Мартин Ван Бюрен

Мартин Ван Бюрен | |

|---|---|

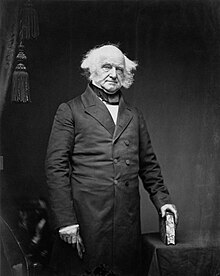

Ван Бюрен в 1855 году | |

| 8-й президент Соединенных Штатов | |

| In office 4 марта 1837 г. - 4 марта 1841 г. | |

| Vice President | Richard Mentor Johnson |

| Preceded by | Andrew Jackson |

| Succeeded by | William Henry Harrison |

| 8th Vice President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1833 – March 4, 1837 | |

| President | Andrew Jackson |

| Preceded by | John C. Calhoun |

| Succeeded by | Richard Mentor Johnson |

| United States Minister to the United Kingdom | |

| In office August 8, 1831 – April 4, 1832 | |

| President | Andrew Jackson |

| Preceded by | Louis McLane |

| Succeeded by | Aaron Vail (acting) |

| 10th United States Secretary of State | |

| In office March 28, 1829 – May 23, 1831 | |

| President | Andrew Jackson |

| Preceded by | Henry Clay |

| Succeeded by | Edward Livingston |

| 9th Governor of New York | |

| In office January 1, 1829 – March 12, 1829 | |

| Lieutenant | Enos T. Throop |

| Preceded by | Nathaniel Pitcher |

| Succeeded by | Enos T. Throop |

| United States Senator from New York | |

| In office March 4, 1821 – December 20, 1828 | |

| Preceded by | Nathan Sanford |

| Succeeded by | Charles E. Dudley |

| 14th Attorney General of New York | |

| In office February 17, 1815 – July 8, 1819 | |

| Governor | |

| Preceded by | Abraham Van Vechten |

| Succeeded by | Thomas J. Oakley |

| Member of the New York Senate from the Middle district | |

| In office July 1, 1813 – June 30, 1820 Serving with various (multimember district) | |

| Preceded by | Edward Philip Livingston |

| Succeeded by |

|

| Surrogate of Columbia County, New York | |

| In office 1808–1813 | |

| Preceded by | James I. Van Alen |

| Succeeded by | James Vanderpoel |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Maarten van Buren December 5, 1782 Kinderhook, Province of New York |

| Died | July 24, 1862 (aged 79) Kinderhook, New York, U.S. |

| Resting place | Kinderhook Reformed Church Cemetery |

| Political party |

|

| Height | 5 ft 6 in (1.68 m)[1] |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 5, including Abraham II and John |

| Parent |

|

| Relatives | Van Buren family |

| Occupation |

|

| Signature | |

| Nicknames | |

Мартин Ван Бюрен ( / v æ n ˈ b jʊər ən / van BURE -ən ; голландский : Маартен ван Бюрен [ˈmaːrtə(n) vɑm‿ˈbyːrə(n)] ; 5 декабря 1782 — 24 июля 1862) — американский юрист , дипломат и государственный деятель , который занимал пост восьмого президента Соединённых Штатов с 1837 по 1841 год. Основной основатель Демократической партии , он занимал пост генерального прокурора Нью-Йорка и Сенатор США , затем некоторое время был девятым губернатором Нью-Йорка , а затем присоединился к Эндрю Джексона администрации в качестве десятого государственного секретаря США , министра Великобритании и, в конечном итоге, восьмого вице-президента с 1833 по 1837 год, после того как был избран по списку Джексона. в 1832 году . Ван Бюрен выиграл президентский пост в 1836 году у разделенных противников-вигов. Ван Бюрен проиграл переизбрание в 1840 году и не смог выдвинуться от Демократической партии в 1844 году . Позже в своей жизни Ван Бюрен стал старейшим государственным деятелем и лидером борьбы с рабством , который возглавил партию «Свободная почва» на президентских выборах 1848 года .

Van Buren was born in Kinderhook, New York, where most residents were of Dutch descent and spoke Dutch as their primary language; he is the only president to have spoken English as a second language. Trained as a lawyer, he entered politics as a member of the Democratic-Republican Party, won a seat in the New York State Senate, and was elected to the United States Senate in 1821. As the leader of the Bucktails faction of the party, Van Buren established the political machine known as the Albany Regency. He ran successfully for governor of New York to support Andrew Jackson's candidacy in the 1828 presidential election but resigned shortly after Jackson was inaugurated so he could accept appointment as Jackson's secretary of state. In the cabinet, Van Buren was a key Jackson advisor and built the organizational structure for the coalescing Democratic Party. He ultimately resigned to help resolve the Petticoat affair and briefly served as ambassador to Great Britain. At Jackson's behest, the 1832 Democratic National Convention nominated Van Buren for vice president, and he took office after the Democratic ticket won the 1832 presidential election.

With Jackson's strong support and the organizational strength of the Democratic Party, Van Buren successfully ran for president in the 1836 presidential election. However, his popularity soon eroded because of his response to the Panic of 1837, which centered on his Independent Treasury system, a plan under which the federal government of the United States would store its funds in vaults rather than in banks; more conservative Democrats and Whigs in Congress ultimately delayed his plan from being implemented until 1840. His presidency was further marred by the costly Second Seminole War and his refusal to admit Texas to the Union as a slave state. In 1840, Van Buren lost his re-election bid to William Henry Harrison. While Van Buren is praised for anti-slavery stances, in historical rankings, historians and political scientists often rank Van Buren as an average or below-average U.S. president, due to his handling of the Panic of 1837.

Van Buren was initially the leading candidate for the Democratic Party's nomination again in 1844, but his continued opposition to the annexation of Texas angered Southern Democrats, leading to the nomination of James K. Polk. Growing opposed to slavery, Van Buren was the newly formed Free Soil Party's presidential nominee in 1848, and his candidacy helped Whig nominee Zachary Taylor defeat Democrat Lewis Cass. Worried about sectional tensions, Van Buren returned to the Democratic Party after 1848 but was disappointed with the pro-southern presidencies of Franklin Pierce and James Buchanan. During the American Civil War, Van Buren was a War Democrat who supported the policies of President Abraham Lincoln, a Republican. He died of asthma at his home in Kinderhook in 1862, aged 79.

Early life and education

[edit]

Martin Van Buren was born on December 5, 1782, in Kinderhook, New York,[5] about 20 miles (32 km) south of Albany in the Hudson River Valley.

His father, Abraham Van Buren, was a descendant of Cornelis Maessen, a native of Buurmalsen, Netherlands who had emigrated to New Netherland in 1631 and purchased a plot of land on Manhattan Island.[6][7] Along with being the first U.S. president who was not born a British subject, Van Buren was also the first U.S. president not of British ancestry; he was of entirely Dutch descent.[8] Abraham Van Buren had been a Patriot during the American Revolution,[9][10] and he later joined the Democratic-Republican Party.[11] He owned an inn and tavern in Kinderhook and served as Kinderhook's town clerk for several years. In 1776, he married Maria Hoes (or Goes) Van Alen (1746–1818) in the town of Kinderhook, also of Dutch extraction and the widow of Johannes Van Alen (1744-c. 1773). She had three children from her first marriage, including future U.S. Representative James I. Van Alen. Her second marriage produced five children, of which Martin was the third.[12]

Van Buren received a basic education at the village schoolhouse, and briefly studied Latin at the Kinderhook Academy and at Washington Seminary in Claverack.[13][14] Van Buren was raised speaking primarily Dutch and learned English while attending school;[15] he is the only president of the United States whose first language was not English.[16] Also during his childhood, Van Buren learned at his father's inn how to interact with people from varied ethnic, income, and societal groups, which he used to his advantage as a political organizer.[17] His formal education ended in 1796, when he began reading law at the office of Peter Silvester and his son Francis.[18]

Van Buren, at 5 feet 6 inches (1.68 m) tall, was small in stature, and affectionately nicknamed "Little Van".[19] When he began his legal studies he wore rough, homespun clothing,[20] causing the Silvesters to admonish him to pay greater heed to his clothing and personal appearance as an aspiring lawyer. He accepted their advice, and subsequently emulated the Silvesters' clothing, appearance, bearing, and conduct.[21][22] The lessons he learned from the Silvesters were reflected in his career as a lawyer and politician, in which Van Buren was known for his amiability and fastidious appearance.[23] Despite Kinderhook's strong affiliation with the Federalist Party, of which the Silvesters were also strong supporters, Van Buren adopted his father's Democratic-Republican leanings.[24] The Silvesters and Democratic-Republican political figure John Peter Van Ness suggested that Van Buren's political leanings constrained him to complete his education with a Democratic-Republican attorney, so he spent a final year of apprenticeship in the New York City office of John Van Ness's brother William P. Van Ness, a political lieutenant of Aaron Burr.[25] Van Ness introduced Van Buren to the intricacies of New York state politics, and Van Buren observed Burr's battles for control of the state Democratic-Republican party against George Clinton and Robert R. Livingston.[26] He returned to Kinderhook in 1803, after his admission to the New York bar.[27]

Van Buren married Hannah Hoes in Catskill, New York, on February 21, 1807, when he was 24 years old and she was 23. She was his childhood sweetheart and a daughter of his maternal first cousin, Johannes Dircksen Hoes.[28] She grew up in Valatie, and like Van Buren her home life was primarily Dutch; she spoke Dutch as her first language, and spoke English with a marked accent.[29] The couple had six children, four of whom lived to adulthood: Abraham (1807–1873), unnamed daughter (stillborn around 1809), John (1810–1866), Martin Jr. (1812–1855), Winfield Scott (born and died in 1814), and Smith Thompson (1817–1876).[30] Hannah contracted tuberculosis, and died in Kinderhook on February 5, 1819.[31] Martin Van Buren never remarried.[32]

Early political career

[edit]

Upon returning to Kinderhook in 1803, Van Buren formed a law partnership with his half-brother, James Van Alen, and became financially secure enough to increase his focus on politics.[33] Van Buren had been active in politics from age 18, if not before. In 1801, he attended a Democratic-Republican Party convention in Troy, New York, where he worked successfully to secure for John Peter Van Ness the party nomination in a special election for the 6th Congressional District seat.[34] Upon returning to Kinderhook, Van Buren broke with the Burr faction, becoming an ally of both DeWitt Clinton and Daniel D. Tompkins. After the faction led by Clinton and Tompkins dominated the 1807 elections, Van Buren was appointed Surrogate of Columbia County, New York.[35] Seeking a better base for his political and legal career, Van Buren and his family moved to the town of Hudson, the seat of Columbia County, in 1808.[36] Van Buren's legal practice continued to flourish, and he traveled all over the state to represent various clients.[37]

In 1812, Van Buren won his party's nomination for a seat in the New York State Senate. Though several Democratic-Republicans, including John Peter Van Ness, joined with the Federalists to oppose his candidacy, Van Buren won election to the state senate in mid-1812.[38] Later in the year, the United States entered the War of 1812 against Great Britain, while Clinton launched an unsuccessful bid to defeat President James Madison in the 1812 presidential election. After the election, Van Buren became suspicious that Clinton was working with the Federalist Party, and he broke from his former political ally.[39]

During the War of 1812, Van Buren worked with Clinton, Governor Tompkins, and Ambrose Spencer to support the Madison administration's prosecution of the war.[40] In addition, he was a special judge advocate appointed to serve as a prosecutor of William Hull during Hull's court-martial following the surrender of Detroit.[41][42] Anticipating another military campaign, he collaborated with Winfield Scott on ways to reorganize the New York Militia in the winter of 1814–1815, but the end of the war halted their work in early 1815.[43] Van Buren was so favorably impressed by Scott that he named his fourth son after him.[44] Van Buren's strong support for the war boosted his standing, and in 1815, he was elected to the position of New York Attorney General. Van Buren moved from Hudson to the state capital of Albany, where he established a legal partnership with Benjamin Butler,[45] and shared a house with political ally Roger Skinner.[46] In 1816, Van Buren won re-election to the state senate, and he would continue to simultaneously serve as both state senator and as the state's attorney general.[47] In 1819, he played an active part in prosecuting the accused murderers of Richard Jennings, the first murder-for-hire case in the state of New York.[48]

Albany regency

[edit]After Tompkins was elected as vice president in the 1816 presidential election, Clinton defeated Van Buren's preferred candidate, Peter Buell Porter, in the 1817 New York gubernatorial election.[49] Clinton threw his influence behind the construction of the Erie Canal, an ambitious project designed to connect Lake Erie to the Atlantic Ocean.[50] Though many of Van Buren's allies urged him to block Clinton's Erie Canal bill, Van Buren believed that the canal would benefit the state. His support for the bill helped it win approval from the New York legislature.[51] Despite his support for the Erie Canal, Van Buren became the leader of an anti-Clintonian faction in New York known as the "Bucktails".[52]

The Bucktails succeeded in emphasizing party loyalty and used it to capture and control many patronage posts throughout New York. Through his use of patronage, loyal newspapers, and connections with local party officials and leaders, Van Buren established what became known as the "Albany Regency", a political machine that emerged as an important factor in New York politics.[53] The Regency relied on a coalition of small farmers, but also enjoyed support from the Tammany Hall machine in New York City.[54] During this era, Van Buren largely determined Tammany Hall's political policy for New York's Democratic-Republicans.[55]

A New York state referendum that expanded state voting rights to all white men in 1821, and which further increased the power of Tammany Hall, was guided by Van Buren.[56] Although Governor Clinton remained in office until late 1822, Van Buren emerged as the leader of the state's Democratic-Republicans after the 1820 elections.[57] Van Buren was a member of the 1820 state constitutional convention, where he favored expanded voting rights, but opposed universal suffrage and tried to maintain property requirements for voting.[58]

Entry into national politics

[edit]In February 1821, the state legislature elected Van Buren to represent New York in the United States Senate.[59] Van Buren arrived in Washington during the "Era of Good Feelings", a period in which partisan distinctions at the national level had faded.[60] Van Buren quickly became a prominent figure in Washington, D.C., befriending Secretary of the Treasury William H. Crawford, among others.[61] Though not an exceptional orator, Van Buren frequently spoke on the Senate floor, usually after extensively researching the subject at hand. Despite his commitments as a father and state party leader, Van Buren remained closely engaged in his legislative duties, and during his time in the Senate he served as the chairman of the Senate Finance Committee and the Senate Judiciary Committee.[62] As he gained renown, Van Buren earned monikers like "Little Magician" and "Sly Fox".[63]

Van Buren chose to back Crawford over John Quincy Adams, Andrew Jackson, and Henry Clay in the presidential election of 1824.[64] Crawford shared Van Buren's affinity for Jeffersonian principles of states' rights and limited government, and Van Buren believed that Crawford was the ideal figure to lead a coalition of New York, Pennsylvania, and Virginia's "Richmond Junto".[65] Van Buren's support for Crawford aroused strong opposition in New York in the form of the People's party, which drew support from Clintonians, Federalists, and others opposed to Van Buren.[66] Nonetheless, Van Buren helped Crawford win the Democratic-Republican party's presidential nomination at the February 1824 congressional nominating caucus.[67] The other Democratic-Republican candidates in the race refused to accept the poorly attended caucus's decision, and as the Federalist Party had all but ceased to function as a national party, the 1824 campaign became a competition among four candidates of the same party. Though Crawford suffered a severe stroke that left him in poor health, Van Buren continued to support his chosen candidate.[68] In May 1824, Van Buren met with 81-year-old former President Thomas Jefferson in an attempt to bolster Crawford's candidacy, and though he was unsuccessful in gaining a public endorsement for Crawford, he nonetheless cherished the chance to meet with his political hero.[69]

The 1824 elections dealt a severe blow to the Albany Regency, as Clinton returned to the governorship with the support of the People's party. By the time the state legislature convened to choose the state's presidential electors, results from other states had made it clear that no individual would win a majority of the electoral vote, necessitating a contingent election in the United States House of Representatives.[70] While Adams and Jackson finished in the top three and were eligible for selection in the contingent election, New York's electors would help determine whether Clay or Crawford would finish third.[71] Though most of the state's electoral votes went to Adams, Crawford won one more electoral vote than Clay in the state, and Clay's defeat in Louisiana left Crawford in third place.[72] With Crawford still in the running, Van Buren lobbied members of the House to support him.[73] He hoped to engineer a Crawford victory on the second ballot of the contingent election, but Adams won on the first ballot with the help of Clay and Stephen Van Rensselaer, a Congressman from New York. Despite his close ties with Van Buren, Van Rensselaer cast his vote for Adams, thus giving Adams a narrow majority of New York's delegation and a victory in the contingent election.[74]

After the House contest, Van Buren shrewdly kept out of the controversy which followed, and began looking forward to 1828. Jackson was angered to see the presidency go to Adams despite Jackson having won more popular votes than Adams had, and he eagerly looked forward to a rematch.[75] Jackson's supporters accused Adams and Clay of having made a "corrupt bargain" in which Clay helped Adams win the contingent election in return for Clay's appointment as Secretary of State.[76] Van Buren was always courteous in his treatment of opponents and showed no bitterness toward either Adams or Clay, and he voted to confirm Clay's nomination to the cabinet.[77] At the same time, Van Buren opposed the Adams-Clay plans for internal improvements like roads and canals and declined to support U.S. participation in the Congress of Panama.[78] Van Buren considered Adams's proposals to represent a return to the Hamiltonian economic model favored by Federalists, which he strongly opposed.[79] Despite his opposition to Adams's public policies, Van Buren easily secured re-election in his divided home state in 1827.[80]

1828 elections

[edit]Van Buren's overarching goal at the national level was to restore a two-party system with party cleavages based on philosophical differences, and he viewed the old divide between Federalists and Democratic-Republicans as beneficial to the nation.[81] Van Buren believed that these national parties helped ensure that elections were decided on national, rather than sectional or local, issues; as he put it, "party attachment in former times furnished a complete antidote for sectional prejudices". After the 1824 election, Van Buren was initially somewhat skeptical of Jackson, who had not taken strong positions on most policy issues. Nonetheless, he settled on Jackson as the one candidate who could beat Adams in the 1828 presidential election, and he worked to bring Crawford's former backers into line behind Jackson.

He also forged alliances with other members of Congress opposed to Adams, including Vice President John C. Calhoun, Senator Thomas Hart Benton, and Senator John Randolph.[82] Seeking to solidify his standing in New York and bolster Jackson's campaign, Van Buren helped arrange the passage of the Tariff of 1828, which opponents labeled as the "Tariff of Abominations". The tariff was intended to protect northern and western agricultural products from foreign competition, but the resulting tax on imports cut into the profits of New England businessmen, who imported raw materials including iron to make into finished goods for subsequent resale, as well as finished goods including clothing for distribution and resale throughout the United States. The tariff also raised the cost of living in the South, because Southern states had little manufacturing capacity, which required them to export raw materials including cotton or sell them to Northern manufacturers, then import higher-priced finished goods or purchase them from the North. The tariff thus satisfied many who sought protection from foreign competition, but angered Southern cotton interests and New England importers and manufacturers.[83] Because Van Buren believed the South would never support Adams, and New England would never support Jackson, he was willing to alienate both regions through passage of the tariff.[84]

Meanwhile, Clinton's death from a heart attack in 1828 dramatically shook up the politics of Van Buren's home state, while the Anti-Masonic Party emerged as an increasingly important factor.[85] After some initial reluctance, Van Buren chose to run for Governor of New York in the 1828 election.[86] Hoping that a Jackson victory would lead to his elevation to Secretary of State or Secretary of the Treasury, Van Buren chose Enos T. Throop as his running mate and preferred successor.[87] Van Buren's candidacy was aided by the split between supporters of Adams, who had adopted the label of National Republicans, and the Anti-Masonic Party.[88]

Reflecting his public association with Jackson, Van Buren accepted the gubernatorial nomination on a ticket that called itself "Jacksonian-Democrat".[89] He campaigned on local as well as national issues, emphasizing his opposition to the policies of the Adams administration.[90] Van Buren ran ahead of Jackson, winning the state by 30,000 votes compared to a margin of 5,000 for Jackson.[91] Nationally, Jackson defeated Adams by a wide margin, winning nearly every state outside of New England.[92] After the election, Van Buren resigned from the Senate to start his term as governor, which began on January 1, 1829.[93] While his term as governor was short, he did manage to pass the Bank Safety Fund Law, an early form of deposit insurance, through the legislature.[94] He also appointed several key supporters, including William L. Marcy and Silas Wright, to important state positions.[95]

Jackson administration (1829–1837)

[edit]Secretary of State

[edit]

In February 1829, Jackson wrote to Van Buren to ask him to become Secretary of State.[96] Van Buren quickly agreed, and he resigned as governor the following month; his tenure of forty-three days is the shortest of any Governor of New York.[97] No serious diplomatic crises arose during Van Buren's tenure as Secretary of State, but he achieved several notable successes, such as settling long-standing claims against France and winning reparations for property that had been seized during the Napoleonic Wars. He reached an agreement with the British to open trade with the British West Indies colonies and concluded a treaty with the Ottoman Empire that gained American merchants access to the Black Sea. Items on which he did not achieve success included settling the Maine-New Brunswick boundary dispute with Great Britain, gaining settlement of the U.S. claim to the Oregon Country, concluding a commercial treaty with Russia, and persuading Mexico to sell Texas.[98][99]

In addition to his foreign policy duties, Van Buren quickly emerged as an important advisor to Jackson on major domestic issues like the tariff and internal improvements.[100] The Secretary of State was instrumental in convincing Jackson to issue the Maysville Road veto, which both reaffirmed limited government principles and also helped prevent the construction of infrastructure projects that could potentially compete with New York's Erie Canal.[101] He also became involved in a power struggle with Calhoun over appointments and other issues, including the Petticoat Affair.[102] The Petticoat Affair arose because Peggy Eaton, wife of Secretary of War John H. Eaton, was ostracized by the other cabinet wives due to the circumstances of her marriage.[103][104]

Led by Floride Calhoun, wife of Vice President John Calhoun, the other cabinet wives refused to pay courtesy calls to the Eatons, receive them as visitors, or invite them to social events.[105] As a widower, Van Buren was unaffected by the position of the cabinet wives.[106] Van Buren initially sought to mend the divide in the cabinet, but most of the leading citizens in Washington continued to snub the Eatons.[107] Jackson was close to Eaton, and he came to the conclusion that the allegations against Eaton arose from a plot against his administration led by Henry Clay.[108] The Petticoat Affair, combined with a contentious debate over the tariff and Calhoun's decade-old criticisms of Jackson's actions in the First Seminole War, contributed to a split between Jackson and Calhoun.[109] As the debate over the tariff and the proposed ability of South Carolina to nullify federal law consumed Washington, Van Buren, not Calhoun, increasingly emerged as Jackson's likely successor.[110]

The Petticoat affair was finally resolved when Van Buren offered to resign. In April 1831, Jackson accepted and reorganized his cabinet by asking for the resignations of the anti-Eaton cabinet members.[111] Postmaster General William T. Barry, who had sided with the Eatons in the Petticoat Affair, was the lone cabinet member to remain in office.[112] The cabinet reorganization removed Calhoun's allies from the Jackson administration, and Van Buren had a major role in shaping the new cabinet.[113] After leaving office, Van Buren continued to play a part in the Kitchen Cabinet, Jackson's informal circle of advisors.[114]

Ambassador to Britain and vice presidency

[edit]

In August 1831, Jackson gave Van Buren a recess appointment as the ambassador to Britain, and Van Buren arrived in London in September.[115] He was cordially received, but in February 1832, shortly after his 49th birthday, he learned that the Senate had rejected his nomination.[116] The rejection of Van Buren was essentially the work of Calhoun.[117] When the vote on Van Buren's nomination was taken, enough pro-Calhoun Jacksonians refrained from voting to produce a tie, which allowed Calhoun to cast the deciding vote against Van Buren.[118]

Calhoun was elated, convinced that he had ended Van Buren's career. "It will kill him dead, sir, kill him dead. He will never kick, sir, never kick", Calhoun exclaimed to a friend.[119] Calhoun's move backfired; by making Van Buren appear the victim of petty politics, Calhoun raised Van Buren in both Jackson's regard and the esteem of others in the Democratic Party. Far from ending Van Buren's career, Calhoun's action gave greater impetus to Van Buren's candidacy for vice president.[120]

Seeking to ensure that Van Buren would replace Calhoun as his running mate, Jackson had arranged for a national convention of his supporters.[121] The May 1832 Democratic National Convention subsequently nominated Van Buren to serve as the party's vice presidential nominee.[122] Van Buren won the nomination over Philip P. Barbour (Calhoun's favored candidate) and Richard Mentor Johnson due to the support of Jackson and the strength of the Albany Regency.[123] Upon Van Buren's return from Europe in July 1832, he became involved in the Bank War, a struggle over the renewal of the charter of the Second Bank of the United States.[124]

Van Buren had long been distrustful of banks, and he viewed the bank as an extension of the Hamiltonian economic program, so he supported Jackson's veto of the bank's re-charter.[125] Henry Clay, the presidential nominee of the National Republicans, made the struggle over the bank the key issue of the presidential election of 1832.[126] The Jackson–Van Buren ticket won the 1832 election by a landslide,[127] and Van Buren took office as the eighth Vice President of the United States on March 4, 1833, at the age of 50.[128] During the Nullification Crisis, Van Buren counseled Jackson to pursue a policy of conciliation with South Carolina leaders.[129] He played little direct role in the passage of the Tariff of 1833, but he quietly hoped that the tariff would help bring an end to the Nullification Crisis, which it did.[130]

As vice president, Van Buren continued to be one of Jackson's primary advisors and confidants, and accompanied Jackson on his tour of the northeastern United States in 1833.[131] Jackson's struggle with the Second Bank of the United States continued, as the president sought to remove federal funds from the bank.[132] Though initially apprehensive of the removal due to congressional support for the bank, Van Buren eventually came to support Jackson's policy.[133] He also helped undermine a fledgling alliance between Jackson and Daniel Webster, a senator from Massachusetts who could have potentially threatened Van Buren's project to create two parties separated by policy differences rather than personalities.[134] During Jackson's second term, the president's supporters began to refer to themselves as members of the Democratic Party. Meanwhile, those opposed to Jackson, including Clay's National Republicans, followers of Calhoun and Webster, and many members of the Anti-Masonic Party, coalesced into the Whig Party.[135]

Presidential election of 1836

[edit]President Andrew Jackson declined to seek another term in the 1836 presidential election, but he remained influential within the Democratic Party as his second term came to an end. Jackson was determined to help elect Van Buren in 1836 so that the latter could continue the Jackson administration's policies. The two men—the charismatic "Old Hickory" and the efficient "Sly Fox"—had entirely different personalities but had become an effective team in eight years in office together.[136] With Jackson's support, Van Buren won the presidential nomination of the 1835 Democratic National Convention without opposition.[137] Two names were put forward for the vice-presidential nomination: Representative Richard M. Johnson of Kentucky, and former Senator William Cabell Rives of Virginia. Southern Democrats, and Van Buren himself, strongly preferred Rives. Jackson, on the other hand, strongly preferred Johnson. Again, Jackson's considerable influence prevailed, and Johnson received the required two-thirds vote after New York Senator Silas Wright prevailed upon non-delegate Edward Rucker to cast the 15 votes of the absent Tennessee delegation in Johnson's favor.[138][137]

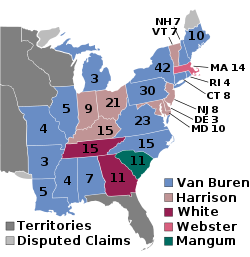

Van Buren's competitors in the election of 1836 were three members of the Whig Party, which remained a loose coalition bound by mutual opposition to Jackson's anti-bank policies. Lacking the party unity or organizational strength to field a single ticket or define a single platform,[138] the Whigs ran several regional candidates in hopes of sending the election to the House of Representatives.[139] The three candidates were Hugh Lawson White of Tennessee, Daniel Webster of Massachusetts, and William Henry Harrison of Indiana. Besides endorsing internal improvements and a national bank, the Whigs tried to tie Democrats to abolitionism and sectional tension, and attacked Jackson for "acts of aggression and usurpation of power".[140]

Southern voters represented the biggest potential impediment to Van Buren's quest for the presidency, as many were apprehensive at the prospect of a Northern president.[141] Van Buren moved to obtain their support by assuring them that he opposed abolitionism and supported maintaining slavery in states where it already existed.[142] To demonstrate consistency regarding his opinions on slavery, Van Buren cast the tie-breaking Senate vote for a bill to subject abolitionist mail to state laws, thus ensuring that its circulation would be prohibited in the South.[143] Van Buren considered slavery to be immoral but sanctioned by the Constitution.[144]

Van Buren won the election with 764,198 popular votes, 50.9% of the total, and 170 electoral votes. Harrison led the Whigs with 73 electoral votes, White receiving 26, and Webster 14.[140] Willie Person Mangum received South Carolina's 11 electoral votes, which were awarded by the state legislature.[145] Van Buren's victory resulted from a combination of his attractive political and personal qualities, Jackson's popularity and endorsement, the organizational power of the Democratic Party, and the inability of the Whig Party to muster an effective candidate and campaign.[146] Despite their lack of organization, the Whigs came close to their goal of forcing the election into the House of Representatives, with Van Buren winning the decisive state of Pennsylvania by a little over 4,000 voters, indicating the fragility of the voting coalition that Van Buren had inherited from Jackson.[146] Virginia's presidential electors voted for Van Buren for president, but voted for William Smith for vice president, leaving Johnson one electoral vote short of election.[147] In accordance with the Twelfth Amendment, the Senate elected Johnson vice president in a contingent vote.[148]

The election of 1836 marked an important turning point in American political history because it saw the establishment of the Second Party System. In the early 1830s, the political party structure was still changing rapidly, and factional and personal leaders continued to play a major role in politics. By the end of the campaign of 1836, the new Second Party System was almost complete, as nearly every faction had been absorbed by either the Democrats or the Whigs.[149]

Presidency (1837–1841)

[edit]Cabinet

[edit]Martin Van Buren was sworn in as the eighth President of the United States on March 4, 1837. He retained much of Jackson's cabinet and lower-level appointees, as he hoped that the retention of Jackson's appointees would stop Whig momentum in the South and restore confidence in the Democrats as a party of sectional unity.[150] The cabinet holdovers represented the different regions of the country: Secretary of the Treasury Levi Woodbury came from New England, Attorney General Benjamin Franklin Butler and Secretary of the Navy Mahlon Dickerson hailed from New York and New Jersey, respectively, Secretary of State John Forsyth of Georgia represented the South, and Postmaster General Amos Kendall of Kentucky represented the West.

For the lone open position of Secretary of War, Van Buren first approached William Cabell Rives, who had sought the vice presidency in 1836. After Rives declined to join the cabinet, Van Buren appointed Joel Roberts Poinsett, a South Carolinian who had opposed secession during the Nullification Crisis. Van Buren's cabinet choices were criticized by Pennsylvanians such as James Buchanan, who argued that their state deserved a cabinet position as well as some Democrats who argued that Van Buren should have used his patronage powers to augment his power. However, Van Buren saw value in avoiding contentious patronage battles, and his decision to retain Jackson's cabinet made it clear that he intended to continue the policies of his predecessor. Additionally, Van Buren had helped select Jackson's cabinet appointees and enjoyed strong working relationships with them.[151]

Van Buren held regular formal cabinet meetings and discontinued the informal gatherings of advisors that had attracted so much attention during Jackson's presidency. He solicited advice from department heads, tolerated open and even frank exchanges between cabinet members, perceiving himself as "a mediator, and to some extent an umpire between the conflicting opinions" of his counselors. Such detachment allowed the president to reserve judgment and protect his prerogative for making final decisions. These open discussions gave cabinet members a sense of participation and made them feel part of a functioning entity, rather than isolated executive agents.[152] Van Buren was closely involved in foreign affairs and matters pertaining to the Treasury Department; but the Post Office, War Department, and Navy Department had significant autonomy under their respective cabinet secretaries.[153]

Panic of 1837

[edit]

When Van Buren entered office, the nation's economic health had taken a turn for the worse and the prosperity of the early 1830s was over. Two months into his presidency, on May 10, 1837, some important state banks in New York, running out of hard currency reserves, refused to convert paper money into gold or silver, and other financial institutions throughout the nation quickly followed suit. This financial crisis would become known as the Panic of 1837.[154] The Panic was followed by a five-year depression in which banks failed and unemployment reached record highs.[155]

Van Buren blamed the economic collapse on greedy American and foreign business and financial institutions, as well as the over-extension of credit by U.S. banks. Whig leaders in Congress blamed the Democrats, along with Andrew Jackson's economic policies,[154] specifically his 1836 Specie Circular. Cries of "rescind the circular!" went up and former president Jackson sent word to Van Buren asking him not to rescind the order, believing that it had to be given enough time to work. Others, like Nicholas Biddle, believed that Jackson's dismantling of the Bank of the United States was directly responsible for the irresponsible creation of paper money by the state banks which had precipitated this panic.[156] The Panic of 1837 loomed large over the 1838 election cycle, as the carryover effects of the economic downturn led to Whig gains in both the U.S. House and Senate. The state elections in 1837 and 1838 were also disastrous for the Democrats,[157] and the partial economic recovery in 1838 was offset by a second commercial crisis later that year.[158]

To address the crisis, the Whigs proposed rechartering the national bank. The president countered by proposing the establishment of an independent U.S. treasury, which he contended would take the politics out of the nation's money supply. Under the plan, the government would hold its money in gold or silver, and would be restricted from printing paper money at will; both measures were designed to prevent inflation.[159] The plan would permanently separate the government from private banks by storing government funds in government vaults rather than in private banks.[160] Van Buren announced his proposal in September 1837,[154] but an alliance of conservative Democrats and Whigs prevented it from becoming law until 1840.[161] As the debate continued, conservative Democrats like Rives defected to the Whig Party, which itself grew more unified in its opposition to Van Buren.[162] The Whigs would abolish the Independent Treasury system in 1841, but it was revived in 1846, and remained in place until the passage of the Federal Reserve Act in 1913.[163] More important for Van Buren's immediate future, the depression would be a major issue in his upcoming re-election campaign.[154]

Indian removal

[edit]Federal policy under Jackson had sought to move Indian tribes to lands west of the Mississippi River through the Indian Removal Act of 1830, and the federal government negotiated 19 treaties with Indian tribes during Van Buren's presidency.[164] The 1835 Treaty of New Echota signed by government officials and representatives of the Cherokee tribe had established terms under which the Cherokees ceded their territory in the southeast and agreed to move west to Oklahoma. In 1838, Van Buren directed General Winfield Scott to forcibly move all those who had not yet complied with the treaty.[165]

The Cherokees were herded violently into internment camps where they were kept for the summer of 1838. The actual transportation west was delayed by intense heat and drought, but in the fall, the Cherokee reluctantly agreed to transport themselves west.[166][167] Some 20,000 people were relocated against their will during the Cherokee removal, part of the Trail of Tears.[168] Notably, Ralph Waldo Emerson, who would go on to become America's foremost man of letters, wrote Van Buren a letter protesting his treatment of the Cherokee.[169]

An estimated 4,000 Cherokee died during the Trail of Tears. Entire Indian nations were relocated, with some losing as much as half their populations. Van Buren claimed that America was "perhaps in the beginning unjustifiable aggressors” toward the Indians, but later became the "guardians". He told Congress that a "mixed occupancy of the same territory by the white and red man is incompatible with the safety or happiness of either", and also claimed the Cherokee had not protested their removal.[170]

President Jackson used the army to force Seminole Indians in Florida to move to the west. Many did surrender but they then escaped from detention camps. In December 1837, in the Second Seminole War the army launched a massive offensive, leading to the Battle of Lake Okeechobee and a new phase of attrition. Realizing it was almost impossible to remove the remaining Seminoles from Florida, the administration negotiated a compromise allowing them to remain in southwest Florida.[171]

Texas

[edit]Just before leaving office in March 1837, Andrew Jackson extended diplomatic recognition to the Republic of Texas, which had won independence from Mexico in the Texas Revolution. By suggesting the prospect of quick annexation, Jackson raised the danger of war with Mexico and heightened sectional tensions at home. New England abolitionists charged that there was a "slaveholding conspiracy to acquire Texas", and Daniel Webster eloquently denounced annexation.[172] Many Southern leaders, meanwhile, strongly desired the expansion of slave-holding territory in the United States.[173]

Boldly reversing Jackson's policies, Van Buren sought peace abroad and harmony at home. He proposed a diplomatic solution to a long-standing financial dispute between American citizens and the Mexican government, rejecting Jackson's threat to settle it by force.[172] Likewise, when the Texas minister at Washington, D.C., proposed annexation to the administration in August 1837, he was told that the proposition could not be entertained. Constitutional scruples and fear of war with Mexico were the reasons given for the rejection,[174] but concern that it would precipitate a clash over the extension of slavery undoubtedly influenced Van Buren and continued to be the chief obstacle to annexation.[175] Northern and Southern Democrats followed an unspoken rule: Northerners helped quash anti-slavery proposals and Southerners refrained from agitating for the annexation of Texas.[173] Texas withdrew the annexation offer in 1838.[174]

Border violence with Canada

[edit]

Caroline episode

[edit]British subjects in Lower Canada (now Quebec) and Upper Canada (now Ontario) rose in rebellion in 1837 and 1838, protesting their lack of responsible government. While the initial insurrection in Upper Canada ended quickly (following the December 1837 Battle of Montgomery's Tavern), many of the rebels fled across the Niagara River into New York, and Upper Canadian rebel leader William Lyon Mackenzie began recruiting volunteers in Buffalo.[176] Mackenzie declared the establishment of the Republic of Canada and put into motion a plan whereby volunteers would invade Upper Canada from Navy Island on the Canadian side of the Niagara River. Several hundred volunteers traveled to Navy Island in the weeks that followed. They procured the steamboat Caroline to deliver supplies to Navy Island from Fort Schlosser.[176] Seeking to deter an imminent invasion, British forces crossed to the American bank of the river in late December 1837, and they burned and sank the Caroline. In the melee, one American was killed and others were wounded.[177]

Considerable sentiment arose within the United States to declare war, and a British ship was burned in revenge.[178] Van Buren, looking to avoid a war with Great Britain, sent General Winfield Scott to the Canada–United States border with large discretionary powers for its protection and its peace.[179] Scott impressed upon American citizens the need for a peaceful resolution to the crisis, and made it clear that the U.S. government would not support adventuresome Americans attacking the British. In early January 1838, the president proclaimed neutrality in the Canadian independence issue,[180] a declaration which Congress endorsed by passing a neutrality law designed to discourage the participation of American citizens in foreign conflicts.[178]

Patriot War of 1837–1838

[edit]During the Canadian rebellions, Charles Duncombe and Robert Nelson created an armed secret society in Vermont, the Hunters' Lodge. It carried out several small attacks in Upper Canada between December 1837 and December 1838, collectively known as the Patriot War. Washington responded using the Neutrality Act. It prosecuted the leaders and actively deterred Americans from subversive activities abroad. In the long term, Van Buren's opposition to the Patriot War contributed to the construction of healthy Anglo-American and Canada–United States relations;. It also led, more immediately, to a backlash among citizens regarding the seeming overreach of federal authority,[181] which hurt congressional Democrats in the 1838 midterm elections.

Northern Maine: the Aroostook "War"

[edit]A new crisis surfaced in late 1838, in the disputed territory on the thinly settled Maine–New Brunswick frontier. Americans were settling on long-disputed land claimed by the United States and the United Kingdom. The British considered possession of the area vital to the defense of Canada.[182] Both American and New Brunswick lumberjack cut timber in the disputed territory during the winter of 1838–1839. On December 29, New Brunswick lumbermen were spotted cutting down trees on an American estate near the Aroostook River. When American woodcutters rushed to stand guard, a shouting match, known as the Battle of Caribou, ensued. Tensions escalated with officials from both Maine and New Brunswick arresting each other's citizens.[183] British troops began to gather along the Saint John River. Maine Governor John Fairfield mobilized the state militia.

The American press clamored for war; "Maine and her soil, or BLOOD!" screamed one editorial. "Let the sword be drawn and the scabbard thrown away!"[184] In June, Congress authorized 50,000 troops and a $10 million budget[185] in the event foreign military troops crossed into United States territory.

Van Buren wanted peace and met with the British minister to the United States. The two men agreed to resolve the border issue diplomatically.[186] Van Buren sent General Scott to the scene to lower the tensions. Scott successfully convinced all sides to submit the border issue to arbitration. The border dispute was put to rest a few years later, with the signing of the 1842 Webster–Ashburton Treaty.[178][180]

Amistad case: victory for the ex-slaves

[edit]The Amistad case was a freedom suit that involved international issues and was decided by the U.S. Supreme Court. It resulted from the successful rebellion of African slaves on board the Spanish schooner La Amistad in 1839. The ship ended up in American waters and was seized by the predecessor agency of the Coast Guard.[187] Van Buren viewed abolitionism as the greatest threat to the nation's unity, and he resisted the slightest interference with slavery in the states where it existed.[188] His administration supported the Spanish government's demand that the ship and its cargo (including the Africans) be turned over to Spain. However, abolitionist lawyers intervened. A federal district court judge ruled that the Africans were legally free and should be transported home, but Van Buren's administration appealed the case to the Supreme Court.[189]

In the Supreme Court in February, 1840, John Quincy Adams argued passionately for the Africans' right to freedom. Van Buren's Attorney General Henry D. Gilpin presented the government's case. In March 1841, the Supreme Court issued its final verdict: the Amistad Africans were free people and should be allowed to return home.[190] The unique nature of the case heightened public interest in the saga, including the participation of former president Adams, Africans testifying in federal court, and their representation by prominent lawyers. Van Buren's administration lost its case and the ex-slaves won. The episode case drew attention to the personal tragedies of slavery and attracted new support for the growing abolition movement in the North. It also transformed the courts into the principal forum for a national debate on the legal foundations of slavery.[191]

Judicial appointments

[edit]Van Buren appointed two Associate Justices to the Supreme Court:[192] John McKinley, confirmed September 25, 1837, and Peter Vivian Daniel, confirmed March 2, 1841. He also appointed eight other federal judges, all to United States district courts.[193]

White House hostess

[edit]For the first half of his presidency, Van Buren, who had been a widower for many years, did not have a specific person to act as White House hostess at administration social events, but tried to assume such duties himself. When his eldest son Abraham Van Buren married Angelica Singleton in 1838, he quickly acted to install his daughter-in-law as his hostess. She solicited the advice of her distant relative, Dolley Madison,[194] who had moved back to Washington after her husband's death,[195] and soon the president's parties livened up. After the 1839 New Year's Eve reception, The Boston Post raved: "[Angelica Van Buren is a] lady of rare accomplishments, very modest yet perfectly easy and graceful in her manners and free and vivacious in her conversation ... universally admired."[194]

As the nation endured a deep economic depression, Angelica Van Buren's receiving style at receptions was influenced by her heavy reading about European court life (and her naive delight in being received as the Queen of the United States when she visited the royal courts of England and France after her marriage). Newspaper coverage of this, and the claim that she intended to re-landscape the White House grounds to resemble the royal gardens of Europe, was used in a political attack on her father-in-law by a Pennsylvania Whig Congressman Charles Ogle. He referred obliquely to her as part of the presidential "household" in his famous Gold Spoon Oration. The attack was delivered in Congress and the depiction of the president as living a royal lifestyle was a primary factor in his defeat for re-election.[196]

Presidential election of 1840

[edit]

Van Buren easily won renomination for a second term at the 1840 Democratic National Convention in Baltimore, Maryland, but he and his party faced a difficult election in 1840. Van Buren's presidency had been a difficult affair, with the U.S. economy mired in a severe downturn, and other divisive issues, such as slavery, western expansion, and tensions with the United Kingdom, providing opportunities for Van Buren's political opponents—including some of his fellow Democrats—to criticize his actions.[146] Although Van Buren's renomination was never in doubt, Democratic strategists began to question the wisdom of keeping Johnson on the ticket. Even former president Jackson conceded that Johnson was a liability and insisted on former House Speaker James K. Polk of Tennessee as Van Buren's new running mate. Van Buren was reluctant to drop Johnson, who was popular with workers and radicals in the North[197] and added military experience to the ticket, which might prove important against likely Whig nominee William Henry Harrison.[138] Rather than re-nominating Johnson, the Democratic convention decided to allow state Democratic Party leaders to select the vice-presidential candidates for their states.[198]

Van Buren hoped that the Whigs would nominate Clay for president, which would allow Van Buren to cast the 1840 campaign as a clash between Van Buren's Independent Treasury system and Clay's support for a national bank. However, rather than nominating longtime party spokesmen like Clay and Daniel Webster, the 1839 Whig National Convention nominated Harrison, who had served in various governmental positions during his career and had earned fame for his military leadership in the Battle of Tippecanoe and the War of 1812. Whig leaders like William Seward and Thaddeus Stevens believed that Harrison's war record would effectively counter the popular appeals of the Democratic Party. For vice president, the Whigs nominated former Senator John Tyler of Virginia. Clay was deeply disappointed by his defeat at the convention, but he nonetheless threw his support behind Harrison.[199]

Whigs presented Harrison as the antithesis of the president, whom they derided as ineffective, corrupt, and effete.[146] Whigs also depicted Van Buren as an aristocrat living in high style in the White House, while they used images of Harrison in a log cabin sipping cider to convince voters that he was a man of the people.[200] They threw such jabs as "Van, Van, is a used-up man" and "Martin Van Ruin" and ridiculed him in newspapers and cartoons.[201] Issues of policy were not absent from the campaign; the Whigs derided the alleged executive overreaches of Jackson and Van Buren, while also calling for a national bank and higher tariffs.[202] Democrats attempted to campaign on the Independent Treasury system, but the onset of deflation undercut these arguments.[203] The enthusiasm for "Tippecanoe and Tyler Too", coupled with the country's severe economic crisis, made it impossible for Van Buren to win a second term.[200] Harrison won by a popular vote of 1,275,612 to 1,130,033, and an electoral vote margin of 234 to 60.[140] An astonishing 80% of eligible voters went to the polls on election day.[146] Van Buren actually won more votes than he had in 1836, but the Whig success in attracting new voters more than canceled out Democratic gains.[204] Additionally, Whigs won majorities for the first time in both the House of Representatives and the Senate.[138]

Post-presidency (1841–1862)

[edit]Election of 1844

[edit]On the expiration of his term, Van Buren returned to his estate of Lindenwald in Kinderhook.[205] He continued to closely watch political developments, including the battle between the Whig alliance of the Great Triumvirate and President John Tyler, who took office after Harrison's death in April 1841.[206] Though undecided on another presidential run, Van Buren made several moves calculated to maintain his support, including a trip to the Southern United States and the Western United States during which he met with Jackson, former Speaker of the House James K. Polk, and others.[207] President Tyler, James Buchanan, Levi Woodbury, and others loomed as potential challengers for the 1844 Democratic nomination, but it was Calhoun who posed the most formidable obstacle.[208]

Van Buren remained silent on major public issues like the debate over the Tariff of 1842, hoping to arrange for the appearance of a draft movement for his presidential candidacy.[209] Tyler made the annexation of Texas his chief foreign policy goal, and many Democrats, particularly in the South, were anxious to quickly complete it.[210] After an explosion on the USS Princeton killed Secretary of State Abel P. Upshur in February 1844, Tyler brought Calhoun into his cabinet to direct foreign affairs.[211] Like Tyler, Calhoun pursued the annexation of Texas to upend the presidential race and to extend slavery into new territories.[212]

Shortly after taking office, Calhoun negotiated an annexation treaty between the United States and Texas.[213] Van Buren had hoped he would not have to take a public stand on annexation, but as the Texas question came to dominate U.S. politics, he decided to make his views on the issue public.[214] Though he believed that his public acceptance of annexation would likely help him win the 1844 Democratic nomination, Van Buren thought that annexation would inevitably lead to an unjust war with Mexico.[215] In a public letter published shortly after Henry Clay also announced his opposition to the annexation treaty, Van Buren articulated his views on the Texas question.[216]

Van Buren's opposition to immediate annexation cost him the support of many pro-slavery Democrats.[217] In the weeks before the 1844 Democratic National Convention, Van Buren's supporters anticipated that he would win a majority of the delegates on the first presidential ballot, but would not be able to win the support of the required two-thirds of delegates.[218] Van Buren's supporters attempted to prevent the adoption of the two-thirds rule, but several Northern delegates joined with Southern delegates in implementing the two-thirds rule for the 1844 convention.[219] Van Buren won 146 of the 266 votes on the first presidential ballot, with only 12 of his votes coming from Southern states.[210]

Senator Lewis Cass won much of the remaining vote, and he gradually picked up support on subsequent ballots until the convention adjourned for the day.[220] When the convention reconvened and held another ballot, James K. Polk, who shared many of Van Buren's views but favored immediate annexation, won 44 votes.[221] On the ninth ballot, Van Buren's supporters withdrew his name from consideration, and Polk won the nomination.[222] Although angered that his opponents had denied him the nomination, Van Buren endorsed Polk in the interest of party unity.[223] He also convinced Silas Wright to run for Governor of New York so that the popular Wright could help boost Polk in the state.[224] Wright narrowly defeated Whig nominee Millard Fillmore in the 1844 gubernatorial election, and Wright's victory in the state helped Polk narrowly defeat Henry Clay in the 1844 presidential election.[225]

After taking office, Polk used George Bancroft as an intermediary to offer Van Buren the ambassadorship to London. Van Buren declined, partly because he was upset with Polk over the treatment the Van Buren delegates had received at the 1844 convention, and partly because he was content in his retirement.[226] Polk also consulted Van Buren in the formation of his cabinet, but offended Van Buren by offering to appoint a New Yorker only to the lesser post of Secretary of War, rather than as Secretary of State or Secretary of the Treasury.[227] Other patronage decisions also angered Van Buren and Wright, and they became permanently alienated from the Polk administration.[228]

Election of 1848

[edit]

Though he had previously helped maintain a balance between the Barnburners and Hunkers, the two factions of the New York Democratic Party, Van Buren moved closer to the Barnburners after the 1844 Democratic National Convention.[229] The split in the state party worsened during Polk's presidency, as his administration lavished patronage on the Hunkers.[230] In his retirement, Van Buren also grew increasingly opposed to slavery.[231]

As the Mexican–American War brought the debate over slavery in the territories to the forefront of American politics, Van Buren published an anti-slavery manifesto. In it, he refuted the notion that Congress did not have the power to regulate slavery in the territories, and argued the Founding Fathers had favored the eventual abolition of slavery.[232] The document, which became known as the "Barnburner Manifesto", was edited at Van Buren's request by John Van Buren and Samuel Tilden, both of whom were leaders of the Barnburner faction.[233] After the publication of the Barnburner Manifesto, many Barnburners urged the former president to seek his old office in the 1848 presidential election.[234] The 1848 Democratic National Convention seated competing Barnburner and Hunker delegations from New York, but the Barnburners walked out of the convention when Lewis Cass, who opposed congressional regulation of slavery in the territories, was nominated on the fourth ballot.[235]

In response to the nomination of Cass, the Barnburners began to organize as a third party. At a convention held in June 1848, in Utica, New York, the Barnburners nominated 65-year-old Van Buren for president.[236] Though reluctant to bolt from the Democratic Party, Van Buren accepted the nomination to show the power of the anti-slavery movement, help defeat Cass, and weaken the Hunkers.[237] At a convention held in Buffalo, New York in August 1848, a group of anti-slavery Democrats, Whigs, and members of the abolitionist Liberty Party met in the first national convention of what became known as the Free Soil Party.[238]

Съезд единогласно выдвинул кандидатуру Ван Бюрена и выбрал Чарльза Фрэнсиса Адамса , сына покойного бывшего президента Джона Куинси Адамса и внука покойного бывшего президента Джона Адамса , в качестве кандидата на пост вице-президента Ван Бюрена. В публичном сообщении о принятии номинации Ван Бюрен полностью поддержал « Условие Уилмота» — предложенный закон, который запретит рабство на всех территориях, приобретенных у Мексики в ходе американо-мексиканской войны. [ 238 ] Оратор вигов, выступающий против рабства , Дэниел Вебстер в своей «Маршфилдской речи» выразил скептицизм в терминах, которые, возможно, повлияли на избирателей-вигов, по поводу искренности поддержки Ван Бюреном идеи борьбы с рабством:

Вебстер не доверял профессиям Ван Бюрена, выступавшим против рабства. Он сказал приятно, но многозначительно, что «если бы он и г-н Ван Бюрен встретились под флагом Свободной почвы, последний со своим привычным добродушием рассмеялся бы». Он добавил с характерным для него юмором, «что лидер партии «Свободная почва», внезапно ставший лидером партии «Свободная почва», - это шутка, способная потрясти его и мою сторону». [ 239 ]

Ван Бюрен не получил голосов выборщиков, но занял второе место после кандидата от вигов Закари Тейлора в Нью-Йорке, набрав достаточно голосов от Кэсс, чтобы отдать штат - и, возможно, выборы - Тейлору. [ 240 ] В целом по стране Ван Бюрен набрал 10,1% голосов избирателей, что является самым высоким показателем среди кандидатов в президенты от третьей партии на тот момент в истории США.

Выход на пенсию

[ редактировать ]

Ван Бюрен больше никогда не стремился к государственной должности после выборов 1848 года, но продолжал внимательно следить за национальной политикой. Он был глубоко обеспокоен всплеском сепаратизма на Юге и приветствовал Компромисс 1850 года как необходимую примирительную меру, несмотря на его оппозицию Закону о беглых рабах 1850 года . [ 241 ] Ван Бюрен также работал над историей американских политических партий и отправился в турне по Европе, став первым бывшим президентом США, посетившим Великобританию. [ 242 ] Хотя Ван Бюрен и его последователи все еще были обеспокоены рабством, они вернулись в лоно демократов, отчасти из-за опасений, что продолжающийся раскол демократов поможет Партии вигов. [ 243 ] Он также пытался примирить Барнбернеров и Ханкеров, но результаты оказались неоднозначными. [ 244 ]

Ван Бюрен поддержал Франклина Пирса на посту президента в 1852 году . [ 245 ] Джеймс Бьюкенен в 1856 году . [ 246 ] и Стивен А. Дуглас в 1860 году . [ 247 ] Ван Бюрен с презрением относился к молодому движению «Незнайка» выступающая против рабства, и чувствовал, что Республиканская партия, усугубляет межсекционную напряженность. [ 248 ] Он считал решение главного судьи Роджера Тейни по делу Дред Скотт против Сэндфорда 1857 года «серьезной ошибкой», поскольку оно отменяло Миссурийский компромисс . [ 249 ] По его оценке, администрация Бьюкенена плохо справилась с проблемой кровоточащего Канзаса и рассматривала Конституцию Лекомптона как подачку южным экстремистам. [ 250 ]

После избрания Авраама Линкольна и отделения нескольких южных штатов в 1860 году Ван Бюрен безуспешно пытался созвать конституционный съезд. [ 247 ] В апреле 1861 года бывший президент Пирс написал другим ныне живущим бывшим президентам и попросил их рассмотреть возможность встречи, чтобы использовать свой статус и влияние, чтобы предложить прекращение войны путем переговоров. Пирс попросил 78-летнего Ван Бюрена использовать свою роль старшего из ныне живущих экс-президентов, чтобы сделать официальный звонок. В ответе Ван Бюрена предполагалось, что Бьюкенен должен созвать встречу, поскольку он был бывшим президентом, занимавшим эту должность совсем недавно, или что Пирс должен сделать призыв сам, если он твердо верит в ценность своего предложения. Ни Бьюкенен, ни Пирс не хотели обнародовать предложение Пирса, и больше из этого ничего не вышло. [ 251 ] Когда началась Гражданская война в США , Ван Бюрен публично заявил о своей поддержке дела Союза . [ 252 ]

Смерть

[ редактировать ]

Здоровье Ван Бюрена начало ухудшаться позже, в 1861 году, и он был прикован к постели из-за пневмонии . осенью и зимой 1861–1862 годов [ 253 ] Он умер от бронхиальной астмы и сердечной недостаточности в своем поместье Линденвальд в 2 часа ночи в четверг, 24 июля 1862 года. [ 254 ] Он похоронен на кладбище реформатской голландской церкви Киндерхук , как и его жена Ханна, его родители и сын Мартин Ван Бюрен-младший. [ 255 ]

Ван Бюрен пережил всех четырех своих непосредственных преемников: Харрисона, Тайлера, Полка и Тейлора. [ 256 ] Кроме того, он видел, как на пост президента пришло больше преемников, чем кто-либо другой (восемь), и до своей смерти дожил до избрания Авраама Линкольна 16-м президентом. [ 257 ]

Наследие

[ редактировать ]Историческая репутация

[ редактировать ]Самым значительным достижением Ван Бюрена была роль политического организатора, который построил Демократическую партию и привел ее к доминированию во второй партийной системе . [ 258 ] и историки стали рассматривать Ван Бюрена как неотъемлемую часть развития американской политической системы. [ 30 ] По словам историка Роберта В. Ремини :

Творческий вклад Ван Бюрена в политическое развитие нации был огромен, и благодаря этому он заслужил себе путь на пост президента. Получив контроль над Республиканской партией Нью-Йорка, он организовал Регентство Олбани, чтобы управлять штатом в его отсутствие, пока он делал национальную карьеру в Вашингтоне. Регентство было управляющим советом в Олбани, состоящим из группы политически проницательных и очень умных людей. Это была одна из первых политических машин штата в стране, чей успех стал результатом профессионального использования патронажа, законодательных собраний и официальной партийной газеты... [В Вашингтоне] он трудился над реорганизацией республиканской партии. Партия посредством союза между тем, что он называл «плантаторами Юга и простыми республиканцами Севера»… [Его Демократическая партия] подчеркивала важность создания народного большинства и совершенствовала политические методы, которые привлекут массы. ...До сих пор партии считались злом, которое следует терпеть; Ван Бюрен утверждал, что партийная система является наиболее разумным и разумным способом демократического ведения дел в стране, и эта точка зрения в конечном итоге получила национальное одобрение. [ 259 ]

Однако его президентство оценивают в лучшем случае как среднее историки . Его обвинили в панике 1837 года и он потерпел поражение на переизбрании. [ 30 ] В его правлении доминировали экономические условия, вызванные паникой, и историки разделились во мнениях относительно адекватности Независимого казначейства в качестве ответа. [ 260 ] Некоторые историки не согласны с этими негативными оценками. Например, либертарианский писатель Иван Эланд в своей книге 2009 года «Перекраивая Рашмора » назвал Ван Бюрена третьим величайшим президентом. [ 261 ] [ 262 ] Он утверждает, что Ван Бюрен хорошо справился с паникой 1837 года и похвалил Ван Бюрена за сокращение государственных расходов , балансировку бюджета и предотвращение потенциальных войн с Канадой и Мексикой. [ 261 ] [ 262 ] Историк Джеффри Роджерс Хаммел утверждает, что Ван Бюрен был величайшим президентом Америки, утверждая, что «историки сильно недооценили его многочисленные выдающиеся достижения перед лицом тяжелых трудностей». [ 263 ]

Некоторые писатели описали Ван Бюрена как одного из самых малоизвестных президентов страны. Как отмечается в статье журнала Time за 2014 год о «10 самых забывчивых президентах»:

Заставить себя почти полностью исчезнуть из учебников истории, вероятно, не был трюком, который имел в виду «Маленький волшебник» Мартин Ван Бюрен, но это был первый по-настоящему незабываемый американский президентский срок. [ 264 ]

Мемориалы

[ редактировать ]Дом Ван Бюрена в Киндерхуке, штат Нью-Йорк, который он назвал Линденвальдом, теперь является Национальным историческим памятником Мартина Ван Бюрена . [ 265 ] Округа названы в честь Ван Бурена в Мичигане , Айове , Арканзасе и Теннесси . [ 266 ] гора Ван Бюрен , военный корабль США Ван Бюрен В его честь были названы , три государственных парка и многочисленные города.

Популярная культура

[ редактировать ]Книги

[ редактировать ]В романе Гора Видала 1973 года «Бёрр » основной темой сюжета является попытка предотвратить избрание Ван Бюрена президентом, доказав, что он является внебрачным сыном Аарона Бёрра . [ 267 ]

Комиксы

[ редактировать ]После президентской кампании 1988 года Джордж Буш- старший, выпускник Йельского университета и член тайного общества «Череп и кости» , стал первым действующим вице-президентом, победившим на президентских выборах со времен Ван Бюрена. В комиксе «Дунсбери » художник Гарри Трюдо изобразил членов «Черепа и костей», похитивших череп Ван Бюрена в качестве поздравительного подарка новому президенту. [ 268 ] [ 269 ]

Валюта

[ редактировать ]Мартин Ван Бюрен появился в серии президентских долларовых монет в 2008 году. [ 270 ] Монетный двор США также выпустил памятные серебряные медали Ван Бюрена, которые поступят в продажу в 2021 году. [ 271 ] [ 272 ]

Кино и телевидение

[ редактировать ]Ван Бюрен изображается Найджелом Хоторном в фильме 1997 года «Амистад» . В фильме изображена судебная тяжба вокруг статуса рабов, которые в 1839 году восстали против своих перевозчиков на невольничьем корабле «Ла Амистад» . [ 273 ]

В телешоу «Сейнфельд » в эпизоде « Мальчики Ван Бюрен » 1997 года рассказывается о вымышленной уличной банде , которая восхищается Ван Бюреном и основывает на нем свои ритуалы и символы, включая знак руки с восемью пальцами, направленными вверх, обозначающими Ван Бюрена, восьмого президент. [ 274 ]

См. также

[ редактировать ]- Шарлотта Дюпюи , рабыня, работавшая на Ван Бюрена в Декейтер-Хаусе ее дело об освобождении Генри Клея. , пока продолжалось

- Список президентов США, владевших рабами

- Президенты США на почтовых марках США

Примечания

[ редактировать ]- ↑ Прозвище «омела» было навеяно тем фактом, что омела — это растение-паразит , которое прикрепляется к дереву-хозяину, чтобы выжить. Сравнение Ван Бюрена с омелой подразумевало, что он продвинулся в политическом плане только благодаря своей связи с деревом «Старый Гикори», которое представляло Эндрю Джексона. Эта идея была распространена в пропагандистских материалах вигов, а также встречалась в политических комиксах, таких как «Отвергнутый министр», где показано, как Ван Бюрен приводится к власти Джексоном и Парскалем.

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ Видмер, Тед и Артур М. Шлезингер, Эдвард Л. Видмер, Мартин Ван Бюрен , Times Books, 2005, стр. 2. ISBN 0-8050-6922-4

- ^ «Мудрый гид: Рыжая лисица из Киндерхука» . Библиотека Конгресса . Декабрь 2011. Архивировано из оригинала 4 февраля 2023 года . Проверено 15 июня 2018 г.

- ^ Силби, Джоэл (26 сентября 2016 г.). «Мартин Ван Бюрен» . Миллер Центр . Архивировано из оригинала 15 июня 2018 года . Проверено 15 июня 2018 г.

- ^ Хэтфилд, Марк О. (1997). «Мартин Ван Бюрен (1833–1837)» (PDF) . Вице-президенты США, 1789–1993 гг. (PDF) . Историческое управление Сената. Вашингтон: Типография правительства США. стр. 105–118. OCLC 606133503 . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 6 марта 2017 г. Проверено 15 июня 2018 г.

- ^ «Мартин ван Бюрен [1782–1862]» . Институт Новых Нидерландов.org . Олбани, Нью-Йорк: Институт Новых Нидерландов. Архивировано из оригинала 14 сентября 2015 года . Проверено 24 февраля 2020 г.

- ^ Коул 1984 , стр. 3, 9.

- ^ Видмер 2005 , стр. 153–165.

- ^ «Наши неанглосаксонские президенты» . 25 июля 2012 года. Архивировано из оригинала 7 мая 2022 года . Проверено 7 мая 2022 г.

- ^ Робертс, Джеймс А. (1898). Нью-Йорк в революции как колония и штат . Олбани: Типография Brandow. п. 109. ИСБН 978-0-8063-0496-0 .

- ^ Кейн, Джозеф Натан (1998). Президентская книга фактов . Случайный дом. п. 53 . ISBN 978-0-375-70244-0 .

- ^ Фосс, Уильям О. (2005). Детство американских президентов . Джефферсон: Издательство McFarland Publishing. п. 45. ИСБН 978-0-7864-2382-8 .

- ^ Нивен 1983 , стр. 5–6.

- ^ «Мартин Ван Бюрен, 1782–1862» . Историческое общество судов Нью-Йорка. Архивировано из оригинала 2 апреля 2015 года . Проверено 4 марта 2015 г.

- ^ Коул 1984 , с. 14.

- ^ Александр, Де Альва С. Александр (1906). Политическая история штата Нью-Йорк . Том. Я. Нью-Йорк, штат Нью-Йорк: Генри Холт и компания. п. 206. ИСБН 9780608374819 – через Google Книги .

- ^ Видмер 2005 , стр. 6–7.

- ^ Сайди, Хью (1999). Президенты Соединенных Штатов Америки . Вашингтон, округ Колумбия: Историческая ассоциация Белого дома. п. 23. ISBN 978-0-912308-73-9 .

- ^ Брук 2010 , с. 230.

- ^ Хенретта, Джеймс А.; Эдвардс, Ребекка; Хиндерейкер, Эрик; Селф, Роберт О. (2015). Америка: краткая история, объединенный том . Бостон: Бедфорд/Сент. Мартина. п. 290. ИСБН 978-1-4576-4862-5 .

- ^ Луазо, Пьер-Мари (2008). Мартин Ван Бюрен: Маленький волшебник . Хауппож: Издательство Nova Science. п. 10. ISBN 978-1-60456-773-1 .

- ^ Кениг, Луи Уильям (1960). Невидимое президентство . Нью-Йорк: Райнхарт и компания. п. 89 .

- ^ Фосс, Уильям О. (2005). Детство американских президентов . Джефферсон, Северная Каролина: McFarland & Company. п. 46. ИСБН 978-0-7864-2382-8 .

- ^ Брайт, Джон В. (1970). Генеральный план Национального исторического памятника Линденвальд, Нью-Йорк . Вашингтон, округ Колумбия: Служба национальных парков. п. 9 – через Google Книги .

- ^ Нивен 1983 , стр. 8–9.

- ^ Нивен 1983 , стр. 10–11.

- ^ Нивен 1983 , стр. 14–15.

- ^ Нивен 1983 , стр. 15–17.

- ^ Лазо, Кэролайн Эвенсен (2005). Мартин Ван Бюрен . Издательская компания Лернера. п. 14. ISBN 978-0-8225-1394-0 .

- ^ Матуз, Роджер (2012). Книга фактов о президентах . Издательство Black Dog & Leventhal. п. 152. ИСБН 978-1-57912-889-0 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Силби, Джоэл (4 октября 2016 г.). «Мартин Ван Бюрен: Жизнь вкратце» . Миллер Центр по связям с общественностью Университета Вирджинии. Архивировано из оригинала 3 апреля 2019 года . Проверено 6 марта 2017 г.

- ^ Силби 2002 , с. 27.

- ^ МакГихан, Джон Р. (2007). Книга «Все по американской истории» . Адамс Медиа. п. 295. ИСБН 978-1-60550-265-6 . [ постоянная мертвая ссылка ]

- ^ Маккензи, Уильям Лайон (1846). Жизнь и времена Мартина Ван Бюрена . Кук и компания. стр. 21–22 .

- ^ Брук 2010 , с. 283.

- ^ Нивен 1983 , стр. 18–22.

- ^ Нивен 1983 , стр. 23–24.

- ^ Нивен 1983 , стр. 25–26.

- ^ Нивен 1983 , стр. 29–32.

- ^ Нивен 1983 , стр. 33–39.

- ^ Нивен 1983 , стр. 41–42.

- ^ Хэннингс, Бад (2012). Война 1812 года: Полная хронология с биографиями 63 генералов . Джефферсон: McFarland & Co. 327. ИСБН 978-0-7864-6385-5 .

- ^ Вайл, Джон Р. (2001). Великие американские юристы: Энциклопедия, Том 1 . Санта-Барбара: ABC-CLIO. п. 689. ИСБН 978-1-57607-202-8 .

- ^ Эйзенхауэр, Джон С.Д. (1997). Агент судьбы: жизнь и времена генерала Уинфилда Скотта . Норман: Университет Оклахомы Пресс. стр. 100–101. ISBN 978-0-8061-3128-3 .

- ^ Нивен 1983 , с. 43.

- ^ Нивен 1983 , стр. 48–50.

- ^ Марш, Дуайт Уитни (1895). Генеалогия Марша: несколько тысяч потомков Джона Марша из Хартфорда, штат Коннектикут. 1636–1895 . Амхерст: Карпентер и Морхаус. п. 71.

- ^ Нивен 1983 , стр. 51–52.

- ^ Льюис, Бенджамин Ф. (1819). Отчет о суде над убийцами Ричарда Дженнингса в округе Ориндж, штат Нью-Йорк (PDF) . Ньюбург. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 15 апреля 2021 г. Проверено 25 ноября 2019 г.

- ^ Нивен 1983 , стр. 58–59.

- ^ Нивен 1983 , стр. 61–62.

- ^ Нивен 1983 , стр. 63–64.

- ^ Нивен 1983 , с. 62.

- ^ Нивен 1983 , стр. 64–65.

- ^ Нивен 1983 , с. 110.

- ^ Лассо , с. 30.

- ^ Аллен, Оливер Э. (1993). Тигр: Взлет и падение Таммани-холла . Издательство Аддисон-Уэсли. стр. 27–50 . ISBN 978-0-201-62463-2 .

- ^ Нивен 1983 , стр. 81–82.

- ^ Кейсар, Александр (2000). Право голоса: спорная история демократии в Соединенных Штатах . Основные книги. п. 55. ИСБН 978-0-465-01014-1 .

- ^ Нивен 1983 , стр. 92–93.

- ^ Уилсон 1984 , стр. 26–27.

- ^ Нивен 1983 , с. 117.

- ^ Нивен 1983 , с. 176.

- ^ Коул 1984 , с. 432.

- ^ Нивен 1983 , стр. 126–127.

- ^ Нивен 1983 , стр. 129–130.

- ^ Нивен 1983 , стр. 139–140.

- ^ Нивен 1983 , стр. 143–144.

- ^ Нивен 1983 , стр. 145–146.

- ^ Нивен 1983 , стр. 146–148.

- ^ Нивен 1983 , стр. 151–152.

- ^ Нивен 1983 , стр. 152–153.

- ^ Нивен 1983 , стр. 156–157.

- ^ Нивен 1983 , стр. 157–158.

- ^ Нивен 1983 , стр. 158, 160–161.

- ^ Силби 2002 , с. 44.

- ^ Нивен 1983 , стр. 164–165.

- ^ Стоддард, Уильям Осборн (1887). Эндрю Джексон и Мартин Ван Бюрен . Фредерик А. Стоукс. п. 284 .

- ^ Коул 1984 , с. 111.

- ^ Нивен 1983 , стр. 163–164.