Guatemala

Republic of Guatemala República de Guatemala (Spanish) | |

|---|---|

| Motto: Libre crezca fecundo[1] (Spanish) "Grow Free and Fecund" | |

| Anthem: Himno Nacional de Guatemala (English: "National Anthem of Guatemala")Duration: 1 minute and 38 seconds. | |

| March: La Granadera (English: "The Song of the Grenadier") | |

| Capital and largest city | Guatemala City 14°38′N 90°30′W / 14.633°N 90.500°W |

| Official languages | Spanish |

| Recognised national languages | Mayan |

| Recognised regional languages | |

| Ethnic groups (2018[2]) | |

| Religion (2017)[3] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Guatemalan Chapín |

| Government | Unitary presidential republic |

| Bernardo Arévalo | |

| Karin Herrera | |

| Nery Ramos | |

| Legislature | Congress of the Republic |

| Independence | |

• Declared from the Spanish Empire | 15 September 1821 |

• Declared from the First Mexican Empire | 1 July 1823 |

• Declared from the Federal Republic of Central America | 17 April 1839 |

• Current constitution | 31 May 1985 |

| Area | |

• Total | 108,889 km2 (42,042 sq mi) (105th) |

• Water (%) | 0.4 |

| Population | |

• 2023 estimate | 17,980,803[4] (70th) |

• Density | 129/km2 (334.1/sq mi) (85th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2014) | 48.3[6] high inequality |

| HDI (2022) | medium (136th) |

| Currency | Quetzal (GTQ) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +502 |

| ISO 3166 code | GT |

| Internet TLD | .gt |

Guatemala,[a] officially the Republic of Guatemala,[b] is a country in Central America. It is bordered to the north and west by Mexico, to the northeast by Belize, to the east by Honduras, and to the southeast by El Salvador. It is hydrologically bordered to the south by the Pacific Ocean and to the northeast by the Gulf of Honduras.

The territory of modern Guatemala hosted the core of the Maya civilization, which extended across Mesoamerica; in the 16th century, most of this was conquered by the Spanish and claimed as part of the viceroyalty of New Spain. Guatemala attained independence from Spain and Mexico in 1821. From 1823 to 1841, it was part of the Federal Republic of Central America. For the latter half of the 19th century, Guatemala suffered instability and civil strife. From the early 20th century, it was ruled by a series of dictators backed by the United States. In 1944, authoritarian leader Jorge Ubico was overthrown by a pro-democratic military coup, initiating a decade-long revolution that led to social and economic reforms. In 1954, a US-backed military coup ended the revolution and installed a dictatorship.[8] From 1960 to 1996, Guatemala endured a bloody civil war fought between the US-backed government and leftist rebels, including genocidal massacres of the Maya population perpetrated by the Guatemalan military.[9][10][11] The United Nations negotiated a peace accord, resulting in economic growth and successive democratic elections.

Guatemala's abundance of biologically significant and unique ecosystems includes many endemic species and contributes to Mesoamerica's designation as a biodiversity hotspot.[12] Although rich in export goods, around a quarter of the population (4.6 million) face food insecurity. Other extant major issues include poverty, crime, corruption, drug trafficking, and civil instability.

With an estimated population of around 17.6 million,[13][14] Guatemala is the most populous country in Central America, the 4th most populous country in North America and the 11th most populous country in the Americas. Its capital and largest city, Guatemala City, is the most populous city in Central America.

Etymology

[edit]The name "Guatemala" comes from the Nahuatl word Cuauhtēmallān, or "place of many trees", a derivative of the K'iche' Mayan word for "many trees"[15][16] or, perhaps more specifically, for the Cuate/Cuatli tree Eysenhardtia. This name was originally used by the Mexica to refer to the Kaqchikel city of Iximche, but was extended to refer to the whole country during the Spanish colonial period.[17][18]

History

[edit]Pre-Columbian

[edit]The first evidence of human habitation in Guatemala dates to 12,000 BC. Archaeological evidence, such as obsidian arrowheads found in various parts of the country, suggests a human presence as early as 18,000 BC.[19] There is archaeological proof that early Guatemalan settlers were hunter-gatherers. Maize cultivation had been developed by the people by 3500 BC.[20] Sites dating to 6500 BC have been found in the Quiché region in the Highlands, and Sipacate and Escuintla on the central Pacific coast.

Archaeologists divide the pre-Columbian history of Mesoamerica into the Preclassic period (3000 BC to 250 AD), the Classic period (250 to 900 AD), and the Postclassic period (900 to 1500 AD).[21] Until recently, the Preclassic was regarded by researchers as a formative period, in which the peoples typically lived in huts in small villages of farmers, with few permanent buildings. This notion has been challenged since the late 20th century by discoveries of monumental architecture from that period, such as the Mirador Basin cities of Nakbé, Xulnal, El Tintal, Wakná and El Mirador.

The Classic period of Mesoamerican civilization corresponds to the height of the Maya civilization. It is represented by countless sites throughout Guatemala, although the largest concentration is in Petén. This period is characterized by urbanisation, the emergence of independent city-states, and contact with other Mesoamerican cultures.[22]

This lasted until approximately 900 AD, when the Classic Maya civilization collapsed.[23] The Maya abandoned many of the cities of the central lowlands or were killed by a drought-induced famine.[23] The cause of the collapse is debated, but the drought theory is gaining currency, supported by evidence such as lakebeds, ancient pollen, and others.[23] A series of prolonged droughts in what is otherwise a seasonal desert is thought to have decimated the Maya, who relied on regular rainfall to support their dense population.[24]

The Post-Classic period is represented by regional kingdoms, such as the Itza, Kowoj, Yalain and Kejache in Petén, and the Mam, Ki'che', Kackchiquel, Chajoma, Tz'utujil, Poqomchi', Q'eqchi' and Ch'orti' peoples in the highlands. Their cities preserved many aspects of Maya culture.

The Maya civilization shares many features with other Mesoamerican civilizations due to the high degree of interaction and cultural diffusion that characterized the region. Advances such as writing, epigraphy, and the calendar did not originate with the Maya; however, their civilization fully developed them. Maya influence can be detected from Honduras, Belize, Guatemala, and Northern El Salvador to as far north as central Mexico, more than 1,000 km (620 mi) from the Maya area. Many outside influences are found in Maya art and architecture, which are thought to have resulted from trade and cultural exchange rather than direct external conquest.

Spanish era (1519–1821)

[edit]

After they arrived in the New World, the Spanish started several expeditions to Guatemala, beginning in 1519. Before long, Spanish contact resulted in an epidemic that devastated native populations. Hernán Cortés, who had led the Spanish conquest of Mexico, granted a permit to Captains Gonzalo de Alvarado and his brother, Pedro de Alvarado, to conquer this land. Alvarado at first allied himself with the Kaqchikel nation to fight against their traditional rivals the K'iche' (Quiché) nation. Alvarado later turned against the Kaqchikel, and eventually brought the entire region under Spanish domination.[26]

During the colonial period, Guatemala was an audiencia, a captaincy-general (Capitanía General de Guatemala) of Spain, and a part of New Spain (Mexico).[27] The first capital, Villa de Santiago de Guatemala (now known as Tecpan Guatemala), was founded on 25 July 1524 near Iximché, the Kaqchikel capital city. The capital was moved to Ciudad Vieja on 22 November 1527, as a result of a Kaqchikel attack on Villa de Santiago de Guatemala. Owing to its strategic location on the American Pacific Coast, Guatemala became a supplementary node to the Transpacific Manila Galleon trade connecting Latin America to Asia via the Spanish owned Philippines.[28]

On 11 September 1541, the new capital was flooded when the lagoon in the crater of the Agua Volcano collapsed due to heavy rains and earthquakes; the capital was then moved 6 km (4 mi) to Antigua in the Panchoy Valley, now a UNESCO World Heritage Site. This city was destroyed by several earthquakes in 1773–1774. The King of Spain authorized moving the capital to its current location in the Ermita Valley, which is named after a Catholic church dedicated to the Virgen del Carmen. This new capital was founded on 2 January 1776.

Independence and Central America (1821–1847)

[edit]

On 15 September 1821, Gabino Gainza Fernandez de Medrano and the Captaincy General of Guatemala, an administrative region of the Spanish Empire consisting of Chiapas, Guatemala, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Honduras, officially proclaimed its independence from Spain at a public meeting in Guatemala City. Independence from Spain was gained, and the Captaincy General of Guatemala joined the First Mexican Empire under Agustín de Iturbide.

Under the First Empire, Mexico reached its greatest territorial extent, stretching from northern California to the provinces of Central America (excluding Panama, which was then part of Colombia), which had not initially approved becoming part of the Mexican Empire but joined the Empire shortly after their independence. This region was formally a part of the Viceroyalty of New Spain throughout the colonial period, but as a practical matter had been administered separately. It was not until 1825 that Guatemala created its own flag.[29]

In 1838 the liberal forces of Honduran leader Francisco Morazán and Guatemalan José Francisco Barrundia invaded Guatemala and reached San Sur, where they executed Chúa Alvarez, father-in-law of Rafael Carrera, then a military commander and later the first president of Guatemala. The liberal forces impaled Alvarez's head on a pike as a warning to followers of the Guatemalan caudillo.[30] Carrera and his wife Petrona – who had come to confront Morazán as soon as they learned of the invasion and were in Mataquescuintla – swore they would never forgive Morazán even in his grave; they felt it impossible to respect anyone who would not avenge family members.[31]

After sending several envoys, whom Carrera would not receive – and especially not Barrundia whom Carrera did not want to murder in cold blood – Morazán began a scorched-earth offensive, destroying villages in his path and stripping them of assets. The Carrera forces had to hide in the mountains.[32] Believing Carrera totally defeated, Morazán and Barrundia marched to Guatemala City, and were welcomed as saviors by state governor Pedro Valenzuela and members of the conservative Aycinena clan, who proposed to sponsor one of the liberal battalions, while Valenzuela and Barrundia gave Morazán all the Guatemalan resources needed to solve any financial problem he had.[33] The criollos of both parties celebrated until dawn that they finally had a criollo caudillo like Morazán, who was able to crush the peasant rebellion.[34]

Morazán used the proceeds to support Los Altos and then replaced Valenzuela with Mariano Rivera Paz, a member of the Aycinena clan, although he did not return to that clan any property confiscated in 1829. In revenge, Juan José de Aycinena y Piñol voted to dissolve the Central American Federation in San Salvador a little later, forcing Morazán to return to El Salvador to fight for his federal mandate. Along the way, Morazán increased repression in eastern Guatemala, as punishment for helping Carrera.[35] Knowing that Morazán had gone to El Salvador, Carrera tried to take Salamá with the small force that remained, but was defeated, and lost his brother Laureano in combat. With just a few men left, he managed to escape, badly wounded, to Sanarate.[36] After recovering somewhat, he attacked a detachment in Jutiapa and got a small amount of booty which he gave to the volunteers who accompanied him. He then prepared to attack Petapa near Guatemala City, where he was victorious, although with heavy casualties.[37]

In September of that year, Carrera attempted an assault on the capital of Guatemala, but the liberal general Carlos Salazar Castro defeated him in the fields of Villa Nueva and Carrera had to retreat.[38] After unsuccessfully trying to take Quetzaltenango, Carrera found himself both surrounded and wounded. He had to capitulate to Mexican General Agustín Guzmán, who had been in Quetzaltenango since Vicente Filísola's arrival in 1823. Morazán had the opportunity to shoot Carrera, but did not, because he needed the support of the Guatemalan peasants to counter the attacks of Francisco Ferrera in El Salvador. Instead, Morazán left Carrera in charge of a small fort in Mita, without any weapons. Knowing that Morazán was going to attack El Salvador, Francisco Ferrera gave arms and ammunition to Carrera and convinced him to attack Guatemala City.[39]

Meanwhile, despite insistent advice to definitively crush Carrera and his forces, Salazar tried to negotiate with him diplomatically; he even went as far as to show that he neither feared nor distrusted Carrera by removing the fortifications of the Guatemalan capital, in place since the battle of Villa Nueva.[38] Taking advantage of Salazar's good faith and Ferrera's weapons, Carrera took Guatemala City by surprise on 13 April 1839; Salazar, Mariano Gálvez and Barrundia fled before the arrival of Carrera's militiamen. Salazar, in his nightshirt, vaulted roofs of neighboring houses and sought refuge,[40][41] reaching the border disguised as a peasant.[40][41] With Salazar gone, Carrera reinstated Rivera Paz as head of state.

Between 1838 and 1840 a secessionist movement in the city of Quetzaltenango founded the breakaway state of Los Altos and sought independence from Guatemala. The most important members of the Liberal Party of Guatemala and liberal enemies of the conservative régime moved to Los Altos, leaving their exile in El Salvador.[42] The liberals in Los Altos began severely criticizing the Conservative government of Rivera Paz.[42] Los Altos was the region with the main production and economic activity of the former state of Guatemala. Without Los Altos, conservatives lost many of the resources that had given Guatemala hegemony in Central America.[42] The government of Guatemala tried to reach a peaceful solution, but two years of bloody conflict followed.

On 17 April 1839, Guatemala declared itself independent from the United Provinces of Central America. In 1840, Belgium began to act as an external source of support for Carrera's independence movement, in an effort to exert influence in Central America. The Compagnie belge de colonisation (Belgian Colonization Company), commissioned by Belgian King Leopold I, became the administrator of Santo Tomas de Castilla[43] replacing the failed British Eastern Coast of Central America Commercial and Agricultural Company.[43] Even though the colony eventually crumbled, Belgium continued to support Carrera in the mid-19th century, although Britain continued to be the main business and political partner to Carrera.[44] Rafael Carrera was elected Guatemalan Governor in 1844.

Republic

[edit]On 21 March 1847, Guatemala declared itself an independent republic and Carrera became its first president.

Carrera government (1847–1851)

[edit]During the first term as president, Carrera brought the country back from extreme conservatism to a traditional moderation; in 1848, the liberals were able to drive him from office, after the country had been in turmoil for several months.[45][46] Carrera resigned of his own free will and left for México. The new liberal regime allied itself with the Aycinena family and swiftly passed a law ordering Carrera's execution if he returned to Guatemalan soil.[45]

The liberal criollos from Quetzaltenango were led by general Agustín Guzmán who occupied the city after Corregidor general Mariano Paredes was called to Guatemala City to take over the presidential office.[47] They declared on 26 August 1848 that Los Altos was an independent state once again. The new state had the support of Doroteo Vasconcelos' régime in El Salvador and the rebel guerrilla army of Vicente and Serapio Cruz, who were sworn enemies of Carrera.[48] The interim government was led by Guzmán himself and had Florencio Molina and the priest Fernando Davila as his Cabinet members.[49] On 5 September 1848, the criollos altenses chose a formal government led by Fernando Antonio Martínez.

In the meantime, Carrera decided to return to Guatemala and did so, entering at Huehuetenango, where he met with native leaders and told them that they must remain united to prevail; the leaders agreed and slowly the segregated native communities started developing a new Indian identity under Carrera's leadership.[50] In the meantime, in the eastern part of Guatemala, the Jalapa region became increasingly dangerous; former president Mariano Rivera Paz and rebel leader Vicente Cruz were both murdered there after trying to take over the Corregidor office in 1849.[50]

When Carrera arrived to Chiantla in Huehuetenango, he received two altenses emissaries who told him that their soldiers were not going to fight his forces because that would lead to a native revolt, much like that of 1840; their only request from Carrera was to keep the natives under control.[50] The altenses did not comply, and led by Guzmán and his forces, they started chasing Carrera; the caudillo hid, helped by his native allies and remained under their protection when the forces of Miguel Garcia Granados arrived from Guatemala City looking for him.[50]

On learning that officer José Víctor Zavala had been appointed as Corregidor in Suchitepéquez, Carrera and his hundred jacalteco bodyguards crossed a dangerous jungle infested with jaguars to meet his former friend. Zavala not only did not capture him, he agreed to serve under his orders, thus sending a strong message to both liberal and conservatives in Guatemala City that they would have to negotiate with Carrera or battle on two fronts – Quetzaltenango and Jalapa.[51] Carrera went back to the Quetzaltenango area, while Zavala remained in Suchitepéquez as a tactical maneuver.[52] Carrera received a visit from a cabinet member of Paredes and told him that he had control of the native population and that he assured Paredes that he would keep them appeased.[51] When the emissary returned to Guatemala City, he told the president everything Carrera said, and added that the native forces were formidable.[53]

Guzmán went to Antigua to meet with another group of Paredes emissaries; they agreed that Los Altos would rejoin Guatemala, and that the latter would help Guzmán defeat his enemy and also build a port on the Pacific Ocean.[53] Guzmán was sure of victory this time, but his plan evaporated when in his absence Carrera and his native allies occupied Quetzaltenango; Carrera appointed Ignacio Yrigoyen as Corregidor and convinced him that he should work with the K'iche', Q'anjobal and Mam leaders to keep the region under control.[54] On his way out, Yrigoyen murmured to a friend: "Now he is the king of the Indians, indeed!"[54]

Guzmán then left for Jalapa, where he struck a deal with the rebels, while Luis Batres Juarros convinced President Paredes to deal with Carrera. Back in Guatemala City within a few months, Carrera was commander-in-chief, backed by military and political support of the Indian communities from the densely populated western highlands.[55] During the first presidency, from 1844 to 1848, he brought the country back from excessive conservatism to a moderate regime, and – with the advice of Juan José de Aycinena y Piñol and Pedro de Aycinena – restored relations with the Church in Rome with a Concordat ratified in 1854.[56]

Second Carrera government (1851–1865)

[edit]

After Carrera returned from exile in 1849 the president of El Salvador, Doroteo Vasconcelos, granted asylum to the Guatemalan liberals, who harassed the Guatemalan government in several different ways. José Francisco Barrundia established a liberal newspaper for that specific purpose. Vasconcelos supported a rebel faction named "La Montaña" in eastern Guatemala, providing and distributing money and weapons. By late 1850, Vasconcelos was getting impatient at the slow progress of the war with Guatemala and decided to plan an open attack. Under that circumstance, the Salvadorean head of state started a campaign against the conservative Guatemalan regime, inviting Honduras and Nicaragua to participate in the alliance; only the Honduran government led by Juan Lindo accepted.[45] In 1851 Guatemala defeated an Allied army from Honduras and El Salvador at the Battle of La Arada.

In 1854 Carrera was declared "supreme and perpetual leader of the nation" for life, with the power to choose his successor. He held that position until he died on 14 April 1865. While he pursued some measures to set up a foundation for economic prosperity to please the conservative landowners, military challenges at home and a three-year war with Honduras, El Salvador, and Nicaragua dominated his presidency.

His rivalry with Gerardo Barrios, President of El Salvador, resulted in open war in 1863. At Coatepeque the Guatemalans suffered a severe defeat, which was followed by a truce. Honduras joined with El Salvador, and Nicaragua and Costa Rica with Guatemala. The contest was finally settled in favor of Carrera, who besieged and occupied San Salvador, and dominated Honduras and Nicaragua. He continued to act in concert with the Clerical Party, and tried to maintain friendly relations with European governments. Before he died, Carrera nominated his friend and loyal soldier, Army Marshall Vicente Cerna y Cerna, as his successor.

Vicente Cerna y Cerna regime (1865–1871)

[edit]

Vicente Cerna y Cerna was president of Guatemala from 24 May 1865 to 29 June 1871.[57] Liberal author Alfonso Enrique Barrientos,[58] described Marshall Cerna's government in the following manner:[58]

A conservative and archaic government, badly organized and with worse intentions, was in charge of the country, centralizing all powers in Vicente Cerna, ambitious military man, who not happy with the general rank, had promoted himself to the Army Marshall rank, even though that rank did not exist and it does not exist in the Guatemalan military. The Marshall called himself President of the Republic, but in reality he was the foreman of oppressed and savaged people, cowardly enough that they had not dared to tell the dictator to leave threatening him with a revolution.

The State and Church were a single unit, and the conservative régime was strongly allied to the power of regular clergy of the Catholic Church, who were then among the largest landowners in Guatemala. The tight relationship between church and state had been ratified by the Concordat of 1852, which was the law until Cerna was deposed in 1871.[59] Even liberal generals like Serapio Cruz realized that Rafael Carrera's political and military presence made him practically invincible. Thus the generals fought under his command,[45] and waited—for a long time—until Carrera's death before beginning their revolt against the tamer Cerna.[60] During Cerna's presidency, liberal party members were prosecuted and sent into exile; among them, those who started the Liberal Revolution of 1871.[45]

In 1871, the merchants guild, Consulado de Comercio, lost their exclusive court privilege. They had major effects on the economics of the time, and therefore land management. From 1839 to 1871, the Consulado held a consistent monopolistic position in the regime.[61]

Liberal governments (1871–1898)

[edit]Guatemala's "Liberal Revolution" came in 1871 under the leadership of Justo Rufino Barrios, who worked to modernize the country, improve trade, and introduce new crops and manufacturing. During this era coffee became an important crop for Guatemala.[62] Barrios had ambitions of reuniting Central America and took the country to war in an unsuccessful attempt to attain it, losing his life on the battlefield in 1885 against forces in El Salvador.

Manuel Barillas was president from 16 March 1886 to 15 March 1892. Manuel Barillas was unique among liberal presidents of Guatemala between 1871 and 1944: he handed over power to his successor peacefully. When election time approached, he sent for the three Liberal candidates to ask them what their government plan would be.[63] Happy with what he heard from general Reyna Barrios,[63] Barillas made sure that a huge column of Quetzaltenango and Totonicapán indigenous people came down from the mountains to vote for him. Reyna was elected president. [64]

José María Reina Barrios was president between 1892 and 1898. During Barrios's first term in office, the power of the landowners over the rural peasantry increased. He oversaw the rebuilding of parts of Guatemala City on a grander scale, with wide, Parisian-style avenues. He oversaw Guatemala hosting the first "Exposición Centroamericana" ("Central American Fair") in 1897. During his second term, Barrios printed bonds to fund his ambitious plans, fueling monetary inflation and the rise of popular opposition to his regime.

His administration also worked on improving the roads, installing national and international telegraphs and introducing electricity to Guatemala City. Completing a transoceanic railway was a main objective of his government, with a goal to attract international investors at a time when the Panama Canal was not yet built.

Manuel Estrada Cabrera regime (1898–1920)

[edit]

After the assassination of general José María Reina Barrios on 8 February 1898, the Guatemalan cabinet called an emergency meeting to appoint a new successor, but declined to invite Estrada Cabrera to the meeting, even though he was the designated successor to the presidency. There are two different descriptions of how Cabrera was able to become president. The first states that Cabrera entered the cabinet meeting "with pistol drawn" to assert his entitlement to the presidency,[65] while the second states that he showed up unarmed to the meeting and demanded the presidency by virtue of being the designated successor.[66]

The first civilian Guatemalan head of state in over 50 years, Estrada Cabrera overcame resistance to his regime by August 1898 and called for elections in September, which he won handily.[67] In 1898 the legislature convened for the election of President Estrada Cabrera, who triumphed thanks to the large number of soldiers and policemen who went to vote in civilian clothes and to the large number of illiterate family that they brought with them to the polls.[68]

One of Estrada Cabrera's most famous and most bitter legacies was allowing the entry of the United Fruit Company (UFCO) into the Guatemalan economic and political arena. As a member of the Liberal Party, he sought to encourage development of the nation's infrastructure of highways, railroads, and sea ports for the sake of expanding the export economy. By the time Estrada Cabrera assumed the presidency there had been repeated efforts to construct a railroad from the major port of Puerto Barrios to the capital, Guatemala City. Owing to lack of funding exacerbated by the collapse of the internal coffee trade, the railway fell 100 kilometres (60 mi) short of its goal. Estrada Cabrera decided, without consulting the legislature or judiciary, that striking a deal with the UFCO was the only way to finish the railway.[69] Cabrera signed a contract with UFCO's Minor Cooper Keith in 1904 that gave the company tax exemptions, land grants, and control of all railroads on the Atlantic side.[70]

In 1906 Estrada faced serious revolts against his rule; the rebels were supported by the governments of some of the other Central American nations, but Estrada succeeded in putting them down. Elections were held by the people against the will of Estrada Cabrera and thus he had the president-elect murdered in retaliation. In 1907 Estrada narrowly survived an assassination attempt when a bomb exploded near his carriage.[71] It has been suggested that the extreme despotic characteristics of Estrada did not emerge until after an attempt on his life in 1907.[72]

Guatemala City was badly damaged in the 1917 Guatemala earthquake.

Estrada Cabrera continued in power until forced to resign after new revolts in 1920. By that time his power had declined drastically and he was reliant upon the loyalty of a few generals. While the United States threatened intervention if he was removed through revolution, a bipartisan coalition came together to remove him from the presidency. He was removed from office after the national assembly charged that he was mentally incompetent, and appointed Carlos Herrera in his place on 8 April 1920.[73]

Guatemala joined with El Salvador and Honduras in the Federation of Central America from 9 September 1921 until 14 January 1922.

Carlos Herrera served as President of Guatemala from 1920 until 1921. He was succeeded by José María Orellana, who served from 1921 until 1926. Lázaro Chacón González then served until 1931.

Jorge Ubico regime (1931–1944)

[edit]

The Great Depression began in 1929 and badly damaged the Guatemalan economy, causing a rise in unemployment, and leading to unrest among workers and laborers. Afraid of a popular revolt, the Guatemalan landed elite lent their support to Jorge Ubico, who had become well known for "efficiency and cruelty" as a provincial governor. Ubico won the election that followed in 1931, in which he was the only candidate.[74][75] After his election his policies quickly became authoritarian. He replaced the system of debt peonage with a brutally enforced vagrancy law, requiring all men of working age who did not own land to work a minimum of 100 days of hard labor.[76] His government used unpaid Indian labor to build roads and railways. Ubico also froze wages at very low levels, and passed a law allowing land-owners complete immunity from prosecution for any action they took to defend their property,[76] an action described by historians as legalizing murder.[77] He greatly strengthened the police force, turning it into one of the most efficient and ruthless in Latin America.[78] He gave them greater authority to shoot and imprison people suspected of breaking the labor laws. These laws created tremendous resentment against him among agricultural laborers.[79] The government became highly militarized; under his rule, every provincial governor was a general in the army.[80]

Ubico continued his predecessor's policy of making massive concessions to the United Fruit Company, often at a cost to Guatemala. He granted the company 200,000 hectares (490,000 acres) of public land in exchange for a promise to build a port, a promise he later waived.[81] Since its entry into Guatemala, the UFCO had expanded its land-holdings by displacing farmers and converting their farmland to banana plantations. This process accelerated under Ubico's presidency, with the government doing nothing to stop it.[82] The company received import duty and real estate tax exemptions from the government and controlled more land than any other individual or group. It also controlled the sole railroad in the country, the sole facilities capable of producing electricity, and the port facilities at Puerto Barrios on the Atlantic coast.[83]

Ubico saw the United States as an ally against the supposed communist threat of Mexico, and made efforts to gain its support. When the US declared war against Germany in 1941, Ubico acted on American instructions and arrested all people in Guatemala of German descent.[84] He also permitted the US to establish an air base in Guatemala, with the stated aim of protecting the Panama Canal.[85] However, Ubico was an admirer of European fascists, such as Francisco Franco and Benito Mussolini,[86] and considered himself to be "another Napoleon".[87] He occasionally compared himself to Adolf Hitler.[88] He dressed ostentatiously and surrounded himself with statues and paintings of Napoleon, regularly commenting on the similarities between their appearances. He militarized numerous political and social institutions—including the post office, schools, and symphony orchestras—and placed military officers in charge of many government posts.[89][90][91][92][93]

Guatemalan Revolution (1944–1954)

[edit]On 1 July 1944 Ubico was forced to resign from the presidency in response to a wave of protests and a general strike inspired by brutal labor conditions among plantation workers.[94] His chosen replacement, General Juan Federico Ponce Vaides, was forced out of office on 20 October 1944 by a coup d'état led by Major Francisco Javier Arana and Captain Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán. About 100 people were killed in the coup. The country was then led by a military junta made up of Arana, Árbenz, and Jorge Toriello Garrido.[95]

The junta organized Guatemala's first free election, which the philosophically conservative writer and teacher Juan José Arévalo, who wanted to turn the country into a liberal capitalist society won with a majority of 86%.[96] His "Christian Socialist" policies were inspired to a large extent by the US New Deal of President Franklin D. Roosevelt during the Great Depression.[97] Arévalo built new health centers, increased funding for education, and drafted a more liberal labor law,[98] while criminalizing unions in workplaces with less than 500 workers,[99] and cracking down on communists.[100] Although Arévalo was popular among nationalists, he had enemies in the church and the military, and faced at least 25 coup attempts during his presidency.[101]

Arévalo was constitutionally prohibited from contesting the 1950 elections. The largely free and fair elections were won by Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán, Arévalo's defense minister.[102] Árbenz continued the moderate capitalist approach of Arévalo.[103] His most important policy was Decree 900, a sweeping agrarian reform bill passed in 1952.[104][105] Decree 900 transferred uncultivated land to landless peasants.[104] Only 1,710 of the nearly 350,000 private land-holdings were affected by the law,[106] which benefited approximately 500,000 individuals, or one-sixth of the population.[106]

Coup and civil war (1954–1996)

[edit]Despite their popularity within the country, the reforms of the Guatemalan Revolution were disliked by the United States government, which was predisposed by the Cold War to see it as communist, and by the UFCO, whose hugely profitable business had been affected by the end to brutal labor practices.[100][107] The attitude of the US government was also influenced by a propaganda campaign carried out by the UFCO.[108]

US President Harry Truman authorized Operation PBFortune to topple Árbenz in 1952, with the support of Nicaraguan dictator Anastasio Somoza García,[109] but the operation was aborted when too many details became public.[109][110] Dwight D. Eisenhower was elected US president in 1952, promising to take a harder line against communism; the close links that his staff members John Foster Dulles and Allen Dulles had to the UFCO also predisposed him to act against Árbenz.[111] Eisenhower authorized the CIA to carry out Operation PBSuccess in August 1953. The CIA armed, funded, and trained a force of 480 men led by Carlos Castillo Armas.[112][113] The force invaded Guatemala on 18 June 1954, backed by a heavy campaign of psychological warfare, including bombings of Guatemala City and an anti-Árbenz radio station claiming to be genuine news.[112] The invasion force fared poorly militarily, but the psychological warfare and the possibility of a US invasion intimidated the Guatemalan army, which refused to fight. Árbenz resigned on 27 June.[114][115]

Following negotiations in San Salvador, Carlos Castillo Armas became president on 7 July 1954.[114] Elections were held in early October, from which all political parties were barred from participating. Castillo Armas was the only candidate and won the election with 99% of the vote.[114] Castillo Armas reversed Decree 900 and ruled until 26 July 1957, when he was assassinated by Romeo Vásquez, a member of his personal guard. After the rigged[97] election that followed, General Miguel Ydígoras Fuentes assumed power. He is celebrated for challenging the Mexican president to a gentleman's duel on the bridge on the south border to end a feud on the subject of illegal fishing by Mexican boats on Guatemala's Pacific coast, two of which were sunk by the Guatemalan Air Force. Ydigoras authorized the training of 5,000 anti-Castro Cubans in Guatemala. He also provided airstrips in the region of Petén for what later became the US-sponsored, failed Bay of Pigs Invasion in 1961.

On 13 November 1960, a group of left-wing junior military officers of the Escuela Politécnica national military academy led a failed revolt against Ydigoras' government. The rebels fled to the mountains of eastern Guatemala and neighboring Honduras and formed MR-13 (Movimiento Revolucionario 13 Noviembre). On 6 February 1962, in Bananera, they attacked the offices of the United Fruit Company. The attack sparked sympathetic strikes and university student walkouts throughout the country, to which the government responded with a violent crackdown.[116]

In 1963, Ydígoras, despite the firm opposition of the Kennedy administration, had pledged to allow Arévalo return from exile and run in a free and open election. Arévalo returned on 27 March 1963 to announce his candidacy for the scheduled November presidential elections, however Ydigoras' government was ousted on March 31, 1963, when the Guatemalan Air Force attacked several military bases; the coup was led by his Defense Minister, Colonel Enrique Peralta Azurdia.[117] The new régime intensified its counterinsurgency campaign against the guerrillas that had begun under Ydígoras-Fuentes.[118]

In 1966, Julio César Méndez Montenegro was elected president of Guatemala under the banner "Democratic Opening". Mendez Montenegro was the candidate of the Revolutionary Party, a center-left party that had its origins in the post-Ubico era. During this time, rightist paramilitary organizations, such as the "White Hand" (Mano Blanca), and the Anticommunist Secret Army (Ejército Secreto Anticomunista) were formed. Those groups were the forerunners of the infamous "Death Squads". Military advisers from the United States Army Special Forces (Green Berets) were sent to Guatemala to train Guatemala's armed forces and help transform it into a modern counter-insurgency force, which eventually made it the most sophisticated in Central America.[119]

In 1970, Colonel Carlos Manuel Arana Osorio was elected president. By 1972, members of the guerrilla movement entered the country from Mexico and settled in the Western Highlands. In the disputed election of 1974, General Kjell Laugerud García defeated General Efraín Ríos Montt, a candidate of the Christian Democratic Party, who claimed that he had been cheated out of a victory through fraud.

On 4 February 1976, a major earthquake destroyed several cities and caused more than 25,000 deaths, especially among the poor, whose housing was substandard. The government's failure to respond rapidly to the aftermath of the earthquake and to relieve homelessness gave rise to widespread discontent, which contributed to growing popular unrest. General Romeo Lucas García assumed power in 1978 in a fraudulent election.

The 1970s saw the rise of two new guerrilla organizations, the Guerrilla Army of the Poor (EGP) and the Organization of the People in Arms (ORPA). They began guerrilla attacks that included urban and rural warfare, mainly against the military and some civilian supporters of the army. The army and the paramilitary forces responded with a brutal counter-insurgency campaign that resulted in tens of thousands of civilian deaths.[120] In 1979, US President Jimmy Carter, who had until then been providing public support for the government forces, ordered a ban on all military aid to the Guatemalan Army because of its widespread and systematic abuse of human rights.[97] However, documents have since come to light that suggest that American aid continued throughout the Carter years, through clandestine channels.[121]

On 31 January 1980, a group of indigenous K'iche' took over the Spanish Embassy to protest army massacres in the countryside. The Guatemalan government armed forces launched an assault that killed almost everyone inside in a fire that consumed the building. The Guatemalan government claimed that the activists set the fire, thus immolating themselves.[122] However the Spanish ambassador survived the fire and disputed this claim, saying that the Guatemalan police intentionally killed almost everyone inside and set the fire to erase traces of their acts. As a result, the government of Spain broke off diplomatic relations with Guatemala.

This government was overthrown in 1982 and General Efraín Ríos Montt was named president of the military junta. He continued the bloody campaign of torture, forced disappearances, and "scorched earth" warfare. The country became a pariah state internationally, although the regime received considerable support from the Reagan Administration,[123] and Reagan himself described Ríos Montt as "a man of great personal integrity."[124] Ríos Montt was overthrown by General Óscar Humberto Mejía Victores, who called for an election of a national constituent assembly to write a new constitution, leading to a free election in 1986, won by Vinicio Cerezo Arévalo, the candidate of the Christian Democracy Party.

In 1982, the four guerrilla groups, EGP, ORPA, FAR and PGT, merged and formed the URNG, influenced by the Salvadoran guerrilla FMLN, the Nicaraguan FSLN and Cuba's government, in order to become stronger. As a result of the Army's "scorched earth" tactics in the countryside, more than 45,000 Guatemalans fled across the border to Mexico. The Mexican government placed the refugees in camps in Chiapas and Tabasco.

In 1992, the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to Rigoberta Menchú for her efforts to bring international attention to the government-sponsored genocide against the indigenous population.[125]

1996–2000

[edit]

The Guatemalan Civil War ended in 1996 with a peace accord between the guerrillas and the government, negotiated by the United Nations through intense brokerage by nations such as Norway and Spain. Both sides made major concessions. The guerrilla fighters disarmed and received land to work. According to the U.N.-sponsored truth commission (the Commission for Historical Clarification), government forces and state-sponsored, CIA-trained paramilitaries were responsible for over 93% of the human rights violations during the war.[126]

In the last few years, millions of documents related to crimes committed during the civil war have been found abandoned by the former Guatemalan police. The families of over 45,000 Guatemalan activists who disappeared during the civil war are now reviewing the documents, which have been digitized. This could lead to further legal actions.[127]

During the first ten years of the civil war, the victims of the state-sponsored terror were primarily students, workers, professionals, and opposition figures, but in the last years they were thousands of mostly rural Maya farmers and non-combatants. More than 450 Maya villages were destroyed and over 1 million people became refugees or displaced within Guatemala.

In 1995, the Catholic Archdiocese of Guatemala began the Recovery of Historical Memory (REMHI) project,[128] known in Spanish as "El Proyecto de la Recuperación de la Memoria Histórica", to collect the facts and history of Guatemala's long civil war and confront the truth of those years. On 24 April 1998, REMHI presented the results of its work in the report "Guatemala: Nunca Más!". This report summarized testimony and statements of thousands of witnesses and victims of repression during the Civil War. "The report laid the blame for 80 per cent of the atrocities at the door of the Guatemalan Army and its collaborators within the social and political elite."[129]

Catholic Bishop Juan José Gerardi Conedera worked on the Recovery of Historical Memory Project and two days after he announced the release of its report on victims of the Guatemalan Civil War, "Guatemala: Nunca Más!", in April 1998, Bishop Gerardi was attacked in his garage and beaten to death.[129] In 2001, in the first trial in a civilian court of members of the military in Guatemalan history, three Army officers were convicted of his death and sentenced to 30 years in prison. A priest was convicted as an accomplice and was sentenced to 20 years in prison.[130]

According to the report, Recuperación de la Memoria Histórica (REMHI), some 200,000 people died. More than one million people were forced to flee their homes and hundreds of villages were destroyed. The Historical Clarification Commission attributed more than 93% of all documented violations of human rights to Guatemala's military government, and estimated that Maya Indians accounted for 83% of the victims. It concluded in 1999 that state actions constituted genocide.[131][132]

In some areas such as Baja Verapaz, the Truth Commission found that the Guatemalan state engaged in an intentional policy of genocide against particular ethnic groups in the Civil War.[126] In 1999, US President Bill Clinton said that the US had been wrong to have provided support to the Guatemalan military forces that took part in these brutal civilian killings.[133]

Since 2000

[edit]Since the peace accords Guatemala has had both economic growth and successive democratic elections, most recently in 2019. In the 2019 elections, Alejandro Giammattei won the presidency. He assumed office in January 2020.

In January 2012 Efrain Rios Montt, the former dictator of Guatemala, appeared in a Guatemalan court on genocide charges. During the hearing, the government presented evidence of over 100 incidents involving at least 1,771 deaths, 1,445 rapes, and the displacement of nearly 30,000 Guatemalans during his 17-month rule from 1982 to 1983. The prosecution wanted him incarcerated because he was viewed as a flight risk but he remained free on bail, under house arrest and guarded by the Guatemalan National Civil Police (PNC). On 10 May 2013, Rios Montt was found guilty and sentenced to 80 years in prison. It marked the first time that a national court had found a former head of state guilty of genocide.[134] The conviction was later overturned, and Montt's trial resumed in January 2015.[135] In August 2015, a Guatemalan court ruled that Rios Montt could stand trial for genocide and crimes against humanity, but that he could not be sentenced due to his age and deteriorating health.[136]

Ex-President Alfonso Portillo was arrested in January 2010 while trying to flee Guatemala. He was acquitted in May 2010, by a panel of judges that threw out some of the evidence and discounted certain witnesses as unreliable.[137] The Guatemalan Attorney-General, Claudia Paz y Paz, called the verdict "a terrible message of injustice," and "a wake up call about the power structures." In its appeal, the International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG), a UN judicial group assisting the Guatemalan government, called the decision's assessment of the meticulously documented evidence against Portillo Cabrera "whimsical" and said the decision's assertion that the president of Guatemala and his ministers had no responsibility for handling public funds ran counter to the constitution and laws of Guatemala.[138] A New York grand jury had indicted Portillo Cabrera in 2009 for embezzlement; following his acquittal on those charges in Guatemala that country's Supreme Court authorized his extradition to the US.[139][140] The Guatemalan judiciary is deeply corrupt and the selection committee for new nominations has been captured by criminal elements.[137]

At the 2012 Summer Olympics in London, Guatemala received its first-ever Olympic medal when Erick Barrondo won the men's 20 kilometre walk.[141]

Pérez Molina government and "La Línea"

[edit]

Retired general Otto Pérez Molina was elected president in 2011 along with Roxana Baldetti, the first woman ever elected vice-president in Guatemala; they began their term in office on 14 January 2012.[142] But on 16 April 2015, a United Nations (UN) anti-corruption agency report implicated several high-profile politicians including Baldetti's private secretary, Juan Carlos Monzón, and the director of the Guatemalan Internal Revenue Service (SAT).[who?][143] The revelations provoked more public outrage than had been seen since the presidency of General Kjell Eugenio Laugerud García. The International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG) worked with the Guatemalan attorney-general to reveal the scam known as "La Línea", following a year-long investigation that included wire taps.

Officials received bribes from importers in exchange for discounted import tariffs,[143] a practice rooted in a long tradition of customs corruption in the country, as a fund-raising tactic of successive military governments for counterinsurgency operations during Guatemala's 36-year-long civil war.[144][145]

A Facebook event using the hashtag #RenunciaYa (Resign Now) invited citizens to go downtown in Guatemala City to ask for Baldetti's resignation. Within days, over 10,000 people RSVPed that they would attend. Organizers made clear that no political party or group was behind the event, and instructed protesters at the event to follow the law. They also urged people to bring water, food and sunblock, but not to cover their faces or wear political party colors.[146] Tens of thousands of people took to the streets of Guatemala City. They protested in front of the presidential palace. Baldetti resigned a few days later. She was forced to remain in Guatemala when the United States revoked her visa. The Guatemalan government arraigned her, since it had enough evidence to suspect her involvement in the "La Linea" scandal. The prominence of US Ambassador Todd Robinson in the Guatemalan political scene once the scandal broke led to the suspicion that the US government was behind the investigation, perhaps because it needed an honest government in Guatemala to counter the presence of China and Russia in the region.[147]

The UN anti-corruption committee has reported on other cases since then, and more than 20 government officials have stepped down. Some were arrested. Two of those cases involved two former presidential private secretaries: Juan de Dios Rodríguez in the Guatemalan Social Service and Gustave Martínez, who was involved in a bribery scandal at the coal power plant company. Jaguar Energy Martínez was also Perez Molina's son-in-law.[148]

Leaders of the political opposition have also been implicated in CICIG investigations: several legislators and members of Libertad Democrática Renovada party (LIDER) were formally accused of bribery-related issues, prompting a large decline in the electoral prospects of its presidential candidate, Manuel Baldizón, who until April had been almost certain to become the next Guatemalan president in the 6 September 2015 presidential elections. Baldizón's popularity steeply declined and he filed accusations with the Organization of American States against CICIG leader Iván Velásquez of international obstruction in Guatemalan internal affairs.[149]

CICIG reported its cases so often on Thursdays that Guatemalans coined the term "CICIG Thursdays". But a Friday press conference brought the crisis to its peak: on Friday 21 August 2015, the CICIG and Attorney General Thelma Aldana presented enough evidence to convince the public that both President Pérez Molina and former vice President Baldetti were the actual leaders of "La Línea". Baldetti was arrested the same day and an impeachment was requested for the president. Several cabinet members resigned and the clamor for the president's resignation grew after Perez Molina defiantly assured the nation in a televised message broadcast on 23 August 2015 that he was not going to resign.[150][151]

Thousands of protesters took to the streets again, this time to demand the increasingly isolated president's resignation. Guatemala's Congress named a commission of five legislators to consider whether to remove the president's immunity from prosecution. The Supreme Court approved. A major day of action kicked off early on 27 August, with marches and roadblocks across the country. Urban groups who had spearheaded regular protests since the scandal broke in April, on the 27th sought to unite with the rural and indigenous organizations who orchestrated the road blocks.

The strike in Guatemala City was full of a diverse and peaceful crowd ranging from the indigenous poor to the well-heeled, and it included many students from public and private universities. Hundreds of schools and businesses closed in support of the protests. The Comité Coordinador de Asociaciones Agrícolas, Comerciales, Industriales y Financieras (CACIF) Guatemala's most powerful business leaders, issued a statement demanding that Pérez Molina step down, and urged Congress to withdraw his immunity from prosecution.[152]

The attorney general's office released its own statement, calling for the president's resignation "to prevent ungovernability that could destabilize the nation." As pressure mounted, the president's former ministers of defense and of the interior, who had been named in the corruption investigation and resigned, abruptly left the country.[153] Pérez Molina meanwhile had been losing support by the day. The private sector called for his resignation; however, he also managed to get support from entrepreneurs that were not affiliated with the private sector chambers: Mario López Estrada – grandchild of former dictator Manuel Estrada Cabrera and the billionaire owner of cellular phone companies – had some of his executives assume the vacated cabinet positions.[154]

The Guatemalan radio station Emisoras Unidas reported exchanging text messages with Perez Molina. Asked whether he planned to resign, he wrote: "I will face whatever is necessary to face, and what the law requires." Some protesters demanded the general election be postponed, both because of the crisis and because it was plagued with accusations of irregularities. Others warned that suspending the vote could lead to an institutional vacuum.[155] However, on 2 September 2015 Pérez Molina resigned, a day after Congress impeached him.[156][157] On 3 September 2015 he was summoned to the Justice Department for his first legal audience for the La Linea corruption case.[158][159]

In June 2016 a United Nations-backed prosecutor described the administration of Pérez Molina as a crime syndicate and outlined another corruption case, this one dubbed Cooperacha (Kick-in). The head of the Social Security Institute and at least five other ministers pooled funds to buy Molina luxurious gifts such as motorboats, spending over $4.7 million in three years.[160]

Jimmy Morales and Alejandro Giammattei in power (2016–2024)

[edit]In the October 2015 presidential election, former TV comedian Jimmy Morales was elected as the new president of Guatemala after huge anti-corruption demonstrations. He took office in January 2016.[161]

In December 2017, President Morales announced that Guatemala will move its embassy in Israel to Jerusalem, becoming the first nation to follow the United States.[162]

In January 2020, Alejandro Giammattei replaced Jimmy Morales as the president of Guatemala. Giammattei had won the presidential election in August 2019 with his "tough-on-crime" agenda.[163]

In November 2020, large protests and demonstrations occurred in Guatemala against President Alejandro Giammattei and the legislature, because of cutting educational and health spending.[164]

In August 2023, Bernardo Arévalo, the candidate of the centre-left Semilla (Seed) Movement, had a landslide victory in Guatemala's presidential election.[165]

Bernardo Arévalo and Movimiento Semilla (2024–present)

[edit]

Bernardo Arévalo is the son of the former president Juan José Arévalo, who was the first democratically chosen president of Guatemala. Arévalo was scheduled to assume the role as the 52nd president of Guatemala with leadership of Semilla on January 14 of 2024,[166] however, his inauguration would be delayed due to the failure of the event's commission to approve a congressional delegation.[167][168]

Minutes after midnight, he was finally sworn in as Guatemala's president on January 15.[169] His campaign promotes anti-corruption and economic opportunities for Guatemalans.[170] In his first few days in office, Arévalo reversed a government agreement signed by his predecessor that would have granted security and vehicles to former officials from the Giammattei cabinet for six years.[171][172]

On 8 February 2024, Arévalo and Francisco Jiménez, the Minister of the Interior, announced the creation of the Special Group Against Extortion (GECE), a special force within the National Civil Police (PNC) aimed at combatting violent crime and extortions.[173] The GECE will consist of 400 motorized officers who will patrol different regions of the country in phases. At the request of Arévalo, the United States government donated equipment to support the new task force.[174]

On 23 April 2024, during a public event marking the first 100 days of his government, Arévalo historically fulfilled one of his campaign promises by reducing the presidential salary by 25%.[175] As a result of this reduction, the head of state of Guatemala is no longer the highest-paid president in Latin America. Concurrently, Vice President Herrera also announced a 25% reduction in her salary.[176]

Geography

[edit]

Guatemala is mountainous with small patches of desert and sand dunes, all hilly valleys, except for the south coast and the vast northern lowlands of Petén department. Two mountain chains enter Guatemala from west to east, dividing Guatemala into three major regions: the highlands, where the mountains are located; the Pacific coast, south of the mountains and the Petén region, north of the mountains.

All major cities are located in the highlands and Pacific coast regions; by comparison, Petén is sparsely populated. These three regions vary in climate, elevation, and landscape, providing dramatic contrasts between hot, humid tropical lowlands and colder, drier highland peaks. Volcán Tajumulco, at 4,220 metres (13,850 feet), is the highest point in the Central American countries.

The rivers are short and shallow in the Pacific drainage basin, larger and deeper in the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico drainage basins. These rivers include the Polochic and Dulce Rivers, which drain into Lake Izabal, the Motagua River, the Sarstún, which forms the boundary with Belize, and the Usumacinta River, which forms the boundary between Petén and Chiapas, Mexico.

Natural disasters

[edit]Guatemala's location between the Caribbean Sea and Pacific Ocean makes it a target for hurricanes such as Hurricane Mitch in 1998 and Hurricane Stan in October 2005, which killed more than 1,500 people. The damage was not wind-related, but rather due to significant flooding and resulting mudslides. The most recent was Hurricane Eta in November 2020, which was responsible for more than 100 people missing or killed with the final tally still uncertain.[177]

Guatemala's highlands lie along the Motagua Fault, part of the boundary between the Caribbean and North American tectonic plates. This fault has been responsible for several major earthquakes in historic times, including a 7.5 magnitude tremor on 4 February 1976 which killed more than 25,000 people. In addition, the Middle America Trench, a major subduction zone, lies off the Pacific coast. Here, the Cocos Plate is sinking beneath the Caribbean Plate, producing volcanic activity inland of the coast. Guatemala has 37 volcanoes, four of them active: Pacaya, Santiaguito, Fuego, and Tacaná.

Natural disasters have a long history in this geologically active part of the world. For example, two of the three moves of the capital of Guatemala have been due to volcanic mudflows in 1541 and earthquakes in 1773.

Biodiversity

[edit]Guatemala has 14 ecoregions ranging from mangrove forests to both ocean littorals with 5 different ecosystems. Guatemala has 252 listed wetlands, including five lakes, 61 lagoons, 100 rivers, and four swamps.[178] Tikal National Park was the first mixed UNESCO World Heritage Site. Guatemala is a country of distinct fauna. It has some 1246 known species. Of these, 6.7% are endemic and 8.1% are threatened. Guatemala is home to at least 8,682 species of vascular plants, of which 13.5% are endemic. 5.4% of Guatemala is protected under IUCN categories I-V.[citation needed]

The Maya Biosphere Reserve in the department of Petén has 2,112,940 ha,[179] making it the second-largest forest in Central America after Bosawas. Guatemala had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 3.85/10, ranking it 138th globally out of 172 countries.[180]

Government and politics

[edit]Political system

[edit]

Guatemala is a constitutional democratic republic whereby the President of Guatemala is both head of state and head of government, and of a multi-party system. Executive power is exercised by the government. Legislative power is vested in both the government and the Congress of the Republic. The judiciary is independent of the executive and the legislature.

On 2 September 2015, Otto Pérez Molina resigned as President of Guatemala due to a corruption scandal and was replaced by Alejandro Maldonado until January 2016.[181] Congress appointed former Universidad de San Carlos President Alfonso Fuentes Soria as the new vice president to replace Maldonado.[182]

Jimmy Morales assumed office on 14 January 2016.[161] In January 2020, he was succeeded by Alejandro Giammattei.[163]

César Bernardo Arévalo de León,[183] a Guatemalan diplomat, sociologist, writer, and politician, and a member and co-founder of the Semilla party, is now serving as the 52nd president of Guatemala.

Foreign relations

[edit]Guatemala has long claimed all or part of the territory of neighboring Belize. Owing to this territorial dispute, Guatemala did not recognize Belize's independence until 6 September 1991,[184] but the dispute is not resolved. Negotiations are currently under way under the auspices of the Organization of American States to conclude it.[185][186]

Military

[edit]Guatemala has a modest military, with between 15,000 and 20,000 personnel.[187]

In 2017, Guatemala signed the United Nations Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.[188]

Administrative divisions

[edit]Guatemala is divided into 22 departments (Spanish: departamentos) and sub-divided into about 335 municipalities (Spanish: municipios).[189]

Human rights

[edit]Killings and death squads have been common in Guatemala since the end of the civil war in 1996. They often had ties to Clandestine Security Apparatuses (Cuerpos Ilegales y Aparatos Clandestinos de Seguridad – CIACS), organizations of current and former members of the military involved in organized crime. They had significant influence, now somewhat lessened,[190] but extrajudicial killings continue.[191] In July 2004, the Inter-American Court condemned the 18 July 1982 massacre of 188 Achi-Maya in Plan de Sanchez, and for the first time in its history, ruled the Guatemalan Army had committed genocide. It was the first ruling by the court against the Guatemalan state for any of the 626 massacres reported in its 1980s scorched-earth campaign.[191] In those massacres, 83 percent of the victims were Maya and 17 percent Ladino.[191]

| Extra-Judicial Killings in Guatemala | |

|---|---|

| 2010 | 5,072 |

| 2011 | 279 |

| 2012 | 439 |

| source: Center for Legal Action in Human Rights (CALDH)[190] | |

In 2008, Guatemala became the first country to officially recognize femicide, the murder of a female because of her sex, as a crime.[192] Guatemala has the third-highest femicide rate in the world, after El Salvador and Jamaica, with around 9.1 murders for every 100,000 women from 2007 to 2012.[192]

Economy

[edit]

Guatemala is the largest economy in Central America, with an estimated 2024 GDP (PPP) per capita of US$10,998. However, Guatemala faces many social problems and is one of the poorest countries in Latin America. The income distribution is highly unequal with more than half of the population below the national poverty line and just over 400,000 (3.2%) unemployed. The CIA World Fact Book considers 54.0% of the population of Guatemala to be living in poverty in 2009.[193][194]

In 2010, the Guatemalan economy grew by 3%, recovering gradually from the 2009 crisis, as a result of the falling demands from the United States and other Central American markets and the slowdown in foreign investment in the middle of the global recession.[195]

Remittances from Guatemalans living in United States now constitute the largest single source of foreign income (two-thirds of exports and one tenth of GDP).[193]

Some of Guatemala's main exports are fruits, vegetables, flowers, handicrafts, cloths and others. It is a leading exporter of cardamom[196] and coffee.[197]

In the face of a rising demand for biofuels, the country is growing and exporting an increasing amount of raw materials for biofuel production, especially sugar cane and palm oil. Critics say that this development leads to higher prices for staple foods like corn, a major ingredient in the Guatemalan diet. As a consequence of the subsidization of US American corn, Guatemala imports nearly half of its corn from the United States that is using 40 percent of its crop harvest for biofuel production.[198] In 2014, the government was considering ways to legalize poppy and marijuana production, hoping to tax production and use tax revenues to fund drug prevention programs and other social projects.[199]

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in purchasing power parity (PPP) in 2010 was estimated at US$70.15 billion. The service sector is the largest component of GDP at 63%, followed by the industry sector at 23.8% and the agriculture sector at 13.2% (2010 est.). Mines produce gold, silver, zinc, cobalt and nickel.[200] The agricultural sector accounts for about two-fifths of exports, and half of the labor force. Organic coffee, sugar, textiles, fresh vegetables, and bananas are the country's main exports. Inflation was 3.9% in 2010.

The 1996 peace accords that ended the decades-long civil war removed a major obstacle to foreign investment. Tourism has become an increasing source of revenue for Guatemala thanks to the new foreign investment.

In March 2006, Guatemala's congress ratified the Dominican Republic–Central America Free Trade Agreement (DR-CAFTA) between several Central American nations and the US.[201] Guatemala also has free trade agreements with Taiwan and Colombia. Guatemala was ranked 122nd in the Global Innovation Index in 2023.[202]

Tourism

[edit]

Tourism has become one of the main drivers of the economy, with tourism estimated at $1.8 billion to the economy in 2008. Guatemala receives around two million tourists annually. In recent years, there has been an increase in the number of cruise ships visiting Guatemalan seaports, leading to higher tourist numbers. Tourist destinations include Maya archaeological sites (e.g. Tikal in the Peten, Quiriguá in Izabal, Iximche in Chimaltenango and Guatemala City), natural attractions (e.g. Lake Atitlán and Semuc Champey) and historical sites such as the colonial city of Antigua Guatemala, which is recognized as a UNESCO Cultural Heritage site.

Demographics

[edit]

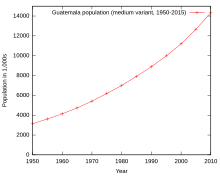

Guatemala has a population of 17,608,483 (2021 est).[13][14] With only 885,000 in 1900, this constitutes the fastest population growth in the Western Hemisphere during the 20th century.[204] The Republic of Guatemala's first census was taken in 1778.[205] The census records for 1778, 1880, 1893 and 1921 were used as scrap paper and no longer exist, although their statistical information was preserved.[206] Censuses have not been taken at regular intervals. The 1837 census was discredited at the time; statistician Don Jose de la Valle made a calculation that in 1837 the population of Guatemala was 600,000.[205] The 1940 census was burned.[207][206] Data from the remaining censuses is in the Historical Population table below.

| Census | Population |

|---|---|

| 1778 | 430,859[205] |

| 1825 | 507,126[205] |

| 1837 | 490,787[205] |

| 1852 | 787,000[205] |

| 1880 | 1,224,602[208] |

| 1893 | 1,364,678[209] |

| 1914 | 2,183,166[207] |

| 1921 | 2,004,900[207] |

| 1950 | 2,870,272[207] |

| 1964 | 4,287,997[210] |

| 1973 | 5,160,221[210] |

| 1981 | 6,054,227[210] |

| 1994 | 8,321,067[210] |

| 2002 | 11,183,388[211] |

| 2018 | 14,901,286[2] |

Guatemala is heavily centralized: transportation, communications, business, politics, and the most relevant urban activity takes place in the capital of Guatemala City,[citation needed] whose urban area has a population of almost 3 million.[193]

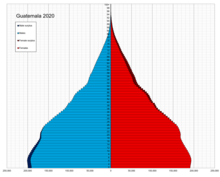

The estimated median age in Guatemala is 20 years old, 19.4 for males and 20.7 years for females.[193] Guatemala is demographically one of the youngest countries in the Western Hemisphere, comparable to most of central Africa and Iraq. The proportion of the population below the age of 15 in 2010 was 41.5%, 54.1% were aged between 15 and 65 years of age, and 4.4% were aged 65 years or older.[203]

Diaspora

[edit]

A significant number of Guatemalans live outside of their country. The majority of the Guatemalan diaspora is located in the United States of America, with estimates ranging from 480,665[212] to 1,489,426.[213] Emigration to the United States has led to the growth of Guatemalan communities in California, Delaware, Florida, Illinois, New York, New Jersey, Texas, Rhode Island and elsewhere since the 1970s.[214] However, as of July 2019, the United States and Guatemala signed a deal to restrict migration and asylum seekers from Guatemala.[215]

Below are estimates of the number of Guatemalans living abroad for certain countries:

| Country | 2019 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,070,743 | ||||

| 44,178 | ||||

| 25,086 | ||||

| 18,398 | ||||

| 9,005 | ||||

| 7,678 | ||||

| 4,681 | ||||

| 3,296 | ||||

| 2,699 | ||||

| 2,299 | ||||

| Total | 1,205,644 | |||

| Source:DatosMacro.[216] | ||||

Ethnic groups

[edit]Guatemala is populated by a variety of ethnic, cultural, racial, and linguistic groups. According to the 2018 Census conducted by the National Institute of Statistics (INE), 56% of the population is Ladino reflecting mixed indigenous and European heritage.[217] Indigenous Guatemalans are 43.6% of the national population, which is one of the largest percentages in Latin America, behind only Peru and Bolivia. Most indigenous Guatemalans (41.7% of the national population) are of the Maya people, namely K'iche' (11.0% of the total population), Q'eqchi (8.3%), Kaqchikel (7.8%), Mam (5.2%), and "other Maya" (7.6%). 2% of the national population is indigenous non-Maya. 1.8% of the population is Xinca (mesoamerican), and 0.1% of the population is Garifuna (African/Carib mix).[217] "However, indigenous rights activists put the indigenous figure closer to 61 per cent." [218]

White Guatemalans of European descent, also called Criollo, are not differentiated from Ladinos (mixed-race) individuals in the Guatemalan census.[217] Most are descendants of German and Spanish settlers, and others derive from Italians, British, French, Swiss, Belgians, Dutch, Russians and Danes. German settlers are credited with bringing the tradition of Christmas trees to Guatemala.[219]

The population includes about 110,000 Salvadorans. The Garífuna, descended primarily from Black Africans who lived and intermarried with indigenous peoples from St. Vincent, live mainly in Livingston and Puerto Barrios. Afro-Guatemalans and mulattos are descended primarily from banana plantation workers. There are also Asians, mostly of Chinese descent but also Arabs of Lebanese and Syrian descent.[220]

Languages

[edit]Guatemala's sole official language is Spanish.

Twenty-one Mayan languages are spoken, especially in rural areas, as well as two non-Mayan Indigenous languages: Xinca, which is indigenous to the country, and Garifuna, an Arawakan language spoken on the Caribbean coast. According to the Language Law of 2003, these languages are recognized as national languages.[221]

Indigenous integration and bilingual education

[edit]Throughout the 20th century there have been many developments in the integration of Mayan languages into the Guatemalan society and educational system. Originating from political reasons, these processes have aided the revival of some Mayan languages and advanced bilingual education in the country.

In 1945, in order to overcome "the Indian problem", the Guatemalan government founded The Institute Indigents ta National (NH), the purpose of which was to teach literacy to Mayan children in their mother tongue instead of Spanish, to prepare the ground for later assimilation of the latter. The teaching of literacy in the first language, which received support from the UN, significantly advanced in 1952, when the SIL (Summer Institute of Linguistics), located in Dallas, Texas, partnered with the Guatemalan Ministry of Education; within 2 years, numerous written works in Mayan languages had been printed and published, and vast advancement was done in the translation of the New Testament. Further efforts to integrate the indigenous into the Ladino[222] society were made in the following years, including the invention of a special alphabet to assist Mayan students transition to Spanish, and bilingual education in the Q'eqchi' area. When Spanish became the official language of Guatemala in 1965, the government started several programs, such as the Bilingual Castellanizacion Program and the Radiophonic Schools, to accelerate the move of Mayan students to Spanish. Unintentionally, the efforts to integrate the indigenous using language, especially the new alphabet, gave institutions tools to use Mayan tongues in schools, and while improving Mayan children's learning, they left them unequipped to learn in a solely Spanish environment. So, an additional expansion of bilingual education took place in 1980, when an experimental program in which children were to be instructed in their mother tongue until they are fluent enough in Spanish was created. The program proved successful when the students of the pilot showed higher academic achievements than the ones in the Spanish-only control schools. In 1987, when the pilot was to finish, bilingual education was made official in Guatemala.

Religion

[edit]

Christianity is very influential in nearly all of Guatemalan society, both in cosmology and social-politic composition. The country, once dominated by Roman Catholicism (introduced by the Spanish during the colonial era), is now influenced by a diversity of Christian denominations. The Roman Catholic Church remains the largest Church denomination, passing from 55% of people in 2001 to 47.9% as of 2012[update] (CID Gallup November 2001, September 2012). During 2001–2012, the already numerous Protestant population, grew from thirty percent of the population to 38.2%. Those claiming no religious affiliation were down from 12.7% to 11.6%. The remainder, including Mormons and adherents of Judaism, Islam, and Buddhism, continued to register at more than 2 percent of the population.[223]

Since the 1960s, and particularly during the 1980s, Guatemala has experienced the rapid growth of Protestantism, especially evangelical varieties. Guatemala has been described as the most heavily evangelical nation in Latin America,[224] with multitudes of unregistered churches,[225] although Brazil[226] or Honduras may be as heavily evangelical as Guatemala.

Over the past two decades, particularly since the end of the civil war, Guatemala has seen heightened missionary activity. Protestant denominations have grown markedly in recent decades, chiefly Evangelical and Pentecostal varieties; growth is particularly strong among the ethnic Maya population, with the National Evangelical Presbyterian Church of Guatemala maintaining 11 indigenous-language presbyteries. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has grown from 40,000 members in 1984 to 164,000 in 1998, and continues to expand.[227][228]

The growth of Eastern Orthodox Church in Guatemala has been especially strong, with hundreds of thousands of converts in the last five years,[229][230][231][better source needed] giving the country the highest proportion of Orthodox adherents in the Western Hemisphere.[citation needed]

Traditional Maya religion persists through the process of inculturation, in which certain practices are incorporated into Catholic ceremonies and worship when they are sympathetic to the meaning of Catholic belief.[232][233] Indigenous religious practices are increasing as a result of the cultural protections established under the peace accords.[citation needed] The government has instituted a policy of providing altars at every Maya ruin to facilitate traditional ceremonies.

Immigration

[edit]During the colonial era Guatemala received immigrants (settlers) only from Spain. Subsequently, Guatemala received waves of immigration from Europe in the mid 19th century and early 20th century.[clarification needed] Primarily from Germany, these immigrants installed coffee and cardamom fincas in Alta Verapaz, Zacapa, Quetzaltenango, Baja Verapaz and Izabal. To a lesser extent people also arrived from Spain, France, Belgium, England, Italy, Sweden, and others.