Кейптаун

Кейптаун | |

|---|---|

| Прозвища: Город-мать, Таверна Морей (архаика) | |

| Девиз: Spes Bona ( лат. «Добрая надежда») | |

| Координаты: 33 ° 55'31 "ю.ш., 18 ° 25'26" в.д. / 33,92528 ° ю.ш., 18,42389 ° в.д. | |

| Страна | |

| Провинция | |

| Муниципалитет | Город Кейптаун |

| Основан | 6 апреля 1652 г |

| Муниципальное правительство | 1839 |

| Правительство | |

| • Тип | Столичный муниципалитет |

| • Мэр | Джордин Хилл-Льюис ( DA ) |

| • Заместитель мэра | Эдди Эндрюс ( DA ) |

| Область | |

| • Столица ( законодательная власть ) | 2461 км 2 (950 квадратных миль) |

| Самая высокая точка | 1590,4 м (5217,8 футов) |

| Самая низкая высота | 0 м (0 футов) |

| Население | |

| • Классифицировать | 13-е место в Африке 2-е место в Южной Африке |

| • Городской (2011) | 433,688 |

| • Плотность города | 1083,47/км 2 (2806,2/кв. миль) |

| • Метро (2022) | 4,770,313 |

| • Плотность метро | 1529,68/км 2 (3961,9/кв. миль) |

| Demonym | Капетонский |

| Расовый макияж (2022) [5] | |

| • Черный | 45.7% |

| • Цветные | 35.1% |

| • Белый | 16.2% |

| • Индийская / азиатская кухня | 1.6% |

| Первые языки (2011) | |

| • Африкаанс | 34.9% |

| • Коса | 29.2% |

| • Английский | 27.8% |

| Часовой пояс | UTC+2 ( САСТ ) |

| Почтовые индексы (улица) | 7400–8099 |

| почтовый ящик | 7000 |

| НПП (2020) | долларов США 121 миллиард [7] |

| ВГП на душу населения (2011 г.) | 19 656 долларов США [8] |

| Веб-сайт | capetown.gov.za |

Кейптаун [а] является законодательной столицей ЮАР . Это старейший город страны и резиденция парламента Южной Африки . [11] Это второй по величине город страны после Йоханнесбурга и самый крупный в Западно-Капской провинции . [12] Город является частью Кейптауна столичного муниципалитета .

Город известен своей гаванью , природной средой в флористическом регионе Кейп-Пойнт , а также такими достопримечательностями, как Столовая гора и Кейп-Пойнт . назвала Кейптаун лучшим местом в мире для посещения В 2014 году The New York Times . [13] и также занимал первое место по версии The Daily Telegraph как в 2016, так и в 2023 году. [14] [15]

Расположенный на берегу Столовой бухты район Сити Боул в Кейптауне является старейшим городским районом Западного Кейптауна со значительным культурным наследием. Он был основан Голландской Ост-Индской компанией (VOC) как станция снабжения голландских кораблей, направляющихся в Восточную Африку , Индию и на Дальний Восток . Яна ван Рибека Прибытие 6 апреля 1652 года основало Капскую колонию ЛОС , первое постоянное европейское поселение в Южной Африке. Кейптаун перерос свою первоначальную цель как первый европейский форпост в Замке Доброй Надежды , став экономическим и культурным центром Капской колонии . До золотой лихорадки Витватерсранда и развития Йоханнесбурга Кейптаун был крупнейшим городом на юге Африки.

Столичный регион имеет длинную береговую линию Атлантического океана , которая включает залив Фолс-Бэй и простирается до гор Готтентотской Голландии на востоке. Национальный парк Столовой горы находится в черте города, а внутри города и рядом с ним есть несколько других природных заповедников и морских охраняемых территорий, защищающих разнообразную наземную и морскую природную среду.

История

[ редактировать ]Ранний период

[ редактировать ]

Самые ранние известные остатки человеческого существования в этом регионе были найдены в пещере Пирс в Фиш-Хуке , их возраст составляет от 15 000 до 12 000 лет. [16]

Об истории первых жителей региона мало что известно, поскольку не существует письменной истории этого района до того, как он был впервые упомянут португальским исследователем Бартоломеу Диашем . Диас, первый европеец, достигший этого района, прибыл в 1488 году и назвал его «Мысом Бурь» ( Cabo das Tormentas ). Позже он был переименован Иоанном II Португальским в « Мыс Доброй Надежды » ( Cabo da Boa Esperança ) из-за большого оптимизма, вызванного открытием морского пути на Индийский субконтинент и в Ост-Индию .

В 1497 году португальский исследователь Васко да Гама зафиксировал появление мыса Доброй Надежды.

В 1510 году в битве при Соленой реке португальский адмирал Франсиско де Алмейда и шестьдесят четыре его человека были убиты, а его отряд потерпел поражение. [17] ( !UriŁ'aekua «Goringhaiqua» в примерном голландском написании) с использованием крупного рогатого скота, специально обученного реагировать на свист и крики. [18] !Уриаекуа были одним из так называемых кланов Кхэкхо , населявших этот район.

В конце 16 века французские, датские, голландские и английские, но в основном португальские корабли регулярно продолжали останавливаться в Столовой бухте по пути в Индию. Они торговали табаком, медью и железом с Кхокхо кланами региона в обмен на свежее мясо и другие необходимые для путешествий продукты.

Голландский период

[ редактировать ]В 1652 году Ян ван Рибек и другие сотрудники Объединенной Ост-Индской компании ( голландский : Verenigde Oost-indische Compagnie , VOC) были отправлены в Капскую колонию, чтобы основать промежуточную станцию для кораблей, направлявшихся в Голландскую Ост-Индию , и форт де Гёде-Хоп (позже заменен Замком Доброй Надежды ). В этот период поселение росло медленно, так как было трудно найти подходящую рабочую силу. Эта нехватка рабочей силы побудила местные власти импортировать порабощенных людей из Индонезии и Мадагаскара . Многие из этих людей являются предками современных общин Кейп-Цветной и Кейп-Малайский . [19] [20]

При Ван Рибеке и его преемниках, в качестве командиров ЛОС, а затем и губернаторов мыса, на мысе был завезен широкий спектр сельскохозяйственных растений. Некоторые из них, в том числе виноград, зерновые, арахис, картофель, яблоки и цитрусовые, оказали большое и продолжительное влияние на общество и экономику региона. [21]

Британский период

[ редактировать ]

Когда Голландская республика превратилась в Революционной Франции вассальную Батавскую республику , Великобритания взяла под свой контроль голландские колонии, включая колониальные владения ЛОС.

Великобритания захватила Кейптаун в 1795 году , но он был возвращен голландцам по договору в 1803 году. Британские войска снова оккупировали мыс в 1806 году после битвы при Блауберге, когда Батавская республика объединилась с соперником Великобритании, Францией, во время наполеоновских войн . После завершения войны Кейптаун был навсегда передан Соединенному Королевству по англо-голландскому договору 1814 года .

Город стал столицей недавно образованной Капской колонии , территория которой значительно расширилась в течение 1800-х годов, частично в результате многочисленных войн с амакоса на восточной границе колонии. В 1833 году рабство в колонии было отменено, в результате чего в городе было освобождено более 5500 рабов, что составляло почти треть населения города на тот момент. [22] Кризис осужденных 1849 года, отмеченный значительными гражданскими волнениями, усилил стремление к самоуправлению в Кейптауне. [23] [24] С расширением пришли призывы к большей независимости от Великобритании: Кейп получил собственный парламент (1854 г.) и премьер-министра, подотчетного на местном уровне (1872 г.). Избирательное право было установлено в соответствии с нерасовым избирательным правом Кейптауна . [25] [26]

В 1850-х и 1860-х годах британские власти завезли из Австралии дополнительные виды растений. В частности, ройкранс был введен для стабилизации песка Кейп-Флэтс, чтобы проложить дорогу, соединяющую полуостров с остальной частью африканского континента. [27] эвкалипт . использовался для осушения болот [28]

В 1859 году первая железнодорожная линия была построена Капской правительственной железной дорогой , а в 1870-х годах система железных дорог быстро расширилась. Открытие алмазов в Западном Грикваленде в 1867 году и золотая лихорадка Витватерсранда в 1886 году вызвали поток иммиграции в Южную Африку. [29] В 1895 году была открыта первая в городе общественная электростанция — Электроосветительный завод Граафа .

Конфликты между бурскими республиками во внутренних районах и британским колониальным правительством привели к Второй англо-бурской войне 1899–1902 годов. Победа Великобритании в этой войне привела к образованию единой Южной Африки. С 1891 по 1901 год население города увеличилось более чем вдвое с 67 000 до 171 000 человек. [30]

Когда XIX век подошел к концу, экономическое и политическое доминирование Кейптауна в регионе Южной Африки в XIX веке начало уступать место доминированию Йоханнесбурга и Претории в XX веке. [31]

Южноафриканский период

[ редактировать ]

В 1910 году Великобритания создала Южно-Африканский Союз , который объединил Капскую колонию с двумя побеждёнными бурскими республиками и британской колонией Наталь . Кейптаун стал законодательной столицей Союза, а затем и Южно-Африканской Республики .

Ко времени переписи 1936 года Йоханнесбург обогнал Кейптаун как крупнейший город страны.

В 1945 году расширение прибрежной полосы Кейптауна было завершено, добавив дополнительные 194 га (480 акров) к территории City Bowl в центре города. [32]

эпоха апартеида

[ редактировать ]До середины двадцатого века Кейптаун был одним из наиболее расово интегрированных городов Южной Африки. [33] [34] На национальных выборах 1948 года Национальная партия победила на платформе апартеида (расовой сегрегации) под лозунгом « сварт геваар » (африкаанс означает «черная опасность»). Это привело к эрозии и, в конечном итоге, отмене многорасового права Кейптауна .

В 1950 году правительство апартеида впервые представило Закон о групповых территориях , который классифицировал и разделял городские территории по расовому признаку. Бывшие многорасовые пригороды Кейптауна были либо очищены от жителей, считавшихся незаконными в соответствии с законодательством апартеида, либо снесены. Самым печально известным примером этого в Кейптауне стал пригород Шестого округа . После того, как в 1965 году он был объявлен зоной только для белых, все жилье там было снесено, а более 60 000 жителей были насильственно выселены. [35] Многие из этих жителей были переселены в Кейп-Флэтс .

Самым ранним из насильственных переселений Кейп-Флэтс было изгнание чернокожих южноафриканцев в Лангу , первый и старейший поселок Кейптауна, в соответствии с Законом о коренных городских территориях 1923 года .

При апартеиде Кейптаун считался « районом предпочтения цветной рабочей силы», за исключением « банту », то есть чернокожих африканцев. Реализация этой политики встретила широкое сопротивление со стороны профсоюзов, гражданского общества и оппозиционных партий. Примечательно, что эту политику не поддерживала ни одна цветная политическая группа, и ее реализация была односторонним решением правительства апартеида. [36] студентов Во время восстания в Соуэто в июне 1976 года школьники из Ланги , Гугулету и Ньянги в Кейптауне отреагировали на новости о протестах против образования банту, организовав собственные собрания и марши. Было сожжено несколько школьных зданий, а акция протеста встретила силовое сопротивление со стороны полиции. [37] [38]

Cape Town has been home to many leaders of the anti-apartheid movement. In Table Bay, 10 km (6 mi) from the city is Robben Island. This penitentiary island was the site of a maximum security prison where many famous apartheird-era political prisoners served long prison sentences. Famous prisoners include activist, lawyer and future president Nelson Mandela who served 18 of his 27 years of imprisonment on the island, as well as two other future presidents, Kgalema Motlanthe and Jacob Zuma.[39]

In one of the most famous moments marking the end of apartheid, Nelson Mandela made his first public speech since his imprisonment, from the balcony of Cape Town City Hall, hours after being released on 11 February 1990. His speech heralded the beginning of a new era for the country. The first democratic election, was held four years later, on 27 April 1994.[40][41][42]

Nobel Square in the Victoria & Alfred Waterfront features statues of South Africa's four Nobel Peace Prize winners: Albert Luthuli, Desmond Tutu, F. W. de Klerk and Nelson Mandela.[relevant? – discuss]

Post-apartheid era

[edit]Cape Town has undergone significant changes in the years since Apartheid. Cape Town has experienced economic growth and development in the post-apartheid era. The city has become a major economic hub in South Africa, attracting international investment and tourism. The Democratic Alliance (DA), a liberal political party which came to power in Cape Town in 2006, has been credited with improving bureaucratic efficiency, public safety and fostering economic development.[43][44] Opinion polls show that South Africans see it as the best governed province and city in the country.[45][46] Of South Africa's 257 municipalities, only 38 received a clean financial audit in 2022 from the Auditor-General. Of those, 21 were in the Western Cape.[43] The city's economy has diversified, with growth in sectors such as finance, real estate, and tourism. The establishment of the City Centre Improvement District (CCID) has been particularly successful in revitalizing the city center, bringing businesses and people back into the area. This initiative has transformed public spaces such as Greenmarket Square, Company's Garden, and St George's Mall, attracting both locals and tourists.[47]

In 2014, Cape Town was named World Design Capital of the Year.[48] Cape Town was voted the best tourist destination in Africa at the 2023 World Travel Awards in Dubai and continues to be the most important tourist destination in the country.[49][50] Cape Town has been named the best travel city in the world every year since 2013 in the Telegraph Travel Awards.[51][52]

The legacy of apartheid's spatial planning is still evident, with significant disparities between affluent areas and impoverished townships.[53] 60% of the city's population live in townships and informal settlements far from the city centre.[54] The legacy of Apartheid means Cape Town remains one of the most racially segregated cities in South Africa.[55] Many Black South Africans continue to live in informal settlements with limited access to basic services such as healthcare, education, and sanitation.[53][56] The unemployment rate remains high at 23% (though nearly 10 points lower than the nationwide average), particularly among historically disadvantaged groups, and economic opportunities are unevenly distributed.[44]

Cape Town faced a severe water shortage from 2015 to 2018.[57] According to Oxfam, "in the face of an imminent water shortage, the city of Cape Town in South Africa successfully reduced its water use by more than half in three years, cutting it from 1.2bn litres per day in February 2015 to 516m litres per day in 2018."[58]

In 2021 Cape Town also experienced a violent turf war between rival taxi firms which led to the deaths of 83 people.

Since the 2010s, Cape Town and the wider Western Cape province have seen the rise of a small secessionist movement.[59] Support for parties "which have formally adopted Cape independence" was around 5% in the 2021 municipal elections.[60]

Geography and the natural environment

[edit]

Cape Town is located at latitude 33.55° S (approximately the same as Sydney and Buenos Aires and equivalent to Casablanca and Los Angeles in the northern hemisphere) and longitude 18.25° E.

Table Mountain, with its near vertical cliffs and flat-topped summit over 1,000 m (3,300 ft) high, and with Devil's Peak and Lion's Head on either side, together form a dramatic mountainous backdrop enclosing the central area of Cape Town, the so-called City Bowl. A thin strip of cloud, known colloquially as the "tablecloth" ("Karos" in Afrikaans), sometimes forms on top of the mountain. To the immediate south of the city, the Cape Peninsula is a scenic mountainous spine jutting 40 km (25 mi) southward into the Atlantic Ocean and terminating at Cape Point.

There are over 70 peaks above 300 m (980 ft) within Cape Town's official metropolitan limits. Many of the city's suburbs lie on the large plain called the Cape Flats, which extends over 50 km (30 mi) to the east and joins the peninsula to the mainland. The Cape Town region is characterised by an extensive coastline, rugged mountain ranges, coastal plains and inland valleys.

Extent

[edit]The extent of Cape Town has varied considerably over time. It originated as a small settlement at the foot of Table Mountain and has grown beyond its city limits as a metropolitan area to encompass the entire Cape Peninsula to the south, the Cape Flats, the Helderberg basin and part of the Steenbras catchment area to the east, and the Tygerberg hills, Blouberg and other areas to the north. Robben Island in Table Bay is also part of Cape Town. It is bounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and False Bay to the south. To the north and east, the extent is demarcated by boundaries of neighbouring municipalities within the Western Cape province.

The official boundaries of the city proper extend between the City Bowl and the Atlantic Seaboard to the east and the Southern Suburbs to the south. The City of Cape Town, the metropolitan municipality that takes its name from the city covers the Greater Cape Town metropolitan area, known as the Cape Metropole, extending beyond the city proper itself to include a number of satellite towns, suburbs and rural areas such as Atlantis, Bellville, Blouberg, Brackenfell, Durbanville, Goodwood, Gordon's Bay, Hout Bay, Khayelitsha, Kraaifontein, Kuilsrivier, Macassar, Melkbosstrand, Milnerton, Muizenberg, Noordhoek, Parow, Philadelphia, Simon's Town, Somerset West and Strand among others.[61][62]

The Cape Peninsula is 52 km (30 mi) long from Mouille Point in the north to Cape Point in the south,[63] with an area of about 470 km2 (180 sq mi), and it displays more topographical variety than other similar sized areas in southern Africa, and consequently spectacular scenery. There are diverse low-nutrient soils, large rocky outcrops, scree slopes, a mainly rocky coastline with embayed beaches, and considerable local variation in climatic conditions.[64] The sedimentary rocks of the Cape Supergroup, of which parts of the Graafwater and Peninsula Formations remain, were uplifted between 280 and 21S million years ago, and were largely eroded away during the Mesozoic. The region was geologically stable during the Tertiary, which has led to slow denudation of the durable sandstones. Erosion rate and drainage has been influenced by fault lines and fractures, leaving remnant steep-sided massifs like Table Mountain surrounded by flatter slopes of deposits of the eroded material overlaying the older rocks,[64]

There are two internationally notable landmarks, Table Mountain and Cape Point, at opposite ends of the Peninsula Mountain Chain, with the Cape Flats and False Bay to the east and the Atlantic Ocean to the west. The landscape is dominated by sandstone plateaux and ridges, which generally drop steeply at their margins to the surrounding debris slopes, interrupted by a major gap at the Fish Hoek–Noordhoek valley. In the south much of the area is a low sandstone plateau with sand dunes. Maximum altitude is 1113 m on Table Mountain.[64] The Cape Flats (Afrikaans: Kaapse Vlakte) is a flat, low-lying, sandy area, area to the east the Cape Peninsula, and west of the Helderberg much of which was wetland and dunes within recent history. To the north are the Tygerberg Hills and the Stellenbosch district.

The Helderberg area of Greater Cape Town, previously known as the "Hottentots-Holland" area, is mostly residential, but also a wine-producing area east of the Cape Flats, west of the Hottentots Holland mountain range and south of the Helderberg mountain, from which it gets its current name. The Helderberg consists of the previous municipalities of Somerset West, Strand, Gordons Bay and a few other towns. Industry and commerce is largely in service of the area. After the Cape Peninsula, Helderberg is the next most mountainous part of Greater Cape Town, bordered to the north and east by the highest peaks in the region along the watershed of the Helderberg and Hottentots Holland Mountains, which are part of the Cape Fold Belt with Cape Supergroup strata on a basement of Tygerberg Formation rocks intruded by part of the Stellenbosch granite pluton. The region includes the entire catchment of the Lourens and Sir Lowry's rivers, separated by the Schapenberg hill, and a small part of the catchment of the Eerste River to the west. The Helderberg is ecologically highly diverse, rivaling the Cape Peninsula, and has its own endemic ecoregions and several conservation areas.

To the east of the Hottentots Holland mountains is the valley of the Steenbras River, in which the Steenbras Dam was built as a water supply for Cape Town. The dam has been supplemented by several other dams around the western Cape, some of them considerably larger. This is almost entirely a conservation area, of high biodiversity. Bellville, Brackenfell, Durbanville, Kraaifontein, Goodwood and Parow are a few of the towns that make up the Northern Suburbs of Cape Town. In current popular culture these areas are often referred to as being beyond the "boerewors curtain," a play on the term "iron curtain."

UNESCO declared Robben Island in the Western Cape a World Heritage Site in 1999. Robben Island is located in Table Bay, some 6 km (3.7 mi) west of Bloubergstrand, a coastal suburb north of Cape Town, and stands some 30m above sea level. Robben Island has been used as a prison where people were isolated, banished, and exiled for nearly 400 years. It was also used as a leper colony, a post office, a grazing ground, a mental hospital, and an outpost.[65]

Geology

[edit]

The Cape Peninsula is a rocky and mountainous peninsula that juts out into the Atlantic Ocean at the south-western extremity of the continent. At its tip is Cape Point and the Cape of Good Hope. The peninsula forms the west side of False Bay and the Cape Flats. On the east side are the Helderberg and Hottentots Holland mountains. The three main rock formations are the late-Precambrian Malmebury group (sedimentary and metamorphic rock), the Cape Granite suit, comprising the huge Peninsula, Kuilsrivier-Helderberg, and Stellenbosch batholiths, that were intruded into the Malmesbury Group about 630 million years ago, and the Table Mountain group sandstones that were deposited on the eroded surface of the granite and Malmesbury series basement about 450 million years ago.

The sand, silt and mud deposits were lithified by pressure and then folded during the Cape Orogeny to form the Cape Fold Belt, which extends in an arc along the western and southern coasts. The present landscape is due to prolonged erosion having carved out deep valleys, removing parts of the once continuous Table Mountain Group sandstone cover from over the Cape Flats and False Bay, and leaving high residual mountain ridges.[66]

At times the sea covered the Cape Flats and Noordhoek valley and the Cape Peninsula was then a group of islands. During glacial periods the sea level dropped to expose the bottom of False Bay to weathering and erosion, with the last major regression leaving the entire bottom of False Bay exposed. During this period an extensive system of dunes was formed on the sandy floor of False Bay. At this time the drainage outlets lay between Rocky Bank Cape Point to the west, and between Rocky Bank and Hangklip Ridge to the east, with the watershed roughly along the line of the contact zone east of Seal Island and Whittle Rock.[66][67]: Ch2

Climate

[edit]

Cape Town has a warm Mediterranean climate (Köppen: Csb),[68][69][70] with mild, moderately wet winters and dry, warm summers. Winter, which lasts from June to September, may see large cold fronts entering for limited periods from the Atlantic Ocean with significant precipitation and strong north-westerly winds. Winter months in the city average a maximum of 18 °C (64 °F) and minimum of 8.5 °C (47 °F). Winters are snow and frost free, except on Table Mountain and on other mountain peaks, where light accumulation of snow and frost can sometimes occur.[71]Total annual rainfall in the city averages 515 mm (20.3 in) although in the Southern Suburbs, close to the mountains, rainfall is significantly higher and averages closer to 1,000 mm (39.4 in).

Summer, which lasts from December to March, is warm and dry with an average maximum of 26 °C (79 °F) and minimum of 16 °C (61 °F). The region can get uncomfortably hot when the Berg Wind, meaning "mountain wind", blows from the Karoo interior. Spring and summer generally feature a strong wind from the south-east, known locally as the south-easter or the Cape Doctor, so called because it blows air pollution away. This wind is caused by a persistent high-pressure system over the South Atlantic to the west of Cape Town, known as the South Atlantic High, which shifts latitude seasonally, following the sun, and influencing the strength of the fronts and their northward reach. Cape Town receives about 3,100 hours of sunshine per year.[72]

Water temperatures range greatly, between 10 °C (50 °F) on the Atlantic Seaboard, to over 22 °C (72 °F) in False Bay. Average annual ocean surface temperatures are between 13 °C (55 °F) on the Atlantic Seaboard (similar to Californian waters, such as San Francisco or Big Sur), and 17 °C (63 °F) in False Bay (similar to Northern Mediterranean temperatures, such as Nice or Monte Carlo).

Unlike other parts of the country the city does not have many thunderstorms, and most of those that do occur, happen around October to December and March to April.

| Climate data for Cape Town (1991–2020) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 45.2 (113.4) | 38.3 (100.9) | 43.0 (109.4) | 38.6 (101.5) | 33.5 (92.3) | 29.8 (85.6) | 29.0 (84.2) | 32.0 (89.6) | 33.1 (91.6) | 37.2 (99.0) | 39.9 (103.8) | 41.4 (106.5) | 45.2 (113.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 27.0 (80.6) | 27.3 (81.1) | 26.0 (78.8) | 23.6 (74.5) | 20.6 (69.1) | 18.2 (64.8) | 17.9 (64.2) | 18.0 (64.4) | 19.6 (67.3) | 22.2 (72.0) | 23.7 (74.7) | 25.8 (78.4) | 22.5 (72.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 21.8 (71.2) | 21.9 (71.4) | 20.5 (68.9) | 17.9 (64.2) | 15.4 (59.7) | 13.2 (55.8) | 12.7 (54.9) | 13.0 (55.4) | 14.5 (58.1) | 16.9 (62.4) | 18.6 (65.5) | 20.7 (69.3) | 17.3 (63.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 16.6 (61.9) | 16.5 (61.7) | 15.0 (59.0) | 12.2 (54.0) | 10.2 (50.4) | 8.1 (46.6) | 7.4 (45.3) | 7.9 (46.2) | 9.4 (48.9) | 11.5 (52.7) | 13.4 (56.1) | 15.6 (60.1) | 12.0 (53.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 7.4 (45.3) | 6.4 (43.5) | 4.6 (40.3) | 2.4 (36.3) | 0.9 (33.6) | −1.2 (29.8) | −1.3 (29.7) | −0.4 (31.3) | 0.2 (32.4) | 1.0 (33.8) | 3.9 (39.0) | 6.2 (43.2) | −1.3 (29.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 9.4 (0.37) | 9.6 (0.38) | 12.5 (0.49) | 40.1 (1.58) | 61.1 (2.41) | 92.3 (3.63) | 84.8 (3.34) | 72.4 (2.85) | 44.3 (1.74) | 28.4 (1.12) | 25.3 (1.00) | 12.8 (0.50) | 492.8 (19.40) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 1.8 | 1.8 | 2.5 | 5.0 | 7.4 | 10.1 | 9.1 | 9.3 | 6.8 | 4.2 | 4.0 | 2.6 | 64.6 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 71 | 72 | 74 | 78 | 81 | 81 | 81 | 80 | 77 | 74 | 71 | 71 | 76 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 352.3 | 304.0 | 289.7 | 240.1 | 196.7 | 175.9 | 197.0 | 206.2 | 228.4 | 283.5 | 302.8 | 338.4 | 3,115 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 12 | 11 | 8 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 12 | 7 |

| Source: NOAA (humidity 1961-1990),[72][73] South African Weather Service,[74] eNCA[75] | |||||||||||||

Climate change

[edit]A 2019 paper published in PLOS One estimated that under Representative Concentration Pathway 4.5, a "moderate" scenario of climate change where global warming reaches ~2.5–3 °C (4.5–5.4 °F) by 2100, the climate of Cape Town in the year 2050 would most closely resemble the current climate of Perth in Australia. The annual temperature would increase by 1.1 °C (2.0 °F), and the temperature of the coldest month by 0.3 °C (0.54 °F), while the temperature of the warmest month would be 2.3 °C (4.1 °F) higher.[76][77] According to Climate Action Tracker, the current warming trajectory appears consistent with 2.7 °C (4.9 °F), which closely matches RCP 4.5.[78]

Moreover, according to the 2022 IPCC Sixth Assessment Report, Cape Town is one of 12 major African cities (Abidjan, Alexandria, Algiers, Cape Town, Casablanca, Dakar, Dar es Salaam, Durban, Lagos, Lomé, Luanda and Maputo) which would be the most severely affected by future sea level rise. It estimates that they would collectively sustain cumulative damages of US$65 billion under RCP 4.5 and US$86.5 billion for the high-emission scenario RCP 8.5 by the year 2050. Additionally, RCP 8.5 combined with the hypothetical impact from marine ice sheet instability at high levels of warming would involve up to US$137.5 billion in damages,[clarification needed] while the additional accounting for the "low-probability, high-damage events" may increase aggregate risks to US$187 billion for the "moderate" RCP4.5, US$206 billion for RCP8.5 and US$397 billion under the high-end ice sheet instability scenario.[79] Since sea level rise would continue for about 10,000 years under every scenario of climate change, future costs of sea level rise would only increase, especially without adaptation measures.[clarification needed][80]

Hydrology

[edit]Sea surface temperatures

[edit]

Cape Town's coastal water ranges from cold to mild, and the difference between the two sides of the peninsula can be dramatic. While the Atlantic Seaboard averages annual sea surface temperatures around 13 °C (55 °F), the False Bay coast is much warmer, averaging between 16 and 17 °C (61 and 63 °F) annually.[citation needed] In summer, False Bay water averages slightly over 20 °C (68 °F), with 22 °C (72 °F) an occasional high. Beaches located on the Atlantic Coast tend to have colder water due to the wind driven upwellings which contribute to the Benguela Current which originates off the Cape Peninsula, while the water at False Bay beaches may occasionally be warmer by up to 10 °C (18 °F) at the same time in summer.

In summer False Bay is thermally stratified, with a vertical temperature variation of 5 to 9˚C between the warmer surface water and cooler depths below 50 m, while in winter the water column is at nearly constant temperature at all depths. The development of a thermocline is strongest around late December and peaks in late summer to early autumn.[82]: 8 In summer the south easterly winds generate a zone of upwelling near Cape Hangklip, where surface water temperatures can be 6 to 7 °C colder than the surrounding areas, and bottom temperatures below 12 °C.[82]: 10

In the summer to early autumn (January–March), cold water upwelling near Cape Hangklip causes a strong surface temperature gradient between the south-western and north-eastern corners of the bay. In winter the surface temperature tends to be much the same everywhere. In the northern sector surface temperature varies a bit more (13 to 22 °C) than in the south (14 to 20 °C) during the year.[81]

Surface temperature variation from year to year is linked to the El Niño–Southern Oscillation. During El Niño years the South Atlantic high is shifted, reducing the south-easterly winds, so upwelling and evaporative cooling are reduced and sea surface temperatures throughout the bay are warmer, while in La Niña years there is more wind and upwelling and consequently lower temperatures. Surface water heating during El Niño increases vertical stratification. The relationship is not linear.[81] Occasionally eddies from the Agulhas current will bring warmer water and vagrant sea life carried from the south and east coasts into False Bay.

Flora and fauna

[edit]

Located in a Conservation International biodiversity hotspot as well as the unique Cape Floristic Region, the city of Cape Town has one of the highest levels of biodiversity of any equivalent area in the world.[83][84] These protected areas are a World Heritage Site, and an estimated 2,200 species of plants are confined to Table Mountain – more than exist in the whole of the United Kingdom which has 1200 plant species and 67 endemic plant species.[85][86][87] Many of these species, including a great many types of proteas, are endemic to the mountain and can be found nowhere else.[88]

It is home to a total of 19 different vegetation types, of which several are endemic to the city and occur nowhere else in the world.[89]It is also the only habitat of hundreds of endemic species,[90] and hundreds of others which are severely restricted or threatened. This enormous species diversity is mainly because the city is uniquely located at the convergence point of several different soil types and micro-climates.[91][92]

Table Mountain has an unusually rich biodiversity. Its vegetation consists predominantly of several different types of the unique and rich Cape Fynbos. The main vegetation type is endangered Peninsula Sandstone Fynbos, but critically endangered Peninsula Granite Fynbos, Peninsula Shale Renosterveld and Afromontane forest occur in smaller portions on the mountain.

Rapid population growth and urban sprawl has covered much of these ecosystems with development. Consequently, Cape Town now has over 300 threatened plant species and 13 which are now extinct. The Cape Peninsula, which lies entirely within the city of Cape Town, has the highest concentration of threatened species of any continental area of equivalent size in the world.[93]Tiny remnant populations of critically endangered or near extinct plants sometimes survive on road sides, pavements and sports fields.[94] The remaining ecosystems are partially protected through a system of over 30 nature reserves – including the massive Table Mountain National Park.[95]

Cape Town reached first place in the 2019 iNaturalist City Nature Challenge in two out of the three categories: Most Observations, and Most Species. This was the first entry by Capetonians in this annual competition to observe and record the local biodiversity over a four-day long weekend during what is considered the worst time of the year for local observations.[96] A worldwide survey suggested that the extinction rate of endemic plants from the City of Cape Town is one of the highest in the world, at roughly three per year since 1900 – partly a consequence of the very small and localised habitats and high endemicity.[97]

Government

[edit]| This article is part of a series on the |

| Politics of the Western Cape |

|---|

Cape Town is governed by a 231-member city council elected in a system of mixed-member proportional representation. The city is divided into 116 wards, each of which elects a councillor by first-past-the-post voting. The remaining 115 councillors are elected from party lists so that the total number of councillors for each party is proportional to the number of votes received by that party.[98][99]

In the 2021 Municipal Elections, the Democratic Alliance (DA) kept its majority, this time diminished, taking 136 seats. The African National Congress lost substantially, receiving 43 of the seats.[100][101] The Democratic Alliance candidate for the Cape Town mayoralty, Geordin Hill-Lewis was elected mayor.[102]

- The Old Cape Town City Hall as seen from the Grand Parade in front of the building.

- The Cape Town Civic Centre, the central offices of the City of Cape Town.

- South Africa's national parliament building is located in Cape Town.

International relations

[edit]Cape Town has nineteen active sister city agreements[103]

Aachen, Germany

Aachen, Germany Accra, Ghana

Accra, Ghana Atlanta, United States

Atlanta, United States Buenos Aires, Argentina

Buenos Aires, Argentina Bujumbura, Burundi

Bujumbura, Burundi Dubai, United Arab Emirates

Dubai, United Arab Emirates Hangzhou, China

Hangzhou, China Houston, United States

Houston, United States Huangshan, China

Huangshan, China İzmir, Turkey

İzmir, Turkey Los Angeles, United States

Los Angeles, United States Malmö, Sweden

Malmö, Sweden Miami-Dade County, United States

Miami-Dade County, United States Monterrey, Mexico

Monterrey, Mexico Munich, Germany

Munich, Germany Nairobi, Kenya

Nairobi, Kenya Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Shenzhen, China

Shenzhen, China Varna, Bulgaria

Varna, Bulgaria Wuhan, China

Wuhan, China

2022 invasion of Ukraine

[edit]

The City of Cape Town has expressed explicit support for Ukraine during the 2022 invasion of the country by Russia.[104] To show this support the City of Cape Town lit up the Old City Hall in the colours of the Ukrainian flag on 2 March 2022.[105][106] This has differentiated the city from the officially neutral foreign policy position taken by the South African national government.[105]

Demographics

[edit]

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Note: Census figures (1996–2011) cover figures after 1994 reflect the greater Cape Town metropolitan municipality reflecting post-1994 reforms. Sources: 1658–1904,[30] 1823,[107] 1833,[22] 1936,[108] 1950–1990,[109] 1996,[110] 2001, and 2011 Census;[111]2007,[112] 2016 & 2021,[113] 2022[114] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

According to the South African National Census of 2011, the population of the City of Cape Town metropolitan municipality – an area that includes suburbs and exurbs – is 3,740,026 people. This represents an annual growth rate of 2.6% compared to the results of the previous census in 2001 which found a population of 2,892,243 people.[115]: 54 Of those residents who were asked about their first language, 35.7% spoke Afrikaans, 29.8% spoke Xhosa and 28.4% spoke English. 24.8% of the population is under the age of 15, while 5.5% is 65 or older.[115]: 64 The sex ratio is 0.96, meaning that there are slightly more women than men.[115]: 55

Of those residents aged 20 or older, 1.8% have no schooling, 8.1% have some schooling but did not finish primary school, 4.6% finished primary school but have no secondary schooling, 38.9% have some secondary schooling but did not finish Grade 12, 29.9% finished Grade 12 but have no higher education, and 16.7% have higher education. Overall, 46.6% have at least a Grade 12 education.[115]: 74 Of those aged between 5 and 25, 67.8% are attending an educational institution.[115]: 78 Amongst those aged between 15 and 65 the unemployment rate is 23.7%.[115]: 79 The average annual household income is R161,762.[115]: 88

The total number of households grew from 653,085 in 1996 to 1,068,572 in 2011, which represents an increase of 63.6%.[115]: 81 The average number of household members declined from 3,92 in 1996 to 3,50 in 2011.[116] Of those households, 78.4% are in formal structures (houses or flats), while 20.5% are in informal structures (shacks).[115]: 81 97.3% of City-supplied households have access to electricity,[117] and 94.0% of households use electricity for lighting.[115]: 84 87.3% of households have piped water to the dwelling, while 12.0% have piped water through a communal tap.[115]: 85 94.9% of households have regular refuse collection service.[115]: 86 91.4% of households have a flush toilet or chemical toilet, while 4.5% still use a bucket toilet.[115]: 87 82.1% of households have a refrigerator, 87.3% have a television and 70.1% have a radio. Only 34.0% have a landline telephone, but 91.3% have a cellphone. 37.9% have a computer, and 49.3% have access to the Internet (either through a computer or a cellphone).[115]

In 2011 over 70% of cross provincial South African migrants coming into the Western Cape settled in Cape Town; 53.64% of South African migrants into the Western Cape came from the Eastern Cape, the old Cape Colony's former native reserve, and 20.95% came from Gauteng province.[118]

According to the 2016 City of Cape Town community survey, there were 4,004,793 people in the City of Cape Town metro. Out of this population, 45.7% identified as Black African, 35.1% identified as Coloured, 16.2% identified as White and 1.6% identified as Asian.[119]

During the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in South Africa, local media reported that increasing numbers of wealthy and middle-class South Africans have started moving from inland areas to coastal regions of the country, most notably Cape Town, in a phenomenon referred to as "semigration" – short for "semi-emigration"[120][121][122] Declining municipal services in the rest of the country and the South African energy crisis are other cited reasons for semigration.[123]

The city's population is expected to grow by an additional 400,000 residents between 2020 and 2025 with 76% of those new residents falling into the low-income bracket earning less than R 13,000 a month.[124]

Religion

[edit]

In the 2015 General Household Survey 82.3% of respondents self identified as Christian, 8% as Muslim, 3.8% as following a traditional African religion and 3.1% as "nothing in particular."[125]

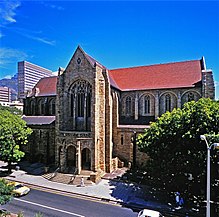

Most places of worship in the city are Christian churches and cathedrals: Dutch Reformed Church in South Africa (NGK), Zion Christian Church, Apostolic Faith Mission of South Africa, Assemblies of God, Baptist Union of Southern Africa (Baptist World Alliance), Methodist Church of Southern Africa (World Methodist Council), Anglican Church of Southern Africa (Anglican Communion), Presbyterian Church of Africa (World Communion of Reformed Churches), Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Cape Town (Catholic Church),[126] the Orthodox Archbishopric of Good Hope (Greek Orthodox Cathedral of St George[127]) and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church).[128] The LDS Church announced 4 April 2021[129] the construction of a temple with groundbreaking dates yet to be announced.

Islam is the city's second largest religion with a long history in Cape Town,[130] resulting in a number of mosques and other Muslim religious sites spread across the city,[131] such as the Auwal Mosque, South Africa's first mosque.

Cape Town's significant Jewish population supports a number of synagogues most notably the historic Gardens Shul, the oldest Jewish congregation in South Africa.[132] Marais Road Shul in the city's Jewish hub, Sea Point, is the largest Jewish congregation in South Africa.[133] Temple Israel (Cape Town Progressive Jewish Congregation) also has three temples in the city.[134] There is also a Chabad centre in Sea Point and a Chabad on Campus at the University of Cape Town, catering to Jewish students.[135]

Other religious sites in the city include Hindu and Buddhist temples and centres.[136][137]

Crime

[edit]

In recent years, Cape Town has experienced a resurgence in violent crime, particularly driven by gang violence in areas like the Cape Flats. This increase in violence is attributed to various factors, including economic inequality, unemployment, and the legacy of apartheid's spatial and social divisions.[56][138] Overall, however, crime has not increased since end of Apartheid.[139]

Crime in Cape Town is a serious problem which affects the quality of life and safety of its residents and visitors. Between 2022 and 2023, Cape Town recorded the highest number of murders in a single year of any city in the world at 2,998, followed by Johannesburg and Durban, an increase of 8.6% year-on-year.[140][141] Household crimes including burglary also increased in the same period.[142] Mexico’s Citizen Council for Public Security and Criminal Justice ranks it among the most violent cities in the world.[143] While the UK Foreign Office considers Cape Town safe to travel to, it notes the extremely high crime rates and highlights a particular increase on violent attacks and murders on the roads to and from Cape Town International Airport.[144][145] At the same time, the economy has grown due to the boom in the tourism and the real estate industries.[146] Since July 2019 widespread violent crime in poorer gang dominated areas of greater Cape Town has resulted in an ongoing military presence in these neighbourhoods.[147][148]

The minibus taxi industry has been the source of a number of violent confrontations in the city. The northern and eastern sections of the city was the scene of the 2021 Cape Town taxi conflict, a violent turf war which led to 83 deaths. The 2023 Cape Town taxi strike resulted in 5 recorded deaths.[149][150]

Economy

[edit]| Top publicly traded companies in the Cape Town/Stellenbosch region for 2021 (ranked by market capitalisation) with Metropolitan and JSE ranks | |||||

| Metro | corporation | JSE | |||

| 1 | Naspers | 4 | |||

| 2 | Capitec | 14 | |||

| 3 | Sanlam | 20 | |||

| 4 | Shoprite | 24 | |||

| 5 | Pepkor | 30 | |||

| 6 | Clicks | 32 | |||

| 7 | Woolworths | 35 | |||

| 8 | Remgro | 37 | |||

| Source: JSE top 40[151] | |||||

The city is South Africa's second main economic centre and Africa's third main economic hub city. It serves as the regional manufacturing centre in the Western Cape. In 2019 the city's GMP of R489 billion[152] (US$33.04 billion)[153] represented 71.1% of the Western Cape's total GRP and 9.6% of South Africa's total GDP;[152] the city also accounted for 11.1%[152] of all employed people in the country and had a citywide GDP per capita of R111,364[152] (US$7,524).[153] Since the Great Recession, the city's economic growth rate has mirrored South Africa's decline in growth whilst the population growth rate for the city has remained steady at around 2% a year.[152] Around 80% of the city's economic activity is generated by the tertiary sector of the economy with the finance, retail, real-estate, food and beverage industries being the four largest contributors to the city's economic growth rate.[152]

In 2008 the city was named as the most entrepreneurial city in South Africa, with the percentage of Capetonians pursuing business opportunities almost three times higher than the national average. Those aged between 18 and 64 were 190% more likely to pursue new business, whilst in Johannesburg, the same demographic group was only 60% more likely than the national average to pursue a new business.[154]

With the highest number of successful information technology companies in Africa, Cape Town is an important centre for the industry on the continent.[155] This includes an increasing number of companies in the space industry.[156] Growing at an annual rate of 8.5% and an estimated worth of R77 billion in 2010, nationwide the high tech industry in Cape Town is becoming increasingly important to the city's economy.[155] A number of entrepreneurship initiatives and universities hosting technology startups such as Jumo, Yoco, Aerobotics, Luno, Rain telecommunication and The Sun Exchange are located in the city.[157]

The city has the largest film industry in the Southern Hemisphere[158] generating R5 billion (US$476.19 million) in revenue and providing an estimated 6,058 direct and 2,502 indirect jobs in 2013.[159] Much of the industry is based out of the Cape Town Film Studios.

Major companies

[edit]

Most companies headquartered in the city are insurance companies, retail groups, publishers, design houses, fashion designers, shipping companies, petrochemical companies, architects and advertising agencies.[160] Some of the most notable companies headquartered in the city are food and fashion retailer Woolworths,[161] supermarket chain Pick n Pay Stores and Shoprite,[162] New Clicks Holdings Limited, fashion retailer Foschini Group,[163] internet service provider MWEB, Mediclinic International, eTV, multinational mass media giant Naspers, and financial services giant Sanlam[164] and Old Mutual Park.[165]

Other notable companies include Belron, Ceres Fruit Juices, Coronation Fund Managers, Vida e Caffè, Capitec Bank. The city is a manufacturing base for several multinational companies including, Johnson & Johnson, GlaxoSmithKline, Levi Strauss & Co., Adidas, Bokomo Foods, Yoco and Nampak.[citation needed] Amazon Web Services maintains one of its largest facilities in the world in Cape Town with the city serving as the Africa headquarters for its parent company Amazon.[166][167]

Inequality

[edit]The city of Cape Town's Gini coefficient of 0.58[168] is lower than South Africa's Gini coefficient of 0.7 making it more equal than the rest of the country or any other major South Africa city although still highly unequal by international standards.[169][170] Between 2001 and 2010 the city's Gini coefficient, a measure of inequality, improved by dropping from 0.59 in 2007 to 0.57 in 2010[171] only to increase to 0.58 by 2017.[172]

Tourism

[edit]

The Western Cape is a highly important tourist region in South Africa; the tourism industry accounts for 9.8% of the GDP of the province and employs 9.6% of the province's workforce. In 2010, over 1.5 million international tourists visited the area.[173] Cape Town is not only a popular international tourist destination in South Africa, but Africa as a whole. This is due to its mild climate, natural setting, and well-developed infrastructure. The city has several well-known natural features that attract tourists, most notably Table Mountain,[174] which forms a large part of the Table Mountain National Park and is the back end of the City Bowl. Reaching the top of the mountain can be achieved either by hiking up, or by taking the Table Mountain Cableway. Cape Point is the dramatic headland at the end of the Cape Peninsula.[175] Many tourists also drive along Chapman's Peak Drive, a narrow road that links Noordhoek with Hout Bay, for the views of the Atlantic Ocean and nearby mountains. It is possible to either drive or hike up Signal Hill for closer views of the City Bowl and Table Mountain.[176]

Many tourists also visit Cape Town's beaches, which are popular with local residents.[177] It is possible to visit several different beaches in the same day, each with a different setting and atmosphere.Both coasts are popular, although the beaches in affluent Clifton and elsewhere on the Atlantic Coast are better developed with restaurants and cafés, with a strip of restaurants and bars accessible to the beach at Camps Bay. The Atlantic seaboard, known as Cape Town's Riviera, is regarded as one of the most scenic routes in South Africa, along the slopes of the Twelve Apostles to the boulders and white sand beaches of Llandudno, with the route ending in Hout Bay, a diverse suburb with a fishing and recreational boating harbour near a small island with a breeding colony of African fur seals. This suburb is also accessible by road from the Constantia valley over the mountains to the northeast, and via the picturesque Chapman's Peak drive from the residential suburb Noordhoek in the Fish Hoek valley to the south-east.[178] Boulders Beach near Simon's Town is known for its colony of African penguins.[179]

The city has several notable cultural attractions. The Victoria & Alfred Waterfront, built on top of part of the docks of the Port of Cape Town, is the city's most visited tourist attraction. It is also one of the city's most popular shopping venues, with several hundred shops as well as the Two Oceans Aquarium.[180][181] The V&A also hosts the Nelson Mandela Gateway, through which ferries depart for Robben Island.[182] It is possible to take a ferry from the V&A to Hout Bay, Simon's Town and the Cape fur seal colonies on Seal and Duiker Islands. Several companies offer tours of the Cape Flats, a region of mostly Coloured & Black townships.[183]

Within the metropolitan area, the most popular areas for visitors to stay include Camps Bay, Sea Point, the V&A Waterfront, the City Bowl, Hout Bay, Constantia, Rondebosch, Newlands, and Somerset West.[184] In November 2013, Cape Town was voted the best global city in The Daily Telegraph's annual Travel Awards.[185] Cape Town offers tourists a range of air, land and sea-based adventure activities, including helicopter rides, paragliding and skydiving, snorkelling and scuba diving, boat trips, game-fishing, hiking, mountain biking and rock climbing. Surfing is popular and the city hosts the Red Bull Big Wave Africa surfing competition every year, and there is some local and international recreational scuba tourism.[186]

The City of Cape Town works closely with Cape Town Tourism to promote the city both locally and internationally. The primary focus of Cape Town Tourism is to represent Cape Town as a tourist destination.[187][188] Cape Town Tourism receives a portion of its funding from the City of Cape Town while the remainder is made up of membership fees and own-generated funds.[189] The Tristan da Cunha government owns and operates a lodging facility in Cape Town which charges discounted rates to Tristan da Cunha residents and non-resident natives.[190] Cape Town's transport system links it to the rest of South Africa; it serves as the gateway to other destinations within the province. The Cape Winelands and in particular the towns of Stellenbosch, Paarl and Franschhoek are popular day trips from the city for sightseeing and wine tasting.[191][192]

Infrastructure and services

[edit]Most goods are handled through the Port of Cape Town or Cape Town International Airport. Most major shipbuilding companies have offices in Cape Town.[193] The province is also a centre of energy development for the country, with the existing Koeberg nuclear power station providing energy for the Western Cape's needs.[194]

Greater Cape Town has four major commercial nodes, with Cape Town Central Business District containing the majority of job opportunities and office space.[citation needed] Century City, the Bellville/Tygervalley strip and Claremont commercial nodes are well established and contain many offices and corporate headquarters.

Health

[edit]

- The Alexandra Hospital is a specialist mental health care hospital in Cape Town, it provides care for complex mental health issues and intellectual disability.[195]

- Groote Schuur Hospital is a large, government-funded, teaching hospital situated on the slopes of Devil's Peak. It was founded in 1938 and is famous for being the institution where the first human-to-human heart transplant took place. Groote Schuur is the chief academic hospital of the University of Cape Town's medical school, providing tertiary care and instruction in all the major branches of medicine. The hospital underwent major extension in 1984 when two new wings were added.

- The Hottentots Holland Hospital, also known as Helderberg Hospital, is a district hospital for the Helderberg basin located in Somerset West, and also serves surrounding areas in the Overberg district.

- Vergelegen Medi-clinic – Private hospital in Somerset West

Education

[edit]

Public primary and secondary schools in Cape Town are run by the Western Cape Education Department. This provincial department is divided into seven districts; four of these are "Metropole" districts – Metropole Central, North, South, and East – which cover various areas of the metropolis.[196] There are also many private schools, both religious and secular. Cape Town has a well-developed higher system of public universities. Cape Town is served by three public universities: the University of Cape Town (UCT), the University of the Western Cape (UWC) and the Cape Peninsula University of Technology (CPUT). Stellenbosch University, while not based in the metropolitan area itself, has its main campus and administrative section 50 kilometres from the City Bowl and has additional campuses, such as the Tygerberg Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences and the Bellville Business Park, north-west of the city in the town of Bellville.

Both the University of Cape Town and Stellenbosch University are leading universities in South Africa. This is due in large part to substantial financial contributions made to these institutions by both the public and private sector. UCT is an English-language tuition institution. It has over 21,000 students and has an MBA programme that was ranked 51st by the Financial Times in 2006.[197] It is also the top-ranked university in Africa, being the only African university to make the world's Top 200 university list at number 146.[198] Since the African National Congress has become the country's ruling party, some restructuring of Western Cape universities has taken place and as such, traditionally non-white universities have seen increased financing, which has evidently benefitted the University of the Western Cape.[199][200]

The Cape Peninsula University of Technology was formed on 1 January 2005, when two separate institutions – Cape Technikon and Peninsula Technikon – were merged. The new university offers education primarily in English, although one may take courses in any of South Africa's official languages. The institution generally awards the National Diploma. Students from the universities and high schools are involved in the South African SEDS, Students for the Exploration and Development of Space. This is the South African SEDS, and there are many SEDS branches in other countries, preparing enthusiastic students and young professionals for the growing Space industry.[citation needed] As well as the Universities, there are also several colleges in and around Cape Town. Including the College of Cape Town, False Bay College and Northlink College. Many students use NSFAS funding to help pay for tertiary education at these TVET colleges.[201] Cape Town has also become a popular study abroad destination for many international college students. Many study abroad providers offer semester, summer, short-term, and internship programs in partnership with Cape Town universities as a chance for international students to gain intercultural understanding.

Water supply

[edit]The Western Cape Water Supply System (WCWSS) is a complex water supply system in the Western Cape region of South Africa, comprising an inter-linked system of six main dams, pipelines, tunnels and distribution networks, and a number of minor dams, some owned and operated by the Department of Water and Sanitation and some by the City of Cape Town.[202]

Water crisis of 2017 to 2018

[edit]

The Cape Town water crisis of 2017 to 2018 was a period of severe water shortage in the Western Cape region, most notably affecting the City of Cape Town. While dam water levels had been declining since 2015, the Cape Town water crisis peaked during mid-2017 to mid-2018 when water levels hovered between 15 and 30 percent of total dam capacity.

In late 2017, there were first mentions of plans for "Day Zero", a shorthand reference for the day when the water level of the major dams supplying the city could fall below 13.5 percent.[203][204][205] "Day Zero" would mark the start of Level 7 water restrictions, when municipal water supplies would be largely switched off and it was envisioned that residents could have to queue for their daily ration of water. If this had occurred, it would have made the City of Cape Town the first major city in the world to run out of water.[206][207]

The city of Cape Town implemented significant water restrictions in a bid to curb water usage, and succeeded in reducing its daily water usage by more than half to around 500 million litres (130,000,000 US gal) per day in March 2018.[208] The fall in water usage led the city to postpone its estimate for "Day Zero", and strong rains starting in June 2018 led to dam levels recovering.[209] In September 2018, with dam levels close to 70 percent, the city began easing water restrictions, indicating that the worst of the water crisis was over.[210] Good rains in 2020 effectively broke the drought and resulting water shortage when dam levels reached 95 percent.[211] Concerns have been raised, however, that unsustainble demand and limited water supply could result in future drought events.[212]

Transport

[edit]Air

[edit]

Cape Town International Airport serves both domestic and international flights.[213] It is the second-largest airport in South Africa and serves as a major gateway for travelers to the Cape region. Cape Town has regularly scheduled services to Southern Africa, East Africa, Mauritius, Middle East, Far East, Europe and the United States as well as eleven domestic destinations.[214] Cape Town International Airport opened a brand new central terminal building that was developed to handle an expected increase in air traffic as tourism numbers increased in the lead-up to the tournament of the 2010 FIFA World Cup.[215] Other renovations include several large new parking garages, a revamped domestic departure terminal, a new Bus Rapid Transit system station and a new double-decker road system. The airport's cargo facilities are also being expanded and several large empty lots are being developed into office space and hotels.

Cape Town is one of five internationally recognised Antarctic gateway cities with transportation connections. Since 2021, commercial flights have operated from Cape Town to Wolf's Fang Runway, Antarctica.[216] The Cape Town International Airport was among the winners of the World Travel Awards for being Africa's leading airport.[217] Cape Town International Airport is located 18 km from the Central Business District.[218]

Sea

[edit]

Cape Town has a long tradition as a port city, and its role as a re-provisioning stop at the midpoint of the Cape Route gained it the nicknames "Tavern of the Seas" and "Tavern of the Indian Ocean".[219] The Port of Cape Town, the city's main port, is in Table Bay directly to the north of the CBD. The port is a hub for ships in the southern Atlantic: it is located along one of the busiest shipping corridors in the world, and acts as a stopover point for goods en route to or from Latin America and Asia. It is also an entry point into the South African market.[220] It is the second-busiest container port in South Africa after Durban. In 2004, it handled 3,161 ships and 9.2 million tonnes of cargo.[221]

Simon's Town Harbour on the False Bay coast of the Cape Peninsula is the main operational base of the South African Navy.

Until the 1970s the city was served by the Union Castle Line with service to the United Kingdom and St Helena.[222] The RMS St Helena provided passenger and cargo service between Cape Town and St Helena until the opening of St Helena Airport.[223]

The cargo vessel M/V Helena, under AW Shipping Management, takes a limited number of passengers,[224] between Cape Town and St Helena and Ascension Island on its voyages.[225] Multiple vessels also take passengers to and from Tristan da Cunha, inaccessible by aircraft, to and from Cape Town.[226] In addition NSB Niederelbe Schiffahrtsgesellschaft takes passengers on its cargo service to the Canary Islands and Hamburg, Germany.[224]

Rail

[edit]

The Shosholoza Meyl is the passenger rail operations of Spoornet and operates one long-distance passenger rail services from Cape Town as of 2024: a weekly service to and from Johannesburg via Kimberley. These trains terminate at Cape Town railway station and make a stop at Bellville. Cape Town also terminates 2 luxury tourist train routes as of 2024 operated by the Ceres Rail Company, traveling from the Waterfront to Simon's Town and Grabouw respectively.

Metrorail operates a commuter rail service in Cape Town and the surrounding area. The Metrorail network consists of 96 stations throughout the suburbs and outskirts of Cape Town.

Road

[edit]Cape Town is the origin of three national roads. The N1 and N2 begin in the foreshore area near the City Centre and the N7, which runs North toward Namibia. The N1 runs East-North-East from Cape Town through the towns of Goodwood, Parow, Bellville, Brackenfell and Kraaifontein before continuing towards Paarl. It connects Cape Town to major cities further inland, namely Bloemfontein, Johannesburg, and Pretoria An older at-grade road, the R101, runs parallel to the N1 from Bellville. The N2 runs East-South-East through Rondebosch, Guguletu, Khayelitsha, Macassar to Somerset West. It becomes a multiple-carriageway, at-grade road from the intersection with the R44 onward. The N2 continues east along the coast, linking Cape Town with Somerset West and the coastal cities of Mossel Bay, George, Port Elizabeth, East London and Durban. An older at-grade road, the R102, runs parallel to the N1 initially, before veering south at Bellville, to join the N2 at Somerset West via the towns of Kuilsrivier and Eersterivier. The N7 originates from the N1 at Wingfield Interchange near Edgemead. It begins, initially as a highway, but becoming an at-grade road from the intersection with the M5 onward.

There are also a number of regional routes linking Cape Town with surrounding areas. The R27 originates from the N1 near the Foreshore and runs north parallel to the N7, but nearer to the coast. It passes through the suburbs of Milnerton, Table View and Bloubergstrand and links the city to the West Coast, ending at the town of Velddrif. The R44 enters the east of the metro from the north, from Stellenbosch. It connects Stellenbosch to Somerset West, then crosses the N2 to Strand and Gordon's Bay. It exits the metro heading south hugging the coast, leading to the towns of Betty's Bay and Kleinmond.

Of the three-digit routes, the R300 is an expressway linking the N1 at Brackenfell to the N2 near Mitchells Plain and the Cape Town International Airport. The R302 runs from the R102 in Bellville, heading north across the N1 through Durbanville leaving the metro to Malmesbury. The R304 enters the northern limits of the metro from Stellenbosch, running NNW before veering west to cross the N7 at Philadelphia to end at Atlantis at a junction with the R307. This R307 starts north of Koeberg from the R27 and, after meeting the R304, continues north to Darling. The R310 originates from Muizenberg and runs along the coast, to the south of Mitchell's Plain and Khayelitsha, before veering north-east, crossing the N2 west of Macassar, and exiting the metro heading to Stellenbosch.

Cape Town, like most South African cities, uses Metropolitan or "M" routes for important intra-city routes, a layer below National (N) roads and Regional (R) routes. Each city's M roads are independently numbered. Most are at-grade roads. The M3 splits from the N2 and runs to the south along the eastern slopes of Table Mountain, connecting the City Bowl with Muizenberg. Except for a section between Rondebosch and Newlands that has at-grade intersections, this route is a highway. The M5 splits from the N1 further east than the M3, and links the Cape Flats to the CBD. It is a highway as far as the interchange with the M68 at Ottery, before continuing as an at-grade road. Cape Town has the worst traffic congestion in South Africa.[227][228]

Buses

[edit]Golden Arrow Bus Services operates scheduled bus services in the Cape Town metropolitan area. Several companies run long-distance bus services from Cape Town to the other cities in South Africa.

MyCiTi

[edit]

Cape Town has a public transport system in about 10% of the city, running north to south along the west coastline of the city, comprising Phase 1 of the IRT system. This is known as the MyCiTi service.[229]

MyCiTi Phase 1 includes services linking the Airport to the Cape Town inner city, as well as the following areas: Blouberg / Table View, Dunoon, Atlantis and Melkbosstrand, Milnerton, Paarden Eiland, Century City, Salt River and Walmer Estate, and all suburbs of the City Bowl and Atlantic Seaboard all the way to Llandudno and Hout Bay.[citation needed]

The MyCiTi N2 Express service consists of four routes each linking the Cape Town inner city and Khayelitsha and Mitchells Plain on the Cape Flats.[230]

The service use high floor articulated and standard size buses in dedicated busways, low floor articulated and standard size buses on the N2 Express service, and smaller 9 m (30 ft) Optare buses in suburban and inner city areas. It offers universal access through level boarding and numerous other measures, and requires cashless fare payment using the EMV compliant smart card system, called myconnect. Headway of services (i.e. the time between buses on the same route) range from three to twenty minutes in peak times to an hour in off-peak times.[citation needed]

Taxis

[edit]

Cape Town has taxis as well as e-hailing services such as Uber. Taxis are either metered taxis or minibus taxis. Unlike many cities, metered taxis can be found at transport hubs as well as other tourist establishments, while minibus taxis can be found at taxi ranks or travelling along main streets.[231] Minibus taxis can be hailed from the road.[232]

Cape Town metered taxi cabs mostly operate in the city bowl, suburbs and Cape Town International Airport areas. Large companies that operate fleets of cabs can be reached by phone and are cheaper than the single operators that apply for hire from taxi ranks and Victoria and Alfred Waterfront. There are about one thousand meter taxis in Cape Town. Their rates vary from R8 per kilometre to about R15 per kilometre. The larger taxi companies in Cape Town are Excite Taxis, Cabnet and Intercab and single operators are reachable by cellular phone. The seven seated Toyota Avanza are the most popular with larger Taxi companies. Meter cabs are mostly used by tourists and are safer to use than minibus taxis.[citation needed]

Minibus taxis are the standard form of transport for the majority of the population who cannot afford private vehicles.[233] Although essential, these taxis are often poorly maintained and are frequently not road-worthy. These taxis make frequent unscheduled stops to pick up passengers, which can cause accidents.[234][235] With the high demand for transport by the working class of South Africa, minibus taxis are often filled over their legal passenger allowance. Minibuses are generally owned and operated in fleets.[236]

Culture

[edit]

Cape Town is noted for its architectural heritage, with the highest density of Cape Dutch style buildings in the world. Cape Dutch style, which combines the architectural traditions of the Netherlands, Germany, France and Indonesia, is most visible in Constantia, the old government buildings in the Central Business District, and along Long Street.[237][238] The annual Cape Town Minstrel Carnival, also known by its Afrikaans name of Kaapse Klopse, is a large minstrel festival held annually on 2 January or "Tweede Nuwe Jaar" (Second New Year). Competing teams of minstrels parade in brightly coloured costumes, performing Cape Jazz, either carrying colourful umbrellas or playing an array of musical instruments. The Artscape Theatre Centre is the largest performing arts venue in Cape Town.[239] The city was named the World Design Capital for 2014 by the International Council of Societies of Industrial Design.[240]

The city also encloses the 36 hectare Kirstenbosch National Botanical Garden that contains protected natural forest and fynbos along with a variety of animals and birds. There are over 7,000 species in cultivation at Kirstenbosch, including many rare and threatened species of the Cape Floristic Region. In 2004 this Region, including Kirstenbosch, was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[241]

Whale watching is popular amongst tourists: southern right whales and humpback whales are seen off the coast during the breeding season (August to November) and Bryde's whales and orca can be seen any time of the year.[242] The nearby town of Hermanus is known for its Whale Festival, but whales can also be seen in False Bay.[242] Heaviside's dolphins are endemic to the area and can be seen from the coast north of Cape Town; dusky dolphins live along the same coast and can occasionally be seen from the ferry to Robben Island.[242]

The only complete windmill in South Africa is Mostert's Mill, Mowbray. It was built in 1796 and restored in 1935 and again in 1995.

Cuisine

[edit]

Еда, происходящая из Кейптауна или синонимичная ему, включает пикантное сладкое мясное блюдо с пряностями Боботи , которое датируется 17 веком. «Гэтсби » , сэндвич с начинкой из чипсов и других начинок, впервые был подан в 1976 году в пригороде Атлон и также является синонимом города. [243] Коэ -сестра — это традиционная капо-малайская выпечка, описываемая как клецки с корицей и текстурой, напоминающей торт, дополненные посыпкой сушеного кокоса. [244] Пудинг Мальва (иногда известный как пудинг Капо-Мальва) — это липкий сладкий десерт, который часто подают с горячим заварным кремом. Он также ассоциируется с городом и восходит к 17 веку. [245] Родственное десертное блюдо « Кейп-Брэнди-пудинг » также ассоциируется с городом и его окрестностями. [246] Кейптаун также является домом южноафриканской винодельческой промышленности: первое вино, произведенное в стране, разливается в бутылки; В городе до сих пор существует ряд известных виноделен, в том числе Groot Constantia и Klein Constantia .

СМИ

[ редактировать ]

В городе есть офисы нескольких газет, журналов и типографий. Independent News and Media издает основные англоязычные газеты города: Cape Argus и Cape Times . Naspers , крупнейший медиа-конгломерат в Южной Африке, издает Die Burger , крупнейшую газету на языке африкаанс. [247]

В Кейптауне есть много местных газет . Некоторые из крупнейших общественных газет на английском языке - это Athlone News из Атлона , Atlantic Sun , Constantiaberg Bulletin из Константиаберга , City Vision из Белвилля , False Bay Echo из False Bay, Helderberg Sun из Хелдерберга , Plainsman из Michell's Plain. , Sentinel News из Хаут-Бэй, Southern Mail с Южного полуострова, Tatler из южных пригородов из южных пригородов , Table Talk из Table View и Tygertalk из Тайгервалли/Дурбанвилля. Газеты сообщества, говорящего на языке африкаанс, включают Landbou-Burger и Tygerburger . Вукани , базирующаяся в Кейп-Флэтс, издается на языке коса . [248]

Кейптаун является центром крупных вещательных СМИ с несколькими радиостанциями, которые вещают только в пределах города. 94,5 Kfm (94,5 МГц FM) и Good Hope FM (94–97 МГц FM ) в основном воспроизводят поп-музыку . Heart FM (104,9 МГц FM), бывшее радио P4, играет джаз и R&B , а Fine Music Radio (101,3 FM) играет классическую музыку и джаз, а Magic Music Radio [249] (828 кГц MW) играет современный и классический рок для взрослых 60-х, 70-х, 80-х, 90-х и 00-х годов. [ нужна ссылка ] Bush Radio - общественная радиостанция (89,5 МГц FM). Voice of the Cape (95,8 МГц FM) и Cape Talk (567 кГц MW ) - основные разговорные радиостанции в городе. [250] Bokradio (98,9 МГц FM) — музыкальная станция на языке африкаанс. [251] также В Кейптаунском университете есть собственная радиостанция UCT Radio (104,5 МГц FM).

SABC Си имеет небольшое присутствие в городе, а спутниковые студии расположены в -Пойнт . e.tv имеет более широкое присутствие благодаря большому комплексу, расположенному в Longkloof Studios в Гарденс . M-Net не очень хорошо представлена инфраструктурой в городе. Cape Town TV — местная телестанция, поддерживаемая многочисленными организациями и специализирующаяся в основном на документальных фильмах. В городе расположены многочисленные продюсерские компании и их вспомогательные предприятия, которые в основном поддерживают производство зарубежной рекламы, модельных съемок, телесериалов и фильмов. [252] Инфраструктура местных СМИ остается в основном в Йоханнесбурге.

Спорт и отдых

[ редактировать ]

Самыми популярными видами спорта в Кейптауне по количеству участников являются крикет , футбол , плавание и регби . [253] В союзе регби Кейптаун является домом для команды Западной провинции , которая играет на стадионе Кейптауна и участвует в розыгрыше Кубка Карри . Кроме того, игроки Западной провинции (вместе с некоторыми из команды Веллингтона «Боланд Кавальерс» ) входят в состав «Стормерс» в соревнованиях Объединенного чемпионата по регби . Кейптаун также был городом-организатором чемпионата мира по регби 1995 года и чемпионата мира по регби 2010 года , а также ежегодно принимает африканский этап чемпионата мира по регби-7 . [254] Здесь прошел чемпионат мира по нетболу 2023 года . [255]

Ассоциативный футбол , который в Южной Африке больше всего известен как футбол , также популярен. Два клуба из Кейптауна играют в Премьер-лиге (PSL), высшей лиге Южной Африки. Этими командами являются «Кейптаун Спёрс» и «Кейптаун Сити». Кейптаун также был местом проведения нескольких матчей чемпионата мира по футболу 2010 года, включая полуфинал, [256] проходил в Южной Африке. Город-мать построил новый стадион на 70 000 мест ( Стадион Кейптауна ) в районе Грин-Пойнт.

В крикете « Кейп Кобры» представляют Кейптаун на стадионе «Ньюлендс Крикет Граунд» . Команда является результатом объединения команд Западной провинции по крикету и Боланда . Они принимают участие в сериях Supersport и Standard Bank Cup . На стадионе Newlands Cricket Ground регулярно проводятся международные матчи.

Кейптаун имел олимпийские амбиции. Например, в 1996 году Кейптаун был одним из пяти городов-кандидатов, включенных МОК в шорт-лист для выдвижения официальных кандидатур на проведение летних Олимпийских игр 2004 года . Хотя Игры в конечном итоге прошли в Афинах , Кейптаун занял третье место. Были некоторые предположения, что Кейптаун добивался номинации Олимпийского комитета Южной Африки в качестве города-заявки Южной Африки на проведение летних Олимпийских игр 2020 года . [257] Это решение было отменено, когда Международный олимпийский комитет передал Токио право проведения Игр 2020 года.