Diatom

| Diatom Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

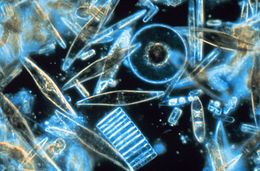

| Light microscopy of a sampling of marine diatoms found living between crystals of annual sea ice in Antarctica, showing a multiplicity of sizes and shapes | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Clade: | Diaphoretickes |

| Clade: | SAR |

| Clade: | Stramenopiles |

| Phylum: | Gyrista |

| Subphylum: | Ochrophytina |

| Infraphylum: | Diatomista |

| Class: | Bacillariophyceae Dangeard, 1933[1] |

| Subclasses[2] | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

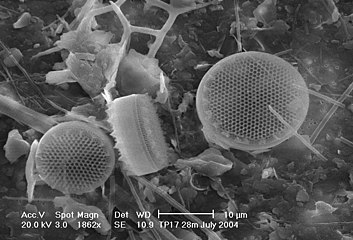

A diatom (Neo-Latin diatoma)[a] is any member of a large group comprising several genera of algae, specifically microalgae, found in the oceans, waterways and soils of the world. Living diatoms make up a significant portion of the Earth's biomass: they generate about 20 to 50 percent of the oxygen produced on the planet each year,[11][12] take in over 6.7 billion tonnes of silicon each year from the waters in which they live,[13] and constitute nearly half of the organic material found in the oceans. The shells of dead diatoms can reach as much as a half-mile (800 m) deep on the ocean floor, and the entire Amazon basin is fertilized annually by 27 million tons of diatom shell dust transported by transatlantic winds from the African Sahara, much of it from the Bodélé Depression, which was once made up of a system of fresh-water lakes.[14][15]

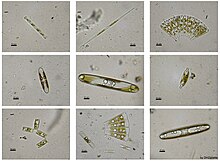

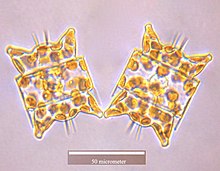

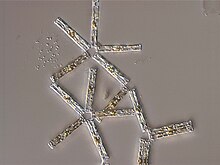

Diatoms are unicellular organisms: they occur either as solitary cells or in colonies, which can take the shape of ribbons, fans, zigzags, or stars. Individual cells range in size from 2 to 2000 micrometers.[16] In the presence of adequate nutrients and sunlight, an assemblage of living diatoms doubles approximately every 24 hours by asexual multiple fission; the maximum life span of individual cells is about six days.[17] Diatoms have two distinct shapes: a few (centric diatoms) are radially symmetric, while most (pennate diatoms) are broadly bilaterally symmetric.

The unique feature of diatoms is that they are surrounded by a cell wall made of silica (hydrated silicon dioxide), called a frustule.[18] These frustules produce structural coloration, prompting them to be described as "jewels of the sea" and "living opals".

Movement in diatoms primarily occurs passively as a result of both ocean currents and wind-induced water turbulence; however, male gametes of centric diatoms have flagella, permitting active movement to seek female gametes. Similar to plants, diatoms convert light energy to chemical energy by photosynthesis, but their chloroplasts were acquired in different ways.[19]

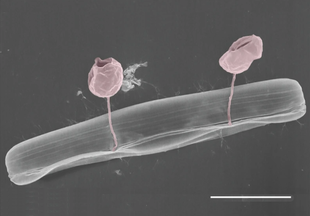

Unusually for autotrophic organisms, diatoms possess a urea cycle, a feature that they share with animals, although this cycle is used to different metabolic ends in diatoms. The family Rhopalodiaceae also possess a cyanobacterial endosymbiont called a spheroid body. This endosymbiont has lost its photosynthetic properties, but has kept its ability to perform nitrogen fixation, allowing the diatom to fix atmospheric nitrogen.[20] Other diatoms in symbiosis with nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria are among the genera Hemiaulus, Rhizosolenia and Chaetoceros.[21]

Dinotoms are diatoms that have become endosymbionts inside dinoflagellates. Research on the dinoflagellates Durinskia baltica and Glenodinium foliaceum has shown that the endosymbiont event happened so recently, evolutionarily speaking, that their organelles and genome are still intact with minimal to no gene loss. The main difference between these and free living diatoms is that they have lost their cell wall of silica, making them the only known shell-less diatoms.[22]

The study of diatoms is a branch of phycology. Diatoms are classified as eukaryotes, organisms with a nuclear envelope-bound cell nucleus, that separates them from the prokaryotes archaea and bacteria. Diatoms are a type of plankton called phytoplankton, the most common of the plankton types. Diatoms also grow attached to benthic substrates, floating debris, and on macrophytes. They comprise an integral component of the periphyton community.[23] Another classification divides plankton into eight types based on size: in this scheme, diatoms are classed as microalgae. Several systems for classifying the individual diatom species exist.

Fossil evidence suggests that diatoms originated during or before the early Jurassic period, which was about 150 to 200 million years ago. The oldest fossil evidence for diatoms is a specimen of extant genus Hemiaulus in Late Jurassic aged amber from Thailand.[24]

Diatoms are used to monitor past and present environmental conditions, and are commonly used in studies of water quality. Diatomaceous earth (diatomite) is a collection of diatom shells found in the Earth's crust. They are soft, silica-containing sedimentary rocks which are easily crumbled into a fine powder and typically have a particle size of 10 to 200 μm. Diatomaceous earth is used for a variety of purposes including for water filtration, as a mild abrasive, in cat litter, and as a dynamite stabilizer.

Displays overlays from four fluorescent channels

(b) Cyan: [PLL-A546 fluorescence] - generic counterstain for visualising eukaryotic cell surfaces

(c) Blue: [Hoechst fluorescence] - stains DNA, identifies nuclei

(d) Red: [chlorophyll autofluorescence] - resolves chloroplasts [27]

Overview

[edit]Diatoms are protists that form massive annual spring and fall blooms in aquatic environments and are estimated to be responsible for about half of photosynthesis in the global oceans.[28] This predictable annual bloom dynamic fuels higher trophic levels and initiates delivery of carbon into the deep ocean biome. Diatoms have complex life history strategies that are presumed to have contributed to their rapid genetic diversification into ~200,000 species [29] that are distributed between the two major diatom groups: centrics and pennates.[30][31]

Morphology

[edit]Diatoms are generally 20 to 200 micrometers in size,[32] with a few larger species. Their yellowish-brown chloroplasts, the site of photosynthesis, are typical of heterokonts, having four cell membranes and containing pigments such as the carotenoid fucoxanthin. Individuals usually lack flagella, but they are present in male gametes of the centric diatoms and have the usual heterokont structure, including the hairs (mastigonemes) characteristic in other groups.

Diatoms are often referred as "jewels of the sea" or "living opals" due to their optical properties.[33] The biological function of this structural coloration is not clear, but it is speculated that it may be related to communication, camouflage, thermal exchange and/or UV protection.[34]

Diatoms build intricate hard but porous cell walls called frustules composed primarily of silica.[35]: 25–30 This siliceous wall[36] can be highly patterned with a variety of pores, ribs, minute spines, marginal ridges and elevations; all of which can be used to delineate genera and species.

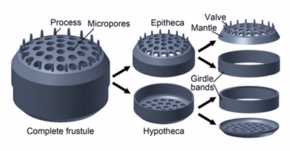

The cell itself consists of two halves, each containing an essentially flat plate, or valve, and marginal connecting, or girdle band. One half, the hypotheca, is slightly smaller than the other half, the epitheca. Diatom morphology varies. Although the shape of the cell is typically circular, some cells may be triangular, square, or elliptical. Their distinguishing feature is a hard mineral shell or frustule composed of opal (hydrated, polymerized silicic acid).

- Nucleus; holds the genetic material

- Nucleolus; location of the chromosomes

- Golgi apparatus; modifies proteins and sends them out of the cell

- Cell wall; outer membrane of the cell

- Pyrenoid; center of carbon fixation

- Chromatophore; pigment carrying membrane structure

- Vacuoles; vesicle of a cell that contains fluid bound by a membrane

- Cytoplasmic strands; hold the nucleus

- Mitochondria; create ATP (energy) for the cell

- Valves/Striae; allow nutrients in, and waste out, of the cell

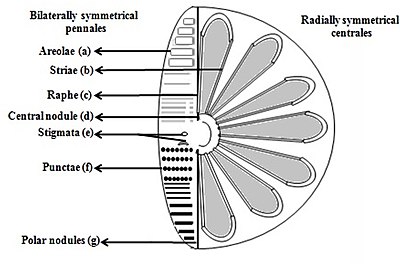

- Areolae (hexagonal or polygonal boxlike perforation with a sieve present on the surface of diatom)

- Striae (pores, punctae, spots or dots in a line on the surface)

- Raphe (slit in the valves)

- Central nodule (thickening of wall at the midpoint of raphe)

- Stigmata (holes through valve surface which looks rounded externally but with a slit like internal)

- Punctae (spots or small perforations on the surface)

- Polar nodules (thickening of wall at the distal ends of the raphe)[37][38]

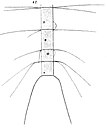

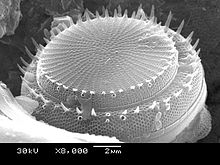

Diatoms are divided into two groups that are distinguished by the shape of the frustule: the centric diatoms and the pennate diatoms.

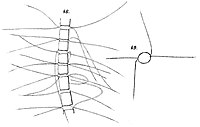

Pennate diatoms are bilaterally symmetric. Each one of their valves have openings that are slits along the raphes and their shells are typically elongated parallel to these raphes. They generate cell movement through cytoplasm that streams along the raphes, always moving along solid surfaces.

Centric diatoms are radially symmetric. They are composed of upper and lower valves – epitheca and hypotheca – each consisting of a valve and a girdle band that can easily slide underneath each other and expand to increase cell content over the diatoms progression. The cytoplasm of the centric diatom is located along the inner surface of the shell and provides a hollow lining around the large vacuole located in the center of the cell. This large, central vacuole is filled by a fluid known as "cell sap" which is similar to seawater but varies with specific ion content. The cytoplasmic layer is home to several organelles, like the chloroplasts and mitochondria. Before the centric diatom begins to expand, its nucleus is at the center of one of the valves and begins to move towards the center of the cytoplasmic layer before division is complete. Centric diatoms have a variety of shapes and sizes, depending on from which axis the shell extends, and if spines are present.

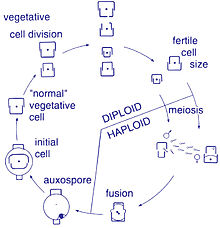

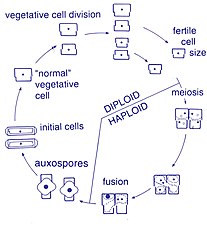

Silicification

[edit]Diatom cells are contained within a unique silica cell wall known as a frustule made up of two valves called thecae, that typically overlap one another.[40] The biogenic silica composing the cell wall is synthesised intracellularly by the polymerisation of silicic acid monomers. This material is then extruded to the cell exterior and added to the wall. In most species, when a diatom divides to produce two daughter cells, each cell keeps one of the two-halves and grows a smaller half within it. As a result, after each division cycle, the average size of diatom cells in the population gets smaller. Once such cells reach a certain minimum size, rather than simply divide, they reverse this decline by forming an auxospore, usually through meiosis and sexual reproduction, but exceptions exist. The auxospore expands in size to give rise to a much larger cell, which then returns to size-diminishing divisions.[41]

The exact mechanism of transferring silica absorbed by the diatom to the cell wall is unknown. Much of the sequencing of diatom genes comes from the search for the mechanism of silica uptake and deposition in nano-scale patterns in the frustule. The most success in this area has come from two species, Thalassiosira pseudonana, which has become the model species, as the whole genome was sequenced and methods for genetic control were established, and Cylindrotheca fusiformis, in which the important silica deposition proteins silaffins were first discovered.[43] Silaffins, sets of polycationic peptides, were found in C. fusiformis cell walls and can generate intricate silica structures. These structures demonstrated pores of sizes characteristic to diatom patterns. When T. pseudonana underwent genome analysis it was found that it encoded a urea cycle, including a higher number of polyamines than most genomes, as well as three distinct silica transport genes.[44] In a phylogenetic study on silica transport genes from 8 diverse groups of diatoms, silica transport was found to generally group with species.[43] This study also found structural differences between the silica transporters of pennate (bilateral symmetry) and centric (radial symmetry) diatoms. The sequences compared in this study were used to create a diverse background in order to identify residues that differentiate function in the silica deposition process. Additionally, the same study found that a number of the regions were conserved within species, likely the base structure of silica transport.

These silica transport proteins are unique to diatoms, with no homologs found in other species, such as sponges or rice. The divergence of these silica transport genes is also indicative of the structure of the protein evolving from two repeated units composed of five membrane bound segments, which indicates either gene duplication or dimerization.[43] The silica deposition that takes place from the membrane bound vesicle in diatoms has been hypothesized to be a result of the activity of silaffins and long chain polyamines. This Silica Deposition Vesicle (SDV) has been characterized as an acidic compartment fused with Golgi-derived vesicles.[45] These two protein structures have been shown to create sheets of patterned silica in-vivo with irregular pores on the scale of diatom frustules. One hypothesis as to how these proteins work to create complex structure is that residues are conserved within the SDV's, which is unfortunately difficult to identify or observe due to the limited number of diverse sequences available. Though the exact mechanism of the highly uniform deposition of silica is as yet unknown, the Thalassiosira pseudonana genes linked to silaffins are being looked to as targets for genetic control of nanoscale silica deposition.

The ability of diatoms to make silica-based cell walls has been the subject of fascination for centuries. It started with a microscopic observation by an anonymous English country nobleman in 1703, who observed an object that looked like a chain of regular parallelograms and debated whether it was just crystals of salt, or a plant.[46] The viewer decided that it was a plant because the parallelograms didn't separate upon agitation, nor did they vary in appearance when dried or subjected to warm water (in an attempt to dissolve the "salt"). Unknowingly, the viewer's confusion captured the essence of diatoms—mineral utilizing plants. It is not clear when it was determined that diatom cell walls are made of silica, but in 1939 a seminal reference characterized the material as silicic acid in a "subcolloidal" state[47] Identification of the main chemical component of the cell wall spurred investigations into how it was made. These investigations have involved, and been propelled by, diverse approaches including, microscopy, chemistry, biochemistry, material characterisation, molecular biology, 'omics, and transgenic approaches. The results from this work have given a better understanding of cell wall formation processes, establishing fundamental knowledge which can be used to create models that contextualise current findings and clarify how the process works.[48]

The process of building a mineral-based cell wall inside the cell, then exporting it outside, is a massive event that must involve large numbers of genes and their protein products. The act of building and exocytosing this large structural object in a short time period, synched with cell cycle progression, necessitates substantial physical movements within the cell as well as dedication of a significant proportion of the cell's biosynthetic capacities.[48]

The first characterisations of the biochemical processes and components involved in diatom silicification were made in the late 1990s.[49][50][51] These were followed by insights into how higher order assembly of silica structures might occur.[52][53][54] More recent reports describe the identification of novel components involved in higher order processes, the dynamics documented through real-time imaging, and the genetic manipulation of silica structure.[55][56] The approaches established in these recent works provide practical avenues to not only identify the components involved in silica cell wall formation but to elucidate their interactions and spatio-temporal dynamics. This type of holistic understanding will be necessary to achieve a more complete understanding of cell wall synthesis.[48]

Behaviour

[edit]Most centric and araphid pennate diatoms are nonmotile, and their relatively dense cell walls cause them to readily sink. Planktonic forms in open water usually rely on turbulent mixing of the upper layers of the oceanic waters by the wind to keep them suspended in sunlit surface waters. Many planktonic diatoms have also evolved features that slow their sinking rate, such as spines or the ability to grow in colonial chains.[57] These adaptations increase their surface area to volume ratio and drag, allowing them to stay suspended in the water column longer. Individual cells may regulate buoyancy via an ionic pump.[58]

Some pennate diatoms are capable of a type of locomotion called "gliding", which allows them to move across surfaces via adhesive mucilage secreted through a seamlike structure called the raphe.[59][60] In order for a diatom cell to glide, it must have a solid substrate for the mucilage to adhere to.

Cells are solitary or united into colonies of various kinds, which may be linked by siliceous structures; mucilage pads, stalks or tubes; amorphous masses of mucilage; or by threads of chitin (polysaccharide), which are secreted through strutted processes of the cell.

This projection of a stack of confocal images shows the diatoms' cell wall (cyan), chloroplasts (red), DNA (blue), membranes and organelles (green).

Life cycle

[edit]Reproduction and cell size

[edit]Reproduction among these organisms is asexual by binary fission, during which the diatom divides into two parts, producing two "new" diatoms with identical genes. Each new organism receives one of the two frustules – one larger, the other smaller – possessed by the parent, which is now called the epitheca; and is used to construct a second, smaller frustule, the hypotheca. The diatom that received the larger frustule becomes the same size as its parent, but the diatom that received the smaller frustule remains smaller than its parent. This causes the average cell size of this diatom population to decrease.[16] It has been observed, however, that certain taxa have the ability to divide without causing a reduction in cell size.[61] Nonetheless, in order to restore the cell size of a diatom population for those that do endure size reduction, sexual reproduction and auxospore formation must occur.[16]

Cell division

[edit]Vegetative cells of diatoms are diploid (2N) and so meiosis can take place, producing male and female gametes which then fuse to form the zygote. The zygote sheds its silica theca and grows into a large sphere covered by an organic membrane, the auxospore. A new diatom cell of maximum size, the initial cell, forms within the auxospore thus beginning a new generation. Resting spores may also be formed as a response to unfavourable environmental conditions with germination occurring when conditions improve.[35]

A defining characteristic of all diatoms is their restrictive and bipartite silica cell wall that causes them to progressively shrink during asexual cell division. At a critically small cell size and under certain conditions, auxosporulation restitutes cell size and prevents clonal death.[62][63][64][65][66] The entire lifecycles of only a few diatoms have been described and rarely have sexual events been captured in the environment.[31]

Sexual reproduction

[edit]Most eukaryotes are capable of sexual reproduction involving meiosis. Sexual reproduction appears to be an obligatory phase in the life cycle of diatoms, particularly as cell size decreases with successive vegetative divisions.[67] Sexual reproduction involves production of gametes and the fusion of gametes to form a zygote in which maximal cell size is restored.[67] The signaling that triggers the sexual phase is favored when cells accumulate together, so that the distance between them is reduced and the contacts and/or the perception of chemical cues is facilitated.[68]

An exploration of the genomes of five diatoms and one diatom transcriptome led to the identification of 42 genes potentially involved in meiosis.[69] Thus a meiotic toolkit appears to be conserved in these six diatom species,[69] indicating a central role of meiosis in diatoms as in other eukaryotes.

Sperm motility

[edit]Diatoms are mostly non-motile; however, sperm found in some species can be flagellated, though motility is usually limited to a gliding motion.[35] In centric diatoms, the small male gametes have one flagellum while the female gametes are large and non-motile (oogamous). Conversely, in pennate diatoms both gametes lack flagella (isogamous).[16] Certain araphid species, that is pennate diatoms without a raphe (seam), have been documented as anisogamous and are, therefore, considered to represent a transitional stage between centric and raphid pennate diatoms, diatoms with a raphe.[61]

Degradation by microbes

[edit]Certain species of bacteria in oceans and lakes can accelerate the rate of dissolution of silica in dead and living diatoms by using hydrolytic enzymes to break down the organic algal material.[70][71]

Ecology

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Plankton |

|---|

|

versus silicate concentration [72]

Distribution

[edit]Diatoms are a widespread group and can be found in the oceans, in fresh water, in soils, and on damp surfaces. They are one of the dominant components of phytoplankton in nutrient-rich coastal waters and during oceanic spring blooms, since they can divide more rapidly than other groups of phytoplankton.[73] Most live pelagically in open water, although some live as surface films at the water-sediment interface (benthic), or even under damp atmospheric conditions. They are especially important in oceans, where a 2003 study found that they contribute an estimated 45% of the total oceanic primary production of organic material.[74] However, a more recent 2016 study estimates that the number is closer to 20%.[75] Spatial distribution of marine phytoplankton species is restricted both horizontally and vertically.[76][35]

Growth

[edit]Planktonic diatoms in freshwater and marine environments typically exhibit a "boom and bust" (or "bloom and bust") lifestyle. When conditions in the upper mixed layer (nutrients and light) are favourable (as at the spring), their competitive edge and rapid growth rate[73] enables them to dominate phytoplankton communities ("boom" or "bloom"). As such they are often classed as opportunistic r-strategists (i.e. those organisms whose ecology is defined by a high growth rate, r).

Impact

[edit]The freshwater diatom Didymosphenia geminata, commonly known as Didymo, causes severe environmental degradation in water-courses where it blooms, producing large quantities of a brown jelly-like material called "brown snot" or "rock snot". This diatom is native to Europe and is an invasive species both in the antipodes and in parts of North America.[77][78] The problem is most frequently recorded from Australia and New Zealand.[79]

When conditions turn unfavourable, usually upon depletion of nutrients, diatom cells typically increase in sinking rate and exit the upper mixed layer ("bust"). This sinking is induced by either a loss of buoyancy control, the synthesis of mucilage that sticks diatoms cells together, or the production of heavy resting spores. Sinking out of the upper mixed layer removes diatoms from conditions unfavourable to growth, including grazer populations and higher temperatures (which would otherwise increase cell metabolism). Cells reaching deeper water or the shallow seafloor can then rest until conditions become more favourable again. In the open ocean, many sinking cells are lost to the deep, but refuge populations can persist near the thermocline.

Ultimately, diatom cells in these resting populations re-enter the upper mixed layer when vertical mixing entrains them. In most circumstances, this mixing also replenishes nutrients in the upper mixed layer, setting the scene for the next round of diatom blooms. In the open ocean (away from areas of continuous upwelling[80]), this cycle of bloom, bust, then return to pre-bloom conditions typically occurs over an annual cycle, with diatoms only being prevalent during the spring and early summer. In some locations, however, an autumn bloom may occur, caused by the breakdown of summer stratification and the entrainment of nutrients while light levels are still sufficient for growth. Since vertical mixing is increasing, and light levels are falling as winter approaches, these blooms are smaller and shorter-lived than their spring equivalents.

In the open ocean, the diatom (spring) bloom is typically ended by a shortage of silicon. Unlike other minerals, the requirement for silicon is unique to diatoms and it is not regenerated in the plankton ecosystem as efficiently as, for instance, nitrogen or phosphorus nutrients. This can be seen in maps of surface nutrient concentrations – as nutrients decline along gradients, silicon is usually the first to be exhausted (followed normally by nitrogen then phosphorus).

Because of this bloom-and-bust cycle, diatoms are believed to play a disproportionately important role in the export of carbon from oceanic surface waters[80][81] (see also the biological pump). Significantly, they also play a key role in the regulation of the biogeochemical cycle of silicon in the modern ocean.[74][82]

Reason for success

[edit]Diatoms are ecologically successful, and occur in virtually every environment that contains water – not only oceans, seas, lakes, and streams, but also soil and wetlands.[citation needed] The use of silicon by diatoms is believed by many researchers to be the key to this ecological success. Raven (1983)[83] noted that, relative to organic cell walls, silica frustules require less energy to synthesize (approximately 8% of a comparable organic wall), potentially a significant saving on the overall cell energy budget. In a now classic study, Egge and Aksnes (1992)[72] found that diatom dominance of mesocosm communities was directly related to the availability of silicic acid – when concentrations were greater than 2 μmol m−3, they found that diatoms typically represented more than 70% of the phytoplankton community. Other researchers[84] have suggested that the biogenic silica in diatom cell walls acts as an effective pH buffering agent, facilitating the conversion of bicarbonate to dissolved CO2 (which is more readily assimilated). More generally, notwithstanding these possible advantages conferred by their use of silicon, diatoms typically have higher growth rates than other algae of the same corresponding size.[73]

Sources for collection

[edit]Diatoms can be obtained from multiple sources.[85] Marine diatoms can be collected by direct water sampling, and benthic forms can be secured by scraping barnacles, oyster and other shells. Diatoms are frequently present as a brown, slippery coating on submerged stones and sticks, and may be seen to "stream" with river current. The surface mud of a pond, ditch, or lagoon will almost always yield some diatoms. Living diatoms are often found clinging in great numbers to filamentous algae, or forming gelatinous masses on various submerged plants. Cladophora is frequently covered with Cocconeis, an elliptically shaped diatom; Vaucheria is often covered with small forms. Since diatoms form an important part of the food of molluscs, tunicates, and fishes, the alimentary tracts of these animals often yield forms that are not easily secured in other ways. Diatoms can be made to emerge by filling a jar with water and mud, wrapping it in black paper and letting direct sunlight fall on the surface of the water. Within a day, the diatoms will come to the top in a scum and can be isolated.[85]

Biogeochemistry

[edit]-

The modern oceanic silicon cycle

Fluxes are in Tmol Si y−1 (1 Tmol = 28 million metric tons of silicon)

Silica cycle

[edit]The diagram shows the major fluxes of silicon in the current ocean. Most biogenic silica in the ocean (silica produced by biological activity) comes from diatoms. Diatoms extract dissolved silicic acid from surface waters as they grow, and return it to the water column when they die. Inputs of silicon arrive from above via aeolian dust, from the coasts via rivers, and from below via seafloor sediment recycling, weathering, and hydrothermal activity.[82]

Although diatoms may have existed since the Triassic, the timing of their ascendancy and "take-over" of the silicon cycle occurred more recently. Prior to the Phanerozoic (before 544 Ma), it is believed that microbial or inorganic processes weakly regulated the ocean's silicon cycle.[86][87][88] Subsequently, the cycle appears dominated (and more strongly regulated) by the radiolarians and siliceous sponges, the former as zooplankton, the latter as sedentary filter-feeders primarily on the continental shelves.[89] Within the last 100 My, it is thought that the silicon cycle has come under even tighter control, and that this derives from the ecological ascendancy of the diatoms.

However, the precise timing of the "take-over" remains unclear, and different authors have conflicting interpretations of the fossil record. Some evidence, such as the displacement of siliceous sponges from the shelves,[90] suggests that this takeover began in the Cretaceous (146 Ma to 66 Ma), while evidence from radiolarians suggests "take-over" did not begin until the Cenozoic (66 Ma to present).[91]

-

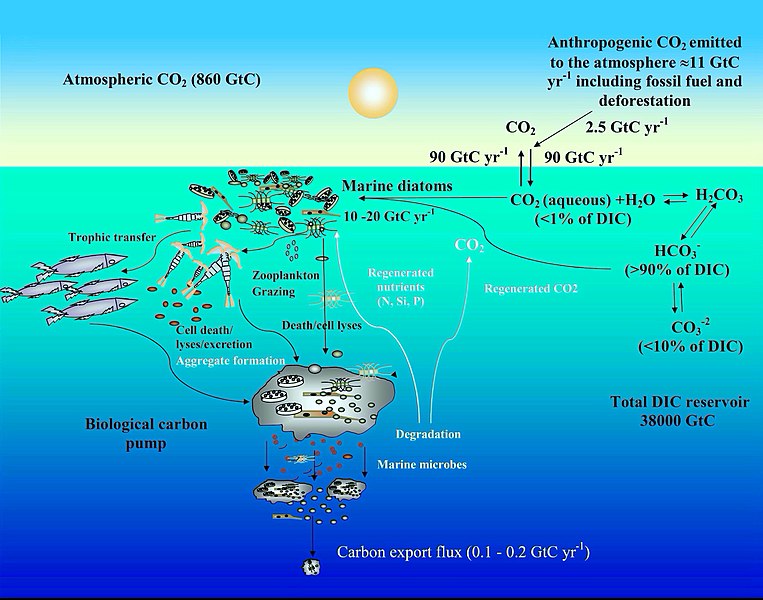

Ocean carbon cycle and diatom carbon dioxide concentration mechanisms [92]

Carbon cycle

[edit]The diagram depicts some mechanisms by which marine diatoms contribute to the biological carbon pump and influence the ocean carbon cycle. The anthropogenic CO2 emission to the atmosphere (mainly generated by fossil fuel burning and deforestation) is nearly 11 gigatonne carbon (GtC) per year, of which almost 2.5 GtC is taken up by the surface ocean. In surface seawater (pH 8.1–8.4), bicarbonate (HCO−

3) and carbonate ions (CO2−

3) constitute nearly 90 and <10% of dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) respectively, while dissolved CO2 (CO2 aqueous) contributes <1%. Despite this low level of CO2 in the ocean and its slow diffusion rate in water, diatoms fix 10–20 GtC annually via photosynthesis thanks to their carbon dioxide concentrating mechanisms, allowing them to sustain marine food chains. In addition, 0.1–1% of this organic material produced in the euphotic layer sinks down as particles, thus transferring the surface carbon toward the deep ocean and sequestering atmospheric CO2 for thousands of years or longer. The remaining organic matter is remineralized through respiration. Thus, diatoms are one of the main players in this biological carbon pump, which is arguably the most important biological mechanism in the Earth System allowing CO2 to be removed from the carbon cycle for very long period.[93][92]

-

Mitochondrial urea cycle in a generic diatom cell and the potential fates of urea cycle intermediates [94]

Urea cycle

[edit]A feature of diatoms is the urea cycle, which links them evolutionarily to animals. In 2011, Allen et al. established that diatoms have a functioning urea cycle. This result was significant, since prior to this, the urea cycle was thought to have originated with the metazoans which appeared several hundreds of millions of years before the diatoms. Their study demonstrated that while diatoms and animals use the urea cycle for different ends, they are seen to be evolutionarily linked in such a way that animals and plants are not.[95]

While often overlooked in photosynthetic organisms, the mitochondria also play critical roles in energy balance. Two nitrogen-related pathways are relevant and they may also change under ammonium (NH+

4) nutrition compared with nitrate (NO−

3) nutrition. First, in diatoms, and likely some other algae, there is a urea cycle.[96][97][98] The long-known function of the urea cycle in animals is to excrete excess nitrogen produced by amino acid Catabolism; like photorespiration, the urea cycle had long been considered a waste pathway. However, in diatoms the urea cycle appears to play a role in exchange of nutrients between the mitochondria and the cytoplasm, and potentially the plastid [99] and may help to regulate ammonium metabolism.[96][97] Because of this cycle, marine diatoms, in contrast to chlorophytes, also have acquired a mitochondrial urea transporter and, in fact, based on bioinformatics, a complete mitochondrial GS-GOGAT cycle has been hypothesised.[97][94]

Other

[edit]Diatoms are mainly photosynthetic; however a few are obligate heterotrophs and can live in the absence of light provided an appropriate organic carbon source is available.[100][101]

Photosynthetic diatoms that find themselves in an environment absent of oxygen and/or sunlight can switch to anaerobic respiration known as nitrate respiration (DNRA), and stay dormant for up till months and decades.[102][103]

Major pigments of diatoms are chlorophylls a and c, beta-carotene, fucoxanthin, diatoxanthin and diadinoxanthin.[16]

Taxonomy

[edit]

Stephanodiscus hantzschii

Isthmia nervosaIsthmia nervosa

Odontella aurita

Diatoms belong to a large group of protists, many of which contain plastids rich in chlorophylls a and c. The group has been variously referred to as heterokonts, chrysophytes, chromists or stramenopiles. Many are autotrophs such as golden algae and kelp; and heterotrophs such as water moulds, opalinids, and actinophryid heliozoa. The classification of this area of protists is still unsettled. In terms of rank, they have been treated as a division, phylum, kingdom, or something intermediate to those. Consequently, diatoms are ranked anywhere from a class, usually called Diatomophyceae or Bacillariophyceae, to a division (=phylum), usually called Bacillariophyta, with corresponding changes in the ranks of their subgroups.

Genera and species

[edit]An estimated 20,000 extant diatom species are believed to exist, of which around 12,000 have been named to date according to Guiry, 2012[104] (other sources give a wider range of estimates[16][105][106][107]). Around 1,000–1,300 diatom genera have been described, both extant and fossil,[108][109] of which some 250–300 exist only as fossils.[110]

Classes and orders

[edit]For many years the diatoms—treated either as a class (Bacillariophyceae) or a phylum (Bacillariophyta)—were divided into just 2 orders, corresponding to the centric and the pennate diatoms (Centrales and Pennales). This classification was extensively overhauled by Round, Crawford and Mann in 1990 who treated the diatoms at a higher rank (division, corresponding to phylum in zoological classification), and promoted the major classification units to classes, maintaining the centric diatoms as a single class Coscinodiscophyceae, but splitting the former pennate diatoms into 2 separate classes, Fragilariophyceae and Bacillariophyceae (the latter older name retained but with an emended definition), between them encompassing 45 orders, the majority of them new.

Today (writing at mid 2020) it is recognised that the 1990 system of Round et al. is in need of revision with the advent of newer molecular work, however the best system to replace it is unclear, and current systems in widespread use such as AlgaeBase, the World Register of Marine Species and its contributing database DiatomBase, and the system for "all life" represented in Ruggiero et al., 2015, all retain the Round et al. treatment as their basis, albeit with diatoms as a whole treated as a class rather than division/phylum, and Round et al.'s classes reduced to subclasses, for better agreement with the treatment of phylogenetically adjacent groups and their containing taxa. (For references refer the individual sections below).

One proposal, by Linda Medlin and co-workers commencing in 2004, is for some of the centric diatom orders considered more closely related to the pennates to be split off as a new class, Mediophyceae, itself more closely aligned with the pennate diatoms than the remaining centrics. This hypothesis—later designated the Coscinodiscophyceae-Mediophyceae-Bacillariophyceae, or Coscinodiscophyceae+(Mediophyceae+Bacillariophyceae) (CMB) hypothesis—has been accepted by D.G. Mann among others, who uses it as the basis for the classification of diatoms as presented in Adl. et al.'s series of syntheses (2005, 2012, 2019), and also in the Bacillariophyta chapter of the 2017 Handbook of the Protists edited by Archibald et al., with some modifications reflecting the apparent non-monophyly of Medlin et al. original "Coscinodiscophyceae". Meanwhile, a group led by E.C. Theriot favours a different hypothesis of phylogeny, which has been termed the structural gradation hypothesis (SGH) and does not recognise the Mediophyceae as a monophyletic group, while another analysis, that of Parks et al., 2018, finds that the radial centric diatoms (Medlin et al.'s Coscinodiscophyceae) are not monophyletic, but supports the monophyly of Mediophyceae minus Attheya, which is an anomalous genus. Discussion of the relative merits of these conflicting schemes continues by the various parties involved.[111][112][113][114]

Adl et al., 2019 treatment

[edit]In 2019, Adl et al.[115] presented the following classification of diatoms, while noting: "This revision reflects numerous advances in the phylogeny of the diatoms over the last decade. Due to our poor taxon sampling outside of the Mediophyceae and pennate diatoms, and the known and anticipated diversity of all diatoms, many clades appear at a high classification level (and the higher level classification is rather flat)." This classification treats diatoms as a phylum (Diatomeae/Bacillariophyta), accepts the class Mediophyceae of Medlin and co-workers, introduces new subphyla and classes for a number of otherwise isolated genera, and re-ranks a number of previously established taxa as subclasses, but does not list orders or families. Inferred ranks have been added for clarity (Adl. et al. do not use ranks, but the intended ones in this portion of the classification are apparent from the choice of endings used, within the system of botanical nomenclature employed).

- Clade Diatomista Derelle et al. 2016, emend. Cavalier-Smith 2017 (diatoms plus a subset of other ochrophyte groups)

- Phylum Diatomeae Dumortier 1821 [= Bacillariophyta Haeckel 1878] (diatoms)

- Subphylum Leptocylindrophytina D.G. Mann in Adl et al. 2019

- Class Leptocylindrophyceae D.G. Mann in Adl et al. 2019 (Leptocylindrus, Tenuicylindrus)

- Class Corethrophyceae D.G. Mann in Adl et al. 2019 (Corethron)

- Subphylum Ellerbeckiophytina D.G. Mann in Adl et al. 2019 (Ellerbeckia)

- Subphylum Probosciophytina D.G. Mann in Adl et al. 2019 (Proboscia)

- Subphylum Melosirophytina D.G. Mann in Adl et al. 2019 (Aulacoseira, Melosira, Hyalodiscus, Stephanopyxis, Paralia, Endictya)

- Subphylum Coscinodiscophytina Medlin & Kaczmarska 2004, emend. (Actinoptychus, Coscinodiscus, Actinocyclus, Asteromphalus, Aulacodiscus, Stellarima)

- Subphylum Rhizosoleniophytina D.G. Mann in Adl et al. 2019 (Guinardia, Rhizosolenia, Pseudosolenia)

- Subphylum Arachnoidiscophytina D.G. Mann in Adl et al. 2019 (Arachnoidiscus)

- Subphylum Bacillariophytina Medlin & Kaczmarska 2004, emend.

- Class Mediophyceae Jouse & Proshkina-Lavrenko in Medlin & Kaczmarska 2004

- Subclass Chaetocerotophycidae Round & R.M. Crawford in Round et al. 1990, emend.

- Subclass Lithodesmiophycidae Round & R.M. Crawford in Round et al. 1990, emend.

- Subclass Thalassiosirophycidae Round & R.M. Crawford in Round et al. 1990

- Subclass Cymatosirophycidae Round & R.M. Crawford in Round et al. 1990

- Subclass Odontellophycidae D.G. Mann in Adl et al. 2019

- Subclass Chrysanthemodiscophycidae D.G. Mann in Adl et al. 2019

- Class Biddulphiophyceae D.G. Mann in Adl et al. 2019

- Subclass Biddulphiophycidae Round and R.M. Crawford in Round et al. 1990, emend.

- Biddulphiophyceae incertae sedis (Attheya)

- Class Bacillariophyceae Haeckel 1878, emend.

- Bacillariophyceae incertae sedis (Striatellaceae)

- Subclass Urneidophycidae Medlin 2016

- Subclass Fragilariophycidae Round in Round, Crawford & Mann 1990, emend.

- Subclass Bacillariophycidae D.G. Mann in Round, Crawford & Mann 1990, emend.

- Class Mediophyceae Jouse & Proshkina-Lavrenko in Medlin & Kaczmarska 2004

- Subphylum Leptocylindrophytina D.G. Mann in Adl et al. 2019

- Phylum Diatomeae Dumortier 1821 [= Bacillariophyta Haeckel 1878] (diatoms)

See taxonomy of diatoms for more details.

Gallery

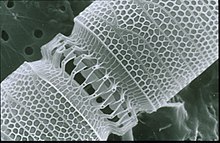

[edit]- Scanning electron microscope images

-

Diatom Surirella spiralis

-

Diatoms Thalassiosira sp. on a membrane filter, pore size 0.4 μm.

-

Diatom Paralia sulcata.

-

Diatom Achanthes trinodis

-

Stand-alone cell of Bacillaria paxillifer

-

Colonial group of Bacillaria paxillifer

| External videos | |

|---|---|

Three diatom species were sent to the International Space Station, including the huge (6 mm length) diatoms of Antarctica and the exclusive colonial diatom, Bacillaria paradoxa. The cells of Bacillaria moved next to each other in partial but opposite synchrony by a microfluidics method.[116]

Evolution and fossil record

[edit]Origin

[edit]Heterokont chloroplasts appear to derive from those of red algae, rather than directly from prokaryotes as occurred in plants. This suggests they had a more recent origin than many other algae. However, fossil evidence is scant, and only with the evolution of the diatoms themselves do the heterokonts make a serious impression on the fossil record.

Earliest fossils

[edit]The earliest known fossil diatoms date from the early Jurassic (~185 Ma ago),[117] although the molecular clock[117] and sedimentary[118] evidence suggests an earlier origin. It has been suggested that their origin may be related to the end-Permian mass extinction (~250 Ma), after which many marine niches were opened.[119] The gap between this event and the time that fossil diatoms first appear may indicate a period when diatoms were unsilicified and their evolution was cryptic.[120] Since the advent of silicification, diatoms have made a significant impression on the fossil record, with major fossil deposits found as far back as the early Cretaceous, and with some rocks such as diatomaceous earth, being composed almost entirely of them.

Relation to grasslands

[edit]The expansion of grassland biomes and the evolutionary radiation of grasses during the Miocene is believed to have increased the flux of soluble silicon to the oceans, and it has been argued that this promoted the diatoms during the Cenozoic era.[121][122] Recent work suggests that diatom success is decoupled from the evolution of grasses, although both diatom and grassland diversity increased strongly from the middle Miocene.[123]

Relation to climate

[edit]Diatom diversity over the Cenozoic has been very sensitive to global temperature, particularly to the equator-pole temperature gradient. Warmer oceans, particularly warmer polar regions, have in the past been shown to have had substantially lower diatom diversity. Future warm oceans with enhanced polar warming, as projected in global-warming scenarios,[124] could thus in theory result in a significant loss of diatom diversity, although from current knowledge it is impossible to say if this would occur rapidly or only over many tens of thousands of years.[123]

Method of investigation

[edit]The fossil record of diatoms has largely been established through the recovery of their siliceous frustules in marine and non-marine sediments. Although diatoms have both a marine and non-marine stratigraphic record, diatom biostratigraphy, which is based on time-constrained evolutionary originations and extinctions of unique taxa, is only well developed and widely applicable in marine systems. The duration of diatom species ranges have been documented through the study of ocean cores and rock sequences exposed on land.[125] Where diatom biozones are well established and calibrated to the geomagnetic polarity time scale (e.g., Southern Ocean, North Pacific, eastern equatorial Pacific), diatom-based age estimates may be resolved to within <100,000 years, although typical age resolution for Cenozoic diatom assemblages is several hundred thousand years.

Diatoms preserved in lake sediments are widely used for paleoenvironmental reconstructions of Quaternary climate, especially for closed-basin lakes which experience fluctuations in water depth and salinity.

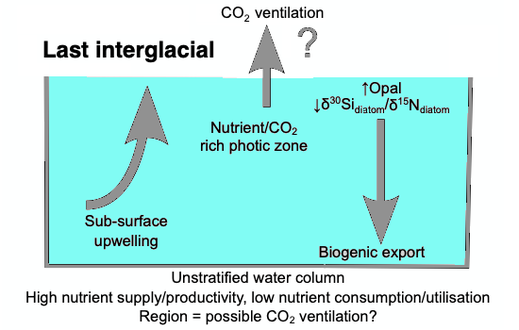

Isotope records

[edit]

When diatoms die their shells (frustules) can settle on the seafloor and become microfossils. Over time, these microfossils become buried as opal deposits in the marine sediment. Paleoclimatology is the study of past climates. Proxy data is used in order to relate elements collected in modern-day sedimentary samples to climatic and oceanic conditions in the past. Paleoclimate proxies refer to preserved or fossilized physical markers which serve as substitutes for direct meteorological or ocean measurements.[126] An example of proxies is the use of diatom isotope records of δ13C, δ18O, δ30Si (δ13Cdiatom, δ18Odiatom, and δ30Sidiatom). In 2015, Swann and Snelling used these isotope records to document historic changes in the photic zone conditions of the north-west Pacific Ocean, including nutrient supply and the efficiency of the soft-tissue biological pump, from the modern day back to marine isotope stage 5e, which coincides with the last interglacial period. Peaks in opal productivity in the marine isotope stage are associated with the breakdown of the regional halocline stratification and increased nutrient supply to the photic zone.[127]

The initial development of the halocline and stratified water column has been attributed to the onset of major Northern Hemisphere glaciation at 2.73 Ma, which increased the flux of freshwater to the region, via increased monsoonal rainfall and/or glacial meltwater, and sea surface temperatures.[128][129][130][131] The decrease of abyssal water upwelling associated with this may have contributed to the establishment of globally cooler conditions and the expansion of glaciers across the Northern Hemisphere from 2.73 Ma.[129] While the halocline appears to have prevailed through the late Pliocene and early Quaternary glacial–interglacial cycles,[132] other studies have shown that the stratification boundary may have broken down in the late Quaternary at glacial terminations and during the early part of interglacials.[133][134][135][136][137][127]

Diversification

[edit]The Cretaceous record of diatoms is limited, but recent studies reveal a progressive diversification of diatom types. The Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, which in the oceans dramatically affected organisms with calcareous skeletons, appears to have had relatively little impact on diatom evolution.[138]

Turnover

[edit]Although no mass extinctions of marine diatoms have been observed during the Cenozoic, times of relatively rapid evolutionary turnover in marine diatom species assemblages occurred near the Paleocene–Eocene boundary,[139] and at the Eocene–Oligocene boundary.[140] Further turnover of assemblages took place at various times between the middle Miocene and late Pliocene,[141] in response to progressive cooling of polar regions and the development of more endemic diatom assemblages.

A global trend toward more delicate diatom frustules has been noted from the Oligocene to the Quaternary.[125] This coincides with an increasingly more vigorous circulation of the ocean's surface and deep waters brought about by increasing latitudinal thermal gradients at the onset of major ice sheet expansion on Antarctica and progressive cooling through the Neogene and Quaternary towards a bipolar glaciated world. This caused diatoms to take in less silica for the formation of their frustules. Increased mixing of the oceans renews silica and other nutrients necessary for diatom growth in surface waters, especially in regions of coastal and oceanic upwelling.

Genetics

[edit]

Expressed sequence tagging

[edit]In 2002, the first insights into the properties of the Phaeodactylum tricornutum gene repertoire were described using 1,000 expressed sequence tags (ESTs).[142] Subsequently, the number of ESTs was extended to 12,000 and the diatom EST database was constructed for functional analyses.[143] These sequences have been used to make a comparative analysis between P. tricornutum and the putative complete proteomes from the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, the red alga Cyanidioschyzon merolae, and the diatom Thalassiosira pseudonana.[144] The diatom EST database now consists of over 200,000 ESTs from P. tricornutum (16 libraries) and T. pseudonana (7 libraries) cells grown in a range of different conditions, many of which correspond to different abiotic stresses.[145]

Genome sequencing

[edit]

In 2004, the entire genome of the centric diatom, Thalassiosira pseudonana (32.4 Mb) was sequenced,[146] followed in 2008 with the sequencing of the pennate diatom, Phaeodactylum tricornutum (27.4 Mb).[147] Comparisons of the two reveal that the P. tricornutum genome includes fewer genes (10,402 opposed to 11,776) than T. pseudonana; no major synteny (gene order) could be detected between the two genomes. T. pseudonana genes show an average of ~1.52 introns per gene as opposed to 0.79 in P. tricornutum, suggesting recent widespread intron gain in the centric diatom.[147][148] Despite relatively recent evolutionary divergence (90 million years), the extent of molecular divergence between centrics and pennates indicates rapid evolutionary rates within the Bacillariophyceae compared to other eukaryotic groups.[147] Comparative genomics also established that a specific class of transposable elements, the Diatom Copia-like retrotransposons (or CoDis), has been significantly amplified in the P. tricornutum genome with respect to T. pseudonana, constituting 5.8 and 1% of the respective genomes.[149]

Endosymbiotic gene transfer

[edit]Diatom Genomics предоставила много информации о степени и динамике процесса переноса эндосимбиотического гена (EGT). Сравнение белков T. pseudonana с гомологами в других организмах показало, что сотни имеют свои самые близкие гомологи в линии Plantae. EGT к геномам диатомовых геномов можно проиллюстрировать тем фактом, что геном T. pseudonana кодирует шесть белков, которые наиболее тесно связаны с генами, кодируемыми Guillardia Theta ( Cryptomonad ) геномом нуклеоморфа . Четыре из этих генов также обнаружены в геномах красных водорослей пластид, демонстрируя, тем самым демонстрируя последовательные EGT от пластида красного водорослевого ядра до красного водоросля (нуклеоморф) до ядра хозяина гетероконта. [ 146 ] Более поздние филогеномные анализы протеомов диатомовых протеомов предоставили доказательства для празинофитного эндосимбионта в общем предке хромальвеолатов , подтверждаемых тем, что 70% генов диатомовых источников происхождения зеленых линий и то, что такие гены также обнаруживаются в геноме. других стрименопилов . Следовательно, было предложено, что хромальвеолаты являются продуктом серийного вторичного эндосимбиоза , сначала с зелеными водорослями , за которыми следуют вторые с красными водорослями , которые сохранили геномные следы предыдущего, но смещали зеленый пластид. [ 150 ] Тем не менее, филогеномный анализ протеомов диатомовых протеомов и эволюционной истории хромальвевелера, вероятно, будет воспользоваться дополнительными геномными данными из недостаточных линий, таких как красные водоросли.

Горизонтальный перенос генов

[ редактировать ]В дополнение к EGT, горизонтальный перенос генов (HGT) может происходить независимо от эндосимбиотического события. Публикация генома P. tricornutum сообщила, что по меньшей мере 587 генов P. tricornutum , по -видимому, наиболее тесно связаны с бактериальными генами, что составляет более 5% протеома P. tricornutum . Около половины из них также встречаются в геноме T. pseudonana , подтверждая их древнее включение в линию диатомовой линии. [ 147 ]

Генетическая инженерия

[ редактировать ]Чтобы понять биологические механизмы, которые лежат в основе большой важности диатомовых средств в геохимических циклах, ученые использовали Phaeodactylum Tricornutum и Thalassiosira Spp. виды как модельные организмы с 90 -х годов. [ 151 ] В настоящее время доступно несколько инструментов молекулярной биологии для генерации мутантов или трансгенных линий: плазмиды, содержащие трансгены, вставляются в клетки с использованием биолистического метода [ 152 ] или конъюгация бактерий трансмиссии [ 153 ] (с 10 −6 и 10 −4 урожай соответственно [ 152 ] [ 153 ] ) и другие классические методы трансфекции, такие как электропорация или использование ПЭГ, дают результаты с более низкой эффективностью. [ 153 ]

Трансфицированные плазмиды могут быть либо случайным образом интегрированы в хромосомы диатома, либо поддерживаются в качестве стабильных круговых эпизодов (благодаря центромерной последовательности CEN6-Arsh4-His3. [ 153 ] ) Ген устойчивости к флеомицину/ зооцинам обычно используется в качестве маркера отбора, [ 151 ] [ 154 ] и различные трансгены были успешно введены и экспрессируются в диатомовых условиях со стабильными передачами через поколения, [ 153 ] [ 154 ] или с возможностью удалить его. [ 154 ]

Кроме того, эти системы в настоящее время позволяют использовать инструмент Crispr-Cas Genome Edition , что приводит к быстрому производству функциональных нокаутированных мутантов [ 154 ] [ 155 ] и более точное понимание клеточных процессов диатомов.

Человеческое использование

[ редактировать ]-

Диатоматическая Земля , состоящая из центрических (радиально симметричных) и типичных (двусторонних симметричных) диатомов, подвешенных в воде.

(Нажмите 3 раза, чтобы полностью увеличить)

Палеонтология

[ редактировать ]Разложение и распад диатомодов приводит к органическому и неорганическому (в форме силикатов ) отложений, неорганический компонент которого может привести к методу анализа прошлых морских средах океанских по этажах или бухте , так как неорганическая вещество вкладывается в Осаждение глин и илтов и образует постоянную геологическую запись таких морских слоев (см. Силисенскую слизную ).

Промышленное

[ редактировать ]Диатомовые средства и их раковины (домочители) в качестве диатомита или диатомовой земли являются важными промышленными ресурсами, используемыми для тонкой полировки и жидкой фильтрации. Сложная структура их микроскопических оболочек была предложена в качестве материала для нанотехнологий. [ 156 ]

Диатомит считается натуральным нано -материалом и имеет много применений и применений, таких как: производство различных керамических продуктов, строительная керамика, рефрактерная керамика, специальная керамика оксида, для производства материалов контроля влажности, используемых в качестве фильтрационного материала, материал в цементе Производственная отрасль, первоначальный материал для производства перевозчиков лекарственных средств с длительным высвобождением, абсорбционный материал в промышленном масштабе, производство пористой керамики, стеклянная промышленность, используется в качестве поддержки катализатора, в качестве наполнитель в пластмассах и красках, очистка промышленных вод, держателя пестицидов, а также для улучшения физических и химических характеристик определенных почв и других видов использования. [ 157 ] [ 158 ] [ 159 ]

Диатомы также используются для определения происхождения их содержащих материалов, включая морскую воду.

Нанотехнология

[ редактировать ]Осаждение кремнезема по диатомовым вопросам также может оказаться полезным для нанотехнологий . [ 160 ] Диатомовые ячейки неоднократно и надежно изготовляют клапаны различных форм и размеров, потенциально позволяя диатомовым процессам производить микро- или наномасштабные структуры, которые могут использоваться в ряде устройств, включая: оптические системы; полупроводниковая нанолитография ; и даже транспортные средства для доставки наркотиков . При подходящей процедуре искусственного отбора диатомовые средства, которые производят клапаны с определенными формами и размерами, могут быть разработаны для выращивания в хемостата культурах массового производства . для наноразмерных компонентов [ 161 ] Также было предложено, чтобы диатомовые средства могли использоваться в качестве компонента солнечных элементов, заменяя фоточувствительный диоксид титана на диоксид кремния, который обычно используют для создания своих клеточных стен. [ 162 ] Также были предложены солнечные батареи, продуцирующие диатомовые биотопливы. [ 163 ]

- Поддержка и регулирование услуг, предоставляемых морскими диатомогами и некоторыми из их негативных воздействий

-

CNN = облачные конденсации ядра , DMS = диметилсульфид , DMSP = диметилсульфониопропионат , VOCS = летучие органические соединения

Пунктирная стрелка: негативное эффект, твердая стрелка: положительные эффекты

Судебно -медицинская экспертиза

[ редактировать ]Основная цель анализа диатомовой криминалистики -дифференцировать смерть от погружения от посмертного погружения тела в воду. Лабораторные испытания могут выявить присутствие диатомовых лиц в организме. Поскольку скелеты на основе кремнезема не легко разлагаются, их иногда можно обнаружить даже в сильно разложенных телах. Поскольку они не встречаются естественным образом в организме, если лабораторные испытания показывают диатомы в трупе, которые имеют тот же вид, что и в воде, где было извлечено тело, то это может быть хорошим доказательством утопления как причины смерти . Смесь видов диатомов, найденных в трупе, может быть одинаковой или отличной от окружающей воды, что указывает, утонула ли жертва в том же месте, в котором было найдено тело. [ 164 ]

История открытия

[ редактировать ]

Первые иллюстрации диатомов обнаружены в статье 1703 года в сделках Королевского общества, показывающие безошибочные рисунки Tabellaria . [ 165 ] Хотя публикация была написана неназванным английским джентльменом, есть недавние доказательства того, что он был Чарльзом Кингом Стаффордшира. [ 165 ] [ 166 ] Спустя всего 80 лет мы находим первую формально идентифицированную Diatom, колониальную Bacillaria paxillifera , обнаруженную и описанную в 1783 году датским натуралистом Отто Фридрихом Мюллером . [ 165 ] Как и многие другие после него, он ошибочно думал, что это животное из -за его способности двигаться. Даже Чарльз Дарвин видел, как Диатом остается в пыли, пока на островах Кейп -Верде, хотя он не был уверен, что они были. Только позже они были идентифицированы для него как кремнистыми полигастриками. Инфузория, которую Дарвин позже отметил на лице, краски Fueguinos, местных жителей Тирра -дель -Фуэго в южной части Южной Америки, были позже идентифицированы таким же образом. В течение своей жизни кремнистые полигастрики были уточнены как принадлежащие Diatomaceae , и Дарвин изо всех сил пытался понять причины, лежащие в основе их красоты. Он обменялся мнениями с известным криптогамическим GHK Thwaites по теме. В четвертом издании «Происхождение видов» он заявил, что « мало объектов красивее, чем минутные кремнистые случаи Diatomaceae: они были созданы, что их можно было исследовать и восхищаться под высокими силами микроскопа »? и рассуждал, что их изысканная морфология должна иметь функциональные основы, а не быть созданным исключительно для того, чтобы люди восхищались. [ 167 ]

Смотрите также

[ редактировать ]- Высоковеченные изопреноидные , длинноцепочечные алкены, продуцируемые небольшим количеством морских диатомов

Примечания

[ редактировать ]- ^ От греческого : Διατομή , романизированный : Diatomé , «прорезание, выходное пособие», [ 7 ] от греческого : Διάτομος , романизированный : диатомос , "вырезан пополам, разделен одинаково" [ 8 ] От греческого : Διατέμνω , романизированный : DiaTémno , «чтобы вырезать в двенах». [ 9 ] [ 10 ] : 718

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ Dangeard, P. (1933). Traite d'algologie. Пол Лечвалье и Филс, Париж, [1] Архивировал 4 октября 2015 года на машине Wayback .

- ^ "Bacillariophyceae" . Черви . Мировой реестр морских видов . 2024 . Получено 9 мая 2024 года .

- ^ Воскресенье, Б.-С. (1822). Ботанические комментарии. Ботанические наблюдения, посвященные Обществу садоводства турниров (PDF ) Турней: гл. Кастерман-бог, Бридж-стрит № 10. стр. таблица, ошибка , [1] -116, [1 , . [i ]

- ^ Рабенхорст, Л. Флора Европейская слой воды и сладкого и подводного лодка (1864-1868). Раздел I. Алгас Диатомацес, состоящий из фигур всего Impressis (1864). стр. 1-359. Нью -Йорк [Лейпциг]: в Эдуарде Куммеруме.

- ^ Haeckel, E. (1878). DAS Protistenreich Archived 10 ноября 2014 года на The Wayback Machine .

- ^ Engler, A. & Gilg, E. (1919). Программа семейств растений: обзор всей системы растений с особым рассмотрением медицинских и полезных растений, в дополнение к обзору цветочных и цветочных районов Земли для использования на лекциях и исследованиях по специальной и медицинской фармацевтической ботанике , 8 -е изд.

- ^ Διατομή . Лидделл, Генри Джордж ; Скотт, Роберт ; Грек -английский лексикон в проекте Персея

- ^ Διάτομος . Лидделл, Генри Джордж ; Скотт, Роберт ; Грек -английский лексикон в проекте Персея

- ^ Διατέμνω . Лидделл, Генри Джордж ; Скотт, Роберт ; Грек -английский лексикон в проекте Персея

- ^ Компактный Оксфордский английский словарь . Кларендон Пресс. 1971. ISBN 0918414083 .

- ^ «Воздух, который ты дышишь? Диатом сделал это» . Живая наука . 11 июня 2014 года. Архивировано с оригинала 30 апреля 2018 года . Получено 30 апреля 2018 года .

- ^ "Что такое диатомовые?" Полем Диатомоты Северной Америки. Архивировано из оригинала 25 января 2020 года . Получено 28 января 2020 года .

- ^ Treguer, P.; Нельсон, DM; Ван Беннеком, AJ; Демастер, диджей; Leynaert, A.; Queguiner, B. (1995). «Баланс кремнезема в мировом океане: рецензия». Наука . 268 (5209): 375–9. Bibcode : 1995sci ... 268..375t . doi : 10.1126/science.268.5209.375 . PMID 17746543 . S2CID 5672525 .

- ^ «Королевский колледж Лондон - Лейк Мегачад» . www.kcl.ac.uk. Архивировано с оригинала 27 ноября 2018 года . Получено 5 мая 2018 года .

- ^ Бристоу, CS; Хадсон-Эдвардс, Ка ; Чаппелл А. (2010). «Оборудование Амазонки и экваториальной Атлантики с западноафриканской пылью». Геофий. Резерв Летал 37 (14): L14807. Bibcode : 2010georl..3714807b . doi : 10.1029/2010gl043486 . S2CID 128466273 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон HASLE, Grete R.; Syvertsen, Erik E.; Steidinger, Karen A.; Танген, Карл (25 января 1996 г.). «Морские диатомовые» . В Томасе, Кармело Р. (ред.). Идентификация морских диатомовых и динофлагеллятов . Академическая пресса. С. 5–385. ISBN 978-0-08-053441-1 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 3 января 2014 года . Получено 13 ноября 2013 года .

- ^ «Газовые гззлеры» . Архивировано из оригинала 22 мая 2018 года . Получено 22 мая 2018 года .

- ^ «Больше на диатомовых условиях» . Калифорнийский музей палеонтологии . Архивировано с оригинала 4 октября 2012 года . Получено 20 мая 2015 года .

- ^ Van The Hoek, C.; Человек, DG; Jahns, HM (1995). Водоросли: и введение в Phyclooly . Кембридж: издательство Кембриджского университета . стр. 165-218. ISBN 978-0-521-31687-3 .

- ^ Накаяма, Т.; Камикава, Р.; Tanifuji, G.; Kashiyama, Y.; Ohkouchi, N.; Арчибальд, JM; Инагаки, Ю. (2014). «Полный геном нефотосинтетического цианобактериума в диатоме выявляет недавние адаптации к внутриклеточному образу жизни» . Труды Национальной академии наук Соединенных Штатов Америки . 111 (31): 11407–11412. BIBCODE : 2014PNAS..11111407N . doi : 10.1073/pnas.1405222111 . PMC 4128115 . PMID 25049384 .

- ^ Пьелла Карлусич, Хуан Хосе; Пеллетье, Эрик; Ломбард, Фабен; Carsique, Madeline; Дворак, Этьен; Колин, Себастьен; Пичерал, Марк; Корнехо-Кастильо, Франциско М.; Акинас, Сильвия Г.; Пепперкок, Рейнер; Карсанти, Эрик (6 июля 2021 года). «Глобальные модели распределения морских азотных фиксеров с помощью визуализации и молекулярных методов» . Природная связь . 12 (1): 4160. Bibcode : 2021Natco..12.4160p . Doi : 10.1038/s41467-021-24299-y . ISSN 2041-1723 . PMC 8260585 . PMID 34230473 .

- ^ Функциональная связь между динофлагеллятным хозяином и его диатомовым эндосимбионтом | Молекулярная биология и эволюция | Оксфордский академический

- ^ Wehr, JD; Оболочка, RG; Kociolek, JP, eds. (2015). Пресноводные водоросли Северной Америки: экология и классификация (2 -е изд.). Сан -Диего: академическая пресса. ISBN 978-0-12-385876-4 .

- ^ Жирар, Винсент; Святой Мартин, Симона; Buffetout, Eric; Святой Мартин, Жан-Поль; Néraudeau, Didier; Пейро, Даниэль; Костры, Гвидо; Ребята, Евгенио; Suteethorn, Varavudh (2020). "Тайский янтарь: понимание истории ранней диатомы?" Полем BSGF - Бюллетень Земли . 191 : 23. doi : 10.1051/bsgf/2020028 . ISSN 1777-5817 .

- ^ Внутреннее пространство Субарктического Тихого океана Архивировано 27 октября 2020 года в машине Wayback Nasa Earth Expeditions , 4 сентября 2018 года.

Эта статья включает текст из этого источника, который находится в общественном доступе .

Эта статья включает текст из этого источника, который находится в общественном доступе .

- ^ Rousseaux, Cecile s.; Грегг, Уотсон В. (2015). «Недавние декадальные тенденции в глобальном композиции фитопланктона» . Глобальные биогеохимические циклы . 29 (10): 1674–1688. Bibcode : 2015gbioc..29.1674R . doi : 10.1002/2015GB005139 .

- ^ Colin, S., Coelho, LP, Sunagawa, S., Bowler, C., Karsenti, E., Bork, P., Pepperkok, R. and de Vargas, C. (2017) "Количественное 3D-изображение для клетки Биология и экология экологических микробных эукариот ». Elife , 6 : E26066. два : 10.7554/elife.26066.002 .

Материал был скопирован из этого источника, который доступен в рамках Attribution Creative Commons 4.0 Международная лицензия, архивная 16 октября 2017 года на машине Wayback .

Материал был скопирован из этого источника, который доступен в рамках Attribution Creative Commons 4.0 Международная лицензия, архивная 16 октября 2017 года на машине Wayback .

- ^ Нельсон, Дэвид М.; Трегер, Пол; Brzezinski, Mark A.; Лейнаерт, Ауде; Quéguiner, Bernard (1995). «Производство и растворение биогенного кремнезема в океане: пересмотренные глобальные оценки, сравнение с региональными данными и связь с биогенным седиментацией». Глобальные биогеохимические циклы . 9 (3). Американский геофизический союз (AGU): 359–372. Bibcode : 1995gbioc ... 9..359n . doi : 10.1029/95GB01070 . ISSN 0886-6236 .

- ^ Манн, Дэвид Г. (1999). «Концепция вида в диатомовых заболеваниях». Phycologia . 38 (6). Informa UK Limited: 437–495. Bibcode : 1999phyco..38..437m . doi : 10.2216/i0031-8884-38-6-437.1 . ISSN 0031-8884 .

- ^ Simonsen, R., (1979). «Система диатома: идеи о филогении», Bacillaria , 2 : 9–71.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Мур, Эрик Р.; Буллингтон, Бриана С.; Вайсберг, Александра Дж.; Цзян, Юань; Чанг, Джефф; Хэлси, Кимберли Х. (7 июля 2017 г.). «Морфологические и транскриптомные доказательства индукции аммония сексуального размножения в талассиозире псевдонана и других центричных диатомовых заболеваний» . Plos один . 12 (7). Публичная библиотека науки (PLOS): E0181098. BIBCODE : 2017PLOSO..1281098M . doi : 10.1371/journal.pone.0181098 . ISSN 1932-6203 . PMC 5501676 . PMID 28686696 .

Модифицированный материал был скопирован из этого источника, который доступен по международной лицензии Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 .

Модифицированный материал был скопирован из этого источника, который доступен по международной лицензии Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 .

- ^ (2002 . ) Университетский колледж Лондон

- ^ Паркер, Эндрю Р.; Таунли, Хелен Э. (2007). «Биомиметика фотонных наноструктур». Природная нанотехнология . 2 (6): 347–53. Bibcode : 2007natna ... 2..347p . doi : 10.1038/nnano.2007.152 . PMID 18654305 .

- ^ Гордон, Ричард; Лосик, Дусан; Тиффани, Мэри Энн; Надь, Стивен С.; Стерренбург, Фритжоф А.С. (2009). «Стеклянный зверинец: диатомовые средства для новых применений в нанотехнологиях». Тенденции в биотехнологии . 27 (2): 116–27. doi : 10.1016/j.tibtech.2008.11.003 . PMID 19167770 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Рита А. Хорнер (2002). Таксономическое руководство по некоторому общему морскому фитопланктону . Биопресс. С. 25–30. ISBN 978-0-948737-65-7 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 1 августа 2020 года . Получено 13 ноября 2013 года .

- ^ «Стекло в природе» . Музей стекла Корнинг. Архивировано из оригинала 7 марта 2013 года . Получено 19 февраля 2013 года .

- ^ Taylor, JC, Harding, WR и Archibald, C. (2007). Иллюстрированное руководство по некоторым общим видам диатомовых видов из Южной Африки . Гезина: Комиссия по исследованию воды. ISBN 97817770054844 .

- ^ Мишра, М., Аруха, А.П., Башир Т., Ядав Д. и Прасад, Гбкс (2017) «Все новые лица диатомов: потенциальный источник наноматериалов и за его пределами». Границы в микробиологии , 8 : 1239. Два : 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01239 .

Материал был скопирован из этого источника, который доступен в рамках Attribution Creative Commons 4.0 Международная лицензия, архивная 16 октября 2017 года на машине Wayback .

Материал был скопирован из этого источника, который доступен в рамках Attribution Creative Commons 4.0 Международная лицензия, архивная 16 октября 2017 года на машине Wayback .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Чжан, Д.; Wang, y.; Cai, J.; Пан, Дж.; Цзян, х.; Цзян, Ю. (2012). «Технология биопроизводства на основе диатомовой микро- и наноструктуры» . Китайский научный бюллетень . 57 (30): 3836–3849. Bibcode : 2012Chsbu..57.3836z . doi : 10.1007/s11434-012-5410-x .

- ^ «Диатомовые» . Архивировано с оригинала 2 февраля 2016 года . Получено 13 февраля 2016 года .

- ^ Молекулярная жизнь диатомовых

- ^ Килиас, Эстель С.; Юнгс, Леандро; Шпраха, Лука; Леонард, парень; Metfies, Katja; Ричардс, Томас А. (2020). «Распределение грибов и совместное распространение грибов с диатомогами коррелирует с таянием морского льда в арктическом океане» . Биология связи . 3 (1): 183. doi : 10.1038/s42003-020-0891-7 . PMC 7174370 . PMID 32317738 . S2CID 216033140 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Thamatrakoln, K.; Алверсон, AJ; Хильдебранд М. (2006). «Сравнительные анализы последовательности транспортеров диатомовых кремния: к механистической модели транспорта кремния». Журнал Phycology . 42 (4): 822–834. Bibcode : 2006jpcgy..42..822t . doi : 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2006.00233.x . S2CID 86674657 .

- ^ Kröger, Nils; Дойцманн, Рейнер; Манфред, Сампер (ноябрь 1999 г.). «Поликационные пептиды из диатомовой биосилики, которые направляют образование наносферы кремнезема». Наука . 286 (5442): 1129–1132. doi : 10.1126/science.286.5442.1129 . PMID 10550045 . S2CID 10925689 . [ Постоянная мертвая ссылка ]

- ^ Kroger, Nils (2007). Справочник по биоминерализации: биологические аспекты и образование структуры . Вайнхайм, Германия: Wiley-VCH Verlag Gmbh. с. Глава 3.

- ^ Аноним (1702). «Два письма от джентльмена в стране, касающиеся письма г -на Левенхука в сделке, № 283.», Филос. Транс. R. Soc. Лонд B , 23 : 1494–1501.

- ^ Rogall, E. (1939). « О тонкой конструкции кремнезема мембраны диатомов» , Planta : 279-291.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Хильдебранд, Марк; Лерч, Сара Дж.Л.; Шрестха, Рошан П. (11 апреля 2018 г.). «Понимание силицификации клеточной стенки диатомовой стенки - продвижение вперед» . Границы в морской науке . 5 Frontiers Media SA. doi : 10.3389/fmars.2018.00125 . ISSN 2296-7745 .

Модифицированный материал был скопирован из этого источника, который доступен по международной лицензии Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 .

Модифицированный материал был скопирован из этого источника, который доступен по международной лицензии Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 .

- ^ Хильдебранд, Марк; Вулкани, Бенджамин Э.; Гассманн, Уолтер; Шредер, Джулиан И. (1997). «Семейство генов кремниевых переносчиков». Природа . 385 (6618). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 688–689. Bibcode : 1997natur.385..688h . doi : 10.1038/385688b0 . ISSN 0028-0836 . PMID 9034185 . S2CID 4266966 .

- ^ Kröger, Nils; Дойцманн, Рейнер; Сампер, Манфред (5 ноября 1999 г.). «Поликационные пептиды из диатомовой биосилики, которые направляют образование наносферы кремнезема». Наука . 286 (5442). Американская ассоциация по развитию науки (AAAS): 1129–1132. doi : 10.1126/science.286.5442.1129 . ISSN 0036-8075 . PMID 10550045 .

- ^ Kröger, Nils; Дойцманн, Рейнер; Бергсдорф, Кристиан; Сампер, Манфред (5 декабря 2000 г.). «Виды-специфические полиамины из диатомовых контрольных морфологии кремнезема» . Труды Национальной академии наук . 97 (26): 14133–14138. Bibcode : 2000pnas ... 9714133K . doi : 10.1073/pnas.260496497 . ISSN 0027-8424 . PMC 18883 . PMID 11106386 .

- ^ Тессон, Бенуа; Хильдебранд, Марк (10 декабря 2010 г.). «Обширная и интимная ассоциация цитоскелета с образованием кремнезема в диатомовых условиях: контроль над паттерном на мезо- и микромасштабах» . Plos один . 5 (12). Публичная библиотека науки (PLOS): E14300. BIBCODE : 2010PLOSO ... 514300T . doi : 10.1371/journal.pone.0014300 . ISSN 1932-6203 . PMC 3000822 . PMID 21200414 .

- ^ Тессон, Бенуа; Хильдебранд, Марк (23 апреля 2013 г.). «Характеристика и локализация нерастворимых органических матриц, связанных с диатомовыми клеточными стенками: понимание их ролей во время образования клеточной стенки» . Plos один . 8 (4). Публичная библиотека науки (PLOS): E61675. BIBCODE : 2013PLOSO ... 861675T . doi : 10.1371/journal.pone.0061675 . ISSN 1932-6203 . PMC 3633991 . PMID 23626714 .

- ^ Шеффель, Андре; Поулсен, Николь; Шиан, Самуил; Крёгер, Нильс (7 февраля 2011 г.). «Нанопатер -белковые микророры от диатомовой, которая направляет морфогенез кремнезема» . Труды Национальной академии наук . 108 (8): 3175–3180. doi : 10.1073/pnas.1012842108 . ISSN 0027-8424 . PMC 3044418 . PMID 21300899 .

- ^ Коцш, Александр; Грёгер, Филипп; Паволски, Дамиан; Боманс, Пол Х.Х.; Sommerdijk, Nico Ajm; Шлиерф, Майкл; Kröger, Nils (24 июля 2017 г.). «Силиканин-1-это консервативный белок диатомовой мембраны, участвующий в биоминерализации кремнезема» . BMC Biology . 15 (1). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 65. DOI : 10.1186/S12915-017-0400-8 . ISSN 1741-7007 . PMC 5525289 . PMID 28738898 .

- ^ Тессон, Бенуа; Лерч, Сара Дж.Л.; Хильдебранд, Марк (18 октября 2017 года). «Характеристика нового семейства белков, связанного с мембраной пузырьков кремнезема, обеспечивает генетические манипуляции с диатомовым кремнеземом» . Научные отчеты . 7 (1). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 13457. Bibcode : 2017natsr ... 713457t . doi : 10.1038/s41598-017-13613-8 . ISSN 2045-2322 . PMC 5647440 . PMID 29044150 .

- ^ Падисак, Джудит; Soróczki-Pintér, Eva; Резнер, Zsuzsanna (2003), Martens, Koen (ed.), «Тонирующие свойства некоторых фитопланктонских форм и связь формы устойчивости к морфологическому разнообразию планктона - экспериментальное исследование» (PDF) , водное биодисность: праздничный объем в честь. Анри Дж. Дюмон , разработки в области гидробиологии, Springer Netherlands, pp. 243–257, doi : 10.1007/978-94-007-1084-9_18 , ISBN 9789400710849 , архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 23 июля 2018 года , получено 4 октября 2019 года

- ^ Андерсон, Ларс WJ; Суини, Беатрис М. (1 мая 1977 г.). «Диэль изменений в характеристиках седиментации Ditylum Brightwelli: изменения клеточных липидов и эффекты ингибиторов дыхания и модификаторов ионного транспорта1» . Лимнология и океанография . 22 (3): 539–552. Bibcode : 1977 Limoc..22..539a . doi : 10.4319/lo.1977.22.3.0539 . ISSN 1939-5590 .

- ^ Поулсен, Николь С.; Спектор, Илан; Сперк, Тимоти П.; Шульц, Томас Ф.; Wetherbee, Richard (1 сентября 1999 г.). «Diatom Glinding является результатом системы подвижности актин-миозина». Клеточная подвижность и цитоскелет . 44 (1): 23–33. doi : 10.1002/(SICI) 1097-0169 (199909) 44: 1 <23 :: AID-CM2> 3.0.CO; 2-D . ISSN 1097-0169 . PMID 10470016 .

- ^ Манн, Дэвид Г. (февраль 2010 г.). «Рафидные диатомовые» . Веб -проект «Дерево жизни» . Архивировано с оригинала 27 сентября 2019 года . Получено 27 сентября 2019 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Г. Дребс (1 января 1977 г.). «Глава 9: Сексуальность» . В Дитрих Вернер (ред.). Биология диатомовых заболеваний . Ботанические монографии. Тол. 13. Университет Калифорнийского университета. С. 250–283. ISBN 978-0-520-03400-6 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 1 августа 2020 года . Получено 14 ноября 2013 года .

- ^ Lewis, Wm, Jr. (1984). «Половые часы Diatom и его эволюционное значение». Американский натуралист , 123 (1): 73–80

- ^ Chepurnov VA, Mann DG, Sabbe K, Vyverman W. (2004). «Экспериментальные исследования по сексуальному размножению в диатомовых условиях». В Чон К.В., изд. Обзор клеточной биологии . Международный обзор цитологии 237 : 91–154. Лондон

- ^ Дребс (1977) "Сексуальность". В: Werner D, ed. Биология диатомов , ботанические монографии 13 250–283. Оксфорд: Blackwell Scientific Publications.

- ^ «Сокращение размера, репродуктивная стратегия и жизненный цикл центрикального диатомора». Философские транзакции Королевского общества Лондона. Серия B: Биологические науки . 336 (1277). Королевское общество: 191–213. 29 мая 1992 г. DOI : 10.1098/rstb.1992.0056 . ISSN 0962-8436 . S2CID 86332060 .

- ^ Кестер, Джули А.; Brawley, Susan H.; Карп-Босс, Ли; Манн, Дэвид Г. (2007). «Сексуальное воспроизведение в морском центре Diatom Ditylum Brightwellii (Bacillariophyta)» . Европейский журнал Phycology . 42 (4). Informa UK Limited: 351–366. Bibcode : 2007ejphy..42..351k . doi : 10.1080/09670260701562100 . ISSN 0967-0262 . S2CID 80737380 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Mouget JL, Gastineau R, Davidovich O, Gaudin P, Davidovich NA. Свет является ключевым фактором, вызванным сексуальным размножением в Pennate Diatom Haslea Ostrearia. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2009 август; 69 (2): 194-201. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2009.00700.x. Epub 2009 мая. PMID 19486155

- ^ SCCALCO E, STEC K, IUDCONE D, Ferrant MI, Montresor M. Динамика сексуального переворачивания в морской диатоме Pseudo-Nitzschia multistiatta (Bacillaryphyceae). J Phycol. 2014 октябрь; 50 (5): 817-2 Doi: 10.1111/jpy.1 Epub 2014 14 сентября. PMID 26988637