Уоррен Дж. Хардинг

Уоррен Дж. Хардинг | |

|---|---|

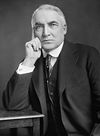

Портрет, ок. 1920 год | |

| 29-й президент США | |

| In office 4 марта 1921 г. - 2 августа 1923 г. | |

| Vice President | Calvin Coolidge |

| Preceded by | Woodrow Wilson |

| Succeeded by | Calvin Coolidge |

| United States Senator from Ohio | |

| In office March 4, 1915 – January 13, 1921 | |

| Preceded by | Theodore E. Burton |

| Succeeded by | Frank B. Willis |

| 28th Lieutenant Governor of Ohio | |

| In office January 11, 1904 – January 8, 1906 | |

| Governor | Myron T. Herrick |

| Preceded by | Harry L. Gordon |

| Succeeded by | Andrew L. Harris |

| Member of the Ohio Senate from the 13th district | |

| In office January 1, 1900 – January 4, 1904 | |

| Preceded by | Henry May |

| Succeeded by | Samuel H. West |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Warren Gamaliel Harding November 2, 1865 Blooming Grove, Ohio, U.S. |

| Died | August 2, 1923 (aged 57) San Francisco, California, U.S. |

| Resting place | Harding Tomb |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse | |

| Children | Elizabeth (with Nan Britton) |

| Parent |

|

| Education | Ohio Central College (BA) |

| Occupation |

|

| Signature | |

| ||

|---|---|---|

Political rise 29th President of the United States

Presidential campaigns Controversies  | ||

Уоррен Гамалиэль Хардинг (2 ноября 1865 — 2 августа 1923) — американский политик, занимавший пост 29-го президента Соединённых Штатов с 1921 года до своей смерти в 1923 году. Член Республиканской партии , он был одним из самых популярных действующие президенты США. После его смерти был разоблачен ряд скандалов, в том числе «Типот Доум» , а также внебрачная связь с Нэн Бриттон , запятнавшая его репутацию.

прожил в сельской местности Огайо Хардинг всю свою жизнь , за исключением тех случаев, когда политическая служба забирала его куда-нибудь еще. В молодости он купил The Marion Star и превратил ее в успешную газету. Хардинг служил в Сенате штата Огайо с 1900 по 1904 год и был вице-губернатором два года . Он потерпел поражение на посту губернатора в 1910 году , но был избран в Сенат США в 1914 году — это были первые прямые выборы в штате на этот пост. считался маловероятным Хардинг баллотировался на пост президента от республиканской партии в 1920 году, но до съезда . Когда ведущие кандидаты не смогли набрать большинства и съезд зашел в тупик, поддержка Хардинга возросла, и он был номинирован в десятом туре голосования. Он провел кампанию на крыльце , оставаясь в основном в Мэрион и позволяя людям приходить к нему. Он пообещал вернуться к нормальной жизни периода , существовавшего до Первой мировой войны , и от Демократической партии победил кандидата Джеймса М. Кокса с большим перевесом и стал первым действующим сенатором, избранным президентом.

Harding appointed a number of respected figures to his cabinet, including Andrew Mellon at Treasury, Herbert Hoover at Commerce, and Charles Evans Hughes at the State Department. A major foreign policy achievement came with the Washington Naval Conference of 1921–1922, in which the world's major naval powers agreed on a naval limitations program that lasted a decade. Harding released political prisoners who had been arrested for their opposition to World War I. In 1923, Harding died of a heart attack in San Francisco while on a western tour, and was succeeded by Vice President Calvin Coolidge.

Harding died as one of the most popular presidents in history, but the subsequent exposure of scandals eroded his popular regard, as did revelations of extramarital affairs. Harding's interior secretary, Albert B. Fall, and his attorney general, Harry Daugherty, were each later tried for corruption in office. Fall was convicted though Daugherty was not. These trials greatly damaged Harding's posthumous reputation. In historical rankings of the U.S. presidents during the decades after his term in office, Harding was often rated among the worst, but in recent decades, some historians have begun to reassess the conventional views of Harding's historical record in office.

Early life and career

Childhood and education

Warren Harding was born on November 2, 1865, in Blooming Grove, Ohio.[1] Nicknamed "Winnie" as a small child, he was the eldest of eight children born to George Tryon Harding (usually known as Tryon) and Phoebe Elizabeth (née Dickerson) Harding.[1] Phoebe was a state-licensed midwife. Tryon farmed and taught school near Mount Gilead. Through apprenticeship, study, and a year of medical school, Tryon became a doctor and started a small practice.[2] Harding's first ancestor in the Americas was Richard Harding, who arrived from England to Massachusetts Bay around 1624.[3][4] Harding also had ancestors from Wales and Scotland,[5] and some of his maternal ancestors were Dutch, including the wealthy Van Kirk family.[6]

It was rumored by a political opponent in Blooming Grove that one of Harding's great-grandmothers was African American.[7] His great-great-grandfather Amos Harding claimed that a thief, who had been caught in the act by the family, started the rumor in an attempt at extortion or revenge.[8] In 2015, genetic testing of Harding's descendants determined, with more than a 95% chance of accuracy, that he lacked sub-Saharan African forebears within four generations.[9][10]

In 1870, the Harding family, who were abolitionists,[10] moved to Caledonia, where Tryon acquired The Argus, a local weekly newspaper. At The Argus, Harding, from the age of 11, learned the basics of the newspaper business.[11] In late 1879, at age 14, he enrolled at his father's alma mater—Ohio Central College in Iberia—where he proved an adept student. He and a friend put out a small newspaper, the Iberia Spectator, during their final year at Ohio Central, intended to appeal to both the college and the town. During his final year, the Harding family moved to Marion, about 6 miles (10 km) from Caledonia, and when he graduated in 1882, he joined them there.[12]

Editor

In Harding's youth, most of the U.S. population still lived on farms and in small towns. Harding spent much of his life in Marion, a small city in rural central Ohio, and became closely associated with it. When he rose to high office, he made clear his love of Marion and its way of life, telling of the many young Marionites who had left and enjoyed success elsewhere, while suggesting that the man, once the "pride of the school", who had remained behind and become a janitor, was "the happiest one of the lot".[13]

Upon graduating, Harding had stints as a teacher and as an insurance man, and made a brief attempt at studying law. He then raised $300 (equivalent to $9,800 in 2023) in partnership with others to purchase a failing newspaper, The Marion Star, the weakest of the growing city's three papers and its only daily. The 18-year-old Harding used the railroad pass that came with the paper to attend the 1884 Republican National Convention, where he hobnobbed with better-known journalists and supported the presidential nominee, former Secretary of State James G. Blaine. Harding returned from Chicago to find that the sheriff had reclaimed the paper.[14] During the election campaign, Harding worked for the Marion Democratic Mirror and was annoyed at having to praise the Democratic presidential nominee, New York Governor Grover Cleveland, who won the election.[15] Afterward, with his father's financial help, Harding gained ownership of the paper.[14]

Through the later years of the 1880s, Harding built the Star. The city of Marion tended to vote Republican (as did Ohio), but Marion County was Democratic. Accordingly, Harding adopted a tempered editorial stance, declaring the daily Star nonpartisan and circulating a weekly edition that was moderately Republican. This policy attracted advertisers and put the town's Republican weekly out of business. According to his biographer, Andrew Sinclair:

The success of Harding with the Star was certainly in the model of Horatio Alger. He started with nothing, and through working, stalling, bluffing, withholding payments, borrowing back wages, boasting, and manipulating, he turned a dying rag into a powerful small-town newspaper. Much of his success had to do with his good looks, affability, enthusiasm, and persistence, but he was also lucky. As Machiavelli once pointed out, cleverness will take a man far, but he cannot do without good fortune.[16]

The population of Marion grew from 4,000 in 1880 to twice that in 1890, and to 12,000 by 1900. This growth helped the Star, and Harding did his best to promote the city, purchasing stock in many local enterprises. A few of these turned out badly, but he was generally successful as an investor, leaving an estate of $850,000 in 1923 (equivalent to $15.2 million in 2023).[17] According to Harding biographer John Dean, Harding's "civic influence was that of an activist who used his editorial page to effectively keep his nose—and a prodding voice—in all the town's public business".[18] To date, Harding is the only U.S. president to have had full-time journalism experience.[14] He became an ardent supporter of Governor Joseph B. Foraker, a Republican.[19]

Harding first came to know Florence Kling, five years older than he, as the daughter of a local banker and developer. Amos Kling was a man accustomed to getting his way, but Harding attacked him relentlessly in the paper. Amos involved Florence in all his affairs, taking her to work from the time she could walk. As hard-headed as her father, Florence came into conflict with him after returning from music college.[a] After she eloped with Pete deWolfe, and returned to Marion without deWolfe and with an infant called Marshall, Amos agreed to raise the boy, but would not support Florence, who made a living as a piano teacher. One of her students was Harding's sister Charity. By 1886, Florence Kling had obtained a divorce, and she and Harding were courting, though who was pursuing whom is uncertain.[20][21]

The budding match snuffed out a truce between the Klings. Amos believed that the Hardings had African American blood, and was also offended by Harding's editorial stances. He started to spread rumors of Harding's supposed black heritage, and encouraged local businessmen to boycott Harding's business interests.[10] When Harding found out what Kling was doing, he warned Kling "that he would beat the tar out of the little man if he didn't cease."[b][22]

The Hardings married on July 8, 1891,[23] at their new home on Mount Vernon Avenue in Marion, which they had designed together in the Queen Anne style.[24] The marriage produced no children.[25] Harding affectionately called his wife "the Duchess" for a character in a serial from The New York Sun who kept a close eye on "the Duke" and their money.[26]

Florence Harding became deeply involved in her husband's career, both at the Star and after he entered politics.[20] Exhibiting her father's determination and business sense, she helped turn the Star into a profitable enterprise through her tight management of the paper's circulation department.[27] She has been credited with helping Harding achieve more than he might have alone; some have suggested that she pushed him all the way to the White House.[28]

Start in politics

Soon after purchasing the Star, Harding turned his attention to politics, supporting Foraker in his first successful bid for governor in 1885. Foraker was part of the war generation that challenged older Ohio Republicans, such as Senator John Sherman, for control of state politics. Harding, always a party loyalist, supported Foraker in the complex internecine warfare that was Ohio Republican politics. Harding was willing to tolerate Democrats as necessary to a two-party system, but had only contempt for those who bolted the Republican Party to join third-party movements.[29] He was a delegate to the Republican state convention in 1888, at the age of 22, representing Marion County, and would be elected a delegate in most years until becoming president.[30]

Harding's success as an editor took a toll on his health. Five times between 1889 (when he was 23) and 1901, he spent time at the Battle Creek Sanitorium for reasons Sinclair described as "fatigue, overstrain, and nervous illnesses".[31] Dean ties these visits to early occurrences of the heart ailment that would kill Harding in 1923. During one such absence from Marion, in 1894, the Star's business manager quit. Florence Harding took his place. She became her husband's top assistant at the Star on the business side, maintaining her role until the Hardings moved to Washington in 1915. Her competence allowed Harding to travel to make speeches—his use of the free railroad pass increased greatly after his marriage.[32] Florence Harding practiced strict economy[27] and wrote of Harding, "he does well when he listens to me and poorly when he does not."[33]

In 1892, Harding traveled to Washington, where he met Democratic Nebraska Congressman William Jennings Bryan, and listened to the "Boy Orator of the Platte" speak on the floor of the House of Representatives. Harding traveled to Chicago's Columbian Exposition in 1893. Both visits were without Florence. Democrats generally won Marion County's offices; when Harding ran for auditor in 1895, he lost, but did better than expected. The following year, Harding was one of many orators who spoke across Ohio as part of the campaign of the Republican presidential candidate, that state's former governor, William McKinley. According to Dean, "while working for McKinley [Harding] began making a name for himself through Ohio".[32]

Rising politician (1897–1919)

State senator

Harding wished to try again for elective office. Though a longtime admirer of Foraker (by then a U.S. senator), he had been careful to maintain good relations with the party faction led by the state's other U.S. senator, Mark Hanna, McKinley's political manager and chairman of the Republican National Committee (RNC). Both Foraker and Hanna supported Harding for state Senate in 1899; he gained the Republican nomination and was easily elected to a two-year term.[34]

Harding began his four years as a state senator as a political unknown; he ended them as one of the most popular figures in the Ohio Republican Party. He always appeared calm and displayed humility, characteristics that endeared him to fellow Republicans even as he passed them in his political rise. Legislative leaders consulted him on difficult problems.[35] It was usual at that time for state senators in Ohio to serve only one term, but Harding gained renomination in 1901. After the assassination of McKinley in September (he was succeeded by Vice President Theodore Roosevelt), much of the appetite for politics was temporarily lost in Ohio. In November, Harding won a second term, more than doubling his margin of victory to 3,563 votes.[36]

Like most politicians of his time, Harding accepted that patronage and graft would be used to repay political favors. He arranged for his sister Mary (who was legally blind) to be appointed as a teacher at the Ohio School for the Blind, although there were better-qualified candidates. In another trade, he offered publicity in his newspaper in exchange for free railroad passes for himself and his family. According to Sinclair, "it is doubtful that Harding ever thought there was anything dishonest in accepting the perquisites of position or office. Patronage and favors seemed the normal reward for party service in the days of Hanna."[37]

Soon after Harding's initial election as senator, he met Harry M. Daugherty, who would take a major role in his political career. A perennial candidate for office who served two terms in the state House of Representatives in the early 1890s, Daugherty had become a political fixer and lobbyist in the state capital of Columbus. After first meeting and talking with Harding, Daugherty commented, "Gee, what a great-looking President he'd make."[38]

Ohio state leader

In early 1903, Harding announced he would run for Governor of Ohio, prompted by the withdrawal of the leading candidate, Congressman Charles W. F. Dick. Hanna and George Cox felt that Harding was not electable due to his work with Foraker—as the Progressive Era commenced, the public was starting to take a dimmer view of the trading of political favors and of bosses such as Cox. Accordingly, they persuaded Cleveland banker Myron T. Herrick, a friend of McKinley's, to run. Herrick was also better-placed to take votes away from the likely Democratic candidate, reforming Cleveland Mayor Tom L. Johnson. With little chance at the gubernatorial nomination, Harding sought nomination as lieutenant governor, and both Herrick and Harding were nominated by acclamation.[39] Foraker and Hanna (who died of typhoid fever in February 1904) both campaigned for what was dubbed the Four-H ticket. Herrick and Harding won by overwhelming margins.[40]

Once he and Harding were inaugurated, Herrick made ill-advised decisions that turned crucial Republican constituencies against him, alienating farmers by opposing the establishment of an agricultural college.[40] On the other hand, according to Sinclair, "Harding had little to do, and he did it very well".[41] His responsibility to preside over the state Senate allowed him to increase his growing network of political contacts.[41] Harding and others envisioned a successful gubernatorial run in 1905, but Herrick refused to stand aside. In early 1905, Harding announced he would accept nomination as governor if offered, but faced with the anger of leaders such as Cox, Foraker and Dick (Hanna's replacement in the Senate), announced he would seek no office in 1905. Herrick was defeated, but his new running mate, Andrew L. Harris, was elected, and succeeded as governor after five months in office on the death of Democrat John M. Pattison. One Republican official wrote to Harding, "Aren't you sorry Dick wouldn't let you run for Lieutenant Governor?"[42]

In addition to helping pick a president, Ohio voters in 1908 were to choose the legislators who would decide whether to re-elect Foraker. The senator had quarreled with President Roosevelt over the Brownsville Affair. Though Foraker had little chance of winning, he sought the Republican presidential nomination against his fellow Cincinnatian, Secretary of War William Howard Taft, who was Roosevelt's chosen successor.[43] On January 6, 1908, Harding's Star endorsed Foraker and upbraided Roosevelt for trying to destroy the senator's career over a matter of conscience. On January 22, Harding in the Star reversed course and declared for Taft, deeming Foraker defeated.[44] According to Sinclair, Harding's change to Taft "was not ... because he saw the light but because he felt the heat".[45] Jumping on the Taft bandwagon allowed Harding to survive his patron's disaster—Foraker failed to gain the presidential nomination, and was defeated for a third term as senator. Also helpful in saving Harding's career was that he was popular with, and had done favors for, the more progressive forces that now controlled the Ohio Republican Party.[46]

Harding sought and gained the 1910 Republican gubernatorial nomination. At that time, the party was deeply divided between progressive and conservative wings, and could not defeat the united Democrats; he lost the election to incumbent Judson Harmon.[47] Harry Daugherty managed Harding's campaign, but the defeated candidate did not hold the loss against him. Despite the growing rift between them, both President Taft and former president Roosevelt came to Ohio to campaign for Harding, but their quarrels split the Republican Party and helped assure Harding's defeat.[48]

The party split grew, and in 1912, Taft and Roosevelt were rivals for the Republican nomination. The 1912 Republican National Convention was bitterly divided. At Taft's request, Harding gave a speech nominating the president, but the angry delegates were not receptive to Harding's oratory. Taft was renominated, but Roosevelt supporters bolted the party. Harding, as a loyal Republican, supported Taft. The Republican vote was split between Taft, the party's official candidate, and Roosevelt, running under the label of the Progressive Party. This allowed the Democratic candidate, New Jersey Governor Woodrow Wilson, to be elected.[49]

U.S. senator

Election of 1914

Congressman Theodore Burton had been elected as senator by the state legislature in Foraker's place in 1909, and announced that he would seek a second term in the 1914 elections. By this time, the Seventeenth Amendment to the United States Constitution had been ratified, giving the people the right to elect senators, and Ohio had instituted primary elections for the office. Foraker and former congressman Ralph D. Cole also entered the Republican primary. When Burton withdrew, Foraker became the favorite, but his Old Guard Republicanism was deemed outdated, and Harding was urged to enter the race. Daugherty claimed credit for persuading Harding to run: "I found him like a turtle sunning himself on a log, and I pushed him into the water."[50] According to Harding biographer Randolph Downes, "he put on a campaign of such sweetness and light as would have won the plaudits of the angels. It was calculated to offend nobody except Democrats."[51] Although Harding did not attack Foraker, his supporters had no such scruples. Harding won the primary by 12,000 votes over Foraker.[52]

Read The Menace and get the dope,

Go to the polls and beat the Pope.

Slogan written on Ohio walls and fences, 1914[53]

Harding's general election opponent was Ohio Attorney General Timothy Hogan, who had risen to statewide office despite widespread prejudice against Roman Catholics in rural areas. In 1914, the start of World War I and the prospect of a Catholic senator from Ohio increased nativist sentiment. Propaganda sheets with names like The Menace and The Defender contained warnings that Hogan was the vanguard in a plot led by Pope Benedict XV through the Knights of Columbus to control Ohio. Harding did not attack Hogan (an old friend) on this or most other issues, but he did not denounce the nativist hatred for his opponent.[54][55]

Harding's conciliatory campaigning style aided him;[55] one Harding friend deemed the candidate's stump speech during the 1914 fall campaign as "a rambling, high-sounding mixture of platitudes, patriotism, and pure nonsense".[56] Dean notes, "Harding used his oratory to good effect; it got him elected, making as few enemies as possible in the process."[56] Harding won by over 100,000 votes in a landslide that also swept into office a Republican governor, Frank B. Willis.[56]

Junior senator

When Harding joined the U.S. Senate, the Democrats controlled both houses of Congress, and were led by President Wilson. As a junior senator in the minority, Harding received unimportant committee assignments, but carried out those duties assiduously.[57] He was a safe, conservative, Republican vote.[58] As during his time in the Ohio Senate, Harding came to be widely liked.[59]

On two issues, women's suffrage, and the prohibition of alcohol, where picking the wrong side would have damaged his presidential prospects in 1920, he prospered by taking nuanced positions. As senator-elect, he indicated that he could not support votes for women until Ohio did. Increased support for suffrage there and among Senate Republicans meant that by the time Congress voted on the issue, Harding was a firm supporter. Harding, who drank,[60] initially voted against banning alcohol. He voted for the Eighteenth Amendment, which imposed prohibition, after successfully moving to modify it by placing a time limit on ratification, which was expected to kill it. Once it was ratified anyway, Harding voted to override Wilson's veto of the Volstead Bill, which implemented the amendment, assuring the support of the Anti-Saloon League.[61]

Harding, as a politician respected by both Republicans and Progressives, was asked to be temporary chairman of the 1916 Republican National Convention and to deliver the keynote address. He urged delegates to stand as a united party. The convention nominated Justice Charles Evans Hughes.[62] Harding reached out to Roosevelt once the former president declined the 1916 Progressive nomination, a refusal that effectively scuttled that party. In the November 1916 presidential election, despite increasing Republican unity, Hughes was narrowly defeated by Wilson.[63]

Harding spoke and voted in favor of the resolution of war requested by Wilson in April 1917 that plunged the United States into World War I.[64] In August, Harding argued for giving Wilson almost dictatorial powers, stating that democracy had little place in time of war.[65] Harding voted for most war legislation, including the Espionage Act of 1917, which restricted civil liberties, though he opposed the excess profits tax as anti-business. In May 1918, Harding, less enthusiastic about Wilson, opposed a bill to expand the president's powers.[66]

In the 1918 midterm congressional elections, held just before the armistice, Republicans narrowly took control of the Senate.[67] Harding was appointed to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee.[68] Wilson took no senators with him to the Paris Peace Conference, confident that he could force what became the Treaty of Versailles through the Senate by appealing to the people.[67] When he returned with a single treaty establishing both peace and a League of Nations, the country was overwhelmingly on his side. Many senators disliked Article X of the League Covenant, that committed signatories to the defense of any member nation that was attacked, seeing it as forcing the United States to war without the assent of Congress. Harding was one of 39 senators who signed a round-robin letter opposing the League. When Wilson invited the Foreign Relations Committee to the White House to informally discuss the treaty, Harding ably questioned Wilson about Article X; the president evaded his inquiries. The Senate debated Versailles in September 1919, and Harding made a major speech against it. By then, Wilson had suffered a stroke while on a speaking tour. With an incapacitated president in the White House and less support in the country, the treaty was defeated.[69]

Presidential election of 1920

Primary campaign

With most Progressives having rejoined the Republican Party, their former leader, Theodore Roosevelt, was deemed likely to make a third run for the White House in 1920, and was the overwhelming favorite for the Republican nomination. These plans ended when Roosevelt suddenly died on January 6, 1919. A number of candidates quickly emerged, including General Leonard Wood, Illinois Governor Frank Lowden, California Senator Hiram Johnson, and a host of relatively minor possibilities such as Herbert Hoover (renowned for his World War I relief work), Massachusetts Governor Calvin Coolidge, and General John J. Pershing.[70]

Harding, while he wanted to be president, was as much motivated in entering the race by his desire to keep control of Ohio Republican politics, enabling his re-election to the Senate in 1920. Among those coveting Harding's seat were former governor Willis (he had been defeated by James M. Cox in 1916) and Colonel William Cooper Procter (head of Procter & Gamble). On December 17, 1919, Harding made a low-key announcement of his presidential candidacy.[71] Leading Republicans disliked Wood and Johnson, both of the progressive faction of the party, and Lowden, who had an independent streak, was deemed little better. Harding was far more acceptable to the "Old Guard" leaders of the party.[72]

Daugherty, who became Harding's campaign manager, was sure none of the other candidates could garner a majority. His strategy was to make Harding an acceptable choice to delegates once the leaders faltered. Daugherty established a "Harding for President" campaign office in Washington (run by his confidant, Jess Smith), and worked to manage a network of Harding friends and supporters, including Frank Scobey of Texas (clerk of the Ohio State Senate during Harding's years there).[73] Harding worked to shore up his support through incessant letter-writing. Despite the candidate's work, according to Russell, "without Daugherty's Mephistophelean efforts, Harding would never have stumbled forward to the nomination."[74]

America's present need is not heroics, but healing; not nostrums, but normalcy; not revolution, but restoration; not agitation, but adjustment; not surgery, but serenity; not the dramatic, but the dispassionate; not experiment, but equipoise; not submergence in internationality, but sustainment in triumphant nationality.

Warren G. Harding, speech before the Home Market Club, Boston, May 14, 1920[75]

There were only 16 presidential primary states in 1920, of which the most crucial to Harding was Ohio. Harding had to have some loyalists at the convention to have any chance of nomination, and the Wood campaign hoped to knock Harding out of the race by taking Ohio. Wood campaigned in the state, and his supporter, Procter, spent large sums; Harding spoke in the non-confrontational style he had adopted in 1914. Harding and Daugherty were so confident of sweeping Ohio's 48 delegates that the candidate went on to the next state, Indiana, before the April 27 Ohio primary.[76] Harding carried Ohio by only 15,000 votes over Wood, taking less than half the total vote, and won only 39 of 48 delegates. In Indiana, Harding finished fourth, with less than ten percent of the vote, and failed to win a single delegate. He was willing to give up and have Daugherty file his re-election papers for the Senate, but Florence Harding grabbed the phone from his hand, "Warren Harding, what are you doing? Give up? Not until the convention is over. Think of your friends in Ohio!"[77] On learning that Daugherty had left the phone line, the future First Lady retorted, "Well, you tell Harry Daugherty for me that we're in this fight until Hell freezes over."[75]

After he recovered from the shock of the poor results, Harding traveled to Boston, where he delivered a speech that according to Dean, "would resonate throughout the 1920 campaign and history."[75] There, he said that "America's present need is not heroics, but healing; not nostrums, but normalcy;[c] not revolution, but restoration."[78] Dean notes, "Harding, more than the other aspirants, was reading the nation's pulse correctly."[75]

Convention

The 1920 Republican National Convention opened at the Chicago Coliseum on June 8, 1920, assembling delegates who were bitterly divided, most recently over the results of a Senate investigation into campaign spending, which had just been released. That report found that Wood had spent $1.8 million (equivalent to $27.38 million in 2023), lending substance to Johnson's claims that Wood was trying to buy the presidency. Some of the $600,000 that Lowden had spent had wound up in the pockets of two convention delegates. Johnson had spent $194,000, and Harding $113,000. Johnson was deemed to be behind the inquiry, and the rage of the Lowden and Wood factions put an end to any possible compromise among the frontrunners. Of the almost 1,000 delegates, 27 were women—the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, guaranteeing women the vote, was within one state of ratification, and would pass before the end of August.[79][80] The convention had no boss, most uninstructed delegates voted as they pleased, and with a Democrat in the White House, the party's leaders could not use patronage to get their way.[81]

Reporters deemed Harding unlikely to be nominated due to his poor showing in the primaries, and relegated him to a place among the dark horses.[79] Harding, who like the other candidates was in Chicago supervising his campaign, had finished sixth in the final public opinion poll, behind the three main candidates as well as former Justice Hughes and Herbert Hoover, and only slightly ahead of Coolidge.[82][83]

After the convention dealt with other matters, the nominations for president opened on the morning of Friday, June 11. Harding had asked Willis to place his name in nomination, and the former governor responded with a speech popular among the delegates, both for its folksiness and for its brevity in the intense Chicago heat.[84] Reporter Mark Sullivan, who was present, called it a splendid combination of "oratory, grand opera, and hog calling." Willis confided, leaning over the podium railing, "Say, boys—and girls too—why not name Warren Harding?"[85] The laughter and applause that followed created a warm feeling for Harding.[85]

I don't expect Senator Harding to be nominated on the first, second, or third ballots, but I think we can well afford to take chances that about eleven minutes after two o'clock on Friday morning at the convention, when fifteen or twenty men, somewhat weary, are sitting around a table, some one of them will say: "Who will we nominate?" At that decisive time, the friends of Senator Harding can suggest him and afford to abide by the result.

Harry M. Daugherty[86]

Four ballots were taken on the afternoon of June 11, and they revealed a deadlock. With 493 votes needed to nominate, Wood was the closest with 3141⁄2; Lowden had 2891⁄2. The best Harding had done was 651⁄2. Chairman Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts, the Senate Majority Leader, adjourned the convention about 7 p.m.[85][87]

The night of June 11–12, 1920 would become famous in political history as the night of the "smoke-filled room", in which, legend has it, party elders agreed to force the convention to nominate Harding. Historians have focused on the session held in the suite of Republican National Committee (RNC) Chairman Will Hays at the Blackstone Hotel, at which senators and others came and went, and numerous possible candidates were discussed. Utah Senator Reed Smoot, before his departure early in the evening, backed Harding, telling Hays and the others that as the Democrats were likely to nominate Governor Cox, they should pick Harding to win Ohio. Smoot also told The New York Times that there had been an agreement to nominate Harding, but that it would not be done for several ballots yet.[88] This was not true: a number of participants backed Harding (others supported his rivals), but there was no pact to nominate him, and the senators had little power to enforce any agreement. Two other participants in the smoke-filled room discussions, Kansas Senator Charles Curtis and Colonel George Brinton McClellan Harvey, a close friend of Hays, predicted to the press that Harding would be nominated because of the liabilities of the other candidates.[89]

Headlines in the morning newspapers suggested intrigue. Historian Wesley M. Bagby wrote, "Various groups actually worked along separate lines to bring about the nomination—without combination and with very little contact." Bagby said that the key factor in Harding's nomination was his wide popularity among the rank and file of the delegates.[90]

The reassembled delegates had heard rumors that Harding was the choice of a cabal of senators. Although this was not true, delegates believed it, and sought a way out by voting for Harding. When balloting resumed on the morning of June 12, Harding gained votes on each of the next four ballots, rising to 1331⁄2 as the two front runners saw little change. Lodge then declared a three-hour recess, to the outrage of Daugherty, who raced to the podium, and confronted him, "You cannot defeat this man this way! The motion was not carried! You cannot defeat this man!"[91] Lodge and others used the break to try to stop the Harding momentum and make RNC Chairman Hays the nominee, a scheme Hays refused to have anything to do with.[92] The ninth ballot, after some initial suspense, saw delegation after delegation break for Harding, who took the lead with 3741⁄2 votes to 249 for Wood and 1211⁄2 for Lowden (Johnson had 83). Lowden released his delegates to Harding, and the tenth ballot, held at 6 p.m., was a mere formality, with Harding finishing with 6721⁄5 votes to 156 for Wood. The nomination was made unanimous. The delegates, desperate to leave town before they incurred more hotel expenses, then proceeded to the vice presidential nomination. Harding wanted Senator Irvine Lenroot of Wisconsin, who was unwilling to run, but before Lenroot's name could be withdrawn and another candidate decided on, an Oregon delegate proposed Governor Coolidge, which was met with a roar of approval from the delegates. Coolidge, popular for his role in breaking the Boston police strike of 1919, was nominated for vice president, receiving two and a fraction votes more than Harding had. James Morgan wrote in The Boston Globe: "The delegates would not listen to remaining in Chicago over Sunday ... the President makers did not have a clean shirt. On such things, Rollo, turns the destiny of nations."[93][94]

General election campaign

The Harding/Coolidge ticket was quickly backed by Republican newspapers, but those of other viewpoints expressed disappointment. The New York World found Harding the least-qualified candidate since James Buchanan, deeming the Ohio senator a "weak and mediocre" man who "never had an original idea."[95] The Hearst newspapers called Harding "the flag-bearer of a new Senatorial autocracy."[96] The New York Times described the Republican presidential candidate as "a very respectable Ohio politician of the second class."[95]

The Democratic National Convention opened in San Francisco on June 28, 1920, under a shadow cast by Woodrow Wilson, who wished to be nominated for a third term. Delegates were convinced Wilson's health would not permit him to serve, and looked elsewhere for a candidate. Former Treasury Secretary William G. McAdoo was a major contender, but he was Wilson's son-in-law, and refused to consider a nomination so long as the president wanted it. Many at the convention voted for McAdoo anyway, and a deadlock ensued with Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer. On the 44th ballot, the Democrats nominated Governor Cox for president, with his running mate Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt. As Cox was, when not in politics, a newspaper owner and editor, this placed two Ohio editors against each other for the presidency, and some complained there was no real political choice. Both Cox and Harding were economic conservatives, and were reluctant progressives at best.[97]

Harding elected to conduct a front porch campaign, like McKinley in 1896.[98] Some years earlier, Harding had had his front porch remodeled to resemble McKinley's, which his neighbors felt signified presidential ambitions.[99] The candidate remained at home in Marion, and gave addresses to visiting delegations. In the meantime, Cox and Roosevelt stumped the nation, giving hundreds of speeches. Coolidge spoke in the Northeast, later on in the South, and was not a significant factor in the election.[98]

In Marion, Harding ran his campaign. As a newspaperman himself, he fell into easy camaraderie with the press covering him, enjoying a relationship few presidents have equaled. His "return to normalcy" theme was aided by the atmosphere that Marion provided, an orderly place that induced nostalgia in many voters. The front porch campaign allowed Harding to avoid mistakes, and as time dwindled towards the election, his strength grew. The travels of the Democratic candidates eventually caused Harding to make several short speaking tours, but for the most part, he remained in Marion. America had no need for another Wilson, Harding argued, appealing for a president "near the normal."[100]

Harding's vague oratory irritated some; McAdoo described a typical Harding speech as "an army of pompous phrases moving over the landscape in search of an idea. Sometimes these meandering words actually capture a straggling thought and bear it triumphantly, a prisoner in their midst, until it died of servitude and over work."[101] H. L. Mencken concurred, "it reminds me of a string of wet sponges, it reminds me of tattered washing on the line; it reminds me of stale bean soup, of college yells, of dogs barking idiotically through endless nights. It is so bad that a kind of grandeur creeps into it. It drags itself out of the dark abysm ... of pish, and crawls insanely up the topmost pinnacle of tosh. It is rumble and bumble. It is balder and dash."[d][101] The New York Times took a more positive view of Harding's speeches, writing that in them the majority of people could find "a reflection of their own indeterminate thoughts."[102]

Wilson had said that the 1920 election would be a "great and solemn referendum" on the League of Nations, making it difficult for Cox to maneuver on the issue—although Roosevelt strongly supported the League, Cox was less enthusiastic.[103] Harding opposed entry into the League of Nations as negotiated by Wilson, but favored an "association of nations,"[25] based on the Permanent Court of Arbitration at The Hague. This was general enough to satisfy most Republicans, and only a few bolted the party over this issue. By October, Cox had realized there was widespread public opposition to Article X, and said that reservations to the treaty might be necessary; this shift allowed Harding to say no more on the subject.[104]

The RNC hired Albert Lasker, an advertising executive from Chicago, to publicize Harding, and Lasker unleashed a broad-based advertising campaign that used many now-standard advertising techniques for the first time in a presidential campaign. Lasker's approach included newsreels and sound recordings. Visitors to Marion had their photographs taken with Senator and Mrs. Harding, and copies were sent to their hometown newspapers.[105] Billboard posters, newspapers and magazines were employed in addition to motion pictures. Telemarketers were used to make phone calls with scripted dialogues to promote Harding.[106]

During the campaign, opponents spread old rumors that Harding's great-great-grandfather was a West Indian black person and that other blacks might be found in his family tree.[107] Harding's campaign manager rejected the accusations. Wooster College professor William Estabrook Chancellor publicized the rumors, based on supposed family research, but perhaps reflecting no more than local gossip.[108]

By Election Day, November 2, 1920, few had any doubts that the Republican ticket would win.[109] Harding received 60.2 percent of the popular vote, the highest percentage since the evolution of the two-party system, and 404 electoral votes. Cox received 34 percent of the national vote and 127 electoral votes.[110] Campaigning from a federal prison where he was serving a sentence for opposing the war, Socialist Eugene V. Debs received 3 percent of the national vote. The Republicans greatly increased their majority in each house of Congress.[111][112]

Presidency (1921–1923)

Inauguration and appointments

Harding was inaugurated on March 4, 1921, in the presence of his wife and father. Harding preferred a subdued inauguration without the customary parade, leaving only the actual ceremony and a brief reception at the White House. In his inaugural address, he declared, "Our most dangerous tendency is to expect too much from the government and at the same time do too little for it."[113]

After the election, Harding announced that no decisions about appointments would be made until he returned from a vacation in December. He traveled to Texas, where he fished and played golf with his friend Frank Scobey (soon to be director of the Mint) and then sailed for the Panama Canal Zone. He visited Washington when Congress opened in early December, and he was afforded a hero's welcome as the first sitting senator to be elected to the White House.[e] Back in Ohio, Harding planned to consult with the country's best minds, who visited Marion to offer their counsel regarding appointments.[114][115]

Harding chose pro-League Charles Evans Hughes as Secretary of State, ignoring the advice of Senator Lodge and others. After Charles G. Dawes declined the Treasury position, he chose Pittsburgh banker Andrew W. Mellon, one of the richest people in the country. He appointed Herbert Hoover as Secretary of Commerce.[116] RNC chairman Will Hays was made Postmaster General, then a cabinet post; he left after a year in the position to become chief censor to the motion-picture industry.[117]

The two Harding cabinet appointees who darkened the reputation of his administration by their involvement in scandal were Harding's Senate friend Albert B. Fall of New Mexico, the Interior Secretary, and Daugherty, the attorney general. Fall was a Western rancher and former miner who favored development.[117] He was opposed by conservationists such as Gifford Pinchot, who wrote, "it would have been possible to pick a worse man for Secretary of the Interior, but not altogether easy."[118] The New York Times mocked the Daugherty appointment, writing that rather than selecting one of the best minds, Harding had been content "to choose merely a best friend."[119] Eugene P. Trani and David L. Wilson, in their volume on Harding's presidency, suggest that the appointment made sense then, as Daugherty was "a competent lawyer well-acquainted with the seamy side of politics ... a first-class political troubleshooter and someone Harding could trust."[120]

| The Harding cabinet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | Warren G. Harding | 1921–1923 |

| Vice President | Calvin Coolidge | 1921–1923 |

| Secretary of State | Charles Evans Hughes | 1921–1923 |

| Secretary of the Treasury | Andrew Mellon | 1921–1923 |

| Secretary of War | John W. Weeks | 1921–1923 |

| Attorney General | Harry M. Daugherty | 1921–1923 |

| Postmaster General | Will H. Hays | 1921–1922 |

| Hubert Work | 1922–1923 | |

| Harry Stewart New | 1923 | |

| Secretary of the Navy | Edwin Denby | 1921–1923 |

| Secretary of the Interior | Albert B. Fall | 1921–1923 |

| Hubert Work | 1923 | |

| Secretary of Agriculture | Henry Cantwell Wallace | 1921–1923 |

| Secretary of Commerce | Herbert Hoover | 1921–1923 |

| Secretary of Labor | James J. Davis | 1921–1923 |

Foreign policy

European relations and formally ending the war

Harding made it clear when he appointed Hughes as Secretary of State that the former justice would run foreign policy, a change from Wilson's hands-on management of international affairs.[121] Hughes had to work within some broad outlines; after taking office, Harding hardened his stance on the League of Nations, deciding the U.S. would not join even a scaled-down version of the League. With the Treaty of Versailles unratified by the Senate, the U.S. remained technically at war with Germany, Austria, and Hungary. Peacemaking began with the Knox–Porter Resolution, declaring the U.S. at peace and reserving any rights granted under Versailles. Treaties with Germany, Austria and Hungary, each containing many of the non-League provisions of the Treaty of Versailles, were ratified in 1921.[122]

This still left the question of relations between the U.S. and the League. Hughes' State Department initially ignored communications from the League, or tried to bypass it through direct contacts with member nations. By 1922, though, the U.S., through its consul in Geneva, was dealing with the League, and though the U.S. refused to participate in any meeting with political implications, it sent observers to sessions on technical and humanitarian matters.[123]

By the time Harding took office, there were calls from foreign governments for reduction of the massive war debt owed to the United States, and the German government sought to reduce the reparations that it was required to pay. The U.S. refused to consider any multilateral settlement. Harding sought passage of a plan proposed by Mellon to give the administration broad authority to reduce war debts in negotiation, but Congress, in 1922, passed a more restrictive bill. Hughes negotiated an agreement for Britain to pay off its war debt over 62 years at low interest, reducing the present value of the obligations. This agreement, approved by Congress in 1923, served as a model for negotiations with other nations. Talks with Germany on reduction of reparations payments resulted in the Dawes Plan of 1924.[124]

A pressing issue not resolved by Wilson was U.S. policy towards Bolshevik Russia. The U.S. had been among the nations that sent troops there after the Russian Revolution. Afterwards, Wilson refused to recognize the Russian SFSR. Harding's Commerce Secretary Hoover, with considerable experience in Russian affairs, took the lead on policy. When famine struck Russia in 1921, Hoover had the American Relief Administration, which he had headed, negotiate with the Russians to provide aid. Leaders of the U.S.S.R. (established in 1922) hoped in vain that the agreement would lead to recognition. Hoover supported trade with the Soviets, fearing U.S. companies would be frozen out of the Soviet market, but Hughes opposed this, and the matter was not resolved under Harding's presidency.[125]

Disarmament

Harding urged disarmament and lower defense costs during the campaign, but it had not been a major issue. He gave a speech to a joint session of Congress in April 1921, setting out his legislative priorities. Among the few foreign policy matters he mentioned was disarmament; he said the government could not "be unmindful of the call for reduced expenditure" on defense.[126]

Idaho Senator William Borah had proposed a conference at which the major naval powers, the U.S., Britain, and Japan, would agree to cuts in their fleets. Harding concurred, and after diplomatic discussions, representatives of nine nations convened in Washington in November 1921. Most of the diplomats first attended Armistice Day ceremonies at Arlington National Cemetery, where Harding spoke at the entombment of the Unknown Soldier of World War I, whose identity, "took flight with his imperishable soul. We know not whence he came, only that his death marks him with the everlasting glory of an American dying for his country."[127]

Hughes, in his speech at the opening session of the conference on November 12, 1921, made the American proposal—the U.S. would decommission or not build 30 warships if Great Britain did likewise for 19 vessels, and Japan for 17.[128] Hughes was generally successful, with agreements reached on this and other points, including settlement of disputes over islands in the Pacific, and limitations on the use of poison gas. The naval agreement applied only to battleships, and to some extent aircraft carriers, and ultimately did not prevent rearmament. Nevertheless, Harding and Hughes were widely applauded in the press for their work. Senator Lodge and the Senate Minority Leader, Alabama's Oscar Underwood, were part of the U.S. delegation, and they helped ensure the treaties made it through the Senate mostly unscathed, though that body added reservations to some.[129][130]

The U.S. had acquired over a thousand vessels during World War I, and still owned most of them when Harding took office. Congress had authorized their disposal in 1920, but the Senate would not confirm Wilson's nominees to the Shipping Board. Harding appointed Albert Lasker as its chairman; the advertising executive undertook to run the fleet as profitably as possible until it could be sold. Few ships were marketable at anything approaching the government's cost. Lasker recommended a large subsidy to the merchant marine to facilitate sales, and Harding repeatedly urged Congress to enact it. The resulting bill was unpopular in the Midwest, and though it passed the House, it was defeated by a filibuster in the Senate, and most government ships were eventually scrapped.[131]

Latin America

Intervention in Latin America had been a minor campaign issue, though Harding spoke against Wilson's decision to send U.S. troops to the Dominican Republic and Haiti, and attacked the Democratic vice presidential candidate, Franklin Roosevelt, for his role in the Haitian intervention. Once Harding was sworn in, Hughes worked to improve relations with Latin American countries who were wary of the American use of the Monroe Doctrine to justify intervention; at the time of Harding's inauguration, the U.S. also had troops in Cuba and Nicaragua. The troops stationed in Cuba were withdrawn in 1921, but U.S. forces remained in the other three nations throughout Harding's presidency.[f][132] In April 1921, Harding gained the ratification of the Thomson–Urrutia Treaty with Colombia, granting that nation $25 million (equivalent to $427.05 million in 2023) as settlement for the U.S.-provoked Panamanian revolution of 1903.[133] The Latin American nations were not fully satisfied, as the U.S. refused to renounce interventionism, though Hughes pledged to limit it to nations near the Panama Canal, and to make it clear what the U.S. aims were.[134]

The U.S. had intervened repeatedly in Mexico under Wilson, and had withdrawn diplomatic recognition, setting conditions for reinstatement. The Mexican government under President Álvaro Obregón wanted recognition before negotiations, but Wilson and his final Secretary of State, Bainbridge Colby, refused. Both Hughes and Fall opposed recognition; Hughes instead sent a draft treaty to the Mexicans in May 1921, which included pledges to reimburse Americans for losses in Mexico since the 1910 revolution there. Obregón was unwilling to sign a treaty before being recognized, and worked to improve the relationship between American business and Mexico, reaching agreement with creditors, and mounting a public relations campaign in the United States. This had its effect, and by mid-1922, Fall was less influential than he had been, lessening the resistance to recognition. The two presidents appointed commissioners to reach a deal, and the U.S. recognized the Obregón government on August 31, 1923, just under a month after Harding's death, substantially on the terms proffered by Mexico.[135]

Domestic policy

Postwar recession and recovery

When Harding took office on March 4, 1921, the nation was in the midst of a postwar economic decline.[136] At the suggestion of legislative leaders, Harding called a special session of Congress, to convene April 11. When Harding addressed the joint session the following day, he urged the reduction of income taxes (raised during the war), an increase in tariffs on agricultural goods to protect the American farmer, as well as more wide-ranging reforms, such as support for highways, aviation, and radio.[137][138] It was not until May 27 that Congress passed an emergency tariff increase on agricultural products. An act authorizing a Bureau of the Budget followed on June 10, and Harding appointed Charles Dawes as bureau director with a mandate to cut expenditures.[139]

Mellon's tax cuts

Treasury Secretary Mellon also recommended that Congress cut income tax rates, and that the corporate excess profits tax be abolished. The House Ways and Means Committee endorsed Mellon's proposals, but some congressmen wanting to raise corporate tax rates fought the measure. Harding was unsure what side to endorse, telling a friend, "I can't make a damn thing out of this tax problem. I listen to one side, and they seem right, and then—God!—I talk to the other side, and they seem just as right."[138] Harding tried compromise, and gained passage of a bill in the House after the end of the excess profits tax was delayed a year. In the Senate, the bill became entangled in efforts to vote World War I veterans a soldier's bonus. Frustrated by the delays, on July 12, Harding appeared before the Senate to urge passage of the tax legislation without the bonus. It was not until November that the revenue bill finally passed, with higher rates than Mellon had proposed.[140][141]

In opposing the veterans' bonus, Harding argued in his Senate address that much was already being done for them by a grateful nation, and that the bill would "break down our Treasury, from which so much is later on to be expected".[142] The Senate sent the bonus bill back to committee, but the issue returned when Congress reconvened in December 1921.[142] A bill providing a bonus, though unfunded, was passed by both houses in September 1922, but Harding's veto was narrowly sustained. A non-cash bonus for soldiers passed over Coolidge's veto in 1924.[143]

In his first annual message to Congress, Harding sought the power to adjust tariff rates. The passage of the tariff bill in the Senate, and in conference committee became a feeding frenzy of lobby interests.[144] When Harding signed the Fordney–McCumber Tariff Act on September 21, 1922, he made a brief statement, praising the bill only for giving him some power to change rates.[145] According to Trani and Wilson, the bill was "ill-considered. It wrought havoc in international commerce and made the repayment of war debts more difficult."[146]

Mellon ordered a study that demonstrated historically that, as income tax rates were increased, money was driven underground or abroad, and he concluded that lower rates would increase tax revenues.[147][148] Based on his advice, Harding's revenue bill cut taxes, starting in 1922. The top marginal rate was reduced annually in four stages from 73% in 1921 to 25% in 1925. Taxes were cut for lower incomes starting in 1923, and the lower rates substantially increased the money flowing to the treasury. They also pushed massive deregulation, and federal spending as a share of GDP fell from 6.5% to 3.5%. By late 1922, the economy began to turn around. Unemployment was pared from its 1921 high of 12% to an average of 3.3% for the remainder of the decade. The misery index, a combined measure of unemployment and inflation, had its sharpest decline in U.S. history under Harding. Wages, profits, and productivity all made substantial gains; annual GDP increases averaged at over 5% during the 1920s. Libertarian historians Larry Schweikart and Michael Allen argue that, "Mellon's tax policies set the stage for the most amazing growth yet seen in America's already impressive economy."[149]

Embracing new technologies

The 1920s were a time of modernization for America—use of electricity became increasingly common. Mass production of motorized vehicles stimulated other industries as well, such as highway construction, rubber, steel, and building, as hotels were erected to accommodate the tourists venturing upon the roads. This economic boost helped bring the nation out of the recession.[150] To improve and expand the nation's highway system, Harding signed the Federal Highway Act of 1921. From 1921 to 1923, the federal government spent $162 million (equivalent to $2.9 billion in 2023) on America's highway system, infusing the U.S. economy with a large amount of capital.[151] In 1922, Harding proclaimed that America was in the age of the "motor car", which "reflects our standard of living and gauges the speed of our present-day life".[152]

Harding urged regulation of radio broadcasting in his April 1921 speech to Congress.[153] Commerce Secretary Hoover took charge of this project, and convened a conference of radio broadcasters in 1922, which led to a voluntary agreement for licensing of radio frequencies through the Commerce Department. Both Harding and Hoover realized something more than an agreement was needed, but Congress was slow to act, not imposing radio regulation until 1927.[154]

Harding also wished to promote aviation, and Hoover again took the lead, convening a national conference on commercial aviation. The discussions focused on safety matters, inspection of airplanes, and licensing of pilots. Harding again promoted legislation but nothing was done until 1926, when the Air Commerce Act created the Bureau of Aeronautics within Hoover's Commerce Department.[154]

Business and labor

Harding's attitude toward business was that government should aid it as much as possible.[155] He was suspicious of organized labor, viewing it as a conspiracy against business.[156] He sought to get them to work together at a conference on unemployment that he called to meet in September 1921 at Hoover's recommendation. Harding warned in his opening address that no federal money would be available. No important legislation came as a result, though some public works projects were accelerated.[157]

Within broad limits, Harding allowed each cabinet secretary to run his department as he saw fit.[158] Hoover expanded the Commerce Department to make it more useful to business. This was consistent with Hoover's view that the private sector should take the lead in managing the economy.[159] Harding greatly respected his Commerce Secretary, often asked his advice, and backed him to the hilt, calling Hoover "the smartest 'gink' I know".[160]

Widespread strikes marked 1922, as labor sought redress for falling wages and increased unemployment. In April, 500,000 coal miners, led by John L. Lewis, struck over wage cuts. Mining executives argued that the industry was seeing hard times; Lewis accused them of trying to break the union. As the strike became protracted, Harding offered compromise to settle it. As Harding proposed, the miners agreed to return to work, and Congress created a commission to look into their grievances.[161]

On July 1, 1922, 400,000 railroad workers went on strike. Harding recommended a settlement that made some concessions, but management objected. Attorney General Daugherty convinced Judge James H. Wilkerson to issue a sweeping injunction to break the strike. Although there was public support for the Wilkerson injunction, Harding felt it went too far, and had Daugherty and Wilkerson amend it. The injunction succeeded in ending the strike; however, tensions remained high between railroad workers and management for years.[162]

By 1922, the eight-hour day had become common in American industry. One exception was in steel mills, where workers labored through a twelve-hour workday, seven days a week. Hoover considered this practice barbaric and got Harding to convene a conference of steel manufacturers with a view to ending the system. The conference established a committee under the leadership of U. S. Steel chairman Elbert Gary, which in early 1923 recommended against ending the practice. Harding sent a letter to Gary deploring the result, which was printed in the press, and public outcry caused the manufacturers to reverse themselves and standardize the eight-hour day.[163]

Civil rights and immigration

Although Harding's first address to Congress called for passage of anti-lynching legislation,[10] he initially seemed inclined to do no more for African Americans than Republican presidents of the recent past had; he asked Cabinet officers to find places for blacks in their departments. Sinclair suggested that the fact that Harding received two-fifths of the Southern vote in 1920 led him to see political opportunity for his party in the Solid South. On October 26, 1921, Harding gave a speech in Birmingham, Alabama, to a segregated audience of 20,000 Whites and 10,000 Blacks. Harding, while saying that the social and racial differences between Whites and Blacks could not be bridged, urged equal political rights for the latter. Many African-Americans at that time voted Republican, especially in the Democratic South, and Harding said he did not mind seeing that support end if the result was a strong two-party system in the South. He was willing to see literacy tests for voting continue, if applied fairly to White and Black voters.[164] "Whether you like it or not," Harding told his segregated audience, "unless our democracy is a lie, you must stand for that equality."[10] The White section of the audience listened in silence, while the Black section cheered.[165] Three days after the Tulsa race massacre of 1921, Harding spoke at the all-Black Lincoln University in Pennsylvania. He declared, "Despite the demagogues, the idea of our oneness as Americans has risen superior to every appeal to mere class and group. And so, I wish it might be in this matter of our national problem of races." Speaking directly about the events in Tulsa, he said, "God grant that, in the soberness, the fairness, and the justice of this country, we never see another spectacle like it."[166]

Harding supported Congressman Leonidas Dyer's federal anti-lynching bill, which passed the House of Representatives in January 1922.[167] When it reached the Senate floor in November 1922, it was filibustered by Southern Democrats, and Lodge withdrew it to allow the ship subsidy bill Harding favored to be debated, though it was likewise blocked. Blacks blamed Harding for the Dyer bill's defeat; Harding biographer Robert K. Murray noted that it was hastened to its end by Harding's desire to have the ship subsidy bill considered.[168]

With the public suspicious of immigrants, especially those who might be socialists or communists, Congress passed the Per Centum Act of 1921, signed by Harding on May 19, 1921, as a quick means of restricting immigration. The act reduced the numbers of immigrants to 3% of those from a given country living in the U.S., based on the 1910 census. This would, in practice, not restrict immigration from Ireland and Germany, but would bar many Italians and eastern European Jews.[169] Harding and Secretary of Labor James Davis believed that enforcement had to be humane, and at the Secretary's recommendation, Harding allowed almost 1,000 deportable immigrants to remain.[170] Coolidge later signed the Immigration Act of 1924, permanently restricting immigration to the U.S.[171]

Eugene Debs and political prisoners

Harding's Socialist opponent in the 1920 election, Eugene Debs, was serving a ten-year sentence in the Atlanta Penitentiary for speaking against the war. Wilson had refused to pardon him before leaving office. Daugherty met with Debs, and was deeply impressed. There was opposition from veterans, including the American Legion, and also from Florence Harding. The president did not feel he could release Debs until the war was officially over, but once the peace treaties were signed, commuted Debs' sentence on December 23, 1921. At Harding's request, Debs visited the president at the White House before going home to Indiana.[172]

Harding released 23 other war opponents at the same time as Debs, and continued to review cases and release political prisoners throughout his presidency. Harding defended his prisoner releases as necessary to return the nation to normalcy.[173]

Judicial appointments

Harding appointed four justices to the Supreme Court of the United States. When Chief Justice Edward Douglass White died in May 1921, Harding was unsure whether to appoint former president Taft or former Utah senator George Sutherland—he had promised seats on the court to both men. After briefly considering awaiting another vacancy and appointing them both, he chose Taft as Chief Justice. Sutherland was appointed to the court in 1922, to be followed by two other economic conservatives, Pierce Butler and Edward Terry Sanford, in 1923.[174]

Harding also appointed six judges to the United States Courts of Appeals, 42 judges to the United States district courts, and two judges to the United States Court of Customs Appeals.[175]

Political setbacks and western tour

Entering the 1922 midterm congressional election campaign, Harding and the Republicans had followed through on many of their campaign promises. But some of the fulfilled pledges, like cutting taxes for the well-off, did not appeal to the electorate. The economy had not returned to normalcy, with unemployment at 11 percent, and organized labor angry over the outcome of the strikes. From 303 Republicans elected to the House in 1920, the new 68th Congress saw that party fall to a 221–213 majority. In the Senate, the Republicans lost eight seats, and had 51 of 96 senators in the new Congress, which Harding did not survive to meet.[176]

A month after the election, the lame-duck session of the outgoing 67th Congress met. Harding then believed his early view of the presidency—that it should propose policies, but leave their adoption to Congress—was no longer enough, and he lobbied Congress, although in vain, to get his ship subsidy bill through.[176] Once Congress left town in early March 1923, Harding's popularity began to recover. The economy was improving, and the programs of Harding's more able Cabinet members, such as Hughes, Mellon and Hoover, were showing results. Most Republicans realized that there was no practical alternative to supporting Harding in 1924 for his re-election campaign.[177]

В первой половине 1923 года Хардинг сделал две вещи, которые, как позже говорили, указывали на предвидение смерти: он продал « Стар» (хотя и обязался оставаться в качестве пишущего редактора в течение десяти лет после своего президентства) и составил новое завещание. [178] Хардинг долгое время страдал от периодических проблем со здоровьем, но когда у него не было симптомов, он имел тенденцию слишком много есть, пить и курить. К 1919 году он понял, что у него больное сердце. Стресс, вызванный президентством и хроническим заболеванием почек Флоренс Хардинг, ослабил его, и он так и не оправился полностью от эпизода гриппа в январе 1923 года. После этого Хардинг, заядлый игрок в гольф, с трудом завершил раунд. В июне 1923 года сенатор от Огайо Уиллис встретился с Хардингом, но довел до сведения президента только два из пяти вопросов, которые он намеревался обсудить. Когда его спросили, почему, Уиллис ответил: «Уоррен выглядел таким усталым». [179]

В начале июня 1923 года Хардинг отправился в путешествие, которое он назвал « Путешествием понимания ». [177] Президент планировал пересечь страну, направиться на север к территории Аляски , отправиться на юг вдоль западного побережья, затем отправиться на корабле ВМС США из Сан-Диего вдоль западного побережья Мексики и Центральной Америки, через Панамский канал в Пуэрто-Рико и вернуться в Вашингтон в конце августа. [180] Хардинг любил путешествовать и давно подумывал о поездке на Аляску. [181] Поездка позволила бы ему широко выступать по всей стране, заниматься политикой и болтовней в преддверии кампании 1924 года и дать ему немного отдохнуть. [182] вдали от гнетущей летней жары Вашингтона. [177]

Политические советники Хардинга установили для него физически напряженный график, хотя президент приказал его сократить. [183] В Канзас-Сити Хардинг говорил о проблемах транспорта; в Хатчинсоне, штат Канзас , темой было сельское хозяйство. В Денвере он высказался о своей поддержке сухого закона и продолжил на запад, произнося серию речей, с которыми не сравнился ни один президент до Франклина Рузвельта. Хардинг стал сторонником Всемирного суда и хотел, чтобы США стали его членом. Помимо выступлений, он посетил Йеллоустон и национальные парки Зайон . [184] и посвятил памятник на Орегонской тропе на празднике, организованном почтенным пионером Эзрой Микером и другими. [185]

5 июля Хардинг сел на борт военного корабля США «Хендерсон» в штате Вашингтон. Он был первым президентом, посетившим Аляску, и часами наблюдал за драматическими пейзажами с палубы «Хендерсона » . [186] После нескольких остановок вдоль побережья президентская партия покинула корабль в Сьюарде, чтобы поехать по Аляскинской железной дороге в Мак-Кинли-парк и Фэрбенкс , где он обратился к толпе из 1500 человек при температуре 94 ° F (34 ° C). Группа должна была вернуться в Сьюард по тропе Ричардсона , но из-за усталости Хардинга они поехали поездом. [187]

26 июля 1923 года Хардинг совершил поездку в Ванкувер , Британская Колумбия, как первый действующий американский президент, посетивший Канаду. Его приветствовал вице-губернатор Британской Колумбии Уолтер Никол . [188] Премьер Британской Колумбии Джон Оливер и мэр Ванкувера выступили перед более чем 50-тысячной толпой. был открыт мемориал Хардингу Через два года после его смерти в Стэнли-парке . [189] Хардинг посетил поле для гольфа, но сделал только шесть лунок, прежде чем утомился. Отдохнув час, он сыграл на 17-й и 18-й лунках, так что казалось, что он завершил раунд. Ему не удалось скрыть своего утомления; один репортер подумал, что он выглядит настолько усталым, что нескольких дней будет недостаточно, чтобы освежить его. [190]

На следующий день в Сиэтле Хардинг продолжил свой напряженный график, выступив с речью перед 25 000 человек на стадионе университета Вашингтонского . В своей заключительной речи Хардинг предсказал государственность Аляски. [191] [192] Президент произнес свою речь торопливо, не дожидаясь аплодисментов зала. [193]

Смерть и похороны

Хардинг лег спать рано вечером 27 июля 1923 года, через несколько часов после выступления в Вашингтонском университете. Позже той же ночью он вызвал своего врача Чарльза Э. Сойера , жалуясь на боль в верхней части живота. Сойер подумал, что это рецидив расстройства желудка, но доктор Джоэл Т. Бун заподозрил проблему с сердцем. Прессе сообщили, что у Хардинга случился «острый желудочно-кишечный приступ», и его запланированные выходные в Портленде были отменены. На следующий день ему стало лучше, когда поезд мчался в Сан-Франциско, куда они прибыли утром 29 июля. Он настоял на том, чтобы пройти от поезда до машины, а затем его срочно доставили в отель Palace . [194] [195] где у него случился рецидив. Врачи обнаружили, что у него не только проблемы с сердцем, но и пневмония , и он был прикован к постельному режиму в своем гостиничном номере. Врачи лечили его жидким кофеином и наперстянкой , и ему, казалось, стало лучше. Гувер опубликовал внешнеполитическое обращение Хардинга, призывающее к членству во Всемирном суде, и президент был рад, что оно было встречено благосклонно. К полудню 2 августа состояние Хардинга, казалось, все еще улучшалось, и врачи разрешили ему сидеть в постели. Около 7:30 того же вечера Флоренс читала ему «Спокойный обзор спокойного человека», лестную статью о нем из The Saturday Evening Post ; она сделала паузу, и он сказал ей: «Это хорошо. Давай, почитай еще». Это должны были быть его последние слова. Она возобновила чтение, когда несколько секунд спустя Хардинг судорожно скрутился и рухнул обратно на кровать, задыхаясь. Флоренс Хардинг немедленно вызвала в палату врачей, но они не смогли привести его в чувство с помощью стимуляторов; Хардинг был объявлен мертвым через несколько минут в возрасте 57 лет. [196] Смерть Хардинга первоначально была приписана кровоизлиянию в мозг , поскольку врачи в то время обычно не понимали симптомы остановки сердца . президента Флоренс Хардинг не согласилась на вскрытие . [25] [194]

Неожиданная смерть Хардинга стала большим потрясением для нации. Его любили и восхищались, и пресса, и общественность внимательно следили за его болезнью и были обнадежены его очевидным выздоровлением. [197] Тело Хардинга в гробу доставили в поезд и отправились в путешествие по стране, за которым внимательно следили в газетах. Девять миллионов человек выстроились вдоль железнодорожных путей, пока поезд с его телом следовал из Сан-Франциско в Вашингтон, округ Колумбия, где он лежал в ротонде Капитолия США . После похорон тело Хардинга было перевезено в Мэрион, штат Огайо, для захоронения. [198]

В Мэрион тело Хардинга было помещено в катафалк, запряженный лошадьми, за которым следовали президент Кулидж и главный судья Тафт, а затем вдова Хардинга и его отец. [199] Они следовали за катафалком через город, мимо здания «Звезда» и, наконец, к кладбищу Мэрион, где гроб был помещен в приемное хранилище кладбища . [200] [201] Среди гостей на похоронах были изобретатель Томас Эдисон и бизнесмены-промышленники Генри Форд и Харви Файерстоун . [202] Уоррен Хардинг и Флоренс Хардинг, умершие в следующем году, покоятся в гробнице Хардинга , которую в 1931 году освятил президент США Герберт Гувер . [203]

Скандалы

Хардинг назначил друзей и знакомых на федеральные должности. Некоторые служили компетентно, например Чарльз Э. Сойер , личный врач Хардингов из Мэрион, который лечил их в Белом доме и предупредил Хардинга о скандале с Бюро ветеранов. Другие оказались неэффективными на своем посту, например, Дэниел Р. Криссинджер , юрист Мэрион, которого Хардинг назначил контролером денежного обращения , а затем управляющим Федеральной резервной системы ; другим был старый друг Хардинга Фрэнк Скоби, директор Монетного двора, который, как отметили Трани и Уилсон, «нанес небольшой ущерб за время своего пребывания в должности». Другие из этих сообщников оказались коррумпированными и позже были названы « бандой Огайо ». [204]

Большинство скандалов, омрачивших репутацию администрации Хардинга, возникли только после его смерти. Скандал с Бюро ветеранов был известен Хардингу в январе 1923 года, но, по словам Трани и Уилсона, «то, как президент справился с этим, не принесло ему особой чести». [205] Хардинг позволил коррумпированному директору бюро Чарльзу Р. Форбсу бежать в Европу, хотя позже он вернулся и отбыл тюремный срок. [206] Хардинг узнал, что помощник Догерти в Министерстве юстиции Джесс Смит был замешан в коррупции. Президент приказал Догерти вывезти Смита из Вашингтона и исключил его имя из предстоящей президентской поездки на Аляску. Смит покончил жизнь самоубийством 30 мая 1923 года. [207] Неизвестно, насколько Хардинг знал о незаконной деятельности Смита. [208] Мюррей отметил, что Хардинг не был причастен к коррупции и не одобряет ее. [209]

Гувер сопровождал Хардинга в поездке на Запад и позже написал, что Хардинг спросил, что сделает Гувер, если узнает о каком-то большом скандале: предать ли ему огласку или похоронить его. Гувер ответил, что Хардинг должен опубликовать и получить признание за честность, и попросил подробностей. Хардинг сказал, что это связано со Смитом, но когда Гувер поинтересовался возможной причастностью Догерти, Хардинг отказался отвечать. [210]

Чайник Купол

Скандал, который, вероятно, нанес наибольший ущерб репутации Хардинга, - это Teapot Dome . Как и большинство скандалов администрации, это стало известно после смерти Хардинга, и он не знал о незаконных аспектах. Teapot Dome задействовал нефтяной резерв в Вайоминге, который был одним из трех, зарезервированных для использования ВМФ в случае чрезвычайной ситуации в стране. Существовал давний аргумент в пользу того, что резервы следует разрабатывать; Первый министр внутренних дел Вильсона Франклин Найт Лейн был сторонником этой позиции. Когда администрация Хардинга пришла к власти, министр внутренних дел Фолл поддержал аргумент Лейна, и в мае 1921 года Хардинг подписал указ о передаче резервов из военно-морского министерства во внутренние дела. Это было сделано с согласия министра военно-морского флота Эдвина Денби . [211] [212]