Домашнее насилие

| Домашнее насилие | |

|---|---|

| Другие имена | Домашнее насилие, насилие в семье |

| |

| Фиолетовая лента используется для повышения осведомленности о домашнем насилии. | |

| Part of a series on |

| Violence against men |

|---|

| Issues |

| Killing |

| Sexual assault and rape |

| Related topics |

Домашнее насилие – это насилие или другое насилие , которое происходит в домашней обстановке, например, в браке или совместном проживании . Домашнее насилие часто используется как синоним насилия со стороны интимного партнера , которое совершается одним из людей, находящихся в интимных отношениях , против другого человека и может иметь место в отношениях или между бывшими супругами или партнерами. В самом широком смысле домашнее насилие также включает насилие в отношении детей, родителей или пожилых людей. Оно может принимать различные формы, включая физическое , вербальное , эмоциональное , экономическое , религиозное , репродуктивное , финансовое или сексуальное насилие или их комбинации. Оно может варьироваться от тонких, принудительных форм до супружеского изнасилования и других жестоких физических злоупотреблений, таких как удушение, избиение, калечащие операции на женских половых органах и обливание кислотой , которые могут привести к уродству или смерти, и включает использование технологий для преследования, контроля и наблюдения. , выслеживать или взломать. [1] [2] К домашним убийствам относятся забивание камнями , сожжение невесты , убийство чести и смерть приданого , в которых иногда участвуют члены семьи, не проживавшие совместно. В 2015 году Министерство внутренних дел Великобритании расширило определение домашнего насилия, включив в него принудительный контроль. [3]

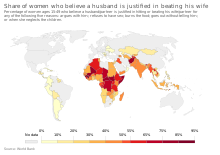

Worldwide, the victims of domestic violence are overwhelmingly women, and women tend to experience more severe forms of violence.[4][5][6][7] The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates one in three of all women are subject to domestic violence at some point in their life.[8] In some countries, domestic violence may be seen as justified or legally permitted, particularly in cases of actual or suspected infidelity on the part of the woman. Research has established that there exists a direct and significant correlation between a country's level of gender inequality and rates of domestic violence, where countries with less gender equality experience higher rates of domestic violence.[9] Domestic violence is among the most underreported crimes worldwide for both men and women.[10][11]

Domestic violence often occurs when the abuser believes that they are entitled to it, or that it is acceptable, justified, or unlikely to be reported. It may produce an intergenerational cycle of violence in children and other family members, who may feel that such violence is acceptable or condoned. Many people do not recognize themselves as abusers or victims, because they may consider their experiences as family conflicts that had gotten out of control.[12] Awareness, perception, definition and documentation of domestic violence differs widely from country to country. Additionally, domestic violence often happens in the context of forced or child marriages.[13]

In abusive relationships, there may be a cycle of abuse during which tensions rise and an act of violence is committed, followed by a period of reconciliation and calm. The victims may be trapped in domestically violent situations through isolation, power and control, traumatic bonding to the abuser,[14] cultural acceptance, lack of financial resources, fear, and shame, or to protect children. As a result of abuse, victims may experience physical disabilities, dysregulated aggression, chronic health problems, mental illness, limited finances, and a poor ability to create healthy relationships. Victims may experience severe psychological disorders, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Children who live in a household with violence often show psychological problems from an early age, such as avoidance, hypervigilance to threats and dysregulated aggression, which may contribute to vicarious traumatization.[15]

Etymology and definitions

[edit]The first known use of the term domestic violence in a modern context, meaning violence in the home, was in an address to the Parliament of the United Kingdom by Jack Ashley in 1973.[16][17] The term previously referred primarily to civil unrest, domestic violence from within a country as opposed to international violence perpetrated by a foreign power.[18][19][nb 1]

Traditionally, domestic violence (DV) was mostly associated with physical violence. Terms such as wife abuse, wife beating, wife battering, and battered woman were used, but have declined in popularity due to efforts to include unmarried partners, abuse other than physical, female perpetrators, and same-sex relationships.[nb 2] Domestic violence is now commonly defined broadly to include "all acts of physical, sexual, psychological or economic violence"[24] that may be committed by a family member or intimate partner.[24][25][26]

The term intimate partner violence is often used synonymously with domestic abuse[27] or domestic violence,[28] but it specifically refers to violence occurring within a couple's relationship (i.e. marriage, cohabitation, or non-cohabiting intimate partners).[29] To these, the World Health Organization (WHO) adds controlling behaviors as a form of abuse.[30] Intimate partner violence has been observed in opposite and same-sex relationships,[31] and in the former instance by both men against women and women against men.[32] Family violence is a broader term, often used to include child abuse, elder abuse, and other violent acts between family members.[28][33][34]In 1993, the UN Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women defined domestic violence as:

Physical, sexual and psychological violence occurring in the family, including battering, sexual abuse of female children in the household, dowry-related violence, marital rape, female genital mutilation and other traditional practices harmful to women, non-spousal violence and violence related to exploitation.[35]

History

[edit]The Encyclopædia Britannica states that "in the early 1800s, most legal systems implicitly accepted wife-beating as a husband's right" over his wife.[36][37] English common law, dating back to the 16th century, treated domestic violence as a crime against the community rather than against the individual woman by charging wife beating as a breach of the peace. Wives had the right to seek redress in the form of a peace bond from a local justice of the peace. Procedures were informal and off the record, and no legal guidance specified the standard of proof or degree of violence which would suffice for a conviction. The two typical sentences were forcing a husband to post bond, or forcing him to stake pledges from his associates to guarantee good behavior in the future. Beatings could also be formally charged as assault, although such prosecutions were rare and save for cases of severe injury or death, sentences were typically small fines.[38]

By extension, this framework held in the American colonies. The 1641 Body of Liberties of the Massachusetts Bay colonists declared that a married woman should be "free from bodily correction or stripes by her husband."[39] New Hampshire and Rhode Island also explicitly banned wife-beating in their criminal codes.[38]

Following the American Revolution, changes in the legal system placed greater power in the hands of precedent-setting state courts rather than local justices. Many states transferred jurisdiction in divorce cases from their legislatures to their judicial system, and the legal recourse available to battered women increasingly became divorce on grounds of cruelty and suing for assault. This placed a greater burden of proof on the woman, as she needed to demonstrate to a court that her life was at risk. In 1824, the Mississippi Supreme Court, citing the rule of thumb, established a positive right to wife-beating in State v. Bradley, a precedent which would hold sway in common law for decades to come.[38]

Political agitation and the first-wave feminist movement, during the 19th century, led to changes in both popular opinion and legislation regarding domestic violence within the UK, the US, and other countries.[40][41] In 1850, Tennessee became the first state in the US to explicitly outlaw wife beating.[42][43][44] Other states soon followed.[37][45] In 1871, the tide of legal opinion began to turn against the idea of a right to wife-beating, as courts in Massachusetts and Alabama reversed the precedent set in Bradley.[38] In 1878, the UK Matrimonial Causes Act made it possible for women in the UK to seek legal separation from an abusive husband.[46] By the end of the 1870s, most courts in the US had rejected a claimed right of husbands to physically discipline their wives.[47] In the early 20th century, paternalistic judges regularly protected perpetrators of domestic violence in order to reinforce gender norms within the family.[48] In divorce and criminal domestic violence cases, judges would levy harsh punishments against male perpetrators, but when the gender roles were reversed they would often give little to no punishment to female perpetrators.[48] By the early 20th century, it was common for police to intervene in cases of domestic violence in the US, but arrests remained rare.[49]

In most legal systems around the world, domestic violence has been addressed only from the 1990s onward; indeed, before the late 20th century, in most countries there was very little protection, in law or in practice, against domestic violence.[50] In 1993, the UN published Strategies for Confronting Domestic Violence: A Resource Manual.[51] This publication urged countries around the world to treat domestic violence as a criminal act, stated that the right to a private family life does not include the right to abuse family members, and acknowledged that, at the time of its writing, most legal systems considered domestic violence to be largely outside the scope of the law, describing the situation at that time as follows: "Physical discipline of children is allowed and, indeed, encouraged in many legal systems and a large number of countries allow moderate physical chastisement of a wife or, if they do not do so now, have done so within the last 100 years. Again, most legal systems fail to criminalize circumstances where a wife is forced to have sexual relations with her husband against her will. ... Indeed, in the case of violence against wives, there is a widespread belief that women provoke, can tolerate or even enjoy a certain level of violence from their spouses."[51]

In recent decades, there has been a call for the end of legal impunity for domestic violence, an impunity often based on the idea that such acts are private.[52][53] The Council of Europe Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence, better known as the Istanbul Convention, is the first legally binding instrument in Europe dealing with domestic violence and violence against women.[54] The convention seeks to put an end to the toleration, in law or in practice, of violence against women and domestic violence. In its explanatory report, it acknowledges the long tradition of European countries of ignoring, de jure or de facto, these forms of violence.[55] At para 219, it states: "There are many examples from past practice in Council of Europe member states that show that exceptions to the prosecution of such cases were made, either in law or in practice, if victim and perpetrator were, for example, married to each other or had been in a relationship. The most prominent example is rape within marriage, which for a long time had not been recognised as rape because of the relationship between victim and perpetrator."[55]

There has been increased attention given to specific forms of domestic violence, such as honor killings, dowry deaths, and forced marriages. India has, in recent decades, made efforts to curtail dowry violence: the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act was enacted in 2005, following years of advocacy and activism by the women's organizations.[56] Crimes of passion in Latin America, a region which has a history of treating such killings with extreme leniency, have also come to international attention. In 2002, Widney Brown, advocacy director for Human Rights Watch, argued that there are similarities between the dynamics of crimes of passion and honor killings, stating that: "crimes of passion have a similar dynamic [to honor killings] in that the women are killed by male family members and the crimes are perceived as excusable or understandable".[57]

Historically, children had few protections from violence by their parents, and in many parts of the world, this is still the case. For example, in Ancient Rome, a father could legally kill his children. Many cultures have allowed fathers to sell their children into slavery. Child sacrifice was also a common practice.[58] Child maltreatment began to garner mainstream attention with the publication of "The Battered Child Syndrome" by pediatric psychiatrist C. Henry Kempe in 1962. Prior to this, injuries to children – even repeated bone fractures – were not commonly recognized as the results of intentional trauma. Instead, physicians often looked for undiagnosed bone diseases or accepted parents' accounts of accidental mishaps, such as falls or assaults by neighborhood bullies.[59]: 100–103

Forms

[edit]Not all domestic violence is equivalent. Differences in frequency, severity, purpose, and outcome are all significant. Domestic violence can take many forms, including physical aggression or assault (hitting, kicking, biting, shoving, restraining, slapping, throwing objects, beating up, etc.), or threats thereof; sexual abuse; controlling or domineering; intimidation; stalking; passive/covert abuse (e.g. neglect); and economic deprivation.[60][61] It can also mean endangerment, criminal coercion, kidnapping, unlawful imprisonment, trespassing, and harassment.[62]

Physical

[edit]Physical abuse is that involving contact intended to cause fear, pain, injury, other physical suffering or bodily harm.[63][64] In the context of coercive control, physical abuse is used to control the victim.[65] The dynamics of physical abuse in a relationship are often complex. Physical violence can be the culmination of other abusive behavior, such as threats, intimidation, and restriction of victim self-determination through isolation, manipulation and other limitations of personal freedom.[66] Denying medical care, sleep deprivation, and forced drug or alcohol use, are also forms of physical abuse.[63] It can also include inflicting physical injury onto other targets, such as children or pets, in order to cause emotional harm to the victim.[67]

Strangulation in the context of domestic violence has received significant attention.[68] It is now recognized as one of the most lethal forms of domestic violence; yet, because of the lack of external injuries, and the lack of social awareness and medical training in regard to it, strangulation has often been a hidden problem.[69] As a result, in recent years, many US states have enacted specific laws against strangulation.[70]

Homicide as a result of domestic violence makes up a greater proportion of female homicides than it does male homicides. More than 50% of female homicides are committed by former or current intimate partners in the US.[71] In the UK, 37% of murdered women were killed by an intimate partner compared to 6% for men. Between 40 and 70 percent of women murdered in Canada, Australia, South Africa, Israel and the US were killed by an intimate partner.[72] The WHO states that globally, about 38% of female homicides are committed by an intimate partner.[73]

During pregnancy, a woman is at higher risk to be abused or long-standing abuse may change in severity, causing negative health effects to the mother and fetus.[74] Pregnancy can also lead to a hiatus of domestic violence when the abuser does not want to harm the unborn child. The risk of domestic violence for women who have been pregnant is greatest immediately after childbirth.[75]

Acid attacks, are an extreme form of violence in which acid is thrown at the victims, usually their faces, resulting in extensive damage including long-term blindness and permanent scarring.[76][77][78][79][80] These are commonly a form of revenge against a woman for rejecting a marriage proposal or sexual advance.[81][82]

In the Middle East and other parts of the world, planned domestic homicides, or honor killings, are carried out due to the belief of the perpetrators that the victim has brought dishonor upon the family or community.[83][84] According to Human Rights Watch, honor killings are generally performed against women for "refusing to enter into an arranged marriage, being the victim of a sexual assault, seeking a divorce" or being accused of committing adultery.[85] In some parts of the world, where there is a strong social expectation for a woman to be a virgin prior to marriage, a bride may be subjected to extreme violence, including an honor killing, if she is deemed not to be a virgin on her wedding night due to the absence of blood.[86][nb 3]

Bride burning or dowry killing is a form of domestic violence in which a newly married woman is killed at home by her husband or husband's family due to their dissatisfaction over the dowry provided by her family. The act is often a result of demands for more or prolonged dowry after the marriage.[102] Dowry violence is most common in South Asia, especially in India. In 2011, the National Crime Records Bureau reported 8,618 dowry deaths in India, but unofficial figures estimate at least three times this amount.[56]

Sexual

[edit]| Country | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Switzerland | 12% |

| Germany | 15% |

| US | 15% |

| Canada | 15% |

| Nicaragua | 22% |

| UK | 23% |

| Zimbabwe | 25% |

| India | 28% |

The WHO defines sexual abuse as any sexual act, attempt to obtain a sexual act, unwanted sexual comments or advances, or acts to traffic, or otherwise directed, against a person's sexuality using coercion. It also includes obligatory inspections for virginity and female genital mutilation.[105] Aside from initiation of the sexual act through physical force, sexual abuse occurs if a person is verbally pressured into consenting,[106] unable to understand the nature or condition of the act, unable to decline participation, or unable to communicate unwillingness to engage in the sexual act. This could be because of underage immaturity, illness, disability, or the influence of alcohol or other drugs, or due to intimidation or pressure.[107]

In many cultures, victims of rape are considered to have brought dishonor or disgrace to their families and face severe familial violence, including honor killings.[108] This is especially the case if the victim becomes pregnant.[109]

Female genital mutilation is defined by WHO as "all procedures that involve partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons." This procedure has been performed on more than 125 million females alive today, and it is concentrated in 29 countries in Africa and Middle East.[110]

Incest, or sexual contact between a related adult and a child, is one form of familial sexual violence.[111] In some cultures, there are ritualized forms of child sexual abuse taking place with the knowledge and consent of the family, where the child is induced to engage in sexual acts with adults, possibly in exchange for money or goods. For instance, in Malawi some parents arrange for an older man, often called a hyena, to have sex with their daughters as a form of initiation.[112][113] The Council of Europe Convention on the Protection of Children Against Sexual Exploitation and Sexual Abuse[114] was the first international treaty to address child sexual abuse occurring within the home or family.[115]

Reproductive coercion (also called coerced reproduction) are threats or acts of violence against a partner's reproductive rights, health and decision-making; and includes a collection of behaviors intended to pressure or coerce a partner into becoming pregnant or ending a pregnancy.[116] Reproductive coercion is associated with forced sex, fear of or inability to make a contraceptive decision, fear of violence after refusing sex, and abusive partner interference with access to healthcare.[117][118]

In some cultures, marriage imposes a social obligation for women to reproduce. In northern Ghana, for example, payment of bride price signifies a woman's requirement to bear children, and women who use birth control face threats of violence and reprisals.[119]WHO includes forced marriage, cohabitation, and pregnancy including wife inheritance within its definition of sexual violence.[120][121] Wife inheritance, or levirate marriage, is a type of marriage in which the brother of a deceased man is obliged to marry his widow, and the widow is obliged to marry her deceased husband's brother.

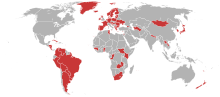

Marital rape is non-consensual penetration perpetrated against a spouse. It is under-reported, under-prosecuted, and legal in many countries, due in part to the belief that through marriage, a woman gives irrevocable consent for her husband to have sex with her when he wishes.[122][123][124][125][126] In Lebanon, for instance, while discussing a proposed law that would criminalize marital rape, Sheik Ahmad Al-Kurdi, a judge in the Sunni religious court, said that the law "could lead to the imprisonment of the man where in reality he is exercising the least of his marital rights."[127] Feminists have worked systematically since the 1960s to criminalize marital rape internationally.[128] In 2006, a study by the UN found that marital rape was a prosecutable offense in at least 104 countries.[129] Once widely condoned or ignored by law and society, marital rape is now repudiated by international conventions and increasingly criminalized. The countries which ratified the Istanbul Convention, the first legally binding instrument in Europe in the field of violence against women,[54] are bound by its provisions to ensure that non-consensual sexual acts committed against a spouse or partner are illegal.[130] The convention came into force in August 2014.[131]

Emotional

[edit]Emotional or psychological abuse is a pattern of behavior that threatens, intimidates, dehumanizes or systematically undermines self-worth.[132] According to the Istanbul Convention, psychological violence is "the intentional conduct of seriously impairing a person's psychological integrity through coercion or threats".[133]

Emotional abuse includes minimizing, threats, isolation, public humiliation, unrelenting criticism, constant personal devaluation, coercive control, repeated stonewalling and gaslighting.[30][67][134][135] Stalking is a common form of psychological intimidation, and is most often perpetrated by former or current intimate partners.[136][137] Victims tend to feel their partner has nearly total control over them, greatly affecting the power dynamic in a relationship, empowering the perpetrator, and disempowering the victim.[138] Victims often experience depression, putting them at increased risk of eating disorders,[139] suicide, and drug and alcohol abuse.[138][self-published source?][140][141][142]

Coercive control involves a controlling behavior designed to make a person dependent by isolating them from support, exploiting them of independence and regulating their everyday activities.[135] It involves the acts of verbal assault, punish, humiliation, threats or intimidation. Coercive control can occur physically, for example through physical abuse, harming or frightening the victims.[143] The victim's human rights might be infringed through being deprived of their right to liberty and reduced ability to act freely. Abusers tend to dehumanize, make threats, deprive basic needs and personal access, isolate, and track the victim's daily schedule via spyware.[144] Victims usually feel a sense of anxiety and fear that seriously affects their personal life, financially, physically and psychologically.

Economic

[edit]Economic abuse (or financial abuse) is a form of abuse when one intimate partner has control over the other partner's access to economic resources.[145] Marital assets are used as a means of control. Economic abuse may involve preventing a spouse from resource acquisition, limiting what the victim may use, or by otherwise exploiting economic resources of the victim.[145][146] Economic abuse diminishes the victim's capacity to support themselves, increasing dependence on the perpetrator, including reduced access to education, employment, career advancement, and asset acquisition.[145][146][147] Forcing or pressuring a family member to sign documents, to sell things, or to change a will are forms of economic abuse.[64]

A victim may be put on an allowance, allowing close monitoring of how much money is spent, preventing spending without the perpetrator's consent, leading to the accumulation of debt or depletion of the victim's savings.[145][146][147] Disagreements about money spent can result in retaliation with additional physical, sexual or emotional abuse.[148] In parts of the world where women depend on husbands' income in order to survive (due to lack of opportunities for female employment and lack of state welfare) economic abuse can have very severe consequences. Abusive relations have been associated with malnutrition among both mothers and children. In India, for example, the withholding of food is a documented form of family abuse.[149]

Contributing factors

[edit]One of the most important factors in domestic violence is a belief that abuse, whether physical or verbal, is acceptable. Other risk factors include substance abuse, lack of education, mental health problems, lack of coping skills, childhood abuse, and excessive dependence on the abuser.[150][151]

An overriding motive for committing acts of domestic and interpersonal violence in a relationship is to establish and maintain relationships based on power and control over victims.[152][153][154][155]

Batterers morality is out of step with the law and society's standards.[156] Research shows the key issue for perpetrators of abuse is their conscious and deliberate decision to offend in the pursuit of self-gratification.[157]

Men who perpetrate violence have specific characteristics: they are narcissistic, they willfully lack empathy, and they choose to treat their needs as more important than others.[157] Perpetrators psychologically manipulate their victim to believe their abuse and violence is caused by the victim's inadequacy (as a wife, a lover, or as a human being) rather than the perpetrators' selfish desire for power and control over them.[153]

Cycle of abuse theory

[edit]Lenore E. Walker presented the model of a cycle of abuse which consists of four phases. First, there is a buildup to abuse when tension rises until a domestic violence incident ensues. During the reconciliation stage, the abuser may be kind and loving and then there is a period of calm. When the situation is calm, the abused person may be hopeful that the situation will change. Then, tensions begin to build, and the cycle starts again.[158]

Intergenerational violence

[edit]A common aspect among abusers is that they witnessed abuse in their childhood. They were participants in a chain of intergenerational cycles of domestic violence.[159] That does not mean, conversely, that if a child witnesses or is subject to violence that they will become abusers.[150] Understanding and breaking the intergenerational abuse patterns may do more to reduce domestic violence than other remedies for managing the abuse.[159]

Responses that focus on children suggest that experiences throughout life influence an individual's propensity to engage in family violence (either as a victim or as a perpetrator). Researchers supporting this theory suggest it is useful to think of three sources of domestic violence: childhood socialization, previous experiences in couple relationships during adolescence, and levels of strain in a person's current life. People who observe their parents abusing each other, or who were themselves abused may incorporate abuse into their behaviour within relationships that they establish as adults.[160][161][162]

Research indicates that the more children are physically punished, the more likely they will be as adults to act violently towards family members, including intimate partners.[163] People who are spanked more as children are more likely as adults to approve of hitting a partner, and also experience more marital conflict and feelings of anger in general.[164] A number of studies have found physical punishment to be associated with "higher levels of aggression against parents, siblings, peers and spouses", even when controlling for other factors.[165] While these associations do not prove a causal relationship, a number of longitudinal studies suggest that the experience of physical punishment does have a direct causal effect on later aggressive behaviors. Such research has shown that corporal punishment of children (e.g. smacking, slapping, or spanking) predicts weaker internalisation of values such as empathy, altruism, and resistance to temptation, along with more antisocial behavior, including dating violence.[166]

In some patrilineal societies around the world, a young bride moves with the family of her husband. As a new girl in the home, she starts as having the lowest (or among the lowest) position in the family, is often subjected to violence and abuse, and is, in particular, strongly controlled by the parents-in-law: with the arrival of the daughter-in-law in the family, the mother-in-law's status is elevated and she now has (often for the first time in her life) substantial power over someone else, and "this family system itself tends to produce a cycle of violence in which the formerly abused bride becomes the abusing mother-in-law to her new daughter-in-law".[167] Amnesty International writes that, in Tajikistan, "it is almost an initiation ritual for the mother-in-law to put her daughter-in-law through the same torments she went through herself as a young wife."[168]

Biological and psychological theories

[edit]These factors include genetics and brain dysfunction and are studied by neuroscience.[169] Psychological theories focus on personality traits and mental characteristics of the offender. Personality traits include sudden bursts of anger, poor impulse control, and poor self-esteem. Various theories suggest that psychopathology is a factor, and that abuse experienced as a child leads some people to be more violent as adults. Correlation has been found between juvenile delinquency and domestic violence in adulthood.[170]

Studies have found a high incidence of psychopathology among domestic abusers.[171][172][173] For instance, some research suggests that about 80% of both court-referred and self-referred men in these domestic violence studies exhibited diagnosable psychopathology, typically personality disorders. "The estimate of personality disorders in the general population would be more in the 15–20% range ... As violence becomes more severe and chronic in the relationship, the likelihood of psychopathology in these men approaches 100%."[174]

Dutton has suggested a psychological profile of men who abuse their wives, arguing that they have borderline personalities that are developed early in life.[175][176] However, these psychological theories are disputed: Gelles suggests that psychological theories are limited, and points out that other researchers have found that only 10% (or less) fit this psychological profile. He argues that social factors are important, while personality traits, mental illness, or psychopathy are lesser factors.[177][178][179]

An evolutionary psychological explanation of domestic violence is that it represents male attempts to control female reproduction and ensure sexual exclusivity.[180] Violence related to extramarital relations is seen as justified in certain parts of the world. For instance, a survey in Diyarbakir, Turkey, found that, when asked the appropriate punishment for a woman who has committed adultery, 37% of respondents said she should be killed, while 21% said her nose or ears should be cut off.[181]

A 1997 report suggested that domestic abusers display higher than average mate retention behaviors, which are attempts to maintain the relationship with the partner. The report had stated that men, more than women, were using "resource display, submission and debasement, and intrasexual threats to retain their mates".[182]

Social theories

[edit]General

[edit]Social theories look at external factors in the offender's environment, such as family structure, stress, social learning, and includes rational choice theories.[183]

Social learning theory suggests that people learn from observing and modeling after others' behavior. With positive reinforcement, the behavior continues. If one observes violent behavior, one is more likely to imitate it. If there are no negative consequences (e.g. the victim accepts the violence, with submission), then the behavior will likely continue.[184][185][186]

Resource theory was suggested by William Goode in 1971.[187] Women who are most dependent on their spouse for economic well-being (e.g. homemakers/housewives, women with disability, women who are unemployed), and are the primary caregiver to their children, fear the increased financial burden if they leave their marriage. Dependency means that they have fewer options and few resources to help them cope with or change their spouse's behavior.[188]

Couples that share power equally experience a lower incidence of conflict, and when conflict does arise, are less likely to resort to violence. If one spouse desires control and power in the relationship, the spouse may resort to abuse.[189] This may include coercion and threats, intimidation, emotional abuse, economic abuse, isolation, making light of the situation and blaming the spouse, using children (threatening to take them away), and behaving as "master of the castle".[190][191]

Another report has stated that domestic abusers may be blinded by rage and therefore see themselves as the victim when it comes to domestically abusing their partner. Due to mainly negative emotions and difficulties in communications between partners, the abusers believe they have been wronged and therefore psychologically they make themselves be seen as the victim.[192]

Social stress

[edit]Stress may be increased when a person is living in a family situation, with increased pressures. Social stresses, due to inadequate finances or other such problems in a family may further increase tensions.[177] Violence is not always caused by stress, but may be one way that some people respond to stress.[193][194] Families and couples in poverty may be more likely to experience domestic violence, due to increased stress and conflicts about finances and other aspects.[195] Some speculate that poverty may hinder a man's ability to live up to his idea of successful manhood, thus he fears losing honor and respect. A theory suggests that when he is unable to economically support his wife, and maintain control, he may turn to misogyny, substance abuse, and crime as ways to express masculinity.[195]

Same-sex relationships may experience similar social stressors. Additionally, violence in same-sex relationships has been linked to internalized homophobia, which contributed to low self-esteem and anger in both the perpetrator and victim.[196] Internalized homophobia also appears to be a barrier in victims seeking help. Similarly, heterosexism can play a key role in domestic violence in the LGBT community. As a social ideology that implies "heterosexuality is normative, morally superior, and better than [homosexuality],"[196] heterosexism can hinder services and lead to an unhealthy self-image in sexual minorities. Heterosexism in legal and medical institutions can be seen in instances of discrimination, biases, and insensitivity toward sexual orientation. For example, as of 2006, seven states explicitly denied LGBT individuals the ability to apply for protective orders,[196] proliferating ideas of LGBT subjugation, which is tied to feelings of anger and powerlessness.

Power and control

[edit]

Power and control in abusive relationships is the way that abusers exert physical, sexual and other forms of abuse to gain control within relationships.[197]

A causalist view of domestic violence is that it is a strategy to gain or maintain power and control over the victim. This view is in alignment with Bancroft's cost-benefit theory that abuse rewards the perpetrator in ways other than, or in addition to, simply exercising power over his or her target(s). He cites evidence in support of his argument that, in most cases, abusers are quite capable of exercising control over themselves, but choose not to do so for various reasons.[198]

Sometimes, one person seeks complete power and control over their partner and uses different ways to achieve this, including resorting to physical violence. The perpetrator attempts to control all aspects of the victim's life, such as their social, personal, professional and financial decisions.[64]

Questions of power and control are integral to the widely utilized Duluth Domestic Abuse Intervention Project. They developed the Power and Control Wheel to illustrate this: it has power and control at the center, surrounded by spokes which represent techniques used. The titles of the spokes include coercion and threats, intimidation, emotional abuse, isolation, minimizing, denying and blaming, using children, economic abuse, and privilege.[199]

Critics of this model argue that it ignores research linking domestic violence to substance abuse and psychological problems.[200] Some modern research into the patterns in domestic violence has found that women are more likely to be physically abusive towards their partner in relationships in which only one partner is violent,[201][202] which draws the effectiveness of using concepts like male privilege to treat domestic violence into question. Some modern research into predictors of injury from domestic violence suggests that the strongest predictor of injury by domestic violence is participation in reciprocal domestic violence.[201]

Non-subordination theory

[edit]Non-subordination theory, sometimes called dominance theory, is an area of feminist legal theory that focuses on the power differential between men and women.[203] Non-subordination theory takes the position that society, and particularly men in society, use sex differences between men and women to perpetuate this power imbalance.[203] Unlike other topics within feminist legal theory, non-subordination theory focuses specifically on certain sexual behaviors, including control of women's sexuality, sexual harassment, pornography, and violence against women generally.[204] Catharine MacKinnon argues that non-subordination theory best addresses these particular issues because they affect almost exclusively women.[205] MacKinnon advocates for non-subordination theory over other theories, like formal equality, substantive equality, and difference theory, because sexual violence and other forms of violence against women are not a question of "sameness and difference", but rather are best viewed as more central inequalities for women.[205] Though non-subordination theory has been discussed at great length in evaluating various forms of sexual violence against women, it also serves as a basis for understanding domestic violence and why it occurs. Non-subordination theory tackles the issue of domestic violence as a subset of the broader problem of violence against women because victims are overwhelmingly female.[206]

Proponents of non-subordination theory propose several reasons why it works best to explain domestic violence. First, there are certain recurring patterns in domestic violence that indicate it is not the result of intense anger or arguments, but rather is a form of subordination.[207] This is evidenced in part by the fact that domestic violence victims are typically abused in a variety of situations and by a variety of means.[207] For example, victims are sometimes beaten after they have been sleeping or have been separated from the batterer, and often the abuse takes on a financial or emotional form in addition to physical abuse.[207] Supporters of non-subordination theory use these examples to dispel the notion that battering is always the result of heat of the moment anger or intense arguments occur.[207] Also, batterers often employ manipulative and deliberate tactics when abusing their victims, which can "range from searching for and destroying a treasured object of hers to striking her in areas of her body that do not show bruises (e.g. her scalp) or in areas where she would be embarrassed to show others her bruises."[207] These behaviors can be even more useful to a batterer when the batterer and the victim share children, because the batterer often controls the family's financial assets, making the victim less likely to leave if it would put her children at risk.[208]

Professor Martha Mahoney, of the University of Miami School of Law, also points to separation assault – a phenomenon where a batterer further assaults a victim who is attempting or has attempted to leave an abusive relationship – as additional evidence that DV is used to subordinate victims to their batterers.[209] A batterer's unwillingness to allow the victim to leave the relationship substantiates the idea that violence is being used to force the victim to continue to fulfill the batterer's wishes that she obey him.[209] Non-subordination theorists argue that all of these actions – the variety of abusive behaviors and settings, exploiting the victim's children, and assault upon separation – suggest a larger problem than merely an inability to properly manage anger, though anger may be a byproduct of these behaviors.[207] The purpose of these actions is to keep the victim, and sometimes the entire family, subordinate to the batterer, according to non-subordination theory.[209]

A second rationale for using non-subordination theory to explain domestic violence is that the frequency with which it occurs overpowers the idea that it is merely the result of a batterer's anger. Professor Mahoney explains that because of the sensationalism generated in media coverage of particularly horrific domestic violence cases, it is difficult for people to conceptualize how frequently domestic violence happens in society.[209] However, domestic violence is a regular occurrence experienced by up to one half of people in the US, and an overwhelming number of victims are female.[209] The sheer number of domestic violence victims in the US suggests that it is not merely the result of intimate partners who cannot control their anger.[209] Non-subordination theory contends that it is the batterer's desire to subordinate the victim, not his uncountainable anger, which explains the frequency of domestic violence.[209] Non-subordination theorists argue that other forms of feminist legal theory do not offer any explanation for the phenomenon of domestic violence generally or the frequency with which it occurs.[210]

Critics of non-subordination theory complain that it offers no solutions to the problems it points out. For example, proponents of non-subordination theory criticize certain approaches that have been taken to address domestic violence in the legal system, such as mandatory arrest or prosecution policies.[211] These policies take discretion away from law enforcement by forcing police officers to arrest suspected domestic violence offenders and prosecutors to prosecute those cases.[211] There is a lot of discourse surrounding mandatory arrest. Opponents argue that it undermines a victim's autonomy, discourages the empowerment of women by discounting other resources available and puts victims at more risk for domestic abuse. States that have implemented mandatory arrest laws have 60% higher homicide rates which have been shown to be consistent with the decline in reporting rates.[212] Advocates of these policies contend that the criminal justice system is sometimes the only way to reach victims of domestic violence, and that if an offender knows he will be arrested, it will deter future domestic violence conduct.[211] People who endorse non-subordination theory argue that these policies only serve to further subordinate women by forcing them to take a certain course of action, thus compounding the trauma they experienced during the abuse.[211] However, non-subordination theory itself offers no better or more appropriate solutions, which is why some scholars argue that other forms of feminist legal theory are more appropriate to address issues of domestic and sexual violence.[213]

Substance abuse

[edit]

Domestic violence typically co-occurs with alcohol abuse. Alcohol use has been reported as a factor by two-thirds of domestic abuse victims. Moderate drinkers are more frequently engaged in intimate violence than are light drinkers and abstainers; however, generally it is heavy or binge drinkers who are involved in the most chronic and serious forms of aggression. The odds, frequency, and severity of physical attacks are all positively correlated with alcohol use. In turn, violence decreases after behavioral marital alcoholism treatment.[214]

Possible link to animal abuse

[edit]There are studies providing evidence of a link between domestic violence and cruelty to animals. A large national survey by the Norwegian Centre for Violence and Traumatic Stress Studies found a "substantial overlap between companion animal abuse and child abuse" and that cruelty to animals "most frequently co-occurred with psychological abuse and less severe forms of physical child abuse," which "resonates with conceptualizations of domestic abuse as an ongoing pattern of psychological abuse and coercive control."[215]

Social influences

[edit]Cultural view

[edit]

How domestic violence is viewed varies from person to person, and from culture to culture, but in many places outside the West, the concept is very poorly understood. In some countries the concept is even widely accepted or completely suppressed. This is because in most of these countries the relation between the husband and wife is not considered one of equals, but instead one in which the wife must submit herself to the husband. This is codified in the laws of some countries – for example, in Yemen, marriage regulations state that a wife must obey her husband and must not leave home without his permission.[216]

According to Violence against Women in Families and Relationships, "globally, wife-beating is seen as justified in some circumstances by a majority of the population in various countries, most commonly in situations of actual or suspected infidelity by wives or their 'disobedience' toward a husband or partner."[217] These violent acts against a wife are often not considered a form of abuse by society (both men and women) but are considered to have been provoked by the behavior of the wife, who is seen as being at fault. In many places extreme acts such as honor killings are also approved by a high section of the society. In one survey, 33.4% of teenagers in Jordan's capital city, Amman, approved of honor killings. This survey was carried in the capital of Jordan, which is much more liberal than other parts of the country; the researchers said that "we would expect that in the more rural and traditional parts of Jordan, support for honor killings would be even higher".[218]

In a 2012 news story, The Washington Post reported, "The Reuters Trust Law group named India one of the worst countries in the world for women this year, partly because [domestic violence] there is often seen as deserved. A 2012 report by UNICEF found that 57 percent of Indian boys and 53 percent of girls between the ages of 15 and 19 think wife-beating is justified."[219]

In conservative cultures, a wife dressing in attire deemed insufficiently modest can suffer serious violence at the hands of her husband or relatives, with such violent responses seen as appropriate by most of the society: in a survey, 62.8% of women in Afghanistan said that a husband is justified in beating his wife if she wears inappropriate clothes.[220]

According to Antonia Parvanova, one of the difficulties of dealing legally with the issue of domestic violence is that men in many male-dominated societies do not understand that inflicting violence against their wives is against the law. She said, referring to a case that occurred in Bulgaria, "A husband was tried for severely beating his wife and when the judge asked him if he understood what he did and if he's sorry, the husband said 'But she's my wife'. He doesn't even understand that he has no right to beat her."[222] The UN Population Fund writes that:[223] "In some developing countries, practices that subjugate and harm women – such as wife-beating, killings in the name of honour, female genital mutilation/cutting and dowry deaths – are condoned as being part of the natural order of things".

Strong views among the population in certain societies that reconciliation is more appropriate than punishment in cases of domestic violence are also another cause of legal impunity; a study found that 64% of public officials in Colombia said that if it were in their hands to solve a case of intimate partner violence, the action they would take would be to encourage the parties to reconcile.[224]

Victim blaming is also prevalent in many societies, including in Western countries: a 2010 Eurobarometer poll found that 52% of respondents agreed with the assertion that the "provocative behaviour of women" was a cause of violence against women; with respondents in Cyprus, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta and Slovenia being most likely to agree with the assertion (more than 70% in each of these countries).[225][226][227]

Religion

[edit]There is controversy regarding the influence of religion on domestic violence. Judaism, Christianity and Islam have traditionally supported male-dominant households and "socially sanctioned violence against women has been persistent since ancient times."[228]

Views on the influence of Islam on domestic violence differ. While some authors[who?] argue that Islam is connected to violence against women, especially in the form of honor killings,[229] others, such as Tahira Shahid Khan, a professor specializing in women's issues at the Aga Khan University in Pakistan, argue that it is the domination of men and inferior status of women in society that lead to these acts, not the religion itself.[230][231] Public (such as through the media) and political discourse debating the relation between Islam, immigration, and violence against women is highly controversial in many Western countries.[232]

Among Christians, men and women who attend church more frequently are less likely to commit domestic violence against their partners.[233] The effect of church attendance is not caused by increased levels of social support and community integration, which are not significantly related to the perpetration of domestic violence. In addition, even when variations in psychological problems (namely depressive symptoms, low self-esteem, and alcoholism) are accounted for, the salutary effect of church attendance remains.[234] People who are theologically conservative are no more likely to commit domestic violence, however, highly conservative men are significantly more likely to commit domestic violence when their partners are much more liberal than them.[235]

Catholic teaching on divorce has led women to fear leaving abusive marriages. However, Catholic bishops specifically state that no person is obliged to remain within an abusive marriage.[236]

Medieval Jewish authorities differed on the subject of wife beating. Most rabbis living in Islamic lands allowed it as a tool of discipline, while those from Christian France and Germany generally saw it as justifying immediate divorce.[237]

Custom and tradition

[edit]

Local customs and traditions are often responsible for maintaining certain forms of domestic violence. Such customs and traditions include son preference (the desire of a family to have a boy and not a girl, which is strongly prevalent in parts of Asia), which can lead to abuse and neglect of girls by disappointed family members; child and forced marriages; dowry; the hierarchic caste system which stigmatizes lower castes and "untouchables", leading to discrimination and restricted opportunities of the females and thus making them more vulnerable to abuse; strict dress codes for women that may be enforced through violence by family members; strong requirement of female virginity before the wedding and violence related to non-conforming women and girls; taboos about menstruation leading to females being isolated and shunned during the time of menstruation; female genital mutilation (FGM); ideologies of marital conjugal rights to sex which justify marital rape; the importance given to family honor.[238][239][240]

A study reported in 2018 that in sub-saharan Africa 38% of women justified the abuse compared to Europe which had 29%, and South Asia having the highest number with 47% of women justifying the abuse.[241] These high rates could be due to the fact that in lower economically developed countries, women are subject to societal norms and are subject to tradition so therefore are to scared to go against that tradition as they would receive backlash[242] whereas in higher econmocially developed countries, women are more educated and therefore will not conform to those traditions which restrict their basic human rights.

According to a 2003 report by Human Rights Watch, "customs such as the payment of 'bride price' (payment made by a man to the family of a woman he wishes to marry), whereby a man essentially purchases his wife's sexual favors and reproductive capacity, underscore men's socially sanctioned entitlement to dictate the terms of sex, and to use force to do so."[243]

In recent years, there has been progress in the area of addressing customary practices that endanger women, with laws being enacted in several countries. The Inter-African Committee on Traditional Practices Affecting the Health of Women and Children is an NGO which works on changing social values, raising consciousness, and enacting laws against harmful traditions which affect the health of women and children in Africa. Laws were also enacted in some countries; for example the 2004 Criminal Code of Ethiopia has a chapter on harmful traditional practices – Chapter III – Crimes committed against life, person and health through harmful traditional practices.[244] In addition, the Council of Europe adopted the Istanbul Convention, which requires the states that ratify it to create and fully adjudicate laws against acts of violence previously condoned by traditional, culture, custom, in the name of honor, or to correct what is deemed unacceptable behavior.[245] The UN created the Handbook on effective police responses to violence against women to provide guidelines to address and manage violence through the creation of effective laws, law enforcement policies and practices and community activities to break down societal norms that condone violence, criminalize it and create effect support systems for survivors of violence.[246]

In cultures where the police and legal authorities have a reputation of corruption and abusive practices, victims of domestic violence are often reluctant to turn to formal help.[247]

Public support for domestic violence

[edit]Violence on women is sometimes justified by women themselves, for example in Mali 60% of women with no education, just over half of women with a primary education, and fewer than 40% of women with a secondary or higher education believe that husbands have the right to use violence for corrective reasons.[248]

Acceptance of domestic violence has decreased in some countries, for example in Nigeria where 62.4% of women supported domestic violence in 2003, 45.7% in 2008, and 37.1% in 2013.[249] However, in some cases the acceptance increased, for example in Zimbabwe where 53% of women justify wife-beating.[250]

In Nigeria, education, place of residence, wealth index, ethnic affiliation, religious affiliation, women's autonomy in household decision-making, and frequency of listening to the radio or watching television significantly influence women's opinions about domestic violence.[249] In the opinion of adolescents aged 15 to 19, 14% of boys in Kazakhstan but 9% of girls believed wife-beating is justified, and in Cambodia, 25% of boys and 42% of girls think it is justified.[251]

Relation to forced and child marriage

[edit]A forced marriage is a marriage where one or both participants are married without their freely given consent.[252] In many parts of the world, it is often difficult to draw a line between 'forced' and 'consensual' marriage: in many cultures (especially in South Asia, the Middle East and parts of Africa), marriages are prearranged, often as soon as a girl is born; the idea of a girl going against the wishes of her family and choosing herself her own future husband is not socially accepted – there is no need to use threats or violence to force the marriage, the future bride will submit because she simply has no other choice. As in the case of child marriage, the customs of dowry and bride price contribute to this phenomenon.[253] A child marriage is a marriage where one or both parties are younger than 18.[254]

Forced and child marriages are associated with a high rate of domestic violence.[13][254] These types of marriages are related to violence both in regard to the spousal violence perpetrated inside marriage, and in regard to the violence related to the customs and traditions of these marriage: violence and trafficking related to the payment of dowry and bride price, honor killings for refusing the marriage.[255][256][257][258]

The UN Population Fund states, "Despite near-universal commitments to end child marriage, one in three girls in developing countries (excluding China) will probably be married before they are 18. One out of nine girls will be married before their 15th birthday."[259] The UN Population Fund estimates, "Over 67 million women 20–24 year old in 2010 had been married as girls, half of which were in Asia, and one-fifth in Africa."[259] The UN Population Fund says that, "In the next decade 14.2 million girls under 18 will be married every year; this translates into 39,000 girls married each day and this will rise to an average of 15.1 million girls a year, starting in 2021 until 2030, if present trends continue."[259]

Legislation

[edit]Lack of adequate legislation which criminalizes domestic violence, or alternatively legislation which prohibits consensual behaviors, may hinder the progress in regard to reducing the incidence of domestic violence. Amnesty International's Secretary General has stated that: "It is unbelievable that in the twenty-first century some countries are condoning child marriage and marital rape while others are outlawing abortion, sex outside marriage and same-sex sexual activity – even punishable by death."[260] According to WHO, "one of the most common forms of violence against women is that performed by a husband or male partner." The WHO notes that such violence is often ignored because often "legal systems and cultural norms do not treat as a crime, but rather as a 'private' family matter, or a normal part of life."[52] The criminalization of adultery has been cited as inciting violence against women, as these prohibitions are often meant, in law or in practice, to control women's and not men's behavior; and are used to rationalize acts of violence against women.[261][262]

Many countries consider domestic violence legal or have not adopted measures meant to criminalize their occurrence,[263][264] especially in countries of Muslim majority, and among those countries, some consider the discipline of wives as a right of the husband, for example in Iraq.[265]

Individual versus family unit rights

[edit]According to High Commissioner for Human Rights Navi Pillay:[53]

Some have argued, and continue to argue, that family violence is placed outside the conceptual framework of international human rights. However, under international laws and standards, there is a clear State responsibility to uphold women's rights and ensure freedom from discrimination, which includes the responsibility to prevent, protect and provide redress – regardless of sex, and regardless of a person's status in the family.

The way the individual rights of a family member versus the rights of the family as a unit are balanced vary significantly in different societies. This may influence the degree to which a government may be willing to investigate family incidents.[266] In some cultures, individual members of the family are expected to sacrifice almost completely their own interests in favor of the interests of the family as a whole. What is viewed as an undue expression of personal autonomy is condemned as unacceptable. In these cultures the family predominates over the individual, and where this interacts with cultures of honor, individualistic choice that may damage the family reputation in the community may result in extreme punishment, such as honor killings.[267]

Terminology

[edit]In Australia, domestic violence refers to occurrences of violence in domestic settings between people in intimate relationships.[268] The term can be altered by each state's legislation and can broaden the spectrum of domestic violence, such as in Victoria, where familial relationships and witnessing any type of violence in the family is defined as a family violence incident.[269] In the Nordic countries the term violence in close relations is used in legal and policy contexts.[270]

Knowledge of legal rights

[edit]Domestic violence occurs in immigrant communities, and often there is little awareness in these communities of the laws and policies of the host country. A study among first-generation South Asians in the UK found that they had little knowledge about what constituted criminal behavior under the English law. The researchers found that "there was certainly no awareness that there could be rape within a marriage".[271][272] A study in Australia showed that among the immigrant women sampled who were abused by partners and did not report it, 16.7% did not know domestic violence was illegal, while 18.8% did not know that they could get protection.[273]

Ability to leave

[edit]The ability of victims of domestic violence to leave the relationship is crucial for preventing further abuse. In traditional communities, divorced women often feel rejected and ostracized. In order to avoid this stigma, many women prefer to remain in the marriage and endure the abuse.[274]

Discriminatory marriage and divorce laws can also play a role in the proliferation of the practice.[275][276] According to Rashida Manjoo, a UN special rapporteur on violence against women:

In many countries a woman's access to property hinges on her relationship to a man. When she separates from her husband or when he dies, she risks losing her home, land, household goods and other property. Failure to ensure equal property rights upon separation or divorce discourages women from leaving violent marriages, as women may be forced to choose between violence at home and destitution in the street.[277]

The legal inability to obtain a divorce is also a factor in the proliferation of domestic violence.[278] In some cultures where marriages are arranged between families, a woman who attempts a separation or divorce without the consent of her husband and extended family or relatives may risk being subjected to honor-based violence.[279][267]

The custom of bride price also makes leaving a marriage more difficult: if a wife wants to leave, the husband may demand back the bride price from her family.[280][281][282]

In advanced nations[clarification needed] like the UK, Domestic violence victims may have difficulties getting alternative housing which can force them to stay in the abusive relationship.[283]

Many domestic violence victims delay leaving the abuser because they have pets and are afraid of what will happen to the pets if they leave. Safehouses need to be more accepting of pets, and many refuse to accept pets.[284]

Immigration policies

[edit]In some countries, the immigration policy is tied to whether the person desiring citizenship is married to his/her sponsor. This can lead to persons being trapped in violent relations – such persons may risk deportation if they attempt to separate (they may be accused of having entered into a sham marriage).[285][286][287][288] Often the women come from cultures where they will suffer disgrace from their families if they abandon their marriage and return home, and so they prefer to stay married, therefore remaining locked in a cycle of abuse.[289]

COVID-19 pandemic

[edit]Some studies have found some association between the COVID-19 pandemic and an upsurge in the rate of domestic violence.[290] The coping mechanisms adopted by individuals during the state of isolation has been implicated in the increase around the globe.[291] Some of the implications of this restriction period are financial distress, induced stress, frustration, and a resulting quest for coping mechanisms, which could trigger violence.[292]

In major cities in Nigeria, such as Lagos, Abuja; in India, and in Hubei province in China, there was a recorded increase in the level of intimate partner violence.[293][294]

An increase in the prevalence of domestic violence during the restrictions has been reported in many countries including the US, China, and many European countries. In India, a 131% increase in domestic violence in areas that had strict lockdown measures was recorded.[295][296]

Effects

[edit]Physical

[edit]

Bruises, broken bones, head injuries, lacerations, and internal bleeding are some of the acute effects of a domestic violence incident that require medical attention and hospitalization.[297] Some chronic health conditions that have been linked to victims of domestic violence are arthritis, irritable bowel syndrome, chronic pain, pelvic pain, ulcers, and migraines.[298] Victims who are pregnant during a domestic violence relationship experience greater risk of miscarriage, pre-term labor, and injury to or death of the fetus.[297]

New research illustrates that there are strong associations between exposure to domestic violence and abuse in all their forms and higher rates of many chronic conditions.[299] The strongest evidence comes from the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study which shows correlations between exposure to abuse or neglect and higher rates in adulthood of chronic conditions, high-risk health behaviors and shortened life span.[300] Evidence of the association between physical health and violence against women has been accumulating since the early 1990s.[301]

HIV/AIDS

[edit]

| No data <0.10 0.10–0.5 0.5–1 | 1–5 5–15 15–50 |

The WHO has stated that women in abusive relations are at significantly higher risk of HIV/AIDS. WHO states that women in violent relationships have difficulty negotiating safer sex with their partners, are often forced to have sex, and find it difficult to ask for appropriate testing when they think they may be infected with HIV.[303] A decade of cross-sectional research from Rwanda, Tanzania, South Africa, and India, has consistently found women who have experienced partner violence to be more likely to be infected with HIV.[304] The WHO stated that:[303]

There is a compelling case to end intimate partner violence both in its own right as well as to reduce women and girls' vulnerability to HIV/AIDS. The evidence on the linkages between violence against women and HIV/AIDS highlights that there are direct and indirect mechanisms by which the two interact.

Same-sex relationships are similarly affected by the HIV/AIDS status in domestic violence. Research by Heintz and Melendez found that same-sex individuals may have difficulty breaching the topic of safe sex for reasons such as "decreased perception of control over sex, fear of violence, and unequal power distributions..."[305] Of those who reported violence in the study, about 50% reported forced sexual experiences, of which only half reported the use of safe sex measures. Barriers to safer sex included fear of abuse, and deception in safe-sex practices. Heintz and Melendez's research ultimately concluded that sexual assault/abuse in same-sex relationships provides a major concern for HIV/AIDS infection as it decreases instances of safe-sex. Furthermore, these incidents create additional fear and stigma surrounding safe-sex conversations and knowing one's STD status.[305]

Psychological

[edit]Among victims who are still living with their perpetrators high amounts of stress, fear, and anxiety are commonly reported. Depression is also common, as victims are made to feel guilty for 'provoking' the abuse and are frequently subjected to intense criticism. It is reported that 60% of victims meet the diagnostic criteria for depression, either during or after termination of the relationship, and have a greatly increased risk of suicide. Those who are battered either emotionally or physically often are also depressed because of a feeling of worthlessness. These feelings often persist long-term and it is suggested that many receive therapy for it because of the heightened risk of suicide and other traumatic symptoms.[306]

In addition to depression, victims of domestic violence also commonly experience long-term anxiety and panic, and are likely to meet the diagnostic criteria for generalized anxiety disorder and panic disorder. The most commonly referenced psychological effect of domestic violence is PTSD, which is characterized by flashbacks, intrusive images, an exaggerated startle response, nightmares, and avoidance of triggers that are associated with the abuse.[307] Studies have indicated that it is important to consider the effect of domestic violence and its psychophysiologic sequelae on women who are mothers of infants and young children. Several studies have shown that maternal interpersonal violence-related PTSD can, despite a traumatized mother's best efforts, interfere with their child's response to the domestic violence and other traumatic events.[15][308]

Financial

[edit]A 2024 study in the Quarterly Journal of Economics, which used Finnish administrative data with unique identifiers for perpetrators and victims of domestic violence, found that "women who begin relationships with (eventually) physically abusive men suffer large and significant earnings and employment falls immediately upon cohabiting with the abusive partner."[309] This contributes to economic dependence on the abuser that makes it hard for the victim to exit the relationship.[309]

Once victims leave their perpetrators, they can be stunned by the reality of the extent to which the abuse has taken away their autonomy. Due to economic abuse and isolation, the victim usually has very little money of their own and few people on whom they can rely when seeking help. This has been shown to be one of the greatest obstacles facing victims of domestic violence, and the strongest factor that can discourage them from leaving their perpetrators.[310]

In addition to lacking financial resources, victims of domestic violence often lack specialized skills, education, and training that are necessary to find gainful employment, and also may have several children to support. In 2003, thirty-six major US cities cited domestic violence as one of the primary causes of homelessness in their areas.[311] It has also been reported that one out of every three women are homeless due to having left a domestic violence relationship. If a victim is able to secure rental housing, it is likely that her apartment complex will have zero tolerance policies for crime; these policies can cause them to face eviction even if they are the victim (not the perpetrator) of violence.[311] While the number of women's shelters and community resources available to domestic violence victims has grown tremendously, these agencies often have few employees and hundreds of victims seeking assistance which causes many victims to remain without the assistance they need.[310]

Women and children experiencing domestic violence undergo occupational apartheid; they are typically denied access to desired occupations.[312] Abusive partners may limit occupations and create an occupationally void environment which reinforces feelings of low self-worth and poor self-efficacy in their ability to satisfactorily perform everyday tasks.[312] In addition, work is impacted by functional losses, an inability to maintain necessary employment skills, and an inability to function within the work place. Often, the victims are very isolated from other relationships as well such as having few to no friends, this is another method of control for the abuser.[313]

On children

[edit]

There has been an increase in acknowledgment that a child who is exposed to domestic abuse during their upbringing will suffer developmental and psychological damage.[314] During the mid-1990s, the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study found that children who were exposed to domestic violence and other forms of abuse had a higher risk of developing mental and physical health problems.[315] Because of the awareness of domestic violence that some children have to face, it also generally impacts how the child develops emotionally, socially, behaviorally and cognitively.[316]

Some emotional and behavioral problems that can result due to domestic violence include increased aggressiveness, anxiety, and changes in how a child socializes with friends, family, and authorities.[314] Depression, emotional insecurity, and mental health disorders can follow due to traumatic experiences.[317] Problems with attitude and cognition in schools can start developing, along with a lack of skills such as problem-solving.[314] Correlation has been found between the experience of abuse and neglect in childhood and perpetrating domestic violence and sexual abuse in adulthood.[318]

Additionally, in some cases the abuser will purposely abuse the mother or father[319] in front of the child to cause a ripple effect, hurting two victims simultaneously.[319] Children may intervene when they witness severe violence against a parent, which can place a child at greater risk for injury or death.[320] It has been found that children who witness mother-assault are more likely to exhibit symptoms of PTSD.[321] Consequences to these children are likely to be more severe if their assaulted mother develops PTSD and does not seek treatment due to her difficulty in assisting her child with processing his or her own experience of witnessing the domestic violence.[322]

On responders

[edit]An analysis in the US showed that 106 of the 771 officer killings between 1996 and 2009 occurred during domestic violence interventions.[323] Of these, 51% were defined as unprovoked or as ambushes, taking place before officers had made contact with suspects. Another 40% occurred after contact and the remainder took place during tactical situations (those involving hostages and attempts to overcome barricades).[323] The FBI's LEOKA system grouped officer domestic violence response deaths into the category of disturbances, along with "bar fights, gang matters, and persons brandishing weapons", which may have given rise to a misperception of the risks involved.[323][324]

Due to the gravity and intensity of hearing victims' stories of abuse, professionals (social workers, police, counselors, therapists, advocates, medical professionals) are at risk themselves for secondary or vicarious trauma, which causes the responder to experience trauma symptoms similar to the original victim after hearing about the victim's experiences with abuse.[325] Research has demonstrated that professionals who experience vicarious trauma show signs of an exaggerated startle response, hypervigilance, nightmares, and intrusive thoughts although they have not experienced a trauma personally and do not qualify for a clinical diagnosis of PTSD.[325]

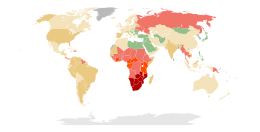

Demographics

[edit]Domestic violence occurs across the world, in various cultures,[326] and affects people of all economic statuses;[21] however, indicators of lower socioeconomic status (such as unemployment and low income) have been shown to be risk factors for higher levels of domestic violence in several studies.[327] Worldwide, domestic violence against women is most common in Central Sub-Saharan Africa, Western Sub-Saharan Africa, Andean Latin America, South Asia, Eastern Sub-Saharan Africa, Northern Africa and the Middle East. The lowest prevalence of domestic violence against women is found in Western Europe, East Asia and North America.[328] In diverse countries there are often ethnic and racial differences in victimization and use of services. In the United States, White women and Black women were more likely to be victims of domestic violence assault than were Asian or Hispanic women, according to a 2012 study.[329]Non-Hispanic White women are two times more likely to use domestic violence services as compared with Hispanic women.[330] In the United Kingdom there is also much research to suggest that income is closely associated with domestic violence, as domestic violence is consistently more common in families with low income.[331] The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that in the United States, 41% of women and 26% of men experience domestic violence within their lifetime.[332]

In the United Kingdom, statistics show that 1 in 3 victims of domestic abuse are male this figure comes from the office of National Statistics and that 1 in 7 men and 1 in 4 women will be a victim at some point in their lifetime. [333]

Underreporting