Аризона СБ 1070

| Аризона СБ 1070 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Законодательное собрание штата Аризона | |

| Полное имя | Поддержите нашу правоохранительную деятельность и Закон о безопасных соседях |

| Палата представителей проголосовала | 13 апреля 2010 г. (35–21) |

| Сенат проголосовал | 19 апреля 2010 г. (17–11) |

| Подписан в закон | 23 апреля 2010 г. |

| Губернатор | Ян Брюэр |

| Счет | СБ 1070 |

Статус: Частично снесен | |

Закон о поддержке наших правоохранительных органов и безопасных районов (представленный как законопроект Сената штата Аризона № 1070 и обычно называемый Arizona SB 1070 ) — это законодательный акт 2010 года , принятый в американском штате Аризона , который был самым широким и строгим законом о борьбе с нелегальной иммиграцией в Соединенных Штатах. Состояния, когда прошло. [2] Это привлекло международное внимание и вызвало серьезные споры. [3] [4]

Федеральный закон США требует, чтобы иммигранты старше 18 лет всегда имели при себе любое свидетельство о регистрации иностранца, выданное ему или ей; нарушение этого требования является федеральным правонарушением . [5] Закон штата Аризона также сделал правонарушением пребывания иностранца в Аризоне без необходимых документов. [6] и потребовал, чтобы сотрудники правоохранительных органов штата пытались определить иммиграционный статус человека во время «законного задержания, задержания или ареста», когда есть обоснованные подозрения , что данное лицо является нелегальным иммигрантом. [7] [8] Закон запрещал государственным или местным должностным лицам или агентствам ограничивать соблюдение федеральных иммиграционных законов . [9] и наложили штрафы на тех, кто укрывает, нанимает и перевозит незарегистрированных иностранцев. [10] The paragraph on intent in the legislation says it embodies an "attrition through enforcement" doctrine.[11][12]

Critics of the legislation say it encourages racial profiling, while supporters say the law prohibits the use of race as the sole basis for investigating immigration status.[13] The law was amended by Arizona House Bill 2162 within a week of its signing, with the goal of addressing some of these concerns. There have been protests in opposition to the law in over 70 U.S. cities,[14] including boycotts and calls for boycotts of Arizona.[15]

The Act was signed into law by Governor Jan Brewer on April 23, 2010.[2] It was scheduled to go into effect on July 29, 2010, ninety days after the end of the legislative session.[16][17] Legal challenges over its constitutionality and compliance with civil rights law were filed, including one by the United States Department of Justice, that also asked for an injunction against enforcement of the law.[18] The day before the law was to take effect, federal judge Susan R. Bolton issued a preliminary injunction that blocked the law's most controversial provisions.[19] In June 2012, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled on the case Arizona v. United States, upholding the provision requiring immigration status checks during law enforcement stops but striking down three other provisions as violations of the Supremacy Clause of the United States Constitution.[20]

Provisions

[edit]U.S. federal law requires aliens 14 years old or older who are in the country for longer than 30 days to register with the U.S. government[21] and have registration documents in their possession at all times.[5] The Act makes it a state misdemeanor for an illegal alien to be in Arizona without carrying the required documents[6] and obligates police to make an attempt, when practicable during a "lawful stop, detention or arrest",[7] to determine a person's immigration status if there is reasonable suspicion that the person is an illegal alien.[9] Any person arrested cannot be released without confirmation of the person's legal immigration status by the federal government pursuant to § 1373(c) of Title 8 of the United States Code.[9] A first offense carries a fine of up to $100, plus court costs, and up to 20 days in jail; subsequent offenses can result in up to 30 days in jail[22] (SB 1070 required a minimum fine of $500 for a first violation, and for a second violation a minimum $1,000 fine and a maximum jail sentence of 6 months).[10] A person is "presumed to not be an immigrant who is unlawfully present in the United States" if he or she presents any of the following four forms of identification: a valid Arizona driver license; a valid Arizona nonoperating identification license; a valid tribal enrollment card or other tribal identification; or any valid federal, state, or local government-issued identification, if the issuer requires proof of legal presence in the United States as a condition of issuance.[9]

The Act prohibits state, county, and local officials from limiting or restricting "the enforcement of federal immigration laws to less than the full extent permitted by federal law" and provides that any legal Arizona resident can sue the agencies or officials in question to compel such full enforcement.[9][23] If the person who brings suit prevails, that person may be entitled to reimbursement of court costs and reasonable attorney fees.[9]

The Act makes it a crime for anyone, regardless of citizenship or immigration status, to hire or to be hired from a vehicle which "blocks or impedes the normal movement of traffic." Vehicles used in such manner are subject to mandatory immobilization or impoundment. For a person in violation of a criminal law, it is an offense to transport an illegal alien "in furtherance" of the illegal immigrant's unauthorized presence in the U.S., to "conceal, harbor or shield" an illegal alien, or to encourage or induce an illegal alien to immigrate to the state, if the person "knows or recklessly disregards the fact" that the alien is in the U.S. without authorization or that immigration would be unlawful.[10] Violation is a class 1 misdemeanor if fewer than ten illegal aliens are involved, and a class 6 felony if ten or more are involved. The offender is subject to a fine of at least $1,000 for each illegal immigrant involved. The transportation provision includes exceptions for child protective services workers, ambulance attendants and emergency medical technicians.[10]

Arizona HB 2162

[edit]On April 30, 2010, the Arizona legislature passed and Governor Brewer signed, House Bill 2162, which modified the Act that had been signed a week earlier, adding text stating that "prosecutors would not investigate complaints based on race, color or national origin."[24] The new text also states that police may only investigate immigration status incident to a "lawful stop, detention, or arrest", lowers the original fine from a minimum of $500 to a maximum of $5000,[22] and changes incarceration limits for first-time offenders from 6 months to 20 days.[7]

Background and passage

[edit]Arizona was the first state to enact such far-reaching legislation.[25] Prior law in Arizona, like most other states, did not require law enforcement personnel to ask the immigration status of people they encountered.[26] Many police departments discourage such inquiries to avoid deterring immigrants from reporting crimes and cooperating in other investigations.[26]

Arizona had an estimated 460,000 illegal immigrants in April 2010,[26] a fivefold increase since 1990.[27] As the state with the most unlawful crossings of the Mexico–United States border, its remote and dangerous deserts are the unlawful entry point for thousands of illegal immigrant Mexicans and Central Americans.[13] By the late 1990s, the Tucson Border Patrol Sector had the highest number of arrests by the United States Border Patrol.[27]

Whether illegal aliens commit a disproportionate number of crimes is uncertain, with different authorities and academics claiming that the rate for this group was the same, greater, or less than that of the overall population.[28] There was also anxiety that the Mexican Drug War, which had caused thousands of deaths, would spill over into the U.S.[28] Moreover, by late in the decade 2000, Phoenix was averaging one kidnapping per day, earning it the reputation as America's worst city in that regard.[27]

Arizona has a history of restricting illegal immigration. In 2007, legislation imposed heavy sanctions on employers hiring undocumented workers.[29] Measures similar to SB 1070 had been passed by the legislature in 2006 and 2008, only to be vetoed by Democratic Governor Janet Napolitano.[2][30][31] She was subsequently appointed as Secretary of Homeland Security in the Obama administration and was replaced by Republican Secretary of State of Arizona Jan Brewer.[2][32] There is a similar history of referendums, such as the Arizona Proposition 200 (2004) that sought to restrict illegal immigrants' use of social services. The 'attrition through enforcement' doctrine had been encouraged by think tanks such as the Center for Immigration Studies for several years.[12]

Impetus for SB 1070 was attributed to demographics shifting towards a larger Hispanic population, increased drugs and human smuggling related violence in Mexico and Arizona, and a struggling state economy and economic anxiety during the late-2000s recession.[4][33] State residents were frustrated by the lack of federal progress on immigration,[4] which they viewed as even more disappointing given that Napolitano had joined the Obama administration.[33]

The major sponsor and legislative force behind the bill was state senator Russell Pearce, who had long been one of Arizona's most vocal opponents of illegal aliens [34] and who had successfully pushed several prior pieces of tough legislation against those he termed "invaders on the American sovereignty".[35][36] Much of the bill was drafted by Kris Kobach,[36] a professor at the University of Missouri–Kansas City School of Law[37] and a figure long associated with the Federation for American Immigration Reform who had drafted immigration bills for many other states.[38] Pearce and Kobach had worked together on prior immigration legislation, and Pearce contacted Kobach when he was ready to pursue stronger state enforcement of federal immigration laws.[36] A December 2009 meeting of the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) in Washington, D.C., produced model legislation that embodied the Pearce initiative.[39]

One explanation for the impetus behind the bill was that ALEC is largely funded by corporate contributions, including some from the private prison industry such as the Corrections Corporation of America, Management and Training Corporation, and GEO Group. These companies would benefit from a large increase in the number of illegal immigrants sent to jail.[39] Pearce later denied that he created the bill for any reason other than to stop illegal immigration. He denied that he submitted the idea to ALEC for any reason other than helping it pass in Arizona and, potentially, in other states.[39]

The bill was introduced in the Arizona legislature in January 2010 and gained 36 cosponsors.[39] The Arizona State Senate approved an early version of the bill in February 2010.[34] Saying, "Enough is enough," Pearce stated figuratively that this new bill would remove handcuffs from law enforcement and place them on violent offenders.[32][40]

On March 27, 2010, 58-year-old Robert Krentz and his dog were shot and killed while Krentz was doing fence work on his large ranch roughly 19 miles (31 km) from the Mexican border. This incident gave a tangible public face to fears about immigration-related crime.[28][41] Arizona police were unable to name a murder suspect but traced a set of footprints from the crime scene south towards the border. The resulting speculation that the killer was an illegal immigrant increased public support for SB 1070.[2][28][31][41] There was talk of naming the law after Krentz.[31] Some state legislators (both for and against the law) believed, however, that the impact of the Krentz killing has been overstated as a factor in the law's passage.[4]

The bill, with several amendments, passed the Arizona House of Representatives on April 13 by a 35–21 party-line vote.[34] The revised measure then passed the State Senate on April 19 by a 17–11 vote that also closely followed party lines,[32] with all but one Republican voting for the bill, ten Democrats voting against it, and two Democrats abstaining.[42]

After a bill passes, the Arizona governor has five days to either sign, veto, or allow it to pass without the governor's signature.[43][44] The question became whether Governor Brewer would sign the bill into law, as she had remained silent on her opinion of SB1070.[2][43] Immigration had not previously been a focus of her political career, although as secretary of state she had supported Arizona Proposition 200 (2004).[45] As governor, she had made another push for Arizona Proposition 100 (2010), a one percent increase in the state sales tax to prevent cuts in education, health and human services, and public safety, despite opposition from within her own party.[43][45] These political moves, along with a tough upcoming Republican Party primary in the 2010 Arizona gubernatorial election with other conservative opponents supporting the bill, were considered major factors in her decision.[2][43][45] During the bill's development, her staff had reviewed its language line by line with state senator Pearce,[43][45] but she had said she had concerns about several of its provisions.[46] The Mexican Senate urged the governor to veto the bill[40] and the Mexican Embassy to the U.S. raised concerns about potential racial profiling that may result.[32] Citizen messages to Brewer, however, were 3–1 in favor of the law.[32] A Rasmussen Reports poll taken between the House and Senate votes showed wide support for the bill among likely voters in the state, with 70 percent in favor and 23 percent opposed.[47] The same poll showed 53 percent were at least somewhat concerned that actions taken due to the measures in the bill would violate the civil rights of some American citizens.[47] Brewer's staff said that she was considering the legal issues, the impact on the state's business, and the feelings of the citizens in coming to her decision.[43] They added that "she agonizes over these things,"[43] and the governor also prayed over the matter.[31] Brewer's political allies said her decision would cause political trouble no matter what she decided.[45] Most observers expected that she would sign the bill, and on April 23 she did.[2]

During the wait for a signing decision, there were over a thousand people at the Arizona State Capitol both in support of and opposition to the bill, and some minor civil unrest occurred.[23] Against concerns that the measure would promote racial profiling, Brewer stated that no such behavior would be tolerated: "We must enforce the law evenly, and without regard to skin color, accent or social status."[48] She vowed to ensure that police forces had proper training relative to the law and civil rights,[2][48] and on the same day as the signing she issued an executive order requiring additional training for all officers on how to implement SB 1070 without engaging in racial profiling.[49][50] Ultimately, she said, "We have to trust our law enforcement."[2] (The training materials developed by the Arizona Peace Officer Standards and Training Board were released in June 2010.[51][52])

Sponsor Pearce called the law's passage "a good day for America."[23]News of the law and the debate around immigration gained national attention, especially on cable news television channels, where topics that attract strong opinions are often given extra airtime.[53]Nevertheless, the legislators were surprised by the reaction it gained. State Representative Michele Reagan reflected three months later: "The majority of us who voted yes on that bill, myself included, did not expect or encourage an outcry from the public. The majority of us just voted for it because we thought we could try to fix the problem. Nobody envisioned boycotts. Nobody anticipated the emotion, the prayer vigils. The attitude was: These are the laws, let's start following them."[4] State Representative Kyrsten Sinema, the assistant House minority leader (and current U.S. Senator) tried to stop the bill and voted against it. She similarly reflected: "I knew it would be bad, but no one thought it would be this big. No one."[4]

The immigration issue also gained center stage in the re-election campaign of Republican U.S. Senator from Arizona John McCain, who had been a past champion of federal immigration reform measures such as the Comprehensive Immigration Reform Act of 2007.[41] Also faced with a primary battle against the more conservative J. D. Hayworth, who had made legislation against unlawful immigration a central theme of his candidacy, McCain supported SB 1070 only hours before its passage in the State Senate.[2][41] McCain subsequently became a vocal defender of the law, saying that the state had been forced to take action given the federal government's inability to control the border.[54][55]

In September 2014, U.S. District Judge Susan Bolton ordered SB 1070 sponsor Russell Pearce to comply with a subpoena calling for him to turn over his emails and documents about the contentious statute. Challengers of the bill wanted to determine from them whether there was a discriminatory intent in composing the statute.[56]

Reaction

[edit]Opinion polls

[edit]A Rasmussen Reports poll done nationally around the time of the signing indicated that 60 percent of Americans were in favor of and 31 percent opposed to legislation that allows local police to "stop and verify the immigration status of anyone they suspect of being an illegal immigrant."[57] The same poll also indicated that 58 percent are at least somewhat concerned that "efforts to identify and deport illegal immigrants will also end up violating the civil rights of some U.S. citizens."[57] A national Gallup Poll found that more than three-quarters of Americans had heard about the law, and of those who had, 51 percent were in favor of it against 39 percent opposed.[58] An Angus Reid Public Opinion poll indicated that 71 percent of Americans said they supported the notion of requiring their own police to determine people's status if there was "reasonable suspicion" the people were illegal immigrants, and arresting those people if they could not prove they were legally in the United States.[59] A nationwide The New York Times/CBS News poll found similar results to the others, with 51 percent of respondents saying the Arizona law was "about right" in its approach to the problem of illegal immigration, 36 percent saying it went too far, and 9 percent saying it did not go far enough.[60] Another CBS News poll, conducted a month after the signing, showed 52 percent seeing the law as about right, 28 percent thinking it goes too far, and 17 percent thinking it does not go far enough.[61] A 57 percent majority thought that the federal government should be responsible for determining immigration law.[60] A national Fox News poll found that 61 percent of respondents thought Arizona was right to take action itself rather than wait for federal action, and 64 percent thought the Obama administration should wait and see how the law works in practice rather than trying to stop it right away.[62] Experts caution that in general, polling has difficulty reflecting complex immigration issues and law.[58]

Another Rasmussen poll, done statewide after several days of heavy news coverage about the controversial law and its signing, found a large majority of Arizonans still supported it, by a 64 percent to 30 percent margin.[63] Rasmussen also found that Brewer's approval ratings as governor had shot up, going from 40 percent of likely voters before the signing to 56 percent after, and that her margin over prospective Democratic gubernatorial opponent, State Attorney General Terry Goddard (who opposes the law) had widened.[64] A poll done by Arizona State University researchers found that 81 percent of registered Latino voters in the state opposed SB 1070.[65]

Public officials

[edit]United States

[edit]In the United States, supporters and opponents of the bill have roughly followed party lines, with most Democrats opposing the bill and most Republicans supporting it.

The bill was criticized by President Barack Obama who called it "misguided" and said it would "undermine basic notions of fairness that we cherish as Americans, as well as the trust between police and our communities that is so crucial to keeping us safe."[2][41] Obama did later note that the HB 2162 modification had stipulated that the law not be applied in a discriminatory fashion, but the president said there was still the possibility of suspected illegal immigrants "being harassed and arrested".[66] He repeatedly called for federal immigration reform legislation to forestall such actions among the states and as the only long-term solution to the problem of unlawful immigration.[2][41][66][67] Governor Brewer and President Obama met at the White House in early June 2010 to discuss immigration and border security issues in the wake of SB 1070; the meeting was termed pleasant, but brought about little change in the participants' stances.[1]

Secretary of Homeland Security and former Arizona governor Janet Napolitano testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee that she had "deep concerns" about the law and that it would divert necessary law enforcement resources from combating violent criminals.[68] (As governor, Napolitano had consistently vetoed similar legislation throughout her term.[2][30]) U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder said the federal government was considering several options, including a court challenge based on the law leading to possible civil rights violations.[38][69] Michael Posner, the Assistant Secretary of State for Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, brought up the law in discussions with a Chinese delegation to illustrate human rights areas the U.S. needed to improve on.[70] This led McCain and fellow senator from Arizona Jon Kyl to strongly object to any possibly implied comparison of the law to human rights abuses in China.[70] Senior Democratic U.S. Senator Chuck Schumer of New York and Mayor of New York City Michael Bloomberg have criticized the law, with Bloomberg stating that it sends exactly the wrong message to international companies and travelers.[48]

In testimony before the Senate Homeland Security Committee, McCain drew out that Napolitano had made her remarks before having actually read the law.[71] Holder also acknowledged that he had not read the statute.[71][72][73] The admissions by the two cabinet secretaries that they had not yet read SB 1070 became an enduring criticism of the reaction against the law.[74][75]Former Alaska governor and vice-presidential candidate Sarah Palin accused the party in power of being willing to "criticize bills (and divide the country with ensuing rhetoric) without actually reading them."[74] Governor Brewer's election campaign issued a video featuring a frog hand puppet that sang "reading helps you know what you're talkin' 'bout" and urged viewers to fully read the law.[75] In reaction to the question, President Obama told a group of Republican senators that he had in fact read the law.[76]

Democrat Linda Sánchez, U.S. Representative from California's 39th congressional district, has claimed that white supremacy groups are in part to blame for the law's passage, saying, "There's a concerted effort behind promoting these kinds of laws on a state-by-state basis by people who have ties to white supremacy groups. It's been documented. It's not mainstream politics."[77] Republican Representative Gary Miller, from California's 42nd congressional district, called her remarks "an outrageous accusation [and a] red herring. [She's] trying to change the debate from what the law says."[77] Sánchez' district is in Los Angeles County and Miller's district is in both Los Angeles County and neighboring Orange County.

The law has been popular among the Republican Party base electorate; however, several Republicans have opposed aspects of the measure, mostly from those who have represented heavily Hispanic states.[78] These include former Governor of Florida Jeb Bush,[79] former Speaker of the Florida House of Representatives and sitting U.S. Senator Marco Rubio,[79] and former George W. Bush chief political strategist Karl Rove.[80] Some analysts have stated that Republican support for the law gives short-term political benefits by energizing their base and independents, but longer term carries the potential of alienating the growing Hispanic population from the party.[78][81] The issue played a role in several Republican primary contests during the 2010 congressional election season.[82]

One Arizona Democrat who defended some of the motivation behind the bill was Congresswoman Gabby Giffords, who said her constituents were "sick and tired" of the federal government failing to protect the border, that the current situation was "completely unacceptable", and that the legislation was a "clear calling that the federal government needs to do a better job".[49] However, she stopped short of supporting the law itself, saying it "does nothing to secure our border" and that it "stands in direct contradiction to our past and, as a result, threatens our future."[83] Her opposition to the law became one of the issues in her 2010 re-election campaign, in which she narrowly prevailed over her Republican opponent, who supported it.[84][85]

U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton included the dispute over SB 1070 in an August 2010 report to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, as an example to other countries of how fractious issues can be resolved under the rule of law.[86] Governor Brewer demanded that the reference to the law be removed from the report, seeing its inclusion as implying that the law was a violation of human rights[87] and saying that any notion of submitting U.S. laws to U.N. review was "internationalism run amok".[86]

Mexico

[edit]Mexican President Felipe Calderón's office said that "the Mexican government condemns the approval of the law [and] the criminalization of migration."[13] President Calderón also characterized the new law as a "violation of human rights".[88] Calderón repeated his criticism during a subsequent state visit to the White House.[66]

The measure was also strongly criticized by Mexican health minister José Ángel Córdova, former education minister Josefina Vázquez Mota, and Governor of Baja California José Guadalupe Osuna Millán, with Osuna saying it "could disrupt the indispensable economic, political and cultural exchanges of the entire border region."[88] The Mexican Foreign Ministry issued a travel advisory for its citizens visiting Arizona, saying "It must be assumed that every Mexican citizen may be harassed and questioned without further cause at any time."[89][90]

In response to these comments, Chris Hawley of USA Today said that "Mexico has a law that is no different from Arizona's", referring to legislation which gives local police forces the power to check documents of people suspected of being in the country unlawful.[91] Immigration and human rights activists have also noted that Mexican authorities frequently engage in racial profiling, harassment, and shakedowns against migrants from Central America.[91]

The law imperiled the 28th annual, binational Border Governors Conference, scheduled to be held in Phoenix in September 2010 and to be hosted by Governor Brewer.[92] The governors of the six Mexican states belonging to the conference vowed to boycott it in protest of the law, saying SB 1070 is "based on ethnic and cultural prejudice contrary to fundamental rights," and Brewer said in response that she was canceling the gathering.[92] Governors Bill Richardson of New Mexico and Arnold Schwarzenegger of California, U.S. border governors who oppose the law, supported moving the conference to another state and going forward with it,[92] and it was subsequently held in Santa Fe, New Mexico without Brewer attending.[93]

Arizona law enforcement

[edit]Arizona's law enforcement groups have been split on the bill,[32][94] with statewide rank-and-file police officer groups generally supporting it and police chief associations opposing it.[23][95]

The Arizona Association of Chiefs of Police criticized the legislation, calling the provisions of the bill "problematic" and expressing that it will negatively affect the ability of law enforcement agencies across the state to fulfill their many responsibilities in a timely manner.[96] Additionally, some officers have repeated the past concern that undocumented immigrants may come to fear the police and not contact them in situations of emergency or in instances where they have valuable knowledge of a crime.[95] However, the Phoenix Law Enforcement Association, which represents the city's police officers, has supported the legislation and lobbied aggressively for its passage.[94][95] Officers supporting the measure say they have many indicators other than race they can use to determine whether someone may be an illegal immigrant, such as absent identification or conflicting statements made.[95]

The measure was hailed by Joe Arpaio, Sheriff of Maricopa County, Arizona – known for his tough crackdowns on undocumented immigration within his own jurisdiction – who hoped the measure would cause the federal action to seal the border.[97] Arpaio said, "I think they'll be afraid that other states will follow this new law that's now been passed."[97]

Religious organizations and perspectives

[edit]Activists within the church were present on both sides of the immigration debate,[98] and both proponents and opponents of the law appealed to religious arguments for support.[99]

State Senator Pearce, a devout member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, which has a substantial population in Arizona, frequently said that his efforts to push forward this legislation was based on that church's 13 Articles of Faith, one of which instructs in obeying the law.[98][100] This association caused a backlash against The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and threatened its proselytizing efforts among the area's Hispanic population.[100] The church emphasized that it took no position on the law or immigration in general and that Pearce did not speak for it.[98][100] It later endorsed the Utah Compact on immigration[101] and in the following year, took an official position on the issue which opposed Pearce's approach to immigration, saying, "The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is concerned that any state legislation that only contains enforcement provisions is likely to fall short of the high moral standard of treating each other as children of God. The Church supports an approach where undocumented immigrants are allowed to square themselves with the law and continue to work without this necessarily leading to citizenship."[102]

The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops denounced the law, characterizing it as draconian and saying it "could lead to the wrongful questioning and arrest of U.S. citizens."[103] The National Council of Churches also criticized the law, saying that it ran counter to centuries of biblical teachings regarding justice and neighborliness.[104]

Other members of the Christian clergy differed on the law.[105] United Methodist Church Bishop Minerva G. Carcaño of Arizona's Desert Southwest Conference opposed it as "unwise, short sighted and mean spirited"[106] and led a mission of prominent religious figures to Washington to lobby for comprehensive immigration reform.[107][108] But others stressed the Biblical command to follow laws.[105] While there was a perception that most Christian groups opposed the law, Mark Tooley of the Institute on Religion and Democracy said that immigration was a political issue that "Christians across the spectrum can disagree about" and that liberal churches were simply more outspoken on this matter.[105]

Concerns over potential civil rights violations

[edit]The National Association of Latino Elected and Appointed Officials said the legislation was "an unconstitutional and costly measure that will violate the civil rights of all Arizonans."[109] Mayor Chris Coleman of Saint Paul, Minnesota, labeled it as "draconian" as did Democratic Texas House of Representatives member Garnet Coleman.[110][111] Edwin Kneedler, the U.S. Deputy Solicitor General, also criticized the legislation for its potential infringement on the civil liberties of Arizona's citizens and lawful permanent residents.[112]

Proponents with the law have rejected such criticism, and argued that the law was reasonable, limited, and carefully crafted.[113] Stewart Baker, a former Homeland Security official in the George W. Bush administration, said, "The coverage of this law and the text of the law are a little hard to square. There's nothing in the law that requires cities to stop people without cause, or encourages racial or ethnic profiling by itself."[38]

Republican member with the Arizona House of Representatives Steve Montenegro supported the law, saying that "This bill has nothing to do with race or profiling. It has to do with the law. We are seeing a lot of crime here in Arizona because of the open borders that we have."[114] Montenegro, who legally immigrated to the U.S. from El Salvador with his family when he was four, stated, "I am saying if you here illegally, get in line, come in the right way."[114]

As one of the main drafters of the law, Kobach has stated that the way the law has been written makes any form of racial profiling unlawful. In particular, Kobach references the phrase in the law that directly states that officers "may not solely consider race, color, or national origin."[115] Kobach also disagrees that the "reasonable suspicion" clause of the bill specifically allows for racial profiling, replying that the term "reasonable suspicion" has been used in other laws prior and therefore has "legal precedent".[115]

However, there are ongoing arguments in legal journal articles that racial profiling does exist and threatens human security, particularly community security of the Mexicans living in the United States. India Williams argues that the Border Patrol is very likely to stop anyone if a suspect resembles "Mexican appearance" and states that such generalization of unchangeable physical features threatens the culture and the heritage of the ethnic group.[116] Andrea Nill argues that it is only a small portion of Mexicans and Latinos that are undocumented immigrants, but there is a demonization and illogical discrimination of Latino community by giving less respect, rights, and freedoms, whereas white American citizens will never have to worry about being stopped by the police due to their skin color.[117]

Some Latino leaders compared the law to Apartheid in South Africa or the Japanese American internment during World War II.[23][118] The law's aspect that officers may question the immigration status of those they suspect are in the country unlawfully became characterized in some quarters as the "show me your papers" or "your papers, please" provision.[119][120][121][122] This echoed a common trope regarding Germans in World War II films.[119][123] Such an association was explicitly made by Congresswoman Jan Schakowsky of Illinois.[123] Congressman Jared Polis of Colorado and Los Angeles Councilwoman Janice Hahn also said the law's requirement to carry papers all the time was reminiscent of the anti-Jewish legislation in prewar Nazi Germany and feared that Arizona was headed towards becoming a police state.[68][124] Cardinal Roger Mahony of Los Angeles said, "I can't imagine Arizonans now reverting to German Nazi and Russian Communist techniques whereby people are required to turn one another in to the authorities on any suspicion of documentation."[125] The Anti-Defamation League called for an end to the comparisons with Nazi Germany, saying that no matter how odious or unconstitutional the Arizona law might be, it did not compare to the role that Nazi identity cards played in what eventually became the extermination of European Jews.[126]

In its final form, HB 2162 limits the use of race. It states: "A law enforcement official or agency of this state or a county, city, town or other political subdivision of this state may not consider race, color or national origin in implementing the requirements of this subsection except to the extent permitted by the United States or Arizona Constitution."[7] The U.S. and Arizona supreme courts have held that race may be considered in enforcing immigration law. In United States v. Brignoni-Ponce, the U.S. Supreme Court found: "The likelihood that any given person of Mexican ancestry is an alien is high enough to make Mexican appearance a relevant factor."[127] The Arizona Supreme Court agrees that "enforcement of immigration laws often involves a relevant consideration of ethnic factors."[128] Both decisions say that race alone, however, is an insufficient basis to stop or arrest.

Protests

[edit]Thousands of people staged protests in state capital Phoenix over the law around the time of its signing, and a pro-immigrant activist called the measure "racist".[40][129] Passage of the HB 2162 modifications to the law, although intended to address some of the criticisms of it, did little to change the minds of the law's opponents.[60][130]

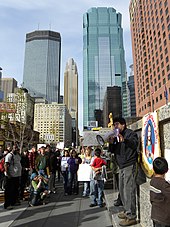

Tens of thousands of people demonstrated against the law in over 70 U.S. cities on May 1, 2010, a day traditionally used around the world to assert workers' rights.[14][131][132] A rally in Los Angeles, attended by Cardinal Mahoney, attracted between 50,000 and 60,000 people, with protesters waving Mexican flags and chanting "Sí se puede".[14][131][133] The city had become the national epicenter of protests against the Arizona law.[133] Around 25,000 people were at a protest in Dallas, and more than 5,000 were in Chicago and Milwaukee, while rallies in other cities generally attracted around a thousand people or so.[131][132] Democratic U.S. Congressman from Illinois Luis Gutiérrez was part of a 35-person group arrested in front of the White House in a planned act of civil disobedience that was also urging President Obama to push for comprehensive immigration reform.[134] There and in some other locations, demonstrators expressed frustration with what they saw as the administration's lack of action on immigration reform, with signs holding messages such as "Hey Obama! Don't deport my mama."[132]

Protests both for and against the Act took place over Memorial Day Weekend in Phoenix and commanded thousands of people.[135] Those opposing it, mostly consisting of Latinos, marched five miles to the State Capitol in high heat, while those supporting it met in a stadium in an event arranged by elements of the Tea Party movement.[135]

Protests against the law extended to the arts and sports world as well. Colombian pop singer Shakira came to Phoenix and gave a joint press conference against the bill with Mayor of Phoenix Phil Gordon.[136] Linda Ronstadt, of part Mexican descent and raised in Arizona, also appeared in Phoenix and said, "Mexican-Americans are not going to take this lying down."[137] A concert of May 16 in Mexico City's Zócalo, called Prepa Si Youth For Dignity: We Are All Arizona, drew some 85,000 people to hear Molotov, Jaguares, and Maldita Vecindad headline a seven-hour show in protest against the law.[138]

The Major League Baseball Players Association, of whose members one quarter are born outside the U.S., said that the law "could have a negative impact on hundreds of major league players," especially since many teams come to Arizona for spring training, and called for it to be "repealed or modified promptly."[139] A Major League Baseball game at Wrigley Field where the Arizona Diamondbacks were visiting the Chicago Cubs saw demonstrators protesting the law.[140] Protesters focused on the Diamondbacks because owner Ken Kendrick had been a prominent fundraiser in Republican causes, but he in fact opposed the law.[141] The Phoenix Suns of the National Basketball Association wore their "Los Suns" uniforms normally used for the league's "Noche Latina" program for their May 5, 2010 (Cinco de Mayo) playoff game against the San Antonio Spurs to show their support for Arizona's Latino community and to voice disapproval of the immigration law.[142] The Suns' political action, rare in American team sports, created a firestorm and drew opposition from many of the teams' fans;[143] President Obama highlighted it, while conservative radio commentator Rush Limbaugh called the move "cowardice, pure and simple."[144]

Boycotts

[edit]Boycotts of Arizona were organized in response to SB 1070, with resolutions by city governments being among the first to materialize.[68][145][146][147] The government of San Francisco, the Los Angeles City Council, and city officials in Oakland, Minneapolis, Saint Paul, Denver, and Seattle all took specific action, usually by banning some of their employees from work-related travel to Arizona or by limiting city business done with companies headquartered in Arizona.[3][110][147][148]

In an attempt to push back against the Los Angeles City Council's action, which was valued at $56 million,[3] Arizona Corporation Commissioner Gary Pierce sent a letter to Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa, suggesting that he'd "be happy to encourage Arizona utilities to renegotiate your power agreements so that Los Angeles no longer receives any power from Arizona-based generation."[149] Such a move was infeasible for reasons of ownership and governance, and Pierce later stated that he was not making a literal threat to cut power to the city.[149]

U.S. Congressman Raúl Grijalva, from Arizona's 7th congressional district, had been the first prominent officeholder to call for an economic boycott of his state, by industries from manufacturing to tourism, in response to SB 1070.[150] His call was echoed by La Opinión, the nation's largest Spanish-language newspaper.[145] Calls for various kinds of boycotts were also spread through social media sites, and there were reports of individuals or groups changing their plans or activities in protest of the law.[129][145][151][152] The prospect of an adverse economic impact made Arizonan business leaders and groups nervous,[68][129][151] and Phoenix officials estimated that the city could lose up to $90 million in hotel and convention business over the next five years due to the controversy over the law.[153] Phoenix Mayor Gordon urged people not to punish the entire state as a consequence.[145]

Major organizations opposing the law, such as the National Council of La Raza, refrained from initially supporting a boycott, knowing that such actions are difficult to execute successfully and even if done cause broad economic suffering, including among the people they are supporting.[15] Arizona did have a past case of a large-scale boycott during the late 1980s and early 1990s, when it lost many conventions and several hundred million dollars in revenues after Governor Evan Mecham's cancellation of a Martin Luther King Jr. Day state holiday and a subsequent failed initial referendum to restore it.[15] La Raza subsequently switched its position regarding SB 1070 and became one of the leaders of the boycott effort.[154]

The Arizona Hispanic Chamber of Commerce opposed both the law and the idea of boycotting, saying the latter would only hurt small businesses and the state's economy, which was already badly damaged by the collapse of real estate prices and the late-2000s recession.[155] Other state business groups opposed a boycott for the same reasons.[156] Religious groups opposed to the law split on whether a boycott was advisable, with Bishop Carcaño saying one "would only extend our recession by three to five years and hit those who are poorest among us."[108] Representative Grijalva said he wanted to keep a boycott restricted to conferences and conventions and only for a limited time: "The idea is to send a message, not grind down the state economy."[15] Governor Brewer said that she was disappointed and surprised at the proposed boycotts – "How could further punishing families and businesses, large and small, be a solution viewed as constructive?" – but said that the state would not back away from the law.[157] President Obama took no position on the matter, saying, "I'm the president of the United States, I don't endorse boycotts or not endorse boycotts. That's something that private citizens can make a decision about."[67]

Sports-related boycotts were proposed as well. U.S. congressman from New York José Serrano asked baseball commissioner Bud Selig to move the 2011 Major League Baseball All-Star Game from Chase Field in Phoenix.[140] The manager of the Chicago White Sox, Ozzie Guillén, stated that he would boycott that game "as a Latin American" and several players indicated they might as well.[158][159] Selig refused to move the game and it took place as scheduled a year later, with no players or coaches staying away.[159] Two groups protesting outside the stadium drew little interest from fans eager to get into the game.[159] The World Boxing Council, based in Mexico City, said it would not schedule Mexican boxers to fight in the state.[140]

A boycott by musicians saying they would not stage performances in Arizona was co-founded by Marco Amador, a Chicano activist and independent media advocate and Zack de la Rocha, the lead singer of Rage Against the Machine and the son of Beto de la Rocha of Chicano art group Los Four, who said, "Some of us grew up dealing with racial profiling, but this law (SB 1070) takes it to a whole new low."[160][161] Called the Sound Strike, artists signing on with the effort included Kanye West, Cypress Hill, Massive Attack, Conor Oberst, Sonic Youth, Joe Satriani, Rise Against, Tenacious D, The Coup, Gogol Bordello, and Los Tigres del Norte.[160][161] Some other Spanish-language artists did not join this effort but avoided playing in Arizona on their tours anyway; these included Pitbull, Wisin & Yandel, and Conjunto Primavera.[160] The Sound Strike boycott failed to gain support from many area- or stadium-level acts, and no country music acts signed on.[162] Elton John very publicly opposed such efforts, saying at a concert performance in Tucson: "We are all very pleased to be playing in Arizona. I have read that some of the artists won't come here. They are fuckwits! Let's face it: I still play in California, and as a gay man I have no legal rights whatsoever. So what's the fuck up with these people?"[163] By November 2010, Pitbull had announced a change of heart, playing a show in Phoenix because large parts of the law had been stopped by the judicial action.[164] My Chemical Romance, an original Sound Strike participant, supposedly dropped out and scheduled a show in the state as well[165] (however, the following day the show was cancelled and the band apologized, explaining that it was an error with tour scheduling and it should not have been booked in the first place due to "the band's affiliation with The Sound Strike" ).[166] De la Rocha said Sound Strike would continue despite the injunction against large parts of SB 1070 in order to battle Arizona's "racist and fear mongering state government" and until the Obama administration stopped participating in federal actions such as the 287(g) program, Secure Communities, and other U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement policies.[164][166][167]

In reaction to the boycott talk, proponents of the law advocated making a special effort to buy products and services from Arizona in order to indicate support for the law.[168][169] These efforts, sometimes termed a "buycott", were spread by social media and talk radio as well as by elements of the Tea Party movement.[168][169] Some supporters of the law and legal scholars have also suggested that the city government boycotts of Arizona represent an unconstitutional violation of the Interstate Commerce Clause.[170][171]

By early May, the state had lost a projected $6–10 million in business revenue, according to the Arizona Hotel & Lodging Association.[156] However, an increase in leisure travel and an overall economic recovery more than compensated for the business travel loss; by July, overall hotel occupancy rates and revenues were up from the same period in 2009.[172] The president of the Greater Phoenix Economic Council said, "Fundamentally, the boycotts have been unsuccessful."[172] A November 2010 study by the progressive-oriented Center for American Progress stated that the boycott had so far cost the state economy as much as $141 million in lost revenues, including $45 million in the lodging industry.[173] However, an examination at the same time by the Associated Press found that while the boycott had been disruptive in some areas, it had had nowhere near the effect some had originally imagined.[174] Visitors at Grand Canyon National Park were up from the year before, several well-known Arizona-based companies that were targeted said they had seen no effect from it, and the actions by the San Francisco and Los Angeles city governments had resulted in few practical consequences.[174] Sports-related boycotts, such as of the Fiesta Bowl, sponsor Frito-Lay and beer distributor Hensley & Co., had also had no effect.[175] In September 2011 La Raza and two associated groups called off their boycott, saying that the action had been successful in discouraging some other states from passing SB 1070-like laws and that continuing the boycott would only punish businesses and workers.[176]

Effects

[edit]Arizona

[edit]Some Christian churches in Arizona with large immigrant congregations reported a 30 percent drop in their attendance figures.[108] Schools, businesses, and health care facilities in certain areas also reported sizable drops in their numbers.[177][178] That and the prevalence of yard sales suggested illegal immigrants were leaving Arizona, with some returning to Mexico and others moving to other U.S. states.[177] A November 2010 study by BBVA Bancomer based upon Current Population Survey figures stated that there were 100,000 fewer Hispanics in Arizona than before the debate about the law began; it said Arizona's poor economic climate could also be contributing to the decline.[179] The government of Mexico reported that over 23,000 of its citizens returned to the country from Arizona between June and September 2010.[179] A report by Seminario Niñez Migrante found that about 8,000 students entered into Sonora public schools in 2009–2011 with families quoting the American economy and SB 1070 as the main causes.[180]

The weeks after the bill's signing saw a sharp increase in the number of Hispanics in the state registering their party affiliations as Democrats.[65]

Some immigration experts said the law might make workers with H-1B visas vulnerable to being caught in public without their hard-to-replace paperwork, which they are ordinarily reluctant to carry with them on a daily basis, and that as a consequence universities and technology companies in the state might find it harder to recruit students and employees.[120] Some college and university administrators shared this fear, and President Robert N. Shelton of the University of Arizona expressed concern regarding the withdrawal of a number of honor roll students from the university in reaction to this bill.[181]

Some women with questionable immigration status avoided domestic abuse hotlines and shelters for fear of deportation.[182] Some critics of SB 1070 feared that it will serve as a roadblock to victims getting needed support, while supporters said such concerns were unfounded and that the Act was directed towards criminals, not victims.[183]

While a few provisions of the law were left standing following the July 2010 blockage of the most controversial parts, authorities often kept following existing local ordinances in those areas in preference to using the new SB 1070 ones.[184][185] One county sheriff said, "The whole thing is still on the shelf until the Supreme Court hears it."[185] By mid-2012, those provisions had still rarely been made use of.[121] The training that police forces had gone through to avoid racial profiling and understand federal immigration policies still had a beneficial effect overall.[184]

A 2016 study found that the legislation "significantly reduced the flow of illegal workers into Arizona from Mexico by 30 to 70 percent."[186]

In April 2020, plans were announced to build a new mural at the Arizona Capitol Museum honoring those harmed by the law.[187]

Other states

[edit]The Arizona legislation was one of several reasons pushing Democratic congressional leaders to introduce a proposal addressing immigration.[188] Senator Schumer sent a letter to Governor Brewer asking her to delay the law while Congress works on comprehensive immigration reform, but Brewer quickly rejected the proposal.[189]

Bills similar to SB 1070 were introduced in Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Michigan, Minnesota, and South Carolina.[190][191] None of them went to final votes in 2010; politicians in nearly twenty states had proposed introducing similar legislation during their 2011 legislative calendars.[190] Such proposals drew strong reaction both for and against.[192] The other states along the Mexican border – Texas, New Mexico, and California – generally showed little interest in following Arizona's path.[27] This was due to their having established, powerful Hispanic communities, deep cultural ties to Mexico, past experience with bruising political battles over the issue (such as with California Proposition 187 in the 1990s), and the perception among their populations that illegal immigration was less severe a problem.[27]

By March 2011, Arizona-like bills had been defeated or had failed to progress in at least six states and momentum had shifted against such imitative efforts.[193] Reasons ranged from opposition from business leaders to fear among legislators of the legal costs of defending any adopted measure.[193] One state that did pass a law based partly on SB 1070, Utah, combined it with a guest worker program that went in the other direction[193] (and fit into the spirit of the Utah Compact). Even in Arizona itself, additional tough measures against undocumented immigration were having a difficult time gaining passage in the Arizona Senate.[193] Other states were still waiting to see what the outcome of the legal battles would be.[194] By September 2011, Indiana, Georgia, and South Carolina had passed somewhat similar measures and were facing legal action.[176] Another anti-illegal immigration measure, Alabama HB 56, was considered tougher even than SB 1070; it was signed into law in June 2011.[195] However, federal courts subsequently blocked many of the key provisions of these laws in those states, and other provisions were dropped following settlements of lawsuits.[196]

Political careers

[edit]This section possibly contains original research. Do the sources say they succeeded or failed because of their involvement with SB 1070? (January 2022) |

State senator Pearce rose to become President of the Arizona Senate in January 2011. He subsequently suffered a major defeat when he lost a November 2011 recall election.[197] Among the reasons given for his loss were the desire for greater civility in politics and a lessening of the tension over immigration policy, and a loss of support for Pearce among LDS Church members based on character issues.[197][198][199] Other reasons for the defeat, such as concerns over Pearce's ethics in taking free trips or the involvement of a third candidacy in the recall election, had little to do with SB 1070.[200] In August 2012, Pearce lost a comeback bid in the Republican primary for the nomination for a state senate seat to businessman Bob Worsley.[201] Pearce was given another government job by the Maricopa County Treasurer.[202]

Drafter of the law Kris Kobach won election as Secretary of State of Kansas, first defeating two other candidates in a Republican primary,[203] then winning the general election against Democratic incumbent Chris Biggs by a wide margin. Sheriff Joe Arpaio was among those who campaigned for Kobach.[204]

State attorney general Goddard did get the Democratic nomination in the 2010 Arizona gubernatorial election. Governor Jan Brewer went on to defeat him by a 54 to 42 percent margin in the November 2010 general election. A 2016 study found that the up-tick in Brewer's approval ratings due to the legislation "proved enduring enough to turn a losing race for re-election into a victory".[205]

Legal challenges

[edit]Supremacy Clause vs. concurrent enforcement

[edit]The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) criticized the statute as a violation of the Supremacy Clause of the United States Constitution, which states that federal law, so long as it is constitutional, is paramount over state laws.[25][206] Erwin Chemerinsky, a constitutional scholar and dean of the University of California, Irvine School of Law said, "The law is clearly pre-empted by federal law under Supreme Court precedents."[38]

According to Kobach, the law embodies the doctrine of "concurrent enforcement" (the state law parallels applicable federal law without any conflict),[38][207] and Kobach stated that he believed that it would thus survive any challenge: "There are some things that states can do and some that states can't do, but this law threads the needle perfectly.... Arizona only penalizes what is already a crime under federal law."[37] State senator Pearce noted that some past state laws on immigration enforcement had been upheld in federal courts.[25]In Gonzales v. City of Peoria (9th Cir. 1983),[208] a court held that the Immigration and Naturalization Act precludes local enforcement of the Act's civil provisions but not the Act's criminal provisions. The US Attorney General may enter a written agreement with a state or local government agency under which that agency's employees perform the function of an immigration officer in relation to the investigation, apprehension, or detention of aliens in the United States;[209]however, such an agreement is not required for the agency's employees to perform those functions.[210]

On the other hand, various legal experts were divided on whether the law would survive a court challenge, with one law professor saying it "sits right on that thin line of pure state criminal law and federally controlled immigration law."[38] Past lower court decisions in the area were not always consistent, and a decision on the bill's legality from the US Supreme Court was one possible outcome.[38]

Initial court actions

[edit]On April 27, 2010, Roberto Javier Frisancho, a natural-born citizen and resident of Washington, D.C., who planned to visit Arizona, filed the first lawsuit against S.B. 1070.[211] On April 29, 2010, the National Coalition of Latino Clergy and Christian Leaders and a Tucson police officer, Martin Escobar, filed suit against SB 1070, both doing so separately in federal court.[212][213] The National Coalition's filing claimed that the law usurped federal responsibilities under the Supremacy Clause that it led to racial profiling by imposing a "reasonable suspicion" requirement upon police officers to check the immigration status of those they come in official conduct with, which would, in turn, be subject to too much personal interpretation by each officer.[213][214] Escobar's suit argued that there was no race-neutral criteria available to him to suspect that a person was an illegal alien and that implementation of the law would hinder police investigations in areas that were predominantly Hispanic.[95][215] The suit also claimed the Act violated federal law because the police and the city have no authority to perform immigration-related duties.[215] The Tucson police department insisted that Escobar was not acting on its behalf and that it had received many calls from citizens complaining about his suit.[215]

A Phoenix police officer, David Salgado, quickly followed with his own federal suit, claiming that to enforce the law would require him to violate the rights of Hispanics.[216] He also said that he would be forced to spend his own time and resources studying the law's requirements and that he was liable to being sued whether he enforced the law or not.[216][217]

On May 5, Tucson and Flagstaff became the first two cities to authorize legal action against the state over the Act.[130] San Luis later joined them.[218] However, as of mid-late May, none of them had actually filed a suit.[219] In late May, however, the city of Tucson filed a cross-claim and joined Officer Escobar in his suit.[220]

17 мая был подан совместный коллективный Friendly иск House et al. Дело против Уайтинга было подано в окружной суд США от имени десяти частных лиц и четырнадцати трудовых, религиозных организаций и организаций по защите гражданских прав. [169][218][219][221] Юрисконсульт, подавший иск, самый крупный из поданных, был сотрудничеством ACLU, Мексикано-американского фонда правовой защиты и образования , Национального центра иммиграционного права , Национальной ассоциации содействия прогрессу цветного населения , организации Национального дня рабочих. Сеть и Азиатско-Тихоокеанский американский юридический центр . [219] Иск направлен на предотвращение вступления в силу SB 1070 путем предъявления обвинений:

- Он нарушает федеральный пункт о превосходстве, пытаясь обойти федеральный иммиграционный закон;

- Он нарушает Четырнадцатую поправку и Положение о равной защите прав меньшинств расового и национального происхождения, подвергая их задержаниям, задержаниям и арестам на основании их расы или происхождения;

- Он нарушает предусмотренные Первой поправкой права на свободу слова, , подвергая говорящих проверке на основе их языка или акцента;

- оно нарушает запрет Четвертой поправки на необоснованные обыски и аресты, поскольку допускает несанкционированные обыски при отсутствии вероятной причины;

- Он нарушает положение о надлежащей правовой процедуре Четырнадцатой поправки, будучи недопустимо расплывчатым;

- Это нарушает конституционные положения, которые защищают право путешествовать без остановки, допроса или задержания. [219]

В этом иске ответчиками были названы прокурор округа и шерифы, а не штат Аризона или губернатор Брюэр, как в предыдущих исках. [218] [219] 4 июня ACLU и другие организации подали запрос о наложении судебного запрета , утверждая, что запланированная дата вступления в силу Закона, 29 июля, должна быть отложена до тех пор, пока не будут решены основные юридические проблемы, связанные с ним. [222]

Адвокаты по уголовному правосудию Аризоны, государственный филиал Национальной ассоциации адвокатов по уголовным делам , заявили в записке amicus curiae для ACLU et al. Дело в том, что длительные задержания, предусмотренные законом, в случае обоснованного подозрения в том, что лицо, подвергнутое законному задержанию, является иммигрантом без документов, не могут быть оправданы, за исключением стандарта вероятной причины , и поэтому закон требует нарушения прав Четвертой поправки. [223] [224] также Антидиффамационная лига подала заключение amicus curiae в поддержку этого дела. [225] Правительство Мексики заявило, что закон является неконституционным и приведет к незаконной дискриминации мексиканских граждан и нанесению ущерба отношениям между двумя странами. [226] так много заключений amicus curiae , что на них были наложены ограничения по размеру. Действительно, по поводу закона было подано [227]

Кобач сохраняет оптимизм по поводу провала исков: «Я думаю, истцам будет сложно оспорить это. Они много говорят о политической риторике, но мало о юридических аргументах». [36] В конце мая 2010 года губернатор Брюэр издал указ о создании Губернаторского фонда пограничной безопасности и правовой защиты иммиграции для рассмотрения исков, связанных с нарушением закона. [227] [228] Брюэр вступил в спор с генеральным прокурором Аризоны Терри Годдардом по поводу того, будет ли он защищать закон от судебных исков, как это обычно делает генеральный прокурор штата. [135] Брюэр обвинил Годдарда, который лично выступал против закона и был одним из возможных соперников Брюэра на выборах губернатора, в сговоре с Министерством юстиции США, когда оно решало, стоит ли оспаривать закон в суде. [135] Впоследствии Годдард согласился отказаться от защиты государства. [227]

Иск Министерства юстиции

[ редактировать ]6 июля 2010 года Министерство юстиции США подал иск против штата Аризона в окружной суд США по округу Аризона , требуя признать закон недействительным, поскольку он противоречит иммиграционным правилам, «принадлежащим исключительно федеральное правительство». [18] [229] В кратком сообщении для прессы юристы департамента сослались на концепцию федерального упреждения и заявили: «Конституция и федеральные иммиграционные законы не допускают разработки лоскутного одеяла иммиграционной политики штатов и местных органов власти по всей стране.... [230] Иммиграционная система, установленная Конгрессом и управляемая федеральными агентствами, отражает тщательный и продуманный баланс национальных правоохранительных органов, международных отношений и гуманитарных проблем – проблем, которые принадлежат нации в целом, а не отдельному штату». [18] Это указывает на дополнительный практический аргумент: закон приведет к тому, что федеральные власти потеряют фокус на своих более широких приоритетах, связанных с наплывом депортаций из Аризоны. [230] Министерство юстиции обратилось к федеральным судам с просьбой обеспечить соблюдение закона до того, как он вступит в силу. [18] В иске не утверждается, что закон приведет к расовому профилированию, но представители ведомства заявили, что продолжат следить за этим аспектом, если мера вступит в силу. [230]

Прямые иски штата со стороны федерального правительства редки, и эта акция имела возможные политические последствия для промежуточных выборов в США в 2010 году . и [230] Это также рассматривалось как упреждающая мера, призванная отговорить другие штаты, рассматривающие аналогичные законы, от дальнейшего их принятия. [231] Непосредственная реакция на решение Министерства юстиции была весьма неоднозначной: либеральные группы приветствовали его, но губернатор Брюэр назвал это «не чем иным, как огромной тратой средств налогоплательщиков». [230] Сенаторы Кил и Маккейн опубликовали совместное заявление, в котором отметили, что «американский народ должен задаться вопросом, действительно ли администрация Обамы привержена обеспечению безопасности границы, когда она предъявляет иск штату, который просто пытается защитить свой народ, обеспечивая соблюдение иммиграционного законодательства». [229] Представитель Даррелл Исса , один из 19 республиканцев, подписавших письмо с критикой иска в день его объявления, сказал: «Чтобы президент Обама встал на пути государства, которое предприняло действия, чтобы встать на защиту своих граждан против ежедневной угроза насилия и страха позорна и является предательством его конституционного обязательства защищать наших граждан». [231] Федеральные меры также привели к резкому увеличению взносов в губернаторский фонд защиты закона. К 8 июля общая сумма пожертвований превысила 500 000 долларов, причем большая часть из них составляла 100 долларов или меньше и поступала со всей страны. [227]

Латиноамериканская республиканская ассоциация Аризоны стала первой латиноамериканской организацией, поддержавшей SB 1070, и подала ходатайство о вмешательстве в иск Министерства юстиции, оспаривающий его. [232] Попытка Сената США заблокировать финансирование иска Министерства юстиции проиграла 55–43 голосами, в основном по партийной линии. [233]

Первоначальные слушания и постановления

[ редактировать ]Слушания по трем из семи исков прошли 15 и 22 июля 2010 года перед окружным судьей США Сьюзен Болтон . [234] [235] [236] Болтон задавала острые вопросы каждой стороне во время обоих слушаний, но не дала никаких указаний на то, как и когда она будет править. [235] [237] [238]

28 июля 2010 года Болтон вынес решение по иску Министерства юстиции США против Аризоны , предоставив предварительный судебный запрет , который заблокировал вступление в силу наиболее ключевых и спорных частей SB 1070. [19] [236] [239] Они включали в себя требование к полиции проверять иммиграционный статус арестованных или остановленных, что, по мнению судьи, затруднит рассмотрение иммиграционных дел федеральным правительством и может означать, что легальные иммигранты будут арестованы по ошибке. [240] Она написала: «Федеральные ресурсы будут облагаться налогом и отвлекаться от приоритетов федерального правоприменения в результате увеличения количества запросов на определение иммиграционного статуса, которые будут поступать из Аризоны». [240] Ее решение не было окончательным решением, но было основано на убеждении, что Министерство юстиции, скорее всего, выиграет позднее полное судебное разбирательство в федеральном суде по этим аспектам. [236] Болтон не вынес решений по остальным шести искам. [236] Губернатор Брюэр заявил, что судебный запрет будет обжалован. [19] и 29 июля это было сделано в Апелляционном суде девятого округа США в Сан-Франциско . [241] [242] Сенатор штата Пирс предсказал, что судебная тяжба в конечном итоге закончится в Верховном суде и, вероятно, будет поддержана перевесом 5–4. [243] [244]

Постановление судьи Болтона позволило ряду других аспектов закона вступить в силу 29 июля, включая возможность препятствовать государственным чиновникам поддерживать политику « города-убежища » и разрешать гражданские иски против этой политики, а также требование, чтобы государственные чиновники работали с федеральными чиновниками по вопросам вопросы, связанные с нелегальной иммиграцией, а также запрет на остановку транспортных средств на дороге, чтобы забрать поденщиков. [236] [243] Эти части закона были оспорены не Министерством юстиции, а некоторыми другими исками. [236]

Коллегия из трех судей Девятого округа заслушала аргументы по апелляционному делу 1 ноября 2010 года и дала понять, что может восстановить, но ослабить некоторые части закона. [245]

В феврале 2011 года Аризона подала встречный иск против федерального правительства по делу США против Аризоны , обвинив его в неспособности защитить мексиканскую границу от большого количества нелегальных иммигрантов. [246] Генеральный прокурор Аризоны Том Хорн признал, что прецедент, связанный с суверенным иммунитетом в Соединенных Штатах , усложнил рассмотрение дела штата, но он сказал: «Мы просим 9-й округ еще раз рассмотреть дело». [246]

11 апреля 2011 года коллегия Девятого округа оставила в силе запрет окружного суда на вступление в силу отдельных частей закона, тем самым вынеся решение в пользу администрации Обамы и против Аризоны. Судья Ричард Паес высказал мнение большинства, к которому судья Джон Т. Нунан-младший присоединился ; Судья Карлос Беа выразил частичное несогласие. [194] [247] Паес согласился с мнением администрации о том, что штат вторгся в федеральные прерогативы. Нунан в своем согласии написал: «Находящийся перед нами статут Аризоны стал символом. Для тех, кто сочувствует иммигрантам в Соединенных Штатах, это вызов и пугающее предвкушение того, что могут предпринять другие штаты». [247] 9 мая 2011 года губернатор Брюэр объявил, что Аризона подаст апелляцию непосредственно в Верховный суд США, а не будет требовать проведения слушания в полном составе в девятом округе. [248] Апелляция была подана 10 августа 2011 года. [249] В ответ Министерство юстиции потребовало, чтобы Верховный суд не вмешивался в это дело, и заявило, что действия судов низшей инстанции были уместными. [250] Наблюдатели считали вполне вероятным, что Верховный суд рассмотрит этот вопрос. [249] но если он откажется вмешаться, дело, скорее всего, будет возвращено судье районного суда для рассмотрения дела по существу и определения того, должен ли временный судебный запрет, блокирующий наиболее спорные положения закона, стать постоянным. [251] В декабре 2011 года Верховный суд объявил, что удовлетворил ходатайство о выдаче судебного приказа, а 25 апреля 2012 года состоялись устные прения.

Суд Болтона продолжал наблюдать за остальными исками; [194] к началу 2012 года три из семи все еще были активны. [252] 29 февраля 2012 года Болтон вынес решение в пользу иска, проведенного Мексикано-американским фондом правовой защиты и образования, и заблокировал положения закона, разрешающие арестовывать поденных рабочих, которые блокируют движение транспорта в попытке получить работу. [252]

Решение Верховного суда США

[ редактировать ]25 июня 2012 года Верховный суд США вынес решение по делу Аризона против США . Большинством в 5–3 голосов, а судья Энтони Кеннеди написал свое мнение, он определил, что разделы 3, 5 (C) и 6 SB 1070 имеют преимущественную силу федерального закона. [253] [254] [255] Эти разделы квалифицировали правонарушением штата отсутствие у иммигранта при себе документов о законном пребывании в стране, разрешили полиции штата производить аресты без ордера в некоторых ситуациях и сделали незаконным в соответствии с законодательством штата подачу заявления о приеме на работу без федерального закона. разрешение на работу. [20] [256] [257] Все судьи согласились поддержать ту часть закона, которая позволяет полиции штата Аризона расследовать иммиграционный статус человека, задержанного, задержанного или арестованного, если есть обоснованные подозрения, что человек находится в стране незаконно. [258] Однако судья Кеннеди уточнил, что, по мнению большинства, полиция штата не может задерживать человека на длительный период времени за отсутствие у него иммиграционных документов и что дела, основанные на обвинениях в расовом профилировании, могут передаваться через суд, если такие дела произойдут позже. [258]

Судья Скалиа не согласился и заявил, что поддержал бы весь закон. [259] Судья Томас также заявил, что он поддержал бы весь закон и что федеральный закон не отменяет его. [259] Судья Алито согласился с судьями Скалиа и Томасом по разделам 5(C) и 6, но присоединился к большинству в выводе, что раздел 3 имеет преимущественную силу. [259]

Дальнейшие решения и вызовы

[ редактировать ]5 сентября 2012 года судья Болтон разрешил полиции выполнить требование закона 2010 года о том, что офицеры, обеспечивая соблюдение других законов, могут подвергать сомнению иммиграционный статус тех, кто, по их подозрению, находится в стране незаконно. [121] Она сказала, что Верховный суд четко заявил, что это положение «не может быть оспорено в дальнейшем до того, как закон вступит в силу», но что оспаривание конституционности на других основаниях может иметь место в будущем. [121] Позже в том же месяце первый арест привлек внимание СМИ. [122] В ноябре 2013 года ACLU подал первый юридический протест этому положению. [260]

См. также

[ редактировать ]- Сводка новостей о Чендлере

- Нелегальная иммиграция в США

- Миссисипи SB 2179

- Специальный заказ 40

- Законопроект Сената Техаса 4

Цитаты

[ редактировать ]- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Раф, Джинджер (4 июня 2010 г.). «Брюэр называет встречу с Обамой «успехом» » . Республика Аризона .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я дж к л м н Арчибольд, Рэндал К. (24 апреля 2010 г.). «Самый жесткий иммиграционный закон США подписан в Аризоне» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . п. 1.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с «Лос-Анджелес одобряет бойкот бизнеса в Аризоне» . CNN . 13 мая 2010 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж Новицкий, Дэн (25 июля 2010 г.). «Имиграционный закон Аризоны влияет на историю и политику США» . Республика Аризона .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б 8 Кодекса США § 1304

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Аризона SB 1070, §3.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Полиция может «перевезти» указанного иностранца в федеральный объект «в этом штате или в любой другой точке», где такой объект существует. Аризона HB 2162, §3.

- ^ «News Time Spanish» (на испанском языке). Сеть Радио Лингва . 1 июня 2010 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж Аризона SB 1070, §2.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Аризона SB 1070, §5.

- ^ Аризона SB 1070, §1.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Воган, Джессика М. (апрель 2006 г.). «Истощение посредством правоприменения: экономически эффективная стратегия по сокращению нелегального населения» . Центр иммиграционных исследований .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Купер, Джонатан Дж. (26 апреля 2010 г.). «Объект протеста по иммиграционному закону штата Аризона» . Новости Эн-Би-Си . Ассошиэйтед Пресс . Архивировано из оригинала 27 февраля 2014 года.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с «Иммиграционный закон Аризоны вызывает огромные митинги» . Новости ЦБК . 1 мая 2010 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Томпсон, Крисса (30 апреля 2010 г.). «Протестующие против нового иммиграционного закона Аризоны пытаются сфокусировать бойкоты» . Вашингтон Пост .

- ^ «Общие даты вступления в силу» . Законодательное собрание штата Аризона . Архивировано из оригинала 14 мая 2010 года . Проверено 30 апреля 2010 г.

- ^ Законодательное собрание штата Аризона . «Аризона Ред. Стат. § 1-103» . Проверено 30 апреля 2010 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д «Федералы подали в суд на отмену иммиграционного закона Аризоны» . CNN . 6 июля 2010 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с «Юридическая битва нависла над иммиграционным законодательством Аризоны» . CNN . 28 июля 2010 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Барнс, Роберт (25 июня 2012 г.). «Верховный суд отклоняет большую часть иммиграционного закона Аризоны» . Вашингтон Пост .

- ^ 8 USC § 1302

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Аризона HB 2162, §4.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и Харрис, Крейг; Рау, Алия Бирд; Крено, Глен (24 апреля 2010 г.). «Губернатор Аризоны подписывает иммиграционный закон; враги обещают борьбу» . Республика Аризона .

- ^ Сильверлейб, Алан (30 апреля 2010 г.). «Губернатор Аризоны подписывает изменения в иммиграционном законе» . CNN .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Новицкий, Дэн (25 апреля 2010 г.). «Судебная тяжба вырисовывается вокруг нового иммиграционного закона» . Республика Аризона .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Купер, Джонатан Дж.; Давенпорт, Пол (25 апреля 2010 г.). «Группы по защите иммиграции бросают вызов закону Аризоны» . Вашингтон Пост . Ассошиэйтед Пресс .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и Спагат, Эллиот (13 мая 2010 г.). «Другие приграничные штаты избегают иммиграционного закона Аризоны» . Новости Эн-Би-Си . Ассошиэйтед Пресс . Архивировано из оригинала 22 января 2015 года.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Арчибольд, Рэндал К. (20 июня 2010 г.). «О пограничном насилии правда меркнет по сравнению с идеями» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . п. 18. Снижение уровня преступлений против собственности отмечено в корректировке от 27 июня 2010 года.