Югослав Партизаны

Югославские партизаны , [ Примечание 1 ] [ 11 ] или Национальная армия освобождения , [ Примечание 2 ] Официально национальная армия освобождения и партизанские отряды Югославии , [ Примечание 3 ] [ 12 ] Было ли коммунистическое антифашистское сопротивление к властям Оси (главным образом нацистской Германии ) в оккупированной Югославии во время Второй мировой войны . Во главе с Джозипом Брозом Тито , [ 13 ] Партизаны считаются наиболее эффективным к антиоссу движением против сопротивления устойчивости во время Второй мировой войны. [ 14 ] [ 15 ] [ 16 ] [ 17 ]

В первую очередь партизанские силы в его начале, партизаны превратились в большие боевые силы, вступающие в обычную войну в конце войны, насчитывая около 650 000 в конце 1944 года и организованную в четырех полевых армиях и 52 подразделениях . Основными заявленными целями партизан было освобождение югославских земель от оккупирующих сил и создание федерального, многоэтнического социалистического государства в Югославии.

The Partisans were organized on the initiative of Tito following the Axis invasion of Yugoslavia in April 1941, and began an active guerrilla campaign against occupying forces after Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June. A large-scale uprising was launched in July, later joined by Draža Mihailović's Chetniks, which led to the creation of the short-lived Republic of Užice. The Axis mounted a series of offensives in response but failed to completely destroy the highly mobile Partisans and their leadership. By late 1943 the Allies had shifted their support from Mihailović to Tito as the extent of Chetnik collaboration became evident, and the Partisans received official recognition at the Tehran Conference. In Autumn 1944, the Partisans and the Soviet Red Army liberated Belgrade following the Belgrade Offensive. By the end of the war, the Partisans had gained control of the entire country as well as Trieste and Carinthia. After the war, the Partisans were reorganized into the regular armed force из недавно созданной федеральной народной Республики Югославия .

Objectives

[edit]

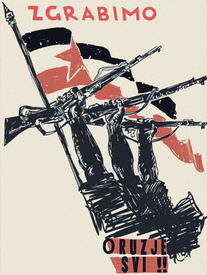

One of two objectives of the movement, which was the military arm of the Unitary National Liberation Front (UNOF) coalition, led by the Communist Party of Yugoslavia (KPJ)[2] and represented by the Anti-Fascist Council for the National Liberation of Yugoslavia (AVNOJ), the Yugoslav wartime deliberative assembly, was to fight the occupying forces. Until British supplies began to arrive in appreciable quantities in 1944, the occupiers were the only source of arms.[18] The other objective was to create a federal multi-ethnic communist state in Yugoslavia.[19] To this end, the KPJ attempted to appeal to all the various ethnic groups within Yugoslavia, by preserving the rights of each group.

The objectives of the rival resistance movement, the Chetniks, were the retention of the Yugoslav monarchy, ensuring the safety of ethnic Serb populations,[20][21] and the establishment of a Greater Serbia[22] through the ethnic cleansing of non-Serbs from territories they considered rightfully and historically Serbian.[23][24][25][26] Relations between the two movements were uneasy from the start, but from October 1941 they degenerated into full-scale conflict. To the Chetniks, Tito's pan-ethnic policies seemed anti-Serbian, whereas the Chetniks' royalism was anathema to the communists.[10] In the early part of the war Partisan forces were predominantly composed of Serbs. In that period names of Muslim and Croat commanders of Partisan forces had to be changed to protect them from their predominantly Serb colleagues.[27]

After the German retreat forced by the Soviet-Bulgarian offensive in Serbia, North Macedonia, and Kosovo in the autumn of 1944, the conscription of Serbs, Macedonians, and Kosovar Albanians increased significantly. By late 1944, the total forces of the Partisans numbered 650,000 men and women organized in four field armies and 52 divisions, which engaged in conventional warfare.[28] By April 1945, the Partisans numbered over 800,000.

Name

[edit]The movement was consistently referred to as the "Partisans" throughout the war. However, due to frequent changes in size and structural reorganizations, the Partisans throughout their history held four full official names (translated here from Serbo-Croatian to English):

- National Liberation Partisan Detachments of Yugoslavia[note 4] (June 1941 – January 1942)

- National Liberation Partisan and Volunteer Army of Yugoslavia[note 5] (January – November 1942)

- National Liberation Army and Partisan Detachments of Yugoslavia (November 1942 – February 1945). Increasingly from November 1942, the Partisan military as a whole was often referred to simply as the National Liberation Army (Narodnooslobodilačka vojska, NOV), whereas the term "Partisans" acquired a wider sense in referring to the entire resistance faction (including, for example, the AVNOJ).

- Yugoslav Army[note 6] – on 1 March 1945, the National Liberation Army was transformed into the regular armed forces of Yugoslavia and renamed accordingly.

The movement was originally named National Liberation Partisan Detachments of Yugoslavia (Narodnooslobodilački partizanski odredi Jugoslavije, NOPOJ) and held that name from June 1941 to January 1942. Because of this, their short name became simply the "Partisans" (capitalized), and stuck henceforward (the adjective "Yugoslav" is used sometimes in exclusively non-Yugoslav sources to distinguish them from other partisan movements).

Between January 1942 and November 1942, the movement's full official name was briefly National Liberation Partisan and Volunteer Army of Yugoslavia (Narodnooslobodilačka partizanska i dobrovoljačka vojska Jugoslavije, NOP i DVJ). The changes were meant to reflect the movement's character as a "volunteer army".

In November 1942 the movement was renamed into the National Liberation Army and Partisan Detachments of Yugoslavia (Narodnooslobodilačka vojska i partizanski odredi Jugoslavije, NOV i POJ), a name which it held until the end of the war. This last official name is the full name most associated with the Partisans, and reflects the fact that the proletarian brigades and other mobile units were organized into the National Liberation Army (Narodnooslobodilačka vojska). The name change also reflects the fact that the latter superseded in importance the partisan detachments themselves.

Shortly before the end of the war, in March 1945, all resistance forces were reorganized into the regular armed force of Yugoslavia and renamed Yugoslav Army. It would keep this name until 1951, when it was renamed the Yugoslav People's Army.

Background and origins

[edit]

On 6 April 1941, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia was invaded from all sides by the Axis powers, primarily by German forces, but also including Italian, Hungarian and Bulgarian formations. During the invasion, Belgrade was bombed by the Luftwaffe. The invasion lasted little more than ten days, ending with the unconditional surrender of the Royal Yugoslav Army on 17 April. Besides being hopelessly ill-equipped when compared to the Wehrmacht, the Army attempted to defend all borders but only managed to thinly spread the limited resources available.[29]

The terms of the capitulation were extremely severe, as the Axis proceeded to dismember Yugoslavia. Germany occupied the northern part of Drava Banovina (roughly modern-day Slovenia),[30] while maintaining direct military occupation of a rump Serbian territory with a puppet government.[31][32] The Independent State of Croatia (NDH) was established under German direction, which extended over much of the territory of today's Croatia and as well contained all the area of modern-day Bosnia and Herzegovina and Syrmia region of modern-day Serbia. Mussolini's Italy occupied the remainder of Drava Banovina (annexed and renamed as the Province of Lubiana), much of Zeta Banovina and large chunks of the coastal Dalmatia region (along with nearly all its Adriatic islands). It also gained control over the newly created Italian governorate of Montenegro, and was granted the kingship in the Independent State of Croatia, though wielding little real power within it. Hungary dispatched the Hungarian Third Army and occupied and annexed the Yugoslav regions of Baranja, Bačka, Međimurje and Prekmurje. Bulgaria, meanwhile, annexed nearly all of Macedonia, and small areas of eastern Serbia and Kosovo.[33] The dissolution of Yugoslavia, the creation of the NDH, Italian governorate of Montenegro and Nedic's Serbia and the annexations of Yugoslav territory by the various Axis countries were incompatible with international law in force at that time.[34]

The occupying forces instituted such severe burdens on the local populace that the Partisans came not only to enjoy widespread support but for many were the only option for survival. Early in the occupation, German forces would hang or shoot indiscriminately, including women, children and the elderly, up to 100 local inhabitants for every one German soldier killed.[35] While these measures for suppressing communist-led resistance were issued in all German-occupied territory, it was only strictly enforced in Serbia.[36] Two of the most significant atrocities by the German forces were the massacre of 2,000 civilians in Kraljevo and 3,000 in Kragujevac. The formula of 100 hostages shot for every German soldier killed and 50 hostages shot for every wounded German soldier was cut in one-half in February 1943 and removed altogether in the fall of that same year.[36]

Furthermore, Yugoslavia experienced a breakdown of law and order, with collaborationist militias roaming the countryside terrorizing the population. The government of the puppet Independent State of Croatia found itself unable to control its territory in the early stages of the occupation, resulting in a severe crackdown by the Ustaše militias and the German army.[citation needed]

Amid the relative chaos that ensued, the Communist Party of Yugoslavia moved to organize and unite anti-fascist factions and political forces into a nationwide uprising. The party, led by Josip Broz Tito, was banned after its significant success in the post-World War I Yugoslav elections and operated underground since. Tito, however, could not act openly without the backing of the USSR, and as the Molotov–Ribbentrop pact was still in force, he was compelled to wait.[37][38][39]

Formation and early rebellion

[edit]During the April invasion of Yugoslavia, the leadership of the Communist Party was in Zagreb, together with Josip Broz Tito. After a month, they left for Belgrade. While the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact between Germany and the Soviet Union was in effect, the communists refrained from open conflict with the new regime of the Independent State of Croatia. In these first two months of occupation, they extended their underground network and began amassing weapons.[40] In early May 1941, a so-called May consultations of Communist Party officials from across the country, who sought to organize the resistance against the occupiers, was held in Zagreb. In June 1941, a meeting of the Central Committee of KPJ was also held, at which it was decided to start preparations for the uprising.[41]

Operation Barbarossa, the Axis invasion of the Soviet Union, began on 22 June 1941.[42]

The extent of support for the Partisan movement varied according to region and nationality, reflecting the existential concerns of the local population and authorities. The first Partisan uprising occurred in Croatia on 22 June 1941, when forty Croatian communists staged an uprising in the Brezovica woods between Sisak and Zagreb, forming the 1st Sisak Partisan Detachment.[43]

The first uprising led by Tito occurred two weeks later, in Serbia.[43] The Communist Party of Yugoslavia formally decided to launch an armed uprising on 4 July, a date which was later marked as Fighter's Day – a public holiday in the SFR Yugoslavia. One Žikica Jovanović Španac shot the first bullet of the campaign on 7 July in the Bela Crkva incident.

The first Zagreb-Sesvete partisan group was formed in Dubrava in July 1941. In August 1941, 7 Partisan Detachments were formed in Dalmatia with the role of spreading the uprising. On 26 August 1941, 21 members of the 1st Split Partisan Detachment were executed by firing squad after being captured by Italian and Ustaše forces.[44][45] A number of other partisan units were formed in the summer of 1941, including in Moslavina and Kalnik. An uprising occurred in Serbia during the summer, led by Tito, when the Republic of Užice was created, but it was defeated by the Axis forces by December 1941, and support for the Partisans in Serbia thereafter dropped.

It was a different story for Serbs in Axis occupied Croatia who turned to the multi-ethnic Partisans, or the Serb royalist Chetniks.[46] The journalist Tim Judah notes that in the early stage of the war the initial preponderance of Serbs in the Partisans meant in effect a Serbian civil war had broken out.[47] A similar civil war existed within the Croatian national corpus with the competing national narratives provided by the Ustaše and Partisans.

In the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina, the cause of Serb rebellion was the Ustaše policy of genocide, deportations, forced conversions and mass killings of Serbs,[48] as was the case elsewhere in the NDH.[49][50] Resistance to communist leadership of the anti-Ustasha rebellion among the Serbs from Bosnia also developed in the form of the Chetnik movement and autonomous bands which were under command of Dragoljub Mihailović.[51] Whereas the Partisans under Serb leadership were open to members of various nationalities, those in the Chetniks were hostile to Muslims and exclusively Serbian. The uprising in Bosnia and Herzegovina started by Serbs in many places were acts of retaliation against the Muslims, with thousands of them killed.[52] A rebellion began in June 1941 in Herzegovina.[50] On 27 July 1941, a Partisan-led uprising began in the area of Drvar and Bosansko Grahovo.[48] It was a coordinated effort from both sides of the Una River in the territory of southeastern Lika and southwestern Bosanska, and succeeded in transferring key NDH territory under rebel control.[53]

On 10 August in Stanulović, a mountain village, the Partisans formed the Kopaonik Partisan Detachment Headquarters. The area they controlled, consisting of nearby villages, was called the "Miners Republic" and lasted 42 days. The resistance fighters formally joined the ranks of the Partisans later on.

At the September 1941 Stolice conference, the unified name partisans and the red star as an identification symbol were adopted for all fighters led by the Communist Party of Yugoslavia.

In 1941 Partisan forces in Serbia and Montenegro had around 55,000 fighters, but only 4,500 succeeded to escape to Bosnia.[54] On 21 December 1941 they formed the 1st Proletarian Assault Brigade (1. Proleterska Udarna Brigada) – the first regular Partisan military unit, capable of operating outside its local area. In 1942 Partisan detachments officially merged into the People's Liberation Army and Partisan Detachments of Yugoslavia (NOV i POJ) with an estimated 236,000 soldiers in December 1942.[55]

Partisan numbers from Serbia would be diminished until 1943 when the Partisan movement gained upswing by spreading the fight against the axis.[56] Increase of number of Partisans in Serbia, similarly to other republics, came partly in response to Tito's offer of amnesty to all collaborators on 17 August 1944. At that point tens of thousands of Chetniks switched sides to the Partisans.[citation needed] The amnesty would be offered again after German withdrawal from Belgrade on 21 November 1944 and on 15 January 1945.[57]

Operations

[edit]

By the middle of 1943 partisan resistance to the Germans and their allies had grown from the dimensions of a mere nuisance to those of a major factor in the general situation. In many parts of occupied Europe the enemy was suffering losses at the hands of partisans that he could ill afford. Nowhere were these losses heavier than in Yugoslavia.[58]

Resistance and retaliation

[edit]The Partisans staged a guerrilla campaign which enjoyed gradually increased levels of success and support of the general populace, and succeeded in controlling large chunks of Yugoslav territory. These were managed via the "People's committees", organized to act as civilian governments in areas of the country controlled by the communists, even limited arms industries were set up. At the very beginning, Partisan forces were relatively small, poorly armed and without any infrastructure. They had two major advantages over other military and paramilitary formations in former Yugoslavia:

- A small but valuable cadre of Yugoslav volunteers in the Spanish Civil War who, unlike anyone else at the time, had experience with modern war fought in circumstances quite similar to those of World War II Yugoslavia

- They were founded on ideology rather than ethnicity, which meant the Partisans could expect at least some levels of support in any corner of the country, unlike other paramilitary formations whose support was limited to territories with Croat or Serb majorities. This allowed their units to be more mobile and fill their ranks with a larger pool of potential recruits.

Occupying and quisling forces, however, were quite aware of the Partisan threat, and attempted to destroy the resistance in what Yugoslav historiographers defined as seven major enemy offensives. These are:

- The First Enemy Offensive, the attack conducted by the Axis in autumn of 1941 against the "Republic of Užice", a liberated territory the Partisans established in western Serbia. In November 1941, German troops attacked and reoccupied this territory, with the majority of Partisan forces escaping towards Bosnia.[59] It was during this offensive that tenuous collaboration between the Partisans and the royalist Chetnik movement broke down and turned into open hostility.[60]

- The Second Enemy Offensive, the coordinated Axis attack conducted in January 1942 against Partisan forces in eastern Bosnia. The Partisan troops once again avoided encirclement and were forced to retreat over Igman mountain near Sarajevo.[61]

- The Third Enemy Offensive, an offensive against Partisan forces in eastern Bosnia, Montenegro, Sandžak and Herzegovina which took place in the spring of 1942. It was known as Operation TRIO by the Germans, and again ended with a timely Partisan escape.[62] This attack is mistakenly identified by some sources as the Battle of Kozara, which took place in the summer of 1942.[citation needed]

- The Fourth Enemy Offensive, against "Republic of Bihać", also known as the Battle of the Neretva or Fall Weiss (Case White), a conflict spanning the area between western Bosnia and northern Herzegovina, and culminating in the Partisan retreat over the Neretva river. It took place from January to April 1943.[63]

- The Fifth Enemy Offensive, also known as the Battle of the Sutjeska or Fall Schwarz (Case Black). The operation immediately followed the Fourth Offensive and included a complete encirclement of Partisan forces in southeastern Bosnia and northern Montenegro in May and June 1943.[citation needed]

- The Sixth Enemy Offensive, a series of operations undertaken by the Wehrmacht and the Ustaše after the capitulation of Italy in an attempt to secure the Adriatic coast. It took place in late 1943 and early 1944.

- The Seventh Enemy Offensive, the final attack in western Bosnia in the second quarter of 1944, which included Operation Rösselsprung (Knight's Leap), an unsuccessful attempt to eliminate Tito and annihilate the leadership of the Partisan movement.

It was the nature of partisan resistance that operations against it must either eliminate it altogether or leave it potentially stronger than before. This had been shown by the sequel to each of the previous five offensives from which, one after another, the partisan brigades and divisions had emerged stronger in experience and armament than they had been before, with the backing of a population which had come to see no alternative to resistance but death, imprisonment, or starvation. There could be no half-measures; the Germans left nothing behind them but a trail of ruin. What in other circumstances might possibly have remained the purely ideological war that reactionaries abroad said it was (and German propaganda did their utmost to support them) became a war for national preservation. So clear was this that no room was left for provincialism; Serbs and Croats and Slovenes, Macedonians, Bosnians, Christian and Moslem, Orthodox and Catholic, sank their differences in the sheer desperation of striving to remain alive.[64]

Partisans operated as a regular army that remained highly mobile across occupied Yugoslavia. Partisan units engaged in overt acts of resistance which led to significant reprisals against civilians by Axis forces.[65] The killing of civilians discouraged the Chetniks from carrying out overt resistance, however the Partisans were not fazed and continued overt resistance which disrupted Axis forces, but led to significant civilian casualties.[66]

Allied support

[edit]

Later in the conflict the Partisans were able to win the moral, as well as limited material support of the western Allies, who until then had supported General Draža Mihailović's Chetnik Forces, but were finally convinced of their collaboration fighting by many military missions dispatched to both sides during the course of the war.[67]

To gather intelligence, agents of the western Allies were infiltrated into both the Partisans and the Chetniks. The intelligence gathered by liaisons to the resistance groups was crucial to the success of supply missions and was the primary influence on Allied strategy in Yugoslavia. The search for intelligence ultimately resulted in the demise of the Chetniks and their eclipse by Tito's Partisans. In 1942, although supplies were limited, token support was sent equally to each. The new year would bring a change. The Germans were executing Operation Schwarz (the Fifth anti-Partisan offensive), one of a series of offensives aimed at the resistance fighters, when F.W.D. Deakin was sent by the British to gather information.[citation needed] On April 13, 1941, Winston Churchill sent his greetings to the Yugoslav people. In his greeting he stated:

You are making a heroic resistance against formidable odds and in doing so you are proving true to your great traditions. Serbs, we know you. You were our allies in the last war and your armies are covered with glory. Croats and Slovenes, we know your military history. For centuries you were the bulwark of Christianity. Your fame as warriors spread far and wide on the Continent. One of the finest incidents in the history of Croatia is the one when, in the 16th Century, long before the French Revolution, the peasants rose to defend the rights of man, and fought for those principles which centuries later gave the world democracy. Yugoslavs, you are fighting for those principles today. The British Empire is fighting with you, and behind us is the great democracy of the U.S.A., with its vast and ever-increasing resources. However hard the fight, our victory is assured.[64][68]

His reports contained two important observations. The first was that the Partisans were courageous and aggressive in battling the German 1st Mountain and 104th Light Division, had suffered significant casualties, and required support. The second observation was that the entire German 1st Mountain Division had traveled from Russia by railway through Chetnik-controlled territory. British intercepts (ULTRA) of German message traffic confirmed Chetnik timidity. All in all, intelligence reports resulted in increased Allied interest in Yugoslavia air operations and shifted policy. In September 1943, at Churchill's request, Brigadier General Fitzroy Maclean was parachuted to Tito's headquarters near Drvar to serve as a permanent, formal liaison to the Partisans. While the Chetniks were still occasionally supplied, the Partisans received the bulk of all future support.[69]

Thus, after the Tehran Conference the Partisans received official recognition as the legitimate national liberation force by the Allies, who subsequently set up the RAF Balkan Air Force (under the influence and suggestion of Brigadier-General Fitzroy Maclean) with the aim to provide increased supplies and tactical air support for Marshal Tito's Partisan forces. During a meeting with Franklin D. Roosevelt and the Combined Chiefs of Staff of 24 November 1943, Winston Churchill pointed out that:

It was a lamentable fact that virtually no supplies had been conveyed by sea to the 222,000 followers of Tito. ... These stalwarts were holding as many Germans in Yugoslavia as the combined Anglo-American forces were holding in Italy south of Rome. The Germans had been thrown into some confusion after the collapse of Italy and the Patriots had gained control of large stretches of the coast. We had not, however, seized the opportunity. The Germans had recovered and were driving the Partisans out bit by bit. The main reason for this was the artificial line of responsibility which ran through the Balkans. (... ) Considering that the Partisans had given us such a generous measure of assistance at almost no cost to ourselves, it was of high importance to ensure that their resistance was maintained and not allowed to flag.

— Winston Churchill, 24 November 1943[70]

Activities increase (1943–1945)

[edit]

The partisan army had long since grown into a regular fighting formation comparable to the armies of other small States, and infinitely superior to most of them, and especially to the pre-war Jugoslav army, in tactical skill, fieldcraft, leadership, fighting spirit and fire-power.[71]

With Allied air support (Operation Flotsam) and assistance from the Red Army, in the second half of 1944 the Partisans turned their attention to Serbia, which had seen relatively little fighting since the fall of the Republic of Užice in 1941. On 20 October, the Red Army and the Partisans liberated Belgrade in a joint operation known as the Belgrade Offensive. At the onset of winter, the Partisans effectively controlled the entire eastern half of Yugoslavia – Serbia, Vardar Macedonia and Montenegro, as well as the Dalmatian coast.[citation needed]

In 1945, the Partisans, numbering over 800,000 strong[28] defeated the Armed Forces of the Independent State of Croatia and the Wehrmacht, achieving a hard-fought breakthrough in the Syrmian front in late winter, taking Sarajevo in early April, and the rest of the NDH and Slovenia through mid-May. After taking Rijeka and Istria, which were part of Italy before the war, they beat the Allies to Trieste by two days.[72] The "last battle of World War II in Europe", the Battle of Poljana, was fought between the Partisans and retreating Wehrmacht and quisling forces at Poljana, near Prevalje in Carinthia, on 14–15 May 1945.[citation needed]

Overview by post-war republic

[edit]Serbia

[edit]

The Axis invasion led to the division of Yugoslavia between the Axis powers and the Independent State of Croatia. The largest part of Serbia was organized into the Territory of the Military Commander in Serbia and as such it was the only example of military regime in occupied Europe.[73] The Military Committee of the Provincial Committee of the Communist Party for Serbia was formed in mid-May 1941. The Central Committee of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia arrived in Belgrade in late May, and this was of great importance for the development of the resistance in Yugoslavia. After their arrival, the Central Committee held conferences with local party officials. The decision for preparing the struggle in Serbia issued on June 23, 1941 at the meeting of the Provincial Committee for Serbia. On July 5, a Communist Party proclamation appeared that called upon the Serbian people to struggle against the invaders. Western Serbia was chosen as the base of the uprising, which later spread to other parts of Serbia. A short-lived republic was created in the liberated west, the first liberated territory in Europe. The uprising was suppressed by German forces by 29 November 1941. The Main National Liberation Committee for Serbia is believed to have been founded in Užice on 17 November 1941. It was the body of the Partisan resistance in Serbian territory.

The Anti-fascist Assembly for the National Liberation of Serbia was held 9–12 November 1944.

Tito's post-war government built numerous monuments and memorials in Serbia after the war.

Bosnia and Herzegovina

[edit]Serbian Partisan detachments entered Bosnian territory after the Operation Uzice which saw the Serbian uprising quelled. The Bosnian Partisans were heavily reduced during Operation Trio (1942) on the resistance in eastern Bosnia.[citation needed]

Croatia

[edit]

The National Liberation Movement in Croatia was part of the anti-fascist National Liberational Movement in the Axis-occupied Yugoslavia which was the most effective anti-Nazi resistance movement[14][15] led by Yugoslav revolutionary communists[13] during the Second World War. NOP was under the leadership of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia (KPJ) and supported by many others, with Croatian Peasant Party members contributing to it significantly. NOP units were able to temporarily or permanently liberate large parts of Croatia from occupying forces. Based on the NOP, the Federal Republic of Croatia was founded as a constituent of the Democratic Federal Yugoslavia.

Services

[edit]

Aside from ground forces, the Yugoslav Partisans were the only resistance movement in occupied Europe to employ significant air and naval forces.[citation needed]

Partisan Navy

[edit]Naval forces of the resistance were formed as early as 19 September 1942, when Partisans in Dalmatia formed their first naval unit made of fishing boats, which gradually evolved into a force able to engage the Italian Navy and Kriegsmarine and conduct complex amphibious operations. This event is considered to be the foundation of the Yugoslav Navy. At its peak during World War II, the Yugoslav Partisans' Navy commanded 9 or 10 armed ships, 30 patrol boats, close to 200 support ships, six coastal batteries, and several Partisan detachments on the islands, around 3,000 men.[citation needed] Their main base was the small port of Podgora, which was bombarded several times by Italian naval forces.[74] On 26 October 1943, it was organized first into four, and later into six, Maritime Coastal Sectors (Pomorsko Obalni Sektor, POS). The task of the naval forces was to secure supremacy at sea, organize defense of coast and islands, and attack enemy sea traffic and forces on the islands and along the coasts.[citation needed]

Partisan Air Force

[edit]The Partisans gained an effective air force in May 1942, when the pilots of two aircraft belonging to the Air Force of the Independent State of Croatia (French-designed and Yugoslav-built Potez 25, and Breguet 19 biplanes, themselves formerly of the Royal Yugoslav Air Force), Franjo Kluz and Rudi Čajavec, defected to the Partisans in Bosnia.[75] Later, these pilots used their aircraft against Axis forces in limited operations. Although short-lived due to a lack of infrastructure, this was the first instance of a resistance movement having its own air force. Later, the air force would be re-established and destroyed several times until its permanent institution. The Partisans later established a permanent air force by obtaining aircraft, equipment, and training from captured Axis aircraft, the British Royal Air Force (see BAF), and later the Soviet Air Force.[citation needed]

Composition

[edit]

Yugoslav Partisans were predominantly Serb in composition into 1943.[76][27] Also, it should be kept in mind that until the middle of the war the Partisans were in control of relatively large liberated areas only in parts of Bosnia.[76] Over the entirety of the war according to the records of recipients of Partisan pensions from 1977, the ethnic composition of the Partisans was 53.0% Serb, 18.6% Croat, 9.2% Slovene, 5.5% Montenegrin, 3.5% Bosnian Muslim, and 2.7% Macedonian.[77][78] Much of the remainder of the NOP's membership was made up of Albanians, Hungarians and those self-identifying as Yugoslavs.[77][79][80] At the moment of the capitulation of Italy to the Allies, the Serbs and Croats were participating equally according to their respective population sizes in Yugoslavia as a whole.[81] According to Tito, by May 1944, the ethnic composition of the Partisans was 44% Serb, 30% Croat, 10% Slovene, 5% Montenegrin, 2.5% Macedonian and 2.5% Bosnian Muslim.[82] Italians were also in the army: more than 40,000 Italian fighters were in several military formations such as 9th Corps (Yugoslav Partisans), Partisan Battalion Pino Budicin, Partisan Division "Garibaldi" and Division Italia (Yugoslavia) later and others.[83][84] Following the Soviet-Bulgarian offensive in Serbia and North Macedonia in the autumn of 1944, mass Partisan conscription of Serbs, Macedonians and eventually Kosovo Albanians increased. The number of Serbian Partisan brigades went up from 28 in June 1944 to 60 by the end of the year. In regional terms, the Partisan movement was therefore disproportionately west Yugoslav, particularly from Croatia, while until the autumn of 1944, Serbia's contribution was disproportionately small.[85] During 1941 until September 1943 from Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina 1,064 of Jews joined the Partisans, and largest part of Jews joined the Partisans after the capitulation of Italy in 1943. At the end of the war 2,339 of Jewish Partisans from Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina survived while 804 were killed.[86] Most of the Jews who joined the Yugoslav Partisans were from Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina and according to Romano this number is 4,572 while them 1,318 were killed.[87]

According to the Encyclopedia of the Holocaust of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum,

In partitioned Yugoslavia, partisan resistance developed among the Slovenes in German-annexed Slovenia, engaging mostly in small-scale sabotage. In Serbia, a cetnik resistance organization developed under a former Yugoslav Army Colonel, Draža Mihailovic. After a disastrous defeat in an uprising in June 1941, this organization tended to withdraw from confrontation with the Axis occupying forces. The communist-dominated Partisan organization under the leadership of Josef Tito was a multi-ethnic resistance force – including Serbs, Croats, Montenegrins, Bosniaks, Jews, and Slovenes. Based primarily in Bosnia and northwestern Serbia, Tito's Partisans fought the Germans and Italians most consistently and played a major role in driving the German forces out of Yugoslavia in 1945.[88]

By April 1945, there were some 800,000 soldiers in the Partisan army. Composition by region (ethnicity is not taken into account) from late 1941 to late 1944 was as follows:[89]

| Late 1941 | Late 1942 | Sept. 1943 | Late 1943 | Late 1944 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 20,000 | 60,000 | 89,000 | 108,000 | 100,000 |

| Croatia | 7,000 | 48,000 | 78,000 | 122,000 | 150,000 |

| Serbia (Kosovo) | 5,000 | 6,000 | 6,000 | 7,000 | 20,000 |

| Macedonia | 1,000 | 2,000 | 10,000 | 7,000 | 66,000 |

| Montenegro | 22,000 | 6,000 | 10,000 | 24,000 | 30,000 |

| Serbia (proper) | 23,000 | 8,000 | 13,000 | 22,000 | 204,000 |

| Slovenia[90][91][92] | 2,000 | 4000 | 6000 | 34,000 | 38,000 |

| Serbia (Vojvodina) | 1,000 | 1,000 | 3,000 | 5,000 | 40,000 |

| Total | 81,000 | 135,000 | 215,000 | 329,000 | 648,000 |

According to Fabijan Trgo in the summer of 1944 the National Liberation Army had about 350,000 soldiers in 39 divisions, which were grouped into 12 Corps. In September 1944 about 100,000 soldiers in 17 divisions were ready to enter the final phase of the battle for the liberation of Serbia, overall in all Yugoslav areas the National Liberation Army had about 400,000 armed soldiers. That is, 15 corps, ie 50 divisions, 2 operational groups, 16 independent brigades, 130 partisan detachments, the navy and the first aviation formations. At the beginning of 1945, the number of soldiers was about 600,000. On March 1, the Yugoslav Army had more than 800,000 soldiers, grouped in 63 divisions.[93]

The Chetniks were a mainly Serb-oriented group and their Serb nationalism resulted in an inability to recruit or appeal to many non-Serbs. The Partisans played down communism in favour of a Popular Front approach which appealed to all Yugoslavs. In Bosnia, the Partisan rallying cry was for a country which was to be neither Serbian nor Croatian nor Muslim, but instead to be free and brotherly in which full equality of all groups would be ensured.[94] Nevertheless, Serbs remained the dominant ethnic group in the Yugoslav Partisans throughout the war.[95][96] Italian collaboration with Chetniks in northern Dalmatia resulted in atrocities which further galvanized support for the Partisans among Dalmatian Croats. Chetnik attacks on Gata, near Split, resulted in the slaughter of some 200 Croatian civilians.[97]

In particular, Mussolini's policy of forced Italianization ensured the first significant number of Croats joining the Partisans in late 1941. In other areas, recruitment of Croats was hindered by some Serbs' tendency to view the organisation as exclusively Serb, rejecting non-Serb members and raiding the villages of their Croat neighbours.[46] A group of Jewish youths from Sarajevo attempted to join a Partisan detachment in Kalinovnik, but the Serbian Partisans turned them back to Sarajevo, where many were captured by the Axis forces and perished.[98] Attacks from Croatian Ustaše on the Serbian population was considered to be one of the important reasons for the rise of guerrilla activities, thus aiding an ever-growing Partisan resistance.[99] Following the capitulation of Italy and subsequent Belgrade Offensive, many members of the Ustaše joined the partisans.[100]

Bosnia and Herzegovina

[edit]

At the beginning of the war, the dominant Serb composition of the Partisan rank and file and alliance with the Chetniks, who were engaged in atrocities and killing of Croat and Muslim civilians, forced Croats and Muslims not to join the Bosnian Partisans.[101] Until early 1942, the Partisans in Bosnia and Herzegovina, who were almost exclusively Serbs, cooperated closely with the Chetniks, and some Partisans in eastern Herzegovina and western Bosnia refused to accept Muslims into their ranks. For many Muslims, the behavior of these Serb Partisans towards them meant that there was little difference for them between the Partisans and Chetniks. However, in some areas of Bosnia and Herzegovina the Partisans were successful in attracting both Muslims and Croats from the beginning, notably in the Kozara Mountain area in north-west Bosnia and the Romanija Mountain area near Sarajevo. In the Kozara area, Muslims and Croats made up 25 percent of Partisan strength by the end of 1941.[102]

According to Hoare, by late 1943, 70% of the Partisans in Bosnia and Herzegovina were Serb and 30% were Croat and Muslim.[103] At the end of 1977, Bosnian recipients of war pensions were 64.1% Serb, 23% Muslim, and 8.8% Croat.[104]

Croatia

[edit]

In 1941–42, the majority of Partisans in Croatia were Serbs, but by October 1943 the majority were Croats. This change was partly due to the decision of a key Croatian Peasant Party member, Božidar Magovac, to join the Partisans in June 1943, and partly due to the surrender of Italy.[105] At the moment of the capitulation of Italy to the Allies the Serbs and Croats were participating equally according to their respective population sizes in Yugoslavia as a whole.[81] According to Goldstein, among Croatian partisans at the end of 1941, 77% were Serbs and 21.5% were Croats, and others as well as unknown nationalities. The percentage of Croats in the Partisans had increased to 32% by August 1942, and 34% by September 1943. After the capitulation of Italy, it increased further. At the end of 1944 there were 60.4% Croats, 28.6% Serbs and 11% of other nationalities (2.8% Muslims, Slovenes, Montenegrins, Italians, Hungarians, Czechs, Jews and Germans) in Croatian partisan units.[82][106] According to Ivo Banac, the Croatian Partisan movement in the second half of 1944 had about 150,000 combatants under arms, while 100,070 were in operative units where Croats numbered 60,703 (60.66%), Serbs 24,528 (24.51%), Slovenes 5,113 (5.11%), and others.[107] The Serb contribution to Croatian Partisans represented more than their proportion of the local population.[46][108][109][110]

Croatian Partisans were integral to overall Yugoslav Partisans with ethnic Croats in prominent positions in the movement since the very beginning of the war; According to some researchers writing during 1990s, like Cohen, by the end of 1943, Croatia proper, with 24% of the Yugoslav population, provided more Partisans than Serbia, Montenegro, Slovenia and Macedonia combined (though not more than Bosnia and Herzegovina).[46] In early 1943 Partisans took steps to establish ZAVNOH (National Anti-Fascist Council of the People's Liberation of Croatia) to act as a parliamentary body for all of Croatia – the only one of its kind in occupied Europe. ZAVNOH held three plenary sessions during the war in areas which remained surrounded by Axis troops. At its fourth and last session, held on 24–25 July 1945 in Zagreb, ZAVNOH proclaimed itself as the Croatian Parliament or Sabor.[111]

К концу 1941 года на территории NDH сербы составляли примерно треть населения, но около 95% всех партизан. [112] This numerical dominance lessened later, but until 1943 Serbs formed a majority of Partisans in Croatia (including Dalmatia).[112] Territories in Croatia proper with a substantial number of Serb inhabitants (Lika, Banija, Kordun) formed the most important source of manpower for the Partisans.[85] В мае 1941 года режим Усташа уступил северной Далматии фашистской Италии, что вызвало все более широкую поддержку партизан среди хорватов Далмации. В других частях хорватии хорватская поддержка по отношению к партизанам постепенно увеличивалась из -за насилия и ошибочных оси Усташей и оси, но гораздо медленнее, чем в Далматии. [ 81 ] Было только 1492 партизан из Сербии из 22 148 партизан из главной операционной группы Тито ( Сербо-хорватская : Главна оперативна Група ) в битве при реке Сутжиш в июне 1943 года, а 8 925 были из Хорваии (из которых 5195 были из Дальмации), а 8 925 были из Хорваии (из которых 5195 были из Дальмации), а 8 925-из Хорваии (из которых 5195 были из Дальмации), а 8 925-из Хорватии (из которых 5195 были из Дальмации), а 8 925-из Хорваии (из которых 5195 были из Дальмации), а 8 925-из Хорваи (из которых 5195 были из Дальмации), а 8 925-из Хорваи (из которых 5195 были из Дальмации). , но в этнических терминах 11 851 были сербами, кроме 5220 хорватов. [ 81 ] В конце 1943 года у всех 13 далматинских партизанских бригад было большинство хорватов, но среди 25 партизанских бригад из собственного хорватского (без Далмации) только 7 имело большинство хорватов (у 17 было большинство серб, а у одного было чешское большинство). [ 81 ] По словам историков Tvrtko Jakovina и Davor Marijan, главной причиной масштабного участия хорватов в битве при Сутжишке в июне 1943 года была продолжающаяся террор итальянских фашистов. [ 113 ]

По словам Тито, в партизанской борьбе участвовала четверть населения Загреба (то есть более 50 000 граждан), участвовала в партизанской борьбе, в ходе которой более 20 000 из них были убиты (половина из них как активные бойцы). [ 114 ] В качестве партизанских комбатантов 4709 граждан Загреба были убиты, в то время как 15 129 были убиты в Усташах и нацистских тюрьмах и концентрационных лагерях, а еще 6500 были убиты во время операций по борьбе с повстанцами. [ 85 ]

В последнем наступлении на освобождение Югославии из Хорватии было вовлечено 165 000 солдат в основном для освобождения Хорватии. На хорватской территории после 30 ноября 1944 года в бою с врагом приняли участие 5 корпусов, 15 подразделений, 54 бригады и 35 партизанских отрядов, в общей сложности 121 341 солдата (117 112 мужчин и 4239 женщина), которые в конце 1944 года составили около треть целые вооруженные силы Национальной армии освобождения. В то же время на территории Хорватии было 340 000 немецких солдат, 150 000 солдат Усташи и домашней гвардии, в то время как Четники в начале 1945 года ушли в сторону Словении. Согласно этническому составу партизан, большинство из них составляли хорваты 73 327 или 60,40%, за которыми следуют сербы 34 753 или 28,64%, мусульмане 3,316 или 2,75%, евреи 284 или 0,25%и словенские, чувакие и другие с 9,671 или 7,96%(число Партизанцы и этническая композиция не включают 9 бригад, которые были задействованы за пределами Хорватии). [ 115 ]

Сербия

[ редактировать ]К концу сентября 1941 года было создано 24 отряда с приблизительно 14 000 солдат. [ 116 ] К концу 1943 года 97 партизанских бригад существовали в целом, в то время как в восточных частях Югославии (Войводина, Сербия, Черногории, Косово и Македонии) существовали 18 партизанских бригад. [ 117 ] В Сербии весной и летом 1944 года многие дезертиры и заключенные Четника присоединились к партизанским подразделениям. [ 118 ] Когда Советы освободили Сербию в конце 1944 года, началась массовая партизанская мобилизация серб, македонцев и косово албанцев, что привело к сбалансированному географическому вкладу между восточными и западными югославскими партизанскими движениями. Вклад Сербии в партизанское движение до осени 1944 года было непропорционально небольшим. [ 119 ] В конце сентября 1944 года у Сербии было около 70 000 солдат под командованием основного персонала Сербии , из которых в 13 -м корпусе было около 30 000 солдат, в 14 -м корпусе 32 463 солдат и во 2 -й пролетарийской дивизии 4600 солдат. [ 120 ]

Словения

[ редактировать ]

Во время Второй мировой войны Словения находилась в уникальной ситуации в Европе. Только Греция поделилась своим опытом ухода за уходом; Тем не менее, Словения была единственной страной, которая испытала еще один шаг - поглощение и аннексия в соседнюю нацистскую Германию, фашистскую Италию и Венгрию . [ 121 ] Поскольку само существование словенской нации угрожало, словенская поддержка партизанского движения была гораздо более твердой, чем в Хорватии или Сербии. [ 104 ] Акцент на защиту этнической идентичности был продемонстрирован, назвав войска после важных словенских поэтов и писателей, следуя примеру батальона Ивана Канкар . [ 122 ]

В самом начале партизанские силы были небольшими, плохо вооруженными и без какой -либо инфраструктуры, но у ветеранов гражданской войны в Испании был некоторый опыт работы с партизанской войной . Партизанское движение в Словении функционировало как военная подразделение Фронта освобождения Словенной Нации , антифашистской платформы сопротивления, созданной в провинции Любляна 26 апреля 1941 года, которая первоначально состояла из нескольких групп ориентации левого крыла, наиболее заметным существом Коммунистическая партия и христианские социалисты. В ходе войны влияние Коммунистической партии Словении начало расти, пока ее превосходство не было официально санкционировано в Декларации Доломити 1 марта 1943 года. [ 123 ] Некоторые из членов Фронта освобождения и партизан были бывшими членами движения сопротивления TIGR .

Представители всех политических групп в фронте освобождения участвовали в высшем фронте освобождения, что привело к усилиям по сопротивлению в Словении. Верховный пленум был активен до 3 октября 1943 года, когда на собрании делегатов словенской нации в Кочевже, фронт освобождения из 120 человек был избран в качестве высшего тела фронта освобождения Словена. Пленум также функционировал как Словенский национальный комитет по освобождению, Верховный авторитет в Словении. Некоторые историки считают, что Ассамблея Кочевже является первым словенским избранным парламентом и словенскими партизанами, поскольку его представители также участвовали на 2-й сессии Avnoj и сыграли важную роль в добавлении положения о самоопределении к резолюции о создании новой федеральной югославии. Пленм освобождения был переименован в Словенский национальный совет освобождения на конференции в Черномельж 19 февраля 1944 года и превратился в Словенский парламент. [ Цитация необходима ]

Славенные партизаны сохранили свою конкретную организационную структуру и словенский язык в качестве командного языка до последних месяцев Второй мировой войны, когда их язык был удален как командный язык. С 1942 года по 1944 год они носили кепку Триглавки , которая затем постепенно заменялась на шапку Титкика как часть своей униформы. [ 124 ] В марте 1945 года подразделения словенской партизаны были официально объединены с югославской армией и, таким образом, перестали существовать как отдельное формирование. [ Цитация необходима ]

Партизанская деятельность в Словении началась в 1941 году и не зависит от партизан Тито на юге. Осенью 1942 года Тито впервые попытался управлять движением сопротивления словенству. Арсо Йованович , ведущий югославский коммунист, который был отправлен из высшего командования Тито югославского партизанского сопротивления, закончил свою миссию по установлению центрального контроля над словенскими партизанами в апреле 1943 года. Слияние словенных партизан с силами Тито произошло в 1944 году. [ 125 ] [ 126 ]

В декабре 1943 года была построена больница Франджи Партизанская больница в сложной и бурной местности, всего в нескольких часах от Австрии и центральных частей Германии. Партизанцы транслировали свою собственную радиопрограмму под названием Radio Kričač , расположение которой никогда не стало известно оккупирующим силам, хотя антенны приемника от местного населения были конфискованы. [ Цитация необходима ]

Жертвы

[ редактировать ]Несмотря на их успех, партизаны понесли тяжелые жертвы на протяжении всей войны. В таблице изображены партизанские потери, 7 июля 1941 г. - 16 мая 1945 года: [ 108 ] [ 109 ] [ 110 ]

| 1941 | 1942 | 1943 | 1944 | 1945 | Общий | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Убит в бою | 18,896 | 24,700 | 48,378 | 80,650 | 72,925 | 245,549 |

| Ранен в действии | 29,300 | 31,200 | 61,730 | 147,650 | 130,000 | 399,880 |

| Умер от ран | 3,127 | 4,194 | 7,923 | 8,066 | 7,800 | 31,200 |

| Отсутствует в действии | 3,800 | 6,300 | 5,423 | 5,600 | 7,800 | 28,925 |

По словам Иво Гольдштейна , на территории NDH были убиты 82 000 сербов и 42 000 хорватов. [ 127 ]

Спасательные операции

[ редактировать ]Партизаны были ответственны за успешную и устойчивую эвакуацию сбитых союзных летчиков с Балканов. Например, в период с 1 января по 15 октября 1944 года, согласно статистике, скомпилированной подразделением спасательного экипажа ВВС США, 1152 американских летчиков были поручены из Югославии, 795 с пристрастной помощью и 356 с помощью Четников. [ 128 ] Югославские партизаны на территории Словенов спасли 303 американских летчиков, 389 британских летчиков и военнопленных, а также 120 французских и других военнопленных и рабочих рабов. [ 129 ]

Партизаны также помогали сотням солдат союзников, которым удалось сбежать из немецких лагерей военнопленных (в основном в Южной Австрии) на протяжении всей войны, но особенно с 1943 по 1945 год. Они были доставлены по всей Словении, откуда многие были в воздухе с полужига , в то время как другие делали другие Более длинный сухопутный путь вниз по Хорватии для прохода лодки в Бари в Италии. Весной 1944 года Британская военная миссия в Словении сообщила, что из этих лагерей наблюдается «устойчивая, медленная струя». Им помогали местные гражданские лица, и, связавшись с партизанами по общей линии реки Дравы , они смогли пробиться в безопасное место с партизанскими гидами. [ Цитация необходима ]

Рейд в О'Ббалт

[ редактировать ]В общей сложности 132 военнопленных союзников были спасены от немцев партизанами в одной операции в августе 1944 года в том, что известно как рейд в Остбалте . В июне 1944 года организация Allied Escape начала активно заинтересоваться в оказании помощи заключенным из лагерей на юге Австрии и эвакуировала их через Югославию. Пост миссии союзников в Северной Словении обнаружил, что в , стороне границы, примерно в 50 км (31 миль) от Марибора , там был плохо охраняемый рабочий лагер Остбалте прямо на австрийской Все заключенные. Более 100 военнопленных были доставлены из Сталага XVIII-D в Мариборе в О'Ббалт каждое утро, чтобы выполнять работу по обслуживанию железной дороги, и вечером возвращались в свои квартиры. Контакт был связан между партизанами и заключенными, в результате чего в конце августа группа из семи человек проскользнула мимо спасательного охранника в 15:00, а в 21:00 мужчины праздновали с партизанами в деревне, 8 км (5,0 миль) на югославской стороне границы. [ 130 ]

Семь побег, организованные с партизанами для остальной части лагеря, будут освобождены на следующий день. На следующее утро семь вернулись с сотнями партизан, чтобы дождаться прибытия рабочей вечеринки в обычном поезде. Как только работа начала партизан, процитировать новозеландский глазное свидетельство, «сбился с склона холма и разоружил восемнадцати охранников». За короткое время заключенных, охранников и гражданских надзирателей сопровождались вдоль маршрута, используемого первыми семью заключенными накануне вечером. В первом лагере штаб -квартиры был взят подробности в общей сложности 132 сбежавших заключенных для передачи по радио в Англию. Прогресс вдоль маршрута эвакуации на юг был трудным, так как немецкие патрули были очень активными. Ночная засада от одного такого патруля вызвала потерю двух заключенных и двух эскорта. В конце концов они достигли Semič , в белом карниоле , Словении, которая была партизанской основой для военнопленных. Они были доставлены в Бари 21 сентября 1944 года из аэропорта острова Недалеко от Градак . [ 130 ]

Послевоенный

[ редактировать ]SFR Yugoslavia была одной из двух европейских стран, которые были в значительной степени освобождены его собственными силами во время Второй мировой войны. Он получил значительную помощь от Советского Союза во время освобождения Сербии и существенной помощи от ВВС Балкан с середины 1944 года, но только ограниченная помощь, в основном от англичан, до 1944 года. В конце войны нет иностранных войск были размещены на его почве. Частично в результате страна оказалась на полпути между двумя лагерями в начале холодной войны .

В 1947–48 гг. Советский Союз попытался командовать послушанием от Югославии, в первую очередь по вопросам внешней политики, что привело к расколу Тито -Сталина и почти зажигал вооруженный конфликт. Последовал период очень холодных отношений с Советским Союзом , в течение которого США и Великобритания рассмотрели ухаживание за Югославией в недавно сформированную НАТО . Это, однако, изменилось в 1953 году с кризисом Триеста, напряженным спором между Югославией и Западными союзниками по поводу возможной югослав-итальянской границы (см. Свободную территорию Триеста ) и с югославским примирением в 1956 году. Это двойственное положение в начале Холодная война превратилась в неординарную внешнюю политику, которую Югославия активно поддерживала до ее роспуска.

Злодеяния

[ редактировать ]Партизаны убили гражданских лиц во время и после войны. [ 131 ] 27 июля 1941 года подразделения, возглавляемые партизанами, убили около 100 хорватных гражданских лиц в Босанско Грахово и 300 в Трубаре во время восстания Дрвара против NDH. [ 132 ] В период с 5 по 8 сентября 1941 года около 1000-3000 мусульманских гражданских лиц и солдат, в том числе 100 хорватов были убиты партизанской бригадой Drvar. [ 133 ] Ряд партизанских подразделений и местного населения в некоторых районах, участвовавших в массовом убийстве в ближайшем послевоенном периоде против военнопленных и других воспринимаемых симпатиков, сотрудников и/или фашистов вместе со своими родственниками, включая детей. [ Цитация необходима ] Эти печально известные убийства включают резней Foibe , резня Tezno , Macelj Massacre , Cočevski Rog Massacre , резня в Барбаре Пит и коммунистические чистки в Сербии в 1944–45 годах .

Блебургские репатриации отступающих колонн вооруженных сил Независимого штата Хорватия , Четник и Словенские войска домашней гвардии , тысячи гражданских лиц, направляющихся или отступавших в сторону Австрии, чтобы сдаться западным союзным силам, привели к массовым казни. «Массл» Foife »вытягивают их имя из ям« Foibe », в которых хорватские партизаны 8 -го далматинского корпуса (часто вместе с группами злых местных жителей) застрелили итальянских фашистов и подозреваемых сотрудников и/или сепаратистов. Согласно смешанной исторической комиссии словен итальянской итальянской [ 134 ] Основано в 1993 году, в котором исследовали только то, что произошло в местах, включенных в современную Италию и Словении, убийства, по-видимому, исходили от попыток удаления лиц, связанных с фашизмом (независимо от их личной ответственности), и стремятся выполнять массовые казни Реальные, потенциальные или только предполагаемые противники коммунистического правительства. Убийства 1944-1945 годов в Бачке были похожи по своей природе и повлекла за собой убийство подозреваемых венгерских, немецких и сербских фашистов и их подозреваемых филиалов, без учета их личной ответственности. Во время этой чистки было убито большое количество гражданских лиц из ассоциированной этнической группы. [ 135 ] [ страница необходима ]

У партизан не было официальной повестки дня ликвидации своих врагов, и их кардинал был « братство и единство » всех югославских стран (фраза стала девизом новой Югославии). Страна погибла от 900 000 до 1150 000 гражданских и военных погибших во время оккупации. [ 136 ] По словам Маркуса Таннера в его работе, Хорватия: Хорватия: Хорватия: Хорватия: Хорватия: Хорватия: Хорватия: Хорватия: Хорватия: Хорватия: нация, созданная в войне . [ Полная цитата необходима ]

Эта глава партизанской истории была табу -предметом для разговора в SFR Yugoslavia до конца 1980 -х годов, и в результате десятилетия официального молчания создала реакцию в виде многочисленных манипуляций с данными для целей националистической пропаганды. [ 137 ]

Оборудование

[ редактировать ]Первое стреляющее оружие для партизан было приобретено у побежденной королевской югославской армии , как винтовка M24 Mauser . На протяжении всей войны партизаны использовали любое оружие, которое они могли найти, в основном оружие, захваченное у немцев , итальянцев , армии NDH , Ustache и Chetniks , таких как винтовка Karabiner 98K , MP 40 Submachine Gun, Mg 34 , пулемет, каркановый винтов и карабин, и Beretta Submachine Gun. Другим способом, который приобрел партизан, был из припасов, предоставленных им Советским Союзом и Соединенным Королевством, включая PPSH-41 и STEN MKII Submachine Guns соответственно. Кроме того, партизанские семинары создали свое собственное оружие, смоделированное на заводском оружии, уже используемом, включая так называемую «партизанскую винтовку» и противотанковую «партизанский миномет».

Звание

[ редактировать ]Офицер ранжирует

[ редактировать ]Ранга знака заказанных офицеров .

| Ранга группа | Генеральные / офицеры -флаги | Старшие офицеры | Младшие офицеры | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Июнь 1941 - декабрь 1942 года [ 138 ] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Бригада | Komendant odrede | Комендант батальон | Командир отряда | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Декабрь 1942 - апрель 1943 г. [ 138 ] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Командир генерального штаба | Операционный командир зона | Zamenik Opetive Komandanta Zone | Бригада | Начальник штабной бригады | Заместитель командира бригады | Komendant odrede | Заместитель команда Comnendend | Начальник штаба | Комендант батальон | Заместитель командира батальона | Командир отряда | |||||||||||||

| Май 1943 г. - есть 1945 [ 138 ] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |||||||||||||

| Маршал Югославии | Генерал-Пуковник | Генерал-Лайтант | Генеральный мажор | Полковник | Подполковник | Главный | Капитан | Лейтенант | Подчинение | Прапорт | ||||||||||||||

| Ранга группа | Генеральные / офицеры -флаги | Старшие офицеры | Младшие офицеры | |||||||||||||||||||||

Другие ряды

[ редактировать ]Знак звания унтер-офицеров и военнослужащих .

| Ранга группа | Старшие НКОС | Младшие северо -восточные | Зачислен | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Июнь 1941 - декабрь 1942 года [ 138 ] | Нет значка | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Гид | Капрал | Истребитель | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Декабрь 1942 - апрель 1943 г. [ 138 ] | Нет значка | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Заместитель командира компании | Гид | Капрал | Истребитель | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Май 1943 г. - есть 1945 [ 138 ] |

|

|

|

|

Нет значка | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Старший сержант | Гид | Младший сержант | Капрал | Солдат | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ранга группа | Старшие НКОС | Младшие северо -восточные | Зачислен | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Женщины

[ редактировать ]

Югославские партизаны мобилизовали многих женщин. [ 139 ] Югославское национальное освободительное движение заявило о 6 000 000 гражданских сторонников; Его две миллиона женщин сформировали антифашистский фронт женщин (AFž), в котором революционер сосуществовал с традиционным. AFž управляли школами, больницами и даже местными органами власти. Около 100 000 женщин служили с 600 000 мужчин в Югославской национальной армии освобождения Тито. Он подчеркнул свою преданность правам женщин и гендерному равенству и использовал образы традиционных героини для фольклора для привлечения и узакофикации партизанки ( Pl. Partizanke ; партизанская женщина). [ 139 ] [ 140 ] Участники включали такие данные, как Джудта Аларгич . [ 141 ]

После войны женщины вернулись к традиционным гендерным ролям, но Югославия уникальна, поскольку ее историки уделяли обширное внимание на роли женщин в сопротивлении, пока страна не рассталась в 1990 -х годах. Затем воспоминания о женщинах -солдатах исчезли. [ 142 ] [ 143 ]

Партизанское наследие

[ редактировать ]Политический

[ редактировать ]

Партизанское наследие является предметом значительных дебатов и споров из -за роста этнического национализма в конце 1980 -х и начале 1990 -х годов. [ 144 ] [ 145 ] Исторический ревизионизм после распада Югославии стал идеологически несовместимым в посткоммунистической социально-политической структуре. Эта ревизионистская историография привела к тому, что роль партизан в Второй мировой войне в целом игнорировалась, унижала или атаковала в государствах -преемниках. [ 146 ] [ 147 ] [ 148 ] [ 149 ] [ 150 ] [ 151 ]

Несмотря на то, что социальные изменения в память о партизанской борьбе все еще наблюдаются по всей бывшей Югославии , и их посещают ассоциации ветеранов, потомки, юго-ностальгики , титоисты , левые и сочувствующие. [ 152 ] [ 153 ]

Преемные филиалы бывших ветеранов Ассоциации войны Народной освободительной войны (поднора) представляют партизанских ветеранов в каждой республике и лоббируют политическую и юридическую реабилитацию военных сотрудников, а также усилия по переименованию улиц и общественных площадок. Эти организации также поддерживают памятники и мемориалы, посвященные народной освободительной войне и антифашизму в каждой соответствующей стране. [ 154 ] [ 155 ] [ 156 ] [ 157 ]

Культурный

[ редактировать ]По словам Владимира Деджира , партизаны были вдохновлены более 40 000 работ народной поэзии. [ 158 ]

Смотрите также

[ редактировать ]Сноски

[ редактировать ]- ^ Сербо-хорватский , македонский , словенский : партизани , партизани

- ^ Сербо-хорватский : народоослободилак военный (новый) , Национальная армия освобождения (новая) ; Македонский : Народнослободитель Армия (новый) ; Славян : Народносвободилна Вожска (ноябрь)

- ^ Сербо-хорватский : Национальная армия освобождения и партизанская отряд Югославии (ноябрь и POJ) , Национальная армия освобождения и партизанская отряд Югославии (новая и заклинающая) ; Македонский : Национальная армия освобождения и партизанские подробности о Югославии (новая и заклинание) ; Словен : Народносвободилна военные в Партизанском Детоди Югославия (ноябрь в Подж)

- ^ Сербо-Хорватский : Национальное месторождение Партизан Назначение Югославии (NOPOJ) , Национальное месторождение Партизан Югославии (NOPOJ) ; Македонский : Национальная лицензионная лицкость о Югославии (NPO) ; Slovene : Narodnosvobodili Partizanski Detodi Yugoslavia (Nopoj)

- ^ Сербо-хорват : национальная освободительная Партизанска и Вольноволджа Вольджия Югославия (NOP и DVJ) , партизанская и добровольная армия национального освобождения (NOP и DVJ) ; Македонский : Национальная Партизан и волонтерская армия в Югославии (NOP и VVJ) ; Славян : Народносвободилна Партисанска в Настагуна Вожска Югославия (NOP в PVJ)

- ^ Сербо-хорватский : югославская армия (I) , югославская армия (I) ; Македонский : Югославская армия (I) ; Славян : Югослав Армада (я)

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ Третья Ось Четвертая союзника: румынские вооруженные силы в Европейской войне, 1941–1945 гг . Марк Аксворти, Корнел Скафеш и Кристиан Крэциууюу, стр. 159

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Фишер, Шарон (2006). Политические изменения в посткоммунистической Словакии и Хорватии: от националистической к европейски . Palgrave Macmillan . п. 27. ISBN 978-1-4039-7286-6 .

- ^ Джонс, Говард (1997). Новый вид войны: глобальная стратегия Америки и доктрина Трумэна в Греции . Издательство Оксфордского университета . п. 67. ISBN 978-0-19-511385-3 .

- ^ Hupchick, Dennis P. (2004). Балканы: от Константинополя до коммунизма . Palgrave Macmillan . п. 374. ISBN 978-1-4039-6417-5 .

- ^ Россер, Джон Баркли ; Марина В. Россер (2004). Сравнительная экономика в трансформирующей мировой экономике . MIT Press . п. 397. ISBN 978-0-262-18234-8 .

- ^ Песнь, Кристофер (1986). Энциклопедия кодовых имени Второй мировой войны . Routledge . п. 109. ISBN 978-0-7102-0718-0 .

- ^ Провозглашение провинциального комитета KPJ для Сербии

- ^ Провозглашение провинциального комитета KPJ для Войводины

- ^ Провозглашение районного комитета KPJ для Kragujevac

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный «Партизаны: война на Балканах 1941–1945» . Би -би -си. Архивировано из оригинала 28 ноября 2011 года . Получено 19 ноября 2011 года .

- ^ Кертис, Гленн Э. (1992). Югославия: страновое исследование . Библиотека Конгресса . п. 39 ISBN 978-0-8444-0735-7 .

- ^ Trifunovska, Snežana (1994). Югославия через документы: от его создания до его роспуска . Martinus Nijhoff Publishers . п. 209. ISBN 978-0-7923-2670-0 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Русинов, Деннисон И. (1978). Югославский эксперимент 1948–1974 гг . Калифорнийский университет . п. 2. ISBN 978-0-520-03730-4 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Джеффрис-Джонс, Р. (2013): В шпионах мы доверяем: история Western Intelligence , Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780199580972 , p. 87

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Адамс, Саймон (2005): Балканы , Черные книги кролика, ISBN 9781583406038 , p. 1981

- ^ «Партизан | Югославская военная сила» . Энциклопедия Британская . Получено 26 марта 2021 года .

- ^ Батинич, Елена (2015). Женщины и югославские партизаны: история сопротивления Второй мировой войны . Издательство Кембриджского университета. п. 3. ISBN 978-1107091078 .

- ^ Дэвидсон 1946 , 1.2 Контакт .

- ^ Tomasevich 2001 , p. 96

- ^ Милаццо 1975 , стр. 30–31.

- ^ Робертс 1973 , с. 48

- ^ Tomasevich 1975 , с. 166–178.

- ^ Banac 1996 , p. 43: «С лета 1941 года Четники все чаще получали контроль над сербскими повстанцами и совершали ужасные преступления против мусульман Восточной Боснии-Херзеговины. Массл мусульман, как правило, вырезая горло и бросая тела в различные воды в различных водах. Пути, особенно в Восточной Боснии, в Фоча, Горажде, Чейниче, Рогатика, Вишеграде, Власенице, Сребенике, все в бассейне реки Дрина, но также в восточной Герцеговине, где отдельные деревни сопротивлялись сельбе с границей до 1942 года. Документы Четника - например, протокол конференции Четника в Джейворе, район Котор Варош, в июне 1942 года - говорят о решимости «очистить Боснию всего, что не серб». Это оригинальное этническое очищение, но его можно учитывать в десятках тысяч ».

- ^ Hirsch 2002 , p. 76

- ^ Музыка 2008 , с. 71

- ^ Velikonja 2003 , p. 166

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Марк Пинсон (1996). Мусульмане Боснии-Герцеговина: их историческое развитие от средневековья до роспуска Югославии . Гарвард CMES. с. 143, 144. ISBN 978-0-932885-12-8 Полем Получено 2 октября 2013 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Перика, Vjekoslav (2004). Балканские идолы: религия и национализм в югославских государствах . Издательство Оксфордского университета . п. 96. ISBN 978-0-19-517429-8 .

- ^ Tomasevich 1975 , с. 64–70.

- ^ «Независимое состояние Хорватии» . Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 2010. Архивировано из оригинала 12 апреля 2008 года . Получено 15 февраля 2010 года .

- ^ Kroener, Müller & Umbreit 2000 , p.

- ^ Tomasevich 2001 , p. 78

- ^ Tomasevich 2001 , с. 61–63.

- ^ «Комментарий к конвенции (iv) относительно защиты гражданских лиц во время войны, статуса III части III и обращения с охраняемыми лицами, раздел III, оккупированные территории, статья 47 Необходимость права» . Международный комитет Красного Креста, Женева. 1952. Архивировано из оригинала 7 ноября 2011 года . Получено 26 декабря 2011 года .

- ^ Гленни, Миша (1999). Балканы: национализм, война и великие державы, 1804–1999 . п. 485.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Tomasevich 2001 , p. 69

- ^ Джонсон, Чалмерс А. (1962). Крестьянский национализм и коммунистическая власть . Стэнфорд, Калифорния: издательство Стэнфордского университета. п. 166

- ^ Безофф, Нора (2019). Неправильное наследие Тито: Югославия и Запад с 1939 года . Нью -Йорк: Routledge.

- ^ Суэйн, Джеффри Р. (1989). «Тито: формирование нелояльного большевика». Международный обзор социальной истории . 34 (2): 249, 261.

- ^ Гольдштейн 1999 , с. 140.

- ^ Davor Marijan, майские обсуждения Центрального комитета Партии коммуникации Югославии, Hrvatski Institut Za Povijest, 2003, p. 325-331, ISBN 953-6324-35-0

- ^ Хиггинс, Трамбулл (1966). Гитлер и Россия . Компания Macmillan. С. 11–59, 98–151.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Cohen 1996 , p. 94

- ^ Kovač & Vojnović 1976 , стр. 367–372.

- ^ Квесич 1960 , стр. 135–145.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Cohen 1996 , p. 95

- ^ Иуда 2000 , с. 119

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Tomasevich 2001 , p. 506

- ^ Tomasevich 2001 , p. 412.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Алонсо, Мигель; Крамер, Алан (2019). Фашистская война, 1922–1945 гг.: Агрессия, оккупация, уничтожение . Спрингер Природа. п. 253. ISBN 978-3-03027-648-5 Полем

Благодаря этническому очищению, корпус Усташи и нерегулярные группы «дикий усташе» убили более 100 000 сербов в сельской местности к концу лета 1941 года. Погромы «Дикого Усташа» были главной причиной извержения крупномасштабного восстания против против режим Усташа.

- ^ Хоаре, Марко Аттла (2013). Боснийские мусульмане во Второй мировой войне . Издательство Оксфордского университета. п. 10. ISBN 978-0-19936-543-2 .

- ^ Реджич, Энвер; ДОНИЯ, Роберт (2004). Босния и Герцеговина во Второй мировой войне . Routledge. п. 180. ISBN 1135767351 .

- ^ Гольдштейн, Славко (2013). 1941: год, который продолжает возвращаться . Нью -Йорк Обзор книг. п. 158. ISBN 978-1-59017-700-6 .

- ^ Рамет, Сабрина П. (2006). Три югославии: государственное строительство и легитимация, 1918–2005 . Издательство Университета Индианы. п. 153. ISBN 978-0-253-34656-8 Полем

В 1941 году у партизан было около 55 000 бойцов в Сербии и Черногории, но едва 4500 партизан сбежали в Боснию.

- ^ «Иностранные новости: партизанский бум» . Время . 3 января 1944 года. Архивировано с оригинала 1 сентября 2009 года . Получено 15 февраля 2010 года .

- ^ Харт, Стивен. «История Би -би -си» . Партизаны: война на Балканах 1941 - 1945 . Би -би -си. Архивировано из оригинала 28 января 2011 года . Получено 12 апреля 2011 года .

- ^ Cohen 1996 , p. 61.

- ^ Дэвидсон 1946 , 1.0 Введение .

- ^ Робертс 1973 , с. 37

- ^ Tomasevich 1975 , с. 151–155.

- ^ Робертс 1973 , с. 55

- ^ Робертс 1973 , с. 56–57.

- ^ Робертс 1973 , с. 100–103.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Дэвидсон 1946 , 2,8 шестой наступление .

- ^ Мартин 1946 , с. 174.

- ^ Мартин 1946 , с. 175.

- ^ Барнетт, Нил (2006). Тито Лондон, Великобритания: Haus Publishing. С. 65–66. ISBN 978-1-904950-31-8 .

- ^ Гилберт, Мартин (1993). Военные документы Черчилля: вечно расширяющаяся война, 1941 год . WW Norton & Company. п. 490.

- ^ Мартин 1946 , с. 34

- ^ Уолтер Р. Робертс, Тито, Михайлович и Союзники Дьюк Университет издательство, 1987; ISBN 0-8223-0773-1 , P. 165

- ^ Дэвидсон 1946 , 4.2 Курс войны .

- ^ Робертс 1973 , с. 319

- ^ Петранович 1992 .

- ^ Talpo, Oddone (1994). «Далматия: хроника для истории 1943-1944 годов, часть I» . МСП Историческое офис. п. 357 . Получено 4 мая 2024 года .

- ^ Đonlagić, Ахмет; Атанакович, Жарко; Плеча, Дусан (1967). Югославия во Второй мировой войне . Международная печать. п. 85

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Милаццо 1975 , с. 186

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Hoare 2011 , с.

- ^ Ленард Дж. Коэн, Пол против Уорика (1983) Политическая сплоченность в хрупкой мозаике: Югославский опыт с. 64; Avalon Publishing, Мичиганский университет; ISBN 0865319677

- ^ Калик 2019 , с. 463.

- ^ Hoare 2002 , p.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и Hoare 2002 , p.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Ramet 2006 , p. 153

- ^ Джакомо Скотти Вентимила упал. Итальянцы в Иугославии 1943–45 гг .

- ^ PDF .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Hoare 2002 , p.

- ^ «Спаситель сбегает в антифашистские отряды: мой папа партизан!» Полем

- ^ Tomasevich 2001 , p. 671.

- ^ «Энциклопедия Холокоста, Мемориальный музей Холокоста Соединенных Штатов» . USHMM.org. 6 января 2011 года. Архивировано с оригинала 20 ноября 2011 года . Получено 19 ноября 2011 года .

- ^ Cohen 1996 , p. 96

- ^ Griesser-Pecar, Tamara (2007). Разведенные люди: Словения, 1941–1945 гг.: Оккупация, сотрудничество, гражданская война, революция [ Разделение Нация: Словения, 1941–1945 гг . Молодежная книга. стр. 345–346. ISBN 978-961-01-0208-3 .

- ^ Словеновское и итальянское движение сопротивления - Структурное сравнение: дипломы тезисов [ Словенное и итальянское движение сопротивления - Структурное сравнение: тезис дипломы ] (PDF) (в словенском). Факультет социальных наук, Университет Любляны. 2008. Стр. 59-62. Cobiss 27504733 . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 19 июня 2013 года . Получено 2 марта 2012 года .

- ^ Гуштин, Дамиджан. "Словения" . Европейский архив сопротивления . ERA Project. Архивировано с оригинала 20 октября 2013 года . Получено 2 марта 2012 года .

- ^ Фабиджан Торговля; (1975) Освобождение Югославии (1944-1945) Югославии (1944-1945) с. Освобождение

- ^ Иуда 2000 , с. 120.

- ^ Век геноцида: критические очерки и свидетельства очевидцев , Сэмюэл Тоттен, Уильям С. Парсонс, с. 430.

- ^ Бильжана Ванковская, Хокан Виберг, между прошлым и будущим: гражданские военные отношения на посткоммунистических Балканах , с. 197

- ^ Иуда 2000 , с. 128

- ^ Cohen 1996 , p. 77

- ^ Иуда 2000 , стр. 127–128.

- ^ Мартин 1946 , с. 233.

- ^ Hoare 2013 , с.

- ^ Tomasevich 2001 , с. 506–07.

- ^ Hoare 2006 , p.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Hoare 2002 .

- ^ Tomasevich 2001 , с. 362–363.

- ^ Гольдштейн. Сербы и хорваты в национальной освободительной войне в Хорватии . , с. 266–267.

- ^ Ivo banac; (1992) Страшная асимметрия войны: причины и последствия кончины Югославии с. 154; MIT Press от имени Американской академии искусств и наук, doi : 10.2307/20025437

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Стругар, Владо (1969). Югославия 1941–1945 . Военное обучение.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Anic, Joksimovic & Gutic 1982 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Вукович, Бозидар; Видакович, Джозип (1976). Дорога главного персонала Хорватии .

- ^ Джелик, Иван (1978). Хорватия в войне и революции 1941–1945 . Загреб: школьная книга .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Hoare 2002 , p.

- ^ «Битва при Сутжисе была« хорватской битвой ». Было убито 3000 далматинцев » . www.vecernji.hr (на хорватском) . Получено 5 января 2020 года .

- ^ Институт истории хорватского движения хорватского (1982) Труды Загреба 1941-1945 гг . . [2]

- ^ Никола Аник; (1985) НОП Хорватские вооруженные силы во время его освобождения в конце 1944 года и в начале 1945 года с. Институт военной истории (Институт военной истории), Белград, Журнал современной истории, вып. 17 Нет. 1, [3]

- ^ Anic, Joksimovic & Gutic 1982 , стр. 25-27.

- ^ Марко Аттла Хоар . «Великая сербская угроза, Zavnobih и мусульманский Босний вступают в народное освободительное движение» (PDF) . anubih.ba . Посебна Изданджа Анубих. п. 122 Получено 21 декабря 2020 года .

- ^ Милан Раданович; (2015) Наказание и преступность: полномочия по сотрудничеству в Сербии: ответственность за преступления на ставку (1941-1944) I Военные морщины (и серб) с. 205, Роза Люксембург Stiftung ISBN 8688745153

- ^ Hoare 2002 , p.

- ^ Anic, Joksimovic & Gutic 1982 , стр. 369–378.

- ^ Грегор Джозеф Кранджк (2013). Прогулка с дьяволом , Университет Торонто Пресс, Отдел научного издательства, с. 5 (Введение)

- ^ Štih, p.; Simoniti, v.; Vodopivec, P. (2008) Славнская история: общество, политика, культура архивирована 20 октября 2013 года на машине Wayback , Институт современной истории. Любляна, с. 426.

- ^ Gow & Carmichael 2010 , с. 48

- ^ Вукшич 2003 , с.

- ^ Стюарт 2006 , с. 15

- ^ Klemenčič & Zagar 2004 , стр. 167–168.

- ^ Bideleux, Robert; Джеффрис, Ян (2017) Балканы: посткоммунистическая история с. 191; Routledge, ISBN 978-1-13458-328-7

- ^ Лири 1995 , с. 34

- ^ Tomasevich 2001 , p. 115.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Мейсон 1954 , с. 383 .