Эдинбургский университет

| |

| Латынь : University Academica Edinburgensis. | |

Прежние имена | Тунисский колледж Колледж короля Джеймса |

|---|---|

| Тип | Государственный исследовательский университет Древний университет |

| Учредил | 1583 [1] |

Академическая принадлежность | |

| Endowment | £559.8 million (2023)[2] |

| Budget | £1.341 billion (2022/23)[2] |

| Chancellor | Anne, Princess Royal |

| Rector | Simon Fanshawe |

| Principal | Sir Peter Mathieson |

Academic staff | 4,952 FTE (2022)[3] |

Administrative staff | 6,215 FTE (2022)[3] |

| Students | 41,250 (2021/22)[4][a] |

| Undergraduates | 26,000 (2021/22)[4] |

| Postgraduates | 15,245 (2021/22)[4] |

| Location | , Scotland, UK 55°57′N 3°11′W / 55.950°N 3.183°W |

| Campus | Urban, suburban |

| Colours | Red Blue[6] |

| Website | www |

| |

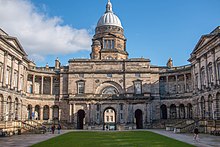

( Эдинбургский университет шотландцы : University o Edinburgh , шотландский гэльский : Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann ; сокращенно Edin. в постноминалах ) — государственный исследовательский университет, расположенный в Эдинбурге , Шотландия . Основанный городским советом на основании королевской хартии короля Джеймса VI в 1582 году и официально открытый в 1583 году, это один из четырех древних университетов Шотландии и шестой старейший постоянно действующий университет в англоязычном мире . [1] Университет сыграл решающую роль в превращении Эдинбурга в ведущий интеллектуальный центр эпохи шотландского Просвещения и способствовал тому, что город получил прозвище « Северные Афины ». [7] [8]

Три основных мировых рейтинга университетов ( ARWU , THE и QS ) постоянно помещают Эдинбургский университет в соответствующие топ-40. [9] [10] [11] Он является членом нескольких ассоциаций исследовательских университетов, в том числе Coimbra Group , Лиги европейских исследовательских университетов , Russell Group , Una Europa и Universitas 21 . [12] В финансовом году, закончившемся 31 июля 2023 года, общий доход университета составил 1,341 миллиарда фунтов стерлингов, из которых 339,5 миллиона фунтов стерлингов были получены от исследовательских грантов и контрактов. Он занимает третье место по величине фонда в Великобритании после Кембриджа и Оксфорда . [2] The university occupies five main campuses in the city of Edinburgh, which include many buildings of historical and architectural significance, such as those in the Old Town.[13]

Edinburgh is the eighth-largest university in the UK by enrolment and receives over 69,000 undergraduate applications per year, making it the third-most popular university in the UK by application volume.[14] In 2021, Edinburgh had the seventh-highest average UCAS points among British universities for new entrants. The university maintains strong links to the royal family, with Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, serving as its chancellor from 1953 to 2010, and Anne, Princess Royal, holding the position since March 2011.[15]

Notable alumni of the University of Edinburgh include inventor Alexander Graham Bell, naturalist Charles Darwin, philosopher David Hume, physicist James Clerk Maxwell, and writers such as Sir J. M. Barrie, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, J. K. Rowling,[b][16] Sir Walter Scott, and Robert Louis Stevenson.[17][18] The university has produced several heads of state and government, including three British prime ministers. Additionally, three UK Supreme Court justices were educated at Edinburgh. As of January 2023, the university has been affiliated with 19 Nobel Prize laureates, four Pulitzer Prize winners, three Turing Award winners, an Abel Prize laureate, and a Fields Medalist. Edinburgh alumni have also won a total of ten Olympic gold medals.

History[edit]

Early history[edit]

In 1557, Bishop Robert Reid of St Magnus Cathedral on Orkney made a will containing an endowment of 8,000 merks to build a college in Edinburgh.[19] Unusually for his time, Reid's vision included the teaching of rhetoric and poetry, alongside more traditional subjects such as philosophy.[19] However, the bequest was delayed by more than 25 years due to the religious revolution that led to the Reformation Parliament of 1560.[19] The plans were revived in the late 1570s through efforts by the Edinburgh Town Council, first minister of Edinburgh James Lawson, and Lord Provost William Little.[1] When Reid's descendants were unwilling to pay out the sum, the town council petitioned King James VI and his Privy Council. The King brokered a monetary compromise and granted a royal charter on 14 April 1582, empowering the town council to create a college of higher education.[19][20][21] A college established by secular authorities was unprecedented in newly Presbyterian Scotland, as all previous Scottish universities had been founded through papal bulls.[22]

Named Tounis College (Town's College), the university opened its doors to students on 14 October 1583, with an attendance of 80–90.[1] At the time, the college mainly covered liberal arts and divinity.[23][24] Instruction began under the charge of a graduate from the University of St Andrews, theologian Robert Rollock, who first served as Regent, and from 1586 as principal of the college.[25] Initially Rollock was the sole instructor for first-year students, and he was expected to tutor the 1583 intake for all four years of their degree in every subject. The first cohort finished their studies in 1587, and 47 students graduated (or 'laureated') with an M.A. degree.[25] When King James VI visited Scotland in 1617, he held a disputation with the college's professors, after which he decreed that it should henceforth be called the "Colledge [sic] of King James".[26][27] The university was known as both Tounis College and King James' College until it gradually assumed the name of the University of Edinburgh during the 17th century.[23][28]

After the deposition of King James II and VII during the Glorious Revolution in 1688, the Parliament of Scotland passed legislation designed to root out Jacobite sympathisers amongst university staff.[29] In Edinburgh, this led to the dismissal of Principal Alexander Monro and several professors and regents after a government visitation in 1690. The university was subsequently led by Principal Gilbert Rule, one of the inquisitors on the visitation committee.[29]

18th and 19th century[edit]

"You are now in a place where the best courses upon earth are within your reach... Such an opportunity you will never again have. I would therefore strongly press on you to fix no other limit to your stay in Edinborough than your having got thro this whole course. The omission of any one part of it will be an affliction & loss to you as long as you live."

Thomas Jefferson, writing to his son-in-law Thomas Mann Randolph, Jr. in 1786.[30]

The late 17th and early 18th centuries were marked by a power struggle between the university and town council, which had ultimate authority over staff appointments, curricula, and examinations.[31] After a series of challenges by the university, the conflict culminated in the council seizing the college records in 1704.[31] Relations were only gradually repaired over the next 150 years and suffered repeated setbacks.

The university expanded by founding a Faculty of Law in 1707, a Faculty of Arts in 1708, and a Faculty of Medicine in 1726.[32] In 1762, Reverend Hugh Blair was appointed by King George III as the first Regius Professor of Rhetoric and Belles-Lettres.[33] This formalised literature as a subject and marks the foundation of the English Literature department, making Edinburgh the oldest centre of literary education in Britain.[34]

During the 18th century, the university was at the centre of the Scottish Enlightenment.[35] The ideas of the Age of Enlightenment fell on especially fertile ground in Edinburgh because of the university's democratic and secular origin; its organization as a single entity instead of loosely connected colleges, which encouraged academic exchange; its adoption of the more flexible Dutch model of professorship, rather than having student cohorts taught by a single regent; and the lack of land endowments as its source of income, which meant its faculty operated in a more competitive environment.[36] Between 1750 and 1800, this system produced and attracted key Enlightenment figures such as chemist Joseph Black, economist Adam Smith, historian William Robertson, philosophers David Hume and Dugald Stewart, physician William Cullen, and early sociologist Adam Ferguson, many of which taught concurrently.[36] By the time the Royal Society of Edinburgh was founded in 1783, the university was regarded as one of the world's preeminent scientific institutions,[37] and Voltaire called Edinburgh a "hotbed of genius" as a result.[38] Benjamin Franklin believed that the university possessed "a set of as truly great men, Professors of the Several Branches of Knowledge, as have ever appeared in any Age or Country".[39] Thomas Jefferson felt that as far as science was concerned, "no place in the world can pretend to a competition with Edinburgh".[40]

In 1785, Henry Dundas introduced the South Bridge Act in the House of Commons; one of the bill's goals was to use South Bridge as a location for the university, which had existed in a hotchpotch of buildings since its establishment. The site was used to construct Old College, the university's first custom-built building, by architect William Henry Playfair to plans by Robert Adam.[41] During the 18th century, the university developed a particular forte in teaching anatomy and the developing science of surgery, and it was considered one of the best medical schools in the English-speaking world.[42] Bodies to be used for dissection were brought to the university's Anatomy Theatre through a secret tunnel from a nearby house (today's College Wynd student accommodation), which was also used by murderers Burke and Hare to deliver the corpses of their victims during the 1820s.[43][44]

The Edinburgh snowball riots of 1838 also known as the 'Wars of the Quadrangle' occurred when University of Edinburgh students engaged in what started as a snowball fight in "a spirit of harmless amusement" before becoming a two-day 'battle' at Old College with local Edinburgh residents on South Bridge which led to the Lord Provost calling from the 79th regiment to be called from Edinburgh Castle to quell the disturbance. This was later immortalised in a 92-page humorous account written by the students entitled The University Snowdrop and then later, in 1853, in a landscape by English artist, Samuel Bough.[45] [46][47]

After 275 years of governance by the town council, the Universities (Scotland) Act 1858 gave the university full authority over its own affairs.[31] The act established governing bodies including a university court and a general council, and redefined the roles of key officials like the chancellor, rector, and principal.[48]

The Edinburgh Seven were the first group of matriculated undergraduate female students at any British university.[49] Led by Sophia Jex-Blake, they began studying medicine at the University of Edinburgh in 1869. Although the university blocked them from graduating and qualifying as doctors, their campaign gained national attention and won them many supporters, including Charles Darwin.[50] Their efforts put the rights of women to higher education on the national political agenda, which eventually resulted in legislation allowing women to study at all Scottish universities in 1889. The university admitted women to graduate in medicine in 1893.[51][52] In 2015, the Edinburgh Seven were commemorated with a plaque at the university,[53] and in 2019 they were posthumously awarded with medical degrees.[54]

Towards the end of the 19th century, Old College was becoming overcrowded. After a bequest from Sir David Baxter, the university started planning new buildings in earnest. Sir Robert Rowand Anderson won the public architectural competition and was commissioned to design new premises for the Medical School in 1877.[55] Initially, the design incorporated a campanile and a hall for examination and graduation, but this was seen as too ambitious. The new Medical School opened in 1884, but the building was not completed until 1888.[56] After funds were donated by politician and brewer William McEwan in 1894, a separate graduation building was constructed after all, also designed by Anderson.[57] The resulting McEwan Hall on Bristo Square was presented to the university in 1897.[58]

The Students' Representative Council (SRC) was founded in 1884 by student Robert Fitzroy Bell.[59][60] In 1889, the SRC voted to establish Edinburgh University Union (EUU), to be housed in Teviot Row House on Bristo Square.[61] Edinburgh University Sports Union (EUSU) was founded in 1866, and Edinburgh University Women's Union (renamed the Chambers Street Union in 1964) in October 1905.[62] The SRC, EUU and Chambers Street Union merged to form Edinburgh University Students' Association (EUSA) on 1 July 1973.[63][64]

20th century[edit]

During World War I, the Science and Medicine buildings had suffered from a lack of repairs or upgrades, which was exacerbated by an influx of students after the end of the war.[65] In 1919, the university bought the land of West Mains Farm in the south of the city for the development of a new satellite campus specialising in the sciences.[66] On 6 July 1920, King George V laid the foundation of the first new building (now called the Joseph Black Building), housing the Department of Chemistry.[65] The campus was named King's Buildings in honour of George V.

New College on The Mound was originally opened in 1846 as a Free Church of Scotland college, later of the United Free Church of Scotland.[67] Since the 1930s it has been the home of the School of Divinity. Prior to the 1929 reunion of the Church of Scotland, candidates for the ministry in the United Free Church studied at New College, whilst candidates for the Church of Scotland studied in the university's Faculty of Divinity.[68] In 1935 the two institutions merged, with all operations moved to the New College site in Old Town.[69] This freed up Old College for Edinburgh Law School.[70]

The Polish School of Medicine was established in 1941 as a wartime academic initiative. While it was originally intended for students and doctors in the Polish Armed Forces in the West, civilians were also allowed to take the courses, which were taught in Polish and awarded Polish medical degrees.[71] When the school was closed in 1949, 336 students had matriculated, of which 227 students graduated with the equivalent of an MBChB and a total of 19 doctors obtained a doctorate or MD.[72] A bronze plaque commemorating the Polish School of Medicine is located in the Quadrangle of the old Medical School in Teviot Place.[73]

On 10 May 1951, the Royal (Dick) Veterinary College, founded in 1823 by William Dick,[74] was reconstituted as the Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies and officially became part of the university.[75] It achieved full faculty status as Faculty of Veterinary Medicine in 1964.

In 1955 the university opened the first department of nursing in Europe for academic study. This department was inspired by the work of Gladys Beaumont Carter and a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation.[76]

By the end of the 1950s, there were around 7,000 students matriculating annually, more than doubling the numbers from the turn of the century.[77] The university addressed this partially through the redevelopment of George Square, demolishing much of the area's historic houses and erecting modern buildings such as 40 George Square, Appleton Tower and the Main Library.[78]

On 1 August 1998, the Moray House Institute of Education, founded in 1848, merged with the University of Edinburgh, becoming its Faculty of Education. Following the internal restructuring of the university in 2002, Moray House became known as the Moray House School of Education.[79] It was renamed the Moray House School of Education and Sport in August 2019.[80]

21st century[edit]

In the 1990s it became apparent that the old Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh buildings in Lauriston Place were no longer adequate for a modern teaching hospital. Donald Dewar, the Scottish Secretary at the time, authorized a joint project between private finance, local authorities, and the university to create a modern hospital and medical campus in the Little France area of Edinburgh.[81] The new campus was named the BioQuarter. The Chancellor's Building was opened on 12 August 2002 by Prince Philip, housing the new Edinburgh Medical School alongside the new Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh.[82] In 2007, the campus saw the addition of the Euan MacDonald Centre as a research centre for motor neuron diseases, which was part-funded by Scottish entrepreneur Euan MacDonald and his father Donald.[83][84] In August 2010, author J. K. Rowling provided £10 million in funding to create the Anne Rowling Regenerative Neurology Clinic,[85] which was officially opened in October 2013.[86] The Centre for Regenerative Medicine (CRM) is a stem cell research centre dedicated to the development of regenerative treatments, which was opened in 2012.[87] CRM is also home to applied scientists working with the Scottish National Blood Transfusion Service (SNBTS) and Roslin Cells.[88]

In December 2002, the Edinburgh Cowgate Fire destroyed a number of university buildings, including some 3,000 m2 (32,000 sq ft) of the School of Informatics at 80 South Bridge.[89][90] This was replaced with the Informatics Forum on Bristo Square, completed in July 2008. Also in 2002, the Edinburgh Cancer Research Centre (ECRC) was opened on the Western General Hospital site.[91] In 2007, the MRC Human Genetics Unit formed a partnership with the Centre for Genomic & Experimental Medicine and the ECRC to create the Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine (renamed the Institute of Genetics and Cancer in 2021) on the same site.[92]

In April 2008, the Roslin Institute – an animal sciences research centre known for cloning Dolly the sheep – became part of the Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies.[93] In 2011, the school moved into a new £60 million building on the Easter Bush campus, which now houses research and teaching facilities, and a hospital for small and farm animals.[94][95]

Edinburgh College of Art, founded in 1760, formally merged with the university's School of Arts, Culture and Environment on 1 August 2011.[96][97] In 2014, the Zhejiang University-University of Edinburgh Institute (ZJE) was founded as an international joint institute offering degrees in biomedical sciences, taught in English.[98] The campus, located in Haining, Zhejiang Province, China, was established on 15 March 2016.[99]

The university began hosting a Wikimedian in Residence in 2016.[100] The residency was made into a full-time position in 2019, with the Wikimedian involved in teaching and learning activities within the scope of the University of Edinburgh WikiProject.[101]

In 2018, the University of Edinburgh was a signatory to the £1.3 billion Edinburgh and South East Scotland City Region Deal, in partnership with the UK and Scottish governments, six local authorities and all universities and colleges in the region.[102] The university committed to delivering a range of economic benefits to the region through the Data-Driven Innovation initiative.[103] In conjunction with Heriot-Watt University, the deal created five innovation hubs: the Bayes Centre, Edinburgh Futures Institute (EFI), Usher Institute, Easter Bush, and one further hub based at Heriot-Watt, the National Robotarium. The deal also included creation of the Edinburgh International Data Facility, which performs high-speed data processing in a secure environment.[104][105]

In September 2020, the university completed work on the Richard Verney Health Centre at its central area campus on Bristo Square. The facility houses a health centre and pharmacy, and the university's disability and counselling services.[106] The university's largest current expansion project is the conversion of some of the historic Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh buildings in Lauriston Place, which had been vacated in 2003 and partially developed into the Quartermile. The £120 million renovations and extension will provide space for the Edinburgh Futures Institute, an interdisciplinary hub linking arts, humanities, and social sciences with other disciplines in the research and teaching of 'complex futures'.[107][108]

Historical links[edit]

Edinburgh has a number of historical links to other universities, chiefly through its influential Medical School and its graduates, who established and developed institutions elsewhere in the world.

- College of William & Mary: the second-oldest college in the US was founded in 1693 by Edinburgh graduate James Blair, who served as the college's founding president for fifty years.[109]

- Columbia University: had its Medical School founded by Samuel Bard, an Edinburgh medical graduate.

- Dalhousie University: Edinburgh alumnus George Ramsay, the 22nd Lieutenant Governor of Nova Scotia, wanted to establish a non-denominational college in Halifax open to all.[110] The school was modelled after the University of Edinburgh, which students could attend regardless of religion or nationality.[111]

- Dartmouth College: had its School of Medicine founded by Nathan Smith, an alumnus of Edinburgh Medical School.[112]

- Harvard University: had its Medical School founded by three surgeons, one of whom was Benjamin Waterhouse, an alumnus of Edinburgh Medical School.[113]

- McGill University: had its Faculty of Medicine founded by four physicians, which included Edinburgh alumni Andrew Fernando Holmes and John Stephenson.[114][115]

- University of Pennsylvania: had its School of Medicine founded by Edinburgh graduate John Morgan, who modelled it after Edinburgh Medical School.[116][117]

- Princeton University: had its academic syllabus and structure reformed along the lines of the University of Edinburgh and other Scottish universities by its sixth president John Witherspoon, an Edinburgh theology graduate.[118][119]

- University of Sydney: founded in 1850 by Sir Charles Nicholson, a graduate of Edinburgh Medical School.

- Yale University: had its School of Medicine co-founded by Nathan Smith, an alumnus of Edinburgh Medical School.

Campuses and buildings[edit]

The university has five main sites in Edinburgh:[120]

- Central Area

- King's Buildings

- BioQuarter

- Easter Bush

- Western General

The university is responsible for several significant historic and modern buildings across the city, including St Cecilia's Hall, Scotland's oldest purpose-built concert hall and the second oldest in use in the British Isles;[121] Teviot Row House, the oldest purpose-built students' union building in the world;[61] and the restored 17th-century Mylne's Court student residence at the head of the Royal Mile.[13]

Central Area[edit]

The Central Area is spread around numerous squares and streets in Edinburgh's Southside, with some buildings in Old Town. It is the university's oldest area, occupied primarily by the College of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences and the School of Informatics. The highest concentration of university buildings is around George Square, which includes 40 George Square (formerly David Hume Tower), Appleton Tower, Main Library, and Gordon Aikman Lecture Theatre, the area's largest lecture hall. Around nearby Bristo Square lie the Dugald Stewart Building, Informatics Forum, McEwan Hall, Potterrow Student Centre, Teviot Row House, and old Medical School, which still houses pre-clinical medical courses and biomedical sciences.[44] The Pleasance, one of Edinburgh University Students' Association's main buildings, is located nearby, as is Edinburgh College of Art in Lauriston. North of George Square lies the university's Old College housing Edinburgh Law School, New College on The Mound housing the School of Divinity, and St Cecilia's Hall. Some of these buildings are used to host events during the Edinburgh International Festival and the Edinburgh Festival Fringe every summer.[122]

Pollock Halls[edit]

Pollock Halls, adjoining Holyrood Park to the east, is the university's largest residence hall for undergraduate students in their first year. The complex houses over 2,000 students during term time and consists of ten named buildings with communal green spaces between them.[123] The two original buildings, St Leonard's Hall and Salisbury Green, were built in the 19th century, while the majority of Pollock Halls dates from the 1960s and early 2000s. Two of the older houses in Pollock Halls were demolished in 2002, and a new building, Chancellor's Court, was built in their place and opened in 2003. Self-catered flats elsewhere account for the majority of university-provided accommodation. The area also includes the John McIntyre Conference Centre opened in 2009, which is the university's premier conference space.[124]

Holyrood[edit]

The Holyrood campus, just off the Royal Mile, used to be the site for Moray House Institute for Education until it merged with the university on 1 August 1998.[79] The university has since extended this campus.[125] The buildings include redeveloped and extended Sports Science, Physical Education and Leisure Management facilities at St Leonard's Land linked to the Sports Institute in the Pleasance.[126] The £80 million O'Shea Hall at Holyrood was named after the former principal of the university Sir Timothy O'Shea and was opened by Princess Anne in 2017, providing a living and social environment for postgraduate students.[127] The Outreach Centre, Institute for Academic Development (University Services Group), and Edinburgh Centre for Professional Legal Studies are also located at Holyrood.[128][129][130]

King's Buildings[edit]

The King's Buildings campus is located in the south of the city. Most of the Science and Engineering College's research and teaching activities take place at the campus, which occupies a 35-hectare site. It includes the Alexander Graham Bell Building (for mobile phones and digital communications systems), James Clerk Maxwell Building (the administrative and teaching centre of the School of Physics and Astronomy and School of Mathematics), Joseph Black Building (home to the School of Chemistry), Royal Observatory, Swann Building (the Wellcome Trust Centre for Cell Biology), Waddington Building (the Centre for Systems Biology at Edinburgh), William Rankine Building (School of Engineering's Institute for Infrastructure and Environment), and others.[131] Until 2012, the KB campus was served by three libraries: Darwin Library, James Clerk Maxwell Library, and Robertson Engineering and Science Library. These were replaced by the Noreen and Kenneth Murray Library opened for the academic year 2012/13.[132][133] The campus also hosts the National e-Science Centre (NeSC), Scotland's Rural College (SRUC), Scottish Institute for Enterprise (SIE), Scottish Microelectronics Centre (SMC), and Scottish Universities Environmental Research Centre (SUERC).

BioQuarter[edit]

The BioQuarter campus, based in the Little France area, is home to the majority of medical facilities of the university, alongside the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh. The campus houses the Anne Rowling Regenerative Neurology Clinic, Centre for Regenerative Medicine, Chancellor's Building, Euan MacDonald Centre, and Queen's Medical Research Institute, which opened in 2005.[82] The Chancellor's Building has two large lecture theatres and a medical library connected to the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh by a series of corridors.

Easter Bush[edit]

The Easter Bush campus, located seven miles south of the city, houses the Jeanne Marchig International Centre for Animal Welfare Education, Roslin Institute, Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies, and Veterinary Oncology and Imaging Centre.[94]

The Roslin Institute is an animal sciences research institute which is sponsored by BBSRC.[134] The Institute won international fame in 1996, when its researchers Sir Ian Wilmut, Keith Campbell and their colleagues created Dolly the sheep, the first mammal to be cloned from an adult cell.[135][136] A year later Polly and Molly were cloned, both sheep contained a human gene.[137]

Western General[edit]

The Western General campus, in proximity to the Western General Hospital, contains the Biomedical Research Facility, Edinburgh Clinical Research Facility, and Institute of Genetics and Cancer (formerly the Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine).

- Modern architecture at the University of Edinburgh

- Erskine Williamson Building, King's Buildings

Organisation and administration[edit]

Governance[edit]

In common with the other ancient universities of Scotland, and in contrast to nearly all other pre-1992 universities which are established by royal charters, the University of Edinburgh is constituted by the Universities (Scotland) Acts 1858 to 1966. These acts provide for three major bodies in the governance of the university: the University Court, the General Council, and the Senatus Academicus.[48]

University Court[edit]

The University Court is the university's governing body and the legal person of the university, chaired by the rector and consisting of the principal, Lord Provost of Edinburgh, and of Assessors appointed by the rector, chancellor, Edinburgh Town Council, General Council, and Senatus Academicus. By the Universities (Scotland) Act 1889, it is a body corporate, with perpetual succession and a common seal. All property belonging to the university at the passing of the Act was vested in the Court.[138] The present powers of the Court are further defined in the Universities (Scotland) Act 1966, including the administration and management of the university's revenue and property, the regulation of staff salaries, and the establishment and composition of committees of its own members or others.

General Council[edit]

The General Council consists of graduates, academic staff, current and former University Court members. It was established to ensure that graduates have a continuing voice in the management of the university. The Council is required to meet twice per year to consider matters affecting the wellbeing and prosperity of the university. The Universities (Scotland) Act 1966 gave the Council the power to consider draft ordinances and resolutions, to be presented with an annual report of the work and activities of the university, and to receive an audited financial statement.[139] The Council elects the chancellor of the university and three Assessors on the University Court.

Senatus Academicus[edit]

The Senatus Academicus is the university's supreme academic body, chaired by the principal and consisting of the professors, heads of departments, and a number of readers, lecturers and other teaching and research staff.[140] The core function of the Senatus is to regulate and supervise the teaching and discipline of the university and to promote research. The Senatus elects four Assessors on the University Court. The Senatus meets three times per year, hosting a presentation and discussion session which is open to all members of staff at each meeting.

University officials[edit]

The university's three most significant officials are its chancellor, rector, and principal, whose rights and responsibilities are largely derived from the Universities (Scotland) Act 1858.

The office of chancellor serves as the titular head and highest office of the university. Their duties include conferring degrees and enhancing the profile and reputation of the university on national and global levels.[141] The chancellor is elected by the university's General Council, and a person generally remains in the office for life. Previous chancellors include former prime minister Arthur Balfour and novelist Sir J. M. Barrie.[141] Princess Anne has held the position since March 2011 succeeding Prince Philip.[15] She is also Patron of the university's Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies.

The principal is responsible for the overall operation of the university in a chief executive role.[142] The principal is formally nominated by the Curators of Patronage and appointed by the University Court. They are the President of the Senatus Academicus and a member of the University Court ex officio.[142] The principal is also automatically appointed vice-chancellor, in which role they confer degrees on behalf of the chancellor. Previous principals include physicist Sir Edward Appleton and religious philosopher Stewart Sutherland. The current principal is nephrologist Sir Peter Mathieson, who has held the position since February 2018.[143]

The office of rector is elected every three years by the staff and matriculated students. The primary role of the rector is to preside at the University Court.[144] The rector also chairs meetings of the General Council in absence of the chancellor. They work closely with students and Edinburgh University Students' Association. Previous rectors include microbiologist Sir Alexander Fleming, and former Prime Ministers Sir Winston Churchill and David Lloyd George. The current rector is activist and writer Simon Fanshawe, who has held the position since March 2024.[144][145]

Colleges and schools[edit]

In 2002, the university was reorganised from its nine faculties into three 'Colleges'.[146] While technically not a collegiate university, it comprises the Colleges of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences (CAHSS), Science & Engineering (CSE) and Medicine & Vet Medicine (CMVM). Within these colleges are 'Schools', which either represent one academic discipline such as Informatics or assemble adjacent academic disciplines such as the School of History, Classics and Archaeology. While bound by College-level policies, individual Schools can differ in their organisation and governance. As of 2021, the university has 21 schools in total.[147]

Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences[edit]

The College took on its current name of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences in 2016 after absorbing the Edinburgh College of Art in 2011.[148] CAHSS offers more than 280 undergraduate degree programmes, 230 taught postgraduate programmes, and 200 research postgraduate programmes.[149][150] Twenty subjects offered by the college were ranked within the top 10 nationally in the 2022 Complete University Guide.[151] It includes the oldest English Literature department in Britain,[34] which was ranked 7th globally in the 2021 QS Rankings by Subject in English Language & Literature.[152] The college hosts Scotland's ESRC Doctoral Training Centre (DTC), the Scottish Graduate School of Social Science. The college is the largest of the three colleges by enrolment, with 26,130 students and 3,089 academic staff.[153][5]

- Business School

- Edinburgh College of Art

- Moray House School of Education and Sport

- School of Divinity

- School of Economics

- School of Health in Social Science

- School of History, Classics and Archaeology

- School of Law

- School of Literatures, Languages and Cultures

- School of Philosophy, Psychology and Language Sciences

- School of Social and Political Science

- Centre for Open Learning

- Edinburgh Futures Institute

Medicine and Veterinary Medicine[edit]

Edinburgh Medical School was widely considered the best medical school in the English-speaking world throughout the 18th century and the first half of the 19th century and contributed significantly to the university's international reputation.[154][155] Its graduates founded medical schools all over the world, including at five of the seven Ivy League universities (Columbia, Dartmouth, Harvard, Pennsylvania, and Yale); those in McGill, Montréal, Sydney, and Vermont; the Royal Postgraduate Medical School (now part of Imperial College London), Middlesex Hospital, and the London School of Medicine for Women (both now part of UCL).

In the 21st century, the medical school has continued to excel, and it is associated with 13 Nobel Prize recipients: seven recipients of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine and six of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry.[156] In 2021, it was ranked third in the UK by The Times University Guide,[157] and the Complete University Guide. In 2022, it was ranked the UK's best medical school by the Guardian University Guide,[158] It also ranked 21st in the world by both the Times Higher Education World University Rankings and the QS World University Rankings in 2021.[159]

The Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies is a world leader in veterinary education, research and practice. The eight original faculties formed four Faculty Groups in August 1992. Medicine and Veterinary Medicine became one of these, and in 2002 became the smallest of the three colleges, with 7,740 students and 1,896 academic staff.[153][5] The university's teaching hospitals include the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, Western General Hospital, St John's Hospital, Livingston, Roodlands Hospital, and Royal Hospital for Children and Young People.[160][161][162]

Science and Engineering[edit]

In the 16th century, science was taught as "natural philosophy" in the university. The 17th century saw the institution of the University Chairs of Mathematics and Botany, followed the next century by Chairs of Natural History, Astronomy, Chemistry and Agriculture. It was Edinburgh's professors who took a leading part in the formation of the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1783. Joseph Black, Professor of Medicine and Chemistry at the time, founded the world's first Chemical Society in 1785.[163] The first named degrees of Bachelor and Doctor of Science was instituted in 1864, and a separate Faculty of Science was created in 1893 after three centuries of scientific advances at Edinburgh.[163] The Regius Chair in Engineering was established in 1868, and the Regius Chair in Geology in 1871. In 1991 the Faculty of Science was renamed the Faculty of Science and Engineering, and in 2002 it became the College of Science and Engineering. The college has 11,745 students and 2,937 academic staff.[153][5]

- School of Biological Sciences

- School of Chemistry

- School of Engineering

- School of GeoSciences

- School of Informatics

- School of Mathematics

- School of Physics and Astronomy

Sub-units, centres and institutes[edit]

Some subunits, centres and institutes within the university are listed as follows:[164]

- Artificial Intelligence Applications Institute (AIAI)

- Bayes Centre

- Centre for the History of the Book (CHB)

- Centre for Regenerative Medicine (CRM)

- Centre for the Study of World Christianity (CSWC)

- Centre for Theology and Public Issues (CTPI)

- Digital Curation Centre (DCC)

- Edinburgh Cancer Research Centre (ECRC)

- Edinburgh Dental Institute (EDI)

- Edinburgh Futures Institute (EFI)

- Edinburgh Parallel Computing Centre (EPCC)

- Edinburgh School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture (ESALA)

- Euan MacDonald Centre

- Higgs Centre for Theoretical Physics

- Institute for Advanced Studies in the Humanities (IASH)

- International Centre for Mathematical Sciences (ICMS)

- Institute for the Study of Science, Technology and Innovation (ISSTI)

- Koestler Parapsychology Unit

- Laboratory for Foundations of Computer Science (LFCS)

- MRC Human Genetics Unit (MRC HGU)

- MRC Centre for Inflammation Research

- Nursing Studies

- Roslin Institute

- Salvesen Mindroom Research Centre

- Scottish Studies

- UK Centre for Astrobiology (UKCA)

- Usher Institute

Staff, Community and Networking[edit]

In June 2024, the University employed over 12,390 full time equivalent staff, an increase of 508 over the previous year:[165]

| College of Arts, Humanities & Social Sciences | 2,949 |

| College of Medicine & Veterinary Medicine | 2,983 |

| College of Science & Engineering | 2,735 |

| Corporate Services Group | 2,281 |

| Information Services Group | 733 |

| University Secretaries Group | 713 |

| University of Edinburgh Total: | 12,394 |

As part of the university's support for researchers,[166] each College has Research Staff Societies that include postdoc societies, and organisations specific to each school.[167] Cross-curricula Research Networks bring together researchers working on similar topics.[168]

Pride Edinburgh parade, 2024.[169]

Independently of the College hierarchy, aligned with the university's EDI policy, seven Staff Networks bring together and represent diverse staff groups:[170]

- Disabled Staff Network[171]

- Staff BAME Network[172]

- Edinburgh Race Equality Network[173]

- Staff Pride Network[169]

- University & College Unions incorporating the national academic union[174] and the in-house Edinburgh University Union[175]

- Long-term Research Staff Network[176]

- Support for Technicians[177] and Steering Committee[178]

Industrial action[edit]

Staff at the university engaged in the sector-wide 2018–2023 UK higher education strikes called by the University and College Union over disputes regarding USS pensions, pay, and working conditions. A Marking and Assessment Boycott[179] that commenced on 20 April 2023[180] was called off on 6 September 2023.[181] However, the UCU voted to continue strike action throughout the rest of September.[182][183]

Academic profile[edit]

The university is a member of the Russell Group of research-led British universities, and the Sutton 13 group of top-ranked universities in the UK.[184] It is the only British university to be a member of both the Coimbra Group and the League of European Research Universities, and it is a founding member of Una Europa and Universitas 21, both international associations of research-intensive universities.[185] The university maintains historically strong ties with the neighbouring Heriot-Watt University for teaching and research. Edinburgh also offers a wide range of free online MOOC courses on three global platforms Coursera, Edx and FutureLearn.[186][187]

Admissions[edit]

| 2023 | 2022 | 2021 | 2020 | 2019 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Applications | 69,377 | 75,438 | 68,954 | 62,220 | 60,983 |

| Offers | 27,608 | 25,210 | 32,432 | 31,510 | 27,878 |

| Offer Rate (%) | 39.8 | 33.0 | 47.0 | 50.6 | 45.7 |

| Enrolls | 6,409 | 6,111 | 8,083 | 7,344 | 6,346 |

| Yield (%) | 23.2 | 24.2 | 24.9 | 23.3 | 22.8 |

| Applicant/Enrolled Ratio | 10.82 | 12.34 | 8.53 | 8.47 | 9.61 |

| Average Entry Tariff[188] | — | — | 197 | 190 | 186 |

| Domicile[189] and Ethnicity[190] | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| British White | 47% | ||

| British Ethnic Minorities[c] | 9% | ||

| International EU | 9% | ||

| International Non-EU | 35% | ||

| Undergraduate Widening Participation Indicators[191][192] | |||

| Female | 61% | ||

| Private School | 36% | ||

| Low Participation Areas[d] | 9% | ||

In 2021, the University of Edinburgh had the seventh-highest average entry standards amongst universities in the UK, with new undergraduates averaging 197 UCAS points, equivalent to just above AAAA in A-level grades.[188] It gave offers of admission to 33% of its 18 year old applicants in 2022, the fourth-lowest amongst the Russell Group.[193]

In 2022, excluding courses within Edinburgh College of Art, the most competitive courses for Scottish applicants were Oral Health Science (9%), Business (11%), Philosophy & Psychology (14%), Social Work (15%), and International Business (15%).[194] For students from the rest of the UK, the most competitive courses were Nursing (5%), Medicine (6%), Veterinary Medicine (6%), Psychology (8%), and Politics, Philosophy and Economics (10%).[195] For international students, the most competitive courses were Medicine (5%), Nursing (7%), Business (11%), Politics, Philosophy andEconomics (12%), and Sociology (13%).[196]

For the academic year 2019/20, 36.8% of Edinburgh's new undergraduates were privately educated, the second-highest proportion among mainstream British universities, behind only Oxford.[197] As of August 2021, it has a higher proportion of female than male students with a male to female ratio of 38:62 in the undergraduate population, and the undergraduate student body is composed of 30% Scottish students, 32% from the rest of the UK, 10% from the EU, and 28% from outside the EU.[5]

Graduation[edit]

At graduation ceremonies, graduates are being 'capped' with the Geneva bonnet, which involves the university's principal tapping them on the head with the cap while they receive their graduation certificate.[198] The velvet-and-silk hat has been used for over 150 years, and legend says that it was originally made from cloth taken from the breeches of 16th-century scholars John Knox or George Buchanan.[199] However, when the hat was last restored in the early 2000s, a label dated 1849 was discovered bearing the name of Edinburgh tailor Henry Banks, although some doubt remains whether he manufactured or restored the hat.[198][200] In 2006, a university emblem that had been taken into space by astronaut and Edinburgh graduate Piers Sellers was incorporated into the Geneva bonnet.[201]

Library system[edit]

Pre-dating the university by three years, Edinburgh University Library was founded in 1580 through the donation of a large collection by Clement Litill, and today is the largest academic library collection in Scotland.[202][203] The Brutalist style eight-storey Main Library building in George Square was designed by Sir Basil Spence. At the time of its completion in 1967, it was the largest building of its type in the UK, and today is a category A listed building.[204] The library system also includes many specialised libraries at the college and school level.[205]

Exchange programmes[edit]

The university offers students the opportunity to study in Europe and beyond via the European Union's Erasmus+ programme[e] and a variety of international exchange agreements with around 300 partners institutions in nearly 40 countries worldwide.[207]

University-wide exchanges are open to almost any student whose degree permits a year abroad and who can find a suitable course combination. The list of partner institutions is shown as follows (part of):[208]

- Asia-Pacific: Fudan University, University of Hong Kong, University of Melbourne, Seoul National University, University of Sydney, National University of Singapore, Nanyang Technological University

- Europe: University of Amsterdam, University of Copenhagen, University of Helsinki, Lund University, Sciences Po, University College Dublin, Uppsala University

- Latin America: National Autonomous University of Mexico, Pontifical Catholic University of Chile, University of São Paulo

- Northern America: Boston College, Barnard College of Columbia University, University of California (except for Merced and San Francisco),[209] Caltech, University of Chicago, Cornell University, Georgetown University, McGill University, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, University of Pennsylvania, University of Texas at Austin, University of Toronto, University of Virginia, Washington University in St. Louis

Subject-specific exchanges are open to students studying in particular schools or subject areas, including exchange programmes with Carnegie Mellon University, Emory University, Ecole du Louvre, EPFL, ETH Zurich, ESSEC Business School, ENS Paris, HEC Paris, Humboldt University of Berlin, Karolinska Institute, Kyoto University, LMU Munich, University of Michigan, Peking University, Rhode Island School of Design, Sorbonne University, TU München, Waseda University, Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, and others.[208]

Rankings and reputation[edit]

| National rankings | |

|---|---|

| Complete (2025)[210] | 15 |

| Guardian (2024)[211] | 14 |

| Times / Sunday Times (2024)[212] | 13 |

| Global rankings | |

| ARWU (2023)[213] | 38 |

| QS (2025)[214] | 27 |

| THE (2024)[215] | =30 |

In the 2021 Research Excellence Framework (REF), which evaluated work produced between 2014 and 2021, Edinburgh ranked 4th by research power and 15th by GPA amongst British universities.[216] The university fell four places in GPA when compared to the 2014 REF, but retained its place in research power.[217] 90 per cent of the university's research activity was judged to be 'world leading' (4*) or 'internationally excellent' (3*), and five departments – Computer Science, Informatics, Sociology, Anthropology, and Development Studies – were ranked as the best in the UK.[218]

In the 2015 THE Global Employability University Ranking, Edinburgh ranked 23rd in the world and 4th in the UK for graduate employability as voted by international recruiters.[219] A 2015 government report found that Edinburgh was one of only two Scottish universities (along with St Andrews) that some London-based elite recruitment firms considered applicants from, especially in the field of financial services and investment banking.[220] When The New York Times ranked universities based on the employability of graduates as evaluated by recruiters from top companies in 20 countries in 2012, Edinburgh was placed at 42nd in the world and 7th in Britain.[221]

Edinburgh was ranked 24th in the world and 5th in the UK by the 2021 Aggregate Ranking of Top Universities, a league table based on the three major world university rankings, ARWU, QS and THE.[222] In the 2022 U.S. News & World Report, Edinburgh ranked 32nd globally and 5th nationally.[223] The 2022 World Reputation Rankings placed Edinburgh at 32nd worldwide and 5th nationwide.[224] In 2023, it ranked 73rd amongst the universities around the world by the SCImago Institutions Rankings.[225]

The disparity between Edinburgh's research capacity, endowment and international status on the one hand, and its ranking in national league tables on the other, is largely due to the impact of measures of 'student satisfaction'.[226] Edinburgh was ranked last in the UK for teaching quality in the 2012 National Student Survey,[227] with the 2015 Good University Guide stating that this stemmed from "questions to do with the promptness, usefulness and extent of academic feedback", and that the university "still has a long way to go to turn around a poor position".[228] Edinburgh improved only marginally over the next years, with the 2021 Good University Guide still ranking it in the bottom 10 domestically in both teaching quality and student experience.[229] Edinburgh was ranked 122nd out of 128 universities for student satisfaction in the 2022 Complete University Guide, although it was ranked 12th overall.[230] The 2024 Guardian University Guide ranked Edinburgh 14th overall, but 50th out of 120 universities in teaching satisfaction, and lowest among all universities in satisfaction with feedback.[231]

In the 2022 Complete University Guide, 32 out of the 49 subjects offered by Edinburgh were ranked within the top 10 in the UK, with Asian Studies (4th), Chemical Engineering (4th), Education (2nd), Geology (5th), Linguistics (5th), Mechanical Engineering (5th), Medicine (5th), Music (5th), Nursing (1st), Physics & Astronomy (5th), Social Policy (5th), Theology & Religious Studies (4th), and Veterinary Medicine (2nd) within the top 5.[230] The 2021 THE World University Rankings by Subject ranked Edinburgh 10th worldwide in Arts and Humanities, 15th in Law, 16th in Psychology, 21st in Clinical, Pre-clinical & Health, 22nd in Computer Science, 28th in Education, 28th in Life Science, 43rd in Business & Economics, 44th in Social Sciences, 45th in Physical Sciences, and 86th in Engineering & Technology.[232] The 2023 QS World University Rankings by Subject placed Edinburgh at 10th globally in Arts & Humanities, 23rd in Life Sciences & Medicine, 36th in Natural Sciences, 50th in Social Sciences & Management, and 59th in Engineering & Technology.[233] According to CSRankings, computer science at Edinburgh was ranked 1st in the UK and 36th globally, and Edinburgh was the best in natural language processing (NLP) in the world.[234]

Student life[edit]

Students' Association[edit]

Edinburgh University Students' Association (EUSA) consists of the students' union and the students' representative council. EUSA's buildings include Teviot Row House, The Pleasance, Potterrow Student Centre, Kings Buildings House, as well as shops, cafés and refectories across the various campuses. Teviot Row House is considered the oldest purpose-built student union building in the world.[61][235] Most of these buildings are operated as Edinburgh Festival Fringe venues during August. EUSA represents students to the university and the wider world, and is responsible for over 250 student societies at the university. The association has five sabbatical office bearers – a president and four vice presidents. EUSA is affiliated with the National Union of Students (NUS).

Performing arts[edit]

Amateur dramatic societies benefit from Edinburgh being an important cultural hub for comedy, amateur and fringe theatre throughout the UK, most prominently through the Edinburgh Festival Fringe.[236]

The Edinburgh University Music Society (EUMS) is a student-run musical organisation, which is Scotland's oldest student's musical society; it can be traced back to a concert in February 1867.[237] It performs three concert series throughout the year whilst also undertaking a programme of charity events and education projects.[238]

The Edinburgh University Theatre Company (EUTC), founded in 1890 as the Edinburgh University Drama Society, is known for running Bedlam Theatre, the oldest student-run theatre in Britain and venue for the Fringe.[239][240] EUTC also funds acclaimed improvisational comedy troupe The Improverts during term time and the Fringe.[241][242] Alumni include Sir Michael Boyd, Ian Charleson, Kevin McKidd, and Greg Wise.

The Edinburgh Studio Opera (formerly Edinburgh University Opera Club) is a student opera company in Edinburgh. It performs at least one fully staged opera each year.[243] The Edinburgh University Savoy Opera Group (EUSOG) is an opera and musical theatre company founded by students in 1961 to promote and perform the comic operettas of Sir William Gilbert and Sir Arthur Sullivan, collectively known as Savoy Operas after the theatre in which they were originally staged.[244]

The Edinburgh University Footlights are a musical theatre company founded in 1989 and produce two large scale shows a year.[245][246] One of the founders is the Theatre Producer Colin Ingram.[247] Theatre Parodok, founded in 2004, is a student theatre company that aims to produce shows that are "experimental without being exclusive". They stage one large show each semester and one for the festival.[248]

Media[edit]

The Student is a fortnightly student newspaper. Founded in 1887 by writer Robert Louis Stevenson, it is the oldest student newspaper in the United Kingdom.[249] Former writers of the newspaper include politicians Gordon Brown, Robin Cook, and Lord Steel of Aikwood.[250][251] It has been independent of the university since 1992, but was forced to temporarily fold in 2002 due to increasing debts. The newspaper won a number of student newspaper awards in the years following its relaunch.[249]

The Journal was an independent publication, established in 2007 by three students and former writers for The Student. It was also distributed to other higher education institutions in the city, such as Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh Napier University, and Telford College. It was the largest such publication in Scotland, with a print run of 10,000 copies. Despite winning a number of awards for its journalism, the magazine folded in 2015 due to financial difficulties.[252]

FreshAir, launched on 3 October 1992, is an alternative music student radio station. The station is one of the oldest surviving student radio stations in the UK, and won the "Student Radio Station of the Year" award at the annual Student Radio Awards in 2004.[253]

In September 2015, the Edinburgh University Student Television (EUTV) became the newest addition to the student media scene at the university, producing a regular magazine-style programme, documentaries and other special events.[254]

Sport[edit]

Student sport at Edinburgh consists of clubs covering the more traditional rugby, football, rowing and judo, to the more unconventional korfball, gliding and mountaineering. In 2021, the university had over 65 sports clubs run by Edinburgh University Sports Union (EUSU).[255]

The Scottish Varsity, known as the "world's oldest varsity match", is a rugby match played annually against the University of St Andrews dating back over 150 years.[256] Discontinued in the 1950s, the match was resurrected in 2011 and was staged in London at the home of London Scottish RFC. It is played at the beginning of the academic year, and since 2015 has been staged at Murrayfield Stadium in Edinburgh.[257]

The Scottish Boat Race is an annual rowing race between the Glasgow University Boat Club and the Edinburgh University Boat Club, rowed between competing eights on the River Clyde in Glasgow, Scotland. Started in 1877, it is believed to be the third-oldest university boat race in the world, predated by the Oxford and Cambridge Boat Race and the Harvard–Yale Regatta.[258]

Edinburgh athletes have repeatedly been successful at the Olympic Games: Sprinter Eric Liddell won gold and bronze at the 1924 Summer Olympics. At the 1948 Summer Olympics, alumnus Jackie Robinson won a gold medal with the American Basketball team. Trap shooter Bob Braithwaite secured a gold medal at the 1968 Summer Olympics. Cyclist Sir Chris Hoy won six gold and one silver medal between 2000 and 2012. Rower Dame Katherine Grainger won a gold medal at the 2012 Summer Olympics, and four further silver medals between 2000 and 2016. Edinburgh was the most successful UK university at the 2012 Games with two gold medals from Hoy and one from Grainger.[259]

Student activism[edit]

There are a number of campaigning societies at the university. The largest of these include the environment and poverty campaigning group People & Planet and Amnesty International Society. International development organisations include Edinburgh Global Partnerships, which was established as a student-led charity in 1990.[260] There is also a significant left-wing presence on campus,[261] including an anti-austerity group, Edinburgh University Anarchist Society, Edinburgh University Socialist Society, Edinburgh Young Greens, Feminist Society, LGBT+ Pride,[262] Marxist Society, and Students for Justice in Palestine.[263]

Protests, demonstrations and occupations are regular occurrences at the university.[264][265][266] The activist group People & Planet took over Charles Stewart House in 2015 and again in 2016 in protest over the university's investment in companies active in arms manufacturing or fossil fuel extraction.[267][268] In May 2015, a security guard was charged in relation to the occupations.[269]

Gaza protest[edit]

In May 2024, student activists set up a protest camp in the Old College Quad, with some also beginning a hunger strike.[270] They alleged the university continued to hold investments that could provide proxy support for the Israeli invasion of the Gaza Strip. A divestment campaign won the support of more than 600 staff and a number of staff networks, and was overwhelmingly endorsed by the students' union.[271] Students pledged to continue their strike until the university sold its investments in Alphabet Inc. and Amazon, which students alleged were providing cloud services to the Israeli government. The students also called for the university to cease using BlackRock as manager for £50 million of the university's £709 million investment portfolio.[272]

In a response to the student protesters, Principal Mathieson said the University would "respect [their] right to peaceful and lawful protest", and appealed to hunger strikers "not to take risks with their own health, safety and wellbeing". He also challenged some of the students' claims, stating that the university practiced responsible investment, including through Blackrock's ESG fund.[273] On 16 May, the university announced a working group designed to "review the definition of armaments and controversial weapons in the context of the University's investments" to begin at the end of the month,[274][275] and a further consultation of staff and student views towards the university's principles of ethical investing. From early June, students removed their encampment.[276]

Student co-operatives[edit]

There are three student-run co-operatives associated with the University: Edinburgh Student Housing Co-operative (ESHC), providing affordable housing for 106 students;[277] the Hearty Squirrel Food Cooperative, providing local, organic and affordable food to students and staff;[278] and the SHRUB Coop, a swap and re-use hub aimed at reducing waste and promoting sustainability.[279] Of these, only the Hearty Squirrel Co-operative operates on campus. ESHC is based on the Bruntsfield Links south of the University's central campus, and hosts students from all three city universities and Edinburgh College. The SHRUB co-operative was formed partly by University of Edinburgh students but is now run by interested members from across Edinburgh. The co-operatives form part of the Students for Cooperation network.[280]

Notable people[edit]

The university is associated with some of the most significant intellectual and scientific contributions in human history, which include: the foundation of Antiseptic surgery (Joseph Lister),[281] Bayesian statistics (Thomas Bayes),[282] Economics (Adam Smith),[283] Electromagnetism (James Clerk Maxwell),[284] Evolution (Charles Darwin),[285][286] Knot theory (Peter Guthrie Tait),[287] modern Geology (James Hutton),[288] Nephrology (Richard Bright),[289] Endocrinology (Edward Albert Sharpey-Schafer),[290] Hematology (William Hewson),[291] Dermatology (Robert Willan),[292] Epigenetics (C. H. Waddington),[293] Gestalt psychology (Kurt Koffka), Thermodynamics (William Rankine),Colloid chemistry (Thomas Graham),[294] and Wave theory (Thomas Young); the discovery of Brownian motion (Robert Brown),[295] Magnesium, carbon dioxide, latent heat and specific heat (Joseph Black),[296][297] chloroform anaesthesia (Sir James Young Simpson),[298] Hepatitis B vaccine (Sir Kenneth Murray),[299] Cygnus X-1 black hole (Paul Murdin),[300] Higgs mechanism (Sir Tom Kibble),[301][302] structure of DNA (Sir John Randall),[303] HPV vaccine (Ian Frazer), Iridium and Osmium (Smithson Tennant),[304] Nitrogen (Daniel Rutherford),[305] Strontium (Thomas Charles Hope),[306] and SARS coronavirus (Zhong Nanshan);[307] and the invention of the Stirling engine (Robert Stirling),[308] Cavity magnetron (Sir John Randall),[309] ATM (John Shepherd-Barron),[310] refrigerator (William Cullen),[311] diving chamber (John Scott Haldane),[312] reflecting telescope (James Gregory),[313] hypodermic syringe (Alexander Wood),[314][315] kaleidoscope (Sir David Brewster),[316] pneumatic tyre (John Boyd Dunlop),[317] telephone (Alexander Graham Bell),[318] telpherage (Fleeming Jenkin), and vacuum flask (Sir James Dewar).[319]

Other notable alumni and academic staff of the university have included signatories to the US Declaration of Independence Benjamin Rush,[320] James Wilson[321] and John Witherspoon,[322] actors Ian Charleson,[323] Robbie Coltrane and Kevin McKidd, architects Robert Adam,[324] William Thornton, William Henry Playfair,[325] Sir Basil Spence and Sir Nicholas Grimshaw, astronaut Piers Sellers,[326] biologists Sir Adrian Bird,[327] Sir Richard Owen[328] and Sir Ian Wilmut,[329] business executives Tony Hayward, Alan Jope, Lars Rasmussen and Susie Wolff, composer Max Richter, economists Kenneth E. Boulding[330] and Thomas Chalmers, historians Thomas Carlyle[331] and Neil MacGregor, journalists Laura Kuenssberg and Peter Pomerantsev, judges Lord Reed[332] and Lord Hodge,[333] mathematicians Sir W. V. D. Hodge,[334] Colin Maclaurin[335] and Sir E. T. Whittaker,[336] philosophers Benjamin Constant, Adam Ferguson,[337] Ernest Gellner and David Hume,[338] physicians Thomas Addison,[339] William Cullen,[340] Valentín Fuster, Thomas Hodgkin[341] and James Lind,[342] pilot Eric Brown,[343] surgeons James Barry,[344] Joseph Bell,[345] Robert Liston[346] and B. K. Misra,[347] sociologists Sir Patrick Geddes[348] and David Bloor,[349] writers Sir J. M. Barrie,[350] Sir Arthur Conan Doyle,[351][352] John Fowles, Oliver Goldsmith, J. K. Rowling,[f][16] Sir Walter Scott[353] and Robert Louis Stevenson,[354] Chancellors of the Exchequer John Anderson[355] and Lord Henry Petty,[356] former Deputy Prime Minister of New Zealand Sir Michael Cullen, current Vice President of Syria Najah al-Attar, former Director General of MI5 Stella Rimington, First Lords of the Admiralty Lord Melville, Robert Dundas, 2nd Viscount Melville, Lord Minto and Lord Selkirk, Foreign Secretaries Robin Cook[357] and Sir Malcolm Rifkind,[358] former acting First Minister of Scotland Jim Wallace, and Olympic gold medallists Bob Braithwaite, Katherine Grainger, Sir Chris Hoy and Eric Liddell.[359]

- Notable Edinburgh alumni before the 20th century

- Robert Adam, neoclassical architect

- J. M. Barrie, novelist and playwright

- James Barry, surgeon

- Thomas Bayes, statistician

- Joseph Black, physicist and chemist

- Richard Bright, physician, father of nephrology

- Robert Brown, botanist, discovered Brownian motion

- Thomas Carlyle, essayist, historian and philosopher

- Thomas Chalmers, political economist

- Charles Darwin, naturalist and biologist

- Adam Ferguson, philosopher and historian

- David Hume, philosopher

- James Hutton, geologist, father of modern geology

- James Clerk Maxwell, mathematician and physicist

- Richard Owen, biologist, coined the term dinosaur

- Macquorn Rankine, engineer, founding contributor to thermodynamics

- Benjamin Rush, signatory of the United States Declaration of Independence

- Walter Scott, novelist and poet

- James Young Simpson, physician

- Robert Louis Stevenson, novelist and poet

- Dugald Stewart, philosopher and mathematician

- John Witherspoon, Founding Father of the United States

Nobel and Nobel equivalent prizes[edit]

As of August 2023[update], 19 Nobel Prize laureates have been affiliated with the university as alumni, faculty members or researchers (three additional laureates acted as administrative staff),[362] including one of the fathers of quantum mechanics Max Born,[363] theoretical physicist Peter Higgs,[364] chemist Sir Fraser Stoddart,[365] immunologist Peter C. Doherty,[366] economist Sir James Mirrlees,[367] discoverer of Characteristic X-ray (Charles Glover Barkla)[368] and the mechanism of ATP synthesis (Peter D. Mitchell),[369] and pioneer in cryo-electron microscopy (Richard Henderson)[370] and in-vitro fertilisation (Sir Robert Edwards).[371] Turing Award winners Geoffrey Hinton,[372] Robin Milner[373] Leslie Valiant,[374] and mathematician Sir Michael Atiyah,[375] Fields Medalist and Abel Prize laureate, are associated with the university.

In the following table, the number following a person's name is the year they received the Nobel prize. In particular, a number with an asterisk (*) means the person received the award while they were working at the university (including emeritus staff). A name underlined implies that this person has been listed previously (i.e., multiple affiliations).

| Category | Alumni | Long-term academic staff | Short-term academic staff |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physics (4) |

|

| |

| Chemistry (6) |

|

|

|

| Physiology or Medicine (7) |

|

|

|

| Economics (1) |

| ||

| Peace (1) |

|

Heads of state and government[edit]

In popular culture[edit]

The University of Edinburgh has featured prominently in a number of works of popular culture.

- События убийств Бёрка и Хэйра , в которых участвовали эдинбургский лектор Роберт Нокс и факультет анатомии, широко появлялись в популярной культуре. [398] They became the basis for Robert Louis Stevenson's short story The Body Snatcher (1884), and most recently in 2010 for Burke & Hare, a black comedy film starring Simon Pegg and Andy Serkis. Scenes were filmed at the old School of Anatomy.[399]

- Многие работы Артура Конан Дойля черпали вдохновение у его наставников в университете. Джозеф Белл , лектор и хирург, известный тем, что делал выводы на основе мельчайших наблюдений, стал архетипом вымышленного сыщика Конан Дойля Шерлока Холмса . Уильям Резерфорд , профессор физиологии Конан Дойля, предоставил шаблон для профессора Челленджера , главного героя его научно-фантастического произведения «Затерянный мир» (1912). Челленджера Эдинбург также является альма-матер в книгах.

- Доктор Фу Маньчжу , вымышленный суперзлодей, созданный Саксом Ромером в 1912 году, заявил, что «я доктор философии из Эдинбурга, доктор права из Крайстс-колледжа , доктор медицины из Гарварда . Мои друзья из вежливости звонят я «Доктор». [г] В 2010 году связи Фу Маньчжурии с университетом, где он предположительно получил докторскую степень, были расследованы в псевдодокументальном фильме Майлза Джаппа (также выпускника Эдинбурга) для BBC Radio 4 . [400] [401]

- В фильме « Путешествие к центру Земли » (1959), экранизации Жюля Верна , одноименного романа главный герой сэр Оливер Линденбрук — профессор геологии в университете. Первая сцена, где Линденбрук обращается к студентам, снята в центральном дворе колледжа Старого . [402]

- Исторический фильм «Огненные колесницы» (1981) основан на истории олимпийского бегуна и выпускника Эдинбурга Эрика Лидделла и включает сцены, снятые за пределами Актового зала Нового колледжа. [403] Лидделла играет Ян Чарльсон , который также является выпускником Эдинбурга.

- В романе «Последний король Шотландии » (1998) Джайлза Фодена вымышленный главный герой доктор Николас Гарриган - врач, недавно окончивший Эдинбург. 2006 года В одноименном фильме играет Джеймс МакЭвой доктора Гарригана с таким же прошлым.

- В американском телешоу NCIS (2003 – настоящее время) главный судмедэксперт доктор Дональд «Даки» Маллард изучал медицину в Эдинбурге. Ари Хасвари , главный антагонист шоу первых двух сезонов, также изучал медицину в Эдинбурге. [404]

- В романе «Один день » (2009) главные герои Декстер и Эмма окончили Эдинбург. В августе 2011 года был выпущен художественный фильм по книге под названием « Один день в главных ролях » с Энн Хэтэуэй и Джимом Стерджесом , некоторые сцены которого были сняты в университете. [405] Производство адаптации фильма для Netflix началось в 2021 году, а съемки пройдут на территории Старого колледжа в 2022 году. [406]

- BBC . Юридическая драма «Закон Гарроу » (2009–2011) в основном снималась в Эдинбурге, несмотря на то, что действие происходит в Лондоне Старый колледж и библиотека Playfair . Видные места занимают [407]

- В триллер-телесериале «Клика» (2017–2019), созданном BBC Three, рассказывается о двух студентах университета. Сериал снимался в основном в Эдинбурге, включая The Meadows , Old College и Potterrow . [408] [409]

- В фильме «Форсаж 9» (2021), действие которого частично происходит в Эдинбурге, представлены сцены в Старом колледже и его окрестностях , снятые в сентябре 2019 года. [410]

См. также [ править ]

- Академическая форма Эдинбургского университета

- Гербовник университетов Великобритании

- Премия Кэмерона в области терапии Эдинбургского университета.

- Издательство Эдинбургского университета

- Поселение Эдинбургского университета

- Эпистемика — термин для обозначения когнитивной науки, придуманный в 1969 году Эдинбургским университетом.

- Гиффордские лекции

- Премия памяти Джеймса Тейта Блэка

- Список университетов раннего Нового времени в Европе

- Список организаций с британской королевской хартией

- Список профессорских должностей Эдинбургского университета

- Список университетов Соединенного Королевства

Примечания [ править ]

- ^ Приведенные здесь цифры HESA значительно ниже, чем те, которые сообщает университет, поскольку HESA не включает в себя невыпускников и приезжающих студентов, аспирантов и студентов, обучающихся онлайн, проживающих за границей. [5]

- ↑ Роулинг указана как выпускница, поскольку в 1996 году она получила аттестат последипломного образования в области среднего образования на современных языках в педагогической школе Морей-Хаус , которая объединилась с университетом в 1998 году. Позже она также получила почетную степень в Эдинбурге, но это это не является основанием для того, чтобы ее считали выпускницей.

- ^ Включает тех, кто указал в своем заявлении UCAS, что они идентифицируют себя как азиаты , чернокожие , смешанного происхождения , арабы или представители любой другой этнической принадлежности, кроме белых.

- ^ Рассчитано на основе измерения Polar4 с использованием Quintile1 в Англии и Уэльсе. Рассчитано на основе Шотландского индекса множественной депривации (SIMD) с использованием SIMD20 в Шотландии.

- ^ После Брексита Великобритания больше не будет участвовать в следующей программе Erasmus+ (2021–2027 гг.), но финансирование для выезда студентов за границу по текущей программе остается доступным до 31 мая 2023 г. [206]

- ↑ Роулинг указана как выпускница, поскольку в 1996 году она получила аттестат последипломного образования в области среднего образования на современных языках в педагогической школе Морей-Хаус , которая объединилась с университетом в 1998 году. Позже она также получила почетную степень в Эдинбурге, но это это не является основанием для того, чтобы ее считали выпускницей.

- ^ Маска Фу Маньчжурии , 1932 г.

Ссылки [ править ]

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с д «Открытие Эдинбургского университета, 1583 год» . Эдинбургский университет . Проверено 11 августа 2021 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с «Годовой отчет и финансовая отчетность за год до 31 июля 2023 г.» (PDF) . Эдинбургский университет . Проверено 30 января 2024 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б «Численность персонала и статистика эквивалента полной занятости (FTE) по состоянию на 22 октября» . Отдел кадров, Эдинбургский университет. Октябрь 2022 года . Проверено 24 января 2023 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с «Где учатся студенты ВО? | HESA» . hesa.ac.uk.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с д и «Информационный бюллетень о студенческих фигурах» (PDF) . Стратегическое планирование, Эдинбургский университет. 11 августа 2021 г. Проверено 14 августа 2021 г.

- ^ «Основные цвета Эдинбурга» . Эдинбургский университет . Проверено 17 июня 2021 г.

- ^ Мосс, Майкл С. (июнь 2004 г.). «Рецензируемая работа: Эдинбургский университет: иллюстрированная история Роберта Д. Андерсона, Майкла Линча, Николаса Филлипсона» . Английский исторический обзор . 119 (482): 810–811. дои : 10.1093/ehr/119.482.810 . JSTOR 3489575 . Проверено 16 августа 2021 г.

- ^ Лоури, Джон (июнь 2001 г.). «От Кесарии до Афин: греческое возрождение, Эдинбург и вопрос шотландской идентичности внутри юнионистского государства» . Журнал Общества историков архитектуры . 60 (2): 136–157. дои : 10.2307/991701 . JSTOR 991701 . Проверено 25 августа 2021 г.

- ^ «Шанхайский рейтинг — Эдинбургский университет» . www.shanghairanking.com . Проверено 17 июня 2024 г.

- ^ «Мировой рейтинг университетов – Эдинбургский университет» . Высшее образование Таймс. 27 сентября 2023 г. Проверено 28 сентября 2023 г.

- ^ «Эдинбургский университет» . Лучшие университеты . Проверено 17 июня 2024 г.

- ^ «Принадлежности» . Эдинбургский университет . Проверено 11 августа 2021 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б «Университетское наследие» . Эдинбург, всемирное наследие. 24 ноября 2017 года . Проверено 16 августа 2021 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б «Статистика приема в бакалавриат» . Эдинбургский университет . Проверено 30 апреля 2024 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б «Избран новый канцлер» . Эдинбургский университет . Проверено 20 сентября 2011 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б «Джоан Роулинг удостоена почетной степени» . Телеграф . 8 июля 2004 года . Проверено 19 июня 2024 г.

- ^ «Выпускники в истории» . Эдинбургский университет . Проверено 18 августа 2021 г.

- ^ «Мемориальные доски» . Эдинбургский университет. 14 мая 2019 года . Проверено 19 ноября 2021 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с д «Завещание епископа Роберта Рида, 1557 год» . Эдинбургский университет . Проверено 11 августа 2021 г.

- ^ «Хартия короля Якова VI» . Эдинбургский университет . Проверено 11 августа 2021 г.

- ^ Грант, Александр (1884). История Эдинбургского университета в течение первых трехсот лет его существования . Лондон: Longmans, Green & Co. Проверено 14 августа 2021 г.

- ^ Хорнер, Уинифред Брайан (1993). Шотландская риторика девятнадцатого века: связь с Америкой . Издательство Университета Южного Иллинойса. п. 19. ISBN 9780809314706 . Проверено 13 сентября 2021 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б «Эдинбургский университет» . Британская энциклопедия . Проверено 19 августа 2021 г.

- ^ Херманс, Джос ММ; Нелиссен, Марк (1 января 2005 г.). Уставы учредителей и ранние документы университетов группы Коимбра . Издательство Левенского университета. п. 42. ИСБН 90-5867-474-6 . Проверено 19 августа 2021 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б «Наша история – Роберт Роллок (1555–1599)» . Эдинбургский университет . Проверено 15 августа 2021 г.

- ^ Вормальд, Дженни (1983). Суд, Кирк и сообщество: Шотландия 1470–1625 (2-е изд.). Издательство Эдинбургского университета. п. 288. ИСБН 978-0-7486-2901-5 . JSTOR 10.3366/j.ctt1tqxtnk . Проверено 13 сентября 2021 г.

- ^ «Наша история – Джеймс VI и я» . Эдинбургский университет . Проверено 19 августа 2021 г.

- ^ «Наша история – Эдинбургский университет» . Эдинбургский университет . Проверено 11 августа 2021 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б «Наша история - чистка епископального и якобитского персонала, 1690 г.» . Эдинбургский университет . Проверено 14 сентября 2021 г.