Лесной пожар

Лесной пожар , лесной пожар или лесной пожар — это незапланированный, неконтролируемый и непредсказуемый пожар на территории с горючей растительностью . [ 1 ] [ 2 ] В зависимости от типа присутствующей растительности лесной пожар можно более конкретно идентифицировать как лесной пожар ( в Австралии ), пожар в пустыне, травяной пожар, горный пожар, торфяной пожар, пожар в прериях, пожар растительности или пожар вельда . [ 3 ] Некоторые естественные лесные экосистемы зависят от лесных пожаров. [ 4 ] Лесные пожары отличаются от контролируемых или предписанных сжиганий , которые проводятся с целью принести пользу людям. В современном лесопользовании часто проводятся предписанные выжигания, чтобы снизить риск пожара и способствовать естественному лесному циклу. Однако контролируемые ожоги могут по ошибке перерасти в лесные пожары.

Лесные пожары можно классифицировать по причине возгорания, физическим свойствам, наличию горючих материалов и влиянию погоды на пожар. [ 5 ] Серьезность лесных пожаров является результатом сочетания таких факторов, как доступное топливо, физические условия и погода. [ 6 ] [ 7 ] [ 8 ] [ 9 ] Климатические циклы с влажными периодами, которые создают большое количество топлива, за которыми следуют засуха и жара, часто предшествуют сильным лесным пожарам. [10] These cycles have been intensified by climate change.[11]: 247

Naturally occurring wildfires can have beneficial effects on those ecosystems that have evolved with fire.[12][13][14] In fact, many plant species depend on the effects of fire for growth and reproduction.[15] Some natural forests are dependent on wildfire.[16] High-severity wildfires may create complex early seral forest habitat (also called snag forest habitat). These types of forest may have higher species richness and biodiversity than an unburned old forest.

Wildfires can severely impact humans and their settlements. Effects include for example the direct health impacts of smoke and fire, as well as destruction of property (especially in wildland–urban interfaces), and economic losses. There is also the potential for contamination of water and soil.

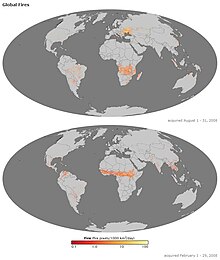

Wildfires are a common type of natural disaster in some regions, including Siberia (Russia), California (United States), British Columbia (Canada), and Australia.[17][18][19][20] Areas with Mediterranean climates or in the taiga biome are particularly susceptible. At a global level, human practices have made the impacts of wildfire worse, with a doubling in land area burned by wildfires compared to natural levels.[11]: 247 Humans have impacted wildfire through climate change (e.g. more intense heat waves and droughts), land-use change, and wildfire suppression.[11]: 247 The carbon released from wildfires can add to carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere and thus contribute to the greenhouse effect. This creates a climate change feedback.[21]: 20

Ignition

[edit]

The ignition of a fire takes place through either natural causes or through human activity (deliberate or not).

Natural causes

[edit]Natural occurrences that can ignite wildfires without the involvement of humans include lightning, volcanic eruptions, sparks from rock falls, and spontaneous combustions.[22][23]

Human activity

[edit]Sources of human-caused fire may include arson, accidental ignition, or the uncontrolled use of fire in land-clearing and agriculture such as the slash-and-burn farming in Southeast Asia.[24] In the tropics, farmers often practice the slash-and-burn method of clearing fields during the dry season.

In middle latitudes, the most common human causes of wildfires are equipment generating sparks (chainsaws, grinders, mowers, etc.), overhead power lines, and arson.[25][26][27][28][29]

Arson may account for over 20% of human caused fires.[30] However, in the 2019–20 Australian bushfire season "an independent study found online bots and trolls exaggerating the role of arson in the fires."[31] In the 2023 Canadian wildfires false claims of arson gained traction on social media; however, arson is generally not a main cause of wildfires in Canada.[32][33] In California, generally 6–10% of wildfires annually are arson. [34]

Coal seam fires burn in the thousands around the world, such as those in Burning Mountain, New South Wales; Centralia, Pennsylvania; and several coal-sustained fires in China. They can also flare up unexpectedly and ignite nearby flammable material.[35]

Spread

[edit]

The spread of wildfires varies based on the flammable material present, its vertical arrangement and moisture content, and weather conditions.[36] Fuel arrangement and density is governed in part by topography, as land shape determines factors such as available sunlight and water for plant growth. Overall, fire types can be generally characterized by their fuels as follows:

- Ground fires are fed by subterranean roots, duff on the forest floor, and other buried organic matter. Ground fires typically burn by smoldering, and can burn slowly for days to months, such as peat fires in Kalimantan and Eastern Sumatra, Indonesia, which resulted from a riceland creation project that unintentionally drained and dried the peat.[37][38][39]

- Crawling or surface fires are fueled by low-lying vegetative matter on the forest floor such as leaf and timber litter, debris, grass, and low-lying shrubbery.[40] This kind of fire often burns at a relatively lower temperature than crown fires (less than 400 °C (752 °F)) and may spread at slow rate, though steep slopes and wind can accelerate the rate of spread.[41] This fuel type is especially susceptible to ignition due to spotting ().

- Ladder fires consume material between low-level vegetation and tree canopies, such as small trees, downed logs, and vines. Kudzu, Old World climbing fern, and other invasive plants that scale trees may also encourage ladder fires.[42]

- Crown, canopy, or aerial fires burn suspended material at the canopy level, such as tall trees, vines, and mosses. The ignition of a crown fire, termed crowning, is dependent on the density of the suspended material, canopy height, canopy continuity, sufficient surface and ladder fires, vegetation moisture content, and weather conditions during the blaze.[43] Stand-replacing fires lit by humans can spread into the Amazon rain forest, damaging ecosystems not particularly suited for heat or arid conditions.[44]

Physical properties

[edit]

Wildfires occur when all the necessary elements of a fire triangle come together in a susceptible area: an ignition source is brought into contact with a combustible material such as vegetation that is subjected to enough heat and has an adequate supply of oxygen from the ambient air. A high moisture content usually prevents ignition and slows propagation, because higher temperatures are needed to evaporate any water in the material and heat the material to its fire point.[45][46]

Dense forests usually provide more shade, resulting in lower ambient temperatures and greater humidity, and are therefore less susceptible to wildfires.[47] Less dense material such as grasses and leaves are easier to ignite because they contain less water than denser material such as branches and trunks.[48] Plants continuously lose water by evapotranspiration, but water loss is usually balanced by water absorbed from the soil, humidity, or rain.[49] When this balance is not maintained, often as a consequence of droughts, plants dry out and are therefore more flammable.[50][51]

A wildfire front is the portion sustaining continuous flaming combustion, where unburned material meets active flames, or the smoldering transition between unburned and burned material.[52] As the front approaches, the fire heats both the surrounding air and woody material through convection and thermal radiation. First, wood is dried as water is vaporized at a temperature of 100 °C (212 °F). Next, the pyrolysis of wood at 230 °C (450 °F) releases flammable gases. Finally, wood can smolder at 380 °C (720 °F) or, when heated sufficiently, ignite at 590 °C (1,000 °F).[53][54] Even before the flames of a wildfire arrive at a particular location, heat transfer from the wildfire front warms the air to 800 °C (1,470 °F), which pre-heats and dries flammable materials, causing materials to ignite faster and allowing the fire to spread faster.[48][55] High-temperature and long-duration surface wildfires may encourage flashover or torching: the drying of tree canopies and their subsequent ignition from below.[56]

Wildfires have a rapid forward rate of spread (FROS) when burning through dense uninterrupted fuels.[57] They can move as fast as 10.8 kilometres per hour (6.7 mph) in forests and 22 kilometres per hour (14 mph) in grasslands.[58] Wildfires can advance tangential to the main front to form a flanking front, or burn in the opposite direction of the main front by backing.[59] They may also spread by jumping or spotting as winds and vertical convection columns carry firebrands (hot wood embers) and other burning materials through the air over roads, rivers, and other barriers that may otherwise act as firebreaks.[60][61] Torching and fires in tree canopies encourage spotting, and dry ground fuels around a wildfire are especially vulnerable to ignition from firebrands.[62] Spotting can create spot fires as hot embers and firebrands ignite fuels downwind from the fire. In Australian bushfires, spot fires are known to occur as far as 20 kilometres (12 mi) from the fire front.[63]

Especially large wildfires may affect air currents in their immediate vicinities by the stack effect: air rises as it is heated, and large wildfires create powerful updrafts that will draw in new, cooler air from surrounding areas in thermal columns.[64] Great vertical differences in temperature and humidity encourage pyrocumulus clouds, strong winds, and fire whirls with the force of tornadoes at speeds of more than 80 kilometres per hour (50 mph).[65][66][67] Rapid rates of spread, prolific crowning or spotting, the presence of fire whirls, and strong convection columns signify extreme conditions.[68]

Intensity variations during day and night

[edit]

Intensity also increases during daytime hours. Burn rates of smoldering logs are up to five times greater during the day due to lower humidity, increased temperatures, and increased wind speeds.[69] Sunlight warms the ground during the day which creates air currents that travel uphill. At night the land cools, creating air currents that travel downhill. Wildfires are fanned by these winds and often follow the air currents over hills and through valleys.[70] Fires in Europe occur frequently during the hours of 12:00 p.m. and 2:00 p.m.[71] Wildfire suppression operations in the United States revolve around a 24-hour fire day that begins at 10:00 a.m. due to the predictable increase in intensity resulting from the daytime warmth.[72]

Climate change effects

[edit]Increasing risks due to climate change

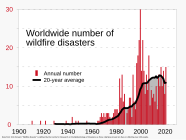

[edit]Climate change promotes the type of weather that makes wildfires more likely. In some areas, an increase of wildfires has been attributed directly to climate change.[11]: 247 Evidence from Earth's past also shows more fire in warmer periods.[75] Climate change increases evapotranspiration. This can cause vegetation and soils to dry out. When a fire starts in an area with very dry vegetation, it can spread rapidly. Higher temperatures can also lengthen the fire season. This is the time of year in which severe wildfires are most likely, particularly in regions where snow is disappearing.[76]

Weather conditions are raising the risks of wildfires. But the total area burnt by wildfires has decreased. This is mostly because savanna has been converted to cropland, so there are fewer trees to burn.[76]

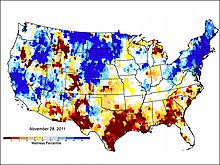

Climate variability including heat waves, droughts, and El Niño, and regional weather patterns, such as high-pressure ridges, can increase the risk and alter the behavior of wildfires dramatically.[77][78][79] Years of high precipitation can produce rapid vegetation growth, which when followed by warmer periods can encourage more widespread fires and longer fire seasons.[80] High temperatures dry out the fuel loads and make them more flammable, increasing tree mortality and posing significant risks to global forest health.[81][82][83] Since the mid-1980s, in the Western US, earlier snowmelt and associated warming has also been associated with an increase in length and severity of the wildfire season, or the most fire-prone time of the year.[84] A 2019 study indicates that the increase in fire risk in California may be partially attributable to human-induced climate change.[85]

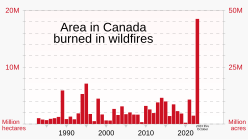

In the summer of 1974–1975 (southern hemisphere), Australia suffered its worst recorded wildfire, when 15% of Australia's land mass suffered "extensive fire damage".[86] Fires that summer burned up an estimated 117 million hectares (290 million acres; 1,170,000 square kilometres; 450,000 square miles).[87][88] In Australia, the annual number of hot days (above 35 °C) and very hot days (above 40 °C) has increased significantly in many areas of the country since 1950. The country has always had bushfires but in 2019, the extent and ferocity of these fires increased dramatically.[89] For the first time catastrophic bushfire conditions were declared for Greater Sydney. New South Wales and Queensland declared a state of emergency but fires were also burning in South Australia and Western Australia.[90]

In 2019, extreme heat and dryness caused massive wildfires in Siberia, Alaska, Canary Islands, Australia, and in the Amazon rainforest. The fires in the latter were caused mainly by illegal logging. The smoke from the fires expanded on huge territory including major cities, dramatically reducing air quality.[91]

As of August 2020, the wildfires in that year were 13% worse than in 2019 due primarily to climate change, deforestation and agricultural burning. The Amazon rainforest's existence is threatened by fires.[92][93][94][95] Record-breaking wildfires in 2021 occurred in Turkey, Greece and Russia, thought to be linked to climate change.[96]

Carbon dioxide and other emissions from fires

[edit]The carbon released from wildfires can add to greenhouse gas concentrations. Climate models do not yet fully reflect this feedback.[21]: 20

Wildfires release large amounts of carbon dioxide, black and brown carbon particles, and ozone precursors such as volatile organic compounds and nitrogen oxides (NOx) into the atmosphere.[97][98] These emissions affect radiation, clouds, and climate on regional and even global scales. Wildfires also emit substantial amounts of semi-volatile organic species that can partition from the gas phase to form secondary organic aerosol (SOA) over hours to days after emission. In addition, the formation of the other pollutants as the air is transported can lead to harmful exposures for populations in regions far away from the wildfires.[99] While direct emissions of harmful pollutants can affect first responders and residents, wildfire smoke can also be transported over long distances and impact air quality across local, regional, and global scales.[100]

The health effects of wildfire smoke, such as worsening cardiovascular and respiratory conditions, extend beyond immediate exposure, contributing to nearly 16,000 annual deaths, a number expected to rise to 30,000 by 2050. The economic impact is also significant, with projected costs reaching $240 billion annually by 2050, surpassing other climate-related damages.[101]

Over the past century, wildfires have accounted for 20–25% of global carbon emissions, the remainder from human activities.[102] Global carbon emissions from wildfires through August 2020 equaled the average annual emissions of the European Union.[103] In 2020, the carbon released by California's wildfires was significantly larger than the state's other carbon emissions.[104]

Forest fires in Indonesia in 1997 were estimated to have released between 0.81 and 2.57 gigatonnes (0.89 and 2.83 billion short tons) of CO2 into the atmosphere, which is between 13%–40% of the annual global carbon dioxide emissions from burning fossil fuels.[105][106]

In June and July 2019, fires in the Arctic emitted more than 140 megatons of carbon dioxide, according to an analysis by CAMS. To put that into perspective this amounts to the same amount of carbon emitted by 36 million cars in a year. The recent wildfires and their massive CO2 emissions mean that it will be important to take them into consideration when implementing measures for reaching greenhouse gas reduction targets accorded with the Paris climate agreement.[107] Due to the complex oxidative chemistry occurring during the transport of wildfire smoke in the atmosphere,[108] the toxicity of emissions was indicated to increase over time.[109][110]

Atmospheric models suggest that these concentrations of sooty particles could increase absorption of incoming solar radiation during winter months by as much as 15%.[111] The Amazon is estimated to hold around 90 billion tons of carbon. As of 2019, the earth's atmosphere has 415 parts per million of carbon, and the destruction of the Amazon would add about 38 parts per million.[112]

Some research has shown wildfire smoke can have a cooling effect.[113][114][115]

Research in 2007 stated that black carbon in snow changed temperature three times more than atmospheric carbon dioxide. As much as 94 percent of Arctic warming may be caused by dark carbon on snow that initiates melting. The dark carbon comes from fossil fuels burning, wood and other biofuels, and forest fires. Melting can occur even at low concentrations of dark carbon (below five parts per billion)”.[116]

Prevention

[edit]Wildfire prevention refers to the preemptive methods aimed at reducing the risk of fires as well as lessening its severity and spread.[117] Prevention techniques aim to manage air quality, maintain ecological balances, protect resources,[118] and to affect future fires.[119] Prevention policies must consider the role that humans play in wildfires, since, for example, 95% of forest fires in Europe are related to human involvement.[120]

Wildfire prevention programs around the world may employ techniques such as wildland fire use (WFU) and prescribed or controlled burns.[121][122] Wildland fire use refers to any fire of natural causes that is monitored but allowed to burn. Controlled burns are fires ignited by government agencies under less dangerous weather conditions.[123] Other objectives can include maintenance of healthy forests, rangelands, and wetlands, and support of ecosystem diversity.[124]

Strategies for wildfire prevention, detection, control and suppression have varied over the years.[125] One common and inexpensive technique to reduce the risk of uncontrolled wildfires is controlled burning: intentionally igniting smaller less-intense fires to minimize the amount of flammable material available for a potential wildfire.[126][127] Vegetation may be burned periodically to limit the accumulation of plants and other debris that may serve as fuel, while also maintaining high species diversity.[128][129] While other people claim that controlled burns and a policy of allowing some wildfires to burn is the cheapest method and an ecologically appropriate policy for many forests, they tend not to take into account the economic value of resources that are consumed by the fire, especially merchantable timber.[130] Some studies conclude that while fuels may also be removed by logging, such thinning treatments may not be effective at reducing fire severity under extreme weather conditions.[131]

Building codes in fire-prone areas typically require that structures be built of flame-resistant materials and a defensible space be maintained by clearing flammable materials within a prescribed distance from the structure.[132][133] Communities in the Philippines also maintain fire lines 5 to 10 meters (16 to 33 ft) wide between the forest and their village, and patrol these lines during summer months or seasons of dry weather.[134] Continued residential development in fire-prone areas and rebuilding structures destroyed by fires has been met with criticism.[135] The ecological benefits of fire are often overridden by the economic and safety benefits of protecting structures and human life.[136]

Detection

[edit]

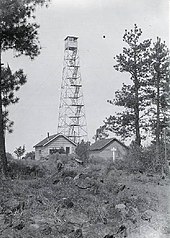

The demand for timely, high-quality fire information has increased in recent years. Fast and effective detection is a key factor in wildfire fighting.[137] Early detection efforts were focused on early response, accurate results in both daytime and nighttime, and the ability to prioritize fire danger.[138] Fire lookout towers were used in the United States in the early 20th century and fires were reported using telephones, carrier pigeons, and heliographs.[139] Aerial and land photography using instant cameras were used in the 1950s until infrared scanning was developed for fire detection in the 1960s. However, information analysis and delivery was often delayed by limitations in communication technology. Early satellite-derived fire analyses were hand-drawn on maps at a remote site and sent via overnight mail to the fire manager. During the Yellowstone fires of 1988, a data station was established in West Yellowstone, permitting the delivery of satellite-based fire information in approximately four hours.[138]

Public hotlines, fire lookouts in towers, and ground and aerial patrols can be used as a means of early detection of forest fires. However, accurate human observation may be limited by operator fatigue, time of day, time of year, and geographic location. Electronic systems have gained popularity in recent years as a possible resolution to human operator error. These systems may be semi- or fully automated and employ systems based on the risk area and degree of human presence, as suggested by GIS data analyses. An integrated approach of multiple systems can be used to merge satellite data, aerial imagery, and personnel position via Global Positioning System (GPS) into a collective whole for near-realtime use by wireless Incident Command Centers.[140]

Local sensor networks

[edit]A small, high risk area that features thick vegetation, a strong human presence, or is close to a critical urban area can be monitored using a local sensor network. Detection systems may include wireless sensor networks that act as automated weather systems: detecting temperature, humidity, and smoke.[141][142][143][144] These may be battery-powered, solar-powered, or tree-rechargeable: able to recharge their battery systems using the small electrical currents in plant material.[145] Larger, medium-risk areas can be monitored by scanning towers that incorporate fixed cameras and sensors to detect smoke or additional factors such as the infrared signature of carbon dioxide produced by fires. Additional capabilities such as night vision, brightness detection, and color change detection may also be incorporated into sensor arrays.[146][147][148]

The Department of Natural Resources signed a contract with PanoAI for the installation of 360 degree 'rapid detection' cameras around the Pacific northwest, which are mounted on cell towers and are capable of 24/7 monitoring of a 15 mile radius.[149] Additionally, Sensaio Tech, based in Brazil and Toronto, has released a sensor device that continuously monitors 14 different variables common in forests, ranging from soil temperature to salinity. This information is connected live back to clients through dashboard visualizations, while mobile notifications are provided regarding dangerous levels.[150]

Satellite and aerial monitoring

[edit]Satellite and aerial monitoring through the use of planes, helicopter, or UAVs can provide a wider view and may be sufficient to monitor very large, low risk areas. These more sophisticated systems employ GPS and aircraft-mounted infrared or high-resolution visible cameras to identify and target wildfires.[151][152] Satellite-mounted sensors such as Envisat's Advanced Along Track Scanning Radiometer and European Remote-Sensing Satellite's Along-Track Scanning Radiometer can measure infrared radiation emitted by fires, identifying hot spots greater than 39 °C (102 °F).[153][154] The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Hazard Mapping System combines remote-sensing data from satellite sources such as Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite (GOES), Moderate-Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS), and Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer (AVHRR) for detection of fire and smoke plume locations.[155][156] However, satellite detection is prone to offset errors, anywhere from 2 to 3 kilometers (1 to 2 mi) for MODIS and AVHRR data and up to 12 kilometers (7.5 mi) for GOES data.[157] Satellites in geostationary orbits may become disabled, and satellites in polar orbits are often limited by their short window of observation time. Cloud cover and image resolution may also limit the effectiveness of satellite imagery.[158] Global Forest Watch[159] provides detailed daily updates on fire alerts.[160]

In 2015 a new fire detection tool is in operation at the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Forest Service (USFS) which uses data from the Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership (NPP) satellite to detect smaller fires in more detail than previous space-based products. The high-resolution data is used with a computer model to predict how a fire will change direction based on weather and land conditions.[161]

In 2014, an international campaign was organized in South Africa's Kruger National Park to validate fire detection products including the new VIIRS active fire data. In advance of that campaign, the Meraka Institute of the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research in Pretoria, South Africa, an early adopter of the VIIRS 375 m fire product, put it to use during several large wildfires in Kruger.[162] There have also been numerous companies and start-ups releasing new drone technology, many of which use AI. Data Blanket, a Seattle-based startup backed by Bill Gates, has developed drones capable of performing self-guided flights in order to conduct comprehensive assessments of wildfires and the surrounding site, providing real-time and critical information such as local vegetation and fuels. The drones are equipped with RGB and infrared cameras, AI-based computational software, 5G/Wi-Fi, and advanced navigational features. Data Blanket has also stated that its system will eventually be capable of producing micro-weather data, further supporting firefighter efforts by delivering crucial information. Additionally, scientists from Imperial College London and Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology, have designed the experimental 'FireDrone', which can handle temperatures of up to 200C for 10 minutes. Another company, the German-based Orora Tech, as of 2023 has two satellites in orbit packaged with infrared sensors that are capable of quickly detecting temperature and soil anomalies, with the ability to predict the likely growth and spread rate of a fire in comparison to others. The company has stated that it will be capable of scanning the earth 48 times per day by 2026.[163]

Artificial intelligence

[edit]Between 2022–2023, wildfires throughout North America prompted an uptake in the delivery and design of various technologies using artificial intelligence for early detection, prevention, and prediction of wildfires.[164][165][166]

Suppression

[edit]

Wildfire suppression depends on the technologies available in the area in which the wildfire occurs. In less developed nations the techniques used can be as simple as throwing sand or beating the fire with sticks or palm fronds.[167] In more advanced nations, the suppression methods vary due to increased technological capacity. Silver iodide can be used to encourage snow fall,[168] while fire retardants and water can be dropped onto fires by unmanned aerial vehicles, planes, and helicopters.[169][170] Complete fire suppression is no longer an expectation, but the majority of wildfires are often extinguished before they grow out of control. While more than 99% of the 10,000 new wildfires each year are contained, escaped wildfires under extreme weather conditions are difficult to suppress without a change in the weather. Wildfires in Canada and the US burn an average of 54,500 square kilometers (13,000,000 acres) per year.[171][172]

Above all, fighting wildfires can become deadly. A wildfire's burning front may also change direction unexpectedly and jump across fire breaks. Intense heat and smoke can lead to disorientation and loss of appreciation of the direction of the fire, which can make fires particularly dangerous. For example, during the 1949 Mann Gulch fire in Montana, United States, thirteen smokejumpers died when they lost their communication links, became disoriented, and were overtaken by the fire.[173] In the Australian February 2009 Victorian bushfires, at least 173 people died and over 2,029 homes and 3,500 structures were lost when they became engulfed by wildfire.[174]

Costs of wildfire suppression

[edit]The suppression of wild fires takes up a large amount of a country's gross domestic product which directly affects the country's economy.[175] While costs vary wildly from year to year, depending on the severity of each fire season, in the United States, local, state, federal and tribal agencies collectively spend tens of billions of dollars annually to suppress wildfires. In the United States, it was reported that approximately $6 billion was spent between 2004–2008 to suppress wildfires in the country.[175] In California, the U.S. Forest Service spends about $200 million per year to suppress 98% of wildfires and up to $1 billion to suppress the other 2% of fires that escape initial attack and become large.[176]

Wildland firefighting safety

[edit]

Wildland fire fighters face several life-threatening hazards including heat stress, fatigue, smoke and dust, as well as the risk of other injuries such as burns, cuts and scrapes, animal bites, and even rhabdomyolysis.[177][178] Between 2000 and 2016, more than 350 wildland firefighters died on-duty.[179]

Especially in hot weather conditions, fires present the risk of heat stress, which can entail feeling heat, fatigue, weakness, vertigo, headache, or nausea. Heat stress can progress into heat strain, which entails physiological changes such as increased heart rate and core body temperature. This can lead to heat-related illnesses, such as heat rash, cramps, exhaustion or heat stroke. Various factors can contribute to the risks posed by heat stress, including strenuous work, personal risk factors such as age and fitness, dehydration, sleep deprivation, and burdensome personal protective equipment. Rest, cool water, and occasional breaks are crucial to mitigating the effects of heat stress.[177]

Smoke, ash, and debris can also pose serious respiratory hazards for wildland firefighters. The smoke and dust from wildfires can contain gases such as carbon monoxide, sulfur dioxide and formaldehyde, as well as particulates such as ash and silica. To reduce smoke exposure, wildfire fighting crews should, whenever possible, rotate firefighters through areas of heavy smoke, avoid downwind firefighting, use equipment rather than people in holding areas, and minimize mop-up. Camps and command posts should also be located upwind of wildfires. Protective clothing and equipment can also help minimize exposure to smoke and ash.[177]

Firefighters are also at risk of cardiac events including strokes and heart attacks. Firefighters should maintain good physical fitness. Fitness programs, medical screening and examination programs which include stress tests can minimize the risks of firefighting cardiac problems.[177] Other injury hazards wildland firefighters face include slips, trips, falls, burns, scrapes, and cuts from tools and equipment, being struck by trees, vehicles, or other objects, plant hazards such as thorns and poison ivy, snake and animal bites, vehicle crashes, electrocution from power lines or lightning storms, and unstable building structures.[177]

Fire retardants

[edit]Fire retardants are used to slow wildfires by inhibiting combustion. They are aqueous solutions of ammonium phosphates and ammonium sulfates, as well as thickening agents.[180] The decision to apply retardant depends on the magnitude, location and intensity of the wildfire. In certain instances, fire retardant may also be applied as a precautionary fire defense measure.[181]

Typical fire retardants contain the same agents as fertilizers. Fire retardants may also affect water quality through leaching, eutrophication, or misapplication. Fire retardant's effects on drinking water remain inconclusive.[182] Dilution factors, including water body size, rainfall, and water flow rates lessen the concentration and potency of fire retardant.[181] Wildfire debris (ash and sediment) clog rivers and reservoirs increasing the risk for floods and erosion that ultimately slow and/or damage water treatment systems.[182][183] There is continued concern of fire retardant effects on land, water, wildlife habitats, and watershed quality, additional research is needed. However, on the positive side, fire retardant (specifically its nitrogen and phosphorus components) has been shown to have a fertilizing effect on nutrient-deprived soils and thus creates a temporary increase in vegetation.[181]

Modeling

[edit]

Wildfire modeling is concerned with numerical simulation of wildfires to comprehend and predict fire behavior.[184][185] Wildfire modeling aims to aid wildfire suppression, increase the safety of firefighters and the public, and minimize damage. Wildfire modeling can also aid in protecting ecosystems, watersheds, and air quality.

Using computational science, wildfire modeling involves the statistical analysis of past fire events to predict spotting risks and front behavior. Various wildfire propagation models have been proposed in the past, including simple ellipses and egg- and fan-shaped models. Early attempts to determine wildfire behavior assumed terrain and vegetation uniformity. However, the exact behavior of a wildfire's front is dependent on a variety of factors, including wind speed and slope steepness. Modern growth models utilize a combination of past ellipsoidal descriptions and Huygens' Principle to simulate fire growth as a continuously expanding polygon.[186][187] Extreme value theory may also be used to predict the size of large wildfires. However, large fires that exceed suppression capabilities are often regarded as statistical outliers in standard analyses, even though fire policies are more influenced by large wildfires than by small fires.[188]Impacts on the natural environment

[edit]On the atmosphere

[edit]

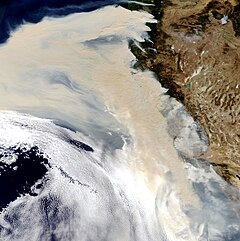

Most of Earth's weather and air pollution resides in the troposphere, the part of the atmosphere that extends from the surface of the planet to a height of about 10 kilometers (6 mi). The vertical lift of a severe thunderstorm or pyrocumulonimbus can be enhanced in the area of a large wildfire, which can propel smoke, soot (black carbon), and other particulate matter as high as the lower stratosphere.[189] Previously, prevailing scientific theory held that most particles in the stratosphere came from volcanoes, but smoke and other wildfire emissions have been detected from the lower stratosphere.[190] Pyrocumulus clouds can reach 6,100 meters (20,000 ft) over wildfires.[191] Satellite observation of smoke plumes from wildfires revealed that the plumes could be traced intact for distances exceeding 1,600 kilometers (1,000 mi).[192] Computer-aided models such as CALPUFF may help predict the size and direction of wildfire-generated smoke plumes by using atmospheric dispersion modeling.[193]

Wildfires can affect local atmospheric pollution,[194] and release carbon in the form of carbon dioxide.[195] Wildfire emissions contain fine particulate matter which can cause cardiovascular and respiratory problems.[196] Increased fire byproducts in the troposphere can increase ozone concentrations beyond safe levels.[197]

On ecosystems

[edit]Wildfires are common in climates that are sufficiently moist to allow the growth of vegetation but feature extended dry, hot periods.[198] Such places include the vegetated areas of Australia and Southeast Asia, the veld in southern Africa, the fynbos in the Western Cape of South Africa, the forested areas of the United States and Canada, and the Mediterranean Basin.

High-severity wildfire creates complex early seral forest habitat (also called “snag forest habitat”), which often has higher species richness and diversity than unburned old forest.[199] Plant and animal species in most types of North American forests evolved with fire, and many of these species depend on wildfires, and particularly high-severity fires, to reproduce and grow. Fire helps to return nutrients from plant matter back to the soil. The heat from fire is necessary to the germination of certain types of seeds, and the snags (dead trees) and early successional forests created by high-severity fire create habitat conditions that are beneficial to wildlife.[199] Early successional forests created by high-severity fire support some of the highest levels of native biodiversity found in temperate conifer forests.[200][201] Post-fire logging has no ecological benefits and many negative impacts; the same is often true for post-fire seeding.[130] The exclusion of wildfires can contribute to vegetation regime shifts, such as woody plant encroachment.[202][203]

Although some ecosystems rely on naturally occurring fires to regulate growth, some ecosystems suffer from too much fire, such as the chaparral in southern California and lower-elevation deserts in the American Southwest. The increased fire frequency in these ordinarily fire-dependent areas has upset natural cycles, damaged native plant communities, and encouraged the growth of non-native weeds.[204][205][206][207] Invasive species, such as Lygodium microphyllum and Bromus tectorum, can grow rapidly in areas that were damaged by fires. Because they are highly flammable, they can increase the future risk of fire, creating a positive feedback loop that increases fire frequency and further alters native vegetation communities.[42][118]

In the Amazon rainforest, drought, logging, cattle ranching practices, and slash-and-burn agriculture damage fire-resistant forests and promote the growth of flammable brush, creating a cycle that encourages more burning.[208] Fires in the rainforest threaten its collection of diverse species and produce large amounts of CO2.[209] Also, fires in the rainforest, along with drought and human involvement, could damage or destroy more than half of the Amazon rainforest by 2030.[210] Wildfires generate ash, reduce the availability of organic nutrients, and cause an increase in water runoff, eroding other nutrients and creating flash flood conditions.[36][211] A 2003 wildfire in the North Yorkshire Moors burned off 2.5 square kilometers (600 acres) of heather and the underlying peat layers. Afterwards, wind erosion stripped the ash and the exposed soil, revealing archaeological remains dating to 10,000 BC.[212] Wildfires can also have an effect on climate change, increasing the amount of carbon released into the atmosphere and inhibiting vegetation growth, which affects overall carbon uptake by plants.[213]

On waterways

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2021) |

Debris and chemical runoff into waterways after wildfires can make drinking water sources unsafe.[214] Though it is challenging to quantify the impacts of wildfires on surface water quality, research suggests that the concentration of many pollutants increases post-fire. The impacts occur during active burning and up to years later.[215] Increases in nutrients and total suspended sediments can happen within a year while heavy metal concentrations may peak 1-2 years after a wildfire. [216]

Benzene is one of many chemicals that have been found in drinking water systems after wildfires. Benzene can permeate certain plastic pipes and thus require long times to be removed from the water distribution infrastructure. Researchers estimated that, in worst case scenarios, more than 286 days of constant flushing of a contaminated HDPE service line were needed to reduce benzene below safe drinking water limits.[217][218] Temperature increases caused by fires, including wildfires, can cause plastic water pipes to generate toxic chemicals[219] such as benzene.[220]

On plant and animals

[edit]

Fire adaptations are traits of plants and animals that help them survive wildfire or to use resources created by wildfire. These traits can help plants and animals increase their survival rates during a fire and/or reproduce offspring after a fire. Both plants and animals have multiple strategies for surviving and reproducing after fire. Plants in wildfire-prone ecosystems often survive through adaptations to their local fire regime. Such adaptations include physical protection against heat, increased growth after a fire event, and flammable materials that encourage fire and may eliminate competition.

For example, plants of the genus Eucalyptus contain flammable oils that encourage fire and hard sclerophyll leaves to resist heat and drought, ensuring their dominance over less fire-tolerant species.[221][222] Dense bark, shedding lower branches, and high water content in external structures may also protect trees from rising temperatures.[223] Fire-resistant seeds and reserve shoots that sprout after a fire encourage species preservation, as embodied by pioneer species. Smoke, charred wood, and heat can stimulate the germination of seeds in a process called serotiny.[224] Exposure to smoke from burning plants promotes germination in other types of plants by inducing the production of the orange butenolide.[225]

Impacts on humans

[edit]Wildfire risk is the chance that a wildfire will start in or reach a particular area and the potential loss of human values if it does. Risk is dependent on variable factors such as human activities, weather patterns, availability of wildfire fuels, and the availability or lack of resources to suppress a fire.[226][227] Wildfires have continually been a threat to human populations. However, human-induced geographic and climatic changes are exposing populations more frequently to wildfires and increasing wildfire risk. It is speculated that the increase in wildfires arises from a century of wildfire suppression coupled with the rapid expansion of human developments into fire-prone wildlands.[228] Wildfires are naturally occurring events that aid in promoting forest health. Global warming and climate changes are causing an increase in temperatures and more droughts nationwide which contributes to an increase in wildfire risk.[229][230]

Airborne hazards

[edit]The most noticeable adverse effect of wildfires is the destruction of property. However, hazardous chemicals released also significantly impact human health.[231]

Wildfire smoke is composed primarily of carbon dioxide and water vapor. Other common components present in lower concentrations are carbon monoxide, formaldehyde, acrolein, polyaromatic hydrocarbons, and benzene.[232] Small airborne particulates (in solid form or liquid droplets) are also present in smoke and ash debris. 80–90% of wildfire smoke, by mass, is within the fine particle size class of 2.5 micrometers in diameter or smaller.[233]

Carbon dioxide in smoke poses a low health risk due to its low toxicity. Rather, carbon monoxide and fine particulate matter, particularly 2.5 μm in diameter and smaller, have been identified as the major health threats.[232] High levels of heavy metals, including lead, arsenic, cadmium, and copper were found in the ash debris following the 2007 Californian wildfires. A national clean-up campaign was organised in fear of the health effects from exposure.[234] In the devastating California Camp Fire (2018) that killed 85 people, lead levels increased by around 50 times in the hours following the fire at a site nearby (Chico). Zinc concentration also increased significantly in Modesto, 150 miles away. Heavy metals such as manganese and calcium were found in numerous California fires as well.[235] Other chemicals are considered to be significant hazards but are found in concentrations that are too low to cause detectable health effects.[citation needed]

The degree of wildfire smoke exposure to an individual is dependent on the length, severity, duration, and proximity of the fire. People are exposed directly to smoke via the respiratory tract through inhalation of air pollutants. Indirectly, communities are exposed to wildfire debris that can contaminate soil and water supplies.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) developed the air quality index (AQI), a public resource that provides national air quality standard concentrations for common air pollutants. The public can use it to determine their exposure to hazardous air pollutants based on visibility range.[236]

Health effects

[edit]

Wildfire smoke contains particulates that may have adverse effects upon the human respiratory system. Evidence of the health effects should be relayed to the public so that exposure may be limited. The evidence can also be used to influence policy to promote positive health outcomes.[237]

Inhalation of smoke from a wildfire can be a health hazard.[238] Wildfire smoke is composed of combustion products i.e. carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, water vapor, particulate matter, organic chemicals, nitrogen oxides and other compounds. The principal health concern is the inhalation of particulate matter and carbon monoxide.[239]

Particulate matter (PM) is a type of air pollution made up of particles of dust and liquid droplets. They are characterized into three categories based on particle diameter: coarse PM, fine PM, and ultrafine PM. Coarse particles are between 2.5 micrometers and 10 micrometers, fine particles measure 0.1 to 2.5 micrometers, and ultrafine particle are less than 0.1 micrometer. lmpact on the body upon inhalation varies by size. Coarse PM is filtered by the upper airways and can accumulate and cause pulmonary inflammation. This can result in eye and sinus irritation as well as sore throat and coughing.[240][241] Coarse PM is often composed of heavier and more toxic materials that lead to short-term effects with stronger impact.[241]

Smaller PM moves further into the respiratory system creating issues deep into the lungs and the bloodstream.[240][241] In asthma patients, PM2.5 causes inflammation but also increases oxidative stress in the epithelial cells. These particulates also cause apoptosis and autophagy in lung epithelial cells. Both processes damage the cells and impact cell function. This damage impacts those with respiratory conditions such as asthma where the lung tissues and function are already compromised.[241] Particulates less than 0.1 micrometer are called ultrafine particle (UFP). It is a major component of wildfire smoke.[242] UFP can enter the bloodstream like PM2.5-0.1 however studies show that it works into the blood much quicker. The inflammation and epithelial damage done by UFP has also shown to be much more severe.[241] PM2.5 is of the largest concern in regards to wildfire.[237] This is particularly hazardous to the very young, elderly and those with chronic conditions such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cystic fibrosis and cardiovascular conditions. The illnesses most commonly associated with exposure to fine PM from wildfire smoke are bronchitis, exacerbation of asthma or COPD, and pneumonia. Symptoms of these complications include wheezing and shortness of breath and cardiovascular symptoms include chest pain, rapid heart rate and fatigue.[240]

Asthma exacerbation

[edit]Several epidemiological studies have demonstrated a close association between air pollution and respiratory allergic diseases such as bronchial asthma.[237]

An observational study of smoke exposure related to the 2007 San Diego wildfires revealed an increase both in healthcare utilization and respiratory diagnoses, especially asthma among the group sampled.[243] Projected climate scenarios of wildfire occurrences predict significant increases in respiratory conditions among young children.[243] PM triggers a series of biological processes including inflammatory immune response, oxidative stress, which are associated with harmful changes in allergic respiratory diseases.[244]

Although some studies demonstrated no significant acute changes in lung function among people with asthma related to PM from wildfires, a possible explanation for these counterintuitive findings is the increased use of quick-relief medications, such as inhalers, in response to elevated levels of smoke among those already diagnosed with asthma.[245]

There is consistent evidence between wildfire smoke and the exacerbation of asthma.[245]

Asthma is one of the most common chronic disease among children in the United States, affecting an estimated 6.2 million children.[246] Research on asthma risk focuses specifically on the risk of air pollution during the gestational period. Several pathophysiology processes are involved in this. Considerable airway development occurs during the 2nd and 3rd trimesters and continues until 3 years of age.[247] It is hypothesized that exposure to these toxins during this period could have consequential effects, as the epithelium of the lungs during this time could have increased permeability to toxins. Exposure to air pollution during parental and pre-natal stage could induce epigenetic changes which are responsible for the development of asthma.[248] Studies have found significant association between PM2.5, NO2 and development of asthma during childhood despite heterogeneity among studies.[249] Furthermore, maternal exposure to chronic stressors is most likely present in distressed communities, and as this can be correlated with childhood asthma, it may further explain links between early childhood exposure to air pollution, neighborhood poverty, and childhood risk.[250]

Carbon monoxide danger

[edit]Carbon monoxide (CO) is a colorless, odorless gas that can be found at the highest concentration at close proximity to a smoldering fire. Thus, it is a serious threat to the health of wildfire firefighters. CO in smoke can be inhaled into the lungs where it is absorbed into the bloodstream and reduces oxygen delivery to the body's vital organs. At high concentrations, it can cause headaches, weakness, dizziness, confusion, nausea, disorientation, visual impairment, coma, and even death. Even at lower concentrations, such as those found at wildfires, individuals with cardiovascular disease may experience chest pain and cardiac arrhythmia.[232] A recent study tracking the number and cause of wildfire firefighter deaths from 1990 to 2006 found that 21.9% of the deaths occurred from heart attacks.[251]

Another important and somewhat less obvious health effect of wildfires is psychiatric diseases and disorders. Both adults and children from various countries who were directly and indirectly affected by wildfires were found to demonstrate different mental conditions linked to their experience with the wildfires. These include post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, anxiety, and phobias.[252][253][254][255][256]

Epidemiology

[edit]The examples and perspective in this section deal primarily with United States and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (July 2023) |

The Western US has seen an increase in both the frequency and intensity of wildfires over the last several decades. This has been attributed to the arid climate of there and the effects of global warming. An estimated 46 million people were exposed to wildfire smoke from 2004 to 2009 in the Western US. Evidence has demonstrated that wildfire smoke can increase levels of airborne particulate.[237]

The EPA has defined acceptable concentrations of PM in the air, through the National Ambient Air Quality Standards and monitoring of ambient air quality has been mandated.[257] Due to these monitoring programs and the incidence of several large wildfires near populated areas, epidemiological studies have been conducted and demonstrate an association between human health effects and an increase in fine particulate matter due to wildfire smoke.

An increase in PM smoke emitted from the Hayman fire in Colorado in June 2002, was associated with an increase in respiratory symptoms in patients with COPD.[258] Looking at the wildfires in Southern California in 2003, investigators have shown an increase in hospital admissions due to asthma symptoms while being exposed to peak concentrations of PM in smoke.[259] Another epidemiological study found a 7.2% (95% confidence interval: 0.25%, 15%) increase in risk of respiratory related hospital admissions during smoke wave days with high wildfire-specific particulate matter 2.5 compared to matched non-smoke-wave days.[237]

Children participating in the Children's Health Study were also found to have an increase in eye and respiratory symptoms, medication use and physician visits.[260] Mothers who were pregnant during the fires gave birth to babies with a slightly reduced average birth weight compared to those who were not exposed. Suggesting that pregnant women may also be at greater risk to adverse effects from wildfire.[261] Worldwide, it is estimated that 339,000 people die due to the effects of wildfire smoke each year.[262]

Besides the size of PM, their chemical composition should also be considered. Antecedent studies have demonstrated that the chemical composition of PM2.5 from wildfire smoke can yield different estimates of human health outcomes as compared to other sources of smoke such as solid fuels.[237]

Post-fire risks

[edit]

After a wildfire, hazards remain. Residents returning to their homes may be at risk from falling fire-weakened trees. Humans and pets may also be harmed by falling into ash pits. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) also reports that wildfires cause significant damage to electric systems, especially in dry regions.[263]

Chemically contaminated drinking water, at levels of hazardous waste concern, is a growing problem. In particular, hazardous waste scale chemical contamination of buried water systems was first discovered in the U.S. in 2017,[264] and has since been increasingly documented in Hawaii, Colorado, and Oregon after wildfires.[265] In 2021, Canadian authorities adapted their post-fire public safety investigation approaches in British Columbia to screen for this risk, but have not found it as of 2023. Another challenge is that private drinking wells and the plumbing within a building can also become chemically contaminated and unsafe.[266] Households experience a wide-variety of significant economic and health impacts related to this contaminated water.[267] Evidence-based guidance on how to inspect and test wildfire impacted wells [268] and building water systems was developed for the first time in 2020.[269] In Paradise, California, for example,[270] the 2018 Camp Fire caused more than $150 million dollars worth of damage. This required almost a year of time to decontaminate and repair the municipal drinking water system from wildfire damage.

The source of this contamination was first proposed after the 2018 Camp Fire in California as originating from thermally degraded plastics in water systems, smoke and vapors entering depressurized plumbing, and contaminated water in buildings being sucked into the municipal water system. In 2020, it was first shown that thermal degradation of plastic drinking water materials was one potential contamination source.[271] In 2023, the second theory was confirmed where contamination could be sucked into pipes that lost water pressure.[272]

Other post-fire risks, can increase if other extreme weather follows. For example, wildfires make soil less able to absorb precipitation, so heavy rainfall can result in more severe flooding and damages like mud slides.[273][274]

At-risk groups

[edit]Firefighters

[edit]Firefighters are at greatest risk for acute and chronic health effects resulting from wildfire smoke exposure. Due to firefighters' occupational duties, they are frequently exposed to hazardous chemicals at close proximity for longer periods of time. A case study on the exposure of wildfire smoke among wildland firefighters shows that firefighters are exposed to significant levels of carbon monoxide and respiratory irritants above OSHA-permissible exposure limits (PEL) and ACGIH threshold limit values (TLV). 5–10% are overexposed.[275]

Between 2001 and 2012, over 200 fatalities occurred among wildland firefighters. In addition to heat and chemical hazards, firefighters are also at risk for electrocution from power lines; injuries from equipment; slips, trips, and falls; injuries from vehicle rollovers; heat-related illness; insect bites and stings; stress; and rhabdomyolysis.[276]

Residents

[edit]

Residents in communities surrounding wildfires are exposed to lower concentrations of chemicals, but they are at a greater risk for indirect exposure through water or soil contamination. Exposure to residents is greatly dependent on individual susceptibility. Vulnerable persons such as children (ages 0–4), the elderly (ages 65 and older), smokers, and pregnant women are at an increased risk due to their already compromised body systems, even when the exposures are present at low chemical concentrations and for relatively short exposure periods.[232] They are also at risk for future wildfires and may move away to areas they consider less risky.[277]

Wildfires affect large numbers of people in Western Canada and the United States. In California alone, more than 350,000 people live in towns and cities in "very high fire hazard severity zones".[278]

Direct risks to building residents in fire-prone areas can be moderated through design choices such as choosing fire-resistant vegetation, maintaining landscaping to avoid debris accumulation and to create firebreaks, and by selecting fire-retardant roofing materials. Potential compounding issues with poor air quality and heat during warmer months may be addressed with MERV 11 or higher outdoor air filtration in building ventilation systems, mechanical cooling, and a provision of a refuge area with additional air cleaning and cooling, if needed.[279]

History

[edit]

The first evidence of wildfires is fossils of the giant fungi Prototaxites preserved as charcoal, discovered in South Wales and Poland, dating to the Silurian period (about 430 million years ago).[280] Smoldering surface fires started to occur sometime before the Early Devonian period 405 million years ago. Low atmospheric oxygen during the Middle and Late Devonian was accompanied by a decrease in charcoal abundance.[281][282] Additional charcoal evidence suggests that fires continued through the Carboniferous period. Later, the overall increase of atmospheric oxygen from 13% in the Late Devonian to 30–31% by the Late Permian was accompanied by a more widespread distribution of wildfires.[283] Later, a decrease in wildfire-related charcoal deposits from the late Permian to the Triassic periods is explained by a decrease in oxygen levels.[284]

Wildfires during the Paleozoic and Mesozoic periods followed patterns similar to fires that occur in modern times. Surface fires driven by dry seasons[clarification needed] are evident in Devonian and Carboniferous progymnosperm forests. Lepidodendron forests dating to the Carboniferous period have charred peaks, evidence of crown fires. In Jurassic gymnosperm forests, there is evidence of high frequency, light surface fires.[284] The increase of fire activity in the late Tertiary[285] is possibly due to the increase of C4-type grasses. As these grasses shifted to more mesic habitats, their high flammability increased fire frequency, promoting grasslands over woodlands.[286] However, fire-prone habitats may have contributed to the prominence of trees such as those of the genera Eucalyptus, Pinus and Sequoia, which have thick bark to withstand fires and employ pyriscence.[287][288]

Human involvement

[edit]

The human use of fire for agricultural and hunting purposes during the Paleolithic and Mesolithic ages altered pre-existing landscapes and fire regimes. Woodlands were gradually replaced by smaller vegetation that facilitated travel, hunting, seed-gathering and planting.[289] In recorded human history, minor allusions to wildfires were mentioned in the Bible and by classical writers such as Homer. However, while ancient Hebrew, Greek, and Roman writers were aware of fires, they were not very interested in the uncultivated lands where wildfires occurred.[290][291] Wildfires were used in battles throughout human history as early thermal weapons. From the Middle Ages, accounts were written of occupational burning as well as customs and laws that governed the use of fire. In Germany, regular burning was documented in 1290 in the Odenwald and in 1344 in the Black Forest.[292] In the 14th century Sardinia, firebreaks were used for wildfire protection. In Spain during the 1550s, sheep husbandry was discouraged in certain provinces by Philip II due to the harmful effects of fires used in transhumance.[290][291] As early as the 17th century, Native Americans were observed using fire for many purposes including cultivation, signaling, and warfare. Scottish botanist David Douglas noted the native use of fire for tobacco cultivation, to encourage deer into smaller areas for hunting purposes, and to improve foraging for honey and grasshoppers. Charcoal found in sedimentary deposits off the Pacific coast of Central America suggests that more burning occurred in the 50 years before the Spanish colonization of the Americas than after the colonization.[293] In the post-World War II Baltic region, socio-economic changes led more stringent air quality standards and bans on fires that eliminated traditional burning practices.[292] In the mid-19th century, explorers from HMS Beagle observed Australian Aborigines using fire for ground clearing, hunting, and regeneration of plant food in a method later named fire-stick farming.[294] Such careful use of fire has been employed for centuries in lands protected by Kakadu National Park to encourage biodiversity.[295]

Wildfires typically occur during periods of increased temperature and drought. An increase in fire-related debris flow in alluvial fans of northeastern Yellowstone National Park was linked to the period between AD 1050 and 1200, coinciding with the Medieval Warm Period.[296] However, human influence caused an increase in fire frequency. Dendrochronological fire scar data and charcoal layer data in Finland suggests that, while many fires occurred during severe drought conditions, an increase in the number of fires during 850 BC and 1660 AD can be attributed to human influence.[297] Charcoal evidence from the Americas suggested a general decrease in wildfires between 1 AD and 1750 compared to previous years. However, a period of increased fire frequency between 1750 and 1870 was suggested by charcoal data from North America and Asia, attributed to human population growth and influences such as land clearing practices. This period was followed by an overall decrease in burning in the 20th century, linked to the expansion of agriculture, increased livestock grazing, and fire prevention efforts.[298] A meta-analysis found that 17 times more land burned annually in California before 1800 compared to recent decades (1,800,000 hectares/year compared to 102,000 hectares/year).[299]

According to a paper published in the journal Science, the number of natural and human-caused fires decreased by 24.3% between 1998 and 2015. Researchers explain this as a transition from nomadism to settled lifestyle and intensification of agriculture that lead to a drop in the use of fire for land clearing.[300][301]

Increases of certain tree species (i.e. conifers) over others (i.e. deciduous trees) can increase wildfire risk, especially if these trees are also planted in monocultures.[302][303] Some invasive species, moved in by humans (i.e., for the pulp and paper industry) have in some cases also increased the intensity of wildfires. Examples include species such as Eucalyptus in California[304][305] and gamba grass in Australia.

Society and culture

[edit]Wildfires have a place in many cultures. "To spread like wildfire" is a common idiom in English, meaning something that "quickly affects or becomes known by more and more people".[306]

Wildfire activity has been attributed as a major factor in the development of Ancient Greece. In modern Greece, as in many other regions, it is the most common natural disaster and figures prominently in the social and economic lives of its people.[307]

In 1937, U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt initiated a nationwide fire prevention campaign, highlighting the role of human carelessness in forest fires. Later posters of the program featured Uncle Sam, characters from the Disney movie Bambi, and the official mascot of the U.S. Forest Service, Smokey Bear.[308] The Smokey Bear fire prevention campaign has yielded one of the most popular characters in the United States; for many years there was a living Smokey Bear mascot, and it has been commemorated on postage stamps.[309]

There are also significant indirect or second-order societal impacts from wildfire, such as demands on utilities to prevent power transmission equipment from becoming ignition sources, and the cancelation or nonrenewal of homeowners insurance for residents living in wildfire-prone areas.[310]

See also

[edit]- Dry thunderstorm

- Fire-adapted communities

- Fire ecology

- List of wildfires

- Pyrogeography

- Remote Automated Weather Station

- Stubble burning

- Wildland–urban interface

- Wildfire risk indices:

References

[edit]- ^ Cambridge Advanced Learner's Dictionary (Third ed.). Cambridge University Press. 2008. ISBN 978-0-521-85804-5. Archived from the original on 13 August 2009.

- ^ "CIFFC Canadian Wildland Fire Management Glossary" (PDF). Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Centre. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- ^ "Forest fire videos – See how fire started on Earth". BBC Earth. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- ^ "Drought, Tree Mortality, and Wildfire in Forests Adapted to Frequent Fire" (PDF). UC Berkeley College of Natural Resources. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- ^ Flannigan, M.D.; B.D. Amiro; K.A. Logan; B.J. Stocks & B.M. Wotton (2005). "Forest Fires and Climate Change in the 21st century" (PDF). Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change. 11 (4): 847–859. doi:10.1007/s11027-005-9020-7. ISSN 1381-2386. S2CID 2757472. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2009. Retrieved 26 June 2009.

- ^ Graham, et al., 12, 36

- ^ National Wildfire Coordinating Group Communicator's Guide For Wildland Fire Management, 4–6.

- ^ "National Wildfire Coordinating Group Fireline Handbook, Appendix B: Fire Behavior" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. April 2006. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 11 December 2008.

- ^ Trigo, Ricardo M.; Provenzale, Antonello; Llasat, Maria Carmen; AghaKouchak, Amir; Hardenberg, Jost von; Turco, Marco (6 March 2017). "On the key role of droughts in the dynamics of summer fires in Mediterranean Europe". Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 81. Bibcode:2017NatSR...7...81T. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-00116-9. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 5427854. PMID 28250442.

- ^ Westerling, A. L.; Hidalgo, H. G.; Cayan, D. R.; Swetnam, T. W. (18 August 2006). "Warming and Earlier Spring Increase Western U.S. Forest Wildfire Activity". Science. 313 (5789): 940–943. Bibcode:2006Sci...313..940W. doi:10.1126/science.1128834. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 16825536.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Parmesan, C., M.D. Morecroft, Y. Trisurat, R. Adrian, G.Z. Anshari, A. Arneth, Q. Gao, P. Gonzalez, R. Harris, J. Price, N. Stevens, and G.H. Talukdarr, 2022: Chapter 2: Terrestrial and Freshwater Ecosystems and Their Services. In: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, pp. 197–377, doi:10.1017/9781009325844.004.

- ^ Heidari, Hadi; Arabi, Mazdak; Warziniack, Travis (August 2021). "Effects of Climate Change on Natural-Caused Fire Activity in Western U.S. National Forests". Atmosphere. 12 (8): 981. Bibcode:2021Atmos..12..981H. doi:10.3390/atmos12080981.

- ^ DellaSalla, Dominick A.; Hanson, Chad T. (2015). The Ecological Importance of Mixed-Severity Fires. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-12-802749-3.

- ^ Hutto, Richard L. (1 December 2008). "The Ecological Importance of Severe Wildfires: Some Like It Hot". Ecological Applications. 18 (8): 1827–1834. Bibcode:2008EcoAp..18.1827H. doi:10.1890/08-0895.1. ISSN 1939-5582. PMID 19263880.

- ^ Stephen J. Pyne. "How Plants Use Fire (And Are Used By It)". NOVA online. Archived from the original on 8 August 2009. Retrieved 30 June 2009.

- ^ "Drought, Tree Mortality, and Wildfire in Forests Adapted to Frequent Fire" (PDF). UC Berkeley College of Natural Resources. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- ^ "Main Types of Disasters and Associated Trends". lao.ca.gov. Legislative Analyst's Office. 10 January 2019.

- ^ Machemer, Theresa (9 July 2020). "The Far-Reaching Consequences of Siberia's Climate-Change-Driven Wildfires". Smithsonian Magazine.

- ^ Australia, Government Geoscience (25 July 2017). "Bushfire". www.ga.gov.au.

- ^ "B.C. wildfires: State of emergency declared in Kelowna, evacuations underway | Globalnews.ca". Global News. Retrieved 18 August 2023.

- ^ Jump up to: a b IPCC, 2021: Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M.I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T.K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, US, pp. 3−32, doi:10.1017/9781009157896.001

- ^ "Wildfire Prevention Strategies" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. March 1998. p. 17. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 December 2008. Retrieved 3 December 2008.

- ^ Scott, A (2000). "The Pre-Quaternary history of fire". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 164 (1–4): 281–329. Bibcode:2000PPP...164..281S. doi:10.1016/S0031-0182(00)00192-9.

- ^ Karki, 7, 11–19.

- ^ Boxall, Bettina (5 January 2020). "Human-caused ignitions spark California's worst wildfires but get little state focus". San Diego Union-Tribune. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ^ Liu, Zhihua; Yang, Jian; Chang, Yu; Weisberg, Peter J.; He, Hong S. (June 2012). "Spatial patterns and drivers of fire occurrence and its future trend under climate change in a boreal forest of Northeast China". Global Change Biology. 18 (6): 2041–2056. Bibcode:2012GCBio..18.2041L. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2012.02649.x. ISSN 1354-1013. S2CID 26410408.

- ^ de Rigo, Daniele; Libertà, Giorgio; Houston Durrant, Tracy; Artés Vivancos, Tomàs; San-Miguel-Ayanz, Jesús (2017). Forest fire danger extremes in Europe under climate change: variability and uncertainty. Luxembourg: Publication Office of the European Union. p. 71. doi:10.2760/13180. ISBN 978-92-79-77046-3.

- ^ Krock, Lexi (June 2002). "The World on Fire". NOVA online – Public Broadcasting System (PBS). Archived from the original on 27 October 2009. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

- ^ Balch, Jennifer K.; Bradley, Bethany A.; Abatzoglou, John T.; Nagy, R. Chelsea; Fusco, Emily J.; Mahood, Adam L. (2017). "Human-started wildfires expand the fire niche across the United States". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 114 (11): 2946–2951. Bibcode:2017PNAS..114.2946B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1617394114. ISSN 1091-6490. PMC 5358354. PMID 28242690.

- ^ "Wildfire Investigation". National Interagency Fire Center.

- ^ "How Rupert Murdoch Is Influencing Australia's Bushfire Debate". The New York Times. 8 January 2020. Retrieved 21 June 2023__"An independent study found online bots and trolls exaggerating the role of arson in the fires, at the same time that an article in [Murdoch-owned] The Australian making similar assertions became the most popular offering on the newspaper’s website,” the New York Times writes. “It’s all part of what critics see as a relentless effort led by the powerful media outlet to do what it has also done in the United States and Britain—shift blame to the left, protect conservative leaders, and divert attention from climate change.”

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Kaminski, Isabella (12 June 2023). "Did climate change cause Canada's wildfires?". BBC News. Retrieved 18 June 2023.

- ^ "Who's fuelling the wild theories about Canada's wildfires". CBC News. 15 June 2023. Retrieved 17 June 2023__When many fires started at once in Quebec then people took that as evidence of arson, and their claims got millions of views online. These claims were debunked by meteorologist Wagstaffe who explained that a series of lightning strikes can cause many smouldering hotspots underneath rain-moistened surface fuels; and then when those surface fuels are all dried by the daytime wind simultaneously, then they are all ignited into full blown fires simultaneously. Wagstaffe also corrected the idea that controlled burns are state-sponsored arson.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ "How Arson factors into California's Wildfires". High Country News. 15 October 2021.

- ^ Krajick, Kevin (May 2005). "Fire in the hole". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on 3 September 2010. Retrieved 30 July 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Graham, et al., iv.

- ^ Graham, et al., 9, 13

- ^ Rincon, Paul (9 March 2005). "Asian peat fires add to warming". British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) News. Archived from the original on 19 December 2008. Retrieved 9 December 2008.

- ^ Hamers, Laurel (29 July 2019). "When bogs burn, the environment takes a hit". Science News. Retrieved 15 August 2019.

- ^ Graham, et al ., iv, 10, 14

- ^ C., Scott, Andrew (2014). Fire on earth : an introduction. Bowman, D. M. J. S.; Bond, William J.; Pyne, Stephen J.; Alexander, Martin E. Chichester, West Sussex. ISBN 978-1-119-95357-9. OCLC 854761793.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jump up to: a b "Global Fire Initiative: Fire and Invasives". The Nature Conservancy. Archived from the original on 12 April 2009. Retrieved 3 December 2008.

- ^ Graham, et al., iv, 8, 11, 15.

- ^ Butler, Rhett (19 June 2008). "Global Commodities Boom Fuels New Assault on Amazon". Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies. Archived from the original on 11 April 2009. Retrieved 9 July 2009.

- ^ "National Wildfire Coordinating Group Fireline Handbook, Appendix B: Fire Behavior" (PDF). National Wildfire Coordinating Group. April 2006. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 11 December 2008.

- ^ "The Science of Wildland fire". National Interagency Fire Center. Archived from the original on 5 November 2008. Retrieved 21 November 2008.

- ^ Graham, et al., 12.

- ^ Jump up to: a b National Wildfire Coordinating Group Communicator's Guide For Wildland Fire Management, 3.

- ^ "Ashes cover areas hit by Southern Calif. fires". NBC News. Associated Press. 15 November 2008. Retrieved 4 December 2008.

- ^ "Influence of Forest Structure on Wildfire Behavior and the Severity of Its Effects" (PDF). US Forest Service. November 2003. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 19 November 2008.

- ^ "Prepare for a Wildfire". Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). Archived from the original on 29 October 2008. Retrieved 1 December 2008.

- ^ Глоссарий терминологии лесных пожаров , 74.

- ^ де Соуза Коста и Сандберг, 229–230.

- ^ «Луч смерти Архимеда: проверка реализуемости идеи» . Массачусетский технологический институт (MIT). Октябрь 2005 г. Архивировано из оригинала 7 февраля 2009 г. Проверено 1 февраля 2009 г.

- ^ «Спутники отслеживают следы лесных пожаров в Европе» . Европейское космическое агентство. 27 июля 2004 г. Архивировано из оригинала 10 ноября 2008 г. Проверено 12 января 2009 г.

- ^ Грэм и др ., 10–11.

- ^ «Защита вашего дома от ущерба, причиненного лесным пожаром» (PDF) . Флоридский альянс за безопасные дома (FLASH). п. 5. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 19 июля 2011 г. Проверено 3 марта 2010 г.

- ^ Биллинг, 5–6

- ^ Грэм и др ., 12.

- ^ Ши, Нил (июль 2008 г.). «Под огнем» . Нэшнл Географик . Архивировано из оригинала 15 февраля 2009 года . Проверено 8 декабря 2008 г.

- ^ Грэм и др ., 16.

- ^ Грэм и др ., 9, 16.

- ^ «Том 1: Пожар в Килморе» . 2009 Викторианская королевская комиссия по лесным пожарам . Королевская комиссия Викторианской эпохи по лесным пожарам, Австралия. Июль 2010 г. ISBN. 978-0-9807408-2-0 . Архивировано из оригинала 29 октября 2013 года . Проверено 26 октября 2013 г.

- ^ Руководство для коммуникаторов Национальной координационной группы по борьбе с лесными пожарами по управлению лесными пожарами , 4.

- ^ Грэм и др ., 16–17.

- ^ Олсон и др. , 2

- ^ «Пожароубежище нового поколения» (PDF) . Национальная координационная группа по лесным пожарам. Март 2003. с. 19. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 16 января 2009 г. . Проверено 16 января 2009 г.

- ^ Глоссарий терминологии лесных пожаров , 69.

- ^ де Соуза Коста и Сандберг, 228

- ^ Руководство для коммуникаторов Национальной координационной группы по борьбе с лесными пожарами по управлению лесными пожарами , 5.

- ^ Сан-Мигель-Аянц и др. , 364.

- ^ Глоссарий терминологии лесных пожаров , 73.