Изменение климата

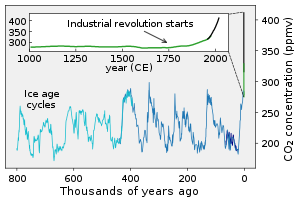

В обычном понимании изменение климата описывает глобальное потепление – продолжающееся повышение глобальной средней температуры – и его влияние на климатическую систему Земли . Изменение климата в более широком смысле также включает предыдущие долгосрочные изменения климата Земли. Нынешний рост средней глобальной температуры вызван в первую очередь тем, что люди сжигают ископаемое топливо со времен промышленной революции . [3] [4] Использование ископаемого топлива , вырубка лесов и некоторые методы ведения сельского хозяйства и промышленности увеличивают выбросы парниковых газов . [5] Эти газы поглощают часть тепла , которое Земля излучает после того, как она нагревается от солнечного света , нагревая нижние слои атмосферы . Уровень углекислого газа , основного парникового газа, вызывающего глобальное потепление, увеличился примерно на 50% и находится на уровне, невиданном в течение миллионов лет. [6]

Изменение климата оказывает все более серьезное воздействие на окружающую среду . Пустыни расширяются , а жара и лесные пожары становятся все более распространенными. [7] [8] Усиление потепления в Арктике способствовало таянию вечной мерзлоты , отступлению ледников и сокращению морского льда . [9] Более высокие температуры также вызывают более сильные штормы , засухи и другие экстремальные погодные явления . [10] Быстрое изменение окружающей среды в горах , коралловых рифах и Арктике вынуждает многие виды перемещаться или вымирать . [11] Даже если усилия по минимизации будущего потепления окажутся успешными, некоторые последствия будут сохраняться в течение столетий. К ним относятся нагревание океана , закисление океана и повышение уровня моря . [12]

Изменение климата угрожает людям усилением наводнений , сильной жарой, увеличением нехватки продовольствия и воды , ростом заболеваемости и экономическими потерями . миграция людей и конфликты. Результатом также могут стать [13] Всемирная организация здравоохранения (ВОЗ) называет изменение климата одной из крупнейших угроз глобальному здоровью в 21 веке. [14] общества и экосистемы столкнутся с более серьезными рисками Без принятия мер по ограничению потепления . [15] Адаптация к изменению климата посредством таких мер, как меры по борьбе с наводнениями или выращивание устойчивых к засухе культур, частично снижает риски изменения климата, хотя некоторые пределы адаптации уже достигнуты. [16] [17] Бедные сообщества несут ответственность за небольшую долю глобальных выбросов , но при этом имеют наименьшую способность к адаптации и наиболее уязвимы к изменению климата . [18] [19]

В последние годы ощущались многочисленные последствия изменения климата: 2023 год стал самым теплым за всю историю наблюдений с температурой +1,48 °C (2,66 °F) с момента начала регулярного отслеживания в 1850 году. [21] [22] Дополнительное потепление усилит эти воздействия и может спровоцировать переломные моменты , такие как таяние всего ледникового щита Гренландии . [23] 2015 года В соответствии с Парижским соглашением страны коллективно согласились поддерживать потепление «значительно ниже 2 °C». Однако, несмотря на обязательства, взятые в рамках Соглашения, глобальное потепление все равно достигнет примерно 2,7 °C (4,9 °F) к концу столетия. [24] Ограничение потепления 1,5 °C потребует сокращения выбросов вдвое к 2030 году и достижения нулевых выбросов к 2050 году. [25] [26] [27] [28]

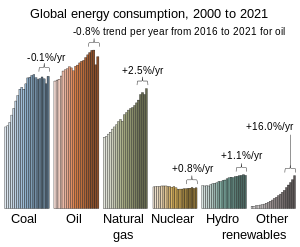

Использование ископаемого топлива может быть прекращено за счет экономии энергии и перехода на источники энергии, которые не производят значительного загрязнения углекислым газом. Эти источники энергии включают ветровую , солнечную , гидро- и ядерную энергию . [29] [30] Чисто вырабатываемая электроэнергия может заменить ископаемое топливо для обеспечения транспорта , отопления зданий и управления промышленными процессами. [31] Углерод также можно удалить из атмосферы , например, за счет увеличения лесного покрова и ведения сельского хозяйства с использованием методов улавливания углерода в почве . [32] [33]

Терминология

До 1980-х годов было неясно, был ли эффект потепления от увеличения выбросов парниковых газов сильнее, чем охлаждающий эффект переносимых по воздуху твердых частиц, содержащихся в загрязнении воздуха . Ученые использовали термин «непреднамеренное изменение климата» для обозначения воздействия человека на климат в то время. [34] В 1980-х годах термины « глобальное потепление» и «изменение климата» стали более распространенными и часто использовались как синонимы. [35] [36] [37] С научной точки зрения, глобальное потепление относится только к усилению приземного потепления, в то время как изменение климата Земли описывает как глобальное потепление, так и его воздействие на климатическую систему , например, изменение количества осадков. [34]

Изменение климата также можно использовать в более широком смысле, включая изменения климата , которые происходили на протяжении всей истории Земли. [38] Глобальное потепление — использовался еще в 1975 году. [39] — стал более популярным термином после того, как НАСА ученый-климатолог Джеймс Хансен использовал его в своих показаниях в Сенате США в 1988 году . [40] С 2000-х годов изменения климата . использование таких технологий возросло из-за [41] Различные ученые, политики и средства массовой информации могут использовать термины «климатический кризис» или «климатическая чрезвычайная ситуация» , говоря об изменении климата, и могут использовать термин « глобальное потепление» вместо «глобальное потепление» . [42] [43]

Глобальное повышение температуры

Температурные рекорды до глобального потепления

За последние несколько миллионов лет люди эволюционировали в климате, который циклически сменял ледниковые периоды , при этом средняя глобальная температура колебалась от 1 °C теплее до 5–6 °C холоднее нынешнего уровня. [46] [47] Одним из самых жарких периодов было последнее межледниковье между 115 000 и 130 000 лет назад, когда уровень моря был на 6–9 метров выше, чем сегодня. [48] Во время последнего ледникового максимума 20 000 лет назад уровень моря был примерно на 125 метров (410 футов) ниже, чем сегодня. [49]

В нынешнем межледниковом периоде, начавшемся 11 700 лет назад, температура стабилизировалась . [50] Исторические закономерности потепления и похолодания, такие как средневековый теплый период и малый ледниковый период , не происходили одновременно в разных регионах. В ограниченном наборе регионов температуры, возможно, достигли таких же высоких значений, как в конце 20-го века. [51] [52] Климатическая информация за этот период поступает от климатических индикаторов , таких как деревья и керны льда . [53] [54]

Потепление после промышленной революции

Около 1850 записей термометров начали охватывать весь мир. [57] В период с 18 века по 1970 год суммарное потепление было незначительным, поскольку воздействие выбросов парниковых газов на потепление компенсировалось охлаждением из-за выбросов диоксида серы . Диоксид серы вызывает кислотные дожди , но он также производит сульфатные в атмосфере аэрозоли, которые отражают солнечный свет и вызывают так называемое глобальное затемнение . После 1970 года растущее накопление парниковых газов и контроль над загрязнением серой привели к заметному повышению температуры. [58] [59] [60]

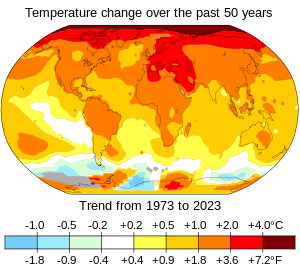

Продолжающиеся изменения климата не имели прецедентов на протяжении нескольких тысяч лет. [61] Множество независимых наборов данных показывают повышение температуры поверхности во всем мире. [62] со скоростью около 0,2 °C за десятилетие. [63] За десятилетие 2013–2022 гг. потепление составило в среднем 1,15 °C [1,00–1,25 °C] по сравнению с базовым доиндустриальным периодом (1850–1900 гг.). [64] Не каждый год был теплее предыдущего: внутренние процессы изменчивости климата могут сделать любой год на 0,2 °C теплее или холоднее среднего показателя. [65] С 1998 по 2013 год наблюдались негативные фазы двух таких процессов — Тихоокеанского десятилетнего колебания (PDO). [66] и Атлантическое многодесятилетнее колебание (АМО) [67] вызвало так называемый « перерыв в глобальном потеплении ». [68] После перерыва произошло обратное: в такие годы, как 2023 год, температура была значительно выше даже недавнего среднего показателя. [69] Вот почему изменение температуры определяется как среднее значение за 20 лет, что снижает шум жарких и холодных лет и десятилетних климатических моделей, а также обнаруживает долгосрочный сигнал. [70] : 5 [71]

Широкий спектр других наблюдений подтверждает доказательства потепления. [72] [73] Верхние слои атмосферы охлаждаются, поскольку парниковые газы удерживают тепло у поверхности Земли, и поэтому в космос излучается меньше тепла. [74] Потепление уменьшает средний снежный покров и приводит к отступлению ледников . В то же время потепление также вызывает большее испарение из океанов , что приводит к увеличению влажности воздуха и увеличению количества осадков . [75] [76] Растения весной цветут раньше, а тысячи видов животных постоянно переселяются в более прохладные районы. [77]

Различия по регионам

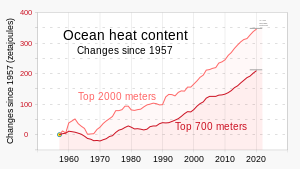

В разных регионах мира тепло происходит с разной скоростью . Картина не зависит от того, где выбрасываются парниковые газы, поскольку газы сохраняются достаточно долго, чтобы диффундировать по планете. Начиная с доиндустриального периода, средняя приземная температура над сушей увеличивалась почти в два раза быстрее, чем глобальная средняя приземная температура. [78] Это связано с тем, что океаны теряют больше тепла в результате испарения и могут хранить много тепла . [79] Тепловая энергия в глобальной климатической системе росла лишь с короткими паузами, по крайней мере, с 1970 года, и более 90% этой дополнительной энергии хранится в океане . [80] [81] Остальное нагрело атмосферу , растопило лед и согрело континенты. [82]

Северное полушарие и Северный полюс нагреваются гораздо быстрее, чем Южный полюс и Южное полушарие . В Северном полушарии не только гораздо больше суши, но и больше сезонного снежного покрова и морского льда . Поскольку после таяния льда эти поверхности перестают отражать много света и становятся темными, они начинают поглощать больше тепла . [83] Местные отложения черного углерода на снегу и льду также способствуют потеплению в Арктике. [84] Температура поверхности Арктики растет в три-четыре раза быстрее, чем в остальном мире. [85] [86] [87] Таяние ледниковых щитов вблизи полюсов ослабляет как атлантическое , так и антарктическое звено термохалинной циркуляции , что еще больше меняет распределение тепла и осадков по земному шару. [88] [89] [90] [91]

Будущие глобальные температуры

По оценкам Всемирной метеорологической организации, вероятность того, что глобальная температура превысит 1,5 °C потепления по сравнению с доиндустриальным базовым уровнем, составляет 66% в течение как минимум одного года между 2023 и 2027 годами. [94] [95] Поскольку МГЭИК использует среднее значение за 20 лет для определения глобальных изменений температуры, один год, превышающий 1,5 °C, не превышает предел.

МГЭИК ожидает, что в начале 2030-х годов средняя глобальная температура за 20 лет превысит +1,5 °C. [96] ( Шестой оценочный доклад МГЭИК 2023 г.) включал прогнозы о том, что к 2100 году глобальное потепление, скорее всего, достигнет 1,0–1,8 °C при сценарии с очень низкими выбросами парниковых газов , 2,1–3,5 °C при сценарии промежуточных выбросов , или 3,3–5,7 °C при сценарии очень высоких выбросов . [97] Потепление продолжится и после 2100 года в сценариях со средним и высоким уровнем выбросов. [98] [99] при этом будущие прогнозы глобальной приземной температуры к 2300 году будут такими же, как и миллионы лет назад. [100]

Оставшийся углеродный баланс , необходимый для того, чтобы оставаться ниже определенного повышения температуры, определяется путем моделирования углеродного цикла и чувствительности климата к парниковым газам. [101] По данным МГЭИК, глобальное потепление можно удержать на уровне ниже 1,5 °C с вероятностью в две трети, если выбросы после 2018 года не превысят 420 или 570 гигатонн CO 2 . Это соответствует 10–13 годам текущих выбросов. Существует большая неопределенность в отношении бюджета. Например, оно может быть на 100 гигатонн эквивалента CO 2 меньше из-за выбросов CO 2 и метана из вечной мерзлоты и водно-болотных угодий . [102] Однако очевидно, что ресурсы ископаемого топлива необходимо активно хранить в земле, чтобы предотвратить существенное потепление. В противном случае их нехватка не возникнет до тех пор, пока выбросы уже не окажут существенное долгосрочное воздействие. [103]

Причины недавнего повышения глобальной температуры

Климатическая система сама по себе испытывает различные циклы, которые могут длиться годами, десятилетиями или даже столетиями. Например, явления Эль-Ниньо вызывают кратковременные скачки приземной температуры, а явления Ла-Нинья вызывают кратковременное похолодание. [104] Их относительная частота может влиять на глобальные температурные тенденции в десятилетнем масштабе. [105] Другие изменения вызваны дисбалансом энергии от внешних воздействий . [106] Примеры этого включают изменения концентрации парниковых газов , солнечной светимости , извержения вулканов и изменения орбиты Земли вокруг Солнца . [107]

Чтобы определить вклад человека в изменение климата, разрабатываются уникальные «отпечатки пальцев» для всех потенциальных причин, которые сравниваются как с наблюдаемыми закономерностями, так и с известной внутренней изменчивостью климата . [108] Например, солнечное воздействие, отпечатком которого является нагревание всей атмосферы, исключено, поскольку нагрелись только нижние слои атмосферы. [109] Атмосферные аэрозоли оказывают меньший охлаждающий эффект. Другие факторы, такие как изменения альбедо , менее эффективны. [110]

Парниковые газы

Парниковые газы прозрачны для солнечного света и, таким образом, позволяют ему проходить через атмосферу и нагревать поверхность Земли. Земля излучает его в виде тепла , а парниковые газы поглощают его часть. Это поглощение замедляет скорость утечки тепла в космос, удерживая тепло у поверхности Земли и со временем нагревая его. [116]

Хотя водяной пар (≈50%) и облака (≈25%) вносят наибольший вклад в парниковый эффект, они в основном изменяются в зависимости от температуры и поэтому в основном считаются обратными связями , которые изменяют чувствительность климата . С другой стороны, концентрации таких газов, как CO 2 (≈20%), тропосферный озон , [117] ХФУ и закись азота добавляются или удаляются независимо от температуры и поэтому считаются внешними факторами, изменяющими глобальную температуру. [118]

До промышленной революции естественное количество парниковых газов приводило к тому, что воздух у поверхности был примерно на 33 °C теплее, чем он был бы в их отсутствие. [119] [120] Человеческая деятельность после промышленной революции, в основном добыча и сжигание ископаемого топлива ( уголь , нефть и природный газ ), [121] увеличило количество парниковых газов в атмосфере, что привело к радиационному дисбалансу . В 2019 году концентрации CO 2 и метана увеличились примерно на 48% и 160% соответственно с 1750 года. [122] Эти уровни CO 2 выше, чем когда-либо за последние 2 миллиона лет. Концентрации метана намного выше, чем они были за последние 800 000 лет. [123]

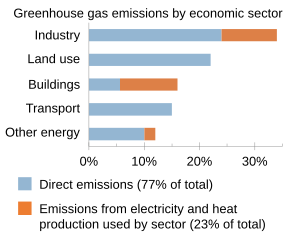

Глобальные антропогенные выбросы парниковых газов в 2019 году были эквивалентны 59 миллиардам тонн CO2 . Из этих выбросов 75% составили CO2 , 18% — метан , 4% — закись азота и 2% — фторированные газы . [124] Выбросы CO 2 в основном происходят в результате сжигания ископаемого топлива для обеспечения энергией транспорта , производства, отопления и электричества. [5] Дополнительные CO 2 выбросы происходят в результате вырубки лесов и промышленных процессов , в том числе CO 2, выделяемого в результате химических реакций при производстве цемента , стали , алюминия и удобрений . [125] [126] [127] [128] Выбросы метана происходят от животноводства , навоза, выращивания риса , свалок, сточных вод и добычи угля , а также добычи нефти и газа . [129] [130] Выбросы закиси азота в основном происходят в результате микробного разложения удобрений . [131] [132]

Хотя метан сохраняется в атмосфере в среднем 12 лет. [133] CO 2 сохраняется гораздо дольше. Поверхность Земли поглощает CO2 в рамках углеродного цикла . Хотя растения на суше и в океане поглощают большую часть избыточных выбросов CO 2 ежегодно , этот CO 2 возвращается в атмосферу при переваривании, сгорании или разложении биологического вещества. [134] на поверхности суши Процессы поглощения углерода , такие как фиксация углерода в почве и фотосинтез, удаляют около 29% годовых глобальных выбросов CO2 . [135] Океан поглотил от 20 до 30% выброшенного CO 2 за последние два десятилетия. [136] CO 2 удаляется из атмосферы только на длительный срок, когда он хранится в земной коре, и этот процесс может занять миллионы лет. [134]

Изменения поверхности суши

По данным Продовольственной и сельскохозяйственной организации , около 30% площади суши Земли в значительной степени непригодны для использования человеком ( ледники , пустыни и т. д.), 26% — леса , 10% — кустарники и 34% — сельскохозяйственные угодья . [138] Вырубка лесов является основным фактором изменения землепользования, способствующим глобальному потеплению. [139] поскольку разрушенные деревья выделяют CO 2 и не заменяются новыми деревьями, удаляя этот поглотитель углерода . [32] В период с 2001 по 2018 год 27% вырубки лесов произошло в результате постоянной вырубки, позволяющей расширить сельское хозяйство для выращивания сельскохозяйственных культур и животноводства. Еще 24% было потеряно из-за временных расчисток в рамках сменной сельскохозяйственной системы. 26% приходится на вырубку древесины и продуктов ее переработки, а на долю лесных пожаров приходится оставшиеся 23%. [140] Некоторые леса не были полностью вырублены, но уже подверглись деградации в результате этих воздействий. Восстановление этих лесов также восстанавливает их потенциал в качестве поглотителя углерода. [141]

Местный растительный покров влияет на то, сколько солнечного света отражается обратно в космос ( альбедо ) и сколько тепла теряется в результате испарения . Например, переход от темного леса к лугам делает поверхность светлее, заставляя ее отражать больше солнечного света. Вырубка лесов также может изменить выброс химических соединений, которые влияют на облака, а также изменить характер ветра. [142] В тропических и умеренных регионах конечным результатом будет значительное потепление, а восстановление лесов может привести к снижению местных температур. [141] На широтах ближе к полюсам наблюдается эффект охлаждения, поскольку лес заменяется заснеженными (и более отражающими свет) равнинами. [142] В глобальном масштабе это увеличение альбедо поверхности оказало доминирующее прямое влияние на температуру в результате изменения землепользования. Таким образом, изменение землепользования на сегодняшний день, по оценкам, будет иметь небольшой охлаждающий эффект. [143]

Другие факторы

Аэрозоли и облака

Загрязнение воздуха в виде аэрозолей влияние на климат . оказывает огромное [144] Аэрозоли рассеивают и поглощают солнечную радиацию. постепенное уменьшение количества солнечного света, достигающего поверхности Земли С 1961 по 1990 годы наблюдалось . Это явление широко известно как глобальное затемнение . [145] и в первую очередь связано с сульфатными аэрозолями, образующимися при сжигании ископаемого топлива с высокими концентрациями серы, такого как уголь и бункерное топливо . [60] Меньший вклад вносит черный углерод , органический углерод от сжигания ископаемого топлива и биотоплива, а также антропогенная пыль. [146] [59] [147] [148] [149] Во всем мире количество аэрозолей сокращается с 1990 года из-за контроля над загрязнением, а это означает, что они больше не маскируют в такой степени потепление парниковых газов. [150] [60]

Аэрозоли также оказывают косвенное воздействие на энергетический баланс Земли . Сульфатные аэрозоли действуют как ядра конденсации облаков и приводят к образованию облаков, в которых капель становится все больше и меньше. Эти облака отражают солнечную радиацию более эффективно, чем облака с меньшим количеством капель и более крупными. [151] Они также уменьшают рост капель дождя , что делает облака более отражающими падающий солнечный свет. [152] Косвенное воздействие аэрозолей представляет собой наибольшую неопределенность в радиационном воздействии . [153]

Хотя аэрозоли обычно ограничивают глобальное потепление, отражая солнечный свет, черный углерод в саже , падающей на снег или лед, может способствовать глобальному потеплению. Это не только увеличивает поглощение солнечного света, но также увеличивает таяние и повышение уровня моря. [154] Ограничение новых залежей черного углерода в Арктике может снизить глобальное потепление на 0,2 °C к 2050 году. [155] Эффект от снижения содержания серы в мазуте для судов с 2020 года [156] по оценкам, приведет к дополнительному повышению глобальной средней температуры на 0,05 °C к 2050 году. [157]

Солнечная и вулканическая активность

Поскольку Солнце является основным источником энергии Земли, изменения в поступающем солнечном свете напрямую влияют на климатическую систему . [153] Солнечное излучение измерялось непосредственно спутниками . [160] а косвенные измерения доступны с начала 1600-х годов. [153] С 1880 года не наблюдается тенденции к увеличению количества солнечной энергии, достигающей Земли, в отличие от потепления нижних слоев атмосферы ( тропосферы ). [161] Верхняя атмосфера ( стратосфера ) также нагревалась бы, если бы Солнце посылало на Землю больше энергии, но вместо этого она охлаждается. [109] Это согласуется с тем, что парниковые газы препятствуют выходу тепла из атмосферы Земли. [162]

Взрывные извержения вулканов могут выделять газы, пыль и пепел, которые частично блокируют солнечный свет и снижают температуру, или они могут выбрасывать в атмосферу водяной пар, который увеличивает количество парниковых газов и повышает температуру. [163] Такое воздействие на температуру длится всего несколько лет, поскольку водяной пар и вулканический материал имеют низкую стойкость в атмосфере. [164] вулканические CO 2 выбросы более устойчивы, но они эквивалентны менее чем 1% текущих выбросов CO 2, вызванных деятельностью человека . [165] Вулканическая активность по-прежнему представляет собой крупнейшее естественное воздействие (воздействие) на температуру в индустриальную эпоху. Тем не менее, как и другие природные факторы, оно оказало незначительное влияние на глобальные температурные тенденции со времен промышленной революции. [164]

Отзывы об изменении климата

Реакция климатической системы на первоначальное воздействие модифицируется обратными связями: увеличивается за счет «самоусиливающихся» или «положительных» обратных связей и снижается за счет «балансирующих» или «отрицательных» обратных связей . [167] Основными усиливающими обратными связями являются обратная связь водяного пара , обратная связь льда и альбедо и суммарный эффект облаков. [168] [169] Основным механизмом балансировки является радиационное охлаждение , поскольку поверхность Земли отдает больше тепла в космос в ответ на повышение температуры. [170] Помимо температурных обратных связей, в углеродном цикле существуют и обратные связи, такие как удобряющее воздействие CO 2 на рост растений. [171] Ожидается, что обратная связь будет иметь положительную тенденцию, поскольку выбросы парниковых газов продолжаются, что повышает чувствительность климата. [172]

Радиационная обратная связь — это физические процессы, которые влияют на скорость глобального потепления в ответ на потепление. Например, более теплый воздух может содержать больше влаги , а водяной пар сам по себе является мощным парниковым газом. [168] Более теплый воздух также может привести к тому, что облака станут выше и тоньше, выступая в качестве изолятора и согревая планету. [173] Другой важной обратной связью является уменьшение снежного покрова и морского льда в Арктике, что снижает отражательную способность земной поверхности и способствует усилению изменений температуры в Арктике . [174] [175] Усиление Арктики также приводит к таянию вечной мерзлоты метана и CO 2 . , что приводит к выбросу в атмосферу [176]

Около половины антропогенных выбросов CO2 поглощается наземными растениями и океанами. [177] Эта доля не является статичной, и если будущие выбросы CO 2 уменьшатся, Земля сможет поглотить примерно до 70%. Если они существенно увеличатся, он все равно будет поглощать больше углерода, чем сейчас, но общая доля снизится до уровня ниже 40%. [178] Это связано с тем, что изменение климата усиливает засухи и волны тепла, которые в конечном итоге подавляют рост растений на суше, а почвы будут выделять больше углерода из мертвых растений , когда они станут теплее . [179] [180] Скорость, с которой океаны поглощают атмосферный углерод, будет снижаться по мере того, как они станут более кислыми и будут испытывать изменения в термохалинной циркуляции и распределении фитопланктона . [181] [182] [89] Неопределенность в отношении обратной связи, особенно облачности, [183] Это основная причина, по которой разные климатические модели прогнозируют разные масштабы потепления для данного количества выбросов. [184]

Моделирование

Климатическая модель — это представление физических, химических и биологических процессов, влияющих на климатическую систему. [185] Модели включают естественные процессы, такие как изменения орбиты Земли, исторические изменения в активности Солнца и вулканическое воздействие. [186] Модели используются для оценки степени потепления, которое вызовут будущие выбросы, при учете силы климатических обратных связей . [187] [188] Модели также предсказывают циркуляцию океанов, годовой цикл времен года и потоки углерода между поверхностью суши и атмосферой. [189]

Физический реализм моделей проверяется путем проверки их способности имитировать современный или прошлый климат. [190] Предыдущие модели недооценивали темпы сокращения Арктики. [191] и недооценили скорость увеличения количества осадков. [192] Повышение уровня моря с 1990 года недооценивалось в старых моделях, но более поздние модели хорошо согласуются с наблюдениями. [193] В опубликованной в США в 2017 году Национальной оценке климата отмечается, что «климатические модели все еще могут недооценивать или отсутствовать соответствующие процессы обратной связи». [194] Кроме того, климатические модели могут оказаться неспособными адекватно предсказать краткосрочные региональные климатические сдвиги. [195]

Подмножество климатических моделей добавляют социальные факторы к физической модели климата. Эти модели моделируют, как население, экономический рост и использование энергии влияют на физический климат и взаимодействуют с ним. Обладая этой информацией, эти модели могут создавать сценарии будущих выбросов парниковых газов. Затем эти данные используются в качестве входных данных для моделей физического климата и моделей углеродного цикла, чтобы предсказать, как могут измениться концентрации парниковых газов в атмосфере. [196] [197] В зависимости от социально-экономического сценария и сценария смягчения последствий, модели дают концентрации CO 2 в атмосфере , которые варьируются в широком диапазоне от 380 до 1400 частей на миллион. [198]

Воздействие

Воздействие на окружающую среду

Экологические последствия изменения климата широки и далеко идущие, затрагивая океаны , лед и погоду. Изменения могут происходить постепенно или быстро. Доказательства этих эффектов получены в результате изучения изменения климата в прошлом, моделирования и современных наблюдений. [199] С 1950-х годов засухи и волны жары возникали одновременно все чаще. [200] Чрезвычайно влажные или засушливые явления в период дождей участились в Индии и Восточной Азии. [201] С 1980 года количество муссонных осадков в Северном полушарии увеличилось. [202] Интенсивность осадков и интенсивность ураганов и тайфунов, вероятно, увеличиваются . [203] а географический ареал, вероятно, расширится к полюсу в ответ на потепление климата. [204] Частота тропических циклонов не увеличилась в результате изменения климата. [205]

Глобальный уровень моря повышается в результате теплового расширения и таяния ледников и ледяных щитов . В период с 1993 по 2020 год рост со временем увеличивался, составив в среднем 3,3 ± 0,3 мм в год. [207] По прогнозам МГЭИК, в XXI веке повышение уровня моря составит 32–62 см при сценарии с низкими выбросами, 44–76 см – при промежуточном сценарии и 65–101 см – при сценарии очень высоких выбросов. [208] Процессы нестабильности морского ледникового покрова в Антарктиде могут существенно увеличить эти значения. [209] включая возможность повышения уровня моря на 2 метра к 2100 году в условиях высоких выбросов. [210]

Изменение климата привело к десятилетиям сокращения и истончения арктического морского льда . [211] Хотя ожидается, что безледное лето будет редким при потеплении на 1,5 °C, оно будет происходить раз в три-десять лет при уровне потепления на 2 °C. [212] CO 2 Более высокие концентрации в атмосфере приводят к растворению большего количества CO 2 в океанах, что делает их более кислыми . [213] Поскольку кислород менее растворим в более теплой воде, [214] его концентрации в океане уменьшаются , а мертвые зоны расширяются. [215]

Переломные моменты и долгосрочные последствия

Более высокая степень глобального потепления увеличивает риск прохождения « переломных точек » — пороговых значений, за которыми уже невозможно избежать некоторых серьезных последствий, даже если температуры вернутся к своему прежнему состоянию. [218] [219] Например, ледниковый щит Гренландии уже тает, но если глобальное потепление достигнет уровня от 1,7°C до 2,3°C, его таяние будет продолжаться до тех пор, пока он полностью не исчезнет. Если позже потепление снизится до 1,5 °C или меньше, оно все равно потеряет гораздо больше льда, чем если бы потеплению вообще не было позволено достичь порогового значения. [220] Хотя ледяные щиты будут таять в течение тысячелетий, другие переломные моменты наступят быстрее и оставят обществам меньше времени для реагирования. Коллапс основных океанских течений, таких как атлантическая меридиональная опрокидывающая циркуляция (AMOC), и необратимый ущерб ключевым экосистемам, таким как тропические леса Амазонки и коралловые рифы, могут произойти в течение нескольких десятилетий. [217]

Долгосрочные последствия изменения климата для океанов включают дальнейшее таяние льда, потепление океана , повышение уровня моря, закисление океана и обезвоживание океана. [221] Временные рамки долгосрочных воздействий составляют от столетий до тысячелетий из-за CO 2 в атмосфере. длительного существования [222] Когда чистые выбросы стабилизируются, температура приземного воздуха также стабилизируется, но океаны и ледяные шапки продолжат поглощать избыточное тепло из атмосферы. Результатом является предполагаемое общее повышение уровня моря на 2,3 метра на градус Цельсия (4,2 фута/°F) за 2000 лет. [223] океаном Поглощение CO 2 происходит достаточно медленно, поэтому закисление океана будет продолжаться в течение сотен и тысяч лет. [224] Глубокие океаны (ниже 2000 метров (6600 футов)) также уже потеряли более 10% растворенного кислорода в результате потепления, которое произошло к настоящему времени. [225] Кроме того, ледяной щит Западной Антарктики , похоже, подвержен практически необратимому таянию, что приведет к повышению уровня моря как минимум на 3,3 м (10 футов 10 дюймов) примерно за 2000 лет. [217] [226] [227]

Природа и дикая природа

Недавнее потепление заставило многие наземные и пресноводные виды переместиться к полюсу и подняться на большую высоту . [228] Например, за последние 55 лет ареал сотен североамериканских птиц сместился на север со средней скоростью 1,5 км/год. [229] Более высокие уровни CO 2 в атмосфере и удлиненный вегетационный период привели к глобальному озеленению. Однако волны тепла и засухи привели к снижению продуктивности экосистем в некоторых регионах. Будущий баланс этих противоположных эффектов неясен. [230] Родственным явлением, вызванным изменением климата, является вторжение древесных растений , затрагивающее до 500 миллионов гектаров во всем мире. [231] Изменение климата способствовало расширению более засушливых климатических зон, например, расширению пустынь в субтропиках . [232] Масштабы и скорость глобального потепления повышают вероятность резких изменений в экосистемах . [233] В целом ожидается, что изменение климата приведет к исчезновению многих видов. [234]

Океаны нагревались медленнее, чем земля, но растения и животные в океане мигрировали к более холодным полюсам быстрее, чем виды на суше. [235] Как и на суше, волны тепла в океане возникают чаще из-за изменения климата, нанося вред широкому спектру организмов, таких как кораллы, водоросли и морские птицы . [236] становится сложнее Из-за закисления океана морским кальцифицирующим организмам, таким как мидии , ракушки и кораллы, производить раковины и скелеты ; а волны тепла обесцвечили коралловые рифы . [237] Вредное цветение водорослей, усиленное изменением климата и эвтрофикацией, снижает уровень кислорода, разрушает пищевые сети и приводит к огромным потерям морской жизни. [238] Прибрежные экосистемы находятся под особым стрессом. Почти половина водно-болотных угодий мира исчезла из-за изменения климата и других антропогенных воздействий. [239] Растения подверглись повышенному стрессу от повреждений насекомыми. [240]

|

Люди

Последствия изменения климата влияют на людей во всем мире. [246] Воздействия можно наблюдать на всех континентах и в регионах океана. [247] низкоширотные, менее развитые районы . при этом наибольшему риску подвергаются [248] Продолжающееся потепление потенциально может иметь «серьезные, всеобъемлющие и необратимые последствия» для людей и экосистем. [249] Риски распределены неравномерно, но, как правило, они выше для обездоленных людей в развивающихся и развитых странах. [250]

Еда и здоровье

Всемирная организация здравоохранения (ВОЗ) называет изменение климата величайшей угрозой глобальному здоровью в 21 веке. [251] Экстремальные погодные условия приводят к травмам и гибели людей. [252] различные инфекционные заболевания В более теплом климате легче передаются , такие как лихорадка денге и малярия . [253] Неурожаи могут привести к нехватке продовольствия и недоеданию , особенно от этого страдают дети . [254] И дети, и пожилые люди уязвимы к сильной жаре. [255] По оценкам ВОЗ, в период с 2030 по 2050 год изменение климата будет вызывать около 250 000 дополнительных смертей в год. Они оценили смертность от воздействия жары среди пожилых людей, рост заболеваемости диареей , малярией, лихорадкой денге, прибрежными наводнениями и недоеданием среди детей. [256] К 2100 году от 50% до 75% населения планеты могут столкнуться с климатическими условиями, опасными для жизни из-за комбинированного воздействия сильной жары и влажности. [257]

Изменение климата влияет на продовольственную безопасность . Это привело к снижению мировых урожаев кукурузы, пшеницы и соевых бобов в период с 1981 по 2010 год. [258] Будущее потепление может еще больше снизить глобальную урожайность основных сельскохозяйственных культур. [259] На растениеводство, вероятно, окажет негативное влияние в странах низких широт, тогда как последствия в северных широтах могут быть положительными или отрицательными. [260] Еще до 183 миллионов человек во всем мире, особенно люди с более низкими доходами, подвергаются риску голода в результате этих воздействий. [261] Изменение климата также влияет на популяцию рыб. В глобальном масштабе для вылова будет меньше ресурсов. [262] Регионы, зависящие от ледниковой воды, уже засушливые регионы и небольшие острова подвержены более высокому риску водного дефицита из-за изменения климата. [263]

Средства к существованию и неравенство

Экономический ущерб из-за изменения климата может быть серьезным, и существует вероятность катастрофических последствий. [264] Серьезные последствия ожидаются в Юго-Восточной Азии и странах Африки к югу от Сахары , где большинство местного населения зависит от природных и сельскохозяйственных ресурсов. [265] [266] Тепловой стресс может помешать работникам на открытом воздухе работать. Если потепление достигнет 4 °C, то производительность труда в этих регионах может сократиться на 30–50%. [267] По оценкам Всемирного банка , в период с 2016 по 2030 год изменение климата может привести к крайней нищете более 120 миллионов человек без адаптации. [268]

Неравенство, основанное на богатстве и социальном статусе, усугубилось из-за изменения климата. [269] С серьезными трудностями в смягчении последствий климатических потрясений, адаптации к ним и восстановлении после них сталкиваются маргинализированные люди, у которых меньше контроля над ресурсами. [270] [265] Коренные народы , живущие за счет своей земли и экосистем, столкнутся с угрозой для своего здоровья и образа жизни из-за изменения климата. [271] Экспертное заключение пришло к выводу, что роль изменения климата в вооруженном конфликте невелика по сравнению с такими факторами, как социально-экономическое неравенство и возможности государства. [272]

Хотя женщины по своей природе не подвергаются большему риску изменения климата и потрясений, ограничения женских ресурсов и дискриминационные гендерные нормы ограничивают их адаптационные способности и устойчивость. [273] Например, во время климатических потрясений, таких как тепловой стресс, рабочая нагрузка женщин, включая часы, отработанные в сельском хозяйстве, снижается меньше, чем у мужчин. [273]

Климатическая миграция

Низколежащим островам и прибрежным населенным пунктам угрожает повышение уровня моря, что делает наводнения в городах более частыми. Иногда земля навсегда теряется в море. [274] Это может привести к безгражданству жителей островных государств, таких как Мальдивы и Тувалу . [275] В некоторых регионах повышение температуры и влажности может оказаться слишком сильным, чтобы люди могли к нему адаптироваться. [276] Модели прогнозируют, что при наихудшем сценарии изменения климата почти треть человечества может жить в непригодном для жизни и чрезвычайно жарком климате, подобном Сахаре. [277]

Эти факторы могут стимулировать климатическую или экологическую миграцию внутри стран и между ними. [13] Ожидается, что больше людей будут перемещены из-за повышения уровня моря, экстремальных погодных условий и конфликтов из-за усиления конкуренции за природные ресурсы. Изменение климата может также повысить уязвимость, что приведет к появлению «попавшего в ловушку населения», которое не сможет передвигаться из-за нехватки ресурсов. [278]

|

Сокращение и улавливание выбросов

Изменение климата можно смягчить за счет снижения скорости выбросов парниковых газов в атмосферу и увеличения скорости удаления углекислого газа из атмосферы. [284] Чтобы ограничить глобальное потепление уровнем ниже 1,5 °C, глобальные выбросы парниковых газов должны стать нулевыми к 2050 году или к 2070 году с целью в 2 °C. [102] Это требует далеко идущих, системных изменений беспрецедентного масштаба в энергетике, земле, городах, транспорте, зданиях и промышленности. [285]

, По оценкам Программы ООН по окружающей среде странам необходимо утроить свои обязательства по Парижскому соглашению в течение следующего десятилетия, чтобы ограничить глобальное потепление 2 °C. Для достижения цели в 1,5 °C необходим еще больший уровень снижения. [286] Учитывая обязательства, взятые в рамках Парижского соглашения в октябре 2021 года, глобальное потепление с вероятностью 66% все равно достигнет примерно 2,7 °C (диапазон: 2,2–3,2 °C) к концу столетия. [24] В глобальном масштабе ограничение потепления 2 °C может привести к более высоким экономическим выгодам, чем экономическим затратам. [287]

Хотя не существует единого способа ограничить глобальное потепление 1,5 или 2 °C, [288] Большинство сценариев и стратегий предусматривают значительное увеличение использования возобновляемых источников энергии в сочетании с усилением мер по повышению энергоэффективности для обеспечения необходимого сокращения выбросов парниковых газов. [289] Чтобы уменьшить нагрузку на экосистемы и повысить их способность связывать углерод, изменения также потребуются в сельском и лесном хозяйстве. [290] такие как предотвращение вырубки лесов и восстановление природных экосистем путем лесовосстановления . [291]

Другие подходы к смягчению последствий изменения климата имеют более высокий уровень риска. Сценарии, которые ограничивают глобальное потепление до 1,5 °C, обычно предполагают широкомасштабное использование методов удаления углекислого газа в XXI веке. [292] Однако существуют опасения по поводу чрезмерной зависимости от этих технологий и воздействия на окружающую среду. [293] Модификация солнечной радиации (SRM) также является возможным дополнением к значительному сокращению выбросов. Однако SRM вызывает серьезные этические и юридические проблемы, а риски не до конца понятны. [294]

Чистая энергия

Возобновляемая энергия является ключом к ограничению изменения климата. [296] На протяжении десятилетий ископаемое топливо составляло примерно 80% мирового потребления энергии. [297] Оставшаяся доля была поделена между ядерной энергетикой и возобновляемыми источниками энергии (включая гидроэнергетику , биоэнергетику , ветровую и солнечную энергию, а также геотермальную энергию ). [298] Ожидается, что использование ископаемого топлива достигнет пика в абсолютном выражении до 2030 года, а затем снизится, причем наиболее резко сократится использование угля. [299] Возобновляемые источники энергии составили 75% всей новой генерации электроэнергии, установленной в 2019 году, почти полностью солнечной и ветровой. [300] Другие формы чистой энергии, такие как атомная и гидроэнергетика, в настоящее время занимают большую долю в энергоснабжении. Однако их прогнозы будущего роста кажутся ограниченными по сравнению с ними. [301]

Хотя солнечные панели и береговая ветроэнергетика в настоящее время являются одними из самых дешевых форм добавления новых мощностей по производству электроэнергии во многих местах, [302] Политика «зеленой» энергетики необходима для достижения быстрого перехода от ископаемого топлива к возобновляемым источникам энергии. [303] Для достижения углеродной нейтральности к 2050 году возобновляемые источники энергии должны стать доминирующей формой производства электроэнергии, а к 2050 году в некоторых сценариях их доля увеличится до 85% или более. К 2050 году инвестиции в уголь будут прекращены, а использование угля практически прекращено. [304] [305]

Электроэнергия, вырабатываемая из возобновляемых источников, также должна будет стать основным источником энергии для отопления и транспорта. [306] Транспорт может перейти от автомобилей с двигателями внутреннего сгорания к электромобилям , общественному транспорту и активному транспорту (езде на велосипеде и пешим прогулкам). [307] [308] Для судоходства и полетов низкоуглеродное топливо позволит сократить выбросы. [307] Отопление можно было бы все больше декарбонизировать с помощью таких технологий, как тепловые насосы . [309]

There are obstacles to the continued rapid growth of clean energy, including renewables. For wind and solar, there are environmental and land use concerns for new projects.[310] Wind and solar also produce energy intermittently and with seasonal variability. Traditionally, hydro dams with reservoirs and conventional power plants have been used when variable energy production is low. Going forward, battery storage can be expanded, energy demand and supply can be matched, and long-distance transmission can smooth variability of renewable outputs.[296] Bioenergy is often not carbon-neutral and may have negative consequences for food security.[311] The growth of nuclear power is constrained by controversy around radioactive waste, nuclear weapon proliferation, and accidents.[312][313] Hydropower growth is limited by the fact that the best sites have been developed, and new projects are confronting increased social and environmental concerns.[314]

Low-carbon energy improves human health by minimising climate change as well as reducing air pollution deaths,[315] which were estimated at 7 million annually in 2016.[316] Meeting the Paris Agreement goals that limit warming to a 2 °C increase could save about a million of those lives per year by 2050, whereas limiting global warming to 1.5 °C could save millions and simultaneously increase energy security and reduce poverty.[317] Improving air quality also has economic benefits which may be larger than mitigation costs.[318]

Energy conservation

Reducing energy demand is another major aspect of reducing emissions.[319] If less energy is needed, there is more flexibility for clean energy development. It also makes it easier to manage the electricity grid, and minimises carbon-intensive infrastructure development.[320] Major increases in energy efficiency investment will be required to achieve climate goals, comparable to the level of investment in renewable energy.[321] Several COVID-19 related changes in energy use patterns, energy efficiency investments, and funding have made forecasts for this decade more difficult and uncertain.[322]

Strategies to reduce energy demand vary by sector. In the transport sector, passengers and freight can switch to more efficient travel modes, such as buses and trains, or use electric vehicles.[323] Industrial strategies to reduce energy demand include improving heating systems and motors, designing less energy-intensive products, and increasing product lifetimes.[324] In the building sector the focus is on better design of new buildings, and higher levels of energy efficiency in retrofitting.[325] The use of technologies like heat pumps can also increase building energy efficiency.[326]

Agriculture and industry

Agriculture and forestry face a triple challenge of limiting greenhouse gas emissions, preventing the further conversion of forests to agricultural land, and meeting increases in world food demand.[327] A set of actions could reduce agriculture and forestry-based emissions by two thirds from 2010 levels. These include reducing growth in demand for food and other agricultural products, increasing land productivity, protecting and restoring forests, and reducing greenhouse gas emissions from agricultural production.[328]

On the demand side, a key component of reducing emissions is shifting people towards plant-based diets.[329] Eliminating the production of livestock for meat and dairy would eliminate about 3/4ths of all emissions from agriculture and other land use.[330] Livestock also occupy 37% of ice-free land area on Earth and consume feed from the 12% of land area used for crops, driving deforestation and land degradation.[331]

Steel and cement production are responsible for about 13% of industrial CO2 emissions. In these industries, carbon-intensive materials such as coke and lime play an integral role in the production, so that reducing CO2 emissions requires research into alternative chemistries.[332]

Carbon sequestration

Natural carbon sinks can be enhanced to sequester significantly larger amounts of CO2 beyond naturally occurring levels.[333] Reforestation and afforestation (planting forests where there were none before) are among the most mature sequestration techniques, although the latter raises food security concerns.[334] Farmers can promote sequestration of carbon in soils through practices such as use of winter cover crops, reducing the intensity and frequency of tillage, and using compost and manure as soil amendments.[335] Forest and landscape restoration yields many benefits for the climate, including greenhouse gas emissions sequestration and reduction.[141] Restoration/recreation of coastal wetlands, prairie plots and seagrass meadows increases the uptake of carbon into organic matter.[336][337] When carbon is sequestered in soils and in organic matter such as trees, there is a risk of the carbon being re-released into the atmosphere later through changes in land use, fire, or other changes in ecosystems.[338]

Where energy production or CO2-intensive heavy industries continue to produce waste CO2, the gas can be captured and stored instead of released to the atmosphere. Although its current use is limited in scale and expensive,[339] carbon capture and storage (CCS) may be able to play a significant role in limiting CO2 emissions by mid-century.[340] This technique, in combination with bioenergy (BECCS) can result in net negative emissions as CO2 is drawn from the atmosphere.[341] It remains highly uncertain whether carbon dioxide removal techniques will be able to play a large role in limiting warming to 1.5 °C. Policy decisions that rely on carbon dioxide removal increase the risk of global warming rising beyond international goals.[342]

Adaptation

Adaptation is "the process of adjustment to current or expected changes in climate and its effects".[343]: 5 Without additional mitigation, adaptation cannot avert the risk of "severe, widespread and irreversible" impacts.[344] More severe climate change requires more transformative adaptation, which can be prohibitively expensive.[345] The capacity and potential for humans to adapt is unevenly distributed across different regions and populations, and developing countries generally have less.[346] The first two decades of the 21st century saw an increase in adaptive capacity in most low- and middle-income countries with improved access to basic sanitation and electricity, but progress is slow. Many countries have implemented adaptation policies. However, there is a considerable gap between necessary and available finance.[347]

Adaptation to sea level rise consists of avoiding at-risk areas, learning to live with increased flooding, and building flood controls. If that fails, managed retreat may be needed.[348] There are economic barriers for tackling dangerous heat impact. Avoiding strenuous work or having air conditioning is not possible for everybody.[349] In agriculture, adaptation options include a switch to more sustainable diets, diversification, erosion control, and genetic improvements for increased tolerance to a changing climate.[350] Insurance allows for risk-sharing, but is often difficult to get for people on lower incomes.[351] Education, migration and early warning systems can reduce climate vulnerability.[352] Planting mangroves or encouraging other coastal vegetation can buffer storms.[353][354]

Ecosystems adapt to climate change, a process that can be supported by human intervention. By increasing connectivity between ecosystems, species can migrate to more favourable climate conditions. Species can also be introduced to areas acquiring a favorable climate. Protection and restoration of natural and semi-natural areas helps build resilience, making it easier for ecosystems to adapt. Many of the actions that promote adaptation in ecosystems, also help humans adapt via ecosystem-based adaptation. For instance, restoration of natural fire regimes makes catastrophic fires less likely, and reduces human exposure. Giving rivers more space allows for more water storage in the natural system, reducing flood risk. Restored forest acts as a carbon sink, but planting trees in unsuitable regions can exacerbate climate impacts.[355]

There are synergies but also trade-offs between adaptation and mitigation.[356] An example for synergy is increased food productivity, which has large benefits for both adaptation and mitigation.[357] An example of a trade-off is that increased use of air conditioning allows people to better cope with heat, but increases energy demand. Another trade-off example is that more compact urban development may reduce emissions from transport and construction, but may also increase the urban heat island effect, exposing people to heat-related health risks.[358]

|

Policies and politics

| High | Medium | Low | Very low |

Countries that are most vulnerable to climate change have typically been responsible for a small share of global emissions. This raises questions about justice and fairness.[359] Limiting global warming makes it much easier to achieve the UN's Sustainable Development Goals, such as eradicating poverty and reducing inequalities. The connection is recognised in Sustainable Development Goal 13 which is to "take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts".[360] The goals on food, clean water and ecosystem protection have synergies with climate mitigation.[361]

The geopolitics of climate change is complex. It has often been framed as a free-rider problem, in which all countries benefit from mitigation done by other countries, but individual countries would lose from switching to a low-carbon economy themselves. Sometimes mitigation also has localised benefits though. For instance, the benefits of a coal phase-out to public health and local environments exceed the costs in almost all regions.[362] Furthermore, net importers of fossil fuels win economically from switching to clean energy, causing net exporters to face stranded assets: fossil fuels they cannot sell.[363]

Policy options

A wide range of policies, regulations, and laws are being used to reduce emissions. As of 2019, carbon pricing covers about 20% of global greenhouse gas emissions.[364] Carbon can be priced with carbon taxes and emissions trading systems.[365] Direct global fossil fuel subsidies reached $319 billion in 2017, and $5.2 trillion when indirect costs such as air pollution are priced in.[366] Ending these can cause a 28% reduction in global carbon emissions and a 46% reduction in air pollution deaths.[367] Money saved on fossil subsidies could be used to support the transition to clean energy instead.[368] More direct methods to reduce greenhouse gases include vehicle efficiency standards, renewable fuel standards, and air pollution regulations on heavy industry.[369] Several countries require utilities to increase the share of renewables in power production.[370]

Climate justice

Policy designed through the lens of climate justice tries to address human rights issues and social inequality. According to proponents of climate justice, the costs of climate adaptation should be paid by those most responsible for climate change, while the beneficiaries of payments should be those suffering impacts. One way this can be addressed in practice is to have wealthy nations pay poorer countries to adapt.[371]

Oxfam found that in 2023 the wealthiest 10% of people were responsible for 50% of global emissions, while the bottom 50% were responsible for just 8%.[372] Production of emissions is another way to look at responsibility: under that approach, the top 21 fossil fuel companies would owe cumulative climate reparations of $5.4 trillion over the period 2025–2050.[373] To achieve a just transition, people working in the fossil fuel sector would also need other jobs, and their communities would need investments.[374]

International climate agreements

Nearly all countries in the world are parties to the 1994 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).[376] The goal of the UNFCCC is to prevent dangerous human interference with the climate system.[377] As stated in the convention, this requires that greenhouse gas concentrations are stabilised in the atmosphere at a level where ecosystems can adapt naturally to climate change, food production is not threatened, and economic development can be sustained.[378] The UNFCCC does not itself restrict emissions but rather provides a framework for protocols that do. Global emissions have risen since the UNFCCC was signed.[379] Its yearly conferences are the stage of global negotiations.[380]

The 1997 Kyoto Protocol extended the UNFCCC and included legally binding commitments for most developed countries to limit their emissions.[381] During the negotiations, the G77 (representing developing countries) pushed for a mandate requiring developed countries to "[take] the lead" in reducing their emissions,[382] since developed countries contributed most to the accumulation of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. Per-capita emissions were also still relatively low in developing countries and developing countries would need to emit more to meet their development needs.[383]

The 2009 Copenhagen Accord has been widely portrayed as disappointing because of its low goals, and was rejected by poorer nations including the G77.[384] Associated parties aimed to limit the global temperature rise to below 2 °C.[385] The Accord set the goal of sending $100 billion per year to developing countries for mitigation and adaptation by 2020, and proposed the founding of the Green Climate Fund.[386] As of 2020[update], only 83.3 billion were delivered. Only in 2023 the target is expected to be achieved.[387]

In 2015 all UN countries negotiated the Paris Agreement, which aims to keep global warming well below 2.0 °C and contains an aspirational goal of keeping warming under 1.5 °C.[388] The agreement replaced the Kyoto Protocol. Unlike Kyoto, no binding emission targets were set in the Paris Agreement. Instead, a set of procedures was made binding. Countries have to regularly set ever more ambitious goals and reevaluate these goals every five years.[389] The Paris Agreement restated that developing countries must be financially supported.[390] As of October 2021[update], 194 states and the European Union have signed the treaty and 191 states and the EU have ratified or acceded to the agreement.[391]

The 1987 Montreal Protocol, an international agreement to stop emitting ozone-depleting gases, may have been more effective at curbing greenhouse gas emissions than the Kyoto Protocol specifically designed to do so.[392] The 2016 Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol aims to reduce the emissions of hydrofluorocarbons, a group of powerful greenhouse gases which served as a replacement for banned ozone-depleting gases. This made the Montreal Protocol a stronger agreement against climate change.[393]

National responses

In 2019, the United Kingdom parliament became the first national government to declare a climate emergency.[394] Other countries and jurisdictions followed suit.[395] That same year, the European Parliament declared a "climate and environmental emergency".[396] The European Commission presented its European Green Deal with the goal of making the EU carbon-neutral by 2050.[397] In 2021, the European Commission released its "Fit for 55" legislation package, which contains guidelines for the car industry; all new cars on the European market must be zero-emission vehicles from 2035.[398]

Major countries in Asia have made similar pledges: South Korea and Japan have committed to become carbon-neutral by 2050, and China by 2060.[399] While India has strong incentives for renewables, it also plans a significant expansion of coal in the country.[400] Vietnam is among very few coal-dependent, fast-developing countries that pledged to phase out unabated coal power by the 2040s or as soon as possible thereafter.[401]

As of 2021, based on information from 48 national climate plans, which represent 40% of the parties to the Paris Agreement, estimated total greenhouse gas emissions will be 0.5% lower compared to 2010 levels, below the 45% or 25% reduction goals to limit global warming to 1.5 °C or 2 °C, respectively.[402]

Society

Denial and misinformation

Public debate about climate change has been strongly affected by climate change denial and misinformation, which originated in the United States and has since spread to other countries, particularly Canada and Australia. Climate change denial has originated from fossil fuel companies, industry groups, conservative think tanks, and contrarian scientists.[404] Like the tobacco industry, the main strategy of these groups has been to manufacture doubt about climate-change related scientific data and results.[405] People who hold unwarranted doubt about climate change are called climate change "skeptics", although "contrarians" or "deniers" are more appropriate terms.[406]

There are different variants of climate denial: some deny that warming takes place at all, some acknowledge warming but attribute it to natural influences, and some minimise the negative impacts of climate change.[407] Manufacturing uncertainty about the science later developed into a manufactured controversy: creating the belief that there is significant uncertainty about climate change within the scientific community in order to delay policy changes.[408] Strategies to promote these ideas include criticism of scientific institutions,[409] and questioning the motives of individual scientists.[407] An echo chamber of climate-denying blogs and media has further fomented misunderstanding of climate change.[410]

Public awareness and opinion

Climate change came to international public attention in the late 1980s.[414] Due to media coverage in the early 1990s, people often confused climate change with other environmental issues like ozone depletion.[415] In popular culture, the climate fiction movie The Day After Tomorrow (2004) and the Al Gore documentary An Inconvenient Truth (2006) focused on climate change.[414]

Significant regional, gender, age and political differences exist in both public concern for, and understanding of, climate change. More highly educated people, and in some countries, women and younger people, were more likely to see climate change as a serious threat.[416] Partisan gaps also exist in many countries,[417] and countries with high CO2 emissions tend to be less concerned.[418] Views on causes of climate change vary widely between countries.[419] Concern has increased over time,[417] to the point where in 2021 a majority of citizens in many countries express a high level of worry about climate change, or view it as a global emergency.[420] Higher levels of worry are associated with stronger public support for policies that address climate change.[421]

Climate movement

Climate protests demand that political leaders take action to prevent climate change. They can take the form of public demonstrations, fossil fuel divestment, lawsuits and other activities.[422] Prominent demonstrations include the School Strike for Climate. In this initiative, young people across the globe have been protesting since 2018 by skipping school on Fridays, inspired by Swedish teenager Greta Thunberg.[423] Mass civil disobedience actions by groups like Extinction Rebellion have protested by disrupting roads and public transport.[424]

Litigation is increasingly used as a tool to strengthen climate action from public institutions and companies. Activists also initiate lawsuits which target governments and demand that they take ambitious action or enforce existing laws on climate change.[425] Lawsuits against fossil-fuel companies generally seek compensation for loss and damage.[426]

History

Early discoveries

Scientists in the 19th century such as Alexander von Humboldt began to foresee the effects of climate change.[428][429][430][431] In the 1820s, Joseph Fourier proposed the greenhouse effect to explain why Earth's temperature was higher than the Sun's energy alone could explain. Earth's atmosphere is transparent to sunlight, so sunlight reaches the surface where it is converted to heat. However, the atmosphere is not transparent to heat radiating from the surface, and captures some of that heat, which in turn warms the planet.[432]

In 1856 Eunice Newton Foote demonstrated that the warming effect of the Sun is greater for air with water vapour than for dry air, and that the effect is even greater with carbon dioxide (CO2). She concluded that "An atmosphere of that gas would give to our earth a high temperature..."[433][434]

Starting in 1859,[435] John Tyndall established that nitrogen and oxygen—together totaling 99% of dry air—are transparent to radiated heat. However, water vapour and gases such as methane and carbon dioxide absorb radiated heat and re-radiate that heat into the atmosphere. Tyndall proposed that changes in the concentrations of these gases may have caused climatic changes in the past, including ice ages.[436]

Svante Arrhenius noted that water vapour in air continuously varied, but the CO2 concentration in air was influenced by long-term geological processes. Warming from increased CO2 levels would increase the amount of water vapour, amplifying warming in a positive feedback loop. In 1896, he published the first climate model of its kind, projecting that halving CO2 levels could have produced a drop in temperature initiating an ice age. Arrhenius calculated the temperature increase expected from doubling CO2 to be around 5–6 °C.[437] Other scientists were initially skeptical and believed that the greenhouse effect was saturated so that adding more CO2 would make no difference, and that the climate would be self-regulating.[438] Beginning in 1938, Guy Stewart Callendar published evidence that climate was warming and CO2 levels were rising,[439] but his calculations met the same objections.[438]

Development of a scientific consensus

In the 1950s, Gilbert Plass created a detailed computer model that included different atmospheric layers and the infrared spectrum. This model predicted that increasing CO2 levels would cause warming. Around the same time, Hans Suess found evidence that CO2 levels had been rising, and Roger Revelle showed that the oceans would not absorb the increase. The two scientists subsequently helped Charles Keeling to begin a record of continued increase, which has been termed the "Keeling Curve".[438] Scientists alerted the public,[444] and the dangers were highlighted at James Hansen's 1988 Congressional testimony.[40] The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), set up in 1988 to provide formal advice to the world's governments, spurred interdisciplinary research.[445] As part of the IPCC reports, scientists assess the scientific discussion that takes place in peer-reviewed journal articles.[446]

There is a near-complete scientific consensus that the climate is warming and that this is caused by human activities. As of 2019, agreement in recent literature reached over 99%.[441][442] No scientific body of national or international standing disagrees with this view.[447] Consensus has further developed that some form of action should be taken to protect people against the impacts of climate change. National science academies have called on world leaders to cut global emissions.[448] The 2021 IPCC Assessment Report stated that it is "unequivocal" that climate change is caused by humans.[442]

See also

Climate change portal

Climate change portal- Anthropocene – proposed geological time interval in which humans are having significant geological impact

- List of climate scientists

References

- ^ "GISS Surface Temperature Analysis (v4)". NASA. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- ^ IPCC AR6 WG1 2021, SPM-7

- ^ IPCC SR15 Ch1 2018, p. 54: "These global-level rates of human-driven change far exceed the rates of change driven by geophysical or biosphere forces that have altered the Earth System trajectory in the past (e.g., Summerhayes, 2015; Foster et al., 2017); even abrupt geophysical events do not approach current rates of human-driven change."

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lynas, Mark; Houlton, Benjamin Z.; Perry, Simon (19 October 2021). "Greater than 99% consensus on human caused climate change in the peer-reviewed scientific literature". Environmental Research Letters. 16 (11): 114005. Bibcode:2021ERL....16k4005L. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ac2966. ISSN 1748-9326. S2CID 239032360.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Our World in Data, 18 September 2020

- ^ IPCC AR6 WG1 Technical Summary 2021, p. 67: "Concentrations of CO2, methane (CH4), and nitrous oxide (N2O) have increased to levels unprecedented in at least 800,000 years, and there is high confidence that current CO2 concentrations have not been experienced for at least 2 million years."

- ^ IPCC SRCCL 2019, p. 7: "Since the pre-industrial period, the land surface air temperature has risen nearly twice as much as the global average temperature (high confidence). Climate change... contributed to desertification and land degradation in many regions (high confidence)."

- ^ IPCC SRCCL 2019, p. 45: "Climate change is playing an increasing role in determining wildfire regimes alongside human activity (medium confidence), with future climate variability expected to enhance the risk and severity of wildfires in many biomes such as tropical rainforests (high confidence)."

- ^ IPCC SROCC 2019, p. 16: "Over the last decades, global warming has led to widespread shrinking of the cryosphere, with mass loss from ice sheets and glaciers (very high confidence), reductions in snow cover (high confidence) and Arctic sea ice extent and thickness (very high confidence), and increased permafrost temperature (very high confidence)."

- ^ IPCC AR6 WG1 Ch11 2021, p. 1517

- ^ EPA (19 January 2017). "Climate Impacts on Ecosystems". Archived from the original on 27 January 2018. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

Mountain and arctic ecosystems and species are particularly sensitive to climate change... As ocean temperatures warm and the acidity of the ocean increases, bleaching and coral die-offs are likely to become more frequent.

- ^ IPCC SR15 Ch1 2018, p. 64: "Sustained net zero anthropogenic emissions of CO2 and declining net anthropogenic non-CO2 radiative forcing over a multi-decade period would halt anthropogenic global warming over that period, although it would not halt sea level rise or many other aspects of climate system adjustment."

- ^ Jump up to: a b Cattaneo et al. 2019; IPCC AR6 WG2 2022, pp. 15, 53

- ^ [1]

- ^ IPCC AR6 WG2 2022, p. 19

- ^ IPCC AR6 WG2 2022, pp. 21–26, 2504

- ^ IPCC AR6 SYR SPM 2023, pp. 8–9: "Effectiveness15 of adaptation in reducing climate risks16 is documented for specific contexts, sectors and regions (high confidence)...Soft limits to adaptation are currently being experienced by small-scale farmers and households along some low-lying coastal areas (medium confidence) resulting from financial, governance, institutional and policy constraints (high confidence). Some tropical, coastal, polar and mountain ecosystems have reached hard adaptation limits (high confidence). Adaptation does not prevent all losses and damages, even with effective adaptation and before reaching soft and hard limits (high confidence)."

- ^ Tietjen, Bethany (2 November 2022). "Loss and damage: Who is responsible when climate change harms the world's poorest countries?". The Conversation. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ^ "Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability". IPCC. 27 February 2022. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ^ Ivanova, Irina (2 June 2022). "California is rationing water amid its worst drought in 1,200 years". CBS News.

- ^ Poyntin, Mark; Rivault, Erwan (10 January 2024). "2023 confirmed as world's hottest year on record". BBC. Retrieved 13 January 2024.

- ^ "Human, economic, environmental toll of climate change on the rise: WMO | UN News". news.un.org. 21 April 2023. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ IPCC AR6 WG1 Technical Summary 2021, p. 71

- ^ Jump up to: a b c United Nations Environment Programme 2021, p. 36: "A continuation of the effort implied by the latest unconditional NDCs and announced pledges is at present estimated to result in warming of about 2.7 °C (range: 2.2–3.2 °C) with a 66 per cent chance."

- ^ IPCC SR15 Ch2 2018, pp. 95–96: "In model pathways with no or limited overshoot of 1.5 °C, global net anthropogenic CO2 emissions decline by about 45% from 2010 levels by 2030 (40–60% interquartile range), reaching net zero around 2050 (2045–2055 interquartile range)"

- ^ IPCC SR15 2018, p. 17, SPM C.3: "All pathways that limit global warming to 1.5 °C with limited or no overshoot project the use of carbon dioxide removal (CDR) on the order of 100–1000 GtCO2 over the 21st century. CDR would be used to compensate for residual emissions and, in most cases, achieve net negative emissions to return global warming to 1.5 °C following a peak (high confidence). CDR deployment of several hundreds of GtCO2 is subject to multiple feasibility and sustainability constraints (high confidence)."

- ^ Rogelj et al. 2015

- ^ Hilaire et al. 2019

- ^ IPCC AR5 WG3 Annex III 2014, p. 1335

- ^ IPCC AR6 WG3 2022, pp. 24–25, 89

- ^ IPCC AR6 WG3 2022, p. 84: "Stringent emissions reductions at the level required for 2°C or 1.5°C are achieved through the increased electrification of buildings, transport, and industry, consequently all pathways entail increased electricity generation (high confidence)."

- ^ Jump up to: a b IPCC SRCCL Summary for Policymakers 2019, p. 18

- ^ IPCC AR6 WG3 2022, pp. 24–25, 114

- ^ Jump up to: a b NASA, 5 December 2008.

- ^ NASA, 7 July 2020

- ^ Shaftel 2016: " 'Climate change' and 'global warming' are often used interchangeably but have distinct meanings. ... Global warming refers to the upward temperature trend across the entire Earth since the early 20th century ... Climate change refers to a broad range of global phenomena ...[which] include the increased temperature trends described by global warming."

- ^ Associated Press, 22 September 2015: "The terms global warming and climate change can be used interchangeably. Climate change is more accurate scientifically to describe the various effects of greenhouse gases on the world because it includes extreme weather, storms and changes in rainfall patterns, ocean acidification and sea level.".

- ^ IPCC AR5 SYR Glossary 2014, p. 120: "Climate change refers to a change in the state of the climate that can be identified (e.g., by using statistical tests) by changes in the mean and/or the variability of its properties and that persists for an extended period, typically decades or longer. Climate change may be due to natural internal processes or external forcings such as modulations of the solar cycles, volcanic eruptions and persistent anthropogenic changes in the composition of the atmosphere or in land use."

- ^ Broeker, Wallace S. (8 August 1975). "Climatic Change: Are We on the Brink of a Pronounced Global Warming?". Science. 189 (4201): 460–463. Bibcode:1975Sci...189..460B. doi:10.1126/science.189.4201.460. JSTOR 1740491. PMID 17781884. S2CID 16702835.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Weart "The Public and Climate Change: The Summer of 1988", "News reporters gave only a little attention ...".

- ^ Joo et al. 2015.

- ^ Hodder & Martin 2009

- ^ BBC Science Focus Magazine, 3 February 2020

- ^ Neukom et al. 2019b.

- ^ "Global Annual Mean Surface Air Temperature Change". NASA. Retrieved 23 February 2020.

- ^ Thomas, Zoë A.; Jones, Richard T.; Turney, Chris S.M.; Golledge, Nicholas; Fogwill, Christopher; Bradshaw, Corey J.A.; Menviel, Laurie; McKay, Nicholas P.; Bird, Michael; Palmer, Jonathan; Kershaw, Peter; Wilmshurst, Janet; Muscheler, Raimund (April 2020). "Tipping elements and amplified polar warming during the Last Interglacial". Quaternary Science Reviews. 233: 106222. Bibcode:2020QSRv..23306222T. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2020.106222. S2CID 216288524.

- ^ Michon, Scott. "What's the coldest the Earth's ever been?". SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION. Retrieved 6 August 2023.

- ^ Barlow, Natasha L. M.; McClymont, Erin L.; Whitehouse, Pippa L.; Stokes, Chris R.; Jamieson, Stewart S. R.; Woodroffe, Sarah A.; Bentley, Michael J.; Callard, S. Louise; Cofaigh, Colm Ó; Evans, David J. A.; Horrocks, Jennifer R.; Lloyd, Jerry M.; Long, Antony J.; Margold, Martin; Roberts, David H. (September 2018). "Lack of evidence for a substantial sea-level fluctuation within the Last Interglacial". Nature Geoscience. 11 (9): 627–634. Bibcode:2018NatGe..11..627B. doi:10.1038/s41561-018-0195-4. ISSN 1752-0894. S2CID 135048938.

- ^ Richard Z. Poore, Richard S. Williams, Jr., and Christopher Tracey. "Sea Level and Climate". United States Geological Survey.

- ^ Marcott, S. A.; Shakun, J. D.; Clark, P. U.; Mix, A. C. (2013). "A reconstruction of regional and global temperature for the past 11,300 years". Science. 339 (6124): 1198–1201. Bibcode:2013Sci...339.1198M. doi:10.1126/science.1228026. PMID 23471405.

- ^ IPCC AR5 WG1 Ch5 2013, p. 386

- ^ Neukom et al. 2019a

- ^ IPCC SR15 Ch1 2018, p. 57: "This report adopts the 51-year reference period, 1850–1900 inclusive, assessed as an approximation of pre-industrial levels in AR5 ... Temperatures rose by 0.0 °C–0.2 °C from 1720–1800 to 1850–1900"

- ^ Hawkins et al. 2017, p. 1844

- ^ "Mean Monthly Temperature Records Across the Globe / Timeseries of Global Land and Ocean Areas at Record Levels for September from 1951-2023". NCEI.NOAA.gov. National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). September 2023. Archived from the original on 14 October 2023. (change "202309" in URL to see years other than 2023, and months other than 09=September)

- ^ Top 700 meters: Lindsey, Rebecca; Dahlman, Luann (6 September 2023). "Climate Change: Ocean Heat Content". climate.gov. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Archived from the original on 29 October 2023. ● Top 2000 meters: "Ocean Warming / Latest Measurement: December 2022 / 345 (± 2) zettajoules since 1955". NASA.gov. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Archived from the original on 20 October 2023.

- ^ IPCC AR5 WG1 Summary for Policymakers 2013, pp. 4–5: "Global-scale observations from the instrumental era began in the mid-19th century for temperature and other variables ... the period 1880 to 2012 ... multiple independently produced datasets exist."

- ^ Mooney, Chris; Osaka, Shannon (26 December 2023). "Is climate change speeding up? Here's what the science says". The Washington Post. Retrieved 18 January 2024.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Global 'Sunscreen' Has Likely Thinned, Report NASA Scientists". NASA. 15 March 2007.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Quaas, Johannes; Jia, Hailing; Smith, Chris; Albright, Anna Lea; Aas, Wenche; Bellouin, Nicolas; Boucher, Olivier; Doutriaux-Boucher, Marie; Forster, Piers M.; Grosvenor, Daniel; Jenkins, Stuart; Klimont, Zbigniew; Loeb, Norman G.; Ma, Xiaoyan; Naik, Vaishali; Paulot, Fabien; Stier, Philip; Wild, Martin; Myhre, Gunnar; Schulz, Michael (21 September 2022). "Robust evidence for reversal of the trend in aerosol effective climate forcing". Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics. 22 (18): 12221–12239. Bibcode:2022ACP....2212221Q. doi:10.5194/acp-22-12221-2022. hdl:20.500.11850/572791. S2CID 252446168.

- ^ IPCC AR6 WG1 2021, p. 43