Латвия

Латвийская Республика | |

|---|---|

| Гимн: Боже, храни Латвию! (латышский) («Боже, благослови Латвию!») | |

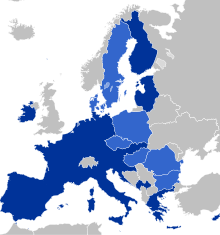

![Расположение Латвии (темно-зеленый) – в Европе (зеленый и темно-серый) – в Европейском Союзе (зеленый) – [Легенда]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/32/EU-Latvia.svg/250px-EU-Latvia.svg.png) Location of Latvia (dark green) – in Europe (green & dark grey) | |

| Capital and largest city | Riga 56°57′N 24°6′E / 56.950°N 24.100°E |

| Official languages | Latviana |

| Recognized languages | Livonian Latgalian |

| Ethnic groups (2022[1]) |

|

| Religion (2018)[2] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Latvian |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary republic |

| Edgars Rinkēvičs | |

| Evika Siliņa | |

| Daiga Mieriņa | |

| Legislature | Saeima |

| Independence | |

| 18 November 1918 | |

• Recognised | 26 January 1921 |

| 7 November 1922 | |

| 21 August 1991 | |

| 1 May 2004 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 64,589 km2 (24,938 sq mi) (122nd) |

• Water (%) | 2.09 (2015)[5] |

| Population | |

• 2022 estimate | 1,842,226[6] (146th) |

• Density | 29.6/km2 (76.7/sq mi) (147th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2021) | medium |

| HDI (2022) | very high (37th) |

| Currency | Euro (€) (EUR) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +371 |

| ISO 3166 code | LV |

| Internet TLD | .lvc |

| |

Латвия ( / ˈ l æ t v i ə / to LAT -vee , иногда / ˈ l ɑː t v i ə / to LAHT -vee ; Латышский : Латвия Латышское произношение: [ˈlatvija] ), [14] официально Латвийская Республика , [15] [16] — страна в Балтийском регионе Северной Европы . Это одно из трех государств Балтии , наряду с Эстонией на севере и Литвой на юге. Он граничит с Россией на востоке и Беларусью на юго-востоке, а также имеет морскую границу со Швецией на западе. Латвия занимает площадь 64 589 км2. 2 (24 938 квадратных миль) с населением 1,9 миллиона человек. В стране умеренный сезонный климат . [17] Столица и крупнейший город – Рига . Латыши принадлежат к этнолингвистической группе балтов , и говорят на латышском языке , одном из двух сохранившихся балтийских языков ветви индоевропейской языковой семьи . [а] Русские являются самым заметным меньшинством в стране, составляя почти четверть населения; 37,7% населения говорят на русском как на родном языке. [18]

After centuries of Teutonic, Swedish, Polish-Lithuanian, and Russian rule, which was mainly implemented through the local Baltic German aristocracy, the independent Republic of Latvia was established on 18 November 1918 after breaking away from the German Empire in the aftermath of World War I.[3] The country became increasingly autocratic after the coup in 1934 established the dictatorship of Kārlis Ulmanis.[19] Latvia's de facto independence was interrupted at the outset of World War II, beginning with Latvia's forcible incorporation into the Soviet Union, followed by the invasion and occupation by Nazi Germany in 1941 and the re-occupation by the Soviets in 1944, which formed the Latvian SSR for the next 45 years. As a result of extensive immigration during the Soviet occupation, ethnic Russians became the most prominent minority in the country. The peaceful Singing Revolution started in 1987 among the Baltic Soviet republics and ended with the restoration of both de facto and officially independence on 21 August 1991.[20] Latvia has since been a democratic unitary parliamentary republic.

Latvia is a developed country with a high-income, advanced economy ranking 39th in the Human Development Index. It is a member of the European Union, Eurozone, NATO, the Council of Europe, the United Nations, the Council of the Baltic Sea States, the International Monetary Fund, the Nordic-Baltic Eight, the Nordic Investment Bank, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, and the World Trade Organization.

Etymology

The name Latvija is derived from the name of the ancient Latgalians, one of four Indo-European Baltic tribes (along with Curonians, Selonians and Semigallians), which formed the ethnic core of modern Latvians together with the Finnic Livonians.[21] Henry of Latvia coined the latinisations of the country's name, "Lettigallia" and "Lethia", both derived from the Latgalians. The terms inspired the variations on the country's name in Romance languages from "Letonia" and in several Germanic languages from "Lettland".[22]

History

Around 3000 BC, the proto-Baltic ancestors of the Latvian people settled on the eastern coast of the Baltic Sea.[23] The Balts established trade routes to Rome and Byzantium, trading local amber for precious metals.[24] By 900 AD, four distinct Baltic tribes inhabited Latvia: Curonians, Latgalians, Selonians, Semigallians (in Latvian: kurši, latgaļi, sēļi and zemgaļi), as well as the Finnic tribe of Livonians (lībieši) speaking a Finnic language.[25]

In the 12th century in the territory of Latvia, there were lands with their rulers: Vanema, Ventava, Bandava, Piemare, Duvzare, Sēlija, Koknese, Jersika, Tālava and Adzele.[26]

Medieval period

Although the local people had contact with the outside world for centuries, they became more fully integrated into the European socio-political system in the 12th century.[27] The first missionaries, sent by the Pope, sailed up the Daugava River in the late 12th century, seeking converts.[28] The local people, however, did not convert to Christianity as readily as the Church had hoped.[28]

German crusaders were sent, or more likely decided to go of their own accord as they were known to do. Saint Meinhard of Segeberg arrived in Ikšķile, in 1184, traveling with merchants to Livonia, on a Catholic mission to convert the population from their original pagan beliefs. Pope Celestine III had called for a crusade against pagans in Northern Europe in 1193. When peaceful means of conversion failed to produce results, Meinhard plotted to convert Livonians by force of arms.[29]

At the beginning of the 13th century, Germans ruled large parts of what is currently Latvia.[28] The influx of German crusaders in the present-day Latvian territory especially increased in the second half of the 13th century following the decline and fall of the Crusader States in the Middle East.[30] Together with southern Estonia, these conquered areas formed the crusader state that became known as Terra Mariana (Medieval Latin for "Land of Mary") or Livonia.[31] In 1282, Riga, and later the cities of Cēsis, Limbaži, Koknese and Valmiera, became part of the Hanseatic League.[28] Riga became an important point of east–west trading[28] and formed close cultural links with Western Europe.[32] The first German settlers were knights from northern Germany and citizens of northern German towns who brought their Low German language to the region, which shaped many loanwords in the Latvian language.[33]

Reformation period and Polish and Swedish rule

Riga became the capital of Swedish Livonia and the largest city in the Swedish Empire.

After the Livonian War (1558–1583), Livonia (Northern Latvia & Southern Estonia) fell under Polish and Lithuanian rule.[28] The southern part of Estonia and the northern part of Latvia were ceded to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and formed into the Duchy of Livonia (Ducatus Livoniae Ultradunensis). Gotthard Kettler, the last Master of the Order of Livonia, formed the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia.[34] Though the duchy was a vassal state to the Lithuanian Grand Duchy and later of the Polish and Lithuanian commonwealth, it retained a considerable degree of autonomy and experienced a golden age in the 16th century. Latgalia, the easternmost region of Latvia, became a part of the Inflanty Voivodeship of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.[35]

In the 17th and early 18th centuries, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Sweden, and Russia struggled for supremacy in the eastern Baltic. After the Polish–Swedish War, northern Livonia (including Vidzeme) came under Swedish rule. Riga became the capital of Swedish Livonia and the largest city in the entire Swedish Empire.[36] Fighting continued sporadically between Sweden and Poland until the Truce of Altmark in 1629.[37][38] In Latvia, the Swedish period is generally remembered as positive; serfdom was eased, a network of schools was established for the peasantry, and the power of the regional barons was diminished.[39][40]

Several important cultural changes occurred during this time. Under Swedish and largely German rule, western Latvia adopted Lutheranism as its main religion.[41] The ancient tribes of the Couronians, Semigallians, Selonians, Livs, and northern Latgallians assimilated to form the Latvian people, speaking one Latvian language.[42][43] Throughout all the centuries, however, an actual Latvian state had not been established, so the borders and definitions of who exactly fell within that group are largely subjective. Meanwhile, largely isolated from the rest of Latvia, southern Latgallians adopted Catholicism under Polish/Jesuit influence. The native dialect remained distinct, although it acquired many Polish and Russian loanwords.[44]

Livonia & Courland in the Russian Empire (1795–1917)

During the Great Northern War (1700–1721), up to 40 percent of Latvians died from famine and plague.[45] Half the residents of Riga were killed by plague in 1710–1711.[46] The capitulation of Estonia and Livonia in 1710 and the Treaty of Nystad, ending the Great Northern War in 1721, gave Vidzeme to Russia (it became part of the Riga Governorate). The Latgale region remained part of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth as Inflanty Voivodeship until 1772, when it was incorporated into Russia. The Duchy of Courland and Semigallia, a vassal state of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, was annexed by Russia in 1795 in the Third Partition of Poland, bringing all of what is now Latvia into the Russian Empire. All three Baltic provinces preserved local laws, German as the local official language and their own parliament, the Landtag.

The emancipation of the serfs took place in Courland in 1817 and in Vidzeme in 1819.[47] In practice, however, the emancipation was actually advantageous to the landowners and nobility, as it dispossessed peasants of their land without compensation, forcing them to return to work at the estates "of their own free will".

During these two centuries Latvia experienced economic and construction boom – ports were expanded (Riga became the largest port in the Russian Empire), railways built; new factories, banks, and a university were established; many residential, public (theatres and museums), and school buildings were erected; new parks formed; and so on. Riga's boulevards and some streets outside the Old Town date from this period.

Numeracy was also higher in the Livonian and Courlandian parts of the Russian Empire, which may have been influenced by the Protestant religion of the inhabitants.[48]

National awakening

During the 19th century, the social structure changed dramatically.[49] A class of independent farmers established itself after reforms allowed the peasants to repurchase their land, but many landless peasants remained, quite a lot Latvians left for the cities and sought for education, industrial jobs.[49] There also developed a growing urban proletariat and an increasingly influential Latvian bourgeoisie.[49] The Young Latvian (Latvian: Jaunlatvieši) movement laid the groundwork for nationalism from the middle of the century, many of its leaders looking to the Slavophiles for support against the prevailing German-dominated social order.[50][51] The rise in use of the Latvian language in literature and society became known as the First National Awakening.[50] Russification began in Latgale after the Polish led the January Uprising in 1863: this spread to the rest of what is now Latvia by the 1880s. The Young Latvians were largely eclipsed by the New Current, a broad leftist social and political movement, in the 1890s.[52] Popular discontent exploded in the 1905 Russian Revolution, which took a nationalist character in the Baltic provinces.[53]

Declaration of independence and interwar period

World War I devastated the territory of what became the state of Latvia, and other western parts of the Russian Empire. Demands for self-determination were initially confined to autonomy, until a power vacuum was created by the Russian Revolution in 1917, followed by the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk between Russia and Germany in March 1918, then the Allied armistice with Germany on 11 November 1918. On 18 November 1918, in Riga, the People's Council of Latvia proclaimed the independence of the new country and Kārlis Ulmanis was entrusted to set up a government and he took the position of prime minister.[54]

The General representative of Germany August Winnig formally handed over political power to the Latvian Provisional Government on 26 November. On 18 November, the Latvian People's Council entrusted him to set up the government. He took the office of Minister of Agriculture from 18 November to 19 December. He took a position of prime minister from 19 November 1918 to 13 July 1919.

The war of independence that followed was part of a general chaotic period of civil and new border wars in Eastern Europe. By the spring of 1919, there were actually three governments: the Provisional government headed by Kārlis Ulmanis, supported by the Tautas padome and the Inter-Allied Commission of Control; the Latvian Soviet government led by Pēteris Stučka, supported by the Red Army; and the Provisional government headed by Andrievs Niedra and supported by the Baltische Landeswehr and the German Freikorps unit Iron Division.

Estonian and Latvian forces defeated the Germans at the Battle of Wenden in June 1919,[55] and a massive attack by a predominantly German force—the West Russian Volunteer Army—under Pavel Bermondt-Avalov was repelled in November. Eastern Latvia was cleared of Red Army forces by Latvian and Polish troops in early 1920 (from the Polish perspective the Battle of Daugavpils was a part of the Polish–Soviet War).

A freely elected Constituent assembly convened on 1 May 1920, and adopted a liberal constitution, the Satversme, in February 1922.[56] The constitution was partly suspended by Kārlis Ulmanis after his coup in 1934 but reaffirmed in 1990. Since then, it has been amended and is still in effect in Latvia today. With most of Latvia's industrial base evacuated to the interior of Russia in 1915, radical land reform was the central political question for the young state. In 1897, 61.2% of the rural population had been landless; by 1936, that percentage had been reduced to 18%.[57]

By 1923, the extent of cultivated land surpassed the pre-war level. Innovation and rising productivity led to rapid growth of the economy, but it soon suffered from the effects of the Great Depression. Latvia showed signs of economic recovery, and the electorate had steadily moved toward the centre during the parliamentary period.[citation needed] On 15 May 1934, Ulmanis staged a bloodless coup, establishing a nationalist dictatorship that lasted until 1940.[58] After 1934, Ulmanis established government corporations to buy up private firms with the aim of "Latvianising" the economy.[59]

Latvia in World War II

Early in the morning of 24 August 1939, the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany signed a 10-year non-aggression pact, called the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact.[60] The pact contained a secret protocol, revealed only after Germany's defeat in 1945, according to which the states of Northern and Eastern Europe were divided into German and Soviet "spheres of influence".[61] In the north, Latvia, Finland and Estonia were assigned to the Soviet sphere.[61] A week later, on 1 September 1939, Germany invaded Poland; on 17 September, the Soviet Union invaded Poland as well.[62]: 32

After the conclusion of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, most of the Baltic Germans left Latvia by agreement between Ulmanis's government and Nazi Germany under the Heim ins Reich programme.[63] In total 50,000 Baltic Germans left by the deadline of December 1939, with 1,600 remaining to conclude business and 13,000 choosing to remain in Latvia.[63] Most of those who remained left for Germany in summer 1940, when a second resettlement scheme was agreed.[64] The racially approved being resettled mainly in Poland, being given land and businesses in exchange for the money they had received from the sale of their previous assets.[62]: 46

On 5 October 1939, Latvia was forced to accept a "mutual assistance" pact with the Soviet Union, granting the Soviets the right to station between 25,000 and 30,000 troops on Latvian territory.[65]State administrators were murdered and replaced by Soviet cadres.[66] Elections were held with single pro-Soviet candidates listed for many positions. The resulting people's assembly immediately requested admission into the USSR, which the Soviet Union granted.[66] Latvia, then a puppet government, was headed by Augusts Kirhenšteins.[67] The Soviet Union incorporated Latvia on 5 August 1940, as the Latvian Soviet Socialist Republic.

The Soviets dealt harshly with their opponents – prior to Operation Barbarossa, in less than a year, at least 34,250 Latvians were deported or killed.[68] Most were deported to Siberia where deaths were estimated at 40 percent.[62]: 48

On 22 June 1941, German troops attacked Soviet forces in Operation Barbarossa.[69] There were some spontaneous uprisings by Latvians against the Red Army which helped the Germans. By 29 June Riga was reached and with Soviet troops killed, captured or retreating, Latvia was left under the control of German forces by early July.[70][62]: 78–96 The occupation was followed immediately by SS Einsatzgruppen troops, who were to act in accordance with the Nazi Generalplan Ost that required the population of Latvia to be cut by 50 percent.[62]: 64 [62]: 56

Under German occupation, Latvia was administered as part of Reichskommissariat Ostland.[71] Latvian paramilitary and Auxiliary Police units established by the occupation authority participated in the Holocaust and other atrocities.[58] 30,000 Jews were shot in Latvia in the autumn of 1941.[62]: 127 Another 30,000 Jews from the Riga ghetto were killed in the Rumbula Forest in November and December 1941, to reduce overpopulation in the ghetto and make room for more Jews being brought in from Germany and the West.[62]: 128 There was a pause in fighting, apart from partisan activity, until after the siege of Leningrad ended in January 1944, and the Soviet troops advanced, entering Latvia in July and eventually capturing Riga on 13 October 1944.[62]: 271

More than 200,000 Latvian citizens died during World War II, including approximately 75,000 Latvian Jews murdered during the Nazi occupation.[58] Latvian soldiers fought on both sides of the conflict, mainly on the German side, with 140,000 men in the Latvian Legion of the Waffen-SS,[72] The 308th Latvian Rifle Division was formed by the Red Army in 1944. On occasions, especially in 1944, opposing Latvian troops faced each other in battle.[62]: 299

In the 23rd block of the Vorverker cemetery, a monument was erected after the Second World War for the people of Latvia who had died in Lübeck from 1945 to 1950.

Soviet era (1940–1941, 1944–1991)

In 1944, when Soviet military advances reached Latvia, heavy fighting took place in Latvia between German and Soviet troops, which ended in another German defeat. In the course of the war, both occupying forces conscripted Latvians into their armies, in this way increasing the loss of the nation's "live resources". In 1944, part of the Latvian territory once more came under Soviet control. The Soviets immediately began to reinstate the Soviet system. After the German surrender, it became clear that Soviet forces were there to stay, and Latvian national partisans, soon joined by some who had collaborated with the Germans, began to fight against the new occupier.[73]

Anywhere from 120,000 to as many as 300,000 Latvians took refuge from the Soviet army by fleeing to Germany and Sweden.[74] Most sources count 200,000 to 250,000 refugees leaving Latvia, with perhaps as many as 80,000 to 100,000 of them recaptured by the Soviets or, during few months immediately after the end of war,[75] returned by the West.[76]The Soviets reoccupied the country in 1944–1945, and further deportations followed as the country was collectivisedand Sovietised.[58]

On 25 March 1949, 43,000 rural residents ("kulaks") and Latvian nationalists were deported to Siberia in a sweeping Operation Priboi in all three Baltic states, which was carefully planned and approved in Moscow already on 29 January 1949.[77] This operation had the desired effect of reducing the anti-Soviet partisan activity.[62]: 326 Between 136,000 and 190,000 Latvians, depending on the sources, were imprisoned or deported to Soviet concentration camps (the Gulag) in the post-war years from 1945 to 1952.[78]

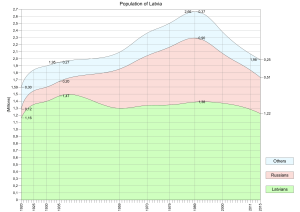

In the post-war period, Latvia was made to adopt Soviet farming methods. Rural areas were forced into collectivization.[79] An extensive program to impose bilingualism was initiated in Latvia, limiting the use of Latvian language in official uses in favor of using Russian as the main language. All of the minority schools (Jewish, Polish, Belarusian, Estonian, Lithuanian) were closed down leaving only two media of instructions in the schools: Latvian and Russian.[80] An influx of new colonists, including laborers, administrators, military personnel and their dependents from Russia and other Soviet republics started. By 1959 about 400,000 Russian settlers arrived and the ethnic Latvian population had fallen to 62%.[81]

Since Latvia had maintained a well-developed infrastructure and educated specialists, Moscow decided to base some of the Soviet Union's most advanced manufacturing in Latvia. New industry was created in Latvia, including a major machinery factory RAF in Jelgava, electrotechnical factories in Riga, chemical factories in Daugavpils, Valmiera and Olaine—and some food and oil processing plants.[82] Latvia manufactured trains, ships, minibuses, mopeds, telephones, radios and hi-fi systems, electrical and diesel engines, textiles, furniture, clothing, bags and luggage, shoes, musical instruments, home appliances, watches, tools and equipment, aviation and agricultural equipment and long list of other goods. Latvia had its own film industry and musical records factory (LPs). However, there were not enough people to operate the newly built factories.[citation needed] To maintain and expand industrial production, skilled workers were migrating from all over the Soviet Union, decreasing the proportion of ethnic Latvians in the republic.[83] The population of Latvia reached its peak in 1990 at just under 2.7 million people.

In late 2018 the National Archives of Latvia released a full alphabetical index of some 10,000 people recruited as agents or informants by the Soviet KGB. 'The publication, which followed two decades of public debate and the passage of a special law, revealed the names, code names, birthplaces and other data on active and former KGB agents as of 1991, the year Latvia regained its independence from the Soviet Union.'[84]

Restoration of independence in 1991

In the second half of the 1980s, Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev started to introduce political and economic reforms in the Soviet Union that were called glasnost and perestroika. In the summer of 1987, the first large demonstrations were held in Riga at the Freedom Monument—a symbol of independence. In the summer of 1988, a national movement, coalescing in the Popular Front of Latvia, was opposed by the Interfront. The Latvian SSR, along with the other Baltic Republics was allowed greater autonomy, and in 1988, the old pre-war Flag of Latvia flew again, replacing the Soviet Latvian flag as the official flag in 1990.[85][86]

In 1989, the Supreme Soviet of the USSR adopted a resolution on the Occupation of the Baltic states, in which it declared the occupation "not in accordance with law", and not the "will of the Soviet people". Pro-independence Popular Front of Latvia candidates gained a two-thirds majority in the Supreme Council in the March 1990 democratic elections. On 4 May 1990, the Supreme Council adopted the Declaration on the Restoration of Independence of the Republic of Latvia, and the Latvian SSR was renamed Republic of Latvia.[87]

However, the central power in Moscow continued to regard Latvia as a Soviet republic in 1990 and 1991. In January 1991, Soviet political and military forces unsuccessfully tried to overthrow the Republic of Latvia authorities by occupying the central publishing house in Riga and establishing a Committee of National Salvation to usurp governmental functions. During the transitional period, Moscow maintained many central Soviet state authorities in Latvia.[87]

The Popular Front of Latvia advocated that all permanent residents be eligible for Latvian citizenship, however, universal citizenship for all permanent residents was not adopted. Instead, citizenship was granted to persons who had been citizens of Latvia on the day of loss of independence in 1940 as well as their descendants. As a consequence, the majority of ethnic non-Latvians did not receive Latvian citizenship since neither they nor their parents had ever been citizens of Latvia, becoming non-citizens or citizens of other former Soviet republics. By 2011, more than half of non-citizens had taken naturalization exams and received Latvian citizenship, but in 2015 there were still 290,660 non-citizens in Latvia, which represented 14.1% of the population. They have no citizenship of any country, and cannot participate in the parliamentary elections.[88] Children born to non-nationals after the re-establishment of independence are automatically entitled to citizenship.

The Republic of Latvia declared the end of the transitional period and restored full independence on 21 August 1991, in the aftermath of the failed Soviet coup attempt.[4] Latvia resumed diplomatic relations with Western states, including Sweden.[89] The Saeima, Latvia's parliament, was again elected in 1993. Russia ended its military presence by completing its troop withdrawal in 1994 and shutting down the Skrunda-1 radar station in 1998.

Since joining the EU in 2004

The major goals of Latvia in the 1990s, to join NATO and the European Union, were achieved in 2004. The NATO Summit 2006 was held in Riga.[90] Vaira Vīķe-Freiberga was President of Latvia from 1999 until 2007. She was the first female head of state in the former Soviet block state and was active in Latvia joining both NATO and the European Union in 2004.[91] Latvia signed the Schengen agreement on 16 April 2003 and started its implementation on 21 December 2007.[92]

Approximately 72% of Latvian citizens are Latvian, while 20% are Russian.[93] The government denationalized private property confiscated by the Soviets, returning it or compensating the owners for it, and privatized most state-owned industries, reintroducing the prewar currency. Albeit having experienced a difficult transition to a liberal economy and its re-orientation toward Western Europe, Latvia is one of the fastest growing economies in the European Union.[94] In November 2013, roof collapsed at a shopping center in Riga, causing Latvia’s worst post-independence disaster with the deaths of 54 rush hour shoppers and rescue personnel.[95]

In 2014, Riga was the European Capital of Culture,[96] Latvia joined the eurozone and adopted the EU single currency euro as the currency of the country[97] and Latvian Valdis Dombrovskis was named vice-president of the European Commission.[98] In 2015 Latvia held the presidency of Council of the European Union.[99] Big European events have been celebrated in Riga such as the Eurovision Song Contest 2003[100] and the European Film Awards 2014.[101] On 1 July 2016, Latvia became a member of the OECD.[102] In May 2023, the parliament elected Edgars Rinkēvičs as new President of Latvia, making him the European Union’s first openly gay head of state.[103] After years of debates, Latvia ratified the EU Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence Against Women and Domestic Violence, otherwise known as the Istanbul Convention in November 2023.[104]

Geography

Latvia lies in Northern Europe, on the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea and northwestern part of the East European Craton (EEC), between latitudes 55° and 58° N (a small area is north of 58°), and longitudes 21° and 29° E (a small area is west of 21°). Latvia has a total area of 64,559 km2 (24,926 sq mi) of which 62,157 km2 (23,999 sq mi) land, 18,159 km2 (7,011 sq mi) agricultural land,[105] 34,964 km2 (13,500 sq mi) forest land[106] and 2,402 km2 (927 sq mi) inland water.[107]

The total length of Latvia's boundary is 1,866 km (1,159 mi). The total length of its land boundary is 1,368 km (850 mi), of which 343 km (213 mi) is shared with Estonia to the north, 276 km (171 mi) with the Russian Federation to the east, 161 km (100 mi) with Belarus to the southeast and 588 km (365 mi) with Lithuania to the south. The total length of its maritime boundary is 498 km (309 mi), which is shared with Estonia, Sweden and Lithuania. Extension from north to south is 210 km (130 mi) and from west to east 450 km (280 mi).[107]

Most of Latvia's territory is less than 100 m (330 ft) above sea level. Its largest lake, Lubāns, has an area of 80.7 km2 (31.2 sq mi), its deepest lake, Drīdzis, is 65.1 m (214 ft) deep. The longest river on Latvian territory is the Gauja, at 452 km (281 mi) in length. The longest river flowing through Latvian territory is the Daugava, which has a total length of 1,005 km (624 mi), of which 352 km (219 mi) is on Latvian territory. Latvia's highest point is Gaiziņkalns, 311.6 m (1,022 ft). The length of Latvia's Baltic coastline is 494 km (307 mi). An inlet of the Baltic Sea, the shallow Gulf of Riga is situated in the northwest of the country.[108]

Climate

Latvia has a temperate climate that has been described in various sources as either humid continental (Köppen Dfb) or oceanic/maritime (Köppen Cfb).[109][110][111]

Coastal regions, especially the western coast of the Courland Peninsula, possess a more maritime climate with cooler summers and milder winters, while eastern parts exhibit a more continental climate with warmer summers and harsher winters.[109] Nevertheless, the temperature variations are little as the territory of Latvia is relatively small.[112] Moreover, Latvia's terrain is particularly flat (no more than 350 meters high), thus the Latvian climate is not differentiated by altitude.[112]

Latvia has four pronounced seasons of near-equal length. Winter starts in mid-December and lasts until mid-March. Winters have average temperatures of −6 °C (21 °F) and are characterized by stable snow cover, bright sunshine, and short days. Severe spells of winter weather with cold winds, extreme temperatures of around −30 °C (−22 °F) and heavy snowfalls are common. Summer starts in June and lasts until August. Summers are usually warm and sunny, with cool evenings and nights. Summers have average temperatures of around 19 °C (66 °F), with extremes of 35 °C (95 °F). Spring and autumn bring fairly mild weather.[113]

| Weather record | Value | Location | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| Highest temperature | 37.8 °C (100 °F) | Ventspils | 4 August 2014 |

| Lowest temperature | −43.2 °C (−46 °F) | Daugavpils | 8 February 1956 |

| Last spring frost | – | Large parts of territory | 24 June 1982 |

| First autumn frost | – | Cenas parish | 15 August 1975 |

| Highest yearly precipitation | 1,007 mm (39.6 in) | Priekuļi parish | 1928 |

| Lowest yearly precipitation | 384 mm (15.1 in) | Ainaži | 1939 |

| Highest daily precipitation | 160 mm (6.3 in) | Ventspils | 9 July 1973 |

| Highest monthly precipitation | 330 mm (13.0 in) | Nīca parish | August 1972 |

| Lowest monthly precipitation | 0 mm (0 in) | Large parts of territory | May 1938 and May 1941 |

| Thickest snow cover | 126 cm (49.6 in) | Gaiziņkalns | March 1931 |

| Month with the most days with blizzards | 19 days | Liepāja | February 1956 |

| The most days with fog in a year | 143 days | Gaiziņkalns area | 1946 |

| Longest-lasting fog | 93 hours | Alūksne | 1958 |

| Highest atmospheric pressure | 31.5 inHg (1,066.7 mb) | Liepāja | January 1907 |

| Lowest atmospheric pressure | 27.5 inHg (931.3 mb) | Vidzeme Upland | 13 February 1962 |

| The most days with thunderstorms in a year | 52 days | Vidzeme Upland | 1954 |

| Strongest wind | 34 m/s, up to 48 m/s | Not specified | 2 November 1969 |

2019 was the warmest year in the history of weather observation in Latvia with an average temperature +8.1 °C higher.[115]

Environment

Most of the country is composed of fertile lowland plains and moderate hills. In a typical Latvian landscape, a mosaic of vast forests alternates with fields, farmsteads, and pastures. Arable land is spotted with birch groves and wooded clusters, which afford a habitat for numerous plants and animals. Latvia has hundreds of kilometres of undeveloped seashore—lined by pine forests, dunes, and continuous white sand beaches.[108][116]

Latvia has the fifth highest proportion of land covered by forests in the European Union, after Sweden, Finland, Estonia and Slovenia.[117] Forests account for 3,497,000 ha (8,640,000 acres) or 56% of the total land area.[106]

Latvia has over 12,500 rivers, which stretch for 38,000 km (24,000 mi). Major rivers include the Daugava River, Lielupe, Gauja, Venta, and Salaca, the largest spawning ground for salmon in the eastern Baltic states. There are 2,256 lakes that are bigger than 1 ha (2.5 acres), with a collective area of 1,000 km2 (390 sq mi). Mires occupy 9.9% of Latvia's territory. Of these, 42% are raised bogs; 49% are fens; and 9% are transitional mires. 70% percent of the mires are untouched by civilization, and they are a refuge for many rare species of plants and animals.[116]

Agricultural areas account for 1,815,900 ha (4,487,000 acres) or 29% of the total land area.[105] With the dismantling of collective farms, the area devoted to farming decreased dramatically – now farms are predominantly small. Approximately 200 farms, occupying 2,750 ha (6,800 acres), are engaged in ecologically pure farming (using no artificial fertilizers or pesticides).[116]

Latvia's national parks are Gauja National Park in Vidzeme (since 1973),[118] Ķemeri National Park in Zemgale (1997), Slītere National Park in Kurzeme (1999), and Rāzna National Park in Latgale (2007).[119]

Latvia has a long tradition of conservation. The first laws and regulations were promulgated in the 16th and 17th centuries.[116] There are 706 specially state-level protected natural areas in Latvia: four national parks, one biosphere reserve, 42 nature parks, nine areas of protected landscapes, 260 nature reserves, four strict nature reserves, 355 nature monuments, seven protected marine areas and 24 microreserves.[120] Nationally protected areas account for 12,790 km2 (4,940 sq mi) or around 20% of Latvia's total land area.[107] Latvia's Red Book (Endangered Species List of Latvia), which was established in 1977, contains 112 plant species and 119 animal species. Latvia has ratified the international Washington, Bern, and Ramsare conventions.[116]

The 2012 Environmental Performance Index ranks Latvia second, after Switzerland, based on the environmental performance of the country's policies.[121]

Access to biocapacity in Latvia is much higher than world average. In 2016, Latvia had 8.5 global hectares[122] of biocapacity per person within its territory, much more than the world average of 1.6 global hectares per person.[123] In 2016 Latvia used 6.4 global hectares of biocapacity per person - their ecological footprint of consumption. This means they use less biocapacity than Latvia contains. As a result, Latvia is running a biocapacity reserve.[122]

Biodiversity

Approximately 30,000 species of flora and fauna have been registered in Latvia.[125] Larger mammalian wildlife in Latvia include deer, wild boar, moose, lynx, bear, fox, beaver and wolves.[126] Non-marine molluscs of Latvia include 170 species.[127]

Species that are endangered in other European countries but common in Latvia include: black stork (Ciconia nigra), corncrake (Crex crex), lesser spotted eagle (Aquila pomarina), white-backed woodpecker (Picoides leucotos), Eurasian crane (Grus grus), Eurasian beaver (Castor fiber), Eurasian otter (Lutra lutra), European wolf (Canis lupus) and European lynx (Felis lynx).[116]

Phytogeographically, Latvia is shared between the Central European and Northern European provinces of the Circumboreal Region within the Boreal Kingdom. According to the WWF, the territory of Latvia belongs to the ecoregion of Sarmatic mixed forests. 56 percent[106] of Latvia's territory is covered by forests, mostly Scots pine, birch, and Norway spruce.[128] It had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 2.09/10, ranking it 159th globally out of 172 countries.[129]

Several species of flora and fauna are considered national symbols. Oak (Quercus robur, Latvian: ozols), and linden (Tilia cordata, Latvian: liepa) are Latvia's national trees and the daisy (Leucanthemum vulgare, Latvian: pīpene) its national flower. The white wagtail (Motacilla alba, Latvian: baltā cielava) is Latvia's national bird. Its national insect is the two-spot ladybird (Adalia bipunctata, Latvian: divpunktu mārīte). Amber, fossilized tree resin, is one of Latvia's most important cultural symbols. In ancient times, amber found along the Baltic Sea coast was sought by Vikings as well as traders from Egypt, Greece and the Roman Empire. This led to the development of the Amber Road.[130]

Several nature reserves protect unspoiled landscapes with a variety of large animals. At Pape Nature Reserve, where European bison, wild horses, and recreated aurochs have been reintroduced, there is now an almost complete Holocene megafauna also including moose, deer, and wolf.[131]

Politics

|  |

| Edgars Rinkēvičs President | Evika Siliņa Prime Minister |

The 100-seat unicameral Latvian parliament, the Saeima, is elected by direct popular vote every four years. The president is elected by the Saeima in a separate election, also held every four years. The president appoints a prime minister who, together with his cabinet, forms the executive branch of the government, which has to receive a confidence vote by the Saeima. This system also existed before World War II.[132] The most senior civil servants are the thirteen Secretaries of State.[133]

Administrative divisions

Courland

Semigallia

Vidzeme

Latgale

Selonia

Latvia is a unitary state, currently divided into 43 local government units consisting of 36 municipalities (Latvian: novadi) and 7 state cities (Latvian: valstspilsētas) with their own city council and administration: Daugavpils, Jelgava, Jūrmala, Liepāja, Rēzekne, Riga, and Ventspils. There are four historical and cultural regions in Latvia – Courland, Latgale, Vidzeme, Zemgale, which are recognised in Constitution of Latvia. Selonia, a part of Zemgale, is sometimes considered culturally distinct region, but it is not part of any formal division. The borders of historical and cultural regions usually are not explicitly defined and in several sources may vary. In formal divisions, Riga region, which includes the capital and parts of other regions that have a strong relationship with the capital, is also often included in regional divisions; e.g., there are five planning regions of Latvia (Latvian: plānošanas reģioni), which were created in 2009 to promote balanced development of all regions. Under this division Riga region includes large parts of what traditionally is considered Vidzeme, Courland, and Zemgale. Statistical regions of Latvia, established in accordance with the EU Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics, duplicate this division, but divides Riga region into two parts with the capital alone being a separate region.[citation needed]The largest city in Latvia is Riga, the second largest city is Daugavpils and the third largest city is Liepaja.

Political culture

In 2010 parliamentary election ruling centre-right coalition won 63 out of 100 parliamentary seats. Left-wing opposition Harmony Centre supported by Latvia's Russian-speaking minority got 29 seats.[134] In November 2013, Latvian Prime Minister Valdis Dombrovskis, in office since 2009, resigned after at least 54 people were killed and dozens injured in the collapse at a supermarket in Riga.[135]

In 2014 parliamentary election was won again by the ruling centre-right coalition formed by the Unity Party, the National Alliance and the Union of Greens and Farmers. They got 61 seats and Harmony got 24.[136] In December 2015, country's first female prime minister, in office since January 2014, Laimdota Straujuma resigned.[137] In February 2016, a coalition of Union of Greens and Farmers, The Unity and National Alliance was formed by new Prime Minister Maris Kucinskis.[138]

In 2018 parliamentary election pro-Russian Harmony was again the biggest party securing 23 out of 100 seats, the second and third were the new populist parties KPV LV and New Conservative Party. Ruling coalition, comprising the Union of Greens and Farmers, the National Alliance and the Unity party, lost.[139] In January 2019, Latvia got a government led by new Prime Minister Krisjanis Karins of the centre-right New Unity. Karins' coalition was formed by five of the seven parties in parliament, excluding only the pro-Russia Harmony party and the Union of Greens and Farmers.[140] On 15 September 2023, Evika Siliņa became the new prime minister of Latvia, following resignation of former Prime Minister Krišjānis Kariņš previous month. Siliņa’s government is a three-party coalition between her own New Unity (JV) party, the Greens and Farmers Union (ZZS), and the social-democratic Progressives (PRO) with total 52 of 100 seats in the parliament.[141]

Foreign relations

Latvia is a member of the United Nations, European Union, Council of Europe, NATO, OECD, OSCE, IMF, and WTO. It is also a member of the Council of the Baltic Sea States and Nordic Investment Bank. It was a member of the League of Nations (1921–1946). Latvia is part of the Schengen Area[142] and joined the Eurozone on 1 January 2014.[143]

Latvia has established diplomatic relations with 158 countries. It has 44 diplomatic and consular missions and maintains 34 embassies and 9 permanent representations abroad. There are 37 foreign embassies and 11 international organisations in Latvia's capital Riga. Latvia hosts one European Union institution, the Body of European Regulators for Electronic Communications (BEREC).[144]

Latvia's foreign policy priorities include co-operation in the Baltic Sea region, European integration, active involvement in international organisations, contribution to European and transatlantic security and defence structures, participation in international civilian and military peacekeeping operations, and development co-operation, particularly the strengthening of stability and democracy in the EU's Eastern Partnership countries.[145][146][147]

Since the early 1990s, Latvia has been involved in active trilateral Baltic states co-operation with its neighbours Estonia and Lithuania, and Nordic-Baltic co-operation with the Nordic countries. Latvia is a member of the interparliamentary Baltic Assembly, the intergovernmental Baltic Council of Ministers and the Council of the Baltic Sea States.[148] Nordic-Baltic Eight (NB-8) is the joint co-operation of the governments of Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Iceland, Latvia, Lithuania, Norway, and Sweden.[149] Nordic-Baltic Six (NB-6), comprising Nordic-Baltic countries that are European Union member states, is a framework for meetings on EU-related issues. Interparliamentary co-operation between the Baltic Assembly and Nordic Council was signed in 1992 and since 2006 annual meetings are held as well as regular meetings on other levels.[149] Joint Nordic-Baltic co-operation initiatives include the education programme NordPlus[150] and mobility programmes for public administration,[151] business and industry[152] and culture.[153] The Nordic Council of Ministers has an office in Riga.[154]

Latvia participates in the Northern Dimension and Baltic Sea Region Programme, European Union initiatives to foster cross-border co-operation in the Baltic Sea region and Northern Europe. The secretariat of the Northern Dimension Partnership on Culture (NDPC) will be located in Riga.[155] In 2013 Riga hosted the annual Northern Future Forum, a two-day informal meeting of the prime ministers of the Nordic-Baltic countries and the UK.[156] The Enhanced Partnership in Northern Europe or e-Pine is the U.S. Department of State diplomatic framework for co-operation with the Nordic-Baltic countries.[157]

Latvia hosted the 2006 NATO Summit and since then the annual Riga Conference has become a leading foreign and security policy forum in Northern Europe.[158] Latvia held the Presidency of the Council of the European Union in the first half of 2015.[159]

Since February 2022 Latvia's relations with Russia have deteriorated to the extent that Latvia withdrew its ambassador from Russia and expelled Russia's ambassador to Latvia in January 2023 [160] and banned Russians from entering Latvia.

Military

The National Armed Forces (Latvian: Nacionālie bruņotie spēki (NAF)) of Latvia consists of the Land Forces, Naval Forces, Air Force, National Guard, Special Tasks Unit, Military Police, NAF staff Battalion, Training and Doctrine Command, and Logistics Command. Latvia's defence concept is based upon the Swedish-Finnish model of a rapid response force composed of a mobilisation base and a small group of career professionals. From 1 January 2007, Latvia switched to a professional fully contract-based army.[161]

Latvia participates in international peacekeeping and security operations. Latvian armed forces have contributed to NATO and EU military operations in Bosnia and Herzegovina (1996–2009), Albania (1999), Kosovo (2000–2009), Macedonia (2003), Iraq (2005–2006), Afghanistan (since 2003), Somalia (since 2011) and Mali (since 2013).[162][163][164] Latvia also took part in the US-led Multi-National Force operation in Iraq (2003–2008)[165] and OSCE missions in Georgia, Kosovo and Macedonia.[166] Latvian armed forces contributed to a UK-led Battlegroup in 2013 and the Nordic Battlegroup in 2015 under the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) of the European Union.[167] Latvia acts as the lead nation in the coordination of the Northern Distribution Network for transportation of non-lethal ISAF cargo by air and rail to Afghanistan.[168][169][170] It is part of the Nordic Transition Support Unit (NTSU), which renders joint force contributions in support of Afghan security structures ahead of the withdrawal of Nordic and Baltic ISAF forces in 2014.[171] Since 1996 more than 3600 military personnel have participated in international operations,[163] of whom 7 soldiers perished.[172] Per capita, Latvia is one of the largest contributors to international military operations.[173]

Latvian civilian experts have contributed to EU civilian missions: border assistance mission to Moldova and Ukraine (2005–2009), rule of law missions in Iraq (2006 and 2007) and Kosovo (since 2008), police mission in Afghanistan (since 2007) and monitoring mission in Georgia (since 2008).[162]

Since March 2004, when the Baltic states joined NATO, fighter jets of NATO members have been deployed on a rotational basis for the Baltic Air Policing mission at Šiauliai Airport in Lithuania to guard the Baltic airspace. Latvia participates in several NATO Centres of Excellence: Civil-Military Co-operation in the Netherlands, Cooperative Cyber Defence in Estonia and Energy Security in Lithuania. It plans to establish the NATO Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence in Riga.[174]

Latvia co-operates with Estonia and Lithuania in several trilateral Baltic defence co-operation initiatives:

- Baltic Battalion (BALTBAT) – infantry battalion for participation in international peace support operations, headquartered near Riga, Latvia;

- Baltic Naval Squadron (BALTRON) – naval force with mine countermeasures capabilities, headquartered near Tallinn, Estonia;

- Baltic Air Surveillance Network (BALTNET) – air surveillance information system, headquartered near Kaunas, Lithuania;

- Joint military educational institutions: Baltic Defence College in Tartu, Estonia, Baltic Diving Training Centre in Liepāja, Latvia and Baltic Naval Communications Training Centre in Tallinn, Estonia.[175]

Future co-operation will include sharing of national infrastructures for training purposes and specialisation of training areas (BALTTRAIN) and collective formation of battalion-sized contingents for use in the NATO rapid-response force.[176] In January 2011, the Baltic states were invited to join Nordic Defence Cooperation, the defence framework of the Nordic countries.[177] In November 2012, the three countries agreed to create a joint military staff in 2013.[178]

On 21 April 2022, Latvian Saeima passed amendments developed by the Ministry of Defence for the legislative draft Amendments to the Law on Financing of National Defence, which provide for gradual increase in the defence budget to 2.5% of the country's GDP over the course of the next three year.[179]

Human rights

According to the reports by Freedom House and the US Department of State, human rights in Latvia are generally respected by the government:[180][181] Latvia is ranked above-average among the world's sovereign states in democracy,[182] press freedom,[183] privacy[184] and human development.[185]

More than 56% of leading positions are held by women in Latvia, which ranks first in Europe; Latvia ranks first in the world in women's rights sharing the position with five other European countries according to World Bank.[186]

The country has a large ethnic Russian community, which was guaranteed basic rights under the constitution and international human rights laws ratified by the Latvian government.[180][187]

Approximately 206,000 non-citizens[188] – including stateless persons – have limited access to some political rights – only citizens are allowed to participate in parliamentary or municipal elections, although there are no limitations in regards to joining political parties or other political organizations.[189][190] In 2011, the OSCE High Commissioner on National Minorities "urged Latvia to allow non-citizens to vote in municipal elections."[191] Additionally, there have been reports of police abuse of detainees and arrestees, poor prison conditions and overcrowding, judicial corruption, incidents of violence against ethnic minorities, and societal violence and incidents of government discrimination against homosexuals.[180][192][193] Same-sex marriage is constitutionally prohibited in Latvia.[194][195]

Economy

Latvia is a member of the World Trade Organization (1999) and the European Union (2004). On 1 January 2014, the euro became the country's currency, superseding the Lats. According to statistics in late 2013, 45% of the population supported the introduction of the euro, while 52% opposed it.[196] Following the introduction of the Euro, Eurobarometer surveys in January 2014 showed support for the euro to be around 53%, close to the European average.[197]

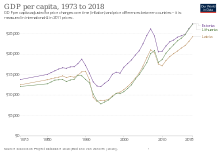

Since the year 2000, Latvia has had one of the highest (GDP) growth rates in Europe.[198] However, the chiefly consumption-driven growth in Latvia resulted in the collapse of Latvian GDP in late 2008 and early 2009, exacerbated by the global economic crisis, shortage of credit and huge money resources used for the bailout of Parex Bank.[199] The Latvian economy fell 18% in the first three months of 2009, the biggest fall in the European Union.[200][201]

The economic crisis of 2009 proved earlier assumptions that the fast-growing economy was heading for implosion of the economic bubble, because it was driven mainly by growth of domestic consumption, financed by a serious increase of private debt, as well as a negative foreign trade balance. The prices of real estate, which rose 150% from 2004 to 2006, was a significant contributor to the economic bubble.[202]

Privatisation in Latvia is almost complete. Virtually all of the previously state-owned small and medium companies have been privatised, leaving only a small number of politically sensitive large state companies. The private sector accounted for 70% of the country's GDP in 2006. [203]

Foreign investment in Latvia is still modest compared with the levels in north-central Europe. A law expanding the scope for selling land, including to foreigners, was passed in 1997. Representing 10.2% of Latvia's total foreign direct investment, American companies invested $127 million in 1999. In the same year, the United States of America exported $58.2 million of goods and services to Latvia and imported $87.9 million. Eager to join Western economic institutions like the World Trade Organization, OECD, and the European Union, Latvia signed a Europe Agreement with the EU in 1995—with a 4-year transition period. Latvia and the United States have signed treaties on investment, trade, and intellectual property protection and avoidance of double taxation.[204][205]

In 2010 Latvia launched a Residence by Investment program (Golden Visa) in order to attract foreign investors and make local economy benefit from it. This program allows investors to get a Latvian residence permit by investing at least €250,000 in property or in an enterprise with at least 50 employees and an annual turnover of at least €10M.

- Economic contraction and recovery (2008–12)

The Latvian economy entered a phase of fiscal contraction during the second half of 2008 after an extended period of credit-based speculation and unrealistic appreciation in real estate values. The national account deficit for 2007, for example, represented more than 22% of the GDP for the year while inflation was running at 10%.[206]

Latvia's unemployment rate rose sharply in this period from a low of 5.4% in November 2007 to over 22%.[207] In April 2010 Latvia had the highest unemployment rate in the EU, at 22.5%, ahead of Spain, which had 19.7%.[208]

Paul Krugman, the Nobel Laureate in economics for 2008, wrote in his New York Times Op-Ed column on 15 December 2008:

The most acute problems are on Europe's periphery, where many smaller economies are experiencing crises strongly reminiscent of past crises in Latin America and Asia: Latvia is the new Argentina[209]

However, by 2010, commentators[210][211] noted signs of stabilisation in the Latvian economy. Rating agency Standard & Poor's raised its outlook on Latvia's debt from negative to stable.[210] Latvia's current account, which had been in deficit by 27% in late 2006 was in surplus in February 2010.[210] Kenneth Orchard, senior analyst at Moody's Investors Service argued that:

The strengthening regional economy is supporting Latvian production and exports, while the sharp swing in the current account balance suggests that the country's 'internal devaluation' is working.[212]

The IMF concluded the First Post-Program Monitoring Discussions with the Republic of Latvia in July 2012 announcing that Latvia's economy has been recovering strongly since 2010, following the deep downturn in 2008–09. Real GDP growth of 5.5 percent in 2011 was underpinned by export growth and a recovery in domestic demand. The growth momentum has continued into 2012 and 2013 despite deteriorating external conditions, and the economy is expected to expand by 4.1 percent in 2014. The unemployment rate has receded from its peak of more than 20 percent in 2010 to around 9.3 percent in 2014.[213]

- Economic recovery

GDP at current prices rose from €23.7 billion in 2014 to €30.5 billion in 2019. The employment rate rose in the same period from 59.1% to 65% with unemployment falling from 10.8% to 6.5%.[214]

Infrastructure

Transport

The transport sector is around 14% of GDP. Transit between Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan as well as other Asian countries and the West used to be large.[215]

The four biggest ports of Latvia are located in Riga, Ventspils, Liepāja and Skulte. Most transit traffic uses these and half the cargo is crude oil and oil products.[215] Free port of Ventspils is one of the busiest ports in the Baltic states. Apart from road and railway connections, Ventspils is also linked to oil extraction fields and prior to 2022, transportation routes of Russian Federation via system of two pipelines from Polotsk, Belarus.[citation needed]

Riga International Airport is the busiest airport in the Baltic states with 7.8 million passengers in 2019. It has direct flight to over 80 destinations in 30 countries. The only other airport handling regular commercial flights is Liepāja International Airport.airBaltic is the Latvian flag carrier airline and a low-cost carrier with hubs in all three Baltic States, but main base in Riga, Latvia.[216]

Latvian Railway's main network consists of 1,860 km of which 1,826 km is 1,520 mm Russian gauge railway of which 251 km are electrified, making it the longest railway network in the Baltic States. Latvia's railway network is currently incompatible with European standard gauge lines.[217] However, Rail Baltica railway, linking Helsinki-Tallinn-Riga-Kaunas-Warsaw is under construction and is set to be completed in 2026.[218]

National road network in Latvia totals 1675 km of main roads, 5473 km of regional roads and 13 064 km of local roads. Municipal roads in Latvia totals 30 439 km of roads and 8039 km of streets.[219] The best known roads are A1 (European route E67), connecting Warsaw and Tallinn, as well as European route E22, connecting Ventspils and Terehova. In 2017 there were a total of 803,546 licensed vehicles in Latvia.[220]

Energy

Latvia has three large hydroelectric power stations in Pļaviņu HES (908 MW), Rīgas HES (402 MW) and Ķeguma HES-2 (248 MW).[221] In recent years a couple of dozen of wind farms as well as biogas or biomass power stations of different scale have been built in Latvia.[222] In 2022, the Latvian Prime Minister announced about the planned investments of 1 billion euros in the new wind farms and the completed project will expectedly provide additional 800 MW of capacity.[223]

Latvia operates Inčukalns underground gas storage facility, one of the largest underground gas storage facilities in Europe and the only one in the Baltic states. Unique geological conditions at Inčukalns and other locations in Latvia are particularly suitable for underground gas storage.[224]

Demographics

The total fertility rate (TFR) in 2018 was estimated to be 1.61 children born/woman, which is lower than the replacement rate of 2.1. In 2012, 45.0% of births were to unmarried women.[225] The life expectancy in 2013 was estimated at 73.2 years (68.1 years male, 78.5 years female).[206] As of 2015, Latvia is estimated to have the lowest male-to-female ratio in the world, at 0.85 males per female.[226] In 2017, there were 1,054,433 females and 895,683 males living in Latvian territory. Every year, more boys are born than girls. Up to the age of 39, there are more males than females. Above the age of 70, there are 2.3 times as many females as males.

Ethnic groups

In 2023, Latvians formed about 62.4% of the population, while 23.7% were Russians, Belarusians 3%, Ukrainians 3%, Poles 2%, Lithuanians 1%.[227]

In some cities, including Daugavpils and Rēzekne, ethnic Latvians constitute a minority of the total population. Despite a steadily increasing proportion of ethnic Latvians for more than a decade, ethnic Latvians also still make up slightly less than a half of the population of the capital city of Latvia – Riga.[citation needed]

The share of ethnic Latvians declined from 77% (1,467,035) in 1935 to 52% (1,387,757) in 1989.[228] In the context of a decreasing overall population, there were fewer Latvians in 2011 than in 1989, but their share of the population was larger – 1,285,136 (62.1% of the population).[229]

The majority of Latvia's population are Latvians, who are an ethnic Baltic people. The country also has a significant Russian minority, as well as smaller populations of Ukrainians, Belarusians, and other Slavic peoples. These ethnic groups are all descended from peoples who settled in Latvia during the centuries of Russian and Soviet rule.

Latvia's ethnic diversity is a result of a number of factors, including a long history of foreign rule, its location on the Baltic Sea trade route, and its proximity to other Slavic countries. The Russian Empire conquered Latvia in the 18th century and ruled the country for over 200 years. During this time, the Russian authorities encouraged the settlement of Russian colonists in Latvia. After the collapse of the Russian Empire in 1918, Latvia became an independent country. However, the country was occupied by the Soviet Union in 1940 and remained under Soviet rule until 1991. The Soviets expelled some groups and resettled others in Latvia, especially Russians. After 1991 many of the expellees returned to Latvia.[230]

As a result of deteriorating relations with Russia, Latvia has decided it does not want Russian citizens in Latvia who will not integrate. In late 2023 it is expected that around 5-6,000 Russians will be returned to Russia as they have made little effort to learn the Latvian language, integrate with Latvia, or apply to become Latvian citizens.[231]

Language

The sole official language of Latvia is Latvian, which belongs to the Baltic language sub-group of the Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European language family. Another notable language of Latvia is the nearly extinct Livonian language of the Finnic branch of the Uralic language family, which enjoys protection by law; Latgalian – as a dialect of Latvian is also protected by Latvian law but as a historical variation of the Latvian language. Russian, which was widely spoken during the Soviet period, is still the most widely used minority language by far (in 2023, 37.7% spoke it as their mother tongue and 34.6% spoke it at home, including people who were not ethnically Russian).[232]While it is now required that all school students learn Latvian, schools also include English, German, French and Russian in their curricula. English is also widely accepted in Latvia in business and tourism. As of 2014[update] there were 109 schools for minorities that use Russian as the language of instruction (27% of all students) for 40% of subjects (the remaining 60% of subjects are taught in Latvian).

On 18 February 2012, Latvia held a constitutional referendum on whether to adopt Russian as a second official language.[233] According to the Central Election Commission, 74.8% voted against, 24.9% voted for and the voter turnout was 71.1%.[234]

From 2019, instruction in the Russian language was gradually discontinued in private colleges and universities in Latvia, as well as general instruction in Latvian public high schools,[235][236] except for subjects related to culture and history of the Russian minority, such as Russian language and literature classes.[237] All schools, including pre-schools, still using the Russian language in 2023 need to transition to using Latvian in all classes within 3 years.[238]

Religion

The largest religion in Latvia is Christianity (79%).[206][239] The largest groups as of 2011[update] were:

- Evangelical Lutheran Church of Latvia – 708,773[239]

- Roman Catholic – 500,000[239]

- Russian Orthodox – 370,000[239]

In the Eurobarometer Poll 2010, 38% of Latvian citizens responded that "they believe there is a God", while 48% answered that "they believe there is some sort of spirit or life force" and 11% stated that "they do not believe there is any sort of spirit, God, or life force".

Lutheranism was more prominent before the Soviet occupation, when it was adhered to by about 60% of the population, a reflection of the country's strong historical links with the Nordic countries, and to the influence of the Hansa in particular and Germany in general. Since then, Lutheranism has declined to a slightly greater extent than Roman Catholicism in all three Baltic states. The Evangelical Lutheran Church, with an estimated 600,000 members in 1956, was affected most adversely. An internal document of 18 March 1987, near the end of communist rule, spoke of an active membership that had shrunk to only 25,000 in Latvia, but the faith has since experienced a revival.[240]

The country's Orthodox Christians belong to the Latvian Orthodox Church, a semi-autonomous body within the Russian Orthodox Church. In 2011, there were 416 religious Jews in Latvia and 319 Muslims in Latvia.[239] As of 2004, there were more than 600 Latvian neopagans, Dievturi (The Godskeepers), whose religion is based on Latvian mythology.[241][242] About 21% of the total population is not affiliated with a specific religion.[239]

Latvia has been seeking for a number of years to separate the Latvian Orthodox Church from Moscow, stating that longstanding ties to Russia pose “national security concerns”.[243] This was achieved in September 2022 with a law removing all influence or power over the Orthodox Church from non Latvians, which would include the Patriarch of Moscow.[244]

Education and science

The University of Latvia and Riga Technical University are two major universities in the country, both successors to Riga Polytechnical Institute, and located in Riga.[245] Other important universities, which were established on the base of State University of Latvia, include the Latvia University of Life Sciences and Technologies (established in 1939 on the basis of the Faculty of Agriculture) and Riga Stradiņš University (established in 1950 on the basis of the Faculty of Medicine). Both nowadays cover a variety of different fields. The University of Daugavpils is another significant centre of education.

Latvia closed 131 schools between 2006 and 2010, which is a 12.9% decline, and in the same period enrolment in educational institutions has fallen by over 54,000 people, a 10.3% decline.[246]

Latvian policy in science and technology has set out the long-term goal of transitioning from labor-consuming economy to knowledge-based economy.[247] By 2020 the government aims to spend 1.5% of GDP on research and development, with half of the investments coming from the private sector. Latvia plans to base the development of its scientific potential on existing scientific traditions, particularly in organic chemistry, medical chemistry, genetic engineering, physics, materials science and information technologies.[248] The greatest number of patents, both nationwide and abroad, are in medical chemistry.[249] Latvia was ranked 37th in the Global Innovation Index in 2023.[250]

Health

The Latvian healthcare system is a universal programme, largely funded through government taxation.[251] It is among the lowest-ranked healthcare systems in Europe, due to excessive waiting times for treatment, insufficient access to the latest medicines, and other factors.[252] There were 59 hospitals in Latvia in 2009, down from 94 in 2007 and 121 in 2006.[253][254][255]

Culture

Traditional Latvian folklore, especially the dance of the folk songs, dates back well over a thousand years. More than 1.2 million texts and 30,000 melodies of folk songs have been identified.[256]

Between the 13th and 19th centuries, Baltic Germans, many of whom were originally of non-German ancestry but had been assimilated into German culture, formed the upper class.[citation needed] They developed distinct cultural heritage, characterised by both Latvian and German influences. It has survived in German Baltic families to this day, in spite of their dispersal to Germany, the United States, Canada and other countries in the early 20th century. However, most indigenous Latvians did not participate in this particular cultural life.[citation needed] Thus, the mostly peasant local pagan heritage was preserved, partly merging with Christian traditions. For example, one of the most popular celebrations is Jāņi, a pagan celebration of the summer solstice—which Latvians celebrate on the feast day of St. John the Baptist.[citation needed]

In the 19th century, Latvian nationalist movements emerged. They promoted Latvian culture and encouraged Latvians to take part in cultural activities. The 19th century and beginning of the 20th century is often regarded by Latvians as a classical era of Latvian culture. Posters show the influence of other European cultures, for example, works of artists such as the Baltic-German artist Bernhard Borchert and the French Raoul Dufy.[257] With the onset of World War II, many Latvian artists and other members of the cultural elite fled the country yet continued to produce their work, largely for a Latvian émigré audience.[258]

The Latvian Song and Dance Festival is an important event in Latvian culture and social life. It has been held since 1873, normally every five years. Approximately 30,000 performers altogether participate in the event.[259] Folk songs and classical choir songs are sung, with emphasis on a cappella singing, though modern popular songs have recently been incorporated into the repertoire as well.[260]

After incorporation into the Soviet Union, Latvian artists and writers were forced to follow the socialist realism style of art. During the Soviet era, music became increasingly popular, with the most popular being songs from the 1980s. At this time, songs often made fun of the characteristics of Soviet life and were concerned about preserving Latvian identity. This aroused popular protests against the USSR and also gave rise to an increasing popularity of poetry. Since independence, theatre, scenography, choir music, and classical music have become the most notable branches of Latvian culture.[261]

During July 2014, Riga hosted the eighth World Choir Games as it played host to over 27,000 choristers representing over 450 choirs and over 70 countries. The festival is the biggest of its kind in the world and is held every two years in a different host city.[262]

Starting in 2019 Latvia hosts the inaugural Riga Jurmala Music Festival Archived 2 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine, a new festival in which world-famous orchestras and conductors perform across four weekends during the summer. The festival takes place at the Latvian National Opera, the Great Guild, and the Great and Small Halls of the Dzintari Concert Hall. This year features the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, the London Symphony Orchestra and the Russian National Orchestra.[263]

Cuisine

Latvian cuisine typically consists of agricultural products, with meat featuring in most main meal dishes. Fish is commonly consumed due to Latvia's location on the Baltic Sea. Latvian cuisine has been influenced by neighbouring countries. Common ingredients in Latvian recipes are found locally, such as potatoes, wheat, barley, cabbage, onions, eggs, and pork. Latvian food is generally quite fatty and uses few spices.[264]

Grey peas with speck are generally considered as staple foods of Latvians. Sorrel soup (skābeņu zupa) is also consumed by Latvians.[265] Rye bread is considered the national staple.[266]

Sport

Хоккей с шайбой обычно считается самым популярным видом спорта в Латвии. В Латвии было много известных хоккейных звезд, таких как Хельмутс Балдерис , Артурс Ирбе , Карлис Скрастиньш и Сандис Озолиньш , а в последнее время и Земгус Гиргенсонс , которого латвийский народ активно поддерживал на международных играх и в НХЛ, что выразилось в стремлении использовать голосование всех звезд НХЛ. вывести Земгуса на первое место в голосовании. [267] «Динамо Рига» — сильнейший хоккейный клуб страны, выступающий в Высшей хоккейной лиге Латвии . Национальный турнир — Латвийская высшая хоккейная лига , проводится с 1931 года. Чемпионат мира по хоккею с шайбой 2006 года проходил в Риге.

Второй по популярности вид спорта – баскетбол. Латвия имеет давнюю баскетбольную традицию: сборная Латвии по баскетболу выиграла первый в истории Евробаскет в 1935 году и серебряные медали в 1939 году , проиграв в финале Литве с разницей в одно очко. В Латвии было много звезд европейского баскетбола, таких как Янис Круминьш , Майгонис Валдманис , Валдис Муйжниекс , Валдис Валтерс , Игорь Миглиниекс , а также первый латвийский НБА игрок Гундарс Ветра . Андрис Биедриньш — один из самых известных латвийских баскетболистов, выступавший в НБА за команды « Голден Стэйт Уорриорз» и « Юта Джаз» . В число нынешних НБА игроков входят Кристапс Порзиньгис , который играет за « Бостон Селтикс» , Давис Бертанс , который играет за « Оклахома-Сити Тандер» , и Родионс Куруц , который в последний раз играл за « Милуоки Бакс» . Бывший латвийский баскетбольный клуб «Ригас АСК» выигрывал турнир Евролиги трижды подряд , прежде чем прекратил свое существование. В настоящее время ВЭФ Рига , выступающий в Еврокубке , является сильнейшим профессиональным баскетбольным клубом Латвии. БК Вентспилс , который участвует в EuroChallenge , является вторым сильнейшим баскетбольным клубом Латвии, ранее выигрывавшим LBL восемь раз и BBL в 2013 году. [ нужна ссылка ] Латвия была одной из принимающих сторон Евробаскета-2015 и снова станет одной из принимающих стран в 2025 году .

Другие популярные виды спорта включают футбол , флорбол , теннис, волейбол, езду на велосипеде, бобслей и скелетон . был , в котором участвовала сборная Латвии по футболу, Единственным крупным турниром ФИФА чемпионат Европы УЕФА 2004 года . [268]

Латвия успешно участвовала как в зимних , так и в летних Олимпийских играх . Самым успешным олимпийским спортсменом в истории независимой Латвии был Марис Штромбергс , который стал двукратным олимпийским чемпионом в 2008 и 2012 годах в мужском BMX. [269]

В боксе Майрис Бриедис на сегодняшний день является первым и единственным латвийцем, выигравшим титул чемпиона мира по боксу, обладателем титула WBC в тяжелом весе с 2017 по 2018 год, титула WBO в тяжелом весе в 2019 году и титулов IBF / журнала The Ring в тяжелом весе в 2020 году. .

В 2017 году латвийская теннисистка Елена Остапенко выиграла Открытый чемпионат Франции по теннису в одиночном разряде среди женщин , став первой незасеянной теннисисткой, сделавшей это в открытую эпоху.

По футзалу Латвия примет Евро-2026 по футзалу вместе с Литвой, их национальная сборная дебютирует в качестве соорганизатора.

Примечания

- ^ Не считая латгальского и жемайтийского языков , которые по некоторым данным являются отдельными языками.

Ссылки

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Департамент социальной статистики Латвии. «Этнический состав постоянных жителей районов и городов республики на начало года» . Архивировано из оригинала 28 сентября 2023 года . Проверено 8 ноября 2021 г.

- ^ «Латвия» . Архивировано из оригинала 28 января 2023 года . Проверено 15 октября 2022 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Германис, Улдис (2007). Оярс Калниньш (ред.). Латышская сага (11-е изд.). Рига: Афина. Мистер. 268. ИСБН 9789984342917 . OCLC 213385330 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «История» . Посольство Финляндии, Рига. 9 июля 2008 года. Архивировано из оригинала 11 мая 2011 года . Проверено 2 сентября 2010 г.

Латвия провозгласила независимость 21 августа 1991 года... Решение о восстановлении дипломатических отношений вступило в силу 29 августа 1991 года.

- ^ «Поверхностные воды и изменение поверхностных вод» . Организация экономического сотрудничества и развития (ОЭСР). Архивировано из оригинала 24 марта 2021 года . Проверено 11 октября 2020 г.

- ^ «Латвия» . Всемирная книга фактов (изд. 2024 г.). Центральное разведывательное управление . Проверено 24 сентября 2022 г. (Архивное издание 2022 г.)

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д «База данных «Перспективы развития мировой экономики», выпуск за апрель 2024 г. (Латвия)» . МВФ.org . Международный валютный фонд . 10 апреля 2024 г. Проверено 14 июля 2024 г.

- ^ «Коэффициент Джини эквивалентного располагаемого дохода» . Евростат . Архивировано из оригинала 9 октября 2020 года . Проверено 22 июня 2022 г.

- ^ «Отчет о человеческом развитии 2023/24» (PDF) . Программа развития ООН . 13 марта 2024 г. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 13 марта 2024 г. . Проверено 13 марта 2024 г.

- ^ «Конституция Латвийской Республики, глава 1 (статья 4)» . Парламент Латвийской Республики. Архивировано из оригинала 5 декабря 2013 года . Проверено 20 ноября 2013 г.

- ^ «Закон об официальном языке, раздел 3 (статья 1)» . Парламент Латвийской Республики. Архивировано из оригинала 4 января 2014 года . Проверено 20 ноября 2013 г.

- ^ «Закон об официальном языке, разделы 4, 5 и 18 (статья 4)» . Ликуми.lv. Архивировано из оригинала 5 июля 2019 года . Проверено 7 октября 2019 г.

- ^ «Закон об официальном языке, раздел 3 (статьи 3 и 4)» . Парламент Латвийской Республики. Архивировано из оригинала 4 января 2014 года . Проверено 20 ноября 2013 г.

- ^ Латгальский : Latveja ; Ливонский : Leōmō

- ^ «Конституция Латвийской Республики (Latvijas Republikas Satversme)» . Ликуми.lv . Архивировано из оригинала 17 апреля 2021 года . Проверено 18 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ (латышский: Латвийская Республика , латгальский: Латвийская Республика , ливонский :

- ^ «Информация о погоде в Латвии» . www.travelsignposts.com. 14 марта 2015 г. Архивировано из оригинала 2 апреля 2015 г. Проверено 14 марта 2015 г.

- ^ https://eng.lsm.lv/article/society/society/24.10.2023-latvian-is-the-mother-tongue-of-64-of-the-population-of-latvia.a528983/#:~ :text=Латвийские%20 и %20Российские%20 являются %20, для %208.4%20%25%20%20%20населения .

- ^ «История Латвии 1918-1940 гг.» . [Latvia.eu] . 3 декабря 2015 года. Архивировано из оригинала 8 июня 2021 года . Проверено 28 января 2021 г.