Buzz Aldrin

Buzz Aldrin | |

|---|---|

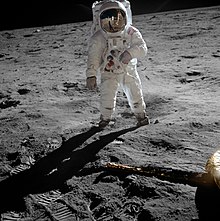

Олдрин в 1969 году | |

| Рожденный | Эдвин Юджин Олдрин младший 20 января 1930 г. Глен Ридж, Нью -Джерси , США |

| Другие имена | Доктор Рендеву |

| Образование | United States Military Academy (BS) Массачусетский технологический институт ( MS , SCD ) |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 3 |

| Awards | |

| Space career | |

| NASA astronaut | |

| Rank | Brigadier General, USAF |

Time in space | 12d 1h 53m |

| Selection | NASA Group 3 (1963) |

Total EVAs | 4 |

Total EVA time | 7h 52m |

| Missions | |

Mission insignia |  |

| Retirement | July 1, 1971 |

| Scientific career | |

| Thesis | Line-of-Sight Guidance Techniques for Manned Orbital Rendezvous (1963) |

| Doctoral advisors |

|

| Website | Official website |

| Signature | |

Buzz Aldrin ( / ˈ ɔː ɔː L D R ɪ N / ; Родился Эдвин Юджин Олдрин младший ; 20 января 1930 г.) - это бывший американский астронавт , инженер и пилот -истребитель . Он сделал три космоса в качестве пилота миссии Gemini 12 1966 года и был пилотом Lunar Module Eagle на миссии Apollo 11 Apollo 11 1969 года . Он был вторым человеком, который ходил по Луне после командира миссии Нила Армстронга . После смерти Майкла Коллинза в 2021 году он является последним выжившим членом экипажа Apollo 11.

Олдрин родился в Глен -Ридж, штат Нью -Джерси , занял третье место в классе 1951 года в военной академии США в Уэст -Пойнт по специальности машиностроение . Он был заказан в ВВС США и служил пилотом истребителями реактивного истребителя во время Корейской войны . Он выполнил 66 боевых миссий и сбил два самолета MIG-15 .

Получив степень доктора наук в области астронавтики из Массачусетского технологического института (MIT), Алдрин был выбран в качестве члена , НАСА группы астронавтов что делает его первым астронавтом с докторской степенью. Его докторская диссертация, методы руководства по линейке на воле в пилотируемом орбитальном свидании , принесли ему прозвище «Доктор Рендевос» от других астронавтов. Его первый космический полет был в 1966 году на Близнецах 12, в течение которого он провел более пяти часов на активность внеквартильны . Три года спустя Олдрин ступил на Луну в 03:15:16 21 июля 1969 года ( UTC ), через девятнадцать минут после того, как Армстронг впервые коснулся поверхности, в то время как пилот командования Майкл Коллинз остался на лунной орбите. Пресвитерианский . старший , Олдрин стал первым человеком, который проведет религиозную церемонию на Луне, когда он в частном порядке принял причастие , которые были первой едой и жидкостью, которые там поглощены

After leaving NASA in 1971, Aldrin became Commandant of the U.S. Air Force Test Pilot School. He retired from the Air Force in 1972 after 21 years of service. His autobiographies Return to Earth (1973) and Magnificent Desolation (2009) recount his struggles with clinical depression and alcoholism in the years after leaving NASA. Aldrin continues to advocate for space exploration, particularly a human mission to Mars. He developed the Aldrin cycler, a special spacecraft trajectory that makes travel to Mars more efficient in terms of time and propellant. He has been accorded numerous honors, including the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1969.

Early life and education

Aldrin was born Edwin Eugene Aldrin Jr. on January 20, 1930, at Mountainside Hospital in Glen Ridge, New Jersey.[1] His parents, Edwin Eugene Aldrin Sr. and Marion Aldrin (née Moon), lived in neighboring Montclair.[2] His father was an Army aviator during World War I and the assistant commandant of the Army's test pilot school at McCook Field, Ohio, from 1919 to 1922, but left the Army in 1928 and became an executive at Standard Oil.[3] Aldrin had two sisters: Madeleine, who was four years older, and Fay Ann, who was a year and a half older.[4] His nickname, which became his legal first name in 1988,[5][6] arose as a result of Fay's mispronouncing "brother" as "buzzer", which was then shortened to "Buzz".[4][7] He was a Boy Scout, achieving the rank of Tenderfoot Scout.[8]

Aldrin did well in school, maintaining an A average.[9] He played football and was the starting center for Montclair High School's undefeated 1946 state champion team.[10][11] His father wanted him to go to the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, and enrolled him at nearby Severn School, a preparatory school for Annapolis, and even secured him a Naval Academy appointment from Albert W. Hawkes, one of the United States senators from New Jersey.[12] Aldrin attended Severn School in 1946,[13] but had other ideas about his future career. He suffered from seasickness and considered ships a distraction from flying airplanes. He faced down his father and told him to ask Hawkes to change the nomination to the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York.[12]

Aldrin entered West Point in 1947.[5] He did well academically, finishing first in his class his plebe (first) year.[9] Aldrin was also an excellent athlete, competing in pole vault for the academy track and field team.[14][15] In 1950, he traveled with a group of West Point cadets to Japan and the Philippines to study the military government policies of Douglas MacArthur.[16] During the trip, the Korean War broke out.[17] On June 5, 1951, Aldrin graduated third in the class of 1951 with a Bachelor of Science degree in mechanical engineering.[18]

Military career

Among the top of his class, Aldrin had his choice of assignments. He chose the United States Air Force, which had become a separate service in 1947 while Aldrin was still at West Point and did not yet have its own academy.[19][a] He was commissioned as a second lieutenant and underwent basic flight training in T-6 Texans at Bartow Air Base in Florida. His classmates included Sam Johnson, who later became a prisoner of war in Vietnam; the two became friends. At one point, Aldrin attempted a double Immelmann turn in a T-28 Trojan and suffered a grayout. He recovered in time to pull out at about 2,000 feet (610 m), averting what would have been a fatal crash.[21]

When Aldrin was deciding what sort of aircraft he should fly, his father advised him to choose bombers, because command of a bomber crew gave an opportunity to learn and hone leadership skills, which could open up better prospects for career advancement. Aldrin chose instead to fly fighters. He moved to Nellis Air Force Base in Las Vegas, where he learned to fly the F-80 Shooting Star and the F-86 Sabre. Like most jet fighter pilots of the era, he preferred the latter.[21]

In December 1952, Aldrin was assigned to the 16th Fighter-Interceptor Squadron, which was part of the 51st Fighter-Interceptor Wing. At the time it was based at Suwon Air Base, about 20 miles (32 km) south of Seoul, and was engaged in combat operations as part of the Korean War.[18][22] During an acclimatization flight, his main fuel system froze at 100 percent power, which would have soon used up all his fuel. He was able to override the setting manually, but this required holding a button down, which in turn made it impossible to also use his radio. He barely managed to make it back under enforced radio silence. He flew 66 combat missions in F-86 Sabres in Korea and shot down two MiG-15 aircraft.[22][23]

The first MiG-15 he shot down was on May 14, 1953. Aldrin was flying about 5 miles (8.0 km) south of the Yalu River, when he saw two MiG-15 fighters below him. Aldrin opened fire on one of the MiGs, whose pilot may never have seen him coming.[22][24] The June 8, 1953, issue of Life magazine featured gun camera footage taken by Aldrin of the pilot ejecting from his damaged aircraft.[25]

Aldrin's second aerial victory came on June 4, 1953, when he accompanied aircraft from the 39th Fighter-Interceptor Squadron in an attack on an airbase in North Korea. Their newer aircraft were faster than his and he had trouble keeping up. He then spotted a MiG approaching from above. This time, Aldrin and his opponent spotted each other at about the same time. They went through a series of scissor maneuvers, attempting to get behind the other. Aldrin was first to do so, but his gun sight jammed. He then manually sighted his gun and fired. He then had to pull out, as the two aircraft had gotten too low for the dogfight to continue. Aldrin saw the MiG's canopy open and the pilot eject, although Aldrin was uncertain whether there was sufficient time for a parachute to open.[24][26] For his service in Korea, he was awarded two Distinguished Flying Crosses and three Air Medals.[27]

Aldrin's year-long tour ended in December 1953, by which time the fighting in Korea had ended. Aldrin was assigned as an aerial gunnery instructor at Nellis.[18] In December 1954 he became an aide-de-camp to Brigadier General Don Z. Zimmerman, the Dean of Faculty at the nascent United States Air Force Academy, which opened in 1955.[28][29] That same year, he graduated from the Squadron Officer School at Maxwell Air Force Base in Alabama.[30] From 1956 to 1959 he flew F-100 Super Sabres equipped with nuclear weapons as a flight commander in the 22nd Fighter Squadron, 36th Fighter Wing, stationed at Bitburg Air Base in West Germany.[18][24][28] Among his squadron colleagues was Ed White, who had been a year behind him at West Point. After White left West Germany to study for a master's degree at the University of Michigan in aeronautical engineering, he wrote to Aldrin encouraging him to do the same.[15]

Through the Air Force Institute of Technology, Aldrin enrolled as a graduate student at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1959 intending to earn a master's degree.[31] Richard Battin was the professor for his astrodynamics class. Two other USAF officers who later became astronauts, David Scott and Edgar Mitchell, took the course around this time. Another USAF officer, Charles Duke, also took the course and wrote his 1964 master's degree at MIT under the supervision of Laurence R. Young.[32]

Aldrin enjoyed the classwork and soon decided to pursue a doctorate instead.[31] In January 1963, he earned a Sc.D. degree in astronautics.[28][33] His doctoral thesis was Line-of-Sight Guidance Techniques for Manned Orbital Rendezvous, the dedication of which read: "In the hopes that this work may in some way contribute to their exploration of space, this is dedicated to the crew members of this country's present and future manned space programs. If only I could join them in their exciting endeavors!"[33] Aldrin chose his doctoral thesis in the hope that it would help him be selected as an astronaut, although it meant foregoing test pilot training, which was a prerequisite at the time.[31]

After completing his doctorate Aldrin was assigned to the Gemini Target Office of the Air Force Space Systems Division in Los Angeles,[15] working with the Lockheed Aircraft Corporation on enhancing the maneuver capabilities of the Agena target vehicle which was to be used by NASA's Project Gemini. He was then posted to the Space Systems Division's field office at NASA's Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston, where he was involved in integrating Department of Defense experiments into Project Gemini flights.[34]

NASA career

Aldrin initially applied to join the astronaut corps when NASA's Astronaut Group 2 was selected in 1962. His application was rejected on the grounds that he was not a test pilot. Aldrin was aware of the requirement and asked for a waiver but the request was turned down.[35] On May 15, 1963, NASA announced another round of selections, this time with the requirement that applicants had either test pilot experience or 1,000 hours of flying time in jet aircraft.[36] Aldrin had over 2,500 hours of flying time, of which 2,200 was in jets.[34] His selection as one of fourteen members of NASA's Astronaut Group 3 was announced on October 18, 1963.[37] This made him the first astronaut with a doctoral degree which, combined with his expertise in orbital mechanics, earned him the nickname "Dr. Rendezvous" from his fellow astronauts.[38][39][40] Although Aldrin was both the most educated and the rendezvous expert in the astronaut corps,[14] he was aware that the nickname was not always intended as a compliment.[15] Upon completion of initial training, each new astronaut was assigned a field of expertise; in Aldrin's case, it was mission planning, trajectory analysis, and flight plans.[41][42]

Gemini program

Jim Lovell and Aldrin were selected as the backup crew of Gemini 10, commander and pilot respectively. Backup crews usually became the prime crew of the third following mission, but the last scheduled mission in the program was Gemini 12.[43] The February 28, 1966, deaths of the Gemini 9 prime crew, Elliot See and Charles Bassett, in an air crash, led to Lovell and Aldrin being moved up one mission to backup for Gemini 9, which put them in position as prime crew for Gemini 12.[44][45] They were designated its prime crew on June 17, 1966, with Gordon Cooper and Gene Cernan as their backups.[46]

Gemini 12

Initially, Gemini 12's mission objectives were uncertain. As the last scheduled mission, it was primarily intended to complete tasks that had not been successfully or fully carried out on earlier missions.[47] While NASA had successfully performed rendezvous during Project Gemini, the gravity-gradient stabilization test on Gemini 11 was unsuccessful. NASA also had concerns about extravehicular activity (EVA). Cernan on Gemini 9 and Richard Gordon on Gemini 11 had suffered from fatigue carrying out tasks during EVA, but Michael Collins had a successful EVA on Gemini 10, which suggested that the order in which he had performed his tasks was an important factor.[48][49]

It therefore fell to Aldrin to complete Gemini's EVA goals. NASA formed a committee to give him a better chance of success. It dropped the test of the Air Force's astronaut maneuvering unit (AMU) that had given Gordon trouble on Gemini 11 so Aldrin could focus on EVA. NASA revamped the training program, opting for underwater training over parabolic flight. Aircraft flying a parabolic trajectory had given astronauts an experience of weightlessness in training, but there was a delay between each parabola which gave astronauts several minutes of rest. It also encouraged performing tasks quickly, whereas in space they had to be done slowly and deliberately. Training in a viscous, buoyant fluid gave a better simulation. NASA also placed additional handholds on the capsule, which were increased from nine on Gemini 9 to 44 on Gemini 12, and created workstations where he could anchor his feet.[48][49]

Gemini 12's main objectives were to rendezvous with a target vehicle, and fly the spacecraft and target vehicle together using gravity-gradient stabilization, perform docked maneuvers using the Agena propulsion system to change orbit, conduct a tethered stationkeeping exercise and three EVAs, and demonstrate an automatic reentry. Gemini 12 also carried 14 scientific, medical, and technological experiments.[50] It was not a trailblazing mission; rendezvous from above had already been successfully performed by Gemini 9, and the tethered vehicle exercise by Gemini 11. Even gravity-gradient stabilization had been attempted by Gemini 11, albeit unsuccessfully.[49]

Gemini 12 was launched from Launch Complex 19 at Cape Canaveral on 20:46 UTC on November 11, 1966. The Gemini Agena Target Vehicle had been launched about an hour and a half before.[50] The mission's first major objective was to rendezvous with this target vehicle. As the target and Gemini 12 capsule drew closer together, radar contact between the two deteriorated until it became unusable, forcing the crew to rendezvous manually. Aldrin used a sextant and rendezvous charts he helped create to give Lovell the right information to put the spacecraft in position to dock with the target vehicle.[51] Gemini 12 achieved the fourth docking with an Agena target vehicle.[52]

The next task was to practice undocking and docking again. On undocking, one of the three latches caught, and Lovell had to use the Gemini's thrusters to free the spacecraft. Aldrin then docked again successfully a few minutes later. The flight plan then called for the Agena main engine to be fired to take the docked spacecraft into a higher orbit, but eight minutes after the Agena had been launched, it had suffered a loss of chamber pressure. The Mission and Flight Directors therefore decided not to risk the main engine. This would be the only mission objective that was not achieved.[52] Instead, the Agena's secondary propulsion system was used to allow the spacecraft to view the solar eclipse of November 12, 1966, over South America, which Lovell and Aldrin photographed through the spacecraft windows.[50]

Aldrin performed three EVAs. The first was a standup EVA on November 12, in which the spacecraft door was opened and he stood up, but did not leave the spacecraft. The standup EVA mimicked some of the actions he would do during his free-flight EVA, so he could compare the effort expended between the two. It set an EVA record of two hours and twenty minutes. The next day Aldrin performed his free-flight EVA. He climbed across the newly installed hand-holds to the Agena and installed the cable needed for the gravity-gradient stabilization experiment. Aldrin performed numerous tasks, including installing electrical connectors and testing tools that would be needed for Project Apollo. A dozen two-minute rest periods prevented him from becoming fatigued. His second EVA concluded after two hours and six minutes. A third, 55-minute standup EVA was conducted on November 14, during which Aldrin took photographs, conducted experiments, and discarded some unneeded items.[50][53]

On November 15, the crew initiated the automatic reentry system and splashed down in the Atlantic Ocean, where they were picked up by a helicopter, which took them to the awaiting aircraft carrier USS Wasp.[50][54] After the mission, his wife realized he had fallen into a depression, something she had not seen before.[51]

Apollo program

Lovell and Aldrin were assigned to an Apollo crew with Neil Armstrong as commander, Lovell as command module pilot (CMP), and Aldrin as lunar module pilot (LMP). Their assignment as the backup crew of Apollo 9 was announced on November 20, 1967.[55] Due to design and manufacturing delays in the lunar module (LM), Apollo 8 and Apollo 9 swapped prime and backup crews, and Armstrong's crew became the backup for Apollo 8. Under the normal crew rotation scheme, Armstrong was expected to command Apollo 11.[56]

Michael Collins, the CMP on the Apollo 8 prime crew, required surgery to remove a bone spur on his spine.[57] Lovell took his place on the Apollo 8 crew. When Collins recovered he joined Armstrong's crew as CMP. In the meantime, Fred Haise filled in as backup LMP, and Aldrin as backup CMP for Apollo 8.[58] While the CMP usually occupied the center couch on launch, Aldrin occupied it rather than Collins, as he had already been trained to operate its console on liftoff before Collins arrived.[59]

Apollo 11 was the second American space mission made up entirely of astronauts who had already flown in space,[60] the first being Apollo 10.[61] The next would not be flown until STS-26 in 1988.[60] Deke Slayton, who was responsible for astronaut flight assignments, gave Armstrong the option to replace Aldrin with Lovell, since some thought Aldrin was difficult to work with. Armstrong thought it over for a day before declining. He had no issues working with Aldrin, and thought Lovell deserved his own command.[62]

Early versions of the EVA checklist had the lunar module pilot as the first to step onto the lunar surface. However, when Aldrin learned that this might be amended, he lobbied within NASA for the original procedure to be followed. Multiple factors contributed to the final decision, including the physical positioning of the astronauts within the compact lunar lander, which made it easier for Armstrong to be the first to exit the spacecraft. Furthermore, there was little support for Aldrin's views among senior astronauts who would command later Apollo missions.[63] Collins has commented that he thought Aldrin "resents not being first on the Moon more than he appreciates being second".[64] Aldrin and Armstrong did not have time to perform much geological training. The first lunar landing focused more on landing on the Moon and making it safely back to Earth than the scientific aspects of the mission. The duo was briefed by NASA and USGS geologists. They made one geological field trip to West Texas. The press followed them, and a helicopter made it hard for Aldrin and Armstrong to hear their instructor.[65]

Apollo 11

On the morning of July 16, 1969, an estimated one million spectators watched the launch of Apollo 11 from the highways and beaches in the vicinity of Cape Canaveral, Florida. The launch was televised live in 33 countries, with an estimated 25 million viewers in the United States alone. Millions more listened to radio broadcasts.[66][67] Propelled by a Saturn V rocket, Apollo 11 lifted off from Launch Complex 39 at the Kennedy Space Center on July 16, 1969, at 13:32:00 UTC (9:32:00 EDT),[68] and entered Earth orbit twelve minutes later. After one and a half orbits, the S-IVB third-stage engine pushed the spacecraft onto its trajectory toward the Moon. About thirty minutes later, the transposition, docking, and extraction maneuver was performed: this involved separating the command module Columbia from the spent S-IVB stage; turning around; and docking with, and extracting, the lunar module Eagle. The combined spacecraft then headed for the Moon, while the S-IVB stage continued on a trajectory past the Moon.[69]

On July 19 at 17:21:50 UTC, Apollo 11 passed behind the Moon and fired its service propulsion engine to enter lunar orbit.[69] In the thirty orbits that followed,[70] the crew saw passing views of their landing site in the southern Sea of Tranquillity about 12 miles (19 km) southwest of the crater Sabine D.[71] At 12:52:00 UTC on July 20, Aldrin and Armstrong entered Eagle, and began the final preparations for lunar descent. At 17:44:00 Eagle separated from the Columbia.[69] Collins, alone aboard Columbia, inspected Eagle as it pirouetted before him to ensure the craft was not damaged and that the landing gear had correctly deployed.[72][73]

Throughout the descent, Aldrin called out navigation data to Armstrong, who was busy piloting the Eagle.[74] Five minutes into the descent burn, and 6,000 feet (1,800 m) above the surface of the Moon, the LM guidance computer (LGC) distracted the crew with the first of several unexpected alarms that indicated that it could not complete all its tasks in real time and had to postpone some of them.[75] Due to the 1202/1201 program alarms caused by spurious rendezvous radar inputs to the LGC,[76] Armstrong manually landed the Eagle instead of using the computer's autopilot. The Eagle landed at 20:17:40 UTC on Sunday July 20 with about 25 seconds of fuel left.[77]

As a Presbyterian elder, Aldrin was the first and only person to hold a religious ceremony on the Moon. He radioed Earth: "I'd like to take this opportunity to ask every person listening in, whoever and wherever they may be, to pause for a moment and contemplate the events of the past few hours, and to give thanks in his or her own way."[78] Using a kit given to him by his pastor,[79] he took communion and read Jesus's words from the New Testament's John 15:5, as Aldrin records it: "I am the vine. You are the branches. Whoever remains in me, and I in him, will bear much fruit; for you can do nothing without me."[80] But he kept this ceremony secret because of a lawsuit over the reading of Genesis on Apollo 8.[81] In 1970 he commented: "It was interesting to think that the very first liquid ever poured on the Moon, and the first food eaten there, were communion elements."[82]

On reflection in his 2009 book, Aldrin said, "Perhaps, if I had it to do over again, I would not choose to celebrate communion. Although it was a deeply meaningful experience for me, it was a Christian sacrament, and we had come to the moon in the name of all mankind – be they Christians, Jews, Muslims, animists, agnostics, or atheists. But at the time I could think of no better way to acknowledge the enormity of the Apollo 11 experience than by giving thanks to God."[83] Aldrin shortly hit upon a more universally human reference on the voyage back to Earth by publicly broadcasting his reading of the Old Testament's Psalm 8:3–4, as Aldrin records: "When I considered the heavens, the work of Thy fingers, the moon and the stars which Thou hast ordained, what is man that Thou art mindful of him."[84] Photos of these liturgical documents reveal the conflict's development as Aldrin expresses faith.[85]

Preparations for the EVA began at 23:43.[69] Once Armstrong and Aldrin were ready to go outside, Eagle was depressurized, and the hatch was opened at 02:39:33 on July 21.[69][86] Aldrin set foot on the Moon at 03:15:16 on July 21, 1969 (UTC), nineteen minutes after Armstrong first touched the surface.[69] Armstrong and Aldrin became the first and second people, respectively, to walk on the Moon. Aldrin's first words after he set foot on the Moon were "Beautiful view", to which Armstrong asked "Isn't that something? Magnificent sight out here." Aldrin answered, "Magnificent desolation."[87] Aldrin and Armstrong had trouble erecting the Lunar Flag Assembly, but with some effort secured it into the surface. Aldrin saluted the flag while Armstrong photographed the scene. Aldrin positioned himself in front of the video camera and began experimenting with different locomotion methods to move about the lunar surface to aid future moonwalkers.[88] During these experiments, President Nixon called the duo to congratulate them on the successful landing. Nixon closed with, "Thank you very much, and all of us look forward to seeing you on the Hornet on Thursday."[89] Aldrin replied, "I look forward to that very much, sir."[89][90]

After the call, Aldrin began photographing and inspecting the spacecraft to document and verify its condition before their flight. Aldrin and Armstrong then set up a seismometer, to detect moonquakes, and a laser beam reflector. While Armstrong inspected a crater, Aldrin began the difficult task of hammering a metal tube into the surface to obtain a core sample.[91] Most of the iconic photographs of an astronaut on the Moon taken by the Apollo 11 astronauts are of Aldrin; Armstrong appears in just two color photographs. "As the sequence of lunar operations evolved," Aldrin explained, "Neil had the camera most of the time, and the majority of the pictures taken on the Moon that include an astronaut are of me. It wasn't until we were back on Earth and in the Lunar Receiving Laboratory looking over the pictures that we realized there were few pictures of Neil. My fault perhaps, but we had never simulated this during our training."[92]

Aldrin reentered Eagle first but, as he tells it, before ascending the module's ladder he became the first person to urinate on the Moon.[93] With some difficulty they lifted film and two sample boxes containing 21.55 kilograms (47.5 lb) of lunar surface material to the hatch using a flat cable pulley device.[94] Armstrong reminded Aldrin of a bag of memorial items in his sleeve pocket, and Aldrin tossed the bag down. It contained a mission patch for the Apollo 1 flight that Ed White never flew due to his death in a cabin fire during the launch rehearsal; medallions commemorating Yuri Gagarin, the first man in space (who had died the previous year in a test flight accident), and Vladimir Komarov, the first man to die in a space flight, and a silicon disk etched with goodwill messages from 73 nations.[95] After transferring to LM life support, the explorers lightened the ascent stage for the return to lunar orbit by tossing out their backpacks, lunar overshoes, an empty Hasselblad camera, and other equipment. The hatch was closed again at 05:01, and they repressurized the lunar module and settled down to sleep.[96]

At 17:54 UTC, they lifted off in Eagle's ascent stage to rejoin Collins aboard Columbia in lunar orbit.[69] After rendezvous with Columbia, the ascent stage was jettisoned into lunar orbit, and Columbia made its way back to Earth.[97] It splashed down in the Pacific 2,660 km (1,440 nmi) east of Wake Island at 16:50 UTC (05:50 local time) on July 24.[69][98] The total mission duration was 195 hours, 18 minutes, 35 seconds.[99]

Bringing back pathogens from the lunar surface was considered a possibility, albeit remote, so divers passed biological isolation garments (BIGs) to the astronauts, and assisted them into the life raft. The astronauts were winched on board the recovery helicopter, and flown to the aircraft carrier USS Hornet,[100] where they spent the first part of the Earth-based portion of 21 days of quarantine.[101] On August 13, the three astronauts rode in ticker-tape parades in their honor in New York and Chicago, attended by an estimated six million people.[102] An official state dinner that evening in Los Angeles celebrated the flight. President Richard Nixon honored each of them with the highest American civilian award, the Presidential Medal of Freedom (with distinction).[103][104]

On September 16, 1969, the astronauts addressed a joint session of Congress where they thanked the representatives for their past support and implored them to continue funding the space effort.[105][106] The astronauts embarked on a 38-day world tour on September 29 that brought the astronauts to 22 foreign countries and included visits with leaders of multiple countries.[107] The last leg of the tour included Australia, South Korea, and Japan; the crew returned to the US on November 5, 1969.[108][109]

After Apollo 11, Aldrin was kept busy giving speeches and making public appearances. In October 1970, he joined Soviet cosmonauts Andriyan Nikolayev and Vitaly Sevastyanov on their tour of the NASA space centers. He was also involved in the design of the Space Shuttle. With the Apollo program coming to an end, Aldrin, now a colonel, saw few prospects at NASA, and decided to return to the Air Force on July 1, 1971.[110] During his NASA career, he had spent 289 hours and 53 minutes in space, of which 7 hours and 52 minutes was in EVA.[28]

Post-NASA activities

Aerospace Research Pilot School

Aldrin hoped to become Commandant of Cadets at the United States Air Force Academy, but the job went to his West Point classmate Hoyt S. Vandenberg Jr. Aldrin was made Commandant of the USAF Aerospace Research Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base, California. Aldrin had neither managerial nor test pilot experience, but a third of the training curriculum was devoted to astronaut training and students flew a modified F-104 Starfighter to the edge of space.[111] Fellow Group 3 astronaut and moonwalker Alan Bean considered him well qualified for the job.[112]

Aldrin did not get along well with his superior, Brigadier General Robert M. White, who had earned his USAF astronaut wings flying the X-15. Aldrin's celebrity status led people to defer to him more than the higher-ranking general.[113] There were two crashes at Edwards, of an A-7 Corsair II and a T-33. No people died, but the aircraft were destroyed and the accidents were attributed to insufficient supervision, which placed the blame on Aldrin. What he had hoped would be an enjoyable job became a highly stressful one.[114]

Aldrin went to see the base surgeon. In addition to signs of depression, he experienced neck and shoulder pains, and hoped that the latter might explain the former.[115] He was hospitalized for depression at Wilford Hall Medical Center for four weeks.[116] His mother had committed suicide in May 1968, and he was plagued with guilt that his fame after Gemini 12 had contributed. His mother's father had also committed suicide, and he believed he inherited depression from them.[117] At the time there was great stigma related to mental illness and he was aware that it could not only be career-ending, but could result in his being ostracized socially.[115]

In February 1972, General George S. Brown paid a visit to Edwards and informed Aldrin that the USAF Aerospace Research Pilot School was being renamed the USAF Test Pilot School and the astronaut training was being dropped. With the Apollo program winding down, and Air Force budgets being cut, the Air Force's interest in space diminished.[114] Aldrin elected to retire as a colonel on March 1, 1972, after 21 years of service. His father and General Jimmy Doolittle, a close friend of his father, attended the formal retirement ceremony.[114]

Post retirement

Aldrin's father died on December 28, 1974, from complications following a heart attack.[118] Aldrin's autobiographies, Return to Earth (1973) and Magnificent Desolation (2009), recounted his struggles with clinical depression and alcoholism in the years after leaving NASA.[119][120][121] Encouraged by a therapist to take a regular job, Aldrin worked selling used cars, at which he had no talent.[122] Periods of hospitalization and sobriety alternated with bouts of heavy drinking. Eventually he was arrested for disorderly conduct. Finally, in October 1978, he quit drinking for good. Aldrin attempted to help others with drinking problems, including actor William Holden. Holden's girlfriend Stefanie Powers had portrayed Marianne, a woman with whom Aldrin had an affair, in the 1976 TV movie version of Return to Earth. Aldrin was saddened by Holden's alcohol-related death in 1981.[123]

Bart Sibrel incident

On September 9, 2002, Aldrin was lured to a Beverly Hills hotel on the pretext of being interviewed for a Japanese children's television show on the subject of space.[124] When he arrived, Moon landing conspiracy theorist Bart Sibrel accosted him with a film crew and demanded he swear on a Bible that the Moon landings were not faked. After a brief confrontation, during which Sibrel followed Aldrin despite being told to leave him alone, and called him "a coward, a liar, and a thief" the 72-year-old Aldrin punched Sibrel in the jaw, which was caught on camera by Sibrel's film crew. Aldrin said he had acted to defend himself and his stepdaughter. Witnesses said Sibrel had aggressively poked Aldrin with a Bible. Additional mitigating factors were that Sibrel sustained no visible injury and did not seek medical attention, and that Aldrin had no criminal record. The police declined to press charges against Aldrin.[125][126]

Detached adapter panel sighting

In 2005, while being interviewed for a Science Channel documentary titled First on the Moon: The Untold Story, Aldrin told an interviewer they had seen an unidentified flying object (UFO). The documentary makers omitted the crew's conclusion that they probably saw one of the four detached spacecraft adapter panels from the upper stage of the Saturn V rocket. The panels had been jettisoned before the separation maneuver so they closely followed the spacecraft until the first mid-course correction. When Aldrin appeared on The Howard Stern Show on August 15, 2007, Stern asked him about the supposed UFO sighting. Aldrin confirmed that there was no such sighting of anything deemed extraterrestrial and said they were, and are, "99.9 percent" sure the object was the detached panel.[128][129] According to Aldrin his words had been taken out of context. He made a request to the Science Channel to make a correction, but was refused.[130]

Polar expedition

In December 2016, Aldrin was part of a tourist group visiting the Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station in Antarctica when he fell ill and was evacuated, first to McMurdo Station and from there to Christchurch, New Zealand.[131] At 86 years of age, Aldrin's visit made him the oldest person to reach the South Pole. He had traveled to the North Pole in 1998.[132][133]

Mission to Mars advocacy

After leaving NASA, Aldrin continued to advocate for space exploration. In 1985 he joined the University of North Dakota (UND)'s College of Aerospace Sciences at the invitation of John D. Odegard, the dean of the college. Aldrin helped to develop UND's Space Studies program and brought David Webb from NASA to serve as the department's first chair.[134] To further promote space exploration, and to commemorate the 40th anniversary of the first lunar landing, Aldrin teamed up with Snoop Dogg, Quincy Jones, Talib Kweli, and Soulja Boy to create the rap single and video "Rocket Experience", proceeds from which were donated to Aldrin's non-profit foundation, ShareSpace.[135] He is also a member of the Mars Society's Steering committee.[136]

In 1985, Aldrin proposed a special spacecraft trajectory now known as the Aldrin cycler.[137][138] Cycler trajectories offer reduced cost of repeated travel to Mars by using less propellant. The Aldrin cycler provided a five and a half month journey from the Earth to Mars, with a return trip to Earth of the same duration on a twin cycler orbit. Aldrin continues to research this concept with engineers from Purdue University.[139] In 1996 Aldrin founded Starcraft Boosters, Inc. (SBI) to design reusable rocket launchers.[140]

In December 2003, Aldrin published an opinion piece in The New York Times criticizing NASA's objectives. In it, he voiced concern about NASA's development of a spacecraft "limited to transporting four astronauts at a time with little or no cargo carrying capability" and declared the goal of sending astronauts back to the Moon was "more like reaching for past glory than striving for new triumphs".[141]

In a June 2013 opinion piece in The New York Times, Aldrin supported a human mission to Mars and which viewed the Moon "not as a destination but more a point of departure, one that places humankind on a trajectory to homestead Mars and become a two-planet species."[142] In August 2015, Aldrin, in association with the Florida Institute of Technology, presented a master plan to NASA for consideration where astronauts, with a tour of duty of ten years, establish a colony on Mars before the year 2040.[143]

Awards and honors

Aldrin was awarded the Air Force Distinguished Service Medal (DSM) in 1969 for his role as lunar module pilot on Apollo 11.[144] He was awarded an oak leaf cluster in 1972 in lieu of a second DSM for his role in both the Korean War and in the space program,[144] and the Legion of Merit for his role in the Gemini and Apollo programs.[144] During a 1966 ceremony marking the end of the Gemini program, Aldrin was awarded the NASA Exceptional Service Medal by President Johnson at LBJ Ranch.[145] He was awarded the NASA Distinguished Service Medal in 1970 for the Apollo 11 mission.[146][147] Aldrin was one of ten Gemini astronauts inducted into the International Space Hall of Fame in 1982.[148][149] He was also inducted into the U.S. Astronaut Hall of Fame in 1993,[150][151] the National Aviation Hall of Fame in 2000,[152] and the New Jersey Hall of Fame in 2008.[153] The Toy Story character Buzz Lightyear was named in honor of Buzz Aldrin.[154]

In 1999, while celebrating the 30th anniversary of the lunar landing, Vice President Al Gore, who was also the vice-chancellor of the Smithsonian Institution's Board of Regents, presented the Apollo 11 crew with the Smithsonian Institution's Langley Gold Medal for aviation. After the ceremony, the crew went to the White House and presented President Bill Clinton with an encased Moon rock.[155][156] The Apollo 11 crew was awarded the New Frontier Congressional Gold Medal in the Capitol Rotunda in 2011. During the ceremony, NASA administrator Charles Bolden said, "Those of us who have had the privilege to fly in space followed the trail they forged."[157][158]

Экипаж Apollo 11 был награжден The Collier Trophy в 1969 году. Президент Национальной авиационной ассоциации присудил дублированный трофей Коллинзу и Олдрину на церемонии. [159] The crew was awarded the 1969 General Thomas D. White USAF Space Trophy.[160] The National Space Club named the crew the winners of the 1970 Dr. Robert H. Goddard Memorial Trophy, awarded annually for the greatest achievement in spaceflight.[ 161 ] Они получили Международный трофей Хармона для авиаторов в 1970 году, [ 162 ] [ 163 ] Присвоенный им вице -президентом Спиро Агнью в 1971 году. [ 164 ] Agnew также представила им медаль Хаббарда Национального географического общества в 1970 году. Он сказал им: «Вы выиграли место вместе с Кристофером Колумбусом в американской истории». [ 165 ] В 1970 году команда Apollo 11 была соавтором премии Iven C. Kincheloe от Общества экспериментальных пилотов-испытаний вместе с Дэррилом Гринамиером, который побил рекорд World Speed для самолетов поршневого двигателя. [ 166 ] За вклады в телевизионную индустрию, они были удостоены круглых бляшек на Голливудской прогулке славы . [ 167 ]

В 2001 году президент Джордж Буш назначил Олдрина в Комиссию о будущем аэрокосмической промышленности США . [ 168 ] Олдрин получил гуманитарную награду 2003 года от Variety, благотворительность детей , которая, по мнению организации, «предоставляется человеку, который продемонстрировал необычное понимание, сочувствие и преданность человечеству». [ 169 ] В 2006 году Космический фонд присудил ему высшую честь, генерал Джеймс Э. Хилл награду «Пространство пространства». [ 170 ]

Олдрин получил почетные степени от шести колледжей и университетов, [ 28 ] и был назван канцлером Международного космического университета в 2015 году. [ 171 ] Он был членом Национального Космического общества , Совета управляющих [ 172 ] и служил председателем организации. В 2016 году его средняя школа в родном городе в Монтклере, штат Нью -Джерси, был переименован в среднюю школу Buzz Aldrin. [ 173 ] Кратер Олдрина на Луне возле места посадки Аполлона 11 и астероида 6470 Олдрин названы в его честь. [ 148 ]

В 2019 году Олдрин был награжден фестивалем Starmus Festival Medal за научную коммуникацию для жизненных достижений. [ 174 ] В свой 93 -й день рождения он был удостоен чести живых легенд авиации . [ 175 ] 5 мая 2023 года он получил почетное повышение по службе в звание бригадного генерала в ВВС США, а также стал почетным опекуном космических сил. [ 176 ] [ 177 ] [ 178 ]

Личная жизнь

Браки и дети

Олдрин был женат четыре раза. Его первый брак был 29 декабря 1954 года с Джоан Арчер, Университет Рутгерса и выпускником Колумбийского университета со степенью магистра. У них было трое детей, Джеймс, Дженис и Эндрю. Они подали на развод в 1974 году. [ 179 ] [ 180 ] Его вторая жена была Беверли Ван Зиль, на которой он женился 31 декабря 1975 года, [ 181 ] и развелся в 1978 году. Его третьей женой была Лоис Дриггс Кэннон, на которой он женился 14 февраля 1988 года. [ 182 ] Их развод был завершен в декабре 2012 года. В урегулирование включало 50 процентов от их банковского счета в размере 475 000 долл. США и 9 500 долл. США в месяц плюс 30 процентов от его годового дохода, оцениваемого в более чем 600 000 долл. США. [ 183 ] [ 184 ] По состоянию на 2017 год, [update] У него был один внук, Джеффри Шусс, родился у его дочери Дженис, а также три правнука и одна правнучка. [ 185 ]

В 2018 году Олдрин участвовал в юридическом споре со своими детьми Эндрю и Дженис и бывшим бизнес -менеджером Кристиной Корп из -за их заявлений о том, что он был психически нарушен в результате деменции и болезни Альцгеймера . Его дети утверждали, что он завел новых друзей, которые отталкивали его от семьи и побуждали его провести сбережения с высокой скоростью. Они стремились их назвать законными опекунами, чтобы они могли контролировать его финансы. [ 186 ] В июне Олдрин подал иск против Эндрю, Дженис, Корпа и предприятий и фондов, управляемых семьей. [ 187 ] Олдрин утверждал, что Дженис не действовал в своих финансовых интересах и что Корп эксплуатирует пожилых людей. Он стремился убрать контроль Эндрю над учетными записями, финансами и предприятиями Алдрина. Ситуация закончилась, когда его дети сняли свою петицию, и он бросил иск в марте 2019 года, за несколько месяцев до 50 -летия миссии «Аполлон 11». [ 188 ]

20 января 2023 года, его 93-й день рождения, Олдрин объявил в Твиттере , что он женился в четвертый раз, со своим 63-летним компаньоном Аной Фаур. [ 189 ] [ 175 ]

Политика

Aldrin является активным сторонником Республиканской партии , хедлайнером сборщиков средств для своих членов Конгресса [ 190 ] и одобряя своих кандидатов. Он появился на митинге для Джорджа Буша в 2004 году и проводил кампанию за Пол Ранкаторе во Флориде в 2008 году, Мид Тредвелл на Аляске в 2014 году [ 191 ] и Дэн Креншоу в Техасе в 2018 году. [ 192 ] Он появился на выступлении штата Союз 2019 года в качестве гостя президента Дональда Трампа . [ 193 ]

Масонство

Buzz Aldrin - первый масон , который ступил на Луну. [ 194 ] Олдрин был инициирован в масонстве в Оук -Парк Лодж № 864 в Алабаме и вырос в Лодже Лоуренса Н. Гринлиф, № 169 в Колорадо. [ 195 ]

К тому времени, когда Олдрин вышел на лунную поверхность, он был членом двух масонских лодок: Montclair Lodge № 144 в Нью -Джерси и Clear Lake Lodge № 1417 в Сибруке, штат Техас, где его пригласили на службу в Высокий совет и был рукоположен в 33 -й степени древнего и принятого шотландского обряда. [ 196 ]

Олдрин также является членом Йоркского обряда и храма Хьюстона Аравии Хьюстона. [ 197 ]

Другой

В 2007 году Олдрин подтвердил журнал Time , что недавно у него был подтяжка лица , шучая, что G-Forces, с которыми он подвергался в космосе, «вызвали провисающую челюсть, которая нуждалась в некотором внимании». [ 198 ]

После смерти 2012 года его коллеги Аполлона 11 Нила Армстронга Алдрин сказал, что он был

... глубоко опечален кончиной ... Я знаю, что ко мне присоединяются многие миллионы других со всего мира, скорбя о кончине настоящего американского героя и лучшего пилота, которого я когда -либо знал ... Я действительно надеялся, что на 20 июля 2019 года, Нил, Майк и я стояли вместе, чтобы отметить 50 -летие нашей лунной посадки. [ 199 ]

Олдрин в основном проживал в районе Лос -Анджелеса, в том числе Беверли -Хиллз и Пляж Лагуна с 1985 года. [ 200 ] [ 201 ] В 2014 году он продал свой Вествуда ; кондоминиум [ 202 ] Это было после его третьего развода в 2012 году. Он также живет в спутниковом пляже, штат Флорида . [ 203 ] [ 204 ] [ когда? ]

Олдрин был титтоталером с 1978 года. [ 205 ]

В СМИ

Фимография

| Год | Заголовок | Роль | Примечания |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1976 | Мальчик в пластиковом пузыре | Сам | Телевизионный фильм [ 206 ] |

| 1986 | Панки Брюстер | Сам | Эпизод «несчастные случаи случаются», 9 марта 1986 г. [ 206 ] |

| 1989 | После наступления темноты | Сам | Расширенное появление в британской дискуссионной программе с другими Хайнцами Вольфом , Джоселин Белл Бернелл и Уитли Стрибер [ 207 ] |

| 1994 | Симпсоны | Сам (голос) | Эпизод: « Глубокий космос Гомер ». Олдрин сопровождает Гомера Симпсона в поездке в космос в рамках плана НАСА по улучшению своего публичного имиджа [ 208 ] [ 209 ] |

| 1997 | Космический призрак побережье до побережья | Сам | Эпизоды: «Блестящий номер один» [ 210 ] и "блестящий номер два" [ 211 ] |

| 1999 | Перерыв Диснея | Сам (голос) | Эпизод: " Космический курсант " [ 212 ] |

| 2003 | Da Ali G Show | Сам | 2 эпизода [ 213 ] |

| 2006 | Numb3rs | Сам | Эпизод: " Killer Chat " [ 214 ] |

| 2007 | В тени Луны | Сам | Документальный фильм [ 215 ] |

| 2008 | Лечь меня на луну | Сам | [ 216 ] |

| 2010 | 30 рок | Сам | Эпизод: " Мамы " [ 217 ] |

| 2010 | Танцы со звездами | Сам/участник | 2 -й устранен в 10 сезоне [ 218 ] |

| 2011 | Трансформеры: темная луна | Сам | Алдрин объясняет Optimus Prime и автоботам , что в высшей секретной миссии Apollo 11 состояла в том, чтобы исследовать кибертронский корабль на дальней стороне Луны , существование которого было скрыто от общественности. [ 219 ] |

| 2011 | Футурама | Сам (голос) | Эпизод: " Холодные воины " [ 220 ] |

| 2012 | Космические братья | Сам | [ 221 ] |

| 2012 | Теория большого взрыва | Сам | Эпизод: «Голографическое возбуждение» [ 222 ] |

| 2012 | Mass Effect 3 | Stargazer (голос) | Алдрин сыграл звездного газера, который появляется в финальной сцене видеоигры [ 223 ] |

| 2015 | Земля около 6 шагов | Сам | Успешно протестировал шесть градусов разделения [ 224 ] |

| 2016 | Позднее шоу со Стивеном Колбертом | Сам | Был опрошен и принял участие в пародии [ 225 ] |

| 2016 | Адская кухня | Сам | Гость в столовой и ужинал, приготовленный синей командой из -за победы в команде [ 226 ] [ 227 ] |

| 2017 | Миль от Tomorrowland | Командир Коперник (голос) | Гостевые звезды в эпизоде [ 228 ] |

Изображается другими

| Внешние видео | |

|---|---|

Олдрин был изображен:

- Клифф Робертсон в ответ на Землю (1976) [ 229 ] Олдрин работал с Робертсоном над этой ролью. [ 230 ]

- Ларри Уильямс в Аполлоне 13 (1995) [ 231 ]

- Ксандер Беркли в Аполлоне 11 (1996). Он также был техническим консультантом фильма. [ 232 ]

- Брайан Крэнстон в Земле до Луны (1998) и великолепное опустошение: ходьба по Луне 3D (2005) [ 233 ] [ 234 ]

- Джеймс Марстерс в самолете (2009) [ 235 ]

- Кори Такер как молодой кайф Алдрин из 1969 года в Transformers: Dark of the Moon (2011) [ 236 ]

- Кори Столл в First Man (2018) [ 237 ]

- Крис Агос для всех человечества (2019). 6 эпизодов. [ 238 ]

- Феликс Скотт в Короне (2019) [ 239 ]

- Роджер Крейг Смит (как настоящий Базз Алдрин) и Генри Винклер (как актер кризиса Мелвин Стувиц) во внутренней работе (2021–2022) [ 240 ]

- Брин Томас в Индиане Джонс и циферблат судьбы (2023) [ 241 ]

Видеоигры

- Олдрин был консультантом в видеоигры Buzz Aldrin's Race Into In Space (1993). [ 242 ]

Работа

- Олдрин, . младший Эдвин 1970 Э. Эдисон Электрический институт Бюллетень . Тол. 38, № 7, с. 266–272.

- Армстронг, Нил; Майкл Коллинз; Эдвин Э. Олдрин; Джин Фармер; и Дора Джейн Хэмблин. 1970. Сначала на Луне: путешествие с Нилом Армстронгом, Майклом Коллинзом, Эдвином Э. Олдрином -младшим. Бостон: Литтл, Браун. ISBN 9780316051606 .

- Олдрин, Базз и Уэйн Варга. 1973. Вернуться на Землю . Нью -Йорк: Рэндом Хаус. ISBN 9781504026444 .

- Олдрин, Базз и Малкольм Макконнелл. 1989. Мужчины с Земли . Нью -Йорк: Bantam Books. ISBN 9780553053746 .

- Олдрин, Базз и Джон Барнс. 1996. Встреча с Тибром . Лондон: Ходдер и Стоутон. ISBN 9780340624500 .

- Олдрин, Базз и Джон Барнс. 2000. Возврат . Нью -Йорк: Кузница. ISBN 9780312874247 .

- Олдрин, Базз и Венделл несовершеннолетний. 2005. Достигнув Луны . Нью -Йорк: HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 9780060554453 .

- Олдрин, Базз и Кен Абрахам. 2009. Великолепное опустошение: долгое путешествие домой с Луны . Нью -Йорк: Книги Harmony. ISBN 9780307463456 .

- Олдрин, Базз и Венделл несовершеннолетний. 2009. Посмотрите на звезды . Camberwell, Vic.: Puffin Books. ISBN 9780143503804 .

- Олдрин, Базз и Леонард Дэвид. 2013. Миссия на Марс: мое видение космического исследования . Вашингтон, округ Колумбия: Национальные географические книги. ISBN 9781426210174 .

- Олдрин, Базз и Марианна Дайсон. 2015. Добро пожаловать на Марс: создание дома на красной планете . Вашингтон, округ Колумбия: Детские книги National Geographic. ISBN 9781426322068 .

- Олдрин, Базз и Кен Абрахам. 2016. Никакая мечта не слишком высока: жизненные уроки от человека, который ходил на Луну . Вашингтон, округ Колумбия: Национальные географические книги. ISBN 9781426216503 .

Смотрите также

Примечания

- ^ Соглашение 1949 года допустило до 25 процентов выпускных классов Вест -Пойнт и Аннаполиса для волонтера в ВВС. В период с 1950 года, когда соглашение вступило в силу, и 1959 год, когда первый класс окончил Академию ВВС США , около 3200 курсантов в Уэст -Пойнт и Аннаполис Мичмане решили сделать это. [ 20 ]

Цитаты

- ^ Kaulessar, Рикардо (22 сентября 2016 г.). «Место, где есть шум» . Монтклер времена . Монтклер, Нью -Джерси. п. A5 - через Newspapers.com.

- ^ Hansen 2005 , с. 348–349.

- ^ Grier 2016 , с. 87–88.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Хансен 2005 , с.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Редд, Нола Тейлор (23 июня 2012 г.). "Buzz Aldrin & Apollo 11" . Space.com . Получено 14 апреля 2018 года .

- ^ Нельсон 2009 , с. 50

- ^ Chaikin 2007 , p. 585.

- ^ «Разведка и исследование космоса» . Бойскауты Америки. Архивировано с оригинала 4 марта 2016 года.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный "Buzz Aldrin ... ученый" . Курьер-пост . Камден, Нью -Джерси. 1 августа 1969 г. с. 46 - через Newspapers.com.

- ^ Гарда, Эндрю (1 июля 2018 г.). «Montclair 150: десятки великих людей, которые занимались спортом в Монтклере» . Монтклер местные новости . Архивировано из оригинала 24 августа 2018 года . Получено 23 августа 2018 года .

- ^ Снайдер, Стив (17 сентября 1969 г.). «В 57, новичок пытается рука» . Tampa Tribune . Тампа, Флорида. УПИ. п. 52 - через Newspapers.com.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Хансен 2005 , с.

- ^ «Buzz Aldrin, чтобы выступить в школе Северн» . Северная школа. 17 сентября 2013 года . Получено 5 ноября 2018 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Коллинз 2001 , с. 314.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Grier 2016 , с. 92

- ^ Grier 2016 , с. 89

- ^ Aldrin & Abraham 2009 , p. 36

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Cullum 1960 , p. 588.

- ^ Grier 2016 , с. 89–90.

- ^ Митчелл 1996 , с. 60–61.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Grier 2016 , с. 90

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Aldrin & Abraham 2009 , с. 90–91.

- ^ Grier 2016 , с. 90–91.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Grier 2016 , с. 91

- ^ «Коммунистический пилот катапультируется от искалеченного мига» . Жизнь . Тол. 34, нет. 23. 8 июня 1953 г. с. 29. ISSN 0024-3019 . Получено 8 ноября 2012 года .

- ^ Aldrin & Abraham 2009 , с. 91–93.

- ^ «2000 Выдающая премия выпускника» . Ассоциация выпускников Вест -Пойнт. 17 мая 2000 года . Получено 5 ноября 2018 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и «Биография астронавта: Базз Алдрин» . НАСА. Архивировано из оригинала 2 апреля 2009 года . Получено 18 августа 2018 года .

- ^ Хансен 2005 , с.

- ^ Хансен 2005 , с.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Chaikin 2007 , p. 139

- ^ Чендлер, Дэвид Л. (3 июня 2009 г.). «На Луну, через MIT» (PDF) . TechTalk . Тол. 53, нет. 27. С. 6–8. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 10 февраля 2017 года . Получено 1 февраля 2019 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Олдрин, Базз (1963). Методы руководства по линейке для пилотируемого орбитального свидания (Sc.D.). Грань HDL : 1721.1/12652 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Burgess 2013 , p. 285

- ^ Burgess 2013 , с. 203.

- ^ Burgess 2013 , с. 199.

- ^ «14 новых астронавтов представлены на пресс -конференции» (PDF) . НАСА. 30 октября 1963 года. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 17 апреля 2017 года . Получено 13 апреля 2018 года .

- ^ Chaikin 2007 , p. 143.

- ^ Бостик, Джерри С. (23 февраля 2000 г.). «Джерри С. Бостик устная история» (интервью). Интервью Кэрол Батлер. НАСА Джонсон Космический Центр Периоральный центр . Получено 10 декабря 2016 года .

- ^ Роджер Рессмейер (15 июля 1999 г.). «Buzz Aldrin планирует следующий гигантский прыжок» . NBC News . Архивировано с оригинала 9 июля 2014 года . Получено 10 декабря 2016 года .

- ^ Burgess 2013 , с. 322.

- ^ Коллинз 2001 , с. 100

- ^ Хансен 2005 , с.

- ^ Hacker & Grimwood 1974 , с. 323–325.

- ^ Chaikin 2007 , p. 51

- ^ Хакер и Гримвуд 1974 , с. 354.

- ^ Hacker & Grimwood 1974 , с. 370–371.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Reichl 2016 , с. 137–138.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Hacker & Grimwood 1974 , с. 372–373.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и "Близнецы 12" . НАСА Космические науки координированные архив . Получено 9 августа 2017 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Chaikin 2007 , p. 140.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Hacker & Grimwood 1974 , с. 375–376.

- ^ Reichl 2016 , с. 141–142.

- ^ Рейхл 2016 , с. 142

- ^ Brooks, Grimwood & Swenson 1979 , p. 374.

- ^ Hansen 2005 , с. 312–313.

- ^ Коллинз 2001 , с. 288–289.

- ^ Каннингем 2010 , с. 109

- ^ Коллинз 2001 , с. 359.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Орлофф 2000 , с. 90

- ^ Orloff 2000 , p. 72

- ^ Hansen 2005 , с. 338–339.

- ^ Chaikin 2007 , p. 148.

- ^ Коллинз 2001 , с. 60

- ^ Chaikin 2007 , p. 179

- ^ Bilstein 1980 , с. 369–370.

- ^ Benson & Faherty 1978 , p. 474.

- ^ Лофф, Сара (21 декабря 2017 г.). «Обзор миссии танца 11 » НАСА Получено 13 , января

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин час Орлофф 2000 , с. 102–110.

- ^ "Аполлон-11 (27)" . Исторический архив для пилотируемых миссий . НАСА . Получено 13 июня 2013 года .

- ^ «Миссия Apollo 11 Lunar Landing» (PDF) (пресс -комплект). Вашингтон, округ Колумбия: НАСА. 6 июля 1969 года. Выпуск №: 69-83K . Получено 13 июня 2013 года .

- ^ Комплексный центр космического корабля 1969 , с. 9

- ^ Collins & Aldrin 1975 , p. 209

- ^ Mindell 2008 , с.

- ^ Collins & Aldrin 1975 , с. 210–212.

- ^ Эйлс, Дон (6 февраля 2004 г.), «Сказки из руководящего компьютера лунного модуля» , 27 -я ежегодная конференция по руководству и контролю , Брекенридж, Колорадо: Американское астронавтическое общество

- ^ Джонс, Эрик М., изд. (1995). «Первая лунная посадка» . Apollo 11 Lunar Surface Journal . НАСА. Архивировано с оригинала 27 декабря 2016 года . Получено 13 июня 2013 года .

- ^ Chaikin 2007 , p. 205.

- ^ Farmer & Hamblin 1970 , p. 251.

- ^ Aldrin & Abraham 2009 , стр. 26–27, онлайн: https://books.google.com/books?id=ey9qauexkawc&q=vine#v=snippet&f=false ..

- ^ Chaikin 2007 , p. 204

- ^ Олдрин, Базз (10 июля 2014 г.) [1970]. "Buzz Aldrin о причастии в космосе" . Руководство . Guidesposts Classics. Архивировано с оригинала 17 апреля 2019 года . Получено 21 января 2019 года .

- ^ Aldrin & Abraham 2009 , p. 27

- ^ Aldrin & Abraham 2009 , стр. 51–52, онлайн: https://books.google.com/books?id=hrlo8_7mzh0c&vq=psalms&pg=pa52#v ..

- ^ «Buzz Aldrin - рукописные ноты и писания, летавшие на поверхности Луны» . Аукционы наследия . Получено 25 июля 2019 года .

- ^ Cortright 1975 , p. 215

- ^ Schwagmeier, Thomas (ed.). «Аполлон 11 транскрипция» . Apollo Lunar Surface Journal . НАСА . Получено 13 января 2019 года .

- ^ Chaikin 2007 , с. 212–213.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Chaikin 2007 , p. 215

- ^ Chaikin 2007 , с. 214–215.

- ^ Chaikin 2007 , с. 216–217.

- ^ Розен, Ребекка Дж. (27 августа 2012 г.). «Пропавший человек: нет хороших фотографий Нила Армстронга на Луне» . Атлантика . Получено 10 ноября 2018 года .

- ^ Пуйу, Тиби (20 июля 2011 г.). «Краткий факт: первый человек, который мочеивается на Луне, Базз Алдрин» . ZME Science . Получено 21 июля 2019 года .

- ^ Джонс, Эрик М.; Гловер, Кен, ред. (1995). "Первые шаги" . Apollo 11 Lunar Surface Journal . НАСА . Получено 23 сентября 2006 года .

- ^ Aldrin & Abraham 2009 , p. 41

- ^ Джонс, Эрик М., изд. (1995). «Попытка отдохнуть» . Apollo 11 Lunar Surface Journal . НАСА . Получено 13 июня 2013 года .

- ^ Уильямс, Дэвид Р. "Аполлон Таблицы" . НАСА. Архивировано из оригинала 1 октября 2006 года . Получено 23 сентября 2006 года .

- ^ Вудс, В. Дэвид; Mactaggart, Kenneth D.; О'Брайен, Фрэнк (ред.). «День 9: повторное въезд и брызг» . Apollo 11 Flight Journal . НАСА . Получено 27 сентября 2018 года .

- ^ Orloff 2000 , p. 98

- ^ Комплексный центр Космического корабля 1969 , с. 164–167.

- ^ Кармайкл 2010 , с. 199–200.

- ^ «Президент предлагает тост за« три смелых человека » . Вечернее солнце . Балтимор, Мэриленд. Ассошиэйтед Пресс. 14 августа 1969 г. с. 1 - через Newspapers.com.

- ^ «Ричард Никсон: Замечания на ужине в Лос -Анджелесе в честь астронавтов Аполлона 11» . Американский президентский проект. 13 августа 1969 . Получено 20 ноября 2018 года .

- ^ Смит, Мерриман (14 августа 1969 г.). «Астронавты победили признание» . Рекламодатель Гонолулу . Гонолулу, Гавайи. УПИ. п. 1 - через Newspapers.com.

- ^ «Члены экипажа Apollo 11 появляются перед совместным собранием Конгресса» . Палата представителей Соединенных Штатов . Получено 3 марта 2018 года .

- ^ Блум, Марк (17 сентября 1969 г.). «Конгресс Astro выставлен на Марс» . Ежедневные новости . Нью-Йорк. п. 6 - через Newspapers.com.

- ^ «Экипаж Apollo 11 начинает World Tour» . Logan Daily News . Логан, Огайо. Ассошиэйтед Пресс. 29 сентября 1969 г. с. 1 - через Newspapers.com.

- ^ «Сато Япония дает медали команде Аполлона» . Los Angeles Times . Лос -Анджелес, Калифорния. 5 ноября 1969 г. с. 20 - через Newspapers.com.

- ^ «Австралия приветствует героев Аполлона 11» . Сиднейский утренний геральд . Сидней, Новый Южный Уэльс. 1 ноября 1969 г. с. 1 - через Newspapers.com.

- ^ Aldrin & Abraham 2009 , с. 81–87.

- ^ Aldrin & Abraham 2009 , с. 88–89.

- ^ Aldrin & Abraham 2009 , с. 120–121.

- ^ Aldrin & Abraham 2009 , с. 113–114.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Aldrin & Abraham 2009 , с. 116–120.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Aldrin & Abraham 2009 , с. 100–103.

- ^ Aldrin & Abraham 2009 , с. 105–109.

- ^ Соломон, Дебора (15 июня 2009 г.). "Человек на Луне" . Журнал New York Times . п. MM13 . Получено 18 декабря 2017 года .

- ^ Aldrin & Abraham 2009 , с. 147–148.

- ^ Сейда, Джим (12 августа 2014 г.). «Смерть Робина Уильямса напоминает Баззу Олдрину о его собственной борьбе» . NBC News . Получено 21 октября 2018 года .

- ^ Чендлер, Крис; Роуз, Энди (17 июля 2009 г.). «После прогулки по Луне астронавты проходят различные пути» . CNN . Архивировано с оригинала 15 января 2014 года . Получено 27 апреля 2010 года .

- ^ Читать, Кимберли (4 января 2005 г.). "Buzz Aldrin" . Биполярный . О. Архивировано из оригинала 28 сентября 2008 года . Получено 2 ноября 2008 года .

- ^ Aldrin & Abraham 2009 , с. 165–166.

- ^ Aldrin & Abraham 2009 , с. 170–173.

- ^ Bancroft, Colette (29 сентября 2002 г.). «Лунное безумие» . Тампа Бэй Таймс . Санкт -Петербург, Флорида. п. 1f - через Newspapers.com.

- ^ «Экс-астронавт избегает нападения» . BBC News . 21 сентября 2002 г. Получено 9 января 2018 года .

- ^ «Базз Олдрин бьет придурок по лицу за то, что назвал его лжецом» . Неделя . 21 июля 2014 года. Архивировано с оригинала 23 июля 2014 года . Получено 21 июля 2014 года .

- ^ Прайс, Уэйн Т. (2 апреля 2017 г.). «Базз Олдрин летит с громовыми птицами» . Флорида сегодня . Получено 10 ноября 2018 года .

- ^ Хортон, Алекс (10 апреля 2018 г.). «Нет, Базз Олдрин не видел НЛО по дороге на Луну» . The Washington Post . Получено 5 ноября 2018 года .

- ^ Моррисон, Дэвид (26 июля 2006 г.). «НАСА спросить астробиолога» . НАСА. Архивировано из оригинала 21 июля 2011 года.

- ^ Моррисон, Дэвид (2009). "НЛО и инопланетяне в космосе" . Скептически скептический запросчик . 33 (1): 30–31. Архивировано с оригинала 23 октября 2015 года . Получено 25 октября 2015 года .

- ^ Макканн, Эрин (1 декабря 2016 г.). «Buzz Aldrin эвакуирован от Южного полюса после заболевания» . New York Times . Получено 1 декабря 2016 года .

- ^ Ван, Эми Б (6 декабря 2016 г.). «Buzz Aldrin лечится доктором по имени Дэвид Боуи (да) после эвакуации Южного полюса» . The Washington Post . Получено 6 декабря 2016 года .

- ^ Холли, Питер (14 декабря 2016 г.). «Базз Алдрин чуть не умер на Южном полюсе. Почему он настаивает, что« на самом деле это стоило того ». " . The Washington Post . Получено 5 ноября 2018 года .

- ^ Райс, Даниэль Р. (1992). Клиффордские годы: Университет Северной Дакоты, 1971–1992. п. 46

- ^ Годдард, Жаки (25 июня 2009 г.). «Buzz Aldrin и Snoop Dogg достигают звезд с ракетным опытом» . Время . Получено 10 ноября 2018 года .

- ^ «Руководящий комитет - 2022» . Марс Общество . Получено 19 июля 2022 года .

- ^ Aldrin, EE, «Концепции циклической траектории», SAIC Presentation на межпланетное собрание исследования быстрого транспорта, Лаборатория реактивного движения, октябрь 1985 года.

- ^ Byrnes, DV; Longuski, JM; и Олдрин Б. (1993). «Орбита циклеров между Землей и Марсом» (PDF) . Журнал космических кораблей и ракетов . 30 (3): 334–336. Bibcode : 1993jspro..30..334b . doi : 10.2514/3.25519 . Получено 25 октября 2015 года .

- ^ "Aldrin Mars Cycler" . Buzzaldrin.com. Архивировано из оригинала 19 августа 2018 года . Получено 18 августа 2018 года .

- ^ "Buzz Aldrin Acdonaut Apollo 11, Gemini 12 | Starbooster" . Buzzaldrin.com . Получено 21 июля 2019 года .

- ^ Олдрин, Базз (5 декабря 2003 г.). «Лети меня в L1» . New York Times . Получено 14 ноября 2009 г.

- ^ Олдрин, Базз (13 июня 2013 г.). «Зорок Марса» . New York Times . Получено 17 июня 2013 года .

- ^ Данн, Марсия (27 августа 2015 г.). «Buzz Aldrin вступает в университет, формируя« генеральный план »для Марса» . Ассошиэйтед Пресс. Архивировано с оригинала 4 сентября 2015 года . Получено 30 августа 2015 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в "Valor Awards для Buzz Aldrin" . Зал доблести . Получено 25 декабря 2017 года .

- ^ «Джонсон видит больший успех США в космосе» . Вечерние времена . Сэйре, Пенсильвания. Ассошиэйтед Пресс. 23 ноября 1966 г. с. 1 - через Newspapers.com.

- ^ Gawdiak & Fedor 1994 , p. 398.

- ^ «Agnew Desters Awards на экипажах 3 Аполлос» . Аризона Республика . Феникс, Аризона. Ассошиэйтед Пресс. 14 ноября 1970 г. с. 23 - через Newspapers.com.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный «Второй человек, чтобы ступать на Луну» . Нью -Мексико Музей космоса. Архивировано из оригинала 7 июля 2010 года . Получено 18 августа 2018 года .

- ^ Шей, Эрин (3 октября 1982 г.). «Астронавты хвалят Близнецам как предшественника шаттла» . Albuquerque Journal . Альбукерке, Нью -Мексико. п. 3 - через Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Buzz Aldrin" . Фонд стипендии астронавта . Получено 20 августа 2018 года .

- ^ Кларк, Эми (14 марта 1993 г.). «Занятия чтят астронавты Близнецов» . Флорида сегодня . Какао, Флорида. п. 41 - через Newspapers.com.

- ^ «Алдрин, Базз: закреплен 2000» . Национальный зал славы авиации. Архивировано с оригинала 17 апреля 2019 года . Получено 19 декабря 2017 года .

- ^ Хестер, Том (25 октября 2007 г.). «Фрэнк, Брюс и Базз среди первых, введенный в Зал славы Нью -Джерси» . Нью-Джерси он-лайн LLC . NJ Advance Media. Архивировано с оригинала 9 ноября 2013 года . Получено 19 августа 2018 года .

- ^ Лафри, Кларисс (31 декабря 2015 г.). «Концепт -арт ранней истории игрушек был немного странным» . Независимый . Получено 16 марта 2019 года .

- ^ Бойл, Алан (20 июля 1999 г.). «Луна годовщина праздновала» . NBC News . Архивировано из оригинала 4 марта 2018 года . Получено 3 марта 2018 года .

- ^ «Аполлон 11 космонавтов удостоены чести за« удивительную »миссию» . CNN . 20 июля 1999 г. Получено 24 апреля 2018 года .

- ^ «Легенды НАСА присудили золотую медаль Конгресса» . НАСА. 16 ноября 2011 года. Архивировано с оригинала 19 мая 2017 года . Получено 19 декабря 2017 года .

- ^ Золотая медаль Конгресса астронавтам Нил А. Армстронг, Базз Олдрин и Майкл Коллинз . 2000 Record Congressal Record , Vol. 146, страница H4714 (20 июня 2000 г.) . Доступ 16 апреля 2015 года.

- ^ «Аполлон 11 Космических жителей выигрывают трофей Коллиер» . Чарльстон Daily Mail . Чарльстон, Западная Вирджиния. Ассошиэйтед Пресс. 18 марта 1970 г. с. 9 - через Newspapers.com.

- ^ «Генерал Томас Д. Белый космический трофей ВВС США» (PDF) . Журнал ВВС . ВВС США. Май 1997 г. с. 156

- ^ «Астронавты Аполлона 11, чтобы быть оправданными» . Время . Шривпорт, Луизиана. Ассошиэйтед Пресс. 6 марта 1970 г. с. 10 - через Newspapers.com.

- ^ «Два пилота RAF, чтобы разделить трофей Harmon Aviator» . New York Times . 7 сентября 1970 г. с. 36 Получено 3 марта 2018 года .

- ^ «Аполлон 11 астронавты добавляют Harmon Trophy к коллекции» . Рекламодатель Монтгомери . Монтгомери, Алабама. Ассошиэйтед Пресс. 6 сентября 1970 г. с. 6e - через Newspapers.com.

- ^ «3 Астронавты получают трофеи Хармона» . Время . Шривпорт, Луизиана. Ассошиэйтед Пресс. 20 мая 1971 г. с. 2–b - через Newspapers.com.

- ^ «Agnew дает медали команде Apollo 11» . La Crosse Tribune . La Crosse, Висконсин. Ассошиэйтед Пресс. 18 февраля 1970 г. с. 6 - через Newspapers.com.

- ^ «Установка записей Авиаторов, честь Pilots Group» . Долина новости . Ван Найс, Калифорния. 10 октября 1970 г. с. 51 - через Newspapers.com.

- ^ Санделл, Скотт (1 марта 2010 г.). «Аполлон Лендинг - Голливудская звездная прогулка» . Los Angeles Times . Получено 20 ноября 2018 года .

- ^ «Профессионалы персонала» . Белый дом. 22 августа 2001 года. Архивировано с оригинала 2 сентября 2017 года.

- ^ «Разнообразие международные гуманитарные награды» . Разнообразие, детская благотворительность. Архивировано из оригинала 27 сентября 2007 года . Получено 7 мая 2007 года .

- ^ «Симпозиумные награды» . Национальный космический симпозиум. Архивировано из оригинала 3 февраля 2009 года . Получено 31 января 2012 года .

{{cite web}}: Cs1 maint: непредвзятый URL ( ссылка ) - ^ Фаркухар, Питер (2 июля 2018 г.). «В Австралии наконец -то есть космическое агентство - вот почему пришло время» . Business Insider Australia. Архивировано с оригинала 17 июля 2019 года . Получено 19 января 2019 года .

- ^ «Совет губернаторов Национального космического общества» . Национальное космическое общество. Архивировано с оригинала 29 марта 2018 года . Получено 19 декабря 2017 года .

- ^ Кент, Спенсер (16 сентября 2016 г.). «Средняя школа Нью -Джерси переименована после Buzz Aldrin Apollo 11» . NJ Advance Media . Получено 14 марта 2017 года .

- ^ Кнаптон, Сара (30 июня 2019 г.). «Стивен Хокинг убедил Базза Алдрина, что люди должны вернуться на Луну, прежде чем отправиться на Марс (30 июня 2019 г.)» . Телеграф . Архивировано из оригинала 11 января 2022 года.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Aldrin, Buzz [@therealbuzz] (20 января 2023 г.). «В мой 93 -й день рождения ... Я рад сообщить, что моя давняя любовь доктор Анка Фаур и я связали себя узами брака» ( твит ) - через Twitter .

- ^ Трибу, Ричард (21 апреля 2023 г.). «Buzz Aldrin для повышения до бригадного генерала ВВС» . Пресс-секретарь . Получено 5 мая 2023 года .

- ^ «Команда Space Systems проводит церемонию в честь почетного назначения астронавта и пилота -истребителя полковника Базза Олдрина к бригадному генералу» (PDF) (пресс -релиз). 21 апреля 2023 года . Получено 6 мая 2023 года .

- ^ «Buzz Aldrin Honaterly выступил до бригадного генерала по просьбе члена палаты представителей Калверт» . Конгрессмен Кен Калверт. 20 апреля 2023 года . Получено 6 мая 2023 года .

- ^ Aldrin & Abraham 2009 , p. 75

- ^ Ву, Элейн (31 июля 2015 г.). «Джоан Арчер Олдрин умирает в 84; имела дело с центром в качестве жены астронавта» . Los Angeles Times . Получено 1 декабря 2018 года .

- ^ Aldrin & Abraham 2009 , p. 154

- ^ Aldrin & Abraham 2009 , p. 224

- ^ «Базз Олдрин официально развелся» . TMZ . 1 июля 2013 г. Получено 20 ноября 2018 года .

- ^ "Buzz Aldrin Fast Facts" . CNN . Получено 20 ноября 2018 года .

- ^ Buzz Aldrin [@therealbuzz] (17 апреля 2017 г.). «Олдрин твит о правнуках» ( твит ) . Получено 18 декабря 2017 года - через Twitter .

- ^ «Us Astronaut Buzz Aldrin предъявляет иск своим двум детям за« неправильное использование финансов » » . BBC News Online . 26 июня 2018 года . Получено 26 июня 2018 года .

- ^ Шнайдер, Майк (25 июня 2018 г.). «Buzz Aldrin представляет 2 своих детей, утверждая, что клевета на деменцию» . Орландо Страж . Ассошиэйтед Пресс. Архивировано из оригинала 24 января 2022 года.

- ^ Шнайдер, Майк (13 марта 2019 г.). «Юридическая борьба Базза Алдрина со своими детьми заканчивается:« трудная ситуация »разрешилась перед годовщиной Аполлона 11» . Орландо Страж . Ассошиэйтед Пресс. Архивировано из оригинала 19 мая 2020 года.

- ^ Амброуз, Том (20 января 2023 г.). «На седьмой луне! Базз Олдрин женится на« давней любви »в свой 93-й день рождения» . Хранитель . Получено 17 июня 2024 года .

- ^ «Лори и Кен Баржес приглашают вас на торжественное мероприятие» (PDF) . Боевые ветераны за Конгресс. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 8 августа 2013 года . Получено 26 февраля 2010 года .

- ^ Фуст, Джефф (19 августа 2014 г.). «Buzz Aldrin поддерживает кандидата в гонке в Сенате Аляски» . Космическая политика . Получено 11 ноября 2018 года .

- ^ Уоллес, Джереми (12 января 2018 г.). «Buzz Aldrin поддерживает претендента на Республиканскую партию в конкурсе, чтобы сменить Теда По» . Хьюстон Хроника . Получено 11 ноября 2018 года .

- ^ «Buzz Aldrin появляется в гостях на обращении Дональда Трампа в сфере профсоюза» . Национальный. 6 февраля 2019 г. Получено 13 февраля 2019 года .

- ^ «Известный масон из истории: Базз Алдрин» . Архивировано из оригинала 30 января 2023 года . Получено 30 января 2023 года .

- ^ «На Луну и обратно с Базз Алдрином» .

- ^ «Масоны на Луне: секретная миссия» .

- ^ «Масоны на Луне: секретная миссия» .

- ^ «10 вопросов для Buzz Aldrin» . Время . 6 сентября 2007 года. Архивировано с оригинала 11 сентября 2007 года . Получено 2 марта 2014 года .

- ^ Олдрин, Базз (25 августа 2012 г.). «Основание Нила Армстронга» (официальное заявление). Buzz Aldrin Enterprises . Получено 25 октября 2015 года .

- ^ "Recorderworks" . cr.ocgov.com . Получено 19 февраля 2023 года .

- ^ Aldrin & Abraham 2009 , p. 256

- ^ Бил, Лорен (25 июня 2014 г.). «Астронавт Buzz Aldrin продает кондо кондо Wilshire коридора» . Los Angeles Times . Архивировано с оригинала 20 декабря 2016 года.

- ^ « Болено», выздоравливающий Алдрин » . Флорида сегодня . Мельбурн, Флорида. 2 декабря 2016 г. с. 1а. Архивировано из оригинала 19 февраля 2017 года . Получено 2 декабря 2016 года .

- ^ Дин, Джеймс (22 июня 2018 г.). «Базз Алдрин подает в суд на свою семью, утверждая, что мошенничество» . Флорида сегодня . Получено 14 ноября 2018 года .

- ^ Aldrin & Abraham 2009 , p. 172, 188–189.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Элман 2014 , с. 39

- ^ "После темной серии 3" . Открытые СМИ. Архивировано из оригинала 30 января 2023 года . Получено 21 октября 2018 года .

- ^ Рабин, Натан (17 марта 2013 г.). «Симпсоны (классика):« Глубокий космос Гомер » . ТВ -клуб . Архивировано из оригинала 13 мая 2021 года . Получено 16 марта 2019 года .

- ^ «Взгляд на Армстронг, Алдин и Коллинз» . Утренний звонок . Аллентаун, Пенсильвания. Ассошиэйтед Пресс. 10 июля 1994 г. с. E2 - через Newspapers.com.

- ^ Блевинс, Тал (13 июля 2005 г.). «Космический призрак побережье до побережья 3» . Магнитный Получено 18 декабря 2017 года .

- ^ «Космический призрак побережье к побережью: сезон 4, эпизод 11 блестящий номер два» . Телевидение . Архивировано из оригинала 16 марта 2019 года . Получено 16 марта 2019 года .

- ^ Перлман, Роберт (25 августа 2017 г.). «Диснейс мили от Tomorrowland: Buzz Aldrin» . Collectspace . Получено 8 августа 2018 года .

- ^ Батлер, Вифони (13 июля 2018 г.). «Вот как Саша Барон Коэн обманывает знаменитостей в неловкие интервью, начиная с« Da Ali G Show » . The Washington Post . Получено 21 октября 2018 года .

- ^ О'Хар, Кейт (13 декабря 2006 г.). «Алдрин заходит в эпизод« Numb3rs » . Zap2it.com . Получено 6 августа 2018 года - через Чикаго Трибьюн.

- ^ Брэдшоу, Петр (2 ноября 2007 г.). «В тени Луны» . Хранитель . Получено 21 октября 2018 года .

- ^ О'Нил, Ян (15 августа 2008 г.). «Обзор фильма:« Лети меня на луну » . Вселенная сегодня . Получено 21 октября 2018 года .

- ^ Карлсон, Даниэль (7 мая 2010 г.). "NBC в четверг вечером: я гулял на вашем лице!" Полем Хьюстон Пресс . Получено 19 августа 2018 года .

- ^ Эшерх, Кэти (7 апреля 2010 г.). «Buzz Aldrin сделал на« танцах со звездами », но гордился тем, что вдохновил людей» . ABC News . Получено 21 октября 2018 года .

- ^ Харт, Хью (29 июня 2011 г.). «История добавляет натюрморт к трансформаторам: темнота боя Луны» . Проводной . Получено 12 августа 2018 года .

- ^ Ferrante, AC (21 июня 2011 г.). «Эксклюзивное интервью: Дэвид X. Коэн из Futurama дает совок в сезоне 6B» . Задание x . Получено 7 января 2012 года .

- ^ «Noguchi Soichi и Buzz Aldrin появляются в« Space Brothers », в главных ролях Oguri Shun & Masao Okada» [Shunichi Noguchi и Buzz Aldrin появляются в «Space Brothers», в главной роли Oguri Shun & Masao Okada] Pia Life) (на японском языке) 22, 2012. Архивировано с оригинала 6 апреля 2019 года. Получено 1 декабря 2016 года .

- ^ Дершовиц, Джессика (10 октября 2012 г.). «Buzz Aldrin Lands Cameo на« Теории Большого взрыва » » . CBS News . Получено 8 августа 2018 года .

- ^ Гриффитс, Даниэль Най (28 июня 2012 г.). «Настоящий герой Mass Effect объясняет, как - и почему -« Отвергнуть окончание »работает» . Форбс . Получено 6 августа 2018 года .

- ^ «Från Senegal Till Buzz Aldrin» [от Сенегала до Базза Алдрина] (на шведском языке). Открытие. 7 октября 2015 года. Архивировано с оригинала 21 августа 2018 года . Получено 21 августа 2018 года .

- ^ Ледерман, Джейсон (5 мая 2016 г.). «Buzz Aldrin раскрывает свой секрет« Scoops »о миссиях Луны» . Популярная наука . Получено 6 августа 2018 года .

- ^ Заархивировано в Ghostarchive и на машине Wayback : «Очень особенный гость: Buzz Aldrin, сезон 15 Ep. 3, Hell's Kitchen» . Адская кухня. 27 января 2016 года . Получено 6 августа 2018 года - через YouTube.

- ^ Райт, Мэри Эллен (28 января 2016 г.). «Местный шеф -повар Алан Паркер подает закуску астронавту Базз Олдрин на« кухне ада » » . Ланкастер онлайн . Получено 30 октября 2019 года .

- ^ Хауэлл, Элизабет (25 августа 2017 г.). «Moonwalker Buzz Aldrin играет« Commander Copernicus »в Disney Kids»: эксклюзивный клип » . Space.com . Получено 6 августа 2018 года .

- ^ О'Коннор, Джон Дж. (14 мая 1976 г.). «Телевизионные выходные: пятница» . New York Times . п. 76 Получено 19 августа 2018 года .

- ^ Ханауэр, Джоан (8 мая 1976 г.). «Клифф Робертсон играет« Buzz Aldrin » . Ежедневный геральд . п. 36 - через Newspapers.com.

- ^ McGee 2010 , с. 23

- ^ Кинг, Сьюзен (17 ноября 1996 г.). «Луна над 'Аполлоном 11' » . Los Angeles Times . п. 433 - через Newspapers.com.

- ^ Леопольд, Тодд (19 сентября 2013 г.). «Emmys 2013: Брайан Крэнстон, человек момента» . CNN . Получено 28 апреля 2018 года .

- ^ Джеймс, Карин (3 апреля 1998 г.). «Телевизионный обзор; мальчишеские глаза на Луне» . New York Times . п. E1 . Получено 5 августа 2018 года .

- ^ Marill (2010) , p. 66

- ^ Уинтерс, Кэрол (10 июля 2011 г.). «Такер обнимает свою« роль »в жизни» . Pontiac Daily Leader . Получено 18 августа 2018 года .