and are able to establish their own trade agreements with other states. The islands have an extensive bilateral free trade agreement with Iceland, known as the Hoyvík Agreement. In the Nordic Council, they are represented as part of the Danish delegation. In certain sports, the Faroe Islands field their own national teams. They did not become a part of the European Economic Community in 1973, instead keeping autonomy over their own fishing waters; as a result, the Faroe Islands are not a part of the European Union today. The Løgting, albeit suspended between 1816 and 1852, holds a claim as one of the oldest continuously running parliaments in the world. One Faroe Islander, Niels Ryberg Finsen, has won the Nobel Prize; due to their small population, the Faroe Islands resultingly hold the most Nobel laureates per capita.

Etymology

[edit]The English name Faroe Islands (alt. Faeroe or the Faroes) derives from the Old Norse Færeyjar,[17][18][19] which is also the origin of the modern-day endonym Føroyar. The second element oyar ('islands') is a holdover from Old Faroese; sound changes have rendered the word's modern form as oyggjar. Names for individual islands (such as Kalsoy and Suðuroy) also preserve the old form.

The name's ultimate etymological origin has been subject to dispute. The most widely-held theory, first attested in Færeyinga Saga, interprets it as a straightforward compound of fær ('sheep') and eyjar ('islands'), meaning "sheep islands", in reference to their abundance on the archipelago. Clergymen Peder Clausson and Lucas Debes began casting doubt on this theory in the 16th and 17th centuries, arguing that the West Norse-speaking settlers, who would have used sauðr as opposed to the East Norse fær, would not have coined it from this exact origin. Debes surmised that it could have derived from fjær ('far'), while Hammershaimb leaned towards fara ('to go, to travel').[20]

Others have theorised an Old Irish origin: relating the name to the variably Celtic etymologies of neighbouring Orkney and Shetland, Scottish writers James Currie and William J. Watson suggested respectively the words feur ('pasture, eaten-up outfield') and fearann ('land, territory') as possible derivations, arguing that the original Celtic attestations of the islands' existence made this more likely.[20] Archaeologist Anton Wilhelm Brøgger concurred, elaborating on Watson's theory by positing that the Norse, having first learned of the islands from Scottish and Irish accounts as a fearann, could have coined Færeyjar as a phono-semantic match.[20]

History

[edit]Archaeological studies from 2021 found evidence of settlement on the islands before the arrival of Norse settlers, uncovering burnt grains of domesticated barley and peat ash deposited in two phases: the first dated between the mid-fourth and mid-sixth centuries, and another between the late-sixth and late-eighth centuries.[21][22] Researchers have also found sheep DNA in lake-bed sediments dating to the year 500. Barley and sheep had to have been brought to the islands by humans; as Scandinavians did not begin using sails until about 750, it is unlikely they could have reached the Faroes before then, leading to the study concluding that the settlers were more likely to originate from Scotland or Ireland.[23][24]

These findings concur with historical accounts from the same period: archaeologist Mike Church noted that Irish monk Dicuil describes a group of islands north of Scotland of very similar character to the Faroe Islands in his work De mensura orbis terrae ("Of the measure of the worlds of the earth"). In this text, Dicuil describes "a group of small islands (...) Nearly all of them (...) separated by narrow stretches of water" that were "always deserted since the beginning of time"[25] and previously populated by heremitae ex nostra Scotia ("hermits from our land of Ireland/Scotland") for almost a hundred years before being displaced by the arrival of Norse "pirates". Church argued that these were likely the eremitic Papar that had similarly resided in parts of Iceland and Scotland in the same period.[26] Writers like Brøgger and Peter Andreas Munch had drawn the same connections from Dicuil's writings, with the latter arguing that these Papar were also the ones to bring sheep to the islands.[25][20] A ninth-century voyage tale concerning Irish saint Brendan, one of Dicuil's contemporaries, details him visiting an unnamed northern group of islands; this has also been argued to be referring to the Faroe Islands, though not nearly as conclusively.[27] A number of toponyms around the islands refer to the Papar and the Irisish, such as Paparøkur near Vestmanna and Papurshílsur near Saksun. Vestmanna is itself short for Vestmannahøvn ("harbour of the Westmen"). Tombstones in a churchyard on Skúvoy display a possible Gaelic origin or influence.[28]

Old Norse-speaking settlers arrived in the early 9th century, and their Old West Norse dialect would later evolve into the modern Faroese language. A number of the settlers were Norse–Gaels who did not come directly from Scandinavia, but rather from Norse communities that spanned the Irish Sea, Northern Isles, and Outer Hebrides of Scotland, including the Shetland and Orkney islands; these settlers also brought thralls of Gaelic origin with them, and this admixture is reflected today in the Faroese genetic makeup and a number of loanwords from Old Irish. A traditional name for the islands in Irish, Na Scigirí, possibly derives from Eyja-Skeggjar, ("Island-Beards"), a nickname given to island dwellers.[citation needed] According to Færeyinga saga, many of the Norwegian settlers in particular were spurred by their disapproval of the monarchy of Harald Fairhair, whose rule was also seen as an inciting factor for the Settlement of Iceland.

The founding date of the Løgting is not historically documented, though the saga implies that it was a well-established institution by the middle of the 10th century, when a legal dispute between chieftains Havgrímur and Einar Suðuroyingur, resulting in the exile of Eldjárn Kambhøttur, is recounted in detail.[29]

Christianity was introduced to the islands in the late 10th and early 11th centuries by chieftain Sigmundur Brestisson.[30] Baptised as an adult by then-King of Norway Olaf Tryggvason, his mission to introduce Christianity was part of a greater plan to seize the islands on behalf of the Norwegian crown.[31] While Christianity arrived at the same time as in Iceland, the process was met with much more conflict and violence, and was defined particularly by Sigmundur's conflict with rival chieftain Tróndur í Gøtu, the latter of whom was converted under threat of decapitation. Although their conflict resulted in Sigmundur's murder, the Islands fell firmly under Norwegian rule following Tróndur's death in 1035.[30]

14th century onwards

[edit]While the Faroe Islands formally remained a Norwegian possession until 1814, Norway's merger into the Kalmar Union in 1397 gradually resulted in the islands coming under de facto Danish control. When the Protestant Reformation reached the Faroe Islands in 1538, the Faroese language was also outlawed in schools, churches and official documentation; thus Faroese remained exclusively a spoken language until the 19th century. Following the Napoleonic Wars, the union between Denmark and Norway was dissolved by the Treaty of Kiel in 1814; while Norway was transferred to the Swedish Crown, Denmark retained possession of Norway's North Atlantic territories, which included the Faroe Islands along with Greenland and Iceland. Shortly afterwards, Denmark asserted control and began to restrict the islands' autonomy. In 1816, the Faroe Islands was reconstituted as a county (amt) within the Danish Kingdom: the Løgting, having operated continuously for almost a millennium, was dissolved and replaced by a Danish judiciary, and the post of løgmaður (lawspeaker) was likewise replaced by a Danish-appointed amtmand (equivalent to a governor-general).[32]

As part of its mercantilist economic policy, Denmark maintained a monopoly over trade with the Faroe Islands and forbade the Faroese from trading with other countries. The trade monopoly in the Faroe Islands was eventually abolished in 1856, after which the area developed into a modern fishing-based economy with its own fishing fleet. In 1846, the Faroe Islands finally regained formal political representation when they were allocated two seats in the Danish Rigsdag; the Løgting itself was reinstated as an advisory body to the amtmand in 1852.

An official Faroese orthography was first introduced in 1846 by Lutheran minister Venceslaus Ulricus Hammershaimb, returning the language to print after 300 years of only existing in oral form. With the return of written Faroese to the public sphere after more than 300 years, nationalism gained a foothold in Faroese society: the modern Faroese national movement is commonly agreed to have begun with the Christmas Meeting of 1888, held to "discuss how to defend the Faroese language and Faroese traditions". This meeting led to the rise of two of the movement's most prominent early figures: Jóannes Patursson and Rasmus Effersøe.

It was initially exclusively concerned with the status of the Faroese language, but it soon gained a political dimension with the advent of the Faroese language conflict in the early 20th century. Both sides of the conflict were represented by the country's first-ever political parties: the Union Party (Sambandsflokkurin), founded in 1906, which supported Faroese literature but opposed its usage in education; and the Self-Government party (Sjálvstýrisflokkurin), which sought to introduce Faroese as the official language in all public spheres and additionally demanded increased political autonomy for the islands. The Faroese language gradually won out; laws and protocols of the Løgting were written in Faroese from 1927 onwards, schools switched to Faroese as the language of instruction in 1938, and Faroese was fully authorised as the language of the Church the following year. Finally in 1944, Faroese gained equal status with Danish in legal proceedings.

In the first year of the Second World War, on 12 April 1940, British troops occupied the Faroe Islands in Operation Valentine. Nazi Germany had invaded Denmark and commenced the invasion of Norway on 9 April 1940 under Operation Weserübung. In 1942–1943, the British Royal Engineers, under the command of lieutenant colonel William Law, built the first and only airport in the Faroe Islands, Vágar Airport. The British refrained from governing Faroese internal affairs, and the islands became effectively self-governing during the war. After the war ended and the British army left, this period and Iceland's declaration as a republic in 1944 served as a precedent and a model in the mind of many Faroe Islanders.

The Løgting held an independence referendum on 14 September 1946, resulting in a very narrow majority for independence; 50.73% voted in favour and 49.27% against; the margin was only 161 votes.[33] The Løgting subsequently declared independence on 18 September 1946; this declaration was annulled by Denmark on 20 September, arguing that the number of invalid votes (481) being greater than the narrow margin in favour made the result invalid. As a result, King Christian X of Denmark ordered that the Faroese Løgting be dissolved on 24 September, with new elections held that November.[34] The Faroese parliamentary election of 1946 resulted in a majority for parties opposed to independence:[35] following protracted negotiations, Denmark granted home rule to the Faroe Islands on 30 March 1948. This agreement granted the islands a high degree of autonomy, and Faroese finally became the official language in all public spheres.[36]

In 1973 the Faroe Islands declined to join Denmark in entering the European Economic Community (EEC); as a result, the islands are not part of the European Union (EU) today (although as Danish citizens, Faroe Islanders are still considered EU citizens). Following the collapse of the fishing industry in the early 1990s, the Faroes experienced considerable economic difficulties.[37]

Geography

[edit]

The Faroe Islands are an island group consisting of 18 major islands (and a total of 779 islands, islets, and skerries) about 655 kilometres (407 mi) off the coast of Northern Europe, between the Norwegian Sea and the North Atlantic Ocean, about halfway between Iceland and Norway, the closest neighbours being the Northern Isles and the Outer Hebrides of Scotland. Its coordinates are 62°00′N 06°47′W / 62.000°N 6.783°W.

Distance from the Faroe Islands to:

- Rona, Scotland (uninhabited): 260 kilometres (160 mi)

- Shetland (Foula), Scotland: 285 kilometres (177 mi)

- Orkney (Westray), Scotland: 300 kilometres (190 mi)

- Scotland (mainland): 320 kilometres (200 mi)

- Iceland: 450 kilometres (280 mi)

- Norway: 580 kilometres (360 mi)

- Ireland: 670 kilometres (420 mi)

- Denmark: 990 kilometres (620 mi)

The islands cover an area of 1,399 square kilometres (540 sq. mi) and have small lakes and rivers, but no major ones. There are 1,117 kilometres (694 mi) of coastline.[38] The only significant uninhabited island is Lítla Dímun.

The islands are rugged and rocky with some low peaks; the coasts are mostly cliffs. The highest point is Slættaratindur in northern Eysturoy, 882 metres (2,894 ft) above sea level.

The Faroe Islands are made up of an approximately six-kilometres-thick succession of mostly basaltic lava that was part of the great North Atlantic Igneous Province during the Paleogene period.[39] The lavas were erupted during the opening of the North Atlantic ocean, which began about 60 million years ago, and what is today the Faroe Islands was then attached to Greenland.[40][41] The lavas are underlain by circa 30 km of unidentified ancient continental crust.[42][43]

Climate

[edit]

The climate is classed as subpolar oceanic climate according to the Köppen climate classification: Cfc, with areas having a tundra climate, especially in the mountains, although some coastal or low-lying areas may have very mild-winter versions of a tundra climate. The overall character of the climate of the islands is influenced by the strong warming influence of the Atlantic Ocean, which produces the North Atlantic Current. This, together with the remoteness of any source of landmass-induced warm or cold airflows, ensures that winters are mild (mean temperature 3.0 to 4.0 °C or 37 to 39 °F) while summers are cool (mean temperature 9.5 to 10.5 °C or 49 to 51 °F).

The islands are windy, cloudy, and cool throughout the year with an average of 210 rainy or snowy days per year. The islands lie in the path of depressions moving northeast, making strong winds and heavy rain possible at all times of the year. Sunny days are rare and overcast days are common. Hurricane Faith struck the Faroe Islands on 5 September 1966 with sustained winds over 100 mph (160 km/h) and only then did the storm cease to be a tropical system.[44]

The climate varies greatly over small distances, due to the altitude, ocean currents, topography, and winds. Precipitation varies considerably throughout the archipelago. In some highland areas, snow cover may last for months with snowfalls possible for the greater part of the year (on the highest peaks, summer snowfall is by no means rare), while in some sheltered coastal locations, several years pass without any snowfall whatsoever. Tórshavn receives frosts more often than other areas just a short distance to the south. Snow also is seen at a much higher frequency than on outlying islands nearby. The area receives on average 49 frosts a year.[45]

The collection of meteorological data on the Faroe Islands began in 1867.[46] Winter recording began in 1891, and the warmest winter occurred in 2016–17 with an average temperature of 6.1 °C (43 °F).[47]

| Climate data for Tórshavn (1981–2010, extremes 1961–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 11.6 (52.9) | 12.0 (53.6) | 12.3 (54.1) | 18.3 (64.9) | 19.7 (67.5) | 20.0 (68.0) | 20.2 (68.4) | 22.0 (71.6) | 19.5 (67.1) | 15.2 (59.4) | 14.7 (58.5) | 13.2 (55.8) | 22.0 (71.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 5.8 (42.4) | 5.6 (42.1) | 6.0 (42.8) | 7.3 (45.1) | 9.2 (48.6) | 11.1 (52.0) | 12.8 (55.0) | 13.1 (55.6) | 11.5 (52.7) | 9.3 (48.7) | 7.2 (45.0) | 6.2 (43.2) | 8.8 (47.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 4.0 (39.2) | 3.6 (38.5) | 4.0 (39.2) | 5.2 (41.4) | 7.0 (44.6) | 9.0 (48.2) | 10.7 (51.3) | 11.0 (51.8) | 9.6 (49.3) | 7.5 (45.5) | 5.5 (41.9) | 4.3 (39.7) | 6.8 (44.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 1.7 (35.1) | 1.3 (34.3) | 1.7 (35.1) | 3.0 (37.4) | 5.1 (41.2) | 7.1 (44.8) | 9.0 (48.2) | 9.2 (48.6) | 7.6 (45.7) | 5.4 (41.7) | 3.4 (38.1) | 2.1 (35.8) | 4.7 (40.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −8.8 (16.2) | −11.0 (12.2) | −9.2 (15.4) | −9.9 (14.2) | −3.0 (26.6) | 0.0 (32.0) | 1.5 (34.7) | 1.5 (34.7) | −0.6 (30.9) | −4.5 (23.9) | −7.2 (19.0) | −10.5 (13.1) | −11.0 (12.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 157.7 (6.21) | 115.2 (4.54) | 131.6 (5.18) | 89.5 (3.52) | 63.3 (2.49) | 57.5 (2.26) | 74.3 (2.93) | 96.0 (3.78) | 119.5 (4.70) | 147.4 (5.80) | 139.3 (5.48) | 135.3 (5.33) | 1,321.3 (52.02) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 26 | 23 | 26 | 22 | 19 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 23 | 26 | 26 | 27 | 273 |

| Average snowy days | 8.3 | 6.6 | 8.0 | 4.4 | 1.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 1.4 | 5.5 | 8.2 | 44.0 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 89 | 88 | 88 | 87 | 87 | 88 | 89 | 90 | 89 | 89 | 88 | 89 | 88 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 14.5 | 36.7 | 72.8 | 108.6 | 137.8 | 128.6 | 103.6 | 100.9 | 82.7 | 53.4 | 21.1 | 7.8 | 868.2 |

| Source: Danish Meteorological Institute (humidity 1961–1990, precipitation days 1961–1990, snowy days 1961–1990)[45][48][49] | |||||||||||||

Flora

[edit]

The Faroes belong to the Faroe Islands boreal grasslands ecoregion.[50] The natural vegetation of the Faroe Islands is dominated by arctic-alpine plants, wildflowers, grasses, moss, and lichen. Most of the lowland area is grassland and some is heath, dominated by shrubby heathers, mainly Calluna vulgaris. Among the herbaceous flora that occur in the Faroe Islands is the cosmopolitan marsh thistle, Cirsium palustre.[51]

Although it is often asserted that the islands are naturally treeless, several tree species, among them shrubby willows (salix), junipers (juniperus), and stunted birches, colonized the island after the Ice Age, but disappeared later - apparently as a result of grazing impacts, possibly aggravated by a shift to relatively wetter cooler climatic conditions about the same time.[52] A limited number of species have been successfully introduced to the region, in particular trees from the Magellanic subpolar forests region of Chile. Conditions in the Magellanic subpolar forests are similar to those in the Faroe Islands, with cold summers and near-continuous subpolar winds. The following species from Tierra del Fuego, Drimys winteri, Nothofagus antarctica, Nothofagus pumilio, and Nothofagus betuloides, have been successfully introduced to the Faroe Islands. A non-Chilean species that has been introduced is the black cottonwood, also known as the California poplar (Populus trichocarpa).[citation needed]

A collection of Faroese marine algae resulting from a survey sponsored by NATO,[citation needed] the British Museum (Natural History) and the Carlsberg Foundation, is preserved in the Ulster Museum (catalogue numbers: F3195–F3307). It is one of ten exsiccatae sets. A few small plantations consisting of plants collected from similar climates such as Tierra del Fuego in South America and Alaska thrive on the islands.

Fauna

[edit]

The bird fauna of the Faroe Islands is dominated by seabirds and birds attracted to open land such as heather, probably because of the lack of woodland and other suitable habitats. Many species have developed special Faroese sub-species: common eider, Common starling, Eurasian wren, common murre, and black guillemot.[53] The pied raven, a colour morph of the North Atlantic subspecies of the common raven, was endemic to the Faroe Islands, but now has become extinct; the ordinary, all-black morph remains fairly widespread in the archipelago.[citation needed]

Only a few species of wild land mammals are found in the Faroe Islands today, all introduced by humans. Three species are thriving on the islands today: mountain hare (Lepus timidus), brown rat (Rattus norvegicus), and the house mouse (Mus musculus). Apart from these, there is a local domestic sheep breed, the Faroe sheep (depicted on the coat of arms), and there once was a variety of feral sheep, which survived on Lítla Dímun until the mid-nineteenth century.[54]

Grey seals (Halichoerus grypus) are common around the shorelines away from human habitations.[55] Several species of cetacea live in the waters around the Faroe Islands. Best known are the long-finned pilot whales (Globicephala melaena), which still are hunted by the islanders in accordance with longstanding local tradition.[56] Orcas (Orcinus orca) are regular visitors around the islands.

The domestic animals of the Faroe Islands are a result of 1,200 years of isolated breeding. As a result, many of the islands' domestic animals are found nowhere else in the world. Faroese domestic breeds include Faroe pony, Faroe cow, Faroe sheep, Faroese goose, and Faroese duck.

Geology

[edit]

The islands were built up during a period of high volcanic activity in the Early Palaeogene around 50–60 million years ago. The islands are built up in layers of different lava flows (basalt) alternating with thin layers of volcanic ash (tuff). The soft ash and the hard basalt thus lie layer upon layer in narrow and thick strips. The soft tuff or ash zones erode away relatively quickly, and the hard lump of basalt above the eroded tuff falls away, forming the first terrace.

Volcanic activity has varied over millions of years, with periods of quiescence and various periods of quiet eruptive fissures and explosive volcanism. In a few places, mainly on Suðuroy, thin layers of coal are present, which are the remains of swamp forests from the time between volcanic eruptions. The plateau has therefore been divided into different basalt series according to the course of volcanism and the age sequence of the layers.

There are major differences in the shapes of the islands' terraces. The lowest and oldest series are thick lava deposits that can be seen on the southern part of Suðuroy, Mykines and Tindhólmur and the western side of Vágar. The basalts of the lower basalt series are often pillared, which is shown by elongated, angular and regular pillars in the mountain side. Very regular vertical columns are found on northern Mykines, where they can be up to 30 metres (100 ft) high.

The middle basalt series consists of thin lava flows with a highly porous interlayer. This series has very little resistance to crumbling and weathering. As these erosion processes are more severe at higher altitudes than lower down, the lowlands are filled with weathering material from the heights, often resulting in a characteristic curved landscape shape. This can be clearly seen on Vágar, the northernmost part of Streymoy and the north-western part of Eysturoy.

Glacial activity has reduced plateau surfaces, especially on the northern islands, where the surfaces have been reduced to a series of narrower or wider zig-zag rows along the length of the islands: especially on the islands of Kunoy, Kalsoy and Borðoy, where an eastward and a westward ice mass have eroded the intervening mountain range into a narrow ridge.

Government and politics

[edit]The Faroe Islands are a self-governing country under the external sovereignty of the Kingdom of Denmark.[57] The Faroese government holds executive power in local government affairs. The head of the government is called the Løgmaður ("Chief Justice") and serves as Prime Minister and head of the Faroese Government. Any other member of the cabinet is called a Minister of the Faroese Government (landsstýrismaður/ráðharri if male, landsstýriskvinna/ráðfrú if female). The Faroese parliament – the Løgting ("Law Thing") – dates back to the early days of settlement and claims to be one of the longest functioning parliaments in the world, alongside the Icelandic Althing and the Manx Tynwald. The parliament currently has 33 members.[58]

Elections are held at municipal and national levels, additionally electing two members to the Folketing. Until 2007, there were seven electoral districts, which were abolished on 25 October of that year in favour of a single nationwide district.

Administrative divisions

[edit]

Administratively, the islands are divided into 29 municipalities (kommunur) within which there are 120 or so settlements.

There are also the six traditional sýslur: Norðoyar, Eysturoy, Streymoy, Vágar, Sandoy, and Suðuroy. While no longer of any legal significance, the term is still commonly used to indicate a geographical region. In earlier times, each sýsla had its own assembly, the so-called várting ("spring assembly").

Relationship with Denmark

[edit]This section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

The Faroe Islands have been under Norwegian-Danish control since 1388. The 1814 Treaty of Kiel terminated the Danish–Norwegian union, and Norway came under the rule of the King of Sweden, while the Faroe Islands, Iceland, and Greenland remained Danish possessions. From ancient times the Faroe Islands had a parliament (Løgting), which was abolished in 1816, and the Faroe Islands were to be governed as an ordinary Danish amt (county), with the Amtmand as its head of government. In 1851, the Løgting was reinstated, but, until 1948, served mainly as an advisory body.

The islands are home to a notable independence movement that has seen an increase in popular support within recent decades. At the end of World War II, some of the population favoured independence from Denmark, and on 14 September 1946, an independence referendum was held on the question of secession. It was a consultative referendum, the parliament not being bound to follow the people's vote. This was the first time that the Faroese people had been asked whether they favoured independence or wanted to continue within the Danish kingdom.

The result of the vote was only a slight majority in favour of secession. The Speaker of the Løgting, together with the majority, initiated the process of becoming an independent state. The minority of the Løgting left in protest, regarding these actions as illegal. One parliament member, Jákup í Jákupsstovu, was shunned by his own party, the Social Democratic Party, for having joined the majority of the Løgting.

The Speaker of the Løgting declared the Faroe Islands independent on 18 September 1946.

On 25 September 1946, a Danish prefect announced to the Løgting that the king, rejecting the majority vote, had dissolved the parliament and ordered new elections.

A parliamentary election was held a few months later, in which the political parties that favoured remaining in the Danish kingdom increased their share of the vote and formed a coalition. Based on this, they chose to reject secession. Instead, a compromise was reached and the Folketing passed a home-rule law that went into effect in 1948. The Faroe Islands' status as a Danish amt was thereby brought to an end; the Faroe Islands were given a high degree of self-governance, supported by a financial subsidy from Denmark to recompense expenses the islands have on Danish services.

In protest against the new Home Rule Act, Republic (Tjóðveldi) was founded.

As of 2021, the islanders were evenly split between those favouring independence and those who prefer to continue as a part of the Kingdom of Denmark.[59] Within both camps there is a wide range of opinions. Of those who favour independence, some are in favour of an immediate unilateral declaration of independence. Others see independence as something to be attained gradually and with the full consent of the Danish government and the Danish nation. In the unionist camp, there are also many who foresee and welcome a gradual increase in autonomy even while strong ties with Denmark are maintained.

Two attempts have been made to draft a separate Faroese constitution. The first time was in 2011, when the then prime minister Lars Løkke Rasmussen denounced it as incompatible with Denmark's constitution, stating that if the Faroe Islands wished to continue with the move, they must declare independence.[60] A second attempt was made in 2015, facing similar criticisms[61] before eventually being withdrawn without a vote.[62]

Relationship with the European Union

[edit]As explicitly asserted by both treaties of the European Union, the Faroe Islands are not part of the European Union. The Faroes are not grouped with the EU when it comes to international trade; for instance, when the EU and Russia imposed reciprocal trade sanctions on each other over the war in Donbas in 2014, the Faroes began exporting significant amounts of fresh salmon to Russia.[63] Moreover, a protocol to the treaty of accession of Denmark to the European Communities stipulates that Danish nationals residing in the Faroe Islands are not considered Danish nationals within the meaning of the treaties. Hence, Danish people living in the Faroes are not citizens of the European Union (though other EU nationals living there remain EU citizens). The Faroes are not covered by the Schengen Agreement, but there are no border checks when travelling between the Faroes and any Schengen country (the Faroes have been part of the Nordic Passport Union since 1966, and since 2001 there have been no permanent border checks between the Nordic countries and the rest of the Schengen Area as part of the Schengen agreement).[64][65][66]

Relationship with international organisations

[edit]The Faroe Islands are not fully independent, but they do have political relations directly with other countries through agreement with Denmark. The Faroe Islands are a member of some international organisations as though they were an independent country. The Faroes have associate membership in the Nordic Council but have expressed wishes for full membership.[67]

The Faroe Islands are a member of several international sports federations like UEFA, FIFA in football[68] and FINA in swimming[69] and EHF in handball[70] and have their own national teams. They also have their own telephone country code, +298, Internet country code top-level domain, .fo, banking code FO and postal code system.

The Faroe Islands make their own agreements with other countries regarding trade and commerce. When the European Union imposed sanctions against the Russian Federation in 2014, the Faroe Islands were not a part of the embargo because they are not a part of EU, and the islands had just themselves experienced a year of embargo from the EU including Denmark against the islands; the Faroese prime minister Kaj Leo Johannesen went to Moscow to negotiate the trade between Russia and the Faroe Islands.[71] The Faroese minister of fisheries negotiates with the EU and other countries regarding the rights to fish.[72]

In mid-2005, representatives of the Faroe Islands raised the possibility of their territory joining the European Free Trade Association (EFTA).[73] According to Article 56 of the EFTA Convention, only states may become members of the EFTA.[74] The Faroes are an autonomous territory of the Kingdom of Denmark, and not a sovereign state in their own right.[75] Consequently, they considered the possibility that the "Kingdom of Denmark in respect of the Faroes" could join the EFTA, though the Danish Government has stated that this mechanism would not allow the Faroes to become a separate member of the EEA because Denmark was already a party to the EEA Agreement.[75] The Government of Denmark officially supports new membership of the EFTA with effect for the Faroe Islands.

Defence

[edit]Defence is the responsibility of the Danish Government. The 1st Squadron of the Royal Danish Navy is primarily focused on national operations in and around the Faroe Islands and Greenland. As of 2023, the 1st Squadron is composed of:

- Four Thetis-class patrol vessels;

- Three Knud Rasmussen-class patrol vessels; and,

- The royal yacht HDMY Dannebrog (having a secondary surveillance and sea-rescue role)[76]

After 2025 the Thetis-class vessels are to be replaced by the planned MPV80-class ships. The new vessels will incorporate a modular concept enabling packages of different systems (for minehunting or minelaying for example) to be fitted to individual ships as may be required.[77][78]

In 2022, the Danish and Faroe Islands governments signed an agreement to establish an air surveillance radar system on the islands. The radar will monitor airspace between Iceland, Norway and Britain with a reported range of 300–400 kilometres (190–250 mi).[79]

In addition to naval units, the Royal Danish Air Force can provide C-130J and Challenger 604 aircraft from Squadron 721 for search and rescue as well as surveillance missions.[80][81]

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1327 | 4,000 | — |

| 1350 | 2,000 | −50.0% |

| 1769 | 4,773 | +138.6% |

| 1801 | 5,225 | +9.5% |

| 1834 | 6,928 | +32.6% |

| 1850 | 8,137 | +17.5% |

| 1880 | 11,220 | +37.9% |

| 1900 | 15,230 | +35.7% |

| 1925 | 22,835 | +49.9% |

| 1950 | 31,781 | +39.2% |

| 1975 | 40,441 | +27.2% |

| 1985 | 45,749 | +13.1% |

| 1995 | 43,358 | −5.2% |

| 2000 | 46,196 | +6.5% |

| 2006 | 48,219 | +4.4% |

| 2011 | 48,346 | +0.3% |

| 2016 | 49,554 | +2.5% |

| 2020 | 52,110 | +5.2% |

| 2011 data[82] 2019:[5] | ||

The vast majority of the population are ethnic Faroese, of Norse and Celtic descent.[83] Recent DNA analyses have revealed that Y chromosomes, tracing male descent, are 87% Scandinavian,[84]while mitochondrial DNA, tracing female descent, is 84% Celtic.[85]

There is a gender deficit of about 2,000 women owing to migration.[86] As a result, some Faroese men have married women from the Philippines and Thailand, whom they met through such channels as online dating websites, and arranged for them to emigrate to the islands. This group of approximately three hundred women make up the largest ethnic minority in the Faroes.[86]

The total fertility rate of the Faroe Islands is one of the highest in Europe.[87] The 2015 fertility rate was 2.409 children born per woman.[88]

The 2011 census shows that of the 48,346 inhabitants of the Faroe Islands (17,441 private households in 2011), 43,135 were born in the Faroe Islands, 3,597 were born elsewhere in the Kingdom of Denmark (Denmark proper or Greenland), and 1,614 were born outside the Kingdom of Denmark. People were also asked about their nationality, including Faroese. Children under 15 were not asked about their nationality. 97% said that they were ethnic Faroese, which means that many of those who were born in either Denmark or Greenland consider themselves as ethnic Faroese. The other 3% of those older than 15 said they were not Faroese: 515 were Danish, 433 were from other European countries, 147 came from Asia, 65 from Africa, 55 from the Americas, 23 from Russia.[89]

At the beginning of the 1990s, the Faroe Islands entered a deep economic crisis leading to heavy emigration; however, this trend reversed in subsequent years to a net immigration. This has been in the form of a population replacement as young Faroese women leave and are replaced with Asian/Pacific brides.[90] In 2011, there were 2,155 more men than women between the age of 0 to 59 in the Faroe Islands.[91]

Language

[edit]As stipulated in section 11 (§ 11) in the 1948 Home Rule Act,[92][93] Faroese is the primary and official language of the country, although Danish is taught in schools and can be used by the Faroese government in public relations, with public services providing Danish translations of documents on request.[92][94] Faroese belongs to the North Germanic language branch and is descended from Old Norse, being most closely related to Icelandic. Due to its geographic isolation, it has preserved more conservative grammatical features that have been lost in Danish, Norwegian and Swedish. It is the only language alongside Icelandic and Elfdalian to preserve the letter Ð, though unlike the others, it is not pronounced.

Faroese sign language was officially adopted as a national language in 2017.[95]

Religion

[edit]According to the Færeyinga saga, Sigmundur Brestisson brought Christianity to the islands in 999. However, archaeology at a site in Toftanes, Leirvík, named Bønhústoftin (English: "the prayer-house ruin") and over a dozen slabs from Ólansgarður in the small island of Skúvoy which in the main display encircled linear and outline crosses, suggest that Celtic Christianity may have arrived at least 150 years earlier.[96] The Faroe Islands' Church Reformation was completed on 1 January 1540. According to official statistics from 2019, 79.7% of the Faroese population are members of the state church, the Church of the Faroe Islands (Fólkakirkjan), following a form of Lutheranism.[97] The Fólkakirkjan became an independent church in 2007; previously it had been a diocese within the Church of Denmark. Faroese members of the clergy who have had historical importance include Venceslaus Ulricus Hammershaimb (1819–1909), Fríðrikur Petersen (1853–1917) and, perhaps most significantly, Jákup Dahl (1878–1944), who had a great influence in ensuring that the Faroese language was spoken in the church instead of Danish. Participation in churches is more prevalent among the Faroese population than among most other Scandinavians.

In the late 1820s, the Christian Evangelical religious movement, the Plymouth Brethren, was established in England. In 1865, a member of this movement, William Gibson Sloan, travelled to the Faroes from Shetland. At the turn of the 20th century, the Faroese Plymouth Brethren numbered thirty. Today, around 10% of the Faroese population are members of the Open Brethren community (Brøðrasamkoman). About 3% belong to the Charismatic Movement. There are several charismatic churches around the islands, the largest of which, called Keldan (The Spring), has about 200 to 300 members. About 2% belong to other Christian groups. The Adventists operate a private school in Tórshavn. Jehovah's Witnesses also have four congregations with a total of 121 members. The Roman Catholic congregation has about 270 members and falls under the jurisdiction of Denmark's Roman Catholic Diocese of Copenhagen. The municipality of Tórshavn has an old Franciscan school.

Unlike Denmark, Sweden and Iceland, the Faroes have no organised Heathen community.

The best-known church buildings in the Faroe Islands include Tórshavn Cathedral, Olaf II of Norway's Church and the Magnus Cathedral in Kirkjubøur; the Vesturkirkjan and the St. Mary's Church, both of which are situated in Tórshavn; the church of Fámjin; the octagonal church in Haldórsvík; Christianskirkjan in Klaksvík; and also the two pictured here.

In 1948, Victor Danielsen completed the first Bible translation into Faroese from different modern languages. Jacob Dahl and Kristian Osvald Viderø (Fólkakirkjan) completed the second translation in 1961. The latter was translated from the original Biblical languages (Hebrew and Greek) into Faroese.

According to the 2011 Census, there were 33,018 Christians (95.44%), 23 Muslims (0.07%), 7 Hindus (0.02%), 66 Buddhists (0.19%), 12 Jews (0.03%), 13 Baháʼís (0.04%), 3 Sikhs (0.01%), 149 others (0.43%), 85 with more than one belief (0.25%), and 1,397 with no religion (4.04%).[98]

Education

[edit]The levels of education in the Faroe Islands are primary, secondary and higher education. Most institutions are funded by the state; there are few private schools in the Faroe Islands. Education is compulsory for 9 years between the ages of 7 and 16.[99]

Compulsory education consists of seven years of primary education and two years of lower secondary education; it is public, free of charge, provided by the respective municipalities, and is called the Fólkaskúli in Faroese. The Fólkaskúli also provides optional preschool education as well as the tenth year of education that is a prerequisite to getting admitted to upper secondary education. Students that complete compulsory education are allowed to continue education in a vocational school, where they can have job-specific training and education. Since the fishing industry is an important part of Faroe Islands' economy, maritime schools are an important part of Faroese education. Upon completion of the tenth year of Fólkaskúli, students can continue to upper secondary education which consists of several different types of schools. Higher education is offered at the University of the Faroe Islands; a part of Faroese youth moves abroad to pursue higher education, mainly in Denmark. Other forms of education comprise adult education and music schools. The structure of the Faroese educational system bears resemblances with its Danish counterpart.[99]

In the 12th century, education was provided by the Catholic Church in the Faroe Islands.[100] The Church of Denmark took over education after the Protestant Reformation.[101]Modern educational institutions started operating in the last quarter of the nineteenth century and developed throughout the twentieth century. The status of the Faroese language in education was a significant issue for decades, until it was accepted as a language of instruction in 1938.[102] Initially education was administered and regulated by Denmark.[102] In 1979 responsibilities on educational issues started transferring to the Faroese authorities, a procedure which was completed in 2002.[102]

The Ministry of Education, Research and Culture has the jurisdiction of educational responsibility in the Faroe Islands.[103] Since the Faroe Islands is a part of the Danish Realm, education in the Faroe Islands is influenced and has similarities with the Danish educational system; there is an agreement on educational cooperation between the Faroe Islands and Denmark.[102][104][105] In 2012 the public spending on education was 8.1% of GDP.[106] The municipalities are responsible for the school buildings for children's education in Fólkaskúlin from age 1st grade to 9th or 10th grade (age 7 to 16).[107] In November 2013 1,615 people, or 6.8% of the total number of employees, were employed in the education sector.[106] Of the 31,270 people aged 25 and above 1,717 (5.5%) have gained at least a master's degrees or a Ph.D., 8,428 (27%) have gained a B.Sc. or a diploma, 11,706 (37.4%) have finished upper secondary education while 9,419 (30.1%) has only finished primary school and have no other education.[108] There is no data on literacy in the Faroe Islands, but the CIA Factbook states that it is probably as high as in Denmark proper, i.e. 99%.[109]

The majority of students in upper secondary schools are women, although men represent the majority in higher education institutions. In addition, most young Faroese people who relocate to other countries to study are women.[110] Out of 8,535 holders of bachelor degrees, 4,796 (56.2%) have had their education in the Faroe Islands, 2,724 (31.9%) in Denmark, 543 in both the Faroe Islands and Denmark, 94 (1.1%) in Norway, 80 in the United Kingdom and the rest in other countries.[111] Out of 1,719 holders of master's degrees or PhDs, 1,249 (72.7%) have had their education in Denmark, 87 (5.1%) in the United Kingdom, 86 (5%) in both the Faroe Islands and Denmark, 64 (3.7%) in the Faroe Islands, 60 (3.5%) in Norway and the rest in other countries (mostly EU and Nordic).[111] Since there is no medical school in the Faroe Islands, all medical students have to study abroad; as of 2013[update], out of a total of 96 medical students, 76 studied in Denmark, 19 in Poland, and 1 in Hungary.[112]

Economy

[edit]Economic troubles caused by a collapse of the Faroese fishing industry in the early 1990s brought high unemployment rates of 10 to 15% by the mid-1990s.[113] Unemployment decreased in the later 1990s, down to about 6% at the end of 1998.[113] By June 2008 unemployment had declined to 1.1%, before rising to 3.4% in early 2009.[113] In December 2019[114] the unemployment reached a record low 0.9%. Nevertheless, the almost total dependence on fishing and fish farming means that the economy remains vulnerable. The biggest private companies of the Faroe Islands is the salmon farming company Bakkafrost, which is the largest of the four salmon farming companies in the Faroe Islands[115] and the third biggest in the world.[116]

In 2011, 13% of the Faroe Islands' national income consists of economic aid from Denmark,[117] corresponding to roughly 5% of GDP.[118]

Since 2000, the government has fostered new information technology and business projects to attract new investment. The introduction of Burger King in Tórshavn was widely publicized as a sign of the globalization of Faroese culture. It remains to be seen whether these projects will succeed in broadening the islands' economic base. The islands have one of the lowest unemployment rates in Europe, but this should not necessarily be taken as a sign of a recovering economy, as many young students move to Denmark and other countries after leaving high school. This leaves a largely middle-aged and elderly population that may lack the skills and knowledge to fill newly developed positions on the Faroes. Nonetheless, in 2008 the Faroes were able to make a $52 million loan to Iceland in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis.[119]

On 5 August 2009, two opposition parties introduced a bill in the Løgting to adopt the euro as the national currency, pending a referendum.[120] The euro was not adopted.

Transport

[edit]

By road, the main islands are connected by bridges and tunnels. Government-owned Strandfaraskip Landsins provides public bus and ferry service to the main towns and villages. There are no railways.

By air, Scandinavian Airlines and the government-owned Atlantic Airways both have scheduled international flights to Vágar Airport, the islands' only airport. Atlantic Airways also provides helicopter service to each of the islands. All civil aviation matters are controlled from the Civil Aviation Administration Denmark.

By sea, Smyril Line operates a regular international passenger, car and freight service linking the Faroe Islands with Seyðisfjörður, Iceland and Hirtshals, Denmark.[121]

The Faroes have a highly developed road network connecting almost all settlements by tunnels through the mountains and between the islands, bridges and causeways that link together the four largest islands and three islands to the northeast. Suðuroy is the only major island not connected by a fixed link.

Koltur and Stóra Dímun have no ferry connection, only a helicopter service. Other small islands—Mykines to the west, Kalsoy, Svínoy and Fugloy to the north, Hestur west of Streymoy, and Nólsoy east of Tórshavn—have smaller ferries and some of these islands also have a helicopter service.

Since 2014, the Faroese government has placed emphasis on expanding fixed road connections between islands. In 2020 the Eysturoyartunnilin opened, greatly reducing travel time between Eysturoy and Tórshavn.[122] In 2023, the Faroes' longest single length tunnel opened, Sandoyartunnilin, linking Sandoy to the greater Faroese road network on Streymoy.[123]

Culture

[edit]The culture of the Faroe Islands has its roots in the Nordic culture. The Faroe Islands were long isolated from the main cultural phases and movements that swept across parts of Europe. This means that they have maintained a great part of their traditional culture. The language spoken is Faroese, which is one of three insular North Germanic languages descended from the Old Norse language spoken in Scandinavia in the Viking Age, the others being Icelandic and the extinct Norn, which is thought to have been mutually intelligible with Faroese. Until the 15th century, Faroese had a similar orthography to Icelandic and Norwegian, but after the Reformation in 1538, the ruling Norwegians outlawed its use in schools, churches and official documents. Although a rich spoken tradition survived, for 300 years the language was not written down. This means that all poems and stories were handed down orally. These works were split into the following divisions: sagnir (historical), ævintýr (stories) and kvæði (ballads), often set to music and the medieval chain dance. These were eventually written down in the 19th century.

Literature

[edit]

Faroese written literature has developed only in the past 100–200 years. This is mainly because of the islands' isolation, and also because the Faroese language did not have a standardised writing system. The Danish language was also encouraged at the expense of Faroese. Nevertheless, the Faroes have produced several authors and poets. A rich centuries-old oral tradition of folk tales and Faroese folk songs accompanied the Faroese chain dance. The people learned these songs and stories by heart, and told or sang them to each other, teaching the younger generations too. This kind of literature was gathered in the 19th century and early 20th century. The Faroese folk songs, in Faroese called kvæði, are still in use although not so large-scale as earlier.[citation needed]

The first Faroese novel, Bábelstornið by Regin í Líð, was published in 1909; the second novel was published 18 years later. In the period 1930 to 1940 a writer from the village Skálavík on Sandoy island, Heðin Brú, published three novels: Lognbrá (1930), Fastatøkur (1935) and Feðgar á ferð (English title: The old man and his sons) (1940). Feðgar á ferð has been translated into several other languages. Martin Joensen from Sandvík wrote about life on Faroese fishing vessels; he published the novels Fiskimenn (1946)[124] and Tað lýsir á landi (1952).

Well-known poets from the early 20th century are among others the two brothers from Tórshavn: Hans Andrias Djurhuus (1883–1951)[125] and Janus Djurhuus (1881–1948);[126] other well known poets from this period and the mid 20th century are Poul F. Joensen (1898–1970),[127] Regin Dahl (1918–2007),[128] and Tummas Napoleon Djurhuus (1928–71).[129] Their poems are popular even today and can be found in Faroese song books and school books. Jens Pauli Heinesen (1932–2011), a school teacher from Sandavágur, was the most productive Faroese novelist; he published 17 novels. Steinbjørn B. Jacobsen (1937–2012), a schoolteacher from Sandvík, wrote short stories, plays, children's books and even novels. Most Faroese writers write in Faroese; two exceptions are William Heinesen (1900–91) and Jørgen-Frantz Jacobsen (1900–38).

Women were not so visible in the early Faroese literature except for Helena Patursson (1864–1916), but in the last decades of the 20th century and in the beginning of the 21st century female writers like Ebba Hentze (born 1933) wrote children's books, short stories, etc. Guðrið Helmsdal published the first modernistic collection of poems, Lýtt lot, in 1963, which at the same time was the first collection of Faroese poems written by a woman.[130] Her daughter, Rakel Helmsdal (born 1966), is also a writer, best known for her children's books, for which she has won several prizes and nominations. Other female writers are the novelists Oddvør Johansen (born 1941), Bergtóra Hanusardóttir (born 1946) and novelist/children's books writers Marianna Debes Dahl (born 1947), and Sólrun Michelsen (born 1948). Other modern Faroese writers include Gunnar Hoydal (born 1941), Hanus Kamban (born 1942), Jógvan Isaksen (born 1950), Jóanes Nielsen (born 1953), Tóroddur Poulsen and Carl Jóhan Jensen (born 1957). Some of these writers have been nominated for the Nordic Council's Literature Prize two to six times, but have never won it. The only Faroese writer who writes in Faroese who has won the prize is the poet Rói Patursson (born 1947), who won the prize in 1986 for Líkasum.[131] In 2007 the first ever Faroese/German anthology "From Janus Djurhuus to Tóroddur Poulsen – Faroese Poetry during 100 Years", edited by Paul Alfred Kleinert, including a short history of Faroese literature was published in Leipzig.

In the 21st century, some new writers had success in the Faroe Islands and abroad. Bárður Oskarsson (born 1972) is a children's book writer and illustrator; his books won prizes in the Faroes, Germany and the West Nordic Council's Children and Youth Literature Prize (2006). Though not born in the Faroe Islands, Matthew Landrum, an American poet and editor for Structo magazine, has written a collection of poems about the Islands. Sissal Kampmann (born 1974) won the Danish literary prize Klaus Rifbjerg's Debutant Prize (2012), and Rakel Helmsdal has won Faroese and Icelandic awards; she has been nominated for the West Nordic Council's Children and Youth Literature Prize and the Children and Youth Literature Prize of the Nordic Council (representing Iceland, wrote the book together with and Icelandic and a Swedish writer/illustrator). Marjun Syderbø Kjelnæs (born 1974) had success with her first novel Skriva í sandin for teenagers; the book was awarded and nominated both in the Faroes and in other countries. She won the Nordic Children's Book Prize (2011) for this book, White Raven Deutsche Jugendbibliothek (2011) and nominated the West Nordic Council's Children and Youth Literature Prize and the Children and Youth Literature Prize of the Nordic Council (2013).[132]

Music

[edit]The Faroe Islands have an active music scene, with live music being a regular part of the Islands' life and many Faroese being proficient at a number of instruments. Multiple Danish Music Award winner Teitur Lassen calls the Faroes home and is arguably the islands' most internationally well-known musical export.

На островах есть свой оркестр (классический ансамбль Альдубаран) и множество различных хоров; самый известный из них — Хавнаркорид. Самыми известными местными фарерскими композиторами являются Санлейф Расмуссен и Кристиан Блак , который также является главой звукозаписывающей компании Tutl . Первую фарерскую оперу написал Санлейф Расмуссен. фильма Премьера состоялась 12 октября 2006 года в Nordic House. Опера основана на рассказе писателя Уильяма Хайнесена .

Молодые фарерские музыканты, получившие в последнее время большую популярность, — это Эйвёр Палсдоттир , Хёгни Рейструп , Хёгни Лисберг , ХЕЙРИК ( Heiðrik á Heygum ), Гудрид Хансдоттир и Брандур Энни . В 2023 году Рейли стала первым фарерцем, представившим Данию на конкурсе песни «Евровидение» . [133]

Среди известных групп — Týr , Hamferð , The Ghost , Boys in a Band , 200 и SIC .

фестиваль современной и классической музыки Summartónar Каждое лето проводится . Г ! Фестиваль в Норрагёте в июле и Summarfestivalurin в Клаксвике в августе — это крупные музыкальные фестивали популярной музыки под открытым небом, в которых принимают участие как местные, так и международные музыканты. Хавнар Джазфелаг был основан 21 ноября 1975 года и действует до сих пор. В настоящее время Havnar Jazzfelag организует VetrarJazz среди других джазовых фестивалей на Фарерских островах.

Северный дом на Фарерских островах

[ редактировать ]Северный дом на Фарерских островах ( фарерский : Norðurlandahúsið ) — самое важное культурное учреждение на Фарерских островах. Его цель — поддерживать и продвигать скандинавскую и фарерскую культуру на местном уровне и в Скандинавском регионе. Эрлендур Патурссон (1913–86), фарерский член Северного совета , выдвинул идею создания дома культуры северных стран на Фарерских островах. В 1977 году был проведен конкурс архитекторов стран Северной Европы, в котором приняли участие 158 архитекторов. Победителями стали Ола Стен из Норвегии и Кольбрун Рагнарсдоттир из Исландии . Оставаясь верными фольклору , архитекторы построили Нордический дом, напоминающий заколдованный холм эльфов . Дом открылся в Торсхавне в 1983 году. Nordic House — культурная организация Северного совета. Северным домом управляет руководящий комитет из восьми человек, трое из которых — фарерцы и пять — из других стран Северной Европы. Существует также местный консультативный орган, состоящий из пятнадцати членов, представляющих фарерские культурные организации. Палатой управляет директор, назначаемый руководящим комитетом сроком на четыре года.

Традиционная еда

[ редактировать ]Традиционная фарерская кухня в основном основана на мясе, морепродуктах и картофеле и включает мало свежих овощей. Баранина фарерских овец является основой многих блюд, и одним из самых популярных лакомств является skerpikjøt , выдержанная, вяленая, довольно жевательная баранина. Сарай для сушки, известный как хьяллур , является стандартным элементом многих фарерских домов, особенно в небольших городах и деревнях. Другими традиционными продуктами являются раст кьот (полусушёная баранина) и растур фискур (зрелая рыба). Еще одно фарерское блюдо – твёст ог спик , приготовленное из гринды мяса и жира . (Параллельное блюдо из мяса и жира, приготовленное из субпродуктов, - это garnatálg .) Традиция употребления мяса и жира гринд возникла из-за того, что за одну добычу можно получить много еды. Свежая рыба также занимает важное место в традиционном местном рационе, как и морские птицы , такие как фарерские тупики , и их яйца. Также часто едят сушеную рыбу.

На Фарерских островах есть две пивоварни. Föroya Bjór производит пиво с 1888 года и экспортирует его в основном в Исландию и Данию. Okkara Bryggjarí была основана в 2010 году. Местным фирменным блюдом является fredrikk , особый напиток, производимый в Нолсое .

Со времени дружественной британской оккупации фарерцы любят британскую еду, в частности шоколад в британском стиле, такой как Cadbury Dairy Milk , который можно найти во многих магазинах острова. [134]

Китобойный промысел

[ редактировать ]

Есть записи о загонной охоте на Фарерских островах, датируемые 1584 годом. [135] Китобойный промысел на Фарерских островах регулируется властями Фарерских островов, а не Международной китобойной комиссией, поскольку существуют разногласия относительно юридических полномочий комиссии регулировать охоту на китообразных . Сотни длинноплавниковых гринд ( Globicephala melaena ) могут быть убиты за год, в основном летом. Охота, называемая на фарерском языке «гриндадрап» , не является коммерческой и организуется на уровне общины; любой может принять участие. Когда китовая стая случайно обнаруживается недалеко от берега, участвующие охотники сначала окружают гринд широким полукругом лодок, а затем медленно и бесшумно начинают гнать китов в сторону выбранной разрешенной бухты. [136] Когда стая китов оказывается на мели, начинается убийство.

Законодательство Фарерских островов о защите животных, которое также применяется к китобойному промыслу, требует, чтобы животных убивали как можно быстрее и с минимальными страданиями. Регулирующее спинальное копье используется для перерезания спинного мозга , что также перекрывает основное кровоснабжение головного мозга, что приводит к потере сознания и смерти в течение нескольких секунд. Спинномозговая копья была введена в качестве предпочтительного стандартного оборудования для добычи гринд и, как было показано, сокращает время убийства до 1–2 секунд. [136]

Этот «гриндадрап» является законным и обеспечивает едой многих жителей Фарерских островов. [137] [138] [139] Однако исследование показало, что китовое мясо и жир в настоящее время загрязнены ртутью и не рекомендуются для употребления в пищу человеку, поскольку слишком большое их количество может вызвать такие неблагоприятные последствия для здоровья, как врожденные дефекты нервной системы, высокое кровяное давление, повреждение иммунной системы, повышенный риск. при развитии болезни Паркинсона , гипертонии , артериосклероза и сахарного диабета 2 типа :

Поэтому мы рекомендуем взрослым есть не чаще одного-двух раз в месяц. Женщинам, планирующим забеременеть в течение трех месяцев, беременным женщинам и кормящим женщинам следует воздерживаться от употребления мяса гринд. Печень и почки пилотного кита употреблять в пищу вообще нельзя. [140]

Группы по защите прав животных, такие как Общество охраны морских пастухов, критикуют его как жестокий и ненужный, поскольку он больше не является источником пищи для фарерцев.

Обсуждается устойчивость фарерской охоты на гринд, но, учитывая, что средний долгосрочный вылов гринд на Фарерских островах составляет около 800 гринд в год, считается, что охота не оказывает существенного влияния на популяцию гринд. По оценкам, в Северо-Восточной Атлантике насчитывается 128 000 гринд, и поэтому правительство Фарерских островов считает китобойный промысел устойчивым уловом. [141] Ежегодные записи о выгоне китов и выбрасывании на берег гринд и других мелких китообразных содержат более чем 400-летнюю документацию, включая статистические данные, и представляют собой один из наиболее полных исторических данных об использовании дикой природы в любой точке мира. [136]

12 сентября 2021 года суперстая из более чем 1420 белобоких дельфинов . была убита [142] Это вызвало серьезные споры на Фарерских островах и за рубежом, в результате чего правительство ввело квоты на количество белобоких дельфинов, на которых разрешено охотиться каждый год. [143] [144] Правительство Великобритании отказалось приостановить действие соглашения о свободной торговле с Фарерскими островами, поскольку к этому призвали защитники природы. [145]

Спорт

[ редактировать ]Фарерские острова участвовали во всех островных играх, проводимых раз в два года , с момента их основания в 1985 году. Игры проводились на островах в 1989 году, а Фарерские острова выиграли Островные игры в 2009 году .

Футбол , безусловно, является крупнейшим видом спорта на островах: на островах зарегистрировано 7 000 игроков из всего населения в 52 000 человек. Десять футбольных команд соревнуются в Премьер-лиге Фарерских островов , которая в настоящее время занимает 39-е место по коэффициенту Лиги УЕФА . Фарерские острова являются полноправными членами УЕФА , а национальная футбольная сборная Фарерских островов участвует в отборочных матчах чемпионата Европы по футболу . Фарерские острова также являются полноправными членами ФИФА , поэтому футбольная команда Фарерских островов также участвует в отборочных матчах чемпионата мира по футболу . Фарерские острова выиграли свой первый официальный матч , когда команда победила Австрию со счетом 1:0 в квалификации Евро-1992.

Самый большой успех страны в футболе пришелся на 2014 год после победы над Грецией со счетом 1:0, результат, который считался «самым большим шоком всех времен» в футболе. [146] благодаря разнице в 169 мест между командами в мировом рейтинге FIFA на момент проведения матча. Команда поднялась на 82 позиции до 105 в рейтинге ФИФА после победы над Грецией со счетом 1:0. [147] 13 июня 2015 года команда снова победила Грецию со счетом 2–1. 9 июля 2015 года сборная Фарерских островов по футболу поднялась еще на 28 позиций в рейтинге ФИФА. [148] Недавно Фарерские острова одержали еще одну знаменитую победу, обыграв Турцию со счетом 2:1 в Лиге наций УЕФА C сезона 2022–23 . помешать Турции добиться перехода в Лигу Б. [149]

выиграла Мужская национальная сборная Фарерских островов первые два чемпионата развивающихся наций IHF , в 2015 и 2017 годах. Команда квалифицировалась на чемпионат Европы по гандболу среди мужчин 2024 года в Германии, где после ничьей с Норвегией и 24 командами заняла 20-е место. плотные игры со Словенией и Польшей . [150]

Фарерские острова являются полноправными членами FINA и выступают под своим флагом на чемпионатах мира, чемпионатах Европы и Кубках мира. Фарерский пловец Пал Йоэнсен (1990 г.р.) завоевал бронзовую медаль на чемпионате мира FINA 2012 по плаванию (25 м). [151] и четыре серебряные медали чемпионатов Европы ( 2010 , 2013 и 2014 годы ), [152] все медали завоеваны на самой длинной и второй по длине дистанции среди мужчин, на дистанциях 1500 и 800 метров вольным стилем, на короткой и длинной дистанции. Фарерские острова также участвуют в Паралимпийских играх и выиграли 1 золотую, 7 серебряных и 5 бронзовых медалей после летних Паралимпийских игр 1984 года .

Два фарерских спортсмена выступали на Олимпийских играх, но под датским флагом , поскольку Олимпийский комитет не разрешает Фарерским островам выступать под своим флагом. Двое фарерцев, участвовавших в соревнованиях, - пловец Пал Йоэнсен в 2012 году и гребец Катрин Олсен . Олсен участвовал в летних Олимпийских играх 2008 года в парной парной лёгком весе вместе с Юлианой Расмуссен . Другой фарерский гребец, являющийся членом национальной сборной Дании по академической гребле, — Сверри Сандберг Нильсен , который в настоящее время участвует в соревнованиях в одиночке в тяжелом весе; он также выступал в парной парной. Он является действующим рекордсменом Дании по гребле в закрытых помещениях среди мужчин в тяжелом весе; в январе 2015 года он побил рекорд девятилетней давности. [153] и улучшил его в январе 2016 года. [154] Он также участвовал в чемпионате мира по академической гребле 2015 года, дойдя до полуфинала; он участвовал в чемпионате мира по академической гребле среди юношей до 23 лет в 2015 году и дошел до финала, где занял четвертое место. [155]

Фарерские острова подали заявку в МОК на полноправное членство в 1984 году, но по состоянию на 2017 год [update] Фарерские острова до сих пор не являются членом МОК. На Европейских играх 2015 года в Баку (Азербайджан) Фарерским островам не разрешили выступать под флагом Фарерских островов; однако им было разрешено выступать под флагом Европейской лиги нации . До этого премьер-министр Фарерских островов Кай Лео Хольм Йоханнесен встретился 21 мая 2015 года в Лозанне с президентом МОК Томасом Бахом , чтобы обсудить членство Фарерских островов в МОК. [156] [157]

Фарерцы очень активно занимаются спортом; у них проводятся внутренние соревнования по футболу, гандболу, волейболу, бадминтону, плаванию, гребле на открытом воздухе ( фарерский каппродур ) и гребле в помещении на гребных тренажерах, верховой езде, стрельбе, настольному теннису, дзюдо, гольфу, теннису, стрельбе из лука, гимнастике, велоспорту , триатлону, бег и другие соревнования по легкой атлетике. [158]

В течение 2014 года Фарерским островам была предоставлена возможность принять участие в чемпионате Европы по киберспорту Electronic Sports European Championship (ESEC) . [159] 5 игроков, все граждане Фарерских островов, встретились со Словенией в первом раунде и в итоге были нокаутированы со счетом 0–2. [160]

На Бакинской шахматной олимпиаде 2016 года на Фарерских островах появился первый гроссмейстер по шахматам. Хельги Зиска выиграл свою третью норму гроссмейстера и, таким образом, завоевал титул гроссмейстера по шахматам. [161]

Фарерским островам был предоставлен еще один шанс посоревноваться в киберспорте на международном уровне , на этот раз на Североевропейском Minor Championship 2018 года. Капитаном команды был Рокур Дам Нордой. [ нужна ссылка ]

Одежда

[ редактировать ]Фарерские ремесла в основном основаны на материалах, доступных в местных деревнях, в основном на шерсти. Одежда включает свитера, шарфы и перчатки. Фарерские джемперы имеют ярко выраженный скандинавский узор; в каждой деревне есть некоторые региональные вариации, передающиеся от матери к дочери. В последнее время наблюдается сильное возрождение интереса к фарерскому вязанию: молодые люди вяжут и носят обновленные версии старых узоров, подчеркнутые яркими цветами и смелыми узорами. Похоже, это реакция на утрату традиционного образа жизни и способ сохранить и утвердить культурную традицию в быстро меняющемся обществе. Многие молодые люди учатся и уезжают за границу, и это помогает им поддерживать культурные связи со своим специфическим фарерским наследием.

Также был большой интерес к фарерским свитерам. [162] из сериала «Убийство» , где главная актриса (детектив-инспектор Сара Лунд, которую играет Софи Гробёль ) носит фарерские свитера. [163]

Вязание кружева – традиционное рукоделие. Самая отличительная черта фарерских кружевных шалей — ластовица по центру спинки . Каждая шаль состоит из двух треугольных боковых панелей, задней ластовицы трапециевидной формы, обработки края и, как правило, формы плеч. Их носят все поколения женщин, особенно как часть традиционного фарерского костюма в качестве верхней одежды.

Традиционное фарерское национальное платье также является местным ремеслом, на изготовление которого люди тратят много времени, денег и усилий. Его носят на свадьбах, традиционных танцевальных мероприятиях, а также в праздничные дни. Культурное значение одежды не следует недооценивать, как выражение местной и национальной идентичности, так и передачу и укрепление традиционных навыков, которые объединяют местные сообщества.

Молодому фарерцу обычно передают комплект детской фарерской одежды, который передается из поколения в поколение. Детей конфирмируют в 14 лет, и они обычно начинают собирать детали, чтобы сделать взрослый наряд, что считается обрядом посвящения. Традиционно цель заключалась в том, чтобы завершить наряд к тому времени, когда молодой человек будет готов жениться и надеть одежду на церемонию – хотя сейчас это делают в основном только мужчины.

Каждое изделие связано вручную, окрашено, соткано или вышито в соответствии с пожеланиями владельца. Например, мужской жилет сшивается вручную из тонкой шерсти ярко-синего, красного или черного цвета. Передняя часть затем замысловато вышивается разноцветными шелковыми нитями, часто родственницей. Мотивами часто являются местные фарерские цветы или травы. После этого к костюму пришивается ряд цельных серебряных пуговиц фарерского производства.

Женщины носят вышитые шелковые, хлопчатобумажные или шерстяные шали и передники, на плетение или вышивку которых могут уйти месяцы с изображением местной флоры и фауны. Они также украшены черно-красной юбкой ручной работы до щиколотки, вязаным черно-красным джемпером, бархатным поясом и черными туфлями в стиле XVIII века с серебряными пряжками. Наряд скреплен рядом цельных серебряных пуговиц, серебряных цепочек, а также серебряных брошей и пряжек местного производства, часто украшенных мотивами в стиле викингов.

Как мужская, так и женская национальная одежда чрезвычайно дорога, и на ее изготовление может уйти много лет. Женщины в семье часто вместе собирают наряды: вяжут облегающие джемперы, ткут и вышивают, шьют и собирают национальное платье.

Эта традиция объединяет семьи, передает традиционные ремесла и укрепляет фарерскую культуру традиционной деревенской жизни в контексте современного общества.

Архивы

[ редактировать ]Национальный архив Фарерских островов ( фарерский : Tjóðskjalasavnið ) расположен в Торсхавне. Их основная задача – собирать, систематизировать, фиксировать и сохранять архивные записи (документы) органов власти, чтобы в будущем сделать их доступными для общественности. В этом контексте Национальный архив контролирует реестр (дневник) и архивы органов государственной власти. В настоящее время на Фарерских островах нет других постоянных архивов, но с конца 2017 года национальное правительство предоставило финансовую поддержку трехлетнему пилотному проекту под названием «Tvøroyrar Skjalasavn», целью которого является сбор частных архивов из Фарерских островов. область.

Библиотеки

[ редактировать ]Национальная библиотека Фарерских островов ( по-фарерски : Føroya Landsbókasavn ) базируется в Торсхавне, и ее основная задача — собирать, записывать, сохранять и распространять знания о литературе, связанной с Фарерскими островами. Национальная библиотека также функционирует как научная библиотека и публичная библиотека. Помимо Национальной библиотеки, на Фарерских островах есть 15 муниципальных библиотек и 11 школьных библиотек.

Музеи и галереи

[ редактировать ]На Фарерских островах имеется множество музеев и галерей.

Исторический музей; Листасавн Фёройя, Фарерский художественный музей; Музей естественной истории; Северный Дом, Дом Севера; Хейма-а-Гарди, Хойвик, Музей под открытым небом в Хойвике; Фарерский морской музей, Фарерский аквариум в Аргире; Галерея Фокус, Стекольный завод; Листаглуггин, Художественная галерея.

Изобразительное искусство

[ редактировать ]Изобразительное искусство Фарерских островов имеет большое значение для памяти о национальной идентичности Фарерских островов , а также для распространения визуальной вселенной Фарерских островов.

Различные периоды и проявления изобразительного искусства встречаются и дополняют друг друга, но также могут создавать напряжение между прошлым и настоящим выражением.

В настоящее время в продаже имеются фарерские марки, созданные фарерскими художниками.