Финикс, Аризона

Финикс | |

|---|---|

|

| |

Nicknames:

| |

Interactive map of Phoenix | |

| Coordinates: 33°26′54″N 112°04′26″W / 33.44833°N 112.07389°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Arizona |

| County | Maricopa |

| Settled | 1867 |

| Incorporated | February 25, 1881 |

| Founded by | Jack Swilling |

| Named for | Phoenix, mythical creature |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council–manager |

| • Body | Phoenix City Council |

| • Mayor | Kate Gallego (D) |

| Area | |

| • State capital | 519.28 sq mi (1,344.94 km2) |

| • Land | 518.27 sq mi (1,342.30 km2) |

| • Water | 1.02 sq mi (2.63 km2) |

| Elevation | 1,086 ft (331 m) |

| Population | |

| • State capital | 1,608,139 |

| • Estimate (2021)[3] | 1,624,569 |

| • Rank | 11th in North America 5th in the United States 1st in Arizona |

| • Density | 3,102.92/sq mi (1,198.04/km2) |

| • Urban | 3,976,313 (US: 11th) |

| • Urban density | 3,580.7/sq mi (1,382.5/km2) |

| • Metro | 4,845,832 (US: 10th) |

| Demonym | Phoenician[6] |

| GDP | |

| • Phoenix (MSA) | $362.1 billion (2022) |

| Time zone | UTC–07:00 (MST (no DST)) |

| ZIP Codes | 85001–85024, 85026-85046, 85048, 85050-85051, 85053-85054, 85060-85076, 85078-85080, 85082-85083, 85085-85087 |

| Area codes | |

| FIPS code | 04-55000 |

| GNIS feature ID | 44784 |

| Website | www |

Феникс ( / ˈ f iː n ɪ k s / ПЛАТА - ничего [ 8 ] [ 9 ] ) — столица и самый густонаселенный город американского штата Аризона , с населением 1 608 139 человек по состоянию на 2020 год. [ 10 ] Это пятый по численности населения город США и самая густонаселенная столица штата в стране. [ 11 ]

Финикс — самый густонаселенный город агломерации Финикс , также известной как Долина Солнца, которая, в свою очередь, является частью Долины Соленой реки и Солнечного коридора Аризоны . Агломерация является 10-й по величине по численности населения в Соединенных Штатах с населением около 4,85 миллиона человек по состоянию на 2020 год. [update], что делает его самым густонаселенным на юго-западе Соединенных Штатов . [ 12 ] [ 13 ] Финикс, административный центр округа Марикопа , является крупнейшим по численности населения и площади городом в Аризоне, его площадь составляет 517,9 квадратных миль (1341 км²). 2 ), а также является по площади . 11-м по величине городом в США [ 14 ]

Phoenix was settled in 1867 as an agricultural community near the confluence of the Salt and Gila Rivers and was incorporated as a city in 1881. It became the capital of Arizona Territory in 1889.[15] Its canal system led to a thriving farming community with the original settlers' crops, such as alfalfa, cotton, citrus, and hay, remaining important parts of the local economy for decades.[16][17] Cotton, cattle, citrus, climate, and copper were known locally as the "Five C's" anchoring Phoenix's economy. These remained the driving forces of the city until after World War II, when high-tech companies began to move into the valley and air conditioning made Phoenix's hot summers more bearable.[18]

Phoenix is the cultural center of Arizona.[19] It is in the northeastern reaches of the Sonoran Desert and is known for its hot desert climate.[20][21] The region's gross domestic product reached over $362 billion by 2022.[22] The city averaged a four percent annual population growth rate over a 40-year period from the mid-1960s to the mid-2000s,[23] and was among the nation's ten most populous cities by 1980. Phoenix is also one of the largest plurality-Hispanic cities in the United States, with 42% of its population being Hispanic.[24]

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]

The Hohokam people occupied the Phoenix area for 2,000 years.[25][26] They created roughly 135 miles (217 kilometers) of irrigation canals, making the desert land arable, and paths of these canals were used for the Arizona Canal, Central Arizona Project Canal, and the Hayden-Rhodes Aqueduct. They also carried out extensive trade with the nearby Ancient Puebloans, Mogollon, and Sinagua, as well as with the more distant Mesoamerican civilizations.[27] It is believed periods of drought and severe floods between 1300 and 1450 led to the Hohokam civilization's abandonment of the area.[28]

After the departure of the Hohokam, groups of Akimel O'odham (commonly known as Pima), Tohono O'odham, and Maricopa tribes began to use the area, as well as segments of the Yavapai and Apache.[29] The O'odham were offshoots of the Sobaipuri tribe, who in turn were thought to be the descendants of the Hohokam.[30][31][32]

The Akimel O'odham were the major group in the area. They lived in small villages with well-defined irrigation systems that spread over the Gila River Valley, from Florence in the east to the Estrellas in the west. Their crops included corn, beans, and squash for food as well as cotton and tobacco. They banded with the Maricopa for protection against incursions by the Yuma and Apache tribes.[33] The Maricopa are part of the larger Yuma people; however, they migrated east from the lower Colorado and Gila Rivers in the early 1800s, when they began to be enemies with other Yuma tribes, settling among the existing communities of the Akimel O'odham.[34][35][29]

The Tohono O'odham also lived in the region, but largely to the south and all the way to the Mexican border.[36] The O'odham lived in small settlements as seasonal farmers who took advantage of the rains, rather than the large-scale irrigation of the Akimel. They grew crops such as sweet corn, tapery beans, squash, lentils, sugar cane, and melons, as well as taking advantage of native plants such as saguaro fruits, cholla buds, mesquite tree beans, and mesquite candy (sap from the mesquite tree). They also hunted local game such as deer, rabbit, and javelina for meat.[37][38]

The Mexican–American War ended in 1848, Mexico ceded its northern zone to the United States, and the region's residents became U.S. citizens. The Phoenix area became part of the New Mexico Territory.[39] In 1863, the mining town of Wickenburg was the first to be established in Maricopa County, to the northwest of Phoenix. Maricopa County had not been incorporated; the land was within Yavapai County, which included the major town of Prescott to the north of Wickenburg.

The Army created Fort McDowell on the Verde River in 1865 to forestall Indian uprisings.[40] The fort established a camp on the south side of the Salt River by 1866, which was the first settlement in the valley after the decline of the Hohokam. Other nearby settlements later merged to become the city of Tempe.[41]

Founding and incorporation

[edit]

The history of Phoenix begins with Jack Swilling, a Confederate veteran of the Civil War who prospected in the nearby mining town of Wickenburg in the newly formed Arizona Territory. As he traveled through the Salt River Valley in 1867, he saw a potential for farming to supply Wickenburg with food. He also noted the eroded mounds of dirt that indicated previous canals dug by native peoples who had long since left the area. He formed the Swilling Irrigation and Canal Company that year, dug a large canal that drew in river water, and erected several crop fields in a location that is now within the eastern portion of central Phoenix near its airport. Other settlers soon began to arrive, appreciating the area's fertile soil and lack of frost, and the farmhouse Swilling constructed became a frequently-visited location in the valley.[42][43] Lord Darrell Duppa was one of the original settlers in Swilling's party, and he suggested the name "Phoenix", as it described a city born from the ruins of a former civilization.[25]

The Board of Supervisors in Yavapai County officially recognized the new town on May 4, 1868, and the first post office was established the following month with Swilling as the postmaster.[25] In October 1870, valley residents met to select a new townsite for the valley's growing population. A new location three miles to the west of the original settlement, containing several allotments of farmland, was chosen, and lots began to officially be sold under the name of Phoenix in December of that year. This established the downtown core in a grid layout pattern that has been the hallmark of Phoenix's urban development ever since.

On February 12, 1871, the territorial legislature created Maricopa County by dividing Yavapai County; it was the sixth one formed in the Arizona Territory. The first election for county office was held in 1871 when Tom Barnum was elected the first sheriff. He ran unopposed when the other two candidates (John A. Chenowth and Jim Favorite) fought a duel; Chenowth killed Favorite and was forced to withdraw from the race.[25]

The town grew during the 1870s, and President Ulysses S. Grant issued a land patent for the site of Phoenix on April 10, 1874. By 1875, the town had a telegraph office, 16 saloons, and four dance halls, but the townsite-commissioner form of government needed an overhaul. An election was held in 1875, and three village trustees and other officials were elected.[25] By 1880, the town's population stood at 2,453.[44]

By 1881, Phoenix's continued growth made the board of trustees obsolete. The Territorial Legislature passed the Phoenix Charter Bill, incorporating Phoenix and providing a mayor-council government; Governor John C. Fremont signed the bill on February 25, 1881, officially incorporating Phoenix as a city with a population of around 2,500.[25]

The railroad's arrival in the valley in the 1880s was the first of several events that made Phoenix a trade center whose products reached eastern and western markets. In response, the Phoenix Chamber of Commerce was organized on November 4, 1888.[45] The city offices moved into the new City Hall at Washington and Central in 1888.[25] The territorial capital moved from Prescott to Phoenix in 1889, and the territorial offices were also in City Hall.[46] The arrival of the Santa Fe, Prescott and Phoenix Railway in 1895 connected Phoenix to Prescott, Flagstaff, and other communities in the northern part of the territory. The increased access to commerce expedited the city's economic rise. The Phoenix Union High School was established in 1895 with an enrollment of 90.[25]

1900 to World War II

[edit]

On February 25, 1901, Governor Oakes Murphy dedicated the permanent Capitol building,[25] and the Carnegie Free Library opened seven years later, on February 18, 1908, dedicated by Benjamin Fowler.[47] The National Reclamation Act was signed by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1902, which allowed dams to be built on waterways in the west for reclamation purposes.[48] The first dam constructed under the act, Salt River Dam#1, began in 1903. It supplied both water and electricity, becoming the first multi-purpose dam, and Roosevelt attended the official dedication on May 18, 1911. At the time, it was the largest masonry dam in the world, forming a lake in the mountains east of Phoenix.[49] The dam would be renamed after Teddy Roosevelt in 1917,[50] and the lake would follow suit in 1959.[51]

On February 14, 1912, Phoenix became a state capital, as Arizona was admitted to the Union as the 48th state under President William Howard Taft.[52] This occurred just six months after Taft had vetoed a joint congressional resolution granting statehood to Arizona, due to his disapproval of the state constitution's position on the recall of judges.[53] In 1913, Phoenix's move from a mayor-council system to council-manager made it one of the first cities in the United States with this form of city government. After statehood, Phoenix's growth started to accelerate; eight years later, its population reached 29,053. In 1920, Phoenix would see its first skyscraper, the Heard Building; it was the tallest building in the state until the completion of the Luhrs Building in 1924.[25] In 1929, Sky Harbor was officially opened, at the time owned by Scenic Airways. The city purchased it in 1935 and continues to operate it today.[54]

On March 4, 1930, former U.S. President Calvin Coolidge dedicated a dam on the Gila River named in his honor. However, the state had just been through a long drought, and the reservoir which was supposed to be behind the dam was virtually dry. The humorist Will Rogers, who was on hand as a guest speaker joked, "If that was my lake, I'd mow it."[55] Phoenix's population had nearly doubled during the 1920s and by 1930 stood at 48,118.[25] It was also during the 1930s that Phoenix and its surrounding area began to be called "The Valley of the Sun", which was an advertising slogan invented to boost tourism.[56]

During World War II, Phoenix's economy shifted to that of a distribution center, transforming into an "embryonic industrial city" with the mass production of military supplies.[25] There were three air force fields in the area: Luke Field, Williams Field, and Falcon Field, as well as two large pilot training camps, Thunderbird Field No. 1 in Glendale and Thunderbird Field No. 2 in Scottsdale.[25][57][58]

Post-World War II explosive growth

[edit]A town that had just over 65,000 residents in 1940 became America's fifth largest city by 2020, with a population of nearly 1.6 million, and millions more in nearby suburbs. After the war, many of the men who had undergone their training in Arizona returned with their new families. Learning of this large untapped labor pool enticed many large industries to move their operations to the area.[25] In 1948, high-tech industry, which would become a staple of the state's economy, arrived in Phoenix when Motorola chose Phoenix as the site of its new research and development center for military electronics. Seeing the same advantages as Motorola, other high-tech companies, such as Intel and McDonnell Douglas, moved into the valley and opened manufacturing operations.[59][60]

By 1950, over 105,000 people resided in the city and thousands more in surrounding communities.[25] The 1950s growth was spurred on by advances in air conditioning, which allowed homes and businesses to offset the extreme heat experienced in Phoenix and the surrounding areas during its long summers. There was more new construction in Phoenix in 1959 alone than from 1914 to 1946.[61]

Like many emerging American cities at the time, Phoenix's spectacular growth did not occur evenly. It largely took place on the city's north side, a region that was nearly all Caucasian. In 1962, one local activist testified at a US Commission on Civil Rights of hearing that of 31,000 homes that had recently sprung up in this neighborhood, not a single one had been sold to an African-American.[62] Phoenix's African-American and Mexican-American communities remained largely sequestered on the south side of town. The color lines were so rigid that no one north of Van Buren Street would rent to the African-American baseball star Willie Mays, in town for spring training in the 1960s.[63] In 1964, a reporter from The New Republic wrote of segregation in these terms: "Apartheid is complete. The two cities look at each other across a golf course."[64]

1960s to present

[edit]

The continued rapid population growth led more businesses to the valley to take advantage of the labor pool,[65] and manufacturing, particularly in the electronics sector, continued to grow.[66] The convention and tourism industries saw rapid expansion during the 1960s, with tourism becoming the third largest industry by the end of the decade.[67] In 1965, the Phoenix Corporate Center opened; at the time it was the tallest building in Arizona, topping off at 341 feet.[68] The 1960s saw many other buildings constructed as the city expanded rapidly, including the Rosenzweig Center (1964), today called Phoenix City Square,[69] the landmark Phoenix Financial Center (1964),[70] as well as many of Phoenix's residential high-rises. In 1965 the Arizona Veterans Memorial Coliseum opened at the Arizona State Fairgrounds, west of downtown. When Phoenix was awarded an NBA franchise in 1968, which would be called the Phoenix Suns,[71][72] they played their home games at the Coliseum until 1992, after which they moved to America West Arena.[73] In 1968, President Lyndon B. Johnson approved the Central Arizona Project, assuring future water supplies for Phoenix, Tucson, and the agricultural corridor between them.[74][75] The following year, Pope Paul VI created the Diocese of Phoenix on December 2, by splitting the Archdiocese of Tucson, with Edward A. McCarthy as the first Bishop.[76]

In the 1970s the downtown area experienced a resurgence, with a level of construction activity not seen again until the urban real estate boom of the 2000s. By the end of the decade, Phoenix adopted the Phoenix Concept 2000 plan which split the city into urban villages, each with its own village core where greater height and density was permitted, further shaping the free-market development culture. The nine original villages[77] have expanded to 15 over the years (see Cityscape below). This officially turned Phoenix into a city of many nodes, which would later be connected by freeways. The Phoenix Symphony Hall opened in 1972;[78] other major structures which saw construction downtown during this decade were the First National Bank Plaza, the Valley Center (the tallest building in Arizona),[79] and the Arizona Bank building.

On September 25, 1981, Phoenix resident Sandra Day O'Connor broke the gender barrier on the U.S. Supreme Court, when she was sworn in as the first female justice.[80] In 1985, the Palo Verde Nuclear Generating Station, the nation's largest nuclear power plant, began electrical production.[81] Pope John Paul II and Mother Teresa both visited the Valley in 1987.[82]

There was an influx of refugees due to low-cost housing in the Sunnyslope area in the 1990s, resulting in 43 different languages being spoken in local schools by 2000.[83] The new 20-story City Hall opened in 1992.[84]

Phoenix has maintained a growth streak in recent years, growing by 24.2% before 2007. This made it the second-fastest-growing metropolitan area in the United States, surpassed only by Las Vegas.[85] In 2008, Squaw Peak, the city's second tallest mountain, was renamed Piestewa Peak after Army Specialist Lori Ann Piestewa, an Arizonan and the first Native American woman to die in combat while serving in the U.S. military, as well as being the first American female casualty of the 2003 Iraq War.[86] 2008 also saw Phoenix as one of the cities hardest hit by the subprime mortgage crisis, and by early 2009 the median home price was $150,000, down from its $262,000 peak in 2007.[87] Crime rates in Phoenix have fallen in recent years, and once troubled, decaying neighborhoods such as South Mountain, Alhambra, and Maryvale have recovered and stabilized. On June 1, 2023, the State of Arizona announced the decision to halt new housing development in the Phoenix metropolitan area that relies solely on groundwater due to a predicted water shortfall.[88]

Geography

[edit]

Phoenix is in the south-central portion of Arizona; about halfway between Tucson to the southeast and Flagstaff to the north, in the southwestern United States. By car, the city is approximately 150 miles (240 kilometers) north of the US–Mexico border at Sonoyta and 180 mi (290 km) north of the border at Nogales. The metropolitan area is known as the "Valley of the Sun" due to its location in the Salt River Valley.[56] It lies at a mean elevation of 1,086 feet (331 m), in the northern reaches of the Sonoran Desert.[89]

Other than the mountains in and around the city, Phoenix's topography is generally flat, which allows the city's main streets to run on a precise grid with wide, open-spaced roadways. Scattered, low mountain ranges surround the valley: McDowell Mountains to the northeast, the White Tank Mountains to the west, the Superstition Mountains far to the east, and both South Mountain and the Sierra Estrella to the south/southwest. Camelback Mountain, North Mountain, Sunnyslope Mountain, and Piestewa Peak are within the heart of the valley. The city's outskirts have large fields of irrigated cropland and Native American reservation lands.[90] The Salt River runs westward through Phoenix, but the riverbed is often dry or contains little water due to large irrigation diversions. South Mountain separates the community of Ahwatukee from the rest of the city.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has an area of 517.9 sq mi (1,341 km2), of which 516.7 sq mi (1,338 km2) is land and 1.2 sq mi (3.1 km2), or 0.2%, is water.

Maricopa County grew by 711% from 186,000 in 1940 to 1,509,000 by 1980, due in part to air conditioning, cheap housing, and an influx of retirees. The once "modest urban sprawl" now "grew by 'epic' proportions—not only a myriad of residential tract developments on both farmland and desert." Retail outlets and office complexes spread out and did not concentrate in the small downtown area. There was low population density and a lack of widespread and significant high-rise development.[91] As a consequence Phoenix became a textbook case of urban sprawl for geographers.[92][93][94][95][96][97] Even though it is the fifth most populated city in the United States, the large area gives it a low density rate of approximately 2,797 people per square mile.[98] In comparison, Philadelphia, the sixth most populous city with nearly the same population as Phoenix, has a density of over 11,000 people per square mile.[99]

Like most of Arizona, Phoenix does not observe daylight saving time. In 1973, Governor Jack Williams argued to the U.S. Congress that energy use would increase in the evening should Arizona observe DST. He went on to say energy use would also rise early in the day "because there would be more lights on in the early morning." Additionally, he said daylight saving time would cause children to go to school in the dark.[100]

Cityscape

[edit]Neighborhoods

[edit]

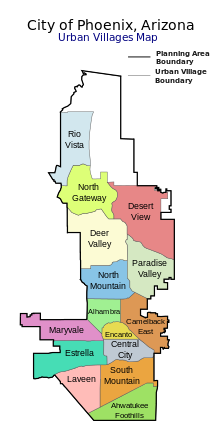

Since 1979, the city of Phoenix has been divided into urban villages, many of which are based upon historically significant neighborhoods and communities that have since been annexed into Phoenix.[101] Each village has a planning committee appointed directly by the city council. According to the city-issued village planning handbook, the purpose of the village planning committees is to "work with the city's planning commission to ensure a balance of housing and employment in each village, concentrate development at identified village cores, and to promote the unique character and identity of the villages."[102] There are 15 urban villages: Ahwatukee Foothills, Alhambra, Camelback East, Central City, Deer Valley, Desert View, Encanto, Estrella, Laveen, Maryvale, North Gateway, North Mountain, Paradise Valley, Rio Vista, and South Mountain.

The urban village of Paradise Valley is distinct from the nearby Town of Paradise Valley. Although the urban village is part of Phoenix, the town is independent.

In addition to the above urban villages, Phoenix has a variety of commonly referred-to regions and districts, such as Downtown, Midtown, Uptown,[103] West Phoenix, North Phoenix, South Phoenix, Biltmore Area, Arcadia, and Sunnyslope.

Flora and fauna

[edit]While some of the native flora and fauna of the Sonoran Desert can be found within Phoenix city limits, most are found in the suburbs and the undeveloped desert areas that surround the city. Native mammal species include coyote, javelina, bobcat, mountain lion, desert cottontail rabbit, jackrabbit, antelope ground squirrel, mule deer, ringtail, coati, and multiple species of bats, such as the Mexican free-tailed bat and western pipistrelle, that roost in and around the city. There are many species of native birds, including Costa's hummingbird, Anna's hummingbird, Gambel's quail, Gila woodpecker, mourning dove, white-winged dove, the greater roadrunner, the cactus wren, and many species of raptors, including falcons, hawks, owls, vultures (such as the turkey vulture and black vulture), and eagles, including the golden and the bald eagle.[104][105]

The greater Phoenix region is home to the only thriving feral population of rosy-faced lovebirds in the U.S. This bird is a popular birdcage pet, native to southwestern Africa. Feral birds were first observed living outdoors in 1987, probably escaped or released pets, and by 2010 the Greater Phoenix population had grown to about 950 birds. These lovebirds prefer older neighborhoods where they nest under untrimmed, dead palm tree fronds.[106][107]

The area is also home to a plethora of native reptile species including the Western diamondback rattlesnake, Sonoran sidewinder, several other types of rattlesnakes, Sonoran coral snake, dozens of species of non-venomous snakes (including the Sonoran gopher snake and the California kingsnake), the gila monster, desert spiny lizard, several types of whiptail lizards, the chuckwalla, desert horned lizard, western banded gecko, Sonora mud turtle, and the desert tortoise. Native amphibian species include the Couch's spadefoot toad, Chiricahua leopard frog, and the Sonoran desert toad.[108]

Phoenix and the surrounding areas are also home to a wide variety of native invertebrates including the Arizona bark scorpion, giant desert hairy scorpion, Arizona blond tarantula, Sonoran Desert centipede, tarantula hawk wasp, camel spider, and tailless whip scorpion. Of great concern is the presence of Africanized bees which can be extremely dangerous—even lethal—when provoked.

The Arizona Upland subdivision of the Sonoran Desert (of which Phoenix is a part) has "the most structurally diverse flora in the United States." One of the most well-known types of succulents, the giant saguaro cactus, is found throughout the city and its neighboring environs. Other native species are the organpipe, barrel, fishhook, senita, prickly pear and cholla cacti; ocotillo; Palo Verde trees and foothill and blue paloverde; California fan palm; agaves; soaptree yucca, Spanish bayonet, desert spoon, and red yucca; ironwood; mesquite; and the creosote bush.[109][110]

Many non-native plants also thrive in Phoenix including, but not limited to, the date palm, Mexican fan palm, pineapple palm, Afghan pine, Canary Island pine, Mexican fencepost cactus, cardon cactus, acacia, eucalyptus, aloe, bougainvillea, oleander, lantana, bottlebrush, olive, citrus, and red bird of paradise.

Climate

[edit]

Phoenix has a hot desert climate (Köppen: BWh),[20][21] typical of the Sonoran Desert, and is the largest city in America in this climatic zone.[111] Phoenix has long, extremely hot summers and short, mild winters. The city is within one of the world's sunniest regions, with its sunshine duration comparable to the Sahara region. With 3,872 hours of bright sunshine annually, Phoenix receives the most sunshine of any major city on Earth.[112] Average high temperatures in summer are the hottest of any major city in the United States.[113] On average, there are 111 days annually with a high of at least 100 °F (38 °C), including most days from the end of May through late September. Highs top 110 °F (43 °C) an average of 21 days during the year.[114] On June 26, 1990, the temperature reached an all-time recorded high of 122 °F (50 °C).[115] The annual minimum temperature in Phoenix is in the mid-to-low 30s.[114] It rarely drops to 32 °F (0 °C) or below. Snow is rare.[citation needed]

Maricopa County, which includes Phoenix, was ranked seventh for most ozone pollution in the United States according to the American Lung Association.[116] Vehicle emissions are cited as precursors to ozone formation. Phoenix also has high levels of particulate pollution; although, cities in California lead the nation in this hazard.[117] PM2.5 particulate matter, which is a component of diesel engine exhaust, and larger PM10 particles, which can come from dust, can both reach concerning levels in Phoenix.[118] In fact, people, pets, and other animals exposed to high concentrations of PM10 dust particles―primarily from dust storms or from disturbed agricultural or construction sites―are at risk of contracting Valley Fever, a fungal lung infection.[119]

Unlike most desert locations which have drastic fluctuations between day and nighttime temperatures, the urban heat island effect limits Phoenix's diurnal temperature variation.[120] As the city has expanded, average summer low temperatures have been steadily rising. Pavement, sidewalks, and buildings store the Sun's heat and radiate it at night.[121] The daily normal low remains at or above 80 °F (27 °C) for an average of 74 days per summer.[114] On July 19, 2023, Phoenix set its record for the warmest daily low temperature, at 97 °F (36 °C).[114]

The city averages approximately 300 days of sunshine, or over 85% of daylight hours, per year,[122][123] and receives scant rainfall―the average annual total at Phoenix Sky Harbor International Airport is 7.22 in (183 mm). The region's trademark dry and sunny weather is interrupted by sporadic Pacific storms in the winter and the arrival of the North American monsoon in the summer.[124] Historically, the monsoon officially started when the average dew point was 55 °F (13 °C) for three days in a row—typically occurring in early July. To increase monsoon awareness and promote safety, however, the National Weather Service decreed that starting in 2008, June 15 would be the official "first day" of the monsoon, and it would end on September 30.[125] When active, the monsoon raises humidity levels and can cause heavy localized precipitation, flash floods, hail, destructive winds, and dust storms[126]—which can rise to the level of a haboob in some years.[127]

| Climate data for Phoenix Int'l, Arizona (1991–2020 normals,[a] extremes 1895–present)[b] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 88 (31) |

92 (33) |

100 (38) |

105 (41) |

114 (46) |

122 (50) |

121 (49) |

117 (47) |

118 (48) |

107 (42) |

99 (37) |

87 (31) |

122 (50) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 78.2 (25.7) |

82.1 (27.8) |

90.4 (32.4) |

99.0 (37.2) |

105.7 (40.9) |

112.7 (44.8) |

114.6 (45.9) |

113.2 (45.1) |

108.9 (42.7) |

100.7 (38.2) |

88.9 (31.6) |

77.7 (25.4) |

115.7 (46.5) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 67.6 (19.8) |

70.8 (21.6) |

78.1 (25.6) |

85.5 (29.7) |

94.5 (34.7) |

104.2 (40.1) |

106.5 (41.4) |

105.1 (40.6) |

100.4 (38.0) |

89.2 (31.8) |

76.5 (24.7) |

66.2 (19.0) |

87.1 (30.6) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 56.8 (13.8) |

59.9 (15.5) |

66.3 (19.1) |

73.2 (22.9) |

82.0 (27.8) |

91.4 (33.0) |

95.5 (35.3) |

94.4 (34.7) |

89.2 (31.8) |

77.4 (25.2) |

65.1 (18.4) |

55.8 (13.2) |

75.6 (24.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 46.0 (7.8) |

49.0 (9.4) |

54.5 (12.5) |

60.8 (16.0) |

69.5 (20.8) |

78.6 (25.9) |

84.5 (29.2) |

83.6 (28.7) |

78.1 (25.6) |

65.6 (18.7) |

53.7 (12.1) |

45.3 (7.4) |

64.1 (17.8) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 36.0 (2.2) |

40.0 (4.4) |

44.4 (6.9) |

50.1 (10.1) |

58.4 (14.7) |

69.4 (20.8) |

74.4 (23.6) |

74.2 (23.4) |

68.3 (20.2) |

53.8 (12.1) |

42.0 (5.6) |

35.4 (1.9) |

33.8 (1.0) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 16 (−9) |

24 (−4) |

25 (−4) |

35 (2) |

39 (4) |

49 (9) |

63 (17) |

58 (14) |

47 (8) |

34 (1) |

27 (−3) |

22 (−6) |

16 (−9) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.87 (22) |

0.87 (22) |

0.83 (21) |

0.22 (5.6) |

0.13 (3.3) |

0.02 (0.51) |

0.91 (23) |

0.93 (24) |

0.57 (14) |

0.56 (14) |

0.57 (14) |

0.74 (19) |

7.22 (183) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 3.8 | 4.1 | 3.1 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 3.9 | 4.6 | 2.5 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 4.0 | 33.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 50.9 | 44.4 | 39.3 | 27.8 | 21.9 | 19.4 | 31.6 | 36.2 | 35.6 | 36.9 | 43.8 | 51.8 | 36.6 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 32.4 (0.2) |

32.2 (0.1) |

32.9 (0.5) |

31.6 (−0.2) |

34.3 (1.3) |

39.0 (3.9) |

56.1 (13.4) |

58.3 (14.6) |

52.3 (11.3) |

43.0 (6.1) |

35.8 (2.1) |

33.1 (0.6) |

40.1 (4.5) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 256.0 | 257.2 | 318.4 | 353.6 | 401.0 | 407.8 | 378.5 | 360.8 | 328.6 | 308.9 | 256.0 | 244.8 | 3,871.6 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 81 | 84 | 86 | 90 | 93 | 95 | 86 | 87 | 89 | 88 | 82 | 79 | 87 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 3.1 | 4.4 | 6.6 | 8.5 | 9.7 | 10.9 | 11.0 | 10.1 | 8.3 | 5.6 | 3.7 | 2.7 | 7.0 |

| Source 1: NOAA (dew points, relative humidity, and sun 1961–1990)[128][129][130], Weather.com[131] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: UV Index Today (1995 to 2022)[132] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1870 | 240 | — | |

| 1880 | 1,708 | 611.7% | |

| 1890 | 3,152 | 84.5% | |

| 1900 | 5,544 | 75.9% | |

| 1910 | 11,314 | 104.1% | |

| 1920 | 29,053 | 156.8% | |

| 1930 | 48,118 | 65.6% | |

| 1940 | 65,414 | 35.9% | |

| 1950 | 106,818 | 63.3% | |

| 1960 | 439,170 | 311.1% | |

| 1970 | 581,572 | 32.4% | |

| 1980 | 789,704 | 35.8% | |

| 1990 | 983,403 | 24.5% | |

| 2000 | 1,321,045 | 34.3% | |

| 2010 | 1,445,632 | 9.4% | |

| 2020 | 1,608,139 | 11.2% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 1,650,070 | [135] | 2.6% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[136] 2010–2020[10] | |||

As of 2020, Phoenix was the fifth most populous city in the United States, with the census bureau placing its population at 1,608,139, edging out Philadelphia with a population of 1,567,872.[137] In the aftermath of the Great Recession, Phoenix had a population of 1,445,632 according to the 2010 United States census, the sixth largest city and still the most populous state capital in the United States.[138] Prior to the Great Recession, in 2006, Phoenix's population was 1,512,986, the fifth largest just ahead of Philadelphia.[138]

After leading the U.S. in population growth for over a decade, the sub-prime mortgage crisis, followed by the recession, led to a slowing in the growth of Phoenix. There were approximately 77,000 people added to the population of the Phoenix metropolitan area in 2009, which was down significantly from its peak in 2006 of 162,000.[139][140] Despite this slowing, Phoenix's population grew by 9.4% since the 2000 census (a total of 124,000 people), while the entire Phoenix metropolitan area grew by 28.9% during the same period. This compares with an overall growth rate nationally during the same time frame of 9.7%.[141][142] Not since 1940–50, when the city had a population of 107,000, had the city gained less than 124,000 in a decade. Phoenix's recent growth rate of 9.4% from the 2010 census is the first time it has recorded a growth rate under 24% in a census decade.[143] However, in 2016, Phoenix once again became the fastest growing city in the United States, adding approximately 88 people per day during the preceding year.[137]

The Phoenix Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) (officially known as the Phoenix-Mesa-Chandler MSA [144]), is one of 10 MSAs in Arizona, and was the 11th largest in the United States, with a 2018 U.S. census population estimate of 4,857,962, up from the 2010 census population of 4,192,887. Consisting of both Pinal and Maricopa counties, the MSA accounts for 65.5% of Arizona's population.[141][142] Phoenix only contributed 13% to the total growth rate of the MSA, down significantly from its 33% share during the prior decade.[143] Phoenix is also part of the Arizona Sun Corridor megaregion (MR), which is the tenth most populous of the 11 MRs, and the eighth largest by area. It had the second largest growth by percentage of the MRs (behind only the Gulf Coast MR) between 2000 and 2010.[145]

The population is almost equally split between men and women, with men making up 50.2% of city's citizens. The population density is 2,797.8 people per square mile, and the city's median age is 32.2 years, with only 10.9 of the population being over 62. 98.5% of Phoenix's population lives in households with an average household size of 2.77 people.

There were 514,806 total households, with 64.2% of those households consisting of families: 42.3% married couples, 7% with an unmarried male as head of household, and 14.9% with an unmarried female as head of household. 33.6% of those households have children below the age of 18. Of the 35.8% of non-family households, 27.1% have a householder living alone, almost evenly split between men and women, with women having 13.7% and men occupying 13.5%.

As of 2020[update], Phoenix has 590,149 dwelling units, with an occupancy rate of 87.2%. The largest segment of vacancies is in the rental market, where the vacancy rate is 14.9%, and 51% of all vacancies are in rentals. Vacant houses for sale only make up 17.7% of the vacancies, with the rest being split among vacation properties and other various reasons.[146]

The city's median household income was $47,866, and the median family income was $54,804. Males had a median income of $32,820 versus $27,466 for females. The city's per capita income was $24,110. 21.8% of the population and 17.1% of families were below the poverty line. Of the total population, 31.4% of those under the age of 18 and 10.5% of those 65 and older were living below the poverty line.[147]

Ethnicity

[edit]

| Racial composition | 1940[148] | 1970[148] | 1990[148] | 2010[149] | 2020[150] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (Non-Hispanic) | n/a | 81.3% | 71.8% | 46.5% | 42.2% |

| Hispanic or Latino | n/a | 12.7% | 20.0% | 40.8% | 42.6% |

| Black or African American | 6.5% | 4.8% | 5.2% | 6.0% | 7.1% |

| Asian | 0.8% | 0.5% | 1.7% | 3.0% | 3.9% |

| Mixed | n/a | n/a | n/a | 1.7% | 3.4% |

According to the 2020 census, the racial breakdown of Phoenix was as follows:[151]

- White: 49.7% (42.2% non-Hispanic)

- Black or African American: 7.8%

- Native American: 2.6%

- Asian: 4.1%

- Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander: 0.2%

- Other race: 20.1%

- Two or more races: 15.5%

- Hispanic: 41.1%

According to the 2010 census, the racial breakdown of Phoenix was as follows:[152]

- White: 65.9% (46.5% non-Hispanic)

- Black or African American: 6.5% (6.0% non-Hispanic)

- Native American: 2.2%

- Asian: 3.2% (0.8% Indian, 0.5% Filipino, 0.5% Korean, 0.4% Chinese, 0.4% Vietnamese, 0.2% Japanese, 0.2% Thai, 0.1% Burmese)

- Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander: 0.2%

- Other race: 18.5%

- Two or more races: 3.6%

Phoenix's population has historically been predominantly white.[citation needed] From 1890 to 1970, over 90% of the citizens were white.[citation needed] In recent years, this percentage has dropped, reaching 65% in 2010. However, a large part of this decrease can be attributed to new guidelines put out by the U.S. Census Bureau in 1980, when a question regarding Hispanic origin was added to the census questionnaire. This has led to an increasing tendency for some groups to no longer self-identify as white, and instead categorize themselves as "other races".[148]

20.6% of the population of the city was foreign born in 2010. Of the 1,342,803 residents over five years of age, 63.5% spoke only English, 30.6% spoke Spanish at home, 2.5% spoke another Indo-European language, 2.1% spoke Asian or Islander languages, with the remaining 1.4% speaking other languages. About 15.7% of non-English speakers reported speaking English less than "very well". The largest national ancestries reported were Mexican (35.9%), German (15.3%), Irish (10.3%), English (9.4%), Black (6.5%), Italian (4.5%), French (2.7%), Polish (2.5%), American Indian (2.2%), and Scottish (2.0%).[153] Hispanics or Latinos of any race make up 40.8% of the population. Of these the largest groups are at 35.9% Mexican, 0.6% Puerto Rican, 0.5% Guatemalan, 0.3% Salvadoran, 0.3% Cuban.

Phoenix has the largest urban Native American population in Arizona. Phoenix has around 200 Dakota Sioux, approximately 100 Minnesota Chippewas, 100 Kiowas, about 175 Creeks, 100 Choctaws, several hundred Cherokees, several hundred Pueblos, and smaller numbers of Shawnees, Blackfeet, Pawnees, Cheyennes, Iroquois, Tlingit, Yakimas and other Native Americans from far away states.[154]

Hispanics are now the majority in Phoenix.[24] African Americans, Hispanics, and Native Americans live primarily in the southern portion of Phoenix, below the downtown district.[155]

According to the National Immigration Forum, the majority of Phoenix's immigrants are from Latin America: Mexico (196,941), Guatemala (5.093), El Salvador (2,980); Asia: India (10,128), Philippines (5.756), Vietnam (4,698); Africa: Ethiopia (1,157), Liberia (1,089), Sudan (1,067) and Europe: Bosnia and Herzegovina (2.944), Germany (2,847) and Romania (1,658).[156]

According to a 2014 study by the Pew Research Center, 66% of the population of the city identified themselves as Christians,[157][158] while 26% claimed no religious affiliation. The same study says other religions (including Judaism, Buddhism, Islam, and Hinduism) collectively make up about 7% of the population. In 2010, according to the Association of Religion Data Archives, which conducts religious census each ten years, 39% of those polled in Maricopa county considered themselves a member of a religious group. Of those who expressed a religious affiliation, the area's religious composition was reported as 35% Catholic, 22% to Evangelical Protestant denominations, 16% Latter-Day Saints (LDS), 14% to nondenominational congregations, 7% to Mainline Protestant denominations, and 2% Hindu. The remaining 4% belong to other religions, such as Buddhism and Judaism.

While the number of religious adherents increased by 103,000 during the decade, the growth did not keep pace with the county's overall population increase of almost three-quarters of million individuals during the same period. The largest aggregate increases were in the LDS (a 58% increase) and Evangelical Protestant churches (14% increase), while all other categories saw their numbers drop slightly or remain static. The Catholic Church had an 8% drop, while mainline Protestant groups saw a 28% decline.[159]

According to the 2022 Point-In-Time Homeless Count, there were 3,096 homeless people in Phoenix.[160]

Economy

[edit]

Phoenix's early economy focused on agriculture and natural resources, especially the "5Cs" of copper, cattle, climate, cotton, and citrus.[18] With the opening of the Union Station in 1923, the establishment of the Southern Pacific rail line in 1926, and the creation of Sky Harbor airport in 1928, the city became more easily accessible.[161] The Great Depression affected Phoenix, but Phoenix had a diverse economy and by 1934 the recovery was underway.[162][163] At the conclusion of World War II, the valley's economy surged, as many men who had completed their military training at bases in and around Phoenix returned with their families. The construction industry, spurred on by the city's growth, further expanded with the development of Sun City. It became the template for suburban development in post-WWII America,[164] and Sun City became the template for retirement communities when it opened in 1960.[165][166] The city averaged a four percent annual growth rate over a 40-year period from the mid-1960s to the mid-2000s.[23]

As the national financial crisis of 2007–10 began, construction in Phoenix collapsed and housing prices plunged.[167] Arizona jobs declined by 11.8% from peak to trough; in 2007 Phoenix had 1,918,100 employed individuals, by 2010 that number had shrunk by 226,500 to 1,691,600.[168] By the end of 2015, the employment number in Phoenix had risen to 1.97 million, finally regaining its pre-recession levels,[169] with job growth occurring across the board.[170]

As of 2017[update], the Phoenix MSA had a Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of just under $243 billion. The top five industries were: real estate ($41.96), finance and insurance ($19.71), manufacturing ($19.91), retail trade ($18.64), and health care ($19.78). Government (including federal, state and local), if it had been a private industry, would have been ranked second on the list, generating $23.37 billion.[171]

In Phoenix, real estate developers face few constraints when planning and developing new projects.[172]

As of January 2016, 10.5% of the workforce were government employees, a high number because the city is both the county seat and state capital. The civilian labor force was 2,200,900, and the unemployment rate stood at 4.6%.[170]

Phoenix is home to four Fortune 500 companies: electronics corporation Avnet,[173] mining company Freeport-McMoRan,[174] retailer PetSmart,[175] and waste hauler Republic Services.[176] Honeywell's Aerospace division is headquartered in Phoenix, and the valley hosts many of their avionics and mechanical facilities.[177] Intel has one of their largest sites in the area, employing about 12,000 employees, the second largest Intel location in the country.[178] The city is also home to the headquarters of U-HAUL International, Best Western, and Apollo Group, parent of the University of Phoenix. Southwest is the largest carrier at Phoenix's Sky Harbor International Airport. Mesa Air Group, a regional airline group, is headquartered in Phoenix.[179]

The U.S. military has a large presence in Phoenix, with Luke Air Force Base in the western suburbs. The city was severely affected by the effects of the sub-prime mortgage crash. However, Phoenix has recovered 83% of the jobs lost due to the recession.[172]

Arts and culture

[edit]Performing arts

[edit]

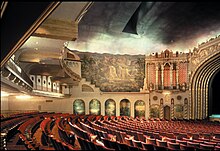

The city has many performing arts venues, most of which are in and around downtown Phoenix or Scottsdale. The Phoenix Symphony Hall is home to the Phoenix Symphony Orchestra, the Arizona Opera and Ballet Arizona.[180] The Arizona Opera company also has intimate performances at its new Arizona Opera Center, which opened in March 2013.[181] Another venue is the Orpheum Theatre, home to the Phoenix Opera.[182] Ballet Arizona, in addition to the Symphony Hall, also has performances at the Orpheum Theatre and the Dorrance Theater. Concerts also regularly make stops in the area. The largest downtown performing art venue is the Herberger Theater Center, which houses three performance spaces and is home to two resident companies, the Arizona Theatre Company and the Centre Dance Ensemble. Three other groups also use the facility: Valley Youth Theatre, iTheatre Collaborative[183] and Actors Theater.[184]

Concerts take place at Footprint Center and Comerica Theatre in downtown Phoenix, Ak-Chin Pavilion in Maryvale, Gila River Arena in Glendale, and Gammage Auditorium in Tempe (the last public building designed by Frank Lloyd Wright).[185] Several smaller theaters including Trunk Space, the Mesa Arts Center, the Crescent Ballroom, Celebrity Theatre, and Modified Arts support regular independent musical and theater performances. Music can also be seen in some of the venues usually reserved for sports, such as the Wells Fargo Arena and State Farm Stadium.[186]

Several television series have been set in Phoenix, including Alice (1976–85), the 2000s paranormal drama Medium, the 1960–61 syndicated crime drama The Brothers Brannagan, and The New Dick Van Dyke Show from 1971 to 1974.

Museums

[edit]

The valley has dozens of museums. They include the Phoenix Art Museum, Arizona Capitol Museum, Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art, Arizona Military Museum, Hall of Flame Fire Museum, Phoenix Police Museum, the Pueblo Grande Museum Archaeological Park, Children's Museum of Phoenix, Arizona Science Center, and the Heard Museum. In 2010, the Musical Instrument Museum opened their doors, featuring the biggest musical instrument collection in the world.[187] In 2015 the Children's Museum of Phoenix was recognized as one of the top three children's museums in the United States.[188]

Designed by Alden B. Dow, a student of Frank Lloyd Wright, the Phoenix Art Museum was constructed in a single year, opening in November 1959.[189] The Phoenix Art Museum has the southwest's largest collection of visual art, containing more than 17,000 works of contemporary and modern art from around the world.[190][191][192] Interactive exhibits can be found in nearby Peoria's Challenger Space Center, where individuals learn about space, renewable energies, and meet astronauts.[193]

The Heard Museum has over 130,000 sq ft (12,000 m2) of gallery, classroom and performance space. Some of the museum's signature exhibits include a full Navajo hogan, the Mareen Allen Nichols Collection of 260 pieces of contemporary jewelry, the Barry Goldwater Collection of 437 historic Hopi kachina dolls, and an exhibit on the 19th-century boarding school experiences of Native Americans. The Heard Museum attracts about 250,000 visitors a year.[194]

Cultural heritage resources

[edit]Arizona has museums, journals, societies, and libraries that serve as sources of important cultural heritage knowledge. They include the Arizona State Archives Historic Photographs Memory Project,[195] which includes over 90,000 images that focus on the unique history of Arizona as a state and territory, the Arizona Historical Society,[196] the Journal of Arizona History,[197] and numerous museum databases.

Fine arts

[edit]The downtown Phoenix art scene has developed in the past decade. The Artlink organization and the galleries downtown have launched a First Friday cross-Phoenix gallery opening.[198] In April 2009, artist Janet Echelman inaugurated her monumental sculpture, Her Secret Is Patience, a civic icon suspended above the new Phoenix Civic Space Park, a two-city-block park in the middle of downtown. This netted sculpture makes the invisible patterns of desert wind visible. During the day, the 100-foot (30 m)-tall sculpture hovers high above heads, treetops, and buildings, creating what the artist calls "shadow drawings", which she says are inspired by Phoenix's cloud shadows. At night, the illumination changes color gradually through the seasons. Author Prof. Patrick Frank writes of the sculpture that "...this unique visual delight will forever mark the city of Phoenix just as the Eiffel Tower marks Paris."[199]

Architecture

[edit]

Phoenix is the home of a unique architectural tradition and community. Frank Lloyd Wright moved to Phoenix in 1937 and built his winter home, Taliesin West, and the main campus for The Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture.[200] Over the years, Phoenix has attracted notable architects who have made it their home and grown successful practices. These architectural studios embrace the desert climate, and are unconventional in their approach to the practice of design. They include the Paolo Soleri (who created Arcosanti),[201] Al Beadle,[202] Will Bruder,[203] Wendell Burnette,[204] and Blank Studio[205] architectural design studios. Another major force in architectural landscape of the city was Ralph Haver whose firm, Haver & Nunn, designed commercial, industrial and residential structures throughout the valley. Of particular note was his trademark, "Haver Home", which were affordable contemporary-style tract houses.[206]

Tourism

[edit]The tourist industry is the longest running of the top industries in Phoenix. Starting with promotions back in the 1920s, the industry has grown into one of the top 10 in the city.[207] With nearly 28,000 hotel rooms in over 175 hotels and resorts Phoenix sees over 19 million visitors each year, most of whom are leisure travelers. Sky Harbor Airport, which serves the Greater Phoenix area, serves about 45 million passengers a year, ranking it among the nation's 10 busiest airports.[208]

One of the biggest attractions of the Phoenix area is golf, with over 200 golf courses.[209] In addition to the sites of interest in the city, there are many attractions near Phoenix, such as Agua Fria National Monument, Arcosanti, Casa Grande Ruins National Monument, Lost Dutchman State Park, Montezuma's Castle, Montezuma's Well, and Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. Phoenix also serves as a central point to many of the sights around the state of Arizona, such as the Grand Canyon, Lake Havasu (where the London Bridge is located), Meteor Crater, the Painted Desert, the Petrified Forest, Tombstone, Kartchner Caverns, Sedona and Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff.

Other attractions and annual events

[edit]

Due to its natural environment and climate, Phoenix has a number of outdoor attractions and recreational activities. The Phoenix Zoo is the largest privately owned nonprofit zoo in the United States. Since opening in 1962, it has developed an international reputation for its efforts on animal conservation, including breeding and reintroducing endangered species into the wild.[210] The adjacent Phoenix Botanical Gardens, opened in 1939, are acclaimed worldwide for their art and flora exhibits and educational programs, featuring the largest collection of arid plants in the U.S.[211][212][213] South Mountain Park, the largest municipal park in the U.S., is also the highest desert mountain preserve in the world.[214]

Other popular sites in the city are Japanese Friendship Garden, Historic Heritage Square, Phoenix Mountains Park, Pueblo Grande Museum, Tovrea Castle, Camelback Mountain, Hole in the Rock, Mystery Castle, St. Mary's Basilica, Taliesin West, and the Wrigley Mansion.[215]

Many annual events in and near Phoenix celebrate the city's heritage and its diversity. They include the Scottsdale Arabian Horse Show, the world's largest horse show; Matsuri, a celebration of Japanese culture; Pueblo Grande Indian Market, an event highlighting Native American arts and crafts; Grand Menorah Lighting, a December event celebrating Hanukah; ZooLights, a December evening event at the Phoenix Zoo that features millions of lights; the Arizona State Fair, begun in 1884; Scottish Gathering & Highland Games, an event celebrating Scottish heritage; Estrella War, a celebration of medieval life; and the Tohono O'odham Nation Rodeo & Fair, Oldest Indian rodeo in Arizona[216][217][218][219]

Cuisine

[edit]Phoenix is also renowned for its Mexican food, thanks to its large Hispanic population and its proximity to Mexico. Some of Phoenix's restaurants have a long history. The Stockyards steakhouse dates to 1947, while Monti's La Casa Vieja (Spanish for "The Old House") was in operation as a restaurant since the 1890s, but closed its doors November 17, 2014.[220][221] Macayo's (a Mexican restaurant chain) was established in Phoenix in 1946, and other major Mexican restaurants include Garcia's (1956) and Manuel's (1964).[222] The population boom has brought people from all over the nation, and to a lesser extent from other countries, and has since influenced the local cuisine. Phoenix boasts cuisines from all over the world, such as barbecue, Cajun/Creole, Greek, Hawaiian, Irish, Japanese, Italian, fusion, Persian, Indian (South Asian), Korean, Spanish, Thai, Chinese, southwestern, Tex-Mex, Vietnamese, Brazilian, and French.[223]

The first McDonald's franchise was sold by the McDonald brothers to a Phoenix entrepreneur in 1952. Neil Fox paid $1,000 for the rights to open an establishment based on the McDonald brothers' restaurant.[224] The hamburger stand opened in 1953 on the southwest corner of Central Avenue and Indian School Road, on the growing north side of Phoenix, and was the first location to sport the now internationally known golden arches, which were initially twice the height of the building. Three other franchise locations opened that year, two years before Ray Kroc purchased McDonald's.[224]

Sports

[edit]Major league

[edit]Phoenix is home to several professional sports franchises, and until recently, was one of only 13 U.S. metropolitan areas to have representatives of all four major professional sports leagues, although only one of these teams actually carry the city name and two of them play within the city limits.[225][226]

The Phoenix Suns were the first major sports team in Phoenix, being granted a National Basketball Association (NBA) franchise in 1968.[227] They lost the 1976 NBA Championship to the Boston Celtics in 6 games. They had originally played at the Arizona Veterans Memorial Coliseum before moving to America West Arena (now Footprint Center) in 1992.[228] The year following their move to the new arena, the Suns made it to the NBA Finals for the second time in franchise history, losing to Michael Jordan's Chicago Bulls, four games to two.[229] The U.S. Airways Center hosted both the 1995 and the 2009 NBA All-Star Games.[230] They also lost the 2021 NBA Finals in 6 games to the Milwaukee Bucks.

The Arizona Diamondbacks of Major League Baseball began play as an expansion team in 1998. The team has played all of its home games in the same downtown park, now known as Chase Field.[231][232] It is the second highest stadium in the U.S. (after Coors Field in Denver), and is known for its swimming pool beyond the outfield fence.[233] In 2001, the Diamondbacks defeated the New York Yankees four games to three in the World Series,[234] becoming the city's first professional sports franchise to win a national championship while in Arizona. The win was also the fastest an expansion team had ever won the World Series, surpassing the old mark of the Florida Marlins of five years, set in 1997.[235]

The Arizona Cardinals are the oldest continuously run professional football franchise in the nation. Founded in 1898 in Chicago, they moved to Phoenix from St. Louis, Missouri in 1988 and play in the Western Division of the National Football League's National Football Conference. Upon their move to Phoenix, the Cardinals played their home games at Sun Devil Stadium on the campus of Arizona State University in nearby Tempe. In 2006, they moved to the new State Farm Stadium in suburban Glendale.[236] Since moving to Phoenix, the Cardinals have made one championship appearance, Super Bowl XLIII in 2009, where they lost 27–23 to the Pittsburgh Steelers.[237]

Sun Devil Stadium held Super Bowl XXX in 1996. State Farm Stadium hosted Super Bowl XLII in 2008, Super Bowl XLIX in 2015, and Super Bowl LVII in 2023 .[238][239]

The Arizona Coyotes of the National Hockey League, formerly the original Winnipeg Jets, moved to the area in 1996.[240] They originally played their home games at America West Arena in downtown Phoenix before moving in December 2003 to the Glendale Arena (now named the Desert Diamond Arena) in Glendale.[241] In 2022, the Coyotes lost their lease in Glendale and moved to the then newly opened Mullett Arena on the campus of Arizona State University.[242] They were working with the city of Tempe to create a new entertainment district. However, after residents of Tempe rejected a bond initiative to pay for a new stadium, the Coyotes were deactivated, and the team's assets were moved to Salt Lake City, Utah.[243] The Coyotes have a five-year window to get a new arena in the area where they will be reactivated as an expansion franchise, otherwise the league will cease all operations for the franchise.[244]

Phoenix Rising FC is a professional soccer team that competes in the USL Championship, the second tier of US professional soccer. Phoenix Rising FC started as Arizona United SC in 2014 and played at the Peoria Sports Complex and Scottsdale Stadium from 2014 to 2016. Rebranded in 2017 as Phoenix Rising FC, the team started play from 2017 to 2020 at the Casino Arizona Field. In 2021, the club moved to a new home, the Phoenix Rising Soccer Complex at Wild Horse Pass, which was located inside the Gila River Indian Community near Chandler and played there throughout the 2022 season. The club began play in 2023 at the newly constructed Phoenix Rising Soccer Stadium, which is modular in design and located in an area north of Phoenix Sky Harbor International Airport.[245]

In 2018, the now-defunct Alliance of American Football announced the league's Phoenix franchise, the Arizona Hotshots, would begin playing in 2019.[246]

| Club | Sport | Year started operations | League | Venue | Titles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arizona Cardinals | Football | 1988* | NFL | State Farm Stadium | 2* |

| Arizona Diamondbacks | Baseball | 1998 | MLB | Chase Field | 1 |

| Phoenix Suns | Basketball | 1968 | NBA | Footprint Center | 0 |

| Phoenix Mercury | Basketball | 1997 | WNBA | Footprint Center | 3 |

| Arizona Rattlers | Indoor football | 1992 | IFL | Desert Diamond Arena | 6 |

| Phoenix Rising FC | Soccer | 2014 | USLC | Phoenix Rising Soccer Stadium | 1 |

*Note: The Cardinals won their two pre-modern era championships while in Chicago. *Note: The Cardinals moved to Phoenix from St. Louis in 1988.

Other sports

[edit]The Phoenix area hosts two annual college football bowl games: the Fiesta Bowl, played at State Farm Stadium,[247] and the Guaranteed Rate Bowl, held at Sun Devil Stadium (though Chase Field has substituted as host while ASU's football stadium undergoes renovations).[248]

Phoenix has an indoor football team, the Arizona Rattlers of the Indoor Football League. Their games are played at the Desert Diamond Arena. They played in the Arena Football League from 1992 to 2016 and had won five AFL championships before leaving the league.[249]

In 1997, the Phoenix Mercury were one of the original eight teams to launch the Women's National Basketball Association (WNBA).[250] They also play at Footprint Center. They have won the WNBA championship three times: first in 2007 when they defeated the Detroit Shock,[251] again in 2009 when they defeated the Indiana Fever,[252] and in 2014 when they swept the Chicago Sky.[253]

The Greater Phoenix area is home to the Cactus League, one of two spring training leagues for Major League Baseball. With the move by the Colorado Rockies and the Diamondbacks to their new facility in the Salt River Indian Community, the league is entirely based in the Greater Phoenix area. With the Cincinnati Reds' move to Goodyear, half of MLB's 30 teams are now included in the Cactus League.[254]

Phoenix International Raceway was built in 1964 with a one-mile (1.6 km) oval, with a one-of-a-kind design, as well as a 2.5-mile (4.0 km) road course.[255] It hosts several NASCAR events per season, and the annual Fall NASCAR weekend, which includes events from four different NASCAR classes, is a huge event.[256][257] Wild Horse Pass Motorsports Park (formerly Firebird International Raceway) hosts NHRA events in the Phoenix metropolitan area.

The city also hosts several major professional golf events, including the LPGA's Founder's Cup[258] and, since 1932, The Phoenix Open of the PGA Tour.[259] The Phoenix Marathon is a new addition to the city's sports scene, and is a qualifier for the Boston Marathon.[260] The Rock 'n' Roll Marathon series has held an event in Phoenix every January since 2004.[261] Phoenix is also home to a soccer club, Phoenix Rising FC.[262]

Parks and recreation

[edit]

Phoenix is home to a large number of parks and recreation areas. The city of Phoenix includes national parks, Maricopa County parks and city parks. Tonto National Forest forms part of the city's northeast boundary, while the county has the largest park system in the country.[263]

The city park system established to preserve the desert landscape in areas that would otherwise have succumbed to development includes South Mountain Park, the world's largest municipal park with 16,500 acres (67 km2).[264] The system's 182 parks contain over 41,900 acres (16,956 ha), making it the largest municipal park system in the country.[265] The park system has facilities for hiking, camping, swimming, horseback riding, cycling, and climbing.[266] Some of the system's other notable parks include Camelback Mountain, Encanto Park, Phoenix Mountains Preserve and Sunnyslope Mountain, also known as "S" Mountain.[267]

Papago Park in east Phoenix is home to both the Desert Botanical Garden and the Phoenix Zoo, in addition to several golf courses and the Hole-in-the-Rock geological formation. The Desert Botanical Garden, which opened in 1939, is one of the few public gardens in the country dedicated to desert plants and displays desert plant life from all over the world. The Phoenix Zoo is the largest privately owned non-profit zoo in the United States and is internationally known for its programs devoted to saving endangered species.[268]

Government

[edit]

In 1913, Phoenix adopted a new form of government, switching from the mayor-council system to the council-manager system, making it one of the first cities in the United States with this form of city government, where a city manager supervises all city departments and executes the policies adopted by the council.[269][270] Today, Phoenix represents the largest municipal government of this type in the country.[271]

The city council consists of a mayor and eight city council members. While the mayor is elected in a citywide election, Phoenix City Council members are elected by votes only in the districts they represent, with both the Mayor and the Council members serving four-year terms.[272] The mayor of Phoenix is Kate Gallego. The mayor and city council members each have equal voting power in regards to setting city policy and passing rules and regulations.[272] Sunshine Review gave the city's website a Sunny Award for its transparency efforts.[273]

State government facilities

[edit]

As the capital of Arizona, Phoenix houses the state legislature,[274] along with numerous state government agencies, many of which are in the State Capitol district immediately west of downtown. The Arizona Department of Juvenile Corrections operates the Adobe Mountain and Black Canyon Schools in Phoenix.[275] Another major state government facility is the Arizona State Hospital, operated by the Arizona Department of Health Services. This is a mental health center and is the only medical facility run by the state government.[276] The headquarters of numerous Arizona state government agencies are in Phoenix, with many in the State Capitol district.

Federal government facilities

[edit]The Federal Bureau of Prisons operates the Federal Correctional Institution (FCI) Phoenix, which is within the city limits, near its northern boundary.[277]

The Sandra Day O'Connor U.S. Courthouse, the U.S. District Court of Arizona, is on Washington Street downtown. It is named in honor of retired U.S. Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O'Connor, who was raised in Arizona.[278]

The Federal Building is at the intersection of Van Buren Street and First Avenue downtown. It contains various federal field offices and the local division of the U.S. Bankruptcy Court.[279] This building formerly housed the U.S. District Court offices and courtrooms, but these were moved in 2001 to the new Sandra Day O'Connor U.S. Courthouse. Before the construction of this building in 1961, federal government offices were housed in the historic U.S. Post Office on Central Avenue, completed in the 1930s.[280]

Crime

[edit]

By the 1960s, crime was a major problem in Phoenix, and by the 1970s, crime continued to increase in the city at a faster rate than almost anywhere else in the country.[281] It was during this time frame when an incident occurred in Phoenix which would have national implications. On March 16, 1963, Ernesto Miranda was arrested and charged with rape. The subsequent Supreme Court ruling on June 13, 1966, Miranda v. Arizona, has led to practice in the United States of issuing a Miranda Warning to all suspected criminals.[282]

With Phoenix's rapid growth, one of the prime areas of criminal activity was land fraud. The practice became so widespread that newspapers would refer to Phoenix as the Tainted Desert.[283] These land frauds led to one of the more infamous murders in the history of the valley, when Arizona Republic writer Don Bolles was murdered by a car bomb in 1976.[284][285] It was believed his investigative reporting on organized crime and land fraud in Phoenix made him a target.[286][287][288] Bolles was the only reporter from a major U.S. newspaper to be murdered on U.S. soil due to his coverage of a story.[286] Max Dunlap was convicted of first-degree murder in the case.[288]

Street gangs and the drug trade had turned into public safety issues by the 1980s, and the crime rate in Phoenix continued to grow.[289] After seeing a peak in the early and mid-1990s, the city has seen a general decrease in crime rates. The Maricopa County Jail system is the fourth-largest in the country.[290] The violent crime rate peaked in 1993 at 1146 crimes per 100,000 people, while the property crime rate peaked a few years earlier, in 1989, at 9,966 crimes per 100,000.[291]

In 2001 and 2002, Phoenix ranked first in the nation in vehicle thefts, with over 22,000 and 25,000 cars stolen each year respectively.[292] It has declined every year since then, eventually falling to 7,200 in 2014, a drop of almost 70% during that timeframe.[293] The Phoenix MSA has dropped to 70th in the nation in terms of car thefts in 2012.[294]

Politics

[edit]Long a swing city, Phoenix has increasingly trended toward the Democratic Party in recent years, leading a shift seen across Arizona. Margaret Hance was elected the city's first female mayor in 1975.

| Year | Democratic | Republican | Third parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 59.6% 388,435 | 38.9% 253,250 | 1.6% 10,238 |

| 2016 | 53.9% 271,946 | 38.7% 195,513 | 7.4% 37,389 |

Education

[edit]33 school districts provide public education in the Phoenix area. This is a legacy of numerous annexations over the years; many of the school districts existed before their territories became part of Phoenix.

There are 21 elementary school districts, which have over 215 elementary schools, paired with four high school districts with 31 high schools serving Phoenix. Three of the high school districts (Glendale Union, Tempe Union, and Tolleson Union) only partially serve Phoenix. With over 27,000 students, and spread over 220 square miles (570 km2), Phoenix Union High School District is one of the largest high school districts in the country, containing 16 schools and nearly 3,000 employees.[296] In addition, there are four unified districts, which cover grades K–12, which add an additional 58 elementary schools and four high schools to Phoenix's educational system. Of those four, only the Paradise Valley district completely serves Phoenix.[297] Phoenix is also served by a growing number of charter schools, with well over 100 operating in the city.[298]

Post-secondary education

[edit]

Arizona State University (ASU) is the region's largest institution of higher education. Primarily based in Tempe, it has a significant presence at the Arizona State University Downtown Phoenix campus. The campus features programs from ten of ASU's colleges, including the primary locations for the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication, Watts College of Public Service & Community Solutions, and Sandra Day O'Connor College of Law.[299] Over 10,000 students are enrolled at ASU's Downtown Phoenix campus.[300]

The University of Arizona College of Medicine – Phoenix is also located in downtown Phoenix,[301][302] as well as a satellite Phoenix Biomedical Campus of Northern Arizona University.[303][304]

The Maricopa County Community College District includes ten community colleges and two skills centers throughout Maricopa County, providing adult education and job training. Phoenix College, part of the district, was founded in 1920 and is the oldest community college in Arizona and one of the oldest in the country.[305]

The city is also home to many other institutions of higher learning such as the Phoenix Seminary, a Protestant seminary that imparts degree in biblical studies, Christian theology, church history and counseling. Notable institutions include: Barrow Neurological Institute, the world's largest neurological disease treatment and research institution;[306] Grand Canyon University, a private Christian university initially founded in 1949 as a non-profit school,[307] it now operates as a for-profit institution;[308] the University of Phoenix, also a for-profit college, is based out of the city.

Media

[edit]Phoenix's first newspaper was the weekly Salt River Valley Herald, established in 1878, which would change its name the following year to the Phoenix Herald. The paper would go through several additional name changes in its early years before finally settling on the Phoenix Herald, which still exists today in an online form.[309] Today, the city is served by one major daily newspaper: The Arizona Republic, which along with its online entity, azcentral.com, serves the greater metropolitan area.[310][311] The Jewish News of Greater Phoenix is an independent weekly newspaper established in 1948. In addition, the city is also served by numerous free neighborhood papers and alternative weeklies such as the Phoenix New Times' the East Valley Tribune, which primarily serves the cities of the East Valley; and Arizona State University's The State Press.[312]

The Phoenix metro area is served by many local television stations and is the largest designated market area (DMA) in the Southwest, and the 12th largest in the U.S., with over 1.8 million homes (1.6% of the total U.S.).[313] The major network television affiliates are KPHO 5 (CBS), Prescott-licensed KAZT-TV 7 (The CW), KAET 8 (PBS, operated by Arizona State University), KSAZ 10 (Fox), KPNX 12 (NBC), KNXV 15 (ABC), and KUTP 45 (MyNetworkTV). Other network television affiliates operating in the area include KPAZ 21 (TBN), KTVW-DT 33 (Univision), KFPH-DT (UniMás), KTAZ 39 (Telemundo), and KPPX-TV 51 (ION). KTVK 3 (3TV) and KASW 61 are independent television stations operating in the metro area. KSAZ-TV, KUTP, KPAZ-TV, KTVW-DT, KFPH-DT, and KTAZ are network owned-and-operated stations.

Many major feature films and television programs have been filmed in the city. From the opening sequences in Psycho,[314] to the night attack by the aliens in 1953's The War of the Worlds,[315] to freeway scenes in Little Miss Sunshine,[314] Phoenix has been the location for numerous major feature films. Other notable pictures filmed at least partially in Phoenix include Raising Arizona, A Home at the End of the World,[315] Bill & Ted's Excellent Adventure, Days of Thunder, The Gauntlet, The Grifters, Waiting to Exhale and Bus Stop.[316]

The radio airwaves in Phoenix cater to a wide variety of musical and talk radio interests. Stations include classic rock formats of KOOL-FM and KSLX-FM, to pop stations like KYOT and alternative stations like KDKB-FM, to the talk radio of KFYI-AM and KKNT-AM, the pop and top 40 programming of KZZP-FM and KALV-FM, and the country sounds of KMLE-FM. With its large Hispanic population there are numerous Spanish stations, such as KHOT-FM and KOMR-FM.[317]

Infrastructure

[edit]Transportation

[edit]Air

[edit]

Phoenix Sky Harbor International Airport (IATA: PHX, ICAO: KPHX), one of the ten busiest airports in the United States, serves over 110,000 people on over 1000 flights per day.[318] Centrally located in the metro area near several major freeway interchanges east of downtown Phoenix, the airport serves more than 100 cities with non-stop flights.[319]

Air Canada, British Airways, Condor, Volaris, and WestJet are among several international carriers as well as American carrier American Airlines (which maintains a hub at the airport) that provide flights to destinations such as Canada, Costa Rica, Mexico, and London.[320] In addition to American, other domestic carriers include Alaska Airlines, Delta, Frontier, Hawaiian, JetBlue, Southwest, Spirit, Sun Country, and United.[321]

The Phoenix-Mesa Gateway Airport (IATA: AZA, ICAO: KIWA) in neighboring Mesa also serves the area's commercial air traffic. It was converted from Williams Air Force Base, which closed in 1993. The airport has recently received substantial commercial service with Allegiant Air opening a hub operation at the airport with non-stop service to over a dozen destinations.[322][323]

Smaller airports that primarily handle private and corporate jets include Phoenix Deer Valley Airport, in the Deer Valley district of north Phoenix, and Scottsdale Airport, just east of the Phoenix/Scottsdale border. There are also other municipal airports including Glendale Municipal Airport, Falcon Field Airport in Mesa, and Phoenix Goodyear Airport.

Rail and bus

[edit]

Amtrak served Phoenix Union Station until 1996 when the Union Pacific Railroad (UP) proposed abandoning the route between Yuma, Arizona, and Phoenix.[324] Amtrak rerouted trains to Maricopa, 30 miles (48 km) south of downtown Phoenix, where passengers can board the Texas Eagle (Los Angeles-San Antonio-Chicago) and Sunset Limited (Los Angeles-New Orleans).[325][326] UP retained the trackage and the station remains. In 2021, Amtrak developed a plan to bring rail service back to Phoenix with connections to Tucson and Los Angeles.[327] This service is supported by the Bipartisan infrastructure bill and could take several years for service to be implemented.

Amtrak Thruway buses connect Phoenix Sky Harbor International Airport to Flagstaff for connection with the Los Angeles-Chicago Southwest Chief.[328] Phoenix is also served by Greyhound bus service, which stops at 24th Street near the airport.[329]

Valley Metro provides public transportation throughout the metropolitan area, with its trains, buses, and a ride-share program. 3.38% of workers commute by public transit. Valley Metro's 20-mile (32 km) light rail project, called Valley Metro Rail, through north-central Phoenix, downtown, and eastward through Tempe and Mesa, opened December 27, 2008. Future rail segments of more than 30 miles (48 km) are planned to open by 2030.[330]

Roads and freeways