История искусственного интеллекта

| Часть серии о |

| Искусственный интеллект |

|---|

| История вычислений |

|---|

|

| Hardware |

| Software |

| Computer science |

| Modern concepts |

| By country |

| Timeline of computing |

| Glossary of computer science |

История искусственного интеллекта ( ИИ ) началась в древности с мифов, историй и слухов об искусственных существах, наделенных интеллектом или сознанием мастерами-ремесленниками. Семена современного ИИ были посажены философами, которые пытались описать процесс человеческого мышления как механическое манипулирование символами. Кульминацией этой работы стало изобретение в 1940-х годах программируемого цифрового компьютера — машины, основанной на абстрактной сущности математических рассуждений. Это устройство и лежащие в его основе идеи вдохновили горстку учёных начать серьёзно обсуждать возможность создания электронного мозга .

Область исследований искусственного интеллекта была основана на семинаре, проходившем в кампусе Дартмутского колледжа , США, летом 1956 года. [1] Те, кто присутствовал, на десятилетия стали лидерами исследований в области искусственного интеллекта. Многие из них предсказывали, что машина, столь же умная, как человек, появится не более чем через одно поколение, и им дали миллионы долларов, чтобы воплотить это видение в жизнь. [2]

Eventually, it became obvious that researchers had grossly underestimated the difficulty of the project.[3] In 1974, in response to the criticism from James Lighthill and ongoing pressure from congress, the U.S. and British Governments stopped funding undirected research into artificial intelligence, and the difficult years that followed would later be known as an "AI winter". Seven years later, a visionary initiative by the Japanese Government inspired governments and industry to provide AI with billions of dollars, but by the late 1980s the investors became disillusioned and withdrew funding again.

Investment and interest in AI boomed in the 2020s when machine learning was successfully applied to many problems in academia and industry due to new methods, the application of powerful computer hardware, and the collection of immense data sets.

Precursors[edit]

Mythical, fictional, and speculative precursors[edit]

Myth and legend[edit]

In Greek mythology, Talos was a giant constructed of bronze who acted as guardian for the island of Crete. He would throw boulders at the ships of invaders and would complete 3 circuits around the island's perimeter daily.[4] According to pseudo-Apollodorus' Bibliotheke, Hephaestus forged Talos with the aid of a cyclops and presented the automaton as a gift to Minos.[5] In the Argonautica, Jason and the Argonauts defeated him by way of a single plug near his foot which, once removed, allowed the vital ichor to flow out from his body and left him inanimate.[6]

Pygmalion was a legendary king and sculptor of Greek mythology, famously represented in Ovid's Metamorphoses. In the 10th book of Ovid's narrative poem, Pygmalion becomes disgusted with women when he witnesses the way in which the Propoetides prostitute themselves.[7] Despite this, he makes offerings at the temple of Venus asking the goddess to bring to him a woman just like a statue he carved.

Medieval legends of artificial beings[edit]

In Of the Nature of Things, written by the Swiss alchemist, Paracelsus, he describes a procedure that he claims can fabricate an "artificial man". By placing the "sperm of a man" in horse dung, and feeding it the "Arcanum of Mans blood" after 40 days, the concoction will become a living infant.[8]

The earliest written account regarding golem-making is found in the writings of Eleazar ben Judah of Worms in the early 13th century.[9][10] During the Middle Ages, it was believed that the animation of a Golem could be achieved by insertion of a piece of paper with any of God’s names on it, into the mouth of the clay figure.[11] Unlike legendary automata like Brazen Heads,[12] a Golem was unable to speak.[13]

Takwin, the artificial creation of life, was a frequent topic of Ismaili alchemical manuscripts, especially those attributed to Jabir ibn Hayyan. Islamic alchemists attempted to create a broad range of life through their work, ranging from plants to animals.[14]

In Faust: The Second Part of the Tragedy by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, an alchemically fabricated homunculus, destined to live forever in the flask in which he was made, endeavors to be born into a full human body. Upon the initiation of this transformation, however, the flask shatters and the homunculus dies.[15]

Modern fiction[edit]

By the 19th century, ideas about artificial men and thinking machines were developed in fiction, as in Mary Shelley's Frankenstein or Karel Čapek's R.U.R. (Rossum's Universal Robots),[16]and speculation, such as Samuel Butler's "Darwin among the Machines",[17] and in real-world instances, including Edgar Allan Poe's "Maelzel's Chess Player".[18] AI is a common topic in science fiction through the present.[19]

Automata[edit]

Realistic humanoid automata were built by craftsman from many civilizations, including Yan Shi,[20] Hero of Alexandria,[21] Al-Jazari,[22]Pierre Jaquet-Droz, and Wolfgang von Kempelen.[23][24]

The oldest known automata were the sacred statues of ancient Egypt and Greece.[25] The faithful believed that craftsman had imbued these figures with very real minds, capable of wisdom and emotion—Hermes Trismegistus wrote that "by discovering the true nature of the gods, man has been able to reproduce it".[26][27]English scholar Alexander Neckham asserted that the Ancient Roman poet Virgil had built a palace with automaton statues.[28]

During the early modern period, these legendary automata were said to possess the magical ability to answer questions put to them. The late medieval alchemist and proto-protestant Roger Bacon was purported to have fabricated a brazen head, having developed a legend of having been a wizard.[29][30] These legends were similar to the Norse myth of the Head of Mímir. According to legend, Mímir was known for his intellect and wisdom, and was beheaded in the Æsir-Vanir War. Odin is said to have "embalmed" the head with herbs and spoke incantations over it such that Mímir’s head remained able to speak wisdom to Odin. Odin then kept the head near him for counsel.[31]

Formal reasoning[edit]

Artificial intelligence is based on the assumption that the process of human thought can be mechanized. The study of mechanical—or "formal"—reasoning has a long history. Chinese, Indian and Greek philosophers all developed structured methods of formal deduction by the first millennium BCE. Their ideas were developed over the centuries by philosophers such as Aristotle (who gave a formal analysis of the syllogism), Euclid (whose Elements was a model of formal reasoning), al-Khwārizmī (who developed algebra and gave his name to "algorithm") and European scholastic philosophers such as William of Ockham and Duns Scotus.[32]

Spanish philosopher Ramon Llull (1232–1315) developed several logical machines devoted to the production of knowledge by logical means;[33] Llull described his machines as mechanical entities that could combine basic and undeniable truths by simple logical operations, produced by the machine by mechanical meanings, in such ways as to produce all the possible knowledge.[34] Llull's work had a great influence on Gottfried Leibniz, who redeveloped his ideas.[35]

In the 17th century, Leibniz, Thomas Hobbes and René Descartes explored the possibility that all rational thought could be made as systematic as algebra or geometry.[36] Hobbes famously wrote in Leviathan: "reason is nothing but reckoning".[37] Leibniz envisioned a universal language of reasoning, the characteristica universalis, which would reduce argumentation to calculation so that "there would be no more need of disputation between two philosophers than between two accountants. For it would suffice to take their pencils in hand, down to their slates, and to say each other (with a friend as witness, if they liked): Let us calculate."[38] These philosophers had begun to articulate the physical symbol system hypothesis that would become the guiding faith of AI research.

In the 20th century, the study of mathematical logic provided the essential breakthrough that made artificial intelligence seem plausible. The foundations had been set by such works as Boole's The Laws of Thought and Frege's Begriffsschrift. Building on Frege's system, Russell and Whitehead presented a formal treatment of the foundations of mathematics in their masterpiece, the Principia Mathematica in 1913. Inspired by Russell's success, David Hilbert challenged mathematicians of the 1920s and 30s to answer this fundamental question: "can all of mathematical reasoning be formalized?"[32] His question was answered by Gödel's incompleteness proof, Turing's machine and Church's Lambda calculus.[32][39]

Their answer was surprising in two ways. First, they proved that there were, in fact, limits to what mathematical logic could accomplish. But second (and more important for AI) their work suggested that, within these limits, any form of mathematical reasoning could be mechanized. The Church-Turing thesis implied that a mechanical device, shuffling symbols as simple as 0 and 1, could imitate any conceivable process of mathematical deduction. The key insight was the Turing machine—a simple theoretical construct that captured the essence of abstract symbol manipulation.[41] This invention would inspire a handful of scientists to begin discussing the possibility of thinking machines.[32][42]

Computer science[edit]

Calculating machines were designed or built in antiquity and throughout history by many people, including Gottfried Leibniz,[43]Joseph Marie Jacquard,[44]Charles Babbage,[45]Percy Ludgate,[46]Leonardo Torres Quevedo,[47]Vannevar Bush,[48]and others. Ada Lovelace speculated that Babbage's machine was "a thinking or ... reasoning machine", but warned "It is desirable to guard against the possibility of exaggerated ideas that arise as to the powers" of the machine.[49][50]

The first modern computers were the massive machines of the Second World War (such as Konrad Zuse's Z3, Alan Turing's Heath Robinson and Colossus, Atanasoff and Berry's and ABC and ENIAC at the University of Pennsylvania).[51] ENIAC was based on the theoretical foundation laid by Alan Turing and developed by John von Neumann,[52] and proved to be the most influential.[51]

Birth of artificial intelligence (1941-56)[edit]

The earliest research into thinking machines was inspired by a confluence of ideas that became prevalent in the late 1930s, 1940s, and early 1950s. Recent research in neurology had shown that the brain was an electrical network of neurons that fired in all-or-nothing pulses. Norbert Wiener's cybernetics described control and stability in electrical networks. Claude Shannon's information theory described digital signals (i.e., all-or-nothing signals). Alan Turing's theory of computation showed that any form of computation could be described digitally. The close relationship between these ideas suggested that it might be possible to construct an "electronic brain".

In the 1940s and 50s, a handful of scientists from a variety of fields (mathematics, psychology, engineering, economics and political science) explored several research directions that would be vital to later AI research.[53] Alan Turing, who developed the theory of computation, was among the first people to seriously investigate the theoretical possibility of "machine intelligence".[54] The field of "artificial intelligence research" was founded as an academic discipline in 1956.[55]

Turing Test[edit]

Alan Turing was thinking about machine intelligence at least as early as 1941, when he circulated a paper on machine intelligence which could be the earliest paper in the field of AI - though it is now lost.[54] In 1950 Turing published a landmark paper "Computing Machinery and Intelligence", in which he speculated about the possibility of creating machines that think and the paper introduced his concept of what is now known as the Turing test to the general public.[56] He noted that "thinking" is difficult to define and devised his famous Turing Test.[57] If a machine could carry on a conversation (over a teleprinter) that was indistinguishable from a conversation with a human being, then it was reasonable to say that the machine was "thinking". This simplified version of the problem allowed Turing to argue convincingly that a "thinking machine" was at least plausible and the paper answered all the most common objections to the proposition.[58] The Turing Test was the first serious proposal in the philosophy of artificial intelligence. Then followed three radio broadcasts on AI by Turing, the lectures: 'Intelligent Machinery, A Heretical Theory', 'Can Digital Computers Think?' and the panel discussion 'Can Automatic Calculating Machines be Said to Think'.

Artificial neural networks[edit]

Walter Pitts and Warren McCulloch analyzed networks of idealized artificial neurons and showed how they might perform simple logical functions in 1943.[59][60] They were the first to describe what later researchers would call a neural network.[61] The paper was influenced by Turing's earlier paper 'On Computable Numbers' from 1936 using similar two-state boolean 'neurons', but was the first to apply it to neuronal function.[54] One of the students inspired by Pitts and McCulloch was a young Marvin Minsky, then a 24-year-old graduate student. In 1951 (with Dean Edmonds) he built the first neural net machine, the SNARC.[62] (Minsky was to become one of the most important leaders and innovators in AI.).

Cybernetic robots[edit]

Experimental robots such as W. Grey Walter's turtles and the Johns Hopkins Beast, were built in the 1950s. These machines did not use computers, digital electronics or symbolic reasoning; they were controlled entirely by analog circuitry.[63]

Game AI[edit]

In 1951, using the Ferranti Mark 1 machine of the University of Manchester, Christopher Strachey wrote a checkers program and Dietrich Prinz wrote one for chess.[64] Arthur Samuel's checkers program, the subject of his 1959 paper "Some Studies in Machine Learning Using the Game of Checkers", eventually achieved sufficient skill to challenge a respectable amateur.[65] Game AI would continue to be used as a measure of progress in AI throughout its history.

Symbolic reasoning and the Logic Theorist[edit]

When access to digital computers became possible in the middle fifties, a few scientists instinctively recognized that a machine that could manipulate numbers could also manipulate symbols and that the manipulation of symbols could well be the essence of human thought. This was a new approach to creating thinking machines.[66]

In 1955, Allen Newell and (future Nobel Laureate) Herbert A. Simon created the "Logic Theorist" (with help from J. C. Shaw). The program would eventually prove 38 of the first 52 theorems in Russell and Whitehead's Principia Mathematica, and find new and more elegant proofs for some.[67]Simon said that they had "solved the venerable mind/body problem, explaining how a system composed of matter can have the properties of mind."[68](This was an early statement of the philosophical position John Searle would later call "Strong AI": that machines can contain minds just as human bodies do.)[69]The symbolic reasoning paradigm they introduced would dominate AI research and funding until the middle 90s, as well as inspire the cognitive revolution.

Dartmouth Workshop[edit]

The Dartmouth workshop of 1956 was a pivotal event that marked the formal inception of AI as an academic discipline.[70]It was organized by Marvin Minsky, John McCarthy and two senior scientists: Claude Shannon and Nathan Rochester of IBM. The primary objective of this workshop was to delve into the possibilities of creating machines capable of simulating human intelligence, marking the commencement of a focused exploration into the realm of AI;[71] the proposal for the conference stated they intended to test the assertion that "every aspect of learning or any other feature of intelligence can be so precisely described that a machine can be made to simulate it".[72]

The term "Artificial Intelligence" itself was officially introduced by John McCarthy at the workshop.[73] (The term "Artificial Intelligence" was chosen by McCarthy to avoid associations with cybernetics and the influence of Norbert Wiener.)[74]

The participants included Ray Solomonoff, Oliver Selfridge, Trenchard More, Arthur Samuel, Allen Newell and Herbert A. Simon, all of whom would create important programs during the first decades of AI research.[75]At the workshop Newell and Simon debuted the "Logic Theorist".[76]

The 1956 Dartmouth workshop was the moment that AI gained its name, its mission, its first major success and its key players, and is widely considered the birth of AI.[77]

Cognitive revolution[edit]

In the fall of 1956, Newell and Simon also presented the Logic Theorist at a meeting of the Special Interest Group in Information Theory at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. At the same meeting, Noam Chomsky discussed his generative grammar, and George Miller described his landmark paper "The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two". Miller wrote "I left the symposium with a conviction, more intuitive than rational, that experimental psychology, theoretical linguistics, and the computer simulation of cognitive processes were all pieces from a larger whole."[78]

This meeting was the beginning of the "cognitive revolution"—an interdisciplinary paradigm shift in psychology, philosophy, computer science and neuroscience. It inspired the creation of the sub-fields of symbolic artificial intelligence, generative linguistics, cognitive science, cognitive psychology, cognitive neuroscience and the philosophical schools of computationalism and functionalism. All these fields used related tools to model the mind and results discovered in one field were relevant to the others.

The cognitive approach allowed researchers to consider "mental objects" like thoughts, plans, goals, facts or memories, often analyzed using high level symbols in functional networks. These objects had been forbidden as "unobservable" by earlier paradigms such as behaviorism. Symbolic mental objects would become the major focus of AI research and funding for the next several decades.

Early successes (1956-1974)[edit]

The programs developed in the years after the Dartmouth Workshop were, to most people, simply "astonishing":[79] computers were solving algebra word problems, proving theorems in geometry and learning to speak English. Few at the time would have believed that such "intelligent" behavior by machines was possible at all.[80] Researchers expressed an intense optimism in private and in print, predicting that a fully intelligent machine would be built in less than 20 years.[81] Government agencies like DARPA poured money into the new field.[82] Artificial Intelligence laboratories were set up at a number of British and US Universities in the latter 1950s and early 1960s.[54]

Approaches[edit]

There were many successful programs and new directions in the late 50s and 1960s. Among the most influential were these:

Reasoning as search[edit]

Many early AI programs used the same basic algorithm. To achieve some goal (like winning a game or proving a theorem), they proceeded step by step towards it (by making a move or a deduction) as if searching through a maze, backtracking whenever they reached a dead end.

The principal difficulty was that, for many problems, the number of possible paths through the "maze" was simply astronomical (a situation known as a "combinatorial explosion"). Researchers would reduce the search space by using heuristics or "rules of thumb" that would eliminate those paths that were unlikely to lead to a solution.[83]

Newell and Simon tried to capture a general version of this algorithm in a program called the "General Problem Solver".[84] Other "searching" programs were able to accomplish impressive tasks like solving problems in geometry and algebra, such as Herbert Gelernter's Geometry Theorem Prover (1958) and Symbolic Automatic Integrator (SAINT), written by Minsky's student James Slagle (1961).[85] Other programs searched through goals and subgoals to plan actions, like the STRIPS system developed at Stanford to control the behavior of their robot Shakey.[86]

Neural networks[edit]

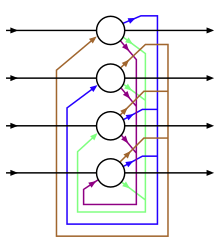

The McCulloch and Pitts paper (1944) inspired approaches to creating computing hardware that realizes the neural network approach to AI in hardware. The most influential was the effort led by Frank Rosenblatt on building Perceptron machines (1957-1962) of up to four layers. He was primarily funded by Office of Naval Research.[87] Bernard Widrow and his student Ted Hoff built ADALINE (1960) and MADALINE (1962), which had up to 1000 adjustable weights.[88] A group at Stanford Research Institute led by Charles A. Rosen and Alfred E. (Ted) Brain built two neural network machines named MINOS I (1960) and II (1963), mainly funded by U.S. Army Signal Corps. MINOS II[89] had 6600 adjustable weights,[90] and was controlled with an SDS 910 computer in a configuration named MINOS III (1968), which could classify symbols on army maps, and recognize hand-printed characters on Fortran coding sheets.[91][92][93]

Most of neural network research during this early period involved building and using bespoke hardware, rather than simulation on digital computers. The hardware diversity was particularly clear in the different technologies used in implementing the adjustable weights. The perceptron machines and the SNARC used potentiometers moved by electric motors. ADALINE used memistors adjusted by electroplating, though they also used simulations on an IBM 1620. The MINOS machines used ferrite cores with multiple holes in them that could be individually blocked, with the degree of blockage representing the weights.[94]

Though there were multi-layered neural networks, most neural networks during this period had only one layer of adjustable weights. There were empirical attempts at training more than a single layer, but they were unsuccessful. Backpropagation did not become prevalent for neural network training until the 1980s.[94]

Natural language[edit]

An important goal of AI research is to allow computers to communicate in natural languages like English. An early success was Daniel Bobrow's program STUDENT, which could solve high school algebra word problems.[95]

A semantic net represents concepts (e.g. "house", "door") as nodes and relations among concepts (e.g. "has-a") as links between the nodes. The first AI program to use a semantic net was written by Ross Quillian[96] and the most successful (and controversial) version was Roger Schank's Conceptual dependency theory.[97]

Joseph Weizenbaum's ELIZA could carry out conversations that were so realistic that users occasionally were fooled into thinking they were communicating with a human being and not a program (See ELIZA effect). But in fact, ELIZA had no idea what she was talking about. She simply gave a canned response or repeated back what was said to her, rephrasing her response with a few grammar rules. ELIZA was the first chatterbot.[98]

Micro-worlds[edit]

In the late 60s, Marvin Minsky and Seymour Papert of the MIT AI Laboratory proposed that AI research should focus on artificially simple situations known as micro-worlds. They pointed out that in successful sciences like physics, basic principles were often best understood using simplified models like frictionless planes or perfectly rigid bodies. Much of the research focused on a "blocks world," which consists of colored blocks of various shapes and sizes arrayed on a flat surface.[99]

This paradigm led to innovative work in machine vision by Gerald Sussman (who led the team), Adolfo Guzman, David Waltz (who invented "constraint propagation"), and especially Patrick Winston. At the same time, Minsky and Papert built a robot arm that could stack blocks, bringing the blocks world to life. The crowning achievement of the micro-world program was Terry Winograd's SHRDLU. It could communicate in ordinary English sentences, plan operations and execute them.[100]

Automata[edit]

In Japan, Waseda University initiated the WABOT project in 1967, and in 1972 completed the WABOT-1, the world's first full-scale "intelligent" humanoid robot,[101][102] or android. Its limb control system allowed it to walk with the lower limbs, and to grip and transport objects with hands, using tactile sensors. Its vision system allowed it to measure distances and directions to objects using external receptors, artificial eyes and ears. And its conversation system allowed it to communicate with a person in Japanese, with an artificial mouth.[103][104][105]

Optimism[edit]

The first generation of AI researchers made these predictions about their work:

- 1958, H. A. Simon and Allen Newell: "within ten years a digital computer will be the world's chess champion" and "within ten years a digital computer will discover and prove an important new mathematical theorem."[106]

- 1965, H. A. Simon: "machines will be capable, within twenty years, of doing any work a man can do."[107]

- 1967, Marvin Minsky: "Within a generation ... the problem of creating 'artificial intelligence' will substantially be solved."[108]

- 1970, Marvin Minsky (in Life Magazine): "In from three to eight years we will have a machine with the general intelligence of an average human being."[109]

Financing[edit]

In June 1963, MIT received a $2.2 million grant from the newly created Advanced Research Projects Agency (later known as DARPA). The money was used to fund project MAC which subsumed the "AI Group" founded by Minsky and McCarthy five years earlier. DARPA continued to provide three million dollars a year until the 70s.[110]DARPA made similar grants to Newell and Simon's program at CMU and to the Stanford AI Project (founded by John McCarthy in 1963).[111] Another important AI laboratory was established at Edinburgh University by Donald Michie in 1965.[112]These four institutions would continue to be the main centers of AI research (and funding) in academia for many years.[113]

The money was proffered with few strings attached: J. C. R. Licklider, then the director of ARPA, believed that his organization should "fund people, not projects!" and allowed researchers to pursue whatever directions might interest them.[114] This created a freewheeling atmosphere at MIT that gave birth to the hacker culture,[115] but this "hands off" approach would not last.

First AI winter (1974–1980)[edit]

In the 1970s, AI was subject to critiques and financial setbacks. AI researchers had failed to appreciate the difficulty of the problems they faced. Their tremendous optimism had raised public expectations impossibly high, and when the promised results failed to materialize, funding targeted at AI nearly disappeared.[116] At the same time, the exploration of simple, single-layer artificial neural networks was shut down almost completely for a decade partially due to Marvin Minsky's book emphasizing the limits of what perceptrons can do.[117]Despite the difficulties with public perception of AI in the late 70s, new ideas were explored in logic programming, commonsense reasoning and many other areas.[118][119]

Problems[edit]

In the early seventies, the capabilities of AI programs were limited. Even the most impressive could only handle trivial versions of the problems they were supposed to solve; all the programs were, in some sense, "toys".[120] AI researchers had begun to run into several fundamental limits that could not be overcome in the 1970s. Although some of these limits would be conquered in later decades, others still stymie the field to this day.[121]

- Limited computer power: There was not enough memory or processing speed to accomplish anything truly useful. For example, Ross Quillian's successful work on natural language was demonstrated with a vocabulary of only twenty words, because that was all that would fit in memory.[122] Hans Moravec argued in 1976 that computers were still millions of times too weak to exhibit intelligence. He suggested an analogy: artificial intelligence requires computer power in the same way that aircraft require horsepower. Below a certain threshold, it's impossible, but, as power increases, eventually it could become easy.[123] With regard to computer vision, Moravec estimated that simply matching the edge and motion detection capabilities of human retina in real time would require a general-purpose computer capable of 109 operations/second (1000 MIPS).[124] As of 2011, practical computer vision applications require 10,000 to 1,000,000 MIPS. By comparison, the fastest supercomputer in 1976, Cray-1 (retailing at $5 million to $8 million), was only capable of around 80 to 130 MIPS, and a typical desktop computer at the time achieved less than 1 MIPS.

- Intractability and the combinatorial explosion. In 1972 Richard Karp (building on Stephen Cook's 1971 theorem) showed there are many problems that can probably only be solved in exponential time (in the size of the inputs). Finding optimal solutions to these problems requires unimaginable amounts of computer time except when the problems are trivial. This almost certainly meant that many of the "toy" solutions used by AI would probably never scale up into useful systems.[125]

- Commonsense knowledge and reasoning. Many important artificial intelligence applications like vision or natural language require simply enormous amounts of information about the world: the program needs to have some idea of what it might be looking at or what it is talking about. This requires that the program know most of the same things about the world that a child does. Researchers soon discovered that this was a truly vast amount of information. No one in 1970 could build a database so large and no one knew how a program might learn so much information.[126]

- Moravec's paradox: Proving theorems and solving geometry problems is comparatively easy for computers, but a supposedly simple task like recognizing a face or crossing a room without bumping into anything is extremely difficult. This helps explain why research into vision and robotics had made so little progress by the middle 1970s.[127]

- The frame and qualification problems. AI researchers (like John McCarthy) who used logic discovered that they could not represent ordinary deductions that involved planning or default reasoning without making changes to the structure of logic itself. They developed new logics (like non-monotonic logics and modal logics) to try to solve the problems.[128]

End of funding[edit]

The agencies which funded AI research (such as the British government, DARPA and NRC) became frustrated with the lack of progress and eventually cut off almost all funding for undirected research into AI. The pattern began as early as 1966 when the ALPAC report appeared criticizing machine translation efforts. After spending 20 million dollars, the NRC ended all support.[129]In 1973, the Lighthill report on the state of AI research in the UK criticized the utter failure of AI to achieve its "grandiose objectives" and led to the dismantling of AI research in that country.[130](The report specifically mentioned the combinatorial explosion problem as a reason for AI's failings.)[131]DARPA was deeply disappointed with researchers working on the Speech Understanding Research program at CMU and canceled an annual grant of three million dollars.[132]By 1974, funding for AI projects was hard to find.

The end of funding occurred even earlier for neural network research, partly due to lack of results and partly due to competition from symbolic AI research. The MINOS project ran out of funding in 1966. Rosenblatt failed to secure continued funding in the 1960s.[94]

Hans Moravec blamed the crisis on the unrealistic predictions of his colleagues. "Many researchers were caught up in a web of increasing exaggeration."[133]However, there was another issue: since the passage of the Mansfield Amendment in 1969, DARPA had been under increasing pressure to fund "mission-oriented direct research, rather than basic undirected research". Funding for the creative, freewheeling exploration that had gone on in the 60s would not come from DARPA. Instead, the money was directed at specific projects with clear objectives, such as autonomous tanks and battle management systems.[134]

Critiques from across campus[edit]

Several philosophers had strong objections to the claims being made by AI researchers. One of the earliest was John Lucas, who argued that Gödel's incompleteness theorem showed that a formal system (such as a computer program) could never see the truth of certain statements, while a human being could.[135] Hubert Dreyfus ridiculed the broken promises of the 1960s and critiqued the assumptions of AI, arguing that human reasoning actually involved very little "symbol processing" and a great deal of embodied, instinctive, unconscious "know how".[136][137] John Searle's Chinese Room argument, presented in 1980, attempted to show that a program could not be said to "understand" the symbols that it uses (a quality called "intentionality"). If the symbols have no meaning for the machine, Searle argued, then the machine can not be described as "thinking".[138]

These critiques were not taken seriously by AI researchers, often because they seemed so far off the point. Problems like intractability and commonsense knowledge seemed much more immediate and serious. It was unclear what difference "know how" or "intentionality" made to an actual computer program. Minsky said of Dreyfus and Searle "they misunderstand, and should be ignored."[139] Dreyfus, who taught at MIT, was given a cold shoulder: he later said that AI researchers "dared not be seen having lunch with me."[140] Joseph Weizenbaum, the author of ELIZA, felt his colleagues' treatment of Dreyfus was unprofessional and childish.[141] Although he was an outspoken critic of Dreyfus' positions, he "deliberately made it plain that theirs was not the way to treat a human being."[142]

Weizenbaum began to have serious ethical doubts about AI when Kenneth Colby wrote a "computer program which can conduct psychotherapeutic dialogue" based on ELIZA.[143] Weizenbaum was disturbed that Colby saw a mindless program as a serious therapeutic tool. A feud began, and the situation was not helped when Colby did not credit Weizenbaum for his contribution to the program. In 1976, Weizenbaum published Computer Power and Human Reason which argued that the misuse of artificial intelligence has the potential to devalue human life.[144]

Perceptrons and opposition to connectionism[edit]

A perceptron was a form of neural network introduced in 1958 by Frank Rosenblatt, who had been a schoolmate of Marvin Minsky at the Bronx High School of Science. Like most AI researchers, he was optimistic about their power, predicting that "perceptron may eventually be able to learn, make decisions, and translate languages." An active research program into the paradigm was carried out throughout the 1960s but came to a sudden halt with the publication of Minsky and Papert's 1969 book Perceptrons. It suggested that there were severe limitations to what perceptrons could do and that Rosenblatt's predictions had been grossly exaggerated. The effect of the book was devastating: virtually no research at all was funded in connectionism for 10 years.

Of the main efforts towards neural networks, Rosenblatt attempted to gather funds for building larger perceptron machines, but died in a boating accident in 1971. Minsky (of SNARC) turned to a staunch objector to pure connectionist AI. Widrow (of ADALINE) turned to adaptive signal processing, using techniques based on the LMS algorithm. The SRI group (of MINOS) turned to symbolic AI and robotics. The main issues were lack of funding and the inability to train multilayered networks (backpropagation was unknown). The competition for government funding ended with the victory of symbolic AI approaches.[93][94]

Logic at Stanford, CMU and Edinburgh[edit]

Logic was introduced into AI research as early as 1959, by John McCarthy in his Advice Taker proposal.[145]In 1963, J. Alan Robinson had discovered a simple method to implement deduction on computers, the resolution and unification algorithm. However, straightforward implementations, like those attempted by McCarthy and his students in the late 1960s, were especially intractable: the programs required astronomical numbers of steps to prove simple theorems.[146] A more fruitful approach to logic was developed in the 1970s by Robert Kowalski at the University of Edinburgh, and soon this led to the collaboration with French researchers Alain Colmerauer and Philippe Roussel who created the successful logic programming language Prolog.[147]Prolog uses a subset of logic (Horn clauses, closely related to "rules" and "production rules") that permit tractable computation. Rules would continue to be influential, providing a foundation for Edward Feigenbaum's expert systems and the continuing work by Allen Newell and Herbert A. Simon that would lead to Soar and their unified theories of cognition.[148]

Critics of the logical approach noted, as Dreyfus had, that human beings rarely used logic when they solved problems. Experiments by psychologists like Peter Wason, Eleanor Rosch, Amos Tversky, Daniel Kahneman and others provided proof.[149]McCarthy responded that what people do is irrelevant. He argued that what is really needed are machines that can solve problems—not machines that think as people do.[150]

MIT's "anti-logic" approach[edit]

Among the critics of McCarthy's approach were his colleagues across the country at MIT. Marvin Minsky, Seymour Papert and Roger Schank were trying to solve problems like "story understanding" and "object recognition" that required a machine to think like a person. In order to use ordinary concepts like "chair" or "restaurant" they had to make all the same illogical assumptions that people normally made. Unfortunately, imprecise concepts like these are hard to represent in logic. Gerald Sussman observed that "using precise language to describe essentially imprecise concepts doesn't make them any more precise."[151] Schank described their "anti-logic" approaches as "scruffy", as opposed to the "neat" paradigms used by McCarthy, Kowalski, Feigenbaum, Newell and Simon.[152]

In 1975, in a seminal paper, Minsky noted that many of his fellow researchers were using the same kind of tool: a framework that captures all our common sense assumptions about something. For example, if we use the concept of a bird, there is a constellation of facts that immediately come to mind: we might assume that it flies, eats worms and so on. We know these facts are not always true and that deductions using these facts will not be "logical", but these structured sets of assumptions are part of the context of everything we say and think. He called these structures "frames". Schank used a version of frames he called "scripts" to successfully answer questions about short stories in English.[153]

The emergence of non-monotonic logics[edit]

The logicians rose to the challenge. Pat Hayes claimed that "most of 'frames' is just a new syntax for parts of first-orderlogic." But he noted that "there are one or two apparently minor details which give a lot of trouble, however, especially defaults".[154] In the meanwhile, Ray Reiter admitted that "conventional logics, such as first-orderlogic, lack the expressive power to adequately represent the knowledge required for reasoning by default".[155] He proposed augmenting first-order logic with a closed world assumption that a conclusion holds (by default) if its contrary cannot be shown. He showed how such an assumption corresponds to the common sense assumption made in reasoning with frames. He also showed that it has its "procedural equivalent" as negation as failure in Prolog.

The closed world assumption, as formulated by Reiter, "is not a first-order notion. (It is a meta notion.)"[155] However, Keith Clark showed that negation as finite failure can be understood as reasoning implicitly with definitions in first-order logic including a unique name assumption that different terms denote different individuals.[156]

During the late 1970s and throughout the 1980s, a variety of logics and extensions of first-order logic were developed both for negation as failure in logic programming and for default reasoning more generally. Collectively, these logics have become known as non-monotonic logics.

Boom (1980–1987)[edit]

In the 1980s, a form of AI program called "expert systems" was adopted by corporations around the world and knowledge became the focus of mainstream AI research. In those same years, the Japanese government aggressively funded AI with its fifth generation computer project. Another encouraging event in the early 1980s was the revival of connectionism in the work of John Hopfield and David Rumelhart. Once again, AI had achieved success.[157]

Rise of expert systems[edit]

An expert system is a program that answers questions or solves problems about a specific domain of knowledge, using logical rules that are derived from the knowledge of experts. The earliest examples were developed by Edward Feigenbaum and his students. Dendral, begun in 1965, identified compounds from spectrometer readings. MYCIN, developed in 1972, diagnosed infectious blood diseases. They demonstrated the feasibility of the approach.[158]

Expert systems restricted themselves to a small domain of specific knowledge (thus avoiding the commonsense knowledge problem) and their simple design made it relatively easy for programs to be built and then modified once they were in place. All in all, the programs proved to be useful: something that AI had not been able to achieve up to this point.[159]

In 1980, an expert system called XCON was completed at CMU for the Digital Equipment Corporation. It was an enormous success: it was saving the company 40 million dollars annually by 1986.[160] Corporations around the world began to develop and deploy expert systems and by 1985 they were spending over a billion dollars on AI, most of it to in-house AI departments.[161] An industry grew up to support them, including hardware companies like Symbolics and Lisp Machines and software companies such as IntelliCorp and Aion.[162]

Knowledge revolution[edit]

The power of expert systems came from the expert knowledge they contained. They were part of a new direction in AI research that had been gaining ground throughout the 70s. "AI researchers were beginning to suspect—reluctantly, for it violated the scientific canon of parsimony—that intelligence might very well be based on the ability to use large amounts of diverse knowledge in different ways,"[163] writes Pamela McCorduck. "[T]he great lesson from the 1970s was that intelligent behavior depended very much on dealing with knowledge, sometimes quite detailed knowledge, of a domain where a given task lay".[164] Knowledge based systems and knowledge engineering became a major focus of AI research in the 1980s.[165]

The 1980s also saw the birth of Cyc, the first attempt to attack the commonsense knowledge problem directly, by creating a massive database that would contain all the mundane facts that the average person knows. Douglas Lenat, who started and led the project, argued that there is no shortcut ― the only way for machines to know the meaning of human concepts is to teach them, one concept at a time, by hand. The project was not expected to be completed for many decades.[166]

Chess playing programs HiTech and Deep Thought defeated chess masters in 1989. Both were developed by Carnegie Mellon University; Deep Thought development paved the way for Deep Blue.[167]

Money returns: Fifth Generation project[edit]

In 1981, the Japanese Ministry of International Trade and Industry set aside $850 million for the Fifth generation computer project. Their objectives were to write programs and build machines that could carry on conversations, translate languages, interpret pictures, and reason like human beings.[168] Much to the chagrin of scruffies, they chose Prolog as the primary computer language for the project.[169]

Other countries responded with new programs of their own. The UK began the £350 million Alvey project. A consortium of American companies formed the Microelectronics and Computer Technology Corporation (or "MCC") to fund large scale projects in AI and information technology.[170][171] DARPA responded as well, founding the Strategic Computing Initiative and tripling its investment in AI between 1984 and 1988.[172]

Revival of neural networks[edit]

In 1982, physicist John Hopfield was able to prove that a form of neural network (now called a "Hopfield net") could learn and process information, and provably converges after enough time under any fixed condition. It was a breakthrough, as it was previously thought that nonlinear networks would, in general, evolve chaotically.[173]

Around the same time, Geoffrey Hinton and David Rumelhart popularized a method for training neural networks called "backpropagation", also known as the reverse mode of automatic differentiation published by Seppo Linnainmaa (1970) and applied to neural networks by Paul Werbos. These two discoveries helped to revive the exploration of artificial neural networks.[171][174]

Starting with the 1986 publication of the Parallel Distributed Processing, a two volume collection of papers edited by Rumelhart and psychologist James McClelland, neural networks research gained new momentum and would become commercially successful in the 1990s, applied to optical character recognition and speech recognition.[171][175]

The development of metal–oxide–semiconductor (MOS) very-large-scale integration (VLSI), in the form of complementary MOS (CMOS) technology, enabled the development of practical artificial neural network technology in the 1980s.

A landmark publication in the field was the 1989 book Analog VLSI Implementation of Neural Systems by Carver A. Mead and Mohammed Ismail.[176]

Bust: second AI winter (1987–1993)[edit]

The business community's fascination with AI rose and fell in the 1980s in the classic pattern of an economic bubble. As dozens of companies failed, the perception was that the technology was not viable.[177] However, the field continued to make advances despite the criticism. Numerous researchers, including robotics developers Rodney Brooks and Hans Moravec, argued for an entirely new approach to artificial intelligence.

AI winter[edit]

Термин « зима искусственного интеллекта » был придуман исследователями, пережившими сокращение финансирования в 1974 году, когда они были обеспокоены тем, что энтузиазм в отношении экспертных систем вышел из-под контроля и что за этим непременно последует разочарование. [178] Их опасения были вполне обоснованными: в конце 1980-х — начале 1990-х годов ИИ пережил ряд финансовых неудач.

Первым признаком изменения погоды стал внезапный обвал рынка специализированного оборудования для искусственного интеллекта в 1987 году. Настольные компьютеры Apple и IBM неуклонно набирали скорость и мощность, и в 1987 году они стали более мощными, чем более дорогие машины Lisp , производимые Символика и другие. Больше не было веской причины их покупать. В одночасье была разрушена целая индустрия стоимостью полмиллиарда долларов. [179]

В конце концов, поддержка первых успешных экспертных систем, таких как XCON , оказалась слишком дорогой. Их было трудно обновлять, они не могли учиться, были « хрупкими » (т. е. могли совершать гротескные ошибки при вводе необычных данных) и становились жертвами проблем (таких как проблема квалификации ), которые были выявлены много лет назад. Экспертные системы оказались полезными, но лишь в нескольких особых контекстах. [180]

В конце 1980-х годов Инициатива по стратегическим вычислениям «глубоко и жестоко» сократила финансирование ИИ. Новое руководство DARPA решило, что искусственный интеллект не является «следующей волной», и направило средства на проекты, которые, казалось, с большей вероятностью дадут немедленные результаты. [181]

К 1991 году впечатляющий список целей, намеченных в 1981 году для японского проекта «Пятое поколение», так и не был достигнут. Действительно, некоторые из них, например «вести непринужденную беседу», к 2010 году не встречались. [182] Как и в случае с другими проектами ИИ, ожидания были намного выше, чем было на самом деле. [182] [183]

К концу 1993 года более 300 компаний, занимающихся искусственным интеллектом, закрылись, обанкротились или были приобретены, что фактически положило конец первой коммерческой волне искусственного интеллекта. [184] В 1994 году HP Ньюквист заявил в книге The Brain Makers , что «ближайшее будущее искусственного интеллекта — в его коммерческой форме — похоже, частично зависит от продолжающегося успеха нейронных сетей». [184]

Новый ИИ воплощенный разум и

В конце 1980-х годов несколько исследователей выступали за совершенно новый подход к искусственному интеллекту, основанный на робототехнике. [185] Они считали, что для проявления настоящего интеллекта машине необходимо иметь тело — ей нужно воспринимать, двигаться, выживать и справляться с миром. Они утверждали, что эти сенсомоторные навыки необходимы для навыков более высокого уровня, таких как здравое рассуждение , и что абстрактное мышление на самом деле является наименее интересным или важным человеческим навыком (см. Парадокс Моравца ). Они выступали за построение разведки «снизу вверх». [186]

Этот подход возродил идеи кибернетики и теории управления , которые были непопулярны с шестидесятых годов. Другим предшественником был Дэвид Марр , который пришел в Массачусетский технологический институт в конце 1970-х годов, имея успешный опыт работы в области теоретической нейробиологии, чтобы возглавить группу, изучающую зрение . Он отверг все символические подходы ( как Маккарти логику , так и рамки Мински ), утверждая, что ИИ необходимо понять физическую машину зрения снизу вверх, прежде чем произойдет какая-либо символическая обработка. (Работа Марра была прервана из-за лейкемии в 1980 году.) [187]

В своей статье 1990 года «Слоны не играют в шахматы» [188] Исследователь робототехники Родни Брукс прямо нацелился на гипотезу системы физических символов , утверждая, что символы не всегда необходимы, поскольку «мир сам по себе является лучшей моделью. Он всегда точно соответствует действительности. В нем всегда есть каждая деталь, которую необходимо знать. Хитрость заключается в том, чтобы чувствовать это правильно и достаточно часто». [189] В 1980-х и 1990-х годах многие ученые-когнитивисты также отвергли модель обработки символов разумом и утверждали, что тело необходимо для рассуждения. Эта теория получила название тезиса о воплощенном разуме . [190]

ИИ (1993–2011) [ править ]

Область искусственного интеллекта, которой уже более полувека, наконец достигла некоторых из своих давних целей. Его начали успешно использовать во всей технологической отрасли, хотя и несколько закулисно. Часть успеха была достигнута благодаря увеличению мощности компьютеров, а часть была достигнута за счет сосредоточения внимания на конкретных изолированных проблемах и их решения с соблюдением самых высоких стандартов научной ответственности. Тем не менее, репутация ИИ, по крайней мере в деловом мире, была далеко не идеальной. [191] В этой области не было единого мнения о причинах неспособности ИИ реализовать мечту об интеллекте человеческого уровня, которая захватила воображение мира в 1960-х годах. В совокупности все эти факторы помогли разделить ИИ на конкурирующие подобласти, сосредоточенные на конкретных проблемах или подходах, иногда даже под новыми названиями, которые скрывали запятнанную родословную «искусственного интеллекта». [192] ИИ был одновременно более осторожным и более успешным, чем когда-либо.

Мура закон Вехи и

11 мая 1997 года Deep Blue стала первой компьютерной системой игры в шахматы, победившей действующего чемпиона мира по шахматам Гарри Каспарова . [193] Суперкомпьютер представлял собой специализированную версию системы, созданной IBM, и был способен обрабатывать в два раза больше ходов в секунду, чем во время первого матча (который Deep Blue проиграл), как сообщается, 200 000 000 ходов в секунду. [194]

В 2005 году робот из Стэнфорда выиграл турнир DARPA Grand Challenge , проехав автономно 131 милю по неизведанной тропе в пустыне. [195] Два года спустя команда из CMU выиграла конкурс DARPA Urban Challenge , автономно проехав 55 миль в городской среде, соблюдая при этом опасности дорожного движения и все правила дорожного движения. [196] В феврале 2011 года в опасности! викторина-шоу показательный матч, , IBM вопросно-ответная система Уотсон , победилдва величайших Jeopardy! чемпионы Брэд Раттер и Кен Дженнингс со значительным отрывом. [197]

Эти успехи были обусловлены не какой-то новой революционной парадигмой, а главным образом утомительным применением инженерных навыков и огромным увеличением скорости и мощности компьютеров к 90-м годам. [198] Фактически, Deep Blue компьютер был в 10 миллионов раз быстрее, чем Ferranti Mark 1 , который Кристофер Стрейчи учил играть в шахматы в 1951 году. [199] Это резкое увеличение измеряется законом Мура , который предсказывает, что скорость и емкость памяти компьютеров удваиваются каждые два года в результате того, что металл-оксид-полупроводник (МОП) количество транзисторов удваивается каждые два года. Фундаментальная проблема «грубой компьютерной мощности» постепенно решалась.

Интеллектуальные агенты не [ править ]

Новая парадигма под названием « интеллектуальные агенты » получила широкое распространение в 1990-е годы. [200] Хотя ранее исследователи предлагали модульные подходы к ИИ по принципу «разделяй и властвуй», [201] интеллектуальный агент не достиг своей современной формы до тех пор, пока Джудея Перл , Аллен Ньюэлл , Лесли П. Кельблинг и другие не привнесли концепции из теории принятия решений и экономики в изучение ИИ. [202] Когда экономическое определение рационального агента сочеталось с компьютерной науке определением объекта или модуля в , парадигма интеллектуального агента была завершена.

Интеллектуальный агент — это система, которая воспринимает окружающую среду и предпринимает действия, которые максимизируют ее шансы на успех. Согласно этому определению, простые программы, решающие конкретные проблемы, являются «интеллектуальными агентами», равно как и люди и организации, состоящие из людей, такие как фирмы . Парадигма интеллектуальных агентов определяет исследования ИИ как «изучение интеллектуальных агентов». Это обобщение некоторых более ранних определений ИИ: он выходит за рамки изучения человеческого интеллекта; он изучает все виды интеллекта. [203]

Эта парадигма давала исследователям право изучать отдельные проблемы и находить решения, которые были бы одновременно проверяемыми и полезными. Он предоставил общий язык для описания проблем и обмена их решениями друг с другом, а также с другими областями, которые также использовали концепции абстрактных агентов, таких как экономика и теория управления . Была надежда, что полная архитектура агентов (подобная Ньюэлла SOAR ) однажды позволит исследователям создавать более универсальные и интеллектуальные системы из взаимодействующих интеллектуальных агентов . [202] [204]

рассуждения и Вероятностные строгость большая

Исследователи ИИ начали разрабатывать и использовать сложные математические инструменты больше, чем когда-либо в прошлом. [205] Было широко распространено понимание того, что многие из проблем, которые должен был решить ИИ, уже разрабатывались исследователями в таких областях, как математика , электротехника , экономика или исследование операций . Общий математический язык позволял как более высокий уровень сотрудничества с более авторитетными и успешными областями, так и достижение измеримых и доказуемых результатов; ИИ стал более строгой «научной» дисциплиной.

Влиятельная книга Джуди Перл 1988 года [206] привнес вероятности и теорию принятия решений в ИИ. Среди множества новых инструментов были байесовские сети , скрытые марковские модели , теория информации , стохастическое моделирование и классическая оптимизация . Точные математические описания были также разработаны для « вычислительного интеллекта парадигм », таких как нейронные сети и эволюционные алгоритмы . [207]

ИИ за кулисами [ править ]

Алгоритмы, первоначально разработанные исследователями ИИ, начали появляться как части более крупных систем. ИИ решил множество очень сложных проблем [208] и их решения оказались полезными во всей технологической отрасли, [209] такой как интеллектуальный анализ данных , промышленная робототехника ,логистика, [210] распознавание речи , [211] банковское программное обеспечение, [212] медицинский диагноз [212] и Google . поисковая система [213]

В области ИИ эти успехи в 1990-х и начале 2000-х годов практически не получили должного признания. Многие из величайших инноваций ИИ были низведены до статуса просто еще одного предмета в наборе инструментов информатики. [214] Ник Бостром объясняет: «Множество передовых технологий ИИ проникло в общие приложения, часто даже не называясь ИИ, потому что, как только что-то становится достаточно полезным и достаточно распространенным, его больше не называют ИИ». [215]

Многие исследователи ИИ в 1990-е годы сознательно называли свою работу другими именами, например , информатика , системы, основанные на знаниях , когнитивные системы или вычислительный интеллект . Частично это могло быть связано с тем, что они считали свою область деятельности фундаментально отличной от ИИ, но новые имена также помогают обеспечить финансирование. По крайней мере, в коммерческом мире неудавшиеся обещания « зимы искусственного интеллекта» продолжали преследовать исследования в области искусственного интеллекта в 2000-е годы, как сообщила газета «Нью-Йорк Таймс» в 2005 году: «Учёные-компьютерщики и инженеры-программисты избегали термина «искусственный интеллект», опасаясь, что их сочтут дикими. -глазые мечтатели». [216] [217] [218] [219]

Глубокое обучение, большие данные (2011–2020 гг . )

В первые десятилетия XXI века доступ к большим объемам данных (известным как « большие данные »), более дешевые и быстрые компьютеры и передовые методы машинного обучения успешно применялись для решения многих проблем в экономике. Фактически, Глобальный институт McKinsey в своей знаменитой статье «Большие данные: следующий рубеж инноваций, конкуренции и производительности» подсчитал, что «к 2009 году почти все сектора экономики США имели в среднем по крайней мере 200 терабайт хранимых данных». .

К 2016 году рынок продуктов, аппаратного и программного обеспечения, связанных с ИИ, достиг более 8 миллиардов долларов, а газета New York Times сообщила, что интерес к ИИ достиг «безумия». [220] Приложения больших данных начали проникать и в другие области, например, в модели обучения в области экологии. [221] и для различных приложений в экономике . [222] Достижения в области глубокого обучения (особенно глубоких сверточных нейронных сетей и рекуррентных нейронных сетей ) способствовали прогрессу и исследованиям в области обработки изображений и видео, анализа текста и даже распознавания речи. [223]

первый глобальный саммит по безопасности ИИ, прошел В ноябре 2023 года в Блетчли-Парке на котором обсуждались краткосрочные и долгосрочные риски ИИ, а также возможность создания обязательных и добровольных нормативных рамок. [224] 28 стран, включая США, Китай и Европейский Союз, в начале саммита опубликовали декларацию, призывающую к международному сотрудничеству для решения проблем и рисков, связанных с искусственным интеллектом. [225] [226]

Глубокое обучение [ править ]

Глубокое обучение — это отрасль машинного обучения, которая моделирует абстракции высокого уровня в данных с помощью глубокого графа со многими уровнями обработки. [223] Согласно универсальной теореме аппроксимации , глубина не обязательна для того, чтобы нейронная сеть могла аппроксимировать произвольные непрерывные функции. Несмотря на это, существует множество проблем, общих для мелких сетей (например, переобучение ), которых глубокие сети помогают избежать. [227] Таким образом, глубокие нейронные сети способны реалистично генерировать гораздо более сложные модели по сравнению с их поверхностными аналогами.

Однако у глубокого обучения есть свои проблемы. Распространенной проблемой рекуррентных нейронных сетей является проблема исчезновения градиента , при которой градиенты, передаваемые между слоями, постепенно сжимаются и буквально исчезают по мере округления до нуля. Для решения этой проблемы было разработано множество методов, например, использование блоков кратковременной памяти .

Современные архитектуры глубоких нейронных сетей иногда могут даже соперничать с человеческой точностью в таких областях, как компьютерное зрение, особенно в таких вещах, как база данных MNIST и распознавание дорожных знаков. [228]

Системы языковой обработки, основанные на интеллектуальных поисковых системах, могут легко обогнать людей в ответах на общие вопросы (например, IBM Watson ), а недавние разработки в области глубокого обучения дали поразительные результаты в конкуренции с людьми в таких вещах, как Go и Doom (которые, будучи шутер от первого лица , вызвал некоторые споры). [229] [230] [231] [232]

Большие данные [ править ]

Большие данные — это набор данных, которые невозможно собрать, управлять и обработать с помощью обычных программных инструментов в течение определенного периода времени. Это огромный объем возможностей принятия решений, понимания и оптимизации процессов, которые требуют новых моделей обработки. В эпоху больших данных, написанную Виктором Мейером Шонбергом и Кеннетом Куком , большие данные означают, что вместо случайного анализа (выборочного опроса) для анализа используются все данные. Характеристики больших данных 5V (предложены IBM): объем , скорость , разнообразие , [233] Ценить , [234] Правдивость . [235]

Стратегическое значение технологии больших данных заключается не в овладении огромными данными, а в специализации на этих значимых данных. Другими словами, если большие данные сравнивать с отраслью, то ключом к достижению прибыльности в этой отрасли является повышение « возможностей обработки » данных и реализация « добавленной стоимости » данных посредством « обработки ».

искусственного интеллекта (2020 – настоящее время Большие языковые модели, эпоха )

Бум искусственного интеллекта начался с первоначальной разработки ключевых архитектур и алгоритмов, таких как архитектура преобразователя , в 2017 году, что привело к масштабированию и разработке крупных языковых моделей, демонстрирующих человеческие черты мышления, познания, внимания и творчества. Говорят, что эра искусственного интеллекта началась примерно в 2022–2023 годах с публичным выпуском масштабируемых крупных языковых моделей, таких как ChatGPT . [236] [237] [238] [239] [240]

Большие языковые модели [ править ]

В 2017 году архитектуру- трансформер предложили исследователи Google. Он использует механизм внимания и позже стал широко использоваться в больших языковых моделях. [241]

Базовые модели , представляющие собой большие языковые модели, обученные на огромных объемах неразмеченных данных и которые можно адаптировать к широкому кругу последующих задач, начали разрабатываться в 2018 году.

Такие модели, как GPT-3, выпущенная OpenAI в 2020 году, и Gato , выпущенная DeepMind в 2022 году, были описаны как важные достижения машинного обучения .

В 2023 году компания Microsoft Research протестировала большую языковую модель GPT-4 с большим количеством задач и пришла к выводу, что «её можно разумно рассматривать как раннюю (но всё ещё неполную) версию системы общего искусственного интеллекта (AGI)». [242]

См. также [ править ]

- История искусственных нейронных сетей

- История представления знаний и рассуждений

- История обработки естественного языка

- Очерк искусственного интеллекта

- Прогресс в области искусственного интеллекта

- Хронология искусственного интеллекта

- Хронология машинного обучения

Примечания [ править ]

- ^ Каплан А., Хенляйн М. (2019). «Сири, Сири, в моей руке: кто самый справедливый на земле? Об интерпретациях, иллюстрациях и значении искусственного интеллекта». Горизонты бизнеса . 62 : 15–25. дои : 10.1016/j.bushor.2018.08.004 . S2CID 158433736 .

- ^ Ньюквист 1994 , стр. 143–156.

- ^ Ньюквист 1994 , стр. 144–152.

- ^ Эпизод Талоса в Argonautica 4

- ^ Библиотеки 1.9.26

- ^ Родиос А (2007). Аргонавтика: Расширенное издание . Издательство Калифорнийского университета. п. 355. ИСБН 978-0-520-93439-9 . OCLC 811491744 .

- ^ Морфорд М. (2007). Классическая мифология . Оксфорд: Издательство Оксфордского университета. п. 184. ИСБН 978-0-19-085164-4 . OCLC 1102437035 .

- ^ Линден С.Дж. (2003). Читатель алхимии: от Гермеса Трисмегиста до Исаака Ньютона . Нью-Йорк: Издательство Кембриджского университета. пп. гл. 18. ISBN 0-521-79234-7 . OCLC 51210362 .

- ^ Кресель М. (1 октября 2015 г.). «36 дней иудейского мифа: День 24, Пражский голем» . Мэтью Кресел . Проверено 15 марта 2020 г.

- ^ Ньюквист 1994 , с. [ нужна страница ] .

- ^ «ГОЛЕМ» . www.jewishencyclepedia.com . Проверено 15 марта 2020 г.

- ^ Ньюквист 1994 , с. 38.

- ^ «Синедрион 65б» . www.sefaria.org . Проверено 15 марта 2020 г.

- ^ О'Коннор К.М. (1994). «Алхимическое создание жизни (таквин) и другие концепции Бытия в средневековом исламе» . Диссертации доступны на сайте ProQuest : 1–435.

- ^ Гете Й.В. (1890). Фауст; трагедия. Перевод в оригинальных метрах... Баярда Тейлора. Авторизованное издание, опубликовано по специальному соглашению с г-жой Баярд Тейлор. С биографическим вступлением . Лондонский Уорд, Лок.

- ^ МакКордак 2004 , стр. 17–25.

- ^ Батлер 1863 .

- ^ Ньюквист 1994 , с. 65.

- ^ Пещера С, Дихал К. (2019). «Надежды и опасения по поводу разумных машин в фантастике и реальности» . Природный машинный интеллект . 1 (2): 74–78. дои : 10.1038/s42256-019-0020-9 . ISSN 2522-5839 . S2CID 150700981 .

- ^ Нидхэм 1986 , с. 53.

- ^ МакКордак 2004 , с. 6.

- ^ Ник 2005 .

- ^ МакКордак 2004 , с. 17.

- ^ Левитт 2000 .

- ^ Ньюквист 1994 , с. 30.

- ^ Цитируется по McCorduck 2004 , с. 8. Кревье 1993 , с. 1 и McCorduck 2004 , стр. 6–9, обсуждаются священные статуи.

- ^ Другие важные автоматы были построены Гаруном аль-Рашидом ( МакКордак 2004 , стр. 10), Жаком де Вокансоном ( Ньюквист 1994 , стр. 40), ( МакКордак 2004 , стр. 16) и Леонардо Торресом-и-Кеведо ( МакКордак 2004 , стр. 16). . 59–62)

- ^ Кейв С., Дихал К., Диллон С. (2020). Повествования об искусственном интеллекте: история творческого мышления об интеллектуальных машинах . Издательство Оксфордского университета. п. 56. ИСБН 978-0-19-884666-6 . Проверено 2 мая 2023 г.

- ^ Батлер, EM (Элиза Мэриан) (1948). Миф о маге . Лондон: Издательство Кембриджского университета. ISBN 0-521-22564-7 . ОСЛК 5063114 .

- ^ Портерфилд А (2006). Протестантский опыт в Америке . Американский религиозный опыт. Гринвуд Пресс. п. 136. ИСБН 978-0-313-32801-5 . Проверено 15 мая 2023 г.

- ^ Холландер Л.М. (1964). Хеймскрингла; История королей Норвегии . Остин: опубликовано для Американо-скандинавского фонда издательством Техасского университета. ISBN 0-292-73061-6 . OCLC 638953 .

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с д Берлин 2000 .

- ^ См. Каррерас Артау, Томас и Хоакин. История испанской философии. Христианская философия 13-15 веков . Мадрид, 1939 год, том I.

- ^ Боннер, Энтони, Искусство и логика Рамона Луллия: Руководство пользователя , Брилл, 2007.

- ^ Энтони Боннер (редактор), Доктор Иллюминат. Читатель Рамона Лулла (Принстонский университет, 1985). Вид. «Влияние Лулла: история луллизма» на 57–71.

- ^ Механизм 17 века и ИИ:

- МакКордак 2004 , стр. 37–46.

- Рассел и Норвиг 2003 , с. 6

- Бьюкенен 2005 , с. 53

- ^ Гоббс и ИИ:

- МакКордак 2004 , с. 42

- Гоббс 1651 , глава 5

- ^ Лейбниц и А.И.:

- МакКордак 2004 , с. 41

- Рассел и Норвиг 2003 , с. 6

- Берлинский 2000 , стр. 12.

- Бьюкенен 2005 , с. 53

- ^ Лямбда -исчисление было особенно важно для ИИ, поскольку оно послужило источником вдохновения для Lisp (наиболее важного языка программирования, используемого в ИИ). ( Кревье 1993 , стр. 190–196, 61)

- ^ Оригинальное фото можно увидеть в статье: Роуз А (апрель 1946 г.). «Математика ударов молний» . Научно-популярный : 83–86 . Проверено 15 апреля 2012 г.

- ^ Ньюквист 1994 , с. 56.

- ^ Машина Тьюринга : МакКордак 2004 , стр. 63–64, Кревье 1993 , стр. 22–24, Рассел и Норвиг 2003 , с. 8 и посмотрим Тьюринг 1936–1937 гг.

- ^ Кутюра 1901 .

- ^ Рассел и Норвиг 2021 , с. 15.

- ^ Рассел и Норвиг (2021 , стр. 15); Ньюквист (1994 , стр. 67)

- ^ Рэндалл (1982 , стр. 4–5); Бирн (2012) ; Малвихилл (2012)

- ^ Рэндалл (1982 , стр. 6, 11–13); Кеведо (1914 ) Кеведо (1915)

- ^ Рэндалл 1982 , стр. 13, 16–17.

- ^ Цитируется по Расселу и Норвигу (2021 , стр. 15).

- ^ Менабреа и Лавлейс 1843 .

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Рассел и Норвиг 2021 , с. 14.

- ^ МакКордак 2004 , стр. 76–80.

- ^ МакКордак 2004 , стр. 51–57, 80–107, Кревье 1993 , стр. 27–32, Рассел и Норвиг 2003 , стр. 15, 940, Моравец 1988 , с. 3, Кордески 2002 , гл. 5.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с д Коупленд Дж ((2004). The Essential Turing: идеи, породившие компьютерную эпоху . Оксфорд: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-825079-7 .

- ^ МакКордак 2004 , стр. 111–136, Кревье 1993 , стр. 49–51, Рассел и Норвиг 2003 , с. 17, Ньюквист 1994 , стр. 91–112 и Каплан А. «Искусственный интеллект, бизнес и цивилизация – наша судьба, созданная машинами» . Проверено 11 марта 2022 г.

- ^ МакКордак 2004 , стр. 70–72, Кревье, 1993 , стр. 22–25, Рассел и Норвиг 2003 , стр. 2–3 и 948, Хаугеланд 1985 , стр. 6–9, Кордески 2002 , стр. 170–176.См. также Тьюринг 1950 г.

- ^ Ньюквист 1994 , стр. 92–98.

- ^ Рассел и Норвиг (2003 , стр. 948) утверждают, что Тьюринг ответил на все основные возражения против ИИ, высказанные за годы, прошедшие с момента появления статьи.

- ^ Маккалок WS, Питтс W (1 декабря 1943 г.). «Логическое исчисление идей, имманентных нервной деятельности». Вестник математической биофизики . 5 (4): 115–133. дои : 10.1007/BF02478259 . ISSN 1522-9602 .

- ^ Пиччинини Дж. (1 августа 2004 г.). «Первая вычислительная теория разума и мозга: внимательный взгляд на «Логическое исчисление идей, имманентных нервной деятельности» Маккаллоха и Питтса ». Синтезируйте . 141 (2): 175–215. дои : 10.1023/B:SYNT.0000043018.52445.3e . ISSN 1573-0964 . S2CID 10442035 .

- ^ МакКордак 2004 , стр. 51–57, 88–94, Crevier 1993 , стр. 30, Рассел и Норвиг 2003 , стр. 15–16, Кордески 2002 , гл. 5, а также см. McCullough & Pitts 1943.

- ^ МакКордак 2004 , с. 102, Crevier 1993 , стр. 34–35 и Russell & Norvig 2003 , стр. 102. 17

- ^ МакКордак 2004 , с. 98, Crevier 1993 , стр. 27–28, Russell & Norvig 2003 , стр. 15, 940, Moravec 1988 , p. 3, Кордески 2002 , гл. 5.

- ^ См . «Краткую историю вычислений» на AlanTuring.net.

- ^ Шеффер, Джонатан. На один прыжок вперед:: Оспаривание человеческого превосходства в шашках , 1997, 2009, Springer, ISBN 978-0-387-76575-4 . Глава 6.

- ^ МакКордак 2004 , стр. 137–170, Кревье 1993 , стр. 44–47.

- ^ McCorduck 2004 , стр. 123–125, Crevier 1993 , стр. 44–46 и Russell & Norvig 2003 , p. 17

- ^ Цитируется по Crevier 1993 , с. 46 и Рассел и Норвиг 2003 , с. 17

- ^ Рассел и Норвиг 2003 , стр. 947, 952.

- ^ МакКордак 2004 , стр. 111–136, Crevier 1993 , стр. 49–51 и Рассел и Норвиг 2003 , с. 17 Ньюквист, 1994 , стр. 91–112.

- ^ Чаттерджи С., Н.С. С., Хуссейн З. (1 января 2021 г.). «Эволюция искусственного интеллекта и ее влияние на права человека: с социально-правовой точки зрения» . Международный журнал права и менеджмента . 64 (2): 184–205. doi : 10.1108/IJLMA-06-2021-0156 . ISSN 1754-243X . S2CID 238670666 .

- ^ См. Маккарти и др. 1955 год . Также см. Crevier 1993 , с. 48, где Кревье утверждает, что «[предложение] позже стало известно как «гипотеза систем физических символов»». Гипотеза системы физических символов была сформулирована и названа Ньюэллом и Саймоном в их статье о GPS . ( Ньюэлл и Саймон, 1963 ). Оно включает более конкретное определение «машины» как агента, манипулирующего символами. См. философию искусственного интеллекта .

- ^ «Я не буду ругаться, и я не видел этого раньше», — сказал Маккарти Памеле МакКордак в 1979 году. ( МакКордак 2004 , стр. 114). Однако Маккарти также недвусмысленно заявил: «Я придумал этот термин» в интервью CNET . ( Навыки, 2006 г. )

- ^ Маккарти Дж (1988). «Обзор вопроса об искусственном интеллекте ». Анналы истории вычислительной техники . 10 (3): 224–229. , собранный в Маккарти Дж (1996). «10. Обзор вопроса об искусственном интеллекте ». Защита исследований в области искусственного интеллекта: сборник эссе и обзоров . ЦСЛИ. , с. 73«Одной из причин изобретения термина «искусственный интеллект» было стремление избежать ассоциации с «кибернетикой». Его концентрация на аналоговой обратной связи казалась ошибочной, и я хотел избежать необходимости принимать Норберта (не Роберта) Винера как гуру или спорить с ним».

- ^ МакКордак (2004 , стр. 129–130) обсуждает, как выпускники Дартмутской конференции доминировали в первые два десятилетия исследований ИИ, называя их «невидимым колледжем».

- ^ МакКордак 2004 , стр. 125.

- ^ Кревье (1993 , стр. 49) пишет: «Конференция общепризнана официальной датой рождения новой науки».

- ^ Миллер Дж. (2003). «Когнитивная революция: историческая перспектива» (PDF) . Тенденции в когнитивных науках . 7 (3): 141–144. дои : 10.1016/s1364-6613(03)00029-9 . ПМИД 12639696 .

- ↑ Рассел и Норвиг пишут: «Это было удивительно, когда компьютер делал что-то хоть сколько-нибудь умное». Рассел и Норвиг 2003 , с. 18

- ^ Crevier 1993 , стр. 52–107, Moravec 1988 , p. 9 и Рассел и Норвиг, 2003 , стр. 18–21.

- ^ МакКордак 2004 , с. 218, Newquist 1994 , стр. 91–112, Crevier 1993 , стр. 108–109 и Russell & Norvig 2003 , стр. 218. 21

- ^ Crevier 1993 , стр. 52–107, Moravec 1988 , p. 9

- ^ Эвристика: МакКордак 2004 , с. 246, Рассел и Норвиг 2003 , стр. 21–22.

- ^ GPS: McCorduck 2004 , стр. 245–250, Crevier 1993 , стр. GPS?, Рассел и Норвиг 2003 , с. GPS?

- ^ Crevier 1993 , стр. 51–58, 65–66 и Russell & Norvig 2003 , стр. 18–19.

- ^ McCorduck 2004 , стр. 268–271, Crevier 1993 , стр. 95–96, Newquist 1994 , стр. 148–156, Moravec 1988 , стр. 14–15

- ^ Розенблатт, Фрэнк. Принципы нейродинамики: Перцептроны и теория механизмов мозга . Том. 55. Вашингтон, округ Колумбия: Спартанские книги, 1962.

- ^ Уидроу Б., Лер М. (сентябрь 1990 г.). «30 лет адаптивных нейронных сетей: персептрон, Мадалин и обратное распространение ошибки» . Труды IEEE . 78 (9): 1415–1442. дои : 10.1109/5.58323 . S2CID 195704643 .

- ^ Розен, Чарльз А., Нильс Дж. Нильссон и Милтон Б. Адамс. « Программа исследований и разработок по применению интеллектуальных автоматов для разведки, этап I ». Предложение по исследованиям НИИ № ЕСУ 65-1, 8 января 1965 г.

- ^ Нильссон, Нильс Дж. Центр искусственного интеллекта SRI: Краткая история . Центр искусственного интеллекта, SRI International, 1984.

- ^ Харт П.Е., Нильссон, Нью-Джерси, Перро Р., Митчелл Т., Куликовский К.А., Лик Д.Б. (15 марта 2003 г.). «Памяти: Чарльза Розена, Нормана Нильсена и Сола Амареля» . Журнал ИИ . 24 (1): 6. дои : 10.1609/aimag.v24i1.1683 . ISSN 2371-9621 .

- ^ Нильссон, Нью-Джерси (2009). «Раздел 4.2: Нейронные сети». В поисках искусственного интеллекта . Кембридж: Издательство Кембриджского университета. дои : 10.1017/cbo9780511819346 . ISBN 978-0-521-11639-8 .

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Нильсон Д.Л. (1 января 2005 г.). «Глава 4: Жизнь и времена успешной лаборатории НИИ: искусственный интеллект и робототехника» (PDF) . НАСЛЕДИЕ ИННОВАЦИЙ Первые полвека SRI (1-е изд.). НИИ Интернешнл. ISBN 978-0-9745208-0-3 .

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с д Олазаран Родригес, Хосе Мигель. Историческая социология исследований нейронных сетей . Кандидатская диссертация. Университет Эдинбурга, 1991 г. См. особенно главы 2 и 3.

- ^ МакКордак 2004 , с. 286, Crevier 1993 , стр. 76–79, Рассел и Норвиг 2003 , стр. 286. 19

- ^ Кревье 1993 , стр. 79–83.

- ^ Кревье 1993 , стр. 164–172.

- ^ МакКордак 2004 , стр. 291–296, Кревье 1993 , стр. 134–139.

- ^ МакКордак 2004 , стр. 299–305, Кревье 1993 , стр. 83–102, Рассел и Норвиг 2003 , стр. 19 и Коупленд 2000 г.

- ^ McCorduck 2004 , стр. 300–305, Crevier 1993 , стр. 84–102, Russell & Norvig 2003 , p. 19

- ^ «История гуманоидов -WABOT-» .

- ^ Зеглул С., Лариби М.А., Газо Дж.П. (21 сентября 2015 г.). Робототехника и мехатроника: материалы 4-го Международного симпозиума IFToMM по робототехнике и мехатронике . Спрингер. ISBN 978-3-319-22368-1 – через Google Книги.

- ^ «Исторические Android-проекты» . androidworld.com .

- ^ Роботы: от научной фантастики к технологической революции , стр. 130.

- ^ Даффи В.Г. (19 апреля 2016 г.). Справочник по цифровому моделированию человека: исследования в области прикладной эргономики и проектирования человеческого фактора . ЦРК Пресс. ISBN 978-1-4200-6352-3 – через Google Книги.

- ^ Саймон и Ньюэлл 1958 , стр. 7-8, цитируется в Crevier 1993 , стр. 108. См. также Рассел и Норвиг 2003 , с. 21

- ^ Саймон 1965 , с. 96, цитируется по Crevier 1993 , с. 109

- ^ Минский 1967 , с. 2 цитируется по Crevier 1993 , с. 109

- ↑ Мински твердо уверен, что его неправильно процитировали. См. McCorduck 2004 , стр. 272–274, Crevier 1993 , p. 96 и Даррач 1970 .

- ^ Кревье 1993 , стр. 64–65.

- ^ Кревье 1993 , с. 94

- ^ Хоу, 1994 г.

- ^ МакКордак 2004 , с. 131, Кревье 1993 , с. 51. МакКордак также отмечает, что финансирование осуществлялось в основном под руководством выпускников Дартмутского семинара 1956 года.

- ^ Кревье 1993 , с. 65

- ^ Crevier 1993 , стр. 68–71 и Turkle 1984.

- ^ Crevier 1993 , стр. 100–144 и Рассел и Норвиг 2003 , стр. 21–22.

- ^ МакКордак 2004 , стр. 104–107, Кревье 1993 , стр. 102–105, Рассел и Норвиг 2003 , с. 22