New Hampshire

New Hampshire | |

|---|---|

| Nickname(s): Granite State White Mountain State[1] | |

| Motto: | |

| Anthem: "Old New Hampshire"[2] | |

Map of the United States with New Hampshire highlighted | |

| Country | United States |

| Before statehood | Province of New Hampshire |

| Admitted to the Union | June 21, 1788 (9th) |

| Capital | Concord |

| Largest city | Manchester |

| Largest county or equivalent | Hillsborough |

| Largest metro and urban areas | Greater Boston (combined and metro) Nashua (urban) |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Chris Sununu (R) |

| • Senate President | Jeb Bradley (R)[note 1] |

| Legislature | General Court |

| • Upper house | Senate |

| • Lower house | House of Representatives |

| Judiciary | New Hampshire Supreme Court |

| U.S. senators | Jeanne Shaheen (D) Maggie Hassan (D) |

| U.S. House delegation | 1: Chris Pappas (D) 2: Ann McLane Kuster (D) (list) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 9,350[3] sq mi (24,216 km2) |

| • Land | 8,954 sq mi (23,190 km2) |

| • Water | 396 sq mi (1,026 km2) 4.2% |

| • Rank | 46th |

| Dimensions | |

| • Length | 190 mi (305 km) |

| • Width | 68 mi (110 km) |

| Elevation | 1,000 ft (300 m) |

| Highest elevation | 6,288 ft (1,916.66 m) |

| Lowest elevation (Atlantic Ocean[5]) | 0 ft (0 m) |

| Population (2023) | |

| • Total | 1,402,054 |

| • Rank | 42nd |

| • Density | 150/sq mi (58/km2) |

| • Rank | 21st |

| • Median household income | $89,992[6] |

| • Income rank | 7th |

| Demonym(s) | Granite Stater New Hampshirite |

| Language | |

| • Official language | English[7] (French allowed for official business with Quebec; other languages allowed for certain specific uses)[8] |

| Time zone | UTC−05:00 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−04:00 (EDT) |

| USPS abbreviation | NH |

| ISO 3166 code | US-NH |

| Traditional abbreviation | N.H. |

| Latitude | 42° 42′ N to 45° 18′ N |

| Longitude | 70° 36′ W to 72° 33′ W |

| Website | nh |

| List of state symbols | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| |

| Living insignia | |

| Amphibian | Red-spotted newt Notophthalmus viridescens |

| Bird | Purple finch Haemorhous purpureus |

| Butterfly | Karner Blue Lycaeides melissa samuelis |

| Dog breed | Chinook |

| Fish | Freshwater: Brook trout Salvelinus fontinalis Saltwater: Striped bass Morone saxatilis |

| Flower | Purple lilac Syringa vulgaris |

| Insect | Ladybug Coccinellidae |

| Mammal | White-tailed deer Odocoileus virginianus |

| Tree | White birch Betula papyrifera |

| Inanimate insignia | |

| Food | Fruit: Pumpkin Vegetable: White Potato Berry: Blackberry[9] |

| Gemstone | Smoky quartz |

| Mineral | Beryl |

| Rock | Granite |

| Sport | Skiing |

| Tartan | New Hampshire state tartan |

| State route marker | |

| |

| State quarter | |

Released in 2000 | |

| Lists of United States state symbols | |

New Hampshire (/ˈhæmpʃər/ HAMP-shər) is a state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east, and the Canadian province of Quebec to the north. Of the 50 U.S. states, New Hampshire is the fifth smallest by area and the tenth least populous, with a population of 1,377,529 residents as of the 2020 census. Concord is the state capital and Manchester is the most populous city. New Hampshire's motto, "Live Free or Die", reflects its role in the American Revolutionary War; its nickname, "The Granite State", refers to its extensive granite formations and quarries.[10] It is well known nationwide for holding the first primary (after the Iowa caucus) in the U.S. presidential election cycle, and for its resulting influence on American electoral politics.

New Hampshire was inhabited for thousands of years by Algonquian-speaking peoples such as the Abenaki. Europeans arrived in the early 17th century, with the English establishing some of the earliest non-indigenous settlements. The Province of New Hampshire was established in 1629, named after the English county of Hampshire.[11] Following mounting tensions between the British colonies and the crown during the 1760s, New Hampshire saw one of the earliest overt acts of rebellion, with the seizing of Fort William and Mary from the British in 1774. In January 1776, it became the first of the British North American colonies to establish an independent government and state constitution; six months later, it signed the United States Declaration of Independence and contributed troops, ships, and supplies in the war against Britain. In June 1788, it was the ninth state to ratify the U.S. Constitution, bringing that document into effect. Through the mid-19th century, New Hampshire was an active center of abolitionism, and fielded close to 32,000 Union soldiers during the U.S. Civil War. After the war, the state saw rapid industrialization and population growth, becoming a center of textile manufacturing, shoemaking, and papermaking; the Amoskeag Manufacturing Company in Manchester was at one time the largest cotton textile plant in the world. The Merrimack and Connecticut rivers were lined with industrial mills, most of which employed workers from Canada and Europe; French Canadians formed the most significant influx of immigrants, and today roughly a quarter of all New Hampshire residents have French American ancestry, second only to Maine.

Reflecting a nationwide trend, New Hampshire's industrial sector declined after World War II. Since 1950, its economy diversified to include financial and professional services, real estate, education, transportation and high-tech, with manufacturing still higher than the national average.[12] Beginning in the 1950s, its population surged as major highways connected it to Greater Boston and led to more commuter towns. New Hampshire is among the wealthiest and most-educated states.[13] It is one of nine states without an income tax and has no taxes on sales, capital gains, or inheritance while relying heavily on local property taxes to fund education; consequently, its state tax burden is among the lowest in the country. It ranks among the top ten states in metrics such as governance, healthcare, socioeconomic opportunity, and fiscal stability.[14][15] New Hampshire is one of the least religious states and known for its libertarian-leaning political culture; it was until recently a swing state in presidential elections.[16]

With its mountainous and heavily forested terrain, New Hampshire has a growing tourism sector centered on outdoor recreation. It has some of the highest ski mountains on the East Coast and is a major destination for winter sports; Mount Monadnock is among the most climbed mountains in the U.S. Other activities include observing the fall foliage, summer cottages along many lakes and the seacoast, motorsports at the New Hampshire Motor Speedway in Loudon, and Motorcycle Week, a popular motorcycle rally held in Weirs Beach in Laconia. The White Mountain National Forest includes most of the Appalachian Trail between Vermont and Maine, and has the Mount Washington Auto Road, where visitors may drive to the top of 6,288-foot (1,917 m) Mount Washington.

History

[edit]

Various Algonquian-speaking Abenaki tribes, largely divided between the Androscoggin, Cowasuck and Pennacook nations, inhabited the area before European settlement.[17] Despite the similar language, they had a very different culture and religion from other Algonquian peoples. Indigenous people lived near Keene, New Hampshire 12,000 years ago, according to 2009 archaeological digs,[18] and the Abenaki were present in New Hampshire in pre-colonial times.[19]

English and French explorers visited New Hampshire in 1600–1605, and David Thompson settled at Odiorne's Point in present-day Rye in 1623. The first permanent European settlement was at Hilton's Point (present-day Dover). By 1631, the Upper Plantation comprised modern-day Dover, Durham and Stratham; in 1679, it became the "Royal Province". Father Rale's War was fought between the colonists and the Wabanaki Confederacy throughout New Hampshire.

New Hampshire was one of the Thirteen Colonies that rebelled against British rule during the American Revolution. During the American Revolution, New Hampshire was economically divided. The Seacoast region revolved around sawmills, shipyards, merchants' warehouses, and established village and town centers, where wealthy merchants built substantial homes, furnished them with luxuries, and invested their capital in trade and land speculation. At the other end of the social scale, there developed a permanent class of day laborers, mariners, indentured servants and slaves.

In December 1774, Paul Revere warned Patriots that Fort William and Mary would be reinforced with British troops. The following day, John Sullivan raided the fort for weapons. During the raid, the British soldiers fired at rebels with cannon and muskets, but there were apparently no casualties. These were among the first shots in the American Revolutionary period, occurring approximately five months before the Battles of Lexington and Concord. On January 5, 1776, New Hampshire became the first colony to declare independence from Great Britain, almost six months before the Declaration of Independence was signed by the Continental Congress.[20]

The United States Constitution was ratified by New Hampshire on June 21, 1788, when New Hampshire became the ninth state to do so.[21]

New Hampshire was a Jacksonian stronghold; the state sent Franklin Pierce to the White House in the election of 1852. Industrialization took the form of numerous textile mills, which in turn attracted large flows of immigrants from Quebec (the "French Canadians") and Ireland. The northern parts of the state produced lumber, and the mountains provided tourist attractions. After 1960, the textile industry collapsed, but the economy rebounded as a center of high technology and as a service provider.

Starting in 1952, New Hampshire gained national and international attention for its presidential primary held early in every presidential election year. It immediately became an important testing ground for candidates for the Republican and Democratic nominations but did not necessarily guarantee victory. [22]The media gave New Hampshire and Iowa significant attention compared to other states in the primary process, magnifying the state's decision powers and spurring repeated efforts by out-of-state politicians to change the rules.[23]

Geography

[edit]

New Hampshire is part of the six-state New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bounded by Quebec, Canada, to the north and northwest; Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east; Massachusetts to the south; and Vermont to the west. New Hampshire's major regions are the Great North Woods, the White Mountains, the Lakes Region, the Seacoast, the Merrimack Valley, the Monadnock Region, and the Dartmouth-Lake Sunapee area. New Hampshire has the shortest ocean coastline of any U.S. coastal state, with a length of 18 miles (29 km),[24] sometimes measured as only 13 miles (21 km).[25]

The White Mountains range in New Hampshire spans the north-central portion of the state. The range includes Mount Washington, the tallest in the northeastern U.S.—site of the second-highest wind speed ever recorded—[26] as well as Mount Adams and Mount Jefferson. With hurricane-force winds every third day on average, more than a hundred recorded deaths among visitors, and conspicuous krumholtz (dwarf, matted trees much like a carpet of bonsai trees), the climate on the upper reaches of Mount Washington has inspired the weather observatory on the peak to claim that the area has the "World's Worst Weather".[27] The White Mountains were home to the rock formation called the Old Man of the Mountain, a face-like profile in Franconia Notch, until the formation disintegrated in May 2003. Even after its loss, the Old Man remains an enduring symbol for the state, seen on state highway signs, automobile license plates, and many government and private entities around New Hampshire.

In southwestern New Hampshire, the landmark Mount Monadnock has given its name to a class of earth-forms—a monadnock—signifying, in geomorphology, any isolated resistant peak rising from a less resistant eroded plain.

New Hampshire has more than 800 lakes and ponds, and approximately 19,000 miles (31,000 km) of rivers and streams.[28] Major rivers include the 110-mile (177 km) Merrimack River, which bisects the lower half of the state north–south before passing into Massachusetts and reaching the sea in Newburyport. Its tributaries include the Contoocook River, Pemigewasset River, and Winnipesaukee River. The 410-mile (660 km) Connecticut River, which starts at New Hampshire's Connecticut Lakes and flows south to Connecticut, defines the western border with Vermont. The state border is not in the center of that river, as is usually the case, but at the low-water mark on the Vermont side; meaning the entire river along the Vermont border (save for areas where the water level has been raised by a dam) lies within New Hampshire.[29] Only one town—Pittsburg—shares a land border with the state of Vermont. The "northwesternmost headwaters" of the Connecticut also define part of the Canada–U.S. border.

The Piscataqua River and its several tributaries form the state's only significant ocean port where they flow into the Atlantic at Portsmouth. The Salmon Falls River and the Piscataqua define the southern portion of the border with Maine. The Piscataqua River boundary was the subject of a border dispute between New Hampshire and Maine in 2001, with New Hampshire claiming dominion over several islands (primarily Seavey's Island) that include the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard. The U.S. Supreme Court dismissed the case in 2002, leaving ownership of the island with Maine. New Hampshire still claims sovereignty of the base, however.[30]

The largest of New Hampshire's lakes is Lake Winnipesaukee, which covers 71 square miles (184 km2) in the east-central part of New Hampshire. Umbagog Lake along the Maine border, approximately 12.3 square miles (31.9 km2), is a distant second. Squam Lake is the second largest lake entirely in New Hampshire.

New Hampshire has the shortest ocean coastline of any state in the United States, approximately 18 miles (29 km) long.[31] Hampton Beach is a popular local summer destination. About 7 miles (11 km) offshore are the Isles of Shoals, nine small islands (four of which are in New Hampshire) known as the site of a 19th-century art colony founded by poet Celia Thaxter, and the alleged location of one of the buried treasures of the pirate Blackbeard.

It is the state with the highest percentage of timberland area in the country.[32] New Hampshire is in the temperate broadleaf and mixed forests biome. Much of the state, in particular the White Mountains, is covered by the conifers and northern hardwoods of the New England-Acadian forests. The southeast corner of the state and parts of the Connecticut River along the Vermont border are covered by the mixed oaks of the Northeastern coastal forests.[33] The state's numerous forests are popular among autumnal leaf peepers seeking the brilliant foliage of the numerous deciduous trees.

The northern third of the state is locally referred to as the "north country" or "north of the notches", in reference to the White Mountain passes that channel traffic. It contains less than 5% of the state's population, suffers relatively high poverty, and is steadily losing population as the logging and paper industries decline. However, the tourist industry, in particular visitors who go to northern New Hampshire to ski, snowboard, hike and mountain bike, has helped offset economic losses from mill closures.

Environmental protection emerged as a key state issue in the early 1900s in response to poor logging practices. In the 1970s, activists defeated a proposal to build an oil refinery along the coast and limited plans for a full-width interstate highway through Franconia Notch to a parkway.[34][35]

Winter season lengths are projected to decline at ski areas across New Hampshire due to the effects of climate change, which is likely to continue the historic contraction and consolidation of the ski industry and threaten individual ski businesses and communities that rely on ski tourism.[36]

Flora and fauna

[edit]Black bears, white-tailed deer, and moose can be found all over New Hampshire. There are also less-common animals such as the marten and the Canadian lynx.[37]

Climate

[edit]New Hampshire experiences a humid continental climate (Köppen climate classification Dfa in some southern areas, Dfb in most of the state, and Dfc subarctic in some northern highland areas), with warm, humid summers, and long, cold, and snowy winters. Precipitation is fairly evenly distributed all year. The climate of the southeastern portion is moderated by the Atlantic Ocean and averages relatively milder winters (for New Hampshire), while the northern and interior portions experience colder temperatures and lower humidity. Winters are cold and snowy throughout the state, and especially severe in the northern and mountainous areas. Average annual snowfall ranges from 60 inches (150 cm) to over 100 inches (250 cm) across the state.[38]

Average daytime highs are in the mid 70s°F to low 80s°F (24–28 °C) throughout the state in July, with overnight lows in the mid 50s°F to low 60s°F (13–15 °C). January temperatures range from an average high of 34 °F (1 °C) on the coast to overnight lows below 0 °F (−18 °C) in the far north and at high elevations. Average annual precipitation statewide is roughly 40 inches (100 cm) with some variation occurring in the White Mountains due to differences in elevation and annual snowfall. New Hampshire's highest recorded temperature was 106 °F (41 °C) in Nashua on July 4, 1911, while the lowest recorded temperature was −47 °F (−44 °C) atop Mount Washington on January 29, 1934. Mount Washington also saw an unofficial −50 °F (−46 °C) reading on January 22, 1885, which, if made official, would tie the record low for New England (also −50 °F (−46 °C) at Big Black River, Maine, on January 16, 2009, and Bloomfield, Vermont on December 30, 1933).

Extreme snow is often associated with a nor'easter, such as the Blizzard of '78 and the Blizzard of 1993, when several feet accumulated across portions of the state over 24 to 48 hours. Lighter snowfalls of several inches occur frequently throughout winter, often associated with an Alberta Clipper.

New Hampshire, on occasion, is affected by hurricanes and tropical storms—although, by the time they reach the state, they are often extratropical—with most storms striking the southern New England coastline and moving inland or passing by offshore in the Gulf of Maine. Most of New Hampshire averages fewer than 20 days of thunderstorms per year and an average of two tornadoes occur annually statewide.[39]

The National Arbor Day Foundation plant hardiness zone map depicts zones 3, 4, 5, and 6 occurring throughout the state[40] and indicates the transition from a relatively cooler to warmer climate as one travels southward across New Hampshire. The 1990 USDA plant hardiness zones for New Hampshire range from zone 3b in the north to zone 5b in the south.[41]

| Location | July (°F) | July (°C) | January (°F) | January (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manchester | 82/64 | 28/17 | 33/15 | 0/−9 |

| Nashua | 82/59 | 28/15 | 33/12 | 0/−11 |

| Concord | 82/57 | 28/14 | 30/10 | −1/−12 |

| Portsmouth | 79/61 | 26/16 | 32/16 | 0/−9 |

| Keene | 82/56 | 28/13 | 31/9 | −1/−12 |

| Laconia | 81/60 | 27/16 | 30/11 | −1/−11 |

| Lebanon | 82/58 | 28/14 | 30/8 | −1/−13 |

| Berlin | 78/55 | 26/13 | 27/5 | –3/–15 |

Metropolitan areas

[edit]

Metropolitan areas in the New England region are defined by the U.S. Census Bureau as New England City and Town Areas (NECTAs). The following is a list of NECTAs fully or partially in New Hampshire:[43][44]

- Berlin

- Boston–Cambridge–Nashua

- Haverhill–Newburyport–Amesbury Town NECTA Division

- Lawrence–Methuen Town–Salem NECTA Division

- Lowell–Billerica–Chelmsford NECTA Division

- Nashua NECTA Division

- Claremont

- Concord

- Dover–Durham

- Franklin

- Keene

- Laconia

- Lebanon

- Manchester

- Portsmouth

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1790 | 141,885 | — | |

| 1800 | 183,858 | 29.6% | |

| 1810 | 214,460 | 16.6% | |

| 1820 | 244,155 | 13.8% | |

| 1830 | 269,328 | 10.3% | |

| 1840 | 284,574 | 5.7% | |

| 1850 | 317,976 | 11.7% | |

| 1860 | 326,073 | 2.5% | |

| 1870 | 318,300 | −2.4% | |

| 1880 | 346,991 | 9.0% | |

| 1890 | 376,530 | 8.5% | |

| 1900 | 411,588 | 9.3% | |

| 1910 | 430,572 | 4.6% | |

| 1920 | 443,083 | 2.9% | |

| 1930 | 465,293 | 5.0% | |

| 1940 | 491,524 | 5.6% | |

| 1950 | 533,242 | 8.5% | |

| 1960 | 606,921 | 13.8% | |

| 1970 | 737,681 | 21.5% | |

| 1980 | 920,610 | 24.8% | |

| 1990 | 1,109,252 | 20.5% | |

| 2000 | 1,235,786 | 11.4% | |

| 2010 | 1,316,470 | 6.5% | |

| 2020 | 1,377,529 | 4.6% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 1,402,054 | 1.8% | |

| Source: 1910–2020[45][46] | |||

Population

[edit]

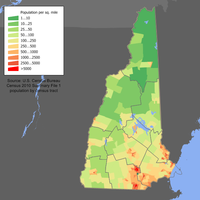

As of the 2020 census, the resident population of New Hampshire was 1,377,529,[45] a 4.6% increase since the 2010 United States Census. The center of population of New Hampshire is in Merrimack County, in the town of Pembroke.[47] The center of population has moved south 12 miles (19 km) since 1950,[48] a reflection of the fact that the state's fastest growth has been along its southern border, which is within commuting range of Boston and other Massachusetts cities.

As indicated in the census, in 2020 88.3% of the population were White; 1.5% were Black or African American; 0.2% were Native American or Alaskan Native; 2.6% were Asian; 0.0% were Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander; 1.7% were some other race; and 5.6% were two or more races. 4.3% of the total population were Hispanic or Latino of any race. 18.6% of the population were under 18 years of age; 19.3% were 65 years and over. The female population was 50.5%.[49]

The most densely populated areas generally lie within 50 miles (80 km) of the Massachusetts border, and are concentrated in two areas: along the Merrimack River Valley running from Concord to Nashua, and in the Seacoast Region along an axis stretching from Rochester to Portsmouth. Outside of those two regions, only one community, the city of Keene, has a population of over 20,000. The four counties covering these two areas account for 72% of the state population, and one (Hillsborough) has nearly 30% of the state population, as well as the two most populous communities, Manchester and Nashua. The northern portion of the state is very sparsely populated: the largest county by area, Coos, covers the northern one-fourth of the state and has only around 31,000 people, about a third of whom live in a single community (Berlin). The trends over the past several decades have been for the population to shift southward, as many northern communities lack the economic base to maintain their populations, while southern communities have been absorbed by the Greater Boston metropolis.

As of the 2010 census, the population of New Hampshire was 1,316,470. The gender makeup of the state at that time was 49.3% male and 50.7% female. 21.8% of the population were under the age of 18; 64.6% were between the ages of 18 and 64; and 13.5% were 65 years of age or older.[50] Additionally, about 57.3% of the population was born out of state.[51]

According to HUD's 2022 Annual Homeless Assessment Report, there were an estimated 1,605 homeless people in New Hampshire.[52][53]

| Racial composition | 1990[54] | 2000[55] | 2010[50] | 2020[49] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 98.0% | 96.0% | 93.9% | 88.3% |

| Black or African American | 0.6% | 0.7% | 1.1% | 1.5% |

| American Indian and Alaska Native | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.2% |

| Asian | 0.8% | 1.3% | 2.2% | 2.6% |

| Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander | – | – | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Other race | 0.3% | 0.6% | 0.9% | 1.7% |

| Two or more races | – | 1.1% | 1.6% | 5.6% |

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) |

1.0% | 1.7% | 2.8% | 4.3% |

Hispanic or Latino of any race were 2.8% of the population in 2010: 0.6% were of Mexican, 0.9% Puerto Rican, 0.1% Cuban, and 1.2% other Hispanic or Latino origin. As of 2020, the Hispanic or Latino population was counted as 4.3%.[49] The Native American/Alaska native population is listed as 0.3% in the 2020 census, but may be higher.[56]

According to the 2012–2017 American Community Survey, the largest ancestry groups in the state were Irish (20.6%), English (16.5%), French (14.0%), Italian (10.4%), German (9.1%), French Canadian (8.9%), and American (4.8%).[57]

New Hampshire has the highest percentage (22.9%) of residents with French/French Canadian/Acadian ancestry of any U.S. state.[58]

In 2018, the top countries of origin for New Hampshire's immigrants were India, Canada, China, Nepal and the Dominican Republic.[59]

According to the Census Bureau's American Community Survey estimates from 2017, 2.1% of the population aged 5 and older speak Spanish at home, while 1.8% speak French.[60] In Coos County, 9.6% of the population speaks French at home,[61] down from 16% in 2000.[62] In the city of Nashua, Hillsborough County, 8.02% of the population speaks Spanish at home.[63]

| Manchester | Nashua | Concord | Derry | Dover | |

| Population, Census (2020) | 115,644 | 91,322 | 43,976 | 34,317 | 32,741 |

| Population, Census (2010) | 109,565 | 86,494 | 42,695 | 33,109 | 29,987 |

| Population change (April 1, 2010, to April 1, 2020) | 5.5% | 5.6% | 3.0% | 3.6% | 9.2% |

| Age and sex (2020) | |||||

| Persons under 5 years | 5.3% | 5.0% | 4.2% | 5.0% | 4.6% |

| Persons under 18 years | 18.7% | 19.2% | 17.2% | 20.6% | 18.1% |

| Persons 65 years and over | 14.9% | 16.7% | 19.1% | 14.2% | 16.8% |

| Female persons | 50.1% | 50.4% | 49.8% | 50.4% | 50.8% |

| Race and ethnicity (2020) | |||||

| White | 76.7% | 73.1% | 85.4% | 89.3% | 85.7% |

| Non-Hispanic White | 74.0% | 70.3% | 84.5% | 88.1% | 84.9% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 11.8% | 13.9% | 3.1% | 4.6% | 3.2% |

| Black or African American | 5.5% | 3.0% | 3.8% | 1.2% | 1.7% |

| American Indian and Alaska Native | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.1% | 0.2% |

| Asian | 4.2% | 7.8% | 4.1% | 1.6% | 5.5% |

| Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander | - | - | - | - | - |

| Two or more races | 7.9% | 9.0% | 5.2% | 6.0% | 5.6% |

| Population characteristics (2017–2022) | |||||

| Veterans | 6,212 | 5,103 | 2,885 | 2,256 | 1,569 |

| Foreign-born persons | 14.9% | 15.8% | 8.2% | 4.8% | 5.8% |

Birth data

[edit]Note: Percentages in the table do not add up to 100, because Hispanics are counted both by their ethnicity and by their race, giving a higher overall number.

| Race | 2013[66] | 2014[67] | 2015[68] | 2016[69] | 2017[70] | 2018[71] | 2019[72] | 2020[73] | 2021[74] | 2022[75] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White: | 11,570 (93.3%) | 11,494 (93.4%) | 11,600 (93.3%) | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| > Non-Hispanic White | 11,064 (89.2%) | 10,917 (88.7%) | 10,928 (87.9%) | 10,641 (86.7%) | 10,524 (86.9%) | 10,317 (86.0%) | 10,079 (85.1%) | 10,075 (85.4%) | 10,848 (85.9%) | 10,318 (85.4%) |

| Asian | 485 (3.9%) | 528 (4.3%) | 527 (4.2%) | 504 (4.1%) | 479 (4.0%) | 472 (3.9%) | 508 (4.3%) | 428 (3.6%) | 432 (3.4%) | 441 (3.7%) |

| Black | 316 (2.5%) | 259 (2.1%) | 280 (2.3%) | 208 (1.7%) | 234 (1.9%) | 241 (2.0%) | 255 (2.2%) | 256 (2.2%) | 274 (2.2%) | 267 (2.2%) |

| American Indian | 25 (0.2%) | 21 (0.2%) | 26 (0.2%) | 8 (0.0%) | 26 (0.2%) | 13 (0.1%) | 18 (0.2%) | 10 (0.1%) | 8 (>0.1%) | 16 (0.1%) |

| Hispanic (of any race) | 513 (4.1%) | 591 (4.8%) | 638 (5.1%) | 697 (5.7%) | 673 (5.6%) | 745 (6.2%) | 771 (6.5%) | 797 (6.7%) | 860 (6.8%) | 812 (6.7%) |

| Total New Hampshire | 12,396 (100%) | 12,302 (100%) | 12,433 (100%) | 12,267 (100%) | 12,116 (100%) | 11,995 (100%) | 11,839 (100%) | 11,791 (100%) | 12,625 (100%) | 12,077 (100%) |

- Since 2016, data for births of White Hispanic origin are not collected, but included in one Hispanic group; persons of Hispanic origin may be of any race.

Religion

[edit]Religion in New Hampshire according to PRRI American Values Atlas (2021)[76]

A Pew survey in 2014 showed that the religious affiliations of the people of New Hampshire was as follows: nonreligious 36%, Protestant 30%, Catholic 26%, Jehovah's Witness 2%, LDS (Mormon) 1%, and Jewish 1%.[77]

A survey suggests people in New Hampshire and Vermont[note 4] are less likely than other Americans to attend weekly services and only 54% say they are "absolutely certain there is a God" compared to 71% in the rest of the nation.[note 5][78] New Hampshire and Vermont are also at the lowest levels among states in religious commitment. In 2012, 23% of New Hampshire residents in a Gallup poll considered themselves "very religious", while 52% considered themselves "non-religious".[79] According to the Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA) in 2010, the largest denominations were the Catholic Church with 311,028 members; the United Church of Christ with 26,321 members; and the United Methodist Church with 18,029 members.[80]

In 2016, a Gallup Poll found that New Hampshire was the least religious state in the United States. Only 20% of respondents in New Hampshire categorized themselves as "very religious", while the nationwide average was 40%.[81]

According to the 2020 Public Religion Research Institute study, 64% of the population was Christian, dominated by Roman Catholicism and evangelical Protestantism.[82] In contrast with varying studies of estimated irreligiosity, the Public Religion Research Institute reported that irreligion declined from 36% at the separate 2014 Pew survey to 25% of the population in 2020. In 2021, the unaffiliated increased to 40% of the population, although Christianity altogether made up 54% of the total population (Catholics, Protestants, and Jehovah's Witnesses).

Economy

[edit]

- Total employment (2016): 594,243

- Number of employer establishments: 37,868[83]

The Bureau of Economic Analysis estimates that New Hampshire's total state product in 2018 was $86 billion, ranking 40th in the United States.[84] Median household income in 2017 was $74,801, the fourth highest in the country (including Washington, DC).[85] Its agricultural outputs are dairy products, nursery stock, cattle, apples and eggs. Its industrial outputs are machinery, electric equipment, rubber and plastic products, and tourism is a major component of the economy.[86]

New Hampshire experienced a major shift in its economic base during the 20th century. Historically, the base was composed of traditional New England textiles, shoemaking, and small machine shops, drawing upon low-wage labor from nearby small farms and parts of Quebec. Today, of the state's total manufacturing dollar value, these sectors contribute only two percent for textiles, two percent for leather goods, and nine percent for machining.[87] They experienced a sharp decline due to obsolete plants and the lure of cheaper wages in the Southern United States.

New Hampshire today has a broad-based and growing economy, with a state GDP growth rate of 2.2% in 2018.[84] The state's largest economic sectors in 2018, based on contribution to GDP, are: 15% real estate and rental and leasing; 13% professional business services; 12% manufacturing; 10% government and government services; and 9% health care and social services.[88]

The state's budget in FY2018 was $5.97 billion, including $1.79 billion in federal funds.[89] The issue of taxation is controversial in New Hampshire, which has a property tax (subject to municipal control) but no broad sales tax or income tax. The state does have narrower taxes on meals, lodging, vehicles, business and investment income, and tolls on state roads.

According to the Energy Information Administration, New Hampshire's energy consumption and per capita energy consumption are among the lowest in the country. The Seabrook Station Nuclear Power Plant, near Portsmouth, is the largest individual electrical generating unit on the New England power grid and provided 57% of New Hampshire's electricity generation in 2017. Power generation from wind power increased strongly in 2012 and 2013, but remained rather flat for the next ten years at around 4% of consumption. In 2016, 2017 and at least 2019–2022, New Hampshire obtained more of its electricity generation from wind power than from coal-fired power plants. hydroelectric and power produce with wood are other important renewable resources). New Hampshire was a net exporter of electricity, exporting 63 trillion British thermal units (18 TWh).[90]

New Hampshire's residential electricity use is low compared with the national average, in part because demand for air conditioning is low during the generally mild summer months and because few households use electricity as their primary energy source for home heating. Nearly half of New Hampshire households use fuel oil for winter heating, which is one of the largest shares in the United States. New Hampshire has potential for renewable energies like wind power, hydroelectricity, and wood fuel.[90]

The state has no general sales tax and no personal state income tax (the state currently does tax, at a five percent rate, income from dividends and interest, but this tax is set to expire in 2027.[91])

New Hampshire's lack of a broad-based tax system has resulted in the state's local jurisdictions having the 8th-highest property taxes as of a 2019 ranking by the Tax Foundation.[92] However, the state's overall tax burden is relatively low; in 2010 New Hampshire ranked 8th-lowest among states in combined average state and local tax burden.[93]

The (preliminary) seasonally unemployment rate in April 2019 was 2.4% based on a 767,500 person civilian workforce with 749,000 people in employment. New Hampshire's workforce is 90% in nonfarm employment, with 18% employed in trade, transportation, and utilities; 17% in education and health care; 12% in government; 11% in professional and business services; and 10% in leisure and hospitality.[94]

Largest employers

[edit]In March 2018, 86% of New Hampshire's workforce were employed by the private sector, with 53% of those workers being employed by firms with fewer than 100 employees. About 14% of private-sector employees are employed by firms with more than 1,000 employees.[95]

According to community surveys by the Economic & Labor Market Information Bureau of NH Employment Security, the following are the largest private employers in the state:[96]

| Employer | Location (base) | Employees |

|---|---|---|

| Dartmouth–Hitchcock Medical Center | Lebanon | 7,000 |

| Fidelity Investments | Merrimack | 6,000 |

| BAE Systems North America | Nashua | 4,700 |

| Liberty Mutual | Dover | 3,800 |

| Elliot Hospital | Manchester | 3,800 |

| Dartmouth College | Hanover | 3,500 |

| Southern New Hampshire University | Manchester | 3,200 |

| Capital Regional Health Care | Concord | 3,000 |

| Catholic Medical Center | Manchester | 2,300 |

| Southern New Hampshire Health System | Nashua | 2,200 |

New Hampshire's state government employs approximately 6,100 people. Additionally, the U.S. Department of State employs approximately 1,600 people at the National Visa Center and National Passport Center in Portsmouth, which process United States immigrant visa petitions and United States passport applications.[96]

Law and government

[edit]

The governor of New Hampshire, since January 5, 2017, is Republican Chris Sununu. New Hampshire's two U.S. senators are Jeanne Shaheen and Maggie Hassan, both of whom are Democrats and former governors. New Hampshire's two U.S. representatives as of January 2019 are Chris Pappas and Ann McLane Kuster, both Democrats.

New Hampshire is an alcoholic beverage control state, and through the State Liquor Commission takes in $100 million from the sale and distribution of liquor.[97]

New Hampshire is the only state in the U.S. that does not require adults to wear seat belts in their vehicles. It is one of three states that have no mandatory helmet law.

Governing documents

[edit]The New Hampshire State Constitution of 1783 is the supreme law of the state, followed by the New Hampshire Revised Statutes Annotated and the New Hampshire Code of Administrative Rules. These are roughly analogous to the federal United States Constitution, United States Code and Code of Federal Regulations respectively.

Branches of government

[edit]New Hampshire has a bifurcated executive branch, consisting of the governor and a five-member executive council which votes on state contracts worth more than $5,000 and "advises and consents" to the governor's nominations to major state positions such as department heads and all judgeships and pardon requests. New Hampshire does not have a lieutenant governor; the Senate president serves as "acting governor" whenever the governor is unable to perform the duties.

The legislature is called the General Court. It consists of the House of Representatives and the Senate. There are 400 representatives, making it one of the largest elected bodies in the English-speaking world,[98] and 24 senators. Legislators are paid a nominal salary of $200 per two-year term plus travel costs, the lowest in the U.S. by far. Thus most are effectively volunteers, nearly half of whom are retirees.[99] (For details, see the article on Government of New Hampshire.)

The state's sole appellate court is the New Hampshire Supreme Court. The Superior Court is the court of general jurisdiction and the only court which provides for jury trials in civil or criminal cases. The other state courts are the Probate Court, District Court, and the Family Division.

Local government

[edit]New Hampshire has 10 counties and 234 cities and towns.

New Hampshire is a "Dillon Rule" state, meaning the state retains all powers not specifically granted to municipalities. Even so, the legislature strongly favors local control, particularly concerning land use regulations. New Hampshire municipalities are classified as towns or cities, which differ primarily by the form of government. Most towns generally operate on the town meeting form of government, where the registered voters in the town act as the town legislature, and a board of selectmen acts as the executive of the town. Larger towns and the state's thirteen cities operate either on a council–manager or council–mayor form of government. There is no difference, from the state government's point of view, between towns and cities besides the form of government. All state-level statutes treat all municipalities identically.

New Hampshire has a small number of unincorporated areas that are titled as grants, locations, purchases, or townships. These locations have limited to no self-government, and services are generally provided for them by neighboring towns or the county or state where needed. As of the 2000 census, there were 25 of these left in New Hampshire, accounting for a total population of 173 people (as of 2000[update]); several were entirely depopulated. All but two of these unincorporated areas are in Coos County.

Politics

[edit]New Hampshire is known for its fiscal conservatism and cultural liberalism. The state's politics are cited as libertarian leaning.[16] It is the least religious state in the Union as of a 2016 Gallup poll.[81] The state has long had a great disdain for state taxation and state bureaucracy.[100][101] As of 2023, New Hampshire has a Republican governor (Chris Sununu) and a Republican-controlled legislature, and is one of nine states (the only one in the American Northeast) to have no general state income tax imposed on individuals.

The Democratic Party and the Republican Party, in that order, are the two largest parties in the state. A plurality of voters are registered as undeclared, and can choose either ballot in the primary and then regain their undeclared status after voting.[102] The Libertarian Party had official party status from 1990 to 1996 and from 2016 to 2018. A movement known as the Free State Project suggests libertarians move to the state to concentrate their power. As of August 30, 2022, there were 869,863 registered voters, of whom 332,008 (38.17%) did not declare a political party affiliation, 273,921 (31.49%) were Democratic, and 263,934 (30.34%) were Republican.[103]

New Hampshire primary

[edit]

New Hampshire is internationally known for the New Hampshire primary, the first primary in the quadrennial American presidential election cycle. State law requires that the Secretary of State schedule this election at least one week before any "similar event". While the Iowa caucus precedes the New Hampshire primary, the New Hampshire election is the nation's first contest that uses the same procedure as the general election, draws more attention than those in other states, and has been decisive in shaping the national contest.

In February 2023, the Democratic National Committee awarded that party's first primary to South Carolina, to be held on February 3, 2024, directing New Hampshire and Nevada to vote three days later.[104] New Hampshire political leaders from both parties have vowed to stand by the state's "first in the nation" law and ignore the DNC.

State law permits a town with fewer than 100 residents to open its polls at midnight and close when all registered citizens have cast their ballots. As such, the communities of Dixville Notch in Coos County and Hart's Location in Carroll County, among others, have chosen to implement these provisions. Dixville Notch and Hart's Location are traditionally the first places in both New Hampshire and the U.S. to vote in presidential primaries and elections.

Nominations for all other partisan offices are decided in a separate primary election. In Presidential election cycles, this is the second primary election held in New Hampshire.

Saint Anselm College in Goffstown has become a popular campaign spot for politicians as well as several national presidential debates because of its proximity to Manchester-Boston Regional Airport.[105][106][107]

Elections

[edit]

In the past, New Hampshire has often voted Republican. Between 1856 and 1988, New Hampshire cast its electoral votes for the Democratic presidential ticket six times: Woodrow Wilson (twice), Franklin D. Roosevelt (three times), and Lyndon B. Johnson (once).

Beginning in 1992, New Hampshire became a swing state in national and local elections, and in that time has supported Democrats in all presidential elections except 2000. It was the only state in the country to switch from supporting Republican George W. Bush in the 2000 election to supporting his Democratic challenger in the 2004 election, when John Kerry, a senator from neighboring Massachusetts, won the state.

Демократы доминировали на выборах в Нью-Гэмпшире в 2006 и 2008 годах. В 2006 году демократы получили оба места в Конгрессе (избрав Кэрол Ши-Портер в первом округе и Пола Хоудса во втором), переизбрали губернатора Джона Линча и получили большинство в Конгрессе. в Исполнительном совете и в обеих палатах впервые с 1911 года. Демократы не занимали ни законодательного органа, ни поста губернатора с 1874 года. [ 108 ] Neither U.S. Senate seat was up for a vote in 2006. In 2008, Democrats retained their majorities, governorship, and Congressional seats; and former governor Jeanne Shaheen defeated incumbent Republican John E. Sununu for the U.S. Senate in a rematch of the 2002 contest.

В результате выборов 2008 года женщины получили большинство, 13 из 24 мест, в Сенате Нью-Гэмпшира, что стало первым для любого законодательного органа в Соединенных Штатах. [ 109 ]

На промежуточных выборах 2010 года республиканцы добились исторических успехов в Нью-Гэмпшире, захватив большинство в законодательном собрании штата, не допускающее вето, получив все пять мест в Исполнительном совете, избрав нового сенатора США Келли Айотт , получив оба места в Палате представителей США и сократив разница в победе действующего губернатора Джона Линча по сравнению с его убедительными победами в 2006 и 2008 годах.

На выборах в законодательные органы штата в 2012 году демократы вернули себе Палату представителей Нью-Гэмпшира и сузили республиканское большинство в Сенате Нью-Гэмпшира до 13–11. [ 110 ] В 2012 году Нью-Гэмпшир стал первым штатом в истории США, который избрал федеральную делегацию, состоящую исключительно из женщин: женщины-конгрессмены-демократы Кэрол Ши-Портер из 1-го округа Конгресса и Энн Маклейн Кастер из 2-го округа Конгресса сопровождали сенаторов США Джин Шахин и Келли Айотт в 2013 году. Кроме того, штат избрал вторую женщину-губернатора: демократа Мэгги Хассан .

На выборах 2014 года республиканцы вернули себе Палату представителей Нью-Гэмпшира с большинством в 239–160 и расширили свое большинство в Сенате Нью-Гэмпшира до 14 из 24 мест в Сенате. На национальном уровне действующий сенатор-демократ Джин Шахин победила своего соперника-республиканца, бывшего сенатора от Массачусетса Скотта Брауна . Нью-Гэмпшир также избрал Фрэнка Гуинту (справа) своим представителем от Первого округа Конгресса и Энн Кастер (демократ) своим представителем от Второго округа Конгресса.

На выборах 2016 года республиканцы получили большинство в Палате представителей Нью-Гэмпшира с большинством в 220–175 и сохранили свои 14 мест в Сенате Нью-Гэмпшира . В губернаторской гонке уходящего в отставку губернатора Мэгги Хассан сменил республиканец Крис Сунуну , который победил кандидата от Демократической партии Колина Ван Остерна . Сунуну стал первым республиканским губернатором штата после Крейга Бенсона , который покинул свой пост в 2005 году после поражения от Джона Линча . Республиканцы контролируют офис губернатора и обе палаты законодательного собрания штата, т.е. управляющую тройку, в которой республиканцы обладают полной управляющей властью. [ 111 ] В президентской гонке штат проголосовал за кандидата от Демократической партии, бывшего госсекретаря Хиллари Клинтон , а не за кандидата от Республиканской партии Дональда Трампа с перевесом в 2736 голосов, или 0,3%, что является одним из самых близких результатов, которые штат когда-либо видел в президентской гонке. президентской гонке, а кандидат от либертарианской партии Гэри Джонсон получил 4,12% голосов. Демократы также выиграли конкурентную гонку во Втором избирательном округе Конгресса, а также конкурентную гонку в Сенате. Делегация Конгресса Нью-Гэмпшира в настоящее время состоит исключительно из демократов. В 116-м Конгрессе США это один из семи штатов с полностью демократической делегацией, пять из которых находятся в Новой Англии (остальные — Делавэр и Гавайи).

Проект Свободного государства

[ редактировать ]Проект «Свободный штат» (FSP) — это движение, основанное в 2001 году с целью вербовки не менее 20 000 либертарианцев для переезда в один малонаселенный штат (Нью-Гэмпшир, был выбран в 2003 году), чтобы сконцентрировать либертарианский активизм вокруг одного региона. [ 112 ] Проект «Свободный штат» делает упор на децентрализованное принятие решений, поощряя новых переселенцев и бывших жителей Нью-Гэмпшира участвовать таким образом, который индивидуальный переезд считает наиболее подходящим. Например, по состоянию на 2017 год в Палату представителей Нью-Гэмпшира было избрано 17 так называемых свободных государств. [ 113 ] а в 2021 году Альянс свободы Нью-Гэмпшира , который ранжирует законопроекты и избранных представителей на основе их приверженности тому, что они считают либертарианскими принципами, получил оценку 150 представителей как представителей с рейтингом «A-» или выше. [ 114 ] Участники также взаимодействуют с другими группами активистов-единомышленников, такими как Rebuild New Hampshire, [ 115 ] Молодые американцы за свободу , [ 116 ] и «Американцы за процветание» . [ 117 ] По состоянию на апрель 2022 года около 6232 участника переехали в Нью-Гэмпшир для участия в проекте «Свободное государство». [ 118 ]

Транспорт

[ редактировать ]Шоссе

[ редактировать ]Нью-Гэмпшир имеет ухоженную и хорошо обозначенную сеть автомагистралей между штатами , автомагистралей США и автомагистралей штата. На указателях шоссе штата по-прежнему изображен Старик с горы, несмотря на то, что это скальное образование рухнуло в 2003 году. Некоторые номера маршрутов совпадают с такими же номерами маршрутов в соседних штатах. Нумерация шоссе штата произвольна и не имеет общей системы, как в системах США и межштатных автомагистралей. Основные маршруты включают:

Автомагистраль между штатами 89 проходит на северо-запад от Конкорда до Ливана на границе с Вермонтом .

Автомагистраль между штатами 89 проходит на северо-запад от Конкорда до Ливана на границе с Вермонтом .  Автомагистраль между штатами 93 — это главная автомагистраль между штатами в Нью-Гэмпшире, которая проходит на север от Салема (на границе с Массачусетсом) до Литтлтона (на границе с Вермонтом). I-93 соединяет более густонаселенную южную часть штата с Озерным регионом и Белыми горами дальше на север.

Автомагистраль между штатами 93 — это главная автомагистраль между штатами в Нью-Гэмпшире, которая проходит на север от Салема (на границе с Массачусетсом) до Литтлтона (на границе с Вермонтом). I-93 соединяет более густонаселенную южную часть штата с Озерным регионом и Белыми горами дальше на север.  Автомагистраль между штатами 95 ненадолго проходит с севера на юг вдоль побережья Нью-Гэмпшира, обслуживая город Портсмут , прежде чем войти в штат Мэн.

Автомагистраль между штатами 95 ненадолго проходит с севера на юг вдоль побережья Нью-Гэмпшира, обслуживая город Портсмут , прежде чем войти в штат Мэн.  Маршрут 1 США на короткое время проходит с севера на юг вдоль побережья Нью-Гэмпшира к востоку от автомагистрали I-95 и параллельно ей.

Маршрут 1 США на короткое время проходит с севера на юг вдоль побережья Нью-Гэмпшира к востоку от автомагистрали I-95 и параллельно ей.  Маршрут 2 США проходит с востока на запад через округ Кус из штата Мэн, пересекая Маршрут 16 , огибая национальный лес Уайт-Маунтин , проходя через Джефферсон и в Вермонт.

Маршрут 2 США проходит с востока на запад через округ Кус из штата Мэн, пересекая Маршрут 16 , огибая национальный лес Уайт-Маунтин , проходя через Джефферсон и в Вермонт.  Маршрут 3 США - это самый длинный пронумерованный маршрут в штате и единственный, который полностью проходит через штат от границы Массачусетса до границы Канады и США. Обычно это соответствует межштатной автомагистрали 93 . К югу от Манчестера он идет по более западному маршруту через Нашуа . К северу от Франконии Нотч US 3 идет по более восточному маршруту и заканчивается на границе Канады и США.

Маршрут 3 США - это самый длинный пронумерованный маршрут в штате и единственный, который полностью проходит через штат от границы Массачусетса до границы Канады и США. Обычно это соответствует межштатной автомагистрали 93 . К югу от Манчестера он идет по более западному маршруту через Нашуа . К северу от Франконии Нотч US 3 идет по более восточному маршруту и заканчивается на границе Канады и США.  Маршрут 4 США заканчивается на кольцевой развязке в Портсмуте и проходит с востока на запад через южную часть штата, соединяя Дарем , Конкорд, Боскауэн и Ливан.

Маршрут 4 США заканчивается на кольцевой развязке в Портсмуте и проходит с востока на запад через южную часть штата, соединяя Дарем , Конкорд, Боскауэн и Ливан.  Маршрут 16 Нью-Гэмпшира - это главная автомагистраль с севера на юг в восточной части штата, которая обычно проходит параллельно границе с штатом Мэн и в конечном итоге входит в штат Мэн как Маршрут 16 штата Мэн. Самая южная часть NH 16 представляет собой четырехполосную автостраду, подписанную совместно. с американским маршрутом 4.

Маршрут 16 Нью-Гэмпшира - это главная автомагистраль с севера на юг в восточной части штата, которая обычно проходит параллельно границе с штатом Мэн и в конечном итоге входит в штат Мэн как Маршрут 16 штата Мэн. Самая южная часть NH 16 представляет собой четырехполосную автостраду, подписанную совместно. с американским маршрутом 4.  Маршрут 101 Нью-Гэмпшира — это крупная автомагистраль с востока на запад в южной части штата, которая соединяет Кин с Манчестером и прибрежным регионом. К востоку от Манчестера NH 101 представляет собой четырехполосное шоссе с ограниченным доступом, ведущее к Хэмптон-Бич и I-95.

Маршрут 101 Нью-Гэмпшира — это крупная автомагистраль с востока на запад в южной части штата, которая соединяет Кин с Манчестером и прибрежным регионом. К востоку от Манчестера NH 101 представляет собой четырехполосное шоссе с ограниченным доступом, ведущее к Хэмптон-Бич и I-95.

Воздух

[ редактировать ]

В Нью-Гэмпшире 25 аэропортов общественного пользования, три из которых осуществляют регулярные коммерческие пассажирские перевозки. Самым загруженным аэропортом по количеству обработанных пассажиров является региональный аэропорт Манчестер-Бостон в Манчестере и Лондондерри , который обслуживает столичный район Большого Бостона . Ближайший международный аэропорт — международный аэропорт Логан в Бостоне .

Общественный транспорт

[ редактировать ]Междугородние пассажирские железнодорожные перевозки на дальние расстояния обеспечиваются Amtrak компании линиями Vermonter и Downeaster .

Greyhound , Concord Coach , Vermont Translines и Dartmouth Coach обеспечивают междугороднее автобусное сообщение с пунктами в Нью-Гэмпшире и обратно, а также с пунктами дальнего следования за его пределами и между ними.

По состоянию на 2013 год [update] с центром в Бостоне Службы пригородной железной дороги MBTA доходят только до северного Массачусетса. Управление железнодорожного транспорта Нью-Гэмпшира работает над расширением услуги «Столичного коридора» от Лоуэлла, штат Массачусетс , до Нэшуа, Конкорда и Манчестера, включая региональный аэропорт Манчестер-Бостон ; и услуга «Прибрежный коридор» из Хаверхилла, Массачусетс , в Плейстоу, Нью-Гэмпшир . [ 119 ] [ 120 ] Законодательство 2007 года создало Управление железнодорожного транзита Нью-Гэмпшира (NHRTA) с целью надзора за развитием пригородного железнодорожного сообщения в штате Нью-Гэмпшир. В 2011 году губернатор Джон Линч наложил вето на HB 218, законопроект, принятый законодателями-республиканцами, который резко ограничил бы полномочия и обязанности NHRTA. [ 121 ] [ 122 ] Исследование транзитного коридора I-93 предложило железнодорожную альтернативу вдоль ветки Манчестера и Лоуренса , которая могла бы обеспечивать грузовые и пассажирские перевозки. [ 123 ] Этот железнодорожный коридор также будет иметь доступ к региональному аэропорту Манчестер-Бостон.

Одиннадцать органов общественного транспорта обслуживают местные и региональные автобусные перевозки по всему штату, а восемь частных перевозчиков обслуживают экспресс-автобусы, которые соединяются с национальной междугородной автобусной сетью. [ 124 ] Департамент транспорта Нью-Гэмпшира управляет службой совместного использования поездок по всему штату, а также независимыми программами подбора поездок и гарантированной поездки домой. [ 124 ]

Туристические железные дороги включают живописную железную дорогу Конвей , железную дорогу Хобо-Виннипесоки и зубчатую железную дорогу на горе Вашингтон .

Грузовые железные дороги

[ редактировать ]Грузовые железные дороги в Нью-Гэмпшире включают Claremont & Concord Railroad (CCRR), Pan Am Railways через дочернюю Springfield Terminal Railway (ST), Центральную железную дорогу Новой Англии (NHCR), St. Lawrence and Atlantic Railroad (SLR) и Северное побережье Нью-Гэмпшира. Корпорация (НХН).

Образование

[ редактировать ]

Средние школы

[ редактировать ]Первыми государственными средними школами в штате были Средняя школа для мальчиков и Средняя школа для девочек в Портсмуте , основанные либо в 1827, либо в 1830 году, в зависимости от источника. [ 125 ] [ 126 ] [ 127 ]

В Нью-Гэмпшире более 80 государственных средних школ, многие из которых обслуживают более чем один город. Крупнейшей из них является Академия Пинкертона в Дерри , которая принадлежит частной некоммерческой организации и служит государственной средней школой нескольких соседних городов. В штате не менее 30 частных средних школ.

Нью-Гэмпшир также является домом для нескольких престижных школ подготовки к университету , таких как Академия Филлипса Эксетера , Школа Святого Павла , Академия Проктора , Академия Брюстера и Академия Кимбалл Юнион .

В 2008 году штат сравнялся с Массачусетсом как имеющий самые высокие баллы по стандартизированным тестам SAT и ACT для старшеклассников. [ 128 ]

Колледжи и университеты

[ редактировать ]- Антиохийский университет Новой Англии

- Колби-Сойер Колледж

- Система общественных колледжей Нью-Гэмпшира :

- Дартмутский колледж

- Университет Франклина Пирса

- Греко-Американский университет

- Колледж свободных искусств Магдалины

- Массачусетский колледж фармацевтики и медицинских наук

- Колледж Новой Англии

- Институт искусств Нью-Гэмпшира

- Речной университет

- Колледж Святого Ансельма

- Университет Южного Нью-Гэмпшира

- Колледж свободных искусств Томаса Мора

- Университетская система Нью-Гэмпшира :

СМИ

[ редактировать ]Ежедневные газеты

[ редактировать ]- Берлин Дейли Сан

- Конкорд Монитор

- Конвей Дейли Сан

- Eagle Times из Клермонта

- Eagle Tribune ( Лоуренс, Массачусетс , включая части южного Нью-Гэмпшира)

- Фостера демократ Дувра Ежедневный

- Кин Сентинел

- Лакония Дейли Сан

- Лидер профсоюза Нью-Гэмпшира в Манчестере , ранее известный как Лидер Манчестерского профсоюза.

- Портсмут Геральд

- The Sun ( Лоуэлл, Массачусетс , включая части южного Нью-Гэмпшира)

- Новости Ливана долины

Другие публикации

[ редактировать ]- Группа новостей района

- Деловой журнал Нью-Гэмпшира

- Кабинет Пресс

- Милфорд Кабинет

- Бедфордский журнал

- Холлис / Бруклинский журнал

- Мерримак Журнал

- Carriage Towne News (охватывающие Кингстон и близлежащие города)

- The Dartmouth ( Дартмутского колледжа ) студенческая газета

- Информационное письмо Эксетера

- Бесплатно Кин

- Хэмптон Юнион

- Hippo Press (охватывает Манчестер, Нэшуа и Конкорд)

- Блок Свободы

- Манчестер Экспресс

- Манчестер Инк Линк [ 129 ]

- The New Hampshire (студенческая газета Университета Нью-Гэмпшира)

- Обзор бизнеса Нью-Гэмпшира

- Свободная пресса Нью-Гэмпшира

- The New Hampshire Gazette (альтернативный портсмутский выпуск раз в две недели)

- Журнал NH Living [ 130 ]

- Нью-Хэмпшир Рокс [ 131 ]

- Salmon Press Newspapers (семейство еженедельных газет, освещающих регион озер и северную страну)

Радиостанции

[ редактировать ]Телевизионные станции

[ редактировать ]- ABC Филиал WMUR , Channel 9, Манчестер

- PBS Дочерний канал 11, Дарем ( Общественное телевидение Нью-Гэмпшира ); ретрансляционные станции в Кине и Литтлтоне

- True Crime Network Филиал WWJE , Channel 50, Дерри/Манчестер

- Ионная телевизионная станция WPXG , канал 21, Конкорд (спутник WBPX в Бостоне)

Спорт

[ редактировать ]Следующие спортивные команды базируются в Нью-Гэмпшире:

Пейнтбол Хенникере был изобретен в в 1981 году. [ 132 ] Саттон был домом для первого в мире коммерческого пейнтбольного комплекса. [ 133 ]

Автодром Нью-Гемпшира в Лаудоне представляет собой овальную трассу и дорожную трассу, которую посещали такие национальные серии чемпионатов по автоспорту, как серия NASCAR Cup , серия NASCAR Xfinity , серия NASCAR Craftsman Truck Series NASCAR , модифицированный тур Whelen , тур по Америке и Канаде ( ACT), Champ Car и IndyCar Series . Другие места проведения автогонок включают Star Speedway и New England Dragway в Эппинге , Lee USA Speedway в Ли , Twin State Speedway в Клермонте , Monadnock Speedway в Винчестере и Canaan Fair Speedway в Ханаане .

В Нью-Гэмпшире есть два университета, соревнующихся в первом дивизионе NCAA по всем университетским видам спорта: Дартмут Биг Грин ( Лига Плюща ) и Нью-Гэмпшир Уайлдкэтс ( Восточная конференция Америки ), а также три команды второго дивизиона NCAA : Франклин Пирс Рэйвенс, Сент-Ансельм. Хоукс и писатели Южного Нью-Гэмпшира ( Конференция Северо-восток-10 ). Большинство других школ соревнуются в III дивизионе NCAA или NAIA .

Ежегодно, начиная с 2002 года, звезды средней школы штата соревнуются с Вермонтом в 10 видах спорта во время плей-офф «Штата-побратима». [ 134 ]

Культура

[ редактировать ]Весной во многих домах сока Нью-Гэмпшира проводятся дни открытых дверей для шугаринга. Летом и в начале осени Нью-Гэмпшир является домом для многих окружных ярмарок , крупнейшей из которых является ярмарка штата Хопкинтон в Контукуке . Нью-Гемпшира Район озер является домом для множества летних лагерей, особенно вокруг озера Виннипесоки , и является популярным туристическим направлением. The Peterborough Players выступают каждое лето в Питерборо с 1933 года. Театр Barnstormers в Тамворте , основанный в 1931 году, является одним из старейших профессиональных летних театров в Соединенных Штатах. [ 135 ]

В сентябре Нью-Гэмпшир принимает Игры горцев Нью-Гэмпшира . Нью-Гэмпшир также зарегистрировал официальный тартан в соответствующих органах Шотландии , который используется для изготовления килтов, которые носят сотрудники полицейского управления Линкольна , когда его сотрудники служат во время игр. Пик осенней листвы приходится на середину октября. Зимой Нью-Гэмпшира горнолыжные курорты и трассы для снегоходов привлекают посетителей со всего мира. [ 136 ] После того, как озера замерзают, на них появляются ледяные домики для зимней рыбалки , известные как бобхаусы.

Funspot , крупнейший в мире игровой зал [ 137 ] [ 138 ] (ныне музей) находится в Лаконии .

В художественной литературе

[ редактировать ]Театр

[ редактировать ]- Вымышленный город Гроверс-Корнерс в Нью-Гемпшире служит местом действия Торнтона Уайлдера пьесы « Наш город» . «Углы Гровера» частично основаны на реальном городе Питерборо . В тексте пьесы упоминаются несколько местных достопримечательностей и близлежащих городов, а сам Уайлдер провел некоторое время в Питерборо, в колонии Макдауэллов , написав по крайней мере часть пьесы, находясь там. [ 139 ]

Комиксы

[ редактировать ]- Эл Кэпп, создатель комикса «Лил Эбнер» , часто шутил, что «Догпатч» , действие которого происходит в комиксе, был основан на Сибруке , где он отдыхал со своей женой. [ 140 ]

Телевидение

[ редактировать ]- В драме канала AMC « Во все тяжкие » (« Гранитный штат »). [ 141 ] ) в сериале Уолтер Уайт сбегает в хижину в вымышленном графстве на севере Нью-Гэмпшира.

- Действие эпизода драмы NBC «Западное крыло» происходит в вымышленном Хартсфилдс-Лендинге , штат Нью-Гэмпшир.

- В шестом сезоне HBO популярного сериала «Клан Сопрано » в эпизоде, названном в честь знаменитого лозунга Нью-Гэмпшира « Живи свободным или умри », персонаж Вито Спатафор бежит из Нью-Джерси в небольшой вымышленный город Дартфорд, штат Нью-Гэмпшир, из-за того, что он случайно был объявлен геем. [ 142 ]

Известные люди

[ редактировать ]Среди выдающихся людей из Нью-Гэмпшира - 14-й президент Соединенных Штатов Франклин Пирс , отец-основатель Николас Гилман , сенатор Дэниел Вебстер , Войны за независимость герой Джон Старк , редактор Гораций Грили , основатель христианской науки религии Мэри Бейкер Эдди , поэт Роберт Фрост , скульптор Дэниел. Честер Френч , астронавт Алан Шепард , рок-музыкант Ронни Джеймс Дио , писатель Дэн Браун , актёр-комик Адам Сэндлер , изобретатель Дин Кеймен , комики Сара Сильверман и Сет Мейерс , рестораторы Ричард и Морис Макдональд , рестлер WWE Triple H и стример Людвиг Агрен .

См. также

[ редактировать ]Примечания

[ редактировать ]- ^ В случае появления вакансии на посту губернатора президент Сената штата первым в очереди принимает на себя губернаторские полномочия и обязанности в качестве исполняющего обязанности губернатора.

- ^ Высота приведена к североамериканской вертикальной системе отсчета 1988 года .

- ^ Вершина горы Вашингтон — самая высокая точка северо-востока Северной Америки .

- ^ которые были опрошены совместно

- ^ 86% в Алабаме и Южной Каролине.

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ Для использования в справочной публикации см. Менкен, Х.Л. (1990). Приложение по американскому языку 2 . Кнопф-Даблдэй.

Соседний Нью-Гемпшир обычно называют Гранитным штатом , а DAE относит его к 1830 году. Его также называли штатом Белой горы , Матерью рек и Американской Швейцарией.

- Для официального использования см. «Быстрые факты о Нью-Гэмпшире» . Нью-Гэмпширский альманах . Штат Нью-Гэмпшир. Архивировано из оригинала 25 мая 2017 года . Проверено 12 февраля 2018 г.

- Для современного использования см. « Живи свободным или умри — история девиза Нью-Гэмпшира» . Новая Англия сегодня . Yankee Publishing, Inc., 10 августа 2017 г. Архивировано из оригинала 12 февраля 2018 г. . Проверено 12 февраля 2018 г.

Однако в туристических целях Нью-Гэмпшир обычно несколько смягчает его, представляя себя как Гранитный штат или Штат Белой горы …

- ^ Государственная библиотека Нью-Гэмпшира. «Государственная официальная и почетная государственная песня» . NH.gov . Штат Нью-Гэмпшир . Проверено 23 февраля 2021 г.

- ^ «Географические идентификаторы: Нью-Гэмпшир» . Бюро переписи населения США . Проверено 29 ноября 2023 г.

- ^ «Маунт-Вош» . Технический паспорт НГС . Национальная геодезическая служба , Национальное управление океанических и атмосферных исследований , Министерство торговли США . Проверено 20 октября 2011 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Высоты и расстояния в США» . Геологическая служба США . 2001. Архивировано из оригинала 15 октября 2011 года . Проверено 24 октября 2011 г.

- ^ «Доход за последние 12 месяцев (в долларах с поправкой на инфляцию 2022 года) (S1901): годовые оценки исследования американского сообщества 2022 года: Нью-Гэмпшир» . data.census.gov . Бюро переписи населения США . Проверено 11 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ «Пересмотренный статут Нью-Гэмпшира, раздел 1, глава 3-C:1 — Официальный государственный язык» . Штат Нью-Гэмпшир. 1995. Архивировано из оригинала 4 октября 2018 года . Проверено 9 декабря 2016 г.

- ^ «Пересмотренный статут Нью-Гэмпшира, раздел 1, глава 3-C:2 — Исключения» . Штат Нью-Гэмпшир. 1995. Архивировано из оригинала 17 ноября 2004 года . Проверено 9 декабря 2016 г.

- ^ Фелау, Эрин (16 июня 2017 г.). «Ежевика теперь ягода штата Нью-Хэмпшир» . Новости ВМУР . Проверено 30 декабря 2019 г.

- ^ «Посетите Нью-Хэмпшир: государственные факты» . Департамент ресурсов и экономического развития штата Нью-Хэмпшир. Архивировано из оригинала 14 октября 2010 года . Проверено 30 августа 2010 г.

- ^ «Происхождение «Нью-Гэмпшира» » . Государственные символы США. 28 сентября 2014. Архивировано из оригинала 4 сентября 2015 года . Проверено 30 августа 2015 г.

- ^ «Экономика по отраслям в Нью-Хэмпшире и США» Школа государственной политики Карси | УНХ . 21 августа 2019 года . Проверено 20 июля 2021 г.

- ^ «Нью-Гэмпшир | Образование» . Данные бюро переписи населения . Проверено 6 августа 2023 г.

- ^ «Выберите Нью-Гэмпшир» . НХ Экономика . Проверено 20 июля 2021 г.

- ^ «Рейтинг лучших штатов» . Новости США и мировой отчет .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Джейкобс, Бен (13 октября 2022 г.). «Политика Нью-Гэмпшира, самого необычного штата Америки, объяснена» . Вокс . Проверено 17 сентября 2023 г.

Разбираем старую, белую, образованную, либертарианскую, антиналоговую политику Нью-Гэмпшира, выступающую за выбор.

- ^ «Абенаки» . tolatsga.org . Архивировано из оригинала 11 апреля 2010 года . Проверено 4 сентября 2017 г.

- ^ «12 000 лет назад в Гранитном штате» . Гуманитарные науки Нью-Гэмпшира . Проверено 4 октября 2023 г.

- ^ Харрис, Майкл (2021). «Ндакинна: Наша родина… Еще – дополнительные примеры присутствия абенаков в Нью-Гэмпшире» . Спектр . 10 (1): 1 . Проверено 5 октября 2023 г.

- ^ «Конституция Нью-Гэмпшира – 1776 г.» . 18 декабря 1998 года.

- ^ «Соблюдение Дня Конституции» . Archives.gov . Архивировано из оригинала 17 августа 2019 года . Проверено 7 апреля 2016 г.

- ^ «Первая начальная школа: почему Нью-Гэмпшир?» . Школа государственной политики Карси . 19 декабря 2019 года . Проверено 6 июня 2024 г.

- ^ «Почему Нью-Гэмпшир — первые праймериз в стране?» . Брукингс . Проверено 6 июня 2024 г.

- ^ Карта доступа к прибрежной полосе Нью-Гэмпшира (PDF) (Карта). Прибрежная программа Нью-Гэмпшира. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 4 марта 2016 г. Проверено 3 февраля 2016 г.

- ^ Бивер, Дженис Шерил (9 ноября 2006 г.). «Международные границы США: краткие факты» (PDF) . Исследовательская служба Конгресса. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 1 апреля 2019 г. Проверено 3 февраля 2016 г.

- ^ Филипов, Давид (31 января 2010 г.). «Рекорд уничтожен, но гордость остается прежней: заявление саммита Нью-Хэмпшира о плохой погоде остается неизменным» . Бостон Глобус . Архивировано из оригинала 3 февраля 2010 года . Проверено 9 февраля 2010 г.

- ^ «Гора Вашингтон… место самой плохой погоды в мире» . Обсерватория Маунт-Вашингтон. Архивировано из оригинала 18 января 2010 года . Проверено 22 марта 2010 г.

- ^ «Реки и озера» . Департамент экологических служб штата Нью-Хэмпшир . Проверено 5 июня 2023 г.

- ^ Вермонт против Нью-Гэмпшира 289 США 593 (1933)

- ^ «HJR 1 — окончательная версия» . Генеральный суд Нью-Гэмпшира . Архивировано из оригинала 16 октября 2015 года . Проверено 22 сентября 2015 г.

- ^ «Букварь по водным ресурсам Нью-Гэмпшира, Глава 6: Прибрежные и устьевые воды» (PDF) . Департамент экологических служб штата Нью-Хэмпшир. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 5 октября 2011 года . Проверено 11 апреля 2011 г.

- ^ Новак, Дэвид Дж.; Гринфилд, Эрик Дж. (9 мая 2012 г.). «Дерево и непроницаемое покрытие в США (2012)» (PDF) . Ландшафт и городское планирование . 107 : 21–30. дои : 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2012.04.005 . ISSN 0169-2046 . S2CID 9352755 . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 12 марта 2014 г. Проверено 3 февраля 2016 г.

- ^ Олсон, DM; Динерштейн, Э.; и др. (2001). «Наземные экорегионы мира: новая карта жизни на Земле» . Бионаука . 51 (11): 933–938. doi : 10.1641/0006-3568(2001)051[0933:TEOTWA]2.0.CO;2 .

- ^ Кимберли А. Джарвис, От гор до моря: защита природы в послевоенном Нью-Гэмпшире (University of Massachusetts Press, 2020) онлайн-обзор

- ^ Кимберли А. Джарвис, Франкония Нотч и женщины, которые ее спасли (Дарем: University of New Hampshire Press, 2007.

- ^ «Уязвимость сектора зимнего туризма на северо-востоке США к изменению климата» (PDF) . Департамент географии и Институт естественных наук Университета Оттавы . Проверено 3 февраля 2019 г.

- ^ Хикс, Терри Аллан; Макгеверан, Уильям; Уоринг, Керри Джонс (15 июля 2015 г.). Нью-Гэмпшир: Третье издание . Кавендиш Сквер Паблишинг, ООО. п. 18. ISBN 978-1-62713-166-7 .

- ^ Деллинджер, Дэн (23 июня 2004 г.). «Снегопад — среднее количество в дюймах» . НОАА . Архивировано из оригинала 19 июня 2011 года . Проверено 25 мая 2007 г.

- ^ «Среднегодовое количество торнадо 1953–2004 гг.» . НОАА. Архивировано из оригинала 16 октября 2011 года . Проверено 25 мая 2007 г.

- ^ «Карта зоны устойчивости arborday.org, 2006 г.» . Национальный фонд Дня посадки деревьев . Архивировано из оригинала 17 февраля 2011 года . Проверено 25 мая 2007 г.

- ^ «Карта зон устойчивости растений Министерства сельского хозяйства США Нью-Гэмпшира» . Карты растений . Архивировано из оригинала 8 декабря 2010 года . Проверено 15 ноября 2010 г.

- ^ «Средние климатические показатели Нью-Гэмпшира» . Метеорологическая база. Архивировано из оригинала 22 ноября 2015 года . Проверено 21 ноября 2015 г.

- ^ «Агломерационные города и поселки Новой Англии — текущие/ACS18 — данные по состоянию на 1 января 2018 г.» . Бюро переписи населения США. Архивировано из оригинала 7 февраля 2019 года . Проверено 5 февраля 2019 г.

- ^ «Подразделения Metropolitan и NECTA, опубликованные CES» . Бюро статистики труда. Архивировано из оригинала 7 февраля 2019 года . Проверено 5 февраля 2019 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Исторические данные об изменении численности населения (1910–2020 гг.)» . Census.gov . Бюро переписи населения США.

- ^ «Общая численность населения штата и компоненты изменений: 2020-2023 гг.» . Бюро переписи населения США . Проверено 19 января 2024 г.

- ^ «Центры народонаселения: 2020» . Бюро переписи населения США . Проверено 3 января 2022 г.

- ^ «Население Нью-Гэмпшира, 1950–2000» (PDF) . Управление энергетики и планирования штата Нью-Хэмпшир. Октябрь 2007 г. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 24 июля 2008 г. . Проверено 10 сентября 2008 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с «Профиль общих характеристик населения и жилья: данные демографического профиля за 2020 год (DP-1): Нью-Гэмпшир» . Бюро переписи населения США . Проверено 16 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Данные демографического профиля за 2010 год» . Бюро переписи населения США. Архивировано из оригинала 12 февраля 2020 года.

- ^ «Ты не отсюда, не так ли?» . Census.gov . 16 мая 2013 года . Проверено 4 сентября 2017 г.

- ^ «Подсчет подоходного налога в 2007–2022 годах по штатам» .

- ^ «Ежегодный отчет об оценке бездомности (AHAR) для Конгресса за 2022 год» (PDF) .

- ^ «Историческая статистика переписи населения по расам, с 1790 по 1990 год, и по латиноамериканскому происхождению, с 1970 по 1990 год, для Соединенных Штатов, регионов, подразделений и штатов» . Census.gov . 25 июля 2008 года. Архивировано из оригинала 25 июля 2008 года . Проверено 4 сентября 2017 г.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: исходный статус URL неизвестен ( ссылка ) - ^ «Просмотр переписи» . Censusviewer.com . 8 января 2014. Архивировано из оригинала 8 января 2014 года . Проверено 4 сентября 2017 г.

- ^ «Несмотря на заблуждения, коренные американцы имеют долгую историю в Нью-Гэмпшире» . Манчестерлинк.com . 30 июля 2022 г. Проверено 21 октября 2023 г.

- ^ «Опрос американского сообщества 2017 года» . Бюро переписи населения США.

- ^ «Избранные социальные характеристики в Соединенных Штатах: оценки американского сообщества 2017 года за 1 год (DP02): все штаты в составе Соединенных Штатов и Пуэрто-Рико» . Бюро переписи населения США . Бюро переписи населения США . Проверено 25 марта 2020 г.

- ^ «Иммигранты в Нью-Гэмпшире» (PDF) .

- ^ «Язык, на котором говорят дома люди, способные говорить по-английски, среди населения в возрасте 5 лет и старше: 5-летние оценки опроса американского сообщества 2015 года (B16001): Нью-Гэмпшир» . Американский фактоискатель . Бюро переписи населения США. Архивировано из оригинала 13 февраля 2020 года . Проверено 6 апреля 2017 г.

- ^ «Язык, на котором говорят дома люди, способные говорить по-английски для населения в возрасте 5 лет и старше: 5-летние оценки опроса американского сообщества 2015 года (B16001): округ Кус, Нью-Гэмпшир» . Американский фактоискатель . Бюро переписи населения США. Архивировано из оригинала 13 февраля 2020 года . Проверено 6 апреля 2017 г.

- ^ «Центр данных языковой карты MLA» . Ассоциация современного языка. 17 июля 2007. Архивировано из оригинала 5 декабря 2010 года . Проверено 31 июля 2010 г.

- ^ «Язык, на котором говорят дома люди, способные говорить по-английски для населения в возрасте 5 лет и старше: 5-летние оценки опроса американского сообщества 2015 года (B16001): ZCTA5 03060-03064, Нью-Гэмпшир» . Бюро переписи населения США . Проверено 30 декабря 2023 г.

- ^ «DP1: ПРОФИЛЬ ОБЩЕГО НАСЕЛЕНИЯ И ХАРАКТЕРИСТИК ЖИЛЬЯ» . Бюро переписи населения США . Проверено 16 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ «DP02Избранные социальные характеристики в Соединенных Штатах» . Бюро переписи населения США . Проверено 16 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ «Рождаемость: окончательные данные за 2013 год» (PDF) . Cdc.gov . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 11 сентября 2017 г. Проверено 4 сентября 2017 г.

- ^ «Рождаемость: окончательные данные за 2014 год» (PDF) . Cdc.gov . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 14 февраля 2017 г. Проверено 4 сентября 2017 г.

- ^ «Рождаемость: окончательные данные за 2015 год» (PDF) . Cdc.gov . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 31 августа 2017 г. Проверено 4 сентября 2017 г.

- ^ «Национальные отчеты о статистике естественного движения населения» (PDF) . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 3 июня 2018 г. Проверено 26 сентября 2018 г.

- ^ «Архивная копия» (PDF) . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 1 февраля 2019 г. Проверено 21 февраля 2019 г.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: архивная копия в заголовке ( ссылка ) - ^ «Данные» (PDF) . www.cdc.gov . Проверено 21 декабря 2019 г.

- ^ «Данные» (PDF) . www.cdc.gov . Проверено 30 марта 2021 г.

- ^ «Данные» (PDF) . www.cdc.gov . Проверено 20 февраля 2022 г.

- ^ «Данные» (PDF) . www.cdc.gov . Проверено 3 февраля 2022 г.

- ^ «Данные» (PDF) . www.cdc.gov . Проверено 5 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ «PRRI – Атлас американских ценностей» . Архивировано из оригинала 4 апреля 2017 года . Проверено 4 марта 2023 г.

- ^ «Взрослые в Нью-Гэмпшире» . Проект «Религия и общественная жизнь» исследовательского центра Pew . 11 мая 2015 года. Архивировано из оригинала 25 сентября 2017 года . Проверено 19 сентября 2017 г.

- ^ Аллен, Майк (23 июня 2008 г.). «Опрос Pew показал, что верующие гибки» . Политик. Архивировано из оригинала 18 сентября 2010 года . Проверено 31 июля 2010 г.

- ^ Фрэнк Ньюпорт (27 марта 2012 г.). «Миссисипи — самый религиозный штат США» . Гэллап. Архивировано из оригинала 28 марта 2012 года . Проверено 28 марта 2012 г.

- ^ «Отчет о членстве штата – Нью-Гэмпшир – Религиозные традиции, 2010 г.» . Ассоциация архивов религиозных данных. Архивировано из оригинала 2 декабря 2013 года . Проверено 22 ноября 2013 г.