Демократическая Республика Конго

Демократическая Республика Конго Демократическая Республика Конго ( французский ) | |

|---|---|

| Девиз: «Справедливость – Мир – Труд». («Справедливость – Мир – Труд») | |

| Гимн: « Дебют Конголезцев ». («Вставай, конголезец») | |

| Capital and largest city | Kinshasa 4°19′S 15°19′E / 4.317°S 15.317°E |

| Official languages | French |

| Recognised national languages | |

| Religion (2021)[1] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Congolese Kinshasa-Congolese |

| Government | Unitary semi-presidential republic |

| Félix Tshisekedi | |

| Judith Suminwa | |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Senate | |

| National Assembly | |

| Formation | |

| 17 November 1879 | |

| 1 July 1885 | |

| 15 November 1908 | |

• Independence from Belgium | 30 June 1960[2] |

| 20 September 1960 | |

• Democratic Republic | 1 August 1964 |

| 27 October 1971 | |

| 17 May 1997 | |

| 18 February 2006 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 2,345,409 km2 (905,567 sq mi) (11th) |

• Water (%) | 3.32 |

| Population | |

• 2024 estimate | |

• Density | 46.3/km2 (119.9/sq mi) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2012) | medium |

| HDI (2022) | low (180th) |

| Currency | Congolese franc (CDF) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 to +2 (WAT and CAT) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +243 |

| ISO 3166 code | CD |

| Internet TLD | .cd |

Демократическая Республика Конго ( ДРК ), [б] также известная как ДР Конго , Конго-Киншаса , Конго-Заир или просто Конго или Конго , — это страна в Центральной Африке . По площади территории ДРК является второй по величине страной в Африке и 11-й в мире . Демократическая Республика Конго с населением около 105 миллионов человек является самой густонаселенной франкоязычной страной в мире. Столица страны и крупнейший город — Киншаса , который также является экономическим центром. Страна граничит с Республикой Конго , Центральноафриканской Республикой , Южным Суданом , Угандой , Руандой , Бурунди , Танзанией (через озеро Танганьика ), Замбией , Анголой , эксклавом Кабинда в Анголе и южной частью Атлантического океана .

Centered on the Congo Basin, the territory of the DRC was first inhabited by Central African foragers around 90,000 years ago and was reached by the Bantu expansion about 3,000 years ago.[7] На западе Королевство Конго управляло в районе устья реки Конго с 14 по 19 века. королевства Азанде , Люба и Лунда На северо-востоке, в центре и на востоке с 16-го и 17-го веков по 19-й век правили . Король Бельгии Леопольд II официально получил права на территорию Конго у колониальных стран Европы в 1885 году и объявил эту землю своей частной собственностью, назвав ее Свободным государством Конго . С 1885 по 1908 год его колониальные военные заставляли местное население производить каучук и совершали массовые злодеяния . В 1908 году Леопольд уступил территорию, которая, таким образом, стала бельгийской колонией .

Congo achieved independence from Belgium on 30 June 1960 and was immediately confronted by a series of secessionist movements, the assassination of Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba, and the seizure of power by Mobutu Sese Seko in a 1965 coup d'état. Mobutu renamed the country Zaire in 1971 and imposed a harsh personalist dictatorship until his overthrow in 1997 by the First Congo War.[2] The country then had its name changed back and was confronted by the Second Congo War from 1998 to 2003, which resulted in the deaths of 5.4 million people.[8][9][10][11] The war ended under President Joseph Kabila, who governed the country from 2001 to 2019 and under whom human rights in the country remained poor and included frequent abuses such as forced disappearances, torture, arbitrary imprisonment and restrictions on civil liberties.[12] Following the 2018 general election, in the country's first peaceful transition of power since independence, Kabila was succeeded as president by Félix Tshisekedi, who has served as president since.[13] Since 2015, the Eastern DR Congo has been the site of an ongoing military conflict in Kivu.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo is extremely rich in natural resources but has suffered from political instability, a lack of infrastructure, corruption, and centuries of both commercial and colonial extraction and exploitation, followed by more than 60 years of independence, with little widespread development.[14] Besides the capital Kinshasa, the two next largest cities, Lubumbashi and Mbuji-Mayi, are both mining communities. The DRC's largest export is raw minerals, with China accepting over 50% of its exports in 2019.[2] In 2021, DR Congo's level of human development was ranked 179th out of 191 countries by the Human Development Index[15] and is classed as a least developed country by the UN. As of 2018[update], following two decades of various civil wars and continued internal conflicts, around 600,000 Congolese refugees were still living in neighbouring countries.[16] Two million children risk starvation, and the fighting has displaced 4.5 million people.[17] The country is a member of the United Nations, Non-Aligned Movement, African Union, COMESA, Southern African Development Community, Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie, and Economic Community of Central African States.

Etymology

[edit]The Democratic Republic of the Congo is named after the Congo River, which flows through the country. The Congo River is the world's deepest river and the world's third-largest river by discharge. The Comité d'études du haut Congo ("Committee for the Study of the Upper Congo"), established by King Leopold II of Belgium in 1876, and the International Association of the Congo, established by him in 1879, were also named after the river.[18]

The Congo River was named by early European sailors after the Kingdom of Kongo and its Bantu inhabitants, the Kongo people, when they encountered them in the 16th century.[19][20] The word Kongo comes from the Kongo language (also called Kikongo). According to American writer Samuel Henry Nelson: "It is probable that the word 'Kongo' itself implies a public gathering and that it is based on the root konga, 'to gather' (trans[itive])."[21] The modern name of the Kongo people, Bakongo, was introduced in the early 20th century.[citation needed]

The Democratic Republic of the Congo has been known in the past as, in chronological order, the Congo Free State, Belgian Congo, the Republic of the Congo-Léopoldville, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Republic of Zaire, before returning to its current name the Democratic Republic of the Congo.[2]

At the time of independence, the country was named the Republic of the Congo-Léopoldville to distinguish it from its neighbour the Republic of the Congo-Brazzaville. With the promulgation of the Luluabourg Constitution on 1 August 1964, the country became the DRC but was renamed Zaire (a past name for the Congo River) on 27 October 1971 by President Mobutu Sese Seko as part of his Authenticité initiative.[22]

The word Zaire is from a Portuguese adaptation of a Kikongo word nzadi ("river"), a truncation of nzadi o nzere ("river swallowing rivers").[23][24][25] The river was known as Zaire during the 16th and 17th centuries; Congo seems to have replaced Zaire gradually in English usage during the 18th century, and Congo is the preferred English name in 19th-century literature, although references to Zaire as the name used by the natives (i.e., derived from Portuguese usage) remained common.[26]

In 1992, the Sovereign National Conference voted to change the name of the country to the "Democratic Republic of the Congo", but the change was not made.[27] The country's name was later restored by President Laurent-Désiré Kabila when he overthrew Mobutu in 1997.[28] To distinguish it from the neighboring Republic of the Congo, it is sometimes referred to as Congo (Kinshasa), Congo-Kinshasa, or Big Congo.[29] Its name is sometimes also abbreviated as Congo DR, DR Congo,[30] DRC,[31] the DROC,[32] and RDC (in French).[31]

History

[edit]Before Bantu expansion, the territory comprising the Democratic Republic of the Congo was home to Central Africa's oldest settled groups, the Mbuti peoples. Most of the remnants of their hunter-gatherer culture remain in the present time.

Early history

[edit]

The geographical area now known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo was populated as early as 90,000 years ago, as shown by the 1988 discovery of the Semliki harpoon at Katanda, one of the oldest barbed harpoons ever found, believed to have been used to catch giant river catfish.[33][34]

Bantu peoples reached Central Africa at some point during the first millennium BC, then gradually started to expand southward. Their propagation was accelerated by the adoption of pastoralism and of Iron Age techniques. The people living in the south and southwest were foraging groups, whose technology involved only minimal use of metal technologies. The development of metal tools during this time period revolutionized agriculture. This led to the displacement of the hunter-gatherer groups in the east and southeast. The final wave of the Bantu expansion was complete by the 10th century, followed by the establishment of the Bantu kingdoms, whose rising populations soon made possible intricate local, regional, and foreign commercial networks that traded mostly in slaves, salt, iron, and copper.

Congo Free State (1877–1908)

[edit]

Belgian exploration and administration took place from the 1870s until the 1920s. It was first led by Henry Morton Stanley, who undertook his explorations under the sponsorship of King Leopold II of Belgium. The eastern regions of the precolonial Congo were heavily disrupted by constant slave raiding, mainly from Arab–Swahili slave traders such as the infamous Tippu Tip, who was well known to Stanley.[35]

Leopold had designs on what was to become the Congo as a colony.[36] In a succession of negotiations, Leopold, professing humanitarian objectives in his capacity as chairman of the front organization Association Internationale Africaine, actually played one European rival against another. [citation needed]

King Leopold formally acquired rights to the Congo territory at the Conference of Berlin in 1885 and made the land his private property. He named it the Congo Free State.[36] Leopold's regime began various infrastructure projects, such as the construction of the railway that ran from the coast to the capital of Leopoldville (now Kinshasa), which took eight years to complete.

In the Free State, colonists coerced the local population into producing rubber, for which the spread of automobiles and development of rubber tires created a growing international market. Rubber sales made a fortune for Leopold, who built several buildings in Brussels and Ostend to honor himself and his country. To enforce the rubber quotas, the Force Publique was called in and made the practice of cutting off the limbs of the natives a matter of policy.[37]

During 1885–1908, millions of Congolese died as a consequence of exploitation and disease. In some areas the population declined dramatically – it has been estimated that sleeping sickness and smallpox killed nearly half the population in the areas surrounding the lower Congo River.[37]

News of the abuses began to circulate. In 1904, the British consul at Boma in the Congo, Roger Casement, was instructed by the British government to investigate. His report, called the Casement Report, confirmed the accusations of humanitarian abuses. The Belgian Parliament forced Leopold II to set up an independent commission of inquiry. Its findings confirmed Casement's report of abuses, concluding that the population of the Congo had been "reduced by half" during this period.[38] Determining precisely how many people died is impossible, as no accurate records exist.

Belgian Congo (1908–1960)

[edit]

In 1908, the Belgian parliament, in spite of initial reluctance, bowed to international pressure (especially from the United Kingdom) and took over the Free State from King Leopold II.[39] On 18 October 1908, the Belgian parliament voted in favour of annexing the Congo as a Belgian colony. Executive power went to the Belgian minister of colonial affairs, assisted by a Colonial Council (Conseil Colonial) (both located in Brussels). The Belgian parliament exercised legislative authority over the Belgian Congo. In 1923 the colonial capital moved from Boma to Léopoldville, some 300 kilometres (190 mi) further upstream into the interior.[40]

The transition from the Congo Free State to the Belgian Congo was a break, but it also featured a large degree of continuity. The last governor-general of the Congo Free State, Baron Théophile Wahis, remained in office in the Belgian Congo and the majority of Leopold II's administration with him.[41] Opening up the Congo and its natural and mineral riches to the Belgian economy remained the main motive for colonial expansion – however, other priorities, such as healthcare and basic education, slowly gained in importance.

Colonial administrators ruled the territory and a dual legal system existed (a system of European courts and another one of indigenous courts, tribunaux indigènes). Indigenous courts had only limited powers and remained under the firm control of the colonial administration. The Belgian authorities permitted no political activity in the Congo whatsoever,[42] and the Force Publique put down any attempts at rebellion.

The Belgian Congo was directly involved in the two world wars. During World War I (1914–1918), an initial stand-off between the Force Publique and the German colonial army in German East Africa turned into open warfare with a joint Anglo-Belgian-Portuguese invasion of German colonial territory in 1916 and 1917 during the East African campaign. The Force Publique gained a notable victory when it marched into Tabora in September 1916 under the command of General Charles Tombeur after heavy fighting.

After 1918, Belgium was rewarded for the participation of the Force Publique in the East African campaign with a League of Nations mandate over the previously German colony of Ruanda-Urundi. During World War II, the Belgian Congo provided a crucial source of income for the Belgian government in exile in London, and the Force Publique again participated in Allied campaigns in Africa. Belgian Congolese forces under the command of Belgian officers notably fought against the Italian colonial army in Ethiopia in Asosa, Bortaï[43] and Saïo under Major-General Auguste-Eduard Gilliaert.[44]

Independence and political crisis (1960–1965)

[edit]

In May 1960, a growing nationalist movement, the Mouvement National Congolais led by Patrice Lumumba, won the parliamentary elections. Lumumba became the first Prime Minister of the Republic of the Congo, on 24 June 1960. The parliament elected Joseph Kasa-Vubu as president, of the Alliance des Bakongo (ABAKO) party. Other parties that emerged included the Parti Solidaire Africain led by Antoine Gizenga, and the Parti National du Peuple led by Albert Delvaux and Laurent Mbariko.[45]

The Belgian Congo achieved independence on 30 June 1960 under the name "République du Congo" ("Republic of Congo" or "Republic of the Congo" in English). As the neighboring French colony of Middle Congo (Moyen Congo) also chose the name "Republic of Congo" upon achieving its independence, the two countries were more commonly known as "Congo-Léopoldville" and "Congo-Brazzaville", after their capital cities.

Shortly after independence the Force Publique mutinied, and on 11 July the province of Katanga (led by Moïse Tshombe) and South Kasai engaged in secessionist struggles against the new leadership.[46][47] Most of the 100,000 Europeans who had remained behind after independence fled the country,[48] opening the way for Congolese to replace the European military and administrative elite.[49] After the United Nations rejected Lumumba's call for help to put down the secessionist movements, Lumumba asked for assistance from the Soviet Union, who accepted and sent military supplies and advisers. On 23 August, the Congolese armed forces invaded South Kasai. Lumumba was dismissed from office on 5 September 1960 by Kasa-Vubu who publicly blamed him for massacres by the armed forces in South Kasai and for involving Soviets in the country.[50] Lumumba declared Kasa-Vubu's action unconstitutional, and a crisis between the two leaders developed.[51]

On 14 September, Colonel Joseph Mobutu, with the backing of the US and Belgium, removed Lumumba from office. On 17 January 1961, Lumumba was handed over to Katangan authorities and executed by Belgian-led Katangan troops.[52] A 2001 investigation by Belgium's Parliament found Belgium "morally responsible" for the murder of Lumumba, and the country has since officially apologised for its role in his death.[53]

On 18 September 1961, in ongoing negotiations of a ceasefire, a plane crash near Ndola resulted in the death of Dag Hammarskjöld, the Secretary-General of the United Nations, along with all 15 passengers, setting off a succession crisis. Amidst widespread confusion and chaos, a temporary government was led by technicians (the Collège des commissaires généraux). Katangan secession ended in January 1963 with the assistance of UN forces. Several short-lived governments of Joseph Ileo, Cyrille Adoula, and Moise Kapenda Tshombe took over in quick succession.

Meanwhile, in the east of the country, Soviet and Cuban-backed rebels called the Simbas rose up, taking a significant amount of territory and proclaiming a communist "People's Republic of the Congo" in Stanleyville. The Simbas were pushed out of Stanleyville in November 1964 during Operation Dragon Rouge, a military operation conducted by Belgian and American forces to rescue hundreds of hostages. Congolese government forces fully defeated the Simba rebels by November 1965.[54]

Lumumba had previously appointed Mobutu chief of staff of the new Congo army, Armée Nationale Congolaise.[55] Taking advantage of the leadership crisis between Kasavubu and Tshombe, Mobutu garnered enough support within the army to launch a coup. A constitutional referendum the year before Mobutu's coup of 1965 resulted in the country's official name being changed to the "Democratic Republic of the Congo".[2] In 1971 Mobutu changed the name again, this time to "Republic of Zaire".[56][22]

Mobutu autocracy and Zaire (1965–1997)

[edit]

Mobutu had the staunch support of the United States because of his opposition to communism; the U.S. believed that his administration would serve as an effective counter to communist movements in Africa.[57] A single-party system was established, and Mobutu declared himself head of state. He periodically held elections in which he was the only candidate. Although relative peace and stability were achieved, Mobutu's government was guilty of severe human rights violations, political repression, a cult of personality and corruption.

By late 1967 Mobutu had successfully neutralized his political opponents and rivals, either through co-opting them into his regime, arresting them, or rendering them otherwise politically impotent.[58] Throughout the late 1960s, Mobutu continued to shuffle his governments and cycle officials in and out of the office to maintain control. Joseph Kasa-Vubu's death in April 1969 ensured that no person with First Republic credentials could challenge his rule.[59] By the early 1970s, Mobutu was attempting to assert Zaire as a leading African nation. He traveled frequently across the continent while the government became more vocal about African issues, particularly those relating to the southern region. Zaire established semi-clientelist relationships with several smaller African states, especially Burundi, Chad, and Togo.[60]

Corruption became so common the term "le mal Zairois" or "Zairian sickness",[61] meaning gross corruption, theft and mismanagement, was coined, reportedly by Mobutu.[62] International aid, most often in the form of loans, enriched Mobutu while he allowed national infrastructure such as roads to deteriorate to as little as one-quarter of what had existed in 1960. Zaire became a kleptocracy as Mobutu and his associates embezzled government funds.

In a campaign to identify himself with African nationalism, starting on 1 June 1966, Mobutu renamed the nation's cities: Léopoldville became Kinshasa (the country was known as Congo-Kinshasa), Stanleyville became Kisangani, Elisabethville became Lubumbashi, and Coquilhatville became Mbandaka. In 1971, Mobutu renamed the country the Republic of Zaire,[22] its fourth name change in eleven years and its sixth overall. The Congo River was renamed the Zaire River.

During the 1970s and 1980s, Mobutu was invited to visit the United States on several occasions, meeting with U.S. Presidents Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush.[63] Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union U.S. relations with Mobutu cooled, as he was no longer deemed necessary as a Cold War ally. Opponents within Zaire stepped up demands for reform. This atmosphere contributed to Mobutu's declaring the Third Republic in 1990, whose constitution was supposed to pave the way for democratic reform. The reforms turned out to be largely cosmetic. Mobutu continued in power until armed forces forced him to flee in 1997. "From 1990 to 1993, the United States facilitated Mobutu's attempts to hijack political change", one academic wrote, and "also assisted the rebellion of Laurent-Desire Kabila that overthrew the Mobutu regime."[64]

In September 1997, Mobutu died in exile in Morocco.[65]

Continental and civil wars (1996–2007)

[edit]

By 1996, following the Rwandan Civil War and genocide and the ascension of a Tutsi-led government in Rwanda, Rwandan Hutu militia forces (Interahamwe) fled to eastern Zaire and used refugee camps as bases for incursions against Rwanda. They allied with the Zairian Armed Forces to launch a campaign against Congolese ethnic Tutsis in eastern Zaire.[66]

A coalition of Rwandan and Ugandan armies invaded Zaire to overthrow the government of Mobutu, launching the First Congo War. The coalition allied with some opposition figures, led by Laurent-Désiré Kabila, becoming the Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo. In 1997 Mobutu fled and Kabila marched into Kinshasa, naming himself as president and reverting the name of the country to the Democratic Republic of the Congo.[67][68]

Kabila later requested that foreign military forces return to their own countries. Rwandan troops retreated to Goma and launched a new Tutsi-led rebel military movement called the Rassemblement Congolais pour la Democratie to fight Kabila, while Uganda instigated the creation of a rebel movement called the Movement for the Liberation of the Congo, led by Congolese warlord Jean-Pierre Bemba.[citation needed] The two rebel movements, along with Rwandan and Ugandan troops, started the Second Congo War by attacking the DRC army in 1998. Angolan, Zimbabwean, and Namibian militaries entered the hostilities on the side of the government.

Kabila was assassinated in 2001.[69] His son Joseph Kabila succeeded him [70] and called for multilateral peace talks. UN peacekeepers, MONUC, now known as MONUSCO, arrived in April 2001. In 2002–03 Bemba intervened in the Central African Republic on behalf of its former president, Ange-Félix Patassé.[71] Talks led to a peace accord under which Kabila would share power with former rebels. By June 2003 all foreign armies except those of Rwanda had pulled out of Congo. A transitional government was set up until after the election. A constitution was approved by voters, and on 30 July 2006 DRC held its first multi-party elections. These were the first free national elections since 1960, which many believed would mark the end to violence in the region.[72] However, an election-result dispute between Kabila and Bemba turned into a skirmish between their supporters in Kinshasa. MONUC took control of the city. A new election took place in October 2006, which Kabila won, and in December 2006 he was sworn in as president.

Continued conflicts (2008–2018)

[edit]

Laurent Nkunda, a member of Rally for Congolese Democracy–Goma, defected along with troops loyal to him and formed the National Congress for the Defence of the People (CNDP), which began an armed rebellion against the government. In March 2009, after a deal between the DRC and Rwanda, Rwandan troops entered the DRC and arrested Nkunda and were allowed to pursue FDLR militants. The CNDP signed a peace treaty with the government in which it agreed to become a political party and to have its soldiers integrated into the national army in exchange for the release of its imprisoned members.[73] In 2012 Bosco Ntaganda, the leader of the CNDP, and troops loyal to him, mutinied and formed the rebel military March 23 Movement (M23), claiming the government had violated the treaty.[74]

In the resulting M23 rebellion, M23 briefly captured the provincial capital of Goma in November 2012.[75][76] Neighboring countries, particularly Rwanda, have been accused of arming rebels groups and using them as proxies to gain control of the resource-rich country, an accusation they deny.[77][78] In March 2013, the United Nations Security Council authorized the United Nations Force Intervention Brigade to neutralize armed groups.[79] On 5 November 2013, M23 declared an end to its insurgency.[80] Additionally, in northern Katanga, the Mai-Mai created by Laurent Kabila slipped out of the control of Kinshasa with Gédéon Kyungu Mutanga's Mai Mai Kata Katanga briefly invading the provincial capital of Lubumbashi in 2013 and 400,000 persons displaced in the province as of 2013[update].[81] On and off fighting in the Ituri conflict occurred between the Nationalist and Integrationist Front and the Union of Congolese Patriots who claimed to represent the Lendu and Hema ethnic groups, respectively. In the northeast, Joseph Kony's Lord's Resistance Army moved from their original bases in Uganda and South Sudan to DR Congo in 2005 and set up camps in the Garamba National Park.[82][83]The war in the Congo has been described as the bloodiest war since World War II.[14] In 2009, The New York Times reported that people in the Congo continued to die at a rate of an estimated 45,000 per month[84] – estimates of the number who have died from the long conflict range from 900,000 to 5,400,000.[85] The death toll is caused by widespread disease and famine; reports indicate that almost half of the individuals who have died are children under five years of age.[86] There have been frequent reports of weapon bearers killing civilians, of the destruction of property, of widespread sexual violence,[87] causing hundreds of thousands of people to flee their homes, and of other breaches of humanitarian and human rights law. One study found that more than 400,000 women are raped in the Democratic Republic of Congo every year.[88] In 2018 and 2019, Congo reported the highest levels of sexual violence in the world.[72] According to the Human Rights Watch and the New York University-based Congo Research Group, armed troops in DRC's eastern Kivu region have killed over 1,900 civilians and kidnapped at least 3,300 people since June 2017 to June 2019.[89] On 10 May 2018, Congolese gynecologist Denis Mukwege was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his effort to end the use of sexual violence as a weapon of war and armed conflict.[90]

In 2015, major protests broke out across the country and protesters demanded that Kabila step down as president. The protests began after the passage of a law by the Congolese lower house that, if also passed by the Congolese upper house, would keep Kabila in power at least until a national census was conducted (a process which would likely take several years and therefore keep him in power past the planned 2016 elections, which he is constitutionally barred from participating in). This bill passed; however, it was gutted of the provision that would keep Kabila in power until a census took place. A census is supposed to take place, but it is no longer tied to when the elections take place. In 2015, elections were scheduled for late 2016 and a tenuous peace held in the Congo.[91] On 27 November 2016 Congolese foreign minister Raymond Tshibanda told the press no elections would be held in 2016: "it has been decided that the voter registration operation will end on July 31, 2017, and that election will take place in April 2018."[92] Protests broke out in the country on 20 December when Kabila's term in office ended. Across the country, dozens of protesters were killed and hundreds were arrested.

According to Jan Egeland, presently Secretary-General of the Norwegian Refugee Council, the situation in the DRC became much worse in 2016 and 2017 and is a major moral and humanitarian challenge comparable to the wars in Syria and Yemen, which receive much more attention. Women and children are abused sexually and "abused in all possible manners". Besides the conflict in North Kivu, violence increased in the Kasai region. The armed groups were after gold, diamonds, oil, and cobalt to line the pockets of rich men both in the region and internationally. There were also ethnic and cultural rivalries at play, as well as religious motives and the political crisis with postponed elections. Egeland says people believe the situation in the DRC is "stably bad" but in fact, it has become much, much worse. "The big wars of the Congo that were really on top of the agenda 15 years ago are back and worsening".[93] Disruption in planting and harvesting caused by the conflict was estimated to escalate starvation in about two million children.[94]

Human Rights Watch said in 2017 that Kabila recruited former March 23 Movement fighters to put down country-wide protests over his refusal to step down from office at the end of his term. "M23 fighters patrolled the streets of Congo's main cities, firing on or arresting protesters or anyone else deemed to be a threat to the president," they said.[95] Fierce fighting has erupted in Masisi between government forces and a powerful local warlord, General Delta. The United Nations mission in the DRC is its largest and most expensive peacekeeping effort, but it shut down five UN bases near Masisi in 2017, after the U.S. led a push to cut costs.[96]

A tribal conflict erupted on 16–17 December 2018 at Yumbi in Mai-Ndombe Province. Nearly 900 Banunu people from four villages were slaughtered by members of the Batende community in a deep-rooted rivalry over monthly tribal duties, land, fields and water resources. Some 100 Banunus fled to Moniende island in the Congo River, and another 16,000 to Makotimpoko District in Republic of Congo. Military-style tactics were employed in the bloodbath, and some assailants were clothed in army uniforms. Local authorities and elements within the security forces were suspected of lending them support.[97]

2018 election and new president (2018–present)

[edit]

On 30 December 2018 a general election was held. On 10 January 2019, the electoral commission announced opposition candidate Félix Tshisekedi as the winner of the presidential vote,[98] and he was officially sworn in as president on 24 January.[99] However, there were widespread suspicions that the results were rigged and that a deal had been made between Tshisekedi and Kabila. The Catholic Church said that the official results did not correspond to the information its election monitors had collected.[100] The government had also "delayed" the vote until March in some areas, citing the Ebola outbreak in Kivu as well as the ongoing military conflict. This was criticized as these regions are known as opposition strongholds.[101][102][103] In August 2019, six months after the inauguration of Félix Tshisekedi, a coalition government was announced.[104]

The political allies of Kabila maintained control of key ministries, the legislature, judiciary and security services. However, Tshisekedi succeeded in strengthening his hold on power. In a series of moves, he won over more legislators, gaining the support of almost 400 out of 500 members of the National Assembly. The pro-Kabila speakers of both houses of parliament were forced out. In April 2021, the new government was formed without the supporters of Kabila.[105]

A major measles outbreak in the country left nearly 5,000 dead in 2019.[106] The Ebola outbreak ended in June 2020, which had caused 2,280 deaths over 2 years.[107] Another, smaller Ebola outbreak in the Équateur Province began in June 2020, ultimately causing 55 deaths.[108][109] The global COVID-19 pandemic also reached the DRC in March 2020, with a vaccination campaign beginning on 19 April 2021.[110][111]

The Italian ambassador to the DRC, Luca Attanasio, and his bodyguard were killed in North Kivu on 22 February 2021.[112] On 22 April 2021, meetings between Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta and Tshisekedi resulted in new agreements increasing international trade and security (counterterrorism, immigration, cyber security, and customs) between the two countries.[113] In February 2022, allegations of a coup d'état in the country led to uncertainty,[114] but the coup attempt failed.[115]

After the 2023 presidential election, Tshisekedi had a clear lead in his run for a second term.[116] On 31 December 2023, officials said that President Felix Tshisekedi had been re-elected with 73% of the vote. Nine opposition candidates signed a declaration rejecting the election and called for a rerun.[117]

In May 2024, during a parliamentary crisis related to the election for the leadership of parliament, Christian Malanga led an attempted coup which was repelled by security forces loyal to President Félix Tshisekedi.[118][119][120] Three belligerents reportedly carrying US passports were arrested by security forces,[121] and videos of their capture shared online.

Geography

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2017) |

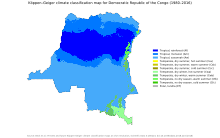

The DRC is located in central sub-Saharan Africa, bordered to the northwest by the Republic of the Congo, to the north by the Central African Republic, to the northeast by South Sudan, to the east by Uganda, Rwanda and Burundi, and by Tanzania (across Lake Tanganyika), to the south and southeast by Zambia, to the southwest by Angola, and to the west by the South Atlantic Ocean and the Cabinda Province exclave of Angola. The country lies between latitudes 6°N and 14°S, and longitudes 12°E and 32°E. It straddles the Equator, with one-third to the north and two-thirds to the south. With an area of 2,345,408 square kilometres (905,567 sq mi), it is the second-largest country in Africa by area, after Algeria.

As a result of its equatorial location, the DRC experiences high precipitation and has the highest frequency of thunderstorms in the world. The annual rainfall can total upwards of 2,000 millimetres (80 in) in some places, and the area sustains the Congo rainforest, the second-largest rain forest in the world after the Amazon rainforest. This massive expanse of lush jungle covers most of the vast, low-lying central basin of the river, which slopes toward the Atlantic Ocean in the west. This area is surrounded by plateaus merging into savannas in the south and southwest, by mountainous terraces in the west, and dense grasslands extending beyond the Congo River in the north. The glaciated Rwenzori Mountains are found in the extreme eastern region.

The tropical climate produced the Congo River system which dominates the region topographically along with the rainforest it flows through. The Congo Basin occupies nearly the entire country and an area of nearly 1,000,000 km2 (390,000 sq mi). The river and its tributaries form the backbone of Congolese economics and transportation. Major tributaries include the Kasai, Sangha, Ubangi, Ruzizi, Aruwimi, and Lulonga.

The Congo River has the second-largest flow and the second-largest watershed of any river in the world (trailing the Amazon in both respects). The sources of the Congo River are in the Albertine Rift Mountains that flank the western branch of the East African Rift, as well as Lake Tanganyika and Lake Mweru. The river flows generally west from Kisangani just below Boyoma Falls, then gradually bends southwest, passing by Mbandaka, joining with the Ubangi River, and running into the Pool Malebo (Stanley Pool). Kinshasa and Brazzaville are on opposite sides of the river at the Pool. Then the river narrows and falls through a number of cataracts in deep canyons, collectively known as the Livingstone Falls, and runs past Boma into the Atlantic Ocean. The river and a 37-kilometre-wide (23 mi) strip of coastline on its north bank provide the country's only outlet to the Atlantic.

The Albertine Rift plays a key role in shaping the Congo's geography. Not only is the northeastern section of the country much more mountainous, but tectonic movement results in volcanic activity, occasionally with loss of life. The geologic activity in this area also created the African Great Lakes, four of which lie on the Congo's eastern frontier: Lake Albert, Lake Kivu, Lake Edward, and Lake Tanganyika.

The rift valley has exposed an enormous amount of mineral wealth throughout the south and east of the Congo, making it accessible to mining. Cobalt, copper, cadmium, industrial and gem-quality diamonds, gold, silver, zinc, manganese, tin, germanium, uranium, radium, bauxite, iron ore, and coal are all found in plentiful supply, especially in the Congo's southeastern Katanga region.[122]

On 17 January 2002, Mount Nyiragongo erupted, with three streams of extremely fluid lava running out at 64 km/h (40 mph) and 46 m (50 yd) wide. One of the three streams flowed directly through Goma, killing 45 people and leaving 120,000 homeless. Over 400,000 people were evacuated from the city during the eruption. The lava flowed into and poisoned the water of Lake Kivu killing its plants, animals and fish. Only two planes left the local airport because of the possibility of the explosion of stored petrol. The lava flowed through and past the airport, destroying a runway and trapping several parked airplanes. Six months after the event, nearby Mount Nyamuragira also erupted. The mountain subsequently erupted again in 2006, and once again in January 2010.[123]

Biodiversity and conservation

[edit]

The rainforests of the Democratic Republic of the Congo contain great biodiversity, including many rare and endemic species, such as the common chimpanzee and the bonobo (or pygmy chimpanzee), the African forest elephant, mountain gorilla, okapi, forest buffalo, leopard and, further south in the country, the southern white rhinoceros. Five of the country's national parks are listed as World Heritage Sites: the Garumba, Kahuzi-Biega, Salonga and Virunga National Parks, and the Okapi Wildlife Reserve. The Democratic Republic of the Congo is one of 17 Megadiverse countries and is the most biodiverse African country.[124]

Conservationists have particularly worried about primates. The Congo is inhabited by several great ape species: the common chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes), the bonobo (Pan paniscus), the eastern gorilla (Gorilla beringei), and possibly a population of the western gorilla (Gorilla gorilla).[125] It is the only country in the world in which bonobos are found in the wild. Much concern has been raised about great ape extinction. Because of hunting and habitat destruction, the numbers of chimpanzee, bonobo and gorilla (each of whose populations once numbered in the millions) have now dwindled down to only about 200,000 gorillas, 100,000 chimpanzees and possibly only about 10,000 bonobos.[126][127] The gorillas, chimpanzee, bonobo, and okapi are all classified as endangered by the World Conservation Union.

Major environmental issues in DRC include deforestation, poaching, which threatens wildlife populations, water pollution and mining. From 2015 to 2019, the rate of deforestation in the Democratic Republic of the Congo doubled.[128] In 2021, deforestation of the Congolian rainforests increased by 5%.[129]

Government and politics

[edit]

After a four-year interlude between two constitutions, with new political institutions established at the various levels of government, as well as new administrative divisions for the provinces throughout the country, a new constitution came into effect in 2006 and politics in the Democratic Republic of the Congo finally settled into a stable presidential democratic republic.The 2003 transitional constitution[130] had established a parliament with a bicameral legislature, consisting of a Senate and a National Assembly.

The Senate had, among other things, the charge of drafting the new constitution of the country. The executive branch was vested in a 60-member cabinet, headed by a President and four vice presidents. The President was also the Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces. The transitional constitution also established a relatively independent judiciary, headed by a Supreme Court with constitutional interpretation powers.[131]

The 2006 constitution, also known as the Constitution of the Third Republic, came into effect in February 2006. It had concurrent authority, however, with the transitional constitution until the inauguration of the elected officials who emerged from the July 2006 elections. Under the new constitution, the legislature remained bicameral; the executive was concomitantly undertaken by a President and the government, led by a Prime Minister, appointed from the party able to secure a majority in the National Assembly.

The government – not the President – is responsible to the Parliament. The new constitution also granted new powers to the provincial governments, creating provincial parliaments which have oversight of the Governor and the head of the provincial government, whom they elect. The new constitution also saw the disappearance of the Supreme Court, which was divided into three new institutions. The constitutional interpretation prerogative of the Supreme Court is now held by the Constitutional Court.[132]

Although located in the Central African UN subregion, the nation is also economically and regionally affiliated with Southern Africa as a member of the Southern African Development Community (SADC).[133]

Administrative divisions

[edit]The country is currently divided into the city-province of Kinshasa and 25 other provinces.[2] The provinces are subdivided into 145 territories and 33 cities. Before 2015, the country had 11 provinces.[134]

| 1. Kinshasa | 14. Ituri Province |

| 2. Kongo Central | 15. Haut-Uele | |

| 3. Kwango | 16. Tshopo | |

| 4. Kwilu Province | 17. Bas-Uele | |

| 5. Mai-Ndombe Province | 18. Nord-Ubangi | |

| 6. Kasaï Province | 19. Mongala | |

| 7. Kasaï-Central | 20. Sud-Ubangi | |

| 8. Kasaï-Oriental | 21. Équateur | |

| 9. Lomami Province | 22. Tshuapa | |

| 10. Sankuru | 23. Tanganyika Province | |

| 11. Maniema | 24. Haut-Lomami | |

| 12. South Kivu | 25. Lualaba Province | |

| 13. North Kivu | 26. Haut-Katanga Province |

Foreign relations

[edit]

The global growth in demand for scarce raw materials and the industrial surges in China, India, Russia, Brazil and other developing countries require that developed countries employ new, integrated and responsive strategies for identifying and ensuring, on a continual basis, an adequate supply of strategic and critical materials required for their security needs.[135] Highlighting the DR Congo's importance to United States national security, the effort to establish an elite Congolese unit is the latest push by the U.S. to professionalize armed forces in this "strategically important" region.[136]

There are economic and strategic incentives (for external countries) to bring more "security" to the Congo, which is rich in natural resources such as cobalt, a metal used in many industrial and military applications.[135] The largest use of cobalt is in superalloys, used to make jet engine parts for high speed war planes. Cobalt is also used in magnetic alloys and in cutting and wear-resistant materials such as cemented carbides. The chemical industry consumes significant quantities of cobalt in a variety of applications including catalysts for petroleum and chemical processing; drying agents for paints and inks; ground coats for porcelain enamels; decolorant for ceramics and glass; and pigments for ceramics, paints, and plastics. The country possesses 80% of the world's cobalt reserves.[137]

It is thought that due to the importance of cobalt for batteries for electric vehicles and stabilization of electric grids with large proportions of intermittent renewables in the electricity mix, the DRC could become an object of increased geopolitical competition.[135]

In the 21st century, Chinese investment in the DRC and Congolese exports to China have grown rapidly. In July 2019, UN ambassadors of 37 countries, including DRC, have signed a joint letter to the UNHRC defending China's treatment of Uyghurs and other Muslim ethnic minorities.[138] In 2021, President Félix Tshisekedi called for a review of mining contracts signed with China by his predecessor Joseph Kabila,[139] in particular the Sicomines multibillion 'minerals-for-infrastructure' deal.[140][141]

Military

[edit]

The military of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, known as the FARDC, consists of the Land Forces, the Air Force, and the Navy.

The FARDC was established in 2003 after the end of the Second Congo War and integrated many former rebel groups into its ranks. Due to the presence of undisciplined and poorly trained ex-rebels, as well as a lack of funding and having spent years fighting against different militias, the FARDC suffers from rampant corruption and inefficiency. The agreements signed at the end of the Second Congo War called for a new "national, restructured and integrated" army that would be made up of Kabila's government forces (the FAC), the RCD, and the MLC. Also stipulated was that rebels like the RCD-N, RCD-ML, and the Mai-Mai would become part of the new armed forces. It also provided for the creation of a Conseil Supérieur de la Défense (Superior Defence Council) which would declare states of siege or war and give advice on security sector reform, disarmament/demobilisation, and national defence policy. The FARDC is organised on the basis of brigades, which are dispersed throughout the provinces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Congolese troops have been fighting the Kivu conflict in the eastern North Kivu region, the Ituri conflict in the Ituri region, and other rebellions since the Second Congo War. Besides the FARDC, the largest peacekeeping mission of the United Nations, known as MONUSCO, is also present in the country with about 18,000 peacekeepers.

The Democratic Republic of Congo signed the UN treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.[142]

Law enforcement and crime

[edit]The Congolese National Police are the primary police force in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.[143]

Corruption

[edit]A relative of Mobutu explained how the government illicitly collected revenue during his rule: "Mobutu would ask one of us to go to the bank and take out a million. We'd go to an intermediary and tell him to get five million. He would go to the bank with Mobutu's authority and take out ten. Mobutu got one, and we took the other nine."[144] Mobutu institutionalized corruption to prevent political rivals from challenging his control, leading to an economic collapse in 1996.[145]

Mobutu allegedly amassed between US$50 million and $125 million during his rule.[146][147] He was not the first corrupt Congolese leader by any means: "Government as a system of organized theft goes back to King Leopold II," noted Adam Hochschild in 2009.[148] In July 2009, a Swiss court determined that the statute of limitations had run out on an international asset recovery case of about $6.7 million of deposits of Mobutu's in a Swiss bank, and therefore the assets should be returned to Mobutu's family.[149]

President Kabila established the Commission of Repression of Economic Crimes upon his ascension to power in 2001.[150] However, in 2016 the Enough Project issued a report claiming that the Congo is run as a violent kleptocracy.[151]

In June 2020, a court in the Democratic Republic of Congo found President Tshisekedi's chief of staff Vital Kamerhe guilty of corruption. He was sentenced to 20 years' hard labour, after facing charges of embezzling almost $50m (£39m) of public funds. He was the most high-profile figure to be convicted of corruption in the DRC.[152] However, Kamerhe was released already in December 2021.[153]

In November 2021, a judicial investigation targeting Kabila and his associates was opened in Kinshasa after revelations of alleged embezzlement of $138 million.[154]

Human rights

[edit]

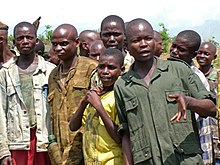

The International Criminal Court investigation in the Democratic Republic of the Congo was initiated by Kabila in April 2004. The International Criminal Court prosecutor opened the case in June 2004. Child soldiers have been used on a large scale in DRC, and in 2011 it was estimated that 30,000 children were still operating with armed groups.[155] Instances of child labor and forced labor have been observed and reported in the U.S. Department of Labor's Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor in the DRC in 2013[156] and six goods produced by the country's mining industry appear on the department's December 2014 List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo has prohibited same-sex marriage since 2006,[157] and attitudes towards the LGBT community are generally negative throughout the nation.[158]Violence against women seems to be perceived by large sectors of society to be normal.[159] The 2013–2014 DHS survey (pp. 299) found that 74.8% of women agreed that a husband is justified in beating his wife in certain circumstances.[160] The United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women in 2006 expressed concern that in the post-war transition period, the promotion of women's human rights and gender equality is not seen as a priority.[161][162] Mass rapes, sexual violence and sexual slavery are used as a weapon of war by the Armed Forces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and armed groups in the eastern part of the country.[163] The eastern part of the country in particular has been described as the "rape capital of the world" and the prevalence of sexual violence there described as the worst in the world.[164][165]

Female genital mutilation (FGM) is also practiced in DRC, although not on a large scale. The prevalence of FGM is estimated at 5% of women.[166][167] FGM is illegal: the law imposes a penalty of two to five years of prison and a fine of 200,000 Congolese francs on any person who violates the "physical or functional integrity" of the genital organs.[168][169]

In July 2007, the International Committee of the Red Cross expressed concern about the situation in eastern DRC.[170] A phenomenon of "pendulum displacement" has developed, where people hasten at night to safety. According to Yakin Ertürk, the UN Special Rapporteur on Violence against Women who toured eastern Congo in July 2007, violence against women in North and South Kivu included "unimaginable brutality". Ertürk added that "Armed groups attack local communities, loot, rape, kidnap women and children, and make them work as sexual slaves".[171] In December 2008, GuardianFilms of The Guardian released a film documenting the testimony of over 400 women and girls who had been abused by marauding militia.[172] In June 2010, Oxfam reported a dramatic increase in the number of rapes in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and researchers from Harvard discovered that rapes committed by civilians had increased seventeenfold.[173] In June 2014, Freedom from Torture published reported rape and sexual violence being used routinely by state officials in Congolese prisons as punishment for politically active women.[174] The women included in the report were abused in several locations across the country including the capital Kinshasa and other areas away from the conflict zones.[174] In 2015, figures both inside and outside of the country, such as Filimbi and Emmanuel Weyi, spoke out about the need to curb violence and instability as the 2016 elections approached.[175][176]

Economy

[edit]

The Central Bank of the Congo is responsible for developing and maintaining the Congolese franc, which serves as the primary form of currency in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. In 2007, The World Bank decided to grant the Democratic Republic of Congo up to $1.3 billion in assistance funds over the following three years.[177] The Congolese government started negotiating membership in the Organization for the Harmonization of Business Law in Africa (OHADA), in 2009.[178]

The DRC is widely considered one of the world's richest countries in natural resources; its untapped deposits of raw minerals are estimated to be worth in excess of US$24 trillion.[179][180][181] The DRC has 70% of the world's coltan, a third of its cobalt, more than 30% of its diamond reserves, and a tenth of its copper.[182][183]

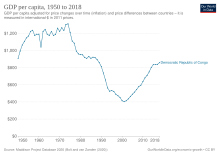

Despite such vast mineral wealth, the economy of the Democratic Republic of the Congo has declined drastically since the mid-1980s. The DRC generated up to 70% of its export revenue from minerals in the 1970s and 1980s and was particularly hit when resource prices deteriorated at that time. By 2005, 90% of the DRC's revenues derived from its minerals.[184] Congolese citizens are among the poorest people on Earth. In 2023, 60% of Congolese subsisted on less than $2.15 a day, and food-price inflation had reached 173%.[185] DR Congo consistently has the lowest, or nearly the lowest, nominal GDP per capita in the world. The DRC is also one of the twenty lowest-ranked countries on the Corruption Perceptions Index.

Mining

[edit]

The DRC is the world's largest producer of cobalt ore, and a major producer of copper and diamonds.[186] As of 2023, the country is estimated to possess around 70% of the world's cobalt production.[185] Diamonds come from Kasaï Province in the west. By far the largest mines in the DRC are located in southern Katanga Province and are highly mechanized, with a capacity of several million tons per year of copper and cobalt ore, and refining capability for metal ore. The DRC is the second-largest diamond-producing nation in the world,[c] and artisanal and small-scale miners account for most of its production.

At independence in 1960, DRC was the second-most-industrialized country in Africa after South Africa; it boasted a thriving mining sector and a relatively productive agriculture sector.[187] Foreign businesses have curtailed operations because of uncertainty about the outcome of long-term conflicts, lack of infrastructure, and the difficult operating environment. The wars intensified the impact of such basic problems as an uncertain legal framework, corruption, inflation, and lack of openness in government economic policy and financial operations.

Conditions improved in late 2002, when a large portion of the invading foreign troops withdrew. A number of International Monetary Fund and World Bank missions met with the government to help it develop a coherent economic plan, and President Kabila began implementing reforms. Much economic activity still lies outside the GDP data. Through 2011 the DRC had the lowest Human Development Index of the 187 ranked countries.[188]

The economy of DRC relies heavily on mining. However, the smaller-scale economic activity from artisanal mining occurs in the informal sector and is not reflected in GDP data.[189] A third of the DRC's diamonds are believed to be smuggled out of the country, making it difficult to quantify diamond production levels.[190] In 2002, tin was discovered in the east of the country but to date has only been mined on a small scale.[191] Smuggling of conflict minerals such as coltan and cassiterite, ores of tantalum and tin, respectively, helped to fuel the war in the eastern Congo.[192]

Katanga Mining Limited, a Swiss-owned company, owns the Luilu Metallurgical Plant, which has a capacity of 175,000 tonnes of copper and 8,000 tonnes of cobalt per year, making it the largest cobalt refinery in the world. After a major rehabilitation program, the company resumed copper production operations in December 2007 and cobalt production in May 2008.[193]

In April 2013, anti-corruption NGOs revealed that Congolese tax authorities had failed to account for $88 million from the mining sector, despite booming production and positive industrial performance. The missing funds date from 2010 and tax bodies should have paid them into the central bank.[194] Later in 2013, the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative suspended the country's candidacy for membership due to insufficient reporting, monitoring and independent audits, but in July 2013 the country improved its accounting and transparency practices to the point where the EITI gave the country full membership.

In February 2018, global asset management firm AllianceBernstein[195] defined the DRC as economically "the Saudi Arabia of the electric vehicle age," because of its cobalt resources, as essential to the lithium-ion batteries that drive electric vehicles.[196]

Transportation

[edit]

Ground transport in the Democratic Republic of Congo has always been difficult. The terrain and climate of the Congo Basin present serious barriers to road and rail construction, and the distances are enormous across this vast country. The DRC has more navigable rivers and moves more passengers and goods by boat and ferry than any other country in Africa, but air transport remains the only effective means of moving goods and people between many places within the country, especially in rural areas. Chronic economic mismanagement, political corruption and internal conflicts have led to long-term under-investment of infrastructure.[citation needed]

Rail transportation is provided by the Congo Railroad Company (Société nationale des chemins de fer du Congo), the Office National des Transports Congo and the Office of the Uele Railways (Office des Chemins de fer des Ueles, CFU).

The DRC has fewer all-weather paved highways than any country of its population and size in Africa — a total of 2,250 km (1,400 mi), of which only 1,226 km (762 mi) is in good condition. To put this in perspective, the road distance across the country in any direction is more than 2,500 km (1,600 mi) (e.g. Matadi to Lubumbashi, 2,700 km (1,700 mi) by road). The figure of 2,250 km (1,400 mi) converts to 35 km (22 mi) of paved road per one million of population. Comparative figures for Zambia and Botswana are 721 km (448 mi) and 3,427 km (2,129 mi), respectively.[d] Three routes in the Trans-African Highway network pass through DR Congo:

- Tripoli–Cape Town Highway: this route crosses the western extremity of the country on National Road No. 1 between Kinshasa and Matadi, a distance of 285 km (177 mi) on one of the only paved sections in fair condition.

- Lagos–Mombasa Highway: the DR Congo is the main missing link in this east–west highway and requires a new road to be constructed before it can function.

- Beira–Lobito Highway: this east–west highway crosses Katanga and requires re-construction over most of its length, being an earth track between the Angolan border and Kolwezi, a paved road in very poor condition between Kolwezi and Lubumbashi, and a paved road in fair condition over the short distance to the Zambian border.

The DRC has thousands of kilometres of navigable waterways. Traditionally water transport has been the dominant means of moving around in approximately two-thirds of the country.

As of February 2024[update], DR Congo had one major national airline (Congo Airways) that offered flights inside DR Congo. Congo Airways was based at Kinshasa's international airport. All air carriers certified by the DRC have been banned from European Union airports by the European Commission, because of inadequate safety standards.[197]

Several international airlines service Kinshasa's international airport and a few also offer international flights to Lubumbashi International Airport.

Energy

[edit]Both coal and crude oil resources were mainly used domestically up to 2008. The DRC has the infrastructure for hydro-electricity from the Congo River at the Inga dams.[198] The country also possesses 50% of Africa's forests and a river system that could provide hydro-electric power to the entire continent, according to a UN report on the country's strategic significance and its potential role as an economic power in central Africa.[199]The generation and distribution of electricity are controlled by Société nationale d'électricité, but only 15% of the country has access to electricity.[200] The DRC is a member of three electrical power pools. These are Southern African Power Pool, East African Power Pool, and Central African Power Pool.

Because of abundant sunlight, the potential for solar development is very high in the DRC. There are already about 836 solar power systems in the DRC, with a total power of 83 MW, located in Équateur (167), Katanga (159), Nord-Kivu (170), the two Kasaï provinces (170), and Bas-Congo (170). Also, the 148 Caritas network system has a total power of 6.31 MW.[201]

Demographics

[edit]Population

[edit]

The CIA World Factbook estimated the population to be over 105 million as of 2024.[202] Between 1950 and 2000, the country's population nearly quadrupled from 12.2 million to 46.9 million.[203]

Ethnic groups

[edit]Over 250 ethnic groups and 450 tribes (ethnic subgroups) populate the DRC. They are in the Bantu, Sudanic, Nilotic, Ubangian and Pygmy linguistic groups. Because of this diversity, there is no dominant ethnic group in the Congo, however the following ethnic groups account for 51.5% of the population:[12]

In 2021, the UN estimated the country's population to be 96 million,[204][205] a rapid increase from 39.1 million in 1992 despite the ongoing war.[206] As many as 250 ethnic groups have been identified and named. About 600,000 Pygmies live in the DRC.[207]

Largest cities

[edit]| Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Kinshasa  Mbuji-Mayi | 1 | Kinshasa | Kinshasa | 15,628,000 |  Lubumbashi  Kisangani | ||||

| 2 | Mbuji-Mayi | Kasai-Oriental | 2,765,000 | ||||||

| 3 | Lubumbashi | Haut-Katanga | 2,695,000 | ||||||

| 4 | Kisangani | Tshopo | 1,640,000 | ||||||

| 5 | Kananga | Kasaï-Central | 1,593,000 | ||||||

| 6 | Mbandaka | Équateur | 1,188,000 | ||||||

| 7 | Bukavu | South Kivu | 1,190,000 | ||||||

| 8 | Tshikapa | Kasaï | 1,024,000 | ||||||

| 9 | Bunia | Ituri | 768,000 | ||||||

| 10 | Goma | North Kivu | 707,000 | ||||||

Migration

[edit]

Given the often unstable situation in the country and the condition of state structures, it is extremely difficult to obtain reliable migration data. However, evidence suggests that DRC continues to be a destination country for immigrants, in spite of recent declines in their numbers. Immigration is very diverse in nature; refugees and asylum-seekers – products of the numerous and violent conflicts in the Great Lakes Region – constitute an important subset of the population. Additionally, the country's large mine operations attract migrant workers from Africa and beyond. There is also considerable migration for commercial activities from other African countries and the rest of the world, but these movements are not well studied.[210] Transit migration towards South Africa and Europe also plays a role.

Immigration to the DRC has decreased steadily over the past two decades, most likely as a result of the armed violence that the country has experienced. According to the International Organization for Migration, the number of immigrants in the DRC has fallen from just over one million in 1960, to 754,000 in 1990, to 480,000 in 2005, to an estimated 445,000 in 2010. Official figures are unavailable, partly due to the predominance of the informal economy in the DRC. Data are also lacking on irregular immigrants, however given neighbouring countries' ethnic links to DRC nationals, irregular migration is assumed to be a significant phenomenon.[210]

Figures for Congolese nationals abroad vary greatly depending on the source, from three to six million. This discrepancy is due to a lack of official, reliable data. Emigrants from the DRC are above all long-term emigrants, the majority of whom live in Africa and to a lesser extent in Europe; 79.7% and 15.3% respectively, according to estimated 2000 data. New destination countries include South Africa and various points en route to Europe. The DRC has produced a considerable number of refugees and asylum-seekers located in the region and beyond. These numbers peaked in 2004 when, according to UNHCR, there were more than 460,000 refugees from the DRC; in 2008, Congolese refugees numbered 367,995 in total, 68% of whom were living in other African countries.[210]

Since 2003, more than 400,000 Congolese migrants have been expelled from Angola.[211]

Languages

[edit]

French is the official language of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. It is culturally accepted as the lingua franca, facilitating communication among the many different ethnic groups of the Congo. According to a 2018 OIF report, 49 million Congolese people (51% of the population) could read and write in French.[212] A 2021 survey found that 74% of the population could speak French, making it the most widely spoken language in the country.[213]

In Kinshasa, 67% of the population in 2014 could read and write French, and 68.5% could speak and understand it.[214]

Approximately 242 languages are spoken in the country, of which four have the status of national languages: Kituba (Kikongo), Lingala, Tshiluba, and Swahili (Congo Swahili). Although some limited number of people speak these as first languages, most of the population speak them as a second language, after the native language of their own ethnic group. Lingala was the official language of the Force Publique under Belgian colonial rule and remains to this day the predominant language of the armed forces. Since the recent rebellions, a good part of the army in the east also uses Swahili, where it competes to be the regional lingua franca .

Under Belgian rule, the Belgians instituted teaching and use of the four national languages in primary schools, making it one of the few African nations to have had literacy in local languages during the European colonial period. This trend was reversed after independence, when French became the sole language of education at all levels.[215] Since 1975, the four national languages have been reintroduced in the first two years of primary education, with French becoming the sole language of education from the third year onward, but in practice many primary schools in urban areas solely use French from the first year of school onward.[215] Portuguese is taught in the Congolese schools as a foreign language. The lexical similarity and phonology with French makes Portuguese a relatively easy language for the people to learn. Most of the roughly 175,000 Portuguese speakers in the DRC are Angolan and Mozambican expatriates.

Religion

[edit]

Christianity is the predominant religion of the DRC. A 2013–14 survey, conducted by the Demographic and Health Surveys Program in 2013–2014 indicated that Christians constituted 93.7% of the population (with Catholics making up 29.7%, Protestants 26.8%, and other Christians 37.2%). A new Christian religious movement, Kimbanguism, had the adherence of 2.8%, while Muslims made up 1%.[216] Other recent estimates have found Christianity the majority religion, followed by 95.8% of the population according to a 2010 Pew Research Center[217] estimate, while the CIA World Factbook reports this figure to be 95.9%.[218] The proportion of followers of Islam is variously estimated from 1%[219] to 12%.[220]

There are about 35 million Catholics in the country[2] with six archdioceses and 41 dioceses.[221] The impact of the Catholic Church is difficult to overestimate. Schatzberg has called it the country's "only truly national institution apart from the state."[222] Its schools have educated over 60% of the nation's primary school students and more than 40% of its secondary students. The church owns and manages an extensive network of hospitals, schools, and clinics, as well as many diocesan economic enterprises, including farms, ranches, stores, and artisans' shops.[citation needed]

Sixty-two Protestant denominations are federated under the umbrella of the Church of Christ in the Congo. It is often referred to as the Protestant Church, since it covers most of the DRC Protestants. With more than 25 million members, it constitutes one of the largest Protestant bodies in the world.

Kimbanguism was seen as a threat to the colonial regime and was banned by the Belgians. Kimbanguism, officially "the church of Christ on Earth by the prophet Simon Kimbangu", has about three million members,[223] primarily among the Bakongo of Kongo Central and Kinshasa.

Islam has been present in the Democratic Republic of the Congo since the 18th century, when Arab traders from East Africa pushed into the interior for ivory- and slave-trading purposes. Today, Muslims constitute approximately 1% of the Congolese population according to the Pew Research Center. The majority are Sunni Muslims.[citation needed]

The first members of the Baháʼí Faith to live in the country came from Uganda in 1953. Four years later the first local administrative council was elected. In 1970 the National Spiritual Assembly (national administrative council) was first elected. Though the religion was banned in the 1970s and 1980s, due to misrepresentations of foreign governments, the ban was lifted by the end of the 1980s. In 2012 plans were announced to build a national Baháʼí House of Worship in the country.[citation needed]

Traditional religions embody such concepts as monotheism, animism, vitalism, spirit and ancestor worship, witchcraft, and sorcery and vary widely among ethnic groups. The syncretic sects often merge elements of Christianity with traditional beliefs and rituals and are not recognized by mainstream churches as part of Christianity. New variants of ancient beliefs have become widespread, led by US-inspired Pentecostal churches which have been in the forefront of witchcraft accusations, particularly against children and the elderly.[clarification needed][224] Children accused of witchcraft are sent away from homes and family, often to live on the street, which can lead to physical violence against these children.[225][clarification needed][226] There are charities supporting street children such as the Congo Children Trust.[227] The Congo Children Trust's flagship project is Kimbilio,[228] which works to reunite street children in Lubumbashi. The usual term for these children is enfants sorciers (child witches) or enfants dits sorciers (children accused of witchcraft). Non-denominational church organizations have been formed to capitalize on this belief by charging exorbitant fees for exorcisms. Though recently outlawed, children have been subjected in these exorcisms to often-violent abuse at the hands of self-proclaimed prophets and priests.[229]

Education

[edit]

In 2014, the literacy rate for the population between the ages of 15 and 49 was estimated to be 75.9% (88.1% male and 63.8% female) according to a DHS nationwide survey.[230] The education system is governed by three government ministries: the Ministère de l'Enseignement Primaire, Secondaire et Professionnel (MEPSP), the Ministère de l'Enseignement Supérieur et Universitaire (MESU) and the Ministère des Affaires Sociales (MAS). Primary education is not free nor compulsory,[citation needed] even though the Congolese constitution says it should be (Article 43 of the 2005 Congolese Constitution).[231]

As a result of the First and Second Congo Wars in the late 1990s—early 2000s, over 5.2 million children in the country did not receive any education.[232] Since the end of the civil war, the situation has improved tremendously, with the number of children enrolled in primary schools rising from 5.5 million in 2002 to 16.8 million in 2018, and the number of children enrolled in secondary schools rising from 2.8 million in 2007 to 4.6 million in 2015 according to UNESCO.[233]

Actual school attendance has also improved greatly in recent years, with primary school net attendance estimated to be 82.4% in 2014 (82.4% of children ages 6–11 attended school; 83.4% for boys, 80.6% for girls).[234]

Health

[edit]

The hospitals in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) include the General Hospital of Kinshasa. The DRC has the world's second-highest rate of infant mortality (after Chad). In April 2011, through aid from Global Alliance for Vaccines, a new vaccine to prevent pneumococcal disease was introduced around Kinshasa.[235] In 2012, it was estimated that about 1.1% of adults aged 15–49 were living with HIV/AIDS.[236] Malaria[237][238] and yellow fever are problems.[239] In May 2019, the death toll from the Ebola outbreak in DRC surpassed 1,000.[240]

The incidence of yellow fever-related fatalities in DRC is relatively low. According to the World Health Organization's (WHO) report in 2021, only two individuals died due to yellow fever in DRC.[241]

According to the World Bank Group, in 2016, 26,529 people died on the roads in DRC due to traffic accidents.[242]

Maternal health is poor in DRC. According to 2010 estimates, DRC has the 17th highest maternal mortality rate in the world.[243] According to UNICEF, 43.5% of children under five are stunted.[244]

United Nations emergency food relief agency warned that amid the escalating conflict and worsening situation following COVID-19 in the DRC, millions of lives were at risk as they could die of hunger. According to the data of the World Food Programme, in 2020 four in ten people in Congo lacked food security and about 15.6 million were facing a potential hunger crisis.[245]

Air pollution levels in the Democratic Republic of the Congo are very unhealthy. In 2020, annual average air pollution in the DRC stood at 34.2 μg/m3, which is almost 6.8 times the World Health Organization PM2.5 guideline (5 μg/m3: set in September 2021).[246] These pollution levels are estimated to reduce the life expectancy of an average citizen of the DRC by almost 2.9 years.[246] Currently, the DRC does not have a national ambient air quality standard.[247]

Culture

[edit]

The culture reflects the diversity of its numerous ethnic groups and their differing ways of life throughout the country—from the mouth of the River Congo on the coast, upriver through the rainforest and savanna in its centre, to the more densely populated mountains in the far east. Since the late 19th century, traditional ways of life have undergone changes brought about by colonialism, the struggle for independence, the stagnation of the Mobutu era, and most recently, the First and Second Congo Wars. Despite these pressures, the customs and cultures of the Congo have retained much of their individuality. The country's 81 million inhabitants (2016) are mainly rural. The 30% who live in urban areas have been the most open to Western influences.

Literature

[edit]Congolese authors use literature as a way to develop a sense of national consciousness amongst the people of the DRC. Frederick Kambemba Yamusangie writes literature for the between generations of those who grew up in the Congo, during the time when they were colonised, fighting for independence and after. Yamusangie in an interview[248] said he felt the distance in literature and wanted to remedy that he wrote the novel, Full Circle, which is a story of a boy named Emanuel who in the beginning of the book feels a difference in culture among the different groups in the Congo and elsewhere.[249] Rais Neza Boneza, an author from the Katanga province, wrote novels and poems to promote artistic expressions as a way to address and deal with conflicts.[250]

Music

[edit]The DRC has a rich musical heritage rooted in traditional rhythms.[251] The earliest known form of popular partnered dance music in Congo was Maringa, denoting a Kongolese dance practiced within the former Kingdom of Loango, encompassing parts of the present-day Republic of the Congo, Southern Gabon and Cabinda.[252] The style gained popularity in the 1920s–1930s, introducing the "bar-dancing" culture in Léopoldville (now Kinshasa), incorporating unique elements like a bass drum, a bottle as a triangle, and an accordion.[253][254]

In the 1940s and 1950s, the influence of Cuban son bands transformed Maringa into "Congolese rumba". Imported records by Sexteto Habanero and Trio Matamoros, often mislabeled as "rumba", played a significant role.[255] Artists such as Antoine Kasongo, Paul Kamba, Henri Bowane, Antoine Wendo Kolosoy, Franco Luambo, Le Grand Kallé, Vicky Longomba, Nico Kasanda, Tabu Ley Rochereau, and Papa Noel Nedule authentically popularized the style and made significant contributions to it in the 1940s and 1950s.[255]

The 1960s and 1970s saw the emergence of soukous, an urban dance music style that evolved from Congolese rumba. Soukous led to diverse offshoots, such as ekonda saccadé, reflecting the Mongo rhythmic influence, and mokonyonyon, emulating pelvic thrust dance movements from the Otetela ethnic background.[255] The same soukous, under the guidance of "le sapeur", Papa Wemba, have set the tone for a generation of young men always dressed up in exorbitant designer clothes. They came to be known as the fourth generation of Congolese music and mostly come from the former prominent band Wenge Musica.[256][257][258][259][260]