Донорство органов

Примеры и перспективы в этой статье касаются главным образом Соединенных Штатов и не отражают мировую точку зрения на этот вопрос . ( июнь 2022 г. ) |

Донорство органов — это процесс, когда человек разрешает пересадить . изъять свой собственный орган и его другому человеку на законных основаниях либо по согласию , пока донор жив , либо через юридическое разрешение на донорство умершего, сделанное до смерти , или на донорство умершего с разрешения законного ближайшего родственника .

Пожертвование может быть сделано для исследования или, что чаще, могут быть пожертвованы здоровые трансплантируемые органы и ткани для трансплантации другому человеку. [ 1 ] [ 2 ]

Обычные трансплантации включают почки , сердце , печень , поджелудочную железу , кишечник , легкие , кости , костный мозг , кожу и роговицу . [ 1 ] Некоторые органы и ткани могут быть пожертвованы живыми донорами, например, почка или часть печени, часть поджелудочной железы, часть легких или часть кишечника. [ 3 ] донора но большинство пожертвований происходит после смерти . [1]

In 2019, Spain had the highest donor rate in the world at 46.91 per million people, followed by the US (36.88 per million), Croatia (34.63 per million), Portugal (33.8 per million), and France (33.25 per million).[4]

As of February 2, 2019, there were 120,000 people waiting for life-saving organ transplants in the United States.[5] Of these, 74,897 people were active candidates waiting for a donor.[5] While views of organ donation are positive, there is a large gap between the numbers of registered donors compared to those awaiting organ donations on a global level.[6]

To increase the number of organ donors, especially among underrepresented populations, current approaches include the use of optimized social network interventions, exposing tailored educational content about organ donation to target social media users.[7] Every year August 13 is observed as World Organ Donation Day to raising awareness about the importance of organ donation.[8]

Process in the United States

[edit]Organ donors are usually dead at the time of donation, but may be living. For living donors, organ donation typically involves extensive testing before the donation, including psychological evaluation to determine whether the would-be donor understands and consents to the donation. On the day of the donation, the donor and the recipient arrive at the hospital, just like they would for any other major surgery.[9]

For dead donors, the process begins with verifying that the person is undoubtedly deceased, determining whether any organs could be donated, and obtaining consent for the donation of any usable organs. Normally, nothing is done until the person has already died, although if death is inevitable, it is possible to check for consent and to do some simple medical tests shortly beforehand, to help find a matching recipient.[9]

The verification of death is normally done by a neurologist (a physician specializing in brain function) that is not involved in the previous attempts to save the patient's life. This physician has nothing to do with the transplantation process.[9] Verification of death is often done multiple times, to prevent doctors from overlooking any remaining sign of life, however small.[10] After death, the hospital may keep the body on a mechanical ventilator and use other methods to keep the organs in good condition.[10] The donor's estate and their families are not charged for any expenses related to the donation.

The surgical process depends upon which organs are being donated. The body is normally restored to as normal an appearance as possible, so that the family can proceed with funeral rites and either cremation or burial.

The lungs are highly vulnerable to injury and thus the most difficult to preserve, with only 15–25% of donated organs utilized.[11]

History

[edit]The first living organ donor in a successful transplant was Ronald Lee Herrick (1931–2010), who donated a kidney to his identical twin brother Richard (1931–1963) in 1954.[12] The lead surgeon, Joseph Murray, and the nephrologist, John Merrill, won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1990 for advances in organ transplantation.

The youngest organ donor was a baby with anencephaly, born in 2014, who lived for only 100 minutes and donated his kidneys to an adult with renal failure.[13] The oldest known cornea donor was a 107-year-old Scottish woman, whose corneas were donated after her death in 2016.[14] The oldest known organ donor for an internal organ was a 98-year-old southern Missouri man, who donated his liver after he died.[15]

The oldest altruistic living organ donor was an 85-year-old woman in Britain, who donated a kidney to a stranger in 2014 after hearing how many people needed to receive a transplant.[16]

Researchers were able to develop a novel way to transplant human fetal kidneys into anephric rats to overcome a significant obstacle in impeding human fetal organ transplantations.[17] The human fetal kidneys demonstrated both growth and function within the rats.[17]

Brain donation

[edit]Donated brain tissue is a valuable resource for research into brain function, neurodiversity, neuropathology and possible treatments. Both divergent and healthy control brains are needed for comparison.[18] Brain banks typically source tissue from donors who had registered with them before their death,[19] since organ donor registries focus on tissue meant for transplantation. In the United States the nonprofit Brain Donor Project facilitates this process.[20][21]

Legislation and global perspectives

[edit]This article needs to be updated. (December 2020) |

The laws of different countries allow potential donors to permit or refuse donation, or give this choice to relatives. The frequency of donations varies among countries.

Consent process

[edit]The term consent is typically defined as a subject adhering to an agreement of principles and regulations; however, the definition becomes difficult to execute concerning the topic of organ donation, mainly because the subject is incapable of consent due to death or mental impairment.[22] There are two types of consent being reviewed; explicit consent and presumed consent. Explicit consent consists of the donor giving direct consent through proper registration depending on the country.[23] The second consent process is presumed consent, which does not need direct consent from the donor or the next of kin.[23] Presumed consent assumes that donation would have been permitted by the potential donor if permission was pursued.[23] Of possible donors an estimated twenty-five percent of families refuse to donate a loved one's organs.[24]

Opt-in versus opt-out

[edit]As medical science advances, the number of people who could be helped by organ donors increases continuously. As opportunities to save lives increase with new technologies and procedures, the demand for organ donors rises faster than the actual number of donors.[25] In order to respect individual autonomy, voluntary consent must be determined for the individual's disposition of their remains following death.[26] There are two main methods for determining voluntary consent: "opt in" (only those who have given explicit consent are donors) and "opt out" (anyone who has not refused consent to donate is a donor). In terms of an opt-out or presumed consent system, it is assumed that individuals do intend to donate their organs to medical use when they expire.[26] Opt-out legislative systems dramatically increase effective rates of consent for donation as a consequence of the default effect.[27] For example, Germany, which uses an opt-in system, has an organ donation consent rate of 12% among its population, while Austria, a country with a very similar culture and economic development, but which uses an opt-out system, has a consent rate of 99.98%.[27][28]

Opt-out consent, otherwise known as "deemed" consent, support refers to the notion that the majority of people support organ donation, but only a small percentage of the population are actually registered, because they fail to go through the actual step of registration, even if they want to donate their organs at the time of death. This could be resolved with an opt-out system, where many more people would be registered as donors when only those who object consent to donation have to register to be on the non-donation list.[26]

For these reasons, countries, such as Wales, have adopted a "soft opt-out" consent, meaning if a citizen has not clearly made a decision to register, then they will be treated as a registered citizen and participate in the organ donation process. Likewise, opt-in consent refers to the consent process of only those who are registered to participate in organ donation. Currently, the United States has an opt-in system, but studies show that countries with an opt-out system save more lives due to more availability of donated organs. The current opt-in consent policy assumes that individuals are not willing to become organ donors at the time of their death, unless they have documented otherwise through organ donation registration.[26]

Registering to become an organ donor heavily depends on the attitude of the individual; those with a positive outlook might feel a sense of altruism towards organ donation, while others may have a more negative perspective, such as not trusting doctors to work as hard to save the lives of registered organ donors. Some common concerns regarding a presumed consent ("opt-out") system are sociologic fears of a new system, moral objection, sentimentality, and worries of the management of the objection registry for those who do decide to opt-out of donation.[26] Additional concerns exist with views of compromising the freedom of choice to donate,[29] conflicts with extant religious beliefs[30] and the possibility of posthumous violations of bodily integrity.[31] Even though concerns exist, the United States still has a 95 percent organ donation approval rate. This level of nationwide acceptance may foster an environment where moving to a policy of presumed consent may help solve some of the organ shortage problem, where individuals are assumed to be willing organ donors unless they document a desire to "opt-out", which must be respected.[30]

Because of public policies, cultural, infrastructural and other factors, presumed consent or opt-out models do not always translate directly into increased effective rates of donation. The United Kingdom has several different laws and policies for the organ donation process, such as consent of a witness or guardian must be provided to participate in organ donation. This policy was consulted on by Department of Health and Social Care in 2018,[32] and was implemented starting 20 May 2020.[33]

In terms of effective organ donations, in some systems like Australia (14.9 donors per million, 337 donors in 2011), family members are required to give consent or refusal, or may veto a potential recovery even if the donor has consented.[34] Some countries with an opt-out system like Spain (40.2 donors per million inhabitants),[35] Croatia (40.2 donors/million)[35] or Belgium (31.6 donors/million)[35] have high donor rates, however some countries such as Greece (6 donors/million) maintain low donor rates even with this system.[36] The president of the Spanish National Transplant Organisation has acknowledged Spain's legislative approach is likely not the primary reason for the country's success in increasing the donor rates, starting in the 1990s.[37]

Looking to the example of Spain, which has successfully adopted the presumed consent donation system, intensive care units (ICUs) must be equipped with enough doctors to maximize the recognition of potential donors and maintain organs while families are consulted for donation. The characteristic that enables the Spanish presumed consent model to be successful is the resource of transplant coordinators; it is recommended to have at least one at each hospital where opt-out donation is practiced to authorize organ procurement efficiently.[38]

Public views are crucial to the success of opt-out or presumed consent donation systems. In a study done to determine if health policy change to a presumed consent or opt-out system would help to increase donors, an increase of 20 to 30 percent was seen among countries who changed their policies from some type of opt-in system to an opt-out system. Of course, this increase must have a great deal to do with the health policy change, but also may be influenced by other factors that could have impacted donor increases.[39]

Transplant Priority for Willing Donors, also known as the "donor-priority rule", is a newer method and the first to incorporate a "non-medical" criterion into the priority system to encourage higher donation rates in the opt-in system.[40][41] Initially implemented in Israel, it allows an individual in need of an organ to move up the recipient list. Moving up the list is contingent on the individual opting-in prior to their need for an organ donation. The policy applies nonmedical criteria when allowing individuals who have previously registered as an organ donor, or whose family has previously donated an organ, priority over other possible recipients. It must be determined that both recipients have identical medical needs prior to moving a recipient up the list. While incentives like this in the opt-in system do help raise donation rates, they are not as successful in doing so as the opt-out, presumed consent default policies for donation.[34]

| Country | Policy | Year implemented |

|---|---|---|

| Argentina | opt-out | 2005 |

| Austria | opt-out | |

| Belarus | opt-out | 2007[42] |

| Belgium | opt-out | |

| Brazil | opt-in | |

| Czech Republic | opt-out | September 2002[43] |

| Chile | opt-out | 2010 |

| Colombia | opt-out | 2017 |

| Guatemala | opt-in | February 2024[44] |

| Israel | opt-in | |

| Netherlands | opt-out | 2020[45] |

| Spain | opt-out | 1979 |

| Ukraine | opt-in | [46] |

| United Kingdom (Scotland, England and Wales only) | opt-out | March 25, 2021, May 20, 2020 & December 1, 2015 |

| United Kingdom (Northern Ireland only) | opt-out | June 1, 2023[47] |

| United States | opt-in |

Argentina

[edit]On November 30, 2005, the Congress introduced an opt-out policy on organ donation, where all people over 18 years of age will be organ donors unless they or their family state otherwise. The law was promulgated on December 22, 2005, as "Law 26,066".[48]

On July 4, 2018, the Congress passed a law removing the family requirement, making the organ donor the only person that can block donation. It was promulgated on July 4, 2018, as Law Justina or "Law 27,447".[49]

Brazil

[edit]A campaign by Sport Club Recife has led to waiting lists for organs in north-east Brazil to drop almost to zero; while according to the Brazilian law the family has the ultimate authority, the issuance of the organ donation card and the ensuing discussions have however eased the process.[50]

Canada

[edit]In 2001, the Government of Canada announced the formation of the Canadian Council for Donation and Transplantation, whose purpose would be to advise the Conference of Deputy Ministers of Health on activities relating to organ donation and transplantation. The deputy ministers of health for all provinces and territories with the exception of Québec decided to transfer the responsibilities of the Canadian Council for Donation and Transplantation to Canadian Blood Services.[51]

In Québec, an organization called Transplant Québec is responsible for managing all organ donation; Héma-Québec is responsible for tissue donation.[52] Consent for organ donation by an individual is given by either registering with the organ donation registry established by the Chambre des notaires du Québec, signing and affixing the sticker to the back of one's health insurance card, or registering with either Régie de l'assurance maladie du Québec or Registre des consentements au don d'organes et de tissus.[53]

In 2017, the majority of transplants completed were kidney transplants.[54] Canadian Blood Services has a program called the kidney paired donation, where transplant candidates are matched with compatible living donors from all over Canada. It also gives individuals an opportunity to be a living donor for an anonymous patient waiting for a transplant. As of December 31, 2017, there were 4,333 patients on the transplant waitlist. In 2017, there were a total of 2,979 transplants, including multi-organ transplants; 242 patients died while on the waitlist. 250 Canadians die on average waiting for transplant organs every year.[55]

Each province has different methods and registries for intent to donate organs or tissues as a deceased donor. In some provinces, such as Newfoundland and Labrador and New Brunswick organ donation registration is completed by completing the "Intent to donate" section when applying or renewing one's provincial medical care.[56][57] In Ontario, one must be 16 years of age to register as an organ and tissue donor and register with ServiceOntario.[58] Alberta requires that a person must be 18 years of age or older and register with the Alberta Organ and Tissue Donation Registry.[59]

Opt-out donation in Canada

[edit]Nova Scotia, Canada, is the first jurisdiction in North America that will be introducing an automatic organ donation program unless residents opt out; this is known as presumed consent.[60] The Human Organ and Tissue Act was introduced on April 2, 2019.[61] When the new legislation is in effect, all people who have been Nova Scotia residents for a minimum of 12 consecutive months, with appropriate decision-making capacity and are over 19 years of age are considered potential donors and will be automatically referred to donation programs if they are determined to be good candidates. In the case of persons under 19 years of age and people without appropriate decision-making capacity, they will only be considered as organ donors if their parent, guardian or decision-maker opts them into the program. The new legislation is scheduled to take effect in mid to late 2020, and will not be applicable to tourists visiting Nova Scotia or post-secondary students from other provinces or countries.[62]

Chile

[edit]On January 6, 2010, the "Law 20,413" was promulgated, introducing an opt-out policy on organ donation, where all people over 18 years of age will be organ donors unless they state their negative.[63][64]

Colombia

[edit]On August 4, 2016, the Congress passed the "Law 1805", which introduced an opt-out policy on organ donation where all people will be organ donors unless they state their negative.[65] The law came into force on February 4, 2017.[66]

Europe

[edit]

Within the European Union, organ donation is regulated by member states. As of 2010, 24 European countries have some form of presumed consent (opt-out) system, with the most prominent and limited opt-out systems in Spain, Austria, and Belgium yielding high donor rates.[67] Spain had the highest donor rate in the world, 46.9 per million people in the population, in 2017.[68] This is attributed to multiple factors in the Spanish medical system, including identification and early referral of possible donors, expanding criteria for donors and standardised frameworks for transplantation after circulatory death.[69]

In England, individuals who wish to donate their organs after death can use the Organ Donation Register, a national database. The government of Wales became the first constituent country in the UK to adopt presumed consent in July 2013.[70] The opt-out organ donation scheme in Wales went live on December 1, 2015, and is expected to increase the number of donors by 25%.[71] In 2008, the UK discussed whether to switch to an opt-out system in light of the success in other countries and a severe British organ donor shortfall.[72] In Italy if the deceased neither allowed nor refused donation while alive, relatives will pick the decision on his or her behalf despite a 1999 act that provided for a proper opt-out system.[73] In 2008, the European Parliament overwhelmingly voted for an initiative to introduce an EU organ donor card in order to foster organ donation in Europe.[74]

Landstuhl Regional Medical Center (LRMC) has become one of the most active organ donor hospitals in all of Germany, which otherwise has one of the lowest organ donation participation rates in the Eurotransplant organ network. LRMC, the largest U.S. military hospital outside the United States, is one of the top hospitals for organ donation in the Rhineland-Palatinate state of Germany, even though it has relatively few beds compared to many German hospitals. According to the German organ transplantation organization, Deutsche Stiftung Organtransplantation (DSO), 34 American military service members who died at LRMC (roughly half of the total number who died there) donated a total of 142 organs between 2005 and 2010. In 2010 alone, 10 of the 12 American service members who died at LRMC were donors, donating a total of 45 organs. Of the 205 hospitals in the DSO's central region—which includes the large cities of Frankfurt and Mainz—only six had more organ donors than LRMC in 2010.[75]

Scotland conforms to the Human Tissue Authority Code of Practice, which grants authority to donate organs, instead of consent of the individual.[76] This helps to avoid conflict of implications and contains several requirements. In order to participate in organ donation, one must be listed on the Organ Donor Registry (ODR). If the subject is incapable of providing consent, and is not on the ODR, then an acting representative, such as a legal guardian or family member can give legal consent for organ donation of the subject, along with a presiding witness, according to the Human Tissue Authority Code of Practice. Consent or refusal from a spouse, family member, or relative is necessary for a subject is incapable.

Austria participates in the "opt-out" consent process, and have laws that make organ donation the default option at the time of death. In this case, citizens must explicitly "opt out" of organ donation. Yet in countries such as U.S.A. and Germany, people must explicitly "opt in" if they want to donate their organs when they die. In Germany and Switzerland there are Organ Donor Cards available.[77][78]

In May 2017, Ireland began the process of introducing an "opt-out" system for organ donation. Minister for Health, Simon Harris, outlined his expectations to have the Human Tissue Bill passed by the end of 2017. This bill would put in place the system of "presumed consent".[79]

The Mental Capacity Act is another legal policy in place for organ donation in the UK. The act is used by medical professionals to declare a patient's mental capacity. The act claims that medical professionals are to "act in a patient's best interest", when the patient is unable to do so.[76]

India

[edit]India has a fairly well developed corneal donation programme; however, donation after brain death has been relatively slow to take off. Most of the transplants done in India are living related or unrelated transplants. To curb organ commerce and promote donation after brain death the government enacted a law called "The Transplantation of Human Organs Act" in 1994 that brought about a significant change in the organ donation and transplantation scene in India.[80][81][82][83][84][85][86] Many Indian states have adopted the law and in 2011 further amendment of the law took place.[87][88][89][90][91] Despite the law there have been stray instances of organ trade in India and these have been widely reported in the press. This resulted in the amendment of the law further in 2011. Deceased donation after brain death have slowly started happening in India and 2012 was the best year for the programme.

| State | No. of Deceased Donors | Total no. of Organs Retrieved | Organ Donation Rate per Million Population |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tamil Nadu | 83 | 252 | 1.15 |

| Maharashtra | 29 | 68 | 0.26 |

| Gujarat | 18 | 46 | 0.30 |

| Karnataka | 17 | 46 | 0.28 |

| Andhra Pradesh | 13 | 37 | 0.15 |

| Kerala | 12 | 26 | 0.36 |

| Delhi-NCR | 12 | 31 | 0.29 |

| Punjab | 12 | 24 | 0.43 |

| Total | 196 | 530 | 0.16 |

- Source the Indian Transplant News Letter of the MOHAN Foundation[92]

The year 2013 has been the best yet for deceased organ donation in India. A total of 845 organs were retrieved from 310 multi-organ donors resulting in a national organ donation rate of 0.26 per million population(Table 2).

| State | Tamil Nadu | Andhra Pradesh | Kerala | Maharashtra | Delhi | Gujarat | Karnataka | Puducherry | Total (National) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Donor | 131 | 40 | 35 | 35 | 27 | 25 | 18 | 2 | 313 |

| * ODR (pmp) | 1.80 | 0.47 | 1.05 | 0.31 | 1.61 | 0.41 | 0.29 | 1.6 | 0.26 |

| Heart | 16 | 2 | 6 | 0 | – | 0 | 1 | 0 | 25 |

| Lung | 20 | 2 | 0 | 0 | – | 0 | 0 | 0 | 22 |

| Liver | 118 | 34 | 23 | 23 | 23 | 20 | 16 | 0 | 257 |

| Kidney | 234 | 75 | 59 | 53 | 40 | 54 | 29 | 4 | 548 |

| Total | 388 | 113 | 88 | 76 | 63 | 74 | 46 | 4 | 852 |

* ODR (pmp) – Organ Donation Rate (per million population)

In the year 2000 through the efforts of a non-governmental organization called MOHAN Foundation state of Tamil Nadu started an organ sharing network between a few hospitals.[93][94] The MOHAN Foundation also set up similar sharing network in the state of Andhra Pradesh and these two states were at the forefront of deceased donation and transplantation programme for many years.[95][96] As a result, retrieval of 1,033 organs and tissues were facilitated in these two states.[97]

Similar sharing networks came up in the states of Maharashtra and Karnataka; however, the numbers of deceased donation happening in these states were not sufficient to make much impact. In 2008, the Government of Tamil Nadu put together government orders laying down procedures and guidelines for deceased organ donation and transplantation in the state.[98] These brought in almost thirty hospitals in the programme and has resulted in significant increase in the donation rate in the state. With an organ donation rate of 1.15 per million population, Tamil Nadu is the leader in deceased organ donation in the country. The small success of Tamil Nadu model has been possible due to the coming together of both government and private hospitals, non-governmental organizations and the State Health Department. Most of the deceased donation programmes have been developed in southern states of India.[99] The various such programmes are as follows:

- Andhra Pradesh – Jeevandan programme

- Karnataka – Zonal Coordination Committee of Karnataka for Transplantation

- Kerala – Mrithasanjeevani – The Kerala Network for Organ Sharing

- Maharashtra – Zonal Transplant Coordination Center in Mumbai

- Rajasthan – Navjeevan – The Rajasthan Network of Organ Sharing

- Tamil Nadu – Cadaver Transplant Programme

In the year 2012 besides Tamil Nadu other southern states too did deceased donation transplants more frequently. An online organ sharing registry for deceased donation and transplantation is used by the states of Tamil Nadu and Kerala. Both these registries have been developed, implemented and maintained by MOHAN Foundation. However. National Organ and Tissue Transplant Organization (NOTTO) is a National level organization set up under Directorate General of Health Services, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India and only official organization.

Organ selling is legally banned in Asia. Numerous studies have documented that organ vendors have a poor quality of life (QOL) following kidney donation. However, a study done by Vemuru reddy et al shows a significant improvement in Quality of life contrary to the earlier belief.[100] Live related renal donors have a significant improvement in the QOL following renal donation using the WHO QOL BREF in a study done at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences from 2006 to 2008. The quality of life of the donor was poor when the graft was lost or the recipient died.[100]

In India, there are six types of life saving organs that can be donated to save the life of a patient. These include Kidneys, Liver, Heart, Lungs, Pancreas and Intestine. Off late, uterus transplant has also been started in India. However, uterus is not a life saving organ as per the Transplantation of Human Organs Act (2011).[101] Recently a scoring system, Seth-Donation of Organs and Tissues (S-DOT) score, has been developed to assess hospitals for best practices in tissue donation and organ donation after brain death.[102]

Iran

[edit]Only one country, Iran has eliminated the shortage of transplant organs—and only Iran has a working and legal payment system for organ donation. It is also the only country where organ trade is legal. The way their system works is, if a patient does not have a living relative or who are not assigned an organ from a deceased donor, apply to the nonprofit Dialysis and Transplant Patients Association (Datpa). The association establishes potential donors, those donors are assessed by transplant doctors who are not affiliated with the Datpa association. The government gives a compensation of $1,200 to the donors and aid them a year of limited health-insurance. Additionally, working through Datpa, kidney recipients pay donors between $2,300 and $4,500.[103] Importantly, it is illegal for the medical and surgical teams involved or any 'middleman' to receive payment.[104] Charity donations are made to those donors whose recipients are unable to pay. The Iranian system began in 1988 and eliminated the shortage of kidneys by 1999. Within the first year of the establishment of this system, the number of transplants had almost doubled; nearly four-fifths were from living unrelated sources.[104] Nobel Laureate economist Gary Becker and Julio Elias estimated that a payment of $15,000 for living donors would alleviate the shortage of kidneys in the U.S.[103]

Israel

[edit]Since 2008, signing an organ donor card in Israel has provided a potential medical benefit to the signer. If two patients require an organ donation and have the same medical need, preference will be given to the one that had signed an organ donation card. (This policy was nicknamed "Don't give, don't get".) Organ donation in Israel increased after 2008.[citation needed]

Japan

[edit]The rate of organ donation in Japan is significantly lower than in Western countries.[105] This is attributed to cultural reasons, some distrust of western medicine, and a controversial organ transplantation in 1968 that provoked a ban on cadaveric organ donation that would last thirty years.[105] Organ donation in Japan is regulated by a 1997 organ transplant law, which defines "brain death" and legalized organ procurement from brain dead donors.

Netherlands

[edit]The Netherlands sends everyone living in the country a postcard when they turn 18 (and everyone living in the country when the 2020 law came into effect), and one reminder if they do not reply. They may choose to donate, not to donate, to delegate the choice to family, or to name a specific person. If they do not reply to either notice, they are considered a donor by default.[106] A family cannot object unless there is reason to show the person would not have wanted to donate. If a person cannot be found in the national donor registry, because they are travelling from another country or because they are undocumented, their organs are not harvested without family consent. Organs are not harvested from people who die an unnatural death without the approval of the local attorney general.

New Zealand

[edit]

New Zealand law allows live donors to participate in altruistic organ donation only. In the five years to 2018, there were 16 cases of liver donation by live donors and 381 cases of kidney donation by live donors.[107] New Zealand has low rates of live donation, which could be due to the fact that it is illegal to pay someone for their organs. The Human Tissue Act 2008 states that trading in human tissue is prohibited, and is punishable by a fine of up to $50,000 or a prison term of up to 1 year.[108] The Compensation for Live Organ Donors Act 2016, which came into force in December 2017, allows live organ donors to be compensated for lost income for up to 12 weeks post-donation.[109]

New Zealand law also allows for organ donation from deceased individuals. In the five years to 2018, organs were taken from 295 deceased individuals.[107] Everyone who applies for a driver's licence in New Zealand indicates whether or not they wish to be a donor if they die in circumstances that would allow for donation.[110] The question is required to be answered for the application to be processed, meaning that the individual must answer yes or no, and does not have the option of leaving it unanswered.[110] However, the answer given on the drivers license does not constitute informed consent, because at the time of drivers license application not all individuals are equipped to make an informed decision regarding whether to be a donor, and it is therefore not the deciding factor in whether donation is carried out or not.[110] It is there to simply give indication of the person's wishes.[110] Family must agree to the procedure for donation to take place.[110][111]

A 2006 bill proposed setting up an organ donation register where people can give informed consent to organ donations and clearly state their legally binding wishes.[112] However, the bill did not pass, and there was condemnation of the bill from some doctors, who said that even if a person had given express consent for organ donation to take place, they would not carry out the procedure in the presence of any disagreement from grieving family members.[113]

The indigenous population of New Zealand also have strong views regarding organ donation. Many Maori people believe organ donation is morally unacceptable due to the cultural need for a dead body to remain fully intact.[114] However, because there is not a universally recognised cultural authority, no one view on organ donation is universally accepted in the Maori population.[114] They are, however, less likely to accept a kidney transplant than other New Zealanders, despite being overrepresented in the population receiving dialysis.[114]

South Korea

[edit]In South Korea, the 2006 provision of the Organ Transplant Act introduced a monetary incentive equivalent to US$4,500 to the surviving family of brain-death donors; the reward is intended as consolation and compensation for funeral expenses and hospital fees.[115][116]

Sri Lanka

[edit]Organ donation in Sri Lanka was ratified by the Human Tissue Transplantation Act No. 48 of 1987. Sri Lanka Eye Donation Society, a non-governmental organization established in 1961 has provided over 60,000 corneas for corneal transplantation, for patients in 57 countries. It is one of the major suppliers of human eyes to the world, with a supply of approximately 3,000 corneas per year.[117]

United Kingdom

[edit]Wales

[edit]Since December 2015, Human Transplantation (Wales) Act 2013 passed by the Welsh Government has enabled an opt-out organ donation register, the first country in the UK to do so. The legislation is 'deemed consent', whereby all citizens are considered to have no objection to becoming a donor, unless they have opted out on this register.[118]

England and Scotland

[edit]

England's Organ Donation Act, also known as Max and Keira's law, came into effect in May 2020. It means adults in England will be automatically be considered potential donors unless they chose to opt out or are excluded.[119] As of March 2021 Scotland also has an opt-out system.[120][121]

Dependencies

[edit]The British Crown dependency of Jersey moved to an opt-out register on July 1, 2019.[122][123]

United States

[edit]Over 121,000 people in need of an organ are on the U.S. government waiting list.[124] This crisis within the United States is growing rapidly because on average there are only 30,000 transplants performed each year. More than 8,000 people die each year from lack of a donor organ, an average of 22 people a day.[125][40] Between the years 1988 and 2006 the number of transplants doubled, but the number of patients waiting for an organ grew six times as large.[126]

In the past presumed consent was urged to try to decrease the need for organs. The Uniform Anatomical Gift Act of 1987 was adopted in several states, and allowed medical examiners to determine if organs and tissues of cadavers could be donated. By the 1980s, several states adopted different laws that allowed only certain tissues or organs to be retrieved and donated, some allowed all, and some did not allow any without consent of the family. In 2006 when the UAGA was revised, the idea of presumed consent was abandoned. In the United States today, organ donation is done only with consent of the family or donator themselves.[127]

In most states, residents can register to become organ donors through the Department of Motor Vehicles. The driver's license will serve as a legal donor card for the registered donor. U.S. Residents may also choose to register as organ, eye, and tissue donors through a national registry maintained by Donate Life America. The national website is RegisterMe.org The national registry allows residents to create a login, password, and edit their donation choice by organ. The most common transplants consists of only six (6) organs: heart, lungs, liver, kidney, pancreas, and small intestines. One healthy donor can potentially save up to eight (8) lives through transplants, using the two lungs and two kidneys separately. The most needed organ for transplants overall are kidneys, due to the high rate of hypertension (HTN) or high blood pressure and diabetes which can lead to end-stage renal disease.

According to economist Alex Tabarrok, the shortage of organs has increased the use of so-called expanded criteria organs, or organs that used to be considered unsuitable for transplant.[103] Five patients that received kidney transplants at the University of Maryland School of Medicine developed cancerous or benign tumors which had to be removed. The head surgeon, Dr. Michael Phelan, explained that "the ongoing shortage of organs from deceased donors, and the high risk of dying while waiting for a transplant, prompted five donors and recipients to push ahead with the surgery."[103] Several organizations such as the American Kidney Fund are pushing for opt-out organ donation in the United States.[128]

Donor Leave Laws

[edit]In addition to their sick and annual leave, federal executive agency employees are entitled to 30 days paid leave for organ donation.[129] Thirty-two states (excluding only Alabama, Connecticut, Florida, Kentucky, Maine, Michigan, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Tennessee, Vermont, and Wyoming) and the District of Columbia also offer paid leave for state employees.[130] Five states (California, Hawaii, Louisiana, Minnesota, and Oregon) require certain private employers to provide paid leave for employees for organ or bone marrow donation, and seven others (Arkansas, Connecticut, Maine, Nebraska, New York, South Carolina, and West Virginia) either require employers to provide unpaid leave, or encourage employers to provide leave, for organ or bone marrow donation.[130]

A bill in the US House of Representatives, the Living Donor Protection Act (introduced in 2016, then reintroduced in 2017[131]), would amend the Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993 to provide leave under the act for an organ donor. If successful, this new law would permit "eligible employee" organ donors to receive up to 12 work weeks of leave in a 12-month period.[132][133]

Tax incentives

[edit]Nineteen US states and the District of Columbia provide tax incentives for organ donation.[130] The most generous state tax incentive is Utah's tax credit, which covers up to $10,000 of unreimbursed expenses (travel, lodging, lost wages, and medical expenses) associated with organ or tissue donation.[130] Idaho (up to $5,000 of unreimbursed expenses) and Louisiana (up to $7,500 of 72% of unreimbursed expenses) also provide donor tax credits.[130] Arkansas, the District of Columbia, Louisiana and Pennsylvania provide tax credits to employers for wages paid to employees on leave for organ donation.[130] Thirteen states (Arkansas, Georgia, Iowa, Massachusetts, Mississippi, New Mexico, New York, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Rhode Island and Wisconsin) have a tax deduction for up to $10,000 of unreimbursed costs, and Kansas and Virginia offer a tax deduction for up to $5,000 of unreimbursed costs.[130]

States have focused their tax incentives on unreimbursed costs associated with organ donation to ensure compliance with the National Organ Transplant Act of 1984.[134] NOTA prohibits, "any person to knowingly acquire, receive, or otherwise transfer any human organ for valuable consideration for use in human transplantation."[135] However, NOTA exempts, "the expenses of travel, housing, and lost wages incurred by the donor of a human organ in connection with the donation of the organ," from its definition of "valuable consideration".[135]

While offering income tax deductions has been the preferred method of providing tax incentives, some commentators have expressed concern that these incentives provide disproportionate benefits to wealthier donors.[136] Tax credits, on the other hand, are perceived as more equitable since the after tax benefit of the incentive is not tied to the marginal tax rate of the donor.[136]

Additional tax favored approaches have been proposed for organ donation, including providing: tax credits to the families of deceased donors (seeking to encourage consent), refundable tax credits (similar to the earned income credit) to provide greater tax equity among potential donors, and charitable deductions for the donation of blood or organs.[137]

Other financial incentives

[edit]As stated above, under the National Organ Transplant Act of 1984, granting monetary incentives for organ donation is illegal in the United States.[138] However, there has been some discussion about providing fixed payment for potential live donors. In 1988, regulated paid organ donation was instituted in Iran and, as a result, the renal transplant waiting list was eliminated. Critics of paid organ donation argue that the poor and vulnerable become susceptible to transplant tourism. Travel for transplantation becomes transplant tourism if the movement of organs, donors, recipients or transplant professionals occurs across borders and involves organ trafficking or transplant commercialism. Poor and underserved populations in underdeveloped countries are especially vulnerable to the negative consequences of transplant tourism because they have become a major source of organs for the 'transplant tourists' that can afford to travel and purchase organs.[139]

In 1994 a law was passed in Pennsylvania which proposed to pay $300 for room and board and $3,000 for funeral expenses to an organ donor's family. Developing the program was an eight-year process; it is the first of its kind. Procurement directors and surgeons across the nation await the outcomes of Pennsylvania's program.[140] There have been at least nineteen families that have signed up for the benefit. Due to investigation of the program, however, there has been some concern whether the money collected is being used to assist families.[141] Nevertheless, funeral aids to induce post-mortem organ donation have also received support from experts and the general public, as the incentives present more ethical values, such as honoring the deceased donor or preserving voluntariness, and potentially increase donation willingness.[142][115]

Some organizations, such as the National Kidney Foundation, oppose financial incentives associated with organ donation claiming, "Offering direct or indirect economic benefits in exchange for organ donation is inconsistent with our values as a society."[143] One argument is it will disproportionately affect the poor.[144] The $300–3,000 reward may act as an incentive for poorer individuals, as opposed to the wealthy who may not find the offered incentives significant. The National Kidney Foundation has noted that financial incentives, such as this Pennsylvania statute, diminish human dignity.[143]

Bioethical issues

[edit]Deontological

[edit]

Deontological issues are issues about whether a person has an ethical duty or responsibility to take an action. Nearly all scholars and societies around the world agree that voluntarily donating organs to sick people is ethically permissible. Although nearly all scholars encourage organ donation, fewer scholars believe that all people are ethically required to donate their organs after death. Similarly, nearly all religions support voluntary organ donation as a charitable act of great benefit to the community. Certain small faiths such as Jehovah Witnesses and Shinto are opposed to organ donation based upon religious teachings; for Jehovah Witnesses this opposition is absolute whereas there exists increasing flexibility amongst Shinto scholars. The Roma People, are also often opposed to organ donation based on prevailing spiritual beliefs and not religious views per se.[145] Issues surrounding patient autonomy, living wills, and guardianship make it nearly impossible for involuntary organ donation to occur.

From the standpoint of deontological ethics, the primary issues surrounding the morality of organ donation are semantic in nature. The debate over the definitions of life, death, human, and body is ongoing. For example, whether or not a brain-dead patient ought to be kept artificially animate in order to preserve organs for donation is an ongoing problem in clinical bioethics. In addition, some[who?] have argued that organ donation constitutes an act of self-harm, even when an organ is donated willingly.[146]

Further, the use of cloning to produce organs with a genotype identical to the recipient is a controversial topic, especially considering the possibility for an entire person to be brought into being for the express purpose of being destroyed for organ procurement. While the benefit of such a cloned organ would be a zero-percent chance of transplant rejection, the ethical issues involved with creating and killing a clone may outweigh these benefits. However, it may be possible in the future to use cloned stem-cells to grow a new organ without creating a new human being.

A relatively new field of transplantation has reinvigorated the debate. Xenotransplantation, or the transfer of animal (usually pig) organs into human bodies, promises to eliminate many of the ethical issues, while creating many of its own.[147] While xenotransplantation promises to increase the supply of organs considerably, the threat of organ transplant rejection and the risk of xenozoonosis, coupled with general anathema to the idea, decreases the functionality of the technique. Some animal rights groups oppose the sacrifice of an animal for organ donation and have launched campaigns to ban them.[148]

Teleological

[edit]On teleological or utilitarian grounds, the moral status of "black market organ donation" relies upon the ends, rather than the means.[citation needed] In so far as those who donate organs are often impoverished[citation needed] and those who can afford black market organs are typically well-off,[citation needed] it would appear that there is an imbalance in the trade. In many cases, those in need of organs are put on waiting lists for legal organs for indeterminate lengths of time—many die while still on a waiting list.

Organ donation is fast becoming an important bioethical issue from a social perspective as well. While most first-world nations have a legal system of oversight for organ transplantation, the fact remains that demand far outstrips supply. Consequently, there has arisen a black market trend often referred to as transplant tourism.[citation needed] The issues are weighty and controversial. On the one hand are those who contend that those who can afford to buy organs are exploiting those who are desperate enough to sell their organs. Many suggest this results in a growing inequality of status between the rich and the poor. On the other hand, are those who contend that the desperate should be allowed to sell their organs and that preventing them from doing so is merely contributing to their status as impoverished. Further, those in favor of the trade hold that exploitation is morally preferable to death, and in so far as the choice lies between abstract notions of justice on the one hand and a dying person whose life could be saved on the other hand, the organ trade should be legalized. Conversely, surveys conducted among living donors postoperatively and in a period of five years following the procedure have shown extreme regret in a majority of the donors, who said that given the chance to repeat the procedure, they would not.[149] Additionally, many study participants reported a decided worsening of economic condition following the procedure.[150] These studies looked only at people who sold a kidney in countries where organ sales are already legal.

A consequence of the black market for organs has been a number of cases and suspected cases of organ theft,[151][152] including murder for the purposes of organ theft.[153][154] Proponents of a legal market for organs say that the black-market nature of the current trade allows such tragedies and that regulation of the market could prevent them. Opponents say that such a market would encourage criminals by making it easier for them to claim that their stolen organs were legal.

Legalization of the organ trade carries with it its own sense of justice as well.[citation needed] Continuing black-market trade creates further disparity on the demand side: only the rich can afford such organs. Legalization of the international organ trade could lead to increased supply, lowering prices so that persons outside the wealthiest segments could afford such organs as well.

Exploitation arguments generally come from two main areas:

- Physical exploitation suggests that the operations in question are quite risky, and, taking place in third-world hospitals or "back-alleys", even more risky. Yet, if the operations in question can be made safe, there is little threat to the donor.

- Financial exploitation suggests that the donor (especially in the Indian subcontinent and Africa) are not paid enough. Commonly, accounts from persons who have sold organs in both legal and black market circumstances put the prices at between $150 and $5,000, depending on the local laws, supply of ready donors and scope of the transplant operation.[155][156][157] In Chennai, India, where one of the largest black markets for organs is known to exist, studies have placed the average sale price at little over $1,000.[150] Many accounts also exist of donors being postoperatively denied their promised pay.[158]

The New Cannibalism is a phrase coined by anthropologist Nancy Scheper-Hughes in 1998 for an article written for The New Internationalist. Her argument was that the actual exploitation is an ethical failing, a human exploitation; a perception of the poor as organ sources which may be used to extend the lives of the wealthy.[159]

Economic drivers leading to increased donation are not limited to areas such as India and Africa, but also are emerging in the United States. Increasing funeral expenses combined with decreasing real value of investments such as homes and retirement savings which took place in the 2000s have purportedly led to an increase in citizens taking advantage of arrangements where funeral costs are reduced or eliminated.[160]

Brain death versus cardiac death

[edit]

Brain death may result in legal death, but still with the heart beating and with mechanical ventilation, keeping all other vital organs alive and functional for a certain period of time. Given long enough, patients who do not fully die in the complete biological sense, but who are declared brain dead, will usually start to build up toxins and wastes in the body. In this way, the organs can eventually dysfunction due to coagulopathy, fluid or electrolyte and nutrient imbalances, or even fail. Thus, the organs will usually only be sustainable and viable for acceptable use up until a certain length of time. This may depend on factors such as how well the patient is maintained, any comorbidities, the skill of the healthcare teams and the quality their facilities.[161][unreliable medical source?] A major point of contention is whether transplantation should be allowed at all if the patient is not yet fully biologically dead, and if brain death is acceptable, whether the person's whole brain needs to have died, or if the death of a certain part of the brain is enough for legal and ethical and moral purposes.

Most organ donation for organ transplantation is done in the setting of brain death. However, in Japan this is a fraught point, and prospective donors may designate either brain death or cardiac death – see organ transplantation in Japan. In some nations such as Belgium, France, Netherlands, New Zealand, Poland, Portugal, Singapore and Spain, everyone is automatically an organ donor unless they opt out of the system. Elsewhere, consent from family members or next-of-kin is required for organ donation. The non-living donor is kept on ventilator support until the organs have been surgically removed. If a brain-dead individual is not an organ donor, ventilator and drug support is discontinued and cardiac death is allowed to occur.

In the United States, where since the 1980s the Uniform Determination of Death Act has defined death as the irreversible cessation of the function of either the brain or the heart and lungs,[162] the 21st century has seen an order-of-magnitude increase of donation following cardiac death. In 1995, only one out of 100 dead donors in the nation gave their organs following the declaration of cardiac death. That figure grew to almost 11 percent in 2008, according to the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients.[162] That increase has provoked ethical concerns about the interpretation of "irreversible" since "patients may still be alive five or even 10 minutes after cardiac arrest because, theoretically, their hearts could be restarted, [and thus are] clearly not dead because their condition was reversible."[162]

Gender inequality

[edit]The majority of organ donors are women. For example, in the United States, 62% of kidney donors and 53% of liver donors are women. In India, women constitute 74% of kidney donors and 60.5% of liver donors. Additionally, the number of female organ recipients is conspicuously lower than that of male recipients. In the U.S., 35% of liver recipients and 39% of kidney recipients are women. In India, the figures are 24% and 19% respectively.[163]

Political issues

[edit]There are also controversial issues regarding how organs are allocated to recipients. For example, some believe that livers should not be given to alcoholics in danger of reversion, while others view alcoholism as a medical condition like diabetes.[citation needed] Faith in the medical system is important to the success of organ donation. Brazil switched to an opt-out system and ultimately had to withdraw it because it further alienated patients who already distrusted the country's medical system.[164] Adequate funding, strong political will to see transplant outcomes improve, and the existence of specialized training, care and facilities also increase donation rates. Expansive legal definitions of death, such as Spain uses, also increase the pool of eligible donors by allowing physicians to declare a patient to be dead at an earlier stage, when the organs are still in good physical condition. Allowing or forbidding payment for organs affects the availability of organs. Generally, where organs cannot be bought or sold, quality and safety are high, but supply is not adequate to the demand. Where organs can be purchased, the supply increases.[165]

Iran adopted a system of paying kidney donors in 1988 and within 11 years it became the only country in the world to clear its waiting list for transplants.

Healthy humans have two kidneys, but can live a healthy life with only one. This enables living donors (inter vivos) to give a kidney to someone who needs it, with little to no long-term risk.[166][167] The most common transplants are to close relatives, but people have given kidneys to other friends. The rarest type of donation is the undirected donation whereby a donor gives a kidney to a stranger. Less than a few hundred of such kidney donations have been performed. In recent years, searching for altruistic donors via the internet has also become a way to find life saving organs. However, internet advertising for organs is a highly controversial practice, as some scholars believe it undermines the traditional list-based allocation system.[168]

Black Market Organ Donation

[edit]The issue of the black market for organs being legalized has become a widespread debate because if this happens then individuals will most likely be coerced into selling their organs. Additionally, even if there were to become regulations against it most individuals who would be coerced into doing this would most likely be unable to afford legal protection.[169]

The National Transplant Organization of Spain is one of the most successful in the world (Spain has been the world leader in organ donation for decades),[170] but it still cannot meet the demand, as 10% of those needing a transplant die while still on the transplant list.[171] Donations from corpses are anonymous, and a network for communication and transport allows fast extraction and transplant across the country.[citation needed] Under Spanish law, every corpse can provide organs unless the deceased person had expressly rejected it.[citation needed] Because family members still can forbid the donation,[citation needed] carefully trained doctors ask the family for permission, making it very similar in practice to the United States system.[172]

In the overwhelming majority of cases, organ donation is not possible for reasons of recipient safety, match failures, or organ condition. Even in Spain, which has the highest organ donation rate in the world, there are only 35.1 actual donors per million people, and there are hundreds of patients on the waiting list.[164] This rate compares to 24.8 per million in Austria, where families are rarely asked to donate organs, and 22.2 per million in France, which—like Spain—has a presumed-consent system.[citation needed]

Prison inmates

[edit]In the United States, prisoners are not discriminated against as organ recipients and are equally eligible for organ transplants along with the general population. A 1976 U.S. Supreme Court case[173] ruled that withholding health care from prisoners constituted "cruel and unusual punishment". United Network for Organ Sharing, the organization that coordinates available organs with recipients, does not factor a patient's prison status when determining suitability for a transplant.[174][175] An organ transplant and follow-up care can cost the prison system up to one million dollars.[175][176] If a prisoner qualifies, a state may allow compassionate early release to avoid high costs associated with organ transplants.[175] However, an organ transplant may save the prison system substantial costs associated with dialysis and other life-extending treatments required by the prisoner with the failing organ. For example, the estimated cost of a kidney transplant is about $111,000.[177] A prisoner's dialysis treatments are estimated to cost a prison $120,000 per year.[178]

Because donor organs are in short supply, there are more people waiting for a transplant than available organs. When a prisoner receives an organ, there is a high probability that someone else will die waiting for the next available organ. A response to this ethical dilemma states that felons who have a history of violent crime, who have violated others' basic rights, have lost the right to receive an organ transplant, though it is noted that it would be necessary "to reform our justice system to minimize the chance of an innocent person being wrongly convicted of a violent crime and thus being denied an organ transplant".[179]

Prisons typically do not allow inmates to donate organs to anyone but immediate family members. There is no law against prisoner organ donation; however, the transplant community has discouraged use of prisoner's organs since the early 1990s due to concern over prisons' high-risk environment for infectious diseases.[180] Physicians and ethicists also criticize the idea because a prisoner is not able to consent to the procedure in a free and non-coercive environment,[181] especially if given inducements to participate. However, with modern testing advances to more safely rule out infectious disease and by ensuring that there are no incentives offered to participate, some have argued that prisoners can now voluntarily consent to organ donation just as they can now consent to medical procedures in general. With careful safeguards, and with over 2 million prisoners in the U.S., they reason that prisoners can provide a solution for reducing organ shortages in the U.S.[182]

Хотя некоторые утверждают, что участие заключенных, вероятно, будет слишком низким, чтобы изменить ситуацию, одна из программ в Аризоне, начатая бывшим шерифом округа Марикопа Джо Арпайо, призывает заключенных добровольно подписаться на пожертвование своего сердца и других органов. [ 183 ] По состоянию на 2015 год количество участников превысило 16 500 человек. [ 184 ] [ 185 ] Подобные инициативы были начаты и в других штатах США. В 2013 году Юта стала первым штатом, разрешившим заключенным подписаться на донорство органов после смерти. [ 186 ]

Религиозные точки зрения

[ редактировать ]Есть несколько разных религий, которые имеют разные точки зрения. Ислам имеет противоречивое мнение по этому вопросу, половина из которых считает, что это противоречит религии. Мусульманам предписано обращаться за медицинской помощью в случае необходимости, и спасение жизни является очень важным фактором исламской религии. Христианство снисходительно относится к теме донорства органов и считает, что это услуга жизни. [ 187 ]

Все основные религии хотя бы в той или иной форме принимают донорство органов. [ 188 ] либо по утилитарным соображениям ( т.е. из-за его способности спасать жизни), либо по деонтологическим соображениям ( например , право отдельного верующего принимать собственное решение). [ нужна ссылка ] Большинство религий, в том числе Римско-католическая церковь , поддерживают донорство органов на том основании, что оно представляет собой акт благотворительности и обеспечивает средство спасения жизни. Одна религиозная группа, « Христиане Иисуса », стала известна как «Культ почек», потому что более половины ее членов альтруистически пожертвовали свои почки. Христиане-Иисус утверждают, что альтруистическое донорство почек — это отличный способ «поступать с другими так, как они хотели бы, чтобы вы делали с ними». [ 189 ] Некоторые религии налагают определенные ограничения на типы органов, которые могут быть пожертвованы, и/или на способы извлечения и/или трансплантации органов. [ 190 ] Например, Свидетели Иеговы требуют, чтобы органы были обескровлены, поскольку они интерпретируют еврейскую Библию /христианский Ветхий Завет как запрещающие переливание крови. [ 191 ] мусульмане требуют , чтобы донор заранее предоставил письменное согласие. [ 191 ] Некоторые группы не одобряют трансплантацию или донорство органов; в частности, к ним относятся синтоистские [ 192 ] и цыгане . [ 191 ]

Ортодоксальный иудаизм считает донорство органов обязательным, если оно спасет жизнь, при условии, что донор считается мертвым, как это определено еврейским законом. [ 191 ] Как в ортодоксальном иудаизме, так и в неортодоксальном иудаизме большинство придерживается мнения, что донорство органов разрешено в случае необратимой остановки сердечного ритма. В некоторых случаях раввинские авторитеты считают, что донорство органов может быть обязательным, тогда как мнение меньшинства считает любое донорство живого органа запрещенным. [ 193 ]

Дефицит органов

[ редактировать ]

Спрос на органы значительно превышает количество доноров во всем мире. В списках ожидания на донорство органов больше потенциальных реципиентов, чем доноров органов. [ 194 ] В частности, благодаря значительному прогрессу в методах диализа , пациенты с терминальной стадией почечной недостаточности (ТПН) могут жить дольше, чем когда-либо прежде. [ 195 ] Поскольку эти пациенты не умирают так быстро, как раньше, а почечная недостаточность увеличивается с увеличением возраста и распространенностью высокого кровяного давления и диабета в обществе, потребность, особенно в почках, возрастает с каждым годом. [ 196 ]

По состоянию на март 2014 г. [update]Около 121 600 человек в США находятся в списке ожидания, хотя около трети этих пациентов неактивны и не могут получить донорский орган. [ 197 ] [ 198 ] Время ожидания и показатели успеха для органов значительно различаются в зависимости от органа из-за спроса и сложности процедуры. По состоянию на 2007 год [update], три четверти пациентов, нуждающихся в трансплантации органов, ждали почку, [ 199 ] и поэтому почки имеют гораздо более длительное время ожидания. Как говорится на веб-сайте донорской программы «Подари жизнь», средний пациент, получивший в конечном итоге орган, ждал 4 месяца сердца или легкого, но 18 месяцев — почки и 18–24 месяца — поджелудочной железы, поскольку спрос на эти органы существенно опережает поставлять. [ 200 ] Растущая распространенность беспилотных автомобилей может усугубить эту проблему: в США 13% донорских органов поступают от жертв автокатастроф, а беспилотные транспортные средства, по прогнозам, сократят частоту автокатастроф. [ 201 ]

В Австралии на миллион населения приходится 10,8 трансплантаций. [ 202 ] около трети испанской ставки. В Институте Львиного Глаза в Западной Австралии находится Банк Львиного Глаза . Банк был основан в 1986 году и координирует сбор, обработку и распределение тканей глаза для трансплантации. Lions Eye Bank также ведет список ожидания пациентов, которым требуется операция по трансплантации роговицы. Ежегодно Банк предоставляет для трансплантации около 100 роговиц, но очередь на роговицы все еще существует. [ 203 ] «Для экономиста это базовый разрыв спроса и предложения с трагическими последствиями». [ 204 ] Подходы к устранению этого недостатка включают в себя:

- Реестры доноров и законы о «первичном согласии», чтобы снять бремя принятия решения о пожертвовании с законных ближайших родственников. В 2006 году Иллинойс принял политику «обязательного выбора», согласно которой лица, получившие водительские права, должны ответить на вопрос: «Хотите ли вы стать донором органов?» В Иллинойсе уровень регистрации составляет 60 процентов по сравнению с 38 процентами по стране. [ 205 ] Дополнительная стоимость добавления вопроса в регистрационную форму минимальна.

- Денежные стимулы за регистрацию в качестве донора. Некоторые экономисты выступают за разрешение продажи органов. Газета «Нью-Йорк Таймс» сообщила, что «Гэри Беккер и Хулио Хорхе Элиас в недавней статье утверждали, что [ 206 ] что «денежные стимулы увеличат предложение органов для трансплантации в достаточной степени, чтобы устранить очень большие очереди на рынках органов, а также страдания и смерти многих из тех, кто ожидает, не увеличивая при этом общую стоимость операций по трансплантации более чем на 12 процентов». [ 204 ] Иран разрешает продажу почек и не имеет листа ожидания. [ 207 ] Фьючерсы на органы были предложены для стимулирования донорства посредством прямой или косвенной компенсации. Основной аргумент против таких предложений — моральный; как отмечается в статье, многим такое предложение кажется отвратительным. [ 204 ] Как заявляет Национальный фонд почек: «Предложение прямых или косвенных экономических выгод в обмен на донорство органов несовместимо с нашими ценностями как общества. Любая попытка присвоить человеческому телу или частям тела денежную ценность, произвольно или путем рыночные силы, унижает человеческое достоинство». [ 208 ]

- Система отказа («решение несогласия»), в которой потенциальный донор или его / ее родственники должны предпринять определенные действия, чтобы быть исключенными из донорства органов, а не конкретные действия, которые необходимо включить. Эта модель используется в нескольких европейских странах, таких как Австрия, где уровень регистрации в восемь раз выше, чем в Германии, где используется система подписки. [ 205 ]

- Программы социального стимулирования, в рамках которых участники подписывают юридическое соглашение о передаче своих органов в первую очередь другим участникам, стоящим в списке ожидания на трансплантацию. Одним из исторических примеров частной организации, использующей эту модель, является LifeSharers, к которой можно свободно присоединиться, и члены которой соглашаются подписать документ, предоставляющий преимущественный доступ к своим органам. [ 209 ] «Предложение [о пуле взаимного страхования органов] можно легко резюмировать: человек получит приоритет при любой необходимой трансплантации, если этот человек согласится, что его или ее органы будут доступны другим членам страхового пула в случае его или ее ее смерть… Основная цель [этого предложения] — увеличить поставки органов для трансплантации, чтобы спасти или улучшить жизнь большего количества людей». [ 210 ]

- Поощрение большего числа людей, получающих паллиативную помощь, стать донорами. Исследователь предполагает, что 46% пациентов, получающих паллиативную помощь, имеют право на участие в программе, но только 4% рассматривают возможность донорства глаз. [ 211 ] [ 212 ]

- Технические достижения позволяют использовать доноров, которые ранее были отклонены. Например, гепатит С можно сознательно трансплантировать и лечить у реципиента органа. [ 213 ]

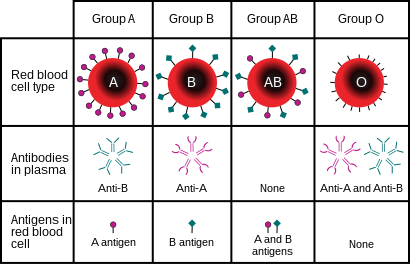

В больницах представители сети органов регулярно проверяют записи пациентов, чтобы выявить потенциальных доноров незадолго до их смерти. [ 214 ] Во многих случаях представители по закупкам органов запрашивают скрининговые тесты (например, определение группы крови ) или органосохраняющие препараты (например, лекарства от артериального давления ), чтобы сохранить жизнеспособность органов потенциальных доноров до тех пор, пока не будет определена их пригодность для трансплантации и не будет получено согласие семьи (если необходимо) можно получить. [ 214 ] Такая практика повышает эффективность трансплантации, поскольку потенциальные доноры, непригодные из-за инфекции или по другим причинам, исключаются из рассмотрения перед их смертью, а также снижается вероятность предотвратимой потери органов. [ 214 ] Это также может принести пользу семьям косвенно, поскольку к семьям неподходящих доноров не обращаются для обсуждения донорства органов. [ 214 ]

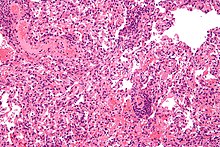

Врачи и пациенты иногда не решаются принимать органы от людей, умерших от опухолей головного мозга. Однако анализ реестра доноров Великобритании не обнаружил никаких доказательств передачи рака при более чем 750 донорах, включая людей с опухолями высокой степени злокачественности. Это говорит о том, что может быть безопасно увеличить использование органов людей, умерших от опухоли головного мозга, что может помочь уменьшить дефицит органов. [ 215 ] [ 216 ]

Распределение

[ редактировать ]В Соединенных Штатах есть два агентства, которые регулируют закупку и распространение органов внутри страны. Объединенная сеть по обмену органами и Сеть по закупкам и трансплантации органов (OPTN) регулируют организации по закупкам органов (OPO) в отношении этики и стандартов закупок и распределения. OPO — это некоммерческие организации, отвечающие за оценку, закупку и распределение органов в пределах своей выделенной зоны обслуживания (DSA). После того, как донор прошел обследование и получил согласие, начинается предварительное распределение органов. UNOS разработала компьютерную программу, которая автоматически генерирует списки доноров для подходящих реципиентов на основе критериев, по которым был указан пациент. Координаторы ОПО вносят в программу информацию о донорах и ведут соответствующие списки. Предложения органов потенциальным реципиентам делаются в центрах трансплантации, чтобы проинформировать их о потенциальном органе. Хирург оценит информацию о доноре и сделает предварительное определение о медицинской пригодности реципиента. Распределение незначительно варьируется в разных органах, но по сути очень похоже. При составлении списков учитывается множество факторов; К этим факторам относятся: расстояние центра трансплантации от донорской больницы, группа крови, неотложность медицинской помощи, время ожидания, размер донора и тип ткани. Для реципиентов сердца неотложная медицинская помощь обозначается «Статусом» реципиента (статус 1A, 1B и статус 2). Легкие распределяются на основе показателя распределения легких (LAS) реципиента, который определяется на основе срочности клинической необходимости, а также вероятности пользы от трансплантата. Печени распределяются с использованием как системы статуса, так и шкалы MELD/PELD (модель терминальной стадии заболевания печени/конечной стадии заболевания печени у детей). Списки почек и поджелудочной железы основаны на местоположении, группе крови, типировании человеческого лейкоцитарного антигена (HLA) и времени ожидания. Когда у реципиента почки или поджелудочной железы нет прямых антител к донорскому HLA, считается, что совпадение 0 ABDR или нулевое несовпадение антигена. Орган с нулевым несовпадением имеет низкий уровень отторжения и позволяет реципиенту получать более низкие дозы иммунодепрессивные препараты . Поскольку отсутствие несоответствий обеспечивает такую высокую выживаемость трансплантата, этим реципиентам предоставляется приоритет независимо от местоположения и времени ожидания. В UNOS имеется система «Расплаты», позволяющая сбалансировать органы, отправленные из DSA из-за нулевого несоответствия.

Расположение центра трансплантации по отношению к донорской больнице имеет приоритет из-за влияния времени холодной ишемии (CIT). Как только орган удаляется от донора, кровь больше не поступает через сосуды и начинает лишать клетки кислорода ( ишемия ). Каждый орган переносит разное время ишемии. Сердца и легкие необходимо трансплантировать в течение 4–6 часов после выздоровления, печень — примерно 8–10 часов, а поджелудочную железу — примерно 15 часов; почки наиболее устойчивы к ишемии. [ нужна ссылка ] Почки, упакованные во льду, можно успешно трансплантировать через 24–36 часов после выздоровления. Развитие консервации почек позволило создать устройство, которое прокачивает холодный раствор для консервации через сосуды почек, чтобы предотвратить отсроченную функцию трансплантата (DGF) из-за ишемии. Перфузионные устройства, часто называемые почечными насосами, могут продлить выживаемость трансплантата до 36–48 часов после восстановления почек. Недавно аналогичные устройства были разработаны для сердца и легких, чтобы увеличить расстояния, которые могут преодолевать группы закупщиков, чтобы забрать орган.

Самоубийство

[ редактировать ]Люди, которые умирают в результате самоубийства, имеют более высокий уровень донорства органов, чем в среднем. Одной из причин является более низкий уровень негативных откликов или отказов со стороны семьи и родственников, но объяснение этому еще предстоит выяснить. [ 217 ] Кроме того, согласие на донорство выше среднего среди людей, покончивших жизнь самоубийством. [ 218 ]

Попытка самоубийства — частая причина смерти мозга (3,8%), преимущественно среди молодых мужчин. [ 217 ] Донорство органов более распространено в этой группе по сравнению с другими причинами смерти. Смерть мозга может привести к юридической смерти , но при этом сердцебиение и искусственная вентиляция легких все остальные жизненно важные органы могут сохранить полностью живыми и функциональными. [ 161 ] обеспечение оптимальных возможностей для трансплантации органов .

Споры

[ редактировать ]В 2008 году калифорнийскому хирургу-трансплантологу Хутану Рузроку было предъявлено обвинение в жестоком обращении с зависимыми взрослыми за назначение, по утверждению прокуроров, чрезмерных доз морфия и седативных препаратов с целью ускорить смерть человека с лейкодистрофией надпочечников и необратимым повреждением головного мозга, чтобы получить его органы для трансплантации. [ 219 ] Дело, возбужденное против Рузроха, стало первым уголовным делом против хирурга-трансплантолога в США и закончилось его оправданием. Кроме того, доктор Рузрох успешно подал в суд за клевету, возникшую в результате инцидента. [ 220 ]

В калифорнийском медицинском центре Эмануэль невролог Наргес Пазуки, доктор медицинских наук, рассказала, что представитель организации по закупкам органов настаивал на том, чтобы она объявила пациента о смерти мозга до того, как будут проведены соответствующие анализы. [ 214 ] В сентябре 1999 года eBay заблокировал аукцион на «одну функциональную человеческую почку», максимальная ставка по которому достигла 5,7 миллиона долларов. Согласно федеральным законам США, eBay был обязан прекратить аукцион по продаже человеческих органов, что карается тюремным заключением на срок до пяти лет и штрафом в размере 50 000 долларов. [ 221 ]

27 июня 2008 года 26-летний индонезиец Сулейман Даманик признал себя виновным в суде Сингапура за продажу своей почки исполнительному председателю CK Tang , 55-летнему Тан Ви Сунгу, за 150 миллионов рупий (17 000 долларов США). Комитет по этике трансплантологии должен одобрить трансплантацию почки от живого донора. Торговля органами запрещена в Сингапуре и во многих других странах, чтобы предотвратить эксплуатацию «бедных и социально незащищенных доноров, которые не могут сделать осознанный выбор и подвергаются потенциальному медицинскому риску». [ Эта цитата нуждается в цитировании ] Тони, 27 лет, еще один обвиняемый, в марте пожертвовал почку индонезийскому пациенту, утверждая, что он был приемным сыном пациента, и получил за это 186 миллионов рупий (21 000 долларов США). [ нужна ссылка ]

Социальные объявления