Пенсильванский университет

В этой статье есть несколько проблем. Пожалуйста, помогите улучшить его или обсудите эти проблемы на странице обсуждения . ( Узнайте, как и когда удалять эти шаблонные сообщения )

|

| |

| Латынь : Пенсильванский университет. [ 1 ] | |

Прежние имена |

|

|---|---|

| Девиз | Законы без морали тщетны ( лат .) |

Motto in English | "Laws without morals are useless" |

| Type | Private research university |

| Established | November 14, 1740[note 2] |

| Founder | Benjamin Franklin |

| Accreditation | MSCHE |

Academic affiliations | |

| Endowment | $21.0 billion (2023)[6] |

| Budget | $4.4 billion (2024)[7] |

| President | J. Larry Jameson (interim) |

| Provost | John L. Jackson Jr. |

Academic staff | 4,793 (2018)[8] |

Total staff | 39,859 (Fall 2020; includes health system)[9] |

| Students | 23,374 (Fall 2022)[10] |

| Undergraduates | 9,760 (Fall 2022)[10] |

| Postgraduates | 13,614 (Fall 2022)[10] |

| Location | , Pennsylvania , United States 39°57′N 75°11′W / 39.95°N 75.19°W |

| Campus | Large city,

|

| Other campuses | San Francisco |

| Newspaper | The Daily Pennsylvanian |

| Colors | Red and blue[11] |

| Nickname | Quakers |

Sporting affiliations | |

| Mascot | The Quaker |

| Website | www |

| |

, Пенсильванский университет обычно называемый Пенн. [ примечание 3 ] или УПенн , [ примечание 4 ] — частный Лиги плюща исследовательский университет в Филадельфии , штат Пенсильвания, США. Это один из девяти колониальных колледжей , который был основан до принятия Декларации независимости США, когда Бенджамин Франклин , основатель и первый президент университета, выступал за создание учебного заведения, которое готовило лидеров в академических кругах, торговле и государственной службе . Пенн считается четвертым старейшим высшим учебным заведением в Соединенных Штатах , хотя это представительство оспаривается другими университетами, поскольку Франклин впервые созвал попечительский совет в 1749 году, что, возможно, делает его пятым по возрасту. [ примечание 2 ]

В университете есть четыре школы бакалавриата и 12 аспирантур и профессиональных школ. Школы, принимающие студентов, включают Колледж искусств и наук , Школу инженерных и прикладных наук , Уортонскую школу и Школу медсестер . Среди его аспирантур - юридический факультет , первый профессор которого Джеймс Уилсон участвовал в написании первого проекта Конституции США , его медицинская школа , которая была первой медицинской школой, созданной в Северной Америке, и Уортонская школа, первая в стране университетская бизнес-школа. школа.

Penn's endowment is $21 billion, making it the sixth-wealthiest private academic institution in the nation as of 2023. In 2021, it ranked fourth among U.S. universities in research expenditures, according to the National Science Foundation.[14] The University of Pennsylvania's main campus is located in the University City neighborhood of West Philadelphia, and is centered around College Hall. Notable campus landmarks include Houston Hall, the first modern student union, and Franklin Field, the nation's first dual-level college football stadium and the nation's longest-standing NCAA Division I college football stadium in continuous operation.[15] The university's athletics program, the Penn Quakers, fields varsity teams in 33 sports as a member of NCAA Division I's Ivy League conference.

Penn alumni, trustees, and faculty include eight Founding Fathers of the United States who signed the Declaration of Independence,[16][17] seven who signed the United States Constitution,[17] 24 members of the Continental Congress, three presidents of the United States,[note 5] 38 Nobel laureates, nine foreign heads of state, three United States Supreme Court justices, at least four Supreme Court justices of foreign nations,[18] 32 U.S. senators, 163 members of the U.S. House of Representatives, 19 U.S. Cabinet Secretaries, 46 governors, 28 State Supreme Court justices, 36 living undergraduate billionaires (the largest number of any U.S. college or university),[19] and five Medal of Honor recipients.[20][21]

History

[edit]In 1740, a group of Philadelphians organized to erect a great preaching hall for George Whitefield, a traveling Anglican evangelist,[22] which was designed and constructed by Edmund Woolley. It was the largest building in Philadelphia at the time, and thousands of people attended it to hear Whitefield preach.[23]: 26

In the fall of 1749, Benjamin Franklin, a Founding Father and polymath in Philadelphia, circulated a pamphlet, "Proposals Relating to the Education of Youth in Pensilvania," his vision for what he called a "Public Academy of Philadelphia".[24]

On June 16, 1755, the College of Philadelphia was chartered, paving the way for the addition of undergraduate instruction.[25]

Campus

[edit]

Much of Penn's current architecture was designed by the Philadelphia-based architecture firm Cope and Stewardson, whose owners were Philadelphia born and raised architects and professors at Penn who also designed Princeton University and a large part of Washington University in St. Louis.[27][28] They were known for having combined the Gothic architecture of the University of Oxford and University of Cambridge with the local landscape to establish the Collegiate Gothic style.[29]

The present core campus covers over 299 acres (121 ha) in a contiguous area of West Philadelphia's University City section, and the older heart of the campus comprises the University of Pennsylvania Campus Historic District. All of Penn's schools and most of its research institutes are located on this campus. The surrounding neighborhood includes several restaurants, bars, a large upscale grocery store, and a movie theater on the western edge of campus. Penn's core campus borders Drexel University and is a few blocks from the University City campus of Saint Joseph's University, which absorbed University of the Sciences in Philadelphia in a merger, and The Restaurant School at Walnut Hill College.

Wistar Institute, a cancer research center, is also located on campus. In 2014, a new seven-story glass and steel building was completed next to the institute's original brick edifice built in 1897 further expanding collaboration between the university and the Wistar Institute.[30]

The Module 6 Utility Plant and Garage at Penn was designed by BLT Architects and completed in 1995. Module 6 is located at 38th and Walnut and includes spaces for 627 vehicles, 9,000 sq ft (840 m2) of storefront retail operations, a 9,500-ton chiller module and corresponding extension of the campus chilled water loop, and a 4,000-ton ice storage facility.[31]

In 2010, in its first significant expansion across the Schuylkill River, Penn purchased 23 acres (9.3 ha) at the northwest corner of 34th Street and Grays Ferry Avenue, the then site of DuPont's Marshall Research Labs. In October 2016, with help from architects Matthias Hollwich, Marc Kushner, and KSS Architects, Penn completed the design and renovation of the center piece of the project, a former paint factory named Pennovation Works, which houses shared desks, wet labs, common areas, a pitch bleacher, and other attributes of a tech incubator. The rest of the site, known as South Bank, is a mixture of lightly refurbished industrial buildings that serve as affordable and flexible workspaces and land for future development. Penn hopes that "South Bank will provide a place for academics, researchers, and entrepreneurs to establish their businesses in close proximity to each other to facilitate cross-pollination of their ideas, creativity, and innovation," according to a March 2017 university statement.[32]

Parks and arboreta

[edit]In 2007, Penn acquired about 35 acres (14 ha) between the campus and the Schuylkill River at the former site of the Philadelphia Civic Center and a nearby 24-acre (9.7 ha) site then owned by the United States Postal Service. Dubbed the Postal Lands, the site extends from Market Street on the north to Penn's Bower Field on the south, including the former main regional U.S. Postal Building at 30th and Market Streets, now the regional office for the U.S. Internal Revenue Service. Over the next decade, the site became the home to educational, research, biomedical, and mixed-use facilities. The first phase, comprising a park and athletic facilities, opened in the fall of 2011.

In September 2011, Penn completed the construction of the $46.5 million, 24-acre (9.7 ha) Penn Park, which features passive and active recreation and athletic components framed and subdivided by canopy trees, lawns, and meadows. It is located east of the Highline Green and stretches from Walnut to South Streets.

Penn maintains two arboreta. The first, the roughly 300-acre (120 ha) Penn Campus Arboretum at the University of Pennsylvania, encompasses the entire University City main campus. The campus arboretum is an urban forest with over 6,500 trees representing 240 species of trees and shrubs, ten specialty gardens and five urban parks,[33] which has been designated as a Tree Campus USA[34] since 2009 and formally recognized as an accredited ArbNet Arboretum since 2017.[33] Penn maintains an interactive website linked to Penn's comprehensive tree inventory, which allows users to explore Penn's entire collection of trees.[35] The second arboretum, Morris Arboretum, which serves as the official arboretum of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is 92 acres and includes over 13,000 labelled plants from over 2,500 types, representing the temperate floras of North America, Asia, and Europe, with a primary focus on Asia. [36]

New Bolton Center

[edit]Penn also owns the 687-acre (278 ha) New Bolton Center, the research and large-animal health care center of its veterinary school.[37] Located near Kennett Square, New Bolton Center received nationwide media attention when Kentucky Derby winner Barbaro underwent surgery at its Widener Hospital for injuries suffered while running in the Preakness Stakes.[38]

Libraries

[edit]

Penn library system has grown into a system of 14 libraries with 400 full-time equivalent (FTE) employees and a total operating budget of more than $48 million.[39] The library system has 6.19 million book and serial volumes as well as 4.23 million microform items and 1.11 million e-books.[8] It subscribes to over 68,000 print serials and e-journals.[40][41]

The university has 15 libraries. Van Pelt Library on the Penn campus is the university's main library. The other 14 are:

- The Annenberg School for Communication library located on Walnut Street between 36th and 37th Streets

- The Archaeology and Anthropology Library located at the Penn Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology

- The Biddle Law Library located on campus on the 3500 block of Sansom Street at the School of Law

- The Chemistry Library located on campus on 3300 block of Spruce Street in the Chemistry Building

- The Dental Medicine Library on campus on the 4000 the block of Locust Street at the Dental School

- The Fisher Fine Arts Library located on campus on the 3400 block of Woodland Avenue

- The Holman Biotech Commons library located on campus on the 3500 block of Hamilton Walk adjacent to the Robert Wood Johnson Pavilion at the Medical School and the Nursing School

- The Humanities and Social Sciences Library, including Weigle Information Commons, located on campus between 34th and 35th streets on Locust Street in the Van Pelt Library

- The Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies library located off campus at 420 Walnut Street near Independence Hall and Washington Square

- The Lea Library, a collection of Catholic Church history, located on campus between 34th and 35th streets on Locust Street on the 6th floor of the Van Pelt Library

- The Lippincott Business Library located on campus between 35th and 36th streets on Locust Street in the second floor of the Van Pelt Library

- The Math/Physics/Astronomy library located on campus on 3200 block of Walnut Streets adjacent to The Palestra on the third floor of the David Rittenhouse Laboratory

- The Rare Books and Manuscripts library and Yarnall Library of Theology located on campus between 34th and 35th streets on Locust Street in Van Pelt Library

- The Veterinary Medicine Library located on the campus between 38th and 39th streets on Sansom Street at the Veterinary Medicine School with satellite library located off campus at New Bolton Center.

Penn also maintains books and records off campus at high density storage facility.

The Penn Design School's Fine Arts Library was built to be Penn's main library and the first with its own building. The main library at the time was designed by Frank Furness to be first library in nation to separate the low ceilings of the library stack, where the books were stored, from forty-foot-plus high ceilinged rooms, where the books were read and studied.[42][43][44]

The Yarnall Library of Theology, a major American rare book collection, is part of Penn's libraries. The Yarnall Library of Theology was formerly affiliated with St. Clement's Church in Philadelphia. It was founded in 1911 under the terms of the wills of Ellis Hornor Yarnall (1839–1907) and Emily Yarnall, and subsequently housed at the former Philadelphia Divinity School. The library's major areas of focus are theology, patristics, and the liturgy, history and theology of the Anglican Communion and the Episcopal Church in the United States of America. It includes a large number of rare books, incunabula, and illuminated manuscripts, and new material continues to be added.[45][46]

Art installations

[edit]

The campus has more than 40 notable art installations, in part because of a 1959 Philadelphia ordinance requiring total budget for new construction or major renovation projects in which governmental resources are used to include 1% for art[47] to be used to pay for installation of site-specific public art,[48] in part because many alumni collected and donated art to Penn, and in part because of the presence of the University of Pennsylvania School of Design on the campus.[49]

In 2020, Penn installed Brick House, a monumental work of art, created by Simone Leigh at the College Green gateway to Penn's campus near the corner of 34th Street and Woodland Walk. This 5,900-pound (2,700 kg) bronze sculpture, which is 16 feet (4.9 m) high and 9 feet (2.7 m) in diameter at its base, depicts an African woman's head crowned with an afro framed by cornrow braids atop a form that resembles both a skirt and a clay house.[50] At the installation, Penn president Amy Guttman proclaimed that "Ms. Leigh's sculpture brings a striking presence of strength, grace, and beauty—along with an ineffable sense of mystery and resilience—to a central crossroad of Penn's campus."[51]

The Covenant, known to the student body as "Dueling Tampons"[52][53] or "The Tampons,"[54] is a large red structure created by Alexander Liberman and located on Locust Walk as a gateway to the high-rise residences "super block." It was installed in 1975 and is made of rolled sheets of milled steel.

A white button, known as The Button and officially called the Split Button is a modern art sculpture designed by designed by Swedish sculptor Claes Oldenburg (who specialized in creating oversize sculptures of everyday objects). It sits at the south entrance of Van Pelt Library and has button holes large enough for people to stand inside. Penn also has a replica of the Love sculpture, part of a series created by Robert Indiana. It is a painted aluminum sculpture and was installed in 1998 overlooking College Green.[49]

In 2019, the Association for Public Art loaned Penn[55] two multi-ton sculptures. The works are Social Consciousness, created by Sir Jacob Epstein in 1954,[56] and Atmosphere and Environment XII, created by Louise Nevelson in 1970.[55] Until the loan, both works had been located at the West Entrance to the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the older since its creation and the Nevelson work since 1973. Social Consciousness was relocated to the walkway between Wharton's Lippincott Library and Phi Phi chapter of Alpha Chi Rho fraternity house, and Atmosphere and Environment XII is sited on Shoemaker Green between Franklin Field and Ringe Squash Courts.[57]

In addition to the contemporary art, Penn also has several traditional statues, including a good number created by Penn's first Director of Physical Education Department, R. Tait McKenzie.[58] Among the notable sculptures is that of Young Ben Franklin, which McKenzie produced and Penn sited adjacent to the fieldhouse contiguous to Franklin Field. The sculpture is titled Benjamin Franklin in 1723 and was created by McKenzie during the pre-World War I era (1910–1914). Other sculptures he produced for Penn include the 1924 sculpture of then Penn provost Edgar Fahs Smith.

Penn is presently reevaluating all of its public art and has formed a working group led by Penn Design dean Frederick Steiner, who was part of a similar effort at the University of Texas at Austin that led to the removal of statues of Jefferson Davis and other Confederate officials, and Penn's Chief Diversity Officer, Joann Mitchell. Penn has begun the process of adding art and removing or relocating art.[59] Penn removed from campus in 2020 the statue of the Reverend George Whitefield (who had inspired the 1740 establishment of a trust to establish a charity school, which trust Penn legally assumed in 1749) when research showed Whitefield owned fifty enslaved people and drafted and advocated for the key theological arguments in favor of slavery in Georgia and the rest of the Thirteen Colonies.[60]

Penn Museum

[edit]

Since the Penn Museum was founded in 1887,[61] it has taken part in 400 research projects worldwide.[62] The museum's first project was an excavation of Nippur, a location in current day Iraq.[63]

Penn Museum is home to the largest authentic sphinx in North America at about seven feet high, four feet wide, 13 feet long, 12.9 tons, and made of solid red granite.

The sphinx was discovered in 1912 by the British archeologist, Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie, during an excavation of the ancient Egyptian city of Memphis, Egypt, where the sphinx had guarded a temple to ward off evil. Since Petri's expedition was partially financed by Penn Petrie offered it to Penn, which arranged for it to be moved to museum in 1913. The sphinx was moved in 2019 to a more prominent spot intended to attract visitors.[64]

The museum has three gallery floors with artifacts from Egypt, the Middle East, Mesoamerica, Asia, the Mediterranean, Africa and indigenous artifacts of the Americas.[62] Its most famous object is the goat rearing into the branches of a rosette-leafed plant, from the royal tombs of Ur.

The Penn Museum's excavations and collections foster a strong research base for graduate students in the Graduate Group in the Art and Archaeology of the Mediterranean World. Features of the Beaux-Arts building include a rotunda and gardens that include Egyptian papyrus.

Other Penn museums and galleries

[edit]Penn maintains a website providing a detailed roadmap to small museums and galleries and over one hundred locations across campus where the public can access Penn's over 8,000 artworks acquired over 250 years, which includes paintings, sculptures, photography, works on paper, and decorative arts.[65] The largest of the art galleries is the Institute of Contemporary Art, one of the only kunsthalles in the country, which showcases various art exhibitions throughout the year. Since 1983, the Arthur Ross Gallery, located at the Fisher Fine Arts Library, has housed Penn's art collection[66] and is named for its benefactor, philanthropist Arthur Ross.

Residences

[edit]Every College House at the University of Pennsylvania has at least four members of faculty in the roles of House Dean, Faculty Master, and College House Fellows.[67] Within the College Houses, Penn has nearly 40 themed residential programs for students with shared interests such as world cinema or science and technology. Many of the nearby homes and apartments in the area surrounding the campus are often rented by undergraduate students moving off campus after their first year, as well as by graduate and professional students. The College Houses include W.E.B. Du Bois, Fisher Hassenfeld, Gregory, Gutmann, Harnwell, Harrison, Hill College House, Kings Court English, Lauder, Riepe, Rodin, Stouffer, and Ware. The first College House was Van Pelt College House, established in the fall of 1971. It was later renamed Gregory House.[68] Fisher Hassenfeld, Ware and Riepe together make up one building called "The Quad." The latest College House to be built is Guttman[69] (formerly named New College House West), which opened in the fall of 2021.[70]

Penn students in Junior or Senior year may live in the 45 sororities and fraternities governed by three student-run governing councils, Interfraternity Council,[71] Intercultural Greek Council, and Panhellenic Council.[72]

-

The university's first purpose-built dormitory in the foreground (on right), built in 1765[73]

-

Woodland Walk pathway between Hill College House and Lauder College House

-

Hill College House, a dormitory designed in 1958 to house female students, was designed by Eero Saarinen

-

"The Quad," formerly known as the Men's Dormitory, in 2014

-

The Alpha Tau Omega fraternity house, built by George W. Childs Drexel as one of two mansions for his daughters

Organization

[edit]| School | Year founded |

|---|---|

| Perelman School of Medicine | 1765[77] |

| School of Engineering and Applied Science | 1852[78] |

| Law School | 1850[note 6] |

| School of Design | 1868 |

| School of Dental Medicine | 1878[80] |

| The Wharton School | 1881[81] |

| Graduate School of Arts and Sciences | 1755[82] |

| School of Veterinary Medicine | 1884[83] |

| School of Social Policy and Practice | 1908 |

| Graduate School of Education | 1915 |

| School of Nursing | 1935 |

| Annenberg School for Communication | 1958 |

The College of Arts and Sciences is the undergraduate division of the School of Arts and Sciences. The School of Arts and Sciences also contains the Graduate Division and the College of Liberal and Professional Studies, which is home to the Fels Institute of Government, the master's programs in Organizational Dynamics, and the Environmental Studies (MES) program. Wharton School is the business school of the University of Pennsylvania. Other schools with undergraduate programs include the School of Nursing and the School of Engineering and Applied Science (SEAS).

The current president is J. Larry Jameson (interim).[84]

Campus police

[edit]The University of Pennsylvania Police Department (UPPD) is the largest, private police department in Pennsylvania, with 117 members. All officers are sworn municipal police officers and retain general law enforcement authority while on the campus.[85]

Seal

[edit]

The official seal of the Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania serves as the signature and symbol of authenticity on documents issued by the corporation.[86] The most recent design, a modified version of the original seal, was approved in 1932, adopted a year later and is still used for much of the same purposes as the original.[86] The official seal of the Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania serves as the signature and symbol of authenticity on documents issued by the corporation.[86] A request for one was first recorded in a meeting of the trustees in 1753 during which some of the Trustees "desired to get a Common Seal engraved for the Use of [the] Corporation." In 1756, a public seal and motto for the college was engraved in silver.[87] The most recent design, a modified version of the original seal, was approved in 1932, adopted a year later and is still used for much of the same purposes as the original.[86]

The outer ring of the current seal is inscribed with "Universitas Pennsylvaniensis," the Latin name of the University of Pennsylvania. The inside contains seven stacked books on a desk with the titles of subjects of the trivium and a modified quadrivium, components of a classical education: Theolog[ia], Astronom[ia], Philosoph[ia], Mathemat[ica], Logica, Rhetorica and Grammatica. Between the books and the outer ring is the Latin motto of the university, "Leges Sine Moribus Vanae."[86]

Academics

[edit]Penn's "One University Policy" allows students to enroll in classes in any of Penn's twelve schools.[88]

Penn has a strong focus on interdisciplinary learning and research. It offers double degree programs, unique majors, and academic flexibility. Penn's "One University" policy allows undergraduates access to courses at all of Penn's undergraduate and graduate schools except the medical, veterinary and dental schools. Undergraduates at Penn may also take courses at Bryn Mawr, Haverford, and Swarthmore under a reciprocal agreement known as the Quaker Consortium.

Admissions

[edit]| 2022[89] | 2019[90] | 2018[91] | 2017[92] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Applicants | 54,588 | 44,961 | 44,491 | 40,413 |

| Admits | 3,404 | 3,446 | 3,740 | 3,757 |

| Admit rate | 4.24% | 6.66% | 7.41% | 8.30% |

| Enrolled | 2,417 | 2,400 | 2,518 | 2,456 |

| Yield | 68.18% | 69.65% | 67.33% | 65.37% |

| SAT range* | 1510–1560 | 1450–1560 | 1440–1560 | 1420–1560 |

| ACT range* | 34–36 | 33–35 | 32–35 | 32–35 |

* SAT and ACT ranges are from the 25th to the 75th percentile. Undergraduate admissions to the University of Pennsylvania is considered by US News to be "most selective." Admissions officials consider a student's GPA to be a very important academic factor, with emphasis on an applicant's high school class rank and letters of recommendation.[93] Admission is need-blind for U.S., Canadian, and Mexican applicants.[94]

For the class of 2026, entering in Fall 2022, the university received 54,588 applications.[95] The Atlantic also ranked Penn among the 10 most selective schools in the country. At the graduate level, based on admission statistics from U.S. News & World Report, Penn's most selective programs include its law school, the health care schools (medicine, dental medicine, nursing, veterinary), the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, and the Wharton School.

Coordinated dual-degree, accelerated, interdisciplinary programs

[edit]

Penn offers unique and specialized coordinated dual-degree (CDD) programs, which selectively award candidates degrees from multiple schools at the university upon completion of graduation criteria of both schools in addition to program-specific programs and senior capstone projects. Additionally, there are accelerated and interdisciplinary programs offered by the university. These undergraduate programs include:

- Huntsman Program in International Studies and Business[96]

- Jerome Fisher Program in Management and Technology (M&T)[97]

- Roy and Diana Vagelos Program in Life Sciences and Management (LSM)[98]

- Nursing and Health Care Management (NHCM)[99]

- Roy and Diana Vagelos Integrated Program in Energy Research (VIPER)[100]

- Vagelos Scholars Program in Molecular Life Sciences (MLS)[101]

- Singh Program in Networked and Social Systems Engineering (NETS)[102]

- Digital Media Design (DMD)[103]

- Computer and Cognitive Science: Artificial Intelligence[104]

- Accelerated 7-Year Bio-Dental Program[105]

- Accelerated 6-Year Law and Medicine Program[106]

Dual-degree programs that lead to the same multiple degrees without participation in the specific above programs are also available. Unlike CDD programs, "dual degree" students fulfill requirements of both programs independently without the involvement of another program. Specialized dual-degree programs include Liberal Studies and Technology as well as an Artificial Intelligence: Computer and Cognitive Science Program. Both programs award a degree from the College of Arts and Sciences and a degree from the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences. Also, the Vagelos Scholars Program in Molecular Life Sciences allows its students to either double major in the sciences or submatriculate and earn both a BA and an MS in four years. The most recent Vagelos Integrated Program in Energy Research (VIPER) was first offered for the class of 2016. A joint program of Penn's School of Arts and Sciences and the School of Engineering and Applied Science, VIPER leads to dual Bachelor of Arts and Bachelor of Science in Engineering degrees by combining majors from each school.

For graduate programs, Penn offers many formalized double degree graduate degrees such as a joint J.D./MBA and maintains a list of interdisciplinary institutions, such as the Institute for Medicine and Engineering, the Joseph H. Lauder Institute for Management and International Studies, and the Institute for Research in Cognitive Science.

The University of Pennsylvania School of Social Policy and Practice, commonly known as Penn SP2, is a school of social policy and social work that offers degrees in a variety of subfields, in addition to several dual degree programs and sub-matriculation programs.[107][108][109] Penn SP2's vision is: "The passionate pursuit of social innovation, impact and justice."[110]

Originally named the School of Social Work, SP2 was founded in 1908 and is a graduate school of the University of Pennsylvania. The school specializes in research, education, and policy development in relation to both social and economic issues.[111][112]

The School of Veterinary Medicine offers five dual-degree programs, combining the Doctor of Veterinary Medicine (VMD) with a Master of Social Work (MSW), Master of Environmental Studies (MES), Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), Master of Public Health (MPH) or Masters in Business Administration (MBA) degree. The Penn Vet dual-degree programs are meant to support veterinarians planning to engage in interdisciplinary work in the areas of human health, environmental health, and animal health and welfare.[113]

Academic medical center and biomedical research complex

[edit]In 2018, the university's nursing school was ranked number one by Quacquarelli Symonds.[114] That year, Quacquarelli Symonds also ranked Penn's school of Veterinary Medicine sixth.[115] In 2019, the Perelman School of Medicine was named the third-best medical school for research in U.S. News & World Report's 2020 ranking.[116]

The University of Pennsylvania Health System, also known as UPHS, is a multi-hospital health system headquartered in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, owned by Trustees of University of Pennsylvania. UPHS and the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania together constitute Penn Medicine, a clinical and research entity of the University of Pennsylvania. UPHS hospitals include the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania,[117] Penn Presbyterian Medical Center, Pennsylvania Hospital, Chester County Hospital, Lancaster General Hospital, and Princeton Medical Center.[118] Penn Medicine owns and operates the first hospital in the United States, the Pennsylvania Hospital.[119] It is also home to America's first surgical amphitheatre[120] and its first medical library.[121]

-

The Pennsylvania Hospital as painted by Pavel Svinyin in 1811

-

Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania

-

Penn-owned Princeton Medical Center, eastern facade

International partnerships

[edit]Students can study abroad for a semester or a year at partner institutions, which include the Singapore Management University, London School of Economics, University of Edinburgh, Chinese University of Hong Kong, University of Melbourne, Sciences Po, University of Queensland, University College London, King's College London, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and ETH Zurich.

Reputation and rankings

[edit]| Academic rankings | |

|---|---|

| National | |

| ARWU[122] | 12 |

| Forbes[123] | 8 |

| U.S. News & World Report[124] | 6 |

| Washington Monthly[125] | 4 |

| WSJ/College Pulse[126] | 7 |

| Global | |

| ARWU[122] | 14 |

| QS[127] | 11 |

| THE[128] | 16 |

| U.S. News & World Report[129] | 14 |

U.S. News & World Report's 2024 rankings place Penn 6th of 394 national universities in the United States.[124] The Princeton Review student survey ranked Penn in 2023 as 7th in their Dream Colleges list.[130] Penn was ranked 4th of 444 in the United States by College Factual for 2024.[131] In 2023, Penn was ranked as having the 7th happiest students in the United States (the highest in the Ivy League).[132][133]

Among its professional schools, the school of education was ranked number one in 2021 and Wharton School was ranked number one in 2022[134] and 2024 [135] and the communication, dentistry, medicine, nursing, law and veterinary schools rank in the top 5 nationally.[136] Penn's Law School was ranked number 4 in 2023[137] and Design school, and its School of Social Policy and Practice are ranked in the top 10.[136]

Research

[edit]

Penn is classified as an "R1" doctoral university: "Highest research activity."[138] Its economic impact on the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania for 2015 amounted to $14.3 billion.[139] Penn's research expenditures in the 2018 fiscal year were $1.442 billion, the fourth largest in the U.S.[140] In fiscal year 2019 Penn received $582.3 million in funding from the National Institutes of Health.[141]

Penn's research centers often span two or more disciplines. In the 2010–2011 academic year, five interdisciplinary research centers were created or substantially expanded; these include the Center for Health-care Financing,[142] the Center for Global Women's Health at the Nursing School,[143] the Morris Arboretum's Horticulture Center,[144] the Jay H. Baker Retailing Center at Wharton[145] and the Translational Research Center at Penn Medicine.[146] With these additions, Penn now counts 165 research centers hosting a research community of over 4,300 faculty and over 1,100 postdoctoral fellows, 5,500 academic support staff and graduate student trainees.[8] To further assist the advancement of interdisciplinary research President Amy Gutmann established the "Penn Integrates Knowledge" title awarded to selected Penn professors "whose research and teaching exemplify the integration of knowledge."[147] These professors hold endowed professorships and joint appointments between Penn's schools.

Penn is also among the most prolific producers of doctoral students. With 487 PhDs awarded in 2009, Penn ranks third in the Ivy League behind Columbia and Cornell; Harvard did not report data.[148] It also has one of the highest numbers of post-doctoral appointees (933 in number for 2004–2007), ranking third in the Ivy League (behind Harvard and Yale) and tenth nationally.[149]

In most disciplines Penn professors' productivity is among the highest in the nation and first in the fields of epidemiology, business, communication studies, comparative literature, languages, information science, criminal justice and criminology, social sciences and sociology.[150] According to the National Research Council nearly three-quarters of Penn's 41 assessed programs were placed in ranges including the top 10 rankings in their fields, with more than half of these in ranges including the top five rankings in these fields.[151]

Penn's research tradition has historically been complemented by innovations that shaped higher education. In addition to establishing the first medical school, the first university teaching hospital, the oldest continuously operating degree-granting program in chemical engineering,[152] the first business school, and the first student union, Penn was also the cradle of other significant developments.

In 1852, Penn Law was the first law school in the nation to publish a law journal still in existence (then called The American Law Register, now the Penn Law Review, one of the most cited law journals in the world).[153] Under the deanship of William Draper Lewis, the law school was also one of the first schools to emphasize legal teaching by full-time professors instead of practitioners, a system that is still followed today.[154]

The Wharton School was home to several pioneering developments in business education. It established the first research center in a business school in 1921 and the first center for entrepreneurship center in 1973[155] and it regularly introduced novel curricula for which BusinessWeek wrote, "Wharton is on the crest of a wave of reinvention and change in management education."[156][157] The university has also contributed major advancements in the fields of economics and management. Among the many discoveries are conjoint analysis, widely used as a predictive tool especially in market research, Simon Kuznets's method of measuring Gross National Product,[158] the Penn effect (the observation that consumer price levels in richer countries are systematically higher than in poorer ones) and the "Wharton Model"[159] developed by Nobel-laureate Lawrence Klein to measure and forecast economic activity. The idea behind Health Maintenance Organizations also belonged to Penn professor Robert Eilers, who put it into practice during then-president Nixon's health reform in the 1970s.[158]

Several major scientific discoveries have also taken place at Penn. The university is probably best known as the place where the first general-purpose electronic computer (ENIAC) was born in 1946 at the Moore School of Electrical Engineering.[160] It was here also where the world's first spelling and grammar checkers were created, as well as the popular COBOL programming language.[160]

Penn can also boast some of the most important discoveries in the field of medicine. The dialysis machine used as an artificial replacement for lost kidney function was conceived and devised out of a pressure cooker by William Inouye while he was still a student at Penn Med;[161] the Rubella and Hepatitis B vaccines were developed at Penn;[161] the discovery of cancer's link with genes, cognitive therapy, Retin-A (the cream used to treat acne), Resistin, the Philadelphia gene (linked to chronic myelogenous leukemia) and the technology behind PET Scans were all discovered by Penn Med researchers.[161] More recent gene research has led to the discovery of the (a) genes for fragile X syndrome, the most common form of inherited mental retardation; (b) spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy, a disorder marked by progressive muscle wasting; (c) Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease, a progressive neurodegenerative disease that affects the hands, feet and limbs;[161] and (d) genetically engineered T cells used to treat lymphoblastic leukemia and refractory diffuse large B cell lymphoma.[162][163] Another contribution to medicine was made by Ralph L. Brinster (Penn faculty member since 1965) who developed the scientific basis for in vitro fertilization and the transgenic mouse at Penn and was awarded the National Medal of Science in 2010.

Penn professors Alan J. Heeger, Alan MacDiarmid and Hideki Shirakawa invented a conductive polymer process that earned them the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. The theory of superconductivity was also partly developed at Penn, by then-faculty member John Robert Schrieffer (along with John Bardeen and Leon Cooper).

Penn professors Carl June and Michael C. Milone at Penn Medicine developed Kymriah, the first FDA-approved CAR T cell therapy for treating certain types of leukemia, approved in August 2017.[164][165]

Student life

[edit]| Ethnic enrollment, fall 2018[166] |

Number (percentage) of undergraduates |

|---|---|

| African American | 715 (7.1%) |

| Native American | 12 (0.1%) |

| Asian American and Pacific Islander |

2,084 (20.7%) |

| Hispanic and Latino American |

1,044 (10.4%) |

| White | 4,278 (42.6%) |

| International | 1,261 (12.6%) |

| Two or more races, non-Hispanic |

460 (4.6%) |

| Unknown | 179 (1.8%) |

| Total | 10,033 (100%) |

Of those accepted for admission in 2018, 48 percent were Asian, Hispanic, African-American or Native American.[8] Fourteen percent of entering undergraduates in 2018 were international students.[8] The composition of international first-year students in 2018 was: 46% from Asia; 15% from Africa and the Middle East; 16% from Europe; 14% from Canada and Mexico; 8% from the Caribbean, Central America and South America; 5% from Australia and the Pacific Islands.[8] The acceptance rate for international students admission in 2018 was 493 out of 8,316 (6.7%).[8] In 2018, 55% of all enrolled students were women.[8]

In the last few decades, Jewish enrollment has been declining. c. 1999 about 28% of the students were Jewish.[167] In early 2020, 1,750 Penn undergraduate students were Jewish,[168] which would be approximately 17%[169] of the some 10,000 undergrads for 2019–20. Penn has been ranked as the number one LGBTQ+ friendly school in the country.[170] Penn's LGBTQ+ center is second oldest in the nation[171] and oldest in Commonwealth of Pennsylvania as it has been serving the LGBTQ+ community since 1979 by providing support and guidance through 25 groups (including Penn J-Bagel a Jewish LGBTQ+ group, the Lambda Alliance a general LGBTQ social organization, and oSTEM a group for LGBTQ people in STEM fields).[172] Penn offers courses in Sexuality and Gender Studies which allows students to discover and learn queer theory, history of sexual norms, and other gender orientation related courses.[173]

Penn Face and behavioral health

[edit]The university's social pressure surrounding academic perfection, extreme competitiveness, and nonguaranteed readmission have created what is known as "Penn Face": students put on a façade of confidence and happiness while enduring mental turmoil.[174][175][176][177][178] Stanford University calls this phenomenon "Duck Syndrome."[177][179] In recent years, mental health has become an issue on campus with ten student suicides between the years of 2013 to 2016.[180] The school responded by launching a task force.[181][182] The most widely covered case of Penn Face has been Madison Holleran.[183][184] In 2018, initiatives were enacted to ameliorate mental health problems, such as requiring sophomores to live on campus and the daily closing of Huntsman Hall at 2:00 a.m.[185][186] The university's suicide rate was the catalyst for a 2018 state bill, introduced by Governor Tom Wolf, to raise Pennsylvania's standards for university suicide prevention.[187] The university's efforts to address mental health on campus came into the national spotlight again in September 2019 when the director of the university's counseling services died by suicide six months after starting the position.[188]

Student organizations

[edit]

The Philomathean Society, founded in 1813, is the United States' oldest continuously existing collegiate literary society and continues to host lectures and intellectual events open to the public.[189]

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper, which has been published daily since it was founded in 1885.[190] The newspaper went unpublished from May 1943 to November 1945 due to World War II.[190] In 1984, the university lost all editorial and financial control of The Daily Pennsylvanian (also known as The DP) when the newspaper became its own corporation.[190] The Daily Pennsylvanian has won the Pacemaker Award administered by the Associated Collegiate Press multiple times, most recently in 2019.[191][192] The DP also publishes a weekly arts and culture magazine called 34th Street Magazine.

The Penn Debate Society (PDS), founded in 1984 as the Penn Parliamentary Debate Society, is Penn's debate team, which competes regularly on the American Parliamentary Debate Association and the international British Parliamentary circuit.[193]

The Penn History Review is a journal, published twice a year, through the Department of History, for undergraduate historical research, by and for undergraduates, and founded in 1991.[194][195][196]

Penn Electric Racing

[edit]

Penn Electric Racing is the university's Formula SAE (FSAE) team, competing in the international electric vehicle (EV) competition. Colloquially known as "PER," the team designs, manufactures, and races custom electric racecars against other collegiate teams. In 2015, PER built and raced their first racecar, REV1, at the Lincoln Nebraska FSAE competition, winning first place.[197] The team repeated their success with their next two racecars: REV2 won second place in 2016,[198] and REV3 won first place in 2017.[199]

Performing arts organizations

[edit]Penn is home to numerous organizations that promote the arts, from dance to spoken word, jazz to stand-up comedy, theatre, a cappella and more. The Performing Arts Council (PAC) oversees 45 student organizations in these areas.[200] The PAC has four subcommittees: A Cappella Council; Dance Arts Council; Singer, Musicians, and Comedians (SMAC); and Theatre Arts Council (TAC-e).

Penn Glee Club

[edit]

The University of Pennsylvania Glee Club, founded in 1862, is tied for fourth oldest continually running glee clubs in the United States[201] and the oldest performing arts group at the University of Pennsylvania.

Each year, the Penn Glee Club writes and produces a fully staged, Broadway-style production with an eclectic mix of Penn standards, Broadway classics, classical favorites, and pop hits, highlighting choral singing from all genders[202]

The Glee Club draws its singing members from the undergraduate and graduate students.

The Penn Glee Club has traveled to nearly all 50 states in the United States and over 40 nations and territories on five continents and has appeared on national television with such celebrities as Bob Hope, Frank Sinatra, Jimmy Stewart, and Ed McMahon. Since its first performance at the White House for President Calvin Coolidge in 1926, the club has sung for numerous heads of state and world leaders.

Penn Band

[edit]

The University of Pennsylvania Band has been a part of student life since 1897.[203] The Penn Band presently mainly performs at football and basketball games as well as university functions (e.g. commencement and convocation). It was the first college band to perform at Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade, and has performed with notable musicians, including John Philip Sousa, members of the Philadelphia Orchestra, and the U.S. Marine Band ("The President's Own").

Penn Band has performed for Princess Grace Kelly of Monaco (sister and aunt to number of alumni), alumnus and District Attorney and Mayor of Philadelphia, and Governor of Pennsylvania Ed Rendell, Vice President Al Gore, presidents Theodore Roosevelt, Lyndon B. Johnson and Ronald Reagan, and Polish dissident and president Lech Wałęsa.

Penn's a cappella community

[edit]

The A Cappella Council (ACK) is composed of 14 a cappella groups. Penn's a cappella groups entertain audiences with repertoires including pop, rock, R&B, jazz, Hindi, and Chinese songs.[204] ACK is also home to Off The Beat, which has received the most contemporary a cappella recording awards of any collegiate group in the United States and the most features on the Best of College A Cappella albums.[205] Penn Masala, formed in 1996, is world's oldest[206][207] and premier[208][209] South Asian a cappella group based in an American university, which has performed for Barack Obama, Joe Biden, Henry Kissinger, Ban Ki-moon, Farooq Abdullah, Imran Khan, Rajkumar Hirani, A.R. Rahman, Narendra Modi[210] and Sunidhi Chauhan, had their a cappella version of Nazia Hassan's Urdu classic "Aap Jaisa Koi," (originally from the movie Qurbani) sung in the movie American Desi.[211]

Penn alumni Elizabeth Banks (class of 1996) and Max Handelman (Banks' husband, class of 1995) invited Masala to appear in Pitch Perfect 2, as Banks reported that Penn's a capella community inspired the film series starring or produced by Banks and Handleman.[212]

Comedy organizations

[edit]

Mask and Wig, a club founded in 1889, was (until fall of 2021[213]) the oldest all-male musical comedy troupe in the country. In 2021 the club voted to become gender-inclusive, with auditions open to all undergraduates: male, female, and non-binary.

Bloomers comedy group, founded in 1978, is the .".. nation's first collegiate all-women musical and sketch comedy troupe...."[214] Bloomers was founded at Penn by Joan Harrison.[215] In the mid teens, Bloomers revised its constitution to be open to .".. anyone who does not identify as a cisgender man...."[214] and now accepts all persons from under-represented gender identities who perform comedy.[216][217] Bloomers performs sketches and elaborate shows almost every semester. The comedy troupe is named after bloomers, the once popular long, loose fitting undergarment, gathered at the ankle, worn under a short skirt (developed in the mid 19th century as a healthy comfortable alternative to the heavy, constricting dresses then worn by American women), which were in turn, named after Amelia Jenks Bloomer. Bloomers' most well-known performing alumna is Vanessa Bayer, formerly of Saturday Night Live and is SNL's longest-serving female cast member.[218]

Religious and spiritual organizations

[edit]The following religious and spiritual organizations have a significant on campus presence at Penn:

(A) Mainstream Protestantism: Dating back to 1857, The Christian Association (a.k.a. The CA), is composed primarily of students from Mainline Protestant backgrounds.[219] Historically, the CA ran several foreign missions including one in China[220] and for decades ran a camp for socio-economically disadvantaged children from Philadelphia.[221] At present the CA occupies part of the parsonage at Tabernacle United Church of Christ.[222]

(B) Judaism: Organized Jewish life did not begin on campus in earnest until the start of 20th century.[223] Jewish Life on campus is centered at Penn branch of Hillel International,[224][169] which inspires students to explore Judaism, creates patterns of Jewish living that can be sustained after graduation, provides religious communities, promotes educational initiatives, social justice projects, social and cultural opportunities, and groups focusing on Israel education and politics, and hosts a Kosher Penn approved dining hall (supervised by the Community Kashrus of Greater Philadelphia).[225] In addition to Hillel, the other major Jewish organization with significant impact on Penn's campus is The Chabad Lubavitch House at Penn (founded in 1980[226]), which, among other activities, brings together Jewish college students with noted Jewish academics for in-depth discussions and debate.[227]

(C) Roman Catholicism: The Penn Newman Catholic Center (the Newman Center), founded in 1893 (as the first Newman Center in the country) with the mission of supporting students, faculty, and staff in their religious endeavors. The organization brings prominent Christian figures to campus, including Rev. Thomas "Tom" J. Hagan, OSFS, who worked in the Newman Center and founded Haiti-based non-profit Hands Together;[228] and James Martin SJ (Wharton School undergraduate class of 1982[229]). Father Martin, an editor-at-large of the Jesuit magazine America,[230] and frequent commentator on the life and teachings of Jesus and Ignatian spirituality, is especially well known for his outreach to the LGBT community, which has drawn a strong backlash from parts of the Catholic Church, but has provided comfort to Penn students and other members of Roman Catholic community who wish to stay connected with their faith and identify as LGBQT.[231][232][233]

(D) Hinduism and Jainism: Penn funds (via the Graduate and Professional Student Assembly or similar undergraduate organization) a variety of official clubs focused on India including a number focused on students who are Hindu or Jain such as: (1) 'Pan-Asian American Community House (PAACH)', a center for students to celebrate South Asian, East Asian, Southeast Asian, culture and religion,[234] (2) 'Rangoli – The South Asian Association at Penn' that educates and informs Penn students (mainly graduate and professional students) with ancestry or interest in South Asia whose goals include a desire to "rekindle the spirit of community" through events,[235] and (3) 'Penn Hindu & Jain Association', a student-run official club at Penn that has 80 to 110 student members and an extensive alumni network, dedicated to raise awareness of the Hindu and Jain faiths and foster further development of these communities in the greater Philadelphia area by providing a variety of services and hosting a number of events such as Holi Festival (which has been held annually at Penn since 1993[236][237][238]) and "... aims to be a home to anyone seeking to explore their spiritual, religious, or social interests."[239]

(E) Islam: In 1963, the Muslim Students' Association (MSA National) and Penn chapter of MSA National were founded to facilitate Muslim life among students on college campuses.[240][241] Penn MSA was established to help Penn Muslims build faith and community by fostering a space under the guidance of Islamic principles[242][243] and towards that goal Penn MSA supports mission of its related umbrella organization, Islamic Society of North America, to "foster the development of the Muslim community, interfaith relations, civic engagement, and better understandings of Islam."[244] The Muslim Life Program at Penn also provides such support and helped cause Penn (in January 2017) to hire its first full-time Muslim chaplain, the co-president of the Association of Campus Muslim Chaplains, Sister Patricia Anton (whose background includes working with Muslim, interfaith, academic and peace-building institutions such as Islamic Society of North America and Islamic Relief). Chaplain Anton's mandate includes supporting and guiding the Penn Muslim community to foster further development of such community by creating a welcoming environment that provides Penn Muslim community opportunities to intellectually and spiritually engage with Islam.[245] Penn also has a residential house, the Muslim Life Residential Program, which provides a live/learn environment focused on the appreciation of Islamic culture, food, history, and practice, and shows its Penn student residents how Islam is deeply integrated in the culture of Philadelphia so they may appreciate how Islam influences daily life.[246]

(F) Buddhism: Penn has a Buddhist chaplain[247][248] (as well as chaplains of other faiths) and funds the Penn Meditation and Buddhism Club, which (1) is dedicated to helping Penn students practice mindfulness and meditation and learning about Buddhism, (2) conducts weekly meetings that begin with a guided meditation and are followed by discussions of topic(s) relating to mindfulness and Buddhism, and (3) organizes other activities such as ramen nights and weekend meditation retreats to the local Won Buddhism center.[249]

Athletics

[edit]Penn's sports teams are nicknamed the Quakers, but the teams are often also referred to as The Red and Blue as reflected in the popular song sung after every athletic contest where the Penn Band or other musical groups are present.[250][251] The athletes participate in the Ivy League and Division I (Division I FCS for football) in the NCAA. In recent decades, they often have been league champions in football (14 times from 1982 to 2010) and basketball (22 times from 1970 to 2006). The first athletic team at Penn was the cricket team, which formed in 1842 and played regularly through 1846, the year it lost its "grounds," and then only played intermittently until 1864, the year it played its first intercollegiate game (against Haverford College).[252] The rowing (or crew) team composed of Penn students but not officially representing Penn was formed in 1854 but did not compete against other colleges as official part of Penn until 1879. The rugby football team began to play against other colleges, most notably against College of New Jersey (now Princeton University) in 1874 using a combination of association football (i.e. soccer) and rugby rules (the twenty players on each side were able to use their hands but were not able to pass or bat the ball forward).[253][254][255]

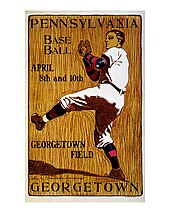

Baseball

[edit]

The University of Pennsylvania's first baseball team was fielded in 1875. Penn has won four championships in the Eastern Intercollegiate Baseball League, a baseball-only conference that existed from 1930 to 1992, which consisted of the eight Ivy League schools and Army and Navy.[256] Since 1992, Penn baseball has claimed an Ivy League title, advancing to the NCAA Division I Baseball Championship five times.[257]

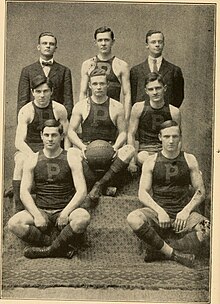

Basketball

[edit]

Penn basketball is steeped in tradition. Penn was retroactively recognized as the pre-NCAA tournament national champion for the 1919–20 and 1920–21 seasons by the Helms Athletic Foundation and for the 1919–20 season by the Premo-Porretta Power Poll.[259] Penn made its only (and the Ivy League's second) Final Four appearance in 1979, where the Quakers lost to Magic Johnson-led Michigan State in Salt Lake City. (Dartmouth twice finished second in the tournament in the 1940s, but that was before the beginning of formal League play.) Penn's team is also a member of the Philadelphia Big 5, along with La Salle, Saint Joseph's, Temple, Villanova, and Drexel. In 2007, the men's team won its third consecutive Ivy League title and then lost in the first round of the NCAA Tournament to Texas A&M. Penn last made the NCAA tournament in 2018 where it lost to top seeded Kansas.[260]

Cricket

[edit]

The first University of Pennsylvania cricket team, reported to be the first cricket team in the United States composed exclusively of Americans,[261] was organized in 1842.[261] On May 7, 1864, Penn played its first intercollegiate game against Haverford College (the 3rd oldest intercollegiate athletic contest after Harvard Yale 1852 crew race and Amherst Williams 1859 Baseball game[262][252]).[263][264] After Penn moved west of the Schuylkill River in 1872, Penn played cricket at one of the local clubs, Belmont Cricket Club, Merion Cricket Club, Germantown Cricket Club, or at Haverford College.[263] Beginning in 1875 and through 1880, Penn fielded a varsity eleven, which played a few matches each year against opponents that included Haverford College and Columbia College.[252]

In 1881, Penn, Harvard College, Haverford College, Princeton College (then known as College of New Jersey), and Columbia College formed the Intercollegiate Cricket Association,[264] which Cornell University later joined.[252] Penn won The Intercollegiate Cricket Association championship, the de facto national championship, 23 times (18 solo, three shared with Haverford and Harvard, one shared with Haverford and Cornell, and one shared with just Haverford) during the 44 years that The Intercollegiate Cricket Association existed from 1881 through 1924.[note 7]

In the 1890s, Penn's cricket team frequently toured Canada and the British Isles.[252] Perhaps the university's most famous cricket player was George Patterson (class of 1888), who still holds the North American batting record and who went on to play for the professional Philadelphia Cricket Team.[265]

Following the World War I, cricket began to experience a serious decline,[266] such that in 1924 Penn fielded its last team in the twentieth century. Starting in 2009, however, Penn once again fielded a cricket team, albeit club, that ended up being the first winner of a tournament for teams from the Ivies.[267]

Curling

[edit]University of Pennsylvania Curling Club qualified for the 2023 National Championship at 6th place, the same ranking they qualified for the 2022 National Championship (where they finished in 2nd place), but in 2023 the team won the national championship by defeating arch rival Princeton University in the championship match (6 to 3).[268][269] Penn Curling also won the National Championship in 2016 and is the only East Coast team to have won the Curling National Championship.[270]

Football

[edit]

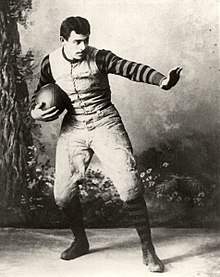

Penn first fielded a football team against Princeton at the Germantown Cricket Club in Philadelphia on November 11, 1876.[271]

During the 1890s, Penn's coach and alumnus George Washington Woodruff introduced the quarterback kick, a forerunner of the forward pass, as well as the place-kick from scrimmage and the delayed pass.

The achievements of two of Penn's other outstanding players from that era, John Heisman, a Law School alumnus, and John Outland, a Penn Med alumnus, are remembered each year with the presentation of the Heisman Trophy to the most outstanding college football player of the year, and the Outland Trophy to the most outstanding college football interior lineman of the year.

The Bednarik Award, named for Chuck Bednarik, a three-time All-American center and linebacker who starred on the 1947, is awarded annually to college football's best defensive player. Bednarik went on to play for 12 years with the Philadelphia Eagles, and was elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1969.

Penn's game against University of California, Berkeley on September 29, 1951, in front of a crowd of 60,000 at Franklin Field, was first college football game to be broadcast in color.[272][273]

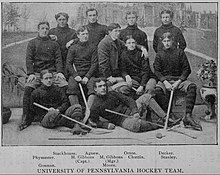

Ice hockey

[edit]

Penn's first ice hockey team competed during the 1896–97 academic year, and joined the nascent Intercollegiate Hockey Association (IHA) in 1898–99. On the first team in 1896–97 were several players of Canadian background, among them middle-distance runner and Olympian George Orton (the first disabled person to compete in the Olympics). Penn fielded teams intermittently until 1965 when it formed a varsity squad that was terminated in 1977. Penn now fields a club team that plays in the American Collegiate Hockey Association Division II,[274] is a member of the Colonial States College Hockey Conference, and continues to play at the Class of 1923 Arena in Philadelphia.[275]

Olympic athletes

[edit]

At least 43 different Penn alumni have earned 81 Olympic medals (26 gold).[277][note 8] Penn won more of its "medals"[277] (which were actually cups, trophies, or plaques, as medals were not introduced until a later Olympics) at 1900 Summer Olympics held in Paris than at any other Olympics.[278] In the 2024 Summer Olympics in Paris, 13 Penn present students or alumni participated in 5 sports (athletics [4], breaking [1], fencing [3], rowing[4], and swimming [1] for 7 countries (Australia [1], Bermuda [1], Canada [2], Egypt [1], Nigeria [1], Slovenia [1], and USA [6]) [279]

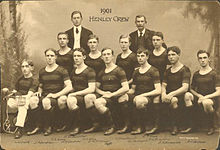

Rowing

[edit]

Rowing at Penn dates back to at least 1854 with the founding of the University Barge Club. The university currently hosts both heavyweight and lightweight men's teams and an open weight women's team, all of which compete as part of the Eastern Sprints League. Ellis Ward was Penn's first intercollegiate crew coach from 1879 through 1912.[281] During the course of Ward's coaching career at Penn his .".. Red and Blue crews won 65 races, in about 150 starts."[282] Ward coached Penn's 8-oared boat to the finals of the Grand Challenge Cup (the oldest and most prized trophy) at the Henley Royal Regatta (but in that final race was defeated by the champion Leander Club).[283]

Penn Rowing has produced a long list of famous coaches and Olympians. Members of Penn crew team, rowers Sidney Jellinek, Eddie Mitchell, and coxswain, John G. Kennedy, won the bronze medal for the United States at 1924 Olympics.[284]

Joe Burk (class of 1935) was captain of Penn crew team, winner of the Henley Diamond Sculls twice, named recipient of the James E. Sullivan Award for nation's best amateur athlete in 1939, and Penn coach from 1950 to 1969. The 1955 Men's Heavyweight 8, coached by Joe Burk, became one of only four American university crews in history to win the Grand Challenge Cup at the Henley Royal Regatta. The outbreak of World War Two canceled the 1940 Olympics for which Burk was favored to win the gold medal.

Other Penn Olympic athletes and or Penn coaches of such athletes include: (a) John Anthony Pescatore (who competed in the 1988 Seoul Olympic Games for the United States as stroke of the men's coxed eight which earned a bronze medal[285] and later competed at the 1992 Barcelona Olympic Games in the men's coxless pair), (b) Susan Francia (winner of gold medals as part of the women's 8 oared boat at 2008 Olympics and 2012 Olympics), (c) Regina Salmons (member of 2021 USA team),[286] (d) Rusty Callow, (e) Harry Parker, (f) Ted Nash,[284] and (g) John B. Kelly Jr., son of John B. Kelly Sr. (winner of three medals at 1920 Summer Olympics) and brother of Princess Grace of Monaco, was the second Penn Crew alumnus to win the James E. Sullivan Award[287] for being nation's best amateur athlete (in 1947), who was winner of a bronze medal at the 1956 Summer Olympics).

Penn men's crew team won the National Collegiate Rowing Championship in 1991. A member of that team, Janusz Hooker (Wharton School class of 1992)[288] won the bronze medal in Men's Quadruple Sculls for Australia at the 1996 Summer Olympics.[289] The Penn teams presently row out of College Boat Club, No. 11 Boathouse Row.

Rugby

[edit]

The Penn men's rugby football team is one of the oldest collegiate rugby teams in the United States. Penn first fielded a team in mid-1870s playing by rules much closer to the rugby union and association football code rules (relative to American football rules, as such American football rules had not yet been invented[253]). Among its earliest games was a game against the College of New Jersey, which became Princeton in 1895, played in Philadelphia on Saturday, November 11, 1876, which was less than two weeks before Princeton met on November 23, 1876, with Harvard and Columbia to confirm that all their games would be played using the rugby union rules.[271][253] Princeton and Penn played their November 1876 game per a combination of rugby (there were 20 players per side and players were able to touch the ball with their hands) and Association football codes. The rugby code influence was due, in part, to the fact that some of their students had been educated in English public schools.[291] Among the prominent alumni to play in a 19th-century version of rugby in which rules then did not allow forward passes or center snaps was John Heisman, namesake of the Heisman Trophy and an 1892 graduate of the University of Pennsylvania Law School.[292]

Heisman was instrumental in the first decade of the 20th century in changing the rules to more closely relate to the present rules of American football.[293] One of Heisman's teammates (who was unanimously voted Captain in the fall after Heisman graduated) was Harry Arista Mackey, Penn Law class of 1893[294] (who subsequently served as Mayor of Philadelphia from 1928 to 1932).[295] In 1906, Rugby per Rugby Union code was reintroduced to Penn[296] (as Penn last played per Rugby Union Code in 1882 as Penn played rugby per a number of different rugby football rulebooks and codes from 1883 through 1890s[297]) by Frank Villeneuve Nicholson (Frank Nicholson (rugby union)) University of Pennsylvania School of Dental Medicine (class of 1910),[298] who in 1904 had captained the Australian national rugby team in its match against England.[299]

Penn played per rugby union code rules at least through 1912, contemporaneously with Penn playing American gridiron football. Evidence of such may be found in an October 22, 1910, Daily Pennsylvanian article (quoted below) and a yearbook photo[300] that rugby per rugby union code was played.

Such is the devotion to English rugby football on the part of University of Pennsylvania's students from New Zealand, Australia, and England that they meet on Franklin Field at 7 o'clock every morning and practice the game. The varsity track and football squads monopolize the field to such an extent that the early hours of the morning are the only ones during which the rugby enthusiasts can play. Any time except Friday, Saturday and Sunday, a squad of 25 men may be seen running through the hardest kind of practice after which they may divide into two teams and play a hard game. Once a week, captain CC Walton, ('11), dental, who hails from New Zealand, gives the enthusiastic players a blackboard talk in which he explains the intricacies of the game in detail.[301]

The player-coach of United States Olympic gold-winning rugby team at the 1924 Summer Olympics was Alan Valentine, who played rugby while at Penn (which he attended during 1921/1922 academic year) as he was getting a master's degree at Wharton.[277]

Though Penn played rugby per rugby union rules from 1929 through 1934,[302] there is no indication that Penn had a rugby team from 1935 through 1959 when Penn men's rugby became permanent due to leadership of Harry "Joe" Edwin Reagan III[303] Penn's College class of 1962 and Penn Law class of 1965, who also went onto help create and incorporate (in 1975) and was Treasurer (in 1981) of USA Rugby and Oreste P. "Rusty" D'Arconte Penn's College class of 1966[300] Thus, with D'Arconte's hustle and Reagan's charisma and organizational skills, a team, which had fielded a side of fifteen intermittently from 1912 through 1960, became permanent.

In spring of 1984, Penn women's rugby,[304][305] led by Social Chair Tamara Wayland (College class of 1985,[306] who subsequently became the women's representative to and vice president of USA Rugby South from 1996 to 1998); club president Marianne Seligson; and Penn Law student Gigi Sohn,[307] began to compete. Penn women's rugby team is coached, as of 2020, by (a) Adam Dick,[308] a 300-level certified coach with over 15 years of rugby coaching experience including being the first coach of the first women's rugby team at the University of Arizona and who was a four-year starter at University of Arizona men's first XV rugby team and (b) Philly women's player Kate Hallinan.

Penn's men's rugby team plays in the Ivy Rugby Conference[309] and have finished as runners-up in both 15s and 7s in the Conference and won the Ivy Rugby Tournament in 1992.[310] As of 2011[update], the club uses the state-of-the-art facilities at Penn Park. The Penn Quakers' rugby team played on national TV at the 2013 Collegiate Rugby Championship, a college rugby tournament that for number of years had been played each June at Subaru Park in Philadelphia, and was broadcast live on NBC. In their inaugural appearance in the tournament, the Penn men's rugby team won the Shield Competition, beating local Big Five rival, Temple University, 17–12 in the final. In the semifinal match of that Shield Competition, Penn Rugby became the first Philadelphia team to beat a non-Philadelphia team in CRC history, with a 14–12 win over the University of Texas.[311]

As of 2020, Penn men's rugby team is coached by Tiger Bax,[312] a former professional rugby player hailing from Cape Town, South Africa, whose playing experience includes stints in the Super Rugby competition with the Stormers (15s) and Mighty Mohicans (7s), as well as with the Gallagher Premiership Rugby side, Saracens[313] and whose coaching experience includes three successful years as coach at Valley Rugby Football Club in Hong Kong; and Tyler May, from Cherry Hill, New Jersey, who played rugby at Pennsylvania State University where he was a first XV player for three years.

Penn's graduate business and law schools also fielded rugby teams. The Wharton rugby team has competed from 1978 to the present.[314] The Penn Law Rugby team (1985 through 1993) counts among its alumni Walter Joseph Jay Clayton, III[315] Penn Law class of 1993, and chair of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission from May 4, 2017, until December 23, 2020, Raymond Hulser, former Chief of Public Integrity Section of United States Department of Justice,[316] and Magistrate Judge Bruce Reinhart[317] who approved the search of Mar-a-Lago, the residence of former U.S. president Donald Trump in Palm Beach, Florida.[318]

Undergraduate Penn Rugby Alumni include (1) Conor Lamb (Penn College class of 2006 and Penn Law class of 2009), who played for undergraduate team, and, as of 2021, is a member of United States House of Representatives, elected originally to Pennsylvania's 18th congressional district, since 2019 is a U.S. Representative from Pennsylvania's 17th congressional district and (2) Argentina's richest person,[319] Marcos Galperin (Wharton Undergraduate Class of 1994), a premier player on the 1992 Ivy League Tournament championship team,[320] who founded Mercado Libre,[321] an online marketplace dedicated to e-commerce and online auction, which, as of 2016,[322] is the most popular e-commerce site in South America by number of visitors.[323]

Facilities

[edit]

Franklin Field, with a present seating capacity of 52,593,[324] is where the Quakers play football, lacrosse, sprint football and track and field (and formerly played baseball, field hockey, soccer, and rugby). It is the oldest stadium still operating for college football games,[15] first stadium to sport two tiers,[325] first stadium in the country to have a scoreboard, second stadium to have a radio broadcast of football, first stadium from which a commercially televised football game was broadcast,[324] and first stadium from which college football game was broadcast in color.[272] Franklin Field also played host to the Philadelphia Eagles from 1958 to 1970.[324] Since 1895, Franklin Field has hosted the annual collegiate track and field event "the Penn Relays," which is the oldest and largest track and field competition in the United States.[326]

Penn's Palestra is home gym of the Penn Quakers men's and women's basketball and volleyball teams, wrestling team, Philadelphia Big Five basketball, and other high school and college sporting events, and is located mere yards from Franklin Field.[328] The Palestra has been called "the most important building in the history of college basketball" and "changed the entire history of the sport for which it was built".[329] . The Palestra has hosted more NCAA Tournament basketball games than any other facility.

Penn's River Fields hosts a number of athletic fields including the Rhodes Soccer Stadium, the Ellen Vagelos C'90 Field Hockey Field, and Irving "Moon" Mondschein Throwing Complex.[330] Penn baseball plays its home games at Meiklejohn Stadium at Murphy Field.

Penn's Class of 1923 Arena (with seating for up to 3,000 people) was built to host the University of Pennsylvania Varsity Ice Hockey Team, which has been disbanded, and now hosts or in the past hosted: Penn's Men's and Penn Women's club ice hockey teams, practices or exhibition games for the Philadelphia Flyers, Colorado Avalanche and Carolina Hurricanes, roller hockey for the Philadelphia Bulldogs professional team, and rock concerts such as one in 1982 featuring Prince.[331][332][333]

People

[edit]Notable people

[edit]Penn alumni, faculty and trustees include those who have distinguished themselves in the sciences, academia, politics, business, military, sports, arts, and media.

Penn alumni include two presidents of the United States: Donald Trump and William Henry Harrison,[note 5] (and eight presidents who were awarded honorary doctorate degrees by Penn).[335] Of the presidents who were awarded the honorary doctorates by Penn, five were awarded prior to them becoming president (Washington, Taft, Wilson, Hoover, and Eisenhower) and three were awarded while they were president (Garfield and both Roosevelts).[336]

In addition, nine foreign heads of state attended Penn (including former prime minister of the Philippines, Cesar Virata; the first president of Nigeria, Nnamdi Azikiwe; the first president of Ghana, Kwame Nkrumah; and the current president of Ivory Coast, Alassane Ouattara).

The current president of the United States, Joe Biden (since January 20, 2021[337][338]) was a Benjamin Franklin Presidential Practice Professor at University of Pennsylvania, where he led the Penn Biden Center for Diplomacy and Global Engagement, a center focused principally on diplomacy, foreign policy, and national security.[339]

Penn alumni or faculty also include three United States Supreme Court justices: William J. Brennan, Owen J. Roberts, and James Wilson and at least four Supreme Court justices of foreign nations, (including Ronald Wilson of the High Court of Australia, Ayala Procaccia of the Israel Supreme Court, Yvonne Mokgoro, former justice of the Constitutional Court of South Africa, and Irish Court of Appeal justice Gerard Hogan).

Since its founding, Penn alumni, trustees, and faculty have included eight Founding Fathers of the United States who signed the Declaration of Independence,[16][17] seven who signed the United States Constitution,[17] and twenty-four members of the Continental Congress.

Penn alumni also include 32 U.S. senators, 163 members of the U.S. House of Representatives, 19 U.S. Cabinet Secretaries, 46 governors, 28 State Supreme Court justices.

Penn alumni in finance and investment banking include Warren Buffett[note 9] (CEO of Berkshire Hathaway), and Elon Musk (co-founder of PayPal, Tesla, OpenAI and Neuralink, founder of SpaceX and The Boring Company) and those on Wall Street[340] who received federal aid, 10 years after starting at Penn, have the highest median incomes among alumni of Ivy League schools.[341] Penn has the largest number of undergraduate alumni (36) who are billionaires (with combined wealth of 367 billion dollars - also largest number among colleges and universities in USA).[19][342]

Penn alumni have won (a) 53 Tony Awards,[343][344] (b) 17 Grammy Awards,[345] (c) 25 Emmy Awards,[346][347] (d) 13 Oscars,and (e) 1 EGOT (John Legend[348])[note 10].

Penn alumni have also had a significant impact on the United States military as they include Samuel Nicholas, United States Marine Corps founder, and William A. Newell, whose congressional action formed a predecessor to the current United States Coast Guard,[349] and numerous alumni have become generals or similar rank in the United States Armed Forces. At least 2 Penn alumni have been NASA astronauts[350] and 5 Penn alumni have been awarded the Medal of Honor.[20][21]