Эхнатон

| |

|---|---|

| Аменофис IV, Нафурурея, Эхнатон [1] [2] | |

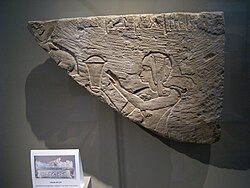

Статуя Эхнатона в Египетском музее | |

| фараон | |

| Царствование | |

| Предшественник | Аменхотеп III |

| Преемник | Smenkhkare |

| Супруги |

|

| Дети | |

| Отец | Аменхотеп III |

| Мать | Убийство |

| Умер | 1336 или 1334 г. до н.э. |

| Похороны |

|

| Памятники | Ахетатон , Гемпаатен |

| Религия | |

| Династия | 18-я династия Египта |

Эхнатон (произносится / ˌ æ k ə ˈ n ɑː t ən / ), [8] также пишется Эхнатон [3] [9] [10] или Эхнатон [11] ( Древний Египет : ꜣḫ-n-jtn ʾŪḫə-nə-yātəy , произносится [ˈʔuːχəʔ nə ˈjaːtəj] , [12] [13] что означает «Действительный для Атона »), древнеегипетский фараон , правивший ок. 1353–1336 гг. [3] или 1351–1334 гг. до н.э., [4] десятый правитель Восемнадцатой династии . До пятого года своего правления он был известен как Аменхотеп IV (древнеегипетское: jmn-ḥtp , что означает « Амон доволен», эллинизированное как Аменофис IV ).

Будучи фараоном, Эхнатон известен тем, что отказался от традиционной религии политеизма древнеегипетской и ввёл атенизм , или поклонение, сосредоточенное вокруг Атона . Мнения египтологов относительно того, была ли религиозная политика абсолютно монотеистической или монолатристичной , синкретической или генотеистической , расходятся . [14] [15] Этот культурный отход от традиционной религии был обращен вспять после его смерти. Памятники Эхнатона были разобраны и спрятаны, его статуи уничтожены, а его имя исключено из списков правителей, составленных более поздними фараонами. [16] Традиционная религиозная практика была постепенно восстановлена, особенно при его близком преемнике Тутанхамоне , который сменил свое имя с Тутанхатен в начале своего правления. [17] Когда несколько десятков лет спустя правители Восемнадцатой династии, не имевшие явных прав наследования, основали новую династию , они дискредитировали Эхнатона и его непосредственных преемников и в архивных записях называли Эхнатона «врагом» или «этим преступником». [18] [19]

Эхнатон был практически потерян для истории до тех пор, пока в конце XIX века не была открыта Амарна , или Ахетатон, новая столица, которую он построил для поклонения Атону. [20] мумию, которая могла принадлежать Эхнатону в гробнице KV55 в Долине царей обнаружил Кроме того, в 1907 году Эдвард Р. Айртон . Генетическое тестирование показало, что мужчина, похороненный в КВ55, был отцом Тутанхамона. [21] но его идентификация как Эхнатона с тех пор подвергается сомнению. [6] [7] [22] [23] [24]

Повторное открытие Эхнатона и ранние раскопки Флиндерса Петри в Амарне вызвали большой общественный интерес к фараону и его царице Нефертити . Его описывали как «загадочного», «таинственного», «революционного», «величайшего идеалиста мира» и «первого человека в истории», но также как «еретика», «фанатика», «возможно, безумного». ", и "безумный". [14] [25] [26] [27] [28] Общественное и научное увлечение Эхнатоном проистекает из его связи с Тутанхамоном, уникального стиля и высокого качества изобразительного искусства, которому он покровительствовал , а также религии, которую он пытался установить, предвещая монотеизм.

Семья

Будущий Эхнатон родился Аменхотепом, младшим сыном фараона Аменхотепа III и его главной жены Тии . У Эхнатона был старший брат, наследный принц Тутмос , признанный наследником Аменхотепа III. У Эхнатона также было четыре или пять сестер: Ситамун , Хенуттанеб , Исет , Небета и, возможно, Бекетатон . [29] Ранняя смерть Тутмоса, возможно, примерно на тридцатом году правления Аменхотепа III, означала, что Эхнатон стал следующим претендентом на египетский трон. [30]

Эхнатон был женат на Нефертити , своей великой царственной жене . Точное время их свадьбы неизвестно, но надписи на строительных проектах фараона позволяют предположить, что они поженились либо незадолго до, либо после того, как Эхнатон занял трон. [10] Например, египтолог Дмитрий Лабори предполагает, что брак состоялся в четвертый год правления Эхнатона. [31] второстепенная жена Эхнатона по имени Кия Из надписей известна также . Некоторые египтологи предполагают, что она приобрела свое значение как мать Тутанхамона . [32] Уильям Мурнейн предполагает, что Кия — это разговорное имя митаннийской принцессы Тадукхипы , дочери митаннийского царя Тушратты , которая вышла замуж за Аменхотепа III, прежде чем стать женой Эхнатона. [33] [34] Другие засвидетельствованные супруги Эхнатона — дочь правителя Шатия Энишаси и еще одна дочь вавилонского царя Бурна-Буриаша II . [35]

Судя по надписям, у Эхнатона могло быть семь или восемь детей. Египтологи вполне уверены в отношении его шести дочерей, которые хорошо засвидетельствованы на современных изображениях. [36] Среди его шести дочерей Меритатен родилась в первый или пятый год правления; Мекетатен в четвертый или шестой год; Анхесенпаатен , позже царица Тутанхамона, до пятого или восьмого года; Нефернефруатен Ташерит в восьмом или девятом году; Нефернеферура в девятом или десятом году; и Сетепенре в десятом или одиннадцатом классе. [37] [38] [39] [40] Тутанхамон, урожденный Тутанхатен, скорее всего, был сыном Эхнатона от Нефертити или другой жены. [41] [42] Меньше определенности относительно отношений Эхнатона со Сменхкаре , соправителем или преемником Эхнатона. [43] и муж его дочери Меритатен; он мог быть старшим сыном Эхнатона от неизвестной жены или младшим братом Эхнатона. [44] [45]

Некоторые историки, такие как Эдвард Венте и Джеймс Аллен , предположили, что Эхнатон взял некоторых из своих дочерей в жены или сексуальные супруги, чтобы стать отцом наследника мужского пола. [46] [47] Хотя этот вопрос обсуждается, существуют некоторые исторические параллели: отец Эхнатона Аменхотеп III женился на его дочери Ситамун, а Рамсес II женился на двух или более своих дочерях, хотя их браки могли быть просто церемониальными. [48] [49] В случае Эхнатона его старшая дочь Меритатон записана как Великая королевская жена Сменхкара, но также указана на ящике из гробницы Тутанхамона рядом с фараонами Эхнатоном и Нефернеферуатоном как Великая королевская жена. Кроме того, в письмах, написанных Эхнатону от иностранных правителей, Меритатон упоминается как «хозяйка дома». Египтологи начала 20 века также считали, что Эхнатон мог быть отцом ребенка от своей второй старшей дочери Мекетатона. Смерть Мекетатона, возможно, в возрасте от десяти до двенадцати лет, записана в царских гробницах в Ахетатоне примерно с тринадцатого или четырнадцатого года правления. Ранние египтологи связывают ее смерть с родами из-за изображения младенца в ее гробнице. Поскольку муж Мекетатона неизвестен, предполагалось, что отцом был Эхнатон. Эйдан Додсон считает, что это маловероятно, поскольку не было найдено ни одной египетской гробницы, в которой упоминалась бы или намекала на причина смерти владельца гробницы. Далее Якобус ван Дейк предполагает, что ребенок является изображением Мекетатона. душа . [50] Наконец, различные памятники, первоначально посвященные Кии, были переписаны в честь дочерей Эхнатона Меритатен и Анхесенпаатен. В исправленных надписях перечислены Меритатен-ташерит («младший») и Анхесенпаатен-ташерит. По мнению некоторых, это указывает на то, что у Эхнатона были собственные внуки. Другие считают, что, поскольку эти внуки нигде не засвидетельствованы, это выдумки, придуманные для того, чтобы заполнить пространство, первоначально изображающее ребенка Кии. [46] [51]

Ранний период жизни

Египтологам очень мало известно о жизни Эхнатона как принца Аменхотепа. Дональд Б. Редфорд датирует свое рождение до 25-го года правления своего отца Аменхотепа III, ок. 1363–1361 гг. до н. э. , основано на рождении первой дочери Эхнатона, которая, вероятно, родилась довольно рано во время его правления. [4] [52] Единственное упоминание о его имени как «Царском сыне Аменхотепе» было найдено на винном ящике во дворце Аменхотепа III в Малкате , где некоторые историки предполагают, что родился Эхнатон. Другие утверждают, что он родился в Мемфисе , где в детстве находился под влиянием поклонения богу Солнца Ра, практиковавшемуся в соседнем Гелиополе . [53] Однако Редфорд и Джеймс К. Хоффмайер утверждают, что культ Ра был настолько широко распространен и утвердился по всему Египту, что на Эхнатона могло повлиять поклонение Солнцу, даже если он вырос не в окрестностях Гелиополя. [54] [55]

Некоторые историки пытались определить, кто был наставником Эхнатона в юности, и предлагали писцов Гекарешу или Мериру II , царского наставника Аменемотепа или визиря Апереля . [56] Единственным человеком, который, как мы знаем наверняка, служил принцу, был Пареннефер которого , в могиле упоминается об этом факте. [57]

Египтолог Сирил Олдред предполагает, что принц Аменхотеп мог быть первосвященником Птаха в Мемфисе, хотя никаких доказательств, подтверждающих это, обнаружено не было. [58] Известно, что в этой роли до своей смерти служил брат Аменхотепа, наследный принц Тутмос . Если бы Аменхотеп унаследовал все роли своего брата при подготовке к восшествию на престол, он мог бы стать первосвященником вместо Тутмоса. Олдред предполагает, что необычные художественные наклонности Эхнатона могли сформироваться во время его службы Птаху , богу-покровителю ремесленников, чьи первосвященники иногда назывались «Величайшими из руководителей мастерства». [59]

Царствование

Соперничество с Аменхотепом III

Существует много споров вокруг того, взошел ли Аменхотеп IV на трон Египта после смерти своего отца Аменхотепа III или существовало соправительство , продолжавшееся, возможно, целых 12 лет. Эрик Клайн , Николас Ривз , Питер Дорман и другие ученые решительно выступают против установления длительного совместного правления между двумя правителями и за то, чтобы либо не было совместного правления, либо оно продолжалось не более двух лет. [60] Дональд Б. Редфорд , Уильям Дж. Мурнейн , Алан Гардинер и Лоуренс Берман оспаривают точку зрения о каком-либо сосуществовании между Эхнатоном и его отцом. [61] [62]

Совсем недавно, в 2014 году, археологи обнаружили имена обоих фараонов, начертанные на стене луксорской гробницы визиря Аменхотепа-Хая . лет . На основании датировки гробницы Министерство древностей Египта назвало это «убедительным доказательством» того, что Эхнатон делил власть со своим отцом в течение как минимум восьми [63] Однако этот вывод с тех пор был поставлен под сомнение другими египтологами, по мнению которых надпись означает лишь то, что строительство гробницы Аменхотепа-Хая началось во время правления Аменхотепа III и закончилось при Эхнатоне, и таким образом Аменхотеп-Хай просто хотел выразить свое почтение оба правителя. [64]

Раннее правление Аменхотепа IV.

Эхнатон занял египетский трон как Аменхотеп IV, скорее всего, в 1353 году. [65] или 1351 г. до н.э. [4] Неизвестно, сколько лет было Аменхотепу IV, когда он это сделал; оценки варьируются от 10 до 23. [66] Скорее всего, он был коронован в Фивах или, что менее вероятно, в Мемфисе или Арманте . [66]

Начало правления Аменхотепа IV соответствовало устоявшимся традициям фараонов. Он не сразу стал перенаправлять поклонение Атону и дистанцироваться от других богов. Египтолог Дональд Б. Редфорд считает, что это подразумевает, что возможная религиозная политика Аменхотепа IV не была задумана до его правления, и он не следовал заранее установленному плану или программе. Редфорд указывает на три доказательства, подтверждающие это. Во-первых, сохранившиеся надписи показывают, что Аменхотеп IV поклонялся нескольким различным богам, включая Атума , Осириса , Анубиса , Нехбет , Хатор , [67] и Глаз Ра , и тексты этой эпохи относятся к «богам» и «каждому богу и каждой богине». Верховный жрец Амона также все еще действовал на четвертом году правления Аменхотепа IV. [68] Во-вторых, хотя позже он перенес свою столицу из Фив в Ахетатон , его первоначальный царский титул был в честь Фив — его именем был «Аменхотеп, бог-правитель Фив» — и, признавая его важность, он назвал город «Южным Гелиополем, первым великим (место) Ре (или) Диска». В-третьих, Аменхотеп IV еще не разрушал храмы другим богам и даже продолжил строительные проекты своего отца в Карнакском округе Амон-Ра . [69] участка он украсил Стены Третьего пилона изображениями себя, поклоняющегося Ра-Хорахти , изображенного в традиционной для бога форме человека с головой сокола. [70]

Художественные изображения оставались неизменными в начале правления Аменхотепа IV. Гробницы, построенные или завершенные в первые несколько лет после того, как он занял трон, например, гробницы Херуефа , Рамоса и Пареннефера , изображают фараона в традиционном художественном стиле. [71] В гробнице Рамоса на западной стене появляется Аменхотеп IV, сидящий на троне, а Рамос предстает перед фараоном. По другую сторону дверного проема в окне явлений показаны Аменхотеп IV и Нефертити, а Атон изображен в виде солнечного диска. В гробнице Пареннефера Аменхотеп IV и Нефертити восседают на троне с солнечным диском, изображенным над фараоном и его царицей. [71]

Продолжая поклонение другим богам, первоначальная программа строительства Аменхотепа IV была направлена на строительство новых мест поклонения Атону. Он приказал построить храмы или святилища Атону в нескольких городах по всей стране, таких как Бубастис , Телль-эль-Борг , Гелиополис , Мемфис, Нехен , Кава и Керма . [72] Он также приказал построить большой храмовый комплекс, посвященный Атону, в Карнаке в Фивах, к северо-востоку от частей Карнакского комплекса, посвященных Амону. Храмовый комплекс Атона , известный под общим названием Пер Атен («Дом Атона»), состоял из нескольких храмов, названия которых сохранились: Гемпаатен («Атон находится в поместье Атона»), Хвт Бенбен («Атон находится в поместье Атона»), Хвт Бенбен («Атон находится в поместье Атона»). Дом или Храм Бенбена » ), Руд-Мену («Непреходящие памятники Атону навеки»), Тени-Мену («Возвышены памятники Атона навеки») и Сехен Атон («киоск Атона "). [73]

Примерно на второй или третий год правления Аменхотеп IV организовал фестиваль Сед . Фестивали Сед представляли собой ритуальное омоложение стареющего фараона, которое обычно проводилось впервые примерно на тридцатом году правления фараона и после этого примерно каждые три года. Египтологи только предполагают, почему Аменхотеп IV организовал фестиваль Сед, когда ему, вероятно, было еще около двадцати лет. Некоторые историки рассматривают это как свидетельство сосуществования Аменхотепа III и Аменхотепа IV и полагают, что фестиваль Сед Аменхотепа IV совпал с одним из праздников его отца. Другие предполагают, что Аменхотеп IV решил провести свой фестиваль через три года после смерти своего отца, стремясь провозгласить свое правление продолжением правления отца. Третьи полагают, что фестиваль проводился в честь Атона, от имени которого фараон правил Египтом, или, поскольку считалось, что Аменхотеп III стал единым целым с Атоном после своей смерти, фестиваль Сед чествовал и фараона, и бога в в то же время. Не исключено также, что целью церемонии было образно наполнить Аменхотепа IV силами перед его великим предприятием: введением культа Атона и основанием новой столицы Ахетатона. Независимо от цели празднования, египтологи полагают, что во время празднеств Аменхотеп IV приносил подношения только Атону, а не многочисленным богам и богиням, как это было принято. [59] [74] [75]

Изменение имени

есть две копии письма фараону от Ипи , верховного управляющего Мемфиса Среди последних документов, в которых Эхнатон упоминается как Аменхотеп IV , . Эти письма, найденные в Гуробе и сообщающие фараону, что царские поместья в Мемфисе «в хорошем состоянии», а храм Птаха «процветает и процветает», датированы пятым годом правления, девятнадцатым днем вегетационного периода третьего месяца . вегетационного периода Примерно месяц спустя, на тринадцатый день четвертого месяца , на одной из пограничных стел в Ахетатоне уже было вырезано имя Эхнатона, подразумевающее, что фараон изменил свое имя между двумя надписями. [76] [77] [78] [79]

Аменхотеп IV изменил свой царский титул , чтобы показать свою преданность Атону. Он больше не будет известен как Аменхотеп IV и будет ассоциироваться с богом Амоном , а скорее полностью переключит свое внимание на Атона. Египтологи спорят о точном значении Эхнатона, его нового личного имени . Слово «ах» ( древнеегипетский : ꜣḫ ) могло иметь разные переводы, например, «удовлетворенный», «эффективный дух» или «пригодный для использования», и, таким образом, имя Эхнатона можно было перевести как «Атон удовлетворен», «эффективный». дух Атона» или «Служащий Атону» соответственно. [80] Герти Инглунд и Флоренс Фридман пришли к переводу «Эффективен для Атона», анализируя современные тексты и надписи, в которых Эхнатон часто описывал себя как «эффективный для» солнечного диска. Энглунд и Фридман приходят к выводу, что частота, с которой Эхнатон использовал этот термин, вероятно, означает, что его собственное имя означало «Действительный для Атона». [80]

Some historians, such as William F. Albright, Edel Elmar, and Gerhard Fecht, propose that Akhenaten's name is misspelled and mispronounced. These historians believe "Aten" should rather be "Jāti", thus rendering the pharaoh's name Akhenjāti or Aḫanjāti (pronounced /ˌækəˈnjɑːtɪ/), as it could have been pronounced in Ancient Egypt.[81][82][83]

| Amenhotep IV | Akhenaten | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Horus name |

Kanakht-qai-Shuti "Strong Bull of the Double Plumes" |

Meryaten "Beloved of Aten" | |||||||||||||||||||

| Nebty name |

Wer-nesut-em-Ipet-swt "Great of Kingship in Karnak" |

Wer-nesut-em-Akhetaten "Great of Kingship in Akhet-Aten" | |||||||||||||||||||

| Golden Horus name |

Wetjes-khau-em-Iunu-Shemay "Crowned in Heliopolis of the South" (Thebes) |

Wetjes-ren-en-Aten "Exalter of the Name of Aten" | |||||||||||||||||||

| Prenomen |

Neferkheperure-waenre "Beautiful are the Forms of Re, the Unique one of Re" | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Nomen |

Amenhotep Netjer-Heqa-Waset "Amun is Satisfied, Divine Lord of Thebes" |

Akhenaten "Effective for the Aten" | |||||||||||||||||||

Founding Amarna

Around the same time he changed his royal titulary, on the thirteenth day of the growing season's fourth month, Akhenaten decreed that a new capital city be built: Akhetaten (Ancient Egyptian: ꜣḫt-jtn, meaning "Horizon of the Aten"), better known today as Amarna. The events Egyptologists know the most about during Akhenaten's life are connected with founding Akhetaten, as several so-called boundary stelae were found around the city to mark its boundary.[84] The pharaoh chose a site about halfway between Thebes, the capital at the time, and Memphis, on the east bank of the Nile, where a wadi and a natural dip in the surrounding cliffs form a silhouette similar to the "horizon" hieroglyph. Additionally, the site had previously been uninhabited. According to inscriptions on one boundary stela, the site was appropriate for Aten's city for "not being the property of a god, nor being the property of a goddess, nor being the property of a ruler, nor being the property of a female ruler, nor being the property of any people able to lay claim to it."[85]

Historians do not know for certain why Akhenaten established a new capital and left Thebes, the old capital. The boundary stelae detailing Akhetaten's founding is damaged where it likely explained the pharaoh's motives for the move. Surviving parts claim what happened to Akhenaten was "worse than those that I heard" previously in his reign and worse than those "heard by any kings who assumed the White Crown", and alludes to "offensive" speech against the Aten. Egyptologists believe that Akhenaten could be referring to conflict with the priesthood and followers of Amun, the patron god of Thebes. The great temples of Amun, such as Karnak, were all located in Thebes and the priests there achieved significant power earlier in the Eighteenth Dynasty, especially under Hatshepsut and Thutmose III, thanks to pharaohs offering large amounts of Egypt's growing wealth to the cult of Amun; historians, such as Donald B. Redford, therefore posited that by moving to a new capital, Akhenaten may have been trying to break with Amun's priests and the god.[86][87][88]

Akhetaten was a planned city with the Great Temple of the Aten, Small Aten Temple, royal residences, records office, and government buildings in the city center. Some of these buildings, such as the Aten temples, were ordered to be built by Akhenaten on the boundary stela decreeing the city's founding.[87][89][90]

The city was built quickly, thanks to a new construction method that used substantially smaller building blocks than under previous pharaohs. These blocks, called talatats, measured 1⁄2 by 1⁄2 by 1 ancient Egyptian cubits (c. 27 by 27 by 54 cm), and because of the smaller weight and standardized size, using them during constructions was more efficient than using heavy building blocks of varying sizes.[91][92] By regnal year eight, Akhetaten reached a state where it could be occupied by the royal family. Only his most loyal subjects followed Akhenaten and his family to the new city. While the city continued to be built, in years five through eight, construction work began to stop in Thebes. The Theban Aten temples that had begun were abandoned, and a village of those working on Valley of the Kings tombs was relocated to the workers' village at Akhetaten. However, construction work continued in the rest of the country, as larger cult centers, such as Heliopolis and Memphis, also had temples built for Aten.[93][94]

International relations

The Amarna letters have provided important evidence about Akhenaten's reign and foreign policy. The letters are a cache of 382 diplomatic texts and literary and educational materials discovered between 1887 and 1979,[95] and named after Amarna, the modern name for Akhenaten's capital Akhetaten. The diplomatic correspondence comprises clay tablet messages between Amenhotep III, Akhenaten, and Tutankhamun, various subjects through Egyptian military outposts, rulers of vassal states, and the foreign rulers of Babylonia, Assyria, Syria, Canaan, Alashiya, Arzawa, Mitanni, and the Hittites.[96]

The Amarna letters portray the international situation in the Eastern Mediterranean that Akhenaten inherited from his predecessors. In the 200 years preceding Akhenaten's reign, following the expulsion of the Hyksos from Lower Egypt at the end of the Second Intermediate Period, the kingdom's influence and military might increased greatly. Egypt's power reached new heights under Thutmose III, who ruled approximately 100 years before Akhenaten and led several successful military campaigns into Nubia and Syria. Egypt's expansion led to confrontation with the Mitanni, but this rivalry ended with the two nations becoming allies. Slowly, however, Egypt's power started to wane. Amenhotep III aimed to maintain the balance of power through marriages—such as his marriage to Tadukhipa, daughter of the Mitanni king Tushratta—and vassal states. Under Amenhotep III and Akhenaten, Egypt was unable or unwilling to oppose the rise of the Hittites around Syria. The pharaohs seemed to eschew military confrontation at a time when the balance of power between Egypt's neighbors and rivals was shifting, and the Hittites, a confrontational state, overtook the Mitanni in influence.[97][98][99][100]

Early in his reign, Akhenaten was evidently concerned about the expanding power of the Hittite Empire under Šuppiluliuma I. A successful Hittite attack on Mitanni and its ruler Tushratta would have disrupted the entire international balance of power in the Ancient Middle East at a time when Egypt had made peace with Mitanni; this would cause some of Egypt's vassals to switch their allegiances to the Hittites, as time would prove. A group of Egypt's allies who attempted to rebel against the Hittites were captured, and wrote letters begging Akhenaten for troops, but he did not respond to most of their pleas. Evidence suggests that the troubles on the northern frontier led to difficulties in Canaan, particularly in a struggle for power between Labaya of Shechem and Abdi-Heba of Jerusalem, which required the pharaoh to intervene in the area by dispatching Medjay troops northwards. Akhenaten pointedly refused to save his vassal Rib-Hadda of Byblos—whose kingdom was being besieged by the expanding state of Amurru under Abdi-Ashirta and later Aziru, son of Abdi-Ashirta—despite Rib-Hadda's numerous pleas for help from the pharaoh. Rib-Hadda wrote a total of 60 letters to Akhenaten pleading for aid from the pharaoh. Akhenaten wearied of Rib-Hadda's constant correspondences and once told Rib-Hadda: "You are the one that writes to me more than all the (other) mayors" or Egyptian vassals in EA 124.[101] What Rib-Hadda did not comprehend was that the Egyptian king would not organize and dispatch an entire army north just to preserve the political status quo of several minor city states on the fringes of Egypt's Asiatic Empire.[102] Rib-Hadda would pay the ultimate price; his exile from Byblos due to a coup led by his brother Ilirabih is mentioned in one letter. When Rib-Hadda appealed in vain for aid from Akhenaten and then turned to Aziru, his sworn enemy, to place him back on the throne of his city, Aziru promptly had him dispatched to the king of Sidon, where Rib-Hadda was almost certainly executed.[103]

In a view discounted by the 21st century,[104] several Egyptologists in the late 19th and 20th centuries interpreted the Amarna letters to mean that Akhenaten was a pacifist who neglected foreign policy and Egypt's foreign territories in favor of his internal reforms. For example, Henry Hall believed Akhenaten "succeeded by his obstinate doctrinaire love of peace in causing far more misery in his world than half a dozen elderly militarists could have done,"[105] while James Henry Breasted said Akhenaten "was not fit to cope with a situation demanding an aggressive man of affairs and a skilled military leader."[106] Others noted that the Amarna letters counter the conventional view that Akhenaten neglected Egypt's foreign territories in favour of his internal reforms. For instance, Norman de Garis Davies praised Akhenaten's emphasis on diplomacy over war, while James Baikie said that the fact "that there is no evidence of revolt within the borders of Egypt itself during the whole reign is surely ample proof that there was no such abandonment of his royal duties on the part of Akhenaten as has been assumed."[107][108] Indeed, several letters from Egyptian vassals notified the pharaoh that they have followed his instructions, implying that the pharaoh sent such instructions.[109] The Amarna letters also show that vassal states were told repeatedly to expect the arrival of the Egyptian military on their lands, and provide evidence that these troops were dispatched and arrived at their destination. Dozens of letters detail that Akhenaten—and Amenhotep III—sent Egyptian and Nubian troops, armies, archers, chariots, horses, and ships.[110]

Only one military campaign is known for certain under Akhenaten's reign. In his second or twelfth year,[111] Akhenaten ordered his Viceroy of Kush Tuthmose to lead a military expedition to quell a rebellion and raids on settlements on the Nile by Nubian nomadic tribes. The victory was commemorated on two stelae, one discovered at Amada and another at Buhen. Egyptologists differ on the size of the campaign: Wolfgang Helck considered it a small-scale police operation, while Alan Schulman considered it a "war of major proportions".[112][113][114]

Other Egyptologists suggested that Akhenaten could have waged war in Syria or the Levant, possibly against the Hittites. Cyril Aldred, based on Amarna letters describing Egyptian troop movements, proposed that Akhenaten launched an unsuccessful war around the city of Gezer, while Marc Gabolde argued for an unsuccessful campaign around Kadesh. Either of these could be the campaign referred to on Tutankhamun's Restoration Stela: "if an army was sent to Djahy [southern Canaan and Syria] to broaden the boundaries of Egypt, no success of their cause came to pass."[115][116][117] John Coleman Darnell and Colleen Manassa also argued that Akhenaten fought with the Hittites for control of Kadesh, but was unsuccessful; the city was not recaptured until 60–70 years later, under Seti I.[118]

Overall, archeological evidence suggests that Akhenaten paid close attention to the affairs of Egyptian vassals in Canaan and Syria, though primarily not through letters such as those found at Amarna but through reports from government officials and agents. Akhenaten managed to preserve Egypt's control over the core of its Near Eastern Empire (which consisted of present-day Israel as well as the Phoenician coast) while avoiding conflict with the increasingly powerful and aggressive Hittite Empire of Šuppiluliuma I, which overtook the Mitanni as the dominant power in the northern part of the region. Only the Egyptian border province of Amurru in Syria around the Orontes River was lost to the Hittites when its ruler Aziru defected to the Hittites; ordered by Akhenaten to come to Egypt, Aziru was released after promising to stay loyal to the pharaoh, nonetheless turning to the Hittites soon after his release.[119]

Later years

Egyptologists know little about the last five years of Akhenaten's reign, beginning in c. 1341[3] or 1339 BC.[4] These years are poorly attested and only a few pieces of contemporary evidence survive; the lack of clarity makes reconstructing the latter part of the pharaoh's reign "a daunting task" and a controversial and contested topic of discussion among Egyptologists.[120]

Among the newest pieces of evidence is an inscription discovered in 2012 at a limestone quarry in Deir el-Bersha, just north of Akhetaten, from the pharaoh's sixteenth regnal year. The text refers to a building project in Amarna and establishes that Akhenaten and Nefertiti were still a royal couple just a year before Akhenaten's death.[121][122][123] The inscription is dated to Year 16, month 3 of Akhet, day 15 of the reign of Akhenaten.[121]

Before the 2012 discovery of the Deir el-Bersha inscription, the last known fixed-date event in Akhenaten's reign was a royal reception in regnal year twelve, in which the pharaoh and the royal family received tributes and offerings from allied countries and vassal states at Akhetaten. Inscriptions show tributes from Nubia, the Land of Punt, Syria, the Kingdom of Hattusa, the islands in the Mediterranean Sea, and Libya. Egyptologists, such as Aidan Dodson, consider this year twelve celebration to be the zenith of Akhenaten's reign.[124] Thanks to reliefs in the tomb of courtier Meryre II, historians know that the royal family, Akhenaten, Nefertiti, and their six daughters, were present at the royal reception in full.[124] However, historians are uncertain about the reasons for the reception. Possibilities include the celebration of the marriage of future pharaoh Ay to Tey, celebration of Akhenaten's twelve years on the throne, the summons of king Aziru of Amurru to Egypt, a military victory at Sumur in the Levant, a successful military campaign in Nubia,[125] Nefertiti's ascendancy to the throne as coregent, or the completion of the new capital city Akhetaten.[126]

Following year twelve, Donald B. Redford and other Egyptologists proposed that Egypt was struck by an epidemic, most likely a plague.[127] Contemporary evidence suggests that a plague ravaged through the Middle East around this time,[128] and ambassadors and delegations arriving to Akhenaten's year twelve reception might have brought the disease to Egypt.[129] Alternatively, letters from the Hattians might suggest that the epidemic originated in Egypt and was carried throughout the Middle East by Egyptian prisoners of war.[130] Regardless of its origin, the epidemic might account for several deaths in the royal family that occurred in the last five years of Akhenaten's reign, including those of his daughters Meketaten, Neferneferure, and Setepenre.[131][132]

Coregency with Smenkhkare or Nefertiti

Akhenaten could have ruled together with Smenkhkare and Nefertiti for several years before his death.[133][134] Based on depictions and artifacts from the tombs of Meryre II and Tutankhamun, Smenkhkare could have been Akhenaten's coregent by regnal year thirteen or fourteen, but died a year or two later. Nefertiti might not have assumed the role of coregent until after year sixteen, when a stela still mentions her as Akhenaten's Great Royal Wife. While Nefertiti's familial relationship with Akhenaten is known, whether Akhenaten and Smenkhkare were related by blood is unclear. Smenkhkare could have been Akhenaten's son or brother, as the son of Amenhotep III with Tiye or Sitamun.[135] Archaeological evidence makes it clear, however, that Smenkhkare was married to Meritaten, Akhenaten's eldest daughter.[136] For another, the so-called Coregency Stela, found in a tomb at Akhetaten, might show queen Nefertiti as Akhenaten's coregent, but this is uncertain as the stela was recarved to show the names of Ankhesenpaaten and Neferneferuaten.[137] Egyptologist Aidan Dodson proposed that both Smenkhkare and Neferiti were Akhenaten's coregents to ensure the Amarna family's continued rule when Egypt was confronted with an epidemic. Dodson suggested that the two were chosen to rule as Tutankhaten's coregent in case Akhenaten died and Tutankhaten took the throne at a young age, or rule in Tutankhaten's stead if the prince also died in the epidemic.[43]

Death and burial

Akhenaten died after seventeen years of rule and was initially buried in a tomb in the Royal Wadi east of Akhetaten. The order to construct the tomb and to bury the pharaoh there was commemorated on one of the boundary stela delineating the capital's borders: "Let a tomb be made for me in the eastern mountain [of Akhetaten]. Let my burial be made in it, in the millions of jubilees which the Aten, my father, decreed for me."[138] In the years following the burial, Akhenaten's sarcophagus was destroyed and left in the Akhetaten necropolis; reconstructed in the 20th century, it is in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo as of 2019.[139] Despite leaving the sarcophagus behind, Akhenaten's mummy was removed from the royal tombs after Tutankhamun abandoned Akhetaten and returned to Thebes. It was most likely moved to tomb KV55 in Valley of the Kings near Thebes.[140][141] This tomb was later desecrated, likely during the Ramesside period.[142][143]

Whether Smenkhkare also enjoyed a brief independent reign after Akhenaten is unclear.[144] If Smenkhkare outlived Akhenaten, and became sole pharaoh, he likely ruled Egypt for less than a year. The next successor was Nefertiti[145] or Meritaten[146] ruling as Neferneferuaten, reigning in Egypt for about two years.[147] She was, in turn, probably succeeded by Tutankhaten, with the country being administered by the vizier and future pharaoh Ay.[148]

While Akhenaten—along with Smenkhkare—was most likely reburied in tomb KV55,[149] the identification of the mummy found in that tomb as Akhenaten remains controversial to this day. The mummy has repeatedly been examined since its discovery in 1907. Most recently, Egyptologist Zahi Hawass led a team of researchers to examine the mummy using medical and DNA analysis, with the results published in 2010. In releasing their test results, Hawass's team identified the mummy as the father of Tutankhamun and thus "most probably" Akhenaten.[150] However, the study's validity has since been called into question.[6][7][151][152][153] For instance, the discussion of the study results does not discuss that Tutankhamun's father and the father's siblings would share some genetic markers; if Tutankhamun's father was Akhenaten, the DNA results could indicate that the mummy is a brother of Akhenaten, possibly Smenkhkare.[153][154]

Legacy

With Akhenaten's death, the Aten cult he had founded fell out of favor: at first gradually, and then with decisive finality. Tutankhaten changed his name to Tutankhamun in Year 2 of his reign (c. 1332 BC) and abandoned the city of Akhetaten.[155] Their successors then attempted to erase Akhenaten and his family from the historical record. During the reign of Horemheb, the last pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty and the first pharaoh after Akhenaten who was not related to Akhenaten's family, Egyptians started to destroy temples to the Aten and reuse the building blocks in new construction projects, including in temples for the newly restored god Amun. Horemheb's successor continued in this effort. Seti I restored monuments to Amun and had the god's name re-carved on inscriptions where it was removed by Akhenaten. Seti I also ordered that Akhenaten, Smenkhkare, Neferneferuaten, Tutankhamun, and Ay be excised from official lists of pharaohs to make it appear that Amenhotep III was immediately succeeded by Horemheb. Under the Ramessides, who succeeded Seti I, Akhetaten was gradually destroyed and the building material reused across the country, such as in constructions at Hermopolis. The negative attitudes toward Akhenaten were illustrated by, for example, inscriptions in the tomb of scribe Mose (or Mes), where Akhenaten's reign is referred to as "the time of the enemy of Akhet-Aten".[156][157][158]

Some Egyptologists, such as Jacobus van Dijk and Jan Assmann, believe that Akhenaten's reign and the Amarna period started a gradual decline in the Egyptian government's power and the pharaoh's standing in Egyptian's society and religious life.[159][160] Akhenaten's religious reforms subverted the relationship ordinary Egyptians had with their gods and their pharaoh, as well as the role the pharaoh played in the relationship between the people and the gods. Before the Amarna period, the pharaoh was the representative of the gods on Earth, the son of the god Ra, and the living incarnation of the god Horus, and maintained the divine order through rituals and offerings and by sustaining the temples of the gods.[161] Additionally, even though the pharaoh oversaw all religious activity, Egyptians could access their gods through regular public holidays, festivals, and processions. This led to a seemingly close connection between people and the gods, especially the patron deity of their respective towns and cities.[162]

Akhenaten, however, banned the worship of gods beside the Aten, including through festivals. He also declared himself to be the only one who could worship the Aten, and required that all religious devotion previously exhibited toward the gods be directed toward himself. After the Amarna period, during the Nineteenth and Twentieth Dynasties—c. 270 years following Akhenaten's death—the relationship between the people, the pharaoh, and the gods did not simply revert to pre-Amarna practices and beliefs. The worship of all gods returned, but the relationship between the gods and the worshipers became more direct and personal,[163] circumventing the pharaoh. Rather than acting through the pharaoh, Egyptians started to believe that the gods intervened directly in their lives, protecting the pious and punishing criminals.[164] The gods replaced the pharaoh as their own representatives on Earth. The god Amun once again became king among all gods.[165] According to van Dijk, "the king was no longer a god, but god himself had become king. Once Amun had been recognized as the true king, the political power of the earthly rulers could be reduced to a minimum."[166] Consequently, the influence and power of the Amun priesthood continued to grow until the Twenty-first Dynasty, c. 1077 BC, by which time the High Priests of Amun effectively became rulers over parts of Egypt.[160][167][168]

Akhenaten's reforms also had a longer-term impact on Ancient Egyptian language and hastened the spread of the spoken Late Egyptian language in official writings and speeches. Spoken and written Egyptian diverged early on in Egyptian history and stayed different over time.[169] During the Amarna period, however, royal and religious texts and inscriptions, including the boundary stelae at Akhetaten or the Amarna letters, started to regularly include more vernacular linguistic elements, such as the definite article or a new possessive form. Even though they continued to diverge, these changes brought the spoken and written language closer to one another more systematically than under previous pharaohs of the New Kingdom. While Akhenaten's successors attempted to erase his religious, artistic, and even linguistic changes from history, the new linguistic elements remained a more common part of official texts following the Amarna years, starting with the Nineteenth Dynasty.[170][171][172]

Akhenaten is also recognized as a Prophet in the Druze faith.[173][174]

Atenism

Egyptians worshipped a sun god under several names, and solar worship had been growing in popularity even before Akhenaten, especially during the Eighteenth Dynasty and the reign of Amenhotep III, Akhenaten's father.[175] During the New Kingdom, the pharaoh started to be associated with the sun disc; for example, one inscription called the pharaoh Hatshepsut the "female Re shining like the Disc", while Amenhotep III was described as "he who rises over every foreign land, Nebmare, the dazzling disc".[176] During the Eighteenth Dynasty, a religious hymn to the sun also appeared and became popular among Egyptians.[177] However, Egyptologists question whether there is a causal relationship between the cult of the sun disc before Akhenaten and Akhenaten's religious policies.[177]

Implementation and development

The implementation of Atenism can be traced through gradual changes in the Aten's iconography, and Egyptologist Donald B. Redford divided its development into three stages—earliest, intermediate, and final—in his studies of Akhenaten and Atenism. The earliest stage was associated with a growing number of depictions of the sun disc, though the disc is still seen resting on the head of the falcon-headed sun god Ra-Horakhty, as the god was traditionally represented.[178] The god was only "unique but not exclusive".[179] The intermediate stage was marked by the elevation of the Aten above other gods and the appearance of cartouches around his inscribed name—cartouches traditionally indicating that the enclosed text is a royal name. The final stage had the Aten represented as a sun disc with sunrays like long arms terminating in human hands and the introduction of a new epithet for the god: "the great living Disc which is in jubilee, lord of heaven and earth".[180]

In the early years of his reign, Amenhotep IV lived at Thebes, the old capital city, and permitted worship of Egypt's traditional deities to continue. However, some signs already pointed to the growing importance of the Aten. For example, inscriptions in the Theban tomb of Parennefer from the early rule of Amenhotep IV state that "one measures the payments to every (other) god with a level measure, but for the Aten one measures so that it overflows," indicating a more favorable attitude to the cult of Aten than the other gods.[179] Additionally, near the Temple of Karnak, Amun-Ra's great cult center, Amenhotep IV erected several massive buildings including temples to the Aten. The new Aten temples had no roof and the god was thus worshipped in the sunlight, under the open sky, rather than in dark temple enclosures as had been the previous custom.[181][182] The Theban buildings were later dismantled by his successors and used as infill for new constructions in the Temple of Karnak; when they were later dismantled by archaeologists, some 36,000 decorated blocks from the original Aten building here were revealed that preserve many elements of the original relief scenes and inscriptions.[183]

One of the most important turning points in the early reign of Amenhotep IV is a speech given by the pharaoh at the beginning of his second regnal year. A copy of the speech survives on one of the pylons at the Karnak Temple Complex near Thebes. Speaking to the royal court, scribes or the people, Amenhotep IV said that the gods were ineffective and had ceased their movements, and that their temples had collapsed. The pharaoh contrasted this with the only remaining god, the sun disc Aten, who continued to move and exist forever. Some Egyptologists, such as Donald B. Redford, compared this speech to a proclamation or manifesto, which foreshadowed and explained the pharaoh's later religious reforms centered around the Aten.[184][185][186] In his speech, Akhenaten said:

The temples of the gods fallen to ruin, their bodies do not endure. Since the time of the ancestors, it is the wise man that knows these things. Behold, I, the king, am speaking so that I might inform you concerning the appearances of the gods. I know their temples, and I am versed in the writings, specifically, the inventory of their primeval bodies. And I have watched as they [the gods] have ceased their appearances, one after the other. All of them have stopped, except the god who gave birth to himself. And no one knows the mystery of how he performs his tasks. This god goes where he pleases and no one else knows his going. I approach him, the things which he has made. How exalted they are.[187]

In Year Five of his reign, Amenhotep IV took decisive steps to establish the Aten as the sole god of Egypt. The pharaoh "disbanded the priesthoods of all the other gods ... and diverted the income from these [other] cults to support the Aten." To emphasize his complete allegiance to the Aten, the king officially changed his name from Amenhotep IV to Akhenaten (Ancient Egyptian: ꜣḫ-n-jtn, meaning "Effective for the Aten").[183] Meanwhile, the Aten was becoming a king itself. Artists started to depict him with the trappings of pharaohs, placing his name in cartouches—a rare, but not unique occurrence, as the names of Ra-Horakhty and Amun-Ra had also been found enclosed in cartouches—and wearing a uraeus, a symbol of kingship.[188] The Aten may also have been the subject of Akhenaten's royal Sed festival early in the pharaoh's reign.[189] With Aten becoming a sole deity, Akhenaten started to proclaim himself as the only intermediary between Aten and his people, and the subject of their personal worship and attention[190]—a feature not unheard of in Egyptian history, with Fifth Dynasty pharaohs such as Nyuserre Ini proclaiming to be sole intermediaries between the people and the gods Osiris and Ra.[191]

By Year Nine of his reign, Akhenaten declared that Aten was not merely the supreme god, but the only worshipable god. He ordered the defacing of Amun's temples throughout Egypt and, in a number of instances, inscriptions of the plural 'gods' were also removed.[192][193] This emphasized the changes encouraged by the new regime, which included a ban on images, with the exception of a rayed solar disc, in which the rays appear to represent the unseen spirit of Aten, who by then was evidently considered not merely a sun god, but rather a universal deity. All life on Earth depended on the Aten and the visible sunlight.[194][195] Representations of the Aten were always accompanied with a sort of hieroglyphic footnote, stating that the representation of the sun as all-encompassing creator was to be taken as just that: a representation of something that, by its very nature as something transcending creation, cannot be fully or adequately represented by any one part of that creation.[196] Aten's name was also written differently starting as early as Year Eight or as late as Year Fourteen, according to some historians.[197] From "Living Re-Horakhty, who rejoices in the horizon in his name Shu-Re who is in Aten", the god's name changed to "Living Re, ruler of the horizon, who rejoices in his name of Re the father who has returned as Aten", removing the Aten's connection to Re-Horakhty and Shu, two other solar deities.[198] The Aten thus became an amalgamation that incorporated the attributes and beliefs around Re-Horakhty, universal sun god, and Shu, god of the sky and manifestation of the sunlight.[199]

Akhenaten's Atenist beliefs are best distilled in the Great Hymn to the Aten.[200] The hymn was discovered in the tomb of Ay, one of Akhenaten's successors, though Egyptologists believe that it could have been composed by Akhenaten himself.[201][202] The hymn celebrates the sun and daylight and recounts the dangers that abound when the sun sets. It tells of the Aten as a sole god and the creator of all life, who recreates life every day at sunrise, and on whom everything on Earth depends, including the natural world, people's lives, and even trade and commerce.[203] In one passage, the hymn declares: "O Sole God beside whom there is none! You made the earth as you wished, you alone."[204] The hymn also states that Akhenaten is the only intermediary between the god and Egyptians, and the only one who can understand the Aten: "You are in my heart, and there is none who knows you except your son."[205]

Atenism and other gods

Some debate has focused on the extent to which Akhenaten forced his religious reforms on his people.[206] Certainly, as time drew on, he revised the names of the Aten, and other religious language, to increasingly exclude references to other gods; at some point, also, he embarked on the wide-scale erasure of traditional gods' names, especially those of Amun.[207] Some of his court changed their names to remove them from the patronage of other gods and place them under that of Aten (or Ra, with whom Akhenaten equated the Aten). Yet, even at Amarna itself, some courtiers kept such names as Ahmose ("child of the moon god", the owner of tomb 3), and the sculptor's workshop where the famous Nefertiti Bust and other works of royal portraiture were found is associated with an artist known to have been called Thutmose ("child of Thoth"). An overwhelmingly large number of faience amulets at Amarna also show that talismans of the household-and-childbirth gods Bes and Taweret, the eye of Horus, and amulets of other traditional deities, were openly worn by its citizens. Indeed, a cache of royal jewelry found buried near the Amarna royal tombs (now in the National Museum of Scotland) includes a finger ring referring to Mut, the wife of Amun. Such evidence suggests that though Akhenaten shifted funding away from traditional temples, his policies were fairly tolerant until some point, perhaps a particular event as yet unknown, toward the end of the reign.[208]

Archaeological discoveries at Akhetaten show that many ordinary residents of this city chose to gouge or chisel out all references to the god Amun on even minor personal items that they owned, such as commemorative scarabs or make-up pots, perhaps for fear of being accused of having Amunist sympathies. References to Amenhotep III, Akhenaten's father, were partly erased since they contained the traditional Amun form of his name: Nebmaatre Amunhotep.[209]

After Akhenaten

Following Akhenaten's death, Egypt gradually returned to its traditional polytheistic religion, partly because of how closely associated the Aten became with Akhenaten.[210] Atenism likely stayed dominant through the reigns of Akhenaten's immediate successors, Smenkhkare and Neferneferuaten, as well as early in the reign of Tutankhaten.[211] For some years the worship of Aten and a resurgent worship of Amun coexisted.[212][213]

Over time, however, Akhenaten's successors, starting with Tutankhaten, took steps to distance themselves from Atenism. Tutankhaten and his wife Ankhesenpaaten dropped the Aten from their names and changed them to Tutankhamun and Ankhesenamun, respectively. Amun was restored as the supreme deity. Tutankhamun reestablished the temples of the other gods, as the pharaoh propagated on his Restoration Stela: "He reorganized this land, restoring its customs to those of the time of Re. ... He renewed the gods' mansions and fashioned all their images. ... He raised up their temples and created their statues. ... When he had sought out the gods' precincts which were in ruins in this land, he refounded them just as they had been since the time of the first primeval age."[214] Additionally, Tutankhamun's building projects at Thebes and Karnak used talatat's from Akhenaten's buildings, which implies that Tutankhamun might have started to demolish temples dedicated to the Aten. Aten temples continued to be torn down under Ay and Horemheb, Tutankhamun's successors and the last pharaohs of the Eighteenth Dynasty. Horemheb might also have ordered the demolition of Akhetaten, Akhenaten's capital city.[215] Further underlining the break with Aten worship, Horemheb claimed to have been chosen to rule by the god Horus. Finally, Seti I, the second pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty, ordered the name of Amun to be restored on inscriptions where it had been removed or replaced by Aten.[216]

Artistic depictions

Styles of art that flourished during the reigns of Akhenaten and his immediate successors, known as Amarna art, are markedly different from the traditional art of ancient Egypt. Representations are more realistic, expressionistic, and naturalistic,[217][218] especially in depictions of animals, plants and people, and convey more action and movement for both non-royal and royal individuals than the traditionally static representations. In traditional art, a pharaoh's divine nature was expressed by repose, even immobility.[219][220][221]

The portrayals of Akhenaten himself greatly differ from the depictions of other pharaohs. Traditionally, the portrayal of pharaohs—and the Egyptian ruling class—was idealized, and they were shown in "stereotypically 'beautiful' fashion" as youthful and athletic.[222] However, Akhenaten's portrayals are unconventional and "unflattering" with a sagging stomach; broad hips; thin legs; thick thighs; large, "almost feminine breasts"; a thin, "exaggeratedly long face"; and thick lips.[223]

Based on Akhenaten's and his family's unusual artistic representations, including potential depictions of gynecomastia and androgyny, some have argued that the pharaoh and his family have either had aromatase excess syndrome and sagittal craniosynostosis syndrome, or Antley–Bixler syndrome.[224] In 2010, results published from genetic studies on Akhenaten's purported mummy did not find signs of gynecomastia or Antley-Bixler syndrome,[21] although these results have since been questioned.[225]

Arguing instead for a symbolic interpretation, Dominic Montserrat in Akhenaten: History, Fantasy and Ancient Egypt states that "there is now a broad consensus among Egyptologists that the exaggerated forms of Akhenaten's physical portrayal... are not to be read literally".[209][226] Because the god Aten was referred to as "the mother and father of all humankind", Montserrat and others suggest that Akhenaten was made to look androgynous in artwork as a symbol of the androgyny of the Aten.[227] This required "a symbolic gathering of all the attributes of the creator god into the physical body of the king himself", which will "display on earth the Aten's multiple life-giving functions".[226] Akhenaten claimed the title "The Unique One of Re", and he may have directed his artists to contrast him with the common people through a radical departure from the idealized traditional pharaoh image.[226]

Depictions of other members of the court, especially members of the royal family, are also exaggerated, stylized, and overall different from traditional art.[219] Significantly, and for the only time in the history of Egyptian royal art, the pharaoh's family life is depicted: the royal family is shown mid-action in relaxed, casual, and intimate situations, taking part in decidedly naturalistic activities, showing affection for each other, such as holding hands and kissing.[228][229][230][231]

Nefertiti also appears, both beside the king and alone, or with her daughters, in actions usually reserved for a pharaoh, such as "smiting the enemy", a traditional depiction of male pharaohs.[232] This suggests that she enjoyed unusual status for a queen. Early artistic representations of her tend to be indistinguishable from her husband's except by her regalia, but soon after the move to the new capital, Nefertiti begins to be depicted with features specific to her. Questions remain whether the beauty of Nefertiti is portraiture or idealism.[233]

Speculative theories

Статус Эхнатона как религиозного революционера вызвал множество спекуляций неакадемическими , начиная от научных гипотез и заканчивая маргинальными теориями. Хотя некоторые считают, что представленная им религия была в основном монотеистической, многие другие считают, что Эхнатон практиковал монолатрию Атона . [234] поскольку он не отрицал активно существование других богов; он просто воздерживался от поклонения кому-либо, кроме Атона.

Эхнатон и монотеизм в авраамических религиях

Идея о том, что Эхнатон был пионером монотеистической религии, которая позже стала иудаизмом, рассматривалась различными учеными. [235] [236] [237] [238] [239] Одним из первых об этом упомянул Зигмунд Фрейд , основатель психоанализа , в своей книге «Моисей и монотеизм» . [235] Основываясь на своей вере в то, что история Исхода носит исторический характер, Фрейд утверждал, что Моисей был священником-атенистом, который был вынужден покинуть Египет вместе со своими последователями после смерти Эхнатона. Фрейд утверждал, что Эхнатон стремился продвигать монотеизм, чего смог достичь библейский Моисей. [235] После публикации его книги эта концепция вошла в массовое сознание и в серьезные исследования. [240] [241]

Фрейд прокомментировал связь между Адонаи , египетским Атоном и сирийским божественным именем Адонис как происходящую от общего корня; [235] в этом он следовал аргументам египтолога Артура Вейгалла . Яна Ассмана , «Атон» и «Адонай» лингвистически не связаны. По мнению [242]

Существует большое сходство между Великим гимном Эхнатона Атону и библейским псалмом 104 , но ведутся споры относительно связи, подразумеваемой этим сходством. [243] [244]

Другие сравнили некоторые аспекты отношений Эхнатона с Атоном с отношениями в христианской традиции между Иисусом Христом и Богом, особенно с интерпретациями, которые подчеркивают более монотеистическую интерпретацию атенизма, чем генотеистическую. Дональд Б. Редфорд отметил, что некоторые считают Эхнатона предвестником Иисуса . «В конце концов, Эхнатон называл себя сыном единственного бога: «Твой единственный сын, произошедший из твоего тела». [245] Джеймс Генри Брестед сравнил его с Иисусом: [246] Артур Вейгалл видел в нем несостоявшегося предшественника Христа, а Томас Манн видел в нем «правого на пути, но не того, кто на этом пути». [247]

Хотя такие ученые, как Брайан Фэган (2015) и Роберт Альтер (2018), возобновили дискуссию, в 1997 году Редфорд пришел к выводу:

До того, как стала доступна большая часть археологических свидетельств из Фив и Телль-эль-Амарны, принятие желаемого за действительное иногда превращало Эхнатона в гуманного учителя истинного Бога, наставника Моисея, христоподобного персонажа, философа, жившего раньше своего времени. Но эти воображаемые существа сейчас исчезают по мере того, как постепенно вырисовывается историческая реальность. Существует мало или совсем нет доказательств, подтверждающих идею о том, что Эхнатон был прародителем полномасштабного монотеизма, который мы находим в Библии. Монотеизм еврейской Библии и Нового Завета получил свое отдельное развитие, которое началось более чем через полтысячелетия после смерти фараона. [248]

Возможная болезнь

Нетрадиционные изображения Эхнатона, отличающиеся от традиционных спортивных норм изображения фараонов, заставили египтологов XIX и XX веков предположить, что у Эхнатона была какая-то генетическая аномалия. [223] Выдвигались различные заболевания, синдром Фрелиха или синдром Марфана . наиболее часто упоминались [249]

Сирил Олдред , [250] продолжение более ранних аргументов Графтона Эллиота Смита [251] и Джеймс Стрейчи , [252] предположил, что у Эхнатона мог быть синдром Фрелиха на основании его длинной челюсти и женственной внешности. Однако это маловероятно, поскольку это заболевание приводит к бесплодию , а Эхнатон, как известно, был отцом множества детей. Его дети неоднократно изображались на протяжении многих лет археологических и иконографических свидетельств. [253]

Берридж [254] предположил, что у Эхнатона мог быть синдром Марфана, который, в отличие от синдрома Фрелиха, не приводит к умственным нарушениям или бесплодию. Люди с синдромом Марфана склонны к высокому росту, имеют длинное, тонкое лицо, вытянутый череп, разросшиеся ребра, воронкообразную или голубиную грудь, высокое изогнутое или слегка расщелину нёба и больший таз, увеличенные бедра и тонкие икры. некоторые изображения Эхнатона. [255] Синдром Марфана является доминирующей характеристикой, а это означает, что у пострадавшего есть 50% вероятность передать его своим детям. [256] Однако тесты ДНК Тутанхамона в 2010 году оказались отрицательными для синдрома Марфана. [257]

К началу 21 века большинство египтологов утверждали, что изображения Эхнатона не являются результатом генетического или медицинского состояния, а скорее должны интерпретироваться как стилизованные изображения, находящиеся под влиянием атенизма. [209] [226] Эхнатон в произведениях искусства выглядел андрогинным как символ андрогинности Атона. [226]

Культурные изображения

Жизнь, достижения и наследие Эхнатона были сохранены и изображены во многих отношениях, и он фигурировал в произведениях как высокой , так и популярной культуры с момента своего повторного открытия в 19 веке нашей эры. Эхнатон — наряду с Клеопатрой и Александром Великим — входит в число наиболее часто популяризируемых и вымышленных древних исторических фигур. [258]

На странице романы Амарны чаще всего принимают одну из двух форм. Они либо Bildungsroman , сосредотачивающиеся на психологическом и моральном росте Эхнатона, поскольку это связано с установлением атенизма и Ахетатона, а также его борьбой против фиванского культа Амона. С другой стороны, его литературные изображения сосредоточены на последствиях его правления и религии. [259] Разделительная линия также существует между изображениями Эхнатона, датируемыми до 1920-х годов и с тех пор, когда все больше и больше археологических открытий начали предоставлять художникам материальные свидетельства о его жизни и времени. Таким образом, до 1920-х годов Эхнатон выступал в искусстве как «призрак, призрачная фигура», а с тех пор он стал реалистом, «материальным и осязаемым». [260] Примеры первых включают любовные романы «В гробницах царей » (1910) Лилиан Бэгналл — первое появление Эхнатона и его жены Нефертити в художественной литературе — и «Жена из Египта» (1913) и «В Египте был царь» ( 1913 ). 1918) Нормы Лоример . Примеры последних включают «Эхнатона, царя Египта » (1924) Дмитрия Мережковского , «Иосиф и его братья» (1933–1943) Томаса Манна , «Эхнатона» (1973) Агаты Кристи и «Эхнатона, Обитателя истины » (1985) Нагиба Махфуза . Эхнатон также появляется в «Египтянин» (1945) фильме Мика Валтари , который был адаптирован для фильма «Египтянин» (1953). В этом фильме Эхнатон, которого сыграл Майкл Уайлдинг , олицетворяет Иисуса Христа и его последователей- протохристиан . [261]

изображениям фараона Сексуализированный образ Эхнатона, основанный на раннем западном интересе к андрогинным , воспринимаемой потенциальной гомосексуальности и отождествлении с Эдиповым повествованием , также повлиял на современные произведения искусства. [262] Два наиболее заметных образа — «Акенатон» (1975), неэкранизированный сценарий Дерека Джармана , и «Эхнатон» (1984), опера Филипа Гласса . [263] [264] Оба находились под влиянием недоказанных и научно не подкрепленных теорий Иммануила Великовского , который приравнивал Эдипа к Эхнатону, [265] хотя Гласс специально отрицает свою личную веру в теорию Эдипа Великовского или заботу о ее исторической достоверности, вместо этого его привлекает ее потенциальная театральность. [266]

В 21 веке Эхнатон появился как антагонист комиксов и видеоигр. Например, он является главным антагонистом ограниченной серии комиксов Marvel: The End (2003). В этом сериале Эхнатон похищен инопланетным орденом в 14 веке до нашей эры и вновь появляется на современной Земле, стремясь восстановить свое царство. Ему противостоят практически все другие супергерои и суперзлодеи вселенной комиксов Marvel, и в конечном итоге он терпит поражение от Таноса . [267] Кроме того, Эхнатон появляется как враг в Assassin's Creed Origins: Проклятие фараонов загружаемом контенте (2017 г.), и его необходимо победить, чтобы снять проклятие с Фив. [267] Его загробная жизнь принимает форму «Атона», места, которое во многом основано на архитектуре города Амарны. [268]

Американская дэт-метал группа Nile изобразила суд, наказание и стирание Эхнатона из истории руками пантеона , которого он заменил Атоном, в песне «Cast Down the Heretic» из их альбома 2005 года Annihilation of the Wicked . Он также был изображен на обложке их альбома 2009 года « The Whom the Gods Detest» .

Родословная

| 16. Тутмос III | |||||||||||||||||||

| 8. Аменхотеп II | |||||||||||||||||||

| 17. Меритра-Хатшепсут | |||||||||||||||||||

| 4. Тутмос IV | |||||||||||||||||||

| 9. Тиаа | |||||||||||||||||||

| 2. Аменхотеп III | |||||||||||||||||||

| 5. Судья | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1. Эхнатон | |||||||||||||||||||

| 6. Юя | |||||||||||||||||||

| 3. Убить | |||||||||||||||||||

| 7. 7.Тьюю | |||||||||||||||||||

См. также

Примечания и ссылки

Примечания

- ^ Коэн и Вестбрук 2002 , с. 6.

- ^ Роджерс 1912 , с. 252.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д Britannica.com 2012 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и фон Бекерат 1997 , с. 190.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж г час я дж к л м н тот п д р Лепроон 2013 , стр. 104–105.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Струхаль 2010 , стр. 97–112.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Духиг 2010 , с. 114.

- ^ Словарь.com 2008 .

- ^ Кухня 2003 , с. 486.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Тилдесли 2005 .

- ^ Монтсеррат 2003 , стр. 105, 111.

- ^ Лоприено, Антонио (1995) Древний Египет: лингвистическое введение , Кембридж: Издательство Кембриджского университета,

- ^ Лоприено, Антонио (2001) «От древнеегипетского до коптского» в Haspelmath, Martin et al. (ред.), Типология языка и языковые универсалии

- ^ Jump up to: а б Ридли, 2019 , стр. 13–15.

- ^ Харт 2000 , с. 44.

- ^ Манниш 2010 , стр. ix.

- ^ Заки 2008 , с. 19.

- ^ Гардинер 1905 , с. 11.

- ^ Триггер и др. 2001 , стр. 186–187.

- ^ Хорнунг 1992 , стр. 43–44.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Хавасс и др. 2010 .

- ^ Маршан 2011 , стр. 404–06.

- ^ Лоренцен и Виллерслев 2010 .

- ^ Бикерстафф 2010 .

- ^ Спенс 2011 .

- ^ Сук 2014 .

- ^ Хесслер 2017 .

- ^ Сильверман, Вегнер и Вегнер 2006 , стр. 185–188.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , стр. 37–39.

- ^ Додсон 2018 , с. 6.

- ^ Лейбори 2010 , стр. 62, 224.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , стр. 220.

- ^ Тилдесли 2006 , с. 124.

- ^ Мурнейн 1995 , стр. 9, 90–93, 210–211.

- ^ Граецки 2005 .

- ^ Додсон 2012 , с. 1.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , с. 78.

- ^ Лейбори 2010 , стр. 314–322.

- ^ Додсон 2009 , стр. 41–42.

- ^ Университетский колледж Лондона, 2001 г.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , с. 262.

- ^ Додсон 2018 , стр. 174–175.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Додсон 2018 , стр. 38–39.

- ^ Додсон 2009 , стр. 84–87.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , стр. 263–265.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Харрис и Венте 1980 , стр. 137–140.

- ^ Аллен 2009 , стр. 15–18.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , с. 257.

- ^ Робинс 1993 , стр. 21–27.

- ^ Додсон 2018 , стр. 19–21.

- ^ Додсон и Хилтон 2004 , с. 154.

- ^ Редфорд 2013 , с. 13.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , стр. 40–41.

- ^ Редфорд 1984 , стр. 57–58.

- ^ Хоффмайер 2015 , с. 65.

- ^ Лейбори 2010 , с. 81.

- ^ С Днем 1995 , с. 78.

- ^ Хоффмайер 2015 , с. 64.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Олдред 1991 , с. 259.

- ^ Ривз 2019 , с. 77.

- ^ Берман 2004 , с. 23.

- ^ Кухня 2000 , с. 44.

- ^ Мартин Валентин и Бедман 2014 .

- ^ Бренд 2020 , стр. 63–64.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , с. 45.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Ридли 2019 , с. 46.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , с. 48.

- ^ Альдред 1991 , стр. 259–268.

- ^ Редфорд 2013 , стр. 13–14.

- ^ Додсон 2014 , стр. 156–160.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Нимс 1973 , стр. 186–187.

- ^ Редфорд 2013 , с. 19.

- ^ Хоффмайер 2015 , стр. 98, 101, 105–106.

- ^ Дерош-Ноблькур, 1963 , стр. 144–145.

- ^ Гохари 1992 , стр. 29–39, 167–169.

- ^ Мурнейн 1995 , стр. 50–51.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , стр. 83–85.

- ^ Хоффмайер 2015 , с. 166.

- ^ Мурнейн и Ван Сиклен III 2011 , с. 150.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Ридли, 2019 , стр. 85–87.

- ^ Фехт 1960 , с. 89.

- ^ Хорнунг 2001 , с. 50.

- ^ Эльмар 1948 .

- ^ Ридли 2019 , с. 85.

- ^ Додсон 2014 , стр. 180–185.

- ^ Додсон 2014 , стр. 186–188.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Ридли, 2019 , стр. 85–90.

- ^ Редфорд 2013 , стр. 9–10, 24–26.

- ^ Альдред 1991 , стр. 269–270.

- ^ Брестед 2001 , стр. 390–400.

- ^ Арнольд 2003 , с. 238.

- ^ Шоу 2003 , с. 274.

- ^ Альдред 1991 , стр. 269–273.

- ^ Шоу 2003 , стр. 293–297.

- ^ Моран 1992 , стр. xiii, xv.

- ^ Моран 1992 , с. xvi.

- ^ Альдред 1991 , гл. 11.

- ^ Моран 1992 , стр. 87–89.

- ^ Дриотон и Вандье 1952 , стр. 411–414.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , стр. 297, 314.

- ^ Моран 1992 , с. 203.

- ^ Росс 1999 , стр. 30–35.

- ^ Брайс 1998 , с. 186.

- ^ Коэн и Вестбрук 2002 , стр. 102, 248.

- ^ Холл 1921 , стр. 42–43.

- ^ Брестед 1909 , с. 355.

- ^ Дэвис 1903–1908 , часть II. п. 42.

- ^ Байки 1926 , с. 269.

- ^ Моран 1992 , стр. 368–369.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , стр. 316–317.

- ^ Мурнейн 1995 , стр. 55–56.

- ^ Дарнелл и Манасса 2007 , стр. 118–119.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , стр. 323–324.

- ^ Шульман 1982 .

- ^ С Днем 1995 , с. 99.

- ^ Альдред 1968 , с. 241.

- ^ Габольде 1998 , стр. 195–205.

- ^ Дарнелл и Манасса 2007 , стр. 172–178.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , стр. 235–236, 244–247.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , с. 346.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Ван дер Перре 2012 , стр. 195–197.

- ^ Ван дер Перре 2014 , стр. 67–108.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , стр. 346–364.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Додсон 2009 , стр. 39–41.

- ^ Дарнелл и Манасса 2007 , с. 127.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , с. 141.

- ^ Редфорд 1984 , стр. 185–192.

- ^ Браверман, Редфорд и Маковяк 2009 , стр. 557.

- ^ Додсон 2009 , с. 49.

- ^ Ларош 1971 , с. 378.

- ^ Габольде 2011 .

- ^ Ридли 2019 , стр. 354, 376.

- ^ Додсон 2014 , с. 144.

- ^ Тилдесли 1998 , стр. 160–175.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , стр. 337, 345.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , с. 252.

- ^ Аллен 1988 , стр. 117–126.

- ^ Кемп 2015 , с. 11.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , стр. 365–371.

- ^ Додсон 2014 , с. 244.

- ^ Альдред 1968 , стр. 140–162.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , стр. 411–412.

- ^ Додсон 2009 , стр. 144–145.

- ^ Аллен 2009 , стр. 1–4.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , с. 251.

- ^ Тилдесли 2006 , стр. 136–137.

- ^ Хорнунг, Краусс и Уорбертон 2006 , стр. 207, 493.

- ^ Ридли 2019 .

- ^ Додсон 2018 , стр. 75–76.

- ^ Хавасс и др. 2010 , с. 644.

- ^ Маршан 2011 , стр. 404–406.

- ^ Додсон 2018 , стр. 16–17.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Ридли, 2019 , стр. 409–411.

- ^ Додсон 2018 , стр. 17, 41.

- ^ Додсон 2014 , стр. 245–249.

- ^ Хоффмайер 2015 , стр. 241–243.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , с. 415.

- ^ Марк 2014 .

- ^ ван Дейк 2003 , с. 303.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Ассманн 2005 , с. 44.

- ^ Уилкинсон 2003 , с. 55.

- ^ Ривз 2019 , стр. 139, 181.

- ^ Брестед 1972 , стр. 344–370.

- ^ Окинга 2001 , стр. 44–46.

- ^ Уилкинсон 2003 , с. 94.

- ^ ван Дейк 2003 , с. 307.

- ^ ван Дейк 2003 , стр. 303–307.

- ^ Кухня 1986 , с. 531.

- ^ Бэйнс 2007 , с. 156.

- ^ Гольдвассер 1992 , стр. 448–450.

- ^ Гардинер 2015 .

- ^ О'Коннор и Сильверман 1995 , стр. 77–79.

- ^ «Друзы» . druze.de . Проверено 18 января 2022 г.

- ^ Дана, LP, изд. (2010). Предпринимательство и религия . Паб Эдвард Элгар. ISBN 978-1-84980-632-9 . OCLC 741355693 .

- ^ Хорнунг 2001 , с. 19.

- ^ Сете 1906–1909 , стр. 19, 332, 1569.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Редфорд 2013 , с. 11.

- ^ Хорнунг 2001 , стр. 33, 35.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Хорнунг 2001 , с. 48.

- ^ Редфорд 1976 , стр. 53–56.

- ^ Хорнунг 2001 , стр. 72–73.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , с. 43.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Дэвид 1998 , с. 125.

- ^ Альдред 1991 , стр. 261–262.

- ^ Хоффмайер 2015 , стр. 160–161.

- ^ Редфорд 2013 , с. 14.

- ^ Перри 2019 , 03:59.

- ^ Хорнунг 2001 , стр. 34–36, 54.

- ^ Хорнунг 2001 , стр. 39, 42, 54.

- ^ Хорнунг 2001 , стр. 55–57.

- ^ Барта и Дуликова 2015 , стр. 41, 43.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , с. 188.

- ^ Харт 2000 , стр. 42–46.

- ^ Хорнунг 2001 , стр. 55, 84.

- ^ Наёвиц 2004 , с. 125.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , стр. 211–213.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , стр. 28, 173–174.

- ^ Додсон 2009 , с. 38.

- ^ Наёвиц 2004 , стр. 123–124.

- ^ Наёвиц 2004 , с. 128.

- ^ Хорнунг 2001 , с. 52.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , стр. 129, 133.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , с. 128.

- ^ Наёвиц 2004 , с. 131.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , стр. 128–129.

- ^ Хорнунг 1992 , с. 47.

- ^ Аллен 2005 , стр. 217–221.

- ^ Ридли 2019 , стр. 187–194.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Ривз, 2019 , стр. 154–155.

- ^ Хорнунг 2001 , с. 56.

- ^ Додсон 2018 , стр. 47, 50.

- ^ Редфорд 1984 , с. 207.

- ^ Сильверман, Вегнер и Вегнер 2006 , стр. 165–166.

- ^ Хоффмайер 2015 , стр. 197, 239–242.

- ^ ван Дейк 2003 , с. 284.

- ^ Хоффмайер 2015 , стр. 239–242.

- ^ Хорнунг 2001 , стр. 43–44.

- ^ Наёвиц 2004 , с. 144.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Баптиста, Сантамарина и Конант, 2017 г.

- ^ Арнольд 1996 , с. viii.

- ^ Хорнунг 2001 , стр. 42–47.

- ^ Сук 2016 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Такач и Клайн 2015 , стр. 5–6.

- ^ Браверман, Редфорд и Маковяк, 2009 .

- ^ Браверман и Маковяк 2010 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и Монтсеррат 2003 .

- ^ Наёвиц 2004 , с. 145.

- ^ Олдред 1985 , с. 174.

- ^ Арнольд 1996 , с. 114.

- ^ Хорнунг 2001 , с. 44.

- ^ Наёвиц 2004 , стр. 146–147.

- ^ Арнольд 1996 , с. 85.

- ^ Арнольд 1996 , стр. 85–86.

- ^ Монтсеррат 2003 , с. 36.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д Фрейд 1939 .

- ^ Стент 2002 , стр. 34–38.

- ^ Ассманн 1997 .

- ^ Шупак 1995 .

- ^ Олбрайт 1973 .

- ^ Чейни 2006a , стр. 62–69.

- ^ Чейни 2006b .

- ^ Ассманн 1997 , стр. 23–24.

- ^ Hoffmeier 2015 , стр. 246–256 : «... на данный момент кажется лучшим заключить, что «параллели» между гимнами Амарны Атону и Псалмом 104 следует отнести к «общему богословию» и «общей схеме». ...";

Хоффмайер 2005 , с. 239 : «...Были некоторые споры о том, являются ли сходства прямыми или косвенными заимствованиями... маловероятно, что «израильтянин, составивший Псалом 104, заимствовал непосредственно из возвышенного египетского «Гимна Атону», как недавно сказал Стагер. заявлено.";

Альтернатива 2018 , с. 54 : «...Я думаю, что может быть некоторая вероятность, хотя и недоказуемая, что наш псалмопевец был знаком по крайней мере с промежуточной версией гимна Эхнатона и перенял некоторые элементы из него»;

Браун 2014 , с. 61–73 » : «вопрос о связи египетских гимнов и псалмов остается открытым

- ^ Assmann 2020 , стр. : ; 40–43 «Стихи 20–30 нельзя понимать иначе, как свободный и сокращенный перевод «Великого гимна»:...»

День 2014 г. , стр. 22–23 : «...значительная часть остальной части Псалма 104 (особенно стихи 20–30) зависит от… Гимна Эхнатона богу Солнца Атону… эти параллели почти все идут в одном порядке:...";

День 2013 , стр. 223–224 : «...эта зависимость ограничивается ст. 20–30. Здесь доказательства особенно впечатляют, поскольку мы имеем шесть параллелей с гимном Эхнатона… происходящих в одинаковом порядке, с одной исключение.";

Landes 2011 , стр. 155 , 178 : «Гимн Атону, приведенный в качестве эпиграфа к этой главе, отражает сильную религиозность и даже язык еврейского Псалма 104. Действительно, большинство египтологов утверждают, что этот гимн вдохновил псалом ...» , «...Для некоторых связь с еврейским монотеизмом кажется чрезвычайно тесной, включая почти дословные отрывки из Псалма 104 и «Гимна Атону», найденные в одной из гробниц Ахетатона...»;

Шоу 2004 , с. 19 : «Интригующей прямой литературной (и, возможно, религиозной) связью между Египтом и Библией является Псалом 104, который имеет большое сходство с гимном Атону».

- ^ Редфорд 1987 .

- ^ Левенсон 1994 , с. 60.

- ^ Хорнунг 2001 , с. 14.

- ^ Редфорд, Шанкс и Мейнхардт 1997 .

- ^ Ридли 2019 , с. 87.

- ^ Олдред 1991 .

- ^ Смит 1923 , стр. 83–88.

- ^ Стрейчи 1939 .

- ^ Хавасс 2010 .

- ^ Берридж 1995 .

- ^ Лоренц 2010 .

- ^ Национальный центр развития трансляционных наук, 2017 .

- ^ Шемм 2010 .

- ^ Монтсеррат 2003 , с. 139.

- ^ Монтсеррат 2003 , с. 144.

- ^ Монтсеррат 2003 , с. 154.

- ^ Монтсеррат 2003 , стр. 163, 200–212.

- ^ Монтсеррат 2003 , стр. 168, 170.

- ^ Монтсеррат 2003 , стр. 175–176.

- ^ Дэвидсон 2019 .

- ^ Монтсеррат 2003 , с. 176.

- ^ Гласс, Филип (1987) Музыка Филипа Гласса Нью-Йорк: Harper & Row. стр.137-138. ISBN 0-06-015823-9

- ^ Jump up to: а б Марвел 2021 .

- ^ Хоттон 2018 .

Библиография

- «Эхнатон» . Словарь.com . Архивировано из оригинала 14 октября 2008 года . Проверено 2 октября 2008 г.

- Дорман, Питер Ф. «Эхнатон (Царь Египта)» . Britannica.com . Проверено 25 августа 2012 г.

- Олбрайт, Уильям Ф. (1973). «От патриархов Моисею II. Моисей из Египта». Библейский археолог . 36 (2): 48–76. дои : 10.2307/3211050 . JSTOR 3211050 . S2CID 135099403 .

- Олдред, Сирил (1968). Эхнатон, фараон Египта: новое исследование . Новые аспекты античности (1-е изд.). Лондон: Темза и Гудзон. ISBN 978-0500390047 .

- Олдред, Сирил (1985) [1980]. Египетское искусство во времена фараонов 3100–32 гг. до н.э. Мир искусства. Лондон; Нью-Йорк: Темза и Гудзон. ISBN 0-500-20180-3 . LCCN 84-51309 .

- Олдред, Сирил (1991) [1988]. Эхнатон, царь Египта . Лондон: Темза и Гудзон. ISBN 0500276218 .

- Аллен, Джеймс Питер (1988). «Две измененные надписи позднего периода Амарны» . Журнал Американского исследовательского центра в Египте . 25 . Сан-Антонио, Техас: Американский исследовательский центр в Египте: 117–126. дои : 10.2307/40000874 . ISSN 0065-9991 . JSTOR 40000874 .

- Аллен, Джеймс П. (2005). «Эхнатон». В Джонсе, Л. (ред.). Энциклопедия религии . Справочник Макмиллана.