Ахнатен

| |

|---|---|

| Аменофис IV, Нафурурейя, Ихнатон [ 1 ] [ 2 ] | |

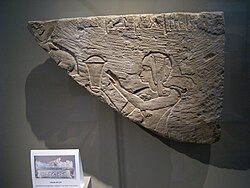

Статуя Ахнатен в египетском музее | |

| Pharaoh | |

| Reign | |

| Predecessor | Amenhotep III |

| Successor | Smenkhkare |

| Consorts |

|

| Children | |

| Father | Amenhotep III |

| Mother | Tiye |

| Died | 1336 or 1334 BC |

| Burial |

|

| Monuments | Akhetaten, Gempaaten |

| Religion | |

| Dynasty | 18th Dynasty of Egypt |

Akhenaten (произносится / ˌ æ k ə ˈ n ː t ən / ), [ 8 ] Также написано Ахнатон [ 3 ] [ 9 ] [ 10 ] или Эхнатон [ 11 ] ( Древний египетский произносится [ˈʔuːχəʔ nə ˈjaːtəj] , [ 12 ] [ 13 ] Значение «Эффективно для Атена »), был древним египетским фараоном , правящим в. 1353–1336 [ 3 ] или 1351–1334 до н.э. [ 4 ] Десятый правитель восемнадцатой династии . До пятого года своего правления он был известен как Аменхотеп IV (Древний египетский: JMN-ḥtp , что означает « Амун удовлетворен», эллинизирован как Аменофис IV ).

Как фараон, Ахнатен отмечен тем, что отказался от традиционной древнегипетской религии политеизма вокруг и введения атенизма или поклонения, сосредоточенного Атена . Взгляды египтологов отличаются относительно того, была ли религиозная политика абсолютно монотеистической , или была ли она монолатристическая , синкретистическая или гиноистическая . [ 14 ] [ 15 ] Эта культура смещается от традиционной религии, была изменена после его смерти. Памятники Ахнатена были демонтированы и скрыты, его статуи были уничтожены, и его имя исключено из списков правителей, составленных более поздними фараонами. [16] Traditional religious practice was gradually restored, notably under his close successor Tutankhamun, who changed his name from Tutankhaten early in his reign.[17] When some dozen years later, rulers without clear rights of succession from the Eighteenth Dynasty founded a new dynasty, they discredited Akhenaten and his immediate successors and referred to Akhenaten as "the enemy" or "that criminal" in archival records.[18][19]

Akhenaten was all but lost to history until the late-19th-century discovery of Amarna, or Akhetaten, the new capital city he built for the worship of Aten.[20] Furthermore, in 1907, a mummy that could be Akhenaten's was unearthed from the tomb KV55 in the Valley of the Kings by Edward R. Ayrton. Genetic testing has determined that the man buried in KV55 was Tutankhamun's father,[21] but its identification as Akhenaten has since been questioned.[6][7][22][23][24]

Akhenaten's rediscovery and Flinders Petrie's early excavations at Amarna sparked great public interest in the pharaoh and his queen Nefertiti. He has been described as "enigmatic", "mysterious", "revolutionary", "the greatest idealist of the world", and "the first individual in history", but also as a "heretic", "fanatic", "possibly insane", and "mad".[14][25][26][27][28] Public and scholarly fascination with Akhenaten comes from his connection with Tutankhamun, the unique style and high quality of the pictorial arts he patronized, and the religion he attempted to establish, foreshadowing monotheism.

Family

The future Akhenaten was born Amenhotep, a younger son of pharaoh Amenhotep III and his principal wife Tiye. Akhenaten had an elder brother, crown prince Thutmose, who was recognized as Amenhotep III's heir. Akhenaten also had four or five sisters: Sitamun, Henuttaneb, Iset, Nebetah, and possibly Beketaten.[29] Thutmose's early death, perhaps around Amenhotep III's thirtieth regnal year, meant that Akhenaten was next in line for Egypt's throne.[30]

Akhenaten was married to Nefertiti, his Great Royal Wife. The exact timing of their marriage is unknown, but inscriptions from the pharaoh's building projects suggest that they married either shortly before or after Akhenaten took the throne.[10] For example, Egyptologist Dimitri Laboury suggests that the marriage took place in Akhenaten's fourth regnal year.[31] A secondary wife of Akhenaten named Kiya is also known from inscriptions. Some Egyptologists theorize that she gained her importance as the mother of Tutankhamun.[32] William Murnane proposes that Kiya is the colloquial name of the Mitanni princess Tadukhipa, daughter of the Mitanni king Tushratta who had married Amenhotep III before becoming the wife of Akhenaten.[33][34] Akhenaten's other attested consorts are the daughter of the Enišasi ruler Šatiya and another daughter of the Babylonian king Burna-Buriash II.[35]

Akhenaten could have had seven or eight children based on inscriptions. Egyptologists are fairly certain about his six daughters, who are well attested in contemporary depictions.[36] Among his six daughters, Meritaten was born in regnal year one or five; Meketaten in year four or six; Ankhesenpaaten, later queen of Tutankhamun, before year five or eight; Neferneferuaten Tasherit in year eight or nine; Neferneferure in year nine or ten; and Setepenre in year ten or eleven.[37][38][39][40] Tutankhamun, born Tutankhaten, was most likely Akhenaten's son, with Nefertiti or another wife.[41][42] There is less certainty around Akhenaten's relationship with Smenkhkare, Akhenaten's coregent or successor[43] and husband to his daughter Meritaten; he could have been Akhenaten's eldest son with an unknown wife or Akhenaten's younger brother.[44][45]

Some historians, such as Edward Wente and James Allen, have proposed that Akhenaten took some of his daughters as wives or sexual consorts to father a male heir.[46][47] While this is debated, some historical parallels exist: Akhenaten's father Amenhotep III married his daughter Sitamun, while Ramesses II married two or more of his daughters, even though their marriages might simply have been ceremonial.[48][49] In Akhenaten's case, his oldest daughter Meritaten is recorded as Great Royal Wife to Smenkhkare but is also listed on a box from Tutankhamun's tomb alongside pharaohs Akhenaten and Neferneferuaten as Great Royal Wife. Additionally, letters written to Akhenaten from foreign rulers make reference to Meritaten as "mistress of the house". Egyptologists in the early 20th century also believed that Akhenaten could have fathered a child with his second oldest daughter Meketaten. Meketaten's death, at perhaps age ten to twelve, is recorded in the royal tombs at Akhetaten from around regnal years thirteen or fourteen. Early Egyptologists attribute her death to childbirth, because of the depiction of an infant in her tomb. Because no husband is known for Meketaten, the assumption had been that Akhenaten was the father. Aidan Dodson believes this to be unlikely, as no Egyptian tomb has been found that mentions or alludes to the cause of death of the tomb owner. Further, Jacobus van Dijk proposes that the child is a portrayal of Meketaten's soul.[50] Finally, various monuments, originally for Kiya, were reinscribed for Akhenaten's daughters Meritaten and Ankhesenpaaten. The revised inscriptions list a Meritaten-tasherit ("junior") and an Ankhesenpaaten-tasherit. According to some, this indicates that Akhenaten fathered his own grandchildren. Others hold that, since these grandchildren are not attested to elsewhere, they are fictions invented to fill the space originally portraying Kiya's child.[46][51]

Early life

Egyptologists know very little about Akhenaten's life as prince Amenhotep. Donald B. Redford dates his birth before his father Amenhotep III's 25th regnal year, c. 1363–1361 BC, based on the birth of Akhenaten's first daughter, who was likely born fairly early in his own reign.[4][52] The only mention of his name, as "the King's Son Amenhotep", was found on a wine docket at Amenhotep III's Malkata palace, where some historians suggested Akhenaten was born. Others contend that he was born at Memphis, where growing up he was influenced by the worship of the sun god Ra practiced at nearby Heliopolis.[53] Redford and James K. Hoffmeier state, however, that Ra's cult was so widespread and established throughout Egypt that Akhenaten could have been influenced by solar worship even if he did not grow up around Heliopolis.[54][55]

Some historians have tried to determine who was Akhenaten's tutor during his youth, and have proposed scribes Heqareshu or Meryre II, the royal tutor Amenemotep, or the vizier Aperel.[56] The only person who we know for certain served the prince was Parennefer, whose tomb mentions this fact.[57]

Egyptologist Cyril Aldred suggests that prince Amenhotep might have been a High Priest of Ptah in Memphis, although no evidence supporting this had been found.[58] It is known that Amenhotep's brother, crown prince Thutmose, served in this role before he died. If Amenhotep inherited all his brother's roles in preparation for his accession to the throne, he might have become a high priest in Thutmose's stead. Aldred proposes that Akhenaten's unusual artistic inclinations might have been formed during his time serving Ptah, the patron god of craftsmen, whose high priests were sometimes referred to as "The Greatest of the Directors of Craftsmanship".[59]

Reign

Coregency with Amenhotep III

There is much controversy around whether Amenhotep IV ascended to Egypt's throne on the death of his father Amenhotep III or whether there was a coregency, lasting perhaps as long as 12 years. Eric Cline, Nicholas Reeves, Peter Dorman, and other scholars argue strongly against the establishment of a long coregency between the two rulers and in favor of either no coregency or one lasting at most two years.[60] Donald B. Redford, William J. Murnane, Alan Gardiner, and Lawrence Berman contest the view of any coregency whatsoever between Akhenaten and his father.[61][62]

Most recently, in 2014, archaeologists found both pharaohs' names inscribed on the wall of the Luxor tomb of vizier Amenhotep-Huy. The Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities called this "conclusive evidence" that Akhenaten shared power with his father for at least eight years, based on the dating of the tomb.[63] However, this conclusion has since been called into question by other Egyptologists, according to whom the inscription only means that construction on Amenhotep-Huy's tomb started during Amenhotep III's reign and ended under Akhenaten's, and Amenhotep-Huy thus simply wanted to pay his respects to both rulers.[64]

Early reign as Amenhotep lV

Akhenaten took Egypt's throne as Amenhotep IV, most likely in 1353[65] or 1351 BC.[4] It is unknown how old Amenhotep IV was when he did this; estimates range from 10 to 23.[66] He was most likely crowned in Thebes, or less likely at Memphis or Armant.[66]

The beginning of Amenhotep IV's reign followed established pharaonic traditions. He did not immediately start redirecting worship toward the Aten and distancing himself from other gods. Egyptologist Donald B. Redford believes this implied that Amenhotep IV's eventual religious policies were not conceived of before his reign, and he did not follow a pre-established plan or program. Redford points to three pieces of evidence to support this. First, surviving inscriptions show Amenhotep IV worshipping several different gods, including Atum, Osiris, Anubis, Nekhbet, Hathor,[67] and the Eye of Ra, and texts from this era refer to "the gods" and "every god and every goddess". The High Priest of Amun was also still active in the fourth year of Amenhotep IV's reign.[68] Second, even though he later moved his capital from Thebes to Akhetaten, his initial royal titulary honored Thebes—his nomen was "Amenhotep, god-ruler of Thebes"—and recognizing its importance, he called the city "Southern Heliopolis, the first great (seat) of Re (or) the Disc". Third, Amenhotep IV did not yet destroy temples to the other gods and he even continued his father's construction projects at Karnak's Precinct of Amun-Re.[69] He decorated the walls of the precinct's Third Pylon with images of himself worshipping Ra-Horakhty, portrayed in the god's traditional form of a falcon-headed man.[70]

Artistic depictions continued unchanged early in Amenhotep IV's reign. Tombs built or completed in the first few years after he took the throne, such as those of Kheruef, Ramose, and Parennefer, show the pharaoh in the traditional artistic style.[71] In Ramose's tomb, Amenhotep IV appears on the west wall, seated on a throne, with Ramose appearing before the pharaoh. On the other side of the doorway, Amenhotep IV and Nefertiti are shown in the window of appearances, with the Aten depicted as the sun disc. In Parennefer's tomb, Amenhotep IV and Nefertiti are seated on a throne with the sun disc depicted over the pharaoh and his queen.[71]

While continuing the worship of other gods, Amenhotep IV's initial building program sought to build new places of worship to the Aten. He ordered the construction of temples or shrines to the Aten in several cities across the country, such as Bubastis, Tell el-Borg, Heliopolis, Memphis, Nekhen, Kawa, and Kerma.[72] He also ordered the construction of a large temple complex dedicated to the Aten at Karnak in Thebes, northeast of the parts of the Karnak complex dedicated to Amun. The Aten temple complex, collectively known as the Per Aten ("House of the Aten"), consisted of several temples whose names survive: the Gempaaten ("The Aten is found in the estate of the Aten"), the Hwt Benben ("House or Temple of the Benben"), the Rud-Menu ("Enduring of monuments for Aten forever"), the Teni-Menu ("Exalted are the monuments of the Aten forever"), and the Sekhen Aten ("booth of Aten").[73]

Around regnal year two or three, Amenhotep IV organized a Sed festival. Sed festivals were ritual rejuvenations of an aging pharaoh, which usually took place for the first time around the thirtieth year of a pharaoh's reign and every three or so years thereafter. Egyptologists only speculate as to why Amenhotep IV organized a Sed festival when he was likely still in his early twenties. Some historians see it as evidence for Amenhotep III and Amenhotep IV's coregency, and believed that Amenhotep IV's Sed festival coincided with one of his father's celebrations. Others speculate that Amenhotep IV chose to hold his festival three years after his father's death, aiming to proclaim his rule a continuation of his father's reign. Yet others believe that the festival was held to honor the Aten on whose behalf the pharaoh ruled Egypt, or, as Amenhotep III was considered to have become one with the Aten following his death, the Sed festival honored both the pharaoh and the god at the same time. It is also possible that the purpose of the ceremony was to figuratively fill Amenhotep IV with strength before his great enterprise: the introduction of the Aten cult and the founding of the new capital Akhetaten. Regardless of the celebration's aim, Egyptologists believe that during the festivities Amenhotep IV only made offerings to the Aten rather than the many gods and goddesses, as was customary.[59][74][75]

Name change

Among the last documents that refer to Akhenaten as Amenhotep IV are two copies of a letter to the pharaoh from Ipy, the high steward of Memphis. These letters, found at Gurob, informing the pharaoh that the royal estates in Memphis are "in good order" and the temple of Ptah is "prosperous and flourishing", are dated to regnal year five, day nineteen of the growing season's third month. About a month later, day thirteen of the growing season's fourth month, one of the boundary stela at Akhetaten already had the name Akhenaten carved on it, implying that the pharaoh changed his name between the two inscriptions.[76][77][78][79]

Amenhotep IV changed his royal titulary to show his devotion to the Aten. No longer would he be known as Amenhotep IV and be associated with the god Amun, but rather he would completely shift his focus to the Aten. Egyptologists debate the exact meaning of Akhenaten, his new personal name. The word "akh" (Ancient Egyptian: ꜣḫ) could have different translations, such as "satisfied", "effective spirit", or "serviceable to", and thus Akhenaten's name could be translated to mean "Aten is satisfied", "Effective spirit of the Aten", or "Serviceable to the Aten", respectively.[80] Gertie Englund and Florence Friedman arrive at the translation "Effective for the Aten" by analyzing contemporary texts and inscriptions, in which Akhenaten often described himself as being "effective for" the sun disc. Englund and Friedman conclude that the frequency with which Akhenaten used this term likely means that his own name meant "Effective for the Aten".[80]

Some historians, such as William F. Albright, Edel Elmar, and Gerhard Fecht, propose that Akhenaten's name is misspelled and mispronounced. These historians believe "Aten" should rather be "Jāti", thus rendering the pharaoh's name Akhenjāti or Aḫanjāti (pronounced /ˌækəˈnjɑːtɪ/), as it could have been pronounced in Ancient Egypt.[81][82][83]

| Amenhotep IV | Akhenaten | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Horus name |

Kanakht-qai-Shuti "Strong Bull of the Double Plumes" |

Meryaten "Beloved of Aten" | |||||||||||||||||||

| Nebty name |

Wer-nesut-em-Ipet-swt "Great of Kingship in Karnak" |

Wer-nesut-em-Akhetaten "Great of Kingship in Akhet-Aten" | |||||||||||||||||||

| Golden Horus name |

Wetjes-khau-em-Iunu-Shemay "Crowned in Heliopolis of the South" (Thebes) |

Wetjes-ren-en-Aten "Exalter of the Name of Aten" | |||||||||||||||||||

| Prenomen |

Neferkheperure-waenre "Beautiful are the Forms of Re, the Unique one of Re" | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Nomen |

Amenhotep Netjer-Heqa-Waset "Amun is Satisfied, Divine Lord of Thebes" |

Akhenaten "Effective for the Aten" | |||||||||||||||||||

Founding Amarna

Around the same time he changed his royal titulary, on the thirteenth day of the growing season's fourth month, Akhenaten decreed that a new capital city be built: Akhetaten (Ancient Egyptian: ꜣḫt-jtn, meaning "Horizon of the Aten"), better known today as Amarna. The events Egyptologists know the most about during Akhenaten's life are connected with founding Akhetaten, as several so-called boundary stelae were found around the city to mark its boundary.[84] The pharaoh chose a site about halfway between Thebes, the capital at the time, and Memphis, on the east bank of the Nile, where a wadi and a natural dip in the surrounding cliffs form a silhouette similar to the "horizon" hieroglyph. Additionally, the site had previously been uninhabited. According to inscriptions on one boundary stela, the site was appropriate for Aten's city for "not being the property of a god, nor being the property of a goddess, nor being the property of a ruler, nor being the property of a female ruler, nor being the property of any people able to lay claim to it."[85]

Historians do not know for certain why Akhenaten established a new capital and left Thebes, the old capital. The boundary stelae detailing Akhetaten's founding is damaged where it likely explained the pharaoh's motives for the move. Surviving parts claim what happened to Akhenaten was "worse than those that I heard" previously in his reign and worse than those "heard by any kings who assumed the White Crown", and alludes to "offensive" speech against the Aten. Egyptologists believe that Akhenaten could be referring to conflict with the priesthood and followers of Amun, the patron god of Thebes. The great temples of Amun, such as Karnak, were all located in Thebes and the priests there achieved significant power earlier in the Eighteenth Dynasty, especially under Hatshepsut and Thutmose III, thanks to pharaohs offering large amounts of Egypt's growing wealth to the cult of Amun; historians, such as Donald B. Redford, therefore posited that by moving to a new capital, Akhenaten may have been trying to break with Amun's priests and the god.[86][87][88]

Akhetaten was a planned city with the Great Temple of the Aten, Small Aten Temple, royal residences, records office, and government buildings in the city center. Some of these buildings, such as the Aten temples, were ordered to be built by Akhenaten on the boundary stela decreeing the city's founding.[87][89][90]

The city was built quickly, thanks to a new construction method that used substantially smaller building blocks than under previous pharaohs. These blocks, called talatats, measured 1⁄2 by 1⁄2 by 1 ancient Egyptian cubits (c. 27 by 27 by 54 cm), and because of the smaller weight and standardized size, using them during constructions was more efficient than using heavy building blocks of varying sizes.[91][92] By regnal year eight, Akhetaten reached a state where it could be occupied by the royal family. Only his most loyal subjects followed Akhenaten and his family to the new city. While the city continued to be built, in years five through eight, construction work began to stop in Thebes. The Theban Aten temples that had begun were abandoned, and a village of those working on Valley of the Kings tombs was relocated to the workers' village at Akhetaten. However, construction work continued in the rest of the country, as larger cult centers, such as Heliopolis and Memphis, also had temples built for Aten.[93][94]

International relations

The Amarna letters have provided important evidence about Akhenaten's reign and foreign policy. The letters are a cache of 382 diplomatic texts and literary and educational materials discovered between 1887 and 1979,[95] and named after Amarna, the modern name for Akhenaten's capital Akhetaten. The diplomatic correspondence comprises clay tablet messages between Amenhotep III, Akhenaten, and Tutankhamun, various subjects through Egyptian military outposts, rulers of vassal states, and the foreign rulers of Babylonia, Assyria, Syria, Canaan, Alashiya, Arzawa, Mitanni, and the Hittites.[96]

The Amarna letters portray the international situation in the Eastern Mediterranean that Akhenaten inherited from his predecessors. In the 200 years preceding Akhenaten's reign, following the expulsion of the Hyksos from Lower Egypt at the end of the Second Intermediate Period, the kingdom's influence and military might increased greatly. Egypt's power reached new heights under Thutmose III, who ruled approximately 100 years before Akhenaten and led several successful military campaigns into Nubia and Syria. Egypt's expansion led to confrontation with the Mitanni, but this rivalry ended with the two nations becoming allies. Slowly, however, Egypt's power started to wane. Amenhotep III aimed to maintain the balance of power through marriages—such as his marriage to Tadukhipa, daughter of the Mitanni king Tushratta—and vassal states. Under Amenhotep III and Akhenaten, Egypt was unable or unwilling to oppose the rise of the Hittites around Syria. The pharaohs seemed to eschew military confrontation at a time when the balance of power between Egypt's neighbors and rivals was shifting, and the Hittites, a confrontational state, overtook the Mitanni in influence.[97][98][99][100]

Early in his reign, Akhenaten was evidently concerned about the expanding power of the Hittite Empire under Šuppiluliuma I. A successful Hittite attack on Mitanni and its ruler Tushratta would have disrupted the entire international balance of power in the Ancient Middle East at a time when Egypt had made peace with Mitanni; this would cause some of Egypt's vassals to switch their allegiances to the Hittites, as time would prove. A group of Egypt's allies who attempted to rebel against the Hittites were captured, and wrote letters begging Akhenaten for troops, but he did not respond to most of their pleas. Evidence suggests that the troubles on the northern frontier led to difficulties in Canaan, particularly in a struggle for power between Labaya of Shechem and Abdi-Heba of Jerusalem, which required the pharaoh to intervene in the area by dispatching Medjay troops northwards. Akhenaten pointedly refused to save his vassal Rib-Hadda of Byblos—whose kingdom was being besieged by the expanding state of Amurru under Abdi-Ashirta and later Aziru, son of Abdi-Ashirta—despite Rib-Hadda's numerous pleas for help from the pharaoh. Rib-Hadda wrote a total of 60 letters to Akhenaten pleading for aid from the pharaoh. Akhenaten wearied of Rib-Hadda's constant correspondences and once told Rib-Hadda: "You are the one that writes to me more than all the (other) mayors" or Egyptian vassals in EA 124.[101] What Rib-Hadda did not comprehend was that the Egyptian king would not organize and dispatch an entire army north just to preserve the political status quo of several minor city states on the fringes of Egypt's Asiatic Empire.[102] Rib-Hadda would pay the ultimate price; his exile from Byblos due to a coup led by his brother Ilirabih is mentioned in one letter. When Rib-Hadda appealed in vain for aid from Akhenaten and then turned to Aziru, his sworn enemy, to place him back on the throne of his city, Aziru promptly had him dispatched to the king of Sidon, where Rib-Hadda was almost certainly executed.[103]

In a view discounted by the 21st century,[104] several Egyptologists in the late 19th and 20th centuries interpreted the Amarna letters to mean that Akhenaten was a pacifist who neglected foreign policy and Egypt's foreign territories in favor of his internal reforms. For example, Henry Hall believed Akhenaten "succeeded by his obstinate doctrinaire love of peace in causing far more misery in his world than half a dozen elderly militarists could have done,"[105] while James Henry Breasted said Akhenaten "was not fit to cope with a situation demanding an aggressive man of affairs and a skilled military leader."[106] Others noted that the Amarna letters counter the conventional view that Akhenaten neglected Egypt's foreign territories in favour of his internal reforms. For instance, Norman de Garis Davies praised Akhenaten's emphasis on diplomacy over war, while James Baikie said that the fact "that there is no evidence of revolt within the borders of Egypt itself during the whole reign is surely ample proof that there was no such abandonment of his royal duties on the part of Akhenaten as has been assumed."[107][108] Indeed, several letters from Egyptian vassals notified the pharaoh that they have followed his instructions, implying that the pharaoh sent such instructions.[109] The Amarna letters also show that vassal states were told repeatedly to expect the arrival of the Egyptian military on their lands, and provide evidence that these troops were dispatched and arrived at their destination. Dozens of letters detail that Akhenaten—and Amenhotep III—sent Egyptian and Nubian troops, armies, archers, chariots, horses, and ships.[110]

Only one military campaign is known for certain under Akhenaten's reign. In his second or twelfth year,[111] Akhenaten ordered his Viceroy of Kush Tuthmose to lead a military expedition to quell a rebellion and raids on settlements on the Nile by Nubian nomadic tribes. The victory was commemorated on two stelae, one discovered at Amada and another at Buhen. Egyptologists differ on the size of the campaign: Wolfgang Helck considered it a small-scale police operation, while Alan Schulman considered it a "war of major proportions".[112][113][114]

Other Egyptologists suggested that Akhenaten could have waged war in Syria or the Levant, possibly against the Hittites. Cyril Aldred, based on Amarna letters describing Egyptian troop movements, proposed that Akhenaten launched an unsuccessful war around the city of Gezer, while Marc Gabolde argued for an unsuccessful campaign around Kadesh. Either of these could be the campaign referred to on Tutankhamun's Restoration Stela: "if an army was sent to Djahy [southern Canaan and Syria] to broaden the boundaries of Egypt, no success of their cause came to pass."[115][116][117] John Coleman Darnell and Colleen Manassa also argued that Akhenaten fought with the Hittites for control of Kadesh, but was unsuccessful; the city was not recaptured until 60–70 years later, under Seti I.[118]

Overall, archeological evidence suggests that Akhenaten paid close attention to the affairs of Egyptian vassals in Canaan and Syria, though primarily not through letters such as those found at Amarna but through reports from government officials and agents. Akhenaten managed to preserve Egypt's control over the core of its Near Eastern Empire (which consisted of present-day Israel as well as the Phoenician coast) while avoiding conflict with the increasingly powerful and aggressive Hittite Empire of Šuppiluliuma I, which overtook the Mitanni as the dominant power in the northern part of the region. Only the Egyptian border province of Amurru in Syria around the Orontes River was lost to the Hittites when its ruler Aziru defected to the Hittites; ordered by Akhenaten to come to Egypt, Aziru was released after promising to stay loyal to the pharaoh, nonetheless turning to the Hittites soon after his release.[119]

Later years

Egyptologists know little about the last five years of Akhenaten's reign, beginning in c. 1341[3] or 1339 BC.[4] These years are poorly attested and only a few pieces of contemporary evidence survive; the lack of clarity makes reconstructing the latter part of the pharaoh's reign "a daunting task" and a controversial and contested topic of discussion among Egyptologists.[120]

Among the newest pieces of evidence is an inscription discovered in 2012 at a limestone quarry in Deir el-Bersha, just north of Akhetaten, from the pharaoh's sixteenth regnal year. The text refers to a building project in Amarna and establishes that Akhenaten and Nefertiti were still a royal couple just a year before Akhenaten's death.[121][122][123] The inscription is dated to Year 16, month 3 of Akhet, day 15 of the reign of Akhenaten.[121]

Before the 2012 discovery of the Deir el-Bersha inscription, the last known fixed-date event in Akhenaten's reign was a royal reception in regnal year twelve, in which the pharaoh and the royal family received tributes and offerings from allied countries and vassal states at Akhetaten. Inscriptions show tributes from Nubia, the Land of Punt, Syria, the Kingdom of Hattusa, the islands in the Mediterranean Sea, and Libya. Egyptologists, such as Aidan Dodson, consider this year twelve celebration to be the zenith of Akhenaten's reign.[124] Thanks to reliefs in the tomb of courtier Meryre II, historians know that the royal family, Akhenaten, Nefertiti, and their six daughters, were present at the royal reception in full.[124] However, historians are uncertain about the reasons for the reception. Possibilities include the celebration of the marriage of future pharaoh Ay to Tey, celebration of Akhenaten's twelve years on the throne, the summons of king Aziru of Amurru to Egypt, a military victory at Sumur in the Levant, a successful military campaign in Nubia,[125] Nefertiti's ascendancy to the throne as coregent, or the completion of the new capital city Akhetaten.[126]

Following year twelve, Donald B. Redford and other Egyptologists proposed that Egypt was struck by an epidemic, most likely a plague.[127] Contemporary evidence suggests that a plague ravaged through the Middle East around this time,[128] and ambassadors and delegations arriving to Akhenaten's year twelve reception might have brought the disease to Egypt.[129] Alternatively, letters from the Hattians might suggest that the epidemic originated in Egypt and was carried throughout the Middle East by Egyptian prisoners of war.[130] Regardless of its origin, the epidemic might account for several deaths in the royal family that occurred in the last five years of Akhenaten's reign, including those of his daughters Meketaten, Neferneferure, and Setepenre.[131][132]

Coregency with Smenkhkare or Nefertiti

Akhenaten could have ruled together with Smenkhkare and Nefertiti for several years before his death.[133][134] Based on depictions and artifacts from the tombs of Meryre II and Tutankhamun, Smenkhkare could have been Akhenaten's coregent by regnal year thirteen or fourteen, but died a year or two later. Nefertiti might not have assumed the role of coregent until after year sixteen, when a stela still mentions her as Akhenaten's Great Royal Wife. While Nefertiti's familial relationship with Akhenaten is known, whether Akhenaten and Smenkhkare were related by blood is unclear. Smenkhkare could have been Akhenaten's son or brother, as the son of Amenhotep III with Tiye or Sitamun.[135] Archaeological evidence makes it clear, however, that Smenkhkare was married to Meritaten, Akhenaten's eldest daughter.[136] For another, the so-called Coregency Stela, found in a tomb at Akhetaten, might show queen Nefertiti as Akhenaten's coregent, but this is uncertain as the stela was recarved to show the names of Ankhesenpaaten and Neferneferuaten.[137] Egyptologist Aidan Dodson proposed that both Smenkhkare and Neferiti were Akhenaten's coregents to ensure the Amarna family's continued rule when Egypt was confronted with an epidemic. Dodson suggested that the two were chosen to rule as Tutankhaten's coregent in case Akhenaten died and Tutankhaten took the throne at a young age, or rule in Tutankhaten's stead if the prince also died in the epidemic.[43]

Death and burial

Akhenaten died after seventeen years of rule and was initially buried in a tomb in the Royal Wadi east of Akhetaten. The order to construct the tomb and to bury the pharaoh there was commemorated on one of the boundary stela delineating the capital's borders: "Let a tomb be made for me in the eastern mountain [of Akhetaten]. Let my burial be made in it, in the millions of jubilees which the Aten, my father, decreed for me."[138] In the years following the burial, Akhenaten's sarcophagus was destroyed and left in the Akhetaten necropolis; reconstructed in the 20th century, it is in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo as of 2019.[139] Despite leaving the sarcophagus behind, Akhenaten's mummy was removed from the royal tombs after Tutankhamun abandoned Akhetaten and returned to Thebes. It was most likely moved to tomb KV55 in Valley of the Kings near Thebes.[140][141] This tomb was later desecrated, likely during the Ramesside period.[142][143]

Whether Smenkhkare also enjoyed a brief independent reign after Akhenaten is unclear.[144] If Smenkhkare outlived Akhenaten, and became sole pharaoh, he likely ruled Egypt for less than a year. The next successor was Nefertiti[145] or Meritaten[146] ruling as Neferneferuaten, reigning in Egypt for about two years.[147] She was, in turn, probably succeeded by Tutankhaten, with the country being administered by the vizier and future pharaoh Ay.[148]

While Akhenaten—along with Smenkhkare—was most likely reburied in tomb KV55,[149] the identification of the mummy found in that tomb as Akhenaten remains controversial to this day. The mummy has repeatedly been examined since its discovery in 1907. Most recently, Egyptologist Zahi Hawass led a team of researchers to examine the mummy using medical and DNA analysis, with the results published in 2010. In releasing their test results, Hawass's team identified the mummy as the father of Tutankhamun and thus "most probably" Akhenaten.[150] However, the study's validity has since been called into question.[6][7][151][152][153] For instance, the discussion of the study results does not discuss that Tutankhamun's father and the father's siblings would share some genetic markers; if Tutankhamun's father was Akhenaten, the DNA results could indicate that the mummy is a brother of Akhenaten, possibly Smenkhkare.[153][154]

Legacy

With Akhenaten's death, the Aten cult he had founded fell out of favor: at first gradually, and then with decisive finality. Tutankhaten changed his name to Tutankhamun in Year 2 of his reign (c. 1332 BC) and abandoned the city of Akhetaten.[155] Their successors then attempted to erase Akhenaten and his family from the historical record. During the reign of Horemheb, the last pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty and the first pharaoh after Akhenaten who was not related to Akhenaten's family, Egyptians started to destroy temples to the Aten and reuse the building blocks in new construction projects, including in temples for the newly restored god Amun. Horemheb's successor continued in this effort. Seti I restored monuments to Amun and had the god's name re-carved on inscriptions where it was removed by Akhenaten. Seti I also ordered that Akhenaten, Smenkhkare, Neferneferuaten, Tutankhamun, and Ay be excised from official lists of pharaohs to make it appear that Amenhotep III was immediately succeeded by Horemheb. Under the Ramessides, who succeeded Seti I, Akhetaten was gradually destroyed and the building material reused across the country, such as in constructions at Hermopolis. The negative attitudes toward Akhenaten were illustrated by, for example, inscriptions in the tomb of scribe Mose (or Mes), where Akhenaten's reign is referred to as "the time of the enemy of Akhet-Aten".[156][157][158]

Some Egyptologists, such as Jacobus van Dijk and Jan Assmann, believe that Akhenaten's reign and the Amarna period started a gradual decline in the Egyptian government's power and the pharaoh's standing in Egyptian's society and religious life.[159][160] Akhenaten's religious reforms subverted the relationship ordinary Egyptians had with their gods and their pharaoh, as well as the role the pharaoh played in the relationship between the people and the gods. Before the Amarna period, the pharaoh was the representative of the gods on Earth, the son of the god Ra, and the living incarnation of the god Horus, and maintained the divine order through rituals and offerings and by sustaining the temples of the gods.[161] Additionally, even though the pharaoh oversaw all religious activity, Egyptians could access their gods through regular public holidays, festivals, and processions. This led to a seemingly close connection between people and the gods, especially the patron deity of their respective towns and cities.[162]

Akhenaten, however, banned the worship of gods beside the Aten, including through festivals. He also declared himself to be the only one who could worship the Aten, and required that all religious devotion previously exhibited toward the gods be directed toward himself. After the Amarna period, during the Nineteenth and Twentieth Dynasties—c. 270 years following Akhenaten's death—the relationship between the people, the pharaoh, and the gods did not simply revert to pre-Amarna practices and beliefs. The worship of all gods returned, but the relationship between the gods and the worshipers became more direct and personal,[163] circumventing the pharaoh. Rather than acting through the pharaoh, Egyptians started to believe that the gods intervened directly in their lives, protecting the pious and punishing criminals.[164] The gods replaced the pharaoh as their own representatives on Earth. The god Amun once again became king among all gods.[165] According to van Dijk, "the king was no longer a god, but god himself had become king. Once Amun had been recognized as the true king, the political power of the earthly rulers could be reduced to a minimum."[166] Consequently, the influence and power of the Amun priesthood continued to grow until the Twenty-first Dynasty, c. 1077 BC, by which time the High Priests of Amun effectively became rulers over parts of Egypt.[160][167][168]

Akhenaten's reforms also had a longer-term impact on Ancient Egyptian language and hastened the spread of the spoken Late Egyptian language in official writings and speeches. Spoken and written Egyptian diverged early on in Egyptian history and stayed different over time.[169] During the Amarna period, however, royal and religious texts and inscriptions, including the boundary stelae at Akhetaten or the Amarna letters, started to regularly include more vernacular linguistic elements, such as the definite article or a new possessive form. Even though they continued to diverge, these changes brought the spoken and written language closer to one another more systematically than under previous pharaohs of the New Kingdom. While Akhenaten's successors attempted to erase his religious, artistic, and even linguistic changes from history, the new linguistic elements remained a more common part of official texts following the Amarna years, starting with the Nineteenth Dynasty.[170][171][172]

Akhenaten is also recognized as a Prophet in the Druze faith.[173][174]

Atenism

Egyptians worshipped a sun god under several names, and solar worship had been growing in popularity even before Akhenaten, especially during the Eighteenth Dynasty and the reign of Amenhotep III, Akhenaten's father.[175] During the New Kingdom, the pharaoh started to be associated with the sun disc; for example, one inscription called the pharaoh Hatshepsut the "female Re shining like the Disc", while Amenhotep III was described as "he who rises over every foreign land, Nebmare, the dazzling disc".[176] During the Eighteenth Dynasty, a religious hymn to the sun also appeared and became popular among Egyptians.[177] However, Egyptologists question whether there is a causal relationship between the cult of the sun disc before Akhenaten and Akhenaten's religious policies.[177]

Implementation and development

The implementation of Atenism can be traced through gradual changes in the Aten's iconography, and Egyptologist Donald B. Redford divided its development into three stages—earliest, intermediate, and final—in his studies of Akhenaten and Atenism. The earliest stage was associated with a growing number of depictions of the sun disc, though the disc is still seen resting on the head of the falcon-headed sun god Ra-Horakhty, as the god was traditionally represented.[178] The god was only "unique but not exclusive".[179] The intermediate stage was marked by the elevation of the Aten above other gods and the appearance of cartouches around his inscribed name—cartouches traditionally indicating that the enclosed text is a royal name. The final stage had the Aten represented as a sun disc with sunrays like long arms terminating in human hands and the introduction of a new epithet for the god: "the great living Disc which is in jubilee, lord of heaven and earth".[180]

In the early years of his reign, Amenhotep IV lived at Thebes, the old capital city, and permitted worship of Egypt's traditional deities to continue. However, some signs already pointed to the growing importance of the Aten. For example, inscriptions in the Theban tomb of Parennefer from the early rule of Amenhotep IV state that "one measures the payments to every (other) god with a level measure, but for the Aten one measures so that it overflows," indicating a more favorable attitude to the cult of Aten than the other gods.[179] Additionally, near the Temple of Karnak, Amun-Ra's great cult center, Amenhotep IV erected several massive buildings including temples to the Aten. The new Aten temples had no roof and the god was thus worshipped in the sunlight, under the open sky, rather than in dark temple enclosures as had been the previous custom.[181][182] The Theban buildings were later dismantled by his successors and used as infill for new constructions in the Temple of Karnak; when they were later dismantled by archaeologists, some 36,000 decorated blocks from the original Aten building here were revealed that preserve many elements of the original relief scenes and inscriptions.[183]

One of the most important turning points in the early reign of Amenhotep IV is a speech given by the pharaoh at the beginning of his second regnal year. A copy of the speech survives on one of the pylons at the Karnak Temple Complex near Thebes. Speaking to the royal court, scribes or the people, Amenhotep IV said that the gods were ineffective and had ceased their movements, and that their temples had collapsed. The pharaoh contrasted this with the only remaining god, the sun disc Aten, who continued to move and exist forever. Some Egyptologists, such as Donald B. Redford, compared this speech to a proclamation or manifesto, which foreshadowed and explained the pharaoh's later religious reforms centered around the Aten.[184][185][186] In his speech, Akhenaten said:

The temples of the gods fallen to ruin, their bodies do not endure. Since the time of the ancestors, it is the wise man that knows these things. Behold, I, the king, am speaking so that I might inform you concerning the appearances of the gods. I know their temples, and I am versed in the writings, specifically, the inventory of their primeval bodies. And I have watched as they [the gods] have ceased their appearances, one after the other. All of them have stopped, except the god who gave birth to himself. And no one knows the mystery of how he performs his tasks. This god goes where he pleases and no one else knows his going. I approach him, the things which he has made. How exalted they are.[187]

In Year Five of his reign, Amenhotep IV took decisive steps to establish the Aten as the sole god of Egypt. The pharaoh "disbanded the priesthoods of all the other gods ... and diverted the income from these [other] cults to support the Aten." To emphasize his complete allegiance to the Aten, the king officially changed his name from Amenhotep IV to Akhenaten (Ancient Egyptian: ꜣḫ-n-jtn, meaning "Effective for the Aten").[183] Meanwhile, the Aten was becoming a king itself. Artists started to depict him with the trappings of pharaohs, placing his name in cartouches—a rare, but not unique occurrence, as the names of Ra-Horakhty and Amun-Ra had also been found enclosed in cartouches—and wearing a uraeus, a symbol of kingship.[188] The Aten may also have been the subject of Akhenaten's royal Sed festival early in the pharaoh's reign.[189] With Aten becoming a sole deity, Akhenaten started to proclaim himself as the only intermediary between Aten and his people, and the subject of their personal worship and attention[190]—a feature not unheard of in Egyptian history, with Fifth Dynasty pharaohs such as Nyuserre Ini proclaiming to be sole intermediaries between the people and the gods Osiris and Ra.[191]

By Year Nine of his reign, Akhenaten declared that Aten was not merely the supreme god, but the only worshipable god. He ordered the defacing of Amun's temples throughout Egypt and, in a number of instances, inscriptions of the plural 'gods' were also removed.[192][193] This emphasized the changes encouraged by the new regime, which included a ban on images, with the exception of a rayed solar disc, in which the rays appear to represent the unseen spirit of Aten, who by then was evidently considered not merely a sun god, but rather a universal deity. All life on Earth depended on the Aten and the visible sunlight.[194][195] Representations of the Aten were always accompanied with a sort of hieroglyphic footnote, stating that the representation of the sun as all-encompassing creator was to be taken as just that: a representation of something that, by its very nature as something transcending creation, cannot be fully or adequately represented by any one part of that creation.[196] Aten's name was also written differently starting as early as Year Eight or as late as Year Fourteen, according to some historians.[197] From "Living Re-Horakhty, who rejoices in the horizon in his name Shu-Re who is in Aten", the god's name changed to "Living Re, ruler of the horizon, who rejoices in his name of Re the father who has returned as Aten", removing the Aten's connection to Re-Horakhty and Shu, two other solar deities.[198] The Aten thus became an amalgamation that incorporated the attributes and beliefs around Re-Horakhty, universal sun god, and Shu, god of the sky and manifestation of the sunlight.[199]

Akhenaten's Atenist beliefs are best distilled in the Great Hymn to the Aten.[200] The hymn was discovered in the tomb of Ay, one of Akhenaten's successors, though Egyptologists believe that it could have been composed by Akhenaten himself.[201][202] The hymn celebrates the sun and daylight and recounts the dangers that abound when the sun sets. It tells of the Aten as a sole god and the creator of all life, who recreates life every day at sunrise, and on whom everything on Earth depends, including the natural world, people's lives, and even trade and commerce.[203] In one passage, the hymn declares: "O Sole God beside whom there is none! You made the earth as you wished, you alone."[204] The hymn also states that Akhenaten is the only intermediary between the god and Egyptians, and the only one who can understand the Aten: "You are in my heart, and there is none who knows you except your son."[ 205 ]

Атенизм и другие боги

Некоторые дебаты были сосредоточены на том, в какой степени Ахнатен наставил свои религиозные реформы в своем народе. [ 206 ] Конечно, со временем он пересмотрел имена Атена и другого религиозного языка, чтобы все больше исключать ссылки на других богов; В какой-то момент он также приступил к широкомасштабному стиранию имен традиционных богов, особенно имен Амуна. [ 207 ] Некоторые из его судов изменили их имена, чтобы убрать их из покровительства других богов и поместить их под имена Атена (или Ра, с которым Ахнатен приравнивал Атен). Тем не менее, даже в самой Амарне некоторые придворные держали такие имена, как Ахмос («Дитя Бога Луны», владелец могилы 3) и мастерскую скульптора, где были обнаружены знаменитый бюст Нефертити и другие работы королевской портреты, связаны с Художник, как известно, был назван Тутмос («Ребенок Тот»). В подавляюще большое количество амулетов из фаянса в Амарне также показывают, что талисманы богов по домохозяйствам и детьми Бес и Таверет, Глаз Гора и амулетов других традиционных божеств, открыто носили его граждане. Действительно, кеш королевских украшений, найденных похороненными возле королевских гробниц Амарны (ныне в Национальном музее Шотландии ), включает кольцо пальца, относящиеся к Муте, жене Амуна. Такие данные свидетельствуют о том, что, хотя Ахнатен сместил финансирование от традиционных храмов, его политика была довольно терпимой, пока какой -то момент, возможно, особое событие, пока неизвестное, к концу правления. [ 208 ]

Археологические открытия в Акетатене показывают, что многие простые жители этого города решили вытащить или выручить все ссылки на Бога Амун на даже незначительные личные предметы, которые им принадлежали, такие как памятные скара за или макияж, возможно, из-за страха быть обвиненными в имея амунистические симпатии. Ссылки на Аменхотеп III, отец Ахнатена, были частично стерты с тех пор, как они содержали традиционную форму Амуна его имени: Nebmaatre Amunhotep. [ 209 ]

После Ахнатен

После смерти Ахнатена Египет постепенно вернулся к своей традиционной политеистической религии, отчасти из -за того, насколько тесно связан Атен с Ахнатеном. [ 210 ] Атенизм, вероятно, оставался доминирующим благодаря правлению непосредственных преемников Ахнатена, Сменхкаре и Нефернеферуатена , а также в начале правления Тутанхатена. [ 211 ] В течение нескольких лет поклонение Атене и возрождающее поклонение Амуну сосуществовали. [ 212 ] [ 213 ]

Однако со временем преемники Ахнатена, начиная с Тутанхатена, предприняли шаги, чтобы дистанцироваться от атенизма. Тутанхатен и его жена Анхесенпаатен высадили Атен с их имен и изменили их на Тутанхамун и Анхеснамун соответственно. Амун был восстановлен как высшее божество. Тутанхамун восстановил храмы других богов, поскольку фараон распространял его восстановление Стела: «Он реорганизовал эту землю, восстановив свою обычаясь к временным времени. ... Он возобновил особняки богов и создал все их изображения. ... Он поднял их храмы и создал их статуи. " [ 214 ] Кроме того, строительные проекты Tutankhamun в Thebes и Karnak использовали Talatat от зданий Ахнатена, что подразумевает, что Тутанхамон, возможно, начал разрушать храмы, посвященные Атене. Храмы Атена продолжали сорваться под Ай и Хоремхебом , преемниками Тутанхамана и последних фараонов восемнадцатой династии. Horemheb, возможно, также заказал снос Akhetaten, столицы Ахнатена. [ 215 ] Далее подчеркивая перерыв с поклонением Атене, Хоремхэб утверждал, что был выбран богом Горусом . Наконец, Сети I , второй фараон девятнадцатой династии, приказал восстановить имя Амуна на надписи, где оно было удалено или заменено Атеном. [ 216 ]

Художественные изображения

Стили искусства, которые процветали во время правления Ахнатена и его непосредственных преемников, известных как Амарна Арт , заметно отличаются от традиционного искусства древнего Египта . Представления более реалистичные , экспрессионистские и натуралистические , [ 217 ] [ 218 ] Особенно в изображениях животных, растений и людей, и передают больше действий и движения как для не-рояльных, так и для королевских людей, чем традиционно статические представления. В традиционном искусстве божественная природа фараона была выражена покой, даже неподвижностью. [ 219 ] [ 220 ] [ 221 ]

Изображения самого Ахнатена сильно отличаются от изображений других фараонов. Традиционно изображение фараонов - и египетского правящего класса - было идеализировано, и они были показаны в «стереотипно« красивой »моде» как молодое и спортивное. [ 222 ] Тем не менее, изображения Ахнатена нетрадиционные и «нелестные» с провисающим желудком; широкие бедра; тонкие ноги; толстые бедра; большая, "почти женская грудь"; тонкое «преувеличенное длинное лицо»; и толстые губы. [ 223 ]

Основываясь на необычных художественных представлениях Ахнатена и его семьи, в том числе потенциальных изображений гинекомастии и андрогинности , некоторые утверждают, что у фараона и его семьи либо избытка ароматазы и сагиттального краниосиностоза синдром синдром . [ 224 ] В 2010 году результаты, опубликованные в результате генетических исследований по предполагаемой маме Ахенатена, не нашли признаков синдрома Gynecomastia или Antley-Bixler, [ 21 ] Хотя с тех пор эти результаты были допрошены. [ 225 ]

Вместо этого аргументируя за символическую интерпретацию, Доминик Монтсеррат в Ахнатене: история, фантазия и древние Египет утверждают, что «сейчас существует широкий консенсус среди египтологов, что преувеличенные формы физического изображения Ахнатена ... нельзя читать буквально». [ 209 ] [ 226 ] Поскольку бог Атен назывался «мать и отец всего человечества», Монтсеррат и другие предполагают, что Ахнатен был заставлен, чтобы выглядеть андрогино в произведении искусства как символ андрогинности Атена. [ 227 ] Это требовало «символического собрания всех атрибутов Бога Создателя в физическое тело самого царя», которое «покажет на земле многочисленные жизненные функции». [ 226 ] Ахнатен заявил о названии «Уникальный из них», и он, возможно, поручил своим художникам противопоставить его простым людям через радикальный отход от идеализированного традиционного изображения фараона. [ 226 ]

Изображения других членов суда, особенно членов королевской семьи, также преувеличены, стилизованы и в целом отличаются от традиционного искусства. [ 219 ] Примечательно, и в течение единственного времени в истории египетского королевского искусства изображена семейная жизнь фараона: королевская семья демонстрирует в середине действия в расслабленных, случайных и интимных ситуациях, принимая участие в решительно натуралистических мероприятиях, демонстрируя привязанность к каждому Другое, например, держась за руки и поцелуи. [ 228 ] [ 229 ] [ 230 ] [ 231 ]

Нефертити также появляется, как рядом с королем, так и в одиночестве, или со своими дочерьми, в действиях, обычно предназначенных для фараона, таких как «поражение врага», традиционное изображение мужских фараонов. [ 232 ] Это говорит о том, что она наслаждалась необычным статусом для королевы. Ранние художественные представления ее, как правило, неразличимы от ее мужа, за исключением ее регалий, но вскоре после перехода в новую столицу, Нефертити начинает изображаться с характеристиками, специфичными для нее. Остаются вопросы, является ли красота Нефертити - это портрет или идеализм. [ 233 ]

Спекулятивные теории

Статус Ахнатена как религиозного революционера привел к большим предположениям , начиная от научных гипотез до неакадемических теорий . Хотя некоторые считают, что религия, которую он ввел, была в основном монотеистическим, многие другие видят в Ахнатене практикующим монолатрии Атена , [ 234 ] поскольку он не активно отрицал существование других богов; Он просто воздерживался от поклонения любому, кроме Атена.

Ахенатен и монотеизм в Авраамических религиях

Идея о том, что Ахнатен был пионером монотеистической религии, которая впоследствии стала иудаизмом, была рассмотрена различными учеными. [ 235 ] [ 236 ] [ 237 ] [ 238 ] [ 239 ] Одним из первых, кто упомянул, это был Зигмунд Фрейд , основатель психоанализа , в своей книге «Моисей и монотеизм» . [ 235 ] Основывая свои аргументы на его убеждении в том, что история Исхода была исторической, Фрейд утверждал, что Моисей был священником Атениста, который был вынужден покинуть Египет со своими последователями после смерти Ахнатена. Фрейд утверждал, что Ахнатен стремился способствовать монотеизму, чего смог достичь библейский Моисей. [ 235 ] После публикации его книги концепция вошла в популярное сознание и серьезные исследования. [ 240 ] [ 241 ]

Фрейд прокомментировал связь между Адонай , египетским Атеном и сирийским божественным именем Адониса как вытекающего из общего корня; [ 235 ] В этом он следил за аргументом египтолога Артура Вейгалла . Мнение Яна Ассманна в том, что «Атен» и «Адонай» не связаны с лингвистически. [ 242 ]

Существует сильное сходство между великим гимном Ахнатена с Атеном и библейским псалом 104 , но в этом сходстве проводится дебаты о отношениях. [ 243 ] [ 244 ]

Другие сравнили некоторые аспекты отношений Ахнатена с Атеном с отношениями, в христианских традициях, между Иисусом Христом и Богом, особенно интерпретациями, которые подчеркивают более монотеистическую интерпретацию атенизма, чем генотеистический. Дональд Б. Редфорд отметил, что некоторые рассматривали Ахнатен как предвестник Иисуса . «В конце концов, Ахнатен действительно назвал себя Сыном единственного Бога:« Только сын Твоего, который вышел из тела ». [ 245 ] Джеймс Генри брасен сравнил его с Иисусом, [ 246 ] Артур Вейгалл рассматривал его как неудавшегося предшественника Христа, и Томас Манн видел его «как правильный в пути, и все же не правильный для того, чтобы». [ 247 ]

Хотя такие ученые, как Брайан Фаган (2015) и Роберт Альтер (2018), вновь открыли дебаты, в 1997 году Редфорд пришел к выводу:

До того, как большая часть археологических доказательств от Фив и от Tell El-Amarna стала доступной, желаемое мышление иногда превращало Ахнатен в гуманного учителя истинного Бога, наставника Моисея, фигуры, похожей на Христос, философа перед своим временем. Но эти воображаемые существа теперь исчезают, когда историческая реальность постепенно возникает. Есть мало или нет доказательств, подтверждающих представление о том, что Ахнатен был прародителем полномасштабного монотеизма, который мы находим в Библии. Монотеизм еврейской Библии и Нового Завета имел свое отдельное развитие, которое началось более чем на половину тысячелетия после смерти фараона. [ 248 ]

Возможная болезнь

Нетрадиционные изображения Ахнатена - дифференцированные от традиционной спортивной нормы в изображении фараонов - привело к тому, что египтологов в 19 и 20 веках предположили, что у Ахнатена была какая -то генетическая аномалия. [ 223 ] Были выдвинуты различные заболевания с синдромом Фрёлиха или синдромом Марфана упоминаются чаще всего. [ 249 ]

Кирилл Олдред , [ 250 ] После более ранних аргументов Графтона Эллиота Смита [ 251 ] и Джеймс Страчи , [ 252 ] предположил, что у Ахнатена, возможно, был синдром Фрёлиха на основе его длинной челюсти и его женской внешности. Тем не менее, это маловероятно, потому что это расстройство приводит к стерильности , а Ахнатен, как известно, родили многочисленных детей. Его дети неоднократно изображаются через годы археологических и иконографических доказательств. [ 253 ]

Берридж [ 254 ] предположил, что у Ахнатен, возможно, был синдром Марфана, который, в отличие от Фрёлиха, не приводит к психическим нарушениям или бесплодием. Люди с синдромом Марфана имеют тенденцию к росту, с длинным тонким лицом, удлиненным черепом, заросшими ребрами, воронкой или голубей, высокой изогнутой или слегка расщелиной неба и большим тазом, с увеличенными бедрами и веретенами, симптомами, которые появляются в Некоторые изображения Ахнатена. [ 255 ] Синдром Марфана является доминирующей характеристикой, что означает, что пострадавшие имеют 50% шанс передать его своим детям. [ 256 ] Тем не менее, ДНК -тесты на Тутанхамун в 2010 году оказались отрицательными для синдрома Марфана. [ 257 ]

К началу 21 -го века большинство египтологов утверждали, что изображения Ахнатена не являются результатами генетического или медицинского состояния, а следует интерпретировать как стилизованные изображения, под влиянием атенизма. [ 209 ] [ 226 ] Ахнатен был заставлен, чтобы выглядеть андрогинным в произведении искусства как символ андрогинности Атена. [ 226 ]

Культурные изображения

Жизнь, достижения и наследие Ахнатена были сохранены и изображены во многих отношениях, и он рассчитывал в работах как высокой , так и популярной культуры с момента своего заново открытия в 19 веке нашей эры. Ахенатен - Альзовательская Клеопатра и Александр Великий - являются одними из наиболее часто популяризированных и вымышленных древних исторических фигур. [ 258 ]

На странице романы Amarna чаще всего принимают одну из двух форм. Они либо билдунгсроман , сосредотачиваясь на психологическом и моральном росте Ахнатена, так как это связано с созданием атенизма и акетатена, а также его борьбе против культового культы Амуна. В качестве альтернативы, его литературные изображения сосредоточены на последствиях его правления и религии. [ 259 ] Разделительная линия также существует между изображениями Ахнатена до 1920 -х годов, и с тех пор, когда все больше и больше археологических открытий начинали предоставлять художникам материальные доказательства его жизни и времени. Таким образом, до 1920 -х годов Ахнатен появился как «призрак, спектральная фигура» в искусстве, в то время как он стал реалистичным, «материальным и осязаемым». [ 260 ] Примеры первого включают романтические романы в гробницах Королей (1910) Лилиан Багналл - первое появление Ахнатена и его жены Нефертити в художественной литературе - и жена из Египта (1913), и в Египте был король ( в Египте король (и королев 1918) Норма Лоример . Примеры последних включают Ахнатона Царь Египта (1924) Дмитрий Мережковский , Джозеф и его братья (1933–1943) Томас Манн , Ахнатон (1973) Агатха Кристи и в Истине (1985) Ахенатен, Житель . Ахнатен также появляется на египетском (1945) Мика Уолтари , которая была адаптирована к фильму «Египтянин» (1953). В этом фильме Ахнатен, изображенный Майклом Уилдингом , кажется, представляет Иисуса Христа и его последователей- протоистов . [ 261 ]

изображениям фараона Сексинизированный образ Ахнатена, основанный на раннем западном интересе к андрогинным , воспринимаемой потенциальной гомосексуализме и идентификации с эдипальным рассказыванием историй , также повлияло на современные произведения искусства. [ 262 ] Двумя наиболее заметными изображениями являются Akenaten (1975), незаконченный сценарий Дерека Джармана и Ахнатен (1984), оперы Филиппа Гласса . [ 263 ] [ 264 ] Оба были под влиянием недоказанных и научно не поддержать теории Иммануила Великовского , который приравнивал Эдипа с Ахнатеном, [ 265 ] Хотя стекло специально отрицает свою личную веру в теорию Эдипа Великовского или заботу о ее исторической обоснованности, вместо этого привлечен к его потенциальной театральности. [ 266 ]

В 21 -м веке Ахнатен появился в качестве антагониста в комиксах и видеоиграх. Например, он является основным антагонистом в ограниченной серии комиксов Marvel: The End (2003). В этой серии Ахнатен похищен инопланетным орденом в 14 -м веке до нашей эры и вновь появляется на современной Земле, стремясь восстановить его королевство. Он против, по сути, все другие супергерои и суперзвезда во вселенной комиксов Marvel, и в конечном итоге он побежден Таносом . [ 267 ] Кроме того, Ахнатен появляется как враг в Assassin's Creed Origins Curse о загружаемом содержании фараонов (2017), и должен быть побежден, чтобы удалить его проклятие на Фивах. [ 267 ] Его загробная жизнь принимает форму «Aten», место, которое в значительной степени опирается на архитектуру города Амарна. [ 268 ]

Американская дэт -металлическая группа Нил изобразила суждение, наказание и стирание Ахнатена от истории от рук Пантеона , которое он заменил Атеном, в песне «Отсепит еретик» из их альбома 2005 года Annhilation of the Wicked . Он также был представлен на обложке их альбома 2009 года, тех, кого боги ненавидят .

Происхождение

| 16. Thutmose III | |||||||||||||||||||

| 8. Amenhotep II | |||||||||||||||||||

| 17. Меритр-Хатшепсут | |||||||||||||||||||

| 4. Thutmose IV | |||||||||||||||||||

| 9. Tiaa | |||||||||||||||||||

| 2. Amenhotep III | |||||||||||||||||||

| 5. Mutemuyiya | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1. Ахнатен | |||||||||||||||||||

| 6. Юя | |||||||||||||||||||

| 3. Убить | |||||||||||||||||||

| 7. Tjuyu | |||||||||||||||||||

Смотрите также

Примечания и ссылки

Примечания

- ^ Cohen & Westbrook 2002 , p. 6

- ^ Роджерс 1912 , с. 252

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Britannica.com 2012 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и Beckerath 1997 , p. 190.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин час я Дж k л м не а п Q. ведущий Leprohon 2013 , с. 104–105.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Strouhal 2010 , с. 97–112.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Адекватный 2010 , с. 114

- ^ Dictionary.com 2008 .

- ^ Кухня 2003 , с. 486.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Tyldesley 2005 .

- ^ Монтсеррат 2003 , стр. 105, 111.

- ^ Loprieno, Antonio (1995) Древний египетский: лингвистическое введение , Кембридж: издательство Кембриджского университета,

- ^ Loprieno, Antonio (2001) «От древнего египетского до коптского» в Haspelmath, Martin et al. (ред.), Языковая типология и языковые универсалии

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Ридли 2019 , с. 13–15.

- ^ Харт 2000 , с.

- ^ Маннише 2010 , с.

- ^ Zaki 2008 , p. 19

- ^ Шторы 1905 , с.

- ^ Trigger et al. 2001 , с. 186–187.

- ^ HORNUNG 1992 , с. 43–44.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Hawass et al. 2010 год .

- ^ Marchant 2011 , с. 404–06.

- ^ Lorenzen & Willerslev 2010 .

- ^ Bickerstaffe 2010 .

- ^ Спенс 2011 .

- ^ Sooke 2014 .

- ^ Hessler 2017 .

- ^ Silverman, Wegner & Wegner 2006 , с. 185–188.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , с. 37–39.

- ^ Додсон 2018 , с. 6

- ^ Laboury 2010 , с. 62, 224.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , с. 220.

- ^ Tyldesley 2006 , p. 124

- ^ Murnine 1995 , стр. 9, 90-93, 210-111.

- ^ Brothzki 2005 .

- ^ Додсон 2012 , с. 1

- ^ Ридли 2019 , с. 78

- ^ Laboury 2010 , с. 314–322.

- ^ Додсон 2009 , с. 41–42.

- ^ Университетский колледж Лондон 2001 .

- ^ Ридли 2019 , с. 262

- ^ Додсон 2018 , с. 174–175.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Додсон 2018 , с. 38–39.

- ^ Додсон 2009 , с. 84–87.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , с. 263–265.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Harris & Wede 1980 , с. 137–140.

- ^ Аллен 2009 , с. 15–18.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , с. 257

- ^ Робинс 1993 , с. 21–27.

- ^ Додсон 2018 , с. 19–21.

- ^ Dodson & Hilton 2004 , p. 154

- ^ Редфорд 2013 , с. 13

- ^ Ридли 2019 , с. 40–41.

- ^ Редфорд 1984 , с. 57–58.

- ^ Надежда в 2015 году , с. Полный.

- ^ Laboury 2010 , с. 81.

- ^ Murnine 1995 , p. Полем

- ^ Надежда в 2015 году , с. 64

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Aldred 1991 , p. 259

- ^ Reeves 2019 , с. 77

- ^ Берман 2004 , с. 23

- ^ Кухня 2000 , с. 44

- ^ Martín Valentín & Bedman 2014 .

- ^ Бренд 2020 , с. 63–64.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , с. 45

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Ридли 2019 , с. 46

- ^ Ридли 2019 , с. 48

- ^ Aldred 1991 , pp. 259–268.

- ^ Редфорд 2013 , с. 13–14.

- ^ Додсон 2014 , с. 156–160.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный NIMS 1973 , с. 186–187.

- ^ Редфорд 2013 , с. 19

- ^ Надежда в 2015 году , стр. 98, 101, 105-106.

- ^ Deshocks-noblecourt 1963 , стр. 144–145.

- ^ Гохари 1992 , с. 29–39, 167–169.

- ^ Murnine 1995 , стр. 50-51.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , с. 83–85.

- ^ Надежда в 2015 году , П. 166

- Murnane & Van Siclen III 2011 , с. 150

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Ридли 2019 , с. 85–87.

- ^ Foy 1960 , P. 89

- ^ Хорнунг 2001 , с. 50

- ^ Эльмар 1948 .

- ^ Ридли 2019 , с. 85

- ^ Додсон 2014 , с. 180–185.

- ^ Додсон 2014 , с. 186–188.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Ридли 2019 , с. 85–90.

- ^ Редфорд 2013 , с. 9–10, 24–26.

- ^ Aldred 1991 , pp. 269–270.

- ^ Брушеная 2001 , с. 390–400.

- ^ Арнольд 2003 , с. 238.

- ^ Шоу 2003 , с. 274

- ^ Aldred 1991 , pp. 269–273.

- ^ Shaw 2003 , с. 293–297.

- ^ Моран 1992 , стр. это, xv.

- ^ Моран 1992 , с. XVI.

- ^ Aldred 1991 , CHPT. 11

- ^ Моран 1992 , стр. 87-89.

- ^ Drioton & Vandier 1952 , стр. 411–414.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , с. 297, 314.

- ^ Моран 1992 , с.

- ^ Росс 1999 , с. 30–35.

- ^ Брайс 1998 , с. 186

- ^ Cohen & Westbrook 2002 , с. 102, 248.

- ^ Зал 1921 , с. 42–43.

- ^ Брушеная в 1909 году , с. 355.

- ^ Дэвис 1903–1908 , часть II. п. 42

- ^ Baikie 1926 , p. 269

- ^ Моран 1992 , стр. 368-369.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , с. 316–317.

- ^ Murnine 1995 , стр. 55-56.

- ^ Darnell & Manassa 2007 , стр. 118–119.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , с. 323–324.

- ^ Schulman 1982 .

- ^ Murnine 1995 , p. 99

- ^ Олдред 1968 , с. 241.

- ^ Габольде 1998 , с. 195–205.

- ^ Darnell & Manassa 2007 , стр. 172–178.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , с. 235–236, 244–247.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , с. 346.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Ван дер Перре 2012 , с. 195-197.

- ^ Van der Perre 2014 , стр. 67–108.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , с. 346–364.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Додсон 2009 , с. 39–41.

- ^ Darnell & Manassa 2007 , p. 127

- ^ Ридли 2019 , с. 141.

- ^ Редфорд 1984 , с. 185–192.

- ^ Braverman, Redford & Mackowiak 2009 , p. 557.

- ^ Додсон 2009 , с. 49

- ^ Laroche 1971 , p. 378.

- ^ Габольде 2011 .

- ^ Ридли 2019 , с. 354, 376.

- ^ Додсон 2014 , с. 144

- ^ Tyldesley 1998 , pp. 160–175.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , с. 337, 345.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , с. 252

- ^ Аллен 1988 , с. 117–126.

- ^ Kemp 2015 , с. 11

- ^ Ридли 2019 , с. 365–371.

- ^ Додсон 2014 , с. 244

- ^ Aldred 1968 , с. 140–162.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , с. 411–412.

- ^ Додсон 2009 , с. 144–145.

- ^ Аллен 2009 , с. 1–4.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , с. 251.

- ^ Tyldesley 2006 , с. 136–137.

- ^ Hornung, Krauss & Warburton 2006 , с. 207, 493.

- ^ Ридли 2019 .

- ^ Додсон 2018 , с. 75–76.

- ^ Hawass et al. 2010 , с. 644.

- ^ Marchant 2011 , с. 404–406.

- ^ Додсон 2018 , с. 16–17.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Ридли 2019 , с. 409–411.

- ^ Додсон 2018 , с. 17, 41.

- ^ Додсон 2014 , с. 245–249.

- ^ Надежда в 2015 году , стр. 241-243.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , с. 415.

- ^ Марк 2014 .

- ^ Ван Дейк 2003 , с. 303.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Assmann 2005 , p. 44

- ^ Уилкинсон 2003 , с. 55

- ^ Reeves 2019 , с. 139, 181.

- ^ Брушено 1972 , с. 344–370.

- ^ Ockinga 2001 , pp. 44-46.

- ^ Уилкинсон 2003 , с. 94

- ^ Ван Дейк 2003 , с. 307

- ^ van Dijk 2003 , стр. 303-307.

- ^ Кухня 1986 , с. 531.

- ^ Baines 2007 , p. 156

- ^ Goldwasser 1992 , с. 448–450.

- ^ Gardiner 2015 .

- ^ O'Connor & Silverman 1995 , с. 77–79.

- ^ "Друз" . Druze.de . Получено 18 января 2022 года .

- ^ Дана, LP, изд. (2010). Предпринимательство и религия . Эдвард Элгар Паб. ISBN 978-1-84980-632-9 Полем OCLC 741355693 .

- ^ Хорнунг 2001 , с. 19

- ^ Sethe 1906–1909 , с. 19, 332, 1569.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Редфорд 2013 , с. 11

- ^ HORNUNG 2001 , с. 33, 35.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Hornung 2001 , p. 48

- ^ Редфорд, 1976 , с. 53–56.

- ^ HORNUNG 2001 , с. 72–73.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , с. 43

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Дэвид 1998 , с. 125

- ^ Aldred 1991 , pp. 261–262.

- ^ Надежда в 2015 году , стр. 160-161.

- ^ Редфорд 2013 , с. 14

- ^ Perry 2019 , 03:59.

- ^ HORNUNG 2001 , с. 34–36, 54.

- ^ Hornung 2001 , с. 39, 42, 54.

- ^ HORNUNG 2001 , с. 55–57.

- ^ Bárta & Dulíková 2015 , стр. 41, 43.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , с. 188.

- ^ Hart 2000 , с. 42–46.

- ^ HORNUNG 2001 , с. 55, 84.

- ^ Najovits 2004 , p. 125

- ^ Ридли 2019 , с. 211–213.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , с. 28, 173–174.

- ^ Додсон 2009 , с. 38

- ^ Najovits 2004 , с. 123–124.

- ^ Najovits 2004 , p. 128

- ^ Хорнунг 2001 , с. 52

- ^ Ридли 2019 , с. 129, 133.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , с. 128

- ^ Najovits 2004 , p. 131.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , с. 128–129.

- ^ Хорнунг 1992 , с. 47

- ^ Аллен 2005 , с. 217–221.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , с. 187–194.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Ривз 2019 , с. 154–155.

- ^ Хорнунг 2001 , с. 56

- ^ Додсон 2018 , с. 47, 50.

- ^ Редфорд 1984 , с. 207

- ^ Silverman, Wegner & Wegner 2006 , с. 165–166.

- ^ Надежда в 2015 году , стр. 1979, 239-242.

- ^ Ван Дейк 2003 , с. 284

- ^ Надежда в 2015 году , стр. 239-242.

- ^ HORNUNG 2001 , с. 43–44.

- ^ Najovits 2004 , p. 144

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Baptista, Santamarina & Conant

- ^ Арнольд 1996 , с. VII

- ^ HORNUNG 2001 , с. 42–47.

- ^ Sooke 2016 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Takács & Cline 2015 , с. 5-6.

- ^ Braverman, Redford & Mackowiak 2009 .

- ^ Braverman & Mackowiak 2010 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и Монтсеррат 2003 .

- ^ Najovits 2004 , p. 145.

- ^ Aldred 1985 , p. 174.

- ^ Арнольд 1996 , с. 114

- ^ Хорнунг 2001 , с. 44

- ^ Najovits 2004 , с. 146–147.

- ^ Арнольд 1996 , с. 85

- ^ Арнольд 1996 , с. 85–86.

- ^ Монтсеррат 2003 , с. 36

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Фрейд 1939 .

- ^ Stent 2002 , с. 34–38.

- ^ Assmann 1997 .

- ^ Шупак 1995 .

- ^ Олбрайт 1973 .

- ^ Chaney 2006a , с. 62–69.

- ^ Chaney 2006b .

- ^ Assmann 1997 , с. 23–24.

- ^ Hoffmeier 2015 , стр. 246–256 : «... кажется, что лучше всего сделать вывод, что« параллели »между гимнами Амарны с Атеном и Псалом 104 должны быть связаны с« общим богословием »и« общим шаблоном » ... ";

Hoffmeier 2005 , p. 239 : «... произошли некоторые дискуссии, прямые сходства или косвенные заимствования ... маловероятно, что« израильтянин, который сочинил Псалом 104, заимствовал непосредственно из возвышенного египетского гимна в Атене », как только авторов утверждается. ";

Альтер 2018 , с. 54 : «... Я думаю, что может быть некоторая вероятность, какая бы недоступная, что наш псалмопевец был знаком, по крайней мере, с промежуточной версией гимна Ахнатона и принял из него некоторые элементы»;

Браун 2014 , с. 61–73 » : «Вопрос о отношениях между египетскими гимнами и псалмами остается открытым

- ^ Assmann 2020 , стр. 40 - 43 : «Стихи 20–30 не могут быть поняты как что -либо, кроме свободного и сокращенного перевода« Великого гимна »: ...»;

День 2014 , стр. 22–23 : «... значительная часть остальной части Псалма 104 (особенно. Все приходят в одном порядке: ... ";

День 2013 , стр. 223 –224: «... эта зависимость ограничена VV. 20–30. Здесь доказательства особенно впечатляют, поскольку у нас шесть параллелей с гимном Ахнатена ... встречающимися в идентичном порядке, с одним исключение.";

Landes 2011 , с. 155 , 178 : «Гимн Атена, цитируемый как эпиграф в этой главе, - пересматривает интенсивную религиозность и даже язык еврейского псалма 104. Действительно, большинство египтологов утверждают, что этот гимн вдохновил псалом ...» , «... для некоторых отношений с гебраическим монотеизмом кажется чрезвычайно близкой, включая почти дословные отрывки в Псалме 104 и« Гимн на Атене », найденные в одной из гробниц в Акетатене ...»;

Shaw 2004 , p. 19 : «Интригующая прямая литературная (и, возможно, религиозная) связь между Египтом и Библией - Псалом 104, которая имеет сильное сходство с гимном с Атеном»

- ^ Редфорд 1987 .

- ^ Levenson 1994 , p. 60

- ^ Хорнунг 2001 , с. 14

- ^ Redford, Shanks & Meinhardt 1997 .

- ^ Ридли 2019 , с. 87

- ^ Олдред 1991 .

- ^ Смит, 1923 , с. 83–88.

- ^ Strachey 1939 .

- ^ Hawass 2010 .

- ^ Барридж 1995 .

- ^ Лоренц 2010 .

- ^ Национальный центр по продвижению трансляционных наук 2017 .

- ^ Схема 2010 .

- ^ Монтсеррат 2003 , с. 139

- ^ Монтсеррат 2003 , с. 144

- ^ Монтсеррат 2003 , с. 154

- ^ Монтсеррат 2003 , стр. 163, 200–212.

- ^ Монтсеррат 2003 , стр. 168, 170.

- ^ Монтсеррат 2003 , стр. 175–176.

- ^ Дэвидсон 2019 .

- ^ Монтсеррат 2003 , с. 176

- ^ Glass, Philip (1987) Музыка Philip Glass New York: Harper & Row. с.137-138. ISBN 0-06-015823-9

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Marvel 2021 .

- ^ Хоттон 2018 .

Библиография

- "Ахнатен" . Dictionary.com . Архивировано из оригинала 14 октября 2008 года . Получено 2 октября 2008 года .

- Дорман, Петр Ф. "Ахенатон (король Египта)" . Britannica.com . Получено 25 августа 2012 года .

- Олбрайт, Уильям Ф. (1973). «От патриархов до Моисея II. Моисей из Египта». Библейский археолог . 36 (2): 48–76. doi : 10.2307/3211050 . JSTOR 3211050 . S2CID 135099403 .

- Олдред, Кирилл (1968). Ахнатен, фараон Египта: новое исследование . Новые аспекты древности (1 -е изд.). Лондон: Темза и Хадсон. ISBN 978-0500390047 .

- Aldred, Cyril (1985) [1980]. Египетское искусство во времена фараонов 3100–32 до н.э. Мир искусства. Лондон; Нью -Йорк: Темза и Хадсон. ISBN 0-500-20180-3 Полем LCCN 84-51309 .

- Aldred, Cyril (1991) [1988]. Ахнатен, король Египта . Лондон: Темза и Хадсон. ISBN 0500276218 .

- Аллен, Джеймс Питер (1988). «Две измененные надписи последнего периода Амарны» . Журнал Американского исследовательского центра в Египте . 25 Сан -Антонио, Техас: Американский исследовательский центр в Египте: 117–126. doi : 10.2307/40000874 . ISSN 0065-9991 . JSTOR 40000874 .

- Аллен, Джеймс П. (2005). "Ахенатон". В Джонс, L (ред.). Энциклопедия религии Macmillan ссылка.