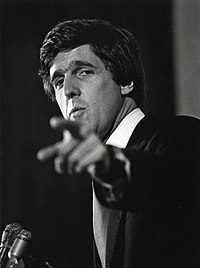

Джон Керри

Джон Керри | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Керри в 2021 году | |||

| 68-й государственный секретарь США | |||

| В офисе 1 февраля 2013 г. – 20 января 2017 г. | |||

| Президент | Barack Obama | ||

| заместитель | Уильям Дж. Бернс Венди Шерман (действующая) Энтони Блинкен | ||

| Предшественник | Hillary Clinton | ||

| Преемник | Рекс Тиллерсон | ||

| Специальный посланник президента США по климату | |||

| В офисе 20 января 2021 г. – 6 марта 2024 г. | |||

| Президент | Джо Байден | ||

| Предшественник | Офис открыт | ||

| Преемник | Джон Подеста (старший советник) | ||

| Сенатор США из Массачусетса | |||

| В офисе 2 января 1985 г. - 1 февраля 2013 г. | |||

| Предшественник | Пол Цонгас | ||

| Преемник | Мо Коуэн | ||

| |||

| 66-й вице-губернатор Массачусетса | |||

| В офисе 6 января 1983 г. - 2 января 1985 г. | |||

| Губернатор | Майкл Дукакис | ||

| Предшественник | Томас П. О'Нил III | ||

| Преемник | Эвелин Мерфи | ||

| Личные данные | |||

| Рожденный | Джон Форбс Керри 11 декабря 1943 г. Аврора, Колорадо , США | ||

| Политическая партия | Демократический | ||

| Супруги | |||

| Дети | |||

| Родители) | Ричард Керри Розмари Форбс | ||

| Родственники | Семья Форбс | ||

| Альма-матер | |||

| Занятие |

| ||

| Гражданские награды | Президентская медаль Свободы (2024 г.) | ||

| Подпись |  | ||

| Военная служба | |||

| Верность | Соединенные Штаты | ||

| Филиал/служба | ВМС США | ||

| Лет службы | 1966–1978 | ||

| Классифицировать | Лейтенант | ||

| Единица |

| ||

| Команды |

| ||

| Битвы/войны | |||

| Военные награды | |||

Джон Форбс Керри (родился 11 декабря 1943 года) — американский адвокат, политик и дипломат, занимавший пост 68-го государственного секретаря США с 2013 по 2017 год в администрации Барака Обамы . Член семьи Форбс и Демократической партии , он ранее представлял Массачусетс в Сенате США с 1985 по 2013 год, а затем был первым специальным посланником президента США по вопросам климата с 2021 по 2024 год. Керри был кандидатом от Демократической партии на пост президента США. Соединенные Штаты на выборах 2004 года проиграли тогдашнему президенту Джорджу Бушу . Он остается последним демократом, проигравшим всенародное голосование на президентских выборах.

Керри вырос в Массачусетсе и Вашингтоне, округ Колумбия. В 1966 году, после окончания Йельского университета , он поступил на службу в военно-морской резерв США , в конечном итоге получив звание лейтенанта . Во время войны во Вьетнаме Керри совершил короткую поездку по Южному Вьетнаму . Командуя катером «Стриж» , он получил три ранения в бою с Вьетконгом , за что получил три медали «Пурпурное сердце» . Керри также был награжден медалью «Серебряная звезда» и медалью «Бронзовая звезда» за поведение в отдельных боевых действиях. После завершения действительной военной службы Керри вернулся в США и стал ярым противником войны во Вьетнаме . Он получил национальное признание как антивоенный активист, выступая представителем организации «Ветераны Вьетнама против войны» . Керри давал показания на слушаниях Фулбрайта перед сенатским комитетом по международным отношениям , где он назвал политику правительства США во Вьетнаме причиной военных преступлений .

В 1972 году Керри вошел в предвыборную политику в качестве кандидата от Демократической партии в Палату представителей США в 5-м избирательном округе Массачусетса . Впоследствии он работал ведущим ток-шоу на радио и исполнительным директором правозащитной организации, одновременно посещая юридический факультет. После периода частной юридической практики он был избран 66-м вице-губернатором Массачусетса в 1982 году. В 1984 году Керри был избран в Сенат США . В 2004 году Керри выиграл номинацию на пост президента от Демократической партии вместе с сенатором Джоном Эдвардсом . Он проиграл Коллегию выборщиков и всенародное голосование с небольшим перевесом, выиграв 251 выборщика против 286 голосов Буша и 48,3% голосов избирателей против 50,7% голосов Буша.

В январе 2013 года Керри был номинирован президентом Обамой на смену госсекретарю Хиллари Клинтон и впоследствии был утвержден его коллегами в Сенате. [ 1 ] Он был госсекретарем США на протяжении второго срока администрации Обамы с 2013 по 2017 год. За время своего пребывания в должности он инициировал израильско-палестинские мирные переговоры 2013–2014 годов и заключил соглашения, ограничивающие ядерную программу Ирана , включая Совместный план 2013 года. Действия и Совместный комплексный план действий 2015 года . В 2015 году Керри подписал Парижское соглашение об изменении климата от имени США.

В январе 2021 года Керри вернулся в правительство, став первым человеком, занявшим должность специального посланника президента США по вопросам климата при президенте Джо Байдене . 6 марта Керри покинул эту должность, чтобы работать над президентской кампанией Байдена в 2024 году . [ 2 ] [ 3 ] Керри был награжден Президентской медалью свободы в мае 2024 года. Байденом [ 4 ]

Молодость и образование (1943–1966)

Джон Форбс Керри родился 11 декабря 1943 года в Армейском медицинском центре Фицсаймонса в Авроре, штат Колорадо . [ 5 ] Он второй из четырех детей Ричарда Джона Керри , американского дипломата и юриста, и Розмари Форбс , медсестры и общественной активистки. Его отец был воспитан католиком (бабушка и дедушка Джона по отцовской линии были австро-венгерскими еврейскими иммигрантами, которые обратились в католицизм), а его мать была членом епископальной церкви . Его воспитывали старшая сестра Маргарет, младшая сестра Диана и младший брат Кэмерон . Дети были воспитаны в католической вере своего отца, а Джон служил прислужником . [ 6 ]

Керри изначально считался военным мальчишкой . [ 7 ] [ нужна ссылка ] пока его отец не был уволен из армейской авиации в 1944 году. [ 8 ] Керри прожил в Гротоне, штат Массачусетс, свой первый год, а затем в Миллисе, штат Массачусетс, прежде чем переехать в район Джорджтаун в Вашингтоне, округ Колумбия, в возрасте семи лет, когда его отец получил место в стал Управлении главного юрисконсульта ВМФ и вскоре дипломат Бюро Государственного департамента по делам ООН . [ 9 ] [ 10 ] [ 11 ]

Будучи членами семей Форбс и Дадли-Уинтроп, его расширенная семья по материнской линии пользовалась большим богатством. [ 12 ] Родители Керри сами принадлежали к высшему среднему классу , и богатая бабушка платила за его обучение в элитных школах-интернатах. [ 6 ] например, Институт Монтаны Цугерберга в Швейцарии. [ 13 ] По материнской линии Керри также происходит от преподобного Джеймса МакГрегора, который был одним из первых 500 шотландско-ирландских иммигрантов, прибывших в Бостонскую гавань в 18 веке. [ 14 ]

В возрасте десяти лет отец Керри занял должность прокурора США в Берлине. Когда Керри было двенадцать, он пересек советскую зону оккупации , чтобы посетить бункер Гитлера и проехать через Бранденбургские ворота . Если бы Керри попал в плен, это вызвало бы международный инцидент. [ 15 ]

В 1957 году его отец был размещен в посольстве США в Осло , Норвегия , и Керри отправили обратно в Соединенные Штаты, чтобы учиться в школе-интернате. Сначала он посещал школу Фессендена в Ньютоне, штат Массачусетс , а затем школу Святого Павла в Конкорде, штат Нью-Гэмпшир , где он освоил навыки публичных выступлений и начал проявлять интерес к политике . [ 6 ] Керри основал Общество Джона Винанта в соборе Святого Павла для обсуждения актуальных проблем; Общество до сих пор существует там. [ 16 ] [ 11 ] В 1960 году, находясь в церкви Святого Павла, он вместе с шестью одноклассниками играл на бас-гитаре в второстепенной рок-группе The Electras. [ 17 ] [ 18 ] [ 19 ] В 1961 году группа напечатала около пятисот копий одного альбома, часть из которых они продали на танцах в школе; много лет спустя он стал доступен на потоковых платформах. [ 17 ] [ 19 ] [ 20 ] [ 21 ]

В 1962 году Керри поступил в Йельский университет по специальности политология и проживал в колледже Джонатана Эдвардса . [ 22 ] К тому же году его родители вернулись в Гротон. [ 23 ] [ 24 ] Во время учебы в Йельском университете Керри некоторое время встречался с Джанет Окинклосс , младшей сводной сестрой первой леди Жаклин Кеннеди . Через Окинклосса Керри пригласили на день плавания с тогдашним президентом Джоном Ф. Кеннеди и его семьей. [ 25 ]

Керри играл в мужской футбольной команде университета «Йель Бульдогс», заработав единственное письмо на последнем курсе. Он также играл среди первокурсников и юношей университета в хоккей , а на старшем курсе - в лакросс среди юношей университета . [ 26 ] Кроме того, он был членом братства Пси Ипсилон и брал уроки пилотирования. [ 27 ] [ 28 ]

In his sophomore year, Kerry became the chairman of the Liberal Party of the Yale Political Union, and a year later he served as president of the union. Amongst his influential teachers in this period was Professor H. Bradford Westerfield, who was himself a former president of the Political Union.[29] His involvement with the Political Union gave him an opportunity to be involved with important issues of the day, such as the civil rights movement and the New Frontier program. He also became a member of Skull and Bones Society, and traveled to Switzerland[30] through AIESEC Yale.[31][32]

Under the guidance of the speaking coach and history professor Rollin G. Osterweis, Kerry won many debates against other college students from across the nation.[33] In March 1965, as the Vietnam War escalated, he won the Ten Eyck prize as the best orator in the junior class for a speech that was critical of U.S. foreign policy. In the speech he said, "It is the spectre of Western imperialism that causes more fear among Africans and Asians than communism and thus, it is self-defeating."[34]

Kerry graduated from Yale with a bachelor of arts degree in 1966. Overall, he had below-average grades, graduating with a cumulative average of 76 over his four years. His freshman-year average was a 71, but he improved to an 81 average for his senior year. He never received an "A" during his time at Yale; his highest grade was an 89.[35]

Military service (1966–1970)

Duty on USS Gridley

On February 18, 1966, Kerry enlisted in the Naval Reserve.[36] He began his active duty military service on August 19, 1966. After completing 16 weeks of Officer Candidate School at the U.S. Naval Training Center in Newport, Rhode Island, Kerry received his officer's commission on December 16, 1966. During the 2004 election, Kerry posted his military records at his website, and permitted reporters to inspect his medical records. In 2005, Kerry released his military and medical records to the representatives of three news organizations, but has not authorized full public access to those records.[37][38]

During his tour on the guided missile frigate USS Gridley, Kerry requested duty in South Vietnam, listing as his first preference a position as the commander of a Fast Patrol Craft (PCF), also known as a "Swift boat".[39] These 50-foot (15 m) boats have aluminum hulls and have little or no armor, but are heavily armed and rely on speed. "I didn't really want to get involved in the war," Kerry said in a book of Vietnam reminiscences published in 1986. "When I signed up for the swift boats, they had very little to do with the war. They were engaged in coastal patrolling and that's what I thought I was going to be doing."[40] However, his second choice of billet was on a river patrol boat, or "PBR", which at the time was serving a more dangerous duty on the rivers of Vietnam.[39]

Military honors

During the night of December 2 and early morning of December 3, 1968, Kerry was in charge of a small boat operating near a peninsula north of Cam Ranh Bay together with a Swift boat (PCF-60). According to Kerry and the two crewmen who accompanied him that night, Patrick Runyon and William Zaladonis, they surprised a group of Vietnamese men unloading sampans at a river crossing, who began running and failed to obey an order to stop. As the men fled, Kerry and his crew opened fire on the sampans and destroyed them, then rapidly left. During this encounter, Kerry received a shrapnel wound in the left arm above the elbow. It was for this injury that Kerry received his first Purple Heart Medal.[41]

Kerry received his second Purple Heart for a wound received in action on the Bồ Đề River on February 20, 1969. The plan had been for the Swift boats to be accompanied by support helicopters. On the way up the Bo De, however, the helicopters were attacked. As the Swift boats reached the Cửa Lớn River, Kerry's boat was hit by a B-40 rocket (rocket propelled grenade round), and a piece of shrapnel hit Kerry's left leg, wounding him. Thereafter, enemy fire ceased and his boat reached the Gulf of Thailand safely. Kerry continues to have shrapnel embedded in his left thigh because the doctors that first treated him decided to remove the damaged tissue and close the wound with sutures rather than make a wide opening to remove the shrapnel.[42] Although wounded like several others earlier that day, Kerry did not lose any time off from duty.[43][44]

Silver Star

Eight days later, on February 28, 1969, came the events for which Kerry was awarded his Silver Star Medal. On this occasion, Kerry was in tactical command of his Swift boat and two other Swift boats during a combat operation. Their mission on the Duong Keo River included bringing an underwater demolition team and dozens of South Vietnamese Marines to destroy enemy sampans, structures and bunkers as described in the story The Death Of PCF 43.[45] Running into heavy small arms fire from the river banks, Kerry "directed the units to turn to the beach and charge the Viet Cong positions" and he "expertly directed" his boat's fire causing the enemy to flee while at the same time coordinating the insertion of the ninety South Vietnamese troops (according to the original medal citation signed by Admiral Elmo Zumwalt). Moving a short distance upstream, Kerry's boat was the target of a B-40 rocket round; Kerry charged the enemy positions and as his boat hove to and beached, a Viet Cong ("VC") insurgent armed with a rocket launcher emerged from a spider hole and ran. While the boat's gunner opened fire, wounding the VC in the leg, and while the other boats approached and offered cover fire, Kerry jumped from the boat to pursue the VC insurgent, subsequently killing him and capturing his loaded rocket launcher.[46][47][48]

Kerry's commanding officer, Lieutenant Commander George Elliott, stated to Douglas Brinkley in 2003 that he did not know whether to court-martial Kerry for beaching the boat without orders or give him a medal for saving the crew. Elliott recommended Kerry for the Silver Star, and Zumwalt flew into An Thoi to personally award medals to Kerry and the rest of the sailors involved in the mission. The Navy's account of Kerry's actions is presented in the original medal citation signed by Zumwalt. The engagement was documented in an after-action report, a press release written on March 1, 1969, and a historical summary dated March 17, 1969.[49]

Bronze Star

On March 13, 1969, on the Bái Háp River, Kerry was in charge of one of five Swift boats that were returning to their base after performing an Operation Sealords mission to transport South Vietnamese troops from the garrison at Cái Nước and MIKE Force advisors for a raid on a Vietcong camp located on the Rach Dong Cung canal. Earlier in the day, Kerry received a slight shrapnel wound in the buttocks from blowing up a rice bunker. Debarking some but not all of the passengers at a small village, the boats approached a fishing weir; one group of boats went around to the left of the weir, hugging the shore, and a group with Kerry's PCF-94 boat went around to the right, along the shoreline. A mine was detonated directly beneath the lead boat, PCF-3, as it crossed the weir to the left, lifting PCF-3 "about 2–3 ft out of water".[50]

James Rassmann, a Green Beret advisor who was aboard Kerry's PCF-94, was knocked overboard when, according to witnesses and the documentation of the event, a mine or rocket exploded close to the boat. According to the documentation for the event, Kerry's arm was injured when he was thrown against a bulkhead during the explosion. PCF 94 returned to the scene and Kerry rescued Rassmann who was receiving sniper fire from the water. Kerry received the Bronze Star Medal with Combat "V" for "heroic achievement", for his actions during this incident; he also received his third Purple Heart.[51]

Return from Vietnam

After Kerry's third qualifying wound, he was entitled per Navy regulations to reassignment away from combat duties. Kerry's preferred choice for reassignment was as a military aide in Boston, New York City or Washington, D.C.[52] On April 11, 1969, he reported to the Brooklyn-based Atlantic Military Sea Transportation Service, where he would remain on active duty for the following year as a personal aide to an officer, Rear Admiral Walter Schlech. On January 1, 1970, Kerry was temporarily promoted to full lieutenant.[53] Kerry had agreed to an extension of his active duty obligation from December 1969 to August 1970 in order to perform Swift Boat duty.[54][55] John Kerry was on active duty in the United States Navy from August 1966 until January 1970. He continued to serve in the Naval Reserve until February 1978.[56]

"Swiftboating" controversy

With the continuing controversy that had surrounded the military service of George W. Bush since the 2000 presidential election (when he was accused of having used his father's political influence to gain entrance to the Texas Air National Guard, thereby protecting himself from conscription into the United States Army, and possible service in the Vietnam War), John Kerry's contrasting status as a decorated Vietnam War veteran posed a problem for Bush's re-election campaign, which Republicans sought to counter by calling Kerry's war record into question. As the presidential campaign of 2004 developed, approximately 250 members of a group called Swift Boat Veterans for Truth (SBVT, later renamed Swift Vets and POWs for Truth) opposed Kerry's campaign. The group held press conferences, ran ads and endorsed a book questioning Kerry's service record and his military awards. The group included several members of Kerry's unit, such as Larry Thurlow, who commanded a swift boat alongside of Kerry's,[57] and Stephen Gardner, who served on Kerry's boat.[58] The campaign inspired the widely used political pejorative '"swiftboating," to describe an unfair or untrue political attack.[59] Most of Kerry's former crewmates have stated that SBVT's allegations are false.[60]

Anti-war activism (1970–1971)

After returning to the United States, Kerry moved to Waltham, Massachusetts and joined the Vietnam Veterans Against the War (VVAW).[61][62] Then numbering about 20,000,[63] VVAW was considered by some (including the administration of President Richard Nixon) to be an effective, if controversial, component of the antiwar movement.[64] Kerry participated in the "Winter Soldier Investigation" conducted by VVAW of U.S. atrocities in Vietnam, and he appears in a film by that name that documents the investigation.[65] According to Nixon Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird, "I didn't approve of what he did, but I understood the protesters quite well", and he declined two requests from the Navy to court martial Reserve Lieutenant Kerry over his antiwar activity.[66]

On April 22, 1971, Kerry appeared before a U.S. Senate committee hearing on proposals relating to ending the war. The day after this testimony, Kerry participated in a demonstration with thousands of other veterans in which he and other Vietnam War veterans threw their medals and service ribbons over a fence erected at the front steps of the United States Capitol building to dramatize their opposition to the war. Jack Smith, a Marine, read a statement explaining why the veterans were returning their military awards to the government. For more than two hours, almost 1,000 angry veterans tossed their medals, ribbons, hats, jackets, and military papers over the fence. Each veteran gave his or her name, hometown, branch of service and a statement. Kerry threw some of his own decorations and awards as well as some given to him by other veterans to throw. As Kerry threw his decorations over the fence, his statement was: "I'm not doing this for any violent reasons, but for peace and justice, and to try and make this country wake up once and for all."[67]

Kerry was arrested on May 30, 1971, during a VVAW march to honor American POWs held captive by North Vietnam. The march was planned as a multi-day event from Concord to Boston, and while in Lexington, participants tried to camp on the village green. At 2:30 a.m., local and state police arrested 441 demonstrators, including Kerry, for trespassing. All were given the Miranda Warning and were hauled away on school buses to spend the night at the Lexington Public Works Garage. Kerry and the other protesters later paid a $5 fine, and were released. The mass arrests caused a community backlash and ended up giving positive coverage to the VVAW.[68][69][70][71][72]

Early political career (1972–1985)

1972 congressional election

In 1970, Kerry had considered running for Congress in the Democratic primary against hawkish Democrat Philip J. Philbin of Massachusetts's 3rd congressional district, but deferred in favor of Robert Drinan, a Jesuit priest and anti-war activist, who went on to defeat Philbin.[23] In February 1972, Kerry's wife bought a house in Worcester, with Kerry intending to run against the 4th district's aging thirteen-term incumbent Democrat, Harold Donohue.[23] The couple never moved in. After Republican Congressman F. Bradford Morse of the neighboring 5th district announced his retirement and then resignation to become Under-Secretary-General for Political and General Assembly Affairs at the United Nations, the couple instead rented an apartment in Lowell, so that Kerry could run to succeed him.[23]

Including Kerry, the Democratic primary race had 10 candidates, including attorney Paul J. Sheehy, State Representative Anthony R. DiFruscia, John J. Desmond and Robert B. Kennedy. Kerry ran a "very expensive, sophisticated campaign", financed by out-of-state backers and supported by many young volunteers.[23] DiFruscia's campaign headquarters shared the same building as Kerry's. On the eve of the September 19 primary, police found Kerry's younger brother Cameron and campaign field director Thomas J. Vallely, breaking into where the building's telephone lines were located. They were arrested and charged with "breaking and entering with the intent to commit grand larceny", but the charges were dropped a year later. At the time of the incident, DiFruscia alleged that the two were trying to disrupt his get-out-the vote efforts. Vallely and Cameron Kerry maintained that they were only checking their own telephone lines because they had received an anonymous call warning that the Kerry lines would be cut.[23]

Despite the arrests, Kerry won the primary with 20,771 votes (27.56%). Sheehy came second with 15,641 votes (20.75%), followed by DiFruscia with 12,222 votes (16.22%), Desmond with 10,213 votes (13.55%) and Kennedy with 5,632 votes (7.47%). The remaining 10,891 votes were split amongst the other five candidates, with 1970 nominee Richard Williams coming last with just 1,706 votes (2.26%).[23][73]

In the general election, Kerry was initially favored to defeat the Republican candidate, former State Representative Paul W. Cronin, and conservative Democrat Roger P. Durkin, who ran as an Independent. A week after the primary, one poll put Kerry 26-points ahead of Cronin.[23] His campaign called for a national health insurance system, discounted prescription drugs for the unemployed, a jobs program to clean up the Merrimack River and rent controls in Lowell and Lawrence. A major obstacle, however, was the district's leading newspaper, the conservative The Sun. The paper editorialized against him. It also ran critical news stories about his out-of-state contributions and his "carpetbagging", because he had only moved into the district in April. Subsequently, released "Watergate" Oval Office tape recordings of the Nixon White House showed that defeating Kerry's candidacy had attracted the personal attention of President Nixon.[74] Kerry himself asserts that Nixon sent operatives to Lowell to help derail his campaign.[23]

The race was the most expensive for Congress in the country that year[23] and four days before the general election, Durkin withdrew and endorsed Cronin, hoping to see Kerry defeated.[75] The week before, a poll had put Kerry 10 points ahead of Cronin, with Durkin at 13%.[23] In the final days of the campaign, Kerry sensed that it was "slipping away" and Cronin emerged victorious by 110,970 votes (53.45%) to Kerry's 92,847 (44.72%).[76] After his defeat, Kerry lamented in a letter to supporters that "for two solid weeks, [The Sun] called me un-American, New Left antiwar agitator, unpatriotic, and labeled me every other 'un-' and 'anti-' that they could find. It's hard to believe that one newspaper could be so powerful, but they were."[23] He later felt that his failure to respond directly to The Sun's attacks cost him the race.[23]

Law career

After Kerry's 1972 defeat, he and his wife bought a house in the Belvidere section of Lowell, Massachusetts,[77][23] entering a decade which his brother Cameron later called "the years in exile".[23] He spent some time working as a fundraiser for the Cooperative for Assistance and Relief Everywhere (CARE), an international humanitarian organization.[78] In September 1973, he entered Boston College Law School.[23] While studying, Kerry worked as a talk radio host on WBZ and, in July 1974, was named executive director of Mass Action, a Massachusetts advocacy association.[23][79]

Kerry received his juris doctor (J.D.) from Boston College in 1976.[80] While in law school he had been a student prosecutor in the office of the District Attorney of Middlesex County, John J. Droney.[81] After passing the bar exam and being admitted to the Massachusetts bar in 1976, he went to work in that office as a full-time prosecutor and moved to Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts.[82][83]

In January 1977, Droney promoted him to First Assistant District Attorney, essentially making Kerry his campaign and media surrogate because Droney was afflicted with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS, or Lou Gehrig's Disease). As First Assistant, Kerry tried cases, which included winning convictions in a high-profile rape case and a murder. He also played a role in administering the office, including initiating the creation of special white-collar and organized crime units, creating programs to address the problems of rape and other crime victims and witnesses, and managing trial calendars to reflect case priorities.[84] It was in this role in 1978 that Kerry announced an investigation into possible criminal charges against then Senator Edward Brooke, regarding "misstatements" in his first divorce trial.[85] The inquiry ended with no charges being brought after investigators and prosecutors determined that Brooke's misstatements were pertinent to the case, but were not material enough to have affected the outcome.[86]

Droney's health was poor and Kerry had decided to run for his position in the 1978 election should Droney drop out. However, Droney was re-elected and his health improved; he went on to re-assume many of the duties that he had delegated to Kerry.[23] Kerry thus decided to leave, departing in 1979 with assistant DA Roanne Sragow to set up their own law firm.[23][84] Kerry also worked as a commentator for WCVB-TV and co-founded a bakery, Kilvert & Forbes Ltd., with businessman and former Kennedy aide K. Dun Gifford.[23]

Lieutenant Governor of Massachusetts

In the 1982 Massachusetts gubernatorial election, Lieutenant Governor Thomas P. O'Neill III declined to seek a third term, instead deciding to run for governor of Massachusetts.[87] Kerry declared his candidacy, entering the primary election alongside Massachusetts Secretary of Environmental Affairs Evelyn Murphy, State Senator Samuel Rotondi, State Representative Lou Nickinello, and Lois Pines.[88]

Kerry won the nomination with 325,890 votes (29%) to Murphy's 286,378 (25.48%), Rotondi's 228,086 (20.29%), Nickinello's 150,829 (13.42%) and Pines' 132,734 (11.81%).[89] In the concurrent gubernatorial primary, former Governor Michael Dukakis defeated O'Neill and incumbent Governor Edward J. King.[90] The Dukakis and Kerry ticket defeated the Republican ticket of John W. Sears and Leon Lombardi in the general election by 1,219,109 votes (61.92%) to 749,679 (38.08%).[91][92]

As Lieutenant Governor, Kerry led meetings of the Massachusetts Governor's Council.[93] Dukakis also delegated other tasks to Kerry, including serving as the state's liaison to the Federal government of the United States.[94] He was also active on environmental issues, including combating acid rain.[95]

1984 U.S. Senate election

The junior U.S. senator from Massachusetts, Paul Tsongas, announced in 1984 that he would be stepping down for health reasons.[96] Kerry ran, and as in his 1982 race for Lieutenant Governor, he did not receive the endorsement of the party regulars at the state Democratic convention.[97] Congressman James Shannon, a favorite of House Speaker Tip O'Neill, was the early favorite to win the nomination, and he "won broad establishment support and led in early polling".[98][99] Again as in 1982, however, Kerry prevailed in a close primary.[100]

In his general election campaign, Kerry promised to mix liberalism with tight budget controls. He defeated Republican Ray Shamie despite a nationwide landslide for the re-election of Republican President Ronald Reagan, for whom Massachusetts voted by a narrow margin.[101][102] In his victory speech, Kerry asserted that his win meant that the people of Massachusetts "emphatically reject the politics of selfishness and the notion that women must be treated as second-class citizens".[103]

Tsongas resigned on January 2, 1985, one day before the end of his term. Dukakis appointed Kerry to fill the vacancy, giving him seniority over other new senators who were sworn in on January 3, the scheduled start of their new terms.[104]

U.S. Senate (1985–2013)

Iran–Contra hearings

On April 18, 1985, a few months after taking his Senate seat, Kerry and Senator Tom Harkin of Iowa traveled to Nicaragua and met the country's president, Daniel Ortega. Although Ortega had won internationally certified elections, the trip was criticized because Ortega and his leftist Sandinista government had strong ties to Cuba and the USSR and were accused of human rights abuses. The Sandinista government was opposed by the right-wing CIA-backed rebels known as the Contras. While in Nicaragua, Kerry and Harkin talked to people on both sides of the conflict. Through the senators, Ortega offered a cease-fire agreement in exchange for the U.S. dropping support of the Contras. The offer was denounced by the Reagan administration as a "propaganda initiative" designed to influence a House vote on a $14 million Contra aid package, but Kerry said "I am willing ... to take the risk in the effort to put to test the good faith of the Sandinistas." The House voted down the Contra aid, but Ortega flew to Moscow to accept a $200 million loan the next day, which in part prompted the House to pass a larger $27 million aid package six weeks later.[105]

Meanwhile, Kerry's staff began their own investigations and, on October 14, issued a report that exposed illegal activities on the part of Lieutenant Colonel Oliver North, who had set up a private network involving the National Security Council and the CIA to deliver military equipment to right-wing Nicaraguan rebels (Contras). In effect, North and certain members of the President's administration were accused by Kerry's report of illegally funding and supplying armed militants without the authorization of Congress. Kerry's staff investigation, based on a year-long inquiry and interviews with fifty unnamed sources, is said to raise "serious questions about whether the United States has abided by the law in its handling of the contras over the past three years".[106]

The Kerry Committee report found that "the Contra drug links included ... payments to drug traffickers by the U.S. State Department of funds authorized by the Congress for humanitarian assistance to the Contras, in some cases after the traffickers had been indicted by federal law enforcement agencies on drug charges, in others while traffickers were under active investigation by these same agencies."[107] The U.S. State Department paid over $806,000 to known drug traffickers to carry humanitarian assistance to the Contras.[108] Kerry's findings provoked little reaction in the media and official Washington.[109]

The Kerry report was a precursor to the Iran–Contra affair. On May 4, 1989, North was convicted of charges relating to the Iran/Contra controversy, including three felonies. On September 16, 1991, however, North's convictions were overturned on appeal.[110]

George H. W. Bush administration

On November 15, 1988, at a businessmen's breakfast in East Lynn, Massachusetts, Kerry made a joke about then-President-elect George H. W. Bush and his running mate, saying "if Bush is shot, the Secret Service has orders to shoot Dan Quayle." He apologized the following day.[111]

During their investigation of General Manuel Noriega, the de facto ruler of Panama, Kerry's staff found reason to believe that the Pakistan-based Bank of Credit and Commerce International (BCCI) had facilitated Noriega's drug trafficking and money laundering. This led to a separate inquiry into BCCI, and as a result, banking regulators shut down BCCI in 1991. In December 1992, Kerry and Senator Hank Brown, a Republican from Colorado, released The BCCI Affair, a report on the BCCI scandal. The report showed that the bank was crooked and was working with terrorists, including Abu Nidal. It blasted the Department of Justice, the Department of the Treasury, the Customs Service, the Federal Reserve Bank, as well as influential lobbyists and the CIA.[112]

Kerry was criticized by some Democrats for having pursued his own party members, including former Secretary of Defense Clark Clifford, although Republicans said he should have pressed against some Democrats even harder. The BCCI scandal was later turned over to the Manhattan District Attorney's office.[113]

Precursors to presidential bid

In 1996, Kerry faced a difficult re-election fight against Governor William Weld, a popular Republican incumbent who had been re-elected in 1994 with 71% of the vote. The race was covered nationwide as one of the most closely watched Senate races that year. Kerry and Weld held several debates and negotiated a campaign spending cap of $6.9 million at Kerry's Beacon Hill townhouse. Both candidates spent more than the cap, with each camp accusing the other of being first to break the agreement.[114] During the campaign, Kerry spoke briefly at the 1996 Democratic National Convention. Kerry won re-election with 52 percent to Weld's 45 percent.[115]

In the 2000 presidential election, Kerry found himself close to being chosen as the vice presidential running mate.[116]

A release from the presidential campaign of presumptive Democratic nominee Al Gore listed Kerry on the short list to be selected as the vice-presidential nominee, along with North Carolina Senator John Edwards, Indiana Senator Evan Bayh, Missouri Congressman Richard Gephardt, New Hampshire Governor Jeanne Shaheen and Connecticut Senator Joe Lieberman.[117] Gore ultimately chose Lieberman.

"You get stuck in Iraq" controversy

On October 30, 2006, Kerry was a headline speaker at a campaign rally being held for Democratic California gubernatorial candidate Phil Angelides at Pasadena City College in Pasadena, California. Speaking to an audience composed mainly of college students, Kerry said, "You know, education, if you make the most of it, you study hard, you do your homework and you make an effort to be smart, you can do well. If you don't, you get stuck in Iraq."[118]

The day after he made the remark, leaders from both sides of the political spectrum criticized Kerry's remarks, which he said were a botched joke. Republicans including President George W. Bush, Senator John McCain and then-Speaker of the House Dennis Hastert, said that Kerry's comments were insulting to American military forces fighting in Iraq. Democratic Representative Harold Ford Jr. called on Kerry to apologize.[119]

Kerry initially stated: "I apologize to no one for my criticism of the president and of his broken policy".[118] Kerry also responded to criticism from George W. Bush and Dick Cheney.[120]

Kerry said that he had intended the remark as a jab at President Bush, and described the remarks as a "botched joke",[121] having inadvertently left out the key word "us" (which would have been, "If you don't, you get us stuck in Iraq"), as well as leaving the phrase "just ask President Bush" off of the end of the sentence. In Kerry's prepared remarks, which he released during the ensuing media frenzy, the corresponding line was "... you end up getting us stuck in a war in Iraq. Just ask President Bush". He also said that from the context of the speech which, prior to the "stuck in Iraq" line, made several specific references to Bush and elements of his biography, that Kerry was referring to President Bush and not American troops in general.[122]

After two days of media coverage, citing a desire not to be a diversion, Kerry apologized to those who took offense at what he called the misinterpretation of his comment.[123]

Afghanistan and Pakistan

A Washington Post report in May 2011 stated that Kerry "has emerged in the past few years as an important envoy for Afghanistan and Pakistan during times of crisis", as he undertook another trip to the two countries. The killing of Osama bin Laden "has generated perhaps the most important crossroads yet", the report continued, as the senator spoke at a press conference and prepared to fly from Kabul to Pakistan.[124] Among matters discussed during the May visit to Pakistan, under the general rubric of "recalibrating" the bilateral relationship, Kerry sought and retrieved from the Pakistanis the tail-section of the U.S. helicopter which had had to be abandoned at Abbottabad during the bin Laden strike.[125] In 2013, Kerry met with Pakistan's army chief Gen. Ashfaq Parvez Kayani to discuss the peace process with the Taliban in Afghanistan.[126]

Voting record

Overall

Most analyses place Kerry's voting record on the left within the Senate Democratic caucus.[127] During the 2004 presidential election he was portrayed as a staunch liberal by conservative groups and the Bush campaign, who often noted that in 2003 Kerry was rated the top Senate liberal by National Journal. However, that rating was based only upon voting on legislation within that past year. In fact, in terms of career voting records, the National Journal found that Kerry is the 11th most liberal member of the Senate. Most analyses find that Kerry is at least slightly more liberal than the typical Democratic Senator. Kerry has stated that he opposes privatizing Social Security, supports abortion rights for adult women and minors, supports same-sex marriage, opposes capital punishment except for terrorists, supports most gun control laws, and is generally a supporter of trade agreements. In some of these, as in the case of abortion, Kerry distinguishes his personal views as in line with his Catholic faith, but believes that separation of church and state demands that he not legislate his religious beliefs upon those who do not share those beliefs.[128] Kerry supported the North American Free Trade Agreement and Most Favored Nation status for China, but opposed the Central American Free Trade Agreement.[129][130]

In July 1997, Kerry joined his Senate colleagues in voting against ratification of the Kyoto Treaty on global warming without greenhouse gas emissions limits on nations deemed developing, including India and China.[131] Since then, Kerry has attacked President Bush, charging him with opposition to international efforts to combat global warming.[132]

On October 1, 2008, Kerry voted for Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008, also known as the TARP bailout.[133]

Iraq

In the lead up to the Iraq War, Kerry said on October 9, 2002; "I will be voting to give the President of the United States the authority to use force, if necessary, to disarm Saddam Hussein because I believe that a deadly arsenal of weapons of mass destruction in his hands is a real and grave threat to our security." Bush relied on that resolution in ordering the 2003 invasion of Iraq. Kerry also gave a January 23, 2003, speech to Georgetown University saying "Without question, we need to disarm Saddam Hussein. He is a brutal, murderous dictator; leading an oppressive regime he presents a particularly grievous threat because he is so consistently prone to miscalculation. So the threat of Saddam Hussein with weapons of mass destruction is real." Kerry did, however, warn that the administration should exhaust its diplomatic avenues before launching war: "Mr. President, do not rush to war, take the time to build the coalition, because it's not winning the war that's hard, it's winning the peace that's hard."[134]

After the invasion of Iraq, when no weapons of mass destruction were found, Kerry strongly criticized Bush, contending that he had misled the country: "When the President of the United States looks at you and tells you something, there should be some trust."[135]

Libya

In 2011, Kerry supported American military action in Libya.[136][137]

Leadership

Kerry chaired the Senate Select Committee on POW/MIA Affairs from 1991 to 1993. The committee's report, which Kerry endorsed, stated there was "no compelling evidence that proves that any American remains alive in captivity in Southeast Asia".[138] In 1994 the Senate passed a resolution, sponsored by Kerry and fellow Vietnam veteran John McCain, that called for an end to the existing trade embargo against Vietnam; it was intended to pave the way for normalization.[139] In 1995, President Bill Clinton normalized diplomatic relations with the country of Vietnam.[140]

Kerry was the chairman of the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee from 1987 to 1989. He was reelected to the Senate in 1990, 1996 (after winning re-election against the then-Governor of Massachusetts Republican William Weld), 2002, and 2008. In January 2009, Kerry replaced Joe Biden as the chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee.[141]

As a role model for campus leaders across the nation and strong advocate for global development, Kerry was honored by the Millennium Campus Network (MCN) as a Global Generation Award winner in 2011.[142][143]

Committee assignments

During his tenure, Kerry served on four Senate committees and nine subcommittees:

- Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation

- Subcommittee on Aviation Operations, Safety, and Security

- Subcommittee on Communications, Technology, and the Internet (chairman)

- Subcommittee on Competitiveness, Innovation, and Export Promotion

- Subcommittee on Oceans, Atmosphere, Fisheries, and Coast Guard

- Subcommittee on Science and Space

- Subcommittee on Surface Transportation and Merchant Marine Infrastructure, Safety, and Security

- Committee on Finance

- Committee on Foreign Relations (Chairman 2009–2013)

- Committee on Small Business and Entrepreneurship

- Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe

- Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction

Caucus memberships

- Congressional Bicameral High-Speed and Intercity Rail Caucus

- Congressional Internet Caucus

- Congressional Vietnam-Era Veterans Caucus (Co-chair)

- International Conservation Caucus

- Senate Prosecutors Caucus (Co-chair)

- Senate Oceans Caucus

Seniority

From the beginning of the 113th United States Congress until his resignation, Kerry ranked as the 7th most senior U.S. Senator. Due to the longevity of Ted Kennedy's service, Kerry was the most senior junior Senator in the 111th United States Congress. On Tuesday, August 25, 2009, Kerry became the senior senator from Massachusetts following Ted Kennedy's death.

Sponsorship of legislation

This section needs to be updated. (January 2023) |

Areas of concern in the bills Kerry introduced into the Senate included small business concerns, education, terrorism, veterans' and POW/MIA issues, and marine resource protection. A full list of Kerry's sponsored legislation was available on his Senate web site.

During his Senate career, Kerry was primary sponsor of the following bills (excluding resolutions and amendments sponsored). This table does not count bills which Kerry co-sponsored.

| Session | Years | Bills Sponsored | Signed into law |

|---|---|---|---|

| 99th | 1985–86 | 15 | 0 |

| 100th | 1987–88 | 21 | 1[permanent dead link] |

| 101st | 1989–90 | 44 | 0 |

| 102nd | 1991–92 | 28 | 1 |

| 103rd | 1993–94 | 27 | 1, 2 |

| 104th | 1995–96 | 32 | 0 |

| 105th | 1997–98 | 19 | 0 |

| 106th | 1999–00 | 33 | 1 |

| 107th | 2001–02 | 81 | 1, 2, 3 |

| 108th | 2003–04 | 30 | 1 |

A chronological list of various bills and resolutions sponsored by Kerry follows.

- A concurrent resolution condemning North Korea's support for terrorist activities. Measure passed Senate, amended. 100th Congress.

- A resolution relating to declassification of Documents, Files, and other materials pertaining to POWs and MIAs. Agreed to without amendment. 100th Congress.

- A bill to authorize appropriations to carry out the National Sea Grant College Program Act, and for other purposes. Signed by President.

- A bill to amend the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 to prohibit certain transactions with respect to managed accounts. Referred to committee. 102nd Congress.

- A bill to authorize appropriations for the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972 and to improve the program to reduce the incidental taking of marine mammals during the course of commercial fishing operations, and for other purposes. Became public law #103-238. 103rd Congress.

- A bill to amend the Small Business Act to enhance the business development opportunities of small business concerns owned and controlled by socially and economically disadvantaged individuals, and for other purposes. Referred to committee. 103rd Congress.

- A bill to designate a portion of the Sudbury, Assabet, and Concord Rivers as a component of the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System. Passed without objection. 105th Congress.

- A bill to amend the Small Business Act with respect to the women's business center program. Became Public Law #106-165. 106th Congress.

- A bill to authorize the Small Business Administration to provide financial and business development assistance to military reservists' small businesses, and for other purposes. Referred to committee. 106th Congress.

- A bill to amend the Small Business Act with respect to the microloan program, and for other purposes. Ordered to be Reported. 107th Congress.

- A bill to reauthorize the Small Business Technology Transfer Program, and for other purposes. Became Public Law #107-50. 107th Congress.

- A bill to provide assistance to small business concerns adversely impacted by the terrorist attacks against the United States on September 11, 2001, and for other purposes. Referred to committee. 107th Congress.

- A bill to provide emergency assistance to nonfarm-related small business concerns that have suffered substantial economic harm from drought. Referred to committee. 108th Congress.

- The Building and Upgrading Infrastructure for Long-Term Development (BUILD) Act, described by the National Taxpayers Union Foundation as its "most expensive bill of the Week" when it was introduced into the Senate in 2011.[144]

2004 presidential campaign

In the 2004 Democratic presidential primaries, John Kerry defeated several Democratic rivals, including Sen. John Edwards (D-North Carolina), former Vermont Governor Howard Dean and retired Army General Wesley Clark. His victory in the Iowa caucuses is widely believed to be the tipping point where Kerry revived his sagging campaign in New Hampshire and the February 3, 2004, primary states like Arizona, South Carolina and New Mexico. Kerry then went on to win landslide victories in Nevada and Wisconsin. Kerry thus won the Democratic nomination to run for President of the United States against incumbent George W. Bush. On July 6, 2004, he announced his selection of John Edwards as his running mate. Democratic strategist Bob Shrum, who was Kerry's 2004 campaign adviser, wrote an article in Time magazine claiming that after the election, Kerry had said that he wished he had never picked Edwards, and that the two have since stopped speaking to each other.[145] In a subsequent appearance on ABC's This Week, Kerry refused to respond to Shrum's allegation, calling it a "ridiculous waste of time".[146]

During his bid to be elected president in 2004, Kerry frequently criticized President George W. Bush for starting the Iraq War.[147] While Kerry had initially voted in support of authorizing President Bush to use force in dealing with Saddam Hussein, he voted against an $87 billion supplemental appropriations bill to pay for the subsequent war. His statement on March 16, 2004, "I actually did vote for the $87 billion before I voted against it", helped the Bush campaign to paint him as a flip-flopper and has been cited as contributing to Kerry's defeat.[148]

On November 3, 2004, Kerry conceded the race. Kerry won 59.03 million votes, or 48.3 percent of the popular vote; Bush won 62.04 million votes, or 50.7 percent of the popular vote. Kerry carried states with a total of 252 electoral votes. One Kerry elector voted for Kerry's running mate, Edwards, so in the final tally Kerry had 251 electoral votes to Bush's 286.[149]

Subsequent presidential-election activities

Immediately after the 2004 election, some Democrats mentioned Kerry as a possible contender for the 2008 Democratic nomination. His brother had said such a campaign was "conceivable", and Kerry himself reportedly said at a farewell party for his 2004 campaign staff, "There's always another four years".[150]

Kerry established a separate political action committee, Keeping America's Promise, which declared as its mandate "A Democratic Congress will restore accountability to Washington and help change a disastrous course in Iraq",[151] and raised money and channeled contributions to Democratic candidates in state and federal races.[152] Through Keeping America's Promise in 2005, Kerry raised over $5.5 million for other Democrats up and down the ballot. Through his campaign account and his political action committee, the Kerry campaign operation generated more than $10 million for various party committees and 179 candidates for the U.S. House, Senate, state and local offices in 42 states focusing on the midterm elections during the 2006 election cycle.[153] "Cumulatively, John Kerry has done as much if not more than any other individual senator", Hassan Nemazee, the national finance chairman of the DSCC said.[154]

On January 10, 2008, Kerry endorsed Illinois Senator Barack Obama for president.[155] He was mentioned as a possible vice presidential candidate for Senator Obama, although fellow Senator Joe Biden was eventually chosen. After Biden's acceptance of the vice presidential nomination, speculation arose that John Kerry would be a candidate for Secretary of State in the Obama administration.[156] However, Senator Hillary Clinton was offered the position.[157]

During the 2012 Obama reelection campaign, Kerry participated in one-on-one debate prep with the president, impersonating the Republican candidate Mitt Romney.[158]

Secretary of State (2013–2017)

Nomination and confirmation

On December 15, 2012, several news outlets reported that President Barack Obama would nominate Kerry to succeed Hillary Clinton as Secretary of State,[159][160] after Susan Rice, widely seen as Obama's preferred choice, withdrew her name from consideration citing a politicized confirmation process following criticism of her response to the 2012 Benghazi attack.[161] On December 21, Obama proposed the nomination,[162][163] which received positive commentary. His confirmation hearing took place on January 24, 2013, before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, the same panel where he first testified in 1971.[164][165] The committee unanimously voted to approve him on January 29, 2013, and the same day the full Senate confirmed him on a vote of 94–3.[166][167] In a letter to Massachusetts Governor Deval Patrick, Kerry announced his resignation from the Senate effective February 1.[168]

Tenure

Kerry was sworn in as Secretary of State on February 1, 2013.[169]

While serving as the Secretary of State, Kerry spoke in the French language on several occasions in his official capacity.[170][171]

After six months of rigorous diplomacy within the Middle East, Kerry was able to have Israeli and Palestinian negotiators agree to start the 2013–2014 Israeli–Palestinian peace talks. Senior U.S. officials stated the two sides were able to meet on July 30, 2013, at the State Department without American mediators following a dinner the previous evening hosted by Kerry.[172]

On September 27, 2013, he met with the Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif during the P5+1 and Iran summit, which eventually led to the JCPOA nuclear agreement. It was the highest-level direct contact between the United States and Iran in the last six years, and made him the first U.S. Secretary of State to have met with his Iranian counterpart since 1979 Iranian Revolution.[173][174][175]

In the State Department, Kerry quickly earned a reputation "for being aloof, keeping to himself, and not bothering to read staff memos". Career State Department officials complained that power became too centralized under Kerry's leadership, which slowed department operations when Kerry was on frequent overseas trips. Others in State described Kerry as having "a kind of diplomatic attention deficit disorder" as he shifted from topic to topic instead of focusing on long-term strategy. When asked whether he was traveling too much, he responded, "Hell no. I'm not slowing down." Despite Kerry's early achievements, morale at State was lower than under Hillary Clinton, according to department employees.[176] However, after Kerry's first six months in the State Department, a Gallup poll found he had high approval ratings among Americans as Secretary of State.[177] After a year, another poll showed Kerry's favorability continued to rise.[178] Less than two years into Kerry's term, the Foreign Policy Magazine's 2014 Ivory Tower survey of international relations scholars asked, "Who was the most effective U.S. Secretary of State in the past 50 years?"; John Kerry and Lawrence Eagleburger tied for 11th place out of the 15 confirmed Secretaries of State in that period.[179][180]

In January 2014, having met with Vatican Secretary of State Archbishop Pietro Parolin, Kerry said: "We touched on just about every major issue that we are both working on, that are issues of concern to all of us. First of all, we talked at great length about Syria, and I was particularly appreciative for the Archbishop's raising this issue, and equally grateful for the Holy Father's comments – the Pope's comments yesterday regarding his support for the Geneva II process. We welcome that support. It is very important to have broad support, and I know that the Pope is particularly concerned about the massive numbers of displaced human beings and the violence that has taken over 130,000 lives."[181]

Kerry expressed support for Israel's right to defend itself during the 2014 Israel–Gaza conflict.[182]

Kerry said the United States supported the Saudi Arabian-led intervention in Yemen because Saudi Arabia, an ally, was threatened "very directly" by the takeover of neighboring Yemen by the Houthis, but noted that the United States would not reflexively support Saudi Arabia's proxy wars against Iran.[183]

On December 28, 2016, soon after United Nations Security Council Resolution 2334 passed 14–0 with the U.S. abstaining, Kerry joined the rest of the U.N. Security Council in strongly criticizing Israel's settlement policies in a speech.[184] His speech and criticisms met negative reactions from Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu,[185] while UK Prime Minister Theresa May distanced the UK from Kerry's strongly worded speech in what appeared to be an attempt to build bridges with the incoming Trump administration.[186] Kerry's speech received positive reactions from Arab nations, but some criticized his remarks as too little, too late from the outgoing administration.[187]

Syria

Following the August 21, 2013, chemical weapons attack on the Ghouta suburbs of Damascus attributed to Syrian government forces, Kerry became a leading advocate for the use of military force against the Syrian government for what he called "a despot's brutal and flagrant use of chemical weapons".[188]

On September 9, in response to a reporter's question about whether Syrian President Bashar al-Assad could avert a military strike, Kerry said "He could turn over every single bit of his chemical weapons to the international community in the next week. Turn it over, all of it, without delay, and allow a full and total accounting for that. But he isn't about to do it, and it can't be done, obviously." This unscripted remark initiated a process that would lead to Syria agreeing to relinquish and destroy its chemical weapons arsenal, as Russia treated Kerry's statement as a serious proposal. Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov said Russia would work "immediately" to convince Syria relinquish and destroy its large chemical weapons arsenal.[189][190][191][192] Syria quickly welcomed this proposal and on September 14, the UN formally accepted Syria's application to join the convention banning chemical weapons, and separately, the U.S. and Russia agreed on a plan to eliminate Syria's chemical weapons by the middle of 2014, leading Kerry to declare on July 20, 2014: "we struck a deal where we got 100 percent of the chemical weapons out".[193] On September 28, the UN Security Council passed a resolution ordering the destruction of Syria's chemical weapons and condemning the August 21 Ghouta attack.[194]

Latin America

In a speech before the Organization of American States in November 2013, Kerry remarked that the era of the Monroe Doctrine was over. He went on to explain, "The relationship that we seek and that we have worked hard to foster is not about a United States declaration about how and when it will intervene in the affairs of other American states. It's about all of our countries viewing one another as equals, sharing responsibilities, cooperating on security issues, and adhering not to doctrine, but to the decisions that we make as partners to advance the values and the interests that we share."[195]

Environmentalism

In April 2016, he signed the Paris Climate Accords at the United Nations in New York.[196]

On November 11, 2016, Kerry became the first Secretary of State and highest-ranking U.S. official to date to visit Antarctica. Kerry spent two days on the continent meeting with researchers and staying overnight at McMurdo Station.[197]

In 1994, Kerry led opposition to continued funding for the Integral Fast Reactor, which resulted in the end of funding for the project.[198] However, in light of increasing concerns regarding climate change, in 2017 Kerry reversed his position on nuclear power, saying "Given this challenge we face today, and given the progress of fourth generation nuclear: go for it. No other alternative, zero emissions."[199]

Global Connect initiative

In September 2015, the U.S. Department of State unveiled a new initiative called "Global Connect" which sought to provide internet access to more than 1.5 billion people around the world within five years.[200] In 2016, in partnership with OPIC, Kerry announced an investment of $171 million to enable "a low-cost and rapidly scalable wireless broadband network in India". OPIC's financing is aimed at helping its Indian Partner, Tikona Digital Networks, to provide Internet through wireless technology.[201][202][203]

Out of government (2017–2021)

Kerry retired from his diplomatic work following the end of the Obama administration on January 20, 2017.[204] He did not attend Donald Trump's inauguration on that day, and the following day took part in the 2017 Women's March in Washington, D.C.[205] Kerry has taken a strong stand against Trump policies and joined in filing a brief arguing against Trump's executive order banning entry of persons from seven Muslim countries.[206] In November 2018, in a "Guardian Live" conversation with Andrew Rawnsley, sponsored by The Guardian at London's Central Hall, Kerry discussed several issues which have developed further since his tenure as Secretary of State, including migration into Europe and climate change.[207]

On December 5, 2019, Kerry endorsed Joe Biden's bid for the Democratic nomination for president, saying "He'll be ready on day one to put back together the country and the world that Donald Trump has broken apart"[208] and asserting that "Joe will defeat Donald Trump next November. He's the candidate with the wisdom and standing to fix what Trump has broken, to restore our place in the world, and improve the lives of working people here at home."[209]

Following retirement from government service, Kerry signed an agreement with Simon & Schuster for publishing his planned memoirs, dealing with his life and career in government.[210] In September 2018, he published Every Day Is Extra.[211]

Leaked audiotape

On April 25, 2021, The New York Times published content from a leaked audiotape of a three-hour taped conversation between economist Saeed Leylaz and Iranian foreign minister Mohammad Javad Zarif. The taped conversation was connected to an oral history project, known as "In the Islamic Republic the military field rules", which documents the work of Iran's current administration.[212][213] The tape was obtained by the London-based news channel Iran International.[214]

In the tape, which the Times referred to as "extraordinary", Zarif reveals that then-Secretary of State Kerry told him that Israel attacked Iranian assets in Syria, "at least 200 times".[215][212][216][217] Although the tape has not been verified, the spokesman[who?] for the Iranian foreign ministry did not deny its validity.[218]

Nineteen Republican senators signed a letter asking President Biden to investigate Zarif's claim[which?].[219] On April 27, 2021, Republicans called on Kerry to resign from the Biden administration's National Security Council. In a tweet, Kerry denied Zarif's account, writing, "I can tell you that this story and these allegations are unequivocally false. This never happened — either when I was Secretary of State or since."[215]

Special Presidential Envoy for Climate (2021–2024)

On November 23, 2020, President-elect Joe Biden's transition team announced that Kerry would be taking a full-time position in the administration, serving as a special envoy for climate;[220] in this role he will be a principal on the National Security Council.[221] Kerry assumed office on January 20, 2021, following Biden's inauguration.

Climate cooperation with China

In July 2023 John Kerry visited China for advance climate cooperation. The main achievement of the visit was some progress in the fields of: "methane reduction commitments; reducing China's reliance on coal; China's objections to trade restrictions on solar panel and battery components; and climate finance." This was obtained despite many currently existing obstacles to cooperation.[222] The visit was made in the middle of the 2023 Asia heat wave that set a new record of 52.2 °C (126.0 °F) in Sanbu, Xinjiang, China, which Kerry mentioned in particular.[223][224][225]

Climate cooperation with India

At the end of July 2023 John Kerry visited India. Among others he declared, the USA will be committed to the target of delivering 100 billion dollars for climate action to low income countries and no future US president can retreat from climate commitment. He criticized Donald Trump for leaving the Paris agreement before.[226]

Climate cooperation with countries in the Middle East

In June 2023 Kerry made visits to Israel, Jordan, and the United Arab Emirates. In Israel, he emphasized the need for climate legislation to reach climate targets and reached an agreement about the renewal of "Memorandum of understanding between Israel and the United States Environmental Protection Agency. Israel is one of the few developed countries which have still not approved a climate law and lags behind other OECD countries in climate action. Israeli environmental protection minister Idit Silman said that Israel intended to go to COP28 "with an ambitious and applicable climate law and put the State of Israel on the same level as the developed countries of the OECD."[227]

Departure

On January 13, 2024, at least three sources close to Kerry revealed that he would step down as U.S. climate envoy by the upcoming spring.[228] He told the Financial Times he planned to stay active in the climate finance space.[229] He officially resigned from his position on March 6, 2024.[230]

Personal and family life

Ancestry

Kerry's paternal grandparents, shoe businessman Frederick A. "Fred" Kerry and musician Ida Löwe, were immigrants from the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Fred, his wife, and his brother converted from Judaism to Catholicism in 1901, and changed their names from Kohn to Kerry. Ida was of remote ancestry of Rabbi Sinai Loew of Worms, brother of Judah Loew ben Bezalel.[231][232][233] Fred and Ida Kerry emigrated to the United States in 1905, living at first in Chicago and eventually moving to Brookline, Massachusetts, by 1915.[234] According to The New York Times, "[the] brother and sister of John Kerry's paternal grandmother, Otto and Jenni Lowe, died in concentration camps". Kerry's Jewish ancestry was publicly revealed during his 2004 presidential campaign; he has stated that he was unaware of it until a reporter informed him of it in 2003.[235]

Kerry's maternal ancestors were of Scottish and English descent,[234][236] and his maternal grandparents were James Grant Forbes II of the Forbes family and Margaret Tyndal Winthrop of the Dudley–Winthrop family. Margaret's paternal grandfather Robert Charles Winthrop served as the 22nd Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives. Robert's father was Governor Thomas Lindall Winthrop. Thomas' father John Still Winthrop was a great-great-grandson of Massachusetts Bay Colony Governor John Winthrop[12] and great-grandson of Governor Thomas Dudley.[234] Through his mother, Kerry is a first cousin once removed of French politician Brice Lalonde.[237]

Marriages and children

Kerry was married to Julia Thorne in 1970, and they had two daughters together: documentary filmmaker Alexandra Kerry (born September 5, 1973) and physician Vanessa Kerry (born December 31, 1976).

Alexandra was born days before Kerry began law school. In 1982, Julia asked Kerry for a separation while she was suffering from severe depression.[238] They were divorced on July 25, 1988, and the marriage was formally annulled in 1997. "After 14 years as a political wife, I associated politics only with anger, fear and loneliness", she wrote in A Change of Heart, her book about depression. Thorne later married Richard Charlesworth, an architect, and moved to Bozeman, Montana, where she became active in local environmental groups such as the Greater Yellowstone Coalition. Thorne supported Kerry's 2004 presidential run. She died of cancer on April 27, 2006.[239]

Kerry and his second wife—Portuguese-born businesswoman and philanthropist Teresa Heinz, the widow of Kerry's late Pennsylvania Republican Senate colleague John Heinz—were introduced to each other by Heinz at an Earth Day rally in 1990. Early the following year, Senator Heinz was killed in a plane crash near Lower Merion. Teresa has three sons from her marriage to Heinz, Henry John IV, André, and Christopher.[240] Heinz and Kerry were married on May 26, 1995, in Nantucket, Massachusetts.[241]

Net worth

The Forbes 400 survey estimated in 2004 that Teresa Heinz Kerry had a net worth of $750 million. However, estimates have frequently varied, ranging from around $165 million to as high as $3.2 billion, according to a study in the Los Angeles Times. Regardless of which figure is correct, Kerry was the wealthiest U.S. Senator while serving in the Senate. Independent of Heinz, Kerry is wealthy in his own right, and is the beneficiary of at least four trusts inherited from Forbes family relatives, including his mother, Rosemary Forbes Kerry, who died in 2002. Forbes magazine (named for the Forbes family of publishers, unrelated to Kerry) estimated that if elected, and if Heinz family assets were included, Kerry would have been the third-richest U.S. president in history, when adjusted for inflation.[242] This assessment was based on Heinz's and Kerry's combined assets, but the couple signed a prenuptial agreement that keeps their assets separate.[243] Kerry's financial disclosure form for 2011 put his personal assets in the range of $230,000,000 to $320,000,000,[244] including the assets of his spouse and any dependent children. This included slightly more than $3,000,000 worth of H. J. Heinz Company assets, which increased in value by over $600,000 in 2013 when Berkshire Hathaway announced their intention to purchase the company.[245]

In April 2017, Kerry purchased an 18-acre property on the northwest corner of Martha's Vineyard overlooking Vineyard Sound in the town of Chilmark, Massachusetts. The property is located in Seven Gates Farm and according to property records, cost $11.75 million for the seven bedroom home.[246]

Religious beliefs

Kerry is a Roman Catholic, and is said to have carried a religious rosary, a prayer book, and a St. Christopher medal (the patron saint of travelers) when he campaigned. Discussing his faith, Kerry said: "I thought of being a priest. I was very religious while at school in Switzerland. I was an altar boy and prayed all the time. I was very centered around the Mass and the church." He also said that the Letters of Paul (Apostle Paul) moved him the most, stating that they taught him to "not feel sorry for myself".[6]

Kerry told Christianity Today in October 2004:

I'm a Catholic and I practice, but at the same time I have an open-mindedness to many other expressions of spirituality that come through different religions ... I've spent some time reading and thinking about religion and trying to study it, and I've arrived at not so much a sense of the differences, but a sense of the similarities in so many ways.[247]

He said that he believed that the Torah, the Quran, and the Bible all share a fundamental story which connects with readers.[247]

Health

In 2003, Kerry was diagnosed with and successfully treated for prostate cancer.[248] On May 31, 2015, Kerry broke his right leg in a biking accident in Scionzier, France, and was flown to Boston's Massachusetts General Hospital for recovery. MGH Hip and Knee Replacement Orthopaedic Surgeon Dr. Dennis Burke,[249] who had met Kerry in France and had accompanied him in the plane from France to Boston, set Kerry's right leg on Tuesday, June 2, in a four-hour operation.[250][251]

Athletics and sailing

Помимо видов спорта, которыми он занимался в Йельском университете, журнал Sports Illustrated описывает Керри , среди прочего, как «заядлого велосипедиста ». [252][253] в основном езда на шоссейном велосипеде. До своей кандидатуры на пост президента Керри участвовал в нескольких поездках на дальние расстояния . Сообщается, что во время своих многочисленных кампаний он посещал магазины велосипедов как в своем родном штате, так и в других местах. Его сотрудники запросили лежачие велотренажеры для его гостиничных номеров. [ 254 ] Он также был сноубордистом, виндсерфером и моряком. [ 255 ]

Газета Boston Herald сообщила 23 июля 2010 года, что Керри заказал строительство новой яхты стоимостью 7 миллионов долларов (Friendship 75) в Новой Зеландии и пришвартовал ее в Портсмуте, штат Род-Айленд , где базируется яхтенная компания Friendship. [ 256 ] В статье утверждалось, что это позволило ему избежать уплаты налогов штата Массачусетс на недвижимость, включая примерно 437 500 долларов налога с продаж и годовой акцизный налог в размере около 500 долларов США. [ 257 ] 27 июля Керри заявил, что добровольно заплатит 500 000 долларов налогов штата Массачусетс на свою яхту. [ 258 ]

Почести

Джон Керри был награжден: [ 259 ]

Национальный

- Президентская медаль свободы (3 мая 2024 г.) [ 260 ]

Иностранный

Германия : Большой крест 1-й степени ордена «За заслуги перед Федеративной Республикой Германия».

Германия : Большой крест 1-й степени ордена «За заслуги перед Федеративной Республикой Германия».  Франция : кавалер ордена Почетного легиона.

Франция : кавалер ордена Почетного легиона.

Почетные степени

Джон Керри получил несколько почетных степеней в знак признания его заслуг перед Соединенными Штатами, в том числе:

| Состояние | Дата | Школа | Степень |

|---|---|---|---|

| Массачусетс | 28 мая 1988 г. | Массачусетский университет в Бостоне | доктор юридических наук [ 261 ] [ 262 ] |

| Массачусетс | 17 июня 2000 г. | Северо-Восточный университет | Доктор государственной службы [ 263 ] |

| Огайо | май 2006 г. | Кеньон Колледж | доктор юридических наук [ 264 ] |

| Массачусетс | 19 мая 2014 г. | Бостонский колледж | доктор юридических наук [ 265 ] |

| Коннектикут | 18 мая 2017 г. | Йельский университет | доктор юридических наук [ 266 ] |

Избирательная история

Работает

- Керри, Джон; Ветераны Вьетнама против войны (1971). Новый Солдат . Нью-Йорк: Издательство Macmillan. ISBN 0-02-073610-Х .

- —— (1997). Новая война: сеть преступности, которая угрожает безопасности Америки . Нью-Йорк: Саймон и Шустер. ISBN 0-684-81815-9 .

- —— (2003). Призыв к служению: мое видение лучшей Америки . Нью-Йорк: Викинг Пресс. ISBN 0-670-03260-3 .

- —— Хайнц Керри, Тереза (2007). Этот момент на Земле: современные новые экологи и их видение будущего . Нью-Йорк: PublicAffairs. ISBN 978-1-58648-431-6 .

- —— (2018). Каждый день дополнительный . Нью-Йорк: Саймон и Шустер. ISBN 9781501178955 . OCLC 1028456250 . Мемуары.

См. также

Ссылки

- ^ Гордон, Майкл Р. (29 января 2013 г.). «Керри проходит через Сенат в качестве государственного секретаря» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . ISSN 0362-4331 . Проверено 27 августа 2023 г.

- ^ Бойл, Луиза (7 марта 2024 г.). «Джон Керри уходит с поста специального посланника по климату, но он еще не закончил с политикой» . Независимый .

- ^ Шапиро, Ари; Труп, Уильям; МакНэми, Кай. «Посланник США по климату Джон Керри отказывается от должности, но не от борьбы» . ЭНЕРГЕТИЧЕСКИЙ ЯДЕРНЫЙ РЕАКТОР .

- ^ Уильямс, Майкл (3 мая 2024 г.). «Байден вручает Медаль Свободы ключевым политическим союзникам, лидерам движения за гражданские права, знаменитостям и политикам» . CNN . Проверено 3 мая 2024 г.

- ^ «КЕРРИ, Джон Форбс (1943–)» . Биографический справочник Конгресса США . Архивировано из оригинала 31 марта 2016 года . Проверено 8 декабря 2019 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д Колдуэлл, Дебора. «Не блудный сын» . Believenet.com. Архивировано из оригинала 17 июня 2018 года . Проверено 23 декабря 2012 г.

- ^ «Армейские ребята взлетают» (PDF) . Армейский журнал . 11 ноября 2014 г. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 2 апреля 2015 г. . Проверено 2 июля 2016 г.

- ^ Бринкли, Дуглас (21 сентября 2004 г.). Дежурство: Джон Керри и война во Вьетнаме . Нью-Йорк, штат Нью-Йорк: Уильям Морроу. стр. 18–39. ISBN 9780060565299 .

- ^ Фоер, Франклин (2 марта 2004 г.). «Мир Керри: отец знает лучше» . Новая Республика . CBSNews.com. Архивировано из оригинала 5 марта 2004 года.

- ^ Керри 2018 , стр. 11–12.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Краниш, Майкл (15 июня 2003 г.). «Привилегированная молодежь, склонность к риску» . Бостон Глобус . Архивировано из оригинала 1 августа 2003 года . Проверено 7 июля 2018 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б « Лейбл «Аутсайдер» следует за Керри в Массачусетсе, несмотря на годы его пребывания у власти» . Новости-Сентинел . 6 июля 2004 г. Архивировано из оригинала 24 ноября 2020 г. . Проверено 23 сентября 2018 г.

- ^ Керри 2018 , с. 18.

- ^ Льюис, Дэйв (2018). «300 лет шотландско-ирландской иммиграции в США» Ирландская Америка . Архивировано из оригинала 29 июня 2020 года . Проверено 28 июня 2020 г.

- ^ Краниш, Майкл; Муни, Брайан; Истон, Нина Дж. (5 февраля 2013 г.). «Глава 2 — Молодёжь» . Джон Ф. Керри Биография Boston Globe . Общественные дела. ISBN 978-1610393379 . Проверено 19 ноября 2021 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Сигал, Дэвид (2 февраля 2004 г.). «Рекорд Джона Керри: под который можно танцевать» . Вашингтон Пост . Архивировано из оригинала 24 ноября 2020 года . Проверено 24 ноября 2020 г.

- ^ Хира, Надира А. (11 марта 2004 г.). «Прошлое рок-звезды Джона Керри: История Электры» . МТВ . Архивировано из оригинала 12 ноября 2020 года . Проверено 24 ноября 2020 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Невинс, Джейк (21 июня 2017 г.). «Раскачивание голосования: политики США и их музыкальные побочные проекты» . Хранитель . Архивировано из оригинала 18 ноября 2020 года . Проверено 24 ноября 2020 г.

- ^ «Джон Керри и Электра» . music.apple.com . 2 сентября 2004 г. Архивировано из оригинала 24 ноября 2020 г. . Проверено 24 ноября 2020 г.

- ^ «Джон Керри и Электры» . open.spotify.com . 2004. Архивировано из оригинала 21 ноября 2019 года . Проверено 24 ноября 2020 г.

- ^ Краниш, Муни и Истон 2013 , с. 35.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж г час я дж к л м н тот п д р с т Муни, Брайан К. (18 июня 2003 г.). «Первая кампания заканчивается поражением» . Бостон Глобус . Архивировано из оригинала 2 октября 2003 года . Проверено 9 апреля 2016 г.