Он слушал меня

| Он слушал меня Муавия | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| 1-й халиф халифата Омейядов | |||||

| Царствование | Январь 661 г. - апрель 680 г. | ||||

| Предшественник |

| ||||

| Преемник | Язид I | ||||

| Губернатор Сирии | |||||

| In Office | 639–661 | ||||

| Predecessor | Yazid ibn Abi Sufyan | ||||

| Successor | Post discontinued | ||||

| Born | c. 597–605 Mecca, Hejaz, Arabia | ||||

| Died | April 680 (aged c. 75–83) Damascus, Umayyad Caliphate | ||||

| Burial | Bab al-Saghir, Damascus | ||||

| Spouse |

| ||||

| Issue |

| ||||

| |||||

| House | Sufyanid | ||||

| Dynasty | Umayyad | ||||

| Father | Abu Sufyan ibn Harb | ||||

| Mother | Hind bint Utba | ||||

| Religion | Islam | ||||

Mu'awiya I ( арабский : معاوية بن أبي سفيان , романизированный : мушавия ибн Аби Суфьян ; ок. 597, 603 или 605 - апрель 680) был основателем и первым халифом Умияда Уэлхада , выходящим из 661 до его смерти. Он стал халифом менее чем через тридцать лет после смерти исламского пророка Мухаммеда и сразу после четырех халифов Рашидун («Правильный путь»). В отличие от своих предшественников, которые были близкими и ранними соратниками Мухаммеда , Муавия был последователем Мухаммеда относительно поздно.

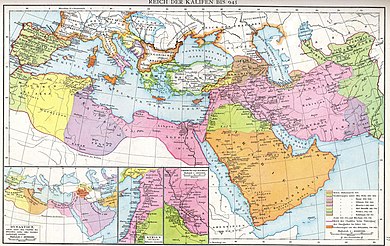

Mu'awiya and his father Abu Sufyan had opposed Muhammad, their distant Qurayshite kinsman and later Mu'awiya's brother-in-law, until Muhammad captured Mecca in 630. Afterward, Mu'awiya became one of Muhammad's scribes. He was appointed by Caliph Abu Bakr (r. 632–634) as a deputy commander in the conquest of Syria. He moved up the ranks through Umar's caliphate (r. 634–644) until becoming governor of Syria during the reign of his Umayyad kinsman, Caliph Uthman (r. 644–656). He allied with the province's powerful Banu Kalb tribe, developed the defenses of its coastal cities, and directed the war effort against the Byzantine Empire, including the first Muslim naval campaigns. In response to Uthman's assassination in 656, Mu'awiya took up the cause of avenging the murdered caliph and opposed the election of Ali. During the First Muslim Civil War, the two led their armies to a stalemate at the Battle of Siffin in 657, prompting an abortive series of arbitration talks to settle the dispute. Afterward, Mu'awiya gained recognition as caliph by his Syrian supporters and his ally Амр ибн аль-Ас , отвоевавший Египет у губернатора Али в 658 году. После убийства Али в 661 году Муавия вынудил сына и преемника Али Хасана отречься от престола, и сюзеренитет Муавии был признан во всем Халифате.

Domestically, Mu'awiya relied on loyalist Syrian Arab tribes and Syria's Christian-dominated bureaucracy. He is credited with establishing government departments responsible for the postal route, correspondence, and chancellery. He was the first caliph whose name appeared on coins, inscriptions, or documents of the nascent Islamic empire. Externally, he engaged his troops in almost yearly land and sea raids against the Byzantines, including a failed siege of Constantinople. In Iraq and the eastern provinces, he delegated authority to the powerful governors al-Mughira and Ziyad ibn Abi Sufyan, the latter of whom he controversially adopted as his brother. Under Mu'awiya's direction, the Muslim conquest of Ifriqiya (central North Africa) was launched by the commander Uqba ibn Nafi in 670, while the conquests in Khurasan and Sijistan on the eastern frontier were resumed.

Although Mu'awiya confined the influence of his Umayyad clan to the governorship of Medina, he nominated his own son, Yazid I, as his successor. It was an unprecedented move in Islamic politics and opposition to it by prominent Muslim leaders, including Ali's son Husayn, and Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr, persisted after Mu'awiya's death, culminating with the outbreak of the Second Muslim Civil War. While there is considerable admiration for Mu'awiya in the contemporary sources, he has been criticized for lacking the justice and piety of the Rashidun and transforming the office of the caliphate into a kingship. Besides these criticisms, Sunni Muslim tradition honors him as a companion of Muhammad and a scribe of Qur'anic revelation. In Shia Islam, Mu'awiya is reviled for opposing Ali, accused of poisoning his son Hasan, and held to have accepted Islam without conviction.

Origins and early life

Mu'awiya's year of birth is uncertain, with 597, 603 or 605 cited by early Islamic sources.[1] His father Abu Sufyan ibn Harb was a prominent Meccan merchant who led trade caravans to Syria, then part of the Byzantine Empire.[2] He emerged as the leader of the Banu Abd Shams clan of the polytheistic Quraysh, the dominant tribe of Mecca, during the early stages of the Quraysh's conflict with Muhammad.[1] The latter also hailed from the Quraysh and was distantly related to Mu'awiya via their common paternal ancestor, Abd Manaf ibn Qusayy.[3] Mu'awiya's mother, Hind bint Utba, was also a member of the Banu Abd Shams.[1]

In 624, Muhammad and his followers attempted to intercept a Meccan caravan led by Mu'awiya's father on its return from Syria, prompting Abu Sufyan to call for reinforcements.[4] The Qurayshite relief army was routed in the ensuing Battle of Badr, in which Mu'awiya's elder brother Hanzala and their maternal grandfather, Utba ibn Rabi'a, were killed.[2] Abu Sufyan replaced the slain leader of the Meccan army, Abu Jahl, and led the Meccans to victory against the Muslims at the Battle of Uhud in 625. After his abortive siege of Muhammad in Medina at the Battle of the Trench in 627, he lost his leadership position among the Quraysh.[1]

Mu'awiya's father was not a participant in the truce negotiations at Hudaybiyya between the Quraysh and Muhammad in 628. The following year, Muhammad married Mu'awiya's widowed sister Umm Habiba, who had embraced Islam fifteen years earlier. The marriage may have reduced Abu Sufyan's hostility toward Muhammad and Abu Sufyan negotiated with him in Medina in 630 after confederates of the Quraysh violated the Hudaybiyya truce.[2] When Muhammad captured Mecca in 630, Mu'awiya, his father, and his elder brother Yazid embraced Islam. According to accounts cited by the early Muslim historians al-Baladhuri and Ibn Hajar, Mu'awiya had secretly become a Muslim from the time of the Hudaybiyya negotiations.[1] By 632 Muslim authority extended across Arabia with Medina as the seat of the Muslim government.[5] As part of Muhammad's efforts to reconcile with the Quraysh, Mu'awiya was made one of his kātibs (scribes), being one of seventeen literate members of the Quraysh at that time.[1] Abu Sufyan moved to Medina to maintain his newfound influence in the nascent Muslim community.[6]

Governorship of Syria

Early military career and administrative promotions

After Muhammad died in 632, Abu Bakr became caliph (leader of the Muslim community).[7] He and his successors Umar, Uthman, and Ali are often known as the Rashidun ('rightly-guided') caliphs to distinguish them from Mu'awiya and his Umayyad dynastic successors.[8] Having to contend with challenges to his leadership from the Ansar, the natives of Medina who had provided Muhammad safe haven from his erstwhile Meccan opponents, and the mass defections of several Arab tribes, Abu Bakr reached out to the Quraysh, particularly its two strongest clans, the Banu Makhzum and Banu Abd Shams, to shore up support for the Caliphate.[9] Among those Qurayshites whom he appointed to suppress the rebel Arab tribes during the Ridda wars (632–633) was Mu'awiya's brother Yazid. Afterward, he was dispatched as one of four commanders in charge of the Muslim conquest of Byzantine Syria in c. 634.[10] The caliph appointed Mu'awiya commander of Yazid's vanguard.[1] Through these appointments Abu Bakr gave the family of Abu Sufyan a stake in the conquest of Syria, where Abu Sufyan already owned property in the vicinity of Damascus.[10][a]

Abu Bakr's successor Umar (r. 634–644) appointed a leading companion of Muhammad, Abu Ubayda ibn al-Jarrah, as the general commander of the Muslim army in Syria in 636 after the rout of the Byzantines at the Battle of Yarmouk,[12] which paved the way for the conquest of the rest of Syria.[13] Mu'awiya was among the Arab troops that entered Jerusalem with Caliph Umar in 637.[1][b] Afterward, Mu'awiya and Yazid were dispatched by Abu Ubayda to conquer the coastal towns of Sidon, Beirut and Byblos.[15] Following the death of Abu Ubayda in the plague of Amwas in 639, Umar split the command of Syria, appointing Yazid as governor of the military districts of Damascus, Jordan and Palestine, and the veteran commander Iyad ibn Ghanm governor of Homs and the Jazira (Upper Mesopotamia).[1][16] When Yazid succumbed to the plague later that year, Umar appointed Mu'awiya the military and fiscal governor of Damascus, and possibly Jordan as well.[1][17] In 640 or 641, Mu'awiya captured Caesarea, the district capital of Byzantine Palestine, and then captured Ascalon, completing the Muslim conquest of Palestine.[1][18][19] As early as 640 or 641, Mu'awiya may have led a campaign against Cilicia and proceeded to Euchaita, deep in Byzantine Anatolia.[20] In 644, he led a foray against the Anatolian city of Amorium.[21]

The successive promotions of Abu Sufyan's sons contradicted Umar's efforts to otherwise curtail the influence of the Qurayshite aristocracy in the Muslim state in favor of the earliest Muslim converts (i.e. the Muhajirun and Ansar groups).[16] According to the historian Leone Caetani, this exceptional treatment stemmed from Umar's personal respect for the Umayyads, the branch of the Banu Abd Shams to which Mu'awiya belonged.[17] This is doubted by the historian Wilferd Madelung, who surmises that Umar had little choice, due to the lack of a suitable alternative to Mu'awiya in Syria and the ongoing plague in the region, which precluded the deployment of commanders more preferable to Umar from Medina.[17]

Upon the accession of Caliph Uthman (r. 644–656), Mu'awiya's governorship was enlarged to include Palestine, while a companion of Muhammad, Umayr ibn Sa'd al-Ansari, was confirmed as governor of the Homs-Jazira district. In late 646 or early 647, Uthman attached the Homs-Jazira district to Mu'awiya's Syrian governorship,[1] greatly increasing the military manpower at his disposal.[22]

Consolidation of local power

During the reign of Uthman, Mu'awiya allied with the Banu Kalb,[23] the predominant tribe in the Syrian steppe extending from the oasis of Dumat al-Jandal in the south to the approaches of Palmyra and the chief component of the Quda'a confederation present throughout Syria.[24][25][26] Medina consistently courted the Kalb, which had remained mostly neutral during the Arab–Byzantine wars, particularly after the central government's entreaties to the Byzantines' principal Arab allies, the Christian Ghassanids, were rebuffed.[27][c] Before the advent of Islam in Syria, the Kalb and the Quda'a, long under the influence of Greco-Aramaic culture and the Monophysite church,[30][31] had served Byzantium as subordinates of its Ghassanid client kings to guard the Syrian frontier against invasions by the Sasanian Persians and the latter's Arab clients, the Lakhmids.[30] By the time the Muslims entered Syria, the Kalb and the Quda'a had accumulated significant military experience and were accustomed to hierarchical order and military obedience.[31] To harness their strength and thereby secure his foothold in Syria, Mu'awiya consolidated ties to the Kalb's ruling house, the clan of Bahdal ibn Unayf, by wedding the latter's daughter Maysun in c. 650.[23][26][32] He also married Maysun's paternal cousin, Na'ila bint Umara, for a short period.[33][d]

Mu'awiya's reliance on the native Syrian Arab tribes was compounded by the heavy toll inflicted on the Muslim troops in Syria by the plague of Amwas,[35] which caused troop numbers to dwindle from 24,000 in 637 to 4,000 in 639.[36] Moreover, the focus of Arabian tribal migration was toward the Sasanian front in Iraq.[35] Mu'awiya oversaw a liberal recruitment policy that resulted in considerable numbers of Christian tribesmen and frontier peasants filling the ranks of his regular and auxiliary forces.[37] Indeed, the Christian Tanukhids and the mixed Muslim–Christian Banu Tayy formed part of Mu'awiya's army in northern Syria.[38][39] To help pay for his troops, Mu'awiya requested and was granted ownership by Uthman of the abundant, income-producing, Byzantine crown lands in Syria, which were previously designated by Umar as communal property for the Muslim army.[40]

Although Syria's rural, Aramaic-speaking Christian population remained largely intact,[41] the Muslim conquest had caused a mass flight of Greek Christian urbanites from Damascus, Aleppo, Latakia and Tripoli to Byzantine territory,[36] while those who remained held pro-Byzantine sympathies.[35] In contrast to the other conquered regions of the Caliphate, where new garrison cities were established to house Muslim troops and their administration, in Syria the troops settled in existing cities, including Damascus, Homs, Jerusalem, Tiberias,[36] Aleppo and Qinnasrin.[29] Mu'awiya restored, repopulated and garrisoned the coastal cities of Antioch, Balda, Tartus, Maraclea and Baniyas.[35] In Tripoli he settled significant numbers of Jews,[35] while sending to Homs, Antioch and Baalbek Persian holdovers from the Sasanian occupation of Byzantine Syria in the early 7th century.[42] Upon Uthman's direction, Mu'awiya settled groups of the nomadic Tamim, Asad and Qays tribes to areas north of the Euphrates in the vicinity of Raqqa.[35][43]

Naval campaigns against Byzantium and conquest of Armenia

Mu'awiya initiated the Arab naval campaigns against the Byzantines in the eastern Mediterranean,[1] requisitioning the harbors of Tripoli, Beirut, Tyre, Acre, and Jaffa.[37][44] Umar had rejected Mu'awiya's request to launch a naval invasion of Cyprus, citing concerns about the Muslim forces' safety at sea, but Uthman allowed him to commence the campaign in 647, after refusing an earlier entreaty.[45] Mu'awiya's rationale was that the Byzantine-held island posed a threat to Arab positions along the Syrian coast, and that it could be easily neutralized.[45] The exact year of the raid is unclear, with the early Arabic sources providing a range between 647 and 650, while two Greek inscriptions in the Cypriot village of Solois cite two raids launched between 648 and 650.[45]

According to the 9th-century historians al-Baladhuri and Khalifa ibn Khayyat, Mu'awiya led the raid in person accompanied by his wife, Katwa bint Qaraza ibn Abd Amr of the Qurayshite Banu Nawfal, alongside the commander Ubada ibn al-Samit.[34][45] Katwa died on the island and at some point Mu'awiya married her sister Fakhita.[34] In a different narrative by the early Muslim sources, the raid was instead conducted by Mu'awiya's admiral Abd Allah ibn Qays, who landed at Salamis before occupying the island.[44] In either case, the Cypriots were forced to pay a tribute equal to that which they had paid the Byzantines.[44][46] Mu'awiya established a garrison and a mosque to maintain the Caliphate's influence on the island, which became a staging ground for the Arabs and the Byzantines to launch raids against each other's territories.[46] The inhabitants of Cyprus were largely left to their own devices and archaeological evidence indicates uninterrupted prosperity during this period.[47]

Dominance of the eastern Mediterranean enabled Mu'awiya's naval forces to raid Crete and Rhodes in 653. From the raid on Rhodes, Mu'awiya remitted significant war spoils to Uthman.[48] In 654 or 655, a joint naval expedition launched from Alexandria, Egypt and the harbors of Syria routed a Byzantine fleet commanded by the Byzantine Emperor Constans II (r. 641–668) off the Lycian coast at the Battle of the Masts. Constans II was forced to sail to Sicily, opening the way for an ultimately unsuccessful Arab naval attack on Constantinople.[49] The Arabs were commanded by either the governor of Egypt, Abd Allah ibn Abi Sarh, or Mu'awiya's lieutenant Abu'l-A'war.[49]

Meanwhile, after two previous attempts by the Arabs to conquer Armenia, the third attempt in 650 ended with a three-year truce reached between Mu'awiya and the Byzantine envoy Procopios in Damascus.[50] In 653, Mu'awiya received the submission of the Armenian leader Theodore Rshtuni, which the Byzantine emperor practically conceded when he withdrew from Armenia that year.[51] In 655, Mu'awiya's lieutenant commander Habib ibn Maslama al-Fihri captured Theodosiopolis and deported Rshtuni to Syria, solidifying Arab rule over Armenia.[51]

First Fitna

Mu'awiya's domain was generally immune to the growing discontent prevailing in Medina, Egypt and Kufa against Uthman's policies in the 650s. The exception was Abu Dharr al-Ghifari,[1] who had been sent to Damascus for openly condemning Uthman's enrichment of his kinsmen.[52] He criticized the lavish sums that Mu'awiya invested in building his Damascus residence, the Khadra Palace, prompting Mu'awiya to expel him.[52] Uthman's confiscation of crown lands in Iraq and his alleged nepotism[e] drove the Quraysh and the dispossessed elites of Kufa and Egypt to oppose the caliph.[54]

Uthman sent for assistance from Mu'awiya when rebels from Egypt besieged his home in June 656. Mu'awiya dispatched a relief army toward Medina, but it withdrew at Wadi al-Qura when word reached them of Uthman's killing.[56] Ali, Muhammad's cousin and son-in-law, was recognized as caliph in Medina.[57] Mu'awiya withheld allegiance to Ali[58] and, according to some reports, the latter deposed him by sending his own governor to Syria, who was denied entry into the province by Mu'awiya.[57] This is rejected by Madelung, according to whom no formal relations existed between the caliph and the governor of Syria for seven months from the date of Ali's election.[59]

Soon after becoming caliph, Ali was opposed by much of the Quraysh led by al-Zubayr and Talha, both prominent companions of Muhammad, and Muhammad's wife A'isha, who feared the loss of their own influence under Ali.[60] The ensuing civil war became known as the First Fitna.[f] Ali defeated the triumvirate near Basra at the Battle of the Camel, which ended in the deaths of al-Zubayr and Talha, both potential contenders for the caliphate, and the retirement of A'isha to Medina.[60] With his position in Iraq, Egypt and Arabia secure, Ali turned his attention toward Mu'awiya. Unlike the other provincial governors, Mu'awiya had a strong and loyal power base, demanded revenge for the slaying of his Umayyad kinsman Uthman, and could not be easily replaced.[62][63] At this point, Mu'awiya did not yet claim the caliphate and his principal aim was keeping power in Syria.[64][65]

Preparations for war

Ali's victory in Basra left Mu'awiya vulnerable, his territory wedged between Ali's forces in Iraq and Egypt, while the war with the Byzantines was ongoing in the north.[66] In 657 or 658 Mu'awiya secured his northern frontier with Byzantium by making a truce with the emperor, enabling him to focus the bulk of his troops on the impending battle with the caliph.[67] After failing to gain the defection of Egypt's governor, Qays ibn Sa'd, he resolved to end the Umayyad family's hostility to Amr ibn al-As, the conqueror and former governor of Egypt, whom they accused of involvement in Uthman's death.[68] Mu'awiya and Amr, who was popular with the Arab troops of Egypt, made a pact whereby the latter joined the coalition against Ali and Mu'awiya publicly agreed to install Amr as Egypt's lifetime governor should they oust Ali's appointee.[69]

Although he had the firm backing of the Kalb, to shore up the rest of his base in Syria, Mu'awiya was advised by his kinsman al-Walid ibn Uqba to secure an alliance with the Yemenite tribes of Himyar, Kinda and Hamdan, who collectively dominated the Homs garrison. He employed the veteran commander and Kindite nobleman Shurahbil ibn Simt, who was widely respected in Syria, to rally the Yemenites to his side.[70] He then enlisted support from the dominant tribal leader of Palestine, the Judham chief Natil ibn Qays, by allowing the latter's confiscation of the district's treasury to go unpunished.[71] The efforts bore fruit and demands for war against Ali grew throughout Mu'awiya's domain.[72] When Ali sent his envoy, the veteran commander and chieftain of the Bajila, Jarir ibn Abd Allah, to Mu'awiya, the latter responded with a letter that amounted to a declaration of war against the caliph, whose legitimacy he refused to recognize.[73]

Battle of Siffin and arbitration

In the first week of June 657, the armies of Mu'awiya and Ali met at Siffin near Raqqa and engaged in days of skirmishes interrupted by a month-long truce on 19 June.[74] During the truce, Mu'awiya dispatched an embassy led by Habib ibn Maslama, who presented Ali with an ultimatum to hand over Uthman's alleged killers, abdicate and allow a shura (consultative council) to decide the caliphate. Ali rebuffed Mu'awiya's envoys and on 18 July declared that the Syrians remained obstinate in their refusal to recognize his sovereignty. On the following day, a week of duels between Ali's and Mu'awiya's top commanders ensued.[75] The main battle between the two armies commenced on 26 July.[76] As Ali's troops advanced toward Mu'awiya's tent, the governor of Syria ordered his elite troops forward and they bested the Iraqis before the tide turned against the Syrians the next day with the deaths of two of Mu'awiya's leading commanders, Ubayd Allah, a son of Caliph Umar, and Dhu'l-Kala Samayfa, the so-called 'king of Himyar'.[77]

Mu'awiya rejected suggestions from his advisers to engage Ali in a duel and definitively end hostilities.[78] The battle climaxed on the so-called 'Night of Clamor' on 28 July, which saw Ali's forces take the advantage in a melée as the death toll mounted on both sides.[79][g] According to the account of the scholar al-Zuhri (d. 742), this prompted Amr ibn al-As to counsel Mu'awiya the following morning to have a number of his men tie leaves of the Qur'an on their lances in an appeal to the Iraqis to settle the conflict through consultation. According to the scholar al-Sha'bi (d. 723), al-Ash'ath ibn Qays, who was in Ali's army, expressed his fears of Byzantine and Persian attacks were the Muslims to exhaust themselves in the civil war. Upon receiving intelligence of this, Mu'awiya ordered the raising of the Qur'an leaves.[81] Though this act represented a surrender of sorts as Mu'awiya abandoned, at least temporarily, his previous insistence on settling the dispute with Ali militarily and pursuing Uthman's killers into Iraq, it had the effect of sowing discord and uncertainty in Ali's ranks.[82]

The caliph adhered to the will of the majority in his army and accepted the proposal to arbitrate.[83] Moreover, Ali agreed to Amr's, or Mu'awiya's, demand to omit his formal title, amir al-mu'minin (commander of the faithful, the traditional title of a caliph), from the initial arbitration document.[84] According to the historian Hugh N. Kennedy, the agreement forced Ali "to deal with Mu'awiya on equal terms and abandon his unchallenged right to lead the community".[85] Madelung asserts it "handed Mu'awiya a moral victory" before inducing a "disastrous split in the ranks of Ali's men".[86] Indeed, upon Ali's return to his capital Kufa in September 658, a large segment of his troops who had opposed the arbitration defected, inaugurating the Kharijite movement.[87]

The initial agreement postponed the arbitration to a later date.[79][88] Information in the early Muslim sources about the time, place and outcome of the arbitration is contradictory, but there were likely two meetings between Mu'awiya's and Ali's respective representatives, Amr and Abu Musa al-Ash'ari, the first in Dumat al-Jandal and the last in Adhruh.[89] Ali abandoned the arbitration after the first meeting in which Abu Musa—who, unlike Amr, was not particularly attached to his principal's cause—[90] accepted the Syrian side's claim that Uthman was wrongfully killed, a verdict that Ali opposed.[91] The final meeting in Adhruh, which had been convened at Mu'awiya's request, collapsed, but by then Mu'awiya had emerged as a major contender for the caliphate.[92]

Claim to the caliphate and resumption of hostilities

Following the breakdown of the arbitration talks, Amr and the Syrian delegates returned to Damascus, where they greeted Mu'awiya as amir al-mu'minin, signaling their recognition of him as caliph.[93] In April or May 658, Mu'awiya received a general pledge of allegiance from the Syrians.[56] In response, Ali broke off communications with Mu'awiya, mobilized for war and invoked a curse against Mu'awiya and his close retinue as a ritual in the morning prayers.[93] Mu'awiya reciprocated in kind against Ali and his closest supporters in his own domain.[94]

In July, Mu'awiya dispatched an army under Amr to Egypt after a request for intervention from pro-Uthman mutineers in the province who were being suppressed by the governor, Caliph Abu Bakr's son and Ali's stepson, Muhammad.[95] The latter's troops were defeated by Amr's forces, the provincial capital Fustat was captured and Muhammad was executed on the orders of Mu'awiya ibn Hudayj, leader of the pro-Uthman rebels.[95] The loss of Egypt was a major blow to the authority of Ali, who was bogged down battling Kharijite defectors in Iraq and whose grip in Basra and Iraq's eastern and southern dependencies was eroding.[56][96] Though his hand was strengthened, Mu'awiya refrained from launching a direct assault against Ali.[96] Instead, his strategy was to bribe the tribal chieftains in Ali's army to his side and harry the inhabitants along Iraq's western frontier.[96] The first raid was conducted by al-Dahhak ibn Qays al-Fihri against nomads and Muslim pilgrims in the desert west of Kufa.[97] This was followed by Nu'man ibn Bashir al-Ansari's abortive attack on Ayn al-Tamr then, in the summer of 660, Sufyan ibn Awf's successful raids against Hit and Anbar.[98]

In 659 or 660, Mu'awiya expanded the operations to the Hejaz (western Arabia, where Mecca and Medina are located), sending Abd Allah ibn Mas'ada al-Fazari to collect the alms tax and oaths of allegiance to Mu'awiya from the inhabitants of the Tayma oasis. This initial foray was defeated by the Kufans,[99] while an attempt to extract oaths of allegiance from the Quraysh of Mecca in April 660 also failed.[100]

In the summer, Mu'awiya dispatched a large army under Busr ibn Abi Artat to conquer the Hejaz and Yemen. He directed Busr to intimidate Medina's inhabitants without harming them, spare the Meccans and kill anyone in Yemen who refused to pledge their allegiance.[101] Busr advanced through Medina, Mecca and Ta'if, encountering no resistance and gaining those cities' recognition of Mu'awiya.[102] In Yemen, Busr executed several notables in Najran and its vicinity on account of past criticism of Uthman or ties to Ali, massacred numerous tribesmen of the Hamdan and townspeople from Sana'a and Ma'rib. Before he could continue his campaign in Hadhramawt, he withdrew upon the approach of a Kufan relief force.[103] News of Busr's actions in Arabia spurred Ali's troops to rally behind his planned campaign against Mu'awiya,[104] but the expedition was aborted as a result of Ali's assassination by a Kharijite in January 661.[105]

Caliphate

Accession

After Ali was killed, Mu'awiya left al-Dahhak ibn Qays in charge of Syria and led his army toward Kufa, where Ali's son Hasan had been nominated as his successor.[106][107] He successfully bribed Ubayd Allah ibn Abbas, the commander of Hasan's vanguard, to desert his post and sent envoys to negotiate with Hasan.[108] In return for a financial settlement, Hasan abdicated and Mu'awiya entered Kufa in July or September 661 and was recognized as caliph. This year is considered by a number of the early Muslim sources as 'the year of unity' and is generally regarded as the start of Mu'awiya's caliphate.[56][109]

Before and/or after Ali's death, Mu'awiya received oaths of allegiance in one or two formal ceremonies in Jerusalem, the first in late 660 or early 661 and the second in July 661.[110] The 10th-century Jerusalemite geographer al-Maqdisi holds that Mu'awiya had further developed a mosque originally built by Caliph Umar on the Temple Mount, the precursor of the Jami Al-Aqsa, and received his formal oaths of allegiance there.[111] According to the earliest extant source about Mu'awiya's accession in Jerusalem, the near-contemporaneous Maronite Chronicles, composed by an anonymous Syriac author, Mu'awiya received the pledges of the tribal chieftains and then prayed at Golgotha and the Tomb of the Virgin Mary in Gethsemane, both adjacent to the Temple Mount.[112] The Maronite Chronicles also maintain that Mu'awiya "did not wear a crown like other kings in the world".[113]

Domestic rule and administration

There is little information in the early Muslim sources about Mu'awiya's rule in Syria, the center of his caliphate.[114][115] He established his court in Damascus and moved the caliphal treasury there from Kufa.[116] He relied on his Syrian tribal soldiery,[114] numbering about 100,000 men,[117] increasing their pay at the expense of the Iraqi garrisons,[114] also about 100,000 soldiers combined.[117] The highest stipends were paid on an inheritable basis to 2,000 nobles of the Quda'a and Kinda tribes, the core components of his support base, who were further awarded the privilege of consultation for all major decisions and the rights to veto or propose measures.[30][118] The respective leaders of the Quda'a and the Kinda, the Kalbite chief Ibn Bahdal and the Homs-based Shurahbil, formed part of his Syrian inner circle along with the Qurayshites Abd al-Rahman ibn Khalid, son of the distinguished commander Khalid ibn al-Walid, and al-Dahhak ibn Qays.[119]

Mu'awiya is credited by the early Muslim sources for establishing diwans (government departments) for correspondences (rasa'il), chancellery (khatam) and the postal route (barid).[30] According to al-Tabari, following an assassination attempt by the Kharijite al-Burak ibn Abd Allah on Mu'awiya while he was praying in the mosque of Damascus in 661, Mu'awiya established a caliphal haras (personal guard) and shurta (select troops) and the maqsura (reserved area) within mosques.[120][121] The caliph's treasury was largely dependent on the tax revenues of Syria and income from the crown lands that he confiscated in Iraq and Arabia. He also received the customary fifth of the war booty acquired by his commanders during expeditions.[30] In the Jazira, Mu'awiya coped with the tribal influx, which spanned previously established groups such as the Sulaym, newcomers from the Mudar and Rabi'a confederations and civil war refugees from Kufa and Basra, by administratively detaching the military district of Qinnasrin–Jazira from Homs, according to the 8th-century historian Sayf ibn Umar.[122][123] However, al-Baladhuri attributes this change to Mu'awiya's successor Yazid I (r. 680–683).[122]

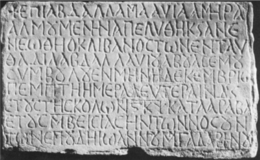

Syria retained its Byzantine-era bureaucracy, which was staffed by Christians including the head of the tax administration, Sarjun ibn Mansur.[124] The latter had served Mu'awiya in the same capacity before his attainment of the caliphate,[125] and Sarjun's father was the likely holder of the office under Emperor Heraclius (r. 610–641).[124] Mu'awiya was tolerant toward Syria's native Christian majority.[126] In turn, the community was generally satisfied with his rule, under which their conditions were at least as favorable as under the Byzantines.[127] Mu'awiya attempted to mint his own coins, but the new currency was rejected by the Syrians as it omitted the symbol of the cross.[128] The sole epigraphic attestation to Mu'awiya's rule in Syria, a Greek inscription dated to 663 discovered at the hot springs of Hamat Gader near the Sea of Galilee,[129] refers to the caliph as Abd Allah Mu'awiya, amir al-mu'minin ("God's Servant Mu'awiya, commander of the faithful"; the caliph's name is preceded by a cross) and credits him for restoring Roman-era bath facilities for the benefit of the sick. According to the historian Yizhar Hirschfeld, "by this deed, the new caliph sought to please" his Christian subjects.[130] The caliph often spent his winters at his Sinnabra palace near the Sea of Galilee.[131] Mu'awiya was also credited with ordering the restoration of Edessa's church after it was ruined in an earthquake in 679.[132] He demonstrated a keen interest in Jerusalem.[133] Although archaeological evidence is lacking, there are indications in medieval literary sources that a rudimentary mosque on the Temple Mount existed as early as Mu'awiya's time or was built by him.[134][h]

Governance in the provinces

Mu'awiya's primary internal challenge was overseeing a Syria-based government that could reunite the politically and socially fractured Caliphate and assert authority over the tribes which formed its armies.[122] He applied indirect rule to the Caliphate's provinces, appointing governors with full civil and military authority.[136] Although in principle governors were obliged to forward surplus tax revenues to the caliph,[122] in practice most of the surplus was distributed among the provincial garrisons and Damascus received a negligible share.[30][137] During Mu'awiya's caliphate, the governors relied on the ashraf (tribal chieftains), who served as intermediaries between the authorities and the tribesmen in the garrisons.[122] Mu'awiya's statecraft was likely inspired by his father, who utilized his wealth to establish political alliances.[137] The caliph generally preferred bribing his opponents over direct confrontation. In the summation of Kennedy, Mu'awiya ruled by "making agreements with those who held power in the provinces, by building up the power of those who were prepared to co-operate with him and by attaching as many important and influential figures to his cause as possible".[137]

Iraq and the east

Challenges to central authority in general, and to Mu'awiya's rule in particular, were most acute in Iraq, where divisions were rife between the ashraf upstarts and the nascent Muslim elite, the latter of which was further divided between Ali's partisans and the Kharijites.[138] Mu'awiya's ascent signaled the rise of the Kufan ashraf represented by Ali's erstwhile backers al-Ash'ath ibn Qays and Jarir ibn Abd Allah, at the expense of Ali's old guard represented by Hujr ibn Adi and Ibrahim, the son of Ali's leading aide Malik al-Ashtar. Mu'awiya's initial choice to govern Kufa in 661 was al-Mughira ibn Shu'ba, who possessed considerable administrative and military experience in Iraq and was highly familiar with the region's inhabitants and issues. Under his nearly decade-long administration, al-Mughira maintained peace in the city, overlooked transgressions that did not threaten his rule, allowed the Kufans to keep possession of the lucrative Sasanian crown lands in the Jibal district and, unlike under past administrations, consistently and timely paid the garrison's stipends.[139]

In Basra, Mu'awiya reappointed his Abd Shams kinsman Abd Allah ibn Amir, who had served in the office under Uthman.[140] During Mu'awiya's reign, Ibn Amir recommenced expeditions into Sistan, reaching as far as Kabul. He was unable to maintain order in Basra, where there was growing resentment toward the distant campaigns. Consequently, Mu'awiya replaced Ibn Amir with Ziyad ibn Abihi in 664 or 665.[141] The latter had been the longest of Ali's loyalists to withhold recognition of Mu'awiya's caliphate and had barricaded himself in the Istakhr fortress in Fars.[142] Busr had threatened to execute three of Ziyad's young sons in Basra to force his surrender, but Ziyad was ultimately persuaded by al-Mughira, his mentor, to submit to Mu'awiya's authority in 663.[143] In a controversial step that secured the loyalty of the fatherless Ziyad, whom the caliph viewed as the most capable candidate to govern Basra,[141] Mu'awiya adopted him as his paternal half-brother, to the protests of his own son Yazid, Ibn Amir and his Umayyad kinsmen in the Hejaz.[143][144]

Following al-Mughira's death in 670, Mu'awiya attached Kufa and its dependencies to Ziyad's Basran governorship, making him the caliph's virtual viceroy over the eastern half of the Caliphate.[141] Ziyad tackled Iraq's core economic problem of overpopulation in the garrison cities and the consequent scarcity of resources by reducing the number of troops on the payrolls and dispatching 50,000 Iraqi soldiers and their families to settle Khurasan. This also consolidated the previously weak and unstable Arab position in the Caliphate's easternmost province and enabled conquests toward Transoxiana.[122] As part of his reorganization efforts in Kufa, Ziyad confiscated its garrison's crown lands, which thenceforth became the possession of the caliph.[136] Opposition to the confiscations raised by Hujr ibn Adi,[122] whose pro-Alid advocacy had been tolerated by al-Mughira,[145] was violently suppressed by Ziyad.[122] Hujr and his retinue were sent to Mu'awiya for punishment and were executed on the caliph's orders, marking the first political execution in Islamic history and serving as a harbinger for future pro-Alid uprisings in Kufa.[144][146] Ziyad died in 673 and his son Ubayd Allah was appointed gradually by Mu'awiya to all of his father's former offices. In effect, by relying on al-Mughira and Ziyad and his sons, Mu'awiya franchised the administration of Iraq and the eastern Caliphate to members of the elite Thaqif clan, which had long-established ties to the Quraysh and were instrumental in the conquest of Iraq.[115]

Egypt

In Egypt Amr governed more as a partner of Mu'awiya than a subordinate until his death in 664.[124] He was permitted to retain the surplus revenues of the province.[95] The caliph ordered the resumption of Egyptian grain and oil shipments to Medina, ending the hiatus caused by the First Fitna.[147] After Amr's death, Mu'awiya's brother Utba (r. 664–665) and an early companion of Muhammad, Uqba ibn Amir (r. 665–667), successively served as governors before Mu'awiya appointed Maslama ibn Mukhallad al-Ansari in 667.[95][124] Maslama remained governor for the duration of Mu'awiya's reign,[124] significantly expanding Fustat and its mosque and boosting the city's importance in 674 by relocating Egypt's main shipyard to the nearby Roda Island from Alexandria due to the latter's vulnerability to Byzantine naval raids.[148]

The Arab presence in Egypt was mostly limited to the central garrison at Fustat and the smaller garrison at Alexandria.[147] The influx of Syrian troops brought by Amr in 658 and the Basran troops sent by Ziyad in 673 swelled Fustat's 15,000-strong garrison to 40,000 during Mu'awiya's reign.[147] Utba increased the Alexandria garrison to 12,000 men and built a governor's residence in the city, whose Greek Christian population was generally hostile to Arab rule. When Utba's deputy in Alexandria complained that his troops were unable to control the city, Mu'awiya deployed a further 15,000 soldiers from Syria and Medina.[149] The troops in Egypt were far less rebellious than their Iraqi counterparts, though elements in the Fustat garrison occasionally raised opposition to Mu'awiya's policies, culminating during Maslama's term with the widespread protest at Mu'awiya's seizure and allotment of crown lands in Fayyum to his son Yazid, which compelled the caliph to reverse his order.[150]

Arabia

Although revenge for Uthman's assassination had been the basis upon which Mu'awiya claimed the right to the caliphate, he neither emulated Uthman's empowerment of the Umayyad clan nor used them to assert his own power.[137][151] With minor exceptions, members of the clan were not appointed to the wealthy provinces nor the caliph's court, Mu'awiya largely limiting their influence to Medina, the old capital of the Caliphate where most of the Umayyads and the wider Qurayshite former aristocracy remained headquartered.[137][152] The loss of political power left the Umayyads of Medina resentful toward Mu'awiya, who may have become wary of the political ambitions of the much larger Abu al-As branch of the clan—to which Uthman had belonged—under the leadership of Marwan ibn al-Hakam.[153] The caliph attempted to weaken the clan by provoking internal divisions.[154] Among the measures taken was the replacement of Marwan from the governorship of Medina in 668 with another leading Umayyad, Sa'id ibn al-As. The latter was instructed to demolish Marwan's house, but refused and when Marwan was restored in 674, he also refused Mu'awiya's order to demolish Sa'id's house.[155] Mu'awiya dismissed Marwan once more in 678, replacing him with his own nephew, al-Walid ibn Utba.[156] Besides his own clan, Mu'awiya's relations with the Banu Hashim (the clan of Muhammad and Caliph Ali), the families of Muhammad's closest companions, the once-prominent Banu Makhzum, and the Ansar was generally characterized by suspicion or outright hostility.[157]

Despite his relocation to Damascus, Mu'awiya remained fond of his original homeland and made known his longing for "the spring in Juddah [sic], the summer in Ta'if, [and] the winter in Mecca".[158] He purchased several large tracts throughout Arabia and invested considerable sums to develop the lands for agricultural use. According to the Muslim literary tradition, in the plain of Arafat and the barren valley of Mecca he dug numerous wells and canals, constructed dams and dikes to protect the soil from seasonal floods, and built fountains and reservoirs. His efforts saw extensive grain fields and date palm groves spring up across Mecca's suburbs, which remained in this state until deteriorating during the Abbasid era, which began in 750.[158] In the Yamama region in central Arabia, Mu'awiya confiscated from the Banu Hanifa the lands of Hadarim, where he employed 4,000 slaves, likely to cultivate its fields.[159] The caliph gained possession of estates in and near Ta'if which, together with the lands of his brothers Anbasa and Utba, formed a considerable cluster of properties.[160]

One of the earliest known Arabic inscriptions from Mu'awiya's reign was found at a soil-conservation dam called Sayisad 32 kilometers (20 mi) east of Ta'if, which credits Mu'awiya for the dam's construction in 677 or 678 and asks God to give him victory and strength.[161] Mu'awiya is also credited as the patron of a second dam called al-Khanaq 15 kilometers (9.3 mi) east of Medina, according to an inscription found at the site.[162] This is possibly the dam between Medina and the gold mines of the Banu Sulaym tribe attributed to Mu'awiya by the historians al-Harbi (d. 898) and al-Samhudi (d. 1533).[163]

War with Byzantium

Mu'awiya possessed more personal experience than any other caliph fighting the Byzantines,[164] the principal external threat to the Caliphate,[56] and pursued the war against the Empire more energetically and continuously than his successors.[165] The First Fitna caused the Arabs to lose control over Armenia to native, pro-Byzantine princes, but in 661 Habib ibn Maslama re-invaded the region.[51] The following year, Armenia became a tributary of the Caliphate and Mu'awiya recognized the Armenian prince Grigor Mamikonian as its commander.[51] Not long after the civil war, Mu'awiya broke the truce with Byzantium,[166] and on a near-annual or bi-annual basis the caliph engaged his Syrian troops in raids across the mountainous Anatolian frontier,[124] the buffer zone between the Empire and the Caliphate.[167] At least until Abd al-Rahman ibn Khalid's death in 666, Homs served as the principal marshaling point for the offensives, and afterward Antioch served this purpose as well.[168] The bulk of the troops fighting on the Anatolian and Armenian fronts hailed from the tribal groups that arrived from Arabia during and after the conquest.[32] During his caliphate, Mu'awiya continued his past efforts to resettle and fortify the Syrian port cities.[56] Due to the reticence of Arab tribesmen to inhabit the coastlands, in 663 Mu'awiya moved Persian civilians and personnel that he had previously settled in the Syrian interior into Acre and Tyre, and transferred Asawira, elite Persian soldiers, from Kufa and Basra to the garrison at Antioch.[35][42] A few years later, Mu'awiya settled Apamea with 5,000 Slavs who had defected from the Byzantines during one of his forces' Anatolian campaigns.[35]

Based on the histories of al-Tabari (d. 923) and Agapius of Hierapolis (d. 941), the first raid of Mu'awiya's caliphate occurred in 662 or 663, during which his forces inflicted a heavy defeat on a Byzantine army with numerous patricians slain. In the next year a raid led by Busr reached Constantinople and in 664 or 665, Abd al-Rahman ibn Khalid raided Koloneia in northeastern Anatolia. In the late 660s, Mu'awiya's forces attacked Antioch of Pisidia or Antioch of Isauria.[166] Following the death of Constans II in July 668, Mu'awiya oversaw an increasingly aggressive policy of naval warfare against the Byzantines.[56] According to the early Muslim sources, raids against the Byzantines peaked between 668 and 669.[166] In each of those years there occurred six ground campaigns and a major naval campaign, the first by an Egyptian and Medinese fleet and the second by an Egyptian and Syrian fleet.[169] The culmination of the campaigns was an assault on Constantinople, but the chronologies of the Arabic, Syriac, and Byzantine sources are contradictory. The traditional view by modern historians is of a great series of naval-borne assaults against Constantinople in c. 674–678, based on the history of the Byzantine chronicler Theophanes the Confessor (d. 818).[170]

However, the dating and the very historicity of this view has been challenged; the Oxford scholar James Howard-Johnston considers that no siege of Constantinople took place, and that the story was inspired by the actual siege a generation later.[171] The historian Marek Jankowiak on the other hand, in a revisionist reconstruction of the events reliant on the Arabic and Syriac sources, asserts that the assault came earlier than what is reported by Theophanes, and that the multitude of campaigns that were reported during 668–669 represented the coordinated efforts by Mu'awiya to conquer the Byzantine capital.[172] Al-Tabari reports that Mu'awiya's son Yazid led a campaign against Constantinople in 669 and Ibn Abd al-Hakam reports that the Egyptian and Syrian navies joined the assault, led by Uqba ibn Amir and Fadala ibn Ubayd respectively.[173] According to Jankowiak, Mu'awiya likely ordered the invasion during an opportunity presented by the rebellion of the Byzantine Armenian general Saborios, who formed a pact with the caliph, in spring 667. The caliph dispatched an army under Fadala, but before it could be joined by the Armenians, Saborios died. Mu'awiya then sent reinforcements led by Yazid who led the Arab army's invasion in the summer.[170] An Arab fleet reached the Sea of Marmara by autumn, while Yazid and Fadala, having raided Chalcedon through the winter, besieged Constantinople in spring 668, but due to famine and disease, lifted the siege in late June. The Arabs continued their campaigns in Constantinople's vicinity before withdrawing to Syria most likely in late 669.[174]

В 669 году флот Муавии совершил набег до Сицилии. В следующем году масштабное укрепление Александрии было завершено. [56] В то время как истории ат-Табари и аль-Баладхури сообщают, что силы Муавии захватили Родос в 672–674 годах и колонизировали остров в течение семи лет, прежде чем отступить во время правления Язида I, современный историк Клиффорд Эдмунд Босворт ставит под сомнение эти события. и утверждает, что на остров совершил набег лейтенант Муавии Джунада ибн Аби Умайя аль-Азди только в 679 или 680 году. [175] При императоре Константине IV ( годы правления 668–685 ) византийцы начали контрнаступление против Халифата, совершив первый набег на Египет в 672 или 673 году. [176] а зимой 673 года адмирал Муавии Абдаллах ибн Кайс возглавил большой флот, совершивший набег на Смирну и побережья Киликии и Ликии. [177] Византийцы одержали крупную победу над арабской армией и флотом под предводительством Суфьяна ибн Ауфа, возможно, при Силийоне , в 673 или 674 году. [178] В следующем году Абдаллах ибн Кайс и Фадала высадились на Крите, а в 675 или 676 году византийский флот напал на Мараклею, убив губернатора Хомса. [176]

По словам Феофана, в 677, 678 или 679 годах Муавия подал иск о мире с Константином IV, возможно, в результате уничтожения его флота или размещения византийцами мардаитов на сирийском побережье в это время. [179] Был заключен тридцатилетний договор, обязывающий Халифат платить ежегодную дань в размере 3000 золотых монет, 50 лошадей и 30 рабов, а также отводить свои войска с занимаемых ими передовых баз на византийском побережье. [180] Но другие византийские и исламские источники не упоминают об этом договоре. [181] Хотя мусульмане не добились каких-либо постоянных территориальных завоеваний в Анатолии за время карьеры Муавии, частые набеги обеспечивали сирийские войска Муавии военной добычей и данью, что помогло обеспечить их постоянную преданность и отточило их боевые навыки. [182] Более того, престиж Муавии был повышен, а византийцы были лишены возможности участвовать в каких-либо согласованных кампаниях против Сирии. [183]

Завоевание центральной части Северной Африки

Хотя арабы не продвигались за пределы Киренаики с 640-х годов, за исключением периодических набегов, экспедиции против Византийской Северной Африки возобновились во время правления Муавии. [184] В 665 или 666 году Ибн Худайдж возглавил армию, которая совершила набег на Бизацену (южный район Византийской Африки ) и Габес и временно захватила Бизерту , прежде чем отступить в Египет. В следующем году Муавия отправил Фадалу и Рувайфи ибн Сабита совершить набег на коммерчески ценный остров Джерба . [185] Между тем, в 662 или 667 году Укба ибн Нафи , курайшитский полководец, сыгравший ключевую роль в захвате арабами Киренаики в 641 году, восстановил мусульманское влияние в регионе Феццан , захватив оазис Завила и гарамантов столицу Джерму . [186] Возможно, он совершил набег на юг до Кавара на территории современного Нигера. [186]

Борьба за престолонаследие Константина IV отвлекла внимание Византии от африканского фронта. [187] В 670 году Муавия назначил Укбу заместителем губернатора Египта на североафриканских землях, находящихся под контролем арабов к западу от Египта. Во главе 10-тысячного войска Укба начал свой поход против территорий к западу от Киренаики. [188] По мере его продвижения к его армии присоединились исламизированные берберы Лувата , и их объединенные силы завоевали Гадамис , Гафсу и Джарид . [186] [188] В последнем регионе он основал постоянный арабский гарнизонный город под названием Кайруан , на относительно безопасном расстоянии от Карфагена и прибрежных районов, которые оставались под контролем Византии, чтобы служить базой для дальнейших экспедиций. Это также способствовало усилиям по обращению в мусульманство среди берберских племен, которые доминировали в окружающей сельской местности. [189]

Муавия уволил Укбу в 673 году, вероятно, из-за опасений, что он сформирует независимую базу власти в прибыльных регионах, которые он завоевал. Новая арабская провинция Ифрикия (современный Тунис) оставалась в подчинении губернатора Египта, который послал своего маула (неарабского, мусульманского вольноотпущенника) Абу аль-Мухаджира Динара заменить Укбу, который был арестован и переведен в Му' содержание под стражей Авии в Дамаске. Абу аль-Мухаджир продолжил кампанию на запад до Тлемсена и победил вождя берберов Авраба Касилу , который впоследствии принял ислам и присоединился к его силам. [189] В 678 году договор между арабами и византийцами передал Визацену Халифату, вынудив арабов уйти из северных частей провинции. [187] После смерти Муавии его преемник Язид повторно назначил Укбу, Касила дезертировал, и византийско-берберский союз положил конец арабскому контролю над Ифрикией. [189] который не был восстановлен до правления халифа Абд аль-Малика ибн Марвана ( годы правления 685–705 ). [190]

Выдвижение Язида преемником

Совершив беспрецедентный в исламской политике шаг, Муавия назначил своим преемником собственного сына Язида. [191] Халиф, вероятно, долгое время питал амбиции относительно преемственности своего сына. [192] В 666 году он якобы отравил своего губернатора в Хомсе Абд ар-Рахмана ибн Халида, чтобы исключить его из числа потенциальных соперников Язида. [193] Сирийские арабы, среди которых был популярен Абд ар-Рахман ибн Халид, считали губернатора наиболее подходящим преемником халифа, учитывая его военный послужной список и происхождение от Халида ибн аль-Валида. [194] [я]

Лишь во второй половине своего правления Муавия публично объявил Язида наследником, хотя ранние мусульманские источники предлагают разные подробности о времени и месте событий, связанных с этим решением. [200] Сообщения аль-Мадаини (752–843) и Ибн аль-Асира (1160–1232) сходятся во мнении, что аль-Мугира был первым, кто предложил признать Язида преемником Муавии, и что Зияд поддержал это назначение с предостерегаем Язида отказаться от нечестивой деятельности, которая может вызвать сопротивление со стороны мусульманского государства. [201] По словам ат-Табари, Муавия публично объявил о своем решении в 675 или 676 году и потребовал принесения присяги на верность Язиду. [202] Один только Ибн аль-Асир сообщает, что делегации из всех провинций были вызваны в Дамаск, где Муавия прочитал им лекцию о своих правах как правителя, их обязанностях как подданных и достойных качествах Язида, после чего последовали звонки ад-Даххака ибн Кайса и другие придворные просили признать Язида преемником халифа. Делегаты оказали свою поддержку, за исключением старшего дворянина Басрана аль-Анафа ибн Кайса , которого в конечном итоге подкупили и заставили подчиниться. [203] Аль-Масуди (896–956) и ат-Табари не упоминают другие провинциальные делегации, кроме посольства в Басране во главе с Убайд Аллахом ибн Зиядом в 678–679 или 679–680 годах соответственно, которые признали Язида. [204]

По словам Хиндса, помимо благородства, возраста и здравого смысла Язида, «самым важным» была его связь с калбами. Конфедерация Кудаа, возглавляемая Калбом, была основой правления Суфьянидов, и смена Язида сигнализировала о продолжении этого союза. [30] Выдвигая кандидатуру Язида, сына калбита Майсуна, Муавия обошел своего старшего сына Абдаллаха от его жены-курайшитки Фахиты. [205] Хотя поддержка со стороны Кальба и Кудаа была гарантирована, Муавия призвал Язида расширить базу поддержки своих племен в Сирии. Поскольку кайситы были преобладающим элементом в северных пограничных армиях, назначение Муавией Язида руководителем военных действий с Византией, возможно, способствовало усилению поддержки кайситами его назначения. [206] Усилия Муавии в этом направлении не были полностью успешными, о чем свидетельствует строка кайситского поэта: «Мы никогда не выразим верность сыну женщины из Калби [т.е. Язиду]». [207] [208]

В Медине дальние родственники Муавии Марван ибн аль-Хакам, Саид ибн аль-Ас и Ибн Амир приняли порядок преемственности Муавии, хотя и неодобрительно. [209] Большинству противников приказа Муавии в Ираке, а также среди Омейядов и курайшитов Хиджаза в конечном итоге угрожали или подкупали, чтобы они согласились. [182] Оставшаяся принципиальная оппозиция исходила от Хусейна ибн Али , Абдаллаха ибн аз-Зубайра , Абдаллаха ибн Умара и Абд ар-Рахмана ибн Аби Бакра , всех видных сыновей предыдущих халифов, живших в Медине, или близких соратников Мухаммеда. [210] Поскольку они имели ближайшие претензии к халифату, Муавия был полон решимости добиться их признания. [211] [212] По словам историка Аваны ибн аль-Хакама (ум. 764), перед смертью Муавия приказал принять против них определенные меры, поручив эти задачи своим лоялистам ад-Даххаку ибн Кайсу и Муслиму ибн Укбе . [213]

Смерть

Муавия умер от болезни в Дамаске в Раджабе 60 года хиджры (апрель или май 680 года нашей эры), примерно в возрасте 80 лет. [1] [214] Средневековые отчеты различаются относительно конкретной даты его смерти: Хишам ибн аль-Кальби (ум. 819) относит ее к 7 апреля, аль-Вакиди - 21 апреля и аль-Мадаини - 29 апреля. [215] Язид, который находился вдали от Дамаска во время смерти своего отца, [216] (ум. 774) считает Абу Михнаф , что он сменил его 7 апреля, а несторианский летописец Элиас Нисибисский (ум. 1046) говорит, что это произошло 21 апреля. [217] В своем последнем завещании Муавия сказал своей семье: «Бойтесь Бога, Всемогущего и Великого, ибо Бог, хвалите Его, защищает тех, кто боится Его, и нет защитника для того, кто не боится Бога». [218] Он был похоронен рядом с городскими воротами Баб ас-Сагир , а поминальные молитвы возглавил ад-Даххак ибн Кайс, который оплакивал Муавию как «палку арабов и клинок арабов, с помощью которого Бог, Всемогущий и Великий, отсек распри, которого Он поставил владыкой над человечеством, посредством которого он завоевал страны, но теперь он умер». [219]

Могила Муавии была местом посещения еще в 10 веке. Аль-Масуди утверждает, что над могилой был построен мавзолей, который был открыт для посетителей по понедельникам и четвергам. Ибн Тагрибирди утверждает, что Ахмад ибн Тулун , автономный правитель Египта и Сирии 9-го века, воздвиг сооружение на могиле в 883 или 884 году и нанял представителей общественности, чтобы те регулярно читали Коран и зажигали свечи вокруг могилы. [220]

Оценка и наследие

Как и Усман, Муавия принял титул халифат Аллах («наместник Бога») вместо халифат расул Аллах («наместник посланника Бога»), титула, который использовали другие халифы, которые предшествовали ему. [221] Этот титул мог подразумевать как политическую, так и религиозную власть и божественную санкцию. [30] Аль-Баладури сообщает, что он сказал: «Земля принадлежит Богу, и я заместитель Бога». [222] Тем не менее, какой бы абсолютистский смысл ни имел этот титул, Муавия, очевидно, не навязывал этот религиозный авторитет. Вместо этого он управлял косвенно, как надплеменный вождь, используя союзы с провинциальными ашрафами , свои личные навыки, силу убеждения и остроумие. [30] [223]

Помимо войны с Али, он не размещал свои сирийские войска внутри страны и часто использовал денежные подарки как инструмент, позволяющий избежать конфликта. [137] По оценке Юлиуса Веллхаузена , Муавия был опытным дипломатом, «позволявшим вопросам созревать самим собой и лишь время от времени содействовавшим их прогрессу». [224] Он далее заявляет, что Муавия обладал способностью выявлять и нанимать к себе на службу самых талантливых людей и заставлял работать на себя даже тех, кому он не доверял. [224]

По мнению историка Патрисии Кроун , успешному правлению Муавии способствовал племенной состав Сирии. Там арабы, составлявшие его базу поддержки, были рассредоточены по всей сельской местности, и в них доминировала одна конфедерация - Кудаа. Это отличалось от Ирака и Египта, где разнообразный племенной состав городов-гарнизонов означал, что правительство не имело сплоченной базы поддержки и должно было создавать хрупкий баланс между противостоящими племенными группами. Как показал распад иракского альянса Али, сохранение этого баланса было несостоятельным. По ее мнению, использование Муавией племенных условий в Сирии предотвратило распад Халифата в результате гражданской войны. [225] По словам востоковеда Мартина Хиндса , успех стиля управления Муавии «подтвержден тем фактом, что ему удалось сохранить целостность своего королевства, даже не прибегая к использованию своих сирийских войск». [30]

В долгосрочной перспективе система Муавии оказалась ненадежной и нежизнеспособной. [30] Опора на личные отношения означала, что его правительство зависело от оплаты и удовлетворения своих агентов, а не от командования ими. По словам Кроуна, это создало «систему снисхождения». [226] Губернаторы становились все более неподотчетными и накопили личное богатство. Племенной баланс, на который он опирался, был ненадежным, и небольшое колебание могло привести к фракционности и распри. [226] Когда Язид стал халифом, он продолжил модель своего отца. Каким бы спорным ни было его назначение, ему пришлось столкнуться с восстаниями Хусейна и Ибн аз-Зубайра. Хотя он смог победить их с помощью своих губернаторов и сирийской армии, система раскололась, как только он умер в ноябре 683 года . Сирия во время правления Муавии и были против конфедерации Кудаа, на которой держалась власть Суфьянидов. В течение нескольких месяцев власть преемника Язида Муавии II была ограничена Дамаском и его окрестностями. Хотя Омейяды при поддержке Кудаа смогли отвоевать Халифат после десятилетней второй гражданской войны , он находился под руководством Марвана, основателя нового правящего дома Омейядов, Марванидов, и его сына Абд аль -Малик. [227] Осознав слабость модели Муавии и отсутствие у него политических навыков, Марваниды отказались от его системы в пользу более традиционной формы правления, где халиф был центральной властью. [228] Тем не менее, наследственная преемственность, введенная Муавией, стала постоянной чертой многих последующих мусульманских правительств. [229]

Кеннеди считает сохранение единства Халифата величайшим достижением Муавии. [230] Выражая аналогичную точку зрения, биограф Муавии Р. Стивен Хамфрис утверждает, что, хотя поддержание целостности Халифата само по себе было бы достижением, Муавия был намерен энергично продолжать завоевания, начатые Абу Бакром и Умаром. . Создав грозный флот, он сделал Халифат доминирующей силой в восточном Средиземноморье и Эгейском море. Был обеспечен контроль над северо-восточным Ираном, а границы Халифата были расширены в Северной Африке. [231] Маделунг считает Муавию коррупционером халифской власти, при котором первенство в исламе ( сабика ), которое было определяющим фактором при выборе более ранних халифов, уступило место силе меча, люди стали его подданными, и он стал «абсолютным господином над их жизнью и смертью». [232] Он задушил общинный дух ислама и использовал религию как инструмент «социального контроля, эксплуатации и военного террора». [232]

Муавия был первым халифом, чье имя появилось на монетах, надписях и документах зарождающейся исламской империи. [233] В надписях времен его правления не было каких-либо явных упоминаний об исламе или Мухаммеде, и единственные титулы, которые встречаются, - это «слуга Бога» и «предводитель верующих». Это заставило некоторых современных историков усомниться в приверженности Муавии исламу. [Дж] Они предположили, что он придерживался неконфессиональной или неопределенной формы монотеизма или, возможно, был христианином. Утверждая, что первые мусульмане не считали свою веру отличающейся от других монотеистических религий, эти историки рассматривают более ранних халифов Медины в том же духе, но никаких публичных заявлений их периода не существует. С другой стороны, историк Роберт Хойланд отмечает, что Муавия бросил очень исламский вызов византийскому императору Константу «отрицать [божественность] Иисуса и обратиться к Великому Богу, которому я поклоняюсь, Богу нашего отца Авраама». и предполагает, что тур Муавии по христианским местам в Иерусалиме был совершен для того, чтобы продемонстрировать «тот факт, что он, а не византийский император, теперь был представителем Бога на земле». [235]

Ранняя историческая традиция

Сохранившиеся мусульманские истории возникли в Ираке эпохи Аббасидов. [236] Составители, рассказчики, от которых были собраны эти истории, и общее общественное мнение в Ираке были враждебны по отношению к базирующимся в Сирии Омейядам. [237] при котором Сирия была привилегированной провинцией, а Ирак воспринимался местными жителями как сирийская колония. [229] Более того, Аббасиды, свергнув Омейядов в 750 году, считали их незаконными правителями и еще больше запятнали их память, чтобы повысить свою легитимность. Халифы Аббасидов, такие как ас-Саффах , аль-Мамун и аль-Мутадид , публично осудили Муавию и других халифов Омейядов. [238] Таким образом, мусульманская историческая традиция в целом направлена против Омейядов. [236] Тем не менее, в случае с Муавией он изображается относительно сбалансированным. [239]

С одной стороны, он изображается как успешный правитель, реализовавший свою волю убеждением, а не силой. [239] Подчеркивается его качество хилма , которое в его случае означало кротость, медлительность на гнев, тонкость и управление людьми через понимание их нужд и желаний. [30] [240] Историческая традиция изобилует анекдотами о его политической хватке и самообладании. В одном из таких анекдотов, когда его спросили о том, позволил ли одному из его придворных обращаться к нему с высокомерием, он заметил: [241]

Я не встаю между народом и его языком, пока они не встают между нами и нашим суверенитетом. [241]

Традиция представляет его действующим как традиционный племенной шейх, которому не хватает абсолютной власти; вызов делегаций ( вуфуд ) вождей племен и убеждение их лестью, аргументами и подарками. Примером этого является приписываемое ему высказывание: «Я никогда не использую свой голос, если я могу использовать свои деньги, никогда не использую свой кнут, если я могу использовать свой голос, никогда не использую свой меч, если я могу использовать свой кнут; мой меч, я это сделаю». [239]

С другой стороны, традиция также изображает его как деспота, превратившего халифат в королевскую власть. По словам аль-Якуби (ум. 898): [239]

[Муавия] был первым, у кого были телохранитель, полиция и камергеры ... Он заставил кого-то идти перед ним с копьем, брать милостыню из стипендий и сидеть на троне с людьми под ним. .. Он использовал принудительный труд для своих строительных проектов ... Он был первым, кто превратил это дело [халифат] в простое царствование. [242]

Аль-Баладхури называет его « Хосровом Арабским » ( Кисра аль-Араб ). [243] Слово «Хосров» использовалось арабами как ссылка на сасанидских персидских монархов в целом, которых арабы ассоциировали с мирским великолепием и авторитаризмом , в отличие от смирения Мухаммеда. [244] Муавию сравнивали с этими монархами главным образом потому, что он назначил своим сыном Язидом следующим халифом, что рассматривалось как нарушение исламского принципа шуры и введение династического правления наравне с византийским и сасанидским. [239] [243] Утверждается, что гражданская война, разразившаяся после смерти Муавии, стала прямым следствием выдвижения Язида. [239] В исламской традиции Муавии и Омейядам дается титул малика (короля) вместо халифа (халифа), хотя последующие Аббасиды признаются халифами. [245]

Современные немусульманские источники обычно представляют Муавию благоприятным образом. [126] [239] Греческий историк Феофан называет его протосимбулосом , «первым среди равных». [239] По словам Кеннеди, христианский летописец-несторианец Джон бар Пенкей, писавший в 690-х годах, «не имеет ничего, кроме похвалы первому халифу Омейядов… о правлении которого он говорит, что «мир во всем мире был таким, о котором мы никогда не слышали ни от наших отцов или от наших бабушек и дедушек, или видели, что когда-либо было что-то подобное». [246]

Мусульманский взгляд

как праведный халиф ( халифа рашид ). В отличие от четырех более ранних халифов, которые считаются образцами благочестия и правили справедливо, Муавия не признается суннитами [242] Считается, что он превратил халифат в мирское и деспотическое царство. Его приобретение халифата в результате гражданской войны и установление им наследственной преемственности путем назначения своего сына Язида наследником - вот основные обвинения, выдвинутые против него. [247] Хотя Усман и Али вызывали большие споры в ранний период, религиозные ученые в 8-м и 9-м веках пошли на компромисс, чтобы успокоить и поглотить фракции Усманидов и сторонников Алидов. Таким образом, Усман и Али считались наряду с первыми двумя халифами божественно руководимыми, тогда как Муавия и те, кто пришел после него, рассматривались как репрессивные тираны. [242] Тем не менее сунниты придают ему статус сподвижника Мухаммеда и считают его переписчиком коранического откровения ( катиб аль-вахи ). За это его тоже уважают. [248] [249] Некоторые сунниты защищают его войну против Али, утверждая, что, хотя он и ошибался, он действовал согласно своему здравому смыслу и не имел никаких злых намерений. [250]

Война Муавии с Али, которого шииты считают истинным преемником Мухаммеда , сделала его фигурой, которую оскорбляют в шиитском исламе. По мнению шиитов, только на основании этого Муавия квалифицируется как неверующий, если он изначально был верующим. [249] Кроме того, он несет ответственность за убийство ряда сподвижников Мухаммеда в Сиффине, приказав проклясть Али с кафедры, назначив Язида своим преемником, который затем убил Хусейна в Кербеле, казнив сторонника Алида Куфана. дворянин Худжр ибн Ади, [251] и убийство Хасана путем отравления. [252] Таким образом, он стал особой мишенью для шиитских традиций. Некоторые традиции считают, что он родился в результате незаконной связи между женой Абу Суфьяна Хинд и дядей Мухаммеда Аббасом . [253] Считается, что его обращение в ислам было лишено каких-либо убеждений и было мотивировано удобством после того, как Мухаммед завоевал Мекку. На этом основании ему дается титул талика (освобожденного раба Мухаммеда). Мухаммеду приписывают ряд хадисов, осуждающих Муавию и его отца Абу Суфьяна, в которых он назван «проклятым человеком ( лаин ) сыном проклятого человека» и предсказывает, что он умрет как неверующий. [254] В отличие от суннитов, шииты отказывают ему в статусе сподвижника. [254] а также опровергнуть утверждения суннитов о том, что он был переписчиком откровения Корана. [249] Как и другие противники Али, Муавия подвергается проклятию в ритуале под названием табарра , который многие шииты считают обязательным. [255]

На фоне роста религиозного сектантства среди мусульман в X веке, когда в халифате Аббасидов доминировали двенадцать шиитских эмиров из династии Буидов , фигура Муавии стала инструментом пропаганды, используемым шиитами и суннитами, выступавшими против них. Сильные промуавийские настроения были высказаны суннитами в нескольких городах Аббасидов, включая Багдад , Васит , Ракку и Исфахан . Примерно в то же время буиды и суннитские халифы Аббасиды разрешили шиитам совершать ритуальное проклятие Муавии в мечетях. [256] В Египте 10–11 веков фигура Муавии иногда играла аналогичную роль: исмаилитские шиитские халифы -фатимиды вводили меры, направленные против памяти Муавии, а противники правительства использовали его как инструмент для оскорбления шиитов. . [257]

| Генеалогическое древо Муавии I |

|---|

Примечания

- ^ По данным аль-Баладхури , Абу Суфьян владел деревней в районе Балка , входившей в состав округа Дамаск . Сирийский географ XIII века Якут аль-Хамави определил это как деревню под названием Бикинис. [11]

- ↑ Муавия, вероятно, является тем «Муавией», который упоминается как «писатель» в арабской надписи, датированной, по-видимому, 652 годом и раскопанной в юго-западной части Храмовой горы в 1968 году. Надпись состоит из девяти строк, лишь немногие из которых которые читабельны, и которые, по предварительному заключению историка Моше Шарона, относятся к капитуляции Иерусалима перед мусульманами ок. 637 . В качестве свидетелей упоминаются Абу Убайда ибн аль-Джарра и Абд ар-Рахман ибн Ауф , два других сподвижника Мухаммеда , которые в ранних исламских источниках сообщают о завоевании города. Дата надписи приходится на несколько лет после смерти Абу Убайды и примерно соответствует смерти Абд ар-Рахмана, но совпадает с периодом правления Муавии, который был писцом . Таким образом, Шарон предполагает, что надпись была юридическим документом, написанным Муавией в память о капитуляции. [14]

- ↑ По словам историка Халила Атамины, усилия халифа Умара сделать коренные сирийские арабские племена основой византийской защиты Сирии от контратаки были основной причиной увольнения Халида ибн аль-Валида от общего командования в Сирии. и последующий отзыв в Ирак многочисленных соплеменников из армии Халида, которые, вероятно, воспринимались Бану Калб и их союзниками как угроза в 636 году. [28] Курайшиты и ранняя мусульманская элита стремились обезопасить для себя Сирию, с которой они были давно знакомы, и поощряли кочевых арабов, поздно обратившихся в мусульманские войска , иммигрировать в Ирак. [29] По мнению Маделунга, Умар, возможно, продвигал Язида и Муавию в качестве гарантов власти Халифата в Сирии против растущей «силы и высоких амбиций» южноаравийских аристократических химьяритов , сыгравших заметную роль в мусульманском завоевании. [17]

- ↑ После того, как Муавия развелся с Наилой бинт Умара аль-Калбия, она вышла замуж за близкого помощника Муавии Хабиба ибн Маслама аль-Фихри , а после смерти последнего - за другого близкого помощника Муавии, Нумана ибн. Башир аль-Ансари . [34]

- ↑ Усилия Усмана по сохранению курайшитского контроля над Халифатом и установлению контроля над свободной финансовой системой Умара, [53] [54] стал свидетелем назначения его близких родственников из Бану Умайя и ее родительского клана Бану Абд Шамс на все основные губернаторские должности Халифата. Эти провинциальные назначения включали Сирию и Джазиру под его двоюродным братом Омейядов Муавией, Куфу последовательно под руководством Омейядов аль-Валида ибн Укбы и Саида ибн аль-Аса , Басру с Бахрейном и Оман под руководством двоюродного брата Усмана по материнской Абдаллаха ибн Амира линии Бану Абд Шамс, Мекка при Али ибн Ади ибн Рабиа из Бану Абд Шамс и Египет при приемном брате Усмана Абдаллахе ибн Аби Сархе . Он также полагался на своего двоюродного брата Омейядов Марвана ибн аль-Хакама в принятии внутренних решений. [55] Усман потребовал, чтобы избыточные доходы от завоеванных земель, которые были объявлены Умаром государственной собственностью, но оставались под контролем соплеменников-завоевателей, были отправлены в Медину. Он также предоставил землю своим родственникам и другим известным курайшитам. [54]

- ↑ Исторически термин «фитна» стал означать гражданскую войну или восстание, которое вызывает раскол в единой мусульманской общине и ставит под угрозу веру верующих. [61]

- ↑ Ранние мусульманские источники сходятся во мнении, что иракские силы халифа Али получили преимущество во время битвы, что побудило сирийцев обратиться за урегулированием конфликта в арбитраж. Этому противопоставляют ряд ранних немусульманских источников, в том числе Феофана Исповедника , согласно которому сирийцы одержали победу, и это утверждение подтверждается придворной поэзией Омейядов . [56] [80]

- ↑ Христианский паломник Аркульф посетил Иерусалим между 679 и 681 годами и отметил, что на Храмовой горе был построен импровизированный мусульманский молитвенный дом, построенный из балок и глины и вмещающий 3000 верующих, а еврейский мидраш утверждает, что Муавия перестроил Храм. Стены горы. Арабский летописец середины X века аль-Мутаххар ибн Тахир аль-Макдиси прямо заявляет, что Муавия построил на этом месте мечеть. [135]

- ↑ Утверждение о том, что Муавия отравил Абд аль-Рахмана ибн Халида своим христианским врачом Ибн Уталом, встречается в средневековых исламских историях аль-Мадаини , аль-Табари , аль-Баладхури и Мусаба аль-Зубайри , среди прочего [195] [196] и принят историком Вильфердом Маделунгом , [195] в то время как историки Мартин Хиндс и Юлиус Велльхаузен рассматривают роль Муавии в этом деле как утверждение ранних мусульманских источников. [196] [197] Востоковеды Михаэль Ян де Гойе и Анри Ламменс отвергают это утверждение; [198] [199] первый назвал «абсурдом» и «невероятным», что Муавия «лишал себя одного из своих лучших людей», и более вероятным сценарием было то, что Абд ар-Рахман ибн Халид был болен, и Муавия пытался поручить ему лечение у Ибн Усаля, но безуспешно. Де Годже далее сомневается в достоверности сообщений, поскольку они исходят из Медины , дома его клана Бану Махзум , а не из Хомса , где умер Абд аль-Рахман ибн Халид. [198]

- ^ К ним относятся Фред М. Доннер , Иегуда Д. Нево , Карл-Хайнц Олиг и Герд Р. Пуин . [234]

- ↑ Хинд бинт Утба , внучка брата Умайи Рабиа, была матерью Муавии, Ханзалы и Утбы .

Ссылки

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я дж к л м н тот Хиндс 1993 , с. 264.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Ватт 1960а , с. 151.

- ^ Хоутинг 2000 , стр. 107-1. 21–22.

- ^ Ватт 1960b , с. 868.

- ^ Веллхаузен 1927 , стр. 22–23.

- ^ Веллхаузен 1927 , стр. 20–21.

- ^ Льюис 2002 , с. 49.

- ^ Кеннеди 2004 , с. 52.

- ^ Кеннеди 2004 , с. 54.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Маделунг 1997 , с. 45.

- ^ Фауден 2004 , с. 151, примечание 54.

- ^ Атамина 1994 , с. 259.

- ^ Доннер 2014 , стр. 133–134.

- ^ Шарон 2018 , стр. 100–101, 108–109.

- ^ Доннер 2014 , с. 154.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Маделунг 1997 , стр. 60–61.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Маделунг 1997 , с. 61.

- ^ Доннер 2014 , с. 153.

- ^ Сурдел 1965 , с. 911.

- ^ Каэги 1995 , стр. 67, 246.

- ^ Каэги 1995 , с. 245.

- ^ Доннер 2012 , с. 152.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Диксон 1978 , с. 493.

- ^ Ламменс 1960 , с. 920.

- ^ Доннер 2014 , с. 106.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Маршам 2013 , с. 104.

- ^ Атамина 1994 , с. 263.

- ^ Атамина 1994 , стр. 262, 265–268.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Кеннеди 2007 , с. 95.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я дж к л Хиндс 1993 , с. 267.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Веллхаузен 1927 , стр. 55, 132.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Хамфрис 2006 , с. 61.

- ^ Мороний 1987 , с. 215.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Мороний 1987 , стр. 215–216.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час Джандора 1986 , с. 111.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Доннер 2014 , с. 245.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Джандора 1986 , с. 112.

- ^ Шахид 2000a , с. 191.

- ^ Шахид 2000b , с. 403.

- ^ Маделунг 1997 , с. 82.

- ^ Доннер 2014 , стр. 248–249.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Кеннеди 2001 , с. 12.

- ^ Доннер 2014 , с. 248.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Босворт 1996 , с. 157.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Линч 2016 , с. 539.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Линч 2016 , с. 540.

- ^ Линч 2016 , стр. 541–542.

- ^ Босворт 1996 , с. 158.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Босворт 1996 , стр. 157–158.

- ^ Каэги 1995 , стр. 184–185.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Каэги 1995 , с. 185.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Маделунг 1997 , с. 84.

- ^ Кеннеди 2004 , с. 70.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Доннер 2012 , стр. 152–153.

- ^ Маделунг 1997 , стр. 86–87.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я Хиндс 1993 , с. 265.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Льюис 2002 , с. 62.

- ^ Хамфрис 2006 , с. 74.

- ^ Маделунг 1997 , с. 184.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Хоутинг 2000 , с. 27.

- ^ Гарде 1965 , стр. 930.

- ^ Веллхаузен 1927 , с. 55–56, 76.

- ^ Кеннеди 2004 , с. 76.

- ^ Хамфрис 2006 , с. 77.

- ^ Хоутинг 2000 , с. 28.

- ^ Веллхаузен 1927 , с. 76.