Членистоногие

| Членистоногие Временный диапазон: Самый ранний кембрий ( Фортуниан ) -

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Subkingdom: | Eumetazoa |

| Clade: | ParaHoxozoa |

| Clade: | Bilateria |

| Clade: | Nephrozoa |

| (unranked): | Protostomia |

| Superphylum: | Ecdysozoa |

| (unranked): | Panarthropoda |

| (unranked): | Tactopoda |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda Gravenhorst, 1843[1][2] |

| Subphyla, unplaced genera, and classes | |

|

| |

| Diversity | |

| around 1,170,000 species. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Condylipoda Latreille, 1802 | |

Arthropods ( / ˈ ɑːr θ r ə p ɒ d / ARTH -rə-pod ) [ 22 ] беспозвоночные в филоме членистоногих . Они обладают экзоскелетом с кутикулой из хитина , часто минерализованной с карбонатом кальция , телом с дифференцированными ( метамеричными ) сегментами и парными соединенными придатками . Чтобы продолжать расти, они должны пройти через стадии линьки , процесс, посредством которого они проливают свой экзоскелет , чтобы раскрыть новый. Они образуют чрезвычайно разнообразную группу до десяти миллионов видов.

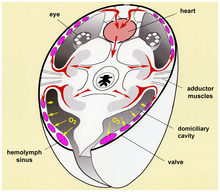

Гемолимфа является аналогом крови для большинства членистоногих. Членистоногие имеют открытую систему кровообращения с полостью тела, называемой гемоцелью, через которое гемолимфа циркулирует внутренние органы . Как и их экстерьеры, внутренние органы членистоногих обычно построены из повторных сегментов. У них есть лестница, похожие на нервные системы , с парными вентральными нервными шнурами, проходящими по всем сегментам и образуют парные ганглии в каждом сегменте. Их головы образуются путем слияния различного количества сегментов, а их мозг образуется путем слияния ганглиев этих сегментов и окружения пищевода . Респираторные подбоя и экскреторные системы членистоногих варьируются в зависимости от их окружающей среды, как и от , к которому они принадлежат.

Arthropods use combinations of compound eyes and pigment-pit ocelli for vision. In most species, the ocelli can only detect the direction from which light is coming, and the compound eyes are the main source of information, but the main eyes of spiders are ocelli that can form images and, in a few cases, can swivel to track prey. Arthropods also have a wide range of chemical and mechanical sensors, mostly based on modifications of the many bristles known as setae that project through their cuticles. Similarly, their reproduction and development are varied; all terrestrial species use internal fertilization, but this is sometimes by indirect transfer of the sperm via an appendage or the ground, rather than by direct injection. Aquatic species use either internal or external fertilization. Almost all arthropods lay eggs, with many species giving birth to live young after the eggs have hatched inside the mother; but a few are genuinely viviparous, such as aphids. Arthropod hatchlings vary from miniature adults to grubs and caterpillars that lack jointed limbs and eventually undergo a total metamorphosis to produce the adult form. The level of maternal care for hatchlings varies from nonexistent to the prolonged care provided by social insects.

The evolutionary ancestry of arthropods dates back to the Cambrian period. The group is generally regarded as monophyletic, and many analyses support the placement of arthropods with cycloneuralians (or their constituent clades) in a superphylum Ecdysozoa. Overall, however, the basal relationships of animals are not yet well resolved. Likewise, the relationships between various arthropod groups are still actively debated. Today, arthropods contribute to the human food supply both directly as food, and more importantly, indirectly as pollinators of crops. Some species are known to spread severe disease to humans, livestock, and crops.

Etymology

[edit]The word arthropod comes from the Greek ἄρθρον árthron 'joint', and πούς pous (gen. ποδός podos) 'foot' or 'leg', which together mean "jointed leg",[23] with the word "arthropodes" initially used in anatomical descriptions by Barthélemy Charles Joseph Dumortier published in 1832.[1] The designation "Arthropoda" appears to have been first used in 1843 by the German zoologist Johann Ludwig Christian Gravenhorst (1777–1857).[24][1] The origin of the name has been the subject of considerable confusion, with credit often given erroneously to Pierre André Latreille or Karl Theodor Ernst von Siebold instead, among various others.[1]

Terrestrial arthropods are often called bugs.[Note 1] The term is also occasionally extended to colloquial names for freshwater or marine crustaceans (e.g., Balmain bug, Moreton Bay bug, mudbug) and used by physicians and bacteriologists for disease-causing germs (e.g., superbugs),[27] but entomologists reserve this term for a narrow category of "true bugs", insects of the order Hemiptera.[27]

Description

[edit]Arthropods are invertebrates with segmented bodies and jointed limbs.[28] The exoskeleton or cuticles consists of chitin, a polymer of N-Acetylglucosamine.[29] The cuticle of many crustaceans, beetle mites, the clades Penetini and Archaeoglenini inside the beetle subfamily Phrenapatinae,[30] and millipedes (except for bristly millipedes) is also biomineralized with calcium carbonate. Calcification of the endosternite, an internal structure used for muscle attachments, also occur in some opiliones,[31] and the pupal cuticle of the fly Bactrocera dorsalis contains calcium phosphate.[32]

Diversity

[edit]

Arthropoda is the largest animal phylum with the estimates of the number of arthropod species varying from 1,170,000 to 5 to 10 million and accounting for over 80 percent of all known living animal species.[33][34] One arthropod sub-group, the insects, includes more described species than any other taxonomic class.[35] The total number of species remains difficult to determine. This is due to the census modeling assumptions projected onto other regions in order to scale up from counts at specific locations applied to the whole world. A study in 1992 estimated that there were 500,000 species of animals and plants in Costa Rica alone, of which 365,000 were arthropods.[35]

They are important members of marine, freshwater, land and air ecosystems and one of only two major animal groups that have adapted to life in dry environments; the other is amniotes, whose living members are reptiles, birds and mammals.[36] Both the smallest and largest arthropods are crustaceans. The smallest belong to the class Tantulocarida, some of which are less than 100 micrometres (0.0039 in) long.[37] The largest are species in the class Malacostraca, with the legs of the Japanese spider crab potentially spanning up to 4 metres (13 ft)[38] and the American lobster reaching weights over 20 kg (44 lbs).

Segmentation

[edit]

The embryos of all arthropods are segmented, built from a series of repeated modules. The last common ancestor of living arthropods probably consisted of a series of undifferentiated segments, each with a pair of appendages that functioned as limbs. However, all known living and fossil arthropods have grouped segments into tagmata in which segments and their limbs are specialized in various ways.[36]

The three-part appearance of many insect bodies and the two-part appearance of spiders is a result of this grouping.[40] There are no external signs of segmentation in mites.[36] Arthropods also have two body elements that are not part of this serially repeated pattern of segments, an ocular somite at the front, where the mouth and eyes originated,[36][41] and a telson at the rear, behind the anus.

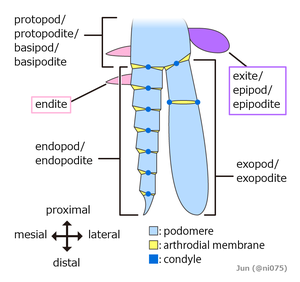

Originally it seems that each appendage-bearing segment had two separate pairs of appendages: an upper, unsegmented exite and a lower, segmented endopod. These would later fuse into a single pair of biramous appendages united by a basal segment (protopod or basipod), with the upper branch acting as a gill while the lower branch was used for locomotion.[42][43][39] The appendages of most crustaceans and some extinct taxa such as trilobites have another segmented branch known as exopods, but whether these structures have a single origin remain controversial.[44][45][39] In some segments of all known arthropods the appendages have been modified, for example to form gills, mouth-parts, antennae for collecting information,[40] or claws for grasping;[46] arthropods are "like Swiss Army knives, each equipped with a unique set of specialized tools."[36] In many arthropods, appendages have vanished from some regions of the body; it is particularly common for abdominal appendages to have disappeared or be highly modified.[36]

The most conspicuous specialization of segments is in the head. The four major groups of arthropods – Chelicerata (sea spiders, horseshoe crabs and arachnids), Myriapoda (symphylans, pauropods, millipedes and centipedes), Pancrustacea (oligostracans, copepods, malacostracans, branchiopods, hexapods, etc.), and the extinct Trilobita – have heads formed of various combinations of segments, with appendages that are missing or specialized in different ways.[36] Despite myriapods and hexapods both having similar head combinations, hexapods are deeply nested within crustacea while myriapods are not, so these traits are believed to have evolved separately. In addition, some extinct arthropods, such as Marrella, belong to none of these groups, as their heads are formed by their own particular combinations of segments and specialized appendages.[48]

Working out the evolutionary stages by which all these different combinations could have appeared is so difficult that it has long been known as "The arthropod head problem".[49] In 1960, R. E. Snodgrass even hoped it would not be solved, as he found trying to work out solutions to be fun.[Note 2]

Exoskeleton

[edit]

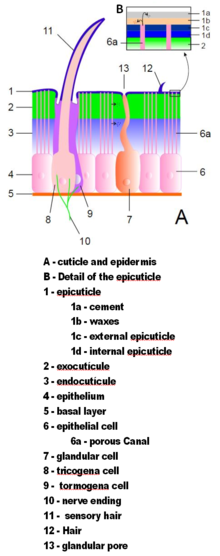

Arthropod exoskeletons are made of cuticle, a non-cellular material secreted by the epidermis.[36] Their cuticles vary in the details of their structure, but generally consist of three main layers: the epicuticle, a thin outer waxy coat that moisture-proofs the other layers and gives them some protection; the exocuticle, which consists of chitin and chemically hardened proteins; and the endocuticle, which consists of chitin and unhardened proteins. The exocuticle and endocuticle together are known as the procuticle.[51] Each body segment and limb section is encased in hardened cuticle. The joints between body segments and between limb sections are covered by flexible cuticle.[36]

The exoskeletons of most aquatic crustaceans are biomineralized with calcium carbonate extracted from the water. Some terrestrial crustaceans have developed means of storing the mineral, since on land they cannot rely on a steady supply of dissolved calcium carbonate.[52] Biomineralization generally affects the exocuticle and the outer part of the endocuticle.[51] Two recent hypotheses about the evolution of biomineralization in arthropods and other groups of animals propose that it provides tougher defensive armor,[53] and that it allows animals to grow larger and stronger by providing more rigid skeletons;[54] and in either case a mineral-organic composite exoskeleton is cheaper to build than an all-organic one of comparable strength.[54][55]

The cuticle may have setae (bristles) growing from special cells in the epidermis. Setae are as varied in form and function as appendages. For example, they are often used as sensors to detect air or water currents, or contact with objects; aquatic arthropods use feather-like setae to increase the surface area of swimming appendages and to filter food particles out of water; aquatic insects, which are air-breathers, use thick felt-like coats of setae to trap air, extending the time they can spend under water; heavy, rigid setae serve as defensive spines.[36]

Although all arthropods use muscles attached to the inside of the exoskeleton to flex their limbs, some still use hydraulic pressure to extend them, a system inherited from their pre-arthropod ancestors;[56] for example, all spiders extend their legs hydraulically and can generate pressures up to eight times their resting level.[57]

Moulting

[edit]

The exoskeleton cannot stretch and thus restricts growth. Arthropods, therefore, replace their exoskeletons by undergoing ecdysis (moulting), or shedding the old exoskeleton, the exuviae, after growing a new one that is not yet hardened. Moulting cycles run nearly continuously until an arthropod reaches full size. The developmental stages between each moult (ecdysis) until sexual maturity is reached is called an instar. Differences between instars can often be seen in altered body proportions, colors, patterns, changes in the number of body segments or head width. After moulting, i.e. shedding their exoskeleton, the juvenile arthropods continue in their life cycle until they either pupate or moult again.[58]

In the initial phase of moulting, the animal stops feeding and its epidermis releases moulting fluid, a mixture of enzymes that digests the endocuticle and thus detaches the old cuticle. This phase begins when the epidermis has secreted a new epicuticle to protect it from the enzymes, and the epidermis secretes the new exocuticle while the old cuticle is detaching. When this stage is complete, the animal makes its body swell by taking in a large quantity of water or air, and this makes the old cuticle split along predefined weaknesses where the old exocuticle was thinnest. It commonly takes several minutes for the animal to struggle out of the old cuticle. At this point, the new one is wrinkled and so soft that the animal cannot support itself and finds it very difficult to move, and the new endocuticle has not yet formed. The animal continues to pump itself up to stretch the new cuticle as much as possible, then hardens the new exocuticle and eliminates the excess air or water. By the end of this phase, the new endocuticle has formed. Many arthropods then eat the discarded cuticle to reclaim its materials.[58]

Because arthropods are unprotected and nearly immobilized until the new cuticle has hardened, they are in danger both of being trapped in the old cuticle and of being attacked by predators. Moulting may be responsible for 80 to 90% of all arthropod deaths.[58]

Internal organs

[edit]Arthropod bodies are also segmented internally, and the nervous, muscular, circulatory, and excretory systems have repeated components.[36] Arthropods come from a lineage of animals that have a coelom, a membrane-lined cavity between the gut and the body wall that accommodates the internal organs. The strong, segmented limbs of arthropods eliminate the need for one of the coelom's main ancestral functions, as a hydrostatic skeleton, which muscles compress in order to change the animal's shape and thus enable it to move. Hence the coelom of the arthropod is reduced to small areas around the reproductive and excretory systems. Its place is largely taken by a hemocoel, a cavity that runs most of the length of the body and through which blood flows.[59]

Respiration and circulation

[edit]

Arthropods have open circulatory systems. Most have a few short, open-ended arteries. In chelicerates and crustaceans, the blood carries oxygen to the tissues, while hexapods use a separate system of tracheae. Many crustaceans and a few chelicerates and tracheates use respiratory pigments to assist oxygen transport. The most common respiratory pigment in arthropods is copper-based hemocyanin; this is used by many crustaceans and a few centipedes. A few crustaceans and insects use iron-based hemoglobin, the respiratory pigment used by vertebrates. As with other invertebrates, the respiratory pigments of those arthropods that have them are generally dissolved in the blood and rarely enclosed in corpuscles as they are in vertebrates.[59]

The heart is a muscular tube that runs just under the back and for most of the length of the hemocoel. It contracts in ripples that run from rear to front, pushing blood forwards. Sections not being squeezed by the heart muscle are expanded either by elastic ligaments or by small muscles, in either case connecting the heart to the body wall. Along the heart run a series of paired ostia, non-return valves that allow blood to enter the heart but prevent it from leaving before it reaches the front.[59]

Arthropods have a wide variety of respiratory systems. Small species often do not have any, since their high ratio of surface area to volume enables simple diffusion through the body surface to supply enough oxygen. Crustacea usually have gills that are modified appendages. Many arachnids have book lungs.[60] Tracheae, systems of branching tunnels that run from the openings in the body walls, deliver oxygen directly to individual cells in many insects, myriapods and arachnids.[61]

Nervous system

[edit]

Living arthropods have paired main nerve cords running along their bodies below the gut, and in each segment the cords form a pair of ganglia from which sensory and motor nerves run to other parts of the segment. Although the pairs of ganglia in each segment often appear physically fused, they are connected by commissures (relatively large bundles of nerves), which give arthropod nervous systems a characteristic ladder-like appearance. The brain is in the head, encircling and mainly above the esophagus. It consists of the fused ganglia of the acron and one or two of the foremost segments that form the head – a total of three pairs of ganglia in most arthropods, but only two in chelicerates, which do not have antennae or the ganglion connected to them. The ganglia of other head segments are often close to the brain and function as part of it. In insects these other head ganglia combine into a pair of subesophageal ganglia, under and behind the esophagus. Spiders take this process a step further, as all the segmental ganglia are incorporated into the subesophageal ganglia, which occupy most of the space in the cephalothorax (front "super-segment").[62]

Excretory system

[edit]There are two different types of arthropod excretory systems. In aquatic arthropods, the end-product of biochemical reactions that metabolise nitrogen is ammonia, which is so toxic that it needs to be diluted as much as possible with water. The ammonia is then eliminated via any permeable membrane, mainly through the gills.[60] All crustaceans use this system, and its high consumption of water may be responsible for the relative lack of success of crustaceans as land animals.[63] Various groups of terrestrial arthropods have independently developed a different system: the end-product of nitrogen metabolism is uric acid, which can be excreted as dry material; the Malpighian tubule system filters the uric acid and other nitrogenous waste out of the blood in the hemocoel, and dumps these materials into the hindgut, from which they are expelled as feces.[63] Most aquatic arthropods and some terrestrial ones also have organs called nephridia ("little kidneys"), which extract other wastes for excretion as urine.[63]

Senses

[edit]

The stiff cuticles of arthropods would block out information about the outside world, except that they are penetrated by many sensors or connections from sensors to the nervous system. In fact, arthropods have modified their cuticles into elaborate arrays of sensors. Various touch sensors, mostly setae, respond to different levels of force, from strong contact to very weak air currents. Chemical sensors provide equivalents of taste and smell, often by means of setae. Pressure sensors often take the form of membranes that function as eardrums, but are connected directly to nerves rather than to auditory ossicles. The antennae of most hexapods include sensor packages that monitor humidity, moisture and temperature.[64]

Most arthropods lack balance and acceleration sensors, and rely on their eyes to tell them which way is up. The self-righting behavior of cockroaches is triggered when pressure sensors on the underside of the feet report no pressure. However, many malacostracan crustaceans have statocysts, which provide the same sort of information as the balance and motion sensors of the vertebrate inner ear.[64]

The proprioceptors of arthropods, sensors that report the force exerted by muscles and the degree of bending in the body and joints, are well understood. However, little is known about what other internal sensors arthropods may have.[64]

Optical

[edit]

Most arthropods have sophisticated visual systems that include one or more usually both of compound eyes and pigment-cup ocelli ("little eyes"). In most cases ocelli are only capable of detecting the direction from which light is coming, using the shadow cast by the walls of the cup. However, the main eyes of spiders are pigment-cup ocelli that are capable of forming images,[64] and those of jumping spiders can rotate to track prey.[65]

Compound eyes consist of fifteen to several thousand independent ommatidia, columns that are usually hexagonal in cross section. Each ommatidium is an independent sensor, with its own light-sensitive cells and often with its own lens and cornea.[64] Compound eyes have a wide field of view, and can detect fast movement and, in some cases, the polarization of light.[66] On the other hand, the relatively large size of ommatidia makes the images rather coarse, and compound eyes are shorter-sighted than those of birds and mammals – although this is not a severe disadvantage, as objects and events within 20 cm (8 in) are most important to most arthropods.[64] Several arthropods have color vision, and that of some insects has been studied in detail; for example, the ommatidia of bees contain receptors for both green and ultra-violet.[64]

Olfaction

[edit]Reproduction and development

[edit]A few arthropods, such as barnacles, are hermaphroditic, that is, each can have the organs of both sexes. However, individuals of most species remain of one sex their entire lives.[67] A few species of insects and crustaceans can reproduce by parthenogenesis, especially if conditions favor a "population explosion". However, most arthropods rely on sexual reproduction, and parthenogenetic species often revert to sexual reproduction when conditions become less favorable.[68] The ability to undergo meiosis is widespread among arthropods including both those that reproduce sexually and those that reproduce parthenogenetically.[69] Although meiosis is a major characteristic of arthropods, understanding of its fundamental adaptive benefit has long been regarded as an unresolved problem,[70] that appears to have remained unsettled.

Aquatic arthropods may breed by external fertilization, as for example horseshoe crabs do,[71] or by internal fertilization, where the ova remain in the female's body and the sperm must somehow be inserted. All known terrestrial arthropods use internal fertilization. Opiliones (harvestmen), millipedes, and some crustaceans use modified appendages such as gonopods or penises to transfer the sperm directly to the female. However, most male terrestrial arthropods produce spermatophores, waterproof packets of sperm, which the females take into their bodies. A few such species rely on females to find spermatophores that have already been deposited on the ground, but in most cases males only deposit spermatophores when complex courtship rituals look likely to be successful.[67]

Most arthropods lay eggs,[67] but scorpions are ovoviviparous: they produce live young after the eggs have hatched inside the mother, and are noted for prolonged maternal care.[72] Newly born arthropods have diverse forms, and insects alone cover the range of extremes. Some hatch as apparently miniature adults (direct development), and in some cases, such as silverfish, the hatchlings do not feed and may be helpless until after their first moult. Many insects hatch as grubs or caterpillars, which do not have segmented limbs or hardened cuticles, and metamorphose into adult forms by entering an inactive phase in which the larval tissues are broken down and re-used to build the adult body.[73] Dragonfly larvae have the typical cuticles and jointed limbs of arthropods but are flightless water-breathers with extendable jaws.[74] Crustaceans commonly hatch as tiny nauplius larvae that have only three segments and pairs of appendages.[67]

Evolutionary history

[edit]Last common ancestor

[edit]Based on the distribution of shared plesiomorphic features in extant and fossil taxa, the last common ancestor of all arthropods is inferred to have been as a modular organism with each module covered by its own sclerite (armor plate) and bearing a pair of biramous limbs.[75] However, whether the ancestral limb was uniramous or biramous is far from a settled debate. This Ur-arthropod had a ventral mouth, pre-oral antennae and dorsal eyes at the front of the body. It was assumed to have been a non-discriminatory sediment feeder, processing whatever sediment came its way for food,[75] but fossil findings hint that the last common ancestor of both arthropods and Priapulida shared the same specialized mouth apparatus; a circular mouth with rings of teeth used for capturing animal prey.[76]

Fossil record

[edit]

It has been proposed that the Ediacaran animals Parvancorina and Spriggina, from around 555 million years ago, were arthropods,[77][78][79] but later study shows that their affinities of being origin of arthropods are not reliable.[80] Small arthropods with bivalve-like shells have been found in Early Cambrian fossil beds dating 541 to 539 million years ago in China and Australia.[81][82][83][84] The earliest Cambrian trilobite fossils are about 520 million years old, but the class was already quite diverse and worldwide, suggesting that they had been around for quite some time.[85] In the Maotianshan shales, which date back to 518 million years ago, arthropods such as Kylinxia and Erratus have been found that seem to represent transitional fossils between stem (e.g. Radiodonta such as Anomalocaris) and true arthropods.[86][6][43] Re-examination in the 1970s of the Burgess Shale fossils from about 505 million years ago identified many arthropods, some of which could not be assigned to any of the well-known groups, and thus intensified the debate about the Cambrian explosion.[87][88][89] A fossil of Marrella from the Burgess Shale has provided the earliest clear evidence of moulting.[90]

The earliest fossil of likely pancrustacean larvae date from about 514 million years ago in the Cambrian, followed by unique taxa like Yicaris and Wujicaris.[91] The purported pancrustacean/crustacean affinity of some cambrian arthropods (e.g. Phosphatocopina, Bradoriida and Hymenocarine taxa like waptiids)[92][93][94] were disputed by subsequent studies, as they might branch before the mandibulate crown-group.[91] Within the pancrustacean crown-group, only Malacostraca, Branchiopoda and Pentastomida have Cambrian fossil records.[91] Crustacean fossils are common from the Ordovician period onwards.[95] They have remained almost entirely aquatic, possibly because they never developed excretory systems that conserve water.[63]

Arthropods provide the earliest identifiable fossils of land animals, from about 419 million years ago in the Late Silurian,[60] and terrestrial tracks from about 450 million years ago appear to have been made by arthropods.[96] Arthropods possessed attributes that were easy coopted for life on land; their existing jointed exoskeletons provided protection against desiccation, support against gravity and a means of locomotion that was not dependent on water.[97] Around the same time the aquatic, scorpion-like eurypterids became the largest ever arthropods, some as long as 2.5 m (8 ft 2 in).[98]

The oldest known arachnid is the trigonotarbid Palaeotarbus jerami, from about 420 million years ago in the Silurian period.[99][Note 3] Attercopus fimbriunguis, from 386 million years ago in the Devonian period, bears the earliest known silk-producing spigots, but its lack of spinnerets means it was not one of the true spiders,[101] which first appear in the Late Carboniferous over 299 million years ago.[102] The Jurassic and Cretaceous periods provide a large number of fossil spiders, including representatives of many modern families.[103] The oldest known scorpion is Dolichophonus, dated back to 436 million years ago.[104] Lots of Silurian and Devonian scorpions were previously thought to be gill-breathing, hence the idea that scorpions were primitively aquatic and evolved air-breathing book lungs later on.[105] However subsequent studies reveal most of them lacking reliable evidence for an aquatic lifestyle,[106] while exceptional aquatic taxa (e.g. Waeringoscorpio) most likely derived from terrestrial scorpion ancestors.[107]

The oldest fossil record of hexapod is obscure, as most of the candidates are poorly preserved and their hexapod affinities had been disputed. An iconic example is the Devonian Rhyniognatha hirsti, dated at 396 to 407 million years ago, its mandibles are thought to be a type found only in winged insects, which suggests that the earliest insects appeared in the Silurian period.[108] However later study shows that Rhyniognatha most likely represent a myriapod, not even a hexapod.[109] The unequivocal oldest known hexapod and insect is the springtail Rhyniella, from about 410 million years ago in the Devonian period, and the palaeodictyopteran Delitzschala bitterfeldensis, from about 325 million years ago in the Carboniferous period, respectively.[109] The Mazon Creek lagerstätten from the Late Carboniferous, about 300 million years ago, include about 200 species, some gigantic by modern standards, and indicate that insects had occupied their main modern ecological niches as herbivores, detritivores and insectivores. Social termites and ants first appear in the Early Cretaceous, and advanced social bees have been found in Late Cretaceous rocks but did not become abundant until the Middle Cenozoic.[110]

Evolutionary relationships to other animal phyla

[edit]

From 1952 to 1977, zoologist Sidnie Manton and others argued that arthropods are polyphyletic, in other words, that they do not share a common ancestor that was itself an arthropod. Instead, they proposed that three separate groups of "arthropods" evolved separately from common worm-like ancestors: the chelicerates, including spiders and scorpions; the crustaceans; and the uniramia, consisting of onychophorans, myriapods and hexapods. These arguments usually bypassed trilobites, as the evolutionary relationships of this class were unclear. Proponents of polyphyly argued the following: that the similarities between these groups are the results of convergent evolution, as natural consequences of having rigid, segmented exoskeletons; that the three groups use different chemical means of hardening the cuticle; that there were significant differences in the construction of their compound eyes; that it is hard to see how such different configurations of segments and appendages in the head could have evolved from the same ancestor; and that crustaceans have biramous limbs with separate gill and leg branches, while the other two groups have uniramous limbs in which the single branch serves as a leg.[112]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Further analysis and discoveries in the 1990s reversed this view, and led to acceptance that arthropods are monophyletic, in other words they are inferred to share a common ancestor that was itself an arthropod.[113][114] For example, Graham Budd's analyses of Kerygmachela in 1993 and of Opabinia in 1996 convinced him that these animals were similar to onychophorans and to various Early Cambrian "lobopods", and he presented an "evolutionary family tree" that showed these as "aunts" and "cousins" of all arthropods.[111][115] These changes made the scope of the term "arthropod" unclear, and Claus Nielsen proposed that the wider group should be labelled "Panarthropoda" ("all the arthropods") while the animals with jointed limbs and hardened cuticles should be called "Euarthropoda" ("true arthropods").[116]

A contrary view was presented in 2003, when Jan Bergström and Hou Xian-guang argued that, if arthropods were a "sister-group" to any of the anomalocarids, they must have lost and then re-evolved features that were well-developed in the anomalocarids. The earliest known arthropods ate mud in order to extract food particles from it, and possessed variable numbers of segments with unspecialized appendages that functioned as both gills and legs. Anomalocarids were, by the standards of the time, huge and sophisticated predators with specialized mouths and grasping appendages, fixed numbers of segments some of which were specialized, tail fins, and gills that were very different from those of arthropods. In 2006, they suggested that arthropods were more closely related to lobopods and tardigrades than to anomalocarids.[117] In 2014, it was found that tardigrades were more closely related to arthropods than velvet worms.[118]

| Protostomes |

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Relationships of Ecdysozoa to each other and to annelids, etc.,[119][failed verification] including euthycarcinoids[120] |

||||||||||||||||||||||

Higher up the "family tree", the Annelida have traditionally been considered the closest relatives of the Panarthropoda, since both groups have segmented bodies, and the combination of these groups was labelled Articulata. There had been competing proposals that arthropods were closely related to other groups such as nematodes, priapulids and tardigrades, but these remained minority views because it was difficult to specify in detail the relationships between these groups.

In the 1990s, molecular phylogenetic analyses of DNA sequences produced a coherent scheme showing arthropods as members of a superphylum labelled Ecdysozoa ("animals that moult"), which contained nematodes, priapulids and tardigrades but excluded annelids. This was backed up by studies of the anatomy and development of these animals, which showed that many of the features that supported the Articulata hypothesis showed significant differences between annelids and the earliest Panarthropods in their details, and some were hardly present at all in arthropods. This hypothesis groups annelids with molluscs and brachiopods in another superphylum, Lophotrochozoa.

If the Ecdysozoa hypothesis is correct, then segmentation of arthropods and annelids either has evolved convergently or has been inherited from a much older ancestor and subsequently lost in several other lineages, such as the non-arthropod members of the Ecdysozoa.[121][119]

Evolution of fossil arthropods

[edit]| Arthropod fossil phylogeny[122] | |||

| |||

| Суммировала кладограмму взаимосвязей между вымершими группами членистоногих. Для получения дополнительной информации см. Deuteropoda . |

Aside from the four major living groups (crustaceans, chelicerates, myriapods and hexapods), a number of fossil forms, mostly from the early Cambrian period, are difficult to place taxonomically, either from lack of obvious affinity to any of the main groups or from clear affinity to several of them. Marrella was the first one to be recognized as significantly different from the well-known groups.[48]

Современные интерпретации базальной, вымершей группы ствола членистоногих признали следующие группы, от большинства базальных до большинства корон. [ 123 ] [ 122 ]

- « Гигантские » или «сибирид лобоподиан» , такие как Цзяньшаноподия , Сибир и Мегадиктион , являются наиболее базальными в чёрподе общей группы.

- «Gilled Lobopodians » , такие как Kerygmachela , Pampdelurion и Opabinia , являются вторым наиболее базальным сортом.

- Radiodonta , которая , традиционно известная как аномалокаридиды, занимает третью позицию и считается монофилетическим .

- Возможная сборка «верхней группы ствола» более неопределенной позиции [ 122 ] но содержится в Deuteropoda : [ 123 ] Fuxianhuiida включая , Megacheira и множественные «двустворчатые формы», изоксида и гименокарину .

Deuteropoda -недавно созданная клада , объединяющая черпотовые членистоногих корон (живая) с этими возможными таксонами «верхняя группа» ствола. [ 123 ] Клада определяется важными изменениями в структуре области головы, такими как появление дифференцированной пары деутоцеребральных придаток, которая исключает больше базальных таксонов, таких как радиодонты и «жареные лобоподианцы». [ 123 ]

Споры остаются в отношении позиций различных вымерших групповых групп членистоногих. Некоторые исследования восстанавливают мегачеру, как тесно связаны с хелисеры, в то время как другие восстанавливают их как за пределами группы, содержащей хелицерат и мандибулата в качестве эуартроподов стволовой группы. [ 124 ] Размещение Artiopoda ( которая содержит вымершие трилобиты и аналогичные формы) также является частым предметом спора. [ 125 ] Основные гипотезы позиционируют их в кладке арахноморфы с хелицератами. Однако одной из более новых гипотез является то, что Chelicerae возникли из той же пары придаток, которые превратились в антенны у предков Мандибулаты , которые будут помещать трилобиты, которые имели антенны, ближе к Мандибулате, чем хелицерата, в клад -антенналата . [ 124 ] [ 126 ] группы . Предполагается, что в некоторых недавних исследованиях Fuxianhuiids, как правило, предполагают, что являются членистоногими стволовой [ 124 ] , Было продемонстрировано, что Hymenocarina группа двустворенных членистоногих, ранее считавшейся членами группы STEM-группы, была продемонстрирована мандибулированием на основе присутствия мандибов. [ 122 ]

- Radiodonts, Opabiniids, Gilled Lobopodians и более традиционные лобоподианцы-все это примеры базальных линий членистоногих стволовых групп от кембрии

- Marellomorphs, Megacherians, Funxianhuiids и фосфатокопины - некоторые примеры кембрийских членистоногих, классификация которых остается трудной

- Другие примеры теперь вымерших групп членистоногих включают

Эволюция и классификация живых членистоногие

[ редактировать ]Phylum Chrothonicoda, как правило, подразделяется на четыре субфилы , из которых один вымер : [ 127 ]

- Артиоподы являются вымершей группой бывших многочисленных морских животных , которые исчезли в рамках пермского и триасного вымирания , хотя до этого удара в упадке были в упадке, что было сокращено до одного порядка в позднем девонском вымирании . Они содержат группы, такие как трилобиты .

- Хелицераты составляют морские морские пауки и подковообразные крабы , а также наземные арахниды, такие как клещи , уборщики , пауки , скорпионы и связанные с ними организмы, характеризуемые наличием Chelicerae , придатками чуть выше/перед ртами . Chelicerae появляются в скорпионах и подковообразных крабах как крошечные когти , которые они используют в кормлении, но у пауков развивались как клыки , которые вводят яд .

- Множество мириподов включают Millipedes , Mentipedes , Pauropods и Symphylans , характеризующие многочисленные сегменты тела , каждая из которых с одной или двумя парами ног (или в некоторых случаях без ног). Все члены исключительно на земле.

- Pancrustaceans включают остракоды , саралы , кобородообразные , малакостраканы , цефалокариданы , ветвиные , переоборудованные и гексаподы . Большинство групп в первую очередь являются водными (двумя заметными исключениями являются леса и гексапод, которые являются чисто наземными ) и характеризуются наличием бириамных придатков. Наиболее распространенной группой пансустакейцев являются наземные гексапод, которые включают насекомых , диплораны , весенние хвосты и протранцы , с шестью грудными ногами.

Филогения . основных существующих членисторонних групп была областью, представляющей значительный интерес и спор [ 128 ] Недавние исследования убедительно свидетельствуют о том, что ракообразные, как это традиционно определено, является парафилетическим , с гексаподой, развивающимися внутри него, [ 129 ] [ 130 ] Так что ракообразные и гексапода образуют кладу, Pancrustacea . Положение мириаподы , челицераты и пансустачеи остается неясной по состоянию на апрель 2012 года [update]Полем В некоторых исследованиях мириапода сгруппирована с Chelicerata (образуя мириохелата ); [ 131 ] [ 132 ] В других исследованиях мириапода сгруппирована с Pancrustacea (формирование Mandibulata ), [ 129 ] или Myriapoda может быть сестрой Chelicerata Plus Pancrustacea. [ 130 ]

Следующая кладограмма показывает внутренние отношения между всеми живыми классами членистоногих с конца 2010 -х годов, [ 133 ] [ 134 ] а также предполагаемое время для некоторых клад: [ 135 ]

| Членистоногие |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Взаимодействие с людьми

[ редактировать ]

Ракообразные, такие как крабы , лобстеры , раки , креветки и креветки , давно являются частью человеческой кухни и в настоящее время выводятся в коммерческих целях. [ 136 ] Насекомые и их личинки, по крайней мере, такие же питательные, как мясо, и их едят как сырые, так и приготовлены во многих культурах, хотя и не большинство европейских, индуистских и исламских культур. [ 137 ] [ 138 ] Приготовленные тарантулы считаются деликатесом в Камбодже , [ 139 ] [ 140 ] [ 141 ] и индейцами Пиароа из Южной Венесуэлы , после того, как очень раздражительные волосы - главная система защиты паука - удаляются. [ 142 ] Люди также непреднамеренно едят членистоногие в других продуктах, [ 143 ] А правила безопасности пищевых продуктов устанавливают приемлемые уровни загрязнения для различных видов пищевых материалов. [ Примечание 4 ] [ Примечание 5 ] Преднамеренное выращивание членистоногих и других мелких животных для еды человека, называемое Миниливестоком , теперь появляется в животноводстве как экологически здравая концепция. [ 147 ] Коммерческое размножение бабочек обеспечивает Lepidoptera Stock для консерваторий -бабочек , образовательных экспонатов, школ, исследовательских учреждений и культурных мероприятий.

Тем не менее, наибольшим вкладом членистоногих в поставки продуктов питания человека является опыление : исследование 2008 года изучало 100 культур, которые ФАО перечисляет как выращенные для пищевых продуктов, и, по оценкам, экономическая стоимость опыления как 153 миллиарда евро, или 9,5 процента от стоимости мирового сельского хозяйства. Производство, используемое для еды человека в 2005 году. [ 148 ] Помимо опыления, пчелы производят мед , который является основой быстро растущей промышленности и международной торговли. [ 149 ]

красная краситель Кохинеальная , произведенная из центральной американской виды насекомых, была экономически важна для ацтеков и майя . [ 150 ] В то время как регион находился под контролем испанского языка , он стал , вторым наиболее хлебительным экспортом Мексики [ 151 ] и теперь восстанавливает часть земли, которую он потерял для синтетических конкурентов. [ 152 ] Shellac , смола, секретируемая видом насекомых, уроженца в Южной Азии, исторически использовалась в больших количествах для многих применений, в которых она в основном заменялась синтетическими смолами, но все еще используется в деревообработке и в качестве пищевой добавки . Кровь крабов подковообразных содержит агент свертывания, лизат амебоцитов Limulus , который в настоящее время используется для проверки того, что антибиотики и машины для почек свободны от опасных бактерий , а также для обнаружения спинного менингита и некоторых раковых заболеваний . [ 153 ] Судебная энтомология использует доказательства, предоставленные членистоногими для установления времени, а иногда и места смерти человека, а в некоторых случаях причина. [ 154 ] Недавно насекомые также привлекли внимание как потенциальные источники лекарств и других лекарственных веществ. [ 155 ]

Относительная простота плана тела членистоногих, позволяющая им двигаться на различных поверхностях как на суше, так и в воде, сделала их полезными в качестве моделей для робототехники . Избыточность, предоставленная сегментами, позволяет членистоногим и биомиметическим роботам перемещаться нормально даже при поврежденных или потерянных придатках. [ 156 ] [ 157 ]

| Болезнь [ 158 ] | Насекомое | Дела в год | Смерть в год |

|---|---|---|---|

| Малярия | Anopheles Mosquito | 267 м | От 1 до 2 м |

| Лихорадка денге | Aedes Mosquito | ? | ? |

| Желтая лихорадка | Aedes Mosquito | 4,432 | 1,177 |

| Филариаз | Culex Mosquito | 250 м | неизвестный |

Хотя членистоногие являются наиболее многочисленным филомом на Земле, а тысячи видов членистоногих ядовиты, они наносят относительно мало серьезных укусов и укусов на людей. Гораздо более серьезные влияние на людей заболеваний, таких как малярия, несущая кровеносники насекомых. Другие кровеносники насекомые заражают скот болезнями, которые убивают многих животных и значительно снижают полезность других. [ 158 ] Клещи могут вызвать паралич клещей и несколько паразитовых заболеваний у людей. [ 159 ] Некоторые из близкородственных клещей также заражают людей, вызывая интенсивный зуд, [ 160 ] и другие вызывают аллергические заболевания, включая сеную лихорадку , астму и экзему . [ 161 ]

Многие виды членистоногих, в основном насекомых, но также и клещи, являются сельскохозяйственными и лесными вредителями. [ 162 ] [ 163 ] Mite Депутатор Varroa стал самой большой проблемой, с которой сталкиваются пчеловоды по всему миру. [ 164 ] Усилия по борьбе с вредителями членистоногих путем крупномасштабного использования пестицидов вызвали долгосрочные последствия на здоровье человека и биоразнообразие . [ 165 ] Увеличение устойчивости членистоногих пестицидов привело к разработке интегрированного лечения вредителей с использованием широкого спектра мер, включая биологический контроль . [ 162 ] Хищные клещи могут быть полезны для контроля некоторых вредителей клещей. [ 166 ] [ 167 ]

Смотрите также

[ редактировать ]Примечания

[ редактировать ]- ^ Музей Новой Зеландии отмечает, что «в повседневном разговоре», BUG »относится к членистоногим, по крайней мере, с шестью ногами, такими как насекомые, пауки и многоноги». [ 25 ] В главе «Ошибки, которые не являются насекомыми», энтомолог Гилберт Уолбауэр указывает многоноги, милипеды, арахниды (пауки, папа Лонглеги , скорпионы, клещи , чиггеры и клеща), а также несколько наземных ракообразных (Sowbugs и Pillbugs), а также несколько наземных ракообразных (Sowbugs и Pillbugs), а также несколько наземных ракообразных (Sowbugs и Pillbugs), а также несколько наземных ракообразных (Sowbugs и Pillbugs), а также несколько наземных ракообразных ( Sowbugs и Pillbugs ), а также несколько наземных ракообразных (Sowbugs и Pillbugs) [ 26 ] Но утверждает, что «включая существа, такие как черви, слизняки и улитки среди ошибок, слишком много растягивает слово». [ 27 ]

- ^ «Было бы очень плохо, если бы вопрос о сегментации головы когда -либо был окончательно урегулирован; это было так долго, что такая плодородная основание для теоретизирования, что членистоногисты будут упустить его как поле для умственных упражнений». [ 50 ]

- ^ Окаменелость первоначально была названа Эотарбусом, но было переименовано в переименование, когда было понято, что каменноугольный арахнид уже был назван Эотарбусом . [ 100 ]

- ^ Для упоминания о загрязнении насекомых в международном стандарте качества пищевых продуктов см. В разделе 3.1.2 и 3.1.3 Кодекса 152 1985 года Кодекса Alimentarius [ 144 ]

- ^ Для примеров количественного приемлемого уровня загрязнения насекомых в пище см. Последний запись (на «пшеничной муке») и определение «постороннего материала» в Codex Alimentarius , [ 145 ] и стандарты, опубликованные FDA. [ 146 ]

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в дюймовый Мартинес-Муньос, Карлос А. (4 мая 2023 г.). «Правильное авторство членистоногих - переоценка» . Интегративная систематика . 6 (1): 1–8. doi : 10.18476/2023.472723 . ISSN 2628-2380 . S2CID 258497632 .

- ^ Gravenhorst, JLC (1843). Сравнительная зоология . Бреслау: Печать и издатель Грасс, Барт и Комп.

- ^ Moysiuk J, Caron JB (январь 2019 г.). «Слаженные окаменелости Берджесса проливают свет на проблему агностида» . Разбирательство. Биологические науки . 286 (1894): 20182314. DOI : 10.1098/rspb.2018.2314 . PMC 6367181 . PMID 30963877 .

- ^ FU, D.; Легг, да; Дейли, AC; Приятель, GE; Wu, y.; Чжан, X. (2022). «Эволюция бириамных придатков, выявленных капитанским членистоногим членистоногим» . Философские транзакции Королевского общества B: биологические науки . 377 (1847): ID статьи 20210034. DOI : 10.1098/rstb.2021.0034 . PMC 8819368 . PMID 35125000 .

- ^ О'Флинн, Роберт Дж.; Уильямс, Марк; Ю, Менгсиао; Харви, Томас; Лю, Ю (2022). «Новый эуартропод с большими лобными придатками из ранней кембрийской биоты Ченгцзяна» . Palaeontologia Electronica . 25 (1): 1–21. doi : 10.26879/1167 . S2CID 246779634 .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в Зенг, Хан; Чжао, Фанхен; Niu, Kecheng; Чжу, Маоян; Хуан, Dious (декабрь 2020 г.). «Ранний кембрийский эуартропод с Radiodont-подобными ресторанами» . Природа . 588 (7836): 101–105. Bibcode : 2020nater.588..101Z . doi : 10.1038/s41586-020-2883-7 . ISSN 1476-4687 . PMID 33149303 . S2CID 226248177 . Получено 8 декабря 2020 года .

- ^ Легг, Дэвид А.; Саттон, Марк Д.; Edgecombe, Gregory D. (30 сентября 2013 г.). «Данные о ископаемых членистоногих повышают конгруэнтность морфологических и молекулярных филогений» . Природная связь . 4 (1): 2485. Bibcode : 2013natco ... 4.2485L . doi : 10.1038/ncomms3485 . ISSN 2041-1723 . PMID 24077329 .

- ^ Пульсифлер, Массачусетс; Андерсон, EP; Райт, LS; Kluessendorf, J.; Микулич, DG; Schiffbauer, JD (2022). «Описание Acheronauta Gen. Nov., Возможный отклонность от силурийской Waukesha Lagerstätte, Висконсин, США». Журнал систематической палеонтологии . 20 (1). 2109216. DOI : 10.1080/14772019.2022.2109216 . S2CID 252839113 .

- ^ Кларк, Нил Д.Л.; Фельдманн, Родни М; Шрам, Фредерик Р; Schweitzer, Carrie E (2020). «Передописание Америкуса Ранкини (Вудворд, 1868) (Pancrustacea: Cyclida: Americlidae) и интерпретация его систематического размещения, морфологии и палеоэкологии» (PDF) . Журнал ракообразной биологии . 40 (2): 181–193. doi : 10.1093/jcbiol/ruaa001 .

- ^ Пил, JS; Стейн М. "Новый членистонный из нижнего кембрийского пассаточного ископаемого Сириуса из Северной Гренландии" (PDF) . Бюллетень из героя . 84 (4): 1158.

- ^ Fayers, Sr; ТРЕВИН, NH; Моррисси Л. (май 2010 г.). «Большой члпаток из нижнего старого красного песчаника (ранний Девониан) карьера Tredomen, Южный Уэльс: членистоногие из нижних ORS». Палеонтология . 53 (3): 627–643. doi : 10.1111/j.1475-4983.2010.00951.x .

- ^ Edgecombe, Gregory D. (1 сентября 2017 г.). «Вывод филогения членистоногих: окаменелости и их взаимодействие с другими источниками данных» . Интегративная и сравнительная биология . 57 (3): 467–476. doi : 10.1093/icb/icx061 . ISSN 1540-7063 . PMID 28957518 .

- ^ Garwood, R.; Саттон, М. (18 февраля 2012 г.), «Загадочный членистоносный камптофильа» , Palaeontologia Electronica , 15 (2): 12, doi : 10.1111/1475-4983.00174 , архивировано (pdf) из оригинала 2 декабря 2013 г. , извлечен 11 июня. 2012

- ^ Чжая, Дейу; Уильямс, Марк; Сиветер, Дэвид Дж.; Siveter, Derek J.; Харви, Томас Х.П.; Сансом, Роберт С.; Май, Хуйджуан; Чжоу, Ранкинг; Хоу, Сянгуанг (22 февраля 2022 г.). «Chuandianella ovata: ранний камбрийский ствол эуартропод с перьевными придатками» . Palaeontologia Electronica . 25 (1): 1–22. doi : 10.26879/1172 . ISSN 1094-8074 . S2CID 247123967 .

- ^ Waloszek, Dieter; Мюллер, Клаус (1 октября 1990 г.). «Верхние кембрийские стволовые ракообразные и их приспособление к монофилии ракообразной и положения агностаса» . Летая . 23 : 409–427. doi : 10.1111/j.1502-3931.1990.tb01373.x .

- ^ Ван Рой, Питер; Рак, Штпан; Будил, Петр; Фатка, Oldřich (13 июня 2022 года). «Передописание хелониэллидного эуартроподного триопуса Draboviensis из верхнего ордовика богемии, с комментариями к сродствам Париоскорпио Венатор ». Геологический журнал . 159 (9): 1471–1489. Bibcode : 2022geom..159.1471V . doi : 10.1017/s0016756822000292 . HDL : 1854/LU-8756253 . ISSN 0016-7568 . S2CID 249652930 .

- ^ Андерсон, Лайалл I.; Треуин, Найджел Х. (май 2003 г.). «Ранняя девонская членисторонняя фауна из Windyfield Cherts, Абердиншир, Шотландия». Палеонтология . 46 (3): 467–509. doi : 10.1111/1475-4983.00308 .

- ^ Haug, JT; Маас, А.; Haug, C.; Waloszek, D. (1 ноября 2011 г.). «Sarotrocercus oblitus - небольшой членисторонний, с большим влиянием на понимание эволюции членистоногих?» Полем Бюллетень из героян : 725–736. doi : 10.3140/bull.geosci.1283 . ISSN 1802-8225 .

- ^ Ортега-Хернандес, Хавьер; Легг, Дэвид А.; Брэдди, Саймон Дж. (2013). «Филогения арпаспидид -членистоногих и внутренние отношения в артиоподе» . Кладистика . 29 (1): 15–45. doi : 10.1111/j.1096-0031.2012.00413.x . PMID 34814371 . S2CID 85744103 .

- ^ Кюль, Габриель; Руст, Джес (2009). « Devonohexapodus bocksbergensis является синонимом Wingertshellicus backesi (Euartropoda) - нет никаких доказательств морских гексапод, живущих в Девонском море Хунсрук» . Организмы разнообразие и эволюция . 9 (3): 215–231. Bibcode : 2009dive ... 9..215K . doi : 10.1016/j.ode.2009.03.002 .

- ^ Патса, Стивен; Леросея-Абрил, Руди; Дейли, Эллисон С.; Киер, Карло; Бонино, Энрико; Ортега-Хернандес, Хавьер (19 января 2021 г.). «Разнообразная фауна Radiodont из формирования Marjum в Юте, США (Cambrian: Drumian) » Палеонтология и эволюционная наука 9 : E1 Doi : 10.7717/ peerj.1 PMC 7821760 PMID 33552709

- ^ «Членистоногие» . Merriam-Webster.com Словарь . Мерриам-Уэбстер.

- ^ «Черпона» . Онлайн этимологический словарь . Архивировано из оригинала 7 марта 2013 года . Получено 23 мая 2013 года .

- ^ Gravenhorst, JLC (1843). Сравнительная зоология [ сравнительная зоология ] (на немецком языке). Бреслау, (Пруссия): Грасс, Барт и Комп. п. Раскрывать.

«Со структурированными органами движения» (с сочлененным органом движения))

- ^ «Что такое ошибка? Насекомые, арахниды и мириаподы» на веб -сайте музея Новой Зеландии Te Papa Tongarewa. Доступ 10 марта 2022 года.

- ^ Гилберт Вальдбауэр. Удобная книга ответов на ошибку. Видимые чернила, 1998. С. 5–26. ISBN 978-1-57859-049-0

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в Гилберт Вальдбауэр. Удобная книга ответов на ошибку. Видимые чернила, 1998. с. 1 ISBN 978-1-57859-049-0

- ^ Валентина, JW (2004), о происхождении Phyla , Университет Чикагской Прессы , с. 33, ISBN 978-0-226-84548-7

- ^ Cutler, B. (август 1980), «Черпоходные особенности кутикулы и монофилия членистоногих», клеточные и молекулярные науки о жизни , 36 (8): 953, doi : 10.1007/BF01953812 , S2CID 84995596

- ^ Австралийские жуки Том 2: archostemata, Myxophaga, Adephaga, Polyphaga

- ^ Kovoor, J. (1978). «Естественная кальцификация просоматического эндостернина у Phalangiidae (Arachnida: Opiliones)». Кальцифицированные ткани исследования . 26 (3): 267–9. doi : 10.1007/bf02013269 . PMID 750069 . S2CID 23119386 .

- ^ Ронг, Цзинцзин; Лин, Юбо; Sui, Zhuoxiao; Ван, Сиджия; Вэй, Сюнфан; Сяо, Джинхуа; Хуан, Давей (ноябрь - декабрь 2019 г.). «Аморфный кальциевый фосфат в кутикуле куколки бактроцеры Dorsalis hendel (Diptera: Tephritidae): новое открытие для пересмотра минерализации кутикулы насекомых» . Журнал физиологии насекомых . 119 : 103964. Bibcode : 2019jinsp.11903964R . doi : 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2019.103964 . PMID 31604063 .

- ^ Thanukos, Anna, The Charthreshoto Story , Калифорнийский университет, Беркли , архивировал из оригинала 16 июня 2008 года , извлеченные 29 сентября 2008 г.

- ^ Ødegaard, Frode (декабрь 2000 г.), «Сколько видов членистоногих? Оценка Эрвина пересмотрено» (PDF) , Биологический журнал Линниского общества , 71 (4): 583–597, Bibcode : 2000bjls ... 71..583o ,, doi : 10.1006/bijl.2000.0468 , архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 26 декабря 2010 года , полученная 6 мая 2010 г.

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Thompson, JN (1994), Коэволюционный процесс , Университет Чикагской Прессы , с. 9, ISBN 978-0-226-79760-1

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин час я Дж k л Ruppert, Fox & Barnes (2004) , с. 518–522

- ^ Инга Мохрбек; Педро Мартинес Арбизу; Томас Глатцель (октябрь 2010). «Тантулокарида (ракообразная) Южного океана глубокого моря и описание трех новых видов Tantulacus Huys, Andersen & Kristensen, 1992». Систематическая паразитология . 77 (2): 131–151. doi : 10.1007/s11230-010-9260-0 . PMID 20852984 . S2CID 7325858 .

- ^ Шмидт-Нильсен, Кнут (1984), «Сила костей и скелетов» , масштабирование: почему размер животных настолько важен? , Издательство Кембриджского университета , с. 42–55 , ISBN 978-0-521-31987-4

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в Лю, Ю; Edgecombe, Gregory D.; Шмидт, Мишель; Бонд, Эндрю Д.; Мелцер, Роланд Р.; Чжая, Дейу; Май, Хуйджуан; Чжан, Маайин; Хоу, Сянгуанг (30 июля 2021 года). «Включается в кембрийском членистоногих и гомологии филиалов конечностей членистоногих» . Природная связь . 12 (1): 4619. Bibcode : 2021Natco..12.4619L . doi : 10.1038/s41467-021-24918-8 . ISSN 2041-1723 . PMC 8324779 . PMID 34330912 .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Гулд (1990) , с. 102–106.

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Ортега-Хернандес, Хавьер; Янссен, Ральф; Бадд, Грэм Э. (2017). «Происхождение и эволюция головы Panartropod - палеобиологическая и перспектива развития» . Членистоногие структура и развитие . 46 (3): 354–379. Bibcode : 2017artsd..46..354o . doi : 10.1016/j.asd.2016.10.011 . PMID 27989966 .

- ^ «Гигантское морское существо намекает на раннюю эволюцию членистоногих» . 11 марта 2015 года. Архивировано с оригинала 2 февраля 2017 года . Получено 22 января 2017 года .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный FU, D.; Легг, да; Дейли, AC; Приятель, GE; Wu, y.; Чжан, X. (2022). «Эволюция бириамных придатков, выявленных капитанским членистоногим членистоногим» . Философские транзакции Королевского общества B: биологические науки . 377 (1847): ID статьи 20210034. DOI : 10.1098/rstb.2021.0034 . PMC 8819368 . PMID 35125000 . S2CID 246608509 .

- ^ Хейнол, Андреас; Шольц, Герхард (1 октября 2004 г.). «Клональный анализ дистальных и закрепленных паттернов экспрессии при раннем морфогенезе однорамных и биримных ракообразных конечностей». Гены развития и эволюция . 214 (10): 473–485. doi : 10.1007/s00427-004-0424-2 . ISSN 1432-041X . PMID 15300435 . S2CID 22426697 .

- ^ Вольф, Карстен; Шольц, Герхард (7 мая 2008 г.). «Клональный композиция бириамных и однорамных членисторонних конечностей» . Труды Королевского общества B: Биологические науки . 275 (1638): 1023–1028. doi : 10.1098/rspb.2007.1327 . PMC 2600901 . PMID 18252674 .

- ^ Шубин, Нил ; Табин, C.; Кэрролл, Шон (2000), «Окаменелости, гены и эволюция конечностей животных» , в Gee, H. (ed.), Встряхивание дерева: чтения от природы в истории жизни , Университет Чикагской Прессы , с. 110, ISBN 978-0-226-28497-2

- ^ Данлоп, Джейсон А.; Ламсделл, Джеймс С. (2017). «Сегментация и тагмоз в Chelicerata» . Членистоногие структура и развитие . 46 (3): 395–418. Bibcode : 2017artsd..46..395d . doi : 10.1016/j.asd.2016.05.002 . PMID 27240897 .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Whittington, HB (1971), «Переоценка Marrella Splendens (Trilobitoidea) из сланца Берджесса, средняя Камбрийская, Британская Колумбия», Геологическая служба Канады , 209 : 1–24, обобщенные в Gould (1990) , с. 107–121. Полем

- ^ Budd, GE (16 мая 2002 г.). «Палеонтологическое решение проблемы головы членистоногих». Природа . 417 (6886): 271–275. Bibcode : 2002natur.417..271b . doi : 10.1038/417271a . PMID 12015599 . S2CID 4310080 .

- ^ Snodgrass, Re (1960), «Факты и теории, касающиеся главы насекомых», Смитсоновские разные коллекции , 142 : 1–61

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Wainwright, SA; Biggs, WD & Gosline, JM (1982). Механический дизайн в организмах . ПРИЗНАЯ УНИВЕРСИТЕТА ПРИСЕТА . С. 162–163 . ISBN 978-0-691-08308-7 .

- ^ Лоуэнстам, Ха; Weiner, S. (1989), о биоминерализации , издательство Оксфордского университета, с. 111, ISBN 978-0-19-504977-0

- ^ Dzik, J (2007), «Синдром Вердена: одновременное происхождение защитных броней и укрытий инфунала при докембрийском-кембрийском переходе» (PDF) , в богатых Викерсах, Патриция; Komarower, Patricia (Eds.), Возможности и падение Ediacaran Biota , Special Publications, Vol. 286, Лондон: Геологическое общество, с. 405–414, doi : 10.1144/sp286.30 , ISBN 978-1-86239-233-5 , OCLC 156823511

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Cohen, BL (2005), «Не броня, но биомеханика, экологическая возможность и увеличение плодовитости как ключи к происхождению и расширению минерализованной бентической метазоанской фауны» (PDF) , биологический журнал Линнового общества , 85 (4): 483 –490, doi : 10.1111/j.1095-8312.2005.00507.x , архивированный (pdf) с оригинала 3 октября 2008 г. , получен 25 сентября 2008 г.

- ^ Бенгтсон С. (2004). «Ранние скелетные окаменелости». В Lipps, JH; Wagoner, BM (ред.). Неопротерозой-камбрийские биологические революции (PDF) . Документы палеонтологического общества. Тол. 10. С. 67–78. doi : 10.1017/s1089332600002345 . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 3 октября 2008 года.

- ^ Барнс, RSK; Калоу, П.; Olive, P.; Golding, D. & Spicer, J. (2001), «Беспозвоночные с ногами: членистоногие и подобные группы» , беспозвоночные: синтез , Blackwell Publishing , p. 168, ISBN 978-0-632-04761-1

- ^ Parry, Da & Brown, RHJ (1959), «Гидравлический механизм ноги паука» (PDF) , Журнал экспериментальной биологии , 36 (2): 423–433, doi : 10.1242/jeb.36.2.423 , архивировано (( Doi: 10.1242/jeb.36.2. PDF) из оригинала 3 октября 2008 года , полученное 25 сентября 2008 г.

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в Ruppert, Fox & Barnes (2004) , с. 523–524

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в Ruppert, Fox & Barnes (2004) , с. 527–528

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в Гарвуд, Рассел Дж.; Edgecombe, Greg (2011). «Ранние наземные животные, эволюция и неопределенность» . Эволюция: образование и охват . 4 (3): 489–501. doi : 10.1007/s12052-011-0357-y .

- ^ Ruppert, Fox & Barnes (2004) , с. 530, 733

- ^ Ruppert, Fox & Barnes (2004) , с. 531–532

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в дюймовый Ruppert, Fox & Barnes (2004) , с. 529–530

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин Ruppert, Fox & Barnes (2004) , с. 532–537

- ^ Ruppert, Fox & Barnes (2004) , с. 578–580

- ^ Völkel, R.; Eisner, M.; Weible, KJ (июнь 2003 г.). «Миниатюрные системы визуализации» (PDF) . Микроэлектронная техника . 67–68: 461–472. doi : 10.1016/s0167-9317 (03) 00102-3 . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 1 октября 2008 года.

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в дюймовый Ruppert, Fox & Barnes (2004) , с. 537–539

- ^ Olive, PJW (2001). «Репродукция и жизненные циклы в беспозвоночных». Энциклопедия наук о жизни . Джон Уайли и сыновья. doi : 10.1038/npg.els.0003649 . ISBN 978-0-470-01617-6 .

- ^ Шурко, Ам; Мазур, диджей; Logsdon, JM (февраль 2010 г.). «Инвентаризация и филогеномное распределение мейотических генов у Nasonia vitripennis и среди разнообразных членистоногие». Молекулярная биология насекомых . 19 (Suppl 1): 165–180. doi : 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2009.00948.x . PMID 20167026 . S2CID 11617147 .

- ^ Bernstein, H.; Хопф, Фа; Мичод, Re (1987). «Молекулярная основа эволюции пола». Молекулярная генетика развития . Достижения в области генетики. Тол. 24. С. 323–370. doi : 10.1016/s0065-2660 (08) 60012-7 . ISBN 978-0-12-017624-3 Полем PMID 3324702 .

- ^ «Факты о подковообразных крабах и часто задаваемых вопросах» . Получено 19 января 2020 года .

- ^ Lourenço, Wilson R. (2002), «Воспроизведение в скорпионах, с особой ссылкой на партеногенез», в Toft, S.; Scharff, N. (Eds.), European Arachnology 2000 (PDF) , издательство Aarhus University Press , стр. 71–85, ISBN 978-87-7934-001-5 Архивировал из (PDF) оригинала 3 октября 2008 года , извлечен 28 сентября 2008 г.

- ^ Трумэн, JW; Riddiford, LM (сентябрь 1999 г.). «Происхождение метаморфозы насекомых» (PDF) . Природа . 401 (6752): 447–452. Bibcode : 1999natur.401..447t . doi : 10.1038/46737 . PMID 10519548 . S2CID 4327078 . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 3 октября 2008 года . Получено 28 сентября 2008 года .

- ^ Смит, Г., Разнообразие и адаптация водных насекомых (PDF) , Новый колледж Флориды , архивируя из оригинала (PDF) 3 октября 2008 года , извлеченные 28 сентября 2008 г.

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Бергстрем, Ян; Hou, Sian-Guang (2005), «Ранние палеозоические неламеллипедические членистоногих», в Стефане Конеманн; Рональд А. Дженнер (ред.), Отношения ракообразных и членистоногих , ракообразные проблемы, вып. 16, Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis , pp. 73–93, doi : 10.1201/9781420037548.ch4 , ISBN 978-0-8493-3498-6

- ^ Маккивер, Конор (30 сентября 2016 г.). «Предк членистоногих имел устье червя полового члена» . Музей естественной истории . Архивировано из оригинала 2 февраля 2017 года.

- ^ Glaessner, MF (1958). «Новые окаменелости от основания кембрийского в Южной Австралии» (PDF) . Сделки Королевского общества Южной Австралии . 81 : 185–188. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 16 декабря 2008 года.

- ^ Лин, JP; Gon, SM; Gehling, JG; Бэбкок, Ле; Чжао, YL; Чжан, XL; HU, SX; Юань, JL; Ю, мой; Пэн, Дж. (2006). « Парванкорина -похожий на членистоногие из кембрия из Южно -Китай». Историческая биология . 18 (1): 33–45. Bibcode : 2006hbio ... 18 ... 33L . doi : 10.1080/08912960500508689 . S2CID 85821717 .

- ^ McMenamin, MAS (2003), « Сприггина - это трилобитоидный экдизозоин» (Аннотация) , Тезисы с программами , 35 (6): 105, архивировано из оригинала 30 августа 2008 года , получен 21 октября 2008 г.

- ^ Дейли, Эллисон С.; Антклифф, Джонатан Б.; Drage, Harriet B.; Патс, Стивен (22 мая 2018 г.). «Ранние ископаемые записи Эуартроподы и кембрийского взрыва» . Труды Национальной академии наук Соединенных Штатов Америки . 115 (21): 5323–5331. Bibcode : 2018pnas..115.5323d . doi : 10.1073/pnas.1719962115 . PMC 6003487 . PMID 29784780 .

- ^ Браун, А.; Чен, Дж.; Waloszek, D.; Маас, А. (2007). «Первая ранняя кембрийская радиолария» (PDF) . Специальные публикации . 286 (1): 143–149. BIBCODE : 2007GSLSP.286..143B . doi : 10.1144/sp286.10 . S2CID 129651908 . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 18 июля 2011 года.

- ^ Юань, х.; Xiao, S.; Петрушка, RL; Чжоу, С.; Chen, Z.; Ху, Дж. (Апрель 2002 г.). «Высокие губки в раннем кембрийском лагрстетте: несоответствие между небилатерианским и билатерианским эпифаунальным тирером на неопротерозой-камбрийском переходе» . Геология . 30 (4): 363–366. Bibcode : 2002geo .... 30..363y . doi : 10.1130/0091-7613 (2002) 030 <0363: TSIAEC> 2,0.CO; 2 .

- ^ Skovsted, христианин; Брок, Гленн; Paterson, John (2006), «Дворветные членистоногие из нижней кембрийской формирования Мернмерны Южной Австралии и их последствия для идентификации камбрийских« небольших ископаемых » , Ассоциация австралийских палеонтологов , 32 : 7–41, ISSN 0810-8899

- ^ Беттс, Марисса; Топпер, Тимоти; Валентин, Джеймс; Skovsted, христианин; Патерсон, Джон; Брок, Гленн (январь 2014 г.), «Новая ранняя камбрийская брадория (членистоногие) с северными хребтами Флиндерс, Южная Австралия» , Gondwana Research , 25 (1): 420–437, Bibcode : 2014gondr..25..420B , doi : 10.1016/j.gr.2013.05.007

- ^ Lieberman, BS (1 марта 1999 г.), «Тестирование дарвиновского наследия кембрийского излучения с использованием трилобитовой филогении и биогеографии» , Журнал палеонтологии , 73 (2): 176, Bibcode : 1999jpal ... 73..176L , doi : 10.1017 /S0022336000027700 , S2CID 88588171 , архивировано с оригинала 19 октября 2008 года , получен 21 октября 2008 г.

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный «Пятиглазый ископаемый 520 миллионов лет обнаруживает ярости членистоногих» . Phys.org . Получено 8 декабря 2020 года .

- ^ Уиттингтон, HB (1979). Ранние членистоногих, их придатки и отношения. В Mr House (ред.), Происхождение основных групп беспозвоночных (стр. 253–268). Специальный том систематической ассоциации, 12. Лондон: Академическая пресса.

- ^ Уиттингтон, HB ; Геологическая служба Канады (1985), Берджесс -сланцевый , издательство Йельского университета, ISBN 978-0-660-11901-4 , OCLC 15630217

- ^ Гулд (1990) , с. [ страница необходима ] .

- ^ Гарсия-Беллидо, округ Колумбия; Коллинз, DH (май 2004). «Груптинг членистоногих попал в действие» . Природа . 429 (6987): 40. Bibcode : 2004natur.429 ... 40G . doi : 10.1038/429040a . PMID 15129272 . S2CID 40015864 .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в Hegna, Thomas A.; Луке, Хавьер; Вулф, Джоанна М. (10 сентября 2020 г.). «Окаменечная запись Pancrustacea» . Эволюция и биогеография . Издательство Оксфордского университета: 21–52. doi : 10.1093/oso/9780190637842.003.0002 . ISBN 978-0-19-063784-2 Полем Получено 5 января 2024 года .

- ^ Хоу, Сянь-Гуан; Siveter, Derek J.; Олдридж, Ричард Дж.; Сиветер, Дэвид Дж. (10 октября 2008 г.). «Коллективное поведение в раннем кембрийском членистоногих» . Наука . 322 (5899): 224. BIBCODE : 2008SCI ... 322..224H . doi : 10.1126/science.1162794 . ISSN 0036-8075 . PMID 18845748 .

- ^ Приятель, GE; Баттерфилд, Нью -Джерси; Дженсен, С. (декабрь 2001 г.), «Ракообразные и" кембрийские взрывы " , наука , 294 (5549): 2047, doi : 10.1126/science.294.5549.2047a , PMID 11739918

- ^ Сянь-Гуан, Хоу; Siveter, Derek J.; Олдридж, Ричард Дж.; Сиветер, Дэвид Дж. (2009). «Новый члпаток в цепных ассоциациях из Cnengjiang Lagerstätte (Нижний Камбрийский), Юньнань, Китай» . Палеонтология . 52 (4): 951–961. Bibcode : 2009Palgy..52..951x . doi : 10.1111/j.1475-4983.2009.00889.x . ISSN 0031-0239 .

- ^ Zhang, X.-G.; Сиветер, DJ; Waloszek, D.; Маас, А. (октябрь 2007 г.). «Эпиподитовая ракообразные ракообразные группы из нижнего кембрия». Природа . 449 (7162): 595–598. Bibcode : 2007natur.449..595Z . doi : 10.1038/nature06138 . PMID 17914395 . S2CID 4329196 .

- ^ Пизани, д.; Poling, LL; Lyons-Weiler M.; Хеджес, SB (2004). «Колонизация земли животными: молекулярная филогения и время дивергенции среди членистоногих» . BMC Biology . 2 : 1. DOI : 10.1186/1741-7007-2-1 . PMC 333434 . PMID 14731304 .

- ^ Коуэн Р. (2000). История жизни (3 -е изд.). Blackwell Science. п. 126. ISBN 978-0-632-04444-3 .

- ^ Брэдди, SJ; Markus Poschmann, M. & Tetlie, OE (2008). «Гигантский когти раскрывает самый большой когда -либо членистонный» . Биологические письма . 4 (1): 106–109. doi : 10.1098/rsbl.2007.0491 . PMC 2412931 . PMID 18029297 .

- ^ Dunlop, JA (сентябрь 1996 г.). «Тригонотарбидный арахнид из верхнего силурийского Шропшира» (PDF) . Палеонтология . 39 (3): 605–614. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 16 декабря 2008 года.

- ^ Dunlop, JA (1999). «Земное имя для тригонотарда ARACHNID EOTARBUS DUNLOP» . Палеонтология . 42 (1): 191. Bibcode : 1999Palgy..42..191d . doi : 10.1111/1475-4983.00068 . S2CID 83825904 .

- ^ Селден, Пенсильвания; Shear, WA (декабрь 2008 г.). «Ископаемые доказательства происхождения спиннеров -пауков» . ПНА . 105 (52): 20781–5. Bibcode : 2008pnas..10520781S . doi : 10.1073/pnas.0809174106 . PMC 2634869 . PMID 19104044 .

- ^ Селден, Пенсильвания (февраль 1996 г.). «Отопия мезотеле пауки». Природа . 379 (6565): 498–499. Bibcode : 1996natur.379..498s . doi : 10.1038/379498b0 . S2CID 26323977 .

- ^ Vollrath, F. & Selden, PA (декабрь 2007 г.). «Роль поведения в эволюции пауков, шелков и сетей» (PDF) . Ежегодный обзор экологии, эволюции и систематики . 38 : 819–846. doi : 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.37.091305.110221 . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 9 декабря 2008 года.

- ^ Андерсон, Эван П.; Шиффбауэр, Джеймс Д.; Жакет, Сара М.; Ламсделл, Джеймс С.; Клюссендорф, Джоан; Микулич, Дональд Г. (2021). Чжан, Си-Гуан (ред.). «Незнакомец, чем скорпион: переоценка париоскорпио -венатора, проблемного членистоногих от Llandoverian Waukesha Lagerstätte». Палеонтология . 64 (3): 429–474. Bibcode : 2021Palgy..64..429a . doi : 10.1111/pala.12534 . ISSN 0031-0239 .

- ^ Джерам, AJ (январь 1990). «Книжные легкие в более низком каменноугольном скорпионе». Природа . 343 (6256): 360–361. Bibcode : 1990natur.343..360j . doi : 10.1038/343360A0 . S2CID 4327169 .

- ^ Говард, Ричард Дж.; Edgecombe, Gregory D.; Легг, Дэвид А.; Пизани, Давид; Лозано-Фернандес, Иисус (1 марта 2019 г.). «Изучение эволюции и земной земли скорпионов (арахнида: скорпионы) с камнями и часами» . Организмы разнообразие и эволюция . 19 (1): 71–86. doi : 10.1007/s13127-019-00390-7 . HDL : 1983/9AB6548B-B4DE-47B5-B1D0-8008D225C375 . ISSN 1618-1077 .

- ^ Посшманн, Маркус; Данлоп, Джейсон А.; Каменц, Карстен; Шольц, Герхард (декабрь 2008 г.). «Нижний Девонский Скорпион Бурингоскарпион и дыхательный характер его нитчатых структур с описанием новых видов из области Вестервальда, Германия». Paläontologische Zeitschrift . 82 (4): 418–436. Bibcode : 2008palz ... 82..418p . doi : 10.1007/bf03184431 . ISSN 0031-0220 .

- ^ Энгель, MS ; Гримальди, да (февраль 2004 г.). «Новый свет проливает на самого старого насекомого». Природа . 427 (6975): 627–630. Bibcode : 2004natur.427..627e . doi : 10.1038/nature02291 . PMID 14961119 . S2CID 4431205 .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Хауг, Каролин; Хауг, Йоахим Т. (30 мая 2017 г.). "Предполагаемое старое летающее насекомое: скорее всего, бесчисленное множество?" Полем ПЕРЕЙ . 5 : E3402. doi : 10.7717/peerj.3402 . PMC 5452959 . PMID 28584727 .

- ^ Labandeira, C.; Eble, GJ (2000). «Окаменечная запись о разнообразии насекомых и неравенстве». В Андерсоне, Дж.; Thackeray, F.; Ван Вик, Б.; де Вит, М. (ред.). Gondwana Alive: биоразнообразие и развивающаяся биосфера (PDF) . Witwatersrand University Press . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 11 сентября 2008 года . Получено 21 октября 2008 года .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в Budd, GE (1996). «Морфология Опабинии Регалис и реконструкция группы ствола членистоногих». Летая . 29 (1): 1–14. Bibcode : 1996Letha..29 .... 1b . doi : 10.1111/j.1502-3931.1996.tb01831.x .

- ^ Гилло, С. (1995). Энтурумология . Пружины. стр. 17-19. ISBN 978-0-306-44967-3 .

- ^ Adrain, J. (15 марта 1999 г.). « Окаменелости и филогения членистоногих , под редакцией Грегори Д. Эджкомба» . Обзор книги. Palaeontologia Electronica . Архивировано из оригинала 8 сентября 2008 года . Получено 28 сентября 2008 года .

- Книга

- ^ Chen, J.Y.; Edgecombe, GD; Ramsköld, L.; Чжоу, Г.-Q. (2 июня 1995 г.). «Сегментация головы в ранней кембрийской Fuxianhuia : последствия для эволюции членистоногих». Наука . 268 (5215): 1339–1343. Bibcode : 1995sci ... 268.1339c . doi : 10.1126/science.268.5215.1339 . PMID 17778981 . S2CID 32142337 .

- ^ Budd, GE (1993). «Камбрийский жареный лобопод из Гренландии». Природа . 364 (6439): 709–711. Bibcode : 1993natur.364..709b . doi : 10.1038/364709a0 . S2CID 4341971 .

- ^ Нильсен, С. (2001). Эволюция животных: взаимосвязь живой фила (2 -е изд.). Издательство Оксфордского университета . С. 194–196. ISBN 978-0-19-850681-2 .

- ^ Hou, X.-G. ; Bergström, J.; Jie, Y. (2006). «Отличительные аномалокариды от членистоногих и приапулидов». Геологический журнал . 41 (3–4): 259–269. Bibcode : 2006geolj..41..259x . doi : 10.1002/gj.1050 . S2CID 83582128 .

- ^ «Неправильно понятый червя, похожий на червя, находит свое место в« Древе жизни » (пресс-релиз). Кембриджский университет . 17 августа 2014 года. Архивировано с оригинала 7 января 2017 года . Получено 24 января 2017 года .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Телфорд, MJ; Bourlat, SJ; Economou, A.; Papillon, D.; Рота-Стабелли, О. (январь 2008 г.). «Эволюция экдизозоиа» . Философские транзакции Королевского общества B: биологические науки . 363 (1496): 1529–1537. doi : 10.1098/rstb.2007.2243 . PMC 2614232 . PMID 18192181 .

- ^ Vaccari, NE; Edgecombe, GD; Escudero, C. (29 июля 2004 г.). «Происхождение кембрии и сродства загадочной ископаемой группы членистоногих». Природа . 430 (6999): 554–557. Bibcode : 2004natur.430..554V . doi : 10.1038/nature02705 . PMID 15282604 . S2CID 4419235 .

- ^ Schmidt-rhaesa, A.; Bartolomaeus, T.; Лембург, C.; Ehlers, U.; Гари, младший (январь 1999 г.). «Положение членистоногих в филогенетической системе». Журнал морфологии . 238 (3): 263–285. doi : 10.1002/(SICI) 1097-4687 (199812) 238: 3 <263 :: AID-JMOR1> 3.0.CO; 2-L . PMID 29852696 . S2CID 46920478 .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в дюймовый Грегори Д. Эджкомб (2020). «Происхождение членистоногих: интеграция палеонтологических и молекулярных доказательств». Анну. Rev. Ecol. Эвол. Система 51 : 1–25. doi : 10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-011720-124437 . S2CID 225478171 .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в дюймовый Ортега-Хернандес, Хавьер (2016). «Изучение« нижней »и« верхней »группы стволовой группы Euartropoda, с комментариями о строгом использовании имени Chrothonica von Siebold, 1848». Биологические обзоры . 91 (1): 255–273. doi : 10.1111/brv.12168 . PMID 25528950 . S2CID 7751936 .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в Ария, Седрика (26 апреля 2022 года). «Происхождение и ранняя эволюция членистоногих» . Биологические обзоры . 97 (5): 1786–1809. doi : 10.1111/brv.12864 . ISSN 1464-7931 . PMID 35475316 . S2CID 243269510 .

- ^ Дженнер, RA (апрель 2006 г.). «Сложные полученные мудрости: некоторые вклад новой микроскопии в новую филогения животных» . Интегративная и сравнительная биология . 46 (2): 93–103. doi : 10.1093/ICB/ICJ014 . PMID 21672726 .

- ^ Данлоп, Джейсон А. (31 января 2011 г.). «Фокус ископаемого: chelicerata» . Палеонтология онлайн . С. 1–8. Архивировано с оригинала 12 сентября 2017 года . Получено 15 марта 2018 года .

- ^ «Черпона» . Интегрированная таксономическая информационная система . Получено 15 августа 2006 года .

- ^ Карапелли, Антонио; Ли, Пьетро; Нарди, Франческо; Ван дер Ват, Элизабет; Фрати, Франческо (16 августа 2007 г.). «Филогенетический анализ генов, кодирующих митохондриальный белок, подтверждает взаимную парафилию гексаподы и ракообразной» . BMC Эволюционная биология . 7 (Suppl 2): S8. Bibcode : 2007bmcee ... 7s ... 8c . doi : 10.1186/1471-2148-7-S2-S8 . PMC 1963475 . PMID 17767736 .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Регье, Джером С.; Шульц, JW; Zwick, A.; Хасси, А.; Ball, B.; Wetzer, R.; Мартин, JW; Каннингем, CW; и др. (2010). «Связь с членистоногими выявлена филогеномным анализом последовательностей кодирования ядерного белка». Природа . 463 (7284): 1079–1084. BIBCODE : 2010NATR.463.1079R . doi : 10.1038/nature08742 . PMID 20147900 . S2CID 4427443 .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный von Reumont, Bjoern M.; Дженнер, Рональд А.; Уиллс, Мэтью А.; Dell'ampio, Emiliano; Пасс, Гюнтер; Ebersberger, Ingo; Мейер, Бенджамин; Koenemann, Stefan; Илифф, Томас М.; Стаматакис, Александрос; Нихуис, Оливер; Меусеманн, Карен; Мисоф, Бернхард (2011). «Pancrustacean Phyologgeny в свете новых филогеномных данных: поддержка Remipedia в качестве возможной сестринской группы гексаподы» . Молекулярная биология и эволюция . 29 (3): 1031–45. doi : 10.1093/molbev/msr270 . PMID 22049065 .