Средиземное море

| Средиземное море | |

|---|---|

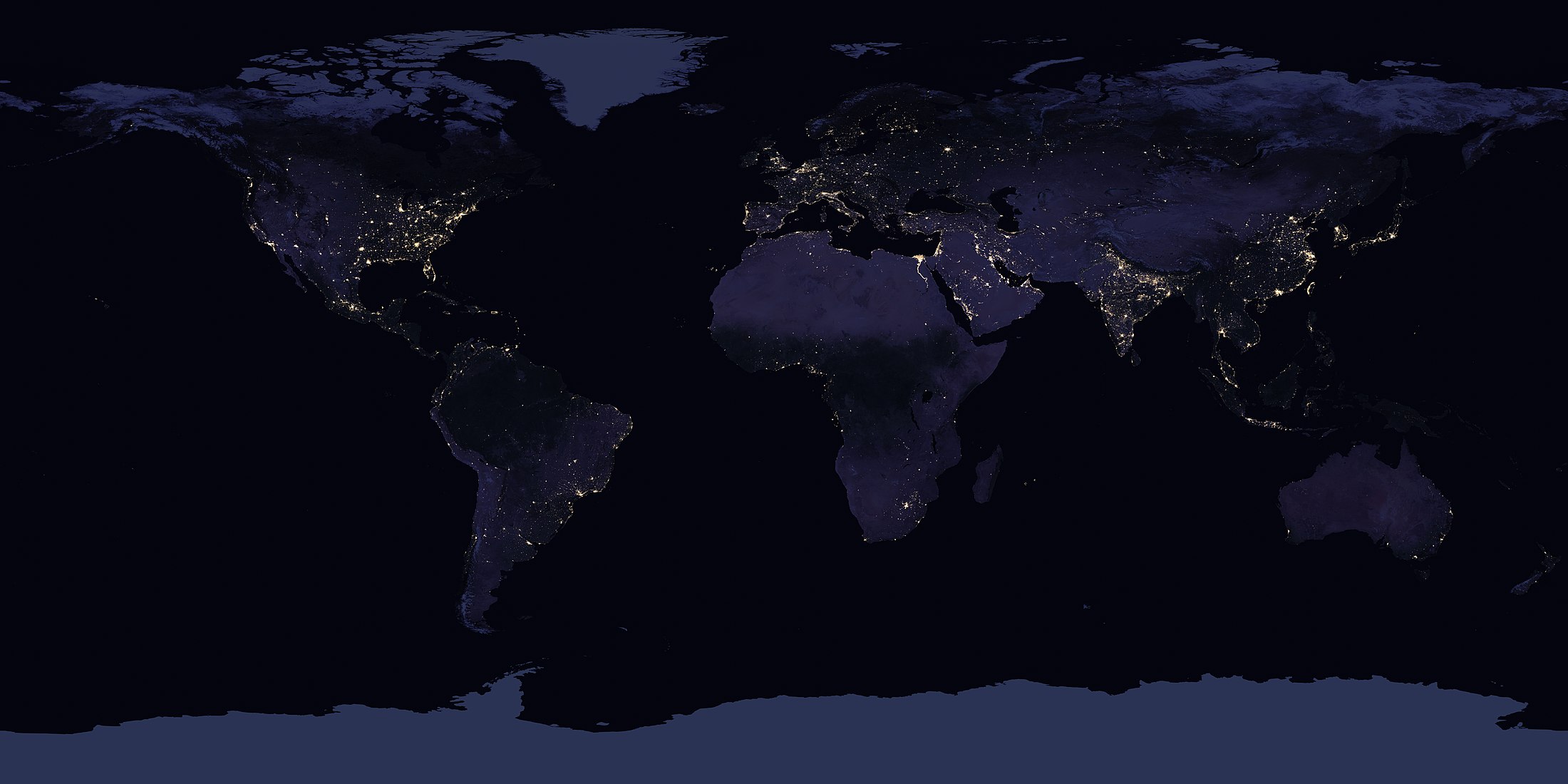

Карта Средиземного моря | |

| Расположение | |

| Координаты | 35 ° с.ш. 35 ° с.ш. 35 ° с.ш. |

| Тип | Море |

| Первичный приток | Залив Кадис , Сезон смерти , Нил , Эбро , Рона , Клелиф , По |

| Primary outflows | Strait of Gibraltar, Dardanelles |

| Basin countries | Coastal countries: |

| Surface area | 2,500,000 km2 (970,000 sq mi) |

| Average depth | 1,500 m (4,900 ft) |

| Max. depth | 5,109 m (16,762 ft) ±1 m (3 ft) |

| Water volume | 3,750,000 km3 (900,000 cu mi) |

| Residence time | 80–100 years[1] |

| Max. temperature | 28 °C (82 °F) |

| Min. temperature | 12 °C (54 °F) |

| Islands | 3300+ |

| Settlements | |

Средиземное море ( / ˌ M ɛ D ɪ T ə ˈ R Eɪ n I ən / med -ih-tə- Ray -nee-ən ) представляет собой море , связанное с атлантическим океаном , окруженное средиземноморским бассейном и почти полностью приложенным Земля: на севере Южной Европы и Анатолией , на юге Северной Африки , на востоке Левантом в Западной Азии и на западе почти на Марокко -Сприсская граница . Средиземноморье сыграло центральную роль в истории западной цивилизации . Геологические данные указывают на то, что около 5,9 миллионов лет назад Средиземноморье было отрезано от Атлантики и было частично или полностью высыпано в течение около 600 000 лет во время кризиса в солености мессинского солонца, прежде чем его наполнили затопление Zanclean около 5,3 миллиона лет назад.

Средиземноморское море охватывает площадь около 2500 000 км 2 (970 000 кв. МИ), [ 2 ] Представляя 0,7% глобальной поверхности океана , но ее связь с Атлантикой через пролив Гибралтар - узкий пролив, который соединяет Атлантический океан с Средиземным морем и отделяет иберийский полуостров в Европе от Марокко в Африке - всего 14 км (только 14 км (только 14 км ( 9 миль) шириной. Средиземное море охватывает огромное количество островов , некоторые из которых из вулканического происхождения. Два крупнейших острова, как в районе, так и в населении, - это Сицилия и Сардиния .

The Mediterranean Sea has an average depth of 1,500 m (4,900 ft) and the deepest recorded point is 5,109 ± 1 m (16,762 ± 3 ft) in the Calypso Deep in the Ionian Sea. It lies between latitudes 30° and 46° N and longitudes 6° W and 36° E. Its west–east length, from the Strait of Gibraltar to the Gulf of Alexandretta, on the southeastern coast of Turkey, is about 4,000 kilometres (2,500 mi). The north–south length varies greatly between different shorelines and whether only straight routes are considered. Also including longitudinal changes, the shortest shipping route between the multinational Gulf of Trieste and the Libyan coastline of the Gulf of Sidra is about 1,900 kilometres (1,200 mi). The water temperatures are mild in winter and warm in summer and give name to the Mediterranean climate type due to the majority of precipitation falling in the cooler months. Its southern and eastern coastlines are lined with hot deserts not far inland, but the immediate coastline on all sides of the Mediterranean tends to have strong maritime moderation.

The sea was an important route for merchants and travellers of ancient times, facilitating trade and cultural exchange between the peoples of the region. The history of the Mediterranean region is crucial to understanding the origins and development of many modern societies. The Roman Empire maintained nautical hegemony over the sea for centuries and is the only state to have ever controlled all of its coast.

The countries surrounding the Mediterranean and its marginal seas in clockwise order are Spain, France, Monaco, Italy, Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, Albania, Greece, Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Palestine, Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco; Malta and Cyprus are island countries in the sea. In addition, two overseas territories of the United Kingdom, Gibraltar and Akrotiri and Dhekelia, have coastlines on the Mediterranean. The drainage basin encompasses a large number of other countries, the Nile being the longest river ending in the Mediterranean Sea.[3]

Names and etymology

[edit]

The Ancient Egyptians called the Mediterranean Wadj-wr/Wadj-Wer/Wadj-Ur. This term (literally "great green") was the name given by the Ancient Egyptians to the semi-solid, semi-aquatic region characterized by papyrus forests to the north of the cultivated Nile delta, and, by extension, the sea beyond.[4]

The Ancient Greeks called the Mediterranean simply ἡ θάλασσα (hē thálassa; "the Sea") or sometimes ἡ μεγάλη θάλασσα (hē megálē thálassa; "the Great Sea"), ἡ ἡμετέρα θάλασσα (hē hēmetérā thálassa; "Our Sea"), or ἡ θάλασσα ἡ καθ’ ἡμᾶς (hē thálassa hē kath’hēmâs; "the sea around us").

The Romans called it Mare Magnum ("Great Sea") or Mare Internum ("Internal Sea") and, starting with the Roman Empire, Mare Nostrum ("Our Sea"). The term Mare Mediterrāneum appears later: Solinus apparently used this in the 3rd century, but the earliest extant witness to it is in the 6th century,[5] in Isidore of Seville.[6] It means 'in the middle of land, inland' in Latin, a compound of medius ("middle"), terra ("land, earth"), and -āneus ("having the nature of").

The modern Greek name Μεσόγειος Θάλασσα (mesógeios; "inland") is a calque of the Latin name, from μέσος (mésos, "in the middle") and γήινος (gḗinos, "of the earth"), from γῆ (gê, "land, earth"). The original meaning may have been 'the sea in the middle of the earth', rather than 'the sea enclosed by land'.[7][8]

Ancient Iranians called it the "Roman Sea", and in Classical Persian texts, it was called Daryāy-e Rōm (دریای روم), which may be from Middle Persian form, Zrēh ī Hrōm (𐭦𐭫𐭩𐭤 𐭩 𐭤𐭫𐭥𐭬).[9]

The Carthaginians called it the "Syrian Sea". In ancient Syrian texts, Phoenician epics and in the Hebrew Bible, it was primarily known as the "Great Sea", הים הגדול HaYam HaGadol, (Numbers; Book of Joshua; Ezekiel) or simply as "The Sea" (1 Kings). However, it has also been called the "Hinder Sea" because of its location on the west coast of the region of Syria or the Holy Land (and therefore behind a person facing the east), which is sometimes translated as "Western Sea". Another name was the "Sea of the Philistines", (Book of Exodus), from the people inhabiting a large portion of its shores near the Israelites. In Modern Hebrew, it is called הים התיכון HaYam HaTikhon 'the Middle Sea'.[10] In Classic Persian texts was called Daryāy-e Šām (دریای شام) "The Western Sea" or "Syrian Sea".[11]

In Modern Standard Arabic, it is known as al-Baḥr [al-Abyaḍ] al-Mutawassiṭ (البحر [الأبيض] المتوسط) 'the [White] Middle Sea'. In Islamic and older Arabic literature, it was Baḥr al-Rūm(ī) (بحر الروم or بحر الرومي) 'the Sea of the Romans' or 'the Roman Sea'. At first, that name referred only to the eastern Mediterranean, but the term was later extended to the whole Mediterranean. Other Arabic names were Baḥr al-šām(ī) (بحر الشام) ("the Sea of Syria") and Baḥr al-Maghrib (بحرالمغرب) ("the Sea of the West").[12][5]

In Turkish, it is the Akdeniz 'the White Sea'; in Ottoman, ﺁق دڭيز, which sometimes means only the Aegean Sea.[13] The origin of the name is not clear, as it is not known in earlier Greek, Byzantine or Islamic sources. It may be to contrast with the Black Sea.[12][10][14] In Persian, the name was translated as Baḥr-i Safīd, which was also used in later Ottoman Turkish.[12] Similarly, in 19th century Greek, the name was Άσπρη Θάλασσα (áspri thálassa; "white sea").[15][16]

According to Johann Knobloch, in classical antiquity, cultures in the Levant used colours to refer to the cardinal points: black referred to the north (explaining the name Black Sea), yellow or blue to east, red to south (e.g., the Red Sea) and white to west. That would explain the Bulgarian Byalo More, the Turkish Akdeniz, and the Arab nomenclature described above, lit. "White Sea".[17]

History

[edit]Ancient civilizations

[edit]

Major ancient civilizations were located around the Mediterranean. The sea provided routes for trade, colonization, and war, as well as food (from fishing and the gathering of other seafood) for numerous communities throughout the ages.[18] The earliest advanced civilizations in the Mediterranean were the Egyptians and the Minoans, who traded extensively with each other. Other notable civilizations that appeared somewhat later are the Hittites and other Anatolian peoples, the Phoenicians, and Mycenean Greece. Around 1200 BC the eastern Mediterranean was greatly affected by the Bronze Age Collapse, which resulted in the destruction of many cities and trade routes.

The most notable Mediterranean civilizations in classical antiquity were the Greek city states and the Phoenicians, both of which extensively colonized the coastlines of the Mediterranean.

Darius I of Persia, who conquered Ancient Egypt, built a canal linking the Red Sea to the Nile, and thus the Mediterranean. Darius's canal was wide enough for two triremes to pass each other with oars extended and required four days to traverse.[19]

Following the Punic Wars in the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC, the Roman Republic defeated the Carthaginians to become the preeminent power in the Mediterranean. When Augustus founded the Roman Empire, the Romans referred to the Mediterranean as Mare Nostrum ("Our Sea"). For the next 400 years, the Roman Empire completely controlled the Mediterranean Sea and virtually all its coastal regions from Gibraltar to the Levant, being the only state in history to ever do so, being given the nickname "Roman Lake".

Middle Ages and empires

[edit]The Western Roman Empire collapsed around 476 AD. The east was again dominant as Roman power lived on in the Byzantine Empire formed in the 4th century from the eastern half of the Roman Empire. Though the Eastern Roman Empire would continue to hold almost all of the Mediterranean, another power arose in the 7th century, and with it the religion of Islam, which soon swept across from the east; at its greatest extent, the Arabs, under the Umayyads, controlled most of the Mediterranean region and left a lasting footprint on its eastern and southern shores.

The Arab invasions disrupted the trade relations between Western and Eastern Europe while disrupting trade routes with Eastern Asian Empires. This, however, had the indirect effect of promoting trade across the Caspian Sea. The export of grains from Egypt was re-routed towards the Eastern world. Products from East Asian empires, like silk and spices, were carried from Egypt to ports like Venice and Constantinople by sailors and Jewish merchants. The Viking raids further disrupted the trade in western Europe and brought it to a halt. However, the Norsemen developed the trade from Norway to the White Sea, while also trading in luxury goods from Spain and the Mediterranean. The Byzantines in the mid-8th century retook control of the area around the north-eastern part of the Mediterranean. Venetian ships from the 9th century armed themselves to counter the harassment by Arabs while concentrating trade of Asian goods in Venice.[20]

The Fatimids maintained trade relations with the Italian city-states like Amalfi and Genoa before the Crusades, according to the Cairo Geniza documents. A document dated 996 mentions Amalfian merchants living in Cairo. Another letter states that the Genoese had traded with Alexandria. The caliph al-Mustansir had allowed Amalfian merchants to reside in Jerusalem about 1060 in place of the Latin hospice.[21]

The Crusades led to the flourishing of trade between Europe and the outremer region.[22] Genoa, Venice and Pisa created colonies in regions controlled by the Crusaders and came to control the trade with the Orient. These colonies also allowed them to trade with the Eastern world. Though the fall of the Crusader states and attempts at banning of trade relations with Muslim states by the Popes temporarily disrupted the trade with the Orient, it however continued.[23]

Europe started to revive, however, as more organized and centralized states began to form in the later Middle Ages after the Renaissance of the 12th century.

Ottoman power based in Anatolia continued to grow, and in 1453 extinguished the Byzantine Empire with the Conquest of Constantinople. Ottomans gained control of much of the eastern part sea in the 16th century and also maintained naval bases in southern France (1543–1544), Algeria and Tunisia. Barbarossa, the Ottoman captain is a symbol of this domination with the victory of the Battle of Preveza (1538). The Battle of Djerba (1560) marked the apex of Ottoman naval domination in the eastern Mediterranean. As the naval prowess of the European powers increased, they confronted Ottoman expansion in the region when the Battle of Lepanto (1571) checked the power of the Ottoman Navy. This was the last naval battle to be fought primarily between galleys.

The Barbary pirates of Northwest Africa preyed on Christian shipping and coastlines in the Western Mediterranean Sea.[24] According to Robert Davis, from the 16th to 19th centuries, pirates captured 1 million to 1.25 million Europeans as slaves.[25]

The development of oceanic shipping began to affect the entire Mediterranean. Once, most of the trade between Western Europe and the East was passing through the region, but after the 1490s the development of a sea route to the Indian Ocean allowed the importation of Asian spices and other goods through the Atlantic ports of western Europe.[26][27][28]

The sea remained strategically important. British mastery of Gibraltar ensured their influence in Africa and Southwest Asia. Especially after the naval battles of Abukir (1799, Battle of the Nile) and Trafalgar (1805), the British had for a long time strengthened their dominance in the Mediterranean.[29] Wars included Naval warfare in the Mediterranean during World War I and Mediterranean theatre of World War II.

With the opening of the lockless Suez Canal in 1869, the flow of trade between Europe and Asia changed fundamentally. The fastest route now led through the Mediterranean towards East Africa and Asia. This led to a preference for the Mediterranean countries and their ports like Trieste with direct connections to Central and Eastern Europe experienced a rapid economic rise. In the 20th century, the 1st and 2nd World Wars as well as the Suez Crisis and the Cold War led to a shift of trade routes to the European northern ports, which changed again towards the southern ports through European integration, the activation of the Silk Road and free world trade.[30]

21st century and migrations

[edit]In 2013, the Maltese president described the Mediterranean Sea as a "cemetery" due to the large number of migrants who drowned there after their boats capsized.[31] European Parliament president Martin Schulz said in 2014 that Europe's migration policy "turned the Mediterranean into a graveyard", referring to the number of drowned refugees in the region as a direct result of the policies.[32] An Azerbaijani official described the sea as "a burial ground ... where people die".[33]

Following the 2013 Lampedusa migrant shipwreck, the Italian government decided to strengthen the national system for the patrolling of the Mediterranean Sea by authorising "Operation Mare Nostrum", a military and humanitarian mission in order to rescue the migrants and arrest the traffickers of immigrants. In 2015, more than one million migrants crossed the Mediterranean Sea into Europe.[34]

Italy was particularly affected by the European migrant crisis. Since 2013, over 700,000 migrants have landed in Italy,[35] mainly sub-Saharan Africans.[36]

Geography

[edit]The Mediterranean Sea connects:

- to the Atlantic Ocean by the Strait of Gibraltar (known in Homer's writings as the "Pillars of Hercules") in the west

- to the Sea of Marmara and the Black Sea, by the Straits of the Dardanelles and the Bosporus respectively, in the east

The 163 km (101 mi) long artificial Suez Canal in the southeast connects the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea without ship lock, because the water level is essentially the same.[10][37]

The westernmost point of the Mediterranean is located at the transition from the Alborán Sea to the Strait of Gibraltar, the easternmost point is on the coast of the Gulf of Iskenderun in southeastern Turkey. The northernmost point of the Mediterranean is on the coast of the Gulf of Trieste near Monfalcone in northern Italy while the southernmost point is on the coast of the Gulf of Sidra near the Libyan town of El Agheila.

Large islands in the Mediterranean include:

- Cyprus, Crete, Euboea, Rhodes, Lesbos, Chios, Kefalonia, Corfu, Limnos, Samos, Naxos, and Andros in the Eastern Mediterranean

- Sicily, Cres, Krk, Brač, Hvar, Pag, Korčula, and Malta in the central Mediterranean

- Sardinia, Corsica, and the Balearic Islands: Ibiza, Majorca, and Menorca in the Western Mediterranean

The Alpine arc, which also has a great meteorological impact on the Mediterranean area, touches the Mediterranean in the west in the area around Nice.

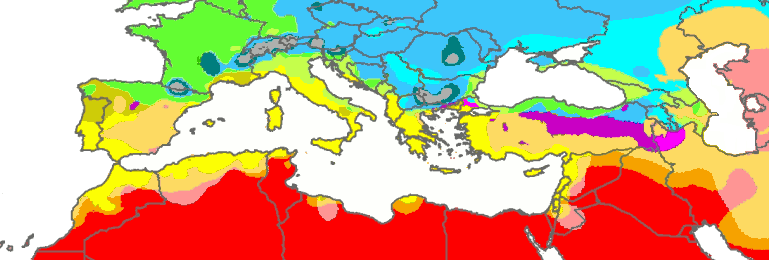

The typical Mediterranean climate has hot, dry summers and mild, rainy winters. Crops of the region include olives, grapes, oranges, tangerines, carobs and cork.

Marginal seas

[edit]

The Mediterranean Sea includes 15 marginal seas:[38][failed verification]

| Number | Sea | Area | Marginal countries and territories | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| km2 | sq mi | |||

| 1 | Libyan Sea | 350,000 | 140,000 | Libya, Turkey, Greece, Malta, Italy |

| 2 | Levantine Sea | 320,000 | 120,000 | Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Palestine, Egypt, Greece, Cyprus, Akrotiri & Dhekelia |

| 3 | Tyrrhenian Sea | 275,000 | 106,000 | Italy, France |

| 4 | Aegean Sea | 214,000 | 83,000 | Greece, Turkey |

| 5 | Icarian Sea | (Part of Aegean) | Greece | |

| 6 | Myrtoan Sea | (Part of Aegean) | Greece | |

| 7 | Thracian Sea | (Part of Aegean) | Greece, Turkey | |

| 8 | Ionian Sea | 169,000 | 65,000 | Greece, Albania, Italy |

| 9 | Balearic Sea | 150,000 | 58,000 | Spain |

| 10 | Adriatic Sea | 138,000 | 53,000 | Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Italy, Montenegro, Slovenia |

| 11 | Sea of Sardinia | 120,000 | 46,000 | Italy, Spain |

| 12 | Sea of Crete | 95,000 | 37,000 (Part of Aegean) | Greece[39] |

| 13 | Ligurian Sea | 80,000 | 31,000 | Italy, France |

| 14 | Alboran Sea | 53,000 | 20,000 | Spain, Morocco, Algeria, Gibraltar |

| 15 | Sea of Marmara | 11,500 | 4,400 | Turkey |

| – | Other | 500,000 | 190,000 | Consists of gulfs, straits, channels and other parts that do not have the name of a specific sea. |

| Total | Mediterranean Sea | 2,500,000 | 970,000 | |

- List of seas

- Category:Marginal seas of the Mediterranean

- Category:Gulfs of the Mediterranean

- Category:Straits of the Mediterranean Sea

- Category:Channels of the Mediterranean Sea

Note 1: The International Hydrographic Organization defines the area as generic Mediterranean Sea, in the Western Basin. It does not recognize the label Sea of Sardinia.[40]

Note 2: Thracian Sea and Myrtoan Sea are seas that are part of the Aegean Sea.

Note 3: The Black Sea is not considered part of it.

Extent

[edit]

The International Hydrographic Organization defines the limits of the Mediterranean Sea as follows:[40] Stretching from the Strait of Gibraltar in the west to the entrances to the Dardanelles and the Suez Canal in the east, the Mediterranean Sea is bounded by the coasts of Europe, Africa, and Asia and is divided into two deep basins:

- Western Basin:

- On the west: A line joining the extremities of Cape Trafalgar (Spain) and Cape Spartel (Africa)

- On the northeast: The west coast of Italy. In the Strait of Messina, a line joining the north extreme of Cape Paci (15°42′E) with Cape Peloro, the east extreme of the Island of Sicily. The north coast of Sicily

- On the east: A line joining Cape Lilibeo the western point of Sicily (37°47′N 12°22′E / 37.783°N 12.367°E), through the Adventure Bank to Cape Bon (Tunisia)

- Eastern Basin:

- On the west: The northeastern and eastern limits of the Western Basin

- On the northeast: A line joining Kum Kale (26°11′E) and Cape Helles, the western entrance to the Dardanelles

- On the southeast: The entrance to the Suez Canal

- On the east: The coasts of Lebanon, Syria, Israel, and Palestine (through the Gaza Strip)

Hydrography

[edit]

The drainage basin of the Mediterranean Sea is particularly heterogeneous and extends much further than the Mediterranean region.[41] Its size has been estimated between 4,000,000 and 5,500,000 km2 (1,500,000 and 2,100,000 sq mi),[note 1] depending on whether non-active parts (deserts) are included or not.[42][43][44] The longest river ending in the Mediterranean Sea is the Nile, which takes its sources in equatorial Africa. The basin of the Nile constitutes about two-thirds of the Mediterranean drainage basin[43] and encompasses areas as high as the Ruwenzori Mountains.[45] Among other important rivers in Africa, are the Moulouya and the Chelif, both on the north side of the Atlas Mountains. In Asia, are the Ceyhan and Seyhan, both on the south side of the Taurus Mountains.[46] In Europe, the largest basins are those of the Rhône, Ebro, Po, and Maritsa.[47] The basin of the Rhône is the largest and extends up as far north as the Jura Mountains, encompassing areas even on the north side of the Alps.[48] The basins of the Ebro, Po, and Maritsa, are respectively south of the Pyrenees, Alps, and Balkan Mountains, which are the major ranges bordering Southern Europe.

Total annual precipitation is significantly higher on the European part of the Mediterranean basin, especially near the Alps (the 'water tower of Europe') and other high mountain ranges. As a consequence, the river discharges of the Rhône and Po are similar to that of the Nile, despite the latter having a much larger basin.[46] These are the only three rivers with an average discharge of over 1,000 m3/s (35,000 cu ft/s).[43] Among large natural fresh bodies of water are Lake Victoria (Nile basin), Lake Geneva (Rhône), and the Italian Lakes (Po). While the Mediterranean watershed is bordered by other river basins in Europe, it is essentially bordered by endorheic basins or deserts elsewhere.

The following countries are in the Mediterranean drainage basin while not having a coastline on the Mediterranean Sea:

- In Europe, through various rivers:[47] Andorra,[note 2] Bulgaria,[note 3] Kosovo,[note 4] North Macedonia,[note 5] San Marino,[note 6] Serbia,[note 7] and Switzerland.[note 8]

- In Africa, through the Nile:[50] Congo, Burundi, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, South Sudan, Sudan, Tanzania and Uganda.

Coastal countries

[edit]

The following countries have a coastline on the Mediterranean Sea:

- Northern shore (from west to east): Spain, France, Monaco, Italy, Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, Albania, Greece, Turkey.

- Eastern shore (from north to south): Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Palestine, Egypt.

- Southern shore (from west to east): Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Egypt.

- Island nations: Malta, Cyprus.

Several other territories also border the Mediterranean Sea (from west to east):

- the British overseas territory of Gibraltar

- the Spanish autonomous cities of Ceuta and Melilla and nearby islands

- the Sovereign Base Areas on Cyprus

- the Palestinian Gaza Strip

Exclusive economic zone

[edit]Exclusive economic zones in Mediterranean Sea:[52][53]

| Number | Country | Area | |

|---|---|---|---|

| km2 | sq mi | ||

| 1 | 541,915 | 209,235 | |

| 2 | 493,708 | 190,622 | |

| 3 | 355,604 | 137,299 | |

| 4 | 260,000 | 100,000 | |

| 5 | 169,125 | 65,300 | |

| 6 | 128,843 | 49,747 | |

| 7 | 102,047 | 39,401 | |

| 8 | 88,389 | 34,127 | |

| 9 | 80,412 | 31,047 | |

| 10 | 72,195 | 27,875 | |

| 11 | 59,032 | 22,792 | |

| 12 | 55,542 | 21,445 | |

| 13 | 25,139 | 9,706 | |

| 14 | 19,265 | 7,438 | |

| 15 | 18,302 | 7,066 | |

| 16 | 13,691 | 5,286 | |

| 17 | 10,189 | 3,934 | |

| 18 | 7,745 | 2,990 | |

| 19 | 2,591 | 1,000 | |

| 20 | 288 | 111 | |

| 21 | 220 | 85 | |

| 22 | 50 | 19 | |

| 23 | 6.8 | 2.6 | |

| Total | Mediterranean Sea | 2,500,000 | 970,000 |

Coastline length

[edit]The Coastline length is about 46,000 km (29,000 mi).[54][55][56]

Coastal cities

[edit]Major cities (municipalities), with populations larger than 200,000 people, bordering the Mediterranean Sea include:

- Algeria: Algiers, Annaba, Oran

- Egypt: Alexandria, Damietta, Port Said

- France: Marseille, Toulon, Nice

- Greece: Athens, Thessaloniki, Patras, Heraklion

- Israel: Ashdod, Haifa, Netanya, Rishon LeZion, Tel Aviv

- Italy: Bari, Catania, Genoa, Messina, Naples, Palermo, Rome, Pescara, Taranto, Trieste, Venice

- Lebanon: Beirut, Tripoli

- Libya: Benghazi, Misrata, Tripoli, Zawiya, Zliten

- Malta: Valletta

- Morocco: Tétouan, Tangier

- Palestine: Gaza City

- Spain: Alicante, Almería, Badalona, Barcelona, Cartagena, Málaga, Palma de Mallorca, Valencia.

- Syria: Latakia, Tartus

- Tunisia: Sfax, Sousse, Tunis

- Turkey: Alanya, Antalya, Çanakkale, İskenderun, İzmir, Mersin

Subdivisions

[edit]

The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) divides the Mediterranean into a number of smaller waterbodies, each with their own designation (from west to east):[40]

- the Strait of Gibraltar

- the Alboran Sea, between Spain and Morocco

- the Balearic Sea, between mainland Spain and its Balearic Islands

- the Ligurian Sea between Corsica and Liguria (Italy)

- the Tyrrhenian Sea enclosed by Sardinia, Corsica, Italian peninsula and Sicily

- the Ionian Sea between Italy, Albania and Greece

- the Adriatic Sea between Italy, Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro and Albania

- the Aegean Sea between Greece and Turkey

Other seas

[edit]

Some other seas whose names have been in common use from the ancient times, or in the present:

- the Sea of Sardinia, between Sardinia and Balearic Islands, as a part of the Balearic Sea

- the Sea of Sicily between Sicily and Tunisia

- the Libyan Sea between Libya and Crete

- In the Aegean Sea,

- the Thracian Sea in its north

- the Myrtoan Sea between the Cyclades and the Peloponnese

- the Sea of Crete north of Crete

- the Icarian Sea between Kos and Chios

- the Cilician Sea between Turkey and Cyprus

- the Levantine Sea at the eastern end of the Mediterranean

Many of these smaller seas feature in local myth and folklore and derive their names from such associations.

Other features

[edit]

In addition to the seas, a number of gulfs and straits are recognised:

- the Saint George Bay in Beirut, Lebanon

- the Ras Ibn Hani cape in Latakia, Syria

- the Ras al-Bassit cape in northern Syria.

- the Minet el-Beida ("White Harbour") bay near ancient Ugarit, Syria

- the Strait of Gibraltar, connects the Atlantic Ocean to the Mediterranean Sea and separates Spain from Morocco

- the Bay of Algeciras, at the southern end of the Iberian Peninsula

- the Gulf of Corinth, an enclosed sea between the Ionian Sea and the Corinth Canal

- the Pagasetic Gulf, the gulf of Volos, south of the Thermaic Gulf, formed by the Mount Pelion peninsula

- the Saronic Gulf, the gulf of Athens, between the Corinth Canal and the Mirtoan Sea

- the Thermaic Gulf, the gulf of Thessaloniki, located in the northern Greek region of Macedonia

- the Kvarner Gulf, Croatia

- the Gulf of Almeria, southeast of Spain

- the Gulf of Lion, south of France

- the Gulf of Valencia, east of Spain

- the Strait of Messina, between Sicily and Calabrian peninsula

- the Gulf of Genoa, northwestern Italy

- the Gulf of Venice, northeastern Italy

- the Gulf of Trieste, northeastern Italy

- the Gulf of Taranto, southern Italy

- the Gulf of Saint Euphemia, southern Italy, with the international airport nearby

- the Gulf of Salerno, southwestern Italy

- the Gulf of Gaeta, southwestern Italy

- the Gulf of Squillace, southern Italy

- the Strait of Otranto, between Italy and Albania

- the Gulf of Haifa, northern Israel

- the Gulf of Sidra, between Tripolitania (western Libya) and Cyrenaica (eastern Libya)

- the Strait of Sicily, between Sicily and Tunisia

- the Corsica Channel, between Corsica and Italy

- the Strait of Bonifacio, between Sardinia and Corsica

- the Gulf of Antalya, between west and east shores of Antalya (Turkey)

- the Gulf of İskenderun, between İskenderun and Adana (Turkey)

- the Gulf of İzmir, in İzmir (Turkey)

- the Gulf of Fethiye, in Fethiye (Turkey)

- the Gulf of Kuşadası, in İzmir (Turkey)

- the Bay of Kotor, in south-western Montenegro and south-eastern Croatia

- the Malta Channel, between Sicily and Malta

- the Gozo Channel, between Malta Island and Gozo

Largest islands

[edit]

The Mediterranean Sea encompasses about 10,000 islands and islets, of which about 250 are permanently inhabited.[57] In the table below are listed the ten largest by size.

| Country | Island | Area | Population | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| km2 | sq mi | |||

| Italy | Sicily | 25,460 | 9,830 | 5,048,995 |

| Italy | Sardinia | 23,821 | 9,197 | 1,672,804 |

| Cyprus | Cyprus | 9,251 | 3,572 | 1,088,503 |

| France | Corsica | 8,680 | 3,350 | 299,209 |

| Greece | Crete | 8,336 | 3,219 | 623,666 |

| Greece | Euboea | 3,655 | 1,411 | 218,000 |

| Spain | Majorca | 3,640 | 1,410 | 869,067 |

| Greece | Lesbos | 1,632 | 630 | 90,643 |

| Greece | Rhodes | 1,400 | 540 | 117,007 |

| Greece | Chios | 842 | 325 | 51,936 |

Climate

[edit]Much of the Mediterranean coast enjoys a hot-summer Mediterranean climate. However, most of its southeastern coast has a hot desert climate, and much of Spain's eastern (Mediterranean) coast has a cold semi-arid climate, while most of Italy's northern (Adriatic) coast has a humid subtropical climate. Although they are rare, tropical cyclones occasionally form in the Mediterranean Sea, typically in September–November.

Sea temperature

[edit]| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Málaga[58] | 16 (61) | 15 (59) | 16 (61) | 16 (61) | 18 (64) | 20 (68) | 22 (72) | 23 (73) | 22 (72) | 20 (68) | 18 (64) | 17 (63) | 18.6 (65.5) |

| Barcelona[59] | 13 (55) | 12 (54) | 13 (55) | 14 (57) | 17 (63) | 20 (68) | 23 (73) | 25 (77) | 23 (73) | 20 (68) | 17 (63) | 15 (59) | 17.8 (64.0) |

| Marseille[60] | 13 (55) | 13 (55) | 13 (55) | 14 (57) | 16 (61) | 18 (64) | 21 (70) | 22 (72) | 21 (70) | 18 (64) | 16 (61) | 14 (57) | 16.6 (61.9) |

| Naples[61] | 15 (59) | 14 (57) | 14 (57) | 15 (59) | 18 (64) | 22 (72) | 25 (77) | 27 (81) | 25 (77) | 22 (72) | 19 (66) | 16 (61) | 19.3 (66.7) |

| Malta[62] | 16 (61) | 16 (61) | 15 (59) | 16 (61) | 18 (64) | 21 (70) | 24 (75) | 26 (79) | 25 (77) | 23 (73) | 21 (70) | 18 (64) | 19.9 (67.8) |

| Venice[63] | 11 (52) | 10 (50) | 11 (52) | 13 (55) | 18 (64) | 22 (72) | 25 (77) | 26 (79) | 23 (73) | 20 (68) | 16 (61) | 14 (57) | 17.4 (63.3) |

| Athens[64] | 16 (61) | 15 (59) | 15 (59) | 16 (61) | 18 (64) | 21 (70) | 24 (75) | 24 (75) | 24 (75) | 21 (70) | 19 (66) | 18 (64) | 19.3 (66.7) |

| Heraklion[65] | 16 (61) | 15 (59) | 15 (59) | 16 (61) | 19 (66) | 22 (72) | 24 (75) | 25 (77) | 24 (75) | 22 (72) | 20 (68) | 18 (64) | 19.7 (67.5) |

| Antalya[66] | 17 (63) | 17 (63) | 16 (61) | 17 (63) | 21 (70) | 24 (75) | 27 (81) | 29 (84) | 27 (81) | 25 (77) | 22 (72) | 19 (66) | 21.8 (71.2) |

| Limassol[67] | 18 (64) | 17 (63) | 17 (63) | 18 (64) | 20 (68) | 24 (75) | 26 (79) | 28 (82) | 27 (81) | 25 (77) | 22 (72) | 19 (66) | 21.7 (71.1) |

| Mersin[68] | 18 (64) | 17 (63) | 17 (63) | 18 (64) | 21 (70) | 25 (77) | 28 (82) | 29 (84) | 28 (82) | 25 (77) | 22 (72) | 19 (66) | 22.3 (72.1) |

| Tel Aviv[69] | 18 (64) | 17 (63) | 17 (63) | 18 (64) | 21 (70) | 24 (75) | 27 (81) | 28 (82) | 28 (82) | 26 (79) | 23 (73) | 20 (68) | 22.3 (72.1) |

| Alexandria[70] | 18 (64) | 17 (63) | 17 (63) | 18 (64) | 20 (68) | 23 (73) | 25 (77) | 26 (79) | 26 (79) | 25 (77) | 22 (72) | 20 (68) | 21.4 (70.5) |

Oceanography

[edit]

Being nearly landlocked affects conditions in the Mediterranean Sea: for instance, tides are very limited as a result of the narrow connection with the Atlantic Ocean. The Mediterranean is characterised and immediately recognised by its deep blue colour.

Evaporation greatly exceeds precipitation and river runoff in the Mediterranean, a fact that is central to the water circulation within the basin.[71] Evaporation is especially high in its eastern half, causing the water level to decrease and salinity to increase eastward.[72] The average salinity in the basin is 38 PSU at 5 m (16 ft) depth.[73] The temperature of the water in the deepest part of the Mediterranean Sea is 13.2 °C (55.8 °F).[73]

The net water influx from the Atlantic Ocean is ca. 70,000 m3/s (2.5 million cu ft/s) or 2.2×1012 m3/a (7.8×1013 cu ft/a).[74] Without this Atlantic water, the sea level of the Mediterranean Sea would fall at a rate of about 1 m (3 ft) per year.[75]

In oceanography, it is sometimes called the Eurafrican Mediterranean Sea, the European Mediterranean Sea or the African Mediterranean Sea to distinguish it from mediterranean seas elsewhere.[76][who else?]

General circulation

[edit]Water circulation in the Mediterranean can be attributed to the surface waters entering from the Atlantic through the Strait of Gibraltar (and also low salinity water entering the Mediterranean from the Black Sea through the Bosphorus). The cool and relatively low-salinity Atlantic water circulates eastwards along the North African coasts. A part of the surface water does not pass the Strait of Sicily, but deviates towards Corsica before exiting the Mediterranean. The surface waters entering the eastern Mediterranean Basin circulate along the Libyan and Israeli coasts. Upon reaching the Levantine Sea, the surface waters having warmed and increased its salinity from its initial Atlantic state, is now denser and sinks to form the Levantine Intermediate Waters (LIW). Most of the water found anywhere between 50 and 600 m (160 and 2,000 ft) deep in the Mediterranean originates from the LIW.[77] LIW are formed along the coasts of Turkey and circulate westwards along the Greek and south Italian coasts. LIW are the only waters passing the Sicily Strait westwards. After the Strait of Sicily, the LIW waters circulate along the Italian, French and Spanish coasts before exiting the Mediterranean through the depths of the Strait of Gibraltar. Deep water in the Mediterranean originates from three main areas: the Adriatic Sea, from which most of the deep water in the eastern Mediterranean originates, the Aegean Sea, and the Gulf of Lion. Deep water formation in the Mediterranean is triggered by strong winter convection fueled by intense cold winds like the Bora. When new deep water is formed, the older waters mix with the overlaying intermediate waters and eventually exit the Mediterranean. The residence time of water in the Mediterranean is approximately 100 years, making the Mediterranean especially sensitive to climate change.[78]

Other events affecting water circulation

[edit]Being a semi-enclosed basin, the Mediterranean experiences transitory events that can affect the water circulation on short time scales. In the mid-1990s, the Aegean Sea became the main area for deep water formation in the eastern Mediterranean after particularly cold winter conditions. This transitory switch in the origin of deep waters in the eastern Mediterranean was termed Eastern Mediterranean Transient (EMT) and had major consequences on water circulation of the Mediterranean.[79][80][81]

Another example of a transient event affecting the Mediterranean circulation is the periodic inversion of the North Ionian Gyre, which is an anticyclonic ocean gyre observed in the northern part of the Ionian Sea, off the Greek coast. The transition from anticyclonic to cyclonic rotation of this gyre changes the origin of the waters fueling it; when the circulation is anticyclonic (most common), the waters of the gyre originate from the Adriatic Sea. When the circulation is cyclonic, the waters originate from the Levantine Sea. These waters have different physical and chemical characteristics, and the periodic inversion of the North Ionian Gyre (called Bimodal Oscillating System or BiOS) changes the Mediterranean circulation and biogeochemistry around the Adriatic and Levantine regions.[82]

Climate change

[edit]Because of the short residence time of waters, the Mediterranean Sea is considered a hot spot for climate change effects.[83] Deep water temperatures have increased by 0.12 °C (0.22 °F) between 1959 and 1989.[84] According to climate projections, the Mediterranean Sea could become warmer. The decrease in precipitation over the region could lead to more evaporation ultimately increasing the Mediterranean Sea salinity.[83][85] Because of the changes in temperature and salinity, the Mediterranean Sea may become more stratified by the end of the 21st century, with notable consequences on water circulation and biogeochemistry. The stratification and warming have already led to the eastern Mediterranean to become a net source of CO2 to the atmosphere [86][87] notably during summer. This strong summer degassing, combined with the prolonged and pronounced stratification results in the formation of aragonite crystals abiotically in the water column.[88] The cumulative warming at the surface of the Mediterranean has a significant impact on the ecological system. Extreme warming has led to biodiversity loss[89] and presents an existential threat to some habitats [90] while making conditions more hospitable to invasive tropical species.[91]

Biogeochemistry

[edit]

In spite of its great biodiversity, concentrations of chlorophyll and nutrients in the Mediterranean Sea are very low, making it one of the most oligotrophic ocean regions in the world. The Mediterranean Sea is commonly referred to as an LNLC (Low-Nutrient, Low-Chlorophyll) area. The Mediterranean Sea fits the definition of a desert in which its nutrient contents are low, making it difficult for plants and animals to develop.

There are steep gradients in nutrient concentrations, chlorophyll concentrations and primary productivity in the Mediterranean. Nutrient concentrations in the western part of the basin are about double the concentrations in the eastern basin. The Alboran Sea, close to the Strait of Gibraltar, has a daily primary productivity of about 0.25 g C (grams of carbon) m−2 day−1 whereas the eastern basin has an average daily productivity of 0.16 g C m−2 day−1.[92] For this reason, the eastern part of the Mediterranean Sea is termed "ultraoligotrophic". The productive areas of the Mediterranean Sea are few and small. High (i.e. more than 0.5 grams of Chlorophyll a per cubic meter) productivity occurs in coastal areas, close to the river mouths which are the primary suppliers of dissolved nutrients. The Gulf of Lion has a relatively high productivity because it is an area of high vertical mixing, bringing nutrients to the surface waters that can be used by phytoplankton to produce Chlorophyll a.[93]

Primary productivity in the Mediterranean is also marked by an intense seasonal variability. In winter, the strong winds and precipitation over the basin generate vertical mixing, bringing nutrients from the deep waters to the surface, where phytoplankton can convert it into biomass.[94] However, in winter, light may be the limiting factor for primary productivity. Between March and April, spring offers the ideal trade-off between light intensity and nutrient concentrations in surface for a spring bloom to occur. In summer, high atmospheric temperatures lead to the warming of the surface waters. The resulting density difference virtually isolates the surface waters from the rest of the water column and nutrient exchanges are limited. As a consequence, primary productivity is very low between June and October.[95][93]

Oceanographic expeditions uncovered a characteristic feature of the Mediterranean Sea biogeochemistry: most of the chlorophyll production does not occur on the surface, but in sub-surface waters between 80 and 200 meters deep.[96] Another key characteristic of the Mediterranean is its high nitrogen-to-phosphorus ratio (N:P). Redfield demonstrated that most of the world's oceans have an average N:P ratio around 16. However, the Mediterranean Sea has an average N:P between 24 and 29, which translates a widespread phosphorus limitation.[clarification needed][97][98][99][100]

Because of its low productivity, plankton assemblages in the Mediterranean Sea are dominated by small organisms such as picophytoplankton and bacteria.[101][92]

Geology

[edit]

The geologic history of the Mediterranean Sea is complex. Underlain by oceanic crust, the sea basin was once thought to be a tectonic remnant of the ancient Tethys Ocean; it is now known to be a structurally younger basin, called the Neotethys, which was first formed by the convergence of the African Plate and Eurasian Plate during the Late Triassic and Early Jurassic. Because it is a near-landlocked body of water in a normally dry climate, the Mediterranean is subject to intensive evaporation and the precipitation of evaporites. The Messinian salinity crisis started about six million years ago (mya) when the Mediterranean became landlocked, and then essentially dried up. There are salt deposits accumulated on the bottom of the basin of more than a million cubic kilometres—in some places more than three kilometres thick.[102][103]

Scientists estimate that the sea was last filled about 5.3 million years ago (mya) in less than two years by the Zanclean flood. Water poured in from the Atlantic Ocean through a newly breached gateway now called the Strait of Gibraltar at an estimated rate of about three orders of magnitude (one thousand times) larger than the current flow of the Amazon River.[104]

The Mediterranean Sea has an average depth of 1,500 m (4,900 ft) and the deepest recorded point is 5,267 m (17,280 ft) in the Calypso Deep in the Ionian Sea. The coastline extends for 46,000 km (29,000 mi). A shallow submarine ridge (the Strait of Sicily) between the island of Sicily and the coast of Tunisia divides the sea in two main subregions: the Western Mediterranean, with an area of about 850,000 km2 (330,000 sq mi); and the Eastern Mediterranean, of about 1.65 million km2 (640,000 sq mi). Coastal areas have submarine karst springs or vruljas, which discharge pressurised groundwater into the water from below the surface; the discharge water is usually fresh, and sometimes may be thermal.[105][106]

Tectonics and paleoenvironmental analysis

[edit]The Mediterranean basin and sea system were established by the ancient African-Arabian continent colliding with the Eurasian continent. As Africa-Arabia drifted northward, it closed over the ancient Tethys Ocean which had earlier separated the two supercontinents Laurasia and Gondwana. At about that time in the middle Jurassic period (roughly 170 million years ago [dubious – discuss]) a much smaller sea basin, dubbed the Neotethys, was formed shortly before the Tethys Ocean closed at its western (Arabian) end. The broad line of collisions pushed up a very long system of mountains from the Pyrenees in Spain to the Zagros Mountains in Iran in an episode of mountain-building tectonics known as the Alpine orogeny. The Neotethys grew larger during the episodes of collisions (and associated foldings and subductions) that occurred during the Oligocene and Miocene epochs (34 to 5.33 mya); see animation: Africa-Arabia colliding with Eurasia. Accordingly, the Mediterranean basin consists of several stretched tectonic plates in subduction which are the foundation of the eastern part of the Mediterranean Sea. Various zones of subduction contain the highest oceanic ridges, east of the Ionian Sea and south of the Aegean. The Central Indian Ridge runs east of the Mediterranean Sea south-east across the in-between[clarification needed] of Africa and the Arabian Peninsula into the Indian Ocean.

Messinian salinity crisis

[edit]

During Mesozoic and Cenozoic times, as the northwest corner of Africa converged on Iberia, it lifted the Betic-Rif mountain belts across southern Iberia and northwest Africa. There the development of the intramontane Betic and Rif basins created two roughly parallel marine gateways between the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea. Dubbed the Betic and Rifian corridors, they gradually closed during the middle and late Miocene: perhaps several times.[107] In the late Miocene the closure of the Betic Corridor triggered the so-called "Messinian salinity crisis" (MSC), characterized by the deposition of a thick evaporitic sequence – with salt deposits up to 2 km thick in the Levantine sea – and by a massive drop in water level in much of the Basin. This event was for long the subject of acute scientific controversy, now much appeased,[108] regarding its sequence, geographic range, processes leading to evaporite facies and salt deposits. The start of the MSC was recently estimated astronomically at 5.96 mya, and it persisted for some 630,000 years until about 5.3 mya;[109] see Animation: Messinian salinity crisis, at right.

After the initial drawdown[clarification needed] and re-flooding, there followed more episodes—the total number is debated—of sea drawdowns and re-floodings for the duration of the MSC. It ended when the Atlantic Ocean last re-flooded the basin—creating the Strait of Gibraltar and causing the Zanclean flood—at the end of the Miocene (5.33 mya). Some research has suggested that a desiccation-flooding-desiccation cycle may have repeated several times, which could explain several events of large amounts of salt deposition.[110][111] Recent studies, however, show that repeated desiccation and re-flooding is unlikely from a geodynamic point of view.[112][113]

Desiccation and exchanges of flora and fauna

[edit]The present-day Atlantic gateway, the Strait of Gibraltar, originated in the early Pliocene via the Zanclean Flood. As mentioned, there were two earlier gateways: the Betic Corridor across southern Spain and the Rifian Corridor across northern Morocco. The Betic closed about 6 mya, causing the Messinian salinity crisis (MSC); the Rifian or possibly both gateways closed during the earlier Tortonian times, causing a "Tortonian salinity crisis" (from 11.6 to 7.2 mya), long before the MSC and lasting much longer. Both "crises" resulted in broad connections between the mainlands of Africa and Europe, which allowed migrations of flora and fauna—especially large mammals including primates—between the two continents. The Vallesian crisis indicates a typical extinction and replacement of mammal species in Europe during Tortonian times following climatic upheaval and overland migrations of new species:[114] see Animation: Messinian salinity crisis (and mammal migrations), at right.

The almost complete enclosure of the Mediterranean basin has enabled the oceanic gateways to dominate seawater circulation and the environmental evolution of the sea and basin. Circulation patterns are also affected by several other factors—including climate, bathymetry, and water chemistry and temperature—which are interactive and can induce precipitation of evaporites. Deposits of evaporites accumulated earlier in the nearby Carpathian foredeep during the Middle Miocene, and the adjacent Red Sea Basin (during the Late Miocene), and in the whole Mediterranean basin (during the MSC and the Messinian age). Many diatomites are found underneath the evaporite deposits, suggesting a connection between their[clarification needed] formations.

Today, evaporation of surface seawater (output) is more than the supply (input) of fresh water by precipitation and coastal drainage systems, causing the salinity of the Mediterranean to be much higher than that of the Atlantic—so much so that the saltier Mediterranean waters sink below the waters incoming from the Atlantic, causing a two-layer flow across the Strait of Gibraltar: that is, an outflow submarine current of warm saline Mediterranean water, counterbalanced by an inflow surface current of less saline cold oceanic water from the Atlantic. In the 1920s, Herman Sörgel proposed the building of a hydroelectric dam (the Atlantropa project) across the Straits, using the inflow current to provide a large amount of hydroelectric energy. The underlying energy grid was also intended to support a political union between Europe and, at least, the Maghreb part of Africa (compare Eurafrika for the later impact and Desertec for a later project with some parallels in the planned grid).[115]

Shift to a "Mediterranean climate"

[edit]The end of the Miocene also marked a change in the climate of the Mediterranean basin. Fossil evidence from that period reveals that the larger basin had a humid subtropical climate with rainfall in the summer supporting laurel forests. The shift to a "Mediterranean climate" occurred largely within the last three million years (the late Pliocene epoch) as summer rainfall decreased. The subtropical laurel forests retreated; and even as they persisted on the islands of Macaronesia off the Atlantic coast of Iberia and North Africa, the present Mediterranean vegetation evolved, dominated by coniferous trees and sclerophyllous trees and shrubs with small, hard, waxy leaves that prevent moisture loss in the dry summers. Much of these forests and shrublands have been altered beyond recognition by thousands of years of human habitation. There are now very few relatively intact natural areas in what was once a heavily wooded region.

Paleoclimate

[edit]Because of its latitude and its landlocked position, the Mediterranean is especially sensitive to astronomically induced climatic variations, which are well documented in its sedimentary record. Since the Mediterranean is subject to the deposition of eolian dust from the Sahara during dry periods, whereas riverine detrital input prevails during wet ones, the Mediterranean marine sapropel-bearing sequences provide high-resolution climatic information. These data have been employed in reconstructing astronomically calibrated time scales for the last 9 Ma of the Earth's history, helping to constrain the time of past geomagnetic reversals.[116] Furthermore, the exceptional accuracy of these paleoclimatic records has improved our knowledge of the Earth's orbital variations in the past.

Biodiversity

[edit]

Unlike the vast multidirectional ocean currents in open oceans within their respective oceanic zones; biodiversity in the Mediterranean Sea is stable due to the subtle but strong locked nature of currents which is favourable to life, even the smallest macroscopic type of volcanic life form. The stable marine ecosystem of the Mediterranean Sea and sea temperature provides a nourishing environment for life in the deep sea to flourish while assuring a balanced aquatic ecosystem excluded from any external deep oceanic factors. It is estimated that there are more than 17,000 marine species in the Mediterranean Sea with generally higher marine biodiversity in coastal areas, continental shelves, and decreases with depth.[117]

As a result of the drying of the sea during the Messinian salinity crisis,[118] the marine biota of the Mediterranean is derived primarily from the Atlantic Ocean. The North Atlantic is considerably colder and more nutrient-rich than the Mediterranean, and the marine life of the Mediterranean has had to adapt to its differing conditions in the five million years since the basin was reflooded.

The Alboran Sea is a transition zone between the two seas, containing a mix of Mediterranean and Atlantic species. The Alboran Sea has the largest population of bottlenose dolphins in the Western Mediterranean, is home to the last population of harbour porpoises in the Mediterranean and is the most important feeding grounds for loggerhead sea turtles in Europe. The Alboran Sea also hosts important commercial fisheries, including sardines and swordfish. The Mediterranean monk seals live in the Aegean Sea in Greece. In 2003, the World Wildlife Fund raised concerns about the widespread drift net fishing endangering populations of dolphins, turtles, and other marine animals such as the spiny squat lobster.

There was a resident population of orcas in the Mediterranean until the 1980s, when they went extinct, probably due to long-term PCB exposure. There are still annual sightings of orca vagrants.[119]

Environmental issues

[edit]For 4,000 years, human activity has transformed most parts of Mediterranean Europe, and the "humanisation of the landscape" overlapped with the appearance of the present Mediterranean climate.[120] The image of a simplistic, environmental determinist notion of a Mediterranean paradise on Earth in antiquity, which was destroyed by later civilisations, dates back to at least the 18th century and was for centuries fashionable in archaeological and historical circles. Based on a broad variety of methods, e.g. historical documents, analysis of trade relations, floodplain sediments, pollen, tree-ring and further archaeometric analyses and population studies, Alfred Thomas Grove's and Oliver Rackham's work on "The Nature of Mediterranean Europe" challenges this common wisdom of a Mediterranean Europe as a "Lost Eden", a formerly fertile and forested region, that had been progressively degraded and desertified by human mismanagement.[120] The belief stems more from the failure of the recent landscape to measure up to the imaginary past of the classics as idealised by artists, poets and scientists of the early modern Enlightenment.[120]

The historical evolution of climate, vegetation and landscape in southern Europe from prehistoric times to the present is much more complex and underwent various changes. For example, some of the deforestation had already taken place before the Roman age. While in the Roman age large enterprises such as the latifundia took effective care of forests and agriculture, the largest depopulation effects came with the end of the empire. Some[who?] assume that the major deforestation took place in modern times—the later usage patterns were also quite different e.g. in southern and northern Italy. Also, the climate has usually been unstable and there is evidence of various ancient and modern "Little Ice Ages",[121][page needed] and plant cover accommodated to various extremes and became resilient to various patterns of human activity.[120]

Even Grove considered that human activity could be the cause of climate change. Modern science has been able to provide clear evidence of this. The wide ecological diversity typical of Mediterranean Europe is predominantly based on human behaviour, as it is and has been closely related to human usage patterns.[120] The diversity range[clarification needed] was enhanced by the widespread exchange and interaction of the longstanding and highly diverse local agriculture, intense transport and trade relations, and the interaction with settlements, pasture and other land use. The greatest human-induced changes, however, came after World War II, in line with the "1950s syndrome"[122] as rural populations throughout the region abandoned traditional subsistence economies. Grove and Rackham suggest that the locals left the traditional agricultural patterns and instead became scenery-setting agents[clarification needed] for tourism. This resulted in more uniform, large-scale formations[of what?].[120] Among further current important threats to Mediterranean landscapes are overdevelopment of coastal areas, abandonment of mountains and, as mentioned, the loss of variety via the reduction of traditional agricultural occupations.[120]

Natural hazards

[edit]

The region has a variety of geological hazards, which have closely interacted with human activity and land use patterns. Among others, in the eastern Mediterranean, the Thera eruption, dated to the 17th or 16th century BC, caused a large tsunami that some experts hypothesise devastated the Minoan civilisation on the nearby island of Crete, further leading some to believe that this may have been the catastrophe that inspired the Atlantis legend.[123] Mount Vesuvius is the only active volcano on the European mainland, while others, Mount Etna and Stromboli, are on neighbouring islands. The region around Vesuvius including the Phlegraean Fields Caldera west of Naples is quite active[124] and constitute the most densely populated volcanic region in the world where an eruptive event may occur within decades.[125]

Vesuvius itself is regarded as quite dangerous due to a tendency towards explosive (Plinian) eruptions.[126] It is best known for its eruption in AD 79 that led to the burying and destruction of the Roman cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum.

The large experience[clarification needed] of member states and regional authorities has led to exchange[of what?] on the international level with the cooperation of NGOs, states, regional and municipality authorities and private persons.[127] The Greek–Turkish earthquake diplomacy is a quite positive example of natural hazards leading to improved relations between traditional rivals in the region after earthquakes in İzmit and Athens in 1999. The European Union Solidarity Fund (EUSF) was set up to respond to major natural disasters and express European solidarity to disaster-stricken regions within all of Europe.[128] The largest amount of funding requests in the EU relates to forest fires, followed by floods and earthquakes. Forest fires, whether human-made or natural, are a frequent and dangerous hazard in the Mediterranean region.[127] Tsunamis are also an often-underestimated hazard in the region. For example, the 1908 Messina earthquake and tsunami took more than 123,000 lives in Sicily and Calabria and were among the deadliest natural disasters in modern Europe.

Invasive species

[edit]

Открытие Суэцкого канала в 1869 году создало первый проход соляной воды между Средиземноморью и Красным морем . Красное море выше, чем восточное Средиземноморье , поэтому канал функционирует как приливный пролив , который наливает воду красного моря в средиземноморье. Горькие озера , которые являются гиперсолиновыми природными озерами, которые образуют часть канала, заблокировали миграцию видов Красного моря в Средиземное море в течение многих десятилетий, но как соленость озер постепенно сравнивалась с соленой красного моря, барьер к миграции были удалены, и растения и животные из Красного моря начали колонизировать восточное Средиземноморье. Красное море, как правило, более соленое и более бедное питательными веществами, чем Атлантика, поэтому виды Красного моря имеют преимущества перед атлантическими видами в соленых и бедных питательными веществами Восточного Средиземноморья. Соответственно, виды Красного моря вторгаются в средиземноморскую биоту, а не наоборот; Это явление известно как миграция меньшепсианской миграции (после Фердинанда де Лессепса , французского инженера) или эритроанского («красного») вторжения. Строительство Асван-высокая плотина через реку Нил в 1960-х годах сократила приток пресноводного и богатого питательными веществами ила из Нила в восточное Средиземноморье, делая там условия еще больше похожи на Красное море и ухудшая влияние инвазивных видов .

Инвазивные виды стали основным компонентом средиземноморской экосистемы и оказывают серьезное влияние на средиземноморскую экологию, угрожая ряду местных и эндемичных средиземноморских видов. Первый взгляд на некоторые группы морских видов показывает, что более 70% экзотических декаподов [ 129 ] и около 2/3 экзотических рыб [ 130 ] В Средиземноморье есть индо-тихоокеанское происхождение, введенное из Красного моря через Суэцкий канал. Это делает канал первым путем прибытия инопланетных видов в Средиземное море. Влияние некоторых меньшепсианских видов оказалось значительным, в основном в левантинском бассейне Средиземноморья, где они заменяют местные виды и становятся знакомым зрелищем.

Согласно определениям Средиземноморской научной комиссии и Международного союза по сохранению природы и соглашения о биологическом разнообразии (CBD) и терминологии Рамсарской конвенции , они являются инопланетными видами, поскольку они не являются местными (некоренными) для Средиземноморья Море, и находятся за пределами их обычной, не приспособленной области распределения. Когда эти виды преуспевают в создании популяций в Средиземноморском море, конкурируют и начинают заменить местных видов, они являются «инопланетными инвазивными видами», так как они являются агентом изменений и угрозой для местного биоразнообразия. В контексте CBD «Введение» относится к движению человеческой воли, косвенной или прямой, инопланетных видов за пределами его естественного диапазона (прошлое или настоящее). Суэцкий канал, являющийся искусственным (человеческим) каналом, является человеческим агентством. Поэтому меньшепсианские мигранты являются «введенными» видами (косвенными и непреднамеренными). Какую бы формулировку выбралась, они представляют угрозу для местного средиземноморского биоразнообразия, потому что они не являются коренными для этого моря. В последние годы египетское правительство объявление о своих намерениях углубить и расширить канал [ 131 ] Вызывая опасения от морских биологов , опасаясь, что такой акт только ухудшит вторжение видов Красного моря в Средиземное море и приведет к еще большему количеству видов, проходящих через канал. [ 132 ]

Прибытие новых тропических атлантических видов

[ редактировать ]В последние десятилетия прибытие экзотических видов из тропической Атлантики стало заметным. Во многих случаях это отражает расширение, предпочитаемое тенденцией потепления субтропических атлантических вод, а также быстрорастущим морским движением-естественного диапазона видов, которые теперь попадают в Средиземное море через Гибралтар . Несмотря на то, что этот процесс не так интенсивна, как меньшепсианская миграция , и поэтому он получает повышенный уровень научного охвата. [ 133 ]

Повышение уровня моря

[ редактировать ]К 2100 году общий уровень Средиземноморья может расти между 3 и 61 см (1,2 и 24,0 дюйма) в результате последствий изменения климата . [ 134 ] Это может оказать неблагоприятное воздействие на популяции по всему средиземноморству:

- Повышение уровня моря погружает части Мальты . Повышение уровня моря также будет означать повышение уровня соленой воды в запасе подземных вод Мальты и снизить доступность питьевой воды. [ 135 ]

- Повышение на 30 см (12 дюймов) на уровне моря затопило бы 200 квадратных километров (77 кв. Миль) дельты Нила , вытеснив более 500 000 египтян . [ 136 ]

- Водно -болотные угодья на Кипре также находятся под угрозой разрушения по повышению температуры и уровня моря. [ 137 ]

Прибрежные экосистемы также, по -видимому, угрожают повышение уровня моря , особенно закрытые моря, такие как Балтийская , Средиземноморье и Черное море. для движения восток -запад Эти моря имеют только небольшие и в основном коридоры , которые могут ограничивать смещение организмов на север в этих областях. [ 138 ] Повышение уровня моря за следующее столетие (2100) может составлять от 30 до 100 см (12 и 39 дюймов), а температурные сдвиги лишь 0,05–0,1 ° C (0,09–0,18 ° F) в глубоком море достаточны, чтобы вызвать значительные Изменения в видовом богатстве и функциональном разнообразии. [ 139 ]

Загрязнение

[ редактировать ]Загрязнение в этом регионе было чрезвычайно высоким в последние годы. [ когда? ] Программа окружающей среды Организации Объединенных Наций по оценкам, 650 000 000 т (720 000 000 коротких тонн) сточных вод , 129 000 т (142 000 тонн) минерального масла , 60 000 т (66 000 коротких тонн) ртути, 3800 т (4200 коротких тонн) и 36 000 T (40 000 коротких тонн) фосфатов сбрасываются в Средиземное море каждый год. [ 140 ] Конвенция Барселоны направлена на то, чтобы «уменьшить загрязнение в Средиземном море, защитить и улучшить морскую среду в этом районе, тем самым способствуя его устойчивому развитию». [ 141 ] Многие морские виды были почти уничтожены из -за загрязнения моря. Одним из них является средиземноморская печать монаха , которая считается одним из самых находящихся в мире морских млекопитающих в мире . [ 142 ] Средиземноморье также страдает от морского мусора . Исследование, проведенное в 1994 году с использованием траловых сетей вокруг побережья Испании, Франции и Италии, сообщило о особенно высокой средней концентрации мусора; в среднем 1 935 пунктов на км 2 (5 010/кв. Миль). [ 143 ]

Перевозки

[ редактировать ]

Некоторые из самых оживленных в мире маршрутов доставки находятся в Средиземном море. В частности, морской шелковый путь из Азии и Африки ведет через Суэцкий канал непосредственно в Средиземное море к его глубоководным портам в Валенсии , Пирее , Триесте , Генуе , Марселе и Барселоне . По оценкам, примерно 220 000 торговых судов с более чем 100 тонн пересекают Средиземное море каждый год-около трети общего торговца в мире. Эти корабли часто несут опасные грузы, которые в случае потеряны приведут к серьезным повреждениям морской среды.

Расхождение химических промывок резервуаров и маслянистых отходов также представляет собой значительный источник морского загрязнения. Средиземное море составляет 0,7% от глобальной поверхности воды и все же получает 17% глобального загрязнения морского масла. По оценкам, каждый год от 100 000 до 150 000 т (98 000 и 148 000 тонн) сырой нефти преднамеренно выпускается в море от судоходных мероприятий.

Приблизительно 370 000 000 000 т (360 000 000 тонн) нефти ежегодно транспортируются в Средиземное море (более 20% от всего мира), причем около 250–300 нефтяных танкеров пересекают море каждый день. Важным пунктом назначения является порт Триесте , отправная точка трансальпийского трубопровода , который покрывает 40% спроса на нефть в Германии (100% федеральных государств Баварии и Баден-Вюртемберг), 90% Австрии и 50% чешских Республика [ 144 ] Случайные разливы нефти часто случаются в среднем 10 разливов в год. Основной разлив нефти может произойти в любое время в любой части Средиземноморья. [ 139 ]

Туризм

[ редактировать ]

Побережье Средиземноморья использовалось для туризма с древних времен, как здания римской виллы на побережье Амальфи или на шоу Баркола . В частности, с конца 19 -го века пляжи стали местами тоски для многих европейцев и путешественников. С тех пор, особенно после Второй мировой войны, массовый туризм в Средиземноморье начался со всех его преимуществ и недостатков. В то время как изначально путешествие находилось на поезде, а затем на автобусе или автомобиле, сегодня самолет все чаще используется. [ 147 ]

Сегодня туризм является одним из наиболее важных источников дохода для многих средиземноморских стран, несмотря на геополитические конфликты, созданные человеком [ нужно разъяснения ] в регионе. Страны попытались погасить растущие хаотические зоны, созданные человеком [ нужно разъяснения ] Это может повлиять на экономику и общества в соседних прибрежных странах и маршруты судоходства . Военно -морские и спасательные компоненты в Средиземноморском море считаются одними из лучших [ Цитация необходима ] Из -за быстрого сотрудничества между различными военно -морскими флотами . В отличие от обширных открытых океанов, закрытое положение моря облегчает эффективные военно -морские и спасательные миссии [ Цитация необходима ] , считается самым безопасным [ Цитация необходима ] и независимо от [ нужно разъяснения ] Любая человеческая или стихийная бедствие . [ 148 ]

Туризм является источником дохода для небольших прибрежных сообществ, включая острова, независимые от городских центров. Тем не менее, туризм также сыграл важную роль в деградации прибрежной и морской среды . Средиземноморское правительства поощряют быстрое развитие к поддержке большого числа туристов, посещающих регион, но это вызвало серьезные нарушения морской среды обитания путем эрозии и загрязнения во многих местах вдоль средиземноморских побережья.

Туризм часто концентрируется в областях с высоким природным богатством [ нужно разъяснения ] , вызывая серьезную угрозу для среды обитания исчезающих видов, таких как морские черепахи и монахи . Сокращение естественного богатства может уменьшить стимул для посещения туристов. [ 139 ]

Перелог

[ редактировать ]Уровень рыб в Средиземном море тревожно низок. Европейское агентство по охране окружающей среды заявляет, что более 65% всех рыбных запасов в регионе являются внешними безопасными биологическими ограничениями и организацией Объединенных Наций по пищевым и сельскому хозяйству, которые некоторые из самых важных рыболовств, такие как Альбакор и голубое тунец , Хак , Марлин , Рыба -меч , красная кефаль и морской леща - находятся под угрозой. [ Дата отсутствует ]

Существуют четкие признаки того, что размер и качество улова и качество снизились, часто резко, и во многих областях большие и долгоживущие виды полностью исчезли из коммерческих уловов.

Большая рыба с открытой водой, такая как тунец, в течение тысячелетий была общим рыболовным ресурсом, но в настоящее время акции опасно низко. В 1999 году Гринпис опубликовал отчет, показывающий, что количество голубого тунца в Средиземноморье снизилось на более чем на 80% за предыдущие 20 лет, и правительственные ученые предупреждают, что без немедленных действий акция рухнет.

Морские тепловые волны

[ редактировать ]Исследование показало, что связанные с изменением климата исключительные морские тепловые волны в Средиземном море в течение 2015–2019 гг. Приводили к широко распространенным массовым вымирающимся выстраиваниям в течение пяти лет подряд. [ 149 ] [ 150 ]

Галерея

[ редактировать ]-

Europa Point , Гибралтар

-

Старый город Ибица Таун , Испания

-

Панорамный вид на кондомини , Монако

-

Пляж Ла -Кортэд в Илсе Д'Хеерс , Франция

-

Сардинии , Италия Южное побережье

-

Наважио , Греция

-

Pretty Bay в Бирзеббуге , Мальта

-

Панорамный вид на Пиран , Словения

-

Панорамный вид на Кавтат , Хорватия

-

Вид на Нейм , Босния и Герцеговина

-

Вид на Свети Стефан , Черногория

-

Ксамильские острова , Албания

-

Oludeniz , бирюзовое побережье , индейка

-

Пафос , Кипр

-

Burj Islam Beach, Латакия , Сирия

-

Взгляд на Хайфу , Израиль

-

Закат на пляже Дейр-аль-Балах , Газа

-

Побережье Александрии , вид из Библиотеки Александрина , Египет

-

Рас пещеры Хилал Беа, Ливия

-

Пляж Хамамет , Тунис

-

Воды возле Бехаи , Алжир

-

Эль -Джебха, портовый город в Марокко

Смотрите также

[ редактировать ]- Эгейский спор - серия споров между Грецией и Турцией над Эгейским морем

- Atlantropa - предлагаемый инженерный проект по созданию новой земли в Средиземном море

- Babelmed , место средиземноморских культур

- Спор на Кипр - спор между греческими и турецкими

- Cyprus -Turkey Maritime Spore - продолжающийся политический спор в Средиземном море

- Восточное Средиземноморье - страны, которые географически расположены к востоку от Средиземного моря

- Евро-Медеренское парламентское собрание -страницы Парламентского собрания,

- Эксклюзивная экономическая зона Греции

- Семейная средиземноморская лихорадка - генетическое аутоинфляционное заболевание

- История Средиземноморья - историческое развитие Средиземноморья

- Священная лига (1571) - католический южный европейский альянс (1571)

- Ливия -Турция Морская сделка - Морской граничный договор между страницами GNA в Ливии и

- Список островов в Средиземноморье

- Список средиземноморских стран

- Средиземноморская диета - диета, вдохновленная средиземноморским регионом

- Средиземноморские леса, лесные массивы и скрабы - среда обитания, определяемая Всемирным фондом для природы

- Средиземноморские игры -многовозможное событие средиземноморских стран

- Средиземноморская раса - устаревшая группировка людей

- Средиземноморское море (океанография) - в основном закрытое море с ограниченным обменом с внешними

- Пири Рейс - турецкий адмирал и Картограф - ранний картографист Средиземного моря

- Проект депрессии Qattara -гидроэлектрическая макро-инженерная концепция в Египте

- Сето Внутреннее море - Японское внутреннее море - также известное как Японское Средиземное море

- Средиземноморье: морские порты и морские маршруты, включая Мадейру, Канарские острова, побережье Марокко, Алжир и Тунис; Справочник для путешественников (1911), Карл Баедекер

- Тирренский бассейн

- Союз для средиземноморской - межправительственная организация

Примечания

[ редактировать ]Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ Пинет, Пол Р. (2008). «Приглашение в океанографию» . Палеоооооооография . Тол. 30, нет. 5. Jones & Barlett Learning. п. 220. ISBN 978-0-7637-5993-3 .

- ^ Боксер, Барух, Средиземноморское море в энциклопдийской британской

- ^ "Река Нила" . Образование | Национальное географическое общество . Архивировано с оригинала 8 марта 2023 года . Получено 12 марта 2023 года .

- ^ Гольвин, Жан-Клод (1991). Египет вернулся, том 3 . Париж: издания ошибки. п. 273. ISBN 978-2-87772-148-6 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Трину Страницы European Regions and Boundaries: A Conceptual History, series European Conceptual History 3. ISBN 1-78533-585-5 , 2017, с. 80

- ^ Рикман, Джеффри (2011). «Создание кобылы ноздры : 300 г. до н.э. - 500 г. н.э.». В Дэвиде Абулафии (ред.). Средиземноморье в истории . Getty Publications. п. 133. ISBN 978-1-60606-057-5 .

- ^ «Вход μεσόγαιος» . Лидделл и Скотт . Архивировано из оригинала 2 декабря 2009 года.

- ^ «Средиземноморье» . Оксфордский английский словарь (онлайн изд.). Издательство Оксфордского университета . (Требуется членство в учреждении или участвующее учреждение .)

- ^ Деххода, Али Акбар. " دریای روم" вход " . Парси Вики . Архивировано из оригинала 22 мая 2020 года . Получено 29 ноября 2019 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Велла, Эндрю П. (1985). «Средиземноморская Мальта» (PDF) . Дефис . 4 (5): 469–472. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 29 марта 2017 года.

- ^ Деххода, Али Акабар. " دریای شام" вход " . Парси Вики . Архивировано из оригинала 22 мая 2020 года . Получено 29 ноября 2019 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в «Бахр аль-Рум» в энциклопедии ислама , 2-е изд.

- ^ Diran Kélékian, Турецкий Францрный Словарь , Константинополь, 1911 год.

- ^ Özhan öztürk утверждает, что в старом турецком АК также означает «запад» и что Акениз, следовательно, означает «Западное море» и что Карадениз (Черное море) означает «Северное море». Ожан Озтюрк . Pontus: Genesis Publications этнической и политической истории Черного моря от древности до настоящего . Анкара: Книга Бытия. 2011. Стр. 5–9. Архивировано из оригинала 15 сентября 2012 года.

- ^ «Карта Средиземноморья и Северной Африки» . Архивировано из оригинала 23 августа 2023 года . Получено 22 августа 2023 года .

- ^ «Карта Османской империи» . Архивировано из оригинала 1 августа 2020 года . Получено 22 августа 2023 года .

- ^ Иоганн Кноблок. Язык и религия , вып. ср. Шмитт, Рудигер (1989). "Черное море". Энциклопедия Ираника . Тол. Iv, фас. 3. С. 310–313. Архивировано из оригинала 5 февраля 2022 года . Получено 31 августа 2018 года .

- ^ Дэвид Абулафия (2011). Великое море: человеческая история Средиземноморья . Издательство Оксфордского университета .

- ^ Rappoport, S. (Доктор философии, Базель). История Египта (без дата, начало 20 -го века), том 12, часть B, Глава V: «Водные пути Египта», с. 248–257 ( онлайн ). Лондон: Общество Глор.

- ^ Купер, Аластер (2015). География морского транспорта . Routledge. С. 33–37. ISBN 978-1-317-35150-4 .

- ^ Балард, Мишель (2003). Булл, Маркус Грэм; Эдбери, Питер; Филлипс, Джонатан (ред.). Опыт крестоносцев, том 2 - определение королевства крестоносцев . Издательство Кембриджского университета. С. 23–35. ISBN 978-0-521-78151-0 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 1 января 2024 года . Получено 17 ноября 2020 года .

- ^ Хьюсли, Норман (2006). Оспаривая крестовые походы . Blackwell Publishing. С. 152–54. ISBN 978-1-4051-1189-8 .

- ^ Брундаж, Джеймс (2004). Средневековая Италия: энциклопедия . Routledge. п. 273. ISBN 978-1-135-94880-1 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 1 января 2024 года . Получено 17 ноября 2020 года .

- ^ Роберт Дэвис (5 декабря 2003 г.). Христианские рабы, мусульманские мастера: белое рабство в Средиземном море, побережье Барбари и Италии, 1500–1800 . Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-71966-4 Полем Получено 17 января 2013 года .

- ^ «Британские рабы на побережье Барбари» . Би -би -си. Архивировано из оригинала 8 февраля 2009 года . Получено 17 января 2013 года .

- ^ Ci Gable - Константинополь падает в османские турки, архивные 29 октября 2014 года на машине Wayback - Timeline Boglewood - 1998 - Получено 3 сентября 2011 года.

- ^ «История Османской империи, исламская нация, в которой жили евреи», архивировали 18 октября 2014 года на машине Wayback - сефардные исследования и культура - Получено 3 сентября 2011 года.

- ^ Роберт Гисепи - Османы: от пограничных воинов до империи строителей [узурпировал] - 1992 - История World International - Получено 3 сентября 2011 года.

- ^ См.: Брайан Лавери "Военно -морской флот Нельсона: Корабли, мужчины и организация, 1793–1815" (2013).