Стивен Хокинг

Стивен Хокинг | |

|---|---|

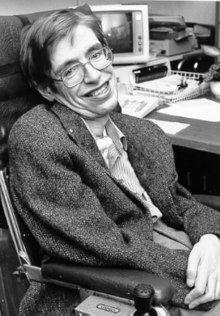

Хокинг ок. 1980 год | |

| Рожденный | Стивен Уильям Хокинг 8 January 1942 Oxford, England |

| Died | 14 March 2018 (aged 76) Cambridge, England |

| Resting place | Westminster Abbey[16] |

| Education | |

| Known for | See list |

| Spouses | |

| Children | 3, including Lucy |

| Awards | See list |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | |

| Institutions | |

| Thesis | Properties of Expanding Universes (1966) |

| Doctoral advisor | Dennis W. Sciama[1] |

| Other academic advisors | Robert Berman[2] |

| Doctoral students | See list |

| Website | hawking |

| Signature | |

| |

| Part of a series on |

| Physical cosmology |

|---|

|

Стивен Уильям Хокинг , CH , CBE , FRS , FRSA (8 января 1942 — 14 марта 2018) — английский физик-теоретик , космолог и автор, который был директором по исследованиям в Центре теоретической космологии Кембриджского университета . [6] [17] [18] В период с 1979 по 2009 год он был профессором математики Лукаса в Кембридже, и многие считали его одной из самых престижных академических должностей в мире. [19]

Хокинг родился в Оксфорде в семье врачей. В октябре 1959 года, в возрасте 17 лет, он начал свое университетское образование в колледже Оксфорда , где получил первоклассную степень бакалавра физики Университетском . В октябре 1962 года он начал свою аспирантуру в Тринити-холле в Кембридже , где в марте 1966 года получил степень доктора философии в области прикладной математики и теоретической физики со специализацией в общей теории относительности и космологии . В 1963 году, в возрасте 21 года, Хокингу поставили диагноз: ранняя, медленно прогрессирующая форма заболевания двигательных нейронов , которая постепенно, на протяжении десятилетий, парализовала его. [20] [21] После потери речи он общался с помощью устройства, генерирующего речь , сначала с помощью ручного переключателя, а затем с помощью одной мышцы щеки. [22]

Hawking's scientific works included a collaboration with Roger Penrose on gravitational singularity theorems in the framework of general relativity, and the theoretical prediction that black holes emit radiation, often called Hawking radiation. Initially, Hawking radiation was controversial. By the late 1970s, and following the publication of further research, the discovery was widely accepted as a major breakthrough in theoretical physics. Hawking was the first to set out a theory of cosmology explained by a union of the general theory of relativity and quantum mechanics. He was a vigorous supporter of the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics.[23][24]

Hawking achieved commercial success with several works of popular science in which he discussed his theories and cosmology in general. His book A Brief History of Time appeared on the Sunday Times bestseller list for a record-breaking 237 weeks. Hawking was a Fellow of the Royal Society, a lifetime member of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, and a recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian award in the United States. In 2002, Hawking was ranked number 25 in the BBC's poll of the 100 Greatest Britons. He died in 2018 at the age of 76, having lived more than 50 years following his diagnosis of motor neurone disease.

Early life

Family

Hawking was born on 8 January 1942[25][26] in Oxford to Frank and Isobel Eileen Hawking (née Walker).[27][28] Hawking's mother was born into a family of doctors in Glasgow, Scotland.[29][30] His wealthy paternal great-grandfather, from Yorkshire, over-extended himself buying farm land and then went bankrupt in the great agricultural depression during the early 20th century.[30] His paternal great-grandmother saved the family from financial ruin by opening a school in their home.[30] Despite their families' financial constraints, both parents attended the University of Oxford, where Frank read medicine and Isobel read Philosophy, Politics and Economics.[28] Isobel worked as a secretary for a medical research institute, and Frank was a medical researcher.[28][31] Hawking had two younger sisters, Philippa and Mary, and an adopted brother, Edward Frank David (1955–2003).[32]

In 1950, when Hawking's father became head of the division of parasitology at the National Institute for Medical Research, the family moved to St Albans, Hertfordshire.[33][34] In St Albans, the family was considered highly intelligent and somewhat eccentric;[33][35] meals were often spent with each person silently reading a book.[33] They lived a frugal existence in a large, cluttered, and poorly maintained house and travelled in a converted London taxicab.[36][37] During one of Hawking's father's frequent absences working in Africa,[38] the rest of the family spent four months in Mallorca visiting his mother's friend Beryl and her husband, the poet Robert Graves.[39]

Primary and secondary school years

Hawking began his schooling at the Byron House School in Highgate, London. He later blamed its "progressive methods" for his failure to learn to read while at the school.[40][33] In St Albans, the eight-year-old Hawking attended St Albans High School for Girls for a few months. At that time, younger boys could attend one of the houses.[39][41]

Hawking attended two private (i.e. fee-paying) schools, first Radlett School[41] and from September 1952, St Albans School, Hertfordshire,[26][42] after passing the eleven-plus a year early.[43] The family placed a high value on education.[33] Hawking's father wanted his son to attend Westminster School, but the 13-year-old Hawking was ill on the day of the scholarship examination. His family could not afford the school fees without the financial aid of a scholarship, so Hawking remained at St Albans.[44][45] A positive consequence was that Hawking remained close to a group of friends with whom he enjoyed board games, the manufacture of fireworks, model aeroplanes and boats,[46] and long discussions about Christianity and extrasensory perception.[47] From 1958 on, with the help of the mathematics teacher Dikran Tahta, they built a computer from clock parts, an old telephone switchboard and other recycled components.[48][49]

Although known at school as "Einstein", Hawking was not initially successful academically.[50] With time, he began to show considerable aptitude for scientific subjects and, inspired by Tahta, decided to read mathematics at university.[51][52][53] Hawking's father advised him to study medicine, concerned that there were few jobs for mathematics graduates.[54] He also wanted his son to attend University College, Oxford, his own alma mater. As it was not possible to read mathematics there at the time, Hawking decided to study physics and chemistry. Despite his headmaster's advice to wait until the next year, Hawking was awarded a scholarship after taking the examinations in March 1959.[55][56]

Undergraduate years

Hawking began his university education at University College, Oxford,[26] in October 1959 at the age of 17.[57] For the first eighteen months, he was bored and lonely – he found the academic work "ridiculously easy".[58][59] His physics tutor, Robert Berman, later said, "It was only necessary for him to know that something could be done, and he could do it without looking to see how other people did it."[2] A change occurred during his second and third years when, according to Berman, Hawking made more of an effort "to be one of the boys". He developed into a popular, lively and witty college-member, interested in classical music and science fiction.[57] Part of the transformation resulted from his decision to join the college boat-club, the University College Boat Club, where he coxed a rowing-crew.[60][61] The rowing-coach at the time noted that Hawking cultivated a daredevil image, steering his crew on risky courses that led to damaged boats.[60][62] Hawking estimated that he studied about 1,000 hours during his three years at Oxford. These unimpressive study habits made sitting his finals a challenge, and he decided to answer only theoretical physics questions rather than those requiring factual knowledge. A first-class degree was a condition of acceptance for his planned graduate study in cosmology at the University of Cambridge.[63][64] Anxious, he slept poorly the night before the examinations, and the result was on the borderline between first- and second-class honours, making a viva (oral examination) with the Oxford examiners necessary.[64][65]

Hawking was concerned that he was viewed as a lazy and difficult student. So, when asked at the viva to describe his plans, he said, "If you award me a First, I will go to Cambridge. If I receive a Second, I shall stay in Oxford, so I expect you will give me a First."[64][66] He was held in higher regard than he believed; as Berman commented, the examiners "were intelligent enough to realise they were talking to someone far cleverer than most of themselves".[64] After receiving a first-class BA degree in physics and completing a trip to Iran with a friend, he began his graduate work at Trinity Hall, Cambridge, in October 1962.[26][67][68]

Post-graduate years

Hawking's first year as a doctoral student was difficult. He was initially disappointed to find that he had been assigned Dennis William Sciama, one of the founders of modern cosmology, as a supervisor rather than the noted astronomer Fred Hoyle,[69][70] and he found his training in mathematics inadequate for work in general relativity and cosmology.[71] After being diagnosed with motor neurone disease, Hawking fell into a depression – though his doctors advised that he continue with his studies, he felt there was little point.[72] His disease progressed more slowly than doctors had predicted. Although Hawking had difficulty walking unsupported, and his speech was almost unintelligible, an initial diagnosis that he had only two years to live proved unfounded. With Sciama's encouragement, he returned to his work.[73][74] Hawking started developing a reputation for brilliance and brashness when he publicly challenged the work of Hoyle and his student Jayant Narlikar at a lecture in June 1964.[75][76]

When Hawking began his doctoral studies, there was much debate in the physics community about the prevailing theories of the creation of the universe: the Big Bang and Steady State theories.[77] Inspired by Roger Penrose's theorem of a spacetime singularity in the centre of black holes, Hawking applied the same thinking to the entire universe; and, during 1965, he wrote his thesis on this topic.[78][79] Hawking's thesis[80] was approved in 1966.[80] There were other positive developments: Hawking received a research fellowship at Gonville and Caius College at Cambridge;[81] he obtained his PhD degree in applied mathematics and theoretical physics, specialising in general relativity and cosmology, in March 1966;[82] and his essay "Singularities and the Geometry of Space–Time" shared top honours with one by Penrose to win that year's prestigious Adams Prize.[83][82]

Career

1966–1975

In his work, and in collaboration with Penrose, Hawking extended the singularity theorem concepts first explored in his doctoral thesis. This included not only the existence of singularities but also the theory that the universe might have started as a singularity. Their joint essay was the runner-up in the 1968 Gravity Research Foundation competition.[84][85] In 1970, they published a proof that if the universe obeys the general theory of relativity and fits any of the models of physical cosmology developed by Alexander Friedmann, then it must have begun as a singularity.[86][87][88] In 1969, Hawking accepted a specially created Fellowship for Distinction in Science to remain at Caius.[89]

In 1970, Hawking postulated what became known as the second law of black hole dynamics, that the event horizon of a black hole can never get smaller.[90] With James M. Bardeen and Brandon Carter, he proposed the four laws of black hole mechanics, drawing an analogy with thermodynamics.[91] To Hawking's irritation, Jacob Bekenstein, a graduate student of John Wheeler, went further—and ultimately correctly—to apply thermodynamic concepts literally.[92][93]

In the early 1970s, Hawking's work with Carter, Werner Israel, and David C. Robinson strongly supported Wheeler's no-hair theorem, one that states that no matter what the original material from which a black hole is created, it can be completely described by the properties of mass, electrical charge and rotation.[94][95] His essay titled "Black Holes" won the Gravity Research Foundation Award in January 1971.[96] Hawking's first book, The Large Scale Structure of Space-Time, written with George Ellis, was published in 1973.[97]

Beginning in 1973, Hawking moved into the study of quantum gravity and quantum mechanics.[98][97] His work in this area was spurred by a visit to Moscow and discussions with Yakov Borisovich Zel'dovich and Alexei Starobinsky, whose work showed that according to the uncertainty principle, rotating black holes emit particles.[99] To Hawking's annoyance, his much-checked calculations produced findings that contradicted his second law, which claimed black holes could never get smaller,[100] and supported Bekenstein's reasoning about their entropy.[99][101]

His results, which Hawking presented from 1974, showed that black holes emit radiation, known today as Hawking radiation, which may continue until they exhaust their energy and evaporate.[102][103][104] Initially, Hawking radiation was controversial. By the late 1970s and following the publication of further research, the discovery was widely accepted as a significant breakthrough in theoretical physics.[105][106][107] Hawking was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1974, a few weeks after the announcement of Hawking radiation. At the time, he was one of the youngest scientists to become a Fellow.[108][109]

Hawking was appointed to the Sherman Fairchild Distinguished Visiting Professorship at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) in 1974. He worked with a friend on the faculty, Kip Thorne,[110][6] and engaged him in a scientific wager about whether the X-ray source Cygnus X-1 was a black hole. The wager was an "insurance policy" against the proposition that black holes did not exist.[111] Hawking acknowledged that he had lost the bet in 1990, a bet that was the first of several he was to make with Thorne and others.[112] Hawking had maintained ties to Caltech, spending a month there almost every year since this first visit.[113]

1975–1990

Hawking returned to Cambridge in 1975 to a more academically senior post, as reader in gravitational physics. The mid-to-late 1970s were a period of growing public interest in black holes and the physicists who were studying them. Hawking was regularly interviewed for print and television.[114][115] He also received increasing academic recognition of his work.[116] In 1975, he was awarded both the Eddington Medal and the Pius XI Gold Medal, and in 1976 the Dannie Heineman Prize, the Maxwell Medal and Prize and the Hughes Medal.[117][118] He was appointed a professor with a chair in gravitational physics in 1977.[119] The following year he received the Albert Einstein Medal and an honorary doctorate from the University of Oxford.[120][116]

In 1979, Hawking was elected Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at the University of Cambridge.[116][121] His inaugural lecture in this role was titled: "Is the End in Sight for Theoretical Physics?" and proposed N = 8 supergravity as the leading theory to solve many of the outstanding problems physicists were studying.[122] His promotion coincided with a health-crisis which led to his accepting, albeit reluctantly, some nursing services at home.[123] At the same time, he was also making a transition in his approach to physics, becoming more intuitive and speculative rather than insisting on mathematical proofs. "I would rather be right than rigorous", he told Kip Thorne.[124] In 1981, he proposed that information in a black hole is irretrievably lost when a black hole evaporates. This information paradox violates the fundamental tenet of quantum mechanics, and led to years of debate, including "the Black Hole War" with Leonard Susskind and Gerard 't Hooft.[125][126]

Cosmological inflation – a theory proposing that following the Big Bang, the universe initially expanded incredibly rapidly before settling down to a slower expansion – was proposed by Alan Guth and also developed by Andrei Linde.[127] Following a conference in Moscow in October 1981, Hawking and Gary Gibbons[6] organised a three-week Nuffield Workshop in the summer of 1982 on "The Very Early Universe" at Cambridge University, a workshop that focused mainly on inflation theory.[128][129][130] Hawking also began a new line of quantum-theory research into the origin of the universe. In 1981 at a Vatican conference, he presented work suggesting that there might be no boundary – or beginning or ending – to the universe.[131][132]

Hawking subsequently developed the research in collaboration with Jim Hartle,[6] and in 1983 they published a model, known as the Hartle–Hawking state. It proposed that prior to the Planck epoch, the universe had no boundary in space-time; before the Big Bang, time did not exist and the concept of the beginning of the universe is meaningless.[133] The initial singularity of the classical Big Bang models was replaced with a region akin to the North Pole. One cannot travel north of the North Pole, but there is no boundary there – it is simply the point where all north-running lines meet and end.[134][135] Initially, the no-boundary proposal predicted a closed universe, which had implications about the existence of God. As Hawking explained, "If the universe has no boundaries but is self-contained... then God would not have had any freedom to choose how the universe began."[136]

Hawking did not rule out the existence of a Creator, asking in A Brief History of Time "Is the unified theory so compelling that it brings about its own existence?",[137] also stating "If we discover a complete theory, it would be the ultimate triumph of human reason – for then we should know the mind of God";[138] in his early work, Hawking spoke of God in a metaphorical sense. In the same book he suggested that the existence of God was not necessary to explain the origin of the universe. Later discussions with Neil Turok led to the realisation that the existence of God was also compatible with an open universe.[139]

Further work by Hawking in the area of arrows of time led to the 1985 publication of a paper theorising that if the no-boundary proposition were correct, then when the universe stopped expanding and eventually collapsed, time would run backwards.[140] A paper by Don Page and independent calculations by Raymond Laflamme led Hawking to withdraw this concept.[141] Honours continued to be awarded: in 1981 he was awarded the American Franklin Medal,[142] and in the 1982 New Year Honours appointed a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE).[143][144][145] These awards did not significantly change Hawking's financial status, and motivated by the need to finance his children's education and home-expenses, he decided in 1982 to write a popular book about the universe that would be accessible to the general public.[146][147] Instead of publishing with an academic press, he signed a contract with Bantam Books, a mass-market publisher, and received a large advance for his book.[148][149] A first draft of the book, called A Brief History of Time, was completed in 1984.[150]

One of the first messages Hawking produced with his speech-generating device was a request for his assistant to help him finish writing A Brief History of Time.[151] Peter Guzzardi, his editor at Bantam, pushed him to explain his ideas clearly in non-technical language, a process that required many revisions from an increasingly irritated Hawking.[152] The book was published in April 1988 in the US and in June in the UK, and it proved to be an extraordinary success, rising quickly to the top of best-seller lists in both countries and remaining there for months.[153][154][155] The book was translated into many languages,[156] and as of 2009, has sold an estimated 9 million copies.[155]

Media attention was intense,[156] and a Newsweek magazine-cover and a television special both described him as "Master of the Universe".[157] Success led to significant financial rewards, but also the challenges of celebrity status.[158] Hawking travelled extensively to promote his work, and enjoyed partying into the late hours.[156] A difficulty refusing the invitations and visitors left him limited time for work and his students.[159] Some colleagues were resentful of the attention Hawking received, feeling it was due to his disability.[160][161]

He received further academic recognition, including five more honorary degrees,[157] the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society (1985),[162] the Paul Dirac Medal (1987)[157] and, jointly with Penrose, the prestigious Wolf Prize (1988).[163] In the 1989 Birthday Honours, he was appointed a Member of the Order of the Companions of Honour (CH).[159][164] He reportedly declined a knighthood in the late 1990s in objection to the UK's science funding policy.[165][166]

1990–2000

Hawking pursued his work in physics: in 1993 he co-edited a book on Euclidean quantum gravity with Gary Gibbons and published a collected edition of his own articles on black holes and the Big Bang.[167] In 1994, at Cambridge's Newton Institute, Hawking and Penrose delivered a series of six lectures that were published in 1996 as "The Nature of Space and Time".[168] In 1997, he conceded a 1991 public scientific wager made with Kip Thorne and John Preskill of Caltech. Hawking had bet that Penrose's proposal of a "cosmic censorship conjecture" – that there could be no "naked singularities" unclothed within a horizon – was correct.[169]

After discovering his concession might have been premature, a new and more refined wager was made. This one specified that such singularities would occur without extra conditions.[170] The same year, Thorne, Hawking and Preskill made another bet, this time concerning the black hole information paradox.[171][172] Thorne and Hawking argued that since general relativity made it impossible for black holes to radiate and lose information, the mass-energy and information carried by Hawking radiation must be "new", and not from inside the black hole event horizon. Since this contradicted the quantum mechanics of microcausality, quantum mechanics theory would need to be rewritten. Preskill argued the opposite, that since quantum mechanics suggests that the information emitted by a black hole relates to information that fell in at an earlier time, the concept of black holes given by general relativity must be modified in some way.[173]

Hawking also maintained his public profile, including bringing science to a wider audience. A film version of A Brief History of Time, directed by Errol Morris and produced by Steven Spielberg, premiered in 1992. Hawking had wanted the film to be scientific rather than biographical, but he was persuaded otherwise. The film, while a critical success, was not widely released.[174] A popular-level collection of essays, interviews, and talks titled Black Holes and Baby Universes and Other Essays was published in 1993,[175] and a six-part television series Stephen Hawking's Universe and a companion book appeared in 1997. As Hawking insisted, this time the focus was entirely on science.[176][177]

2000–2018

Hawking continued his writings for a popular audience, publishing The Universe in a Nutshell in 2001,[178] and A Briefer History of Time, which he wrote in 2005 with Leonard Mlodinow to update his earlier works with the aim of making them accessible to a wider audience, and God Created the Integers, which appeared in 2006.[179] Along with Thomas Hertog at CERN and Jim Hartle, from 2006 on Hawking developed a theory of top-down cosmology, which says that the universe had not one unique initial state but many different ones, and therefore that it is inappropriate to formulate a theory that predicts the universe's current configuration from one particular initial state.[180] Top-down cosmology posits that the present "selects" the past from a superposition of many possible histories. In doing so, the theory suggests a possible resolution of the fine-tuning question.[181][182]

Hawking continued to travel widely, including trips to Chile, Easter Island, South Africa, Spain (to receive the Fonseca Prize in 2008),[183][184] Canada,[185] and numerous trips to the United States.[186] For practical reasons related to his disability, Hawking increasingly travelled by private jet, and by 2011 that had become his only mode of international travel.[187]

By 2003, consensus among physicists was growing that Hawking was wrong about the loss of information in a black hole.[188] In a 2004 lecture in Dublin, he conceded his 1997 bet with Preskill, but described his own, somewhat controversial solution to the information paradox problem, involving the possibility that black holes have more than one topology.[189][173] In the 2005 paper he published on the subject, he argued that the information paradox was explained by examining all the alternative histories of universes, with the information loss in those with black holes being cancelled out by those without such loss.[172][190] In January 2014, he called the alleged loss of information in black holes his "biggest blunder".[191]

As part of another longstanding scientific dispute, Hawking had emphatically argued, and bet, that the Higgs boson would never be found.[192] The particle was proposed to exist as part of the Higgs field theory by Peter Higgs in 1964. Hawking and Higgs engaged in a heated and public debate over the matter in 2002 and again in 2008, with Higgs criticising Hawking's work and complaining that Hawking's "celebrity status gives him instant credibility that others do not have."[193] The particle was discovered in July 2012 at CERN following construction of the Large Hadron Collider. Hawking quickly conceded that he had lost his bet[194][195] and said that Higgs should win the Nobel Prize for Physics,[196] which he did in 2013.[197]

In 2007, Hawking and his daughter Lucy published George's Secret Key to the Universe, a children's book designed to explain theoretical physics in an accessible fashion and featuring characters similar to those in the Hawking family.[198] The book was followed by sequels in 2009, 2011, 2014 and 2016.[199]

In 2002, following a UK-wide vote, the BBC included Hawking in their list of the 100 Greatest Britons.[200] He was awarded the Copley Medal from the Royal Society (2006),[201] the Presidential Medal of Freedom, which is America's highest civilian honour (2009),[202] and the Russian Special Fundamental Physics Prize (2013).[203]

Several buildings have been named after him, including the Stephen W. Hawking Science Museum in San Salvador, El Salvador,[204] the Stephen Hawking Building in Cambridge,[205] and the Stephen Hawking Centre at the Perimeter Institute in Canada.[206] Appropriately, given Hawking's association with time, he unveiled the mechanical "Chronophage" (or time-eating) Corpus Clock at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge in September 2008.[207][208]

During his career, Hawking supervised 39 successful PhD students.[1] One doctoral student did not successfully complete the PhD.[1][better source needed] As required by Cambridge University policy, Hawking retired as Lucasian Professor of Mathematics in 2009.[121][209] Despite suggestions that he might leave the United Kingdom as a protest against public funding cuts to basic scientific research,[210] Hawking worked as director of research at the Cambridge University Department of Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics.[211]

On 28 June 2009, as a tongue-in-cheek test of his 1992 conjecture that travel into the past is effectively impossible, Hawking held a party open to all, complete with hors d'oeuvres and iced champagne, but publicised the party only after it was over so that only time-travellers would know to attend; as expected, nobody showed up to the party.[212]

On 20 July 2015, Hawking helped launch Breakthrough Initiatives, an effort to search for extraterrestrial life.[213] Hawking created Stephen Hawking: Expedition New Earth, a documentary on space colonisation, as a 2017 episode of Tomorrow's World.[214][215]

In August 2015, Hawking said that not all information is lost when something enters a black hole and there might be a possibility to retrieve information from a black hole according to his theory.[216] In July 2017, Hawking was awarded an Honorary Doctorate from Imperial College London.[217]

Hawking's final paper – A smooth exit from eternal inflation? – was posthumously published in the Journal of High Energy Physics on 27 April 2018.[218][219]

Personal life

Marriages

Hawking met his future wife, Jane Wilde, at a party in 1962. The following year, Hawking was diagnosed with motor neurone disease. In October 1964, the couple became engaged to marry, aware of the potential challenges that lay ahead due to Hawking's shortened life expectancy and physical limitations.[120][220] Hawking later said that the engagement gave him "something to live for".[221] The two were married on 14 July 1965 in their shared hometown of St Albans.[81]

The couple resided in Cambridge, within Hawking's walking distance to the Department of Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics (DAMTP). During their first years of marriage, Jane lived in London during the week as she completed her degree at Westfield College. They travelled to the United States several times for conferences and physics-related visits. Jane began a PhD programme through Westfield College in medieval Spanish poetry (completed in 1981). The couple had three children: Robert, born May 1967,[222][223] Lucy, born November 1970,[224] and Timothy, born April 1979.[116]

Hawking rarely discussed his illness and physical challenges—even, in a precedent set during their courtship, with Jane.[225] His disabilities meant that the responsibilities of home and family rested firmly on his wife's increasingly overwhelmed shoulders, leaving him more time to think about physics.[226] Upon his appointment in 1974 to a year-long position at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, California, Jane proposed that a graduate or post-doctoral student live with them and help with his care. Hawking accepted, and Bernard Carr travelled with them as the first of many students who fulfilled this role.[227][228] The family spent a generally happy and stimulating year in Pasadena.[229]

Hawking returned to Cambridge in 1975 to a new home and a new job, as reader. Don Page, with whom Hawking had begun a close friendship at Caltech, arrived to work as the live-in graduate student assistant. With Page's help and that of a secretary, Jane's responsibilities were reduced so she could return to her doctoral thesis and her new interest in singing.[230]

Around December 1977, Jane met organist Jonathan Hellyer Jones when singing in a church choir. Hellyer Jones became close to the Hawking family and, by the mid-1980s, he and Jane had developed romantic feelings for each other.[119][231][232] According to Jane, her husband was accepting of the situation, stating "he would not object so long as I continued to love him".[119][233][234] Jane and Hellyer Jones were determined not to break up the family, and their relationship remained platonic for a long period.[235]

By the 1980s, Hawking's marriage had been strained for many years. Jane felt overwhelmed by the intrusion into their family life of the required nurses and assistants.[236] The impact of his celebrity status was challenging for colleagues and family members, while the prospect of living up to a worldwide fairytale image was daunting for the couple.[237][181] Hawking's views of religion also contrasted with her strong Christian faith and resulted in tension.[181][238][239] After a tracheotomy in 1985, Hawking required a full-time nurse and nursing care was split across three shifts daily. In the late 1980s, Hawking grew close to one of his nurses, Elaine Mason, to the dismay of some colleagues, caregivers, and family members, who were disturbed by her strength of personality and protectiveness.[240] In February 1990, Hawking told Jane that he was leaving her for Mason[241] and departed the family home.[143] After his divorce from Jane in 1995, Hawking married Mason in September,[143][242] declaring, "It's wonderful – I have married the woman I love."[243]

In 1999, Jane Hawking published a memoir, Music to Move the Stars, describing her marriage to Hawking and its breakdown. Its revelations caused a sensation in the media but, as was his usual practice regarding his personal life, Hawking made no public comment except to say that he did not read biographies about himself.[244] After his second marriage, Hawking's family felt excluded and marginalised from his life.[239] For a period of about five years in the early 2000s, his family and staff became increasingly worried that he was being physically abused.[245] Police investigations took place, but were closed as Hawking refused to make a complaint.[246]

In 2006, Hawking and Mason quietly divorced,[247][248] and Hawking resumed closer relationships with Jane, his children, and his grandchildren.[181][248] Reflecting on this happier period, a revised version of Jane's book, re-titled Travelling to Infinity: My Life with Stephen, appeared in 2007,[246] and was made into a film, The Theory of Everything, in 2014.[249]

Disability

Hawking had a rare early-onset, slow-progressing form of motor neurone disease (MND; also known as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) or Lou Gehrig's disease), a fatal neurodegenerative disease that affects the motor neurones in the brain and spinal cord, which gradually paralysed him over decades.[21]

Hawking had experienced increasing clumsiness during his final year at Oxford, including a fall on some stairs and difficulties when rowing.[250][251] The problems worsened, and his speech became slightly slurred. His family noticed the changes when he returned home for Christmas, and medical investigations were begun.[252][253] The MND diagnosis came when Hawking was 21, in 1963. At the time, doctors gave him a life expectancy of two years.[254][255]

In the late 1960s, Hawking's physical abilities declined: he began to use crutches and could no longer give lectures regularly.[256] As he slowly lost the ability to write, he developed compensatory visual methods, including seeing equations in terms of geometry.[257][258] The physicist Werner Israel later compared the achievements to Mozart composing an entire symphony in his head.[259][260] Hawking was fiercely independent and unwilling to accept help or make concessions for his disabilities. He preferred to be regarded as "a scientist first, popular science writer second, and, in all the ways that matter, a normal human being with the same desires, drives, dreams, and ambitions as the next person".[261] His wife Jane later noted: "Some people would call it determination, some obstinacy. I've called it both at one time or another."[262] He required much persuasion to accept the use of a wheelchair at the end of the 1960s,[263] but ultimately became notorious for the wildness of his wheelchair driving.[264] Hawking was a popular and witty colleague, but his illness, as well as his reputation for brashness, distanced him from some.[262]

When Hawking first began using a wheelchair he was using standard motorised models. The earliest surviving example of these chairs was made by BEC Mobility and sold by Christie's in November 2018 for £296,750.[265] Hawking continued to use this type of chair until the early 1990s, at which time his ability to use his hands to drive a wheelchair deteriorated. Hawking used a variety of different chairs from that time, including a DragonMobility Dragon elevating powerchair from 2007, as shown in the April 2008 photo of Hawking attending NASA's 50th anniversary;[266] a Permobil C350 from 2014; and then a Permobil F3 from 2016.[267]

Hawking's speech deteriorated, and by the late 1970s he could be understood by only his family and closest friends. To communicate with others, someone who knew him well would interpret his speech into intelligible speech.[268] Spurred by a dispute with the university over who would pay for the ramp needed for him to enter his workplace, Hawking and his wife campaigned for improved access and support for those with disabilities in Cambridge,[269][270] including adapted student housing at the university.[271] In general, Hawking had ambivalent feelings about his role as a disability rights champion: while wanting to help others, he also sought to detach himself from his illness and its challenges.[272] His lack of engagement in this area led to some criticism.[273]

During a visit to CERN on the border of France and Switzerland in mid-1985, Hawking contracted pneumonia, which in his condition was life-threatening; he was so ill that Jane was asked if life support should be terminated. She refused, but the consequence was a tracheotomy, which required round-the-clock nursing care and caused the loss of what remained of his speech.[274][275] The National Health Service was ready to pay for a nursing home, but Jane was determined that he would live at home. The cost of the care was funded by an American foundation.[276][277] Nurses were hired for the three shifts required to provide the round-the-clock support he required. One of those employed was Elaine Mason, who was to become Hawking's second wife.[278]

For his communication, Hawking initially raised his eyebrows to choose letters on a spelling card,[279] but in 1986 he received a computer program called the "Equalizer" from Walter Woltosz, CEO of Words Plus, who had developed an earlier version of the software to help his mother-in-law, who also had ALS and had lost her ability to speak and write.[280] In a method he used for the rest of his life, Hawking could now simply press a switch to select phrases, words or letters from a bank of about 2,500–3,000 that were scanned.[281][282] The program was originally run on a desktop computer. Elaine Mason's husband, David, a computer engineer, adapted a small computer and attached it to his wheelchair.[283]

Released from the need to use somebody to interpret his speech, Hawking commented that "I can communicate better now than before I lost my voice."[284] The voice he used had an American accent and is no longer produced.[285][286] Despite the later availability of other voices, Hawking retained this original voice, saying that he preferred it and identified with it.[287] Originally, Hawking activated a switch using his hand and could produce up to 15 words per minute.[151] Lectures were prepared in advance and were sent to the speech synthesiser in short sections to be delivered.[285]

Hawking gradually lost the use of his hand, and in 2005 he began to control his communication device with movements of his cheek muscles,[288][289][290] with a rate of about one word per minute.[289] With this decline there was a risk of him developing locked-in syndrome, so Hawking collaborated with Intel Corporation researchers on systems that could translate his brain patterns or facial expressions into switch activations. After several prototypes that did not perform as planned, they settled on an adaptive word predictor made by the London-based startup SwiftKey, which used a system similar to his original technology. Hawking had an easier time adapting to the new system, which was further developed after inputting large amounts of Hawking's papers and other written materials and uses predictive software similar to other smartphone keyboards.[181][280][290][291]

By 2009, he could no longer drive his wheelchair independently, but the same people who created his new typing mechanics were working on a method to drive his chair using movements made by his chin. This proved difficult, since Hawking could not move his neck, and trials showed that while he could indeed drive the chair, the movement was sporadic and jumpy.[280][292] Near the end of his life, Hawking experienced increased breathing difficulties, often resulting in his requiring the usage of a ventilator, and being regularly hospitalised.[181]

Disability outreach

Starting in the 1990s, Hawking accepted the mantle of role model for disabled people, lecturing and participating in fundraising activities.[293] At the turn of the century, he and eleven other humanitarians signed the Charter for the Third Millennium on Disability, which called on governments to prevent disability and protect the rights of disabled people.[294][295] In 1999, Hawking was awarded the Julius Edgar Lilienfeld Prize of the American Physical Society.[296]

In August 2012, Hawking narrated the "Enlightenment" segment of the 2012 Summer Paralympics opening ceremony in London.[297] In 2013, the biographical documentary film Hawking, in which Hawking himself is featured, was released.[298] In September 2013, he expressed support for the legalisation of assisted suicide for the terminally ill.[299] In August 2014, Hawking accepted the Ice Bucket Challenge to promote ALS/MND awareness and raise contributions for research. As he had pneumonia in 2013, he was advised not to have ice poured over him, but his children volunteered to accept the challenge on his behalf.[300]

Plans for a trip to space

In late 2006, Hawking revealed in a BBC interview that one of his greatest unfulfilled desires was to travel to space.[301] On hearing this, Richard Branson offered a free flight into space with Virgin Galactic, which Hawking immediately accepted. Besides personal ambition, he was motivated by the desire to increase public interest in spaceflight and to show the potential of people with disabilities.[302] On 26 April 2007, Hawking flew aboard a specially-modified Boeing 727–200 jet operated by Zero-G Corp off the coast of Florida to experience weightlessness.[303] Fears that the manoeuvres would cause him undue discomfort proved incorrect, and the flight was extended to eight parabolic arcs.[301] It was described as a successful test to see if he could withstand the g-forces involved in space flight.[304] At the time, the date of Hawking's trip to space was projected to be as early as 2009, but commercial flights to space did not commence before his death.[305]

Death

Hawking died at his home in Cambridge on 14 March 2018, at the age of 76.[306][307][308] His family stated that he "died peacefully".[309][310] He was eulogised by figures in science, entertainment, politics, and other areas.[311][312][313][314] The Gonville and Caius College flag flew at half-mast and a book of condolences was signed by students and visitors.[315][316][317] A tribute was made to Hawking in the closing speech by IPC President Andrew Parsons at the closing ceremony of the 2018 Paralympic Winter Games in Pyeongchang, South Korea.[318]

His private funeral took place on 31 March 2018,[319] at Great St Mary's Church, Cambridge.[319][320] Guests at the funeral included The Theory of Everything actors Eddie Redmayne and Felicity Jones, Queen guitarist and astrophysicist Brian May, and model Lily Cole.[321][322] In addition, actor Benedict Cumberbatch, who played Stephen Hawking in Hawking, astronaut Tim Peake, Astronomer Royal Martin Rees and physicist Kip Thorne provided readings at the service.[323] Although Hawking was an atheist, the funeral took place with a traditional Anglican service.[324][325] Following the cremation, a service of thanksgiving was held at Westminster Abbey on 15 June 2018, after which his ashes were interred in the Abbey's nave, between the graves of Sir Isaac Newton and Charles Darwin.[16][321][326][327]

Inscribed on his memorial stone are the words "Here lies what was mortal of Stephen Hawking 1942–2018" and his most famed equation.[328] He directed, at least fifteen years before his death, that the Bekenstein–Hawking entropy equation be his epitaph.[329][330][note 1] In June 2018, it was announced that Hawking's words, set to music by Greek composer Vangelis, would be beamed into space from a European space agency satellite dish in Spain with the aim of reaching the nearest black hole, 1A 0620-00.[335]

Hawking's final broadcast interview, about the detection of gravitational waves resulting from the collision of two neutron stars, occurred in October 2017.[336] His final words to the world appeared posthumously, in April 2018, in the form of a Smithsonian TV Channel documentary entitled, Leaving Earth: Or How to Colonize a Planet.[337][338] One of his final research studies, entitled A smooth exit from eternal inflation?, about the origin of the universe, was published in the Journal of High Energy Physics in May 2018.[339][218][340] Later, in October 2018, another of his final research studies, entitled Black Hole Entropy and Soft Hair,[341] was published, and dealt with the "mystery of what happens to the information held by objects once they disappear into a black hole".[342][343] Also in October 2018, Hawking's last book, Brief Answers to the Big Questions, a popular science book presenting his final comments on the most important questions facing humankind, was published.[344][345][346]

On 8 November 2018, an auction of 22 personal possessions of Stephen Hawking, including his doctoral thesis ("Properties of Expanding Universes", PhD thesis, Cambridge University, 1965) and wheelchair, took place, and fetched about £1.8 m.[347][348] Proceeds from the auction sale of the wheelchair went to two charities, the Motor Neurone Disease Association and the Stephen Hawking Foundation;[349] proceeds from Hawking's other items went to his estate.[348]

In March 2019, it was announced that the Royal Mint would issue a commemorative 50p coin, only available as a commemorative edition,[350] in honour of Hawking.[351] The same month, Hawking's nurse, Patricia Dowdy, was struck off the nursing register for "failures over his care and financial misconduct."[352]

In May 2021 it was announced that an Acceptance-in-Lieu agreement between HMRC, the Department for Culture, Media and Sport, Cambridge University Library, Science Museum Group, and the Hawking Estate, would see around 10,000 pages of Hawking's scientific and other papers remain in Cambridge, while objects including his wheelchairs, speech synthesisers, and personal memorabilia from his former Cambridge office would be housed at the Science Museum.[353] In February 2022 the "Stephen Hawking at Work" display opened at the Science Museum, London as the start of a two-year nationwide tour.[354]

Personal views

Philosophy is unnecessary

At Google's Zeitgeist Conference in 2011, Stephen Hawking said that "philosophy is dead". He believed that philosophers "have not kept up with modern developments in science", "have not taken science sufficiently seriously and so Philosophy is no longer relevant to knowledge claims", "their art is dead" and that scientists "have become the bearers of the torch of discovery in our quest for knowledge". He said that philosophical problems can be answered by science, particularly new scientific theories which "lead us to a new and very different picture of the universe and our place in it".[355] His view was both praised and criticised.[356]

Future of humanity

In 2006, Hawking posed an open question on the Internet: "In a world that is in chaos politically, socially and environmentally, how can the human race sustain another 100 years?", later clarifying: "I don't know the answer. That is why I asked the question, to get people to think about it, and to be aware of the dangers we now face."[357]

Hawking expressed concern that life on Earth is at risk from a sudden nuclear war, a genetically engineered virus, global warming, or other dangers humans have not yet thought of.[302][358] Hawking stated: "I regard it as almost inevitable that either a nuclear confrontation or environmental catastrophe will cripple the Earth at some point in the next 1,000 years", and considered an "asteroid collision" to be the biggest threat to the planet.[344] Such a planet-wide disaster need not result in human extinction if the human race were to be able to colonise additional planets before the disaster.[358] Hawking viewed spaceflight and the colonisation of space as necessary for the future of humanity.[302][359]

Hawking stated that, given the vastness of the universe, aliens likely exist, but that contact with them should be avoided.[360][361] He warned that aliens might pillage Earth for resources. In 2010 he said, "If aliens visit us, the outcome would be much as when Columbus landed in America, which didn't turn out well for the Native Americans."[361]

Hawking warned that superintelligent artificial intelligence could be pivotal in steering humanity's fate, stating that "the potential benefits are huge... Success in creating AI would be the biggest event in human history. It might also be the last, unless we learn how to avoid the risks."[362][363] He feared that "an extremely intelligent future AI will probably develop a drive to survive and acquire more resources as a step toward accomplishing whatever goal it has", and that "The real risk with AI isn't malice but competence. A super-intelligent AI will be extremely good at accomplishing its goals, and if those goals aren't aligned with ours, we're in trouble".[364] He also considered that the enormous wealth generated by machines needs to be redistributed to prevent exacerbated economic inequality.[364]

Hawking was concerned about the future emergence of a race of "superhumans" that would be able to design their own evolution[344] and, as well, argued that computer viruses in today's world should be considered a new form of life, stating that "maybe it says something about human nature, that the only form of life we have created so far is purely destructive. Talk about creating life in our own image."[365]

Religion and atheism

Hawking was an atheist.[366][367] In an interview published in The Guardian, Hawking regarded "the brain as a computer which will stop working when its components fail", and the concept of an afterlife as a "fairy story for people afraid of the dark".[307][138] In 2011, narrating the first episode of the American television series Curiosity on the Discovery Channel, Hawking declared:

We are each free to believe what we want and it is my view that the simplest explanation is there is no God. No one created the universe and no one directs our fate. This leads me to a profound realisation. There is probably no heaven, and no afterlife either. We have this one life to appreciate the grand design of the universe, and for that, I am extremely grateful.[368][369]

Hawking's association with atheism and freethinking was in evidence from his university years onwards, when he had been a member of Oxford University's humanist group. He was later scheduled to appear as the keynote speaker at a 2017 Humanists UK conference.[370] In an interview with El Mundo, he said:

Before we understand science, it is natural to believe that God created the universe. But now science offers a more convincing explanation. What I meant by 'we would know the mind of God' is, we would know everything that God would know, if there were a God, which there isn't. I'm an atheist.[366]

In addition, Hawking stated:

If you like, you can call the laws of science 'God', but it wouldn't be a personal God that you would meet and put questions to.[344]

Politics

Hawking was a longstanding Labour Party supporter.[371][372] He recorded a tribute for the 2000 Democratic presidential candidate Al Gore,[373] called the 2003 invasion of Iraq a "war crime",[372][374] campaigned for nuclear disarmament,[371][372] and supported stem cell research,[372][375] universal health care,[376] and action to prevent climate change.[377] In August 2014, Hawking was one of 200 public figures who were signatories to a letter to The Guardian expressing their hope that Scotland would vote to remain part of the United Kingdom in September's referendum on that issue.[378] Hawking believed a United Kingdom withdrawal from the European Union (Brexit) would damage the UK's contribution to science as modern research needs international collaboration, and that free movement of people in Europe encourages the spread of ideas.[379] Hawking said to Theresa May, "I deal with tough mathematical questions every day, but please don't ask me to help with Brexit."[380] Hawking was disappointed by Brexit and warned against envy and isolationism.[381]

Hawking was greatly concerned over health care, and maintained that without the UK National Health Service, he could not have survived into his 70s.[382] Hawking especially feared privatisation. He stated, "The more profit is extracted from the system, the more private monopolies grow and the more expensive healthcare becomes. The NHS must be preserved from commercial interests and protected from those who want to privatise it."[383] Hawking blamed the Conservatives for cutting funding to the NHS, weakening it by privatisation, lowering staff morale through holding pay back and reducing social care.[384] Hawking accused Jeremy Hunt of cherry picking evidence which Hawking maintained debased science.[382] Hawking also stated, "There is overwhelming evidence that NHS funding and the numbers of doctors and nurses are inadequate, and it is getting worse."[385]In June 2017, Hawking endorsed the Labour Party in the 2017 UK general election, citing the Conservatives' proposed cuts to the NHS. But he was also critical of Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn, expressing scepticism over whether the party could win a general election under him.[386]

Hawking feared Donald Trump's policies on global warming could endanger the planet and make global warming irreversible. He said, "Climate change is one of the great dangers we face, and it's one we can prevent if we act now. By denying the evidence for climate change, and pulling out of the Paris Agreement, Donald Trump will cause avoidable environmental damage to our beautiful planet, endangering the natural world, for us and our children."[387] Hawking further stated that this could lead Earth "to become like Venus, with a temperature of two hundred and fifty degrees, and raining sulphuric acid".[388]

Hawking was also a supporter of a universal basic income.[389] He was critical of the Israeli government's position on the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, stating that their policy "is likely to lead to disaster."[390]

Appearances in popular media

In 1988, Hawking, Arthur C. Clarke and Carl Sagan were interviewed in God, the Universe and Everything Else. They discussed the Big Bang theory, God and the possibility of extraterrestrial life.[391]

At the release party for the home video version of the A Brief History of Time, Leonard Nimoy, who had played Spock on Star Trek, learned that Hawking was interested in appearing on the show. Nimoy made the necessary contact, and Hawking played a holographic simulation of himself in an episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation in 1993.[392][393] The same year, his synthesiser voice was recorded for the Pink Floyd song "Keep Talking",[394][175] and in 1999 for an appearance on The Simpsons.[395] Hawking appeared in documentaries titled The Real Stephen Hawking (2001),[295] Stephen Hawking: Profile (2002)[396] and Hawking (2013), and the documentary series Stephen Hawking, Master of the Universe (2008).[397] Hawking also guest-starred in Futurama[181] and had a recurring role in The Big Bang Theory.[398]

Hawking allowed the use of his copyrighted voice[399][400] in the biographical 2014 film The Theory of Everything, in which he was portrayed by Eddie Redmayne in an Academy Award-winning role.[401] Hawking was featured at the Monty Python Live (Mostly) show in 2014. He was shown to sing an extended version of the "Galaxy Song", after running down Brian Cox with his wheelchair, in a pre-recorded video.[402][403]

Hawking used his fame to advertise products, including a wheelchair,[295] National Savings,[404] British Telecom, Specsavers, Egg Banking,[405] and Go Compare.[406] In 2015, he applied to trademark his name.[407]

Broadcast in March 2018 just a week or two before his death, Hawking was the voice of The Book Mark II on The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy radio series, and he was the guest of Neil deGrasse Tyson on StarTalk.[408]

The 2021 animated sitcom The Freak Brothers features a recurring character, Mayor Pimco, who is apparently modeled after Stephen Hawking.[409]

On 8 January 2022, Google featured Hawking in a Google Doodle on the occasion of his 80th birthday.[410]

Awards and honours

Hawking received numerous awards and honours. Already early in the list, in 1974 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS).[6] At that time, his nomination read:

Hawking has made major contributions to the field of general relativity. These derive from a deep understanding of what is relevant to physics and astronomy, and especially from a mastery of wholly new mathematical techniques. Following the pioneering work of Penrose he established, partly alone and partly in collaboration with Penrose, a series of successively stronger theorems establishing the fundamental result that all realistic cosmological models must possess singularities. Using similar techniques, Hawking has proved the basic theorems on the laws governing black holes: that stationary solutions of Einstein's equations with smooth event horizons must necessarily be axisymmetric; and that in the evolution and interaction of black holes, the total surface area of the event horizons must increase. In collaboration with G. Ellis, Hawking is the author of an impressive and original treatise on "Space-time in the Large".

The citation continues, "Other important work by Hawking relates to the interpretation of cosmological observations and to the design of gravitational wave detectors."[411]

Hawking was also a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (1984),[412] the American Philosophical Society (1984),[413] and the United States National Academy of Sciences (1992).[414]

Hawking received the 2015 BBVA Foundation Frontiers of Knowledge Award in Basic Sciences shared with Viatcheslav Mukhanov for discovering that the galaxies were formed from quantum fluctuations in the early Universe. At the 2016 Pride of Britain Awards, Hawking received the lifetime achievement award "for his contribution to science and British culture".[415] After receiving the award from Prime Minister Theresa May, Hawking humorously requested that she not seek his help with Brexit.[415]

The Hawking Fellowship

In 2017, the Cambridge Union Society, in conjunction with Hawking, established the Professor Stephen Hawking Fellowship. The fellowship is awarded annually to an individual who has made an exceptional contribution to the STEM fields and social discourse,[416] with a particular focus on impacts affecting the younger generations. Each fellow delivers a lecture on a topic of their choosing, known as the 'Hawking Lecture'.[417]

Hawking himself accepted the inaugural fellowship, and he delivered the first Hawking Lecture in his last public appearance before his death. [418][419]

Medal for Science Communication

Hawking was a member of the advisory board of the Starmus Festival, and had a major role in acknowledging and promoting science communication. The Stephen Hawking Medal for Science Communication is an annual award initiated in 2016 to honour members of the arts community for contributions that help build awareness of science.[420] Recipients receive a medal bearing a portrait of Hawking by Alexei Leonov, and the other side represents an image of Leonov himself performing the first spacewalk along with an image of the "Red Special", the guitar of Queen musician and astrophysicist Brian May (with music being another major component of the Starmus Festival).[421]

The Starmus III Festival in 2016 was a tribute to Stephen Hawking and the book of all Starmus III lectures, "Beyond the Horizon", was also dedicated to him. The first recipients of the medals, which were awarded at the festival, were chosen by Hawking himself. They were composer Hans Zimmer, physicist Jim Al-Khalili, and the science documentary Particle Fever.[422]

Publications

Popular books

- A Brief History of Time (1988)[199]

- Black Holes and Baby Universes and Other Essays (1993)[423]

- The Universe in a Nutshell (2001)[199]

- On the Shoulders of Giants (2002)[199]

- God Created the Integers: The Mathematical Breakthroughs That Changed History (2005)[199]

- The Dreams That Stuff Is Made of: The Most Astounding Papers of Quantum Physics and How They Shook the Scientific World (2011)[424]

- My Brief History (2013)[199] Hawking's memoir.

- Brief Answers to the Big Questions (2018)[344][425]

Co-authored

- The Nature of Space and Time (with Roger Penrose) (1996)

- The Large, the Small and the Human Mind (with Roger Penrose, Abner Shimony and Nancy Cartwright) (1997)

- The Future of Spacetime (with Kip Thorne, Igor Novikov, Timothy Ferris and introduction by Alan Lightman, Richard H. Price) (2002)

- A Briefer History of Time (with Leonard Mlodinow) (2005)[199]

- The Grand Design (with Leonard Mlodinow) (2010)[199]

Forewords

- Black Holes & Time Warps: Einstein's Outrageous Legacy (Kip Thorne, and introduction by Frederick Seitz) (1994)

- The Physics of Star Trek (Lawrence Krauss) (1995)

Children's fiction

Co-written with his daughter Lucy.

- George's Secret Key to the Universe (2007)[199]

- George's Cosmic Treasure Hunt (2009)[199]

- George and the Big Bang (2011)[199]

- George and the Unbreakable Code (2014)

- George and the Blue Moon (2016)

Films and series

- A Brief History of Time (1992)[426]

- Stephen Hawking's Universe (1997)[427][233]

- Hawking – BBC television film (2004) starring Benedict Cumberbatch

- Horizon: The Hawking Paradox (2005)[428]

- Masters of Science Fiction (2007)[429]

- Stephen Hawking and the Theory of Everything (2007)

- Stephen Hawking: Master of the Universe (2008)[430]

- Into the Universe with Stephen Hawking (2010)[431]

- Brave New World with Stephen Hawking (2011)[432]

- Stephen Hawking's Grand Design (2012)[433]

- The Big Bang Theory (2012, 2014–2015, 2017)

- Stephen Hawking: A Brief History of Mine (2013)[434]

- The Theory of Everything – Feature film (2014) starring Eddie Redmayne[435]

- Genius by Stephen Hawking (2016)

Selected academic works

- S. W. Hawking; R. Penrose (27 January 1970). "The Singularities of Gravitational Collapse and Cosmology". Proceedings of the Royal Society A. 314 (1519): 529–548. Bibcode:1970RSPSA.314..529H. doi:10.1098/RSPA.1970.0021. ISSN 1364-5021. S2CID 120208756. Zbl 0954.83012. Wikidata Q55872061.

- S. W. Hawking (May 1971). "Gravitational Radiation from Colliding Black Holes". Physical Review Letters. 26 (21): 1344–1346. Bibcode:1971PhRvL..26.1344H. doi:10.1103/PHYSREVLETT.26.1344. ISSN 0031-9007. Wikidata Q21706376.

- Stephen Hawking (June 1972). "Black holes in general relativity". Communications in Mathematical Physics. 25 (2): 152–166. Bibcode:1972CMaPh..25..152H. doi:10.1007/BF01877517. ISSN 0010-3616. S2CID 121527613. Wikidata Q56453197.

- Stephen Hawking (March 1974). "Black hole explosions?". Nature. 248 (5443): 30–31. Bibcode:1974Natur.248...30H. doi:10.1038/248030A0. ISSN 1476-4687. S2CID 4290107. Zbl 1370.83053. Wikidata Q54017915.

- Stephen Hawking (September 1982). "The development of irregularities in a single bubble inflationary universe". Physics Letters B. 115 (4): 295–297. Bibcode:1982PhLB..115..295H. doi:10.1016/0370-2693(82)90373-2. ISSN 0370-2693. Wikidata Q29398982.

- J. B. Hartle; S. W. Hawking (December 1983). "Wave function of the Universe". Physical Review D. 28 (12): 2960–2975. Bibcode:1983PhRvD..28.2960H. doi:10.1103/PHYSREVD.28.2960. ISSN 1550-7998. Zbl 1370.83118. Wikidata Q21707690.

- Stephen Hawking; C J Hunter (1 October 1996). "The gravitational Hamiltonian in the presence of non-orthogonal boundaries". Classical and Quantum Gravity. 13 (10): 2735–2752. arXiv:gr-qc/9603050. Bibcode:1996CQGra..13.2735H. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.339.8756. doi:10.1088/0264-9381/13/10/012. ISSN 0264-9381. S2CID 10715740. Zbl 0859.58038. Wikidata Q56551504.

- S. W. Hawking (October 2005). "Information loss in black holes". Physical Review D. 72 (8). arXiv:hep-th/0507171. Bibcode:2005PhRvD..72h4013H. doi:10.1103/PHYSREVD.72.084013. ISSN 1550-7998. S2CID 118893360. Wikidata Q21651473.

- Stephen Hawking; Thomas Hertog (April 2018). "A smooth exit from eternal inflation?". Journal of High Energy Physics. 2018 (4). arXiv:1707.07702. Bibcode:2018JHEP...04..147H. doi:10.1007/JHEP04(2018)147. ISSN 1126-6708. S2CID 13745992. Zbl 1390.83455. Wikidata Q55878494.

См. также

- Список вещей, названных в честь Стивена Хокинга

- О происхождении времени , книга Томаса Хертога о теориях Хокинса.

Примечания

- ↑ Рассматривая влияние горизонта событий черной дыры на образование виртуальных частиц , Хокинг, к своему большому удивлению, в 1974 году обнаружил, что черные дыры излучают излучение черного тела , связанное с температурой, которую можно выразить (в невращающемся случае ) как:

Ссылки

Цитаты

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я дж к л м н тот Стивен Хокинг в проекте «Математическая генеалогия»

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Фергюсон 2011 , с. 29.

- ^ Аллен, Брюс (1983). Энергия вакуума и общая теория относительности (кандидатская диссертация). Кембриджский университет. Архивировано из оригинала 25 января 2016 года . Проверено 5 февраля 2014 г.

- ^ Буссо, Рафаэль (1997). Парное рождение черных дыр в космологии (кандидатская диссертация). Кембриджский университет. Архивировано из оригинала 25 января 2016 года . Проверено 5 февраля 2014 г.

- ^ Карр, Бернард Джон (1976). Первичные черные дыры (кандидатская диссертация). Кембриджский университет. Архивировано из оригинала 25 января 2016 года . Проверено 5 февраля 2014 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час Бернард Карр ; Джордж Ф.Р. Эллис ; Гэри Гиббонс ; Джеймс Хартл ; Томас Хертог ; Роджер Пенроуз ; Малкольм Перри ; Кип С. Торн (июль 2019 г.). «Стивен Уильям Хокинг, CH CBE. 8 января 1942 г. — 14 марта 2018 г.» . Биографические мемуары членов Королевского общества . 66 : 267–308. arXiv : 2002.03185 . дои : 10.1098/RSBM.2019.0001 . ISSN 0080-4606 . S2CID 131986323 . Викиданные Q63347107 .

- ^ Даукер, Хелен Фэй (1991). Пространственно-временные червоточины (кандидатская диссертация). Кембриджский университет. Архивировано из оригинала 25 января 2016 года . Проверено 5 февраля 2014 г.

- ^ Гальфард, Кристоф Жорж Гуннар Свен (2006). Информация о черных дырах и браны (кандидатская диссертация). Кембриджский университет. Архивировано из оригинала 25 января 2016 года . Проверено 5 февраля 2014 г.

- ^ Гиббонс, Гэри Уильям (1973). Некоторые аспекты гравитационного излучения и гравитационного коллапса (кандидатская диссертация). Кембриджский университет. Архивировано из оригинала 25 января 2016 года . Проверено 5 февраля 2014 г.

- ^ Хертог, Томас (2002). Происхождение инфляции (кандидатская диссертация). Кембриджский университет. Архивировано из оригинала 25 января 2016 года . Проверено 5 февраля 2014 г.

- ^ Лафламм, Раймонд (1988). Время и квантовая космология (кандидатская диссертация). Кембриджский университет. Архивировано из оригинала 25 января 2016 года . Проверено 5 февраля 2014 г.

- ^ Пейдж, Дон Нельсон (1976). Аккреция в черные дыры и излучение из них (кандидатская диссертация). Калифорнийский технологический институт. Архивировано из оригинала 21 февраля 2014 года . Проверено 6 февраля 2014 г.

- ^ Перри, Малкольм Джон (1978). Черные дыры и квантовая механика (кандидатская диссертация). Кембриджский университет. Архивировано из оригинала 25 января 2016 года . Проверено 6 февраля 2014 г.

- ^ Тейлор-Робинсон, Марика Максин (1998). Проблемы теории М. lib.cam.ac.uk (кандидатская диссертация). Кембриджский университет. OCLC 894603647 . EThOS uk.bl.ethos.625075 . Архивировано из оригинала 1 мая 2018 года . Проверено 1 мая 2018 г.

- ^ Ву, Чжунчао (1984). Космологические модели и инфляционная Вселенная (кандидатская диссертация). Кембриджский университет. Архивировано из оригинала 25 января 2016 года . Проверено 7 февраля 2014 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Ширбон, Эстель (20 марта 2018 г.). «Стивен Хокинг присоединится к Ньютону и Дарвину в месте последнего упокоения» . Лондон: Рейтер. Архивировано из оригинала 21 марта 2018 года . Проверено 21 марта 2018 г.

- ^ «Центр теоретической космологии: работа со Стивеном Хокингом» . Кембриджский университет. Архивировано из оригинала 30 августа 2015 года . Проверено 23 июня 2013 г.

- ^ «О Стефане» . Официальный сайт Стивена Хокинга. Архивировано из оригинала 30 августа 2015 года . Проверено 23 июня 2013 г.

- ^ «Майкл Грин станет профессором математики Лукаса» . «Дейли телеграф» . Архивировано из оригинала 25 мая 2019 года . Проверено 11 декабря 2012 г.

- ^ «Разум превыше материи: как Стивен Хокинг в течение 50 лет боролся с болезнью двигательных нейронов» . Независимый . 26 ноября 2015 года. Архивировано из оригинала 23 августа 2017 года . Проверено 15 сентября 2017 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Как Стивен Хокинг дожил до 70 лет с БАС?» . Научный американец . 7 января 2012 года. Архивировано из оригинала 30 августа 2015 года . Проверено 23 декабря 2014 г.

Вопрос: Насколько часты случаи очень медленно прогрессирующих форм БАС? Ответ: Я бы сказал, что, вероятно, меньше нескольких процентов.

- ^ Стивен Хокинг: Вдохновляющая история силы воли и силы. Свагатем, Канада https://www.swagathamcanada.com/inspirational/stephen-hawking-an-inspirational-story-of-willpower-and-strength/. Архивировано 6 ноября 2021 г. в Wayback Machine, 26 октября 2021 г.

- ^ Гарднер, Мартин (сентябрь/октябрь 2001 г.). «Мультивселенные и Blackberry». Архивировано 28 июля 2016 года в Wayback Machine . «Записки краеведа». Скептический исследователь . Том 25, № 5.

- ^ Прайс, Майкл Клайв (февраль 1995 г.). «Часто задаваемые вопросы об ЭВЕРЕТТЕ». Архивировано 20 апреля 2016 г. в Wayback Machine . Факультет физики Вашингтонского университета в Сент-Луисе . Проверено 17 декабря 2014 г.

- ^ «Альманах УПИ на понедельник, 8 января 2018 г.» . Юнайтед Пресс Интернэшнл . 8 января 2018 г. Архивировано из оригинала 8 января 2018 г. . Проверено 21 сентября 2019 г.

…Британский физик и писатель Стивен Хокинг, 1942 год (76 лет).

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Анон (2015). «Хокинг, профессор Стивен Уильям» . Кто есть кто (онлайн- изд. Oxford University Press ). А&С Черный. дои : 10.1093/ww/9780199540884.013.19510 . (Требуется подписка или членство в публичной библиотеке Великобритании .)

- ^ Ларсен 2005 , стр. ХIII, 2.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Фергюсон 2011 , с. 21.

- ^ «Разум превыше материи, Стивен Хокинг» . Вестник . Глазго. Архивировано из оригинала 30 мая 2016 года . Проверено 14 марта 2018 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Фергюсон, Китти (6 января 2012 г.). «Стивен Хокинг, «Равно всему!» [Отрывок]» . Научный американец. Архивировано из оригинала 22 марта 2018 года . Проверено 21 марта 2018 г.

- ^ Уайт и Гриббин 2002 , с. 6.

- ^ Ларсен 2005 , стр. 2, 5.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и Фергюсон 2011 , с. 22.

- ^ Ларсен 2005 , с. xiii.

- ^ Уайт и Гриббин 2002 , с. 12.

- ^ Фергюсон 2011 , стр. 22–23.

- ^ Уайт и Гриббин 2002 , стр. 11–12.

- ^ Уайт и Гриббин 2002 , с. 13.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Ларсен 2005 , стр. 3.

- ^ Хокинг, Стивен (7 декабря 2013 г.). «Стивен Хокинг: «Я счастлив, если я что-то добавил к нашему пониманию Вселенной» » . Радио Таймс . Архивировано из оригинала 7 января 2017 года . Проверено 6 января 2017 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Фергюсон 2011 , с. 24.

- ^ Уайт и Гриббин 2002 , с. 8.

- ^ Хокинг, Стивен (2013). Моя краткая история . Петух. ISBN 978-0-345-53528-3 . Проверено 9 сентября 2013 г.

- ^ Уайт и Гриббин 2002 , стр. 7–8.

- ^ Ларсен 2005 , стр. 4.

- ^ Фергюсон 2011 , стр. 25–26.

- ^ Уайт и Гриббин 2002 , стр. 14–16.

- ^ Фергюсон 2011 , с. 26.

- ^ Уайт и Гриббин 2002 , стр. 19–20.

- ^ Фергюсон 2011 , с. 25.

- ^ Уайт и Гриббин 2002 , стр. 17–18.

- ^ Фергюсон 2011 , с. 27.

- ^ Хоар, Джеффри; С любовью, Эрик (5 января 2007 г.). «Дик Тахта» . Хранитель . Лондон. Архивировано из оригинала 8 января 2014 года . Проверено 5 марта 2012 г.

- ^ Уайт и Гриббин 2002 , с. 41.

- ^ Фергюсон 2011 , стр. 27–28.

- ^ Уайт и Гриббин 2002 , стр. 42–43.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Фергюсон 2011 , с. 28.

- ^ Фергюсон 2011 , стр. 28–29.

- ^ Уайт и Гриббин 2002 , стр. 46–47, 51.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Фергюсон, 2011 , стр. 30–31.

- ^ Хокинг 1992 , с. 44.

- ^ Уайт и Гриббин 2002 , с. 50.

- ^ Уайт и Гриббин 2002 , с. 53.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Фергюсон 2011 , с. 31.

- ^ Уайт и Гриббин 2002 , с. 54.

- ^ Уайт и Гриббин 2002 , стр. 54–55.

- ^ Уайт и Гриббин 2002 , с. 56.

- ^ Фергюсон 2011 , стр. 31–32.

- ^ Фергюсон 2011 , с. 33.

- ^ Уайт и Гриббин 2002 , с. 58.

- ^ Фергюсон 2011 , стр. 33–34.

- ^ Уайт и Гриббин 2002 , стр. 61–63.

- ^ Фергюсон 2011 , с. 36.

- ^ Уайт и Гриббин 2002 , стр. 69–70.

- ^ Фергюсон 2011 , с. 42.

- ^ Уайт и Гриббин 2002 , стр. 68–69.

- ^ Фергюсон 2011 , с. 34.

- ^ «Докторская диссертация Стивена Хокинга, объясненная просто» . 30 октября 2017 года. Архивировано из оригинала 13 декабря 2017 года . Проверено 27 ноября 2017 г.

- ^ Уайт и Гриббин 2002 , стр. 71–72.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Стивен Хокинг (1966), Свойства расширяющихся вселенных , doi : 10.17863/CAM.11283 , OCLC 62793673 , Wikidata Q42307084

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Фергюсон, 2011 , стр. 43–44.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Фергюсон 2011 , с. 47.

- ^ Ларсен 2005 , с. XIX.

- ^ Уайт и Гриббин 2002 , с. 101.

- ^ Фергюсон 2011 , стр. 61, 64.

- ^ Фергюсон 2011 , стр. 64–65.

- ^ Уайт и Гриббин 2002 , стр. 115–16.

- ^ С.В. Хокинг ; Р. Пенроуз (27 января 1970 г.). «Особенности гравитационного коллапса и космологии» . Труды Королевского общества А. 314 (1519): 529–548. Бибкод : 1970RSPSA.314..529H . дои : 10.1098/RSPA.1970.0021 . ISSN 1364-5021 . S2CID 120208756 . Збл 0954.83012 . Викиданные Q55872061 .

- ^ Фергюсон 2011 , с. 49.

- ^ Фергюсон 2011 , стр. 65–67.

- ^ Ларсен 2005 , стр. 38.

- ^ Фергюсон 2011 , стр. 67–68.

- ^ Уайт и Гриббин 2002 , стр. 123–24.

- ^ Ларсен 2005 , стр. 33.

- ^ Р. Д. Бландфорд (30 марта 1989 г.). «Астрофизические черные дыры» . В Хокинге, Юго-Запад; Израиль, В. (ред.). Триста лет гравитации . Издательство Кембриджского университета. п. 278. ИСБН 978-0-521-37976-2 .

- ^ Ларсен 2005 , стр. 35.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Фергюсон 2011 , с. 68.

- ^ Ларсен 2005 , стр. 39.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Уайт и Гриббин 2002 , с. 146.

- ^ Фергюсон 2011 , с. 70.

- ^ Ларсен 2005 , стр. 41.

- ^ Стивен Хокинг (март 1974 г.). «Взрывы черных дыр?». Природа . 248 (5443): 30–31. Бибкод : 1974Natur.248...30H . дои : 10.1038/248030A0 . ISSN 1476-4687 . S2CID 4290107 . Збл 1370.83053 . Викиданные Q54017915 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Стивен Хокинг (август 1975 г.). «Создание частиц черными дырами». Связь в математической физике . 43 (3): 199–220. Бибкод : 1975CMaPh..43..199H . дои : 10.1007/BF02345020 . ISSN 0010-3616 . S2CID 55539246 . Збл 1378.83040 . Викиданные Q55869076 .

- ^ Фергюсон 2011 , стр. 69–73.

- ^ Фергюсон 2011 , стр. 70–74.

- ^ Ларсен 2005 , стр. 42–43.

- ^ Уайт и Гриббин 2002 , стр. 150–51.

- ^ Ларсен 2005 , стр. 44.

- ^ Уайт и Гриббин 2002 , с. 133.

- ^ Фергюсон 2011 , стр. 82, 86.

- ^ Фергюсон 2011 , стр. 86–88.

- ^ Фергюсон 2011 , стр. 150, 189, 219.

- ^ Фергюсон 2011 , с. 95.

- ^ Фергюсон 2011 , с. 90.

- ^ Уайт и Гриббин 2002 , стр. 132–33.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Фергюсон 2011 , с. 92.

- ^ Уайт и Гриббин 2002 , с. 162.

- ^ Ларсен 2005 , стр. xv.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Фергюсон 2011 , с. 91.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Ларсен 2005 , с. xiv.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Стивен Хокинг уходит в отставку с поста профессора математики Кембриджа» . «Дейли телеграф» . 23 октября 2008 г. Архивировано из оригинала 16 марта 2018 г. . Проверено 15 марта 2018 г.

- ^ Фергюсон 2011 , стр. 93–94.

- ^ Фергюсон 2011 , стр. 92–93.

- ^ Фергюсон 2011 , с. 96.

- ^ Фергюсон 2011 , стр. 96–101.

- ^ Сасскинд, Леонард (7 июля 2008 г.). Война черных дыр: моя битва со Стивеном Хокингом за то, чтобы сделать мир безопасным для квантовой механики . Hachette Digital, Inc., стр. 9, 18. ISBN 978-0-316-01640-7 . Архивировано из оригинала 18 января 2017 года . Проверено 23 февраля 2016 г.

- ^ Фергюсон 2011 , стр. 108–11.

- ^ Фергюсон 2011 , стр. 111–14.

- ↑ См. популярное описание мастерской Гута (1997) или «Очень ранняя Вселенная» , ISBN 0-521-31677-4 под редакцией Гиббонса, Хокинга и Сиклоса для подробного отчета.

- ^ Стивен Хокинг (сентябрь 1982 г.). «Развитие нарушений в инфляционной Вселенной с одним пузырем». Буквы по физике Б. 115 (4): 295–297. Бибкод : 1982PhLB..115..295H . дои : 10.1016/0370-2693(82)90373-2 . ISSN 0370-2693 . Викиданные Q29398982 .

- ^ Фергюсон 2011 , стр. 102–103.

- ^ Уайт и Гриббин 2002 , с. 180.

- ^ Дж. Б. Хартл ; С.В. Хокинг (декабрь 1983 г.). «Волновая функция Вселенной». Физический обзор D . 28 (12): 2960–2975. Бибкод : 1983PhRvD..28.2960H . дои : 10.1103/PHYSREVD.28.2960 . ISSN 1550-7998 . Збл 1370.83118 . Викиданные Q21707690 .

- ^ Бэрд 2007 , с. 234.

- ^ Уайт и Гриббин 2002 , стр. 180–83.

- ^ Фергюсон 2011 , с. 129.

- ^ Фергюсон 2011 , с. 130.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Сэмпл, Ян (15 мая 2011 г.). «Стивен Хокинг: «Рая не существует; это сказка» » . Хранитель . Архивировано из оригинала 20 сентября 2013 года . Проверено 17 мая 2011 г.

- ^ Юльсман 2003 , стр. 174–176.

- ^ Фергюсон 2011 , стр. 180–182.

- ^ Фергюсон 2011 , с. 182.

- ^ Уайт и Гриббин 2002 , с. 274.