Взрыв в Оклахома-Сити

| Взрыв в Оклахома-Сити | |

|---|---|

Федеральное здание Альфреда П. Мюрры через два дня после взрыва, вид со стороны прилегающей парковки. | |

| Расположение | Федеральное здание Альфреда П. Мурры Оклахома-Сити, Оклахома , США |

| Координаты | 35°28′22″N 97°31′01″W / 35.47278°N 97.51694°W |

| Дата | 19 апреля 1995 г 9:02 CDT ( UTC-05:00 ) |

| Цель | Федеральное правительство США |

Тип атаки | Взрыв грузовика , массовые убийства , внутренний терроризм , правый терроризм |

| Оружие |

|

| Летальные исходы | 168–169 [ а ] |

| Раненый | 680–720+ |

| Преступники | Тимоти Джеймс Маквей и Терри Линн Николс |

| Мотив | Антиправительственные настроения ; возмездие за противостояние в Руби-Ридж и осаду Уэйко ; возмездие за федеральный запрет на боевое оружие |

| Часть серии о |

| Neo-fascism |

|---|

|

|

|

Взрыв в Оклахома-Сити — террористами взрыв грузовика внутри федерального здания Альфреда П. Мурры в Оклахома-Сити , штат Оклахома, США, 19 апреля 1995 года, во вторую годовщину окончания осады Уэйко . В то время взрыв считался самым смертоносным актом внутреннего терроризма в истории США, однако расовая резня в Талсе , также в Оклахоме, теперь, по оценкам, унесла больше жизней.

Взрыв , совершенный антиправительственными экстремистами Тимоти Маквеем и Терри Николсом , произошел в 9:02 утра, в результате чего 168 человек погибли, 680 получили ранения, а также было разрушено более трети здания, которое пришлось снести. Взрыв уничтожил или повредил еще 324 здания и нанес ущерб на сумму около 652 миллионов долларов. [ 1 ] [ 2 ] [ 3 ] Местные, государственные, федеральные и всемирные агентства провели масштабные спасательные работы после взрыва. Федеральное агентство по чрезвычайным ситуациям (FEMA) активизировало 11 своих городских поисково-спасательных групп , состоящих из 665 спасателей. [ 4 ] [ 5 ]

Через 90 минут после взрыва Маквей был остановлен дорожным патрульным Оклахомы Чарли Хэнгером за вождение без номерного знака и арестован за незаконное хранение оружия. [ 6 ] [ 7 ] Судебно-медицинские доказательства быстро связали Маквея и Николса с нападением; Николс был арестован. [ 8 ] и через несколько дней обоим были предъявлены обвинения. Позже Майкл и Лори Фортье были идентифицированы как сообщники. Маквей, ветеран войны в Персидском заливе и сочувствующий движению ополченцев США , взорвал арендованный Райдером грузовик, полный взрывчатки, который он припарковал перед зданием. Николс помогал в подготовке бомбы. Мотивированный своей неприязнью к федеральному правительству США и его действиям в отношении Руби-Ридж в 1992 году и осаде Уэйко в 1993 году, Маквей приурочил свое нападение ко второй годовщине пожара, положившего конец осаде Уэйко. [ 9 ] [ 10 ] Хотя прямая связь со взрывом не подтверждена, сторонник превосходства белой расы Ричард Снелл ранее выражал желание взорвать федеральное здание Мурры за 12 лет до того, как произошел взрыв. [ 11 ] [ 12 ]

Официальное расследование ФБР, известное как «ОКБОМБА», включало 28 000 допросов, 3200 кг улик и почти миллиард единиц информации. [ 13 ] Когда ФБР совершило обыск в доме Маквея, они нашли номер телефона, который привел их на ферму, где Маквей закупил материалы для взрыва. [14][15][16] The bombers were tried and convicted in 1997. McVeigh was executed by lethal injection on June 11, 2001, at the U.S. federal penitentiary in Terre Haute, Indiana. Nichols was sentenced to life in prison in 2004. In response to the bombing, the U.S. Congress passed the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996, which limited access to habeas corpus in the United States, among other provisions.[17] Он также принял закон об усилении защиты вокруг федеральных зданий для предотвращения будущих террористических атак.

Events

[edit]Planning

[edit]Motive

[edit]

The chief conspirators, Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols, met in 1988 at Fort Benning during basic training for the U.S. Army.[18] McVeigh met Michael Fortier as his Army roommate.[19] The three shared interests in survivalism.[20][21] McVeigh and Nichols were radicalized by white supremacist and antigovernment propaganda.[22][23] They expressed anger at the federal government's handling of the 1992 Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) standoff with Randy Weaver at Ruby Ridge, as well as the Waco siege, a 51-day standoff in 1993 between the FBI and Branch Davidian members that began with a botched Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms (ATF) attempt to execute a search warrant. There was a firefight and ultimately a siege of the compound, resulting in the burning and shooting deaths of David Koresh and 75 others.[24] In March 1993, McVeigh visited the Waco site during the standoff, and again after the siege ended.[25] He later decided to bomb a federal building as a response to the raids and to protest what he believed to be U.S. government efforts to restrict rights of private citizens, particularly those under the Second Amendment.[10][26][27][28][29] McVeigh believed that federal agents were acting like soldiers, thus making an attack on a federal building an attack on their command centers.[30]

Target selection

[edit]

McVeigh later said that, instead of attacking a building, he had contemplated assassinating Attorney General Janet Reno; FBI sniper Lon Horiuchi, who had become infamous among extremists because of his participation in the Ruby Ridge and Waco sieges; and others. McVeigh claimed he sometimes regretted not carrying out an assassination campaign.[27][31] He initially intended to destroy only a federal building, but he later decided that his message would be more powerful if many people were killed in the bombing.[32] McVeigh's criterion for attack sites was that the target should house at least two of these three federal law enforcement agencies: the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF), the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), and the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA). He regarded the presence of additional law enforcement agencies, such as the Secret Service or the U.S. Marshals Service, as a bonus.[33]

A resident of Kingman, Arizona, McVeigh considered targets in Missouri, Arizona, Texas, and Arkansas.[33] He said in his authorized biography that he wanted to minimize non-governmental casualties, so he ruled out Simmons Tower, a 40-story building in Little Rock, Arkansas, because a florist's shop occupied space on the ground floor.[34] In December 1994, McVeigh and Fortier visited Oklahoma City to inspect what would become the target of their campaign: the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building.[26]

The nine-story building, built in 1977, was named for a federal judge and housed 14 federal agencies, including the DEA, ATF, Social Security Administration, and recruiting offices for the Army and Marine Corps.[35]

McVeigh chose the Murrah building because he expected its glass front to shatter under the impact of the blast. He also believed that its adjacent large, open parking lot across the street might absorb and dissipate some of the force, and protect the occupants of nearby non-federal buildings.[34] In addition, McVeigh believed that the open space around the building would provide better photo opportunities for propaganda purposes.[34] He planned the attack for April 19, 1995, to coincide with not only the second anniversary of the Waco siege but also the 220th anniversary of the Battles of Lexington and Concord during the American Revolution.[36] Rumors have also alleged that the bombing was also connected to the planned execution of Richard Snell, an Arkansas white supremacist who was a member of the Covenant, the Sword, and the Arm of the Lord (CSA) and who was set to be executed the day the bombing took place.[37] Prior to his execution, Snell "predicted" that a bombing would take place that day.[37] Though his execution was not confirmed to be a motive for the bombing, Fort Smith–based federal prosecutor Steven Snyder told the FBI in May 1995 that Snell wanted to blow up the Oklahoma City building as revenge for the IRS raiding his home.[38][11][12]

Gathering materials

[edit]

McVeigh and Nichols purchased or stole the materials they needed to manufacture the bomb and stored them in rented sheds. In August 1994, McVeigh obtained nine binary-explosive Kinestiks from gun collector Roger E. Moore, and with Nichols ignited the devices outside Nichols's home in Herington, Kansas.[39][40] On September 30, 1994, Nichols bought forty 50-pound (23 kg) bags of ammonium nitrate fertilizer from Mid-Kansas Coop in McPherson, Kansas, enough to fertilize 12.5 acres (5.1 hectares) of farmland at a rate of 160 pounds (73 kg) of nitrogen per acre (.4 ha), an amount commonly used for corn. Nichols bought an additional 50-pound (23 kg) bag on October 18, 1994.[26] McVeigh approached Fortier and asked him to assist with the bombing project, but he refused.[41][42]

McVeigh and Nichols robbed Moore in his home of $60,000 worth of guns, gold, silver, and jewels, transporting the property in the victim's van.[41] McVeigh wrote Moore a letter in which he claimed that government agents had committed the robbery.[43] Items stolen from Moore were later found in Nichols's home and in a storage shed he had rented.[44][45]

In October 1994, McVeigh showed Michael and his wife Lori Fortier a diagram he had drawn of the bomb he wanted to build.[46] McVeigh planned to construct a bomb containing more than 5,000 pounds (2,300 kg) of ammonium nitrate fertilizer mixed with about 1,200 pounds (540 kg) of liquid nitromethane and 350 pounds (160 kg) of Tovex. Including the weight of the sixteen 55-gallon drums in which the explosive mixture was to be packed, the bomb would have a combined weight of about 7,000 pounds (3,200 kg).[47] McVeigh originally intended to use hydrazine rocket fuel, but it proved too expensive.[41]

McVeigh and his accomplices then attempted to purchase 55-U.S.-gallon (46 imp gal; 210 L) drums of nitromethane at various NHRA Drag Racing Series events during the season. His first attempt was at the Sears Craftsman Nationals, held at Heartland Motorsports Park in Pauline, Kansas. World Wide Racing Fuels representative Steve LeSueur, one of three dealers of nitromethane, was at his unit when he noted a "young man in fatigues" wanted to purchase nitromethane and hydrazine. Another fuel salesman, Glynn Tipton, of VP Racing Fuels, testified on May 1, 1997, about McVeigh's attempts to purchase both nitromethane and hydrazine. After the event, Tipton informed Wade Gray of Texas Allied Chemical, a chemical agent for VP Racing Fuels, who informed Tipton of the explosiveness of a nitromethane and hydrazine mixture. McVeigh, using an assumed name, then called Tipton's office. Suspicious of his behavior, Tipton refused to sell McVeigh the fuel.[48]

The next round of the NHRA championship tour was the Chief Auto Parts Nationals at the Texas Motorplex in Ennis, Texas, where McVeigh posed as a motorcycle racer and attempted to purchase nitromethane on the pretext that he and some fellow bikers needed it for racing. However, there were no nitromethane-powered motorcycles at the meeting, and he did not have an NHRA competition license. LeSueur again refused to sell McVeigh the fuel because he was suspicious of McVeigh's actions and attitudes, but VP Racing Fuels representative Tim Chambers sold McVeigh three barrels.[49] Chambers questioned the purchase of three barrels, when typically no more than five gallons would be purchased by a Top Fuel Harley rider, and the class was not even raced that weekend.

McVeigh rented a storage space in which he stockpiled seven crates of 18-inch-long (46 cm) Tovex "sausages", 80 spools of shock tube, and 500 electric blasting caps, which he and Nichols had stolen from a Martin Marietta Aggregates quarry in Marion, Kansas. He decided not to steal any of the 40,000 pounds (18,000 kg) of ANFO (ammonium nitrate/fuel oil) he found at the scene, as he did not believe it was powerful enough (he did obtain 17 bags of ANFO from another source for use in the bomb). McVeigh made a prototype bomb that was detonated in the desert to avoid detection.[50]

Think about the people as if they were storm troopers in Star Wars. They may be individually innocent, but they are guilty because they work for the Evil Empire.

—McVeigh reflecting on the deaths of victims in the bombing[51]

Later, speaking about the military mindset with which he went about the preparations, he said, "You learn how to handle killing in the military. I face the consequences, but you learn to accept it." He compared his actions to the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, rather than the attack on Pearl Harbor, reasoning it was necessary to prevent more lives from being lost.[51]

On April 14, 1995, McVeigh paid for a motel room at the Dreamland Motel in Junction City, Kansas.[52] The next day, he rented a 1993 Ford F-700 truck from Ryder under the name Robert D. Kling, an alias he adopted because he knew an Army soldier named Kling with whom he shared physical characteristics, and because it reminded him of the Klingon warriors of Star Trek.[53][54] On April 16, 1995, he and Nichols drove to Oklahoma City, where he parked a getaway car, a yellow 1977 Mercury Marquis, several blocks from the Murrah Federal Building.[55] The nearby Regency Towers Apartments' lobby security camera recorded images of Nichols's blue 1984 GMC pickup truck on April 16.[56] After removing the car's license plate, he left a note covering the Vehicle Identification Number (VIN) plate that read, "Not abandoned. Please do not tow. Will move by April 23. (Needs battery & cable)."[26][57] Both men then returned to Kansas.

Building the bomb

[edit]

On April 17–18, 1995, McVeigh and Nichols removed the bomb supplies from their storage unit in Herington, Kansas, where Nichols lived, and loaded them into the Ryder rental truck.[58] They then drove to Geary Lake State Park, where they nailed boards onto the floor of the truck to hold the 13 barrels in place and mixed the chemicals using plastic buckets and a bathroom scale.[59] Each filled barrel weighed nearly 500 pounds (230 kg).[60] McVeigh added more explosives to the driver's side of the cargo bay so he could ignite at close range with his Glock 21 pistol in case the primary fuses failed.[61] During McVeigh's trial, Lori Fortier stated that McVeigh claimed to have arranged the barrels in order to form a shaped charge.[46] This was achieved by tamping (placing material against explosives opposite the target of the explosion) the aluminum side panel of the truck with bags of ammonium nitrate fertilizer to direct the blast laterally towards the building.[62] Specifically, McVeigh arranged the barrels in the shape of a backwards "J"; he later said that for pure destructive power, he would have put the barrels on the side of the cargo bay closest to the Murrah Building; however, such an unevenly distributed 7,000-pound (3,200 kg) load might have broken an axle, flipped the truck over, or at least caused it to lean to one side, which could have drawn attention.[60] All or most of the barrels of ANNM (ammonium nitrate–nitromethane mixture) contained metal cylinders of acetylene intended to increase the fireball and the brisance of the explosion.[63]

McVeigh then added a dual-fuse ignition system accessible from the truck's front cab. He drilled two holes in the cab of the truck under the seat, while two more holes were drilled in the body of the truck. One green cannon fuse was run through each hole into the cab. These time-delayed fuses led from the cab through plastic fish-tank tubing conduit to two sets of non-electric blasting caps which would ignite around 350 pounds (160 kg) of the high-grade explosives that McVeigh stole from a rock quarry.[60] The tubing was painted yellow to blend in with the truck's livery, and duct-taped in place to the wall to make it harder to disable by yanking from the outside.[60] The fuses were set up to initiate, through shock tubes, the 350 pounds (160 kg) of Tovex Blastrite Gel sausages, which would in turn set off the configuration of barrels. Of the 13 filled barrels, nine contained ammonium nitrate and nitromethane, and four contained a mixture of the fertilizer and about 4 U.S. gallons (3.3 imp gal; 15 L) of diesel fuel.[60] Additional materials and tools used for manufacturing the bomb were left in the truck to be destroyed in the blast.[60] After finishing the truck bomb, the two men separated; Nichols returned home to Herington and McVeigh traveled with the truck to Junction City. The bomb cost about $5,000 (equivalent to about $11,000 in 2023) to make.[64]

Bombing

[edit]

McVeigh's original plan had been to detonate the bomb at 11:00 a.m., but at dawn on April 19, 1995, he decided instead to destroy the building at 9:00 a.m.[65] As he drove toward the Murrah Federal Building in the Ryder truck, McVeigh carried with him an envelope containing pages from The Turner Diaries—a fictional account of white supremacists who ignite a revolution by blowing up the FBI headquarters at 9:15 one morning using a truck bomb.[26] McVeigh wore a printed T-shirt with Sic semper tyrannis ("Thus always to tyrants")—what according to legend Brutus said as he assassinated Julius Caesar and is also claimed to have been shouted by John Wilkes Booth immediately after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln—and "The tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants" (from Thomas Jefferson).[36] He also carried an envelope full of revolutionary materials that included a bumper sticker with the slogan, falsely attributed[66] to Thomas Jefferson, "When the government fears the people, there is liberty. When the people fear the government, there is tyranny." Underneath, McVeigh had written, "Maybe now, there will be liberty!" with a hand-copied quote by John Locke asserting that a man has a right to kill someone who takes away his liberty.[26][67]

McVeigh entered Oklahoma City at 8:50 a.m.[68] At 8:57 a.m., the Regency Towers Apartments' lobby security camera that had recorded Nichols's pickup truck three days earlier recorded the Ryder truck heading towards the Murrah Federal Building.[69] At the same moment, McVeigh lit the five-minute fuse. Three minutes later, still a block away, he lit the two-minute fuse. He parked the Ryder truck in a drop-off zone situated under the building's day-care center, exited, and locked the truck. As he headed to his getaway vehicle, he dropped the keys to the truck a few blocks away.[70]

At 9:02 a.m. (14:02 UTC), the Ryder truck, containing over 4,800 pounds (2,200 kg)[71] of ammonium nitrate fertilizer, nitromethane, and diesel fuel mixture, detonated in front of the north side of the nine-story Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building.[46] In total, 168 people were killed and hundreds more injured. One-third of the building was destroyed by the explosion,[72] which created a 30-foot-wide (9.1 m), 8-foot-deep (2.4 m) crater on NW 5th Street next to the building.[73] The blast destroyed or damaged 324 buildings within a four-block radius, and shattered glass in 258 nearby buildings.[1][2] The broken glass alone accounted for five percent of the death total and 69 percent of the injuries outside the Murrah Federal Building.[2] The blast destroyed or burned 86 cars around the site.[1][74] The destruction of the buildings left several hundred people homeless and shut down a number of offices in downtown Oklahoma City.[75] The explosion was estimated to have caused at least $652 million worth of damage.[76]

The effects of the blast were equivalent to over 5,000 pounds (2,300 kg) of TNT,[62][77] and could be heard and felt up to 55 miles (89 km) away.[75] Seismometers at the Omniplex Science Museum in Oklahoma City, 4.3 miles (6.9 km) away, and in Norman, Oklahoma, 16.1 miles (25.9 km) away, recorded the blast as measuring approximately 3.0 on the Richter magnitude scale.[78]

The collapse of the northern half of the building took roughly seven seconds. As the truck exploded, it first destroyed the column next to it, designated as G20, and shattered the entire glass facade of the building. The shockwave of the explosion forced the lower floors upwards, before the fourth and fifth floors collapsed onto the third floor, which housed a transfer beam that ran the length of the building and was being supported by four pillars below, as well as supporting the pillars that hold the upper floors. The added weight meant that the third floor gave way along with the transfer beam, which in turn caused the collapse of the building.[79]

Arrests

[edit]Initially, the FBI had three hypotheses about responsibility for the bombing: international terrorists, possibly the same group that had carried out the World Trade Center bombing; a drug cartel, carrying out an act of vengeance against DEA agents in the building's DEA office; and anti-government radicals attempting to start a rebellion against the federal government.[80]

McVeigh was arrested within 90 minutes of the explosion,[81] as he was traveling north on Interstate 35 near Perry in Noble County, Oklahoma. Oklahoma State Trooper Charlie Hanger stopped McVeigh for driving his yellow 1977 Mercury Marquis without a license plate, and arrested him for having a concealed weapon.[6][82] For his home address, McVeigh falsely claimed he resided at Terry Nichols's brother James's house in Michigan.[83] After booking McVeigh into jail, Trooper Hanger searched his patrol car and found a business card which had been concealed by McVeigh after being handcuffed.[84] Written on the back of the card, which was from a Wisconsin military surplus store, were the words "TNT at $5 a stick. Need more."[85] The card was later used as evidence during McVeigh's trial.[85]

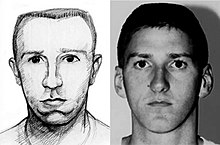

While investigating the VIN on an axle of the truck used in the explosion and the remnants of the license plate, federal agents were able to link the truck to a specific Ryder rental agency in Junction City, Kansas. Using a sketch created with the assistance of Eldon Elliot, owner of the agency, the agents were able to implicate McVeigh in the bombing.[14][26][86] McVeigh was also identified by Lea McGown of the Dreamland Motel, who remembered him parking a large yellow Ryder truck in the lot; McVeigh had signed in under his real name at the motel, using an address that matched the one on his forged license and the charge sheet at the Perry Police Station.[7][26] Before signing his real name at the motel, McVeigh had used false names for his transactions. However, McGown noted, "People are so used to signing their own name that when they go to sign a phony name, they almost always go to write, and then look up for a moment as if to remember the new name they want to use. That's what [McVeigh] did, and when he looked up I started talking to him, and it threw him."[26]

After an April 21, 1995, court hearing on the gun charges, but before McVeigh's release, federal agents took him into custody as they continued their investigation into the bombing.[26] Rather than talk to investigators about the bombing, McVeigh demanded an attorney. Having been tipped off by the arrival of police and helicopters that a bombing suspect was inside, a restless crowd began to gather outside the jail. While McVeigh's requests for a bulletproof vest or transport by helicopter were denied,[87] authorities did use a helicopter to transport him from Perry to Oklahoma City.[88]

Federal agents obtained a warrant to search the house of McVeigh's father, Bill, after which they broke down the door and wired the house and telephone with listening devices.[89] FBI investigators used the resulting information gained, along with the fake address McVeigh had been using, to begin their search for the Nichols brothers, Terry and James.[83] On April 21, 1995, Terry Nichols learned that he was being hunted, and turned himself in.[8] Investigators discovered incriminating evidence at his home: ammonium nitrate and blasting caps, the electric drill used to drill out the locks at the quarry, books on bomb-making, a copy of Hunter (a 1989 novel by William Luther Pierce, the founder and chairman of the National Alliance, a white nationalist group) and a hand-drawn map of downtown Oklahoma City, on which the Murrah Building and the spot where McVeigh's getaway car was hidden were marked.[90][91] After a nine-hour interrogation, Terry Nichols was formally held in federal custody until his trial.[92] On April 25, 1995, James Nichols was also arrested, but he was released after 32 days due to lack of evidence.[93] McVeigh's sister Jennifer was accused of illegally mailing ammunition to McVeigh,[94] but she was granted immunity in exchange for testifying against him.[95]

A Jordanian-American man traveling from his home in Oklahoma City to visit family in Jordan on April 19, 1995, was detained and questioned by the FBI at the airport. Several Arab-American groups criticized the FBI for racial profiling, and the subsequent media coverage for publicizing the man's name.[96][97] Attorney General Reno denied claims that the federal government relied on racial profiling, while FBI director Louis J. Freeh told a press conference that the man was never a suspect, and was instead treated as a "witness" to the Oklahoma City bombing, who assisted the government's investigation.[98]

Casualties

[edit]

An estimated 646 people were inside the building when the bomb exploded.[99] By the end of the day, 14 adults and six children were confirmed dead, and over 100 injured.[100] The toll eventually reached 168 confirmed dead, not including an unmatched left leg that could have belonged to an unidentified 169th victim.[101][102] Most of the deaths resulted from the collapse of the building, rather than the bomb blast itself.[103] Those killed included 163 who were in the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building, one person in the Athenian Building, one woman in a parking lot across the street, a man and woman in the Oklahoma Water Resources building and a rescue worker struck on the head by debris.[104]

The victims ranged in age from three months to 73 years and included three pregnant women.[105][104] Of the dead, 108 worked for the Federal government: Drug Enforcement Administration (5); Secret Service (6); Department of Housing and Urban Development (35); Department of Agriculture (7); Customs Office (2); Department of Transportation/Federal Highway Administration (11); General Services Administration (2); and the Social Security Administration (40).[106] Eight of the federal government victims were federal law enforcement agents. Of those law enforcement agents, four were members of the U.S. Secret Service; two were members of the U.S. Customs Service; one was a member of the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration and one was a member of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Six of the victims were U.S. military personnel; two were members of the U.S. Army; two were members of the U.S. Air Force, and two were members of the U.S. Marine Corps.[104][107] The victims also included 19 children, of whom 15 were in the America's Kids Day Care Center.[108] The bodies of the 168 victims were identified at a temporary morgue set up at the scene.[109] A team of 24 identified the victims using full-body X-rays, dental examinations, fingerprinting, blood tests, and DNA testing.[106][110][111] More than 680 people were injured. The majority of the injuries were abrasions, severe burns, and bone fractures.[112]

McVeigh later acknowledged the casualties, saying, "I didn't define the rules of engagement in this conflict. The rules, if not written down, are defined by the aggressor. It was brutal, no holds barred. Women and kids were killed at Waco and Ruby Ridge. You put back in [the government's] faces exactly what they're giving out." He later stated, "I wanted the government to hurt like the people of Waco and Ruby Ridge had."[113]

Response and relief

[edit]Rescue efforts

[edit]

At 9:03 a.m., the first of over 1,800 911 calls related to the bombing were received by Emergency Medical Services Authority (EMSA).[114] By that time, EMSA ambulances, police, and firefighters had heard the blast and were already headed to the scene.[115] Nearby civilians, who had also witnessed or heard the blast, arrived to assist the victims and emergency workers.[72] Within 23 minutes of the bombing, the State Emergency Operations Center (SEOC) was set up, consisting of representatives from the state departments of public safety, human services, military, health, and education. Assisting the SEOC were agencies including the National Weather Service, the Air Force, the Civil Air Patrol, and the American Red Cross.[4] Immediate assistance also came from 465 members of the Oklahoma National Guard, who arrived within the hour to provide security, and from members of the Department of Civil Emergency Management.[115] Terrance Yeakey and Jim Ramsey, from the Oklahoma City Police Department, were among the first officers to arrive at the site.[116][117][118]

The EMS command post was set up almost immediately following the attack and oversaw triage, treatment, transportation, and decontamination. A simple plan/objective was established: treatment and transportation of the injured was to be done as quickly as possible, supplies and personnel to handle a large number of patients was needed immediately, the dead needed to be moved to a temporary morgue until they could be transferred to the coroner's office, and measures for a long-term medical operation needed to be established.[119] The triage center was set up near the Murrah Building and all the wounded were directed there. Two hundred and ten patients were transported from the primary triage center to nearby hospitals within the first couple of hours following the bombing.[119]

Within the first hour, 50 people were rescued from the Murrah Federal Building.[120] Victims were sent to every hospital in the area. The day of the bombing, 153 people were treated at St. Anthony Hospital, eight blocks from the blast, over 70 people were treated at Presbyterian Hospital, 41 people were treated at University Hospital, and 18 people were treated at Children's Hospital.[121] Temporary silences were observed at the blast site so that sensitive listening devices capable of detecting human heartbeats could be used to locate survivors. In some cases, limbs had to be amputated without anesthetics (avoided because of the potential to induce shock) in order to free those trapped under rubble.[122] The scene had to be periodically evacuated as the police received tips claiming that other bombs had been planted in the building.[87]

At 10:28 a.m., rescuers found what they believed to be a second bomb. Some rescue workers refused to leave until police ordered the mandatory evacuation of a four-block area around the site.[114][123] The device was determined to be a three-foot (.9-m) long TOW missile used in the training of federal agents and bomb-sniffing dogs;[1][124] although actually inert, it had been marked "live" in order to mislead arms traffickers in a planned law enforcement sting.[124] On examination the missile was determined to be inert, and relief efforts resumed 45 minutes later.[124][125] The last survivor, a 15-year-old girl found under the base of the collapsed building, was rescued at around 7 p.m.[126]

In the days following the blast, over 12,000 people participated in relief and rescue operations. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) activated 11 of its Urban Search and Rescue Task Forces, bringing in 665 rescue workers.[4][5] One nurse was killed in the rescue attempt after she was hit on the head by debris, and 26 other rescuers were hospitalized because of various injuries.[127] Twenty-four K-9 units and out-of-state dogs were brought in to search for survivors and bodies in the building debris.[1][128][129] In an effort to recover additional bodies, 100 to 350 short tons (91 to 318 t) of rubble were removed from the site each day from April 24 to 29.[130]

Rescue and recovery efforts were concluded at 12:05 a.m. on May 5, by which time the bodies of all but three of the victims had been recovered.[72] For safety reasons, the building was initially slated to be demolished shortly afterward. McVeigh's attorney, Stephen Jones, filed a motion to delay the demolition until the defense team could examine the site in preparation for the trial.[131] At 7:02 a.m. on May 23, more than a month after the bombing, the Murrah Federal building was demolished.[72][132] The EMS Command Center remained active and was staffed 24 hours a day until the demolition.[119] The final three bodies to be recovered were those of two credit union employees and a customer.[133] For several days after the building's demolition, trucks hauled away 800 short tons (730 t) of debris a day from the site. Some of the debris was used as evidence in the conspirators' trials, incorporated into memorials, donated to local schools, or sold to raise funds for relief efforts.[134]

Humanitarian aid

[edit]The national humanitarian response was immediate, and in some cases even overwhelming. Large numbers of items such as wheelbarrows, bottled water, helmet lights, knee pads, rain gear, and even football helmets were donated.[4][80] The sheer quantity of such donations caused logistical and inventory control problems until drop-off centers were set up to accept and sort the goods.[72] The Oklahoma Restaurant Association, which was holding a trade show in the city, assisted rescue workers by providing 15,000 to 20,000 meals over ten days.[135]

The Salvation Army served over 100,000 meals and provided over 100,000 ponchos, gloves, hard hats, and knee pads to rescue workers.[136] Local residents and those from further afield responded to the requests for blood donations.[137][138] Of the over 9,000 units of blood donated, 131 were used; the rest were stored in blood banks.[139]

Federal and state government aid

[edit]

At 9:45 a.m., Governor Frank Keating declared a state of emergency and ordered all non-essential workers in the Oklahoma City area to be released from their duties for their safety.[72] President Bill Clinton learned about the bombing at around 9:30 a.m. while he was meeting with Turkish Prime Minister Tansu Çiller at the White House.[100][140] Before addressing the nation, President Clinton considered grounding all planes in the Oklahoma City area to prevent the bombers from escaping by air, but decided against it.[141] At 4:00 p.m., President Clinton declared a federal emergency in Oklahoma City[115] and spoke to the nation:[100]

The bombing in Oklahoma City was an attack on innocent children and defenseless citizens. It was an act of cowardice and it was evil. The United States will not tolerate it, and I will not allow the people of this country to be intimidated by evil cowards.

He ordered that flags for all federal buildings be flown at half-staff for 30 days in remembrance of the victims.[142] Four days later, on April 23, 1995, Clinton spoke from Oklahoma City.[143]

No major federal financial assistance was made available to the survivors of the Oklahoma City bombing, but the Murrah Fund set up in the wake of the bombing attracted over $300,000 in federal grants.[4] Over $40 million was donated to the city to aid disaster relief and to compensate the victims. Funds were initially distributed to families who needed it to get back on their feet, and the rest was held in trust for longer-term medical and psychological needs. By 2005, $18 million of the donations remained, some of which was earmarked to provide a college education for each of the 219 children who lost one or both parents in the bombing.[144] A committee chaired by Daniel Kurtenbach of Goodwill Industries provided financial assistance to the survivors.[145]

International reaction

[edit]International reactions to the bombing varied. President Clinton received many messages of sympathy, including those from Queen Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom, Yasser Arafat of the Palestine Liberation Organization, and P. V. Narasimha Rao of India.[146] Iran condemned the bombing as an attack on innocent people, but also blamed the U.S. government's policies for inciting it.[citation needed] Other condolences came from Russia, Canada, Australia, the United Nations, and the European Union, among other nations and organizations.[146][147]

Several countries offered to assist in both the rescue efforts and the investigation. France offered to send a special rescue unit,[146] and Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin offered to send agents with anti-terrorist expertise to help in the investigation.[147] President Clinton declined Israel's offer, believing that accepting it would increase anti-Muslim sentiments and endanger Muslim-Americans.[141]

Children affected

[edit]

In the wake of the bombing, the national media focused on the fact that 19 of the victims had been babies and children, many in the day-care center. At the time of the bombing, there were 100 day-care centers in the United States in 7,900 federal buildings.[141] McVeigh later stated that he was unaware of the day-care center when choosing the building as a target, and if he had known "... it might have given me pause to switch targets. That's a large amount of collateral damage."[149] The FBI stated that McVeigh scouted the interior of the building in December 1994 and likely knew of the day-care center before the bombing.[26][149] This was corroborated by Nichols, who said that he and McVeigh did know about the daycare center in the building, and that they did not care.[150][151] In April 2010, Joseph Hartzler, the prosecutor at McVeigh's trial, questioned how McVeigh could have decided to pass over a prior target building because of a florist shop but at the Murrah building, not "... notice that there's a child day-care center there, that there was a credit union there and a Social Security office?"[152]

Schools across the country were dismissed early and ordered closed. A photograph of firefighter Chris Fields emerging from the rubble with infant Baylee Almon, who later died in a nearby hospital, was reprinted worldwide and became a symbol of the attack. The photo, taken by bank employee Charles H. Porter IV, won the 1996 Pulitzer Prize for Spot News Photography and appeared on newspapers and magazines for months following the attack.[153][154] Aren Almon Kok, mother of Baylee Almon, said of the photo, "It was very hard to go to stores because they are in the check out aisle. It was always there. It was devastating. Everybody had seen my daughter dead. And that's all she became to them. She was a symbol. She was the girl in the fireman's arms. But she was a real person that got left behind."[155]

The images and media reports of children dying terrorized many children who, as demonstrated by later research, showed symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder.[156] Children became a primary focus of concern in the mental health response to the bombing and many bomb-related services were delivered to the community, young and old alike. These services were delivered to public schools of Oklahoma and reached approximately 40,000 students. One of the first organized mental health activities in Oklahoma City was a clinical study of middle and high school students conducted seven weeks after the bombing. The study focused on middle and high school students who had no connection or relationship to the victims of the bombing. This study showed that these students, although deeply moved by the event and showing a sense of vulnerability on the matter, had no difficulty with the demands of school or home life, as contrasted to those who were connected to the bombing and its victims, who had post-traumatic stress disorder.[157]

Children were also affected through the loss of parents in the bombing. Many children lost one or both parents in the blast, with a reported seven children losing their only remaining parent. Children of the disaster have been raised by single parents, foster parents, and other family members. Adjusting to the loss has made these children suffer psychologically and emotionally. One orphan who was interviewed (of the at least ten orphaned children) reported sleepless nights and an obsession with death.[158]

President Clinton stated that after seeing images of babies being pulled from the wreckage, he was "beyond angry" and wanted to "put [his] fist through the television".[159] Clinton and his wife Hillary requested that aides talk to child care specialists about how to communicate with children regarding the bombing. President Clinton said to the nation three days after the bombing, "I don't want our children to believe something terrible about life and the future and grownups in general because of this awful thing ... most adults are good people who want to protect our children in their childhood and we are going to get through this".[160] On April 22, 1995, the Clintons spoke in the White House with over 40 federal agency employees and their children, and in a live nationwide television and radio broadcast, addressed their concerns.[161][162]

Media coverage

[edit]Hundreds of news trucks and members of the press arrived at the site to cover the story. The press immediately noticed that the bombing took place on the second anniversary of the Waco incident.[100]

Many initial news stories hypothesized the attack had been undertaken by Islamic terrorists, such as those who had masterminded the 1993 World Trade Center bombing.[163][164][165] Some media reported that investigators wanted to question men of Middle Eastern appearance.[166] Hamzi Moghrabi, chairman of the American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee, blamed the media for harassment of Muslims and Arabs that took place after the bombing.[167]

As the rescue effort wound down, the media interest shifted to the investigation, arrests, and trials of Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols, and on the search for an additional suspect named "John Doe Number Two." Several witnesses claimed to have seen a second suspect, who did not resemble Nichols, with McVeigh.[168][169]

Those who expressed sympathy for McVeigh typically described his deed as an act of war, as in the case of Gore Vidal's essay The Meaning of Timothy McVeigh.[170][171]

Trials and sentencing of the conspirators

[edit]

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) led the official investigation, known as OKBOMB,[172] with Weldon L. Kennedy acting as special agent in charge.[173] Kennedy oversaw 900 federal, state, and local law enforcement personnel, including 300 FBI agents, 200 officers from the Oklahoma City Police Department, 125 members of the Oklahoma National Guard, and 55 officers from the Oklahoma Department of Public Safety.[174] The crime task force was deemed the largest since the investigation into the assassination of John F. Kennedy.[174] OKBOMB was the largest criminal case in America's history, with FBI agents conducting 28,000 interviews, amassing 3.5 short tons (3.2 t) of evidence, and collecting nearly one billion pieces of information.[14][16][175] Federal judge Richard Paul Matsch ordered that the venue for the trial be moved from Oklahoma City to Denver, Colorado, ruling that the defendants would be unable to receive a fair trial in Oklahoma.[176] The investigation led to the separate trials and convictions of McVeigh, Nichols and Fortier.

Timothy McVeigh

[edit]Opening statements in McVeigh's trial began on April 24, 1997. The United States was represented by a team of prosecutors led by Joseph Hartzler. In his opening statement Hartzler outlined McVeigh's motivations, and the evidence against him. McVeigh, he said, had developed a hatred of the government during his time in the army, after reading The Turner Diaries. His beliefs were supported by what he saw as the militia's ideological opposition to increases in taxes and the passage of the Brady Bill, and were further reinforced by the Waco and Ruby Ridge incidents.[9] The prosecution called 137 witnesses, including Michael Fortier and his wife Lori, and McVeigh's sister, Jennifer McVeigh, all of whom testified to confirm McVeigh's hatred of the government and his desire to take militant action against it.[177] Both Fortiers testified that McVeigh had told them of his plans to bomb the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building. Michael Fortier revealed that McVeigh had chosen the date, and Lori Fortier testified that she had created the false identification card McVeigh used to rent the Ryder truck.[178]

McVeigh was represented by a team of six principal attorneys, led by Stephen Jones.[179] According to law professor Douglas O. Linder, McVeigh wanted Jones to present a "necessity defense"—which would argue that he was in "imminent danger" from the government (that his bombing was intended to prevent future crimes by the government, such as the Waco and Ruby Ridge incidents).[178] McVeigh argued that "imminent" does not mean "immediate": "If a comet is hurtling toward the earth, and it's out past the orbit of Pluto, it's not an immediate threat to Earth, but it is an imminent threat."[180] Despite McVeigh's wishes, Jones attempted to discredit the prosecution's case in an attempt to instill reasonable doubt. Jones also believed that McVeigh was part of a larger conspiracy, and sought to present him as "the designated patsy",[178] but McVeigh disagreed with Jones arguing that rationale for his defense. After a hearing, Judge Matsch independently ruled the evidence concerning a larger conspiracy to be too insubstantial to be admissible.[178] In addition to arguing that the bombing could not have been carried out by two men alone, Jones also attempted to create reasonable doubt by arguing that no one had seen McVeigh near the scene of the crime, and that the investigation into the bombing had lasted only two weeks.[178] Jones presented 25 witnesses, including Frederic Whitehurst, over a one-week period. Although Whitehurst described the FBI's sloppy investigation of the bombing site and its handling of other key evidence, he was unable to point to any direct evidence that he knew to be contaminated.[178]

A key point of contention in the case was the unmatched left leg found after the bombing. Although it was initially believed to be from a male, it was later determined to belong to Lakesha Levy, a female member of the Air Force who was killed in the bombing.[181] Levy's coffin had to be re-opened so that her leg could replace another unmatched leg that had previously been buried with her remains. The unmatched leg had been embalmed, which prevented authorities from being able to extract DNA to determine its owner.[101] Jones argued that the leg could have belonged to another bomber, possibly John Doe No. 2.[101] The prosecution disputed the claim, saying that the leg could have belonged to any one of eight victims who had been buried without a left leg.[102]

Numerous damaging leaks, which appeared to originate from conversations between McVeigh and his defense attorneys, emerged. They included a confession said to have been inadvertently included on a computer disk that was given to the press, which McVeigh believed seriously compromised his chances of getting a fair trial.[178] A gag order was imposed during the trial, prohibiting attorneys on either side from commenting to the press on the evidence, proceedings, or opinions regarding the trial proceedings. The defense was allowed to enter into evidence six pages of a 517-page Justice Department report criticizing the FBI crime laboratory and David Williams, one of the agency's explosives experts, for reaching unscientific and biased conclusions. The report claimed that Williams had worked backward in the investigation rather than basing his determinations on forensic evidence.[182]

The jury deliberated for 23 hours. On June 2, 1997, McVeigh was found guilty on 11 counts of murder and conspiracy.[183][184] Although the defense argued for a reduced sentence of life imprisonment, McVeigh was sentenced to death.[185] In May 2001, the Justice Department announced that the FBI had mistakenly failed to provide over 3,000 documents to McVeigh's defense counsel.[186] The Justice Department also announced that the execution would be postponed for one month for the defense to review the documents. On June 6, federal judge Richard Paul Matsch ruled the documents would not prove McVeigh innocent and ordered the execution to proceed.[187] McVeigh invited conductor David Woodard to perform pre-requiem Mass music on the eve of his execution; while reproachful of McVeigh's capital wrongdoing, Woodard consented.[188]: 240–241 After President George W. Bush approved the execution (McVeigh was a federal inmate and federal law dictates that the president must approve the execution of federal prisoners), he was executed by lethal injection at the Federal Correctional Complex, Terre Haute in Terre Haute, Indiana, on June 11, 2001.[189][190][191] The execution was transmitted on closed-circuit television so that the relatives of the victims could witness his death.[192] McVeigh's execution was the first federal execution in 38 years.[193]

Terry Nichols

[edit]Nichols stood trial twice. He was first tried by the federal government in 1997, and found guilty of conspiring to build a weapon of mass destruction and of eight counts of involuntary manslaughter of federal officers.[194] After he was sentenced on June 4, 1998, to life without parole, the State of Oklahoma in 2000 sought a death-penalty conviction on 161 counts of first-degree murder (160 non-federal-agent victims and one fetus).[195] On May 26, 2004, the jury found him guilty on all charges, but deadlocked on the issue of sentencing him to death. Presiding Judge Steven W. Taylor then determined the sentence of 161 consecutive life terms without the possibility of parole.[196] In March 2005, FBI investigators, acting on a tip from Gregory Scarpa Jr., searched a buried crawl space in Nichols's former house, and found additional explosives missed in the preliminary search after Nichols was arrested.[197]

Michael and Lori Fortier

[edit]Michael and Lori Fortier were considered accomplices for their foreknowledge of the planning of the bombing. In addition to Michael Fortier's assisting McVeigh in scouting the federal building, Lori Fortier had helped McVeigh laminate the fake driver's license that was later used to rent the Ryder truck.[46] Michael Fortier agreed to testify against McVeigh and Nichols in exchange for a reduced sentence and immunity for his wife.[198] He was sentenced on May 27, 1998, to 12 years in prison, and fined $75,000 for failing to warn authorities about the attack.[199] On January 20, 2006, Fortier was released from prison, transferred into the Witness Protection Program, and given a new identity.[200]

Others

[edit]No "John Doe #2" was ever identified, nothing conclusive was ever reported regarding the owner of the unmatched leg, and the government never openly investigated anyone else in conjunction with the bombing. Although the defense teams in both McVeigh's and Nichols's trials suggested that others were involved, Judge Steven W. Taylor found no credible, relevant, or legally admissible evidence of anyone other than McVeigh and Nichols having directly participated in the bombing.[178] When McVeigh was asked if there were other conspirators in the bombing, he replied: "You can't handle the truth! Because the truth is, I blew up the Murrah Building, and isn't it kind of scary that one man could wreak this kind of hell?"[201] On the morning of McVeigh's execution a letter was released in which he had written "For those die-hard conspiracy theorists who will refuse to believe this, I turn the tables and say: Show me where I needed anyone else. Financing? Logistics? Specialized tech skills? Brainpower? Strategy? ... Show me where I needed a dark, mysterious 'Mr. X'!"[202]

Aftermath

[edit]Within 48 hours of the attack, and with the assistance of the General Services Administration (GSA), the targeted federal offices were able to resume operations in other parts of the city.[203] According to Mark Potok, director of Intelligence Project at the Southern Poverty Law Center, his organization tracked another 60 domestic smaller-scale terrorism plots from 1995 to 2005.[204][205] Several of the plots were uncovered and prevented while others caused various infrastructure damage, deaths, or other destruction. Potok revealed that in 1996 there were approximately 858 domestic militias and other antigovernment groups but the number had dropped to 152 by 2004.[206] Shortly after the bombing, the FBI hired an additional 500 agents to investigate potential domestic terrorist attacks.[207] A 2005 Federal Bureau of Investigations report said the bombing "brought the threat of right-wing terrorism to the forefront of American law enforcement attention."[208]

Legislation

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Terrorism |

|---|

In the wake of the bombing, the U.S. government enacted several pieces of legislation including the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996.[17] In response to the trials of the conspirators being moved out-of-state, the Victim Allocution Clarification Act of 1997 was signed on March 20, 1997, by President Clinton to allow the victims of the bombing (and the victims of any other future acts of violence) the right to observe trials and to offer impact testimony in sentencing hearings. In response to passing the legislation, Clinton stated that "when someone is a victim, he or she should be at the center of the criminal justice process, not on the outside looking in."[209]

In the years since the bombing, scientists, security experts, and the ATF have called on Congress to develop legislation that would require customers to produce identification when purchasing ammonium nitrate fertilizer, and for sellers to maintain records of its sale. Critics argue that farmers lawfully use large quantities of the fertilizer,[210] and as of 2009, only Nevada and South Carolina require identification from purchasers.[210] In June 1995, Congress enacted legislation requiring chemical taggants to be incorporated into dynamite and other explosives so that a bomb could be traced to its manufacturer.[211] In 2008, Honeywell announced that it had developed a nitrogen-based fertilizer that would not detonate when mixed with fuel oil. The company got assistance from the Department of Homeland Security to develop the fertilizer (Sulf-N 26) for commercial use.[212] It uses ammonium sulfate to make the fertilizer less explosive.[213]

Oklahoma school curriculum

[edit]In the decade following the bombing, there was criticism of Oklahoma public schools for not requiring the bombing to be covered in the curriculum of mandatory Oklahoma history classes. Oklahoma History is a one-semester course required by state law for graduation from high school; however, the bombing was only covered for one to two pages at most in textbooks. The state's PASS standards (Priority Academic Student Skills) did not require that a student learn about the bombing, and focused more on other subjects such as corruption and the Dust Bowl.[214] On April 6, 2010, House Bill 2750 was signed by Governor Brad Henry, requiring the bombing to be entered into the school curriculum for Oklahoma, U.S. and world history classes.[215][216][217]

On the signing, Governor Henry said, "Although the events of April 19, 1995, may be etched in our minds and in the minds of Oklahomans who remember that day, we have a generation of Oklahomans that has little to no memory of the events of that day ... We owe it to the victims, the survivors and all of the people touched by this tragic event to remember April 19, 1995, and understand what it meant and still means to this state and this nation."[217]

Building security and construction

[edit]

In the weeks following the bombing, the federal government ordered that all federal buildings in all major cities be surrounded with prefabricated Jersey barriers to prevent similar attacks.[218] As part of a longer-term plan for United States federal building security, most of those temporary barriers have since been replaced with permanent and more aesthetically considerate security barriers, which are driven deep into the ground for sturdiness.[219][220] All new federal buildings must now be constructed with truck-resistant barriers and with deep setbacks from surrounding streets to minimize their vulnerability to truck bombs.[221][222][223] FBI buildings, for instance, must be set back 100 feet (30 m) from traffic.[224] The total cost of improving security in federal buildings across the country in response to the bombing reached over $600 million.[225]

The Murrah Federal Building had been considered so safe that it only employed one security guard.[226] In June 1995, the DOJ issued Vulnerability Assessment of Federal Facilities, also known as The Marshals Report, the findings of which resulted in a thorough evaluation of security at all federal buildings and a system for classifying risks at over 1,300 federal facilities owned or leased by the federal government. Federal sites were divided into five security levels ranging from Level 1 (minimum security needs) to Level 5 (maximum).[227] The Alfred P. Murrah Building was deemed a Level 4 building.[228] Among the 52 security improvements were physical barriers, closed-circuit television monitoring, site planning and access, hardening of building exteriors to increase blast resistance, glazing systems to reduce flying glass shards and fatalities, and structural engineering design to prevent progressive collapse.[229][230]

The attack led to engineering improvements allowing buildings to better withstand tremendous forces, improvements which were incorporated into the design of Oklahoma City's new federal building. The National Geographic Channel documentary series Seconds From Disaster suggested that the Murrah Federal Building would probably have survived the blast had it been built according to California's earthquake design codes.[231]

Дрэг-рейсинг

[ редактировать ]Национальная ассоциация хот-родов ужесточила правила в отношении нитрометана. [ 232 ] Согласно действующему своду правил, количество нитрометана ограничено 400 фунтами (180 кг) или 42 галлонами США (160 л) в бочке вместо обычных 55 галлонов США (210 л). NHRA требует, чтобы участники подали анкету Top Screen в Министерство внутренней безопасности . Кроме того, участникам не разрешается иметь при себе нитрометан; после всех событий NHRA неиспользованный нитрометан должен быть возвращен поставщику топлива Sunoco . [ нужна ссылка ]

Воздействие по Маквею

[ редактировать ]Маквей считал, что взрыв оказал положительное влияние на политику правительства. В качестве доказательства он привел мирное разрешение противостояния Монтана Фримен в 1996 году, выплату правительством компенсации Рэнди Уиверу и его выжившим детям на сумму 3,1 миллиона долларов через четыре месяца после взрыва, а также заявления Билла Клинтона в апреле 2000 года, в которых он сожалел о своем решении штурмовать комплекс Бранч-Дэвидиан. Маквей заявил: «Как только вы разобьете нос хулигану, и он поймет, что его снова ударят, он уже не вернется». [ 233 ]

Вопросы эвакуации

[ редактировать ]Несколько агентств, в том числе Федеральное управление шоссейных дорог и город Оклахома-Сити , оценили меры экстренного реагирования на взрыв и предложили планы более эффективного реагирования, а также решения проблем, которые препятствовали бесперебойной спасательной операции. [ 234 ] Из-за многолюдности улиц и большого количества направленных на место аварийных служб связь между органами власти и спасателями была затруднена. Группы не знали об операциях, которые проводили другие, что создавало беспорядки и задержки в процессе поиска и спасения. Городские власти Оклахома-Сити в своем отчете о последствиях [ 235 ] заявил, что улучшение связи и единые базы для агентств улучшат помощь тем, кто находится в катастрофических ситуациях.

После терактов 11 сентября 2001 года, принимая во внимание другие события, включая взрыв в Оклахома-Сити, Федеральное управление шоссейных дорог предложило крупным мегаполисам создать маршруты эвакуации для гражданского населения. Эти выделенные маршруты позволят аварийным бригадам и правительственным учреждениям быстрее проникать в районы стихийных бедствий. Мы надеемся, что если помочь гражданским лицам выбраться и попасть спасателям, число жертв будет уменьшено. [ 236 ]

Мемориальные мероприятия

[ редактировать ]Национальный мемориал Оклахома-Сити

[ редактировать ]В течение двух лет после взрыва единственными памятниками жертвам были плюшевые игрушки, распятия, письма и другие личные вещи, оставленные тысячами людей у защитного ограждения вокруг здания. [ 237 ] [ 238 ] В Оклахома-Сити было отправлено множество предложений по поводу подходящих мемориалов, но официальный комитет по планированию мемориала не был создан до начала 1996 года. [ 239 ] когда была создана Целевая группа по мемориалу федерального здания Мурры, состоящая из 350 членов, для разработки планов строительства мемориала в память жертв взрыва. [ 160 ] 1 июля 1997 года дизайн-победитель был выбран единогласно комиссией из 15 человек из 624 представленных работ. [ 240 ] Мемориал был спроектирован и обошелся в 29 миллионов долларов, которые были собраны за счет государственных и частных средств. [ 241 ] [ 242 ] Национальный мемориал является частью системы национальных парков как дочерняя территория и был спроектирован архитекторами Оклахома-Сити Хансом и Торри Батцером и Свеном Бергами. [ 238 ] Он был посвящен президентом Клинтоном 19 апреля 2000 года, ровно через пять лет после взрыва. [ 240 ] [ 243 ] За первый год его посетило 700 000 человек. [ 238 ]

Мемориал включает в себя отражающий бассейн, окруженный двумя большими воротами, на одном из которых указано время 9:01, на другом - 9:03, причем бассейн представляет момент взрыва. В южном конце мемориала находится поле из символических бронзовых и каменных стульев — по одному для каждого погибшего человека, расположенных в зависимости от того, на каком этаже здания они находились. Стулья представляют собой пустые стулья за обеденными столами семей жертв. Места погибших детей меньше, чем места погибших взрослых. На противоположной стороне находится «дерево выживших», часть первоначального ландшафта здания, пережившего взрыв и последовавшие за ним пожары. Мемориал оставил нетронутой часть фундамента здания, что позволило посетителям увидеть масштабы разрушений. Часть сетчатого забора, установленного вокруг места взрыва, который собрал более 800 000 личных памятных вещей, позже собранных Мемориальным фондом Оклахома-Сити, теперь находится на западном краю мемориала. [ 244 ] К северу от мемориала находится здание Journal Record Building , в котором сейчас находится Национальный мемориальный музей Оклахома-Сити, филиал Службы национальных парков. В здании также находился Национальный мемориальный институт по предотвращению терроризма , учебный центр правоохранительных органов.

Старый собор Святого Иосифа

[ редактировать ]Старый собор Святого Иосифа , одна из первых каменных церквей города, расположен к юго-западу от мемориала и сильно пострадал от взрыва. [ 245 ] [ 246 ] статуя и скульптура под названием « И Иисус плакал» В ознаменование этого события рядом с Национальным мемориалом Оклахома-Сити была установлена . Работа была освящена в мае 1997 года, а 1 декабря того же года церковь была переосвящена. Церковь, статуя и скульптура не являются частью мемориала Оклахома-Сити. [ 247 ]

Соблюдение памяти

[ редактировать ]Ежегодно проводятся памятные мероприятия в память о жертвах бомбардировок. Ежегодный марафон собирает тысячи людей и позволяет бегунам спонсировать жертву взрыва. [ 248 ] [ 249 ] К десятой годовщине взрыва в городе было проведено 24 дня мероприятий, включая недельную серию мероприятий, известную как Национальная неделя надежды, с 17 по 24 апреля 2005 года. [ 250 ] [ 251 ] Как и в предыдущие годы, десятая годовщина теракта началась со службы в 9:02 утра, посвященной моменту взрыва бомбы, с традиционными 168 секундами молчания - по одной секунде за каждого человека, погибшего в результате взрыва. взрыв. Служба также включала традиционное чтение имен, которые дети читали, чтобы символизировать будущее Оклахома-Сити. [ 252 ]

Вице-президент Дик Чейни , бывший президент Клинтон, губернатор Оклахомы Брэд Генри , Фрэнк Китинг , губернатор Оклахомы на момент взрыва, и другие политические деятели присутствовали на службе и произнесли речи, в которых подчеркнули, что «добро победило зло». [ 253 ] Родственники жертв и выжившие после взрыва также отметили это во время службы в Первой объединенной методистской церкви в Оклахома-Сити. [ 254 ]

Президент Джордж Буш отметил годовщину в письменном заявлении, часть которого перекликалась с его высказываниями по поводу казни Тимоти Маквея в 2001 году: «Для переживших это преступление и для семей погибших боль продолжается». [ 255 ] Буш был приглашен, но не присутствовал на службе, поскольку направлялся в Спрингфилд, штат Иллинойс , чтобы открыть Президентскую библиотеку и музей Авраама Линкольна . Чейни присутствовал на службе вместо него. [ 253 ]

Из-за пандемии COVID-19 мемориал был закрыт для публики 19 апреля 2020 года, а местные телеканалы транслировали заранее записанные воспоминания, посвященные 25-летию. [ 256 ]

См. также

[ редактировать ]- 2011 Норвегия атакует

- Взрыв АМИА

- Список террористических инцидентов

- Катастрофа в школе Бата , самый смертоносный взрыв здания в Соединенных Штатах до взрыва в Оклахома-Сити.

Пояснительные примечания

[ редактировать ]- ↑ Среди обломков была найдена отрезанная левая нога, но жертве так и не опознали. Он мог принадлежать одной из 168 жертв или 169-й жертве, которую не нашли.

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и Отчет Департамента полиции Оклахома-Сити Альфреда П. Мурры о взрыве федерального здания после действий (PDF) . Информация о терроризме. п. 58. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 3 июля 2007 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с «Пример 30: Не допустить превращения стекла в смертоносное оружие» . Решения по безопасности онлайн. Архивировано из оригинала 13 февраля 2007 года . Проверено 3 февраля 2007 г.

- ^ Хьюитт, Кристофер (2003). Понимание терроризма в Америке: от Клана до Аль-Каиды . Рутледж. п. 106 . ISBN 978-0-415-27765-5 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и «Реагирование жертв терроризма: Оклахома-Сити и за его пределами: Глава II: Немедленное реагирование на кризис» . Министерство юстиции США . Октябрь 2000 г. Архивировано из оригинала 25 апреля 2009 г. Проверено 24 марта 2009 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б «Сводка городских поисково-спасательных служб (USAR) FEMA» (PDF) . Федеральное агентство по чрезвычайным ситуациям . п. 64. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 27 сентября 2006 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б «Тимоти Маквей задержан» . Репортаж NBC News. 22 апреля 1995 года. Архивировано из оригинала (Видео, 3 минуты) 12 октября 2013 года.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Оттли, Тед (14 апреля 2005 г.). «Загвоздка с лицензионным тегом» . ТруТВ . Архивировано из оригинала 29 августа 2011 года.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Уиткин, Гордон; Карен Робак (28 сентября 1997 г.). «Террорист или семьянин? Терри Николс предстает перед судом за взрыв в Оклахома-Сити» . Новости США и мировой отчет . Архивировано из оригинала 18 октября 2012 года.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Фельдман, Пол (18 июня 1995 г.). «Группы ополченцев растут, исследование говорит об экстремизме: несмотря на негативную огласку после взрыва в Оклахоме, число членов возросло, считает Антидиффамационная лига» . Лос-Анджелес Таймс . Архивировано из оригинала 25 июля 2012 года . Проверено 7 апреля 2010 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б «Маквей в письмах мало раскаивается» . Топика Капитал-Журнал . Ассошиэйтед Пресс. 10 июня 2001 года. Архивировано из оригинала 27 мая 2012 года . Проверено 1 июня 2009 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Томас, Джо; Рональд Смотерс (20 мая 1995 г.). «Здание Оклахома-Сити было целью заговора еще в 1983 году, - утверждает чиновник» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . Архивировано из оригинала 7 января 2013 года.

- ^ Jump up to: а б «Суд о взрыве бомбы в Оклахома-Сити: The Denver Post Online» . extras.denverpost.com . Проверено 22 марта 2024 г.

- ^ «Взрыв в Оклахома-Сити» . Федеральное бюро расследований . Проверено 7 апреля 2023 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Серано, Ричард. Один из наших: Тимоти Маквей и взрыв в Оклахома-Сити . стр. 139–141.

- ^ «Уроки извлечены и не усвоены 11 лет спустя» . Новости Эн-Би-Си . Ассошиэйтед Пресс. 16 апреля 2006 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Хэмм, Марк С. (1997). Апокалипсис в Оклахоме . Издательство Северо-Восточного университета. п. VII. ISBN 978-1-55553-300-7 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Дойл, Чарльз (3 июня 1996 г.). «Закон о борьбе с терроризмом и эффективной смертной казни 1996 года: Краткое изложение» . ФАС . Архивировано из оригинала 14 марта 2011 года . Проверено 25 ноября 2015 г.

- ^ Суикард, Джо (11 мая 1995 г.). «Жизнь Терри Николса» . Сиэтл Таймс . Архивировано из оригинала 27 сентября 2012 года . Проверено 23 мая 2023 г.

- ^ «Суд о взрыве» . Онлайн фокус . Служба общественного вещания . 13 мая 1997 года. Архивировано из оригинала 25 января 2011 года . Проверено 7 сентября 2017 г.

- ^ Джонсон, Кевин (16 апреля 2010 г.). «По мере приближения даты Окла-Сити ополченцы набирают силу» . США сегодня . Архивировано из оригинала 5 января 2013 года . Проверено 23 мая 2023 г.

- ^ Минс, Марианна (20 апреля 1996 г.). «Поиск смысла порождает козлов отпущения» (требуется плата) . Тампа Трибьюн . Проверено 25 мая 2010 г. [ мертвая ссылка ]

- ^ Белью, Кэтлин (2019). Верните войну домой: движение «Белая сила» и военизированная Америка . Издательство Гарвардского университета. п. 210. ИСБН 978-0-674-23769-8 .

- ^ «25 лет спустя взрыв в Оклахома-Сити все еще вдохновляет антиправительственных экстремистов» . Южный юридический центр по борьбе с бедностью . Проверено 23 декабря 2020 г.

- ^ Цезарь, Эд (14 декабря 2008 г.). «Выжившие британские Уэйко» . Санди Таймс . Лондон. Архивировано из оригинала 29 июня 2011 года.

- ^ Бейкер, Эл; Дэйв Эйзенштадт; Пол Шварцман; Карен Болл (22 апреля 1995 г.). «Месть за удар Уэйко Бывший солдат обвиняется в Оклахоме. Взрыв» . Ежедневные новости . Нью-Йорк. Архивировано из оригинала 27 февраля 2011 года.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж г час я дж к Коллинз, Джеймс; Патрик Э. Коул; Элейн Шеннон (28 апреля 1997 г.). «Оклахома-Сити: Вес доказательств» . Время . стр. 1–8. Архивировано из оригинала 11 февраля 2012 года . Проверено 25 марта 2009 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б «Письмо Маквея в Fox News от 26 апреля» . Канал «Фокс Ньюс» . 26 апреля 2001 г. Архивировано из оригинала 9 февраля 2011 г.

- ^ Русаков, Дейл; Серж Ф. Ковалески (2 июля 1995 г.). «Необычайная ярость обычного мальчика» . Вашингтон Пост . Архивировано из оригинала 31 января 2011 года.

- ^ Браннан, Дэвид (2010). «Левый и правый политический терроризм» . В Тане, Эндрю Т.Х. (ред.). Политика терроризма: обзор . Рутледж . стр. 68–69. ISBN 978-1-85743-579-5 .

- ^ Саулни, Сьюзен (27 апреля 2001 г.). «Маквей говорит, что подумывал об убийстве Рино» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . Архивировано из оригинала 14 июля 2012 года . Проверено 28 марта 2010 г.

- ^ «Маквей рассматривал возможность убийства Рино и других официальных лиц» . Канал «Фокс Ньюс». 27 апреля 2001 г. Архивировано из оригинала 9 февраля 2011 г.

- ^ Мишель и Хербек (2001) , с. 224.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Мишель и Хербек (2001) , с. 167.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Мишель и Хербек (2001) , стр. 168–169.

- ^ Льюис, Кэрол В. (май – июнь 2000 г.). «Террор, который провалился: общественное мнение после взрыва в Оклахома-Сити» . Обзор государственного управления . 60 (3): 201–210. дои : 10.1111/0033-3352.00080 . Архивировано из оригинала 7 марта 2012 года . Проверено 20 марта 2010 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Мишель и Хербек (2001) , с. 226.

- ^ Jump up to: а б «Ричард Уэйн Снелл (1930–1995)» . Энциклопедия Арканзаса . Проверено 22 марта 2024 г.

- ^ «Джон Ронсон о Тимоти Маквее» . Хранитель . 5 мая 2001 года . Проверено 22 марта 2024 г.

- ^ Смит, Мартин. «Хронология Маквея» . Линия фронта . Служба общественного вещания . Архивировано из оригинала 28 июля 2011 года.

- ^ Скарпа, Грег-младший «Отчет AP о возможном расследовании подкомитета взрыва в Оклахома-Сити, недавние разведданные относительно (а) участия информатора ФБР; и (б) непосредственной угрозы» (PDF) . Международная судебно-медицинская экспертиза. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 29 октября 2012 года . Проверено 5 июня 2009 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Оттли, Тед. «Подражая Тернеру» . ТруТВ. Архивировано из оригинала 19 января 2012 года.

- ^ Мишель и Хербек (2001) , с. 201.

- ^ Мишель и Хербек (2001) , стр. 197–198.

- ^ «Доказательства накапливаются против Николса в суде» . Новости Бока-Ратона . Ассошиэйтед Пресс. 16 декабря 1997 года. Архивировано из оригинала 25 ноября 2015 года . Проверено 29 июня 2009 г.

- ^ Томас, Джо (20 ноября 1997 г.). «Подозреваемый в взрыве спрятал деньги, свидетельствует бывшая жена» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . Архивировано из оригинала 5 июня 2013 года.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д Томас, Джо (30 апреля 1996 г.). «Впервые женщина рассказала Маквею о плане взрыва» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . Архивировано из оригинала 25 апреля 2009 года.

- ^ Мишель и Хербек (2001) , стр. 163–164.

- ↑ Стенограмма слушания от 1 мая 1995 г.

- ^ Флорио, Гвен (6 мая 1997 г.). «Сестра Маквея выступает против него, он говорил о переходе от антиправительственных разговоров к действию, как она свидетельствовала, и о транспортировке взрывчатых веществ». Филадельфийский исследователь .

- ^ Мишель и Хербек (2001) , с. 165.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Мишель и Хербек (2001) , с. 166.

- ^ Мишель и Хербек (2001) , с. 209.

- ^ Мишель и Хербек (2001) , стр. 199, 209.

- ^ Хронис, Питер. «Ключ «гениальный ход» » . Денвер Пост . Архивировано из оригинала 16 июня 2013 года . Проверено 8 ноября 2011 г.

- ^ Мишель и Хербек (2001) , с. 212.

- ^ Болдуин, Диана (13 декабря 1998 г.). «ФБР будет вечно расследовать дело о взрыве» . Новости ОК. Архивировано из оригинала 10 мая 2017 года . Проверено 11 сентября 2016 г.

- ^ Мишель и Хербек (2001) , стр. 206–208.

- ^ Мишель и Хербек (2001) , с. 215.

- ^ Мишель и Хербек (2001) , с. 216.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж Мишель и Хербек (2001) , стр. 217–218.

- ^ Мишель и Хербек (2001) , с. 219.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Роджерс, Дж. Дэвид; Кейт Д. Копер. «Некоторые практические применения судебной сейсмологии» (PDF) . Миссурийский университет науки и технологий . стр. 25–35. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 29 октября 2013 г. Проверено 5 июня 2009 г.

- ^ «Маквей задержан в связи со взрывом в Оклахома-Сити» . mit.edu . Архивировано из оригинала 5 февраля 2015 года . Проверено 21 июня 2014 г.

- ^ Клэй, Нолан; Оуэн, Пенни (12 мая 1997 г.). «Прокуроры подсчитали стоимость бомбы: 5000 долларов» . Оклахоман . Денвер . Архивировано из оригинала 7 мая 2022 года . Проверено 12 января 2024 г.

- ^ Мишель и Хербек (2001) , с. 220.

- ^ «Когда правительство боится народа, есть свобода… (Ложная цитата)» . Монтичелло Томаса Джефферсона . Проверено 22 мая 2020 г.

Мы не нашли никаких доказательств того, что Томас Джефферсон говорил или писал: «Когда правительство боится народа, существует свобода. Когда люди боятся правительства, существует тирания», а также никаких доказательств того, что он написал перечисленные варианты.

- ^ Мишель и Хербек (2001) , с. 228.

- ^ Мишель и Хербек (2001) , с. 229.

- ^ Тим, Тэлли (15 апреля 2004 г.). «Мужчина свидетельствует, что ось грузовика упала с неба после взрыва в Оклахома-Сити» . UT Сан-Диего . Архивировано из оригинала 13 марта 2012 года.

- ^ «Исследование взрыва в Оклахома-Сити». Телевидение национальной безопасности . 2006. 10:42 минута.

- ^ Ирвинг, Клайв (1995). Во имя их . Случайный дом. п. 76 . ISBN 978-0-679-44825-9 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж «Отчет после действий Департамента по управлению гражданскими чрезвычайными ситуациями штата Оклахома» (PDF) . Отдел центрального обслуживания Центральный полиграфический отдел. 1996. с. 77. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 21 января 2014 года . Проверено 26 июня 2009 г.

- ^ Управление документами города Оклахома-Сити (1996). Итоговый отчет . Публикации пожарной защиты, Университет штата Оклахома, стр. 10–12. ISBN 978-0-87939-130-0 .

- ^ Ирвинг, Клайв (1995). Во имя их . Случайный дом. п. 52 . ISBN 978-0-679-44825-9 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б «Реагирование жертв терроризма: Оклахома-Сити и за его пределами: Глава I, Взрыв федерального здания Альфреда П. Мурры» . Министерство юстиции США . Октябрь 2000 г. Архивировано из оригинала 5 ноября 2010 г.

- ^ Хьюитт, Кристофер (2003). Понимание терроризма в Америке . п. 106 . ISBN 978-0-415-27766-2 .

- ^ Млакар, Пол Ф. старший; В. Джин Корли ; Мете А. Созен; Чарльз Х. Торнтон (август 1998 г.). «Взрыв в Оклахома-Сити: анализ ущерба от взрыва здания Мюрра». Журнал эффективности построенных объектов . 12 (3): 113–119. дои : 10.1061/(ASCE)0887-3828(1998)12:3(113) .

- ^ Хольцер, ТЛ; Джо Б. Флетчер; Гэри С. Фьюс; Тронд Райберг; Томас М. Брочер; Кристофер М. Дитель (1996). «Сейсмограммы дают представление о взрыве в Оклахома-Сити» . Эос, Труды Американского геофизического союза . 77 (41): 393, 396–397. Бибкод : 1996EOSTr..77..393H . дои : 10.1029/96EO00269 . Архивировано из оригинала 13 ноября 2007 года . Проверено 25 марта 2009 г.

- ^ «Бомба в Оклахома-Сити» («Оклахома-Сити»). Секунды до катастрофы .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Хэмм, Марк С. (1997). Апокалипсис в Оклахоме . Издательство Северо-Восточного университета. стр. 62–63. ISBN 978-1-55553-300-7 .

- ^ «Библиотечные факты: взрыв в Оклахома-Сити» . Звезда Индианаполиса . 9 августа 2004 года. Архивировано из оригинала 28 апреля 2011 года . Проверено 31 марта 2006 г.

- ^ Кроган, Джим (24 марта 2004 г.). «Тайны Тимоти Маквея» . Лос-Анджелес Еженедельник . Архивировано из оригинала 25 мая 2011 года.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Цуккино, Дэвид (14 мая 1995 г.). «По следу к разрушению; подсказки о взрыве в Оклахома-Сити привели к; небольшой круг недовольных – не широкая сеть» (требуется плата) . Филадельфийский исследователь . Архивировано из оригинала 9 июня 2011 года . Проверено 14 июня 2009 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б «Обратимся к доказательствам: ось и отпечатки пальцев» . Кингман Дейли Майнер . Ассошиэйтед Пресс. 21 апреля 1997 года. Архивировано из оригинала 25 ноября 2015 года . Проверено 27 июня 2009 г.

- ^ Хэмм, Марк С. (1997). Апокалипсис в Оклахоме . Издательство Северо-Восточного университета. п. 65. ИСБН 978-1-55553-300-7 .