Белл Боинг V-22 Оспри

| V-22 Osprey | |

|---|---|

| |

| МВ-22 используется во время демонстрации MAGTF 2014. на авиасалоне Мирамар | |

| Роль | конвертоплан Военно-транспортный самолет |

| Национальное происхождение | Соединенные Штаты |

| Производитель | |

| Первый полет | 19 марта 1989 г. |

| Introduction | 13 June 2007[1] |

| Status | In service |

| Primary users | United States Marine Corps |

| Produced | 1988–present |

| Number built | 400 as of 2020[update][2] |

| Developed from | Bell XV-15 |

| Variants | Bell Boeing Quad TiltRotor |

Bell Boeing V-22 Osprey — американский многоцелевой конвертоплан STOL с возможностью как вертикального взлета и посадки ( VTOL ), так и короткого взлета и посадки ( ) . чтобы сочетать в себе функциональность обычного вертолета с дальнобойностью и крейсерской скоростью турбовинтового Он спроектирован так , самолета. V-22 эксплуатируется в США и Японии и представляет собой не только новую конструкцию самолета, но и новый тип самолета, поступивший на вооружение в 2000-х годах, конвертоплан по сравнению с конструкциями самолетов и вертолетов. V-22 впервые поднялся в воздух в 1988 году и после длительной разработки был принят на вооружение в 2007 году. Конструкция по существу сочетает в себе способность вертикального взлета вертолета и дальность полета самолета.

The failure of Operation Eagle Claw in 1980 during the Iran hostage crisis underscored that there were military roles for which neither conventional helicopters nor fixed-wing transport aircraft were well-suited. The United States Department of Defense (DoD) initiated a program to develop an innovative transport aircraft with long-range, high-speed, and vertical-takeoff capabilities, and the Joint-service Vertical take-off/landing Experimental (JVX) program officially began in 1981. A partnership between Bell Helicopter and Boeing Helicopters was awarded a development contract in 1983 for the V-22 tiltrotor aircraft. The Bell-Boeing team jointly produces the aircraft.[3] V-22 впервые поднялся в воздух в 1989 году, после чего начались летные испытания и изменения конструкции; Сложность и трудности, связанные с тем, чтобы стать первым конвертопланом для военной службы, привели к многолетним разработкам.

The United States Marine Corps (USMC) began crew training for the MV-22B Osprey in 2000 and fielded it in 2007; it supplemented and then replaced their Boeing Vertol CH-46 Sea Knights. The U.S. Air Force (USAF) fielded its version of the tiltrotor, the CV-22B, in 2009. Since entering service with the Marine Corps and Air Force, the Osprey has been deployed in transportation and medevac operations over Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya, and Kuwait. The U.S. Navy began using the CMV-22B for carrier onboard delivery duties in 2021.

Development

[edit]

In the late 20th century VTOL aircraft gained popularity, and many prototype designs were developed, but only one entered service; the Harrier fighter/attack jet used a turbo fan engine. A practical tilt-rotor remained more elusive, until finally in the 1980s the United States moved forward with V-22 design. Overcoming many challenges over 400 aircraft were fielded by the 2020s.

Origins

[edit]The failure of Operation Eagle Claw, the Iran hostage rescue mission, in 1980 demonstrated to the U.S. military a need[4][5] for "a new type of aircraft, that could not only take off and land vertically but also could carry combat troops, and do so at speed."[6] Additionally, a concentrated force is vulnerable to a single nuclear weapon. Airborne solutions with high speed and range allow for their rapid dispersal to reduce this vulnerability.[7] The U.S. Department of Defense began the JVX aircraft program in 1981, under U.S. Army leadership.[8]

The established tactical purpose of the USMC is to perform an amphibious landing, which the JVX program promised to facilitate. The USMC's primary helicopter model, the CH-46 Sea Knight, was aging, and no replacement had been accepted.[9] Because the USMC's amphibious capability would be significantly reduced without the CH-46, USMC leadership believed a proposal to merge the Marine Corps with the Army was a credible threat.[10][11] This potential merger was akin to a proposal by President Truman following World War II.[12] The Office of the Secretary of Defense and Navy administration opposed the tiltrotor project, but pressure from Congress had a significant effect on the program's development.[13]

The Navy and USMC were given the lead in 1983.[8][14][15] The JVX combined requirements from the USMC, USAF, Army and Navy.[16][17] A request for preliminary design proposals was issued in December 1982. Interest was expressed by Aérospatiale, Bell Helicopter, Boeing Vertol, Grumman, Lockheed, and Westland. Contractors were encouraged to form teams. Bell partnered with Boeing Vertol to submit a proposal for an enlarged version of the Bell XV-15 prototype on 17 February 1983. Since this was the only proposal the JVX program received, a preliminary design contract was awarded on 26 April 1983.[18][19]

The JVX aircraft was designated V-22 Osprey on 15 January 1985; by that March, the first six prototypes were being produced, and Boeing Vertol was expanded to handle the workload.[20][21] Production work is split between Bell and Boeing. Bell Helicopter manufactures and integrates the wing, nacelles, rotors, drive system, tail surfaces, and aft ramp, as well as integrating the Rolls-Royce engines and performing final assembly. Boeing Helicopters manufactures and integrates the fuselage, cockpit, avionics, and flight controls.[3][22] The USMC variant received the MV-22 designation, and the USAF variant received CV-22; this was reversed from normal procedure to prevent USMC Ospreys from having a conflicting CV designation with aircraft carriers.[23] Full-scale development began in 1986.[24] On 3 May 1986, Bell Boeing was awarded a US$1.714 billion contract for the V-22 by the U.S. Navy. At this point, all four U.S. military services had acquisition plans for the V-22.[25]

The first V-22 was publicly rolled out in May 1988.[26][27] That year, the U.S. Army left the program, citing a need to focus its budget on more immediate aviation programs.[8] In 1989, the V-22 survived two separate Senate votes that could have resulted in cancellation.[28][29] Despite the Senate's decision, the Department of Defense instructed the Navy not to spend more money on the V-22.[30] As development cost projections greatly increased in 1988, Defense Secretary Dick Cheney tried to defund it from 1989 to 1992, but was overruled by Congress,[14][31] which provided unrequested program funding.[32] Multiple studies of alternatives found the V-22 provided more capability and effectiveness with similar operating costs.[33] The Clinton Administration was supportive of the V-22, helping it attain funding.[14]

Although the Army departed the program, it eventually developed and chose a tiltrotor to replace the UH-60 Blackhawk in the 21st century, and as of the mid-2020s the Army is planning to field the V-280 Valor tiltrotor.[34]

Flight testing and design changes

[edit]

The first of six prototypes first flew on 19 March 1989 in the helicopter mode[35] and on 14 September 1989 in fixed-wing mode.[36] The third and fourth prototypes successfully completed the first sea trials on USS Wasp in December 1990.[37] The fourth and fifth prototypes crashed in 1991–92.[38] From October 1992 to April 1993, the V-22 was redesigned to reduce empty weight, simplify manufacture, and reduce build costs; it was designated V-22B.[39] Flights resumed in June 1993 after safety changes were made to the prototypes.[40] Bell Boeing received a contract for the engineering manufacturing development (EMD) phase in June 1994.[39] The prototypes were also modified to resemble the V-22B standard. At this stage, testing focused on flight envelope expansion, measuring flight loads, and supporting the EMD redesign. Flight testing with the early V-22s continued into 1997.[41]

Flight testing of four full-scale development V-22s began at the Naval Air Warfare Test Center, Naval Air Station Patuxent River, Maryland. The first EMD flight took place on 5 February 1997. Testing soon fell behind schedule.[42] The first of four low rate initial production aircraft, ordered on 28 April 1997, was delivered on 27 May 1999. The second sea trials were completed onboard USS Saipan in January 1999.[24] During external load testing in April 1999, a V-22 transported the lightweight M777 howitzer.[43][44]

In 2000, there were two fatal crashes, killing a total of 23 marines, and the V-22 was again grounded while the crashes' causes were investigated and various parts were redesigned.[31] In June 2005, the V-22 completed its final operational evaluation, including long-range deployments, high altitude, desert and shipboard operations; problems previously identified had reportedly been resolved.[45]

U.S. Naval Air Systems Command (NAVAIR) worked on software upgrades to increase the maximum speed from 250 to 270 knots (460 to 500 km/h; 290 to 310 mph), increase helicopter mode altitude limit from 10,000 to 12,000 feet (3,000 to 3,700 m) or 14,000 feet (4,300 m), and increase lift performance.[46] By 2012, changes had been made to the hardware, software, and procedures in response to hydraulic fires in the nacelles, vortex ring state control issues, and opposed landings;[47][48] reliability has improved accordingly.[49]

An MV-22 landed and refueled on board Nimitz in an evaluation in October 2012.[50] In 2013, cargo handling trials occurred on Harry S. Truman.[51] In October 2015, NAVAIR tested rolling landings and takeoffs on a carrier, preparing for carrier onboard delivery.[52]

Discussions

[edit]

Development was protracted and controversial, partly because of large cost increases,[53] some of which were caused by a requirement to fold wings and rotors to fit aboard ships.[54] The development budget was first set at US$2.5 billion in 1986, increasing to a projected US$30 billion in 1988.[31] By 2008, US$27 billion had been spent and another US$27.2 billion was required for planned production numbers.[24] Between 2008 and 2011, the V-22's estimated lifetime cost grew by 61%, mostly for maintenance and support.[55]

Its [The V-22's] production costs are considerably greater than for helicopters with equivalent capability – specifically, about twice as great as for the CH-53E, which has a greater payload and an ability to carry heavy equipment the V-22 cannot ... an Osprey unit would cost around $60 million to produce, and $35 million for the helicopter equivalent.[56]

— Michael E. O'Hanlon, 2002

In 2001, Lieutenant Colonel Odin Leberman, commander of the V-22 squadron at Marine Corps Air Station New River, was relieved of duty after allegations that he instructed his unit to falsify maintenance records to make it appear more reliable.[24][57] Three officers were implicated for their roles in the falsification scandal.[53]

In October 2007, a Time magazine article condemned the V-22 as unsafe, overpriced, and inadequate;[58] the USMC responded that the article's data was partly obsolete, inaccurate, and held high expectations for any new field of aircraft.[59] In 2011, the controversial defense industry-supported Lexington Institute[60][61][62] reported that the average mishap rate per flight hour over the past 10 years was the lowest of any USMC rotorcraft, approximately half of the average fleet accident rate.[63] In 2011, Wired magazine reported that the safety record had excluded ground incidents;[64] the USMC responded that MV-22 reporting used the same standards as other Navy aircraft.[65]

By 2012, the USMC reported fleetwide readiness rate had risen to 68%;[66] however, the DOD's Inspector General later found 167 of 200 reports had "improperly recorded" information.[67] Captain Richard Ulsh blamed errors on incompetence, saying that they were "not malicious" or deliberate.[68] The required mission capable rate was 82%, but the average was 53% from June 2007 to May 2010.[69] In 2010, Naval Air Systems Command aimed for an 85% reliability rate by 2018.[70] From 2009 to 2014, readiness rates rose 25% to the "high 80s", while cost per flight hour had dropped 20% to $9,520 through a rigorous maintenance improvement program that focused on diagnosing problems before failures occur.[71] As of 2015[update], although the V-22 requires more maintenance and has lower availability (62%) than traditional helicopters, it also has a lower mishap rate. The average cost per flight hour is US$9,156,[72] whereas the Sikorsky CH-53E Super Stallion cost about $20,000 (~$28,320 in 2023) per flight hour in 2007.[73] V-22 ownership cost was $83,000 per hour in 2013.[74] In 2022, the Pentagon evaluated its cost per flight hour at $23,941.[75]

While technically capable of autorotation if both engines fail in helicopter mode, a safe landing is difficult.[76] In 2005, a director of the Pentagon's testing office stated that in a loss of power while hovering below 1,600 feet (490 m), emergency landings "are not likely to be survivable." V-22 pilot Captain Justin "Moon" McKinney stated that: "We can turn it into a plane and glide it down, just like a C-130."[58] A complete loss of power requires both engines to fail, as one engine can power both proprotors via interconnected drive shafts.[77] Though vortex ring state (VRS) contributed to a deadly V-22 accident, flight testing found it to be less susceptible to VRS than conventional helicopters.[4] A GAO report stated that the V-22 is "less forgiving than conventional helicopters" during VRS.[78] Several test flights to explore VRS characteristics were canceled.[79] The USMC trains pilots in the recognition of and recovery from VRS, and has instituted operational envelope limits and instrumentation to help avoid VRS conditions.[31][80]

Production

[edit]On 28 September 2005, the Pentagon formally approved full-rate production,[81] increasing from 11 V-22s per year to between 24 and 48 per year by 2012. Of the 458 total planned, 360 are for the USMC, 50 for the USAF, and 48 for the Navy at an average cost of $110 million per aircraft, including development costs.[24] The V-22 had an incremental flyaway cost of $67 million per aircraft in 2008,[82] The Navy had hoped to shave about $10 million off that cost via a five-year production contract in 2013.[83] Each CV-22 cost $73 million (~$92.6 million in 2023) in the FY 2014 budget.[84]

On 15 April 2010, the Naval Air Systems Command awarded Bell Boeing a $42.1 million (~$57.4 million in 2023) contract to design an integrated processor in response to avionics obsolescence and add new network capabilities.[85] By 2014, Raytheon began providing an avionics upgrade that includes situational awareness and blue force tracking.[86] In 2009, a contract for Block C upgrades was awarded to Bell Boeing.[87] In February 2012, the USMC received the first V-22C, featuring a new radar, additional mission management and electronic warfare equipment.[88] In 2015, options for upgrading all aircraft to the V-22C standard were examined.[89]

On 12 June 2013, the U.S. DoD awarded a $4.9 billion contract for 99 V-22s in production Lots 17 and 18, including 92 MV-22s for the USMC, for completion in September 2019.[90] A provision gives NAVAIR the option to order 23 more Ospreys.[91] As of June 2013, the combined value of all contracts placed totaled $6.5 billion.[92] In 2013, Bell laid off production staff following the US's order being cut to about half of the planned number.[93][94] Production rate went from 40 in 2012 to 22 planned for 2015.[95] Manufacturing robots have replaced older automated machines for increased accuracy and efficiency; large parts are held in place by suction cups and measured electronically.[96][97]

In March 2014, Air Force Special Operations Command issued a Combat Mission Need Statement for armor to protect V-22 passengers. NAVAIR worked with a Florida-based composite armor company and the Army Aviation Development Directorate to develop and deliver the advanced ballistic stopping system (ABSS) by October 2014. Costing $270,000, the ABSS consists of 66 plates fitting along interior bulkheads and deck, adding 800 lb (360 kg) to the aircraft's weight, affecting payload and range. The ABSS can be installed or removed when needed in hours and partially assembled in pieces for partial protection of specific areas. As of May 2015, 16 kits had been delivered to the USAF.[98][99]

In 2015, Bell Boeing set up the V-22 Readiness Operations Center at Ridley Park, Pennsylvania, to gather information from each aircraft to improve fleet performance in a similar manner as the F-35's Autonomic Logistics Information System.[100]

Design

[edit]

Overview

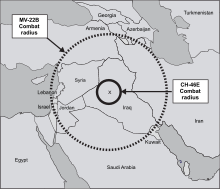

[edit]The Osprey is the world's first production tiltrotor aircraft,[101] with one three-bladed proprotor, turboshaft engine, and transmission nacelle mounted on each wingtip.[102] It is classified as a powered lift aircraft by the Federal Aviation Administration.[103] For takeoff and landing, it typically operates as a helicopter with the nacelles vertical and rotors horizontal. Once airborne, the nacelles rotate forward 90° in as little as 12 seconds for horizontal flight, converting the V-22 to a more fuel-efficient, higher-speed aircraft, like a turboprop aircraft.[104] STOL rolling-takeoff and landing capability is achieved by having the nacelles tilted forward up to 45°.[105][106] Other orientations are possible.[107] Pilots describe the V-22 in airplane mode as comparable to the C-130 in feel and speed.[108] It has a ferry range of over 2,100 nmi. Its operational range is 1,100 nmi.[109]

Composite materials make up 43% of the airframe, and the proprotor blades also use composites.[105] For storage, the V-22's rotors fold in 90 seconds and its wing rotates to align, front-to-back, with the fuselage.[110] Because of the requirement for folding rotors, their 38-foot (12 m) diameter is 5 feet (1.5 m) less than would be optimal for an aircraft of this size to conduct vertical takeoff, resulting in high disk loading.[107] Most missions use fixed wing flight 75% or more of the time, reducing wear and tear and operational costs. This fixed wing flight is higher than typical helicopter missions allowing longer range line-of-sight communications for improved command and control.[24]

Exhaust heat from the V-22's engines can potentially damage ships' flight decks and coatings. NAVAIR devised a temporary fix of portable heat shields placed under the engines and determined that a long-term solution would require redesigning decks with heat resistant coating, passive thermal barriers, and ship structure changes. Similar changes are required for F-35B operations.[111] In 2009, DARPA requested solutions for installing robust flight deck cooling.[112] A heat-resistant anti-skid metal spray named Thermion has been tested on USS Wasp.[113]

Propulsion

[edit]

The V-22's two Rolls-Royce AE 1107C engines are connected by drive shafts to a common central gearbox so that one engine can power both proprotors if an engine failure occurs.[77] Either engine can power both proprotors through the wing driveshaft.[76] However, the V-22 is generally not capable of hovering on one engine.[114] If a proprotor gearbox fails, that proprotor cannot be feathered, and both engines must be stopped before an emergency landing. The autorotation characteristics are poor because of the rotors' low inertia.[76] The AE 1107C engine has a two-shaft axial design with a 14-stage compressor, an effusion-cooled annular combustor, a two-stage gas generator turbine, and two-stage power turbine.[115]

In September 2013, Rolls-Royce announced that it had increased the AE-1107C engine's power by 17% via the adoption of a new Block 3 turbine, increased fuel valve flow capacity, and software updates; it should also improve reliability in high-altitude, high-heat conditions and boost maximum payload limitations from 6,000 to 8,000 ft (1,800 to 2,400 m). A Block 4 upgrade is reportedly being examined, which may increase power by up to 26%, producing close to 10,000 shp (7,500 kW), and improve fuel consumption.[116]

In August 2014, the U.S. military issued a request for information for a potential drop-in replacement for the AE-1107C engines. Submissions must have a power rating of no less than 6,100 shp (4,500 kW) at 15,000 rpm, operate at up to 25,000 ft (7,600 m) at up to 130 degrees Fahrenheit (54 degrees Celsius), and fit into the existing wing nacelles with minimal structural or external modifications.[117] In September 2014, the U.S. Navy, who already purchase engines separately to airframes, was reportedly considering an alternative engine supplier to reduce costs.[118] The General Electric GE38 is one option, giving commonality with the Sikorsky CH-53K King Stallion.[119]

The V-22 has a maximum rotor downwash speed of over 80 knots (92 mph; 150 km/h), more than the 64-knot (74 mph; 119 km/h) lower limit of a hurricane.[120][121] The rotorwash usually prevents the starboard door's usage in hover; the rear ramp is used for rappelling and hoisting instead.[76][122] The V-22 loses 10% of its vertical lift over a tiltwing design when operating in helicopter mode because of the wings' airflow resistance, while the tiltrotor design has better short takeoff and landing performance.[123] V-22s must keep at least 25 ft (7.6 m) of vertical separation between each other to avoid each other's rotor wake, which causes turbulence and potentially control loss.[99]

Avionics

[edit]

The V-22 is equipped with a glass cockpit, which incorporates four multi-function displays (MFDs, compatible with night-vision goggles)[76] and one shared central display unit, to display various images including: digimaps, imagery from the Turreted forward-looking infrared system[124] primary flight instruments, navigation (TACAN, VOR, ILS, GPS, INS), and system status. The flight director panel of the cockpit management system allows for fully coupled (autopilot) functions that take the aircraft from forward flight into a 50 ft (15 m) hover with no pilot interaction other than programming the system.[125] The fuselage is not pressurized, and personnel must wear on-board oxygen masks above 10,000 feet.[76]

The V-22 has triple-redundant fly-by-wire flight control systems; these have computerized damage control to automatically isolate damaged areas.[126][127] With the nacelles pointing straight up in conversion mode at 90° the flight computers command it to fly like a helicopter, cyclic forces being applied to a conventional swashplate at the rotor hub. With the nacelles in airplane mode (0°) the flaperons, rudder, and elevator fly similar to an airplane. This is a gradual transition, occurring over the nacelles' rotation range; the lower the nacelles, the greater effect of the airplane-mode control surfaces.[128] The nacelles can rotate past vertical to 97.5° for rearward flight.[129][130] The V-22 can use the "80 Jump" orientation with the nacelles at 80° for takeoff to quickly achieve high altitude and speed.[107] The controls automate to the extent that it can hover in low wind without hands on the controls.[107][76]

New USMC V-22 pilots learn to fly helicopter and multiengine fixed-wing aircraft before the tiltrotor.[131] Some V-22 pilots believe that former fixed-wing pilots may be preferable over helicopter users, as they are not trained to constantly adjust the controls in hover. Others say that experience with helicopters' hovering and precision is most important.[107][76] As of April 2021[update] the US military does not track whether fixed-wing or helicopter pilots transition more easily to the V-22, according to USMC Colonel Matthew Kelly, V-22 project manager. He said that fixed-wing pilots are more experienced at instrument flying, while helicopter pilots are more experienced at scanning outside when the aircraft is moving slowly.[108]

Armament

[edit]

The V-22 can be armed with one 7.62×51mm NATO (.308 in caliber) M240 machine gun or .50 in caliber (12.7 mm) M2 machine gun on the rear loading ramp. A 12.7 mm (.50 in) GAU-19 three-barrel Gatling gun mounted below the nose was studied.[132] BAE Systems developed a belly-mounted, remotely operated gun turret system,[133] the Interim Defense Weapon System (IDWS);[134] it is remotely operated by a gunner, targets are acquired via a separate pod using color television and forward looking infrared imagery.[135] The IDWS was installed on half of the V-22s deployed to Afghanistan in 2009;[134] it found limited use because of its 800 lb (360 kg) weight and restrictive rules of engagement.[136]

There were 32 IDWSs available to the USMC in June 2012; V-22s often flew without it as the added weight reduced cargo capacity. The V-22's speed allows it to outrun conventional support helicopters, thus a self-defense capability was required on long-range independent operations. The infrared gun camera proved useful for reconnaissance and surveillance. Other weapons were studied to provide all-quadrant fire, including nose guns, door guns, and non-lethal countermeasures to work with the current ramp-mounted machine gun and the IDWS.[137]

In 2014, the USMC studied new weapons with "all-axis, stand-off, and precision capabilities", akin to the AGM-114 Hellfire, AGM-176 Griffin, Joint Air-to-Ground Missile, and GBU-53/B SDB II.[138] In November 2014, Bell Boeing conducted self-funded weapons tests, equipping a V-22 with a pylon on the front fuselage and replacing the AN/AAQ-27A EO camera with an L-3 Wescam MX-15 sensor/laser designator. 26 unguided Hydra 70 rockets, two guided APKWS rockets, and two Griffin B missiles were fired over five flights. The USMC and USAF sought a traversable nose-mounted weapon connected to a helmet-mounted sight; recoil complicated integrating a forward-facing gun.[139] A pylon could carry 300 lb (140 kg) of munitions.[140] However, by 2019, the USMC opted for IDWS upgrades over adopting new weapons.[141]

Refueling capability

[edit]

Boeing is developing a roll-on/roll-off aerial refueling kit, which would give the V-22 the ability to refuel other aircraft. Having an aerial refueling capability that can be based on Wasp-class amphibious assault ships would increase the F-35B's strike power, removing reliance on refueling assets solely based on large Nimitz-class aircraft carriers or land bases. The roll-on/roll-off kit can also be applicable to intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) functions.[142] Boeing funded a non-functional demonstration on a VMX-22 aircraft; a prototype kit was successfully tested with an F/A-18 on 5 September 2013.[143]

The high-speed version of the hose/drogue refueling system can be deployed at 185 knots (213 mph; 343 km/h) and function at up to 250 knots (290 mph; 460 km/h). A mix of tanks and a roll-on/roll-off bladder house up to 12,000 lb (5,400 kg) of fuel. The ramp must open to extend the hose, then raised once extended. It can refuel rotorcraft, needing a separate drogue used specifically by helicopters and a converted nacelle.[144] Many USMC ground vehicles can run on aviation fuel; a refueling V-22 could service these. In late 2014, it was stated that V-22 tankers could be in use by 2017,[145] but contract delays pushed IOC to late 2019.[146] As part of a 26 May 2016 contract award to Boeing,[147] Cobham was contracted to adapt their FR-300 hose drum unit as used by the KC-130 in October 2016.[148] While the Navy has not declared its interest in the capability, it could be leveraged later on.[149]

Operational history

[edit]In October 2019, the fleet of 375 V-22s operated by the U.S. Armed Forces surpassed the 500,000 flight hour mark.[150] A fatal accident in December 2023, lead the fleet being grounded until March 2024 by the US and Japan.[151]

U.S. Marine Corps

[edit]

Since March 2000, VMMT-204 has conducted training for the type. In December 2005, Lieutenant General James Amos, commander of II Marine Expeditionary Force, accepted delivery of the first batch of MV-22s. The unit reactivated in March 2006 as the first MV-22 squadron, redesignated as VMM-263. In 2007, HMM-266 became Marine Medium Tiltrotor Squadron 266 (VMM-266)[152] and reached initial operational capability.[1] It started replacing the CH-46 Sea Knight in 2007; the CH-46 was retired in October 2014.[153][154] On 13 April 2007, the USMC announced the first V-22 combat deployment at Al Asad Airbase, Iraq.[155][156]

V-22s in Iraq's Anbar province were used for transport and scout missions. General David Petraeus, the top U.S. military commander in Iraq, used one to visit troops on Christmas Day 2007;[157] as did Barack Obama during his 2008 presidential campaign tour in Iraq.[158] USMC Col. Kelly recalled how visitors were reluctant to fly on the unfamiliar aircraft, but after seeing its speed and ability to fly above ground fire, "All of a sudden, the entire flight schedule was booked. No senior officer wanted to go anywhere unless they could fly on the V-22".[108] Obtaining spares proved problematic.[159] By July 2008, the V-22 had flown 3,000 sorties totaling 5,200 hours in Iraq.[160] General George J. Trautman III praised its greater speed and range over legacy helicopters, saying "it turned his battle space from the size of Texas into the size of Rhode Island."[161] Despite attacks by man-portable air-defense systems and small arms, none were lost to enemy fire by late 2009.[162]

A Government Accountability Office study stated that by January 2009, the 12 MV-22s in Iraq had completed all assigned missions; mission capable rates averaged 57% to 68%, and an overall full mission capable rate of 6%. It also noted weaknesses in situational awareness, maintenance, shipboard operations and transport capability.[163][164] The report concluded: "deployments confirmed that the V-22's enhanced speed and range enable personnel and internal cargo to be transported faster and farther than is possible with the legacy helicopters".[163]

MV-22s deployed to Afghanistan in November 2009 with VMM-261;[165][166] it saw its first offensive combat mission, Operation Cobra's Anger, on 4 December 2009. V-22s assisted in inserting 1,000 USMC and 150 Afghan troops into the Now Zad Valley of Helmand Province in southern Afghanistan to disrupt Taliban operations.[134] General James Amos stated that Afghanistan's MV-22s had surpassed 100,000 flight hours, calling it "the safest airplane, or close to the safest airplane" in the USMC inventory.[167] The V-22's Afghan deployment was set to end in late 2013 with the drawdown of combat operations; however, VMM-261 was directed to extend operations for casualty evacuation, being quicker than helicopters enabled more casualties to reach a hospital within the 'golden hour'; they were fitted with medical equipment such as heart monitors and triage supplies.[168]

In January 2010, the MV-22 was sent to Haiti as part of Operation Unified Response relief efforts after an earthquake, the type's first humanitarian mission.[169] In March 2011, two MV-22s from Kearsarge helped rescue a downed USAF F-15E crew member during Operation Odyssey Dawn.[170][171] On 2 May 2011, following Operation Neptune's Spear, the body of Osama bin Laden, founder of the al-Qaeda terrorist group, was flown by an MV-22 to the aircraft carrier Carl Vinson in the Arabian Sea, prior to his burial at sea.[172]

In 2013, several MV-22s received communications and seating modifications to support the Marine One presidential transport squadron because of the urgent need for CH-53Es in Afghanistan.[173][174] In May 2010, Boeing announced plans to submit the V-22 for the VXX presidential transport replacement.[175]

From 2 to 5 August 2013, two MV-22s completed the longest distance Osprey tanking mission to date. Flying from Marine Corps Air Station Futenma in Okinawa alongside two KC-130J tankers, they flew to Clark Air Base in the Philippines on 2 August; then to Darwin, Australia, on 3 August; to Townsville, Australia, on 4 August; and finally rendezvoused with Bonhomme Richard on 5 August.[176]

In 2013, the USMC formed an intercontinental response force, the Special Purpose Marine Air-Ground Task Force – Crisis Response – Africa,[177] using V-22s outfitted with specialized communications gear.[178] In 2013, following Typhoon Haiyan, 12 MV-22s of the 3rd Marine Expeditionary Brigade were deployed to the Philippines for disaster relief operations;[179] its abilities were described as "uniquely relevant", flying faster and with greater payloads while moving supplies throughout the island archipelago.[180]

U.S. Air Force

[edit]

The USAF's first operational CV-22 was delivered to the 58th Special Operations Wing (58th SOW) at Kirtland Air Force Base, New Mexico, in March 2006. Early aircraft were delivered to the 58th SOW and used for training personnel for special operations use.[181] On 16 November 2006, the USAF officially accepted the CV-22 in a ceremony conducted at Hurlburt Field, Florida.[182] The USAF's first operational deployment sent four CV-22s to Mali in November 2008 in support of Exercise Flintlock. The CV-22s flew nonstop from Hurlburt Field, Florida, with in-flight refueling.[4] AFSOC declared that the 8th Special Operations Squadron reached Initial Operational Capability in March 2009, with six CV-22s in service.[183]

In December 2013, three CV-22s came under small arms fire while trying to evacuate American civilians in Bor, South Sudan, during the 2013 South Sudanese political crisis; the aircraft flew 500 mi (800 km) to Entebbe, Uganda, after the mission was aborted. South Sudanese officials stated that the attackers were rebels.[184][185] The CV-22s had flown to Bor over three countries across 790 nmi (910 mi; 1,460 km). The formation was hit 119 times, wounding four crew and causing flight control failures and hydraulic and fuel leaks on all three aircraft. Fuel leaks resulted in multiple air-to-air refuelings en route.[186] After the incident, AFSOC developed optional armor floor panels.[98]

The USAF found that "CV-22 wake modeling is inadequate for a trailing aircraft to make accurate estimations of safe separation from the preceding aircraft."[187] In 2015, the USAF sought to configure the CV-22 to perform combat search and rescue in addition to its long-range special operations transport mission. It would complement the HH-60G Pave Hawk and planned HH-60W rescue helicopters, being employed in scenarios where high speed is better suited to search and rescue than more nimble but slower helicopters.[188]

On 29 November 2023, a CV-22B assigned to the US Air Force's 353rd Special Operations Wing crashed into the East China Sea off Yakushima Island, Japan, killing all eight airmen aboard. The Osprey, based at Yokota Air Base, was flying from Marine Corps Air Station Iwakuni to Kadena Air Base on Okinawa Island in clear weather and light winds. An Air Force investigation into the cause of the crash is ongoing.[189][190] A preliminary investigation has revealed a "potential materiel failure" could have caused the accident.[191] On 6 December 2023, the U.S. Navy (NAVAIR) and the Air Force (AFSOC) grounded their V-22 fleets. Japan (Maritime Self Defense Force) also has grounded their fleet.[191] In early March the US and Japan resumed flights of the V-22 with revised maintenance and pilot training focuses but no changes to the aircraft.[192][193] The V-22 was returned to flight with no changes; the part that failed was identified and how it failed determined, although the accident was still under scrutiny.[194]

U.S. Navy

[edit]

The V-22 program originally included Navy 48 HV-22s, but none were ordered.[24] In 2009, it was proposed that it replace the C-2 Greyhound for carrier onboard delivery (COD) duties. One advantage of the V-22 is the ability to deliver supplies and people between non-carrier ships beyond helicopter range.[195][196] Proponents said that it is capable of similar speed, payload capacity, and lift performance to the C-2, and can carry greater payloads over short ranges, up to 20,000 lb, including suspended external loads. The C-2 can only deliver cargo to carriers, requiring further distribution to smaller vessels via helicopters, while the V-22 is certified for operating upon amphibious ships, aircraft carriers, and logistics ships. It could also take some helicopter roles by fitting a 600 lb hoist to the ramp and a cabin configuration for 12 non-ambulatory patients and 5 seats for medical attendants.[197] Bell and P&W designed a frame for the V-22 to transport the Pratt & Whitney F135 engine of the F-35.[198]

On 5 January 2015, the Navy and USMC signed a memorandum of understanding to buy the V-22 for the COD mission.[199] Initially designated HV-22, four aircraft were bought each year from 2018 to 2020.[200] It incorporates an extended-range fuel system for an 1,150 nmi (1,320 mi; 2,130 km) unrefueled range, a high-frequency radio for over-the-horizon communications, and a public address system to communicate with passengers;[201][202] the range increase comes from extra fuel bladders[203] in larger external sponsons, the only external difference from other variants. Its primary mission is long-range logistics; other conceivable missions include personnel recovery and special warfare.[204] In February 2016, the Navy officially designated it the CMV-22B.[205] The Navy's Program of Record originally called for 48 aircraft, it later determined that only 44 were required. Production began in FY 2018, and deliveries started in 2020.[206][207]

The Navy ordered the first 39 CMV-22Bs in June 2018; initial operating capability was achieved in 2021, with fielding to the fleet by the mid-2020s.[208][209] The first CMV-22B made its initial flight in December 2019.[210] The first deployment began in summer 2021 aboard the USS Carl Vinson.[211]

Japan Self-Defense Forces

[edit]

Japan bought the V-22 and they entered defense service in 2020, becoming the first international customer for the tiltrotor.[212]

In 2012, former Defense Minister Satoshi Morimoto ordered an investigation of the costs of V-22 operations. The V-22's capabilities exceeded current Japan Self-Defense Forces helicopters in terms of range, speed and payload. The ministry anticipated deployments to the Nansei Islands and the Senkaku Islands, as well as in multinational cooperation with the U.S.[213] In November 2014, the Japanese Ministry of Defense decided to procure 17 V-22s.[214] The first V-22 for Japan undertook its first flight in August 2017[215] and the aircraft began delivery to the Japanese military in 2020.[216]

In September 2018, the Japanese Ministry of Defense decided to delay the deployment of the first five MV-22Bs it had received amid opposition and ongoing negotiations in the Saga Prefecture, where the aircraft are to be based.[217] On 8 May 2020, the first two of the five aircraft were delivered to the JGSDF at Kisarazu Air Field after failing to reach an agreement with Saga prefecture residents.[218] It is planned to eventually station some V-22s on board the Izumo-class helicopter destroyers. In September 2023, the first V-22 landings were conducted on the helicopter carrier Ise. The aircraft are planned to be based at Saga Airport in Kyushu starting in 2025 where the V-22s will be deployed together with Sikorsky Black Hawk and Apache Longbow helicopters in order to better defend Japan's southern Nansei Islands.[219]

Following the fatal crash of a US Air Force CV-22 off Yakushima on 29 November 2023, Japan suspended flights of its 14 MV-22s.[220] In early 2024 it was reported that the Japanese would resume flights of the V-22, and in March 2024 flights resumed.[192][221]

Potential operators

[edit]The V-22 can carry a power-module of certain fighter jets such as the F-35, and also is noted it could be useful to nations with island chains or carriers.[222] One question was why the U.S. Army did not procure the V-22 Osprey, and it was actually in the project at the start, but ended up heavily investing in traditional rotor craft such as the UH-60 Black Hawk and CH-47 Chinook.[223] The V-22 production line is planned to be open to around 2026 to complete the orders for the Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corp.[224]

Early on in the 2010s, some of the possible export buyers included Canada, Japan, United Arab Emirates, and the United Kingdom.[225] Other potential interest came from India and Indonesia.[226][227] In Europe, there was some interest on the continent from France, Spain, and Italy also.[228] Canada is thought to have considered the V-22 for the Fixed Wing Search and Rescue (FWSAR), but it was not entered as the overall goals prioritized conventional aircraft; that program was won by the C-295.[229][230]

The Air Force is also considering some additional V-22 for search and rescue, to supplement the HH-60W with a longer range aircraft, especially in the Indo-Pacific region where longer range is typically needed.[231]

France

[edit]France had shown some interest in the V-22 especially for Naval operations. It tested the V-22 in operations on the Mistral class LHDs, and also its CVN.[228] The French had two year long program to insure that the V-22 could operate from the Mistral class LHD working with USMC V-22.[228]

India

[edit]In 2015, the Indian Aviation Research Centre showed interest in acquiring four V-22s for personnel evacuation in hostile conditions, logistic supplies, and deployment of the Special Frontier Force in border areas. US V-22s performed relief operations after the April 2015 Nepal earthquake.[226] The Indian Navy also studied the V-22 rather than the E-2D for airborne early warning and control to replace the short-range Kamov Ka-31.[232] India is interested in purchasing six attack version V-22s for rapid troop insertion in border areas.[233][234]

Indonesia

[edit]On 6 July 2020, the U.S. State Department announced that they had approved a possible Foreign Military Sale to Indonesia of eight Block C MV-22s and related equipment for an estimated cost of $2 billion (~$2.32 billion in 2023). The U.S. Defense Security Cooperation Agency notified Congress of this possible sale.[235] The sale was approved, but in the end Indonesia decided against the purchase at that time due to the cost. It was noted that the V-22 could provide a unique logistical support to the island chain nation, but the concerns about purchase and maintenance costs were an issue.[227]

Israel

[edit]On 22 April 2013, an agreement was signed to sell six V-22 to the Israeli Air Force.[236] By the end of 2016, Israel had not ordered the V-22 and was instead interested in buying the CH-47 Chinook helicopter or the CH-53K helicopter.[237] As of 2017, Israel had frozen its evaluation of the V-22, "with a senior defence source indicating that the tiltrotor is unable to perform some missions currently conducted using its Sikorsky CH-53 transport helicopters."[238]

United Kingdom

[edit]The U.K. has had a watchful eye on V-22 program, and a combined UK/US study evaluated possible use.[239] One of the more serious evaluations, came in the late 2010s when it was considered to use them on the new Queen Elizabeth class carriers.[240] In the 2020s, it was thought to be one of the possible aircraft for the U.K.'s New Medium Helicopter program but was not a finalist, a program that is seeking to replace the Westland Puma medium helicopter fleet.[241]

Variants

[edit]

- V-22 ("V-22A")

- Pre-production full-scale development aircraft used for flight testing. These are unofficially considered A-variants after the 1993 redesign.[242]

- CV-22B

- U.S. Air Force variant for the U.S. Special Operations Command. It conducts long-range special operations missions and is equipped with extra wing fuel tanks, an AN/APQ-186 terrain-following radar, and other equipment such as the AN/ALQ-211,[243][244] and AN/AAQ-24 Nemesis Directional Infrared Counter Measures.[245] The fuel capacity is increased by 588 gallons (2,230 L) with two inboard wing tanks; three auxiliary tanks (200 or 430 gal) can also be added in the cabin.[246] The CV-22 replaced the MH-53 Pave Low.[24]

- MV-22B

- U.S. Marine Corps variant. The Marine Corps is the lead service in the V-22's development. The Marine Corps variant is an assault transport for troops, equipment and supplies, capable of operating from ships or expeditionary airfields ashore. It replaced the Marine Corps' CH-46E and CH-53D fleets.[247][248]

- CMV-22B

- U.S. Navy variant for the carrier onboard delivery role, replacing the C-2. Similar to the MV-22B but includes an extended-range fuel system, a high-frequency radio, and a public address system.[205]

- EV-22

- Proposed airborne early warning and control variant. The Royal Navy studied this variant as a replacement for its fleet of carrier-based Sea King ASaC.7 helicopters.[249]

- HV-22

- The U.S. Navy considered an HV-22 to provide combat search and rescue, delivery and retrieval of special warfare teams along with fleet logistic support transport. It chose the MH-60S for this role in 2001.[250][251]

- SV-22

- Proposed anti-submarine warfare variant. The U.S. Navy studied the SV-22 in the 1980s to replace S-3 and SH-2 aircraft.[252]

Operators

[edit]

- Japan Ground Self-Defense Force (14 delivered, 3 on order as of Dec 2023)[253][218][254]

- United States Air Force[255]

- 7th Special Operations Squadron[256]

- 8th Special Operations Squadron[257]

- 20th Special Operations Squadron[258]

- 21st Special Operations Squadron[259]

- 71st Special Operations Squadron[260]

- 249th Special Operations Squadron - Florida Air National Guard associate unit to 1st Special Operations Wing[261]

- 418th Flight Test Squadron[262]

- United States Marine Corps[255]

- United States Navy – 44 CMV-22Bs ordered, with deliveries started in 2020.[206][207]

Accidents

[edit]The V-22 Osprey has had 16 hull-loss accidents with a total of 62 fatalities as of 29 November 2023[update]. During testing from 1991 to 2000, there were four crashes causing 30 fatalities.[31] As of 2023[update], the V-22 has had 13 crashes which caused 32 fatalities since becoming operational in 2007.[285] The aircraft's accident history has generated controversy over its perceived safety issues.[286] Following the November 2023 crash in Japan,[287] the Osprey was grounded for three months.[288]

Aircraft on display

[edit]

- 163911 - V-22A на выставке в Мемориале авиации на авиабазе морской пехоты Нью-Ривер в Джексонвилле, Северная Каролина . [289] [290]

- 163913 - V-22A на выставке в Американском музее вертолетов и образовательном центре в Вест-Честере, штат Пенсильвания . [291] [292]

- 99-0021 (ранее 164939) — CV-22B выставлен в Национальном музее ВВС США на авиабазе Райт-Паттерсон в Дейтоне, штат Огайо . [293]

- 164940 - MV-22B на выставке в Музее военно-морской авиации Патаксент-Ривер в Лексингтон-парке, штат Мэриленд . [294]

Технические характеристики (МВ-22Б)

[ редактировать ]

Данные Нортона , [295] Боинг , [296] Белл Гид , [105] Командование авиационных систем ВМФ , [297] и информационный бюллетень USAF CV-22 [243]

Общие характеристики

- Экипаж: 3–4 человека (пилот, второй пилот и 1 или 2 бортинженера/начальника экипажа/нагрузчиков/стрелков)

- Емкость:

- 24 военнослужащих (сидячих), 32 военнослужащих (на полу) или

- 20 000 фунтов (9 100 кг) внутреннего груза или до 15 000 фунтов (6 800 кг) внешнего груза (двойной крюк)

- 1 × M1161 Growler легкая переносимая наземная машина [298] [299]

- Длина: 57 футов 4 дюйма (17,48 м) Длина в сложенном виде: 62 фута 7,6 дюйма (19,091 м)

- Размах крыльев: 45 футов 10 дюймов (13,97 м)

- Ширина: 84 фута 6,8 дюйма (25,776 м), включая роторы

- Ширина в сложенном виде: 18 футов 5 дюймов (5,61 м)

- Высота: 22 фута 1 дюйм (6,73 м), мотогондолы вертикальные;

- 17 футов 7,8 дюйма (5 м) до верха хвостового плавника

- Высота в сложенном виде: 18 футов 1 дюйм (5,51 м)

- Площадь крыла: 301,4 кв. футов (28,00 м 2 )

- Вес пустого: 31 818 фунтов (14 432 кг)

- Эксплуатационная масса пустого: 32 623 фунта (14 798 кг)

- Полная масса: 39 500 фунтов (17 917 кг)

- Боевая масса: 42 712 фунтов (19 374 кг)

- Максимальная взлетная масса ВТО: 47 500 фунтов (21 546 кг)

- Максимальная взлетная масса STO: 55 000 фунтов (24 948 кг)

- Максимальная взлетная масса STO, паром: 60 500 фунтов (27 442 кг)

- Запас топлива: Максимум на пароме: 4451 галлон США (3706 имп галлонов; 16850 л) JP-4 / JP-5 / JP-8 в соответствии с MIL-T-5624.

- Силовая установка: 2 двигателя Rolls-Royce T406-AD-400 турбовинтовых / турбовальных мощностью 6150 л.с. (4590 кВт) каждый максимум при 15 000 об/мин на уровне моря, 59 °F (15 °C)

- Максимальная продолжительная мощность 5890 л.с. (4392 кВт) при 15 000 об/мин на уровне моря, 59 ° F (15 ° C)

- Диаметр несущего винта: 2 × 38 футов (12 м)

- Площадь несущего винта: 2268 кв. футов (210,7 м ). 2 ) 3-лопастной

Производительность

- Максимальная скорость: 275 узлов (316 миль в час, 509 км/ч) [300]

- 305 узлов (565 км/ч; 351 миль в час) на высоте 15 000 футов (4600 м) [301]

- Скорость сваливания: 110 узлов (130 миль в час, 200 км/ч) [76]

- Диапазон: 879 миль (1012 миль, 1628 км)

- Боевая дальность: 390 миль (450 миль, 720 км)

- Перегоночная дальность: 2230 миль (2570 миль, 4130 км)

- Практический потолок: 25 000 футов (7600 м)

- пределы g: + 4 макс / - 1 мин

- Максимальное качество планирования: 4,5:1 [76]

- Скорость набора высоты: 2320–4000 футов/мин (11,8–20,3 м/с). [76]

- Нагрузка на крыло: 20,9 фунтов/кв. футов (102 кг/м). 2 ) при 47 500 фунтов (21 546 кг)

- Мощность/масса : 0,259 л.с./фунт (0,426 кВт/кг)

Вооружение

- 1 × 7,62-мм (0,308 дюйма) пулемет M240 или 0,50 дюйма (12,7 мм) пулемет M2 Browning на рампе, съемный

- 1 × 7,62-мм (0,308 дюйма) миниган GAU-17 , устанавливаемый на животе, выдвижной, с дистанционным видеоуправлением в системе Remote Guardian [опционально] [135] [302]

Авионика

- AN/ARC-182 УКВ/УВЧ Радиостанция

- KY-58 VHF/UHF Шифрование

- ANDVT ВЧ-шифрование

- Система предупреждения о приближении ракет AN/AAR-47

- AN/AYK-14 Компьютеры миссии

- APQ-168 Многофункциональный радар

- Направленные инфракрасные меры противодействия (DIRCM) [303]

Заметные выступления в СМИ

[ редактировать ]См. также

[ редактировать ]Связанные разработки

Самолеты сопоставимой роли, конфигурации и эпохи

Связанные списки

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ Jump up to: а б «Оспрей признан готовым к развертыванию» . Корпус морской пехоты США. 14 июня 2007 г. Архивировано из оригинала 1 декабря 2016 г. Проверено 19 июня 2019 г.

- ^ Брат Эрик (11 июня 2020 г.). «Bell Boeing поставила 400-й конвертоплан V-22 Osprey» . Аэрокосмическое производство и проектирование . Архивировано из оригинала 26 июня 2020 года . Проверено 22 июня 2020 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б "Справочник по V-22 Osprey" . Архивировано 6 февраля 2010 г. в Wayback Machine Boeing Defense, Space & Security , февраль 2010 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Крейшер, Отто. «Наконец-то скопа» . Архивировано 11 февраля 2009 г. в журнале Wayback Machine Air Force Magazine , февраль 2009 г.

- ^ Уиттл 2010, с. 62.

- ^ Маккензи, Ричард (писатель). «Полет V-22 Osprey» (Телепродукция) . Архивировано 28 февраля 2009 года в Wayback Machine Mackenzie Productions для Military Channel , 7 апреля 2008 года. Проверено 29 марта 2009 года.

- ^ Уиттл 2010, с. 55.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Нортон 2004, с. 35.

- ^ Уиттл 2010, с. 91.

- ^ Уиттл 2010, с. 87: «По мнению Келли, от этого зависело будущее морской пехоты».

- ^ Уиттл 2010, с. 155.

- ^ Уиттл 2010, стр. 53, 55–56.

- ^ Скроггс, Стивен К. «Отношения армии с Конгрессом: толстая броня, тупой меч, медленная лошадь» с. 232. Гринвуд Пресс, 2000. ISBN 9780313019265 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Мойерс, Эл (директор по истории и исследованиям). «Долгая дорога: два с лишним десятилетия участия AFOTEC в V-22» . Архивировано 1 декабря 2008 года в Центре эксплуатационных испытаний и оценки штаб-квартиры ВВС Wayback Machine , ВВС США , 1 августа 2007 года.

- ^ «Глава 9: Исследования, разработки и приобретение» . Архивировано 10 февраля 2009 года в Департаменте машин Wayback Machine Историческая справка: 1982 финансовый год . Центр военной истории (CMH), армия США, 1988 г. ISSN 0092-7880 .

- ^ Нортон 2004, стр. 22–30.

- ^ «AIAA-83-2726, Программа наклонного ротора Bell-Boeing JVX» . Архивировано 11 февраля 2009 года в Wayback Machine Американском институте аэронавтики и астронавтики (AIAA) , 16–18 ноября 1983 года.

- ^ Нортон 2004, стр. 31–33.

- ^ Кисияма, Дэвид. «Гибридный корабль разрабатывается для военного и гражданского использования» . Лос-Анджелес Таймс , 31 августа 1984 г.

- ^ Адамс, Лоррейн. «Журны продаж о Bell Helicopter» . Архивировано 24 октября 2012 года в Wayback Machine Dallas Morning News , 10 марта 1985 года.

- ^ «Boeing Vertol запускает трехлетнюю программу расширения стоимостью 50 миллионов долларов» . Архивировано 24 октября 2012 года в Wayback Machine The Philadelphia Inquirer , 4 марта 1985 года.

- ^ «Военный самолет: Bell-Boeing V-22» . Архивировано 28 марта 2010 года на вертолёте Wayback Machine Bell Helicopter , 2007 год. Проверено 30 декабря 2010 года.

- ^ Нортон 2004, с. 30.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж г час RL31384, «Самолет с поворотным винтом V-22 Osprey: предыстория и проблемы для Конгресса» . Архивировано 10 февраля 2009 года в Wayback Machine Исследовательской службе Конгресса , 22 декабря 2009 года.

- ^ Гудрич, Джозеф Л. «Команда Bell-Boeing заключила контракт на разработку нового конвертоплана, ожидается 600 рабочих мест в рамках проекта стоимостью 1,714 миллиарда долларов для ВМФ» . Провиденс Джорнал , 3 мая 1986 г.

- ^ Белден, Том. «Самолет с вертикальным взлетом может стать междугородним автобусом XXI века » Торонто Стар , 23 мая 1988 года.

- ^ «Корабль с поворотным винтом летает, как вертолет, самолет». Архивировано 28 августа 2023 года в Wayback Machine Sports Ghoda , 28 августа 2023 года.

- ^ "2 сенатора - ключ к судьбе Boeing V-22 Osprey" . Архивировано 24 октября 2012 года в Wayback Machine The Philadelphia Inquirer , 6 июля 1989 года.

- ^ Митчелл, Джим. «Грэмм защищает бюджетные расходы Osprey: сенатор делает ставку на V-22, в то время как президент ставит в тупик бомбардировщик B-2» . Архивировано 24 октября 2012 года в Wayback Machine Dallas Morning News , 22 июля 1989 года.

- ^ «Пентагон прекращает расходы на V-22 Osprey» . Чикаго Трибьюн , 3 декабря 1989 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и Берлер, Рон. «Спасение вертолета-убийцы Пентагона» . Архивировано 6 ноября 2012 года в Wayback Machine Wired (CondéNet, Inc), том 13, выпуск 7, июль 2005 года.

- ^ Нортон 2004, с. 49.

- ^ Нортон 2004, с. 52.

- ^ www.nationaldefensemagazine.org https://www.nationaldefensemagazine.org/articles/2022/12/5/bell-tiltrotor-wins-billion-dollar-helo-contract . Проверено 27 апреля 2024 г.

{{cite web}}: Отсутствует или пусто|title=( помощь ) - ^ «Революционный самолет прошел первое испытание». Архивировано 22 декабря 2020 года в Wayback Machine . Толедо Блейд , 20 марта 1989 года.

- ^ Митчелл, Джим. «В-22 совершил первый полет в полном самолетном режиме» . Архивировано 24 октября 2012 года в Wayback Machine Dallas Morning News , 15 сентября 1989 года.

- ^ Джонс, Кэтрин. «Торговый винт В-22 проходит испытания на море» . Даллас Морнинг Ньюс , 14 декабря 1990 г.

- ^ «ВМФ прекращает испытательные полеты V-22 в связи с расследованием крушения» . Архивировано 24 октября 2012 года в Wayback Machine Fort Worth Star-Telegram , 13 июня 1991 года.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Нортон 2004, стр. 52–54.

- ^ Нортон 2004, с. 55.

- ^ Нортон 2004, стр. 55–57.

- ^ Схинаси 2008, с. 23.

- ^ «M777: Он не тяжелый, он моя гаубица» . Архивировано 10 сентября 2012 года в Wayback Machine Defense Industry Daily , 18 июля 2012 года.

- ↑ «Lots Riding on V-22 Osprey». Архивировано 5 января 2012 года в Wayback Machine Defense Industry Daily , 12 марта 2007 года.

- ^ Шаванн, Беттина Х. «V-22 для повышения производительности» . [ постоянная мертвая ссылка ] Неделя авиации , 25 июня 2009 г.

- ^ Паппалардо, Джо. «Настоящая проблема Osprey не в безопасности, а в деньгах» . Архивировано 17 июня 2012 года в Wayback Machine Popular Mechanics , 14 июня 2012 года.

- ^ «Изменение программного обеспечения дает пилотам V-22 больше возможностей подъема» . Архивировано 25 сентября 2011 года на сайте Wayback Machine thebaynet.com . Проверено 24 апреля 2012 г.

- ^ Капаччо, Тони. «По результатам испытаний Пентагона надежность самолета V-22 Osprey повысилась» . Bloomberg News , 13 января 2012 г.

- ^ Канделарио, Рене (8 октября 2012 г.). «Проверка летных операций MV-22 Osprey на борту военного корабля США Нимиц » . ННС121008-13 . USS Nimitz по связям с общественностью. Архивировано из оригинала 24 мая 2013 года.

- ^ Батлер, Эми (18 апреля 2013 г.). «Скопа на «Трумэне», ловля трески» . Авиационная неделя . Компании МакГроу-Хилл. Архивировано из оригинала 20 мая 2013 года.

- ^ Тони Осборн (12 ноября 2015 г.). «Испытания V-22 Osprey могут привести к увеличению взлетной массы» . Авиационная неделя . Архивировано из оригинала 16 ноября 2015 года.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Брайс, Роберт. «Обзор политических сил, принимавших участие в формировании программы V-22» . Архивировано 27 сентября 2007 года в Wayback Machine Texas Observer , 17 июня 2004 года.

- ^ Уиттл, Ричард. « Полусамолет, полувертолет, полный крут » NY Post, 24 мая 2015 г. Архивировано 25 мая 2015 г.

- ^ Капаччо, Тони. «Пожизненная стоимость V-22 выросла на 61% за три года» . [ постоянная мертвая ссылка ] Bloomberg News , 29 ноября 2011 г.

- ^ О'Хэнлон 2002, с. 119.

- ^ Рикс, Томас Э. «Командир морской пехоты скопы; расследована предполагаемая фальсификация данных» . Вашингтон Пост , 19 января 2001 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Томпсон, Марк. «V-22 Osprey: Летающий позор» . Архивировано 11 октября 2008 года в Wayback Machine Time , 26 сентября 2007 года. Проверено 8 августа 2011 года.

- ^ Хоэллварт, Джон. «Лидеры и эксперты раскритиковали статью Time об Osprey» . Архивировано 10 декабря 2007 года в Wayback Machine Marine Corps Times (издательская компания Army Times), 16 октября 2007 года.

- ^ ДиМашио, Джен (9 декабря 2010 г.). «Игра в защите – но какой ценой?» . Политик . Архивировано из оригинала 25 мая 2015 года.

- ^ Акерман, Спенсер (12 апреля 2012 г.). «Любимые мечты аналитических центров оборонной промышленности о поражении Обамы» . Проводной . Архивировано из оригинала 16 апреля 2016 года.

- ^ Сильверстайн, Кен (1 апреля 2010 г.). «Безумцы – представляем платное рекламное агентство оборонной промышленности». Журнал Харпера .

- ^ «V-22 — самый безопасный и живучий винтокрылый аппарат у морской пехоты» . Архивировано 3 марта 2011 г. в Wayback Machine Лексингтонском институте , февраль 2011 г.

- ^ Акс, Дэвид. «Морские пехотинцы: на самом деле наш конвертоплан «эффективен и надежен» (не говоря уже об этих авариях)» . Архивировано 9 декабря 2013 года в Wayback Machine Wired , 13 октября 2011 года.

- ^ «Заявление морской пехоты США в ответ на статью о безопасности морского корабля V-22 Osprey» . Архивировано 16 января 2012 года в Wayback Machine USMC , 13 октября 2011 года.

- ^ «Наблюдательный орган Пентагона опубликует секретную проверку V-22 Osprey» . Таймс морской пехоты . Архивировано из оригинала 17 августа 2013 года . Проверено 6 апреля 2015 г.

- ^ Капаччо, Тони (25 октября 2013 г.). «Генеральный инспектор Пентагона считает показатели готовности V-22 ошибочными» . Блумберг БизнесУик . Новости Блумберга. Архивировано из оригинала 25 октября 2013 года.

- ^ Ламот, Дэн (2 ноября 2013 г.). «Не подделывают ли морские пехотинцы показатели надежности своего суперсамолета стоимостью 79 миллионов долларов?» . Внешняя политика . Архивировано из оригинала 3 ноября 2013 года.

- ^ Шалал-Эса, Андреа. «США рассматривают возможность продажи самолетов V-22 Израилю, Канаде, ОАЭ» . Архивировано 24 сентября 2015 г. в Wayback Machine Reuters , 26 февраля 2012 г.

- ^ Рид, Джон. «Boeing сделает новое многолетнее предложение Osprey» . Navy Times , 5 мая 2010 г.

- ^ Хоффман, Майкл. « Показатель готовности Osprey увеличился на 25% за 5 лет. Архивировано 13 апреля 2014 г. в Wayback Machine » , DODbuzz , 9 апреля 2014 г.

- ^ Уиттл, Ричард. « Скопа показывает свой характер. Архивировано 25 января 2024 года в Wayback Machine », стр. 23–26. Американское вертолетное общество / Vertiflite, май/июнь 2015 г., Том. 61, № 3.

- ^ Уиттл, Ричард. Стоимость USMC CH-53E растет вместе с темпом эксплуатации. Архивировано 2 мая 2014 г. в Wayback Machine Rotor & Wing, Aviation Today , январь 2007 г. Цитата: Каждый час Корпус летает на −53E, он тратит 44 часа на техническое обслуживание на его ремонт. Каждый час полета Super Stallion стоит около 20 000 долларов.

- ^ Магнусон, Стью. « Будущее поворотно-винтовых самолетов неопределенно, несмотря на успехи V-22 » Национальная оборонно-промышленная ассоциация , июль 2015 г. Архив

- ^ «2022 финансовый год (2022 финансовый год) Министерства обороны (DoD) Ставки возмещения расходов на самолеты и вертолеты» (PDF) . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 12 ноября 2021 года . Проверено 29 августа 2023 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж г час я дж к МакКинни, Майк. «Полет на V-22» по вертикали , 28 марта 2012 г. Архивировано 30 апреля 2014 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Нортон 2004, стр. 98–99.

- ^ Схинаси 2008, с. 16.

- ^ Схинаси 2008, с. 11.

- ^ Гросс, Кевин, подполковник Корпуса морской пехоты США и Том Макдональд, летчик-испытатель MV-22, и Рэй Дагенхарт, ведущий правительственный инженер MV-22. NI_Myth_0904,00.html «Разоблачение мифа о MV-22». Архивировано 25 января 2024 года в Wayback Machine . Труды: Военно-морской институт . Сентябрь 2004 г.

- ^ "Скопа ОК" . Архивировано 6 декабря 2009 г. в Wayback Machine Defense Tech , 28 сентября 2005 г.

- ^ «Оценка бюджета на 2009 финансовый год» . п. 133. Архивировано 3 октября 2008 г. в Wayback Machine ВВС США , февраль 2008 г.

- ^ Кристи, Ребекка (31 мая 2007 г.). «Ди-джей ВМС США ожидает, что иностранный интерес к V-22 возрастет в следующем году» . Командование военно-морских авиационных систем ВМС США . Новости Доу-Джонса. Архивировано из оригинала 1 декабря 2016 года.

- ^ Джон Т. Беннетт (14 января 2014 г.). «Впервые с 2010 года в сводном законопроекте увеличилось финансирование войны» . Новости обороны . Архивировано из оригинала 1 апреля 2014 года.

- ^ Келлер, Джон. «Bell-Boeing разработает новый интегрированный процессор авионики для конвертоплана V-22 Osprey» . Архивировано 14 июля 2011 г. на сайте Wayback Machine Militaryearospace.com , 18 апреля 2010 г.

- ^ «Raytheon выигрывает контракт на 250 миллионов долларов на поставку авионики самолета V-22 из США» . Архивировано 23 июля 2011 года на сайте Wayback Machine Defenseworld.net . Проверено: 30 декабря 2010 г.

- ^ "Контракты Министерства обороны" . Архивировано 29 мая 2010 года в Wayback Machine Министерства обороны США. 24 ноября 2009 г.

- ^ Макхейл, Джон. «Блок C V-22 Osprey с новым радаром, дисплеями в кабине и функциями радиоэлектронной борьбы, доставленными морской пехоте». Архивировано 22 мая 2013 года на Wayback Machine . Военные встраиваемые системы , 15 февраля 2012 г.

- ^ «LTG Davis ведет переговоры с Boeing по поводу обновления половины парка морских V-22» . Прорыв защиты . 13 августа 2015 года. Архивировано из оригинала 23 октября 2015 года . Проверено 31 октября 2015 г.

- ↑ Многолетний контракт Bell-Boeing с V-22. Архивировано 6 октября 2013 г. на Wayback Machine - Flightglobal.com, 12 июня 2013 г.

- ↑ Военные США заказывают дополнительные V-22 Osprey. Архивировано 1 февраля 2014 г. на Wayback Machine - Shephardmedia.com, 13 июня 2013 г.

- ^ Пентагон подписывает многолетний контракт на V-22. Архивировано 3 февраля 2014 г. на Wayback Machine - Aviationweek.com, 13 июня 2013 г.

- ^ Берард, Ямиль. « Bell уволит 325 рабочих, поскольку заказы на V-22 сокращаются ». Fort Worth Star-Telegram , 5 мая 2014 г. Проверено 8 мая 2014 г.

- ^ Берард, Ямиль (5 мая 2014 г.). «Bell уволит 325 рабочих, поскольку заказы на V-22 сокращаются» . Звездная телеграмма Форт-Уэрта . Архивировано из оригинала 2 июля 2014 года.

- ^ Хубер, Марк (25 февраля 2015 г.). «Новые программы на полной скорости» . Международные авиационные новости . Архивировано из оригинала 2 марта 2015 года.

- ^ Лэрд, Роббин. « Производитель гибридного самолета для гибридного самолета » Новости производства и технологий , 27 августа 2015 г., том 22, № 10. Архив

- ^ Лэрд, Роббин. « Перспектива посещения завода Boeing недалеко от Филадельфии » SLD , 28 мая 2015 г. Архив

- ^ Jump up to: а б Специальные операции ВВС планируют добавить броню и огневую мощь к Ospreys – Air Force Times , 17 сентября 2014 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Уиттл, Ричард. « Броня AFSOC Ospreys поднята после болезненных уроков, извлеченных в Южном Судане », Прорыв обороны , 15 мая 2015 г. Архив

- ^ Бэти, Ангус (12 июля 2016 г.). «Дети ALIS: сетевой прогноз для V-22» . Неделя авиации и космических технологий . Пентон. Архивировано из оригинала 13 июля 2016 года.

- ^ Мизоками, Кайл (8 февраля 2019 г.). «V-22 Osprey: как работает скандальный американский конвертоплан» . Популярная механика . Архивировано из оригинала 26 мая 2021 года . Проверено 26 мая 2021 г.

- ^ Крофт, Джон. «Тилтеры» . Архивировано 25 июля 2008 года в Wayback Machine Альтернативная ссылка. Архивировано 6 мая 2015 года в Wayback Machine Air & Space/Smithsonian , 1 сентября 2007 года. Проверено 6 мая 2015 года.

- ^ Пилоты Osprey получили первые рейтинги подъемной силы FAA (архив 1999 г. от Boeing)

- ^ Махаффи, Джей Дуглас (1991). «Наклонный винт V-22, сравнение с существующими самолетами береговой охраны» (PDF) . Институциональный архив Военно-морской аспирантуры . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 17 мая 2021 года . Проверено 17 мая 2021 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с «Путеводитель V-22 Osprey, 2013/2014» . Архивировано 20 октября 2014 года в Wayback Machine Bell-Boeing , 2013. Проверено 6 февраля 2014 года . Архивировано в 2014 году.

- ^ Шаванн, Беттина Х. «USMC V-22 Osprey находит подход в Афганистане» . [ постоянная мертвая ссылка ] Aviation Week , 12 января 2010 г. Проверено 23 июня 2010 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и Уиттл, Ричард. « Полет на скопе не опасен, он просто другой: пилоты-ветераны. Архивировано 14 сентября 2012 г. на Wayback Machine » Defense.aol.com , 5 сентября 2012 г. Проверено 16 сентября 2012 г. Архивировано 3 октября 2013 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Адде, Ник (14 апреля 2021 г.). «Модернизация V-22 находится в разработке по мере того, как самолет проходит важные этапы» . Национальная оборона . Архивировано из оригинала 23 апреля 2021 года . Проверено 22 апреля 2021 г.

- ^ «Дальность и потолок V-22 Osprey». Архивировано 4 марта 2016 г. в Wayback Machine . AirForceWorld.com, 6 октября 2015 г.

- ^ Карри, майор Том П. младший, ВВС США. «Отчет об исследовании, представленный факультету при частичном выполнении выпускных требований: CV-22 «Оспри» и его влияние на боевые поисковые и спасательные операции ВВС» . Архивировано 6 марта 2016 года в Wayback Machine Авиакомандно-штабном колледже , апрель 1999 года.

- ^ «Настойчивые усилия по достижению еще одной вехи V-22» . ВМС США . 17 июня 2009 г. Архивировано из оригинала 1 декабря 2016 г. Проверено 19 июня 2019 г.

- ^ Лазарь, Аарон. DARPA-BAA 10-10, Система управления температурным режимом (TMS). Архивировано 16 января 2018 года на Wayback Machine. DARPA , 16 ноября 2009 года. Проверено 18 марта 2012 года. Цитата: «MV-22 Osprey привел к короблению полетной палубы корабля, которое было объяснено Из-за чрезмерного теплового воздействия выхлопных газов двигателей исследования ВМФ показали, что повторяющееся коробление палубы, скорее всего, приведет к разрушению палубы до запланированного срока службы корабля».

- ^ Батлер, Эми (5 сентября 2013 г.). «Обновление F-35B DT 2: несколько часов на USS Wasp» . Неделя авиации и космических технологий . Архивировано из оригинала 3 сентября 2014 года . Проверено 4 апреля 2015 г.

- ^ Уиттл, Ричард. « Смертельная авария побудила морских пехотинцев изменить правила полетов скопы. Архивировано 19 июля 2015 г. в Wayback Machine ». Прорыв обороны , 16 июля 2015 г.

- ^ Вельт, Полет (14 мая 2023 г.). «Bell Boeing V 22 Osprey, первый в мире серийный военный конвертоплан» . Летающий рант . Архивировано из оригинала 24 ноября 2023 года . Проверено 24 ноября 2023 г.

- ^ «Rolls-Royce повышает мощность двигателей V-22» . Новости обороны, 16 сентября 2013 г.

- ^ Военные США ищут замену двигателям V-22. Архивировано 7 сентября 2014 г. на Wayback Machine - Flightglobal.com, 29 августа 2014 г.

- ^ Уолл, Роберт, «США обдумывают варианты двигателей для своего самолета Osprey», The Wall Street Journal , 2 сентября 2014 г., стр.B3.

- ^ «ВМС США разрабатывают ранние планы модернизации V-22 среднего возраста». Архивировано 16 апреля 2015 г. на Wayback Machine - Flightglobal.com, 15 апреля 2015 г.

- ^ Джон Гордон IV и др. Оценка вариантов тяжелых самолетов ВМФ стр. 39. RAND Corporation , 2005. Проверено 18 марта 2012 года. ISBN 0-8330-3791-9 . Архивировано в 2011 году.

- ^ «Ураганы... Высвобождая ярость природы: Руководство по готовности» . Национальное управление океанических и атмосферных исследований , Национальная метеорологическая служба , сентябрь 2006 г.

- ^ Уотерс, капрал морской пехоты США. Лана Д. V-22 Osprey Fast Rope 1 USMC , 6 ноября 2004 г. Архивировано 21 марта 2005 г.

- ^ Тримбл, Стивен. «Boeing ожидает появления V-23 Osprey» . Архивировано 25 июня 2009 года на сайте Wayback Machine Flight Global , 22 июня 2009 года. Архивировано 12 января 2015 года.

- ^ «Боинг: V-22 Osprey» (PDF) . Боинг. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 27 ноября 2013 года . Проверено 15 февраля 2014 г.

- ^ Рингенбах, Дэниел П. и Скотт Брик. «Аппаратное тестирование при разработке и интеграции системы автопилота В-22, стр. 28–36» . Архивировано 28 июня 2007 г. в технических документах Wayback Machine (A95-39235 10–01): Технические документы конференции AIAA Flight Simulation Technologies , Балтимор, Мэриленд, 3 августа 2008 г.

- ^ Лэндис, Кеннет Х. и др. «Достижения передовых технологий управления полетом на Boeing Helicopters». Архивировано 15 апреля 2021 года в Wayback Machine . Международный журнал контроля , том 59, выпуск 1, 1994 г., стр. 263–290.

- ^ «Афганский отчет: скопа возвращается из Афганистана, 2012» . SLD , 13 сентября 2012 г. Архивировано 11 января 2015 г.

- ^ Нортон 2004, стр. 6–9, 95–96.

- ^ Маркман и Холдер 2000, стр. 58.

- ^ Нортон 2004, с. 97.

- ^ Фридберг, Сидней-младший (30 апреля 2021 г.). «FVL: не выбирайте конвертоплан, - говорит летчик-испытатель V-22 армии» . Прорыв защиты . Архивировано из оригинала 3 мая 2021 года . Проверено 3 мая 2021 г.

- ^ «Защитное вооружение для выбора, интеграции и разработки V-22» . Bell Helicopter и General Dynamics . Проверено: 30 декабря 2010 г.

- ^ «BAE Systems запускает новую систему оборонительного вооружения V-22 и начинает испытания на ходу» . Архивировано 18 ноября 2018 года в Wayback Machine BAE Systems , 2 октября 2007 года.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Маккалоу, Эми. «Скопы с усилением огневой мощи входят в Афганистан». Marine Corps Times , 7 декабря 2009 г., с. 24.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Уиттл, Ричард. «Удаленные стражи BAE присоединяются к флоту Osprey» . Архивировано 22 июня 2011 года в Wayback Machine Rotor & Wing , 1 января 2010 года.

- ^ Ламот, Дэн. «Скопы оставляют в пыли новый брюшный пистолет» . Архивировано 8 января 2012 года в Wayback Machine Marine Corps Times , 28 июня 2010 года.

- ^ «Корпус ищет лучшее вооружение на Ospreys». Архивировано 2 января 2014 года в Wayback Machine . Marine Corps Times , 13 февраля 2012 г.

- ^ Авиационный план корпуса предусматривает использование вооруженных скоп. Архивировано 18 декабря 2014 г. в Wayback Machine - Marine Corps Times , 23 ноября 2014 г.

- ^ Osprey запускает управляемые ракеты и ракеты в ходе новых испытаний. Архивировано 12 февраля 2015 г. на Wayback Machine - Aviationweek.com, 8 декабря 2014 г.

- ^ V-22 демонстрирует возможности ракеты, стреляющей вперед. Архивировано 27 декабря 2014 г. на Wayback Machine - Flightglobal.com, 23 декабря 2014 г.

- ^ Корпус работает над усовершенствованным разведывательным дроном, который будет запускаться из задней части MV-22 Osprey. Архивировано 31 мая 2019 года в Wayback Machine . Таймс морской пехоты . 14 мая 2019 г.

- ↑ Boeing разрабатывает комплект для дозаправки в воздухе Osprey. Архивировано 25 августа 2013 г. на сайте Wayback Machine Flightglobal.com, 10 апреля 2013 г.

- ^ «Bell Boeing V-22 Osprey использует дозаправочное оборудование во время летных испытаний» . Боинг. 5 сентября 2013 года. Архивировано из оригинала 10 апреля 2015 года . Проверено 4 апреля 2015 г.

- ^ «Новые фотографии: MV-22, Hornet в испытаниях дозаправки». Архивировано 2 января 2014 г. в Wayback Machine . Aviationweek.com, 3 сентября 2013 г.

- ↑ V-22 получит вариант танкера. Архивировано 29 декабря 2014 г. в Wayback Machine – MilitaryTimes , 28 декабря 2014 г.

- ↑ Морские пехотинцы США установили цель на 2019 год для установки танкера Osprey. Архивировано 7 февраля 2017 года на Wayback Machine - Flightglobal.com, 7 февраля 2017 года.

- ^ Уиттл, Ричард (27 мая 2016 г.). «Контракт на дозаправку V-22 подчеркивает тесную связь с F-35» . Breakingdefense.com . Breaking Media, Inc. Архивировано из оригинала 28 октября 2016 года.

- ^ Сек, Хоуп Ходж (26 октября 2016 г.). «Новая система позволит «Скопам» дозаправлять F-35 в полете» . dodbuzz.com . Военный.com. Архивировано из оригинала 27 октября 2016 года.

- ↑ Военно-морской флот не следует примеру морской пехоты в разработке танкера V-22 Osprey. Архивировано 6 мая 2015 г. на Wayback Machine - News.USNI.org, 4 мая 2015 г.

- ^ «Налет Bell Boeing V-22 Osprey превысил 500 000 часов» (пресс-релиз). Боинг. 7 октября 2019 года. Архивировано из оригинала 8 октября 2019 года . Проверено 8 октября 2019 г.

- ^ «Военно-морской флот разрешил вернуться в полет самолету V-22 Osprey» . Министерство обороны США . Проверено 27 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ "История 266-й эскадрильи морских средних конвертопланов" . Архивировано 22 января 2012 года в Wayback Machine Корпуса морской пехоты США . Проверено 16 октября 2011 г.

- ^ Картер, Челси Дж. «База Мирамар для получения эскадрилий скоп» . Архивировано 17 марта 2012 года в Wayback Machine USA Today (Associated Press), 18 марта 2008 года.

- ^ Почтенный «Морской рыцарь» совершает прощальные полеты. Архивировано 21 декабря 2014 г. на Wayback Machine - Military.com, 3 октября 2014 г.

- ^ Маунт, Майк. «Морские пехотинцы отправят в Ирак конвертопланы» . Архивировано 31 мая 2007 г. на Wayback Machine CNN, 14 апреля 2007 г.

- ^ «Спорный самолет Osprey направляется в Ирак; морские пехотинцы надеются на гибридный вертолет-самолет, несмотря на прошлые происшествия» . MSNBC, 13 апреля 2007 г.

- ^ Маунт, Майк. «Оклеветанный самолет находит искупление в Ираке, заявляют военные» . Архивировано 10 февраля 2009 г. на Wayback Machine CNN, 8 февраля 2008 г.

- ^ Хэмблинг, Дэвид. фотосессия Оспри » . « Отличная Архивировано 5 августа 2008 г. в Wayback Machine Wired (CondéNet, Inc.), 31 июля 2008 г.

- ^ Уорик, Грэм. «Корпус морской пехоты США заявляет, что V-22 Osprey хорошо себя зарекомендовал в Ираке» . Архивировано 9 февраля 2009 г. в Wayback Machine Flightglobal , 7 февраля 2008 г.

- ^ Хойл, Крейг. «Морская пехота США рассматривает афганский вызов для V-22 Osprey» . Архивировано 7 декабря 2008 г. в Wayback Machine Flight International , 22 июля 2008 г.

- ^ «Круглый стол блоггеров Министерства обороны с генерал-лейтенантом Джорджем Траутманом, заместителем командующего морской пехотой по авиации, посредством телеконференции из Ирака» . Министерство обороны США, 6 мая 2009 г. Архивировано 21 января 2012 г. в Wayback Machine .

- ^ Гертлер, Иеремия. (цитата по морской пехоте США Карстена Хекла) «Самолет V-22 Osprey Tilt-Rotor: предыстория и проблемы для Конгресса». Архивировано 5 ноября 2012 г. в Wayback Machine , стр. 30. Отчеты Исследовательской службы Конгресса , 22 декабря 2009 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б «GAO-09-482: Оборонные закупки, оценки, необходимые для решения проблем, связанных с эксплуатацией и стоимостью самолетов V-22, для определения будущих инвестиций» (резюме) . Архивировано 24 июня 2009 года в Счетной палате правительства Wayback Machine . Проверено: 30 декабря 2010 г.

- ^ «GAO-09-482: Оборонные закупки, оценки, необходимые для решения проблем, связанных с эксплуатацией и стоимостью самолетов V-22, для определения будущих инвестиций» (полный отчет)» Архивировано 24 июня 2009 г. в Счетной палате правительства США Wayback Machine , 11 мая 2009 г. .

- ^ Маклири, Пол. «Испытание огнем» . [ постоянная мертвая ссылка ] Авиационная неделя , 15 марта 2010 г.

- ^ Шанц, Марк В. «V-22 испачкались в Анбаре» . Архивировано 16 июня 2012 года в журнале Wayback Machine Air Force, Daily Report , 25 февраля 2009 года.

- ^ «MV-22 налетал 100 000 часов» . Архивировано 21 февраля 2011 г. в Wayback Machine DefenseTech , февраль 2011 г.

- ↑ Casevac, новая миссия Osprey в Афганистане. Архивировано 5 июня 2014 г. в Wayback Machine – Marine Corps Times , 17 мая 2014 г.

- ^ Талтон, Триста. «24-й MEU присоединяется к усилиям по оказанию помощи Гаити» . Архивировано 18 января 2012 года в Wayback Machine Marine Corps Times , 20 января 2010 года. Проверено 21 января 2010 года.

- ^ Малрин, Анна. «Как MV-22 Osprey спас сбитого американского пилота в Ливии» . Архивировано 25 марта 2011 г. в Wayback Machine Christian Science Monitor , 22 марта 2011 г.

- ^ Ламот, Дэн. «Сообщения: Морские пехотинцы спасают сбитого пилота в Ливии» . Navy Times , 22 марта 2011 г.

- ^ Ки Мэй Хойснер (2 мая 2011 г.). «Военный корабль США Карл Винсон : Похороны Усамы бен Ладена в море» . Технология . Новости АВС . Архивировано из оригинала 4 мая 2011 года. ; Джим Гарамон (2 мая 2011 г.). «Бен Ладен похоронен в море» . ННС110502-22 . Пресс-служба американских вооруженных сил . Архивировано из оригинала 23 мая 2012 года .