Теории заговора о высадке на Луну

Теории заговора о высадке на Луну утверждают, что некоторые или все элементы программы «Аполлон» и связанные с ней высадки на Луну были мистификацией , организованной НАСА , возможно, с помощью других организаций. Наиболее примечательным утверждением этих теорий заговора является то, что шесть высадок экипажа (1969–1972 годы) были сфальсифицированы и что двенадцать астронавтов Аполлона на самом деле не приземлились на Луну . С середины 1970-х годов различные группы и отдельные лица заявляли, что НАСА и другие сознательно ввели общественность в заблуждение, заставив поверить в то, что посадки произошли, путем изготовления, фальсификации или уничтожения доказательств, включая фотографии, телеметрические записи, радио- и телепередачи, а также лунного камня образцы . .

Существует множество сторонних доказательств высадки , и были даны подробные опровержения утверждений о мистификации. [1] С конца 2000-х годов на фотографиях посадочных площадок Аполлона, сделанных Лунным разведывательным орбитальным аппаратом (LRO), в высоком разрешении запечатлены этапы спуска лунного модуля и следы, оставленные астронавтами. [2] [3] В 2012 году были опубликованы изображения, на которых видно, что пять из шести американских флагов миссий «Аполлон», установленных на Луне, все еще стоят. Исключением является корабль «Аполлон-11» , который лежал на лунной поверхности после того, как его сбила двигательная установка для подъема лунного модуля . [4] [5]

Despite the fact that they are demonstrably false[6] and universally regarded as pseudoscience, opinion polls taken in various locations between 1994 and 2009 have shown that between 6% and 20% of Americans, 25% of Britons, and 28% of Russians surveyed believe that the crewed landings were faked. Even as late as 2001, the Fox television network documentary Conspiracy Theory: Did We Land on the Moon? claimed NASA faked the first landing in 1969 to win the Space Race.[7]

Origins

An early and influential book about the subject of a Moon-landing conspiracy, We Never Went to the Moon: America's Thirty Billion Dollar Swindle, was self-published in 1976 by Bill Kaysing, a former US Navy officer with a Bachelor of Arts in English.[8] Despite having no knowledge of rockets or technical writing,[9] Kaysing was hired as a senior technical writer in 1956 by Rocketdyne, the company that built the F-1 engines used on the Saturn V rocket.[10][11] He served as head of the technical publications unit at the company's Propulsion Field Laboratory until 1963. The many allegations in Kaysing's book effectively began discussion of the Moon landings being faked.[12][13] The book claims that the chance of a successful crewed landing on the Moon was calculated to be 0.0017%, and that despite close monitoring by the USSR, it would have been easier for NASA to fake the Moon landings than to really go there.[14][15]

In 1980, the Flat Earth Society accused NASA of faking the landings, arguing that they were staged by Hollywood with Walt Disney sponsorship, based on a script by Arthur C. Clarke and directed by Stanley Kubrick.[a][16] Folklorist Linda Dégh suggests that writer-director Peter Hyams' film Capricorn One (1978), which shows a hoaxed journey to Mars in a spacecraft that looks identical to the Apollo craft, might have given a boost to the hoax theory's popularity in the post-Vietnam War era. Dégh sees a parallel with other attitudes during the post-Watergate era, when the American public were inclined to distrust official accounts. Dégh writes: "The mass media catapult these half-truths into a kind of twilight zone where people can make their guesses sound as truths. Mass media have a terrible impact on people who lack guidance."[17] In A Man on the Moon,[18] first published in 1994, Andrew Chaikin mentions that at the time of Apollo 8's lunar-orbit mission in December 1968,[19] similar conspiracy ideas were already in circulation.[20]

Claimed motives of the United States and NASA

Those who believe the Moon landings were faked offer several theories about the motives of NASA and the United States government. The three main theories are below.

Space Race

Motivation for the United States to engage the Soviet Union in a Space Race can be traced to the Cold War. Landing on the Moon was viewed as a national and technological accomplishment that would generate world-wide acclaim. But going to the Moon would be risky and expensive, as exemplified by President John F. Kennedy famously stating in a 1962 speech that the United States chose to go because it was hard.[21]

Hoax theory debunker Phil Plait says in his 2002 book Bad Astronomy[b] that the Soviets – with their own competing Moon program, an extensive intelligence network and a formidable scientific community able to analyze NASA data – would have "cried foul" if the United States tried to fake a Moon landing,[22] especially since their own program had failed. Proving a hoax would have been a huge propaganda win for the Soviets. Instead, far from calling the landings a hoax, the third edition (1970–1979) of the Great Soviet Encyclopedia (which was translated into English between 1974 and 1983 by Macmillan Publishers, and was later made available online by TheFreeDictionary.com[23]) contained many articles reporting the landings as factual, such as its article on Neil Armstrong.[24] Indeed their article on space exploration describes the Apollo 11 landing as "the third historic event" of the space age, following the launch of Sputnik in 1957, and Yuri Gagarin's flight in 1961.[25]

Conspiracist Bart Sibrel responded, incorrectly asserting that, "the Soviets did not have the capability to track deep space craft until late in 1972, immediately after which, the last three Apollo missions were abruptly canceled."[26] Those missions were canceled, not abruptly, but for cost-cutting reasons. The announcements were made in January and September 1970,[27] two full years before the "late 1972" claimed by Sibrel.[28] (See Vietnam War below.)

In fact, the Soviets had been sending uncrewed spacecraft to the Moon since 1959,[29] and "during 1962, deep space tracking facilities were introduced at IP-15 in Ussuriisk and IP-16 in Evpatoria (Crimean Peninsula), while Saturn communication stations were added to IP-3, 4 and 14,"[30] the last of which having a 100 million km (62 million mi) range.[31] The Soviet Union tracked the Apollo missions at the Space Transmissions Corps, which was "fully equipped with the latest intelligence-gathering and surveillance equipment."[32] Vasily Mishin, in an interview for the article "The Moon Programme That Faltered," describes how the Soviet Moon program dwindled after the Apollo landings.[33]

In May 2023 Dmitry Rogozin, former director general of the Russian space agency Roscosmos, expressed doubt that U.S. astronauts landed on the Moon. He complained of not receiving a satisfactory answer when he asked his agency to provide evidence. He said his colleagues at Roscosmos were angry about his questions and did not want to undermine cooperation with NASA.[34]

NASA funding and prestige

Conspiracy theorists claim that NASA faked the landings to avoid humiliation and to ensure that it continued to get funding. NASA raised "about US$30 billion" to go to the Moon, and Kaysing claimed in his book that this could have been used to "pay off" many people.[35] Since most conspiracists believe that sending men to the Moon was impossible at the time,[36] they argue that landings had to be faked to fulfill Kennedy's 1961 goal, "before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth."[37] In fact, NASA accounted for the cost of Apollo to the US Congress in 1973, totaling US$25.4 billion.[38]

Mary Bennett and David Percy claimed in the 2001 book Dark Moon: Apollo and the Whistle-Blowers, that, with all the known and unknown hazards,[39] NASA would not risk broadcasting an astronaut getting sick or dying on live television.[40] The counter-argument generally given is that NASA in fact did incur a great deal of public humiliation and potential political opposition to the program by losing an entire crew in the Apollo 1 fire during a ground test, leading to its upper management team being questioned by Senate and House of Representatives space oversight committees.[41] There was in fact no video broadcast during either the landing or takeoff because of technological limitations.[42]

Vietnam War

The American Patriot Friends Network claimed in 2009 that the landings helped the United States government distract public attention from the unpopular Vietnam War, and so crewed landings suddenly ended about the same time that the United States ended its involvement in the war.[43] In fact, the ending of the landings was not "sudden" (see Space Race above). The war was one of several federal budget items with which NASA had to compete; NASA's budget peaked in 1966, and fell by 42% by 1972.[44] This was the reason the final flights were cut, along with plans for even more ambitious follow-on programs such as a permanent space station and crewed flight to Mars.[45]

Hoax claims and rebuttals

Many Moon-landing conspiracy theories have been proposed, alleging that the landings either did not occur and NASA staff lied, or that the landings did occur but not in the way that has been reported. Conspiracists have focused on perceived gaps or inconsistencies in the historical record of the missions. The foremost idea is that the whole crewed landing program was a hoax from start to end. Some claim that the technology did not exist to send men to the Moon or that the Van Allen radiation belts, solar flares, solar wind, coronal mass ejections, and cosmic rays made such a trip impossible.[12]

Scientists Vince Calder and Andrew Johnson have given detailed answers to conspiracists' claims on the Argonne National Laboratory website.[46] They show that NASA's portrayal of the Moon landing is fundamentally accurate, allowing for such common mistakes as mislabeled photos and imperfect personal recollections. Using the scientific process, any hypothesis may be rejected if it is contradicted by the observable facts. The "real landing" hypothesis is a single story since it comes from a single source, but there is no unity in the hoax hypothesis because hoax accounts vary between conspiracists.[47]

Number of conspirators involved

According to James Longuski, the conspiracy theories are impossible because of their size and complexity. The conspiracy would have to involve more than 400,000 people who worked on the Apollo project for nearly ten years, the twelve men who walked on the Moon, the six others who flew with them as command module pilots, and another six astronauts who orbited the Moon.[c] Hundreds of thousands of people would have had to keep the secret, including astronauts, scientists, engineers, technicians, and skilled laborers. Longuski argues that it would have been much easier to really land on the Moon than to generate such a huge conspiracy to fake the landings.[48][49] To date, nobody from the United States government or NASA linked to the Apollo program has said that the Moon landings were hoaxes. Penn Jillette made note of this in the "Conspiracy Theories" episode of his television show Penn & Teller: Bullshit! in 2005.[50] Physicist David Robert Grimes estimated the time that it would take for a conspiracy to be exposed based on the number of people involved.[51][52] His calculations used data from the PRISM surveillance program, the Tuskegee syphilis experiment, and the FBI forensic scandal. Grimes estimated that a Moon landing hoax would require the involvement of 411,000 people and would be exposed within 3.68 years. His study did not consider exposure by sources outside of the alleged conspiracy; it only considered exposure from within through whistleblowers or incompetence.[53]

Photographic and film oddities

Moon-landing conspiracists focus heavily on NASA photos, pointing to oddities in photos and films taken on the Moon. Photography experts (including those unrelated to NASA) have replied that the oddities are consistent with what should be expected from a real Moon landing, and are not consistent with manipulated or studio imagery. Some main arguments (set in plain text) and counter-arguments (set in italics) are listed below.

1. In some photos, the crosshairs appear to be behind objects. The cameras were fitted with a Réseau plate (a clear glass plate with a reticle etched on), making it impossible for any photographed object to appear in front of the grid. Conspiracists often use this evidence to suggest that objects were "pasted" over the photographs, and hence obscure the reticle.

- This effect only appears in copied and scanned photos, not any originals. It is caused by overexposure: the bright white areas of the emulsion "bleed" over the thin black crosshairs. The crosshairs are only about 0.004 inches thick (0.1 mm) and emulsion would only have to bleed about half that much to fully obscure it. Furthermore, there are many photos where the middle of the crosshair is "washed-out" but the rest is intact. In some photos of the American flag, parts of one crosshair appear on the red stripes, but parts of the same crosshair are faded or invisible on the white stripes. There would have been no reason to "paste" white stripes onto the flag.[54]

- Enlargement of a poor-quality 1998 scan; both the crosshair and part of the red stripe have "bled out"

- Enlargement of a higher-quality 2004 scan, crosshair and red stripe visible

- David Scott salutes the American flag during the Apollo 15 mission. The arms of the crosshair are washed-out on the white stripes of the flag (Photo ID: AS15-88-11863).

- Close-up of the flag, showing washed-out crosshairs

2. Crosshairs are sometimes rotated or in the wrong place.

- This is a result of popular photos being cropped or rotated for aesthetic impact.[54]

3. The quality of the photographs is implausibly high.

- There are many poor quality photos taken by the Apollo astronauts. NASA chose to publish only the best examples.[54][55]

- The Apollo astronauts used high-resolution Hasselblad 500 EL cameras with Carl Zeiss optics and a 70 mm medium format film magazine.[56][57]

4. There are no stars in any of the photos; the Apollo 11 astronauts also stated in post-mission press conferences that they did not remember seeing any stars during extravehicular activity (EVA).[58] Conspiracists contend that NASA chose not to put the stars into the photos because astronomers would have been able to use them to determine whether the photos were taken from the Earth or the Moon, by means of identifying them and comparing their celestial position and parallax to what would be expected for either observation site.

- The astronauts were talking about naked-eye sightings of stars during the lunar daytime. They regularly sighted stars through the spacecraft navigation optics while aligning their inertial reference platforms, the Apollo PGNCS.[59]

- Stars are rarely seen in Space Shuttle, Mir, Earth observation photos, or even photos taken at sporting events held at night. The light from the Sun in outer space in the Earth-Moon system is at least as bright as the sunlight that reaches the Earth's surface on a clear day at noon, so cameras used for imaging subjects illuminated by sunlight are set for a daylight exposure. The dim light of the stars simply does not provide enough exposure to record visible images. All crewed landings happened during the lunar daytime. Thus, the stars were outshone by the Sun and by sunlight reflected off the Moon's surface. The astronauts' eyes were adapted to the sunlit landscape around them so that they could not see the relatively faint stars.[60][61] The astronauts could see stars with the naked eye only when they were in the shadow of the Moon.[62][63]

- Camera settings can turn a well-lit background to black when the foreground object is brightly lit, forcing the camera to increase shutter speed so that the foreground light does not wash out the image. A demonstration of this effect is here.[64] The effect is similar to not being able to see stars from a brightly lit parking lot at night; the stars only become visible when the lights are turned off.

- The Far Ultraviolet Camera was taken to the lunar surface on Apollo 16 and operated in the shadow of the Apollo Lunar Module (LM). It took photos of Earth and of many stars, some of which are dim in visible light but bright in the ultraviolet. These observations were later matched with observations taken by orbiting ultraviolet telescopes. Furthermore, the positions of those stars with respect to Earth are correct for the time and location of the Apollo 16 photos.[65][66]

- Photos of the planet Venus were taken from the Moon's surface by astronaut Alan Shepard during the Apollo 14 mission.[68]

- Short-exposure photo of the International Space Station (ISS) taken from Space Shuttle Atlantis in February 2008 during STS-122 – one of many photos taken in space where no stars are visible

- Earth and Mir in June 1995, an example of how sunlight can outshine the stars, making them invisible

- Long-exposure photo taken from the Moon's surface by Apollo 16 astronauts using the Far Ultraviolet Camera. It shows the Earth with the correct background of stars.

- Long-exposure photo (1.6 seconds at f-2.8, ISO 10000) from the ISS in July 2011 of Space Shuttle Atlantis re-entry in which some stars are visible. In this image, the Earth is lit by moonlight, not sunlight.

5. The angle and color of shadows are inconsistent. This suggests that artificial lights were used.

- Shadows on the Moon are complicated by reflected light, uneven ground, wide-angle lens distortion, and lunar dust. There are several light sources: the Sun, sunlight reflected from the Earth, sunlight reflected from the Moon's surface, and sunlight reflected from the astronauts and the Lunar Module. Light from these sources is scattered by lunar dust in many directions, including into shadows. Shadows falling into craters and hills may appear longer, shorter, and distorted.[69] Furthermore, shadows display the properties of vanishing point perspective, leading them to converge to a point on the horizon.

- This theory was further debunked on the MythBusters episode "NASA Moon Landing".

6. There are identical backgrounds in photos which were allegedly taken miles apart. This suggests that a painted background was used.

- Backgrounds were not identical, just similar. What appear as nearby hills in some photos are actually mountains many miles away. On Earth, objects that are farther away will appear fainter and less detailed. On the Moon, there is no atmosphere or haze to obscure far-away objects, thus they appear clearer and nearer.[70] Furthermore, there are very few objects such as trees to help judge distance. One such case is debunked in "Who Mourns For Apollo?" by Mike Bara.[71]

7. The number of photos taken is implausibly high—up to one photo per 50 seconds.[72]

- Simplified gear with fixed settings allowed two photos a second. Many were taken immediately after each other as stereo pairs or panorama sequences. The calculation (one per 50 seconds) was based on a lone astronaut on the surface, and does not take into account that there were two astronauts sharing the workload and simultaneously taking photographs during an Extra-vehicular activity (EVA).

8. The photos contain artifacts like the two seemingly matching "C"s on a rock and on the ground. These may be labeled studio props.

9. A woman named Una Ronald (a pseudonym created by the authors of the source[74]) from Perth, Australia, said that she saw a Coca-Cola bottle roll across the lower right quadrant of her television screen that was displaying the live broadcast of the Apollo 11 EVA. She also said that several letters appeared in The West Australian discussing the Coca-Cola bottle incident within ten days of the lunar landing.[75]

- No such newspaper reports or recordings have been found.[76] Ronald's claims have only been relayed by one source.[77] There are also flaws in the story, such as the statement that she had to stay up late to watch the Moon landing live, which is easily discounted by many witnesses in Australia who watched the landing in the middle of the daytime.[78][79]

10. The 1994 book Moon Shot[80] contains an obviously fake composite photo of Alan Shepard hitting a golf ball on the Moon with another astronaut.

- It was used instead of the only existing real images from the TV monitor, which the editors seemingly felt were too grainy for their book. The book publishers did not work for NASA, although the authors were retired NASA astronauts.

11. There appear to be "hot spots" in some photos which look as though a large spotlight was used in place of the Sun.

- Pits on the Moon's surface focus and reflect light like the tiny glass spheres used in the coating of street signs, or dewdrops on wet grass. This creates a glow around the photographer's own shadow when it appears in a photograph (see Heiligenschein).

- If the astronaut is standing in sunlight while photographing into shade, light reflected off his white spacesuit yields a similar effect to a spotlight.[81]

- Some widely published Apollo photos were high-contrast copies. Scans of the original transparencies are generally much more evenly lit. An example is shown below:

- Original photo of Buzz Aldrin during Apollo 11

- The more famous edited version. The contrast has been increased, yielding the "spotlight effect", and a black band has been pasted at the top.

12. Who filmed Neil Armstrong stepping onto the Moon?

- Cameras on the Lunar Module did. The Apollo TV camera mounted in the Modularized Equipment Stowage Assembly (MESA) of the Apollo Lunar Module gave a view from the exterior. While still on the Module's ladder steps, Armstrong deployed the MESA from the side of the Lunar Module, unpacking the TV camera. The camera was then powered on and a signal transmitted back to Earth. This meant that upwards of 600 million people on Earth could watch the live feed with only a very slight delay. Similar technology was also used on subsequent Apollo missions.[82][83][84][85] It was also filmed from an automatic 16mm movie camera mounted in a window of the Lunar Module.

Environment

1. The astronauts could not have survived the trip because of exposure to radiation from the Van Allen radiation belt and galactic ambient radiation (see radiation poisoning and health threat from cosmic rays). Some conspiracists have suggested that Starfish Prime (a high-altitude nuclear test in 1962) formed another intense layer on the Van Allen belt.[86]

- There are two main Van Allen belts – the inner belt and the outer belt – and a transient third belt.[87] The inner belt is the more dangerous one, containing energetic protons. The outer one has less-dangerous low-energy electrons (Beta particles).[88][89] The Apollo spacecraft passed through the inner belt in a matter of minutes and the outer belt in about 1+1⁄2 hours.[89] The astronauts were shielded from the ionizing radiation by the aluminum hulls of the spacecraft.[89][90] Furthermore, the orbital transfer trajectory from Earth to the Moon through the belts was chosen to lessen radiation exposure.[90] Even James Van Allen, the discoverer of the Van Allen belt, rebutted the claims that radiation levels were too harmful for the Apollo missions.[86] Phil Plait cited an average dose of less than 1 rem (10 mSv), which is equivalent to the ambient radiation received by living at sea level for three years.[91] The total radiation received on the trip was about the same as allowed for workers in the nuclear energy field for a year[89][92] and not much more than what Space Shuttle astronauts received.[88]

2. Film in the cameras would have been fogged by this radiation.

- The film was kept in metal containers that stopped radiation from fogging the emulsion.[93] Furthermore, film was not fogged in lunar probes such as the Lunar Orbiter and Luna 3 (which used on-board film development processes).

3. The Moon's surface during the daytime is so hot that camera film would have melted.

- There is no atmosphere to efficiently bind lunar surface heat to devices that are not in direct contact with it. In a vacuum, only radiation remains as a heat transfer mechanism. The physics of radiative heat transfer are thoroughly understood, and the proper use of passive optical coatings and paints was enough to control the temperature of the film within the cameras; Lunar Module temperatures were controlled with similar coatings that gave them a gold color. The Moon's surface does get very hot at lunar noon, but every Apollo landing was made shortly after lunar sunrise at the landing site; the Moon's day is about 29+1⁄2 Earth days long, meaning that one Moon day (dawn to dusk) lasts nearly fifteen Earth days. During the longer stays, the astronauts did notice increased cooling loads on their spacesuits as the sun and surface temperature continued to rise, but the effect was easily countered by the passive and active cooling systems.[94] The film was not in direct sunlight, so it was not overheated.[95]

4. The Apollo 16 crew could not have survived a big solar flare firing out when they were on their way to the Moon.

5. The flag placed on the surface by the astronauts fluttered despite there being no wind on the Moon. This suggests that it was filmed on Earth and a breeze caused it to flutter. Sibrel said that it may have been caused by indoor fans used to cool the astronauts, since their spacesuit cooling systems would have been too heavy on Earth.

- The flag was fastened to an Г-shaped rod (see Lunar Flag Assembly) so that it did not hang down. It only seemed to flutter when the astronauts were moving it into position. Without air drag, these movements caused the free corner of the flag to swing like a pendulum for some time. It was rippled because it had been folded during storage, and the ripples could be mistaken for movement in a still photo. Videos show that, when the astronauts let go of the flagpole, it vibrates briefly but then remains still.[98][99][100]

- This theory was further debunked on the MythBusters episode "NASA Moon Landing".

- Cropped photo of Buzz Aldrin saluting the flag. The fingers of Aldrin's right hand can be seen behind his helmet.

- Cropped photo taken a few seconds later. Buzz Aldrin's hand is down, head turned toward the camera; the flag is unchanged.

- Animation of the two photos, showing that Armstrong's camera moved between exposures, but the flag is not waving.

6. Footprints in the Moondust are unexpectedly well preserved, despite the lack of moisture.

- Moondust has not been weathered like the sand on Earth, and it has sharp edges. This allows the dust particles to stick together and hold their shape in the vacuum. The astronauts likened it to "talcum powder or wet sand".[71]

- This theory was further debunked on the MythBusters episode "NASA Moon Landing".

7. The alleged Moon landings used either a sound stage or were filmed outside in a remote desert with the astronauts either using harnesses or slow-motion photography to make it look like they were on the Moon.

- The HBO miniseries "From the Earth to the Moon" used the sound-stage and harness setup, as did a scene from the movie "Apollo 13". It is clearly seen from those films that, when dust rose, it did not quickly settle; some dust briefly formed clouds. In the film footage from the Apollo missions, dust kicked up by the astronauts' boots and the wheels of the Lunar Roving Vehicles rose quite high due to the lower lunar gravity, and it settled quickly to the ground in an uninterrupted parabolic arc since there was no air to suspend it. Even if there had been a sound stage for hoax Moon landings that had the air pumped out, the dust would have reached nowhere near the height and trajectory as in the Apollo film footage because of Earth's greater gravity.

- During the Apollo 15 mission, David Scott did an experiment by dropping a hammer and a falcon feather at the same time. Both fell at the same rate and hit the ground at the same time. This proved that he was in a vacuum.[101]

- If the landings were filmed outside in a desert, heat waves would be present on the surface in mission videos, but no such heat waves exist in the footage. If the landings were filmed in a sound stage, several anomalies would occur, including a lack of parallax, and an increase or decrease in the size of the backdrop if the camera moved. Footage was filmed while the rover was in motion, and yet no evidence is present of any change in the size of the background.

- This theory was further debunked on the MythBusters episode "NASA Moon Landing".

Mechanical issues

1. The Lunar Modules made no blast craters or any sign of dust scatter.[102]

- No crater should be expected. The 10,000 lb (4,500 kg) thrust Descent Propulsion System was throttled down very far during the final landing.[103] The Lunar Module was no longer quickly decelerating, so the descent engine only had to support the lander's own weight, which was lessened by the Moon's gravity and by the near exhaustion of the descent propellants. At landing, the engine thrust divided by the nozzle exit area is only about 1.5 psi (10 kPa).[104][105]

- Beyond the engine nozzle, the plume spreads, and the pressure drops very quickly. Rocket exhaust gasses expand much more quickly after leaving the engine nozzle in a vacuum than in an atmosphere. The effect of an atmosphere on rocket plumes can be easily seen in launches from Earth; as the rocket rises through the thinning atmosphere, the exhaust plumes broaden very noticeably. To lessen this, rocket engines made for vacuums have longer bells than those made for use on Earth, but they still cannot stop this spreading. The lander's exhaust gases, therefore, expanded quickly well beyond the landing site. The descent engines did scatter a lot of very fine surface dust as seen in 16mm movies of each landing, and many mission commanders spoke of its effect on visibility. The landers were generally moving horizontally as well as vertically, and photos do show scouring of the surface along the final descent path. Finally, the lunar regolith is very compact below its surface dust layer, making it impossible for the descent engine to blast out a crater.[106] A blast crater was measured under the Apollo 11 lander using shadow lengths of the descent engine bell and estimates of the amount that the landing gear had compressed and how deep the lander footpads had pressed into the lunar surface, and it was found that the engine had eroded between 100 and 150 mm (4 and 6 in) of regolith out from underneath the engine bell during the final descent and landing.[107]

2. The second stage of the launch rocket or the Lunar Module ascent stage or both made no visible flame.

- The Lunar Modules used Aerozine 50 (fuel) and dinitrogen tetroxide (oxidizer) propellants, chosen for simplicity and reliability; they ignite hypergolically (upon contact) without the need for a spark. These propellants produce a nearly transparent exhaust.[108] The same fuel was used by the core of the American Titan II rocket. The transparency of their plumes is apparent in many launch photos. The plumes of rocket engines fired in a vacuum spread out very quickly as they leave the engine nozzle (see above), further lessening their visibility. Finally, rocket engines often run "rich" to slow internal corrosion. On Earth, the excess fuel burns in contact with atmospheric oxygen, enhancing the visible flame. This cannot happen in a vacuum.

- Apollo 17 LM leaving the Moon; rocket exhaust visible only briefly

- Apollo 8 launch through the first stage separation

- Exhaust flame may not be visible outside the atmosphere, as in this photo. Rocket engines are the dark structures at the bottom center.

- The launch of a Titan II, burning hypergolic Aerozine-50/N2O4, 1.9 MN (430,000 lbf) of thrust. Note the near-transparency of the exhaust, even in air (water is being sprayed up from below).

- Bright flame from first stage of the Saturn V, burning RP-1

3. The Lunar Modules weighed 17 tons and made no mark on the Moondust, yet footprints can be seen beside them.[109]

- On the surface of the Earth, Apollo 11's fueled and crewed Lunar Module Eagle would have weighed approximately 17 short tons (15,000 kg). On the surface of the Moon, however, after expending fuel and oxidizer on its descent from lunar orbit, the lander weighed about 1,200 kg (2,700 pounds).[110] The astronauts were much lighter than the lander, but their boots were much smaller than the lander's approximately 91 cm (3 ft) diameter footpads.[111] Pressure (or force per unit area) rather than mass determines the amount of regolith compression. In some photos, the footpads did press into the regolith, especially when they moved sideways at touchdown. (The bearing pressure under Apollo 11's footpads, with the lander being about 44 times the weight of an EVA-configured astronaut, would have been of similar magnitude to the bearing pressure exerted by the astronauts' boots.)[112]

4. The air conditioning units that were part of the astronauts' spacesuits could not have worked in an environment of no atmosphere.[113]

- The cooling units could only work in a vacuum. Water from a tank in the backpack flowed out through tiny pores in a metal sublimator plate where it quickly vaporized into space. The loss of the heat of vaporization froze the remaining water, forming a layer of ice on the outside of the plate that also sublimated into space (turning from a solid directly into a gas). A separate water loop flowed through the LCG (Liquid Cooling Garment) worn by the astronaut, carrying his metabolic waste heat through the sublimator plate where it was cooled and returned to the LCG. The 5.4 kg (12 lb) of feedwater gave about eight hours of cooling; because of its bulk, it was often the limiting consumable on the length of an EVA.

Transmissions

1. There should have been more than a two-second delay in communications between Earth and the Moon, at a distance of 250,000 mi (400,000 km).

- The round-trip light travel time of more than two seconds is apparent in all the real-time recordings of the lunar audio, but this does not always appear as expected. There may also be some documentary films where the delay has been edited out. Reasons for editing the audio may be time constraints or in the interest of clarity.[114]

2. Typical delays in communication were about 0.5 seconds.

- Claims that the delays were only half a second are untrue, as examination of the original recordings shows. Also, there should not be a consistent time delay between every response, as the conversation is being recorded at one end by Mission Control. Responses from Mission Control could be heard without any delay, as the recording is being made at the same time that Houston receives the transmission from the Moon.

3. The Parkes Observatory in Australia was billed to the world for weeks as the site that would be relaying communications from the first moonwalk. However, five hours before transmission they were told to stand down.

- The timing of the first moonwalk was changed after the landing. In fact, delays in getting the moonwalk started meant that Parkes did cover almost the entire Apollo 11 moonwalk.[115]

4. Parkes supposedly had the clearest video feed from the Moon, but Australian media and all other known sources ran a live feed from the United States.

- That was the original plan and the official policy, but the Australian Broadcasting Commission (ABC) did take the transmission direct from the Parkes and Honeysuckle Creek radio telescopes. These were converted to NTSC television at Paddington in Sydney. This meant that Australian viewers saw the moonwalk several seconds before the rest of the world.[116] See also Parkes radio astronomer John Sarkissian's article "On Eagle's Wings: The Parkes Observatory's Support of the Apollo 11 Mission".[117] The events surrounding the Parkes Observatory's role in relaying the live television of the moonwalk were portrayed in a slightly fictionalized Australian film comedy "The Dish" (2000).

5. Better signal was supposedly received at Parkes Observatory when the Moon was on the opposite side of the planet.

- This is not supported by the detailed evidence and logs from the missions.[118]

Missing data

Blueprints and design and development drawings of the machines involved are missing.[119][120] Apollo 11 data tapes are also missing, containing telemetry and the high-quality video (before scan conversion from slow-scan TV to standard TV) of the first moonwalk.[121][122]

Tapes

Dr. David R. Williams (NASA archivist at Goddard Space Flight Center) and Apollo 11 flight director Eugene F. Kranz both acknowledged that the original high-quality Apollo 11 telemetry data tapes are missing. Conspiracists see this as evidence that they never existed.[121] The Apollo 11 telemetry tapes were different from the telemetry tapes of the other Moon landings because they contained the raw television broadcast. For technical reasons, the Apollo 11 lander carried a slow-scan television (SSTV) camera (see Apollo TV camera). To broadcast the pictures to regular television, a scan conversion had to be done. The radio telescope at Parkes Observatory in Australia was able to receive the telemetry from the Moon at the time of the Apollo 11 moonwalk.[117] Parkes had a bigger antenna than NASA's antenna in Australia at the Honeysuckle Creek Tracking Station, so it received a better picture. It also received a better picture than NASA's antenna at Goldstone Deep Space Communications Complex. This direct TV signal, along with telemetry data, was recorded onto one-inch fourteen-track analog tape at Parkes. The original SSTV transmission had better detail and contrast than the scan-converted pictures, and it is this original tape that is missing.[123] A crude, real-time scan conversion of the SSTV signal was done in Australia before it was broadcast worldwide. However, still photos of the original SSTV image are available (see photos). About fifteen minutes of it were filmed by an amateur 8 mm film camera and these are also available. Later Apollo missions did not use SSTV. At least some of the telemetry tapes still exist from the ALSEP scientific experiments left on the Moon (which ran until 1977), according to Dr. Williams. Copies of those tapes have been found.[124]

Others are looking for the missing telemetry tapes for different reasons. The tapes contain the original and highest quality video feed from the Apollo 11 landing. Some former Apollo personnel want to find the tapes for posterity, while NASA engineers looking towards future Moon missions believe that the tapes may be useful for their design studies. They have found that the Apollo 11 tapes were sent for storage at the U.S. National Archives in 1970, but by 1984, all the Apollo 11 tapes had been returned to the Goddard Space Flight Center at their request. The tapes are believed to have been stored rather than re-used.[125] Goddard was storing 35,000 new tapes per year in 1967,[126] even before the Moon landings.

In November 2006, COSMOS Online reported that about 100 data tapes recorded in Australia during the Apollo 11 mission had been found in a small marine science laboratory in the main physics building at the Curtin University of Technology in Perth, Australia. One of the old tapes has been sent to NASA for analysis. The slow-scan television images were not on the tape.[124]

In July 2009, NASA indicated that it must have erased the original Apollo 11 Moon footage years ago so that it could re-use the tape. In December 2009, NASA issued a final report on the Apollo 11 telemetry tapes.[127] Senior engineer Dick Nafzger was in charge of the live TV recordings during the Apollo missions, and he was put in charge of the restoration project. After a three-year search, the "inescapable conclusion" was that about 45 tapes (estimated 15 tapes recorded at each of the three tracking stations) of Apollo 11 video were erased and re-used, said Nafzger.[128] Lowry Digital had been tasked with restoring the surviving footage in time for the 40th anniversary of the Apollo 11 landing. Lowry Digital president Mike Inchalik said that "this is by far and away the lowest quality" video that the company has dealt with. Nafzger praised Lowry for restoring "crispness" to the Apollo video, which will remain in black and white and contains conservative digital enhancements. The US$230,000 restoration project took months to complete and did not include sound quality improvements. Some selections of restored footage in high definition have been made available on the NASA website.[129]

Blueprints

Grumman appears to have destroyed most of its LM documentation,[120][130] but copies exist in microfilm for the blueprints for the Saturn V.[131]

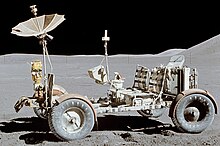

Four mission-worthy Lunar Roving Vehicles (LRV) were built by Boeing.[132] Three of them were carried to the Moon on Apollos 15, 16, and 17, used by the astronauts for transportation on the Moon, and left there. After Apollo 18 was canceled, the other LRV was used for spare parts for the Apollos 15 to 17 missions. The 221-page operation manual for the LRV contains some detailed drawings,[133] although not the blueprints.

NASA technology compared to USSR

Bart Sibrel cites the relative level of the United States and USSR space technology as evidence that the Moon landings could not have happened. For much of the early stages of the Space Race, the USSR was ahead of the United States, yet in the end, the USSR was never able to fly a crewed spacecraft to the Moon, let alone land one on the surface. It is argued that, because the USSR was unable to do this, the United States should have also been unable to develop the technology to do so.

For example, he claims that, during the Apollo program, the USSR had five times more crewed hours in space than the United States, and notes that the USSR was the first to achieve many of the early milestones in space: the first artificial satellite in orbit (October 1957, Sputnik 1);[d] the first living creature in orbit (a dog named Laika, November 1957, Sputnik 2); the first man in space and in orbit (Yuri Gagarin, April 1961, Vostok 1); the first woman in space (Valentina Tereshkova, June 1963, Vostok 6); and the first spacewalk (Alexei Leonov in March 1965, Voskhod 2).

However, most of the Soviet gains listed above were matched by the United States within a year, and sometimes within weeks. In 1965, the United States started to achieve many firsts (such as the first successful space rendezvous), which were important steps in a mission to the Moon. Furthermore, NASA and others say that these gains by the Soviets are not as impressive as they seem; that a number of these firsts were mere stunts that did not advance the technology greatly, or at all, e.g., the first woman in space.[134][135] In fact, by the time of the launch of the first crewed Earth-orbiting Apollo flight (Apollo 7), the USSR had made only nine spaceflights (seven with one cosmonaut, one with two, one with three) compared to 16 by the United States. In terms of spacecraft hours, the USSR had 460 hours of spaceflight; the United States had 1,024 hours. In terms of astronaut/cosmonaut time, the USSR had 534 hours of crewed spaceflight whereas the United States had 1,992 hours. By the time of Apollo 11, the United States had a lead much wider than that. (See List of human spaceflights, 1961–1970, and refer to individual flights for the length of time.)

Moreover, the USSR did not develop a successful rocket capable of a crewed lunar mission until the 1980s – their N1 rocket failed on all four launch attempts between 1969 and 1972.[136] The Soviet LK lunar lander was tested in uncrewed low-Earth-orbit flights three times in 1970 and 1971.

Technology used by NASA

Digital technology was in its infancy during the time of the Moon landings. The astronauts had relied on computers to aid in the Moon missions. The Apollo Guidance Computer was on the Lunar Module and the command and service module. Many computers at the time were very large despite poor specs.[137][138] For example, the Xerox Alto was released in 1973, one year after the final Moon landing.[139] This computer had 96kB of memory.[140] Most personal computers as of 2019 use 50,000 to 100,000 times this amount of RAM.[141] Conspiracy theorists claim that the computers during the time of the Moon landings would not have been advanced enough to enable space travel to the Moon and back;[142] they similarly claim that other contemporaneous technology (radio transmission, radar, and other instrumentation) was likewise insufficient for the task.[143]

Deaths of NASA personnel

In a televised program about the Moon-landing hoax allegations, Fox Entertainment Group listed the deaths of ten astronauts and two civilians related to the crewed spaceflight program as part of an alleged cover-up.

- Theodore Freeman (killed ejecting from a T-38 which had suffered a bird strike, October 1964)

- Elliot See and Charlie Bassett (T-38 crash in bad weather, February 1966)

- Virgil "Gus" Grissom, Ed White, and Roger B. Chaffee (killed in a fire during the "plugs-out test" preceding Apollo 1, January 1967)

- Edward "Ed" Givens (killed in a car accident, June 1967)

- Clifton "C. C." Williams (killed ejecting from a T-38, October 1967)

- Michael J. "Mike" Adams (died in an X-15 crash, November 1967. Adams was the only pilot killed during the X-15 flight test program. He was a test pilot, not a NASA astronaut, but had flown the X-15 above 80 kilometres or 50 miles)

- Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. (killed in an F-104 crash, December 1967, shortly after being selected as a pilot with the United States Air Force's Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL) program, which was canceled in 1969)

- Thomas Ronald Baron (North American Aviation employee. Baron died in an automobile collision with a train, April 27, 1967, six days after testifying before Rep. Olin E. Teague's House Subcommittee on NASA Oversight hearings held following the Apollo 1 fire, after which he was fired)

Two of the above, X-15 pilot Mike Adams and MOL pilot Robert Lawrence, had no connection with the civilian crewed space program that oversaw the Apollo missions. Baron was a quality control inspector who wrote a report critical of the Apollo program and was an outspoken critic of NASA's safety record after the Apollo 1 fire. Baron and his family were killed as their car was struck by a train at a train crossing. The deaths were an accident.[144][145] All of the deaths occurred at least 20 months before Apollo 11 and subsequent flights.

As of January 2024[update], four of the twelve Apollo astronauts who landed on the Moon between 1969 and 1972 are still alive, including Buzz Aldrin. Also, four of the twelve Apollo astronauts who flew to the Moon without landing between 1968 and 1972 are still alive.

The number of deaths within the American astronaut corps during the run-up to Apollo and during the Apollo missions is similar to the number of deaths incurred by the Soviets. During the period 1961 to 1972, at least eight Soviet serving and former cosmonauts died:

- Valentin Bondarenko (ground training accident, March 1961)

- Grigori Nelyubov (suicide, February 1966)

- Vladimir Komarov (Soyuz 1 accident, April 1967)

- Yuri Gagarin (MiG-15 crash, March 1968)

- Pavel Belyayev (complications following surgery, January 1970)

- Georgi Dobrovolski, Vladislav Volkov, and Viktor Patsayev (Soyuz 11 accident, June 1971)

Additionally, the overall chief of their crewed-spaceflight program, Sergei Korolev, died while undergoing surgery in January 1966.

Post flight conference

During the post flight conference for Apollo 11, there were moments in which the astronauts appeared serious or tired in a press conference otherwise filled with laughter. Conspiracy theorists often present images of those moments and portray it as the astronauts feeling guilty about faking the landing. This supposed evidence can be explained as a case of cherry picking and an appeal to emotion.[146][147]

NASA response

In June 1977, NASA issued a fact sheet responding to recent claims that the Apollo Moon landings had been hoaxed.[148] The fact sheet is particularly blunt and regards the idea of faking the Moon landings to be preposterous and outlandish. NASA refers to the rocks and particles collected from the Moon as being evidence of the program's legitimacy, as they claim that these rocks could not have been formed under conditions on Earth. NASA also notes that all of the operations and phases of the Apollo program were closely followed and under the scrutiny of the news media, from liftoff to splashdown. NASA responds to Bill Kaysing's book, We Never Went to the Moon, by identifying one of his claims of fraud regarding the lack of a crater left on the Moon's surface by the landing of the lunar module, and refuting it with facts about the soil and cohesive nature of the surface of the Moon.

The fact sheet was reissued on February 14, 2001, the day before Fox television's broadcast of Conspiracy Theory: Did We Land on the Moon? The documentary reinvigorated the public's interest in conspiracy theories and the possibility that the Moon landings were faked, which has provoked NASA to once again defend its name.

Alleged Stanley Kubrick involvement

Filmmaker Stanley Kubrick is accused of having produced much of the footage for Apollos 11 and 12, presumably because he had just directed 2001: A Space Odyssey, which is partly set on the Moon and featured advanced special effects.[149] It has been claimed that when 2001 was in post-production in early 1968, NASA secretly approached Kubrick to direct the first three Moon landings. The launch and splashdown would be real but the spacecraft would stay in Earth orbit and fake footage broadcast as "live from the Moon." No evidence was offered for this theory, which overlooks many facts. For example, 2001 was released before the first Apollo landing and Kubrick's depiction of the Moon's surface differs greatly from its appearance in the Apollo footage. The movement of characters on the Moon in 2001 differs from that of the filmed movement of Apollo astronauts and does not resemble an environment with 1/6 the gravity of Earth. Several scenes in 2001 show dust billowing as spacecraft landed, something that would not happen in the vacuum environment of the Moon. Kubrick did hire Frederick Ordway and Harry Lange, both of whom had worked for NASA and major aerospace contractors, to work with him on 2001. Kubrick also used some 50 mm f/0.7 lenses that were left over from a batch made by Zeiss for NASA. However, Kubrick only got this lens for Barry Lyndon (1975). The lens was originally a still photo lens and needed changes to be used for motion filming.

The mockumentary based on this idea, Dark Side of the Moon, could have fueled the conspiracy theory. This French mockumentary, directed by William Karel, was originally aired on Arte channel in 2002 with the title Opération Lune. It parodies conspiracy theories with faked interviews, stories of assassinations of Stanley Kubrick's assistants by the CIA, and a variety of conspicuous mistakes, puns, and references to old movie characters, inserted through the film as clues for the viewer. Nevertheless, Opération Lune is still taken at face value by some conspiracy believers.

An article titled "Stanley Kubrick and the Moon Hoax" appeared on Usenet in 1995, in the newsgroup "alt.humor.best-of-usenet". One passage – on how Kubrick was supposedly coerced into the conspiracy – reads:

NASA further leveraged their position by threatening to publicly reveal the heavy involvement of Mr. Kubrick's younger brother, Raul, with the American Communist Party. This would have been an intolerable embarrassment to Mr. Kubrick, especially since the release of Dr. Strangelove.

Kubrick had no such brother – the article was a spoof, complete with a giveaway sentence describing Kubrick shooting the moonwalk "on location" on the Moon. Nevertheless, the claim was taken up in earnest;[150] Clyde Lewis used it almost word-for-word,[149] whereas Jay Weidner gave the brother a more senior status within the party:

No one knows how the powers-that-be convinced Kubrick to direct the Apollo landings. Maybe they had compromised Kubrick in some way. The fact that his brother, Raul Kubrick, was the head of the American Communist Party may have been one of the avenues pursued by the government to get Stanley to cooperate.[151]

In July 2009, Weidner posted on his webpage "Secrets of the Shining", where he states that Kubrick's The Shining (1980) is a veiled confession of his role in the scam project.[152][153] This thesis was the subject of refutation in an article published on Seeker nearly half a year later.[154]

The 2015 movie Moonwalkers is a fictional account of a CIA agent's claim of Kubrick's involvement.

In December 2015, a video surfaced which allegedly shows Kubrick being interviewed shortly before his 1999 death; the video purportedly shows the director confessing to T. Patrick Murray that the Apollo Moon landings had been faked.[155] Research quickly found, however, that the video was a hoax.[156]

Academic work

In 2002, NASA granted $15,000 to James Oberg to write a point-by-point rebuttal of the hoax claims. However, NASA canceled the commission later that year, after complaints that the book would dignify the accusations.[157] Oberg said that he meant to finish the book.[157][158] In November 2002, Peter Jennings said that "NASA is going to spend a few thousand dollars trying to prove to some people that the United States did indeed land men on the Moon", and "NASA had been so rattled" that they hired somebody to write a book refuting the conspiracy theorists. Oberg says that belief in the hoax theories is not the fault of the conspiracists, but rather that of teachers and people who should provide information to the public—especially NASA.[157]

In 2004, Martin Hendry and Ken Skeldon of the University of Glasgow were awarded a grant by the UK-based Particle Physics and Astronomy Research Council to investigate Moon landing conspiracy theories.[159] In November 2004, they gave a lecture at the Glasgow Science Centre where the top ten claims by conspiracists were individually addressed and refuted.[160]

MythBusters special

An episode of MythBusters in August 2008 was dedicated to the Moon landings. The MythBusters crew tested many of the conspiracists' claims. Some of the testings were done in a NASA training facility. All of the conspiracists' claims examined on the show were labeled as having been "Busted", meaning that the conspiracists' claims were not true.

Third-party evidence of Moon landings

Снимки мест посадки

Сторонники высадки на Луну утверждают, что обсерватории и космический телескоп Хаббл должны иметь возможность фотографировать места посадки. Это означает, что крупнейшие мировые обсерватории (а также программа «Хаббл») замешаны в мистификации, отказываясь фотографировать места посадки. Фотографии Луны были сделаны Хабблом, включая как минимум две посадочные площадки Аполлона, но разрешение Хаббла ограничивает просмотр лунных объектов размерами не менее 55–69 м (60–75 ярдов), что недостаточно для того, чтобы увидеть какие-либо особенности посадочной площадки. [162]

статью В апреле 2001 года Леонард Дэвид опубликовал на сайте space.com : [163] [164] на котором была показана фотография, сделанная миссией «Клементина», на которой видно размытое темное пятно на месте, которое, по словам НАСА, является посадочным модулем Аполлона-15. Доказательства заметили Миша Креславский с факультета геологических наук Университета Брауна и Юрий Шкуратов из Харьковской астрономической обсерватории в Украине. Европейского космического агентства прислал беспилотный зонд SMART-1 обратно фотографии мест посадки . По словам Бернарда Фоинга , главного научного сотрудника научной программы ЕКА, [165] «Однако, учитывая начальную высокую орбиту SMART-1, увидеть артефакты может оказаться затруднительно», — сказал Фоинг в интервью на сайте space.com.

В 2002 году Алекс Р. Блэквелл из Гавайского университета отметил, что некоторые фотографии, сделанные астронавтами Аполлона, [164] на орбите Луны показаны места посадки.

В 2002 году газета Daily Telegraph опубликовала статью, в которой говорилось, что европейские астрономы на Очень Большом Телескопе (VLT) будут использовать его для наблюдения за местами посадки. Согласно статье, доктор Ричард Уэст заявил, что его команда сделает «снимок с высоким разрешением одной из посадочных площадок Аполлона». Маркус Аллен, конспиролог, ответил, что никакие фотографии оборудования на Луне не убедят его в том, что высадка людей произошла. [166] Телескоп использовался для изображения Луны и обеспечивал разрешение 130 метров (430 футов), что было недостаточно для разрешения лунных кораблей шириной 4,2 метра (14 футов) или их длинных теней. [167]

Японское агентство аэрокосмических исследований (JAXA) запустило свой лунный орбитальный аппарат SELENE 14 сентября 2007 года ( JST ) из космического центра Танегасима . SELENE вращалась вокруг Луны на высоте около 100 км (62 мили). В мае 2008 года JAXA сообщило об обнаружении «ореола», создаваемого выхлопами двигателя лунного модуля Аполлона-15, на изображении камеры местности. [168] Трехмерная реконструированная фотография также соответствовала ландшафту фотографии Аполлона-15, сделанной с поверхности.

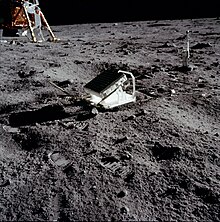

17 июля 2009 года НАСА опубликовало фотографии с низким разрешением инженерных испытаний посадочных площадок Аполлона-11, Аполлона-14, Аполлона-15, Аполлона-16 и Аполлона-17, которые были сфотографированы лунным разведывательным орбитальным аппаратом в рамках процесса запуска его основного спутника. миссия. [169] На фотографиях показаны этапы спуска посадочных аппаратов каждой миссии на поверхность Луны. На фотографии места посадки Аполлона-14 также видны следы, оставленные астронавтом между научным экспериментом (ALSEP) и посадочным модулем. [169] Фотографии места посадки Аполлона-12 были опубликованы НАСА 3 сентября 2009 года. [170] и тропинки астронавтов . Видны ступень спуска посадочного модуля «Интрепид», экспериментальный комплекс (ALSEP), космический корабль «Сервейор 3» Хотя изображения LRO понравились научному сообществу в целом, они не сделали ничего, чтобы убедить заговорщиков в том, что высадка произошла. [171]

1 сентября 2009 года индийская лунная миссия «Чандраян-1» сфотографировала место посадки «Аполлона-15» и следы луноходов. [172] [173] Индийская организация космических исследований запустила свой беспилотный лунный зонд 8 сентября 2008 года (IST) из Космического центра Сатиш Дхаван . Фотографии были сделаны гиперспектральной камерой , входящей в состав аппаратуры миссии. [172]

Второй китайский лунный зонд «Чанъэ-2» , запущенный в 2010 году, может фотографировать лунную поверхность с разрешением до 7 м (23 фута). Он обнаружил следы приземления Аполлона. [174]

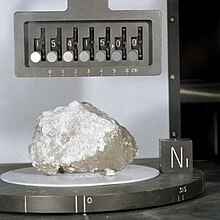

Лунные камни

Программа «Аполлон» собрала 380 кг (838 фунтов) лунных камней во время шести миссий с экипажем. Все анализы ученых со всего мира сходятся во мнении, что эти камни пришли с Луны – в рецензируемых научных журналах не существует опубликованных отчетов, оспаривающих это утверждение. Образцы Аполлона легко отличить как от метеоритов , так и от земных пород. [7] в том, что они демонстрируют отсутствие продуктов гидролиза , они демонстрируют свидетельства того, что подверглись ударам о безвоздушное тело, и обладают уникальными геохимическими характеристиками. Более того, большинство из них более чем на 200 миллионов лет старше самых старых земных пород. Лунные камни имеют те же характеристики, что и советские образцы. [175]

Конспирологи утверждают, что директора Центра космических полетов имени Маршалла Вернера фон Брауна поездка в Антарктиду в 1967 году (примерно за два года до запуска «Аполлона-11») заключалась в сборе лунных метеоритов для использования в качестве поддельных лунных камней. Поскольку фон Браун был бывшим офицером СС (правда, задержанным гестапо ) , [176] документальный фильм « Мы пошли?» [121] предполагает, что на него могли оказать давление, чтобы он согласился на заговор, чтобы защитить себя от взаимных обвинений в отношении своего прошлого. В НАСА заявили, что миссия фон Брауна заключалась в «изучении экологических и логистических факторов, которые могут иметь отношение к планированию будущих космических миссий и оборудования». [177] НАСА продолжает отправлять команды для работы в Антарктиде, чтобы имитировать условия на других планетах.

В настоящее время научное сообщество признает, что с марсианской и лунной поверхностью во время столкновений были выброшены камни , и что некоторые из них упали на Землю в виде метеоритов . [178] [179] Однако первый антарктический лунный метеорит был найден в 1979 году, а его лунное происхождение не было признано до 1982 года. [180] Более того, лунные метеориты настолько редки, что маловероятно, что они могли составлять 380 кг (840 фунтов) лунных камней, собранных НАСА в период с 1969 по 1972 год. На Земле было обнаружено только около 30 кг (66 фунтов) лунных метеоритов. до сих пор, несмотря на то, что частные коллекционеры и государственные учреждения по всему миру ведут поиск более 20 лет. [180]

В то время как миссии «Аполлон» собрали 380 кг (840 фунтов) лунных камней, советские роботы «Луна-16» , «Луна-20» и «Луна-24» собрали всего 326 г (11,5 унций ) вместе взятых (то есть менее одной тысячной от этого количества). Действительно, текущие планы по возвращению образцов с Марса предусматривают сбор всего лишь около 500 г (18 унций) почвы. [181] а недавно предложенная миссия роботов Южный полюс-Эйткен позволит собрать всего около 1 кг (2,2 фунта) лунного камня. [182] [183] [184] Если бы НАСА использовало подобную роботизированную технологию, то для сбора текущего количества лунных камней, находящихся в распоряжении НАСА, потребовалось бы от 300 до 2000 миссий роботов.

Что касается состава лунных камней, Кейсинг спросил: «Почему на Луне никогда не упоминалось о золоте, серебре, алмазах или других драгоценных металлах? Разве это не было жизнеспособным соображением? Почему этот факт никогда не обсуждался [ sic ] в прессой или астронавтами?» [185] Геологи понимают, что месторождения золота и серебра на Земле являются результатом действия гидротермальных флюидов, концентрирующих драгоценные металлы в рудных жилах. Поскольку в 1969 году считалось, что на Луне нет воды, ни один геолог не обсуждал возможность обнаружения ее на Луне в больших количествах. [ нужна ссылка ]

Миссии, отслеживаемые независимыми сторонами

Помимо НАСА, ряд групп и отдельных лиц отслеживали миссии Аполлона по мере их осуществления. В ходе последующих миссий НАСА обнародовало информацию, объясняющую, где и когда можно было увидеть космический корабль. Траектории их полета отслеживались с помощью радара, а их видели и фотографировали с помощью телескопов. Также независимо записывались радиопереговоры между космонавтами на поверхности и на орбите.

Световозвращатели

Наличие ретрорефлекторов (зеркал, используемых в качестве мишеней для наземных следящих лазеров) в ходе эксперимента с ретрорефлекторами лазерной локации (LRRR) является свидетельством того, что приземления были. [186] Ликская обсерватория попыталась провести обнаружение с помощью ретрорефлектора Аполлона-11, когда Армстронг и Олдрин все еще находились на Луне, но не добилась успеха до 1 августа 1969 года. [187] Астронавты Аполлона-14 задействовали ретрорефлектор 5 февраля 1971 года, и обсерватория Макдональда обнаружила его в тот же день. Ретрорефлектор Аполлона-15 был развернут 31 июля 1971 года и через несколько дней был обнаружен обсерваторией Макдональда. [188] Русские также установили на Луну ретрорефлекторы меньшего размера; они были прикреплены к беспилотным луноходам «Луноход-1» и «Луноход-2» . [189]

Общественное мнение

В опросе The Washington Post 1994 года 9% респондентов заявили, что астронавты могли не полететь на Луну, а еще 5% не были в этом уверены. [190] 1999 года Опрос Gallup показал, что 6% опрошенных американцев сомневаются в том, что высадка на Луну произошла, и что 5% опрошенных не имеют своего мнения. [191] [192] [193] [194] что примерно соответствует результатам аналогичного опроса Time/CNN 1995 года . [191] Представители телеканала Fox заявили, что такой скептицизм вырос примерно до 20% после выхода в эфир в феврале 2001 года телевизионного специального выпуска их телеканала « Теория заговора: высадились ли мы на Луне?» , который посмотрели около 15 миллионов зрителей. [192] Этот специальный выпуск Fox рассматривается как пропаганда утверждений о мистификации. [195] [196]

Опрос 2000 года, проведённый Фондом ФОМ в России , показал, что 28% опрошенных не верят в то, что американские астронавты высадились на Луне, и этот процент примерно одинаков во всех социально-демографических группах. [197] [198] [199] В 2009 году опрос, проведенный британским журналом Engineering & Technology, показал, что 25% опрошенных не верят в то, что люди высадились на Луне. [200] Другой опрос показал, что 25% опрошенных молодых людей в возрасте от 18 до 25 лет не были уверены, что приземление произошло. [201]

Во всем мире существуют субкультуры, которые пропагандируют веру в то, что высадка на Луну была фальсификацией. В 1977 году Харе Кришна журнал «Назад к Богу» назвал высадку обманом, утверждая, что, поскольку Солнце находится на расстоянии 150 миллионов км (93 миллиона миль), а «согласно индуистской мифологии, Луна находится на 800 000 миль [1 300 000 км] дальше, чем что» Луна будет находиться на расстоянии почти 94 миллионов миль (151 миллион км); Чтобы преодолеть этот промежуток времени за 91 час, потребуется скорость более миллиона миль в час, что «явно невозможно даже по расчетам ученых». [202] [203]

Джеймс Оберг из ABC News сказал, что теория заговора преподается во многих кубинских школах, как на Кубе, так и там, где нанимают кубинских учителей. [157] [204] Опрос, проведенный в 1970-х годах Информационным агентством США в нескольких странах Латинской Америки, Азии и Африки, показал, что большинство респондентов не знали о высадках на Луну, многие другие отвергли их как пропаганду или научную фантастику, и многие считали, что это русские высадились на Луне. [205]

В 2019 году Ipsos провела исследование для C-SPAN, чтобы оценить уровень уверенности в том, что высадка на Луну в 1969 году была фальсификацией. Шесть процентов респондентов считали, что это неправда, но одиннадцать процентов миллениалов (достигших совершеннолетия в начале XXI века) с наибольшей вероятностью считали, что это неправда. [206]

Сводка опросов общественного мнения

| Даты проведенный | Опросник | Площадь и демография | Образец размер | Настоящий | Поддельный | Не уверен/Нет мнения | Ссылка(и) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1994 | Вашингтон Пост | Соединенные Штаты | 86% | 9% | 5% | [190] | |

| 1999 | Опрос Гэллапа | Соединенные Штаты | 89% | 6% | 5% | [191] | |

| 2000 | Фонд «Общественное мнение» | Россия | 72% | 28% | - | [197] [198] [199] | |

| 2009 | Инженерия и технологии | 75% | 25% | - | [200] | ||

| 2009 | Астрономия | Великобритания, 18-25 лет | 75% | 25% | - | [201] |

См. также

- Астронавты сошли с ума - фильм Барта Сибрела, 2004 г.

- В тени луны - британский документальный фильм Дэвида Сингтона 2007 года.

- Пропавшие космонавты – Теория заговора о советских космонавтах

- Список тем, характеризуемых как лженаука

- Украденные и пропавшие лунные камни

Примечания

- ↑ В 1968 году Кларк и Кубрик вместе работали над фильмом « 2001: Космическая одиссея» , в котором реалистично изображалась миссия на Луну.

- ^ делает это на своем сайте . Он тоже

- ↑ В это число входят экипажи Аполлонов 8, 10 и 13 , хотя последний технически совершил лишь пролет. На эти три миссии приходится только шесть дополнительных астронавтов, поскольку Джеймс Ловелл дважды облетел Луну (Аполлон 8 и 13), а Джон Янг и Джин Сернан облетели Аполлон 10, и оба позже приземлились на Луне.

- ^ Согласно эпизоду NOVA 2007 года « Рассекреченный спутник », Соединенные Штаты могли запустить зонд «Эксплорер-1» раньше «Спутника», но администрация Эйзенхауэра колебалась, во-первых, потому что они не были уверены, означает ли международное право, что национальные границы продолжают проходить до самого конца. орбите (и, таким образом, их орбитальный спутник мог вызвать международный резонанс, нарушив границы десятков стран), а во-вторых, потому, что появилось желание, чтобы еще не готовая спутниковая программа «Вэнгард» , разработанная американскими гражданами, стала первым спутником Америки а не программа Explorer, которая в основном была разработана бывшими конструкторами ракет из нацистской Германии . Стенограмма соответствующего раздела передачи доступна на сайте « Влияние спутника на Америку ».

Цитаты

![]() Эта статья включает общедоступные материалы с веб-сайтов или документов Национального управления по аэронавтике и исследованию космического пространства .

Эта статья включает общедоступные материалы с веб-сайтов или документов Национального управления по аэронавтике и исследованию космического пространства .

- ^ Коса 2002 , стр. 154–173

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Нил-Джонс, Нэнси; Зубрицкий, Елизавета; Коул, Стив (6 сентября 2011 г.). Гарнер, Роберт (ред.). «Снимки космического корабля НАСА дают более четкое представление о местах посадки Аполлона» . НАСА. Выпуск Годдарда № 11-058 (совместно с выпуском штаб-квартиры НАСА № 11-289) . Проверено 22 сентября 2011 г.

- ^ Робинсон, Марк (27 июля 2012 г.). «LRO повернулся на 19° вниз по Солнцу, что позволило запечатлеть освещенную сторону все еще стоящего американского флага на месте посадки Аполлона-17. M113751661L» (Подпись). Система новостей LROC. Архивировано из оригинала 24 октября 2012 года . Проверено 29 апреля 2013 г.

- ^ «Флаги Аполлона и Луны все еще стоят, как видно на изображениях» . Новости Би-би-си . Лондон: Би-би-си . 30 июля 2012 года . Проверено 29 апреля 2013 г.

- ^ Эбби, Дженнифер (31 июля 2012 г.). «Американские флаги миссий Аполлона все еще стоят» . Новости ABC (блог). Нью-Йорк: ABC . Проверено 29 апреля 2013 г.

- ^ Плейт, Филип К. (2002). Плохая астрономия: раскрыты заблуждения и злоупотребления, от астрологии до «мистификации» высадки на Луну . Нью-Йорк: Джон Уайли и сыновья . ISBN 0471409766 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Филлипс, Тони (23 февраля 2001 г.). «Великая лунная мистификация» . Наука@НАСА . НАСА . Архивировано из оригинала 10 апреля 2010 года . Проверено 30 июля 2012 г.

- ^ Кейсинг 2002 г.

- ^ Кейсинг 2002 , с. 30

- ^ Кейсинг 2002 , с. 80

- ^ Кейсинг, Венди Л. «Краткая биография Билла Кейсинга» . BillKaysing.com . Проверено 28 февраля 2013 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Кайсинг 2002 , стр. 7–8.

- ^ Коса 2002 , с. 157

- ^ Бреуниг, Роберт А. (ноябрь 2006 г.). «Мы высадились на Луне?» . Ракетно-космическая техника . Роберт Бреуниг. Архивировано из оригинала 22 мая 2013 года . Проверено 3 мая 2013 г.

- ^ Галуппини, Альбинос. «Теория обмана» . BillKaysing.com . Проверено 3 мая 2013 г.

- ^ Шадевальд, Роберт Дж. (июль 1980 г.). «Чистая правда: земные орбиты? Посадки на Луну? Мошенничество! Говорит этот пророк» . Научный дайджест . Нью-Йорк: Журналы Hearst . Архивировано из оригинала 28 января 2013 года . Проверено 29 апреля 2013 г.

- ^ ван Бакель, Рожье (сентябрь 1994 г.). «Неправильный материал» . Проводной . Том. 2, нет. 9. Нью-Йорк: Публикации Condé Nast . п. 5 . Проверено 13 августа 2009 г.

- ^ Чайкин 2007 (нужна страница)

- ^ Аттивиссимо 2013 , с. 70

- ^ Дик и Лауниус 2007 , стр. 63–64.

- ^ Чайкин 2007 , с. 2: «Мы выбираем полет на Луну! Мы выбираем полет на Луну в этом десятилетии и займемся другими делами – не потому, что это легко, а потому, что это . сложно » — Кеннеди выступает в Университете Райса , 12 сентября, 1962.

- ^ Коса 2002 , с. 173

- ^ TheFreeDictionary.com , Наши основные источники , дата обращения 17 августа 2013 г.

- ^ « Нил Армстронг». Большая советская энциклопедия , 3-е издание. 1970–1979. The Gale Group, Inc» . Бесплатный словарь [Интернет] . Проверено 25 февраля 2021 г.

...Армстронг совершил исторический первый полет на Луну вместе с Э. Олдрином и М. Коллинзом с 16 по 24 июля 1969 года, будучи командиром космического корабля «Аполлон-11». Лунный модуль с Армстронгом и Олдрином приземлился на Луну в район Моря Спокойствия 20 июля 1969 года. Армстронг был первым человеком, ступившим на Луну (21 июля 1969 года); он провел два часа 21 минуту и 16 секунд вне космического корабля. После успешного завершения своей программы экипаж «Аполлона II» вернулся на Землю. … Большая советская энциклопедия , 3-е издание (1970–1979). 2010 Гейл Групп, Инк.

- ^ « Освоение космоса». Большая советская энциклопедия , 3-е издание. 1970–1979. The Gale Group, Inc.» . Бесплатный словарь [Интернет] . Проверено 25 февраля 2021 г.

... Космическая эра. 4 октября 1957 года, дата запуска в СССР первого искусственного спутника Земли, считается началом космической эры. Вторая важная дата — 12 апреля 1961 года, дата первого полета человека в космос Ю. А. Гагарин, начало прямого проникновения человека в космос. Третье историческое событие — первая лунная экспедиция Н. Армстронга, Э. Олдрина и М. Коллинза (США) 16–24 июля 1969 г.. ... Большая советская энциклопедия , 3-е издание (1970–1979) . 2010 The Gale Group, Inc.

(Предупреждение во избежание возможной путаницы: по тому же цитируемому веб-адресу статье советской эпохи предшествует статья 2013 года об освоении космоса из Электронной энциклопедии Колумбии ) - ^ «Лунная мистификация: Часто задаваемые вопросы на Moonmovie.com» . Moonmovie.com . АФТ, ООО. Архивировано из оригинала 12 февраля 2008 года . Проверено 26 августа 2009 г.

- ^ «Наука: Программа убывающей луны» . Время . 14 сентября 1970 года.

- ^ « Аполлон с 18 по 20 – Отмененные миссии », доктор Дэвид Р. Уильямс, НАСА, по состоянию на 19 июля 2006 г.

- ^ «Советские лунные программы» . Космическая гонка (онлайн-версия выставки представлена в Галерее 114). Вашингтон, округ Колумбия: Национальный музей авиации и космонавтики . Архивировано из оригинала 10 мая 2013 года . Проверено 13 ноября 2010 г.

- ^ Зак, Анатолий. «Инфраструктура управления космическим пространством России» . RussianSpaceWeb.com . Анатолий Зак. Архивировано из оригинала 8 июля 2010 года . Проверено 13 ноября 2010 г.

- ^ «Советские системы космического слежения» . Энциклопедия астронавтики . Марк Уэйд. Архивировано из оригинала 1 ноября 2010 года . Проверено 13 ноября 2010 г.

- ^ Шеффер 2004 , с. 247

- ^ «Лунная программа, которая провалилась». Космический полет . 33 . Лондон: Британское межпланетное общество : 2–3. Март 1991 г. Бибкод : 1991СпФл...33....2.

- ^ Бергер, Эрик (8 мая 2023 г.). "Бывший глава Роскосмоса теперь считает, что НАСА не высаживалось на Луну" . Арс Техника . Проверено 12 мая 2023 г.

- ^ Кейсинг 2002 , с. 71

- ^ Аттивиссимо 2013 , с. 163

- ^ Кеннеди, Джон Ф. (25 мая 1961 г.). Специальное послание Конгрессу о неотложных национальных потребностях (Кинофильм (отрывок)). Бостон, Массачусетс: Президентская библиотека и музей Джона Ф. Кеннеди. Инвентарный номер: TNC:200; Цифровой идентификатор: TNC-200-2 . Проверено 1 августа 2013 г.

- ^ Конгресс, Палата представителей, Комитет по науке и космонавтике (1973). Слушания по разрешению НАСА в 1974 году (слушание по HR 4567). Вашингтон, округ Колумбия: 93-й Конгресс , первая сессия. ОСЛК 23229007 .

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: несколько имен: список авторов ( ссылка ) - ^ Беннетт и Перси 2001 , с. 77

- ^ Беннетт и Перси 2001 , стр. 330–331.

- ^ Андерсон, Клинтон П. (30 января 1968 г.), Авария Аполлона-204: отчет Комитета по аэронавтике и космическим наукам Сената США, с дополнительными соображениями , том. Отчет Сената № 956, Вашингтон, округ Колумбия: Типография правительства США, заархивировано из оригинала 20 декабря 2014 г.

- ^ Стивен-Бониецки, Дуайт (2010). Прямой эфир с Луны . Берлингтон, Онтарио: Книги Апогея. ISBN 978-1926592169 . Архивировано из оригинала 5 ноября 2018 года . Проверено 14 сентября 2014 г.

- ^ «Была ли высадка Аполлона на Луну фальшивкой?» . Сеть друзей американских патриотов (APFN) . 21 июля 2009 года. Архивировано из оригинала 16 мая 2018 года . Проверено 25 ноября 2008 г.

- ^ Управление управления и бюджета США

- ^ Хепплуайт, Т. А. Решение о космическом шаттле: поиск НАСА космического корабля многоразового использования , глава 4. Вашингтон, округ Колумбия: Национальное управление по аэронавтике и исследованию космического пространства, 1999.

- ^ Колдер, Винс; Джонсон, Эндрю, PE; и др. (12 октября 2002 г.). «Спроси учёного» . Ньютон . Аргоннская национальная лаборатория . Архивировано из оригинала 30 июля 2014 года . Проверено 14 августа 2009 г.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: несколько имен: список авторов ( ссылка ) CS1 maint: числовые имена: список авторов ( ссылка ) - ^ Рамзи 2006 г. [ нужна страница ]

- ^ Лонгуски 2006 , с. 102

- ^ Ааронович 2010 , стр. 1–2, 6.

- ^ «Теории заговора». Пенн и Теллер: Чушь собачья! . 3 сезон. 3 серия. 9 мая 2005. Showtime .

- ^ Барахас, Джошуа (15 февраля 2016 г.). «Сколько людей нужно, чтобы поддерживать заговор?» . PBS НОВОСТИ . Служба общественного вещания (PBS). Архивировано из оригинала 13 октября 2017 года . Проверено 22 июля 2016 г.

- ^ Граймс, Дэвид Р. (26 января 2016 г.). «О жизнеспособности конспирологических убеждений» . ПЛОС ОДИН . 11 (1): e0147905. Бибкод : 2016PLoSO..1147905G . дои : 10.1371/journal.pone.0147905 . ПМЦ 4728076 . ПМИД 26812482 .

- ^ Новелла, Стивен; Новелла, Боб; Санта-Мария, Кара; Новелла, Джей; Бернштейн, Эван (2018). Путеводитель по Вселенной для скептиков: как узнать, что на самом деле реально в мире, который все больше наполнен фейками . Издательство Гранд Сентрал. стр. 209–210. ISBN 978-1538760536 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Уиндли, Джей. «Клавиус: Фотография – Перекрестие» . Лунная база Клавиус . Клавиус.орг . Проверено 20 апреля 2013 г.

- ^ Уиндли, Джей. «Клавиус: Фотография – качество изображения» . Лунная база Клавиус . Клавиус.орг . Проверено 5 сентября 2009 г.

- ^ «Фотографии миссии Аполлона-11» . Лунно-планетарный институт . Проверено 23 июля 2009 г.