Северные Ryukyuan Languages

| Северный Рюкюан | |

|---|---|

| Амами - Окинаван | |

| Географический распределение | Острова Амами , префектура Кагосима , Окинава Острова ( префектура Окинава , Япония ) |

| Лингвистическая классификация | Японии

|

| Прото-языка | Прото-Нортерн Рюкюан |

| Подразделения | |

| Глотолог | NORT3255 |

| |

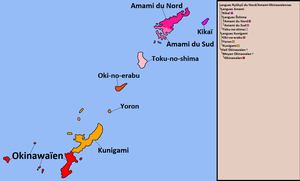

Северные языки Ryukyuan представляют собой группу языков, на которых говорят на островах Ахами , префектуре Кагосимы и на островах Окинава , префектура Окинава на юго -западной Японии . Это одна из двух основных ветвей языков Ryukyuan , которые затем являются частью японских языков . Подразделения северного Рюкюана являются вопросом научных дебатов.

Внутренняя классификация

[ редактировать ]В королевстве Рюкю территория была разделена на Магири , которая, в свою очередь, была разделена на Шиму . [ 1 ] Магири был сопоставим с японской префектурой, в то время как Шима была отдельными деревнями. В королевстве Рюкю было около 800 шимы. Лингвисты «Приизен Накасоне» и «Сатоши Нишиока» предположили, что каждый шима разработал свои собственные различные диалекты или акценты из -за людей, очень редко путешествующих за пределами своей шимы. [ 2 ]

At high level, linguists mostly agree to make the north–south division. In this framework, Northern Ryukyuan covers the Amami Islands, Kagoshima Prefecture and the Okinawa Islands, Okinawa Prefecture. The subdivision of Northern Ryukyuan, however, remains a matter of scholarly debate.[3]

In the Okinawa-go jiten (1963), Uemura Yukio simply left its subgroups flat:

- Amami–Okinawan dialect group

- Kikai language

- Amami Ōshima language

- Northern dialect

- Southern dialect

- Tokunoshima language

- Okinoerabu language

- Eastern dialect

- Western dialect

- Yoron language

- Northern Okinawan (Kunigami dialect)

- Southern Okinawan

Several others have attempted to create intermediate groups. One of two major hypotheses divides Northern Ryukyuan into Amami and Okinawan, drawing a boundary between Amami's Yoron Island and Okinawa Island. The same boundary was also set by early studies including Nakasone (1961) and Hirayama (1964). Nakamoto (1990) offered a detailed argument for it. He proposed the following classification.

- Northern Ryukyuan dialect

- Amami dialect

- Northern Amami[clarification needed]

- Southern Amami[clarification needed]

- Okinawan dialect

- Amami dialect

The other hypothesis, the three-subdivision hypothesis, is proposed by Uemura (1972). He first presented a flat list of dialects and then discussed possible groupings, one of which is as follows:

- Amami–Okinawan dialect group

- Ōshima–Tokunoshima group

- Okinoerabu–Northern Okinawan group

- South–Central Okinawan dialects

The difference between the two hypotheses is whether Southern Amami and Northern Okinawan form a cluster. Thorpe (1983) presented a "tentative" classification similar to Uemura's:[4]

- Amami–Okinawa

- North Amami

- Kikai

- North Ōshima

- South Ōshima (with Kakeroma, Yoro, Uke)

- Tokunoshima

- South Amami–North Okinawa

- Central and South Okinawa

- Central Okinawa

- Kume, Aguni, Kerama

- South Okinawa

- North Amami

Karimata (2000) investigated Southern Amami in detail and found inconsistency among isoglosses. Nevertheless, he favored the three-subdivision hypothesis:

- Amami–Okinawan dialect group

- Amami–Tokunoshima dialects

- Okinoerabu–Yoron–Northern Okinawan dialects

- South–Central Okinawan dialects[3]

Karimata (2000)'s proposal is based mostly on phonetic grounds. Standard Japanese /e/ corresponds to /ɨ/ in Northern Amami while it was merged into /i/ in Southern Amami and Okinawan.

| eye | hair | front | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Itsubu, Naze (Amami Ōshima) | mɨ | k˭ɨ[5] | mɘ |

| Shodon, Setouchi | mɨː | k˭ɨː | mɘː |

| Inokawa, Tokunoshima | mɨː | k˭ɨː | mɘː |

| Inutabu, Isen (Tokunoshima) | mɨː | k˭ɨː | mɘː |

| Nakazato, Kikai (Southern Kikai) | miː | k˭iː | meː |

| Kunigami, Wadomari (Eastern Okinoerabu) | miː | k˭iː | meː |

| Gushiken, China (Western Okinoerabu) | miː | kʰiː | meː |

| Jana, Nakijin (Northern Okinawa) | miː | k˭iː | meː |

| Shuritonokura, Naha (Southern Okinawa) | miː | kʰiː | meː |

Word-initial /kʰ/ changed to /h/ before certain vowels in Southern Amami and several Northern Okinawan dialects while Northern Amami has /k˭/. The boundary between Northern and Southern Amami is clear while Southern Amami and Northern Okinawan have no clear isogloss.

| Japanese | /ka/ | /ko/ | /ke/ | /ku/ | /ki/ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Itsubu, Naze (Amami Ōshima) | k˭ | kʰ | |||

| Shodon, Setouchi | k˭ | kʰ | |||

| Inokawa, Tokunoshima | k˭ | kʰ | |||

| Inutabu, Isen (Tokunoshima) | k˭ | kʰ | |||

| Shitooke, Kikai (Northern Kikai) | h | kʰ | |||

| Nakazato, Kikai (Southern Kikai) | h | kʰ | t͡ʃʰ | ||

| Kunigami, Wadomari (Eastern Okinoerabu) | h | kʰ | t͡ʃʰ | ||

| Wadomari, Wadomari (Eastern Okinoerabu) | h | kʰ | t͡ʃʰ | ||

| Gushiken, China (Okinoerabu) | h | kʰ | |||

| Gusuku, Yoron | h | kʰ | |||

| Benoki, Kunigami (Northern Okinawa) | h | kʰ | |||

| Ōgimi, Ōgimi (Northern Okinawa) | h | kʰ | |||

| Yonamine, Nakijin (Northern Okinawa) | h | k˭ | kʰ | tʒ[clarification needed] | |

| Kushi, Nago (Northern Okinawa) | k˭ | kʰ | |||

| Onna, Onna (Northern Okinawa) | k˭ | kʰ | |||

| Iha, Ishikawa (Southern Okinawa) | kʰ | t͡ʃʰ | |||

| Shuri, Naha (Southern Okinawa) | kʰ | t͡ʃʰ | |||

The pan-Japonic shift of /p > ɸ > h/ can be observed at various stages in Amami–Okinawan. Unlike Northern Amami and Southern Okinawan, Southern Amami and Northern Okinawan tend to maintain labiality, though the degree of preservation varies considerably.

| Japanese | /ha/ | /he/ | /ho/ | /hu/ | /hi/ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Itsubu, Naze (Amami Ōshima) | h | ||||

| Shodon, Setouchi | h | ||||

| Inokawa, Tokunoshima | h | ||||

| Inutabu, Isen (Tokunoshima) | h | ||||

| Shitooke, Kikai (Northern Kikai) | p˭ | ɸ | p˭ | ||

| Nakazato, Kikai (Southern Kikai) | ɸ | h | ɸ | ||

| Kunigami, Wadomari (Eastern Okinoerabu) | ɸ | ||||

| Gushiken, China (Western Okinoerabu) | ɸ | h | ɸ | h | |

| Gusuku, Yoron | ɸ | ||||

| Benoki, Kunigami (Northern Okinawa) | ɸ | ||||

| Ōgimi, Ōgimi (Northern Okinawa) | ɸ | pʰ | ɸ | pʰ | |

| Yonamine, Nakijin (Northern Okinawa) | p˭ | p˭ | pʰ | ||

| Kushi, Nago (Northern Okinawa) | ɸ | pʰ | |||

| Onna, Onna (Northern Okinawa) | p˭ | pʰ | |||

| Iha, Ishikawa (Southern Okinawa) | h | ||||

| Shuri, Naha (Southern Okinawa) | h | ɸ | h | ɸ | |

These shared features appear to support the three-subdivision hypothesis. However, Karimata also pointed out several features that group Northern and Southern Amami together. In Amami, word-medial /kʰ/ changed to /h/ or even dropped entirely when it was surrounded by /a/, /e/ or /o/. This can rarely be observed in Okinawan dialects. Japanese /-awa/ corresponds to /-oː/ in Amami and /-aː/ in Okinawan. Uemura (1972) also argued that if the purpose of classification was not of phylogeny, the two-subdivision hypothesis of Amami and Okinawan was also acceptable.

Pellard (2009) took a computational approach to the classification problem. His phylogenetic inference was based on phonological and lexical traits. The results dismissed the three-subdivision hypothesis and re-evaluated the two-subdivision hypothesis although the internal classification of Amami is substantially different from conventional ones.[6] The renewed classification is adopted in Heinrich et al. (2015).[7]

The membership of Kikai Island remains highly controversial. The northern three communities of Kikai Island share the seven-vowel system with Amami Ōshima and Tokunoshima while the rest is grouped with Okinoerabu and Yoron for their five-vowel systems. For this reason, Nakamoto (1990) subdivided Kikai:

- Amami dialect

- Northern Amami dialect

- Northern Amami Ōshima

- Southern Amami Ōshima

- Northern Kikai

- Southern Amami dialect

- Southern Kikai

- Okinoerabu

- Yoron

- Northern Amami dialect

Based on other evidence, however, Karimata (2000) tentatively grouped Kikai dialects together.[3] Lawrence (2011) argued that lexical evidence supported the Kikai cluster although he refrained from determining its phylogenetic relationship with other Amami dialects.[8]

As of 2014, Ethnologue presents another two-subdivision hypothesis: it groups Southern Amami, Northern Okinawa and Southern Okinawa to form Southern Amami–Okinawan, which is contrasted with Northern Amami–Okinawan. It also identifies Kikai as Northern Amami–Okinawan.[9]

Heinrich et al. (2015) refers to the subdivisions of Northern Ryukyuan as only "Amami" and "Okinawan". There is a note that other languages, specifically within the Yaeyama language, should be recognized as independent due to mutual unintelligibility.[10]

References

[edit]- ^ Smits, Gregory. "Examining the Myth of Ryukyuan Pacifism". Asia-Pacific Journal, 2010. Date accessed=7 October 2015. <http://www.japanfocus.org/-Gregory-Smits/3409/article.html>.

- ^ Satoshi Nishioka 西岡敏 (2011). "Ryūkyūgo: shima goto ni kotonaru hōgen 琉球語: 「シマ」ごとに異なる方言". In Kurebito Megumi 呉人恵 (ed.). Nihon no kiki gengo 日本の危機言語 (in Japanese).

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Karimata Shigehisa 狩俣繁久 (2000). "Amami Okinawa hōgengun ni okeru Okinoerabu hōgen no ichizuke" 奄美沖縄方言群における沖永良部方言の位置づけ (Position of Okierabu Dialect in Northern Ryukyu Dialects)". Nihon Tōyō bunka ronshū 日本東洋文化論集 (in Japanese) (6): 43–69.

- ^ Thorpe, Maner L. (1983). Ryūkyūan language history (Thesis). University of Southern California.

- ^ Гласные / ɨ / и / ɘ / традиционно транскрибируются ⟨⟨ и ⟨⟨⟩ . (Слегка) аспирированные остановки [Cʰ] и Tenuis останавливаются [C˭], как правило, описываются как «простые» ⟨c'⟩ и «напряженные» или «глоттализованные» ⟨c'⟩ соответственно. (Мартин (1970) «Шодон: диалект северного Рюкюса», журнал Американского восточного общества 90: 1).)

- ^ Пеллард, Томас (2009). Огами: Описание элементы того, что говорится о юге Рюкюса (PDF) (тезис) (на французском языке). Париж, Франция: Школа передовых исследований в области социальных наук.

- ^ ; Генрих Патрик

- ^ Уэйн Лоуренс 2011 ( . ) Для исследования и сохранения находящихся под угрозой исчезновения диалектов: общее исследование исследований и сохранения исчезающих диалектов в Японии: отчет об исследованиях на диалектах Кикайджима) (PDF) (стр. 115–122.

- ^ «Амами-Окинаван» . SIL International . Получено 1 февраля 2014 года .

- ^ Heinrich, Patrick et al. Справочник по ryukyuan . 2015. Стр. 13–15.